испанский язык

| испанский | |

|---|---|

| кастильский | |

| |

| Произношение | [испанский] [кастеэно] , [кастаано] |

| Спикеры | Родной: 500 миллионов (2023 г.) [ 1 ] Итого: 600 миллионов [ 1 ] 100 миллионов говорящих с ограниченной вместимостью (23 миллиона студентов) [ 1 ] |

Early forms | |

| Latin script (Spanish alphabet) Spanish Braille | |

| Signed Spanish (using signs of the local language) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in |

|

| Regulated by | Association of Spanish Language Academies (Real Academia Española and 22 other national Spanish language academies) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | es |

| ISO 639-2 | spa |

| ISO 639-3 | spa |

| Glottolog | stan1288 |

| Linguasphere | 51-AAA-b |

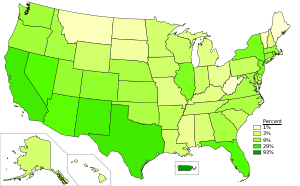

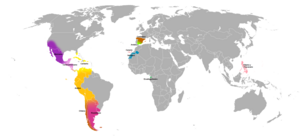

Official majority language

Co-official or administrative language but not majority native language

Secondary language (more than 20% Spanish speakers) or culturally important | |

Испанский ( español ) или кастильский ( castellano ) — романский язык индоевропейской языковой семьи , произошедший от народной латыни, которой говорят на Пиренейском полуострове Европы на . Сегодня это глобальный язык , на котором говорят около 500 миллионов человек, в основном в Америке и Испании , и около 600 миллионов, если учитывать носителей второго языка. [ 4 ] [ 5 ] Испанский язык является официальным языком 20 стран , а также одним из шести официальных языков Организации Объединенных Наций . [ 6 ] [ 7 ] в мире Испанский является вторым по распространенности родным языком после китайского ; [ 5 ] [ 8 ] в мире четвертый по распространенности язык после английского , китайского и хиндустани ( хинди - урду ); и самый распространенный романский язык в мире. Страна с самым большим населением носителей языка — Мексика . [ 9 ]

Spanish is part of the Ibero-Romance language group, in which the language is also known as Castilian (castellano). The group evolved from several dialects of Vulgar Latin in Iberia after the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century. The oldest Latin texts with traces of Spanish come from mid-northern Iberia in the 9th century,[10] and the first systematic written use of the language happened in Toledo, a prominent city of the Kingdom of Castile, in the 13th century. Spanish colonialism in the early modern period spurred the introduction of the language to overseas locations, most notably to the Americas.[11]

As a Romance language, Spanish is a descendant of Latin. Around 75% of modern Spanish vocabulary is Latin in origin, including Latin borrowings from Ancient Greek.[12][13] Alongside English and French, it is also one of the most taught foreign languages throughout the world.[14] Spanish is well represented in the humanities and social sciences.[15] Spanish is also the third most used language on the internet by number of users after English and Chinese[16] and the second most used language by number of websites after English.[17]

Spanish is used as an official language by many international organizations, including the United Nations, European Union, Organization of American States, Union of South American Nations, Community of Latin American and Caribbean States, African Union, among others.[6]

Name of the language and etymology

[edit]Name of the language

[edit]In Spain and some other parts of the Spanish-speaking world, Spanish is called not only español but also castellano (Castilian), the language from the Kingdom of Castile, contrasting it with other languages spoken in Spain such as Galician, Basque, Asturian, Catalan/Valencian, Aragonese, Occitan and other minor languages.

The Spanish Constitution of 1978 uses the term castellano to define the official language of the whole of Spain, in contrast to las demás lenguas españolas (lit. "the other Spanish languages"). Article III reads as follows:

El castellano es la lengua española oficial del Estado. ... Las demás lenguas españolas serán también oficiales en las respectivas Comunidades Autónomas...

Castilian is the official Spanish language of the State. ... The other Spanish languages shall also be official in their respective Autonomous Communities...

The Royal Spanish Academy (Real Academia Española), on the other hand, currently uses the term español in its publications. However, from 1713 to 1923, it called the language castellano.

The Diccionario panhispánico de dudas (a language guide published by the Royal Spanish Academy) states that, although the Royal Spanish Academy prefers to use the term español in its publications when referring to the Spanish language, both terms—español and castellano—are regarded as synonymous and equally valid.[18]

Etymology

[edit]The term castellano is related to Castile (Castilla or archaically Castiella), the kingdom where the language was originally spoken. The name Castile, in turn, is usually assumed to be derived from castillo ('castle').

In the Middle Ages, the language spoken in Castile was generically referred to as Romance and later also as Lengua vulgar.[19] Later in the period, it gained geographical specification as Romance castellano (romanz castellano, romanz de Castiella), lenguaje de Castiella, and ultimately simply as castellano (noun).[19]

Different etymologies have been suggested for the term español (Spanish). According to the Royal Spanish Academy, español derives from the Occitan word espaignol and that, in turn, derives from the Vulgar Latin *hispaniolus ('of Hispania').[20] Hispania was the Roman name for the entire Iberian Peninsula.

There are other hypotheses apart from the one suggested by the Royal Spanish Academy. Spanish philologist Ramón Menéndez Pidal suggested that the classic hispanus or hispanicus took the suffix -one from Vulgar Latin, as happened with other words such as bretón (Breton) or sajón (Saxon).

History

[edit]

Like the other Romance languages, the Spanish language evolved from Vulgar Latin, which was brought to the Iberian Peninsula by the Romans during the Second Punic War, beginning in 210 BC. Several pre-Roman languages (also called Paleohispanic languages)—some distantly related to Latin as Indo-European languages, and some that are not related at all—were previously spoken in the Iberian Peninsula. These languages included Proto-Basque, Iberian, Lusitanian, Celtiberian and Gallaecian.

The first documents to show traces of what is today regarded as the precursor of modern Spanish are from the 9th century. Throughout the Middle Ages and into the modern era, the most important influences on the Spanish lexicon came from neighboring Romance languages—Mozarabic (Andalusi Romance), Navarro-Aragonese, Leonese, Catalan/Valencian, Portuguese, Galician, Occitan, and later, French and Italian. Spanish also borrowed a considerable number of words from Arabic, as well as a minor influence from the Germanic Gothic language through the migration of tribes and a period of Visigoth rule in Iberia. In addition, many more words were borrowed from Latin through the influence of written language and the liturgical language of the Church. The loanwords were taken from both Classical Latin and Renaissance Latin, the form of Latin in use at that time.

According to the theories of Ramón Menéndez Pidal, local sociolects of Vulgar Latin evolved into Spanish, in the north of Iberia, in an area centered in the city of Burgos, and this dialect was later brought to the city of Toledo, where the written standard of Spanish was first developed, in the 13th century.[22] In this formative stage, Spanish developed a strongly differing variant from its close cousin, Leonese, and, according to some authors, was distinguished by a heavy Basque influence (see Iberian Romance languages). This distinctive dialect spread to southern Spain with the advance of the Reconquista, and meanwhile gathered a sizable lexical influence from the Arabic of Al-Andalus, much of it indirectly, through the Romance Mozarabic dialects (some 4,000 Arabic-derived words, make up around 8% of the language today).[23] The written standard for this new language was developed in the cities of Toledo, in the 13th to 16th centuries, and Madrid, from the 1570s.[22]

The development of the Spanish sound system from that of Vulgar Latin exhibits most of the changes that are typical of Western Romance languages, including lenition of intervocalic consonants (thus Latin vīta > Spanish vida). The diphthongization of Latin stressed short e and o—which occurred in open syllables in French and Italian, but not at all in Catalan or Portuguese—is found in both open and closed syllables in Spanish, as shown in the following table:

| Latin | Spanish | Ladino | Aragonese | Asturian | Galician | Portuguese | Catalan | Gascon / Occitan | French | Sardinian | Italian | Romanian | English |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| petra | piedra | pedra | pedra, pèira | pierre | pedra, perda | pietra | piatră | 'stone' | |||||

| terra | tierra | terra | tèrra | terre | terra | țară | 'land' | ||||||

| moritur | muere | muerre | morre | mor | morís | meurt | mòrit | muore | moare | 'dies (v.)' | |||

| mortem | muerte | morte | mort | mòrt | mort | morte, morti | morte | moarte | 'death' | ||||

Spanish is marked by palatalization of the Latin double consonants (geminates) nn and ll (thus Latin annum > Spanish año, and Latin anellum > Spanish anillo).

The consonant written u or v in Latin and pronounced [w] in Classical Latin had probably "fortified" to a bilabial fricative /β/ in Vulgar Latin. In early Spanish (but not in Catalan or Portuguese) it merged with the consonant written b (a bilabial with plosive and fricative allophones). In modern Spanish, there is no difference between the pronunciation of orthographic b and v.

Typical of Spanish (as also of neighboring Gascon extending as far north as the Gironde estuary, and found in a small area of Calabria), attributed by some scholars to a Basque substratum was the mutation of Latin initial f into h- whenever it was followed by a vowel that did not diphthongize. The h-, still preserved in spelling, is now silent in most varieties of the language, although in some Andalusian and Caribbean dialects, it is still aspirated in some words. Because of borrowings from Latin and neighboring Romance languages, there are many f-/h- doublets in modern Spanish: Fernando and Hernando (both Spanish for "Ferdinand"), ferrero and herrero (both Spanish for "smith"), fierro and hierro (both Spanish for "iron"), and fondo and hondo (both words pertaining to depth in Spanish, though fondo means "bottom", while hondo means "deep"); additionally, hacer ("to make") is cognate to the root word of satisfacer ("to satisfy"), and hecho ("made") is similarly cognate to the root word of satisfecho ("satisfied").

Compare the examples in the following table:

| Latin | Spanish | Ladino | Aragonese | Asturian | Galician | Portuguese | Catalan | Gascon / Occitan | French | Sardinian | Italian | Romanian | English |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| filium | hijo | fijo (or hijo) | fillo | fíu | fillo | filho | fill | filh, hilh | fils | fizu, fìgiu, fillu | figlio | fiu | 'son' |

| facere | hacer | fazer | fer | facer | fazer | fer | far, faire, har (or hèr) | faire | fàghere, fàere, fàiri | fare | a face | 'to do' | |

| febrem | fiebre (calentura) | febre | fèbre, frèbe, hrèbe (or herèbe) |

fièvre | calentura | febbre | febră | 'fever' | |||||

| focum | fuego | fueu | fogo | foc | fuòc, fòc, huèc | feu | fogu | fuoco | foc | 'fire' | |||

Some consonant clusters of Latin also produced characteristically different results in these languages, as shown in the examples in the following table:

| Latin | Spanish | Ladino | Aragonese | Asturian | Galician | Portuguese | Catalan | Gascon / Occitan | French | Sardinian | Italian | Romanian | English |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| clāvem | llave | clave | clau | llave | chave | chave | clau | clé | giae, crae, crai | chiave | cheie | 'key' | |

| flamma | llama | flama | chama | chama, flama | flama | flamme | framma | fiamma | flamă | 'flame' | |||

| plēnum | lleno | pleno | plen | llenu | cheo | cheio, pleno | ple | plen | plein | prenu | pieno | plin | 'plenty, full' |

| octō | ocho | güeito | ocho, oito | oito | oito (oito) | vuit, huit | uèch, uòch, uèit | huit | oto | otto | opt | 'eight' | |

| multum | mucho muy |

muncho muy |

muito mui |

munchu mui |

moito moi |

muito | molt | molt (arch.) | très, beaucoup, moult | meda | molto | mult | 'much, very, many' |

In the 15th and 16th centuries, Spanish underwent a dramatic change in the pronunciation of its sibilant consonants, known in Spanish as the reajuste de las sibilantes, which resulted in the distinctive velar [x] pronunciation of the letter ⟨j⟩ and—in a large part of Spain—the characteristic interdental [θ] ("th-sound") for the letter ⟨z⟩ (and for ⟨c⟩ before ⟨e⟩ or ⟨i⟩). See History of Spanish (Modern development of the Old Spanish sibilants) for details.

The Gramática de la lengua castellana, written in Salamanca in 1492 by Elio Antonio de Nebrija, was the first grammar written for a modern European language.[25] According to a popular anecdote, when Nebrija presented it to Queen Isabella I, she asked him what was the use of such a work, and he answered that language is the instrument of empire.[26] In his introduction to the grammar, dated 18 August 1492, Nebrija wrote that "... language was always the companion of empire."[27]

From the 16th century onwards, the language was taken to the Spanish-discovered America and the Spanish East Indies via Spanish colonization of America. Miguel de Cervantes, author of Don Quixote, is such a well-known reference in the world that Spanish is often called la lengua de Cervantes ("the language of Cervantes").[28]

In the 20th century, Spanish was introduced to Equatorial Guinea and the Western Sahara, and to areas of the United States that had not been part of the Spanish Empire, such as Spanish Harlem in New York City. For details on borrowed words and other external influences upon Spanish, see Influences on the Spanish language.

Geographical distribution

[edit]

Spanish is the primary language in 20 countries worldwide. As of 2023, it is estimated that about 486 million people speak Spanish as a native language, making it the second most spoken language by number of native speakers.[29] An additional 75 million speak Spanish as a second or foreign language, making it the fourth most spoken language in the world overall after English, Mandarin Chinese, and Hindi with a total number of 538 million speakers.[30] Spanish is also the third most used language on the Internet, after English and Chinese.[31]

Europe

[edit]

Spanish is the official language of Spain. Upon the emergence of the Castilian Crown as the dominant power in the Iberian Peninsula by the end of the Middle Ages, the Romance vernacular associated with this polity became increasingly used in instances of prestige and influence, and the distinction between "Castilian" and "Spanish" started to become blurred.[32] Hard policies imposing the language's hegemony in an intensely centralising Spanish state were established from the 18th century onward.[33]

Other European territories in which it is also widely spoken include Gibraltar and Andorra.[34]

Spanish is also spoken by immigrant communities in other European countries, such as the United Kingdom, France, Italy, and Germany.[35] Spanish is an official language of the European Union.

Americas

[edit]Hispanic America

[edit]Today, the majority of the Spanish speakers live in Hispanic America. Nationally, Spanish is the official language—either de facto or de jure—of Argentina, Bolivia (co-official with 36 indigenous languages), Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico (co-official with 63 indigenous languages), Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay (co-official with Guaraní),[36] Peru (co-official with Quechua, Aymara, and "the other indigenous languages"),[37] Puerto Rico (co-official with English),[38] Uruguay, and Venezuela.

United States

[edit]

Spanish language has a long history in the territory of the current-day United States dating back to the 16th century.[39] In the wake of the 1848 Guadalupe Hidalgo Treaty, hundreds of thousands of Spanish speakers became a minoritized community in the United States.[39] The 20th century saw further massive growth of Spanish speakers in areas where they had been hitherto scarce.[40]

According to the 2020 census, over 60 million people of the U.S. population were of Hispanic or Hispanic American by origin.[41] In turn, 41.8 million people in the United States aged five or older speak Spanish at home, or about 13% of the population.[42] Spanish predominates in the unincorporated territory of Puerto Rico, where it is also an official language along with English.

Spanish is by far the most common second language in the country, with over 50 million total speakers if non-native or second-language speakers are included.[43] While English is the de facto national language of the country, Spanish is often used in public services and notices at the federal and state levels. Spanish is also used in administration in the state of New Mexico.[44] The language has a strong influence in major metropolitan areas such as those of Los Angeles, Miami, San Antonio, New York, San Francisco, Dallas, Tucson and Phoenix of the Arizona Sun Corridor, as well as more recently, Chicago, Las Vegas, Boston, Denver, Houston, Indianapolis, Philadelphia, Cleveland, Salt Lake City, Atlanta, Nashville, Orlando, Tampa, Raleigh and Baltimore-Washington, D.C. due to 20th- and 21st-century immigration.

Rest of the Americas

[edit]Although Spanish has no official recognition in the former British colony of Belize (known until 1973 as British Honduras) where English is the sole official language, according to the 2010 census it was then spoken natively by 45% of the population and 56.6% of the total population were able to speak the language.[45]

Due to its proximity to Spanish-speaking countries and small existing native Spanish speaking minority, Trinidad and Tobago has implemented Spanish language teaching into its education system. The Trinidadian and Tobagonian government launched the Spanish as a First Foreign Language (SAFFL) initiative in March 2005.[46]

In addition to sharing most of its borders with Spanish-speaking countries, the creation of Mercosur in the early 1990s induced a favorable situation for the promotion of Spanish language teaching in Brazil.[47][48] In 2005, the National Congress of Brazil approved a bill, signed into law by the President, making it mandatory for schools to offer Spanish as an alternative foreign language course in both public and private secondary schools in Brazil.[49] In September 2016 this law was revoked by Michel Temer after the impeachment of Dilma Rousseff.[50] In many border towns and villages along Paraguay and Uruguay, a mixed language known as Portuñol is spoken.[51]

Africa

[edit]Sub-Saharan Africa

[edit]

Equatorial Guinea is the only Spanish-speaking country located entirely in Africa, with the language introduced during the Spanish colonial period.[52] Enshrined in the constitution as an official language (alongside French and Portuguese), Spanish features prominently in the Equatoguinean education system and is the primary language used in government and business.[53] Whereas it is not the mother tongue of virtually any of its speakers, the vast majority of the population is proficient in Spanish.[54] The Instituto Cervantes estimates that 87.7% of the population is fluent in Spanish.[55] The proportion of proficient Spanish speakers in Equatorial Guinea exceeds the proportion of proficient speakers in other West and Central African nations of their respective colonial languages.[56]

Spanish is spoken by very small communities in Angola due to Cuban influence from the Cold War and in South Sudan among South Sudanese natives that relocated to Cuba during the Sudanese wars and returned for their country's independence.[57]

North Africa and Macaronesia

[edit]Spanish is also spoken in the integral territories of Spain in Africa, namely the cities of Ceuta and Melilla and the Canary Islands, located in the Atlantic Ocean some 100 km (62 mi) off the northwest of the African mainland. The Spanish spoken in the Canary Islands traces its origins back to the Castilian conquest in the 15th century, and, in addition to a resemblance to Western Andalusian speech patterns, it also features strong influence from the Spanish varieties spoken in the Americas,[58] which in turn have also been influenced historically by Canarian Spanish.[59] The Spanish spoken in North Africa by native bilingual speakers of Arabic or Berber who also speak Spanish as a second language features characteristics involving the variability of the vowel system.[60]

While far from its heyday during the Spanish protectorate in Morocco, the Spanish language has some presence in northern Morocco, stemming for example from the availability of certain Spanish-language media.[61] According to a 2012 survey by Morocco's Royal Institute for Strategic Studies (IRES), penetration of Spanish in Morocco reaches 4.6% of the population.[62] Many northern Moroccans have rudimentary knowledge of Spanish,[61] with Spanish being particularly significant in areas adjacent to Ceuta and Melilla.[63] Spanish also has a presence in the education system of the country (through either selected education centers implementing Spain's education system, primarily located in the North, or the availability of Spanish as foreign language subject in secondary education).[61]

In Western Sahara, formerly Spanish Sahara, a primarily Hassaniya Arabic-speaking territory, Spanish was officially spoken as the language of the colonial administration during the late 19th and 20th centuries. Today, Spanish is present in the partially-recognized Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic as its secondary official language,[64] and in the Sahrawi refugee camps in Tindouf (Algeria), where the Spanish language is still taught as a second language, largely by Cuban educators.[65][66][67] The number of Spanish speakers is unknown.[failed verification][68][69]

Spanish is also an official language of the African Union.[70]

Asia

[edit]

Spanish was an official language of the Philippines from the beginning of Spanish administration in 1565 to a constitutional change in 1973. During Spanish colonization, it was the language of government, trade, and education, and was spoken as a first language by Spaniards and educated Filipinos (Ilustrados). Despite a public education system set up by the colonial government, by the end of Spanish rule in 1898, only about 10% of the population had knowledge of Spanish, mostly those of Spanish descent or elite standing.[71]

Spanish continued to be official and used in Philippine literature and press during the early years of American administration after the Spanish–American War but was eventually replaced by English as the primary language of administration and education by the 1920s.[72] Nevertheless, despite a significant decrease in influence and speakers, Spanish remained an official language of the Philippines upon independence in 1946, alongside English and Filipino, a standardized version of Tagalog.

Spanish was briefly removed from official status in 1973 but reimplemented under the administration of Ferdinand Marcos two months later.[73] It remained an official language until the ratification of the present constitution in 1987, in which it was re-designated as a voluntary and optional auxiliary language.[74] Additionally, the constitution, in its Article XIV, stipulates that the Government shall provide the people of the Philippines with a Spanish-language translation of the country's constitution.[75] In recent years changing attitudes among non-Spanish speaking Filipinos have helped spur a revival of the language,[76][77] and starting in 2009 Spanish was reintroduced as part of the basic education curriculum in a number of public high schools, becoming the largest foreign language program offered by the public school system,[78] with over 7,000 students studying the language in the 2021–2022 school year alone.[79] The local business process outsourcing industry has also helped boost the language's economic prospects.[80] Today, while the actual number of proficient Spanish speakers is around 400,000, or under 0.5% of the population,[81] a new generation of Spanish speakers in the Philippines has likewise emerged, though speaker estimates vary widely.[82]

Aside from standard Spanish, a Spanish-based creole language called Chavacano developed in the southern Philippines. However, it is not mutually intelligible with Spanish.[83] The number of Chavacano-speakers was estimated at 1.2 million in 1996.[84] The local languages of the Philippines also retain significant Spanish influence, with many words derived from Mexican Spanish, owing to the administration of the islands by Spain through New Spain until 1821, until direct governance from Madrid afterwards to 1898.[85][86]

Oceania

[edit]

Spanish is the official and most spoken language on Easter Island, which is geographically part of Polynesia in Oceania and politically part of Chile. However, Easter Island's traditional language is Rapa Nui, an Eastern Polynesian language.

As a legacy of comprising the former Spanish East Indies, Spanish loan words are present in the local languages of Guam, Northern Mariana Islands, Palau, Marshall Islands and Micronesia.[87][88]

In addition, in Australia and New Zealand, there are native Spanish communities, resulting from emigration from Spanish-speaking countries (mainly from the Southern Cone).[89]

Spanish speakers by country

[edit]20 countries and one United States territory speak Spanish officially, and the language has a significant unofficial presence in the rest of the United States along with Andorra, Belize and the territory of Gibraltar.

| Country | Population[90] | Speakers of Spanish as a native language[91] | Native speakers and proficient speakers as a second language[92] | Total number of Spanish speakers (including limited competence speakers)[92][93] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mexico* | 132,274,416[94] | 124,073,402 (93.8%)[95] | 128,041,635 (96.8%)[1] | 131,216,221 (99.2%)[95] |

| United States | 333,287,557[96] | 42,032,538 (13.3%)[97] | 42,032,538 (82% of U.S. Hispanics speak Spanish very well (according to a 2011 survey).[98] There are 63.5 million Hispanics in the U.S. as of 2022[99] + 2.8 mill. non Hispanic Spanish speakers[100]) | 57,532,538[1] (42 million as a first language + 15.5 million as a second language. To avoid double counting, the number does not include 8 million Spanish students and some of the 7.7 million undocumented Hispanics not accounted by the Census) |

| Colombia* | 52,695,952[101] | 52,168,992 (99%)[102] | 52,274,384 (99.2%)[1] | |

| Spain* | 48,692,804[103] | 41,595,530 (85.6%)[104] | 46,649,193 (96%)[104] | 48,349,944 (99.5%)[104] |

| Argentina* | 47,067,641[105][107] | 45,561,476 (96.8%)[108] | 46,173,356 (98.1%)[1] | 46,785,235 (99.4%)[93] |

| Venezuela* | 32,605,423[109] | 31,507,179 (1,098,244 with another mother tongue)[110] | 31,725,077 (97.3%)[1] | 32,214,158 (98.8%)[93] |

| Peru* | 34,102,668[111] | 28,271,112 (82.9%)[112][113] | 29,532,910 (86.6%)[1] | |

| Chile* | 20,086,377[114] | 19,015,592 (281,600 with another mother tongue)[115] | 19,262,836 (95.9%)[1] | 19,945,772 (99.3%)[93] |

| Ecuador* | 18,350,000[116] | 17,065,500 (93%)[117] | 17,579,300 (95.8%)[1] | 18,001,350 (98.1%)[93] |

| Guatemala* | 17,357,886[118] | 12,133,162 (69.9%)[119] | 13,591,225 (78.3%)[1] | 14,997,214 (86.4%)[93] |

| Cuba* | 11,181,595[120] | 11,159,232 (99.8%)[1] | 11,159,232 (99.8%)[1] | |

| Bolivia* | 12,006,031[121] | 7,287,661 (60.7%)[122] | 9,965,006 (83%)[1] | 10,553,301 (87.9%)[93] |

| Dominican Republic* | 10,621,938[123] | 10,367,011 (97.6%)[1] | 10,367,011 (97.6%)[1] | 10,473,231 (99.6%)[93] |

| Honduras* | 9,526,440[124] | 9,318,690 (207,750 with another mother tongue)[125] | 9,402,596 (98.7%)[1] | |

| France | 67,407,241[126] | 477,564 (1%[127] of 47,756,439[128]) | 1,910,258 (4%[129] of 47,756,439[128]) | 6,685,901 (14%[130] of 47,756,439[128]) |

| Paraguay* | 7,453,695[131] | 5,083,420 (61.5%)[132] | 6,596,520 (68.2%)[1] | 6,484,714 (87%)[133][134] |

| Nicaragua* | 6,595,674[135] | 6,285,677 (490,124 with another mother tongue)[136] | 6,404,399 (97.1%)[1] | |

| El Salvador* | 6,330,947[137] | 6,316,847 (14,100 with another mother tongue)[138] | 6,311,954 (99.7%)[1] | |

| Brazil | 214,100,000[139] | 460,018[1] | 460,018 | 6,056,018 (460,018 immigrants native speakers + 96,000 descendants of Spanish immigrants + 5,500,000 can hold a conversation)[140][93] |

| Italy | 60,542,215[141] | 255,459[142] | 1,037,248 (2%[129] of 51,862,391[128]) | 5,704,863 (11%[130] of 51,862,391[128]) |

| Costa Rica* | 5,262,374[143] | 5,176,956 (84,310 with another mother tongue)[144] | 5,225,537 (99.3%)[1] | |

| Panama* | 4,278,500[145] | 3,777,457 (501,043 with another mother tongue)[146] | 3,931,942 (91.9%)[1] | |

| Uruguay* | 3,543,026[147] | 3,392,826 (150,200 with another mother tongue)[148] | 3,486,338 (98.4%)[1] | |

| Puerto Rico* | 3,285,874[149] | 3,095,293 (94.2%)[150] | 3,253,015 (99%)[1] | |

| United Kingdom | 67,081,000[151] | 120,000[152] | 518,480 (1%[129] of 51,848,010[128]) | 3,110,880 (6%[130] of 51,848,010[128]) |

| Germany | 83,190,556[153] | 375,207[154] | 644,091 (1%[129] of 64,409,146[128]) | 2,576,366 (4%[130] of 64,409,146[128]) |

| Canada | 34,605,346[155] | 600,795 (1.6%)[156] | 1,171,450[157] (3.2%)[158] | 1,775,000[159][160] |

| Morocco | 35,601,000[161] | 6,586[162] | 6,586 | 1,664,823[1][163] (10%)[164] |

| Equatorial Guinea* | 1,505,588[165] | 1,114,135 (74%)[1] | 1,320,401 (87.7%)[166] | |

| Portugal | 10,352,042[167] | 323,237 (4%[129] of 8,080,915[128]) | 1,089,995[168] | |

| Romania | 21,355,849[169] | 182,467 (1%[129] of 18,246,731[128]) | 912,337 (5%[130] of 18,246,731[128]) | |

| Netherlands | 16,665,900[170] | 133,719 (1%[129] of 13,371,980[128]) | 668,599 (5%[130] of 13,371,980[128]) | |

| Ivory Coast | 21,359,000[171] | 566,178 (students)[1] | ||

| Australia | 21,507,717[172] | 117,498[1] | 117,498 | 547,397 (117,498 native speakers + 374,571 limited competence speakers + 55,328 students)[1] |

| Philippines | 101,562,305[173] | 4,803[1][174] | 4,803 | 500,092[1][175] (4,803 native + 461,689 limited competence + 33,600 students) |

| Sweden | 9,555,893[176] | 77,912 (1%[127] of 7,791,240[128]) | 77,912 (1% of 7,791,240) | 467,474 (6%[130] of 7,791,240[128]) |

| Belgium | 10,918,405[177] | 89,395 (1%[129] of 8,939,546[128]) | 446,977 (5%[130] of 8,939,546[128]) | |

| Benin | 10,008,749[178] | 412,515 (students)[1] | ||

| Senegal | 12,853,259 | 356,000 (students)[1] | ||

| Poland | 38,092,000 | 324,137 (1%[129] of 32,413,735[128]) | 324,137 (1% of 32,413,735) | |

| Austria | 8,205,533 | 70,098 (1%[129] of 7,009,827[128]) | 280,393 (4%[130] of 7,009,827[128]) | |

| Belize | 430,191[179] | 224,130 (52.1%)[180] | 224,130 (52.1%) | 270,160 (62.8%)[180] |

| Algeria | 33,769,669 | 175,000[1] | 223,000[1] | |

| Switzerland | 8,570,146[181] | 197,113 (2.3%)[182][183] | 197,113 | 211,533 (14,420 students)[184] |

| Cameroon | 21,599,100[185] | 193,018 (students)[1] | ||

| Denmark | 5,484,723 | 45,613 (1%[129] of 4,561,264[128]) | 182,450 (4%[130] of 4,561,264[128]) | |

| Israel | 7,112,359 | 130,000[1] | 175,000[1] | |

| Japan | 127,288,419 | 108,000[1] | 108,000 | 168,000 (60,000 students)[186] |

| Gabon | 1,545,255[187] | 167,410 (students)[188] | ||

| Bonaire and Curaçao | 223,652 | 10,006[1] | 10,006 | 150,678[1] |

| Ireland | 4,581,269[189] | 35,220 (1%[129] of 3,522,000[128]) | 140,880 (4%[130] of 3,522,000[128]) | |

| Finland | 5,244,749 | 133,200 (3%[130] of 4,440,004[128]) | ||

| Bulgaria | 7,262,675 | 130,750 (2%[129] of 6,537,510[128]) | 130,750 (2%[130] of 6,537,510[128]) | |

| Norway | 5,165,800 | 13,000[1] | 13,000 | 129,168 (92,168 students)[1] |

| Czech Republic | 10,513,209[190] | 90,124 (1%[130] of 9,012,443[128]) | ||

| Russia | 146,171,015[191] | 3,000[1] | 3,000 | 87,313 (84,313 students)[1] |

| Hungary | 9,957,731[192] | 83,206 (1%[130] of 8,320,614[128]) | ||

| Aruba | 101,484[193] | 13,710[1] | 75,402[162] | 83,064[1] |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 1,317,714[194] | 4,000[1] | 4,000 | 70,401[1] |

| Guam | 1,201[1] | 1,201 | 60,582[1] | |

| China | 1,411,778,724[195] | 5,000[1] | 5,000 | 59,499 (54,499 students)[1] |

| New Zealand | 22,000[1] | 22,000 | 58,373 (36,373 students)[1] | |

| Slovenia | 35,194 (2%[129] of 1,759,701[128]) | 52,791 (3%[130] of 1,759,701[128]) | ||

| India | 1,386,745,000[196] | 1,000[1] | 1,000 | 50,264 (49,264 students)[1] |

| Andorra | 84,484 | 30,414[1] | 30,414 | 47,271[1] |

| Slovakia | 5,455,407 | 45,500 (1%[130] of 4,549,955[128]) | ||

| Gibraltar | 29,441[197] | 22,758 (77.3%[198]) | ||

| Lithuania | 2,972,949[199] | 28,297 (1%[130] of 2,829,740[128]) | ||

| Luxembourg | 524,853 | 4,049 (1%[127] of 404,907[128]) | 8,098 (2%[129] of 404,907[128]) | 24,294 (6%[130] of 404,907[128]) |

| Western Sahara | 513,000[200] | N/A[201] | 22,000[1] | |

| Turkey | 83,614,362 | 1,000[1] | 1,000 | 20,346[1] (4,346 students)[202] |

| US Virgin Islands | 16,788[1] | 16,788 | 16,788 | |

| Latvia | 2,209,000[203] | 13,943 (1%[130] of 1,447,866[128]) | ||

| Cyprus | 2%[130] of 660,400[128] | |||

| Estonia | 9,457 (1%[130] of 945,733[128]) | |||

| Jamaica | 2,711,476[204] | 8,000[1] | 8,000 | 8,000 |

| Namibia | 666 | 3,866[205] | 3,866 | |

| Egypt | 3,500 (students)[206] | |||

| Malta | 3,354 (1%[130] of 335,476[128]) | |||

| Total | 7,626,000,000 (total world population)[207] | 480,000,000[208][209] (6%) | 506,650,703[1] (6.5%) | 595,000,000[1] (7.5%) |

Grammar

[edit]

Most of the grammatical and typological features of Spanish are shared with the other Romance languages. Spanish is a fusional language. The noun and adjective systems exhibit two genders and two numbers. In addition, articles and some pronouns and determiners have a neuter gender in their singular form. There are about fifty conjugated forms per verb, with 3 tenses: past, present, future; 2 aspects for past: perfective, imperfective; 4 moods: indicative, subjunctive, conditional, imperative; 3 persons: first, second, third; 2 numbers: singular, plural; 3 verboid forms: infinitive, gerund, and past participle. The indicative mood is the unmarked one, while the subjunctive mood expresses uncertainty or indetermination, and is commonly paired with the conditional, which is a mood used to express "would" (as in, "I would eat if I had food"); the imperative is a mood to express a command, commonly a one word phrase – "¡Di!" ("Talk!").

Verbs express T-V distinction by using different persons for formal and informal addresses. (For a detailed overview of verbs, see Spanish verbs and Spanish irregular verbs.)

Spanish syntax is considered right-branching, meaning that subordinate or modifying constituents tend to be placed after head words. The language uses prepositions (rather than postpositions or inflection of nouns for case), and usually—though not always—places adjectives after nouns, as do most other Romance languages.

Spanish is classified as a subject–verb–object language; however, as in most Romance languages, constituent order is highly variable and governed mainly by topicalization and focus. It is a "pro-drop", or "null-subject" language—that is, it allows the deletion of subject pronouns when they are pragmatically unnecessary. Spanish is described as a "verb-framed" language, meaning that the direction of motion is expressed in the verb while the mode of locomotion is expressed adverbially (e.g. subir corriendo or salir volando; the respective English equivalents of these examples—'to run up' and 'to fly out'—show that English is, by contrast, "satellite-framed", with mode of locomotion expressed in the verb and direction in an adverbial modifier).

Phonology

[edit]The Spanish phonological system evolved from that of Vulgar Latin. Its development exhibits some traits in common with other Western Romance languages, others with the neighboring Hispanic varieties—especially Leonese and Aragonese—as well as other features unique to Spanish. Spanish is alone among its immediate neighbors in having undergone frequent aspiration and eventual loss of the Latin initial /f/ sound (e.g. Cast. harina vs. Leon. and Arag. farina).[210] The Latin initial consonant sequences pl-, cl-, and fl- in Spanish typically merge as ll- (originally pronounced [ʎ]), while in Aragonese they are preserved in most dialects, and in Leonese they present a variety of outcomes, including [tʃ], [ʃ], and [ʎ]. Where Latin had -li- before a vowel (e.g. filius) or the ending -iculus, -icula (e.g. auricula), Old Spanish produced [ʒ], that in Modern Spanish became the velar fricative [x] (hijo, oreja), whereas neighboring languages have the palatal lateral [ʎ] (e.g. Portuguese filho, orelha; Catalan fill, orella).

Segmental phonology

[edit]

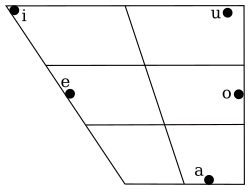

The Spanish phonemic inventory consists of five vowel phonemes (/a/, /e/, /i/, /o/, /u/) and 17 to 19 consonant phonemes (the exact number depending on the dialect[211]). The main allophonic variation among vowels is the reduction of the high vowels /i/ and /u/ to glides—[j] and [w] respectively—when unstressed and adjacent to another vowel. Some instances of the mid vowels /e/ and /o/, determined lexically, alternate with the diphthongs /je/ and /we/ respectively when stressed, in a process that is better described as morphophonemic rather than phonological, as it is not predictable from phonology alone.

The Spanish consonant system is characterized by (1) three nasal phonemes, and one or two (depending on the dialect) lateral phoneme(s), which in syllable-final position lose their contrast and are subject to assimilation to a following consonant; (2) three voiceless stops and the affricate /tʃ/; (3) three or four (depending on the dialect) voiceless fricatives; (4) a set of voiced obstruents—/b/, /d/, /ɡ/, and sometimes /ʝ/—which alternate between approximant and plosive allophones depending on the environment; and (5) a phonemic distinction between the "tapped" and "trilled" r-sounds (single ⟨r⟩ and double ⟨rr⟩ in orthography).

In the following table of consonant phonemes, /ʎ/ is marked with an asterisk (*) to indicate that it is preserved only in some dialects. In most dialects it has been merged with /ʝ/ in the merger called yeísmo. Similarly, /θ/ is also marked with an asterisk to indicate that most dialects do not distinguish it from /s/ (see seseo), although this is not a true merger but an outcome of different evolution of sibilants in Southern Spain.

The phoneme /ʃ/ is in parentheses () to indicate that it appears only in loanwords. Each of the voiced obstruent phonemes /b/, /d/, /ʝ/, and /ɡ/ appears to the right of a pair of voiceless phonemes, to indicate that, while the voiceless phonemes maintain a phonemic contrast between plosive (or affricate) and fricative, the voiced ones alternate allophonically (i.e. without phonemic contrast) between plosive and approximant pronunciations.

| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | |||||||

| Stop | p | b | t | d | tʃ | ʝ | k | ɡ | ||

| Continuant | f | θ* | s | (ʃ) | x | |||||

| Lateral | l | ʎ* | ||||||||

| Flap | ɾ | |||||||||

| Trill | r | |||||||||

Prosody

[edit]Spanish is classified by its rhythm as a syllable-timed language: each syllable has approximately the same duration regardless of stress.[213][214]

Spanish intonation varies significantly according to dialect but generally conforms to a pattern of falling tone for declarative sentences and wh-questions (who, what, why, etc.) and rising tone for yes/no questions.[215][216] There are no syntactic markers to distinguish between questions and statements and thus, the recognition of declarative or interrogative depends entirely on intonation.

Stress most often occurs on any of the last three syllables of a word, with some rare exceptions at the fourth-to-last or earlier syllables. Stress tends to occur as follows:[217][better source needed]

- in words that end with a monophthong, on the penultimate syllable

- when the word ends in a diphthong, on the final syllable.

- in words that end with a consonant, on the last syllable, with the exception of two grammatical endings: -n, for third-person-plural of verbs, and -s, for plural of nouns and adjectives or for second-person-singular of verbs. However, even though a significant number of nouns and adjectives ending with -n are also stressed on the penult (joven, virgen, mitin), the great majority of nouns and adjectives ending with -n are stressed on their last syllable (capitán, almacén, jardín, corazón).

- Preantepenultimate stress (stress on the fourth-to-last syllable) occurs rarely, only on verbs with clitic pronouns attached (e.g. guardándoselos 'saving them for him/her/them/you').

In addition to the many exceptions to these tendencies, there are numerous minimal pairs that contrast solely on stress such as sábana ('sheet') and sabana ('savannah'); límite ('boundary'), limite ('he/she limits') and limité ('I limited'); líquido ('liquid'), liquido ('I sell off') and liquidó ('he/she sold off').

The orthographic system unambiguously reflects where the stress occurs: in the absence of an accent mark, the stress falls on the last syllable unless the last letter is ⟨n⟩, ⟨s⟩, or a vowel, in which cases the stress falls on the next-to-last (penultimate) syllable. Exceptions to those rules are indicated by an acute accent mark over the vowel of the stressed syllable. (See Spanish orthography.)

Speaker population

[edit]Spanish is the official, or national language in 18 countries and one territory in the Americas, Spain, and Equatorial Guinea. With a population of over 410 million, Hispanophone America accounts for the vast majority of Spanish speakers, of which Mexico is the most populous Spanish-speaking country. In the European Union, Spanish is the mother tongue of 8% of the population, with an additional 7% speaking it as a second language.[218] Additionally, Spanish is the second most spoken language in the United States and is by far the most popular foreign language among students.[219] In 2015, it was estimated that over 50 million Americans spoke Spanish, about 41 million of whom were native speakers.[220] With continued immigration and increased use of the language domestically in public spheres and media, the number of Spanish speakers in the United States is expected to continue growing over the forthcoming decades.[221]

Dialectal variation

[edit]

While being mutually intelligible, there are important variations (phonological, grammatical, and lexical) in the spoken Spanish of the various regions of Spain and throughout the Spanish-speaking areas of the Americas.

The national variety with the most speakers is Mexican Spanish. It is spoken by more than twenty percent of the world's Spanish speakers (more than 112 million of the total of more than 500 million, according to the table above). One of its main features is the reduction or loss of unstressed vowels, mainly when they are in contact with the sound /s/.[222][223]

In Spain, northern dialects are popularly thought of as closer to the standard, although positive attitudes toward southern dialects have increased significantly in the last 50 years. The speech from the educated classes of Madrid is the standard variety for use on radio and television in Spain and it is indicated by many as the one that has most influenced the written standard for Spanish.[224] Central (European) Spanish speech patterns have been noted to be in the process of merging with more innovative southern varieties (including Eastern Andalusian and Murcian), as an emerging interdialectal levelled koine buffered between the Madrid's traditional national standard and the Seville speech trends.[225]

Phonology

[edit]The four main phonological divisions are based respectively on (1) the phoneme /θ/, (2) the debuccalization of syllable-final /s/, (3) the sound of the spelled ⟨s⟩, (4) and the phoneme /ʎ/.

- The phoneme /θ/ (spelled c before e or i and spelled ⟨z⟩ elsewhere), a voiceless dental fricative as in English thing, is maintained by a majority of Spain's population, especially in the northern and central parts of the country. In other areas (some parts of southern Spain, the Canary Islands, and the Americas), /θ/ does not exist and /s/ occurs instead. The maintenance of phonemic contrast is called distinción in Spanish, while the merger is generally called seseo (in reference to the usual realization of the merged phoneme as [s]) or, occasionally, ceceo (referring to its interdental realization, [θ], in some parts of southern Spain). In most of Hispanic America, the spelled ⟨c⟩ before ⟨e⟩ or ⟨i⟩, and spelled ⟨z⟩ is always pronounced as a voiceless dental sibilant.

- The debuccalization (pronunciation as [h], or loss) of syllable-final /s/ is associated with the southern half of Spain and lowland Americas: Central America (except central Costa Rica and Guatemala), the Caribbean, coastal areas of southern Mexico, and South America except Andean highlands. Debuccalization is frequently called "aspiration" in English, and aspiración in Spanish. When there is no debuccalization, the syllable-final /s/ is pronounced as voiceless "apico-alveolar" sibilant or as a voiceless dental sibilant in the same fashion as in the next paragraph.

- The sound that corresponds to the letter ⟨s⟩ is pronounced in northern and central Spain as a voiceless "apico-alveolar" sibilant [s̺] (also described acoustically as "grave" and articulatorily as "retracted"), with a weak "hushing" sound reminiscent of retroflex fricatives. In Andalusia, Canary Islands and most of Hispanic America (except in the Paisa region of Colombia) it is pronounced as a voiceless dental sibilant [s], much like the most frequent pronunciation of the /s/ of English.

- The phoneme /ʎ/, spelled ⟨ll⟩, a palatal lateral consonant that can be approximated by the sound of the ⟨lli⟩ of English million, tends to be maintained in less-urbanized areas of northern Spain and in the highland areas of South America, as well as in Paraguay and lowland Bolivia. Meanwhile, in the speech of most other Spanish speakers, it is merged with /ʝ/ ("curly-tail j"), a non-lateral, usually voiced, usually fricative, palatal consonant, sometimes compared to English /j/ (yod) as in yacht and spelled ⟨y⟩ in Spanish. As with other forms of allophony across world languages, the small difference of the spelled ⟨ll⟩ and the spelled ⟨y⟩ is usually not perceived (the difference is not heard) by people who do not produce them as different phonemes. Such a phonemic merger is called yeísmo in Spanish. In Rioplatense Spanish, the merged phoneme is generally pronounced as a postalveolar fricative, either voiced [ʒ] (as in English measure or the French ⟨j⟩) in the central and western parts of the dialectal region (zheísmo), or voiceless [ʃ] (as in the French ⟨ch⟩ or Portuguese ⟨x⟩) in and around Buenos Aires and Montevideo (sheísmo).[226]

Morphology

[edit]The main morphological variations between dialects of Spanish involve differing uses of pronouns, especially those of the second person and, to a lesser extent, the object pronouns of the third person.

Voseo

[edit]

Virtually all dialects of Spanish make the distinction between a formal and a familiar register in the second-person singular and thus have two different pronouns meaning "you": usted in the formal and either tú or vos in the familiar (and each of these three pronouns has its associated verb forms), with the choice of tú or vos varying from one dialect to another. The use of vos and its verb forms is called voseo. In a few dialects, all three pronouns are used, with usted, tú, and vos denoting respectively formality, familiarity, and intimacy.[227]

In voseo, vos is the subject form (vos decís, "you say") and the form for the object of a preposition (voy con vos, "I am going with you"), while the direct and indirect object forms, and the possessives, are the same as those associated with tú: Vos sabés que tus amigos te respetan ("You know your friends respect you").

The verb forms of the general voseo are the same as those used with tú except in the present tense (indicative and imperative) verbs. The forms for vos generally can be derived from those of vosotros (the traditional second-person familiar plural) by deleting the glide [i̯], or /d/, where it appears in the ending: vosotros pensáis > vos pensás; vosotros volvéis > vos volvés, pensad! (vosotros) > pensá! (vos), volved! (vosotros) > volvé! (vos).[228]

| Indicative | Subjunctive | Imperative | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present | Simple past | Imperfect past | Future | Conditional | Present | Past | |

| pensás | pensaste | pensabas | pensarás | pensarías | pienses | pensaras pensases |

pensá |

| volvés | volviste | volvías | volverás | volverías | vuelvas | volvieras volvieses |

volvé |

| dormís | dormiste | dormías | dormirás | dormirías | duermas | durmieras durmieses |

dormí |

| The forms in bold coincide with standard tú-conjugation. | |||||||

In Central American voseo, the tú and vos forms differ in the present subjunctive as well:

| Indicative | Subjunctive | Imperative | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present | Simple past | Imperfect past | Future | Conditional | Present | Past | |

| pensás | pensaste | pensabas | pensarás | pensarías | pensés | pensaras pensases |

pensá |

| volvés | volviste | volvías | volverás | volverías | volvás | volvieras volvieses |

volvé |

| dormís | dormiste | dormías | dormirás | dormirías | durmás | durmieras durmieses |

dormí |

| The forms in bold coincide with standard tú-conjugation. | |||||||

In Chilean voseo, almost all vos forms are distinct from the corresponding standard tú-forms.

| Indicative | Subjunctive | Imperative | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present | Simple past | Imperfect past | Future[229] | Conditional | Present | Past | |

| pensái(s) | pensaste | pensabais | pensarí(s) pensaráis |

pensaríai(s) | pensí(s) | pensarai(s) pensases |

piensa |

| volví(s) | volviste | volvíai(s) | volverí(s) volveráis |

volveríai(s) | volvái(s) | volvierai(s) volvieses |

vuelve |

| dormís | dormiste | dormíais | dormirís dormiráis |

dormiríais | durmáis | durmierais durmieses |

duerme |

| The forms in bold coincide with standard tú-conjugation. | |||||||

The use of the pronoun vos with the verb forms of tú (vos piensas) is called "pronominal voseo". Conversely, the use of the verb forms of vos with the pronoun tú (tú pensás or tú pensái) is called "verbal voseo". In Chile, for example, verbal voseo is much more common than the actual use of the pronoun vos, which is usually reserved for highly informal situations.

Distribution in Spanish-speaking regions of the Americas

[edit]Although vos is not used in Spain, it occurs in many Spanish-speaking regions of the Americas as the primary spoken form of the second-person singular familiar pronoun, with wide differences in social consideration.[230][better source needed] Generally, it can be said that there are zones of exclusive use of tuteo (the use of tú) in the following areas: almost all of Mexico, the West Indies, Panama, most of Colombia, Peru, Venezuela and coastal Ecuador.

Tuteo as a cultured form alternates with voseo as a popular or rural form in Bolivia, in the north and south of Peru, in Andean Ecuador, in small zones of the Venezuelan Andes (and most notably in the Venezuelan state of Zulia), and in a large part of Colombia. Some researchers maintain that voseo can be heard in some parts of eastern Cuba, and others assert that it is absent from the island.[231]

Tuteo exists as the second-person usage with an intermediate degree of formality alongside the more familiar voseo in Chile, in the Venezuelan state of Zulia, on the Caribbean coast of Colombia, in the Azuero Peninsula in Panama, in the Mexican state of Chiapas, and in parts of Guatemala.

Areas of generalized voseo include Argentina, Nicaragua, eastern Bolivia, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Costa Rica, Paraguay, Uruguay and the Colombian departments of Antioquia, Caldas, Risaralda, Quindio and Valle del Cauca.[227]

Ustedes

[edit]Ustedes functions as formal and informal second-person plural in all of Hispanic America, the Canary Islands, and parts of Andalusia. It agrees with verbs in the 3rd person plural. Most of Spain maintains the formal/familiar distinction with ustedes and vosotros respectively. The use of ustedes with the second person plural is sometimes heard in Andalusia, but it is non-standard.

Usted

[edit]Usted is the usual second-person singular pronoun in a formal context, but it is used jointly with the third-person singular voice of the verb. It is used to convey respect toward someone who is a generation older or is of higher authority ("you, sir"/"you, ma'am"). It is also used in a familiar context by many speakers in Colombia and Costa Rica and in parts of Ecuador and Panama, to the exclusion of tú or vos. This usage is sometimes called ustedeo in Spanish.

In Central America, especially in Honduras, usted is often used as a formal pronoun to convey respect between the members of a romantic couple. Usted is also used that way between parents and children in the Andean regions of Ecuador, Colombia and Venezuela.

Third-person object pronouns

[edit]Most speakers use (and the Real Academia Española prefers) the pronouns lo and la for direct objects (masculine and feminine respectively, regardless of animacy, meaning "him", "her", or "it"), and le for indirect objects (regardless of gender or animacy, meaning "to him", "to her", or "to it"). The usage is sometimes called "etymological", as these direct and indirect object pronouns are a continuation, respectively, of the accusative and dative pronouns of Latin, the ancestor language of Spanish.

Deviations from this norm (more common in Spain than in the Americas) are called "leísmo", "loísmo", or "laísmo", according to which respective pronoun, le, lo, or la, has expanded beyond the etymological usage (le as a direct object, or lo or la as an indirect object).

Vocabulary

[edit]Some words can be significantly different in different Hispanophone countries. Most Spanish speakers can recognize other Spanish forms even in places where they are not commonly used, but Spaniards generally do not recognize specifically American usages. For example, Spanish mantequilla, aguacate and albaricoque (respectively, 'butter', 'avocado', 'apricot') correspond to manteca (word used for lard in Peninsular Spanish), palta, and damasco, respectively, in Argentina, Chile (except manteca), Paraguay, Peru (except manteca and damasco), and Uruguay. In the healthcare context, an assessment of the Spanish translation of the QWB-SA identified some regional vocabulary choices and US-specific concepts, which cannot be successfully implemented in Spain without adaptation.[232]

Vocabulary

[edit]Around 85% of everyday Spanish vocabulary is of Latin origin. Most of the core vocabulary and the most common words in Spanish comes from Latin. The Spanish words first learned by children as they learn to speak are mainly words of Latin origin. These words of Latin origin can be classified as heritage words, cultisms and semi-cultisms.

Most of the Spanish lexicon is made up of heritage lexicon. Heritage or directly inherited words are those whose presence in the spoken language has been continued since before the differentiation of the Romance languages. Heritage words are characterized by having undergone all the phonetic changes experienced by the language. This differentiates it from the cultisms and semi-cultisms that were no longer used in the spoken language and were later reintroduced for restricted uses. Because of this, cultisms generally have not experienced some of the phonetic changes and present a different form than they would have if they had been transmitted with heritage words.

In the philological tradition of Spanish, cultism is called a word whose morphology very strictly follows its Greek or Latin etymological origin, without undergoing the changes that the evolution of the Spanish language followed from its origin in Vulgar Latin. The same concept also exists in other Romance languages. Reintroduced into the language for cultural, literary or scientific considerations, cultism only adapts its form to the orthographic and phonological conventions derived from linguistic evolution, but ignores the transformations that the roots and morphemes underwent in the development of the Romance language.

In some cases, cultisms are used to introduce technical or specialized terminology that, present in the classical language, did not appear in the Romance language due to lack of use; This is the case of many of the literary, legal and philosophical terms of classical culture, such as ataraxia (from the Greek ἀταραξία, "dispassion") or legislar (built from the Latin legislator). In other cases, they construct neologisms, such as the name of most scientific disciplines.

A semi-cultism is a word that did not evolve in the expected way, in the vernacular language (Romance language), unlike heritage words; its evolution is incomplete. Many times interrupted by cultural influences (ecclesiastical, legal, administrative, etc.). For the same reason, they maintain some features of the language of origin. Dios is a clear example of semi-cultism, where it came from the Latin Deus. It is a semi-cultism, because it maintains (without fully adapting to Castilianization, in this case) some characteristics of the Latin language—the ending in -s—, but, at the same time, it undergoes slight phonetic modifications (change of eu for io). Deus > Dios (instead of remaining cultist: Deus > *Deus, or becoming a heritage word: Deus > *Dío). The Catholic Church influenced by stopping the natural evolution of this word, and, in this way, converted this word into a semi-cultism and unconsciously prevented it from becoming a heritage word.

Spanish vocabulary has been influenced by several languages. As in other European languages, Classical Greek words (Hellenisms) are abundant in the terminologies of several fields, including art, science, politics, nature, etc.[233] Its vocabulary has also been influenced by Arabic, having developed during the Al-Andalus era in the Iberian Peninsula, with around 8% of its vocabulary having Arabic lexical roots.[234][235][236][237] It has also been influenced by Basque, Iberian, Celtiberian, Visigothic, and other neighboring Ibero-Romance languages.[238][237] Additionally, it has absorbed vocabulary from other languages, particularly other Romance languages such as French, Mozarabic, Portuguese, Galician, Catalan, Occitan, and Sardinian, as well as from Quechua, Nahuatl, and other indigenous languages of the Americas.[239] In the 18th century, words taken from French referring above all to fashion, cooking and bureaucracy were added to the Spanish lexicon. In the 19th century, new loanwords were incorporated, especially from English and German, but also from Italian in areas related to music, particularly opera and cooking. In the 20th century, the pressure of English in the fields of technology, computing, science and sports was greatly accentuated.

In general, Latin America is more susceptible to loanwords from English or Anglicisms. For example: mouse (computer mouse) is used in Latin America, in Spain ratón is used. This happens largely due to closer contact with the United States. For its part, Spain is known by the use of Gallicisms or words taken from neighboring France (such as the Gallicism ordenador in the European Spanish, in contrast to the Anglicism computador or computadora in American Spanish).

Relation to other languages

[edit]Spanish is closely related to the other West Iberian Romance languages, including Asturian, Aragonese, Galician, Ladino, Leonese, Mirandese and Portuguese. It is somewhat less similar, to varying degrees, from other members of the Romance language family.

It is generally acknowledged that Portuguese and Spanish speakers can communicate in written form, with varying degrees of mutual intelligibility.[240][241][242][243] Mutual intelligibility of the written Spanish and Portuguese languages is high, lexically and grammatically. Ethnologue gives estimates of the lexical similarity between related languages in terms of precise percentages. For Spanish and Portuguese, that figure is 89%, although phonologically the two languages are quite dissimilar. Italian on the other hand, is phonologically similar to Spanish, while sharing lower lexical and grammatical similarity of 82%. Mutual intelligibility between Spanish and French or between Spanish and Romanian is lower still, given lexical similarity ratings of 75% and 71% respectively.[244][245] Comprehension of Spanish by French speakers who have not studied the language is much lower, at an estimated 45%. In general, thanks to the common features of the writing systems of the Romance languages, interlingual comprehension of the written word is greater than that of oral communication.

The following table compares the forms of some common words in several Romance languages:

| Latin | Spanish | Galician | Portuguese | Astur-Leonese | Aragonese | Catalan | French | Italian | Romanian | English |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nōs (alterōs)1,2 "we (others)" |

nosotros | nós, nosoutros3 | nós, nós outros3 | nós, nosotros | nusatros | nosaltres (arch. nós) |

nous4 | noi, noialtri5 | noi | 'we' |

| frātre(m) germānu(m) "true brother" |

hermano | irmán | irmão | hermanu | chirmán | germà (arch. frare)6 |

frère | fratello | frate | 'brother' |

| die(m) mārtis (Classical) "day of Mars" tertia(m) fēria(m) (Late Latin) "third (holi)day" |

martes | Martes, Terza Feira | Terça-Feira | Martes | Martes | Dimarts | Mardi | Martedì | Marți | 'Tuesday' |

| cantiōne(m) canticu(m) |

canción7 (arch. cançón) |

canción, cançom8 | canção | canción (also canciu) |

canta | cançó | chanson | canzone | cântec | 'song' |

| magis plūs |

más (arch. plus) |

máis | mais | más | más (also més) |

més (arch. pus or plus) |

plus | più | mai | 'more' |

| manu(m) sinistra(m) | mano izquierda9 (arch. mano siniestra) |

man esquerda9 | mão esquerda9 (arch. mão sẽestra) |

manu izquierda9 (or esquierda; also manzorga) |

man cucha | mà esquerra9 (arch. mà sinistra) |

main gauche | mano sinistra | mâna stângă | 'left hand' |

| rēs, rĕm "thing" nūlla(m) rem nāta(m) "no born thing" mīca(m) "crumb" |

nada | nada (also ren and res) |

nada (arch. rés) | nada (also un res) |

cosa | res | rien, nul | niente, nulla mica (negative particle) |

nimic, nul | 'nothing' |

| cāseu(m) fōrmāticu(m) "form-cheese" |

queso | queixo | queijo | quesu | queso | formatge | fromage | formaggio/cacio | caș10 | 'cheese' |

1. In Romance etymology, Latin terms are given in the Accusative since most forms derive from this case.

2. As in "us very selves", an emphatic expression.

3. Also nós outros in early modern Portuguese (e.g. The Lusiads), and nosoutros in Galician.

4. Alternatively nous autres in French.

5. noialtri in many Southern Italian dialects and languages.

6. Medieval Catalan (e.g. Llibre dels fets).

7. Modified with the learned suffix -ción.

8. Depending on the written norm used (see Reintegrationism).

9. From Basque esku, "hand" + erdi, "half, incomplete". This negative meaning also applies for Latin sinistra(m) ("dark, unfortunate").

10. Romanian caș (from Latin cāsevs) means a type of cheese. The universal term for cheese in Romanian is brânză (from unknown etymology).[246]

Judaeo-Spanish

[edit]

Judaeo-Spanish, also known as Ladino,[247] is a variety of Spanish which preserves many features of medieval Spanish and some old Portuguese and is spoken by descendants of the Sephardi Jews who were expelled from Spain in the 15th century.[247] While in Portugal the conversion of Jews occurred earlier and the assimilation of New Christians was overwhelming, in Spain the Jews kept their language and identity. The relationship of Ladino and Spanish is therefore comparable with that of the Yiddish language to German. Ladino speakers today are almost exclusively Sephardi Jews, with family roots in Turkey, Greece, or the Balkans, and living mostly in Israel, Turkey, and the United States, with a few communities in Hispanic America.[247] Judaeo-Spanish lacks the Native American vocabulary which was acquired by standard Spanish during the Spanish colonial period, and it retains many archaic features which have since been lost in standard Spanish. It contains, however, other vocabulary which is not found in standard Spanish, including vocabulary from Hebrew, French, Greek and Turkish, and other languages spoken where the Sephardim settled.

Judaeo-Spanish is in serious danger of extinction because many native speakers today are elderly as well as elderly olim (immigrants to Israel) who have not transmitted the language to their children or grandchildren. However, it is experiencing a minor revival among Sephardi communities, especially in music. In Latin American communities, the danger of extinction is also due to assimilation by modern Spanish.

A related dialect is Haketia, the Judaeo-Spanish of northern Morocco. This too, tended to assimilate with modern Spanish, during the Spanish occupation of the region.

Writing system

[edit]Spanish is written in the Latin script, with the addition of the character ⟨ñ⟩ (eñe, representing the phoneme /ɲ/, a letter distinct from ⟨n⟩, although typographically composed of an ⟨n⟩ with a tilde). Formerly the digraphs ⟨ch⟩ (che, representing the phoneme /t͡ʃ/) and ⟨ll⟩ (elle, representing the phoneme /ʎ/ or /ʝ/), were also considered single letters. However, the digraph ⟨rr⟩ (erre fuerte, 'strong r', erre doble, 'double r', or simply erre), which also represents a distinct phoneme /r/, was not similarly regarded as a single letter. Since 1994 ⟨ch⟩ and ⟨ll⟩ have been treated as letter pairs for collation purposes, though they remained a part of the alphabet until 2010. Words with ⟨ch⟩ are now alphabetically sorted between those with ⟨cg⟩ and ⟨ci⟩, instead of following ⟨cz⟩ as they used to. The situation is similar for ⟨ll⟩.[248][249]

Thus, the Spanish alphabet has the following 27 letters:

- A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, J, K, L, M, N, Ñ, O, P, Q, R, S, T, U, V, W, X, Y, Z.

Since 2010, none of the digraphs (ch, ll, rr, gu, qu) are considered letters by the Royal Spanish Academy.[250]

The letters k and w are used only in words and names coming from foreign languages (kilo, folklore, whisky, kiwi, etc.).

With the exclusion of a very small number of regional terms such as México (see Toponymy of Mexico), pronunciation can be entirely determined from spelling. Under the orthographic conventions, a typical Spanish word is stressed on the syllable before the last if it ends with a vowel (not including ⟨y⟩) or with a vowel followed by ⟨n⟩ or an ⟨s⟩; it is stressed on the last syllable otherwise. Exceptions to this rule are indicated by placing an acute accent on the stressed vowel.

The acute accent is used, in addition, to distinguish between certain homophones, especially when one of them is a stressed word and the other one is a clitic: compare el ('the', masculine singular definite article) with él ('he' or 'it'), or te ('you', object pronoun) with té ('tea'), de (preposition 'of') versus dé ('give' [formal imperative/third-person present subjunctive]), and se (reflexive pronoun) versus sé ('I know' or imperative 'be').

The interrogative pronouns (qué, cuál, dónde, quién, etc.) also receive accents in direct or indirect questions, and some demonstratives (ése, éste, aquél, etc.) can be accented when used as pronouns. Accent marks used to be omitted on capital letters (a widespread practice in the days of typewriters and the early days of computers when only lowercase vowels were available with accents), although the Real Academia Española advises against this and the orthographic conventions taught at schools enforce the use of the accent.

When u is written between g and a front vowel e or i, it indicates a "hard g" pronunciation. A diaeresis ü indicates that it is not silent as it normally would be (e.g., cigüeña, 'stork', is pronounced [θiˈɣweɲa]; if it were written *cigueña, it would be pronounced *[θiˈɣeɲa]).

Interrogative and exclamatory clauses are introduced with inverted question and exclamation marks (¿ and ¡, respectively) and closed by the usual question and exclamation marks.

Organizations

[edit]Royal Spanish Academy

[edit]The Royal Spanish Academy (Real Academia Española), founded in 1713,[251] together with the 21 other national ones (see Association of Spanish Language Academies), exercises a standardizing influence through its publication of dictionaries and widely respected grammar and style guides.[252] Because of influence and for other sociohistorical reasons, a standardized form of the language (Standard Spanish) is widely acknowledged for use in literature, academic contexts and the media.

Association of Spanish Language Academies

[edit]

Ассоциация академий испанского языка ( Asociación de Academias de la Lengua Española , или ASALE ) является организацией, которая регулирует испанский язык. Она была создана в Мексике в 1951 году и представляет собой союз всех отдельных академий испаноязычного мира. В его состав входят академии 23 стран, упорядоченные по дате основания академии: Испания (1713 г.), [ 254 ] Колумбия (1871 г.), [ 255 ] Эквадор (1874 г.), [ 256 ] Мексика (1875 г.), [ 257 ] Сальвадор (1876 г.), [ 258 ] Венесуэла (1883 г.), [ 259 ] Чили (1885 г.), [ 260 ] Перу (1887 г.), [ 261 ] Гватемала (1887 г.), [ 262 ] Коста-Рика (1923 г.), [ 263 ] Филиппины (1924 г.), [ 264 ] Панама (1926 г.), [ 265 ] Куба (1926), [ 266 ] Парагвай (1927 г.), [ 267 ] Доминиканская Республика (1927 г.), [ 268 ] Боливия (1927), [ 269 ] Никарагуа (1928), [ 270 ] Аргентина (1931), [ 271 ] Уругвай (1943), [ 272 ] Гондурас (1949), [ 273 ] Пуэрто-Рико (1955), [ 274 ] США (1973) [ 275 ] и Экваториальная Гвинея (2016 г.). [ 276 ]

Институт Сервантеса

[ редактировать ]Instituto Cervantes («Институт Сервантеса») — это всемирная некоммерческая организация, созданная правительством Испании в 1991 году. Эта организация имеет филиалы в 45 странах, при этом 88 центров посвящены испанской и латиноамериканской культуре и испанскому языку. [ 277 ] Целями Института являются всеобщее содействие образованию, изучению и использованию испанского языка в качестве второго языка, поддержка методов и мероприятий, которые помогают процессу образования на испанском языке, а также содействие развитию испанского и Латиноамериканские культуры в неиспаноязычных странах. В отчете института за 2015 год «El español, una lengua viva» (испанский, живой язык) оценивается, что во всем мире насчитывается 559 миллионов человек, говорящих по-испански. В последнем ежегодном отчете El español en el mundo 2018 (Испанский в мире, 2018) насчитывается 577 миллионов говорящих по-испански во всем мире. Среди источников, цитируемых в докладе, — Бюро переписи населения США , согласно которому к 2050 году в США будет 138 миллионов человек, говорящих по-испански, что сделает страну крупнейшей испаноязычной нацией на земле, причем испанский язык является родным языком почти трети ее граждан. . [ 278 ]

Официальное использование международными организациями

[ редактировать ]Испанский является одним из официальных языков Организации Объединенных Наций , Европейского Союза , Всемирной торговой организации , Организации американских государств , Организации иберо-американских государств , Африканского союза , Союза южноамериканских наций , Секретариата Договора об Антарктике. Латинский союз , Карибское сообщество , Североамериканское соглашение о свободной торговле , Межамериканский банк развития и многие другие международные организации.

Пример текста

[ редактировать ]Статья 1 Всеобщей декларации прав человека на испанском языке:

- Все люди рождаются свободными и равными в достоинстве и правах и, наделенные разумом и совестью, должны вести себя по-братски друг к другу. [ 279 ]

Статья 1 Всеобщей декларации прав человека на английском языке:

- Все люди рождаются свободными и равными в своем достоинстве и правах. Они наделены разумом и совестью и должны поступать по отношению друг к другу в духе братства. [ 280 ]

См. также

[ редактировать ]

Испанские слова и фразы[ редактировать ]

Испаноязычный мир[ редактировать ] |

Влияние на испанский язык[ редактировать ]

Диалекты и языки под влиянием испанского языка[ редактировать ] |

Испанские диалекты и разновидности[ редактировать ]

|

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]Цитаты

[ редактировать ]- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж г час я дж к л м н тот п д р с т в v В х и С аа аб и объявление но из в ах есть также и аль являюсь а к ап ак с как в В из хорошо топор является тот нет бб до нашей эры др. быть парень бг чб с минет БК с бм млрд быть б.п. Фернандес Виторес, Давид (2023). Испанский: живой язык – Отчет 2023 (PDF) (Отчет). Институт Сервантеса . стр. 23–142. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 8 декабря 2023 года . Проверено 2 декабря 2023 г.

- ^ Эберхард, Саймонс и Фенниг (2020)

- ^ Хаммарстрем, Харальд; Форкель, Роберт; Хаспельмат, Мартин; Банк, Себастьян, ред. (2022). «Кастилик» . Глоттолог 4.6 . Йена, Германия: Институт эволюционной антропологии Макса Планка. Архивировано из оригинала 28 мая 2022 года . Проверено 19 июня 2022 г.

- ^ «Этнолог, 2022» . Архивировано из оригинала 7 мая 2023 года . Проверено 2 декабря 2023 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Эберхард, Дэвид М.; Саймонс, Гэри Ф.; Фенниг, Чарльз Д. (2022). «Сводка по размеру языка» . Этнолог . СИЛ Интернешнл. Архивировано из оригинала 18 июня 2023 года . Проверено 2 декабря 2023 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б «Официальные языки» . Объединенные Нации. Архивировано из оригинала 5 января 2024 года . Проверено 5 января 2024 г.

- ^ «В каких странах мира говорят на этом языке?» . Архивировано из оригинала 29 июня 2023 года . Проверено 23 января 2024 г.

- ^ Сальвадор, Иоланда Мансебо (2002). «К истории постановки «Жизнь - это мечта»» . Кальдерон в Европе (на испанском языке). Вервюрт Верлагсгезельшафт. стр. 91–100. дои : 10.31819/9783964565013-007 . ISBN 978-3-96456-501-3 . Архивировано из оригинала 3 марта 2022 года . Проверено 3 марта 2022 г.

- ^ «Страны с наибольшим количеством испаноговорящих в 2021 году» . Статистика . Архивировано из оригинала 17 мая 2022 года . Проверено 17 мая 2022 г.

- ^ Вергаз, Мигель А. (7 ноября 2010 г.), RAE гарантирует, что в Бургосе будут размещены первые слова, написанные на кастильском языке (на испанском языке), ES: El Mundo, заархивировано из оригинала 24 ноября 2010 г. , получено 24 ноября 2010 г.

- ^ Райс, Джон (2010). «Лингвистические занятия в Испании» . sejours-linguistiques-en-espagne.com . Архивировано из оригинала 18 января 2013 года . Проверено 3 марта 2022 г.

- ^ Эриберто Роблес; Камачо Бесерра; Хуан Хосе Компаран Ризо; Фелипе Кастильо (1998). Руководство по греко-латинской этимологии (3-е изд.). Мексика: Лимуса. п. 19. ISBN 968-18-5542-6 . Архивировано из оригинала 24 января 2023 года . Проверено 9 января 2023 г.

- ^ Сравните Ризо, Хуана Хосе. Греческие и латинские корни (на испанском языке). Умбральные издания. п. 17. ISBN 978-968-5430-01-2 . Архивировано из оригинала 23 апреля 2017 года . Проверено 22 августа 2017 г.

- ↑ Испанский в мире. Архивировано 6 февраля 2021 г. в Wayback Machine , Language Magazine , 18 ноября 2019 г.

- ^ «Испанский язык застревает как научный язык» . Служба научной информации и новостей (на испанском языке). 5 марта 2014 г. Архивировано из оригинала 22 февраля 2019 г. . Проверено 29 января 2019 г.

- ^ Девлин, Томас Мур (30 января 2019 г.). «Какие языки наиболее часто используются в Интернете?» . +Журнал «Баббель» . Архивировано из оригинала 6 декабря 2021 года . Проверено 13 июля 2021 г.

- ^ «Статистика использования языков контента для веб-сайтов» . 10 февраля 2024 года. Архивировано из оригинала 17 августа 2019 года . Проверено 10 февраля 2024 г.

- ^ Паниспаноязычный словарь сомнений, 2005, с. 271–272.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Кано Агилар, Рафаэль (2013). «Ещё раз о средневековых названиях языка Кастилии» . Электронная Испания (15). дои : 10.4000/e-spania.22518 . ISSN 1951-6169 . Архивировано из оригинала 7 июля 2022 года . Проверено 7 июля 2022 г.

- ^ «Испанский, ла» . Словарь испанского языка . Реал Академия Испании. Архивировано из оригинала 24 апреля 2017 года . Проверено 13 июля 2021 г.

- ^ «Картуляриосистория» . www.euskonews.com . Архивировано из оригинала 2 апреля 2016 года . Проверено 22 сентября 2016 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Пенни (2000 :16)

- ^ «Краткий оксфордский справочник по английскому языку» . Издательство Оксфордского университета. Архивировано из оригинала 25 сентября 2008 года . Проверено 24 июля 2008 г.

- ^ «Гарольд Блум о Дон Кихоте, первый современный роман | Книги | The Guardian» . Лондон: Books.guardian.co.uk. 12 декабря 2003 г. Архивировано из оригинала 14 июня 2008 г. Проверено 18 июля 2009 г.