Республиканская партия (США)

Республиканская партия , также известная как Республиканская партия ( Великая старая партия ), является одной из двух крупнейших современных политических партий в Соединенных Штатах . В середине 1850-х годов она стала главным политическим соперником доминировавшей тогда Демократической партии , и с тех пор обе партии доминируют в американской политике.

Партия была основана в 1854 году активистами, выступавшими против рабства , которые выступали против Закона Канзаса-Небраски , закона, который допускал потенциальное расширение рабства движимого имущества на западные территории Канзаса и Небраски. [ 19 ] Он поддерживал классический либерализм и экономические реформы. [ 20 ] выступая против распространения рабства на свободные территории. Изначально партия имела очень ограниченное присутствие на Юге , но добилась успеха на Севере. К 1858 году он привлек большинство бывших вигов и бывших фрисойлеров, чтобы сформировать большинство почти в каждом северном штате. Белые южане были встревожены угрозой работорговли. С избранием в 1860 году Авраама Линкольна , первого президента-республиканца, южные штаты отделились от Соединенных Штатов.

Under the leadership of Lincoln and a Republican Congress, the Republican Party led the fight to defeat the Confederate States in the American Civil War, preserving the Union and abolishing slavery. Afterward, the party largely dominated the national political scene until the Great Depression in the 1930s, when it lost its congressional majorities and the Democrats' New Deal programs proved popular. Dwight D. Eisenhower's election was a rare break in between Democratic presidents and he presided over a period of increased economic prosperity after World War II. His former vice president Richard Nixon carried 49 states in 1972 with what he touted as his silent majority. The 1980 election of Ronald Reagan realigned national politics, bringing together advocates of free-market economics, social conservatives, and Cold War foreign policy hawks under the Republican banner.[21] Since 2009, the party has faced significant factionalism within its own ranks and has shifted towards right-wing populism.[a]

In the 21st century, the Republican Party receives its strongest support from rural voters, evangelical Christians, men, senior citizens, and white voters without college degrees.[29] On economic issues, the party has maintained a pro-business attitude since its inception. It supports low taxes and deregulation while opposing socialism, labor unions and single-payer healthcare.[30][27] The populist faction supports economic protectionism, including tariffs.[31][32] On social issues, it advocates for restricting the legality of abortion, discouraging and often prohibiting recreational drug use, promoting gun ownership and easing gun restrictions, and opposing the transgender rights movement. In foreign policy, the party establishment is neoconservative, supports an aggressive foreign policy and tough stances against China, Iran, North Korea and Russia, while the populist faction is isolationist and supports non-interventionism.

History

19th century

In 1854, the Republican Party was founded in the Northern United States by forces opposed to the expansion of slavery, ex-Whigs, and ex-Free Soilers. The Republican Party quickly became the principal opposition to the dominant Democratic Party and the briefly popular Know Nothing Party. The party grew out of opposition to the Kansas–Nebraska Act, which repealed the Missouri Compromise and opened the Kansas and Nebraska Territories to slavery and future admission as slave states.[33][34] They denounced the expansion of slavery as a great evil, but did not call for ending it in the Southern states. While opposition to the expansion of slavery was the most consequential founding principle of the party, like the Whig Party it replaced, Republicans also called for economic and social modernization.[35]

At the first public meeting of the anti-Nebraska movement on March 20, 1854, at the Little White Schoolhouse in Ripon, Wisconsin, the name "Republican" was proposed as the name of the party.[36] The name was partly chosen to pay homage to Thomas Jefferson's Democratic-Republican Party.[37] The first official party convention was held on July 6, 1854, in Jackson, Michigan.[38]

The party emerged from the great political realignment of the mid-1850s, united in pro-capitalist stances with members often valuing Radicalism.[39] Historian William Gienapp argues that the great realignment of the 1850s began before the Whigs' collapse, and was caused not by politicians but by voters at the local level. The central forces were ethno-cultural, involving tensions between pietistic Protestants versus liturgical Catholics, Lutherans, and Episcopalians regarding Catholicism, prohibition and nativism. The Know Nothing Party embodied the social forces at work, but its weak leadership was unable to solidify its organization, and the Republicans picked it apart. Nativism was so powerful that the Republicans could not avoid it, but they did minimize it and turn voter wrath against the threat that slave owners would buy up the good farm lands wherever slavery was allowed. The realignment was powerful because it forced voters to switch parties, as typified by the rise and fall of the Know Nothings, the rise of the Republican Party and the splits in the Democratic Party.[40][41]

At the Republican Party's first National Convention in 1856, held at Musical Fund Hall in Philadelphia, the party adopted a national platform emphasizing opposition to the expansion of slavery into the free territories.[42] While Republican nominee John C. Frémont lost that year's presidential election to Democrat James Buchanan, Buchanan managed to win only four of the fourteen northern states and won his home state of Pennsylvania only narrowly.[43][44] Republicans fared better in congressional and local elections, but Know Nothing candidates took a significant number of seats, creating an awkward three-party arrangement. Despite the loss of the presidency and the lack of a majority in the U.S. Congress, Republicans were able to orchestrate a Republican speaker of the House of Representatives, which went to Nathaniel P. Banks. Historian James M. McPherson writes regarding Banks' speakership that "if any one moment marked the birth of the Republican party, this was it."[45]

The Republicans were eager for the 1860 elections.[46] Former Illinois U.S. representative Abraham Lincoln spent several years building support within the party, campaigning heavily for Frémont in 1856 and making a bid for the Senate in 1858, losing to Democrat Stephen A. Douglas but gaining national attention from the Lincoln–Douglas debates it produced.[44][47] At the 1860 Republican National Convention, Lincoln consolidated support among opponents of New York U.S. senator William H. Seward, a fierce abolitionist who some Republicans feared would be too radical for crucial states such as Pennsylvania and Indiana, as well as those who disapproved of his support for Irish immigrants.[46] Lincoln won on the third ballot and was ultimately elected president in the general election in a rematch against Douglas. Lincoln had not been on the ballot in a single Southern state, and even if the vote for Democrats had not been split between Douglas, John C. Breckinridge and John Bell, the Republicans would have still won but without the popular vote.[46] This election result helped kickstart the American Civil War, which lasted from 1861 until 1865.[48]

The 1864 presidential election united War Democrats with the GOP in support of Lincoln and Tennessee Democratic senator Andrew Johnson, who ran for president and vice president on the National Union Party ticket;[43] Lincoln was re-elected.[49] By June 1865, slavery was dead in the ex-Confederate States but remained legal in some border states. Under Republican congressional leadership, the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution—which banned slavery, except as punishment for a crime—passed the Senate on April 8, 1864, the House of Representatives on January 31, 1865, and was ratified by the required 27 of the then 36 states on December 6, 1865.[50]

Reconstruction, the gold standard, and the Gilded Age

Radical Republicans during Lincoln's presidency felt he was too moderate in his efforts to eradicate slavery and opposed his ten percent plan. Radical Republicans passed the Wade–Davis Bill in 1864, which sought to enforce the taking of the Ironclad Oath for all former Confederates. Lincoln vetoed the bill, believing it would jeopardize the peaceful reintegration of the ex-Confederate states.[51]

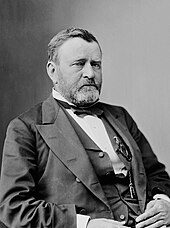

Following the assassination of Lincoln, Johnson ascended to the presidency and was deplored by Radical Republicans. Johnson was vitriolic in his criticisms of the Radical Republicans during a national tour ahead of the 1866 elections.[52] Anti-Johnson Republicans won a two-thirds majority in both chambers of Congress following the elections, which helped lead the way toward his impeachment and near ouster from office in 1868,[52] the same year former Union Army general Ulysses S. Grant was elected as the next Republican president.

Grant was a Radical Republican, which created some division within the party. Massachusetts senator Charles Sumner and Illinois senator Lyman Trumbull opposed most of his Reconstructionist policies.[53] Others took issue with the large-scale corruption present in the Grant administration, with the emerging Stalwart faction defending Grant and the spoils system, and the Half-Breeds advocating reform of the civil service.[54] Republicans who opposed Grant branched off to form the Liberal Republican Party, nominating Horace Greeley in the 1872 presidential election. The Democratic Party attempted to capitalize on this divide in the GOP by co-nominating Greeley under their party banner. Greeley's positions proved inconsistent with the Liberal Republican Party that nominated him, with Greeley supporting high tariffs despite the party's opposition.[55] Grant was easily re-elected.[56][57]

The 1876 presidential election saw a contentious conclusion as both parties claimed victory despite three southern states still not officially declaring a winner at the end of election day. Voter suppression had occurred in the South to depress the black and white Republican vote, which gave Republican-controlled returning officers enough of a reason to declare that fraud, intimidation and violence had soiled the states' results. They proceeded to throw out enough Democratic votes for Republican Rutherford B. Hayes to be declared the winner.[58] Still, Democrats refused to accept the results and the Electoral Commission made up of members of Congress was established to decide who would be awarded the states' electors. After the Commission voted along party lines in Hayes' favor, Democrats threatened to delay the counting of electoral votes indefinitely so no president would be inaugurated on March 4. This resulted in the Compromise of 1877 and Hayes finally became president.[59]

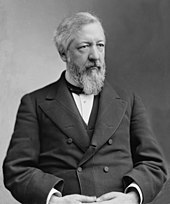

Hayes doubled down on the gold standard, which had been signed into law by Grant with the Coinage Act of 1873, as a solution to the depressed American economy in the aftermath of that year's panic. He also believed greenbacks posed a threat; greenbacks being money printed during the Civil War that was not backed by specie, which Hayes objected to as a proponent of hard money. Hayes sought to restock the country's gold supply, which by January 1879 succeeded as gold was more frequently exchanged for greenbacks compared to greenbacks being exchanged for gold.[60] Ahead of the 1880 presidential election, Republican James G. Blaine ran for the party nomination, supporting both Hayes' gold standard push and his civil service reforms. After both Blaine and opponent John Sherman failed to win the Republican nomination, each of them backed James A. Garfield for president. Garfield agreed with Hayes' move in favor of the gold standard, but opposed his civil reform efforts.[61][62]

Garfield won the 1880 presidential election, but was assassinated early in his term. His death helped create support for the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act, which was passed in 1883;[63] the bill was signed into law by Republican president Chester A. Arthur, who succeeded Garfield.

In 1884, Blaine once again ran for president. He won the Republican nomination, but lost the general election to Democrat Grover Cleveland. Cleveland was the first Democrat to be elected president since James Buchanan. Dissident Republicans, known as Mugwumps, had defected from Blaine due to the corruption which had plagued his political career.[64][65] Cleveland stuck to the gold standard policy,[66] but he came into conflict with Republicans regarding budding American imperialism.[67]

Republican Benjamin Harrison defeated Cleveland in the 1888 election. During his presidency, Harrison signed the Dependent and Disability Pension Act, which established pensions for all veterans of the Union who had served for more than 90 days and were unable to perform manual labor.[68] Following his loss to Cleveland in the 1892 presidential election, Harrison unsuccessfully attempted to pass a treaty annexing Hawaii before Cleveland could be inaugurated. Most Republicans supported the proposed annexation,[69] but Cleveland opposed it.[70]

In the 1896 presidential election, Republican William McKinley's platform supported the gold standard and high tariffs, having been the creator and namesake for the McKinley Tariff of 1890. Though having been divided on the issue prior to that year's National Convention, McKinley decided to heavily favor the gold standard over free silver in his campaign messaging, but promised to continue bimetallism to ward off continued skepticism over the gold standard, which had lingered since the Panic of 1893.[71][72] Democrat William Jennings Bryan proved to be a devoted adherent to the free silver movement, which cost Bryan the support of Democratic institutions such as Tammany Hall, the New York World and a large majority of the Democratic Party's upper and middle-class support.[73] McKinley defeated Bryan[74] and returned the presidency to Republican control until the 1912 presidential election.[75]

First half of the 20th century

Progressives vs. Standpatters

The 1896 realignment cemented the Republicans as the party of big businesses while president Theodore Roosevelt added more small business support by his embrace of trust busting. He handpicked his successor William Howard Taft in the 1908 election, but they became enemies as the party split down the middle. Taft defeated Roosevelt for the 1912 nomination so Roosevelt stormed out of the convention and started a new party. Roosevelt ran on the ticket of his new Progressive Party. He called for social reforms, many of which were later championed by New Deal Democrats in the 1930s. He lost and when most of his supporters returned to the GOP, they found they did not agree with the new conservative economic thinking, leading to an ideological shift to the right in the Republican Party.[76]

The Republicans returned to the presidency in the 1920s, winning on platforms of normalcy, business-oriented efficiency, and high tariffs.[77] The national party platform avoided mention of prohibition, instead issuing a vague commitment to law and order.[78] The Teapot Dome scandal threatened to hurt the party under Warren G. Harding. He died in 1923 and Calvin Coolidge easily defeated the splintered opposition in 1924.[79] The pro-business policies of the decade produced an unprecedented prosperity until the Wall Street Crash of 1929 heralded the Great Depression.[80]

Roosevelt and the New Deal era

The New Deal coalition forged by Democratic president Franklin D. Roosevelt controlled American politics for most of the next three decades, excluding the presidency of Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower in the 1950s. After Roosevelt took office in 1933, New Deal legislation sailed through Congress and the economy moved sharply upward from its nadir in early 1933. However, long-term unemployment remained a drag until 1940. In the 1934 elections, 10 Republican senators went down to defeat, leaving the GOP with only 25 senators against 71 Democrats. The House likewise had overwhelming Democratic majorities.[81]

The Republican Party factionalized into a majority Old Right, based predominantly in the Midwest, and a liberal wing based in the Northeast that supported much of the New Deal. The Old Right sharply attacked the Second New Deal, saying it represented class warfare and socialism. Roosevelt was easily re-elected president in 1936; however, as his second term began, the economy declined, strikes soared, and he failed to take control of the Supreme Court and purge the Southern conservatives from the Democratic Party. Republicans made a major comeback in the 1938 House elections and had new rising stars such as Robert A. Taft of Ohio on the right and Thomas E. Dewey of New York on the left.[82] Southern conservatives joined with most Republicans to form the conservative coalition, which dominated domestic issues in Congress until 1964. By the time of World War II, both parties split on foreign policy issues, with the anti-war isolationists dominant in the Republican Party and the interventionists who wanted to stop German dictator Adolf Hitler dominant in the Democratic Party. Roosevelt won a third term in 1940 and a fourth in 1944. Conservatives abolished most of the New Deal during the war, but they did not attempt to do away with Social Security or the agencies that regulated business.[83]

Historian George H. Nash argues:

Unlike the "moderate", internationalist, largely eastern bloc of Republicans who accepted (or at least acquiesced in) some of the "Roosevelt Revolution" and the essential premises of President Harry S. Truman's foreign policy, the Republican Right at heart was counterrevolutionary. Anti-collectivist, anti-Communist, anti-New Deal, passionately committed to limited government, free market economics, and congressional (as opposed to executive) prerogatives, the G.O.P. conservatives were obliged from the start to wage a constant two-front war: against liberal Democrats from without and "me-too" Republicans from within.[84]

After 1945, the internationalist wing of the GOP cooperated with Truman's Cold War foreign policy, funded the Marshall Plan and supported NATO, despite the continued isolationism of the Old Right.[85]

Second half of the 20th century

Post-Roosevelt era

Eisenhower had defeated conservative leader senator Robert A. Taft for the 1952 Republican presidential nomination, but conservatives dominated the domestic policies of the Eisenhower administration. Voters liked Eisenhower much more than they liked the GOP and he proved unable to shift the party to a more moderate position.[86]

From Goldwater to Reagan

Historians cite the 1964 presidential election and its respective National Convention as a significant shift, which saw the conservative wing, helmed by Arizona senator Barry Goldwater, battle liberal New York governor Nelson Rockefeller and his eponymous Rockefeller Republican faction for the nomination. With Goldwater poised to win, Rockefeller, urged to mobilize his liberal faction, retorted, "You're looking at it, buddy. I'm all that's left."[87][88]

Following the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965, the southern states became more reliably Republican in presidential politics, while northeastern states became more reliably Democratic.

Though Goldwater lost the election in a landslide, Ronald Reagan would make himself known as a prominent supporter of his throughout the campaign, delivering his famous "A Time for Choosing" speech for Goldwater. Reagan would go on to win the California governorship two years later.

The GOP would go on to control the White House from 1969 to 1977 under 37th president Richard Nixon, and when he resigned in 1974 due to the Watergate scandal, Gerald Ford became the 38th president, serving until 1977. Ronald Reagan would later go on to defeat incumbent Democratic President Jimmy Carter in the 1980 United States presidential election, becoming the 40th president on January 20, 1981.[89]

Reagan era

The Reagan presidency, lasting from 1981 to 1989, constituted what is known as "the Reagan Revolution".[90] It was seen as a fundamental shift from the stagflation of the 1970s preceding it, with the introduction of Reagan's economic policies intended to cut taxes, prioritize government deregulation and shift funding from the domestic sphere into the military to check the Soviet Union by utilizing deterrence theory. During a visit to then-West Berlin in June 1987, he addressed Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev during a speech at the Berlin Wall, demanding that he "Tear down this wall!". The remark was later seen as influential in the fall of the wall in November 1989, and was retroactively seen as a soaring achievement over the years.[91] The Soviet Union was dissolved in 1991.[92][93][94] Following Reagan's presidency, Republican presidential candidates frequently claimed to share Reagan's views and aimed to portray themselves and their policies as heirs to his legacy.[95]

Reagan's vice president, George H. W. Bush, won the presidency in a landslide in the 1988 presidential election. However, his term was characterized by division within the Republican Party. Bush's vision of economic liberalization and international cooperation with foreign nations saw the negotiation and, during the presidency of Democrat Bill Clinton in the 1990s, the signing of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the conceptual beginnings of the World Trade Organization.[96] Independent politician and businessman Ross Perot decried NAFTA and predicted that it would lead to the outsourcing of American jobs to Mexico; however, Clinton agreed with Bush's trade policies.[97]

Bush lost his re-election bid in 1992, receiving 37 percent of the popular vote; Clinton garnered a plurality of 43 percent, and Perot took third place with 19 percent. While there is debate about whether Perot's candidacy cost Bush re-election, Charlie Cook asserted that Perot's messaging carried weight with Republican and conservative voters.[98] Perot subsequently formed the Reform Party; future Republican president Donald Trump was a member.[99]

Gingrich Revolution

In the 1994 elections, the Republican Party, led by House minority whip Newt Gingrich, who campaigned on the "Contract with America", won majorities in both chambers of Congress, gained 12 governorships, and regained control of 20 state legislatures. However, most voters had not heard of the Contract and the Republican victory was attributed to traditional mid-term anti-incumbent voting and Republicans becoming the majority party in Dixie for the first time since Reconstruction.[100] It was the first time the Republican Party had achieved a majority in the House since 1952.[101] Gingrich was made speaker, and within the first 100 days of the Republican majority, every proposition featured in the Contract was passed, with the exception of term limits for members of Congress, which did not pass in the Senate.[102][100] One key to Gingrich's success in 1994 was nationalizing the election,[101] which in turn led to his becoming a national figure during the 1996 House elections, with many Democratic leaders proclaiming Gingrich was a zealous radical.[103][104] The Republicans maintained their majority for the first time since 1928 despite Bob Dole losing handily to Clinton in the presidential election. However, Gingrich's national profile proved a detriment to the Republican Congress, which enjoyed majority approval among voters in spite of Gingrich's relative unpopularity.[103]

After Gingrich and the Republicans struck a deal with Clinton on the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, which included tax cuts, the Republican House majority had difficulty convening on a new agenda ahead of the 1998 elections.[105] During the ongoing impeachment of Bill Clinton in 1998, Gingrich decided to make Clinton's misconduct the party message heading into the elections, believing it would add to their majority. The strategy proved mistaken and the Republicans lost five seats, though whether it was due to poor messaging or Clinton's popularity providing a coattail effect is debated.[106] Gingrich was ousted from party power due to the performance, ultimately deciding to resign from Congress altogether. For a short time afterward, it appeared Louisiana representative Bob Livingston would become his successor; Livingston, however, stepped down from consideration and resigned from Congress after damaging reports of affairs threatened the Republican House's legislative agenda if he were to serve as speaker.[107] Illinois representative Dennis Hastert was promoted to speaker in Livingston's place, serving in that position until 2007.[108]

21st century

George W. Bush

Republican George W. Bush won the 2000 and 2004 presidential elections.[109] He campaigned as a "compassionate conservative" in 2000, wanting to better appeal to immigrants and minority voters.[110] The goal was to prioritize drug rehabilitation programs and aid for prisoner reentry into society, a move intended to capitalize on President Clinton's tougher crime initiatives such as his administration's 1994 crime bill. The platform failed to gain much traction among members of the party during his presidency.[111]

The Republican Party remained fairly cohesive for much of the 2000s, as both strong economic libertarians and social conservatives opposed the Democrats, whom they saw as the party of bloated, secular, and liberal government.[112] This period saw the rise of "pro-government conservatives"—a core part of the Bush's base—a considerable group of the Republicans who advocated for increased government spending and greater regulations covering both the economy and people's personal lives, as well as for an activist and interventionist foreign policy.[113] Survey groups such as the Pew Research Center found that social conservatives and free market advocates remained the other two main groups within the party's coalition of support, with all three being roughly equal in number.[114][115] However, libertarians and libertarian-leaning conservatives increasingly found fault with what they saw as Republicans' restricting of vital civil liberties while corporate welfare and the national debt hiked considerably under Bush's tenure.[116] In contrast, some social conservatives expressed dissatisfaction with the party's support for economic policies that conflicted with their moral values.[117]

The Republican Party lost its Senate majority in 2001 when the Senate became split evenly; nevertheless, the Republicans maintained control of the Senate due to the tie-breaking vote of Bush's vice president, Dick Cheney. Democrats gained control of the Senate on June 6, 2001, when Vermont Republican senator Jim Jeffords switched his party affiliation to Democrat. The Republicans regained the Senate majority in the 2002 elections, helped by Bush's surge in popularity following the September 11 attacks, and Republican majorities in the House and Senate were held until the Democrats regained control of both chambers in the 2006 elections, largely due to increasing opposition to the Iraq War.[118][119][120]

In the 2008 presidential election, Arizona Republican senator John McCain was defeated by Illinois Democratic senator Barack Obama.[121]

Tea Party movement

The Republicans experienced electoral success in the 2010 elections. The 2010 elections coincided with the ascendancy of the Tea Party movement,[122][123][124][125] an anti-Obama protest movement of fiscal conservatives.[126] Members of the movement called for lower taxes, and for a reduction of the national debt and federal budget deficit through decreased government spending.[127][128] The Tea Party movement was also described as a popular constitutional movement[129] composed of a mixture of libertarian,[130] right-wing populist,[131] and conservative activism.[132]

The Tea Party movement's electoral success began with Scott Brown's upset win in the January Senate special election in Massachusetts; the seat had been held for decades by Democrat Ted Kennedy.[133] In November, Republicans recaptured control of the House, increased their number of seats in the Senate, and gained a majority of governorships.[134] The Tea Party would go on to strongly influence the Republican Party, in part due to the replacement of establishment Republicans with Tea Party-style Republicans.[126]

When Obama was re-elected president in 2012, defeating Republican Mitt Romney,[135] the Republican Party lost seven seats in the House, but still retained control of that chamber.[136] However, Republicans were unable to gain control of the Senate, continuing their minority status with a net loss of two seats.[137] In the aftermath of the loss, some prominent Republicans spoke out against their own party.[138][139][140] A 2012 election post-mortem by the Republican Party concluded that the party needed to do more on the national level to attract votes from minorities and young voters.[141] In March 2013, Republican National Committee chairman Reince Priebus issued a report on the party's electoral failures in 2012, calling on Republicans to reinvent themselves and officially endorse immigration reform. He proposed 219 reforms, including a $10 million marketing campaign to reach women, minorities, and gay people; the setting of a shorter, more controlled primary season; and the creation of better data collection facilities.[142]

Following the 2014 elections, the Republican Party took control of the Senate by gaining nine seats.[143] With 247 seats in the House and 54 seats in the Senate, the Republicans ultimately achieved their largest majority in the Congress since the 71st Congress in 1929.[144]

Trump era

In the 2016 presidential election, Republican nominee Donald Trump defeated Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton. The result was unexpected; polls leading up to the election showed Clinton leading the race.[145] Trump's victory was fueled by narrow victories in three states—Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin—that had been part of the Democratic blue wall for decades.[146] It was attributed to strong support amongst working-class white voters, who felt dismissed and disrespected by the political establishment.[147][148] Trump became popular with them by abandoning Republican establishment orthodoxy in favor of a broader nationalist message.[146]

After the 2016 elections, Republicans maintained their majority in the Senate, the House, and governorships, and wielded newly acquired executive power with Trump's election. The Republican Party controlled 69 of 99 state legislative chambers in 2017, the most it had held in history.[149] The Party also held 33 governorships,[150] the most it had held since 1922.[151] The party had total control of government in 25 states;[152][153] it had not held total control of this many states since 1952.[154] The opposing Democratic Party held full control of only five states in 2017.[155] In the 2018 elections, Republicans lost control of the House of Representatives, but strengthened their hold on the Senate.[156]

Over the course of his presidency, Trump appointed three justices to the Supreme Court: Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett. It was the most Supreme Court appointments for any president in a single term since Richard Nixon.[157] Trump appointed 260 judges in total, creating overall Republican-appointed majorities on every branch of the federal judiciary except for the Court of International Trade by the time he left office, shifting the court system to the right. Other notable achievements during his presidency included the passing of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act in 2017; the creation of the U.S. Space Force, the first new independent military service since 1947; and the brokering of the Abraham Accords, a series of normalization agreements between Israel and various Arab states.[158][159][160] Trump was impeached by the House of Representatives in 2019 on charges of abuse of power and obstruction of Congress. On February 5, 2020, the Senate voted to acquit him.[161]

Trump lost the 2020 presidential election to Democrat Joe Biden. He refused to concede the race, claiming widespread electoral fraud and attempting to overturn the results. On January 6, 2021, the United States Capitol was attacked by Trump supporters following a rally at which Trump spoke. After the attack, the House impeached Trump for a second time on the charge of incitement of insurrection, making him the only federal officeholder to be impeached twice.[162][163] Trump left office on January 20, 2021. His impeachment trial continued into the early weeks of the Biden presidency, and he was acquitted on February 13, 2021.[164] Since the 2020 election, election denial has become increasingly mainstream in the party,[165] with the majority of 2022 Republican candidates being election deniers.[166]

In 2022 and 2023, Supreme Court justices appointed by Trump proved decisive in landmark decisions on gun rights, abortion, and affirmative action.[167][168] The party went into the 2022 elections confident and with analysts predicting a red wave, but it ultimately underperformed expectations, with voters in swing states and competitive districts joining Democrats in rejecting candidates who had been endorsed by Trump or who had denied the results of the 2020 election.[169][170][171] The party won control of the House with a narrow majority,[172] but lost the Senate and several state legislative majorities and governorships.[173][174][175] The results led to many Republicans and conservative thought leaders questioning whether Trump should continue as the party's main figurehead and leader.[176][177]

Current status

As of 2024, the GOP holds a majority in the U.S. House of Representatives. It also holds 27 state governorships, 28 state legislatures, and 23 state government trifectas. Six of the nine current U.S. Supreme Court justices were appointed by Republican presidents. Its most recent presidential nominee is Donald Trump, who served as the 45th president of the United States and is the party's candidate again in the 2024 presidential election.[178] There have been 19 Republican presidents, the most from any one political party.

Name and symbols

The Republican Party's founding members chose its name as homage to the values of republicanism promoted by Democratic-Republican Party, which its founder, Thomas Jefferson, called the "Republican Party".[179] The idea for the name came from an editorial by the party's leading publicist, Horace Greeley, who called for "some simple name like 'Republican' [that] would more fitly designate those who had united to restore the Union to its true mission of champion and promulgator of Liberty rather than propagandist of slavery".[180] The name reflects the 1776 republican values of civic virtue and opposition to aristocracy and corruption.[181] "Republican" has a variety of meanings around the world, and the Republican Party has evolved such that the meanings no longer always align.[182][118]

The term "Grand Old Party" is a traditional nickname for the Republican Party, and the abbreviation "GOP" is a commonly used designation. The term originated in 1875 in the Congressional Record, referring to the party associated with the successful military defense of the Union as "this gallant old party". The following year in an article in the Cincinnati Commercial, the term was modified to "grand old party". The first use of the abbreviation is dated 1884.[183]

The traditional mascot of the party is the elephant. A political cartoon by Thomas Nast, published in Harper's Weekly on November 7, 1874, is considered the first important use of the symbol.[184] An alternate symbol of the Republican Party in states such as Indiana, New York and Ohio is the bald eagle as opposed to the Democratic rooster or the Democratic five-pointed star.[185][186] In Kentucky, the log cabin is a symbol of the Republican Party.[187]

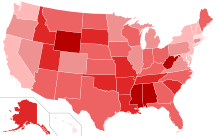

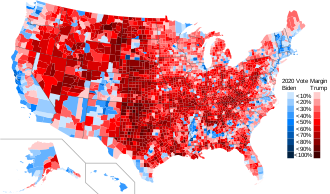

Traditionally the party had no consistent color identity.[188][189][190] After the 2000 presidential election, the color red became associated with Republicans. During and after the election, the major broadcast networks used the same color scheme for the electoral map: states won by Republican nominee George W. Bush were colored red and states won by Democratic nominee Al Gore were colored blue. Due to the weeks-long dispute over the election results, these color associations became firmly ingrained, persisting in subsequent years. Although the assignment of colors to political parties is unofficial and informal, the media has come to represent the respective political parties using these colors. The party and its candidates have also come to embrace the color red.[191]

-

An 1874 cartoon by Thomas Nast, featuring the first notable appearance of the Republican elephant[192]

-

The red, white and blue elephant

-

The GOP banner logo, c. 2013

-

A GOP banner logo, c. 2017

Factions

Civil War and Reconstruction era

During the 19th century, Republican factions included the Radical Republicans. They were a major factor of the party from its inception in 1854 until the end of the Reconstruction Era in 1877. They strongly opposed slavery, were hard-line abolitionists, and later advocated equal rights for the freedmen and women. They were heavily influenced by religious ideals and evangelical Christianity; many were Christian reformers who saw slavery as evil and the Civil War as God's punishment for it.[193] Radical Republicans pressed for abolition as a major war aim and they opposed the moderate Reconstruction plans of Abraham Lincoln as both too lenient on the Confederates and not going far enough to help former slaves who had been freed during or after the Civil War by the Emancipation Proclamation and the Thirteenth Amendment. After the war's end and Lincoln's assassination, the Radicals clashed with Andrew Johnson over Reconstruction policy. Radicals led efforts after the war to establish civil rights for former slaves and fully implement emancipation. After unsuccessful measures in 1866 resulted in violence against former slaves in the rebel states, Radicals pushed the Fourteenth Amendment for statutory protections through Congress. They opposed allowing ex-Confederate officers to retake political power in the Southern U.S., and emphasized liberty, equality, and the Fifteenth Amendment which provided voting rights for the freedmen. Many later became Stalwarts, who supported machine politics.

Moderate Republicans were known for their loyal support of President Abraham Lincoln's war policies and expressed antipathy towards the more militant stances advocated by the Radical Republicans. According to historian Eric Foner, congressional leaders of the faction were James G. Blaine, John A. Bingham, William P. Fessenden, Lyman Trumbull, and John Sherman. In contrast to Radicals, Moderate Republicans were less enthusiastic on the issue of Black suffrage even while embracing civil equality and the expansive federal authority observed throughout the American Civil War. They were also skeptical of the lenient, conciliatory Reconstruction policies of President Andrew Johnson. Members of the Moderate Republicans comprised in part of previous Radical Republicans who became disenchanted with the alleged corruption of the latter faction. Charles Sumner, a Massachusetts senator who led Radical Republicans in the 1860s, later joined reform-minded moderates as he later opposed the corruption associated with the Grant administration. They generally opposed efforts by Radical Republicans to rebuild the Southern U.S. under an economically mobile, free-market system.[194]

20th century

The dawn on the 20th century saw the Republican party split into an Old Right and a moderate-liberal faction in the Northeast that eventually became known as Rockefeller Republicans. Opposition to Roosevelt's New Deal saw the formation of the conservative coalition.[82] The 1950s saw fusionism of traditionalist and social conservatism and right-libertarianism,[195] along with the rise of the First New Right to be followed in 1964 with a more populist Second New Right.[196] The rise of the Reagan coalition via the "Reagan Revolution" in the 1980s began what has been called the Reagan era. Reagan's rise displaced the liberal-moderate faction of the GOP and established Reagan-style conservatism as the prevailing ideological faction of the Party for the next thirty years.[9][23]

21st century

Republicans began the 21st century with the election of George W. Bush in the 2000 United States presidential election and saw the peak of a neoconservative faction that held significant influence over the initial American response to the September 11 attacks through the War on Terror.[197] The election of Barack Obama saw the formation of the Tea Party movement in 2009 that coincided with a global rise in right-wing populist movements from the 2010s to 2020's.[198]

Right-wing populism became an increasingly dominant ideological faction within the GOP throughout the 2010s and helped lead to the election of Donald Trump in 2016.[147] Starting in the 1970s and accelerating in the 2000s, American right-wing interest groups invested heavily in external mobilization vehicles that led to the organizational weakening of the GOP establishment. The outsize role of conservative media, in particular Fox News, led to it being followed and trusted more by the Republican base over traditional party elites. The depletion of organizational capacity partly led to Trump's victory in the Republican primaries against the wishes of a very weak party establishment and traditional power brokers.[199]: 27–28 Trump's election exacerbated internal schisms within the GOP,[199]: 18 and saw the GOP move from a center coalition of moderates and conservatives to a solidly right-wing party hostile to liberal views and any deviations from the party line.[200]

The Party has since faced intense factionalism,[201][202] and has also undergone a major decrease in influence of the traditional establishment conservative faction.[22][13][203][24] Trump's election split both the GOP and larger conservative movement into Trumpist and anti-Trump factions.[204][205]

These factions are particularly apparent in the U.S House of Representatives. Three Republican House leaders have been deposed since 2009.[206] House Majority Leader Eric Cantor was defeat in a primary election in 2014 by Tea Party supporter Dave Brat.[207] John Boehner, Speaker of the House from 2011 to 2015, resigned in 2015 after facing a motion to vacate.[208][209] On January 7, 2023, after 15 rounds of voting, Kevin McCarthy was elected to the speakership. It was the first multiple ballot speaker election since 1923.[210] Subsequently, he was ousted from his position on October 3, 2023, by a vote led by 8 members of the Trumpist faction along with 208 House Democrats.[211]

Conservatives

Ronald Reagan's presidential election in 1980 established Reagan-style American conservatism as the dominant ideological faction of the Republican Party until the election of Donald Trump in 2016.[9][22][13][23][24][25][26][27][28] Traditional modern conservatives combine support for free-market economic policies with social conservatism and a hawkish approach to foreign policy.[21] Other parts of the conservative movement are composed of fiscal conservatives and deficit hawks.[213] Conservatives generally support policies that favor limited government, individualism, traditionalism, republicanism, and limited federal governmental power in relation to the states.[214]

In foreign policy, neoconservatives are a small faction of the GOP that support an interventionist foreign policy and increased military spending. They previously held significant influence in the early 2000s in planning the initial response to the 9/11 attacks through the War on Terror.[197] Since the election of Trump in 2016, neoconservatism has declined and non-interventionism and isolationism has grown among elected federal Republican officeholders.[30][215][216]

Long-term shifts in conservative thinking following the election of Trump have been described as a "new fusionism" of traditional conservative ideology and right-wing populist themes.[30] These have resulted in shifts towards greater support for national conservatism,[217] protectionism,[218] cultural conservatism, a more realist foreign policy, a repudiation of neoconservatism, reduced efforts to roll back entitlement programs, and a disdain for traditional checks and balances.[30][219] There are significant divisions within the party on the issues of abortion and same-sex marriage.[220][221]

Conservative caucuses include the Republican Study Committee and Freedom Caucus.[222][223]

Christian right

Since the rise of the Christian right in the 1970s, the Republican Party has drawn significant support from traditionalists in the Catholic Church and evangelicals, partly due to opposition to abortion after Roe v. Wade.[224] The Christian right faction is characterized by strong support of socially conservative and Christian nationalist policies.[b] Christian conservatives seek to use the teachings of Christianity to influence law and public policy.[237] Compared to other Republicans, the socially conservative Christian right faction of the party is more likely to oppose LGBT rights, marijuana legalization, and support significantly restricting the legality of abortion.[238]

The Christian right is strongest in the Bible Belt, which covers most of the South.[239] Mike Pence, Donald Trump's vice president from 2017 to 2021, was a member of the Christian right.[240] In October 2023, a member of the Christian right faction, Louisiana representative Mike Johnson, was elected the 56th Speaker of the United States House of Representatives.[241][242]

Libertarians

The Republican Party has a prominent right-libertarian faction.[12][220] This faction of the party tends to prevail in the Midwestern and Western United States.[220] Right-libertarianism emerged from fusionism in the 1950s and 60s.[243] Barry Goldwater had a substantial impact on the conservative-libertarian movement of the 1960s.[244] Compared to other Republicans, they are more likely to favor the legalization of marijuana, LGBT rights such as same-sex marriage, gun rights, oppose mass surveillance, and support reforms to current laws surrounding civil asset forfeiture. Right-wing libertarians are strongly divided on the subject of abortion.[245] Prominent libertarian conservatives within the Republican Party include Rand Paul, a U.S. senator from Kentucky,[246][247] Kentucky's 4th congressional district congressman Thomas Massie,[248] Utah senator Mike Lee[249][246] and Wyoming senator Cynthia Lummis.[250]

Moderates

Moderates in the Republican Party are an ideologically centrist group that predominantly come from the Northeastern United States,[251] and are typically located in swing states or blue states. Moderate Republican voters are typically highly educated, affluent, fiscally conservative, socially moderate or liberal and often Never Trump.[220][251] While they sometimes share the economic views of other Republicans (i.e. lower taxes, deregulation, and welfare reform), moderate Republicans differ in that some are for affirmative action,[252] LGBT rights and same-sex marriage, legal access to and even public funding for abortion, gun control laws, more environmental regulation and action on climate change, fewer restrictions on immigration and a path to citizenship for illegal immigrants.[253] In the 21st century, some former Republican moderates have switched to the Democratic Party.[254][255][256]

Notable moderate Republicans include Senators Lisa Murkowski of Alaska and Susan Collins of Maine,[257][258][259][260] Nevada governor Joe Lombardo, Vermont governor Phil Scott, former Massachusetts governor Charlie Baker, and former Maryland governor Larry Hogan.[261][262][263]

Right-wing populists

Right-wing populism is a dominant political faction of the GOP.[c] Sometimes referred to as the MAGA or "America First" movement,[272][273] Republican populists have been described as consisting of a range of right-wing ideologies including but not limited to right-wing populism,[147][274][275] national conservatism,[276] neo-nationalism,[277] and Trumpism.[278][279][280] They have been described as the American political variant of the far-right.[d] The election of Trump in 2016 split the party into pro-Trump and anti-Trump factions.[204][205]

The Republican Party's populist and far-right movements emerged in concurrence with a global increase in populist movements in the 2010s and 2020s,[198] coupled with entrenchment and increased partisanship within the party since 2010, fueled by the rise of the Tea Party movement which has also been described as far-right.[284] According to political scientists Matt Grossmann and David A. Hopkins, the Republican Party's gains among white voters without college degrees contributed to the rise of right-wing populism.[29] According to historian Gary Gerstle, Trumpism gained support in opposition to neoliberalism, including opposition to free trade, immigration, and internationalism.[27]

The far-right faction supports cuts to spending.[285][286] In international relations, populists support U.S. aid to Israel but not to Ukraine,[287][288] are generally supportive towards Russia,[289][290][291] and favor an isolationist "America First" foreign policy agenda.[292][293][294][220] They generally reject compromise within the party and with the Democrats,[295][296] and are willing to oust fellow Republican office holders they deem to be too moderate.[297][298] Compared to other Republicans, the populist faction is more likely to oppose legal immigration,[299] free trade,[300] neoconservatism,[301] and environmental protection laws.[302]

The party's far-right faction includes members of the Freedom Caucus,[303][304][305] as well as Lauren Boebert, Marjorie Taylor Greene and Matt Gaetz. Gaetz led the 2023 rebellion against then-Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy.[306][307]

Joseph Lowndes, a professor of political science at the University of Oregon, argued that while current far-right Republicans support Trump, the faction rose before and will likely exist after Trump.[308] Lilliana Mason, associate professor of political science at Johns Hopkins University, states that Donald Trump solidified the trend among Southern white conservative Democrats since the 1960s of leaving the Democratic Party and joining the Republican Party: "Trump basically worked as a lightning rod to finalize that process of creating the Republican Party as a single entity for defending the high status of white, Christian, rural Americans. It's not a huge percentage of Americans that holds these beliefs, and it's not even the entire Republican Party; it's just about half of it. But the party itself is controlled by this intolerant, very strongly pro-Trump faction."[309] According to sociologist Joe Feagin, political polarization by racially extremist Republicans as well as their increased attention from conservative media has perpetuated the near extinction of moderate Republicans and created legislative paralysis at numerous government levels in the last few decades.[310]

Political positions

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in the United States |

|---|

|

Economic policies

Republicans believe that free markets and individual achievement are the primary factors behind economic prosperity.[311] Reduction in income taxes is a core component of Republicans' fiscal agenda.[312]

Taxes

Tax cuts have been at the core of Republican economic policy since 1980.[313] At the national level and state level, Republicans tend to pursue policies of tax cuts and deregulation.[314] Modern Republicans advocate the theory of supply-side economics, which holds that lower tax rates increase economic growth.[315] Many Republicans oppose higher tax rates for higher earners, which they believe are unfairly targeted at those who create jobs and wealth. They believe private spending is more efficient than government spending. Republican lawmakers have also sought to limit funding for tax enforcement and tax collection.[316]

As per a 2021 study that measured Republicans' congressional votes, the modern Republican Party's economic policy positions tend to align with business interests and the affluent.[317][318][319][320][321]

Spending

Republicans frequently advocate in favor of fiscal conservatism during Democratic administrations; however, the party has a record of increasing federal debt during periods when it controls the government (the implementation of the Bush tax cuts, Medicare Part D and the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 are examples of this record).[322][323][324] Republican administrations have, since the late 1960s, sustained or increased previous levels of government spending.[325][326]

Entitlements

Republicans believe individuals should take responsibility for their own circumstances. They also believe the private sector is more effective in helping the poor through charity than the government is through welfare programs and that social assistance programs often cause government dependency.[327] As of November 2022, all 11 states that had not expanded Medicaid had Republican-controlled state legislatures.[328]

Labor unions and the minimum wage

The Republican Party is generally opposed to labor unions.[329][330] Republicans believe corporations should be able to establish their own employment practices, including benefits and wages, with the free market deciding the price of work. Since the 1920s, Republicans have generally been opposed by labor union organizations and members. At the national level, Republicans supported the Taft–Hartley Act of 1947, which gives workers the right not to participate in unions. Modern Republicans at the state level generally support various right-to-work laws.[e][citation needed]

Most Republicans also oppose increases in the minimum wage, believing that such increases hurt businesses by forcing them to cut and outsource jobs while passing on costs to consumers.[332]

Trade

The Republican Party has taken widely varying views on international trade throughout its history. The official Republican Party platform adopted in 2024 opposes free trade and supports enacting tariffs on imports, though it supports maintaining existing free trade agreements.[334] At its inception, the Republican Party supported protective tariffs, with the Morrill Tariff being implemented during the presidency of Abraham Lincoln.[335][333] In the 1896 presidential election, Republican presidential candidate William McKinley campaigned heavily on high tariffs, having been the creator and namesake for the McKinley Tariff of 1890.[71]

In the early 20th century the Republican Party began splitting on tariffs, with the great battle over the high Payne–Aldrich Tariff Act in 1910 splitting the party and causing a realignment.[336] Democratic president Woodrow Wilson cut rates with the 1913 Underwood Tariff and the coming of World War I in 1914 radically revised trade patterns due to reduced trade. Also, the new revenues generated by the federal income tax due to the 16th amendment made tariffs less important in terms of economic impact and political rhetoric.[337] When the Republicans returned to power in 1921 they again imposed a protective tariff. They raised it again with the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act of 1930 to meet the Great Depression in the United States, but the depression only worsened and Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt became president from 1932 to 1945.[338]

The Reciprocal Tariff Act of 1934 marked a sharp departure from the era of protectionism in the United States. American duties on foreign products declined from an average of 46% in 1934 to 12% by 1962, which included the presidency of Republican president Dwight D. Eisenhower.[339] After World War II, the U.S. promoted the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) established in 1947, to minimize tariffs and other restrictions, and to liberalize trade among all capitalist countries.[340][341]

During the Reagan and George H. W. Bush administrations, Republicans abandoned protectionist policies[342] and came out against quotas and in favor of the GATT and the World Trade Organization policy of minimal economic barriers to global trade. Free trade with Canada came about as a result of the Canada–U.S. Free Trade Agreement of 1987, which led in 1994 to the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) based on Reagan's plan to enlarge the scope of the market for American firms to include Canada and Mexico. President Bill Clinton, with strong Republican support in 1993, pushed NAFTA through Congress over the vehement objection of labor unions.[343][344]

The 2016 election marked a return to supporting protectionism, beginning with Donald Trump's presidency.[345][346] In 2017, only 36% of Republicans agreed that free trade agreements are good for the United States, compared to 67% of Democrats. When asked if free trade has helped respondents specifically, the approval numbers for Democrats drop to 54%, however approval ratings among Republicans remain relatively unchanged at 34%.[347] During his presidency, Trump withdrew the United States from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, initiated a trade war with China, and negotiated the USMCA as a successor to NAFTA.[346][348]

Trump also blocked appointments to the Appellate Body of the World Trade Organization, rendering it unable to enforce and punish violators of WTO rules.[349][31] Subsequently, disregard for trade rules has increased, leading to more trade protectionist measures.[350] The Biden administration has maintained Trump's freeze on new appointments.[31] The proposed 2024 Republican Party platform was even more protectionist, calling for enacting tariffs on most imports.[32]

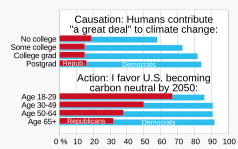

Environmental policies

Historically, progressive leaders in the Republican Party supported environmental protection. Republican President Theodore Roosevelt was a prominent conservationist whose policies eventually led to the creation of the National Park Service.[353] While Republican President Richard Nixon was not an environmentalist, he signed legislation to create the Environmental Protection Agency in 1970 and had a comprehensive environmental program.[354] However, this position has changed since the 1980s and the administration of President Ronald Reagan, who labeled environmental regulations a burden on the economy.[355] Since then, Republicans have increasingly taken positions against environmental regulation,[356][357][358] with many Republicans rejecting the scientific consensus on climate change.[355][359][360][361]

In 2006, then-California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger broke from Republican orthodoxy to sign several bills imposing caps on carbon emissions in California. Then-President George W. Bush opposed mandatory caps at a national level. Bush's decision not to regulate carbon dioxide as a pollutant was challenged in the Supreme Court by 12 states,[362] with the court ruling against the Bush administration in 2007.[363] Bush also publicly opposed ratification of the Kyoto Protocols[355][364] which sought to limit greenhouse gas emissions and thereby combat climate change; his position was heavily criticized by climate scientists.[365]

The Republican Party rejects cap-and-trade policy to limit carbon emissions.[366] In the 2000s, Senator John McCain proposed bills (such as the McCain-Lieberman Climate Stewardship Act) that would have regulated carbon emissions, but his position on climate change was unusual among high-ranking party members.[355] Some Republican candidates have supported the development of alternative fuels in order to achieve energy independence for the United States. Some Republicans support increased oil drilling in protected areas such as the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, a position that has drawn criticism from activists.[367]

Many Republicans during the presidency of Barack Obama opposed his administration's new environmental regulations, such as those on carbon emissions from coal. In particular, many Republicans supported building the Keystone Pipeline; this position was supported by businesses, but opposed by indigenous peoples' groups and environmental activists.[368][369][370]

According to the Center for American Progress, a non-profit liberal advocacy group, more than 55% of congressional Republicans were climate change deniers in 2014.[371][372] PolitiFact in May 2014 found "relatively few Republican members of Congress ... accept the prevailing scientific conclusion that global warming is both real and man-made." The group found eight members who acknowledged it, although the group acknowledged there could be more and that not all members of Congress have taken a stance on the issue.[373][374]

From 2008 to 2017, the Republican Party went from "debating how to combat human-caused climate change to arguing that it does not exist", according to The New York Times.[375] In January 2015, the Republican-led U.S. Senate voted 98–1 to pass a resolution acknowledging that "climate change is real and is not a hoax"; however, an amendment stating that "human activity significantly contributes to climate change" was supported by only five Republican senators.[376]

Health care

The party opposes a single-payer health care system,[377][378] describing it as socialized medicine. It also opposes the Affordable Care Act[379] and expansions of Medicaid.[380] Historically, there have been diverse and overlapping views within both the Republican Party and the Democratic Party on the role of government in health care, but the two parties became highly polarized on the topic during 2008–2009 and onwards.[381]

Both Republicans and Democrats made various proposals to establish federally funded aged health insurance prior to the bipartisan effort to establish Medicare and Medicaid in 1965.[382][383][384] No Republican member of Congress voted for the Affordable Care Act in 2009, and after it passed, the party made frequent attempts to repeal it.[381][385] At the state level, the party has tended to adopt a position against Medicaid expansion.[314][384]

According to a 2023 YouGov poll, Republicans are slightly more likely to oppose intersex medical alterations than Democrats.[386][387]

Foreign policy

The Republican Party has a persistent history of skepticism and opposition to multilateralism in American foreign policy.[388] Neoconservatism, which supports unilateralism and emphasizes the use of force and hawkishness in American foreign policy, has been a prominent strand of foreign policy thinking in all Republican presidential administration since Ronald Reagan's presidency.[389] Some, including paleoconservatives,[390] call for non-interventionism and an isolationist "America First" foreign policy agenda.[30][215][216] This faction gained strength starting in 2016 with the rise of Donald Trump, demanding that the United States reset its previous interventionist foreign policy and encourage allies and partners to take greater responsibility for their own defense.[391]

Israel

During the 1940s, Republicans predominantly opposed the cause of an independent Jewish state due to the influence of conservatives of the Old Right.[392] In 1948, Democratic President Harry Truman became the first world leader to recognize an independent state of Israel.[393]

The rise of neoconservatism saw the Republican Party become predominantly pro-Israel by the 1990s and 2000s,[394] although notable anti-Israel sentiment persisted through paleoconservative figures such as Pat Buchanan.[395] As president, Donald Trump generally supported Israel during most of his term, but became increasingly critical of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu towards the end of it.[396] After the 7 October 2023 Hamas terrorist attack on Israel, Trump blamed Netanyahu for having failed to prevent the attack.[397] Trump previously criticized the Israeli settlements in the West Bank and expressed doubt about whether Netanyahu truly desired peace with the Palestinians.[398] According to i24NEWS, the 2020s have seen declining support for Israel among nationalist Republicans, led by individuals such as Tucker Carlson.[399][392]

Taiwan

In the party's 2016 platform,[400] its stance on Taiwan is: "We oppose any unilateral steps by either side to alter the status quo in the Taiwan Straits on the principle that all issues regarding the island's future must be resolved peacefully, through dialogue, and be agreeable to the people of Taiwan." In addition, if "China were to violate those principles, the United States, in accord with the Taiwan Relations Act, will help Taiwan defend itself".

War on terror

Since the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, neoconservatives in the party have supported the War on Terror, including the War in Afghanistan and the Iraq War. The George W. Bush administration took the position that the Geneva Conventions do not apply to unlawful combatants, while other prominent Republicans, such as Ted Cruz, strongly oppose the use of enhanced interrogation techniques, which they view as torture.[401] In the 2020s, Trumpist Republicans such as Matt Gaetz supported reducing U.S. military presence abroad and ending intervention in countries such as Somalia.[402]

Europe, Russia and Ukraine

The 2016 Republican platform eliminated references to giving weapons to Ukraine in its fight with Russia and rebel forces; the removal of this language reportedly resulted from intervention from staffers to presumptive Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump.[403] However, the Trump administration approved a new sale of anti-tank weapons to Ukraine in 2017.[404] Republicans generally question European NATO members' insufficient investment in defense funding, and some are dissatisfied with U.S. aid to Ukraine.[405][406] Some Republican members of the U.S. Congress support foreign aid to Israel but not to Ukraine,[287][288] accused by U.S. media of being pro-Russian.[220][289][290][291][292][293][294]

Amid the Russian invasion of Ukraine, several prominent Republicans criticized some colleagues and conservative media outlets for echoing Russian propaganda. Liz Cheney, formerly the third-ranking House Republican, said "a Putin wing of the Republican Party" had emerged. Republican Senator Mitt Romney characterized pro-Putin sentiments expressed by some Republicans as "almost treasonous." Former vice president Mike Pence said, "There is no room in the Republican Party for apologists for Putin." House Foreign Affairs Committee chairman Michael McCaul asserted that Russian propaganda had "infected a good chunk of my party's base," attributing the cause to "nighttime entertainment shows" and "conspiracy-theory outlets that are just not accurate, and they actually model Russian propaganda." House Intelligence Committee chairman Mike Turner confirmed McCaul's assessment, asserting that some propaganda coming directly from Russia could be heard on the House floor. Republican senator Thom Tillis characterized the influential conservative commentator Tucker Carlson, who frequently expresses pro-Russia sentiments, as Russia's "useful idiot".[407][408][409][410]

In April 2024, a majority of Republican members of the U.S. House of Representatives voted against a military aid package to Ukraine.[411] Both Trump and Senator JD Vance, the 2024 Republican presidential nominee and vice presidential nominee respectively, have been vocal critics of military aid to Ukraine.[412][413] The 2024 Republican Party platform did not mention Russia or Ukraine, but stated the party's objectives to "prevent World War III" and "restore peace to Europe".[414]

Foreign relations and aid

In a 2014 poll, 59% of Republicans favored doing less abroad and focusing on the country's own problems instead.[415]

Republicans have frequently advocated for restricting foreign aid as a means of asserting the national security and immigration interests of the United States.[416][417][418]

A survey by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs shows that "Trump Republicans seem to prefer a US role that is more independent, less cooperative, and more inclined to use military force to deal with the threats they see as the most pressing".[419]

Social issues

The Republican Party is generally associated with social conservative policies, although it does have dissenting centrist and libertarian factions. The social conservatives support laws that uphold their traditional values, such as opposition to same-sex marriage, abortion, and marijuana.[420] The Republican Party's positions on social and cultural issues are in part a reflection of the influential role that the Christian right has had in the party since the 1970s.[421][422][423] Most conservative Republicans also oppose gun control, affirmative action, and illegal immigration.[420][424]

Abortion and embryonic stem cell research

The Republican position on abortion has changed significantly over time.[224][425] During the 1960s and early 1970s, opposition to abortion was concentrated among members of the political left and the Democratic Party; most liberal Catholics — which tended to vote for the Democratic Party — opposed expanding abortion access while most conservative evangelical Protestants supported it.[425]

During this period, Republicans generally favored legalized abortion more than Democrats,[426][427] although significant heterogeneity could be found within both parties.[428] Leading Republican political figures, including Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, Ronald Reagan, and George H. W. Bush, took pro-choice positions until the early 1980s.[426] However, starting at this point, both George H.W. Bush and Ronald Reagan described themselves as pro-life during their presidencies.

In the 21st century, both George W. Bush[429] and Donald Trump described themselves as "pro-life" during their terms. However, Trump stated that he supported the legality and ethics of abortion before his candidacy in 2015.[430]

Summarizing the rapid shift in the Republican and Democratic positions on abortion, Sue Halpern writes:[224]

...in the late 1960s and early 1970s, many Republicans were behind efforts to liberalize and even decriminalize abortion; theirs was the party of reproductive choice, while Democrats, with their large Catholic constituency, were the opposition. Republican governor Ronald Reagan signed the California Therapeutic Abortion Act, one of the most liberal abortion laws in the country, in 1967, legalizing abortion for women whose mental or physical health would be impaired by pregnancy, or whose pregnancies were the result of rape or incest. The same year, the Republican strongholds of North Carolina and Colorado made it easier for women to obtain abortions. New York, under Governor Nelson Rockefeller, a Republican, eliminated all restrictions on women seeking to terminate pregnancies up to twenty-four weeks gestation.... Richard Nixon, Barry Goldwater, Gerald Ford, and George H.W. Bush were all pro-choice, and they were not party outliers. In 1972, a Gallup poll found that 68 percent of Republicans believed abortion to be a private matter between a woman and her doctor. The government, they said, should not be involved...

Since the 1980s, opposition to abortion has become strongest in the party among traditionalist Catholics and conservative Protestant evangelicals.[224][428][431] Initially, evangelicals were relatively indifferent to the cause of abortion and overwhelmingly viewed it as a concern that was sectarian and Catholic.[431] Historian Randall Balmer notes that Billy Graham's Christianity Today published in 1968 a statement by theologian Bruce Waltke that:[432] "God does not regard the fetus as a soul, no matter how far gestation has progressed. The Law plainly exacts: "If a man kills any human life he will be put to death" (Lev. 24:17). But according to Exodus 21:22-24, the destruction of the fetus is not a capital offense. ... Clearly, then, in contrast to the mother, the fetus is not reckoned as a soul." Typical of the time, Christianity Today "refused to characterize abortion as sinful" and cited "individual health, family welfare, and social responsibility" as "justifications for ending a pregnancy."[433] Similar beliefs were held among conservative figures in the Southern Baptist Convention, including W. A. Criswell, who is partially credited with starting the "conservative resurgence" within the organization, who stated: "I have always felt that it was only after a child was born and had a life separate from its mother that it became an individual person and it has always, therefore, seemed to me that what is best for the mother and for the future should be allowed." Balmer argues that evangelical American Christianity being inherently tied to opposition to abortion is a relatively new occurrence.[433][434] After the late 1970s, he writes, opinion against abortion among evangelicals rapidly shifted in favor of its prohibition.[431]

Today, opinion polls show that Republican voters are heavily divided on the legality of abortion,[221] although vast majority of the party's national and state candidates are anti-abortion and oppose elective abortion on religious or moral grounds. While many advocate exceptions in the case of incest, rape or the mother's life being at risk, in 2012 the party approved a platform advocating banning abortions without exception.[435] There were not highly polarized differences between the Democratic Party and the Republican Party prior to the Roe v. Wade 1973 Supreme Court ruling (which made prohibitions on abortion rights unconstitutional), but after the Supreme Court ruling, opposition to abortion became an increasingly key national platform for the Republican Party.[436][437][438] As a result, Evangelicals gravitated towards the Republican Party.[436][437] Most Republicans oppose government funding for abortion providers, notably Planned Parenthood.[439] This includes support for the Hyde Amendment.

Until its dissolution in 2018, Republican Majority for Choice, an abortion rights PAC, advocated for amending the GOP platform to include pro-abortion rights members.[440]

The Republican Party has pursued policies at the national and state-level to restrict embryonic stem cell research beyond the original lines because it involves the destruction of human embryos.[441][442]

After the overturning of Roe v. Wade in 2022, a majority of Republican-controlled states passed near-total bans on abortion, rendering it largely illegal throughout much of the United States.[443][444]

Affirmative action

Republicans generally oppose affirmative action, often describing it as a "quota system" and believing that it is not meritocratic and is counter-productive socially by only further promoting discrimination. According to a 2023 ABC poll, a majority of Americans (52%) and 75% of Republicans supported the Supreme Court's decision in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard prohibiting race as a factor in college admissions, compared to only 26% of Democrats.[445]

The 2012 Republican national platform stated, "We support efforts to help low-income individuals get a fair chance based on their potential and individual merit; but we reject preferences, quotas, and set-asides, as the best or sole methods through which fairness can be achieved, whether in government, education or corporate boardrooms…Merit, ability, aptitude, and results should be the factors that determine advancement in our society."[446][447][448][449]

Gun ownership

Republicans generally support gun ownership rights and oppose laws regulating guns. According to a 2023 Pew Research Center poll, 45% of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents personally own firearms, compared to 32% for the general public and 20% of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents.[451]

The National Rifle Association of America, a special interest group in support of gun ownership, has consistently aligned itself with the Republican Party.[452] Following gun control measures under the Clinton administration, such as the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, the Republicans allied with the NRA during the Republican Revolution in 1994.[453] Since then, the NRA has consistently backed Republican candidates and contributed financial support,[454] such as in the 2013 Colorado recall election which resulted in the ousting of two pro-gun control Democrats for two anti-gun control Republicans.[455]

In contrast, George H. W. Bush, formerly a lifelong NRA member, was highly critical of the organization following their response to the Oklahoma City bombing authored by CEO Wayne LaPierre, and publicly resigned in protest.[456]

Drug legalization

Republican elected officials have historically supported the War on Drugs. They generally oppose legalization or decriminalization of drugs such as marijuana.[457][458][459]

Opposition to the legalization of marijuana has softened significantly over time among Republican voters.[460][461] A 2021 Quinnipiac poll found that 62% of Republicans supported the legalization of recreational marijuana use and that net support for the position was +30 points.[457]

Immigration

The Republican Party has taken widely varying views on immigration throughout its history.[9] In the period between 1850 and 1870, the Republican Party was more opposed to immigration than the Democrats. The GOP's opposition was, in part, caused by its reliance on the support of anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant parties such as the Know-Nothings. In the decades following the Civil War, the Republican Party grew more supportive of immigration, as it represented manufacturers in the northeast (who wanted additional labor); during this period, the Democratic Party came to be seen as the party of labor (which wanted fewer laborers with which to compete). Starting in the 1970s, the parties switched places again, as the Democrats grew more supportive of immigration than Republicans.[462]