История рабства

| Часть серии о |

| Принудительный труд и рабство |

|---|

|

История рабства охватывает многие культуры , народности и религии с древнейших времен до наших дней . Кроме того, его жертвы принадлежат к разным этническим и религиозным группам. Социальное, экономическое и правовое положение рабов сильно различалось в разных системах рабства, в разные времена и в разных местах. [1]

Рабство было обнаружено у некоторых популяций охотников-собирателей , особенно в виде наследственного рабства. [2] [3] но условия сельского хозяйства с возрастающей социальной и экономической сложностью открывают больше возможностей для массового рабства движимого имущества . [4] Рабство было институционализировано ко времени возникновения первых цивилизаций (таких как Шумер в Месопотамии , [5] который датируется 3500 годом до нашей эры). Рабство представлено в Месопотамском кодексе Хаммурапи (ок. 1750 г. до н. э.), в котором оно упоминается как устоявшийся институт. [6] Рабство было широко распространено в древнем мире в Европе, Азии, на Ближнем Востоке и в Африке. [7] [8] [4]

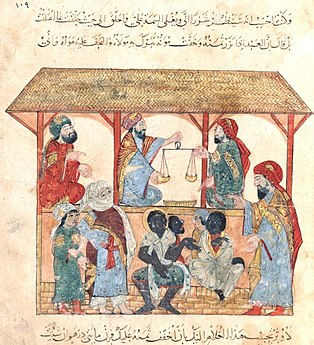

он стал менее распространенным по всей Европе В период раннего средневековья , хотя в некоторых регионах его продолжали практиковать. И христиане , и мусульмане захватывали и порабощали друг друга на протяжении веков войн в Средиземноморье и Европе. [9] Исламское рабство охватывало в основном Западную и Центральную Азию, Северную и Восточную Африку, Индию и Европу с VII по XX век. Исламский закон одобрял порабощение немусульман, и рабов вывозили из немусульманских земель: с Севера через балканскую работорговлю и крымскую работорговлю ; с Востока через работорговлю в Бухаре ; с Запада через андалузскую работорговлю ; и с Юга через работорговлю через Транссахару , работорговлю в Красном море и работорговлю в Индийском океане .

С 16 в. европейские купцы , главным образом купцы из Португалии , положили начало трансатлантической работорговле . Лишь немногие торговцы отваживались заходить далеко вглубь страны, пытаясь избежать тропических болезней и насилия. В основном они покупали заключенных в тюрьмы африканцев (и экспортировали товары, включая золото и слоновую кость ) из западноафриканских королевств, перевозя их в европейские колонии в Америке . Купцы были источниками желаемых товаров, включая оружие, порох, медные маниллы и ткани, и этот спрос на импортные товары привел к местным войнам и другим средствам для порабощения африканцев во все большем количестве. [10] В Индии и по всему Новому Свету людей заставляли обращаться в рабство, чтобы создать местную рабочую силу. Трансатлантическая работорговля в конечном итоге была прекращена после того, как правительства Европы и Америки приняли закон, запрещающий участие в ней своих стран. Практические усилия по обеспечению отмены рабства включали Британскую превентивную эскадрилью и Американский африканский патруль работорговли , отмену рабства в Америке и повсеместное введение европейского политического контроля в Африке.

В наше время торговля людьми остается международной проблемой. По оценкам, по состоянию на 2013 год 25–40 миллионов человек были порабощены. [update], большинство из них в Азии . [11] 1983–2005 годов Во время Второй гражданской войны в Судане люди были взяты в рабство. [12] В конце 1990-х годов появились доказательства систематического детского рабства и торговли людьми на плантациях какао в Западной Африке. [13]

Рабство в 21 веке продолжается и приносит около 150 миллиардов долларов годовой прибыли. [14] Население в регионах, где происходят вооруженные конфликты , особенно уязвимо, а современный транспорт облегчил торговлю людьми. [15] По оценкам, в 2019 году в мире насчитывалось около 40 миллионов человек, находящихся в той или иной форме рабства, из них 25% составляли дети. [14] Шестьдесят один процент [номер 1] используются для принудительного труда , в основном в частном секторе . Тридцать восемь процентов [номер 2] живут в принудительных браках. [14] Другими видами современного рабства являются тюремный труд , торговля людьми в целях сексуальной эксплуатации и сексуальное рабство .

Доисторическое и древнее рабство

[ редактировать ]Свидетельства рабства появились раньше письменных источников; такая практика существовала во многих культурах [16] [8] и его можно проследить 11 000 лет назад из-за условий, созданных изобретением сельского хозяйства во время неолитической революции . [17] [8] [7] Экономический профицит и высокая плотность населения были условиями, которые сделали массовое рабство жизнеспособным. [18] [19]

Рабство существовало в таких цивилизациях, как Древний Египет , Древний Китай , Аккадская империя , Ассирия , Вавилония , Персия , древний Израиль , [20] [21] [22] Древняя Греция , древняя Индия , Римская империя , арабские исламские халифаты и султанаты , Нубия , доколониальные империи Африки к югу от Сахары и доколумбовые цивилизации Америки. [23] Древнее рабство состоит из смеси долгового рабства , наказания за преступления, военнопленных , отказа от детей и детей, рожденных рабами. [24]

- Около 1480 г. до н.э., договор о беглых рабах между Идрими из Алакаха (ныне Телль-Атчана ) и Пиллией из Киццуватны (ныне Киликия).

- Подошвы древнеегипетской мумии , изображающие двух пленных иностранцев, сирийца (слева) и нубийца (справа). [25] между 332 г. до н.э. и 395 г. н.э. ( период Птолемеев или римлян ).

- Рабы в цепях в период римского правления в Смирне (современный Измир ), 200 г. н.э.

Африка

[ редактировать ]

В 1984 году французский историк Фернан Бродель отметил, что рабство было эндемичным явлением в Африке и было частью структуры повседневной жизни на протяжении 15-18 веков. «Рабство в разных обществах принимало разные формы: были придворные рабы, рабы, включенные в княжеские армии, домашние и домашние рабы, рабы, работавшие на земле, в промышленности, в качестве курьеров и посредников, даже в качестве торговцев». [26] В 16 веке Европа начала опережать арабский мир в экспортных перевозках рабов из Африки в Америку. [ нужна ссылка ] Голландцы импортировали рабов из Азии в свою колонию на мысе Доброй Надежды (ныне Кейптаун ) в 17 веке. [ нужна ссылка ] В 1807 году Великобритания (которая уже владела небольшой прибрежной территорией, предназначенной для переселения бывших рабов, во Фритауне , Сьерра-Леоне ) объявила работорговлю внутри своей империи незаконной Законом о работорговле 1807 года и работала над распространением запрета на другие территории. , [27] : 42 как и Соединенные Штаты в 1808 году. [28]

В Сенегамбии между 1300 и 1900 годами около трети населения было порабощено. В ранних исламских государствах Западного Судана , включая Гану (750–1076 гг.), Мали (1235–1645 гг.), Сегу (1712–1861 гг.) и Сонгай (1275–1591 гг.), около трети населения было порабощено. Самое раннее акан государство Бономан , треть населения которого была порабощена в 17 веке. В Сьерра-Леоне в XIX веке около половины населения составляли рабы. В 19 в. не менее половины населения было порабощено среди , игбо дуала Камеруна и других народов нижнего Нигера , Конго , королевства Касандже и чокве в Анголе . Среди ашанти и йоруба треть населения, как и боно, составляли рабы . [29] населения Канема было Около трети порабощено. В Борну (1396–1893) это было около 40%. Между 1750 и 1900 годами от одной до двух третей всего населения государств джихада Фулани составляли рабы. Население халифата Сокото , образованного хауса на севере Нигерии и Камеруна, в 19 веке было полурабским. Подсчитано, что до 90% населения арабо - суахили Занзибара было порабощено. Примерно половина населения Мадагаскара была порабощена. [30] [31] [ нужна страница ] [32] [33] [34]

Рабство в Эфиопии сохранялось до 1942 года. По оценкам Общества борьбы с рабством , в начале 1930-х годов насчитывалось 2 000 000 рабов из примерно 8-16 миллионов человек. [35] Окончательно он был упразднен по приказу императора Хайле Селассие 26 августа 1942 года. [36]

Когда британское правление впервые было введено в халифате Сокото и прилегающих районах северной Нигерии на рубеже 20-го века, примерно от 2 до 2,5 миллионов человек, живущих там, были порабощены. [37] Рабство в северной Нигерии было окончательно объявлено вне закона в 1936 году. [38]

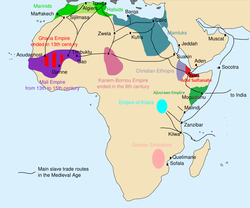

В 1998 году, рассказывая о масштабах торговли, проходящей через Африку и из Африки, конголезский журналист Эликия Мбоколо писала: «Африканский континент лишился человеческих ресурсов всеми возможными маршрутами. Через Сахару , через Красное море, из Индийского океана». портов и через Атлантику По меньшей мере десять веков рабства на благо мусульманских стран (с девятого по девятнадцатый век)». Он продолжает: «Четыре миллиона рабов вывезены через Красное море , еще четыре миллиона — через порты суахили в Индийском океане , возможно, целых девять миллионов — по транссахарскому караванному маршруту, и от одиннадцати до двадцати миллионов (в зависимости от автора) через Атлантический океан» [39]

Африка к югу от Сахары

[ редактировать ]

Занзибар когда-то был главным портом работорговли в Восточной Африке, во времена работорговли в Индийском океане и под властью оманских арабов в 19 веке, и каждый год через город проходило до 50 000 рабов. [41]

До 16 века основная часть рабов, вывозимых из Африки, отправлялась из Восточной Африки на Аравийский полуостров . Занзибар стал ведущим портом в этой торговле. [42] Арабские торговцы рабами отличались от европейских тем, что часто сами проводили набеги, иногда проникая в глубь континента. Они также отличались тем, что их рынок предпочитал покупать порабощенных женщин, а не мужчин. [43]

Растущее присутствие европейских конкурентов на восточном побережье заставило арабских торговцев сконцентрироваться на сухопутных караванных маршрутах рабов через Сахару из Сахеля в Северную Африку. Немецкий исследователь Густав Нахтигаль сообщил, что в 1870 году видел караваны рабов, отправлявшиеся из Кукавы в Борну в Триполи и Египет. Еще в 1898 году торговля рабами представляла собой основной источник дохода для штата Борну. Восточные регионы Центральноафриканской Республики никогда не оправились демографически от последствий набегов из Судана в 19 веке и до сих пор имеют плотность населения менее 1 человека на км. 2 . [44] В 1870-х годах европейские инициативы против работорговли вызвали экономический кризис в северном Судане, ускорив подъем сил махдистов . Махди Победа создала исламское государство , которое быстро восстановило рабство. [45] [46]

Участие Европы в торговле порабощенными людьми в Восточной Африке началось, когда Португалия основала Estado da India в начале 16 века. С тех пор и до 1830-х годов, ок. вывозилось 200 порабощенных людей Ежегодно из португальского Мозамбика , и аналогичные цифры были оценены для порабощенных людей, привезенных из Азии на Филиппины во время Пиренейского союза (1580–1640). [47] [48] [ нужна ссылка ]

Средний проход , переход через Атлантику в Америку , проходивший через ряды рабов, уложенных в трюмах кораблей, был лишь одним из элементов хорошо известной трехсторонней торговли, которую вели португальцы, американцы, голландцы, датско-норвежцы, [49] французы, британцы и другие. Корабли с рабами, приземлившиеся в карибских портах, принимали сахар, индиго, хлопок-сырец, а затем и кофе и направлялись в Ливерпуль , Нант , Лиссабон или Амстердам . Корабли, отправляющиеся из европейских портов в Западную Африку, будут перевозить набивные хлопчатобумажные ткани, некоторые из которых были родом из Индии, медную посуду и браслеты, оловянные тарелки и горшки, железные слитки, которые ценятся больше, чем золото, шляпы, безделушки, порох, огнестрельное оружие и алкоголь. Тропические корабельные черви были уничтожены в холодных водах Атлантики, и при каждой разгрузке получалась прибыль. [ нужна ссылка ]

пришелся Пик работорговли в Атлантике на конец 18 века, когда наибольшее количество людей было захвачено и порабощено во время набегов во внутренние районы Западной Африки. Эти экспедиции обычно проводились африканскими государствами, такими как штат Боно , империя Ойо ( йоруба ), империя Конг , Королевство Бенин , Имамат Фута Джаллон , Имамат Фута Торо , Королевство Койя , Королевство Хассо , Королевство Каабу. , Конфедерация Фанте , Конфедерация Ашанти , Конфедерация Аро и королевство Дагомея . [50] [51] Европейцы редко заходили во внутренние районы Африки из-за страха перед болезнями и, кроме того, из-за ожесточенного сопротивления африканцев. Рабов привозили на прибрежные заставы, где их обменивали на товары. Захваченные в ходе этих экспедиций люди были переправлены европейскими торговцами в колонии Нового Света . Подсчитано, что на протяжении веков европейские торговцы вывозили из Африки от двенадцати до двадцати миллионов рабов, из которых около 15 процентов погибли во время ужасного путешествия, многие — во время тяжелого путешествия через Средний проход . Подавляющее большинство было отправлено в Америку, но некоторые также отправились в Европу и Южную Африку. [ нужна ссылка ]

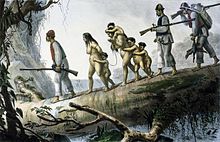

о торговле рабами в Восточной Африке Рассказывая в своих журналах , Дэвид Ливингстон сказал:

Преодолеть его зло просто невозможно. [52]

Путешествуя по региону Великих африканских озер в 1866 году, Ливингстон описал след рабов:

19 июня 1866 г. – Мы прошли мимо мертвой женщины, привязанной за шею к дереву. Жители страны объяснили, что она не могла идти в ногу с другими рабами в банде, и ее хозяин решил, что она не должна становиться чью-либо собственность, если она выздоровеет.

26 июня. – …Мы прошли мимо простреленной или зарезанной женщины-рабыни, лежащей на тропе: группа мужчин стояла ярдах в ста с одной стороны, а другая из женщин – с другой стороны и смотрела; они сказали, что араб, который ушел рано утром, сделал это в гневе из-за того, что потерял цену, которую он заплатил за нее, потому что она больше не могла идти.

27 июня 1866 г. Сегодня мы нашли человека, умершего от голода, так как он был очень худым. Один из наших людей бродил и нашел много рабов с рабскими палками, брошенных хозяевами из-за недостатка еды; они были слишком слабы, чтобы говорить или сказать, откуда они пришли; некоторые были довольно молоды. [53]

Самая странная болезнь, которую я видел в этой стране, на самом деле кажется разбитым сердцем, и она поражает свободных людей, которые были схвачены и превращены в рабов... Двадцать один был освобожден от цепей, поскольку теперь находится в безопасности; однако все тотчас же убежали; но восемь человек, а также многие другие, все еще закованные в цепи, умерли через три дня после перехода. Они описали свою единственную боль в сердце и правильно положили руку на это место, хотя многие думают, что орган расположен высоко в грудине. [54]

Участие Африки в работорговле

[ редактировать ]

Африканские государства играли ключевую роль в торговле рабами, и рабство было обычной практикой среди африканцев к югу от Сахары даже до того, как в нее вошли арабы , берберы и европейцы . Было три типа: те, кто был порабощен в результате завоевания вместо невыплаченных долгов, или те, чьи родители отдали их в собственность вождям племен. Вожди обменивали своих рабов арабским, берберским, османским или европейским покупателям на ром, специи, ткань или другие товары. [55] Продажа пленников или заключенных была обычной практикой среди африканцев, турок, берберов и арабов в ту эпоху. Однако по мере того, как работорговля в Атлантике увеличивала спрос, местные системы, которые в первую очередь обслуживали наемное рабство, расширялись. В результате европейская торговля рабами стала самым кардинальным изменением в социальной, экономической, культурной, духовной, религиозной и политической динамике концепции торговли рабами. В конечном итоге это подорвало местную экономику и политическую стабильность, поскольку жизненно важная рабочая сила деревень была отправлена за границу, а набеги рабов и гражданские войны стали обычным явлением. Преступления, которые ранее наказывались другими способами, стали наказываться порабощением. [56]

Рабство уже существовало в Королевстве Конго до прибытия португальцев . Поскольку работорговля была установлена в его королевстве, Афонсу I из Конго считал, что работорговля должна регулироваться законодательством Конго. Когда он заподозрил португальцев в незаконном получении рабов для продажи, он написал письма королю Португалии Жуану III в 1526 году, умоляя его положить конец этой практике. [57]

Короли Дагомеи продавали своих военнопленных в трансатлантическое рабство, которых в противном случае могли убить на церемонии, известной как Ежегодная таможня . Будучи одним из главных рабовладельческих государств Западной Африки, Дагомея стала крайне непопулярной среди соседних народов. [58] [59] [60] Как и империя Бамбара на востоке, экономика королевств Хассо сильно зависела от работорговли . Статус семьи определялся количеством принадлежащих ей рабов, что приводило к войнам с единственной целью - взять больше пленников. Эта торговля привела хассо к расширению контактов с европейскими поселениями западного побережья Африки, особенно с французами . [61] Бенин становился все более богатым в течение 16 и 17 веков благодаря торговле рабами с Европой; рабов из внутренних вражеских государств продавали и отправляли в Америку на голландских и португальских кораблях. Берег Бенина вскоре стал известен как «Невольничий берег». [62]

Гезо В 1840-х годах король Дагомеи сказал: [13] [63]

«Работорговля — правящий принцип моего народа. Это источник и слава их богатства… мать убаюкивает ребенка нотами триумфа над врагом, обращенным в рабство».

В 1807 году Великобритания объявила международную торговлю рабами незаконной Законом о работорговле . Королевский флот был задействован для предотвращения работорговцев из США , Франции , Испании , Португалии , Голландии , Западной Африки и Аравии . Король Бонни (сейчас в Нигерии ) якобы стал недоволен британским вмешательством в прекращение торговли рабами: [64]

«Мы считаем, что эта торговля должна продолжаться. Таков вердикт нашего оракула и священников. Они говорят, что ваша страна, какой бы великой она ни была, никогда не сможет остановить торговлю, установленную самим Богом».

Джозеф Миллер утверждает, что африканские покупатели предпочли бы мужчин, но на самом деле женщин и детей было бы легче поймать, поскольку мужчины бежали. Захваченные будут проданы по разным причинам, например, в виде еды, долгов или рабства. После захвата путешествие к побережью убило многих и ослабило других. Болезнь охватила многих, а недостаток еды повредил тех, кто добрался до побережья. Цинга была обычным явлением, и ее часто называли Mal de Luanda («болезнь Луанды», в честь порта в Анголе). [65] Предположение о том, что погибшие в пути умерли от недоедания . Поскольку еда была ограничена, вода могла быть не менее плохой. Дизентерия была широко распространена, и плохие санитарные условия в портах не помогли. Поскольку запасы были плохими, рабы не были оснащены лучшей одеждой, а это означало, что они были еще более подвержены болезням. [65]

Помимо страха перед болезнями, люди боялись того, почему их схватили. Популярное предположение заключалось в том, что европейцы были каннибалами . Распространялись истории и слухи о том, что белые захватывали в плен африканцев, чтобы съесть их. [65] Олауда Эквиано рассказывает о своем опыте скорби рабов, с которыми они столкнулись в портах. Он рассказывает о своем первом пребывании на корабле рабов и спрашивает, собираются ли его съесть. [66] Однако худшее для рабов только началось, и путешествие по воде оказалось еще более мучительным. Из каждых 100 захваченных африканцев только 64 доберутся до побережья и только около 50 доберутся до Нового Света. [65]

Другие полагают, что работорговцы были заинтересованы в захвате, а не в убийстве, и в сохранении жизни своих пленников; и что это в сочетании с непропорциональным удалением самцов и введением новых культур из Америки ( маниока , кукуруза) ограничило бы общее сокращение численности населения отдельными регионами Западной Африки примерно в 1760–1810 годах, а в Мозамбике и соседних регионах - на полвека. позже. Также высказывались предположения, что в Африке женщин чаще всего ловили в качестве невест , а их защитники-мужчины были «приловом», которого бы убили, если бы для них не было экспортного рынка.

Британский исследователь Мунго Парк, встретил группу рабов путешествуя по стране Мандинка, :

Все они были очень любопытны, но сначала смотрели на меня с ужасом и неоднократно спрашивали, не каннибалы ли мои соотечественники. Им очень хотелось знать, что стало с рабами после того, как они пересекли соленую воду. Я сказал им, что они обрабатывают землю; но они мне не поверили... Глубоко укоренившаяся идея о том, что белые покупают негров с целью их пожирания или продажи другим, чтобы они могли быть сожраны в будущем, естественно, заставляет рабов обдумывать путешествие к побережью с великий ужас, настолько, что сланцевцы вынуждены постоянно держать их в кандалах и очень внимательно следить за ними, чтобы не допустить их побега. [67]

В период с конца 19-го и начала 20-го века спрос на трудоемкую заготовку каучука привел к расширению границ и принудительному труду . Личная монархия бельгийского короля Леопольда II в Свободном государстве Конго сопровождалась массовыми убийствами и рабством для добычи каучука. [68]

Африканцы на кораблях

[ редактировать ]

Главной задачей было выжить в путешествии. Тесное окружение означало, что все, включая экипаж, были заражены распространявшимися болезнями. Смерть была настолько распространена, что корабли называли тумбейрос, или плавучие гробницы. [69] Больше всего африканцев шокировало то, как обращались со смертью на кораблях. Смоллвуд говорит, что традиции африканской смерти были деликатными и основывались на общине. На кораблях тела выбрасывали в море. Поскольку море символизировало плохие предзнаменования, тела в море представляли собой чистилище, а корабль — ад. Любой африканец, совершивший это путешествие, пережил бы тяжелую болезнь и недоедание, а также травмы, полученные в открытом океане и смерть своих друзей. [69]

Северная Африка

[ редактировать ]

В Алжире во времена Регентства Алжира в Северной Африке в XIX веке до 1,5 миллиона христиан и европейцев были схвачены и отправлены в рабство. [70] В конечном итоге это привело к бомбардировке Алжира в 1816 году британцами и голландцами , что вынудило алжирского дея освободить множество рабов. [71]

Новое время

[ редактировать ]Торговля детьми зарегистрирована в современной Нигерии и Бенине . В некоторых частях Ганы семья может быть наказана за правонарушение путем передачи девственной женщины в качестве сексуальной рабыни в обиженной семье. В этом случае женщина не получает титула или статуса «жены». В некоторых частях Ганы, Того и Бенина рабство при святилищах сохраняется, несмотря на то, что оно незаконно в Гане с 1998 года. В этой системе ритуального рабства , иногда называемой «трокоси» (в Гане) или «вудуси» в Того и Бенине, молодых девственных девушек отдают в рабство. к традиционным святыням и используются священниками в сексуальном плане, а также предоставляют бесплатную рабочую силу для храма. [ нужна ссылка ]

В статье, опубликованной в журнале Middle East Quarterly в 1999 году, сообщалось, что рабство является эндемичным явлением в Судане . [72] По оценкам, количество похищений во время Второй суданской гражданской войны колеблется от 14 000 до 200 000 человек. [73]

Во время Второй гражданской войны в Судане люди были взяты в рабство; оценки похищений варьируются от 14 000 до 200 000. Похищение женщин и детей динка было обычным явлением. [12] По оценкам, в Мавритании до 600 000 мужчин, женщин и детей, или 20% населения, в настоящее время находятся в рабстве, многие из них используются в качестве подневольного труда . [74] Рабство в Мавритании было криминализировано в августе 2007 года. [75]

Во время конфликта в Дарфуре, начавшегося в 2003 году, многие люди были похищены Джанджавидами и проданы в рабство в качестве сельскохозяйственных рабочих, домашней прислуги и сексуальных рабов. [76] [77] [78]

В Нигере рабство также является нынешним явлением. Исследование в Нигере показало, что более 800 000 человек находятся в рабстве, почти 8% населения. [79] [80] [81] Нигер принял положение, запрещающее рабство, в 2003 году. [82] [83] В знаковом постановлении, принятом в 2008 году, Суд Сообщества ЭКОВАС заявил, что Республика Нигер не смогла защитить Хадиджату Мани Корау от рабства, и присудил Мани 10 000 000 КФА (приблизительно 20 000 долларов США ) в качестве компенсации. [84]

Сексуальное рабство и принудительный труд распространены в Демократической Республике Конго. [85] [86] [87]

Многие пигмеи в Республике Конго и Демократической Республике Конго с рождения принадлежат банту в системе рабства. [88] [89]

В конце 1990-х годов появились доказательства систематического рабства на плантациях какао в Западной Африке; см. статью о шоколаде и рабстве . [13]

По данным Госдепартамента США , в 2002 году более 109 000 детей работали какао только на фермах в Кот-д’Ивуаре, применяя «наихудшие формы детского труда ». [90]

В ночь с 14 на 15 апреля 2014 года группа боевиков напала на государственную женскую среднюю школу в Чибоке , Нигерия. Они ворвались в школу, притворившись охранниками, [91] велел девочкам выйти и пойти с ними. [92] Большое количество студентов было увезено на грузовиках, возможно, в Кондуга район леса Самбиса , где, как известно, Боко Харам располагала укрепленными лагерями. [92] В результате инцидента также сгорели дома в Чибоке. [93] По данным полиции, в результате нападения было захвачено около 276 детей, из которых по состоянию на 2 мая 53 сбежали. [94] В других сообщениях говорится, что 329 девочек были похищены, 53 сбежали, а 276 все еще числятся пропавшими без вести. [95] [96] [97] Студентов заставили принять ислам [98] и вступить в брак с членами Боко Харам с предполагаемым « выкупом за невесту » в размере 2000 фунтов стерлингов за каждого ( долларов США 12,50 / 7,50 фунтов стерлингов ). [99] [100] Многие из студентов были доставлены в соседние страны Чад и Камерун , при этом сообщалось о наблюдениях студентов, пересекающих границу с боевиками, а также о наблюдениях студентов жителями деревни, живущей в лесу Самбиса , который считается убежищем для Боко Харам. [100] [101]

5 мая 2014 года появилось видео, на котором Боко Харам лидер Абубакар Шекау взял на себя ответственность за похищения. Шекау заявил, что «Аллах велел мне продать их... Я выполню его указания» [102] и « [s] рабство разрешено в моей религии , и я буду захватывать людей и делать их рабами ». [103] Он сказал, что девочкам не следовало ходить в школу, а вместо этого они должны были выйти замуж, поскольку для замужества подходят девятилетние девочки. [102] [103]

Ливийская работорговля

[ редактировать ]Во время Второй гражданской войны в Ливии ливийцы начали захватывать [104] некоторые африканские мигранты из стран Африки к югу от Сахары пытаются попасть в Европу через Ливию и продают их на невольничьих рынках. [105] [106] Рабов часто выкупают перед их семьями, а тем временем, пока выкуп не будет выплачен, их могут пытать, заставлять работать, иногда работать до смерти, и в конечном итоге их могут казнить или оставить голодать, если выплата не будет произведена после период времени. Женщин часто насилуют, используют в качестве сексуальных рабынь и продают в публичные дома . [107] [108] [109] [110]

Многие дети-мигранты также страдают от жестокого обращения и изнасилования детей в Ливии. [111] [112]

Америка

[ редактировать ]

Чтобы участвовать в работорговле в Испанской Америке , банкиры и торговые компании должны были заплатить испанскому королю за лицензию, названную Asiento de Negros , но неизвестная сумма торговли была незаконной. После 1670 года, когда Испанская империя существенно пришла в упадок, они передали часть работорговли голландцам (1685–1687), португальцам, французам (1698–1713) и англичанам (1713–1750), а также предоставили организованные склады в Карибском бассейне. острова в Голландскую , Британскую и Французскую Америку . В результате Войны за испанское наследство британское правительство получило монополию ( asiento de negros ) на продажу африканских рабов в Испанской Америке , которая была предоставлена Компании Южных морей . Тем временем работорговля стала основным бизнесом для частных предприятий в Америке.

Среди коренных народов

[ редактировать ]В доколумбовой Мезоамерике наиболее распространенными формами рабства были рабство военнопленных и должников. Люди, неспособные выплатить долги, могли быть приговорены к работе в качестве рабов у людей, у которых была задолженность, до тех пор, пока долги не были отработаны, как форма кабального рабства . Война была важна для общества майя , поскольку набеги на прилегающие территории давали жертвы, необходимые для человеческих жертвоприношений , а также рабов для строительства храмов. [113] Большинство жертв человеческих жертвоприношений были военнопленными или рабами. [114] Рабство обычно не передавалось по наследству; дети рабов рождались свободными. В Империи инков рабочие облагались митой вместо налогов, которые они платили, работая на правительство. Каждый айллу , или большая семья, решал, кого из членов семьи отправить на работу. Неясно, эта принудительная работа или барщина считается ли рабством . Испанцы приняли эту систему, особенно на своих серебряных рудниках в Боливии. [115]

Другими рабовладельческими обществами и племенами Нового Света были, например, теуэльче в Патагонии, команчи в Техасе, карибы в Доминике, тупинамба в Бразилии, рыболовные общества, такие как юрок , жившие на западе. побережье Северной Америки от нынешней Аляски до Калифорнии, Пауни и Кламата . [116] Многие коренные народы северо-западного побережья Тихого океана , такие как хайда и тлинкиты , традиционно были известны как свирепые воины и работорговцы, совершавшие набеги вплоть до Калифорнии. Рабство было наследственным, рабы были военнопленными . [ нужны разъяснения ] Среди некоторых племен Тихоокеанского Северо-Запада около четверти населения было порабощено. [117] [118] Один рассказ о рабах был написан англичанином Джоном Р. Джуиттом , который был взят живым, когда его корабль был захвачен в 1802 году; в его мемуарах подробно рассматривается жизнь рабов и утверждается, что многие из них содержались под стражей.

Бразилия

[ редактировать ]

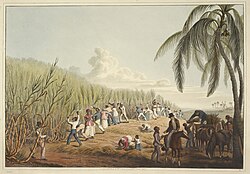

Рабство было основой бразильской колониальной экономики , особенно в горнодобывающей промышленности и сахарного тростника . производстве [119] 35,3% всех рабов из Атлантической работорговли отправились в колониальную Бразилию . Бразилия получила 4 миллиона рабов, что на 1,5 миллиона больше, чем в любой другой стране. [120] Примерно с 1550 года португальцы начали торговать порабощенными африканцами для работы на сахарных плантациях, когда коренной народ тупи пришел в упадок. Хотя Португалии премьер-министр Себастьян Жозе де Карвалью э Мелу , 1-й маркиз Помбал запретил ввоз рабов в континентальную Португалию 12 февраля 1761 года, рабство продолжалось в ее заморских колониях. Рабство практиковалось среди всех классов. рабы принадлежали высшим и средним классам, беднякам и даже другим рабам. [121]

Из Сан-Паулу бандейрантес , искатели приключений , в основном смешанного португальского и местного происхождения, неуклонно продвигались на запад в поисках индейцев для порабощения. Вдоль реки Амазонки и ее основных притоков неоднократные набеги рабов и карательные нападения оставили свой след. Один французский путешественник в 1740-х годах описал сотни миль речных берегов без признаков человеческой жизни и некогда процветающие деревни, которые были опустошены и пусты. В некоторых районах бассейна Амазонки , особенно среди гуарани на юге Бразилии и Парагвая , иезуиты организовали свои иезуитские сокращения по военному принципу для борьбы с работорговцами. В середине-конце XIX века многие американские индейцы были порабощены для работы на каучуковых плантациях. [122] [123] [124]

Сопротивление и отмена

[ редактировать ]Сбежавшие рабы сформировали общины маронов , которые сыграли важную роль в истории Бразилии и других стран, таких как Суринам , Пуэрто-Рико , Куба и Ямайка . В Бразилии деревни маронов назывались паленкес или киломбо . Мароны выживали за счет выращивания овощей и охоты. Они также совершали набеги на плантации . Во время этих нападений мароны сжигали посевы, крали скот и инструменты, убивали рабовладельцев и приглашали других рабов присоединиться к их общинам. [125]

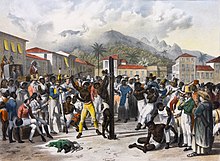

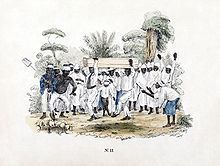

Жан-Батист Дебре , французский художник, работавший в Бразилии в первые десятилетия XIX века, начинал с портретов членов бразильской императорской семьи, но вскоре увлекся рабством как чернокожих, так и коренных жителей. Его картины на эту тему (две из них представлены на этой странице) помогли привлечь внимание к этой теме как в Европе, так и в самой Бразилии.

, Секта Клэпхема группа евангелических реформаторов, на протяжении большей части XIX века проводила кампанию за то, чтобы Великобритания использовала свое влияние и власть, чтобы остановить торговлю рабами в Бразилию. Помимо моральных сомнений, низкая стоимость бразильского сахара, произведенного рабами, означала, что Британская Вест-Индия не могла соответствовать рыночным ценам на бразильский сахар, и к 19 веку каждый британец потреблял 16 фунтов (7 кг) сахара в год. Эта комбинация привела к интенсивному давлению со стороны британского правительства на Бразилию с целью положить конец этой практике, что оно и делало поэтапно в течение нескольких десятилетий. [126]

Сначала в 1850 году была запрещена внешняя торговля рабами. Затем, в 1871 году, были освобождены сыновья рабов. В 1885 году были освобождены рабы старше 60 лет. Парагвайская война способствовала прекращению рабства, поскольку многие рабы вступили в армию в обмен на свободу. В колониальной Бразилии рабство было скорее социальным, чем расовым состоянием. [ нужна ссылка ] . Некоторые из величайших деятелей того времени, такие как писатель Мачадо де Ассис и инженер Андре Ребусас, имели черное происхождение.

(Великая засуха) в Бразилии в 1877–1878 годах Гранде Сека на хлопководческом северо-востоке привела к серьезным беспорядкам, голоду, бедности и внутренней миграции. Когда богатые плантаторы бросились продавать своих рабов на юг, народное сопротивление и недовольство росло, вдохновляя многочисленные общества освобождения. К 1884 году им удалось полностью запретить рабство в провинции Сеара. [127] Рабство было юридически прекращено по всей стране 13 мая Законом Lei Áurea («Золотым законом») 1888 года. В то время это был институт, находившийся в упадке, поскольку с 1880-х годов вместо этого страна начала использовать труд европейских иммигрантов. Бразилия была последней страной в Западном полушарии, отменившей рабство. [128]

Британский и французский Карибский бассейн

[ редактировать ]

Рабство широко использовалось в частях Карибского бассейна, контролируемых Францией и Британской империей . Малые Антильские острова Барбадос , Сент-Китс , Антигуа , Мартиника и Гваделупа , которые были первыми важными обществами рабов в Карибском бассейне , начали широкое использование порабощенных африканцев к концу 17 века, поскольку их экономика перешла на сахарную промышленность. производство. [129]

У Англии было несколько сахарных колоний в Карибском бассейне, особенно на Ямайке, Барбадосе, Невисе и Антигуа, что обеспечивало стабильный поток продаж сахара; принудительный труд рабов производил сахар. [130] К 1700-м годам на Барбадосе было больше рабов, чем во всех английских колониях на материке вместе взятых. Поскольку на Барбадосе было немного гор, английские плантаторы могли расчищать землю для сахарного тростника. Первоначально наемных слуг отправили на Барбадос для работы на сахарных полях. С этими наемными слугами обращались так плохо, что будущие наемные слуги перестали ездить на Барбадос, а людей для работы на полях не хватало. Именно тогда британцы начали привозить порабощенных африканцев. Английским плантаторам на Барбадосе использование порабощенного труда было необходимо, чтобы иметь возможность получать прибыль от производства тростникового сахара для растущего рынка сахара в Европе и на других рынках. [ нужна ссылка ]

В Утрехтском договоре , положившем конец войне за испанское наследство (1702–1714), различные европейские державы, обсуждавшие условия договора, также обсуждали колониальные вопросы. [131] Особое значение в переговорах в Утрехте имели успешные переговоры между британской и французской делегациями о получении Британией тридцатилетней монополии на право продажи рабов в Испанской Америке, получившей название Asiento de Negros . Королева Анна также разрешила своим североамериканским колониям , таким как Вирджиния, принимать законы, поощряющие ввоз рабов. Анна тайно вела переговоры с Францией, чтобы получить ее одобрение на Азиенто. [132] В 1712 году она произнесла речь, в которой публично объявила о своем успехе в отводе Азиенто у Франции; многие лондонские купцы праздновали ее экономический переворот. [133] Большая часть торговли рабами заключалась в продаже испанским колониям в Карибском бассейне и Мексике, а также в европейских колониях в Карибском бассейне и в Северной Америке. [134] Историк Винита Рикс говорит, что соглашение предоставило королеве Анне «22,5% (а королю Испании Филиппу V 28%) всей прибыли, собранной для монополии Asiento . Рикс заключает, что связь королевы с доходами от работорговли означала, что она больше не была нейтральный наблюдатель. Она была заинтересована в том, что происходило на невольничьих кораблях». [135]

К 1778 году французы ежегодно импортировали около 13 000 африканцев для порабощения во Французскую Вест-Индию. [136]

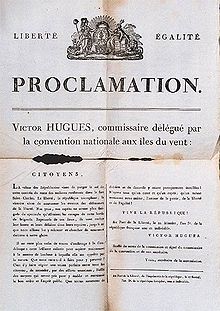

Чтобы упорядочить рабство, в 1685 году Людовик XIV принял Кодекс Нуар , рабский кодекс, наделявший рабов определенными правами человека и обязанностями хозяина, который был обязан кормить, одевать и обеспечивать общее благополучие своей человеческой собственности. Свободные цветные люди владели одной третью плантационной собственности и одной четвертью рабов в Сан-Доминго (позже Гаити ). [137] Рабство в Первой республике было отменено 4 февраля 1794 года. Когда стало ясно, что Наполеон намеревается восстановить рабство в Сен-Доминго (Гаити), Жан-Жак Дессалин и Александр Петион перешли на другую сторону в октябре 1802 года. 1 января 1804 года Дессалин, новый лидер согласно диктаторской конституции 1801 года, провозгласил Гаити свободной республикой. [138] Таким образом, Гаити стала второй независимой страной в Западном полушарии после Соединенных Штатов в результате единственного успешного восстания рабов в мировой истории. [139]

Уайтхолл в Англии объявил в 1833 году, что рабы в британских колониях будут полностью освобождены к 1838 году. Тем временем правительство заявило рабам, что они должны оставаться на своих плантациях и будут иметь статус «учеников» в течение следующих шести лет.

В Порт-оф-Спейне , Тринидад , 1 августа 1834 года невооруженная группа, в основном пожилых негров, к которой губернатор обратился в Доме правительства по поводу новых законов, начала скандировать: «Pas de Six ans. Point de Six Ans» («Pas de Six Ans. Point de Six Ans» («Pas de Six Ans. Point de Six Ans»). Не шесть лет. Нет шесть лет»), заглушая голос губернатора. Мирные протесты продолжались до тех пор, пока не была принята резолюция об отмене ученичества и не была достигнута фактическая свобода. Полное освобождение для всех было юридически предоставлено досрочно 1 августа 1838 года, что сделало Тринидад первой британской колонией с рабами, полностью отменившей рабство. [140]

После того как Великобритания отменила рабство, она начала оказывать давление на другие страны , чтобы они сделали то же самое. Франция также отменила рабство. К тому времени Сен-Доминго уже завоевал независимость и образовал независимую Республику Гаити , хотя Франция все еще контролировала Гваделупу , Мартинику и несколько небольших островов.

Канада

[ редактировать ]Рабство в Канаде практиковалось коренными народами и продолжалось во время европейской колонизации Канады. [141] Предполагается, что были 4200 рабов во французской колонии Канада , а затем и Британской Северной Америке, между 1671 и 1831 годами. [142] Две трети из них были коренного происхождения. (обычно называемый панис ) [143] тогда как другая треть имела африканское происхождение. [142] Они были домашней прислугой и сельскохозяйственными рабочими. [144] Число цветных рабов увеличилось во время британского правления , особенно с приходом лоялистов Объединенной Империи после 1783 года. [145] Небольшая часть современных чернокожих канадцев произошла от этих рабов. [146]

Практика рабства в Канаде прекратилась благодаря прецедентному праву; вымерли в начале 19 века в результате судебных исков от имени рабов, добивавшихся освобождения . [147] Суды в той или иной степени признали рабство неисполнимым как в Нижней Канаде , так и в Новой Шотландии . В Нижней Канаде, например, после судебных решений конца 1790-х годов «раба нельзя было заставить служить дольше, чем он хотел бы, и... он мог покинуть своего хозяина по своему желанию». [148] Верхняя Канада приняла Закон против рабства в 1793 году, один из первых законов против рабства в мире. [149] Это учреждение было официально запрещено на большей части территории Британской империи, включая Канаду, в 1834 году, после принятия Закона об отмене рабства 1833 года в британском парламенте. Эти меры привели к тому, что ряд чернокожих людей (свободных и рабов) из Соединенных Штатов переехали в Канаду после американской революции , известных как черные лоялисты ; и снова после войны 1812 года , когда несколько черных беженцев поселились в Канаде. В середине 19-го века Британская Северная Америка служила конечной станцией Подземной железной дороги — сети маршрутов, используемых порабощенными афроамериканцами для побега из рабовладельческого государства .

Латинская Америка

[ редактировать ]

В период с конца 19-го и начала 20-го веков спрос на трудоемкую добычу каучука привел к расширению границ и рабству в Латинской Америке и других странах. Коренные народы были порабощены в результате каучукового бума в Эквадоре, Перу , Колумбии и Бразилии . [150] В Центральной Америке сборщики каучука участвовали в порабощении коренного населения Гуатусо-Малеку для выполнения домашних работ. [151]

Соединенные Штаты

[ редактировать ]Ранние события

[ редактировать ]В конце августа 1619 года фрегат «Белый лев» , каперский корабль, принадлежавший Роберту Ричу, 2-му графу Уорику , но под голландским флагом, прибыл в Пойнт-Комфорт, штат Вирджиния (несколько миль вниз по течению от колонии Джеймстаун, штат Вирджиния ) с первым зарегистрированным рабов из Африки в Вирджинию. Примерно 20 африканцев были выходцами из современной Анголы . Они были сняты командой « Белого льва » с португальского грузового судна « Сан-Жуан-Баутиста» . [152] [153]

Историки не уверены, началась ли в колонии легальная практика рабства, поскольку по крайней мере некоторые из них имели статус наемных слуг . Олден Т. Вон говорит, что большинство согласны с тем, что к 1640 году существовали как черные рабы, так и наемные слуги. [154]

Лишь небольшая часть порабощенных африканцев, привезенных в Новый Свет, прибыла в Британскую Северную Америку , возможно, всего 5% от общего числа. Подавляющее большинство рабов было отправлено в сахарные колонии Карибского бассейна , Бразилию или Испанскую Америку .

К 1680-м годам, с консолидацией английской Королевской африканской компании , порабощенные африканцы стали прибывать в английские колонии в больших количествах, и это учреждение продолжало находиться под защитой британского правительства. Колонисты теперь начали закупать рабов в больших количествах.

Рабство в американском колониальном праве

[ редактировать ]

- 1640: Суды Вирджинии приговаривают Джона Панча к пожизненному рабству, что стало первой юридической санкцией рабства в английских колониях. [155]

- 1641: Массачусетс легализует рабство . [156]

- 1650: Коннектикут легализует рабство .

- 1652: Род-Айленд запрещает порабощение или принудительное рабство любого белого или негра на срок более десяти лет или старше 24 лет. [157] [158]

- 1654: Вирджиния санкционирует «право негров владеть рабами своей расы» после того, как африканец Энтони Джонсон , бывший наемный слуга, подал в суд, чтобы его соотечественник-африканец Джон Касор был объявлен не наемным слугой, а «рабом на всю жизнь». [159]

- 1661: Вирджиния официально признает рабство по закону.

- 1662: Статут Вирджинии провозглашает, что рожденные дети будут иметь тот же статус, что и их мать.

- 1663: Мэриленд легализует рабство .

- 1664: Рабство легализовано в Нью-Йорке и Нью-Джерси . [160]

- 1670: Каролина (позже Южная Каролина и Северная Каролина ) основана в основном плантаторами из перенаселенной британской сахарной островной колонии Барбадос , которые привезли с этого острова относительно большое количество африканских рабов. [161]

- 1676: Род-Айленд запрещает порабощение коренных американцев. [162]

Развитие рабства

[ редактировать ]Переход от наемных слуг к порабощенным африканцам был вызван сокращением класса бывших слуг, которые выполнили условия своих договоров и, таким образом, стали конкурентами своих бывших хозяев. Эти недавно освобожденные слуги редко могли комфортно себя содержать, а в табачной промышленности все больше доминировали крупные плантаторы. Это вызвало внутренние волнения, кульминацией которых стало восстание Бэкона . Со временем рабство движимого имущества стало нормой в регионах, где доминировали плантации .

The Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina established a model in which a rigid social hierarchy placed slaves under the absolute authority of their master. With the rise of a plantation economy in the Carolina Lowcountry based on rice cultivation, a society of slaves was created that later became the model for the King Cotton economy across the Deep South. The model created by South Carolina was driven by the emergence of a majority enslaved population that required repressive and often brutal force to control. Justification for such an enslaved society developed into a conceptual framework of white supremacy in the American colonies.[163]

Several local slave rebellions took place during the 17th and 18th centuries: Gloucester County, Virginia Revolt (1663);[164] New York Slave Revolt of 1712; Stono Rebellion (1739); and New York Slave Insurrection of 1741.[165]

Early United States law

[edit]

Within the British Empire, the Massachusetts courts began to follow England when, in 1772, England became the first country in the world to outlaw the slave trade within its borders (see Somerset v Stewart) followed by the Knight v. Wedderburn decision in Scotland in 1778. Between 1764 and 1774, seventeen slaves appeared in Massachusetts courts to sue their owners for freedom.[166] In 1766, John Adams' colleague Benjamin Kent won the first trial in the present-day United States to free a slave (Slew vs. Whipple).[167][168][169][170][171][172]

The Republic of Vermont allowed the enslavement of children in its constitution of 1777 suggesting that people "ought not" enslave adults, but there was no enforcement of this suggestion. Vermont entered the United States in 1791 with the same constitutional provisions.[173] Through the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 under the Congress of the Confederation, slavery was prohibited in the territories north west of the Ohio River. In 1794, Congress banned American vessels from being used in the slave trade, and also banned the export of slaves from America to other countries.[174] However, little effort was made to enforce this legislation. The slave ship owners of Rhode Island were able to continue in trade, and the USA's slaving fleet in 1806 was estimated to be nearly 75% as large as that of Britain, with dominance of the transportation of slaves into Cuba.[27]: 63 By 1804, abolitionists succeeded in passing legislation that ended legal slavery in every northern state (with slaves above a certain age legally transformed to indentured servants).[175] Congress passed an Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves as of 1 January 1808; but not the internal slave trade.[176]

Despite the actions of abolitionists, free blacks were subject to racial segregation in the Northern states.[177] While the United Kingdom did not ban slavery throughout most of the empire, including British North America till 1833, free blacks found refuge in the Canadas after the American Revolutionary War and again after the War of 1812. Refugees from slavery fled the South across the Ohio River to the North via the Underground Railroad. Midwestern state governments asserted States Rights arguments to refuse federal jurisdiction over fugitives. Some juries exercised their right of jury nullification and refused to convict those indicted under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.

After the passage of the Kansas–Nebraska Act in 1854, armed conflict broke out in Kansas Territory, where the question of whether it would be admitted to the Union as a slave state or a free state had been left to the inhabitants. The radical abolitionist John Brown was active in the mayhem and killing in "Bleeding Kansas." The true turning point in public opinion is better fixed at the Lecompton Constitution fraud. Pro-slavery elements in Kansas had arrived first from Missouri and quickly organized a territorial government that excluded abolitionists. Through the machinery of the territory and violence, the pro-slavery faction attempted to force the unpopular pro-slavery Lecompton Constitution through the state. This infuriated Northern Democrats, who supported popular sovereignty, and was exacerbated by the Buchanan administration reneging on a promise to submit the constitution to a referendum—which would surely fail. Anti-slavery legislators took office under the banner of the newly formed Republican Party. The Supreme Court in the Dred Scott decision of 1857 asserted that one could take one's property anywhere, even if one's property was chattel and one crossed into a free territory. It also asserted that African Americans could not be federal citizens. Outraged critics across the North denounced these episodes as the latest of the Slave Power (the politically organized slave owners) taking more control of the nation.[178]

American Civil War

[edit]The enslaved population in the United States stood at four million.[179] Ninety-five percent of blacks lived in the South, constituting one third of the population there as opposed to 1% of the population of the North. The central issue in politics in the 1850s involved the extension of slavery into the western territories, which settlers from the Northern states opposed. The Whig Party split and collapsed on the slavery issue, to be replaced in the North by the new Republican Party, which was dedicated to stopping the expansion of slavery. Republicans gained a majority in every northern state by absorbing a faction of anti-slavery Democrats, and warning that slavery was a backward system that undercut liberal democracy and economic modernization.[180] Numerous compromise proposals were put forward, but they all collapsed. A majority of Northern voters were committed to stopping the expansion of slavery, which they believed would ultimately end slavery. Southern voters were overwhelmingly angry that they were being treated as second-class citizens. In the election of 1860, the Republicans swept Abraham Lincoln into the Presidency and his party took control with legislators into the United States Congress. The states of the Deep South, convinced that the economic power of what they called "King Cotton" would overwhelm the North and win support from Europe voted to secede from the U.S. (the Union). They formed the Confederate States of America, based on the promise of maintaining slavery. War broke out in April 1861, as both sides sought wave after wave of enthusiasm among young men volunteering to form new regiments and new armies. In the North, the main goal was to preserve the union as an expression of American nationalism.

Rebel leaders Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee, Nathan Bedford Forrest and others were slavers and slave-traders.

By 1862 most northern leaders realized that the mainstay of Southern secession, slavery, had to be attacked head-on. All the border states rejected President Lincoln's proposal for compensated emancipation. However, by 1865 all had begun the abolition of slavery, except Kentucky and Delaware. The Emancipation Proclamation was an executive order issued by Lincoln on 1 January 1863. In a single stroke, it changed the legal status, as recognized by the U.S. government, of 3 million slaves in designated areas of the Confederacy from "slave" to "free." It had the practical effect that as soon as a slave escaped the control of the Confederate government, by running away or through advances of the Union Army, the slave became legally and actually free. Plantation owners, realizing that emancipation would destroy their economic system, sometimes moved their human property as far as possible out of reach of the Union Army. By June 1865, the Union Army controlled all of the Confederacy and liberated all of the designated slaves. The owners were never compensated.[181] About 186,000 free blacks and newly freed people fought for the Union in the Army and Navy, thereby validating their claims to full citizenship.[182]

The severe dislocations of war and Reconstruction had a severe negative impact on the black population, with a large amount of sickness and death.[183][184] After liberation, many of the Freedmen remained on the same plantation. Others fled or crowded into refugee camps operated by the Freedmen's Bureau. The Bureau provided food, housing, clothing, medical care, church services, some schooling, legal support, and arranged for labor contracts.[185] Fierce debates about the rights of the Freedmen, and of the defeated Confederates, often accompanied by killings of black leaders, marked the Reconstruction Era, 1863–77.[186]

Slavery was never reestablished, but after President Ulysses S. Grant left the White House in 1877, white-supremacist "Redeemer" Southern Democrats took control of all the southern states, and blacks lost nearly all the political power they had achieved during Reconstruction. By 1900, they also lost the right to vote – they had become second class citizens. The great majority lived in the rural South in poverty working as laborers, sharecroppers or tenant farmers; a small proportion owned their own land. The black churches, especially the Baptist Church, was the center of community activity and leadership.[187]

Asia

[edit]

Slavery has existed all throughout Asia, and forms of slavery still exist today. In the ancient Near East and Asia Minor slavery was common practice, dating back to the very earliest recorded civilisations in the world such as Sumer, Elam, Ancient Egypt, Akkad, Assyria, Ebla and Babylonia, as well as amongst the Hattians, Hittites, Hurrians, Mycenaean Greece, Luwians, Canaanites, Israelites, Amorites, Phoenicians, Arameans, Ammonites, Edomites, Moabites, Byzantines, Philistines, Medes, Phrygians, Lydians, Mitanni, Kassites, Parthians, Urartians, Colchians, Chaldeans and Armenians.[188][189][190]

Slavery in the Middle East first developed out of the slavery practices of the Ancient Near East,[191] and these practices were radically different at times, depending on social-political factors such as the Muslim slave trade. Two rough estimates by scholars of the number of slaves held over twelve centuries in Muslim lands are 11.5 million[192]and 14 million.[193][194]

Under Sharia (Islamic law),[191][195] children of slaves or prisoners of war could become slaves, but only if they are non-Muslim, leading to the Islamic world to import many slaves from other regions, predominantly Europe.[196] Manumission of a slave was encouraged as a way of expiating sins.[197] Many early converts to Islam, such as Bilal ibn Rabah al-Habashi, were poor and former slaves.[198][199][200][201]

Byzantine Empire

[edit]Slavery played a notable role in the economy of the Byzantine Empire. Many slaves were sourced from wars within the Mediterranean and Europe while others were sourced from trading with Vikings visiting the empire. Slavery's role in the economy and the power of slave owners slowly diminished while laws gradually improved the rights of slaves.[202][203][204] Under the influence of Christianity, views of slavery shifted leading to slaves gaining more rights and independence, and although slavery became rare and was seen as evil by many citizens it was still legal.[205][206]

During the Arab–Byzantine wars many prisoners of war were ransomed into slavery while others took part in Arab–Byzantine prisoner exchanges. Exchanges of prisoners became a regular feature of the relations between the Byzantine Empire and the Abbasid Caliphate.[207][208][209]

After the fall of the Byzantine empire thousands of Byzantine citizens were enslaved, with 30,000–50,000 citizens being enslaved by the Ottoman Empire after the Fall of Constantinople.[210][211]

Ottoman Empire

[edit]

Slavery was a legal and important part of the economy of the Ottoman Empire and Ottoman society[212] until the slavery of Caucasians was banned in the early 19th century, although slaves from other groups were allowed.[213] In Constantinople (present-day Istanbul), the administrative and political center of the Empire, about a fifth of the population consisted of slaves in 1609.[214] Even after several measures to ban slavery in the late 19th century, the practice continued largely unaffected into the early 20th century. As late as 1908, female slaves were still sold in the Ottoman Empire. Sexual slavery was a central part of the Ottoman slave system throughout the history of the institution.[215][216]

A member of the Ottoman slave class, called a kul in Turkish, could achieve high status. Harem guards and janissaries are some of the better-known positions a slave could hold, but slaves were actually often at the forefront of Ottoman politics. The majority of officials in the Ottoman government were bought slaves, raised as slaves of the Sultan, and integral to the success of the Ottoman Empire from the 14th century into the 19th. Many officials themselves owned a large number of slaves, although the Sultan himself owned by far the largest amount.[217] By raising and specially training slaves as officials in palace schools such as Enderun, the Ottomans created administrators with intricate knowledge of government and fanatic loyalty.

Ottomans practiced devşirme, a sort of "blood tax" or "child collection", young Christian boys from the Balkans and Anatolia were taken from their homes and families, brought up as Muslims, and enlisted into the most famous branch of the kapıkulu, the Janissaries, a special soldier class of the Ottoman army that became a decisive faction in the Ottoman invasions of Europe.[218]

During the various 18th and 19th century persecution campaigns against Christians as well as during the culminating Assyrian, Armenian and Greek genocides of World War I, many indigenous Armenian, Assyrian and Greek Christian women and children were carried off as slaves by the Ottoman Turks and their Kurdish allies. Henry Morgenthau, Sr., U.S. Ambassador in Constantinople from 1913 to 1916, reports in his Ambassador Morgenthau's Story that there were gangs trading white slaves during his term in Constantinople.[219] He also reports that Armenian girls were sold as slaves during the Armenian Genocide.[220][221]

According to Ronald Segal, the male:female gender ratio in the Atlantic slave trade was 2:1, whereas in Islamic lands the ratio was 1:2. Another difference between the two was, he argues, that slavery in the west had a racial component, whereas the Qur'an explicitly condemned racism. This, in Segal's view, eased assimilation of freed slaves into society.[222] Men would often take their female slaves as concubines; in fact, most Ottoman sultans were sons of such concubines.[222]

Ancient history

[edit]Ancient India

[edit]Scholars differ as to whether or not slaves and the institution of slavery existed in ancient India. These English words have no direct, universally accepted equivalent in Sanskrit or other Indian languages, but some scholars translate the word dasa, mentioned in texts like Manu Smriti,[223] as slaves.[224] Ancient historians who visited India offer the closest insights into the nature of Indian society and slavery in other ancient civilizations. For example, the Greek historian Arrian, who chronicled India about the time of Alexander the Great, wrote in his Indika,[225]

The Indians do not even use aliens as slaves, much less a countryman of their own.

— The Indika of Arrian[225]

Ancient China

[edit]- Qin dynasty (221–206 BC) Men sentenced to castration became eunuch slaves of the Qin dynasty state and as a result they were made to do forced labor, on projects like the Terracotta Army.[226] The Qin government confiscated the property and enslaved the families of those who received castration as a punishment for rape.[227]

- Slaves were deprived of their rights and connections to their families.[228]

- Han dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD) One of Emperor Gao's first acts was to set free from slavery agricultural workers who were enslaved during the Warring States period, although domestic servants retained their status.

- Men punished with castration during the Han dynasty were also used as slave labor.[229]

- Deriving from earlier Legalist laws, the Han dynasty set in place rules that the property of and families of criminals doing three years of hard labor or sentenced to castration were to have their families seized and kept as property by the government.[230]

During the millennium long Chinese domination of Vietnam, Vietnam was a great source of slave girls who were used as sex slaves in China.[231][232] The slave girls of Viet were even eroticized in Tang dynasty poetry.[231]

The Tang dynasty purchased Western slaves from the Radhanite Jews.[233] Tang Chinese soldiers and pirates enslaved Koreans, Turks, Persians, Indonesians, and people from Inner Mongolia, Central Asia, and northern India.[234][235][236][237] The greatest source of slaves came from southern tribes, including Thais and aboriginals from the southern provinces of Fujian, Guangdong, Guangxi, and Guizhou. Malays, Khmers, Indians, and black Africans were also purchased as slaves in the Tang dynasty.[238] Slavery was prevalent until the late 19th century and early 20th century China.[239] All forms of slavery have been illegal in China since 1910.[240]

Postclassical history

[edit]Indian subcontinent

[edit]The Islamic invasions, starting in the 8th century, also resulted in hundreds of thousands of Indians being enslaved by the invading armies, one of the earliest being the armies of the Umayyad commander Muhammad bin Qasim.[241][242][243][244][245] Qutb-ud-din Aybak, a Turkic slave of Muhammad Ghori rose to power following his master's death. For almost a century, his descendants ruled North-Central India in form of Slave Dynasty. Several slaves were also brought to India by the Indian Ocean trades; for example, the Siddi are descendants of Bantu slaves brought to India by Arab and Portuguese merchants.[246]

Andre Wink summarizes the slavery in 8th and 9th century India as follows,

(During the invasion of Muhammad al-Qasim), invariably numerous women and children were enslaved. The sources insist that now, in dutiful conformity to religious law, 'the one-fifth of the slaves and spoils' were set apart for the caliph's treasury and despatched to Iraq and Syria. The remainder was scattered among the army of Islam. At Rūr, a random 60,000 captives reduced to slavery. At Brahamanabad 30,000 slaves were allegedly taken. At Multan 6,000. Slave raids continued to be made throughout the late Umayyad period in Sindh, but also much further into Hind, as far as Ujjain and Malwa. The Abbasid governors raided Punjab, where many prisoners and slaves were taken.

— Al Hind, André Wink[247]

In the early 11th century Tarikh al-Yamini, the Arab historian Al-Utbi recorded that in 1001 the armies of Mahmud of Ghazna conquered Peshawar and Waihand (capital of Gandhara) after Battle of Peshawar (1001), "in the midst of the land of Hindustan", and captured some 100,000 youths.[242][243] Later, following his twelfth expedition into India in 1018–19, Mahmud is reported to have returned with such a large number of slaves that their value was reduced to only two to ten dirhams each. This unusually low price made, according to Al-Utbi, "merchants [come] from distant cities to purchase them, so that the countries of Central Asia, Iraq and Khurasan were swelled with them, and the fair and the dark, the rich and the poor, mingled in one common slavery". Elliot and Dowson refer to "five hundred thousand slaves, beautiful men and women.".[244][248][249] Later, during the Delhi Sultanate period (1206–1555), references to the abundant availability of low-priced Indian slaves abound. Levi attributes this primarily to the vast human resources of India, compared to its neighbors to the north and west (India's Mughal population being approximately 12 to 20 times that of Turan and Iran at the end of the 16th century).[250]

Slavery and empire-formation tied in particularly well with iqta and it is within this context of Islamic expansion that elite slavery was later commonly found. It became the predominant system in North India in the thirteenth century and retained considerable importance in the fourteenth century. Slavery was still vigorous in fifteenth-century Bengal, while after that date it shifted to the Deccan where it persisted until the seventeenth century. It remained present to a minor extent in the Mughal provinces throughout the seventeenth century and had a notable revival under the Afghans in North India again in the eighteenth century.

— Al Hind, André Wink[251]

The Delhi sultanate obtained thousands of slaves and eunuch servants from the villages of Eastern Bengal (a widespread practice which Mughal emperor Jahangir later tried to stop). Wars, famines, pestilences drove many villagers to sell their children as slaves. The Muslim conquest of Gujarat in Western India had two main objectives. The conquerors demanded and more often forcibly wrested both land owned by Hindus and Hindu women. Enslavement of women invariably led to their conversion to Islam.[252] In battles waged by Muslims against Hindus in Malwa and Deccan plateau, a large number of captives were taken. Muslim soldiers were permitted to retain and enslave POWs as plunder.[253]

The first Bahmani sultan, Alauddin Bahman Shah is noted to have captured 1,000 singing and dancing girls from Hindu temples after he battled the northern Carnatic chieftains. The later Bahmanis also enslaved civilian women and children in wars; many of them were converted to Islam in captivity.[254][255] About the Mughal empire, W.H. Moreland observed, "it became a fashion to raid a village or group of villages without any obvious justification, and carry off the inhabitants as slaves."[256][257][258]

During the rule of Shah Jahan, many peasants were compelled to sell their women and children into slavery to meet the land revenue demand.[259] Slavery was officially abolished in British India by the Indian Slavery Act, 1843. However, in modern India, Pakistan and Nepal, there are millions of bonded laborers, who work as slaves to pay off debts.[260][261][262]

Modern history

[edit]Iran

[edit]Reginald Dyer, recalling operations against tribes in Iranian Baluchistan in 1916, stated in a 1921 memoir that the local Balochi tribes would regularly carry out raids against travellers and small towns. During these raids, women and children would often be abducted to become slaves, and would be sold for prices varying based on quality, age and looks. He stated that the average price for a young woman was 300 rupees, and the average price for a small child 25 rupees. The slaves, it was noted, were often half starved.[263]

Japan

[edit]Slavery in Japan was, for most of its history, indigenous, since the export and import of slaves was restricted by Japan being a group of islands. In late-16th-century Japan, slavery was officially banned; but forms of contract and indentured labor persisted alongside the period penal codes' forced labor. During the Second Sino-Japanese War and the Pacific War, the Imperial Japanese Armed Forces used millions of civilians and prisoners of war from several countries as forced laborers.[264][265][266]

Korea

[edit]In Korea, slavery was officially abolished with the Gabo Reform of 1894. During the Joseon period, in times of poor harvest and famine, many peasants voluntarily sold themselves into the nobi system in order to survive.[267]

Southeast Asia

[edit]In Southeast Asia, there was a large slave class in Khmer Empire who built the enduring monuments in Angkor Wat and did most of the heavy work.[268] Between the 17th and the early 20th centuries one-quarter to one-third of the population of some areas of Thailand and Burma were slaves.[269] By the 19th century, Bhutan had developed a slave trade with Sikkim and Tibet, also enslaving British subjects and Brahmins.[270][271] According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), during the early 21st century an estimated 800,000people are subject to forced labor in Myanmar.[272]

Slavery in pre-Spanish Philippines was practiced by the tribal Austronesian peoples who inhabited the culturally diverse islands. The neighbouring Muslim states conducted slave raids from the 1600s into the 1800s in coastal areas of the Gulf of Thailand and the Philippine islands.[273][274] Slaves in Toraja society in Indonesia were family property. People would become slaves when they incurred a debt. Slaves could also be taken during wars, and slave trading was common. Torajan slaves were sold and shipped out to Java and Siam. Slaves could buy their freedom, but their children still inherited slave status. Slavery was abolished in 1863 in all Dutch colonies.[275][276]

Islamic State slave trade

[edit]According to media reports from late 2014, the Islamic State (IS) was selling Yazidi and Christian women as slaves.[277] According to Haleh Esfandiari of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, after IS militants have captured an area "[t]hey usually take the older women to a makeshift slave market and try to sell them."[278] In mid-October 2014, the UN estimated that 5,000 to 7,000 Yazidi women and children were abducted by IS and sold into slavery.[279] In the digital magazine Dabiq, IS claimed religious justification for enslaving Yazidi women whom they consider to be from a heretical sect. IS claimed that the Yazidi are idol worshipers and their enslavement is part of the old shariah practice of spoils of war.[280][281][282][283][284] According to The Wall Street Journal, IS appeals to apocalyptic beliefs and claims "justification by a Hadith that they interpret as portraying the revival of slavery as a precursor to the end of the world".[285]

IS announced the revival of slavery as an institution.[286] In 2015 the official slave prices set by IS were following:[287][288]

- Children aged 1 to 9 were sold for 200,000 dinars ($169).

- Women and children 10 to 20 years sold for 150,000 dinars ($127).

- Women 20 to 30 years old for 100,000 dinar ($85).

- Women 30 to 40 years old are 75,000 dinar ($63).

- Women 40 to 50 years old for 50,000 dinar ($42).

However some slaves have been sold for as little as a pack of cigarettes.[289]Sex slaves were sold to Saudi Arabia, other Persian Gulf states and Turkey.[290]

Europe

[edit]

Ancient history

[edit]Ancient Greece

[edit]Records of slavery in Ancient Greece go as far back as Mycenaean Greece. The origins are not known, but it appears that slavery became an important part of the economy and society only after the establishment of cities.[291] Slavery was common practice and an integral component of ancient Greece, as it was in other societies of the time. It is estimated that in Athens, the majority of citizens owned at least one slave. Most ancient writers considered slavery not only natural but necessary, but some isolated debate began to appear, notably in Socratic dialogues. The Stoics produced the first condemnation of slavery recorded in history.[22]

During the 8th and the 7th centuries BC, in the course of the two Messenian Wars, the Spartans reduced an entire population to a pseudo-slavery called helotry.[292] According to Herodotus (IX, 28–29), helots were seven times as numerous as Spartans. Following several helot revolts around the year 600 BC, the Spartans restructured their city-state along authoritarian lines, for the leaders decided that only by turning their society into an armed camp could they hope to maintain control over the numerically dominant helot population.[293] In some Ancient Greek city-states, about 30% of the population consisted of slaves, but paid and slave labor seem to have been equally important.[294]

Rome

[edit]Romans inherited the institution of slavery from the Greeks and the Phoenicians.[295] As the Roman Republic expanded outward, it enslaved entire populations, thus ensuring an ample supply of laborers to work in Rome's farms, quarries and households. The people subjected to Roman slavery came from all over Europe and the Mediterranean. Slaves were used for labor, and also for amusement (e.g. gladiators and sex slaves). In the late Republic, the widespread use of recently enslaved groups on plantations and ranches led to slave revolts on a large scale; the Third Servile War led by Spartacus was the most famous and most threatening to Rome.

Other European tribes

[edit]Various tribes of Europe are recorded by Roman sources as owning slaves.[296] Strabo records slaves as an export commodity from Britannia,[297] From Llyn Cerrig Bach in Anglesey, an iron gang chain dated to 100 BCE-50 CE was found, over 3 metres long with neck-rings for five captives.[298]

Post-classical history

[edit]The chaos of invasion and frequent warfare also resulted in victorious parties taking slaves throughout Europe in the early Middle Ages. St. Patrick, himself captured and sold as a slave, protested against an attack that enslaved newly baptized Christians in his "Letter to the Soldiers of Coroticus". As a commonly traded commodity, like cattle, slaves could become a form of internal or trans-border currency.[299]Slavery during the Early Middle Ages had several distinct sources.

The Vikings raided across Europe, but took the most slaves in raids on the British Isles and in Eastern Europe. While the Vikings kept some slaves as servants, known as thralls, they sold most captives in the Byzantine via the Black sea slave trade or Islamic markets such as the Khazar slave trade, Volga Bulgarian slave trade and Bukhara slave trade. In the West, their target populations were primarily English, Irish, and Scottish, while in the East they were mainly Slavs (saqaliba). The Viking slave-trade slowly ended in the 11th century, as the Vikings settled in the European territories they had once raided. They converted serfs to Christianity and themselves merged with the local populace.[300]

In central Europe, specifically the Frankish/German/Holy Roman Empire of Charlemagne, raids and wars to the east generated a steady supply of slaves from the Slavic captives of these regions. Because of high demand for slaves in the wealthy Muslim empires of Northern Africa, Spain, and the Near East, especially for slaves of European descent, a market for these slaves rapidly emerged. So lucrative was this market that it spawned an economic boom in central and western Europe, today known as the Carolingian Renaissance.[301][302][303] This boom period for slaves stretched from the early Muslim conquests to the High Middle Ages but declined in the later Middle Ages as the Islamic Golden Age waned.

Medieval Spain and Portugal saw almost constant warfare between Muslims and Christians. Al-Andalus sent periodic raiding expeditions to loot the Iberian Christian kingdoms, bringing back booty and slaves. In a raid against Lisbon, Portugal in 1189, for example, the Almohad caliph Yaqub al-Mansur took 3,000 female and child captives. In a subsequent attack upon Silves, Portugal in 1191, his governor of Córdoba took 3,000 Christian slaves.[304]

Ottoman Empire

[edit]

The Byzantine-Ottoman wars and the Ottoman wars in Europe resulted in the taking of large numbers of Christian slaves and using or selling them in the Islamic world too.[305] After the battle of Lepanto the victors freed approximately 12,000 Christian galley slaves from the Ottoman fleet.[306]

Similarly, Christians sold Muslim slaves captured in war. The Order of the Knights of Malta attacked pirates and Muslim shipping, and their base became a centre for slave trading, selling captured North Africans and Turks. Malta remained a slave market until well into the late 18th century. One thousand slaves were required to man the galleys (ships) of the Order.[307][page needed][308]

Eastern Europe

[edit]Poland banned slavery in the 15th century; in Lithuania, slavery was formally abolished in 1588; the institution was replaced by the second enserfment. Slavery remained a minor institution in Russia until 1723, when Peter the Great converted the household slaves into house serfs. Russian agricultural slaves were formally converted into serfs earlier, in 1679.[309]

British Isles

[edit]Capture in war, voluntary servitude and debt slavery became common within the British Isles before 1066. The Bodmin manumissions show both that slavery existed in 9th and 10th Century Cornwall and that many Cornish slave owners did set their slaves free. Slaves were routinely bought and sold. Running away was also common and slavery was never a major economic factor in the British Isles during the Middle Ages. Ireland and Denmark provided markets for captured Anglo-Saxon and Celtic slaves. Pope Gregory I reputedly made the pun, Non Angli, sed Angeli ("Not Angles, but Angels"), after a response to his query regarding the identity of a group of fair-haired Angles, slave children whom he had observed in the marketplace. After the Norman Conquest, the law no longer supported chattel slavery and slaves became part of the larger body of serfs.[310][311]

France

[edit]In the early Middle Ages, the city of Verdun was the centre of the thriving European slave trade in young boys who were sold to the Islamic emirates of Iberia where they were enslaved as eunuchs.[312] The Italian ambassador Liutprand of Cremona, as one example in the 10th century, presented a gift of four eunuchs to Emperor Constantine VII.[313]

Barbary pirates and Maltese corsairs

[edit]