Рональд Рейган

Рональд Рейган | |

|---|---|

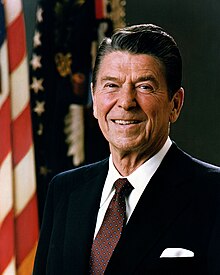

Официальный портрет, 1981 год. | |

| 40-й президент США | |

| В офисе 20 января 1981 г. - 20 января 1989 г. | |

| Vice President | George H. W. Bush |

| Preceded by | Jimmy Carter |

| Succeeded by | George H. W. Bush |

| 33rd Governor of California | |

| In office January 2, 1967 – January 6, 1975[1] | |

| Lieutenant | |

| Preceded by | Pat Brown |

| Succeeded by | Jerry Brown |

| 9th and 13th President of the Screen Actors Guild | |

| In office November 16, 1959 – June 7, 1960 | |

| Preceded by | Howard Keel |

| Succeeded by | George Chandler |

| In office March 10, 1947 – November 10, 1952 | |

| Preceded by | Robert Montgomery |

| Succeeded by | Walter Pidgeon |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Ronald Wilson Reagan February 6, 1911 Tampico, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died | June 5, 2004 (aged 93) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Resting place | Ronald Reagan Presidential Library |

| Political party | Republican (from 1962) |

| Other political affiliations | Democratic (until 1962) |

| Spouses | |

| Children | 5, including Maureen, Michael, Patti, and Ron |

| Parents | |

| Relatives | Neil Reagan (brother) |

| Alma mater | Eureka College (BA) |

| Occupation |

|

| Awards | Full list |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Service | United States Army |

| Years of service | |

| Rank | Captain |

| Unit | |

| Wars | World War II |

Other offices | |

Рональд Уилсон Рейган ( / ˈ r eɪ ɡ ən / РЭЙ -gən ; 6 февраля 1911 — 5 июня 2004) — американский политик и актёр, занимавший пост 40-го президента Соединённых Штатов с 1981 по 1989 год. Член Республиканской партии , его президентство составило эпоху Рейгана , и он считается одним из них. из самых выдающихся консервативных деятелей в американской истории.

Выросший в маленьких городках северного Иллинойса , Рейган окончил колледж Юрика в 1932 году и работал спортивным диктором на нескольких региональных радиостанциях. Он переехал в Калифорнию в 1937 году и стал там известным киноактером. Рейган дважды занимал пост президента Гильдии киноактеров: с 1947 по 1952 год и с 1959 по 1960 год. В 1950-е годы он работал на телевидении и выступал от имени General Electric . Речь Рейгана « Время выбора » во время президентской кампании 1964 года возвысила его как новую консервативную фигуру. Он был избран губернатором Калифорнии в 1966 году . Во время своего губернаторства он поднял налоги , превратил дефицит государственного бюджета в профицит и осуществил жесткие репрессии против Движения за свободу слова . и проиграл ему После того, как Рейган бросил вызов действующему президенту Джеральду Форду на республиканских президентских праймериз 1976 года , он выиграл номинацию от республиканцев , а затем одержал убедительную победу над действующим -демократом президентом Джимми Картером на президентских выборах 1980 года .

In his first term, Reagan implemented "Reaganomics", which involved economic deregulation and cuts in both taxes and government spending during a period of stagflation. He escalated an arms race and transitioned Cold War policy away from the policies of détente with the Soviet Union that had been established by Richard Nixon. Reagan also ordered the U.S. invasion of Grenada in 1983. Additionally, he survived an assassination attempt, fought public-sector labor unions, expanded the war on drugs, and was slow to respond to the AIDS epidemic in the United States, which began early in his presidency. In the 1984 presidential election, he defeated Carter's vice president Walter Mondale in another landslide victory. Foreign affairs dominated Reagan's second term, including the 1986 bombing of Libya, the Iran–Iraq War, the secret and illegal sale of arms to Iran to fund the Contras, and a more conciliatory approach in talks with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev that culminated in the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty.

Reagan left the presidency in 1989 with the American economy having seen a significant reduction of inflation, the unemployment rate having fallen, and the United States having entered its then-longest peacetime expansion. At the same time, the national debt had nearly tripled since 1981 as a result of his cuts in taxes and increased military spending, despite cuts to domestic discretionary spending. Reagan's policies also contributed to the end of the Cold War and the end of Soviet communism.[7] Alzheimer's disease hindered Reagan post-presidency, and his physical and mental capacities rapidly deteriorated, ultimately leading to his death in 2004. Historians and scholars have typically ranked him above average among American presidents, and his post-presidential approval ratings by the general public are usually high.[8]

Early life

Ronald Wilson Reagan was born on February 6, 1911, in a commercial building in Tampico, Illinois, as the younger son of Nelle Clyde Wilson and Jack Reagan.[9] Nelle was committed to the Disciples of Christ,[10] which believed in the Social Gospel.[11] She led prayer meetings and ran mid-week prayers at her church when the pastor was out of town.[10] Reagan credited her spiritual influence[12] and he became a Christian.[13] According to American political figure Stephen Vaughn, Reagan's values came from his pastor, and the First Christian Church's religious, economic and social positions "coincided with the words, if not the beliefs of the latter-day Reagan".[14] Jack focused on making money to take care of the family,[9] but this was complicated by his alcoholism.[15] Reagan had an older brother, Neil.[16] The family lived in Chicago, Galesburg, and Monmouth before returning to Tampico. In 1920, they settled in Dixon, Illinois,[17] living in a house near the H. C. Pitney Variety Store Building.[18]

Reagan attended Dixon High School, where he developed interests in drama and football.[19] His first job involved working as a lifeguard at the Rock River in Lowell Park.[20] In 1928, Reagan began attending Eureka College[21] at Nelle's approval on religious grounds.[22] He was a mediocre student[23] who participated in sports, drama, and campus politics. He became student body president and joined a student strike that resulted in the college president's resignation.[24] Reagan was initiated as a member of Tau Kappa Epsilon Fraternity and served as president of the local chapter.[25] Reagan played at the guard position for the 1930 and 1931 Eureka Red Devils football teams and recalled a time when two black football teammates were refused service at a segregated hotel; he invited them to his parents' home nearby in Dixon and his parents welcomed them. At the time, his parents' stance on racial questions was unusually progressive in Dixon.[26] Reagan himself had grown up with very few black Americans there and was oblivious to racial discrimination.[27]

Entertainment career

Radio and film

After obtaining a Bachelor of Arts degree in economics and sociology from Eureka College in 1932,[28][29] Reagan took a job in Davenport, Iowa, as a sports broadcaster for four football games in the Big Ten Conference.[30] He then worked for WHO radio in Des Moines as a broadcaster for the Chicago Cubs. His specialty was creating play-by-play accounts of games using only basic descriptions that the station received by wire as the games were in progress.[31] Simultaneously, he often expressed his opposition to racism.[32] In 1936, while traveling with the Cubs to their spring training in California, Reagan took a screen test that led to a seven-year contract with Warner Bros.[33]

Reagan arrived at Hollywood in 1937, debuting in Love Is on the Air (1937).[34] Using a simple and direct approach to acting and following his directors' instructions,[35] Reagan made thirty films, mostly B films, before beginning military service in April 1942.[36] He broke out of these types of films by portraying George Gipp in Knute Rockne, All American (1940), which would be rejuvenated when reporters called Reagan "the Gipper" while he campaigned for president of the United States.[37] Afterward, Reagan starred in Kings Row (1942) as a leg amputee, asking, "Where's the rest of me?"[38] His performance was considered his best by many critics.[39] Reagan became a star,[40] with Gallup polls placing him "in the top 100 stars" from 1941 to 1942.[39]

World War II interrupted the movie stardom that Reagan would never be able to achieve again[40] as Warner Bros. became uncertain about his ability to generate ticket sales. Reagan, who had a limited acting range, was dissatisfied with the roles he received. As a result, Lew Wasserman renegotiated his contract with his studio, allowing him to also make films with Universal Pictures, Paramount Pictures, and RKO Pictures as a freelancer. With this, Reagan appeared in multiple western films, something that had been denied to him while working at Warner Bros.[41] In 1952, he ended his relationship with Warner Bros.,[42] but went on to appear in a total of 53 films,[36] his last being The Killers (1964).[43]

Military service

In April 1937, Reagan enlisted in the United States Army Reserve. He was assigned as a private in Des Moines' 322nd Cavalry Regiment and reassigned to second lieutenant in the Officers Reserve Corps.[44] He later became a part of the 323rd Cavalry Regiment in California.[45] As relations between the United States and Japan worsened, Reagan was ordered for active duty while he was filming Kings Row. Wasserman and Warner Bros. lawyers successfully sent draft deferments to complete the film in October 1941. However, to avoid accusations of Reagan being a draft dodger, the studio let him go in April 1942.[46]

Reagan reported for duty with severe near-sightedness. His first assignment was at Fort Mason as a liaison officer, a role that allowed him to transfer to the United States Army Air Forces (AAF). Reagan became an AAF public relations officer and was subsequently assigned to the 18th AAF Base Unit in Culver City[47] where he felt that it was "impossible to remove an incompetent or lazy worker" due to what he felt was "the incompetence, the delays, and inefficiencies" of the federal bureaucracy.[48] Despite this, Reagan participated in the Provisional Task Force Show Unit in Burbank[49] and continued to make theatrical films.[50] He was also ordered to temporary duty in New York City to participate in the sixth War Loan Drive before being reassigned to Fort MacArthur until his discharge on December 9, 1945, as a captain. Throughout his military service, Reagan produced over 400 training films.[49]

Screen Actors Guild presidency

When Robert Montgomery resigned as president of the Screen Actors Guild (SAG) on March 10, 1947, Reagan was elected to that position in a special election.[51] Reagan's first tenure saw various labor–management disputes,[52] the Hollywood blacklist,[53] and the Taft–Hartley Act's implementation.[54] On April 10, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) interviewed Reagan and he provided them with the names of actors whom he believed to be communist sympathizers.[55] During a House Un-American Activities Committee hearing, Reagan testified that some guild members were associated with the Communist Party[56] and that he was well-informed about a "jurisdictional strike".[57] When asked if he was aware of communist efforts within the Screen Writers Guild, he called information about the efforts "hearsay".[58] Reagan resigned as SAG president November 10, 1952, but remained on the board;[59] Walter Pidgeon succeeded him as president.[60]

The SAG fought with film producers for the right to receive residual payments,[61] and on November 16, 1959, the board elected Reagan SAG president for the second time;[62] he replaced Howard Keel, who had resigned. During this second stint, Reagan managed to secure payments for actors whose theatrical films had been released between 1948 and 1959 and subsequently televised. The producers were initially required to pay the actors fees, but they ultimately settled instead for providing pensions and paying residuals for films made after 1959. Reagan resigned from the SAG presidency on June 7, 1960, and also left the board;[63] George Chandler succeeded him as SAG president.[64]

Marriages and children

In January 1940, Reagan married Jane Wyman, his co-star in the 1938 film Brother Rat.[65][66] Together, they had two biological daughters: Maureen in 1941,[67] and Christine in 1947 (born prematurely and died the following day).[68] They adopted one son, Michael, in 1945.[48] Wyman filed to divorce Reagan in June 1948. She was uninterested in politics, and occasionally recriminated, reconciled and separated with him. Although Reagan was unprepared,[68] the divorce was finalized in July 1949. Reagan would also remain close to his children.[69] Later that year, Reagan met Nancy Davis after she contacted him in his capacity as the SAG president about her name appearing on a communist blacklist in Hollywood; she had been mistaken for another Nancy Davis.[70] They married in March 1952,[71] and had two children, Patti in October 1952, and Ron in May 1958.[72] Reagan has three grandchildren.[73]

Television

Reagan became the host of MCA Inc. television production General Electric Theater[42] at Wasserman's recommendation. It featured multiple guest stars,[74] and Ronald and Nancy Reagan, continuing to use her stage name Nancy Davis, acted together in three episodes.[75] When asked how Reagan was able to recruit such stars to appear on the show during television's infancy, he replied, "Good stories, top direction, production quality".[76] However, the viewership declined in the 1960s and the show was canceled in 1962.[77] In 1965, Reagan became the host[78] of another MCA production, Death Valley Days.[79]

Early political activities

Reagan began as a Democrat, viewing Franklin D. Roosevelt as "a true hero".[80] He joined the American Veterans Committee and Hollywood Independent Citizens Committee of the Arts, Sciences and Professions (HICCASP), worked with the AFL–CIO to fight right-to-work laws,[81] and continued to speak out against racism when he was in Hollywood.[82] In 1945, Reagan planned to lead an HICCASP anti-nuclear rally, but Warner Bros. prevented him from going.[83] In 1946, he appeared in a radio program called Operation Terror to speak out against rising Ku Klux Klan activity in the country, citing the attacks as a "capably organized systematic campaign of fascist violence and intimidation and horror".[84] Reagan also supported Harry S. Truman in the 1948 presidential election,[85] and Helen Gahagan Douglas for the U.S. Senate in 1950. It was Reagan's belief that communism was a powerful backstage influence in Hollywood that led him to rally his friends against them.[81]

Reagan began shifting to the right when he supported the presidential campaigns of Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1952 and Richard Nixon in 1960.[86] When Reagan was contracted by General Electric (GE), he gave speeches to their employees. His speeches had a positive take on free markets.[87] Under GE vice president Lemuel Boulware, a staunch anti-communist,[88] employees were encouraged to vote for business-friendly politicians.[89]

In 1961, Reagan adapted his speeches into another speech to criticize Medicare.[90] In his view, its legislation would have meant "the end of individual freedom in the United States".[91] In 1962, Reagan was dropped by GE,[92] and he formally registered as a Republican.[86]

In 1964, Reagan gave a speech for presidential contender Barry Goldwater[93] that was eventually referred to as "A Time for Choosing".[94] Reagan argued that the Founding Fathers "knew that governments don't control things. And they knew when a government sets out to do that, it must use force and coercion to achieve its purpose"[95] and that "We've been told increasingly that we must choose between left or right".[96] Even though the speech was not enough to turn around the faltering Goldwater campaign, it increased Reagan's profile among conservatives. David S. Broder and Stephen H. Hess called it "the most successful national political debut since William Jennings Bryan electrified the 1896 Democratic convention with his famous 'Cross of Gold' address".[93]

1966 California gubernatorial election

In January 1966, Reagan announced his candidacy for the California governorship,[97] repeating his stances on individual freedom and big government.[98] When he met with black Republicans in March,[99] he was criticized for opposing the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Reagan responded that bigotry was not in his nature[100] and later argued that certain provisions of the act infringed upon the rights of property owners.[101] After the Supreme Court of California ruled that the initiative that repealed the Rumford Act was unconstitutional in May, he voiced his support for the act's repeal,[102] but later preferred amending it.[103] In the Republican primary, Reagan defeated George Christopher,[104] a moderate Republican[105] who William F. Buckley Jr. thought had painted Reagan as extreme.[98]

Reagan's general election opponent, incumbent governor Pat Brown, attempted to label Reagan as an extremist and tout his own accomplishments.[106] Reagan portrayed himself as a political outsider,[107] and charged Brown as responsible for the Watts riots and lenient on crime.[106] In numerous speeches, Reagan "hit the Brown administration about high taxes, uncontrolled spending, the radicals at the University of California, Berkeley, and the need for accountability in government".[108] Meanwhile, many in the press perceived Reagan as "monumentally ignorant of state issues", though Lou Cannon said that Reagan benefited from an appearance he and Brown made on Meet the Press in September.[109] Ultimately, Reagan won the governorship with 57 percent of the vote compared to Brown's 42 percent.[110]

California governorship (1967–1975)

Brown had spent much of California's funds on new programs, prompting them to use accrual accounting to avoid raising taxes. Consequently, it generated a larger deficit,[111] and Reagan would call for reduced government spending and tax hikes to balance the budget.[112] He worked with Jesse M. Unruh on securing tax increases and promising future property tax cuts. This caused some conservatives to accuse Reagan of betraying his principles.[113] As a result, taxes on sales, banks, corporate profits, inheritances, liquor, and cigarettes jumped. Kevin Starr states, Reagan "gave Californians the biggest tax hike in their history—and got away with it".[114] In the 1970 gubernatorial election, Unruh used Reagan's tax policy against him, saying it disproportionally favored the wealthy. Reagan countered that he was still committed to reducing property taxes.[115] By 1973, the budget had a surplus, which Reagan preferred "to give back to the people".[116]

In 1967, Reagan reacted to the Black Panther Party's strategy of copwatching by signing the Mulford Act[117] to prohibit the public carrying of firearms. The act was California's most restrictive piece of gun control legislation, with critics saying that it was "overreacting to the political activism of organizations such as the Black Panthers".[118] The act marked the beginning of both modern legislation and public attitude studies on gun control.[117] Reagan also signed the 1967 Therapeutic Abortion Act that allowed abortions in the cases of rape and incest when a doctor determined the birth would impair the physical or mental health of the mother. He later expressed regret over signing it, saying that he was unaware of the mental health provision. He believed that doctors were interpreting the provision loosely and more abortions were resulting.[119]

After Reagan won the 1966 election, he and his advisors planned a run in the 1968 Republican presidential primaries.[120] He ran as an unofficial candidate to cut into Nixon's southern support and be a compromise candidate if there were to be a brokered convention. He won California's delegates,[121] but Nixon secured enough delegates for the nomination.[122]

Reagan had previously been critical of former governor Brown and university administrators for tolerating student demonstrations in the city of Berkeley, making it a major theme in his campaigning.[123] On February 5, 1969, Reagan declared a state of emergency in response to ongoing protests and acts of violence at the University of California, Berkeley, and sent in the California Highway Patrol. In May 1969, these officers, along with local officers from Berkeley and Alameda county, clashed with protestors over a site known as the People's Park.[124][125] One student was shot and killed while many police officers and two reporters were injured. Reagan then commanded the state National Guard troops to occupy Berkeley for seventeen days to subdue the protesters, allowing other students to attend class safely. In February 1970, violent protests broke out near the University of California, Santa Barbara, where he once again deployed the National Guard. On April 7, Reagan defended his policies regarding campus protests, saying, "If it takes a bloodbath, let's get it over with. No more appeasement".[126]

During his victorious reelection campaign in 1970, Reagan, remaining critical of government, promised to prioritize welfare reform.[127] He was concerned that the programs were disincentivizing work and that the growing welfare rolls would lead to both an unbalanced budget and another big tax hike in 1972.[128] At the same time, the Federal Reserve increased interest rates to combat inflation, putting the American economy in a mild recession. Reagan worked with Bob Moretti to tighten up the eligibility requirements so that the financially needy could continue receiving payments. This was only accomplished after Reagan softened his criticism of Nixon's Family Assistance Plan. Nixon then lifted regulations to shepherd California's experiment.[129] In 1976, the Employment Development Department published a report suggesting that the experiment that ran from 1971 to 1974 was unsuccessful.[130]

Reagan declined to run for the governorship in 1974 and it was won by Pat Brown's son, Jerry.[131] Reagan's governorship, as professor Gary K. Clabaugh writes, saw public schools deteriorate due to his opposition to additional basic education funding.[132] As for higher education, journalist William Trombley believed that the budget cuts Reagan enacted damaged Berkeley's student-faculty ratio and research.[133] Additionally, the homicide rate doubled and armed robbery rates rose by even more during Reagan's eight years, even with the many laws Reagan signed to try toughening criminal sentencing and reforming the criminal justice system.[134] Reagan strongly supported capital punishment, but his efforts to enforce it were thwarted by People v. Anderson in 1972.[135] According to his son, Michael, Reagan said that he regretted signing the Family Law Act that granted no-fault divorces.[136]

Seeking the presidency (1975–1981)

1976 Republican primaries

Insufficiently conservative to Reagan[137] and many other Republicans,[138] President Gerald Ford suffered from multiple political and economic woes. Ford, running for president, was disappointed to hear him also run.[139] Reagan was strongly critical of détente and Ford's policy of détente with the Soviet Union.[140] He repeated "A Time for Choosing" around the country[141] before announcing his campaign on November 20, 1975, when he discussed economic and social problems, and to a lesser extent, foreign affairs.[142] Both candidates were determined to knock each other out early in the primaries,[143] but Reagan would devastatingly lose the first five primaries beginning with New Hampshire,[144] where he popularized the welfare queen narrative about Linda Taylor, exaggerating her misuse of welfare benefits and igniting voter resentment for welfare reform,[145] but never overtly mentioning her name or race.[146]

In Florida, Reagan referred to a "strapping young buck",[147] which became an example of dog whistle politics,[148] and accused Ford for handing the Panama Canal to Panama's government while Ford implied that he would end Social Security.[144] Then, in Illinois, he again criticized Ford's policy and his secretary of state, Henry Kissinger.[149] Losing the first five primaries prompted Reagan to desperately win North Carolina's by running a grassroots campaign and uniting with the Jesse Helms political machine that viciously attacked Ford. Reagan won an upset victory, convincing party delegates that Ford's nomination was no longer guaranteed.[150] Reagan won subsequent victories in Texas, Alabama, Georgia, and Indiana with his attacks on social programs, opposition to forced busing, increased support from inclined voters of a declining George Wallace campaign for the Democratic nomination,[151] and repeated criticisms of Ford and Kissinger's policies, including détente.[152]

The result was a seesaw battle for the 1,130 delegates required for their party's nomination that neither would reach before the Kansas City convention[153] in August[154] and Ford replacing mentions of détente with Reagan's preferred phrase, "peace through strength".[155] Reagan took John Sears' advice of choosing liberal Richard Schweiker as his running mate, hoping to pry loose of delegates from Pennsylvania and other states,[156] and distract Ford. Instead, conservatives were left alienated, and Ford picked up the remaining uncommitted delegates and prevailed, earning 1,187 to Reagan's 1,070. Before giving his acceptance speech, Ford invited Reagan to address the convention; Reagan emphasized individual freedom[157] and the dangers of nuclear weapons. In 1977, Ford told Cannon that Reagan's primary challenge contributed to his own narrow loss to Democrat Jimmy Carter in the 1976 United States presidential election.[158]

1980 election

Reagan emerged as a vocal critic of President Carter in 1977. The Panama Canal Treaty's signing, the 1979 oil crisis, and rise in the interest, inflation and unemployment rates helped set up his 1980 presidential campaign,[159] which he announced on November 13, 1979[160] with an indictment of the federal government.[161] His announcement stressed his fundamental principles of tax cuts to stimulate the economy and having both a small government and a strong national defense,[162] since he believed the United States was behind the Soviet Union militarily.[163] Heading into 1980, his age became an issue among the press, and the United States was in a severe recession.[164]

In the primaries, Reagan unexpectedly lost the Iowa caucus to George H. W. Bush. Three days before the New Hampshire primary, the Reagan and Bush campaigns agreed to a one-on-one debate sponsored by The Telegraph at Nashua, New Hampshire, but hours before the debate, the Reagan campaign invited other candidates including Bob Dole, John B. Anderson, Howard Baker and Phil Crane.[165] Debate moderator Jon Breen denied seats to the other candidates, asserting that The Telegraph would violate federal campaign contribution laws if it sponsored the debate and changed the ground rules hours before the debate.[166] As a result, the Reagan campaign agreed to pay for the debate. Reagan said that as he was funding the debate, he could decide who would debate.[167] During the debate, when Breen was laying out the ground rules and attempting to ask the first question, Reagan interrupted in protest to make an introductory statement and wanted other candidates to be included before the debate began.[168] The moderator asked Bob Malloy, the volume operator, to mute Reagan's microphone. After Breen repeated his demand to Malloy, Reagan furiously replied, "I am paying for this microphone, Mr. Green! [sic]".[a][170] This turned out to be the turning point of the debate and the primary race.[171] Ultimately, the four additional candidates left, and the debate continued between Reagan and Bush. Reagan's polling numbers improved, and he won the New Hampshire primary by more than 39,000 votes.[172] Soon thereafter, Reagan's opponents began dropping out of the primaries, including Anderson, who left the party to become an independent candidate. Reagan easily captured the presidential nomination and chose Bush as his running mate at the Detroit convention in July.[173]

The general election pitted Reagan against Carter amid the multitude of domestic concerns and ongoing Iran hostage crisis that began on November 4, 1979.[174] Reagan's campaign worried that Carter would be able to secure the release of the American hostages in Iran as part of the October surprise,[175] Carter "suggested that Reagan would wreck Social Security" and portrayed him as a warmonger,[176] and Anderson carried support from liberal Republicans dissatisfied with Reagan's conservatism.[175][b] One of Reagan's key strengths was his appeal to the rising conservative movement. Though most conservative leaders espoused cutting taxes and budget deficits, many conservatives focused more closely on social issues like abortion and gay rights.[178] Evangelical Protestants became an increasingly important voting bloc, and they generally supported Reagan.[179] Reagan also won the backing of Reagan Democrats.[180] Though he advocated socially conservative view points, Reagan focused much of his campaign on attacks against Carter's foreign policy.[181]

In August, Reagan gave a speech at the Neshoba County Fair, stating his belief in states' rights. Joseph Crespino argues that the visit was designed to reach out to Wallace-inclined voters,[182] and some also saw these actions as an extension of the Southern strategy to garner white support for Republican candidates.[183] Reagan's supporters have said that this was his typical anti-big government rhetoric, without racial context or intent.[184][185][186] In the October 28 debate, Carter chided Reagan for being against national health insurance. Reagan replied, "There you go again", though the audience laughed and viewers found him more appealing.[187] Reagan later asked the audience if they were better off than they were four years ago, slightly paraphrasing Roosevelt's words in 1934.[188] In 1983, Reagan's campaign managers were revealed to having obtained Carter's debate briefing book before the debates.[189] On November 4, 1980, Reagan won in a decisive victory in the Electoral College over Carter, carrying 44 states and receiving 489 electoral votes to Carter's 49 in six states and the District of Columbia. He won the popular vote by a narrower margin, receiving nearly 51 percent to Carter's 41 percent and Anderson's 7 percent. In the United States Congress, Republicans won a majority of seats in the Senate for the first time since 1952[190] while Democrats retained the House of Representatives.[191]

Presidency (1981–1989)

First inauguration

Reagan was inaugurated as the 40th president of the United States on Tuesday, January 20, 1981.[192] Chief Justice Warren E. Burger administered the presidential oath of office.[193] In his inaugural address, Reagan commented on the country's economic malaise, arguing, "In this present crisis, government is not the solution to our problem, government is the problem".[194] As a final insult to President Carter, Iran waited until Reagan had been sworn in before announcing the release of their American hostages.[195][196]

"Reaganomics" and the economy

Reagan advocated a laissez-faire philosophy,[197] and promoted a set of neoliberal reforms dubbed "Reaganomics", which included monetarism and supply-side economics.[198]

Taxation

This section is missing information about analysis. (November 2023) |

Reagan worked with the boll weevil Democrats to pass tax and budget legislation in a Congress led by Tip O'Neill, a liberal who strongly criticized Reaganomics.[199][c] He lifted federal oil and gasoline price controls on January 28, 1981,[201] and in August, he signed the Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981[202] to dramatically lower federal income tax rates and require exemptions and brackets to be indexed for inflation starting in 1985.[203] Amid growing concerns about the mounting federal debt, Reagan signed the Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act of 1982,[204] one of the eleven times Reagan raised taxes.[205] The bill doubled the federal cigarette tax, rescinded a portion of the corporate tax cuts from the 1981 tax bill,[206] and according to Paul Krugman, "a third of the 1981 cut" overall.[207] Many of his supporters condemned the bill, but Reagan defended his preservation of cuts on individual income tax rates.[208] By 1983, the amount of federal tax had fallen for all or most taxpayers, but most strongly affected the wealthy.[209]

The Tax Reform Act of 1986 reduced the number of tax brackets and top tax rate, and almost doubled personal exemptions.[210]

To Reagan, the tax cuts would not have increased the deficit as long as there was enough economic growth and spending cuts. His policies proposed that economic growth would occur when the tax cuts spur investments, which would result in more spending, consumption, and ergo tax revenue. This theoretical relationship has been illustrated by some with the controversial Laffer curve.[211] Critics labeled this "trickle-down economics", the belief that tax policies that benefit the wealthy will spread to the poor.[212] Milton Friedman and Robert Mundell argued that these policies invigorated America's economy and contributed to the economic boom of the 1990s.[213]

Inflation and unemployment

Reagan took office in the midst of stagflation.[214] The economy briefly experienced growth before plunging into a recession in July 1981.[215] As Federal Reserve chairman, Paul Volcker fought inflation by pursuing a tight money policy of high interest rates,[216] which restricted lending and investment, raised unemployment, and temporarily reduced economic growth.[217] In December 1982, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) measured the unemployment rate at 10.8 percent.[218] Around the same time, economic activity began to rise until its end in 1990, setting the record for the longest peacetime expansion.[219] In 1983, the recession ended[220] and Reagan nominated Volcker to a second term in fear of damaging confidence in the economic recovery.[221]

Reagan appointed Alan Greenspan to succeed Volcker in 1987. Greenspan raised interest rates in another attempt to curb inflation, setting off the Black Monday stock market crash, although the markets eventually recovered.[222] By 1989, the BLS measured the unemployment rate at 5.3 percent.[223] The inflation rate dropped from 12 percent during the 1980 election to under 5 percent in 1989. Likewise, the interest rate dropped from 15 percent to under 10 percent.[224] Yet, not all shared equally in the economic recovery, and both economic inequality[225] and the number of homeless individuals increased during the 1980s.[226] Critics have contended that a majority of the jobs created during this decade paid the minimum wage.[227]

Government spending

In 1981, in an effort to keep it solvent, Reagan approved a plan for cuts to Social Security. He later backed off of these plans due to public backlash.[228] He then created the Greenspan Commission to keep Social Security financially secure, and in 1983 he signed amendments to raise both the program's payroll taxes and retirement age for benefits.[229] He had signed the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1981 to cut funding for federal assistance such as food stamps, unemployment benefits, subsidized housing and the Aid to Families with Dependent Children,[230] and would discontinue the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act.[231] On the other side, defense spending doubled between 1981 and 1985.[163] During Reagan's presidency, Project Socrates operated within the Defense Intelligence Agency to discover why the United States was unable to maintain its economic competitiveness. According to program director Michael Sekora, their findings helped the country surpass the Soviets in terms of missile defense technology.[232][233]

Deregulation

Reagan sought to loosen federal regulation of economic activities, and he appointed key officials who shared this agenda. William Leuchtenburg writes that by 1986, the Reagan administration eliminated almost half of the federal regulations that had existed in 1981.[234] The 1982 Garn–St. Germain Depository Institutions Act deregulated savings and loan associations by letting them make a variety of loans and investments outside of real estate.[235] After the bill's passage, savings and loans associations engaged in riskier activities, and the leaders of some institutions embezzled funds. The administration's inattentiveness toward the industry contributed to the savings and loan crisis and costly bailouts.[236]

Deficits

The deficits were exacerbated by the early 1980s recession, which cut into federal revenue.[237] The national debt tripled between the fiscal years of 1980 and 1989, and the national debt as a percentage of the gross domestic product rose from 33 percent in 1981 to 53 percent by 1989. During his time in office, Reagan never fulfilled his 1980 campaign promise of submitting a balanced budget. The United States borrowed heavily to cover newly spawned federal budget deficits.[238] Reagan described the tripled debt the "greatest disappointment of his presidency".[239] Jeffrey Frankel opined that the deficits were a major reason why Reagan's successor, Bush, reneged on his campaign promise by raising taxes through the Budget Enforcement Act of 1990.[240]

Assassination attempt

On March 30, 1981, Reagan was shot by John Hinckley Jr. outside the Washington Hilton. Also struck were: James Brady, Thomas Delahanty, and Tim McCarthy. Although "right on the margin of death" upon arrival at George Washington University Hospital, Reagan underwent surgery and recovered quickly from a broken rib, a punctured lung, and internal bleeding. Professor J. David Woodard says that the assassination attempt "created a bond between him and the American people that was never really broken".[241] Later, Reagan came to believe that God had spared his life "for a chosen mission".[242]

Supreme Court appointments

Reagan appointed three Associate Justices to the Supreme Court of the United States: Sandra Day O'Connor in 1981, which fulfilled a campaign promise to name the first female justice to the Court, Antonin Scalia in 1986, and Anthony Kennedy in 1988. He also elevated William Rehnquist from Associate Justice to Chief Justice in 1986.[243] The direction of the Supreme Court's reshaping has been described as conservative.[244][245]

Public sector labor union fights

Early in August 1981, the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO) went on strike, violating a federal law prohibiting government unions from striking.[246] On August 3, Reagan said that he would fire air traffic controllers if they did not return to work within 48 hours; according to him, 38 percent did not return. On August 13, Reagan fired roughly 12,000 striking air traffic controllers who ignored his order.[247] He used military controllers[248] and supervisors to handle the nation's commercial air traffic until new controllers could be hired and trained.[249] The breaking of the PATCO strike demoralized organized labor, and the number of strikes fell greatly in the 1980s.[248] With the assent of Reagan's sympathetic National Labor Relations Board appointees, many companies also won wage and benefit cutbacks from unions, especially in the manufacturing sector.[250] During Reagan's presidency, the share of employees who were part of a labor union dropped from approximately one-fourth of the total workforce to approximately one-sixth of the total workforce.[251]

Civil rights

Despite Reagan having opposed the Voting Rights Act of 1965,[32] the bill was extended for 25 years in 1982.[252] He initially opposed the establishment of Martin Luther King Jr. Day,[253] and alluded to claims that King was associated with communists during his career, but signed a bill to create the holiday in 1983 after it passed both houses of Congress with veto-proof margins.[254] In 1984, he signed legislation intended to impose fines for fair housing discrimination offenses.[255] In March 1988, Reagan vetoed the Civil Rights Restoration Act of 1987, but Congress overrode his veto. He had argued that the bill unreasonably increased the federal government's power and undermined the rights of churches and business owners.[256] Later in September, legislation was passed to correct loopholes in the Fair Housing Act of 1968.[257][258]

Early in his presidency, Reagan appointed Clarence M. Pendleton Jr., known for his opposition to affirmative action and equal pay for men and women, as chair of the United States Commission on Civil Rights despite Pendleton's hostility toward long-established civil rights views. Pendleton and Reagan's subsequent appointees greatly eroded the enforcement of civil rights law, arousing the ire of civil rights advocates.[259] In 1987, Reagan unsuccessfully nominated Robert Bork to the Supreme Court as a way to achieve his civil rights policy that could not be fulfilled during his presidency; his administration had opposed affirmative action, particularly in education, federal assistance programs, housing and employment,[260] but Reagan reluctantly continued these policies.[261] In housing, Reagan's administration saw considerably fewer fair housing cases filed than the three previous administrations.[262]

War on drugs

In response to concerns about the increasing crack epidemic, Reagan intensified the war on drugs in 1982.[263] While the American public did not see drugs as an important issue then, the FBI, Drug Enforcement Administration and the United States Department of Defense all increased their anti-drug funding immensely.[264] Reagan's administration publicized the campaign to gain support after crack became widespread in 1985.[265] Reagan signed the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 and 1988 to specify penalties for drug offenses.[266] Both bills have been criticized in the years since for promoting racial disparities.[267] Additionally, Nancy Reagan founded the "Just Say No" campaign to discourage others from engaging in recreational drug use and raise awareness about the dangers of drugs.[268] A 1988 study showed 39 percent of high school seniors using illegal drugs compared to 53 percent in 1980,[269] but Scott Lilienfeld and Hal Arkowitz say that the success of these types of campaigns have not been found to be affirmatively proven.[270]

Escalation of the Cold War

Reagan ordered a massive defense buildup;[271] he revived the B-1 Lancer program that had been rejected by the Carter administration,[272] and deployed the MX missile.[273] In response to Soviet deployment of the SS-20, he oversaw NATO's deployment of the Pershing missile in Western Europe.[274] In 1982, Reagan tried to cut off the Soviet Union's access to hard currency by impeding its proposed gas line to Western Europe. It hurt the Soviet economy, but it also caused much ill will among American allies in Europe who counted on that revenue; he later retreated on this issue.[275] In March 1983, Reagan introduced the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) to protect the United States from space intercontinental ballistic missiles. He believed that this defense shield could protect the country from nuclear destruction in a hypothetical nuclear war with the Soviet Union.[276] There was much disbelief among the scientific community surrounding the program's scientific feasibility, leading opponents to dub the SDI "Star Wars",[277] though Soviet leader Yuri Andropov said it would lead to "an extremely dangerous path".[278]

In a 1982 address to the British Parliament, Reagan said, "the march of freedom and democracy... will leave Marxism–Leninism on the ash heap of history". Dismissed by the American press as "wishful thinking", Margaret Thatcher called the address a "triumph".[279] David Cannadine says of Thatcher that "Reagan had been grateful for her interest in him at a time when the British establishment refused to take him seriously" with the two agreeing on "building up stronger defenses against Soviet Russia" and both believing in outfacing "what Reagan would later call 'the evil empire'"[280] in reference to the Soviet Union during a speech to the National Association of Evangelicals in March 1983.[235] After Soviet fighters downed Korean Air Lines Flight 007 in September, which included Congressman Larry McDonald and 61 other Americans, Reagan expressed outrage towards the Soviet Union.[281] The next day, reports suggested that the Soviets had fired on the plane by mistake.[282] In spite of the harsh, discordant rhetoric,[283] Reagan's administration continued discussions with the Soviet Union on START I.[284]

Although the Reagan administration agreed with the communist government in China to reduce the sale of arms to Taiwan in 1982,[285] Reagan himself was the first president to reject containment and détente, and to put into practice the concept that the Soviet Union could be defeated rather than simply negotiated with.[286] His covert aid to Afghan mujahideen forces through Pakistan against the Soviets has been given credit for assisting in ending the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan.[287] However, the United States was subjected to blowback in the form of the Taliban that opposed them in the war in Afghanistan.[288] In his 1985 State of the Union Address, Reagan proclaimed, "Support for freedom fighters is self-defense".[289] Through the Reagan Doctrine, his administration supported anti-communist movements that fought against groups backed by the Soviet Union in an effort to rollback Soviet-backed communist governments and reduce Soviet influence across the world.[290] Critics have felt that the administration ignored the human rights violations in the countries they backed,[291] including genocide in Guatemala[292] and mass killings in Chad.[293]

Invasion of Grenada

On October 19, 1983, Maurice Bishop was overthrown and murdered by one of his colleagues. Several days later, Reagan ordered American forces to invade Grenada. Reagan cited a regional threat posed by a Soviet-Cuban military build-up in the Caribbean nation and concern for the safety of hundreds of American medical students at St. George's University as adequate reasons to invade. Two days of fighting commenced, resulting in an American victory.[294] While the invasion enjoyed public support in the United States, it was criticized internationally, with the United Nations General Assembly voting to censure the American government.[295] Cannon later noted that throughout Reagan's 1984 presidential campaign, the invasion overshadowed the 1983 Beirut barracks bombings,[296] which killed 241 Americans taking part in an international peacekeeping operation during the Lebanese Civil War.[297]

1984 election

Reagan announced his reelection campaign on January 29, 1984, declaring, "America is back and standing tall".[230] In February, his administration reversed the unpopular decision to send the United States Marine Corps to Lebanon, thus eliminating a political liability for him. Reagan faced minimal opposition in the Republican primaries,[298] and he and Bush accepted the nomination at the Dallas convention in August.[299] In the general election, his campaign ran the commercial, "Morning in America".[300] At a time when the American economy was already recovering,[220] former vice president Walter Mondale[301] was attacked by Reagan's campaign as a "tax-and-spend Democrat", while Mondale criticized the deficit, the SDI, and Reagan's civil rights policy. However, Reagan's age induced his campaign managers to minimize his public appearances. Mondale's campaign believed that Reagan's age and mental health were issues before the October presidential debates.[302]

Following Reagan's performance in the first debate where he struggled to recall statistics, his age was brought up by the media in negative fashion. Reagan's campaign changed his tactics for the second debate where he quipped, "I will not make age an issue of this campaign. I am not going to exploit, for political purposes, my opponent's youth and inexperience". This remark generated applause and laughter,[303] even from Mondale. At that point, Broder suggested that age was no longer a liability for Reagan,[304] and Mondale's campaign felt that "the election was over".[305] In November, Reagan won a landslide reelection victory with 59 percent of the popular vote and 525 electoral votes from 49 states. Mondale won 41 percent of the popular vote and 13 electoral votes from the District of Columbia and his home state of Minnesota.[306]

Response to the AIDS epidemic

The AIDS epidemic began to unfold in 1981,[307] and AIDS was initially difficult to understand for physicians and the public.[308] As the epidemic advanced, according to White House physician and later physician to the president, brigadier general John Hutton, Reagan thought of AIDS as though "it was the measles and would go away". The October 1985 death of the President's friend Rock Hudson affected Reagan's view; Reagan approached Hutton for more information on the disease. Still, between September 18, 1985, and February 4, 1986, Reagan did not mention AIDS in public.[309]

In 1986, Reagan asked C. Everett Koop to draw up a report on the AIDS issue. Koop angered many evangelical conservatives, both in and out of the Reagan administration, by stressing the importance of sex education including condom usage in schools.[310] A year later, Reagan, who reportedly had not read the report,[311] gave his first speech on the epidemic when 36,058 Americans had been diagnosed with AIDS, and 20,849 had died of it.[312] Reagan called for increased testing (including routine testing for marriage applicants) and mandatory testing of select groups (including federal prisoners).[313] Even after this speech, however, Reagan remained reluctant to publicly address AIDS.[314]

Scholars and AIDS activists have argued that the Reagan administration largely ignored the AIDS crisis.[315][316][317] Randy Shilts and Michael Bronski said that AIDS research was chronically underfunded during Reagan's administration, and Bronski added that requests for more funding by doctors at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention were routinely denied.[318][319] In a September 1985 press conference (soon after Hollywood celebrity Rock Hudson had announced his AIDS diagnosis) Reagan called a government AIDS research program a "top priority", but also cited budgetary constraints.[320] Between the fiscal years of 1984 and 1989, federal spending on AIDS totaled $5.6 billion. The Reagan administration proposed $2.8 billion during this time period, but pressure from congressional Democrats resulted in the larger amount.[321]

Addressing apartheid

Popular opposition to apartheid increased during Reagan's first term in office and the Disinvestment from South Africa movement achieved critical mass after decades of growing momentum. Criticism of apartheid was particularly strong on college campuses and among mainline Protestant denominations.[324][325] President Reagan was opposed to divestiture because he personally thought, as he wrote in a letter to Sammy Davis Jr., it "would hurt the very people we are trying to help and would leave us no contact within South Africa to try and bring influence to bear on the government". He also noted the fact that the "American-owned industries there employ more than 80,000 blacks" and that their employment practices were "very different from the normal South African customs".[326]

The Reagan administration developed constructive engagement[327] with the South African government as a means of encouraging it to gradually move away from apartheid and to give up its nuclear weapons program.[328] It was part of a larger initiative designed to foster peaceful economic development and political change throughout southern Africa.[329] This policy, however, engendered much public criticism, and renewed calls for the imposition of stringent sanctions.[330] In response, Reagan announced the imposition of new sanctions on the South African government, including an arms embargo in late 1985.[331] These sanctions were seen as weak by anti-apartheid activists and as insufficient by the president's opponents in Congress.[330] In 1986, Congress approved the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act, which included tougher sanctions; Reagan's veto was overridden by Congress. Afterward, he remained opposed to apartheid and unsure of "how best to oppose it". Several European countries, as well as Japan, also imposed their sanctions on South Africa soon after.[332]

Libya bombing

Contentious relations between Libya and the United States under President Reagan were revived in the West Berlin discotheque bombing that killed an American soldier and injured dozens of others on April 5, 1986. Stating that there was irrefutable evidence that Libya had a direct role in the bombing, Reagan authorized the use of force against the country. On April 14, the United States launched a series of airstrikes on ground targets in Libya.[333] Thatcher allowed the United States Air Force to use Britain's air bases to launch the attack, on the justification that the United Kingdom was supporting America's right to self-defense under Article 51 of the Charter of the United Nations.[334] The attack was, according to Reagan, designed to halt Muammar Gaddafi's "ability to export terrorism", offering him "incentives and reasons to alter his criminal behavior".[335] The attack was condemned by many countries; by an overwhelming vote, the United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution to condemn the attack and deem it a violation of the Charter and international law.[336]

Iran–Contra affair

Reagan authorized William J. Casey to arm the Contras, fearing that Communists would take over Nicaragua if it remained under the leadership of the Sandinistas. Congress passed the 1982 Boland Amendment, prohibiting the CIA and United States Department of Defense from using their budgets to provide aid to the Contras. Still, the Reagan administration raised funds for the Contras from private donors and foreign governments.[337] When Congress learned that the CIA had secretly placed naval mines in Nicaraguan harbors, Congress passed a second Boland Amendment that barred granting any assistance to the Contras.[338] By mid-1985, Hezbollah began to take American hostages in Lebanon, holding seven of them in reaction to the United States' support of Israel.[339]

Reagan procured the release of seven American hostages held by Hezbollah by selling American arms to Iran, then engaged in the Iran–Iraq War, in hopes that Iran would pressure Hezbollah to release the hostages.[340] The Reagan administration sold over 2,000 missiles to Iran without informing Congress; Hezbollah released four hostages but captured an additional six Americans. On Oliver North's initiative, the administration redirected the proceeds from the missile sales to the Contras.[340] The transactions were exposed by Ash-Shiraa in early November 1986. Reagan initially denied any wrongdoing, but on November 25, he announced that John Poindexter and North had left the administration and that he would form the Tower Commission to investigate the transactions. A few weeks later, Reagan asked a panel of federal judges to appoint a special prosecutor who would conduct a separate investigation.[341]

The Tower Commission released a report in February 1987 confirming that the administration had traded arms for hostages and sent the proceeds of the weapons sales to the Contras. The report laid most of the blame on North, Poindexter, and Robert McFarlane, but it was also critical of Donald Regan and other White House staffers.[342] Investigators did not find conclusive proof that Reagan had known about the aid provided to the Contras, but the report noted that Reagan had "created the conditions which made possible the crimes committed by others" and had "knowingly participated or acquiesced in covering up the scandal".[343] The affair damaged the administration and raised questions about Reagan's competency and the wisdom of conservative policies.[344] The administration's credibility was also badly damaged on the international stage as it had violated its own arms embargo on Iran.[345]

Soviet decline and thaw in relations

Although the Soviets did not accelerate military spending in response to Reagan's military buildup,[346] their enormous military expenses, in combination with collectivized agriculture and inefficient planned manufacturing, were a heavy burden for the Soviet economy. At the same time, the prices of oil, the primary source of Soviet export revenues, fell to one third of the previous level in 1985. These factors contributed to a stagnant economy during the tenure of Mikhail Gorbachev as Soviet leader.[347]

Reagan's foreign policy towards the Soviets wavered between brinkmanship and cooperation.[348] Reagan appreciated Gorbachev's revolutionary change in the direction of the Soviet policy and shifted to diplomacy, intending to encourage him to pursue substantial arms agreements.[286] They held four summit conferences between 1985 and 1988.[349] Reagan believed that if he could persuade the Soviets to allow for more democracy and free speech, this would lead to reform and the end of communism.[350] The critical summit was in Reykjavík in 1986, where they agreed to abolish all nuclear weapons. However, Gorbachev added the condition that SDI research must be confined to laboratories during the ten-year period when disarmament would take place. Reagan refused, stating that it was defensive only and that he would share the secrets with the Soviets, thus failing to reach a deal.[351]

In June 1987, Reagan addressed Gorbachev during a speech at the Berlin Wall, demanding that he "tear down this wall". The remark was ignored at the time, but after the wall fell in November 1989, it was retroactively recast as a soaring achievement.[352][353][354] In December, Reagan and Gorbachev met again at the Washington Summit[355] to sign the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, committing to the total abolition of their respective short-range and medium-range missile stockpiles.[356] The treaty established an inspections regime designed to ensure that both parties honored the agreement.[357] In May 1988, the U.S. Senate overwhelmingly voted in favor of ratifying the treaty,[358] providing a major boost to Reagan's popularity in the aftermath of the Iran–Contra affair. A new era of trade and openness between the two powers commenced, and the United States and Soviet Union cooperated on international issues such as the Iran–Iraq War.[359]

Post-presidency (1989–2004)

Upon leaving the presidency on January 20, 1989, at the age of 77, Reagan became the oldest president at the end of his tenure, surpassing Dwight D. Eisenhower who left office on January 20, 1961, at the age of 70. This distinction will eventually pass to incumbent president Joe Biden who is currently 81 years old.[360][361]

In retirement, Ronald and Nancy Reagan lived at 668 St. Cloud Road in Bel Air, in addition to Rancho del Cielo in Santa Barbara.[362] He received multiple awards and honors[363] in addition to generous payments for speaking engagements. In 1989 he supported repealing the Twenty-second Amendment's presidential term limits. In 1991, the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library opened. Reagan also addressed the 1992 Republican National Convention "to inspire allegiance to the party regulars";[364] and favored a constitutional amendment requiring a balanced budget.

Support for Brady Bill

Reagan publicly favored the Brady Bill, drawing criticism from gun control opponents.[365] In 1989, in his first public appearance after leaving office and shortly after a mass shooting at Cleveland Elementary School in Stockton, California, he stated: "I do not believe in taking away the right of the citizen to own guns for sporting, for hunting, and so forth, or for home defense. But I do believe that an AK-47, a machine gun, is not a sporting weapon or needed for the defense of the home".[366][367]

В марте 1991 года Рейган написал статью в «Нью-Йорк Таймс» под названием «Почему я за законопроект Брейди ». [368][369] В мае 1994 года Рейган, Джеральд Форд и Джимми Картер направили письмо членам Палаты представителей, призывая их поддержать спорный федеральный запрет на боевое оружие . [ 370 ]

болезнь Альцгеймера

Его последнее публичное выступление произошло 3 февраля 1994 года во время чествования его в Вашингтоне, округ Колумбия; его последнее крупное публичное выступление состоялось на похоронах Ричарда Никсона 27 апреля 1994 года. [ 364 ] В августе 1994 года Рейгану поставили диагноз « болезнь Альцгеймера» , о чем он объявил в рукописном письме в ноябре. [ 371 ] Были предположения о том, как долго он демонстрировал симптомы психического вырождения. [ 372 ] но наблюдения непрофессионалов о том, что он страдал болезнью Альцгеймера, еще находясь на своем посту, оспариваются медицинскими экспертами; [ 373 ] [ 374 ] [ 375 ] его врачи сказали, что явные симптомы болезни у него впервые начали проявляться в конце 1992 года. [ 376 ] или 1993 год. [ 375 ] Со временем болезнь уничтожила умственные способности Рейгана. Сообщалось, что к 1997 году он узнавал мало кого, кроме своей жены, хотя продолжал гулять по паркам и пляжам, играть в гольф и посещать свой офис в соседнем Сенчури-Сити . [ 375 ] В конце концов его семья решила, что он будет жить в тихой полуизоляции со своей женой. [ 377 ] К концу 2003 года Рейган потерял способность говорить и в основном был прикован к постели, не узнавая никого из членов семьи. [ 378 ]

Смерть и похороны

Рейган умер от пневмонии , осложненной болезнью Альцгеймера. [ 379 ] в своем доме в Лос-Анджелесе, 5 июня 2004 года. [ 380 ] Президент Джордж Буш назвал смерть Рейгана «печальным часом в жизни Америки». [ 379 ] Его публичные похороны прошли в Вашингтонском национальном соборе . [ 381 ] где панегирики произнесли Маргарет Тэтчер, Брайан Малруни , Джордж Буш-старший и Джордж Буш-младший. [ 382 ] На мероприятии присутствовали и другие мировые лидеры, в том числе Михаил Горбачев и Лех Валенса . [ 383 ] Рейган был похоронен в своей президентской библиотеке. [ 382 ]

Наследие

Историческая репутация

В 2008 году британский историк М. Дж. Хил резюмировал, что ученые достигли широкого консенсуса, согласно которому «Рейган реабилитировал консерватизм, повернул страну вправо, практиковал « прагматический консерватизм », который уравновешивал идеологию с ограничениями правительства, возродил веру в президентство и американское самоуважение и способствовал критическому окончанию холодной войны». [ 384 ] который закончился распадом Советского Союза в 1991 году. [ 385 ] Многие консервативные и либеральные ученые согласились с тем, что Рейган был самым влиятельным президентом со времен Рузвельта, оставив свой след в американской политике, дипломатии, культуре и экономике благодаря своей эффективной передаче своей консервативной программы и прагматическому компромиссу. [ 386 ] В первые годы постпрезидентства Рейгана исторические рейтинги помещали его президентство в двадцатые годы. [ 387 ] На протяжении 2000-х и 2010-х годов его президентство часто попадало в десятку лучших. [ 388 ] [ 389 ]

Многие сторонники, в том числе его современники по холодной войне, [ 390 ] [ 391 ] считают, что его оборонная политика, экономическая политика, военная политика и жесткая риторика против Советского Союза и коммунизма, а также его встречи на высшем уровне с Горбачевым сыграли значительную роль в прекращении холодной войны. [ 392 ] [ 286 ] Профессор Джеффри Кнопф утверждает, что, хотя практика Рейгана называть Советский Союз «злом», вероятно, не имела никакого значения для советских лидеров, она, возможно, дала поддержку гражданам Восточной Европы, которые выступали против своих коммунистических режимов. [ 286 ] Политика сдерживания президента Трумэна также рассматривается как причина падения Советского Союза, а советское вторжение в Афганистан подорвало саму советскую систему. [ 393 ] Тем не менее, Мелвин П. Леффлер назвал Рейгана «второстепенным, но незаменимым партнером Горбачева, заложившим основу для драматических изменений, которые никто не ожидал в ближайшее время». [ 394 ]

Критики, например Пол Кругман, отмечают, что срок правления Рейгана положил начало периоду увеличения неравенства доходов, которое иногда называют « Великой дивергенцией ». Кругман также считает, что Рейган положил начало идеологии нынешней Республиканской партии, которую, по его мнению, возглавляют «радикалы», стремящиеся «свести на нет достижения двадцатого века» в области равенства доходов и создания профсоюзов. [ 395 ] Другие, такие как министр торговли при Никсоне Питер Г. Петерсон , также критикуют то, что, по их мнению, было не только финансовой безответственностью Рейгана, но и началом эпохи, когда снижение налогов «стало основной платформой Республиканской партии», что привело к дефициту и лидерам Республиканской партии. (особенно по мнению Петерсона), утверждая, что увеличение предложения позволит стране «вырасти» до выхода из дефицита. [ 396 ]

Рейган был известен своим повествованием и юмором. [ 397 ] в котором использовались каламбуры [ 398 ] и самоуничижение. [ 399 ] Рейган также часто подчеркивал семейные ценности , несмотря на то, что он был первым разведенным президентом. [ 400 ] Он продемонстрировал способность утешать американцев после космического корабля " Челленджер" катастрофы . [ 401 ] Способность Рейгана говорить о существенных вопросах понятными терминами и концентрироваться на основных проблемах Америки принесла ему хвалебное прозвище «Великий коммуникатор». [ 402 ] [ 397 ] Он также получил прозвище «Тефлоновый президент» потому, что общественное мнение о нем не было существенно запятнано множеством противоречий, возникших во время его правления . [ 403 ] [ 404 ]

Политическое влияние

Рейган возглавил новое консервативное движение , изменившее политическую динамику Соединённых Штатов. [ 405 ] Консерватизм стал доминирующей идеологией республиканцев, вытеснив партийную фракцию либералов и умеренных. [ 406 ] В его время мужчины стали больше голосовать за республиканцев, а женщины стали больше голосовать за демократов – гендерное различие сохранилось. [ 405 ] Его поддержали молодые избиратели, и эта преданность привела многих из них к партии. [ 407 ] Он пытался обратиться к чернокожим избирателям в 1980 году. [ 408 ] но на тот момент получил бы наименьшее количество голосов чернокожих среди кандидата в президенты от республиканской партии. [ 409 ] На протяжении всего президентства Рейгана республиканцы не смогли получить полный контроль над Конгрессом. [ 410 ]

Период американской истории, в котором больше всего доминировал Рейган и его политика (особенно в вопросах налогов, социального обеспечения, обороны, федеральной судебной системы и «холодной войны»), известен как эпоха Рейгана . США во внутренней и внешней политике. Администрацию Клинтона часто рассматривают как продолжение эпохи, как и администрацию Джорджа Буша-младшего . [ 411 ] С 1988 года кандидаты в президенты от республиканской партии ссылаются на политику и убеждения Рейгана . [ 412 ]

Примечания

- ↑ Рейган неверно указал фамилию Брина как «мистер Грин». [ 169 ]

- ↑ Джон Б. Андерсон поставил под сомнение реалистичность бюджетных предложений Рейгана, заявив: «Единственный способ, которым Рейган собирается сократить налоги, увеличить расходы на оборону и в то же время сбалансировать бюджет, - это использовать синий дым и зеркала». [ 177 ]

- ↑ Несмотря на различные разногласия, Рейган и О'Нил подружились, несмотря на партийные линии. О'Нил сказал Рейгану, что оппоненты-республиканцы стали друзьями «после шести часов». Рейган иногда в любое время звонил О'Нилу и спрашивал, уже ли сейчас шесть часов, на что О'Нил неизменно отвечал: «Абсолютно, господин президент». [ 200 ]

Ссылки

Цитаты

- ^ Холмс 2020 , с. 210.

- ^ Оливер, Мирна (11 октября 1995 г.). «Роберт Х. Финч, лейтенант-губернатор. При Рейгане умер: Политика: Лидеру Республиканской партии Калифорнии было 70 лет. Он также работал в кабинете Никсона, а также в качестве специального советника президента и руководителя кампании» . Лос-Анджелес Таймс . Архивировано из оригинала 26 декабря 2022 года . Проверено 4 апреля 2020 г.

- ^ Чанг, Синди (25 декабря 2016 г.). «Эд Рейнеке, который ушел с поста вице-губернатора Калифорнии после того, как был признан виновным в лжесвидетельстве, умер в возрасте 92 лет» . Лос-Анджелес Таймс . Архивировано из оригинала 26 декабря 2022 года . Проверено 4 апреля 2020 г.

- ^ Юг, Гарри (21 мая 2018 г.). «Вице-губернаторы Калифорнии редко занимают высшие должности» . Хроники Сан-Франциско . Архивировано из оригинала 26 декабря 2022 года . Проверено 4 апреля 2020 г.

- ^ Отчет председателя за 1968 год: членам Республиканского национального комитета, 16–17 января 1969 года . Республиканский национальный комитет . Январь 1969 г. с. 41 . Проверено 16 января 2023 г.

- ^ Синергия, Тома 13–30 . Справочный центр района залива . 1969. с. 41 . Проверено 16 января 2023 г.

Губернатор Пенсильвании Рэймонд Шафер был избран 13 декабря, сменив губернатора Рональда Рейгана на посту председателя Ассоциации губернаторов-республиканцев.

- ^ «Рональд Рейган» . Британская энциклопедия . 9 июня 2023 г. . Проверено 27 июня 2023 г.

- ^ «Ретроспективное одобрение президентов» . Gallup, Inc., 17 июля 2023 г. Проверено 23 августа 2023 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Кенгор 2004 , с. 5.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Кенгор 2004 , с. 12.

- ^ Шпиц 2018 , с. 36.

- ^ Кенгор 2004 , с. 48.

- ^ Кенгор 2004 , с. 10.

- ^ Вон 1995 , с. 109.

- ^ Бренды 2015 , с. 10.

- ^ Кенгор 2004 , с. 4.

- ^ Пембертон 1998 , с. 5.

- ^ Вудард 2012 , с. 4.

- ^ Бренды 2015 , с. 14.

- ^ Бренды 2015 , с. 16.

- ^ Пембертон 1998 , с. 10.

- ^ Бренды 2015 , с. 17.

- ^ Бренды 2015 , с. 20.

- ^ Пембертон 1998 , стр. 10–11.

- ^ Редеске, Хизер (лето 2004 г.). «Вспоминая Рейгана» (PDF) . Теке . Том. 97, нет. 3. Тау Каппа Эпсилон . стр. 8–13 . Проверено 11 ноября 2023 г.

- ^ Кэннон 2000 , с. 457; Майер 2015 , с. 73.

- ^ Примут 2016 , с. 42.

- ^ Маллен 1999 , с. 207.

- ^ «Посетите кампус Рейгана» . Общество Рональда Рейгана при колледже Эврика . Архивировано из оригинала 18 апреля 2023 года . Проверено 19 февраля 2023 г.

- ^ Бренды 2015 , стр. 24–26.

- ^ Бренды 2015 , стр. 29–30.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Кэннон 2000 , с. 458.

- ^ Вудард 2012 , стр. 18–19.

- ^ Бренды 2015 , с. 39–40.

- ^ Бесплатно, 2015 , стр. 43–44.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Вон 1994 , с. 30.

- ^ Кэннон 2001 , стр. 13–15.

- ^ Вудард 2012 , стр. 25–26.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Вон 1994 , с. 37.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Фридрих 1997 , с. 89.

- ^ Кэннон 2003 , с. 59.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Вон 1994 , с. 236.

- ^ Вон 1994 , с. 312.

- ^ Оливер и Мэрион 2010 , с. 148.

- ^ Вон 1994 , с. 96.

- ^ Вудард 2012 , с. 26; Бренды 2015 , стр. 54–55.

- ^ Оливер и Мэрион 2010 , стр. 148–149.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Вудард 2012 , с. 27.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Оливер и Мэрион 2010 , с. 149.

- ^ Бренды 2015 , с. 57.

- ^ Кэннон 2003 , с. 86.

- ^ Вон 1994 , с. 133.

- ^ Вон 1994 , с. 146.

- ^ Вон 1994 , с. 154.

- ^ Пембертон 1998 , с. 32.

- ^ Кэннон 2003 , с. 97.

- ^ Кэннон 2003 , с. 98.

- ^ Бренды 2015 , с. 89.

- ^ Элиот 2008 , с. 266.

- ^ Вон 1994 , с. 179.

- ^ Пембертон 1998 , с. 35.

- ^ «Рейган возглавляет Гильдию актеров» . Республика Аризона . Юнайтед Пресс Интернэшнл . 17 ноября 1959 г. с. 47 . Проверено 15 августа 2024 г.

- ^ Кэннон 2003 , стр. 111–112.

- ^ Ландесман 2015 , с. 173.

- ^ Бренды 2015 , с. 43.

- ^ Вудард 2012 , с. 23.

- ^ Вудард 2012 , с. 25.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Вудард 2012 , с. 29.

- ^ Кэннон 2003 , стр. 73–74.

- ^ Бренды 2015 , с. 109.

- ^ Бренды 2015 , с. 113.

- ^ Бренды 2015 , с. 199.

- ^ «Семья Рональда Рейгана» . Рональд Рейган . Проверено 27 июня 2024 г.

- ^ Бренды 2015 , с. 120.

- ^ Мецгер 1989 , с. 26.

- ^ Бренды 2015 , с. 122.

- ^ Бренды 2015 , стр. 131–132.

- ^ Бренды 2015 , с. 145.

- ^ Пембертон 1998 , с. 36.

- ^ Ягер 2006 , стр. 12–13.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Вудард 2012 , с. 28.

- ^ Пембертон 1998 , с. 139.

- ^ Леттоу 2006 , стр. 4–5.

- ^ Вон, Стивен (2002). «Рональд Рейган и борьба за достоинство чернокожих в кино, 1937–1953» . Журнал афроамериканской истории . Прошлое перед нами (зима, 2002 г.) (87): 83–97. дои : 10.1086/JAAHv87n1p83 . ISSN 1548-1867 . JSTOR 1562493 . S2CID 141324540 . Проверено 1 мая 2023 г.

- ^ Вудард 2012 , с. 49.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Кэннон 2000 , с. 53.

- ^ Вудард 2012 , стр. 42–43.

- ^ Эванс 2006 , с. 21.

- ^ Эванс 2006 , с. 4.

- ^ Скидмор 2008 , стр. 103.

- ^ Редко 2017 , с. 240.

- ^ Кэннон 2003 , с. 112.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Вудард 2012 , с. 55.

- ^ Кэннон 2003 , с. 132.

- ^ Рейган 1990 , с. 27.

- ^ Рейган 1990 , стр. 99–100.

- ^ Кэннон 2003 , с. 141.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Бренды 2015 , с. 148.

- ^ Бренды 2015 , с. 149.

- ^ Кэннон 2003 , с. 142.

- ^ Бренды 2015 , с. 150.

- ^ Кэннон 2003 , с. 147.

- ^ Патнэм 2006 , с. 27.

- ^ Кэннон 2003 , стр. 147–148.

- ^ Кэннон 2003 , с. 135.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Пембертон 1998 , с. 69.

- ^ Кэннон 2003 , с. 149.

- ^ Вудард 2012 , с. 59.

- ^ Кэннон 2003 , стр. 158–159.

- ^ Вудард 2012 , с. 60.

- ^ Кэннон 2003 , с. 5.

- ^ Вудард 2012 , с. 64.

- ^ Бренды 2015 , стр. 157–159.

- ^ Патнэм 2006 , с. 26.

- ^ Шупарра 2015 , стр. 47–48.

- ^ Кэннон 2003 , с. 370.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Хейс, Фортунато и Хиббинг 2020 , с. 819.

- ^ Картер 2002 , с. 493.

- ^ Кэннон 2003 , стр. 209–214.

- ^ Пембертон 1998 , с. 76.

- ^ Гулд 2010 , стр. 92–93.

- ^ Гулд 2010 , стр. 96–97.

- ^ Кэннон 2003 , с. 271.

- ^ Кэннон 2003 , стр. 291–292.

- ^ «Вспоминая «Кровавый четверг»: бунт в Народном парке 1969 года» . Ежедневный калифорнийец . 21 апреля 2017 года . Проверено 25 мая 2023 г.

- ^ Кэннон 2003 , с. 295.

- ^ Вудард 2012 , стр. 73, 75.

- ^ Вудард 2012 , с. 75.

- ^ Бренды 2015 , стр. 179–181.

- ^ Рич, Спенсер (30 марта 1981 г.). «Программа Рейгана по обеспечению труда в Калифорнии провалилась, как следует из отчета» . Вашингтон Пост . Архивировано из оригинала 24 декабря 2022 года . Проверено 24 декабря 2022 г.

- ^ Кэннон 2000 , стр. 754–755.

- ^ Клабо 2004 , с. 257.

- ^ Кэннон 2003 , с. 296.

- ^ Кэннон 2003 , с. 388.

- ^ Кэннон 2003 , стр. 223–224.

- ^ Рейган 2011 , с. 67.

- ^ Вудард 2012 , с. 78.

- ^ Примут 2016 , с. 45.

- ^ Вудард 2012 , стр. 84–87.

- ^ Кенгор 2006 , с. 48.

- ^ Бренды 2015 , стр. 193–194.

- ^ Примут 2016 , с. 47.

- ^ Witcover 1977 , с. 433.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Вудард 2012 , стр. 89–90.

- ^ Борис 2007 , стр. 612–613.

- ^ Кэннон 2000 , с. 457.

- ^ Примут 2016 , с. 48.

- ^ Хейни Лопес 2014 , с. 4.

- ^ Witcover 1977 , с. 404.

- ^ Вудард 2012 , с. 91; Примут 2016 , с. 48.

- ^ Примут 2016 , стр. 49–50.

- ^ Паттерсон 2005 , с. 104.

- ^ Вудард 2012 , стр. 92–93.

- ^ Боллер 2004 , стр. 345.

- ^ Кенгор 2006 , с. 49.

- ^ Бренды 2015 , с. 204.

- ^ Вудард 2012 , стр. 93–94.

- ^ Кэннон 2003 , стр. 432, 434.

- ^ Вудард 2012 , стр. 99–101.

- ^ Пембертон 1998 , стр. 86.

- ^ Вудард 2012 , с. 102.

- ^ Пембертон 1998 , стр. 86–87.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Боуман, Том (8 июня 2004 г.). «Рейган руководил огромным наращиванием гонки вооружений» . Балтимор Сан . Архивировано из оригинала 1 января 2023 года . Проверено 1 января 2023 г.

- ^ Вудард 2012 , стр. 102–103.

- ^ «Дебаты Республиканской партии разжигают настроение» . Сан-Бернардино Сан . 24 февраля 1980 года. Архивировано из оригинала 22 мая 2021 года . Проверено 22 мая 2021 г. - из коллекции цифровых газет Калифорнии .

- ^ Биркнер 1987 , стр. 283–289.

- ^ «Республиканская партия игнорирует правила, затмевает дебаты» . Толедо Блейд . 24 февраля 1980 года. Архивировано из оригинала 22 мая 2021 года . Проверено 22 мая 2021 г.

- ^ Дюфрен, Луиза (11 февраля 2016 г.). «Вспыльчивый момент Рональда Рейгана в дебатах Республиканской партии 1980 года» . Новости CBS . Архивировано из оригинала 22 мая 2021 года . Проверено 22 мая 2021 г.

- ^ Марквард, Брайан (2 октября 2017 г.). «Джон Брин, 81 год, редактор, который модерировал знаменитые дебаты Рейгана и Буша» . Бостон Глобус . Архивировано из оригинала 8 октября 2017 года . Проверено 20 июля 2021 г.

- ^ «RealClearSports – Рональд Рейган: «Я плачу за этот микрофон » . RealClearPolitics . 11 ноября 2015 года. Архивировано из оригинала 15 апреля 2021 года . Проверено 22 мая 2021 г.

- ^ «Кампания штата Нью-Гэмпшир в разгаре перед первичными выборами» . Питтсбург Пост-Газетт . 25 февраля 1980 года. Архивировано из оригинала 22 мая 2021 года . Проверено 22 мая 2021 г.

- ^ «Рейган одерживает убедительную победу в Хью-Гемпшире» . Толедо Блейд . 27 февраля 1980 года. Архивировано из оригинала 22 мая 2021 года . Проверено 22 мая 2021 г.

- ^ Пембертон 1998 , стр. 87–89.

- ^ Пембертон 1998 , стр. 89–90; Вудард 2012 , с. 101.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Вудард 2012 , с. 110.

- ^ Кэннон 2001 , стр. 83–84.

- ^ Андерсон 1990 , с. 126.

- ^ Паттерсон, стр. 130–134.

- ^ Паттерсон, стр. 135–141, 150.

- ^ Паттерсон, с. 131

- ^ Паттерсон, стр. 145–146.

- ^ Барбарис 2021 , с. 1.

- ^ Герберт, Боб (6 октября 2005 г.). «Невозможно, смешно, отвратительно» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Архивировано из оригинала 29 декабря 2022 года . Проверено 29 декабря 2022 г.

- ^ Мердок, Дерой (20 ноября 2007 г.). «Рейган, никакого расиста» . Национальное обозрение . Архивировано из оригинала 29 декабря 2022 года . Проверено 29 декабря 2022 г.

- ^ Беннетт и Ливингстон, 2021 , с. 279.

- ^ Гайяр, Фрай; Такер, Синтия (2022). Юзеризация Америки: история демократии на волоске . Новые южные книги. п. 25,28. ISBN 9781588384560 .

- ^ Бренды 2015 , стр. 228–229.

- ^ Кэннон 2001 , с. 83.