Hippocampus

| Hippocampus | |

|---|---|

Hippocampus (lowest pink bulb) as part of the limbic system | |

Animation of both hippocampi in humans, located in the medial temporal lobes of the cerebrum | |

| Details | |

| Part of | Temporal lobe |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | hippocampus |

| MeSH | D006624 |

| NeuroNames | 3157 |

| NeuroLex ID | birnlex_721 |

| TA98 | A14.1.09.321 |

| TA2 | 5518 |

| FMA | 275020 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

The hippocampus (pl.: hippocampi; via Latin from Greek ἱππόκαμπος, 'seahorse') is a major component of the brain of humans and other vertebrates. Humans and other mammals have two hippocampi, one in each side of the brain. The hippocampus is part of the limbic system, and plays important roles in the consolidation of information from short-term memory to long-term memory, and in spatial memory that enables navigation. The hippocampus is located in the allocortex, with neural projections into the neocortex, in humans[1][2][3] as well as other primates.[4] The hippocampus, as the medial pallium, is a structure found in all vertebrates.[5] In humans, it contains two main interlocking parts: the hippocampus proper (also called Ammon's horn), and the dentate gyrus.[6][7]

In Alzheimer's disease (and other forms of dementia), the hippocampus is one of the first regions of the brain to suffer damage;[8] short-term memory loss and disorientation are included among the early symptoms. Damage to the hippocampus can also result from oxygen starvation (hypoxia), encephalitis, or medial temporal lobe epilepsy. People with extensive, bilateral hippocampal damage may experience anterograde amnesia: the inability to form and retain new memories.

Since different neuronal cell types are neatly organized into layers in the hippocampus, it has frequently been used as a model system for studying neurophysiology. The form of neural plasticity known as long-term potentiation (LTP) was initially discovered to occur in the hippocampus and has often been studied in this structure. LTP is widely believed to be one of the main neural mechanisms by which memories are stored in the brain.

In rodents as model organisms, the hippocampus has been studied extensively as part of a brain system responsible for spatial memory and navigation. Many neurons in the rat and mouse hippocampus respond as place cells: that is, they fire bursts of action potentials when the animal passes through a specific part of its environment. Hippocampal place cells interact extensively with head direction cells, whose activity acts as an inertial compass, and conjecturally with grid cells in the neighboring entorhinal cortex.[citation needed]

Name

[edit]

The earliest description of the ridge running along the floor of the temporal horn of the lateral ventricle comes from the Venetian anatomist Julius Caesar Aranzi (1587), who likened it first to a silkworm and then to a seahorse (Latin hippocampus, from Greek ἱππόκαμπος, from ἵππος, 'horse' + κάμπος, 'sea monster'). The German anatomist Duvernoy (1729), the first to illustrate the structure, also wavered between "seahorse" and "silkworm". "Ram's horn" was proposed by the Danish anatomist Jacob Winsløw in 1732; and a decade later his fellow Parisian, the surgeon de Garengeot, used cornu Ammonis – horn of Amun,[10] the ancient Egyptian god who was often represented as having a ram's head.[11]

Another reference appeared with the term pes hippocampi, which may date back to Diemerbroeck in 1672, introducing a comparison with the shape of the folded back forelimbs and webbed feet of the mythological hippocampus, a sea monster with a horse's forequarters and a fish's tail. The hippocampus was then described as pes hippocampi major, with an adjacent bulge in the occipital horn, described as the pes hippocampi minor and later renamed as the calcar avis.[10][12] The renaming of the hippocampus as hippocampus major, and the calcar avis as hippocampus minor, has been attributed to Félix Vicq-d'Azyr systematizing nomenclature of parts of the brain in 1786. Mayer mistakenly used the term hippopotamus in 1779, and was followed by some other authors until Karl Friedrich Burdach resolved this error in 1829. In 1861 the hippocampus minor became the center of a dispute over human evolution between Thomas Henry Huxley and Richard Owen, satirized as the Great Hippocampus Question. The term hippocampus minor fell from use in anatomy textbooks and was officially removed in the Nomina Anatomica of 1895.[13] Today, the structure is just called the hippocampus,[10] with the term cornu Ammonis (that is, 'Ammon's horn') surviving in the names of the hippocampal subfields CA1-CA4.[14][6]

Relation to limbic system

[edit]The term limbic system was introduced in 1952 by Paul MacLean[15] to describe the set of structures that line the deep edge of the cortex (Latin limbus meaning border): These include the hippocampus, cingulate cortex, olfactory cortex, and amygdala. Paul MacLean later suggested that the limbic structures comprise the neural basis of emotion. The hippocampus is anatomically connected to parts of the brain that are involved with emotional behavior – the septum, the hypothalamic mammillary body, and the anterior nuclear complex in the thalamus, and is generally accepted to be part of the limbic system.[16]

Anatomy

[edit]

The hippocampus can be seen as a ridge of gray matter tissue, elevating from the floor of each lateral ventricle in the region of the inferior or temporal horn.[17][18] This ridge can also be seen as an inward fold of the archicortex into the medial temporal lobe.[19] The hippocampus can only be seen in dissections as it is concealed by the parahippocampal gyrus.[19][20] The cortex thins from six layers to the three or four layers that make up the hippocampus.[21]

The term hippocampal formation is used to refer to the hippocampus proper and its related parts. However, there is no consensus as to what parts are included. Sometimes the hippocampus is said to include the dentate gyrus and the subiculum. Some references include the dentate gyrus and the subiculum in the hippocampal formation,[1] and others also include the presubiculum, parasubiculum, and entorhinal cortex.[2] The neural layout and pathways within the hippocampal formation are very similar in all mammals.[3]

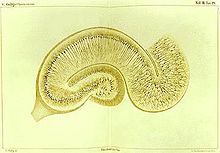

The hippocampus, including the dentate gyrus, has the shape of a curved tube, which has been compared to a seahorse, and to a horn of a ram, which after the ancient Egyptian god often portrayed as such takes the name cornu Ammonis. Its abbreviation CA is used in naming the hippocampal subfields CA1, CA2, CA3, and CA4.[20] It can be distinguished as an area where the cortex narrows into a single layer of densely packed pyramidal neurons, which curl into a tight U shape. One edge of the "U," – CA4, is embedded into the backward-facing, flexed dentate gyrus. The hippocampus is described as having an anterior and posterior part (in primates) or a ventral and dorsal part in other animals. Both parts are of similar composition but belong to different neural circuits.[22] In the rat, the two hippocampi resemble a pair of bananas, joined at the stems by the commissure of fornix (also called the hippocampal commissure). In primates, the part of the hippocampus at the bottom, near the base of the temporal lobe, is much broader than the part at the top. This means that in cross-section the hippocampus can show a number of different shapes, depending on the angle and location of the cut.[citation needed]

In a cross-section of the hippocampus, including the dentate gyrus, several layers will be shown. The dentate gyrus has three layers of cells (or four if the hilus is included). The layers are from the outer in – the molecular layer, the inner molecular layer, the granular layer, and the hilus. The CA3 in the hippocampus proper has the following cell layers known as strata: lacunosum-moleculare, radiatum, lucidum, pyramidal, and oriens. CA2 and CA1 also have these layers except the lucidum stratum.[23][24]

The input to the hippocampus (from varying cortical and subcortical structures) comes from the entorhinal cortex via the perforant path. The entorhinal cortex (EC) is strongly and reciprocally connected with many cortical and subcortical structures as well as with the brainstem. Different thalamic nuclei, (from the anterior and midline groups), the medial septal nucleus, the supramammillary nucleus of the hypothalamus, and the raphe nuclei and locus coeruleus of the brainstem all send axons to the EC, so that it serves as the interface between the neocortex and the other connections, and the hippocampus.[citation needed]

The EC is located in the parahippocampal gyrus,[2] a cortical region adjacent to the hippocampus.[25] This gyrus conceals the hippocampus. The parahippocampal gyrus is adjacent to the perirhinal cortex, which plays an important role in the visual recognition of complex objects. There is also substantial evidence that it makes a contribution to memory, which can be distinguished from the contribution of the hippocampus. It is apparent that complete amnesia occurs only when both the hippocampus and the parahippocampus are damaged.[25]

Circuitry

[edit]

The major input to the hippocampus is through the entorhinal cortex (EC), whereas its major output is via CA1 to the subiculum.[26] Information reaches CA1 via two main pathways, direct and indirect. Axons from the EC that originate in layer III are the origin of the direct perforant pathway and form synapses on the very distal apical dendrites of CA1 neurons. Conversely, axons originating from layer II are the origin of the indirect pathway, and information reaches CA1 via the trisynaptic circuit. In the initial part of this pathway, the axons project through the perforant pathway to the granule cells of the dentate gyrus (first synapse). From then, the information follows via the mossy fibres to CA3 (second synapse). From there, CA3 axons called Schaffer collaterals leave the deep part of the cell body and loop up to the apical dendrites and then extend to CA1 (third synapse).[26] Axons from CA1 then project back to the entorhinal cortex, completing the circuit.[27]

Basket cells in CA3 receive excitatory input from the pyramidal cells and then give an inhibitory feedback to the pyramidal cells. This recurrent inhibition is a simple feedback circuit that can dampen excitatory responses in the hippocampus. The pyramidal cells give a recurrent excitation which is an important mechanism found in some memory processing microcircuits.[28]

Several other connections play important roles in hippocampal function.[20] Beyond the output to the EC, additional output pathways go to other cortical areas including the prefrontal cortex. A major output goes via the fornix to the lateral septal area and to the mammillary body of the hypothalamus (which the fornix interconnects with the hippocampus).[19] The hippocampus receives modulatory input from the serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine systems, and from the nucleus reuniens of the thalamus to field CA1. A very important projection comes from the medial septal nucleus, which sends cholinergic, and gamma amino butyric acid (GABA) stimulating fibers (GABAergic fibers) to all parts of the hippocampus. The inputs from the medial septal nucleus play a key role in controlling the physiological state of the hippocampus; destruction of this nucleus abolishes the hippocampal theta rhythm and severely impairs certain types of memory.[29]

Regions

[edit]

Areas of the hippocampus are shown to be functionally and anatomically distinct. The dorsal hippocampus (DH), ventral hippocampus (VH) and intermediate hippocampus serve different functions, project with differing pathways, and have varying degrees of place cells.[30] The dorsal hippocampus serves for spatial memory, verbal memory, and learning of conceptual information. Using the radial arm maze, lesions in the DH were shown to cause spatial memory impairment while VH lesions did not. Its projecting pathways include the medial septal nucleus and supramammillary nucleus.[31] The dorsal hippocampus also has more place cells than both the ventral and intermediate hippocampal regions.[32]

The intermediate hippocampus has overlapping characteristics with both the ventral and dorsal hippocampus.[30] Using anterograde tracing methods, Cenquizca and Swanson (2007) located the moderate projections to two primary olfactory cortical areas and prelimbic areas of the medial prefrontal cortex. This region has the smallest number of place cells. The ventral hippocampus functions in fear conditioning and affective processes.[33] Anagnostaras et al. (2002) showed that alterations to the ventral hippocampus reduced the amount of information sent to the amygdala by the dorsal and ventral hippocampus, consequently altering fear conditioning in rats.[34] Historically, the earliest widely held hypothesis was that the hippocampus is involved in olfaction.[35] This idea was cast into doubt by a series of anatomical studies that did not find any direct projections to the hippocampus from the olfactory bulb.[36] However, later work did confirm that the olfactory bulb does project into the ventral part of the lateral entorhinal cortex, and field CA1 in the ventral hippocampus sends axons to the main olfactory bulb,[37] the anterior olfactory nucleus, and to the primary olfactory cortex. There continues to be some interest in hippocampal olfactory responses, in particular, the role of the hippocampus in memory for odors, but few specialists today believe that olfaction is its primary function.[38][39]

Function

[edit]Theories of hippocampal functions

[edit]Over the years, three main ideas of hippocampal function have dominated the literature: response inhibition, episodic memory, and spatial cognition. The behavioral inhibition theory (caricatured by John O'Keefe and Lynn Nadel as "slam on the brakes!")[40] was very popular up to the 1960s. It derived much of its justification from two observations: first, that animals with hippocampal damage tend to be hyperactive; second, that animals with hippocampal damage often have difficulty learning to inhibit responses that they have previously been taught, especially if the response requires remaining quiet as in a passive avoidance test. British psychologist Jeffrey Gray developed this line of thought into a full-fledged theory of the role of the hippocampus in anxiety.[41] The inhibition theory is currently the least popular of the three.[42]

The second major line of thought relates the hippocampus to memory. Although it had historical precursors, this idea derived its main impetus from a famous report by American neurosurgeon William Beecher Scoville and British-Canadian neuropsychologist Brenda Milner[43] describing the results of surgical destruction of the hippocampi when trying to relieve epileptic seizures in an American man Henry Molaison,[44] known until his death in 2008 as "Patient H.M." The unexpected outcome of the surgery was severe anterograde and partial retrograde amnesia; Molaison was unable to form new episodic memories after his surgery and could not remember any events that occurred just before his surgery, but he did retain memories of events that occurred many years earlier extending back into his childhood. This case attracted such widespread professional interest that Molaison became the most intensively studied subject in medical history.[45] In the ensuing years, other patients with similar levels of hippocampal damage and amnesia (caused by accident or disease) have also been studied, and thousands of experiments have studied the physiology of activity-driven changes in synaptic connections in the hippocampus. There is now universal agreement that the hippocampi play some sort of important role in memory; however, the precise nature of this role remains widely debated.[46][47] A recent theory proposed – without questioning its role in spatial cognition – that the hippocampus encodes new episodic memories by associating representations in the newborn granule cells of the dentate gyrus and arranging those representations sequentially in the CA3 by relying on the phase precession generated in the entorhinal cortex.[48]

The third important theory of hippocampal function relates the hippocampus to space. The spatial theory was originally championed by O'Keefe and Nadel, who were influenced by American psychologist E.C. Tolman's theories about "cognitive maps" in humans and animals. O'Keefe and his student Dostrovsky in 1971 discovered neurons in the rat hippocampus that appeared to them to show activity related to the rat's location within its environment.[49] Despite skepticism from other investigators, O'Keefe and his co-workers, especially Lynn Nadel, continued to investigate this question, in a line of work that eventually led to their very influential 1978 book The Hippocampus as a Cognitive Map.[50] There is now almost universal agreement that hippocampal function plays an important role in spatial coding, but the details are widely debated.[51]

Later research has focused on trying to bridge the disconnect between the two main views of hippocampal function as being split between memory and spatial cognition. In some studies, these areas have been expanded to the point of near convergence. In an attempt to reconcile the two disparate views, it is suggested that a broader view of the hippocampal function is taken and seen to have a role that encompasses both the organisation of experience (mental mapping, as per Tolman's original concept in 1948) and the directional behaviour seen as being involved in all areas of cognition, so that the function of the hippocampus can be viewed as a broader system that incorporates both the memory and the spatial perspectives in its role that involves the use of a wide scope of cognitive maps.[52] This relates to the purposive behaviorism born of Tolman's original goal of identifying the complex cognitive mechanisms and purposes that guided behaviour.[53]

It has also been proposed that the spiking activity of hippocampal neurons is associated spatially, and it was suggested that the mechanisms of memory and planning both evolved from mechanisms of navigation and that their neuronal algorithms were basically the same.[54]

Many studies have made use of neuroimaging techniques such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), and a functional role in approach-avoidance conflict has been noted. The anterior hippocampus is seen to be involved in decision-making under approach-avoidance conflict processing. It is suggested that the memory, spatial cognition, and conflict processing functions may be seen as working together and not mutually exclusive.[55]

Role in memory

[edit]Psychologists and neuroscientists generally agree that the hippocampus plays an important role in the formation of new memories about experienced events (episodic or autobiographical memory).[47][56] Part of this function is hippocampal involvement in the detection of new events, places and stimuli.[57] Some researchers regard the hippocampus as part of a larger medial temporal lobe memory system responsible for general declarative memory (memories that can be explicitly verbalized – these would include, for example, memory for facts in addition to episodic memory).[46] The hippocampus also encodes emotional context from the amygdala. This is partly why returning to a location where an emotional event occurred may evoke that emotion. There is a deep emotional connection between episodic memories and places.[58]

Due to bilateral symmetry the brain has a hippocampus in each cerebral hemisphere. If damage to the hippocampus occurs in only one hemisphere, leaving the structure intact in the other hemisphere, the brain can retain near-normal memory functioning.[59] Severe damage to the hippocampi in both hemispheres results in profound difficulties in forming new memories (anterograde amnesia) and often also affects memories formed before the damage occurred (retrograde amnesia). Although the retrograde effect normally extends many years back before the brain damage, in some cases older memories remain. This retention of older memories leads to the idea that consolidation over time involves the transfer of memories out of the hippocampus to other parts of the brain.[56]: Ch. 1 Experiments using intrahippocampal transplantation of hippocampal cells in primates with neurotoxic lesions of the hippocampus have shown that the hippocampus is required for the formation and recall, but not the storage, of memories.[60] It has been shown that a decrease in the volume of various parts of the hippocampus in people leads to specific memory impairments. In particular, efficiency of verbal memory retention is related to the anterior parts of the right and left hippocampus. The right head of the hippocampus is more involved in executive functions and regulation during verbal memory recall. The tail of the left hippocampus tends to be closely related to verbal memory capacity.[61]

Damage to the hippocampus does not affect some types of memory, such as the ability to learn new skills (playing a musical instrument or solving certain types of puzzles, for example). This fact suggests that such abilities depend on different types of memory (procedural memory) and different brain regions. Furthermore, amnesic patients frequently show "implicit" memory for experiences even in the absence of conscious knowledge. For example, patients asked to guess which of two faces they have seen most recently may give the correct answer most of the time in spite of stating that they have never seen either of the faces before. Some researchers distinguish between conscious recollection, which depends on the hippocampus, and familiarity, which depends on portions of the medial temporal lobe.[62]

When rats are exposed to an intense learning event, they may retain a life-long memory of the event even after a single training session. The memory of such an event appears to be first stored in the hippocampus, but this storage is transient. Much of the long-term storage of the memory seems to take place in the anterior cingulate cortex.[63] When such an intense learning event was experimentally applied, more than 5,000 differently methylated DNA regions appeared in the hippocampus neuronal genome of the rats at one hour and at 24 hours after training.[64] These alterations in methylation pattern occurred at many genes that were down-regulated, often due to the formation of new 5-methylcytosine sites in CpG rich regions of the genome. Furthermore, many other genes were upregulated, likely often due to the removal of methyl groups from previously existing 5-methylcytosines (5mCs) in DNA. Demethylation of 5mC can be carried out by several proteins acting in concert, including TET enzymes as well as enzymes of the DNA base excision repair pathway (see Epigenetics in learning and memory).

Between-systems memory interference model

[edit]The between-systems memory interference model describes the inhibition of non-hippocampal systems of memory during concurrent hippocampal activity. Specifically, Fraser Sparks, Hugo Lehmann, and Robert Sutherland[65] found that when the hippocampus was inactive, non-hippocampal systems located elsewhere in the brain were found to consolidate memory in its place. However, when the hippocampus was reactivated, memory traces consolidated by non-hippocampal systems were not recalled, suggesting that the hippocampus interferes with long-term memory consolidation in other memory-related systems.

One of the major implications that this model illustrates is the dominant effects of the hippocampus on non-hippocampal networks when information is incongruent. With this information in mind, future directions could lead towards the study of these non-hippocampal memory systems through hippocampal inactivation, further expanding the labile constructs of memory. Additionally, many theories of memory are holistically based around the hippocampus. This model could add beneficial information to hippocampal research and memory theories such as the multiple trace theory. Lastly, the between-system memory interference model allows researchers to evaluate their results on a multiple-systems model, suggesting that some effects may not be simply mediated by one portion of the brain.

Role in spatial memory and navigation

[edit]

Studies on freely moving rats and mice have shown many hippocampal neurons to act as place cells that cluster in place fields, and these fire bursts of action potentials when the animal passes through a particular location. This place-related neural activity in the hippocampus has also been reported in monkeys that were moved around a room whilst in a restraint chair.[66] However, the place cells may have fired in relation to where the monkey was looking rather than to its actual location in the room.[67] Over many years, many studies have been carried out on place-responses in rodents, which have given a large amount of information.[51] Place cell responses are shown by pyramidal cells in the hippocampus and by granule cells in the dentate gyrus. Other cells in smaller proportion are inhibitory interneurons, and these often show place-related variations in their firing rate that are much weaker. There is little, if any, spatial topography in the representation; in general, cells lying next to each other in the hippocampus have uncorrelated spatial firing patterns. Place cells are typically almost silent when a rat is moving around outside the place field but reach sustained rates as high as 40 Hz when the rat is near the center. Neural activity sampled from 30 to 40 randomly chosen place cells carries enough information to allow a rat's location to be reconstructed with high confidence. The size of place fields varies in a gradient along the length of the hippocampus, with cells at the dorsal end showing the smallest fields, cells near the center showing larger fields, and cells at the ventral tip showing fields that cover the entire environment.[51] In some cases, the firing rate of hippocampal cells depends not only on place but also the direction a rat is moving, the destination toward which it is traveling, or other task-related variables.[68] The firing of place cells is timed in relation to local theta waves, a process termed phase precession.[69]

In humans, cells with location-specific firing patterns have been reported during a study of patients with drug-resistant epilepsy. They were undergoing an invasive procedure to localize the source of their seizures, with a view to surgical resection. The patients had diagnostic electrodes implanted in their hippocampus and then used a computer to move around in a virtual reality town.[70] Similar brain imaging studies in navigation have shown the hippocampus to be active.[71] A study was carried out on taxi drivers. London's black cab drivers need to learn the locations of a large number of places and the fastest routes between them in order to pass a strict test known as The Knowledge in order to gain a license to operate. A study showed that the posterior part of the hippocampus is larger in these drivers than in the general public, and that a positive correlation exists between the length of time served as a driver and the increase in the volume of this part. It was also found the total volume of the hippocampus was unchanged, as the increase seen in the posterior part was made at the expense of the anterior part, which showed a relative decrease in size. There have been no reported adverse effects from this disparity in hippocampal proportions.[72] Another study showed opposite findings in blind individuals. The anterior part of the right hippocampus was larger and the posterior part was smaller, compared with sighted individuals.[73]

There are several navigational cells in the brain that are either in the hippocampus itself or are strongly connected to it, such as the speed cells present in the medial entorhinal cortex. Together these cells form a network that serves as spatial memory. The first of such cells discovered in the 1970s were the place cells, which led to the idea of the hippocampus acting to give a neural representation of the environment in a cognitive map.[50] When the hippocampus is dysfunctional, orientation is affected; people may have difficulty in remembering how they arrived at a location and how to proceed further. Getting lost is a common symptom of amnesia.[74] Studies with animals have shown that an intact hippocampus is required for initial learning and long-term retention of some spatial memory tasks, in particular ones that require finding the way to a hidden goal.[75][76][77][78] Other cells have been discovered since the finding of the place cells in the rodent brain that are either in the hippocampus or the entorhinal cortex. These have been assigned as head direction cells, grid cells and boundary cells.[51][79] Speed cells are thought to provide input to the hippocampal grid cells.

Role in approach-avoidance conflict processing

[edit]Approach-avoidance conflict happens when a situation is presented that can either be rewarding or punishing, and the ensuing decision-making has been associated with anxiety.[80] fMRI findings from studies in approach-avoidance decision-making found evidence for a functional role that is not explained by either long-term memory or spatial cognition. Overall findings showed that the anterior hippocampus is sensitive to conflict, and that it may be part of a larger cortical and subcortical network seen to be important in decision-making in uncertain conditions.[80]

A review makes reference to a number of studies that show the involvement of the hippocampus in conflict tasks. The authors suggest that one challenge is to understand how conflict processing relates to the functions of spatial navigation and memory and how all of these functions need not be mutually exclusive.[55]

Role in social memory

[edit]The hippocampus has received renewed attention for its role in social memory. Epileptic human subjects with depth electrodes in the left posterior, left anterior or right anterior hippocampus demonstrate distinct, individual cell responses when presented with faces of presumably recognizable famous people.[81] Associations among facial and vocal identity were similarly mapped to the hippocampus of rheseus monkeys. Single neurons in the CA1 and CA3 responded strongly to social stimuluys recognition by MRI. The CA2 was not distinguished, and may likely comprise a proportion of the claimed CA1 cells in the study.[82] The dorsal CA2 and ventral CA1 subregions of the hippocampus have been implicated in social memory processing. Genetic inactivation of CA2 pyramidal neurons leads to pronounced loss of social memory, while maintaining intact sociability in mice.[83] Similarly, ventral CA1 pyramidal neurons have also been demonstrated as critical for social memory under optogenetic control in mice.[84][85]

Electroencephalography

[edit]

The hippocampus shows two major "modes" of activity, each associated with a distinct pattern of neural population activity and waves of electrical activity as measured by an electroencephalogram (EEG). These modes are named after the EEG patterns associated with them: theta and large irregular activity (LIA). The main characteristics described below are for the rat, which is the animal most extensively studied.[86]

The theta mode appears during states of active, alert behavior (especially locomotion), and also during REM (dreaming) sleep.[87] In the theta mode, the EEG is dominated by large regular waves with a frequency range of 6 to 9 Hz, and the main groups of hippocampal neurons (pyramidal cells and granule cells) show sparse population activity, which means that in any short time interval, the great majority of cells are silent, while the small remaining fraction fire at relatively high rates, up to 50 spikes in one second for the most active of them. An active cell typically stays active for half a second to a few seconds. As the rat behaves, the active cells fall silent and new cells become active, but the overall percentage of active cells remains more or less constant. In many situations, cell activity is determined largely by the spatial location of the animal, but other behavioral variables also clearly influence it.

The LIA mode appears during slow-wave (non-dreaming) sleep, and also during states of waking immobility such as resting or eating.[87] In the LIA mode, the EEG is dominated by sharp waves that are randomly timed large deflections of the EEG signal lasting for 25–50 milliseconds. Sharp waves are frequently generated in sets, with sets containing up to 5 or more individual sharp waves and lasting up to 500 ms. The spiking activity of neurons within the hippocampus is highly correlated with sharp wave activity. Most neurons decrease their firing rate between sharp waves; however, during a sharp wave, there is a dramatic increase in firing rate in up to 10% of the hippocampal population

These two hippocampal activity modes can be seen in primates as well as rats, with the exception that it has been difficult to see robust theta rhythmicity in the primate hippocampus. There are, however, qualitatively similar sharp waves and similar state-dependent changes in neural population activity.[88]

Theta rhythm

[edit]

The underlying currents producing the theta wave are generated mainly by densely packed neural layers of the entorhinal cortex, CA3, and the dendrites of pyramidal cells. The theta wave is one of the largest signals seen on EEG, and is known as the hippocampal theta rhythm.[89] In some situations the EEG is dominated by regular waves at 3 to 10 Hz, often continuing for many seconds. These reflect subthreshold membrane potentials and strongly modulate the spiking of hippocampal neurons and synchronise across the hippocampus in a travelling wave pattern.[90] The trisynaptic circuit is a relay of neurotransmission in the hippocampus that interacts with many brain regions. From rodent studies it has been proposed that the trisynaptic circuit generates the hippocampal theta rhythm.[91]

Theta rhythmicity is very obvious in rabbits and rodents and also clearly present in cats and dogs. Whether theta can be seen in primates is not yet clear.[92] In rats (the animals that have been the most extensively studied), theta is seen mainly in two conditions: first, when an animal is walking or in some other way actively interacting with its surroundings; second, during REM sleep.[93] The function of theta has not yet been convincingly explained although numerous theories have been proposed.[86] The most popular hypothesis has been to relate it to learning and memory. An example would be the phase with which theta rhythms, at the time of stimulation of a neuron, shape the effect of that stimulation upon its synapses. What is meant here is that theta rhythms may affect those aspects of learning and memory that are dependent upon synaptic plasticity.[94] It is well established that lesions of the medial septum – the central node of the theta system – cause severe disruptions of memory.[95] However, the medial septum is more than just the controller of theta; it is also the main source of cholinergic projections to the hippocampus.[20] It has not been established that septal lesions exert their effects specifically by eliminating the theta rhythm.[96]

Sharp waves

[edit]During sleep or during resting, when an animal is not engaged with its surroundings, the hippocampal EEG shows a pattern of irregular slow waves, somewhat larger in amplitude than theta waves. This pattern is occasionally interrupted by large surges called sharp waves.[97] These events are associated with bursts of spike activity lasting 50 to 100 milliseconds in pyramidal cells of CA3 and CA1. They are also associated with short-lived high-frequency EEG oscillations called "ripples", with frequencies in the range 150 to 200 Hz in rats, and together they are known as sharp waves and ripples. Sharp waves are most frequent during sleep when they occur at an average rate of around 1 per second (in rats) but in a very irregular temporal pattern. Sharp waves are less frequent during inactive waking states and are usually smaller. Sharp waves have also been observed in humans and monkeys. In macaques, sharp waves are robust but do not occur as frequently as in rats.[88]

One of the most interesting aspects of sharp waves is that they appear to be associated with memory. Wilson and McNaughton 1994,[98] and numerous later studies, reported that when hippocampal place cells have overlapping spatial firing fields (and therefore often fire in near-simultaneity), they tend to show correlated activity during sleep following the behavioral session. This enhancement of correlation, commonly known as reactivation, has been found to occur mainly during sharp waves.[99] It has been proposed that sharp waves are, in fact, reactivations of neural activity patterns that were memorized during behavior, driven by strengthening of synaptic connections within the hippocampus.[100] This idea forms a key component of the "two-stage memory" theory,[101] advocated by Buzsáki and others, which proposes that memories are stored within the hippocampus during behavior and then later transferred to the neocortex during sleep. Sharp waves in Hebbian theory are seen as persistently repeated stimulations by presynaptic cells, of postsynaptic cells that are suggested to drive synaptic changes in the cortical targets of hippocampal output pathways.[102] Suppression of sharp waves and ripples in sleep or during immobility can interfere with memories expressed at the level of the behavior,[103][104] nonetheless, the newly formed CA1 place cell code can re-emerge even after a sleep with abolished sharp waves and ripples, in spatially non-demanding tasks.[105]

Long-term potentiation

[edit]Since at least the time of Ramon y Cajal (1852–1934), psychologists have speculated that the brain stores memory by altering the strength of connections between neurons that are simultaneously active.[106] This idea was formalized by Donald Hebb in 1949,[107] but for many years remained unexplained. In 1973, Tim Bliss and Terje Lømo described a phenomenon in the rabbit hippocampus that appeared to meet Hebb's specifications: a change in synaptic responsiveness induced by brief strong activation and lasting for hours or days or longer.[108] This phenomenon was soon referred to as long-term potentiation (LTP). As a candidate mechanism for long-term memory, LTP has since been studied intensively, and a great deal has been learned about it. However, the complexity and variety of the intracellular signalling cascades that can trigger LTP is acknowledged as preventing a more complete understanding.[109]

The hippocampus is a particularly favorable site for studying LTP because of its densely packed and sharply defined layers of neurons, but similar types of activity-dependent synaptic change have also been observed in many other brain areas.[110] The best-studied form of LTP has been seen in CA1 of the hippocampus and occurs at synapses that terminate on dendritic spines and use the neurotransmitter glutamate.[109] The synaptic changes depend on a special type of glutamate receptor, the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor, a cell surface receptor which has the special property of allowing calcium to enter the postsynaptic spine only when presynaptic activation and postsynaptic depolarization occur at the same time.[111] Drugs that interfere with NMDA receptors block LTP and have major effects on some types of memory, especially spatial memory. Genetically modified mice that are modified to disable the LTP mechanism, also generally show severe memory deficits.[111]

Disorders

[edit]Aging

[edit]Age-related conditions such as Alzheimer's disease and other forms of dementia (for which hippocampal disruption is one of the earliest signs[112]) have a severe impact on many types of cognition including memory. Even normal aging is associated with a gradual decline in some types of memory, including episodic memory and working memory (or short-term memory). Because the hippocampus is thought to play a central role in memory, there has been considerable interest in the possibility that age-related declines could be caused by hippocampal deterioration.[113]: 105 Some early studies reported substantial loss of neurons in the hippocampus of elderly people, but later studies using more precise techniques found only minimal differences.[113] Similarly, some MRI studies have reported shrinkage of the hippocampus in elderly people, but other studies have failed to reproduce this finding. There is, however, a reliable relationship between the size of the hippocampus and memory performance; so that where there is age-related shrinkage, memory performance will be impaired.[113]: 107 There are also reports that memory tasks tend to produce less hippocampal activation in the elderly than in the young.[113]: 107 Furthermore, a randomized control trial published in 2011 found that aerobic exercise could increase the size of the hippocampus in adults aged 55 to 80 and also improve spatial memory.[114]

Stress

[edit]The hippocampus contains high levels of glucocorticoid receptors, which make it more vulnerable to long-term stress than most other brain areas.[115] There is evidence that humans having experienced severe, long-lasting traumatic stress show atrophy of the hippocampus more than of other parts of the brain.[116] These effects show up in post-traumatic stress disorder,[117] and they may contribute to the hippocampal atrophy reported in schizophrenia[118] and severe depression.[119] Anterior hippocampal volume in children is positively correlated with parental family income and this correlation is thought to be mediated by income related stress.[120] A recent study has also revealed atrophy as a result of depression, but this can be stopped with anti-depressants even if they are not effective in relieving other symptoms.[121]

Хронический стресс, приводящий к повышенным уровням глюкокортикоидов , особенно в кортизоле , является причиной атрофии нейронов в гиппокампе. Эта атрофия приводит к меньшему объему гиппокампа, который также наблюдается при синдроме Кушинга . Более высокие уровни кортизола при синдроме Кушинга обычно являются результатом лекарств, принимаемых для других состояний. [ 122 ] [ 123 ] Потеря нейронов также происходит в результате нарушения нейрогенеза. Другим фактором, который способствует меньшему объему гиппокампа, является Дендритный ретракцию, где дендриты сокращаются по длине и снижаются по количеству в ответ на повышенные глюкокортикоиды. Эта дендритная ретракция обратима. [ 123 ] После лечения лекарствами, чтобы уменьшить кортизол при синдроме Кушинга, объем гиппокампа, как видно, восстанавливается на целых 10%. [ 122 ] Это изменение рассматривается из -за реформирования дендритов. [ 123 ] Это дендритное восстановление также может произойти, когда стресс удаляется. Однако существуют доказательства, полученные в основном из исследований с использованием крыс, что стресс, возникающий вскоре после рождения, может повлиять на функцию гиппокампа таким образом, которые сохраняются на протяжении всей жизни. [ 124 ] : 170–171

Половые реакции на стресс также были продемонстрированы у крысы, чтобы оказать влияние на гиппокамп. Хронический стресс у мужской крысы показал дендритную ретракцию и потерю клеток в области CA3, но это не было показано у самки. Считалось, что это связано с нейропротекторными гормонами яичников. [ 125 ] [ 126 ] У крыс повреждение ДНК увеличивается в гиппокампе в условиях стресса. [ 127 ]

Эпилепсия

[ редактировать ]

Гиппокамп является одной из немногих областей мозга, где генерируются новые нейроны. Этот процесс нейрогенеза ограничен зубчатой извилиной. [ 128 ] На производство новых нейронов может быть положительно повлиять на физические упражнения или отрицательно затронуты эпилептическими припадками . [ 128 ]

Приступы в эпилепсии височной доли могут влиять на нормальное развитие новых нейронов и могут вызвать повреждение тканей. Склероз гиппокампа, включая склероз рога Аммона , специфичный для мезиальной височной доли, является наиболее распространенным типом такого повреждения ткани. [ 129 ] [ 130 ] Однако еще не ясно, что обычно эпилепсия обычно вызвана аномалиями гиппокампа или гиппокамп поврежден кумулятивными эффектами судорог. [ 131 ] Однако в экспериментальных условиях, где повторяющиеся судороги искусственно индуцируются у животных, повреждение гиппокампа является частым результатом. Это может быть следствием концентрации возбудимых глутаматных рецепторов в гиппокампе. Гиперксуальность может привести к цитотоксичности и гибели клеток. [ 123 ] Это также может быть связано с тем, что гиппокамп является сайтом, где новые нейроны продолжают создаваться на протяжении всей жизни, [ 128 ] и на отклонения в этом процессе. [ 123 ]

Шизофрения

[ редактировать ]Причины шизофрении не совсем понятны, но сообщалось о многочисленных аномалиях структуры мозга. Наиболее тщательно исследуемые изменения включают кору головного мозга, но также были описаны влияние на гиппокамп. Многие сообщения обнаружили сокращение размера гиппокампа у людей с шизофренией. [ 132 ] [ 133 ] Левый гиппокамп, по -видимому, затронут больше, чем на правый. [ 132 ] Отмеченные изменения в значительной степени были приняты как результат ненормального развития. Неясно, играют ли изменения гиппокампа какую -либо роль в выборе психотических симптомов, которые являются наиболее важной особенностью шизофрении. Было высказано предположение, что на основе экспериментальной работы с использованием животных дисфункция гиппокампа может привести к изменению высвобождения дофамина в базальных ганглиях , тем самым косвенно влияя на интеграцию информации в префронтальную кору . [ 134 ] Также было высказано предположение, что дисфункция гиппокампа может учитывать возмущения в долговременной памяти, часто наблюдаемых. [ 135 ]

Исследования МРТ обнаружили меньший объем мозга и большие желудочки у людей с шизофренией - однако исследователи не знают, является ли усадка от шизофрении или от лекарства. [ 136 ] [ 137 ] Было показано, что гиппокамп и таламус уменьшаются в объеме; и объем глобуса Pallidus увеличен. Корковые узоры изменяются, и было отмечено уменьшение объема и толщины коры, особенно во фронтальных и височных долях. Кроме того, было предложено, что многие из заметных изменений присутствуют в начале расстройства, что придает вес теории, что существует аномальная нейродевизация. [ 138 ]

Гиппокамп считался центральным в патологии шизофрении, как в нейронных, так и в физиологических эффектах. [ 132 ] Общепринято, что лежит ненормальная синаптическая связь, лежащая в основе шизофрении. Несколько линий доказательств участвуют в изменениях в синаптической организации и связности, в гиппокампе и обратном [ 132 ] Многие исследования обнаружили дисфункцию в синаптической схеме в гиппокампе и ее активности на префронтальной коре. Глутаматергические пути, как видно, в значительной степени затронуты. Подполе CA1 считается наименее вовлеченным из других подпол, [ 132 ] [ 139 ] и CA4 и Subiculum были зарегистрированы в других местах как наиболее заметные области. [ 139 ] В обзоре пришел вывод, что патология может быть связана с генетикой, неисправной нейроразвитием или аномальной нейронной пластичностью. Кроме того, был сделан вывод, что шизофрения не связана с каким -либо известным нейродегенеративным расстройством. [ 132 ] Окислительное повреждение ДНК существенно увеличивается в гиппокампе у пожилых пациентов с хронической шизофренией . [ 140 ]

Переходная глобальная амнезия

[ редактировать ]Переходная глобальная амнезия является драматической, внезапной, временной, почти тотальной потерей кратковременной памяти. Различные причины были выдвинуты на гипотезу, включая ишемию, эпилепсию, мигрень [ 141 ] и нарушение церебрального венозного кровотока, [ 142 ] приводя к ишемии структур, как гиппокамп, которые участвуют в памяти. [ 143 ]

Не было никаких научных доказательств какой -либо причины. Тем не менее, диффузионные исследования МРТ, проведенные с 12 до 24 часов после эпизода, показали, что в гиппокампе появляются небольшие точечные поражения. Эти результаты показали возможное значение нейронов CA1, уязвимых с помощью метаболического стресса. [ 141 ]

ПТСР

[ редактировать ]Некоторые исследования показывают корреляцию уменьшенного объема гиппокампа и посттравматического стрессового расстройства (ПТСР). [ 144 ] [ 145 ] [ 146 ] Исследование ветеранов боевых действий во Вьетнаме с ПТСР показало сокращение объема их гиппокампа на 20% по сравнению с ветеранами, которые не страдали от таких симптомов. [ 147 ] Это открытие не было воспроизведено у пациентов с хроническим ПТСР, травмированным на авиационной авиационной авиакатастрофе в 1988 году (Рамштейн, Германия). [ 148 ] Это также тот случай, когда не боевые братья-близнецы ветеранов Вьетнама с ПТСР также имели меньшие гиппокампы, чем у других контролей, поднимая вопросы о природе корреляции. [ 149 ] Исследование 2016 года усилило теорию о том, что меньший гиппокамп увеличивает риск посттравматического стрессового расстройства, а более крупный гиппокамп увеличивает вероятность эффективного лечения. [ 150 ]

Микроцефалия

[ редактировать ]Атрофия гиппокампа была охарактеризована у тех, кто имеет микроцефалию , [ 151 ] и мышиные модели с мутациями WDR62, которые повторяют мутации точек человека , показали дефицит развития гиппокампа и нейрогенеза. [ 152 ]

Другие животные

[ редактировать ]

Другие млекопитающие

[ редактировать ]Гиппокамп имеет в целом сходное появление в диапазоне млекопитающих, от монотримов, таких как эхидна, до приматов, таких как люди. [ 153 ] Соотношение гиппокампа размером с тела широко увеличивается, примерно в два раза больше для приматов, чем для эхидны. Это, однако, не увеличивается в ближайшее время к скорости неокортексного соотношения к размере к телу. Следовательно, гиппокамп занимает гораздо большую долю кортикальной мантии у грызунов, чем у приматов. У взрослых людей объем гиппокампа на каждой стороне мозга составляет от 3,0 до 3,5 см 3 по сравнению с 320-420 см 3 Для объема неокортекс. [ 154 ]

Существует также общая связь между размером гиппокампа и пространственной памятью. Когда проводятся сравнения между похожими видами, те, которые имеют большую способность к пространственной памяти, имеют тенденцию иметь большие объемы гиппокампа. [ 155 ] Эти отношения также распространяются на половые различия; У видов, где мужчины и женщины демонстрируют сильные различия в способности пространственной памяти, они также имеют тенденцию демонстрировать соответствующие различия в объеме гиппокампа. [ 156 ]

Другие позвоночные

[ редактировать ]Виды, не являющиеся млекопитающими, не имеют структуры мозга, которая похожа на гиппокамп млекопитающих, но у них есть тот, который считается гомологичным для него. Гиппокамп, как указано выше, по сути является частью Allocortex. Только млекопитающие имеют полностью разработанную кору, но структура, из которой она развивалась, называемая паллием , присутствует у всех позвоночных, даже самые примитивные, такие как миноги или Hagfish . [ 157 ] Паллий обычно разделен на три зоны: медиальные, боковые и дорсальные. Медиальный паллий образует предшественник гиппокампа. Он не похож на гиппокамп визуально, потому что слои не деформируются в форму S или охватываются зубчатой извилиной, но гомология обозначена сильной химической и функциональной аффинностью. В настоящее время есть доказательства того, что эти гиппокампа, подобные структурам, участвуют в пространственном познании у птиц, рептилий и рыбы. [ 158 ]

Птицы

[ редактировать ]У птиц переписка достаточно хорошо установлена, что большинство анатомистов называют медиальную паллиальную зону «птичьим гиппокампом». [ 159 ] Многочисленные виды птиц обладают сильными пространственными навыками, в частности те, которые кешируют пищу. Существуют доказательства того, что птицы с продовольствием имеют больший гиппокамп, чем другие виды птиц, и что повреждение гиппокампа вызывает нарушения в пространственной памяти. [ 160 ]

Рыба

[ редактировать ]История для рыбы более сложна. В Teleost Fish (которые составляют подавляющее большинство существующих видов), передний мозг искажается по сравнению с другими типами позвоночных: большинство нейроанатомистов считают, что передний мозг телеоста по сути, как носок, перевернутый внутри, так что структуры Это лежит на внутренней части, рядом с желудочками, для большинства позвоночных встречаются снаружи в телеост -рыбе, и наоборот. [ 161 ] Одним из последствий этого является то, что медиальный паллий («гиппокампа») типичного позвоночного, как полагают, соответствует боковой паллиуму типичной рыбы. Несколько видов рыб (особенно золотая рыбка) были показаны экспериментально, чтобы обладать сильными способностями пространственной памяти, даже формируя «когнитивные карты» областей, в которых они обитают. [ 155 ] Существуют доказательства того, что повреждение бокового паллия ухудшает пространственную память. [ 162 ] [ 163 ] Пока не известно, играет ли медиальный паллиум аналогичной ролью в еще более примитивных позвоночных, таких как акулы и лучи, или даже миноги и гаг -рыбы. [ 164 ]

Насекомые и моллюски

[ редактировать ]Некоторые типы насекомых и моллюсков , такие как осьминог, также имеют сильные пространственные и навигационные способности, но они, по -видимому, работают иначе, чем пространственная система млекопитающих, поэтому пока нет веских причин думать, что они имеют общее эволюционное происхождение ; Также нет достаточного сходства в структуре мозга, чтобы что -либо напоминало «гиппокамп», чтобы быть идентифицированным у этих видов. насекомого Некоторые предложили, однако, что грибные тела могут иметь функцию, аналогичную функции гиппокампа. [ 165 ]

Вычислительные модели

[ редактировать ]Были собраны тщательные исследования гиппокампа в различных организмах, всеобъемлющей базы данных о морфологии, подключении, физиологии и вычислительных моделях. [ 166 ]

Дополнительные изображения

[ редактировать ]-

Гиппокамп выделяется зеленым на корональных изображениях МРТ T1

-

Гиппокамп выделяется зеленым на сагиттальных изображениях МРТ T1

-

Гиппокамп выделен зеленым

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Мартин Дж. Х. (2003). «Лимбическая система и церебральные схемы для эмоций, обучения и памяти» . Нейроанатомия: текст и атлас (третье изд.). McGraw-Hill Companies. п. 382. ISBN 978-0071212373 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 2020-03-27 . Получено 2016-12-16 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Amaral D, Lavenex P (2007). «Гиппокампальная нейроанатомия» . В Андерсоне П., Моррис Р., Амарал, Блисс Т, О'Киф Дж. (Ред.). Книга гиппокампа (первое изд.). Нью -Йорк: издательство Оксфордского университета. п. 37. ISBN 978-0195100273 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 2020-03-16 . Получено 2016-12-15 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Андерсон П., Моррис Р., Амарал, Блисс Т, О'Киф Дж. (2007). «Формирование гиппокампа» . В Андерсоне П., Моррис Р., Амарал, Блисс Т, О'Киф Дж. (Ред.). Книга гиппокампа (первое изд.). Нью -Йорк: издательство Оксфордского университета. п. 3. ISBN 978-0195100273 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 2020-03-15 . Получено 2016-12-15 .

- ^ Bachevalier J (декабрь 2019 г.). «Нечеловеческие приматы модели развития и дисфункции гиппокампа» . Труды Национальной академии наук Соединенных Штатов Америки . 116 (52): 26210–26216. Bibcode : 2019pnas..11626210B . doi : 10.1073/pnas.1902278116 . PMC 6936345 . PMID 31871159 .

- ^ Bingman VP, Salas C, Rodriguez F (2009). «Эволюция гиппокампа». В Binder MD, Hirokawa N, Windhorst U (Eds.). Энциклопедия нейробиологии . Берлин, Гейдельберг: Спрингер. С. 1356–1360. doi : 10.1007/978-3-540-29678-2_3158 . ISBN 978-3-540-29678-2 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный «Результаты поиска для рога Аммона» . Оксфордская ссылка . Получено 9 декабря 2021 года .

- ^ Colman Am (21 мая 2015 г.). «зубчатая извилина» . Словарь психологии . Издательство Оксфордского университета. doi : 10.1093/acref/9780199657681.001.0001 . ISBN 978-0-19-965768-1 Полем Получено 10 декабря 2021 года .

- ^ Dubois B, Hampel H, Feldman HH, Scheltens P, Aisen P, Andrieu S, et al. (Март 2016 г.). «Доклиническая болезнь Альцгеймера: определение, естественная история и диагностические критерии» . Альцгеймер и деменция . 12 (3): 292–323. doi : 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.02.002 . PMC 6417794 . PMID 27012484 .

- ^ Подготовка Ласло Сересса в 1980 году.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Duvernoy HM (2005). "Введение" . Человеческий гиппокамп (3 -е изд.). Берлин: Springer-Verlag. п. 1. ISBN 978-3-540-23191-2 Полем Архивировано с оригинала 2016-08-28 . Получено 2016-03-05 .

- ^ "Cornu Ammonis" . FreeDictionary.com . Архивировано с оригинала 2016-12-20 . Получено 2016-12-17 .

- ^ Оуэн С.М., Говард А., Биндер Д.К. (декабрь 2009 г.). «Минординг гиппокампа, кальцский авис и дебаты Хаксли-Оуэна». Нейрохирургия . 65 (6): 1098–1104, обсуждение 1104–1105. doi : 10.1227/01.neu.0000359535.844455.0b . PMID 19934969 . S2CID 19663125 .

- ^ Гросс CG (октябрь 1993 г.). «Младший гиппокамп и место человека в природе: тематическое исследование в социальной конструкции нейроанатомии». Гиппокамп . 3 (4): 403–415. doi : 10.1002/hipo.450030403 . PMID 8269033 . S2CID 15172043 .

- ^ Pang CC, Kiecker C, O'Brien JT, Noble W, Chang RC (апрель 2019). «Рог Аммона 2 (CA2) гиппокампа: давно известная область с новой потенциальной ролью в нейродегенерации» . Нейробиолог . 25 (2): 167–180. doi : 10.1177/1073858418778747 . PMID 29865938 . S2CID 46929253 .

- ^ Roxo MR, Franceschini PR, Zubaran C, Kleber FD, Sander JW (2011). «Концепция лимбической системы и ее историческая эволюция» . Thecestificworldjournal . 11 : 2428–2441. doi : 10.1100/2011/157150 . PMC 3236374 . PMID 22194673 .

- ^ «Глава 9: Лимбическая система» . www.dartmouth.edu . Архивировано из оригинала 2007-11-05 . Получено 2016-12-16 .

- ^ Андерсен П., Моррис Р., Амарал Д., Блисс Т, О'Киф Дж. (2006). Книга гиппокампа . Издательство Оксфордского университета. ISBN 978-0199880133 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 13 апреля 2021 года . Получено 25 октября 2020 года .

- ^ Альбертс Д.А. (2012). Иллюстрированный медицинский словарь Дорланда (32 -е изд.). Филадельфия, Пенсильвания: Сондерс/Elsevier. п. 860. ISBN 978-1416062578 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Purves D (2011). Нейробиология (5 -е изд.). Сандерленд, Массачусетс: Синауэр. С. 730–735. ISBN 978-0878936953 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Amaral D, Lavenex P (2006). «CH 3. Гиппокампальная нейроанатомия». В Andersen P, Morris R, Amaral D, Bliss T, O'Keefe J (Eds.). Книга гиппокампа . Издательство Оксфордского университета. ISBN 978-0-19-510027-3 .

- ^ Purves D (2011). Нейробиология (5 -е изд.). Сандерленд, Массачусетс: Синауэр. п. 590. ISBN 978-0878936953 .

- ^ Moser MB, Moser EI (1998). «Функциональная дифференциация в гиппокампе». Гиппокамп . 8 (6): 608–619. doi : 10.1002/(SICI) 1098-1063 (1998) 8: 6 <608 :: AID-HIPO3> 3.0.CO; 2-7 . PMID 9882018 . S2CID 32384692 .

- ^ Мураками Г., Цуругизава Т., Хатанака Ю., Комацузаки Ю., Танабе Н., Мукай Х. и др. (Декабрь 2006 г.). «Сравнение базальных и апикальных дендритных шипов в индуцированном эстрогенам быстрого спиногенеза основных нейронов CA1 в гиппокампе взрослых». Биохимическая и биофизическая исследовательская коммуникация . 351 (2): 553–558. doi : 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.10.066 . PMID 17070772 .

Нейроны CA1 состоят из четырех областей, т.е. Pratum Oriens, клеточного тела, радиатум слоя и Lacunosum-Moleculare

- ^ Rissman RA, Nocera R, Fuller LM, Kordower JH, Armstrong DM (февраль 2006 г.). «Возрастные изменения в субъединицах рецепторов ГАМК (а) в нечеловеческом примате гиппокампа». Исследование мозга . 1073–1074: 120–130. doi : 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.12.036 . PMID 16430870 . S2CID 13600454 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Eichenbaum H, Yonelinas AP, Ranganath C (2007). «Медиальная височная доля и память распознавания» . Ежегодный обзор нейробиологии . 30 : 123–152. doi : 10.1146/annurev.neuro.30.051606.094328 . PMC 2064941 . PMID 17417939 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Rocket ER, Schwartz JH, Jessell TM, Siegelbaum SA, Hudspeth AJ (2012). Принципы нейронной науки (5 -е изд.). Нью-Йорк: McGraw-Hill Medical. Стр. 1490–1 ISBN 9780071390118 Полем OCLC 820110349 .

- ^ Purves D (2011). Нейробиология (5 -е изд.). Сандерленд, Массачусетс: Синауэр. п. 171. ISBN 978-0878936953 .

- ^ Бирн Дж. Х. «Раздел 1, глава вступления» . Введение в нейроны и нейрональные сети . Neuroscience Online: электронный учебник для нейронаук. Кафедра нейробиологии и анатомии - Медицинская школа Техасского университета в Хьюстоне. Архивировано из оригинала 2013-12-03.

- ^ Уинсон Дж (июль 1978 г.). «Потеря тета -ритма гиппокампа приводит к дефициту пространственной памяти у крысы». Наука . 201 (4351): 160–163. Bibcode : 1978sci ... 201..160W . doi : 10.1126/science.663646 . PMID 663646 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Fanselow MS, Dong HW (январь 2010 г.). "Функционально различные структуры дорсального и вентрального гиппокампа?" Полем Нейрон . 65 (1): 7–19. doi : 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.11.031 . PMC 2822727 . PMID 20152109 .

- ^ * Потуйзен Х.Х., Чжан В.Н., Чонген-Руло А.Л., Фелдон Дж., Йи Б.К. (февраль 2004 г.). «Диссоциация функции между дорсальным и вентральным гиппокампом в способностях пространственных обучения крысы: в пределах задачи, сравнение эталонного и рабочей пространственной памяти». Европейский журнал нейробиологии . 19 (3): 705–712. doi : 10.1111/j.0953-816x.2004.03170.x . PMID 14984421 . S2CID 33385275 .

- ^ Юнг М.В., Винер С.И., Макнотон Б.Л. (декабрь 1994 г.). «Сравнение характеристик пространственного стрельбы единиц в дорсальном и вентральном гиппокампе крысы» . Журнал нейробиологии . 14 (12): 7347–7356. doi : 10.1523/jneurosci.14-12-07347.1994 . PMC 6576902 . PMID 7996180 .

- ^ Cenquizca LA, Swanson LW (ноябрь 2007 г.). «Пространственная организация прямого поля прямого гиппокампа CA1 аксонов для остальной части коры головного мозга» . Обзоры исследований мозга . 56 (1): 1–26. doi : 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.05.002 . PMC 2171036 . PMID 17559940 .

- ^ Anagnostaras SG, Gale GD, Fanselow MS (2002). «Гиппокамп и павловийский кондиционирование страха: ответьте на Bast et al.» (PDF) . Гиппокамп . 12 (4): 561–565. doi : 10.1002/hipo.10071 . PMID 12201641 . S2CID 733197 . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) на 2005-02-16.

- ^ Finger S (2001). «Определение и управление цепями эмоций». Происхождение нейробиологии: история исследований в функции мозга . Оксфорд/Нью -Йорк: издательство Оксфордского университета. п. 286. ISBN 978-0195065039 .

- ^ Finger S (2001). Происхождение нейробиологии: история исследований в функции мозга . Oxford University Press США. п. 183. ISBN 978-0-19-514694-3 .

- ^ Ван Гроен Т., Wyss JM (декабрь 1990 г.). «Внешние проекции из площади CA1 гиппокампа крысы: обонятельные, кортикальные, подкорковые и двусторонние проекции гиппокампа». Журнал сравнительной неврологии . 302 (3): 515–528. doi : 10.1002/cne.903020308 . PMID 1702115 . S2CID 7175722 .

- ^ Eichenbaum H, Otto TA, Wible CG, Piper JM (1991). «Ch 7. Создание модели гиппокампа в обонянии и памяти». В Davis JL, Eichenbaum H (Eds.). Обоняние . MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-04124-9 .

- ^ Vanderwolf CH (декабрь 2001 г.). «Гиппокамп как обонянный моторный механизм: в конце концов, классические анатомисты?». Поведенческое исследование мозга . 127 (1–2): 25–47. doi : 10.1016/s0166-4328 (01) 00354-0 . PMID 11718883 . S2CID 21832964 .

- ^ Надель Л., О'Киф Дж, Блэк А (июнь 1975 г.). «Удар на тормоза: критика модели Альтмана, Бруннера и Байера по ингибированию функции гиппокампа». Поведенческая биология . 14 (2): 151–162. doi : 10.1016/s0091-6773 (75) 90148-0 . PMID 1137539 .

- ^ Грей Дж.А., Макнотон Н. (2000). Нейропсихология тревоги: исследование функций системы септо-гиппокампа . Издательство Оксфордского университета.

- ^ Best PJ, White Am (1999). «Размещение одноразовых исследований гиппокампа в историческом контексте». Гиппокамп . 9 (4): 346–351. doi : 10.1002/(SICI) 1098-1063 (1999) 9: 4 <346 :: AID-HIPO2> 3.0.CO; 2-3 . PMID 10495017 . S2CID 18393297 .

- ^ Scoville WB, Milner B (февраль 1957 г.). «Потеря недавней памяти после двусторонних поражений гиппокампа» . Журнал неврологии, нейрохирургии и психиатрии . 20 (1): 11–21. doi : 10.1136/jnnp.20.1.11 . PMC 497229 . PMID 13406589 .

- ^ Кэри Б. (2008-12-04). «HM, незабываемый амнезиак, умирает в 82» . New York Times . Архивировано с оригинала 2018-06-13 . Получено 2009-04-27 .

- ^ Squire LR (январь 2009 г.). «Наследие пациента HM для нейробиологии» . Нейрон . 61 (1): 6–9. doi : 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.12.023 . PMC 2649674 . PMID 19146808 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Squire LR (апрель 1992 г.). «Память и гиппокамп: синтез из результатов с крысами, обезьянами и людьми». Психологический обзор . 99 (2): 195–231. doi : 10.1037/0033-295x.99.2.195 . PMID 1594723 . S2CID 14104324 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Eichenbaum H, Cohen NJ (1993). Память, амнезия и система гиппокампа . MIT Press.

- ^ Kovács Ka (сентябрь 2020 г.). «Эпизодические воспоминания: как гиппокамп и энтерхинальные кольцевые аттракторы сотрудничают, чтобы создать их?» Полем Границы в системах нейробиологии . 14 : 559168. DOI : 10.3389/fnsys.2020.559186 . PMC 7511719 . PMID 33013334 .

- ^ О'Киф Дж, Достровский Дж (ноябрь 1971 г.). «Гиппокамп как пространственная карта. Предварительные данные от единичной активности у свободно движущейся крысы». Исследование мозга . 34 (1): 171–175. doi : 10.1016/0006-8993 (71) 90358-1 . PMID 5124915 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный О'Киф Дж., Надель Л. (1978). Гиппокамп как когнитивная карта . Издательство Оксфордского университета. Архивировано из оригинала 2011-03-24 . Получено 2008-10-23 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Moser EI, Kropff E, Moser MB (2008). «Поместите клетки, клетки сетки и систему пространственного представления мозга». Ежегодный обзор нейробиологии . 31 : 69–89. doi : 10.1146/annurev.neuro.31.061307.090723 . PMID 18284371 . S2CID 16036900 .

- ^ Schiller D, Eichenbaum H, Buffalo EA, Davachi L, Foster DJ, Leutgeb S, et al. (Октябрь 2015). «Память и пространство: к пониманию когнитивной карты» . Журнал нейробиологии . 35 (41): 13904–13911. doi : 10.1523/jneurosci.2618-15.2015 . PMC 6608181 . PMID 26468191 .

- ^ Эйхенбаум H (декабрь 2001 г.). «Гиппокамп и декларативная память: когнитивные механизмы и нейронные коды». Поведенческое исследование мозга . 127 (1–2): 199–207. doi : 10.1016/s0166-4328 (01) 00365-5 . PMID 11718892 . S2CID 20843130 .

- ^ Buzsáki G, Moser EI (февраль 2013 г.). «Память, навигация и тета-ритм в гиппокампале-энторинальной системе» . Nature Neuroscience . 16 (2): 130–138. doi : 10.1038/nn.3304 . PMC 4079500 . PMID 23354386 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Ito R, Lee AC (октябрь 2016 г.). «Роль гиппокампа в конфликте по договоренности по конфликту: данные об исследованиях грызунов и на людях» . Поведенческое исследование мозга . 313 : 345–357. doi : 10.1016/j.bbr.2016.07.039 . PMID 27457133 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Squire LR, Schacter DL (2002). Нейропсихология памяти . Guilford Press.

- ^ Vanelzakker M, Fevurly RD, Breindel T, Spencer RL (декабрь 2008 г.). «Новинка окружающей среды связана с селективным увеличением экспрессии FOS в выходных элементах образования гиппокампа и периринальной коры» . Обучение и память . 15 (12): 899–908. doi : 10.1101/lm.1196508 . PMC 2632843 . PMID 19050162 .

- ^ Gluck M, Mercado E, Myers C (2014). Обучение и память от мозга к поведению (второе изд.). Нью -Йорк: Кевин Фейен. п. 416. ISBN 978-1429240147 .

- ^ Di Gennaro G, Grammaldo LG, Cavanato PP, Esposito V, Mascia A, Sparano A, et al. (Июнь 2006 г.). «Тяжелая амнезия после двустороннего медиального повреждения височной доли, возникающей в двух разных случаях». Неврологические науки . 27 (2): 129–133. doi : 10.1007/s10072-006-0614-y . PMID 16816912 . S2CID 7741607 .

- ^ Вирли Д., Ридли Р.М., Синден Д.Д., Кершоу Т.Р., Харленд С., Рашид Т. и др. (Декабрь 1999). «Первичный CA1 и условно бессмертные клеточные трансплантаты MHP36 восстанавливают обучение условной дискриминации и отзыв в мармозиях после экситотоксических поражений поля Hippocampal CA1» . Мозг: журнал неврологии . 122 (12): 2321–2335. doi : 10.1093/мозг/122.12.2321 . PMID 10581225 .

- ^ Sozinova EV, Kozlovskiy SA, Vartanov AV, Skvortsova VB, Pirogov YA, Anisimov NV, et al. (Сентябрь 2008 г.). «Роль частей гиппокампа в процессах вербальной памяти и активации». Международный журнал психофизиологии . 69 (3): 312. DOI : 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2008.05.328 .

- ^ Diana RA, Yonelinas AP, Ranganath C (сентябрь 2007 г.). «Воспоминание о визуализации и знакомство в медиальной височной доле: трехкомпонентная модель». Тенденции в когнитивных науках . 11 (9): 379–386. doi : 10.1016/j.tics.2007.08.001 . PMID 17707683 . S2CID 1443998 .

- ^ Франкленд PW, Bontempi B, Talton LE, Kaczmarek L, Silva AJ (май 2004 г.). «Участие передней поясной коры в отдаленную контекстуальную память страха». Наука . 304 (5672): 881–883. Bibcode : 2004sci ... 304..881f . doi : 10.1126/science.1094804 . PMID 15131309 . S2CID 15893863 .

- ^ Герцог К.Г., Кеннеди А.Дж., Гэвин К.Ф., Дэй Дж.Дж., Поттит Дж.Д. (июль 2017 г.). «В зависимости от опыта эпигеномная реорганизация в гиппокампе» . Обучение и память . 24 (7): 278–288. doi : 10.1101/lm.045112.117 . PMC 5473107 . PMID 28620075 .

- ^ Sparks F, Lehmann H., Sutherland RJ (2011). «Межсистемные помехи памяти во время поиска». Европейский журнал нейробиологии . 34 (5): 780–786. doi : 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07796.x . PMID 21896061 . S2CID 25745773 .

- ^ Matsumura N, Nishijo H, Tamura R, Eifuku S, Endo S, Ono T (март 1999 г.). «Пространственные и зависимые от задачи нейрональные реакции во время реальной и виртуальной транслокации в формировании гиппокампа обезьяны» . Журнал нейробиологии . 19 (6): 2381–2393. doi : 10.1523/jneurosci.19-06-02381.1999 . PMC 6782547 . PMID 10066288 .

- ^ Rolls ET, Xiang JZ (2006). «Пространственное представление ячейки в примате гиппокампа и воспоминания о памяти». Отзывы в нейронауках . 17 (1–2): 175–200. doi : 10.1515/revneuro.2006.17.1-2.175 . PMID 16703951 . S2CID 147636287 .

- ^ Смит Д.М., Мизумори С.Дж. (2006). «Гиппокамп помещает клетки, контекст и эпизодическая память». Гиппокамп . 16 (9): 716–729. Citeseerx 10.1.1.141.1450 . doi : 10.1002/hipo.20208 . PMID 16897724 . S2CID 720574 .

- ^ О'Киф Дж, Recce ML (июль 1993 г.). «Фазовая взаимосвязь между подразделениями гиппокампа и ритмом ЭЭГ тета». Гиппокамп . 3 (3): 317–330. doi : 10.1002/hipo.450030307 . PMID 8353611 . S2CID 6539236 .

- ^ Ekstrom AD, Kahana MJ, Caplan JB, Fields TA, Isham EA, Newman EL и др. (Сентябрь 2003 г.). «Сотовые сети, лежащие в основе пространственной навигации человека» (PDF) . Природа . 425 (6954): 184–188. Bibcode : 2003natur.425..184e . Citeseerx 10.1.1.408.4443 . doi : 10.1038/nature01964 . PMID 12968182 . S2CID 1673654 . Архивировано из оригинала 2021-10-20 . Получено 2013-01-24 .

- ^ Duarte IC, Ferreira C, Marques J, Castelo-Branco M (2014-01-27). «Передняя/апостериорная конкурентная дезактивация/дихотомия активации в гиппокампе человека, как выявилось с помощью трехмерной навигационной задачи» . Plos один . 9 (1): E86213. Bibcode : 2014ploso ... 986213d . doi : 10.1371/journal.pone.0086213 . PMC 3903506 . PMID 24475088 .

- ^ Maguire EA, Gadian DG, Johnsrude IS, Good CD, Ashburner J, Frackowiak RS, et al. (Апрель 2000). «Связанные с навигацией структурные изменения в гиппокампе водителей такси» . Труды Национальной академии наук Соединенных Штатов Америки . 97 (8): 4398–4403. Bibcode : 2000pnas ... 97.4398m . doi : 10.1073/pnas.070039597 . PMC 18253 . PMID 10716738 .

- ^ Leporé N, Shi Y, Lepore F, Fortin M, Voss P, Chou Yy, et al. (Июль 2009 г.). «Схема формы гиппокампа и различия в объеме у слепых субъектов» . Нейроамиж . 46 (4): 949–957. doi : 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.01.071 . PMC 2736880 . PMID 19285559 .

- ^ Chiu YC, Algase D, Whall A, Liang J, Liu HC, Lin KN, et al. (2004). «Потеряться: направлено внимание и исполнительные функции у ранних пациентов с болезнью Альцгеймера». Деменция и гериатрические когнитивные расстройства . 17 (3): 174–180. doi : 10.1159/000076353 . PMID 14739541 . S2CID 20454273 .

- ^ Моррис Р.Г., Гарруд П., Роулинс Дж.Н., О'Киф Дж. (Июнь 1982). «Поместите навигационную навигацию у крыс с поражениями гиппокампа». Природа . 297 (5868): 681–683. Bibcode : 1982natur.297..681m . doi : 10.1038/297681A0 . PMID 7088155 . S2CID 4242147 .

- ^ Сазерленд Р.Дж., Колб Б., Уишоу IQ (август 1982). «Пространственное картирование: окончательное нарушение гиппокампаль или медиальное лобное повреждение коры у крысы». Нейробиологические буквы . 31 (3): 271–276. doi : 10.1016/0304-3940 (82) 90032-5 . PMID 7133562 . S2CID 20203374 .

- ^ Sutherland RJ, Weisend MP, Mumby D, Astur RS, Hanlon FM, Koerner A, et al. (2001). «Ретроградная амнезия после повреждения гиппокампа: недавние против отдаленных воспоминаний в двух задачах». Гиппокамп . 11 (1): 27–42. doi : 10.1002/1098-1063 (2001) 11: 1 <27 :: Aid-Hipo1017> 3.0.co; 2-4 . PMID 11261770 . S2CID 142515 .

- ^ Кларк Р.Е., Бродбент Нью -Джерси, Сквайр Л.Р. (2005). «Гиппокамп и удаленная пространственная память у крыс» . Гиппокамп . 15 (2): 260–272. doi : 10.1002/hipo.20056 . PMC 2754168 . PMID 15523608 .

- ^ Solstad T, Boccara CN, Kropff E, Moser MB, Moser EI (декабрь 2008 г.). «Представление геометрических границ в энторинальной коре». Наука . 322 (5909): 1865–1868. Bibcode : 2008Sci ... 322.1865S . doi : 10.1126/science.1166466 . PMID 19095945 . S2CID 260976755 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный О'Нил Э.Б., Ньюсом Р.Н., Ли И.Х., Тавабаласингам С., Ито Р., Ли А.К. (ноябрь 2015). «Изучение роли гиппокампа человека в принятии решений о предотвращении подходов с использованием новой парадигмы конфликта и многомерной функциональной магнитно-резонансной томографии» . Журнал нейробиологии . 35 (45): 15039–15049. doi : 10.1523/jneurosci.1915-15.2015 . PMC 6605357 . PMID 26558775 .

- ^ Quiroga RQ, Reddy L, Kreiman G, Koch C, Fried I (июнь 2005 г.). «Инвариантное визуальное представление отдельными нейронами в человеческом мозге» . Природа . 435 (7045): 1102–1107. Bibcode : 2005natur.435.1102Q . doi : 10.1038/nature03687 . PMID 15973409 . S2CID 1234637 .

- ^ Sliwa J, Planté A, Duhamel Jr, Wirth S (март 2016 г.). «Независимое нейрональное представление лицевой и вокальной идентичности в гиппокампе обезьяны и неполнористого коры». Кора головного мозга . 26 (3): 950–966. doi : 10.1093/cercor/bhu257 . PMID 25405945 .

- ^ Hitti FL, Siegelbaum SA (апрель 2014 г.). «Область CA2 гиппокампа необходима для социальной памяти» . Природа . 508 (7494): 88–92. Bibcode : 2014natur.508 ... 88h . doi : 10.1038/nature13028 . PMC 4000264 . PMID 24572357 .

- ^ Okuyama T, Kitamura T, Roy DS, Itohara S, Tonegawa S (сентябрь 2016 г.). «Вентральные нейроны CA1 хранят социальную память» . Наука . 353 (6307): 1536–1541. BIBCODE : 2016SCI ... 353.1536O . doi : 10.1126/science.aaf7003 . PMC 5493325 . PMID 27708103 .

- ^ Meira T, Leroy F, Buss EW, Oliva A, Park J, Siegelbaum SA (октябрь 2018 г.). «Гиппокампальная схема, связывающая дорсальный CA2 с вентральным CA1, критическим для динамики социальной памяти» . Природная связь . 9 (1): 4163. Bibcode : 2018natco ... 9.4163m . doi : 10.1038/s41467-018-06501-w . PMC 6178349 . PMID 30301899 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Бузсаки Г. (2006). Ритмы мозга . Издательство Оксфордского университета. ISBN 978-0-19-530106-9 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Buzsáki G, Chen LS, Gage FH (1990). «Глава 19 Глава Пространственная организация физиологической деятельности в области гиппокампа: отношение к формированию памяти». Пространственная организация физиологической активности в области гиппокампа: отношение к формированию памяти . Прогресс в исследовании мозга. Тол. 83. С. 257–268. doi : 10.1016/s0079-6123 (08) 61255-8 . ISBN 9780444811493 Полем PMID 2203100 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Skaggs WE, McNaughton BL, Permenter M, Archibeque M, Vogt J, Amaral DG, et al. (Август 2007 г.). «ЭЭГ Шорп волны и разреженная ансамблевая активность в макаке гиппокамп». Журнал нейрофизиологии . 98 (2): 898–910. doi : 10.1152/jn.00401.2007 . PMID 17522177 . S2CID 941428 .

- ^ Бузсаки Г. (январь 2002 г.). «Тета -колебания в гиппокампе» . Нейрон . 33 (3): 325–340. doi : 10.1016/s0896-6273 (02) 00586-x . PMID 11832222 . S2CID 15410690 .

- ^ Любенов Э.В., Сиапас А.Г. (май 2009 г.). «Гиппокамп -тета -колебания движутся волнами» (PDF) . Природа . 459 (7246): 534–539. Bibcode : 2009natur.459..534L . doi : 10.1038/nature08010 . PMID 19489117 . S2CID 4429491 . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 2018-07-23 . Получено 2019-07-13 .

- ^ Komisaruk BR (март 1970 г.). «Синхронность между активностью тета -лимбической системы и ритмическим поведением у крыс». Журнал сравнительной и физиологической психологии . 70 (3): 482–492. doi : 10.1037/h0028709 . PMID 5418472 .

- ^ Cantero JL, Atienza M, Stickgold R, Kahana MJ, Madsen Jr, Kocsis B (ноябрь 2003 г.). «Зависимые от сна тета-колебания в гиппокампе человека и неокортекс» . Журнал нейробиологии . 23 (34): 10897–10903. doi : 10.1523/jneurosci.23-34-10897.2003 . PMC 6740994 . PMID 14645485 .

- ^ Vanderwolf CH (апрель 1969 г.). «Электрическая активность гиппокампа и добровольное движение у крысы». Электроэнцефалография и клиническая нейрофизиология . 26 (4): 407–418. doi : 10.1016/0013-4694 (69) 90092-3 . PMID 4183562 .

- ^ Уэрта П.Т., Лисман Дж. (Август 1993 г.). «Повышенная синаптическая пластичность нейронов Гиппокампа CA1 во время холинергически индуцированного ритмического состояния». Природа . 364 (6439): 723–725. Bibcode : 1993natur.364..723H . doi : 10.1038/364723A0 . PMID 8355787 . S2CID 4358000 .

- ^ Numan R, Feloney MP, Pham KH, Tieber LM (декабрь 1995 г.). «Влияние медиальных перегородок на оперативную задачу с задержкой отклика оперантного GO/без задержки с задержкой ответа» . Физиология и поведение . 58 (6): 1263–1271. doi : 10.1016/0031-9384 (95) 02044-6 . PMID 8623030 . S2CID 876694 . Архивировано из оригинала 2021-04-27 . Получено 2020-03-09 .

- ^ Кахана М.Дж., Силиг Д., Мэдсен младший (декабрь 2001 г.). «Тета возвращает». Современное мнение о нейробиологии . 11 (6): 739–744. doi : 10.1016/s0959-4388 (01) 00278-1 . PMID 11741027 . S2CID 43829235 .

- ^ Бузсаки Г (ноябрь 1986 г.). «Грапкие волны гиппокампа: их происхождение и значение». Исследование мозга . 398 (2): 242–252. doi : 10.1016/0006-8993 (86) 91483-6 . PMID 3026567 . S2CID 37242634 .