Охрана труда и здоровье

| Часть серии о |

| Organised labour |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Public health |

|---|

|

Охрана труда и гигиена труда ( OSH ) или гигиена и безопасность труда ( OHS ) — это междисциплинарная область, занимающаяся безопасностью , здоровьем и благополучием людей на работе (т. е. при выполнении обязанностей, предусмотренных профессией). Охрана труда связана с областями медицины труда и гигиены труда. [а] и согласуется с по укреплению здоровья на рабочем месте инициативами . БГТ также защищает все население, на которого может повлиять профессиональная среда. [4]

По официальным оценкам Организации Объединенных Наций , Совместной оценке ВОЗ и МОТ бремени болезней и травм, связанных с работой , почти 2 миллиона человек умирают каждый год из-за воздействия профессиональных факторов риска. [5] Во всем мире более 2,78 миллиона человек ежегодно умирают в результате несчастных случаев или заболеваний на рабочем месте, что соответствует одной смерти каждые пятнадцать секунд. Ежегодно происходит еще 374 миллиона несмертельных травм на производстве. По оценкам, экономическое бремя производственных травм и смертей составляет почти четыре процента мирового валового внутреннего продукта каждый год. Человеческая цена этого бедствия огромна. [6]

In common-law jurisdictions, employers have the common law duty (also called duty of care) to take reasonable care of the safety of their employees.[7] Statute law may, in addition, impose other general duties, introduce specific duties, and create government bodies with powers to regulate occupational safety issues. Details of this vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction.

Prevention of workplace incidents and occupational diseases is addressed through the implementation of occupational safety and health programs at company level.[8]

Definitions

[edit]The International Labour Organization (ILO) and the World Health Organization (WHO) share a common definition of occupational health.[b] It was first adopted by the Joint ILO/WHO Committee on Occupational Health at its first session in 1950:[10][11]

Occupational health should aim at the promotion and maintenance of the highest degree of physical, mental and social well-being of workers in all occupations; the prevention amongst workers of departures from health caused by their working conditions; the protection of workers in their employment from risks resulting from factors adverse to health; the placing and maintenance of the worker in an occupational environment adapted to his physiological and psychological capabilities and; to summarize: the adaptation of work to man and of each man to his job.

— Joint ILO/WHO Committee on Occupational Health, 1st Session (1950)

In 1995, a consensus statement was added:[10][11]

The main focus in occupational health is on three different objectives: (i) the maintenance and promotion of workers' health and working capacity; (ii) the improvement of working environment and work to become conducive to safety and health and (iii) development of work organizations and working cultures in a direction which supports health and safety at work and in doing so also promotes a positive social climate and smooth operation and may enhance productivity of the undertakings. The concept of working culture is intended in this context to mean a reflection of the essential value systems adopted by the undertaking concerned. Such a culture is reflected in practice in the managerial systems, personnel policy, principles for participation, training policies and quality management of the undertaking.

— Joint ILO/WHO Committee on Occupational Health, 12th session (1995)

An alternative definition for occupational health given by the WHO is: "occupational health deals with all aspects of health and safety in the workplace and has a strong focus on primary prevention of hazards."[12]

The expression "occupational health", as originally adopted by the WHO and the ILO, refers to both short- and long-term adverse health effects. In more recent times, the expressions "occupational safety and health" and "occupational health and safety" have come into use (and have also been adopted in works by the ILO),[13] based on the general understanding that occupational health refers to hazards associated to disease and long-term effects, while occupational safety hazards are those associated to work accidents causing injury and sudden severe conditions.[14]

History

[edit]Research and regulation of occupational safety and health are a relatively recent phenomenon. As labor movements arose in response to worker concerns in the wake of the industrial revolution, workers' safety and health entered consideration as a labor-related issue.[15]

Beginnings

[edit]

Written works on occupational diseases began to appear by the end of the 15th century, when demand for gold and silver was rising due to the increase in trade and iron, copper, and lead were also in demand from the nascent firearms market. Deeper mining became common as a consequence. In 1473, Ulrich Ellenbog, a German physician, wrote a short treatise On the Poisonous Wicked Fumes and Smokes, focused on coal, nitric acid, lead, and mercury fumes encountered by metal workers and goldsmiths. In 1587, Paracelsus (1493–1541) published the first work on the mine and smelter workers diseases. In it, he gave accounts of miners' "lung sickness". In 1526, Georgius Agricola's (1494–1553) De re metallica, a treaty on metallurgy, described accidents and diseases prevalent among miners and recommended practices to prevent them. Like Paracelsus, Agricola mentioned the dust that "eats away the lungs, and implants consumption."[16]

The seeds of state intervention to correct social ills were sown during the reign of Elizabeth I by the Poor Laws, which originated in attempts to alleviate hardship arising from widespread poverty. While they were perhaps more to do with a need to contain unrest than morally motivated, they were significant in transferring responsibility for helping the needy from private hands to the state.[15]

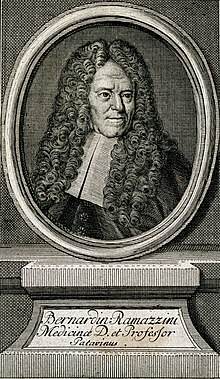

In 1713, Bernardino Ramazzini (1633–1714), often described as the father of occupational medicine and a precursor to occupational health, published his De morbis artificum diatriba (Dissertation on Workers' Diseases), which outlined the health hazards of chemicals, dust, metals, repetitive or violent motions, odd postures, and other disease-causative agents encountered by workers in more than fifty occupations. It was the first broad-ranging presentation of occupational diseases.[16][17][18]

Percivall Pott (1714–1788), an English surgeon, described cancer in chimney sweeps (chimney sweeps' carcinoma), the first recognition of an occupational cancer in history.[16]

The Industrial Revolution in Britain

[edit]

The United Kingdom was the first nation to industrialize. Soon shocking evidence emerged of serious physical and moral harm suffered by children and young persons in the cotton textile mills, as a result of exploitation of cheap labor in the factory system. Responding to calls for remedial action from philanthropists and some of the more enlightened employers, in 1802 Sir Robert Peel, himself a mill owner, introduced a bill to parliament with the aim of improving their conditions. This would engender the Health and Morals of Apprentices Act 1802, generally believed to be the first attempt to regulate conditions of work in the United Kingdom. The act applied only to cotton textile mills and required employers to keep premises clean and healthy by twice yearly washings with quicklime, to ensure there were sufficient windows to admit fresh air, and to supply "apprentices" (i.e., pauper and orphan employees) with "sufficient and suitable" clothing and accommodation for sleeping.[15] It was the first of the 19th century Factory Acts.

Charles Thackrah (1795–1833), another pioneer of occupational medicine, wrote a report on The State of Children Employed in Cotton Factories, which was sent to the Parliament in 1818. Thackrah recognized issues of inequalities of health in the workplace, with manufacturing in towns causing higher mortality than agriculture.[16]

The Act of 1833 created a dedicated professional Factory Inspectorate.[19] The initial remit of the Inspectorate was to police restrictions on the working hours in the textile industry of children and young persons (introduced to prevent chronic overwork, identified as leading directly to ill-health and deformation, and indirectly to a high accident rate).[15]

In 1840 a Royal Commission published its findings on the state of conditions for the workers of the mining industry that documented the appallingly dangerous environment that they had to work in and the high frequency of accidents. The commission sparked public outrage which resulted in the Mines and Collieries Act of 1842. The act set up an inspectorate for mines and collieries which resulted in many prosecutions and safety improvements, and by 1850, inspectors were able to enter and inspect premises at their discretion.[20]

On the urging of the Factory Inspectorate, a further act in 1844 giving similar restrictions on working hours for women in the textile industry introduced a requirement for machinery guarding (but only in the textile industry, and only in areas that might be accessed by women or children).[21] The latter act was the first to take a significant step toward improvement of workers' safety, as the former focused on health aspects alone.[15]

The first decennial British Registrar-General's mortality report was issued in 1851. Deaths were categorized by social classes, with class I corresponding to professionals and executives and class V representing unskilled workers. The report showed that mortality rates increased with the class number.[16]

Continental Europe

[edit]Otto von Bismarck inaugurated the first social insurance legislation in 1883 and the first worker's compensation law in 1884 – the first of their kind in the Western world. Similar acts followed in other countries, partly in response to labor unrest.[16]

United States

[edit]

The United States are responsible for the first health program focusing on workplace conditions. This was the Marine Hospital Service, inaugurated in 1798 and providing care for merchant seamen. This was the beginning of what would become the US Public Health Service (USPHS).[16]

The first worker compensation acts in the United States were passed in New York in 1910 and in Washington and Wisconsin in 1911. Later rulings included occupational diseases in the scope of the compensation, which was initially restricted to accidents.[16]

In 1914 the USPHS set up the Office of Industrial Hygiene and Sanitation, the ancestor of the current National Institute for Safety and Health (NIOSH). In the early 20th century, workplace disasters were still common. For example, in 1911 a fire at the Triangle Shirtwaist Company in New York killed 146 workers, mostly women and immigrants. Most died trying to open exits that had been locked. Radium dial painter cancers,"phossy jaw", mercury and lead poisonings, silicosis, and other pneumoconioses were extremely common.[16]

The enactment of the Federal Coal Mine Health and Safety Act of 1969 was quickly followed by the 1970 Occupational Safety and Health Act, which established the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and NIOSH in their current form`.[16]

Workplace hazards

[edit]

A wide array of workplace hazards can damage the health and safety of people at work. These include but are not limited to, "chemicals, biological agents, physical factors, adverse ergonomic conditions, allergens, a complex network of safety risks," as well a broad range of psychosocial risk factors.[23] Personal protective equipment can help protect against many of these hazards.[24] A landmark study conducted by the World Health Organization and the International Labour Organization found that exposure to long working hours is the occupational risk factor with the largest attributable burden of disease, i.e. an estimated 745,000 fatalities from ischemic heart disease and stroke events in 2016.[25] This makes overwork the globally leading occupational health risk factor.[26]

Physical hazards affect many people in the workplace. Occupational hearing loss is the most common work-related injury in the United States, with 22 million workers exposed to hazardous occupational noise levels at work and an estimated $242 million spent annually on worker's compensation for hearing loss disability.[27] Falls are also a common cause of occupational injuries and fatalities, especially in construction, extraction, transportation, healthcare, and building cleaning and maintenance.[28] Machines have moving parts, sharp edges, hot surfaces and other hazards with the potential to crush, burn, cut, shear, stab or otherwise strike or wound workers if used unsafely.[29]

Biological hazards (biohazards) include infectious microorganisms such as viruses, bacteria and toxins produced by those organisms such as anthrax. Biohazards affect workers in many industries; influenza, for example, affects a broad population of workers.[30] Outdoor workers, including farmers, landscapers, and construction workers, risk exposure to numerous biohazards, including animal bites and stings,[31][32][33] urushiol from poisonous plants,[34] and diseases transmitted through animals such as the West Nile virus and Lyme disease.[35][36] Health care workers, including veterinary health workers, risk exposure to blood-borne pathogens and various infectious diseases,[37][38] especially those that are emerging.[39]

Dangerous chemicals can pose a chemical hazard in the workplace. There are many classifications of hazardous chemicals, including neurotoxins, immune agents, dermatologic agents, carcinogens, reproductive toxins, systemic toxins, asthmagens, pneumoconiotic agents, and sensitizers.[40] Authorities such as regulatory agencies set occupational exposure limits to mitigate the risk of chemical hazards.[41] International investigations are ongoing into the health effects of mixtures of chemicals, given that toxins can interact synergistically instead of merely additively. For example, there is some evidence that certain chemicals are harmful at low levels when mixed with one or more other chemicals. Such synergistic effects may be particularly important in causing cancer. Additionally, some substances (such as heavy metals and organohalogens) can accumulate in the body over time, thereby enabling small incremental daily exposures to eventually add up to dangerous levels with little overt warning.[42]

Psychosocial hazards include risks to the mental and emotional well-being of workers, such as feelings of job insecurity, long work hours, and poor work-life balance.[43] Psychological abuse has been found present within the workplace as evidenced by previous research. A study by Gary Namie on workplace emotional abuse found that 31% of women and 21% of men who reported workplace emotional abuse exhibited three key symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (hypervigilance, intrusive imagery, and avoidance behaviors).[44] Sexual harassment is a serious hazard that can be found in workplaces.[45]

By industry

[edit]Specific occupational safety and health risk factors vary depending on the specific sector and industry. Construction workers might be particularly at risk of falls, for instance, whereas fishermen might be particularly at risk of drowning. Similarly psychosocial risks such as workplace violence are more pronounced for certain occupational groups such as health care employees, police, correctional officers and teachers.[46]

Primary sector

[edit]Agriculture

[edit]

Agriculture workers are often at risk of work-related injuries, lung disease, noise-induced hearing loss, skin disease, as well as certain cancers related to chemical use or prolonged sun exposure. On industrialized farms, injuries frequently involve the use of agricultural machinery. The most common cause of fatal agricultural injuries in the United States is tractor rollovers, which can be prevented by the use of roll over protection structures which limit the risk of injury in case a tractor rolls over.[47] Pesticides and other chemicals used in farming can also be hazardous to worker health,[48] and workers exposed to pesticides may experience illnesses or birth defects.[49] As an industry in which families, including children, commonly work alongside their families, agriculture is a common source of occupational injuries and illnesses among younger workers.[50] Common causes of fatal injuries among young farm worker include drowning, machinery and motor vehicle-related accidents.[51]

The 2010 NHIS-OHS found elevated prevalence rates of several occupational exposures in the agriculture, forestry, and fishing sector which may negatively impact health. These workers often worked long hours. The prevalence rate of working more than 48 hours a week among workers employed in these industries was 37%, and 24% worked more than 60 hours a week.[52] Of all workers in these industries, 85% frequently worked outdoors compared to 25% of all US workers. Additionally, 53% were frequently exposed to vapors, gas, dust, or fumes, compared to 25% of all US workers.[53]

Mining and oil and gas extraction

[edit]The mining industry still has one of the highest rates of fatalities of any industry.[54] There are a range of hazards present in surface and underground mining operations. In surface mining, leading hazards include such issues as geological instability,[55] contact with plant and equipment, rock blasting, thermal environments (heat and cold), respiratory health (black lung), etc.[56] In underground mining, operational hazards include respiratory health, explosions and gas (particularly in coal mine operations), geological instability, electrical equipment, contact with plant and equipment, heat stress, inrush of bodies of water, falls from height, confined spaces. ionising radiation, etc.[57]

According to data from the 2010 NHIS-OHS, workers employed in mining and oil and gas extraction industries had high prevalence rates of exposure to potentially harmful work organization characteristics and hazardous chemicals. Many of these workers worked long hours: 50% worked more than 48 hours a week and 25% worked more than 60 hours a week in 2010. Additionally, 42% worked non-standard shifts (not a regular day shift). These workers also had high prevalence of exposure to physical/chemical hazards. In 2010, 39% had frequent skin contact with chemicals. Among nonsmoking workers, 28% of those in mining and oil and gas extraction industries had frequent exposure to secondhand smoke at work. About two-thirds were frequently exposed to vapors, gas, dust, or fumes at work.[58]

Secondary sector

[edit]Construction

[edit]

Construction is one of the most dangerous occupations in the world, incurring more occupational fatalities than any other sector in both the United States and in the European Union.[59][60] In 2009, the fatal occupational injury rate among construction workers in the United States was nearly three times that for all workers.[59] Falls are one of the most common causes of fatal and non-fatal injuries among construction workers.[59] Proper safety equipment such as harnesses and guardrails and procedures such as securing ladders and inspecting scaffolding can curtail the risk of occupational injuries in the construction industry.[61] Due to the fact that accidents may have disastrous consequences for employees as well as organizations, it is of utmost importance to ensure health and safety of workers and compliance with HSE construction requirements. Health and safety legislation in the construction industry involves many rules and regulations. For example, the role of the Construction Design Management (CDM) Coordinator as a requirement has been aimed at improving health and safety on-site.[62]

The 2010 National Health Interview Survey Occupational Health Supplement (NHIS-OHS) identified work organization factors and occupational psychosocial and chemical/physical exposures which may increase some health risks. Among all US workers in the construction sector, 44% had non-standard work arrangements (were not regular permanent employees) compared to 19% of all US workers, 15% had temporary employment compared to 7% of all US workers, and 55% experienced job insecurity compared to 32% of all US workers. Prevalence rates for exposure to physical/chemical hazards were especially high for the construction sector. Among nonsmoking workers, 24% of construction workers were exposed to secondhand smoke while only 10% of all US workers were exposed. Other physical/chemical hazards with high prevalence rates in the construction industry were frequently working outdoors (73%) and frequent exposure to vapors, gas, dust, or fumes (51%).[63]

Tertiary sector

[edit]The service sector comprises diverse workplaces. Each type of workplace has its own health risks. While some occupations have become more mobile, others still require people to sit at desks. As the number of service sector jobs has risen in developed countries, more and more jobs have become sedentary, presenting an array of health problems that differ from health problems associated with manufacturing and the primary sector. Contemporary health problems include obesity. Some working conditions, such as occupational stress, workplace bullying, and overwork, have negative consequences for physical and mental health.[64][65]

Tipped wage workers are at a higher risk of negative mental health outcomes like addiction or depression.[citation needed] "The higher prevalence of mental health problems may be linked to the precarious nature of service work, including lower and unpredictable wages, insufficient benefits, and a lack of control over work hours and assigned shifts."[65] Close to 70% of tipped wage workers are women.[66] Additionally, "almost 40 percent of people who work for tips are people of color: 18 percent are Latino, 10 percent are African American, and 9 percent are Asian. Immigrants are also overrepresented in the tipped workforce."[67] According to data from the 2010 NHIS-OHS, hazardous physical/chemical exposures in the service sector were lower than national averages. On the other hand, potentially harmful work organization characteristics and psychosocial workplace exposures were relatively common in this sector. Among all workers in the service industry, 30% experienced job insecurity in 2010, 27% worked non-standard shifts (not a regular day shift), 21% had non-standard work arrangements (were not regular permanent employees).[68]

Due to the manual labor involved and on a per employee basis, the US Postal Service, UPS and FedEx are the 4th, 5th and 7th most dangerous companies to work for in the US.[69]

Healthcare and social assistance

[edit]Healthcare workers are exposed to many hazards that can adversely affect their health and well-being.[70] Long hours, changing shifts, physically demanding tasks, violence, and exposures to infectious diseases and harmful chemicals are examples of hazards that put these workers at risk for illness and injury. Musculoskeletal injury (MSI) is the most common health hazard in for healthcare workers and in workplaces overall.[71] Injuries can be prevented by using proper body mechanics.[72]

According to the Bureau of Labor statistics, US hospitals recorded 253,700 work-related injuries and illnesses in 2011, which is 6.8 work-related injuries and illnesses for every 100 full-time employees.[73] The injury and illness rate in hospitals is higher than the rates in construction and manufacturing – two industries that are traditionally thought to be relatively hazardous.[citation needed]

Workplace fatality and injury statistics

[edit]Worldwide

[edit]

An estimated 2.90 million work-related deaths occurred in 2019, increased from 2.78 million death from 2015. About, one-third of the total work-related deaths (31%) were due to circulatory diseases, while cancer contributed 29%, respiratory diseases 17%, and occupational injuries contributed 11% (or about 319,000 fatalities). Other diseases such as work-related communicable diseases contributed 6%, while neuropsychiatric conditions contributed 3% and work-related digestive disease and genitourinary diseases contributed 1% each. The contribution of cancers and circulatory diseases to total work-related deaths increased from 2015, while deaths due to occupational injuries decreased. Although work-related injury deaths and non-fatal injuries rates were on a decreasing trend, the total deaths and non-fatal outcomes were on the rise. Cancers represented the most significant cause of mortality in high-income countries. The number of non-fatal occupational injuries for 2019 was estimated to be 402 million.[74]

Mortality rate is unevenly distributed, with male mortality rate (108.3 per 100,000 employed male individuals) being significantly higher than female rate (48.4 per 100,000). 6.7% of all deaths globally are represented by occupational fatalities.[75]

European Union

[edit]Certain EU member states admit to having lacking quality control in occupational safety services, to situations in which risk analysis takes place without any on-site workplace visits and to insufficient implementation of certain EU OSH directives. Disparities between member states result in different impact of occupational hazards on the economy. In the early 2000s, the total societal costs of work-related health problems and accidents varied from 2.6% to 3.8% of the national GDPs across the member states.[76]

In 2021, in the EU-27 as a whole, 93% of deaths due to injury were of males.[77]

Russia

[edit]

One of the decisions taken by the communist regime under Stalin was to reduce the number of accidents and occupational diseases to zero.[79] The tendency to decline remained in the Russian Federation in the early 21st century. However, as in previous years, data reporting and publication was incomplete and manipulated, so that the actual number of work-related diseases and accidents are unknown.[80] The ILO reports that, according to the information provided by the Russian government, there are 190,000 work-related fatalities each year, of which 15,000 due to occupational accidents.[81]

After the demise of the USSR, enterprises became owned by oligarchs who were not interested in upholding safe and healthy conditions in the workplace. Expenditure on equipment modernization was minimal and the share of harmful workplaces increased.[82] The government did not interfere in this, and sometimes it helped employers.[citation needed] At first, the increase in occupational diseases and accidents was slow, due to the fact that in the 1990s it was compensated by mass deindustrialization.[citation needed] However, in the 2000s deindustrialization slowed and occupational diseases and injuries started to rise in earnest. Therefore, in the 2010s the Ministry of Labor adopted federal law no. 426-FZ. This piece of legislation has been described as ineffective and based on the superficial assumption that the issuance of personal protective equipment to the employee means real improvement of working conditions. Meanwhile, the Ministry of Health made significant changes in the methods of risk assessment in the workplace.[83] However, specialists from the Izmerov Research Institute of Occupational Health found that the post-2014 apparent decrease in the share of employees engaged in hazardous working conditions is due to the change in definitions consequent to the Ministry of Health's decision, but does not reflect actual improvements. This was most clearly shown in the results for the aluminum industry.[84]

Further problems in the accounting of workplace fatalities arise from the fact that multiple Russian federal entities collect and publish records, a practice that should be avoided. In 2008 alone, 2074 accidents at work may have not been reported in official government sources.[85]

| Number of workplace fatalities in Russia[85] | ||||

| Year | Russian Federal State Statistics Service | Social Insurance Fund of the Russian Federation | Federal Service for Labor and Employment | Max. discrepancy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 4368 | 5755 | 6194 | 1826 |

| 2002 | 3920 | 5715 | 5865 | 1945 |

| 2003 | 3536 | 5180 | 5185 | 1649 |

| 2004 | 3292 | 4684 | 4924 | 1632 |

| 2005 | 3091 | 4235 | 4604 | 1513 |

| 2006 | 2881 | 3591 | 4301 | 1420 |

| 2007 | 2966 | 3677 | 4417 | 1451 |

| 2008 | 2548 | 3238 | 3931 | 1383 |

| 2009 | 1967 | 2598 | 3200 | 1233 |

| 2010 | 2004 | 2438 | 3120 | 1116 |

United Kingdom

[edit]In the UK there were 135 fatal injuries at work in financial year 2022–2023, compared with 651 in 1974 (the year when the Health and Safety at Work Act was promulgated). The fatal injury rate declined from 2.1 fatalities per 100,000 workers in 1981 to 0.41 in financial year 2022–2023.[86] Over recent decades reductions in both fatal and non-fatal workplace injuries have been very significant. However, illnesses statistics have not uniformly improved: while musculoskeletal disorders have diminished, the rate of self-reported work-related stress, depression or anxiety has increased, and the rate of mesothelioma deaths has remained broadly flat (due to past asbestos exposures).[87]

United States

[edit]

The Occupational Safety and Health Statistics (OSHS) program in the Bureau of Labor Statistics of the United States Department of Labor compiles information about workplace fatalities and non-fatal injuries in the United States. The OSHS program produces three annual reports:

- Counts and rates of nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses by detailed industry and case type (SOII summary data)

- Case circumstances and worker demographic data for nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses resulting in days away from work (SOII case and demographic data)

- Counts and rates of fatal occupational injuries (CFOI data)[88]

The Bureau also uses tools like AgInjuryNews.org to identify and compile additional sources of fatality reports for their datasets.[89][90]

Between 1913 and 2013, workplace fatalities dropped by approximately 80%.[91] In 1970, an estimated 14,000 workers were killed on the job. By 2021, in spite of the workforce having since more than doubled, workplace deaths were down to about 5,190.[92] According to the census of occupational injuries 5,486 people died on the job in 2022, up from the 2021 total of 5,190. The fatal injury rate was 3.7 per 100,000 full-time equivalent workers.[93] The decrease in the mortality rate is only partly (about 10–15%) explained by the deindustrialization of the US in the last 40 years.[94]

| 2022 number and rate of fatal work injuries for selected occupation groups[93] | |

|---|---|

| Occupation Group | Fatalities per 100,000 employees |

| Farming, fishing and forestry | 23.5 |

| Transportation and material moving | 14.6 |

| Construction and extraction | 13.0 |

| Protective service | 10.2 |

| Installation, maintenance, and repair | 8.8 |

| Building and grounds cleaning and maintenance | 7.4 |

| All occupations | 3.7 |

| Fatal occupational injuries for selected events or exposures[93] | |

|---|---|

| Cause of injury and illness | Number |

| Violence and other injuries by persons or animals | 849 |

| Transportation incidents | 2,066 |

| Fire or explosion | 107 |

| Falls, slips and trips | 865 |

| Exposure to harmful substances or environments | 839 |

| Contact with objects and equipment | 738 |

| All events | 89.4 |

About 3.5 million nonfatal workplace injuries and illnesses were reported by private industry employers in 2022, occurring at a rate of 3.0 cases per 100 full-time workers.[95][96]

| 2022 injuries and illnesses[95][96] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Industry | Rate per 100 full-time

employees |

Number |

| Private Industry | 2.7 | 2,804,200 |

| Goods-producing | 2.9 | 614,400 |

| Natural resources and mining | 3.1 | 48,000 |

| Agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting | 3.5 | 39,500 |

| Mining, quarrying, and oil and gas extraction | 1.4 | 8,500 |

| Construction | 2.4 | 169,600 |

| Manufacturing | 3.2 | 396,800 |

| Service-providing | 2.7 | 2,189,800 |

| Trade, transportation, and utilities | 3.7 | 856,100 |

| Wholesale trade | 2.6 | 147,600 |

| Retail trade | 3.7 | 422,700 |

| Transportation and warehousing | 4.8 | 276,300 |

| Utilities | 1.7 | 9,500 |

| Information | 1.0 | 27,200 |

| Finance, insurance, and real estate | 0.8 | 60,300 |

| Finance and insurance | 0.3 | 15,900 |

| Real estate and rental and leasing | 2.2 | 44,400 |

| Professional and business services | 1.2 | 205,900 |

| Professional, scientific, and technical services | 0.9 | 81,100 |

| Management of companies and enterprises | 0.8 | 18,600 |

| Administrative and support etc. | 1.9 | 88,700 |

| Educational and health services | 4.2 | 705,600 |

| Educational services | 2.0 | 40,200 |

| Health care and social assistance | 4.5 | 665,300 |

| Leisure, entertainment, and hospitality | 2.9 | 276,100 |

| Arts, entertainment, and recreation | 4.2 | 55,000 |

| Accommodation and food services | 2.7 | 221,100 |

| Other services (except public administration) | 1.8 | 58,600 |

| State and local government | 4.9 | 700,400 |

| All industries including state and local government | 3.0 | 3,504,600 |

Management systems

[edit]Companies may adopt a safety and health management system (SMS),[c] either voluntarily or because required by applicable regulations, to deal in a structured and systematic way with safety and health risks in their workplace. An SMS provides a systematic way to assess and improve prevention of workplace accidents and incidents based on structured management of workplace risks and hazards. It must be adaptable to changes in the organization's business and legislative requirements. It is usually based on the Deming cycle, or plan-do-check-act (PDCA) principle.[97] An effective SMS should:

- Define how the organization is set up to manage risk

- Identify workplace hazards and implement suitable controls

- Implement effective communication across all levels of the organization

- Implement a process to identify and correct non-conformity and non-compliance issues

- Implement a continual improvement process

Management standards across a range of business functions such as environment, quality and safety are now being designed so that these traditionally disparate elements can be integrated and managed within a single business management system and not as separate and stand-alone functions. Therefore, some organizations dovetail other management system functions, such as process safety, environmental resource management or quality management together with safety management to meet both regulatory requirements, industry sector requirements and their own internal and discretionary standard requirements.

Standards

[edit]International

[edit]The ILO published ILO-OSH 2001 on Guidelines on Occupational Safety and Health Management Systems to assist organizations with introducing OSH management systems. These guidelines encouraged continual improvement in employee health and safety, achieved via a constant process of policy; organization; planning and implementation; evaluation; and action for improvement, all supported by constant auditing to determine the success of OSH actions.[98]

From 1999 to 2018, OHSAS 18001 was adopted as a British and Polish standard and widely used internationally. It was developed by a selection of trade bodies, international standards and certification bodies to address a gap where no third-party certifiable international standard existed.[citation needed] It was designed for integration with ISO 9001 and ISO 14001.[99]

OHSAS 18001 was replaced by ISO 45001, which was published in March 2018 and implemented in March 2021.[citation needed]

National

[edit]National management system standards for occupational health and safety include AS/NZS 4801 for Australia and New Zealand (now superseded by ISO 45001),[100][101] CSA Z1000:14 for Canada (which is due to be discontinued in favor of CSA Z45001:19, the Canadian adoption of ISO 45000)[102] and ANSI/ASSP Z10 for the United States.[103] In Germany, the Bavarian state government, in collaboration with trade associations and private companies, issued their OHRIS standard for occupational health and safety management systems. A new revision was issued in 2018.[104] The Taiwan Occupational Safety and Health Management System (TOSHMS) was issued in 1997 under the auspices of Taiwan's Occupational Safety and Health Administration.[105]

Identifying OSH hazards and assessing risk

[edit]Hazards, risks, outcomes

[edit]The terminology used in OSH varies between countries, but generally speaking:

- A hazard is something that can cause harm if not controlled.

- The outcome is the harm that results from an uncontrolled hazard.

- A risk is a combination of the probability that a particular outcome may occur and the severity of the harm involved.[106]

"Hazard", "risk", and "outcome" are used in other fields to describe e.g., environmental damage or damage to equipment. However, in the context of OSH, "harm" generally describes the direct or indirect degradation, temporary or permanent, of the physical, mental, or social well-being of workers. For example, repetitively carrying out manual handling of heavy objects is a hazard. The outcome could be a musculoskeletal disorder (MSD) or an acute back or joint injury. The risk can be expressed numerically (e.g., a 0.5 or 50/50 chance of the outcome occurring during a year), in relative terms (e.g., "high/medium/low"), or with a multi-dimensional classification scheme (e.g., situation-specific risks).[citation needed]

Hazard identification

[edit]Hazard identification is an important step in the overall risk assessment and risk management process. It is where individual work hazards are identified, assessed and controlled or eliminated as close to source (location of the hazard) as reasonably practicable. As technology, resources, social expectation or regulatory requirements change, hazard analysis focuses controls more closely toward the source of the hazard. Thus, hazard control is a dynamic program of prevention. Hazard-based programs also have the advantage of not assigning or implying there are "acceptable risks" in the workplace.[107] A hazard-based program may not be able to eliminate all risks, but neither does it accept "satisfactory" – but still risky – outcomes. And as those who calculate and manage the risk are usually managers, while those exposed to the risks are a different group, a hazard-based approach can bypass conflict inherent in a risk-based approach.[citation needed]

The information that needs to be gathered from sources should apply to the specific type of work from which the hazards can come from. Examples of these sources include interviews with people who have worked in the field of the hazard, history and analysis of past incidents, and official reports of work and the hazards encountered. Of these, the personnel interviews may be the most critical in identifying undocumented practices, events, releases, hazards and other relevant information. Once the information is gathered from a collection of sources, it is recommended for these to be digitally archived (to allow for quick searching) and to have a physical set of the same information in order for it to be more accessible. One innovative way to display the complex historical hazard information is with a historical hazards identification map, which distills the hazard information into an easy-to-use graphical format.[citation needed]

Risk assessment

[edit]Modern occupational safety and health legislation usually demands that a risk assessment be carried out prior to making an intervention. This assessment should:

- Identify the hazards

- Identify all affected by the hazard and how

- Evaluate the risk

- Identify and prioritize appropriate control measures.[citation needed]

The calculation of risk is based on the likelihood or probability of the harm being realized and the severity of the consequences. This can be expressed mathematically as a quantitative assessment (by assigning low, medium and high likelihood and severity with integers and multiplying them to obtain a risk factor), or qualitatively as a description of the circumstances by which the harm could arise.[citation needed]

The assessment should be recorded and reviewed periodically and whenever there is a significant change to work practices. The assessment should include practical recommendations to control the risk. Once recommended controls are implemented, the risk should be re-calculated to determine if it has been lowered to an acceptable level. Generally speaking, newly introduced controls should lower risk by one level, i.e., from high to medium or from medium to low.[108]

National legislation and public organizations

[edit]Occupational safety and health practice vary among nations with different approaches to legislation, regulation, enforcement, and incentives for compliance. In the EU, for example, some member states promote OSH by providing public monies as subsidies, grants or financing, while others have created tax system incentives for OSH investments. A third group of EU member states has experimented with using workplace accident insurance premium discounts for companies or organizations with strong OSH records.[109][110]

Australia

[edit]In Australia, four of the six states and both territories have enacted and administer harmonized work health and safety legislation in accordance with the Intergovernmental Agreement for Regulatory and Operational Reform in Occupational Health and Safety.[111] Each of these jurisdictions has enacted work health and safety legislation and regulations based on the Commonwealth Work Health and Safety Act 2011 and common codes of practice developed by Safe Work Australia.[112] Some jurisdictions have also included mine safety under the model approach. However, most have retained separate legislation for the time being. In August 2019, Western Australia committed to join nearly every other state and territory in implementing the harmonized Model WHS Act, Regulations and other subsidiary legislation.[113] Victoria has retained its own regime, although the Model WHS laws themselves drew heavily on the Victorian approach.[citation needed]

Canada

[edit]In Canada, workers are covered by provincial or federal labor codes depending on the sector in which they work. Workers covered by federal legislation (including those in mining, transportation, and federal employment) are covered by the Canada Labour Code; all other workers are covered by the health and safety legislation of the province in which they work.[citation needed] The Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety (CCOHS), an agency of the Government of Canada, was created in 1978 by an act of parliament. The act was based on the belief that all Canadians had "a fundamental right to a healthy and safe working environment." CCOHS is mandated to promote safe and healthy workplaces and help prevent work-related injuries and illnesses.[114]

China

[edit]

In China, the Ministry of Health is responsible for occupational disease prevention and the State Administration of Work Safety workplace safety issues.[citation needed] The Work Safety Law (安全生产法) was issued on 1 November 2002.[115][116] The Occupational Disease Control Act came into force on 1 May 2002.[117] In 2018, the National Health Commission (NHC) was formally established to formulating national health policies. The NHC formulated the "National Occupational Disease Prevention and Control Plan (2021–2025)" in the context of the activities leading to the "Healthy China 2030" initiative.[115]

European Union

[edit]The European Agency for Safety and Health at Work was founded in 1994. In the European Union, member states have enforcing authorities to ensure that the basic legal requirements relating to occupational health and safety are met. In many EU countries, there is strong cooperation between employer and worker organizations (e.g., unions) to ensure good OSH performance, as it is recognized this has benefits for both the worker (through maintenance of health) and the enterprise (through improved productivity and quality).[citation needed]

Member states have all transposed into their national legislation a series of directives that establish minimum standards on occupational health and safety. These directives (of which there are about 20 on a variety of topics) follow a similar structure requiring the employer to assess workplace risks and put in place preventive measures based on a hierarchy of hazard control. This hierarchy starts with elimination of the hazard and ends with personal protective equipment.[citation needed]

| Number of full-time OSH inspectors

per 10,000 full-time employees[118] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Country | Value | Year |

| 2.76 | 2022 | |

| 1.8 | 2021 | |

| 1.41 | 2022 | |

| 1.4 | 2012 | |

| 1.3 | 2022 | |

| 1.13 | 2022 | |

| 1.13 | 2022 | |

| 1.1 | 2022 | |

| 1.07 | 2021 | |

| 1.01 | 2022 | |

| 0.95 | 2021 | |

| 0.92 | 2022 | |

| 0.88 | 2022 | |

| 0.87 | 2021 | |

| 0.8 | 2019 | |

| 0.71 | 2022 | |

| 0.68 | 2022 | |

| 0.58 | 2022 | |

| 0.58 | 2022 | |

| 0.52 | 2022 | |

| 0.46 | 2021 | |

| 0.25 | 2022 | |

| 0.21 | 2022 | |

Denmark

[edit]In Denmark, occupational safety and health is regulated by the Danish Act on Working Environment and Cooperation at the Workplace.[119] The Danish Working Environment Authority (Arbejdstilsynet) carries out inspections of companies, draws up more detailed rules on health and safety at work and provides information on health and safety at work.[120] The result of each inspection is made public on the web pages of the Danish Working Environment Authority so that the general public, current and prospective employees, customers and other stakeholders can inform themselves about whether a given organization has passed the inspection.[citation needed]

Netherlands

[edit]In the Netherlands, the laws for safety and health at work are registered in the Working Conditions Act (Arbeidsomstandighedenwet and Arbeidsomstandighedenbeleid). Apart from the direct laws directed to safety and health in working environments, the private domain has added health and safety rules in Working Conditions Policies (Arbeidsomstandighedenbeleid), which are specified per industry. The Ministry of Social Affairs and Employment (SZW) monitors adherence to the rules through their inspection service. This inspection service investigates industrial accidents and it can suspend work and impose fines when it deems the Working Conditions Act has been violated. Companies can get certified with a VCA certificate for safety, health and environment performance. All employees have to obtain a VCA certificate too, with which they can prove that they know how to work according to the current and applicable safety and environmental regulations.[citation needed]

Ireland

[edit]The main health and safety regulation in Ireland is the Safety, Health and Welfare at Work Act 2005,[121] which replaced earlier legislation from 1989. The Health and Safety Authority, based in Dublin, is responsible for enforcing health and safety at work legislation.[121]

Spain

[edit]In Spain, occupational safety and health is regulated by the Spanish Act on Prevention of Labor Risks. The Ministry of Labor is the authority responsible for issues relating to labor environment. The National Institute for Safety and Health at Work (Instituto Nacional de Seguridad y Salud en el Trabajo, INSST) is the government's scientific and technical organization specialized in occupational safety and health.[122]

Sweden

[edit]In Sweden, occupational safety and health is regulated by the Work Environment Act.[123] The Swedish Work Environment Authority (Arbetsmiljöverket) is the government agency responsible for issues relating to the working environment. The agency works to disseminate information and furnish advice on OSH, has a mandate to carry out inspections, and a right to issue stipulations and injunctions to any non-compliant employer.[124]

India

[edit]In India, the Ministry of Labour and Employment formulates national policies on occupational safety and health in factories and docks with advice and assistance from its Directorate General Factory Advice Service and Labour Institutes (DGFASLI), and enforces its policies through inspectorates of factories and inspectorates of dock safety. The DGFASLI provides technical support in formulating rules, conducting occupational safety surveys and administering occupational safety training programs.[125]

Indonesia

[edit]In Indonesia, the Ministry of Manpower (Kementerian Ketenagakerjaan, or Kemnaker) is responsible to ensure the safety, health and welfare of workers. Important OHS acts include the Occupational Safety Act 1970 and the Occupational Health Act 1992.[126] Sanctions, however, are still low (with a maximum of 15 million rupiahs fine and/or a maximum of one year in prison) and violations are still very frequent.[127]

Japan

[edit]The Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (MHLW) is the governmental agency overseeing occupational safety and health in Japan. The MHLW is responsible for enforcing Industrial Safety and Health Act of 1972 – the key piece of OSH legislation in Japan –, setting regulations and guidelines, supervising labor inspectors who monitor workplaces for compliance with safety and health standards, investigating accidents, and issuing orders to improve safety conditions. The Labor Standards Bureau is an arm of MHLW tasked with supervising and guiding businesses, inspecting manufacturing facilities for safety and compliance, investigating accidents, collecting statistics, enforcing regulations and administering fines for safety violations, and paying accident compensation for injured workers.[128][129]

The Japan Industrial Safety and Health Association (JISHA) is a non-profit organization established under the Industrial Safety and Health Act of 1972. It works closely with MHLW, the regulatory body, to promote workplace safety and health. The responsibilities of JISHA include: Providing education and training on occupational safety and health, conducting research and surveys on workplace safety and health issues, offering technical guidance and consultations to businesses, disseminating information and raising awareness about occupational safety and health, and collaborating with international organizations to share best practices and improve global workplace safety standards.[130]

The Japan National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (JNIOSH) conducts research to support governmental policies in occupational safety and health. The organization categorizes its research into project studies, cooperative research, fundamental research, and government-requested research. Each category focuses on specific themes, from preventing accidents and ensuring workers' health, to addressing changes in employment structure. The organization sets clear goals, develops road maps, and collaborates with the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare to discuss progress and policy contributions.[131]

Malaysia

[edit]In Malaysia, the Department of Occupational Safety and Health (DOSH) under the Ministry of Human Resources is responsible to ensure that the safety, health and welfare of workers in both the public and private sector is upheld. DOSH is responsible to enforce the Factories and Machinery Act 1967 and the Occupational Safety and Health Act 1994. Malaysia has a statutory mechanism for worker involvement through elected health and safety representatives and health and safety committees.[132] This followed a similar approach originally adopted in Scandinavia.[citation needed]

Saudi Arabia

[edit]In Saudi Arabia, the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Development administrates workers' rights and the labor market as a whole, consistent with human rights rules upheld by the Human Rights Commission of the kingdom.[133]

Singapore

[edit]In Singapore, the Ministry of Manpower (MOM) is the government agency in charge of OHS policies and enforcement. The key piece of legislation regulating aspects of OHS is the Workplace Safety and Health Act.[134] The MOM promotes and manages campaigns against unsafe work practices, such as when working at height, operating cranes and in traffic management. Examples include Operation Cormorant and the Falls Prevention Campaign.[135]

South Africa

[edit]In South Africa the Department of Employment and Labour is responsible for occupational health and safety inspection and enforcement in the commercial and industrial sectors, with the exclusion of mining, where the Department of Mineral Resources is responsible.[136][137] The main statutory legislation on health and safety in the jurisdiction of the Department of Employment and Labour is the OHS Act or OHSA (Act No. 85 of 1993: Occupational Health and Safety Act, as amended by the Occupational Health and Safety Amendment Act, No. 181 of 1993).[136] Regulations implementing the OHS Act include:[138]

- General Safety Regulations, 1986[139]

- Environmental Regulations for Workplaces, 1987[140]

- Driven Machinery Regulations, 1988[141]

- General Machinery Regulations, 1988[142]

- Noise Induced Hearing Loss Regulations, 2003[143]

- Pressure Equipment Regulations, 2004

- General Administrative Regulations, 2003[144]

- Diving Regulations, 2009[145]

- Construction Regulations, 2014

Syria

[edit]In Syria, health and safety is the responsibility of the Ministry of Social Affairs and Labor (Arabic: وزارة الشؤون الاجتماعية والعمل, romanized: Wizārat al-Shuʼūn al-ijtimāʻīyah wa-al-ʻamal).[146]

Taiwan

[edit]In Taiwan, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration of the Ministry of Labor is in charge of occupational safety and health.[147] The matter is governed under the Occupational Safety and Health Act.[148]

United Arab Emirates

[edit]In the United Arab Emirates, national OSH legislation is based on the Federal Law on Labor (1980). Order No. 32 of 1982 on Protection from Hazards and Ministerial Decision No. 37/2 of 1982 are also of importance.[149] The competent authority for safety and health at work at the federal level is the Ministry of Human Resources and Emiratisation (MoHRE).[150]

United Kingdom

[edit]Health and safety legislation in the UK is drawn up and enforced by the Health and Safety Executive and local authorities under the Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974 (HASAWA or HSWA).[151][152] HASAWA introduced (section 2) a general duty on an employer to ensure, so far as is reasonably practicable, the health, safety and welfare at work of all his employees, with the intention of giving a legal framework supporting codes of practice not in themselves having legal force but establishing a strong presumption as to what was reasonably practicable (deviations from them could be justified by appropriate risk assessment). The previous reliance on detailed prescriptive rule-setting was seen as having failed to respond rapidly enough to technological change, leaving new technologies potentially unregulated or inappropriately regulated.[153] HSE has continued to make some regulations giving absolute duties (where something must be done with no "reasonable practicability" test) but in the UK the regulatory trend is away from prescriptive rules, and toward goal setting and risk assessment. Recent major changes to the laws governing asbestos and fire safety management embrace the concept of risk assessment. The other key aspect of the UK legislation is a statutory mechanism for worker involvement through elected health and safety representatives and health and safety committees. This followed a similar approach in Scandinavia, and that approach has since been adopted in countries such as Australia, Canada, New Zealand and Malaysia.[citation needed]

The Health and Safety Executive service dealing with occupational medicine has been the Employment Medical Advisory Service. In 2014 a new occupational health organization, the Health and Work Service, was created to provide advice and assistance to employers in order to get back to work employees on long-term sick-leave.[154] The service, funded by the government, offers medical assessments and treatment plans, on a voluntary basis, to people on long-term absence from their employer; in return, the government no longer foots the bill for statutory sick pay provided by the employer to the individual.[citation needed]

United States

[edit]In the United States, President Richard Nixon signed the Occupational Safety and Health Act into law on 29 December 1970. The act created the three agencies which administer OSH: the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), and the Occupational Safety and Health Review Commission (OSHRC).[155] The act authorized OSHA to regulate private employers in the 50 states, the District of Columbia, and territories.[156] It includes a general duty clause (29 U.S.C. §654, 5(a)) requiring an employer to comply with the Act and regulations derived from it, and to provide employees with "employment and a place of employment which are free from recognized hazards that are causing or are likely to cause [them] death or serious physical harm."[157]

OSHA was established in 1971 under the Department of Labor. It has headquarters in Washington, DC, and ten regional offices, further broken down into districts, each organized into three sections: compliance, training, and assistance. Its stated mission is "to ensure safe and healthful working conditions for workers by setting and enforcing standards and by providing training, outreach, education and assistance."[156] The original plan was for OSHA to oversee 50 state plans with OSHA funding 50% of each plan, but this did not work out that way: As of 2023[update] there are 26 approved state plans (with four covering only public employees) and OSHA manages the plan in the states not participating.[92]

OSHA develops safety standards in the Code of Federal Regulations and enforces those safety standards through compliance inspections conducted by Compliance Officers; enforcement resources are focused on high-hazard industries. Worksites may apply to enter OSHA's Voluntary Protection Program (VPP). A successful application leads to an on-site inspection; if this is passed, the site gains VPP status and OSHA no longer inspect it annually nor (normally) visit it unless there is a fatal accident or an employee complaint until VPP revalidation (after three–five years). VPP sites generally have injury and illness rates less than half the average for their industry.[citation needed]

OSHA has a number of specialists in local offices to provide information and training to employers and employees at little or no cost.[4] Similarly OSHA produces a range of publications and funds consultation services available for small businesses.[citation needed]

OSHA has strategic partnership and alliance programs to develop guidelines, assist in compliance, share resources, and educate workers in OHS.[92] OSHA manages Susan B. Harwood grants to non-profit organizations to train workers and employers to recognize, avoid, and prevent safety and health hazards in the workplace.[158] Grants focus on small business, hard-to-reach workers and high-hazard industries.[159]

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), also created under the Occupational Safety and Health Act, is the federal agency responsible for conducting research and making recommendations for the prevention of work-related injury and illness. NIOSH is part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) within the Department of Health and Human Services.[160]

Professional roles and responsibilities

[edit]Those in the field of occupational safety and health come from a wide range of disciplines and professions including medicine, occupational medicine, epidemiology, physiotherapy and rehabilitation, psychology, human factors and ergonomics, and many others. Professionals advise on a broad range of occupational safety and health matters. These include how to avoid particular pre-existing conditions causing a problem in the occupation, correct posture, frequency of rest breaks, preventive actions that can be undertaken, and so forth. The quality of occupational safety is characterized by (1) the indicators reflecting the level of industrial injuries, (2) the average number of days of incapacity for work per employer, (3) employees' satisfaction with their work conditions and (4) employees' motivation to work safely.[161]

The main tasks undertaken by the OSH practitioner include:

- Inspecting, testing and evaluating workplace environments, programs, equipment, and practices to ensure that they follow government safety regulation.

- Designing and implementing workplace programs and procedures that control or prevent chemical, physical, or other risks to workers.

- Educating employers and workers about maintaining workplace safety.

- Demonstrating use of safety equipment and ensuring proper use by workers.

- Investigating incidents to determine the cause and possible prevention.

- Preparing written reports of their findings.

OSH specialists examine worksites for environmental or physical factors that could harm employee health, safety, comfort or performance. They then find ways to improve potential risk factors. For example, they may notice potentially hazardous conditions inside a chemical plant and suggest changes to lighting, equipment, materials, or ventilation. OSH technicians assist specialists by collecting data on work environments and implementing the worksite improvements that specialists plan. Technicians also may check to make sure that workers are using required protective gear, such as masks and hardhats. OSH specialists and technicians may develop and conduct employee training programs. These programs cover a range of topics, such as how to use safety equipment correctly and how to respond in an emergency. In the event of a workplace safety incident, specialists and technicians investigate its cause. They then analyze data from the incident, such as the number of people impacted, and look for trends in occurrence. This evaluation helps them to recommend improvements to prevent future incidents.[162]

Given the high demand in society for health and safety provisions at work based on reliable information, OSH professionals should find their roots in evidence-based practice. A new term is "evidence-informed decision making". Evidence-based practice can be defined as the use of evidence from literature, and other evidence-based sources, for advice and decisions that favor the health, safety, well-being, and work ability of workers. Therefore, evidence-based information must be integrated with professional expertise and the workers' values. Contextual factors must be considered related to legislation, culture, financial, and technical possibilities. Ethical considerations should be heeded.[163]

The roles and responsibilities of OSH professionals vary regionally but may include evaluating working environments, developing, endorsing and encouraging measures that might prevent injuries and illnesses, providing OSH information to employers, employees, and the public, providing medical examinations, and assessing the success of worker health programs.[citation needed]

The Netherlands

[edit]In the Netherlands, the required tasks for health and safety staff are only summarily defined and include:[164]

- Providing voluntary medical examinations.

- Providing a consulting room on the work environment to the workers.

- Providing health assessments (if needed for the job concerned).

Dutch law influences the job of the safety professional mainly through the requirement on employers to use the services of a certified working-conditions service for advice. A certified service must employ sufficient numbers of four types of certified experts to cover the risks in the organizations which use the service:

- A safety professional

- An occupational hygienist

- An occupational physician

- A work and organization specialist.

In 2004, 14% of health and safety practitioners in the Netherlands had an MSc and 63% had a BSc. 23% had training as an OSH technician.[165]

Norway

[edit]In Norway, the main required tasks of an occupational health and safety practitioner include:

- Systematic evaluations of the working environment.

- Endorsing preventive measures which eliminate causes of illnesses in the workplace.

- Providing information on the subject of employees' health.

- Providing information on occupational hygiene, ergonomics, and environmental and safety risks in the workplace.

In 2004, 37% of health and safety practitioners in Norway had an MSc and 44% had a BSc. 19% had training as an OSH technician.[165]

Education and training

[edit]Formal education

[edit]There are multiple levels of training applicable to the field of occupational safety and health. Programs range from individual non-credit certificates and awareness courses focusing on specific areas of concern, to full doctoral programs. The University of Southern California was one of the first schools in the US to offer a PhD program focusing on the field. Further, multiple master's degree programs exist, such as that of the Indiana State University who offer MSc and MA programs. Other masters-level qualifications include the MSc and Master of Research (MRes) degrees offered by the University of Hull in collaboration with the National Examination Board in Occupational Safety and Health (NEBOSH). Graduate programs are designed to train educators, as well as high-level practitioners.[citation needed]

Many OSH generalists focus on undergraduate studies; programs within schools, such as that of the University of North Carolina's online BSc in environmental health and safety, fill a large majority of hygienist needs. However, smaller companies often do not have full-time safety specialists on staff, thus, they appoint a current employee to the responsibility. Individuals finding themselves in positions such as these, or for those enhancing marketability in the job-search and promotion arena, may seek out a credit certificate program. For example, the University of Connecticut's online OSH certificate[166] provides students familiarity with overarching concepts through a 15-credit (5-course) program. Programs such as these are often adequate tools in building a strong educational platform for new safety managers with a minimal outlay of time and money. Further, most hygienists seek certification by organizations that train in specific areas of concentration, focusing on isolated workplace hazards. The American Society of Safety Professionals (ASSP), Board for Global EHS Credentialing (BGC), and American Industrial Hygiene Association (AIHA) offer individual certificates on many different subjects from forklift operation to waste disposal and are the chief facilitators of continuing education in the OSH sector.[citation needed]

In the US, the training of safety professionals is supported by NIOSH through their NIOSH Education and Research Centers.

In the UK, both NEBOSH and the Institution of Occupational Safety and Health (IOSH) develop health and safety qualifications and courses which cater to a mixture of industries and levels of study. Although both organizations are based in the UK, their qualifications are recognized and studied internationally as they are delivered through their own global networks of approved providers. The Health and Safety Executive has also developed health and safety qualifications in collaboration with the NEBOSH.[citation needed]

In Australia, training in OSH is available at the vocational education and training level, and at university undergraduate and postgraduate level. Such university courses may be accredited by an accreditation board of the Safety Institute of Australia. The institute has produced a Body of Knowledge which it considers is required by a generalist safety and health professional and offers a professional qualification.[167] The Australian Institute of Health and Safety has instituted the national Eric Wigglesworth OHS Education Medal to recognize achievement in OSH doctorate education.[168]

Field training

[edit]One form of training delivered in the workplace is known as toolbox talk. According to the UK's Health and Safety Executive, a toolbox talk is a short presentation to the workforce on a single aspect of health and safety.[169] Such talks are often used, especially in the construction industry, by site supervisors, frontline managers and owners of small construction firms to prepare and deliver advice on matters of health, safety and the environment and to obtain feedback from the workforce.[170]

Use of virtual reality

[edit]Virtual reality is a novel tool to deliver safety training in many fields. Some applications have been developed and tested especially for fire and construction safety training.[171][172] Preliminary findings seem to support that virtual reality is more effective than traditional training in knowledge retention.[173]

Contemporary developments

[edit]On an international scale, the World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Labour Organization (ILO) have begun focusing on labor environments in developing nations with projects such as Healthy Cities.[174] Many of these developing countries are stuck in a situation in which their relative lack of resources to invest in OSH leads to increased costs due to work-related illnesses and accidents.[citation needed] The ILO estimates that work-related illness and accidents cost up to 10% of GDP in Latin America, compared with just 2.6% to 3.8% in the EU.[175] There is continued use of asbestos, a notorious hazard, in some developing countries. So asbestos-related disease is expected to continue to be a significant problem well into the future.[citation needed]

Artificial intelligence

[edit]

There are several broad aspects of artificial intelligence (AI) that may give rise to specific hazards.

Many hazards of AI are psychosocial in nature due to its potential to cause changes in work organization.[176] For example, AI is expected to lead to changes in the skills required of workers, requiring retraining of existing workers, flexibility, and openness to change.[177] Increased monitoring may lead to micromanagement or perception of surveillance, and thus to workplace stress. There is also the risk of people being forced to work at a robot's pace, or to monitor robot performance at nonstandard hours. Additionally, algorithms may show algorithmic bias through being trained on past decisions may mimic undesirable human biases, for example, past discriminatory hiring and firing practices.[178] Some approaches to accident analysis may be biased to safeguard a technological system and its developers by assigning blame to the individual human operator instead.[179]

Physical hazards in the form of human–robot collisions may arise from robots using AI, especially collaborative robots (cobots). Cobots are intended to operate in close proximity to humans, which makes it impossible to implement the common hazard control of isolating the robot using fences or other barriers, which is widely used for traditional industrial robots. Automated guided vehicles are a type of cobot in common use, often as forklifts or pallet jacks in warehouses or factories.[180]

Both applications and hazards arising from AI can be considered as part of existing frameworks for occupational health and safety risk management. As with all hazards, risk identification is most effective and least costly when done in the design phase.[176] AI, in common with other computational technologies, requires cybersecurity measures to stop software breaches and intrusions,[181] as well as information privacy measures.[182] Communication and transparency with workers about data usage is a control for psychosocial hazards arising from security and privacy issues.[182] Workplace health surveillance, the collection and analysis of health data on workers, is challenging for AI because labor data are often reported in aggregate, does not provide breakdowns between different types of work, and is focused on economic data such as wages and employment rates rather than skill content of jobs.[183]

Coronavirus

[edit]The National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) National Occupational Research Agenda Manufacturing Council established an externally-lead COVID-19 workgroup to provide exposure control information specific to working in manufacturing environments. The workgroup identified disseminating information most relevant to manufacturing workplaces as a priority, and that would include providing content in Wikipedia. This includes evidence-based practices for infection control plans,[184] and communication tools.

Nanotechnology

[edit]

Nanotechnology is an example of a new, relatively unstudied technology. A Swiss survey of 138 companies using or producing nanoparticulate matter in 2006 resulted in forty completed questionnaires. Sixty-five per cent of respondent companies stated they did not have a formal risk assessment process for dealing with nanoparticulate matter.[185] Nanotechnology already presents new issues for OSH professionals that will only become more difficult as nanostructures become more complex. The size of the particles renders most containment and personal protective equipment ineffective. The toxicology values for macro sized industrial substances are rendered inaccurate due to the unique nature of nanoparticulate matter. As nanoparticulate matter decreases in size its relative surface area increases dramatically, increasing any catalytic effect or chemical reactivity substantially versus the known value for the macro substance. This presents a new set of challenges in the near future to rethink contemporary measures to safeguard the health and welfare of employees against a nanoparticulate substance that most conventional controls have not been designed to manage.[186]

Occupational health inequalities

[edit]Occupational health inequalities refer to differences in occupational injuries and illnesses that are closely linked with demographic, social, cultural, economic, and/or political factors.[187] Although many advances have been made to rectify gaps in occupational health within the past half century, still many persist due to the complex overlapping of occupational health and social factors.[188] There are three main areas of research on occupational health inequities:

- Identifying which social factors, either individually or in combination, contribute to the inequitable distribution of work-related benefits and risks.[189]

- Examining how the related structural disadvantages materialize in the lives of workers to put them at greater risk for occupational injury or illness.[190]

- Преобразование этих результатов в интервенционные исследования для создания доказательной базы эффективных способов сокращения неравенства в области гигиены труда. [191]

Транснациональные рабочие и иммигранты

[ редактировать ]Популяции рабочих-иммигрантов часто подвергаются большему риску травм и смертельных исходов на рабочем месте. Например, в Соединенных Штатах мексиканские рабочие-иммигранты имеют один из самых высоких показателей смертельных травм на рабочем месте среди всего работающего населения. Подобные статистические данные объясняются сочетанием социальных, структурных и физических аспектов рабочего места. Этим работникам трудно получить доступ к информации и ресурсам по безопасности на своих родных языках из-за отсутствия социальной и политической вовлеченности. В дополнение к лингвистически адаптированным вмешательствам также важно, чтобы вмешательства были культурно приемлемыми. [192]

Те, кто проживает в стране для работы без визы или другого официального разрешения, также могут не иметь доступа к правовым ресурсам и средствам правовой защиты, которые предназначены для защиты большинства работников. Организации по охране труда и технике безопасности, которые полагаются на информаторов вместо собственных независимых проверок, могут особенно подвергаться риску получить неполную картину о здоровье работников.

См. также

[ редактировать ]Связанные темы

[ редактировать ]- Достойный труд – занятость, при которой уважаются основные права человека.

- Examinetics – поставщик услуг мобильного и выездного обследования профессионального здоровья.

- Трудовые права - Юридические права и права человека, касающиеся трудовых отношений между работниками и работодателями.

- Национальная программа профессиональных исследований - программа Национального института безопасности и гигиены труда США.

- Профессиональное заболевание – любое хроническое заболевание, возникающее в результате работы или профессиональной деятельности.

- Профессиональные сердечно-сосудистые заболевания – заболевания сердца и кровеносных сосудов, вызванные условиями труда.

- Профессиональный стресс – напряжение, связанное с работой.

- Профилактика посредством проектирования . Снижение профессиональных рисков за счет раннего планирования в процессе проектирования.

- Принципы экономии движения . Свод правил и предложений по улучшению ручного труда на производстве.

- Джекпот безопасности

- Сеульская декларация по безопасности и гигиене труда – Декларация, увековечивающая национальную профилактическую культуру безопасности и здоровья.