Уйгуры

| |

|---|---|

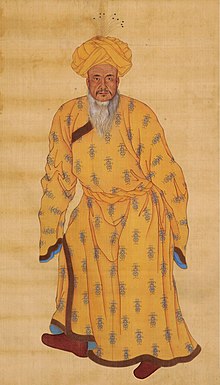

Уйгур в Кашгаре | |

| Общая численность населения | |

| в. 13,5 миллионов [ примечание 1 ] | |

| Регионы со значительной численностью населения | |

| Китай (в основном в Синьцзяне ) | 11,8 миллиона [ 1 ] |

| Казахстан | 301,584 (2024) [ 2 ] |

| Pakistan | 200,000 (2010)[3] |

| Turkey | 100,000–300,000[4] |

| Kyrgyzstan | 200,000[5] |

| Uzbekistan | 48,500 (2019)[6] |

| United States | 8,905 (per US Census Bureau 2015)[7] – 15,000 (per ETGE estimate 2021)[8] |

| Saudi Arabia | 8,730 (2018)[9] |

| Australia | 5,000–10,000[10] |

| Russia | 3,696 (2010)[11] |

| India | ~3,500[12] |

| Turkmenistan | ~3,000[13] |

| Afghanistan | 2,000[14] |

| Japan | 2,000 (2021)[15] |

| Sweden | 2,000 (2019)[16] |

| Canada | ~1,555 (2016)[17] |

| Germany | ~750 (2013)[18] |

| Finland | 327 (2021)[19] |

| Mongolia | 258 (2000)[20] |

| Ukraine | 197 (2001)[21] |

| Languages | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Sunni Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Uzbeks,[22] Ili Turks, Äynus | |

| Uyghurs | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Uyghur name | |||

| Uyghur | ئۇيغۇرلار | ||

| |||

| Chinese name | |||

| Simplified Chinese | 维吾尔 | ||

| Traditional Chinese | 維吾爾 | ||

| |||

| Part of a series on |

| Uyghurs |

|---|

|

Uyghurs outside of Xinjiang Uyghur organizations |

Уйгуры , [ примечание 2 ] альтернативно пишется уйгуры , [ 25 ] [ 26 ] [ 27 ] Уйгуры или уйгуры — тюркская этническая группа, происходящая из Центральной и Восточной Азии и культурно связанная с ней . Уйгуры признаны титульной национальностью Синьцзян - Уйгурского автономного района на северо-западе Китая . Они являются одним из 55 официально признанных этнических меньшинств Китая . [ 28 ]

Уйгуры традиционно населяли ряд оазисов, разбросанных по пустыне Такла-Макан в пределах Таримской котловины . Эти оазисы исторически существовали как независимые государства или находились под контролем многих цивилизаций, включая Китай , монголов , тибетцев и различные тюркские государства. Уйгуры постепенно начали исламизироваться в 10 веке, а к 16 веку большинство уйгуров идентифицировали себя как мусульмане. С тех пор ислам сыграл важную роль в уйгурской культуре и самобытности.

An estimated 80% of Xinjiang's Uyghurs still live in the Tarim Basin.[29] The rest of Xinjiang's Uyghurs mostly live in Ürümqi, the capital city of Xinjiang, which is located in the historical region of Dzungaria. The largest community of Uyghurs living outside of Xinjiang are the Taoyuan Uyghurs of north-central Hunan's Taoyuan County.[30] Significant diasporic communities of Uyghurs exist in other Turkic countries such as Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan and Turkey.[31] Smaller communities live in Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Australia, Russia and Sweden.[32]

Since 2014,[33][34] the Chinese government has been accused by various organizations, such as Human Rights Watch[35] of subjecting Uyghurs living in Xinjiang to widespread persecution, including forced sterilization[36][37] and forced labor.[38][39][40] Scholars[who?] estimate that at least one million Uyghurs have been arbitrarily detained in the Xinjiang internment camps since 2017;[41][42][43] Chinese government officials claim that these camps, created under CCP general secretary Xi Jinping's administration, serve the goals of ensuring adherence to Chinese Communist Party (CCP) ideology, preventing separatism, fighting terrorism, and providing vocational training to Uyghurs.[44] Various scholars[who?], human rights organizations and governments consider abuses perpetrated against the Uyghurs to amount to crimes against humanity, or even genocide.

Etymology

In the Uyghur language, the ethnonym is written ئۇيغۇر in Arabic script, Уйғур in Uyghur Cyrillic and Uyghur or Uygur (as the standard Chinese romanization, GB 3304–1991) in Latin;[45] they are all pronounced as [ʔʊjˈʁʊːr].[46][47] In Chinese, this is transcribed into characters as 维吾尔 / 維吾爾, which is romanized in pinyin as Wéiwú'ěr.

In English, the name is officially spelled Uyghur by the Xinjiang government[48] but also appears as Uighur,[49] Uigur[49] and Uygur (these reflect the various Cyrillic spellings Уиғур, Уигур and Уйгур). The name is usually pronounced in English as /ˈwiːɡʊər, -ɡər/ WEE-goor, -gər (and thus may be preceded by the indefinite article "a"),[49][50][51][25] although some Uyghurs advocate the use of a more native pronunciation /ˌuːiˈɡʊər/ OO-ee-GOOR instead (which, in contrast, calls for the indefinite article "an").[23][24][52]

The term's original meaning is unclear. Old Turkic inscriptions record the word uyɣur[53] (Old Turkic: 𐰆𐰖𐰍𐰆𐰺); an example is found on the Sudzi inscription, "I am khan ata of Yaglaqar, came from the Uigur land." (Old Turkic: Uyγur jerinte Yaγlaqar qan ata keltim).[54] It is transcribed into Tang annals as 回纥 / 回紇 (Mandarin: Huíhé, but probably *[ɣuɒiɣət] in Middle Chinese).[55] It was used as the name of one of the Turkic polities formed in the interim between the First and Second Göktürk Khaganates (AD 630–684).[56] The Old History of the Five Dynasties records that in 788 or 809, the Chinese acceded to a Uyghur request and emended their transcription to 回鹘 / 回鶻 (Mandarin: Huíhú, but [ɣuɒiɣuət] in Middle Chinese).[57][58]

Modern etymological explanations for the name Uyghur range from derivation from the verb "follow, accommodate oneself"[49] and adjective "non-rebellious" (i.e., from Turkic uy/uð-) to the verb meaning "wake, rouse or stir" (i.e., from Turkic oðğur-). None of these is thought to be satisfactory because the sound shift of /ð/ and /ḏ/ to /j/ does not appear to be in place by this time.[57] The etymology therefore cannot be conclusively determined and its referent is also difficult to fix. The "Huihe" and "Huihu" seem to be a political rather than a tribal designation[59] or it may be one group among several others collectively known as the Toquz Oghuz.[60] The name fell out of use in the 15th century, but was reintroduced in the early 20th century[46][47] by the Soviet Bolsheviks to replace the previous terms Turk and Turki.[61][note 3] The name is currently used to refer to the settled Turkic urban dwellers and farmers of the Tarim Basin who follow traditional Central Asian sedentary practices, distinguishable from the nomadic Turkic populations in Central Asia.

The earliest record of a Uyghur tribe appears in accounts from the Northern Wei (4th–6th century A.D.), wherein they were named 袁紇 Yuanhe (< MC ZS *ɦʉɐn-ɦət) and derived from a confederation named 高车 / 高車 (lit. "High Carts"), read as Gāochē in Mandarin Chinese but originally with the reconstructed Middle Chinese pronunciation *[kɑutɕʰĭa], later known as the Tiele (铁勒 / 鐵勒, Tiělè).[63][64][65] Gāochē in turn has been connected to the Uyghur Qangqil (قاڭقىل or Қаңқил).[66]

Identity

Throughout its history, the term Uyghur has had an increasingly expansive definition. Initially signifying only a small coalition of Tiele tribes in northern China, Mongolia and the Altai Mountains, it later denoted citizenship in the Uyghur Khaganate. Finally, it was expanded into an ethnicity whose ancestry originates with the fall of the Uyghur Khaganate in the year 842, causing Uyghur migration from Mongolia into the Tarim Basin. The Uyghurs who moved to the Tarim Basin mixed with the local Tocharians, and converted to the Tocharian religion, and adopted their culture of oasis agriculture.[67][68] The fluid definition of Uyghur and the diverse ancestry of modern Uyghurs create confusion as to what constitutes true Uyghur ethnography and ethnogenesis. Contemporary scholars consider modern Uyghurs to be the descendants of a number of peoples, including the ancient Uyghurs of Mongolia migrating into the Tarim Basin after the fall of the Uyghur Khaganate, Iranic Saka tribes and other Indo-European peoples inhabiting the Tarim Basin before the arrival of the Turkic Uyghurs.[69]

Uyghur activists identify with the Tarim mummies, remains of an ancient people inhabiting the region, but research into the genetics of ancient Tarim mummies and their links with modern Uyghurs remains problematic, both to Chinese government officials concerned with ethnic separatism and to Uyghur activists concerned the research could affect their indigenous claim.[70]

A genomic study published in 2021 found that these early mummies had high levels of Ancient North Eurasian ancestry (ANE, about 72%), with smaller admixture from Ancient Northeast Asians (ANA, about 28%), but no detectable Western Steppe-related ancestry.[71][72] They formed a genetically isolated local population that "adopted neighbouring pastoralist and agriculturalist practices, which allowed them to settle and thrive along the shifting riverine oases of the Taklamakan Desert."[73] These mummified individuals were long suspected to have been "Proto-Tocharian-speaking pastoralists", ancestors of the Tocharians, but the authors of this study found no genetic connection with Indo-European-speaking migrants, particularly the Afanasievo or BMAC cultures.[74]

Origin of modern nomenclature

The Uighurs are the people whom old Russian travelers called "Sart" (a name they used for sedentary, Turkish-speaking Central Asians in general), while Western travelers called them Turki, in recognition of their language. The Chinese used to call them "Ch'an-t'ou" ('Turbaned Heads') but this term has been dropped, being considered derogatory, and the Chinese, using their own pronunciation, now called them Weiwuerh. As a matter of fact there was for centuries no 'national' name for them; people identified themselves with the oasis they came from, such as Kashgar or Turfan.

— Owen Lattimore, "Return to China's Northern Frontier." The Geographical Journal, Vol. 139, No. 2, June 1973[75]

The term "Uyghur" was not used to refer to a specific existing ethnicity in the 19th century: it referred to an 'ancient people'. A late-19th-century encyclopedia entitled The Cyclopædia of India and of Eastern and Southern Asia said "the Uigur are the most ancient of Turkish tribes and formerly inhabited a part of Chinese Tartary (Xinjiang), now occupied by a mixed population of Turk, Mongol and Kalmuck".[76] Before 1921/1934,[clarification needed] Western writers called the Turkic-speaking Muslims of the oases "Turki" and the Turkic Muslims who had migrated from the Tarim Basin to Ili, Ürümqi and Dzungaria in the northern portion of Xinjiang during the Qing dynasty were known as "Taranchi", meaning "farmer". The Russians and other foreigners referred to them as "Sart",[77] "Turk" or "Turki".[78][note 3] In the early 20th century they identified themselves by different names to different peoples and in response to different inquiries: they called themselves Sarts in front of Kazakhs and Kyrgyz while they called themselves "Chantou" if asked about their identity after first identifying as a Muslim.[79][80] The term "Chantou" (纏頭; Chántóu, meaning "Turban Head") was used to refer to the Turkic Muslims of Altishahr (now Southern Xinjiang),[81][82] including by Hui (Tungan) people.[83] These groups of peoples often identify themselves by their originating oasis instead of an ethnicity;[84] for example those from Kashgar may refer to themselves as Kashgarliq or Kashgari, while those from Hotan identity themselves as "Hotani".[80][85] Other Central Asians once called all the inhabitants of Xinjiang's Southern oases Kashgari,[86] a term still used in some regions of Pakistan.[87] The Turkic people also used "Musulman", which means "Muslim", to describe themselves.[85][88][89]

Rian Thum explored the concepts of identity among the ancestors of the modern Uyghurs in Altishahr (the native Uyghur name for Eastern Turkestan or Southern Xinjiang) before the adoption of the name "Uyghur" in the 1930s, referring to them by the name "Altishahri" in his article Modular History: Identity Maintenance before Uyghur Nationalism. Thum indicated that Altishahri Turkis did have a sense that they were a distinctive group separate from the Turkic Andijanis to their west, the nomadic Turkic Kirghiz, the nomadic Mongol Qalmaq and the Han Chinese Khitay before they became known as Uyghurs. There was no single name used for their identity; various native names Altishahris used for identify were Altishahrlik (Altishahr person), yerlik (local), Turki and Musulmān (Muslim); the term Musulmān in this situation did not signify religious connotations, because the Altishahris exclude other Muslim peoples like the Kirghiz while identifying themselves as Musulmān.[90][91] Dr. Laura J Newby says the sedentary Altishahri Turkic people considered themselves separate from other Turkic Muslims since at least the 19th century.[92]

The name "Uyghur" reappeared after the Soviet Union took the 9th-century ethnonym from the Uyghur Khaganate, then reapplied it to all non-nomadic Turkic Muslims of Xinjiang.[93] It followed western European orientalists like Julius Klaproth in the 19th century who revived the name and spread the use of the term to local Turkic intellectuals[94] and a 19th-century proposal from Russian historians that modern-day Uyghurs were descended from the Kingdom of Qocho and Kara-Khanid Khanate formed after the dissolution of the Uyghur Khaganate.[95] Historians generally agree that the adoption of the term "Uyghur" is based on a decision from a 1921 conference in Tashkent, attended by Turkic Muslims from the Tarim Basin (Xinjiang).[93][96][97][98] There, "Uyghur" was chosen by them as the name of their ethnicity, although they themselves note that they were not to be confused with the Uyghur Empire of medieval history.[77][99] According to Linda Benson, the Soviets and their client Sheng Shicai intended to foster a Uyghur nationality to divide the Muslim population of Xinjiang, whereas the various Turkic Muslim peoples preferred to identify themselves as "Turki", "East Turkestani" or "Muslim".[77]

On the other hand, the ruling regime of China at that time, the Kuomintang, grouped all Muslims, including the Turkic-speaking people of Xinjiang, into the "Hui nationality".[100][101] The Qing dynasty and the Kuomintang generally referred to the sedentary oasis-dwelling Turkic Muslims of Xinjiang as "turban-headed Hui" to differentiate them from other predominantly Muslim ethnicities in China.[77][102][note 4] In the 1930s, foreigners travelers in Xinjiang such as George W. Hunter, Peter Fleming, Ella Maillart and Sven Hedin, referred to the Turkic Muslims of the region as "Turki" in their books. Use of the term Uyghur was unknown in Xinjiang until 1934. The area governor, Sheng Shicai, came to power, adopting the Soviet ethnographic classification instead of the Kuomintang's and became the first to promulgate the official use of the term "Uyghur" to describe the Turkic Muslims of Xinjiang.[77][95][104] "Uyghur" replaced "rag-head".[105]

Sheng Shicai's introduction of the "Uighur" name for the Turkic people of Xinjiang was criticized and rejected by Turki intellectuals such as Pan-Turkist Jadids and East Turkestan independence activists Muhammad Amin Bughra (Mehmet Emin) and Masud Sabri. They demanded the names "Türk" or "Türki" be used instead as the ethnonyms for their people. Masud Sabri viewed the Hui people as Muslim Han Chinese and separate from his people,[106] while Bughrain criticized Sheng for his designation of Turkic Muslims into different ethnicities which could sow disunion among Turkic Muslims.[107][108] After the Communist victory, the Chinese Communist Party under Chairman Mao Zedong continued the Soviet classification, using the term "Uyghur" to describe the modern ethnicity.[77]

In current usage, Uyghur refers to settled Turkic-speaking urban dwellers and farmers of the Tarim Basin and Ili who follow traditional Central Asian sedentary practices, as distinguished from nomadic Turkic populations in Central Asia. However, Chinese government agents[clarification needed] designate as "Uyghur" certain peoples with significantly divergent histories and ancestries from the main group. These include the Lopliks of Ruoqiang County and the Dolan people, thought to be closer to the Oirat Mongols and the Kyrgyz.[109][110] The use of the term Uyghur led to anachronisms when describing the history of the people.[111] In one of his books, the term Uyghur was deliberately not used by James Millward.[112]

Another ethnicity, the Western Yugur of Gansu, identify themselves as the "Yellow Uyghur" (Sarïq Uyghur).[113] Some scholars say the Yugurs' culture, language and religion are closer to the original culture of the original Uyghur Karakorum state than is the culture of the modern Uyghur people of Xinjiang.[114] Linguist and ethnographer S. Robert Ramsey argues for inclusion of both the Eastern and Western Yugur and the Salar as sub-groups of the Uyghur based on similar historical roots for the Yugur and on perceived linguistic similarities for the Salar.[115]

"Turkistani" is used as an alternate ethnonym by some Uyghurs.[116] For example, the Uyghur diaspora in Arabia, adopted the identity "Turkistani". Some Uyghurs in Saudi Arabia adopted the Arabic nisba of their home city, such as "Al-Kashgari" from Kashgar. Saudi-born Uyghur Hamza Kashgari's family originated from Kashgar.[117][118]

Population

The Uyghur population within China generally remains centered in Xinjiang region with some smaller subpopulations elsewhere in the country, such as in Taoyuan County where an estimated 5,000–10,000 live.[119][120]

The size of the Uyghur population, particularly in China, has been the subject of dispute. Chinese authorities place the Uyghur population within the Xinjiang region to be just over 12 million, comprising approximately half of the total regional population.[121] As early as 2003, however, some Uyghur groups wrote that their population was being vastly undercounted by Chinese authorities, claiming that their population actually exceeded 20 million.[122] Population disputes have continued into the present, with some activists and groups such as the World Uyghur Congress and Uyghur American Association claiming that the Uyghur population ranges between 20 and 30 million.[123][124][125][126] Some have even claimed that the real number of Uyghurs is actually 35 million.[127][128] Scholars, however, have generally rejected these claims, with Professor Dru C. Gladney writing in the 2004 book Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland that there is "scant evidence" to support Uyghur claims that their population within China exceeds 20 million.[129]

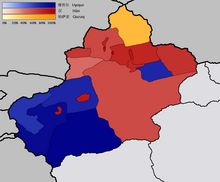

Population in Xinjiang

| Area | 1953 Census | 1964 Census | 1982 Census | 1990 Census | 2000 Census | 2010 Census | Ref. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | PCT. | Total | PCT. | Total | PCT. | Total | PCT. | Total | PCT. | Total | PCT. | ||

| Ürümqi | 28,786 | 19.11% | 56,345 | 9.99% | 121,561 | 10.97% | 266,342 | 12.79% | 387,878 | 12.46% | [130] | ||

| Karamay | Not applicable | 23,730 | 14.54% | 30,895 | 15.09% | 37,245 | 13.78% | 44,866 | 11.47% | [131] | |||

| Turpan | 139,391 | 89.93% | 170,512 | 75.61% | 294,039 | 71.14% | 351,523 | 74.13% | 385,546 | 70.01% | 429,527 | 68.96% | [132] |

| Hami | 33,312 | 41.12% | 42,435 | 22.95% | 75,557 | 20.01% | 84,790 | 20.70% | 90,624 | 18.42% | 101,713 | 17.77% | [133] |

| Changji | 18,784 | 7.67% | 23,794 | 5.29% | 44,944 | 3.93% | 52,394 | 4.12% | 58,984 | 3.92% | 63,606 | 4.45% | [134] |

| Bortala | 8,723 | 21.54% | 18,432 | 15.53% | 38,428 | 13.39% | 53,145 | 12.53% | 59,106 | 13.32% | [135] | ||

| Bayingolin | 121,212 | 75.79% | 153,737 | 46.07% | 264,592 | 35.03% | 310,384 | 36.99% | 345,595 | 32.70% | 406,942 | 31.83% | [136] |

| Kizilsu | Not applicable | 122,148 | 68.42% | 196,500 | 66.31% | 241,859 | 64.36 | 281,306 | 63.98% | 339,926 | 64.68% | [137] | |

| Ili | 568,109 | 23.99% | 667,202 | 26.87% | |||||||||

| Aksu | 697,604 | 98.17% | 778,920 | 80.44% | 1,158,659 | 76.23% | 1,342,138 | 79.07% | 1,540,633 | 71.93% | 1,799,512 | 75.90% | [138] |

| Kashgar | 1,567,069 | 96.99% | 1,671,336 | 93.63% | 2,093,152 | 87.92% | 2,606,775 | 91.32% | 3,042,942 | 89.35% | 3,606,779 | 90.64% | [139] |

| Hotan | 717,277 | 99.20% | 774,286 | 96.52% | 1,124,331 | 96.58% | 1,356,251 | 96.84% | 1,621,215 | 96.43% | 1,938,316 | 96.22% | [140] |

| Tacheng | 36,437 | 6.16% | 36,804 | 4.12% | 38,476 | 3.16% | [141] | ||||||

| Altay | 3,622 | 3.73% | 6,471 | 3.09% | 10,255 | 2.19% | 10,688 | 2.09% | 10,068 | 1.79% | 8,703 | 1.44% | [142] |

| Shihezi | Not applicable | Not applicable | 7,064 | 1.20% | 7,574 | 1.99% | |||||||

| Aral | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable | 9,481 | 5.78% | ||||||

| Tumxuk | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable | 91,472 | 67.39% | ||||||

| Wujiaqu | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable | 223 | 0.23% | ||||||

| Ref. | [143] | [144] | – | ||||||||||

Genetics

A study of mitochondrial DNA (2004) (therefore the matrilineal genetic contribution) found the frequency of Western Eurasian-specific haplogroup in Uyghurs to be 42.6% and East Asian haplogroup to be 57.4%.[145][146] Uyghurs in Kazakhstan on the other hand were shown to have 55% European/Western Eurasian maternal mtDNA.[146]

A study based on paternal DNA (2005) shows West Eurasian haplogroups (J and R) in Uyghurs make up 65% to 70% and East Asian haplogroups (C, N, D and O) 30% to 35%.[147]

One study by Xu et al. (2008), using samples from Hetian (Hotan) only, found Uyghurs have about an average of 60% European or West Asian (Western Eurasian) ancestry and about 40% East Asian or Siberian ancestry (Eastern Eurasian). From the same area, it is found that the proportion of Uyghur individuals with European/West Asian ancestry ranges individually from 40.3% to 84.3% while their East Asian/Siberian ancestry ranges individually from 15.7% to 59.7%.[148] Further study by the same team showed an average of slightly greater European/West Asian component at 52% (ranging individually from 44.9% to 63.1%) in the Uyghur population in southern Xinjiang but only 47% (ranging individually from 30% to 55%) in the northern Uyghur population.[149]

A different study by Li et al. (2009) used a larger sample of individuals from a wider area and found a higher East Asian component of about 70% on average, while the European/West Asian component was about 30%. Overall, Uyghur show relative more similarity to "Western East Asians" than to "Eastern East Asians". The authors also cite anthropologic studies which also estimate about 30% "Western proportions", which are in agreement with their genetic results.[150]

A study (2013) based on autosomal DNA shows that average Uyghurs are closest to other Turkic people in Central Asia and China as well as various Chinese populations. The analysis of the diversity of cytochrome B further suggests Uyghurs are closer to Chinese and Siberian populations than to various Caucasoid groups in West Asia or Europe. However, there is significant genetic distance between the Xinjiang's southern Uyghurs and Chinese population, but not between the northern Uyghurs and Chinese.[152]

A Study (2016) of Uyghur males living in southern Xinjiang used high-resolution 26 Y-STR loci system high-resolution to infer the genetic relationships between the Uyghur population and European and Asian populations. The results showed the Uyghur population of southern Xinjiang exhibited a genetic admixture of Eastern Asian and European populations but with slightly closer relationship with European populations than to Eastern Asian populations.[153]

An extensive genome study in 2017 analyzed 951 samples of Uyghurs from 14 geographical subpopulations in Xinjiang and observed a southwest and northeast differentiation in the population, partially caused by the Tianshan Mountains which form a natural barrier, with gene flows from the east and west. The study identifies four major ancestral components that may have arisen from two earlier admixed groups: one that migrated from the west harbouring a West-Eurasian component associated with European ancestry (25–37%) and a South Asian ancestry component (12–20%) and one from the east, harbouring a Siberian ancestry component (15–17%) and an East Asian ancestry component (29–47%). In total, Uyghurs on average are 33.3% West Eurasian, 32.9% East Asian, 17.9% South Asian, and 16% Siberian. Western parts of Xinjiang are more West Eurasian components than East Eurasian. It suggests at least two major waves of admixture, one ~3,750 years ago coinciding with the age range of the mummies with European feature found in Xinjiang, and another occurring around 750 years ago.[154]

A 2018 study of 206 Uyghur samples from Xinjiang, using the ancestry-informative SNP (AISNP) analysis, found that the average genetic ancestry of Uyghurs is 63.7% East Asian-related and 36.3% European-related.[155]

History

The history of the Uyghur people, as with the ethnic origin of the people, is a matter of contention.[156] Uyghur historians viewed the Uyghurs as the original inhabitants of Xinjiang with a long history. Uyghur politician and historian Muhammad Amin Bughra wrote in his book A History of East Turkestan, stressing the Turkic aspects of his people, that the Turks have a continuous 9000-year-old history, while historian Turghun Almas incorporated discoveries of Tarim mummies to conclude that Uyghurs have over 6400 years of continuous history,[157] and the World Uyghur Congress claimed a 4,000-year history in East Turkestan.[158] However, the official Chinese view, as documented in the white paper History and Development of Xinjiang, asserts that the Uyghur ethnic group formed after the collapse of the Uyghur Khaganate in 840, when the local residents of the Tarim Basin and its surrounding areas were merged with migrants from the khaganate.[159] The name "Uyghur" reappeared after the Soviet Union took the 9th-century ethnonym from the Uyghur Khaganate, then reapplied it to all non-nomadic Turkic Muslims of Xinjiang.[160] Many contemporary western scholars, however, do not consider the modern Uyghurs to be of direct linear descent from the old Uyghur Khaganate of Mongolia. Rather, they consider them to be descendants of a number of peoples, one of them the ancient Uyghurs.[69][161][162][163]

Early history

Discovery of well-preserved Tarim mummies of a people European in appearance indicates the migration of a European-looking people into the Tarim area at the beginning of the Bronze Age around 1800 BC. These people may have been of Tocharian origin, and some have suggested them to be the Yuezhi mentioned in ancient Chinese texts.[164][165] The Tocharians are thought to have developed from the Indo-European speaking Afanasevo culture of Southern Siberia (c. 3500–2500 BC).[166] A study published in 2021 showed that the earliest Tarim Basin cultures had high levels of Ancient North Eurasian ancestry, with smaller admixture from Northeast Asians.[167] Uyghur activist Turgun Almas claimed that Tarim mummies were Uyghurs because the earliest Uyghurs practiced shamanism and the buried mummies' orientation suggests that they had been shamanists; meanwhile, Qurban Wäli claimed words written in Kharosthi and Sogdian scripts as "Uyghur" rather than Sogdian words absorbed into Uyghur according to other linguists.[168]

Later migrations brought peoples from the west and northwest to the Xinjiang region, probably speakers of various Iranian languages such as the Saka tribes, who were closely related to the European Scythians and descended from the earlier Andronovo culture,[169] and who may have been present in the Khotan and Kashgar area in the first millennium BC, as well as the Sogdians who formed networks of trading communities across the Tarim Basin from the 4th century AD.[170] There may also be an Indian component as the founding legend of Khotan suggests that the city was founded by Indians from ancient Taxila during the reign of Ashoka.[171][172] Other people in the region mentioned in ancient Chinese texts include the Dingling as well as the Xiongnu who fought for supremacy in the region against the Chinese for several hundred years. Some Uyghur nationalists also claimed descent from the Xiongnu (according to the Chinese historical text the Book of Wei, the founder of the Uyghurs was descended from a Xiongnu ruler),[57] but the view is contested by modern Chinese scholars.[157]

The Yuezhi were driven away by the Xiongnu but founded the Kushan Empire, which exerted some influence in the Tarim Basin, where Kharosthi texts have been found in Loulan, Niya and Khotan. Loulan and Khotan were some of the many city-states that existed in the Xinjiang region during the Han Dynasty; others include Kucha, Turfan, Karasahr and Kashgar. These kingdoms in the Tarim Basin came under the control of China during the Han and Tang dynasties. During the Tang dynasty they were conquered and placed under the control of the Protectorate General to Pacify the West, and the Indo-European cultures of these kingdoms never recovered from Tang rule after thousands of their inhabitants were killed during the conquest.[173] The settled population of these cities later merged with the incoming Turkic people, including the Uyghurs of Uyghur Khaganate, to form the modern Uyghurs. The Indo-European Tocharian language later disappeared as the urban population switched to a Turkic language such as the Old Uyghur language.[174]

The early Turkic peoples descended from agricultural communities in Northeast Asia who moved westwards into Mongolia in the late 3rd millennium BC, where they adopted a pastoral lifestyle.[175][176][177][178][179] By the early 1st millennium BC, these peoples had become equestrian nomads.[175] In subsequent centuries, the steppe populations of Central Asia appear to have been progressively Turkified by East Asian nomadic Turks, moving out of Mongolia.[180][181]

Uyghur Khaganate (8th–9th centuries)

The Uyghurs of the Uyghur Khaganate were part of a Turkic confederation called the Tiele,[182] who lived in the valleys south of Lake Baikal and around the Yenisei River. They overthrew the First Turkic Khaganate and established the Uyghur Khaganate.

The Uyghur Khaganate lasted from 744 to 840.[69] It was administered from the imperial capital Ordu-Baliq, one of the biggest ancient cities built in Mongolia. In 840, following a famine and civil war, the Uyghur Khaganate was overrun by the Yenisei Kirghiz, another Turkic people. As a result, the majority of tribal groups formerly under Uyghur control dispersed and moved out of Mongolia.

Uyghur kingdoms (9th–11th centuries)

The Uyghurs who founded the Uyghur Khaganate dispersed after the fall of the Khaganate, to live among the Karluks and to places such as Jimsar, Turpan and Gansu.[183][note 5] These Uyghurs soon founded two kingdoms and the easternmost state was the Ganzhou Kingdom (870–1036) which ruled parts of Xinjiang, with its capital near present-day Zhangye, Gansu, China. The modern Yugurs are believed to be descendants of these Uyghurs. Ganzhou was absorbed by the Western Xia in 1036.

The second Uyghur kingdom, the Kingdom of Qocho ruled a larger section of Xinjiang, also known as Uyghuristan in its later period, was founded in the Turpan area with its capital in Qocho (modern Gaochang) and Beshbalik. The Kingdom of Qocho lasted from the ninth to the fourteenth century and proved to be longer-lasting than any power in the region, before or since.[69] The Uyghurs were originally Tengrists, shamanists, and Manichaean, but converted to Buddhism during this period. Qocho accepted the Qara Khitai as its overlord in the 1130s, and in 1209 submitted voluntarily to the rising Mongol Empire. The Uyghurs of Kingdom of Qocho were allowed significant autonomy and played an important role as civil servants to the Mongol Empire, but was finally destroyed by the Chagatai Khanate by the end of the 14th century.[69][185]

Islamization

| Part of a series on Islam in China |

|---|

|

|

|

In the tenth century, the Karluks, Yagmas, Chigils and other Turkic tribes founded the Kara-Khanid Khanate in Semirechye, Western Tian Shan, and Kashgaria and later conquered Transoxiana. The Karakhanid rulers were likely to be Yaghmas who were associated with the Toquz Oghuz and some historians therefore see this as a link between the Karakhanid and the Uyghurs of the Uyghur Khaganate, although this connection is disputed by others.[186]

The Karakhanids converted to Islam in the tenth century beginning with Sultan Satuq Bughra Khan, the first Turkic dynasty to do so.[187] Modern Uyghurs see the Muslim Karakhanids as an important part of their history; however, Islamization of the people of the Tarim Basin was a gradual process. The Indo-Iranian Saka Buddhist Kingdom of Khotan was conquered by the Turkic Muslim Karakhanids from Kashgar in the early 11th century, but Uyghur Qocho remained mainly Buddhist until the 15th century, and the conversion of the Uyghur people to Islam was not completed until the 17th century.

The 12th and 13th century saw the domination by non-Muslim powers: first the Kara-Khitans in the 12th century, followed by the Mongols in the 13th century. After the death of Genghis Khan in 1227, Transoxiana and Kashgar became the domain of his second son, Chagatai Khan. The Chagatai Khanate split into two in the 1340s, and the area of the Chagatai Khanate where the modern Uyghurs live became part of Moghulistan, which meant "land of the Mongols". In the 14th century, a Chagatayid khan Tughluq Temür converted to Islam, Genghisid Mongol nobilities also followed him to convert to Islam.[188] His son Khizr Khoja conquered Qocho and Turfan (the core of Uyghuristan) in the 1390s, and the Uyghurs there became largely Muslim by the beginning of the 16th century.[186] After being converted to Islam, the descendants of the previously Buddhist Uyghurs in Turfan failed to retain memory of their ancestral legacy and falsely believed that the "infidel Kalmuks" (Dzungars) were the ones who built Buddhist structures in their area.[189]

From the late 14th through 17th centuries, the Xinjiang region became further subdivided into Moghulistan in the north, Altishahr (Kashgar and the Tarim Basin), and the Turfan area, each often ruled separately by competing Chagatayid descendants, the Dughlats, and later the Khojas.[186]

Islam was also spread by the Sufis, and branches of its Naqshbandi order were the Khojas who seized control of political and military affairs in the Tarim Basin and Turfan in the 17th century. The Khojas however split into two rival factions, the Aqtaghlik ("White Mountainers") Khojas (also called the Afaqiyya) and the Qarataghlik ("Black Mountainers") Khojas (also called the Ishaqiyya). The legacy of the Khojas lasted until the 19th century. The Qarataghlik Khojas seized power in Yarkand where the Chagatai Khans ruled in the Yarkent Khanate, forcing the Aqtaghlik Afaqi Khoja into exile.

Qing rule

In the 17th century, the Buddhist Dzungar Khanate grew in power in Dzungaria. The Dzungar conquest of Altishahr ended the last independent Chagatai Khanate, the Yarkent Khanate, after the Aqtaghlik Afaq Khoja sought aid from the 5th Dalai Lama and his Dzungar Buddhist followers to help him in his struggle against the Qarataghlik Khojas. The Aqtaghlik Khojas in the Tarim Basin then became vassals to the Dzungars.

The expansion of the Dzungars into Khalkha Mongol territory in Mongolia brought them into direct conflict with Qing China in the late 17th century, and in the process also brought Chinese presence back into the region a thousand years after Tang China lost control of the Western Regions.[191]

The Dzungar–Qing War lasted a decade. During the Dzungar conflict, two Aqtaghlik brothers, the so-called "Younger Khoja" (Chinese: 霍集佔), also known as Khwāja-i Jahān, and his sibling, the Elder Khoja (Chinese: 波羅尼都), also known as Burhān al-Dīn, after being appointed as vassals in the Tarim Basin by the Dzungars, first joined the Qing and rebelled against Dzungar rule until the final Qing victory over the Dzungars, then they rebelled against the Qing in the Revolt of the Altishahr Khojas (1757–1759), an action which prompted the invasion and conquest of the Tarim Basin by the Qing in 1759. The Uyghurs of Turfan and Hami such as Emin Khoja were allies of the Qing in this conflict, and these Uyghurs also helped the Qing rule the Altishahr Uyghurs in the Tarim Basin.[192][193]

The final campaign against the Dzungars in the 1750s ended with the Dzungar genocide. The Qing "final solution" of genocide to solve the problem of the Dzungar Mongols created a land devoid of Dzungars, which was followed by the Qing sponsored settlement of millions of other people in Dzungaria.[194][195] In northern Xinjiang, the Qing brought in Han, Hui, Uyghur, Xibe, Daurs, Solons, Turkic Muslim Taranchis and Kazakh colonists, with one third of Xinjiang's total population consisting of Hui and Han in the northern area, while around two thirds were Uyghurs in southern Xinjiang's Tarim Basin.[196] In Dzungaria, the Qing established new cities like Ürümqi and Yining.[197] The Dzungarian basin itself is now inhabited by many Kazakhs.[198] The Qing therefore unified Xinjiang and changed its demographic composition as well.[199]: 71 The crushing of the Buddhist Dzungars by the Qing led to the empowerment of the Muslim Begs in southern Xinjiang, migration of Muslim Taranchis to northern Xinjiang, and increasing Turkic Muslim power, with Turkic Muslim culture and identity was tolerated or even promoted by the Qing.[199]: 76 It was therefore argued by Henry Schwarz that "the Qing victory was, in a certain sense, a victory for Islam".[199]: 72

In Beijing, a community of Uyghurs was clustered around the mosque near the Forbidden City, having moved to Beijing in the 18th century.[200]

The Ush rebellion in 1765 by Uyghurs against the Manchus occurred after several incidents of misrule and abuse that had caused considerable anger and resentment.[201][202][203] The Manchu Emperor ordered that the Uyghur rebel town be massacred, and the men were executed and the women and children enslaved.[204]

Yettishar

During the Dungan Revolt (1862–1877), Andijani Uzbeks from the Khanate of Kokand under Buzurg Khan and Yaqub Beg expelled Qing officials from parts of southern Xinjiang and founded an independent Kashgarian kingdom called Yettishar ("Country of Seven Cities"). Under the leadership of Yaqub Beg, it included Kashgar, Yarkand, Khotan, Aksu, Kucha, Korla, and Turpan.[citation needed] Large Qing dynasty forces under Chinese General Zuo Zongtang attacked Yettishar in 1876.

Qing reconquest

After this invasion, the two regions of Dzungaria, which had been known as the Dzungar region or the Northern marches of the Tian Shan,[209][210] and the Tarim Basin, which had been known as "Muslim land" or southern marches of the Tian Shan,[211] were reorganized into a province named Xinjiang, meaning "New Territory".[212][213]

First East Turkestan Republic

In 1912, the Qing Dynasty was replaced by the Republic of China. By 1920, Pan-Turkic Jadidists had become a challenge to Chinese warlord Yang Zengxin, who controlled Xinjiang. Uyghurs staged several uprisings against Chinese rule. In 1931, the Kumul Rebellion erupted, leading to the establishment of an independent government in Khotan in 1932,[214] which later led to the creation of the First East Turkestan Republic, officially known as the Turkish Islamic Republic of East Turkestan. Uyghurs joined with Uzbeks, Kazakhs, and Kyrgyz and successfully declared their independence on 12 November 1933.[215] The First East Turkestan Republic was a short-lived attempt at independence around the areas encompassing Kashgar, Yarkent, and Khotan, and it was attacked during the Qumul Rebellion by a Chinese Muslim army under General Ma Zhancang and Ma Fuyuan and fell following the Battle of Kashgar (1934). The Soviets backed Chinese warlord Sheng Shicai's rule over East Turkestan/Xinjiang from 1934 to 1943. In April 1937, remnants of the First East Turkestan Republic launched an uprising known as the Islamic Rebellion in Xinjiang and briefly established an independent government, controlling areas from Atush, Kashgar, Yarkent, and even parts of Khotan, before it was crushed in October 1937, following Soviet intervention.[216] Sheng Shicai purged 50,000 to 100,000 people, mostly Uyghurs, following this uprising.[216]

Second East Turkestan Republic

The oppressive reign of Sheng Shicai fueled discontent by Uyghur and other Turkic peoples of the region, and Sheng expelled Soviet advisors following U.S. support for the Kuomintang of the Republic of China.[217] This led the Soviets to capitalize on the Uyghur and other Turkic people's discontent in the region, culminating in their support of the Ili Rebellion in October 1944. The Ili Rebellion resulted in the establishment of the Second East Turkestan Republic on 12 November 1944, in the three districts of what is now the Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture.[218] Several pro-KMT Uyghurs like Isa Yusuf Alptekin, Memet Emin Bugra, and Mesut Sabri opposed the Second East Turkestan Republic and supported the Republic of China.[219][220][221] In the summer of 1949, the Soviets purged the thirty top leaders of the Second East Turkestan Republic[222] and its five top officials died in a mysterious plane crash on 27 August 1949.[223] On 13 October 1949, the People's Liberation Army entered the region and the East Turkestan National Army was merged into the PLA's 5th Army Corps, leading to the official end of the Second East Turkestan Republic on 22 December 1949.[224][225][226]

Contemporary era

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1990[227] | 7,214,431 | — |

| 2000 | 8,405,416 | +1.54% |

| 2010 | 10,069,346 | +1.82% |

| Figures from Chinese Census | ||

Mao declared the founding of the People's Republic of China on 1 October 1949. He turned the Second East Turkistan Republic into the Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture, and appointed Saifuddin Azizi as the region's first Communist Party governor. Many Republican loyalists fled into exile in Turkey and Western countries. The name Xinjiang was changed to Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, where Uyghurs are the largest ethnicity, mostly concentrated in the south-western Xinjiang.[228]

The Xinjiang conflict is a separatist conflict in China's far-west province of Xinjiang, whose northern region is known as Dzungaria and whose southern region (the Tarim Basin) is known as East Turkestan. Uyghur separatists and independence groups claim that the Second East Turkestan Republic was illegally incorporated by China in 1949 and has since been under Chinese occupation. Uyghur identity remains fragmented, as some support a Pan-Islamic vision, exemplified by the East Turkestan Islamic Movement, while others support a Pan-Turkic vision, such as the East Turkestan Liberation Organization. A third group which includes the Uyghur American Association supports a western liberal vision and hopes for a US-led intervention into Xinjiang.[229] Some Uyghur fighters in Syria have also studied Zionism as a model for their homeland.[230][231] As a result, "no Uyghur or East Turkestan group speaks for all Uyghurs", and Uyghurs in Pan-Turkic and Pan-Islamic camps have committed violence including assassinations on other Uyghurs who they think are too assimilated to Chinese society.[229] Uyghur activists like Rebiya Kadeer have mainly tried to garner international support for Uyghurs, including the right to demonstrate, although China's government has accused her of orchestrating the deadly July 2009 Ürümqi riots.[232]

Eric Enno Tamm's 2011 book stated that "authorities have censored Uyghur writers and 'lavished funds' on official histories that depict Chinese territorial expansion into ethnic borderlands as 'unifications (tongyi), never as conquests (zhengfu) or annexations (tunbing)' "[233]

Human rights abuses against Uyghurs in Xinjiang

| Part of a series on |

| Discrimination |

|---|

|

In 2014, the Chinese government announced a "people's war on terror". Since then, Uyghurs in Xinjiang have been affected by extensive controls and restrictions which the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the Chinese government has imposed upon their religious, cultural, economic and social lives.[234][235][236][237] In order to forcibly assimilate them, the government has arbitrarily detained more than an estimated one million Uyghurs in internment camps.[238][239] Human Rights Watch says that the camps have been used to indoctrinate Uyghurs and other Muslims since 2017.[240][241]

Leaked Chinese government operating procedures state that the main feature of the camps is to ensure adherence to CCP ideology, with the inmates being continuously held captive in the camps for a minimum of 12 months depending on their performance on Chinese ideology tests.[242] The New York Times has reported inmates are required to "sing hymns praising the Chinese Communist Party and write 'self-criticism' essays," and that prisoners are also subjected to physical and verbal abuse by prison guards.[243] Chinese officials have sometimes assigned to monitor the families of current inmates, and women have been detained due to actions by their sons or husbands.[243]

Other policies have included forced labor,[244][245] suppression of Uyghur religious practices,[246] political indoctrination,[247] severe ill-treatment,[248] forced sterilization,[249] forced contraception,[250][251] and forced abortion.[252][253] According to German researcher Adrian Zenz, hundreds of thousands of children have been forcibly separated from their parents and sent to boarding schools.[254][255] The Australian Strategic Policy Institute estimates that some sixteen thousand mosques have been razed or damaged since 2017.[256] Associated Press reported that from 2015 to 2018, birth rates in the mostly Uyghur regions of Hotan and Kashgar fell by more than 60%,[249] compared to a decrease by 9.69% in the whole country.[257] The allegation of Uyghur birth rates being lower than those of Han Chinese have been disputed by pundits from Pakistan Observer,[258] Antara,[259] and Detik.com.[260]

The policies have drawn widespread condemnation, with some characterizing them as a genocide. In an assessment by the UN Human Rights Office, the United Nations (UN) stated that China's policies and actions in the Xinjiang region may be crimes against humanity, although it did not use the term genocide.[261][262] The United States[263] and legislatures in several countries have described the policies as a genocide. The Chinese government denies having committed human rights abuses in Xinjiang.[264][265]

Uyghurs of Taoyuan, Hunan

Around 5,000 Uyghurs live around Taoyuan County and other parts of Changde in Hunan province.[266][267] They are descended from Hala Bashi, a Uyghur leader from Turpan (Kingdom of Qocho), and his Uyghur soldiers sent to Hunan by the Ming Emperor in the 14th century to crush the Miao rebels during the Miao Rebellions in the Ming Dynasty.[30][268] The 1982 census recorded 4,000 Uyghurs in Hunan.[269] They have genealogies which survive 600 years later to the present day. Genealogy keeping is a Han Chinese custom which the Hunan Uyghurs adopted. These Uyghurs were given the surname Jian by the Emperor.[270] There is some confusion as to whether they practice Islam or not. Some say that they have assimilated with the Han and do not practice Islam anymore and only their genealogies indicate their Uyghur ancestry.[271] Chinese news sources report that they are Muslim.[30]

The Uyghur troops led by Hala were ordered by the Ming Emperor to crush Miao rebellions and were given titles by him. Jian is the predominant surname among the Uyghur in Changde, Hunan. Another group of Uyghur have the surname Sai. Hui and Uyghur have intermarried in the Hunan area. The Hui are descendants of Arabs and Han Chinese who intermarried and they share the Islamic religion with the Uyghur in Hunan. It is reported that they now number around 10,000 people. The Uyghurs in Changde are not very religious and eat pork. Older Uyghurs disapprove of this, especially elders at the mosques in Changde and they seek to draw them back to Islamic customs.[272]

In addition to eating pork, the Uyghurs of Changde Hunan practice other Han Chinese customs, like ancestor worship at graves. Some Uyghurs from Xinjiang visit the Hunan Uyghurs out of curiosity or interest. Also, the Uyghurs of Hunan do not speak the Uyghur language, instead, they speak Chinese[clarification needed] as their native language and Arabic for religious reasons at the mosque.[272]

Culture

Religion

The ancient Uyghurs believed in many local deities. These practices gave rise to shamanism and Tengrism. Uyghurs also practiced aspects of Zoroastrianism such as fire altars, and adopted Manichaeism as a state religion for the Uyghur Khaganate,[273] possibly in 762 or 763. Ancient Uyghurs also practiced Buddhism after they moved to Qocho, and some believed in Church of the East.[274][275][276][277]

People in the Western Tarim Basin region began their conversion to Islam early in the Kara-Khanid Khanate period.[187] Some pre-Islamic practices continued under Muslim rule; for example, while the Quran dictated many rules on marriage and divorce, other pre-Islamic principles based on Zoroastrianism also helped shape the laws of the land.[278] There had been Christian conversions in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, but these were suppressed by the First East Turkestan Republic government agents.[279][280][281] Because of persecution, the churches were destroyed and the believers were scattered.[282] According to the national census, 0.5% or 1,142 Uyghurs in Kazakhstan were Christians in 2009.[283]

Modern Uyghurs are primarily Muslim and they are the second-largest predominantly Muslim ethnicity in China after the Hui.[284] The majority of modern Uyghurs are Sunnis, although additional conflicts exist between Sufi and non-Sufi religious orders.[284] While modern Uyghurs consider Islam to be part of their identity, religious observance varies between different regions. In general, Muslims in the southern region, Kashgar in particular, are more conservative. For example, women wearing the veil (a piece of cloth covering the head completely) are more common in Kashgar than some other cities.[285] The veil, however, has been banned in some cities since 2014 after it became more popular.[286]

There is also a general split between the Uyghurs and the Hui Muslims in Xinjiang and they normally worship in different mosques.[287] The Chinese government discourages religious worship among the Uyghurs,[288] and there is evidence of thousands of Uyghur mosques including historic ones being destroyed.[289] According to a 2020 Australian Strategic Policy Institute report, Chinese authorities since 2017 have destroyed or damaged 16,000 mosques in Xinjiang.[290][291]

In the early 21st century, a new trend of Islam, Salafism, emerged in Xinjiang, mostly among the Turkic population including Uyghurs, although there are Hui Salafis. These Salafis tended to demonstrate pan-Islamism and abandoned nationalism in favor of a caliphate to rule Xinjiang in the event of independence from China.[292][293] Many Uyghur Salafis have allied themselves with the Turkistan Islamic Party in response to growing repression of Uyghurs by China.[294]

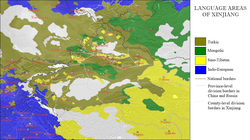

Language

The ancient people of the Tarim Basin originally spoke different languages, such as Tocharian, Saka (Khotanese), and Gandhari. The Turkic people who moved into the region in the 9th century brought with them their languages, which slowly supplanted the original tongues of the local inhabitants. In the 11th century, Mahmud al-Kashgari noted that the Uyghurs (of Qocho) spoke a pure Turkic language, but they also still spoke another language among themselves and had two different scripts. He also noted that the people of Khotan did not know Turkic well and had their own language and script (Khotanese).[295] Writers of the Karakhanid period, Al-Kashgari and Yusuf Balasagun, referred to their Turkic language as Khāqāniyya (meaning royal) or the "language of Kashgar" or simply Turkic.[296][297]

The modern Uyghur language is classified under the Karluk branch of the Turkic language family. It is closely related to Äynu, Lop, Ili Turki and Chagatay (the East Karluk languages) and slightly less closely to Uzbek (which is West Karluk). The Uyghur language is an agglutinative language and has a subject-object-verb word order. It has vowel harmony like other Turkic languages and has noun and verb cases but lacks distinction of gender forms.[298]

Modern Uyghurs have adopted a number of scripts for their language. The Arabic script, known as the Chagatay alphabet, was adopted along with Islam. This alphabet is known as Kona Yëziq (old script). Political changes in the 20th century led to numerous reforms of the scripts, for example the Cyrillic-based Uyghur Cyrillic alphabet, a Latin Uyghur New Script and later a reformed Uyghur Arabic alphabet, which represents all vowels, unlike Kona Yëziq. A new Latin version, the Uyghur Latin alphabet, was also devised in the 21st century.

In the 1990s, many Uyghurs in parts of Xinjiang could not speak Mandarin Chinese.[299]

Literature

The literary works of the ancient Uyghurs were mostly translations of Buddhist and Manichaean religious texts,[300] but there were also narrative, poetic and epic works apparently original to the Uyghurs. However it is the literature of the Kara-Khanid period that is considered by modern Uyghurs to be the important part of their literary traditions. Amongst these are Islamic religious texts and histories of Turkic peoples, and important works surviving from that era are Kutadgu Bilig, "Wisdom of Royal Glory" by Yusuf Khass Hajib (1069–70), Mahmud al-Kashgari's Dīwānu l-Luġat al-Turk, "A Dictionary of Turkic Dialects" (1072) and Ehmed Yükneki's Etebetulheqayiq. Modern Uyghur religious literature includes the Taẕkirah, biographies of Islamic religious figures and saints.[301][90][302] The Turki language Tadhkirah i Khwajagan was written by M. Sadiq Kashghari.[303] Between the 1600s and 1900s many Turki-language tazkirah manuscripts devoted to stories of local sultans, martyrs and saints were written.[304] Perhaps the most famous and best-loved pieces of modern Uyghur literature are Abdurehim Ötkür's Iz, Oyghanghan Zimin, Zordun Sabir's Anayurt and Ziya Samedi's novels Mayimkhan and Mystery of the years.[citation needed]

Exiled Uyghur writers and poets, such as Muyesser Abdul'ehed, use literature to highlight the issues facing their community.[305]

Music

Muqam is the classical musical style. The 12 Muqams are the national oral epic of the Uyghurs. The muqam system was developed among the Uyghur in northwestern China and Central Asia over approximately the last 1500 years from the Arabic maqamat modal system that has led to many musical genres among peoples of Eurasia and North Africa. Uyghurs have local muqam systems named after the oasis towns of Xinjiang, such as Dolan, Ili, Kumul and Turpan. The most fully developed at this point is the Western Tarim region's 12 muqams, which are now a large canon of music and songs recorded by the traditional performers Turdi Akhun and Omar Akhun among others in the 1950s and edited into a more systematic system. Although the folk performers probably improvized their songs, as in Turkish taksim performances, the present institutional canon is performed as fixed compositions by ensembles.

The Uyghur Muqam of Xinjiang has been designated by UNESCO as part of the Intangible Heritage of Humanity.[306]

Amannisa Khan, sometimes called Amanni Shahan (1526–1560), is credited with collecting and thereby preserving the Twelve Muqam.[307] Russian scholar Pantusov writes that the Uyghurs manufactured their own musical instruments, they had 62 different kinds of musical instruments, and in every Uyghur home there used to be an instrument called a "duttar".

Uzbek composer Shakhida Shaimardanova uses themes from Uyghur folk music in her compositions.[308]

Dance

Sanam is a popular folk dance among the Uyghur people.[309] It is commonly danced by people at weddings, festive occasions, and parties.[310] The dance may be performed with singing and musical accompaniment. Sama is a form of group dance for Newruz (New Year) and other festivals.[310] Other dances include the Dolan dances, Shadiyane, and Nazirkom.[311] Some dances may alternate between singing and dancing, and Uyghur hand-drums called dap are commonly used as accompaniment for Uyghur dances.

Art

During the late-19th and early-20th centuries, scientific and archaeological expeditions to the region of Xinjiang's Silk Road discovered numerous cave temples, monastery ruins, and wall paintings, as well as miniatures, books, and documents. There are 77 rock-cut caves at the site. Most have rectangular spaces with round arch ceilings often divided into four sections, each with a mural of Buddha. The effect is of an entire ceiling covered with hundreds of Buddha murals. Some ceilings are painted with a large Buddha surrounded by other figures, including Indians, Persians and Europeans. The quality of the murals vary with some being artistically naïve while others are masterpieces of religious art.[312]

Education

Historically, the education level of Old Uyghur people was higher than the other ethnicities around them. The Buddhist Uyghurs of Qocho became the civil servants of Mongol Empire and Old Uyghur Buddhists enjoyed a high status in the Mongol empire. They also introduced the written script for the Mongolian language. In the Islamic era, education was provided by the mosques and madrassas. During the Qing era, Chinese Confucian schools were also set up in Xinjiang[313] and in the late 19th century Christian missionary schools.[314]

In the late nineteenth and early 20th century, schools were often located in mosques and madrassas. Mosques ran informal schools, known as mektep or maktab, attached to the mosques,[315] The maktab provided most of the education and its curriculum was primarily religious and oral.[316] Boys and girls might be taught in separate schools, some of which offered modern secular subjects in the early 20th century.[313][314][317] In madrasas, poetry, logic, Arabic grammar and Islamic law were taught.[318] In the early 20th century, the Jadidists Turkic Muslims from Russia spread new ideas on education[319][320][321][322] and popularized the identity of "Turkestani".[323]

In more recent times, religious education is highly restricted in Xinjiang and the Chinese authority had sought to eradicate any religious school they considered illegal.[324][325] Although Islamic private schools (Sino-Arabic schools (中阿學校)) have been supported and permitted by the Chinese government in Hui Muslim areas since the 1980s, this policy does not extend to schools in Xinjiang due to fear of separatism.[326][327][328]

Beginning in the early 20th century, secular education became more widespread. Early in the communist era, Uyghurs had a choice of two separate secular school systems, one conducted in their own language and one offering instructions only in Chinese.[329] Many Uyghurs linked the preservation of their cultural and religious identity with the language of instruction in schools and therefore preferred Uyghur language schools.[314][330] However, from the mid-1980s onward, the Chinese government began to reduce teaching in Uyghur and starting mid-1990s also began to merge some schools from the two systems. By 2002, Xinjiang University, originally a bilingual institution, had ceased offering courses in the Uyghur language. From 2004 onward, the government policy has been that classes should be conducted in Chinese as much as possible and in some selected regions, instruction in Chinese began in the first grade.[331] A special senior-secondary boarding school program for Uyghurs, the Xinjiang Class, with course work conducted entirely in Chinese was also established in 2000.[332] Many schools have also moved toward using mainly Chinese in the 2010s, with teaching in the Uyghur language limited to only a few hours a week.[333] The level of educational attainment among Uyghurs is generally lower than that of the Han Chinese; this may be due to the cost of education, the lack of proficiency in the Chinese language (now the main medium of instruction) among many Uyghurs, and poorer employment prospects for Uyghur graduates due to job discrimination in favor of Han Chinese.[334][335] Uyghurs in China, unlike the Hui and Salar who are also mostly Muslim, generally do not oppose coeducation,[336] however girls may be withdrawn from school earlier than boys.[314]

Traditional medicine

Uyghur traditional medicine is known as Unani (طب یونانی), as historically used in the Mughal Empire.[337] Sir Percy Sykes described the medicine as "based on the ancient Greek theory" and mentioned how ailments and sicknesses were treated in Through Deserts and Oases of Central Asia.[338] Today, traditional medicine can still be found at street stands. Similar to other traditional medicine, diagnosis is usually made through checking the pulse, symptoms and disease history and then the pharmacist pounds up different dried herbs, making personalized medicines according to the prescription. Modern Uyghur medical hospitals adopted modern medical science and medicine and applied evidence-based pharmaceutical technology to traditional medicines. Historically, Uyghur medical knowledge has contributed to Chinese medicine in terms of medical treatments, medicinal materials and ingredients and symptom detection.[339]

Cuisine

Uyghur food shows both Central Asian and Chinese elements. A typical Uyghur dish is polu (or pilaf), a dish found throughout Central Asia. In a common version of the Uyghur polu, carrots and mutton (or chicken) are first fried in oil with onions, then rice and water are added and the whole dish is steamed. Raisins and dried apricots may also be added. Kawaplar (Uyghur: Каваплар) or chuanr (i.e., kebabs or grilled meat) are also found here. Another common Uyghur dish is leghmen (لەغمەن, ләғмән), a noodle dish with a stir-fried topping (säy, from Chinese cai, 菜) usually made from mutton and vegetables, such as tomatoes, onions, green bell peppers, chili peppers and cabbage. This dish is likely to have originated from the Chinese lamian, but its flavor and preparation method are distinctively Uyghur.[340]

Uyghur food (Uyghur Yemekliri, Уйғур Йәмәклири) is characterized by mutton, beef, camel (solely bactrian), chicken, goose, carrots, tomatoes, onions, peppers, eggplant, celery, various dairy foods and fruits.

A Uyghur-style breakfast consists of tea with home-baked bread, hardened yogurt, olives, honey, raisins and almonds. Uyghurs like to treat guests with tea, naan and fruit before the main dishes are ready.

Sangza (ساڭزا, Саңза) are crispy fried wheat flour dough twists, a holiday specialty. Samsa (سامسا, Самса) are lamb pies baked in a special brick oven. Youtazi is steamed multi-layer bread. Göshnan (گۆشنان, Гөшнан) are pan-grilled lamb pies. Pamirdin (Памирдин) are baked pies stuffed with lamb, carrots and onions. Shorpa is lamb soup (شۇرپا, Шорпа). Other dishes include Toghach (Тоғач) (a type of tandoor bread) and Tunurkawab (Тунуркаваб). Girde (Гирде) is also a very popular bagel-like bread with a hard and crispy crust that is soft inside.

A cake sold by Uyghurs is the traditional Uyghur nut cake.[341][342][343]

Clothing

Chapan, a coat, and doppa, a type of hat for men, is commonly worn by Uyghurs. Another type of headwear, salwa telpek (salwa tälpäk, салва тәлпәк), is also worn by Uyghurs.[344]

In the early 20th century, face covering veils with velvet caps trimmed with otter fur were worn in the streets by Turki women in public in Xinjiang as witnessed by the adventurer Ahmad Kamal in the 1930s.[345] Travelers of the period Sir Percy Sykes and Ella Sykes wrote that in Kashghar women went into the bazar "transacting business with their veils thrown back" but mullahs tried to enforce veil wearing and were "in the habit of beating those who show their face in the Great Bazar".[346] In that period, belonging to different social statuses meant a difference in how rigorously the veil was worn.[347]

Muslim Turkestani men traditionally cut all the hair off their head.[348] Sir Aurel Stein observed that the "Turki Muhammadan, accustomed to shelter this shaven head under a substantial fur-cap when the temperature is so low as it was just then".[349] No hair cutting for men took place on the ajuz ayyam, days of the year that were considered inauspicious.[350]

Traditional handicrafts

Yengisar is famous for manufacturing Uyghur handcrafted knives.[351][352][353] The Uyghur word for knife is pichaq (پىچاق, пичақ) and the word for knifemaking (cutler) is pichaqchiliq (پىچاقچىلىقى, пичақчилиқ).[354] Uyghur artisan craftsmen in Yengisar are known for their knife manufacture. Uyghur men carry such knives as part of their culture to demonstrate the masculinity of the wearer,[355] but it has also led to ethnic tension.[356][357] Limitations were placed on knife vending due to concerns over terrorism and violent assaults.[358]

Livelihood

Most Uyghurs are agriculturists.[citation needed] Cultivating crops in an arid region has made the Uyghurs excel in irrigation techniques. This includes the construction and maintenance of underground channels called karez that brings water from the mountains to their fields. A few of the well-known agricultural goods include apples (especially from Ghulja), sweet melons (from Hami), and grapes from Turpan. However, many Uyghurs are also employed in the mining, manufacturing, cotton, and petrochemical industries. Local handicrafts like rug-weaving and jade-carving are also important to the cottage industry of the Uyghurs.[359]

Some Uyghurs have been given jobs through Chinese government affirmative action programs.[360] Uyghurs may also have difficulty receiving non-interest loans (per Islamic beliefs).[361] The general lack of Uyghur proficiency in Mandarin Chinese also creates a barrier to access private and public sector jobs.[362]

Names

Since the arrival of Islam, most Uyghurs have used "Arabic names", but traditional Uyghur names and names of other origin are still used by some.[363] After the establishment of the Soviet Union, many Uyghurs who studied in Soviet Central Asia added Russian suffixes to Russify their surnames.[364] Names from Russia and Europe are used in Qaramay and Ürümqi by part of the population of city-dwelling Uyghurs. Others use names with hard-to-understand etymologies, with the majority dating from the Islamic era and being of Arabic or Persian derivation.[365] Some pre-Islamic Uyghur names are preserved in Turpan and Qumul.[363] The government has banned some two dozen Islamic names.[288]

See also

Explanatory notes

- ^ The size of the Uyghur population is disputed between Chinese authorities and Uyghur organizations outside of China. The § Population section of this article further discusses this dispute.

- ^ .

- Uyghur: ئۇيغۇرلار, Уйғурлар, Uyghurlar, IPA: [ujɣurˈlɑr]

- simplified Chinese: 维吾尔; traditional Chinese: 維吾爾; pinyin: Wéiwú'ěr, IPA: [wěɪ.ǔ.àɚ][23][24]

- For the English pronunciation, see Etymology

- ^ Jump up to: a b The term Turk was a generic label used by members of many ethnicities in Soviet Central Asia. Often the deciding factor for classifying individuals belonging to Turkic nationalities in the Soviet censuses was less what the people called themselves by nationality than what language they claimed as their native tongue. Thus, people who called themselves "Turk" but spoke Uzbek were classified in Soviet censuses as Uzbek by nationality.[62]

- ^ This contrasts to the Hui people, called Huihui or "Hui" (Muslim) by the Chinese and the Salar people, called "Sala Hui" (Salar Muslims) by the Chinese. Use of the term "Chan Tou Hui" was considered a demeaning slur.[103]

- ^ "Soon the great chief Julumohe and the Kirghiz gathered a hundred thousand riders to attack the Uyghur city; they killed the Kaghan, executed Jueluowu, and burnt the royal camp. All the tribes were scattered – its ministers Sazhi and Pang Tele with fifteen clans fled to the Karluks, the remaining multitude went to Tibet and Anxi." (Chinese: 俄而渠長句錄莫賀與黠戛斯合騎十萬攻回鶻城,殺可汗,誅掘羅勿,焚其牙,諸部潰其相馺職與厖特勒十五部奔葛邏祿,殘眾入吐蕃、安西。)[184]

References

Citations

- ^ "Geographic Distribution and Population of Ethnic Minorities". China Statistical Yearbook 2021. Retrieved 4 February 2023.

- ^ Kazakhstan population by ethnic groups

- ^ "Чей Кашмир? Индусов,Пакистацев или уйгуров?". Retrieved 29 January 2023.

- ^ "About The Uyghurs". East Turkistan Government in Exile. 4 March 2021. Archived from the original on 2 October 2022. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ "Национальная самобытность: О жизни уйгуров в Кыргызстане". Moskovskij Komsomolets (in Russian). 14 April 2021.

- ^ "Uyghur". Ethnologue. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- ^ "Detailed Languages Spoken at Home and Ability to Speak English for the Population 5 Years and Over: 2009–2013". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ Hawkins, Samantha (18 March 2021). "Uighur Rally Puts Genocide in Focus Ahead of US-China Talks". Courthouse News. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ "Uyghurs in Saudia Arabia".

- ^ "Uighur abuse: Australia urged to impose sanctions on China". www.sbs.com.au. Archived from the original on 11 September 2018. Retrieved 11 September 2018.

- ^ "Перепись населения России 2010 года" [Russian census 2010]. Archived from the original on 1 February 2012. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- ^ Kumar, Kumar (18 December 2016). "For Uighur exiles, Kashmir is heaven". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 5 October 2020. Retrieved 9 September 2023.

- ^ Uyghur (in Russian). Historyland. Archived from the original on 12 February 2019. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- ^ Gunter, Joel (27 August 2021). "Afghanistan's Uyghurs fear the Taliban, and now China too". BBC News. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- ^ "ウイグル族 訪れぬ平安 ... 日本暮らしでも「中国の影」". 読売新聞オンライン (in Japanese). 6 November 2021. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ^ Lintner, Bertil (31 October 2019). "Where the Uighurs are free to be". Asia Times. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- ^ Canada, Government of Canada, Statistics (8 February 2017). "Census Profile, 2016 Census – Canada [Country] and Canada [Country]". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Archived from the original on 28 April 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Shichor, Yitzhak (July 2013). "Nuisance Value: Uyghur activism in Germany and Beijing–Berlin relations". Journal of Contemporary China. 22 (82): 612–629. doi:10.1080/10670564.2013.766383. S2CID 145666712.

- ^ "Language according to age and sex by region, 1990-2021". stat.fi. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

- ^ "Khovd Aimak Statistical Office. 1983–2008 Dynamics Data Sheet". Archived from the original on 22 July 2011.

- ^ State statistics committee of Ukraine – National composition of population, 2001 census Archived 8 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine (Ukrainian)

- ^ Touraj Atabaki, Sanjyot Mehendale (2004). Central Asia and the Caucasus: Transnationalism and Diaspora. p. 31.

The Uighurs, too, are Turkic Muslims, linguistically and culturally more closely related to the Uzbeks than the Kazakhs.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hahn 2006, p. 4.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Drompp 2005, p. 7.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Uighur". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ "Uighur". CollinsDictionary.com. HarperCollins. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ^ "Uighur | History, Language, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 17 December 2018. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- ^ "The mystery of China's celtic mummies". The Independent. London. 28 August 2006. Archived from the original on 3 April 2008. Retrieved 28 June 2008.

- ^ Dillon 2004, p. 24.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Ethnic Uygurs in Hunan Live in Harmony with Han Chinese". People's Daily. 29 December 2000. Archived from the original on 16 October 2007. Retrieved 15 March 2007.

- ^ "Ethno-Diplomacy: The Uyghur Hitch in Sino-Turkish Relations" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 28 August 2011.

- ^ Castets, Rémi (1 October 2003). "The Uyghurs in Xinjiang – The Malaise Grows". China Perspectives (in French). 2003 (5). doi:10.4000/chinaperspectives.648. ISSN 2070-3449. "The rest of the Diaspora is settled in Turkey (about 10,000 people) and, in smaller numbers, in Germany, Australia, Saudi Arabia, Sweden, Canada, the US, India and Pakistan."

- ^ Brouwer, Joseph (30 September 2020). "Xi Defends Xinjiang Policy as "Entirely Correct"". China Digital Times.

- ^ Davidson, Helen (18 September 2020). "Clues to scale of Xinjiang labour operation emerge as China defends camps". The Guardian.

- ^ "China: Unrelenting Crimes Against Humanity Targeting Uyghurs | Human Rights Watch". 31 August 2023.

- ^ Vanderklippe, Nathan (9 March 2011). "Lawsuit against Xinjiang researcher marks new effort to silence critics of China's treatment of Uyghurs". The Globe and Mail.

- ^ Falconer, Rebecca (9 March 2021). "Report: "Clear evidence" China is committing genocide against Uyghurs". Axios.

- ^ Chase, Steven (24 January 2021). "Canada urged to formally label China's Uyghur persecution as genocide". The Globe and Mail.

- ^ Brouwer, Joseph (25 June 2021). "China Uses Global Influence Campaign To Deny Forced Labor, Mass Incarceration in Xinjiang". China Digital Times.

- ^ Cheng, Yangyang (10 December 2020). "The edge of our existence". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 76 (6): 315–320. Bibcode:2020BuAtS..76f.315C. doi:10.1080/00963402.2020.1846417. S2CID 228097031.

- ^ Raza, Zainab (24 October 2019). "China's 'Political Re-Education of Uyghur Muslims'". Asian Affairs. 50 (4): 488–501. doi:10.1080/03068374.2019.1672433. S2CID 210448190.

- ^ Parton, Charles (11 February 2020). "Foresight 2020: The Challenges Facing China". The RUSI Journal. 165 (2): 10–24. doi:10.1080/03071847.2020.1723284. S2CID 213331666.

- ^ van Ess, Margaretha A.; ter Laan, Nina; Meinema, Erik (5 April 2021). "Beyond 'radical' versus 'moderate'? New perspectives on the politics of moderation in Muslim majority and Muslim minority settings". Religion. 51 (2). Utrecht University: 161–168. doi:10.1080/0048721X.2021.1865616.

- ^ McCormick, Andrew (16 June 2021). "Uyghurs outside China are traumatized. Now they're starting to talk about it". MIT Technology Review.

- ^ Mair, Victor (13 July 2009). "A Little Primer of Xinjiang Proper Nouns". Language Log. Archived from the original on 18 July 2009. Retrieved 30 July 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Fairbank & Chʻen 1968, p. 364.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Özoğlu 2004, p. 16.

- ^ The Terminology Normalization Committee for Ethnic Languages of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (11 October 2006). "Recommendation for English transcription of the word 'ئۇيغۇر'/《维吾尔》". Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Uighur, n. and adj.", Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford, England: Oxford University Press

- ^ Jones, Daniel (2011). Roach, Peter; Setter, Jane; Esling, John (eds.). "Uyghur". Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-15255-6.

- ^ "How to say: Chinese names and ethnic groups". BBC. 9 July 2009. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- ^ Wells, John C. (2008). "Uighur". Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^ Russell-Smith 2005, p. 33.

- ^ Sudzi inscription, text at Türik Bitig

- ^ Mackerras 1968, p. 224.

- ^ Güzel 2002.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Golden 1992, p. 155.

- ^ Jiu Wudaishi, "vol. 138: Huihu" quote: "回鶻,其先匈奴之種也。後魏時,號爲鐵勒,亦名回紇。唐元和四年,本國可汗遣使上言,改爲回鶻,義取迴旋搏擊,如鶻之迅捷也。" translation: "Huihu, their ancestors had been a kind of Xiongnu. In Later Wei time, they were also called Tiele, and also named Huihe. In the fourth year of Tang dynasty's Yuanhe era [809 CE], their country's Qaghan sent envoys and requested [the name be] changed to Huihu, whose meaning is taken from a strike-and-return action, like a swift and rapid falcon."

- ^ Hakan Özoğlu, p. 16.

- ^ Russell-Smith 2005, p. 32.

- ^ Ramsey, S. Robert (1987), The Languages of China, Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 185–6

- ^ Silver, Brian D. (1986), "The Ethnic and Language Dimensions in Russian and Soviet Censuses", in Ralph S. Clem (ed.), Research Guide to the Russian and Soviet Censuses, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, pp. 70–97

- ^ Weishu "vol. 103 section Gāochē" text: 高車,蓋古赤狄之餘種也,初號為狄歷,北方以為勑勒,諸夏以為高車、丁零。其語略與匈奴同而時有小異,或云其先匈奴之甥也。其種有狄氏、袁紇氏、斛律氏、解批氏、護骨氏、異奇斤氏。 transl. "Gaoche, probably remnant stocks of the ancient Red Di. Initially they had been called Dili, in the North they are considered Chile, the various Xia (i.e. Chinese) consider them Gaoche Dingling / Dingling with High-Carts. Their language and the Xiongnu's are similar though there are small differences. Or one may say they were sons-in-law / sororal nephews of their Xiongnu predecessors. Their tribes are Di, Yuanhe, Hulu, Jiepi, Hugu, Yiqijin."

- ^ Theobald, Ulrich. (2012) "Huihe 回紇, Huihu 回鶻, Weiwur 維吾爾, Uyghurs" ChinaKnowledge.de – An Encyclopaedia on Chinese History, Literature and Art

- ^ Mair 2006, pp. 137–8.

- ^ Rong, Xinjiang. (2018) "Sogdian Merchants and Sogdian Culture on the Silk Road" in Empires and Exchanges in Eurasian Late Antiquity: Rome, China, Iran, and the Steppe, Ca. 250–750 ed. Di Cosmo & Maas. p. 92 of 84–95

- ^ Hong, Sun-Kee; Wu, Jianguo; Kim, Jae-Eun; Nakagoshi, Nobukazu (25 December 2010). Landscape Ecology in Asian Cultures. Springer. p. 284. ISBN 978-4-431-87799-8. p.284: "The Uyghurs mixed with the Tocharian people and adopted their religion and their culture of oasis agriculture (Scharlipp 1992; Soucek 2000)."

- ^ Li, Hui; Cho, Kelly; Kidd, Judith R.; Kidd, Kenneth K. (December 2009). "Genetic Landscape of Eurasia and "Admixture" in Uyghurs". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 85 (6): 934–937. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.10.024. PMC 2790568. PMID 20004770.