Церковь Востока

| Церковь Востока | |

|---|---|

| ܥܕܬܐ ܕܡܕܢܚܐ | |

| |

| Тип | Восточно-христианский |

| Ориентация | Сирийское христианство [ 1 ] |

| Теология | Восточно-сирийское богословие |

| Политика | епископальный |

| Head | Catholicos-Patriarch of the East |

| Region | Middle East, Central Asia, Far East, India[2] |

| Liturgy | East Syriac Rite (Liturgy of Addai and Mari) |

| Headquarters | Seleucia-Ctesiphon (410–775)[3] Baghdad (775–1317)[4] |

| Founder | Jesus Christ by sacred tradition Thomas the Apostle |

| Origin | Apostolic Age, by its tradition Edessa,[5][6] Mesopotamia[1][note 1] |

| Branched from | Nicene Christianity |

| Separations | Its schism of 1552 divided it originally into two patriarchates, and later four, but by 1830 it returned to two, one of which is now the Chaldean Catholic Church, while the other sect split further in 1968 into the Assyrian Church of the East and the Ancient Church of the East. |

| Other name(s) | Nestorian Church, Persian Church, East Syrian Church, Chaldean Church, Assyrian Church, Babylonian Church[11] |

| Part of a series on |

| Eastern Christianity |

|---|

|

Церковь Востока ( Классический сирийский ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������” » : Восточно ) или -сирийская церковь» , [ 12 ] также называемая церковью Селевкии-Ктесифона , [ 13 ] Персидская церковь , Ассирийская церковь , Вавилонская церковь [ 11 ] [ 14 ] [ 15 ] или несторианская церковь , [ примечание 2 ] — одна из трех основных ветвей никейского восточного христианства , возникших в результате христологических споров V и VI веков, наряду с миафизитскими церквями (которые стали известны как восточные православные церкви ) и Халкидонской церковью (чья восточная ветвь позже стала Восточная Православная Церковь ).

Having its origins in the pre-Sasanian Mesopotamia, the Church of the East developed its own unique form of Christian theology and liturgy. During the early modern period, a series of schisms gave rise to rival patriarchates, sometimes two, sometimes three.[16] In the latter half of the 20th century the traditionalist patriarchate of the church underwent a split into two rival patriarchates, namely the Assyrian Church of the East and the Ancient Church of the East, which continue to follow the traditional theology and liturgy of the mother church. The Chaldean Catholic Church based in Iraq and the Syro-Malabar Church in India are two Eastern Catholic churches which also claim the heritage of the Church of the East.[2]

The Church of the East organized itself initially in the year 410 as the national church of the Sasanian Empire through the Council of Seleucia-Ctesiphon.[17] In 424, it declared itself independent of the state church of the Roman Empire, which it calls the 'Church of the West'. The Church of the East was headed by the Catholicose of the East seated originally in Seleucia-Ctesiphon, continuing a line that, according to its tradition, stretched back to the Apostolic Age. According to its tradition, the Church of the East was established by Thomas the Apostle in the first century. Its liturgical rite is the East Syrian rite that employs the Divine Liturgy of Saints Addai and Mari.

The Church of the East, which was part of the Great Church, shared communion with those in the Roman Empire until the Council of Ephesus condemned Nestorius in 431.[1] Supporters of Nestorius took refuge in Sasanian Persia, where the Church refused to condemn Nestorius and became accused of Nestorianism, a heresy attributed to Nestorius. It was therefore called the Nestorian Church by all the other Eastern churches, both Chalcedonian and non-Chalcedonian, and by the Western Church. Politically the Sasanian and Roman Empires were at war with each other, which forced the Church of the East to distance itself from the churches within Roman territory.[18][19][20]

More recently, the "Nestorian" appellation has been called "a lamentable misnomer",[21][22] and theologically incorrect by scholars.[15] However, the Church of the East started to call itself Nestorian, it anathematized the Council of Ephesus, and in its liturgy Nestorius was mentioned as a saint.[23][24] In 544, the general Council of the Church of the East approved the Council of Chalcedon at the Synod of Mar Aba I.[25][5]

Continuing as a dhimmi community under the Rashidun Caliphate after the Muslim conquest of Persia (633–654), the Church of the East played a major role in the history of Christianity in Asia. Between the 9th and 14th centuries, it represented the world's largest Christian denomination in terms of geographical extent, and in the Middle Ages was one of the three major Christian powerhouses of Eurasia alongside Latin Catholicism and Greek Orthodoxy.[26] It established dioceses and communities stretching from the Mediterranean Sea and today's Iraq and Iran, to India (the Saint Thomas Syrian Christians of Kerala), the Mongol kingdoms and Turkic tribes in Central Asia, and China during the Tang dynasty (7th–9th centuries). In the 13th and 14th centuries, the church experienced a final period of expansion under the Mongol Empire, where influential Church of the East clergy sat in the Mongol court.

Even before the Church of the East underwent a rapid decline in its field of expansion in Central Asia in the 14th century, it had already lost ground in its home territory. The decline is indicated by the shrinking list of active dioceses. Around the year 1000, there were more than sixty dioceses throughout the Near East, but by the middle of the 13th century there were about twenty, and after Timur Leng the number was further reduced to seven only.[27] In the aftermath of the division of the Mongol Empire, the rising Buddhist and Islamic Mongol leaderships pushed out and nearly eradicated the Church of the East and its followers. Thereafter, Church of the East dioceses remained largely confined to Upper Mesopotamia and to the Saint Thomas Syrian Christians in the Malabar Coast (modern-day Kerala, India).

The Church faced a major schism in 1552 following the consecration of monk Yohannan Sulaqa by Pope Julius III in opposition to the reigning Catholicos-Patriarch Shimun VII, leading to the formation of the Chaldean Catholic Church (an Eastern Catholic church in communion with the pope). Divisions occurred within the two factions (the traditionalist and the newly formed Eastern Catholic) but by 1830 two unified patriarchates and distinct churches remained: the traditionalist Assyrian Church of the East and the Eastern Catholic Chaldean Church. The Ancient Church of the East split from the traditionalist patriarchate of the Church of the East in 1968. In 2017, the Chaldean Catholic Church had approximately 628,405 members[28] and the Assyrian Church of the East had 323,300 to 380,000,[29][30] while the Ancient Church of the East had 100,000.

Background

[edit]

- (Not shown are ante-Nicene, nontrinitarian, and restorationist denominations.)

The Church of the East's declaration in 424 of the independence of its head, the Patriarch of the East, preceded by seven years the 431 Council of Ephesus, which condemned Nestorius and declared that Mary, mother of Jesus, can be described as Mother of God. Two of the generally accepted ecumenical councils were held earlier: the First Council of Nicaea, in which a Persian bishop took part, in 325, and the First Council of Constantinople in 381. The Church of the East accepted the teaching of these two councils, but ignored the 431 Council and those that followed, seeing them as concerning only the patriarchates of the Roman Empire (Rome, Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, Jerusalem), all of which were for it "Western Christianity".[31]

Theologically, the Church of the East adopted the dyophysite doctrine of Theodore of Mopsuestia[32] that emphasised the "distinctiveness" of the divine and the human natures of Jesus; this doctrine was misleadingly labelled as 'Nestorian' by its theological opponents.[32]

In the 6th century and thereafter, the Church of the East expanded greatly, establishing communities in India (the Saint Thomas Syrian Christians), among the Mongols in Central Asia, and in China, which became home to a thriving community under the Tang dynasty from the 7th to the 9th century. At its height, between the 9th and 14th centuries, the Church of the East was the world's largest Christian church in geographical extent, with dioceses stretching from its heartland in Upper Mesopotamia to the Mediterranean Sea and as far afield as China, Mongolia, Central Asia, Anatolia, the Arabian Peninsula and India.

From its peak of geographical extent, the church entered a period of rapid decline that began in the 14th century, due largely to outside influences. The Chinese Ming dynasty overthrew the Mongols (1368) and ejected Christians and other foreign influences from China, and many Mongols in Central Asia converted to Islam. The Muslim Turco-Mongol leader Timur (1336–1405) nearly eradicated the remaining Christians in the Middle East. Nestorian Christianity remained largely confined to communities in Upper Mesopotamia and the Saint Thomas Syrian Christians of the Malabar Coast in the Indian subcontinent.

In the early modern period, the schism of 1552 led to a series of internal divisions and ultimately to its branching into three separate churches: the Chaldean Catholic Church, in full communion with the Holy See, the independent Assyrian Church of the East and the Ancient Church of the East.[33]

Description as Nestorian

[edit]

Nestorianism is a Christological doctrine that emphasises the distinction between the human and divine natures of Jesus. It was attributed to Nestorius, Patriarch of Constantinople from 428 to 431, whose doctrine represented the culmination of a philosophical current developed by scholars at the School of Antioch, most notably Nestorius's mentor Theodore of Mopsuestia, and stirred controversy when Nestorius publicly challenged the use of the title Theotokos (literally, "Bearer of God") for Mary, mother of Jesus,[34] suggesting that the title denied Christ's full humanity. He argued that Jesus had two loosely joined natures, the divine Logos and the human Jesus, and proposed Christotokos (literally, "Bearer of the Christ") as a more suitable alternative title. His statements drew criticism from other prominent churchmen, particularly from Cyril, Patriarch of Alexandria, who had a leading part in the Council of Ephesus of 431, which condemned Nestorius for heresy and deposed him as Patriarch.[35]

After 431, the state authorities in the Roman Empire suppressed Nestorianism, a reason for Christians under Persian rule to favour it and so allay suspicion that their loyalty lay with the hostile Christian-ruled empire.[36][37]

It was in the aftermath of the slightly later Council of Chalcedon (451), that the Church of the East formulated a distinctive theology. The first such formulation was adopted at the Synod of Beth Lapat in 484. This was developed further in the early seventh century, when in an at first successful war against the Byzantine Empire the Sasanid Persian Empire incorporated broad territories populated by West Syrians, many of whom were supporters of the Miaphysite theology of Oriental Orthodoxy which its opponents term "Monophysitism" (Eutychianism), the theological view most opposed to Nestorianism. They received support from Khosrow II, influenced by his wife Shirin. Shirin was a member of the Church of East, but later joined the miaphysite church of Antioch.[citation needed]

Drawing inspiration from Theodore of Mopsuestia, Babai the Great (551−628) expounded, especially in his Book of Union, what became the normative Christology of the Church of the East. He affirmed that the two qnome (a Syriac term, plural of qnoma, not corresponding precisely to Greek φύσις or οὐσία or ὑπόστασις)[38] of Christ are unmixed but eternally united in his single parsopa (from Greek πρόσωπον prosopon "mask, character, person"). As happened also with the Greek terms φύσις (physis) and ὐπόστασις (hypostasis), these Syriac words were sometimes taken to mean something other than what was intended; in particular "two qnome" was interpreted as "two individuals".[39][40][41][42] Previously, the Church of the East accepted a certain fluidity of expressions, always within a dyophysite theology, but with Babai's assembly of 612, which canonically sanctioned the "two qnome in Christ" formula, a final christological distinction was created between the Church of the East and the "western" Chalcedonian churches.[43][44][45]

The justice of imputing Nestorianism to Nestorius, whom the Church of the East venerated as a saint, is disputed.[46][21][47] David Wilmshurst states that for centuries "the word 'Nestorian' was used both as a term of abuse by those who disapproved of the traditional East Syrian theology, as a term of pride by many of its defenders [...] and as a neutral and convenient descriptive term by others. Nowadays it is generally felt that the term carries a stigma".[48] Sebastian P. Brock says: "The association between the Church of the East and Nestorius is of a very tenuous nature, and to continue to call that church 'Nestorian' is, from a historical point of view, totally misleading and incorrect – quite apart from being highly offensive and a breach of ecumenical good manners".[49]

Apart from its religious meaning, the word "Nestorian" has also been used in an ethnic sense, as shown by the phrase "Catholic Nestorians".[50][51][52][53]

In his 1996 article, "The 'Nestorian' Church: a lamentable misnomer", published in the Bulletin of the John Rylands Library, Sebastian Brock, a Fellow of the British Academy, lamented the fact that "the term 'Nestorian Church' has become the standard designation for the ancient oriental church which in the past called itself 'The Church of the East', but which today prefers a fuller title 'The Assyrian Church of the East'. Such a designation is not only discourteous to modern members of this venerable church, but also − as this paper aims to show − both inappropriate and misleading".[54]

Organisation and structure

[edit]At the Council of Seleucia-Ctesiphon in 410,[17] the Church of the East was declared to have at its head the bishop of the Persian capital Seleucia-Ctesiphon, who in the acts of the council was referred to as the Grand or Major Metropolitan, and who soon afterward was called the Catholicos of the East. Later, the title of Patriarch was used.

The Church of the East had, like other churches, an ordained clergy in the three traditional orders of bishop, priest (or presbyter), and deacon. Also like other churches, it had an episcopal polity: organisation by dioceses, each headed by a bishop and made up of several individual parish communities overseen by priests. Dioceses were organised into provinces under the authority of a metropolitan bishop. The office of metropolitan bishop was an important one, coming with additional duties and powers; canonically, only metropolitans could consecrate a patriarch.[55] The Patriarch also has the charge of the Province of the Patriarch.

For most of its history the church had six or so Interior Provinces. In 410, these were listed in the hierarchical order of: Seleucia-Ctesiphon (central Iraq), Beth Lapat (western Iran), Nisibis (on the border between Turkey and Iraq), Prat de Maishan (Basra, southern Iraq), Arbela (Erbil, Kurdistan region of Iraq), and Karka de Beth Slokh (Kirkuk, northeastern Iraq). In addition it had an increasing number of Exterior Provinces further afield within the Sasanian Empire and soon also beyond the empire's borders. By the 10th century, the church had between 20[36] and 30 metropolitan provinces.[48] According to John Foster, in the 9th century there were 25 metropolitans[56] including those in China and India. The Chinese provinces were lost in the 11th century, and in the subsequent centuries other exterior provinces went into decline as well. However, in the 13th century, during the Mongol Empire, the church added two new metropolitan provinces in North China, one being Tangut, the other Katai and Ong.[48]

Scriptures

[edit]The Peshitta, in some cases lightly revised and with missing books added, is the standard Syriac Bible for churches in the Syriac tradition: the Syriac Orthodox Church, the Syrian Catholic Church, the Assyrian Church of the East, the Ancient Church of the East, the Chaldean Catholic Church, the Maronites, the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church, the Syro-Malabar Catholic Church and the Syro-Malankara Catholic Church.

The Old Testament of the Peshitta was translated from Hebrew, although the date and circumstances of this are not entirely clear. The translators may have been Syriac-speaking Jews or early Jewish converts to Christianity. The translation may have been done separately for different texts, and the whole work was probably done by the second century. Most of the deuterocanonical books of the Old Testament are found in the Syriac, and the Wisdom of Sirach is held to have been translated from the Hebrew and not from the Septuagint.[57]

The New Testament of the Peshitta, which originally excluded certain disputed books (Second Epistle of Peter, Second Epistle of John, Third Epistle of John, Epistle of Jude, Book of Revelation), had become the standard by the early 5th century.

Iconography

[edit]It was often said in the 19th century that the Church of the East was opposed to religious images of any kind. The cult of the image was never as strong in the Syriac Churches as it was in the Byzantine Church, but they were indeed present in the tradition of the Church of the East.[58] Opposition to religious images eventually became the norm due to the rise of Islam in the region, which forbade any type of depictions of Saints and biblical prophets.[59] As such, the Church was forced to get rid of icons.[59][60]

There is both literary and archaeological evidence for the presence of images in the church. Writing in 1248 from Samarkand, an Armenian official records visiting a local church and seeing an image of Christ and the Magi. John of Cora (Giovanni di Cori), Latin bishop of Sultaniya in Persia, writing about 1330 of the East Syrians in Khanbaliq says that they had 'very beautiful and orderly churches with crosses and images in honour of God and of the saints'.[58] Apart from the references, a painting of a Christian figure discovered by Aurel Stein at the Library Cave of the Mogao Caves in 1908 is probably a representation of Jesus Christ.[61]

An illustrated 13th-century Nestorian Peshitta Gospel book written in Estrangela from northern Mesopotamia or Tur Abdin, currently in the State Library of Berlin, proves that in the 13th century the Church of the East was not yet aniconic.[62] The Nestorian Evangelion preserved in the Bibliothèque nationale de France contains an illustration depicting Jesus Christ in the circle of a ringed cross surrounded by four angels.[63] Three Syriac manuscripts from early 19th century or earlier—they were published in a compilation titled The Book of Protection by Hermann Gollancz in 1912—contain some illustrations of no great artistic worth that show that use of images continued.

A life-size male stucco figure discovered in a late-6th-century church in Seleucia-Ctesiphon, beneath which were found the remains of an earlier church, also shows that the Church of the East used figurative representations.[62]

-

Palm Sunday procession of Nestorian clergy in a 7th- or 8th-century wall painting from a church at Karakhoja, Chinese Turkestan

-

Mogao Christian painting, a late-9th-century silk painting preserved in the British Museum.

-

Feast of the Discovery of the Cross, from a 13th-century Nestorian Peshitta Gospel book written in Estrangela, preserved in the SBB.

-

An angel announces the resurrection of Christ to Mary and Mary Magdalene, from the Nestorian Peshitta Gospel.

-

The twelve apostles are gathered around Peter at Pentecost, from the Nestorian Peshitta Gospel.

-

Portraits of the Four Evangelists, from a gospel lectionary according to the Nestorian use. Mosul, Iraq, 1499.

-

Drawing of a rider (Entry into Jerusalem), a lost wall painting from the Nestorian church at Khocho, 9th century.

-

Nestorian Christian statuette probably from Imperial China

-

Anikova Plate, showing the Siege of Jericho. It was probably made in and for a Sogdian Nestorian Christian community located in Semirechye. 9th–10th century.

-

The Grigorovskoye Plate: Paten with biblical scenes in medallions, counterclockwise from bottom left: women at the empty tomb, the crucifixion, and the Ascension. Semirechye, 9th–10th century.[64]

-

Detail of the rubbing of the Nestorian pillar of Luoyang, discovered in Luoyang. 9th century.

-

Detail of the rubbing of the Nestorian pillar of Luoyang, discovered in Luoyang. 9th century.

Early history

[edit]Although the East Syriac Christian community traced their history to the 1st century AD, the Church of the East first achieved official state recognition from the Sasanian Empire in the 4th century with the accession of Yazdegerd I (reigned 399–420) to the throne of the Sasanian Empire. The policies of the Sasanian Empire, which encouraged syncretic forms of Christianity, greatly influenced the Church of the East.[65]

The early Church had branches that took inspiration from Neo-Platonism,[66][67] other Near Eastern religions[68][65] like Judaism,[69] and other forms of Christianity.[65]

In 410, the Synod of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, held at the Sasanian capital, allowed the church's leading bishops to elect a formal Catholicos (leader). Catholicos Isaac was required both to lead the Assyrian Christian community and to answer on its behalf to the Sasanian emperor.[70][71]

Under pressure from the Sasanian Emperor, the Church of the East sought to increasingly distance itself from the Pentarchy (at the time being known as the church of the Eastern Roman Empire). Therefore, in 424, the bishops of the Sasanian Empire met in council under the leadership of Catholicos Dadishoʿ (421–456) and determined that they would not, henceforth, refer disciplinary or theological problems to any external power, and especially not to any bishop or church council in the Roman Empire.[72]

Thus, the Mesopotamian churches did not send representatives to the various church councils attended by representatives of the "Western Church". Accordingly, the leaders of the Church of the East did not feel bound by any decisions of what came to be regarded as Roman Imperial Councils. Despite this, the Creed and Canons of the First Council of Nicaea of 325, affirming the full divinity of Christ, were formally accepted at the Council of Seleucia-Ctesiphon in 410.[73] The church's understanding of the term hypostasis differs from the definition of the term offered at the Council of Chalcedon of 451. For this reason, the Assyrian Church has never approved the Chalcedonian definition.[73]

The theological controversy that followed the Council of Ephesus in 431 proved a turning point in the Christian Church's history. The Council condemned as heretical the Christology of Nestorius, whose reluctance to accord the Virgin Mary the title Theotokos "God-bearer, Mother of God" was taken as evidence that he believed two separate persons (as opposed to two united natures) to be present within Christ.

The Sasanian Emperor, hostile to the Byzantines, saw the opportunity to ensure the loyalty of his Christian subjects and lent support to the Nestorian Schism. The Emperor took steps to cement the primacy of the Nestorian party within the Assyrian Church of the East, granting its members his protection,[74] and executing the pro-Roman Catholicos Babowai in 484, replacing him with the Nestorian Bishop of Nisibis, Barsauma. The Catholicos-Patriarch Babai (497–503) confirmed the association of the Assyrian Church with Nestorianism.

Parthian and Sasanian periods

[edit]

Christians were already forming communities in Mesopotamia as early as the 1st century under the Parthian Empire. In 266, the area was annexed by the Sasanian Empire (becoming the province of Asōristān), and there were significant Christian communities in Upper Mesopotamia, Elam, and Fars.[75] The Church of the East traced its origins ultimately to the evangelical activity of Thaddeus of Edessa, Mari and Thomas the Apostle. Leadership and structure remained disorganised until 315 when Papa bar Aggai (310–329), bishop of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, imposed the primacy of his see over the other Mesopotamian and Persian bishoprics which were grouped together under the Catholicate of Seleucia-Ctesiphon; Papa took the title of Catholicos, or universal leader.[76] This position received an additional title in 410, becoming Catholicos and Patriarch of the East.[77][78]

These early Christian communities in Mesopotamia, Elam, and Fars were reinforced in the 4th and 5th centuries by large-scale deportations of Christians from the eastern Roman Empire.[79] However, the Persian Church faced several severe persecutions, notably during the reign of Shapur II (339–79), from the Zoroastrian majority who accused it of Roman leanings.[80] Shapur II attempted to dismantle the catholicate's structure and put to death some of the clergy including the catholicoi Simeon bar Sabba'e (341),[81] Shahdost (342), and Barba'shmin (346).[82] Afterward, the office of Catholicos lay vacant nearly 20 years (346–363).[83] In 363, under the terms of a peace treaty, Nisibis was ceded to the Persians, causing Ephrem the Syrian, accompanied by a number of teachers, to leave the School of Nisibis for Edessa still in Roman territory.[84] The church grew considerably during the Sasanian period,[36] but the pressure of persecution led the Catholicos, Dadisho I, in 424 to convene the Council of Markabta of the Arabs and declare the Catholicate independent from "the western Fathers".[85]

Meanwhile, in the Roman Empire, the Nestorian Schism had led many of Nestorius' supporters to relocate to the Sasanian Empire, mainly around the theological School of Nisibis. The Persian Church increasingly aligned itself with the Dyophisites, a measure encouraged by the Zoroastrian ruling class. The church became increasingly Dyophisite in doctrine over the next decades, furthering the divide between Roman and Persian Christianity. In 484 the Metropolitan of Nisibis, Barsauma, convened the Synod of Beth Lapat where he publicly accepted Nestorius' mentor, Theodore of Mopsuestia, as a spiritual authority.[44] In 489, when the School of Edessa in Mesopotamia was closed by Byzantine Emperor Zeno for its Nestorian teachings, the school relocated to its original home of Nisibis, becoming again the School of Nisibis, leading to a wave of Nestorian immigration into the Sasanian Empire.[86][87] The Patriarch of the East Mar Babai I (497–502) reiterated and expanded upon his predecessors' esteem for Theodore, solidifying the church's adoption of Dyophisitism.[36]

Now firmly established in the Persian Empire, with centres in Nisibis, Ctesiphon, and Gundeshapur, and several metropolitan sees, the Church of the East began to branch out beyond the Sasanian Empire. However, through the 6th century the church was frequently beset with internal strife and persecution from the Zoroastrians. The infighting led to a schism, which lasted from 521 until around 539, when the issues were resolved. However, immediately afterward Byzantine-Persian conflict led to a renewed persecution of the church by the Sasanian emperor Khosrau I; this ended in 545. The church survived these trials under the guidance of Patriarch Aba I, who had converted to Christianity from Zoroastrianism.[36]

By the end of the 5th century and the middle of the 6th, the area occupied by the Church of the East included "all the countries to the east and those immediately to the west of the Euphrates", including the Sasanian Empire, the Arabian Peninsula, with minor presence in the Horn of Africa, Socotra, Mesopotamia, Media, Bactria, Hyrcania, and India; and possibly also to places called Calliana, Male, and Sielediva (Ceylon).[88] Beneath the Patriarch in the hierarchy were nine metropolitans, and clergy were recorded among the Huns, in Persarmenia, Media, and the island of Dioscoris in the Indian Ocean.[89]

The Church of the East also flourished in the kingdom of the Lakhmids until the Islamic conquest, particularly after the ruler al-Nu'man III ibn al-Mundhir officially converted in c. 592.

Islamic rule

[edit]

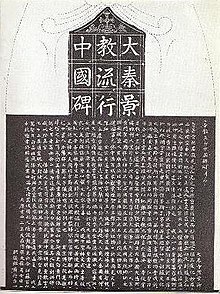

After the Sasanian Empire was conquered by Muslim Arabs in 644, the newly established Rashidun Caliphate designated the Church of the East as an official dhimmi minority group headed by the Patriarch of the East. As with all other Christian and Jewish groups given the same status, the church was restricted within the Caliphate, but also given a degree of protection. In order to resist the growing competition from Muslim courts, patriarchs and bishops of the Church of the East developed canon law and adapted the procedures used in the episcopal courts.[90] Nestorians were not permitted to proselytise or attempt to convert Muslims, but their missionaries were otherwise given a free hand, and they increased missionary efforts farther afield. Missionaries established dioceses in India (the Saint Thomas Christians). They made some advances in Egypt, despite the strong Monophysite presence there, and they entered Central Asia, where they had significant success converting local Tartars. Nestorian missionaries were firmly established in China during the early part of the Tang dynasty (618–907); the Chinese source known as the Nestorian Stele describes a mission under a proselyte named Alopen as introducing Nestorian Christianity to China in 635. In the 7th century, the church had grown to have two Nestorian archbishops, and over 20 bishops east of the Iranian border of the Oxus River.[91]

Patriarch Timothy I (780–823), a contemporary of the Caliph Harun al-Rashid, took a particularly keen interest in the missionary expansion of the Church of the East. He is known to have consecrated metropolitans for Damascus, for Armenia, for Dailam and Gilan in Azerbaijan, for Rai in Tabaristan, for Sarbaz in Segestan, for the Turks of Central Asia, for China, and possibly also for Tibet. He also detached India from the metropolitan province of Fars and made it a separate metropolitan province, known as India.[92] By the 10th century the Church of the East had a number of dioceses stretching from across the Caliphate's territories to India and China.[36]

Nestorian Christians made substantial contributions to the Islamic Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates, particularly in translating the works of the ancient Greek philosophers to Syriac and Arabic.[93][94] Nestorians made their own contributions to philosophy, science (such as Hunayn ibn Ishaq, Qusta ibn Luqa, Masawaiyh, Patriarch Eutychius, Jabril ibn Bukhtishu) and theology (such as Tatian, Bar Daisan, Babai the Great, Nestorius, Toma bar Yacoub). The personal physicians of the Abbasid Caliphs were often Assyrian Christians such as the long serving Bukhtishu dynasty.[95][96]

Expansion

[edit]

After the split with the Western World and synthesis with Nestorianism, the Church of the East expanded rapidly due to missionary works during the medieval period.[97] During the period between 500 and 1400 the geographical horizon of the Church of the East extended well beyond its heartland in present-day northern Iraq, north eastern Syria and south eastern Turkey. Communities sprang up throughout Central Asia, and missionaries from Assyria and Mesopotamia took the Christian faith as far as China, with a primary indicator of their missionary work being the Nestorian Stele, a Christian tablet written in Chinese found in China dating to 781 AD. Their most important conversion, however, was of the Saint Thomas Christians of the Malabar Coast in India, who alone escaped the destruction of the church by Timur at the end of the 14th century, and the majority of whom today constitute the largest group who now use the liturgy of the Church of the East, with around 4 million followers in their homeland, in spite of the 17th-century defection to the West Syriac Rite of the Syriac Orthodox Church.[98] The St Thomas Christians were believed by tradition to have been converted by St Thomas, and were in communion with the Church of the East until the end of the medieval period.[99]

India

[edit]

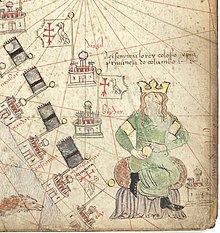

, identified as Christian due to the early Christian presence there)[100] in the contemporary Catalan Atlas of 1375.[101][102] The caption above the king of Kollam reads: Here rules the king of Colombo, a Christian.[103] The black flags (

, identified as Christian due to the early Christian presence there)[100] in the contemporary Catalan Atlas of 1375.[101][102] The caption above the king of Kollam reads: Here rules the king of Colombo, a Christian.[103] The black flags ( ) on the coast belong to the Delhi Sultanate.

) on the coast belong to the Delhi Sultanate.The Saint Thomas Christian community of Kerala, India, who according to tradition trace their origins to the evangelizing efforts of Thomas the Apostle, had a long association with the Church of the East. The earliest known organised Christian presence in Kerala dates to 295/300 when Christian settlers and missionaries from Persia headed by Bishop David of Basra settled in the region.[104] The Saint Thomas Christians traditionally credit the mission of Thomas of Cana, a Nestorian from the Middle East, with the further expansion of their community.[105] From at least the early 4th century, the Patriarch of the Church of the East provided the Saint Thomas Christians with clergy, holy texts, and ecclesiastical infrastructure. And around 650 Patriarch Ishoyahb III solidified the church's jurisdiction in India.[106] In the 8th century Patriarch Timothy I organised the community as the Ecclesiastical Province of India, one of the church's Provinces of the Exterior. After this point the Province of India was headed by a metropolitan bishop, provided from Persia, who oversaw a varying number of bishops as well as a native Archdeacon, who had authority over the clergy and also wielded a great amount of secular power. The metropolitan see was probably in Cranganore, or (perhaps nominally) in Mylapore, where the Shrine of Thomas was located.[105]

In the 12th century Indian Nestorianism engaged the Western imagination in the figure of Prester John, supposedly a Nestorian ruler of India who held the offices of both king and priest. The geographically remote Malabar Church survived the decay of the Nestorian hierarchy elsewhere, enduring until the 16th century when the Portuguese arrived in India. With the establishment of Portuguese power in parts of India, the clergy of that empire, in particular members of the Society of Jesus (Jesuits), determined to actively bring the Saint Thomas Christians into full communion with Rome under the Latin Church and its Latin liturgical rites. After the Synod of Diamper in 1599, they installed Padroado Portuguese bishops over the local sees and made liturgical changes to accord with the Latin practice and this led to a revolt among the Saint Thomas Christians.[107] The majority of them broke with the Catholic Church and vowed never to submit to the Portuguese in the Coonan Cross Oath of 1653. In 1661, Pope Alexander VII responded by sending a delegations of Carmelites headed by two Italians, one Fleming and one German priests to reconcile the Saint Thomas Christians to Catholic fold.[108] These priests had two advantages – they were not Portuguese and they were not Jesuits.[108] By the next year, 84 of the 116 Saint Thomas Christian churches had returned, forming the Syrian Catholic Church (modern day Syro-Malabar Catholic Church). The rest, which became known as the Malankara Church, soon entered into communion with the Syriac Orthodox Church. The Malankara Church also produced the Syro-Malankara Catholic Church.

Sri Lanka

[edit]Nestorian Christianity is said to have thrived in Sri Lanka with the patronage of King Dathusena during the 5th century. There are mentions of involvement of Persian Christians with the Sri Lankan royal family during the Sigiriya Period. Over seventy-five ships carrying Murundi soldiers from Mangalore are said to have arrived in the Sri Lankan town of Chilaw most of whom were Christians. King Dathusena's daughter was married to his nephew Migara who is also said to have been a Nestorian Christian, and a commander of the Sinhalese army. Maga Brahmana, a Christian priest of Persian origin is said to have provided advice to King Dathusena on establishing his palace on the Sigiriya Rock.[109]

The Anuradhapura Cross discovered in 1912 is also considered to be an indication of a strong Nestorian Christian presence in Sri Lanka between the 3rd and 10th century in the then capitol of Anuradhapura of Sri Lanka.[109][110][111][112]

China

[edit]

Christianity reached China by 635, and its relics can still be seen in Chinese cities such as Xi'an. The Nestorian Stele, set up on 7 January 781 at the then-capital of Chang'an, attributes the introduction of Christianity to a mission under a Persian cleric named Alopen in 635, in the reign of Emperor Taizong of Tang during the Tang dynasty.[113][114] The inscription on the Nestorian Stele, whose dating formula mentions the patriarch Hnanishoʿ II (773–80), gives the names of several prominent Christians in China, including Metropolitan Adam, Bishop Yohannan, 'country-bishops' Yazdbuzid and Sargis and Archdeacons Gigoi of Khumdan (Chang'an) and Gabriel of Sarag (Loyang). The names of around seventy monks are also listed.[115]

Nestorian Christianity thrived in China for approximately 200 years, but then faced persecution from Emperor Wuzong of Tang (reigned 840–846). He suppressed all foreign religions, including Buddhism and Christianity, causing the church to decline sharply in China. A Syrian monk visiting China a few decades later described many churches in ruin. The church disappeared from China in the early 10th century, coinciding with the collapse of the Tang dynasty and the tumult of the next years (the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period).[116]

Christianity in China experienced a significant revival during the Mongol-created Yuan dynasty, established after the Mongols had conquered China in the 13th century. Marco Polo in the 13th century and other medieval Western writers described many Nestorian communities remaining in China and Mongolia; however, they clearly were not as active as they had been during Tang times.

Mongolia and Central Asia

[edit]

The Church of the East enjoyed a final period of expansion under the Mongols. Several Mongol tribes had already been converted by Nestorian missionaries in the 7th century, and Christianity was therefore a major influence in the Mongol Empire.[117] Genghis Khan was a shamanist, but his sons took Christian wives from the powerful Kerait clan, as did their sons in turn. During the rule of Genghis's grandson, the Great Khan Mongke, Nestorian Christianity was the primary religious influence in the Empire, and this also carried over to Mongol-controlled China, during the Yuan dynasty. It was at this point, in the late 13th century, that the Church of the East reached its greatest geographical reach. But Mongol power was already waning as the Empire dissolved into civil war; and it reached a turning point in 1295, when Ghazan, the Mongol ruler of the Ilkhanate, made a formal conversion to Islam when he took the throne.

Jerusalem and Cyprus

[edit]

Rabban Bar Sauma had initially conceived of his journey to the West as a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, so it is possible that there was a Nestorian presence in the city ca.1300. There was certainly a recognisable Nestorian presence at the Holy Sepulchre from the years 1348 through 1575, as contemporary Franciscan accounts indicate.[118] At Famagusta, Cyprus, a Nestorian community was established just before 1300, and a church was built for them c. 1339.[119][120]

Decline

[edit]The expansion was followed by a decline. There were 68 cities with resident Church of the East bishops in the year 1000; in 1238 there were only 24, and at the death of Timur in 1405, only seven. The result of some 20 years under Öljaitü, ruler of the Ilkhanate from 1304 to 1316, and to a lesser extent under his predecessor, was that the overall number of the dioceses and parishes was further reduced.[121]

Когда Тимур , тюрко-монгольский лидер империи Тимуридов , известный также как Тамерлан, пришел к власти в 1370 году, он намеревался очистить свои владения от немусульман. Он уничтожил христианство в Центральной Азии. [122] The Church of the East "lived on only in the mountains of Kurdistan and in India".[123] Таким образом, за исключением христиан Святого Фомы на Малабарском побережье , Церковь Востока была ограничена территорией внутри и вокруг грубого треугольника, образованного Мосулом и озерами Ван и Урмия , включая Амид (современный Диярбакыр ), Мердин (современный Мардин ). и Эдесса на западе, Салмас на востоке, Хаккари и Харран на севере, а также Мосул , Киркук и Арбела (современный Эрбиль ) на юге — регион, включающий на современных картах север Ирака , юго-восток Турции , северо-восток Сирии и северо-западная окраина Ирана . Небольшие несторианские общины располагались дальше на запад, особенно в Иерусалиме и на Кипре , но малабарские христиане Индии представляли собой единственный значительный остаток некогда процветающих внешних провинций Церкви Востока. [ 124 ] Полное исчезновение несторианских епархий в Центральной Азии, вероятно, произошло в результате сочетания преследований, болезней и изоляции: «то, что пережило монголов, не пережило Черную смерть четырнадцатого века». [ 122 ] Во многих частях Центральной Азии христианство вымерло за десятилетия до походов Тимура. Сохранившиеся свидетельства из Средней Азии, в том числе большое количество датированных могил, указывают на то, что кризис Церкви Востока произошел в 1340-х, а не в 1390-х годах. Некоторые современные наблюдатели, в том числе папский посланник Джованни де Мариньолли , упоминают убийство латинского епископа в 1339 или 1340 году мусульманской толпой в Алмалыке , главном городе Тангута , и насильственное обращение христиан города в ислам. Надгробия на двух восточно-сирийских кладбищах в Монголии датируются 1342 годом, некоторые из них посвящены смерти во время вспышки чумы в 1338 году. В Китае последние упоминания о несторианских и латинских христианах датируются 1350-ми годами, незадолго до замены в 1368 году монгольских Династия Юань с ксенофобской династией Мин и, как следствие, добровольная изоляция Китая от иностранного влияния, включая Христианство. [ 125 ]

Расколы

[ редактировать ]С середины XVI века и на протяжении последующих двух столетий Церковь Востока переживала ряд внутренних расколов . Некоторые из этих расколов были вызваны отдельными людьми или группами, которые решили принять унию с католической церковью . Другие расколы были спровоцированы соперничеством между различными фракциями внутри Церкви Востока. Отсутствие внутреннего единства и частая смена пристрастий привели к созданию и продолжению отдельных патриархальных линий. Несмотря на множество внутренних и внешних трудностей (политическое притеснение со стороны османских властей и частые преследования со стороны местных нехристиан), традиционные ветви Церкви Востока сумели пережить этот бурный период и в конечном итоге консолидироваться в XIX веке в форма Ассирийской церкви Востока . В то же время, после многих подобных трудностей, группы, объединившиеся с Католической Церковью, окончательно объединились в Халдейскую Католическую Церковь.

Раскол 1552 г.

[ редактировать ]Примерно в середине пятнадцатого века патриарх Сим на IV Басиди сделал патриаршую преемственность наследственной - обычно от дяди к племяннику. Эта практика, которая привела к нехватке подходящих наследников, в конечном итоге привела к расколу в Церкви Востока, создав временное католическое ответвление, известное как линия Шимун. [ 126 ] Патриарх Сим , на VII Ишо яхбе предположительно потому (1539–1558) вызвал большие волнения в начале своего правления, назначив своим преемником своего двенадцатилетнего племянника Хнанишо , что не было старших родственников. [ 127 ] Несколько лет спустя, вероятно, потому, что Хнанишо тем временем умер, он назначил преемником своего пятнадцатилетнего брата Элию, будущего Патриарха Элию VI (1558–1591). [ 55 ] Эти назначения в сочетании с другими обвинениями в неподобающем поведении вызвали недовольство во всей церкви, и к 1552 году Шем на VII Ишо -яхбе стал настолько непопулярным, что группа епископов, в основном из округов Амид , Сирт и Салмас в северной Месопотамии, предпочла новый патриарх. Они избрали монаха по имени Йоханнан Сулака , бывшего настоятеля монастыря Раббан Хормизд недалеко от Алькоша , который был резиденцией действующих патриархов; [ 128 ] однако ни один епископ митрополичьего ранга не смог его посвятить, как того требовало канон. Францисканские миссионеры уже действовали среди несториан. [ 129 ] и, используя их в качестве посредников, [ 130 ] Сторонники Сулаки стремились узаконить свою позицию, добиваясь посвящения своего кандидата Папой Юлием III (1550–1555 гг.). [ 131 ] [ 55 ]

Сулака отправился в Рим, прибыв туда 18 ноября 1552 года, и представил письмо, составленное его сторонниками в Мосуле , в котором излагались его претензии и просили Папу посвятить его в сан Патриарха. 15 февраля 1553 года он дважды пересматривал исповедание веры, которое было признано удовлетворительным, и буллой Divina Disponte Clementia от 20 февраля 1553 года был назначен «Патриархом Мосула в Восточной Сирии». [ 132 ] Мосула или «Патриарх Халдейской церкви » . [ 133 ] Он был рукоположен в епископа в соборе Святого Петра 9 апреля. 28 апреля Папа Юлий III вручил ему паллий, дающий патриархальный сан, подтвержденный буллой Cum Nos Nuper . Эти события, в результате которых Рим заставили поверить, что Шем на VII Ишо - яхбе мертв, создали внутри Церкви Востока прочный раскол между линией Элия патриархов в Алкоше и новой линией, берущей начало из Сулаки. Последнее в течение полувека признавалось Римом как находящееся в общении, но оно вернулось как к наследственной преемственности, так и к несторианству и продолжилось у патриархов Ассирийской церкви Востока . [ 131 ] [ 134 ]

Сулака покинул Рим в начале июля и в Константинополе подал заявление о гражданском признании. После возвращения в Месопотамию он получил от османских властей в декабре 1553 г. признание главой «халдейского народа по примеру всех патриархов». В следующем году во время пятимесячного пребывания в Амиде ( Диярбакыре ) он рукоположил двух митрополитов и трёх других епископов. [ 130 ] (для Газарты , Хесны д'Кифы , Амида , Мардина и Серта ). Со своей стороны, Шем на VII Ишо- яхбе из линии Алкош посвятил в митрополиты еще двух несовершеннолетних членов своей патриархальной семьи ( Нисибиса и Газарты ). сторону губернатора Амадии Он также склонил на свою , который пригласил Сулаку в Амадию , заключил его в тюрьму на четыре месяца и казнил в январе 1555 года. [ 128 ] [ 134 ]

Линии Элия и Шимун

[ редактировать ]Эта новая католическая линия, основанная Сулакой, сохранила свое место в Амиде и известна как линия «Шимун». Уилмшерст предполагает, что принятие ими имени Шимун (в честь Симона Петра ) должно было указать на легитимность их католической линии. [ 135 ] Преемник Сулаки Абдишо IV Марон (1555–1570) посетил Рим, и его патриарший титул был подтвержден Папой в 1562 году. [ 136 ] В какой-то момент он переехал в Серт .

Патриарх линии Элии Шемон VII Ишояхб (1539–1558), который проживал в монастыре Раббан Хормизд недалеко от Алькоша , продолжал активно выступать против союза с Римом, и ему наследовал его племянник Элия (обозначаемый как Элия «VII» в старой историографии, [ 137 ] [ 138 ] но в недавних научных работах переименован в Элию «VI»). [ 139 ] [ 140 ] [ 141 ] Во время его патриаршего пребывания, с 1558 по 1591 год, Церковь Востока сохранила свою традиционную христологию и полную церковную независимость. [ 142 ]

Следующим патриархом Шимуна, вероятно, был Яхбаллаха IV , который был избран в 1577 или 1578 году и умер в течение двух лет, прежде чем искать или получать подтверждение из Рима. [ 135 ] По мнению Тиссерана, проблемы, созданные «несторианскими» традиционалистами и властями Османской империи, помешали досрочным выборам преемника Абдишо. [ 143 ] Дэвид Уилмшерст и Хелен Мюрр полагают, что в период между 1570 годом и патриархальными выборами Яхбаллы на него или другого человека с таким же именем смотрели как на патриарха. [ 144 ] Преемник Яхбаллы Шимун IX Динха (1580–1600), переехавший из-под турецкого владычества в Салмас на озере Урмия в Персии, [ 145 ] был официально подтвержден Папой в 1584 году. [ 146 ] Есть теории, что он назначил своего племянника Шимуна X Элию (1600–1638), но другие утверждают, что его избрание не было связано с каким-либо таким назначением. своим преемником [ 144 ] Тем не менее, с тех пор и до 21 века в линии Симун использовалась наследственная система преемственности, отказ от которой был одной из причин создания этой линии.

Два несторианских патриарха

[ редактировать ]

Следующий патриарх Элии, Элия VII (VIII) (1591–1617), несколько раз вел переговоры с католической церковью в 1605, 1610 и 1615–1616 годах, но без окончательного решения. [ 147 ] Это, вероятно, встревожило Шимуна X, который в 1616 году отправил в Рим исповедание веры, которое Рим счел неудовлетворительным, а также еще одно в 1619 году, которое также не принесло ему официального признания. [ 147 ] Уилмшерст говорит, что именно этот патриарх Шимун вернулся к «старой вере» несторианства. [ 144 ] [ 148 ] что привело к изменению лояльности, в результате которой линия Элия получила контроль над низменностями, а над горами - линия Шимун. Дальнейшие переговоры между линией Элии и католической церковью были отменены во время патриаршего правления Элии VIII (IX) (1617–1660). [ 149 ]

Следующие два патриарха Шимуна, Шимун XI Эшуйоу (1638–1656) и Шимун XII Йоалаха (1656–1662), писали Папе в 1653 и 1658 годах, согласно Уилмсхерсту, в то время как Хелен Мюрре говорит только о 1648 и 1653 годах. Уилмшерст говорит, что Шимун XI был отправлен мантию , хотя Хелин Мюрре утверждает, что ни один из них не получил официального признания. В письме предполагается, что один из двоих был отстранен от должности (предположительно несторианскими традиционалистами) за прокатолические взгляды: Шимун XI, согласно Хелен Мюрре, вероятно, Шимун XII, согласно Уилмшерсту. [ 150 ] [ 144 ]

Элия IX (X) (1660–1700) был «энергичным защитником традиционной [несторианской] веры», [ 150 ] и одновременно следующий патриарх Шимун, Шимун XIII Динкха (1662–1700), окончательно порвал с католической церковью. В 1670 году он дал традиционалистский ответ на подход, исходивший из Рима, и к 1672 году все связи с Папой были прерваны. [ 151 ] [ 152 ] Тогда существовало две традиционалистские патриархальные линии: старшая линия Элия в Алкоше и младшая линия Шимуна в Кочанисе . [ 153 ]

Линия иосифлян

[ редактировать ]Поскольку линия Шимун «постепенно вернулась к традиционному поклонению Церкви Востока, тем самым потеряв преданность западных регионов», [ 154 ] он переместился с территории, контролируемой Турцией, в Урмию в Персии . Епископство Амид ( Диярбакыр ), первоначальная штаб-квартира Шимун Сулака, перешло в подчинение Патриарха Алкоша. В 1667 или 1668 году епископ этой кафедры принял католическую веру. В 1677 году он добился от турецких властей признания обладателя независимой власти в Амиде и Мардине , а в 1681 году был признан Римом «Патриархом халдейского народа, лишенного своего Патриарха» (Амидского патриархата). Таким образом была учреждена иосифлянская линия, третья линия патриархов и единственная католическая линия в то время. [ 155 ] Все преемники Иосифа I взяли имя «Иосиф». Жизнь этого Патриархата была трудной: руководство постоянно раздражалось традиционалистами, а община боролась с налоговым бременем, наложенным османскими властями.

В 1771 году Элия XI (XII) и назначенный им преемник (будущий Элия XII (XIII) Ишо Яхб ) исповедовали веру, которая была принята Римом, установив таким образом общение. К тому времени католическая позиция была повсеместно принята в районе Мосула . Когда Элия XI (XII) умер в 1778 году, Элия XII (XIII) вновь исповедовал католическую веру и был признан Римом Патриархом Мосула, но в мае 1779 года отказался от этой профессии в пользу традиционной веры. Его младший двоюродный брат Йоханнан Хормизд был избран на местное место вместо него в 1780 году, но по разным причинам был признан Римом только как митрополит Мосула и администратор католиков партии Алкош, имеющий полномочия Патриарха, но не титул или знаки отличия. Когда Иосиф IV из Амидского патриархата подал в отставку в 1780 году, Рим также сделал его племянника Августина Хинди , которого он хотел сделать своим преемником, не патриархом, а администратором. В течение следующих 47 лет никто не носил титул халдейского католического патриарха.

Уплотнение патриархальных линий

[ редактировать ]Когда Элия XII (XIII) умер в 1804 году, вместе с ним умерла несторианская ветвь линии Элия. [ 156 ] [ 141 ] Поскольку Хормизд склонил большинство его подданных к союзу с Римом, они не избрали нового патриарха-традиционалиста. В 1830 году Хормизд был наконец признан халдейским католическим патриархом Вавилона , что стало последним остатком наследственной системы внутри Халдейской католической церкви.

Это также положило конец соперничеству между старшей линией Элия и младшей линией Шимуна, поскольку Шимун XVI Йоханнан (1780–1820) стал единственным предстоятелем традиционалистской Церкви Востока, «законным преемником первоначально униатского патриархата [Шимун ] линия". [ 157 ] [ 158 ] В 1976 году она приняла название Ассирийская Церковь Востока . [ 159 ] [ 15 ] [ 160 ] и его патриархат оставался наследственным до смерти в 1975 году Шимуна XXI Эшая .

Соответственно, Иоахим Якоб отмечает, что первоначальный Патриархат Церкви Востока (линия Элия) вступил в союз с Римом и продолжает существовать по сей день в форме Халдейской [Католической] Церкви, [ 161 ] в то время как первоначальный Патриархат Халдейской Католической Церкви (линия Шимуна) продолжается и сегодня в Ассирийской Церкви Востока.

См. также

[ редактировать ]- Древняя церковь Востока

- Ассирийский геноцид

- Халдейская католическая церковь

- Христианство в Восточной Аравии

- Совет Селевкии-Ктесифона (410 г.)

- Епархии Церкви Востока после 1552 г.

- Епархии Церкви Востока до 1318 г.

- Епархии Церкви Востока, 1318–1552 гг.

- Список патриархов Церкви Востока

- Патриархи Церкви Востока

- Раскол трех глав

- Синод Бет Лапат

- Сирийское христианство

- Сирийская Православная Церковь

Пояснительные примечания

[ редактировать ]- ^ Традиционная западная историография Церкви датирует ее основание Эфесским собором 431 года и последовавшим за ним « несторианским расколом ». Однако Церковь Востока уже существовала как отдельная организация в 431 году, и имя Нестория не упоминается ни в одном из актов церковных синодов вплоть до VII века. [ 7 ] Христианские общины, изолированные от церкви в Римской империи, вероятно, существовали в Персии уже со II века. [ 8 ] Независимая церковная иерархия Церкви сложилась на протяжении IV века. [ 9 ] и она обрела свою полную институциональную идентичность с учреждением в качестве официально признанной христианской церкви в Персии шахом Йездигердом I в 410 году. [ 10 ]

- ^ Ярлык «Несторианство» популярен, но он вызывает споры, уничижительный и считается неправильным. См. раздел § «Описание как несторианство», чтобы узнать о проблеме названия и альтернативных обозначениях церкви.

Цитаты

[ редактировать ]- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Уилкен, Роберт Луи (2013). «Сирийскоязычные христиане: Церковь Востока» . Первое тысячелетие: Глобальная история христианства . Нью-Хейвен и Лондон : Издательство Йельского университета . стр. 222–228. ISBN 978-0-300-11884-1 . JSTOR j.ctt32bd7m.28 . LCCN 2012021755 . S2CID 160590164 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Баум и Винклер 2003 , с. 2.

- ^ Стюарт 1928 , с. 15.

- ^ Вайн, Обри Р. (1937). Несторианские церкви . Лондон: Независимая пресса. п. 104.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Мейендорф 1989 , с. 287-289.

- ^ Бродхед, Эдвин К. (2010). Еврейские способы следовать за Иисусом: перерисовка религиозной карты древности . Тюбинген: Мор Зибек. п. 123. ИСБН 9783161503047 .

- ^ Брок 2006 , с. 8.

- ^ Брок 2006 , с. 11.

- ^ Ланге 2012 , стр. 477–9.

- ^ Пейн 2015 , с. 13.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Пол, Дж.; Паллат, П. (1996). Папа Иоанн Павел II и католическая церковь в Индии . Публикации Мар Тома Йогам. Центр индийских христианских археологических исследований. п. 5 . Проверено 17 июня 2022 г.

Авторы используют разные названия для обозначения одной и той же Церкви: Церковь Селевкии-Ктесифона, Церковь Востока, Вавилонская Церковь, Ассирийская Церковь или Персидская Церковь.

- ^ Баум и Винклер 2003 , с. 3,4.

- ^ Восточно-христианские аналекты . Мост институт востоковедения. 1971. с. 2 . Проверено 17 июня 2022 г.

Церковь Селевкии-Ктесифона называлась Восточно-Сирийской Церковью или Церковью Востока.

- ^ Фией 1994 , с. 97-107.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Баум и Винклер 2003 , с. 4.

- ^ Баум и Винклер 2003 , с. 112-123.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Кертин, ДП (май 2021 г.). Совет Селевкии-Ктесифона: при Маре Исааке . Далкасская издательская компания. ISBN 9781088234327 .

- ^ Прокопий, Войны , I.7.1–2.

* Грейтрекс-Лью (2002), II, 62 - ↑ Иисус Навин Столпник, Хроники , XLIII.

* Грейтрекс-Лью (2002), II, 62 - ^ Прокопий, Войны , I.9.24.

* Грейтрекс-Лью (2002), II, 77 - ^ Перейти обратно: а б Брок 1996 , с. 23–35.

- ^ Брок 2006 , с. 1-14.

- ^ Джозеф 2000 , с. 42.

- ^ Вуд 2013 , с. 140.

- ^ Моффетт, Сэмюэл Х. (1992). История христианства в Азии. Том I: Начало 1500 года . ХарперКоллинз. п. 219.

- ^ Винклер, Дитмар (2009). Скрытые сокровища и межкультурные встречи: исследования восточно-сирийского христианства в Китае и Центральной Азии . ЛИТ Верлаг Мюнстер. ISBN 978-3-643-50045-8 .

- ^ Баум и Винклер 2003 , с. 84-89.

- ^ Восточно-католические церкви, 2017 г. Архивировано 24 октября 2018 г. на Wayback Machine. Получено в декабре 2010 г. Информация взята из Annuario Pontificio 2017 г. издания

- ^ «Святая Апостольская Католическая Ассирийская Церковь Востока — Всемирный Совет Церквей» . www.oikoumene.org . Январь 1948 года.

- ^ Рассам, Суха (2005). Христианство в Ираке: его истоки и развитие до наших дней . Издательская группа Гринвуд. п. 166. ИСБН 9780852446331 .

Число верующих в начале двадцать первого века, принадлежащих к Ассирийской церкви Востока под руководством Мар-Динхи, оценивалось примерно в 385 000, а число верующих, принадлежавших к Древней церкви Востока под руководством Мар-Аддия, - в 50 000 человек. 70 000.

- ^ Баум и Винклер 2003 , с. 3, 30.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Брок, Себастьян П ; Кокли, Джеймс Ф. «Церковь Востока» . e-GEDSH: Энциклопедический словарь сирийского наследия Горгия . Проверено 27 июня 2022 г.

Церковь Востока следует строго диофизитской («двухприродной») христологии Теодора Мопсуестийского, в результате чего ее богословские оппоненты ошибочно назвали ее «несторианской».

- ^ Уилмшерст 2000 .

- ^ Фольц 1999 , с. 63.

- ^ Селезнев 2010 , с. 165–190.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж «Несторианство» . Британская энциклопедия . Проверено 28 января 2010 г.

- ^ "Несторий" . Британская энциклопедия . Проверено 11 ноября 2018 г.

- ^ Кун 2019 , с. 130.

- ^ Брок 1999 , с. 286−287.

- ^ Вуд 2013 , с. 136.

- ^ Алфеев Иларион (24 марта 2016 г.). Духовный мир Исаака Сирина . Литургическая пресса. ISBN 978-0-87907-724-2 .

- ^ Брок 2006 , с. 174.

- ^ Мейендорф 1989 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Баум и Винклер 2003 , с. 28-29.

- ^ Пейн 2009 , с. 398-399.

- ^ Бетьюн-Бейкер 1908 , с. 82-100.

- ^ Винклер 2003 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Уилмшерст 2000 , с. 4.

- ^ Брок 2006 , с. 14.

- ^ Йост Йонгерден, Джелле Верхей, Социальные отношения в Османском Диярбекире, 1870-1915 (BRILL 2012), стр. 21

- ^ Гертруда Лотиан Белл , Амурат Амурату (Хайнеманн, 1911), стр. 281

- ^ Уссани, Габриэль (1901). «Современные халдеи и несториане и изучение сирийского языка среди них» . Журнал Американского восточного общества . 22:81 . дои : 10.2307/592420 . JSTOR 592420 .

- ^ Альбрехт Классен (редактор), «Восток встречается с Западом в средние века и раннее Новое время» (Вальтер де Грюйтер, 2013), стр. 704

- ^ Брок 1996 , с. 23-35.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Уилмшерст 2000 , с. 21-22.

- ^ Фостер 1939 , с. 34.

- ^ Сирийские версии Библии Томаса Никола

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Парри, Кен (1996). «Образы в Церкви Востока: свидетельства Центральной Азии и Китая» (PDF) . Бюллетень библиотеки Джона Райлендса . 78 (3): 143–162. дои : 10.7227/BJRL.78.3.11 . Проверено 23 июля 2018 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Баумер 2006 , с. 168.

- ^ «Тень Нестория» .

- ^ Кунг, Тянь Мин (1960). в ( династии Тан ( PDF) на китайском языке (Гонконг)).

Христианство утверждает, что эта статуя - статуя Иисуса из Кейки.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Баумер 2006 , с. 75, 94.

- ^ Дреге 1992 , стр. 43, 187.

- ^ О'Дейли, британец (Йельский университет) (2021). «Израиль семирек» (PDF) . Китайско-платонические статьи : 10–12.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Хьюстон, GW (1980). «Обзор несторианства во Внутренней Азии» . Центральноазиатский журнал . 24 (1/2). Висбаден, Германия: 60–68. ISSN 0008-9192 . JSTOR 41927279 .

- ^ Краусмюллер, Дирк (16 ноября 2015 г.). «Христианский платонизм и спор о загробной жизни: Иоанн Скифопольский и Максим Исповедник о бездействии бестелесной души» . Скриниум . 11 (1). Брилл : 246. doi : 10.1163/18177565-00111p21 . ISSN 1817-7530 . S2CID 170249994 .

- ^ Хури, Джордж (22 января 1997 г.). «Восточное христианство накануне ислама» . ЭВТН . Проверено 01 марта 2023 г.

- ^ Чуа, Эми (2007). День Империи: как сверхдержавы достигают глобального доминирования и почему они падают (1-е изд.). Нью-Йорк : Даблдэй . п. 71. ИСБН 978-0-385-51284-8 . OCLC 123079516 .

- ^ Раухорст, Джерард (март 1997 г.). «Еврейские литургические традиции в раннем сирийском христианстве» . бдения Христианские 51 (1): 72–93. дои : 10.2307/1584359 . ISSN 0042-6032 . JSTOR 1584359 – через JSTOR.

- ^ Фий, Жан Морис (1970). Вехи истории Церкви в Ираке . Левен: Секретариат CSCO.

- ^ Шомон 1988 .

- ^ Хилл 1988 , с. 105.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Кросс и Ливингстон 2005 , с. 354.

- ^ Аутербридж 1952 .

- ^ Баум и Винклер 2003 , с. 1.

- ^ Илария Рамелли , «Папа бар Аггай», в Энциклопедии древнего христианства , 2-е изд., 3 тома, изд. Анджело Ди Берардино (Даунерс-Гроув, Иллинойс: InterVarsity Press, 2014), 3:47.

- ^ Фией 1967 , с. 3–22.

- ^ Роберсон 1999 , с. 15.

- ^ Даниэль и Махди 2006 , с. 61.

- ^ Фостер 1939 , с. 26-27.

- ^ Берджесс и Мерсье 1999 , с. 9-66.

- ^ Дональд Аттуотер и Кэтрин Рэйчел Джон, Словарь святых Пингвина , 3-е изд. (Нью-Йорк: Penguin Books, 1993), 116, 245.

- ^ Таджадод 1993 , с. 110–133.

- ^ Лаборт 1909 .

- ^ Джуги 1935 , с. 5–25.

- ^ Рейнинк 1995 , с. 77-89.

- ^ Брок 2006 , с. 73.

- ^ Стюарт 1928 , с. 13-14.

- ^ Стюарт 1928 , с. 14.

- ^ Тилье, Матье (08.11.2019), «Глава 5. Справедливость немусульман на исламском Ближнем Востоке» , Изобретение кади: справедливость мусульман, евреев и христиан в первые века ислама , Историческая библиотека стран ислама, Париж: Éditions de la Sorbonne, стр. 455–533, ISBN 979-10-351-0102-2

- ^ Фостер 1939 , с. 33.

- ^ Фией 1993 , с. 47 (Армения), 72 (Дамаск), 74 (Дайлам и Гилян), 94–6 (Индия), 105 (Китай), 124 (Рай), 128–9 (Сарбаз), 128 (Самарканд и Бет Туркае), 139 (Тибет).

- ^ Хилл 1993 , с. 4-5, 12.

- ^ Браг, Реми (2009). Легенда средневековья: философские исследования средневекового христианства, иудаизма и ислама . Издательство Чикагского университета. п. 164. ИСБН 9780226070803 .

Среди переводчиков девятого века также не было мусульман. Почти все они были христианами различных восточных конфессий: якобиты, мельхиты и, прежде всего, несториане.

- ^ Реми Браг, Вклад ассирийцев в исламскую цивилизацию. Архивировано 27 сентября 2013 г. в Wayback Machine.

- ^ Британика, несторианин

- ^ Джарретт, Джонатан (24 июня 2019 г.). «Когда несторианин не несторианин? Чаще всего именно тогда» . Уголок Европы десятого века . Проверено 01 марта 2023 г.

- ^ Рональд Г. Роберсон, «Сиро-Малабарская католическая церковь»

- ^ «СЕТЬ NSC - Ранние упоминания об апостольстве Святого Фомы в Индии, записи об индийской традиции, христианах Святого Фомы и заявления индийских государственных деятелей» . Насрани.нет. 16 февраля 2007 г. Архивировано из оригинала 3 апреля 2010 года . Проверено 31 марта 2010 г.

- ^ Лищак, Владимир (2017). «Mapa mondi (Каталонский атлас 1375 года), картографическая школа Майорки и Азия XIV века» (PDF) . Международная картографическая ассоциация . 1 : 4–5. Бибкод : 2018PrICA...1...69L . doi : 10.5194/ica-proc-1-69-2018 .

- ^ Массинг, Жан Мишель; АЛЬБУКЕРКЕ, Луис де; Браун, Джонатан; Гонсалес, Джей Джей Мартин (1 января 1991 г.). Около 1492 года: Искусство в эпоху открытий . Издательство Йельского университета. ISBN 978-0-300-05167-4 .

- ^ Картография между христианской Европой и арабо-исламским миром, 1100-1500: различные традиции . БРИЛЛ. 17 июня 2021 г. с. 176. ИСБН 978-90-04-44603-8 .

- ^ Лищак, Владимир (2017). «Mapa mondi (Каталонский атлас 1375 года), картографическая школа Майорки и Азия XIV века» (PDF) . Международная картографическая ассоциация . 1 : 5. Бибкод : 2018PrICA...1...69L . doi : 10.5194/ica-proc-1-69-2018 .

- ^ Фрикенберг 2008 , стр. 102–107, 115.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Баум и Винклер 2003 , с. 52.

- ^ Баум и Винклер 2003 , с. 53.

- ^ «Синод Диампера» . britannica.com . Британская энциклопедия . Проверено 11 июля 2022 г.

Местный патриарх, представлявший Ассирийскую церковь Востока, к которой древние христиане в Индии стремились получить церковную власть, был затем отстранен от юрисдикции в Индии и заменен португальским епископом; восточно-сирийская литургия Аддаи и Мари была «очищена от ошибок»; и латинские облачения, ритуалы и обычаи были введены, чтобы заменить древние традиции.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Нил, Стивен (1984). История христианства в Индии: от начала до 1707 года нашей эры . Издательство Кембриджского университета. п. 322. ИСБН 0521243513 .

Тогда папа решил бросить в бассейн еще один камень. Очевидно, по предложению некоторых каттанаров он отправил в Индию четырех босых кармелитов - двух итальянцев, одного фламандца и одного немца. У этих отцов было два преимущества: они не были португальцами и не были иезуитами. Главе миссии был присвоен титул апостольского комиссара, и на него была возложена особая обязанность по восстановлению мира в Серре.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Пинто, Леонард (14 июля 2015 г.). Быть христианином в Шри-Ланке: исторические, политические, социальные и религиозные соображения . Издательство Бальбоа. стр. 55–57. ISBN 978-1452528632 .

- ^ «Митрополит Мар Апрем посещает древний крест Анурадхапуры в рамках официальной поездки в Шри-Ланку» . Новости Ассирийской церкви. Архивировано из оригинала 26 февраля 2015 г. Проверено 6 августа 2013 г.

- ^ Виракун, Раджита (26 июня 2011 г.). «Существовало ли христианство в древней Шри-Ланке?» . Санди Таймс . Проверено 2 августа 2021 г.

- ^ «Основной интерес» . Ежедневные новости . 22 апреля 2011 г. Архивировано из оригинала 29 марта 2015 г. Проверено 2 августа 2021 г.

- ^ Дин 2006 , с. 149-162.

- ^ Стюарт 1928 , с. 169.

- ^ Стюарт 1928 , с. 183.

- ^ Моффетт 1999 , с. 14-15.

- ^ Джексон 2014 , с. 97.

- ^ Люк 1924 , с. 46–56.

- ^ Фией 1993 , с. 71.

- ^ Уилмшерст 2000 , с. 66.

- ^ Уилмшерст 2000 , с. 16-19.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Питер К. Фан, Христианство в Азии (John Wiley & Sons, 2011), стр. 243

- ^ Баум и Винклер 2003 , с. 105.

- ^ Уилмшерст 2000 , с. 345-347.

- ^ Баум и Винклер 2003 , с. 104.

- ^ Уилмшерст 2000 , с. 19.

- ^ Уилмшерст 2000 , с. 21.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Уилмшерст 2000 , с. 22.

- ^ Лемменс 1926 , с. 17-28.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Фернандо Филони, Церковь в Ираке, CUA Press, 2017), стр. 35–36.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Хабби 1966 , с. 99-132.

- ^ Патриарх Мозаля в Восточной Сирии ( Антон Баумстарк (редактор), Oriens Christianus , IV:1, Рим и Лейпциг, 2004, стр. 277)

- ^ Ассемани 1725 , с. 661

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Уилкинсон 2007 , с. 86−88.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Уилмшерст 2000 , с. 23.

- ^ Уилмшерст 2000 , с. 22-23.

- ^ Тиссеран 1931 , с. 261-263.

- ^ Фией 1993 , с. 37.

- ^ Мурре ван ден Берг 1999 , с. 243-244.

- ^ Баум и Винклер 2003 , с. 116, 174.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Сад 2007 , с. 473.

- ^ Уилмшерст 2000 , с. 22, 42, 194, 260, 355.

- ^ Тиссеран 1931 , стр. 230.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Мурре ван ден Берг 1999 , с. 252-253.

- ^ Баум и Винклер 2003 , с. 114.

- ^ Уилмшерст 2000 , с. 23-24.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Уилмшерст 2000 , с. 24.

- ^ Уилмшерст 2000 , с. 352.

- ^ Уилмшерст 2000 , с. 24-25.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Уилмшерст 2000 , с. 25.

- ^ Уилмшерст 2000 , с. 25, 316.

- ^ Баум и Винклер 2003 , с. 114, 118, 174-175.

- ^ Мурре ван ден Берг 1999 , с. 235-264.

- ^ Уилмшерст 2000 , с. 24, 352.

- ^ Баум и Винклер 2003 , с. 119, 174.

- ^ Уилмшерст 2000 , с. 263.

- ^ Баум и Винклер 2003 , с. 118, 120, 175.

- ^ Уилмшерст 2000 , с. 316-319, 356.

- ^ Джозеф 2000 , с. 1.

- ^ Фред Априм, «Ассирия и ассирийцы после американской оккупации Ирака в 2003 году»

- ^ Якоб 2014 , с. 100-101.

Общие и цитируемые ссылки

[ редактировать ]- Абуна, Хирмис (2008). Ассирийцы, курды и османы: межобщинные отношения на периферии Османской империи . Амхерст: Камбрия Пресс. ISBN 9781604975833 .

- Ассемани, Джузеппе Симоне (1719). Восточная библиотека Клементины-Ватикана . Том. 1. Рим.

- Ассемани, Джузеппе Симоне (1721). Восточная библиотека Клементины-Ватикана . Том. 2. Рим.

- Ассемани, Джузеппе Симоне (1725). Восточная библиотека Клементины-Ватикана . Том. 3. Рим.

- Ассемани, Джузеппе Симоне (1728). Восточная библиотека Клементины-Ватикана . Том. 3. Рим.

- Ассемани, Джузеппе Луиджи (1775). Историко-хронологический комментарий о католиках или патриархах халдеев и несториан . Рим

- Ассемани, Джузеппе Луиджи (2004). История халдейских и несторианских патриархов . Пискатауэй, Нью-Джерси: Gorgias Press.

- Бэджер, Джордж Перси (1852). Несториане и их ритуалы . Том. 1. Лондон: Джозеф Мастерс.

- Бэджер, Джордж Перси (1852). Несториане и их ритуалы . Том. 2. Лондон: Джозеф Мастерс. ISBN 9780790544823 .

- Баум, Вильгельм ; Винклер, Дитмар В. (2003). Церковь Востока: Краткая история . Лондон-Нью-Йорк: Рутледж-Керзон. ISBN 9781134430192 .

- Баумер, Кристоф (2006). Церковь Востока: иллюстрированная история ассирийского христианства . Лондон-Нью-Йорк: Таурис. ISBN 9781845111151 .

- Беккетти, Филиппо Анджелико (1796). История последних четырех веков Церкви . Том 10. Рим.

- Бельтрами, Джузеппе (1933). La Chiesa Chaldea nel secolo dell'Unione . Рим: Папский институт востоковедения. ISBN 9788872102626 .

- Бетьюн-Бейкер, Джеймс Ф. (1908). Несторий и его учение: новый анализ доказательств . Кембридж: Издательство Кембриджского университета. ISBN 9781107432987 .

- Беван, Джордж А. (2009). «Последние дни Нестория в сирийских источниках» . Журнал Канадского общества сирийских исследований . 7 (2007): 39–54. дои : 10.31826/9781463216153-004 . ISBN 9781463216153 .

- Беван, Джордж А. (2013). «Интерполяции в сирийском переводе «Liber Heraclidis» Нестория» . Студия Патристика . 68 : 31–39.

- Биннс, Джон (2002). Введение в христианские православные церкви . Кембридж: Издательство Кембриджского университета. ISBN 9780521667388 .

- Брок, Себастьян П. (1992). Исследования сирийского христианства: история, литература и теология . Олдершот: Вариорум. ISBN 9780860783053 .

- Брок, Себастьян П. (1996). «Несторианская церковь: прискорбное неправильное название» (PDF) . Бюллетень библиотеки Джона Райлендса . 78 (3): 23–35. дои : 10.7227/BJRL.78.3.3 .

- Брок, Себастьян П. (1999). «Христология Церкви Востока в синодах пятого — начала седьмого веков: предварительные соображения и материалы» . Доктринальное разнообразие: разновидности раннего христианства . Нью-Йорк и Лондон: Издательство Garland Publishing. стр. 281–298. ISBN 9780815330714 .

- Брок, Себастьян П. (2006). Огонь с небес: исследования по сирийскому богословию и литургии . Олдершот: Эшгейт. ISBN 9780754659082 .

- Брок, Себастьян П. (2007). «Ранние рукописи Церкви Востока VII-XIII веков» . Журнал ассирийских академических исследований . 21 (2): 8–34. Архивировано из оригинала 6 октября 2008 г.

- Берджесс, Стэнли М. (1989). Святой Дух: восточно-христианские традиции . Пибоди, Массачусетс: Издательство Хендриксон. ISBN 9780913573815 .

- Берджесс, Ричард В.; Мерсье, Раймонд (1999). «Даты мученической кончины Симеона бар-Саввы и «Великой резни » Болландианская Аналекта . 117 (1–2): 9–66. дои : 10.1484/j.ABOL.4.01773 .

- Берлесон, Сэмюэл; Ромпей, Лукас ван (2011). «Список патриархов главных сирийских церквей на Ближнем Востоке» . Энциклопедический словарь сирийского наследия Горгия . Пискатауэй, Нью-Джерси: Gorgias Press. стр. 481–491.

- Карлсон, Томас А. (2017). «Сирийская христология и христианская община в Восточной церкви пятнадцатого века» . Сирийский язык в его мультикультурном контексте . Левен: Издательство Peeters. стр. 265–276. ISBN 9789042931640 .

- Шабо, Жан-Батист (1902). Восточный синодик или собрание несторианских соборов (PDF) . Париж: Национальная империя.

- Чепмен, Джон (1911). «Несторий и несторианство» . Католическая энциклопедия . Том. 10. Нью-Йорк: Компания Роберта Эпплтона.

- Шомон, Мария-Луиза (1964). «Сасаниды и христианизация Иранской империи в III веке нашей эры». Обзор истории религий . 165 (2): 165–202. дои : 10.3406/rhr.1964.8015 .

- Шомон, Мария-Луиза (1988). Христианизация Иранской империи: от истоков до великих гонений IV века . Левен: Питерс. ISBN 9789042905405 .

- Чеснут, Роберта К. (1978). «Две Просопы на Гераклидском базаре Нестория». Журнал богословских исследований . 29 (29): 392–409. дои : 10.1093/jts/XXIX.2.392 . JSTOR 23958267 .

- Коакли, Джеймс Ф. (1992). Церковь Востока и Англиканская церковь: история ассирийской миссии архиепископа Кентерберийского . Оксфорд: Кларендон Пресс. ISBN 9780198267447 .

- Коакли, Джеймс Ф. (1996). «Церковь Востока с 1914 года» . Бюллетень библиотеки Джона Райлендса . 78 (3): 179–198. дои : 10.7227/BJRL.78.3.14 .

- Коакли, Джеймс Ф. (2001). Мар Элиа Абуна и история Восточно-Сирийского Патриархата Том. 85. Харрасовиц. стр. 100-1 119–138. ISBN 9783447042871 .

- Кросс, Фрэнк Л.; Ливингстон, Элизабет А., ред. (2005). Оксфордский словарь христианской церкви (3-е исправленное изд.). Оксфорд: Издательство Оксфордского университета. ISBN 9780192802903 .

- Дэниел, Элтон Л.; Махди, Али Акбар (2006). Культура и обычаи Ирана . Гринвуд Пресс. ISBN 9780313320538 .

- Дин, Ван (2006). «Остатки христианства из китайской Средней Азии в средневековье». В Малеке, Роман; Хофрихтер, Питер Л. (ред.). Цзинцзяо: Церковь Востока в Китае и Центральной Азии . Институт Монумента Серика. стр. 149–162. ISBN 9783805005340 .

- Дрег, Жан-Пьер (1992) [1989]. Марко Поло и Шелковый путь . Сборник « Aguilar Universal ●Historia» (№ 31) (на испанском языке). Перевод Лопеса Кармоны, Мари Пепа. Мадрид: Агилар, SA de Ediciones. стр. 43 и 187. ISBN 978-84-0360-187-1 . ОСЛК 1024004171 .

- Эбейд, Бишара (2016). «Христология Церкви Востока: анализ христологических заявлений и исповеданий веры официальных синодов Церкви Востока до 612 года нашей эры» . Восточная христианская периодика . 82 (2): 353–402.

- Эбейд, Бишара (2017). «Христология и обожение в Церкви Востока: Мар Геваргис I, Его Синод и его письмо Мине как полемика против Мартирия-Сахдоны» . Кристианесимо Нелла История . 38 (3): 729–784.

- Фий, Жан Морис (1967). «Этапы осознания Восточно-Сирийской Церковью своей патриархальной идентичности» . Сирийский Восток . 12 :3–22.

- Фий, Жан Морис (1970a). Вехи истории Церкви в Ираке . Левен: Секретариат CSCO.

- Фий, Жан Морис (1970b). «Элам, первая из восточно-сирийских церковных метрополий» (PDF) . Слово Востока . 1 (1): 123–153. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 19 июня 2021 г. Проверено 18 августа 2018 г.

- Фий, Жан Морис (1970c). «Кретьенская медицина» (PDF) . Пароль де л'Ориент . 1 (2): 357–384. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 19 июня 2021 г. Проверено 18 августа 2018 г.

- Фий, Жан Морис (1979) [1963]. Сирийские общины в Иране и Ираке от зарождения до 1552 года . Лондон: Перепечатки Variorum. ISBN 9780860780519 .

- Фий, Жан Морис (1993). Для Oriens Christianus Novus: Справочник восточно- и западно-сирийских епархий . Бейрут: Институт Востока. ISBN 9783515057189 .

- Фий, Жан Морис (1994). «Распространение Персидской церкви» . Сирийский диалог: первая неофициальная консультация по диалогу в рамках сирийской традиции . Вена: Про Ориенте. стр. 97–107. ISBN 9783515057189 .

- Филони, Фернандо (2017). Церковь в Ираке . Вашингтон, округ Колумбия: Издательство Католического университета Америки. ISBN 9780813229652 .

- Фольц, Ричард (1999). Религии Шелкового пути: сухопутная торговля и культурный обмен от древности до пятнадцатого века . Пэлгрейв Макмиллан. ISBN 9780312233389 .

- Фостер, Джон (1939). Церковь династии Тан . Лондон: Общество распространения христианских знаний.

- Фрейзи, Чарльз А. (2006) [1983]. Католики и султаны: Церковь и Османская империя 1453-1923 гг . Кембридж: Издательство Кембриджского университета. ISBN 9780521027007 .

- Фрикенберг, Роберт Эрик (2008). Христианство в Индии: от истоков до наших дней . Оксфорд: Издательство Оксфордского университета. ISBN 9780198263777 .