Христианский мистицизм

В этой статье есть несколько проблем. Пожалуйста, помогите улучшить его или обсудите эти проблемы на странице обсуждения . ( Узнайте, как и когда удалять эти шаблонные сообщения )

|

| Часть серии о |

| Христианский мистицизм |

|---|

|

| Часть серии о |

| Паламизм |

|---|

|

| Часть серии о |

| Восточная Православная Церковь |

|---|

| Обзор |

| Часть серии о |

| христианство |

|---|

|

Христианский мистицизм - это традиция мистических практик и мистического богословия в христианстве , которая «касается подготовки [человека] к осознанию и воздействию [...] прямого и преобразующего присутствия Бога ». [1] или божественная любовь . [2] До шестого века практика того, что сейчас называется мистицизмом, обозначалась термином contemplatio , cq theoria , от contemplatio ( лат.; греч . θεωρία , theoria ), [3] «смотреть», «глядеть», «осознавать» Бога или божественное. [4] [5] [6] Христианство взяло на себя использование как греческой ( theoria ), так и латинской ( contemplatio , созерцание) терминологии для описания различных форм молитвы и процесса познания Бога.

Созерцательные практики варьируются от простого молитвенного размышления над Священным Писанием (т.е. Lectio Divina ) до созерцания присутствия Бога, приводящего к обожению (духовному союзу с Богом) и экстатическим души видениям мистического союза с Богом . В созерцательной практике различают три стадии: катарсис (очищение), [7] [8] собственно созерцание и видение Бога.

Созерцательные практики занимают видное место в восточном православии и восточном православии , а также вызвали новый интерес в западном христианстве.

Этимология

[ редактировать ]Теория

[ редактировать ]Греческая theorein теория (θεωρία) означала «созерцание, размышление, рассматривание, рассматривание вещей», от ( θεωρεῖν) «рассматривать, размышлять, смотреть», от theoros (θεωρός) «зритель», от thea (θέα) «вид» + хоран (ὁρᾶν) «видеть». [9] Оно выражало состояние зрителя . И греческое θεωρία , и латинское contemplatio в первую очередь означали смотреть на вещи глазами или умом. [10]

Согласно Уильяму Джонстону, до шестого века практика того, что сейчас называется мистицизмом, обозначалась термином contemplatio , cq theoria . [4] По словам Джонстона, «[б] и созерцание, и мистицизм говорят об оке любви, которое смотрит, всматривается, осознает божественные реальности». [4]

Некоторые ученые продемонстрировали сходство между греческой идеей теории и индийской идеей даршана (даршана), в том числе Ян Резерфорд. [11] и Грегори Грив. [12]

Мистика

[ редактировать ]

Слово «мистицизм» происходит от греческого μύω, что означает «скрывать». [13] и его производное μυστικός , мистикос , что означает «посвященный». В эллинистическом мире «мистикос» был посвященным в мистериальную религию . «Мистический» относится к тайным религиозным ритуалам. [14] и в использовании этого слова не было прямых ссылок на трансцендентное. [15]

В раннем христианстве термин мистикос относился к трем измерениям, которые вскоре стали переплетаться, а именно: библейскому, литургическому и духовному или созерцательному. [16] Библейское измерение относится к «скрытым» или аллегорическим толкованиям Священного Писания . [14] [16] Литургическое измерение относится к литургической тайне Евхаристии , присутствию Христа в Евхаристии. [14] [16] Третье измерение — это созерцательное или основанное на опыте познание Бога. [16]

Определение мистики

[ редактировать ]

Преобразующее присутствие Бога

[ редактировать ]Бернард Макгинн определяет христианский мистицизм как:

[Эта] часть или элемент христианской веры и практики, которая касается подготовки, осознания и воздействия [...] прямого и преобразующего присутствия Бога. [1]

Макгинн утверждает, что «присутствие» более точно, чем «союз», поскольку не все мистики говорили о союзе с Богом и поскольку многие видения и чудеса не обязательно были связаны с союзом. [1]

Присутствие против опыта

[ редактировать ]Макгинн также утверждает, что нам следует говорить о «сознании» присутствия Бога, а не об «опыте», поскольку мистическая деятельность — это не просто ощущение Бога как внешнего объекта, но, в более широком смысле, об

...новые способы познания и любви, основанные на состояниях осознания, в которых Бог присутствует в наших внутренних действиях. [1]

Уильям Джеймс популяризировал использование термина « религиозный опыт » в своей книге 1902 года «Разнообразия религиозного опыта» . [17] Это также повлияло на понимание мистицизма как особого опыта, дающего знания. [14]

Уэйн Праудфут прослеживает корни понятия религиозного опыта у немецкого теолога Фридриха Шлейермахера (1768–1834), который утверждал, что религия основана на ощущении бесконечности. Понятие религиозного опыта использовалось Шлейермахером для защиты религии от растущей научной и светской критики. Его переняли многие ученые-религиоведы, из которых наиболее влиятельным был Уильям Джеймс. [18]

Межличностная трансформация

[ редактировать ]

Акцент Макгинна на трансформации, происходящей посредством мистической деятельности, связан с идеей «присутствия», а не «опыта»:

Вот почему единственным известным христианству тестом для определения подлинности мистика и его послания была личностная трансформация, как со стороны мистика, так и – особенно – со стороны тех, на кого мистик повлиял. [1]

Парсонс указывает, что акцент на «опыте» сопровождается предпочтением атомарной личности, а не совместной жизни в сообществе. Он также не может провести различие между эпизодическим опытом и мистицизмом как процессом, который встроен в общую религиозную матрицу литургии, Священных Писаний, поклонения, добродетелей, теологии, ритуалов и практик. [19]

Ричард Кинг также указывает на расхождение между «мистическим опытом» и социальной справедливостью: [20]

Приватизация мистицизма – то есть растущая тенденция помещать мистическое в психологическую сферу личного опыта – служит исключению его из политических проблем, таких как социальная справедливость. Таким образом, мистицизм становится личным делом культивирования внутренних состояний спокойствия и невозмутимости, которые вместо того, чтобы стремиться преобразовать мир, служат приспособлению человека к статус-кво посредством облегчения тревоги и стресса. [20]

Социальное строительство

[ редактировать ]Мистический опыт — это не просто вопрос между мистиком и Богом, он часто формируется под влиянием культурных проблем. Например, Кэролайн Байнум показала, как в позднем средневековье чудеса, сопровождавшие принятие Евхаристии, были не просто символами истории Страстей мистика , но служили подтверждением богословской ортодоксальности , доказывая, что мистик не стал жертвой еретические идеи, такие как неприятие катарами материального мира как зла, что противоречит ортодоксальному учению о том, что Бог принял человеческую плоть и остался безгрешным. [21] Таким образом, природа мистического опыта могла быть адаптирована к конкретным культурным и теологическим проблемам того времени.

Происхождение

[ редактировать ]Идея мистической реальности широко распространена в христианстве со второго века нашей эры и относится не только к духовным практикам, но и к вере в то, что их ритуалы и даже их писания имеют скрытый («мистический») смысл. [1]

Связь между мистицизмом и видением божественного была введена ранними отцами церкви , которые использовали этот термин как прилагательное, как в мистическом богословии, так и в мистическом созерцании. [15]

В последующие века, особенно когда христианская апологетика начала использовать греческую философию для объяснения христианских идей, неоплатонизм стал оказывать влияние на христианскую мистическую мысль и практику через таких авторов, как Августин Гиппопотам и Ориген . [22]

Еврейские предшественники

[ редактировать ]Еврейская духовность в период до Иисуса была очень коллективной и публичной, основанной главным образом на богослужениях в синагогах, которые включали чтение и толкование Еврейских Писаний и чтение молитв, а также на крупных праздниках. Таким образом, литургия и Священные Писания (например, использование псалмов для молитвы) оказали сильное влияние на частную духовность, а отдельные молитвы часто напоминали исторические события в такой же степени, как и их собственные насущные нужды. [23]

Особое значение имеют следующие понятия:

- Бина (понимание) и Хокма (мудрость), которые приходят в результате многих лет чтения, молитв и размышлений над Священными Писаниями;

- Шхина , присутствие Бога в нашей повседневной жизни, превосходство этого присутствия над земными богатствами, боль и тоска, которые приходят, когда Бог отсутствует; и заботливый женский аспект Бога;

- сокрытость Бога, которая происходит из-за нашей неспособности пережить полное откровение славы Божией и которая заставляет нас стремиться познать Бога через веру и послушание;

- « Мистика Торы », взгляд на законы Бога как на центральное выражение воли Бога и, следовательно, как на достойный объект не только послушания, но и любовного размышления и изучения Торы ; и

- бедность, аскетическая ценность, основанная на апокалиптическом ожидании предстоящего пришествия Бога, которая характеризовала реакцию еврейского народа на угнетение со стороны ряда иностранных империй.

В христианском мистицизме Шехина стала тайной , Даат (знание) стала гнозисом , а бедность стала важной составляющей монашества . [24]

Греческие влияния

[ редактировать ]Термин «теория» использовался древними греками для обозначения акта переживания или наблюдения, а затем постижения посредством ума .

Влияние греческой мысли очевидно в самых ранних христианских мистиках и их сочинениях. Платон (428–348 до н. э.) считается самым важным из древних философов, и его философская система составляет основу большинства более поздних мистических форм. Плотин (ок. 205–270 гг. н.э.) обеспечил нехристианскую, неоплатоническую основу для большей части христианского, еврейского и исламского мистицизма . [25]

Платон

[ редактировать ]

Для Платона то, что созерцатель ( theoros ) созерцает ( theorei ) — это Формы , реальности, лежащие в основе индивидуальных явлений, и тот, кто созерцает эти вневременные и апространственные реальности, обогащается взглядом на обычные вещи, превосходящим взгляд обычных людей. [26] Филипп Опусский рассматривал теорию как созерцание звезд с практическими эффектами в повседневной жизни, подобными тем, которые Платон считал следующими из созерцания Форм. [26]

Плотин

[ редактировать ]

В «Эннеадах» ( Плотина ок. 204/5–270 н. э.), основателя неоплатонизма , всё есть созерцание ( теория ). [27] и все происходит от созерцания. [28] Первая ипостась, Единая, есть созерцание. [29] [30] (нусом, или второй ипостасью) [ не удалось пройти проверку ] в том, что «он обращается к самому себе в самом простом смысле, не подразумевая никакой сложности или необходимости»; это отражение само себя эманировало (не создало) [ не удалось пройти проверку ] вторую ипостась, Интеллект (по-гречески Νοῦς, Nous ), Плотин описывает как «живое созерцание», являющееся «саморефлексивной и созерцательной деятельностью по преимуществу», а третий ипостасный уровень имеет теорию . [31] Познание Единого достигается через опыт его силы, опыт, который есть созерцание ( теория ) источника всех вещей. [32]

Плотин согласился с систематическим различием Аристотеля между созерцанием ( theoria ) и практикой ( praxis ): посвящение высшей жизни теории требует воздержания от практической, активной жизни. Плотин объяснил: «Смысл действия – это созерцание… Следовательно, созерцание – это конец действия» и «Такова жизнь божества, божественных и блаженных людей: отстраненность от всего сущего здесь, внизу, презрение ко всем земным удовольствиям». , бегство одинокого к Одинокому». [33]

Ранняя церковь

[ редактировать ]Писания Нового Завета

[ редактировать ]

The Christian scriptures, insofar as they are the founding narrative of the Christian church, provide many key stories and concepts that become important for Christian mystics in all later generations: practices such as the Eucharist, baptism and the Lord's Prayer all become activities that take on importance for both their ritual and symbolic values. Other scriptural narratives present scenes that become the focus of meditation: the crucifixion of Jesus and his appearances after his resurrection are two of the most central to Christian theology; but Jesus' conception, in which the Holy Spirit overshadows Mary, and his transfiguration, in which he is briefly revealed in his heavenly glory, also become important images for meditation. Moreover, many of the Christian texts build on Jewish spiritual foundations, such as chokmah, shekhinah.[34]

But different writers present different images and ideas. The Synoptic Gospels (in spite of their many differences) introduce several important ideas, two of which are related to Greco-Judaic notions of knowledge/gnosis by virtue of being mental acts: purity of heart, in which we will to see in God's light; and repentance, which involves allowing God to judge and then transform us. Another key idea presented by the Synoptics is the desert, which is used as a metaphor for the place where we meet God in the poverty of our spirit.[35]

The Gospel of John focuses on God's glory in his use of light imagery and in his presentation of the cross as a moment of exaltation; he also sees the cross as the example of agape love, a love which is not so much an emotion as a willingness to serve and care for others. But in stressing love, John shifts the goal of spiritual growth away from knowledge/gnosis, which he presents more in terms of Stoic ideas about the role of reason as being the underlying principle of the universe and as the spiritual principle within all people. Although John does not follow up on the Stoic notion that this principle makes union with the divine possible for humanity, it is an idea that later Christian writers develop. Later generations will also shift back and forth between whether to follow the Synoptics in stressing knowledge or John in stressing love.[36]

In his letters, Paul also focuses on mental activities, but not in the same way as the Synoptics, which equate renewing the mind with repentance. Instead, Paul sees the renewal of our minds as happening as we contemplate what Jesus did on the cross, which then opens us to grace and to the movement of the Holy Spirit into peoples' hearts. Like John, Paul is less interested in knowledge, preferring to emphasize the hiddenness, the "mystery" of God's plan as revealed through Christ. But Paul's discussion of the Cross differs from John's in being less about how it reveals God's glory and more about how it becomes the stumbling block that turns our minds back to God. Paul also describes the Christian life as that of an athlete, demanding practice and training for the sake of the prize; later writers will see in this image a call to ascetical practices.[37]

Apostolic Fathers

[edit]The texts attributed to the Apostolic Fathers, the earliest post-Biblical texts we have, share several key themes, particularly the call to unity in the face of internal divisions and perceptions of persecution, the reality of the charisms, especially prophecy, visions, and Christian gnosis, which is understood as "a gift of the Holy Spirit that enables us to know Christ" through meditating on the scriptures and on the cross of Christ.[38] (This understanding of gnosis is not the same as that developed by the Gnostics, who focused on esoteric knowledge that is available only to a few people but that allows them to free themselves from the evil world.[39][40]) These authors also discuss the notion of the "two ways", that is, the way of life and the way of death; this idea has biblical roots, being found in both the Sermon on the Mount and the Torah. The two ways are then related to the notion of purity of heart, which is developed by contrasting it against the divided or duplicitous heart and by linking it to the need for asceticism, which keeps the heart whole/pure.[41][42] Purity of heart was especially important given perceptions of martyrdom, which many writers discussed in theological terms, seeing it not as an evil but as an opportunity to truly die for the sake of God—the ultimate example of ascetic practice.[43] Martyrdom could also be seen as symbolic in its connections with the Eucharist and with baptism.[44]

Theoria enabled the Fathers to perceive depths of meaning in the biblical writings that escape a purely scientific or empirical approach to interpretation.[45] The Antiochene Fathers, in particular, saw in every passage of Scripture a double meaning, both literal and spiritual.[46][note 1] As Frances Margaret Young notes, "Best translated in this context as a type of "insight", theoria was the act of perceiving in the wording and "story" of Scripture a moral and spiritual meaning,"[48] and may be regarded as a form of allegory.[49]

Alexandrian mysticism

[edit]The Alexandrian contribution to Christian mysticism centers on Origen (c. 185 – c. 253) and Clement of Alexandria (150–215 AD). Clement was an early Christian humanist who argued that reason is the most important aspect of human existence and that gnosis (not something we can attain by ourselves, but the gift of Christ) helps us find the spiritual realities that are hidden behind the natural world and within the scriptures. Given the importance of reason, Clement stresses apatheia as a reasonable ordering of our passions in order to live within God's love, which is seen as a form of truth.[50] Origen, who had a lasting influence on Eastern Christian thought, further develops the idea that the spiritual realities can be found through allegorical readings of the scriptures (along the lines of Jewish aggadah tradition), but he focuses his attention on the cross and on the importance of imitating Christ through the cross, especially through spiritual combat and asceticism. Origen stresses the importance of combining intellect and virtue (theoria and praxis) in our spiritual exercises, drawing on the image of Moses and Aaron leading the Israelites through the wilderness, and he describes our union with God as the marriage of our souls with Christ the Logos, using the wedding imagery from the Song of Songs.[51] Alexandrian mysticism developed alongside Hermeticism and Neoplatonism and therefore share some of the same ideas, images, etc. in spite of their differences.[52]

Philo of Alexandria (20 BCE – c. 50 CE) was a Jewish Hellenistic philosopher who was important for connecting the Hebrew Scriptures to Greek thought, and thereby to Greek Christians, who struggled to understand their connection to Jewish history. In particular, Philo taught that allegorical interpretations of the Hebrew scriptures provides access to the real meanings of the texts. Philo also taught the need to bring together the contemplative focus of the Stoics and Essenes with the active lives of virtue and community worship found in Platonism and the Therapeutae. Using terms reminiscent of the Platonists, Philo described the intellectual component of faith as a sort of spiritual ecstasy in which our nous (mind) is suspended and God's spirit takes its place. Philo's ideas influenced the Alexandrian Christians, Clement, and Origen, and through them, Gregory of Nyssa.[53]

Monasticism

[edit]Desert Fathers

[edit]Inspired by Christ's teaching and example, men and women withdrew to the deserts of Sketes where, either as solitary individuals or communities, they lived lives of austere simplicity oriented towards contemplative prayer. These communities formed the basis for what later would become known as Christian monasticism.[54]

Early monasticism

[edit]

The Eastern church then saw the development of monasticism and the mystical contributions of Gregory of Nyssa, Evagrius Ponticus, and Pseudo-Dionysius. Monasticism, also known as anchoritism (meaning "to withdraw") was seen as an alternative to martyrdom, and was less about escaping the world than about fighting demons (who were thought to live in the desert) and about gaining liberation from our bodily passions in order to be open to the word of God. Anchorites practiced continuous meditation on the scriptures as a means of climbing the ladder of perfection—a common religious image in the Mediterranean world and one found in Christianity through the story of Jacob's ladder—and sought to fend off the demon of acedia ("un-caring"), a boredom or apathy that prevents us from continuing on in our spiritual training. Anchorites could live in total solitude ("hermits", from the word erēmitēs, "of the desert") or in loose communities ("cenobites", meaning "common life").[55]

Monasticism eventually made its way to the West and was established by the work of John Cassian and Benedict of Nursia. Meanwhile, Western spiritual writing was deeply influenced by the works of such men as Jerome and Augustine of Hippo.[56]

Neo-Platonism

[edit]Neo-Platonism has had a profound influence on Christian contemplative traditions. Neoplatonic ideas were adopted by Christianity,[note 2] among them the idea of theoria or contemplation, taken over by Gregory of Nyssa for example.[note 3] The Brill Dictionary of Gregory of Nyssa remarks that contemplation in Gregory is described as a "loving contemplation",[59] and, according to Thomas Keating, the Greek Fathers of the Church, in taking over from the Neoplatonists the word theoria, attached to it the idea expressed by the Hebrew word da'ath, which, though usually translated as "knowledge", is a much stronger term, since it indicates the experiential knowledge that comes with love and that involves the whole person, not merely the mind.[60] Among the Greek Fathers, Christian theoria was not contemplation of Platonic Ideas nor of the astronomical heavens of Pontic Heraclitus, but "studying the Scriptures", with an emphasis on the spiritual sense.[10]

Later, contemplation came to be distinguished from intellectual life, leading to the identification of θεωρία or contemplatio with a form of prayer[10] distinguished from discursive meditation in both East[61] and West.[62] Some make a further distinction, within contemplation, between contemplation acquired by human effort and infused contemplation.[62][63]

Mystical theology

[edit]In early Christianity the term "mystikos" referred to three dimensions, which soon became intertwined, namely the biblical, the liturgical and the spiritual or contemplative.[64] The biblical dimension refers to "hidden" or allegorical interpretations of Scriptures.[65][64] The liturgical dimension refers to the liturgical mystery of the Eucharist, the presence of Christ at the Eucharist.[65][64] The third dimension is the contemplative or experiential knowledge of God.[64]

The 9th century saw the development of mystical theology through the introduction of the works of sixth-century theologian Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, such as On Mystical Theology. His discussion of the via negativa was especially influential.[66]

Under the influence of Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite (late 5th to early 6th century) the mystical theology came to denote the investigation of the allegorical truth of the Bible,[64] and "the spiritual awareness of the ineffable Absolute beyond the theology of divine names."[67] Pseudo-Dionysius' apophatic theology, or "negative theology", exerted a great influence on medieval monastic religiosity.[68] It was influenced by Neo-Platonism, and very influential in Eastern Orthodox Christian theology. In western Christianity it was a counter-current to the prevailing Cataphatic theology or "positive theology".

Practice

[edit]Cataphatic and apophatic mysticism

[edit]Within theistic mysticism two broad tendencies can be identified. One is a tendency to understand God by asserting what he is and the other by asserting what he is not. The former leads to what is called cataphatic theology and the latter to apophatic theology.

- Cataphatic (imaging God, imagination or words) – e.g., The Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius of Loyola, Julian of Norwich, Francis of Assisi; and

- Apophatic (imageless, stillness, and wordlessness) – inspired by the writings of Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, which forms the basis of Eastern Orthodox mysticism and hesychasm, and became influential in western Catholic mysticism from the 12th century AD onward, as in The Cloud of Unknowing and Meister Eckhart.[69]

Urban T. Holmes III categorized mystical theology in terms of whether it focuses on illuminating the mind, which Holmes refers to as speculative practice, or the heart/emotions, which he calls affective practice. Combining the speculative/affective scale with the apophatic/cataphatic scale allows for a range of categories:[70]

- Rationalism = Cataphatic and speculative

- Pietism = Cataphatic and affective

- Encratism = Apophatic and speculative

- Quietism = Apophatic and affective

Meditation and contemplation

[edit]In discursive meditation, such as Lectio Divina, mind and imagination and other faculties are actively employed in an effort to understand Christians' relationship with God.[71][72] In contemplative prayer, this activity is curtailed, so that contemplation has been described as "a gaze of faith", "a silent love".[note 4] There is no clear-cut boundary between Christian meditation and Christian contemplation, and they sometimes overlap. Meditation serves as a foundation on which the contemplative life stands, the practice by which someone begins the state of contemplation.[73]

John of the Cross described the difference between discursive meditation and contemplation by saying:

The difference between these two conditions of the soul is like the difference between working, and enjoyment of the fruit of our work; between receiving a gift, and profiting by it; between the toil of travelling and the rest of our journey's end".[74][75]

Mattá al-Miskīn, an Oriental Orthodox monk has posited:

Meditation is an activity of one's spirit by reading or otherwise, while contemplation is a spontaneous activity of that spirit. In meditation, man's imaginative and thinking power exert some effort. Contemplation then follows to relieve man of all effort. Contemplation is the soul's inward vision and the heart's simple repose in God.[73]

Threefold path

[edit]According to the standard formulation of the process of Christian perfection, going back to Evagrius Ponticus (345–399 AD)[76] and Dionysius the Pseudo-Areopagite (late 5th to early 6th century),[77][78] there are three stages:[79][62][78]

- Katharsis or purification;

- Theoria or illumination, also called "natural" or "acquired contemplation;"

- Union or Theosis; also called "infused" or "higher contemplation"; indwelling in God; vision of God; deification; union with God

The three aspects later became purgative, illuminative, and unitive in the western churches and prayer of the lips, the mind, the heart in the eastern churches.[76]

Purification and illumination of the noetic faculty are preparations for the vision of God. Without these preparations it is impossible for man's selfish love to be transformed into selfless love. This transformation takes place during the higher level of the stage of illumination called theoria, literally meaning vision, in this case vision by means of unceasing and uninterrupted memory of God. Those who remain selfish and self-centered with a hardened heart, closed to God's love, will not see the glory of God in this life. However, they will see God's glory eventually, but as an eternal and consuming fire and outer darkness.[80]

Catharsis (purification)

[edit]In the Orthodox Churches, theosis results from leading a pure life, practicing restraint and adhering to the commandments, putting the love of God before all else. This metamorphosis (transfiguration) or transformation results from a deep love of God. Saint Isaac the Syrian says in his Ascetical Homilies that "Paradise is the love of God, in which the bliss of all the beatitudes is contained," and that "the tree of life is the love of God" (Homily 72). Theoria is thus achieved by the pure of heart who are no longer subject to the afflictions of the passions. It is a gift from the Holy Spirit to those who, through observance of the commandments of God and ascetic practices (see praxis, kenosis, Poustinia and schema), have achieved dispassion.[note 5]

Purification constitutes a turning away from all that is unclean and unwholesome. This is a purification of mind and body. As preparation for theoria, however, the concept of purification in this three-part scheme refers most importantly to the purification of consciousness (nous), the faculty of discernment and knowledge (wisdom), whose awakening is essential to coming out of the state of delusion that is characteristic of the worldly-minded. After the nous has been cleansed, the faculty of wisdom may then begin to operate more consistently. With a purified nous, clear vision and understanding become possible, making one fit for contemplative prayer.

In the Eastern Orthodox ascetic tradition called hesychasm, humility, as a saintly attribute, is called holy wisdom or Sophia. Humility is the most critical component to humanity's salvation.[note 6] Following Christ's instruction to "go into your room or closet and shut the door and pray to your father who is in secret" (Matthew 6:6), the hesychast withdraws into solitude in order that he or she may enter into a deeper state of contemplative stillness. By means of this stillness, the mind is calmed, and the ability to see reality is enhanced. The practitioner seeks to attain what the apostle Paul called 'unceasing prayer'.

Some Eastern Orthodox theologians object to what they consider an overly speculative, rationalistic, and insufficiently experiential nature of Roman Catholic theology.[note 7] and confusion between different aspects of the Trinity.[note 8]

Theoria (illumination) – contemplative prayer

[edit]

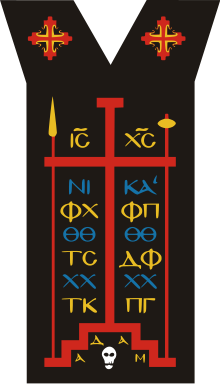

An exercise long used among Christians for acquiring contemplation, one that is "available to everyone, whether he be of the clergy or of any secular occupation",[85] is that of focusing the mind by constant repetition of a phrase or word. Saint John Cassian recommended using the phrase "O God, make speed to save me: O Lord, make haste to help me".[86][87] Another formula for repetition is the name of Jesus,[88][89] or the Jesus Prayer: "Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner," which has been called "the mantra of the Orthodox Church",[87] although the term "Jesus Prayer" is not found in the writings of the Fathers of the Church.[90] The author of The Cloud of Unknowing recommended use of a monosyllabic word, such as "God" or "Love".[91]

Contemplative prayer in the Eastern Church

[edit]In the Eastern Church, noetic prayer is the first stage of theoria,[92][note 9] the vision of God, which is beyond conceptual knowledge,[93] like the difference between reading about the experience of another, and reading about one's own experience.[81] Noetic prayer is the first stage of the Jesus Prayer, a short formulaic prayer: "Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner."[citation needed] The second stage of the Jesus Prayer is the Prayer of the Heart (Καρδιακή Προσευχή), in which the prayer is internalized into 'the heart'.[94]

The Jesus Prayer, which, for the early Fathers, was just a training for repose,[95] the later Byzantines developed into hesychasm, a spiritual practice of its own, attaching to it technical requirements and various stipulations that became a matter of serious theological controversy.[95] Via the Jesus Prayer, the practice of the Hesychast is seen to cultivate nepsis, watchful attention. Sobriety contributes to this mental asceticism that rejects tempting thoughts; it puts a great emphasis on focus and attention. The practitioner of the hesychast is to pay extreme attention to the consciousness of his inner world and to the words of the Jesus Prayer, not letting his mind wander in any way at all. The Jesus Prayer invokes an attitude of humility believed to be essential for the attainment of theoria.[96] The Jesus Prayer is also invoked to pacify the passions, as well as the illusions that lead a person to actively express these passions. It is believed that the worldly, neurotic mind is habitually accustomed to seek pleasant sensations and to avoid unpleasant ones. This state of incessant agitation is attributed to the corruption of primordial knowledge and union with God (the fall of man and the defilement and corruption of consciousness, or nous).[note 10] According to St. Theophan the Recluse, though the Jesus Prayer has long been associated with the Prayer of the Heart, they are not synonymous.[98]

Contemplative prayer in the Roman Catholic Church

[edit]Methods of prayer in the Roman Catholic Church include recitation of the Jesus Prayer, which "combines the Christological hymn of Philippians 2:6–11 with the cry of the publican (Luke 18:13) and the blind man begging for light (Mark 10:46–52). By it the heart is opened to human wretchedness and the Saviour's mercy";[99] invocation of the holy name of Jesus;[99] recitation, as recommended by Saint John Cassian, of "O God, come to my assistance; O Lord, make haste to help me" or other verses of Scripture; repetition of a single monosyllabic word, as suggested by the Cloud of Unknowing, such as "God" or "Love";[91] the method used in centering prayer; the use of Lectio Divina.[100] The Congregation for Divine Worship's directory of popular piety and the liturgy emphasizes the contemplative characteristic of the Holy Rosary and states that the Rosary is essentially a contemplative prayer which requires "tranquility of rhythm or even a mental lingering which encourages the faithful to meditate on the mysteries of the Lord's life."[101] Pope John Paul II placed the Rosary at the very center of Christian spirituality and called it "among the finest and most praiseworthy traditions of Christian contemplation."[102]In modern times, centering prayer, which is also called "Prayer of the heart" and "Prayer of Simplicity,"[note 11] has been popularized by Thomas Keating, drawing on Hesychasm and the Cloud of Unknowing.[note 12] The practice of contemplative prayer has also been encouraged by the formation of associations like The Julian Meetings and the Fellowship of Meditation.

Unification

[edit]The third phase, starting with infused or higher contemplation (or Mystical Contemplative Prayer[104]) in the Western tradition, refers to the presence or consciousness of God. This presence or consciousness varies, but it is first and foremost always associated with a reuniting with divine love, the underlying theme being that God, the perfect goodness,[2] is known or experienced at least as much by the heart as by the intellect since, in the words 1 John 4:16: "God is love, and he who abides in love abides in God and God in him." Some approaches to classical mysticism would consider the first two phases as preparatory to the third, explicitly mystical experience, but others state that these three phases overlap and intertwine.[105]

In the Orthodox Churches, the highest theoria, the highest consciousness that can be experienced by the whole person, is the vision of God.[note 13] God is beyond being; He is a hyper-being; God is beyond nothingness. Nothingness is a gulf between God and man. God is the origin of everything, including nothingness. This experience of God in hypostasis shows God's essence as incomprehensible, or uncreated. God is the origin, but has no origin; hence, he is apophatic and transcendent in essence or being, and cataphatic in foundational realities, immanence and energies. This ontic or ontological theoria is the observation of God.[106]

A nous in a state of ecstasy or ekstasis, called the eighth day, is not internal or external to the world, outside of time and space; it experiences the infinite and limitless God.[note 5][note 14] Nous is the "eye of the soul" (Matthew 6:22–34).[note 15] Insight into being and becoming (called noesis) through the intuitive truth called faith, in God (action through faith and love for God), leads to truth through our contemplative faculties. This theory, or speculation, as action in faith and love for God, is then expressed famously as "Beauty shall Save the World". This expression comes from a mystical or gnosiological perspective, rather than a scientific, philosophical or cultural one.[109][110][111][112]

Alternate models

[edit]Augustine

[edit]In the advance to contemplation Augustine spoke of seven stages:[113]

- the first three are merely natural preliminary stages, corresponding to the vegetative, sensitive and rational levels of human life;

- the fourth stage is that of virtue or purification;

- the fifth is that of the tranquillity attained by control of the passions;

- the sixth is entrance into the divine light (the illuminative stage);

- the seventh is the indwelling or unitive stage that is truly mystical contemplation.

Meister Eckhart

[edit]Meister Eckhart did not articulate clear-cut stages,[114] yet a number of divisions can be found in his works.[115]

Teresa of Avila

[edit]

According to Jordan Aumann, Saint Teresa of Ávila distinguishes nine grades of prayer:

- vocal prayer,

- mental prayer or prayer of meditation,

- affective prayer,

- prayer of simplicity, or acquired contemplation or recollection,

- infused contemplation or recollection,

- prayer of quiet,

- prayer of union,

- prayer of conforming union, and

- prayer of transforming union.

According to Aumann, "The first four grades belong to the predominantly ascetical stage of spiritual life; the remaining five grades are infused prayer and belong to the mystical phase of spiritual life."[116] According to Augustin Pulain, for Teresa, ordinary prayer "comprises these four degrees: first, vocal prayer; second, meditation, also called methodical prayer, or prayer of reflection, in which may be included meditative reading; third, affective prayer; fourth, prayer of simplicity, or of simple gaze."[62]

Prayer of simplicity – natural or acquired contemplation

[edit]For Teresa, in natural or acquired contemplation, also called the prayer of simplicity[note 11] there is one dominant thought or sentiment which recurs constantly and easily (although with little or no development) amid many other thoughts, beneficial or otherwise. The prayer of simplicity often has a tendency to simplify itself even in respect to its object, leading one to think chiefly of God and of his presence, but in a confused manner.[62] Definitions similar to that of Saint Alphonsus Maria de Liguori are given by Adolphe Tanquerey ("a simple gaze on God and divine things proceeding from love and tending thereto") and Saint Francis de Sales ("a loving, simple and permanent attentiveness of the mind to divine things").[117]

In the words of Saint Alphonsus Maria de Liguori, acquired contemplation "consists in seeing at a simple glance the truths which could previously be discovered only through prolonged discourse": reasoning is largely replaced by intuition and affections and resolutions, though not absent, are only slightly varied and expressed in a few words. Similarly, Saint Ignatius of Loyola, in his 30-day retreat or Spiritual Exercises beginning in the "second week" with its focus on the life of Jesus, describes less reflection and more simple contemplation on the events of Jesus' life. These contemplations consist mainly in a simple gaze and include an "application of the senses" to the events,[118]: 121 to further one's empathy for Jesus' values, "to love him more and to follow him more closely."[118]: 104

Natural or acquired contemplation has been compared to the attitude of a mother watching over the cradle of her child: she thinks lovingly of the child without reflection and amid interruptions. The Catechism of the Catholic Church states:

What is contemplative prayer? St. Teresa answers: 'Contemplative [sic][note 16] prayer [oración mental] in my opinion is nothing else than a close sharing between friends; it means taking time frequently to be alone with him who we know loves us.' Contemplative prayer seeks him 'whom my soul loves'. It is Jesus, and in him, the Father. We seek him, because to desire him is always the beginning of love, and we seek him in that pure faith which causes us to be born of him and to live in him. In this inner prayer we can still meditate, but our attention is fixed on the Lord himself.[122]

Infused or higher contemplation

[edit]In the mystical experience of Teresa of Avila, infused or higher contemplation, also called intuitive, passive or extraordinary, is a supernatural gift by which a person's mind will become totally centered on God.[123] It is a form of mystical union with God, a union characterized by the fact that it is God, and God only, who manifests himself.[62] Under this influence of God, which assumes the free cooperation of the human will, the intellect receives special insights into things of the spirit, and the affections are extraordinarily animated with divine love.[123] This union that it entails may be linked with manifestations of a created object, as, for example, visions of the humanity of Christ or an angel or revelations of a future event, etc. They include miraculous bodily phenomena sometimes observed in ecstatics.[62]

In Teresa's mysticism, infused contemplation is described as a "divinely originated, general, non-conceptual, loving awareness of God".[124] According to Dubay:

It is a wordless awareness and love that we of ourselves cannot initiate or prolong. The beginnings of this contemplation are brief and frequently interrupted by distractions. The reality is so unimposing that one who lacks instruction can fail to appreciate what exactly is taking place. Initial infused prayer is so ordinary and unspectacular in the early stages that many fail to recognize it for what it is. Yet with generous people, that is, with those who try to live the whole Gospel wholeheartedly and who engage in an earnest prayer life, it is common.[124]

According to Thomas Dubay, infused contemplation is the normal, ordinary development of discursive prayer (mental prayer, meditative prayer), which it gradually replaces.[124] Dubay considers infused contemplation as common only among "those who try to live the whole Gospel wholeheartedly and who engage in an earnest prayer life". Other writers view contemplative prayer in its infused supernatural form as far from common. John Baptist Scaramelli, reacting in the 17th century against quietism, taught that asceticism and mysticism are two distinct paths to perfection, the former being the normal, ordinary end of the Christian life, and the latter something extraordinary and very rare.[125] Jordan Aumann considered that this idea of the two paths was "an innovation in spiritual theology and a departure from the traditional Catholic teaching".[126] And Jacques Maritain proposed that one should not say that every mystic necessarily enjoys habitual infused contemplation in the mystical state, since the gifts of the Holy Spirit are not limited to intellectual operations.[127]

Mystical union

[edit]According to Charles G. Herbermann, in the Catholic Encyclopedia (1908), Teresa of Avila described four degrees or stages of mystical union:

- incomplete mystical union, or the prayer of quiet or supernatural recollection, when the action of God is not strong enough to prevent distractions, and the imagination still retains a certain liberty;

- full or semi-ecstatic union, when the strength of the divine action keeps the person fully occupied but the senses continue to act, so that by making an effort, the person can cease from prayer;

- ecstatic union, or ecstasy, when communications with the external world are severed or nearly so, and one can no longer at will move from that state; and

- transforming or deifying union, or spiritual marriage (properly) of the soul with God.

The first three are weak, medium, and the energetic states of the same grace.

The Prayer of Quiet

[edit]For Teresa of Avila, the Prayer of Quiet is a state in which the soul experiences an extraordinary peace and rest, accompanied by delight or pleasure in contemplating God as present.[128][129][130][131][132] The Prayer of Quiet is also discussed in the writings of Francis de Sales, Thomas Merton and others.[133][134]

Evelyn Underhill

[edit]Author and mystic Evelyn Underhill recognizes two additional phases to the mystical path. First comes the awakening, the stage in which one begins to have some consciousness of absolute or divine reality. Purgation and illumination are followed by a fourth stage which Underhill, borrowing the language of St. John of the Cross, calls the dark night of the soul. This stage, experienced by the few, is one of final and complete purification and is marked by confusion, helplessness, stagnation of the will, and a sense of the withdrawal of God's presence. This dark night of the soul is not, in Underhill's conception, the Divine Darkness of the pseudo-Dionysius and German Christian mysticism. It is the period of final "unselfing" and the surrender to the hidden purposes of the divine will. Her fifth and final stage is union with the object of love, the one Reality, God. Here the self has been permanently established on a transcendental level and liberated for a new purpose.[135]

Eastern Orthodox Christianity

[edit]Eastern Christianity has preserved a mystical emphasis in its theology[136] and retains in hesychasm a tradition of mystical prayer dating back to Christianity's beginnings. Hesychasm concerns a spiritual transformation of the egoic self, the following of a path designed to produce more fully realized human persons, "created in the Image and Likeness of God" and as such, living in harmonious communion with God, the Church,[citation needed] the rest of the world, and all creation, including oneself. The Eastern Christian tradition speaks of this transformation in terms of theosis or divinization, perhaps best summed up by an ancient aphorism usually attributed to Athanasius of Alexandria: "God became human so that man might become god."[note 17]

According to John Romanides, in the teachings of Eastern Orthodox Christianity the quintessential purpose and goal of the Christian life is to attain theosis or 'deification', understood as 'likeness to' or 'union with' God.[note 18] Theosis is expressed as "Being, union with God" and having a relationship or synergy between God and man.[note 19] God is the Kingdom of Heaven.

Theosis or unity with God is obtained by engaging in contemplative prayer, the first stage of theoria,[92][note 9] which results from the cultivation of watchfulness (Gk: nepsis). In theoria, one comes to see or "behold" God or "uncreated light," a grace which is "uncreated."[note 20][note 21] In the Eastern Christian traditions, theoria is the most critical component needed for a person to be considered a theologian; however it is not necessary for one's salvation.[144] An experience of God is necessary to the spiritual and mental health of every created thing, including human beings.[80] Knowledge of God is not intellectual, but existential. According to eastern theologian Andrew Louth, the purpose of theology as a science is to prepare for contemplation,[145] rather than theology being the purpose of contemplation.

Theoria is the main aim of hesychasm, which has its roots in the contemplative practices taught by Evagrius Ponticus (345–399), John Climacus (6th–7th century), Maximus the Confessor (c. 580–662), and Symeon the New Theologian (949–1022).[146] John Climacus, in his influential Ladder of Divine Ascent, describes several stages of contemplative or hesychast practice, culminating in agape. Symeon believed that direct experience gave monks the authority to preach and give absolution of sins, without the need for formal ordination. While Church authorities also taught from a speculative and philosophical perspective, Symeon taught from his own direct mystical experience,[147] and met with strong resistance for his charismatic approach, and his support of individual direct experience of God's grace.[147] According to John Romanides, this difference in teachings on the possibility to experience God or the uncreated light is at the very heart of many theological conflicts between Eastern Orthodox Christianity and Western Christianity, which is seen to culminate in the conflict over hesychasm.[83][note 22]

According to John Romanides, following Vladimir Lossky[148] in his interpretation of St. Gregory Palamas, the teaching that God is transcendent (incomprehensible in ousia, essence or being), has led in the West to the (mis)understanding that God cannot be experienced in this life.[note 23] Romanides states that Western theology is more dependent upon logic and reason, culminating in scholasticism used to validate truth and the existence of God, than upon establishing a relationship with God (theosis and theoria).[note 24][note 25]

False spiritual knowledge

[edit]In the Orthodox Churches, theoria is regarded to lead to true spiritual knowledge, in contrast to the false or incomplete knowledge of rational thought, c.q. conjecture, speculation,[note 14] dianoia, stochastic and dialectics).[154] After illumination or theoria, humanity is in union with God and can properly discern, or have holy wisdom. Hence theoria, the experience or vision of God, silences all humanity.

The most common false spiritual knowledge is derived not from an experience of God, but from reading another person's experience of God and subsequently arriving at one's own conclusions, believing those conclusions to be indistinguishable from the actual experienced knowledge.

False spiritual knowledge can also be iniquitous, generated from an evil rather than a holy source. The gift of the knowledge of good and evil is then required, which is given by God. Humanity, in its finite existence as created beings or creatures, can never, by its own accord, arrive at a sufficiently objective consciousness. Theosis is the gradual submission of a person to the good, who then with divine grace from the person's relationship or union with God, attains deification. Illumination restores humanity to that state of faith existent in God, called noesis, before humanity's consciousness and reality was changed by their fall.[97]

Spiritual somnolence

[edit]In the orthodox Churches, false spiritual knowledge is regarded as leading to spiritual delusion (Russian prelest, Greek plani), which is the opposite of sobriety. Sobriety (called nepsis) means full consciousness and self-realization (enstasis), giving true spiritual knowledge (called true gnosis).[155] Prelest or plani is the estrangement of the person to existence or objective reality, an alienation called amartía. This includes damaging or vilifying the nous, or simply having a non-functioning noetic and neptic faculty.[note 26]

Evil is, by definition, the act of turning humanity against its creator and existence. Misotheism, a hatred of God, is a catalyst that separates humanity from nature, or vilifies the realities of ontology, the spiritual world and the natural or material world. Reconciliation between God (the uncreated) and man is reached through submission in faith to God the eternal, i.e. transcendence rather than transgression[note 27] (magic).

The Trinity as Nous, Word and Spirit (hypostasis) is, ontologically, the basis of humanity's being or existence. The Trinity is the creator of humanity's being via each component of humanity's existence: origin as nous (ex nihilo), inner experience or spiritual experience, and physical experience, which is exemplified by Christ (logos or the uncreated prototype of the highest ideal) and his saints. The following of false knowledge is marked by the symptom of somnolence or "awake sleep" and, later, psychosis.[157] Theoria is opposed to allegorical or symbolic interpretations of church traditions.[158]

False asceticism or cults

[edit]In the Orthodox practice, once the stage of true discernment (diakrisis) is reached (called phronema), one is able to distinguish false gnosis from valid gnosis and has holy wisdom. The highest holy wisdom, Sophia, or Hagia Sophia, is cultivated by humility or meekness, akin to that personified by the Theotokos and all of the saints that came after her and Christ, collectively referred to as the ecclesia or church. This community of unbroken witnesses is the Orthodox Church.[97]

Wisdom is cultivated by humility (emptying of oneself) and remembrance of death against thymos (ego, greed and selfishness) and the passions. Vlachos of Nafpaktos wrote:[156]

But let him not remain in this condition. If he wishes to see Christ, then let him do what Zacchaeus did. Let him receive the Word in his home, after having previously climbed up into the sycamore tree, 'mortifying his limbs on the earth and raising up the body of humility'.

— Metropolitan Hierotheos of Nafpaktos (1996), Life after Death

Practicing asceticism is being dead to the passions and the ego, collectively known as the world.

God is beyond knowledge and the fallen human mind, and, as such, can only be experienced in his hypostases through faith (noetically). False ascetism leads not to reconciliation with God and existence, but toward a false existence based on rebellion to existence.[note 27]

Latin Catholic mysticism

[edit]Contemplatio

[edit]In the Latin Church terms derived from the Latin word contemplatio such as, in English, "contemplation" are generally used in languages largely derived from Latin, rather than the Greek term theoria. The equivalence of the Latin and Greek terms[159] was noted by John Cassian, whose writings influenced the whole of Western monasticism,[160] in his Conferences.[161] However, Catholic writers do sometimes use the Greek term.[162]

Middle ages

[edit]

The Early Middle Ages in the West includes the work of Gregory the Great and Bede, as well as developments in Celtic Christianity and Anglo-Saxon Christianity, and comes to fulfillment in the work of Johannes Scotus Eriugena and the Carolingian Renaissance.[163]

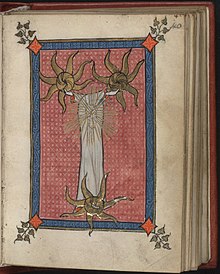

The High Middle Ages saw a flourishing of mystical practice and theorization corresponding to the flourishing of new monastic orders, with such figures as Guigo II, Hildegard of Bingen, Bernard of Clairvaux, the Victorines, all coming from different orders, as well as the first real flowering of popular piety among the laypeople.

The Late Middle Ages saw the clash between the Dominican and Franciscan schools of thought, which was also a conflict between two different mystical theologies: on the one hand that of Dominic de Guzmán and on the other that of Francis of Assisi, Anthony of Padua, Bonaventure, Jacopone da Todi, Angela of Foligno. Moreover, there was the growth of groups of mystics centered on geographic regions: the Beguines, such as Mechthild of Magdeburg and Hadewijch (among others); the Rhenish-Flemish mystics Meister Eckhart, Johannes Tauler, Henry Suso, and John of Ruysbroeck; and the English mystics Richard Rolle, Walter Hilton and Julian of Norwich. This period also saw such individuals as Catherine of Siena and Catherine of Genoa, the Devotio Moderna, and such books as the Theologia Germanica, The Cloud of Unknowing and The Imitation of Christ.[citation needed]

Reformation

[edit]The Protestant Reformation downplayed mysticism, although it still produced a fair amount of spiritual literature. Even the most active reformers can be linked to Medieval mystical traditions. Martin Luther, for instance, was a monk who was influenced by the German Dominican mystical tradition of Eckhart and Tauler as well by the Dionysian-influenced Wesenmystik ("essence mysticism") tradition. He also published the Theologia Germanica, which he claimed was the most important book after the Bible and Augustine for teaching him about God, Christ, and humanity.[164] Even John Calvin, who rejected many Medieval ascetic practices and who favored doctrinal knowledge of God over affective experience, has Medieval influences, namely, Jean Gerson and the Devotio Moderna, with its emphasis on piety as the method of spiritual growth in which the individual practices dependence on God by imitating Christ and the son-father relationship. Meanwhile, his notion that we can begin to enjoy our eternal salvation through our earthly successes leads in later generations to "a mysticism of consolation".[165]Nevertheless, Protestantism was not devoid of mystics. Several leaders of the Radical Reformation had mystical leanings such as Caspar Schwenckfeld and Sebastian Franck. The Magisterial traditions also produced mystics, notably Peter Sterry (Calvinist), and Jakob Böhme (Lutheran).

As part of the Protestant Reformation, theologians turned away from the traditions developed in the Middle Ages and returned to what they consider to be biblical and early Christian practices. Accordingly, they were often skeptical of Catholic mystical practices, which seemed to them to downplay the role of grace in redemption and to support the idea that human works can play a role in salvation. Thus, Protestant theology developed a strong critical attitude, oftentimes even an animosity towards Christian mysticism.[166] However, Quakers, Anglicans, Methodists, Episcopalians, Lutherans, Presbyterians, Local Churches, Pentecostals, Adventists, and Charismatics have in various ways remained open to the idea of mystical experiences.[167]

Counter-reformation

[edit]But the Reformation brought about the Counter-Reformation and, with it, a new flowering of mystical literature, often grouped by nationality.[168]

Spanish mysticism

[edit]

The Spanish had Ignatius Loyola, whose Spiritual Exercises were designed to open people to a receptive mode of consciousness in which they can experience God through careful spiritual direction and through understanding how the mind connects to the will and how to weather the experiences of spiritual consolation and desolation;[169] Teresa of Ávila, who used the metaphors of watering a garden and walking through the rooms of a castle to explain how meditation leads to union with God;[170] and John of the Cross, who used a wide range of biblical and spiritual influences both to rewrite the traditional "three ways" of mysticism after the manner of bridal mysticism and to present the two "dark nights": the dark night of the senses and the dark night of the soul, during which the individual renounces everything that might become an obstacle between the soul and God and then experiences the pain of feeling separated from God, unable to carry on normal spiritual exercises, as it encounters the enormous gap between its human nature and God's divine wisdom and light and moves up the 10-step ladder of ascent towards God.[171] Another prominent mystic was Miguel de Molinos, the chief apostle of the religious revival known as Quietism. No breath of suspicion arose against Molinos until 1681, when the Jesuit preacher Paolo Segneri, attacked his views, though without mentioning his name, in his Concordia tra la fatica e la quiete nell' orazione. The matter was referred to the Inquisition. A report got abroad that Molinos had been convicted of moral enormities, as well as of heretical doctrines; and it was seen that he was doomed. On September 3, 1687 he made public profession of his errors, and was sentenced to imprisonment for life. Contemporary Protestants saw in the fate of Molinos nothing more than a persecution by the Jesuits of a wise and enlightened man, who had dared to withstand the petty ceremonialism of the Italian piety of the day. Molinos died in prison in 1696 or 1697.[172]

Italy

[edit]Lorenzo Scupoli, from Otranto in Apulia, was an Italian mystic best known for authoring The Spiritual Combat, a key work in Catholic mysticism.[173]

France

[edit]

French mystics included Francis de Sales, Jeanne Guyon, François Fénelon, Brother Lawrence and Blaise Pascal.[174]

England

[edit]The English had a denominational mix, from Catholic Augustine Baker and Julian of Norwich (the first woman to write in English), to Anglicans William Law, John Donne, and Lancelot Andrewes, to Puritans Richard Baxter and John Bunyan (The Pilgrim's Progress), to the first "Quaker", George Fox and the first "Methodist", John Wesley, who was well-versed in the continental mystics.[citation needed]

An example of "scientific reason lit up by mysticism in the Church of England"[175]is seen in the work of Sir Thomas Browne, a Norwich physician and scientist whose thought often meanders into mystical realms, as in his self-portrait, Religio Medici, and in the "mystical mathematics" of The Garden of Cyrus, whose full running title reads, Or, The Quincuncial Lozenge, or Network Plantations of the ancients, Naturally, Artificially, Mystically considered. Browne's highly original and dense symbolism frequently involves scientific, medical, or optical imagery to illustrate a religious or spiritual truth, often to striking effect, notably in Religio Medici, but also in his posthumous advisory Christian Morals.[176]

Browne's latitudinarian Anglicanism, hermetic inclinations, and Montaigne-like self-analysis on the enigmas, idiosyncrasies, and devoutness of his own personality and soul, along with his observations upon the relationship between science and faith, are on display in Religio Medici. His spiritual testament and psychological self-portrait thematically structured upon the Christian virtues of Faith, Hope and Charity, also reveal him as "one of the immortal spirits waiting to introduce the reader to his own unique and intense experience of reality".[177] Though his work is difficult and rarely read, he remains, paradoxically, one of England's perennial, yet first, "scientific" mystics.[citation needed]

Germany

[edit]Similarly, well-versed in the mystic tradition was the German Johann Arndt, who, along with the English Puritans, influenced such continental Pietists as Philipp Jakob Spener, Gottfried Arnold, Nicholas Ludwig von Zinzendorf of the Moravians, and the hymnodist Gerhard Tersteegen. Arndt, whose book True Christianity was popular among Protestants, Catholics and Anglicans alike, combined influences from Bernard of Clairvaux, John Tauler and the Devotio Moderna into a spirituality that focused its attention away from the theological squabbles of contemporary Lutheranism and onto the development of the new life in the heart and mind of the believer.[178] Arndt influenced Spener, who formed a group known as the collegia pietatis ("college of piety") that stressed the role of spiritual direction among lay-people—a practice with a long tradition going back to Aelred of Rievaulx and known in Spener's own time from the work of Francis de Sales. Pietism as known through Spener's formation of it tended not just to reject the theological debates of the time, but to reject both intellectualism and organized religious practice in favor of a personalized, sentimentalized spirituality.[179]

Pietism

[edit]This sentimental, anti-intellectual form of pietism is seen in the thought and teaching of Zinzendorf, founder of the Moravians; but more intellectually rigorous forms of pietism are seen in the teachings of John Wesley, which were themselves influenced by Zinzendorf, and in the teachings of American preachers Jonathan Edwards, who restored to pietism Gerson's focus on obedience and borrowed from early church teachers Origen and Gregory of Nyssa the notion that humans yearn for God,[180] and John Woolman, who combined a mystical view of the world with a deep concern for social issues; like Wesley, Woolman was influenced by Jakob Böhme, William Law and The Imitation of Christ.[181] The combination of pietistic devotion and mystical experiences that are found in Woolman and Wesley are also found in their Dutch contemporary Tersteegen, who brings back the notion of the nous ("mind") as the site of God's interaction with our souls; through the work of the Spirit, our mind is able to intuitively recognize the immediate presence of God in our midst.[182]

Scientific research

[edit]Fifteen Carmelite nuns allowed scientists to scan their brains with fMRI while they were meditating, in a state known as Unio Mystica or Theoria.[183] The results showed that multiple regions of the brain were activated when they considered themselves to be in mystical union with God. These regions included the right medial orbitofrontal cortex, right middle temporal cortex, right inferior and superior parietal lobules, caudate, left medial prefrontal cortex, left anterior cingulate cortex, left inferior parietal lobule, left insula, left caudate, left brainstem, and extra-striate visual cortex.[183]

Modern philosophy

[edit]In modern times theoria is sometimes treated as distinct from the meaning given to it in Christianity, linking the word not with contemplation but with speculation. Boethius (c. 480–524 or 525) translated the Greek word theoria into Latin, not as contemplatio but as speculatio, and theoria is taken to mean speculative philosophy.[184] A distinction is made, more radical than in ancient philosophy, between theoria and praxis, theory and practice.[185]

Influential Christian mystics and texts

[edit]Early Christians

[edit]- Justin Martyr (c. 105 – c. 165) used Greek philosophy as the stepping-stone to Christian theology. The mystical conclusions at which some Greeks arrived pointed to Christ. He was influenced by Pythagoras, Plato, and Aristotle, as well as by Stoicism.

- Origen (c. 185–254) wrote On the First Principles and Against Celsus. Studied under Clement of Alexandria, and probably also Ammonius Saccus (Plotinus' teacher). He Christianized and theologized Neoplatonism.

- Athanasius of Alexandria (c. 296/8–373) wrote The Life of Antony (c. 360).[186]

- Gregory of Nyssa (c. 335–after 394) focused on the stages of spiritual growth, the need for constant progress, and the "divine darkness" as seen in the story of Moses.

- Augustine (354–430) wrote On the Trinity and Confessions. Important source for much mediaeval mysticism. He brings Platonism and Christianity together. Influenced by: Plato and Plotinus.

- Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite (c. 500) wrote Mystical Theology.

- Abba Or (c. 400 – c. 490) was an early Egyptian Christian ascetic and mystic. See also Anoub of Scetis.

Eastern Orthodox Christianity

[edit]- Philokalia, a collection of texts on prayer and solitary mental ascesis written from the 4th to the 15th centuries, which exists in a number of independent redactions;

- the Ladder of Divine Ascent;

- the collected works of St. Symeon the New Theologian (949–1022);

- the works of St. Isaac the Syrian (7th century), as they were selected and translated into Greek at the Monastery of St. Savas near Jerusalem about the 10th century.

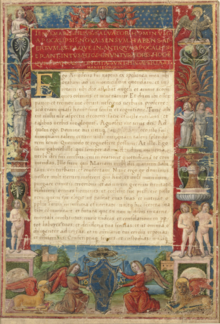

Western European Middle Ages and Renaissance

[edit]

- John Scotus Eriugena (c. 810 – c. 877): Periphyseon. Eriugena translated Pseudo-Dionysius from Greek into Latin. Influenced by: Plotinus, Augustine, Pseudo-Dionysius.

- Bernard of Clairvaux (1090–1153): Cistercian theologian, author of The Steps of Humility and Pride, On Loving God, and Sermons on the Song of Songs; strong blend of scripture and personal experience.

- Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179): Benedictine abbess and reformist preacher, known for her visions, recorded in such works as Scivias (Know the Ways) and Liber Divinorum Operum (Book of Divine Works). Influenced by: Pseudo-Dionysius, Gregory the Great, Rhabanus Maurus, John Scotus Eriugena.

- Victorines: fl. 11th century; stressed meditation and contemplation; helped popularize Pseudo-Dionysius; influenced by Augustine

- Hugh of Saint Victor (d. 1141): The Mysteries of the Christian Faith, Noah's Mystical Ark, etc.

- Richard of Saint Victor (d. 1173): The Twelve Patriarchs and The Mystical Ark (e.g. Benjamin Minor and Benjamin Major). Influenced Dante, Bonaventure, Cloud of Unknowing.

- Franciscans:

- Francis of Assisi (c.1182 – 1226): founder of the order, stressed simplicity and penitence; first documented case of stigmata

- Anthony of Padua (1195–1231): priest, Franciscan friar and theologian; visions; sermons

- Bonaventure (c. 1217 – 1274): The Soul's Journey into God, The Triple Way, The Tree of Life and others. Influenced by: Pseudo-Dionysius, Augustine, Bernard, Victorines.

- Jacopone da Todi (c. 1230 – 1306): Franciscan friar; prominent member of "The Spirituals"; The Lauds

- Angela of Foligno (c. 1248 – 1309): tertiary anchoress; focused on Christ's Passion; Memorial and Instructions.

- Amadeus of Portugal (c. 1420 – 1482): Franciscan friar; revelations; Apocalypsis nova

- Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274): priest, Dominican friar and theologian.

- Beguines (fl. 13th century):

- Mechthild of Magdeburg (c. 1212 – c. 1297): visions, bridal mysticism, reformist; The Flowing Light of the Godhead

- Hadewijch of Antwerp (13th century): visions, bridal mysticism, essence mysticism; writings are mostly letters and poems. Influenced John of Ruysbroeck.

- Rhineland mystics (fl. 14th century): sharp move towards speculation and apophasis; mostly Dominicans

- Meister Eckhart (1260–1327): sermons

- Johannes Tauler (d. 1361): sermons

- Henry Suso (c. 1295 – 1366): Life of the Servant, Little Book of Eternal Wisdom

- Theologia Germanica (anon.). Influenced: Martin Luther

- John of Ruysbroeck (1293–1381): Flemish, Augustinian; The Spiritual Espousals and many others. Similar themes as the Rhineland Mystics. Influenced by: Beguines, Cistercians. Influenced: Geert Groote and the Devotio Moderna.

- Catherine of Siena (1347–1380): Letters

- The English Mystics (fl. 14th century):

- Anonymous – The Cloud of the Unknowing (c. 1375)—Intended by ascetic author as a means of instruction in the practice of mystic and contemplative prayer.

- Richard Rolle (c. 1300 – 1349): The Fire of Love, Mending of Life, Meditations on the Passion

- Walter Hilton (c. 1340 – 1396): The Ladder of Perfection (a.k.a., The Scale of Perfection) – suggesting familiarity with the works of Pseudo-Dionysius (see above), the author provides an early English language seminal work for the beginner.

- Julian of Norwich (1342 – c. 1416): Revelations of Divine Love (a.k.a. Showing of Love)

- Margery Kempe (1373 - c. 1438): The Book of Margery Kempe

Renaissance, Reformation and Counter-Reformation

[edit]- The Spanish Mystics (fl. 16th century):

- Ignatius of Loyola (1491–1556): St. Ignatius had a number of mystical experiences in his life, the most significant was an experience of enlightenment by the river Cardoner, in which, he later stated, he learnt more in that one occasion than he did in the rest of his life. Another significant mystical experience was in 1537, at a chapel in La Storta, outside Rome, in which he saw God the Father place him with the Son, who was carrying the Cross. This was after he had spent a year praying to Mary for her to place him with her Son (Jesus), and was one of the reasons why he insisted that the group that followed his 'way of proceeding' be called the Society of Jesus.[187]

- Teresa of Ávila (1515–1582): Two of her works, The Interior Castle and The Way of Perfection, were intended as instruction in (profoundly mystic) prayer based upon her experiences. Influenced by: Augustine.

- John of the Cross (Juan de Yepes) (1542–1591): Wrote three related instructional works, with Ascent of Mount Carmel as a systematic approach to mystic prayer; together with the Spiritual Canticle and the Dark Night of the Soul, these provided poetic and literary language for the Christian Mystical practice and experience. Influenced by and collaborated with Teresa of Ávila.

- Joseph of Cupertino (1603–1663): An Italian Franciscan friar who is said to have been prone to miraculous levitation and intense ecstatic visions that left him gaping.[188]

- Jakob Böhme (1575–1624): German theosopher; author of The Way to Christ.

- Thomas Browne (1605–1682): English physician and philosopher, author of Religio Medici.

- Brother Lawrence (1614–1691): Author of The Practice of the Presence of God.

- Isaac Ambrose (1604–1664): Puritan, author of Looking Unto Jesus.

- Angelus Silesius (1624–1677): German Catholic priest, physician, and religious poet.

- George Fox (1624–1691): Founder of the Religious Society of Friends.

- Madame Jeanne Guyon (1648–1717): Visionary and Writer.

- William Law (1686–1761): English mystic interested in Jakob Böhme who wrote several mystical treatises.

- Emanuel Swedenborg (1688–1772): Influential and controversial Swedish writer and visionary.

- Rosa Egipcíaca (1719–1771): Afro-Brazilian mystic who wrote Sagrada Teologia do Amor Divino das Almas Peregrinas – the first religious text (or indeed any book) to be written by a black woman in colonial Brazil.

Modern era

[edit]

- Domenico da Cese (1905–1978): Stigmatist Capuchin friar.

- Maria Valtorta (1898–1963): Visionary and writer.

- Mary of Saint Peter (1816–1848): Carmelite nun.

- Marie Lataste (1822–1899): Visionary, nun and writer.

- Andrew Murray (1828–1917): Evangelical Missionary and Writer, Author of over 240 books.

- Marie Martha Chambon (1841–1907): Nun and visionary.

- Marie Julie Jahenny (1850–1941): Stigmatist.

- Mary of the Divine Heart Droste zu Vischering (1863–1899): Sister of the Good Shepherd.

- Réginald Garrigou-Lagrange (1877-1964): French Dominican friar, philosopher and neo-Thomist theologian. His magnum opus The Three Ages of the Interior Life (Les trois âges de la vie intérieure) is a synthesis of previous theological thought of Catholic saints and Church Fathers.

- Frank Laubach (1884–1970): Evangelical missionary, author of Letters by a Modern Mystic.

- Padre Pio of Pietrelcina (1887–1968): Capuchin friar, priest, stigmatic.

- Садху Сундар Сингх (1889–1929): индийский миссионер-евангелист, аскет.

- Мария Пьерина Де Микели (1890–1945): итальянская монахиня и провидица.

- Томас Рэймонд Келли (1893–1941): квакер .

- Александрина Балазарская (1904–1955): провидец и писатель.

- Даг Хаммаршельд (1905–1961): шведский дипломат (второй генеральный секретарь Организации Объединенных Наций). Его посмертно опубликованный духовный дневник «Vägmärken» («Отметины») принес ему репутацию одного из немногих мистиков на политической арене.

- Мария Фаустина Ковальская (1905–1938): польская монахиня и провидица.

- Евгения Равазио (1907–1990): итальянская монахиня и провидица Бога-Отца.

- Симона Вейль (1909–1943): французская писательница, политическая активистка и восторженная провидица.

- Флауэр А. Ньюхаус (1909–1994): американский ясновидящий.

- Кармела Карабелли (1910–1978): итальянский писатель.

- Пьерина Джилли (1911–1991): итальянский провидец.

- А. В. Тозер (1897–1963): Христианский и миссионерский союз ; автор книги «В поисках Бога» .

- Томас Мертон (1915–1968): монах- траппист и писатель.

- Вочман Ни (1903–1972): провидец и писатель.

- Уитнесс Ли (1905–1997): провидец поместных церквей и писатель, автор более 400 книг.

- Сестра Люсия (1907–2005): португальская участница явлений Фатимы 1917 года , монахиня и пророчица.

- Бернадетт Робертс (1931–2017): монахиня- кармелитка и писательница, специализирующаяся на состояниях отсутствия самости .

- Ричард Дж. Фостер (род. 1942): квакер -теолог; автор книги «Праздник дисциплины и молитвы» .

- Ричард Рор (род. 1943): францисканский священник, писатель и пророк; автор книг «Падение вверх» и «Вселенский Христос».

- Аннелиза Мишель (1952–1976): молодая немецкая католичка, утверждающая, что она была одержима обращением грешников; утверждал, что получил религиозные видения и принес с собой стигматы . [191]

- Джеймс Голл (р. 1952): харизматичный писатель и пророк; автор книг «Впустую на Иисуса» и «Провидец» .

См. также

[ редактировать ]- Анахорит

- Амвросий Оптинский

- Аподиктичность

- Апофеоз

- Аргумент от красоты

- Добавьте это

- Блаженное видение

- Свадебное богословие

- Венчик в честь Святого Духа и семи Его даров

- Христианская теософия

- Список христианских мистиков

- Христианская мифология

- Христианские взгляды на астрологию

- Христианские взгляды на магию

- Отцы пустыни

- Диодор Тарсийский

- Божественное освещение

- Эзотерическое христианство

- Х. Тристрам Энгельхардт-младший.

- Полное освящение

- Гносеология

- Кенозис

- Томас Мертон

- Джон Мейендорф

- Глаз разума

- Михаил Помазанский

- Открытый теизм

- Участие во Христе

- Пятидесятничество

- Священные тайны

- Sobornost

- Софроний

- Сотериология

- Полет души

- Неявное знание

- Бдительность (христианин)

- Мировое сообщество христианской медитации

Примечания

[ редактировать ]- ^ В своей библейской экзегезе, будь то александрийской или антиохийской традиции, отцы «с небольшим пониманием или вообще без понимания прогрессивной природы откровения, где буквального смысла было бы недостаточно, [...] прибегали к аллегории или теории ( Златоуст и антиохийцы)». [47]

- ^ «С точки зрения историка, наличие неоплатонических идей в христианской мысли неоспоримо» [57]

- ^ «Аналогия между терминологией и мышлением (Григория) и древними инициаторами философского идеала жизни является совершенной. Сами подвижники называются им «философами» или «философским хором». Их деятельность называется « созерцание' (θεωρία), и до сих пор это слово, даже когда мы употребляем его для обозначения θεωρητικός βίος древнегреческих философов, сохранило тот подтекст, который придало ему превращение в технический термин христианского аскетизма». [58]

- ^ «Созерцательная молитва - это простое выражение тайны молитвы. Это взгляд веры, устремленный на Иисуса, внимательность к слову Божьему, молчаливая любовь. Она достигает настоящего единения с молитвой Христовой в той мере, в какой она заставляет нас приобщиться к Его тайне» ( Катехизис Католической Церкви, 2724).