Афина

| Афина | |

|---|---|

Богиня мудрости, войны и ремесленника | |

| Член двенадцати олимпийцев | |

Mattei Athena at Louvre. Roman copy from the 1st century BC/AD after the Greek original Piraeus Athena of the 4th century BC attributed to Cephisodotos or Euphranor. | |

| Abode | Mount Olympus |

| Animals | Owl, serpent, horse |

| Symbol | Aegis, helmet, spear, armor, Gorgoneion, chariot, distaff |

| Tree | Olive |

| Genealogy | |

| Parents | Zeus and Metis[a][1] |

| Siblings | Several paternal half-siblings |

| Children | Erichthonius (adopted) |

| Equivalents | |

| Canaanite equivalent | Anat[2] |

| Roman equivalent | Minerva |

| Egyptian equivalent | Neith |

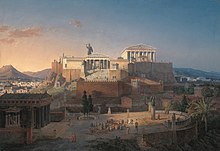

Афина [ B ] или Афина , [ C ] часто с учетом эпитета Палласа , [ D ] Является ли древняя греческая богиня, связанная с мудростью, войной и ремесленником [ 3 ] который был позже синкретизирован с римской богиней Минервой . [ 4 ] Афина считалась покровителем и защитником различных городов по всей Греции, особенно в Афинском городе , от которого она, скорее всего, получила свое имя. [ 5 ] Парфенон Акрополе на Афин посвящен ей. Ее основные символы включают сов , оливковые деревья , змеи и горгоне . В искусстве ее обычно изображают в шлеме и держат копье.

Из ее происхождения как богини Эгейского дворца Афина была тесно связана с городом. Она была известна как Полиас и Полише (оба получены из Полиса , что означает «городское государство»), и ее храмы обычно располагались на укрепленном акрополе в центральной части города. Парфенон на афинском акрополе посвящен ей вместе с множеством других храмов и памятников. Как покровитель ремесла и ткачества, Афина была известна как Эрган . Она также была богиней воина , и, как полагают, ведила солдат в битву как Афина Промачос . Ее главным фестивалем в Афинах была Панатеная , которая была отмечена в течение месяца Хекамбайона в середине лета и был самым важным фестивалем в афинском календаре.

In Greek mythology, Athena was believed to have been born from the forehead of her father Zeus. In some versions of the story, Athena has no mother and is born from Zeus' forehead by parthenogenesis. In others, such as Hesiod's Theogony, Zeus swallows his consort Metis, who was pregnant with Athena; in this version, Athena is first born within Zeus and then escapes from his body through his forehead. In the founding myth of Athens, Athena bested Poseidon in a competition over patronage of the city by creating the first olive tree. She was known as Athena Parthenos "Athena the Virgin". In one archaic Attic myth, the god Hephaestus tried and failed to rape her, resulting in Gaia giving birth to Erichthonius, an important Athenian founding hero. Athena was the patron goddess of heroic endeavor; she was believed to have aided the heroes Perseus, Heracles, Bellerophon, and Jason. Along with Aphrodite and Hera, Athena was one of the three goddesses whose feud resulted in the beginning of the Trojan War.

She plays an active role in the Iliad, in which she assists the Achaeans and, in the Odyssey, she is the divine counselor to Odysseus. In the later writings of the Roman poet Ovid, Athena was said to have competed against the mortal Arachne in a weaving competition, afterward transforming Arachne into the first spider; Ovid also describes how Athena transformed her priestess Medusa and the latter's sisters, Stheno and Euryale, into the Gorgons after witnessing the young woman being raped by Poseidon in the goddess's temple. Since the Renaissance, Athena has become an international symbol of wisdom, the arts, and classical learning. Western artists and allegorists have often used Athena as a symbol of freedom and democracy.

Etymology

Athena is associated with the city of Athens.[5][7] The name of the city in ancient Greek is Ἀθῆναι (Athȇnai), a plural toponym, designating the place where—according to myth—she presided over the Athenai, a sisterhood devoted to her worship.[6] In ancient times, scholars argued whether Athena was named after Athens or Athens after Athena.[5] Now scholars generally agree that the goddess takes her name from the city;[5][7] the ending -ene is common in names of locations, but rare for personal names.[5] Testimonies from different cities in ancient Greece attest that similar city goddesses were worshipped in other cities[6] and, like Athena, took their names from the cities where they were worshipped.[6] For example, in Mycenae there was a goddess called Mykene, whose sisterhood was known as Mykenai,[6] whereas at Thebes an analogous deity was called Thebe, and the city was known under the plural form Thebai (or Thebes, in English, where the 's' is the plural formation).[6] The name Athenai is likely of Pre-Greek origin because it contains the presumably Pre-Greek morpheme *-ān-.[8]

In his dialogue Cratylus, the ancient Greek philosopher Plato (428–347 BC) gives some rather imaginative etymologies of Athena's name, based on the theories of the ancient Athenians and his etymological speculations:

That is a graver matter, and there, my friend, the modern interpreters of Homer may, I think, assist in explaining the view of the ancients. Most of these in their explanations of the poet, assert that he meant by Athena "mind" [νοῦς, noũs] and "intelligence" [διάνοια, diánoia], and the maker of names appears to have had a singular notion about her; and indeed calls her by a still higher title, "divine intelligence" [θεοῦ νόησις, theoũ nóēsis], as though he would say: This is she who has the mind of God [ἁ θεονόα, a theonóa]. Perhaps, however, the name Theonoe may mean "she who knows divine things" [τὰ θεῖα νοοῦσα, ta theia noousa] better than others. Nor shall we be far wrong in supposing that the author of it wished to identify this Goddess with moral intelligence [εν έθει νόεσιν, en éthei nóesin], and therefore gave her the name Etheonoe; which, however, either he or his successors have altered into what they thought a nicer form, and called her Athena.

— Plato, Cratylus 407b

Thus, Plato believed that Athena's name was derived from Greek Ἀθεονόα, Atheonóa—which the later Greeks rationalised as from the deity's (θεός, theós) mind (νοῦς, noũs). The second-century AD orator Aelius Aristides attempted to derive natural symbols from the etymological roots of Athena's names to be aether, air, earth, and moon.[9]

Origins

Athena was originally the Aegean goddess of the palace, who presided over household crafts and protected the king.[11][12][13][14] A single Mycenaean Greek inscription 𐀀𐀲𐀙𐀡𐀴𐀛𐀊 a-ta-na po-ti-ni-ja appears at Knossos in the Linear B tablets from the Late Minoan II-era "Room of the Chariot Tablets";[15][16][10] these comprise the earliest Linear B archive anywhere.[15] Although Athana potnia is often translated as "Mistress Athena", it could also mean "the Potnia of Athana", or the Lady of Athens.[10][17] However, any connection to the city of Athens in the Knossos inscription is uncertain.[18] A sign series a-ta-no-dju-wa-ja appears in the still undeciphered corpus of Linear A tablets, written in the unclassified Minoan language.[19] This could be connected with the Linear B Mycenaean expressions a-ta-na po-ti-ni-ja and di-u-ja or di-wi-ja (Diwia, "of Zeus" or, possibly, related to a homonymous goddess),[15] resulting in a translation "Athena of Zeus" or "divine Athena". Similarly, in the Greek mythology and epic tradition, Athena figures as a daughter of Zeus (Διός θυγάτηρ; cfr. Dyeus).[20] However, the inscription quoted seems to be very similar to "a-ta-nū-tī wa-ya", quoted as SY Za 1 by Jan Best.[20] Best translates the initial a-ta-nū-tī, which is recurrent in line beginnings, as "I have given".[20]

A Mycenean fresco depicts two women extending their hands towards a central figure, who is covered by an enormous figure-eight shield; this may depict the warrior-goddess with her palladium, or her palladium in an aniconic representation.[21][22] In the "Procession Fresco" at Knossos, which was reconstructed by the Mycenaeans, two rows of figures carrying vessels seem to meet in front of a central figure, which is probably the Minoan precursor to Athena.[23] The early twentieth-century scholar Martin Persson Nilsson argued that the Minoan snake goddess figurines are early representations of Athena.[11][12]

Nilsson and others have claimed that, in early times, Athena was either an owl herself or a bird goddess in general.[24] In the third book of the Odyssey, she takes the form of a sea-eagle.[24] Proponents of this view argue that she dropped her prophylactic owl mask before she lost her wings. "Athena, by the time she appears in art," Jane Ellen Harrison remarks, "has completely shed her animal form, has reduced the shapes she once wore of snake and bird to attributes, but occasionally in black-figure vase-paintings she still appears with wings."[25]

It is generally agreed that the cult of Athena preserves some aspects of the Proto-Indo-European transfunctional goddess.[27][28] The cult of Athena may have also been influenced by those of Near Eastern warrior goddesses such as the East Semitic Ishtar and the Ugaritic Anat,[10] both of whom were often portrayed bearing arms.[12] Classical scholar Charles Penglase notes that Athena resembles Inanna in her role as a "terrifying warrior goddess"[29] and that both goddesses were closely linked with creation.[29] Athena's birth from the head of Zeus may be derived from the earlier Sumerian myth of Inanna's descent into and return from the Underworld.[30][31]

Plato notes that the citizens of Sais in Egypt worshipped a goddess known as Neith,[e] whom he identifies with Athena.[32] Neith was the ancient Egyptian goddess of war and hunting, who was also associated with weaving; her worship began during the Egyptian Pre-Dynastic period. In Greek mythology, Athena was reported to have visited mythological sites in North Africa, including Libya's Triton River and the Phlegraean plain.[f] Based on these similarities, the Sinologist Martin Bernal created the "Black Athena" hypothesis, which claimed that Neith was brought to Greece from Egypt, along with "an enormous number of features of civilization and culture in the third and second millennia".[33][34] The "Black Athena" hypothesis stirred up widespread controversy near the end of the twentieth century,[35][36] but it has now been widely rejected by modern scholars.[37][38]

Epithets and attributes

Athena was also the goddess of peace.[39]

In a similar manner to her patronage of various activities and Greek cities, Athena was thought to be a "protector of heroes" and a "patron of art" and various local traditions related to the arts and handicrafts.[39]

Athena was known as Atrytone (Άτρυτώνη "the Unwearying"), Parthenos (Παρθένος "Virgin"), and Promachos (Πρόμαχος "she who fights in front"). The epithet Polias (Πολιάς "of the city"), refers to Athena's role as protectress of the city.[40] The epithet Ergane (Εργάνη "the Industrious") pointed her out as the patron of craftsmen and artisans.[40] Burkert notes that the Athenians sometimes simply called Athena "the Goddess", hē theós (ἡ θεός), certainly an ancient title.[5] After serving as the judge at the trial of Orestes in which he was acquitted of having murdered his mother Clytemnestra, Athena won the epithet Areia (Αρεία).[40] Some have described Athena, along with the goddesses Hestia and Artemis as being asexual, this is mainly supported by the fact that in the Homeric Hymns, 5, To Aphrodite, where Aphrodite is described as having "no power" over the three goddesses.[41]

Athena was sometimes given the epithet Hippia (Ἵππια "of the horses", "equestrian"),[42][43] referring to her invention of the bit, bridle, chariot, and wagon.[42] The Greek geographer Pausanias mentions in his Guide to Greece that the temple of Athena Chalinitis ("the bridler")[43] in Corinth was located near the tomb of Medea's children.[43] Other epithets include Ageleia, Itonia and Aethyia, under which she was worshiped in Megara.[44][45] She was worshipped as Assesia in Assesos. The word aíthyia (αἴθυια) signifies a "diver", also some diving bird species (possibly the shearwater) and figuratively, a "ship", so the name must reference Athena teaching the art of shipbuilding or navigation.[46] In a temple at Phrixa in Elis, reportedly built by Clymenus, she was known as Cydonia (Κυδωνία).[47] Pausanias wrote that at Buporthmus there was a sanctuary of Athena Promachorma (Προμαχόρμα), meaning protector of the anchorage.[48][49]

The Greek biographer Plutarch describes Pericles's dedication of a statue to her as Athena Hygieia (Ὑγίεια, "Health") after she inspired, in a dream, his successful treatment of a man injured during the construction of the gateway to the Acropolis.[50]

At Athens there is the temple of Athena Phratria, as patron of a phratry, in the Ancient Agora of Athens.[51]

Pallas Athena

Athena's epithet Pallas – her most renowned one – is derived either from πάλλω, meaning "to brandish [as a weapon]", or, more likely, from παλλακίς and related words, meaning "youth, young woman".[52] On this topic, Walter Burkert says "she is the Pallas of Athens, Pallas Athenaie, just as Hera of Argos is Here Argeie."[5] In later times, after the original meaning of the name had been forgotten, the Greeks invented myths to explain its origins, such as those reported by the Epicurean philosopher Philodemus and the Bibliotheca of Pseudo-Apollodorus, which claim that Pallas was originally a separate entity, whom Athena had slain in combat.[53]

In one version of the myth, Pallas was the daughter of the sea-god Triton,[54] and she and Athena were childhood friends. Zeus one day watched Athena and Pallas have a friendly sparring match. Not wanting his daughter to lose, Zeus flapped his aegis to distract Pallas, whom Athena accidentally impaled.[55] Distraught over what she had done, Athena took the name Pallas for herself as a sign of her grief and tribute to her friend and Zeus gave her the aegis as an apology.[55] In another version of the story, Pallas was a Giant;[56] Athena slew him during the Gigantomachy and flayed off his skin to make her cloak, which she wore as a victory trophy.[56][12][57][58] In an alternative variation of the same myth, Pallas was instead Athena's father,[56][12] who attempted to assault his own daughter,[59] causing Athena to kill him and take his skin as a trophy.[60]

The palladium was a statue of Athena that was said to have stood in her temple on the Trojan Acropolis.[61] Athena was said to have carved the statue herself in the likeness of her dead friend Pallas.[61] The statue had special talisman-like properties[61] and it was thought that, as long as it was in the city, Troy could never fall.[61] When the Greeks captured Troy, Cassandra, the daughter of Priam, clung to the palladium for protection,[61] but Ajax the Lesser violently tore her away from it and dragged her over to the other captives.[61] Athena was infuriated by this violation of her protection.[62] Although Agamemnon attempted to placate her anger with sacrifices, Athena sent a storm at Cape Kaphereos to destroy almost the entire Greek fleet and scatter all of the surviving ships across the Aegean.[63]

Glaukopis

In Homer's epic works, Athena's most common epithet is Glaukopis (γλαυκῶπις), which usually is translated as, "bright-eyed" or "with gleaming eyes".[64] The word is a combination of glaukós (γλαυκός, meaning "gleaming, silvery", and later, "bluish-green" or "gray")[65] and ṓps (ὤψ, "eye, face").[66]

The word glaúx (γλαύξ,[67] "little owl")[68] is from the same root, presumably according to some, because of the bird's own distinctive eyes. Athena was associated with the owl from very early on;[69] in archaic images, she is frequently depicted with an owl perched on her hand.[69] Through its association with Athena, the owl evolved into the national mascot of the Athenians and eventually became a symbol of wisdom.[4]

Tritogeneia

In the Iliad (4.514), the Odyssey (3.378), the Homeric Hymns, and in Hesiod's Theogony, Athena is also given the curious epithet Tritogeneia (Τριτογένεια), whose significance remains unclear.[70] It could mean various things, including "Triton-born", perhaps indicating that the homonymous sea-deity was her parent according to some early myths.[70] One myth relates the foster father relationship of this Triton towards the half-orphan Athena, whom he raised alongside his own daughter Pallas.[54] Kerényi suggests that "Tritogeneia did not mean that she came into the world on any particular river or lake, but that she was born of the water itself; for the name Triton seems to be associated with water generally."[71][72] In Ovid's Metamorphoses, Athena is occasionally referred to as "Tritonia".

Another possible meaning may be "triple-born" or "third-born", which may refer to a triad or to her status as the third daughter of Zeus or the fact she was born from Metis, Zeus, and herself; various legends list her as being the first child after Artemis and Apollo, though other legends identify her as Zeus' first child.[73] Several scholars have suggested a connection to the Rigvedic god Trita,[74] who was sometimes grouped in a body of three mythological poets.[74] Michael Janda has connected the myth of Trita to the scene in the Iliad in which the "three brothers" Zeus, Poseidon, and Hades divide the world between them, receiving the "broad sky", the sea, and the underworld respectively.[75][76] Janda further connects the myth of Athena being born of the head (i. e. the uppermost part) of Zeus, understanding Trito- (which perhaps originally meant "the third") as another word for "the sky".[75] In Janda's analysis of Indo-European mythology, this heavenly sphere is also associated with the mythological body of water surrounding the inhabited world (cfr. Triton's mother, Amphitrite).[75]

Yet another possible meaning is mentioned in Diogenes Laertius' biography of Democritus, that Athena was called "Tritogeneia" because three things, on which all mortal life depends, come from her.[77]

Cult and patronages

Panhellenic and Athenian cult

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Greek religion |

|---|

|

In her aspect of Athena Polias, Athena was venerated as the goddess of the city and the protectress of the citadel.[12][78][42] In Athens, the Plynteria, or "Feast of the Bath", was observed every year at the end of the month of Thargelion.[79] The festival lasted for five days. During this period, the priestesses of Athena, or plyntrídes, performed a cleansing ritual within the Erechtheion, a sanctuary devoted to Athena and Poseidon.[80] Here Athena's statue was undressed, her clothes washed, and body purified.[80] Athena was worshipped at festivals such as Chalceia as Athena Ergane,[81][42] the patroness of various crafts, especially weaving.[81][42] She was also the patron of metalworkers and was believed to aid in the forging of armor and weapons.[81] During the late fifth century BC, the role of goddess of philosophy became a major aspect of Athena's cult.[82]

As Athena Promachos, she was believed to lead soldiers into battle.[83][40] Athena represented the disciplined, strategic side of war, in contrast to her brother Ares, the patron of violence, bloodlust, and slaughter—"the raw force of war".[84][85] Athena was believed to only support those fighting for a just cause[84] and was thought to view war primarily as a means to resolve conflict.[84] The Greeks regarded Athena with much higher esteem than Ares.[84][85] Athena was especially worshipped in this role during the festivals of the Panathenaea and Pamboeotia,[86] both of which prominently featured displays of athletic and military prowess.[86] As the patroness of heroes and warriors, Athena was believed to favor those who used cunning and intelligence rather than brute strength.[87]

In her aspect as a warrior maiden, Athena was known as Parthenos (Παρθένος "virgin"),[83][89][90] because, like her fellow goddesses Artemis and Hestia, she was believed to remain perpetually a virgin.[91][92][83][90][93] Athena's most famous temple, the Parthenon on the Athenian Acropolis, takes its name from this title.[93] According to Karl Kerényi, a scholar of Greek mythology, the name Parthenos is not merely an observation of Athena's virginity, but also a recognition of her role as enforcer of rules of sexual modesty and ritual mystery.[93] Even beyond recognition, the Athenians allotted the goddess value based on this pureness of virginity, which they upheld as a rudiment of female behavior.[93] Kerényi's study and theory of Athena explains her virginal epithet as a result of her relationship to her father Zeus and a vital, cohesive piece of her character throughout the ages.[93] This role is expressed in several stories about Athena. Marinus of Neapolis reports that when Christians removed the statue of the goddess from the Parthenon, a beautiful woman appeared in a dream to Proclus, a devotee of Athena, and announced that the "Athenian Lady" wished to dwell with him.[94]

Athena was also credited with creating the pebble-based form of divination. Those pebbles were called thriai, which was also the collective name of a group of nymphs with prophetic powers. Her half-brother Apollo, however, angered and spiteful at the practitioners of an art rival to his own, complained to their father Zeus about it, with the pretext that many people took to casting pebbles, but few actually were true prophets. Zeus, sympathizing with Apollo's grievances, discredited the pebble divination by rendering the pebbles useless. Apollo's words became the basis of an ancient Greek idiom.[95]

Regional cults

Athena was not only the patron goddess of Athens, but also other cities, including Pergamon,[39] Argos, Sparta, Gortyn, Lindos, and Larisa.[40] The various cults of Athena were all branches of her panhellenic cult[40] and often proctored various initiation rites of Grecian youth, such as the passage into citizenship by young men or the passage of young women into marriage.[40] These cults were portals of a uniform socialization, even beyond mainland Greece.[40] Athena was frequently equated with Aphaea, a local goddess of the island of Aegina, originally from Crete and also associated with Artemis and the nymph Britomartis.[96] In Arcadia, she was assimilated with the ancient goddess Alea and worshiped as Athena Alea.[97] Sanctuaries dedicated to Athena Alea were located in the Laconian towns of Mantineia and Tegea. The temple of Athena Alea in Tegea was an important religious center of ancient Greece.[g] The geographer Pausanias was informed that the temenos had been founded by Aleus.[98]

Athena had a major temple on the Spartan Acropolis,[99][42] where she was venerated as Poliouchos and Khalkíoikos ("of the Brazen House", often latinized as Chalcioecus).[99][42] This epithet may refer to the fact that cult statue held there may have been made of bronze,[99] that the walls of the temple itself may have been made of bronze,[99] or that Athena was the patron of metal-workers.[99] Bells made of terracotta and bronze were used in Sparta as part of Athena's cult.[99] An Ionic-style temple to Athena Polias was built at Priene in the fourth century BC.[100] It was designed by Pytheos of Priene,[101] the same architect who designed the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus.[101] The temple was dedicated by Alexander the Great[102] and an inscription from the temple declaring his dedication is now held in the British Museum.[100] She was worshipped as Athena Asia in Colchis -- supposedly on an account of a nearby mountain with that name -- from which her worship was believed to have been brought by Castor and Pollux to Laconia, where a temple was built to her at Las.[103][104][105]

In Pergamon, Athena was thought to have been a god of the cosmos and the aspects of it that aided Pergamon and its fate.[39]

Mythology

Birth

She was the daughter of Zeus, produced without a mother, and emerged full-grown from his forehead. There was an alternate story that Zeus swallowed Metis, the goddess of counsel, while she was pregnant with Athena and when she was fully grown she emerged from Zeus' forehead. Being the favorite child of Zeus, she had great power. In the classical Olympian pantheon, Athena was regarded as the favorite child of Zeus, born fully armed from his forehead.[106][107][108][h] The story of her birth comes in several versions.[109][110][111] The earliest mention is in Book V of the Iliad, when Ares accuses Zeus of being biased in favor of Athena because "autos egeinao" (literally "you fathered her", but probably intended as "you gave birth to her").[112][113] She was essentially urban and civilized, the antithesis in many respects of Artemis, goddess of the outdoors. Athena was probably a pre-Hellenic goddess and was later taken over by the Greeks. In the version recounted by Hesiod in his Theogony, Zeus married the goddess Metis, who is described as the "wisest among gods and mortal men", and engaged in sexual intercourse with her.[114][115][113][116] After learning that Metis was pregnant, however, he became afraid that the unborn offspring would try to overthrow him, because Gaia and Ouranos had prophesied that Metis would bear children wiser than their father.[114][115][113][116] In order to prevent this, Zeus tricked Metis into letting him swallow her, but it was too late because Metis had already conceived.[114][117][113][116] A later account of the story from the Bibliotheca of Pseudo-Apollodorus, written in the second century AD, makes Metis Zeus's unwilling sexual partner, rather than his wife.[118][119] According to this version of the story, Metis transformed into many different shapes in effort to escape Zeus,[118][119] but Zeus successfully raped her and swallowed her.[118][119]

After swallowing Metis, Zeus took six more wives in succession until he married his seventh and present wife, Hera.[116] Then Zeus experienced an enormous headache.[120][113][116] He was in such pain that he ordered someone (either Prometheus, Hephaestus, Hermes, Ares, or Palaemon, depending on the sources examined) to cleave his head open with the labrys, the double-headed Minoan axe.[56][113][121][119] Athena leaped from Zeus's head, fully grown and armed.[56][113][108][122] The "First Homeric Hymn to Athena" states in lines 9–16 that the gods were awestruck by Athena's appearance[123] and even Helios, the god of the sun, stopped his chariot in the sky.[123] Pindar, in his "Seventh Olympian Ode", states that she "cried aloud with a mighty shout" and that "the Sky and mother Earth shuddered before her."[124][123]

Hesiod states that Hera was so annoyed at Zeus for having given birth to a child on his own that she conceived and bore Hephaestus by herself,[116] but in Imagines 2. 27 (trans. Fairbanks), the third-century AD Greek rhetorician Philostratus the Elder writes that Hera "rejoices" at Athena's birth "as though Athena were her daughter also." The second-century AD Christian apologist Justin Martyr takes issue with those pagans who erect at springs images of Kore, whom he interprets as Athena: "They said that Athena was the daughter of Zeus not from intercourse, but when the god had in mind the making of a world through a word (logos) his first thought was Athena."[125] According to a version of the story in a scholium on the Iliad (found nowhere else), when Zeus swallowed Metis, she was pregnant with Athena by the Cyclops Brontes.[126] The Etymologicum Magnum[127] instead deems Athena the daughter of the Daktyl Itonos.[128] Fragments attributed by the Christian Eusebius of Caesarea to the semi-legendary Phoenician historian Sanchuniathon, which Eusebius thought had been written before the Trojan war, make Athena instead the daughter of Cronus, a king of Byblos who visited "the inhabitable world" and bequeathed Attica to Athena.[129][130]

Lady of Athens

In Homer's Iliad, Athena, as a war goddess, inspired and fought alongside the Greek heroes; her aid was synonymous with military prowess. Also in the Iliad, Zeus, the chief god, specifically assigned the sphere of war to Ares, the god of war, and Athena. Athena's moral and military superiority to Ares derived in part from the fact that she represented the intellectual and civilized side of war and the virtues of justice and skill, whereas Ares represented mere blood lust. Her superiority also derived in part from the vastly greater variety and importance of her functions and the patriotism of Homer's predecessors, Ares being of foreign origin. In the Iliad, Athena was the divine form of the heroic, martial ideal: she personified excellence in close combat, victory, and glory. The qualities that led to victory were found on the aegis, or breastplate, that Athena wore when she went to war: fear, strife, defense, and assault. Athena appears in Homer's Odyssey as the tutelary deity of Odysseus, and myths from later sources portray her similarly as the helper of Perseus and Heracles (Hercules). As the guardian of the welfare of kings, Athena became the goddess of good counsel, prudent restraint and practical insight, and war. In a founding myth reported by Pseudo-Apollodorus,[127] Athena competed with Poseidon for the patronage of Athens.[131] They agreed that each would give the Athenians one gift[131] and that Cecrops, the king of Athens, would determine which gift was better.[131] Poseidon struck the ground with his trident and a salt water spring sprang up;[131] this gave the Athenians access to trade and water.[132] Athens at its height was a significant sea power, defeating the Persian fleet at the Battle of Salamis[132]—but the water was salty and undrinkable.[132] In an alternative version of the myth from Vergil's Georgics,[127] Poseidon instead gave the Athenians the first horse.[131] Athena offered the first domesticated olive tree.[131][90] Cecrops accepted this gift[131] and declared Athena the patron goddess of Athens.[131] The olive tree brought wood, oil, and food,[132] and became a symbol of Athenian economic prosperity.[90][133] Robert Graves was of the opinion that "Poseidon's attempts to take possession of certain cities are political myths",[132] which reflect the conflict between matriarchal and patriarchal religions.[132]

Afterwards, Poseidon was so angry over his defeat that he sent one of his sons, Halirrhothius, to cut down the tree. But as he swung his axe, he missed his aim and it fell in himself, killing him. This was supposedly the origin of calling Athena's sacred olive tree moria, for Halirrhotius's attempt at revenge proved fatal (moros in Greek). Poseidon in fury accused Ares of murder, and the matter was eventually settled on the Areopagus ("hill of Ares") in favour of Ares, which was thereafter named after the event.[135][136]

Pseudo-Apollodorus[127] records an archaic legend, which claims that Hephaestus once attempted to rape Athena, but she pushed him away, causing him to ejaculate on her thigh.[137][88][138] Athena wiped the semen off using a tuft of wool, which she tossed into the dust,[137][88][138] impregnating Gaia and causing her to give birth to Erichthonius.[137][88][138] Athena adopted Erichthonius as her son and raised him.[137][138] The Roman mythographer Hyginus[127] records a similar story in which Hephaestus demanded Zeus to let him marry Athena since he was the one who had smashed open Zeus's skull, allowing Athena to be born.[137] Zeus agreed to this and Hephaestus and Athena were married,[137] but, when Hephaestus was about to consummate the union, Athena vanished from the bridal bed, causing him to ejaculate on the floor, thus impregnating Gaia with Erichthonius.[137]

The geographer Pausanias[127] records that Athena placed the infant Erichthonius into a small chest[139] (cista), which she entrusted to the care of the three daughters of Cecrops: Herse, Pandrosos, and Aglauros of Athens.[139] She warned the three sisters not to open the chest,[139] but did not explain to them why or what was in it.[139] Aglauros, and possibly one of the other sisters,[139] opened the chest.[139] Differing reports say that they either found that the child itself was a serpent, that it was guarded by a serpent, that it was guarded by two serpents, or that it had the legs of a serpent.[140] In Pausanias's story, the two sisters were driven mad by the sight of the chest's contents and hurled themselves off the Acropolis, dying instantly,[141] but an Attic vase painting shows them being chased by the serpent off the edge of the cliff instead.[141]

Erichthonius was one of the most important founding heroes of Athens[88] and the legend of the daughters of Cecrops was a cult myth linked to the rituals of the Arrhephoria festival.[88][142] Pausanias records that, during the Arrhephoria, two young girls known as the Arrhephoroi, who lived near the temple of Athena Polias, would be given hidden objects by the priestess of Athena,[143] which they would carry on their heads down a natural underground passage.[143] They would leave the objects they had been given at the bottom of the passage and take another set of hidden objects,[143] which they would carry on their heads back up to the temple.[143] The ritual was performed in the dead of night[143] and no one, not even the priestess, knew what the objects were.[143] The serpent in the story may be the same one depicted coiled at Athena's feet in Pheidias's famous statue of the Athena Parthenos in the Parthenon.[134] Many of the surviving sculptures of Athena show this serpent.[134]

Herodotus records that a serpent lived in a crevice on the north side of the summit of the Athenian Acropolis[134] and that the Athenians left a honey cake for it each month as an offering.[134] On the eve of the Second Persian invasion of Greece in 480 BC, the serpent did not eat the honey cake[134] and the Athenians interpreted it as a sign that Athena herself had abandoned them.[134] Another version of the myth of the Athenian maidens is told in Metamorphoses by the Roman poet Ovid (43 BC – 17 AD); in this late variant Hermes falls in love with Herse. Herse, Aglaulus, and Pandrosus go to the temple to offer sacrifices to Athena. Hermes demands help from Aglaulus to seduce Herse. Aglaulus demands money in exchange. Hermes gives her the money the sisters have already offered to Athena. As punishment for Aglaulus's greed, Athena asks the goddess Envy to make Aglaulus jealous of Herse. When Hermes arrives to seduce Herse, Aglaulus stands in his way instead of helping him as she had agreed. He turns her to stone.[144]

Athena gave her favour to an Attic girl named Myrsine, a chaste girl who outdid all her fellow athletes in both the palaestra and the race. Out of envy, the other athletes murdered her, but Athena took pity in her and transformed her dead body into a myrtle, a plant thereafter as favoured by her as the olive was.[145] An almost exact story was said about another girl, Elaea, who transformed into an olive, Athena's sacred tree.[146]

Patron of heroes

According to Pseudo-Apollodorus's Bibliotheca, Athena advised Argos, the builder of the Argo, the ship on which the hero Jason and his band of Argonauts sailed, and aided in the ship's construction.[148][149] Pseudo-Apollodorus also records that Athena guided the hero Perseus in his quest to behead Medusa.[150][151][152] She and Hermes, the god of travelers, appeared to Perseus after he set off on his quest and gifted him with tools he would need to kill the Gorgon.[152][153] Athena lent Perseus her polished bronze shield to view Medusa's reflection without becoming petrified himself.[152][154] Hermes lent Perseus his harpe to behead Medusa with.[152][155] When Perseus swung the blade to behead Medusa, Athena guided it, allowing the blade to cut the Gorgon's head clean off.[152][154] According to Pindar's Thirteenth Olympian Ode, Athena helped the hero Bellerophon tame the winged horse Pegasus by giving him a bit.[156][157]

In ancient Greek art, Athena is frequently shown aiding the hero Heracles.[158] She appears in four of the twelve metopes on the Temple of Zeus at Olympia depicting Heracles's Twelve Labors,[159][158] including the first, in which she passively watches him slay the Nemean lion,[158] and the tenth, in which she is shown actively helping him hold up the sky.[160] She is presented as his "stern ally",[161] but also the "gentle... acknowledger of his achievements."[161] Artistic depictions of Heracles's apotheosis show Athena driving him to Mount Olympus in her chariot and presenting him to Zeus for his deification.[160] In Aeschylus's tragedy Orestes, Athena intervenes to save Orestes from the wrath of the Erinyes and presides over his trial for the murder of his mother Clytemnestra.[162] When half the jury votes to acquit and the other half votes to convict, Athena casts the deciding vote to acquit Orestes[162] and declares that, from then on, whenever a jury is tied, the defendant shall always be acquitted.[163]

In The Odyssey, Odysseus' cunning and shrewd nature quickly wins Athena's favour.[164][149] For the first part of the poem, however, she largely is confined to aiding him only from afar, mainly by implanting thoughts in his head during his journey home from Troy. Her guiding actions reinforce her role as the "protectress of heroes," or, as mythologian Walter Friedrich Otto dubbed her, the "goddess of nearness", due to her mentoring and motherly probing.[165][150][166] It is not until he washes up on the shore of the island of the Phaeacians, where Nausicaa is washing her clothes that Athena arrives personally to provide more tangible assistance.[167] She appears in Nausicaa's dreams to ensure that the princess rescues Odysseus and plays a role in his eventual escort to Ithaca.[168] Athena appears to Odysseus upon his arrival, disguised as a herdsman;[169][170][164] she initially lies and tells him that Penelope, his wife, has remarried and that he is believed to be dead,[169] but Odysseus lies back to her, employing skillful prevarications to protect himself.[171][170] Impressed by his resolve and shrewdness, she reveals herself and tells him what he needs to know to win back his kingdom.[172][170][164] She disguises him as an elderly beggar so that he will not be recognized by the suitors or Penelope,[173][170] and helps him to defeat the suitors.[173][174][170] Athena also appears to Odysseus's son Telemachus.[175] Her actions lead him to travel around to Odysseus's comrades and ask about his father.[176] He hears stories about some of Odysseus's journey.[176] Athena's push for Telemachus's journey helps him grow into the man role, that his father once held.[177] She also plays a role in ending the resultant feud against the suitors' relatives. She instructs Laertes to throw his spear and to kill Eupeithes, the father of Antinous.

-

Athena, detail from a silver kantharos with Theseus in Crete (c. 440-435 BC), part of the Vassil Bojkov collection, Sofia, Bulgaria

-

Silver coin showing Athena with Scylla decorated helmet and Heracles fighting the Nemean lion (Heraclea Lucania, 390-340 BC)

Punishment myths

The Gorgoneion appears to have originated as an apotropaic symbol intended to ward off evil.[178] In a late myth invented to explain the origins of the Gorgon,[179] Medusa is described as having been a young priestess who served in the temple of Athena in Athens.[180] Poseidon lusted after Medusa, and raped her in the temple of Athena,[180] refusing to allow her vow of chastity to stand in his way.[180] Upon discovering the desecration of her temple, Athena transformed Medusa into a hideous monster with serpents for hair whose gaze would turn any mortal to stone.[181]

In his Twelfth Pythian Ode, Pindar recounts the story of how Athena invented the aulos, a kind of flute, in imitation of the lamentations of Medusa's sisters, the Gorgons, after she was beheaded by the hero Perseus.[182] According to Pindar, Athena gave the aulos to mortals as a gift.[182] Later, the comic playwright Melanippides of Melos (c. 480–430 BC) embellished the story in his comedy Marsyas,[182] claiming that Athena looked in the mirror while she was playing the aulos and saw how blowing into it puffed up her cheeks and made her look silly, so she threw the aulos away and cursed it so that whoever picked it up would meet an awful death.[182] The aulos was picked up by the satyr Marsyas, who was later killed by Apollo for his hubris.[182] Later, this version of the story became accepted as canonical[182] and the Athenian sculptor Myron created a group of bronze sculptures based on it, which was installed before the western front of the Parthenon in around 440 BC.[182]

A myth told by the early third-century BC Hellenistic poet Callimachus in his Hymn 5 begins with Athena bathing in a spring on Mount Helicon at midday with one of her favorite companions, the nymph Chariclo.[138][183] Chariclo's son Tiresias happened to be hunting on the same mountain and came to the spring searching for water.[138][183] He inadvertently saw Athena naked, so she struck him blind to ensure he would never again see what man was not intended to see.[138][184][185] Chariclo intervened on her son's behalf and begged Athena to have mercy.[138][185][186] Athena replied that she could not restore Tiresias's eyesight,[138][185][186] so, instead, she gave him the ability to understand the language of the birds and thus foretell the future.[187][186][138]

Myrmex was a clever and chaste Attic girl who became quickly a favourite of Athena. However, when Athena invented the plough, Myrmex went to the Atticans and told them that it was in fact her own invention. Hurt by the girl's betrayal, Athena transformed her into the small insect bearing her name, the ant.[188]

The fable of Arachne appears in Ovid's Metamorphoses (8 AD) (vi.5–54 and 129–145),[189][190][191] which is nearly the only extant source for the legend.[190][191] The story does not appear to have been well known prior to Ovid's rendition of it[190] and the only earlier reference to it is a brief allusion in Virgil's Georgics, (29 BC) (iv, 246) that does not mention Arachne by name.[191] According to Ovid, Arachne (whose name means spider in ancient Greek[192]) was the daughter of a famous dyer in Tyrian purple in Hypaipa of Lydia, and a weaving student of Athena.[193] She became so conceited of her skill as a weaver that she began claiming that her skill was greater than that of Athena herself.[193][194] Athena gave Arachne a chance to redeem herself by assuming the form of an old woman and warning Arachne not to offend the deities.[189][194] Arachne scoffed and wished for a weaving contest, so she could prove her skill.[195][194]

Athena wove the scene of her victory over Poseidon in the contest for the patronage of Athens.[195][196][194] Athena's tapestry also depicted the 12 Olympian gods and defeat of mythological figures who challenged their authority.[197] Arachne's tapestry featured twenty-one episodes of the deities' infidelity,[195][196][194] including Zeus being unfaithful with Leda, with Europa, and with Danaë.[196] It represented the unjust and discrediting behavior of the gods towards mortals.[197] Athena admitted that Arachne's work was flawless,[195][194][196] but was outraged at Arachne's offensive choice of subject, which displayed the failings and transgressions of the deities.[195][194][196] Finally, losing her temper, Athena destroyed Arachne's tapestry and loom, striking it with her shuttle.[195][194][196] Athena then struck Arachne across the face with her staff four times.[195][194][196] Arachne hanged herself in despair,[195][194][196] but Athena took pity on her and brought her back from the dead in the form of a spider.[195][194][196]

In a rarer version, surviving in the scholia of an unnamed scholiast on Nicander, whose works heavily influenced Ovid, Arachne is placed in Attica instead and has a brother named Phalanx. Athena taught Arachne the art of weaving and Phalanx the art of war, but when brother and sister laid together in bed, Athena was so disgusted with them that she turned them both into spiders, animals forever doomed to be eaten by their own young.[198]

Trojan War

Миф о решении Парижа кратко упоминается в Илиаде , [199] but is described in depth in an epitome of the Cypria, a lost poem of the Epic Cycle,[200] который записывает, что все боги и богини, а также различные смертные были приглашены на брак Пелеуса и Тетиса (возможные родители Ахилла ). [ 199 ] Только Эрис , богиня раздора, не была приглашена. [ 200 ] Она была раздражена этим, поэтому она прибыла с золотым яблоком, надписанным со словом καλλίστῃ (kallistēi, «для самых справедливых»), которое она бросила среди богинь. [ 201 ] Афродита, Гера и Афина все утверждали, что являются самым справедливым, и, следовательно, законным владельцем яблока. [ 201 ] [ 138 ]

Богини решили разместить вопрос перед Зевсом, который, не желая отдать предпочтение одному из богинь, вложил выбор в руки Парижа, троянского принца. [ 201 ] [ 138 ] После купания весной Маунт -Ида , где находился Трой, богини появились перед Парисом за его решение. [ 201 ] В существующих древних изображениях суждения Парижа Афродита лишь иногда представлена обнаженной, а Афина и Гера всегда полностью одеты. [ 202 ] Однако после эпохи Возрождения западные картины обычно изображают все три богини как совершенно обнаженные. [ 202 ]

Все три богини были в идеале прекрасны, и Париж не мог решить между ними, поэтому они прибегали к взяткам. [ 201 ] Гера попыталась подкупить Париж с властью над всей Азией и Европой, [ 201 ] [ 138 ] и Афина предложила славу и славу в битве, [ 201 ] [ 138 ] Но Афродит пообещала Парису, что, если бы он выбрал ее самой справедливой, она позволила бы ему жениться на самой красивой женщине на земле. [ 203 ] [ 138 ] Эта женщина была Хелен , которая уже была замужем за королем Менелаусом из Спарты . [ 203 ] Париж выбрал Афродиту и наградил ей Apple. [ 203 ] [ 138 ] Две другие богини были в ярости и, как прямой результат, встали на сторону греков в Троянской войне . [ 203 ] [ 138 ]

В книгах v -vi Илиады Афина помогает герою Диомедес , который, в отсутствие Ахилла, доказывает себя самым эффективным греческим воином. [ 204 ] [ 149 ] Несколько художественных представлений начала шестого века до нашей эры могут показать Афину и Диомедс, [ 204 ] Включая группу BC Shield в начале шестого века с изображением Афины и неопознанного воина, катаясь на колеснице, картину вазы воина с его колесницей, стоящим перед Афиной, и вписанную глиняную табличку, показывающую диомед и Афину на колеснице. [ 204 ] Многочисленные отрывки в Илиаде также упоминают, что Афина ранее служила покровителем отца Диомеда Тайдеуса . [ 205 ] [ 206 ] Когда троянские женщины отправляются в Храм Афины на Акрополе, чтобы умолять ее о защите от Диомедеса, Афина игнорирует их. [ 62 ]

В книге XXII о Илиаде , в то время как Ахиллес преследует Гектор вокруг стен Трои, Афина, похоже, замаскирован под его брата Дейфобуса [ 207 ] и убеждает его удержать его земли, чтобы они могли сражаться с Ахиллесом вместе. [ 207 ] Затем Гектор бросает свое копье в Ахиллес и промахи, ожидая, что Дейфхобус передаст его другому, [ 208 ] Но вместо этого Афина исчезает, оставляя Гектора встретиться с Ахиллесом в одиночестве без его копья. [ 208 ] В Софокла «Трагедии » она наказывает соперника Одиссея Аякса Великого , сводя его с ума и заставляя его резни скота ахейцев, думая, что он сами убивает ахейцев. [ 209 ] Даже после того, как сам Одиссей выражает жалость к Аяксу, [ 210 ] Афина заявляет: «Смеяться над твоими врагами - какой может быть более сладкий смех, чем это?» (строки 78–9). [ 210 ] Аякс позже совершает самоубийство в результате своего унижения. [ 210 ]

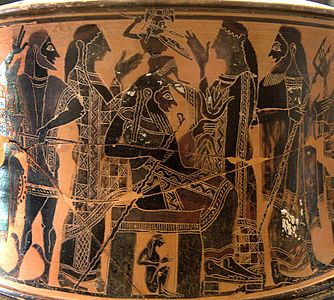

Классическое искусство

Афина часто появляется в классическом греческом искусстве, в том числе на монетах и на картинах на керамике. [ 211 ] [ 212 ] Она особенно известна в работах, произведенных в Афинах. [ 211 ] В классических изображениях Афина обычно изображается стоящей в вертикальном положении, одетый в полнометражный хитон . [ 213 ] Она чаще всего представляется в броне, как солдат мужского пола [ 212 ] [ 213 ] [ 7 ] и носить коринфский шлем, поднятый высоко на лбу. [ 214 ] [ 7 ] [ 212 ] Ее щит несет в своем центре эгида с головой Горгона ( Горгонион ) в центре и змеи вокруг края. [ 179 ] Иногда она показывается в эгиде как плащ. [ 212 ] Как Athena Promachos, она показывается, что размахивает копье. [ 211 ] [ 7 ] [ 212 ] Сцены, в которых была представлена Афина, включают ее рождение от главы Зевса, ее битву с Гигантами , рождение Эрихтониуса и решение Парижа. [ 211 ]

Смешанная Афина или Афина медитирует - это известная скульптура облегчения, датируемая около 470–460 гг. До н.э. [ 214 ] [ 211 ] Это было истолковано как представление Афины Полиас. [ 214 ] Самым известным классическим изображением Афины был Афина Парфенос , ныне упущенная 11,5 м (38 футов) [ 215 ] Золотая и слоновая статуя ее в Парфеноне, созданная афинским скульптором Фидия . [ 213 ] [ 211 ] Копии показывают, что эта статуя изображала Афину, держащую ее щит в левой руке с Найком , крылатой богиней победы, стоящей в ее праве. [ 211 ] Афина Полиас также представлен в нео-атитическом облегчении, в настоящее время проводимом в Музее изящных искусств Вирджинии , [ 214 ] который изображает ее, держащую сову в руке [ я ] и носить ее характерный коринфский шлем, отдыхая на ее щите на соседнюю Герму . [ 214 ] Римская богиня Минерва приняла большинство греческих иконографических ассоциаций Афины, [ 216 ] но также был интегрирован в капитолиновую триаду . [ 216 ]

-

Акдад красный фигура Каликс из Афины Промачос, держащий копье и стоящее рядом с дорической колонкой ( ок. 500-490 до н.э.)

-

Восстановление полихромного украшения статуи Афины из храма Афаи в Aegina , c. 490 г. до н.э. (из экспозиции "Bunte Götter" Munich Glyptothek )

-

Аттик красный фигура Кайликса, показывающая Афину, убивающую гигантскую энделадус ( ок. 550–500 г. до н.э.)

-

Классическая мозаика из виллы в Tusculum , 3-й век, сейчас в Museo Pio-Clementino , Ватикан

-

Афина портрет Евкляйды на тетрадрахме из Сиракузы, Сицилия c. 400 г. до н.э.

-

Мифологическая сцена с Афиной (слева) и Гераклсом (справа), на каменной палитре греко -буддийского искусства Гандхары , Индия

-

Атена Фарнзе , римская копия греческого оригинала из круга доктора философии, c. 430 г. н.э., музейный археолог, Неаполь

-

Афина (2 -й век до н.э.) в искусстве Гандхара , выставленная в музее Лахора , Пакистан

Постклассическая культура

Искусство и символика

Ранние христианские писатели, такие как Клемент Александрии и фирм , унизили Афину как представитель всех вещей, которые были ненавидели в отношении язычества; [ 218 ] Они осудили ее как «нескромную и аморальную». [ 219 ] В средние века, однако, многие атрибуты Афины были переданы Деве Марии , [ 219 ] Который в изображении четвертого века часто изображали в Gorgoneion . [ 219 ] Некоторые даже рассматривали Деву Марию как девушку -воина, очень как Афина Парфенос; [ 219 ] Один анекдот говорит, что Дева Мария когда -то появилась на стенах Константинополя , когда авары осадали, сжимая копье и призывая людей сражаться. [ 220 ] В средние века Афина стала широко использованной в качестве христианского символа и аллегории, и она появилась на семейных гребнях определенных благородных домов. [ 221 ]

Во время Ренессанса Афина надела мантию покровителя искусств и человеческих усилий; [ 222 ] Аллегорические картины с участием Афины были фаворитом итальянских художников Ренессанса. [ 222 ] На Сандро Боттичелли живописи Паллас и Кентавр , вероятно, нарисованные когда -то в 1480 -х годах, Афина - олицетворение целомудрия, которому показано, что схватывает переднюю часть кентавра, который представляет жажду. [ 223 ] [ 224 ] Картина Андреа Мантегны 1502 года Минерва изгнала пороки из сада добродетели, использует Афину в качестве олицетворения Греко-римского обучения, преследующего пороки средневековья из сада современной стипендии. [ 225 ] [ 224 ] [ 226 ] Афина также используется в качестве олицетворения мудрости в Варфоломее Спрэнджере 1591 года, рисуя триумф мудрости или Минервы, победивших из -за невежества . [ 216 ]

В течение шестнадцатого и семнадцатого веков Афина использовалась в качестве символа для женщин -правителей. [ 227 ] В своей книге «Откровение истинной Минервы» (1582) Томас Бленнерхассетт изображает королеву Елизавету I из Англии как «новую минерву» и «величайшую богиню на земле». [ 228 ] Серия картин Питера Пола Рубенса изображает Афину как Мари де Медичи ; покровителя и наставника [ 229 ] Последняя картина в серии идет еще дальше и показывает Мари Де Медичи с иконографией Афины, как смертельное воплощение самой богини. [ 229 ] Фламандский скульптор Жан-Пьер-Антуан Тассаерт (Ян Питер Антон Тассаерт) позже изобразил Кэтрин II из России в качестве Афины в мраморном бюсте в 1774 году. [ 216 ] Во время французской революции статуи языческих богов были снесены по всей Франции, но статуи Афины не были. [ 229 ] Вместо этого Афина была преобразована в олицетворение свободы и республики [ 229 ] и статуя богини стояла в центре революции места в Париже. [ 229 ] В годы после революции художественные представления Афины размножались. [ 230 ]

Статуя Афины стоит прямо перед австрийским зданием парламента в Вене, [ 231 ] И изображения Афины повлияли на другие символы западной свободы, включая Статую Свободы и Британства . [ 231 ] Более века полномасштабная копия Парфенона стояла в Нэшвилле, штат Теннесси . [ 232 ] В 1990 году кураторы добавили позолоченную копию сорока двух футов (12,5 м) высотой Фидия в Афине Парфеноса , построенной из бетона и стекловолокна. [ 232 ] Великая печать Калифорнии носит изображение Афины, стоящего на коленях рядом с коричневым медведем гризли. [ 233 ] Афина иногда появлялась на современных монетах, как и на древней афинской драхме . Ее голова появляется на памятной монете в Панаме-Тихоокеанском регионе за 50 долларов США . [ 234 ]

-

Паллас и Кентавр ( ок. 1482) Сандро Боттичелли

-

Афина презирала достижения Гефеста ( ок. 1555–1560) Парижа Бордоне

-

Минерва победительна над невежеством ( ок. 1591) Барфоломея Спрейнгер

-

Мария де Медичи (1622) Питер Пол Рубенс , показывая ее как воплощение Афины [ 229 ]

-

Минерва защищает мир от Марса (1629) Питером Полом Рубенсом

-

Минерва раскрывает Итаку в Улисс (пятнадцатый век) Джузеппе Боттани

-

Бой Марса и Минервы (1771) Джозеф-Бенуа Суве

-

Minerva of Peace Mosaic в библиотеке Конгресса

-

Афина на великой печати Калифорнии

Современные интерпретации

Одним из самых ценных вещей Сигмунда Фрейда была небольшая бронзовая скульптура Афины, которая сидела на его столе. [ 236 ] Фрейд однажды назвал Афину «женщиной, которая недоступна и отталкивает все сексуальные желания - так как она демонстрирует ужасающие гениталии матери». [ 237 ] Феминистские взгляды на Афину резко разделены; [ 237 ] Некоторые феминистки считают ее символом расширения прав и возможностей женщин, [ 237 ] В то время как другие считают ее «окончательным патриархальным распродажами ... кто использует ее способности для продвижения и продвижения мужчин, а не других ее пола». [ 237 ] В современной Викке Афина почитается как аспект богини [ 238 ] И некоторые викканы считают, что она может даровать «дар совы» («способность четко писать и общаться») своим поклонникам. [ 238 ] Из -за ее статуса одного из двенадцати олимпийцев, Афина - главное божество в эллинизме , [ 239 ] неопаганская религия , которая стремится достоверно оживить и воссоздать религию древней Греции в современном мире. [ 240 ]

Афина является естественным покровителем университетов: в колледже Брин Маур в Пенсильвании, статуя Афины (реплика оригинальной бронзовой библиотеки искусства и археологии) находится в Большом зале. [ 241 ] Студенты традиционны в экзамене, чтобы студенты оставлять предложения богине с запиской с просьбой о удаче, [ 241 ] Или покаяться за случайное нарушение любой из многочисленных других традиций колледжа. [ 241 ] Паллас Афина - богиня опекуна международного социального братства Phi Delta Theta . [ 242 ] Ее сова также является символом братства. [ 242 ]

Генеалогия

| Семейное древо Афины |

|---|

Смотрите также

- Athenaeum (устранение неоднозначности)

- Амбулия , спартанское эпитетное использование для Афины, Зевса , и Кастора и Поллукса

Примечания

- ^ В других традициях отец Афины иногда упоминается как Зевс сам или Паллас , Бронтес или Итонос .

- ^ / ə ˈ θ iː n ə / ; Чердак греческий : Атин , атен или афинян , афнааааааааааааааааааааааааааааааааааааааааааааааааааааааааааааааааааааааааа , Эпический : афинян , афнаацицицированный ; Дорик : Бессмертный , Атха

- ^ / ə ˈ θ iː n iː / ; Ionic : ἀθήνη , Athḗnē

- ^ / ˈ p æ l ə s / ; Паллас Паллас

- ^ «Граждане имеют божество за свою основу; ее называют на египетском языке Нейт и утверждают, что они являются теми, кого эллины называют Афиной; они великие любители афинян и говорят, что они в некотором роде Связано с ними. " ( Timeus 21e.)

- ^ Aeschilus , Euminedes , v. 292 ф. ср. Традиционная, что она была дочерью Нилоса: Смотри, e. глин Клемент Александрии Пров. 2.28.2; Cicero, de natura deorum

- ^ «Это святилище было уважаемом всеми пелопоннесами и обеспечивало своеобразное безопасность своим поставкам» (Павсания, описание Греции III.5.6)

- этого Знаменитая характеристика Джейн Эллен Харрисон мифа как «отчаянное богословское целесообразное избавление земной коры от ее матриархальных условий» (Харрисон, 1922: 302) никогда не была опровергана и не подтверждена.

- ^ Роль Совы как символа мудрости возникает в этой связи с Афиной.

- ^ По словам Гомера , ILIAD 1,570–579 , 14.338 , Odyssey 8.312 , Hephaestus, по -видимому, был сыном Геры и Зевса, см. Gantz, p. 74

- ^ По словам Гесиода , Теогония 927–929 , Гефест был произведен только Герой, без отца, см. Ганц, с. 74

- ^ По словам Гесиода , Теогония 183–200 , Афродита родилась из отрубленных гениталий Урана, см. Ганц, с. 99–100.

- ^ По словам Гомера , Афродита была дочерью Зевса ( ILIAD 3,374 , 20,105 ; Одиссея 8.308 , 320 ) и Дионе ( ILIAD 5,370–71 ), см. Ганц, стр. 99–100.

Ссылки

- ^ Kerényi 1951 , стр. 121-122.

- ^ L. Day 1999 , p. 39

- ^ Энциклопедия литературы Мерриам-Уэбстера . Мерриам-Уэбстер. 1995. с. 81 . ISBN 9780877790426 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Deacy & Silling 2001 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин час Burkert 1985 , p. 139

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон Ruck & Staples 1994 , p. 24

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и Пауэлл 2012 , с. 230.

- ^ знал 2009 , с. 29

- ^ Johrns 1981 , стр. 438-452.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Hurwit 1999 , p. 14

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Нильссон 1967 , с. 347, 433.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон Burkert 1985 , p. 140.

- ^ Puhvel 1987 , p. 133.

- ^ Кинсли 1989 , с. 141–142.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Желудок и Чедвик 1973 , с. 126

- ^ Чедвик 1976 , с. 88–89.

- ^ Bliss 2004 , p. 444.

- ^ Burkert 1985 , p. 44

- ^ Или выберите описание, строка 1.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Лучший 1989 , с. 30

- ^ Mylonas 1966 , p. 159

- ^ Hurwit 1999 , стр. 13–14.

- ^ Fururmark 1978 , p. 672.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Нильссон 1950 , с.

- ^ Харрисон 1922: 306. CFR. там же. , с. 307, рис. 84: «Деталь чашки в коллекции Faina» . Архивировано из оригинала 5 ноября 2004 года . Получено 6 мая 2007 года . Полем

- ^ Wolkstein & Kramer 1983 , с. 92, 193.

- ^ Puhvel 1987 , с. 133–134.

- ^ Mallory & Adams 2006 , p. 433.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Penglase 1994 , p. 235.

- ^ Deacy 2008 , с. 20–21, 41.

- ^ Penglase 1994 , стр. 233-325.

- ^ Ср. Также Геродот, История 2: 170–175.

- ^ Бернал, 1987 , с. 21, 51 фр.

- ^ Fritze 2009 , с. 221–229.

- ^ Berlinerblau 1999 , p. 93ff.

- ^ Fritze 2009 , с. 221–255.

- ^ Jasanoff & Nussbaum 1996 , p. 194.

- ^ Fritze 2009 , с. 250–255.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Янсон, Хорст Волдер ; Янсон, Энтони Ф. (2004). Toubg, Сара; Мур, Джулия; Оппенгеймер, Маргарет; Кастриан, Аната (ред.). История искусства: западная традиция Тол. 1 (пересмотрено 6 -е изд.). Верхняя Седл -Ривер, Нью -Джерси: Парсон Образование Стр. 111, 160. ISBN 0-13-182622-0 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин час Schmitt 2000 , с. 1059–1073.

- ^ Гомеровские гимны . Перевод Кэшфорда, Жюля. Лондон: книги пингвинов. 2003. ISBN 0-14-043782-7 Полем OCLC 59339816 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин Hurwit 1999 , p. 15

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Хаббард 1986 , с. 28

- ^ Bell 1993 , p. 13

- ^ Паусания , я. 5. § 3; 41. § 6.

- ^ Johnzes , Ad Lycocoh

- ^ Schaus & If 2007 , p. 30

- ^ "Паусания, описание Греции, 2.34.8" . Архивировано из оригинала 29 июня 2021 года . Получено 20 февраля 2021 года .

- ^ «Павсания, описание Греции, 2.34.9» . Архивировано из оригинала 24 июня 2021 года . Получено 20 февраля 2021 года .

- ^ «Жизнь Перикла 13,8» . Плутарх, параллельная жизнь . uchicago.edu. 1916.

Параллельная жизнь Плутарха, опубликованная в том. III из издания Классической библиотеки Loeb, 1916

- ^ Лесли А. Бомонт (2013). Детство в древних Афинах: иконография и социальная история . Routledge. п. 69. ISBN 978-0415248747 .

- ^ Chantraine, Sv; Новый Поли говорит, что этимология просто неизвестна

- ^ New Pauly s.v. Pallas

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Грейвс 1960 , с. 50–55.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Грейвс 1960 , с. 50

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и Kerényi 1951 , p. 120.

- ^ Deacy 2008 , p. 51

- ^ Пауэлл 2012 , с. 231.

- ^ Kerényi 1951 , p. 120-121.

- ^ Kerényi 1951 , p. 121.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон Decy 2008 , p. 68

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Decy 2008 , с. 68–69.

- ^ Deacy 2008 , p. 71

- ^ Глаук в Лидделле и Скотте .

- ^ Глаук в Лидделле и Скотте .

- ^ ὤὤ в Лидделле и Скотте .

- ^ Томпсон, Д'Арси Вентворт (1895). Глоссарий греческих птиц . Оксфорд, Кларендон Пресс. п. 45

- ^ γλαύξ в Лидделле и Скотте .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Нильссон 1950 , с. 491–496.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Грейвс 1960 , с. 55

- ^ Kerényi 1951 , p. 128

- ^ Третичный в Лидделле и Скотте .

- ^ Hesod, Теогония II, 886-900.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Вдова 2005 , с. 289-298.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Вдова 2005 , с. 293.

- ^ Гомер, Илиад XV, 187–195.

- ^ «Диоген жизни выдающихся философов, книга 9, глава 7. Демократ (? 460-357 до н.э.)» .

- ^ Херрингтон 1955 , с. 11–15.

- ^ Саймон 1983 , с. 46

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Саймон 1983 , с. 46–49.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Херрингтон 1955 , с. 1–11.

- ^ Burkert 1985 , с. 305–337.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Херрингтон 1955 , с. 11–14.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Darmon 1992 , pp. 114-115.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Hansen 2004 , с. 123–124.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Робертсон 1992 , с. 90–109.

- ^ Hurwit 1999 , p. 18

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон Burkert 1985 , p. 143.

- ^ Голдхилл 1986 , с. 121.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Garland 2008 , с. 217

- ^ Хансен 2004 , с.

- ^ Голдхилл 1986 , с. 31

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и Kerényi 1952 .

- ^ «Маринус Самарии, жизнь Прокала или о счастье» . tertullian.org . 1925. С. 15–55.

Перевод Кеннета С. Гатри (пункт: 30)

- ^ Аполлон Афин 2016 , с. 224

- ^ Pilafidis-Williams 1998 .

- ^ Jost 1996 , pp. 134–135.

- ^ Паусания, описание Греции VIII.4.8.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон Decy 2008 , p. 127

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Burn 2004 , p. 10

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Burn 2004 , p. 11

- ^ Burn 2004 , с. 10–11.

- ^ Паусания , описание Греции 3.24.5

- ^ Манхейм, Ральф (1963). Прометей: Архетипический образ человеческого существования . ПРИЗНАЯ УНИВЕРСИТЕТА ПРИСЕТА . п. 56. ISBN 9780691019079 .

- ^ Фарнелл, Льюис Ричард (1921). Греческий герой культов и идеи бессмертия: лекции Гиффорда, проведенные в Университете Святого Андрея в 1920 году . Кларендон Пресс . п. 199. ISBN 978-0-19-814292-8 .

- ^ Kerényi 1951 , стр. 118-120.

- ^ Deacy 2008 , с. 17–32.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Penglase 1994 , pp. 230-231.

- ^ Kerényi 1951 , стр. 118-122.

- ^ Deacy 2008 , с. 17–19.

- ^ Hansen 2004 , с. 121–123.

- ^ Илиада книга V, строка 880

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин Decy 2008 , p. 18

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Гесиод, Теогония 885–900 Архивировал 24 февраля 2021 года на машине Wayback , 929E-929T Архивировал 28 октября 2021 года на машине Wayback

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Kerényi 1951 , стр. 118-119.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон Hansen 2004 , с. 121–122.

- ^ Kerényi 1951 , p. 119

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 1.3.6 Архивировано 24 февраля 2021 года на машине Wayback

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Hansen 2004 , с. 122–123.

- ^ Kerényi 1951 , стр. 119-120.

- ^ Penglase 1994 , p. 231.

- ^ Hansen 2004 , с. 122–124.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Penglase 1994 , p. 233.

- ^ Пиндар , « Седьмая олимпийская ода архивировал 25 февраля 2021 года на машине Wayback ». Линии 37–38

- ^ Джастин, извинения 64.5, цитируется в Роберте МакКуине Грант, Богах и Едином Боге , том. 1: 155, который отмечает, что это порфир », который аналогично идентифицирует Афину с« предвидели » .

- ^ Ганц, с. 51; Ягумура, с. 89 Архивировано 27 декабря 2022 года на машине Wayback ; Scholia bt Iliad to

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон Kerényi 1951 , p. 281.

- ^ Kerényi 1951 , p. 122

- ^ Олденбург 1969 , с. 86

- ^ IP, Cory, ed. (1832). «Богословие финицианцев из Санчониито» . Древние фрагменты . Перевод Кори. Архивировано из оригинала 5 сентября 2010 года . Получено 25 августа 2010 г. - через интернет -сакральный текстовый архив.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин час Kerényi 1951 , p. 124

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон Грейвс 1960 , с. 62

- ^ Кинсли 1989 , с. 143.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин Decy 2008 , p. 88

- ^ Сервис на Груги Вирджила 1.18 ; Шолия на Аристофана облаках 1005

- ^ Wunder 1855 , p. Примечание в стихе 703 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин Kerényi 1951 , p. 123.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин час я Дж k л м не а п Q. Хансен 2004 , с.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон Kerényi 1951 , p. 125

- ^ Kerényi 1951 , стр. 125-126.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Kerényi 1951 , p. 126

- ^ Deacy 2008 , с. 88–89.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон Decy 2008 , p. 89

- ^ Ovid , Metamorphoses , X. Aglaura, книга II, 708–751; Xi. Зависть, Книга II, 752–832.

- ^ Канцик, Хьюберт; Шнайдер, Гельмут; Салазар, Кристина Ф.; Ортон, Дэвид Э. (2002). Новый Поли Брилла: Энциклопедия древнего мира . Тол. IX. Brill Publications . п. 423. ISBN 978-90-04-12272-7 .

- ^ Forbes Irving, Paul MC (1990). Метаморфоза в греческих мифах . Кларендон Пресс . п. 278. ISBN 0-19-814730-9 .

- ^ Deacy 2008 , p. 62

- ^ Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 1.9.16 Архивировано 25 февраля 2021 года на машине Wayback

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Хансен 2004 , с.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Burkert 1985 , p. 141.

- ^ Кинсли 1989 , с. 151.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и Decy 2008 , p. 61.

- ^ Pseudo-Apollo, Bibliotheca 2.37, 38, 39

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Pseudo-Apollo, Bibliotheca 2.41

- ^ Pseudo-Apollo, Bibliotheca 2.39

- ^ Deacy 2008 , p. 48

- ^ Пиндар, Олимпийская Ода 13,75–78 Архивировано 6 января 2021 года на машине Wayback

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Decy 2008 , с. 64–65.

- ^ Поллитт 1999 , с. 48–50.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Decy 2008 , p. 65

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Поллитт 1999 , с. 50

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Roman & Roman 2010 , с. 161.

- ^ Roman & Roman 2010 , с. 161–162.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Jenkyns 2016 , с. 19

- ^ Wfotto, Gotter Greece (55–77) .bonn: F.Cohen, 1929

- ^ Deacy 2008 , p. 59

- ^ De Jong 2001 , p. 152

- ^ de Jong 2001 , pp. 152–153.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Trahman 1952 , с. 31–35.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и Burkert 1985 , p. 142

- ^ Trahman 1952 , p. 35

- ^ Trahman 1952 , с. 35–43.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Trahman 1952 , с. 35–42.

- ^ Jenkyns 2016 , стр. 19–20.

- ^ Murrin 2007 , p. 499.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Murrin 2007 , с. 499-500.

- ^ Murrin 2007 , стр. 499-514.

- ^ Phinney 1971 , с. 445–447.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Phinney 1971 , с. 445–463.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Seelig 2002 , p. 895.

- ^ Seelig 2002 , p. 895-911.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин Poehlmann 2017 , с. 330.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Morford & Lenardon 1999 , p. 315

- ^ Morford & Lenardon 1999 , pp. 315–316.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в BOWLMANN 1983 , P. 73.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Morford & Lenardon 1999 , p. 316

- ^ Edmunds 1990 , p. 373.

- ^ Servius , комментарий к Aeneid от Вирджила 4.402 Архивирован 1 января 2022 года на машине Wayback ; Смит 1873, SV Myrmex Archived 25 декабря 2022 года на машине Wayback

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Powell 2012 , с. 233–234.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Roman & Roman 2010 , с. 78

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Norton 2013 , p. 166

- ^ ἀράχνη , ἀράχνης . Лидделл, Генри Джордж ; Скотт, Роберт ; Грек -английский лексикон в проекте Персея .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Пауэлл 2012 , с. 233.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин час я Дж k Harries 1990 , pp. 64–82.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин час я Пауэлл 2012 , с. 234.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин час я Leach 1974 , с. 102–142.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Roman & Roman 2010 , с. 92

- ^ Зальцман-Митчелл, Патриция Б. (2005). Сеть фантазий: взгляд, изображение и пол в метаморфозах Овидида . Издательство штата Огайо издательство . п. 228 ISBN 0-8142-0999-8 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Walcot 1977 , p. 31

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Walcot 1977 , с. 31–32.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин Walcot 1977 , p. 32

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Bull 2005 , с. 346–347.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Walcot 1977 , с. 32–33.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Burgess 2001 , p. 84

- ^ ILIAD 4.390 Архивировано 30 ноября 2021 года в The Wayback Machine , 5.115–120 Archived 30 ноября 2021 года на машине Wayback , 10.284-94 Архивировано 30 ноября 2021 года на машине Wayback

- ^ Burgess 2001 , с. 84–85.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Decy 2008 , p. 69

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Decy 2008 , с. 69–70.

- ^ Deacy 2008 , с. 59–60.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Decy 2008 , p. 60

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин час я Aghion, Barbillon & Lissarrague 1996 , p. 193.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и Хансен 2004 , с.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Bale & Pollitt 1996 , p. 28-32.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон Bale & Pollitt 1996 , p. 32

- ^ «Афина Парфенос Фидия» . Всемирная история энциклопедии . Получено 26 июня 2019 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Aghion, Barbillon & Lissarrague 1996 , p. 194.

- ^ Deacy 2008 , с. 145–149.

- ^ Deacy 2008 , с. 141–144.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Decy 2008 , p. 144

- ^ Deacy 2008 , с. 144–145.

- ^ Deacy 2008 , с. 146–148.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Decy 2008 , с. 145–146.

- ^ Рэндольф 2002 , с. 221

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Decy 2008 , p. 145.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Браун 2007 , с. 1

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Aghion, Barbillon & Lissarrague 1996 , стр. 193–194.

- ^ Deacy 2008 , p. 147-148.

- ^ Deacy 2008 , p. 147

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон Decy 2008 , p. 148.

- ^ Deacy 2008 , с. 148–149.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Decy 2008 , p. 149

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Garland 2008 , с. 330.

- ^ «Символы печать Калифорнии» . LearnCalifornia.org. Архивировано с оригинала 24 ноября 2010 года . Получено 25 августа 2010 года .

- ^ Swiatek & Breen 1981 , стр. 201–2

- ^ Deacy 2008 , p. 163.

- ^ Deacy 2008 , p. 153

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Decy 2008 , p. 154

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Галлахер 2005 , с. 109

- ^ Александр 2007 , с. 31–32.

- ^ Александр 2007 , с. 11–20.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Friedman 2005 , p. 121.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный «Phi Delta Theta International - символы» . Phideltatheta.org. Архивировано из оригинала 7 июня 2008 года . Получено 7 июня 2008 года .

Библиография

Древние источники

- Аполлон, библиотека, 3180

- Августин, город XVIII.8-9

- Цицерон, природа богов III.21.53, 23.59

- Евсевий, Chronicon 30.21–26, 42.11–14

- Гомер , Илиада с английским переводом в Мюррее, доктор философии в двух томах . Кембридж, штат Массачусетс, издательство Гарвардского университета; Лондон, Уильям Хейнеманн, Ltd. 1924. Онлайн -версия в Цифровой библиотеке Персея Архивировала 15 апреля 2021 года на машине Wayback .

- Гомер ; Одиссея с английским переводом в Мюррею, доктор философии. в двух томах . Кембридж, штат Массачусетс, издательство Гарвардского университета; Лондон, Уильям Хейнеманн, Ltd. 1919. Онлайн -версия в Цифровой библиотеке Персея Архивировал 29 октября 2021 года на машине Wayback .

- Гесиод , Теогония , в гомеровских гимнах и Гомерике с английским переводом Хью Дж. Эвелин-Уайт , Кембридж, Массачусетс., Гарвардский университет издательство; Лондон, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914. Онлайн -версия в Цифровой библиотеке Персея Архивировала 17 ноября 2021 года на машине Wayback .

- Lactantius, Божественные институты I.17.12-13, 18.22-23

- Цицерон, городская книга VII.3.7

- Лукан, гражданская война IX.350

- Туллиус (1881). Песни Вергили Комментарии. Servii Grammatici, которые носили в комментариях Vergilis Carmina . Лейпциг: University Press.

Современные источники

- Агион, Ирен; Барбиллон, Клэр; Древность , Gods and Heroes of Classical Antiquity, 192–194 , ISBN 978-2-0801-3580-3

- Александр, Тимоти Джей (2007), «Боги разума: подлинное богословие для современных эллинизмов» (первое изд.), Lulu Press, Inc., ISBN 978-1-4303-2763-9

- Apollodorus из Афин (13 февраля 2016 года). Библиотека Аполлодоруса (Delphi Classics) . Великобритания: Delphi Classics. ISBN 9781786563712 .

- Beekes, Robert SP (2009), этимологический словарь греческого , Лейден и Бостон: Brill

- Белл, Роберт Э. (1993), Женщины классической мифологии: биографический словарь , Оксфорд, Англия: издательство Оксфордского университета, ISBN 9780195079777

- Бернал, Мартин (1987), Черная Афина: афроазиатские корни классической цивилизации , Нью -Брансуик: издательство Рутгерса Университета, стр. 21, 51 и след

- Berlinerblau, Jacques (1999), ересь в университете: полемика Черной Афины и обязанности американских интеллектуалов , Нью -Брансуик: Рутгерс Университетское издательство, с. 93ff, ISBN 9780813525884

- Лучший, Ян (1989), Фред Вудхуйзен (ред.), Потерянные языки из Средиземного моря , Лейден, Германия и др.: Брилл, с. 30, ISBN 978-9004089341

- Браун, Джейн К. (2007), Постоянство аллегории: драма и неоклассицизм от Шекспира в Вагнер , Филадельфия, Пенсильвания: Университет Пенсильвания, издательство ISBN 978-0-8122-3966-9

- Bull, Malcolm (2005), Зеркало богов: как художники эпохи Возрождения вновь открыли язычники , Оксфорд, Англия: издательство Оксфордского университета, ISBN 978-0-19-521923-4

- Берджесс, Джонатан С. (2001), Традиция Троянской войны в Гомере и Эпическом цикле , Балтимор, Мэриленд: издательство Университета Джона Хопкинса, ISBN 978-0-8018-6652-4

- Беркерт, Уолтер (1985), Греческая религия , Кембридж, Массачусетс: издательство Гарвардского университета, ISBN 978-0-674-36281-9

- Burn, Lucilla (2004), Эллинистическое искусство: от Александра Великого до Августа , Лондон, Англия: Британская музейная пресса, ISBN 978-0-89236-776-4

- Чедвик, Джон (1976), Микенский мир , Кембридж, Англия: издательство Кембриджского университета, ISBN 978-0-521-29037-1

- Дармон, Жан-Пьер (1992), Венди Донигер (изд.), « Сила войны: Афина и Арес в греческой мифологии» , перевод Даниэль Бове, Чикаго, Иллинойс: Университет Чикагского пресса

- Деаси, Сьюзен ; Villing, Alexandra (2001), Афина в классическом мире , Лейден, Нидерланды: Koninklijke Brill NV

- Decy, Susan (2008), Афина , Лондон и Нью -Йорк: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-30066-7

- De Jong, Irene JF (2001), Нарратологический комментарий к Odyssey , Кембридж, Англия: издательство Кембриджского университета, ISBN 978-0-521-46844-2

- Эдмундс, Лоуэлл (1990), подходы к греческому мифу , Балтимор, Мэриленд: издательство Университета Джона Хопкинса, ISBN 978-0-8018-3864-4

- Фридман, Сара (2005), колледж Брин Маур с записи , колледж Prowler, ISBN 978-1-59658-018-3

- Фрице, Рональд Х. (2009), Изобретенные знания: ложная история, фальшивая наука и псевдорелигионы , Лондон, Англия: книги о рисковании, ISBN 978-1-86189-430-4

- Fururmark, A. (1978), «Катастрофа-контакты Thera для европейской цивилизации», Thera и Aegean World I , Лондон, Англия: издательство Кембриджского университета

- Ганц, Тимоти, ранний греческий миф: руководство по литературным и художественным источникам , издательство Джона Хопкинса, 1996, два тома: 978-0-8018–5360-9 (том 1 ), ISBN 978-0-8018-5362-3 (том 2).

- Gallagher, Ann-Marie (2005), Библия Викка: окончательное руководство по магии и ремеслу , Нью-Йорк, Нью-Йорк: Sterling Publishing Co., Inc., ISBN 978-1-4027-3008-5

- Гарленд, Роберт (2008), Древняя Греция: повседневная жизнь в месте рождения западной цивилизации , Нью -Йорк, Нью -Йорк: Стерлинг, ISBN 978-1-4549-0908-8

- Goldhill, S. (1986), Чтение греческой трагедии (Aesch.eum.737) , Кембридж, Англия: издательство Кембриджского университета

- Грейвс, Роберт (1960) [1955], Греческие мифы , Лондон, Англия: Пингвин, ISBN 978-0241952740