История Соединенных Штатов

| Эта статья является частью серии статей о |

| История Соединенные Штаты |

|---|

|

История земель, ставших Соединенными Штатами, началась с прибытия первых людей на Америку около 15 000 г. до н. э. многочисленные местные культуры Сформировались . После того, как европейская колонизация Северной Америки в конце 15 века началась , войны и эпидемии опустошили коренные народы. Начиная с 1585 года Британская империя колонизировала Атлантическое побережье , и к 1760-м годам было основано тринадцать британских колоний . Южные колонии построили сельскохозяйственную систему на рабском труде , поработив для этой цели миллионы жителей Африки . После победы над Францией британский парламент ввел ряд налогов, в том числе Закон о гербовых сборах 1765 года , отвергая конституционный аргумент колонистов о том, что новые налоги нуждаются в их одобрении . Сопротивление этим налогам, особенно Бостонскому чаепитию в 1773 году, привело к тому, что парламент издал невыносимые законы, призванные положить конец самоуправлению. Вооруженный конфликт начался в Массачусетсе в 1775 году .

В 1776 году в Филадельфии Второй Континентальный Конгресс провозгласил независимость колоний как «Соединённых Штатов Америки». Возглавляемая генералом Джорджем Вашингтоном , она выиграла Войну за независимость в 1783 году. Парижский договор установил границы нового суверенного государства. Статьи Конфедерации , хотя и установили центральное правительство, оказались неэффективными в обеспечении стабильности. Конвент , написал новую Конституцию , которая была принята в 1789 году, а в 1791 году был добавлен Билль о правах гарантирующий неотъемлемые права . Вашингтон, первый президент , и его советник Александр Гамильтон создали сильное центральное правительство. Покупка Луизианы в 1803 году увеличила размер страны вдвое.

Воодушевленная доступной недорогой землей и идеей предопределенной судьбы , страна расширилась до Тихоокеанского побережья . После 1830 г. индейские племена были насильственно переселены на Запад. В результате расширение рабства становилось все более противоречивым и разжигало политические и конституционные баталии, которые разрешались путем компромиссов. К 1804 году рабство было отменено во всех штатах к северу от линии Мейсон-Диксон , но оно продолжалось в южных штатах для поддержки их сельскохозяйственной экономики. После избрания Авраама Линкольна президентом в 1860 году южные штаты вышли из Союза, образовав Конфедеративные Штаты Америки, выступающие за рабство , и начали Гражданскую войну . Поражение конфедератов в 1865 году привело к отмене рабства . В последующую Реконструкции эпоху юридические права и избирательные права были распространены на освобожденных рабов-мужчин. Национальное правительство стало намного сильнее и получило четкую обязанность защищать права личности . Белые южные демократы восстановили свою политическую власть на Юге в 1877 году, часто используя военизированные формирования. подавление голосования и законы Джима Кроу для поддержания превосходства белых , а также новые конституции штатов , которые узаконили расовую дискриминацию и не позволили большинству афроамериканцев участвовать в общественной жизни.

Соединенные Штаты стали ведущей промышленной державой мира в 20 веке благодаря предпринимательству, индустриализации и прибытию миллионов рабочих-иммигрантов и фермеров . Была построена национальная железнодорожная сеть, созданы крупные шахты и фабрики. Недовольство коррупцией, неэффективностью и традиционной политикой стимулировало Прогрессивное движение , что привело к реформам, включая федеральный подоходный налог , прямые выборы сенаторов, гражданство для многих коренных народов, запрет на алкоголь и избирательное право женщин . Первоначально нейтральные во время Первой мировой войны , Соединенные Штаты объявили войну Германии в 1917 году, присоединившись к успешным союзникам . После процветающих « ревущих двадцатых » крах Уолл-стрит в 1929 году ознаменовал начало десятилетней всемирной Великой депрессии . президента Франклина Д. Рузвельта , Программы «Нового курса» включая помощь по безработице и социальное обеспечение , определили современный американский либерализм . [ 1 ] После нападения Японии на Перл-Харбор Соединенные Штаты вступили во Вторую мировую войну и финансировали военные усилия союзников , помогая победить нацистскую Германию и фашистскую Италию на европейском театре военных действий . В войне на Тихом океане Америка победила императорскую Японию после применения ядерного оружия в Хиросиме и Нагасаки .

Соединенные Штаты и Советский Союз стали соперничающими сверхдержавами после Второй мировой войны . Во время Холодной войны две страны косвенно противостояли друг другу в гонке вооружений , космической гонке , пропагандистских кампаниях и прокси-войнах . В 1960-х годах, во многом благодаря движению за гражданские права , социальные реформы обеспечили соблюдение конституционных прав голоса и свободы передвижения афроамериканцев. В 1980-е годы президентство Рональда Рейгана переориентировало американскую политику в сторону снижения налогов и регулирования. Холодная война закончилась, когда Советский Союз распался в 1991 году , в результате чего Соединенные Штаты остались единственной сверхдержавой в мире. Внешняя политика после холодной войны часто была сосредоточена на многих конфликтах на Ближнем Востоке , особенно после терактов 11 сентября . В 21 веке на страну негативно повлияли Великая рецессия и пандемия COVID-19 .

Коренные жители

[ редактировать ]

Точно не известно, как и когда коренные американцы впервые заселили Америку и территорию современных Соединенных Штатов. Преобладающая теория предполагает, что люди из Евразии преследовали дичь через Берингию , сухопутный мост , который соединял Сибирь с современной Аляской во время ледникового периода , а затем распространились на юг по всей Америке. Эта миграция могла начаться еще 30 000 лет назад. [ 2 ] и продолжалось примерно 10 000 лет назад, когда сухопутный мост был затоплен из-за повышения уровня моря, вызванного таянием ледников. [ 3 ] Эти ранние жители, называемые палеоиндейцами , вскоре разделились на сотни культурно различных поселений и стран .

Эта доколумбовая эпоха включает в себя все периоды истории Америки до появления европейского влияния на американских континентах, начиная от первоначального поселения в верхнего палеолита период и заканчивая европейской колонизацией в период раннего Нового времени . Хотя технически этот термин относится к эпохе, предшествовавшей путешествию Христофора Колумба в 1492 году, на практике этот термин обычно включает в себя историю американских коренных культур до тех пор, пока они не были завоеваны или подверглись значительному влиянию европейцев, даже если это произошло через десятилетия или столетия после первой высадки Колумба. [ 4 ]

Палеоиндейцы

[ редактировать ]

К 10 000 г. до н.э. люди были относительно прочно обосновались по всей Северной Америке. Первоначально палеоиндейцы охотились на мегафауну ледникового периода, например на мамонтов , но когда они начали вымирать, люди вместо этого обратились к зубрам в качестве источника пищи. Со временем добыча ягод и семян стала важной альтернативой охоте. Палеоиндейцы центральной Мексики были первыми в Америке, кто начал заниматься сельским хозяйством, начав сеять кукурузу, фасоль и тыкву около 8000 г. до н.э. Со временем знания начали распространяться на север. К 3000 г. до н. э. кукуруза выращивалась в долинах Аризоны и Нью -Мексико , затем появились примитивные ирригационные системы, а к 300 г. до н. э. — первые деревни Хохокам . [ 5 ] [ 6 ]

Одной из ранних культур на территории современных Соединенных Штатов была культура Хлодвига , которую в первую очередь идентифицируют по рифленым наконечникам копий , называемым острием Хлодвига . С 9100 по 8850 год до нашей эры культура распространилась на большую часть Северной Америки и появилась в Южной Америке. Артефакты этой культуры были впервые раскопаны в 1932 году недалеко от Кловиса, штат Нью-Мексико . Культура Фолсома была похожей, но отмечена точкой Фолсома .

Более поздняя миграция, выявленная лингвистами, антропологами и археологами, произошла около 8000 г. до н.э. Сюда входили народы, говорящие на языке на-дене , которые достигли северо-запада Тихого океана к 5000 году до нашей эры. [ 7 ] Оттуда они мигрировали вдоль Тихоокеанского побережья и во внутренние районы и построили в своих деревнях большие многосемейные жилища, которые использовались только сезонно летом для охоты и рыбалки, а зимой для сбора продовольствия. [ 8 ] Другая группа, люди традиции Ошара , жившие с 5500 г. до н.э. по 600 г. н.э., были частью архаического юго-запада .

Строители курганов и пуэбло

[ редактировать ]

Адена земляные начала строить большие н.э. курганы около 600 г. до Это самые ранние известные люди, строившие курганы есть курганы , однако в Соединенных Штатах , которые появились еще до этой культуры. Уотсон-Брейк — это комплекс из 11 курганов в Луизиане , датируемый 3500 годом до нашей эры, а близлежащий Поверти-Пойнт , построенный культурой Бедности-Пойнт , представляет собой комплекс земляных валов, датируемый 1700 годом до нашей эры. Эти курганы, вероятно, служили религиозной цели.

Аденцы были поглощены традицией Хоупвелла , могущественным народом, который торговал инструментами и товарами на обширной территории. Они продолжили традицию строительства курганов в Адене, остатки нескольких тысяч человек все еще существуют в центре их бывшей территории в южном Огайо . Хоупвелл был пионером торговой системы под названием «Обменная система Хоупвелла», которая в наибольшей степени простиралась от современного юго-востока до канадской стороны озера Онтарио . [ 9 ] К 500 г. н.э. хоупуэллианцы исчезли, поглощенные более широкой культурой Миссисипи .

Жители Миссисипи представляли собой обширную группу племен. Их самым важным городом была Кахокия , недалеко от современного Сент-Луиса, штат Миссури . На пике своего развития в 12 веке население города составляло 20 000 человек, что превышало население Лондона того времени. Весь город был сосредоточен вокруг кургана высотой 100 футов (30 м). Кахокия, как и многие другие города и деревни того времени, зависела от охоты, собирательства, торговли и сельского хозяйства и разработала классовую систему с рабами и человеческими жертвоприношениями, которая находилась под влиянием южных обществ, таких как майя . [ 5 ]

На юго-западе анасази начали строить каменные и глинобитные пуэбло около 900 г. до н.э. [ 10 ] Эти подобные квартирам структуры часто были встроены в скалы, как это видно в Скальном дворце в Меса-Верде . Некоторые из них выросли до размеров городов: Пуэбло Бонито вдоль реки Чако в Нью-Мексико когда-то состояло из 800 комнат. [ 5 ]

Северо-запад и северо-восток

[ редактировать ]

Коренные народы северо-запада Тихого океана, вероятно, были самыми богатыми коренными американцами. Здесь возникло множество различных культурных групп и политических образований, но все они разделяли определенные верования, традиции и практики, такие как центральная роль лосося как ресурса и духовного символа. Постоянные деревни начали развиваться в этом регионе еще в 1000 г. до н. э., и эти общины отмечали праздник раздачи подарков — потлач . Эти собрания обычно организовывались в ознаменование особых событий, таких как возведение тотемного столба или празднование нового вождя.

В современной северной части штата Нью-Йорк ирокезы каюга образовали конфедерацию середине 15 века племенных народов, состоящую из онейда , ирокезов , онондага , в и сенека . Их система принадлежности представляла собой своего рода федерацию, отличную от сильных централизованных европейских монархий. [ 11 ] [ 12 ] [ 13 ] Каждое племя имело места в группе из 50 вождей сахемов . Было высказано предположение, что их культура способствовала политическому мышлению во время развития правительства Соединенных Штатов. Ирокезы были могущественны и вели войны со многими соседними племенами, а позже и с европейцами. По мере расширения их территории более мелкие племена были вынуждены двигаться дальше на запад, включая народы осейджей , кау , понка и омаха . [ 13 ] [ 14 ]

Коренные гавайцы

[ редактировать ]Точная дата заселения Гавайев оспаривается, но первое поселение, скорее всего, произошло между 940 и 1130 годами нашей эры. [ 15 ] Около 1200 г. н.э. таитянские исследователи обнаружили и начали заселять эту территорию, а также установили новую кастовую систему. Это ознаменовало возникновение гавайской цивилизации, которая была в значительной степени отделена от остального мира до прибытия британцев 600 лет спустя. [ 16 ] [ 17 ] [ 18 ] Европейцы под руководством британского исследователя Джеймса Кука прибыли на Гавайские острова в 1778 году, и в течение пяти лет контакта европейские военные технологии помогли Камеамеа I завоевать большую часть группы островов и, в конечном итоге, впервые объединить острова; создание Гавайского королевства . [ 19 ]

Пуэрто-Рико

[ редактировать ]Остров Пуэрто-Рико был заселен, по крайней мере, 4000 лет назад, начиная с останков человека из Пуэрто-Ферро. Начиная с культуры ортоироидов , прибывали последовательные поколения миграций коренных жителей, заменяя или поглощая местное население. К году 1000 араваков прибыли из Южной Америки через Малые Антильские острова , эти поселенцы стали таино, которыми испанцы столкнулись в 1493 году. с . [ 20 ] Колонизация привела к истреблению местного населения из-за суровой системы Энкомьенды и эпидемий, вызванных болезнями Старого Света. Пуэрто-Рико оставалось частью Испании до американской аннексии в 1898 году. [ 20 ]

Европейская колонизация (1075–1754 гг.)

[ редактировать ]

Скандинавские исследования

[ редактировать ]Самое раннее зарегистрированное европейское упоминание об Америке находится в историческом трактате средневекового летописца Адама Бременского около 1075 года, где она упоминается как Винланд . [ а ] Он также широко упоминается в норвежских сагах о Винланде 13-го века , которые относятся к событиям, произошедшим около 1000 года. Хотя самые убедительные археологические свидетельства существования норвежских поселений в Америке находятся в Канаде, особенно в Л'Анс-о-Медоуз. и датированный примерно 1000 годом, ведутся серьезные научные споры о том, выходили ли норвежские исследователи также на берег в Новой Англии и других районах восточного побережья. [ 22 ] В 1925 году президент Кэлвин Кулидж заявил, что норвежский исследователь Лейф Эриксон (ок. 970 – ок. 1020) был первым европейцем, открывшим Америку. [ 23 ]

Ранние поселения

[ редактировать ]Затем испанцы заново открыли Америку в 1492 году. После периода исследований, спонсируемых крупными европейскими государствами , первое успешное английское поселение было основано в 1607 году. Европейцы привезли лошадей, крупный рогатый скот и свиней в Америку и, в свою очередь, забрали обратно кукурузу, индеек. , помидоры, картофель, табак, фасоль и кабачки в Европу. Многие исследователи и первые поселенцы умерли после заражения новыми болезнями в Америке. Однако последствия новых евразийских болезней, переносимых колонистами, особенно оспы и кори, были гораздо хуже для коренных американцев, поскольку у них не было иммунитета к ним. Они страдали от эпидемий и умирали в очень большом количестве, обычно до начала крупномасштабного европейского заселения. Их общества были разрушены и опустошены масштабами смертей. [ 24 ] [ 25 ]

Испанский контакт

[ редактировать ]

Испанские исследователи были первыми европейцами после норвежцев, достигшими территории современных Соединенных Штатов после того, как Христофора Колумба ( экспедиции начавшиеся в 1492 году) установили владения в Карибском бассейне , включая современные территории США Пуэрто -Рико и некоторые его части. Американских Виргинских островов . Хуан Понсе де Леон высадился во Флориде в 1513 году. [ 26 ] Испанские экспедиции быстро достигли Аппалачей , реки Миссисипи , Большого Каньона , [ 27 ] и Великие равнины . [ 28 ]

В 1539 году Эрнандо де Сото широко исследовал Юго-Восток. [ 28 ] а год спустя Франсиско Коронадо исследовал территорию от Аризоны до центрального Канзаса в поисках золота. [ 28 ] Сбежавшие лошади из отряда Коронадо распространились по Великим равнинам, и равнинные индейцы за несколько поколений освоили искусство верховой езды. [ 5 ] Небольшие испанские поселения со временем превратились в важные города, такие как Сан-Антонио , Альбукерке , Тусон , Лос-Анджелес и Сан-Франциско. [ 29 ]

Голландский среднеатлантический

[ редактировать ]

Голландская Ост-Индская компания отправила исследователя Генри Гудзона на поиски Северо-Западного пути в Азию в 1609 году. Новые Нидерланды были основаны компанией в 1621 году для извлечения выгоды из торговли мехом в Северной Америке . Поначалу рост был медленным из-за плохого управления конфликтами в Нидерландах и коренных американцах. После того, как голландцы купили остров Манхэттен у коренных американцев по заявленной цене в 24 доллара США, эта земля была названа Новым Амстердамом и стала столицей Новых Нидерландов. Город быстро разрастался и в середине 1600-х годов стал важным торговым центром и портом. были кальвинистами и строили реформатскую церковь в Америке Несмотря на то, что голландцы , они были терпимы к другим религиям и культурам и торговали с ирокезами на севере. [ 30 ]

Колония служила барьером на пути британской экспансии из Новой Англии , в результате чего серия войн произошла . Колония была передана Великобритании под названием Нью-Йорк в 1664 году, а ее столица была переименована в Нью-Йорк. Новые Нидерланды оставили в американской культурной и политической жизни неизгладимое наследие религиозной терпимости и разумной торговли в городских районах и сельского традиционализма в сельской местности (типичным примером которого является история Рипа Ван Винкля ). Известные американцы голландского происхождения включают Мартина Ван Бюрена , Теодора Рузвельта , Франклина Д. Рузвельта , Элеонору Рузвельт и Фрелингхейсенов . [ 30 ]

Шведское поселение

[ редактировать ]

В первые годы существования Шведской империи шведские, голландские и немецкие акционеры сформировали компанию «Новая Швеция» для торговли мехами и табаком в Северной Америке. Первую экспедицию компании возглавил Питер Минуит , который был губернатором Новых Нидерландов с 1626 по 1631 год, но покинул его после спора с голландским правительством, и высадился в заливе Делавэр в марте 1638 года. Поселенцы основали форт Кристина на месте современного -день Уилмингтон, штат Делавэр , и заключил договоры с коренными народами о владении землей по обе стороны реки Делавэр . [ 31 ] [ 32 ]

В течение следующих семнадцати лет еще 12 экспедиций доставили поселенцев из Шведской империи (которая также включала современные Финляндию, Эстонию и некоторые части Латвии, Норвегии, России, Польши и Германии) в Новую Швецию. Колония основала 19 постоянных поселений, а также множество ферм, простирающихся до современных Мэриленда , Пенсильвании и Нью-Джерси . Он был включен в состав Новых Нидерландов в 1655 году после голландского вторжения из соседней колонии Новые Нидерланды во время Второй Северной войны . [ 31 ] [ 32 ]

французский и испанский

[ редактировать ]

Джованни да Верраццано высадился в Северной Каролине в 1524 году и был первым европейцем, вошедшим в гавань Нью-Йорка и залив Наррагансетт . В 1540-х годах французские гугеноты поселились в форте Кэролайн недалеко от современного Джексонвилля во Флориде. В 1565 году испанские войска под предводительством Педро Менендеса разрушили поселение и основали первое испанское поселение на территории, которая впоследствии стала Соединенными Штатами, — Сент-Огастин .

Большинство французов проживало в Квебеке и Акадии (современная Канада), но их влияние распространили далеко идущие торговые отношения с коренными американцами по всему Великим озерам и Среднему Западу. Французские колонисты в небольших деревнях вдоль рек Миссисипи и Иллинойс жили в фермерских общинах, которые служили источником зерна для поселений на побережье Мексиканского залива. Французы основали плантации в Луизиане, а также заселили Новый Орлеан , Мобил и Билокси .

Британские колонии

[ редактировать ]

Англичане, привлеченные набегами Фрэнсиса Дрейка на испанские корабли с сокровищами, покидавшие Новый Свет, заселили полосу земли вдоль восточного побережья в 1600-х годах. Первая британская колония в Северной Америке была основана в Роаноке Уолтером Рэли в 1585 году, но потерпела неудачу. Пройдет двадцать лет до новой попытки. [ 5 ]

Первые британские колонии были основаны частными группами в поисках прибыли и отмечены голодом, болезнями и нападениями коренных американцев. Многие иммигранты были людьми, ищущими религиозную свободу или спасающимися от политического угнетения, крестьянами, перемещенными в результате промышленной революции , или теми, кто просто искал приключений и возможностей. В период с конца 1610-х годов до революции британцы отправили в свои американские колонии от 50 000 до 120 000 заключенных. [ 33 ]

В некоторых районах коренные американцы учили колонистов сажать и собирать местные культуры. В других случаях они нападали на поселенцев. Девственные леса давали достаточно строительных материалов и дров. Естественные заливы и гавани вдоль побережья служили удобными портами для важной торговли с Европой. Поселения оставались близко к побережью из-за этого, а также из-за сопротивления коренных американцев и Аппалачей, которые находились внутри страны. [ 5 ]

Первое поселение в Джеймстауне

[ редактировать ]

Первая успешная английская колония, Джеймстаун , была основана Вирджинской компанией в 1607 году на реке Джеймс в Вирджинии . Колонисты были заняты поисками золота и были плохо подготовлены к жизни в Новом Свете. Капитан Джон Смит удерживал молодой Джеймстаун вместе в первый год, и колония погрузилась в анархию и едва не потерпела крах, когда он вернулся в Англию два года спустя. Джон Рольф начал экспериментировать с табаком из Вест-Индии в 1612 году, а к 1614 году первая партия табака прибыла в Лондон. За десять лет он стал основным источником дохода Вирджинии.

В 1624 году, после многих лет болезней и нападений индейцев, включая нападение Поухатана в 1622 году , король Джеймс I отменил устав Компании Вирджиния и сделал Вирджинию королевской колонией.

Колонии Новой Англии

[ редактировать ]

Первоначально Новая Англия была заселена в основном пуританами , спасавшимися от религиозных преследований. Паломники отплыли в Вирджинию на «Мэйфлауэре » в 1620 году, но были сбиты с курса штормом и высадились в Плимуте , где согласились на общественный договор, основанный на правилах Мэйфлауэрского договора . В первую зиму в Плимуте погибло около половины пилигримов. [ 34 ] Как и Джеймстаун, Плимут страдал от болезней и голода, но местные индейцы вампаноаг научили колонистов выращивать кукурузу.

За Плимутом в 1630 году последовали пуритане и колония Массачусетского залива. Они сохранили хартию самоуправления отдельно от Англии и избрали основателя Джона Уинтропа губернатором на протяжении большей части первых лет своего существования. Роджер Уильямс выступил против обращения Уинтропа с коренными американцами и религиозной нетерпимости и основал колонию Плантации Провиденс , позже Род-Айленд , на основе свободы религии. Другие колонисты основали поселения в долине реки Коннектикут и на побережьях современных Нью-Гэмпшира и Мэна . Нападения коренных американцев продолжались, наиболее значительные из них произошли во время Пекотской войны 1637 года и Войны короля Филиппа 1675 года .

Новая Англия стала центром торговли и промышленности из-за бедной гористой почвы, затрудняющей сельское хозяйство. Реки использовались для питания зерновых и лесопилок, а многочисленные гавани способствовали торговле. Вокруг этих промышленных центров возникли дружные деревни, и Бостон стал одним из важнейших портов Америки.

Средние колонии

[ редактировать ]

В 1660-х годах колонии на территории бывших голландских Новых Нидерландов были основаны средние Нью-Йорк , Нью-Джерси и Делавэр , которые характеризовались большой степенью этнического и религиозного разнообразия. В то же время ирокезы Нью-Йорка, усиленные многолетней торговлей мехом с европейцами, сформировали мощную Конфедерацию ирокезов.

Последней колонией в этом регионе была Пенсильвания , основанная в 1681 году Уильямом Пенном как дом для религиозных инакомыслящих, включая квакеров , методистов и амишей . [ 35 ] Столица колонии, Филадельфия , за несколько лет стала доминирующим торговым центром с оживленными доками и кирпичными домами. Пока квакеры населяли город, немецкие иммигранты начали наводнять холмы и леса Пенсильвании, в то время как шотландцы и ирландцы продвинулись к дальней западной границе.

Южные колонии

[ редактировать ]

Подавляющее большинство сельских южных колоний резко контрастировали с Новой Англией и Средними колониями. После Вирджинии второй британской колонией к югу от Новой Англии был Мэриленд , основанный как католическая гавань в 1632 году. Экономика этих двух колоний полностью строилась на фермерах -йоменах и плантаторах. Плантаторы обосновались в районе Тайдуотер в Вирджинии, создав огромные плантации с использованием рабского труда.

В 1670 году была основана провинция Каролина , и Чарльстон стал крупным торговым портом региона. В то время как экономика Вирджинии также была основана на табаке, Каролина была более диверсифицированной, экспортируя также рис, индиго и пиломатериалы. В 1712 году она была разделена на две части, образовав Северную и Южную Каролину . Колония Джорджия – последняя из Тринадцати колоний – была основана Джеймсом Оглторпом в 1732 году как граница с испанской Флоридой и исправительная колония для бывших заключенных и бедняков. [ 35 ]

Религия

[ редактировать ]

Религиозность значительно расширилась после Первого Великого Пробуждения , религиозного возрождения в 1740-х годах, которое возглавили такие проповедники, как Джонатан Эдвардс и Джордж Уайтфилд . Американские евангелисты, затронутые Пробуждением, сделали новый акцент на божественных излияниях Святого Духа и обращениях, которые привили новым верующим сильную любовь к Богу. Возрождения воплотили в себе эти отличительные черты и перенесли недавно созданное евангелическое движение в раннюю республику, подготовив почву для Второго Великого Пробуждения в конце 1790-х годов. [ 36 ] На ранних этапах евангелисты Юга, такие как методисты и баптисты , проповедовали свободу вероисповедания и отмену рабства; они обратили многих рабов и признали некоторых проповедниками.

Правительство

[ редактировать ]Каждая из 13 американских колоний имела немного разную правительственную структуру. Обычно колонией управлял губернатор, назначаемый из Лондона, который контролировал исполнительную администрацию и полагался на избранный на местном уровне законодательный орган для голосования по налогам и принятия законов. К 18 веку американские колонии росли очень быстро благодаря низкому уровню смертности, а также обильным запасам земли и еды. Колонии были богаче, чем большинство частей Британии, и привлекали постоянный поток иммигрантов, особенно подростков, прибывших в качестве наемных слуг. [ 37 ]

Рабство и рабство

[ редактировать ]

Более половины всех европейских иммигрантов в колониальную Америку прибыли в качестве наемных слуг . [ 38 ] Мало кто мог позволить себе поездку в Америку, и поэтому эта форма несвободного труда предоставила возможность иммигрировать. Обычно люди подписывали контракт на определенный срок работы, обычно от четырех до семи лет, и взамен получали транспорт в Америку и участок земли по окончании своего рабства. В некоторых случаях капитаны кораблей получали вознаграждение за доставку бедных мигрантов, поэтому экстравагантные обещания и похищения были обычным явлением. Компания Вирджиния и Компания Массачусетского залива также использовали наемную рабочую силу. [ 5 ]

Первые африканские рабы были привезены в Вирджинию. [ 39 ] в 1619 году, [ 40 ] всего через двенадцать лет после основания Джеймстауна. Первоначально институт рабства считался наемными слугами, которые могли купить себе свободу, но затем начал ужесточаться, и принудительное рабство стало пожизненным. [ 40 ] поскольку спрос на рабочую силу на табачных и рисовых плантациях вырос в 1660-х годах. [ нужна ссылка ] Рабство стало отождествляться с коричневым цветом кожи, который в то время считался « черной расой », а дети рабынь рождались рабами ( partus sequitur ventrem ). [ 40 ] К 1770-м годам африканские рабы составляли пятую часть населения Америки.

Вопрос о независимости от Великобритании не возникал до тех пор, пока колонии нуждались в британской военной поддержке против французских и испанских держав. Эти угрозы исчезли к 1765 году. Однако Лондон продолжал рассматривать американские колонии как существующие на благо метрополии в рамках политики, известной как меркантилизм . [ 37 ]

Колониальная Америка характеризовалась острой нехваткой рабочей силы, которая использовала такие формы несвободного труда , как рабство и подневольное состояние. Британские колонии также отличались политикой уклонения от строгого соблюдения парламентских законов, известной как благотворное пренебрежение . Это позволило развить американский дух, отличный от духа его европейских основателей. [ 41 ]

Революционный период (1754–1793)

[ редактировать ]Подготовка к революции

[ редактировать ]Высший класс возник в Южной Каролине и Вирджинии, чье богатство основывалось на больших плантациях, на которых использовался рабский труд. Уникальная классовая система действовала в северной части штата Нью-Йорк , где голландские фермеры-арендаторы арендовали землю у очень богатых голландских владельцев, таких как семья Ван Ренсселер . Другие колонии были более эгалитарными, представительной была Пенсильвания. К середине 18-го века Пенсильвания была в основном колонией среднего класса с ограниченным уважением к своему небольшому высшему классу. [ 42 ]

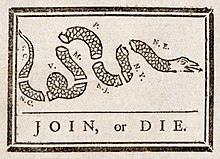

Французско -индийская война (1754–1763), часть более крупной Семилетней войны , стала переломным событием в политическом развитии колоний. Влияние французов и коренных американцев, главных соперников британской короны в колониях и Канаде, было значительно уменьшено, а территория Тринадцати колоний расширилась до Новой Франции , как в Канаде, так и в Луизиане . [ нужна ссылка ] Военные усилия также привели к большей политической интеграции колоний, что отражено в Конгрессе Олбани и символизировано призывом Бенджамина Франклина к колониям « Присоединяйтесь или умрите ». Франклин был человеком многих изобретений, одним из которых была концепция Соединенных Штатов Америки, которая возникла после 1765 года и была реализована десятилетие спустя. [ 43 ]

После приобретения Великобританией французской территории в Северной Америке король Георг III издал Королевскую прокламацию 1763 года , чтобы организовать новую Североамериканскую империю и защитить коренных американцев от колониальной экспансии на западные земли за пределами Аппалачей. В последующие годы в отношениях между колонистами и Короной возникла напряженность. Британский парламент принял Закон о гербовых марках 1765 года , облагающий колонии налогом без прохождения через колониальные законодательные органы. Ставился вопрос: имел ли парламент право облагать налогом американцев, которые в нем не были представлены? Под лозунгом « Нет налогам без представительства » колонисты отказались платить налоги по мере обострения напряженности в конце 1760-х и начале 1770-х годов. [ 44 ]

Бостонское чаепитие 1773 года было прямой акцией активистов города Бостона в знак протеста против нового налога на чай. В следующем году парламент быстро отреагировал « Нетерпимыми законами» , лишив Массачусетс его исторического права на самоуправление и поставив его под военное правление, что вызвало возмущение и сопротивление во всех тринадцати колониях. Лидеры патриотов каждой колонии созвали Первый Континентальный Конгресс, чтобы координировать свое сопротивление невыносимым действиям. Конгресс призвал к бойкоту британской торговли , опубликовал список прав и претензий и обратился к королю с просьбой исправить эти претензии. [ 45 ] Однако это обращение к короне не имело никакого эффекта, и поэтому в 1775 году был созван Второй Континентальный конгресс для организации защиты колоний от британской армии.

Простые люди стали повстанцами против британцев, хотя они были незнакомы с предлагаемыми идеологическими обоснованиями. Они очень твердо придерживались чувства «прав», которые, по их мнению, британцы намеренно нарушали – прав, которые подчеркивали местную автономию, честное ведение дел и управление по согласию. Они были очень чувствительны к проблеме тирании, проявлением которой, по их мнению, было прибытие в Бостон британской армии, чтобы наказать бостонцев. Это усилило их чувство нарушенных прав, что привело к ярости и требованиям мести, и они поверили, что Бог на их стороне. [ 46 ]

Американская революция

[ редактировать ]

Второй Континентальный Конгресс проголосовал за провозглашение независимости 2 июля 1776 года, и Декларацию независимости разработал Комитет пяти . Декларация независимости представила аргументы в пользу прав граждан, заявив, что все люди созданы равными , поддерживая права на жизнь, свободу и стремление к счастью , и требуя согласия управляемых . В нем также перечислялись претензии к короне. [ 47 ] Отцы -основатели руководствовались идеологией республиканизма , отвергая монархизм Великобритании. [ 48 ] Декларация независимости была подписана членами Конгресса 4 июля. [ 47 ] С тех пор эта дата отмечается как День независимости . [ 49 ]

Война за независимость США началась с битв при Лексингтоне и Конкорде, когда американские и британские войска столкнулись 19 апреля 1775 года. [ 50 ] Джордж Вашингтон был назначен генералом Континентальной армии . [ 51 ] Кампания в Нью-Йорке и Нью-Джерси была первой крупной кампанией войны, начавшейся в 1776 году. Переход Вашингтона через реку Делавэр положил начало серии побед, изгнавших британские войска из Нью-Джерси. [ 52 ] Британцы начали кампанию Саратоги в 1777 году с целью захватить Олбани, штат Нью-Йорк , как перевалочный пункт . [ 53 ] После победы Америки при Саратоге Франция, Нидерланды и Испания начали оказывать поддержку Континентальной армии. [ 54 ] Британия ответила на поражение на северном театре военных действий наступлением на южном театре военных действий , начиная с захвата Саванны в 1778 году. [ 55 ] Американские войска вернули себе юг в 1781 году, а британская армия потерпела поражение при осаде Йорктауна 19 октября 1781 года. [ 56 ]

Король Георг III официально приказал прекратить военные действия 5 декабря 1782 года, признав независимость Америки. [ 57 ] был Парижский договор заключен между Великобританией и Соединенными Штатами для установления условий мира. Он был подписан 3 сентября 1783 года. [ 58 ] и он был ратифицирован Конгрессом Конфедерации 14 января 1784 года. [ 59 ] Вашингтон подал в отставку с поста главнокомандующего Континентальной армией 23 декабря 1783 года. [ 60 ]

Период Конфедерации

[ редактировать ]Статьи Конфедерации были ратифицированы как регулирующий закон Соединенных Штатов, написанный для ограничения полномочий центрального правительства в пользу правительств штатов. Это вызвало экономический спад , поскольку правительство не смогло принять экономическое законодательство и выплатить свои долги. [ 61 ] Националисты были обеспокоены тем, что конфедеративный характер союза был слишком хрупким, чтобы выдержать вооруженный конфликт с любыми враждебными государствами или даже внутренние восстания, такие как восстание Шейса 1786 года в Массачусетсе. [ 62 ] В 1780-х годах национальное правительство смогло решить вопрос о западных регионах молодых Соединенных Штатов, которые были переданы штатами Конгрессу и стали территориями. С миграцией поселенцев на Северо-Запад вскоре они стали государствами . [ 62 ] Войны с американскими индейцами продолжались в 1780-х годах, когда поселенцы двинулись на запад, что спровоцировало нападения коренных американцев на мирное население Америки и, в свою очередь, спровоцировало нападения американцев на мирное население коренных американцев. [ 63 ] Северо -Западная Конфедерация и американские поселенцы начали вести Северо-западную индейскую войну в конце 1780-х годов; Северо-Западная Конфедерация получила поддержку Великобритании, но поселенцы получили небольшую помощь от американского правительства. [ 64 ] [ 65 ]

Националисты – большинство из которых были ветеранами войны – организовались в каждом штате и убедили Конгресс созвать Филадельфийский съезд в 1787 году. Делегаты от каждого штата написали новую конституцию , которая создала федеральное правительство с сильным президентом и налоговыми полномочиями. Новое правительство отразило преобладающие республиканские идеалы гарантий индивидуальной свободы и ограничения власти правительства посредством системы разделения властей . [ 62 ] На национальном уровне прошли дебаты о том, следует ли ратифицировать конституцию, и в 1788 году она была ратифицирована достаточным количеством штатов, чтобы начать формирование федерального правительства. [ 66 ] Коллегия выборщиков Соединенных Штатов выбрала Джорджа Вашингтона первым президентом Соединенных Штатов в 1789 году. [ 67 ]

Ранняя республика (1793–1830)

[ редактировать ]

Президент Джордж Вашингтон

[ редактировать ]

Джордж Вашингтон стал первым президентом Соединенных Штатов в соответствии с новой Конституцией в 1789 году. Столица страны переехала из Нью-Йорка в Филадельфию в 1790 году и окончательно обосновалась в Вашингтоне, округ Колумбия, в 1800 году.

Главным достижением администрации Вашингтона было создание сильного национального правительства, которое безоговорочно признавалось всеми американцами. [ 68 ] Его правительство, следуя энергичному руководству министра финансов Александра Гамильтона , взяло на себя долги штатов (держатели долга получили федеральные облигации), создало Банк Соединённых Штатов для стабилизации финансовой системы и установило единую систему тарифов ( налоги на импорт) и другие налоги для погашения долга и обеспечения финансовой инфраструктуры. Для поддержки своих программ Гамильтон создал новую политическую партию – первую в мире, основанную на избирателях. [ нечеткий ] – Партия федералистов .

Чтобы успокоить антифедералистов, опасавшихся слишком сильного центрального правительства, Конгресс принял в 1791 году Билль о правах Соединенных Штатов. Включая первые десять поправок к Конституции, он гарантировал такие индивидуальные свободы, как свобода слова и религиозной практики, судебных процессах и заявил, что граждане и государства имеют зарезервированные права (которые не были указаны). [ 69 ]

Двухпартийная система

[ редактировать ]Томас Джефферсон и Джеймс Мэдисон сформировали оппозиционную Республиканскую партию ( обычно называют ее Демократической республиканской партией политологи ). Гамильтон и Вашингтон подарили стране в 1794 году Договор Джея , который восстановил хорошие отношения с Великобританией. Джефферсонианцы яростно протестовали, и избиратели встали на сторону той или иной партии, создав таким образом Первую партийную систему . Федералисты продвигали деловые, финансовые и коммерческие интересы и хотели расширения торговли с Великобританией. Республиканцы обвинили федералистов в планах установить монархию, превратить богатых в правящий класс и превратить Соединенные Штаты в пешку британцев. [ 70 ] Договор был принят, но политика стала очень горячей. [ 71 ]

Вызовы федеральному правительству

[ редактировать ]Серьезные вызовы новому федеральному правительству включали Северо-западную индейскую войну , продолжающиеся войны между чероки и американцами и восстание виски 1794 года , в ходе которого западные поселенцы протестовали против федерального налога на спиртные напитки. Вашингтон вызвал ополчение штата и лично возглавил армию против поселенцев, поскольку повстанцы растаяли, а власть федерального правительства прочно утвердилась. [ 72 ]

Вашингтон отказался служить более двух сроков, создав прецедент, и в своей знаменитой прощальной речи он превознес преимущества федерального правительства и важность этики и морали, одновременно предостерегая от иностранных альянсов и создания политических партий. [ 73 ]

Джон Адамс , федералист, победил Джефферсона на выборах 1796 года. Надвигалась война с Францией, и федералисты использовали эту возможность, чтобы попытаться заставить республиканцев замолчать с помощью Законов об иностранцах и подстрекательстве к мятежу , создать большую армию во главе с Гамильтоном и подготовиться к французскому вторжению. Однако федералисты разделились после того, как Адамс отправил успешную миротворческую миссию во Францию, положившую конец квазивойне 1798 года. [ 70 ] [ 74 ]

Растущий спрос на рабский труд

[ редактировать ]

В течение первых двух десятилетий после Войны за независимость произошли драматические изменения в статусе рабства в штатах и увеличилось число освобожденных чернокожих . Вдохновленные революционными идеалами равенства людей и под влиянием меньшей экономической зависимости от рабства, северные штаты отменили рабство.

Штаты Верхнего Юга облегчили освобождение на свободу , что привело к увеличению доли свободных чернокожих на Верхнем Юге (в процентах от общей численности небелого населения) с менее чем одного процента в 1792 году до более чем 10 процентов к 1810 году. К тому времени в общей сложности 13,5 процентов всех чернокожих в Соединенных Штатах были свободными. [ 75 ] После этой даты, когда спрос на рабов рос из-за расширения выращивания хлопка на Глубоком Юге, количество освобожденных от рабства резко сократилось; а внутренняя работорговля в США стала важным источником богатства для многих плантаторов и торговцев. [ нужна ссылка ] В 1807 году, когда в Соединенных Штатах уже находились четыре миллиона рабов, Конгресс прекратил участие США в работорговле в Атлантике . [ 76 ] В течение 50 из первых 72 лет существования страны президентом был рабовладелец, и за этот период только президенты-рабовладельцы были переизбраны на второй срок. [ 77 ]

Второе великое пробуждение

[ редактировать ]

Второе великое пробуждение было протестантским движением возрождения, которое затронуло практически все общество в начале 19 века и привело к быстрому росту церкви. Движение началось примерно в 1790 году, набрало силу к 1800 году, а после 1820 года членство быстро росло среди баптистских и методистских общин, проповедники которых возглавляли движение. К 1840-м годам он прошел свой пик. [ 78 ]

It enrolled millions of new members in existing evangelical denominations and led to the formation of new denominations. Many converts believed that the Awakening heralded a new millennial age. The Second Great Awakening stimulated the establishment of many reform movements – including abolitionism and temperance designed to remove the evils of society before the anticipated Second Coming of Jesus Christ.[79]

Louisiana and Jeffersonian republicanism

[edit]

Jefferson defeated Adams massively for the presidency in the 1800 election. Jefferson's major achievement as president was the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, which provided U.S. settlers with vast potential for expansion west of the Mississippi River.[80] Jefferson, a scientist, supported expeditions to explore and map the new domain, most notably the Lewis and Clark Expedition.[81] Jefferson believed deeply in republicanism and argued it should be based on the independent yeoman farmer and planter; he distrusted cities, factories and banks. He also distrusted the federal government and judges, and tried to weaken the judiciary. However he met his match in John Marshall, a Federalist from Virginia. Although the Constitution specified a Supreme Court, its functions were vague until Marshall, the Chief Justice of the United States (1801–1835), defined them, especially the power to overturn acts of Congress or states that violated the Constitution, first enunciated in 1803 in Marbury v. Madison.[82]

War of 1812

[edit]Americans were increasingly angry at the British violation of American ships' neutral rights to hurt France, the impressment (seizure) of 10,000 American sailors needed by the Royal Navy to fight Napoleon, and British support for hostile Indians attacking American settlers in the American Midwest with the goal of creating a pro-British Indian barrier state to block American expansion westward. They may also have desired to annex all or part of British North America, although this is still heavily debated.[83][84][85][86][87] Despite strong opposition from the Northeast, especially from Federalists who did not want to disrupt trade with Britain, Congress declared war on June 18, 1812.[88]

The war was frustrating for both sides. Both sides tried to invade the other and were repulsed. The American high command remained incompetent until the last year. The American militia proved ineffective because the soldiers were reluctant to leave home and efforts to invade Canada repeatedly failed. The British blockade ruined American commerce, bankrupted the Treasury, and further angered New Englanders, who smuggled supplies to Britain. The Americans under General William Henry Harrison finally gained naval control of Lake Erie and defeated the Indians under Tecumseh in Canada,[90] while Andrew Jackson ended the Indian threat in the Southeast. The Indian threat to expansion into the Midwest was permanently ended. The British invaded and occupied much of Maine.

The British raided and burned Washington, but were repelled at Baltimore in 1814 – where the "Star Spangled Banner" was written to celebrate the American success. In upstate New York a major British invasion of New York State was turned back at the Battle of Plattsburgh. Finally in early 1815 Andrew Jackson decisively defeated a major British invasion at the Battle of New Orleans, making him the most famous war hero.[91]

With Napoleon (apparently) gone, the causes of the war had evaporated and both sides agreed to a peace that left the prewar boundaries intact. Americans claimed victory on February 18, 1815, as news came almost simultaneously of Jackson's victory of New Orleans and the peace treaty that left the prewar boundaries in place. Americans swelled with pride at success in the "second war of independence"; the naysayers of the antiwar Federalist Party were put to shame and the party never recovered. This helped lead to an emerging American identity that cemented national pride over state pride.[92]

Britain never achieved the war goal of granting the Indians a barrier state to block further American settlement and this allowed settlers to pour into the Midwest without fear of a major threat.[91] The War of 1812 also destroyed America's negative perception of a standing army, which had proven useful in many areas against the British as opposed to ill-equipped and poorly-trained militias in the early months of the war, and War Department officials instead decided to place regular troops as the main military capabilities of the government.[93]

Era of Good Feelings

[edit]

As strong opponents of the War of 1812, the Federalists held the Hartford Convention in 1814 that hinted at disunion. National euphoria after the victory at New Orleans ruined the prestige of the Federalists and they no longer played a significant role as a political party.[94] President Madison and most Republicans realized they were foolish to let the First Bank of the United States close down, for its absence greatly hindered the financing of the war. So, with the assistance of foreign bankers, they chartered the Second Bank of the United States in 1816.[95][96]

The Republicans also imposed tariffs designed to protect the infant industries that had been created when Britain was blockading the U.S. With the collapse of the Federalists as a party, the adoption of many Federalist principles by the Republicans, and the systematic policy of President James Monroe in his two terms (1817–1825) to downplay partisanship, society entered an Era of Good Feelings, with far less partisanship than before (or after), and closed out the First Party System.[95][96]

The Monroe Doctrine, expressed in 1823, proclaimed the United States' opinion that European powers should no longer colonize or interfere in the Americas. This was a defining moment in the foreign policy of the United States. The Monroe Doctrine was adopted in response to American and British fears over Russian and French expansion into the Western Hemisphere.[97]

In 1832, President Andrew Jackson, 7th President of the United States, ran for a second term under the slogan "Jackson and no bank" and did not renew the charter of the Second Bank, dissolving the bank in 1836.[98] Jackson was convinced that central banking was used by the elite to take advantage of the average American, and instead implemented publicly owned banks in various states, popularly known as "pet banks".[98]

Expansion and reform (1830–1848)

[edit]Second Party System

[edit]After the First Party System of Federalists and Republicans withered away in the 1820s, the stage was set for the emergence of a new party system based on well organized local parties that appealed for the votes of (almost) all adult white men. The former Jeffersonian (Democratic-Republican) party split into factions. They split over the choice of a successor to President James Monroe, and the party faction that supported many of the old Jeffersonian principles, led by Andrew Jackson and Martin Van Buren, became the Democratic Party. As Norton explains the transformation in 1828:

Jacksonians believed the people's will had finally prevailed. Through a lavishly financed coalition of state parties, political leaders, and newspaper editors, a popular movement had elected the president. The Democrats became the nation's first well-organized national party, and tight party organization became the hallmark of nineteenth-century American politics.[99]

Opposing factions led by Henry Clay helped form the Whig Party. The Democratic Party had a small but decisive advantage over the Whigs until the 1850s, when the Whigs fell apart over the issue of slavery.

Westward expansion and manifest destiny

[edit]

The American colonies and the newly formed union grew rapidly in population and area, as pioneers pushed the frontier of settlement west.[100][101] The process finally ended around 1890–1912 as the last major farmlands and ranch lands were settled. Native American tribes in some places resisted militarily, but they were overwhelmed by settlers and the army, and after 1830, were relocated to reservations in the west.[102] That year, Congress passed the Indian Removal Act, which authorized the president to negotiate treaties that exchanged Native American tribal lands in the eastern states for lands west of the Mississippi River.[103] Its goal was primarily to remove Native Americans, including the Five Civilized Tribes, from the American Southeast – they occupied land that settlers wanted.[104]

Jacksonian Democrats demanded the forcible removal of native populations who refused to acknowledge state laws to reservations in the West. Whigs and religious leaders opposed the move as inhumane. Thousands of deaths resulted from the relocations, as seen in the Cherokee Trail of Tears.[104] The Trail of Tears resulted in approximately 2,000 to 8,000 of the 16,543 relocated Cherokee dying along the way.[105][106] Many of the Seminole Indians in Florida refused to move west, and fought the Army for years in the Seminole Wars.

The first settlers in the west were the Spanish in New Mexico ("Californios"), followed by over 100,000 California Gold Rush miners ('49ers). California grew rapidly, and by 1880, San Francisco had become the economic hub of the entire Pacific Coast, with a diverse population of a quarter million. From the early 1830s to 1869, the Oregon Trail and its many offshoots were used by over 300,000 settlers. '49ers, ranchers, farmers, entrepreneurs, and their families headed to California, Oregon, and other points in the far west. Wagon-trains took five or six months on foot.[107]

Manifest destiny was the belief that American settlers were destined to expand across the continent. This concept was born out of "A sense of mission to redeem the Old World by high example ... generated by the potentialities of a new earth for building a new heaven".[108] Manifest destiny was rejected by modernizers, especially the Whigs like Henry Clay and Abraham Lincoln who wanted to build cities and factories – not more farms.[b] Democrats strongly favored expansion, and won the key election of 1844. After a bitter debate in Congress, the Republic of Texas was annexed in 1845, leading to war with Mexico, who considered Texas to be a part of Mexico due to the large numbers of Mexican settlers.[110]

The Mexican–American War broke out in 1846, with the Whigs opposed to the war, and the Democrats supporting it. The U.S. Army, using regulars and large numbers of volunteers, defeated the Mexican armies, invaded at several points, captured Mexico City, and won decisively. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the war in 1848. Many Democrats wanted to annex all of Mexico, but that idea was rejected by White Southerners, who argued that by incorporating millions of Mexican people, mainly of mixed race, would undermine the U.S. as an exclusively white republic.[109]

Instead, the U.S. took Texas and the lightly settled northern parts (California and New Mexico). The Hispanic residents were given full citizenship, and the Mexican Indians became American Indians. Simultaneously, gold was discovered in California in 1848. To clear the state for settlers, the U.S. government began a policy of extermination since termed the California genocide.[111] A peaceful compromise with Britain gave the U.S. ownership of the Oregon Country, which was renamed the Oregon Territory.[110]

The demand for guano (prized as an agricultural fertilizer) led the U.S. to pass the Guano Islands Act in 1856, which enabled U.S. citizens to take possession, in the name of the country, of unclaimed islands containing guano deposits. Under the act, the U.S. annexed nearly 100 islands in the Pacific Ocean and the Caribbean Sea. By 1903, 66 of these islands were recognized as territories of the United States.[112]

The women's suffrage movement began with the 1848 National Convention of the Liberty Party. Presidential candidate Gerrit Smith argued for and established women's suffrage as a party goal. One month later, the Seneca Falls Convention was organized, signing the Declaration of Sentiments demanding equal rights for women, including the right to vote.[c] Many of these activists became politically aware during the abolitionist movement. The women's rights campaign during first-wave feminism was led by Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucy Stone and Susan B. Anthony, among others. Stone and Paulina Wright Davis organized the prominent and influential National Women's Rights Convention in 1850.[114]

Civil War and Reconstruction (1848–1877)

[edit]Divisions between North and South

[edit]

The central issue after 1848 was the expansion of slavery, with the anti-slavery elements in the North pitted against the pro-slavery elements in the South.[115] By 1860, there were four million slaves in the South, nearly eight times as many as there were nationwide in 1790.[citation needed] A small number of active Northerners were abolitionists who followed William Lloyd Garrison, and declared that ownership of slaves was a sin and demanded its immediate abolition. Much larger numbers in the North were against the expansion of slavery, seeking to put it on the path to extinction so that America would be committed to free land (as in low-cost farms owned and cultivated by a family), free labor, and free speech (as opposed to censorship of abolitionist material in the South).[115] However, before 1860, only a minority of Northern white people supported abolition, which was often seen as a 'radical' measure. There were violent reactions to abolitionist advocates in the North, notably the burning of an anti-slavery society in Pennsylvania Hall.[116]

There was resistance to slavery by both peaceful and violent means. Slave rebellions, by Gabriel Prosser (1800), Denmark Vesey (1822), Nat Turner (1831), and John Brown (1859) caused fear in the white South, which imposed stricter oversight of slaves and reduced the rights of free Black people.[citation needed] Former slaves Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman became leading advocates for abolition.[117][118] The issue was discussed in the best-selling anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom's Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe.[119]

Southern white Democrats insisted that slavery was of economic, social, and cultural benefit to all white people and even to the slaves themselves.[115] Justifications of slavery included history, religion, legality, social good, and economics. Defenders argued that the sudden end to the slave economy would have had a fatal economic impact in the South, and there would be widespread unemployment and chaos; slave labor was the foundation of their economy.[120] Southern slavery-based societies had become wealthy based on their cotton and other agricultural commodity production, as well as the internal slave trade. The plantations were highly profitable, due to the heavy European demand for raw cotton. Northern cities and regional industries were tied economically to slavery by banking, shipping, and manufacturing, including textile mills. In addition, southern states benefited by their increased apportionment in Congress due to the partial counting of slaves in their populations.

Religious activists were split on slavery, with the Methodists and Baptists dividing into northern and southern denominations. In the North, the Methodists, Congregationalists, and Quakers included many abolitionists, especially among women activists. The Catholic, Episcopal, and Lutheran denominations largely ignored the issue.[121]

The issue of slavery in the new territories was seemingly settled by the Compromise of 1850, brokered by Whig Henry Clay and Democrat Stephen Douglas; the Compromise included the admission of California as a free state in exchange for no federal restrictions on slavery placed on Utah or New Mexico.[122] A point of contention was the Fugitive Slave Act, which required the states to cooperate with slave owners when attempting to recover escaped slaves. Formerly, an escaped slave that reached a non-slave state was presumed to have attained sanctuary and freedom under the Missouri Compromise.[123][124][119]

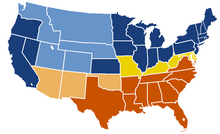

The Compromise of 1820 was repealed in 1854 with the Kansas–Nebraska Act, promoted by Stephen Douglas in the name of "popular sovereignty" and democracy. It permitted voters to decide on the legality of slavery in each territory, and allowed Douglas to adopt neutrality on the issue of slavery. Anti-slavery forces rose in anger and alarm, forming the new Republican Party. Pro- and anti- contingents rushed to Kansas to vote for or against slavery, resulting in a miniature civil war called Bleeding Kansas. By the late 1850s, the young Republican Party dominated nearly all northern states, and thus, the electoral college. It insisted that slavery would never be allowed to expand, and thus would slowly die out.[125]

The Supreme Court's 1857 decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford ruled that the Compromise was unconstitutional and that free Black people were not U.S. citizens; the decision enraged Northerners. The Republicans worried the decision could be used to expand slavery throughout all states and territories. With Senator Abraham Lincoln leading criticism of the ruling, the stage was set for the 1860 presidential election.[123][124][119]

Civil War

[edit]Start of the war

[edit]

After Abraham Lincoln won the 1860 election, seven Southern states seceded from the Union and formed a sovereign state, the Confederate States of America (Confederacy), on February 8, 1861.[126] The Civil War began on April 12, 1861, when Confederate forces attacked a U.S. military installation at Fort Sumter in South Carolina. In response, Lincoln called on the states to send troops to recapture forts, protect Washington D.C., and "preserve the Union," which in his view still existed despite the secession.[127] Lincoln's call led to four more states seceding and joining the Confederacy. A few of the (northernmost) slave states did not secede and became known as the border states; these were Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri.[citation needed] During the war, the northwestern portion of Virginia seceded from the Confederacy, which became the new Union state of West Virginia.[128]

The two armies' first major battle was the First Battle of Bull Run, which proved to both sides that the war would be much longer than anticipated.[127] In the western theater, the Union Army was relatively successful, with major battles such as Perryville and Shiloh, along with Union Navy gunboat dominance of navigable rivers producing strategic Union victories and destroying major Confederate operations.[129] Warfare in the eastern theater began poorly for the Union. U.S. General George B. McClellan failed to capture the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia, in his Peninsula campaign and retreated after attacks from Confederate General Robert E. Lee.[130] Meanwhile, in 1861 and 1862, both sides concentrated on raising and training new armies. The Union successfully gained control the border states, driving the Confederates out.[131]

Confederate losses

[edit]

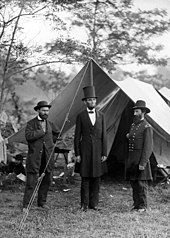

(People in the image are clickable.)

The autumn 1862 Confederate retreat at the Battle of Antietam led to Lincoln's warning he would issue the Emancipation Proclamation in January 1863 if the states did not return. Making slavery a central war goal energized Northern Republicans, as well as their enemies, the anti-war Copperhead Democrats. It ended the chance of British and French intervention.[131] Lee's smaller Army of Northern Virginia won battles in late 1862 and spring 1863, but he pushed too hard and ignored the Union threat in the west. He invaded Pennsylvania in search of supplies and to cause war-weariness in the North.[133]

The Emancipation Proclamation was an executive order issued by Lincoln on January 1, 1863. It freed 3 million slaves in designated areas of the Confederacy. The owners were not compensated. Plantation owners, realizing that emancipation would destroy their economic system, sometimes moved their slaves as far as possible from the Union army.[134]

In perhaps the turning point of the war, Lee's army was badly beaten by the Army of the Potomac at the July 1863 Battle of Gettysburg, and barely made it back to Virginia.[131] Survivors of the battle were immediately redeployed to suppress the New York City draft riots by Irish Americans protesting Civil War conscription and the city's free Black population.[133] In July 1863, Union forces under General Ulysses S. Grant gained control of the Mississippi River at the Battle of Vicksburg, thereby splitting the Confederacy. In 1864, Union General William Tecumseh Sherman marched south from Chattanooga to capture Atlanta, a decisive victory that ended war jitters among Republicans in the North and helped Lincoln win re-election.

End of the war

[edit]The Civil War was the world's earliest industrial war. Railroads, the telegraph, steamships, and mass-produced weapons were employed extensively. Civilian factories, mines, shipyards, and were mobilized.[135] Foreign trade increased, with the U.S. providing both food and cotton to Britain, and Britain sending in manufactured products and thousands of volunteers for the Union Army (and a few to the Confederate army). The Union blockade shut down Confederate ports, and by late 1864, the British blockade runners supplying Confederates were usually captured before they could make more than a handful of runs.

Sherman's march to the sea was almost unopposed, and demonstrated that the South was unable to resist a Union invasion. Much of the South was destroyed, and could no longer provide desperately needed supplies to its armies. In spring 1864, Grant launched a war of attrition and pursued Lee to the final Appomattox campaign, which resulted in Lee surrendering in April 1865.[citation needed] By June 1865, the Union Army controlled all of the Confederacy and liberated all of the designated slaves.[134]

It remains the deadliest war in American history, resulting in the deaths of about 750,000 soldiers and an undetermined number of civilian casualties.[d] About ten percent of all Northern males 20–45 years old, and 30 percent of all Southern white males aged 18–40 died.[135] Many Black people died after being dislocated during the war and Reconstruction.[138]

Reconstruction

[edit]Reconstruction lasted from the end of the war until 1877.[127][139][140] Lincoln had to decide the statuses of the ex-slaves ("Freedmen"), ex-Confederates, and ex-Confederate states. He supported the Ten Percent Plan for states' re-admission, and the right of Black people to vote.[141] Lincoln was assassinated in April 1865 by John Wilkes Booth, and succeeded by Andrew Johnson.[142]

The severe threats of starvation and displacement of the unemployed Freedmen were met by the first major federal relief agency, the Freedmen's Bureau, operated by the Army.[143] The bureau also took in freed slaves.[citation needed] Three "Reconstruction Amendments" expanded civil rights for black Americans: the 1865 Thirteenth Amendment outlawed slavery;[144] the 1868 Fourteenth Amendment guaranteed equal rights for all and citizenship for Black people;[145] the 1870 Fifteenth Amendment prevented race from being used to disenfranchise men.[146]

Ex-Confederates remained in control of most Southern states for over two years, until the Radical Republicans gained control of Congress in the 1866 elections. Johnson, who sought good treatment for ex-Confederates, was virtually powerless in the face of Congress; he was impeached, but the Senate's attempt to remove him from office failed by one vote. Congress enfranchised black men and temporarily banned many ex-Confederate leaders from holding office. New Republican governments came to power based on a coalition of Freedmen made up of Carpetbaggers (new arrivals from the North), and Scalawags (native white Southerners). They were backed by the Army. Opponents said they were corrupt and violated the rights of whites.[147]

After the war, the far west was developed and settled, first by wagon trains and riverboats, and then by the first transcontinental railroad. Many Northern European immigrants took up low-cost or free farms in the Prairie States. Mining for silver and copper encouraged development.[148]

KKK and the rise of Jim Crow laws

[edit]

State by state, the New Republicans lost power to a conservative-Democratic coalition, which gained control of the South by 1877. In response to Radical Reconstruction, the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) emerged in 1867 as a white-supremacist organization opposed to black civil rights and Republican rule. President Ulysses Grant's enforcement of the Ku Klux Klan Act of 1870 shut them down.[147] Paramilitary groups, such as the White League and Red Shirts emerging around 1874, openly intimidated and attacked Black people voting, to regain white political power in states across the South. One historian described them as the military arm of the Democratic Party.[147]

Reconstruction ended after the disputed 1876 election. The Compromise of 1877 gave Republican candidate Rutherford B. Hayes the presidency in exchange for removing all remaining federal troops in the South. The federal government withdrew its troops, and Southern Democrats took control of the region[149] In 1882, the United States passed the Chinese Exclusion Act (which barred all Chinese immigrants except for students and businessmen),[150] and the Immigration Act of 1882 (which barred all immigrants with mental health issues).[151] From 1890 to 1908, southern states effectively disenfranchised Black and poor white voters by making voter registration more difficult through poll taxes and literacy tests. Black people were segregated from whites in the violently-enforced Jim Crow system that lasted until roughly 1968.[152][153][154]

Gilded Age and the Progressive Era (1877–1914)

[edit]After Reconstruction

[edit]The "Gilded Age" was a term that Mark Twain used to describe the period of the late 19th century with a dramatic expansion of American wealth and prosperity, underscored by the mass corruption in the government.[156] Some historians have argued that the United States was effectively plutocratic for at least part of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era.[157][158][159] As financiers and industrialists such as J.P. Morgan and John D. Rockefeller began to amass vast fortunes, many observers were concerned that the nation was losing its pioneering egalitarian spirit.[160]

An unprecedented wave of immigration from Europe served to both provide the labor for American industry and create diverse communities in previously undeveloped areas. From 1880 to 1914, peak years of immigration, more than 22 million people migrated to the country.[161] By 1890, American industrial production and per capita income exceeded those of all other countries.[citation needed] Most were unskilled workers who quickly found jobs in mines, mills, and factories. Many immigrants were craftsmen and farmers (especially from Britain, Germany, and Scandinavia) who purchased inexpensive land on the prairies. Poverty, growing inequality and dangerous working conditions, along with socialist and anarchist ideas diffusing from European immigrants, led to the rise of the labor movement.[162][163][164]

Dissatisfaction on the part of the growing middle class with the corruption and inefficiency of politics, and the failure to deal with increasingly important urban and industrial problems, led to the dynamic progressive movement starting in the 1890s. In every major city, and at the federal level, progressives called for the modernization and reform of decrepit institutions in the fields of politics, education, medicine, and industry.[165]

Leading politicians from both parties, most notably Republicans Theodore Roosevelt, Charles Evans Hughes, and Robert La Follette, and Democrats William Jennings Bryan and Woodrow Wilson, took up the cause of progressive reform.[165] "Muckraking" journalists such as Upton Sinclair, Lincoln Steffens and Jacob Riis exposed corruption in business and government, and highlighted rampant inner-city poverty. Progressives implemented antitrust laws and regulated such industries of meat-packing, drugs, and railroads. Four new constitutional amendments – the Sixteenth through Nineteenth – resulted from progressive activism, bringing the federal income tax, direct election of Senators, prohibition, and female suffrage.[165]

In 1881, President James A. Garfield was assassinated by Charles Guiteau.[166]

Unions and strikes

[edit]

Skilled workers banded together to control their crafts and raise wages by forming labor unions in industrial areas of the Northeast. Samuel Gompers led the American Federation of Labor (1886–1924), coordinating multiple unions. In response to heavy debts and decreasing farm prices, wheat and cotton farmers joined the Populist Party.[167]

The Panic of 1893 broke out, and created a severe nationwide depression impacted farmers, workers, and businessmen.[168] Many railroads went bankrupt. The resultant political reaction fell on the Democratic Party, whose leader President Grover Cleveland shouldered much of the blame. Labor unrest involved numerous strikes, most notably the violent Pullman Strike of 1894, which was forcibly shut down by federal troops under Cleveland's orders. One of the disillusioned leaders of the Pullman strike, Eugene V. Debs, went on to become the leader of the Socialist Party of America, eventually going on to win almost 1 million votes in the 1912 presidential election.[169]

Economic growth

[edit]Important legislation of the era included the 1883 Civil Service Act, which mandated a competitive examination for applicants for government jobs, the 1887 Interstate Commerce Act, which ended railroads' discrimination against small shippers, and the 1890 Sherman Antitrust Act, which outlawed monopolies in business.[156]

After 1893, the Populist Party gained strength among farmers and coal miners, but was overtaken by the even more popular Free silver movement, which demanded using silver to enlarge the money supply, leading to inflation that the silverites promised would end the depression.[170] Financial and railroad communities fought back hard, arguing that only the gold standard would save the economy. In the 1896 presidential election, conservative Republican William McKinley defeated silverite William Jennings Bryan, who ran on the Democratic, Populist, and Silver Republican tickets. Bryan swept the South and West, but McKinley ran up landslides among the middle class, industrial workers, cities, and among upscale farmers in the Midwest.[171]

Prosperity returned under McKinley. The gold standard was enacted, and the tariff was raised. By 1900, the U.S. had the strongest economy in the world. Republicans, citing McKinley's policies, took the credit for the growth.[172] McKinley was assassinated by Leon Czolgosz in 1901, and was succeeded by Theodore Roosevelt.[173]

The period also saw a major transformation of the banking system, with the arrival of the first credit union in 1908 (and thus, cooperative banking) and the creation of the Federal Reserve System in 1913.[174][175] Apart from two short recessions in 1907 and 1920, the economy remained prosperous and growing until 1929.[172]

Imperialism

[edit]

The United States Army continued to fight wars with Native Americans as settlers encroached on their traditional lands. Gradually the U.S. purchased the Native American tribal lands and extinguished their claims, forcing most tribes onto subsidized reservations. According to the U.S. Census Bureau in 1894, from 1789 to 1894, the Indian Wars killed 19,000 white people and more than 30,000 Indians.[177]

The United States emerged as a world economic and military power after 1890. The main episode was the Spanish–American War, which began when Spain refused American demands to reform its oppressive policies in Cuba.[178] The war was a series of quick American victories on land and at sea. At the Treaty of Paris peace conference the United States acquired the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Guam.[179]

Cuba became an independent country, under close American tutelage. Although the war itself was widely popular, the peace terms proved controversial. William Jennings Bryan led his Democratic Party in opposition to control of the Philippines, which he denounced as imperialism unbecoming to American democracy.[179] President William McKinley defended the acquisition and was riding high as society had returned to prosperity and felt triumphant in the war. McKinley easily defeated Bryan in a rematch in the 1900 presidential election.[180]

After defeating an insurrection by Filipino nationalists, the United States achieved little in the Philippines except in education, and it did something in the way of public health. It also built roads, bridges, and wells, but infrastructural development lost much of its early vigor with the failure of the railroads.[181] By 1908, however, Americans lost interest in an empire and turned their international attention to the Caribbean, especially the building of the Panama Canal. The canal opened in 1914 and increased trade with Japan and the rest of the Far East. A key innovation was the Open Door Policy, whereby the imperial powers were given equal access to Chinese business, with not one of them allowed to take control of China.[182]

Women's suffrage

[edit]The women's suffrage movement reorganized after the Civil War, gaining experienced campaigners, many of whom had worked for prohibition in the Women's Christian Temperance Union. By the end of the century, a few Western states had granted women full voting rights,[114] and women gained rights in areas such as property and child custody law.[183]

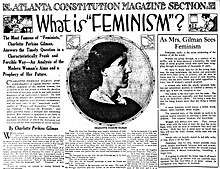

Around 1912, the feminist movement reawakened, putting an emphasis on its demands for equality, and arguing that the corruption of American politics demanded purification by women.[184] Protests became increasingly common, as suffragette Alice Paul led parades through the capital and major cities. Paul split from the large, moderate National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) led by Carrie Chapman Catt, and formed the more militant National Woman's Party. Suffragists were arrested during their "Silent Sentinels" pickets at the White House, and were taken as political prisoners.[185] Another prominent leader of the movement was Jane Addams of Chicago, who created settlement houses.[165]

The anti-suffragist argument that only men could fight in a war, and therefore only men deserve the right to vote, was refuted by the participation of American women on the home front in World War I. The success of woman's suffrage was demonstrated by the politics of states which already allowed women to vote, including Montana, who elected the first woman to the House of Representatives, Jeannette Rankin. The main resistance came from the South, where white leaders were worried about the threat of Black women voting. Congress passed the Nineteenth Amendment in 1919, and women could vote in 1920.[187] NAWSA became the League of Women Voters. Politicians responded to the new electorate by emphasizing issues of special interest to women, especially prohibition, child health, and world peace.[188][189] Notably, in 1928, women were mobilized to support both candidates in the year's presidential election between Al Smith and Herbert Hoover.[190]

Modern America and World Wars (1914–1945)

[edit]World War I and the interwar years

[edit]

As World War I raged in Europe from 1914, President Woodrow Wilson took full control of foreign policy, declaring neutrality, but warning Germany that resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare against American ships supplying goods to Allied nations would mean war. Germany decided to take the risk, and try to win by cutting off supplies to Britain through the sinking of ships such as the RMS Lusitania. The U.S. declared war in April 1917, mainly from the threat of the Zimmermann Telegram.[191]