Еврейская история

этой статьи Начальный раздел может оказаться слишком длинным . ( июнь 2024 г. ) |

| Part of a series on |

| Jews and Judaism |

|---|

| Part of a series on |

| History of religions |

|---|

Еврейская история — это история евреев , их нации , религии и культуры , как они развивались и взаимодействовали с другими народами, религиями и культурами.

Евреи произошли от израильтян и евреев исторического Израиля и Иуды , двух родственных царств, возникших в Леванте в период железного века . [1] [2] Хотя самое раннее упоминание об Израиле встречается на стеле Мернептаха около 1213–1203 гг. до н.э., в религиозной литературе рассказывается история израильтян, восходящая, по крайней мере, к ок. 1500 г. до н.э. Королевство Израиль пало под властью Неоассирийской империи примерно в 720 г. до н. э. [3] и Иудейское царство в составе Нововавилонской империи в 586 г. до н.э. [4] Часть населения Иудеи была сослана в Вавилон . Ассирийское Вавилонское и пленение считается началом еврейской диаспоры .

После того, как Персидская империя Ахеменидов завоевала этот регион, изгнанным евреям было разрешено вернуться и восстановить храм ; эти события знаменуют начало периода Второго Храма . [5] [6] После нескольких столетий иностранного правления восстание Маккавеев против империи Селевкидов привело к созданию независимого Хасмонейского царства . [7] but it was gradually incorporated into Roman rule.[8] The Jewish-Roman wars, a series of unsuccessful revolts against the Romans in the 1st and 2nd centuries CE, resulted in the destruction of Jerusalem and the Second Temple,[9] and the expulsion of many Jews.[10] The Jewish population in Syria Palaestina gradually decreased during the following centuries, enhancing the role of the Jewish diaspora and shifting the spiritual and demographic centre from the depopulated Judea to Galilee and then to Babylon, with smaller communities spread out across the Roman Empire. During the same period, the Mishnah and the Talmud, central Jewish texts, were composed. In the following millennia, the diaspora communities coalesced into three major ethnic subdivisions according to where their ancestors settled: the Ashkenazim (Central and Eastern Europe), the Sephardim (initially in the Iberian Peninsula), and the Mizrahim (Middle East and North Africa).[11][12]

Byzantine rule over the Levant was lost in the 7th century as the newly established Islamic Caliphate expanded into the Eastern Mediterranean, Mesopotamia, North Africa, and later into the Iberian Peninsula. Jewish culture enjoyed a golden age in Spain, with Jews becoming widely accepted in society and their religious, cultural, and economic life blossomed. However, in 1492 the Jews were forced to leave Spain and migrated in great numbers to the Ottoman Empire and Italy. Between the 12th and 15th centuries, Ashkenazi Jews experienced extreme persecution in Central Europe, which prompted their mass migration to Poland.[13][14] The 18th century saw the rise of the Haskalah intellectual movement. Also starting in the 18th century, Jews began to campaign for Jewish emancipation from restrictive laws and integration into the wider European society.

In the 19th century, when Jews in Western Europe were increasingly granted equality before the law, Jews in the Pale of Settlement faced growing persecution, legal restrictions and widespread pogroms. During the 1870s and 1880s, the Jewish population in Europe began to more actively discuss emigration to Ottoman Syria with the aim of re-establishing a Jewish polity in Palestine. The Zionist movement was officially founded in 1897. The pogroms also triggered a mass exodus of more than two million Jews to the United States between 1881 and 1924.[15] The Jews of Europe and the United States gained success in the fields of science, culture and the economy. Among those generally considered the most famous were Albert Einstein and Ludwig Wittgenstein. Many Nobel Prize winners at this time were Jewish, as is still the case.[16]

In 1933, with the rise to power of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party in Germany, the Jewish situation became severe. Economic crises, racial antisemitic laws, and a fear of an upcoming war led many to flee from Europe to Mandatory Palestine, to the United States and to the Soviet Union. In 1939, World War II began and until 1941 Hitler occupied almost all of Europe. In 1941, following the invasion of the Soviet Union, the Final Solution began, an extensive organized operation on an unprecedented scale, aimed at the annihilation of the Jewish people, and resulting in the persecution and murder of Jews in Europe and North Africa. In Poland, three million were murdered in gas chambers in all concentration camps combined, with one million at the Auschwitz camp complex alone. This genocide, in which approximately six million Jews were methodically exterminated, is known as the Holocaust.

Before and during the Holocaust, enormous numbers of Jews immigrated to Mandatory Palestine. On May 14, 1948, upon the termination of the British Mandate, David Ben-Gurion declared the creation of the State of Israel, a Jewish and democratic state in Eretz Israel (Land of Israel). Immediately afterwards, all neighbouring Arab states invaded, yet the newly formed IDF resisted. In 1949, the war ended and Israel started building the state and absorbing massive waves of Aliyah from all over Europe and Middle Eastern countries. As of 2022,[update] Israel is a parliamentary democracy with a population of 9.6 million people, of whom 7 million are Jewish. The largest Jewish community outside Israel is the United States, while large communities also exist in France, Canada, Argentina, Russia, United Kingdom, Australia, and Germany. For statistics related to modern Jewish demographics, see Jewish population.

Overview

[edit]Ancient Jewish history is known from the Bible, extra-biblical sources, apocrypha and pseudoepigrapha, the writings of Josephus, Greco-Roman authors and church fathers, as well as archaeological finds, inscriptions, ancient documents (such as the Papyri from Elephantine and the Fayyum, the Dead Sea scrolls, the Bar Kokhba letters, the Babatha Archives and the Cairo Genizah documents) supplemented by oral history and the collection of commentaries in the Midrash and Talmud.

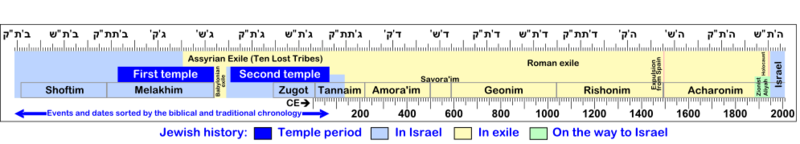

With the rise of the printing press and movable type in the early modern period, Jewish histories and early editions of the Torah/Tanakh were published which dealt with the history of the Jewish religion, and increasingly, national histories of the Jews, Jewish peoplehood and identity. This was a move from a manuscript or scribal culture to a printing culture. Jewish historians wrote accounts of their collective experiences, but also increasingly used history for political, cultural, and scientific or philosophical exploration. Writers drew upon a corpus of culturally inherited text in seeking to construct a logical narrative to critique or advance the state of the art. Modern Jewish historiography intertwines with intellectual movements such as the European Renaissance and the Age of Enlightenment but drew upon earlier works in the Late Middle Ages and into diverse sources in antiquity. Today, the history of the Jews and Judaism is often divided into six periods:

- Ancient Israel and Judah (c. 1200–586 BCE)

- Second Temple period (c. 516 BCE–70 CE)[17]

- Talmudic period (70–640 CE)[18]

- Middle Ages (640–1492)

- Early Modern period (1492–1750)

- Modern period (1750–20th century)

- Zionism, the Holocaust and the establishment of Israel (20th–21st centuries)

Ancient Israel (1500–586 BCE)

[edit]The early Israelites

[edit]

The history of the early Jews, and their neighbours, centres on the Fertile Crescent and east coast of the Mediterranean Sea. It begins among those people who occupied the area lying between the river Nile and Mesopotamia. Surrounded by ancient seats of culture in Egypt and Babylonia, by the deserts of Arabia, and by the highlands of Asia Minor, the land of Canaan (roughly corresponding to modern Israel, the Palestinian Territories, Jordan, and Lebanon) was a meeting place of civilizations.

The earliest recorded evidence of a people by the name of Israel appears in the Merneptah Stele of ancient Egypt, dated to about 1200 BCE. According to the modern archaeological account, the Israelites and their culture branched out of the Canaanite peoples and their cultures through the development of a distinct monolatristic—and later monotheistic—religion centred on the national god Yahweh.[19][20][21] They spoke an archaic form of the Hebrew language, known today as Biblical Hebrew.[22]

The traditional religious view of Jews and Judaism of their own history was based on the narrative of the ancient Hebrew Bible. In this view, Abraham, signifying that he is both the biological progenitor of the Jews and the father of Judaism, is the first Jew.[23] Later, Isaac was born to Abraham, and Jacob was born to Isaac. Following a struggle with an angel, Jacob was given the name Israel. Following a severe drought, Jacob and his twelve sons fled to Egypt, where they eventually formed the Twelve Tribes of Israel. The Israelites were later led out of slavery in Egypt and subsequently brought to Canaan by Moses; they eventually conquered Canaan under the leadership of Joshua.

Modern scholars agree that the Bible does not provide an authentic account of the Israelites' origins; the consensus supports that the archaeological evidence showing largely indigenous origins of Israel in Canaan, not Egypt, is "overwhelming" and leaves "no room for an Exodus from Egypt or a 40-year pilgrimage through the Sinai wilderness".[24] Many archaeologists have abandoned the archaeological investigation of Moses and the Exodus as "a fruitless pursuit".[24] However, it is accepted that this narrative does have a "historical core" to it.[25][26][27] A century of research by archaeologists and Egyptologists has arguably found no evidence that can be directly related to the Exodus narrative of an Egyptian captivity and the escape and travels through the wilderness, leading to the suggestion that Iron Age Israel—the kingdoms of Judah and Israel—has its origins in Canaan, not in Egypt:[28][29] The culture of the earliest Israelite settlements is Canaanite, their cult-objects are those of the Canaanite god El, the pottery remains in the local Canaanite tradition, and the alphabet used is early Canaanite. The almost sole marker distinguishing the "Israelite" villages from Canaanite sites is an absence of pig bones, although whether this can be taken as an ethnic marker or is due to other factors remains a matter of dispute.[30]

According to the Biblical narrative, the Land of Israel was organized into a confederacy of twelve tribes ruled by a series of Judges for several hundred years.

The Kingdoms of Israel and Judah

[edit]Two Israelite kingdoms emerged during the Iron Age II: Israel and Judah. The Bible portrays Israel and Judah as the successors of an earlier United Kingdom of Israel, although its historicity is disputed.[31][32] Historians and archaeologists agree that the northern Kingdom of Israel existed by ca. 900 BCE[1]: 169–195 [33] and that the Kingdom of Judah existed by ca. 700 BCE.[2] The Tel Dan Stele, discovered in 1993, shows that the kingdom, at least in some form, existed by the middle of the 9th century BCE, but it does not indicate the extent of its power.[34][35][36]

Biblical tradition tells that the Israelite monarchy was established in 1037 BCE under Saul, and continued under David and his son, Solomon. David greatly expanded the kingdom's borders and conquered Jerusalem from the Jebusites, turning it into the national, political and religious capital of the kingdom. Solomon, his son, later built the First Temple on Mount Moriah in Jerusalem. Upon his death, traditionally dated to c. 930 BCE, a civil war erupted between the ten northern Israelite tribes, and the tribes of Judah (Simeon was absorbed into Judah) and Benjamin in the south. The kingdom then split into the Kingdom of Israel in the north, and the Kingdom of Judah in the south.

The Kingdom of Israel was the more prosperous of the two kingdoms and soon developed into a regional power.[37] During the days of the Omride dynasty, it controlled Samaria, Galilee, the upper Jordan Valley, the Sharon and large parts of the Transjordan.[38] Samaria, the capital, was home to one of the largest Iron Age palaces in the Levant.[39][40] The kingdom of Israel was destroyed around 720 BCE, when it was conquered by the Neo-Assyrian Empire.[3]

The Kingdom of Judah, with its capital in Jerusalem, controlled the Judaean Mountains, the Shephelah, the Judaean Desert and parts of the Negev. After the fall of Israel, Judah became a client state of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. In the 7th century BCE, the kingdom's population increased greatly, prospering under Assyrian vassalage, despite Hezekiah's revolt against the Assyrian king Sennacherib.[41]

Large parts of the Hebrew Bible were written during this period. This include the earliest portions of Hosea,[42] Isaiah,[43] Amos[44] and Micah,[45] along with Nahum,[46] Zephaniah,[47] most of Deuteronomy,[48] the first edition of the Deuteronomistic history (the books of Joshua/Judges/Samuel/Kings),[49] and Habakkuk.[50]

With the collapse of the Neo-Assyrian Empire in 605 BCE, a power struggle emerged between Egypt and the Neo-Babylonian Empire for control of the Levant,[51] leading to Judah's rapid decline. In 601 BCE, King Jehoiakim of Judah, who had recently submitted to Babylon, rebelled against the empire. He was soon succeeded by his son, Jehoiachin, who continued his father's policy and faced a Babylonian invasion.[51] In March 597 BCE,[52] Jehoiachin surrendered to the Babylonians and was taken captive to Babylon.[53] This defeat is documented in the Babylonian Chronicles.[54][55] Zedekiah, Jehoiachin's uncle, was then installed as king by the Babylonians.[53]

In 587 or 586 BCE, Nebuchadnezzar II, responding to a second revolt in Judah, besieged and destroyed Jerusalem.[56][51] The First Temple was razed, and its sacred vessels were seized as spoils.[57] The destruction was followed by a mass exile: the surviving inhabitants of the city, including other segments of the population, were carried off to Mesopotamia,[57] marking the onset of the era known in Jewish history as the "Babylonian Captivity". Zedekiah himself was captured, blinded, and transported to Babylon.[57] Others fled to Egypt.[citation needed] The people of Judah lost their statehood, and, for those in exile, their homeland.[58] Following the dissolution of the monarchy, the former kingdom was annexed as a province of the Babylonian Empire.[51][57]

The Babylonian captivity (c. 587–538 BCE)

[edit]

During the several decades between the fall of Judah and their return to Zion under Persian rule, Jewish history enters an obscure phase. Many Jews were exiled across Babylonia, Elam, and Egypt, while others remained in Judea. Jeremiah refers to communities in Egypt, including settlements in Migdol, Tahpanhes, Noph, and Pathros. Moreover, a Jewish military colony existed at Elephantine, established before the exile, where they built their own shrine.[58] Deuteronomy was expanded and earlier scriptures were edited during the exilic period. The first edition of Jeremiah, the Book of Ezekiel, the majority of Obadiah, and what is referred to in research as "Second Isaiah" were all written during this time period as well.[citation needed]

Second Temple period (538 BCE–70 CE)

[edit]Persian period (c. 538–332 BCE)

[edit]

According to the Book of Ezra, Persian Cyrus the Great, king of the Achaemenid Empire, brought an end to the Babylonian exile in 538 BCE,[59] a year after his conquest of Babylon.[60] The return from exile was led by Zerubbabel, a prince from the royal line of David, and Joshua the Priest, descended from former High Priests of the Temple. They oversaw the construction of the Second Temple, completed between 521 and 516 BCE.[59] As part of the Persian Empire, the former Kingdom of Judah became the province of Judah (Yehud Medinata)[61] with different borders, covering a smaller territory.[62] Contemporary scholars point to a gradual return process that extended into the late 6th and early 5th centuries BCE.[63] The population of Persian Judah was greatly reduced from that of the kingdom, archaeological surveys showing a population of around 30,000 people in the 5th to 4th centuries BCE.[64]: 308

The final Torah is widely seen as a product of the Persian period (539–333 BCE, probably 450–350 BCE).[65] This consensus echoes a traditional Jewish view which gives Ezra, the leader of the Jewish community on its return from Babylon, a pivotal role in its promulgation.[66]

Three prophets, considered the last in Jewish tradition—Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi—were active during this period.[citation needed] After the death of the last Jewish prophet and while still under Persian rule, the leadership of the Jewish people passed into the hands of five successive generations of zugot ("pairs of") leaders. They flourished first under the Persians and then under the Greeks. As a result, the Pharisees and Sadducees were formed. Under the Persians then under the Greeks, Jewish coins were minted in Judea as Yehud coinage.[citation needed]

The Hellenistic period (c. 332–110 BCE)

[edit]In 332 BCE, Alexander the Great of Macedon defeated the Persians. After Alexander's death and the division of his empire among his generals, the Seleucid Kingdom was formed.

The Alexandrian conquests spread Greek culture to the Levant. During this time, currents of Judaism were influenced by Hellenistic philosophy developed from the 3rd century BCE, notably the Jewish diaspora in Alexandria, culminating in the compilation of the Septuagint. An important advocate of the symbiosis of Jewish theology and Hellenistic thought is Philo.

The Hasmonean Kingdom (110–63 BCE)

[edit]Triggered by anti-Jewish decrees from Seleucid king Antiochus IV Epiphanes and tensions between Hellenized and conservative Jews, the Maccabean Revolt erupted in Judea in 167 BCE under the leadership of Mattathias. His son, Judas Maccabeus, recaptured Jerusalem in 164 BCE, purifying the Second Temple and reinstating sacrificial worship.[67] The successful revolt eventually led to the formation of an independent Jewish state under the Hasmonean dynasty, which lasted from 165 BCE to 63 BCE.[68]

Initially governing as both political leaders and High Priests, the Hasmoneans later assumed the title of kings. They employed military campaigns and diplomacy to consolidate power.[67] Under the rule of Alexander Jannaeus and Salome Alexandra, the kingdom reached its zenith in size and influence. However, internal strife erupted between Salome Alexandra's sons, Hyrcanus II and Aristobulus II, leading to civil war and appeals to Roman authorities for intervention. Responding to these appeals, Pompey led a Roman campaign of conquest and annexation, which marked the end of Hasmonean sovereignty and ushered in Roman rule over Judea.[69]

The Roman period (63 BCE – 135 CE)

[edit]

Judea had been an independent Jewish kingdom under the Hasmoneans, but it was conquered and reorganized as a client state by the Roman general Pompey in 63 BCE. Roman expansion was going on in other areas as well, and it would continue for more than a hundred and fifty years. Later, Herod the Great was appointed "King of the Jews" by the Roman Senate, supplanting the Hasmonean dynasty. Some of his offspring held various positions after him, known as the Herodian dynasty. Briefly, from 4 BCE to 6 CE, Herod Archelaus ruled the tetrarchy of Judea as ethnarch, the Romans denying him the title of King.

After the Census of Quirinius in 6 CE, the Roman province of Judaea was formed as a satellite of Roman Syria under the rule of a prefect (as was Roman Egypt) until 41 CE, then procurators after 44 CE. The empire was often callous and brutal in its treatment of its Jewish subjects, (see Anti-Judaism in the pre-Christian Roman Empire). In 30 CE (or 33 CE), Jesus of Nazareth, an itinerant rabbi from Galilee, and the central figure of Christianity, was put to death by crucifixion in Jerusalem under the Roman prefect of Judaea, Pontius Pilate.[70]

Roman oppressive rule, combined with economic, religious, and ethnic tensions, eventually led to the outbreak of the First Jewish–Roman War, also known as the Great Revolt, in 66 CE. Future emperor Vespasian quelled the rebellion in Galilee by 67 CE, capturing key strongholds.[71] He was succeeded by his son Titus, who led the brutal siege of Jerusalem, culminating in the city's fall in 70 CE. The Romans burned Jerusalem and destroyed the Second Temple.[72][73] The Roman victory was celebrated with a triumph in Rome, showcasing Jewish artifacts like the menorah, which were then put on display in the new Temple of Peace.[74] The Flavian dynasty leveraged this victory for political gain, erecting monuments in Rome and minting Judaea Capta coins.[75] The war concluded with the siege of Masada (73-74 CE). The Jewish population suffered widespread devastation, with displacement, enslavement, and Roman confiscation of Jewish-owned land.[76][77]

The destruction of the Second Temple marked a cataclysmic event in Jewish history, triggering far-reaching transformations within Judaism.[78][79][80] With the central role of sacrificial worship obliterated, religious practices shifted towards prayer, Torah study, and communal gatherings in synagogues. According to Rabbinic tradition, Yohanan ben Zakkai secured permission from the Romans to establish a center for Torah study in Yavneh, which then served as a focal point for Jewish religious and cultural life for a generation.[81][82][83] Judaism also underwent a significant shift away from its sectarian divisions.[84][85] The Sadducees and Essenes, two prominent sects in the late Second Temple period, faded into obscurity,[80] while the traditions of the Pharisees, including their halakhic interpretations, the centrality of the Oral Torah, and belief in resurrection became the foundation of Rabbinic Judaism.[81]

The Diaspora during the Second Temple period

[edit]The Jewish diaspora existed well before the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE and had been ongoing for centuries, with the dispersal driven by both forced expulsions and voluntary migrations.[86][87] In Mesopotamia, a testimony to the beginnings of the Jewish community can be found in Joachin's ration tablets, listing provisions allotted to the exiled Judean king and his family by Nebuchadnezzar II, and further evidence are the Al-Yahudu tablets, dated to the 6th-5th centuries BCE and related to the exiles from Judea arriving after the destruction of the First Temple,[88] though there is ample evidence for the presence of Jews in Babylonia even from 626 BCE.[89] In Egypt, the documents from Elephantine reveal the trials of a community founded by a Persian Jewish garrison at two fortresses on the frontier during the 5th-4th centuries BCE, and according to Josephus the Jewish community in Alexandria existed since the founding of the city in the 4th century BCE by Alexander the Great.[90] By 200 BCE, there were well established Jewish communities both in Egypt and Mesopotamia ("Babylonia" in Jewish sources) and in the two centuries that followed, Jewish populations were also present in Asia Minor, Greece, Macedonia, Cyrene, and, beginning in the middle of the first century BCE, in the city of Rome.[91][87]

In the first centuries CE, as a result of the Jewish-Roman Wars,[92] a large number of Jews were taken as captives, sold into slavery, or compelled to flee from the regions affected by the wars, contributing to the formation and expansion of Jewish communities across the Roman Empire as well as in Arabia and Mesopotamia.

The book of Acts in the New Testament, as well as other Pauline texts, make frequent reference to the large populations of Hellenised Jews in the cities of the Roman world. These Hellenised Jews were affected by the diaspora only in its spiritual sense, absorbing the feeling of loss and homelessness that became a cornerstone of the Jewish creed, much supported by persecutions in various parts of the world. Of critical importance to the reshaping of Jewish tradition from the Temple-based religion to the rabbinic traditions of the Diaspora, was the development of the interpretations of the Torah found in the Mishnah and Talmud.

Talmudic period (70–640 CE)

[edit]Bar Kokhba revolt

[edit]

From 132 to 136 CE, Judaea was the center of the Bar Kokhba revolt, triggered by Hadrian's decision to establish the pagan colony of Aelia Capitolina on the ruins of Jerusalem.[93] Early successes led to the establishment of a short-lived Jewish state in Judea under the leadership of Simon Bar Kokhba, styled as nasi or prince of Israel.[93] The rebel state's coinage proclaimed "Freedom of Israel" and "For the Freedom of Jerusalem," using ancient Hebrew script for nationalistic symbolism.[94][93] However, the Romans soon amassed six legions and additional auxiliaries under Julius Severus, who then brutally crushed the uprising. Historical accounts report the destruction of fifty major strongholds and 985 villages, resulting in 580,000 Jewish deaths and widespread famine and disease.[95] Archaeological research confirms the widespread destruction and depopulation of the Jewish heartland in Judea proper, where most of the Jewish population was either killed, sold into slavery, expelled, or forced to flee.[95][96][97] The Romans also suffered heavy losses.[94] Post-revolt, Jews were prohibited from entering Jerusalem, and Hadrian issued religious edicts,[98][99] including a ban on circumcision, later repealed by Antoninus Pius.[citation needed] The province of Judaea was renamed Syria Palaestina as a punitive act against the Jews, aimed at placating non-Jewish residents and erasing Jewish historical ties to the land.[93][100][101]

Late Roman period in the Land of Israel

[edit]The relations of the Jews with the Roman Empire in the region continued to be complicated. Constantine I allowed Jews to mourn their defeat and humiliation once a year on Tisha B'Av at the Western Wall. In 351–352 CE, the Jews of Galilee launched yet another revolt, provoking heavy retribution.[102] The Gallus revolt came during the rising influence of early Christians in the Eastern Roman Empire, under the Constantinian dynasty. In 355, however, the relations with the Roman rulers improved, upon the rise of Emperor Julian, the last of the Constantinian dynasty, who unlike his predecessors defied Christianity. In 363, not long before Julian left Antioch to launch his campaign against Sasanian Persia, in keeping with his effort to foster religions other than Christianity, he ordered the Jewish Temple rebuilt.[103] The failure to rebuild the Temple has mostly been ascribed to the dramatic Galilee earthquake of 363 and traditionally also to the Jews' ambivalence about the project. Sabotage is a possibility, as is an accidental fire. Divine intervention was the common view among Christian historians of the time.[104] Julian's support of Jews caused Jews to call him "Julian the Hellene".[105] Julian's fatal wound in the Persian campaign and his consequent death had put an end to Jewish aspirations, and Julian's successors embraced Christianity through the entire timeline of Byzantine rule of Jerusalem, preventing any Jewish claims.

In 438 CE, when the Empress Eudocia removed the ban on Jews' praying at the Temple site, the heads of the Community in Galilee issued a call "to the great and mighty people of the Jews" which began: "Know that the end of the exile of our people has come!" However, the Christian population of the city, who saw this as a threat to their primacy, did not allow it and a riot erupted after which they chased away the Jews from the city.[106][107]

During the 5th and the 6th centuries, a series of Samaritan insurrections broke out across the Palaestina Prima province. Especially violent were the third and the fourth revolts, which resulted in almost the entire annihilation of the Samaritan community. It is likely that the Samaritan Revolt of 556 was joined by the Jewish community, which had also suffered a brutal suppression of Israelite religion.

In the belief of restoration to come, in the early 7th century the Jews made an alliance with the Persians, who invaded Palaestina Prima in 614, fought at their side, overwhelmed the Byzantine garrison in Jerusalem, and were given Jerusalem to be governed as an autonomy.[108] However, their autonomy was brief: the Jewish leader in Jerusalem was shortly assassinated during a Christian revolt and though Jerusalem was reconquered by Persians and Jews within 3 weeks, it fell into anarchy. With the consequent withdrawal of Persian forces, Jews surrendered to Byzantines in 625 or 628 CE, but were massacred by Christian radicals in 629 CE, with the survivors fleeing to Egypt. The Byzantine (Eastern Roman Empire) control of the region was finally lost to the Muslim Arab armies in 637 CE, when Umar ibn al-Khattab completed the conquest of Akko.

The Jews of pre-Muslim Babylonia (219–638 CE)

[edit]After the fall of Jerusalem, Babylonia (modern day Iraq) would become the focus of Judaism for more than a thousand years. The first Jewish communities in Babylonia started with the exile of the Tribe of Judah to Babylon by Jehoiachin in 597 BCE as well as after the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem in 586 BCE.[92] Many more Jews migrated to Babylon in 135 CE after the Bar Kokhba revolt and in the centuries after.[92] Babylonia, where some of the largest and most prominent Jewish cities and communities were established, became the centre of Jewish life all the way up to the 13th century. By the first century, Babylonia already held a speedily growing[92] population of an estimated 1,000,000 Jews, which increased to an estimated 2 million[109] between the years 200 CE and 500 CE, both by natural growth and by immigration of more Jews from Judea, making up about 1/6 of the world Jewish population at that era.[109] It was there that they would write the Babylonian Talmud in the languages used by the Jews of ancient Babylonia: Hebrew and Aramaic. The Jews established Talmudic Academies in Babylonia, also known as the Geonic Academies ("Geonim" meaning "splendour" in Biblical Hebrew or "geniuses"), which became the centre for Jewish scholarship and the development of Jewish law in Babylonia from roughly 500 CE to 1038 CE. The two most famous academies were the Pumbedita Academy and the Sura Academy. Major yeshivot were also located at Nehardea and Mahuza.[110] The Talmudic Yeshiva Academies became a main part of Jewish culture and education, and Jews continued establishing Yeshiva Academies in Western and Eastern Europe, North Africa, and in later centuries, in America and other countries around the world where Jews lived in the Diaspora. Talmudic study in Yeshiva academies, most of them located in The United States and Israel, continues today.

These Talmudic Yeshiva academies of Babylonia followed the era of the Amoraim ("expounders")—the sages of the Talmud who were active (both in Judah and in Babylon) during the end of the era of the sealing of the Mishnah and until the times of the sealing of the Talmud (220CE – 500CE), and following the Savoraim ("reasoners")—the sages of beth midrash (Torah study places) in Babylon from the end of the era of the Amoraim (5th century) and until the beginning of the era of the Geonim. The Geonim (Hebrew: גאונים) were the presidents of the two great rabbinical colleges of Sura and Pumbedita, and were the generally accepted spiritual leaders of the worldwide Jewish community in the early medieval era, in contrast to the Resh Galuta (Exilarch) who wielded secular authority over the Jews in Islamic lands. According to traditions, the Resh Galuta were descendants of Judean kings, which is why the kings of Parthia would treat them with much honour.[111]

For the Jews of late antiquity and the early Middle Ages, the yeshivot of Babylonia served much the same function as the ancient Sanhedrin—that is, as a council of Jewish religious authorities. The academies were founded in pre-Islamic Babylonia under the Zoroastrian Sassanid dynasty and were located not far from the Sassanid capital of Ctesiphon, which at that time was the largest city in the world. After the conquest of Persia in the 7th century, the academies subsequently operated for four hundred years under the Islamic caliphate. The first gaon of Sura, according to Sherira Gaon, was Mar bar Rab Chanan, who assumed office in 609. The last gaon of Sura was Samuel ben Hofni, who died in 1034; the last gaon of Pumbedita was Hezekiah Gaon, who was tortured to death in 1040; hence the activity of the Geonim covers a period of nearly 450 years.

One of principal seats of Babylonian Judaism was Nehardea, which was then a very large city made up mostly of Jews.[92] A very ancient synagogue, built, it was believed, by King Jehoiachin, existed in Nehardea. At Huzal, near Nehardea, there was another synagogue, not far from which could be seen the ruins of Ezra's academy. In the period before Hadrian, Akiba, on his arrival at Nehardea on a mission from the Sanhedrin, entered into a discussion with a resident scholar on a point of matrimonial law (Mishnah Yeb., end). At the same time there was at Nisibis (northern Mesopotamia), an excellent Jewish college, at the head of which stood Judah ben Bathyra, and in which many Judean scholars found refuge at the time of the persecutions. A certain temporary importance was also attained by a school at Nehar-Pekod, founded by the Judean immigrant Hananiah, nephew of Joshua ben Hananiah, which school might have been the cause of a schism between the Jews of Babylonia and those of Judea-Israel, had not the Judean authorities promptly checked Hananiah's ambition.

The Byzantine period (324–638 CE)

[edit]Jews were also widespread throughout the Roman Empire, and this carried on to a lesser extent in the period of Byzantine rule in the central and eastern Mediterranean. The militant and exclusive Christianity and caesaropapism of the Byzantine Empire did not treat Jews well, and the condition and influence of diaspora Jews in the Empire declined dramatically.

It was official Christian policy to convert Jews to Christianity, and the Christian leadership used the official power of Rome in their attempts. In 351 CE the Jews revolted against the added pressures of their Governor, Constantius Gallus. Gallus put down the revolt and destroyed the major cities in the Galilee area where the revolt had started. Tzippori and Lydda (site of two of the major legal academies) never recovered.

In this period, the Nasi in Tiberias, Hillel II, created an official calendar, which needed no monthly sightings of the moon. The months were set, and the calendar needed no further authority from Judea. At about the same time, the Jewish academy at Tiberius began to collate the combined Mishnah, braitot, explanations, and interpretations developed by generations of scholars who studied after the death of Judah HaNasi. The text was organized according to the order of the Mishna: each paragraph of Mishnah was followed by a compilation of all of the interpretations, stories, and responses associated with that Mishnah. This text is called the Jerusalem Talmud.

The Jews of Judea received a brief respite from official persecution during the rule of the Emperor Julian the Apostate. Julian's policy was to return the Roman Empire to Hellenism, and he encouraged the Jews to rebuild Jerusalem. As Julian's rule lasted only from 361 to 363, the Jews could not rebuild sufficiently before Roman Christian rule was restored over the Empire. Beginning in 398 with the consecration of St. John Chrysostom as Patriarch, Christian rhetoric against Jews grew sharper; he preached sermons with titles such as "Against the Jews" and "On the Statues, Homily 17," in which John preaches against "the Jewish sickness".[112] Such heated language contributed to a climate of Christian distrust and hate toward the large Jewish settlements, such as those in Antioch and Constantinople.

In the beginning of the 5th century, the Emperor Theodosius issued a set of decrees establishing official persecution of Jews. Jews were not allowed to own slaves, build new synagogues, hold public office or try cases between a Jew and a non-Jew. Intermarriage between Jew and non-Jew was made a capital offence, as was the conversion of Christians to Judaism. Theodosius did away with the Sanhedrin and abolished the post of Nasi. Under the Emperor Justinian, the authorities further restricted the civil rights of Jews,[113] and threatened their religious privileges.[114] The emperor interfered in the internal affairs of the synagogue,[115] and forbade, for instance, the use of the Hebrew language in divine worship. Those who disobeyed the restrictions were threatened with corporal penalties, exile, and loss of property. The Jews at Borium, not far from Syrtis Major, who resisted the Byzantine General Belisarius in his campaign against the Vandals, were forced to embrace Christianity, and their synagogue was converted to a church.[116]

Justinian and his successors had concerns outside the province of Judea, and he had insufficient troops to enforce these regulations. As a result, the 5th century was a period when a wave of new synagogues were built, many with beautiful mosaic floors. Jews adopted the rich art forms of the Byzantine culture. Jewish mosaics of the period portray people, animals, menorahs, zodiacs, and Biblical characters. Excellent examples of these synagogue floors have been found at Beit Alpha (which includes the scene of Abraham sacrificing a ram instead of his son Isaac along with a zodiac), Tiberius, Beit Shean, and Tzippori.

The precarious existence of Jews under Byzantine rule did not long endure, largely due to the explosion of the Muslim religion out of the remote Arabian peninsula (where large populations of Jews resided, see History of the Jews under Muslim Rule for more). The Muslim Caliphate ejected the Byzantines from the Holy Land (or the Levant, defined as modern Israel, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria) within a few years of their victory at the Battle of Yarmouk in 636. Numerous Jews fled the remaining Byzantine territories in favour of residence in the Caliphate over the subsequent centuries.

The size of the Jewish community in the Byzantine Empire was not affected by attempts by some emperors (most notably Justinian) to forcibly convert the Jews of Anatolia to Christianity, as these attempts met with very little success.[117] Historians continue to research the status of the Jews in Asia Minor under Byzantine rule. (for a sample of views, see, for instance, J. Starr The Jews in the Byzantine Empire, 641–1204; S. Bowman, The Jews of Byzantium; R. Jenkins Byzantium; Averil Cameron, "Byzantines and Jews: Recent Work on Early Byzantium", Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies 20 (1996)). No systematic persecution of the type endemic at that time in Western Europe (pogroms, the stake, mass expulsions, etc.) has been recorded in Byzantium.[118] Much of the Jewish population of Constantinople remained in place after the conquest of the city by Mehmet II.[citation needed]

- Mosaic of Menorah with Lulav and Ethrog, 6th century CE Brooklyn Museum

- Mosaic pavement of a synagogue at Beit Alpha (5th century)

- Mosaic in the Tzippori Synagogue (5th century)

- Mosaic pavement recovered from the Hamat Gader synagogue (5th or 6th century)

Diaspora communities

[edit]

Cochin Jewish tradition holds that the roots of their community go back to the arrival of Jews at Shingly in 72 CE, after the Destruction of the Second Temple. It also states that a Jewish kingdom, understood to mean the granting of autonomy by a local king, Cheraman Perumal, to the community, under their leader Joseph Rabban, in 379 CE. The first synagogue there was built in 1568. The legend of the founding of Indian Christianity in Kerala by Thomas the Apostle relates that on his arrival there, he encountered a local girl who understood Hebrew.[119]

Perhaps in the 4th century, the Kingdom of Semien, a Jewish nation in modern Ethiopia was established, lasting until the 17th century.[120]

The Medieval period

[edit]The Islamic period (638–1099)

[edit]In 638 CE the Byzantine Empire lost control of the Levant. The Arab Islamic Empire under Caliph Omar conquered Jerusalem and the lands of Mesopotamia, Syria, Palestine and Egypt. As a political system, Islam created radically new conditions for Jewish economic, social, and intellectual development.[121] Caliph Omar permitted the Jews to reestablish their presence in Jerusalem–after a lapse of 500 years.[122] Jewish tradition regards Caliph Omar as a benevolent ruler and the Midrash (Nistarot de-Rav Shimon bar Yoḥai) refers to him as a "friend of Israel."[122]

According to the Arab geographer Al-Muqaddasi, the Jews worked as "the assayers of coins, the dyers, the tanners and the bankers in the community".[123] During the Fatimid period, many Jewish officials served in the regime.[123] Professor Moshe Gil believes that at the time of the Arab conquest in the 7th century CE, the majority of the population was Christian and Jewish.[124]

During this time Jews lived in thriving communities all across ancient Babylonia. In the Geonic period (650–1250 CE), the Babylonian Yeshiva Academies were the chief centres of Jewish learning; the Geonim (meaning either "Splendor" or "Geniuses"), who were the heads of these schools, were recognized as the highest authorities in Jewish law.

In the 7th century, the new Muslim rulers institute the kharaj land tax, which led to mass migration of Babylonian Jews from the countryside to cities like Baghdad. This in turn led to greater wealth and international influence, as well as a more cosmopolitan outlook from Jewish thinkers such as Saadiah Gaon, who now deeply engaged with Western philosophy for the first time. When the Abbasid Caliphate and the city of Baghdad declined in the 10th century, many Babylonian Jews migrated to the Mediterranean region, contributing to the spread of Babylonian Jewish customs throughout the Jewish world.[125]

The Jewish Golden Age in early Muslim Spain (711–1031)

[edit]The golden age of Jewish culture in Spain coincided with the Middle Ages in Europe, a period of Muslim rule throughout much of the Iberian Peninsula. During that time, Jews were generally accepted in society and Jewish religious, cultural, and economic life blossomed.

A period of tolerance thus dawned for the Jews of the Iberian Peninsula, whose number was considerably augmented by immigration from Africa in the wake of the Muslim conquest. Especially after 912, during the reign of Abd-ar-Rahman III and his son, Al-Hakam II, the Jews prospered, devoting themselves to the service of the Caliphate of Cordoba, to the study of the sciences, and to commerce and industry, especially to trading in silk and slaves, in this way promoting the prosperity of the country. Jewish economic expansion was unparalleled. In Toledo, Jews were involved in translating Arabic texts to the Romance languages, as well as translating Greek and Hebrew texts into Arabic. Jews also contributed to botany, geography, medicine, mathematics, poetry and philosophy.[126][127]

Generally, the Jewish people were allowed to practice their religion and live according to the laws and scriptures of their community. Furthermore, the restrictions to which they were subject were social and symbolic rather than tangible and practical in character. That is to say, these regulations served to define the relationship between the two communities, and not to oppress the Jewish population.[128]

'Abd al-Rahman's court physician and minister was Hasdai ben Isaac ibn Shaprut, the patron of Menahem ben Saruq, Dunash ben Labrat, and other Jewish scholars and poets. Jewish thought during this period flourished under famous figures such as Samuel Ha-Nagid, Moses ibn Ezra, Solomon ibn Gabirol Judah Halevi and Moses Maimonides.[126] During 'Abd al-Rahman's term of power, the scholar Moses ben Enoch was appointed rabbi of Córdoba, and as a consequence al-Andalus became the centre of Talmudic study, and Córdoba the meeting-place of Jewish savants.

The Golden Age ended with the invasion of al-Andalus by the Almohades, a conservative dynasty originating in North Africa, who were highly intolerant of religious minorities.

The Crusaders period (1099–1260)

[edit]

Sermonical messages to avenge the death of Jesus encouraged Christians to participate in the Crusades. The twelfth century Jewish narration from R. Solomon ben Samson records that crusaders en route to the Holy Land decided that before combating the Ishmaelites they would massacre the Jews residing in their midst to avenge the crucifixion of Christ. The massacres began at Rouen and Jewish communities in Rhine Valley were seriously affected.[129]

Crusading attacks were made upon Jews in the territory around Heidelberg. A huge loss of Jewish life took place. Many were forcibly converted to Christianity and many committed suicide to avoid baptism. A major driving factor behind the choice to commit suicide was the Jewish realisation that upon being slain their children could be taken to be raised as Christians. The Jews were living in the middle of Christian lands and felt this danger acutely.[130] This massacre is seen as the first in a sequence of antisemitic events which culminated in the Holocaust.[131] Jewish populations felt that they had been abandoned by their Christian neighbours and rulers during the massacres and lost faith in all promises and charters.[132]

Many Jews chose self-defence. But their means of self-defence were limited and their casualties only increased. Most of the forced conversions proved ineffective. Many Jews reverted to their original faith later. The pope protested this but Emperor Henry IV agreed to permitting these reversions.[129] The massacres began a new epoch for Jewry in Christendom. The Jews had preserved their faith from social pressure, now they had to preserve it at sword point. The massacres during the crusades strengthened Jewry from within spiritually. The Jewish perspective was that their struggle was Israel's struggle to hallow the name of God.[133]

In 1099, Jews helped the Arabs to defend Jerusalem against the Crusaders. When the city fell, the Crusaders gathered many Jews in a synagogue and set it on fire.[129] In Haifa, the Jews almost single-handedly defended the town against the Crusaders, holding out for a month, (June–July 1099).[123] At this time there were Jewish communities scattered all over the country, including Jerusalem, Tiberias, Ramleh, Ashkelon, Caesarea, and Gaza. As Jews were not allowed to hold land during the Crusader period, they worked at trades and commerce in the coastal towns during times of quiescence. Most were artisans: glassblowers in Sidon, furriers and dyers in Jerusalem.[123]

During this period, the Masoretes of Tiberias established the niqqud, a system of diacritical signs used to represent vowels or distinguish between alternative pronunciations of letters of the Hebrew alphabet. Numerous piyutim and midrashim were recorded in Palestine at this time.[123]

Maimonides wrote that in 1165 he visited Jerusalem and went to the Temple Mount, where he prayed in the "great, holy house".[134] Maimonides established a yearly holiday for himself and his sons, the 6th of Cheshvan, commemorating the day he went up to pray on the Temple Mount, and another, the 9th of Cheshvan, commemorating the day he merited to pray at the Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron.

In 1141 Yehuda Halevi issued a call to Jews to emigrate to Palestine and took on the long journey himself. After a stormy passage from Córdoba, he arrived in Egyptian Alexandria, where he was enthusiastically greeted by friends and admirers. At Damietta, he had to struggle against his heart, and the pleadings of his friend Ḥalfon ha-Levi, that he remain in Egypt, where he would be free from intolerant oppression. He started on the rough route overland. He was met along the way by Jews in Tyre and Damascus. Jewish legend relates that as he came near Jerusalem, overpowered by the sight of the Holy City, he sang his most beautiful elegy, the celebrated "Zionide" (Zion ha-lo Tish'ali). At that instant, an Arab had galloped out of a gate and rode him down; he was killed in the accident.[citation needed]

The Mamluk period (1260–1517)

[edit]Nahmanides is recorded as settling in the Old City of Jerusalem in 1267. He moved to Acre, where he was active in spreading Jewish learning, which was at that time neglected in the Holy Land. He gathered a circle of pupils around him, and people came in crowds, even from the district of the Euphrates, to hear him. Karaites were said to have attended his lectures, among them Aaron ben Joseph the Elder. He later became one of the greatest Karaite authorities. Shortly after Nahmanides' arrival in Jerusalem, he addressed a letter to his son Nahman, in which he described the desolation of the Holy City. At the time, it had only two Jewish inhabitants—two brothers, dyers by trade. In a later letter from Acre, Nahmanides counsels his son to cultivate humility, which he considers to be the first of virtues. In another, addressed to his second son, who occupied an official position at the Castilian court, Nahmanides recommends the recitation of the daily prayers and warns above all against immorality. Nahmanides died after reaching seventy-six, and his remains were interred at Haifa, by the grave of Yechiel of Paris.

Yechiel had emigrated to Acre in 1260, along with his son and a large group of followers.[135][136] There he established the Talmudic academy Midrash haGadol d'Paris.[137] He is believed to have died there between 1265 and 1268. In 1488 Obadiah ben Abraham, commentator on the Mishnah, arrived in Jerusalem; this marked a new period of return for the Jewish community in the land.

Spain, North Africa, and the Middle East

[edit]During the Middle Ages, Jews were generally better treated by Islamic rulers than Christian ones. Despite second-class citizenship, Jews played prominent roles in Muslim courts, and experienced a Golden Age in Moorish Spain about 900–1100, though the situation deteriorated after that time. Riots resulting in the deaths of Jews did however occur in North Africa through the centuries and especially in Morocco, Libya and Algeria, where eventually Jews were forced to live in ghettos.[138]

During the 11th century, Muslims in Spain conducted pogroms against the Jews; those occurred in Cordoba in 1011 and in Granada in 1066.[139] During the Middle Ages, the governments of Egypt, Syria, Iraq and Yemen enacted decrees ordering the destruction of synagogues. At certain times, Jews were forced to convert to Islam or face death in some parts of Yemen, Morocco and Baghdad.[140][better source needed] The Almohads, who had taken control of much of Islamic Iberia by 1172, surpassed the Almoravides in fundamentalist outlook. They treated the dhimmis harshly. They expelled both Jews and Christians from Morocco and Islamic Spain. Faced with the choice of death or conversion, many Jews emigrated.[141] Some, such as the family of Maimonides, fled south and east to more tolerant Muslim lands, while others went northward to settle in the growing Christian kingdoms.[142][143][better source needed]

Europe

[edit]According to the American writer James Carroll, "Jews accounted for 10% of the total population of the Roman Empire. By that ratio, if other factors had not intervened, there would be 200 million Jews in the world today, instead of something like 13 million."[144]

Jewish populations have existed in Europe, especially in the area of the former Roman Empire, from very early times. As Jewish males had emigrated, some sometimes took wives from local populations, as is shown by the various MtDNA, compared to Y-DNA among Jewish populations.[145] These groups were joined by traders and later on by members of the diaspora.[citation needed] Records of Jewish communities in France (see History of the Jews in France) and Germany (see History of the Jews in Germany) date from the 4th century, and substantial Jewish communities in Spain were noted even earlier.[citation needed]

The historian Norman Cantor and other 20th-century scholars dispute the tradition that the Middle Ages was a uniformly difficult time for Jews. Before the Church became fully organized as an institution with an increasing array of rules, early medieval society was tolerant. Between 800 and 1100, an estimated 1.5 million Jews lived in Christian Europe. As they were not Christians, they were not included as a division of the feudal system of clergy, knights and serfs. This means that they did not have to satisfy the oppressive demands for labor and military conscription that Christian commoners suffered. In relations with the Christian society, the Jews were protected by kings, princes and bishops, because of the crucial services they provided in three areas: finance, administration and medicine.[146] The lack of political strengths did leave Jews vulnerable to exploitation through extreme taxation.[147]

Christian scholars interested in the Bible consulted with Talmudic rabbis. As the Roman Catholic Church strengthened as an institution, the Franciscan and Dominican preaching orders were founded, and there was a rise of competitive middle-class, town-dwelling Christians. By 1300, the friars and local priests staged the Passion Plays during Holy Week, which depicted Jews (in contemporary dress) killing Christ, according to Gospel accounts. From this period, persecution of Jews and deportations became endemic. Around 1500, Jews found relative security and a renewal of prosperity in present-day Poland.[146]

After 1300, Jews suffered more discrimination and persecution in Christian Europe. Europe's Jewry was mainly urban and literate. The Christians were inclined to regard Jews as obstinate deniers of the truth because in their view the Jews were expected to know of the truth of the Christian doctrines from their knowledge of the Jewish scriptures. Jews were aware of the pressure to accept Christianity.[148] As Catholics were forbidden by the church to loan money for interest, some Jews became prominent moneylenders. Christian rulers gradually saw the advantage of having such a class of people who could supply capital for their use without being liable to excommunication. As a result, the money trade of western Europe became a specialty of the Jews. But, in almost every instance when Jews acquired large amounts through banking transactions, during their lives or upon their deaths, the king would take it over.[149] Jews became imperial "servi cameræ", the property of the King, who might present them and their possessions to princes or cities.

Jews were frequently massacred and exiled from various European countries. The persecution hit its first peak during the Crusades. In the People's Crusade (1096) flourishing Jewish communities on the Rhine and the Danube were utterly destroyed. In the Second Crusade (1147) the Jews in France were subject to frequent massacres. They were also subjected to attacks by the Shepherds' Crusades of 1251 and 1320. The Crusades were followed by massive expulsions, including the expulsion of the Jews from England in 1290;[150] in 1396 100,000 Jews were expelled from France; and in 1421, thousands were expelled from Austria. Over this time many Jews in Europe, either fleeing or being expelled, migrated to Poland, where they prospered into another Golden Age.

In Italy, Jews were allowed to live in Venice but were required to live in a ghetto, and the practice spread across Italy (see Cum nimis absurdum) and was adopted in many places in Catholic Europe. Jews outside the Ghetto often had to wear a yellow star.[151][152]

Expulsions of the Jews of Spain and Portugal

[edit]Significant repression of Spain's numerous community occurred during the 14th century, notably a major pogrom in 1391 which resulted in the majority of Spain's 300,000 Jews converting to Catholicism. With the conquest of the Muslim Kingdom of Granada in 1492, the Catholic monarchs issued the Alhambra Decree, and Spain's remaining 100,000 Jews were forced to choose between conversion and exile. The expulsion of the Jews of Spain, is regarded by Jews as the worst catastrophe between the destruction of Jerusalem in 73 CE and the Holocaust of the 1940s.[153]

As a result, an estimated 50,000 to 70,000 Jews left Spain, the remainder joining Spain's already numerous Converso community. Perhaps a quarter of a million Conversos thus were gradually absorbed by the dominant Catholic culture, although those among them who secretly practiced Judaism were subject to 40 years of intense repression by the Spanish Inquisition. This was particularly the case up until 1530, after which the trials of Conversos by the Inquisition dropped to 3% of the total. Similar expulsions of Sephardic Jews occurred 1493 in Sicily (37,000 Jews) and Portugal in 1496. The expelled Spanish Jews fled mainly to the Ottoman Empire and North Africa and Portugal. A small number also settled in Holland and England.

The expulsion followed a long process of expulsions and bans from what are now England, France, Germany, Austria, and Holland. In January 1492, the last Muslim state was defeated in Spain and six months later the Jews of Spain (the largest community in the world) were required to convert or leave without their property. 100,000 converted with many continuing to secretly practice Judaism, for which the Catholic church's inquisition (led by Torquemada) now mandated a sentence of death by public burning. 175,000 left Spain.[154]

Many Spanish Jews moved to North Africa, Poland and the Ottoman Empire, especially Thessaloniki (now in Greece) which became the world's largest Jewish city. Some groups headed to the Middle East and Palestine, within the domains of the Ottoman Empire. About 100,000 Spanish Jews were allowed into Portugal, however five years later, their children were seized and they were given the choice of conversion or departing without them.[155]

The Early Modern period

[edit]Historians who study modern Jewry have identified four different paths by which European Jews were "modernized" and thus integrated into the mainstream of European society. A common approach has been to view the process through the lens of the European Enlightenment as Jews faced the promise and the challenges posed by political emancipation. Scholars that use this approach have focused on two social types as paradigms for the decline of Jewish tradition and as agents of the sea changes in Jewish culture that led to the collapse of the ghetto. The first of these two social types is the Court Jew who is portrayed as a forerunner of the modern Jew, having achieved integration with and participation in the proto-capitalist economy and court society of central European states such as the Habsburg Empire. In contrast to the cosmopolitan Court Jew, the second social type presented by historians of modern Jewry is the maskil, (learned person), a proponent of the Haskalah (Enlightenment). This narrative sees the maskil's pursuit of secular scholarship and his rationalistic critiques of rabbinic tradition as laying a durable intellectual foundation for the secularization of Jewish society and culture. The established paradigm has been one in which Ashkenazic Jews entered modernity through a self-conscious process of westernization led by "highly atypical, Germanized Jewish intellectuals". Haskalah gave birth to the Reform and Conservative movements and planted the seeds of Zionism while at the same time encouraging cultural assimilation into the countries in which Jews resided.[156]At around the same time that Haskalah was developing, Hasidic Judaism was spreading as a movement that preached a world view nearly opposed to the Haskalah.

In the 1990s, the concept of the "Port Jew" has been suggested as an "alternate path to modernity" that was distinct from the European Haskalah. In contrast to the focus on Ashkenazic Germanized Jews, the concept of the Port Jew focused on the Sephardi conversos who fled the Inquisition and resettled in European port towns on the coast of the Mediterranean, the Atlantic and the Eastern seaboard of the United States.[157]

Court Jews

[edit]Court Jews were Jewish bankers or businessmen who lent money and handled the finances of some of the Christian European noble houses. Corresponding historical terms are Jewish bailiff and shtadlan.

Examples of what would be later called court Jews emerged when local rulers used services of Jewish bankers for short-term loans. They lent money to nobles and in the process gained social influence. Noble patrons of court Jews employed them as financiers, suppliers, diplomats and trade delegates. Court Jews could use their family connections, and connections between each other, to provision their sponsors with, among other things, food, arms, ammunition and precious metals. In return for their services, court Jews gained social privileges, including up to noble status for themselves, and could live outside the Jewish ghettos. Some nobles wanted to keep their bankers in their own courts. And because they were under noble protection, they were exempted from rabbinical jurisdiction.

From medieval times, court Jews could amass personal fortunes and gained political and social influence. Sometimes they were also prominent people in the local Jewish community and could use their influence to protect and influence their brethren. Sometimes they were the only Jews who could interact with the local high society and present petitions of the Jews to the ruler. However, the court Jew had social connections and influence in the Christian world mainly through his Christian patrons. Due to the precarious position of Jews, some nobles could just ignore their debts. If the sponsoring noble died, his Jewish financier could face exile or execution.[citation needed]

Port Jews

[edit]The Port Jew is a descriptive term for Jews who were involved in the seafaring and maritime economy of Europe, especially during the 17th and 18th centuries. Helen Fry suggests that they can be considered "the earliest modern Jews". According to Fry, Port Jews frequently arrived as "refugees from the Inquisition" and the expulsion of Jews from Iberia. They were allowed to settle in port cities because merchants granted them permission to trade in ports such as Amsterdam, London, Trieste and Hamburg. Fry notes that their connections to the Jewish Diaspora and their expertise in maritime trade made them particularly valuable to the mercantilist governments of Europe.[157] Lois Dubin describes Port Jews as Jewish merchants who were "valued for their engagement in the international maritime trade upon which such cities thrived".[158] Sorkin and others have characterized the socio-cultural profile of these men as marked by a flexibility towards religion and a "reluctant cosmopolitanism that was alien to both traditional and 'enlightened' Jewish identities".

From the 16th to the 18th century, Jewish merchants dominated the chocolate and vanilla trade, exporting to Jewish centres across Europe, mainly Amsterdam, Bayonne, Bordeaux, Hamburg and Livorno.[159]

The Ottoman Empire

[edit]During the Classical Ottoman period (1300–1600), the Jews, together with most other communities of the empire, enjoyed a certain level of prosperity. Compared with other Ottoman subjects, they were the predominant power in commerce and trade as well in diplomacy and other high offices. In the 16th century especially, the Jews were the most prominent under the millets, the apogee of Jewish influence could arguably be the appointment of Joseph Nasi to Sanjak-bey (governor, a rank usually only bestowed upon Muslims) of the island of Naxos.[160]

At the time of the Battle of Yarmuk when the Levant passed under Muslim Rule, thirty Jewish communities existed in Haifa, Sh'chem, Hebron, Ramleh, Gaza, Jerusalem, and many in the north. Safed became a spiritual centre for the Jews and the Shulchan Aruch was compiled there as well as many Kabbalistic texts. The first Hebrew printing press, and the first printing in Western Asia began in 1577.

Jews lived in the geographic area of Asia Minor (modern Turkey, but more geographically either Anatolia or Asia Minor) for more than 2,400 years. Initial prosperity in Hellenistic times had faded under Christian Byzantine rule, but recovered somewhat under the rule of the various Muslim governments that displaced and succeeded rule from Constantinople. For much of the Ottoman period, Turkey was a safe haven for Jews fleeing persecution, and it continues to have a small Jewish population today. The situation where Jews both enjoyed cultural and economical prosperity at times but were widely persecuted at other times was summarised by G.E. Von Grunebaum :

It would not be difficult to put together the names of a very sizeable number of Jewish subjects or citizens of the Islamic area who have attained to high rank, to power, to great financial influence, to significant and recognized intellectual attainment; and the same could be done for Christians. But it would again not be difficult to compile a lengthy list of persecutions, arbitrary confiscations, attempted forced conversions, or pogroms.[161]

Poland

[edit]In the 17th century, there were many significant Jewish populations in Western and Central Europe. The relatively tolerant Poland had the largest Jewish population in Europe that dated back to 13th century and enjoyed relative prosperity and freedom for nearly four hundred years. However, the calm situation ended when Polish and Lithuanian Jews of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth were slaughtered in the hundreds of thousands by Ukrainian Cossacks during the Khmelnytsky Uprising (1648) and by the Swedish wars (1655). Driven by these and other persecutions, some Jews moved back to Western Europe in the 17th century, notably to Amsterdam. The last ban on Jewish residency in a European nation was revoked in 1654, but periodic expulsions from individual cities still occurred, and Jews were often restricted from land ownership, or forced to live in ghettos.

With the Partitions of Poland in the late 18th century, the Polish-Jewish population was split between the Russian Empire, Austria-Hungary, and German Prussia, which divided Poland among themselves.

The European Enlightenment and the Haskalah (18th century)

[edit]During the period of the European Renaissance and Enlightenment, significant changes occurred within the Jewish community. The Haskalah movement paralleled the wider Enlightenment, as Jews in the 18th century began to campaign for emancipation from restrictive laws and integration into the wider European society. Secular and scientific education was added to the traditional religious instruction received by students, and interest in a national Jewish identity, including a revival in the study of Jewish history and Hebrew, started to grow. Haskalah gave birth to the Reform and Conservative movements and planted the seeds of Zionism while at the same time encouraging cultural assimilation into the countries in which Jews resided. At around the same time another movement was born, one preaching almost the opposite of Haskalah, Hasidic Judaism. Hasidic Judaism began in the 18th century by Rabbi Israel Baal Shem Tov, and quickly gained a following with its more exuberant, mystical approach to religion. These two movements, and the traditional orthodox approach to Judaism from which they spring, formed the basis for the modern divisions within Jewish observance.

At the same time, the outside world was changing, and debates began over the potential emancipation of the Jews (granting them equal rights). The first country to do so was France, during the French Revolution in 1789. Even so, Jews were expected to assimilate, not continue their traditions. This ambivalence is demonstrated in the famous speech of Clermont-Tonnerre before the National Assembly in 1789:

We must refuse everything to the Jews as a nation and accord everything to Jews as individuals. We must withdraw recognition from their judges; they should only have our judges. We must refuse legal protection to the maintenance of the so-called laws of their Judaic organization; they should not be allowed to form in the state either a political body or an order. They must be citizens individually. But, some will say to me, they do not want to be citizens. Well then! If they do not want to be citizens, they should say so, and then, we should banish them. It is repugnant to have in the state an association of non-citizens, and a nation within the nation...

Hasidic Judaism

[edit]

Hasidic Judaism is a branch of Orthodox Judaism that promotes spirituality and joy through the popularisation and internalisation of Jewish mysticism as the fundamental aspects of the Jewish faith. Hasidism comprises part of contemporary Ultra-Orthodox Judaism, alongside the previous Talmudic Lithuanian-Yeshiva approach and the Oriental Sephardi tradition.

It was founded in 18th-century Eastern Europe by Rabbi Israel Baal Shem Tov as a reaction against overly legalistic Judaism. Opposite to this, Hasidic teachings cherished the sincerity and concealed holiness of the unlettered common folk, and their equality with the scholarly elite. The emphasis on the Immanent Divine presence in everything gave new value to prayer and deeds of kindness, alongside Rabbinic supremacy of study, and replaced historical mystical (kabbalistic) and ethical (musar) asceticism and admonishment with optimism, encouragement, and daily fervour. This populist emotional revival accompanied the elite ideal of nullification to paradoxical Divine Panentheism, through intellectual articulation of inner dimensions of mystical thought. The adjustment of Jewish values sought to add to required standards of ritual observance, while relaxing others where inspiration predominated. Its communal gatherings celebrate soulful song and storytelling as forms of mystical devotion.[citation needed]

The 19th century

[edit]

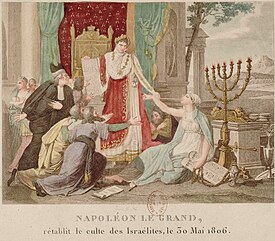

Though persecution still existed, emancipation spread throughout Europe in the 19th century. Napoleon invited Jews to leave the Jewish ghettos in Europe and seek refuge in the newly created tolerant political regimes that offered equality under Napoleonic Law (see Napoleon and the Jews). By 1871, with Germany's emancipation of Jews, every European country except Russia had emancipated its Jews.

Despite increasing integration of the Jews with secular society, a new form of antisemitism emerged, based on the ideas of race and nationhood rather than the religious hatred of the Middle Ages. This form of antisemitism held that Jews were a separate and inferior race from the Aryan people of Western Europe, and led to the emergence of political parties in France, Germany, and Austria-Hungary that campaigned on a platform of rolling back emancipation. This form of antisemitism emerged frequently in European culture, most famously in the Dreyfus Trial in France. These persecutions, along with state-sponsored pogroms in Russia in the late 19th century, led a number of Jews to believe that they would only be safe in their own nation. See Theodor Herzl and History of Zionism.

During this period, Jewish migration to the United States (see American Jews) created a large new community mostly freed of the restrictions of Europe. Over 2 million Jews arrived in the United States between 1890 and 1924, most from Russia and Eastern Europe. A similar case occurred in the southern tip of the continent, specifically in the countries of Argentina and Uruguay.

The 20th century

[edit]Modern Zionism

[edit]

During the 1870s and 1880s, the Jewish population in Europe began to more actively discuss emigration to Ottoman Syria with the aim of re-establishing a Jewish polity in Palestine and fulfilling the biblical prophecies related to Shivat Tzion. In 1882 the first Zionist settlement—Rishon LeZion—was founded by immigrants who belonged to the "Hovevei Zion" movement. Later on, the "Bilu" movement established many other settlements in Palestine.

The Zionist movement was officially founded after the Kattowitz convention (1884) and the World Zionist Congress (1897), and it was Theodor Herzl who initiated the struggle to establish a state for the Jews.

After the First World War, it seemed that the conditions that made it possible for the Jews to establish such a state had arrived: The United Kingdom captured Palestine from the Ottoman Empire, and the Jews received the promise of a "National Home" from the British in the form of the Balfour Declaration of 1917, given to Chaim Weizmann.

In 1920, the British Mandate of Palestine was established and the pro-Jewish Herbert Samuel was appointed High Commissioner of Palestine, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem was established and several large Jewish immigration waves to Palestine occurred. The Arab co-inhabitants of Palestine were hostile to increasing Jewish immigration, however, and as a result, they began to express their opposition to the establishment of Jewish settlements and they also began to express their opposition to the pro-Jewish policy of the British government in violent ways.

Arab gangs began to commit violent acts which included the murder of individual Jews, attacks on convoys and attacks on the Jewish population. After the 1920 Arab riots and the 1921 Jaffa riots, the Jewish leadership in Palestine believed that the British had no desire to confront local Arab gangs and punish them for their attacks on Palestinian Jews. Believing that they could not rely on the British administration for protection from these gangs, the Jewish leadership created the Haganah organization in order to protect its community's farms and Kibbutzim.

Major riots occurred during the 1929 Palestine riots and the 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine.

Due to the increasing violence, the United Kingdom gradually started to backtrack from its original idea of supporting the establishment of a Jewish homeland and it also started to speculate on a binational solution to the crisis or the establishment of an Arab state that would have a Jewish minority.

Meanwhile, the Jews of Europe and the United States gained success in the fields of science, culture and the economy. Among those Jews who were generally considered the most famous were the scientist Albert Einstein and the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein. At that time, a disproportionate number of Nobel Prize winners were Jewish, as is still the case.[16] In Russia, many Jews were involved in the October Revolution and belonged to the Communist Party.

The Holocaust

[edit]

In 1933, with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi party's rise to power in Germany, the Jewish situation became more severe. Economic crises, racial Anti-Jewish laws, and fear of an upcoming war led many Jews to flee from Europe and settle in Palestine, the United States and the Soviet Union.

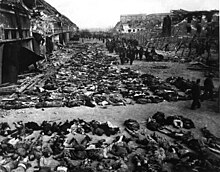

В 1939 году началась Вторая мировая война , и до 1945 года Германия оккупировала почти всю Европу , включая Польшу , где в то время жили миллионы евреев , и Францию . В 1941 году, после вторжения в Советский Союз , началось «Окончательное решение» — масштабная организованная операция беспрецедентного масштаба, направленная на уничтожение еврейского народа и приведшая к преследованию и убийству евреев в Европе, а также евреев. в европейской Северной Африке (пронацистское Виши — Северная Африка и итальянская Ливия ). Этот геноцид , в ходе которого около шести миллионов евреев были методично убиты с ужасающей жестокостью, известен как Холокост или Шоа (термин на иврите). В Польше около миллиона евреев были убиты в газовых камерах лагерного комплекса Освенцим .

Масштаб Холокоста и ужасы, произошедшие во время него, стали понятны только после войны, и они сильно повлияли на еврейскую нацию и мировое общественное мнение. Затем были активизированы усилия по созданию еврейского государства в Палестине.

Создание Государства Израиль

[ редактировать ]| История Израиля |

|---|

|

В 1945 году еврейские организации сопротивления в Палестине объединились и основали Еврейское движение сопротивления. Движение начало партизанские нападения на арабские военизированные формирования и британские власти. [163] [ нужен лучший источник ] После взрыва в отеле «Кинг Давид» Хаим Вейцман , президент ВСО , обратился к движению с призывом прекратить всю дальнейшую военную деятельность до тех пор, пока решение не будет принято Еврейским агентством . Еврейское агентство поддержало рекомендацию Вейцмана о прекращении деятельности, решение, которое неохотно приняла Хагана, но не Иргун и Лехи . JRM была распущена, и каждая из групп-основателей продолжила действовать в соответствии со своей собственной политикой. [164]

Еврейское руководство решило сосредоточить борьбу на нелегальной иммиграции в Палестину и без одобрения британских властей начало организовывать массовое количество еврейских военных беженцев из Европы. Эта иммиграция внесла большой вклад в еврейские поселения в Израиле в мировом общественном мнении, и британские власти решили позволить Организации Объединенных Наций решать судьбу Палестины. [ нужна ссылка ]

29 ноября 1947 года Генеральная Ассамблея ООН приняла резолюцию 181 (II), рекомендующую разделить Палестину на арабское государство, еврейское государство и город Иерусалим. Еврейское руководство приняло это решение, но против него выступили Лига арабских государств и руководство палестинских арабов. После периода гражданской войны началась арабо -израильская война 1948 года . [ нужна ссылка ]

В разгар войны, после того как последние британские солдаты палестинского мандата ушли, Давид Бен-Гурион провозгласил 14 мая 1948 года создание еврейского государства в Эрец Исраэль , которое будет известно как Государство Израиль . Война закончилась в 1949 году, и Израиль начал строить государство и поглощать огромные волны сотен тысяч евреев со всего мира, особенно из арабских стран .

С 1948 года Израиль участвовал в ряде крупных военных конфликтов, включая Суэцкий кризис 1956 года , Шестидневную войну 1967 года , Войну Судного дня 1973 года , Ливанскую войну 1982 года и Ливанскую войну 2006 года , а также почти постоянную серию продолжающихся военных конфликтов . мелкие конфликты .