Арт Деко

Возможно, эту статью необходимо реорганизовать, чтобы она соответствовала рекомендациям Википедии по оформлению . ( Август 2023 г. ) |

Сверху вниз: Крайслер-билдинг в Нью-Йорке (1930 г.); плакат для Всемирной выставки в Чикаго Веймера Перселла (1933 г.); и «Виктуар» орнамент на капоте Рене Лалика (1928). | |

| Годы активности | в. 1910–1950-е годы |

|---|---|

| Расположение | Глобальный |

Ар-деко , сокращение от французского декоративного искусства ( букв. « Декоративное искусство » ), [1] — стиль изобразительного искусства, архитектуры и дизайна изделий , впервые появившийся в Париже в 1910-х годах (незадолго до Первой мировой войны ), [2] и процветал в США и Европе в период с 1920-х по начало 1930-х годов. Благодаря стилю и дизайну экстерьера и интерьера чего-либо, от крупных построек до небольших предметов, включая внешний вид людей (одежды, моды и украшений), ар-деко оказал влияние на мосты, здания (от небоскребов до кинотеатров), корабли, океанские лайнеры , поезда, автомобили, грузовики, автобусы, мебель и предметы повседневного обихода, включая радиоприемники и пылесосы. [3]

Арт-деко получил свое название в честь Международной выставки современного декоративного и промышленного искусства 1925 года, проходившей в Париже . [4] Арт-деко берет свое начало в смелых геометрических формах венского сецессиона и кубизма . С самого начала на него повлияли яркие краски фовизма и Русского балета , а также экзотические стили искусства Китая , Японии , Индии , Персии , Древнего Египта и майя .

В период своего расцвета арт-деко олицетворял роскошь, гламур, изобилие и веру в социальный и технологический прогресс. В механизме использовались редкие и дорогие материалы, такие как черное дерево и слоновая кость, а также изысканное мастерство. Также были представлены новые материалы, такие как хромирование , нержавеющая сталь и пластик. В Нью-Йорке Эмпайр-стейт-билдинг , Крайслер-билдинг и другие здания 1920-х и 1930-х годов памятниками этого стиля являются .

В 1930-х годах, во время Великой депрессии , ар-деко постепенно становилось более приглушенным. Более изящная форма стиля, названная Streamline Moderne , появилась в 1930-х годах и отличалась изогнутыми формами и гладкими полированными поверхностями. [5] Арт-деко был поистине интернациональным стилем, но его доминирование закончилось с началом Второй мировой войны и возникновением строго функциональных и неприукрашенных стилей современной архитектуры и последовавшего за ней международного стиля архитектуры. [6] [7]

Этимология

[ редактировать ]Арт-деко получил свое название, сокращение от Arts Décoratifs , от Международной выставки современного декоративного и промышленного искусства, проходившей в Париже в 1925 году. [4] хотя разнообразные стили, характеризующие его, уже появились в Париже и Брюсселе еще до Первой мировой войны .

Декоративное искусство впервые было использовано во Франции в 1858 году в Бюллетене Французского общества фотографии . [8] В 1868 году газета Le Figaro использовала термин objets d'artdecoratifs для объектов сценических декораций, созданных для Театра оперы . [9] [10] [11] В 1875 году французское правительство официально присвоило статус художников дизайнерам мебели, текстильщикам, ювелирам, стекольщикам и другим мастерам. В ответ École royale gratuite de dessin (Королевская свободная школа дизайна), основанная в 1766 году при короле Людовике XVI для обучения художников и ремесленников ремеслам, связанным с изобразительным искусством, была переименована в Национальную школу декоративного искусства ( Национальную школу декоративного искусства). искусства). Свое нынешнее название, ENSAD ( Национальная школа декоративного искусства ), она получила в 1927 году.

Фактический термин «ар-деко» не появлялся в печати до 1966 года в названии первой современной выставки по этой теме, проведенной Музеем декоративного искусства в Париже, Les Années 25: Art déco, Bauhaus, Stijl, Esprit nouveau , которая охватывал множество основных стилей 1920-х и 1930-х годов. [12] Затем этот термин был использован в газетной статье Хиллари Гелсон в газете «Таймс» 1966 года (Лондон, 12 ноября), в которой описывались различные стили, представленные на выставке. [13]

Арт-деко получил признание как широко применяемый стилистический ярлык в 1968 году, когда историк Бевис Хиллиер опубликовал по нему первую крупную академическую книгу « Ар-деко 20-х и 30-х годов» . [3] Он отметил, что этот термин уже использовался арт-дилерами, и в качестве примеров приводит The Times (2 ноября 1966 г.) и эссе под названием Les Arts Déco в журнале Elle (ноябрь 1967 г.). [14] В 1971 году он организовал выставку в Институте искусств Миннеаполиса , о которой подробно рассказывает в своей книге «Мир ар-деко» . [15] [16]

В свое время арт-деко назывался другими названиями, такими как стиль модерн , модерн , модерн или стиль современности , и не был признан отдельным и однородным стилем. [7]

Происхождение

[ редактировать ]Новые материалы и технологии

[ редактировать ]Новые материалы и технологии, особенно железобетон , сыграли ключевую роль в развитии и появлении ар-деко. Первый бетонный дом был построен в 1853 году в пригороде Парижа Франсуа Куанье. В 1877 году Жозеф Монье предложил идею укрепления бетона сеткой из железных стержней в виде решеток. В 1893 году Огюст Перре построил в Париже первый бетонный гараж, затем жилой дом, дом, а затем, в 1913 году, Театр Елисейских полей . Один критик осудил театр как «Цеппелин с авеню Монтень», предполагаемое германское влияние, скопированное с Венского сецессиона . После этого большинство зданий в стиле ар-деко были построены из железобетона, что давало большую свободу форм и меньшую потребность в усилении опор и колонн. Перре также был пионером в покрытии бетона керамической плиткой как для защиты, так и для украшения. Архитектор Ле Корбюзье впервые узнал о применении железобетона, работая чертежником в студии Перре. [17]

Другими новыми технологиями, которые были важны для ар-деко, были новые методы производства листового стекла , которое было менее дорогим и позволяло создавать окна гораздо большего и прочного размера, а также массовое производство алюминия , который использовался для строительства и оконных рам, а позже, Корбюзье, Уоррен Макартур и другие за легкую мебель.

Венский сецессион и Wiener Werkstätte (1897–1912)

[ редактировать ]Архитекторы Венского сецессиона (основанного в 1897 году), особенно Йозеф Хоффманн , оказали заметное влияние на ар-деко. Его дворец Стокле в Брюсселе (1905–1911) был прототипом стиля ар-деко, отличавшегося геометрическими объемами, симметрией, прямыми линиями, бетоном, покрытым мраморными досками, изящным орнаментом и роскошными интерьерами, включая мозаичные фризы Густава . Климт . Хоффманн также был основателем Wiener Werkstätte (1903–1932), ассоциации мастеров и дизайнеров интерьеров, работающих в новом стиле. Это стало моделью для Compagnie des arts français , созданной в 1919 году и объединившей Андре Маре и Луи Сюэ , первых ведущих французских дизайнеров и декораторов в стиле ар-деко. [18]

- Церковь Святого Леопольда в Вене работы Отто Вагнера (1903–1907)

- Австрийский почтово-сберегательный банк в Вене работы Вагнера (1904–1912)

- Деталь фасада дворца Стокле, выполненного из железобетона и покрытого мраморными досками.

Общество художников-декораторов (1901–1945).

[ редактировать ]Возникновение ар-деко было тесно связано с повышением статуса художников-декораторов, которые до конца XIX века считались просто ремесленниками. Термин «декоративное искусство» был изобретен в 1875 году. [ нужна ссылка ] , давая дизайнерам мебели, текстиля и других украшений официальный статус. Société des Artistes Decorateurs (Общество художников-декораторов), или SAD, было основано в 1901 году, и художникам-декораторам были предоставлены те же права авторства, что и художникам и скульпторам. Подобное движение развилось в Италии. Первая международная выставка, полностью посвященная декоративному искусству, Esposizione Internazionale d'Arte Decorativa Moderna , прошла в Турине в 1902 году. В Париже было основано несколько новых журналов, посвященных декоративному искусству, в том числе Arts et Decoratione и L'Art Decoratif Moderne . Секции декоративного искусства были введены в ежегодных салонах Общества французских художников , а затем и в Осеннем салоне . Французский национализм также сыграл свою роль в возрождении декоративного искусства, поскольку французские дизайнеры почувствовали себя перед лицом растущего экспорта менее дорогой немецкой мебели. В 1911 году SAD предложил провести новую крупную международную выставку декоративного искусства в 1912 году. Никакие копии старых стилей не разрешались, только современные произведения. Выставку отложили до 1914 года; а затем, из-за войны, до 1925 года, когда он дал название целому семейству стилей, известных как «Деко». [19]

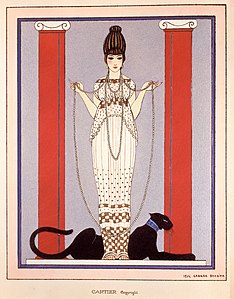

- Дама с пантерой работы Жоржа Барбье для Луи Картье (1914). На демонстрационном стенде, заказанном Cartier, изображена женщина в платье от Поля Пуаре .

Парижские универмаги и модельеры также сыграли важную роль в развитии ар-деко. Известные компании, такие как фирма по производству столового серебра Christofle , дизайнер стекла Рене Лалик и ювелиры Louis Cartier и Boucheron , начали разрабатывать продукцию в более современных стилях. [20] [21] Начиная с 1900 года универмаги нанимали художников-декораторов для работы в своих дизайнерских студиях. Оформление Осеннего салона 1912 года было поручено универмагу Printemps . [22] [23] и в том же году была создана собственная мастерская Primavera . [23] К 1920 году в Примавере работало более 300 художников, чьи стили варьировались от обновленных версий мебели Людовика XIV , Людовика XVI и особенно мебели Луи-Филиппа, созданной Луи Сюэ и мастерской Примавера , до более современных форм из мастерской Au Louvre универмага . Другие дизайнеры, в том числе Эмиль-Жак Рульманн и Поль Фолло, отказались от массового производства, настаивая на том, чтобы каждое изделие изготавливалось индивидуально. В раннем стиле ар-деко использовались роскошные и экзотические материалы, такие как черное дерево , слоновая кость и шелк, очень яркие цвета и стилизованные мотивы , особенно корзины и букеты цветов всех цветов, придающие модернистский вид. [24]

Осенний салон (1903–1914)

[ редактировать ]- Кресло в стиле ар-деко, сделанное для коллекционера Жака Дусе (1912–13).

- Демонстрация ранней мебели в стиле ар-деко от Atelier français на Осеннем салоне 1913 года из Art et Decoration (1914). журнала

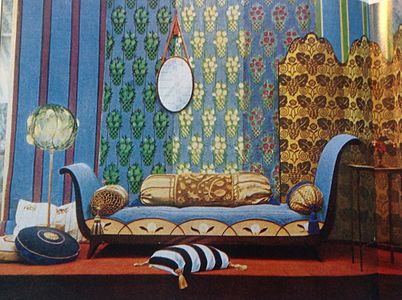

При своем зарождении между 1910 и 1914 годами арт-деко представлял собой взрыв красок с яркими и часто противоречивыми оттенками, часто с цветочным орнаментом, представленным в обивке мебели , коврах, ширмах, обоях и тканях. Множество красочных работ, в том числе стулья и стол Мориса Дюфрена и яркий гобеленовый ковер Поля Фолло, были представлены на Салоне художников-декораторов 1912 года . В 1912–1913 годах дизайнер Адриен Карбовски изготовил цветочное кресло с изображением попугая для охотничьего домика коллекционера произведений искусства Жака Дусе . [25] Дизайнеры мебели Луи Зюэ и Андре Маре впервые появились на выставке 1912 года под названием Atelier français , сочетая полихромные ткани с экзотическими и дорогими материалами, включая черное дерево и слоновую кость. После Первой мировой войны они стали одной из самых известных французских фирм по дизайну интерьеров, производящей мебель для первоклассных салонов и кают французских трансатлантических океанских лайнеров . [26]

Яркие оттенки ар-деко пришли из многих источников, в том числе из экзотических декораций Леона Бакста для «Русского балета» , которые произвели фурор в Париже незадолго до Первой мировой войны. Некоторые цвета были вдохновлены ранним движением фовизма , возглавляемым Анри Матисс ; другие - орфизмом таких художников, как Соня Делоне ; [27] другие - движением, известным как Les Nabis , и работами художника-символиста Одилона Редона, который создавал каминные перегородки и другие декоративные предметы. Яркие оттенки были особенностью творчества модельера Поля Пуаре , творчество которого повлияло как на моду ар-деко, так и на дизайн интерьера. [26] [28] [29]

Театр Елисейских полей (1910–1913)

[ редактировать ]- Театр Елисейских полей Огюста Перре на авеню Монтень, 15, Париж (1910–1913). Железобетон дал архитекторам возможность создавать новые формы и большие пространства.

- Ла Данс , барельеф на фасаде Театра Елисейских Полей работы Антуана Бурделя (1912)

- Интерьер Театра Елисейских Полей с барельефами Бурделя над сценой.

- Купол театра с розой в стиле ар-деко Мориса Дени.

Театр Елисейских Полей (1910–1913), построенный Огюстом Перре , был первым знаковым зданием в стиле ар-деко, построенным в Париже. Раньше железобетон использовался только для промышленных и жилых домов. Перре построил первый современный железобетонный жилой дом в Париже на улице Бенджамина Франклина в 1903–04 годах. Анри Соваж , еще один важный будущий архитектор в стиле ар-деко, построил еще один в 1904 году на улице Третень, 7 (1904). С 1908 по 1910 год 21-летний Ле Корбюзье работал чертежником в конторе Перре, изучая приемы бетонного строительства. Здание Перре имело чистую прямоугольную форму, геометрический декор и прямые линии — будущие отличительные черты ар-деко. Революционным было и оформление театра; фасад Кер был украшен горельефами Антуана Бурделя , куполом Мориса Дени , картинами Эдуарда Вюйяра и занавесом в стиле ар-деко -Ксавье Русселя . Театр стал местом проведения многих первых представлений « Русского балета». . [30] Перре и Соваж стали ведущими архитекторами ар-деко в Париже 1920-х годов. [31] [32]

Кубизм

[ редактировать ]- Дизайн фасада La Maison Cubiste ( Дом кубистов ) Раймона Дюшана-Вийона (1912 г.)

- Деталь входа в La Maison Cubiste на Осеннем салоне 1912 года.

- Le Salon Bourgeois , спроектированный Андре Маре внутри La Maison Cubiste , в разделе декоративного искусства Осеннего салона 1912 года. Метцингера . «Женщину с веером» На левой стене можно увидеть

- Кубистическая вилла на улице Либушина, 3-49, Вышеград ( Прага ), работы Йозефа Хохола (1912–13). Хохол был одним из трех чешских архитекторов (членов Союза изящных искусств Манеса ) вместе с Павлом Янаком и Йозефом Гочаром , испытавшими влияние кубизма.

Художественное движение, известное как кубизм, появилось во Франции между 1907 и 1912 годами, оказав влияние на развитие ар-деко. [30] [27] [28] В книге «Полное ар-деко: полное руководство по декоративному искусству 1920-х и 1930-х годов» Аластер Дункан пишет: «Кубизм, в той или иной уродливой форме, стал лингва-франка художников-декораторов той эпохи». [28] [33] Кубисты, сами под влиянием Поля Сезанна , были заинтересованы в упрощении форм до их геометрических основ: цилиндра, сферы, конуса. [34] [35]

В 1912 году художники Золотой секции выставили работы, значительно более доступные широкой публике, чем аналитический кубизм Пикассо и Брака. Кубистический словарь был готов привлечь дизайнеров моды, мебели и интерьеров. [27] [29] [35] [36]

В разделе Art Décoratif Осеннего салона 1912 года была выставлена архитектурная инсталляция, известная как La Maison Cubiste . [37] [38] Фасад был спроектирован Раймоном Дюшаном-Вийоном . Декор дома выполнил Андре Маре . [39] [40] La Maison Cubiste представлял собой меблированную инсталляцию с фасадом, лестницей, коваными перилами, спальней и гостиной — Салон «Буржуа» , где были представлены картины Альбера Глеза , Жана Метценже , Мари Лорансен , Марселя Дюшана , Фернана Леже и Роже де Ла. Френе повесили. [41] [42] [43] Тысячи зрителей в салоне прошли мимо полномасштабной модели. [44]

Фасад дома, спроектированный Дюшаном-Вийоном, по современным меркам не был очень радикальным; перемычки и фронтоны имели призматическую форму, но в остальном фасад напоминал обычный дом того периода. Для двух комнат Маре разработал обои со стилизованными розами и цветочными узорами, а также обивку, мебель и ковры с яркими и красочными мотивами. Это был явный отход от традиционного декора. Критик Эмиль Седейн описал работу Маре в журнале Art et Décoration : «Он не смущает себя простотой, ибо размножает цветы везде, где их можно поставить. Очевидно, он ищет эффекта живописности и веселья. Он достигает этого». [45] Кубистический элемент был представлен картинами. Некоторые критики раскритиковали инсталляцию как чрезвычайно радикальную, что способствовало ее успеху. [46] Эта архитектурная инсталляция впоследствии была выставлена на Оружейной выставке 1913 года в Нью-Йорке, Чикаго и Бостоне. [27] [35] [47] [48] [49] Во многом благодаря выставке термин «кубизм» стал применяться ко всему современному: от женских стрижек до одежды и театральных представлений». [46]

Влияние кубизма продолжалось в ар-деко, даже несмотря на то, что деко разветвлялось во многих других направлениях. [27] [28]

Намеченная геометрия кубизма стала монетой королевства в 1920-х годах. Развитие в ар-деко выборочной геометрии кубизма в более широком спектре форм привело кубизм как изобразительную таксономию к гораздо более широкой аудитории и более широкой привлекательности. (Ричард Харрисон Мартин, Метрополитен-музей) [50]

Влияния

[ редактировать ]Европейские стили до Первой мировой войны

[ редактировать ]- Влияние русского балета - Рисунок танцора Вацлава Нижинского парижского художника - модельера Жоржа Барбье (1913).

- Рококо – Комод работы Жака Дюбуа (1750–1755), различные породы дерева и крепления из позолоченной бронзы, поместье Уоддесдон , Бакингемшир , Великобритания.

- Влияние рококо - Комод Поля Ирибарна Гарая ( около 1912 г. ), каркас из красного дерева и тюльпана, столешница из сланца, шагреневая обивка зеленого оттенка, ручки из черного дерева, основание и гирлянды, Музей декоративного искусства , Париж.

- Влияние изящного искусства – Авеню Версаль №. 70-72, Париж, «Модерн» декор в устоявшейся типологии, спроектированный Полем Делапласом и созданный Жаном Буше (1928).

- Стиль Людовика XVI – Угловой стол, работа Жана-Франсуа-Терезы Шальгрена (1770 г.), позолоченное дерево, Галерея искусств Коркоран , Вашингтон, округ Колумбия

- Влияние стиля Людовика XVI - Туалетный столик и стул Поля Фолло (1919), инкрустированный мрамором и деревом, лакированный и позолоченный, Музей современного искусства Парижа .

- Неоклассические влияния - Прометей , стилизованное обновление классической скульптуры в стиле ар-деко работы Пола Мэншипа (1936), позолоченная бронза, Рокфеллер-центр , Нью-Йорк.

- Влияние модерна – Извилистые изгибы фасада Avenue Montaigne no. 26, Париж, Луи Дюэон и Марсель Жюльен (1937) [51]

Арт-деко представлял собой не единый стиль, а совокупность разных, порой противоречивых стилей. В архитектуре ар-деко был преемником (и реакцией на) модерна, стиля, который процветал в Европе между 1895 и 1900 годами и сосуществовал с изящными искусствами и неоклассикой , которые преобладали в европейской и американской архитектуре. В 1905 году Эжен Грассе написал и опубликовал «Метод декоративной композиции», «Элементы прямоугольных». [52] в котором он систематически исследовал декоративные (орнаментальные) аспекты геометрических элементов, форм, мотивов и их вариаций, в отличие (и как отход от) волнистого стиля модерн Эктора Гимара , столь популярного в Париже несколькими годами ранее. Грассе подчеркнул принцип, согласно которому различные простые геометрические формы, такие как треугольники и квадраты, являются основой всех композиционных аранжировок. Железобетонные здания Огюста Перре и Анри Соважа, и особенно Театр Елисейских Полей , предложили новую форму строительства и отделки, которая копировалась во всем мире. [53]

Древние и неевропейские цивилизации

[ редактировать ]- Древнеегипетское искусство – Растительные капители во дворе храма Исиды, Филе , Египет, неизвестный архитектор (380 г. до н.э. – 117 г. н.э.) [54] : 30

- Египетское влияние - Платье с цветами лотоса, вдохновленное древнеегипетскими украшениями, от Дженни (кутюрье) и Лесажа (вышивальщица) (1925), шелк, металлическая нить и вышивка, связанная крючком, Musée Galliera , Париж.

- Месопотамское искусство – Зиккурат Ура в Телль-эль-Мукайяре , провинция Ди-Кар , Ирак, неизвестный архитектор (21 век до н. э.) [55]

- Месопотамские влияния - Здание Western Union ( Гудзон-стрит, № 60) в Нью-Йорке , построенное Вурхисом, Гмелином и Уокером (1928–1930).

- Доколумбовое искусство (в данном случае майя ) – Яшчилан Линтел 24 (702 г. н. э.), известняк, Британский музей , Лондон [56]

- Доколумбовые влияния (в данном случае майя) – Деталь интерьера дома по адресу Саттер-стрит, 450 в Сан-Франциско , Калифорния , работы Тимоти Л. Пфлюгера (1929).

- к югу от Сахары Африка (в данном случае произведенная в Королевстве Куба на территории современной Демократической Республики Конго ) – Ндоп короля Мише миШьяанга МаМбула (1760–1780), дерево, Бруклинский музей , Нью-Йорк.

- Влияние Африки к югу от Сахары. Зима 1930 года, автор Леон Бениньи , холст, масло, частная коллекция.

В отделке было заимствовано и использовано множество различных стилей ар-деко. Они включали досовременное искусство со всего мира и можно было увидеть в Музее Лувра , Музее человека и Национальном музее искусств Африки и Океании . Был также популярный интерес к археологии в связи с раскопками в Помпеях , Трое и гробнице фараона 18-й династии Тутанхамона . Художники и дизайнеры объединили мотивы Древнего Египта , Африки , Месопотамии , Греции , Рима , Азии, Мезоамерики и Океании с элементами века машин . [57] [58] [59] [60] [61] [62]

Авангардные движения начала 20 века.

[ редактировать ]- Примитивизм – Голова женщины , картина Амедео Модильяни (1910–11), известняк, Национальная галерея искусств , Вашингтон, округ Колумбия.

- Влияния примитивизма – Бюст для витрины, анонимный бельгийский художник ( ок. 1920 ), роспись папье-маше , частное собрание, Кёльн , Германия

- Влияние Де Стиджа – «Павильон туризма» Роберта Малле-Стивенса , Международная выставка современного декоративного и промышленного искусства , Париж (1925). [64]

- Кубизм – Фигура в кресле (Сидящая обнаженная) , Пабло Пикассо (1909–10), холст, масло, Tate Modern , Лондон

- Влияния кубизма - Кубический кофейный сервиз работы Эрика Магнуссена (1927), серебро, на временной выставке под названием « Эпоха джаза » в Кливлендском художественном музее , США.

- Конструктивизм — Красными клиньями бейте белых , Эль Лисицкий (1919–1920), литографический плакат, Российская государственная библиотека , Москва

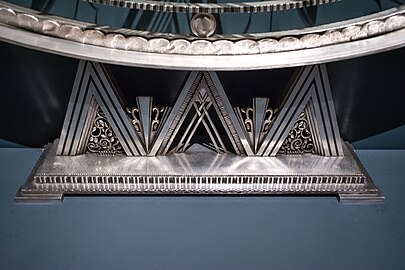

- Влияния конструктивизма - Часы, украшенные плоскими геометрическими фигурами, работы Джина Гулдена (1928), посеребренная бронза с эмалью, Коллекция Стивена Э. Келли. [65]

- Влияние экспрессионистского театра и кино - Интерьер театра Аполло-Виктория в Лондоне, Эрнест Уомсли Льюис (1928–1930). [66]

- Футуризм – Лестничный дом с лифтами с четырех уровней улицы, часть La Città Nuova , автор Антонио Сант'Элия (1914), бумага, тушь и карандаш, Musei Civici, Комо , Италия [67]

- Футуристические влияния – Rue du Laos no. 25 в Париже, Чарльз Томас (1930) [67]

- Экспрессионистская архитектура - Здание типографии и издательства Рудольфа Моссе в Берлине , работы Эриха Мендельсона (1921–1923). [68]

- Влияние экспрессионистской архитектуры - Aux Trois-Quartiers универмаг в Париже, Луи Фор-Дюжаррик (1932). [68]

Другие заимствованные стили включали футуризм , орфизм, функционализм и модернизм в целом. Кубизм раскрывает свой декоративный потенциал в эстетике ар-деко, когда он переносится с холста на текстильный материал или обои. Соня Делоне представляет свои модели платьев в абстрактном и геометрическом стиле, «как живые картины или скульптуры живых форм». Кубистические узоры созданы Луи Барриле в витражах американского бара казино «Атриум» в Даксе (1926 г.), но также включают названия модных коктейлей. В архитектуре четкий контраст между горизонтальными и вертикальными объемами, характерный как для русского конструктивизма , так и для линии Фрэнка Ллойда Райта - Виллема Маринуса Дудока , становится распространенным приемом при создании фасадов в стиле ар-деко, от отдельных домов и многоквартирных домов до кинотеатров или нефтяных станций. [69] [35] [57] [70] [71] Ар-деко также использовал противоречивые цвета и дизайн фовизма, особенно в работах Анри Матисса и Андре Дерена , вдохновлял дизайн текстиля, обоев и расписной керамики в стиле ар-деко. [35] Он взял идеи из словаря высокой моды того периода, который включал геометрические узоры, шевроны, зигзаги и стилизованные букеты цветов. На него повлияли открытия в египтологии и растущий интерес к Востоку и африканскому искусству. Начиная с 1925 года, его часто вдохновляла страсть к новым машинам, таким как дирижабли, автомобили и океанские лайнеры, и к 1930 году это влияние привело к появлению стиля под названием Streamline Moderne . [72]

Международная выставка современного декоративного и промышленного искусства (1925).

[ редактировать ]- Открытка Международной выставки современного декоративного и промышленного искусства в Париже (1925 г.)

- Вход на выставку 1925 года с площади Согласия, автор Пьер Пату.

- Польский павильон, спроектированный Юзефом Чайковским и Войцехом Ястшембовским.

- Павильон Галери Лафайет универмага

- Салон Hôtel du Collectionneur, оформленный Эмилем-Жаком Рульманом , картина Жана Дюпа , дизайн Пьера Пату.

Событием, которое ознаменовало зенит стиля и дало ему название, стала Международная выставка современного декоративного и промышленного искусства , которая проходила в Париже с апреля по октябрь 1925 года. Она официально спонсировалась французским правительством и охватывала территорию в Париж площадью 55 акров, простирающийся от Гран-Пале на правом берегу до Дома Инвалидов на левом берегу и вдоль берегов Сены. Гран-Пале, самый большой зал города, был заполнен экспонатами декоративного искусства стран-участниц. В выставке приняли участие 15 000 экспонентов из двадцати разных стран, включая Австрию, Бельгию, Чехословакию, Данию, Великобританию, Италию, Японию, Нидерланды, Польшу, Испанию, Швецию и новый Советский Союз . Германию не пригласили из-за напряженности после войны; Соединенные Штаты, неправильно поняв цель выставки, отказались от участия. За семь месяцев мероприятие посетили шестнадцать миллионов человек. Правила выставки требовали, чтобы все работы были современными; никакие исторические стили не допускались. Основной целью выставки было продвижение французских производителей элитной мебели, фарфора, стекла, металлоконструкций, текстиля и других декоративных изделий. Для дальнейшего продвижения продукции все крупные универмаги Парижа и крупные дизайнеры имели собственные павильоны. У выставки была второстепенная цель - продвигать продукцию из французских колоний в Африке и Азии, в том числе слоновую кость и экзотические породы дерева.

Отель du Collectionneur был популярной достопримечательностью на выставке; на нем были представлены новые дизайны мебели Эмиля-Жака Рульмана, а также ткани, ковры и ковры в стиле ар-деко, а также картины Жана Дюпа . Дизайн интерьера следовал тем же принципам симметрии и геометрических форм, которые отличали его от модерна, а яркие цвета, тонкое мастерство, редкие и дорогие материалы отличали его от строгой функциональности модерна. В то время как большинство павильонов были богато украшены и наполнены роскошной мебелью ручной работы, два павильона, Советского Союза и Павильон « Дух модерн» , построенный одноименным журналом, которым руководил Ле Корбюзье, были построены в строгом стиле. стиль с простыми белыми стенами и без декора; они были одними из самых ранних примеров модернистской архитектуры . [73]

Late Art Deco

[ редактировать ]- Piața Sfântul Ștefan no. 1 in Bucharest, by unknown architect (c. 1930)

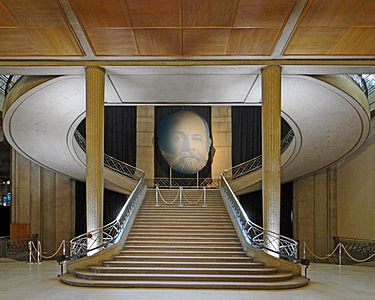

- Stairway of the Economic and Social Council in Paris, originally the Museum of Public Works, built for the 1937 Exposition, by Auguste Perret (1937)

- High School in King City, California, built by Robert Stanton for the Works Progress Administration (1939)

In 1925, two different competing schools coexisted within Art Deco: the traditionalists, who had founded the Society of Decorative Artists; included the furniture designer Emile-Jacques Ruhlmann, Jean Dunand, the sculptor Antoine Bourdelle, and designer Paul Poiret; they combined modern forms with traditional craftsmanship and expensive materials. On the other side were the modernists, who increasingly rejected the past and wanted a style based upon advances in new technologies, simplicity, a lack of decoration, inexpensive materials, and mass production. The modernists founded their own organisation, The French Union of Modern Artists, in 1929. Its members included architects Pierre Chareau, Francis Jourdain, Robert Mallet-Stevens, Corbusier, and, in the Soviet Union, Konstantin Melnikov; the Irish designer Eileen Gray; the French designer Sonia Delaunay; and the jewellers Georges Fouquet and Jean Puiforcat. They fiercely attacked the traditional art deco style, which they said was created only for the wealthy, and insisted that well-constructed buildings should be available to everyone, and that form should follow function. The beauty of an object or building resided in whether it was perfectly fit to fulfil its function. Modern industrial methods meant that furniture and buildings could be mass-produced, not made by hand.[74][75][page needed]

The Art Deco interior designer Paul Follot defended Art Deco in this way: "We know that man is never content with the indispensable and that the superfluous is always needed...If not, we would have to get rid of music, flowers, and perfumes..!"[76] However, Le Corbusier was a brilliant publicist for modernist architecture; he stated that a house was simply "a machine to live in", and tirelessly promoted the idea that Art Deco was the past and modernism was the future. Le Corbusier's ideas were gradually adopted by architecture schools, and the aesthetics of Art Deco were abandoned. The same features that made Art Deco popular in the beginning, its craftsmanship, rich materials and ornament, led to its decline. The Great Depression that began in the United States in 1929, and reached Europe shortly afterwards, greatly reduced the number of wealthy clients who could pay for the furnishings and art objects. In the Depression economic climate, few companies were ready to build new skyscrapers.[35] Even the Ruhlmann firm resorted to producing pieces of furniture in series, rather than individual hand-made items. The last buildings built in Paris in the new style were the Museum of Public Works by Auguste Perret (now the French Economic, Social and Environmental Council), the Palais de Chaillot by Louis-Hippolyte Boileau, Jacques Carlu and Léon Azéma, and the Palais de Tokyo of the 1937 Paris International Exposition; they looked out at the grandiose pavilion of Nazi Germany, designed by Albert Speer, which faced the equally grandiose socialist-realist pavilion of Stalin's Soviet Union.

After World War II, the dominant architectural style became the International Style pioneered by Le Corbusier, and Mies van der Rohe. A handful of Art Deco hotels were built in Miami Beach after World War II, but elsewhere the style largely vanished, except in industrial design, where it continued to be used in automobile styling and products such as jukeboxes. In the 1960s, it experienced a modest academic revival, thanks in part to the writings of architectural historians such as Bevis Hillier. In the 1970s efforts were made in the United States and Europe to preserve the best examples of Art Deco architecture, and many buildings were restored and repurposed. Postmodern architecture, which first appeared in the 1980s, like Art Deco, often includes purely decorative features.[35][57][77][78] Deco continues to inspire designers, and is often used in contemporary fashion, jewellery, and toiletries.[79]

Painting

[edit]- Workers sorting the mail, a mural in the Ariel Rios Federal Building, Washington, D.C., by Reginald Marsh (1936)

- Art in the Tropics, mural in the William Jefferson Clinton Federal Building, Washington, D.C., by Rockwell Kent (1938)

- Detail of Time, ceiling mural in lobby of 30 Rockefeller Plaza in New York City, by Josep Maria Sert (1941)

There was no section set aside for painting at the 1925 Exposition. Art deco painting was by definition decorative, designed to decorate a room or work of architecture, so few painters worked exclusively in the style, but two painters are closely associated with Art Deco. Jean Dupas painted Art Deco murals for the Bordeaux Pavilion at the 1925 Decorative Arts Exposition in Paris, and also painted the picture over the fireplace in the Maison du Collectionneur exhibit at the 1925 Exposition, which featured furniture by Ruhlmann and other prominent Art Deco designers. His murals were also prominent in the décor of the French ocean liner SS Normandie. His work was purely decorative, designed as a background or accompaniment to other elements of the décor.[80]

The other painter closely associated with the style is Tamara de Lempicka. Born in Poland, she emigrated to Paris after the Russian Revolution. She studied under Maurice Denis and André Lhote, and borrowed many elements from their styles. She painted portraits in a realistic, dynamic and colourful Art Deco style.[81]

In the 1930s, a dramatic new form of Art Deco painting appeared in the United States. During the Great Depression, the Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration was created to give work to unemployed artists. Many were given the task of decorating government buildings, hospitals and schools. There was no specific art deco style used in the murals; artists engaged to paint murals in government buildings came from many different schools, from American regionalism to social realism; they included Reginald Marsh, Rockwell Kent and the Mexican painter Diego Rivera. The murals were Art Deco because they were all decorative and related to the activities in the building or city where they were painted: Reginald Marsh and Rockwell Kent both decorated U.S. postal buildings, and showed postal employees at work while Diego Rivera depicted automobile factory workers for the Detroit Institute of Arts. Diego Rivera's mural Man at the Crossroads (1933) for 30 Rockefeller Plaza featured an unauthorized portrait of Lenin.[82][83] When Rivera refused to remove Lenin, the painting was destroyed and a new mural was painted by the Spanish artist Josep Maria Sert.[84][85][86]

Sculpture

[edit]Monumental and public sculpture

[edit]- Christ the Redeemer, reinforced concrete and soapstone sculpture on Corcovado Mountain, Rio de Janeiro, by Paul Landowski (1931)

- Guardians of Traffic, pylon on Hope Memorial Bridge in Cleveland, Ohio, by Henry Hering and Frank Walker (1932)

- Britain, relief sculpture in the lobby of the former Daily Express Building in London, by Ronald Atkinson (1932)

- Spirit of Light or Spirit of Power, metal sculpture on the façade of the Niagara Mohawk Building in Syracuse, N.Y., by Clayton Frye (1932)

- Polish coat of arms (unofficial) on the façade of the post office in Warsaw, by Julian Puterman-Sadłowski (1934)

- Atlas, bronze sculpture in front of the Rockefeller Center, by Lawrie (1936–37)

- Mail Delivery East, one of four bas-relief sculptures on the Nix Federal Building in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, by Edmond Amateis (1937)

- Man Controlling Trade at the Federal Trade Commission Building in Washington, D.C., by Michael Lantz (1942)

Sculpture was a very common and integral feature of Art Deco architecture. In France, allegorical bas-reliefs representing dance and music by Antoine Bourdelle decorated the earliest Art Deco landmark in Paris, the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, in 1912. The 1925 Exposition had major sculptural works placed around the site, pavilions were decorated with sculptural friezes, and several pavilions devoted to smaller studio sculpture. In the 1930s, a large group of prominent sculptors made works for the 1937 Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne at Chaillot. Alfred Janniot made the relief sculptures on the façade of the Palais de Tokyo. The Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, and the esplanade in front of the Palais de Chaillot, facing the Eiffel Tower, was crowded with new statuary by Charles Malfray, Henry Arnold, and many others.[87]

Public art deco sculpture was almost always representational, usually of heroic or allegorical figures related to the purpose of the building or room. The themes were usually selected by the patrons, not the artist. Abstract sculpture for decoration was extremely rare.[88][89]

In the United States, the most prominent Art Deco sculptor for public art was Paul Manship, who updated classical and mythological subjects and themes in an Art Deco style. His most famous work was the statue of Prometheus at Rockefeller Center in New York City, a 20th-century adaptation of a classical subject. Other important works for Rockefeller Center were made by Lee Lawrie, including the sculptural façade and the Atlas statue.

During the Great Depression in the United States, many sculptors were commissioned to make works for the decoration of federal government buildings, with funds provided by the WPA, or Works Progress Administration. They included sculptor Sidney Biehler Waugh, who created stylized and idealized images of workers and their tasks for federal government office buildings.[90] In San Francisco, Ralph Stackpole provided sculpture for the façade of the new San Francisco Stock Exchange building. In Washington D.C., Michael Lantz made works for the Federal Trade Commission building.

In Britain, Deco public statuary was made by Eric Gill for the BBC Broadcasting House, while Ronald Atkinson decorated the lobby of the former Daily Express Building in London (1932).

One of the best known and certainly the largest public Art Deco sculpture is the Christ the Redeemer by the French sculptor Paul Landowski, completed between 1922 and 1931, located on a mountain top overlooking Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Studio sculpture

[edit]- Tête (front and side view), limestone, by Joseph Csaky (c. 1920), Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands

- The Hunter by Pierre Le Faguays (1920s)

- Actaeon by Paul Manship (1925), in a temporary exhibition called the "Jazz Age" at the Cleveland Museum of Art, US

- Speed, a design for a radiator ornament by Harriet Whitney Frishmuth (1925)

- The Flight of Europa, bronze with gold leaf, by Paul Manship (1925), Whitney Museum of American Art, New York City

- Tânără (Girl), bronze, ivory and onyx, by Demétre Chiparus (c. 1925)

- Dansatoare (Dancer), bronze and ivory, by Chiparus (c. 1925)

Many early Art Deco sculptures were small, designed to decorate salons. One genre of this sculpture was called the Chryselephantine statuette, named for a style of ancient Greek temple statues made of gold and ivory. They were sometimes made of bronze, or sometimes with much more lavish materials, such as ivory, onyx, alabaster, and gold leaf.

One of the best-known Art Deco salon sculptors was the Romanian-born Demétre Chiparus, who produced colourful small sculptures of dancers. Other notable salon sculptors included Ferdinand Preiss, Josef Lorenzl, Alexander Kelety, Dorothea Charol and Gustav Schmidtcassel.[91] Another important American sculptor in the studio format was Harriet Whitney Frishmuth, who had studied with Auguste Rodin in Paris.

Pierre Le Paguays was a prominent Art Deco studio sculptor, whose work was shown at the 1925 Exposition. He worked with bronze, marble, ivory, onyx, gold, alabaster and other precious materials.[92]

François Pompon was a pioneer of modern stylised animalier sculpture. He was not fully recognised for his artistic accomplishments until the age of 67 at the Salon d'Automne of 1922 with the work Ours blanc, also known as The White Bear, now in the Musée d'Orsay in Paris.[93]

Parallel with these Art Deco sculptors, more avant-garde and abstract modernist sculptors were at work in Paris and New York City. The most prominent were Constantin Brâncuși, Joseph Csaky, Alexander Archipenko, Henri Laurens, Jacques Lipchitz, Gustave Miklos, Jean Lambert-Rucki, Jan et Joël Martel, Chana Orloff and Pablo Gargallo.[94]

Graphic arts

[edit]- Program design for Afternoon of a Faun by Léon Bakst for Ballets Russes (1912)

- Deutscher Werkbund exhibition poster by Peter Behrens (1914)

- A Vanity Fair cover by Georges Lepape (1919)

- Interpretation of Harlem Jazz I by Winold Reiss (c. 1920)

- Cover of Harper's Bazaar by Erté (1922)

- London Underground poster by Horace Taylor (1924)

- Moulin Rouge poster by Charles Gesmar (1925)

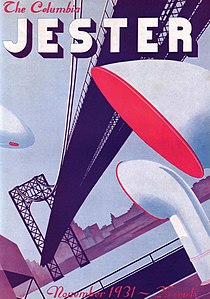

The Art Deco style appeared early in the graphic arts, in the years just before World War I. It appeared in Paris in the posters and the costume designs of Léon Bakst for the Ballets Russes, and in the catalogues of the fashion designers Paul Poiret.[95] The illustrations of Georges Barbier, and Georges Lepape and the images in the fashion magazine La Gazette du bon ton perfectly captured the elegance and sensuality of the style. In the 1920s, the look changed; the fashions stressed were more casual, sportive and daring, with the woman models usually smoking cigarettes. American fashion magazines such as Vogue, Vanity Fair and Harper's Bazaar quickly picked up the new style and popularized it in the United States. It also influenced the work of American book illustrators such as Rockwell Kent. In Germany, the most famous poster artist of the period was Ludwig Hohlwein, who created colourful and dramatic posters for music festivals, beers, and, late in his career, for the Nazi Party.[96]

During the Art Nouveau period, posters usually advertised theatrical products or cabarets. In the 1920s, travel posters, made for steamship lines and airlines, became extremely popular. The style changed notably in the 1920s, to focus attention on the product being advertised. The images became simpler, precise, more linear, more dynamic, and were often placed against a single-color background. In France, popular Art Deco designers included Charles Loupot and Paul Colin, who became famous for his posters of American singer and dancer Josephine Baker. Jean Carlu designed posters for Charlie Chaplin movies, soaps, and theatres; in the late 1930s he emigrated to the United States, where, during the World War, he designed posters to encourage war production. The designer Charles Gesmar became famous making posters for the singer Mistinguett and for Air France. Among the best-known French Art Deco poster designers was Cassandre, who made the celebrated poster of the ocean liner SS Normandie in 1935.[96]

In the 1930s a new genre of posters appeared in the United States during the Great Depression. The Federal Art Project hired American artists to create posters to promote tourism and cultural events.

Architecture

[edit]- Church of St. Joan of Arc in Nice, France, by Jacques Droz (1934)

- National Diet Building in Tokyo, after a design by Watanabe Fukuzo (1936)

Styles

[edit]The architectural style of art deco made its debut in Paris in 1903–04, with the construction of two apartment buildings in Paris, one by Auguste Perret on rue Benjamin Franklin and the other on rue Trétaigne by Henri Sauvage. The two young architects used reinforced concrete for the first time in Paris residential buildings; the new buildings had clean lines, rectangular forms, and no decoration on the façades; they marked a clean break with the art nouveau style.[97] Between 1910 and 1913, Perret used his experience in concrete apartment buildings to construct the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, 15 avenue Montaigne. Between 1925 and 1928 Sauvage constructed the new art deco façade of La Samaritaine department store in Paris.[98]

The Art Deco style was not limited to buildings on land; the ocean liner SS Normandie, whose first voyage was in 1935, featured Art Deco design, including a dining room whose ceiling and decoration were made of glass by Lalique.[99]

Art Deco architecture is sometimes classified into three types: Zigzag [Moderne] (aka Jazz Moderne[100]); Classic Moderne; and Streamline Moderne.[101]

Zigzag Moderne

[edit]Zigzag Moderne (aka Jazz Moderne) was the first style to arrive in the United States. "Zigzag" refers to the stepping of the outline of a skyscraper to exaggerate its height,[101][100] and was mainly used for large public and commercial buildings, in particular hotels, movie theaters, restaurants, skyscrapers, and department stores.[102]

Classic Moderne

[edit]Classic Moderne has a more graceful appearance, and there is less ornamentation. Classic Moderne is also sometimes referred to as PWA (Public Works Administration) Moderne or Depression Moderne, as it was undertaken by the PWA during the Great Depression.[102][100][101]

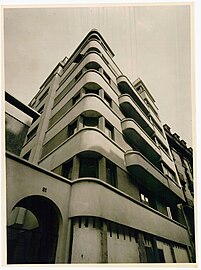

Streamline Moderne

[edit]In the late 1930s, a new variety of Art Deco architecture became common; it was called Streamline Moderne or simply Streamline, or, in France, the Style Paquebot, or Ocean Liner style. Buildings in the style had rounded corners and long horizontal lines; they were built of reinforced concrete and were almost always white; and they sometimes had nautical features, such as railings and portholes that resembled those on a ship. The rounded corner was not entirely new; it had appeared in Berlin in 1923 in the Mossehaus by Erich Mendelsohn, and later in the Hoover Building, an industrial complex in the London suburb of Perivale. In the United States, it became most closely associated with transport; Streamline moderne was rare in office buildings but was often used for bus stations and airport terminals, such as the terminal at La Guardia airport in New York City that handled the first transatlantic flights, via the PanAm Clipper flying boats; and in roadside architecture, such as gas stations and diners. In the late 1930s a series of diners, modelled upon streamlined railroad cars, were produced and installed in towns in New England; at least two examples still remain and are now registered historic buildings.[103]

- The nautical-style rounded corner of Broadcasting House in London (1931)

- Building in the Paquebot or ocean liner style, at 3, boulevard Victor, Paris, by Pierre Patout (1935)

- The Marine Air Terminal at La Guardia Airport (1937) was New York City's terminal for the flights of Pan Am Clipper flying boats to Europe.

- The Hoover Building canteen in Perivale in London's suburbs, by Wallis, Gilbert and Partners (1938)

- Former Belgian National Institute of Radio Broadcasting in Ixelles (Brussels) by Joseph Diongre (1938)

- The Ford Pavilion at the 1939 New York World's Fair

- Streamline Moderne church, First Church of Deliverance in Chicago, Illinois, by Walter T. Bailey (1939). Towers added in 1948.

Building types

[edit]Skyscrapers

[edit]- Chrysler Building in New York City by William Van Alen (1930)

- Empire State Building in New York City by Shreve, Lamb & Harmon (1931)

- Crown of the General Electric Building (also known as 570 Lexington Avenue) in New York City by Cross & Cross (1933)

- 30 Rockefeller Plaza, now the Comcast Building, in New York City by Raymond Hood (1933)

American skyscrapers marked the summit of the Art Deco style; they became the tallest and most recognizable modern buildings in the world. They were designed to show the prestige of their builders through their height, their shape, their color, and their dramatic illumination at night.[104] The American Radiator Building by Raymond Hood (1924) combined Gothic and Deco modern elements in the design of the building. Black brick on the frontage of the building (symbolizing coal) was selected to give an idea of solidity and to give the building a solid mass. Other parts of the façade were covered in gold bricks (symbolizing fire), and the entry was decorated with marble and black mirrors. Another early Art Deco skyscraper was Detroit's Guardian Building, which opened in 1929. Designed by modernist Wirt C. Rowland, the building was the first to employ stainless steel as a decorative element, and the extensive use of colored designs in place of traditional ornaments.

New York City's skyline was radically changed by the Chrysler Building in Manhattan (completed in 1930), designed by William Van Alen. It was a giant seventy-seven-floor tall advertisement for Chrysler automobiles. The top was crowned by a stainless steel spire, and was ornamented by deco "gargoyles" in the form of stainless steel radiator cap decorations. The base of the tower, thirty-three stories above the street, was decorated with colorful art deco friezes, and the lobby was decorated with art deco symbols and images expressing modernity.[105]

The Chrysler Building was soon surpassed in height by the Empire State Building by William F. Lamb (1931), in a slightly less lavish Deco style and the RCA Building (now 30 Rockefeller Plaza) by Raymond Hood (1933) which together completely changed New York City's skyline. The tops of the buildings were decorated with Art Deco crowns and spires covered with stainless steel, and, in the case of the Chrysler building, with Art Deco gargoyles modeled after radiator ornaments, while the entrances and lobbies were lavishly decorated with Art Deco sculpture, ceramics, and design. Similar buildings, though not quite as tall, soon appeared in Chicago and other large American cities. Rockefeller Center added a new design element: several tall buildings grouped around an open plaza, with a fountain in the middle.[106]

"Cathedrals of Commerce"

[edit]- Lower lobby of the Guardian Building in Detroit by Wirt Rowland (1929)

- Interior door in the Chrysler Building (1930)

- Ceiling and chandelier detail on the lobby of the Carew Tower in Cincinnati, Ohio, by Walter W. Ahlschlager (1930)

- Salon d'Afrique of the Palais de la Porte Dorée in Paris, with furnitures by Jacques-Emile Ruhlmann and frescos by Louis Bouquet (1931)

- Foyer of the Tuschinski Theatre in Amsterdam by Hijman Louis de Jong (1921)

The grand showcases of American Art Deco interior design were the lobbies of government buildings, theaters, and particularly office buildings. Interiors were extremely colorful and dynamic, combining sculpture, murals, and ornate geometric design in marble, glass, ceramics and stainless steel. An early example was the Fisher Building in Detroit, by Joseph Nathaniel French; the lobby was highly decorated with sculpture and ceramics. The Guardian Building (originally the Union Trust Building) in Detroit, by Wirt Rowland (1929), decorated with red and black marble and brightly colored ceramics, highlighted by highly polished steel elevator doors and counters. The sculptural decoration installed in the walls illustrated the virtues of industry and saving; the building was immediately termed the "Cathedral of Commerce". The Medical and Dental Building called 450 Sutter Street in San Francisco by Timothy Pflueger was inspired by Mayan architecture, in a highly stylized form; it used pyramid shapes, and the interior walls were covered with highly stylized rows of hieroglyphs.[107]

In France, the best example of an Art Deco interior during this period was the Palais de la Porte Dorée (1931) by Albert Laprade, Léon Jaussely and Léon Bazin. The building (now the National Museum of Immigration, with an aquarium in the basement) was built for the Paris Colonial Exposition of 1931, to celebrate the people and products of French colonies. The exterior façade was entirely covered with sculpture, and the lobby created an Art Deco harmony with a wood parquet floor in a geometric pattern, a mural depicting the people of French colonies; and a harmonious composition of vertical doors and horizontal balconies.[107]

Movie palaces

[edit]- Tuschinski Theatre in Amsterdam by Hijman Louis de Jong and Willem Kromhout (1921)

- Four-story high grand lobby of the Paramount Theatre in Oakland, California, by Timothy Pflueger (1932)

- Auditorium and stage of Radio City Music Hall in New York City by Edward Durell Stone and Donald Deskey (1932)

- Grand Rex in Paris by Auguste Bluysen, John Eberson, Henri-Édouard Navarre and Maurice Dufrêne (1932)

Many of the best surviving examples of Art Deco are cinemas built in the 1920s and 1930s. The Art Deco period coincided with the conversion of silent films to sound, and movie companies built large display destinations in major cities to capture the huge audience that came to see movies. Movie palaces in the 1920s often combined exotic themes with art deco style; Grauman's Egyptian Theatre in Hollywood (1922) was inspired by ancient Egyptian tombs and pyramids, while the Fox Theater in Bakersfield, California attached a tower in California Mission style to an Art Deco Hall. The largest of all is Radio City Music Hall in New York City, which opened in 1932. Originally designed as theatrical performance space, it quickly transformed into a cinema, which could seat 6,015 customers. The interior design by Donald Deskey used glass, aluminum, chrome, and leather to create a visual escape from reality. The Paramount Theatre in Oakland, California, by Timothy Pflueger, had a colorful ceramic façade, a lobby four stories high, and separate Art Deco smoking rooms for gentlemen and ladies. Similar grand palaces appeared in Europe. The Grand Rex in Paris (1932), with its imposing tower, was the largest cinema in Europe after the 6,000 seats of the Gaumont-Palace (1931–1973). The Gaumont State Cinema in London (1937) had a tower modelled on the Empire State building, covered with cream ceramic tiles and an interior in an Art Deco-Italian Renaissance style. The Paramount Theatre in Shanghai, China (1933) was originally built as a dance hall called The gate of 100 pleasures; it was converted to a cinema after the Communist Revolution in 1949, and now is a ballroom and disco. In the 1930s Italian architects built a small movie palace, the Cinema Impero, in Asmara in what is now Eritrea. Today, many of the movie theatres have been subdivided into multiplexes, but others have been restored and are used as cultural centres in their communities.[108]

Decoration and motifs

[edit]- Birds – Quai d'Orsay no. 55 in Paris, designed by Louis-Hippolyte Boileau and carved by Léon Binet (1913)

- Stylized flowers (especially spiral flowers and converging fascicles) – Architectural element for the Parfumerie d'Orsay in Paris, by Georges Béal (1922)

- The urn – Corner cabinet made of mahogany with rose basket design of inlaid ivory, by Jacques-Émile Ruhlmann (1923), Brooklyn Museum, New York City

- The flower basket – Balconies and pediment of Avenue Montaigne no. 41 in Paris, unknown architect or sculptor (1924)[109]

- Repeating patterns – Decorative ironwork of the Madison Belmont Building (Madison Avenue no. 181–183) in New York City, by Ferrobrandt (1925)[110]

- The papyrus flower – Porte d'honneur, at the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris, by Edgar Brandt (1925)[111]

- The foliage scroll – Elevator doors, by Brandt (1926), wrought iron, glass, patinated and gilded bronze, Calouste Gulbenkian Museum, Lisbon[112]

- Simplified reinterpretations of the Doric columns (with a basic rectangular capital or base, or just as a shaft) – Grave of Gustave Simon in Préville Cemetery, Nancy, France, unknown architect (after 1926)

- Decoration not just through ornaments, but also through combinations of volumes - Withuis (Avenue Charles Woeste no. 183) in Brussels, Belgium, by Joseph Diongre (1927)[113]

- Ingenious games of light and darkness – Stage design for Meșterul Manole (The Master Builder Manole), by Victor Feodorov (1927–28), collection of the National Theatre, Bucharest

- The octagon-shaped medallion – Sign of the La Samaritaine department store in Paris, by Henri Sauvage (1928)[114]

- Mosaics – Maison bleue (Rue d'Alsace no. 28) in Angers, France, designed by Roger Jusserand, and decorated with mosaics by the Odorico fréres (1928)

- Vertical mouldings – Greybrook House (Brook Street no. 28) in London, by Sir John Burnet & Partners (1928–29)[115]

- The stepped motif – Entrance hall of the Chrysler Building in New York City, by William Van Allen (1928–1930)

- The artesian fountain – Lamp, by Paul Kiss (c. 1930), glass and metal, in a temporary exhibition called the "Jazz Age" at the Cleveland Museum of Art, US

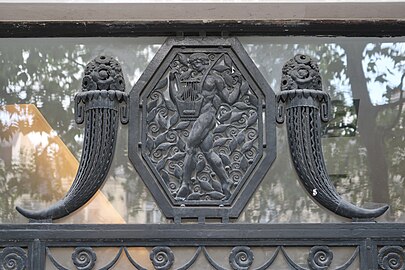

- The cornucopia – Avenue des Champs-Élysées no. 77 in Paris, unknown architect (c. 1930)

- Complex zigzags – Foot of a console table, by Paul Fehér (c. 1930), metal, in a temporary exhibition called the "Jazz Age" at the Cleveland Museum of Art

- Streamlining – Rue Gramme no. 17–21 in Paris, by Marcel Chappey (1930)

- The sunburst – Detail above the entrance of the Eastern Columbia Building (S. Broadway no. 849) in L.A., by Claud Beelman (1930)

- An aesthetic of artificial lighting – Maison de France (now showroom for Louis Vuitton), Avenue des Champs-Élysées no. 101 in Paris, by Louis-Hippolyte Boileau and Charles-Henri Besnard (1931)[116]

- Vertical and horizontal luminous surfaces – Entrance hall of the Villa Cavrois in Croix, France, by Rob Mallet-Stevens (1932)[117]

- The undulating line – Relief on the Grave of the Străjescu Family in Bellu Cemetery, Bucharest, by George Cristinel (1934)[118]

Decoration in the Art Deco period went through several distinct phases. Between 1910 and 1920, as Art Nouveau was exhausted, design styles saw a return to tradition, particularly in the work of Paul Iribe. In 1912 André Vera published an essay in the magazine L'Art Décoratif calling for a return to the craftsmanship and materials of earlier centuries and using a new repertoire of forms taken from nature, particularly baskets and garlands of fruit and flowers. A second tendency of Art Deco, also from 1910 to 1920, was inspired by the bright colours of the artistic movement known as the Fauves and by the colourful costumes and sets of the Ballets Russes. This style was often expressed with exotic materials such as sharkskin, mother of pearl, ivory, tinted leather, lacquered and painted wood, and decorative inlays on furniture that emphasized its geometry. This period of the style reached its high point in the 1925 Paris Exposition of Decorative Arts. In the late 1920s and the 1930s, the decorative style changed, inspired by new materials and technologies. It became sleeker and less ornamental. Furniture, like architecture, began to have rounded edges and to take on a polished, streamlined look, taken from the streamline modern style. New materials, such as nickel or chrome-plated steel, aluminium and bakelite, an early form of plastic, began to appear in furniture and decoration.[119]

Throughout the Art Deco period, and particularly in the 1930s, the motifs of the décor expressed the function of the building. Theatres were decorated with sculpture which illustrated music, dance, and excitement; power companies showed sunrises, the Chrysler building showed stylized hood ornaments; The friezes of Palais de la Porte Dorée at the 1931 Paris Colonial Exposition showed the faces of the different nationalities of French colonies. The Streamline style made it appear that the building itself was in motion. The WPA murals of the 1930s featured ordinary people; factory workers, postal workers, families and farmers, in place of classical heroes.[120]

- Angular – Entrance of the Chrysler Building in New York City, by William Van Allen (1928–1930)

- Asymmetric - Ministry of Justice (Bulevardul Regina Elisabeta no. 53), Bucharest, by Constantin Iotzu (1929–1932)

- Symmetric – Rue Chomel no. 14, Paris, designed by Émile Boursier and sculpted by Raymond Delamarre (1934)

- Maximalist – Fire screen, by Edgar Brandt (1925), wrought iron, in a temporary exhibition called the "Jazz Age" at the Cleveland Museum of Art, US

- Minimalist – William K. Nakamura Federal Courthouse in Seattle, US, by Gilbert Stanley Underwood (1940)

Art Deco, like the complex times that engendered it, can best be characterized by a series of contradictions: minimalist vs maximalist, angular vs fluid, ziggurat vs streamline, symmetrical vs irregular, to name a few. The iconography chosen by Art Deco artists to express the period is also laden with contradictions. Fair maidens in 18th-century dress seem to coexist with chic sophisticated ladies and recumbent nudes, and flashes of lightning illuminate stylized rosebuds.[121]

Furniture

[edit]- Chair by Paul Follot (1912–1914)

- Armchair by Louis Süe (1912) and painted screen by André Mare (1920)

- Dressing table and chair of marble and encrusted, lacquered, and gilded wood by Follot (1919–20)

- Corner cabinet of Mahogany with rose basket design of inlaid ivory by Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann (1923)

- Cabinet covered with shagreen or sharkskin by André Groult (1925)

- Cabinet by Ruhlmann (1926)

- Cabinet design by Ruhlmann

- Furniture by Gio Ponti (1927)

- Desk of an administrator, by Michel Roux-Spitz for the 1930 Salon of Decorative Artists

- Art Deco club chair (1930s)

- Late Art Deco furniture and rug by Jules Leleu (1930s)

- A Waterfall style buffet table

French furniture from 1910 until the early 1920s was largely an updating of French traditional furniture styles, and the art nouveau designs of Louis Majorelle, Charles Plumet and other manufacturers. French furniture manufacturers felt threatened by the growing popularity of German manufacturers and styles, particularly the Biedermeier style, which was simple and clean-lined. The French designer Frantz Jourdain, the President of the Paris Salon d'Automne, invited designers from Munich to participate in the 1910 Salon. French designers saw the new German style and decided to meet the German challenge. The French designers decided to present new French styles in the Salon of 1912. The rules of the Salon indicated that only modern styles would be permitted. All of the major French furniture designers took part in Salon: Paul Follot, Paul Iribe, Maurice Dufrêne, André Groult, André Mare and Louis Suë took part, presenting new works that updated the traditional French styles of Louis XVI and Louis Philippe with more angular corners inspired by Cubism and brighter colours inspired by Fauvism and the Nabis.[122]

The painter André Mare and furniture designer Louis Süe both participated the 1912 Salon. After the war the two men joined to form their own company, formally called the Compagnie des Arts Française, but usually known simply as Suë and Mare. Unlike the prominent art nouveau designers like Louis Majorelle, who personally designed every piece, they assembled a team of skilled craftsmen and produced complete interior designs, including furniture, glassware, carpets, ceramics, wallpaper and lighting. Their work featured bright colors and furniture and fine woods, such as ebony encrusted with mother of pearl, abalone and silvered metal to create bouquets of flowers. They designed everything from the interiors of ocean liners to perfume bottles for the label of Jean Patou.The firm prospered in the early 1920s, but the two men were better craftsmen than businessmen. The firm was sold in 1928, and both men left.[123]

The most prominent furniture designer at the 1925 Decorative Arts Exposition was Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann, from Alsace. He first exhibited his works at the 1913 Autumn Salon, then had his own pavilion, the "House of the Rich Collector", at the 1925 Exposition. He used only most rare and expensive materials, including ebony, mahogany, rosewood, ambon and other exotic woods, decorated with inlays of ivory, tortoise shell, mother of pearl, Little pompoms of silk decorated the handles of drawers of the cabinets.[124] His furniture was based upon 18th-century models, but simplified and reshaped. In all of his work, the interior structure of the furniture was completely concealed. The framework usually of oak, was completely covered with an overlay of thin strips of wood, then covered by a second layer of strips of rare and expensive woods. This was then covered with a veneer and polished, so that the piece looked as if it had been cut out of a single block of wood. Contrast to the dark wood was provided by inlays of ivory, and ivory key plates and handles. According to Ruhlmann, armchairs had to be designed differently according to the functions of the rooms where they appeared; living room armchairs were designed to be welcoming, office chairs comfortable, and salon chairs voluptuous. Only a small number of pieces of each design of furniture was made, and the average price of one of his beds or cabinets was greater than the price of an average house.[125]

Jules Leleu was a traditional furniture designer who moved smoothly into Art Deco in the 1920s; he designed the furniture for the dining room of the Élysée Palace, and for the first-class cabins of the steamship Normandie. his style was characterized by the use of ebony, Macassar wood, walnut, with decoration of plaques of ivory and mother of pearl. He introduced the style of lacquered art deco furniture in the late 1920s, and in the late 1930s introduced furniture made of metal with panels of smoked glass.[126] In Italy, the designer Gio Ponti was famous for his streamlined designs.

The costly and exotic furniture of Ruhlmann and other traditionalists infuriated modernists, including the architect Le Corbusier, causing him to write a famous series of articles denouncing the arts décoratif style. He attacked furniture made only for the rich and called upon designers to create furniture made with inexpensive materials and modern style, which ordinary people could afford. He designed his own chairs, created to be inexpensive and mass-produced.[127]

In the 1930s, furniture designs adapted to the form, with smoother surfaces and curved forms. The masters of the late style included Donald Deskey, who was one of the most influential designers; he created the interior of the Radio City Music Hall. He used a mixture of traditional and very modern materials, including aluminium, chrome, and bakelite, an early form of plastic.[128] Other top designers of Art Deco furniture of the 1930s in the United States included Gilbert Rohde, Warren McArthur, and Kem Weber.

The Waterfall style was popular in the 1930s and 1940s, the most prevalent Art Deco form of furniture at the time. Pieces were typically of plywood finished with blond veneer and with rounded edges, resembling a waterfall.[129]

Design

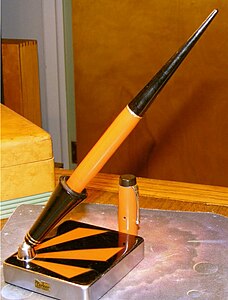

[edit]- Parker Duofold desk set (c. 1930)

- Beau Brownie camera, design by Walter Dorwin Teague for Eastman Kodak (1930)

- Philips radio set (1931)

- Chrysler Airflow sedan, designed by Carl Breer (1934)

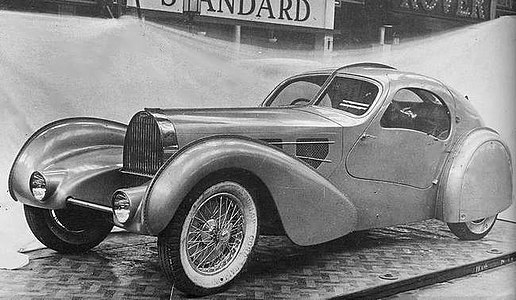

- Bugatti Aérolithe (1936)

- Philco table radio (c. 1937)

- Electrolux vacuum cleaner (1937)

- Cord automobile model 812, designed by Gordon M. Buehrig and staff (1937)

- Phantom Corsair, designed by Rust Heinz (1938)

Streamline was a variety of Art Deco which emerged during the mid-1930s. It was influenced by modern aerodynamic principles developed for aviation and ballistics to reduce aerodynamic drag at high velocities. The bullet shapes were applied by designers to cars, trains, ships, and even objects not intended to move, such as refrigerators, gas pumps, and buildings.[59] One of the first production vehicles in this style was the Chrysler Airflow of 1933. It was unsuccessful commercially, but the beauty and functionality of its design set a precedent; meant modernity. It continued to be used in car design well after World War II.[130][131][132][133]

New industrial materials began to influence the design of cars and household objects. These included aluminium, chrome, and bakelite, an early form of plastic. Bakelite could be easily moulded into different forms, and soon was used in telephones, radios and other appliances.

Ocean liners also adopted a style of Art Deco, known in French as the Style Paquebot, or "Ocean Liner Style". The most famous example was the SS Normandie, which made its first transatlantic trip in 1935. It was designed particularly to bring wealthy Americans to Paris to shop. The cabins and salons featured the latest Art Deco furnishings and decoration. The Grand Salon of the ship, which was the restaurant for first-class passengers, was bigger than the Hall of Mirrors of the Palace of Versailles. It was illuminated by electric lights within twelve pillars of Lalique crystal; thirty-six matching pillars lined the walls. This was one of the earliest examples of illumination being directly integrated into architecture. The style of ships was soon adapted to buildings. A notable example is found on the San Francisco waterfront, where the Maritime Museum building, built as a public bath in 1937, resembles a ferryboat, with ship railings and rounded corners. The Star Ferry Terminal in Hong Kong also used a variation of the style.[35]

Textiles

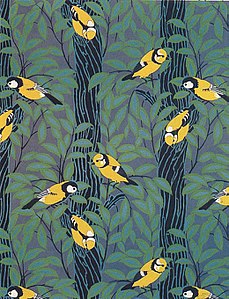

[edit]- Design of birds from Les Ateliers de Martine by Paul Iribe (1918)

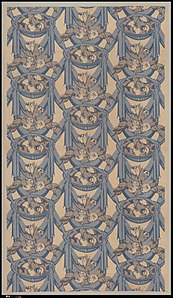

- Rose pattern textiles designed by Mare (c. 1919), Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Rose Mousse pattern for upholstery, cotton and silk (1920), Metropolitan Museum of Art

Textiles were an important part of the Art Deco style, in the form of colourful wallpaper, upholstery and carpets, In the 1920s, designers were inspired by the stage sets of the Ballets Russes, fabric designs and costumes from Léon Bakst and creations by the Wiener Werkstätte. The early interior designs of André Mare featured brightly coloured and highly stylized garlands of roses and flowers, which decorated the walls, floors, and furniture. Stylized Floral motifs also dominated the work of Raoul Dufy and Paul Poiret, and in the furniture designs of J.E. Ruhlmann. The floral carpet was reinvented in Deco style by Paul Poiret.[134]

The use of the style was greatly enhanced by the introduction of the pochoir stencil-based printing system, which allowed designers to achieve crispness of lines and very vivid colours. Art Deco forms appeared in the clothing of Paul Poiret, Charles Worth and Jean Patou. After World War I, exports of clothing and fabrics became one of the most important currency earners of France.[135]

Late Art Deco wallpaper and textiles sometimes featured stylized industrial scenes, cityscapes, locomotives and other modern themes, as well as stylized female figures, metallic finishes and geometric designs.[135]

Fashion

[edit]- Evening dress from the Journal des Dames et des Modes, illustrated by George Barbier (1913), Chester Beatty Library, Dublin

- Illustration by Barbier of a gown by Paquin (1914). Stylised floral designs and bright colours were a feature of early Art Deco.

- Cécile Sorel at the Comédie-Française (1920)

- Evening dress by the Maison Agnès (1920–1930), silk, pearls, strass, cabochon, and other materials, Musée Galliera, Paris

- Skirt by the Maison Agnès (1925–1927), silk, Musée Galliera

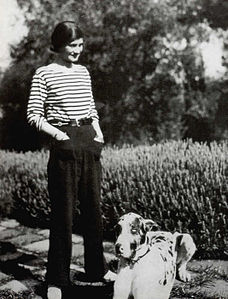

- Coco Chanel in a sailor's blouse and trousers (1928)

- Louise Brooks with an à la garçonne hairstyle, in a publicity photo for Diary of Lost Girl (1929)

- Advertisement for pyjamas in Lisières Fleuries fabric, from Le Jardin des Modes (1930)

The new woman of pre-WW1 days became the Amazon of the Art Deco era. Fashion changed dramatically during this period, thanks in particular to designers Paul Poiret and later Coco Chanel. Poiret introduced an important innovation to fashion design, the concept of draping, a departure from the tailoring and patternmaking of the past.[136] He designed clothing cut along straight lines and constructed of rectangular motifs.[136] His styles offered structural simplicity[136] The corseted look and formal styles of the previous period were abandoned, and fashion became more practical, and streamlined. With the use of new materials, brighter colours and printed designs.[136] The designer Coco Chanel continued the transition, popularising the style of sporty, casual chic.[137]

A particular typology of the era was the Flapper, a woman who cut her hair into a short bob, drank cocktails, smoked in public, and danced late into the night at fashionable clubs, cabarets or bohemian dives. Of course, most women didn't live like this, the Flapper being more a character present in popular imagination than a reality. Another female Art Deco style was the androgynous garçonne of the 1920s, with flattened bosom, dispelled waist and revealed legs, reducing the silhouette to a short tube, topped with a head-hugging cloche hat.[138]

Jewelry

[edit]- Cigarette case of leather and gold leaf by Pierre Legrain (1922), presenting a polychrome geometric decoration, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

- Bracelet of gold, coral and jade (1925), Museum of Decorative Arts, Paris

- Gold buckle set with diamonds and carved onyx, lapis lazuli, jade, and coral, by Boucheron (1925)

- Molded glass pendants on silk cords by René Lalique (1925–1930)

- Mackay Emerald Necklace, emerald, diamond and platinum, by Cartier (1930), Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, Washington, D.C.

In the 1920s and 1930s, designers including René Lalique and Cartier tried to reduce the traditional dominance of diamonds by introducing more colourful gemstones, such as small emeralds, rubies and sapphires. They also placed greater emphasis on very elaborate and elegant settings, featuring less-expensive materials such as enamel, glass, horn and ivory. Diamonds themselves were cut in less traditional forms; the 1925 Exposition saw many diamonds cut in the form of tiny rods or matchsticks. Other popular Art Deco cuts include:

- emerald cut, with long step-cut facets;

- asscher cut, more square-shaped than emerald with a high crown and the first diamond cut to ever be patented;

- marquise cut, to give the illusion of being bigger and bolder;

- baguette cut: small, rectangular step-cut shapes often used to outline bolder stones;[139]

- old European cut, round in shape and cut by hand so sparks of color (called fire) flash from within the stone.[140]

The settings for diamonds also changed; More and more often jewellers used platinum instead of gold, since it was strong and flexible, and could set clusters of stones. Jewellers also began to use more dark materials, such as enamels and black onyx, which provided a higher contrast with diamonds.[141]

Jewellery became much more colourful and varied in style. Cartier and the firm of Boucheron combined diamonds with colourful other gemstones cut into the form of leaves, fruit or flowers, to make brooches, rings, earrings, clips and pendants. Far Eastern themes also became popular; plaques of jade and coral were combined with platinum and diamonds, and vanity cases, cigarette cases and powder boxes were decorated with Japanese and Chinese landscapes made with mother of pearl, enamel and lacquer.[141]

Rapidly changing fashions in clothing brought new styles of jewellery. Sleeveless dresses of the 1920s meant that arms needed decoration, and designers quickly created bracelets of gold, silver and platinum encrusted with lapis-lazuli, onyx, coral, and other colourful stones; Other bracelets were intended for the upper arms, and several bracelets were often worn at the same time. The short haircuts of women in the twenties called for elaborate deco earring designs. As women began to smoke in public, designers created very ornate cigarette cases and ivory cigarette holders. The invention of the wristwatch before World War I inspired jewelers to create extraordinary, decorated watches, encrusted with diamonds and plated with enamel, gold and silver. Pendant watches, hanging from a ribbon, also became fashionable.[142]

The established jewellery houses of Paris in the period, Cartier, Chaumet, Georges Fouquet, Mauboussin, and Van Cleef & Arpels all created jewellery and objects in the new fashion. The firm of Chaumet made highly geometric cigarette boxes, cigarette lighters, pillboxes and notebooks, made of hard stones decorated with jade, lapis lazuli, diamonds and sapphires. They were joined by many young new designers, each with his own idea of deco. Raymond Templier designed pieces with highly intricate geometric patterns, including silver earrings that looked like skyscrapers. Gerard Sandoz was only 18 when he started to design jewelry in 1921; he designed many celebrated pieces based on the smooth and polished look of modern machinery. The glass designer René Lalique also entered the field, creating pendants of fruit, flowers, frogs, fairies or mermaids made of sculpted glass in bright colors, hanging on cords of silk with tassels.[142] The jeweller Paul Brandt contrasted rectangular and triangular patterns, and embedded pearls in lines on onyx plaques. Jean Despres made necklaces of contrasting colours by bringing together silver and black lacquer, or gold with lapis lazuli. Many of his designs looked like highly polished pieces of machines. Jean Dunand was also inspired by modern machinery, combined with bright reds and blacks contrasting with polished metal.[142]

Glass art

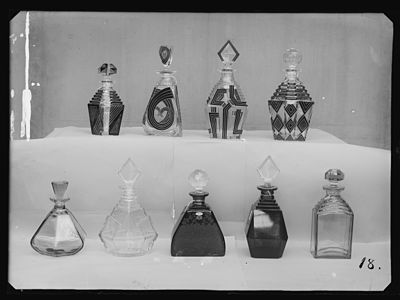

[edit]- Bottles, unknown designer or producer (1920s)

- The Firebird by René Lalique (1922), Dayton Art Institute, US

- Parrot vase by Lalique (1922), Cincinnati Art Museum, US

- Window for a steel mill office by Louis Majorelle (1928), Grands bureaux des Aciéries de Longwy, Longlaville, France

- Skyscraper Lamp, designed by Arnaldo dell'Ira (1929), Arnaldo dell'Ira Collection

- Angular chandeliers by Lanchester & Lodge (c. 1929–1936), Brotherton Library, University of Leeds, West Yorkshire, UK[143]