Английская Реформация

| Part of a series on the |

| Reformation |

|---|

|

| Protestantism |

| Part of a series on |

| Anglicanism |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of a series on the |

| History of the Church of England |

|---|

|

Английская Реформация произошла в Англии 16-го века, когда англиканская церковь была вынуждена своими монархами и элитами оторваться от власти Папы и католической церкви . Эти события были частью более широкой европейской Реформации , религиозного и политического движения, которое повлияло на практику христианства в Западной и Центральной Европе .

Идеологически основу Реформации заложили гуманисты эпохи Возрождения, которые считали Священное Писание лучшим источником христианской веры и критиковали религиозные практики, которые они считали суеверными. К 1520 году новые идеи Мартина Лютера были известны и обсуждались в Англии, но протестанты считались религиозным меньшинством и еретиками по закону . Английская Реформация началась скорее как политическое дело, чем как богословский спор. [ примечание 1 ] В 1527 году Генрих VIII потребовал аннулирования его брака, но папа Климент VII отказался. В ответ Реформационный парламент (1529–1536) принял законы, отменяющие папскую власть в Англии, и объявил Генриха главой англиканской церкви . Окончательная власть в доктринальных спорах теперь принадлежала монарху. Хотя Генри сам был религиозным традиционалистом, он полагался на протестантов в поддержке и реализации своей религиозной программы.

The theology and liturgy of the Church of England became markedly Protestant during the reign of Henry's son Edward VI (1547–1553) largely along lines laid down by Archbishop Thomas Cranmer. Under Mary I (1553–1558), Catholicism was briefly restored. The Elizabethan Religious Settlement reintroduced the Protestant religion but in a more moderate manner. Nevertheless, disputes over the structure, theology, and worship of the Church of England continued for generations.

The English Reformation is generally considered to have concluded during the reign of Elizabeth I (1558–1603), but scholars also speak of a "Long Reformation" stretching into the 17th and 18th centuries. This time period includes the violent disputes over religion during the Stuart period, most famously the English Civil War which resulted in the rule of Puritan Oliver Cromwell. After the Stuart Restoration and the Glorious Revolution, the Church of England remained the established church, but a number of nonconformist churches now existed whose members suffered various civil disabilities until these were removed many years later. A substantial but dwindling minority of people from the late 16th to early 19th centuries remained Catholics in England – their church organization remained illegal until the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1829.

Competing religious ideas

[edit]The medieval English church was part of the larger Catholic Church led by the Pope in Rome. The dominant view of salvation in the late medieval church taught that contrite persons should cooperate with God's grace towards their salvation by performing good works (see synergism).[1] God's grace was ordinarily given through the seven sacraments—Baptism, Confirmation, Marriage, Holy Orders, Anointing of the Sick, Penance and the Eucharist.[2] The Eucharist was celebrated during the Mass, the central act of Catholic worship. In this service, a priest consecrated bread and wine to become the body and blood of Christ through transubstantiation. The church taught that, in the name of the congregation, the priest offered to God the same sacrifice of Christ on the cross that provided atonement for the sins of humanity.[3][4] The Mass was also an offering of prayer by which the living could help souls in purgatory.[5] While genuine penance removed the guilt attached to sin, Catholicism taught that a penalty could still remain, in the case of imperfect contrition. It was believed that most people would end their lives with these penalties unsatisfied and would have to spend "time" in purgatory. Time in purgatory could be lessened through indulgences and prayers for the dead, which were made possible by the communion of saints.[6]

Lollardy was a sometimes rebellious movement that anticipated some Protestant teachings. Derived from the writings of John Wycliffe, a 14th-century theologian and, it was thought, Bible translator, Lollardy stressed the primacy of scripture and emphasised preaching over the Eucharist, holding the latter to be but a memorial.[7][8] Though persecuted and much reduced in numbers and influence by the 15th century,[9] Lollards were receptive to Protestant ideas.[10][page needed]

Some Renaissance humanists, such as Erasmus (who lived in England for a time), John Colet and Thomas More, called for a return ad fontes ("back to the sources") of Christian faith—the scriptures as understood through textual, linguistic, classical and patristic scholarship[11]—and wanted to make the Bible available in the vernacular. Humanists criticised so-called superstitious practices and clerical corruption, while emphasising inward piety over religious ritual. Some of the early Protestant leaders went through a humanist phase before embracing the new movement.[12] A notable early use of the English word "reformation" came in 1512, when the English bishops were called together by King Henry VIII, notionally to discuss the extirpation of the rump Lollard heresy. John Colet (then working with Erasmus on the establishment of his school) gave a notoriously confrontational sermon on Romans 12:2 Be ye not conformed to this world, but be ye reformed in the newness of your minds... saying that the first to reform must be the bishops themselves, then the clergy, and only then the laity.[13]: 250

The Protestant Reformation was initiated by the German monk Martin Luther. By the early 1520s, Luther's views were known and disputed in England.[14] The main plank of Luther's theology was justification by faith alone rather than by good works. In this view, God's unmerited favour is the only way for humans to be justified—it cannot be achieved or earned by righteous living. In other words, justification is a gift from God received through faith.[15]

If Luther was correct, then the Mass, the sacraments, charitable acts, prayers to saints, prayers for the dead, pilgrimage, and the veneration of relics do not mediate divine favour. To believe otherwise would be superstition at best and idolatry at worst.[16][17] Early Protestants portrayed Catholic practices such as confession to priests, clerical celibacy, and requirements to fast and keep vows as burdensome and spiritually oppressive. Not only did purgatory lack any biblical basis according to Protestants, but the clergy were also accused of leveraging the fear of purgatory to make money from prayers and masses. The Catholics countered that justification by faith alone was a "licence to sin".[18]

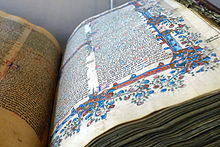

The publication of William Tyndale's English New Testament in 1526 helped to spread Protestant ideas. Printed abroad and smuggled into the country, the Tyndale Bible was the first English Bible to be mass produced; there were probably 16,000 copies in England by 1536. Tyndale's translation was highly influential, forming the basis of all subsequent English translations until the 20th century.[19] An attack on traditional religion, Tyndale's translation included an epilogue explaining Luther's theology of justification by faith, and many translation choices were designed to undermine traditional Catholic teachings. Tyndale translated the Greek word charis as favour rather than grace to de-emphasize the role of grace-giving sacraments. His choice of love rather than charity to translate agape de-emphasized good works. When rendering the Greek verb metanoeite into English, Tyndale used repent rather than do penance. The former word indicated an internal turning to God, while the latter translation supported the sacrament of confession.[20]

The Protestant ideas were popular among some parts of the English population, especially among academics and merchants with connections to continental Europe.[21] Protestant thought was better received at Cambridge University than Oxford.[12] A group of reform-minded Cambridge students (known by moniker "Little Germany") met at the White Horse tavern from the mid-1520s. Its members included Robert Barnes, Hugh Latimer, John Frith, Thomas Bilney, George Joye and Thomas Arthur.[22]

Nevertheless, English Catholicism was strong and popular in the early 1500s, and those who held Protestant sympathies remained a religious minority until political events intervened.[23] As heretics in the eyes of church and state, early Protestants were persecuted. Between 1530 and 1533, Thomas Hitton (England's first Protestant martyr), Thomas Bilney, Richard Bayfield, John Tewkesbury, James Bainham, Thomas Benet, Thomas Harding, John Frith and Andrew Hewet were burned to death.[24] William Tracy was posthumously convicted of heresy for denying purgatory and affirming justification by faith, and his corpse was disinterred and burned.[25]

Henrician Reformation

[edit]Annulment controversy

[edit]

Henry VIII acceded to the English throne in 1509 at the age of 17. He made a dynastic marriage with Catherine of Aragon, widow of his brother Arthur, in June 1509, just before his coronation on Midsummer's Day. Unlike his father, who was secretive and conservative, the young Henry appeared the epitome of chivalry and sociability. An observant Catholic, he heard up to five masses a day (except during the hunting season);[citation needed] of "powerful but unoriginal mind", he let himself be influenced by his advisors from whom he was never apart, by night or day. He was thus susceptible to whoever had his ear.[note 2]

This contributed to a state of hostility between his young contemporaries and the Lord Chancellor, Cardinal Thomas Wolsey. As long as Wolsey had his ear, Henry's Catholicism was secure: in 1521, he had defended the Catholic Church from Martin Luther's accusations of heresy in a book he wrote—probably with considerable help from the conservative Bishop of Rochester John Fisher[26]—entitled The Defence of the Seven Sacraments, for which he was awarded the title "Defender of the Faith" (Fidei Defensor) by Pope Leo X.[27] (Successive English and British monarchs have retained this title to the present, even after the Anglican Church broke away from Catholicism, in part because the title was re-conferred by Parliament in 1544, after the split.) Wolsey's enemies at court included those who had been influenced by Lutheran ideas,[28] among whom was the attractive, charismatic Anne Boleyn.[citation needed]

Anne arrived at court in 1522 as maid of honour to Queen Catherine, having spent some years in France being educated by Queen Claude of France. She was a woman of "charm, style and wit, with will and savagery which made her a match for Henry".[note 3] Anne was a distinguished French conversationalist, singer, and dancer. She was cultured and is the disputed author of several songs and poems.[29] By 1527, Henry wanted his marriage to Catherine annulled.[note 4] She had not produced a male heir who survived longer than two months, and Henry wanted a son to secure the Tudor dynasty. Before Henry's father (Henry VII) ascended the throne, England had been beset by civil warfare over rival claims to the English crown. Henry wanted to avoid a similar uncertainty over the succession.[30] Catherine of Aragon's only surviving child was Princess Mary.[citation needed]

Henry claimed that this lack of a male heir was because his marriage was "blighted in the eyes of God".[31] Catherine had been his late brother's wife, and it was therefore against biblical teachings for Henry to have married her (Leviticus 20:21); a special dispensation from Pope Julius II had been needed to allow the wedding in the first place.[32] Henry argued the marriage was never valid because the biblical prohibition was part of unbreakable divine law, and even popes could not dispense with it.[note 5] In 1527, Henry asked Pope Clement VII to annul the marriage, but the Pope refused. According to canon law, the Pope could not annul a marriage on the basis of a canonical impediment previously dispensed. Clement also feared the wrath of Catherine's nephew, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, whose troops earlier that year had sacked Rome and briefly taken the Pope prisoner.[33]

The combination of Henry's "scruple of conscience" and his captivation by Anne Boleyn made his desire to rid himself of his queen compelling.[34] The indictment of his chancellor Cardinal Wolsey in 1529 for praemunire (taking the authority of the papacy above the Crown) and Wolsey's subsequent death in November 1530 on his way to London to answer a charge of high treason left Henry open to both the influences of the supporters of the queen and the opposing influences of those who sanctioned the abandonment of the Roman allegiance, for whom an annulment was but an opportunity.[35]

Actions against clergy

[edit]In 1529, the King summoned Parliament to deal with the annulment and other grievances against the church. The Catholic Church was a powerful institution in England with a number of privileges. The King could not tax or sue clergy in civil courts. The church could also grant fugitives sanctuary, and many areas of the law―such as family law―were controlled by the church. For centuries, kings had attempted to reduce the church's power, and the English Reformation was a continuation of this power struggle.[36]

The Reformation Parliament sat from 1529 to 1536 and brought together those who wanted reform but who disagreed what form it should take. There were common lawyers who resented the privileges of the clergy to summon laity to their ecclesiastical courts,[37] and there were those who had been influenced by Lutheranism and were hostile to the theology of Rome. Henry's chancellor, Thomas More, successor to Wolsey, also wanted reform: he wanted new laws against heresy.[38] Lawyer and member of Parliament Thomas Cromwell saw how Parliament could be used to advance royal supremacy over the church and further Protestant beliefs.[39]

Initially, Parliament passed minor legislation to control ecclesiastical fees, clerical pluralism, and sanctuary.[40] In the matter of the annulment, no progress seemed possible. The Pope seemed more afraid of Emperor Charles V than of Henry. Anne, Cromwell and their allies wished simply to ignore the Pope, but in October 1530 a meeting of clergy and lawyers advised that Parliament could not empower the Archbishop of Canterbury to act against the Pope's prohibition. Henry thus resolved to bully the priests.[41]

Having first charged eight bishops and seven other clerics with praemunire, the King decided in 1530 to proceed against the whole clergy for violating the 1392 Statute of Praemunire, which forbade obedience to the Pope or any foreign ruler.[42] Henry wanted the clergy of Canterbury province to pay £100,000 for their pardon; this was a sum equal to the Crown's annual income.[43] This was agreed by the Convocation of Canterbury on 24 January 1531. It wanted the payment spread over five years, but Henry refused. The convocation responded by withdrawing their payment altogether and demanded Henry fulfil certain guarantees before they would give him the money. Henry refused these conditions, agreeing only to the five-year period of payment.[44] On 7 February, Convocation was asked to agree to five articles that specified that:

- The clergy recognise Henry as the "sole protector and supreme head of the English Church and clergy"

- The King was responsible for the souls of his subjects

- The privileges of the church were upheld only if they did not detract from the royal prerogative and the laws of the realm

- The King pardoned the clergy for violating the Statute of Praemunire

- The laity were also pardoned.[45]

In Parliament, Bishop Fisher championed Catherine and the clergy, inserting into the first article the phrase "as far as the word of God allows".[46][47][page needed] On 11 February, William Warham, Archbishop of Canterbury, presented the revised wording to Convocation. The clergy were to acknowledge the King to be "singular protector, supreme lord and even, so far as the law of Christ allows, supreme head of the English Church and clergy". When Warham requested a discussion, there was silence. Warham then said, "He who is silent seems to consent", to which a bishop responded, "Then we are all silent."[48] The Convocation granted consent to the King's five articles and the payment on 8 March 1531.[citation needed] Later, the Convocation of York agreed to the same on behalf of the clergy of York province.[48] That same year, Parliament passed the Pardon to Clergy Act 1531.[citation needed]

By 1532, Cromwell was responsible for managing government business in the House of Commons. He authored and presented to the Commons the Supplication against the Ordinaries, which was a list of grievances against the bishops, including abuses of power and Convocation's independent legislative authority. After passing the Commons, the Supplication was presented to the King as a petition for reform on 18 March.[49] On 26 March, the Act in Conditional Restraint of Annates mandated the clergy pay no more than five percent of their first year's revenue (annates) to Rome.[50]

On 10 May, the King demanded of Convocation that the church renounce all authority to make laws.[51] On 15 May, Convocation renounced its authority to make canon law without royal assent—the so called Submission of the Clergy. (Parliament subsequently gave this statutory force with the Submission of the Clergy Act.) The next day, More resigned as lord chancellor.[52] This left Cromwell as Henry's chief minister. (Cromwell never became chancellor. His power came—and was lost—through his informal relations with Henry.)[citation needed]

Separation from Rome

[edit]

Archbishop Warham died in August 1532. Henry wanted Thomas Cranmer—a Protestant who could be relied on to oppose the papacy—to replace him.[53] The Pope reluctantly approved Cranmer's appointment, and he was consecrated on 30 March 1533. By this time, Henry was secretly married to a pregnant Anne. The impending birth of an heir gave new urgency to annulling his marriage to Catherine. Nevertheless, a decision continued to be delayed because Rome was the final authority in all ecclesiastical matters.[50] To address this issue, Parliament passed the Act in Restraint of Appeals, which outlawed appeals to Rome on ecclesiastical matters and declared that

This realm of England is an Empire, and so hath been accepted in the world, governed by one Supreme Head and King having the dignity and royal estate of the Imperial Crown of the same, unto whom a body politic compact of all sorts and degrees of people divided in terms and by names of Spirituality and Temporality, be bounden and owe to bear next to God a natural and humble obedience.[54]

This declared England an independent country in every respect. English historian Geoffrey Elton called this act an "essential ingredient" of the "Tudor revolution" in that it expounded a theory of national sovereignty.[55] Cranmer was now able to grant an annulment of the marriage to Catherine as Henry required, pronouncing on 23 May the judgment that Henry's marriage with Catherine was against the law of God.[56] The Pope responded by excommunicating Henry on 11 July 1533. Anne gave birth to a daughter, Princess Elizabeth, on 7 September 1533.[57]

In 1534, Parliament took further action to limit papal authority in England. A new Heresy Act ensured that no one could be punished for speaking against the Pope and also made it more difficult to convict someone of heresy; however, sacramentarians and Anabaptists continued to be vigorously persecuted.[58] The Act in Absolute Restraint of Annates outlawed all annates to Rome and also ordered that if cathedrals refused the King's nomination for bishop, they would be liable to punishment by praemunire.[59] The Act of First Fruits and Tenths transferred the taxes on ecclesiastical income from the Pope to the Crown. The Act Concerning Peter's Pence and Dispensations outlawed the annual payment by landowners of Peter's Pence to the Pope, and transferred the power to grant dispensations and licences from the Pope to the Archbishop of Canterbury. This Act also reiterated that England had "no superior under God, but only your Grace" and that Henry's "imperial crown" had been diminished by "the unreasonable and uncharitable usurpations and exactions" of the Pope.[60][page needed][57]

The First Act of Supremacy made Henry Supreme Head of the Church of England and disregarded any "usage, custom, foreign laws, foreign authority [or] prescription".[59] In case this should be resisted, Parliament passed the Treasons Act 1534, which made it high treason punishable by death to deny royal supremacy. The following year, Thomas More and John Fisher were executed under this legislation.[61] Finally, in 1536, Parliament passed the Act against the Pope's Authority, which removed the last part of papal authority still legal. This was Rome's power in England to decide disputes concerning Scripture.[citation needed]

Moderate religious reform

[edit]The break with Rome gave Henry VIII power to administer the English Church, tax it, appoint its officials, and control its laws. It also gave him control over the church's doctrine and ritual.[62] While Henry remained a traditional Catholic, his most important supporters in breaking with Rome were the Protestants. Yet, not all of his supporters were Protestants. Some were traditionalists, such as Stephen Gardiner, opposed to the new theology but felt papal supremacy was not essential to the Church of England's identity.[63] The King relied on Protestants, such as Thomas Cromwell and Thomas Cranmer, to carry out his religious programme and embraced the language of the continental Reformation, while maintaining a middle way between religious extremes.[64] What followed was a period of doctrinal confusion as both conservatives and reformers attempted to shape the church's future direction.[65]

The reformers were aided by Cromwell, who in January 1535 was made vicegerent in spirituals. Effectively the King's vicar general, Cromwell's authority was greater than that of bishops, even the Archbishop of Canterbury.[66] Largely due to Anne Boleyn's influence, a number of Protestants were appointed bishops between 1534 and 1536. These included Latimer, Thomas Goodrich, John Salcot, Nicholas Shaxton, William Barlow, John Hilsey and Edward Foxe.[67] During the same period, the most influential conservative bishop, Stephen Gardiner, was sent to France on a diplomatic mission and thus removed from an active role in English politics for three years.[68]

Cromwell's programme, assisted by Anne Boleyn's influence over episcopal appointments, was not merely against the clergy and the power of Rome. He persuaded Henry that safety from political alliances that Rome might attempt to bring together lay in negotiations with the German Lutheran princes of the Schmalkaldic League.[note 6] There also seemed to be a possibility that Emperor Charles V might act to avenge his rejected aunt (Queen Catherine) and enforce the Pope's excommunication. The negotiations did not lead to an alliance but did bring Lutheran ideas to England.[69]

In 1536, Convocation adopted the first doctrinal statement for the Church of England, the Ten Articles. This was followed by the Bishops' Book in 1537. These established a semi-Lutheran doctrine for the church. Justification by faith, qualified by an emphasis on good works following justification, was a core teaching. The traditional seven sacraments were reduced to three only—baptism, Eucharist and penance. Catholic teaching on praying to saints, purgatory and the use of images in worship was undermined.[70]

In August 1536, the same month the Ten Articles were published, Cromwell issued a set of Royal Injunctions to the clergy. Minor feast days were changed into normal work days, including those celebrating a church's patron saint and most feasts during harvest time (July through September). The rationale was partly economic as too many holidays led to a loss of productivity and were "the occasion of vice and idleness".[71] In addition, Protestants considered feast days to be examples of superstition.[72] Clergy were to discourage pilgrimages and instruct the people to give to the poor rather than make offerings to images. The clergy were also ordered to place Bibles in both English and Latin in every church for the people to read.[73] This last requirement was largely ignored by the bishops for a year or more due to the lack of any authorised English translation. The only complete vernacular version was the Coverdale Bible finished in 1535 and based on Tyndale's earlier work. It lacked royal approval, however.[74]

Historian Diarmaid MacCulloch in his study of The Later Reformation in England, 1547–1603 argues that after 1537, "England's Reformation was characterized by its hatred of images, as Margaret Aston's work on iconoclasm and iconophobia has repeatedly and eloquently demonstrated."[75] In February 1538, the famous Rood of Grace was condemned as a mechanical fraud and destroyed at St Paul's Cross. In July, the statues of Our Lady of Walsingham, Our Lady of Ipswich, and other Marian images were burned at Chelsea on Cromwell's orders. In September, Cromwell issued a second set of royal injunctions ordering the destruction of images to which pilgrimage offerings were made, the prohibition of lighting votive candles before images of saints, and the preaching of sermons against the veneration of images and relics.[76] Afterwards, the shrine and bones of Thomas Becket, considered by many to have been martyred in defence of the church's liberties, were destroyed at Canterbury Cathedral.[77]

Dissolution of the monasteries

[edit]

For Cromwell and Cranmer, a step in the Protestant agenda was attacking monasticism, which was associated with the doctrine of purgatory.[78] One of the primary functions of monasteries was to pray for the souls of their benefactors and for the souls of all Christians.[79] While the King was not opposed to religious houses on theological grounds, there was concern over the loyalty of the monastic orders, which were international in character and resistant to the Royal Supremacy.[80] The Franciscan Observant houses were closed in August 1534 after that order refused to repudiate papal authority. Between 1535 and 1537, 18 Carthusians were killed for doing the same.[81]

The Crown was also experiencing financial difficulties, and the wealth of the church, in contrast to its political weakness, made confiscation of church property both tempting and feasible.[82] Seizure of monastic wealth was not unprecedented; it had happened before in 1295, 1337, and 1369.[78] The church owned between one-fifth and one-third of the land in all England; Cromwell realised that he could bind the gentry and nobility to Royal Supremacy by selling to them the huge amount of church lands, and that any reversion to pre-Royal Supremacy would entail upsetting many of the powerful people in the realm.[83]

In 1534, Cromwell initiated a visitation of the monasteries ostensibly to examine their character, but in fact, to value their assets with a view to expropriation.[82] The visiting commissioners claimed to have uncovered sexual immorality and financial impropriety amongst the monks and nuns, which became the ostensible justification for their suppression.[83] There were also reports of the possession and display of false relics, such as Hailes Abbey's vial of the Holy Blood, upon investigation announced to be "honey clarified and coloured with saffron".[84] The Compendium Competorum compiled by the visitors documented ten pieces of the True Cross, seven portions of the Virgin Mary's milk and numerous saints' girdles.[85]

Leading reformers, led by Anne Boleyn, wanted to convert monasteries into "places of study and good letters, and to the continual relief of the poor", but this was not done.[86] In 1536, the Dissolution of the Lesser Monasteries Act closed smaller houses valued at less than £200 a year.[73] Henry used the revenue to help build coastal defences (see Device Forts) against expected invasion, and all the land was given to the Crown or sold to the aristocracy.[additional citation(s) needed] Thirty-four houses were saved by paying for exemptions. Monks and nuns affected by closures were transferred to larger houses, and monks had the option of becoming secular clergy.[87]

The Royal Supremacy and the abolition of papal authority had not caused widespread unrest, but the attacks on monasteries and the abolition of saints' days and pilgrimages provoked violence. Mobs attacked those sent to break up monastic buildings. Suppression commissioners were attacked by local people in several places.[88] In Northern England, there were a series of uprisings against the dissolutions in late 1536 and early 1537. The Lincolnshire Rising occurred in October 1536 and culminated in a force of 40,000 rebels assembling at Lincoln. They demanded an end to taxation during peacetime, the repeal of the statute of uses, an end to the suppression of monasteries, and that heresy be purged and heretics punished. Henry refused to negotiate, and the revolt collapsed as the nervous gentry convinced the common people to disperse.[89]

The Pilgrimage of Grace was a more serious matter. The pro-Catholic, anti-land-tax revolt began in October at Yorkshire and spread to the other northern counties. Around 50,000 strong, the rebels under Robert Aske's leadership restored 16 of the 26 northern monasteries that had been dissolved. Due to the size of the rebellion, the King was persuaded to negotiate. In December, Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk offered the rebels a pardon and a parliament to consider their grievances. Aske then sent the rebels home. The promises made to them, however, were ignored by the King, and Norfolk was instructed to put the rebellion down. Forty-seven of the Lincolnshire rebels were executed, and 132 from the Pilgrimage of Grace. In Southern England, smaller disturbances took place in Cornwall and Walsingham in 1537.[90]

The failure of the Pilgrimage of Grace only sped up the process of dissolution and may have convinced Henry VIII that all religious houses needed to be closed. In 1540, the last monasteries were dissolved, wiping out an important element of traditional religion.[91] Former monks were given modest pensions from the Court of Augmentations, and those that could sought work as parish priests. Former nuns received smaller pensions and, as they were still bound by vows of chastity, forbidden to marry.[92] Henry personally devised a plan to form at least thirteen new dioceses so that most counties had one based on a former monastery (or more than one), though this scheme was only partly carried out. New dioceses were established at Bristol, Gloucester, Oxford, Peterborough, Westminster and Chester, but not, for instance, at Shrewsbury, Leicester or Waltham.[93]

Reforms reversed

[edit]According to the historian Peter Marshall, Henry's religious reforms were based on the principles of "unity, obedience and the refurbishment of ancient truth".[94] Yet, the outcome was disunity and disobedience. Impatient Protestants took it upon themselves to further reform. Priests said Mass in English rather than Latin and were marrying in violation of clerical celibacy. Not only were there divisions between traditionalists and reformers, but Protestants themselves were divided between establishment reformers who held Lutheran beliefs and radicals who held Anabaptist and Sacramentarian views.[95] Reports of dissension from every part of England reached Cromwell daily—developments he tried to hide from the King.[96]

In September 1538, Stephen Gardiner returned to England, and the official religious policy began to drift in a conservative direction.[97] This was due in part to the eagerness of establishment Protestants to disassociate themselves from religious radicals. In September, two Lutheran princes, the Elector of Saxony and Landgrave of Hesse, sent warnings of Anabaptist activity in England. A commission was swiftly created to seek out Anabaptists.[98] Henry personally presided at the trial of John Lambert in November 1538 for denying the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist. At the same time, he shared in the drafting of a proclamation ordering Anabaptists and Sacramentaries to get out of the country or face death. Discussion of the real presence (except by those educated in the universities) was forbidden, and priests who married were to be dismissed.[96][99]

It was becoming clear that the King's views on religion differed from those of Cromwell and Cranmer. Henry made his traditional preferences known during the Easter Triduum of 1539, where he crept to the cross on Good Friday.[100] Later that year, Parliament passed the Six Articles reaffirming the Catholic beliefs and practices such as transubstantiation, clerical celibacy, confession to a priest, votive masses, and withholding communion wine from the laity.[101]

On 28 June 1540 Cromwell, Henry's longtime advisor and loyal servant, was then executed. Different reasons were advanced: that Cromwell would not enforce the Act of Six Articles; that he had supported Robert Barnes, Hugh Latimer and other heretics; and that he was responsible for Henry's marriage to Anne of Cleves, his fourth wife. Many other arrests under the Act followed.[102] On the 30 July, the reformers Barnes, William Jerome and Thomas Gerrard were burned at the stake. In a display of religious impartiality, Thomas Abell, Richard Featherstone and Edward Powell—all Catholics—were hanged and quartered while the Protestants burned.[103] European observers were very shocked and bewildered. French diplomat Charles de Marillac wrote that Henry's religious policy was a "climax of evils" and that:

[I]t is difficult to have a people entirely opposed to new errors which does not hold with the ancient authority of the Church and of the Holy See, or, on the other hand, hating the Pope, which does not share some opinions with the Germans. Yet the government will not have either the one or the other, but insists on their keeping what is commanded, which is so often altered that it is difficult to understand what it is.[104]

Despite some setbacks, Protestants managed to win some victories. In May 1541, the King ordered copies of the Great Bible to be placed in all churches; any failure to comply would result in a £2 fine. The Protestants could celebrate the growing access to vernacular scripture as most churches had Bibles by 1545.[105][106] The iconoclastic policies of 1538 were continued in the autumn when the Archbishops of Canterbury and York were ordered to destroy all the remaining shrines in England.[107] Furthermore, Cranmer survived formal charges of heresy in the Prebendaries' Plot of 1543.[108]

Traditionalists, nevertheless, seemed to have the upper hand. By the spring of 1543, Protestant innovations had been reversed, and only the break with Rome and the dissolution of the monasteries remained unchanged.[109] In May 1543, a new formulary was published to replace the Bishops' Book. This King's Book rejected justification by faith alone and defended traditional ceremonies and the use of images.[110] This was followed days later by passage of the Act for the Advancement of True Religion, which restricted the Bible reading to men and women of noble birth. Henry expressed his fears to Parliament in 1545 that "the Word of God, is disputed, rhymed, sung and jangled in every ale house and tavern, contrary to the true meaning and doctrine of the same."[111]

By the spring of 1544, the conservatives appeared to be losing influence once again. In March, Parliament made it more difficult to prosecute people for violating the Six Articles. Cranmer's Exhortation and Litany, the first official vernacular service, was published in June 1544, and the King's Primer became the only authorised English prayer book in May 1545. Both texts had a reformed emphasis.[note 7] After the death of the conservative Edward Lee in September 1544, the Protestant Robert Holgate replaced him as Archbishop of York.[112] In December 1545, the King was empowered to seize the property of chantries (trust funds endowed to pay for priests to say masses for the dead). While Henry's motives were largely financial (England was at war with France and desperately in need of funds), the passage of the Chantries Act was "an indication of how deeply the doctrine of purgatory had been eroded and discredited".[113]

In 1546, the conservatives were once again in the ascendant. A series of controversial sermons preached by the Protestant Edward Crome set off a persecution of Protestants that the traditionalists used to effectively target their rivals. It was during this time that Anne Askew was tortured in the Tower of London and burnt at the stake. Even Henry's last wife, Katherine Parr, was suspected of heresy but saved herself by appealing to the King's mercy. With the Protestants on the defensive, traditionalists pressed their advantage by banning Protestant books.[114]

The conservative persecution of Queen Katherine, however, backfired.[115] By November 1546, there were already signs that religious policy was once again tilting towards Protestantism.[note 8] The King's will provided for a regency council to rule after his death, which would have been dominated by traditionalists, such as the Duke of Norfolk, Lord Chancellor Wriothesly, Bishop Gardiner and Bishop Tunstall.[116] After a dispute with the King, Bishop Gardiner, the leading conservative churchman, was disgraced and removed as a councilor. Later, the Duke of Norfolk, the most powerful conservative nobleman, was arrested.[117] By the time Henry died in 1547, the Protestant Edward Seymour, brother of Jane Seymour, Henry's third wife (and therefore uncle to the future Edward VI), managed—by a number of alliances such as with Lord Lisle—to gain control over the Privy Council.[118]

Edwardian Reformation

[edit]

When Henry died in 1547, his nine-year-old son, Edward VI, inherited the throne. Because Edward was given a Protestant humanist education, Protestants held high expectations and hoped he would be like Josiah, the biblical king of Judah who destroyed the altars and images of Baal.[note 9] During the seven years of Edward's reign, a Protestant establishment would gradually implement religious changes that were "designed to destroy one Church and build another, in a religious revolution of ruthless thoroughness".[119]

Initially, however, Edward was of little account politically.[120] Real power was in the hands of the regency council, which elected Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset, to be Lord Protector. The Protestant Somerset pursued reform hesitantly at first, partly because his powers were not unchallenged.[121] The Six Articles remained the law of the land, and a proclamation was issued on 24 May reassuring the people against any "innovations and changes in religion".[122]

Nevertheless, Seymour and Cranmer did plan to further the reformation of religion. In July, a Book of Homilies was published, from which all clergy were to preach from on Sundays.[123] The homilies were explicitly Protestant in their content, condemning relics, images, rosary beads, holy water, palms, and other "papistical superstitions". It also directly contradicted the King's Book by teaching "we be justified by faith only, freely, and without works". Despite objections from Gardiner, who questioned the legality of bypassing both Parliament and Convocation, justification by faith had been made a central teaching of the English Church.[124]

Iconoclasm and abolition of chantries

[edit]In August 1547, thirty commissioners—nearly all Protestants—were appointed to carry out a royal visitation of England's churches.[125] The Royal Injunctions of 1547 issued to guide the commissioners were borrowed from Cromwell's 1538 injunctions but revised to be more radical. Historian Eamon Duffy calls them a "significant shift in the direction of full-blown Protestantism".[126] Church processions—one of the most dramatic and public aspects of the traditional liturgy—were banned.[127] The injunctions also attacked the use of sacramentals, such as holy water. It was emphasized that they imparted neither blessing nor healing but were only reminders of Christ.[128] Lighting votive candles before saints' images had been forbidden in 1538, and the 1547 injunctions went further by outlawing those placed on the rood loft.[129] Reciting the rosary was also condemned.[126]

The injunctions set off a wave of iconoclasm in the autumn of 1547.[130] While the injunctions only condemned images that were abused as objects of worship or devotion, the definition of abuse was broadened to justify the destruction of all images and relics.[131] Stained glass, shrines, statues, and roods were defaced or destroyed. Church walls were whitewashed and covered with biblical texts condemning idolatry.[132]

Conservative bishops Edmund Bonner and Gardiner protested the visitation, and both were arrested. Bonner spent nearly two weeks in the Fleet Prison before being released.[133] Gardiner was sent to the Fleet Prison in September and remained there until January 1548. However, he continued to refuse to enforce the new religious policies and was arrested once again in June when he was sent to the Tower of London for the rest of Edward's reign.[134]

When a new Parliament met in November 1547, it began to dismantle the laws passed during Henry VIII's reign to protect traditional religion.[135] The Act of Six Articles was repealed—decriminalizing denial of the real, physical presence of Christ in the Eucharist.[136] The old heresy laws were also repealed, allowing free debate on religious questions.[137] In December, the Sacrament Act allowed the laity to receive communion under both kinds, the wine as well as the bread. This was opposed by conservatives but welcomed by Protestants.[138]

The Chantries Act 1547 abolished the remaining chantries and confiscated their assets. Unlike the Chantry Act 1545, the 1547 act was intentionally designed to eliminate the last remaining institutions dedicated to praying for the dead. Confiscated wealth funded the Rough Wooing of Scotland. Chantry priests had served parishes as auxiliary clergy and schoolmasters, and some communities were destroyed by the loss of the charitable and pastoral services of their chantries.[139][140]

Historians dispute how well this was received. A. G. Dickens contended that people had "ceased to believe in intercessory masses for souls in purgatory",[141] but Eamon Duffy argued that the demolition of chantry chapels and the removal of images coincided with the activity of royal visitors.[142] The evidence is often ambiguous.[note 10] In some places, chantry priests continued to say prayers and landowners to pay them to do so.[143] Some parishes took steps to conceal images and relics in order to rescue them from confiscation and destruction.[144][145] Opposition to the removal of images was widespread—so much so that when during the Commonwealth, William Dowsing was commissioned to the task of image breaking in Suffolk, his task, as he records it, was enormous.[146]

1549 prayer book

[edit]The second year of Edward's reign was a turning point for the English Reformation; many people identified the year 1548, rather than the 1530s, as the beginning of the English Church's schism from the Catholic Church.[147] On 18 January 1548, the Privy Council abolished the use of candles on Candlemas, ashes on Ash Wednesday and palms on Palm Sunday.[148] On 21 February, the council explicitly ordered the removal of all church images.[149]

On 8 March, a royal proclamation announced a more significant change—the first major reform of the Mass and of the Church of England's official eucharistic theology.[150] The "Order of the Communion" was a series of English exhortations and prayers that reflected Protestant theology and were inserted into the Latin Mass.[151][152] A significant departure from tradition was that individual confession to a priest—long a requirement before receiving the Eucharist—was made optional and replaced with a general confession said by the congregation as a whole. The effect on religious custom was profound as a majority of laypeople, not just Protestants, most likely ceased confessing their sins to their priests.[149] By 1548, Cranmer and other leading Protestants had moved from the Lutheran to the Reformed position on the Eucharist.[153] Significant to Cranmer's change of mind was the influence of Strasbourg theologian Martin Bucer.[154] This shift can be seen in the Communion order's teaching on the Eucharist. Laypeople were instructed that when receiving the sacrament they "spiritually eat the flesh of Christ", an attack on the belief in the real, bodily presence of Christ in the Eucharist.[155] The Communion order was incorporated into the new prayer book largely unchanged.[156]

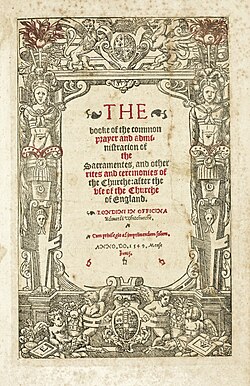

That prayer book and liturgy, the Book of Common Prayer, was authorized by the Act of Uniformity 1549. It replaced the several regional Latin rites then in use, such as the Use of Sarum, the Use of York and the Use of Hereford with an English-language liturgy.[157] Authored by Cranmer, this first prayer book was a temporary compromise with conservatives.[158] It provided Protestants with a service free from what they considered superstition, while maintaining the traditional structure of the mass.[159]

The cycles and seasons of the church year continued to be observed, and there were texts for daily Matins (Morning Prayer), Mass and Evensong (Evening Prayer). In addition, there was a calendar of saints' feasts with collects and scripture readings appropriate for the day. Priests still wore vestments—the prayer book recommended the cope rather than the chasuble. Many of the services were little changed. Baptism kept a strongly sacramental character, including the blessing of water in the baptismal font, promises made by godparents, making the sign of the cross on the child's forehead, and wrapping it in a white chrism cloth. The confirmation and marriage services followed the Sarum rite.[160] There were also remnants of prayer for the dead and the Requiem Mass, such as the provision for celebrating holy communion at a funeral.[161]

Nevertheless, the first Book of Common Prayer was a "radical" departure from traditional worship in that it "eliminated almost everything that had till then been central to lay Eucharistic piety".[162] Communion took place without any elevation of the consecrated bread and wine. The elevation had been the central moment of the old liturgy, attached as it was to the idea of real presence. In addition, the prayer of consecration was changed to reflect Protestant theology.[157] Three sacrifices were mentioned; the first was Christ's sacrifice on the cross. The second was the congregation's sacrifice of praise and thanksgiving, and the third was the offering of "ourselves, our souls and bodies, to be a reasonable, holy and lively sacrifice" to God.[163] While the medieval Canon of the Mass "explicitly identified the priest's action at the altar with the sacrifice of Christ", the Prayer Book broke this connection by stating the church's offering of thanksgiving in the Eucharist was not the same as Christ's sacrifice on the cross.[160] Instead of the priest offering the sacrifice of Christ to God the Father, the assembled offered their praises and thanksgivings. The Eucharist was now to be understood as merely a means of partaking in and receiving the benefits of Christ's sacrifice.[164][165]

There were other departures from tradition. At least initially, there was no music because it would take time to replace the church's body of Latin music.[161] Most of the liturgical year was simply "bulldozed away" with only the major feasts of Christmas, Easter and Whitsun along with a few biblical saints' days (Apostles, Evangelists, John the Baptist and Mary Magdalene) and only two Marian feast days (the Purification and the Annunciation).[162] The Assumption, Corpus Christi and other festivals were gone.[161]

In 1549, Parliament also legalized clerical marriage, something already practised by some Protestants (including Cranmer) but considered an abomination by conservatives.[166]

Rebellion

[edit]Enforcement of the new liturgy did not always take place without a struggle. In the West Country, the introduction of the Book of Common Prayer was the catalyst for a series of uprisings through the summer of 1549. There were smaller upheavals elsewhere from the West Midlands to Yorkshire. The Prayer Book Rebellion was not only in reaction to the prayer book; the rebels demanded a full restoration of pre-Reformation Catholicism.[167] They were also motivated by economic concerns, such as enclosure.[168] In East Anglia, however, the rebellions lacked a Catholic character. Kett's Rebellion in Norwich blended Protestant piety with demands for economic reforms and social justice.[169]

The insurrections were put down only after considerable loss of life.[170] Somerset was blamed and was removed from power in October. It was wrongly believed by both conservatives and reformers that the Reformation would be overturned. Succeeding Somerset as de facto regent was John Dudley, 1st Earl of Warwick, newly appointed Lord President of the Privy Council. Warwick saw further implementation of the reforming policy as a means of gaining Protestant support and defeating his conservative rivals.[171]

Further reform

[edit]

From that point on, the Reformation proceeded apace. Since the 1530s, one of the obstacles to Protestant reform had been the bishops, bitterly divided between a traditionalist majority and a Protestant minority. This obstacle was removed in 1550–1551 when the episcopate was purged of conservatives.[173] Edmund Bonner of London, William Rugg of Norwich, Nicholas Heath of Worcester, John Vesey of Exeter, Cuthbert Tunstall of Durham, George Day of Chichester and Stephen Gardiner of Winchester were either deprived of their bishoprics or forced to resign.[174][175] Thomas Thirlby, Bishop of Westminster, managed to stay a bishop only by being translated to the Diocese of Norwich, "where he did virtually nothing during his episcopate".[176] Traditionalist bishops were replaced by Protestants such as Nicholas Ridley, John Ponet, John Hooper and Miles Coverdale.[177][175]

The newly enlarged and emboldened Protestant episcopate turned its attention to ending efforts by conservative clergy to "counterfeit the popish mass" through loopholes in the 1549 prayer book. The Book of Common Prayer was composed during a time when it was necessary to grant compromises and concessions to traditionalists. This was taken advantage of by conservative priests who made the new liturgy as much like the old one as possible, including elevating the Eucharist.[178] The conservative Bishop Gardiner endorsed the prayer book while in prison,[159] and historian Eamon Duffy notes that many lay people treated the prayer book "as an English missal".[179]

To attack the mass, Protestants began demanding the removal of stone altars. Bishop Ridley launched the campaign in May 1550 when he commanded all altars to be replaced with wooden communion tables in his London diocese.[178] Other bishops throughout the country followed his example, but there was also resistance. In November 1550, the Privy Council ordered the removal of all altars in an effort to end all dispute.[180] While the prayer book used the term "altar", Protestants preferred a table because at the Last Supper Christ instituted the sacrament at a table. The removal of altars was also an attempt to destroy the idea that the Eucharist was Christ's sacrifice. During Lent in 1550, John Hooper preached, "as long as the altars remain, both the ignorant people, and the ignorant and evil-persuaded priest, will dream always of sacrifice".[178]

In March 1550, a new ordinal was published that was based on Martin Bucer's own treatise on the form of ordination. While Bucer had provided for only one service for all three orders of clergy, the English ordinal was more conservative and had separate services for deacons, priests and bishops.[171][181] During his consecration as bishop of Gloucester, John Hooper objected to the mention of "all saints and the holy Evangelist" in the Oath of Supremacy and to the requirement that he wear a black chimere over a white rochet. Hooper was excused from invoking the saints in his oath, but he would ultimately be convinced to wear the offensive consecration garb. This was the first battle in the vestments controversy, which was essentially a conflict over whether the church could require people to observe ceremonies that were neither necessary for salvation nor prohibited by scripture.[182]

1552 prayer book and parish confiscations

[edit]

The 1549 Book of Common Prayer was criticized by Protestants both in England and abroad for being too susceptible to Catholic re-interpretation. Martin Bucer identified 60 problems with the prayer book, and the Italian Peter Martyr Vermigli provided his own complaints. Shifts in Eucharistic theology between 1548 and 1552 also made the prayer book unsatisfactory—during that time English Protestants achieved a consensus rejecting any real bodily presence of Christ in the Eucharist. Some influential Protestants such as Vermigli defended Zwingli's symbolic view of the Eucharist. Less radical Protestants such as Bucer and Cranmer advocated for a spiritual presence in the sacrament.[183] Cranmer himself had already adopted receptionist views on the Lord's Supper.[note 11] In April 1552, a new Act of Uniformity authorized a revised Book of Common Prayer to be used in worship by November 1.[184]

This new prayer book removed many of the traditional elements in the 1549 prayer book, resulting in a more Protestant liturgy. The communion service was designed to remove any hint of consecration or change in the bread and wine. Instead of unleavened wafers, ordinary bread was to be used.[185] The prayer of invocation was removed, and the minister no longer said "the body of Christ" when delivering communion. Rather, he said, "Take and eat this, in remembrance that Christ died for thee, and feed on him in thy heart by faith, with thanksgiving". Christ's presence in the Lord's Supper was a spiritual presence "limited to the subjective experience of the communicant".[185] Anglican bishop and scholar Colin Buchanan interprets the prayer book to teach that "the only point where the bread and wine signify the body and blood is at reception".[186] Rather than reserving the sacrament (which often led to Eucharistic adoration), any leftover bread or wine was to be taken home by the curate for ordinary consumption.[187]

In the new prayer book, the last vestiges of prayers for the dead were removed from the funeral service.[188] Unlike the 1549 version, the 1552 prayer book removed many traditional sacramentals and observances that reflected belief in the blessing and exorcism of people and objects. In the baptism service, infants no longer received minor exorcism and the white chrisom robe. Anointing was no longer included in the services for baptism, ordination and visitation of the sick.[189] These ceremonies were altered to emphasise the importance of faith, rather than trusting in rituals or objects. Clerical vestments were simplified—ministers were only allowed to wear the surplice and bishops had to wear a rochet.[185]

Throughout Edward's reign, inventories of parish valuables, ostensibly for preventing embezzlement, convinced many the government planned to seize parish property, just as was done to the chantries.[190] These fears were confirmed in March 1551 when the Privy Council ordered the confiscation of church plate and vestments "for as much as the King's Majestie had neede [sic] presently of a mass of money".[191] No action was taken until 1552–1553 when commissioners were appointed. They were instructed to leave only the "bare essentials" required by the 1552 Book of Common Prayer—a surplice, tablecloths, communion cup and a bell. Items to be seized included copes, chalices, chrismatories, patens, monstrances and candlesticks.[192] Many parishes sold their valuables rather than have them confiscated at a later date.[190] The money funded parish projects that could not be challenged by royal authorities.[note 12] In many parishes, items were concealed or given to local gentry who had, in fact, lent them to the church.[note 13]

The confiscations caused tensions between Protestant church leaders and Warwick, now Duke of Northumberland. Cranmer, Ridley and other Protestant leaders did not fully trust Northumberland. Northumberland in turn sought to undermine these bishops by promoting their critics, such as Jan Laski and John Knox.[193] Cranmer's plan for a revision of English canon law, the Reformatio legum ecclesiasticarum, failed in Parliament due to Northumberland's opposition.[194] Despite such tensions, a new doctrinal statement to replace the King's Book was issued on royal authority in May 1553. The Forty-two Articles reflected the Reformed theology and practice taking shape during Edward's reign, which historian Christopher Haigh describes as a "restrained Calvinism".[195] It affirmed predestination and that the King of England was Supreme Head of the Church of England under Christ.[196]

Edward's succession

[edit]King Edward became seriously ill in February and died in July 1553. Before his death, Edward was concerned that Mary, his devoutly Catholic sister, would overturn his religious reforms. A new plan of succession was created in which both of Edward's sisters Mary and Elizabeth were bypassed on account of illegitimacy in favour of the Protestant Jane Grey, the granddaughter of Edward's aunt Mary Tudor and daughter in law of the Duke of Northumberland. This new succession violated the Third Succession Act of 1543 and was widely seen as an attempt by Northumberland to stay in power.[197] Northumberland was unpopular due to the church confiscations, and support for Jane collapsed.[198] On 19 July, the Privy Council proclaimed Mary queen to the acclamation of the crowds in London.[199]

Marian Restoration

[edit]

Reconciling with Rome

[edit]Both Protestants and Catholics understood that the accession of Mary I to the throne meant a restoration of traditional religion.[200] Before any official sanction, Latin Masses began reappearing throughout England, despite the 1552 Book of Common Prayer remaining the only legal liturgy.[201] Mary began her reign cautiously by emphasising the need for tolerance in matters of religion and proclaiming that, for the time being, she would not compel religious conformity. This was in part Mary's attempt to avoid provoking Protestant opposition before she could consolidate her power.[202] While Protestants were not a majority of the population, their numbers had grown through Edward's reign. Historian Eamon Duffy writes that "Protestantism was a force to be reckoned with in London and in towns like Bristol, Rye, and Colchester, and it was becoming so in some northern towns such as Hessle, Hull, and Halifax."[203]

Following Mary's accession, the Duke of Norfolk along with the conservative bishops Bonner, Gardiner, Tunstall, Day and Heath were released from prison and restored to their former dioceses. By September 1553, Hooper and Cranmer were imprisoned. Northumberland himself was executed but not before his conversion to Catholicism.[204]

The break with Rome and the religious reforms of Henry VIII and Edward VI were achieved through parliamentary legislation and could only be reversed through Parliament. When Parliament met in October, Bishop Gardiner, now Lord Chancellor, initially proposed the repeal of all religious legislation since 1529. The House of Commons refused to pass this bill, and after heated debate,[205] Parliament repealed all Edwardian religious laws, including clerical marriage and the prayer book, in the First Statute of Repeal.[206] By 20 December, the Mass was reinstated by law.[207] There were disappointments for Mary: Parliament refused to penalise non-attendance at Mass, would not restore confiscated church property, and left open the question of papal supremacy.[208]

If Mary was to secure England for Catholicism, she needed an heir and her Protestant half-sister Elizabeth had to be prevented from inheriting the Crown. On the advice of her cousin Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, she married his son, Philip II of Spain, in 1554. There was opposition, and even a rebellion in Kent (led by Sir Thomas Wyatt); even though it was provided that Philip would never inherit the kingdom if there was no heir, received no estates and had no coronation.[209]

By the end of 1554, Henry VIII's religious settlement had been re-instituted, but England was still not reunited with Rome. Before reunion could occur, church property disputes had to be settled—which, in practice, meant letting the nobility and gentry who had bought confiscated church lands keep them. Cardinal Reginald Pole, the Queen's cousin, arrived in November 1554 as papal legate to end England's schism with the Catholic Church.[209] On 28 November, Pole addressed Parliament to ask it to end the schism, declaring "I come not to destroy, but to build. I come to reconcile, not to condemn. I come not to compel, but to call again."[210] In response, Parliament submitted a petition to the Queen the next day asking that "this realm and dominions might be again united to the Church of Rome by the means of the Lord Cardinal Pole".[210]

30 ноября поляк выступил перед обеими палатами парламента, освободив членов парламента «со всем королевством и его владениями от всякой ереси и раскола». [ 211 ] После этого архиереи освободили епархиальное духовенство, а оно, в свою очередь, освободило прихожан. [ 212 ] 26 декабря Тайный совет представил закон, отменяющий религиозное законодательство времен правления Генриха VIII и осуществляющий воссоединение с Римом. Этот законопроект был принят как Второй Статут об отмене . [ 213 ]

Католическое восстановление

[ редактировать ]Историк Имон Даффи пишет, что религиозная «программа Марии была не программой реакции, а творческой реконструкцией», вобравшей в себя все, что считалось положительным в реформах Генриха VIII и Эдуарда VI. [ 214 ] Результат «незначительно, но явно отличался от католицизма 1520-х годов». [ 214 ] По словам историка Кристофера Хэя, католицизм, формирующийся во время правления Марии, «отражал зрелый эразмовский католицизм» его ведущих священнослужителей, которые все получили образование в 1520-х и 1530-х годах. [ 215 ] Церковная литература Марии, церковные благодеяния и рассказы церковных старост предполагают меньший акцент на святых, изображениях и молитвах за умерших. Больше внимания уделялось необходимости внутреннего раскаяния в дополнение к внешним актам покаяния. [ 216 ] Сам кардинал Поул был членом Spirituali , католического реформаторского движения, которое разделяло с протестантами акцент на полной зависимости человека от Божьей благодати по вере и взгляды Августина на спасение. [ 217 ] [ 218 ]

Кардинал Поул в конечном итоге заменит Кранмера на посту архиепископа Кентерберийского в 1556 году, поскольку юрисдикционные проблемы между Англией и Римом помешали смещению Кранмера. Мэри могла бы судить и казнить Кранмера за государственную измену — он поддержал претензии леди Джейн Грей, — но она решила, что его будут судить за ересь. Его отречение от своего протестантизма было бы крупным переворотом. К несчастью для нее, он неожиданно в последнюю минуту отказался от своего отречения, поскольку его должны были сжечь на костре, тем самым разрушив пропагандистскую победу ее правительства. [ 219 ]

Как папский легат, Поул обладал властью как над своей провинцией Кентербери, так и над провинцией Йорк , что позволяло ему контролировать Контрреформацию по всей Англии. [ 220 ] Он заново установил в церквях образы, облачения и утварь. Около 2000 женатых священнослужителей были разлучены со своими женами, но большинству из них было разрешено продолжать свою священническую деятельность. [ 219 ] [ 221 ] Полю помогали некоторые ведущие католические интеллектуалы, испанские члены Доминиканского ордена : Педро де Сото , Хуан де Вильягарсия и Бартоломе Карранса . [ 219 ]

В 1556 году поляк приказал духовенству каждое воскресенье читать одну главу из «Полезного и необходимого учения» прихожанам епископа Боннэра. Созданная по образцу Королевской книги 1543 года, работа Боннера представляла собой обзор основных католических учений, организованных вокруг Апостольского Символа веры , Десяти заповедей , семи смертных грехов , таинств, Молитвы Господней и Радуйся, Мария . [ 222 ] Боннэр также выпустила детский катехизис и сборник проповедей. [ 223 ]

С декабря 1555 по февраль 1556 года кардинал Поул председательствовал на национальном синоде легатов, который издал ряд декретов, озаглавленных Reformatio Angliae или Реформация Англии. [ 224 ] Действия, предпринятые синодом, предвосхитили многие реформы, проведенные во всей католической церкви после Тридентского собора . [ 220 ] Поул считал, что невежество и отсутствие дисциплины среди духовенства привели к религиозным беспорядкам в Англии, и реформы Синода были призваны решить обе проблемы. прогулы духовенства (практика отсутствия духовенства в своей епархии или приходе), плюрализм и симония . Осуждены были [ 225 ] Проповедь была поставлена в центр пастырского служения, [ 226 ] и все духовенство должно было читать проповеди народу (настоятели и викарии, не сделавшие этого, были оштрафованы). [ 225 ] Важнейшей частью плана было постановление об учреждении в каждой епархии семинарии, которая заменила бы беспорядочный порядок обучения священников ранее. Позже Тридентский собор навязал систему семинарии остальной части католической церкви. [ 226 ] Он также был первым, кто представил алтарную скинию , в которой хранился евхаристический хлеб для преданности и поклонения. [ 220 ]

Мария сделала все, что могла, чтобы восстановить церковные финансы и земли, отнятые во времена правления ее отца и брата. В 1555 году она вернула церкви доходы от первых плодов и десятых доходов, но с этими новыми средствами пришла ответственность за выплату пенсий бывшим монашествующим. На свои деньги она восстановила шесть религиозных домов, в частности Вестминстерское аббатство для бенедиктинцев и Сионское аббатство для бриджиттинок . [ 227 ] Однако были пределы тому, что можно было восстановить. В период с 1555 по 1558 год было восстановлено только семь религиозных домов, хотя планировалось восстановить еще больше. Из 1500 бывших монашествующих, все еще живущих, только около сотни возобновили монашескую жизнь, и лишь небольшое количество часовен было вновь основано. Восстановлению препятствовало изменение характера благотворительных пожертвований. План по восстановлению Грейфрайарс в Лондоне был сорван, поскольку его здания были заняты больницей Христа , школой для детей-сирот. [ 228 ]

Среди историков ведутся споры о том, насколько яркой была реставрация на местном уровне. По словам историка А. Г. Диккенса, «приходская религия отличалась религиозной и культурной бесплодностью». [ 229 ] хотя историк Кристофер Хей заметил энтузиазм, омраченный только плохими урожаями, которые привели к бедности и нужде. [ 230 ] Набор в английское духовенство начал расти после почти десятилетия снижения рукоположений. [ 231 ] Начался ремонт давно заброшенных церквей. В приходах «продолжались реставрация и ремонт, закупались новые колокола, и церковные эли приносили свою буколическую прибыль». [ 232 ] Были восстановлены великие церковные праздники, которые отмечались спектаклями, театрализованными представлениями и крестными ходами. Однако попытка епископа Боннера организовать еженедельные шествия в 1556 году потерпела неудачу. Хей пишет, что за годы, когда шествия были запрещены, люди нашли «лучшее применение своему времени», а также «лучшее применение своим деньгам, чем подношение свечей изображениям». [ 233 ] Основное внимание уделялось «распятому Христу в мессе, кресту и преданности Тела Христова». [ 231 ]

-

Консервативный епископ Эдмунд Боннер

-

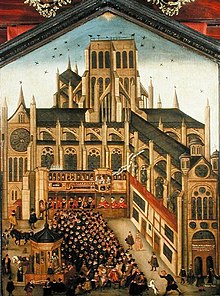

Вестминстерское аббатство было одним из семи монастырей, воссозданных во время Реставрации Марии.

Препятствия

[ редактировать ]

Протестанты, отказавшиеся подчиняться, оставались препятствием для планов католиков. Около 800 протестантов бежали из Англии в поисках безопасности в протестантских районах Германии и Швейцарии, создав сети независимых общин. Защищенные от преследований, эти марианские изгнанники вели пропагандистскую кампанию против католицизма и испанского брака королевы, иногда призывая к восстанию. [ 234 ] [ 235 ] Те, кто остался в Англии, были вынуждены тайно исповедовать свою веру и собираться в подпольных общинах. [ 236 ]

В 1555 году первоначальный примирительный тон режима начал ужесточаться с возрождением средневековых законов о ереси , которые разрешали смертную казнь в качестве наказания за ересь. [ 237 ] Преследование еретиков было нескоординированным: иногда аресты производились Тайным советом, иногда епископами, а иногда мирскими судьями. [ 238 ] Протестанты привлекали к себе внимание обычно из-за какого-либо инакомыслия, например, осуждения мессы или отказа принять причастие. [ 239 ] Особенно жестоким актом протеста стало нападение Уильяма Флауэра на священника во время мессы в пасхальное воскресенье, 14 апреля 1555 года. [ 240 ] Лица, обвиняемые в ереси, допрашивались церковным чиновником и, в случае обнаружения ереси, предоставляли выбор между смертью и подписанием отречения . [ 241 ] В некоторых случаях протестантов сжигали на кострах после отказа от отречения. [ 242 ]

Около 284 протестантов были сожжены на кострах за ересь. [ 243 ] Были казнены несколько ведущих реформаторов, в том числе Томас Кранмер, Хью Латимер, Николас Ридли, Джон Роджерс , Джон Хупер , Роберт Феррар , Роуленд Тейлор и Джон Брэдфорд . [ 244 ] Среди жертв были и менее известные личности, в том числе около 51 женщины, такие как Джоан Уэйст и Агнес Перст . [ 245 ] Историк О.Т. Харгрейв пишет, что преследования Мариан не были «чрезмерными» по «современным континентальным стандартам»; однако «это было беспрецедентно в английском опыте». [ 246 ] Историк Кристофер Хей пишет, что ему «не удалось запугать всех протестантов», чья храбрость на костре вдохновила других; однако это «не было катастрофой: если это не помогло делу католиков, то и не нанесло ему особого вреда». [ 232 ] После ее смерти королева стала известна как «Кровавая Мэри» из-за влияния Джона Фокса , одного из изгнанников Марии. [ 247 ] Опубликованная в 1563 году Фокса» «Книга мучеников содержала отчеты о казнях, а в 1571 году Кентерберийский созыв распорядился разместить книгу Фокса в каждом соборе страны. [ 248 ]

Усилия Марии по восстановлению католицизма также были сорваны самой церковью. Папа Павел IV объявил Филиппу войну и отозвал поляка в Рим, чтобы его судили как еретика. Мэри отказалась отпустить его. Таким образом, ей было отказано в поддержке, которую она могла ожидать от благодарного Папы. [ 249 ] С 1557 года Папа отказывался утверждать английских епископов, что привело к появлению вакансий и нанесению ущерба религиозной программе Мариан. [ 225 ]

Несмотря на эти препятствия, пятилетняя реставрация прошла успешно. Среди народа существовала поддержка традиционной религии, а протестанты оставались меньшинством. Следовательно, протестанты, тайно служившие подпольным общинам, такие как Томас Бентам , планировали долгосрочное служение выживания. Смерть Марии в ноябре 1558 года, бездетной и не предусмотревшей, чтобы католик стал ее преемником, означала, что ее сестра-протестантка Елизавета станет следующей королевой. [ 250 ]

Елизаветинское поселение

[ редактировать ]

| Часть серии о |

| пуритане |

|---|

|

Елизавета I унаследовала королевство, в котором большинство людей, особенно политическая элита, были религиозно консервативными, а главным союзником Англии была католическая Испания. [ 251 ] По этим причинам прокламация, объявляющая о ее вступлении на престол, запрещала любое «нарушение, изменение или изменение любого порядка или обычаев, установленных в настоящее время в этом нашем царстве». [ 252 ] Это было лишь временно. Новая королева была протестанткой, хотя и консервативной. [ 253 ] Она также наполнила свое новое правительство протестантами. королевы Главным секретарем был сэр Уильям Сесил , умеренный протестант. [ 254 ] Ее Тайный совет был заполнен бывшими эдвардианскими политиками, и при дворе проповедовали только протестанты . [ 255 ] [ 256 ]

В 1558 году парламент принял Акт о верховенстве , который восстановил независимость англиканской церкви от Рима и даровал Елизавете титул верховного губернатора англиканской церкви . Закон о единообразии 1559 года утвердил 1559 года Книгу общих молитв , которая представляла собой переработанную версию Молитвенника 1552 года времен правления Эдварда. Некоторые изменения были внесены, чтобы привлечь католиков и лютеран, в том числе предоставляли людям большую свободу в отношении веры в реальное присутствие и разрешали использование традиционных священнических облачений. В 1571 году « Тридцать девять статей» были приняты в качестве исповедального заявления церкви, и была выпущена Книга проповедей, в которой более подробно излагалось реформированное богословие церкви. [ нужна ссылка ]

Елизаветинское поселение основало церковь, реформатскую по доктрине, но сохранившую некоторые характеристики средневекового католицизма, такие как соборы , церковные хоры , официальную литургию, содержащуюся в Молитвеннике, традиционные облачения и епископское устройство. [ 257 ] По словам историка Диармайда Маккалока, конфликты по поводу елизаветинского поселения проистекают из этого «напряжения между католической структурой и протестантским богословием». [ 258 ] Во время правления Елизаветы и Якова I внутри англиканской церкви возникло несколько фракций. [ нужна ссылка ]

«Церковными папистами » были католики, которые внешне соответствовали установленной церкви, сохраняя при этом свою католическую веру в тайне. Католические власти не одобряли такое внешнее соответствие. Отказниками были католики, отказавшиеся посещать службы англиканской церкви, как того требует закон. [ 259 ] Непокорность наказывалась штрафом в размере 20 фунтов стерлингов в месяц (пятидесятикратная заработная плата ремесленника ). [ 260 ] К 1574 году бунтовщики-католики организовали подпольную католическую церковь, отличную от англиканской церкви. Однако у нее было два основных недостатка: потеря членства, поскольку церковные паписты полностью соответствовали англиканской церкви, и нехватка священников. Между 1574 и 1603 годами в Англию было отправлено 600 католических священников. [ 261 ] Приток обученных за границей католических священников, неудачное восстание северных графов , отлучение Елизаветы от церкви и раскрытие заговора Ридольфи — все это способствовало восприятию католицизма как предательства. [ 262 ] Казни католических священников стали более распространенными: первая в 1577 году, четыре в 1581 году, одиннадцать в 1582 году, две в 1583 году, шесть в 1584 году, пятьдесят три к 1590 году и еще семьдесят между 1601 и 1608 годами. [ примечание 14 ] [ 263 ] В 1585 году въезд в страну католического священника считался изменой, а также тех, кто помогал ему или приютил его. [ 260 ] Когда вымерло старшее поколение непокорных священников, католицизм рухнул среди низших классов на севере, западе и в Уэльсе. Без священников эти социальные классы перешли в Англиканскую церковь, и католицизм был забыт. После смерти Елизаветы в 1603 году католицизм стал «верой небольшой секты», в основном ограниченной дворянскими семьями. [ 264 ]

Постепенно Англия превратилась в протестантскую страну, поскольку Молитвенник сформировал религиозную жизнь Елизаветы. К 1580-м годам протестанты-конформисты (те, кто согласовывал свою религиозную практику с религиозными постановлениями) стали большинством. [ 265 ] Кальвинизм нравился многим конформистам, и во время правления Елизаветы кальвинистское духовенство владело лучшими епископствами и благочиниями. [ 266 ] Другие кальвинисты были недовольны элементами елизаветинского урегулирования и хотели дальнейших реформ, чтобы сделать Англиканскую церковь более похожей на континентальные реформатские церкви . Эти нонконформисты-кальвинисты стали известны как пуритане . Некоторые пуритане отказывались поклоняться имени Иисуса , креститься при крещении , использовать обручальные кольца или органную музыку в церкви. Особенно их возмущало требование к духовенству носить белый стихарь и церковный колпак . [ 267 ] Пуританские священнослужители предпочитали носить черную академическую одежду (см. Споры об облачениях ). [ 268 ] Многие пуритане считали, что англиканская церковь должна последовать примеру реформатских церквей в других частях Европы и принять пресвитерианскую систему правления , при которой правительство епископов будет заменено правительством старейшин . [ 269 ] Однако все попытки провести дальнейшие реформы через парламент были заблокированы королевой. [ 270 ]

Последствия

[ редактировать ]

Традиционно историки относят конец английской Реформации к религиозному поселению Елизаветы. Есть ученые, которые выступают за «долгую Реформацию», которая продолжалась в 17 и 18 веках. [ 271 ]

В ранний период Стюартов доминирующим богословием англиканской церкви по-прежнему был кальвинизм, но группа богословов, связанная с епископом Ланселотом Эндрюсом, не соглашалась со многими аспектами реформатской традиции, особенно с ее учением о предопределении . Они обращались к отцам церкви, а не к реформаторам, и предпочитали использовать более традиционный Молитвенник 1549 года. [ 272 ] Из-за своей веры в свободу воли эта новая фракция известна как арминианская партия , но их высокая церковная ориентация была более спорной. Яков I пытался сбалансировать пуританские силы внутри своей церкви с последователями Эндрюса, продвигая многих из них в конце своего правления. [ 273 ]