Chinese characters

| Chinese characters | |

|---|---|

"Chinese character" written in traditional (left) and simplified (right) forms | |

| Script type | Logographic |

Time period | c. 13th century BCE – present |

| Direction |

|

| Languages | (among others) |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | (Proto-writing)

|

Child systems | |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Hani (500), Han (Hanzi, Kanji, Hanja) |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Han |

| U+4E00–U+9FFF CJK Unified Ideographs (full list) | |

| Chinese characters | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||

| Simplified Chinese | 汉字 | ||

| Traditional Chinese | 漢字 | ||

| Literal meaning | Han characters | ||

| |||

| Vietnamese name | |||

| Vietnamese alphabet |

| ||

| Hán-Nôm |

| ||

| Chữ Hán | 漢字 | ||

| Zhuang name | |||

| Zhuang | sawgun | ||

| Sawndip | 𭨡倱[1] | ||

| Korean name | |||

| Hangul | 한자 | ||

| Hanja | 漢字 | ||

| |||

| Japanese name | |||

| Kanji | 漢字 | ||

| |||

Chinese characters[a] are logographs used to write the Chinese languages and others from regions historically influenced by Chinese culture. Chinese characters have a documented history spanning over three millennia, representing one of the four independent inventions of writing accepted by scholars; of these, they comprise the only writing system continuously used since its invention. Over time, the function, style, and means of writing characters have evolved greatly. Unlike letters in alphabets that reflect the sounds of speech, Chinese characters generally represent morphemes, the units of meaning in a language. Writing a language's entire vocabulary requires thousands of different characters. Characters are created according to several different principles, where aspects of both shape and pronunciation may be used to indicate the character's meaning.

The first attested characters are oracle bone inscriptions made during the 13th century BCE in what is now Anyang, Henan, as part of divinations conducted by the Shang dynasty royal house. Character forms were originally highly pictographic in style, but evolved over time as writing spread across China. Numerous attempts have been made to reform the script, including the promotion of small seal script by the Qin dynasty (221–206 BCE). Clerical script, which had matured by the early Han dynasty (202 BCE – 220 CE), abstracted the forms of characters—obscuring their pictographic origins in favour of making them easier to write. Following the Han, regular script emerged as the result of cursive influence on clerical script, and has been the primary style used for characters since. Informed by a long tradition of lexicography, states using Chinese characters have standardised their forms: broadly, simplified characters are used to write Chinese in mainland China, Singapore, and Malaysia, while traditional characters are used in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macau.

After being introduced in order to write Literary Chinese, characters were often adapted to write local languages spoken throughout the Sinosphere. In Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese, Chinese characters are known as kanji, hanja, and chữ Hán respectively. Writing traditions also emerged for some of the other languages of China, like the sawndip script used to write the Zhuang languages of Guangxi. Each of these written vernaculars used existing characters to write the language's native vocabulary, as well as the loanwords it borrowed from Chinese. In addition, each invented characters for local use. In written Korean and Vietnamese, Chinese characters have largely been replaced with alphabets, leaving Japanese as the only major non-Chinese language still written using them.

At the most basic level, characters are composed of strokes that are written in a fixed order. Methods of writing characters have historically included being carved into stone, being inked with a brush onto silk, bamboo, or paper, and being printed using woodblocks and movable type. Technologies invented since the 19th century allowing for wider use of characters include telegraph codes and typewriters, as well as input methods and text encodings on computers.

Development

[edit]Chinese characters are accepted as representing one of four independent inventions of writing in human history.[b] In each instance, writing evolved from a system using two distinct types of ideographs. Ideographs could either be pictographs visually depicting objects or concepts, or fixed signs representing concepts only by shared convention. These systems are classified as proto-writing, because the techniques they used were insufficient to carry the meaning of spoken language by themselves.[3]

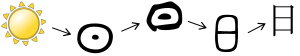

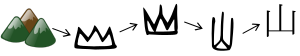

Various innovations were required for Chinese characters to emerge from proto-writing. Firstly, pictographs became distinct from simple pictures in use and appearance: for example, the pictograph 大, meaning 'large', was originally a picture of a large man, but one would need to be aware of its specific meaning in order to interpret the sequence 大鹿 as signifying 'large deer', rather than being a picture of a large man and a deer next to one another. Due to this process of abstraction, as well as to make characters easier to write, pictographs gradually became more simplified and regularised—often to the extent that the original objects represented are no longer obvious.[4]

This proto-writing system was limited to representing a relatively narrow range of ideas with a comparatively small library of symbols. This compelled innovations that allowed for symbols to directly encode spoken language.[5] In each historical case, this was accomplished by some form of the rebus technique, where the symbol for a word is used to indicate a different word with a similar pronunciation, depending on context.[6] This allowed for words that lacked a plausible pictographic representation to be written down for the first time. This technique pre-empted more sophisticated methods of character creation that would further expand the lexicon. The process whereby writing emerged from proto-writing took place over a long period; when the purely pictorial use of symbols disappeared, leaving only those representing spoken words, the process was complete.[7]

Classification

[edit]Chinese characters have been used in several different writing systems throughout history. The concept of a writing system includes both the written symbols themselves, called graphemes—which may include characters, numerals, or punctuation—as well as the rules by which they are used to record language.[8] Chinese characters are logographs, which are graphemes that represent units of meaning in a language. Specifically, characters represent the smallest units of meaning in a language, which are referred to as morphemes. Morphemes in Chinese—and therefore the characters used to write them—are nearly always a single syllable in length. In some special cases, characters may denote non-morphemic syllables as well; due to this, written Chinese is often characterised as morphosyllabic.[9][c] Logographs may be contrasted with letters in an alphabet, which generally represent phonemes, the distinct units of sound used by speakers of a language.[11] Despite their origins in picture-writing, Chinese characters are no longer ideographs capable of representing ideas directly; their comprehension relies on the reader's knowledge of the particular language being written.[12]

The areas where Chinese characters were historically used—sometimes collectively termed the Sinosphere—have a long tradition of lexicography attempting to explain and refine their use; for most of history, analysis revolved around a model first popularised in the 2nd-century Shuowen Jiezi dictionary.[13] More recent models have analysed the methods used to create characters, how characters are structured, and how they function in a given writing system.[14]

Structural analysis

[edit]Most characters can be analysed structurally as compounds made of smaller components (部件; bùjiàn), which are often independent characters in their own right, adjusted to occupy a given position in the compound.[15] Components within a character may serve a specific function: phonetic components provide a hint for the character's pronunciation, and semantic components indicate some element of the character's meaning. Components that serve neither function may be classified as pure signs with no particular meaning, other than their presence distinguishing one character from another.[16]

A straightforward structural classification scheme may consist of three pure classes of semantographs, phonographs and signs—having only semantic, phonetic, and form components respectively, as well as classes corresponding to each combination of component types.[17] Of the 3500 characters that are frequently used in Standard Chinese, pure semantographs are estimated to be the rarest, accounting for about 5% of the lexicon, followed by pure signs with 18%, and semantic–form and phonetic–form compounds together accounting for 19%. The remaining 58% are phono-semantic compounds.[18]

The Chinese palaeographer Qiu Xigui (b. 1935) presents three principles of character function adapted from earlier proposals by Tang Lan (1901–1979) and Chen Mengjia (1911–1966),[19] with semantographs describing all characters whose forms are wholly related to their meaning, regardless of the method by which the meaning was originally depicted, phonographs that include a phonetic component, and loangraphs encompassing existing characters that have been borrowed to write other words. Qiu also acknowledges the existence of character classes that fall outside of these principles, such as pure signs.[20]

Semantographs

[edit]Pictographs

[edit]Most of the oldest characters are pictographs (象形; xiàngxíng), representational pictures of physical objects.[21] Examples include 日 ('Sun'), 月 ('Moon'), and 木 ('tree'). Over time, the forms of pictographs have been simplified in order to make them easier to write.[22] As a result, it is often no longer evident what thing was originally being depicted by a pictograph; without knowing the context of its origin in picture-writing, it may be interpreted instead as a pure sign. However, if its use in compounds still reflects a pictograph's original meaning, as with 日 in 晴 ('clear sky'), it can still be analysed as a semantic component.[23][24]

Pictographs have often been extended from their original meanings to take on additional layers of metaphor and synecdoche, which sometimes displace the character's original sense. This process has sometimes created excess ambiguity between the different senses of a character, which is usually resolved by creating new compound characters.[25]

Indicatives

[edit]Indicatives (指事; zhǐshì), also called simple ideographs or self-explanatory characters,[21] are visual representations of abstract concepts that lack any tangible form. Examples include 上 ('up') and 下 ('down')—these characters were originally written as dots placed above and below a line, and later evolved into their present forms with less potential for graphical ambiguity in context.[26] More complex indicatives include 凸 ('convex'), 凹 ('concave'), and 平 ('flat and level').[27]

Compound ideographs

[edit]Compound ideographs (会意; 會意; huìyì)—also called logical aggregates, associative idea characters, or syssemantographs—combine other characters to convey a new, synthetic meaning. A canonical example is 明 ('bright'), interpreted as the juxtaposition of the two brightest objects in the sky: ⽇ 'SUN' and ⽉ 'MOON', together expressing their shared quality of brightness. Other examples include 休 ('rest'), composed of pictographs ⼈ 'MAN' and ⽊ 'TREE', and 好 ('good'), composed of ⼥ 'WOMAN' and ⼦ 'CHILD'.[28]

Many traditional examples of compound ideographs are now believed to have actually originated as phono-semantic compounds, made obscure by subsequent changes in pronunciation.[29] For example, the Shuowen Jiezi describes 信 ('trust') as an ideographic compound of ⼈ 'MAN' and ⾔ 'SPEECH', but modern analyses instead identify it as a phono-semantic compound—though with disagreement as to which component is phonetic.[30] Peter A. Boodberg and William G. Boltz go so far as to deny that any compound ideographs were devised in antiquity, maintaining that secondary readings that are now lost are responsible for the apparent absence of phonetic indicators,[31] but their arguments have been rejected by other scholars.[32]

Phonographs

[edit]Phono-semantic compounds

[edit]Phono-semantic compounds (形声; 形聲; xíngshēng) are composed of at least one semantic component and one phonetic component.[33] They may be formed by one of several methods, often by adding a phonetic component to disambiguate a loangraph, or by adding a semantic component to represent a specific extension of a character's meaning.[34] Examples of phono-semantic compounds include 河 (hé; 'river'), 湖 (hú; 'lake'), 流 (liú; 'stream'), 沖 (chōng; 'surge'), and 滑 (huá; 'slippery'). Each of these characters have three short strokes on their left-hand side: 氵, a simplified combining form of ⽔ 'WATER'. This component serves a semantic function in each example, indicating the character has some meaning related to water. The remainder of each character is its phonetic component: 湖 (hú) is pronounced identically to 胡 (hú) in Standard Chinese, 河 (hé) is pronounced similarly to 可 (kě), and 沖 (chōng) is pronounced similarly to 中 (zhōng).[35]

The phonetic components of most compounds may only provide an approximate pronunciation, even before subsequent sound shifts in the spoken language. Some characters may only have the same initial or final sound of a syllable in common with phonetic components.[36] A phonetic series comprises all the characters created using the same phonetic component, which may have diverged significantly in their pronunciations over time. For example, 茶 (chá; caa4; 'tea') and 途 (tú; tou4; 'route') are part of the phonetic series of characters using 余 (yú; jyu4), a literary first-person pronoun. The Old Chinese pronunciations of these characters were similar, but the phonetic component no longer serves as a useful hint for their pronunciation due to subsequent sound shifts.[37]

Loangraphs

[edit]The phenomenon of existing characters being adapted to write other words with similar pronunciations was necessary in the initial development of Chinese writing, and has remained common throughout its subsequent history. Some loangraphs (假借; jiǎjiè; 'borrowing') are introduced to represent words previously lacking another written form—this is often the case with abstract grammatical particles such as 之 and 其.[38] The process of characters being borrowed as loangraphs should not be conflated with the distinct process of semantic extension, where a word acquires additional senses, which often remain written with the same character. As both processes often result in a single character form being used to write several distinct meanings, loangraphs are often misidentified as being the result of semantic extension, and vice versa.[39]

Loangraphs are also used to write words borrowed from other languages, such as the Buddhist terminology introduced to China in antiquity, as well as contemporary non-Chinese words and names. For example, each character in the name 加拿大 (Jiānádà; 'Canada') is often used as a loangraph for its respective syllable. However, the barrier between a character's pronunciation and meaning is never total: when transcribing into Chinese, loangraphs are often chosen deliberately as to create certain connotations. This is regularly done with corporate brand names: for example, Coca-Cola's Chinese name is 可口可乐; 可口可樂 (Kěkǒu Kělè; 'delicious enjoyable').[40][41][42]

Signs

[edit]Some characters and components are pure signs, whose meaning merely derives from their having a fixed and distinct form. Basic examples of pure signs are found with the numerals beyond four, e.g. 五 ('five') and 八 ('eight'), whose forms do not give visual hints to the quantities they represent.[43]

Traditional Shuowen Jiezi classification

[edit]The Shuowen Jiezi is a character dictionary authored c. 100 CE by the scholar Xu Shen (c. 58 – c. 148 CE). In its postface, Xu analyses what he sees as all the methods by which characters are created. Later authors iterated upon Xu's analysis, developing a categorisation scheme known as the 'six writings' (六书; 六書; liùshū), which identifies every character with one of six categories that had previously been mentioned in the Shuowen Jiezi. For nearly two millennia, this scheme was the primary framework for character analysis used throughout the Sinosphere.[44] Xu based most of his analysis on examples of Qin seal script that were written down several centuries before his time—these were usually the oldest specimens available to him, though he stated he was aware of the existence of even older forms.[45] The first five categories are pictographs, indicatives, compound ideographs, phono-semantic compounds, and loangraphs. The sixth category is given by Xu as 轉注 (zhuǎnzhù; 'reversed and refocused'); however, its definition is unclear, and it is generally disregarded by modern scholars.[46]

Modern scholars agree that the theory presented in the Shuowen Jiezi is problematic, failing to fully capture the nature of Chinese writing, both in the present, as well as at the time Xu was writing.[47] Traditional Chinese lexicography as embodied in the Shuowen Jiezi has suggested implausible etymologies for some characters.[48] Moreover, several categories are considered to be ill-defined: for example, it is unclear whether characters like 大 ('large') should be classified as pictographs or indicatives.[34] However, awareness of the 'six writings' model has remained a common component of character literacy, and often serves as a tool for students memorising characters.[49]

History

[edit]

The broadest trend in the evolution of Chinese characters over their history has been simplification, both in graphical shape (字形; zìxíng), the "external appearances of individual graphs", and in graphical form (字体; 字體; zìtǐ), "overall changes in the distinguishing features of graphic[al] shape and calligraphic style, [...] in most cases refer[ring] to rather obvious and rather substantial changes".[50] The traditional notion of an orderly procession of script styles, each suddenly appearing and displacing the one previous, has been disproven by later scholarship and archaeological work. Instead, scripts evolved gradually, with several coexisting in a given area.[51]

Traditional invention narrative

[edit]Several of the Chinese classics indicate that knotted cords were used to keep records prior to the invention of writing.[52] Works that reference the practice include chapter 80 of the Tao Te Ching[B] and the "Xici II" commentary to the I Ching.[C] According to one tradition, Chinese characters were invented during the 3rd millennium BCE by Cangjie, a scribe of the legendary Yellow Emperor. Cangjie is said to have invented symbols called 字 (zì) due to his frustration with the limitations of knotting, taking inspiration from his study of the tracks of animals, landscapes, and the stars in the sky. On the day that these first characters were created, grain rained down from the sky; that night, the people heard the wailing of ghosts and demons, lamenting that humans could no longer be cheated.[53][54]

Neolithic

[edit]Collections of graphs and pictures have been discovered at the sites of several Neolithic settlements throughout the Yellow River valley, including Jiahu (c. 6500 BCE), Dadiwan and Damaidi (6th millennium BCE), and Banpo (5th millennium BCE). Symbols at each site were inscribed or drawn onto artifacts, appearing one at a time and without indicating any greater context. Qiu concludes, "We simply possess no basis for saying that they were already being used to record language."[55] A historical connection with the symbols used by the late Neolithic Dawenkou culture (c. 4300 – c. 2600 BCE) in Shandong has been deemed possible by palaeographers, with Qiu concluding that they "cannot be definitively treated as primitive writing, nevertheless they are symbols which resemble most the ancient pictographic script discovered thus far in China... They undoubtedly can be viewed as the forerunners of primitive writing."[56]

Oracle bone script

[edit]The oldest attested Chinese writing comprises a body of inscriptions produced during the Late Shang period (c. 1250 – 1050 BCE), with the very earliest examples from the reign of Wu Ding dated between 1250 and 1200 BCE.[57] Many of these inscriptions were made on oracle bones—usually either ox scapulae or turtle plastrons—and recorded official divinations carried out by the Shang royal house. Contemporaneous inscriptions in a related but distinct style were also made on ritual bronze vessels. This oracle bone script (甲骨文; jiǎgǔwén) was first documented in 1899, after specimens were discovered being sold as "dragon bones" for medicinal purposes, with the symbols carved into them identified as early character forms. By 1928, the source of the bones had been traced to a village near Anyang in Henan—discovered to be the site of Yin, the final Shang capital—which was excavated by a team led by Li Ji (1896–1979) from the Academia Sinica between 1928 and 1937.[58] To date, over 150000 oracle bone fragments have been found.[59]

Oracle bone inscriptions recorded divinations undertaken to communicate with the spirits of royal ancestors. The inscriptions range from a few characters in length at their shortest, to several dozen at their longest. The Shang king would communicate with his ancestors by means of scapulimancy, inquiring about subjects such as the royal family, military success, and the weather. Inscriptions were made in the divination material itself before and after it had been cracked by exposure to heat; they generally include a record of the questions posed, as well as the answers as interpreted in the cracks.[60][61] A minority of bones feature characters that were inked with a brush before their strokes were incised; the evidence of this also shows that the conventional stroke orders used by later calligraphers had already been established for many characters by this point.[62]

Oracle bone script is the direct ancestor of later forms of written Chinese. The oldest known inscriptions already represent a well-developed writing system, which suggests an initial emergence predating the late second millennium BCE. Although written Chinese is first attested in official divinations, it is widely believed that writing was also used for other purposes during the Shang, but that the media used in other contexts—likely bamboo and wooden slips—were less durable than bronzes or oracle bones, and have not been preserved.[63]

Zhou scripts

[edit]As early as the Shang, the oracle bone script existed as a simplified form alongside another that was used in bamboo books, in addition to elaborate pictorial forms often used in clan emblems. These other forms have been preserved in what is called bronze script (金文; jīnwén), where inscriptions were made using a stylus in a clay mould, which was then used to cast ritual bronzes.[65] These differences in technique generally resulted in character forms that were less angular in appearance than their oracle bone script counterparts.[66]

Study of these bronze inscriptions has revealed that the mainstream script underwent slow, gradual evolution during the late Shang, which continued during the Zhou dynasty (c. 1046 – 256 BCE) until assuming the form now known as small seal script (小篆; xiǎozhuàn) within the Zhou state of Qin.[67][68] Other scripts in use during the late Zhou include the bird-worm seal script (鸟虫书; 鳥蟲書; niǎochóngshū), as well as the regional forms used in non-Qin states. Examples of these styles were preserved as variants in the Shuowen Jiezi.[69] Historically, Zhou forms were collectively referred to as large seal script (大篆; dàzhuàn), a term which has fallen out of favour due to its lack of precision.[70]

Qin unification and small seal script

[edit]Following Qin's conquest of the other Chinese states that culminated in the founding of the imperial Qin dynasty in 221 BCE, the Qin small seal script was standardised for use throughout the entire country under the direction of Chancellor Li Si (c. 280 – 208 BCE).[71] It was traditionally believed that Qin scribes only used small seal script, and the later clerical script was a sudden invention during the early Han. However, more than one script was used by Qin scribes: a rectilinear vulgar style had also been in use in Qin for centuries prior to the wars of unification. The popularity of this form grew as writing became more widespread.[72]

Clerical script

[edit]By the Warring States period (c. 475 – 221 BCE), an immature form of clerical script (隶书; 隸書; lìshū) had emerged based on the vulgar form developed within Qin, often called "early clerical" or "proto-clerical".[73] The proto-clerical script evolved gradually; by the Han dynasty (202 BCE – 220 CE), it had arrived at a mature form, also called 八分 (bāfēn). Bamboo slips discovered during the late 20th century point to this maturation being completed during the reign of Emperor Wu of Han (r. 141–87 BCE). This process, called libian (隶变; 隸變), involved character forms being mutated and simplified, with many components being consolidated, substituted, or omitted. In turn, the components themselves were regularised to use fewer, straighter, and more well-defined strokes. The resulting clerical forms largely lacked any of the pictorial qualities that remained in seal script.[74]

Around the midpoint of the Eastern Han (25–220 CE), a simplified and easier form of clerical script appeared, which Qiu terms 'neo-clerical' (新隶体; 新隸體; xīnlìtǐ).[75] By the end of the Han, this had become the dominant script used by scribes, though clerical script remained in use for formal works, such as engraved stelae. Qiu describes neo-clerical as a transitional form between clerical and regular script which remained in use through the Three Kingdoms period (220–280 CE) and beyond.[76]

Cursive and semi-cursive

[edit]Cursive script (草书; 草書; cǎoshū) was in use as early as 24 BCE, synthesising elements of the vulgar writing that had originated in Qin with flowing cursive brushwork. By the Jin dynasty (266–420), the Han cursive style became known as 章草 (zhāngcǎo; 'orderly cursive'), sometimes known in English as 'clerical cursive', 'ancient cursive', or 'draft cursive'. Some attribute this name to the fact that the style was considered more orderly than a later form referred to as 今草 (jīncǎo; 'modern cursive'), which had first emerged during the Jin and was influenced by semi-cursive and regular script. This later form was exemplified by the work of figures like Wang Xizhi (303–361), who is often regarded as the most important calligrapher in Chinese history.[77][78]

An early form of semi-cursive script (行书; 行書; xíngshū; 'running script') can be identified during the late Han, with its development stemming from a cursive form of neo-clerical script. Liu Desheng (劉德升; c. 147 – 188 CE) is traditionally recognised as the inventor of the semi-cursive style, though accreditations of this kind often indicate a given style's early masters, rather than its earliest practitioners. Later analysis has suggested popular origins for semi-cursive, as opposed to it being an invention of Liu.[79] It can be characterised partly as the result of clerical forms being written more quickly, without formal rules of technique or composition: what would be discrete strokes in clerical script frequently flow together instead. The semi-cursive style is commonly adopted in contemporary handwriting.[80]

Regular script

[edit]

Regular script (楷书; 楷書; kǎishū), based on clerical and semi-cursive forms, is the predominant form in which characters are written and printed.[81] Its innovations have traditionally been credited to the calligrapher Zhong Yao (c. 151 – 230), who was living in the state of Cao Wei (220–266); he is often called the "father of regular script".[82] The earliest surviving writing in regular script comprises copies of Zhong Yao's work, including at least one copy by Wang Xizhi. Characteristics of regular script include the 'pause' (頓; dùn) technique used to end horizontal strokes, as well as heavy tails on diagonal strokes made going down and to the right. It developed further during the Eastern Jin (317–420) in the hands of Wang Xizhi and his son Wang Xianzhi (344–386).[83] However, most Jin-era writers continued to use neo-clerical and semi-cursive styles in their daily writing. It was not until the Northern and Southern period (420–589) that regular script became the predominant form.[84] The system of imperial examinations for the civil service established during the Sui dynasty (581–618) required test takers to write in Literary Chinese using regular script, which contributed to the prevalence of both throughout later Chinese history.[85]

Structure

[edit]Each character of a text is written within a uniform square allotted for it. As part of the evolution from seal script into clerical script, character components became regularised as discrete series of strokes (笔画; 壁畫; bìhuà).[86] Strokes can be considered both the basic unit of handwriting, as well as the writing system's basic unit of graphemic organisation. In clerical and regular script, individual strokes traditionally belong to one of eight categories according to their technique and graphemic function. In what is known as the Eight Principles of Yong, calligraphers practice their technique using the character 永 (yǒng; 'eternity'), which can be written with one stroke of each type.[87] In ordinary writing, 永 is now written with five strokes instead of eight, and a system of five basic stroke types is commonly employed in analysis—with certain compound strokes treated as sequences of basic strokes made in a single motion.[88]

Characters are constructed according to predictable visual patterns. Some components have distinct combining forms when occupying specific positions within a character—for example, the ⼑ 'KNIFE' component appears as 刂 on the right side of characters, but as ⺈ at the top of characters.[89] The order in which components are drawn within a character is fixed. The order in which the strokes of a component are drawn is also largely fixed, but may vary according to several different standards.[90][91] This is summed up in practice with a few rules of thumb, including that characters are generally assembled from left to right, then from top to bottom, with "enclosing" components started before, then closed after, the components they enclose.[92] For example, 永 is drawn in the following order:

Variant characters

[edit]

Over a character's history, variant character forms (异体字; 異體字; yìtǐzì) emerge via several processes. Variant forms have distinct structures, but represent the same morpheme; as such, they can be considered instances of the same underlying character. This is comparable to visually distinct double-storey |a| and single-storey |ɑ| forms both representing the Latin letter ⟨A⟩. Variants also emerge for aesthetic reasons, to make handwriting easier, or to correct what the writer perceives to be errors in a character's form.[93] Individual components may be replaced with visually, phonetically, or semantically similar alternatives.[94] The boundary between character structure and style—and thus whether forms represent different characters, or are merely variants of the same character—is often non-trivial or unclear.[95]

For example, prior to the Qin dynasty the character meaning 'bright' was written as either 明 or 朙—with either ⽇ 'SUN' or 囧 'WINDOW' on the left, and ⽉ 'MOON' on the right. As part of the Qin programme to standardise small seal script across China, the 朙 form was promoted. Some scribes ignored this, and continued to write the character as 明. However, the increased usage of 朙 was followed by the proliferation of a third variant: 眀, with ⽬ 'EYE' on the left—likely derived as a contraction of 朙. Ultimately, 明 became the character's standard form.[96]

Layout

[edit]From the earliest inscriptions until the 20th century, texts were generally laid out vertically—with characters written from top to bottom in columns, arranged from right to left. A horizontal writing direction—with characters written from left to right in rows, arranged from top to bottom—only became predominant in the Sinosphere during the 20th century as a result of Western influence.[97] Many publications outside mainland China continue to use the traditional vertical writing direction.[98] Word boundaries are generally not indicated with spaces. Western influence also resulted in the generalised use of punctuation being widely adopted in print during the 19th and 20th centuries. Prior to this, the context of a passage was considered adequate to guide readers; this was enabled by characters being easier than alphabets to read when written scriptio continua, due to their more discretised shapes.[99]

Methods of writing

[edit]

The earliest attested Chinese characters were carved into bone, or marked using a stylus in clay moulds used to cast ritual bronzes. Characters have also been incised into stone, or written in ink onto slips of silk, wood, and bamboo. The invention of paper for use as a writing medium occurred during the 1st century CE, and is traditionally credited to Cai Lun (d. 121 CE).[100] There are numerous styles, or scripts (书; 書; shū) in which characters can be written, including the historical forms like seal script and clerical script. Most styles used throughout the Sinosphere originated within China, though they may display regional variation. Styles that have been created outside of China tend to remain localised in their use: these include the Japanese edomoji and Vietnamese lệnh thư scripts.[101]

Calligraphy

[edit]

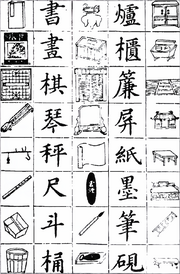

Calligraphy was traditionally one of the four arts to be mastered by Chinese scholars, considered to be an artful means of expressing thoughts and teachings. Chinese calligraphy typically makes use of an ink brush to write characters. Strict regularity is not required, and character forms may be accentuated to evoke a variety of aesthetic effects.[102] Traditional ideals of calligraphic beauty often tie into broader philosophical concepts native to East Asia. For example, aesthetics can be conceptualised using the framework of yin and yang, where the extremes of any number of mutually reinforcing dualities are balanced by the calligrapher—such as the duality between strokes made quickly or slowly, between applying ink heavily or lightly, between characters written with symmetrical or asymmetrical forms, and between characters representing concrete or abstract concepts.[103]

Printing and typefaces

[edit]

Woodblock printing was invented in China between the 6th and 9th centuries,[104] followed by the invention of movable type by Bi Sheng (972–1051) during the 11th century.[105] The increasing use of print during the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing dynasties (1644–1912) led to considerable standardisation in character forms, which prefigured later script reforms during the 20th century. This print orthography, exemplified by the 1716 Kangxi Dictionary, was later dubbed the jiu zixing ('old character shapes').[106]Printed Chinese characters may use different typefaces,[107] of which there are four broad classes in use:[108]

- Song (宋体; 宋體) or Ming (明体; 明體) typefaces—with "Song" generally used with simplified Chinese typefaces, and "Ming" with others—broadly correspond to Western serif styles. Song typefaces are broadly within the tradition of historical Chinese print; both names for the style refer to eras regarded as high points for printing in the Sinosphere. While type during the Song dynasty (960–1279) generally resembled the regular script style of a particular calligrapher, most modern Song typefaces are intended for general purpose use and emphasise neutrality in their design.

- Sans-serif typefaces are called 'black form' (黑体; 黑體; hēitǐ) in Chinese and 'Gothic' (ゴシック体) in Japanese. Sans-serif strokes are rendered as simple lines of even thickness.

- "Kai" typefaces (楷体; 楷體) imitate a handwritten style of regular script.

- Fangsong typefaces (仿宋体; 仿宋體), called "Song" in Japan, correspond to semi-script styles in the Western paradigm.

Use with computers

[edit]

Before computers became ubiquitous, earlier electro-mechanical communications devices like telegraphs and typewriters were originally designed for use with alphabets, often by means of alphabetic text encodings like Morse code and ASCII. Adapting these technologies for use with a writing system comprising thousands of distinct characters was non-trivial.[109][110]

Input methods

[edit]Chinese characters are predominantly input on computers using a standard keyboard. Many input methods (IMEs) are phonetic, where typists enter characters according to schemes like pinyin or bopomofo for Mandarin, Jyutping for Cantonese, or Hepburn for Japanese. For example, 香港 ('Hong Kong') could be input as xiang1gang3 using pinyin, or as hoeng1gong2 using Jyutping.[111]

Character input methods may also be based on form, using the shape of characters and existing rules of handwriting to assign unique codes to each character, potentially increasing the speed of typing. Popular form-based input methods include Wubi on the mainland, and Cangjie—named after the mythological inventor of writing—in Taiwan and Hong Kong.[111] Often, unnecessary parts are omitted from the encoding according to predictable rules. For example, 疆 ('border') is encoded using the Cangjie method as NGMWM, which corresponds to the components 弓土一田一.[112]

Contextual constraints may be used to improve candidate character selection. When ignoring tones, 大学; 大學 and 大雪 are both transcribed as daxue, the system may prioritize which candidate should appear first based on the surrounding context.[113]

Encoding and interchange

[edit]While special text encodings for Chinese characters were introduced prior to its popularisation, The Unicode Standard is the predominant text encoding worldwide.[114] According to the philosophy of the Unicode Consortium, each distinct graph is assigned a number in the standard, but specifying its appearance or the particular allograph used is a choice made by the engine rendering the text.[F] Unicode's Basic Multilingual Plane (BMP) represents the standard's 216 smallest code points. Of these, 20992 (or 32%) are assigned to CJK Unified Ideographs, a designation comprising characters used in each of the Chinese family of scripts. As of version 15.1, Unicode defines a total of 98682 Chinese characters.[G]

Vocabulary and adaptation

[edit]Writing first emerged during the historical stage of the Chinese language known as Old Chinese. Most characters correspond to morphemes that originally functioned as stand-alone Old Chinese words.[115] Classical Chinese is the form of written Chinese used in the classic works of Chinese literature between roughly the 5th century BCE and the 2nd century CE.[116] This form of the language was imitated by later authors, even as it began to diverge from the language they spoke. This later form, referred to as "Literary Chinese", remained the predominant written language in China until the 20th century. Its use in the Sinosphere was loosely analogous to that of Latin in pre-modern Europe. While it was not static over time, Literary Chinese retained many properties of spoken Old Chinese. Informed by the local spoken vernaculars, texts were read aloud using literary and colloquial readings that varied by region. Over time, sound mergers created ambiguities in vernacular speech as more words became homophonic. This ambiguity was often reduced through the introduction of multi-syllable compound words,[117] which comprise much of the vocabulary in modern varieties of Chinese.[118][119]

Over time, use of Literary Chinese spread to neighbouring countries, including Vietnam, Korea, and Japan. Alongside other aspects of Chinese culture, local elites adopted writing for record-keeping, histories, and official communications, forming what is sometimes called the Sinosphere.[120] Excepting hypotheses by some linguists of the latter two sharing a common ancestor, Chinese, Vietnamese, Korean, and Japanese each belong to different language families,[121] and tend to function differently from one another. Reading systems were devised to enable non-Chinese speakers to interpret Literary Chinese texts in terms of their native language, a phenomenon that has been variously described as either a form of diglossia, as reading by gloss,[122] or as a process of translation into and out of Chinese. Compared to other traditions that wrote using alphabets or syllabaries, the literary culture that developed in this context was less directly tied to a specific spoken language. This is exemplified by the cross-linguistic phenomenon of brushtalk, where mutual literacy allowed speakers of different languages to engage in face-to-face conversations.[123][124]

Following the introduction of Literary Chinese, characters were later adapted to write many non-Chinese languages spoken throughout the Sinosphere. These new writing systems used characters to write both native vocabulary and the numerous loanwords each language had borrowed from Chinese, collectively referred to as Sino-Xenic vocabulary. Characters may have native readings, Sino-Xenic readings, or both.[125] Comparison of Sino-Xenic vocabulary across the Sinosphere has been useful in the reconstruction of Middle Chinese phonology.[126] Literary Chinese was used in Vietnam during the millennium of Chinese rule that began in 111 BCE. By the 15th century, a system that adapted characters to write Vietnamese called chữ Nôm had fully matured.[127] The 2nd century BCE is the earliest possible period for the introduction of writing to Korea; the oldest surviving manuscripts in the country date to the early 5th century CE. Also during the 5th century, writing spread from Korea to Japan.[128] Characters were being used to write both Korean and Japanese by the 6th century.[129] By the late 20th century, characters had largely been replaced with alphabets designed to write Vietnamese and Korean. This leaves Japanese as the only major non-Sinitic language typically written using Chinese characters.[130]

Literary and vernacular Chinese

[edit]

Words in Classical Chinese were generally a single character in length.[132] An estimated 25–30% of the vocabulary used in Classical Chinese texts consists of two-character words.[133] Over time, the introduction of multi-syllable vocabulary into vernacular varieties of Chinese was encouraged by phonetic shifts that increased the number of homophones.[134] The most common process of Chinese word formation after the Classical period has been to create compounds of existing words. Words have also been created by appending affixes to words, by reduplication, and by borrowing words from other languages.[135] While multi-syllable words are generally written with one character per syllable, abbreviations are occasionally used.[136] For example, 二十 (èrshí; 'twenty') may be written as the contracted form 廿.[137]

Sometimes, different morphemes come to be represented by characters with identical shapes. For example, 行 may represent either 'road' (xíng) or the extended sense of 'row' (háng): these morphemes are ultimately cognates that diverged in pronunciation but remained written with the same character. However, Qiu reserves the term homograph to describe identically shaped characters with different meanings that emerge via processes other than semantic extension. An example homograph is 铊; 鉈, which originally meant 'weight used at a steelyard' (tuó). In the 20th century, this character was created again with the meaning 'thallium' (tā). Both of these characters are phono-semantic compounds with ⾦ 'GOLD' as the semantic component and 它 as the phonetic component, but the words represented by each are not related.[138]

There are a number of 'dialect characters' (方言字; fāngyánzì) that are not used in standard written vernacular Chinese, but reflect the vocabulary of other spoken varieties. The most complete example of an orthography based on a variety other than Standard Chinese is Written Cantonese. A common Cantonese character is 冇 (mou5; 'to not have'), derived by removing two strokes from 有 (jau5; 'to have').[139] It is common to use standard characters to transcribe previously unwritten words in Chinese dialects when obvious cognates exist. When no obvious cognate exists due to factors like irregular sound changes, semantic drift, or an origin in a non-Chinese language, characters are often borrowed or invented to transcribe the word—either ad hoc, or according to existing principles.[140] These new characters are generally phono-semantic compounds.[141]

Japanese

[edit] |

| Japanese writing |

|---|

| Components |

| Uses |

| Transliteration |

In Japanese, Chinese characters are referred to as kanji. Beginning in the Nara period (710–794), readers and writers of kanbun—the Japanese term for Literary Chinese writing—began employing a system of reading techniques and annotations called kundoku. When reading, Japanese speakers would adapt the syntax and vocabulary of Literary Chinese texts to reflect their Japanese-language equivalents. Writing essentially involved the inverse of this process, and resulted in ordinary Literary Chinese.[142] When adapted to write Japanese, characters were used to represent both Sino-Japanese vocabulary loaned from Chinese, as well as the corresponding native synonyms. Most kanji were subject to both borrowing processes, and as a result have both Sino-Japanese and native readings, known as on'yomi and kun'yomi respectively. Moreover, kanji may have multiple readings of either kind. Distinct classes of on'yomi were borrowed into Japanese at different points in time from different varieties of Chinese.[143]

Японская система письма представляет собой смешанное письмо, в которое также включены слоговые буквы, называемые кана, для обозначения фонетических единиц, называемых мора , а не морфем. До эпохи Мэйдзи (1868–1912) писатели вместо этого использовали определенные кандзи для обозначения своих звуковых значений в системе, известной как манъёгана . Начиная с 9-го века, определенные манъёганы были графически упрощены, чтобы создать два отдельных слоговых письма, названных хирагана и катакана , которые постепенно заменили более раннее соглашение. по-прежнему используются кандзи В современном японском языке для обозначения большинства основ слов , тогда как силлабограммы кана обычно используются для грамматических аффиксов, частиц и заимствованных слов. Формы хираганы и катаканы визуально отличаются друг от друга, во многом благодаря разным методам упрощения: катакана произошли от более мелких компонентов каждой манъёганы , тогда как хирагана произошли от рукописных форм манъёганы в целом. . Кроме того, хирагана и катакана для некоторых мор произошли от разных маньёгана . [144] Символы, придуманные для использования в японском языке, называются кокудзи . Методы, используемые для создания кокудзи , эквивалентны тем, которые используются для создания иероглифов китайского происхождения, хотя большинство из них представляют собой идеографические составные части. Например, 峠 ( tōge ; «горный перевал») — это составное кокудзи, состоящее из ⼭ «ГОРА» , 上 «ВЫШЕ» и 下 «НИЖЕ» . [145]

Хотя иероглифы, используемые для написания китайского языка, односложны, многие кандзи имеют многосложное чтение. Например, кандзи 刀 имеет родное кунёми прочтение катаны . В различных контекстах его также можно читать с онёми , читающим то , например, в китайском заимствованном слове 日本刀 ( нихонто ; «японский меч»), с произношением, соответствующим китайскому на момент заимствования. До повсеместного принятия катаканы заимствованные слова обычно писались несвязанными кандзи с чтением онёми, соответствующим слогам в заимствованном слове. Эти варианты написания называются атэдзи : например, 亜米利加 ( Америка ) было написанием атэтзи слова «Америка», которое теперь переводится как アメリカ . В отличие от манъёгана, используемого исключительно для произношения, атэдзи по-прежнему соответствовал конкретным японским словам. Некоторые из них используются до сих пор: официальный список дзёё кандзи включает 106 вариантов прочтения атэдзи . [146]

корейский

[ редактировать ]В корейском языке китайские иероглифы называются ханджа . Литературный китайский язык, возможно, был написан в Корее еще во II веке до нашей эры. В период Троецарствия (57 г. до н. э. – 668 г. н. э.) иероглифы также использовались для написания иду — формы корейскоязычной литературы, в которой в основном использовалась китайско-корейская лексика . В период Корё (918–1392 гг.) корейские писатели разработали систему фонетических аннотаций для литературного китайского языка, называемую гугёль , сравнимую с кундоку в Японии, хотя широкое распространение она получила только в более поздний период Чосон (1392–1897 гг.). [147] Хотя алфавит хангыль был изобретен королем Чосон Седжоном ( годы правления 1418–1450 ) в 1443 году, он не был принят корейскими литераторами и использовался в глоссах для литературных китайских текстов до конца 19 века. [148]

Большая часть корейской лексики состоит из китайских заимствованных слов, особенно технической и академической лексики. [149] Хотя ханджа обычно использовалась только для написания китайско-корейского словаря, есть свидетельства того, что иногда использовались народные чтения. [126] По сравнению с другими письменными диалектами, для написания корейских слов было изобретено очень мало символов; их называют гукджа . [150] В конце 19-го и начале 20-го веков корейский язык писался либо с использованием смешанного письма хангыль и ханджа, либо только с использованием хангыля. [151] После окончания оккупации Кореи Японской империей в 1945 году полная замена ханджи на хангыль пропагандировалась по всей стране как часть более широкого «движения за очищение» национального языка и культуры. [152] Однако из-за отсутствия тонов в разговорном корейском языке существует множество китайско-корейских слов, которые являются омофонами с идентичным написанием хангыля. Например, статья фонетического словаря для 기사 ( гиса ) дает более 30 различных записей. Эта двусмысленность исторически разрешалась путем включения связанной с ней ханджи. Хотя родные корейские слова все еще иногда используются для китайско-корейской лексики, гораздо реже родные корейские слова пишутся с использованием ханджа. [153] При изучении новых иероглифов корейским студентам предлагается связать каждый из них как с китайско-корейским произношением, так и с родным корейским синонимом. [154] Примеры включают в себя:

| Ханджа | хангыль | Блеск | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Родной перевод | Китайско-корейский | ||

| вода | вода ; мул | число ; Су | 'вода' |

| люди | человек ; Сарам | 인 ; в | 'человек' |

| большой | 큰большой Ын | большой ; даэ | 'большой' |

| Маленький | маленький ; Джейкель | корова ; так | 'маленький' |

| Вниз | под ; аре | под ; ха | 'вниз' |

| отец | отец ; аби | богатство ; бу | 'отец' |

вьетнамский

[ редактировать ]

Китайские иероглифы на вьетнамском языке называются chữ Hán ( 𡨸漢 ), chữ Nho ( 𡨸儒 ; « конфуцианские символы») или Hán tự ( 漢字 ). Литературный китайский язык использовался для всех формальных письменных работ во Вьетнаме до современной эпохи. [155] впервые получил официальный статус в 1010 году. Литературный китайский язык, написанный вьетнамскими авторами, впервые засвидетельствован в конце 10 века, хотя местная практика письма, вероятно, на несколько столетий старше. [156] Иероглифы, используемые для написания вьетнамского языка, называемые chữ Nôm ( 𡨸喃 ), впервые упоминаются в надписи, датированной 1209 годом, сделанной на месте пагоды. [157] Зрелое письмо тёном, вероятно, появилось к 13 веку и первоначально использовалось для записи вьетнамской народной литературы. Некоторые иероглифы тхоном представляют собой фоносемантические соединения, соответствующие разговорным вьетнамским слогам. [158] Другая техника, не имеющая аналогов в Китае, позволила создать составные слова чу ном с использованием двух фонетических компонентов. Это было сделано потому, что вьетнамская фонология включала группы согласных, которых нет в китайском языке, и поэтому плохо аппроксимировалась звуковыми значениями заимствованных символов. В составных соединениях использовались компоненты с двумя отдельными согласными звуками для обозначения кластера, например 𢁋 ( blăng ; [д] «Луна») было создано как соединение 巴 ( ба ) и 陵 ( lăng ). [159] Как система, Тёном была очень сложной, и уровень грамотности среди вьетнамского населения никогда не превышал 5%. [160] И литературный китайский, и чу ном на основе латиницы вышли из употребления во время французского колониального периода и постепенно были заменены вьетнамским алфавитом . После окончания колониального правления в 1954 году вьетнамский алфавит стал единственной официальной системой письма во Вьетнаме и используется исключительно в средствах массовой информации на вьетнамском языке. [161]

Другие языки

[ редактировать ]Несколько языков меньшинств Южного и Юго-Западного Китая написаны с использованием как заимствованных, так и местных символов. Наиболее хорошо документированным из них является письмо пиломатериалов для языков Гуанси чжуанских . Хотя о ее раннем развитии мало что известно, традиция народного письма чжуан, вероятно, впервые возникла во времена династии Тан (618–907). Современные исследования пиломатериалов описывают сеть региональных письменных традиций, демонстрирующих как взаимное влияние, так и характерные различия друг с другом. [162] Как и вьетнамский язык, некоторые изобретенные чжуанские иероглифы представляют собой фонетико-фонетические соединения, хотя в первую очередь они не предназначены для описания групп согласных. [163] на латинской основе Несмотря на то, что китайское правительство поощряет замену алфавита Чжуан , опилки продолжают использоваться. [164] Другие несинитские языки Китая, написанные китайскими иероглифами, включают мяо , яо , буэй , бай и хани . Каждый из этих языков теперь в официальном контексте пишется с использованием латинского алфавита. [165]

Графически производные сценарии

[ редактировать ]

Между 10 и 13 веками династии, основанные неханьскими народами в северном Китае, также создавали сценарии для своих языков, вдохновленные китайскими иероглифами, но не использовали их напрямую: к ним относились киданьское большое письмо , киданьское маленькое письмо , тангутское письмо. и чжурчжэньское письмо . [165] Это происходило и в других контекстах: Нушу — это письмо, которое женщины Яо использовали для написания языка Сяннань Тухуа , [166] и бопомофо ( фонетический символ ; фонетический символ ; zhùyīn fúhào ) — полуслоговое письмо, впервые изобретенное в 1907 году. [167] представлять звуки стандартного китайского языка; [168] оба используют формы, графически полученные из китайских иероглифов. Другие сценарии в Китае, которые адаптировали некоторые символы, но в остальном отличаются друг от друга, включают слоговое письмо геба , используемое для написания языка наси , письмо для языка Суй , письмо для языков И и слоговое письмо для языка Лису . [165]

Китайские иероглифы также были фонетически изменены для расшифровки звуков некитайских языков. Например, в единственных рукописях « Тайной истории монголов» XIII века , сохранившихся со времен средневековья, для написания монгольского языка символы используются таким образом . [169]

Грамотность и лексикография

[ редактировать ]Запоминание тысяч различных символов необходимо для достижения грамотности в языках, на которых они написаны, в отличие от относительно небольшого количества графем, используемых в фонетическом письме. [170] Исторически сложилось так, что иероглифическая грамотность часто приобреталась с помощью китайских букварей, таких как « Тысячезначная классика» XIII века VI века и «Трёхсимвольная классика» . [171] эпохи Сун» а также словари фамилий, такие как «Сотня семейных фамилий . [172] Исследования грамотности на китайском языке показывают, что грамотные люди обычно имеют активный словарный запас в три-четыре тысячи символов; для специалистов в таких областях, как литература или история, эта цифра может составлять от пяти до шести тысяч. [173]

Словари

[ редактировать ]Согласно анализу источников материкового Китая, Тайваня, Гонконга, Японии и Кореи, общее количество символов в современном лексиконе составляет около 15 000 . [174] Были разработаны десятки схем индексации китайских иероглифов и их упорядочения в словарях, однако лишь немногие из них получили широкое распространение. Символы можно упорядочить по методам, основанным на их значении, визуальной структуре или произношении. [175]

Эрья . ( ок. III век до н.э. ) организовала китайскую лексику на 16 семантических категорий, а также на 3, описывающие абстрактные символы, такие как грамматические частицы [176] Шуовэнь Цзецзы ( ок. 100 г. н.э. ) представил то, что в конечном итоге станет преобладающим методом организации, используемым в более поздних словарях символов, согласно которому символы группируются в соответствии с определенными визуально заметными компонентами, называемыми радикалами ( 部首 ; bùshǒu ; «заголовки разделов»). Шуовэнь Цзецзы использовал систему из 540 радикалов, в то время как последующие словари обычно использовали меньшее количество радикалов. [177] Набор из 214 радикалов Канси был популяризирован Словарем Канси (1716 г.), но первоначально появился в более раннем Цзихуэй (1615 г.). [178] Словари символов исторически индексировались с использованием радикальной и штриховой сортировки , при которой символы группируются по радикалу и сортируются внутри каждой группы по номеру штриха . Некоторые современные словари сортируют записи символов в алфавитном порядке в соответствии с их написанием пиньинь, а также предоставляют традиционный указатель на основе радикалов. [179]

До изобретения систем латинизации китайского языка произношение иероглифов передавалось через словари рима . В них использовался метод fanqie ( 反切 ; «обратный разрез»), при котором в каждой записи указан общий символ с тем же начальным звуком , что и рассматриваемый символ, а также один с тем же конечным звуком. [180]

Нейролингвистика

[ редактировать ]С помощью функциональной магнитно-резонансной томографии (фМРТ) нейролингвисты изучили активность мозга, связанную с грамотностью. По сравнению с фонетическими системами чтение и письмо с помощью символов задействуют дополнительные области мозга, в том числе те, которые связаны с обработкой визуальных данных. [181] Хотя уровень запоминания, необходимый для грамотности символов, значителен, идентификация фонетических и семантических компонентов в сложных словах, составляющих подавляющее большинство символов, также играет ключевую роль в понимании прочитанного. На легкость распознавания данного иероглифа влияет регулярность расположения его компонентов, а также надежность его фонетического компонента при указании конкретного произношения. [182] Более того, из-за высокого уровня гомофонии в китайских языках и более нерегулярного соответствия между письмом и звуками речи было высказано предположение, что знание орфографии играет большую роль в распознавании речи для грамотных носителей китайского языка. [183]

Дислексия развития у читателей языков, основанных на символах, по-видимому, включает в себя одновременное возникновение независимых зрительно-пространственных и фонологических нарушений. Кажется, это явление отличается от дислексии, наблюдаемой при фонетической орфографии, которая может быть результатом только одного из вышеупомянутых нарушений. [184]

Реформа и стандартизация

[ редактировать ]

Попытки реформировать и стандартизировать использование символов, включая аспекты формы, порядка штрихов и произношения, предпринимались государствами на протяжении всей истории. Тысячи упрощенных символов были стандартизированы и приняты в материковом Китае в 1950-х и 1960-х годах, причем большинство из них либо уже существовали как распространенные варианты, либо создавались путем систематического упрощения их компонентов. [186] После Второй мировой войны японское правительство также упростило сотни форм символов, включая некоторые упрощения, отличные от тех, которые были приняты в Китае. [187] Православные формы, не претерпевшие упрощения, называются традиционными иероглифами . В китайскоязычных государствах материковый Китай, Малайзия и Сингапур используют упрощенные иероглифы, а Тайвань, Гонконг и Макао используют традиционные иероглифы. [188] В целом, китайские и японские читатели могут успешно идентифицировать символы всех трех стандартов. [189]

До 20-го века реформы в целом были консервативными и были направлены на сокращение использования упрощенных вариантов. [190] В конце 19-го и начале 20-го веков все большее число интеллектуалов в Китае начало рассматривать как китайскую систему письма, так и отсутствие национального разговорного диалекта как серьезные препятствия на пути достижения массовой грамотности и взаимопонимания, необходимых для успешной модернизации страны. Многие начали выступать за замену литературного китайского языка письменным языком, который более точно отражает речь, а также за массовое упрощение форм иероглифов или даже полную замену иероглифов алфавитом, адаптированным к определенному разговорному варианту. В 1909 году педагог и лингвист Луфэй Куй (1886–1941) впервые официально предложил использовать упрощенные символы в образовании. [191]

В 1911 году Синьхайская революция привела к созданию Китайской Республики свергла династию Цин и в следующем году . Ранняя республиканская эпоха (1912–1949) характеризовалась растущим социальным и политическим недовольством, которое вылилось в Движение четвертого мая послужило катализатором замены литературного китайского языка письменным народным китайским языком 1919 года, которое в последующие десятилетия . Наряду с соответствующей разговорной разновидностью, ныне известной как стандартный китайский язык , этот письменный разговорный язык пропагандировался интеллектуалами и писателями, такими как Лу Синь (1881–1936) и Ху Ши (1891–1962). [192] Он был основан на пекинском диалекте языка мандаринского . [193] а также о существующем корпусе народной литературы, написанной в предыдущие столетия, включая такие классические романы , как «Путешествие на Запад» ( ок. 1592 г. ) и «Сон о Красной палате» (середина 18 века). [194] В это время упрощение символов и фонетическое письмо обсуждались как в правящей партии Гоминьдан (Гоминьдан), так и в Коммунистической партии Китая (КПК). В 1935 году республиканское правительство опубликовало первый официальный список упрощенных иероглифов, включавший 324 формы, составленный Пекинского университета профессором Цянь Сюаньтуном (1887–1939). Однако сильная оппозиция внутри партии привела к аннулированию списка в 1936 году. [195]

Китайская Народная Республика

[ редактировать ]Проект реформы письменности в Китае в конечном итоге был унаследован коммунистами, которые возобновили работу после провозглашения Китайской Народной Республики в 1949 году. В 1951 году премьер-министр Чжоу Эньлай (1898–1976) приказал создать Комитет по реформе письменности, в состав которого вошли подгруппы, исследующие как упрощение, так и алфавитизацию. Подгруппа по упрощению приступила к обследованию и сопоставлению упрощенных форм в следующем году. [196] в конечном итоге опубликовав проект схемы упрощенных символов и компонентов в 1956 году. В 1958 году Чжоу Эньлай объявил о намерении правительства сосредоточиться на упрощении, а не на замене символов Ханью Пиньинь , которая была введена ранее в том же году. [197] Схема 1956 года была в значительной степени ратифицирована пересмотренным списком из 2235 символов , обнародованным в 1964 году. [198] Большинство этих символов были взяты из обычных сокращений или древних форм с меньшим количеством штрихов. [199] Комитет также стремился сократить общее количество используемых символов путем объединения некоторых форм. [199] Например, 雲 («облако») писалось как 云 шрифтом кости оракула. Более простая форма по-прежнему использовалась как заимствование, означающее «говорить»; оно было заменено в первоначальном смысле слова «облако» на форму, в которую добавлен семантический компонент ⾬ «ДОЖДЬ» . Упрощенные формы этих двух иероглифов были объединены в 云 . [200]

Второй раунд упрощенных символов был обнародован в 1977 году, но был плохо принят публикой и быстро вышел из официального использования. В конечном итоге он был официально отменен в 1986 году. [201] Упрощения второго раунда были непопулярны во многом потому, что большинство форм были совершенно новыми, в отличие от знакомых вариантов, составляющих большую часть первого раунда. [202] С отменой второго тура работа по дальнейшему упрощению персонажей в значительной степени подошла к концу. [203] Таблица общеупотребительных иероглифов современного китайского языка была опубликована в 1988 году и включала 7000 упрощенных и неупрощенных иероглифов. Из них половина также была включена в пересмотренный Список часто используемых иероглифов современного китайского языка , в котором указано 2500 распространенных иероглифов и 1000 менее распространенных иероглифов. [204] В 2013 году Таблица общих стандартных китайских иероглифов была опубликована как пересмотренная версия списков 1988 года; Всего в нем было 8105 символов. [205]

Япония

[ редактировать ]

После Второй мировой войны японское правительство разработало собственную программу орфографических реформ. Некоторым персонажам были присвоены упрощенные формы, называемые синдзитай ; более старые формы тогда назывались кюдзитай . Непоследовательное использование различных вариантов форм не поощрялось, и были разработаны списки символов, которые следует преподавать учащимся на каждом уровне обучения. Первым из них был 1850 символов тоё из список кандзи , опубликованный в 1946 году, который позже был заменен списком 1945 года в дзёё кандзи 1981 году. В 2010 году кандзи дзёё были расширены и теперь включают в общей сложности 2136 символов. [206] [207] Правительство Японии ограничивает использование символов в именах кандзи дзёё , а также дополнительным списком из 983 дзинмейё кандзи , использование которых исторически преобладает в именах. [208] [209]

Южная Корея

[ редактировать ]Ханджа до сих пор используются в Южной Корее, хотя и не в такой степени, как кандзи в Японии. В целом наблюдается тенденция к использованию хангыля исключительно в обычном контексте. [210] Символы по-прежнему используются в географических названиях, газетах и для устранения неоднозначности омофонов. Они также используются в практике каллиграфии. Использование ханджи в образовании является политически спорным, поскольку официальная политика в отношении значимости ханджи в учебных программах колебалась с момента обретения страной независимости. [211] [212] Некоторые поддерживают полный отказ от ханджи, в то время как другие выступают за увеличение ее использования до уровня, наблюдавшегося ранее в 1970-х и 1980-х годах. Учащиеся 7–12 классов в настоящее время обучаются с упором на простое узнавание и достижение достаточной грамотности, чтобы читать газету. [148] В 1972 году Министерство образования Южной Кореи опубликовало « Базовый ханджа для образовательных целей» , в котором указано 1800 символов, предназначенных для изучения учащимися средних школ. [213] В 1991 году Верховный суд Кореи опубликовал Таблицу ханджа для использования в личных именах ( 인명용한자 ; Inmyeong-yong hanja ), которая первоначально включала 2854 символа. [214] С тех пор список несколько раз расширялся; по состоянию на 2022 год [update], он включает 8319 символов. [215]

Северная Корея

[ редактировать ]В годы после своего создания правительство Северной Кореи стремилось исключить использование ханджи в стандартном письме; к 1949 году в северокорейских публикациях иероглифы были почти полностью заменены на хангыль. [216] Хотя ханджа по большей части не используется в письменной форме, она остается важной частью северокорейского образования: учебник 1971 года для факультетов истории университетов содержал 3323 различных символа, а в 1990-х годах северокорейские школьники все еще должны были выучить 2000 символов. [217] Учебник 2013 года, похоже, интегрирует использование ханджи в среднее школьное образование. [218] Подсчитано, что северокорейские студенты изучают около 3000 ханджа. к моменту окончания университета [219]

Тайвань

[ редактировать ]Таблица стандартных форм общенациональных иероглифов была опубликована Министерством образования Тайваня в 1982 году и насчитывает 4808 традиционных иероглифов. [220] Министерство образования также составляет словари символов тайваньских хоккиен и хакка . [ЧАС]

Другие региональные стандарты

[ редактировать ]Министерство образования Сингапура обнародовало три последовательных раунда упрощений: первый раунд в 1969 году включал 502 упрощенных символа, а второй раунд в 1974 году включал 2287 упрощенных символов, в том числе 49, которые отличались от тех, что были в КНР, которые в конечном итоге были удалены в последнем раунде. в 1976 году. В 1993 году Сингапур принял поправки, внесенные в материковом Китае в 1986 году. [221]

Гонконгского бюро образования и трудовых ресурсов Список графем часто используемых китайских иероглифов включает 4762 традиционных иероглифа, используемых в начальной и неполной средней школе. [222]

Примечания

[ редактировать ]- ^ Китайские иероглифы ; упрощены как китайские иероглифы

- Китайский пиньинь : Песня ; Уэйд-Джайлз : Хан 4 -цзы 4 ; Джютпинг : Hon3 zi6

- Японское Хепберн : кандзи

- Корейская пересмотренная латинизация : Hanja ; МакКьюн – Райшауэр : Ханча

- Вьетнамский : китайские иероглифы

- ^ Зев Гендель перечисляет: [2]

- шумерской клинописи Появление ок. 3200 г. до н.э.

- египетских иероглифов Появление ок. 3100 г. до н. э.

- Появляются китайские иероглифы c. 13 век до н.э.

- письменности майя Появление c. 1 год н. э.

- ^ По словам Генделя: «Хотя односложность обычно превосходит морфемность - то есть, двусложная морфема почти всегда пишется двумя символами, а не одним - существует безошибочная тенденция для пользователей письменности навязывать морфемную идентичность языковым единицам, представленным эти персонажи». [10]

- ^ Это средневьетнамское произношение; это слово произносится на современном вьетнамском языке как trăng .

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]Цитаты

[ редактировать ]- ^ Издательство национальностей Гуанси, 1989 .

- ^ Гендель 2019 , с. 1.

- ^ Цю 2000 , стр. 2.

- ^ Цю 2000 , стр. 3–4.

- ^ Цю 2000 , стр. 5.

- ^ Норман 1988 , с. 59; Ли 2020 , с. 48.

- ^ Цю 2000 , стр. 11, 16.

- ^ Цю 2000 , с. 1; Гендель 2019 , стр. 4–5.

- ^ Цю 2000 , стр. 22–26; Норман 1988 , с. 74.

- ^ Гендель 2019 , с. 33.

- ^ Цю 2000 , стр. 13–15; Коулмас 1991 , стр. 104–109.

- ^ Ли 2020 , стр. 56–57; Больц 1994 , стр. 3–4.

- ^ Гендель 2019 , с. 51; Юн и Пэн 2008 , стр. 95–98.

- ^ Цю 2000 , стр. 19, 162–168.

- ^ Больц 2011 , стр. 57, 60.

- ^ Цю 2000 , стр. 14–18.

- ^ Инь 2007 , стр. 97–100; В 2014 году , стр. 102–111.

- ^ Ян 2008 , стр. 147–148.

- ^ Дематте 2022 , с. 14.

- ^ Цю 2000 , стр. 163–171.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Юн и Пэн 2008 , с. 19.

- ^ Цю 2000 , стр. 44–45; Чжоу 2003 , с. 61.

- ^ Цю 2000 , стр. 18–19.

- ^ Цю 2000 , с. 154; Норман 1988 , с. 68.

- ^ Йип 2000 , стр. 39–42.

- ^ Цю 2000 , стр. 46.

- ^ Норман 1988 , с. 68; Цю 2000 , стр. 185–187.

- ^ Цю 2000 , стр. 15, 190–202.

- ^ Сэмпсон и Чен 2013 , с. 261.

- ^ Цю 2000 , стр. 155.

- ^ Больц 1994 , стр. 104–110.

- ^ Сэмпсон и Чен 2013 , стр. 265–268.

- ^ Норман 1988 , с. 68.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Цю 2000 , стр. 154.

- ^ Круттенден 2021 , стр. 167–168.

- ^ Уильямс 2010 .

- ^ Фогельсанг 2021 , стр. 51–52.

- ^ Цю 2000 , стр. 261–265.

- ^ Цю 2000 , стр. 273–274, 302.

- ^ Тейлор и Тейлор 2014 , стр. 30–32.

- ^ Рэмси 1987 , с. 60.

- ^ Гнанадэсикан 2011 , с. 61.

- ^ Цю 2000 , с. 168; Норман 1988 , с. 60.

- ^ Норман 1988 , стр. 67–69; Гендель 2019 , с. 48.

- ^ Норман 1988 , стр. 170–171.

- ^ Торговля 2019 , стр. 48–49.

- ^ Цю 2000 , стр. 153–154, 161; Норман 1988 , с. 170.

- ^ Цю 2013 , стр. 102–108; Норман 1988 , с. 69.

- ^ Гендель 2019 , с. 43.

- ^ Цю 2000 , стр. 44–45.

- ^ Цю 2000 , стр. 59–60, 66.

- ^ Дематте 2022 , стр. 79–80.

- ^ Ян и Ан 2008 , стр. 84–86.

- ^ Больц 1994 , стр. 130–138.

- ^ Цю 2000 , стр. 31.

- ^ Цю 2000 , стр. 39.

- ^ Больц 1999 , стр. 74, 107–108; Лю и др. 2017 , стр. 155–175.

- ^ Лю и Чен 2012 , с. 6.

- ^ Керн 2010 , с. 1; Уилкинсон 2012 , стр. 681–682.

- ^ Кейтли 1978 , стр. 28–42.

- ^ Керн 2010 , с. 1.

- ^ Кейтли 1978 , стр. 46–47.

- ^ Больц 1986 , с. 424; Керн 2010 , с. 2.

- ^ Шонесси 1991 , с. 1–4.

- ^ Цю 2000 , стр. 63–66.

- ^ Цю 2000 , стр. 88–89.

- ^ Цю 2000 , стр. 76–78.

- ^ Чен 2003 .

- ^ Луи 2003 .

- ^ Цю 2000 , стр. 77.

- ^ Больц 1994 , с. 156.

- ^ Цю 2000 , стр. 104–107.

- ^ Цю 2000 , стр. 59, 119.

- ^ Цю 2000 , стр. 119–124.

- ^ Цю 2000 , стр. 113, 139, 466.

- ^ Цю 2000 , стр. 138–139.

- ^ Цю 2000 , стр. 130–148.

- ^ Кнехтгес и Чанг 2014 , стр. 1257–1259.

- ^ Цю 2000 , стр. 113, 139–142.

- ^ Ли 2020 , с. 51; Цю 2000 , с. 149; Норман 1988 , с. 70.

- ^ Цю 2000 , стр. 113, 149.

- ^ Чан 2020 , с. 125.

- ^ Цю 2000 , стр. 143.

- ^ Цю 2000 , стр. 144–145.

- ^ Ли 2020 , с. 41.

- ^ Ли 2020 , стр. 54, 196–197; Пекинский университет, 2004 г. , стр. 148–152; Чжоу 2003 , с. 88.

- ^ Норман 1988 , с. 86; Чжоу 2003 , с. 58; Чжан 2013 .

- ^ Ли 2009 , стр. 65–66; Чжоу 2003 , с. 88.

- ^ Торговля 2019 , стр. 43–44.

- ^ Инь 2016 , стр. 58–59.

- ^ Майерс 2019 , стр. 106–116.

- ^ Ли 2009 , с. 70.

- ^ Цю 2000 , стр. 204–215, 373.

- ^ Чжоу 2003 , стр. 57–60, 63–65.

- ^ Цю 2000 , стр. 297–300, 373.

- ^ Бёксет 2006 , стр. 16, 19.

- ^ Ли 2020 , с. 54; Гендель 2019 , с. 27; Кейтли 1978 , с. 50.

- ^ Тейлор и Тейлор 2014 , стр. 372–373; Бахнер 2014 , с. 245.

- ^ Needham & Harbsmeier 1998 , стр. 175–176; Тейлор и Тейлор 2014 , стр. 374–375.

- ^ Нидхэм и Цянь 2001 , стр. стр. 23–25, 38–4.

- ^ Предложение 2020 года .

- ^ Ли 2009 , стр. 180-183.

- ^ Ли 2009 , стр. 175-179.

- ^ Нидхэм и Цянь 2001 , стр. 146–147, 159.

- ^ Нидхэм и Цянь 2001 , стр. 201–205.

- ^ Юн и Пэн 2008 , стр. 280–282, 293–297.

- ^ Ли 2013 , с. 62.

- ^ Лунде 2008 , стр. 23–25.

- ^ Вс 2014 , с. 218.

- ^ Маллани 2017 , с. 25.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Ли 2020 , стр. 152-153.

- ^ Чжан 2016 , с. 422.

- ^ Вс 2014 , с. 222.

- ^ Лунде 2008 , стр. 193.

- ^ Норман 1988 , стр. 74–75.

- ^ Vogelsang 2021 , стр. xvii–xix.

- ^ Уилкинсон 2012 , с. 22.

- ^ Тонг, Лю и Макбрайд-Чанг 2009 , стр. 203.

- ^ Йип 2000 , с. 18.

- ^ Гендель 2019 , стр. 11–12; Корницкий 2018 , стр. 15–16.

- ^ Торговля 2019 , стр. 28, 69, 126, 169.

- ^ Кин 2021 , с. XII.

- ^ Денеке 2014 , стр. 204–216.

- ^ Корницкий 2018 , стр. 72–73.

- ^ Гендель 2019 , с. 212.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Корницкий 2018 , стр. 168.

- ^ Торговля 2019 , стр. 124–125, 133.

- ^ Торговля 2019 , стр. 64–65.

- ^ Корницкий 2018 , стр. 57.

- ^ Ханнас 1997 , стр. 136–138.

- ^ Эбри 1996 , с. 205.

- ^ Норман 1988 , с. 58.

- ^ Уилкинсон 2012 , стр. 22–23.

- ^ Норман 1988 , стр. 86–87.

- ^ Норман 1988 , стр. 155–156.

- ^ Норман 1988 , с. 74.

- ^ Гендель 2019 , с. 34.

- ^ Цю 2000 , стр. 301–302.

- ^ Гендель 2019 , с. 59.

- ^ Cheung & Bauer 2002 , стр. 12–20.

- ^ Норман 1988 , стр. 75–77.

- ^ Ли 2020 , с. 88.

- ^ Коулмас 1991 , стр. 122–129.

- ^ Коулмас 1991 , стр. 129–132.

- ^ Торговля 2019 , стр. 192–196.

- ^ Тейлор и Тейлор 2014 , стр. 275–279.

- ^ Ли 2020 , стр. 78-80.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Фишер 2004 , стр. 189–194.

- ^ Ханнас 1997 , с. 49; Тейлор и Тейлор 2014 , с. 435.

- ^ Торговля 2019 , стр. 88, 102.

- ^ Торговля 2019 , стр. 112–113; Ханнас 1997 , стр. 60–61.

- ^ Ханнас 1997 , стр. 64–66.

- ^ Норман 1988 , с. 79.

- ^ Торговля 2019 , стр. 75–82.

- ^ Гендель 2019 , стр. 124–126; Кин 2021 , с. XI.

- ^ Ханнас 1997 , стр. 73.

- ^ ДеФрэнсис 1977 , стр. 23–24.

- ^ Корницкий 2018 , стр. 63.

- ^ Торговля 2019 , стр. 145, 150.

- ^ ДеФрэнсис 1977 , с. 19.

- ^ Коулмас 1991 , стр. 113–115; Ханнас 1997 , стр. 73, 84–87.

- ^ Торговля 2019 , стр. 239–240.

- ^ Торговля 2019 , стр. 251–252.

- ^ Гендель 2019 , стр. 231, 234–235; Чжоу 2003 , стр. 140–142, 151.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Чжоу 1991 .

- ^ Чжао 1998 .

- ^ Кузуоглу 2023 , с. 71.

- ^ ДеФрэнсис 1984 , с. 242; Тейлор и Тейлор 2014 , с. 14; Ли 2020 , с. 123.

- ^ Хунг 1951 , с. 481.

- ^ Дематте 2022 , с. 8; Тейлор и Тейлор, 2014 , стр. 110–111.

- ^ Корницкий 2018 , стр. 273–277.

- ^ Юн и Пэн 2008 , стр. 55–58.

- ^ Норман 1988 , с. 73.

- ^ В 2014 году , стр. 47, 51.

- ^ Вс 2014 , с. 183; Нидхэм и Харбсмайер, 1998 , стр. 65–66.

- ^ Сюэ 1982 , стр. 152–153.

- ^ Юн и Пэн 2008 , стр. 100–103, 203.

- ^ Чжоу 2003 , с. 88; Норман 1988 , стр. 170–172; Needham & Harbsmeier 1998 , стр. 79–80.

- ^ Юн и Пэн 2008 , стр. 145, 400–401.

- ^ Норман 1988 , стр. 27–28.

- ^ Дематте 2022 , с. 9.

- ^ Ли 2015b .

- ^ Ли 2015a , Мозговая сеть для обработки китайского языка.

- ^ Макбрайд, Тонг и Мо, 2015 , стр. 688–690; Хо 2015 г .; Тейлор и Тейлор 2014 , стр. 150–151, 346–349, 393–394.

- ^ Чен 1999 , стр. 153.

- ^ Чжоу 2003 , стр. 60–67.

- ^ Тейлор и Тейлор 2014 , стр. 117–118.

- ^ Ли 2020 , с. 136.

- ^ Деньги 2016 , с. 171.

- ^ Цю 2000 , стр. 404.

- ^ Чжоу 2003 , стр. xvii–xix; Ли 2020 , с. 136.

- ^ Чжоу 2003 , стр. xviii–xix.

- ^ ДеФрэнсис 1972 , стр. 11–13.

- ^ Чжун 2019 , стр. 113–114; Чен 1999 , стр. 70–74, 80–82.