Тибетский буддизм

| Часть серии на |

| Тибетский буддизм |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Vajrayana Buddhism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

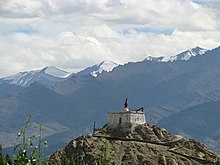

Тибетский буддизм [ Примечание 1 ] это форма буддизма, практикуемой в Тибете , Бутане и Монголии . Он также имеет значительное количество приверженцев в районах, окружающих Гималаи , в том числе индийские регионы Ладакха , Сиккима и Аруначал -Прадеш , а также в Непале . Меньшие группы практикующих могут быть найдены в Центральной Азии , в некоторых регионах Китая, таких как Синьцзян , Внутренняя Монголия и некоторые регионы России, такие как Тува , Бурьятия и Кальмикия .

Тибетский буддизм развивался как форма буддизма Махайны , вытекающего из последних стадий буддизма (который включал в себя множество элементов ваджраяны ). Таким образом, он сохраняет многие индийские буддийские тантрические практики в периода постгупты начале средневекового (500–1200 гг. С.), А также многочисленные местные тибетские разработки. [ 1 ] [ 2 ] В до-современную эпоху тибетский буддизм, распространяющийся за пределами Тибета, в первую очередь из-за влияния монгольской династии Юань (1271–1368), основанной Кулай-ханом , который управлял Китаем, Монголией и частями Сибирии. В современную эпоху тибетский буддизм распространился за пределами Азии из -за усилий тибетской диаспоры (1959 год). Когда Далай -лама сбежал в Индию, индийский субконтинент также известен своим возрождением тибетских буддизма, в том числе восстановление трех основных монастырей гелугной традиции .

Apart from classical Mahāyāna Buddhist practices like the ten perfections, Tibetan Buddhism also includes tantric practices, such as deity yoga and the Six Dharmas of Naropa, as well as methods that are seen as transcending tantra, like Dzogchen. Its main goal is Buddhahood.[3][4] The primary language of scriptural study in this tradition is classical Tibetan.

Tibetan Buddhism has four major schools, namely Nyingma (8th century), Kagyu (11th century), Sakya (1073), and Gelug (1409). The Jonang is a smaller school that exists, and the Rimé movement (19th century), meaning "no sides",[5] is a more recent non-sectarian movement that attempts to preserve and understand all the different traditions. The predominant spiritual tradition in Tibet before the introduction of Buddhism was Bon, which has been strongly influenced by Tibetan Buddhism (particularly the Nyingma school). While each of the four major schools is independent and has its own monastic institutions and leaders, they are closely related and intersect with common contact and dialogue.

Nomenclature

[edit]The native Tibetan term for Buddhism is "The Dharma of the insiders" (nang chos) or "The Buddha Dharma of the insiders" (nang pa sangs rgyas pa'i chos).[6][7] "Insider" means someone who seeks the truth not outside but within the nature of mind. This is contrasted with other forms of organized religion, which are termed chos lugs (dharma system). For example, Christianity is termed Yi shu'i chos lugs (Jesus dharma system).[7]

Westerners unfamiliar with Tibetan Buddhism initially turned to China for understanding. In Chinese, the term used is Lamaism (literally, "doctrine of the lamas": 喇嘛教 lama jiao) to distinguish it from a then-traditional Chinese Buddhism (佛教 fo jiao). The term was taken up by western scholars, including Hegel, as early as 1822.[8][9] Insofar as it implies a discontinuity between Indian and Tibetan Buddhism, the term has been discredited.[10]

Another term, "Vajrayāna" (Tibetan: dorje tegpa) is occasionally misused for Tibetan Buddhism. More accurately, Vajrayāna signifies a certain subset of practices and traditions that are not only part of Tibetan Buddhism but also prominent in other Buddhist traditions such as Chinese Esoteric Buddhism[11] and Shingon in Japan.[12][13]

In the west, the term "Indo-Tibetan Buddhism" has become current in acknowledgement of its derivation from the latest stages of Buddhist development in northern India.[14] "Northern Buddhism" is sometimes used to refer to Indo-Tibetan Buddhism, for example, in the Brill Dictionary of Religion.

Another term, "Himalayan" (or "Trans-Himalayan") Buddhism is sometimes used to indicate how this form of Buddhism is practiced not just in Tibet but throughout the Himalayan Regions.[15][16]

The Provisional Government of Russia, by a decree of 7 July 1917, prohibited the appellation of Buryat and Kalmyk Buddhists as "Lamaists" in official papers. After the October revolution the term "Buddho-Lamaism" was used for some time by the Bolsheviks with reference to Tibetan Buddhism, before they finally reverted, in the early 1920s, to a more familiar term "Lamaism", which remains in official and scholarly usage in Russia to this day.[17]

History

[edit]Pre–6th century

[edit]Centuries after Buddhism originated in India, the Mahayana Buddhism arrived in China through the Silk Route in 1st century CE via Tibet, then to Korean peninsula in 3rd century during the Three Kingdoms period from where it transmitted to Japan.[18]

During the 3rd century CE, Buddhism began to spread into the Tibetan region, and its teachings affected the Bon religion in the Kingdom of Zhangzhung.[19]

First dissemination (7th–9th centuries)

[edit]While some stories depict Buddhism in Tibet before this period, the religion was formally introduced during the Tibetan Empire (7th–9th century CE). Sanskrit Buddhist scriptures from India were first translated into Tibetan under the reign of the Tibetan king Songtsän Gampo (618–649 CE).[20] This period also saw the development of the Tibetan writing system and classical Tibetan.[21][22]

In the 8th century, King Trisong Detsen (755–797 CE) established it as the official religion of the state[23] and commanded his army to wear robes and study Buddhism. Trisong Detsen invited Indian Buddhist scholars to his court, including Padmasambhāva (8th century CE) and Śāntarakṣita (725–788), who are considered the founders of Nyingma (The Ancient Ones), the oldest tradition of Tibetan Buddhism.[24] Padmasambhava, who is considered by the Tibetans as Guru Rinpoche ("Precious Master"), is also credited with building the first monastery building named "Samye" around the late 8th century. According to some legend, it is noted that he pacified the Bon demons and made them the core protectors of Dharma.[25] Modern historians also argue that Trisong Detsen and his followers adopted Buddhism as an act of international diplomacy, especially with the major power of those times such as China, India, and states in Central Asia that had strong Buddhist influence in their culture.[26]

Yeshe Tsogyal, the most important female in the Nyingma Vajrayana lineage, was a member of Trisong Detsen's court and became Padmasambhava's student before gaining enlightenment. Trisong Detsen also invited the Chan master Moheyan[note 2] to transmit the Dharma at Samye Monastery. Some sources state that a debate ensued between Moheyan and the Indian master Kamalaśīla, without consensus on the victor, and some scholars consider the event to be fictitious.[27][28][note 3][note 4]

Era of fragmentation (9th–10th centuries)

[edit]A reversal in Buddhist influence began under King Langdarma (r. 836–842), and his death was followed by the so-called Era of Fragmentation, a period of disunity during the 9th and 10th centuries. During this era, the political centralization of the earlier Tibetan Empire collapsed and civil wars ensued.[31]

In spite of this loss of state power and patronage however, Buddhism survived and thrived in Tibet. According to Geoffrey Samuel this was because "Tantric (Vajrayana) Buddhism came to provide the principal set of techniques by which Tibetans dealt with the dangerous powers of the spirit world [...] Buddhism, in the form of Vajrayana ritual, provided a critical set of techniques for dealing with everyday life. Tibetans came to see these techniques as vital for their survival and prosperity in this life."[32] This includes dealing with the local gods and spirits (sadak and shipdak), which became a specialty of some Tibetan Buddhist lamas and ngagpas (mantrikas, mantra specialists).[33]

Second dissemination (10th–12th centuries)

[edit]The late 10th and 11th centuries saw a revival of Buddhism in Tibet with the founding of "New Translation" (Sarma) lineages as well as the appearance of "hidden treasures" (terma) literature which reshaped the Nyingma tradition.[34][35] In 1042 the Bengali saint, Atiśa (982–1054) arrived in Tibet at the invitation of a west Tibetan king and further aided dissemination of Buddhist values in Tibetan culture and in consequential affairs of state.

His erudition supported the translation of major Buddhist texts, which evolved into the canons of Bka'-'gyur (Translation of the Buddha Word) and Bstan-'gyur (Translation of Teachings). The Bka'-'gyur has six main categories: (1) Tantra, (2) Prajñāpāramitā, (3) Ratnakūṭa Sūtra, (4) Avataṃsaka Sūtra, (5) Other sutras, and (6) Vinaya. The Bstan-'gyur comprises 3,626 texts and 224 volumes on such things as hymns, commentaries and suppplementary tantric material.

Atiśa's chief disciple, Dromtön founded the Kadampa school of Tibetan Buddhism, one of the first Sarma schools.[36] The Sakya (Grey Earth) school, was founded by Khön Könchok Gyelpo (1034–1102), a disciple of the great scholar, Drogmi Shākya. It is headed by the Sakya Trizin, and traces its lineage to the mahasiddha Virūpa.[24]

Other influential Indian teachers include Tilopa (988–1069) and his student Nāropā (probably died ca. 1040). Their teachings, via their student Marpa, are the foundations of the Kagyu (Oral lineage) tradition, which focuses on the practices of Mahāmudrā and the Six Dharmas of Nāropā. One of the most famous Kagyu figures was the hermit Milarepa, an 11th-century mystic. The Dagpo Kagyu was founded by the monk Gampopa who merged Marpa's lineage teachings with the monastic Kadam tradition.[24]

All the sub-schools of the Kagyu tradition of Tibetan Buddhism surviving today, including the Drikung Kagyu, the Drukpa Kagyu and the Karma Kagyu, are branches of the Dagpo Kagyu. The Karma Kagyu school is the largest of the Kagyu sub-schools and is headed by the Karmapa.[37]

Mongol dominance (13th–14th centuries)

[edit]Tibetan Buddhism exerted a strong influence from the 11th century CE among the peoples of Inner Asia, especially the Mongols, and Tibetan and Mongolian Buddhism influenced each other. This was done with the help of Kublai Khan and Mongolian theologians influenced by the Church of the East.[38][39][40]

The Mongols invaded Tibet in 1240 and 1244.[41][42][43][44] They eventually annexed Amdo and Kham and appointed the great scholar and abbot Sakya Pandita (1182–1251) as Viceroy of Central Tibet in 1249.[45]

In this way, Tibet was incorporated into the Mongol Empire, with the Sakya hierarchy retaining nominal power over religious and regional political affairs, while the Mongols retained structural and administrative[46] rule over the region, reinforced by the rare military intervention. Tibetan Buddhism was adopted as the de facto state religion by the Mongol Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) of Kublai Khan.[47]

It was also during this period that the Tibetan Buddhist canon was compiled, primarily led by the efforts of the scholar Butön Rinchen Drup (1290–1364). A part of this project included the carving of the canon into wood blocks for printing, and the first copies of these texts were kept at Narthang monastery.[48]

Tibetan Buddhism in China was also syncretized with Chinese Buddhism and Chinese folk religion.[49]

From family rule to Ganden Phodrang government (14th–18th centuries)

[edit]

With the decline and end of the Mongol Yuan dynasty, Tibet regained independence and was ruled by successive local families from the 14th to the 17th century.[50]

Jangchub Gyaltsän (1302–1364) became the strongest political family in the mid 14th century.[51] During this period the reformist scholar Je Tsongkhapa (1357–1419) founded the Gelug school which would have a decisive influence on Tibet's history. The Ganden Tripa is the nominal head of the Gelug school, though its most influential figure is the Dalai Lama. The Ganden Tripa is an appointed office and not a reincarnation lineage. The position can be held by an individual for seven years and this has led to more Ganden Tripas than Dalai Lamas [52]

Internal strife within the Phagmodrupa dynasty, and the strong localism of the various fiefs and political-religious factions, led to a long series of internal conflicts. The minister family Rinpungpa, based in Tsang (West Central Tibet), dominated politics after 1435.[53]

In 1565, the Rinpungpa family was overthrown by the Tsangpa Dynasty of Shigatse, which expanded its power in different directions of Tibet in the following decades and favoured the Karma Kagyu sect. They would play a pivotal role in the events which led to the rise of power of the Dalai Lama's in the 1640s.[citation needed]

In China, Tibetan Buddhism continued to be patronized by the elites of the Ming Dynasty. According to David M. Robinson, during this era, Tibetan Buddhist monks "conducted court rituals, enjoyed privileged status and gained access to the jealously guarded, private world of the emperors".[54] The Ming Yongle Emperor (r. 1402–1424) promoted the carving of printing blocks for the Kangyur, now known as "the Yongle Kanjur", and seen as an important edition of the collection.[55]

The Ming Dynasty also supported the propagation of Tibetan Buddhism in Mongolia during this period. Tibetan Buddhist missionaries also helped spread the religion in Mongolia. It was during this era that Altan Khan the leader of the Tümed Mongols, converted to Buddhism, and allied with the Gelug school, conferring the title of Dalai Lama to Sonam Gyatso in 1578.[56]

During a Tibetan civil war in the 17th century, Sonam Choephel (1595–1657 CE), the chief regent of the 5th Dalai Lama, conquered and unified Tibet to establish the Ganden Phodrang government with the help of the Güshi Khan of the Khoshut Mongols. The Ganden Phodrang and the successive Gelug tulku lineages of the Dalai Lamas and Panchen Lamas maintained regional control of Tibet from the mid-17th to mid-20th centuries.[57]

Qing rule (18th–20th centuries)

[edit]

The Qing dynasty (1644–1912) established a Chinese rule over Tibet after a Qing expeditionary force defeated the Dzungars (who controlled Tibet) in 1720, and lasted until the fall of the Qing dynasty in 1912.[58] The Manchu rulers of the Qing dynasty supported Tibetan Buddhism, especially the Gelug sect, during most of their rule.[47] The reign of the Qianlong Emperor (respected as the Emperor Manjushri) was the high mark for this promotion of Tibetan Buddhism in China, with the visit of the 6th Panchen Lama to Beijing, and the building of temples in the Tibetan style, such as Xumi Fushou Temple, the Puning Temple and Putuo Zongcheng Temple (modeled after the potala palace).[59]

This period also saw the rise of the Rimé movement, a 19th-century nonsectarian movement involving the Sakya, Kagyu and Nyingma schools of Tibetan Buddhism, along with some Bon scholars.[60] Having seen how the Gelug institutions pushed the other traditions into the corners of Tibet's cultural life, scholars such as Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo (1820–1892) and Jamgön Kongtrül (1813–1899) compiled together the teachings of the Sakya, Kagyu and Nyingma, including many near-extinct teachings.[61] Without Khyentse and Kongtrul's collecting and printing of rare works, the suppression of Buddhism by the Communists would have been much more final.[62] The Rimé movement is responsible for a number of scriptural compilations, such as the Rinchen Terdzod and the Sheja Dzö.[citation needed]

During the Qing, Tibetan Buddhism also remained the major religion of the Mongols under Qing rule (1635–1912), as well as the state religion of the Kalmyk Khanate (1630–1771), the Dzungar Khanate (1634–1758) and the Khoshut Khanate (1642–1717).[citation needed]

20th century

[edit]

In 1912, following the fall of the Qing Dynasty, Tibet became de facto independent under the 13th Dalai Lama government based in Lhasa, maintaining the current territory of what is now called the Tibetan Autonomous Region.[63]

During the Republic of China (1912–1949), the "Chinese Tantric Buddhist Revival Movement" (Chinese: 密教復興運動) took place, and important figures such as Nenghai (能海喇嘛, 1886–1967) and Master Fazun (法尊, 1902–1980) promoted Tibetan Buddhism and translated Tibetan works into Chinese.[64] This movement was severely damaged during the Cultural Revolution, however.[citation needed]

After the Battle of Chamdo, Tibet was annexed by China in 1950. In 1959 the 14th Dalai Lama and a great number of clergy and citizenry fled the country, to settle in India and other neighbouring countries. The events of the Cultural Revolution (1966–76) saw religion as one of the main political targets of the Chinese Communist Party, and most of the several thousand temples and monasteries in Tibet were destroyed, with many monks and lamas imprisoned.[65] During this time, private religious expression, as well as Tibetan cultural traditions, were suppressed. Much of the Tibetan textual heritage and institutions were destroyed, and monks and nuns were forced to disrobe.[66]

Outside of Tibet, however, there has been a renewed interest in Tibetan Buddhism in places such as Nepal and Bhutan.[67][68][69][70][71]

Meanwhile, the spread of Tibetan Buddhism in the Western world was accomplished by many of the refugee Tibetan Lamas who escaped Tibet,[65] such as Akong Rinpoche and Chögyam Trungpa who in 1967 were founders of Kagyu Samye Ling the first Tibetan Buddhist Centre to be established in the West.[72]

After the liberalization policies in China during the 1980s, the religion began to recover with some temples and monasteries being reconstructed.[73] Tibetan Buddhism is now an influential religion among Chinese people, and also in Taiwan.[73] However, the Chinese government retains strict control over Tibetan Buddhist Institutions in the PRC. Quotas on the number of monks and nuns are maintained, and their activities are closely supervised.[74]

Within the Tibetan Autonomous Region, violence against Buddhists has been escalating since 2008.[75][76] Widespread reports document the arrests and disappearances[77] of nuns and monks, while the Chinese government classifies religious practices as "gang crime".[78] Reports include the demolition of monasteries, forced disrobing, forced reeducation, and detentions of nuns and monks, especially those residing at Yarchen Gar's center, the most highly publicized.[79][80]

21st century

[edit]

Today, Tibetan Buddhism is adhered to widely in the Tibetan Plateau, Mongolia, northern Nepal, Kalmykia (on the north-west shore of the Caspian), Siberia (Tuva and Buryatia), the Russian Far East and northeast China. It is the state religion of Bhutan.[82] The Indian regions of Sikkim and Ladakh, both formerly independent kingdoms, are also home to significant Tibetan Buddhist populations, as are the Indian states of Himachal Pradesh (which includes Dharamshala and the district of Lahaul-Spiti), West Bengal (the hill stations of Darjeeling and Kalimpong) and Arunachal Pradesh. Religious communities, refugee centers and monasteries have also been established in South India.[83]

The 14th Dalai Lama is the leader of the Tibetan government in exile which was initially dominated by the Gelug school, however, according to Geoffrey Samuel:

The Dharamsala administration under the Dalai Lama has nevertheless managed, over time, to create a relatively inclusive and democratic structure that has received broad support across the Tibetan communities in exile. Senior figures from the three non-Gelukpa Buddhist schools and from the Bonpo have been included in the religious administration, and relations between the different lamas and schools are now on the whole very positive. This is a considerable achievement, since the relations between these groups were often competitive and conflict-ridden in Tibet before 1959, and mutual distrust was initially widespread. The Dalai Lama's government at Dharamsala has also continued under difficult circumstances to argue for a negotiated settlement rather than armed struggle with China.[83]

In the wake of the Tibetan diaspora, Tibetan Buddhism has also gained adherents in the West and throughout the world. Tibetan Buddhist monasteries and centers were first established in Europe and North America in the 1960s, and most are now supported by non-Tibetan followers of Tibetan lamas. Some of these westerners went on to learn Tibetan, undertake extensive training in the traditional practices and have been recognized as lamas.[84] Fully ordained Tibetan Buddhist Monks have also entered Western societies in other ways, such as working academia.[85]

Samuel sees the character of Tibetan Buddhism in the West as

...that of a national or international network, generally centred around the teachings of a single individual lama. Among the larger ones are the FPMT, which I have already mentioned, now headed by Lama Zopa and the child-reincarnation of Lama Yeshe; the New Kadampa, in origin a break-away from the FPMT; the Shambhala Buddhist network, deriving from Chögyam Trungpa's organization and now headed by his son; and the networks associated with Namkhai Norbu Rinpoche (the Dzogchen Community) and Sogyal Rinpoche (Rigpa).[86]

Teachings

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Mahāyāna Buddhism |

|---|

|

Tibetan Buddhism upholds classic Buddhist teachings such as the four noble truths (Tib. pakpé denpa shyi), anatman (not-self, bdag med), the five aggregates (phung po) karma and rebirth, and dependent arising (rten cing ’brel bar ’byung ba).[87] They also uphold various other Buddhist doctrines associated with Mahāyāna Buddhism (theg pa chen po) as well as the tantric Vajrayāna tradition.[88]

Buddhahood and Bodhisattvas

[edit]The Mahāyāna goal of spiritual development is to achieve the enlightenment of Buddhahood in order to help all other sentient beings attain this state.[89] This motivation is called bodhicitta (mind of awakening)—an altruistic intention to become enlightened for the sake of all sentient beings.[90] Bodhisattvas (Tib. jangchup semba, literally "awakening hero") are revered beings who have conceived the will and vow to dedicate their lives with bodhicitta for the sake of all beings.[citation needed]

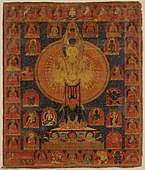

Widely revered Bodhisattvas in Tibetan Buddhism include Avalokiteshvara, Manjushri, Vajrapani, and Tara. The most important Buddhas are the five Buddhas of the Vajradhatu mandala[91] as well as the Adi Buddha (first Buddha), called either Vajradhara or Samantabhadra.[citation needed]

Buddhahood is defined as a state free of the obstructions to liberation as well as those to omniscience (sarvajñana).[92] When one is freed from all mental obscurations,[93] one is said to attain a state of continuous bliss mixed with a simultaneous cognition of emptiness,[94] the true nature of reality.[95] In this state, all limitations on one's ability to help other living beings are removed.[96] Tibetan Buddhism teaches methods for achieving Buddhahood more quickly (known as the Vajrayāna path).[97]

It is said that there are countless beings who have attained Buddhahood.[98] Buddhas spontaneously, naturally and continuously perform activities to benefit all sentient beings.[99] However it is believed that one's karma could limit the ability of the Buddhas to help them. Thus, although Buddhas possess no limitation from their side on their ability to help others, sentient beings continue to experience suffering as a result of the limitations of their own former negative actions.[100]

An important schema which is used in understanding the nature of Buddhahood in Tibetan Buddhism is the Trikaya (Three bodies) doctrine.[101]

The Bodhisattva path

[edit]A central schema for spiritual advancement used in Tibetan Buddhism is that of the five paths (Skt. pañcamārga; Tib. lam nga) which are:[102]

- The path of accumulation – in which one collects wisdom and merit, generates bodhicitta, cultivates the four foundations of mindfulness and right effort (the "four abandonments").

- The path of preparation – Is attained when one reaches the union of calm abiding and higher insight meditations (see below) and one becomes familiar with emptiness.

- The path of seeing – one perceives emptiness directly, all thoughts of subject and object are overcome, one becomes an arya.

- The path of meditation – one removes subtler traces from one's mind and perfects one's understanding.

- The path of no more learning – which culminates in Buddhahood.

The schema of the five paths is often elaborated and merged with the concept of the bhumis or the bodhisattva levels.[citation needed]

Lamrim

[edit]Lamrim ("stages of the path") is a Tibetan Buddhist schema for presenting the stages of spiritual practice leading to liberation. In Tibetan Buddhist history there have been many different versions of lamrim, presented by different teachers of the Nyingma, Kagyu and Gelug schools (the Sakya school uses a different system named Lamdre).[103] However, all versions of the lamrim are elaborations of Atiśa's 11th-century root text A Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment (Bodhipathapradīpa).[104]

Atisha's lamrim system generally divides practitioners into those of lesser, middling and superior scopes or attitudes:

- The lesser person is to focus on the preciousness of human birth as well as contemplation of death and impermanence.

- The middling person is taught to contemplate karma, dukkha (suffering) and the benefits of liberation and refuge.

- The superior scope is said to encompass the four Brahmaviharas, the bodhisattva vow, the six paramitas as well as Tantric practices.[105]

Although lamrim texts cover much the same subject areas, subjects within them may be arranged in different ways and with different emphasis depending on the school and tradition it belongs to. Gampopa and Tsongkhapa expanded the short root-text of Atiśa into an extensive system to understand the entire Buddhist philosophy. In this way, subjects like karma, rebirth, Buddhist cosmology and the practice of meditation are gradually explained in logical order.[citation needed]

Vajrayāna

[edit]

Tibetan Buddhism incorporates Vajrayāna (Vajra vehicle), "Secret Mantra" (Skt. Guhyamantra) or Buddhist Tantra, which is espoused in the texts known as the Buddhist Tantras (dating from around the 7th century CE onwards).[106]

Tantra (Tib. rgyud, "continuum") generally refers to forms of religious practice which emphasize the use of unique ideas, visualizations, mantras, and other practices for inner transformation.[106] The Vajrayana is seen by most Tibetan adherents as the fastest and most powerful vehicle for enlightenment because it contains many skillful means (upaya) and because it takes the effect (Buddhahood itself, or Buddha nature) as the path (and hence is sometimes known as the "effect vehicle", phalayana).[106]

An important element of Tantric practice are tantric deities and their mandalas. These deities come in peaceful (shiwa) and fierce (trowo) forms.[107]

Tantric texts also generally affirm the use of sense pleasures and other defilements in Tantric ritual as a path to enlightenment, as opposed to non-Tantric Buddhism which affirms that one must renounce all sense pleasures.[108] These practices are based on the theory of transformation which states that negative or sensual mental factors and physical actions can be cultivated and transformed in a ritual setting. As the Hevajra Tantra states:

Those things by which evil men are bound, others turn into means and gain thereby release from the bonds of existence. By passion the world is bound, by passion too it is released, but by heretical Buddhists this practice of reversals is not known.[109]

Another element of the Tantras is their use of transgressive practices, such as drinking taboo substances such as alcohol or sexual yoga. While in many cases these transgressions were interpreted only symbolically, in other cases they are practiced literally.[110]

Philosophy

[edit]

The Indian Buddhist Madhyamaka ("Middle Way" or "Centrism") philosophy, also called Śūnyavāda (the emptiness doctrine) is the dominant Buddhist philosophy in Tibetan Buddhism. In Madhyamaka, the true nature of reality is referred to as Śūnyatā, which is the fact that all phenomena are empty of inherent existence or essence (svabhava). Madhyamaka is generally seen as the highest philosophical view by most Tibetan philosophers, but it is interpreted in numerous different ways.[citation needed]

The other main Mahayana philosophical school, Yogācāra has also been very influential in Tibetan Buddhism, but there is more disagreement among the various schools and philosophers regarding its status. While the Gelug school generally sees Yogācāra views as either false or provisional (i.e. only pertaining to conventional truth), philosophers in the other three main schools, such as Ju Mipham and Sakya Chokden, hold that Yogācāra ideas are as important as Madhyamaka views.[111]

In Tibetan Buddhist scholasticism, Buddhist philosophy is traditionally propounded according to a hierarchical classification of four classical Indian philosophical schools, known as the "four tenets" (Tib. drubta shyi, Sanskrit: siddhānta).[112] While the classical tenets-system is limited to four tenets (Vaibhāṣika, Sautrāntika, Yogācāra, and Madhyamaka), there are further sub-classifications within these different tenets (see below).[113] This classification does not include Theravada, the only surviving of the 18 classical schools of Buddhism. It also does not include other Indian Buddhist schools, such as Mahasamghika and Pudgalavada.[citation needed]

Two tenets belong to the path referred to as the Hinayana ("lesser vehicle") or Sravakayana ("the disciples' vehicle"), and are both related to the north Indian Sarvastivada tradition:[114]

- Vaibhāṣika (Wylie: bye brag smra ba). The primary source for the Vaibhāṣika in Tibetan Buddhism is the Abhidharma-kośa of Vasubandhu and its commentaries. This Abhidharma system affirms an atomistic view of reality which states ultimate reality is made up of a series of impermanent phenomena called dharmas. It also defends eternalism regarding the philosophy of time, as well the view that perception directly experiences external objects.[115]

- Sautrāntika (Wylie: mdo sde pa). The main sources for this view is the Abhidharmakośa, as well as the work of Dignāga and Dharmakīrti. As opposed to Vaibhāṣika, this view holds that only the present moment exists (presentism), as well as the view that we do not directly perceive the external world only the mental images caused by objects and our sense faculties.[115]

The other two tenets are the two major Indian Mahayana philosophies:

- Yogācāra, also called Vijñānavāda (the doctrine of consciousness) and Cittamātra ("Mind-Only", Wylie: sems-tsam-pa). Yogacārins base their views on texts from Maitreya, Asaṅga and Vasubandhu. Yogacara is often interpreted as a form of Idealism due to its main doctrine, the view that only ideas or mental images exist (vijñapti-mātra).[115] Some Tibetan philosophers interpret Yogācāra as the view that the mind (citta) exists in an ultimate sense, because of this, it is often seen as inferior to Madhyamaka. However, other Tibetan thinkers deny that the Indian Yogacāra masters held the view of the ultimate existence of the mind, and thus, they place Yogācāra on a level comparable to Madhyamaka. This perspective is common in the Nyingma school, as well as in the work of the Third Karmapa, the Seventh Karmapa and Jamgon Kongtrul.[116][117]

- Madhyamaka (Wylie: dbu-ma-pa) – The philosophy of Nāgārjuna and Āryadeva, which affirms that everything is empty of essence (svabhava) and is ultimately beyond concepts.[115] There are various further classifications, sub-schools and interpretations of Madhymaka in Tibetan Buddhism and numerous debates about various key disagreements remain a part of Tibetan Buddhist scholasticism today. One of the key debates is that between the rangtong (self-empty) interpretation and the shentong (other empty) interpretation.[118] Another major disagreement is the debate on the Svātantrika Madhyamaka method and the Prasaṅgika method.[119] There are further disagreements regarding just how useful an intellectual understanding of emptiness can be and whether emptiness should only be described as an absolute negation (the view of Tsongkhapa).[120]

Monks debating at Sera monastery, Tibet, 2013. Debate is seen as an important practice in Tibetan Buddhist education.

The tenet systems are used in monasteries and colleges to teach Buddhist philosophy in a systematic and progressive fashion, each philosophical view being seen as more subtle than its predecessor. Therefore, the four tenets can be seen as a gradual path from a rather easy-to-grasp, "realistic" philosophical point of view, to more and more complex and subtle views on the ultimate nature of reality, culminating in the philosophy of the Mādhyamikas, which is widely believed to present the most sophisticated point of view.[121] Non-Tibetan scholars point out that historically, Madhyamaka predates Yogacara, however.[122]

Texts and study

[edit]

Study of major Buddhist Indian texts is central to the monastic curriculum in all four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism. Memorization of classic texts as well as other ritual texts is expected as part of traditional monastic education. Another important part of higher religious education is the practice of formalized debate.[123]

The canon was mostly finalized in the 13th century, and divided into two parts, the Kangyur (containing sutras and tantras) and the Tengyur (containing shastras and commentaries). The Nyingma school also maintains a separate collection of texts called the Nyingma Gyubum, assembled by Ratna Lingpa in the 15th century and revised by Jigme Lingpa.[124]

Among Tibetans, the main language of study is classical Tibetan, however, the Tibetan Buddhist canon was also translated into other languages, such as Mongolian and Manchu.[citation needed]

During the Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties, many texts from the Tibetan canon were also translated into Chinese.[125]

Numerous texts have also recently been translated into Western languages by Western academics and Buddhist practitioners.[126]

Sutras

[edit]

Among the most widely studied sutras in Tibetan Buddhism are Mahāyāna sutras such as the Perfection of Wisdom or Prajñāpāramitā sutras,[127] and others such as the Saṃdhinirmocana-sūtra, and the Samādhirāja Sūtra.[128]

According to Tsongkhapa, the two authoritative systems of Mahayana Philosophy (viz. that of Asaṅga – Yogacara and that of Nāgārjuna – Madhyamaka) are based on specific Mahāyāna sūtras: the Saṃdhinirmocana Sūtra and the Questions of Akṣayamati (Akṣayamatinirdeśa Sūtra) respectively. Furthermore, according to Thupten Jinpa, for Tsongkhapa, "at the heart of these two hermeneutical systems lies their interpretations of the Perfection of Wisdom sūtras, the archetypal example being the Perfection of Wisdom in Eight Thousand Lines."[129]

Treatises of the Indian masters

[edit]The study of Indian Buddhist treatises called shastras is central to Tibetan Buddhist scholasticism. Some of the most important works are those by the six great Indian Mahayana authors which are known as the Six Ornaments and Two Supreme Ones (Tib. gyen druk chok nyi, Wyl. rgyan drug mchog gnyis), the six being: Nagarjuna, Aryadeva, Asanga, Vasubandhu, Dignaga, and Dharmakirti and the two being: Gunaprabha and Shakyaprabha (or Nagarjuna and Asanga depending on the tradition).[130]

Since the late 11th century, traditional Tibetan monastic colleges generally organized the exoteric study of Buddhism into "five great textual traditions" (zhungchen-nga).[131]

- Abhidharma

- Prajnaparamita

- Madhyamaka

- Nagarjuna's Mūlamadhyamakakārikā

- Aryadeva's Four Hundred Verses (Catuhsataka)

- Candrakīrti's Madhyamakāvatāra

- Śāntarakṣita's Madhyamākalaṃkāra

- Shantideva's Bodhisattvacaryāvatāra

- Pramana

- Vinaya

- Gunaprabha's Vinayamula Sutra

Other important texts

[edit]Also of great importance are the "Five Treatises of Maitreya" including the influential Ratnagotravibhāga, a compendium of the tathāgatagarbha literature, and the Mahayanasutralankara, a text on the Mahayana path from the Yogacara perspective, which are often attributed to Asanga. Practiced focused texts such as the Yogācārabhūmi-Śāstra and Kamalaśīla's Bhāvanākrama are the major sources for meditation.[citation needed]

While the Indian texts are often central, original material by key Tibetan scholars is also widely studied and collected into editions called sungbum.[132] The commentaries and interpretations that are used to shed light on these texts differ according to tradition. The Gelug school for example, use the works of Tsongkhapa, while other schools may use the more recent work of Rimé movement scholars like Jamgon Kongtrul and Jamgon Ju Mipham Gyatso.[citation needed]

A corpus of extra-canonical scripture, the treasure texts (terma) literature is acknowledged by Nyingma practitioners, but the bulk of the canon that is not commentary was translated from Indian sources. True to its roots in the Pāla system of North India, however, Tibetan Buddhism carries on a tradition of eclectic accumulation and systematisation of diverse Buddhist elements, and pursues their synthesis. Prominent among these achievements have been the Stages of the Path and mind training literature, both stemming from teachings by the Indian scholar Atiśa.[citation needed]

Tantric literature

[edit]In Tibetan Buddhism, the Buddhist Tantras are divided into four or six categories, with several sub-categories for the highest Tantras.

In the Nyingma, the division is into Outer Tantras (Kriyayoga, Charyayoga, Yogatantra); and Inner Tantras (Mahayoga, Anuyoga, Atiyoga/Dzogchen), which correspond to the "Anuttarayoga-tantra".[133] For the Nyingma school, important tantras include the Guhyagarbha Tantra, the Guhyasamaja Tantra,[134] the Kulayarāja Tantra and the 17 Dzogchen Tantras.

In the Sarma schools, the division is:[135]

- Kriya-yoga – These have an emphasis on purification and ritual acts and include texts like the Mañjuśrīmūlakalpa.

- Charya-yoga – Contain "a balance between external activities and internal practices", mainly referring to the Mahāvairocana Abhisaṃbodhi Tantra.

- Yoga-tantra, is mainly concerned with internal yogic techniques and includes the Tattvasaṃgraha Tantra.

- Anuttarayoga-tantra, contains more advanced techniques such as subtle body practices and is subdivided into:

- Father tantras, which emphasize illusory body and completion stage practices and includes the Guhyasamaja Tantra and Yamantaka Tantra.

- Mother tantras, which emphasize the development stage and clear light mind and includes the Hevajra Tantra and Cakrasamvara Tantra.

- Non-dual tantras, which balance the above elements, and mainly refers to the Kalacakra Tantra

The root tantras themselves are almost unintelligible without the various Indian and Tibetan commentaries, therefore, they are never studied without the use of the tantric commentarial apparatus.[citation needed]

Transmission and realization

[edit]There is a long history of oral transmission of teachings in Tibetan Buddhism. Oral transmissions by lineage holders traditionally can take place in small groups or mass gatherings of listeners and may last for seconds (in the case of a mantra, for example) or months (as in the case of a section of the Tibetan Buddhist canon). It is held that a transmission can even occur without actually hearing, as in Asanga's visions of Maitreya.[citation needed]

An emphasis on oral transmission as more important than the printed word derives from the earliest period of Indian Buddhism, when it allowed teachings to be kept from those who should not hear them.[136] Hearing a teaching (transmission) readies the hearer for realization based on it. The person from whom one hears the teaching should have heard it as one link in a succession of listeners going back to the original speaker: the Buddha in the case of a sutra or the author in the case of a book. Then the hearing constitutes an authentic lineage of transmission. Authenticity of the oral lineage is a prerequisite for realization, hence the importance of lineages.[citation needed]

Practices

[edit]In Tibetan Buddhism, practices are generally classified as either Sutra (or Pāramitāyāna) or Tantra (Vajrayāna or Mantrayāna), though exactly what constitutes each category and what is included and excluded in each is a matter of debate and differs among the various lineages. According to Tsongkhapa for example, what separates Tantra from Sutra is the practice of Deity yoga.[137] Furthermore, the adherents of the Nyingma school consider Dzogchen to be a separate and independent vehicle, which transcends both sutra and tantra.[138]

While it is generally held that the practices of Vajrayāna are not included in Sutrayāna, all Sutrayāna practices are common to Vajrayāna practice. Traditionally, Vajrayāna is held to be a more powerful and effective path, but potentially more difficult and dangerous and thus they should only be undertaken by the advanced who have established a solid basis in other practices.[139]

Pāramitā

[edit]The pāramitās (perfections, transcendent virtues) is a key set of virtues which constitute the major practices of a bodhisattva in non-tantric Mahayana. They are:

- Dāna pāramitā: generosity, giving (Tibetan: སབྱིན་པ sbyin-pa)

- Śīla pāramitā: virtue, morality, discipline, proper conduct (ཚུལ་ཁྲིམས tshul-khrims)

- Kṣānti pāramitā: patience, tolerance, forbearance, acceptance, endurance (བཟོད་པ bzod-pa)

- Vīrya pāramitā: energy, diligence, vigor, effort (བརྩོན་འགྲུས brtson-’grus)

- Dhyāna pāramitā: one-pointed concentration, meditation, contemplation (བསམ་གཏན bsam-gtan)

- Prajñā pāramitā: wisdom, knowledge (ཤེས་རབ shes-rab)

The practice of dāna (giving) while traditionally referring to offerings of food to the monastics can also refer to the ritual offering of bowls of water, incense, butter lamps and flowers to the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas on a shrine or household altar.[140] Similar offerings are also given to other beings such as hungry ghosts, dakinis, protector deities, and local divinities.

Like other forms of Mahayana Buddhism, the practice of the five precepts and bodhisattva vows is part of Tibetan Buddhist moral (sila) practice. In addition to these, there are also numerous sets of Tantric vows, termed samaya, which are given as part of Tantric initiations.

Compassion (karuṇā) practices are also particularly important in Tibetan Buddhism. One of the foremost authoritative texts on the Bodhisattva path is the Bodhisattvacaryāvatāra by Shantideva. In the eighth section entitled Meditative Concentration, Shantideva describes meditation on Karunā as thus:

Strive at first to meditate upon the sameness of yourself and others. In joy and sorrow all are equal; Thus be guardian of all, as of yourself. The hand and other limbs are many and distinct, But all are one—the body to kept and guarded. Likewise, different beings, in their joys and sorrows, are, like me, all one in wanting happiness. This pain of mine does not afflict or cause discomfort to another's body, and yet this pain is hard for me to bear because I cling and take it for my own. And other beings' pain I do not feel, and yet, because I take them for myself, their suffering is mine and therefore hard to bear. And therefore I'll dispel the pain of others, for it is simply pain, just like my own. And others I will aid and benefit, for they are living beings, like my body. Since I and other beings both, in wanting happiness, are equal and alike, what difference is there to distinguish us, that I should strive to have my bliss alone?"[141]

A popular compassion meditation in Tibetan Buddhism is tonglen (sending and taking love and suffering respectively). Practices associated with Chenrezig (Avalokiteshvara), also tend to focus on compassion.

Samatha and Vipaśyanā

[edit]

The 14th Dalai Lama defines meditation (bsgom pa) as "familiarization of the mind with an object of meditation."[142] Traditionally, Tibetan Buddhism follows the two main approaches to meditation or mental cultivation (bhavana) taught in all forms of Buddhism, śamatha (Tib. Shine) and vipaśyanā (lhaktong).

The practice of śamatha (calm abiding) is one of focusing one's mind on a single object such as a Buddha figure or the breath. Through repeated practice one's mind gradually becomes more stable, calm and happy. It is defined by Takpo Tashi Namgyal as "fixing the mind upon any object so as to maintain it without distraction...focusing the mind on an object and maintaining it in that state until finally it is channeled into one stream of attention and evenness."[143] The nine mental abidings is the main progressive framework used for śamatha in Tibetan Buddhism.[144]

Once a meditator has reached the ninth level of this schema they achieve what is termed "pliancy" (Tib. shin tu sbyangs pa, Skt. prasrabdhi), defined as "a serviceability of mind and body such that the mind can be set on a virtuous object of observation as long as one likes; it has the function of removing all obstructions." This is also said to be very joyful and blissful for the body and the mind.[145]

The other form of Buddhist meditation is vipaśyanā (clear seeing, higher insight), which in Tibetan Buddhism is generally practiced after having attained proficiency in śamatha.[146] This is generally seen as having two aspects, one of which is analytic meditation, which is based on contemplating and thinking rationally about ideas and concepts. As part of this process, entertaining doubts and engaging in internal debate over them is encouraged in some traditions.[147] The other type of vipaśyanā is a non-analytical, "simple" yogic style called trömeh in Tibetan, which means "without complication".[148]

A meditation routine may involve alternating sessions of vipaśyanā to achieve deeper levels of realization, and samatha to consolidate them.[95]

Preliminary practices

[edit]

Vajrayāna is believed by Tibetan Buddhists to be the fastest method for attaining Buddhahood but for unqualified practitioners it can be dangerous.[149] To engage in it one must receive an appropriate initiation (also known as an "empowerment") from a lama who is fully qualified to give it. The aim of preliminary practices (ngöndro) is to start the student on the correct path for such higher teachings.[150] Just as Sutrayāna preceded Vajrayāna historically in India, so sutra practices constitute those that are preliminary to tantric ones.

Preliminary practices include all Sutrayāna activities that yield merit like hearing teachings, prostrations, offerings, prayers and acts of kindness and compassion, but chief among the preliminary practices are realizations through meditation on the three principal stages of the path: renunciation, the altruistic bodhicitta wish to attain enlightenment and the wisdom realizing emptiness. For a person without the basis of these three in particular to practice Vajrayāna can be like a small child trying to ride an unbroken horse.[151]

The most widespread preliminary practices include: taking refuge, prostration, Vajrasattva meditation, mandala offerings and guru yoga.[152] The merit acquired in the preliminary practices facilitates progress in Vajrayāna. While many Buddhists may spend a lifetime exclusively on sutra practices, an amalgam of the two to some degree is common. For example, in order to train in calm abiding, one might visualize a tantric deity.

Guru yoga

[edit]As in other Buddhist traditions, an attitude of reverence for the teacher, or guru, is also highly prized.[153] At the beginning of a public teaching, a lama will do prostrations to the throne on which he will teach due to its symbolism, or to an image of the Buddha behind that throne, then students will do prostrations to the lama after he is seated. Merit accrues when one's interactions with the teacher are imbued with such reverence in the form of guru devotion, a code of practices governing them that derives from Indian sources.[154] By such things as avoiding disturbance to the peace of mind of one's teacher, and wholeheartedly following his prescriptions, much merit accrues and this can significantly help improve one's practice.

There is a general sense in which any Tibetan Buddhist teacher is called a lama. A student may have taken teachings from many authorities and revere them all as lamas in this general sense. However, he will typically have one held in special esteem as his own root guru and is encouraged to view the other teachers who are less dear to him, however more exalted their status, as embodied in and subsumed by the root guru.[155]

One particular feature of the Tantric view of teacher student relationship is that in Tibetan Buddhist Tantra, one is instructed to regard one's guru as an awakened Buddha.[156]

Esotericism and vows

[edit]

In Vajrayāna particularly, Tibetan Buddhists subscribe to a voluntary code of self-censorship, whereby the uninitiated do not seek and are not provided with information about it. This self-censorship may be applied more or less strictly depending on circumstances such as the material involved. A depiction of a mandala may be less public than that of a deity. That of a higher tantric deity may be less public than that of a lower. The degree to which information on Vajrayāna is now public in western languages is controversial among Tibetan Buddhists.

Buddhism has always had a taste for esotericism since its earliest period in India.[157] Tibetans today maintain greater or lesser degrees of confidentiality also with information on the vinaya and emptiness specifically. In Buddhist teachings generally, too, there is caution about revealing information to people who may be unready for it.

Practicing tantra also includes the maintaining of a separate set of vows, which are called Samaya (dam tshig). There are various lists of these and they may differ depending on the practice and one's lineage or individual guru. Upholding these vows is said to be essential for tantric practice and breaking them is said to cause great harm.[158]

Ritual

[edit]There has been a "close association" between the religious and the secular, the spiritual and the temporal[159] in Tibet. The term for this relationship is chos srid zung 'brel. Traditionally Tibetan lamas have tended to the lay populace by helping them with issues such as protection and prosperity. Common traditions have been the various rites and rituals for mundane ends, such as purifying one's karma, avoiding harm from demonic forces and enemies, and promoting a successful harvest.[160] Divination and exorcism are examples of practices a lama might use for this.[161]

Ritual is generally more elaborate than in other forms of Buddhism, with complex altar arrangements and works of art (such as mandalas and thangkas), many ritual objects, hand gestures (mudra), chants, and musical instruments.[108]

A special kind of ritual called an initiation or empowerment (Sanskrit: Abhiseka, Tibetan: Wangkur) is central to Tantric practice. These rituals consecrate a practitioner into a particular Tantric practice associated with individual mandalas of deities and mantras. Without having gone through initiation, one is generally not allowed to practice the higher Tantras.[162]

Another important ritual occasion in Tibetan Buddhism is that of mortuary rituals which are supposed to assure that one has a positive rebirth and a good spiritual path in the future.[163] Of central importance to Tibetan Buddhist Ars moriendi is the idea of the bardo (Sanskrit: antarābhava), the intermediate or liminal state between life and death.[163] Rituals and the readings of texts such as the Bardo Thodol are done to ensure that the dying person can navigate this intermediate state skillfully. Cremation and sky burial are traditionally the main funeral rites used to dispose of the body.[63]

Mantra

[edit]The use of (mainly Sanskrit) prayer formulas, incantations or phrases called mantras (Tibetan: sngags) is another widespread feature of Tibetan Buddhist practice.[156] So common is the use of mantras that Vajrayana is also sometimes called "Mantrayāna" (the mantra vehicle). Mantras are widely recited, chanted, written or inscribed, and visualized as part of different forms of meditation. Each mantra has symbolic meaning and will often have a connection to a particular Buddha or Bodhisattva.[164] Each deity's mantra is seen as symbolizing the function, speech and power of the deity.[165]

Tibetan Buddhist practitioners repeat mantras like Om Mani Padme Hum in order to train the mind, and transform their thoughts in line with the divine qualities of the mantra's deity and special power.[166] Tibetan Buddhists see the etymology of the term mantra as meaning "mind protector", and mantras is seen as a way to guard the mind against negativity.[167]

According to Lama Zopa Rinpoche:

Mantras are effective because they help keep your mind quiet and peaceful, automatically integrating it into one-pointedness. They make your mind receptive to very subtle vibrations and thereby heighten your perception. Their recitation eradicates gross negativities and the true nature of things can then be reflected in your mind's resulting clarity. By practising a transcendental mantra, you can in fact purify all the defiled energy of your body, speech, and mind.[168]

Mantras also serve to focus the mind as a samatha (calming) practice as well as a way to transform the mind through the symbolic meaning of the mantra. In Buddhism, it is important to have the proper intention, focus and faith when practicing mantras, if one does not, they will not work. Unlike in Hinduism, mantras are not believed to have inherent power of their own, and thus without the proper faith, intention and mental focus, they are just mere sounds.[169] Thus according to the Tibetan philosopher Jamgon Ju Mipham:

if a mantra is thought to be something ordinary and not seen for what it is, it will not be able to perform its intended function. Mantras are like non-conceptual wish-fulfilling jewels. Infusing one's being with the blessings of mantra, like the form of a moon reflected on a body of water, necessitates the presence of faith and other conditions that set the stage for the spiritual attainments of mantra. Just as the moon's reflection cannot appear without water, mantras cannot function without the presence of faith and other such factors in one's being.[170]

Mantras are part of the highest tantric practices in Tibetan Buddhism, such as Deity Yoga and are recited and visualized during tantric sadhanas. Thus, Tsongkhapa says that mantra "protects the mind from ordinary appearances and conceptions".[171] This is because in Tibetan Buddhist Tantric praxis, one must develop a sense that everything is divine.

Tantric sadhana and yoga

[edit]

In what is called higher yoga tantra the emphasis is on various spiritual practices, called yogas (naljor) and sadhanas (druptap) which allow the practitioner to realize the true nature of reality.[110]

Deity Yoga (Tibetan: lha'i rnal 'byor; Sanskrit: Devata-yoga) is a fundamental practice of Vajrayana Buddhism involving visualization of mental images consisting mainly of Buddhist deities such as Buddhas, Bodhisattvas and fierce deities, along mantra repetition. According to Geoffrey Samuel:

If Buddhahood is a source of infinite potentiality accessible at any time, then the Tantric deities are in a sense partial aspects, refractions of that total potentiality. Visualizing one of these deities, or oneself identifying with one of them, is not, in Tibetan Tantric thought, a technique to worship an external entity. Rather, it is a way of accessing or tuning into something that is an intrinsic part of the structure of the universe—as of course is the practitioner him or herself.[172]

Deity yoga involves two stages, the generation stage (utpattikrama) and the completion stage (nispannakrama). In the generation stage, one dissolves the mundane world and visualizes one's chosen deity (yidam), its mandala and companion deities, resulting in identification with this divine reality.[173]

In the completion stage, one dissolves the visualization of and identification with the yidam in the realization ultimate reality. Completion stage practices can also include subtle body energy practices,[174] such as tummo (lit. "Fierce Woman", Skt. caṇḍālī, inner fire), as well as other practices that can be found in systems such as the Six Yogas of Naropa (like Dream Yoga, Bardo Yoga and Phowa) and the Six Vajra-yogas of Kalacakra.

Dzogchen and Mahamudra

[edit]Another form of high level Tibetan Buddhist practice are the meditations associated with the traditions of Mahāmudrā ("Great Seal") and Dzogchen ("Great Perfection"). These traditions focus on direct experience of the very nature of reality, which is variously termed dharmakaya, buddha nature, or the "basis' (gzhi). These techniques do not rely on deity yoga methods but on direct pointing-out instruction from a master and are often seen as the most advanced form of Buddhist practice.[175] The instructions associated with these approaches to meditation and realization are collectively referred to as mind teachings since both provide practical guidance on the "recognition of the nature of mind."[176]

The views and practices associated with Dzogchen and Mahāmudrā are also often seen as the culmination of the Buddhist path.[177] In some traditions, they are seen as a separate vehicle to liberation. In the Nyingma school (as well as in Bon), Dzogchen is considered to be a separate and independent vehicle (also called Atiyoga), as well as the highest of all vehicles.[178] Similarly, in Kagyu, Mahāmudrā is sometimes seen as a separate vehicle, the "Sahajayana" (Tibetan: lhen chig kye pa), also known as the vehicle of self-liberation.[179]

Institutions and clergy

[edit]

Buddhist monasticism is an important part of the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, all the major and minor schools maintain large monastic institutions based on the Mulasarvastivada Vinaya (monastic rule) and many religious leaders come from the monastic community. That being said, there are also many religious leaders or teachers (called Lamas and Gurus) which are not celibate monastics. According to Geoffrey Samuel this is where "religious leadership in Tibetan Buddhism contrasts most strongly with much of the rest of the Buddhist world."[180]

According to Namkhai Norbu, in Tibet, Tibetan lamas had four main types of lifestyles:

those who were monks, living in monasteries; those who lived a lay life, with their homes in villages; lay masters who lived as tent-dwelling nomads, travelling with their disciples, in some cases following their herds; and those who were yogis, often living in caves.[181]

Lamas are generally skilled and experienced tantric practitioners and ritual specialists in a specific initiation lineage and may be laypersons or monastics. They act not just as teachers, but as spiritual guides and guardians of the lineage teachings that they have received through a long and intimate process of apprenticeship with their Lamas.[182]

Tibetan Buddhism also includes a number of lay clergy and lay tantric specialists, such as Ngagpas (Skt. mantrī), Gomchens, Serkyims, and Chödpas (practitioners of Chöd). According to Samuel, in the more remote parts of the Himalayas, communities were often led by lay religious specialists.[183] Thus, while the large monastic institutions were present in the regions of the Tibetan plateau which were more centralized politically, in other regions they were absent and instead smaller gompas and more lay oriented communities prevailed.[184]

Samuel outlines four main types of religious communities in Tibet:[185]

- Small communities of lay practitioners attached to a temple and a lama. Lay practitioners might stay in the gompa for periodic retreats.

- Small communities of celibate monastics attached to a temple and a lama, often part of a village.

- Medium to large communities of celibate monastics. These could maintain several hundred monks and might have extensive land holdings, be financially independent, and sometimes also act as trading centers.

- Large teaching monasteries with thousands of monks, such as the big Gelug establishments of Sera (with over 6000 monks in the first half of the 20th century) and Drepung (over 7000).[186]

In some cases a lama is the leader of a spiritual community. Some lamas gain their title through being part of particular family which maintains a lineage of hereditary lamas (and are thus often laypersons). One example is the Sakya family of Kon, who founded the Sakya school and another is the hereditary lamas of Mindrolling monastery.[187]

In other cases, lamas may be seen as tülkus ("incarnations"). Tülkus are figures which are recognized as reincarnations of a particular bodhisattva or a previous religious figure. They are often recognized from a young age through the use of divination and the use of the possessions of the deceased lama, and therefore are able to receive extensive training. They are sometimes groomed to become leaders of monastic institutions.[188] Examples include the Dalai Lamas and the Karmapas, each of which are seen as key leaders in their respective traditions.

Система воплощенных лам в основном считается тибетским изменением индийского буддизма.

Другим названием, уникальным для тибетского буддизма, является название Тертона (Scuesure Discoverer), который считается способным раскрывать или открывать специальные откровения или тексты, называемые Termas (Lit. «скрытые сокровища»). Они также связаны с идеей Бейула («скрытые долины»), которые представляют собой власти, связанные с божествами и скрытыми религиозными сокровищами. [ 189 ]

Тибетские учителя, в том числе Далай Ламас , иногда консультируются с Oracles за советом.

Женщины в тибетском буддизме

[ редактировать ]

Женщины в тибетском обществе, хотя и все еще неравные, имели тенденцию иметь относительно большую автономию и власть, чем в окружающих обществах. Это может быть связано с меньшими размерами домохозяйства и низкой плотностью населения в Тибете. [ 190 ] Женщины традиционно играли много ролей в тибетском буддизме, от сторонников мирян до монатиков, лам и тантрических практикующих.

Существуют доказательства важности практикующих женщин в индийском тантрическом буддизме и до-модерн тибетского буддизма. По крайней мере, одна важная линия тантрических учений, Шанпа Кагью , прослеживает себя для индийских учителей -женщин, и в нем была серия важных женских тибетских учителей, таких как Йеше Цогил и Мачиг Лабдр . [ 191 ] Похоже, что, хотя женщинам могло бы быть сложнее стать серьезными тантрическими йогини, они все равно могли найти Лама, которые научили бы их высокой тантрической практике.

Некоторые тибетские женщины становятся ламами, родившись в одной из наследственных семей Ламы, таких как Mindrolling Jetsün Khandro Rinpoche и Sakya Jetsün Kushok Chimey Luding. [ 192 ] Также были случаи влиятельных женских лам, которые также были Тертонами, такими как Сера Хандро , Таре Лхамо и Аю Хандро .

Некоторые из этих цифр были также тантрическими консортами ( Sangyum, Kandroma ) с мужскими ламами, и, таким образом, участвовали в сексуальных практиках, связанных с самыми высокими уровнями тантрической практики. [ 193 ]

Восточные монахини

[ редактировать ]В то время как монашизм практикуется там женщинами, он гораздо реже (2 процента населения в 20 -м веке по сравнению с 12 процентами мужчин). Тибетские общество также гораздо меньше уважали монахи, чем монахи, и могут получить меньшую поддержку, чем мужской монасты. [ 194 ]

Традиционно тибетские буддийские монахини также не были «полностью рукоположены», как бхикшюни (которые принимают полный набор монашеских клятв в винойе ). Когда буддизм путешествовал из Индии в Тибет, очевидно, кворум бхикшуни, необходимый для подавления полного старения, никогда не достигала Тибета. [ 195 ] [ Примечание 5 ] Несмотря на отсутствие ордена, Бхикшюнис поехал в Тибет. Примечательным примером была Шри -Ланки -нюн Кэндрамала, чья работа с Шридженьной ( Wylie : Dpal Ye Shes ) привела к тантрическому тексту Шрикандрамала Тантрараджа . [ Примечание 6 ] [ 196 ]

Существуют отчеты о полностью рукоположенных тибетских женщинах, таких как Samding Dorje Phagmo (1422–1455), который когда -то был оценен самым высоким мастером женского пола и тулку в Тибете, но очень мало известно о точных обстоятельствах их постановления. [ 197 ]

В современную эпоху тибетские буддийские монахини приняли полные постановления через восточную азиатскую линии Виная. [ 198 ] Далай -лама уполномочил последователей тибетской традиции быть предопределенным как монахини в традициях, которые имеют такое посвящение. [ Примечание 7 ] Официальная линия тибетского буддийского буддийского бхикшиса, возобновляемого 23 июня 2022 года в Бутане, когда 144 монахиня, большинство из которых бутанцы, были полностью рукоположены. [ 201 ] [ 202 ]

Западные монахини и ламы

[ редактировать ]Буддийский автор Микаэла Хаас отмечает, что тибетский буддизм переживает морские изменения на Западе, и женщины играют гораздо более центральную роль. [ 203 ]

Фрида Беди [ Примечание 8 ] была британская женщина, которая была первой западной женщиной, которая приняла рукоположение в тибетском буддизме, которое произошло в 1966 году. [ 204 ] Пема Чодран была первой американской женщиной, которая была рукоположена в буддийской монахини в тибетской буддийской традиции. [ 205 ] [ 206 ]

В 2010 году был официально освящен первый тибетский буддийский монастырь в Америке. Он предлагает начинающую посвящение и следует за Drikung Kagyu линией буддизма . Абботом монастыря Ваджры Дакини является Хенмо Дрольма , американская женщина, которая является первой бхикшюни в линии буддизма Дрикунг, будучи рукоположенным в Тайване в 2002 году. [ 207 ] [ 208 ] Она также является первым западным, мужчинами или женщиной, которая будет установлена в качестве аббата в линии буддизма Drikung Kagyu , которая была установлена в качестве аббата монастыря Ваджры Дакини в 2004 году. [ 207 ] Монастырь Ваджра Дакини не следует за восемью Гарудамасом . [ 209 ]

В апреле 2011 года Институт буддийских диалектических исследований (IBD) в Дхарамсале, Индия, получил степень Геше , тибетской буддийской академической степени для монастики, на Келсанг Вангмо , немецкая монахиня, таким образом, получив первую женскую женщину в мире. [ 210 ] [ 211 ] В 2013 году тибетские женщины смогли сдать экзамены Geshe в первый раз. [ 212 ] В 2016 году двадцать тибетских буддийских монахинь стали первыми тибетскими женщинами, получившими степень Геше . [ 213 ] [ 214 ]

Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo привлекла международное внимание в конце 1980 -х годов в качестве первой западной женщины, которая стала пенор Ринпоче, выдвинутая на Tulku в Нингма -Палюле . [ 215 ]

Основные линии

[ редактировать ]Тибетский ученый (несектарный) ученый Джамгон Конгтрул в своем сокровищничестве знаний описывает «восемь великих практик», которые были переданы в Тибет. Его подход не связан с «школами» или сектами, а скорее фокусируется на передаче решающих учений по медитации. Они есть: [ 216 ]

- Традиции Нингма , связанные с первыми фигурами передачи, такими как Shantarakshita , Padmasambhava и King Trisong Deutsen и с Dzogchen . учениями

- Линия Кадама Атишей , связанная с . и его учеником Дромтёном (1005–1064)

- Ламдре , прослежившись обратно в индийскую махасиддху Вирупу и сегодня сохранился в школе Сакья .

- Марпа Кагью, происхождение, которое связано с Марпой , Миларепой и Гампопой , практикует Махамудру и шесть дхарм Наропы , и включает в себя четыре основных и восемь незначительных линий Кагью.

- Шанпа Кагью , происхождение Нигумы

- Shyijé и Chöd , которые происходят из Падампы Сангьи и Мачиг Лабрён .

- Дорье Налджор Друк («Шесть ветвей практики Ваджрайога»), которая получена из линии Калачакры .

- Dorje Sumgyi Nyndrup («подход и достижение трех ваджр»), от Mahasiddha orgyenpa rconchen pal.

Тибетские буддийские школы

[ редактировать ]Существуют различные школы или традиции тибетского буддизма. Четыре основные традиции заметно пересекаются, так что «около восьмидесяти процентов или более особенностей тибетских школ одинаковы». [ 217 ] Различия включают в себя использование, по -видимому,, но на самом деле не противоречивой терминологии, открытия посвящений текстов различным божествам и то, описываются ли явления с точки зрения нездорового врача или будды. [ 217 ] По вопросам философии исторически были разногласия относительно природы учения йогакары и будды-природы (и имеют ли они целесообразное значение или окончательное значение), которые до сих пор окрашивают нынешние презентации суньяты (пустота) и окончательной реальности . [ 218 ] [ 219 ] [ 220 ]

19 -го века Движение Rimé преуменьшало эти различия, что все еще отражалось в позиции четырнадцатого Далай -ламы, который заявляет, что между этими школами нет фундаментальных различий. [ 221 ] Тем не менее, между различными традициями все еще существуют философские разногласия, такие как дискуссия относительно в Рангтонге и Шентонге интерпретации философии Мадхьямака . [ 222 ]

Четыре основных школы иногда делятся на традиции Нингмы (или «старый перевод») и сарма (или «новый перевод»), которые следуют за различными канонами Писания ( Нингма Гюбум вместе с Термасом и Тенгюром - Кангюром соответственно). [ 223 ]

Каждая школа также отслеживается до определенной родословной, возвращающейся в Индию, а также к определенным важным основателям тибета. В то время как все школы разделяют большинство практик и методов, каждая школа имеет тенденцию иметь определенную предпочтительную цель (см. Таблицу ниже). Другая распространенная, но тривиальная дифференциация-в сектах с желтой шляпой (гелуг) и красной шляпой (не геляг).

Особенности каждой крупной школы (наряду с одной влиятельной второстепенной школой, Джонанг), заключаются в следующем: [ 224 ]

| Школа | Нингма | Кадам (несуществующий) | Кагью | Сакья | Голос | Джонанг |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Традиции | Старый перевод | Новый перевод | Новый перевод | Новый перевод | Новый перевод | Новый перевод |

| Источник | Разработан с 8 -го века | Основан в 11 веке Атиной и его учениками. Перестал существовать как независимая школа к 16 веку. | Передается Марпой в 11 веке. Дагпо Кагью был основан в 12 веке Гэмпопой. | Монастырь Сакья основан в 1073 году. | Даты 1409 года с основанием монастыря Ганден | Датируется 12 веком |

| Акцент | Подчеркивает Дзогчен и его тексты, а также Гухьягарбха Тантра | Подчеркивает классическое исследование Махаяны и практику в монашеской обстановке, источник Ложонга и Ламрима | Подчеркивает Махамудру и шесть дхарм Наропы | Благоприятствует Hevajra Tantra как основу их Lamdre системы | Сосредоточится на Гухьясамаджа Тантра , Какрасамвара Тантра и Калачакра Тантра | Сосредоточится на калачакра -тантре и ратнаготравибхаге |

| Ключевые фигуры | ŚāntarakṣitaТы Garab Dorje , Вималамитра , Padmasambhava , Rongzom Chökyi Zangpo , Longchenpa , и Jamgön Ju Mipe Gyatso |

Ати , Dromön , Нгогпай Шерб, остаться Вы можете Senge Chaba Chokyi, и Пассаб Нима Дракпа . |

Maitripada , Наропа , Тилопа , Марпа , Миларепа , и Гэмпопа . |

Наропа , Инвалидная коляска , Основатель Drugmi , Хон Кончог Гьялпо , Сакья Пандита и Горампа . |

Умножить , его ученик Дромтин , основатель Gelug Je Tsongkhapa , и Далай Ламас . |

Юмо Микио Дорье , Дольпопа , и Таранатха |

В своей работе, четыре традиции Дхармы Земли Тибета , Мипхэм Ринпоче описал четыре основных школы следующим образом:

Последователи Секретной Мантры Нингма подчеркивают фактическую тантру.

Они преследуют высшую точку зрения и удовольствие от стабильного поведения.

Многие достигают уровня Видьядхары и достигают достижения,

И многие - мантрины, чья сила больше других.

Последователи Кагю, защитники существ, подчеркивают преданность.

Многие считают, что получить благословения линии достаточно.

И многие получают достижение через настойчивость в практике

Они похожи и смешиваются с Nyingmapas.

Riwo Gendenpas (то есть Gelugpas) подчеркивает пути ученых.

Они любят аналитическую медитацию и удовольствие от дебатов.

И они впечатляют всех своим элегантным, образцовым поведением.

Они популярны, процветают и прилагают усилия к обучению.

Славный сакьяпы подчеркивают подход и достижение.

Многие благословлены силой чтения и визуализации,

Они ценят свои собственные пути, и их обычная практика превосходна.

По сравнению с любой другой школой, у них есть что -то из них.

Эма! Все четыре традиции дхармы этой земли Тибета

Имейте лишь один настоящий источник, даже если они возникли индивидуально.

Какой бы вы ни следовали, если вы практикуете его должным образом

Это может принести качества обучения и достижения.

Есть еще одна незначительная секта, школа Бодонга . Эта традиция была основана в 1049 году учителем Кадама Мудра Ченпо, который также основал монастырь Бодун. Его самым известным учителем был Бодунг Пенчен Ленам Джильчок (1376–1451), который написал более ста тридцати пяти томов. Эта традиция также известна тем, что поддержала женскую линию Tulku воплощенных лам, называемые Samding Dorje Phagmo .

В то время как Yungdrung Bon считает себя отдельной религией с додипуддистским происхождением, и основные тибетские традиции считаются небуддистскими, он разделяет так много сходств и практик с основным тибетским буддизмом, что некоторые ученые, такие как Geoffry Samuel, видят его как » По сути, вариант тибетского буддизма ». [ 225 ] Yungdrung BON тесно связан с буддизмом Нингмы и включает в себя учения Дзогхена , подобные божества, ритуалы и формы монашюка.

Глоссарий используемых терминов

[ редактировать ]| Английский | разговорный тибетский | Wylie Tibetan | Санскритская транслитерация |

|---|---|---|---|

| страдания | Nyenmong | Ньон-монги | сыпь |

| аналитическая медитация | Jegom | DPYAD-SGOM | Дхьяна |

| спокойный пребывание | светить | Чжи-Гнас | Шаматха |

| преданность гуру | Отсутствует Тенпа | Bla-ma-la bsten-pa | Гурупариупасати |

| фиксация медитация | joggom | 'Закон | Нибандхита Дхьяна |

| основополагающее средство | Мужчины | Смань ярмарка | китайская |

| воплощенное лезвие | Тюлку | Спрал-Ску | Нирманакая |

| присущее существованию | Rangzhingi Drubpa | Rang-Bzhin-Gyi Grub-Pa | Svabhāvasidddha |

| ум просветления | втирать | Byang-chhub sems | Бодхититта |

| мотивационное обучение | Ложонг | Blo-Sbyong | Autsukya dhyāna |

| всеведение | T'amcé k'yempa | THAMS-CAD MKHYEN-PA | Сарваджья |

| Предварительные практики | Нгёндро | Sngon-'gro | Прарамбамхика Крийяни |

| Корневой учитель | Заве Лама | Rtsa-ba'i bla-ma | мулагуриальный |

| стадии пути | Ламрим | Лам-Рим | Пайхейя |

| передача и реализация | легкий | легкие-ртоги | Агамадхигама |

Смотрите также

[ редактировать ]Примечания

[ редактировать ]- ^ Также известный как тибето-монгол буддизм , индо-тибетский буддизм , ламаизм , ламаистический буддизм , гималайский буддизм и северный буддизм

- ^ 和尚摩訶衍; Его имя состоит из тех же китайских иероглифов, которые использовались для транспорта « Махаяна » (Тибетс: Хва Шан Махаяна )

- ^ Kamalaśīla написал три текста Бхаванакрамы (практикуйте главу 3) после этого.

- ^ Тем не менее, китайский источник, найденный в Данхуанге, написанный Мо-Хо-Йен, говорит, что их сторона победила, и некоторые ученые приходят к выводу, что весь эпизод является вымышленным. [ 29 ] [ 30 ]

- ^ Под муласарвастивадином Виная, как и в случае с двумя другими существующими линиями Виная сегодня ( Thuravada и Dharmaguptaka ), чтобы использовать бхикшуни, должны быть кворумы как бхикшуни, так и бхикшуса; Без обоих женщина не может быть назначена как монахиня ( тибетская : DGE Slong MA , THL : Gélongma ).

- ^ Тибетский : Китай , : Китай : Китай

- ^ По словам Тубтен Чодрон , нынешний Далай -лама сказал по этому вопросу: [ 199 ]

- В 2005 году Далай -лама неоднократно говорил о рукоположении Бхикшуни на общественных собраниях. В Дхарамсале он поощрял: «Мы должны довести это до вывода. Мы, тибетцы, только не можем решить это. Скорее, это должно быть решено в сотрудничестве с буддистами со всего мира. Говоря в общих чертах, были буддой с Приходите в этот мир 21 -го века, я чувствую, что, скорее всего, увидев реальную ситуацию в мире, он может несколько изменить правила ... »

- Позже, в Цюрихе во время конференции тибетских буддийских центров 2005 года, он сказал: «Теперь я думаю, что пришло время; мы должны начать рабочую группу или комитет» для встречи с монахами из других буддийских традиций. Глядя на немецкую бхикшуни Джампа Цедроен , он проинструктировал: «Я предпочитаю, чтобы западные буддийские монахини выполняли эту работу… ходить в разные места для дальнейших исследований и обсудить со старшими монахами (из разных буддийских стран). Я думаю, во -первых, старшие бхикшуни. Чтобы исправить мышление монахов.

- «Это 21 -й век. Везде мы говорим о равенстве… Бхикшуни клятва ".

Иногда в религии был акцент на мужскую значимость. Однако в буддизме самые высокие клятвы, а именно бхикшу и бхикшуни, равны и влечет за собой те же права. Это так, несмотря на то, что в некоторых ритуальных областях из -за социального обычая Bhikshus идет первым. Но Будда дал основные права одинаково на обе группы Сангы. Нет смысла обсуждать, возродить рукоположение Бхикшуни; Вопрос в том, как сделать это правильно в контексте винойи. [ 200 ]

- ^ Иногда пишется Фрида Беди, также называемой сестрой Пальмо, или Гелонгма Карма Кечог Пальмо

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]Цитаты

[ редактировать ]- ^ Уайт, Дэвид Гордон, изд. (2000). Тантра на практике . ПРИЗНАЯ УНИВЕРСИТЕТА ПРИСЕТА. п. 21. ISBN 0-691-05779-6 .