Языки США

В США нет официального языка на федеральном уровне, но наиболее часто используемым языком является английский (в частности, американский английский ), который де-факто является национальным языком . Кроме того, 32 штата США из 50 и все пять территорий США объявили английский официальным языком. Подавляющее большинство населения США (около 78%) говорит дома только по-английски. [5] Остальная часть населения говорит дома на многих других языках, в первую очередь на испанском (13,3% населения), согласно опросу американского сообщества (ACS) Бюро переписи населения США ; другие включают языки коренных народов , на которых изначально говорили коренные американцы , коренные жители Аляски , коренные гавайцы и коренное население некорпоративных территорий США . Другие языки были привезены людьми из Европы , Африки , Азии , других частей Америки и Океании , включая многочисленные диалекты , креольские языки, пиджин -языки и языки жестов , возникшие на территории нынешних Соединенных Штатов. Интерлингва , международный вспомогательный язык , также был создан в США.

The majority of foreign language speakers in the U.S. are bilingual or multilingual, and they commonly speak English. Although 21.7% of U.S. residents report that they speak a language other than English at home, only 8.2% speak English less than "very well."[6] Approximately 430 languages are spoken or signed by the population, of which 177 are indigenous to the U.S. or its territories.[7]

Most common languages

[edit]Based on annual data from the American Community Survey (ACS), the U.S. Census Bureau regularly publishes information on the most common languages spoken at home. It also reports on the English-speaking ability of people who speak a language other than English at home.[8] In 2023, Spanish speakers made up about three-fifths of all foreign language speakers in the United States. In 2017, the U.S. Census Bureau published information on the number of speakers of some 350 languages as surveyed by the ACS from 2009 to 2013,[9][10] but it does not regularly tabulate and report data for that many languages.

The most spoken native languages in the United States in 2021 were:[8]

- English (only language spoken in the household) – 245 million

- Spanish – 41.3 million

- Chinese (including Mandarin, Cantonese, Hokkien and all other varieties) – 3.40 million

- Tagalog (including Filipino) – 1.72 million

- Vietnamese – 1.52 million

- Arabic – 1.39 million

- French – 1.18 million

- Korean – 1.07 million

- Russian – 1.04 million

- Portuguese – 937,000

- Haitian Creole – 895,000

- Hindi – 865,000

- German – 857,000

- Polish – 533,000

- Italian – 513,000

- Urdu – 508,000

- Persian (including Farsi, Dari and Tajik) – 472,000

- Telugu – 460,000

- Japanese – 455,000

- Gujarati – 437,000

- Bengali – 403,000

- Tamil – 341,000

- Punjabi – 319,000

- Thais (including Central Thai and Lao) – 284,000

- Serbo-Croatian (including Bosnian, Croatian, Montenegrin, and Serbian) – 266,000

- Armenian – 256,000

- Greek – 253,000

- Hmong – 240,000

- Hebrew – 215,000

- Khmer – 193,000

- Navajo – 155,000

- other Indo-European languages – 662,000

- Yoruba, Twi, Igbo and other languages of West Africa – 640,000

- Amharic, Somali, and other Afro-Asiatic languages – 596,000

- Dutch, Afrikaans, Frisian, Yiddish, Pennsylvania Dutch, Low German, and other West Germanic languages – 574,000

- Ilocano, Samoan, Hawaiian, and other Austronesian languages – 486,000

- Other languages of Asia – 460,000

- Nepali, Marathi, and other Indic languages – 448,000

- Ukrainian and other Slavic languages – 385,000

- Swahili and other languages of Central, Eastern, and Southern Africa – 288,000

- Malayalam, Kannada, and other Dravidian languages – 280,000

- Other Native languages of North America – 169,000

- other and unspecified languages – 327,000

The ACS is not a full census but an annual sample-based survey conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau. The language statistics are based on responses to a three-part question asked about all members of a target U.S. household who are at least five years old. The first part asks if they "speak a language other than English at home." If so, the head of the household or main respondent is asked to report which language each member speaks in the home, and how well each individual speaks English. It does not ask how well individuals speak any other language of the household. Thus, some respondents might have only limited speaking ability in those languages.[11] In addition, it is difficult to make historical comparisons of the numbers of speakers because language questions used by the U.S. Census changed numerous times before 1980.[12]

The ACS does not tabulate the number of people who report the use of American Sign Language at home, so such data must come from other sources. While modern estimates indicate that American Sign Language was signed by as many as 500,000 Americans in 1972 (the last official survey of sign language), estimates as recently as 2011 were closer to 100,000. Various cultural factors, such as the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act, have resulted in far greater educational opportunities for hearing-impaired children, which could double or triple the number of current users of American Sign Language.

English is the most common language spoken in U.S. homes, with approximately 239 million speakers as well as numerous bilingual speakers. Spanish is spoken by approximately 35 million people.[13] The United States has the world's fourth largest Spanish-speaking population, outnumbered only by Mexico, Colombia, and Argentina; other estimates[which?] put the United States at over 50 million, second only to Mexico. Throughout the Southwestern United States and Puerto Rico, long-established Spanish-speaking communities coexist with large numbers of more recent Hispanophone immigrants. Although many new Latin American immigrants are less than fluent in English, nearly all second-generation Hispanic and Latino Americans speak English fluently, while only about half still speak Spanish.[14]

According to the 2000 U.S. Census, people of German ancestry made up the largest single ethnic group in the United States, but German language was the fourth most-spoken language in the country.[15][16] Italian, Polish, and French are still widely spoken among populations descending from immigrants from those countries in the early 20th century, but the use of these languages is dwindling as the older generations die. Russian is also spoken by immigrant populations.

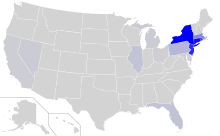

Tagalog and Vietnamese have over one million speakers each in the United States, almost entirely within recent immigrant populations. Both languages, along with the varieties of Chinese (mostly Cantonese, Taishanese, and Standard Mandarin), Japanese, and Korean, are now used in elections in Alaska, California, Hawaii, Illinois, New York, Texas, and Washington.[17]

Native American languages are spoken in smaller pockets of the country, but these populations are decreasing, and the languages are seldom widely used outside of reservations. Besides English, Spanish, French, German, Navajo and other Native American languages, all other languages are usually learned from immigrant ancestors that came after the time of independence or learned through some form of education.

American Sign Language is the most common sign language in the United States, although there are unrelated sign languages that have also been developed in the States and territories—mostly in the Pacific. No concrete numbers exist for signers but something upwards of 250,000 is common.The most widely taught foreign languages in the United States, in terms of enrollment numbers from kindergarten through university undergraduate education, are Spanish, French, and German. Other commonly taught languages include Latin, Japanese, American Sign Language, Italian, and Chinese.[18][19]

Official languages

[edit]

The United States has never had an official language at the federal level,[20][21] but English is typically used at the federal level and in states that do not have an official language. Outside of Puerto Rico, English is the primary language used for legislation, regulations, executive orders, treaties, federal court rulings, and all other official pronouncements. Nonetheless, laws require documents such as ballots to be printed in multiple languages when there are large numbers of non-English speakers in an area.

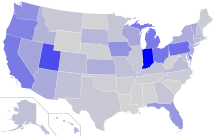

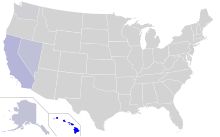

Thirty-two of the 50 states have adopted legislation granting official or co-official status to English, in some cases as part of what has been called the English-only movement.[22][23] Typically only "English" is specified, not a particular variety like American English. (From 1923 to 1969, the state of Illinois recognized its official language as "American".)[24][25] Hawaiian, although having few native speakers, is an official language along with English of the state of Hawaii. Alaska has made some 20 native languages official, along with English;[26][27] for example, Alaska provides voting information in Iñupiaq, Central Yup'ik, Gwich'in, Siberian Yupik, and Koyukon among others.[28] On July 1, 2019, a law went into effect making Lakota, Dakota, and Nakota the official indigenous languages of South Dakota.[29]French is a de facto, but unofficial, language in Maine and Louisiana, while New Mexico law grants Spanish a special status. The government of Louisiana offers services and most documents in both English and French, and New Mexico does so in English and Spanish.

English is at least one of the official languages in all five permanently inhabited U.S. territories. In Puerto Rico both English and Spanish are official, although Spanish has been declared the principal official language. The school system and the government operate almost entirely in Spanish, but federal law requires the United States District Court for the District of Puerto Rico to use English,[30] like the rest of the federal court system. Guam recognizes English and Chamorro. In the U.S. Virgin Islands, English is the only official language. In American Samoa, both English and Samoan are officially recognized; English is common but Samoan is also seen in some official communications. In the Northern Mariana Islands, English, Chamorro, and Carolinian are official.[citation needed]

In New Mexico, although the state constitution does not specify an official language, laws are published in English and Spanish, and government materials and services are legally required (by Act) to be made accessible to speakers of both languages as well as Navajo and various Pueblo languages. New Mexico also has its own dialect of Spanish, which differs from Spanish spoken in Latin America.

Algonquian, Cherokee, and Sioux are among many other Native American languages which are official or co-official on many U.S. Indian reservations and Pueblos. In Oklahoma before statehood in 1907, territory officials debated whether or not to have Cherokee, Choctaw, and Muscogee languages as co-official, but the idea never gained ground. Cherokee is officially recognized by the Cherokee Nation within the Cherokee tribal jurisdiction area in eastern Oklahoma.[31]

After New Amsterdam (formerly a Dutch colony) was transferred to English administration (becoming the Province of New York) in the late 17th century, English supplanted Dutch as the official language. However, "Dutch remained the primary language for many civil and ecclesiastical functions and most private affairs for the next century."[32] The Jersey Dutch dialect is now extinct.

California has agreed to allow the publication of state documents in other languages to represent minority groups and immigrant communities. Languages such as Spanish, Chinese, Korean, Tagalog, Persian, Russian, Vietnamese, and Thai appear in official state documents, and the Department of Motor Vehicles publishes in nine languages.[33]

The issue of multilingualism also applies in the states of Arizona and Texas. While the constitution of Texas has no official language policy, Arizona passed a proposition in 2006 declaring English as the official language.[34] Nonetheless, Arizona law requires the distribution of voting ballots in Spanish, as well as indigenous languages such as Navajo, O'odham and Hopi, in counties where they are spoken.[35]

A popular urban legend called the Muhlenberg legend claims that German was almost made an official language of the United States but lost by one vote. In reality, it was a request by a group of German immigrants to have an official translation of laws into German. House speaker Frederick Muhlenberg has since become associated with the legend.[36][37][38]

| Place | English official | Other official language(s) | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | Yes | None | since 1990[39] |

| Alaska | Yes | Inupiaq, Siberian Yupik, Central Alaskan Yup'ik, Alutiiq, Unangax, Dena'ina, Deg Xinag, Holikachuk, Koyukon, Upper Kuskokwim, Gwich'in, Tanana, Upper Tanana, Tanacross, Hän, Ahtna, Eyak, Tlingit, Haida, Tsimshian[40] | since 2015[40] |

| Arizona | Yes | None | since 2006, 1988 law ruled unconstitutional[41] |

| Arkansas | Yes | None | since 1987[39] |

| California | Yes | None | since 1986 with Proposition 63.[39] Proposition 63 is unenforceable due to the lack of appropriate legislation,[42] and the Bilingual Services Act provides for the use of other languages in public outreach.[43] |

| Colorado | Yes | None | since 1988;[39] from 1876–1990 the Colorado Constitution required laws to be published in English, Spanish, and German[44] |

| Connecticut | No | None[39] | |

| Delaware | No | None[39] | |

| Florida | Yes | None | since 1988[39] |

| Georgia | Yes | None | since 1996[39] |

| Hawaii | Yes | Hawaiian | since 1978[39] |

| Idaho | Yes | None | since 2007[39] |

| Illinois | Yes | None | since 1969; "American" was the official language 1923–1969.[39] |

| Indiana | Yes | None | since 1984[39] |

| Iowa | Yes | None | since 2002[39] |

| Kansas | Yes | None | since 2007[39] |

| Kentucky | Yes | None | since 1984[39] |

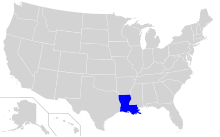

| Louisiana | No | None | French has had special status since 1968 founding of CODOFIL.[39][45] |

| Maine | No | None[39] | |

| Maryland | No | None[39] | |

| Massachusetts | Yes | None[39] | since 2002; 1975 law ruled unconstitutional |

| Michigan | No | None[39] | |

| Minnesota | No | None[39] | |

| Mississippi | Yes | None | since 1987[39] |

| Missouri | Yes | None[39] | since 1998; state constitution amended accordingly in 2008[46] |

| Montana | Yes | None | since 1995[39] |

| Nebraska | Yes | None | since 1920[47] |

| Nevada | No | None[39] | |

| New Hampshire | Yes | None | since 1995[39] |

| New Jersey | No | None[39] | |

| New Mexico | No | None | Spanish has had special recognition since 1912 passage of state constitution. See article. English Plus since 1989[39] |

| New York | No | None[39] | |

| North Carolina | Yes | None | since 1987[39] |

| North Dakota | Yes | None | since 1987[39] |

| Ohio | No | None[39] | |

| Oklahoma | Yes | None | since 2010. The Choctaw language is official within the Choctaw Nation; the Cherokee language has been official among the Cherokee and the UKB since 1991.[48][49][50][51] |

| Oregon | No | None | English Plus since 1989[39] |

| Pennsylvania | No | None[39] | |

| Rhode Island | No | None | English Plus since 1992[39] |

| South Carolina | Yes | None | since 1987[39] |

| South Dakota | Yes | Sioux | since 1995,[39] since 2019[52] |

| Tennessee | Yes | None | since 1984[39] |

| Texas | No | None[39] | |

| Utah | Yes | None | English only from 2000–2021;[39] since 2021, the Utah code has been amended to be English official but not English only.[53] |

| Vermont | No | None[39] | |

| Virginia | Yes | None | since 1996[39] |

| Washington | No | None | English Plus since 1989[39] |

| West Virginia | Yes | None[39] | since 2016[54] |

| Wisconsin | No | None[39] | |

| Wyoming | Yes | None | since 1996[39] |

| District of Columbia | No | None[55][56] | The Language Access Act of 2004 guarantees equal access and participation in public services, programs, and activities for residents of the District of Columbia who cannot (or have limited capacity to) speak, read, or write English. Speakers of Amharic, French, Chinese, Spanish, Vietnamese and Korean receive additional accommodations.[57][58] |

| American Samoa | Yes | Samoan[59] | |

| Guam | Yes | Chamorro[60] | |

| Northern Mariana Islands | Yes | Chamorro, Carolinian[61] | |

| Puerto Rico | Yes | Spanish[62] | |

| U.S. Virgin Islands | Yes | None[63] |

Education

[edit]Bilingual education in the United States, often a different concept from language immersion or dual-language school programs, is an area of political controversy. In standard bilingual classes, the non-English language (typically Spanish or Chinese) is utilized over a period of time when students' English-language proficiency is lacking. Otherwise the medium of instruction at almost all U.S. schools, at all levels, is English. The exceptions are in language classes such as French or German, or in general education in the territory of Puerto Rico, where Spanish is standard. English is the language of instruction in the territory of American Samoa, despite most students speaking Samoan as their native language.[64]

There are also hundreds of language immersion and dual-language schools across the United States that teach in a variety of languages, including Spanish, Hawaiian, Chamorro, French, and Mandarin Chinese (for example, the Mandarin Immersion Magnet School in Texas). However, English is a mandatory class in all these schools.

African, Asian and European languages

[edit]

Some of the first European languages to be spoken in the U.S. were English, Dutch, French, Spanish, and Swedish.

From the mid-19th century, the nation had large numbers of immigrants who spoke little or no English. The laws, constitutions, and legislative proceedings of some states and territories appeared in the languages of politically important immigrant groups. There have been bilingual schools and local newspapers in such languages as German, Ukrainian, Hungarian, Irish, Italian, Norwegian, Greek, Polish, Swedish, Romanian, Czech, Japanese, Yiddish, Hebrew, Lithuanian, Welsh, Cantonese, Bulgarian, Dutch, Portuguese Persian, arabic and others. These flourished despite English-only laws in some jurisdictions prohibiting church services, telephone conversations, and even conversations in the street or on railway platforms in a language other than English, up until the first of these laws was ruled unconstitutional in 1923 (Meyer v. Nebraska).

Typically, immigrant languages tend to be lost through assimilation within two or three generations.[66]

Several states and territories have native populations who spoke their own language prior to joining the United States, and have maintained their original languages for centuries. The languages include Alaskan Russian, Louisiana French, Pennsylvania Dutch, and Puerto Rican Spanish.

Historic languages

[edit]English (245 million speakers)

[edit]

English was inherited from British colonization, and it is spoken by the majority of the population. English has become increasingly common; when the United States was founded, just 40% of Americans spoke English.[67][better source needed]. In 2002, 87% of Americans spoke English as their first language.[68][69] It serves as the de facto national language, the language in which government business is carried out. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, 80% spoke only English at home and all but approximately 13,600,000 U.S. residents age 5 and over speak English "well" or "very well".[70]

American English is different from British English in terms of spelling (one example being the dropped "u" in words such as color/colour), grammar, vocabulary, pronunciation, and slang usage. The differences are not usually a barrier to effective communication between an American English and a British English speaker.

Some states, like California, have amended their constitutions to make English the only official language, but in practice, this only means that official government documents must at least be in English, and does not mean that they should be exclusively available only in English. For example, the standard California Class C driver's license examination is available in 32 different languages.[71]

Spanish (41.3 million speakers)

[edit]

Spanish was also inherited from colonization and is sanctioned as official in the commonwealth of Puerto Rico, where it is the general language of instruction in schools and universities. In the 50 states, the District of Columbia, and all territories except Puerto Rico, Spanish is taught as a foreign or second language. It is spoken at home in areas with large Hispanic populations: the Southwestern United States along the border with Mexico, as well as in Florida, parts of California, the District of Columbia, Illinois, New Jersey, and New York. In Hispanic communities across the country, bilingual signs in both Spanish and English may be quite common. Furthermore, numerous neighborhoods exist (such as Washington Heights in New York City or Little Havana in Miami) in which entire city blocks will have only Spanish-language signs and Spanish-speaking people.

| Year | Number of Spanish speakers | Percent of US population |

|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 11 million | 5% |

| 1990 | 17.3 million | 7% |

| 2000 | 28.1 million | 10% |

| 2010 | 37 million | 13% |

| 2012 | 38.3 million | 13% |

| 2015 | 41 million | 14% |

| Sources:[16][72][73][74] | ||

Younger generations of non-Hispanics in the United States choose to study Spanish as a foreign or second language in far greater numbers than other second-language options. This might be due in part to the growing Hispanic population and the increasing popularity of Latin American movies and music performed in the Spanish language. A 2009 American Community Survey (ACS) conducted by the United States Census Bureau, showed that Spanish was spoken at home by over 35 million people aged 5 or older,[75] making the United States the world's fifth-largest Spanish-speaking community, outnumbered only by Mexico, Colombia, Spain, and Argentina.[76][77] Since then, the number of persons reported on the ACS to speak Spanish at home has increased (see table).

New Mexican Spanish

[edit]

In northern New Mexico and southern Colorado, Spanish speakers have been isolated for centuries in the southern Rockies, and developed a distinct dialect of Spanish spoken nowhere else: New Mexican Spanish. The dialect features a mix of Castilian, Galician and, more recently, Mexican Spanish, as well as Pueblo loan words. New Mexican Spanish also contains a large proportion of English loan words, particularly for technological words (e.g. bos, troca, and telefón).

Speakers of New Mexican Spanish are mainly descendants of Spanish colonists who arrived in New Mexico in the sixteenth through the eighteenth centuries. During this time, contact with the rest of Spanish America was limited, and New Mexican Spanish developed on its own course. In the meantime, Spanish colonists coexisted with and intermarried with Puebloan peoples and Navajos. After the Mexican–American War, New Mexico and all its inhabitants came under the governance of the English-speaking United States, and for the next hundred years, English-speakers increased in number.

Puerto Rican Spanish

[edit]

Puerto Rican Spanish is the main language and dialect of the people of Puerto Rico, as well as many people descended from Puerto Ricans elsewhere throughout the United States.

Spanglish

[edit]Spanglish is a code-switching variant of Spanish and English and is spoken in areas with large bilingual populations of Spanish and English speakers, such as along the Mexico–United States border (California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas), Florida, and New York City.

French (2.08 million speakers)

[edit]

French, the fourth-most-common language (when all varieties of French are combined and separate yet related languages such as Haitian Creole are counted as French), is spoken mainly by the Louisiana Creole, native French, Cajun, Haitian, and French-Canadian populations. It is widely spoken in Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, and in Louisiana, with notable Francophone enclaves in St. Clair County, Michigan, many rural areas of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan and the northern San Francisco Bay area. [citation needed] Because of its legacy in Louisiana, that state is served by the Council for the Development of French in Louisiana (CODOFIL), the only state agency in the United States whose mission is to serve a linguistic population. In October 2018, Louisiana became the first U.S. state to join the Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie.[78]

Three varieties of French developed within what is now the United States in colonial times including Louisiana French, Missouri French, and New England French (essentially a variant of Canadian French).[79] French is the second-most-spoken language in the states of Louisiana and Maine. The largest French-speaking communities in the United States reside in Northeast Maine; Hollywood and Miami, Florida; New York City;[citation needed] certain areas of rural Louisiana; and small minorities in Vermont and New Hampshire. Many of the New England communities are connected to the dialect found across the border in Quebec or New Brunswick. More than 13 million Americans possess primary French heritage, but only 2 million speak French, or any regional creoles and variations language at home. The largest concentration of French speakers in the country is in Louisiana.

Louisiana French

[edit]

Louisiana French (Cajun French: français de la Louisiane; Louisiana Creole: françé la lwizyàn) is an umbrella term for the dialects and varieties of the French language spoken traditionally in colonial Lower Louisiana. As of today Louisiana French is primarily used in the U.S. state of Louisiana, specifically in the southern parishes.

French is spoken across ethnic and racial lines by Louisiana French people who may identify as Cajuns or Creoles as well as Chitimacha, Houma, Biloxi, Tunica, Choctaw, Acadians, and French Indian among others.[80][81] For these reasons, as well as the relatively small influence Acadian French has had on the region, the label Louisiana French or Louisiana Regional French (French: français régional louisianais) is generally regarded as more accurate and inclusive than "Cajun French" and is the preferred term by linguists and anthropologists.[82][83][84][85] However, "Cajun French" is commonly used in lay discourse by speakers of the language and other inhabitants of Louisiana.[86]

German (1.29 million speakers)

[edit]

German was a widely spoken language in some of the colonies, especially Pennsylvania, where a number of German-speaking Protestants and other religious minorities settled to escape persecution in Europe. Another wave of settlement occurred when Germans fleeing the failure of 19th Century German revolutions emigrated to the United States. A large number of these German immigrants settled in the urban areas, with neighborhoods in many cities being German-speaking and numerous local German language newspapers and periodicals established. German farmers also took up farming around the country, including the Texas Hill Country, at this time. The language was widely spoken until the United States entered World War I.

In the early twentieth century, German was the most widely studied foreign language in the United States, and prior to World War I, more than 6%[citation needed] of American schoolchildren received their primary education exclusively in German, though some of these Germans came from areas outside of Germany proper. Currently, more than 49 million Americans claim German ancestry, the largest self-described ethnic group in the U.S., but less than 4% of them speak a language other than English at home, according to the 2005 American Community Survey.[87] The Amish speak a dialect of German known as Pennsylvania Dutch. One reason for this decline of German language was the perception during both World Wars that speaking the language of the enemy was unpatriotic; foreign language instruction was banned in places during the First World War. Unlike earlier waves, they were more concentrated in cities and integrated quickly. Another reason for the decline in German was the lack of first-generation immigrants, as immigration to the United States from Western Europe slowed following the World Wars.

Waves of colonial Palatines from the Rhenish Palatinate, one of the Holy Roman states, settled in the Province of New York and the Province of Pennsylvania. The first Palatines arrived in the late 1600s but the majority came throughout the 1700s; they were known collectively as the Palatine Dutch. The Pennsylvania Dutch settled other states, including Indiana and Ohio.[88][89] For many years, the term "Palatine" meant German American.[90]

There is a myth (known as the Muhlenberg Vote) that German was to be the official language of the U.S., but this is inaccurate and based on a failed early attempt to have government documents translated into German.[91] The myth also extends to German being the second official language of Pennsylvania; however, Pennsylvania has no official language. Although more than 49 million Americans claim they have German ancestors, only 1.24 million Americans speak German at home. Many of these people are either Amish and Mennonites or Germans having newly immigrated (e.g. for professional reasons).

Pennsylvania Dutch

[edit]

Pennsylvania Dutch or Pennsylvania German is a dialect of Palatine German that is traditionally spoken by the Pennsylvania Dutch, and has settled the Midwest, in places such as Ohio, Indiana, Iowa and other states, where many of the speakers live today. It evolved from the German dialect of the Palatinate brought over to America by Palatines from the Holy Roman Empire in the 1600s.[92] They settled on land sold to them by William Penn. Germantown included not only Mennonites, but also Quakers.[93] The Pennsylvania Dutch speak Pennsylvania Dutch, and adhere to different Christian denominations: Lutherans, German Reformed, Mennonites, Amish, German Baptist Brethren, Roman Catholics; today Pennsylvania Dutch is mainly spoken by Old Order Amish and Old Order Mennonites.

Texas German

[edit]

Texas German is a group of High German dialects spoken by Texas Germans, descendants of German immigrants who settled in Texas in the mid-19th century.

Yiddish

[edit]Yiddish has a much longer history in the United States than Hebrew.[94] It has been present since at least the late 19th century and continues to have roughly 148,000 speakers as of the 2009 American Community Survey. Though they came from varying geographic backgrounds and nuanced approaches to worship, immigrant Jews of Central Europe, Germany and Russia were often united under a common understanding of the Yiddish language once they settled in America, and at one point dozens of publications were available in most East Coast cities. Though it has declined by quite a bit since the end of WWII, it has by no means disappeared. Many Israeli immigrants and expatriates have at least some understanding of the language in addition to Hebrew, and many of the descendants of the great migration of Ashkenazi Jews of the past century pepper their mostly English vocabulary with some loan words. Furthermore, it is a lingua franca among American Jews (particularly Hasidic Jewry), concentrated in Los Angeles, Miami, and New York.[95] A significant diffusion of Yiddish loan words into the non-Jewish population continues to be a distinguishing feature of New York City English. Some of these words include glitch, chutzpah, mensch, kvetch, klutz, etc.

Russian (1.04 million speakers)

[edit]The Russian language is spoken in areas of some states, including New York, California, Washington, New Jersey, Illinois, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and Alaska. It is especially spoken in immigrant neighborhoods of some cities: New York City, Boston, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Philadelphia, Chicago, Seattle, Sacramento, Spokane, Miami, Vancouver, Washington, Portland, Oregon, and Woodburn, Oregon. The Russian-American Company owned most all of what became Alaska Territory until its sale right after the Crimean War. The presence of Russian speakers in the United States had always been limited, especially after the assassination of the Romanov dynasty of tsars. Starting in the 1970s and continuing until the mid-1990s, however, many Russian-speaking people from the Soviet Union and later its constituent republics such as Russia, Moldova, Ukraine, Belarus, and Uzbekistan have immigrated to the United States, increasing the use of Russian in the country.

The largest Russian-speaking neighborhoods in the United States are found in Brooklyn, Queens, and Staten Island in New York City (specifically the Brighton Beach area of Brooklyn); parts of Los Angeles, particularly West Los Angeles and West Hollywood; parts of Philadelphia, particularly the Far Northeast; and parts of Miami like Sunny Isles Beach.

The Russian-language media group Slavic Voice of America, based in Dallas, Texas, serves Russian-speaking Americans.

Alaskan Russian

[edit]

Alaskan Russian, known locally as Old Russian, is a dialect of Russian influenced by the Alutiiq language spoken by Alaskan Creoles. Most of its speakers live on Kodiak Island and in the Ninilchik (Kenai Peninsula). It has been isolated from other varieties of Russian for over a century.[96]

Kodiak Russian was natively spoken along the Afognak Strait until the Great Alaskan earthquake and tsunami of 1964. It has become moribund, spoken by only a handful of elderly people, and is virtually undocumented.[97]

Ninilchik Russian has been better studied and is more vibrant. It developed from the Russian colonial settlement of the village of Ninilchik in 1847.[98][99]

Ninilchik Russian vocabulary is clearly Russian, with a few borrowings from English and Alaskan native languages.

In Nikolaevsk, Alaska, 66.57% of the population still spoke Russian at home as late as 2017.[100]

Dutch (142 thousand speakers)

[edit]

In a 1990 demographic consensus, 3% of surveyed citizens claimed to be of Dutch descent. Modern estimates place the Dutch American population (with total or partial Dutch heritage) at 3.1 million, or 0.93%,[101] lagging just a bit behind Norwegian Americans and Swedish Americans,[101] while 885,000[102] Americans claimed total Dutch heritage.

An estimated 141,580 people, or 0.0486%,[103] in the United States still speak the Dutch language, including its Flemish variant, at home as of 2013. This is in addition to the 23,010 and 510 speakers, respectively, of the Afrikaans and West-Frisian languages, both closely related to Dutch.[103] Dutch speakers in the U.S are concentrated mainly in California (23,500), Florida (10,900), Pennsylvania (9,900), Ohio (9,600), New York (8,700) and Michigan (6,600, residing almost entirely in the city of Holland).[104] In 2021, 95.3% of the total Dutch-American population aged 5 years and over spoke only English at home.[105]

History

[edit]There has been a Dutch presence in North America since establishment of 17th-century colony of New Netherland (parts of New York, New Jersey and Delaware), where Dutch was spoken by the New Netherlander, the original settlers, and their descendants. It was still spoken in the region at the time of the American Revolution and thereafter. For example, Alexander Hamilton's wife, Eliza Hamilton, attended a Dutch-language church during their marriage. African-American abolitionist and women's rights activist Sojourner Truth (born "Isabella Baumfree") was a native speaker of Dutch. Martin Van Buren, the first president born in the United States following its independence from Great Britain, spoke Dutch as his native language. He is the only U.S. president whose first language was not English.

Vernacular dialects of Dutch were spoken in northeastern New Jersey (Bergen, Hudson, Passaic county) and the Capital District of New York until they gradually declined throughout the 20th century.

Indigenous languages

[edit]

Native American languages

[edit]Native American languages predate European settlement of the New World. In a few parts of the U.S. (mostly on Indian reservations), they continue to be spoken fluently. Most of these languages are endangered, although there are efforts to revive them. Normally the fewer the speakers of a language the greater the degree of endangerment, but there are many small Native American language communities in the Southwest (Arizona and New Mexico) which continue to thrive despite their small size.

In 1929, speaking of indigenous Native American languages, linguist Edward Sapir observed:[106]

Few people realize that within the confines of the United States there is spoken today a far greater variety of languages ... than in the whole of Europe. We may go further. We may say, quite literally and safely, that in the state of California alone there are greater and more numerous linguistic extremes than can be illustrated in all the length and breadth of Europe.

Navajo

[edit]According to the 2000 Census and other language surveys, the largest Native American language-speaking community by far is the Navajo. Navajo is an Athabaskan language of the Na-Dené family, with 178,000 speakers, primarily in the states of Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah. Altogether, Navajo speakers make up more than 50% of all Native American language speakers in the United States. Western Apache, with 12,500 speakers, also mostly in Arizona, is closely related to Navajo but not mutually intelligible with it. Navajo and other Athabaskan languages in the Southwest are relative outliers; most other Athabascan languages are spoken in the Pacific Northwest and Alaska. Navajo has struggled to keep a healthy speaker base, although this problem has been alleviated to some extent by extensive education programs on the Navajo Nation, including a Navajo language immersion school in Fort Defiance, Arizona.

Cherokee

[edit]

Cherokee is the Iroquoian language spoken by the Cherokee people, and the official language of the Cherokee Nation.[107] Significant numbers of Cherokee speakers of all ages[108] still populate the Qualla Boundary in Cherokee, North Carolina and several counties within the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, significantly Cherokee, Sequoyah, Mayes, Adair, and Delaware. Increasing numbers of Cherokee youth are renewing interest in the traditions, history, and language of their ancestors.[108] Cherokee-speaking communities stand at the forefront of language preservation, and at local schools, all lessons are taught in Cherokee and thus it serves as the medium of instruction from pre-school on up.[107] Also, church services and traditional ceremonial stomp dances are held in the language in Oklahoma and on the Qualla Boundary in North Carolina.[107]

Cherokee is one of the few, or perhaps the only, Native American language with an increasing population of speakers,[109] and along with Navajo it is the only indigenous American language with more than 50,000 speakers,[110] a figure most likely achieved through the tribe's 10-year long language preservation plan involving growing new speakers through immersion schools for children,[111][112] developing new words for modern phrases, teaching the language to non-Cherokees in schools and universities,[113] fostering the language among young adults so their children can use that language at home, developing iPhone and iPad apps for language education, the development of Cherokee language radio stations including Cherokee Voices, Cherokee Sounds,[114] and promoting the writing system through public signage, products like the Apple iPhone, internet use through Google including Gmail, and others so the language remains relevant in the 21st century.

Other Native American languages

[edit]Dakota is a Siouan language with 18,000 speakers in the US alone (22,000 including speakers in Canada), not counting 6,000 speakers of the closely related Lakota. Most speakers live in the states of North Dakota and South Dakota. Other Siouan languages include the closely related Winnebago, and the more distant Crow, among others.

Central Alaskan Yup'ik is an Eskimo–Aleut language with 16,000 speakers, most of whom live in Alaska. The term "Yupik" is applied to its relatives, which are not necessarily mutually intelligible with Central Alaskan, including Naukan and Central Siberian, among others.

The O'odham language, spoken by the Pima and the Tohono O'odham, is a Uto-Aztecan language with more than 12,000 speakers, most of whom live in central and southern Arizona and northern Sonora. Other Uto-Aztecan languages include Hopi, Shoshone, and the Pai-Ute languages.

Choctaw has 11,000 speakers. Choctaw is part of the Muskogean family, like Seminole and Alabama.

The Algonquian language family includes languages like Chippewa/Ojibwe, Cheyenne, and Cree.

Keres has 11,000 speakers in New Mexico and is a language isolate. The Keres pueblo people are the largest of the Pueblo nations. The Keres pueblo of Acoma is the oldest continually inhabited community in the United States. Zuni, another isolate, has around 10,000 speakers, most of whom reside within the Zuni pueblo.

Because of immigration from Mexico, there are Mexican native American languages speakers in the US. There are thousands of Nahuatl, Mixtec, Zapotec and Trique speakers in communities established mainly in the southern states.

Although the languages of the Americas have a history stretching back about 17,000 to 12,000 years, current knowledge of them is limited. There are doubtlessly a number of undocumented languages that were once spoken in the United States that are missing from historical record.

List of Native American languages

[edit]Below is an estimate of Native American languages "spoken at home" in the United States (American Community Survey 2006–2008).[115] This is not an exhaustive list of Native American languages in the US. Because the distinction between dialect and language is not always clear, multiple dialects of varying mutual intelligibility may be classified as a single language, while a group of effectively identical dialects may be classified separately for historical or cultural reasons. Languages included here may be classified as "extinct" (having no living native speakers), but many extinct or moribund Native American languages are the subjects of ongoing language revitalization efforts; other extinct languages undergoing revitalization might not be listed here.

| Language | Endonym[a] | Family | Speakers (% of total) | Does not speak English "Very Well"[b] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | — | — | 444,124 (100) | 19.22% |

| Total (excl. Navajo) | — | — | 203,127 (54.32) | 15.82% |

| Navajo | Diné bizaad | Na-Dené | 170,822 (45.68) | 23.25% |

| Dakota | Dakȟótiyapi | Siouan | 18,804 (5.03) | 9.86% |

| Yupik | — | Eskimo–Aleut | 18,626 (4.98) | 37.02% |

| O'odham | — | Uto-Aztecan | 15,123 (3.59) | 8.03% |

| Apache | Ndee biyati' | Na-Dené | 14,012 (3.75) | 3.53% |

| Keres | — | Isolate | 13,073 (3.50) | 6.20% |

| Cherokee | Tsalagi Gawonihisdi (ᏣᎳᎩ ᎦᏬᏂᎯᏍᏗ) | Iroquoian | 12,320 (3.29) | 16.33% |

| Choctaw | Chahta' | Muskogean | 10,368 (2.77) | 23.44% |

| Zuni | Shiwi'ma | Isolate | 9432 (2.52) | 14.22% |

| American Indian (Other) | — | — | 8888 (2.38) | 16.73% |

| O'odham (Pima) | Oʼodham ñiʼokĭ | Uto-Aztecan | 8190 (2.19) | 14.70% |

| Ojibwe (Chippewa) | Anishinaabemowin | Algic | 6986 (1.87) | 11.28% |

| Hopi | Hopilàvayi | Uto-Aztecan | 6776 (1.81) | 18.80% |

| Inupiat (Inupik) | Iñupiatun | Eskimo–Aleut | 5580 (1.49) | 26.04% |

| Tewa | — | Tanoan | 5123 (1.37) | 13.80% |

| Muskogee (Creek) | Mvskoke | Muskogean | 5072 (1.36) | 19.62% |

| Crow | Apsáalooke | Siouan | 3962 (1.06) | 6.59% |

| Shoshoni | Sosoni' da̲i̲gwape | Uto-Aztecan | 2512 (0.67) | 7.25% |

| Cheyenne | Tsėhésenėstsestȯtse | Algic | 2399 (0.64) | 3.21% |

| Tiwa | — | Tanoan | 2269 (0.61) | 3.22% |

| Towa (Jemez) | — | Tanoan | 2192 (0.59) | 27.65% |

| Inuit (Eskimo) | — | Eskimo–Aleut | 2168 (0.58) | 25.46% |

| Blackfoot | Siksiká (ᓱᖽᐧᖿ) | Algic | 1970 (0.53) | 11.02% |

| Sahaptin | Ichishkíin sɨ́nwit | Plateau Penutian | 1654 (0.44) | 6.17% |

| Paiute | — | Uto-Aztecan | 1638 (0.44) | 11.78% |

| Athapascan | — | Na-Dené | 1627 (0.44) | 19.55% |

| Ute | Núu-'apaghapi | Uto-Aztecan | 1625 (0.43) | 5.23% |

| Southern Tiwa | — | Tanoan | 1600 (0.42) | |

| Mohawk | Kanien’kéha' | Iroquoian | 1423 (0.38) | 11.67% |

| Seneca | Onödowága | Iroquoian | 1353 (0.36) | 11.23% |

| Winnebago | Hocąk | Siouan | 1340 (0.36) | 6.27% |

| Kiowa | Cáuijògà | Tanoan | 1274 (0.34) | 9.58% |

| Aleut | Unangam tunuu | Eskimo–Aleut | 1236 (0.33) | 19.01% |

| Salish | — | Salishan | 1233 (0.33) | 22.87% |

| Gwich’in (Kuchin) | Gwich’in | Na-Dené | 1217 (0.33) | 25.82% |

| Kickapoo | Kiwikapawa | Algic | 1141 (0.31) | 41.72% |

| Arapaho | Hinónoʼeitíít | Algic | 1087 (0.29) | 1.20% |

| Tlingit | Lingít | Na-Dené | 1026 (0.27) | 8.19% |

| Siberian Yupik (SLI Yupik) | Sivuqaghmiistun | Eskimo–Aleut | 993 (0.27) | 39.48% |

| Passamaquoddy | Peskotomuhkat | Algic | 982 (0.26) | 6.11% |

| Comanche | Nʉmʉ tekwapʉ | Uto-Aztecan | 963 (0.26) | 10.59% |

| Cree | Nēhiyawēwin | Algic | 951 (0.25) | 8.73% |

| Menominee | Omāēqnomenew | Algic | 946 (0.25) | 39.64% |

| Nez Perce | Niimiipuutímt | Plateau Penutian | 942 (0.25) | 12.10% |

| Potawatomi | Bodéwadmi | Algic | 824 (0.22) | 9.95% |

| Hidatsa | Hidatsa | Siouan | 806 (0.22) | 4.47% |

| Kickapoo | — | Algic | 800 (0.22) | |

| Mesquakie (Fox) | Meshkwahkihaki | Algic | 727 (0.19) | 22.15% |

| Karok | Káruk | Isolate | 700 (0.19) | 5.43% |

| Pomo | — | Pomoan | 648 (0.17) | 14.81% |

| Oneida | Oneyota'aaka | Iroquoian | 527 (0.14) | 58.63% |

| Yurok | Puliklah | Algic | 491 (0.13) | 1.63% |

| Cocopah | Kwikapa | Yuman | 483 (0.13) | 22.77% |

| Hualapai | Hwalbáy | Yuman | 458 (0.12) | 4.80% |

| Omaha | Umoⁿhoⁿ | Siouan | 457 (0.12) | 1.97% |

| Chiricahua | Ndee bizaa | Na-Dené | 457 (0.12) | — |

| Jicarilla | Abáachi mizaa | Na-Dené | 455 (0.12) | 14.51% |

| Yaqui | Yoem noki | Uto-Aztecan | 425 (0.11) | 10.12% |

| Yokuts | — | Yokutsan | 407 (0.11) | 27.27% |

| Koasati | Coushatta | Muskoeaen | 370 (0.10) | — |

| Mono | Mono | Uto-Aztecan | 349 (0.09) | — |

| Mohave | Hamakhav | Yuman | 330 (0.09) | 6.36% |

| Luiseño | Cham'teela | Uto-Aztecan | 327 (0.09) | 4.28% |

| Shawnee | Sawanwa | Algic | 321 (0.09) | 6.23% |

| Maidu (NE Maidu) | Májdy | Maiduan | 319 (0.09) | 6.90% |

| Ottawa | Nishnaabemwin | Algic | 312 (0.08) | 10.90% |

| Algonquin | Anicinâbemowin | Algic | 288 (0.08) | 19.79% |

| Okanogan | Nsəlxcin | Salishan | 284 (0.08) | 10.92% |

| Osage | Wazhazhe ie | Siouan | 260 (0.07) | 20.38% |

| Wichita | Kirikirʔi:s | Caddoan | 242 (0.06) | 16.12% |

| Onondaga | Onǫda’gegá | Iroquoian | 239 (0.06) | 2.93% |

| Mi'kmaq (Micmac) | Míkmawísimk | Algic | 230 (0.06) | 10.87% |

| Digueño (Ipai-Kumiai-Tipai) | — | Yuman | 228 (0.06) | 60.96% |

| Washo | Wá:šiw ʔítlu | Isolate | 227 (0.06) | 9.69% |

| Miwok | Miwok | Utian | 216 (0.06) | — |

| Lushootseed (Puget Salish) | Xʷəlšucid | Salishan | 207 (0.06) | 47.83% |

| Kutenai | Ktunaxa | Isolate | 200 (0.05) | 32.50% |

| Miccosukee | Mikisúkî | Muskogean | 188 (0.05) | 22.87% |

| Tuscarora | Ska:rù:rę' | Iroquoian | 179 (0.05) | 10.06% |

| Makah | Qʷi·qʷi·diččaq | Wakashan | 176 (0.05) | 30.11% |

| Coeur d'Alene | Snchitsuʼumshtsn | Salishan | 174 (0.05) | — |

| Hupa | Na:tinixwe | Na-Dené | 174 (0.05) | — |

| Quechan (Yuma) | Kwtsaan | Yuman | 172 (0.05) | 31.98% |

| Miami | Myaamia | Algic | 168 (0.04) | 50.60% |

| Alabama | Albaamo innaaɬiilka | Muskogean | 165 (0.04) | 20.00% |

| Delaware | Lënape / Lunaapeew | Algic | 146 (0.04) | 25.34% |

| Clallam | Nəxʷsƛ̕ay̕əmúcən | Salishan | 146 (0.04) | 1.37% |

| Penobscot (E Abenaki) | Panawahpskek | Algic | 144 (0.04) | 5.56% |

| Yavapai | — | Yuman | 139 (0.04) | — |

| Cahuilla | Ivia | Uto-Aztecan | 139 (0.04) | — |

| Ponca | Paⁿka | Siouan | 131 (0.04) | 6.87% |

| Quinault | Kʷínaył | Salishan | 128 (0.03) | — |

| Deg Xinag (Ingalit) | Degexit’an | Na-Dené | 127 (0.03) | — |

| Pawnee | Paári | Caddoan | 122 (0.03) | 16.39% |

| Haida | X̱aat Kíl | Isolate | 118 (0.03) | 19.49% |

| Cowlitz | Stl'pulimuhkl | Salishan | 110 (0.03) | 82.73% |

| Mandan | Nų́ʔetaːre | Siouan | 104 (0.03) | 38.46% |

| Arikara | Sáhniš | Caddoan | 103 (0.03) | — |

| Klamath | Maqlaqs | Plateau Penutian | 95 (0.03) | 27.37% |

| Havasupai | Havasu’baaja | Yuman | 90 (0.02) | 52.22% |

| Chitimacha | Sitimaxa | Isolate | 89 (0.02) | 21.35% |

| Abenaki (W Abenaki) | Wôbanakiôdwawôgan | Algic | 86 (0.02) | — |

| Kwak'wala (Kwakiutl) | Kwak'wala | Wakashan | 85 (0.02) | 24.71% |

| Tututni (Rogue River) | Dotodəni | Na-Dené | 84 (0.02) | — |

| Iroquois | — | Iroquoian | 76 (0.02) | — |

| Tsimshian | Sm'algyax | Tsimshianic | 68 (0.02) | — |

| Achumawi | — | Palaihnihan | 68 (0.02) | — |

| Chiwere | Jíwere | Siouan | 60 (0.02) | — |

| Koasati | Kowassá:ti | Muskogean | 59 (0.02) | 6.78% |

| Koyukon | Denaakkʼe | Na-Dené | 58 (0.02) | 12.07% |

| Upper Chinook | Kiksht | Chinookan | 58 (0.02) | 10.34% |

| Caddo | Hasí:nay | Caddoan | 51 (0.01) | 23.53% |

| Kalapuya (Santiam) | — | Kalapuyan | 50 (0.01) | — |

| Gros Ventre (Atsina) | Ahahnelin | Algic | 45 (0.01) | — |

| Tachi | — | Yokutsan | 45 (0.01) | 57.78% |

| Maricopa | Piipaash chuukwer | Yuman | 44 (0.01) | 22.73% |

| Chumash | S.hamala | Chumashan | 39 (0.01) | 100.00% |

| Nomlaki | Nomlāqa | Wintuan | 38 (0.01) | — |

| Konkow (NW Maidu) | Koyoom k'awi | Maiduan | 32 | 100.00% |

| Tunica | Yuron | Isolate | 32 | — |

| Tonkawa | Tickanwa•tic | Isolate | 29 | — |

| Caddo | — | Caddoan | 25 | — |

| Wintu | Wintʰu:h | Wintuan | 24 | — |

| Spokane | Npoqínišcn | Salishan | 20 | 40.00% |

| Ahtna | Atnakenaege’ | Na-Dené | 18 | — |

| Columbia (Sinkiuse) | Nxaảmxcín | Salishan | 17 | — |

| Atsugewi | Atsugé | Palaihnihan | 15 | — |

| Chemehuevi | Nüwüvi | Uto-Aztecan | 15 | — |

| Abenaki | — | Algic | 14 | — |

| Northern Paiute | Numu | Uto-Aztecan | 12 | — |

| Dena'ina (Tanaina) | Dena’ina qenaga | Na-Dené | 11 | — |

| Cupeño | Kupangaxwicham | Uto-Aztecan | 11 | — |

| Nuu-chah-nulth (Nootka) | Nuučaan̓uł | Wakashan | 10 | — |

| Pawnee | Chatiks si chatiks | Caddoan | 10 | |

| Arikara | Sanish | Caddoan | 10 | |

| Alutiiq (Gulf Yupik) | Sugpiaq | Eskimo–Aleut | 8 | — |

| Kansa | Káⁿza | Siouan | 7 | — |

| Siuslaw | Šáayušła | Isolate | 6 | — |

| Cayuga | Gayogo̱hó:nǫ’ | Iroquoian | 6 | — |

| Serrano | Taaqtam | Uto-Aztecan | 5 | — |

| Tübatulabal | — | Uto-Aztecan | 5 | — |

| Yuchi | Tsoyaha | Isolate | 4 | — |

| Shasta | — | Shastan | 2 | 100.00% |

| Wukcumni | — | Yokutsan | 1 | 0.00% |

| Quapaw | — | Siouan | 1 | — |

Native American sign languages

[edit]A sign-language trade pidgin, known as Plains Indian Sign Language, Plains Standard or Plains Sign Talk, arose among the Native Americans of the plains. Each signing nation had a separate signed version of their oral language, that was used by the hearing, and these were not mutually intelligible. Plains Standard was used to communicate between these nations. It seems to have started in Texas and then spread north, through the Great Plains, as far as British Columbia. There are still a few users today, especially among the Crow, Cheyenne, and Arapaho. Unlike other sign languages developed by hearing people, it shares the spatial grammar of deaf sign languages. Through intergenerational transmission, Plains Sign Talk became a working language still in use today in some Deaf First Nations or Native American communities.

As Plains Sign Talk was so widespread and was a spectrum of dialects and accents, it probably hosted several languages under its umbrella. One is potentially Navajo Sign Language which is in use by a sole Navajo clan.

Additionally, Plateau Sign Language existed alongside Plains Sign Talk as either a trade pidgin or another language around the Columbia Plateau and surrounding regions.

Austronesian languages

[edit]Hawaiian

[edit]

Hawaiian is an official state language of Hawaii as prescribed in the Constitution of Hawaii. Hawaiian has 1,000 native speakers. Formerly considered critically endangered, Hawaiian is showing signs of language renaissance. The recent trend is based on new Hawaiian language immersion programs of the Hawaii State Department of Education and the University of Hawaii, as well as efforts by the Hawaii State Legislature and county governments to preserve Hawaiian place names. In 1993, about 8,000 could speak and understand it; today estimates range up to 27,000. Hawaiian is related to the Māori language spoken by around 150,000 New Zealanders and Cook Islanders as well as the Tahitian language which is spoken by another 120,000 people of Tahiti.

Samoan

[edit]Samoan is an official territorial language of American Samoa. Samoans make up 90% of the population, and most people are bilingual.

Chamorro

[edit]Chamorro is co-official in the Mariana Islands, both in the territory of Guam and in the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands. In Guam, the indigenous Chamorro people make up about 60% of the population.

Carolinian

[edit]Carolinian is also co-official in the Northern Marianas, where only 14% of people speak English at home.

Creole languages

[edit]Several distinct natural languages and pidgins have developed on American soil, including full languages like creole and sign languages.

Angloromani

[edit]Angloromani is an English creole or mixed language spoken by Romani Americans.[116]

Chinuk Wawa or Chinook Jargon

[edit]A pidgin of 700–800 words of French, English, Cree and other Native origins is the old trade language of the Pacific Northwest. It was used extensively among both European and Native peoples of the Oregon Territory, even used instead of English at home by many pioneer families. It is estimated that around 100,000 people spoke it at its peak, between 1858 and 1900, and it was last widely used in Seattle just before World War II.[117]

Gullah

[edit]An English creole language with African influence spoken on the Sea Islands of South Carolina and Georgia retains strong influences of West African languages. The language is sometimes referred to as "Geechee".

Hawaii Creole English

[edit]The Hawaiian English creole language, locally known as Hawaiian Pidgin, is used by locals and is considered an unofficial language of the state of Hawaii.[118]

Louisiana Creole French

[edit]A French Creole language spoken by the Louisiana Creole people of the state of Louisiana, close to Haitian Creole, Colonial French, and Cajun French (language of Acadians deported from New France after 1755 and the Grand Dérangement).French Creole languages are spoken by millions of people worldwide, mainly in the United States, Caribbean, and Indian Ocean areas.

U.S. Virgin Islands Creole Dutch (extinct)

[edit]

Negerhollands ('Negro-Dutch') was a Dutch-based creole language that was spoken in the Danish West Indies, now known as the U.S. Virgin Islands. Dutch was its superstrate language with Danish, English, French, Spanish, and African elements incorporated. Notwithstanding its name, Negerhollands drew primarily from the Zeelandic rather than the Hollandic dialect of Dutch.[119]

Sign languages

[edit]

Alongside the numerous and varied oral languages, the United States also boasts several sign languages. Historically, the US was home to some six or more sign languages (that number rising with the probability that Plains Sign Talk is actually a language family with several languages under its umbrella) which has fallen with the death of several of these.

As with all sign languages around the world that developed organically, these are full languages distinct from any oral language. American Sign Language (unlike Signed English) is not a derivation of English.[120] Some languages present here were trade pidgins which were used first as a system of communication across national and linguistic boundaries of the Native Americans, however, they have since developed into mature languages as children learned them as a first language.

American Sign Language

[edit]American Sign Language (ASL) is the native language of a number of deaf and hearing people in America (roughly 100,000 to 500,000). While some sources have stated that ASL is the third most frequently used language in the United States, after English and Spanish,[121] recent scholarship has pointed out that most of these estimates are based on numbers conflating deafness with ASL use, and that the last actual study of this (in 1972) seems to indicate an upper bound of 500,000 ASL speakers at the time.[122]

- Black American Sign Language (BASL) developed in the southeastern US, where separate residential schools were maintained for white and black deaf children. BASL shares much of the same vocabulary and grammatical structure as ASL and is generally considered one of its dialects.[120][121][123]

Hawai'i Sign Language

[edit]Hawaii Sign Language is moribund with only a handful of speakers on O'ahu, Lana'i, Kaua'i and possibly Ni'ihau. Some of these speakers may actually be speaking a creolized version of HSL and ASL, however; research is slow-going. The language was once called Hawai'i Pidgin Sign Language, as many people thought it was a derivative of ASL, but it was discovered to be a separate language altogether.[124]

Plains Sign Talk

[edit]Once a trade pidgin and the most far-reaching sign language in North America, Plains Sign Talk or Plains Sign Language is now critically endangered with an unknown number of speakers.

- Navajo Sign Language has been found to be in use in one clan of Navajo; however, whether it is a dialect of Plains Sign Talk or a separate language remains unknown.[125]

- Plateau Sign Language is another trade pidgin that may have become a separate language, Plateau Sign Language replaced Plains Sign Talk in the Columbia Plateau and surrounding regions of British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, and Idaho. It is now extinct.

Martha's Vineyard Sign Language

[edit]Martha's Vineyard Sign Language is now extinct. Along with French Sign Language, it was one of several main contributors to American Sign Language.

Henniker Sign Language

[edit]Henniker Sign Language is now extinct but was once found around the Henniker region of New Hampshire and formed a basis for American Sign Language.

Sandy River Valley Sign Language

[edit]Sandy River Valley Sign Language is now extinct but once could be found around the Sandy River Valley in Maine. It was one of several main contributors to American Sign Language.

Immigrant languages

[edit]Arabic

[edit]Varieties of Arabic are spoken by immigrants from the Middle East as well as many Muslim Americans. The highest concentrations of native Arabic speakers reside in heavily urban areas like Chicago, New York City, and Los Angeles. Detroit and the surrounding areas of Michigan boast a significant Arabic-speaking population including many Arab Christians of Lebanese, Syrian, and Palestinian descent.

Arabic is used for religious purposes by Muslim Americans and by some Arab Christians (notably Catholics of the Melkite and Maronite Churches as well as Rum Orthodox, i.e. Antiochian Orthodox Christians and Coptic churches.). A significant number of educated Arab professionals who immigrate often already know English quite well, as it is widely used in the Middle East. Lebanese immigrants also have a broader understanding of French as do many Arabic-speaking immigrants from North Africa.[126][127][128][129]

китайский

[ редактировать ]Население говорящих на китайском языке в Соединенных Штатах быстро росло в 20 веке, поскольку число китайских иммигрантов увеличилось более чем на 50% с 1940 года. [130] 2,8 миллиона американцев говорят на той или иной разновидности китайского языка , который, по данным федеральной переписи населения, является третьим по распространенности языком в стране. До конца 20 века диалекты Юэ , включая тайшаньский и кантонский диалекты , были наиболее распространенными диалектами среди иммигрантов и потомков иммигрантов, особенно в Калифорнии . С момента образования Китайской Народной Республики , мандаринский язык официальный язык КНР и Китайской Республики (Тайвань), становится все более распространенным. [131] Многие американцы всех этнических групп также изучают китайский и, в гораздо меньшей степени, кантонский диалект. [131]

В Нью-Йорке в 2002 году на мандаринском языке говорили как на родном только 10% говорящих по-китайски, но, по прогнозам, он заменит кантонский диалект в качестве лингва-франка среди говорящих по-китайски. [132]

чешский

[ редактировать ]Техасский чешский

[ редактировать ]12 805 техасцев могут говорить на чешском языке . [133]

Опираясь на модель Боаса для опроса носителей языка и цифровой каталогизации диалектов, Джон Томечек основал, а Лида Коуп из Университета Восточной Каролины разработала в Техасском университете в Остине проект «Техасское чешское наследие» для документирования и сохранения сокращающегося языка. [134] [135] [136] Поскольку большинство техасских иммигрантов прибыли из Моравии, чешский язык, на котором говорят в Техасе, в основном характеризуется моравскими диалектами ( лахский и моравский валашский ), которые в некоторой степени отличаются от богемских диалектов, на которых говорит большинство американцев чешского происхождения. Чешскоязычная журналистика на протяжении многих лет была очень активна в государстве. Вышло 33 газеты и периодические издания. По состоянию на 1993 год одна еженедельная газета « Нашинец» , издававшаяся в Грейнджере , и одна ежемесячная газета «Господарж» , издававшаяся в Весте , все еще издавались полностью на чешском языке. Другие периодические издания, такие как «Вестник» и « Братьевский журнал», содержали разделы, напечатанные на чешском языке. [137]

финский

[ редактировать ]

Первые финские поселенцы в Америке были среди поселенцев, прибывших из Швеции и Финляндии в колонию Новая Швеция . Большинство колонистов были финнами. Однако финский язык не сохранился среди последующих поколений так же хорошо, как шведский.

Между 1890-ми годами и началом Первой мировой войны около четверти миллиона финских граждан иммигрировали в Соединенные Штаты, в основном в сельских районах Среднего Запада и, в частности, в горнодобывающих регионах северо-восточной Миннесоты , Северного Висконсина и Мичигана . Верхнего полуострова . В Хэнкок, штат Мичиган , по состоянию на 2005 год все еще имеются двуязычные уличные указатели, написанные на английском и финском языках. [138] [139] Американцы финского происхождения составляют 800 000 человек, хотя только 26 000 говорят на этом языке дома. На Верхнем полуострове существует особый диалект английского языка, известный как Йопер . Йопер часто использует финскую каденцию и использует финскую структуру предложений с модифицированным словарным запасом английского, немецкого, шведского, норвежского и финского языков. [ нужна ссылка ] Известные финские американцы включают лидера Коммунистической партии США Гаса Холла , кинорежиссера Ренни Харлина и актрису канадского происхождения Памелу Андерсон .

В округе Северный Кларк, штат Вашингтон (включающем Якольт, Амбой, Батл Граунд и Челатчи), находится большой эксклав староапостольских лютеран , которые первоначально иммигрировали из Финляндии. Многие семьи в этой части округа свободно говорят дома по-фински, прежде чем изучать английский. [ нужна ссылка ] Еще одна заслуживающая внимания финская община в Соединенных Штатах находится в Лейк-Уорте, штат Флорида , к северу от Майами.

иврит

[ редактировать ]На современном иврите говорят израильские иммигранты. Литургический иврит используется как религиозный или литургический язык. [140] многими из примерно 7 миллионов евреев Соединенных Штатов. [141]

Гэльские языки

[ редактировать ]Около 40 миллионов американцев имеют ирландское происхождение, многие из которых говорили на ирландском гэльском языке . В 2013 году около 20 600 американцев говорили дома по-ирландски, а по состоянию на 2008 год [update] это был 76-й по распространенности язык в Соединенных Штатах. [142] Еще 1600 человек говорили на шотландском гэльском языке. [143]

Итальянская, сицилийская и неаполитанская

[ редактировать ]

Итальянский язык и другие итало-далматинские языки широко распространены в Соединенных Штатах уже более ста лет, в первую очередь благодаря крупномасштабной иммиграции с конца 19 века до середины 20 века.

Помимо итальянского языка, который сегодня изучает большинство людей, среди иммигрантов широко представлены языки Южной Италии ( сицилийский и неаполитанский в частности, ). По состоянию на 2009 год, хотя 15 638 348 американских граждан считают себя американцами итальянского происхождения, только 753 992 из них говорят на итальянском языке дома (0,3264% населения США).

Кхмерский (камбоджийский)

[ редактировать ]В период с 1981 по 1985 год около 150 000 камбоджийцев переселились в США. [144] До 1975 года очень немногие камбоджийцы приезжали в Соединенные Штаты. Те, кто это сделал, были детьми из семей высшего сословия, которых отправили за границу учиться в школе. После захвата Пномпеня красными кхмерами в 1975 году некоторым камбоджийцам удалось бежать. В 2007 году исследование американского сообщества сообщило, что в Соединенных Штатах проживает около 200 000 камбоджийцев, что составляет около 2% населения Азии. Однако это население сильно сконцентрировано в двух районах: агломерации Лос-Анджелеса в Калифорнии , особенно в городе Лонг-Бич ; и Большой Бостон в Новой Англии , особенно Лоуэлл, Массачусетс . В этих двух районах проживает большинство камбоджийцев, проживающих в США.

корейский

[ редактировать ]В 2011 году более 1,1 миллиона американцев говорили корейском языке дома на . Это число значительно увеличилось в конце 20-го века, увеличившись на 327% по сравнению с 300 000 говорящих в 1980 году. Наибольшая концентрация этих говорящих была в районах метро Лос-Анджелеса , Нью-Йорка и Вашингтона . [145] Носители корейского языка встречаются в корейских кварталах . [ нужна ссылка ]

Польский и Силезский

[ редактировать ]По состоянию на 2013 год около 580 000 американцев говорили дома по-польски. [143] Польский язык очень распространен в агломерации Чикаго . Чикаго Третьими по величине белыми этническими группами являются представители польского происхождения после немцев и ирландцев . [146] Поляки . и польский язык в Чикаго были очень распространены в первые годы существования города, и сегодня 650 000 поляков в Чикаго составляют одну из крупнейших этнически польских популяций в мире , сравнимую с городом Вроцлавом , четвертым по величине городом город в Польше. Это делает его одним из самых важных центров Полонии и польского языка в Соединенных Штатах, и город празднует каждые выходные, посвященные Дню труда, на фестивале «Вкус Полонии» в Джефферсон-парке . [147]

Техас Силезский

[ редактировать ]Техас-Силезский язык , диалект силезского языка (который некоторые лингвисты спорно считают ветвью польского языка), использовался техасскими силезцами в американских поселениях с 1852 года по настоящее время.

португальский

[ редактировать ]Первыми носителями португальского языка в Америке были португальские евреи , бежавшие от португальской инквизиции . Они говорили на иудео-португальском языке и основали первые еврейские общины в Тринадцати колониях , две из которых существуют до сих пор: Конгрегация Шеарит Исраэль в Нью-Йорке и Конгрегация Микве Исраэль в Филадельфии. Однако к концу 18 века португальский язык был заменен английским.

В конце 19-го века многие португальцы, в основном азорцы , мадейрцы и жители Кабо-Верде (которые до обретения независимости в 1975 году были гражданами Португалии), иммигрировали в Соединенные Штаты, поселившись в таких городах, как Провиденс, Род-Айленд , Нью-Бедфорд, Массачусетс и Санта-Клаус. Круз, Калифорния . Также наблюдалась значительная иммиграция португальцев на Гавайи , которые в то время еще не были частью Соединенных Штатов.

В середине-конце 20-го века произошла еще одна волна португальской иммиграции в США, в основном на северо-восток (Нью-Джерси, Нью-Йорк, Коннектикут, Массачусетс), и на какое-то время португальский язык стал основным языком в Ньюарке, штат Нью-Джерси . Многие американцы португальского происхождения могут включать потомков португальских поселенцев, родившихся в португальской Африке (известных как португальские африканцы или, в Португалии, как реторнадо ) и Азии (в основном в Макао ). проживало около 1 миллиона американцев португальского происхождения. К 2000 году в Соединенных Штатах На португальском ( европейском португальском ) языке в Соединенных Штатах говорили небольшие общины иммигрантов, в основном в столичном районе Нью-Йорка , например, в Ньюарке, штат Нью-Джерси .

На португальском языке также широко говорят американцы бразильского происхождения , сконцентрированные в Майами , Нью-Йорке и Бостоне .

Шведский

[ редактировать ]

Шведское присутствие в Америке существовало с момента Новая Швеция основания колонии в марте 1638 года.

Широко распространенная диаспора шведской иммиграции возникла только во второй половине XIX века, в результате чего в общей сложности прибыл миллион шведов. Ни в одной другой стране не было такого высокого процента населения, уехавшего в Соединенные Штаты, кроме Ирландии и Норвегии. В начале 20-го века в Миннесоте было самое большое количество этнических шведов в мире после города Стокгольма .

3,7% жителей США заявляют о своем происхождении от скандинавских предков, что составляет примерно 11–12 миллионов человек. По данным журнала SIL «Этнолог», более полумиллиона этнических шведов до сих пор говорят на этом языке, хотя, согласно опросу американского сообщества 2007 года, только 56 715 человек говорят на нем дома. Культурная ассимиляция способствовала постепенному и неуклонному упадку языка в США. После обретения США независимости от Королевства Великобритании правительство поощряло колонистов принять английский язык в качестве общего средства общения, а в некоторых случаях навязывало им его. Последующие поколения американцев шведского происхождения получали образование на английском языке и говорили на нем как на своем родном языке. Лютеранские церкви, разбросанные по Среднему Западу, начали отказываться от шведского языка в пользу английского в качестве языка богослужения. Шведские газеты и издания постепенно исчезли.

Значительные шведские общины есть в Миннесоте, Огайо, Мэриленде, Филадельфии и Делавэре, а также небольшие изолированные районы в Пенсильвании, Сан-Франциско, Форт-Лодердейле и Нью-Йорке. В Чикаго когда-то находился большой шведский анклав под названием Андерсонвилль на северной стороне города.

Джон Мортон , человек, который отдал решающий голос, приведший к поддержке Пенсильванией Декларации независимости Соединенных Штатов , был финского происхождения. Финляндия была частью Королевства Швеция в 18 веке.

валлонский

[ редактировать ]Висконсин Валлония

[ редактировать ]Висконсинский валлонский язык — это диалект валлонского языка, привезенный в Висконсин из Валлонии , преимущественно франкоязычного региона Бельгии. На нем говорят на полуострове Дор в Висконсине , США . [148]

Носители висконсинской валлонии являются потомками бельгийских иммигрантов из волны иммиграции, длившейся с 1853 по 1857 год. В нее входит около 2000 бельгийцев, иммигрировавших в Висконсин. [149] Носители языка иногда называют Валлонию «бельгийской». [150] Потомки носителей валлонского языка с тех пор перешли на английский язык, и по состоянию на 2021 год на валлонском языке в Соединенных Штатах проживает менее 50 человек. [148]

валлийский

[ редактировать ]

Считается, что до двух миллионов американцев имеют валлийское происхождение. очень мало валлийского языка Однако в Соединенных Штатах . По данным опроса американского сообщества 2007 года, 2285 человек говорят дома на валлийском языке; в основном говорят в Калифорнии (415), Флориде (225), Нью-Йорке (204), Огайо (135) и Нью-Джерси (130). [151] Некоторые географические названия, такие как Брин-Мор в Чикаго и Брин-Мор в Пенсильвании (англ. Big Hill ), являются валлийскими. Несколько городов в Пенсильвании , в основном в Уэльском районе , имеют валлийские тезки, в том числе Увчлан , Бала Синвид , Гвинед и Тредиффрин .

Тагальский

[ редактировать ]

Носители тагальского языка уже присутствовали в Соединенных Штатах еще в конце шестнадцатого века в качестве моряков, нанятых испанским колониальным правительством . В восемнадцатом веке они основали поселения в Луизиане , такие как Сен-Мало . После аннексии Филиппин американцами число говорящих на тагальском языке неуклонно росло, поскольку филиппинцы начали мигрировать в США в качестве студентов или рабочих по контракту. Однако их число уменьшилось после обретения Филиппинами независимости , поскольку некоторые филиппинцы были репатриированы .

Сегодня на тагальском языке, вместе с его стандартизированной формой филиппинского языка , говорят более полутора миллионов американцев филиппинского происхождения , и его пропагандируют американские гражданские организации филиппинского происхождения и филиппинские консульства. Поскольку филиппинцы являются второй по величине азиатской этнической группой в Соединенных Штатах, тагальский язык является вторым по распространенности азиатским языком в стране после китайского . На таглише , форме переключения кода между тагальским и английским языками, также говорит ряд американцев филиппинского происхождения.

Тагальский язык также преподается в некоторых университетах, где проживает значительное количество филиппинцев. Поскольку это национальный и наиболее распространенный язык Филиппин, большинство филиппинцев в Соединенных Штатах владеют тагальским языком в дополнение к своему местному региональному языку.

вьетнамский

[ редактировать ]

Согласно переписи 2010 года , более 1,5 миллионов американцев считают себя вьетнамцами по происхождению, занимая четвертое место среди групп американцев азиатского происхождения и образуя самое большое вьетнамское население за рубежом.

Округ Ориндж, штат Калифорния , является домом для самой большой концентрации этнических вьетнамцев за пределами Вьетнама, особенно в районе Маленького Сайгона . Другие значительные вьетнамские общины находятся в мегаполисах Сан-Хосе , Хьюстоне , Далласе-Форт-Уэрте , Сиэтле , Северной Вирджинии и Новом Орлеане . Подобно другим зарубежным вьетнамским общинам в западных странах (кроме Франции), вьетнамское население в Соединенных Штатах образовалось после падения Сайгона в 1975 году и коммунистического захвата Южного Вьетнама после войны во Вьетнаме .

Южноазиатские языки

[ редактировать ]В Соединенных Штатах много выходцев из Южной Азии. К ним относятся индийцы , пакистанцы и бангладешцы , говорящие на различных языках Южной Азии. Основные южноазиатские языки, на которых говорят в США, включают телугу (см. «Телугу» ниже), малаялам , каннада , тамильский (см. «Тамильский» ниже), гуджарати , хинди и урду (см. «Хинди-урду» ниже), бенгали , пенджаби , Сингальский , непальский (см. «Непальский» ниже) и маратхи .

Хинди и урду

[ редактировать ]Хинди и урду — два стандартных регистра языка хиндустани, индоарийского языка, родного для Северной Индии , Центральной Индии и Пакистана . В то время как формальные регистры основаны на словарном запасе санскрита, арабского и персидского языка соответственно, разговорные формы неотличимы. Хинди и урду широко распространены среди индийских и пакистанских общин в Соединенных Штатах как первый или второй язык. Спикеры сконцентрированы в штатах с большим населением Южной Азии, включая Калифорнию, Иллинойс, Нью-Джерси, Нью-Йорк, Техас и Вирджинию. [152]

Кроме того, хинди-урду (хиндустани) является культурным языком для многих жителей Южной Азии, у которых разные родные языки и диалекты. В частности, Болливуд, как и музыка из фильмов, является важным культурным продуктом, который влияет на многих молодых людей Южной Азии. Некоторые жители Южной Индии, бангладешцы и индийские бенгальцы изучают язык или его диалекты с помощью фильмов. [153] [154]

непальский

[ редактировать ]Первые непальцы, въехавшие в Соединенные Штаты, были классифицированы как «другие азиаты». Иммиграционные записи показывают, что между 1881 и 1890 годами в Соединенные Штаты были приняты 1910 «других азиатов». Однако Непал не открывал свои границы до 1950 года, и большинство непальцев, покинувших страну в это время, отправились в основном в Индию на учебу. Непальские американцы впервые были классифицированы как отдельная этническая группа в 1974 году, когда 56 непальцев иммигрировали в Соединенные Штаты. Нью-Йорке, Бостоне, Далласе-Форт-Уэрте, Колумбусе, Лос-Анджелесе, Цинциннати, Эри, Гаррисберге, Чикаго, Денвере, Гейнсвилле Наибольшее количество непальцев проживает в , Портленде и Сент-Поле. В каждом американском штате есть некоторые непальские общественные или культурные мероприятия, включая Дашайн , Тихар , Холи , Тидж Специальный и непальский Новый год .

тамильский