Древнегреческое искусство

Искусство Древней Греции выделяется среди искусств других древних культур развитием натуралистических, но идеализированных изображений человеческого тела, в которых в основном обнаженные мужские фигуры обычно были в центре новаторства. Скорость стилистического развития между 750 и 300 гг. до н. э. была примечательной по древним меркам, и в сохранившихся работах лучше всего это видно в скульптуре . В живописи произошли важные нововведения, которые пришлось существенно реконструировать из-за отсутствия оригинальных качественных пережитков, кроме отдельной области расписной керамики.

Греческая архитектура , технически очень простая, создала гармоничный стиль с многочисленными детальными условностями, которые в значительной степени были приняты римской архитектурой и до сих пор соблюдаются в некоторых современных зданиях. Он использовал словарь орнаментов , который был общим с керамикой, металлообработкой и другими средствами массовой информации, и оказал огромное влияние на евразийское искусство, особенно после того, как буддизм вынес его за пределы расширенного греческого мира, созданного Александром Великим . Социальный контекст греческого искусства включал радикальные политические события и значительный рост благосостояния; не менее впечатляющие достижения Греции в философии , литературе и других областях хорошо известны.

Самое раннее искусство греков обычно исключается из «древнегреческого искусства» и вместо этого известно как греческое неолитическое искусство, за которым следует эгейское искусство ; последний включает кикладское искусство и искусство минойской и микенской культур греческого бронзового века . [1] Искусство Древней Греции принято стилистически разделять на четыре периода: геометрический , архаический , классический и эллинистический . Геометрический век обычно датируется примерно 1000 годом до нашей эры, хотя на самом деле мало что известно об искусстве Греции в течение предшествующих 200 лет, традиционно известных как греческие темные века . В VII веке до н. э. происходит медленное развитие архаического стиля, примером которого является чернофигурный стиль вазописи. Около 500 г. до н. э., незадолго до начала Персидских войн (480–448 гг. до н. э.), обычно считается разделительной линией между архаическим и классическим периодами, а период правления Александра Великого (336–323 гг. до н. э.) принято считать отделяющим классический период от эллинистического. С какого-то момента в I веке до нашей эры используется слово «греко-римский», или более местные термины, обозначающие восточно-греческий мир. [2]

В действительности резкого перехода от одного периода к другому не было. Формы искусства развивались с разной скоростью в разных частях греческого мира, и, как и в любую эпоху, некоторые художники работали в более новаторских стилях, чем другие. Сильные местные традиции и требования местных культов позволяют историкам определять происхождение даже произведений искусства, найденных далеко от места их происхождения. Греческое искусство различных видов широко экспортировалось. В течение всего периода наблюдался в целом устойчивый рост благосостояния и торговых связей внутри греческого мира и с соседними культурами.

Уровень выживаемости греческого искусства резко различается в разных средствах массовой информации. У нас есть огромное количество керамики и монет, много каменных скульптур, хотя еще больше римских копий, и несколько больших бронзовых скульптур. Почти полностью отсутствуют картины, тонкие металлические сосуды и все, что изготовлено из скоропортящихся материалов, включая дерево. Каменные корпуса ряда храмов и театров сохранились, но от их обширного убранства мало что осталось. [3]

Керамика

[ редактировать ]

Условно, тонко расписанные сосуды всех форм называются «вазами», и сохранилось более 100 000 значительно полных предметов. [5] давая (с надписями, которые есть у многих) беспрецедентное понимание многих аспектов греческой жизни. Скульптурная или архитектурная керамика, также очень часто раскрашенная, называется терракотой и также сохранилась в больших количествах. В большей части литературы «керамика» означает только расписные сосуды или «вазы». Керамика была основным видом погребального инвентаря, хранившегося в гробницах, часто в виде «погребальных урн», содержащих кремированный прах, и широко экспортировалась.

The famous and distinctive style of Greek vase-painting with figures depicted with strong outlines, with thin lines within the outlines, reached its peak from about 600 to 350 BC, and divides into the two main styles, almost reversals of each other, of black-figure and red-figure painting, the other colour forming the background in each case. Other colours were very limited, normally to small areas of white and larger ones of a different purplish-red. Within the restrictions of these techniques and other strong conventions, vase-painters achieved remarkable results, combining refinement and powerful expression. White ground technique allowed more freedom in depiction, but did not wear well and was mostly made for burial.[6]

Conventionally, the ancient Greeks are said to have made most pottery vessels for everyday use, not for display. Exceptions are the large Archaic monumental vases made as grave-markers, trophies won at games, such as the Panathenaic Amphorae filled with olive oil, and pieces made specifically to be left in graves; some perfume bottles have a money-saving bottom just below the mouth, so a small quantity makes them appear full.[7] In recent decades many scholars have questioned this, seeing much more production than was formerly thought as made to be placed in graves, as a cheaper substitute for metalware in both Greece and Etruria.[8]

Most surviving pottery consists of vessels for storing, serving or drinking liquids such as amphorae, kraters (bowls for mixing wine and water), hydria (water jars), libation bowls, oil and perfume bottles for the toilet, jugs and cups. Painted vessels for serving and eating food are much less common. Painted pottery was affordable even by ordinary people, and a piece "decently decorated with about five or six figures cost about two or three days' wages".[9] Miniatures were also produced in large numbers, mainly for use as offerings at temples.[10] In the Hellenistic period a wider range of pottery was produced, but most of it is of little artistic importance.

In earlier periods even quite small Greek cities produced pottery for their own locale. These varied widely in style and standards. Distinctive pottery that ranks as art was produced on some of the Aegean islands, in Crete, and in the wealthy Greek colonies of southern Italy and Sicily.[12] By the later Archaic and early Classical period, however, the two great commercial powers, Corinth and Athens, came to dominate. Their pottery was exported all over the Greek world, driving out the local varieties. Pots from Corinth and Athens are found as far afield as Spain and Ukraine, and are so common in Italy that they were first collected in the 18th century as "Etruscan vases".[13] Many of these pots are mass-produced products of low quality. In fact, by the 5th century BC, pottery had become an industry and pottery painting ceased to be an important art form.

The range of colours which could be used on pots was restricted by the technology of firing: black, white, red, and yellow were the most common. In the three earlier periods, the pots were left their natural light colour, and were decorated with slip that turned black in the kiln.[6]

Greek pottery is frequently signed, sometimes by the potter or the master of the pottery, but only occasionally by the painter. Hundreds of painters are, however, identifiable by their artistic personalities: where their signatures have not survived they are named for their subject choices, as "the Achilles Painter", by the potter they worked for, such as the Late Archaic "Kleophrades Painter", or even by their modern locations, such as the Late Archaic "Berlin Painter".[14]

History

[edit]

The history of ancient Greek pottery is divided stylistically into five periods:

- the Protogeometric from about 1050 BC

- the Geometric from about 900 BC

- the Late Geometric or Archaic from about 750 BC

- the Black Figure from the early 7th century BC

- and the Red Figure from about 530 BC

During the Protogeometric and Geometric periods, Greek pottery was decorated with abstract designs, in the former usually elegant and large, with plenty of unpainted space, but in the Geometric often densely covering most of the surface, as in the large pots by the Dipylon Master, who worked around 750. He and other potters around his time began to introduce very stylised silhouette figures of humans and animals, especially horses. These often represent funeral processions, or battles, presumably representing those fought by the deceased.[15]

The Geometric phase was followed by an Orientalizing period in the late 8th century, when a few animals, many either mythical or not native to Greece (like the sphinx and lion respectively) were adapted from the Near East, accompanied by decorative motifs, such as the lotus and palmette. These were shown much larger than the previous figures. The Wild Goat Style is a regional variant, very often showing goats. Human figures were not so influenced from the East, but also became larger and more detailed.[16]

The fully mature black-figure technique, with added red and white details and incising for outlines and details, originated in Corinth during the early 7th century BC and was introduced into Attica about a generation later; it flourished until the end of the 6th century BC.[17] The red-figure technique, invented in about 530 BC, reversed this tradition, with the pots being painted black and the figures painted in red. Red-figure vases slowly replaced the black-figure style. Sometimes larger vessels were engraved as well as painted. Erotic themes, both heterosexual and male homosexual, became common.[18]

By about 320 BC fine figurative vase-painting had ceased in Athens and other Greek centres, with the polychromatic Kerch style a final flourish; it was probably replaced by metalwork for most of its functions. West Slope Ware, with decorative motifs on a black glazed body, continued for over a century after.[19] Italian red-figure painting ended by about 300, and in the next century the relatively primitive Hadra vases, probably from Crete, Centuripe ware from Sicily, and Panathenaic amphorae, now a frozen tradition, were the only large painted vases still made.[20]

- Late Geometric pyxis, British Museum

- Corinthian orientalising jug, c. 620 BC, Antikensammlungen Munich

- Black-figure olpe (wine vessel) by the Amasis Painter, depicting Heracles and Athena, c. 540 BC, Louvre

- Hellenistic relief bowl with the head of a maenad, 2nd century BC (?), British Museum

Metalwork

[edit]

Fine metalwork was an important art in ancient Greece, but later production is very poorly represented by survivals, most of which come from the edges of the Greek world or beyond, from as far as France or Russia. Vessels and jewellery were produced to high standards, and exported far afield. Objects in silver, at the time worth more relative to gold than it is in modern times, were often inscribed by the maker with their weight, as they were treated largely as stores of value, and likely to be sold or re-melted before very long.[22]

During the Geometric and Archaic phases, the production of large metal vessels was an important expression of Greek creativity, and an important stage in the development of bronzeworking techniques, such as casting and repousse hammering. Early sanctuaries, especially Olympia, yielded many hundreds of tripod-bowl or sacrificial tripod vessels, mostly in bronze, deposited as votives. These had a shallow bowl with two handles raised high on three legs; in later versions the stand and bowl were different pieces. During the Orientalising period, such tripods were frequently decorated with figural protomes, in the shape of griffins, sphinxes and other fantastic creatures.[23]

Swords, the Greek helmet and often body armour such as the muscle cuirass were made of bronze, sometimes decorated in precious metal, as in the 3rd-century Ksour Essef cuirass.[24] Armour and "shield-bands" are two of the contexts for strips of Archaic low relief scenes, which were also attached to various objects in wood; the band on the Vix Krater is a large example.[25] Polished bronze mirrors, initially with decorated backs and kore handles, were another common item; the later "folding mirror" type had hinged cover pieces, often decorated with a relief scene, typically erotic.[26] Coins are described below.

From the late Archaic the best metalworking kept pace with stylistic developments in sculpture and the other arts, and Phidias is among the sculptors known to have practiced it.[27] Hellenistic taste encouraged highly intricate displays of technical virtuousity, tending to "cleverness, whimsy, or excessive elegance".[28] Many or most Greek pottery shapes were taken from shapes first used in metal, and in recent decades there has been an increasing view that much of the finest vase-painting reused designs by silversmiths for vessels with engraving and sections plated in a different metal, working from drawn designs.[29]

Exceptional survivals of what may have been a relatively common class of large bronze vessels are two volute kraters, for mixing wine and water.[30] These are the Vix Krater, c. 530 BC, 1.63 m (5 ft 4 in) high and over 200 kg (440 lb) in weight, holding some 1,100 litres, and found in the burial of a Celtic woman in modern France,[31] and the 4th-century Derveni Krater, 90.5 cm (35.6 in) high.[32] The elites of other neighbours of the Greeks, such as the Thracians and Scythians, were keen consumers of Greek metalwork, and probably served by Greek goldsmiths settled in their territories, who adapted their products to suit local taste and functions. Such hybrid pieces form a large part of survivals, including the Panagyurishte Treasure, Borovo Treasure, and other Thracian treasures, and several Scythian burials, which probably contained work by Greek artists based in the Greek settlements on the Black Sea.[33] As with other luxury arts, the Macedonian royal cemetery at Vergina has produced objects of top quality from the cusp of the Classical and Hellenistic periods.[34]

Jewellery for the Greek market is often of superb quality,[35] with one unusual form being intricate and very delicate gold wreaths imitating plant-forms, worn on the head. These were probably rarely, if ever, worn in life, but were given as votives and worn in death.[36] Many of the Fayum mummy portraits wear them. Some pieces, especially in the Hellenistic period, are large enough to offer scope for figures, as did the Scythian taste for relatively substantial pieces in gold.[37]

- The Vix Krater, a late Archaic monumental bronze vessel, exported to French Celts

- Fancy Early Classical bronze mirror with human caryatid handle, c. 460 BC

- Golden wreath, 370–360, from southern Italy

- 4th century BC Greek gold and bronze rhyton with head of Dionysus, Tamoikin Art Fund

- Fragment of a gold wreath, c. 320-300 BC, from a burial in Crimea

- Gold hair ornament and net, 3rd century BC

- Late Hellenistic silver medallion

Monumental sculpture

[edit]

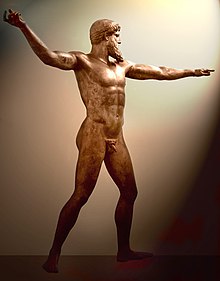

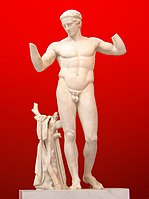

The Greeks decided very early on that the human form was the most important subject for artistic endeavour.[39] Seeing their gods as having human form, there was little distinction between the sacred and the secular in art—the human body was both secular and sacred. A male nude of Apollo or Heracles had only slight differences in treatment to one of that year's Olympic boxing champion. In the Archaic Period the most important sculptural form was the kouros (plural kouroi), the standing male nude (See for example Biton and Kleobis). The kore (plural korai), or standing clothed female figure, was also common, but since Greek society did not permit the public display of female nudity until the 4th century BC, the kore is considered to be of less importance in the development of sculpture.[40] By the end of the period architectural sculpture on temples was becoming important.

As with pottery, the Greeks did not produce monumental sculpture merely for artistic display. Statues were commissioned either by aristocratic individuals or by the state, and used for public memorials, as offerings to temples, oracles and sanctuaries (as is frequently shown by inscriptions on the statues), or as markers for graves. Statues in the Archaic period were not all intended to represent specific individuals. They were depictions of an ideal—beauty, piety, honor or sacrifice. These were always depictions of young men, ranging in age from adolescence to early maturity, even when placed on the graves of (presumably) elderly citizens. Kouroi were all stylistically similar. Graduations in the social stature of the person commissioning the statue were indicated by size rather than artistic innovations.[41]

Unlike authors, those who practiced the visual arts, including sculpture, initially had a low social status in ancient Greece, though increasingly leading sculptors might become famous and rather wealthy, and often signed their work (often on the plinth, which typically became separated from the statue itself).[42] Plutarch (Life of Pericles, II) said "we admire the work of art but despise the maker of it"; this was a common view in the ancient world. Ancient Greek sculpture is categorised by the usual stylistic periods of "Archaic", "Classical" and "Hellenistic", augmented with some extra ones mainly applying to sculpture, such as the Orientalizing Daedalic style and the Severe style of early Classical sculpture.[43]

Materials, forms

[edit]

Surviving ancient Greek sculptures were mostly made of two types of material. Stone, especially marble or other high-quality limestones was used most frequently and carved by hand with metal tools. Stone sculptures could be free-standing fully carved in the round (statues), or only partially carved reliefs still attached to a background plaque, for example in architectural friezes or grave stelai.[44]

Bronze statues were of higher status, but have survived in far smaller numbers, due to the reusability of metals. They were usually made in the lost wax technique. Chryselephantine, or gold-and-ivory, statues were the cult-images in temples and were regarded as the highest form of sculpture, but only some fragmentary pieces have survived. They were normally over-lifesize, built around a wooden frame, with thin carved slabs of ivory representing the flesh, and sheets of gold leaf, probably over wood, representing the garments, armour, hair, and other details.[45]

In some cases, glass paste, glass, and precious and semi-precious stones were used for detail such as eyes, jewellery, and weaponry. Other large acrolithic statues used stone for the flesh parts, and wood for the rest, and marble statues sometimes had stucco hairstyles. Most sculpture was painted (see below), and much wore real jewellery and had inlaid eyes and other elements in different materials.[46]

Terracotta was occasionally employed, for large statuary. Few examples of this survived, at least partially due to the fragility of such statues. The best known exception to this is a statue of Zeus carrying Ganymede found at Olympia, executed around 470 BC. In this case, the terracotta is painted. There were undoubtedly sculptures purely in wood, which may have been very important in early periods, but effectively none have survived.[47]

Archaic

[edit]

Bronze Age Cycladic art, to about 1100 BC, had already shown an unusual focus on the human figure, usually shown in a straightforward frontal standing position with arms folded across the stomach. Among the smaller features only noses, sometimes eyes, and female breasts were carved, though the figures were apparently usually painted and may have originally looked very different.

Inspired by the monumental stone sculpture of Egypt and Mesopotamia, during the Archaic period the Greeks began again to carve in stone: Greek mercenaries and merchants were active abroad, as in Egypt in the service of Pharaoh Psamtik I (664–610 BC), and were exposed to the monumental art of these countries.[48][49] It is generally agreed that "Egyptian statuary of the 2nd millennium BC gave the decisive impulse for the innovation of Greeksculpture in life-size and in hyper formats in the Archaic Period during the late 7th century."[48] Free-standing figures share the solidity and frontal stance characteristic of Eastern models, but their forms are more dynamic than those of Egyptian sculpture, as for example the Lady of Auxerre and Torso of Hera (Early Archaic period, c. 660–580 BC, both in the Louvre, Paris). After about 575 BC, figures, such as these, both male and female, wore the so-called archaic smile. This expression, which has no specific appropriateness to the person or situation depicted, may have been a device to give the figures a distinctive human characteristic.[50]

Three types of figures were used—the standing nude youth (kouros), the standing draped girl (kore) and, less frequently, the seated woman.[51] All emphasize and generalize the essential features of the human figure and show an increasingly accurate comprehension of human anatomy. The youths were either sepulchral or votive statues. Examples are Apollo (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), an early work; the Strangford Apollo from Anafi (British Museum, London), a much later work; and the Anavyssos Kouros (National Archaeological Museum of Athens). More of the musculature and skeletal structure is visible in this statue than in earlier works. The standing, draped girls have a wide range of expression, as in the sculptures in the Acropolis Museum of Athens. Their drapery is carved and painted with the delicacy and meticulousness common in the details of sculpture of this period.[52]

Archaic reliefs have survived from many tombs, and from larger buildings at Foce del Sele (now in the National Archaeological Museum of Paestum) in Italy, with two groups of metope panels, from about 550 and 510, and the Siphnian Treasury at Delphi, with friezes and a small pediment. Parts, all now in local museums, survive of the large triangular pediment groups from the Temple of Artemis, Corfu (c. 580), dominated by a huge Gorgon, and the Old Temple of Athena in Athens (c. 530-500).[53]

- Dipylon Kouros, c. 600 BC, Athens, Kerameikos Museum

- Frieze of the Siphnian Treasury, Delphi, depicting a Gigantomachy, c. 525 BC, Delphi Archaeological Museum

- The Strangford Apollo, 500–490, one of the last kouroi

- The Sabouroff head, an important example of Late Archaic Greek marble sculpture, c. 550-525 BCE.

- The Perserschutt, or "Persian rubble", dating from the destruction of Athens in 480/479 BC during the Second Persian invasion of Greece offer a clear datation marker for Archaic statuary.

Classical

[edit]

In the Classical period there was a revolution in Greek statuary, usually associated with the introduction of democracy and the end of the aristocratic culture associated with the kouroi. The Classical period saw changes in the style and function of sculpture. Poses became more naturalistic (see the Charioteer of Delphi for an example of the transition to more naturalistic sculpture), and the technical skill of Greek sculptors in depicting the human form in a variety of poses greatly increased. From about 500 BC statues began to depict real people. The statues of Harmodius and Aristogeiton set up in Athens to mark the overthrow of the tyranny were said to be the first public monuments to actual people.[54]

At the same time sculpture and statues were put to wider uses. The great temples of the Classical era such as the Parthenon in Athens, and the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, required relief sculpture for decorative friezes, and sculpture in the round to fill the triangular fields of the pediments. The difficult aesthetic and technical challenge stimulated much in the way of sculptural innovation. These works survive only in fragments, the most famous of which are the Parthenon Marbles, half of which are in the British Museum.[57]

Funeral statuary evolved during this period from the rigid and impersonal kouros of the Archaic period to the highly personal family groups of the Classical period. These monuments are commonly found in the suburbs of Athens, which in ancient times were cemeteries on the outskirts of the city. Although some of them depict "ideal" types—the mourning mother, the dutiful son—they increasingly depicted real people, typically showing the departed taking his dignified leave from his family. They are among the most intimate and affecting remains of the ancient Greeks.[58]

In the Classical period for the first time we know the names of individual sculptors. Phidias oversaw the design and building of the Parthenon. Praxiteles made the female nude respectable for the first time in the Late Classical period (mid-4th century): his Aphrodite of Knidos, which survives in copies, was said by Pliny to be the greatest statue in the world.[59]

The most famous works of the Classical period for contemporaries were the colossal Statue of Zeus at Olympia and the Statue of Athena Parthenos in the Parthenon. Both were chryselephantine and executed by Phidias or under his direction, and are now lost, although smaller copies (in other materials) and good descriptions of both still exist. Their size and magnificence prompted emperors to seize them in the Byzantine period, and both were removed to Constantinople, where they were later destroyed in fires.[60]

- The Marathon Youth, 4th-century BC bronze statue, possibly by Praxiteles, National Archaeological Museum, Athens

Hellenistic

[edit]

The transition from the Classical to the Hellenistic period occurred during the 4th century BC. Following the conquests of Alexander the Great (336 BC to 323 BC), Greek culture spread as far as India, as revealed by the excavations of Ai-Khanoum in eastern Afghanistan, and the civilization of the Greco-Bactrians and the Indo-Greeks. Greco-Buddhist art represented a syncretism between Greek art and the visual expression of Buddhism. Thus Greek art became more diverse and more influenced by the cultures of the peoples drawn into the Greek orbit.[61]

In the view of some art historians, it also declined in quality and originality. This, however, is a judgement which artists and art-lovers of the time would not have shared. Indeed, many sculptures previously considered as classical masterpieces are now recognised as being Hellenistic. The technical ability of Hellenistic sculptors is clearly in evidence in such major works as the Winged Victory of Samothrace, and the Pergamon Altar. New centres of Greek culture, particularly in sculpture, developed in Alexandria, Antioch, Pergamum, and other cities, where the new monarchies were lavish patrons.[62] By the 2nd century the rising power of Rome had also absorbed much of the Greek tradition—and an increasing proportion of its products as well.[63]

During this period sculpture became more naturalistic, and also expressive; the interest in depicting extremes of emotion being sometimes pushed to extremes. Genre subjects of common people, women, children, animals and domestic scenes became acceptable subjects for sculpture, which was commissioned by wealthy families for the adornment of their homes and gardens; the Boy with Thorn is an example. Realistic portraits of men and women of all ages were produced, and sculptors no longer felt obliged to depict people as ideals of beauty or physical perfection.[64]

The world of Dionysus, a pastoral idyll populated by satyrs, maenads, nymphs and sileni, had been often depicted in earlier vase painting and figurines, but rarely in full-size sculpture. Now such works were made, surviving in copies including the Barberini Faun, the Belvedere Torso, and the Resting Satyr; the Furietti Centaurs and Sleeping Hermaphroditus reflect related themes.[65] At the same time, the new Hellenistic cities springing up all over Egypt, Syria, and Anatolia required statues depicting the gods and heroes of Greece for their temples and public places. This made sculpture, like pottery, an industry, with the consequent standardisation and some lowering of quality. For these reasons many more Hellenistic statues have survived than is the case with the Classical period.

Some of the best known Hellenistic sculptures are the Winged Victory of Samothrace (2nd or 1st century BC),[66] the statue of Aphrodite from the island of Melos known as the Venus de Milo (mid-2nd century BC), the Dying Gaul (about 230 BC), and the monumental group Laocoön and His Sons (late 1st century BC). All these statues depict Classical themes, but their treatment is far more sensuous and emotional than the austere taste of the Classical period would have allowed or its technical skills permitted.

The multi-figure group of statues was a Hellenistic innovation, probably of the 3rd century, taking the epic battles of earlier temple pediment reliefs off their walls, and placing them as life-size groups of statues. Their style is often called "baroque", with extravagantly contorted body poses, and intense expressions in the faces. The reliefs on the Pergamon Altar are the nearest original survivals, but several well known works are believed to be Roman copies of Hellenistic originals. These include the Dying Gaul and Ludovisi Gaul, as well as a less well known Kneeling Gaul and others, all believed to copy Pergamene commissions by Attalus I to commemorate his victory around 241 over the Gauls of Galatia, probably comprising two groups.[67]

The Laocoön Group, the Farnese Bull, Menelaus supporting the body of Patroclus ("Pasquino group"), Arrotino, and the Sperlonga sculptures, are other examples.[68] From the 2nd century the Neo-Attic or Neo-Classical style is seen by different scholars as either a reaction to baroque excesses, returning to a version of Classical style, or as a continuation of the traditional style for cult statues.[69] Workshops in the style became mainly producers of copies for the Roman market, which preferred copies of Classical rather than Hellenistic pieces.[70]

Discoveries made since the end of the 19th century surrounding the (now submerged) ancient Egyptian city of Heracleum include a 4th-century BC, unusually sensual, detailed and feministic (as opposed to deified) depiction of Isis, marking a combination of Egyptian and Hellenistic forms beginning around the time of Egypt's conquest by Alexander the Great. However this was untypical of Ptolemaic court sculpture, which generally avoided mixing Egyptian styles with its fairly conventional Hellenistic style,[71] while temples in the rest of the country continued using late versions of traditional Egyptian formulae.[72] Scholars have proposed an "Alexandrian style" in Hellenistic sculpture, but there is in fact little to connect it with Alexandria.[73]

Hellenistic sculpture was also marked by an increase in scale, which culminated in the Colossus of Rhodes (late 3rd century), which was the same size as the Statue of Liberty. The combined effect of earthquakes and looting have destroyed this as well as other very large works of this period.

- The Hellenistic Prince, a bronze statue originally thought to be a Seleucid, or Attalus II of Pergamon, now considered a portrait of a Roman general, made by a Greek artist working in Rome in the 2nd century BC.

- Laocoön and His Sons (Late Hellenistic), Vatican Museum

- Late Hellenistic bronze of a mounted jockey, National Archaeological Museum, Athens

Figurines

[edit]Terracotta figurines

[edit]

Clay is a material frequently used for the making of votive statuettes or idols, even before the Minoan civilization and continuing until the Roman period. During the 8th century BC tombs in Boeotia often contain "bell idols", female statuettes with mobile legs: the head, small compared to the remainder of the body, is perched at the end of a long neck, while the body is very full, in the shape of a bell.[74] Archaic heroon tombs, for local heroes, might receive large numbers of crudely-shaped figurines, with rudimentary figuration, generally representing characters with raised arms.

By the Hellenistic period most terracotta figurines have lost their religious nature, and represent characters from everyday life. Tanagra figurines, from one of several centres of production, are mass-manufactured using moulds, and then painted after firing. Dolls, figures of fashionably-dressed ladies and of actors, some of these probably portraits, were among the new subjects, depicted with a refined style. These were cheap, and initially displayed in the home much like modern ornamental figurines, but were quite often buried with their owners. At the same time, cities like Alexandria, Smyrna or Tarsus produced an abundance of grotesque figurines, representing individuals with deformed members, eyes bulging and contorting themselves. Such figurines were also made from bronze.[75]

For painted architectural terracottas, see Architecture below.

Metal figurines

[edit]Figurines made of metal, primarily bronze, are an extremely common find at early Greek sanctuaries like Olympia, where thousands of such objects, mostly depicting animals, have been found. They are usually produced in the lost wax technique and can be considered the initial stage in the development of Greek bronze sculpture. The most common motifs during the Geometric period were horses and deer, but dogs, cattle and other animals are also depicted. Human figures occur occasionally. The production of small metal votives continued throughout Greek antiquity. In the Classical and Hellenistic periods, more elaborate bronze statuettes, closely connected with monumental sculpture, also became common. High quality examples were keenly collected by wealthy Greeks, and later Romans, but relatively few have survived.[76]

- Bell Idol, 7th century BC

- 8th-century BC bronze votive horse from Olympia

- Actor from the New Comedy, about 200 BC

- Tanagra figurine of fashionable lady, 32.5 cm (12.8 in), 330-300 BC

Architecture

[edit]

Architecture (meaning buildings executed to an aesthetically considered design) ceased in Greece from the end of the Mycenaean period (about 1200 BC) until the 7th century, when urban life and prosperity recovered to a point where public building could be undertaken. Since most Greek buildings in the Archaic and Early Classical periods were made of wood or mudbrick, nothing remains of them except a few ground-plans, and there are almost no written sources on early architecture or descriptions of buildings. Most of our knowledge of Greek architecture comes from the surviving buildings of the Late Archaic, Classical, Hellenistic and Roman periods (since ancient Roman architecture heavily used Greek styles), and from late written sources such as Vitruvius (1st century BC). This means that there is a strong bias towards temples, the most common major buildings to survive. Here the squared blocks of stone used for walls were useful for later buildings, and so often all that survives are parts of columns and metopes that were harder to recycle.[77]

For most of the period a strict stone post and lintel system of construction was used, held in place only by gravity. Corbelling was known in Mycenean Greece, and the arch was known from the 5th century at the latest, but hardly any use was made of these techniques until the Roman period.[78] Wood was only used for ceilings and roof timbers in prestigious stone buildings. The use of large terracotta roof tiles, only held in place by grooving, meant that roofs needed to have a low pitch.[79]

Until Hellenistic times only public buildings were built using the formal stone style; these included above all temples, and the smaller treasury buildings which often accompanied them, and were built at Delphi by many cities. Other building types, often not roofed, were the central agora, often with one or more colonnaded stoa around it, theatres, the gymnasium and palaestra or wrestling-school, the ekklesiasterion or bouleuterion for assemblies, and the propylaea or monumental gateways.[80] Round buildings for various functions were called a tholos,[81] and the largest stone structures were often defensive city walls.

Tombs were for most of the period only made as elaborate mausolea around the edges of the Greek world, especially in Anatolia.[82] Private houses were built around a courtyard where funds allowed, and showed blank walls to the street. They sometimes had a second story, but very rarely basements. They were usually built of rubble at best, and relatively little is known about them; at least for males, much of life was spent outside them.[83] A few palaces from the Hellenistic period have been excavated.[84]

Temples and some other buildings such as the treasuries at Delphi were planned as either a cube or, more often, a rectangle made from limestone, of which Greece has an abundance, and which was cut into large blocks and dressed. This was supplemented by columns, at least on the entrance front, and often on all sides.[85] Other buildings were more flexible in plan, and even the wealthiest houses seem to have lacked much external ornament. Marble was an expensive building material in Greece: high quality marble came only from Mt Pentelus in Attica and from a few islands such as Paros, and its transportation in large blocks was difficult. It was used mainly for sculptural decoration, not structurally, except in the very grandest buildings of the Classical period such as the Parthenon in Athens.[86]

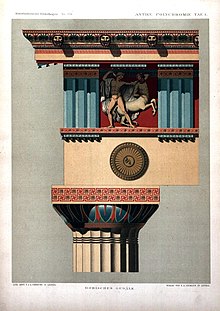

There were two main classical orders of Greek architecture, the Doric and the Ionic, with the Corinthian order only appearing in the Classical period, and not becoming dominant until the Roman period. The most obvious features of the three orders are the capitals of the columns, but there are significant differences in other points of design and decoration between the orders.[87] These names were used by the Greeks themselves, and reflected their belief that the styles descended from the Dorian and Ionian Greeks of the Dark Ages, but this is unlikely to be true. The Doric was the earliest, probably first appearing in stone in the earlier 7th century, having developed (though perhaps not very directly) from predecessors in wood.[88] It was used in mainland Greece and the Greek colonies in Italy. The Ionic style was first used in the cities of Ionia (now the west coast of Turkey) and some of the Aegean islands, probably beginning in the 6th century.[89] The Doric style was more formal and austere, the Ionic more relaxed and decorative. The more ornate Corinthian order was a later development of the Ionic, initially apparently only used inside buildings, and using Ionic forms for everything except the capitals. The famous and well-preserved Choragic Monument of Lysicrates near the Acropolis of Athens (335/334) is the first known use of the Corinthian order on the exterior of a building.[90]

Most of the best known surviving Greek buildings, such as the Parthenon and the Temple of Hephaestus in Athens, are Doric. The Erechtheum, next to the Parthenon, however, is Ionic. The Ionic order became dominant in the Hellenistic period, since its more decorative style suited the aesthetic of the period better than the more restrained Doric. Some of the best surviving Hellenistic buildings, such as the Library of Celsus, can be seen in Turkey, at cities such as Ephesus and Pergamum.[91] But in the greatest of Hellenistic cities, Alexandria in Egypt, almost nothing survives.

- Model of the processional way at Ancient Delphi, without much of the statuary shown.[92]

- The Ancient Theatre of Epidaurus, 4th century BC

- The Erechtheion on the Acropolis of Athens, late 5th century BC

- Choragic Monument of Lysicrates, Athens, 335/334

Coin design

[edit]

Coins were (probably) invented in Lydia in the 7th century BC, but they were first extensively used by the Greeks,[93] and the Greeks set the canon of coin design which has been followed ever since. Coin design today still recognisably follows patterns descended from ancient Greece. The Greeks did not see coin design as a major art form, although some were expensively designed by leading goldsmiths, especially outside Greece itself, among the Central Asian kingdoms and in Sicilian cities keen to promote themselves. Nevertheless, the durability and abundance of coins have made them one of the most important sources of knowledge about Greek aesthetics.[94] Greek coins are the only art form from the ancient Greek world which can still be bought and owned by private collectors of modest means.

The most widespread coins, used far beyond their native territories and copied and forged by others, were the Athenian tetradrachm, issued from c. 510 to c. 38 BC, and in the Hellenistic age the Macedonian tetradrachm, both silver.[95] These both kept the same familiar design for long periods.[96] Greek designers began the practice of putting a profile portrait on the obverse of coins. This was initially a symbolic portrait of the patron god or goddess of the city issuing the coin: Athena for Athens, Apollo at Corinth, Demeter at Thebes and so on. Later, heads of heroes of Greek mythology were used, such as Heracles on the coins of Alexander the Great.

The first human portraits on coins were those of Achaemenid Empire Satraps in Asia Minor, starting with the exiled Athenian general Themistocles who became a Satrap of Magnesia c. 450 BC, and continuing especially with the dynasts of Lycia towards the end of the 5th century.[97] Greek cities in Italy such as Syracuse began to put the heads of real people on coins in the 4th century BC, as did the Hellenistic successors of Alexander the Great in Egypt, Syria and elsewhere.[98] On the reverse of their coins the Greek cities often put a symbol of the city: an owl for Athens, a dolphin for Syracuse and so on. The placing of inscriptions on coins also began in Greek times. All these customs were later continued by the Romans.[94]

The most artistically ambitious coins, designed by goldsmiths or gem-engravers, were often from the edges of the Greek world, from new colonies in the early period and new kingdoms later, as a form of marketing their "brands" in modern terms.[99] Of the larger cities, Corinth and Syracuse also issued consistently attractive coins. Some of the Greco-Bactrian coins are considered the finest examples of Greek coins with large portraits with "a nice blend of realism and idealization", including the largest coins to be minted in the Hellenistic world: the largest gold coin was minted by Eucratides (reigned 171–145 BC), the largest silver coin by the Indo-Greek king Amyntas Nikator (reigned c. 95–90 BC). The portraits "show a degree of individuality never matched by the often bland depictions of their royal contemporaries further West".[100]

- Heracles fighting the Nemean lion. Silver coin from Heraclea Lucania

- Arethusa on a coin of Syracuse, Sicily, 415–400

Painting

[edit]The Greeks seem to have valued painting above even sculpture, and by the Hellenistic period the informed appreciation and even the practice of painting were components in a gentlemanly education. The ekphrasis was a literary form consisting of a description of a work of art, and we have a considerable body of literature on Greek painting and painters, with further additions in Latin, though none of the treatises by artists that are mentioned have survived.[101] We have hardly any of the most prestigious sort of paintings, on wood panel or in fresco, that this literature was concerned with, and very few of the copies that undoubtedly existed, equivalent to those which give us most of our knowledge of Greek sculpture.

The contrast with vase-painting is total. There are no mentions of that in literature at all, but over 100,000 surviving examples, giving many individual painters a respectable surviving oeuvre.[102] Our idea of what the best Greek painting was like must be drawn from a careful consideration of parallels in vase-painting, late Greco-Roman copies in mosaic and fresco, some very late examples of actual painting in the Greek tradition, and the ancient literature.[103]

There were several interconnected traditions of painting in ancient Greece. Due to their technical differences, they underwent somewhat differentiated developments. Early painting seems to have developed along similar lines to vase-painting, heavily reliant on outline and flat areas of colour, but then flowered and developed at the time that vase-painting went into decline. By the end of the Hellenistic period, technical developments included modelling to indicate contours in forms, shadows, foreshortening, some probably imprecise form of perspective, interior and landscape backgrounds, and the use of changing colours to suggest distance in landscapes, so that "Greek artists had all the technical devices needed for fully illusionistic painting".[104]

Panel and wall painting

[edit]

The most common and respected form of art, according to authors like Pliny or Pausanias, were panel paintings, individual, portable paintings on wood boards. The techniques used were encaustic (wax) painting and tempera. Such paintings normally depicted figural scenes, including portraits and still-lifes; we have descriptions of many compositions. They were collected and often displayed in public spaces. Pausanias describes such exhibitions at Athens and Delphi. We know the names of many famous painters, mainly of the Classical and Hellenistic periods, from literature (see expandable list to the right). The most famous of all ancient Greek painters was Apelles of Kos, whom Pliny the Elder lauded as having "surpassed all the other painters who either preceded or succeeded him."[105][106]

Due to the perishable nature of the materials used and the major upheavals at the end of antiquity, not one of the famous works of Greek panel painting has survived. We have slightly more significant survivals of mural compositions. The most important surviving Greek examples from before the Roman period are the fairly low-quality Pitsa panels from c. 530 BC,[107] the Tomb of the Diver from Paestum, and various paintings from the royal tombs at Vergina. More numerous paintings in Etruscan and Campanian tombs are based on Greek styles. In the Roman period, there are a number of wall paintings in Pompeii and the surrounding area, as well as in Rome itself, some of which are thought to be copies of specific earlier masterpieces.[108]

In particular copies of specific wall-paintings have been confidently identified in the Alexander Mosaic and Villa Boscoreale.[109] There is a large group of much later Greco-Roman archaeological survivals from the dry conditions of Egypt, the Fayum mummy portraits, together with the similar Severan Tondo, and a small group of painted portrait miniatures in gold glass.[110] Byzantine icons are also derived from the encaustic panel painting tradition, and Byzantine illuminated manuscripts sometimes continued a Greek illusionistic style for centuries.

The tradition of wall painting in Greece goes back at least to the Minoan and Mycenaean Bronze Age, with the lavish fresco decoration of sites like Knossos, Tiryns and Mycenae. It is not clear, whether there is any continuity between these antecedents and later Greek wall paintings.

Wall paintings are frequently described in Pausanias, and many appear to have been produced in the Classical and Hellenistic periods. Due to the lack of architecture surviving intact, not many are preserved. The most notable examples are a monumental Archaic 7th-century BC scene of hoplite combat from inside a temple at Kalapodi (near Thebes), and the elaborate frescoes from the 4th-century "Grave of Phillipp" and the "Tomb of Persephone" at Vergina in Macedonia, or the tomb at Agios Athanasios, Thessaloniki, which are sometimes suggested to be closely linked to the high-quality panel paintings mentioned above. The unusual survival of the Tomb of the Palmettes (3rd-century BC, excavated in 1971) with painting in good condition includes portraits of the couple buried inside on the tympanum.

Greek wall painting tradition is also reflected in contemporary grave decorations in the Greek colonies in Italy, e.g. the famous Tomb of the Diver at Paestum. Scholars believe that the celebrated Roman frescoes at sites like Pompeii are descendants of the Greek tradition, and some copy particular famous panel paintings. These Roman copies are all loose adaptations, however, with extra figures added, poses altered, and colouring changed.

- Ancient Macedonian paintings of armour, arms, and gear from the Tomb of Lyson and Kallikles in ancient Mieza (modern-day Lefkadia), Imathia, Central Macedonia, Greece, 2nd century BC.

- Стела Диоскурида, датированная II веком до нашей эры, с изображением птолемеевского солдата -тиреофора , характерный пример « романизации » армии Птолемеев.

- Фреска из Гробницы Суда в древней Миезе (современная Лефкадия), Иматия , Центральная Македония , Греция, изображающая религиозные образы загробной жизни , 4 век до нашей эры.

- Фреска, изображающая Аида и Персефону , едущих в колеснице , из гробницы царицы Эвридики I Македонской в Вергине , Греция, IV век до нашей эры.

- Сцена банкета из македонской гробницы Святого Афанасия, Салоники , IV век до нашей эры; Шесть мужчин изображены лежащими на диванах , на соседних столах расставлена еда, присутствует слуга-мужчина и музыканты-женщины развлекают. [111]

- Фреска древнего македонского солдата ( торакитая ) в кольчужных доспехах и со щитом- туреосом , III век до нашей эры.

- , Гобелен Сампул настенная подвеска из округа Лоп , Хотан , Синьцзян , Китай , изображающая, возможно, греческого солдата из Греко-Бактрийского царства (250–125 гг. шерстяная префектура быть диадемой на голову; над ним изображен кентавр из греческой мифологии , распространенный мотив в эллинистическом искусстве ; [112] Музей Синьцзянского региона .

- Эллинистическая греческая энкаустика на мраморном надгробии, изображающая портрет молодого человека по имени Теодор, датированная I веком до нашей эры в период Римской Греции , Археологический музей Фив.

Полихромия: живопись по скульптуре и архитектуре.

[ редактировать ]

Большая часть фигуративной или архитектурной скульптуры Древней Греции была красочно окрашена. Этот аспект греческой каменной кладки описывается как полихромия (от греческого πολυχρωμία , πολύ = много и χρώμα = цвет). Из-за интенсивного выветривания полихромия в скульптуре и архитектуре в большинстве случаев существенно или полностью выцвела.

Хотя слово «полихромия» образовано от сочетания двух греческих слов, в Древней Греции оно не использовалось. Этот термин был придуман в начале девятнадцатого века Антуаном Хризостомом Катремером де Квинси. [113]

Архитектура

[ редактировать ]Живопись также использовалась для улучшения визуальных аспектов архитектуры. Некоторые части надстройки греческих храмов обычно расписывались еще с архаического периода. Такая архитектурная полихромия могла принимать форму ярких цветов, непосредственно нанесенных на камень (например, Парфенон ), или сложных узоров, часто архитектурных элементов, сделанных из терракоты (архаические примеры в Олимпии и Дельфах ). Иногда на терракотах также изображались фигуральные сцены. VII века до нашей эры , как и терракотовые метопы из Термона . [114]

Скульптура

[ редактировать ]Большинство греческих скульптур были окрашены в яркие и насыщенные цвета; это называется « полихромия ». Краска часто ограничивалась частями изображения одежды, волос и т. д., оставляя кожу естественного цвета камня или бронзы, но могла покрывать и скульптуры целиком; женская кожа в мраморе, как правило, была бесцветной, а мужская кожа могла быть светло-коричневой. Роспись греческих скульптур следует рассматривать не просто как улучшение их скульптурной формы, но и как проявление особого стиля искусства. [115]

Например, недавно было продемонстрировано, что фронтонные скульптуры храма Афайи на Эгине были расписаны смелыми и сложными узорами, изображающими, среди других деталей, узорчатую одежду. Полихромия каменных статуй сопровождалась использованием разных материалов для различения кожи, одежды и других деталей в хризоэлефантиновых скульптурах , а также использованием разных металлов для изображения губ, ногтей и т. д. на высококачественных бронзах, таких как бронзы Риаче . [115]

Роспись вазы

[ редактировать ]Наиболее многочисленные свидетельства древнегреческой живописи сохранились в виде росписей на вазах. Они описаны в разделе « Гончарное дело » выше. Они дают хоть какое-то представление об эстетике греческой живописи. Однако использованные техники сильно отличались от тех, которые используются в широкоформатной живописи. То же самое, вероятно, относится и к изображенному предмету. Художники по вазам, по-видимому, обычно были специалистами в гончарной мастерской, а не художниками в других средах или гончарами. Следует также иметь в виду, что роспись ваз, хотя и является наиболее заметным сохранившимся источником древнегреческой живописи, в древности не пользовалась большим уважением и никогда не упоминалась в классической литературе. [116]

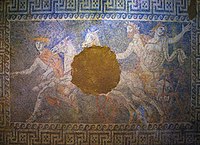

Мозаика

[ редактировать ]

Первоначально мозаика изготавливалась из округлой гальки, а затем из стекла с мозаикой , которая придавала больше цвета и плоскую поверхность. Они были популярны в эллинистический период, сначала как украшение полов дворцов, а затем и частных домов. [118] Часто центральное изображение эмблемы на центральной панели было выполнено гораздо лучше, чем окружающий его декор. [119] Мотивы Ксении , где в доме демонстрировались образцы разнообразной еды, которую гости могут ожидать, представляют собой большинство сохранившихся образцов греческого натюрморта . В целом мозаику следует рассматривать как вторичное средство копирования живописи, часто очень непосредственное, как в Александровской мозаике . [120]

«Неподметенный пол» Соса из Пергама ( ок. 200 г. до н.э. ) был оригинальной и знаменитой пьесой в стиле тромпель , известной по многим греко-римским копиям. По словам Джона Бордмана , Сосус — единственный художник-мозаика, имя которого сохранилось; его Голуби также упоминаются в литературе и копируются. [121] Однако Кэтрин, доктор медицинских наук Данбабин, утверждает, что два разных художника-мозаика оставили свои подписи на мозаиках Делоса . [122] Художник мозаики «Охота на оленя» IV века до нашей эры , возможно, также оставил свою подпись как «Гнозис» , хотя это слово может быть ссылкой на абстрактную концепцию знания. [123]

Мозаики являются важным элементом сохранившегося македонского искусства, большое количество образцов сохранилось в руинах Пеллы , древней македонской столицы , в сегодняшней Центральной Македонии . [124] Мозаики, такие как мозаика «Охота на оленя и охота на льва», демонстрируют иллюзионистские и трехмерные качества, обычно присущие эллинистическим картинам, хотя деревенское македонское стремление к охоте заметно более выражено, чем другие темы. [125] (Греция ) II века до нашей эры Мозаика Делоса была оценена Франсуа Шаму как вершина эллинистического мозаичного искусства, с похожими стилями, которые продолжались на протяжении всего римского периода и, возможно, заложили основу для широкого использования мозаики в западном мире через до средневековья . [118]

- Мозаика изображающая кастовой гробницы в Амфиполе, , IV век похищение Персефоны Плутоном до нашей эры.

- Александр Македонский (слева) в каузии и сражается с азиатским львом со своим другом Кратером (фрагмент); конца IV века до н.э. Мозаика из Пеллы [126]

- Деталь напольной панели с александрийским попугаем , Пергам, современная Турция , середина II века до нашей эры (правление Евмена II и Аттала II )

- Птолемеевская мозаика с изображением собаки и сосуда для вина аскоса из эллинистического Египта , датированная 200-150 гг. до н. э.

- Эллинистическая мозаика из Тмуиса ( Мендеса ), Египет, подписанная Софилом ок. 200 г. до н. э .; Птолемеевская царица Береника II (совместная правительница со своим мужем Птолемеем III ) как олицетворение Александрии. [127]

Гравированные драгоценные камни

[ редактировать ]

Гравированный драгоценный камень был произведением искусства класса люкс и имел высокий престиж; Помпей и Юлий Цезарь были среди более поздних коллекционеров. [128] Эта техника имеет древнюю традицию на Ближнем Востоке , а цилиндрические печати , дизайн которых появляется только при катании по влажной глине, из которой развился тип плоского кольца, распространились в Минойский мир, включая части Греции и Кипра . Греческая традиция возникла под минойским влиянием на культуру материковой Эллады и достигла апогея утонченности и утонченности в эллинистический период. [129]

Круглые или овальные греческие драгоценные камни (наряду с аналогичными предметами из кости и слоновой кости) встречаются с 8-го и 7-го веков до нашей эры, обычно с животными в энергичных геометрических позах, часто с границей, отмеченной точками или ободком. [130] Ранние образцы в основном выполнены из более мягких камней. Геммы VI века чаще овальные, [131] со спиной скарабея (в прошлом этот тип назывался «скарабей») и фигурами людей или божеств, а также животных; форма скарабея, по-видимому, была заимствована из Финикии . [132]

Формы для того периода сложны, несмотря на обычно небольшой размер драгоценных камней. [96] В V веке драгоценные камни стали несколько крупнее, но все еще имели высоту всего 2–3 сантиметра. Несмотря на это, показаны очень мелкие детали, в том числе ресницы на одной мужской голове, возможно, на портрете. Четыре драгоценных камня, подписанные Дексаменом Хиосским, являются лучшими того периода, на двух из них изображены цапли . [133]

Рельефная резьба стала распространенной в Греции в V веке до нашей эры, и постепенно большинство впечатляющих резных драгоценных камней стали рельефными. Обычно рельефное изображение производит большее впечатление, чем глубокое; в более ранней форме получатель документа видел это в отпечатанном сургуче, тогда как в более поздних рельефах владелец печати сохранял ее себе, что, вероятно, знаменовало появление драгоценных камней, предназначенных для коллекционирования или ношения в качестве ювелирных подвесок. в ожерельях и тому подобном, а не в качестве печатей - более поздние иногда бывают довольно большими, чтобы использовать их для запечатывания писем. Однако надписи обычно по-прежнему перевернуты («зеркальное письмо»), поэтому правильно читаются только по отпечаткам (или при просмотре сзади с помощью прозрачных камней). Этот аспект также частично объясняет коллекционирование оттисков из гипса или воска с драгоценных камней, которые, возможно, легче оценить, чем оригинал.

Более крупные резные изделия из твердого камня и камеи , которые редко встречаются в форме глубокой печати, по-видимому, достигли Греции примерно в III веке; Фарнезе Тацца - единственный крупный сохранившийся эллинистический образец (в зависимости от дат, присвоенных камее Гонзаги и Чаше Птолемеев ), но другие имитации стеклянной пасты с портретами предполагают, что камеи типа драгоценных камней были изготовлены в этот период. [134] Завоевания Александра открыли новые торговые пути в греческий мир и увеличили ассортимент доступных драгоценных камней. [135]

Орнамент

[ редактировать ]

Синтез в архаический период местного репертуара простых геометрических мотивов с импортированными, в основном растительными мотивами с дальнего востока, создал значительный словарь орнаментов, который художники и мастера использовали уверенно и бегло. [136] Сегодня этот словарь можно увидеть, прежде всего, в большом корпусе расписной керамики, а также в архитектурных памятниках, но изначально он использовался в широком спектре средств массовой информации, поскольку более поздняя его версия используется в европейском неоклассицизме .

Элементы этого словаря включают геометрический меандр или «греческий ключ», яйцо и дротик , бусину и катушку , витрувианский свиток , гильошировку , а из растительного мира — стилизованные листья аканта , волюту , пальметту и полупальметту, растительные свитки из различные виды , розетка , цветок лотоса и цветок папируса . Первоначально они широко использовались на архаических вазах, но по мере развития фигуративной живописи их обычно использовали в качестве границ, разграничивающих края вазы или различные зоны декора. [137] Греческая архитектура отличалась разработкой сложных способов использования лепнины и других архитектурных декоративных элементов, в которых эти мотивы использовались в гармонично интегрированном целом.

Еще до классического периода этот словарь оказал влияние на кельтское искусство, а расширение греческого мира после Александра и экспорт греческих предметов еще дальше открыли для него большую часть Евразии , включая регионы на севере Индийского субконтинента. где буддизм распространялся и создавал греко-буддийское искусство . По мере того как буддизм распространялся по Центральной Азии в Китай и остальную Восточную Азию , в форме, которая широко использовала религиозное искусство, версии этого словаря были взяты вместе с ним и использовались для окружения изображений будд и других религиозных изображений, часто размером и акцент, который древним грекам показался бы чрезмерным. Лексика впиталась в орнамент Индии, Китая, Персии и других азиатских стран, а также получила дальнейшее развитие в византийском искусстве . [138] Римляне переняли словарный запас более или менее полностью, и, хотя он сильно изменился, его можно проследить во всем европейском средневековом искусстве , особенно в растительном орнаменте.

Исламское искусство , где орнамент в значительной степени заменяет фигуру, развило византийский растительный свиток в полную, бесконечную арабеску и особенно в результате монгольских завоеваний 14 века получило новое влияние из Китая, включая потомков греческой лексики. [139] Начиная с эпохи Возрождения, некоторые из этих азиатских стилей были представлены в текстиле, фарфоре и других товарах, импортированных в Европу, и повлияли на орнамент там, и этот процесс продолжается до сих пор.

Другое искусство

[ редактировать ]Справа: эллинистический сатир, носящий деревенскую перизому (набедренную повязку) и несущий педум (пастушеский посох). Аппликация цвета слоновой кости, вероятно, для мебели.

Хотя стекло производилось на Кипре в 9 веке до нашей эры и к концу этого периода было значительно развито, сохранилось лишь несколько сохранившихся изделий из стекла до греко-римского периода, которые демонстрируют художественное качество лучших работ. [140] Большинство сохранившихся предметов представляют собой небольшие флаконы для духов, выполненные в причудливом цветном стиле с «перьями», похожие на другое средиземноморское стекло . [141] Эллинистическое стекло стало дешевле и доступно более широким слоям населения.

Никакой греческой мебели не сохранилось, но ее изображений много на вазах и мемориальных рельефах, например, Хегесо . Очевидно, он часто был очень элегантным, как и стили, возникшие на его основе, начиная с 18 века. Сохранились некоторые кусочки резной слоновой кости, которые использовались в качестве инкрустаций, как, например, в Вергине, а также несколько резных фигурок из слоновой кости; это было роскошное искусство, которое могло быть очень высокого качества. [142]

Судя по росписям на вазах, греки часто носили одежду с искусным узором, а умение ткать было признаком респектабельной женщины. Сохранились два роскошных куска ткани из гробницы Филиппа Македонского . [143] Существует множество упоминаний о декоративных драпировках как для домов, так и для храмов, но ни одно из них не сохранилось.

Распространение и наследие

[ редактировать ]

Древнегреческое искусство оказало значительное влияние на культуру многих стран мира, прежде всего на трактовку человеческой фигуры. На Западе греческая архитектура также имела огромное влияние, и как на Востоке, так и на Западе влияние греческого декора можно проследить до наших дней. Этрусское и римское искусство во многом и непосредственно заимствовано из греческих моделей. [144] а греческие предметы и влияние проникли в кельтское искусство к северу от Альп, [145] а также по всему Средиземноморью и в Персию. [146]

На Востоке завоевания Александра Великого положили начало многовековому обмену между греческой, среднеазиатской и индийской культурами, чему во многом способствовало распространение буддизма , который на раннем этапе ухватил многие греческие черты и мотивы в греко-буддийском искусстве . которые затем были переданы как часть культурного пакета в Восточную Азию , даже в Японию , среди художников, которые, несомненно, совершенно не знали о происхождении мотивов и стилей, которые они использовали. [147]

После эпохи Возрождения в Европе гуманистическая эстетика и высокие технические стандарты греческого искусства вдохновили поколения европейских художников, при этом значительное возрождение движения неоклассицизма началось в середине 18 века, что совпало с облегчением доступа из Западной Европы в Грецию. сам по себе, а также возобновление импорта греческих оригиналов, в первую очередь Элгинских мраморов из Парфенона. В XIX веке классическая традиция, заимствованная из Греции, доминировала в искусстве западного мира. [148]

Историография

[ редактировать ]Эллинизированные римские высшие классы Поздней республики и Ранней Империи в целом без особых придирок признавали греческое превосходство в искусстве, хотя похвала Плиния за скульптуру и живопись доэллинистических художников может быть основана на более ранних греческих сочинениях, а не на личных знаниях. . Плиний и другие классические авторы были известны в эпоху Возрождения, и это предположение о превосходстве Греции снова стало общепринятым. Однако критики эпохи Возрождения и намного позже неясно, какие произведения на самом деле были греческими. [149]

входившую в состав Османской империи До середины 18 века в Грецию, , могли попасть лишь очень немногие западноевропейцы. Не только греческие вазы, найденные на этрусских кладбищах, но также (что более спорно) греческие храмы Пестума считались этрусскими или, иначе говоря, италийскими, до конца 18 века и позже, заблуждение, поддерживаемое итальянскими националистическими настроениями. [149]

Сочинения Иоганна Иоахима Винкельмана , особенно его книги « Мысли о подражании греческим произведениям в живописи и скульптуре» (1750) и «Geschichte der Kunst des Alterthums » («История древнего искусства», 1764) были первыми, в которых резко различалось древнегреческое, Этрусское и римское искусство, а также определяют периоды в греческом искусстве, прослеживая траекторию от роста к зрелости, а затем к имитации или декадансу, которая продолжает оказывать влияние и по сей день. [150]

Полное отделение греческих статуй от их более поздних римских копий и лучшее понимание баланса между греческим и римским характером в греко-римском искусстве заняло гораздо больше времени и, возможно, продолжается до сих пор. [151] Греческое искусство, особенно скульптура, продолжало пользоваться огромной репутацией, и его изучение и копирование составляли значительную часть подготовки художников вплоть до упадка академического искусства в конце 19 века. За этот период фактически известный корпус греческого искусства и, в меньшей степени, архитектуры значительно расширился. В конце 19-го и 20-го веков по изучению ваз возникла огромная литература, во многом основанная на идентификации рук отдельных художников, которых был сэр Джон Бизли ведущей фигурой . В этой литературе обычно предполагалось, что роспись ваз представляет собой развитие независимой среды, лишь в общих чертах опираясь на стилистическое развитие других художественных средств. В последние десятилетия это предположение все чаще подвергается сомнению, и некоторые ученые теперь рассматривают его как вторичный носитель, в основном представляющий собой дешевые копии ныне утраченных металлических изделий, большая часть которых была сделана не для обычного использования, а для хранения в захоронениях. [152]

См. также

[ редактировать ]| История искусства |

|---|

| Часть серии о |

| История греческого искусства |

|---|

|

| История древнего искусства |

|---|

| Средний Восток |

| Азия |

| Европейская предыстория |

| Классическое искусство |

- Дионисийское искусство

- Смерть в древнегреческом искусстве

- Парфянское искусство

- Список древнегреческих храмов

- Национальный археологический музей Афин

- Классическая архитектура

Примечания

[ редактировать ]- ^ Бордман, 3–4; Кук, 1–2

- ^ Кук, 12 лет.

- ^ Кук, 14–18.

- ↑ Афина в эгиде, фрагмент сцены, изображающей Геракла и Иолая в сопровождении Афины, Аполлона и Гермеса. Брюшко аттической чернофигурной гидрии, Кабинет медалей, Париж, инв. 254.

- ↑ Домашняя страница. Архивировано 18 мая 2019 г. в Wayback Machine of the Corpus vasorum antiquorum , по состоянию на 16 мая 2016 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Кук, 24–26 лет.

- ^ Кук, 27–28; Бордман, 26, 32, 108–109; Вудфорд, 12 лет

- ^ Предисловие к древнегреческой керамике (Справочники Ашмола) Майкла Викерса (1991)

- ↑ Бордман, 86 лет, цитируется.

- ^ Кук, 24–29.

- ^ Аполлон в лавровом или миртовом венке, белом пеплосе, красном гиматии и сандалиях, восседающий на дифросе со львиными лапами; в левой руке он держит кифару, а правой совершает возлияние. Перед ним черная птица, идентифицированная как голубь, галка, ворона (что может быть намеком на его роман с Коронис) или ворон (мантическая птица). Тондо аттического киликса с белым фоном, приписываемое художнику Пистоксену (или берлинскому художнику, или Онисиму). Диам. 18 см (7,1 дюйма)

- ^ Кук, 30, 36, 48–51.

- ^ Кук, 37–40, 30, 36, 42–48.

- ^ Кук, 29 лет; Вудворд, 170 лет.

- ^ Бордман, 27 лет; Кук, 34–38 лет; Уильямс, 36, 40, 44; Вудфорд, 3–6

- ^ Кук, 38–42; Уильямс, 56 лет

- ^ Вудфорд, 8–12; Кук, 42–51.

- ^ Вудфорд, 57–74; Кук, 52–57 лет.

- ^ Бордман, 145–147; Кук, 56–57 лет.

- ^ Трендалл, Артур Д. (апрель 1989 г.). Краснофигурные вазы Южной Италии: Справочник . Темза и Гудзон. п. 17. ISBN 978-0500202258 .

- ^ Бордман, 185–187.

- ^ Бордман, 150; Кук, 159 лет; Уильямс, 178 лет

- ^ Кук, 160 лет.

- ^ Кук, 161–163.

- ^ Бордман, 64–67; Карузу, 102

- ^ Карузу, 114–118; Кук, 162–163; Бордман, 131–132.

- ^ Кук, 159

- ↑ Кук, 159 лет, цитируется.

- ^ Расмуссен, xiii. Однако, поскольку металлические сосуды не сохранились, «такое отношение далеко не продвинет».

- ^ Соудер, Эми. «Древнегреческие бронзовые сосуды» на Хронологии истории искусств Хайльбрунна. Нью-Йорк: Метрополитен-музей, 2000–. онлайн (апрель 2008 г.)

- ^ Кук, 162; Бордман, 65–66 лет.

- ^ Бордман, 185–187; Кук, 163 года

- ^ Бордман, 131–132, 150, 355–356.

- ^ Бордман, 149–150.

- ^ Бордман, 131, 187; Уильямс, 38–39, 134–135, 154–155, 180–181, 172–173

- ^ Бордман, 148; Уильямс, 164–165.

- ^ Бордман, 131–132; Уильямс, 188–189, пример, сделанный для иберийского кельтского рынка.

- ^ Ритон. Верхняя часть роскошного сосуда для питья вина выполнена из серебряной пластины с позолоченным краем с рельефной веткой плюща. Нижняя часть выполнена из литой лошади Протома. Работа греческого мастера, вероятно, для фракийского аристократа. Возможно, Фракия, конец IV века до н.э. НГ Прага, Дворец Кинских, NM-HM10 1407.

- ^ Кук, 19 лет.

- ^ Вудфорд, 39–56.

- ^ Кук, 82–85.

- ^ Смит, 11 лет.

- ^ Кук, 86–91, 110–111.

- ^ Кук, 74–82.

- ^ Кеннет Д.С. Лапатин. Хризелефантиновая скульптура в древнем средиземноморском мире . Издательство Оксфордского университета, 2001. ISBN 0-19-815311-2

- ^ Кук, 74–76.

- ^ Бордман, 33–34.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Коннор, Саймон (1 января 2019 г.). «Ашмави, Айман, Саймон Коннор и Дитрих Рауэ 2019. Псамтик I в Гелиополе. Египетская археология 55, 34-39» . Египетская археология : 38–39.

- ^ Смит, Уильям Стивенсон; Симпсон, Уильям Келли (1 января 1998 г.). Искусство и архитектура Древнего Египта . Издательство Йельского университета. п. 235. ИСБН 978-0-300-07747-6 .

- ^ Кук, 99 лет; Вудфорд, 44, 75 лет.

- ^ Кук, 93 года.

- ^ Бордман, 47–52; Кук, 104–108; Вудфорд, 38–56.

- ^ Бордман, 47–52; Кук, 104–108; Вудфорд, 27–37 лет.

- ^ Бордман, 92–103; Кук, 119–131; Вудфорд, 91–103, 110–133.

- ^ Таннер, Джереми (2006). Изобретение истории искусств в Древней Греции: религия, общество и художественная рационализация . Издательство Кембриджского университета. п. 97. ИСБН 9780521846141 .

- ^ КАН, ГЕРБЕРТ А.; ЖЕРЕН, ДОМИНИК (1988). «Фемистокл в Магнезии». Нумизматическая хроника . 148 : 19. JSTOR 42668124 .

- ^ Бордман, 111–120; Кук, 128 лет; Вудфорд, 91–103, 110–127.

- ^ Бордман, 135, 141; Кук, 128–129, 140; Вудфорд, 133

- ^ Вудфорд, 128–134; Бордман, 136–139; Кук, 123–126.

- ^ Бордман, 119; Вудфорд, 128–130.

- ^ Смит, 7, 9

- ^ Смит, 11, 19–24, 99.

- ^ Смит, 14–15, 255–261, 272.

- ^ Смит, 33–40, 136–140.

- ^ Смит, 127–154.

- ^ Смит, 77–79

- ^ Смит, 99–104; Фотография Коленопреклоненного юного Галла , Лувр

- ^ Смит, 104–126.

- ^ Смит, 240–241.

- ^ Смит, 258-261.

- ^ Смит, 206, 208-209.

- ^ Смит, 210

- ^ Смит, 205

- ^ «Идол колокола» , Лувр.

- ^ Уильямс, 182, 198–201; Бордман, 63–64; Смит, 86 лет

- ^ Уильямс, 42, 46, 69, 198.

- ^ Кук, 173–174.

- ^ Кук, 178, 183–184.

- ^ Кук, 178–179.

- ^ Кук, 184–191; Бордман, 166–169.

- ^ Кук, 186

- ^ Кук, 190–191.

- ^ Кук, 241–244.

- ^ Бордман, 169–171.

- ^ Кук, 185–186.

- ^ Кук, 179–180, 186.

- ^ Кук, 193–238 дает подробное описание.

- ^ Кук, 191–193.

- ^ Кук, 211–214.

- ^ Кук, 218

- ^ Бордман, 159–160, 164–167.

- ^ еще одна реконструкция

- ^ Хоугего, 1–2

- ^ Jump up to: а б Кук, 171–172.

- ^ Хоугего, 44–46, 48–51.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Бордман, 68–69 лет.

- ^ «Редкая фракция серебра, недавно идентифицированная как монета Фемистокла из Магнезии, даже имеет бородатый портрет великого человека, что делает ее, безусловно, самой ранней датируемой портретной монетой. Другие ранние портреты можно увидеть на монетах ликийских династий». Каррадис, Ян; Прайс, Мартин (1988). Чеканка монет в греческом мире . Сиби. п. 84. ИСБН 9780900652820 .

- ^ Хоугего, 63–67.

- ^ Уильямс, 112

- ^ Роджер Линг, «Греция и эллинистический мир»

- ^ Кук, 22, 66.

- ↑ 24-летний Кук говорит, что более 1000 художников-вазописцев были идентифицированы по их стилю.

- ^ Кук, 59–70.

- ^ Кук, 59–69, 66, цитируется.

- ^ Босток, Джон. «Естественная история» . Персей . Университет Тафтса . Проверено 23 марта 2017 г.

- ^ Леонард Уибли, Товарищ по греческим исследованиям, 3-е изд. 1916, с. 329.

- ^ Кук, 61 год;

- ^ Бордман, 177–180.

- ^ Бордман, 174–177.

- ^ Бордман, 338–340; Уильямс, 333 года

- ^ Коэн, 28 лет.

- ^ Христопулос, Лукас (август 2012 г.). Майр, Виктор Х. (ред.). «Эллины и римляне в Древнем Китае (240 г. до н.э. – 1398 г. н.э.)» (PDF) . Китайско-платонические статьи (230). Кафедра восточноазиатских языков и цивилизаций Пенсильванского университета: 15–16. ISSN 2157-9687 .

- ^ Сабатини, Паоло (2 мая 2012 г.). «Антуан Златоуст Катремер де Куинси (1755-1849) и повторное открытие полихромии в греческой архитектуре: цветовые техники и археологические исследования на страницах «Зевса Олимпийского». » (PDF) .

- ^ Кук, 182–183.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Вудфорд, 173–174; Кук, 75–76, 88, 93–94, 99.

- ^ Кук, 59–63.

- ^ См.: Чагг, Эндрю (2006). Любовники Александра . Роли, Северная Каролина: Лулу. ISBN 978-1-4116-9960-1 , стр. 78-79.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Шаму, 375

- ^ Бордман, 154 года.

- ^ Бордман, 174–175, 181–185.

- ^ Бордман, 183–184.

- ^ Данбабин, 33 года.

- ^ Коэн, 32 года.

- ^ Хардиман, 517

- ^ Хардиман, 518

- ^ Палагия, Ольга (2000). «Костер Гефестиона и царская охота Александра». В Босворте, AB; Бэйнхэм, Э.Дж. (ред.). Александр Македонский в реальности и вымысле . Издательство Оксфордского университета. п. 185. ИСБН 9780198152873 .

- ^ Флетчер, Джоанн (2008). Клеопатра Великая: женщина, стоящая за легендой . Нью-Йорк: Харпер. ISBN 978-0-06-058558-7 , изображения и подписи между стр. 246–247.

- ^ для Цезаря: De Vita Caesarum, Divus Iulius , (Жизни Цезарей, Обожествленный Юлий), онлайн-текст Фордхэма ; для Помпея: главы 4–6 книги 37 « Естественной истории Плиния Старшего» дают краткое изложение истории искусства греческой и римской традиции, а также римского коллекционирования.

- ^ Бордман, 39, 67–68, 187, 350.

- ^ Бордман, 39 лет. Для получения более подробной информации см. Бизли.

- ^ «Лентикулярные» или «лентоидные» драгоценные камни имеют форму линзы .

- ^ Бизли, Поздние архаичные греческие драгоценные камни: введение.

- ^ Бордман, 129–130.

- ^ Бордман, 187–188.

- ^ Бизли, «Эллинистические жемчужины: введение»

- ^ Кук, 39–40.

- ^ Роусон, 209–222; Кук, 39 лет

- ^ Роусон, повсюду, но для справки: 23, 27, 32, 39–57, 75–77.

- ^ Роусон, 146–163, 173–193.

- ^ Уильямс, 190

- ^ Уильямс, 214

- ^ Бордман, 34, 127, 150.

- ^ Бордман, 150 лет.

- ^ Бордман, 349–353; Кук, 155–156; Уильямс, 236–248.

- ^ Бордман, 353–354.

- ^ Бордман, 354–369.

- ^ Бордман, 370–377.

- ^ Кук, 157–158.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Чезерани, Джованна (2012). Затерянная Греция Италии: Великая Греция и создание современной археологии . Издательство Оксфордского университета. стр. 49–66. ISBN 978-0-19-987679-2 .

- ^ Честь, 57–62.

- ^ См . «Классическое искусство от Греции до Рима » Джона Хендерсона и Мэри Бирд , 2001), ISBN 0-19-284237-4 ; Честь, 45–46.

- ^ См. Расмуссен, «Принятие подхода» Мартина Робертсона и Мэри Бирд , а также предисловие к книге «Древнегреческая керамика (Справочники Ашмола)» Майкла Викерса (1991).

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- «Бизли» Центр исследования классического искусства Оксфордского университета. Архив Бизли. Архивировано 19 августа 2010 г. на Wayback Machine - обширный веб-сайт, посвященный классическим драгоценным камням; заголовки страниц, используемые в качестве ссылок

- Бордман, редактор Джона, Оксфордская история классического искусства , Oxford University Press , 1993, ISBN 0198143869