Swami Vivekananda

Vivekananda | |

|---|---|

স্বামী বিবেকানন্দ | |

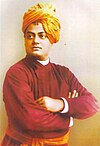

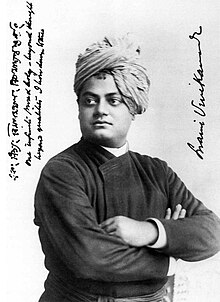

Vivekananda in Chicago, September 1893. In note on the left Vivekananda wrote: "One infinite pure and holy – beyond thought beyond qualities I bow down to thee".[1] | |

| Personal | |

| Born | Narendranath Datta 12 January 1863 |

| Died | 4 July 1902 (aged 39) |

| Religion | Hinduism |

| Citizenship | British subject |

| Era | Modern philosophy |

| Region | Eastern philosophy |

| School | |

| Lineage | Daśanāmi Sampradaya |

| Alma mater | University of Calcutta (BA) |

| Signature | |

| Organization | |

| Founder of | |

| Philosophy | Advaita Vedanta[2][3] Rāja Yoga[3] |

| Religious career | |

| Guru | Ramakrishna |

Disciples | |

Influenced by | |

| Literary works | |

"Arise, awake, and stop not till the goal is reached"

(more on Wikiquote)

Swami Vivekananda (/ˈswɑːmi ˌvɪveɪˈkɑːnəndə/; Bengali: [ʃami bibekanɔndo] ; IAST: Svāmī Vivekānanda ; 12 January 1863 – 4 July 1902), born Narendranath Datta (Bengali: [nɔrendronatʰ dɔto]), was an Indian Hindu monk, philosopher, author, religious teacher, and the chief disciple of the Indian mystic Ramakrishna.[4][5] He was a key figure in the introduction of Vedanta and Yoga to the Western world,[6][7][8] and is the father of modern Indian nationalism who is credited with raising interfaith awareness and bringing Hinduism to the status of a major world religion in the late nineteenth century.[9]

Born into an aristocratic Bengali Kayastha family in Calcutta, Vivekananda was inclined from a young age towards religion and spirituality. He later found his guru Ramakrishna and became a monk. After the death of Ramakrishna, Vivekananda extensively toured the Indian subcontinent as a wandering monk and acquired first-hand knowledge of the living conditions of Indian people in then British India. Moved by their plight, he resolved to help them and found a way to travel to the United States, where he became a popular figure after the 1893 Parliament of Religions in Chicago at which he delivered his famous speech beginning with the words: "Sisters and brothers of America ..." while introducing Hinduism to Americans.[10][11] He made such an impression there that an American newspaper described him as "an orator by divine right and undoubtedly the greatest figure at the Parliament".[12]

After great success at the Parliament, in the subsequent years, Vivekananda delivered hundreds of lectures across the United States, England, and Europe, disseminating the core tenets of Hindu philosophy, and founded the Vedanta Society of New York and the Vedanta Society of San Francisco (now Vedanta Society of Northern California),[13] both of which became the foundations for Vedanta Societies in the West. In India, he founded the Ramakrishna Math, which provides spiritual training for monastics and householders, and the Ramakrishna Mission, which provides charity, social work and education.[7]

Vivekananda was one of the most influential philosophers and social reformers in his contemporary India, and the most successful missionary of Vedanta to the Western world. He was also a major force in contemporary Hindu reform movements and contributed to the concept of nationalism in colonial India.[14] He is now widely regarded as one of the most influential people of modern India and a patriotic saint. His birthday in India is celebrated as National Youth Day.[15][16]

Early life (1863–1888)

Birth and childhood

Vivekananda was born as Narendranath Datta (name shortened to Narendra or Naren)[18] in a Bengali Kayastha family[19][20] in his ancestral home at 3 Gourmohan Mukherjee Street in Calcutta,[21] the capital of British India, on 12 January 1863 during the Makar Sankranti festival.[22] He belonged to a traditional family and was one of nine siblings.[23] His father, Vishwanath Datta, was an attorney at the Calcutta High Court.[19][24] Durgacharan Datta, Narendra's grandfather was a Sanskrit and Persian scholar[25] who left his family and became a monk at age twenty-five.[26] His mother, Bhubaneswari Devi, was a devout housewife.[25] The progressive, rational attitude of Narendra's father and the religious temperament of his mother helped shape his thinking and personality.[27][28] Narendranath was interested in spirituality from a young age and used to meditate before the images of deities such as Shiva, Rama, Sita, and Mahavir Hanuman.[29] He was fascinated by wandering ascetics and monks.[28] Narendra was mischievous and restless as a child, and his parents often had difficulty controlling him. His mother said, "I prayed to Shiva for a son and he has sent me one of his demons".[26]

Education

In 1871, at the age of eight, Narendranath enrolled at Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar's Metropolitan Institution, where he went to school until his family moved to Raipur in 1877.[30] In 1879, after his family's return to Calcutta, he was the only student to receive first-division marks in the Presidency College entrance examination. [31] He was an avid reader in a wide range of subjects, including philosophy, religion, history, social science, art and literature.[32] He was also interested in Hindu scriptures, including the Vedas, the Upanishads, the Bhagavad Gita, the Ramayana, the Mahabharata and the Puranas. Narendra was trained in Indian classical music,[33] and regularly participated in physical exercise, sports and organised activities. Narendra studied Western logic, Western philosophy and European history at the General Assembly's Institution (now known as the Scottish Church College).[34] In 1881, he passed the Fine Arts examination, and completed a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1884.[35][36] Narendra studied the works of David Hume, Immanuel Kant, Johann Gottlieb Fichte, Baruch Spinoza, Georg W. F. Hegel, Arthur Schopenhauer, Auguste Comte, John Stuart Mill and Charles Darwin.[37][38] He became fascinated with the evolutionism of Herbert Spencer and corresponded with him,[39][40] translating Herbert Spencer's book Education (1861) into Bengali.[41] While studying Western philosophers, he also learned Sanskrit scriptures and Bengali literature.[38]

William Hastie (principal of Christian College, Calcutta; from where Narendra graduated) wrote, "Narendra is really a genius. I have travelled far and wide but I have never come across a lad of his talents and possibilities, even in German universities, among philosophical students. He is bound to make his mark in life".[42]

Narendra was known for his prodigious memory and the ability at speed reading. Several incidents have been given as examples. In a talk, he once quoted verbatim, two or three pages from Pickwick Papers. Another incident that is given is his argument with a Swedish national where he gave reference to some details on Swedish history that the Swede originally disagreed with but later conceded. In another incident with Dr. Paul Deussen's at Kiel in Germany, Vivekananda was going over some poetical work and did not reply when the professor spoke to him. Later, he apologised to Dr. Deussen explaining that he was too absorbed in reading and hence did not hear him. The professor was not satisfied with this explanation, but Vivekananda quoted and interpreted verses from the text, leaving the professor dumbfounded about his feat of memory. Once, he requested some books written by Sir John Lubbock from a library and returned them the very next day, claiming that he had read them. The librarian refused to believe him, until cross-examination about the contents convinced him that Vivekananda was indeed being truthful.[43]

Some accounts have called Narendra a shrutidhara (a person with a prodigious memory).[44]

Initial spiritual forays

In 1880, Narendra joined Keshab Chandra Sen's Nava Vidhan, which was established by Sen after meeting Ramakrishna Paramahamsa and reconverting from Christianity to Hinduism.[45] Narendra became a member of a Freemasonry lodge "at some point before 1884"[46] and of the Sadharan Brahmo Samaj in his twenties, a breakaway faction of the Brahmo Samaj led by Keshab Chandra Sen and Debendranath Tagore.[45][34][47][48] From 1881 to 1884, he was also active in Sen's Band of Hope, which tried to discourage youths from smoking and drinking.[45]

It was in this cultic[49] milieu that Narendra became acquainted with Western esotericism.[50] His initial beliefs were shaped by Brahmo concepts, which denounced polytheism and caste restrictions,[29][51] and a "streamlined, rationalized, monotheistic theology strongly coloured by a selective and modernistic reading of the Upanisads and of the Vedanta."[52] Rammohan Roy, the founder of the Brahmo Samaj who was strongly influenced by unitarianism, strove towards a universalistic interpretation of Hinduism.[52] His ideas were "altered [...] considerably" by Debendranath Tagore, who had a romantic approach to the development of these new doctrines, and questioned central Hindu beliefs like reincarnation and karma, and rejected the authority of the Vedas.[53] Tagore also brought this "neo-Hinduism" closer in line with western esotericism, a development which was furthered by Sen.[54] Sen was influenced by transcendentalism, an American philosophical-religious movement strongly connected with unitarianism, which emphasised personal religious experience over mere reasoning and theology.[55] Sen strived to "an accessible, non-renunciatory, everyman type of spirituality", introducing "lay systems of spiritual practice" which can be regarded as an influence to the teachings Vivekananda later popularised in the west.[56]

Not satisfied with his knowledge of philosophy, Narendra came to "the question which marked the real beginning of his intellectual quest for God."[47] He asked several prominent Calcutta residents if they had come "face to face with God", but none of their answers satisfied him.[57][36] At this time, Narendra met Debendranath Tagore (the leader of Brahmo Samaj) and asked if he had seen God. Instead of answering his question, Tagore said, "My boy, you have the Yogi's eyes."[47][41] According to Banhatti, it was Ramakrishna who really answered Narendra's question, by saying "Yes, I see Him as I see you, only in an infinitely intenser sense."[47] According to De Michelis, Vivekananda was more influenced by the Brahmo Samaj's and its new ideas, than by Ramakrishna.[56] Swami Medhananda agrees that the Brahmo Samaj was a formative influence,[58] but that "it was Narendra's momentous encounter with Ramakrishna that changed the course of his life by turning him away from Brahmoism."[59] According to De Michelis, it was Sen's influence which brought Vivekananda fully into contact with western esotericism, and it was also via Sen that he met Ramakrishna.[60]

Meeting Ramakrishna

In 1881, Narendra first met Ramakrishna, who became his spiritual focus after his own father had died in 1884.[61]

Narendra's first introduction to Ramakrishna occurred in a literature class at General Assembly's Institution when he heard Professor William Hastie lecturing on William Wordsworth's poem, The Excursion.[51] While explaining the word "trance" in the poem, Hastie suggested that his students visit Ramakrishna of Dakshineswar to understand the true meaning of trance. This prompted some of his students (including Narendra) to visit Ramakrishna.[62][63][64]

They probably first met personally in November 1881,[note 1] though Narendra did not consider this their first meeting, and neither man mentioned this meeting later.[62] At this time, Narendra was preparing for his upcoming F. A. examination, when Ram Chandra Datta accompanied him to Surendra Nath Mitra's, house where Ramakrishna was invited to deliver a lecture.[66] According to Makarand Paranjape, at this meeting Ramakrishna asked young Narendra to sing. Impressed by his singing talent, he asked Narendra to come to Dakshineshwar.[67]

In late 1881 or early 1882, Narendra went to Dakshineswar with two friends and met Ramakrishna.[62] This meeting proved to be a turning point in his life.[68] Although he did not initially accept Ramakrishna as his teacher and rebelled against his ideas, he was attracted by his personality and began to frequently visit him at Dakshineswar.[69] He initially saw Ramakrishna's ecstasies and visions as "mere figments of imagination"[27] and "hallucinations".[70] As a member of Brahmo Samaj, he opposed idol worship, polytheism and Ramakrishna's worship of Kali.[71] He even rejected the Advaita Vedanta of "identity with the absolute" as blasphemy and madness, and often ridiculed the idea.[70] Narendra tested Ramakrishna, who faced his arguments patiently: "Try to see the truth from all angles", he replied.[69]

Narendra's father's sudden death in 1884 left the family bankrupt; creditors began demanding the repayment of loans, and relatives threatened to evict the family from their ancestral home. Narendra, once a son of a well-to-do family, became one of the poorest students in his college.[72] He unsuccessfully tried to find work and questioned God's existence,[73] but found solace in Ramakrishna and his visits to Dakshineswar increased.[74]

One day, Narendra requested Ramakrishna to pray to goddess Kali for their family's financial welfare. Ramakrishna instead suggested him to go to the temple himself and pray. Following Ramakrishna's suggestion, he went to the temple thrice, but failed to pray for any kind of worldly necessities and ultimately prayed for true knowledge and devotion from the goddess.[75][76][77] Narendra gradually grew ready to renounce everything for the sake of realising God, and accepted Ramakrishna as his Guru.[69]

In 1885, Ramakrishna developed throat cancer, and was transferred to Calcutta and (later) to a garden house in Cossipore. Narendra and Ramakrishna's other disciples took care of him during his last days, and Narendra's spiritual education continued. At Cossipore, he experienced Nirvikalpa samadhi.[78] Narendra and several other disciples received ochre robes from Ramakrishna, forming his first monastic order.[79] He was taught that service to men was the most effective worship of God.[27][78] Ramakrishna asked him to care of the other monastic disciples, and in turn asked them to see Narendra as their leader.[80] Ramakrishna died in the early-morning hours of 16 August 1886 in Cossipore.[80][81]

Founding of Ramakrishna Math

After Ramakrishna's death, his devotees and admirers stopped supporting his disciples.[82] Unpaid rent accumulated, and Narendra and the other disciples had to find a new place to live.[83] Many returned home, adopting a Grihastha (family-oriented) way of life.[84] Narendra decided to convert a dilapidated house at Baranagar into a new math (monastery) for the remaining disciples. Rent for the Baranagar Math was low, raised by "holy begging" (mādhukarī). The math became the first building of the Ramakrishna Math: the monastery of the monastic order of Ramakrishna.[68] Narendra and other disciples used to spend many hours in practising meditation and religious austerities every day.[85] Narendra later reminisced about the early days of the monastery:[86]

We underwent a lot of religious practice at the Baranagar Math. We used to get up at 3:00 am and become absorbed in japa and meditation. What a strong spirit of detachment we had in those days! We had no thought even as to whether the world existed or not.

In 1887, Narendra compiled a Bengali song anthology named Sangeet Kalpataru with Vaishnav Charan Basak. Narendra collected and arranged most of the songs of this compilation, but could not finish the work of the book for unfavourable circumstances.[87]

Monastic vows

In December 1886, the mother of Baburam[note 2] invited Narendra and his other brother monks to Antpur village. Narendra and the other aspiring monks accepted the invitation and went to Antpur to spend a few days. In Antpur, on the Christmas Eve of 1886, Narendra, aged 23, and eight other disciples took formal monastic vows at the Radha Gobinda Jiu temple.[88][85] They decided to live their lives as their master lived.[85] Narendranath took the name "Swami Vivekananda".[89]

Travels in India (1888–1893)

In 1888, Narendra left the monastery as a Parivrâjaka— the Hindu religious life of a wandering monk, "without fixed abode, without ties, independent and strangers wherever they go".[90] His sole possessions were a kamandalu (water pot), staff and his two favourite books: the Bhagavad Gita and The Imitation of Christ.[91] Narendra travelled extensively in India for five years, visiting centres of learning and acquainting himself with diverse religious traditions and social patterns.[92][93] He developed sympathy for the suffering and poverty of the people, and resolved to uplift the nation.[92][94] Living primarily on bhiksha (alms), Narendra travelled on foot and by railway (with tickets bought by admirers). During his travels he met, and stayed with Indians from all religions and walks of life: scholars, dewans, rajas, Hindus, Muslims, Christians, paraiyars (low-caste workers) and government officials.[94] On 31 May 1893, Narendra left Bombay for Chicago with the name, as suggested by Ajit Singh of Khetri, "Vivekananda"–a conglomerate of the Sanskrit words: viveka and ānanda, meaning "the bliss of discerning wisdom".[95][96]

First visit to the West (1893–1897)

Vivekananda started his journey to the West on 31 May 1893[97] and visited several cities in Japan (including Nagasaki, Kobe, Yokohama, Osaka, Kyoto and Tokyo),[98] China and Canada en route to the United States,[97] reaching Chicago on 30 July 1893,[99][97] where the "Parliament of Religions" took place in September 1893.[100] The Congress was an initiative of the Swedenborgian layman, and judge of the Illinois Supreme Court, Charles C. Bonney,[101][102] to gather all the religions of the world, and show "the substantial unity of many religions in the good deeds of the religious life."[101] It was one of the more than 200 adjunct gatherings and congresses of the Chicago's World's Fair,[101] and was "an avant-garde intellectual manifestation of [...] cultic milieus, East and West,"[103] with the Brahmo Samaj and the Theosophical Society being invited as representative of Hinduism.[104]

Vivekananda wanted to join, but was disappointed to learn that no one without credentials from a bona fide organisation would be accepted as a delegate.[105] Vivekananda contacted Professor John Henry Wright of Harvard University, who invited him to speak at Harvard.[105] Vivekananda wrote of the professor, "He urged upon me the necessity of going to the Parliament of Religions, which he thought would give an introduction to the nation".[106][note 3] Vivekananda submitted an application, "introducing himself as a monk 'of the oldest order of sannyāsis ... founded by Sankara,'"[104] supported by the Brahmo Samaj representative Protapchandra Mozoombar, who was also a member of the Parliament's selection committee, "classifying the Swami as a representative of the Hindu monastic order."[104] Hearing Vivekananda speak, Harvard psychology professor William James said, "that man is simply a wonder for oratorical power. He is an honor to humanity."[107]

Parliament of the World's Religions

The Parliament of the World's Religions opened on 11 September 1893 at the Art Institute of Chicago, as part of the World's Columbian Exposition.[108][109][110] On this day, Vivekananda gave a brief speech representing India and Hinduism.[111] He was initially nervous, bowed to Saraswati (the Hindu goddess of learning) and began his speech with "Sisters and brothers of America!".[112][110] At these words, Vivekananda received a two-minute standing ovation from the crowd of seven thousand.[113] According to Sailendra Nath Dhar, when silence was restored he began his address, greeting the youngest of the nations on behalf of "the most ancient order of monks in the world, the Vedic order of sannyasins, a religion which has taught the world both tolerance and universal acceptance".[114][note 4] Vivekananda quoted two illustrative passages from the "Shiva mahimna stotram": "As the different streams having their sources in different places all mingle their water in the sea, so, O Lord, the different paths which men take, through different tendencies, various though they appear, crooked or straight, all lead to Thee!" and "Whosoever comes to Me, through whatsoever form, I reach him; all men are struggling through paths that in the end lead to Me."[117] According to Sailendra Nath Dhar, "it was only a short speech, but it voiced the spirit of the Parliament."[117][118]

Parliament President John Henry Barrows said, "India, the Mother of religions was represented by Swami Vivekananda, the Orange-monk who exercised the most wonderful influence over his auditors".[112] Vivekananda attracted widespread attention in the press, which called him the "cyclonic monk from India". The New York Critique wrote, "He is an orator by divine right, and his strong, intelligent face in its picturesque setting of yellow and orange was hardly less interesting than those earnest words, and the rich, rhythmical utterance he gave them". The New York Herald noted, "Vivekananda is undoubtedly the greatest figure in the Parliament of Religions. After hearing him we feel how foolish it is to send missionaries to this learned nation".[119] American newspapers reported Vivekananda as "the greatest figure in the parliament of religions" and "the most popular and influential man in the parliament".[120] The Boston Evening Transcript reported that Vivekananda was "a great favourite at the parliament... if he merely crosses the platform, he is applauded".[121] He spoke several more times "at receptions, the scientific section, and private homes"[114] on topics related to Hinduism, Buddhism and harmony among religions until the parliament ended on 27 September 1893. Vivekananda's speeches at the Parliament had the common theme of universality, emphasising religious tolerance.[122] He soon became known as a "handsome oriental" and made a huge impression as an orator.[123]

Lecture tours in the UK and US

"I do not come", said Swamiji on one occasion in America, "to convert you to a new belief. I want you to keep your own belief; I want to make the Methodist a better Methodist; the Presbyterian a better Presbyterian; the Unitarian a better Unitarian. I want to teach you to live the truth, to reveal the light within your own soul."[124]

After the Parliament of Religions, he toured many parts of the US as a guest. His popularity opened up new views for expanding on "life and religion to thousands".[123] During a question-answer session at Brooklyn Ethical Society, he remarked, "I have a message to the West as Buddha had a message to the East."

Vivekananda spent nearly two years lecturing in the eastern and central United States, primarily in Chicago, Detroit, Boston, and New York. He founded the Vedanta Society of New York in 1894.[125] By spring 1895 his busy, tiring schedule had affected his health.[126] He ended his lecture tours and began giving free, private classes in Vedanta and yoga. Beginning in June 1895, Vivekananda gave private lectures to a dozen of his disciples at Thousand Island Park, New York for two months.[126]

During his first visit to the West he travelled to the UK twice, in 1895 and 1896, lecturing successfully there.[127] In November 1895, he met Margaret Elizabeth Noble an Irish woman who would become Sister Nivedita.[126] During his second visit to the UK in May 1896 Vivekananda met Max Müller, a noted Indologist from Oxford University who wrote Ramakrishna's first biography in the West.[118] From the UK, Vivekananda visited other European countries. In Germany, he met Paul Deussen, another Indologist.[128] Vivekananda was offered academic positions in two American universities (one the chair in Eastern Philosophy at Harvard University and a similar position at Columbia University); he declined both, since his duties would conflict with his commitment as a monk.[126]

Vivekananda's success led to a change in mission, namely the establishment of Vedanta centres in the West.[130] Vivekananda adapted traditional Hindu ideas and religiosity to suit the needs and understandings of his western audiences, who were especially attracted by and familiar with western esoteric traditions and movements like Transcendentalism and New thought.[131] An important element in his adaptation of Hindu religiosity was the introduction of his "four yogas" model, which includes Raja yoga, his interpretation of Patanjali's Yoga sutras,[132] which offered a practical means to realise the divine force within which is central to modern western esotericism.[131] In 1896, his book Raja Yoga was published, becoming an instant success; it was highly influential in the western understanding of yoga, in Elizabeth de Michelis's view marking the beginning of modern yoga.[133][134]

Vivekananda attracted followers and admirers in the US and Europe, including Josephine MacLeod, Betty Leggett, Lady Sandwich, William James, Josiah Royce, Robert G. Ingersoll, Lord Kelvin, Harriet Monroe, Ella Wheeler Wilcox, Sarah Bernhardt, Nikola Tesla, Emma Calvé and Hermann Ludwig Ferdinand von Helmholtz.[27][126][128][135][136] He initiated several followers : Marie Louise (a French woman) became Swami Abhayananda, and Leon Landsberg became Swami Kripananda,[137] so that they could continue the work of the mission of the Vedanta Society. This society still is filled with foreign nationals and is also located in Los Angeles.[138] During his stay in America, Vivekananda was given land in the mountains to the southeast of San Jose, California to establish a retreat for Vedanta students. He called it "Peace retreat", or, Shanti Asrama.[139] The largest American centre is the Vedanta Society of Southern California in Hollywood, one of the twelve main centres. There is also a Vedanta Press in Hollywood which publishes books about Vedanta and English translations of Hindu scriptures and texts.[140] Christina Greenstidel of Detroit was also initiated by Vivekananda with a mantra and she became Sister Christine,[141] and they established a close father–daughter relationship.[142]

From the West, Vivekananda revived his work in India. He regularly corresponded with his followers and brother monks,[note 5] offering advice and financial support. His letters from this period reflect his campaign of social service,[143] and were strongly worded.[144] He wrote to Akhandananda, "Go from door to door amongst the poor and lower classes of the town of Khetri and teach them religion. Also, let them have oral lessons on geography and such other subjects. No good will come of sitting idle and having princely dishes, and saying "Ramakrishna, O Lord!"—unless you can do some good to the poor".[145][146] In 1895, Vivekananda founded the periodical Brahmavadin to teach the Vedanta.[147] Later, Vivekananda's translation of the first six chapters of The Imitation of Christ was published in Brahmavadin in 1899.[148] Vivekananda left for India on 16 December 1896 from England with his disciples Captain and Mrs. Sevier and J.J. Goodwin. On the way, they visited France and Italy, and set sail for India from Naples on 30 December 1896.[149] He was later followed to India by Sister Nivedita, who devoted the rest of her life to the education of Indian women and India's independence.[126][150]

Back in India (1897–1899)

The ship from Europe arrived in Colombo, British Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) on 15 January 1897,[149] and Vivekananda received a warm welcome. In Colombo, he gave his first public speech in the East. From there on, his journey to Calcutta was triumphant. Vivekananda travelled from Colombo to Pamban, Rameswaram, Ramnad, Madurai, Kumbakonam and Madras, delivering lectures. Common people and rajas gave him an enthusiastic reception. During his train travels, people often sat on the rails to force the train to stop, so they could hear him.[149] From Madras (now Chennai), he continued his journey to Calcutta and Almora. While in the West, Vivekananda spoke about India's great spiritual heritage; in India, he repeatedly addressed social issues: uplifting the people, eliminating the caste system, promoting science and industrialisation, addressing widespread poverty and ending colonial rule. These lectures, published as Lectures from Colombo to Almora, demonstrate his nationalistic fervour and spiritual ideology.[151]

On 1 May 1897 in Calcutta, Vivekananda founded the Ramakrishna Mission for social service. Its ideals are based on Karma Yoga,[152][153] and its governing body consists of the trustees of the Ramakrishna Math (which conducts religious work).[154] Both Ramakrishna Math and Ramakrishna Mission have their headquarters at Belur Math.[118][155] Vivekananda founded two other monasteries: one in Mayavati in the Himalayas (near Almora), the Advaita Ashrama and another in Madras (now Chennai). Two journals were founded: Prabuddha Bharata in English and Udbhodan in Bengali.[156] That year, famine-relief work was begun by Swami Akhandananda in the Murshidabad district.[118][154]

Vivekananda earlier inspired Jamsetji Tata to set up a research and educational institution when they travelled together from Yokohama to Chicago on Vivekananda's first visit to the West in 1893. Tata now asked him to head his Research Institute of Science; Vivekananda declined the offer, citing a conflict with his "spiritual interests".[157][158][159] He visited Punjab, attempting to mediate an ideological conflict between Arya Samaj (a reformist Hindu movement) and sanatan (orthodox Hindus).[160] After brief visits to Lahore,[154] Delhi and Khetri, Vivekananda returned to Calcutta in January 1898. He consolidated the work of the math and trained disciples for several months. Vivekananda composed "Khandana Bhava–Bandhana", a prayer song dedicated to Ramakrishna, in 1898.[161]

Второе визит на Запад и последние годы (1899–1902)

Несмотря на снижение здоровья, Вивекананда уехал на Запад во второй раз в июне 1899 года. [ 162 ] в сопровождении сестры Ниведиты и Свами Турияянанда . После краткого пребывания в Англии он отправился в Соединенные Штаты. Во время этого визита Вивекананда основала общества Веданты в Сан -Франциско и Нью -Йорке и основала Шанти Ашрама (Мирное отступление) в Калифорнии. [ 163 ] Затем он отправился в Париж на Конгресс религий в 1900 году. [ 164 ] Его лекции в Париже касались поклонения Лингаму и подлинности Бхагавад Гиты . [ 163 ] Затем Вивекананда посетила Бриттани , Вену , Стамбул , Афины и Египет . Французский философ Жюль Буа был его хозяином в течение большей части этого периода, пока он не вернулся в Калькутту 9 декабря 1900 года. [ 163 ]

После короткого визита в Адваиту Ашраму в Майавати Вивекананда поселился в Белур-Математике, где он продолжил координировать работы миссии Рамакришны, математики и работы в Англии и США. У него было много посетителей, в том числе королевская власть и политики. Хотя Вивекананда не смог присутствовать на Конгрессе религий в 1901 году в Японии из -за ухудшения здоровья, он совершил паломничество в Бодхгая и Варанаси . [ 165 ] Снижение здоровья (включая астму , диабет и хроническую бессонницу ) ограничило его активность. [ 166 ]

Смерть

4 июля 1902 года (день его смерти), [ 167 ] Вивекананда проснулась рано, пошла в монастырь в Белур -Математике и медитировал три часа. Он преподавал Шукла-Яджур-Веда , санскритскую грамматику и философию йоги для учеников, [ 168 ] [ 169 ] Позже обсуждая с коллегами запланированный ведический колледж в математике Рамакришны. В 7:00 вечера Вивекананда отправился в свою комнату, прося не беспокоиться; [ 168 ] Он умер в 9:20 вечера во время медитации . [ 170 ] По словам его учеников, Вивекананда достиг Махасамадхи ; [ 171 ] Разрыв кровеносного сосуда в его мозге был зарегистрирован как возможная причина смерти. [ 172 ] Его ученики полагали, что разрыв произошел из -за его Брахмарандры (открытие в короне его головы), когда он достиг Махасамадхи . Вивекананда выполнил свое пророчество, что он не будет жить сорок лет. [ 173 ] Он был кремирован на сандаловом похоронном пайле на берегу Ганги в Белуре, напротив, где Рамакришна кремировали шестнадцать лет назад. [ 174 ]

Учения и философия

| Часть серии на | |

| Индуистская философия | |

|---|---|

| |

| Ортодоксальный | |

|

|

|

| Гетеродоксальный | |

|

|

|

| Часть серии на |

| Адваита |

|---|

|

|

|

Синтезируя и популяризируя различные пряди индуистской мысли, в первую очередь классическую йогу и (Адваита) Веданту, Вивекананда находился под влиянием западных идей, таких как универсализм , через унитарных миссионеров, которые сотрудничали с Брахмо Самадж . [ 175 ] [ 176 ] [ 177 ] [ 178 ] [ 179 ] Его первоначальные убеждения были сформированы концепциями Брахмо, которые включали в себя веру в бесформенного Бога и искажение идолопоклонства , [ 29 ] [ 51 ] и «обтекаемое, рационализированное монотеистическое богословие, сильно окрашенное селективным и модернистским чтением Упанишадов и Веданты». [ 180 ] Он распространял идею о том, что «божественный, абсолютный, существует во всех людях независимо от социального статуса», [ 181 ] и что «видя божественного как сущность других, будет способствовать любви и социальной гармонии». [ 181 ] Через его принадлежность с Кешуба Чандры Сена Нава Видхан , [ 182 ] Масонство Лодж , [ 183 ] Садхаран Брахмо Самадж , [ 182 ] [ 34 ] [ 47 ] [ 48 ] и группа Сена надежды , Вивекананда познакомилась с западным эзотеризмом . [ 184 ]

На него также повлиял Рамакришна , который постепенно привлек Нарендру к мировоззрению в Веданте, которое «обеспечивает онтологическую основу для« Шиваджьяне дживер Сева », духовной практики служения человеческим существам как реальным проявлениям Бога». [ 185 ]

Вивекананда распространила, что сущность индуизма была лучше всего выражена в философии Аджи Шанкара Адваита Веданта . [ 186 ] Тем не менее, следуя за Рамакришной и в отличие от Адваиты Веданта, Вивекананда полагал, что абсолют является как имманентным, так и трансцендентным. [ Примечание 6 ] По словам Анил Соклала, нео-вантанта «Примирает дваиту или дуализм и адваиту или не-двойник», рассматривает Брахмана как «без секунды», но «как квалифицированные, сагуна и бесстрастные, ниргуна». [ 189 ] [ Примечание 7 ] Вивекананда суммировала Веданту следующим образом, придавая ему современную и универсалистскую интерпретацию, [ 186 ] показывая влияние классической йоги:

Каждая душа потенциально божественна. Цель состоит в том, чтобы проявить эту божественность внутри, контролируя природу, внешнюю и внутреннюю. Делайте это либо на работе, либо поклонениям, либо умственной дисциплинам, либо философией - одним, или несколькими, или все это - и будьте свободны. Это вся религия. Доктрины, или догмы, или ритуалы, или книги, или храмы, или формы, являются всего лишь вторичными деталями.

Акцент Вивекананды на Нирвикалпу Самадхи предшествовали средневековые йогические влияния на Адваиту Веданту. [ 190 ] В соответствии с текстами Адваиты Веданты, такими как Dŗg-Dŗya-Viveka (14 век) и Ведантасара (из Садананды) (15 век), Вивекананда рассматривал Самадхи как средство достижения освобождения. [ 191 ] [ Примечание 8 ]

Вивекананда популяризировал понятие инволюции , термин, который Вивекананда, вероятно, взял у западных , особенно Хелена Блавацкий , в дополнение к представлению Дарвина об эволюции и, возможно, ссылке на Самкхья термин теософов . [ 194 ] Теософские идеи о инволюции имеют «много общего» с «теориями происхождения Бога в гностицизме, каббале и других эзотерических школах». [ 194 ] Согласно Мире Нанде, «Вивекананда использует слово« инволюция », как оно появляется в теософии: происхождение или участие божественного коснга в материю». [ 195 ] С духом Вивекананда ссылается на Прану или Пурушу , полученную («с некоторыми оригинальными поворотами») от Самкхьи и классической йоги , представленных Патанджали в йога -сутрах . [ 195 ]

Вивекананда связала мораль с контролем над разумом, рассматривая истину, чистоту и бескорыстность как черты, которые укрепили ее. [ 196 ] Он посоветовал своим последователям быть святыми, бескорыстными и иметь Шраддху (веру). Вивекананда поддержала Брахмачарья , [ 197 ] полагая в это источник его физической и умственной выносливости и красноречия. [ 198 ]

Знакомство Вивекананды с западным эзотеризмом сделало его очень успешным в западных эзотерических кругах, начиная с его речи в 1893 году в парламенте религий. Вивекананда адаптировал традиционные индуистские идеи и религиозность в соответствии с потребностями и пониманием его западной аудитории, которые особенно привлекали и знакомы с западными эзотерическими традициями и движениями, такими как трансцендентализм и новая мысль . [ 199 ] Важным элементом в его адаптации индуистской религиозности было введение модели его четырех йоги, которая включает в себя Раджа Йогу , его интерпретацию йоги Патанджали йоги , [ 200 ] которые предлагали практические средства для реализации божественной силы, в которой является центральное место для современного западного эзотеризма. [ 201 ] В 1896 году была опубликована его книга Раджа Йога , которая стала мгновенным успехом и оказала большое влияние на западное понимание йоги. [ 202 ] [ 203 ]

Национализм был выдающейся темой в мысли Вивекананды. Он считал, что будущее страны зависит от ее народа, а его учения сосредоточены на человеческом развитии. [ 204 ] Он хотел «привести в движение машины, которая принесет самые благородные идеи к порогу даже самых бедных и самых подлых». [ 205 ]

Влияние и наследие

Вивекананда был одним из самых влиятельных философов и социальных реформаторов в его современной Индии и самых успешных и влиятельных миссионеров Веданты в западный мир . [ 206 ] [ 207 ] В настоящее время он считается одним из самых влиятельных людей современной Индии и индуизма . Махатма Ганди сказал, что после прочтения произведений Вивекананды его любовь к его нации стала в тысячу раз. [ Цитация необходима ] Рабиндранат Тагор предложил изучить работы Вивекананды, чтобы узнать об Индии. [ Цитация необходима ] Активист независимости Индии Субхас Чандра Бозе считал Вивекананду своим духовным учителем. [ Цитация необходима ]

Нео-ведущий

Вивекананда был одним из главных представителей Neo-Vedanta , современной интерпретации отдельных аспектов индуизма в соответствии с западными эзотерическими традициями , особенно трансцендентализмом , новой мыслью и теософией . [ 3 ] Его переосмысление было и очень успешным, создавая новое понимание и оценку индуизма внутри и за пределами Индии, [ 3 ] и была главной причиной восторженного приема йоги, трансцендентальной медитации и других форм индийского духовного самосовершенствования на Западе. [ 208 ] Эйдхананда Бхарати объяснила: «... современные индусы получают свои знания индуизма из Вивекананды, прямо или косвенно». [ 209 ] Вивекананда поддержал идею о том, что все секты в индуизме (и все религии) являются разными путями к одной и той же цели. [ 210 ] Тем не менее, эта точка зрения подверглась критике как упрощение индуизма. [ 210 ]

Индийский национализм

На фоне появляющегося национализма в британской управляемой Индии Вивекананда кристаллизовала националистический идеал. По словам социального реформатора Чарльза Фрира Эндрюса , «бесстрашный патриотизм Свами дал новый цвет национальному движению по всей Индии. Больше, чем любой другой отдельный человек того периода, Вивекананда внес свой вклад в новое пробуждение Индии». [ 211 ] Вивекананда обратил внимание на степень бедности в стране и утверждала, что решение такой бедности была предпосылкой для национального пробуждения. [ 212 ] Его националистические идеи повлияли на многих индийских мыслителей и лидеров. Шри Ауробиндо считал Вивекананду того, кто духовно разбудил Индию. [ 213 ] Махатма Ганди считал его среди немногих индуистских реформаторов, «которые сохранили эту индуистскую религию в состоянии великолепия, сокращая мертвую древесину традиции». [ 214 ]

Именем

В сентябре 2010 года тогдашний министр финансов профсоюзов Пранаб Мукерджи , который впоследствии стал президентом Индии с 2012 по 2017 год, в принципе одобрил проект «Свами Вивекананда» по цене фунтов стерлингов 1 миллиард (12 миллионов долларов США), в том числе в том числе: вовлечение Молодежь с соревнованиями, эссе, дискуссиями и учебными кругами и публикацией работ Вивекананды на нескольких языках. [ 215 ] В 2011 году Колледж полиции Западной Бенгалии был переименован в Академию полиции штата Свами Вивекананда, Западная Бенгалия. [ 216 ] Государственный технический университет в Чхаттисгархе был назван Техническим университетом Чхаттисгарх Свами Вивекананд . [ 217 ] В 2012 году аэропорт Райпур был переименован в аэропорт Свами Вивекананда . [ 218 ]

Празднования

Национальный день молодежи в Индии наблюдается в день рождения Вивекананды (12 января). В тот день, когда он произнес свою речь в парламенте религий (11 сентября), считается «Днем Братства мира». [ 219 ] [ 220 ] 150 -я годовщина рождения Свами Вивекананды была отмечена в Индии и за рубежом. Министерство по делам молодежи и спорта в Индии, официально заметило 2013 год как случай в декларации. [ 221 ]

Фильмы

Индийский режиссер Утпал Синха снял фильм «Свет: Свами Вивекананда» как дань его 150 -й годовщине рождения. [ 222 ] Другие индийские фильмы о его жизни включают в себя: Свами Маллик Вивананда Свами ( 1955 ) Амар Маллик, Вивекананда Модху Бозе Life and . , 1964 ( ) , , Swammy Биресвар 2012) Laser Light Film от Маника Соркара . [ 223 ] Sound of Joy , индийский 3D- анимационный короткометражный фильм, режиссер Суканканский Рой, изображает духовное путешествие Вивекананды. Он выиграл национальную премию кино за лучший нефтеночный анимационный фильм в 2014 году. [ 224 ]

Работа

Лекции

Хотя Вивекананда был могущественным оратором и писателем на английском и бенгальском языке, [ 225 ] Он не был тщательным ученым, [ 226 ] и большинство его опубликованных работ были составлены из лекций, проведенных по всему миру, которые были «в основном доставлены [...] импровизированными и с небольшой подготовкой». [ 226 ] Его главная работа, Раджа Йога , состоит из переговоров, которые он совершил в Нью -Йорке . [ 227 ]

Литературные произведения

Бартаман Бхарат , означает «современная Индия», [ 228 ] это эссе на бенгальском языке, написанное им, впервые опубликованное в марте 1899 года в выпуске Удбодхана , единственного бенгальского журнала по математике Рамакришны и Рамакришны. Эссе было переиздано как книга в 1905 году, а затем собрано в четвертый том полных произведений Свами Вивекананды . [ 229 ] [ 230 ] В этом эссе его рефрен для читателей состоял в том, чтобы почтить и относиться к каждому индейцу как к брату, независимо от того, родился ли он бедным или в Нижней касте. [ 231 ]

Публикации

- Опубликовано в его жизни [ 232 ]

- Sangeet Kalpataru (1887, с Вайшнавским Чараном Басаком) [ 87 ]

- Karma Yoga (1896) [ 233 ] [ 234 ]

- Раджа Йога (1896 [1899 издание]) [ 235 ]

- Философия Веданты: обращение перед выпускником Философского общества (1896)

- Лекции от Коломбо до Альморы (1897)

- Бартаман Бхарат (в бенгальском) (март 1899 г.), Удбодхан

- My Master (1901), компания Baker and Taylor, Нью -Йорк

- Философия Веданты: лекции по Обществу Джанана Йога (1902) Веды, Нью -Йорк OCLC 919769260

- Jnana йога (1899)

- Опубликовано посмертно

Опубликовано после его смерти (1902) [ 232 ]

- Адреса на бхакти йога

- Бхакти Йога

- Восток и Запад (1909) [ 236 ]

- Вдохновленные переговоры (1909)

- Нарада бхакти сутра - перевод

- Para bhakti или высшая преданность

- Практическая Веданта

- Речи и сочинения Свами Вивекананды; Комплексная коллекция

- Полные работы : коллекция его работ, лекций и дискурсов в наборе из девяти томов [ 237 ]

- Видя за пределами круга (2005) [ 238 ]

Смотрите также

Примечания

- ^ Точная дата встречи неизвестна. Исследователь Вивекананды Шайлендра Нат Дхар изучил календарь Университета Калькутты 1881–1882 годы и обнаружено в этом году, экзамен начался 28 ноября и закончился 2 декабря [ 65 ]

- ^ Брат монах Нарендранатха

- ^ Узнав, что у Вивекананды не хватало полномочий, чтобы выступить в Чикагском парламенте, Райт сказал: «Просить ваши полномочия - все равно что попросить солнце утверждать, что его право сиять на небесах». [ 106 ]

- ^ Mcrae цитирует "[А] сектантская биография Вивекананды" [ 115 ] а именно Saileendra Nath Dhar. Комплексная биография Swami Vivekananda, часть первой , (Мадрас, Индия: Вивекананда Пракашан Кендра, 1975), с. 461, который «описывает его речь в день открытия». [ 116 ]

- ^ Брат монахи или братские ученики означает других учеников Рамакришны, которые жили монашеской жизнью.

- ^ По словам Майкла Тафта, Рамакришна примирил дуализм формы и бесформенного, [ 187 ] Относительно высшего существа, чтобы быть личным и безличным, активным и неактивным. [ 188 ] Рамакришна: «Когда я думаю о высшем существовании как неактивном - ни создании, ни сохранении и не разрушаю - я называю его Брахманом или Пурушей, безличным Богом. Когда я думаю о нем как о активном - создавая, сохраняя и разрушаю - я называю его Сакти или Майя или Пракрити, личный бог зачать одно без другого. [ 188 ]

- ^ Sooklalmquoytes chatterjee: «Веданта Шанкары известна как Адваита или не-дуализм , чистый и простой. Следовательно, его иногда называют Кевала-Адваита или неквалифицированным монизмом. Он также может быть назван абстрактным монинизмом в отношении Брахмана, окончательная реальность. , согласно этому, лишено всех качеств и различий, Nirguna и Nirvisesa [...] Не-Веданта также является адвеляцией, поскольку он считает, что Брахман, конечная реальность, является одним из секунды Ekamevadvitiyam , Отличившись от традиционной Адваиты Санкары, это синтетическая Веданта, которая примиряет Дваиту или Дуализм и Адваита или не-дуализм, а также другие теории реальности. И квалифицированные, сагуна и бесстрастные, ниргуна (Chatterjee, 1963: 260) ». [ 189 ]

- ^ Традиция Адваита Веданта в средневековые времена находилась под влиянием и включала элементы из йогической традиции и текстов, таких как йога Васистха и Бхагавата Пурана . [ 192 ] Йога Васишта Видьярагья стала авторитетным источником текста в традиции Адваита Веданты в 14-м веке, в то время как Дживанмуктививка (14-й век) находился под влиянием (лагху) Йога-Васистха , который, в свою очередь, повлиял Кашмир Шайвизм . [ 193 ]

Ссылки

- ^ «Мировая ярмарка 1893 года распространена» . vivekananda.net . Получено 11 апреля 2012 года .

- ^ «Бхаджанананда (2010), четыре основных принципа Адваиты Веданта , с.3» (PDF) . Получено 28 декабря 2019 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Мишелис 2005 .

- ^ «Свами Вивекананда: короткая биография» . www.oneindia.com . Получено 3 мая 2017 года .

- ^ «История жизни и учения Свами Вивекананд» . Получено 3 мая 2017 года .

- ^ «Международный день йоги: как Свами Вивекананда помог популяризировать древний индийский режим на Западе» . 21 июня 2017 года.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Feuerstein 2002 , p. 600.

- ^ Симан, Стефани (2010). Тонкое тело: история йоги в Америке . Нью -Йорк: Фаррар, Страус и Жиру . п. 59. ISBN 978-0-374-23676-2 .

- ^ Кларк 2006 , с. 209

- ^ Барроуз, Джон Генри (1893). Мировой парламент религий . Парламент религии издательской компании. п. 101.

- ^ Датт 2005 , с. 121.

- ^ «Сестры и братья Америки - полный текст культовой речи Свами Вивекананды в Чикаго» . Печать. 4 июля 2019 года.

- ^ Джексон 1994 , с. 115.

- ^ Из плотного 1999 , с. 191.

- ^ «Знайте о Свами Вивекананде в Национальный день молодежи 2022 года» . SA News Channel . 11 января 2022 года . Получено 12 января 2022 года .

- ^ «Национальный день молодежи 2022 года: изображения, пожелания и цитаты Свами Вивекананды, которые продолжают вдохновлять нас даже сегодня!» Полем News18 . 12 января 2022 года . Получено 12 января 2022 года .

- ^ Virajananda 2006 , p. 21

- ^ Пол 2003 , с.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Banhatti 1995 , p. 1

- ^ Стивен Кемпер (2015). Спасенный от нации: Анагарика Дхармапала и буддийский мир . Университет Чикагской Прессы. п. 236. ISBN 978-0-226-19910-8 .

- ^ «Devdutt Pattanaik: Dayanand & Vivekanand» . 15 января 2017 года.

- ^ Badrinath 2006 , p. 2

- ^ Мукерджи 2011 , с. 5

- ^ Badrinath 2006 , p. 3

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Bhuyan 2003 , p. 4

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Banhatti 1995 , p. 2

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Никхиланда 1964 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Его 2003 , с.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Bhuyan 2003 , p. 5

- ^ Banhatti 1995 , p. [ страница необходима ] .

- ^ Banhatti 1995 , p. 4

- ^ Arrington & Chakrabarti 2001 , с. 628–631.

- ^ Его 2003 г. , с.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Sen 2006 , с. 12–14.

- ^ Sen 2003 , с. 104–105.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Pang Born & Smith 1976 , p. 106

- ^ Дхар 1976 , с. 53

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Malagi & Up 2003 , стр. 36-37.

- ^ Prabhananda 2003 , p. 233.

- ^ Banking 1995 , стр. 7-9.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Chattopadhyaya 1999 , p. 31

- ^ Krgupta; Амита Гупта, ред. (2006). Краткая энциклопедия Индии Атлантика. П. 1066. ISBN 978-81-269-0639-0 .

- ^ Banking 1995 , стр. 156, 157.

- ^ 114 -я годовщина смерти Свами Вивекананды: менее известные факты о духовном лидере . Индия сегодня . 4 июля 2016 года.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Michelis 2005 , p. 99

- ^ Michelis 2005 , p. 100

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и Banhatti 1995 , p. 8

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Badrinath 2006 , p. 20

- ^ Michelis 2005 , p. 31-35.

- ^ Michelis 2005 , p. 19-90, 97-100.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Chattopadhyaya 1999 , p. 29

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Michelis 2005 , p. 46

- ^ Michelis 2005 , p. 46-47.

- ^ Michelis 2005 , p. 47

- ^ Michelis 2005 , p. 81.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Michelis 2005 , p. 49

- ^ Sen 2006 , с. 12–13.

- ^ Медхананда 2022 , с. 17

- ^ Медхананда 2022 , с. 22

- ^ Michelis 2005 , p. 50

- ^ Michelis 2005 , p. 101.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Chattopadhyaya 1999 , p. 43

- ^ Ghosh 2003 , p. 31

- ^ Badrinath 2006 , p. 18

- ^ Chattopadhyaya 1999 , p. 30

- ^ Badrinath 2006 , p. 21

- ^ Paranjape 2012 , с. 132.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Prabhananda 2003 , p. 232.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Bankatti 1995 , с. 10-13.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Rolland 1929a , с. 169–193.

- ^ Арара 1968 , с.

- ^ Bhuyan 2003 , p. 8

- ^ Sil 1997 , p. 38.

- ^ Sil 1997 , pp. 39–40.

- ^ Kishore 2001 , с. 23–25.

- ^ Вы не ползаете 1953 , стр. 25-26.

- ^ Sil 1997 , p. 27.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Ишервуд 1976 , с. 20

- ^ Pangborn & Smith 1976 , p. 98

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Rolland 1929b , с. 201–214.

- ^ Banhatti 1995 , p. 17

- ^ «Скелет, согнутый, как лук», битва Шри Рамакришны с раком сделала его детским » . Pprint . 30 октября 2020 года . Получено 12 января 2022 года .

- ^ Sil 1997 , pp. 46–47.

- ^ Banhatti 1995 , p. 18

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Никхиланда 1953 , с. 40

- ^ Четананда 1997 , с. 38

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Chattopadhyaya 1999 , p. 33.

- ^ «Аатпур - Бенгальская деревня, где Свами Вивекананда взял саньяс» .

- ^ Bhuyan 2003 , p. 10

- ^ Rolland 2008 , с. 7

- ^ Дхар 1976 , с. 243.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Ричардс 1996 , с. 77–78.

- ^ Bhuyan 2003 , p. 12

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Rolland 2008 , с. 16–25.

- ^ Banhatti 1995 , p. 24

- ^ Гослинг 2007 , с. 18

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Bhuyan 2003 , p. 15

- ^ Paranjape 2005 , стр. 246-248.

- ^ Badrinath 2006 , p. 158

- ^ Michelis 2005 , p. 110.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в «Чарльз Бонни и идея мирового парламента религий» . Межконфессиональный наблюдатель . 15 июня 2012 года . Получено 28 декабря 2019 года .

- ^ «Всемирный парламент религий, 1893 г. (Бостонская совместная энциклопедия западной богословия)» . People.bu.edu . Получено 28 декабря 2019 года .

- ^ Michelis 2005 , p. 111-112.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Michelis 2005 , p. 112.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Минор 1986 , с. 133.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Bhuyan 2003 , p. 16

- ^ «Когда Восток встретился с западом - в 1893 году» . Чердак . Архивировано из оригинала 20 апреля 2020 года . Получено 5 ноября 2019 года .

- ^ Хоутон 1893 , с. 22

- ^ Bhide 2008 , с. 9

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Пол 2003 , с.

- ^ Banhatti 1995 , p. 27

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Bhuyan 2003 , p. 17

- ^ Пол 2003 , с.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный McRae 1991 , p. 17

- ^ McRae 1991 , p. 16

- ^ McRae 1991 , p. 34, примечание 20.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный McRae 1991 , с. 18.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Prabhananda 2003 , p. 234.

- ^ Фаркухар 1915 , с. 202

- ^ Шарма 1988 , с. 87

- ^ Adiswarananda 2006 , с. 177–179.

- ^ Bhuyan 2003 , p. 18

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Thomas 2003 , с. 74–77.

- ^ Vivekananda 2001 , p. 419.

- ^ Гупта 1986 , с. 118

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон Isherwood & Adjemian 1987 , с. 121–122.

- ^ Banhatti 1995 , p. 30

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Cheetman 1997 , стр. 49-50.

- ^ «Свами Вивекананда знает фотографии Америки 1893–1895» . vivekananda.net . Получено 6 апреля 2012 года .

- ^ Michelis 2005 , p. 120.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Michelis 2005 , p. 119-123.

- ^ Michelis 2005 , p. 123-126.

- ^ Michelis 2005 , p. 125-126.

- ^ Michelis 2005 , p. 149-180.

- ^ Четананда 1997 , с. 47

- ^ Бардач, Ал. (30 марта 2012 г.). «Что общего у Дж.Д. Сэлинджера, Лео Толстого и Сары Бернхардт?» Полем Wall Street Journal . Получено 31 марта 2022 года .

- ^ Берк 1958 , с.

- ^ Thomas 2003 , с. 78–81.

- ^ Wuthnow 2011 , с. 85–86.

- ^ Rinehart 2004 , p. 392.

- ^ Vrajaprana 1996 , p. 7

- ^ Шак, Джоан (2012). «Монументальная встреча» (PDF) . Шри Сарада Общество отмечает . 18 (1). Олбани, Нью -Йорк.

- ^ Каттакал 1982 , с.

- ^ Majumdar 1963 , p.

- ^ Берк 1985 , с.

- ^ Шарма 1963 , с. 227

- ^ Wiean 2005 , p. 345.

- ^ Шарма 1988 , с. 83.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Bankatti 1995 , с. 33-34.

- ^ Дхар 1976 , с. 852.

- ^ Bhuyan 2003 , p. 20

- ^ Томас 1974 , с. 44

- ^ Миллер 1995 , с. 181.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Bankatti 1995 , с. 34-35.

- ^ Гангули 2001 , с. 27

- ^ Kraemer 1960 , p. 151.

- ^ Prabhananda 2003 , p. 235.

- ^ Лулла, Анил Бадди (3 сентября 2007 г.). «IISC смотрит на Белур за семенами рождения» . Телеграф . Архивировано с оригинала 20 октября 2017 года . Получено 6 мая 2009 года .

- ^ Kapur 2010 , с. 142

- ^ Virajananda 2006 , p. 291.

- ^ Banking 1995 , стр. 35-36.

- ^ Virajananda 2006 , p. 450.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Bankatti 1995 , с. 4142.

- ^ Banking 1995 , p. XV.

- ^ Banking 1995 , стр. 43-44.

- ^ Banking 1995 , стр. 45-46.

- ^ Chattopadhyaya 1999 , с. 218, 274, 299.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Chattopadhyaya 1999 , p. 283.

- ^ Banhatti 1995 , p. 46

- ^ Bharathi 1998b , p. 25

- ^ Его 2006 г. , с.

- ^ Virajananda 1918 , p. 81.

- ^ Virajananda 2006 , с. 645–662.

- ^ "Ближе к концу" . Вивекананда биография . www.ramakrishnavivekananda.info . Получено 11 марта 2012 года .

- ^ King 2002 .

- ^ KIPF 1979 .

- ^ Rambachan 1994 .

- ^ Halbfass 1995 .

- ^ Rinehart 2004 .

- ^ Michelis 2004 , p. 46

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Flup 1996 , p. 258

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Michelis 2004 , p. 99

- ^ Michelis 2004 , p. 100

- ^ Michelis 2004 , p. 19-90, 97-100.

- ^ Махарадж 2020 , с. 177.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Джексон 1994 , с. 33–34.

- ^ Тафт 2014 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Свами Сарадананда. Шри Рамакриша Великий Мастер . Тол. 1. Перевод Свами Джагадананды (5 -е изд.). Мадрас.: Шри Рамакришна Математика. С. 558–561. ISBN 978-81-7823-483-0 Полем Архивировано с оригинала 4 марта 2016 года.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Sookel 1993 , p. 33.

- ^ Madaio 2017 , с. 5

- ^ Comans 1993 .

- ^ Madaio 2017 , с. 4-5.

- ^ Madaio 2017 , с. 4

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Heehs 2020 , с. 175.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Nanda 2010 , с. 335.

- ^ Bhuyan 2003 , p. 93.

- ^ Seifer 2001 , p. 164.

- ^ Vivekananda 2001 , разговоры и диалоги, глава «VI - X Шри Прия Нат -Синха», том 5 .

- ^ Michelis 2004 , p. 119-123.

- ^ Michelis 2004 , p. 123-126.

- ^ Michelis 2004 , p. 119-123.

- ^ Michelis 2004 , p. 125-126.

- ^ Michelis 2004 , p. 149-180.

- ^ Vivekananda 1996 , с. 1–2.

- ^ «Свами Вивекананда Жизнь и преподавание» . Belur Math. Архивировано с оригинала 30 марта 2012 года . Получено 23 марта 2012 года .

- ^ Мохапатра 2009 , с. 14

- ^ Piazza 1978 , p. 59

- ^ Duta 2003 , p. 110.

- ^ 1994 , с. 6–8

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Shattuck 1999 , с. 93–94.

- ^ Bharathi 1998b , p. 37

- ^ Bharathi 1998b , pp. 37–38.

- ^ Bhide 2008 , с. 69

- ^ Parl 2000 , p. 77

- ^ «Национальный комитет по реализации утверждает средства для образования Swami Vivekananda Values Project» . 6 сентября 2010 года. Архивировано с оригинала 10 мая 2013 года . Получено 14 апреля 2012 года .

- ^ «Свами Вивекананда государственная академия полиции» . Свами Вивекананда государственная академия полиции. Архивировано из оригинала 4 августа 2013 года . Получено 9 января 2013 года .

- ^ «Чхаттисгарх Свами Вивекананда Технический университет» . Csvtu.ac.in. 19 ноября 2012 года. Архивировано с оригинала 15 января 2013 года . Получено 7 февраля 2013 года .

- ^ «Пранаб надеется, что новый терминал аэропорта Райпура поддержат рост Чхаттисгарха» . Индус . Архивировано с оригинала 17 января 2013 года . Получено 7 февраля 2013 года .

- ^ «Национальный день молодежи» (PDF) . Национальный портал Индии . Правительство Индии. 10 января 2009 г. Получено 5 октября 2011 года .

- ^ «Вспоминая Свами Вивекананда» . Zee News.india. 11 января 2011 года . Получено 9 сентября 2013 года .

- ^ «2013–14 объявил год развития навыков Молодежного консультативного комитета, прикрепленного к Министерству по делам о молодежи и спорте» . ПТИ . Получено 3 марта 2013 года .

- ^ «Годовые мероприятия, чтобы отметить 150-летие Вивекананды» . The Times of India . Архивировано из оригинала 11 мая 2013 года . Получено 3 марта 2013 года .

- ^ Раджадхьякша, Ашиш; Willemen, Paul (1999). Энциклопедия индийского кино . Британский институт кино. ISBN 9780851706696 .

- ^ «История Свамиджи в 3D -анимации» . Телеграф Индия .

- ^ Это 1991 , с. 530.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Michelis 2005 , p. 150

- ^ Michelis 2005 , p. 149-150.

- ^ Mittra 2001 , p. 88

- ^ Chattopadhyaya 1999 , p. 118

- ^ Вивекананда, Свами. «Современная Индия (Полные работы Vivekananda - Том IV - Переводы: проза)» . www.ramakrishnavivekananda.info . Рамакришна миссия . Получено 22 мая 2022 года .

- ^ Далал 2011 , с. 465.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный «Библиотека Vivekananda Online» . vivekananda.net . Получено 22 марта 2012 года .

- ^ Michelis 2005 , p. 124

- ^ Kearney 2013 , p. 169

- ^ Banhatti 1995 , p. 145.

- ^ Urban 2007 , p. 314

- ^ Вивекананда, Свами. «Полные работы - индекс - объемы» . www.ramakrishnavivekananda.info . Рамакришна миссия . Получено 22 мая 2022 года .

- ^ Вивекананда, Свами (2005). Видя за пределами круга: лекции Свами Вивекананды о универсальном подходе к медитации . [Соединенные Штаты: Temple Universal Pub. ISBN 9780977483006 .

Источники

- Adiswarananda, Swami, ed. (2006), Вивекананда, Учитель мира: его учения о духовном единстве человечества , Вудсток, Вермонт: Паб Skylight Paths, ISBN 1-59473-210-8

- Аррингтон, Роберт Л.; Чакрабарти, Тапан Кумар (2001), "Свами Вивекананда", компаньон для философов , Blackwell Publishing, ISBN 978-0-631-22967-4

- Арора, В.К. (1968), «Причастие с Брахмо Самадж», социальная и политическая философия Свами Вивекананды , Панти Пустак

- Badrinath, Chaturvedi (2006). Свами Вивекананда, живая Веданта . Пингвин книги Индия. ISBN 978-0-14-306209-7 .

- Banhatti, GS (1995), Life and Philosophy of Swami Vivekananda , Atlantic Publishers & Distributors, ISBN 978-81-7156-291-6

- Banhatti, GS (1963), квинтэссенция Вивекананды , Пуна, Индия: Сувичар Пракашан Мандал, OCLC 1048955252

- Bharathi, KS (1998b), Энциклопедия выдающихся мыслителей , Vol. 8, Нью -Дели: концептуальная издательская компания, ISBN 978-81-7022-709-0

- Bhide, Nivedita Raghunath (2008), Свами Вивекананда в Америке , Вивекананда Кендра, ISBN 978-81-89248-22-2

- Bhuyan, PR (2003), Swami Vivekananda: Messiah of Resurging India , Нью -Дели: Атлантические издатели и дистрибьюторы, ISBN 978-81-269-0234-7

- Берк, Мари Луиза (1958), Свами Вивекананда в Америке: новые открытия , Калькутта: Адваита Ашрама, ISBN 978-0-902479-99-9

- Берк, Мари Луиза (1985), Свами Вивекананда на Западе: новые открытия (в шести томах) (3 -е изд.), Калькута: Адваита Ашрама, ISBN 978-0-87481-219-0

- Chattopadhyaya, Rajagopal (1999), Swami Vivekananda в Индии: корректирующая биография , Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1586-5

- Четананда, Свами (1997). Бог жил с ними: жизненные истории шестнадцати монашеских учеников Шри Рамакришны . Сент -Луис, штат Миссури: Ведантское общество Сент -Луиса. ISBN 0-916356-80-9 .

- Кларк, Питер Бернард (2006), Новые религии в глобальной перспективе , Routledge

- Comans, Michael (1993), вопрос о важности самадхи в современной и классической Адваите Веданте. В кн.: Философия Восток и Запад, том. 43, № 1 (январь 1993 г.), с. 19-38.

- Даллал, Рошен (октябрь 2011 г.). Индуизм: алфавитный путеводитель Пингвин книги Индия. ISBN 978-0-14-341421-6 .

- Дас, Сисир Кумар (1991), История индийской литературы: 1800–1910, Западное воздействие: ответ индийского ответа , Sahitya akademi, ISBN 978-81-7201-006-5

- Фон Денс, Кристиан Д. (1999), Философы и религиозные лидеры , издательская группа Greenwood

- Дхар, Шайлендра Нат (1976), Комплексная биография Свами Вивекананды (2 -е изд.), Мадрас, Индия: Вивекананда Пракашан Кендра, OCLC 708330405

- Датта, Кришна (2003), Калькутта: культурная и литературная история , Оксфорд: книги сигналов, ISBN 978-1-56656-721-3

- Датт, Харшавардхан (2005), Бессмертные речи , Нью -Дели: книги Единорога, с. 121, ISBN 978-81-7806-093-4

- Фаркухар, JN (1915), Современные религиозные движения в Индии , Лондон: Макмиллан

- Flood, Gavin D. (1996), Введение в индуизм , издательство Кембриджского университета

- Ganguly, Adwaita P. (2001), Life and Times of Netaji Subhas: от Cuttack до Кембриджа, 1897–1921 , VRC Publications, ISBN 978-81-87530-02-2

- Feuerstein, Georg (2002), Традиция йоги , Дели: Motilal Banarsidass

- Гош, Гаутам (2003). Пророк современной Индии: биография Свами Вивекананды . Рупа и компания. ISBN 978-81-291-0149-5 .

- Гослинг, Дэвид Л. (2007). Наука и индийская традиция: когда Эйнштейн встретил Тагора . Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-14333-7 .

- Гупта, Радж Кумар (1986), Великая встреча: изучение индо-американских литературных и культурных отношений , Дели: Абхинавские публикации, ISBN 978-81-7017-211-6 , Получено 19 декабря 2012 года

- Halbfass, Wilhelm (1995), Филология и конфронтация: Пол Хакер на традиционной и современной Ведане , Suny Press

- Петр (2020), «Теория духовной эволюции Шри Ауробиндо», в Маккензи Брауне, С. (ред. Хис , )

- Хоутон, Уолтер Роли, изд. (1893), Парламент религий и религиозных конгрессов на мировой колумбийской экспозиции (3 -е изд.), Фрэнк Теннисон Нили, OL 14030155M

- Ишервуд, Кристофер (1976), Медитация и ее методы, согласно Свами Вивекананде , Голливуд, Калифорния: Веданта Пресс, ISBN 978-0-87481-030-1

- Ишервуд, Кристофер ; Adjemian, Robert (1987), «о Свами Вивекананде», The Wishing Tree , Голливуд, Калифорния: Vedanta Press, ISBN 978-0-06-250402-9

- Джексон, Карл Т. (1994), «Основатели», Веданта для Запада: Движение Рамакришны в Соединенных Штатах , Индианаполис, Индиана: издательство Университета Индианы, ISBN 978-0-253-33098-7

- Кашьяп, Шивендра (2012), Спасение человечества: Свами Вивекананд Перспектива , Вивекананд Свадхьяй Мандал, ISB 978-81-923019-0-7

- Капур, Девеш (2010), Диаспора, развитие и демократия: внутреннее влияние международной миграции из Индии , Принстон, Нью -Джерси: издательство Принстонского университета, ISBN 978-0-691-12538-1

- Каттакал, Джейкоб (1982), Религия и этика в Адваите , Котаям, Керала: Апостольская семинария Святого Томаса, ISBN 978-3-451-27922-5

- Кирни, Ричард (13 августа 2013 г.). Анатеизм: возвращение к Богу после Бога . Издательство Колумбийского университета. ISBN 978-0-231-51986-1 .

- Кинг, Ричард (2002), Ориентализм и религия: постколониальная теория, Индия и «Мистический Восток» , Рутледж

- Кипф, Дэвид (1979), Брахмо Самадж и формирование современного индийского разума , Атлантические издатели и дистрибутивы

- Кишор, Б.Р. (2001). Свами Вивекананд . Алмазные карманные книги. ISBN 978-81-7182-952-1 .

- Kraemer, Hendrik (1960), «Культурный ответ индуистской Индии», Мировые культуры и мировые религии , Лондон: Вестминстерская Пресс, Асин Б.0007dlyak

- Madaio, James (2017), «Переосмысление нео-введы: Свами Вивекананда и селективная историография Адваиты Веды», религии , 8 (6): 101, doi : 10.3390/rel8060101

- Махарадж, Айон (2020). «Шиваджане дживер Сева: пересмотреть практическую Веду Свами Вивекананды в свете Шри Рамакришны». Журнал Dharma Studies . 2 (2): 175–187. doi : 10.1007/s42240-019-00046-x . S2CID 202387300 .

- Маджамдар, Рамеш Чандра (1963), Свами Вивекананда столетний мемориал , Калькутта: Свами Вивекананда Столетие, с. 577, ASIN B0007J2FTS

- Малаги, Ра; Найк, М.К. (2003), «Развисный дух: проза Свами Вивекананды», Перспективы индийской прозы на английском языке , Нью -Дели: Абхинавские публикации, ISBN 978-81-7017-150-8

- McRae, John R. (1991), «Восточные истины на американской границе: парламент религий 1893 года и мысль о Масао Абе», буддийско-христианские исследования , 11 , Университет Гавайских островов: 7–36, doi : 10.2307/1390252 , JSTOR 1390252

- Медхананда, Свами (2022). Ведтический космополитизм Свами Вивекананды . Издательство Оксфордского университета. ISBN 978-0-19-762446-3 .

- Мишелис, Элизабет де (2004), История современной йоги: Патанджали и Западный Эзотеризм , континуум, ISBN 978-0-8264-8772-8

- Де Мишелис, Элизабет (8 декабря 2005 г.). История современной йоги: патанджали и западный эзотеризм . Континуум. ISBN 978-0-8264-8772-8 .

- Miller, Timothy (1995), «Общение с движением и самореализацией Веданты» , Американские альтернативные религии , Олбани, Нью-Йорк: Suny Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-2398-1

- Несовершеннолетний, Роберт Нил (1986), «Использование Свами Вивекананды Бхагавад Гиты » , современные индийские переводчики Бхагавад Гиты , Олбани, Нью -Йорк: Suny Press, ISBN 978-0-88706-297-1

- Миттра, Ситансу Сехар (2001). Бенгальский ренессанс . Академические издатели. ISBN 978-81-87504-18-4 .

- Mukherji, Mani Shankar (2011), Монах как человек: неизвестная жизнь Свами Вивекананды , Пингвин Книги Индия, ISBN 978-0-14-310119-2

- Нанда, Мира (2010), «Дети мадам Блаватски: современные индуистские встречи с дарвинизмом», в Льюисе, Джеймс Р.; Хаммер, Олав (ред.), Справочник по религии и авторитет науки , Brill

- Нихиланданд, Свами (апрель 1964 г.), «Свами Вивекананда», Философия Восток и Запад , 14 (1), Университет Гавайской прессы: 73–75, doi : 10.2307/1396757 , jstor 1396757

- Нихиланданд, Свами (1953), Вивекананда: биография (PDF) , Нью-Йорк: Центр Рамакришна-Вивекананда, ISBN 0-911206-25-6 , Получено 19 марта 2012 года

- Пангборн, Сайрус Р.; Смит, Бардвелл Л. (1976), «Математика и миссия Рамакришны», Индуизм: новые очерки в истории религий , Архив Брилла

- Paranjape, Makarand (2005), Penguin Swami Vivekananda Reader , Penguin India, ISBN 0-14-303254-2

- Paranjape, Makarand R. (2012). Создание Индии: колониализм, национальная культура и загробная жизнь индийской английской власти . Спрингер. ISBN 978-94-007-4661-9 .

- Парел, Энтони (2000), Ганди, свобода и самоуправление , Лексингтонские книги, ISBN 978-0-7391-0137-7

- Пол, доктор С. (2003). Великие люди Индии: Свами Вивекананда . Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 978-81-207-9138-1 .

- Prabhananda, Swami (June 2003), "Profiles of famous educators: Swami Vivekananda" (PDF) , Prospects , XXXIII (2), Netherlands: Springer : 231–245, doi : 10.1023/A:1023603115703 , S2CID 162659685 , archived from the Оригинал (PDF) 10 октября 2008 года , полученная 20 декабря 2008 г.

- Амбачан, Анананданд (1994), Пределы Священных Писаний: Рецепция Вивекана Ведах , Гонолулу, Гавайи: Университет Гавайской прессы, ISBN 978-0-8248-1542-4

- Ричардс, Глин (1996), «Вивекананда», источник современного индуизма , Routledge, с. 77–78, ISBN 978-0-7007-0317-3

- Райнхарт, Робин (1 января 2004 г.). Современный индуизм: ритуал, культура и практика . ABC-Clio. ISBN 978-1-57607-905-8 .

- Ролланд, Роман (1929a), «Нарен любимый ученик», жизнь Рамакришны , Голливуд, Калифорния: Веданта Пресс, с. 169–193, ISBN 978-81-85301-44-0

- Ролланд, Роман (1929b), «Река возвращается в море», « Жизнь Рамакришны » , Голливуд, Калифорния: Веданта Пресс, с. 201–214, ISBN 978-81-85301-44-0

- Ролланд, Роман (2008), «Жизнь Вивекананды и Универсального Евангелия» (24 -е изд.), Адваита Ашрама, с. 328 , ISBN 978-81-85301-01-3

- Seifer, Marc (2001), Wizard: Жизнь и времена Никола Теслы: Биография гения , цитадель, ISBN 978-0-8065-1960-9

- Сен, Амия (2003), Гупта, Нараяни (ред.), Свами Вивекананда , Нью -Дели: издательство Оксфордского университета, ISBN 0-19-564565-0

- Sen, Amiya (2006), незаменимый Vivekananda: антология для нашего времени , Orient Blackswan, ISBN 978-81-7824-130-2

- Шарма, Арвинд (1988), «Опыт Свами Вивекананды», Нео-Гудв Взгляды на христианство , Лейден, Нидерланды: Брилл, ISBN 978-90-04-08791-0

- Sharma, Benishankar (1963), Swami Vivekananda: забытая глава его жизни , Калькутта: Oxford Book & Staterary Co., Asin B0007jr46c

- Shattuck, Cybelle T. (1999), «Современный период II: силы перемен», Индуизм , Лондон: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-21163-5

- Шиан, Винсент (2005), «Предулки Ганди», Lead, любезный свет: Ганди и путь к миру , Kessinger Publishing, ISBN 978-1-4179-9383-3

- Shetty, B. Vithal (2009), World, как видно под объективом ученого , Блумингтон, Индиана: Xlibris Corporation, ISBN 978-1-4415-0471-5

- SIL, Нарасингха Просад (1997), Свами Вивекананда: переоценка , Селинсгроув, Пенсильвания: издательство Университета Саскуэханны, ISBN 0-945636-97-0

- (1993), «Не-васта-философия Свами Вивекаканда» (PDF) , Нидан , Sooklaal, Anil

- Taft, Michael (2014), Nondualism: Краткая история вневременной концепции , Cephalopod Rex

- Томас, Авраам Важхайил (1974), христиане в светской Индии , Мэдисон, Нью -Джерси: издательство Университета Фэрли Дикинсон, ISBN 978-0-8386-1021-3

- Томас, Венделл (1 августа 2003 г.). Индуизм вторгается в Америку 1930 . Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7661-8013-0 .

- Урбан, Хью Б. (1 января 2007 г.). Тантра: пол, секретность, политика и власть в изучении религии . Motilal Banarsidass Publisher. ISBN 978-81-208-2932-9 .

- Virajananda, Swami, ed. ) ( . 2006 81-7505-044-6

- Virajananda, Swami (1918), жизнь Свами Вивекананды , вып. 4, Офис Prabuddha Bharata, Адваита Ашрама , получен 21 декабря 2012 г.

- Vivekananda, Swami (2001) [1907], Полные работы Swami Vivekananda , vol. 9 томов, Advaita Ashrama, ISBN 978-81-85301-75-4

- Vivekananda, Swami (1996), Swami Lokeswarananda (ed.), My India: India Eternal (1 -е изд.), Калькутта: Институт культуры Рамакришны, стр. 1–2, ISBN. 81-85843-51-1

- Vrajaprana, Pravrajika (1996). Портрет сестры Кристины . Калькутта: Рамакришна Миссионерский институт культуры. ISBN 978-81-85843-80-3 .

- Wuthnow, Robert (1 июля 2011 г.). Америка и проблемы религиозного разнообразия . ПРИЗНАЯ УНИВЕРСИТЕТА ПРИСЕТА. ISBN 978-1-4008-3724-3 .

- Вольфф, Джон (2004). Религия в истории: конфликт, обращение и сосуществование . Манчестерское университетское издательство. ISBN 978-0-7190-7107-2 .

Дальнейшее чтение

Библиография

- Сестра Ниведита (1913). Свами Сарадананда (ред.). Примечания к странствий с Свами Вивеканандой . Калькутта: Брахмачари Гонедрант Удбодханский офис.

- Берк, Мари Луиза (1957). Свами Вивекананда на Западе: новые открытия . Калькутта: Адваита Ашрама .

- Sambudhdhananda, Swami (1963). Свами Вивекананда на себе . Калькутта: Адваита Ашрама . ISBN 81-7505-280-5 .

- Гохале, Б.Г. (январь 1964 г.). «Свами Вивекананда и индийский национализм». Журнал Библии и религии . 32 (1). Издательство Оксфордского университета : 35–42. JSTOR 1460427 .

- Banhatti, GS (1989). Жизнь и философия Свами Вивекананды . Нью -Дели: Atlantic Publishers & Dist. ISBN 978-81-7156-291-6 .

- Majumdar, RC (1999). Свами Вивекананда: исторический обзор . Калькутта: Адваита Ашрама .

- Кинг, Ричард (2002). Ориентализм и религия: постколониальная теория, Индия и «Мистический Восток» . Routledge .

- Bhuyan, Pranaba Ranjan (2003). Свами Вивекананда: Мессия возрождающейся Индии . Нью -Дели: Atlantic Publishers & Dist. ISBN 978-81-269-0234-7 .

- Мукерджи, Мани Шанкар (2011) [2003]. Ахена Аджана Вивекананда [ Монах как человек: неизвестная жизнь Свами Вивекананды ]. Пингвин книги Индия .

- Чаухан, Абниш Сингх (2004). Свами Вивекананда: Выбор речи . Prakash Book Depot. ISBN 978-81-7977-466-3 .

- Чаухан, Абниш Сингх (2006). Речи Свами Вивекананды и Субхаш Чандра Бозе: сравнительное исследование . Prakash Book Depot. ISBN 978-81-7977-149-5 .

- Шарма, Jyotirmaya (2013). Пересмотр религии: Свами Вивекананда и создание индуистского национализма . Издательство Йельского университета . ISBN 978-0-300-19740-2 . [ Постоянная мертвая ссылка ]

- Малхотра, Раджив (2016). Сеть Индры: защита философского единства индуизма (пересмотренное изд.). Нойда, Индия: HarperCollins Publishers India . ISBN 978-93-5177-179-1 . ISBN 93-5177-179-2

Другие источники

- Митра, Сарбаджит (22 октября 2023 г.). «Матч по крикету в Чинсуре Бенгалии и его увлекательная связь с восстанием 1857 года» . Thewire.in . Калькутта: проволока. Архивировано из оригинала 22 октября 2023 года . Получено 24 октября 2023 года .

- Мукхопадхьяй, Атрейо (4 мая 2019 г.). «Когда Свами Вивекананда заявил о семи калитках и других рассказах о садах Эдема» . Newindianexpress.com . Калькутта: новый индийский экспресс. Экспресс -новостная служба. Архивировано из оригинала 16 апреля 2023 года . Получено 17 ноября 2021 года .

Внешние ссылки

- Свами Вивекананда в Керли

- Работает о Вивекананде через открытую библиотеку

- Работает Вивекананда через открытую библиотеку

- Работает на Свами Вивекананде в Интернете

- Работа Свами Вивекананда в Librivox (общественные аудиокниги)

- Биография на Belur Math официальном сайте

- Полные работы Vivekananda, Belur Math Publication Archived 21 февраля 2018 года на The Wayback Machine

- WBEZ Chicago Curious City Podcast : В ответ на вопрос слушателя репортер объясняет Чикагскую связь Свами Вивекананды, отслеживая его пропавший почетный уличный знак.

- Свами Вивекананда

- 1863 Рождение

- 1902 Смерть

- Индуистские новые религиозные движения

- Основатели новых религиозных движений

- Индуистские аскеты

- Возрождения

- Бенгальский народ

- Индуистские философы и теологии

- Индуистские философы и богословы 19-го века

- Индийские индуистские миссионеры

- Индийские богословы

- Индуистские возрождения

- Люди в межконфессиональном диалоге

- Индийские индуистские святые

- Индийские индуистские духовные учителя

- Индийские гуру йоги

- Монашеские ученики Рамакришны

- Люди из Калькутты

- Президентский университет, выпускники Калькутты

- Рамакришна миссия

- Выпускники шотландского церковного колледжа

- Духовная практика

- Выпускники университета Калькутты

- Веданта

- Индуистские реформаторы

- Нео-ведущий

- Бенгальские индуистские святые

- Индийские масоны

- Активисты против касты

- Современные гуру йоги

- Люди, связанные с Шиллонгом

- Индийские публичные ораторы

- Индуистские монахи