Международный фонетический алфавит

| Международный фонетический алфавит | |

|---|---|

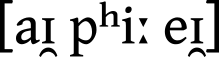

«IPA» в IPA ( [aɪ̯ pʰiː eɪ̯] ) | |

| Тип сценария | Алфавит

- частично функционально |

Период времени | 1888 г. по настоящее время |

| Языки | Используется для фонетической и фонематической транскрипции любого устного языка. |

| Связанные скрипты | |

Родительские системы | |

| Unicode | |

| See Phonetic symbols in Unicode § Unicode blocks | |

Международный фонетический алфавит ( IPA ) представляет собой алфавитную систему фонетической записи , основанную главным образом на латинском алфавите . Он был разработан Международной фонетической ассоциацией в конце 19 века как стандартное письменное представление звуков речи . [ 1 ] IPA используется лексикографами , иностранных языков студентами и преподавателями , лингвистами , патологами речи , певцами, актерами, создателями искусственных языков и переводчиками . [ 2 ] [ 3 ]

МПА предназначен для представления тех качеств речи , которые входят в состав лексических (и, в ограниченной степени, просодических ) звуков устной речи : звуков , интонации и разделения слогов . [ 1 ] Для представления дополнительных качеств речи, таких как скрежет зубов , шепелявость и звуки, издаваемые расщелиной неба , расширенный набор символов . может использоваться [ 2 ]

Segments are transcribed by one or more IPA symbols of two basic types: letters and diacritics. For example, the sound of the English digraph ⟨ch⟩ may be transcribed in IPA with a single letter: [c], or with multiple letters plus diacritics: [t̠̺͡ʃʰ], depending on how precise one wishes to be. Slashes are used to signal phonemic transcription; therefore, /tʃ/ is more abstract than either [t̠̺͡ʃʰ] or [c] and might refer to either, depending on the context and language.[note 1]

Occasionally, letters or diacritics are added, removed, or modified by the International Phonetic Association. As of the most recent change in 2005,[4] there are 107 segmental letters, an indefinitely large number of suprasegmental letters, 44 diacritics (not counting composites), and four extra-lexical prosodic marks in the IPA. These are illustrated in the current IPA chart, posted below in this article and at the website of the IPA.[5]

History

[edit]In 1886, a group of French and English language teachers, led by the French linguist Paul Passy, formed what would be known from 1897 onwards as the International Phonetic Association (in French, l'Association phonétique internationale).[6] Their original alphabet was based on a spelling reform for English known as the Romic alphabet, but to make it usable for other languages the values of the symbols were allowed to vary from language to language.[note 2] For example, the sound [ʃ] (the sh in shoe) was originally represented with the letter ⟨c⟩ in English, but with the digraph ⟨ch⟩ in French.[6] In 1888, the alphabet was revised to be uniform across languages, thus providing the base for all future revisions.[6][8] The idea of making the IPA was first suggested by Otto Jespersen in a letter to Passy. It was developed by Alexander John Ellis, Henry Sweet, Daniel Jones, and Passy.[9]

Since its creation, the IPA has undergone a number of revisions. After revisions and expansions from the 1890s to the 1940s, the IPA remained primarily unchanged until the Kiel Convention in 1989. A minor revision took place in 1993 with the addition of four letters for mid central vowels[2] and the removal of letters for voiceless implosives.[10] The alphabet was last revised in May 2005 with the addition of a letter for a labiodental flap.[11] Apart from the addition and removal of symbols, changes to the IPA have consisted largely of renaming symbols and categories and in modifying typefaces.[2]

Extensions to the International Phonetic Alphabet for speech pathology (extIPA) were created in 1990 and were officially adopted by the International Clinical Phonetics and Linguistics Association in 1994.[12]

Description

[edit]The general principle of the IPA is to provide one letter for each distinctive sound (speech segment).[note 3] This means that:

- It does not normally use combinations of letters to represent single sounds, the way English does with ⟨sh⟩, ⟨th⟩ and ⟨ng⟩, nor single letters to represent multiple sounds, the way ⟨x⟩ represents /ks/ or /ɡz/ in English.

- There are no letters that have context-dependent sound values, the way ⟨c⟩ and ⟨g⟩ in several European languages have a "hard" or "soft" pronunciation.

- The IPA does not usually have separate letters for two sounds if no known language makes a distinction between them, a property known as "selectiveness".[2][note 4] However, if a large number of phonemically distinct letters can be derived with a diacritic, that may be used instead.[note 5]

The alphabet is designed for transcribing sounds (phones), not phonemes, though it is used for phonemic transcription as well. A few letters that did not indicate specific sounds have been retired (⟨ˇ⟩, once used for the "compound" tone of Swedish and Norwegian, and ⟨ƞ⟩, once used for the moraic nasal of Japanese), though one remains: ⟨ɧ⟩, used for the sj-sound of Swedish. When the IPA is used for broad phonetic or for phonemic transcription, the letter–sound correspondence can be rather loose. The IPA has recommended that more 'familiar' letters be used when that would not cause ambiguity.[14] For example, ⟨e⟩ and ⟨o⟩ for [ɛ] and [ɔ], ⟨t⟩ for [t̪] or [ʈ], ⟨f⟩ for [ɸ], etc. Indeed, in the illustration of Hindi in the IPA Handbook, the letters ⟨c⟩ and ⟨ɟ⟩ are used for /t͡ʃ/ and /d͡ʒ/.

Among the symbols of the IPA, 107 letters represent consonants and vowels, 31 diacritics are used to modify these, and 17 additional signs indicate suprasegmental qualities such as length, tone, stress, and intonation.[note 6] These are organized into a chart; the chart displayed here is the official chart as posted at the website of the IPA.

Letter forms

[edit]

The letters chosen for the IPA are meant to harmonize with the Latin alphabet.[note 7] For this reason, most letters are either Latin or Greek, or modifications thereof. Some letters are neither: for example, the letter denoting the glottal stop, ⟨ʔ⟩, originally had the form of a question mark with the dot removed. A few letters, such as that of the voiced pharyngeal fricative, ⟨ʕ⟩, were inspired by other writing systems (in this case, the Arabic letter ⟨ﻉ⟩, ʿayn, via the reversed apostrophe).[10]

Some letter forms derive from existing letters:

- The right-swinging tail, as in ⟨ʈ ɖ ɳ ɽ ʂ ʐ ɻ ɭ ⟩, indicates retroflex articulation. It originates from the hook of an r.

- The top hook, as in ⟨ɠ ɗ ɓ⟩, indicates implosion.

- Several nasal consonants are based on the form ⟨n⟩: ⟨n ɲ ɳ ŋ⟩. ⟨ɲ⟩ and ⟨ŋ⟩ derive from ligatures of gn and ng, and ⟨ɱ⟩ is an ad hoc imitation of ⟨ŋ⟩.

- Letters turned 180 degrees for suggestive shapes, such as ⟨ɐ ɔ ə ɟ ɥ ɯ ɹ ʌ ʍ ʎ⟩ from ⟨a c e f h m r v w y⟩.[note 8] Either the original letter may be reminiscent of the target sound (e.g., ⟨ɐ ə ɹ ʍ⟩) or the turned one (e.g., ⟨ɔ ɟ ɥ ɯ ʌ ʎ⟩). Rotation was popular in the era of mechanical typesetting, as it had the advantage of not requiring the casting of special type for IPA symbols, much as the sorts had traditionally often pulled double duty for ⟨b⟩ and ⟨q⟩, ⟨d⟩ and ⟨p⟩, ⟨n⟩ and ⟨u⟩, ⟨6⟩ and ⟨9⟩ to reduce cost.

- Among consonant letters, the small capital letters ⟨ɢ ʜ ʟ ɴ ʀ ʁ⟩, and also ⟨ꞯ⟩ in extIPA, indicate more guttural sounds than their base letters. (⟨ʙ⟩ is a late exception.) Among vowel letters, small capitals indicate "lax" vowels. Most of the original small-cap vowel letters have been modified into more distinctive shapes (e.g. ⟨ʊ ɤ ɛ ʌ⟩ from U Ɐ E A), with only ⟨ɪ ʏ⟩ remaining as small capitals.

Typography and iconicity

[edit]The International Phonetic Alphabet is based on the Latin script, and uses as few non-Latin letters as possible.[6] The Association created the IPA so that the sound values of most letters would correspond to "international usage" (approximately Classical Latin).[6] Hence, the consonant letters ⟨b⟩, ⟨d⟩, ⟨f⟩, ⟨ɡ⟩, ⟨h⟩, ⟨k⟩, ⟨l⟩, ⟨m⟩, ⟨n⟩, ⟨p⟩, ⟨s⟩, ⟨t⟩, ⟨v⟩, ⟨w⟩, and ⟨z⟩ have more or less their word-initial values in English (g as in gill, h as in hill, though p t k are unaspirated as in spill, still, skill); and the vowel letters ⟨a⟩, ⟨e⟩, ⟨i⟩, ⟨o⟩, ⟨u⟩ correspond to the (long) sound values of Latin: [i] is like the vowel in machine, [u] is as in rule, etc. Other Latin letters, particularly ⟨j⟩, ⟨r⟩ and ⟨y⟩, differ from English, but have their IPA values in Latin or other European languages.

This basic Latin inventory was extended by adding small-capital and cursive forms, diacritics and rotation. The sound values of these letters are related to those of the original letters, and their derivation may be iconic.[note 9] For example, letters with a rightward-facing hook at the bottom represent retroflex equivalents of the source letters, and small capital letters usually represent uvular equivalents of their source letters.

There are also several letters from the Greek alphabet, though their sound values may differ from Greek. For most Greek letters, subtly different glyph shapes have been devised for the IPA, specifically ⟨ɑ⟩, ⟨ꞵ⟩, ⟨ɣ⟩, ⟨ɛ⟩, ⟨ɸ⟩, ⟨ꭓ⟩ and ⟨ʋ⟩, which are encoded in Unicode separately from their parent Greek letters. One, however – ⟨θ⟩ – has only its Greek form, while for ⟨ꞵ ~ β⟩ and ⟨ꭓ ~ χ⟩, both Greek and Latin forms are in common use.[17][citation needed] The tone letters are not derived from an alphabet, but from a pitch trace on a musical scale.

Beyond the letters themselves, there are a variety of secondary symbols which aid in transcription. Diacritic marks can be combined with IPA letters to add phonetic detail such as tone and secondary articulations. There are also special symbols for prosodic features such as stress and intonation.

Brackets and transcription delimiters

[edit]There are two principal types of brackets used to set off (delimit) IPA transcriptions:

| Symbol | Use |

|---|---|

| [ ... ] | Square brackets are used with phonetic notation, whether broad or narrow[18] – that is, for actual pronunciation, possibly including details of the pronunciation that may not be used for distinguishing words in the language being transcribed, which the author nonetheless wishes to document. Such phonetic notation is the primary function of the IPA. |

| / ... / | Slashes[note 10] are used for abstract phonemic notation,[18] which note only features that are distinctive in the language, without any extraneous detail. For example, while the 'p' sounds of English pin and spin are pronounced differently (and this difference would be meaningful in some languages), the difference is not meaningful in English. Thus, phonemically the words are usually analyzed as /ˈpɪn/ and /ˈspɪn/, with the same phoneme /p/. To capture the difference between them (the allophones of /p/), they can be transcribed phonetically as [pʰɪn] and [spɪn]. Phonemic notation commonly uses IPA symbols that are rather close to the default pronunciation of a phoneme, but for legibility often uses simple and 'familiar' letters rather than precise notation, for example /r/ and /o/ for the English [ɹʷ] and [əʊ̯] sounds, or /c, ɟ/ for [t͜ʃ, d͜ʒ] as mentioned above. |

Less common conventions include:

| Symbol | Use |

|---|---|

| { ... } | Braces ("curly brackets") are used for prosodic notation.[19] See Extensions to the International Phonetic Alphabet for examples in this system. |

| ( ... ) | Parentheses are used for indistinguishable[18] or unidentified utterances. They are also seen for silent articulation (mouthing),[20] where the expected phonetic transcription is derived from lip-reading, and with periods to indicate silent pauses, for example (…) or (2 sec). The latter usage is made official in the extIPA, with unidentified segments circled.[21] |

| ⸨ ... ⸩ | Double parentheses indicate either a transcription of obscured speech or a description of the obscuring noise. The IPA specifies that they mark the obscured sound,[19] as in ⸨2σ⸩, two audible syllables obscured by another sound. The current extIPA specifications prescribe double parentheses for the extraneous noise, such as ⸨cough⸩ or ⸨knock⸩ for a knock on a door, but the IPA Handbook identifies IPA and extIPA usage as equivalent.[22] Early publications of the extIPA explain double parentheses as marking "uncertainty because of noise which obscures the recording," and that within them "may be indicated as much detail as the transcriber can detect."[23] |

All three of the above are provided by the IPA Handbook. The following are not, but may be seen in IPA transcription or in associated material (especially angle brackets):

| Symbol | Field | Description |

|---|---|---|

| ⟦ ... ⟧ | Phonetics | Double square brackets are used for especially precise phonetic transcription, often finer than is normally practicable.[24] This is consistent with the IPA convention of doubling a symbol to indicate greater degree. Double brackets may indicate that a letter has its cardinal IPA value. For example, ⟦a⟧ is an open front vowel, rather than the perhaps slightly different value (such as open central) that "[a]" may be used to transcribe in a particular language. Thus, two vowels transcribed for easy legibility as ⟨[e]⟩ and ⟨[ɛ]⟩ may be clarified as actually being ⟦e̝⟧ and ⟦e⟧; ⟨[ð]⟩ may be more precisely ⟦ð̠̞ˠ⟧.[25] Double brackets may also be used for a specific token or speaker; for example, the pronunciation of a child as opposed to the adult phonetic pronunciation that is their target.[26] |

|

Morphophonology or diaphonology |

Double slashes are used for morphophonemic and diaphonemic transcription. This is also consistent with the IPA convention of doubling a symbol to indicate greater degree (in this case, more abstract than phonemic transcription).

Other symbols sometimes seen are pipes and double pipes, from Americanist phonetic notation; exclamation marks; and braces from set theory, especially when enclosing the set of phonemes that constitute the morphophoneme, e.g. {t d} or {t|d} or {/t/, /d/}. Only double slashes are unambiguous: both pipes and braces conflict with IPA prosodic transcription.[note 11] |

|

Graphemics | Angle brackets[note 12] are used to mark both original Latin orthography and transliteration from another script; they are also used to identify individual graphemes of any script.[29][30] In IPA literature, they are used to indicate the IPA letters themselves rather than the sound values that they carry. Double angle brackets may occasionally be useful to distinguish original orthography from transliteration, or the idiosyncratic spelling of a manuscript from the normalized orthography of the language.

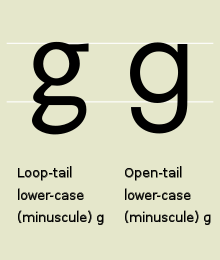

For example, ⟨cot⟩ would be used for the orthography of the English word cot, as opposed to its pronunciation /ˈkɒt/. Italics are usual when words are written as themselves (as with cot in the previous sentence) rather than to specifically note their orthography. However, this is sometimes ambiguous, and italic markup is not always accessible to sight-impaired readers who rely on screen reader technology. Vertical lines are used to denote glyphs, the etic units which represent individual concrete realizations of graphemes. For example, the different shapes of single-storey |a| and double-storey |ɑ| glyphs both represent the single grapheme ⟨a⟩ in ordinary English writing, but represent distinct graphemes in the IPA.[31] |

Some examples of contrasting brackets in the literature:

In some English accents, the phoneme /l/, which is usually spelled as ⟨l⟩ or ⟨ll⟩, is articulated as two distinct allophones: the clear [l] occurs before vowels and the consonant /j/, whereas the dark [ɫ]/[lˠ] occurs before consonants, except /j/, and at the end of words.[32]

the alternations /f/ – /v/ in plural formation in one class of nouns, as in knife /naɪf/ – knives /naɪvz/, which can be represented morphophonemically as {naɪV} – {naɪV+z}. The morphophoneme {V} stands for the phoneme set {/f/, /v/}.[33]

[ˈf\faɪnəlz ˈhɛld ɪn (.) ⸨knock on door⸩ bɑɹsə{𝑝ˈloʊnə and ˈmədɹɪd 𝑝}] — f-finals held in Barcelona and Madrid.[34]

Other representations

[edit]IPA letters have cursive forms designed for use in manuscripts and when taking field notes, but the Handbook recommended against their use, as cursive IPA is "harder for most people to decipher."[35] A braille representation of the IPA for blind or visually impaired professionals and students has also been developed.[36]

Modifying the IPA chart

[edit]

The International Phonetic Alphabet is occasionally modified by the Association. After each modification, the Association provides an updated simplified presentation of the alphabet in the form of a chart. (See History of the IPA.) Not all aspects of the alphabet can be accommodated in a chart of the size published by the IPA. The alveolo-palatal and epiglottal consonants, for example, are not included in the consonant chart for reasons of space rather than of theory (two additional columns would be required, one between the retroflex and palatal columns and the other between the pharyngeal and glottal columns), and the lateral flap would require an additional row for that single consonant, so they are listed instead under the catchall block of "other symbols".[37] The indefinitely large number of tone letters would make a full accounting impractical even on a larger page, and only a few examples are shown, and even the tone diacritics are not complete; the reversed tone letters are not illustrated at all.

The procedure for modifying the alphabet or the chart is to propose the change in the Journal of the IPA. (See, for example, December 2008 on an open central unrounded vowel[38] and August 2011 on central approximants.)[39] Reactions to the proposal may be published in the same or subsequent issues of the Journal (as in August 2009 on the open central vowel).[40][better source needed] A formal proposal is then put to the Council of the IPA[41][clarification needed] – which is elected by the membership[42] – for further discussion and a formal vote.[43][44]

Many users of the alphabet, including the leadership of the Association itself, deviate from its standardized usage.[note 13] The Journal of the IPA finds it acceptable to mix IPA and extIPA symbols in consonant charts in their articles. (For instance, including the extIPA letter ⟨𝼆⟩, rather than ⟨ʎ̝̊⟩, in an illustration of the IPA.)[45]

Usage

[edit]Of more than 160 IPA symbols, relatively few will be used to transcribe speech in any one language, with various levels of precision. A precise phonetic transcription, in which sounds are specified in detail, is known as a narrow transcription. A coarser transcription with less detail is called a broad transcription. Both are relative terms, and both are generally enclosed in square brackets.[1] Broad phonetic transcriptions may restrict themselves to easily heard details, or only to details that are relevant to the discussion at hand, and may differ little if at all from phonemic transcriptions, but they make no theoretical claim that all the distinctions transcribed are necessarily meaningful in the language.

For example, the English word little may be transcribed broadly as [ˈlɪtəl], approximately describing many pronunciations. A narrower transcription may focus on individual or dialectical details: [ˈɫɪɾɫ] in General American, [ˈlɪʔo] in Cockney, or [ˈɫɪːɫ] in Southern US English.

Phonemic transcriptions, which express the conceptual counterparts of spoken sounds, are usually enclosed in slashes (/ /) and tend to use simpler letters with few diacritics. The choice of IPA letters may reflect theoretical claims of how speakers conceptualize sounds as phonemes or they may be merely a convenience for typesetting. Phonemic approximations between slashes do not have absolute sound values. For instance, in English, either the vowel of pick or the vowel of peak may be transcribed as /i/, so that pick, peak would be transcribed as /ˈpik, ˈpiːk/ or as /ˈpɪk, ˈpik/; and neither is identical to the vowel of the French pique which would also be transcribed /pik/. By contrast, a narrow phonetic transcription of pick, peak, pique could be: [pʰɪk], [pʰiːk], [pikʲ].

Linguists

[edit]IPA is popular for transcription by linguists. Some American linguists, however, use a mix of IPA with Americanist phonetic notation or Sinological phonetic notation or otherwise use nonstandard symbols for various reasons.[46] Authors who employ such nonstandard use are encouraged to include a chart or other explanation of their choices, which is good practice in general, as linguists differ in their understanding of the exact meaning of IPA symbols and common conventions change over time.

Dictionaries

[edit]English

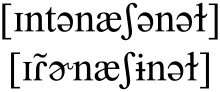

[edit]Many British dictionaries, including the Oxford English Dictionary and some learner's dictionaries such as the Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary and the Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary, now use the International Phonetic Alphabet to represent the pronunciation of words.[47] However, most American (and some British) volumes use one of a variety of pronunciation respelling systems, intended to be more comfortable for readers of English and to be more acceptable across dialects, without the implication of a preferred pronunciation that the IPA might convey. For example, the respelling systems in many American dictionaries (such as Merriam-Webster) use ⟨y⟩ for IPA [ j] and ⟨sh⟩ for IPA [ ʃ ], reflecting the usual spelling of those sounds in English.[48][49][note 14] (In IPA, [y] represents the sound of the French ⟨u⟩, as in tu, and [sh] represents the sequence of consonants in grasshopper.)

Other languages

[edit]The IPA is also not universal among dictionaries in languages other than English. Monolingual dictionaries of languages with phonemic orthographies generally do not bother with indicating the pronunciation of most words, and tend to use respelling systems for words with unexpected pronunciations. Dictionaries produced in Israel use the IPA rarely and sometimes use the Hebrew alphabet for transcription of foreign words.[note 15] Bilingual dictionaries that translate from foreign languages into Russian usually employ the IPA, but monolingual Russian dictionaries occasionally use pronunciation respelling for foreign words.[note 16] The IPA is more common in bilingual dictionaries, but there are exceptions here too. Mass-market bilingual Czech dictionaries, for instance, tend to use the IPA only for sounds not found in Czech.[note 17]

Standard orthographies and case variants

[edit]IPA letters have been incorporated into the alphabets of various languages, notably via the Africa Alphabet in many sub-Saharan languages such as Hausa, Fula, Akan, Gbe languages, Manding languages, Lingala, etc. Capital case variants have been created for use in these languages. For example, Kabiyè of northern Togo has Ɖ ɖ, Ŋ ŋ, Ɣ ɣ, Ɔ ɔ, Ɛ ɛ, Ʋ ʋ. These, and others, are supported by Unicode, but appear in Latin ranges other than the IPA extensions.

In the IPA itself, however, only lower-case letters are used. The 1949 edition of the IPA handbook indicated that an asterisk ⟨*⟩ might be prefixed to indicate that a word was a proper name,[51] but this convention was not included in the 1999 Handbook, which notes the contrary use of the asterisk as a placeholder for a sound or feature that does not have a symbol.[52]

Classical singing

[edit]The IPA has widespread use among classical singers during preparation as they are frequently required to sing in a variety of foreign languages. They are also taught by vocal coaches to perfect diction and improve tone quality and tuning.[53] Opera librettos are authoritatively transcribed in IPA, such as Nico Castel's volumes[54] and Timothy Cheek's book Singing in Czech.[55] Opera singers' ability to read IPA was used by the site Visual Thesaurus, which employed several opera singers "to make recordings for the 150,000 words and phrases in VT's lexical database ... for their vocal stamina, attention to the details of enunciation, and most of all, knowledge of IPA".[56]

Letters

[edit]The International Phonetic Association organizes the letters of the IPA into three categories: pulmonic consonants, non-pulmonic consonants, and vowels.[note 18][58]

Pulmonic consonant letters are arranged singly or in pairs of voiceless (tenuis) and voiced sounds, with these then grouped in columns from front (labial) sounds on the left to back (glottal) sounds on the right. In official publications by the IPA, two columns are omitted to save space, with the letters listed among "other symbols" even though theoretically they belong in the main chart.[note 19] They are arranged in rows from full closure (occlusives: stops and nasals) at top, to brief closure (vibrants: trills and taps), to partial closure (fricatives), and finally minimal closure (approximants) at bottom, again with a row left out to save space. In the table below, a slightly different arrangement is made: All pulmonic consonants are included in the pulmonic-consonant table, and the vibrants and laterals are separated out so that the rows reflect the common lenition pathway of stop → fricative → approximant, as well as the fact that several letters pull double duty as both fricative and approximant; affricates may then be created by joining stops and fricatives from adjacent cells. Shaded cells represent articulations that are judged to be impossible or not distinctive.

Vowel letters are also grouped in pairs—of unrounded and rounded vowel sounds—with these pairs also arranged from front on the left to back on the right, and from maximal closure at top to minimal closure at bottom. No vowel letters are omitted from the chart, though in the past some of the mid central vowels were listed among the "other symbols".

Consonants

[edit]Pulmonic consonants

[edit]A pulmonic consonant is a consonant made by obstructing the glottis (the space between the vocal folds) or oral cavity (the mouth) and either simultaneously or subsequently letting out air from the lungs. Pulmonic consonants make up the majority of consonants in the IPA, as well as in human language. All consonants in English fall into this category.[60]

The pulmonic consonant table, which includes most consonants, is arranged in rows that designate manner of articulation, meaning how the consonant is produced, and columns that designate place of articulation, meaning where in the vocal tract the consonant is produced. The main chart includes only consonants with a single place of articulation.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- In rows where some letters appear in pairs (the obstruents), the letter to the right represents a voiced consonant (except breathy-voiced [ɦ]).[61] In the other rows (the sonorants), the single letter represents a voiced consonant.

- While IPA provides a single letter for the coronal places of articulation (for all consonants but fricatives), these do not always have to be used exactly. When dealing with a particular language, the letters may be treated as specifically dental, alveolar, or post-alveolar, as appropriate for that language, without diacritics.

- Shaded areas indicate articulations judged to be impossible.

- The letters [β, ð, ʁ, ʕ, ʢ] are canonically voiced fricatives but may be used for approximants.[note 20]

- In many languages, such as English, [h] and [ɦ] are not actually glottal, fricatives, or approximants. Rather, they are bare phonation.[63]

- It is primarily the shape of the tongue rather than its position that distinguishes the fricatives [ʃ ʒ], [ɕ ʑ], and [ʂ ʐ].

- [ʜ, ʢ] are defined as epiglottal fricatives under the "Other symbols" section in the official IPA chart, but they may be treated as trills at the same place of articulation as [ħ, ʕ] because trilling of the aryepiglottic folds typically co-occurs.[64]

- Some listed phones are not known to exist as phonemes in any language.

Non-pulmonic consonants

[edit]Non-pulmonic consonants are sounds whose airflow is not dependent on the lungs. These include clicks (found in the Khoisan languages and some neighboring Bantu languages of Africa), implosives (found in languages such as Sindhi, Hausa, Swahili and Vietnamese), and ejectives (found in many Amerindian and Caucasian languages).

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- Clicks have traditionally been described as consisting of a forward place of articulation, commonly called the click "type" or historically the "influx", and a rear place of articulation, which when combined with the quality of the click is commonly called the click "accompaniment" or historically the "efflux". The IPA click letters indicate only the click type (forward articulation and release). Therefore, all clicks require two letters for proper notation: ⟨k͡ǀ, ɡ͡ǀ, q͡ǀ⟩, etc., or with the order reversed if both the forward and rear releases are audible. The letter for the rear articulation is frequently omitted, in which case a ⟨k⟩ may usually be assumed. However, some researchers dispute the idea that clicks should be analyzed as doubly articulated, as the traditional transcription implies, and analyze the rear occlusion as solely a part of the airstream mechanism.[65] In transcriptions of such approaches, the click letter represents both places of articulation, with the different letters representing the different click types, and diacritics are used for the elements of the accompaniment: ⟨ǀ, ǀ̬, ǀ̃⟩, etc.

- Letters for the voiceless implosives ⟨ƥ, ƭ, ƈ, ƙ, ʠ⟩ are no longer supported by the IPA, though they remain in Unicode. Instead, the IPA typically uses the voiced equivalent with a voiceless diacritic: ⟨ɓ̥, ɗ̥⟩, etc..

- The letter for the retroflex implosive, ⟨ᶑ ⟩, is not "explicitly IPA approved",[66] but has the expected form if such a symbol were to be approved.

- The ejective diacritic is placed at the right-hand margin of the consonant, rather than immediately after the letter for the stop: ⟨t͜ʃʼ⟩, ⟨kʷʼ⟩. In imprecise transcription, it often stands in for a superscript glottal stop in glottalized but pulmonic sonorants, such as [mˀ], [lˀ], [wˀ], [aˀ] (also transcribable as creaky [m̰], [l̰], [w̰], [a̰]).

Affricates

[edit]Affricates and co-articulated stops are represented by two letters joined by a tie bar, either above or below the letters with no difference in meaning.[note 21] Affricates are optionally represented by ligatures (e.g. ⟨ʧ, ʤ ⟩), though this is no longer official IPA usage[1] because a great number of ligatures would be required to represent all affricates this way. Alternatively, a superscript notation for a consonant release is sometimes used to transcribe affricates, for example ⟨tˢ⟩ for [t͜s], paralleling [kˣ] ~ [k͜x]. The letters for the palatal plosives ⟨c⟩ and ⟨ɟ⟩ are often used as a convenience for [t͜ʃ] and [d͜ʒ] or similar affricates, even in official IPA publications, so they must be interpreted with care.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Co-articulated consonants

[edit]Co-articulated consonants are sounds that involve two simultaneous places of articulation (are pronounced using two parts of the vocal tract). In English, the [w] in "went" is a coarticulated consonant, being pronounced by rounding the lips and raising the back of the tongue. Similar sounds are [ʍ] and [ɥ]. In some languages, plosives can be double-articulated, for example in the name of Laurent Gbagbo.

|

|

Notes

- [ɧ], the Swedish sj-sound, is described by the IPA as a "simultaneous [ʃ] and [x]", but it is unlikely such a simultaneous fricative actually exists in any language.[68]

- Multiple tie bars can be used: ⟨a͡b͡c⟩ or ⟨a͜b͜c⟩. For instance, a pre-voiced velar affricate may be transcribed as ⟨g͡k͡x⟩

- If a diacritic needs to be placed on or under a tie bar, the combining grapheme joiner (U+034F) needs to be used, as in [b͜͏̰də̀bdʊ̀] 'chewed' (Margi). Font support is spotty, however.

Vowels

[edit]

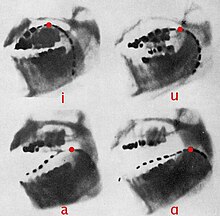

The IPA defines a vowel as a sound which occurs at a syllable center.[69] Below is a chart depicting the vowels of the IPA. The IPA maps the vowels according to the position of the tongue.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The vertical axis of the chart is mapped by vowel height. Vowels pronounced with the tongue lowered are at the bottom, and vowels pronounced with the tongue raised are at the top. For example, [ɑ] (the first vowel in father) is at the bottom because the tongue is lowered in this position. [i] (the vowel in "meet") is at the top because the sound is said with the tongue raised to the roof of the mouth.

In a similar fashion, the horizontal axis of the chart is determined by vowel backness. Vowels with the tongue moved towards the front of the mouth (such as [ɛ], the vowel in "met") are to the left in the chart, while those in which it is moved to the back (such as [ʌ], the vowel in "but") are placed to the right in the chart.

In places where vowels are paired, the right represents a rounded vowel (in which the lips are rounded) while the left is its unrounded counterpart.

Diphthongs

[edit]Diphthongs are typically specified with a non-syllabic diacritic, as in ⟨ui̯⟩ or ⟨u̯i⟩, or with a superscript for the on- or off-glide, as in ⟨uⁱ⟩ or ⟨ᵘi⟩. Sometimes a tie bar is used: ⟨u͜i⟩, especially when it is difficult to tell if the diphthong is characterized by an on-glide or an off-glide or when it is variable.

Notes

- ⟨a⟩ officially represents a front vowel, but there is little if any distinction between front and central open vowels (see Vowel § Acoustics), and ⟨a⟩ is frequently used for an open central vowel.[46] If disambiguation is required, the retraction diacritic or the centralized diacritic may be added to indicate an open central vowel, as in ⟨a̠⟩ or ⟨ä⟩.

Diacritics and prosodic notation

[edit]Diacritics are used for phonetic detail. They are added to IPA letters to indicate a modification or specification of that letter's normal pronunciation.[70]

By being made superscript, any IPA letter may function as a diacritic, conferring elements of its articulation to the base letter. Those superscript letters listed below are specifically provided for by the IPA Handbook; other uses can be illustrated with ⟨tˢ⟩ ([t] with fricative release), ⟨ᵗs⟩ ([s] with affricate onset), ⟨ⁿd⟩ (prenasalized [d]), ⟨bʱ⟩ ([b] with breathy voice), ⟨mˀ⟩ (glottalized [m]), ⟨sᶴ⟩ ([s] with a flavor of [ʃ], i.e. a voiceless alveolar retracted sibilant), ⟨oᶷ⟩ ([o] with diphthongization), ⟨ɯᵝ⟩ (compressed [ɯ]). Superscript diacritics placed after a letter are ambiguous between simultaneous modification of the sound and phonetic detail at the end of the sound. For example, labialized ⟨kʷ⟩ may mean either simultaneous [k] and [w] or else [k] with a labialized release. Superscript diacritics placed before a letter, on the other hand, normally indicate a modification of the onset of the sound (⟨mˀ⟩ glottalized [m], ⟨ˀm⟩ [m] with a glottal onset). (See § Superscript IPA.)

| Airstream diacritics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ◌ʼ | kʼ sʼ | Ejective | |||

| Syllabicity diacritics | |||||

| ◌̩ | ɹ̩ n̩ | Syllabic | ◌̯ | ɪ̯ ʊ̯ | Non-syllabic |

| ◌̍ | ɻ̍ ŋ̍ | ◌̑ | y̑ | ||

| Consonant-release diacritics | |||||

| ◌ʰ | tʰ | Aspirated[α] | ◌̚ | p̚ | No audible release |

| ◌ⁿ | dⁿ | Nasal release | ◌ˡ | dˡ | Lateral release |

| ◌ᶿ | tᶿ | Voiceless dental fricative release | ◌ˣ | tˣ | Voiceless velar fricative release |

| ◌ᵊ | dᵊ | Mid central vowel release | |||

| Phonation diacritics | |||||

| ◌̥ | n̥ d̥ | Voiceless | ◌̬ | s̬ t̬ | Voiced |

| ◌̊ | ɻ̊ ŋ̊ | ||||

| ◌̤ | b̤ a̤ | Breathy voiced[α] | ◌̰ | b̰ a̰ | Creaky voiced |

| Articulation diacritics | |||||

| ◌̪ | t̪ d̪ | Dental | ◌̼ | t̼ d̼ | Linguolabial |

| ◌͆ | ɮ͆ | ||||

| ◌̺ | t̺ d̺ | Apical | ◌̻ | t̻ d̻ | Laminal |

| ◌̟ | u̟ t̟ | Advanced (fronted) | ◌̠ | i̠ t̠ | Retracted (backed) |

| ◌᫈ | ɡ᫈ | ◌̄ | q̄[β] | ||

| ◌̈ | ë ä | Centralized | ◌̽ | e̽ ɯ̽ | Mid-centralized |

| ◌̝ | e̝ r̝ | Raised ([r̝], [ɭ˔] are fricatives) |

◌̞ | e̞ β̞ | Lowered ([β̞], [ɣ˕] are approximants) |

| ◌˔ | ɭ˔ | ◌˕ | y˕ ɣ˕ | ||

| Co-articulation diacritics | |||||

| ◌̹ | ɔ̹ x̹ | More rounded / less spread (over-rounding) |

◌̜ | ɔ̜ xʷ̜ | Less rounded / more spread (under-rounding)[γ] |

| ◌͗ | y͗ χ͗ | ◌͑ | y͑ χ͑ʷ | ||

| ◌ʷ | tʷ dʷ | Labialized | ◌ʲ | tʲ dʲ | Palatalized |

| ◌ˠ | tˠ dˠ | Velarized | ◌̴ | ɫ ᵶ | Velarized or pharyngealized |

| ◌ˤ | tˤ aˤ | Pharyngealized | |||

| ◌̘ | e̘ o̘ | Advanced tongue root | ◌̙ | e̙ o̙ | Retracted tongue root |

| ◌꭪ | y꭪ | ◌꭫ | y꭫ | ||

| ◌̃ | ẽ z̃ | Nasalized | ◌˞ | ɚ ɝ | Rhoticity |

Notes:

- ^ Jump up to: a b With aspirated voiced consonants, the aspiration is usually also voiced (voiced aspirated – but see voiced consonants with voiceless aspiration). Many linguists prefer one of the diacritics dedicated to breathy voice over simple aspiration, such as ⟨b̤⟩. Some linguists restrict that diacritic to sonorants, such as breathy-voice ⟨m̤⟩, and transcribe voiced-aspirated obstruents as e.g. ⟨bʱ⟩.

- ^ Care must be taken that a superscript retraction sign is not mistaken for mid tone.

- ^ These are relative to the cardinal value of the letter. They can also apply to unrounded vowels: [ɛ̜] is more spread (less rounded) than cardinal [ɛ], and [ɯ̹] is less spread than cardinal [ɯ].[71]

Since ⟨xʷ⟩ can mean that the [x] is labialized (rounded) throughout its articulation, and ⟨x̜⟩ makes no sense ([x] is already completely unrounded), ⟨x̜ʷ⟩ can only mean a less-labialized/rounded [xʷ]. However, readers might mistake ⟨x̜ʷ⟩ for "[x̜]" with a labialized off-glide, or might wonder if the two diacritics cancel each other out. Placing the 'less rounded' diacritic under the labialization diacritic, ⟨xʷ̜⟩, makes it clear that it is the labialization that is 'less rounded' than its cardinal IPA value.

Subdiacritics (diacritics normally placed below a letter) may be moved above a letter to avoid conflict with a descender, as in voiceless ⟨ŋ̊⟩.[70] The raising and lowering diacritics have optional spacing forms ⟨˔⟩, ⟨˕⟩ that avoid descenders.

The state of the glottis can be finely transcribed with diacritics. A series of alveolar plosives ranging from open-glottis to closed-glottis phonation is:

| Open glottis | [t] | voiceless |

|---|---|---|

| [d̤] | breathy voice, also called murmured | |

| [d̥] | slack voice | |

| Sweet spot | [d] | modal voice |

| [d̬] | stiff voice | |

| [d̰] | creaky voice | |

| Closed glottis | [ʔ͡t] | glottal closure |

Additional diacritics are provided by the Extensions to the IPA for speech pathology.

Suprasegmentals

[edit]These symbols describe the features of a language above the level of individual consonants and vowels, that is, at the level of syllable, word or phrase. These include prosody, pitch, length, stress, intensity, tone and gemination of the sounds of a language, as well as the rhythm and intonation of speech.[72] Various ligatures of pitch/tone letters and diacritics are provided for by the Kiel Convention and used in the IPA Handbook despite not being found in the summary of the IPA alphabet found on the one-page chart.

Under capital letters below we will see how a carrier letter may be used to indicate suprasegmental features such as labialization or nasalization. Some authors omit the carrier letter, for e.g. suffixed [kʰuˣt̪s̟]ʷ or prefixed [ʷkʰuˣt̪s̟],[note 22] or place a spacing variant of a diacritic such as ⟨˔⟩ or ⟨˜⟩ at the beginning or end of a word to indicate that it applies to the entire word.[note 23]

| Length, stress, and rhythm | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| ˈke | Primary stress (appears before stressed syllable) |

ˌke | Secondary stress (appears before stressed syllable) |

| eː kː | Long (long vowel or geminate consonant) |

eˑ | Half-long |

| ə̆ ɢ̆ | Extra-short | ||

| ek.ste eks.te |

Syllable break (internal boundary) |

es‿e | Linking (lack of a boundary; a phonological word)[note 24] |

| Intonation | |||

| |[α] | Minor or foot break | ‖[α] | Major or intonation break |

| ↗︎ | Global rise[note 25] | ↘︎ | Global fall[note 25] |

| Up- and down-step | |||

| ꜛke | Upstep | ꜜke | Downstep |

Notes:

- ^ Jump up to: a b The pipes for intonation breaks should be a heavier weight than the letters for click consonants. Because fonts do not reflect this, the intonation breaks in the official IPA charts are set in bold typeface.

| Pitch diacritics[note 26] | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ŋ̋ e̋ | Extra high | ŋ̌ ě | Rising | ŋ᷄ e᷄ | Mid-rising | |||||||

| ŋ́ é | High | ŋ̂ ê | Falling | ŋ᷅ e᷅ | Low-rising | |||||||

| ŋ̄ ē | Mid | ŋ᷈ e᷈ | Peaking (rising–falling) | ŋ᷇ e᷇ | High-falling | |||||||

| ŋ̀ è | Low | ŋ᷉ e᷉ | Dipping (falling–rising) | ŋ᷆ e᷆ | Mid-falling | |||||||

| ŋ̏ ȅ | Extra low | (etc.)[note 27] | ||||||||||

| Chao tone letters[note 26] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ˥e | ꜒e | e˥ | e꜒ | High |

| ˦e | ꜓e | e˦ | e꜓ | Half-high |

| ˧e | ꜔e | e˧ | e꜔ | Mid |

| ˨e | ꜕e | e˨ | e꜕ | Half-low |

| ˩e | ꜖e | e˩ | e꜖ | Low |

| ˩˥e | ꜖꜒e | e˩˥ | e꜖꜒ | Rising (low to high or generic) |

| ˥˩e | ꜒꜖e | e˥˩ | e꜒꜖ | Falling (high to low or generic) |

| (etc.) | ||||

The old staveless tone letters, which are effectively obsolete, include high ⟨ˉe⟩, mid ⟨˗e⟩, low ⟨ˍe⟩, rising ⟨ˊe⟩, falling ⟨ˋe⟩, low rising ⟨ˏe⟩ and low falling ⟨ˎe⟩.

Stress

[edit]Officially, the stress marks ⟨ˈ ˌ⟩ appear before the stressed syllable, and thus mark the syllable boundary as well as stress (though the syllable boundary may still be explicitly marked with a period).[75] Occasionally the stress mark is placed immediately before the nucleus of the syllable, after any consonantal onset.[76] In such transcriptions, the stress mark does not mark a syllable boundary. The primary stress mark may be doubled ⟨ˈˈ⟩ for extra stress (such as prosodic stress). The secondary stress mark is sometimes seen doubled ⟨ˌˌ⟩ for extra-weak stress, but this convention has not been adopted by the IPA.[75] Some dictionaries place both stress marks before a syllable, ⟨¦⟩, to indicate that pronunciations with either primary or secondary stress are heard, though this is not IPA usage.[note 28]

Boundary markers

[edit]There are three boundary markers: ⟨.⟩ for a syllable break, ⟨|⟩ for a minor prosodic break and ⟨‖⟩ for a major prosodic break. The tags 'minor' and 'major' are intentionally ambiguous. Depending on need, 'minor' may vary from a foot break to a break in list-intonation to a continuing–prosodic unit boundary (equivalent to a comma), and while 'major' is often any intonation break, it may be restricted to a final–prosodic unit boundary (equivalent to a period). The 'major' symbol may also be doubled, ⟨‖‖⟩, for a stronger break.[note 29]

Although not part of the IPA, the following additional boundary markers are often used in conjunction with the IPA: ⟨μ⟩ for a mora or mora boundary, ⟨σ⟩ for a syllable or syllable boundary, ⟨+⟩ for a morpheme boundary, ⟨#⟩ for a word boundary (may be doubled, ⟨##⟩, for e.g. a breath-group boundary),[78] ⟨$⟩ for a phrase or intermediate boundary and ⟨%⟩ for a prosodic boundary. For example, C# is a word-final consonant, %V a post-pausa vowel, and σC a syllable-initial consonant.

Pitch and tone

[edit]⟨ꜛ ꜜ⟩ are defined in the Handbook as "upstep" and "downstep", concepts from tonal languages. However, the upstep symbol can also be used for pitch reset, and the IPA Handbook uses it for prosody in the illustration for Portuguese, a non-tonal language.

Phonetic pitch and phonemic tone may be indicated by either diacritics placed over the nucleus of the syllable (e.g., high-pitch ⟨é⟩) or by Chao tone letters placed either before or after the word or syllable. There are three graphic variants of the tone letters: with or without a stave, and facing left or facing right from the stave. The stave was introduced with the 1989 Kiel Convention, as was the option of placing a staved letter after the word or syllable, while retaining the older conventions. There are therefore six ways to transcribe pitch/tone in the IPA: i.e., ⟨é⟩, ⟨˦e⟩, ⟨e˦⟩, ⟨꜓e⟩, ⟨e꜓⟩ and ⟨ˉe⟩ for a high pitch/tone.[75][79][80] Of the tone letters, only left-facing staved letters and a few representative combinations are shown in the summary on the Chart, and in practice it is currently more common for tone letters to occur after the syllable/word than before, as in the Chao tradition. Placement before the word is a carry-over from the pre-Kiel IPA convention, as is still the case for the stress and upstep/downstep marks. The IPA endorses the Chao tradition of using the left-facing tone letters, ⟨˥ ˦ ˧ ˨ ˩⟩, for underlying tone, and the right-facing letters, ⟨꜒ ꜓ ꜔ ꜕ ꜖⟩, for surface tone, as occurs in tone sandhi, and for the intonation of non-tonal languages.[note 30] In the Portuguese illustration in the 1999 Handbook, tone letters are placed before a word or syllable to indicate prosodic pitch (equivalent to [↗︎] global rise and [↘︎] global fall, but allowing more precision), and in the Cantonese illustration they are placed after a word/syllable to indicate lexical tone. Theoretically therefore prosodic pitch and lexical tone could be simultaneously transcribed in a single text, though this is not a formalized distinction.

Rising and falling pitch, as in contour tones, are indicated by combining the pitch diacritics and letters in the table, such as grave plus acute for rising [ě] and acute plus grave for falling [ê]. Only six combinations of two diacritics are supported, and only across three levels (high, mid, low), despite the diacritics supporting five levels of pitch in isolation. The four other explicitly approved rising and falling diacritic combinations are high/mid rising [e᷄], low rising [e᷅], high falling [e᷇], and low/mid falling [e᷆].[note 31]

The Chao tone letters, on the other hand, may be combined in any pattern, and are therefore used for more complex contours and finer distinctions than the diacritics allow, such as mid-rising [e˨˦], extra-high falling [e˥˦], etc. There are 20 such possibilities. However, in Chao's original proposal, which was adopted by the IPA in 1989, he stipulated that the half-high and half-low letters ⟨˦ ˨⟩ may be combined with each other, but not with the other three tone letters, so as not to create spuriously precise distinctions. With this restriction, there are 8 possibilities.[81]

The old staveless tone letters tend to be more restricted than the staved letters, though not as restricted as the diacritics. Officially, they support as many distinctions as the staved letters,[note 32] but typically only three pitch levels are distinguished. Unicode supports default or high-pitch ⟨ˉ ˊ ˋ ˆ ˇ ˜ ˙⟩ and low-pitch ⟨ˍ ˏ ˎ ꞈ ˬ ˷⟩. Only a few mid-pitch tones are supported (such as ⟨˗ ˴⟩), and then only accidentally.

Although tone diacritics and tone letters are presented as equivalent on the chart, "this was done only to simplify the layout of the chart. The two sets of symbols are not comparable in this way."[82] Using diacritics, a high tone is ⟨é⟩ and a low tone is ⟨è⟩; in tone letters, these are ⟨e˥⟩ and ⟨e˩⟩. One can double the diacritics for extra-high ⟨e̋⟩ and extra-low ⟨ȅ⟩; there is no parallel to this using tone letters. Instead, tone letters have mid-high ⟨e˦⟩ and mid-low ⟨e˨⟩; again, there is no equivalent among the diacritics. Thus in a three-register tone system, ⟨é ē è⟩ are equivalent to ⟨e˥ e˧ e˩⟩, while in a four-register system, ⟨e̋ é è ȅ⟩ may be equivalent to ⟨e˥ e˦ e˨ e˩⟩.[75]

The correspondence breaks down even further once they start combining. For more complex tones, one may combine three or four tone diacritics in any permutation,[75] though in practice only generic peaking (rising-falling) e᷈ and dipping (falling-rising) e᷉ combinations are used. Chao tone letters are required for finer detail (e˧˥˧, e˩˨˩, e˦˩˧, e˨˩˦, etc.). Although only 10 peaking and dipping tones were proposed in Chao's original, limited set of tone letters, phoneticians often make finer distinctions, and indeed an example is found on the IPA Chart.[note 33] The system allows the transcription of 112 peaking and dipping pitch contours, including tones that are level for part of their length.

| Register | Level [note 35] |

Rising | Falling | Peaking | Dipping |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| e˩ | e˩˩ | e˩˧ | e˧˩ | e˩˧˩ | e˧˩˧ |

| e˨ | e˨˨ | e˨˦ | e˦˨ | e˨˦˨ | e˦˨˦ |

| e˧ | e˧˧ | e˧˥ | e˥˧ | e˧˥˧ | e˥˧˥ |

| e˦ | e˦˦ | e˧˥˩ | e˧˩˥ | ||

| e˥ | e˥˥ | e˩˥ | e˥˩ | e˩˥˧ | e˥˩˧ |

More complex contours are possible. Chao gave an example of [꜔꜒꜖꜔] (mid-high-low-mid) from English prosody.[81]

Chao tone letters generally appear after each syllable, for a language with syllable tone (⟨a˧vɔ˥˩⟩), or after the phonological word, for a language with word tone (⟨avɔ˧˥˩⟩). The IPA gives the option of placing the tone letters before the word or syllable (⟨˧a˥˩vɔ⟩, ⟨˧˥˩avɔ⟩), but this is rare for lexical tone. (And indeed reversed tone letters may be used to clarify that they apply to the following rather than to the preceding syllable: ⟨꜔a꜒꜖vɔ⟩, ⟨꜔꜒꜖avɔ⟩.) The staveless letters are not directly supported by Unicode, but some fonts allow the stave in Chao tone letters to be suppressed.

Comparative degree

[edit]IPA diacritics may be doubled to indicate an extra degree (greater intensity) of the feature indicated.[83] This is a productive process, but apart from extra-high and extra-low tones being marked by doubled high- and low-tone diacritics, ⟨ə̋, ə̏⟩, the major prosodic break ⟨‖⟩ being marked as a doubled minor break ⟨|⟩, and a couple other instances, such usage is not enumerated by the IPA.

For example, the stress mark may be doubled (or even tripled, etc.) to indicate an extra degree of stress, such as prosodic stress in English.[84] An example in French, with a single stress mark for normal prosodic stress at the end of each prosodic unit (marked as a minor prosodic break), and a double or even triple stress mark for contrastive/emphatic stress: [ˈˈɑ̃ːˈtre | məˈsjø ‖ ˈˈvwala maˈdam ‖] Entrez monsieur, voilà madame.[85] Similarly, a doubled secondary stress mark ⟨ˌˌ⟩ is commonly used for tertiary (extra-light) stress, though a proposal to officially adopt this was rejected.[86] In a similar vein, the effectively obsolete staveless tone letters were once doubled for an emphatic rising intonation ⟨˶⟩ and an emphatic falling intonation ⟨˵⟩.[87]

Length is commonly extended by repeating the length mark, which may be phonetic, as in [ĕ e eˑ eː eːˑ eːː] etc., as in English shhh! [ʃːːː], or phonemic, as in the "overlong" segments of Estonian:

- vere /vere/ 'blood [gen.sg.]', veere /veːre/ 'edge [gen.sg.]', veere /veːːre/ 'roll [imp. 2nd sg.]'

- lina /linɑ/ 'sheet', linna /linːɑ/ 'town [gen. sg.]', linna /linːːɑ/ 'town [ine. sg.]'

(Normally additional phonemic degrees of length are handled by the extra-short or half-long diacritic, i.e. ⟨e eˑ eː⟩ or ⟨ĕ e eː⟩, but the first two words in each of the Estonian examples are analyzed as typically short and long, /e eː/ and /n nː/, requiring a different remedy for the additional words.)

Delimiters are similar: double slashes indicate extra phonemic (morpho-phonemic), double square brackets especially precise transcription, and double parentheses especially unintelligible.

Occasionally other diacritics are doubled:

- Rhoticity in Badaga /be/ "mouth", /be˞/ "bangle", and /be˞˞/ "crop".[88]

- Mild and strong aspiration, [kʰ], [kʰʰ].[note 36]

- Nasalization, as in Palantla Chinantec lightly nasalized /ẽ/ vs heavily nasalized /ẽ̃/,[89] though some care can be needed to distinguish this from the extIPA diacritic for velopharyngeal frication in disordered speech, /e͌/, which has also been analyzed as extreme nasalization.

- Weak vs strong ejectives, [kʼ], [kˮ].[90]

- Especially lowered, e.g. [t̞̞] (or [t̞˕], if the former symbol does not display properly) for /t/ as a weak fricative in some pronunciations of register.[91]

- Especially retracted, e.g. [ø̠̠] or [s̠̠],[note 37][83][92] though some care might be needed to distinguish this from indications of alveolar or alveolarized articulation in extIPA, e.g. [s͇].

- Especially guttural, e.g. [ɫ] (velarized l), [ꬸ] (pharyngealized l).[93]

- The transcription of strident and harsh voice as extra-creaky /a᷽/ may be motivated by the similarities of these phonations.

The extIPA provides combining parentheses for weak intensity, which when combined with a doubled diacritic indicate an intermediate degree. For instance, increasing degrees of nasalization of the vowel [e] might be written ⟨e ẽ᪻ ẽ ẽ̃᪻ ẽ̃⟩.

Ambiguous letters

[edit]As noted above, IPA letters are often used quite loosely in broad transcription if no ambiguity would arise in a particular language. Because of that, IPA letters have not generally been created for sounds that are not distinguished in individual languages. A distinction between voiced fricatives and approximants is only partially implemented by the IPA, for example. Even with the relatively recent addition of the palatal fricative ⟨ʝ⟩ and the velar approximant ⟨ɰ⟩ to the alphabet, other letters, though defined as fricatives, are often ambiguous between fricative and approximant. For forward places, ⟨β⟩ and ⟨ð⟩ can generally be assumed to be fricatives unless they carry a lowering diacritic. Rearward, however, ⟨ʁ⟩ and ⟨ʕ⟩ are perhaps more commonly intended to be approximants even without a lowering diacritic. ⟨h⟩ and ⟨ɦ⟩ are similarly either fricatives or approximants, depending on the language, or even glottal "transitions", without that often being specified in the transcription.

Another common ambiguity is among the letters for palatal consonants. ⟨c⟩ and ⟨ɟ⟩ are not uncommonly used as a typographic convenience for affricates, typically [t͜ʃ] and [d͜ʒ], while ⟨ɲ⟩ and ⟨ʎ⟩ are commonly used for palatalized alveolar [n̠ʲ] and [l̠ʲ]. To some extent this may be an effect of analysis, but it is common to match up single IPA letters to the phonemes of a language, without overly worrying about phonetic precision.

It has been argued that the lower-pharyngeal (epiglottal) fricatives ⟨ʜ⟩ and ⟨ʢ⟩ are better characterized as trills, rather than as fricatives that have incidental trilling.[94] This has the advantage of merging the upper-pharyngeal fricatives [ħ, ʕ] together with the epiglottal plosive [ʡ] and trills [ʜ ʢ] into a single pharyngeal column in the consonant chart. However, in Shilha Berber the epiglottal fricatives are not trilled.[95][96] Although they might be transcribed ⟨ħ̠ ʢ̠⟩ to indicate this, the far more common transcription is ⟨ʜ ʢ⟩, which is therefore ambiguous between languages.

Among vowels, ⟨a⟩ is officially a front vowel, but is more commonly treated as a central vowel. The difference, to the extent it is even possible, is not phonemic in any language.

For all phonetic notation, it is good practice for an author to specify exactly what they mean by the symbols that they use.

Superscript letters

[edit]

Superscript IPA letters are used to indicate secondary aspects of articulation. These may be aspects of simultaneous articulation that are considered to be in some sense less dominant than the basic sound, or may be transitional articulations that are interpreted as secondary elements.[97] Examples include secondary articulation; onsets, releases and other transitions; shades of sound; light epenthetic sounds and incompletely articulated sounds. Morphophonemically, superscripts may be used for assimilation, e.g. ⟨aʷ⟩ for the affect of labialization on a vowel /a/, which may be realized as phonemic /o/.[98] The IPA and ICPLA endorse Unicode encoding of superscript variants of all contemporary segmental letters, including the "implicit" IPA retroflex letters ⟨ꞎ 𝼅 𝼈 ᶑ 𝼊 ⟩.[45][99][100]

Superscripts are often used as a substitute for the tie bar, for example ⟨tᶴ⟩ for [t͜ʃ] and ⟨kᵖ⟩ or ⟨ᵏp⟩ for [k͜p]. However, in precise notation there is a difference between a fricative release in [tᶴ] and the affricate [t͜ʃ], between a velar onset in [ᵏp] and doubly articulated [k͜p].[101]

Superscript letters can be meaningfully modified by combining diacritics, just as baseline letters can. For example, a superscript dental nasal in ⟨ⁿ̪d̪⟩, a superscript voiceless velar nasal in ⟨ᵑ̊ǂ⟩, and labial-velar prenasalization in ⟨ᵑ͡ᵐɡ͡b⟩. Although the diacritic may seem a bit oversized compared to the superscript letter it modifies, e.g. ⟨ᵓ̃⟩, this can be an aid to legibility, just as it is with the composite superscript c-cedilla ⟨ᶜ̧⟩ and rhotic vowels ⟨ᵊ˞ ᶟ˞⟩. Superscript length marks can be used to indicate the length of aspiration of a consonant, e.g. [pʰ tʰ𐞂 kʰ𐞁]. Another option is to use extIPA parentheses and a doubled diacritic: ⟨p⁽ʰ⁾ tʰ kʰʰ⟩.[45]

Obsolete and nonstandard symbols

[edit]A number of IPA letters and diacritics have been retired or replaced over the years. This number includes duplicate symbols, symbols that were replaced due to user preference, and unitary symbols that were rendered with diacritics or digraphs to reduce the inventory of the IPA. The rejected symbols are now considered obsolete, though some are still seen in the literature.

The IPA once had several pairs of duplicate symbols from alternative proposals, but eventually settled on one or the other. An example is the vowel letter ⟨ɷ⟩, rejected in favor of ⟨ʊ⟩. Affricates were once transcribed with ligatures, such as ⟨ʧ ʤ ⟩ (and others, some of which not found in Unicode). These have been officially retired but are still used. Letters for specific combinations of primary and secondary articulation have also been mostly retired, with the idea that such features should be indicated with tie bars or diacritics: ⟨ƍ⟩ for [zʷ] is one. In addition, the rare voiceless implosives, ⟨ƥ ƭ ƈ ƙ ʠ ⟩, were dropped soon after their introduction and are now usually written ⟨ɓ̥ ɗ̥ ʄ̊ ɠ̊ ʛ̥ ⟩. The original set of click letters, ⟨ʇ, ʗ, ʖ, ʞ⟩, was retired but is still sometimes seen, as the current pipe letters ⟨ǀ, ǃ, ǁ, ǂ⟩ can cause problems with legibility, especially when used with brackets ([ ] or / /), the letter ⟨l⟩ (small L), or the prosodic marks ⟨|, ‖⟩. (For this reason, some publications which use the current IPA pipe letters disallow IPA brackets.)[102]

Individual non-IPA letters may find their way into publications that otherwise use the standard IPA. This is especially common with:

- Affricates, such as the Americanist barred lambda ⟨ƛ⟩ for [t͜ɬ] or ⟨č⟩ for [t͜ʃ ].[note 38]

- The Karlgren letters for Chinese vowels, ⟨ɿ, ʅ , ʮ, ʯ ⟩.

- Digits for tonal phonemes that have conventional numbers in a local tradition, such as the four tones of Standard Chinese. This may be more convenient for comparison between related languages and dialects than a phonetic transcription would be, because tones vary more unpredictably than segmental phonemes do.

- Digits for tone levels, which are simpler to typeset, though the lack of standardization can cause confusion (e.g. ⟨1⟩ is high tone in some languages but low tone in others; ⟨3⟩ may be high, medium or low tone, depending on the local convention).

- Iconic extensions of standard IPA letters that are implicit in the alphabet, such as retroflex ⟨ᶑ ⟩ and ⟨ꞎ ⟩. These are referred to in the Handbook and have been included in Unicode at IPA request.

- Even presidents of the IPA have used para-IPA notation, such as resurrecting the old diacritic ⟨◌̫⟩ for purely labialized sounds (not simultaneously velarized), the lateral fricative letter ⟨ꞎ ⟩, and either the old dot diacritic ⟨ṣ ẓ⟩ or the novel letters ⟨ ᶘ ᶚ⟩ for the not-quite-retroflex fricatives of Polish sz, ż and of Russian ш ж.

In addition, it is common to see ad hoc typewriter substitutions, generally capital letters, for when IPA support is not available, e.g. S for ⟨ ʃ ⟩. (See also SAMPA and X-SAMPA substitute notation.)

Extensions

[edit]

The Extensions to the International Phonetic Alphabet for Disordered Speech, commonly abbreviated "extIPA" and sometimes called "Extended IPA", are symbols whose original purpose was to accurately transcribe disordered speech. At the Kiel Convention in 1989, a group of linguists drew up the initial extensions,[note 39] which were based on the previous work of the PRDS (Phonetic Representation of Disordered Speech) Group in the early 1980s.[104] The extensions were first published in 1990, then modified, and published again in 1994 in the Journal of the International Phonetic Association, when they were officially adopted by the ICPLA.[105] While the original purpose was to transcribe disordered speech, linguists have used the extensions to designate a number of sounds within standard communication, such as hushing, gnashing teeth, and smacking lips,[2] as well as regular lexical sounds such as lateral fricatives that do not have standard IPA symbols.

In addition to the Extensions to the IPA for disordered speech, there are the conventions of the Voice Quality Symbols, which include a number of symbols for additional airstream mechanisms and secondary articulations in what they call "voice quality".

Associated notation

[edit]Capital letters and various characters on the number row of the keyboard are commonly used to extend the alphabet in various ways.

Associated symbols

[edit]Существуют различные соглашения, подобные пунктуации, для лингвистической транскрипции, которые обычно используются вместе с IPA. Некоторые из наиболее распространенных:

- ⟨*⟩

- а) Реконструированная форма .

- (б) Неграмматическая форма (включая немонематическую форму).

- ⟨**⟩

- (а) Реконструированная форма, более глубокая (более древняя), чем одиночная ⟨*⟩ , используемая при реконструкции еще дальше от уже отмеченных звездочками форм.

- (б) Неграмматическая форма. Менее распространенное соглашение, чем ⟨*⟩ (b), оно иногда используется, когда в одном тексте встречаются реконструированные и неграмматические формы. [ 106 ]

- ⟨×⟩ , ⟨✗⟩

- Неграмматическая форма. Менее распространенное соглашение, чем ⟨*⟩ (b), оно иногда используется, когда в одном тексте встречаются реконструированные и неграмматические формы. [ 107 ]

- ⟨?⟩

- Сомнительная грамматическая форма.

- ⟨%⟩

- Обобщенная форма, например типичная форма странника, фактически не реконструированная. [ 108 ]

- ⟨#⟩

- Граница слова – например, ⟨#V⟩ для гласной в начале слова.

- ⟨$⟩

- Фонологическая граница слова ; например, ⟨H$⟩ для высокого тона, возникающего в такой позиции.

- ⟨_⟩

- Местоположение сегмента – например, ⟨V_V⟩ для межвокальной позиции или ⟨_#⟩ для позиции конца слова.

- ⟨~⟩

- Чередование – например, ⟨[f] ~ [v]⟩ или ⟨[f ~ v]⟩ для вариации между ⟨[f]⟩ и ⟨[v]⟩ .

- ⟨∅⟩

- Нулевой сегмент или морфема. Это может указывать на отсутствие аффикса, например ⟨kæt-∅⟩ , когда аффикс может появиться, но не появляется ( кот вместо кошек ), или на удаленный сегмент, оставляющий после себя объект, например ⟨∅ʷ⟩ для теоретический лабиализованный сегмент, который реализуется только как лабиализация соседних сегментов. [ 98 ]

Заглавные буквы

[ редактировать ]Полные заглавные буквы не используются в качестве символов IPA, за исключением заменителей пишущей машинки (например, N для ⟨ ŋ ⟩, S для ⟨ ʃ ⟩, O для ⟨ ɔ ⟩ – см. SAMPA ). Однако они часто используются вместе с IPA в двух случаях:

- для (архи)фонем и естественных классов звуков (то есть в качестве подстановочных знаков). буквы . Например, в диаграмме extIPA на иллюстрациях в качестве подстановочных знаков используются заглавные

- как символы, обозначающие качество голоса .

Подстановочные знаки обычно используются в фонологии для суммирования форм слогов или слов или для демонстрации эволюции классов звуков. Например, возможные формы слогов мандаринского языка можно абстрагировать как диапазон от /V/ (атоническая гласная) до /CGVNᵀ/ (согласный-скользящий-гласный-носовой слог с тоном), а озвучивание в конце слова можно схематизировать как C → C̥ /_#. При патологии речи заглавные буквы обозначают неопределенные звуки и могут быть надстрочными, чтобы указать на их слабую артикулированность: например, [ᴰ] — слабый неопределенный альвеолярный звук, [ᴷ] — слабый неопределенный велярный звук. [ 109 ]

Между авторами существуют определенные различия в использовании заглавных букв, но ⟨ C ⟩ для {согласной}, ⟨ V ⟩ для {гласной} и ⟨ N ⟩ для {носовой} повсеместно встречаются в англоязычном материале. Другими распространенными условными обозначениями являются ⟨ T ⟩ для {тона/акцента} (тоничность), ⟨ P ⟩ для {взрывного звука}, ⟨ F ⟩ для {фрикативного}, ⟨ S ⟩ для {свистящего}, [ примечание 40 ] ⟨ G ⟩ для {скользящего/полугласного}, ⟨ L ⟩ для {латерального} или {жидкого}, ⟨ R ⟩ для {ротического} или {резонансного/звучного}, [ примечание 41 ] ⟨ ₵ ⟩ для {загромождать}, ⟨ Ʞ ⟩ для {щелчка}, ⟨ A, E, O, Ɨ, U ⟩ для {открытой, передней, задней, закрытой, закругленной гласной} [ примечание 42 ] и ⟨ B, D, Ɉ, K, Q, Φ, H ⟩ для {губных, альвеолярных, постальвеолярных/небных, велярных, увулярных, глоточных, гортанных [ примечание 43 ] согласная} соответственно и ⟨ X ⟩ для {любого звука}, как в ⟨ CVX ⟩ для тяжелого слога { CVC , CVV̯ , CVː }. Буквы можно изменить с помощью диакритических знаков IPA, например ⟨ Cʼ ⟩ для {выталкивающего}, ⟨ Ƈ ⟩ для {имплозивного}, ⟨ N͡C ⟩ или ⟨ ᴺC ⟩ для {преназализованного согласного}, ⟨ Ṽ ⟩ для { носового гласного }, ⟨ CʰV́ ⟩ для {придыхательного слога CV с высоким тоном}, ⟨ S̬ ⟩ для {звонкого шипящего}, ⟨ N̥ ⟩ для {глушенного носового}, ⟨ P͡F ⟩ или ⟨ Pꟳ ⟩ для {аффрикаты}, ⟨ Cᴳ ⟩ для согласного с a скользить как вторичная артикуляция (например, ⟨ Cʲ ⟩ для {палатализованного согласного} и ⟨ Cʷ ⟩ для {лабиализованного согласного}) и ⟨ D̪ ⟩ для {зубного согласного}. ⟨ H ⟩, ⟨ M ⟩, ⟨ L ⟩ также обычно используются для высокого, среднего и низкого тона, с ⟨ LH ⟩ для повышающегося тона и ⟨ HL ⟩ для нисходящего тона, вместо того, чтобы слишком точно транскрибировать их тональными буквами IPA или с помощью неоднозначные цифры. [ примечание 44 ]

Типичными примерами архифонемного использования заглавных букв являются ⟨ I ⟩ для набора турецких гармонических гласных {i y ɯ u }; [ примечание 45 ] ⟨ D ⟩ для слитной средней согласной американского английского писателя и наездника ; ⟨ N ⟩ для гомоорганического носового слога-кода в таких языках, как испанский и японский (по сути, эквивалентно использованию буквы с подстановочным знаком); и ⟨ R ⟩ в случаях, когда фонематическое различие между трелью / r / и взмахом / ɾ / объединяется, как в испанском enrejar / eNreˈxaR / ( n является гомоорганическим, а первый r - это трель, но второй r является переменной) . [ 110 ] Аналогичное использование встречается и при фонематическом анализе, когда язык не различает звуки, имеющие отдельные буквы в IPA. Например, кастильский испанский язык был проанализирован как имеющий фонемы /Θ/ и /S/ , которые проявляются как [θ] и [s] в глухой среде и как [ð] и [z] в звонкой среде (например, hazte /ˈaΘte/ , → [ˈaθte] , vs hazme /ˈaΘme/ , → [ˈaðme] или las manos /laS ; ˈmanoS/ , → [lazˈmanos] ). [ 111 ]

⟨ V ⟩, ⟨ F ⟩ и ⟨ C ⟩ имеют совершенно разные значения как символы качества голоса , где они обозначают «голос» (жаргон VoQS, обозначающий вторичную артикуляцию ), [ примечание 46 ] «фальцет» и «скрип». Эти три буквы могут использовать диакритические знаки, чтобы указать, какое качество голоса имеет высказывание, и могут использоваться в качестве несущих букв для выделения супрасегментарной функции, которая встречается во всех восприимчивых сегментах на участке IPA. Например, транскрипцию шотландского гэльского языка [kʷʰuˣʷt̪ʷs̟ʷ] «кошка» и [kʷʰʉˣʷt͜ʃʷ] «кошки» ( диалект острова Айлей ) можно сделать более экономичной, извлекая надсегментарную лабиализацию слов: Vʷ[kʰuˣt̪s̟] и Вʷ[кʰʉˣt͜ʃ] . [ 112 ] ⟩ можно использовать обычные подстановочные знаки ⟨ X ⟩ или ⟨ C Вместо VoQS ⟨ V ⟩ , чтобы читатель не ошибочно истолковал ⟨ Vʷ ⟩ как означающий, что лабиализируются только гласные (т. е. Xʷ[kʰuˣt̪s̟] для всех лабиализованных сегментов, Cʷ[kʰuˣt̪s̟] для всех согласных, лабиализованных), или буква-носитель может быть вообще опущена (например, ʷ[kʰuˣt̪s̟] , [ʷkʰuˣt̪s̟] или [kʰuˣt̪s̟]ʷ ). (Другие соглашения о транскрипции см. в § Супрасегменталы .)

Это резюме в некоторой степени действительно на международном уровне, но лингвистический материал, написанный на других языках, может иметь другие ассоциации с заглавными буквами, используемыми в качестве подстановочных знаков. Например, в немецком языке ⟨ K ⟩ и ⟨ V ⟩ используются для Konsonant (согласная) и Vokal (гласная); на французском языке тон может быть записан с помощью ⟨ H ⟩ и ⟨ B ⟩ для haut (высокий) и bas (низкий). [ 113 ]

Сегменты без букв

[ редактировать ]Пустые ячейки сводной диаграммы IPA можно без особого труда заполнить, если возникнет такая необходимость.

Отсутствующие ретрофлексные буквы, а именно ⟨ ᶑ ꞎ 𝼅 𝼈 𝼊 ⟩, «неявно» присутствуют в алфавите, и IPA поддержало их принятие в Unicode. [ 45 ] В литературе засвидетельствованы ретрофлексный имплозивный ⟨ ᶑ ⟩, глухой ретрофлексный латеральный фрикативный ⟨ ꞎ ⟩, ретрофлексный латеральный лоскут ⟨ 𝼈 ⟩ и ретрофлексный щелчок ⟨ 𝼊 ⟩; первый также упоминается в Справочнике IPA , а боковые фрикативы предусмотрены extIPA .

Надгортанная трель, возможно, перекрывается обычно трелью надгортанных «фрикативных звуков» ⟨ ʜ ʢ ⟩. Специальные буквы для почти близких центральных гласных, ⟨ ᵻ ᵿ ⟩, используются в некоторых описаниях английского языка, хотя это специально сокращенные гласные (образующие набор с сокращенными гласными IPA ⟨ ə ɐ ⟩), а также простые точки в гласных. пространства легко транскрибируются диакритическими знаками: ⟨ ɪ̈ ʊ̈ ⟩ или ⟨ ɨ̞ ʉ̞ ⟩. Диакритические знаки могут заполнить большую часть оставшейся части диаграмм. [ примечание 47 ] Если звук невозможно транскрибировать, можно использовать звездочку ⟨ * ⟩ либо как букву, либо как диакритический знак (как в ⟨ k* ⟩, иногда встречающемся для корейского «фортис» веляр).

Согласные

[ редактировать ]Представления согласных звуков за пределами основного набора создаются путем добавления диакритических знаков к буквам со схожим звуковым значением. Испанские двугубные и зубные аппроксиманты обычно пишутся пониженными фрикативами, [β̞] и [ð̞] соответственно. [ примечание 48 ] Точно так же звонкие латеральные фрикативы могут быть записаны как приподнятые латеральные аппроксиманты, [ɭ˔ ʎ̝ ʟ̝] , хотя extIPA также предоставляет ⟨ 𝼅 ⟩ для первого из них. В некоторых языках, таких как банда, двугубный лоскут является предпочтительным аллофоном того, что в других местах является губно-зубным лоскутом. Было предложено писать это с помощью буквы губно-зубного лоскута и расширенного диакритического знака [ⱱ̟] . [ 115 ] Точно так же губно-зубная трель будет писаться [ʙ̪] (двугубная трель и зубной знак), а губно-зубные взрывные вещества теперь повсеместно обозначаются ⟨ p̪ b̪ ⟩, а не специальными буквами ⟨ ş ş ⟩, когда-то встречавшимися в бантуистской литературе. Другие постукивания могут быть написаны как очень короткие взрывные или латеральные звуки, например [ ɟ̆ ɢ̆ ʟ̆] , хотя в некоторых случаях диакритический знак необходимо писать под буквой. Ретрофлексная трель может быть записана как втянутый [r̠] , так же, как иногда это делают несубапикальные ретрофлексные фрикативные звуки. Остальные легочные согласные - увулярные латеральные ( [ʟ̠ 𝼄̠ ʟ̠˔] ) и небная трель - хотя и не являются строго невозможными, их очень трудно произнести, и они вряд ли встречаются даже в качестве аллофонов в языках мира.

гласные

[ редактировать ]С гласными аналогично можно справиться, используя диакритические знаки для повышения, понижения, переднего, заднего, центрирования и среднего центрирования. [ примечание 49 ] Например, неокругленный эквивалент [ʊ] можно транскрибировать как центрированный [ɯ̽] , а округленный эквивалент [æ] как повышенный [ɶ̝] или пониженный [œ̞] (хотя для тех, кто воспринимает пространство гласных как треугольник, простой [ɶ] уже является округленным эквивалентом [æ] ). Истинные средние гласные понижены [e̞ ø̞ ɘ̞ ɵ̞ ɤ̞ o̞] или повышены [ɛ̝ œ̝ ɜ̝ ɞ̝ ʌ̝ ɔ̝] , а центрированные [ɪ̈ ʊ̈] и [ä] (или, реже, [ɑ̈] ) почти близки и открыты. центральные гласные, соответственно.

Единственные известные гласные, которые не могут быть представлены в этой схеме, — это гласные с неожиданной округлостью , для которых потребуется специальный диакритический знак, например, выступающий ⟨ ʏʷ ⟩ и сжатый ⟨ uᵝ ⟩ (или выступающий ⟨ ɪʷ ⟩ и сжатый ⟨ ɯᶹ ⟩), хотя это транскрипция предполагает, что они дифтонги (как и в шведском языке). « Диакритический знак extIPA распространение» ⟨ ◌͍ ⟩ иногда встречается для сжатых ⟨ u͍ ⟩, ⟨ o͍ ⟩, ⟨ ɔ͍ ⟩, ⟨ ɒ͍ ⟩, хотя предполагаемое значение необходимо объяснить, иначе они будут интерпретированы как распространяющиеся. [я] есть. Ladefoged & Maddieson использовали старый омега-диакритический знак IPA для обозначения лабиализации, ⟨ ◌̫ ⟩, для выступания ( w -подобная лабиализация без веляризации), например, выступающий ⟨ y᫇ ⟩, ⟨ ʏ̫ ⟩, ⟨ ø̫ ⟩, ⟨ œ̫ ⟩; в то время как Kelly & Local используют комбинированный диакритический знак w ⟨ ◌ᪿ ⟩ для выступания (например, ⟨ yᷱ øᪿ ⟩) и комбинированный диакритический знак w ⟨ ◌ᫀ ⟩ для сжатия (например, ⟨ uᫀ oᫀ ⟩). [ 117 ] ⟨ ◌̫ ⟩ — это рукописная форма ⟨ ◌ᪿ ⟩, и эти решения напоминают старое соглашение IPA, заключающееся в округлении неокругленной гласной буквы, например i, с нижним индексом ⟨ ◌̫ ⟩/omega и округлении округленной буквы, такой как u, с помощью перевернутой буквы. омега. [ 118 ] По состоянию на 2024 год [update], преобразованный диакритический знак омега находится в стадии разработки для Unicode. [ 119 ]

Имена символов

[ редактировать ]Символ IPA часто отличают от звука, который он предназначен для представления, поскольку в широкой транскрипции между буквой и звуком не обязательно существует однозначное соответствие, что приводит к артикуляционным описаниям, таким как «закругленная гласная среднего переднего ряда» или «звонкая велярная гласная». стоп» ненадежно. Хотя в Справочнике Международной фонетической ассоциации говорится, что официальных названий его символов не существует, он допускает наличие одного или двух общих названий для каждого из них. [ 120 ] Символы также имеют одноразовые имена в стандарте Unicode . Во многих случаях имена в Юникоде и Справочнике IPA различаются. Например, в Справочнике ⟩ называется ⟨ ɛ «эпсилон», а в Юникоде он называется «открытой маленькой буквой е».

Для неизмененных букв обычно используются традиционные названия латинских и греческих букв. [ примечание 50 ] Буквы, которые не произошли напрямую от этих алфавитов, например ⟨ ʕ ⟩, могут иметь множество названий, иногда в зависимости от внешнего вида символа или звука, который он представляет. В Юникоде некоторые буквы греческого происхождения имеют латинские формы для использования в IPA; остальные используют символы из греческого блока.

Для диакритических знаков существует два метода именования. Что касается традиционных диакритических знаков, IPA отмечает имя на хорошо известном языке; например, ⟨ é ⟩ — это «е- акут », основанное на названии диакритического знака на английском и французском языках. Нетрадиционные диакритические знаки часто называют в честь объектов, на которые они похожи, поэтому ⟨ d̪ ⟩ называется «d-мостом».

Джеффри Пуллум и Уильям Ладусо [ д ] перечислите различные имена, используемые как для текущих, так и для устаревших символов IPA, в своем Руководстве по фонетическим символам . Многие из них нашли применение в Unicode. [ 10 ]

Компьютерная поддержка

[ редактировать ]Юникод

[ редактировать ]Unicode поддерживает почти все IPA. Помимо основных блоков латыни, греческого языка и общей пунктуации, основными блоками являются расширения IPA , буквы-модификаторы пробелов и объединение диакритических знаков , с меньшей поддержкой фонетических расширений , дополнения к фонетическим расширениям , дополнения по объединению диакритических знаков и разбросанных символов в других местах. Расширенный IPA поддерживается в основном этими блоками и Latin Extended-G .

номера IPA

[ редактировать ]После Кильской конвенции 1989 года большинству символов IPA был присвоен идентификационный номер, чтобы предотвратить путаницу между похожими символами во время печати рукописей. Коды никогда особо не использовались и были заменены Unicode.

Гарнитуры

[ редактировать ]

Многие шрифты поддерживают символы IPA, но хорошая отрисовка диакритических знаков остается редкостью. [ 122 ] Веб-браузерам обычно не требуется какая-либо настройка для отображения символов IPA, при условии, что в операционной системе доступен шрифт, способный это сделать.

Бесплатные шрифты

[ редактировать ]Гарнитуры, обеспечивающие полную поддержку IPA и почти полную поддержку extIPA, включая правильное отображение диакритических знаков, включают Gentium Plus , Charis SIL , Doulos SIL и Andika , разработанные SIL International . Действительно, IPA выбрало Doulos для публикации своей диаграммы в формате Unicode. В дополнение к уровню поддержки, присутствующему в коммерческих и системных шрифтах, эти шрифты поддерживают весь спектр тоновых букв без нотоносца старого стиля (до Киля) посредством опции варианта символа , которая подавляет нотоносец тональных букв Чао. У них также есть возможность сохранить различие гласных [a] ~ [ɑ] курсивом. Единственные заметные пробелы связаны с extIPA: не поддерживаются объединяющие круглые скобки, в которые заключены диакритические знаки, а также окружающий кружок, который отмечает неопознанные звуки и который Unicode считает знаком копирования и редактирования и, следовательно, не имеет права на поддержку Unicode.