Гелиос

| Гелиос | |

|---|---|

Олицетворение Солнца | |

| |

| Главный культовый центр | Родос , Коринфия |

| Обитель | Небо |

| Планета | Солнце |

| Животные | Лошадь , петух , волк , скотина |

| Символ | Солнце, колесница , кони, ореол , кнут, гелиотропий , земной шар , рог изобилия , [ 1 ] спелые фрукты [ 1 ] |

| Дерево | Ладан , тополь |

| День | Воскресенье ( hēméra Hēlíou ) |

| Устанавливать | Колесница, запряженная четырьмя белыми лошадьми |

| Пол | Мужской |

| Фестивали | Имбирь |

| Генеалогия | |

| Родители | Гиперион и Тейя |

| Братья и сестры | Селена и Эос |

| Супруга | Климена , Клития , Персе , Родос , Левкотея и другие. |

| Дети | , Acheron, Actis, Aeëtes, Aex, Aegle, Aetheria, Aethon, Aloeus, Astris, Augeas, Bisaltes, Candalus, Cercaphus, the Charites, Chrysus, Cheimon, Circe, Clymenus, the Corybantes, Cos, Dioxippe, Dirce, Eiar, Электрион , Гелия , Гемера Ichnaea, Lampetia, Lelex, Macareus, Mausolus, Merope, Ochimus, Pasiphaë, Perses, Phaethon, Phaethusa, Phasis, Phoebe, Phorbas, Phthinoporon, Sterope, Tenages, Theros, Thersanon, Triopas and . |

| Эквиваленты | |

| Ханаанский эквивалент | शापाश |

| Этрусский эквивалент | любопытный |

| Индуистский эквивалент | Сурья [ 2 ] |

| Скандинавский эквивалент | Солнце |

| Римский эквивалент | Солнце , непокоренное солнце |

| Месопотамский эквивалент | Цена |

| Египетский эквивалент | Солнце |

| Часть серии о |

| Древнегреческая религия |

|---|

|

В древнегреческой и мифологии религии Гелиос ( / ˈ h iː l i ə s , - ɒ s / ; древнегреческий : Ἥλιος произносится [hɛ̌ːlios] , букв. 'Солнце'; Гомеровский греческий : Ἠέλιος ) — бог олицетворяющий Солнце , . Его имя также латинизируется как Гелиус , и ему часто дают эпитеты Гиперион («тот, что выше») и Фаэтон («сияющий»). [ а ] Гелиос часто изображается в искусстве с сияющей короной и управляющим по небу на конной колеснице. Он был хранителем клятв, а также богом зрения. Хотя Гелиос был относительно второстепенным божеством в классической Греции, его поклонение стало более заметным в поздней античности благодаря его отождествлению с несколькими главными солнечными божествами римского периода, особенно с Аполлоном и Солнцем . Римский император Юлиан сделал Гелиоса центральным божеством своего недолговечного возрождения традиционных римских религиозных практик в 4 веке нашей эры.

Гелиос занимает видное место в нескольких произведениях греческой мифологии, поэзии и литературы, в которых его часто описывают как сына титанов Гипериона и Тейи и брата богинь Селены (Луны) и Эос (Рассвета). Самая заметная роль Гелиоса в греческой мифологии — история его смертного сына Фаэтона . [ 3 ]

В гомеровских эпосах его наиболее заметная роль — та, которую он играет в « Одиссее» , где люди Одиссея, Гелиоса несмотря на его предупреждения, нечестиво убивают и едят священный скот , который бог держал на Тринасии , своем священном острове. Узнав об их проступке, Гелиос в гневе просит Зевса наказать тех, кто обидел его, и Зевс соглашается поражает их корабль молнией, убивая всех, кроме самого Одиссея, единственного, кто не причинил вреда скоту и которому было разрешено жить. [ 4 ]

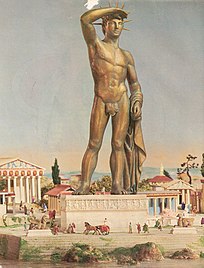

Из-за своего положения солнца он считался всевидящим свидетелем, и поэтому на него часто ссылались в клятвах. Он также сыграл значительную роль в древней магии и заклинаниях. В искусстве его обычно изображают как безбородого юношу в хитоне, держащего кнут и управляющего своей квадригой , в сопровождении различных других небесных богов, таких как Селена , Эос или звезды. В древние времена ему поклонялись в нескольких местах древней Греции, хотя его основными культовыми центрами были остров Родос , богом-покровителем которого он был, Коринф и большая Коринфская область. Колосс Родосский , гигантская статуя бога, украшал порт Родоса, пока не был разрушен землетрясением, после чего его больше не строили.

Имя

[ редактировать ]

Греческое существительное ἥλιος ( GEN ἡλίου , DAT ἡλίῳ , ACC ἥλιον , VOC ἥλιε ) (от более раннего ἁϝέλιος /hāwelios/) — унаследованное слово для обозначения Солнца от протоиндоевропейского * seh₂u-el [ 5 ] который родственен латинскому sol , санскритскому surya , древнеанглийскому swegl , древнескандинавскому sól , валлийскому haul , авестийскому hvar и т. д. [ 6 ] [ 7 ] Дорическая . и эолская форма имени Ἅλιος , Галиос — На гомеровском греческом его имя пишется Ἠέλιος , Элиос , а дорическое написание этого слова — Ἀέλιος , Элиос . На Крите это было Ἀβέλιος ( Абелиос ) или Ἀϝέλιος ( Авелиос ). [ 8 ] Греческий взгляд на гендер также присутствовал в их языке. В Древней Греции было три рода (мужской, женский и средний), поэтому, когда объект или понятие персонифицировалось как божество, оно наследовало род соответствующего существительного; Гелиос — существительное мужского рода, поэтому бог, воплощающий его, по необходимости также является мужчиной. [ 9 ] Женское потомство Гелиоса называлось Гелиадами , мужское – Гелиадами .

Автор лексикона Суда пытался этимологически связать ἥλιος со словом ἀολλίζεσθαι , aollizesthai , «собираясь вместе» в дневное время, или, возможно, от ἀλεαίνειν , aleainein , «согревающий». [ 10 ] Платон в своем диалоге Кратил предложил несколько этимологий этого слова, предложив, среди прочего, связь через дорическую форму слова halios со словами ἁλίζειν , halizein , означающими сбор людей, когда он поднимается, или с фразой ἀεὶ εἱλεῖν , aeí heileín , «вечно вращающийся», потому что он всегда переворачивает землю его курс.

Дорический греческий язык сохранил протогреческое длинное *ā как α , в то время как аттический изменил его в большинстве случаев, в том числе и в этом слове, на η . Кратил и этимологии Платона противоречат современной науке. [ 11 ] От слова helios происходит современная английская приставка helio- , означающая «относящийся к Солнцу», используемая в составных словах, таких как гелиоцентризм , афелий , гелиотропий , гелиофобия (боязнь солнца) и гелиолатрия («поклонение солнцу»). [ 12 ]

Происхождение

[ редактировать ]

Гелиос, скорее всего, имеет протоиндоевропейское происхождение. Вальтер Буркерт писал, что «... Гелиос, бог солнца, и Эос - Аврора , богиня зари , имеют безупречное индоевропейское происхождение как по этимологии, так и по своему статусу богов» и, возможно, играли роль в прото- -Индоевропейская поэзия. [ 13 ] Образы, окружающие солнечное божество, управляющее колесницей, вероятно, имеют индоевропейское происхождение. [ 14 ] [ 15 ] [ 16 ] Греческие солярные образы начинаются с богов Гелиоса и Эос, брата и сестры, которые в дневно-ночном цикле становятся днем ( гемера ) и вечером ( геспера ), поскольку Эос сопровождает Гелиоса в его путешествии по небо. Ночью он пасет своих коней и отправляется на восток в золотой лодке. В них очевидна индоевропейская группировка бога солнца и его сестры, а также ассоциация с лошадьми. [ 17 ]

Елены Троянской имеет ту же этимологию, что и имя Гелиоса. Считается, что имя [ 18 ] [ 19 ] [ 20 ] и она может выражать раннюю альтернативную персонификацию солнца у эллинских народов. Первоначально Елену можно было считать дочерью Солнца, поскольку она вылупилась из яйца и ей поклонялись деревьям - черты, связанные с протоиндоевропейской Солнечной Девой; [ 21 ] Однако в сохранившихся греческих традициях Елена никогда не упоминается как дочь Гелиоса, вместо этого она является дочерью Зевса . [ 22 ]

Было высказано предположение, что финикийцы принесли культ своего бога-покровителя Ваала (например, Астарты ) в Коринф , которому затем продолжали поклоняться под местным именем / богом Гелиосом, подобно тому, как Астарте поклонялись как Афродите . а финикийский Мелькарт был принят как морской бог Мелицертес / Палеемон , который также имел значительный культ на Коринфском перешейке . [ 23 ]

Путешествие Гелиоса на колеснице днем и путешествие на лодке по океану ночью, возможно, отражает египетского бога солнца Ра, плывущего по небу в барке, чтобы каждое утро возрождаться на рассвете заново; кроме того, оба бога, связанные с солнцем, считались «Небесным оком». [ 24 ]

Описание

[ редактировать ]

Гелиос — сын Гипериона и Тейи , [ 25 ] [ 26 ] [ 27 ] или Эврифэсса, [ 28 ] или Базилея, [ 29 ] и единственный брат богинь Эос и Селены. Если порядок упоминания трех братьев и сестер следует принять за порядок их рождения, то из четырех авторов, указывающих порядок рождения его и его сестер, двое делают его старшим ребенком, один - средним, а другой - старшим. самый младший. [ б ] Гелиос не входил в число обычных и наиболее выдающихся божеств, скорее он был более призрачным членом олимпийского круга. [ 31 ] несмотря на то, что он был одним из самых древних. [ 32 ] Судя по его происхождению, Гелиоса можно было бы назвать Титаном второго поколения. [ 33 ] Он ассоциируется с гармонией и порядком, как буквально в смысле движения небесных тел, так и метафорически в смысле наведения порядка в обществе. [ 34 ]

Гелиоса обычно изображают в виде красивого юноши, увенчанного сияющим ореолом Солнца, которое традиционно имело двенадцать лучей, символизирующих двенадцать месяцев в году. [ 35 ] Помимо его «Гомеровского гимна», не так много текстов описывают его внешний вид; Еврипид описывает его как χρυσωπός (khrysōpós), что означает «золотоглазый/лицый» или «сияющий, как золото». [ 36 ] Мезомед Критский пишет , что у него золотые волосы, [ 37 ] и Аполлоний Родий , что у него светящиеся золотые глаза. [ 38 ] По словам поэта-августовца Овидия , он облачился в тирийские пурпурные одежды и восседал на троне из ярких изумрудов . [ 39 ] В древних артефактах (таких как монеты, вазы или рельефы) он представлен красивым, полнолицым юношей. [ 40 ] с волнистыми волосами, [ 41 ] носить корону, украшенную солнечными лучами. [ 42 ]

Говорят, что Гелиос управляет золотой колесницей, запряженной четырьмя лошадьми: [ 43 ] [ 44 ] Пируа («Огненный»), Эос («Тот, кто на заре»), Этон («Пылающий») и Флегон («Пылающий»). [ 45 ] В митраистском заклинании внешний вид Гелиоса описывается следующим образом:

Затем вызывается бог. Его описывают как «юношу, красивого вида, с огненными волосами, одетого в белую тунику и алый плащ и носящего огненный венец». Его называют «Гелиосом, повелителем неба и земли, богом богов». [ 46 ]

Как упоминалось выше, образы, окружающие солнечное божество, управляющее колесницей, вероятно, имеют индоевропейское происхождение и являются общими как для ранних греческих, так и для ближневосточных религий. [ 47 ] [ 48 ]

Гелиос рассматривается как олицетворение Солнца и фундаментальной творческой силы, стоящей за ним. [ 49 ] и в результате ему часто поклоняются как богу жизни и творения. Его буквальный «свет» часто сочетается с метафорической жизненной силой. [ 50 ] и другие древние тексты дают ему эпитет «милостивый» ( ἱλαρός ). Комический драматург . Аристофан описывает Гелиоса как «поводыря лошадей, наполняющего равнину земли чрезвычайно яркими лучами, могущественного божества среди богов и смертных» [ 51 ] В одном отрывке, записанном в «Греческих магических папирусах», о Гелиосе говорится: «Земля процветала, когда ты сиял, и растения давали плоды, когда ты смеялся, и оживляли живых существ, когда ты позволял». [ 14 ] Говорят, что он помог создать животных из первобытной грязи. [ 52 ]

Мифология

[ редактировать ]Бог Солнца

[ редактировать ]Восхождение и установка

[ редактировать ]

Гелиос представлялся богом, который каждый день вел свою колесницу с востока на запад, поднимаясь из реки Океан и садясь на западе под землю. Неясно, означает ли это путешествие, что он путешествует через Тартар . [ 53 ]

Афиней в своих «Deipnosophistae» рассказывает, что в час заката Гелиос забирается в большую чашу из чистого золота, в которой он проходит от Гесперид на крайнем западе до земли эфиопов, с которыми он проводит темные часы. По словам Афинея, Мимнерм сказал, что ночью Гелиос путешествует на восток, используя кровать (также созданную Гефестом), на которой он спит, а не чашу. [ 54 ] как засвидетельствовано в Титаномахии VIII века до нашей эры. [ 53 ] Эсхил описывает закат так:

«Там [есть] священная волна, и коралловое дно Эритрейского моря , и [там] пышное болото эфиопов, расположенное недалеко от океана, блестит, как полированная медь; где ежедневно в мягком и теплом потоке все -видя Солнце, он омывает свое бессмертное «я» и освежает своих утомленных коней».

Афиней добавляет, что «Гелиос получил часть труда за все свои дни», так как ни ему, ни его коням нет покоя. [ 56 ]

Хотя обычно говорят, что колесница была работой Гефеста , [ 57 ] [ 58 ] Гигин утверждает, что его построил сам Гелиос. [ 59 ] Его колесница описана как золотая, [ 43 ] или иногда «розовый», [ 60 ] и запряженный четырьмя белыми лошадьми. [ 61 ] [ 62 ] [ 63 ] [ 48 ] Хоры . , богини времен года, входят в его свиту и помогают ему запрягать его колесницу [ 64 ] [ 65 ] [ 66 ] Говорят, что его сестра Эос не только открыла врата Гелиосу, но и часто сопровождала его. [ 67 ] Говорят, что на крайнем востоке и западе жили люди, ухаживавшие за его лошадьми, для которых лето было вечным и плодотворным. [ 41 ]

Нарушенный график

[ редактировать ]

В мифологии в нескольких случаях нормальный солнечный график нарушается; ему было приказано не вставать в течение трех дней во время зачатия Геракла , и он продлил зимние дни, чтобы посмотреть на Левкофою . Рождение Афины было зрелищем столь впечатляющим, что Гелиос остановил своих коней и надолго замер в небе. [ 68 ] как небо и земля дрожат при виде новорожденной богини. [ 69 ]

В «Илиаде» Гера , поддерживающая греков, заставляет его против его воли выступить во время битвы раньше обычного, [ 70 ] , сын его сестры Эос, а еще позже, во время той же войны, после того как Мемнон был убит, она заставила его унывать, заставив его свет померкнуть, чтобы она могла свободно украсть тело своего сына, незамеченное армиями, когда он утешал свою сестру в ее горе из-за смерти Мемнона. [ 71 ]

Говорили, что летние дни длиннее из-за того, что Гелиос часто останавливал свою колесницу в воздухе, чтобы наблюдать сверху за танцующими нимфами летом. [ 72 ] [ 73 ] а иногда он опаздывает с подъемом, потому что задерживается со своей супругой. [ 74 ] Если другие боги того пожелают, Гелиос может ускорить свой ежедневный путь, когда они захотят, чтобы наступила ночь. [ 75 ]

Когда Зевс пожелал переспать с Алкменой , он продлил одну ночь троекратно, скрыв свет Солнца, приказав Гелиосу не вставать в течение этих трех дней. [ 76 ] [ 77 ] Автор-сатирик инсценировал этот Лукиан Самосатский миф в одном из своих «Диалогов богов» . [ 78 ] [ с ]

Когда Геракл направлялся в Эритею, чтобы забрать скот Гериона для своего десятого подвига, он пересек Ливийскую пустыню и был настолько расстроен жарой, что выпустил стрелу в Гелиоса, Солнца. Почти сразу же Геракл осознал свою ошибку и обильно извинился ( Ферекид писал, что Геракл грозно протянул ему стрелу, но Гелиос приказал ему остановиться, и Геракл в страхе воздержался [ 54 ] ); В свою очередь, столь же вежливо, Гелиос подарил Гераклу золотую чашу, с помощью которой он каждую ночь переплывал море с запада на восток, потому что находил действия Геракла чрезвычайно смелыми. В версиях Аполлодора и Ферекида Геракл только собирался застрелить Гелиоса, но, по словам Паниассиса , он выстрелил и ранил бога. [ 80 ]

Солнечные затмения

[ редактировать ]

Солнечные затмения были в Древней Греции явлением страха, а также удивления, и рассматривались как отказ Солнца от человечества. [ 81 ] Согласно фрагменту Архилоха , именно Зевс блокирует Гелиоса и заставляет его исчезнуть с неба. [ 82 ] В одном из своих гимнов лирик Пиндар описывает солнечное затмение как свет Солнца, скрытый от мира, дурное предзнаменование разрушения и гибели: [ 83 ]

Луч солнца! Что задумала ты, наблюдательная, мать очей, звезда высочайшая, скрывшись среди бела дня? Зачем ты лишил людей силы и пути мудрости, мчась по темной дороге? Вы едете по более незнакомой трассе, чем раньше? Во имя Зевса, быстрого погонщика лошадей, я умоляю вас, госпожа, превратите вселенское предзнаменование в какое-нибудь безболезненное процветание для Фив... Приносите ли вы знак какой-то войны, или опустошения урожая, или массы снега, не поддающийся описанию? или губительная борьба, или опустошение моря на суше, или иней на земле, или дождливое лето, протекающее с бушующей водой, или ты затопишь землю и создашь новую расу людей с самого начала?

Лошади Гелиоса

[ редактировать ]

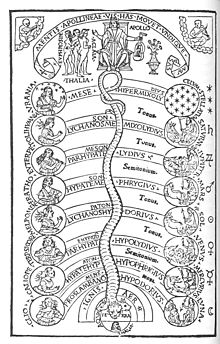

Некоторые списки имен лошадей, которые тянули колесницу Гелиоса, цитируемые Гигином, следующие. Ученые признают, что, несмотря на различия между списками, имена лошадей всегда относятся к огню, пламени, свету и другим светящимся качествам. [ 85 ]

- По словам Евмела Коринфского - конец 7-го / начало 6-го века до нашей эры: приспешные кони-самцы - это Эус (он переворачивает небо) и Эфиопс (как будто пылает, иссушает зерно), а женщины-несущие ярмо - Бронте («Громовой ") и Стеропа ("Молния").

- По словам Овидия-Римляна, I век до н. э. поездка Фаэтона : Пируа («огненный»), Эус («он зари»), Этон («пылающий») и Флегон («пылающий»). [ 86 ] [ 87 ]

Гигин пишет, что, по словам Гомера, имена лошадей — Абраксас и Тербео; но Гомер не упоминает ни лошадей, ни колесниц. [ 86 ]

Александр Этолийский , цитируемый у Афинея, рассказывал, что волшебная трава росла на острове Тринасия , посвященном Гелиосу, и служила средством против усталости коням бога Солнца. Эсхрион Самосский сообщил, что он известен как «собачий зуб» и, как полагают, был посеян Кроносом. [ 88 ]

Награждение Родоса

[ редактировать ]

По мнению Пиндара, [ 89 ] когда боги делили землю между собой, Гелиоса не было, и поэтому ему не достался участок земли. Он пожаловался на это Зевсу, который предложил снова произвести раздел частей, но Гелиос отказался от предложения, ибо увидел новую землю, выходящую из морской пучины; богатая, продуктивная земля для людей и хорошая для скота. Гелиос попросил отдать ему этот остров, и Зевс согласился на это, при этом Лахезис (одна из трех Судьб ) подняла руки в подтверждение клятвы. В качестве альтернативы, согласно другой традиции, именно Гелиос заставил остров подняться из моря, когда он заставил воду, заполнившую его, исчезнуть. [ 90 ] Он назвал его Родосом в честь своей возлюбленной Роды (дочери Посейдона и Афродиты) . [ 91 ] или Амфитрита [ 92 ] ), и он стал священным островом бога, где его почитали выше всех других богов. От Рода Гелиос произвел на свет семь сыновей, известных как Гелиады («сыны Солнца»), которые стали первыми правителями острова, а также одну дочь Электриону . [ 90 ] города Ялисос , Камирос и Линдос , названные в их честь; Трое их внуков основали на острове [ 89 ] таким образом, Родос стал принадлежать ему и его линии, а автохтонные народы Родоса утверждали, что произошли от гелиад. [ 93 ]

Фаэтон

[ редактировать ]

Самая известная история о Гелиосе связана с его сыном Фаэтоном , который попросил его один день управлять его колесницей. Хотя все версии сходятся во мнении, что Фаэтон убедил Гелиоса отдать ему свою колесницу, и что он не справился со своей задачей, что привело к катастрофическим результатам, существует множество деталей, которые различаются в зависимости от версии, включая личность матери Фаэтона, место действия истории. , роль, которую играют сестры Фаэтона, Гелиады , мотивация решения Фаэтона попросить своего отца о такой вещи и даже точные отношения между богом и смертным.

Традиционно Фаэтон был сыном Гелиоса от нимфы Океаниды Климены . [ 94 ] или альтернативно Род [ 95 ] или иначе неизвестный Проте. [ 96 ] В одной из версий истории Фаэтон является внуком Гелиоса, а не сыном от отца мальчика Климена . В этой версии мать Фаэтона — нимфа Океанид по имени Меропа. [ 97 ]

В утраченной пьесе Еврипида «Фаэтон» , сохранившейся лишь в двенадцати фрагментах, Фаэтон является продуктом незаконной связи между его матерью Клименой (которая сейчас замужем за Меропсом , царем Эфиопии ) и Гелиосом, хотя она утверждала, что ее законным мужем был отец ее всех ее детей. [ 98 ] [ 99 ] Климена раскрывает правду своему сыну и убеждает его отправиться на восток, чтобы получить подтверждение от отца после того, как она сообщает ему, что Гелиос обещал исполнить любое желание их ребенка, когда он спал с ней. Хотя поначалу Фаэтон сопротивлялся, он убедился и отправился на поиски своего биологического отца. [ 100 ] В сохранившемся фрагменте пьесы Гелиос сопровождает сына в его злополучном путешествии по небесам, пытаясь дать ему инструкции, как управлять колесницей, пока он едет на запасной лошади по имени Сириус. [ 101 ] как кто-то, возможно, педагог сообщает Климене о судьбе Фаэтона, которого, вероятно, сопровождают рабыни:

Возьмем, к примеру, тот отрывок, в котором Гелиос, передавая бразды правления своему сыну, говорит:

«Двигайтесь дальше, но избегайте горящих ливийских дорог;

Горячий сухой воздух подведет твою ось:

К семи Плеядам держи свой твердый путь».

А потом-

«Сказав это, его сын бесстрашно схватил поводья,

Затем ударил крылатых скакунов по бокам: они связали

Вперед, в пустоту и пещеристый свод воздуха.

Его отец садится на другого коня и едет

С предупредительным голосом направляя своего сына. «Езжай туда!»

Поверни, поверни свою машину сюда».

Если этот посланник сам был свидетелем бегства, возможно, был также отрывок, в котором он описал, как Гелиос взял под свой контроль бегущих лошадей так же, как описал Лукреций . [ 103 ] Фаэтон неизбежно умирает; во фрагменте ближе к концу пьесы Климена приказывает рабыням спрятать все еще тлеющее тело Фаэтона от Меропса и оплакивает роль Гелиоса в смерти ее сына, говоря, что он уничтожил его и ее обоих. [ 104 ] Ближе к концу пьесы кажется, что Меропс, узнав о романе Климены и истинном происхождении Фаэтона, пытается ее убить; ее дальнейшая судьба неясна, но предполагается, что ее спас какой-то deus ex machina . [ 105 ] Для идентификации этого возможного deus ex machina было предложено несколько божеств, в том числе Гелиос. [ 105 ]

По словам Овидия, сын Зевса Эпаф высмеивает заявление Фаэтона о том, что он сын бога Солнца; его мать Климена велит Фаэтону самому пойти к Гелиосу, чтобы попросить подтверждения своего отцовства. Гелиос обещает ему на реке Стикс любой подарок, который он попросит в доказательство отцовства; Фаэтон просит о привилегии управлять колесницей Гелиоса в течение одного дня. Хотя Гелиос предупреждает своего сына о том, насколько это будет опасно и катастрофично, он, тем не менее, не может изменить мнение Фаэтона или отменить свое обещание. Фаэтон берет в свои руки поводья, и земля горит, когда он едет слишком низко, и замерзает, когда он поднимает колесницу слишком высоко. Зевс поражает Фаэтона молнией, убивая его. Гелиос отказывается возобновить свою работу, но возвращается к своей задаче и долгу по призыву других богов, а также угрозам Зевса. Затем он вымещает свой гнев на своих четырех лошадях, в ярости избивая их за то, что они стали причиной смерти его сына. [ 106 ]

Нонн Панопольский представил несколько иную версию мифа, рассказанную Гермесом; по его словам, Гелиос встретил и полюбил Климену, дочь Океана , и вскоре они поженились по благословению ее отца. Когда он вырастает, увлеченный работой своего отца, он просит его хотя бы один день поводить его колесницу. Гелиос изо всех сил пытается отговорить его, утверждая, что сыновья не обязательно способны занять место своих отцов. Но под давлением Фаэтона и мольбы Климены он в конце концов сдается. Согласно всем другим версиям мифа, путешествие Фаэтона является катастрофическим и заканчивается его смертью. [ 107 ]

Гигин писал, что Фаэтон тайно сел на машину своего отца без ведома и разрешения отца, но с помощью своих сестер Гелиад, которые запрягали лошадей. [ 108 ]

Во всех пересказах Гелиос вовремя возвращает себе бразды правления, спасая таким образом землю. [ 109 ] Другая последовательная деталь во всех версиях заключается в том, что сестры Фаэтона, Гелиады, оплакивают его у Эридана и превращаются в черные тополя, проливающие янтарные слезы . По словам Квинта Смирнея , именно Гелиос превратил их в деревья, за честь Фаэтона. [ 110 ] В одной из версий мифа Гелиос перенес своего умершего сына к звездам в виде созвездия ( Аурига ). [ 111 ]

Сторож

[ редактировать ]Персефона

[ редактировать ]

Но, Богиня, оставь навсегда свой великий плач.

Вы не должны питать напрасно ненасытный гнев.

Среди богов Аидоней неподходящий жених,

Повелитель многих и родной брат Зевса того же происхождения.

Что касается чести, то он получил третье место в первом дивизионе мира.

и живет с теми, чье правление выпало на его долю.

Говорят, что Гелиос видел и был свидетелем всего, что происходило там, где сиял его свет. Когда Аид похищает Персефону , Гелиос становится единственным свидетелем этого. [ 113 ]

» Овидия В «Фасти Деметра сначала спрашивает звезды о местонахождении Персефоны, и именно Гелика советует ей пойти спросить Гелиоса. Деметра не замедлит подойти к нему, и тогда Гелиос говорит ей не терять времени и искать «царицу третьего мира». [ 114 ]

Арес и Афродита

[ редактировать ]

В другом мифе Афродита была замужем за Гефестом, но изменила ему с его братом Аресом , богом войны. В восьмой книге « Одиссеи » слепой певец Демодок описывает, как незаконные любовники совершали прелюбодеяние, пока однажды Гелиос не поймал их с поличным и немедленно сообщил об этом мужу Афродиты Гефесту. Узнав об этом, Гефест выковал настолько тонкую сеть, что ее едва можно было увидеть, чтобы поймать их. Затем он объявил, что отправляется на Лемнос . Услышав это, Арес подошел к Афродите, и двое влюбленных соединились. [ 115 ] Гелиос еще раз сообщил об этом Гефесту, который вошел в комнату и поймал их в сеть. Затем он призвал других богов стать свидетелями этого унизительного зрелища. [ 116 ]

Гораздо более поздние версии добавляют в историю молодого человека, воина по имени Алектрион , которому Арес поручил стоять на страже, если кто-нибудь приблизится. Но Алектрион заснул, позволив Гелиосу обнаружить двух влюбленных и сообщить об этом Гефесту. За это Афродита навеки возненавидела Гелиоса и его расу. [ 117 ] В некоторых версиях она прокляла его дочь Пасифаю, чтобы та влюбилась в Критского Быка , чтобы отомстить ему. [ 118 ] [ 119 ] Говорят, что страсть дочери Пасифаи Федры к своему пасынку Ипполиту была причинена ей Афродитой по той же причине. [ 117 ]

Лейкото и Клити

[ редактировать ]

Афродита стремится отомстить, заставив Гелиоса влюбиться в смертную принцессу по имени Левкото свою предыдущую возлюбленную Океаниду Клити , забыв ради нее . Гелиос наблюдает за ней сверху, даже делая зимние дни длиннее, чтобы у него было больше времени, глядя на нее. Приняв облик ее матери Эвриномы , Гелиос входит в их дворец, входит в комнату девушки, прежде чем открыться ей.

Однако Клити сообщает отцу Левкото Орхаму об этом деле, и тот заживо закапывает Левкото в землю. Гелиос приходит слишком поздно, чтобы спасти ее, поэтому вместо этого он выливает нектар в землю и превращает мертвую Левкотою в благовонное дерево . Клити, отвергнутая Гелиосом за ее роль в смерти его возлюбленной, раздевается догола, не принимая ни еды, ни питья, и сидит на камне в течение девяти дней, тоскуя по нему, пока в конце концов не превратится в фиолетовый, созерцающий солнце цветок, гелиотроп . . [ 120 ] [ 121 ] Предполагалось, что этот миф мог быть использован для объяснения использования смолы ладана ароматической в поклонении Гелиосу. [ 122 ] Левкотоя, похороненная заживо в качестве наказания стражем-мужчиной, что мало чем отличается от судьбы Антигоны , также может указывать на древнюю традицию, включающую человеческие жертвоприношения в культе растений. [ 122 ] Поначалу истории о Левкотее и Клитии могли быть двумя отдельными мифами о Гелиосе, которые позже были объединены вместе с третьей историей, о том, как Гелиос обнаружил роман Ареса и Афродиты и затем сообщил Гефесту, в единый рассказ либо самого Овидия, либо его источника. . [ 123 ]

Другой

[ редактировать ]В Софокла пьесе Аякс « » Аякс Великий за несколько минут до самоубийства призывает Гелиоса остановить свои золотые поводья, когда он достигнет родины Аякса, Саламина , и сообщить своему стареющему отцу Теламону и матери о судьбе и смерти их сына, и приветствует его. в последний раз, прежде чем он убьет себя. [ 124 ]

Участие в войнах

[ редактировать ]

Гелиос встает на сторону других богов в нескольких битвах. [ 125 ] Сохранившиеся фрагменты Титаномахии подразумевают сцены, где Гелиос - единственный среди Титанов, кто воздержался от нападения на олимпийских богов . [ 126 ] и они, после окончания войны, дали ему место на небе и наградили его колесницей. [ 127 ] [ 128 ]

Он также принимает участие в войнах гигантов; сказал, Псевдо-Аполлодор что во время битвы гигантов с богами великан Алкионей украл скот Гелиоса из Эритеи , где бог держал его, [ 129 ] или, альтернативно, война началась именно с кражи скота Алкионеем. [ 130 ] [ 131 ] Поскольку богиня земли Гея, мать и союзница гигантов, узнала о пророчестве о том, что гиганты погибнут от руки смертного, она попыталась найти волшебную траву, которая защитила бы их и сделала бы практически неразрушимыми; таким образом Зевс приказал Гелиосу, а также его сестрам Селене (Луне) и Эос ( Рассвету ) не светиться, и собрал все растение себе, лишив Гею возможности сделать Гигантов бессмертными, в то время как Афина вызвала на бой смертного Геракла. рядом с ними. [ 132 ]

В какой-то момент во время битвы богов и гигантов во Флегре , [ 133 ] Гелиос везет на своей колеснице измученного Гефеста. [ 134 ] После окончания войны один из гигантов, Пиколус , бежит в Эею , где жила дочь Гелиоса, Цирцея. Он попытался прогнать Цирцею с острова, но был убит Гелиосом. [ 135 ] [ 136 ] [ 137 ] Из крови убитого великана, пролитой на землю, выросло новое растение, трава моли , названная так в честь битвы («малос» по- древнегречески ). [ 138 ]

Гелиос изображен на Пергамском алтаре , ведущим войну против гигантов рядом с Эос, Селеной и Тейей на южном фризе. [ 139 ] [ 140 ] [ 141 ] [ 128 ] [ 142 ]

Столкновения и наказания

[ редактировать ]Боги

[ редактировать ]Миф о происхождении Коринфа гласит: Гелиос и Посейдон спорили о том, кому достанется город. Гекатонхейру Бриарею было поручено урегулировать спор между двумя богами; он отдал Акрокоринф Гелиосу, а Посейдону - перешеек . Коринфский [ 143 ] [ 144 ]

Элиан писал, что Нерит был сыном морского бога Нерея и океаниды Дориды . В версии, где Нерита стала возлюбленной Посейдона, говорится, что Гелиос по неизвестным причинам превратил его в моллюска. Сначала Элиан пишет, что Гелиос был обижен на скорость мальчика, но, пытаясь объяснить, почему он изменил свою форму, предполагает, что, возможно, Посейдон и Гелиос были соперниками в любви. [ 145 ] [ 146 ]

В басне Эзопа Гелиос и бог северного ветра Борей спорили о том, кто из них самый сильный бог. Они договорились, что победителем будет объявлен тот, кто сможет заставить проходящего путника снять плащ. Борей был первым, кто попытал счастья; но как бы сильно он ни дул, он не смог снять с человека плащ, а вместо этого заставил его еще плотнее закутаться в плащ. Тогда Гелиос ярко засиял, и путник, охваченный жарой, снял плащ, дав ему победу. Мораль такова: убеждение лучше силы. [ 147 ]

Смертные

[ редактировать ]

Что касается его природы как Солнца, [ 148 ] Гелиоса представляли как бога, способного вернуть и лишить людей зрения, поскольку считалось, что его свет создает способность зрения и позволяет видеть видимые вещи. [ 149 ] [ 150 ] В одном мифе после того, как Орион был ослеплен царем Энопионом , он отправился на восток, где встретил Гелиоса. Затем Гелиос исцелил глаза Ориона, вернув ему зрение. [ 151 ] В « истории Финея его ослепление, как сообщается в Аргонавтике» Аполлония Родия , было наказанием Зевса за то, что Финей открыл человечеству будущее. [ 152 ] Однако по одной из альтернативных версий именно Гелиос лишил Финея зрения. [ 153 ] Псевдо-Оппиан писал, что гнев Гелиоса был вызван какой-то неясной победой пророка; после того, как Кале и Зет убили гарпий, мучивших Финея, Гелиос превратил его в крота , слепое существо. [ 154 ] По еще одной версии, он ослепил Финея по просьбе своего сына Ээта. [ 155 ]

В другой сказке афинский изобретатель Дедал и его маленький сын Икар вылепили себе крылья из птичьих перьев, склеенных воском, и улетели. [ 156 ] Согласно схолиям Еврипида, Икар, будучи молодым и опрометчивым, считал себя выше Гелиоса. Разгневанный Гелиос метнул в него свои лучи, расплавив воск и погрузив Икара в море, чтобы он утонул. Позже именно Гелиос постановил, что это море будет названо в честь несчастного юноши — Икарийское море . [ 157 ] [ 158 ]

Арге была охотницей, которая, охотясь на особенно быстрого оленя, утверждала, что, каким бы быстрым ни было Солнце, она в конечном итоге догонит его. Гелиос, оскорбленный словами девушки, изменил ее облик на оленя. [ 159 ] [ 160 ]

В одной из редких версий истории Смирны разгневанный Гелиос проклял ее полюбить ее собственного отца Цинираса из-за какого-то неустановленного проступка, совершенного девушкой против него; Однако в подавляющем большинстве других версий виновницей проклятия Смирны является богиня любви Афродита. [ 161 ]

Быки Солнца

[ редактировать ]

Говорят, что Гелиос держал своих овец и крупный рогатый скот на своем священном острове Тринасия или, в некоторых случаях, Эритея. [ 162 ] Каждое стадо насчитывает пятьдесят животных, всего 350 коров и 350 овец — количество дней в году в раннем древнегреческом календаре; семь стад соответствуют неделе , состоящей из семи дней. [ 163 ] Коровы не размножались и не умирали. [ 164 ] В гомеровском гимне 4 Гермесу после того, как разгневанный Аполлон привел Гермеса к Зевсу за кражу священных коров Аполлона, молодой бог извиняется за свои действия и говорит своему отцу, что «я очень уважаю Гелиоса и других богов». [ 165 ] [ 166 ]

Авгий , который в некоторых версиях является его сыном, хранит стадо из двенадцати быков, посвященных богу. [ 167 ] Более того, говорили, что огромное стадо крупного рогатого скота Авгию было подарком ему отца. [ 168 ]

Аполлония в Иллирии была еще одним местом, где он держал стадо своих овец; человек по имени Пифиний над ними был поставлен , но овцы были растерзаны волками. Остальные Аполлонии, думая, что он проявил небрежность, выкололи Пифению глаза. Разгневанный обращением с этим человеком, Гелиос сделал землю бесплодной и перестала приносить плоды; земля снова стала плодородной только после того, как Аполлониаты умилостивили Пифения хитростью, и он выбрал два предместья и дом, угодив богу. [ 169 ] Эту историю также засвидетельствовал греческий историк Геродот , который называет этого человека Эвением. [ 170 ] [ 171 ]

Одиссея

[ редактировать ]

Во время путешествия Одиссея, чтобы вернуться домой, он прибывает на остров Цирцеи, которая предупреждает его не прикасаться к священным коровам Гелиоса, когда он достигнет Тринасии, иначе бог не позволит им вернуться домой. Хотя Одиссей предупреждает своих людей, когда припасы заканчиваются, они убивают и съедают часть скота. Об этом отцу рассказывают хранительницы острова — дочери Гелиоса Фаэтуса и Лампетия. Затем Гелиос обращается к Зевсу и просит его избавиться от людей Одиссея, отказываясь от компенсации членам экипажа за строительство нового храма на Итаке. [ 172 ] Зевс уничтожает корабль своей молнией, убивая всех людей, кроме Одиссея. [ 173 ]

Другие работы

[ редактировать ]

Гелиос фигурирует в нескольких работах Люциана , помимо его «Диалогов богов» . В другом произведении Лукиана, «Икароменипп» , Селена жалуется главному герою на философов, желающих разжечь раздор между ней и Гелиосом. [ 174 ] Позже его видят пирующим с другими богами на Олимпе, что заставляет Мениппа задуматься, как может ночь опуститься на Небеса, пока он там. [ 175 ]

Диодор Сицилийский записал неортодоксальную версию мифа, в которой Базилея, унаследовавшая царский трон своего отца Урана , вышла замуж за своего брата Гипериона и родила двоих детей, сына Гелиоса и дочь Селену. Поскольку другие братья Базилеи завидовали этому отпрыску, они предали Гипериона мечу и утопили Гелиоса в реке Эридан , а Селена покончила с собой. После резни Гелиос явился во сне своей скорбящей матери и заверил ее и их убийц, что они будут наказаны, и что он и его сестра теперь превратятся в бессмертные божественные существа; то, что было известно как Мене [ 176 ] теперь будет называться Селеной, а «святой огонь» на небесах будет носить его собственное имя. [ 29 ] [ 177 ]

Говорили, что Селена, поглощенная своей страстью к смертному Эндимиону, [ 178 ] отдала свою лунную колесницу Гелиосу, чтобы тот управлял ею. [ 179 ]

Клавдиан писал, что в младенчестве Гелиоса кормила его тетя Тефия . [ 180 ]

Павсаний пишет, что жители Титана считали Титана братом Гелиоса, первого жителя Титана, в честь которого был назван город; [ 181 ] Однако Титан обычно идентифицировался как сам Гелиос, а не как отдельная фигура. [ 182 ]

По словам лирика шестого века до нашей эры Стесихора , вместе с Гелиосом в его дворце живет его мать Тейя . [ 183 ]

В мифе об убийстве дракона Пифона Аполлоном труп убитого змея, как говорят, сгнил под действием «сияющего Гипериона». [ 184 ]

Супруги и дети

[ редактировать ]

Бог Гелиос обычно изображается как глава большой семьи, и места, где его больше всего почитали, также обычно заявляли о своем мифологическом и генеалогическом происхождении от него; [ 148 ] например, критяне проследили родословную своего царя Идоменея до Гелиоса через его дочь Пасифаю. [ 185 ]

Традиционно нимфу Океанид Персе считали женой бога Солнца. [ 186 ] от которого у него были разные дети, в первую очередь Цирцея , Ээт, Миноса жена Пасифая, Перс и, в некоторых версиях, коринфский царь Алоей . [ 187 ] Иоанн Цецес добавляет Калипсо , иначе дочь Атласа , в список детей Гелиоса от Персе, возможно, из-за сходства ролей и личностей, которые она и Цирцея отображают в « Одиссее» как хозяева Одиссея. [ 188 ]

В какой-то момент Гелиос предупредил Ээта о пророчестве, в котором говорилось, что он пострадает от предательства со стороны одного из своих потомков (под которым Ээт имел в виду его дочь Халкиопу и ее детей от Фрикса ). [ 189 ] [ 190 ] Helios also bestowed several gifts on his son, such as a chariot with swift steeds,[191] a golden helmet with four plates,[192] a giant's war armor,[193] and robes and a necklace as a pledge of fatherhood.[194] When his daughter Medea betrays him and flees with Jason after stealing the golden fleece, Aeëtes calls upon his father and Zeus to witness their unlawful actions against him and his people.[195]

As father of Aeëtes, Helios was also the grandfather of Medea and would play a significant role in Euripides' rendition of her fate in Corinth. When Medea offers Princess Glauce the poisoned robes and diadem, she says they were gifts to her from Helios.[196] Later, after Medea has caused the deaths of Glauce and King Creon, as well as her own children, Helios helps her escape Corinth and her husband.[197][198] In Seneca's rendition of the story, a frustrated Medea criticizes the inaction of her grandfather, wondering why he has not darkened the sky at sight of such wickedness, and asks from him his fiery chariot so she can burn Corinth to the ground.[199][200]

However, he is also stated to have married other women instead like Rhodos in the Rhodian tradition,[201] by whom he had seven sons, the Heliadae (Ochimus, Cercaphus, Macar, Actis, Tenages, Triopas, Candalus), and the girl Electryone.

In Nonnus' account from the Dionysiaca, Helios and the nymph Clymene met and fell in love with each other in the mythical island of Kerne and got married.[202] Soon Clymene fell pregnant with Phaetheon. Her and Helios raised their child together, until the ill-fated day the boy asked his father for his chariot.[203] A passage from Greek anthology mentions Helios visiting Clymene in her room.[204]

The mortal king of Elis Augeas was said to be Helios' son, but Pausanias states that his actual father was the mortal king Eleios.[205]

In some rare versions, Helios is the father, rather than the brother, of his sisters Selene and Eos. A scholiast on Euripides explained that Selene was said to be his daughter since she partakes of the solar light, and changes her shape based on the position of the sun.[206]

- Anaxibia, an Indian Naiad, was lusted after by Helios according to Pseudo-Plutarch.[259]

Worship

[edit]Cult

[edit]Archaic and Classical Athens

[edit]

Scholarly focus on the ancient Greek cults of Helios has generally been rather slim, partially due to how scarce both literary and archaeological sources are.[148] L.R. Farnell assumed "that sun-worship had once been prevalent and powerful among the people of the pre-Hellenic culture, but that very few of the communities of the later historic period retained it as a potent factor of the state religion".[260] The largely Attic literary sources used by scholars present ancient Greek religion with an Athenian bias, and, according to J. Burnet, "no Athenian could be expected to worship Helios or Selene, but he might think them to be gods, since Helios was the great god of Rhodes and Selene was worshiped at Elis and elsewhere".[261]Aristophanes' Peace (406–413) contrasts the worship of Helios and Selene with that of the more essentially Greek Twelve Olympians.[262]

The tension between the mainstream traditional religious veneration of Helios, which had become enriched with ethical values, poetical symbolism,[263] and the Ionian proto-scientific examination of the sun, clashed in the trial of Anaxagoras c. 450 BC, in which Anaxagoras asserted that the Sun was in fact a gigantic red-hot ball of metal.[264]

Hellenistic period

[edit]Helios was not worshipped in Athens until the Hellenistic period, in post-classical times.[265] His worship might be described as a product of the Hellenistic era, influenced perhaps by the general spread of cosmic and astral beliefs during the reign of Alexander III.[266] A scholiast on Sophocles wrote that the Athenians did not offer wine as an offering to the Helios among other gods, making instead nephalia, or wineless, sober sacrifices;[267][268] Athenaeus also reported that those who sacrificed to him did not offer wine, but brought honey instead, to the altars reasoning that the god who held the cosmos in order should not succumb to drunkenness.[269]

Lysimachides in the first century BC or first century AD reported of a festival Skira:

that the skiron is a large sunshade under which the priestess of Athena, the priest of Poseidon, and the priest of Helios walk as it is carried from the acropolis to a place called Skiron.[270]

During the Thargelia, a festival in honour of Apollo, the Athenians had cereal offerings for Helios and the Horae.[271] They were honoured with a procession, due to their clear connections and relevance to agriculture.[272][273][274][275] Helios and the Horae were also apparently worshipped during another Athenian festival held in honor of Apollo, the Pyanopsia, with a feast;[276][273] an attested procession, independent from the one recorded at the Thargelia, might have been in their honour.[277]

Side B of LSCG 21.B19 from the Piraeus Asclepium prescribe cake offerings to several gods, among them Helios and Mnemosyne,[278] two gods linked to incubation through dreams,[279] who are offered a type of honey cake called arester and a honeycomb.[280][281] The cake was put on fire during the offering.[282] A type of cake called orthostates[283][284] made of wheaten and barley flour was offered to him and the Hours.[285][286] Phthois, another flat cake[287] made with cheese, honey and wheat was also offered to him among many other gods.[286]

In many places people kept herds of red and white cattle in his honour, and white animals of several kinds, but especially white horses, were considered to be sacred to him.[42] Ovid writes that horses were sacrificed to him because no slow animal should be offered to the swift god.[288]

In Plato's Republic Helios, the Sun, is the symbolic offspring of the idea of the Good.[289]

The ancient Greeks called Sunday "day of the Sun" (ἡμέρα Ἡλίου) after him.[290] According to Philochorus, Athenian historian and Atthidographer of the 3rd century BC, the first day of each month was sacred to Helios.[291]

It was during the Roman period that Helios actually rose into an actual significant religious figure and was elevated in public cult.[292][266]

Rhodes

[edit]

The island of Rhodes was an important cult center for Helios, one of the only places where he was worshipped as a major deity in ancient Greece.[293][294] One of Pindar's most notable greatest odes is an abiding memorial of the devotion of the island of Rhodes to the cult and personality of Helios, and all evidence points that he was for the Rhodians what Olympian Zeus was for Elis or Athena for the Athenians; their local myths, especially those concerning the Heliadae, suggest that Helios in Rhodes was revered as the founder of their race and their civilization.[295]

The worship of Helios at Rhodes included a ritual in which a quadriga, or chariot drawn by four horses, was driven over a precipice into the sea, in reenactment to the myth of Phaethon. Annual gymnastic tournaments were held in Helios' honor;[42] according to Festus (s. v. October Equus) during the Halia each year the Rhodians would also throw quadrigas dedicated to him into the sea.[296][297][298] Horse sacrifice was offered to him in many places, but only in Rhodes in teams of four; a team of four horses was also sacrificed to Poseidon in Illyricum, and the sea god was also worshipped in Lindos under the epithet Hippios, denoting perhaps a blending of the cults.[299]

It was believed that if one sacrificed to the rising Sun with their day's work ahead of them, it would be proper to offer a fresh, bright white horse.[300]

The Colossus of Rhodes was dedicated to him. In Xenophon of Ephesus' work of fiction, Ephesian Tale of Anthia and Habrocomes, the protagonist Anthia cuts and dedicates some of her hair to Helios during his festival at Rhodes.[301] The Rhodians called shrine of Helios, Haleion (Ancient Greek: Ἄλειον).[302]

A colossal statue of the god, known as the Colossus of Rhodes and named as one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, was erected in his honour and adorned the port of the city of Rhodes.[303]

The best of these are, first, the Colossus of Helius, of which the author of the iambic verse says, "seven times ten cubits in height, the work of Chares the Lindian"; but it now lies on the ground, having been thrown down by an earthquake and broken at the knees. In accordance with a certain oracle, the people did not raise it again.[304]

According to most contemporary descriptions, the Colossus stood approximately 70 cubits, or 33 metres (108 feet) high – approximately the height of the modern Statue of Liberty from feet to crown – making it the tallest statue in the ancient world.[305] It collapsed after an earthquake that hit Rhodes in 226 BC, and the Rhodians did not build it again, in accordance with an oracle.

In Rhodes, Helios seems to have absorbed the worship and cult of the island's local hero and mythical founder Tlepolemus.[306] In ancient Greek city foundation, the use of the archegetes in its double sense of both founder and progenitor of a political order, or a polis, can be seen with Rhodes; real prominence was transferred from the local hero Tlepolemus, onto the god, Helios, with an appropriate myth explaining his relative insignificance; thus games originally celebrated for Tlepolemus were now given to Helios, who was seen as both ancestor and founder of the polis.[307] A sanctuary of Helios and the nymphs stood in Loryma near Lindos.[308]

The priesthood of Helios was, at some point, appointed by lot, though in the great city a man and his two sons held the office of priesthood for the sun god in succession.[309]

Peloponnese

[edit]The scattering of cults in Sicyon, Argos, Hermione, Epidaurus and Laconia seem to suggest that Helios was considerably important in Dorian religion, compared to other parts of ancient Greece. It may have been the Dorians who brought his worship to Rhodes.[310][311]

Helios was an important god in Corinth and the greater Corinthia region.[312] Pausanias in his Description of Greece describes how Helios and Poseidon vied over the city, with Poseidon getting the isthmus of Corinth and Helios being awarded with the Acrocorinth.[143] Helios' prominence in Corinth might go as back as Mycenaean times, and predate Poseidon's arrival,[313] or it might be due to Oriental immigration.[314] At Sicyon, Helios had an altar behind Hera's sanctuary.[315] It would seem that for the Corinthians, Helios was notable enough to even have control over thunder, which is otherwise the domain of the sky god Zeus.[148]

Helios had a cult in Laconia as well. Taletos, a peak of Mt. Taygetus, was sacred to Helios.[316][317] At Thalamae, Helios together with his daughter Pasiphaë were revered in an oracle, where the goddess revealed to the people consulting her what they needed to know in their dreams.[318][313] While the predominance of Helios in Sparta is currently unclear, it seems Helen was the local solar deity.[319] Helios (and Selene's) worship in Gytheum, near Sparta, is attested by an inscription (C.I.G. 1392).[320]

In Argolis, an altar was dedicated to Helios near Mycenae,[321] and another in Troezen, where he was worshipped as the God of Freedom, seeing how the Troezenians had escaped slavery at the hands of Xerxes I.[322] Over at Hermione stood a temple of his.[313][323][324] He appears to have also been venerated in Epidaurus.[325]

In Arcadia, he had a cult in Megalopolis as the Saviour, and an altar near Mantineia.[326]

Elsewhere

[edit]Traces of Helios's worship can also be found in Crete. In the earliest period Rhodes stood in close relations with Crete, and it is relatively safe to suggest that the name "Taletos" is associated with the Eteocretan word for the sun "Talos", surviving in Zeus' epithet Tallaios,[313] a solar aspect of the thunder god in Crete.[327][328] Helios was also invoked in an oath of alliance between Knossos and Dreros.[329]

In his little-attested cults in Asia Minor it seems his identification with Apollo was the strongest.[330][331][332] It is possible that the solar elements of Apollo's Anatolian cults were influenced by Helios' cult in Rhodes, as Rhodes lies right off the southwest coast of Asia Minor.[333]

Archaeological evidence has proven the existence of a shrine to Helios and Hemera, the goddess of the day and daylight, at the island of Kos[313] and excavations have revealed traces of his cult at Sinope, Pozzuoli, Ostia and elsewhere.[266] After a plague hit the city of Cleonae, in Phocis, Central Greece, the people there sacrificed a he-goat to Helios, and were reportedly then spared from the plague.[334]

Helios also had a cult in the region of Thessaly.[335] Plato in his Laws mentions the state of the Magnetes making a joint offering to Helios and Apollo, indicating a close relationship between the cults of those two gods,[336] but it is clear that they were nevertheless distinct deities in Thessaly.[335]

Helios is also depicted on first century BC coins found at Halicarnassus,[337] Syracuse in Sicily[338] and at Zacynthus.[339] From Pergamon originates a hymn to Helios in the style of Euripides.[340]

In Apollonia he was also venerated, as evidenced from Herodotus' account where a man named Evenius was harshly punished by his fellow citizens for allowing wolves to devour the flock of sheep sacred to the god out of negligence.[170]

The Alexander Romance names a temple of Helios in the city of Alexandria.[341]

Other functions

[edit]In oath-keeping

[edit]

Gods were often called upon by the Greeks when an oath was sworn; Helios is among the three deities to be invoked in the Iliad to witness the truce between Greeks and Trojans.[342] He is also often appealed to in ancient drama to witness the unfolding events or take action, such as in Oedipus Rex and Medea.[343] The notion of Helios as witness to oaths and vows also led to a view of Helios as a witness of wrong-doings.[344][345][346] He was thus seen as a guarantor of cosmic order.[347]

Helios was invoked as a witness to several alliances such as the one between Athens and Cetriporis, Lyppeus of Paeonia and Grabus, and the oaths of the League of Corinth.[348] In a treaty between the cities of Smyrna and Magnesia, the Magnesians swore their oath by Helios among others.[349] The combination of Zeus, Gaia and Helios in oath-swearing is also found among the non-Greek 'Royal Gods' in an agreement between Maussollus and Phaselis (360s BC) and in the Hellenistic period with the degree of Chremonides' announcing the alliance of Athens and Sparta.[348]

In magic

[edit]He also had a role in necromancy magic. The Greek Magical Papyri contain several recipes for such, for example one which involves invoking the Sun over the skull-cup of a man who suffered a violent death; after the described ritual, Helios will then send the man's ghost to the practitioner to tell them everything they wish to know.[350] Helios is also associated with Hecate in cursing magic.[351] In some parts of Asia Minor Helios was adjured not to permit any violation of the grave in tomb inscriptions and to warn potential violators not to desecrate the tomb, like one example from Elaeussa-Sebaste in Cilicia:

We adjure you by the heavenly god [Zeus] and Helios and Selene and the gods of the underworld, who receive us, that no one [. . .] will throw another corpse upon our bones.[352]

Helios was also often invoked in funeral imprecations.[353] Helios might have been chosen for this sort of magic because as an all-seeing god he could see everything on earth, even hidden crimes, and thus he was a very popular god to invoke in prayers for vengeance.[353] Additionally, in ancient magic evil-averting aid and apotropaic defense were credited to Helios.[354] Some magic rituals were associated with the engraving of images and stones, as with one such spell which asks Helios to consecrate the stone and fill with luck, honour, success and strength, thus giving the user incredible power.[355]

Helios was also associated with love magic, much like Aphrodite, as there seems to have been another but rather poorly documented tradition of people asking him for help in such love matters,[356] including homosexual love[357] and magical recipes invoking him for affection spells.[358]

In dreams

[edit]It has been suggested that in Ancient Greece people would reveal their dreams to Helios and the sky or the air in order to avert any evil foretold or presaged in them.[359][360]

According to Artemidorus' Oneirocritica, the rich dreaming of transforming into a god was an auspicious sign, as long as the transformation had no deficiencies, citing the example of a man who dreamt he was Helios but wore a sun crown of just eleven rays.[35] He wrote that the sun god was also an auspicious sign for the poor.[361] In dreams, Helios could either appear in 'sensible' form (the orb of the sun) or his 'intelligible' form (the humanoid god).[362]

Late antiquity

[edit]

By Late Antiquity, Helios had accumulated a number of religious, mythological, and literary elements from other deities, particularly Apollo and the Roman sun god Sol. In 274 AD, on December 25, the Roman Emperor Aurelian instituted an official state cult to Sol Invictus (or Helios Megistos, "Great Helios"). This new cult drew together imagery not only associated with Helios and Sol, but also a number of syncretic elements from other deities formerly recognized as distinct.[363] Helios in these works is frequently equated not only with deities such as Mithras and Harpocrates, but even with the monotheistic Judaeo-Christian god.[364]

The last pagan emperor of Rome, Julian, made Helios the primary deity of his revived pagan religion, which combined elements of Mithraism with Neoplatonism. For Julian, Helios was a triunity: The One; Helios-Mithras; and the Sun. Because the primary location of Helios in this scheme was the "middle" realm, Julian considered him to be a mediator and unifier not just of the three realms of being, but of all things.[49] Julian's theological conception of Helios has been described as "practically monotheistic", in contrast to earlier Neoplatonists like Iamblichus.[49]

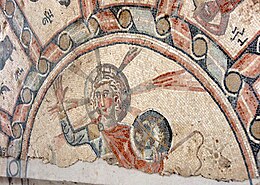

A mosaic found in the Vatican Necropolis (mausoleum M) depicts a figure very similar in style to Sol / Helios, crowned with solar rays and driving a solar chariot. Some scholars have interpreted this as a depiction of Christ, noting that Clement of Alexandria wrote of Christ driving his chariot across the sky.[365] Some scholars doubt the Christian associations,[366] or suggest that the figure is merely a non-religious representation of the sun.[367]

In the Greek Magical Papyri

[edit]

Helios figured prominently in the Greek Magical Papyri. In these mostly fragmentary texts, Helios is credited with a broad domain, being regarded as the creator of life, the lord of the heavens and the cosmos, and the god of the sea. He is said to take the form of 12 animals representing each hour of the day, a motif also connected with the 12 signs of the zodiac.[14]

The Papyri often syncretize Helios with a variety of related deities. He is described as "seated on a lotus, decorated with rays", in the manner of Harpocrates, who was often depicted seated on a lotus flower, representing the rising sun.[368][14]

Helios is also assimilated with Mithras in some of the Papyri, as he was by Emperor Julian. The Mithras Liturgy combines them as Helios-Mithras, who is said to have revealed the secrets of immortality to the magician who wrote the text. Some of the texts describe Helios-Mithras navigating the Sun's path not in a chariot but in a boat, an apparent identification with the Egyptian sun god Ra. Helios is also described as "restraining the serpent", likely a reference to Apophis, the serpent god who, in Egyptian myth, is said to attack Ra's ship during his nightly journey through the underworld.[14]

In many of the Papyri, Helios is also strongly identified with Iao, a name derived from that of the Hebrew god Yahweh, and shares several of his titles including Sabaoth and Adonai.[14] He is also assimilated as the Agathos Daemon, who is also identified elsewhere in the texts as "the greatest god, lord Horus Harpokrates".[14]

The Neoplatonist philosophers Proclus and Iamblichus attempted to interpret many of the syntheses found in the Greek Magical Papyri and other writings that regarded Helios as all-encompassing, with the attributes of many other divine entities. Proclus described Helios as a cosmic god consisting of many forms and traits. These are "coiled up" within his being, and are variously distributed to all that "participate in his nature", including angels, daemons, souls, animals, herbs, and stones. All of these things were important to the Neoplatonic practice of theurgy, magical rituals intended to invoke the gods in order to ultimately achieve union with them. Iamblichus noted that theurgy often involved the use of "stones, plants, animals, aromatic substances, and other such things holy and perfect and godlike."[369] For theurgists, the elemental power of these items sacred to particular gods utilizes a kind of sympathetic magic.[14]

Epithets

[edit]

The Greek sun god had various bynames or epithets, which over time in some cases came to be considered separate deities associated with the Sun. Among these are:

Acamas (/ɑːˈkɑːmɑːs/; ah-KAH-mahss; Άκάμας, "Akàmas"), meaning "tireless, unwearying", as he repeats his never-ending routine day after day without cease.

Apollo (/əˈpɒləʊ/; ə-POL-oh; Ἀπόλλων, "Apóllōn") here understood to mean "destroyer", the sun as a more destructive force.[104]

Callilampetes (/kəˌliːlæmˈpɛtiːz/; kə-LEE-lam-PET-eez; Καλλιλαμπέτης, "Kallilampétēs"), "he who glows lovely".[370]

Elasippus (/ɛlˈæsɪpəs/; el-AH-sip-əss; Ἐλάσιππος, "Elásippos"), meaning "horse-driving".[371]

Elector (/əˈlɛktər/; ə-LEK-tər; Ἠλέκτωρ, "Ēléktōr") of uncertain derivation (compare Electra), often translated as "beaming" or "radiant", especially in the combination Ēlektōr Hyperiōn.[372]

Eleutherius (/iːˈljuːθəriəs/; ee-LOO-thər-ee-əs; Ἐλευθέριος, "Eleuthérios) "the liberator", epithet under which he was worshipped in Troezen in Argolis,[322] also shared with Dionysus and Eros.

Hagnus (/ˈhæɡnəs/; HAG-nəs; Ἁγνός, Hagnós), meaning "pure", "sacred" or "purifying."[89]

Hecatus (/ˈhɛkətəs/; HEK-ə-təs; Ἕκατος, "Hékatos"), "from afar," also Hecatebolus (/hɛkəˈtɛbəʊləs/; hek-ə-TEB-əʊ-ləs; Ἑκατήβολος, "Hekatḗbolos") "the far-shooter", i.e. the sun's rays considered as arrows.[373]

Horotrophus (/hɔːrˈɔːtrɔːfəs/; hor-OT-roff-əss; Ὡροτρόφος, "Hо̄rotróphos"), "nurturer of the Seasons/Hours", in combination with kouros, "youth".[374]

Hyperion (/haɪˈpɪəriən/; hy-PEER-ree-ən; Ὑπερίων, "Hyperíōn") and Hyperionides (/haɪˌpɪəriəˈnaɪdiːz/; hy-PEER-ee-ə-NY-deez; Ὑπεριονίδης, "Hyperionídēs"), "superus, high up" and "son of Hyperion" respectively, the sun as the one who is above,[375] and also the name of his father.

Isodaetes (/ˌaɪsəˈdeɪtiːz/; EYE-sə-DAY-teez; Ἰσοδαίτης, "Isodaítēs"), literally "he that distributes equal portions", cult epithet also shared with Dionysus.[376]

Paean (/ˈpiːən/ PEE-ən; Παιάν, Paiān), physician, healer, a healing god and an epithet of Apollo and Asclepius.[377]

Panoptes (/pæˈnɒptiːs/; pan-OP-tees; Πανόπτης, "Panóptēs") "all-seeing" and Pantepoptes (/pæntɛˈpɒptiːs/; pan-tep-OP-tees; Παντεπόπτης, "Pantepóptēs") "all-supervising", as the one who witnessed everything that happened on earth.

Pasiphaes (/pəˈsɪfiiːs/; pah-SIF-ee-eess; Πασιφαής, "Pasiphaḗs"), "all-shining", also the name of one of his daughters.[378]

Patrius (/ˈpætriəs/; PAT-ree-əs; Πάτριος, "Pátrios") "of the fathers, ancestral", related to his role as primogenitor of royal lines in several places.[352]

Phaethon (/ˈfeɪθən/; FAY-thən; Φαέθων, "Phaéthōn") "the radiant", "the shining", also the name of his son and daughter.

Phasimbrotus (/ˌfæsɪmˈbrɒtəs/; FASS-im-BROT-əs; Φασίμβροτος, "Phasímbrotos") "he who sheds light to the mortals", the sun.

Philonamatus (/ˌfɪloʊˈnæmətəs/; FIL-oh-NAM-ə-təs; Φιλονάματος, "Philonámatos") "water-loving", a reference to him rising from and setting in the ocean.[379]

Phoebus (/ˈfiːbəs/ FEE-bəs; Φοῖβος, Phoîbos), literally "bright", several Roman authors applied Apollo's byname to their sun god Sol.

Sirius (/ˈsɪrɪəs/; SEE-ree-əss; Σείριος, "Seírios") literally meaning "scorching", and also the name of the Dog Star.[380][101]

Soter (/ˈsoʊtər/; SOH-tər; Σωτὴρ, "Sōtḗr") "the saviour", epithet under which he was worshipped in Megalopolis, Arcadia.[381]

Terpsimbrotus (/ˌtɜːrpsɪmˈbrɒtəs/; TURP-sim-BROT-əs; Τερψίμβροτος, "Terpsímbrotos") "he who gladdens mortals", with his warm, life-giving beams.

Titan (/ˈtaɪtən/; TY-tən; Τιτάν, "Titán"), possibly connected to τιτώ meaning "day" and thus "god of the day".[382]

Whether Apollo's epithets Aegletes and Asgelatas in the island of Anaphe, both connected to light, were borrowed from epithets of Helios either directly or indirectly is hard to say.[378]

Identification with other gods

[edit]Apollo

[edit]

Helios is sometimes identified with Apollo: "Different names may refer to the same being," Walter Burkert argues, "or else they may be consciously equated, as in the case of Apollo and Helios."[383] Apollo was associated with the Sun as early as the fifth century BC, though widespread conflation between him and the Sun god was a later phaenomenon.[384] The earliest certain reference to Apollo being identified with Helios appears in the surviving fragments of Euripides' play Phaethon in a speech near the end.[104]

By Hellenistic times Apollo had become closely connected with the Sun in cult and Phoebus (Greek Φοῖβος, "bright"), the epithet most commonly given to Apollo, was later applied by Latin poets to the Sun-god Sol.

The identification became a commonplace in philosophic and some Orphic texts. Pseudo-Eratosthenes writes about Orpheus in Placings Among the Stars, section 24:

- But having gone down into Hades because of his wife and seeing what sort of things were there, he did not continue to worship Dionysus, because of whom he was famous, but he thought Helios to be the greatest of the gods, Helios whom he also addressed as Apollo. Rousing himself each night toward dawn and climbing the mountain called Pangaion, he would await the Sun's rising, so that he might see it first. Therefore, Dionysus, being angry with him, sent the Bassarides, as Aeschylus the tragedian says; they tore him apart and scattered the limbs.[385]

Dionysus and Asclepius are sometimes also identified with this Apollo Helios.[386][387]

Strabo wrote that Artemis and Apollo were associated with Selene and Helios respectively due to the changes those two celestial bodies caused in the temperature of the air, as the twins were gods of pestilential diseases and sudden deaths.[388] Pausanias also linked Apollo's association with Helios as a result of his profession as a healing god.[389] In the Orphic Hymns, Helios is addressed as Paean ("healer") and holding a golden lyre,[390][33] both common descriptions for Apollo; similarly Apollo in his own hymn is described as Titan and shedding light to the mortals, both common epithets of Helios.[391]

According to Athenaeus, Telesilla wrote that the song sung in honour of Apollo is called the "Sun-loving song" (φιληλιάς, philhēliás),[392] that is, a song meant to make the Sun come forth from the clouds, sung by children in bad weather; but Julius Pollux describing a philhelias in greater detail makes no mention of Apollo, only Helios.[393] Scythinus of Teos wrote that Apollo uses the bright light of the Sun (λαμπρὸν πλῆκτρον ἡλίου φάος) as his harp-quill[394] and in a fragment of Timotheus' lyric, Helios is invoked as an archer with the invocation Ἰὲ Παιάν (a common way of addressing the two medicine gods), though it most likely was part of esoteric doctrine, rather than a popular and widespread belief.[393]

Classical Latin poets also used Phoebus as a byname for the Sun-god, whence come common references in later European poetry to Phoebus and his chariot as a metaphor for the Sun.[395] Ancient Roman authors who used "Phoebus" for Sol as well as Apollo include Ovid,[396] Virgil,[397] Statius,[398] and Seneca.[399] Representations of Apollo with solar rays around his head in art also belong to the time of the Roman Empire, particularly under Emperor Elagabalus in 218-222 AD.[400]

Usil

[edit]

The Etruscan god of the Sun was Usil. His name appears on the bronze liver of Piacenza, next to Tiur, the Moon.[401] He appears, rising out of the sea, with a fireball in either outstretched hand, on an engraved Etruscan bronze mirror in late Archaic style.[402] On Etruscan mirrors in Classical style, he appears with a halo. In ancient artwork, Usil is shown in close association with Thesan, the goddess of the dawn, something almost never seen with Helios and Eos,[403] however in the area between Cetona and Chiusi a stone obelisk is found, whose relief decorations seem to have been interpreted as referring to a solar sanctuary: what appears to be a Sun boat, the heads of Helios and Thesan, and a cock, likewise referring to the Sunrise.[404]

Zeus

[edit]

Helios is also sometimes conflated in classical literature with the highest Olympian god, Zeus. An attested cult epithet of Zeus is Aleios Zeus, or "Zeus the Sun," from the Doric form of Helios' name.[405] The inscribed base of Mammia's dedication to Helios and Zeus Meilichios, dating from the fourth or third century BC, is a fairly and unusually early evidence of the conjoint worship of Helios and Zeus.[406] According to Plutarch, Helios is Zeus in his material form that one can interact with, and that's why Zeus owns the year,[407] while the chorus in Euripides' Medea also link him to Zeus when they refer to Helios as "light born from Zeus".[408] In his Orphic hymn, Helios is addressed as "immortal Zeus".[390] In Crete, the cult of Zeus Tallaios had incorporated several solar elements into his worship; "Talos" was the local equivalent of Helios.[327] Helios is referred either directly as Zeus' eye,[409] or clearly implied to be. For instance, Hesiod effectively describes Zeus's eye as the Sun.[410] This perception is possibly derived from earlier Proto-Indo-European religion, in which the Sun is believed to have been envisioned as the eye of *Dyḗus Pḥatḗr (see Hvare-khshaeta). An Orphic saying, supposedly given by an oracle of Apollo, goes:

- "Zeus, Hades, Helios-Dionysus, three gods in one godhead!"

The Hellenistic period gave birth to Serapis, a Greco-Egyptian deity conceived by the Greeks as a chthonic aspect of Zeus, whose solar nature is indicated by the Sun crown and rays the Greeks depicted him with.[411] Frequent joint dedications to "Zeus-Serapis-Helios" have been found all over the Mediterranean.[411][412][413][414][415] There is evidence of Zeus being worshipped as a solar god in the Aegean island of Amorgos which, if correct, could mean that Sun elements in Zeus' worship could be as early as the fifth century BC.[416]

Hades

[edit]Helios seems to have been connected to some degree with Hades, the god of the Underworld. A dedicatory inscription from Smyrna describes a 1st–2nd century sanctuary to "God Himself" as the most exalted of a group of six deities, including clothed statues of Plouton Helios and Koure Selene, or in other words "Pluto the Sun" and "Kore the Moon".[417] Roman poet Apuleius describes a rite in which the Sun appears at midnight to the initiate at the gates of Proserpina; the suggestion here is that this midnight Sun could be Plouton Helios.[418] Pluto-Helios seems to reflect the Egyptian idea of the nocturnal Sun that penetrated the realm of the dead.[419]

An old oracle from Claros said that the names of Zeus, Hades, Helios, Dionysus and Jao all represented the Sun at different seasons.[420] Macrobius wrote that Iao/Jao is "Hades in winter, Zeus in spring, Helios in summer, and Iao in autumn."[421]

Cronus

[edit]Diodorus Siculus reported that the Chaldeans called Cronus (Saturnus) by the name Helios, or the Sun, and he explained that this was because Saturn was the "most conspicuous" of the planets.[422]

Mithras

[edit]Helios is frequently conflated with Mithras in iconography, as well as being worshipped alongside him as Helios-Mithras.[49] The earliest artistic representations of the "chariot god" come from the Parthian period (3rd century) in Persia where there is evidence of rituals being performed for the sun god by Magi, indicating an assimilation of the worship of Helios and Mithras.[14]

Iconography

[edit]Depiction and symbols

[edit]

The earliest depictions of Helios in a humanoid form date from the late sixth and early fifth centuries BC in Attic black-figure vases, and typically show him frontally as a bearded man on his chariot with a sun disk. A red-figure on a polychrome bobbin by a follower of the Brygos painter already signifies a shift in the god's depiction, painting him as a youthful, beardless figure. In later art, he is consistently drawn as beardless and young. In it, he is typically depicted with a radiant crown,[423] with the right hand often raised, a gesture of power (which came to be a definitional feature of solar iconography), the left hand usually holding a whip or a globe.[424]

In Rhodian coins, he was shown as a beardless god, with thick and flowing hair, surrounded by beams.[425] He was also presented as a young man clad in tunic, with curling hair and wearing buskins.[426] Just like Selene, who is sometimes depicted with a lunar disk rather than a crescent, Helios too has his own solar one instead of a sun crown in some depictions.[427] It is likely that Helios' later image as a warrior-charioteer might be traced back to the Mycenaean period;[428] the symbol of the disc of the sun is displayed in scenes of rituals from both Mycenae and Tiryns, and large amounts of chariots used by the Mycenaeans are recorded in Linear B tablets.[429]

In archaic art, Helios rising in his chariot was a type of motive.[430] Helios in ancient pottery is usually depicted rising from the sea in his four-horse chariot, either as a single figure or connecting to some myth, indicating that it takes place at dawn. An Attic black-figure vase shows Heracles sitting on the shores of the Ocean river, while next to him a pair of arrows protrude from Helios, crowned with a solar disk and driving his chariot.[431]

Helios adorned the east pediment of the Parthenon, along with Selene.[432][433] Helios (again with Selene) also framed the birth of Aphrodite on the base of the Statue of Zeus at Olympia,[434][435] the Judgement of Paris,[436] and possibly the birth of Pandora on the base of the Athena Parthenos statue.[437] They were also featured in the pedimental group of the temple at Delphi.[438] In dynamic Hellenistic art, Helios along with other luminary deities and Rhea-Cybele, representing reason, battle the Giants (who represent irrationality).[439]

In Elis, he was depicted with rays coming out of his head in an image made of wood with gilded clothing and marble head, hands and feet.[440] Outside the market of the city of Corinth stood a gateway on which stood two gilded chariots; one carrying Helios' son Phaethon, the other Helios himself.[441]

Helios appears infrequently in gold jewelry before Roman times; extant examples include a gold medallion with its bust from the Gulf of Elaia in Anatolia, where he's depicted frontally with a head of unruly hair, and a golden medallion of the Pelinna necklace.

His iconography, used by the Ptolemies after representations of Alexander the Great as Alexander-Helios, came to symbolize power and epiphany, and was borrowed by several Egyptian deities in the Roman period.[442] Other rulers who had their portraits done with solar features include Ptolemy III Euergetes, one of the Ptolemaic kings of Egypt, of whom a bust with holes in the fillet for the sunrays and gold coins depicting him with a radiant halo on his head like Helios and holding the aegis exist.[443][444]

Late Roman era

[edit]

Helios was also frequently depicted in mosaics, usually surrounded by the twelve zodiac signs and accompanied by Selene. From the third and fourth centuries CE onwards, the sun god was seen as an official imperial Roman god and thus appeared in various forms in monumental artworks. The cult of Helios/Sol had a notable function in Eretz Israel; Helios was Constantine the Great's patron, and so that ruler came to be identified with Helios.[445] In his new capital city, Constantinople, Constantine recycled a statue of Helios to represent himself in his portrait, as Nero had done with Sol, which was not an uncommon practice among pagans.[446] A considerable portion if not the majority of Jewish Helios material dates from the 3rd through the 6th centuries CE, including numerous mosaics of the god in Jewish synagogues and invocation in papyri.[447]

The sun god was depicted in mosaics in three places of the Land of Israel; at the synagogues of Hammat Tiberias, Beth Alpha and Naaran. In the mosaic of the Hammat Tiberias, Helios is wrapped in a partially gilded tunic fastened with a fibula and sporting a seven-rayed halo[445] with his right hand uplifted, while his left holds a globe and a whip; his chariot is drawn as a frontal box with two large wheels pulled by four horses.[448] At the Beth Alpha synagogue, Helios is at the centre of the circle of the zodiac mosaic, together with the Torah shrine between menorahs, other ritual objects, and a pair of lions, while the Seasons are in spandrels. The frontal head of Helios emerges from the chariot box, with two wheels in side view beneath, and the four heads of the horses, likewise frontal, surmounting an array of legs.[449][445] In the synagogue of Naaran, the god is dressed in a white tunic embellished with gemstones on the upper body; over the tunic is a paludamentum pinned with a fibula or bulla and decorated with a star motif, as he holds in his hand a scarf, the distinctive symbol of a ruler from the fourth century onward, and much like all other mosaics he's seated in his four-horse chariot. Temporary writings record "the sun has three letters of [God's] name written at its heart and the angels lead it" and "[t]he sun is riding on a chariot and rises decorated like a bridegroom".[445] Both at Naaran and Beth Alpha the image of the sun is presented in a bust in frontal position, and a crown with nimbus and rays on his head.[448] Helios at both Hammath Tiberias and Beth Alpha is depicted with seven rays emanating from his head, it has been argued that those two are significantly different; the Helios of Hammath Tiberias possesses all the attributes of Sol Invictus and thus the Roman emperors, those being the rayed crown, the raised right hand and the globe, all common Helios-Sol iconography of the late third and early fourth centuries AD.[424]

Helios and Selene were also personified in the mosaic of the Monastery of Lady Mary at Beit She'an.[448] Here he is not shown as Sol Invictus, the Unconquered Sun, but rather as a celestial body, his red hair symbolizing the sun.[445]

The poplar tree was considered sacred to Helios, due to the sun-like brilliance its shining leaves have.[450] A sacred poplar in an epigram written by Antipater of Thessalonica warns the reader not to harm her because Helios cares for her.[451]

Aelian wrote that the wolf is a beloved animal to Helios;[452] the wolf is also Apollo's sacred animal, and the god was often known as Apollo Lyceus, "wolf Apollo".[453]

In post-antiquity art

[edit]In painting

[edit]

Helios/Sol had little independent identity and presence during the Renaissance, where the main solar gods were Apollo, Bacchus and Hercules.[454][455] In post-antiquity art, Apollo assimilates features and attributes of both classical Apollo and Helios, so that Apollo, along with his own iconography, is many times depicted as driving the four-horse chariot, representing both of them.[456] In medieval tradition, each of the four horses had its own distinctive colour; in the Renaissance, however, all four are shown as white.[456][457] In Versailles, a gilded statue depicts Apollo as the god of the sun, driving his quadriga as he sinks in the ocean;[458] Apollo in this regard represents the king of France, le roi-soleil, "the Sun King".[459]