Социализм

| Часть серии о |

| Социализм |

|---|

|

Социализм — это экономическая и политическая философия, охватывающая разнообразные экономические и социальные системы. [1] характеризуется общественной собственностью на средства производства , [2] в отличие от частной собственности . [3] [4] [5] В нем описываются экономические , политические и социальные теории и движения, связанные с внедрением таких систем. [6] Социальная собственность может принимать различные формы, в том числе общественную , общинную , коллективную , кооперативную , [7] [8] [9] или сотрудник . [10] [11] Традиционно социализм находится на левом крыле спектра политического . [12] Типы социализма различаются в зависимости от роли рынков и планирования в распределении ресурсов, а также структуры управления в организациях. [13] [14]

Социалистические системы делятся на нерыночные и рыночные формы. [15] [16] Нерыночная социалистическая система стремится устранить предполагаемую неэффективность, иррациональность, непредсказуемость и кризисы , которые социалисты традиционно связывают с накоплением капитала и системой прибыли . [17] Рыночный социализм сохраняет использование денежных цен, рынков факторов производства и иногда мотивов получения прибыли . [18] [19] [20] Социалистические партии и идеи остаются политической силой с разной степенью власти и влияния, возглавляющей национальные правительства в ряде стран. Социалистическая политика была интернационалистической и националистической ; организованы через политические партии и противостоят партийной политике; иногда пересекающиеся с профсоюзами, а иногда независимые и критически настроенные по отношению к ним и присутствующие в промышленно развитых и развивающихся странах. [21] Социал-демократия зародилась внутри социалистического движения. [22] поддержка экономических и социальных мер по обеспечению социальной справедливости . [23] [24] Сохраняя социализм как долгосрочную цель, [25] В послевоенный период социал-демократия охватывала смешанную экономику, основанную на кейнсианстве, в рамках преимущественно развитой капиталистической рыночной экономики и либерально-демократического государства, которое расширяет государственное вмешательство, включив в него перераспределение доходов , регулирование и государство всеобщего благосостояния . [26] [27]

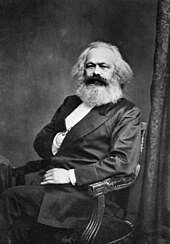

Социалистическое политическое движение включает в себя политические философии, зародившиеся в революционных движениях середины-конца XVIII века и вызванные беспокойством по поводу социальных проблем , которые социалисты связывали с капитализмом. [28] К концу 19-го века, после работы Карла Маркса и его сотрудника Фридриха Энгельса , социализм стал означать антикапитализм и защиту посткапиталистической системы, основанной на той или иной форме общественной собственности на средства производства. [29] [30] К началу 1920-х годов коммунизм и социал-демократия стали двумя доминирующими политическими тенденциями в международном социалистическом движении. [31] социализм сам по себе стал самым влиятельным светским движением 20 века. [32] Многие социалисты также переняли идеи других социальных движений, таких как феминизм , энвайронментализм и прогрессизм . [33]

Хотя возникновение Советского Союза как первого в мире номинально социалистического государства привело к широкой ассоциации социализма с советской экономической моделью , ученые отмечают, что некоторые западноевропейские страны управлялись социалистическими партиями или имели смешанную экономику , которую иногда называют « демократической социалистической моделью». ". [34] [35] После революций 1989 года многие из этих стран отошли от социализма, поскольку неолиберальный консенсус заменил социал-демократический консенсус в развитом капиталистическом мире. [36] в то время как многие бывшие социалистические политики и политические партии придерживались политики « третьего пути », оставаясь приверженными равенству и благосостоянию, отказываясь при этом от общественной собственности и классовой политики. [37] Социализм пережил возрождение популярности в 2010-х годах, особенно в форме демократического социализма. [38] [39]

Этимология

По словам Эндрю Винсента, «слово «социализм» происходит от латинского sociare , что означает объединять или разделять. Родственным, более техническим термином в римском, а затем и в средневековом праве было societas . Это последнее слово могло означать товарищество и товарищество, а также более законническая идея обоюдного договора между свободными людьми». [40]

Первоначальное использование социализма было заявлено Пьером Леру , который утверждал, что впервые использовал этот термин в парижском журнале Le Globe в 1832 году. [41] [42] Леру был последователем Анри де Сен-Симона , одного из основателей того, что позже будет названо утопическим социализмом . Социализм контрастировал с либеральной доктриной индивидуализма , которая подчеркивала моральную ценность личности, одновременно подчеркивая, что люди действуют или должны действовать так, как если бы они были изолированы друг от друга. Первые социалисты-утописты осуждали эту доктрину индивидуализма за неспособность решить социальные проблемы во время промышленной революции , включая бедность, угнетение и огромное имущественное неравенство . Они считали, что их общество наносит вред общественной жизни, основывая общество на конкуренции. Они представили социализм как альтернативу либеральному индивидуализму, основанному на совместной собственности на ресурсы. [43] Сен-Симон предложил экономическое планирование , научное управление и применение научного понимания к организации общества. Напротив, Роберт Оуэн предлагал организовать производство и собственность через кооперативы . [43] [44] Социализм также приписывают во Франции Мари Рош-Луи Рейбо, а в Великобритании — Оуэну, который стал одним из отцов кооперативного движения . [45] [46]

Определение и использование социализма утвердились к 1860-м годам, заменив ассоциативный , кооперативный , мутуалистический и коллективистский , которые использовались как синонимы, в то время как коммунизм в этот период вышел из употребления. [47] Раннее различие между коммунизмом и социализмом заключалось в том, что последний стремился только к обобществлению производства, тогда как первый стремился к обобществлению как производства , так и потребления (в форме свободного доступа к конечным товарам). [48] К 1888 году марксисты использовали социализм вместо коммунизма , поскольку последний стал считаться старомодным синонимом социализма . Лишь после большевистской революции , что социализм понял Владимир Ленин означает стадию между капитализмом и коммунизмом. России Он использовал его для защиты большевистской программы от марксистской критики, утверждавшей, что производительные силы недостаточно развиты для коммунизма. [49] Различие между коммунизмом и социализмом стало очевидным в 1918 году после того, как Российская социал-демократическая рабочая партия переименовала себя во Всероссийскую коммунистическую партию , интерпретируя коммунизм конкретно как означающих социалистов, которые поддерживали политику и теории большевизма , ленинизма , а затем и марксизма-ленинизма. , [50] хотя коммунистические партии продолжали называть себя социалистами, приверженными социализму. [51] Согласно «Оксфордскому справочнику Карла Маркса» , «Маркс использовал множество терминов для обозначения посткапиталистического общества — позитивный гуманизм , социализм, коммунизм, царство свободной индивидуальности, свободное объединение производителей и т. д. Он использовал эти термины совершенно взаимозаменяемо. Представление о том, что «социализм» и «коммунизм» представляют собой отдельные исторические стадии, чуждо его творчеству и вошло в лексикон марксизма только после его смерти». [52]

Считалось, что в христианской Европе коммунисты приняли атеизм . В протестантской Англии коммунизм был слишком близок к римско-католическому обряду причастия , поэтому «социалист» . предпочтительным термином был [53] Энгельс писал, что в 1848 году, когда был опубликован «Манифест Коммунистической партии» , социализм пользовался уважением в Европе, а коммунизм — нет. Оуэнисты во Франции считались респектабельными социалистами, в то время как движения рабочего класса , в Англии и фурьеристы «провозглашавшие необходимость тотальных социальных перемен», называли себя коммунистами . [54] Эта ветвь социализма породила коммунистическую работу Этьена Кабе во Франции и Вильгельма Вейтлинга в Германии. [55] Британский философ-моралист Джон Стюарт Милль обсуждал форму экономического социализма в рамках свободного рынка. В более поздних изданиях своих «Принципов политической экономии» (1848 г.) Милль утверждал, что «что касается экономической теории, в экономической теории нет ничего принципиального, что исключало бы экономический порядок, основанный на социалистической политике». [56] [57] и способствовал замене капиталистического бизнеса рабочими кооперативами . [58] В то время как демократы смотрели на революцию 1848 года как на демократическую революцию , которая в конечном итоге обеспечила свободу, равенство и братство , марксисты осудили ее как предательство идеалов рабочего класса со стороны буржуазии, безразличной к пролетариату . [59]

История

История социализма берет свое начало в эпоху Просвещения и Французской революции 1789 года , а также связанных с ней изменений, хотя у нее есть прецеденты в более ранних движениях и идеях. «Манифест Коммунистической партии» был написан Карлом Марксом и Фридрихом Энгельсом в 1847–1848 годах, незадолго до того, как революция 1848 года охватила Европу, выражая то, что они назвали научным социализмом . В последней трети XIX века в Европе возникли партии, приверженные демократическому социализму , опиравшиеся главным образом на марксизм . Австралийская Лейбористская партия была первой избранной социалистической партией, когда она сформировала правительство в колонии Квинсленд на неделю в 1899 году. [60]

In the first half of the 20th century, the Soviet Union and the communist parties of the Third International around the world, came to represent socialism in terms of the Soviet model of economic development and the creation of centrally planned economies directed by a state that owns all the means of production, although other trends condemned what they saw as the lack of democracy. The establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949, saw socialism introduced. China experienced land redistribution and the Anti-Rightist Movement, followed by the disastrous Great Leap Forward. In the UK, Herbert Morrison said that "socialism is what the Labour government does" whereas Aneurin Bevan argued socialism requires that the "main streams of economic activity are brought under public direction", with an economic plan and workers' democracy.[61] Some argued that capitalism had been abolished.[62] Социалистические правительства установили смешанную экономику с частичной национализацией и социальным обеспечением.

By 1968, the prolonged Vietnam War gave rise to the New Left, socialists who tended to be critical of the Soviet Union and social democracy. Anarcho-syndicalists and some elements of the New Left and others favoured decentralised collective ownership in the form of cooperatives or workers' councils. In 1989, the Soviet Union saw the end of communism, marked by the Revolutions of 1989 across Eastern Europe, culminating in the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. Socialists have adopted the causes of other social movements such as environmentalism, feminism and progressivism.[63]

Early 21st century

Top-left: a picture of the red flags found by the Monument to the People's Heroes, China.

Top-right: a demonstration in Austin, Texas, US by the Democratic Socialists of America.

Bottom-left: a demonstration by the Portuguese Socialist Youth.

Bottom-right: a rally for abortion rights in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia being led by members of the Victorian Socialists.

In 1990, the São Paulo Forum was launched by the Workers' Party (Brazil), linking left-wing socialist parties in Latin America. Its members were associated with the Pink tide of left-wing governments on the continent in the early 21st century. Member parties ruling countries included the Front for Victory in Argentina, the PAIS Alliance in Ecuador, Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front in El Salvador, Peru Wins in Peru, and the United Socialist Party of Venezuela, whose leader Hugo Chávez initiated what he called "Socialism of the 21st century".

Many mainstream democratic socialist and social democratic parties continued to drift right-wards. On the right of the socialist movement, the Progressive Alliance was founded in 2013 by current or former members of the Socialist International. The organisation states the aim of becoming the global network of "the progressive, democratic, social-democratic, socialist and labour movement".[64][65] Mainstream social democratic and socialist parties are also networked in Europe in the Party of European Socialists formed in 1992. Many of these parties lost large parts of their electoral base in the early 21st century. This phenomenon is known as Pasokification[66][67] from the Greek party PASOK, which saw a declining share of the vote in national elections—from 43.9% in 2009 to 13.2% in May 2012, to 12.3% in June 2012 and 4.7% in 2015—due to its poor handling of the Greek government-debt crisis and implementation of harsh austerity measures.[68][69]

In Europe, the share of votes for such socialist parties was at its 70-year lowest in 2015. For example, the Socialist Party, after winning the 2012 French presidential election, rapidly lost its vote share, the Social Democratic Party of Germany's fortunes declined rapidly from 2005 to 2019, and outside Europe the Israeli Labor Party fell from being the dominant force in Israeli politics to 4.43% of the vote in the April 2019 Israeli legislative election, and the Peruvian Aprista Party went from ruling party in 2011 to a minor party. The decline of these mainstream parties opened space for more radical and populist left parties in some countries, such as Spain's Podemos, Greece's Syriza (in government, 2015–19), Germany's Die Linke, and France's La France Insoumise. In other countries, left-wing revivals have taken place within mainstream democratic socialist and centrist parties, as with Jeremy Corbyn in the United Kingdom and Bernie Sanders in the United States.[38] Few of these radical left parties have won national government in Europe, while some more mainstream socialist parties have managed to, such as Portugal's Socialist Party.[70]

Bhaskar Sunkara, the founding editor of the American socialist magazine Jacobin, argued that the appeal of socialism persists due to the inequality and "tremendous suffering" under current global capitalism, the use of wage labor "which rests on the exploitation and domination of humans by other humans," and ecological crises, such as climate change.[71] In contrast, Mark J. Perry of the conservative American Enterprise Institute (AEI) argued that despite socialism's resurgence, it is still "a flawed system based on completely faulty principles that aren't consistent with human behavior and can't nurture the human spirit.", adding that "While it promised prosperity, equality, and security, it delivered poverty, misery, and tyranny."[72] Some in the scientific community have suggested that a contemporary radical response to social and ecological problems could be seen in the emergence of movements associated with degrowth, eco-socialism and eco-anarchism.[73][74]

Social and political theory

Early socialist thought took influences from a diverse range of philosophies such as civic republicanism, Enlightenment rationalism, romanticism, forms of materialism, Christianity (both Catholic and Protestant), natural law and natural rights theory, utilitarianism and liberal political economy.[75] Another philosophical basis for a great deal of early socialism was the emergence of positivism during the European Enlightenment. Positivism held that both the natural and social worlds could be understood through scientific knowledge and be analysed using scientific methods.

The fundamental objective of socialism is to attain an advanced level of material production and therefore greater productivity, efficiency and rationality as compared to capitalism and all previous systems, under the view that an expansion of human productive capability is the basis for the extension of freedom and equality in society.[76] Many forms of socialist theory hold that human behaviour is largely shaped by the social environment. In particular, socialism holds that social mores, values, cultural traits and economic practices are social creations and not the result of an immutable natural law.[77][78] The object of their critique is thus not human avarice or human consciousness, but the material conditions and man-made social systems (i.e. the economic structure of society) which give rise to observed social problems and inefficiencies. Bertrand Russell, often considered to be the father of analytic philosophy, identified as a socialist. Russell opposed the class struggle aspects of Marxism, viewing socialism solely as an adjustment of economic relations to accommodate modern machine production to benefit all of humanity through the progressive reduction of necessary work time.[79]

Socialists view creativity as an essential aspect of human nature and define freedom as a state of being where individuals are able to express their creativity unhindered by constraints of both material scarcity and coercive social institutions.[80] The socialist concept of individuality is intertwined with the concept of individual creative expression. Karl Marx believed that expansion of the productive forces and technology was the basis for the expansion of human freedom and that socialism, being a system that is consistent with modern developments in technology, would enable the flourishing of "free individualities" through the progressive reduction of necessary labour time. The reduction of necessary labour time to a minimum would grant individuals the opportunity to pursue the development of their true individuality and creativity.[81]

Criticism of capitalism

Socialists argue that the accumulation of capital generates waste through externalities that require costly corrective regulatory measures. They also point out that this process generates wasteful industries and practices that exist only to generate sufficient demand for products such as high-pressure advertisement to be sold at a profit, thereby creating rather than satisfying economic demand.[82][83] Socialists argue that capitalism consists of irrational activity, such as the purchasing of commodities only to sell at a later time when their price appreciates, rather than for consumption, even if the commodity cannot be sold at a profit to individuals in need and therefore a crucial criticism often made by socialists is that "making money", or accumulation of capital, does not correspond to the satisfaction of demand (the production of use-values).[82] The fundamental criterion for economic activity in capitalism is the accumulation of capital for reinvestment in production, but this spurs the development of new, non-productive industries that do not produce use-value and only exist to keep the accumulation process afloat (otherwise the system goes into crisis), such as the spread of the financial industry, contributing to the formation of economic bubbles.[84] Such accumulation and reinvestment, when it demands a constant rate of profit, causes problems if the earnings in the rest of society do not increase in proportion.[85]

Socialists view private property relations as limiting the potential of productive forces in the economy. According to socialists, private property becomes obsolete when it concentrates into centralised, socialised institutions based on private appropriation of revenue—but based on cooperative work and internal planning in allocation of inputs—until the role of the capitalist becomes redundant.[86] With no need for capital accumulation and a class of owners, private property in the means of production is perceived as being an outdated form of economic organisation that should be replaced by a free association of individuals based on public or common ownership of these socialised assets.[87][88] Private ownership imposes constraints on planning, leading to uncoordinated economic decisions that result in business fluctuations, unemployment and a tremendous waste of material resources during crisis of overproduction.[89]

Excessive disparities in income distribution lead to social instability and require costly corrective measures in the form of redistributive taxation, which incurs heavy administrative costs while weakening the incentive to work, inviting dishonesty and increasing the likelihood of tax evasion while (the corrective measures) reduce the overall efficiency of the market economy.[90] These corrective policies limit the incentive system of the market by providing things such as minimum wages, unemployment insurance, taxing profits and reducing the reserve army of labour, resulting in reduced incentives for capitalists to invest in more production. In essence, social welfare policies cripple capitalism and its incentive system and are thus unsustainable in the long run.[91] Marxists argue that the establishment of a socialist mode of production is the only way to overcome these deficiencies. Socialists and specifically Marxian socialists argue that the inherent conflict of interests between the working class and capital prevent optimal use of available human resources and leads to contradictory interest groups (labour and business) striving to influence the state to intervene in the economy in their favour at the expense of overall economic efficiency. Early socialists (utopian socialists and Ricardian socialists) criticised capitalism for concentrating power and wealth within a small segment of society.[92] In addition, they complained that capitalism does not use available technology and resources to their maximum potential in the interests of the public.[88]

Marxism

At a certain stage of development, the material productive forces of society come into conflict with the existing relations of production or—this merely expresses the same thing in legal terms—with the property relations within the framework of which they have operated hitherto. Then begins an era of social revolution. The changes in the economic foundation lead sooner or later to the transformation of the whole immense superstructure.[93]

—Karl Marx, Critique of the Gotha Program

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels argued that socialism would emerge from historical necessity as capitalism rendered itself obsolete and unsustainable from increasing internal contradictions emerging from the development of the productive forces and technology. It was these advances in the productive forces combined with the old social relations of production of capitalism that would generate contradictions, leading to working-class consciousness.[94]

Marx and Engels held the view that the consciousness of those who earn a wage or salary (the working class in the broadest Marxist sense) would be moulded by their conditions of wage slavery, leading to a tendency to seek their freedom or emancipation by overthrowing ownership of the means of production by capitalists and consequently, overthrowing the state that upheld this economic order. For Marx and Engels, conditions determine consciousness and ending the role of the capitalist class leads eventually to a classless society in which the state would wither away.

Marx and Engels used the terms socialism and communism interchangeably, but many later Marxists defined socialism as a specific historical phase that would displace capitalism and precede communism.[49][52]

The major characteristics of socialism (particularly as conceived by Marx and Engels after the Paris Commune of 1871) are that the proletariat would control the means of production through a workers' state erected by the workers in their interests.

For orthodox Marxists, socialism is the lower stage of communism based on the principle of "from each according to his ability, to each according to his contribution" while upper stage communism is based on the principle of "from each according to his ability, to each according to his need", the upper stage becoming possible only after the socialist stage further develops economic efficiency and the automation of production has led to a superabundance of goods and services.[95][96] Marx argued that the material productive forces (in industry and commerce) brought into existence by capitalism predicated a cooperative society since production had become a mass social, collective activity of the working class to create commodities but with private ownership (the relations of production or property relations). This conflict between collective effort in large factories and private ownership would bring about a conscious desire in the working class to establish collective ownership commensurate with the collective efforts their daily experience.[93]

Role of the state

Socialists have taken different perspectives on the state and the role it should play in revolutionary struggles, in constructing socialism and within an established socialist economy.

In the 19th century, the philosophy of state socialism was first explicitly expounded by the German political philosopher Ferdinand Lassalle. In contrast to Karl Marx's perspective of the state, Lassalle rejected the concept of the state as a class-based power structure whose main function was to preserve existing class structures. Lassalle also rejected the Marxist view that the state was destined to "wither away". Lassalle considered the state to be an entity independent of class allegiances and an instrument of justice that would therefore be essential for achieving socialism.[97]

Preceding the Bolshevik-led revolution in Russia, many socialists including reformists, orthodox Marxist currents such as council communism, anarchists and libertarian socialists criticised the idea of using the state to conduct central planning and own the means of production as a way to establish socialism. Following the victory of Leninism in Russia, the idea of "state socialism" spread rapidly throughout the socialist movement and eventually state socialism came to be identified with the Soviet economic model.[98]

Joseph Schumpeter rejected the association of socialism and social ownership with state ownership over the means of production because the state as it exists in its current form is a product of capitalist society and cannot be transplanted to a different institutional framework. Schumpeter argued that there would be different institutions within socialism than those that exist within modern capitalism, just as feudalism had its own distinct and unique institutional forms. The state, along with concepts like property and taxation, were concepts exclusive to commercial society (capitalism) and attempting to place them within the context of a future socialist society would amount to a distortion of these concepts by using them out of context.[99]

Utopian versus scientific

Utopian socialism is a term used to define the first currents of modern socialist thought as exemplified by the work of Henri de Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier and Robert Owen which inspired Karl Marx and other early socialists.[100] Visions of imaginary ideal societies, which competed with revolutionary social democratic movements, were viewed as not being grounded in the material conditions of society and as reactionary.[101] Although it is technically possible for any set of ideas or any person living at any time in history to be a utopian socialist, the term is most often applied to those socialists who lived in the first quarter of the 19th century who were ascribed the label "utopian" by later socialists as a negative term to imply naivete and dismiss their ideas as fanciful or unrealistic.[102]

Religious sects whose members live communally such as the Hutterites are not usually called "utopian socialists", although their way of living is a prime example. They have been categorised as religious socialists by some. Similarly, modern intentional communities based on socialist ideas could also be categorised as "utopian socialist". For Marxists, the development of capitalism in Western Europe provided a material basis for the possibility of bringing about socialism because according to The Communist Manifesto "[w]hat the bourgeoisie produces above all is its own grave diggers",[103] namely the working class, which must become conscious of the historical objectives set it by society.

Reform versus revolution

Revolutionary socialists believe that a social revolution is necessary to effect structural changes to the socioeconomic structure of society. Among revolutionary socialists there are differences in strategy, theory and the definition of revolution. Orthodox Marxists and left communists take an impossibilist stance, believing that revolution should be spontaneous as a result of contradictions in society due to technological changes in the productive forces. Lenin theorised that under capitalism the workers cannot achieve class consciousness beyond organising into trade unions and making demands of the capitalists. Therefore, Leninists argue that it is historically necessary for a vanguard of class conscious revolutionaries to take a central role in coordinating the social revolution to overthrow the capitalist state and eventually the institution of the state altogether.[104] Revolution is not necessarily defined by revolutionary socialists as violent insurrection,[105] but as a complete dismantling and rapid transformation of all areas of class society led by the majority of the masses: the working class.

Reformism is generally associated with social democracy and gradualist democratic socialism. Reformism is the belief that socialists should stand in parliamentary elections within capitalist society and if elected use the machinery of government to pass political and social reforms for the purposes of ameliorating the instabilities and inequities of capitalism. Within socialism, reformism is used in two different ways. One has no intention of bringing about socialism or fundamental economic change to society and is used to oppose such structural changes. The other is based on the assumption that while reforms are not socialist in themselves, they can help rally supporters to the cause of revolution by popularizing the cause of socialism to the working class.[106]

The debate on the ability for social democratic reformism to lead to a socialist transformation of society is over a century old. Reformism is criticized for being paradoxical as it seeks to overcome the existing economic system of capitalism while trying to improve the conditions of capitalism, thereby making it appear more tolerable to society. According to Rosa Luxemburg, capitalism is not overthrown, "but is on the contrary strengthened by the development of social reforms".[107] In a similar vein, Stan Parker of the Socialist Party of Great Britain argues that reforms are a diversion of energy for socialists and are limited because they must adhere to the logic of capitalism.[106] French social theorist André Gorz criticized reformism by advocating a third alternative to reformism and social revolution that he called "non-reformist reforms", specifically focused on structural changes to capitalism as opposed to reforms to improve living conditions within capitalism or to prop it up through economic interventions.[108]

Culture

Under Socialism, solidarity will be the basis of society. Literature and art will be tuned to a different key.

In the Leninist conception, the role of the vanguard party was to politically educate the workers and peasants to dispel the societal false consciousness of institutional religion and nationalism that constitute the cultural status quo taught by the bourgeoisie to the proletariat to facilitate their economic exploitation of peasants and workers. Influenced by Lenin, the Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party stated that the development of the socialist workers' culture should not be "hamstrung from above" and opposed the Proletkult (1917–1925) organisational control of the national culture.[111] Similarly, Trotsky viewed the party as transmitters of culture to the masses for raising the standards of education, as well as entry into the cultural sphere, but that the process of artistic creation in terms of language and presentation should be the domain of the practitioner. According to political scientist Baruch Knei-Paz, this represented one of several distinctions between Trotsky's approach on cultural matters and Stalin's policy in the 1930s.[112]

In Literature and Revolution, Trotsky examined aesthetic issues in relation to class and the Russian revolution. Soviet scholar Robert Bird considered his work as the "first systematic treatment of art by a Communist leader" and a catalyst for later, Marxist cultural and critical theories.[113] He would later co-author the 1938 Manifesto for an Independent Revolutionary Art with the endorsement of prominent artists Andre Breton and Diego Rivera.[114] Trotsky's writings on literature such as his 1923 survey which advocated tolerance, limited censorship and respect for literary tradition had strong appeal to the New York Intellectuals.[115]

Prior to Stalin's rule, literary, religious and national representatives had some level of autonomy in Soviet Russia throughout the 1920s but these groups were later rigorously repressed during the Stalinist era. Socialist realism was imposed under Stalin in artistic production and other creative industries such as music, film along with sports were subject to extreme levels of political control.[116]

The counter-cultural phenomenon which emerged in the 1960s shaped the intellectual and radical outlook of the New Left; this movement placed a heavy emphasis on anti-racism, anti-imperialism and direct democracy in opposition to the dominant culture of advanced industrial capitalism.[117]Socialist groups have also been closely involved with a number of counter-cultural movements such as Vietnam Solidarity Campaign, Stop the War Coalition, Love Music Hate Racism, Anti-Nazi League[118] and Unite Against Fascism.[119]

Economics

The economic anarchy of capitalist society as it exists today is, in my opinion, the real source of the evil. ... I am convinced there is only one way to eliminate these grave evils, namely through the establishment of a socialist economy, accompanied by an educational system which would be oriented toward social goals. In such an economy, the means of production are owned by society itself and are utilised in a planned fashion. A planned economy, which adjusts production to the needs of the community, would distribute the work to be done among all those able to work and would guarantee a livelihood to every man, woman, and child. The education of the individual, in addition to promoting his own innate abilities, would attempt to develop in him a sense of responsibility for his fellow men in place of the glorification of power and success in our present society.[120]

—Albert Einstein, "Why Socialism?", 1949

Socialist economics starts from the premise that "individuals do not live or work in isolation but live in cooperation with one another. Furthermore, everything that people produce is in some sense a social product, and everyone who contributes to the production of a good is entitled to a share in it. Society as whole, therefore, should own or at least control property for the benefit of all its members".[121]

The original conception of socialism was an economic system whereby production was organised in a way to directly produce goods and services for their utility (or use-value in classical and Marxian economics), with the direct allocation of resources in terms of physical units as opposed to financial calculation and the economic laws of capitalism (see law of value), often entailing the end of capitalistic economic categories such as rent, interest, profit and money.[122] In a fully developed socialist economy, production and balancing factor inputs with outputs becomes a technical process to be undertaken by engineers.[123]

Market socialism refers to an array of different economic theories and systems that use the market mechanism to organise production and to allocate factor inputs among socially owned enterprises, with the economic surplus (profits) accruing to society in a social dividend as opposed to private capital owners.[124] Variations of market socialism include libertarian proposals such as mutualism, based on classical economics, and neoclassical economic models such as the Lange Model. Some economists, such as Joseph Stiglitz, Mancur Olson, and others not specifically advancing anti-socialists positions have shown that prevailing economic models upon which such democratic or market socialism models might be based have logical flaws or unworkable presuppositions.[125][126] These criticisms have been incorporated into the models of market socialism developed by John Roemer and Nicholas Vrousalis.[127][128][when?]

The ownership of the means of production can be based on direct ownership by the users of the productive property through worker cooperative; or commonly owned by all of society with management and control delegated to those who operate/use the means of production; or public ownership by a state apparatus. Public ownership may refer to the creation of state-owned enterprises, nationalisation, municipalisation or autonomous collective institutions. Some socialists feel that in a socialist economy, at least the "commanding heights" of the economy must be publicly owned.[129] Economic liberals and right libertarians view private ownership of the means of production and the market exchange as natural entities or moral rights which are central to their conceptions of freedom and liberty and view the economic dynamics of capitalism as immutable and absolute, therefore they perceive public ownership of the means of production, cooperatives and economic planning as infringements upon liberty.[130][131]

Management and control over the activities of enterprises are based on self-management and self-governance, with equal power-relations in the workplace to maximise occupational autonomy. A socialist form of organisation would eliminate controlling hierarchies so that only a hierarchy based on technical knowledge in the workplace remains. Every member would have decision-making power in the firm and would be able to participate in establishing its overall policy objectives. The policies/goals would be carried out by the technical specialists that form the coordinating hierarchy of the firm, who would establish plans or directives for the work community to accomplish these goals.[132][133]

The role and use of money in a hypothetical socialist economy is a contested issue. Nineteenth century socialists including Karl Marx, Robert Owen, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and John Stuart Mill advocated various forms of labour vouchers or labour credits, which like money would be used to acquire articles of consumption, but unlike money they are unable to become capital and would not be used to allocate resources within the production process. Bolshevik revolutionary Leon Trotsky argued that money could not be arbitrarily abolished following a socialist revolution. Money had to exhaust its "historic mission", meaning it would have to be used until its function became redundant, eventually being transformed into bookkeeping receipts for statisticians and only in the more distant future would money not be required for even that role.[134]

Planned economy

A planned economy is a type of economy consisting of a mixture of public ownership of the means of production and the coordination of production and distribution through economic planning. A planned economy can be either decentralised or centralised. Enrico Barone provided a comprehensive theoretical framework for a planned socialist economy. In his model, assuming perfect computation techniques, simultaneous equations relating inputs and outputs to ratios of equivalence would provide appropriate valuations to balance supply and demand.[135]

The most prominent example of a planned economy was the economic system of the Soviet Union and as such the centralised-planned economic model is usually associated with the communist states of the 20th century, where it was combined with a single-party political system. In a centrally planned economy, decisions regarding the quantity of goods and services to be produced are planned in advance by a planning agency (see also the analysis of Soviet-type economic planning). The economic systems of the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc are further classified as "command economies", which are defined as systems where economic coordination is undertaken by commands, directives and production targets.[136] Studies by economists of various political persuasions on the actual functioning of the Soviet economy indicate that it was not actually a planned economy. Instead of conscious planning, the Soviet economy was based on a process whereby the plan was modified by localised agents and the original plans went largely unfulfilled. Planning agencies, ministries and enterprises all adapted and bargained with each other during the formulation of the plan as opposed to following a plan passed down from a higher authority, leading some economists to suggest that planning did not actually take place within the Soviet economy and that a better description would be an "administered" or "managed" economy.[137]

Although central planning was largely supported by Marxist–Leninists, some factions within the Soviet Union before the rise of Stalinism held positions contrary to central planning. Leon Trotsky rejected central planning in favour of decentralised planning. He argued that central planners, regardless of their intellectual capacity, would be unable to coordinate effectively all economic activity within an economy because they operated without the input and tacit knowledge embodied by the participation of the millions of people in the economy. As a result, central planners would be unable to respond to local economic conditions.[138] State socialism is unfeasible in this view because information cannot be aggregated by a central body and effectively used to formulate a plan for an entire economy, because doing so would result in distorted or absent price signals.[139]

Self-managed economy

Socialism, you see, is a bird with two wings. The definition is 'social ownership and democratic control of the instruments and means of production.'[140]

A self-managed, decentralised economy is based on autonomous self-regulating economic units and a decentralised mechanism of resource allocation and decision-making. This model has found support in notable classical and neoclassical economists including Alfred Marshall, John Stuart Mill and Jaroslav Vanek. There are numerous variations of self-management, including labour-managed firms and worker-managed firms. The goals of self-management are to eliminate exploitation and reduce alienation.[141] Guild socialism is a political movement advocating workers' control of industry through the medium of trade-related guilds "in an implied contractual relationship with the public".[142] It originated in the United Kingdom and was at its most influential in the first quarter of the 20th century.[142] It was strongly associated with G. D. H. Cole and influenced by the ideas of William Morris.

One such system is the cooperative economy, a largely free market economy in which workers manage the firms and democratically determine remuneration levels and labour divisions. Productive resources would be legally owned by the cooperative and rented to the workers, who would enjoy usufruct rights.[143] Another form of decentralised planning is the use of cybernetics, or the use of computers to manage the allocation of economic inputs. The socialist-run government of Salvador Allende in Chile experimented with Project Cybersyn, a real-time information bridge between the government, state enterprises and consumers.[144] This had been preceded by similar efforts to introduce a form of cybernetic economic planning as seen with the proposed OGAS system in the Soviet Union. The OGAS project was conceived to oversee a nationwide information network but was never implemented due to conflicting, bureaucratic interests.[145] Another, more recent variant is participatory economics, wherein the economy is planned by decentralised councils of workers and consumers. Workers would be remunerated solely according to effort and sacrifice, so that those engaged in dangerous, uncomfortable and strenuous work would receive the highest incomes and could thereby work less.[146] A contemporary model for a self-managed, non-market socialism is Pat Devine's model of negotiated coordination. Negotiated coordination is based upon social ownership by those affected by the use of the assets involved, with decisions made by those at the most localised level of production.[147]

Michel Bauwens identifies the emergence of the open software movement and peer-to-peer production as a new alternative mode of production to the capitalist economy and centrally planned economy that is based on collaborative self-management, common ownership of resources and the production of use-values through the free cooperation of producers who have access to distributed capital.[148]

Anarcho-communism is a theory of anarchism which advocates the abolition of the state, private property and capitalism in favour of common ownership of the means of production.[149][150] Anarcho-syndicalism was practised in Catalonia and other places in the Spanish Revolution during the Spanish Civil War. Sam Dolgoff estimated that about eight million people participated directly or at least indirectly in the Spanish Revolution.[151]

The economy of the former Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia established a system based on market-based allocation, social ownership of the means of production and self-management within firms. This system substituted Yugoslavia's Soviet-type central planning with a decentralised, self-managed system after reforms in 1953.[152]

The Marxian economist Richard D. Wolff argues that "re-organising production so that workers become collectively self-directed at their work-sites" not only moves society beyond both capitalism and state socialism of the last century, but would also mark another milestone in human history, similar to earlier transitions out of slavery and feudalism.[153] As an example, Wolff claims that Mondragon is "a stunningly successful alternative to the capitalist organisation of production".[154]

State-directed economy

State socialism can be used to classify any variety of socialist philosophies that advocates the ownership of the means of production by the state apparatus, either as a transitional stage between capitalism and socialism, or as an end-goal in itself. Typically, it refers to a form of technocratic management, whereby technical specialists administer or manage economic enterprises on behalf of society and the public interest instead of workers' councils or workplace democracy.

A state-directed economy may refer to a type of mixed economy consisting of public ownership over large industries, as promoted by various Social democratic political parties during the 20th century. This ideology influenced the policies of the British Labour Party during Clement Attlee's administration. In the biography of the 1945 United Kingdom Labour Party Prime Minister Clement Attlee, Francis Beckett states: "[T]he government ... wanted what would become known as a mixed economy."[155]

Nationalisation in the United Kingdom was achieved through compulsory purchase of the industry (i.e. with compensation). British Aerospace was a combination of major aircraft companies British Aircraft Corporation, Hawker Siddeley and others. British Shipbuilders was a combination of the major shipbuilding companies including Cammell Laird, Govan Shipbuilders, Swan Hunter and Yarrow Shipbuilders, whereas the nationalisation of the coal mines in 1947 created a coal board charged with running the coal industry commercially so as to be able to meet the interest payable on the bonds which the former mine owners' shares had been converted into.[156][157]

Market socialism

Market socialism consists of publicly owned or cooperatively owned enterprises operating in a market economy. It is a system that uses the market and monetary prices for the allocation and accounting of the means of production, thereby retaining the process of capital accumulation. The profit generated would be used to directly remunerate employees, collectively sustain the enterprise or finance public institutions.[158] In state-oriented forms of market socialism, in which state enterprises attempt to maximise profit, the profits can be used to fund government programs and services through a social dividend, eliminating or greatly diminishing the need for various forms of taxation that exist in capitalist systems. Neoclassical economist Léon Walras believed that a socialist economy based on state ownership of land and natural resources would provide a means of public finance to make income taxes unnecessary.[159] Yugoslavia implemented a market socialist economy based on cooperatives and worker self-management.[160] Some of the economic reforms introduced during the Prague Spring by Alexander Dubček, the leader of Czechoslovakia, included elements of market socialism.[161]

Mutualism is an economic theory and anarchist school of thought that advocates a society where each person might possess a means of production, either individually or collectively, with trade representing equivalent amounts of labour in the free market.[162] Integral to the scheme was the establishment of a mutual-credit bank that would lend to producers at a minimal interest rate, just high enough to cover administration.[163] Mutualism is based on a labour theory of value that holds that when labour or its product is sold, in exchange it ought to receive goods or services embodying "the amount of labour necessary to produce an article of exactly similar and equal utility".[164]

The current economic system in China is formally referred to as a socialist market economy with Chinese characteristics. It combines a large state sector that comprises the commanding heights of the economy, which are guaranteed their public ownership status by law,[165] with a private sector mainly engaged in commodity production and light industry responsible from anywhere between 33%[166] to over 70% of GDP generated in 2005.[167] Although there has been a rapid expansion of private-sector activity since the 1980s, privatisation of state assets was virtually halted and were partially reversed in 2005.[168] The current Chinese economy consists of 150 corporatised state-owned enterprises that report directly to China's central government.[169] By 2008, these state-owned corporations had become increasingly dynamic and generated large increases in revenue for the state,[170][171] resulting in a state-sector led recovery during the 2009 financial crises while accounting for most of China's economic growth.[172] The Chinese economic model is widely cited as a contemporary form of state capitalism, the major difference between Western capitalism and the Chinese model being the degree of state-ownership of shares in publicly listed corporations. The Socialist Republic of Vietnam has adopted a similar model after the Doi Moi economic renovation but slightly differs from the Chinese model in that the Vietnamese government retains firm control over the state sector and strategic industries, but allows for private-sector activity in commodity production.[173]

Politics

While major socialist political movements include anarchism, communism, the labour movement, Marxism, social democracy, and syndicalism, independent socialist theorists, utopian socialist authors, and academic supporters of socialism may not be represented in these movements. Some political groups have called themselves socialist while holding views that some consider antithetical to socialism. Socialist has been used by members of the political right as an epithet, including against individuals who do not consider themselves to be socialists and against policies that are not considered socialist by their proponents. While there are many variations of socialism, and there is no single definition encapsulating all of socialism, there have been common elements identified by scholars.[174]

In his Dictionary of Socialism (1924), Angelo S. Rappoport analysed forty definitions of socialism to conclude that common elements of socialism include general criticism of the social effects of private ownership and control of capital—as being the cause of poverty, low wages, unemployment, economic and social inequality and a lack of economic security; a general view that the solution to these problems is a form of collective control over the means of production, distribution and exchange (the degree and means of control vary among socialist movements); an agreement that the outcome of this collective control should be a society based upon social justice, including social equality, economic protection of people and should provide a more satisfying life for most people.[175]

In The Concepts of Socialism (1975), Bhikhu Parekh identifies four core principles of socialism and particularly socialist society, namely sociality, social responsibility, cooperation and planning.[176] In his study Ideologies and Political Theory (1996), Michael Freeden states that all socialists share five themes: the first is that socialism posits that society is more than a mere collection of individuals; second, that it considers human welfare a desirable objective; third, that it considers humans by nature to be active and productive; fourth, it holds the belief of human equality; and fifth, that history is progressive and will create positive change on the condition that humans work to achieve such change.[176]

Anarchism

Anarchism advocates stateless societies often defined as self-governed voluntary institutions,[177][178][179][180] but that several authors have defined as more specific institutions based on non-hierarchical free associations.[181][182][183][184] While anarchism holds the state to be undesirable, unnecessary or harmful,[185][186] it is not the central aspect.[187] Anarchism entails opposing authority or hierarchical organisation in the conduct of human relations, including the state system.[181][188][189][190][191] Mutualists support market socialism, collectivist anarchists favour workers cooperatives and salaries based on the amount of time contributed to production, anarcho-communists advocate a direct transition from capitalism to libertarian communism and a gift economy and anarcho-syndicalists prefer workers' direct action and the general strike.[192]

The authoritarian–libertarian struggles and disputes within the socialist movement go back to the First International and the expulsion in 1872 of the anarchists, who went on to lead the Anti-authoritarian International and then founded their own libertarian international, the Anarchist St. Imier International.[193] In 1888, the individualist anarchist Benjamin Tucker, who proclaimed himself to be an anarchistic socialist and libertarian socialist in opposition to the authoritarian state socialism and the compulsory communism, included the full text of a "Socialistic Letter" by Ernest Lesigne[194] in his essay on "State Socialism and Anarchism". According to Lesigne, there are two types of socialism: "One is dictatorial, the other libertarian".[195] Tucker's two socialisms were the authoritarian state socialism which he associated to the Marxist school and the libertarian anarchist socialism, or simply anarchism, that he advocated. Tucker noted that the fact that the authoritarian "State Socialism has overshadowed other forms of Socialism gives it no right to a monopoly of the Socialistic idea".[196] According to Tucker, what those two schools of socialism had in common was the labor theory of value and the ends, by which anarchism pursued different means.[197]

According to anarchists such as the authors of An Anarchist FAQ, anarchism is one of the many traditions of socialism. For anarchists and other anti-authoritarian socialists, socialism "can only mean a classless and anti-authoritarian (i.e. libertarian) society in which people manage their own affairs, either as individuals or as part of a group (depending on the situation). In other words, it implies self-management in all aspects of life", including at the workplace.[192] Michael Newman includes anarchism as one of many socialist traditions.[102] Peter Marshall argues that "[i]n general anarchism is closer to socialism than liberalism. ... Anarchism finds itself largely in the socialist camp, but it also has outriders in liberalism. It cannot be reduced to socialism, and is best seen as a separate and distinctive doctrine."[198]

Democratic socialism and social democracy

You can't talk about ending the slums without first saying profit must be taken out of slums. You're really tampering and getting on dangerous ground because you are messing with folk then. You are messing with captains of industry. Now this means that we are treading in difficult water, because it really means that we are saying that something is wrong with capitalism. There must be a better distribution of wealth, and maybe America must move toward a democratic socialism.[199][200]

—Martin Luther King Jr., 1966

Democratic socialism represents any socialist movement that seeks to establish an economy based on economic democracy by and for the working class. Democratic socialism is difficult to define and groups of scholars have radically different definitions for the term. Some definitions simply refer to all forms of socialism that follow an electoral, reformist or evolutionary path to socialism rather than a revolutionary one.[201] According to Christopher Pierson, "[i]f the contrast which 1989 highlights is not that between socialism in the East and liberal democracy in the West, the latter must be recognised to have been shaped, reformed and compromised by a century of social democratic pressure". Pierson further claims that "social democratic and socialist parties within the constitutional arena in the West have almost always been involved in a politics of compromise with existing capitalist institutions (to whatever far distant prize its eyes might from time to time have been lifted)". For Pierson, "if advocates of the death of socialism accept that social democrats belong within the socialist camp, as I think they must, then the contrast between socialism (in all its variants) and liberal democracy must collapse. For actually existing liberal democracy is, in substantial part, a product of socialist (social democratic) forces".[202]

Social democracy is a socialist tradition of political thought.[203][204] Many social democrats refer to themselves as socialists or democratic socialists and some such as Tony Blair employ these terms interchangeably.[205][206][207] Others found "clear differences" between the three terms and prefer to describe their own political beliefs by using the term social democracy.[208] The two main directions were to establish democratic socialism or to build first a welfare state within the capitalist system. The first variant advances democratic socialism through reformist and gradualist methods.[209] In the second variant, social democracy is a policy regime involving a welfare state, collective bargaining schemes, support for publicly financed public services and a mixed economy. It is often used in this manner to refer to Western and Northern Europe during the later half of the 20th century.[210][211] It was described by Jerry Mander as "hybrid economics", an active collaboration of capitalist and socialist visions.[212] Some studies and surveys indicate that people tend to live happier and healthier lives in social democratic societies rather than neoliberal ones.[213][214][215][216]

Social democrats advocate a peaceful, evolutionary transition of the economy to socialism through progressive social reform.[217][218] It asserts that the only acceptable constitutional form of government is representative democracy under the rule of law.[219] It promotes extending democratic decision-making beyond political democracy to include economic democracy to guarantee employees and other economic stakeholders sufficient rights of co-determination.[219] It supports a mixed economy that opposes inequality, poverty and oppression while rejecting both a totally unregulated market economy or a fully planned economy.[220] Common social democratic policies include universal social rights and universally accessible public services such as education, health care, workers' compensation and other services, including child care and elder care.[221] Social democracy supports the trade union labour movement and supports collective bargaining rights for workers.[222] Most social democratic parties are affiliated with the Socialist International.[209]

Modern democratic socialism is a broad political movement that seeks to promote the ideals of socialism within the context of a democratic system. Some democratic socialists support social democracy as a temporary measure to reform the current system while others reject reformism in favour of more revolutionary methods. Modern social democracy emphasises a program of gradual legislative modification of capitalism to make it more equitable and humane while the theoretical end goal of building a socialist society is relegated to the indefinite future. According to Sheri Berman, Marxism is loosely held to be valuable for its emphasis on changing the world for a more just, better future.[223]

The two movements are widely similar both in terminology and in ideology, although there are a few key differences. The major difference between social democracy and democratic socialism is the object of their politics in that contemporary social democrats support a welfare state and unemployment insurance as well as other practical, progressive reforms of capitalism and are more concerned to administrate and humanise it. On the other hand, democratic socialists seek to replace capitalism with a socialist economic system, arguing that any attempt to humanise capitalism through regulations and welfare policies would distort the market and create economic contradictions.[224]

Ethical and liberal socialism

Ethical socialism appeals to socialism on ethical and moral grounds as opposed to economic, egoistic, and consumeristic grounds. It emphasizes the need for a morally conscious economy based upon the principles of altruism, cooperation, and social justice while opposing possessive individualism.[225] Ethical socialism has been the official philosophy of mainstream socialist parties.[226]

Liberal socialism incorporates liberal principles to socialism.[227] It has been compared to post-war social democracy[228] for its support of a mixed economy that includes both public and private capital goods.[229][230] While democratic socialism and social democracy are anti-capitalist positions insofar as criticism of capitalism is linked to the private ownership of the means of production,[175] liberal socialism identifies artificial and legalistic monopolies to be the fault of capitalism[231] and opposes an entirely unregulated market economy.[232] It considers both liberty and social equality to be compatible and mutually dependent.[227]

Principles that can be described as ethical or liberal socialist have been based upon or developed by philosophers such as John Stuart Mill, Eduard Bernstein, John Dewey, Carlo Rosselli, Norberto Bobbio, and Chantal Mouffe.[233] Other important liberal socialist figures include Guido Calogero, Piero Gobetti, Leonard Trelawny Hobhouse, John Maynard Keynes and R. H. Tawney.[232] Liberal socialism has been particularly prominent in British and Italian politics.[232]

Leninism and precedents

Blanquism is a conception of revolution named for Louis Auguste Blanqui. It holds that socialist revolution should be carried out by a relatively small group of highly organised and secretive conspirators.[234] Upon seizing power, the revolutionaries introduce socialism.[235] Rosa Luxemburg and Eduard Bernstein[236] criticised Lenin, stating that his conception of revolution was elitist and Blanquist.[237] Marxism–Leninism combines Marx's scientific socialist concepts and Lenin's anti-imperialism, democratic centralism and vanguardism.[238]

Hal Draper defined socialism from above as the philosophy which employs an elite administration to run the socialist state. The other side of socialism is a more democratic socialism from below.[239] The idea of socialism from above is much more frequently discussed in elite circles than socialism from below—even if that is the Marxist ideal—because it is more practical.[240] Draper viewed socialism from below as being the purer, more Marxist version of socialism.[241] According to Draper, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels were devoutly opposed to any socialist institution that was "conducive to superstitious authoritarianism". Draper makes the argument that this division echoes the division between "reformist or revolutionary, peaceful or violent, democratic or authoritarian, etc." and further identifies six major varieties of socialism from above, among them "Philanthropism", "Elitism", "Pannism", "Communism", "Permeationism" and "Socialism-from-Outside".[242]

According to Arthur Lipow, Marx and Engels were "the founders of modern revolutionary democratic socialism", described as a form of "socialism from below" that is "based on a mass working-class movement, fighting from below for the extension of democracy and human freedom". This type of socialism is contrasted to that of the "authoritarian, anti-democratic creed" and "the various totalitarian collectivist ideologies which claim the title of socialism" as well as "the many varieties of 'socialism from above' which have led in the twentieth century to movements and state forms in which a despotic 'new class' rules over a stratified economy in the name of socialism", a division that "runs through the history of the socialist movement". Lipow identifies Bellamyism and Stalinism as two prominent authoritarian socialist currents within the history of the socialist movement.[243]

Trotsky viewed himself to be an adherent of Leninism but opposed the bureaucratic and authoritarian methods of Stalin.[244] A number of scholars and Western socialists have regarded Leon Trotsky as a democratic alternative rather than a forerunner to Stalin with particular emphasis drawn to his activities in the pre-Civil War period and as leader of the Left Opposition.[245][246][247][248] More specifically, Trotsky advocated for a decentralised form of economic planning,[249] mass soviet democratization,[250][251][252] elected representation of Soviet socialist parties,[253][254] the tactic of a united front against far-right parties,[255]cultural autonomy for artistic movements,[256] voluntary collectivisation,[257][258] a transitional program,[259] and socialist internationalism.[260]

Several scholars state that in practice, the Soviet model functioned as a form of state capitalism.[261][262][263]

Libertarian socialism

Libertarian socialism, sometimes called left-libertarianism,[266][267] social anarchism[268][269] and socialist libertarianism,[270] is an anti-authoritarian, anti-statist and libertarian[271] tradition within socialism that rejects centralised state ownership and control[272] including criticism of wage labour relationships (wage slavery)[273] as well as the state itself.[274] It emphasises workers' self-management and decentralised structures of political organisation.[274][275] Libertarian socialism asserts that a society based on freedom and equality can be achieved through abolishing authoritarian institutions that control production.[276] Libertarian socialists generally prefer direct democracy and federal or confederal associations such as libertarian municipalism, citizens' assemblies, trade unions and workers' councils.[277][278]

Anarcho-syndicalist Gaston Leval explained:

We therefore foresee a Society in which all activities will be coordinated, a structure that has, at the same time, sufficient flexibility to permit the greatest possible autonomy for social life, or for the life of each enterprise, and enough cohesiveness to prevent all disorder. ... In a well-organised society, all of these things must be systematically accomplished by means of parallel federations, vertically united at the highest levels, constituting one vast organism in which all economic functions will be performed in solidarity with all others and that will permanently preserve the necessary cohesion".[279]

All of this is typically done within a general call for libertarian[280] and voluntary free associations[281] through the identification, criticism and practical dismantling of illegitimate authority in all aspects of human life.[282][283][189]

As part of the larger socialist movement, it seeks to distinguish itself from Bolshevism, Leninism and Marxism–Leninism as well as social democracy.[284] Past and present political philosophies and movements commonly described as libertarian socialist include anarchism (anarcho-communism, anarcho-syndicalism,[citation needed] collectivist anarchism, individualist anarchism[285][286][287] and mutualism),[288] autonomism, Communalism, participism, libertarian Marxism (council communism and Luxemburgism),[289][290] revolutionary syndicalism and utopian socialism (Fourierism).[291]

Religious socialism

Christian socialism is a broad concept involving an intertwining of Christian religion with socialism.[292]

Islamic socialism is a more spiritual form of socialism. Muslim socialists believe that the teachings of the Quran and Muhammad are not only compatible with, but actively promoting the principles of equality and public ownership, drawing inspiration from the early Medina welfare state he established. Muslim socialists are more conservative than their Western contemporaries and find their roots in anti-imperialism, anti-colonialism[293][294] and sometimes, if in an Arab speaking country, Arab nationalism. Islamic socialists believe in deriving legitimacy from political mandate as opposed to religious texts.

Social movements

Socialist feminism is a branch of feminism that argues that liberation can only be achieved by working to end both economic and cultural sources of women's oppression.[295] Marxist feminism's foundation was laid by Engels in The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State (1884). August Bebel's Woman under Socialism (1879), is the "single work dealing with sexuality most widely read by rank-and-file members of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD)".[296] In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, both Clara Zetkin and Eleanor Marx were against the demonisation of men and supported a proletariat revolution that would overcome as many male-female inequalities as possible.[297] As their movement already had the most radical demands in women's equality, most Marxist leaders, including Clara Zetkin[298][299] and Alexandra Kollontai,[300][301] counterposed Marxism against liberal feminism rather than trying to combine them. Anarcha-feminism began with late 19th- and early 20th-century authors and theorists such as anarchist feminists Goldman and Voltairine de Cleyre.[302] In the Spanish Civil War, an anarcha-feminist group, Mujeres Libres ("Free Women") linked to the Federación Anarquista Ibérica, organised to defend both anarchist and feminist ideas.[303] In 1972, the Chicago Women's Liberation Union published "Socialist Feminism: A Strategy for the Women's Movement", which is believed to be the first published use of the term "socialist feminism".[304]

Many socialists were early advocates of LGBT rights. For early socialist Charles Fourier, true freedom could only occur without suppressing passions, as the suppression of passions is not only destructive to the individual, but to society as a whole. Writing before the advent of the term "homosexuality", Fourier recognised that both men and women have a wide range of sexual needs and preferences which may change throughout their lives, including same-sex sexuality and androgénité. He argued that all sexual expressions should be enjoyed as long as people are not abused and that "affirming one's difference" can actually enhance social integration.[305][306] In Oscar Wilde's The Soul of Man Under Socialism, he advocates an egalitarian society where wealth is shared by all, while warning of the dangers of social systems that crush individuality.[307] Edward Carpenter actively campaigned for homosexual rights. His work The Intermediate Sex: A Study of Some Transitional Types of Men and Women was a 1908 book arguing for gay liberation.[308] who was an influential personality in the foundation of the Fabian Society and the Labour Party. After the Russian Revolution under the leadership of Lenin and Trotsky, the Soviet Union abolished previous laws against homosexuality.[309] Harry Hay was an early leader in the American LGBT rights movement as well as a member of the Communist Party USA. He is known for his involvement in the founding of gay organisations, including the Mattachine Society, the first sustained gay rights group in the United States which in its early days reflected a strong Marxist influence. The Encyclopedia of Homosexuality reports that "[a]s Marxists the founders of the group believed that the injustice and oppression which they suffered stemmed from relationships deeply embedded in the structure of American society".[310] Emerging from events such as the May 1968 insurrection in France, the anti-Vietnam war movement in the US and the Stonewall riots of 1969, militant gay liberation organisations began to spring up around the world. Many sprang from left radicalism more than established homophile groups,[311] although the Gay Liberation Front took an anti-capitalist stance and attacked the nuclear family and traditional gender roles.[312]

Eco-socialism is a political strain merging aspects of socialism, Marxism or libertarian socialism with green politics, ecology and alter-globalisation. Eco-socialists generally claim that the expansion of the capitalist system is the cause of social exclusion, poverty, war and environmental degradation through globalisation and imperialism under the supervision of repressive states and transnational structures.[313] Contrary to the depiction of Karl Marx by some environmentalists,[314] social ecologists[315] and fellow socialists[316] as a productivist who favoured the domination of nature, eco-socialists revisited Marx's writings and believe that he "was a main originator of the ecological world-view".[317] Marx discussed a "metabolic rift" between man and nature, stating that "private ownership of the globe by single individuals will appear quite absurd as private ownership of one man by another" and his observation that a society must "hand it [the planet] down to succeeding generations in an improved condition".[318] English socialist William Morris is credited with developing principles of what was later called eco-socialism.[319] During the 1880s and 1890s, Morris promoted his ideas within the Social Democratic Federation and Socialist League.[320] Green anarchism blends anarchism with environmental issues. An important early influence was Henry David Thoreau and his book Walden[321] as well as Élisée Reclus.[322][323]

In the late 19th century, anarcho-naturism fused anarchism and naturist philosophies within individualist anarchist circles in France, Spain, Cuba[324] and Portugal.[325] Murray Bookchin's first book Our Synthetic Environment[326] was followed by his essay "Ecology and Revolutionary Thought" which introduced ecology as a concept in radical politics.[327] In the 1970s, Barry Commoner, claimed that capitalist technologies were chiefly responsible for environmental degradation as opposed to population pressures.[328] In the 1990s socialist/feminists Mary Mellor[329] and Ariel Salleh[330] adopt an eco-socialist paradigm. An "environmentalism of the poor" combining ecological awareness and social justice has also become prominent.[331] Pepper critiqued the current approach of many within green politics, particularly deep ecologists.[332]

Syndicalism

Syndicalism operates through industrial trade unions. It rejects state socialism and the use of establishment politics. Syndicalists reject state power in favour of strategies such as the general strike. Syndicalists advocate a socialist economy based on federated unions or syndicates of workers who own and manage the means of production. Some Marxist currents advocate syndicalism, such as De Leonism. Anarcho-syndicalism views syndicalism as a method for workers in capitalist society to gain control of an economy. The Spanish Revolution was largely orchestrated by the anarcho-syndicalist trade union CNT.[333] The International Workers' Association is an international federation of anarcho-syndicalist labour unions and initiatives.[334]

Public views

A multitude of polls have found significant levels of support for socialism among modern populations.[335][336]

A 2018 IPSOS poll found that 50% of the respondents globally strongly or somewhat agreed that present socialist values were of great value for societal progress. In China this was 84%, India 72%, Malaysia 62%, Turkey 62%, South Africa 57%, Brazil 57%, Russia 55%, Spain 54%, Argentina 52%, Mexico 51%, Saudi Arabia 51%, Sweden 49%, Canada 49%, Great Britain 49%, Australia 49%, Poland 48%, Chile 48%, South Korea 48%, Peru 48%, Italy 47%, Serbia 47%, Germany 45%, Belgium 44%, Romania 40%, United States 39%, France 31%, Hungary 28% and Japan 21%.[337]

A 2021 survey conducted by the Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA) found that 67% of young British (16–24) respondents wanted to live in a socialist economic system, 72% supported the re-nationalisation of various industries such as energy, water along with railways and 75% agreed with the view that climate change was a specifically capitalist problem.[338]