Зороастризм

| Зороастризм | |

|---|---|

Аташ Бехрам в Храме Огня Йезд в Иране | |

| Тип | Этническая религия |

| Классификация | Иранский |

| Scripture | Avesta |

| Theology | Dualistic[1][2] |

| Language | Avestan |

| Founder | Zoroaster (traditional) |

| Origin | c. 2nd millennium BCE Iranian Plateau |

| Separated from | Proto-Indo-Iranian religion |

| Number of followers | 100,000–200,000 |

Зороастризм ( персидский : دین زرتشتی , латинизированный : Дин-е Зартошти ), также известный как Маздаясна и Бехдин , — иранская религия . Среди старейших организованных религий в мире она основана на учении иранского пророка Заратустры, широко известного под своим греческим именем Зороастр , как изложено в основном религиозном тексте, называемом Авестой . Зороастрийцы превозносят несотворенное и доброжелательное божество мудрости, обычно называемое Ахура Мазда ( авестийский : 𐬀𐬵𐬎𐬭𐬋 𐬨𐬀𐬰𐬛𐬃 ), как высшее существо вселенной; Противоположностью Ахура Мазды является Ангра-Майнью ( 𐬀𐬢𐬭𐬀⸱𐬨𐬀𐬌𐬥𐬌𐬌𐬎 ), который олицетворяется разрушительным духом и противником всего хорошего. Зороастризм сочетает в себе дуалистическую космологию добра и зла с эсхатологией , предсказывающей окончательную победу Ахура Мазды над злом. [ 1 ] Мнения ученых относительно того, является ли религия монотеистической , расходятся. [ 1 ] политеистический , [ 2 ] генотеистический , [ 3 ] or a combination of all three.[4] Zoroastrianism shaped Iranian culture and history, while scholars differ on whether it significantly influenced ancient Western philosophy and the Abrahamic religions, [5][6] or gradually reconciled with other religions and traditions, such as Christianity and Islam.[7]

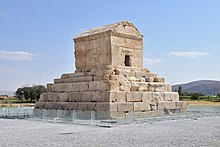

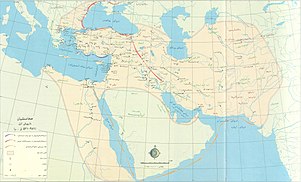

Originating from Zoroaster's reforms of the ancient Iranian religion, Zoroastrianism may have roots in the Avestan period of the second millennium BCE, but was first recorded in the mid sixth century BCE. For the next thousand years, it was the official religion of successive Iranian polities, beginning with the Achaemenid Empire, which formalized and institutionalized many of its tenets and rituals, through the Sasanian Empire, which revitalized the faith and standardized its teachings.[8] Following the Muslim conquest of Persia in the mid seventh century CE, Zoroastrianism declined amid persecution and forced conversions by the early Muslims; many Zoroastrians fled to the Indian subcontinent, where they received refugees and became the progenitors of today's Parsis. Once numbering millions of adherents at its height, the world's current Zoroastrian population is estimated at between 110,000–200,000, with the vast majority residing in India (50,000–60,000), Iran (15,000–25,000), and North America (21,000); the religion is thought to be declining due to restrictions on conversion, strict endogamy, and low birth rates.[9]

The central beliefs and practices of Zoroastrianism are contained in the Avesta, a compendium of texts assembled over several centuries. Its oldest and most central component are the Gathas, purported to be the direct teachings of Zoroaster and his account of conversations with Ahura Mazda. These writings are part of a major section of the Avesta called the Yasna, which forms the core of Zoroastrian liturgy. Zoroaster's religious philosophy divided the early Iranian gods of Proto-Indo-Iranian paganism into emanations of the natural world, known as ahuras and daevas; the former are to be revered, and the latter rejected. Zoroaster proclaimed that Ahura Mazda was the supreme creator and sustaining force of the universe, working in gētīg (the visible material realm) and mēnōg (the invisible spiritual and mental realm) through seven Amesha Spentas, which variably represent aspects of the universe as well as the highest moral goods. Emanating from Ahura Mazda is Spenta Mainyu (the Holy or Bountiful Spirit), the source of life and goodness,[10] which is opposed by Angra Mainyu (the Destructive or Opposing Spirit), who is born from Aka Manah (evil thought). Angra Mainyu was further developed by Middle Persian literature into Ahriman (𐭠𐭧𐭫𐭬𐭭𐭩), Mazda's direct adversary.

Zoroastrianism holds that within this cosmic dichotomy, humans have the choice between Asha (truth, cosmic order), the principle of righteousness or "rightness" that is promoted and embodied by Ahura Mazda, and Druj (falsehood, deceit), the essential nature of Angra Mainyu that expresses itself as greed, wrath, and envy.[11] The central moral precepts of the religion are good thoughts (hwnata) good words (hakhta), good deeds (hvarshta), which are recited in many prayers and ceremonies.[5][12][13] Zoroastrianism maintains many practices and beliefs from ancient Iranian religion, such as revering nature and its elements. Fire is held to be particularly sacred as a symbol of Ahura Mazda, serving as focal point of many ceremonies and rituals, and Zoroastrian places of worship are known as Fire Temples.

Etymology

The name Zoroaster (Ζωροάστηρ) is a Greek rendering of the Avestan name Zarathustra. He is known as Zartosht and Zardosht in Persian and Zaratosht in Gujarati.[14] The Zoroastrian name of the religion is Mazdayasna, which combines Mazda- with the Avestan word yasna, meaning "worship, devotion".[15] In English, an adherent of the faith is commonly called a Zoroastrian or a Zarathustrian. An older expression still used today is Behdin, meaning "of the good religion", deriving from beh < Middle Persian weh 'good' + din < Middle Persian dēn < Avestan daēnā".[16] In the Zoroastrian liturgy, this term is used as a title for a lay individual who has been formally inducted into the religion in a Navjote ceremony, in contrast to the priestly titles of osta, osti, ervad (hirbod), mobed and dastur.[17]

The first surviving reference to Zoroaster in English scholarship is attributed to Thomas Browne (1605–1682), who briefly refers to Zoroaster in his 1643 Religio Medici.[18] The term Mazdaism (/ˈmæzdə.ɪzəm/) is an alternative form in English used as well for the faith, taking Mazda- from the name Ahura Mazda and adding the suffix -ism to suggest a belief system.[19]

Theology

Some scholars believe Zoroastrianism started as an Indo-Iranian polytheistic religion: according to Yujin Nagasawa, "like the rest of the Zoroastrian texts, the Old Avesta does not teach monotheism".[20] By contrast, Md. Sayem characterizes Zoroastrianism as being one of the oldest monotheistic religions in the world.[21]

Zoroastrians treat Ahura Mazda as the supreme god, but believe in lesser divinities known as Yazatas, who share some similarities with the angels in Abrahamic religions.[22] These yazatas ("good agents") include Anahita, Sraosha, Mithra, Rashnu, and Tishtrya. Historian Richard Foltz has put forth evidence that Iranians of pre-Islamic era worshipped all these figures; especially the gods Mithra and Anahita.[23] Prods Oktor Skjærvø states Zoroastrianism is henotheistic, and "a dualistic and polytheistic religion, but with one supreme god, who is the father of the ordered cosmos".[3]

Brian Arthur Brown states that this is unclear, because historic texts present a conflicting picture, ranging from Zoroastrianism's belief in "one god, two gods, or a best god henotheism".[24]

Economist Mario Ferrero suggests that Zoroastrianism transitioned from polytheism to monotheism due to political and economic pressures.[25]

In the 19th century, through contact with Western academics and missionaries, Zoroastrianism experienced a massive theological change that still affects it today. The Rev. John Wilson led various missionary campaigns in India against the Parsi community, disparaging the Parsis for their "dualism" and "polytheism" and as having unnecessary rituals while declaring the Avesta to not be "divinely inspired". This caused mass dismay in the relatively uneducated Parsi community, which blamed its priests and led to some conversions towards Christianity.[citation needed]

The arrival of the German orientalist and philologist Martin Haug led to a rallied defense of the faith through Haug's reinterpretation of the Avesta through Christianized and European orientalist lens. Haug postulated that Zoroastrianism was solely monotheistic with all other divinities reduced to the status of angels while Ahura Mazda became both omnipotent and the source of evil as well as good. Haug's thinking was subsequently disseminated as a Parsi interpretation, thus corroborating Haug's theory, and the idea became so popular that it is now almost universally accepted as doctrine (though being reevaluated in modern Zoroastrianism and academia).[26] It has been argued by Almut Hintze that this designation of monotheism is not wholly perfect and that Zoroastrianism instead has its "own form of monotheism" which combines elements of dualism and polytheism.[27] Farhang Mehr asserts that Zoroastrianism is principally monotheistic with some dualistic elements.[28]

Lenorant and Chevallier assert that Zoroastrianism's concept of divinity covers both being and mind as immanent entities, describing Zoroastrianism as having a belief in an immanent self-creating universe with consciousness as its special attribute, thereby putting Zoroastrianism in the pantheistic fold sharing its origin with Indian Hinduism.[29][30]

Nature of the divine

Zoroastrianism contains multiple classes of divine beings, who are typically organised into tiers and spheres of influence.[citation needed]

Ahuras

The Ahura are a class of divine beings "inherited by Zoroastrianism from the prehistoric Indo-Iranian religion. In the Rig Veda, asura denotes the "older gods," such as the "Father Asura".... Varuna, and Mitra, who originally ruled over the primeval undifferentiated Chaos."[31]

Ahura Mazda

Ahura Mazda, also known as Oromasdes, Ohrmazd, Ormazd, Ormusd, Hoormazd, Harzoo, Hormazd, Hormaz and Hurmz, is the creator deity and the supreme god in Zoroastrianism. Ahura Mazda stands for the dual deity Mitrāˊ-Váruṇā of the Hindu holy book known as the Rigveda.[31]

According to scholars, Ahura Mazda is an uncreated, omniscient, omnipotent and benevolent God who has created the spiritual and material existences out of infinite light, and maintains the cosmic law of Asha. He is the first and most invoked spirit in Yasna, and is unrivaled, has no equals and presides over all creation.[32] In Avesta, Ahura Mazda is the only true God, and the representation of goodness, light, and truth. He is in conflict with the evil spirit Angra Mainyu, the representation of evil, darkness, and deceit. Angru Mainyu's goal is to tempt humans away from Ahura Mazda. Notably, Angra Mainyu is not a creation of Ahura Mazda but an independent entity.[33] The belief in Ahura Mazda, the "Lord of Wisdom" who is considered an all-encompassing Deity and the only existing one, is the foundation of Zoroastrianism.[34]

Ahura Mithra

Mitra, also called Mithra, was originally an Indo-Iranian god of "covenant, agreement, treaty, alliance, promise." Mitra is considered a being worthy of worship and is "characterized by riches".[35]

Yazata

The Yazata (Avestan: 𐬫𐬀𐬰𐬀𐬙𐬀) are divine beings worshiped by song and sacrifice in Zoroastrianism, in accordance with the Avesta. The word 'Yazata' is derived from 'Yazdan', the Old Persian word for 'god',[36] and literally means "divinity worthy of worship or veneration". As a concept, it also contains a wide range of other meanings; though generally signifying (or used as an epithet of) a divinity.[37][38]

The origins of Yazata are varied, with many also being featured as gods in Hinduism, or other Iranian religions. In modern Zoroastrianism, the Yazata are considered holy emanations of the creator, always devoted to him and obey the will of Ahura Mazda. While subject to repression by the Islamic Caliphate, the Yazata were often framed as "angels" to counter accusation of polytheism (shirk).[39] According to the Avesta The Yazata assist Ahura Mazda in his battle against the evil spirit, and are hypostases of moral or physical aspects of creation. The yazatas collectively are "the good powers under Ahura Mazda", who is "the greatest of the yazatas".[36]

Notable Yazata

- Ahura Mazda

- Mitra or Mithra

- Anahita - formerly an Iranian water goddess

- Ātar (Fire)

- Rashnu, one of the three judges who pass judgment on the souls of people after death

- Sraosha or Srōsh

- Verethragna - who may be the Vedic god Indra

Amesha Spentas

Yazatas are further divided into Amesha Spentas, their "ham-kar" or "Collaborators" who are Lower Ranking divinities,[40] and also certain healing plants, primordial creatures, the fravashis of the dead, and certain prayers that are themselves considered holy.

The Amesha Spentas and their "ham-kar" or "collaborator" Yazatas are as follows:

- Vohu Manah + Mah / Geush Urvan / Ram;

- Asha Vahishta + Atar / Sraosha / Verethraghna;

- Kshatra Vairya + Khwar / Mithra / Asman / Anaghran;

- Spenta Armaiti + Ap / Daena / Ashi / Manthra Spenta;

- Haurvatat + Tishtriya / Fravashi / Vata;

- Ameretat + Rashnu / Arshtat / Zamyad; [40]

Principal beliefs

Tenets of faith

In Zoroastrianism, Ahura Mazda is the beginning and the end, the creator of everything that can and cannot be seen, the eternal and uncreated, the all-good and source of Asha.[15] In the Gathas, the most sacred texts of Zoroastrianism thought to have been composed by Zoroaster himself, Zoroaster acknowledged the highest devotion to Ahura Mazda, with worship and adoration also given to Ahura Mazda's manifestations (Amesha Spenta) and the other ahuras (Yazata) that support Ahura Mazda.[41]

Daena (din in modern Persian and meaning "that which is seen") is representative of the sum of one's spiritual conscience and attributes, which through one's choice Asha is either strengthened or weakened in the Daena.[42] Traditionally, the manthras (similar to the Hindu sacred utterance mantra) prayer formulas, are believed to be of immense power and the vehicles of Asha and creation used to maintain good and fight evil.[43] Daena should not be confused with the fundamental principle of Asha, believed to be the cosmic order which governs and permeates all existence, and the concept of which governed the life of the ancient Indo-Iranians. For these, asha was the course of everything observable—the motion of the planets and astral bodies; the progression of the seasons; and the pattern of daily nomadic herdsman life, governed by regular metronomic events such as sunrise and sunset, and was strengthened through truth-telling and following the Threefold Path.[44]

All physical creation (getig) was thus determined to run according to a master plan—inherent to Ahura Mazda—and violations of the order (druj) were violations against creation, and thus violations against Ahura Mazda.[45] This concept of asha versus the druj should not be confused with Western and especially Christian notions of good versus evil, for although both forms of opposition express moral conflict, the asha versus druj concept is more systemic and less personal, representing, for instance, chaos (that opposes order); or "uncreation", evident as natural decay (that opposes creation); or more simply "the lie" (that opposes truth and goodness).[44] Moreover, in the role as the one uncreated creator of all, Ahura Mazda is not the creator of druj, which is "nothing", anti-creation, and thus (likewise) uncreated and developed as the antithesis of existence through choice.[46]

In this schema of asha versus druj, mortal beings (both humans and animals) play a critical role, for they too are created. Here, in their lives, they are active participants in the conflict, and it is their spiritual duty to defend Asha, which is under constant assault and would decay in strength without counteraction.[44] Throughout the Gathas, Zoroaster emphasizes deeds and actions within society and accordingly extreme asceticism is frowned upon in Zoroastrianism but moderate forms are allowed within.[47]

Humata, Huxta, Huvarshta (Good Thoughts, Good Words, Good Deeds), the Threefold Path of Asha, is considered the core maxim of Zoroastrianism especially by modern practitioners. In Zoroastrianism, good transpires for those who do righteous deeds for its own sake, not for the search of reward. Those who do evil are said to be attacked and confused by the druj and are responsible for aligning themselves back to Asha by following this path.[48] There is also a heavy emphasis on spreading happiness, mostly through charity,[49] and respecting the spiritual equality and duty of both men and women.[50]

Central to Zoroastrianism is the emphasis on moral choice, to choose the responsibility and duty for which one is in the mortal world, or to give up this duty and so facilitate the work of druj. Similarly, predestination is rejected in Zoroastrian teaching and the absolute free will of all conscious beings is core, with even divine beings having the ability to choose. Humans bear responsibility for all situations they are in, and in the way they act toward one another. Reward, punishment, happiness, and grief all depend on how individuals live their lives.[51]

In Zoroastrian tradition, life is a temporary state in which a mortal is expected to participate actively in the continuing battle between Asha and Druj. Prior to its incarnation at the birth of the child, the urvan (soul) of an individual is still united with its fravashi (personal/higher spirit), which has existed since Ahura Mazda created the universe. Prior to the splitting off of the urvan, the fravashi participates in the maintenance of creation led by Ahura Mazda. During the life of a given individual, the fravashi acts as a source of inspiration to perform good actions and as a spiritual protector. The fravashis of ancestors cultural, spiritual, and heroic, associated with illustrious bloodlines, are venerated and can be called upon to aid the living.[52]

The religion states that active and ethical participation in life through good deeds formed from good thoughts and good words is necessary to ensure happiness and to keep chaos at bay. This active participation is a central element in Zoroaster's concept of free will, and Zoroastrianism as such rejects extreme forms of asceticism and monasticism but historically has allowed for moderate expressions of these concepts.[47] On the fourth day after death, the urvan is reunited with its fravashi, whereupon the experiences of life in the material world are collected for use in the continuing battle for good in the spiritual world. For the most part, Zoroastrianism does not have a notion of reincarnation; albeit Followers of Ilm-e-Kshnoom in India, among other currently non-traditional opinions, believe in reincarnation and practice vegetarianism.[53]

Zoroastrianism's emphasis on the protection and veneration of nature and its elements has led some to proclaim it as the "world's first proponent of ecology."[54] The Avesta and other texts call for the protection of water, earth, fire, and air making it, in effect, an ecological religion: "It is not surprising that Mazdaism...is called the first ecological religion. The reverence for Yazatas (divine spirits) emphasizes the preservation of nature (Avesta: Yasnas 1.19, 3.4, 16.9; Yashts 6.3–4, 10.13)."[55] However, this particular assertion is limited to natural forces held as emanations of asha by the fact that early Zoroastrians had a duty to exterminate "evil" species, a dictate no longer followed in modern Zoroastrianism.[56] Although there have been various theological statements supporting vegetarianism in Zoroastrianism's history and those who believe that Zoroaster was vegetarian.[57]

Zoroastrianism is not entirely uniform in theological and philosophical thought, especially with historical and modern influences having a significant impact on individual and local beliefs, practices, values, and vocabulary, sometimes merging with tradition and in other cases displacing it.[58] The ultimate purpose in the life of a practicing Zoroastrian is to become an ashavan (a master of Asha) and to bring happiness into the world, which contributes to the cosmic battle against evil. The core teachings of Zoroastrianism include:

- Following the threefold path of Asha: Humata, Hūxta, Huvarshta (lit. 'good thoughts, good words, good deeds').[48]

- Practicing charity to keep one's soul aligned with Asha and thus with spreading happiness.[49]

- The spiritual equality and duty of men and women alike.[50]

- Being good for the sake of goodness and without the hope of reward (see Ashem Vohu).

Cosmology

Cosmogony

According to the Zoroastrian creation myth, there is one universal, transcendent, all-good, and uncreated supreme creator deity Ahura Mazda,[15] or the "Wise Lord" (Ahura meaning "Lord" and Mazda meaning "Wisdom" in Avestan).[15][59] Zoroaster keeps the two attributes separate as two different concepts in most of the Gathas yet sometimes combines them into one form. Zoroaster also proclaims that Ahura Mazda is omniscient but not omnipotent.[15] Ahura Mazda existed in light and goodness above, while Angra Mainyu, (also referred to in later texts as "Ahriman"),[60][61] the destructive spirit/mentality, existed in darkness and ignorance below. They have existed independently of each other for all time, and manifest contrary substances. In the Gathas, Ahura Mazda is noted as working through emanations known as the Amesha Spenta[62] and with the help of "other ahuras".[26] These divine beings called Amesha Spentas, support him and are representative and guardians of different aspects of creation and the ideal personality.[62] Ahura Mazda is immanent in humankind and interacts with creation through these bounteous/holy divinities. In addition to these, He is assisted by a league of countless divinities called Yazatas, meaning "worthy of worship." Each Yazata is generally a hypostasis of a moral or physical aspect of creation. Asha,[15][44] is the main spiritual force which comes from Ahura Mazda.[44] It is the cosmic order and is the antithesis of chaos, which is evident as druj, falsehood and disorder, that comes from Angra Mainyu.[46][32] The resulting cosmic conflict involves all of creation, mental/spiritual and material, including humanity at its core, which has an active role to play in the conflict.[63] The main representative of Asha in this conflict is Spenta Mainyu, the creative spirit/mentality.[60] Ahura Mazda then created the material and visible world itself in order to ensnare evil. He created the floating, egg-shaped universe in two parts: first the spiritual (menog) and 3,000 years later, the physical (getig).[45] Ahura Mazda then created Gayomard, the archetypical perfect man, and Gavaevodata, the primordial bovine.[51]

While Ahura Mazda created the universe and humankind, Angra Mainyu, whose very nature is to destroy, miscreated demons, evil daevas, and noxious creatures (khrafstar) such as snakes, ants, and flies. Angra Mainyu created an opposite, evil being for each good being, except for humans, which he found he could not match. Angra Mainyu invaded the universe through the base of the sky, inflicting Gayomard and the bull with suffering and death. However, the evil forces were trapped in the universe and could not retreat. The dying primordial man and bovine emitted seeds, which were protect by Mah, the Moon. From the bull's seed grew all beneficial plants and animals of the world and from the man's seed grew a plant whose leaves became the first human couple. Humans thus struggle in a two-fold universe of the material and spiritual trapped and in long combat with evil. The evils of this physical world are not products of an inherent weakness but are the fault of Angra Mainyu's assault on creation. This assault turned the perfectly flat, peaceful, and daily illuminated world into a mountainous, violent place that is half night.[51] According to Zoroastrian cosmology, in articulating the Ahuna Vairya formula, Ahura Mazda made the ultimate triumph of good against Angra Mainyu evident.[64] Ahura Mazda will ultimately prevail over the evil Angra Mainyu, at which point reality will undergo a cosmic renovation called Frashokereti[65] and limited time will end. In the final renovation, all of creation—even the souls of the dead that were initially banished to or chose to descend into "darkness"—will be reunited with Ahura Mazda in the Kshatra Vairya (meaning "best dominion"),[66] being resurrected to immortality.

Cosmography

Zoroastrian cosmography, which refers to the description of the structure of the cosmos in Zoroastrian literature and theology, involves a primary division of the cosmos into heaven and earth.[67] The heaven is composed of three parts: the lower-most part, which is where the fixed stars may be found; the middle part, where the domain of the moon is located, and the upper part, which is the domain of the sun and unreachable by Ahirman.[68] Further above the highest level of the heaven/sky includes regions described as the Endless Lights, as well as the Thrones of Amahraspandān and Ohrmazd.[69] Although this is the basic framework which occurs in Avestan texts, later Zoroastrian literature would elaborate on this picture by further subdividing the lowest part of heaven to achieve a total of six or seven layers.[70] The Earth itself was described as possessing three primary mountains: Mount Hukairiia, whose peak was the focal point of the revolution of the star Sadwēs; Mount Haraitī, whose peak was the focal point of the revolution of the sun and the moon, and the greatest of them all, the Harā Bərəz whose peak was located at the center of the Earth and which was the first in a chain of 2,244 mountains which, together, encircled the Earth.[71] Although the planets are not described in early Zoroastrian sources, they entered Zoroastrian thought in the Middle Persian period: they were demonized and took on the names Anāhīd (Pahlavi for Venus), Tīr (Mercury), Wahrām (Mars), Ohrmazd (Jupiter), and Kēwān (Saturn).[72]

Eschatology

Individual judgment at death is at the Chinvat Bridge ("bridge of judgement" or "bridge of choice"), which each human must cross, facing a spiritual judgment, though modern belief is split as to whether it is representative of a mental decision during life to choose between good and evil or an afterworld location. Humans' actions under their free will through choice determine the outcome. According to tradition, the soul is judged by the Yazatas Mithra, Sraosha, and Rashnu, where depending on the verdict one is either greeted at the bridge by a beautiful, sweet-smelling maiden or by an ugly, foul-smelling old hag representing their Daena affected by their actions in life. The maiden leads the dead safely across the bridge, which widens and becomes pleasant for the righteous, towards the House of Song. The hag leads the dead down a bridge that narrows to a razor's edge and is full of stench until the departed falls off into the abyss towards the House of Lies.[51][73] Those with a balance of good and evil go to Hamistagan, a purgatorial realm mentioned in the 9th century work Dadestan-i Denig.[74]

The House of Lies is considered temporary and reformative; punishments fit the crimes, and souls do not rest in eternal damnation. Hell contains foul smells and evil food, a smothering darkness, and souls are packed tightly together although they believe they are in total isolation.[51]

In ancient Zoroastrian eschatology, a 3,000-year struggle between good and evil will be fought, punctuated by evil's final assault. During the final assault, the sun and moon will darken, and humankind will lose its reverence for religion, family, and elders. The world will fall into winter, and Angra Mainyu's most fearsome miscreant, Azi Dahaka, will break free and terrorize the world.[51]

According to legend, the final savior of the world, known as the Saoshyant, will be born to a virgin impregnated by the seed of Zoroaster while bathing in a lake. The Saoshyant will raise the dead—including those in all afterworlds—for final judgment, returning the wicked to hell to be purged of bodily sin. Next, all will wade through a river of molten metal in which the righteous will not burn but through which the impure will be completely purified. The forces of good will ultimately triumph over evil, rendering it forever impotent but not destroyed. The Saoshyant and Ahura Mazda will offer a bull as a final sacrifice for all time and all humans will become immortal. Mountains will again flatten and valleys will rise; the House of Song will descend to the moon, and the earth will rise to meet them both.[51] Humanity will require two judgments because there are as many aspects to our being: spiritual (menog) and physical (getig).[51]

Practices and rituals

Throughout Zoroastrian history, shrines and temples have been the focus of worship and pilgrimage for adherents of the religion. Early Zoroastrians were recorded as worshiping in the 5th century BCE on mounds and hills where fires were lit below the open skies.[76] In the wake of Achaemenid expansion, shrines were constructed throughout the empire and particularly influenced the role of Mithra, Aredvi Sura Anahita, Verethragna and Tishtrya, alongside other traditional Yazata who all have hymns within the Avesta and also local deities and culture-heroes. Today, enclosed and covered fire temples tend to be the focus of community worship where fires of varying grades are maintained by the clergy assigned to the temples.[77]

The incorporation of cultural and local rituals is quite common and traditions have been passed down in historically Zoroastrian communities such as herbal healing practices, wedding ceremonies, and the like.[78][79][43] Traditionally, Zoroastrian rituals have also included shamanic elements involving mystical methods such as spirit travel to the invisible realm and involving the consumption of fortified wine, Haoma, mang, and other ritual aids.[80][45][81][82][83]

In Zoroastrianism, water (aban) and fire (atar) are agents of ritual purity, and the associated purification ceremonies are considered the basis of ritual life. In Zoroastrian cosmogony, water and fire are respectively the second and last primordial elements to have been created, and scripture considers fire to have its origin in the waters (re. which conception see Apam Napat).

A corpse is considered a host for decay, i.e., of druj. Consequently, scripture enjoins the safe disposal of the dead in a manner such that a corpse does not pollute the good creation. These injunctions are the doctrinal basis of the fast-fading traditional practice of ritual exposure, most commonly identified with the so-called Towers of Silence for which there is no standard technical term in either scripture or tradition. Ritual exposure is currently mainly practiced by Zoroastrian communities of the Indian subcontinent, in locations where it is not illegal and diclofenac poisoning has not led to the virtual extinction of scavenger birds.[citation needed]

The central ritual of Zoroastrianism is the Yasna, which is a recitation of the eponymous book of the Avesta and sacrificial ritual ceremony involving Haoma.[85] Extensions to the Yasna ritual are possible through use of the Visperad and Vendidad, but such an extended ritual is rare in modern Zoroastrianism.[86][87] The Yasna itself descended from Indo-Iranian sacrificial ceremonies and animal sacrifice of varying degrees are mentioned in the Avesta and are still practiced in Zoroastrianism albeit through reduced forms such as the sacrifice of fat before meals.[88] High rituals such as the Yasna are considered to be the purview of the Mobads with a corpus of individual and communal rituals and prayers included in the Khordeh Avesta.[85][89]

A Zoroastrian is welcomed into the faith through the Navjote/Sedreh Pushi ceremony, which is traditionally conducted during the later childhood or pre-teen years of the aspirant, though there is no defined age limit for the ritual.[43][90] After the ceremony, Zoroastrians are encouraged to wear their sedreh (ritual shirt) and kushti (ritual girdle) daily as a spiritual reminder and for mystical protection, though reformist Zoroastrians tend to only wear them during festivals, ceremonies, and prayers.[91][43][90]

Historically, Zoroastrians are encouraged to pray the five daily Gāhs and to maintain and celebrate the various holy festivals of the Zoroastrian calendar, which can differ from community to community.[92][93] Zoroastrian prayers, called manthras, are conducted usually with hands outstretched in imitation of Zoroaster's prayer style described in the Gathas and are of a reflectionary and supplicant nature believed to be endowed with the ability to banish evil.[94][95][64] Devout Zoroastrians are known to cover their heads during prayer, either with traditional topi, scarves, other headwear, or even just their hands. However, full coverage and veiling which is traditional in Islamic practice is not a part of Zoroastrianism and Zoroastrian women in Iran wear their head coverings displaying hair and their faces to defy mandates by the Islamic Republic of Iran.[96]

Scripture

Avesta

The Avesta is a collection of the central religious texts of Zoroastrianism written in the old Iranian dialect of Avestan. The history of the Avesta is speculated upon in many Pahlavi texts with varying degrees of authority, with the current version of the Avesta dating at oldest from the times of the Sasanian Empire.[97] The Avesta was "composed at different times, providing a series of snapshots of the religion that allow historians to see how it changed over time".[98] According to Middle Persian tradition, Ahura Mazda created the twenty-one Nasks of the original Avesta which Zoroaster brought to Vishtaspa. Here, two copies were created, one which was put in the house of archives and the other put in the Imperial treasury. During Alexander's conquest of Persia, the Avesta (written on 1200 ox-hides) was burned, and the scientific sections that the Greeks could use were dispersed among themselves. However, there is no strong historical evidence for this and they remain contested despite affirmations from the Zoroastrian tradition, whether it be the Denkart, Tansar-nāma, Ardāy Wirāz Nāmag, Bundahsin, Zand-i Wahman yasn or the transmitted oral tradition.[97][99]

As tradition continues, under the reign of King Valax (identified with a Vologases of the Arsacid dynasty[100]), an attempt was made to restore what was considered the Avesta. During the Sassanid Empire, Ardeshir ordered Tansar, his high priest, to finish the work that King Valax had started. Shapur I sent priests to locate the scientific text portions of the Avesta that were in the possession of the Greeks.[101] Under Shapur II, Arderbad Mahrespandand revised the canon to ensure its orthodox character, while under Khosrow I, the Avesta was translated into Pahlavi.

The compilation of the Avesta can be authoritatively traced, however, to the Sasanian Empire, of which only fraction survive today if the Middle Persian literature is correct.[97] The later manuscripts all date from after the fall of the Sasanian Empire, the latest being from 1288, 590 years after the fall of the Sasanian Empire. The texts that remain today are the Gathas, Yasna, Visperad and the Vendidad, of which the latter's inclusion is disputed within the faith.[102] Along with these texts is the individual, communal, and ceremonial prayer book called the Khordeh Avesta, which contains the Yashts and other important hymns, prayers, and rituals. The rest of the materials from the Avesta are called "Avestan fragments" in that they are written in Avestan, incomplete, and generally of unknown provenance.[103]

Middle Persian (Pahlavi)

Middle Persian and Pahlavi works created in the 9th and 10th century contain many religious Zoroastrian books, as most of the writers and copyists were part of the Zoroastrian clergy. The most significant and important books of this era include the Denkard, Bundahishn, Menog-i Khrad, Selections of Zadspram, Jamasp Namag, Epistles of Manucher, Rivayats, Dadestan-i-Denig, and Arda Viraf Namag. All Middle Persian texts written on Zoroastrianism during this time period are considered secondary works on the religion, and not scripture.[citation needed]

History

Zoroaster

Zoroastrianism was founded by Zoroaster in ancient Iran. The precise date of the founding of the religion is uncertain and estimates vary wildly from 2000 BCE to "200 years before Alexander". Zoroaster was born – in either Northeast Iran or Southwest Afghanistan – into a culture with a polytheistic religion, which featured excessive animal sacrifice[104] and the excessive ritual use of intoxicants. His life was influenced profoundly by the attempts of his people to find peace and stability in the face of constant threats of raiding and conflict. Zoroaster's birth and early life are little documented but speculated upon heavily in later texts. What is known is recorded in the Gathas, forming the core of the Avesta, which contain hymns thought to have been composed by Zoroaster himself. Born into the Spitama clan, he refers to himself as a poet-priest and prophet. He had a wife, three sons, and three daughters, the numbers of which are gathered from various texts.[105]

Zoroaster rejected many of the gods of the Bronze Age Iranians and their oppressive class structure, in which the Kavis and Karapans (princes and priests) controlled the ordinary people. He also opposed cruel animal sacrifices and the excessive use of the possibly hallucinogenic Haoma plant (conjectured to have been a species of ephedra or Peganum harmala), but did not condemn either practice outright, providing moderation was observed.[88][106]

Legendary accounts

According to later Zoroastrian tradition, when Zoroaster was 30 years old, he went into the Daiti river to draw water for a Haoma ceremony; when he emerged, he received a vision of Vohu Manah. After this, Vohu Manah took him to the other six Amesha Spentas, where he received the completion of his vision.[107] This vision radically transformed his view of the world, and he tried to teach this view to others. Zoroaster believed in one supreme creator deity and acknowledged this creator's emanations (Amesha Spenta) and other divinities which he called Ahuras (Yazata).[31] Some of the deities of the old religion, the Daevas (etymologically similar to the Sanskrit Devas), appeared to delight in war and strife and were condemned as evil workers of Angra Mainyu by Zoroaster.[108]

Zoroaster's ideas were not taken up quickly; he originally only had one convert: his cousin Maidhyoimanha.[109]

Cypress of Kashmar

The Cypress of Kashmar is a mythical cypress tree of legendary beauty and gargantuan dimensions. It is said to have sprung from a branch brought by Zoroaster from Paradise and to have stood in today's Kashmar in northeastern Iran and to have been planted by Zoroaster in honor of the conversion of King Vishtaspa to Zoroastrianism. According to the Iranian physicist and historian Zakariya al-Qazwini King Vishtaspa had been a patron of Zoroaster who planted the tree himself. In his ʿAjā'ib al-makhlūqāt wa gharā'ib al-mawjūdāt, he further describes how the Abbasid caliph Al-Mutawakkil in 247 AH (861 CE) caused the mighty cypress to be felled, and then transported it across Iran, to be used for beams in his new palace at Samarra. Before, he wanted the tree to be reconstructed before his eyes. This was done in spite of protests by the Iranians, who offered a very great sum of money to save the tree. Al-Mutawakkil never saw the cypress, because he was murdered by a Turkish soldier (possibly in the employ of his son) on the night when it arrived on the banks of the Tigris.[110][111]

Fire Temple of Kashmar

Kashmar Fire Temple was the first Zoroastrian fire temple built by Vishtaspa at the request of Zoroaster in Kashmar. In a part of Ferdowsi's Shahnameh, the story of finding Zarathustra and accepting Vishtaspa's religion is regulated that after accepting Zoroastrian religion, Vishtaspa sends priests all over the universe And Azar enters the fire temples (domes) and the first of them is Adur Burzen-Mihr who founded in Kashmar and planted a cypress tree in front of the fire temple and made it a symbol of accepting the Bahi religion And he sent priests all over the world, and commanded all the famous men and women to come to that place of worship.[112]

According to the Paikuli inscription, during the Sasanian Empire, Kashmar was part of Greater Khorasan, and the Sasanians worked hard to revive the ancient religion. It still remains a few kilometers above the ancient city of Kashmar in the castle complex of Atashgah.[113]

Early history

The roots of Zoroastrianism are thought to lie in a common prehistoric Indo-Iranian religious system dating back to the early 2nd millennium BCE.[114] The prophet Zoroaster himself, though traditionally dated to the 6th century BCE,[115][14][116] is thought by many modern historians to have been a reformer of the polytheistic Iranian religion who lived much earlier during the second half of the second millennium BCE.[117][118][119][120] Zoroastrian tradition names Airyanem Vaejah as the home of Zarathustra and the birthplace of the religion. No consensus exists as to the localiazation of Airyanem Vaejah, but the region of Khwarezm has been considered by modern scholars as a candidate.[121] Zoroastrianism as a religion was not firmly established until centuries later during the Young Avestan period. At this time, the Zoroastrian community was concentrated in the eastern portion of Greater Iran.[122] Although no consensus exists on the chronology of the Avestan period, the lack of any discernable Persian and Median influence in the Avesta makes a time frame in the first half of the first millennium BCE likely.[123]

Classical antiquity

Zoroastrianism enters recorded history in the mid-5th century BCE. Herodotus' The Histories (completed c. 440 BCE) includes a description of Greater Iranian society with what may be recognizably Zoroastrian features, including exposure of the dead.[124]

The Histories is a primary source of information on the early period of the Achaemenid era (648–330 BCE), in particular with respect to the role of the Magi. According to Herodotus, the Magi were the sixth tribe of the Medes (until the unification of the Persian empire under Cyrus the Great, all Iranians were referred to as "Mede" or "Mada" by the peoples of the Ancient World) and wielded considerable influence at the courts of the Median emperors.[125]

Following the unification of the Median and Persian empires in 550 BCE, Cyrus the Great and later his son Cambyses II curtailed the powers of the Magi after they had attempted to sow dissent following their loss of influence. In 522 BCE, the Magi revolted and set up a rival claimant to the throne. The usurper, pretending to be Cyrus' younger son Smerdis, took power shortly thereafter.[126] Owing to the despotic rule of Cambyses and his long absence in Egypt, "the whole people, Persians, Medes and all the other nations" acknowledged the usurper, especially as he granted a remission of taxes for three years.[125]

Darius I and later Achaemenid emperors acknowledged their devotion to Ahura Mazda in inscriptions, as attested to several times in the Behistun inscription and appear to have continued the model of coexistence with other religions. Whether Darius was a follower of the teachings of Zoroaster has not been conclusively established as there is no indication of note that worship of Ahura Mazda was exclusively a Zoroastrian practice.[127]

According to later Zoroastrian legend (Denkard and the Book of Arda Viraf), many sacred texts were lost when Alexander the Great's troops invaded Persepolis and subsequently destroyed the royal library there. Diodorus Siculus's Bibliotheca historica, which was completed c. 60 BCE, appears to substantiate this Zoroastrian legend.[128] According to one archaeological examination, the ruins of the palace of Xerxes I bear traces of having been burned.[129] Whether a vast collection of (semi-)religious texts "written on parchment in gold ink", as suggested by the Denkard, actually existed remains a matter of speculation.[130]

Alexander's conquests largely displaced Zoroastrianism with Hellenistic beliefs,[120] though the religion continued to be practiced many centuries following the demise of the Achaemenids in mainland Persia and the core regions of the former Achaemenid Empire, most notably Anatolia, Mesopotamia, and the Caucasus. In the Cappadocian kingdom, whose territory was formerly an Achaemenid possession, Persian colonists, cut off from their co-religionists in Iran proper, continued to practice the faith [Zoroastrianism] of their forefathers; and there Strabo, observing in the first century BCE, records (XV.3.15) that these "fire kindlers" possessed many "holy places of the Persian Gods", as well as fire temples.[131] Strabo further states that these were "noteworthy enclosures; and in their midst there is an altar, on which there is a large quantity of ashes and where the magi keep the fire ever burning."[131] It was not until the end of the Parthian Empire (247 BCE – 224 CE) that Zoroastrianism would receive renewed interest.[120]

Late antiquity

As late as the Parthian period, a form of Zoroastrianism was without a doubt the dominant religion in the Armenian lands.[133] The Sassanids aggressively promoted the Zurvanite form of Zoroastrianism, often building fire temples in captured territories to promote the religion. During the period of their centuries-long suzerainty over the Caucasus, the Sassanids made attempts to promote Zoroastrianism there with considerable successes.[citation needed]

Due to its ties to the Christian Roman Empire, Persia's arch-rival since Parthian times, the Sassanids were suspicious of Roman Christianity, and after the reign of Constantine the Great, sometimes persecuted it.[134] In 451 CE, The Sassanid authority clashed with their Armenian subjects in the Battle of Avarayr, making them officially break with the Roman Church. But the Sassanids tolerated or even sometimes favored the Christianity of the Church of the East. The acceptance of Christianity in Georgia (Caucasian Iberia) saw the Zoroastrian religion there slowly but surely decline,[135] but as late the 5th century CE, it was still widely practised as something like a second established religion.[136][137]

Decline in the Middle Ages

Over the course of 16 years during the 7th century, most of the Sasanian Empire was conquered by the emerging Muslim caliphate.[138] Although the administration of the state was rapidly Islamicized and subsumed under the Umayyad Caliphate, in the beginning "there was little serious pressure" exerted on newly subjected people to adopt Islam.[139] Because of their sheer numbers, the conquered Zoroastrians had to be treated as dhimmis (despite doubts of the validity of this identification that persisted down the centuries),[140] which made them eligible for protection. Islamic jurists took the stance that only Muslims could be perfectly moral, but "unbelievers might as well be left to their iniquities, so long as these did not vex their overlords."[140] In the main, once the conquest was over and "local terms were agreed on", the Arab governors protected the local populations in exchange for tribute.[140]

The Arabs adopted the Sasanian tax-system, both the land-tax levied on landowners and the poll-tax levied on individuals,[140] called jizya, a tax levied on non-Muslims (i.e., the dhimmis). In time, this poll-tax came to be used as a means to humble the non-Muslims, and a number of laws and restrictions evolved to emphasize their inferior status. Under the early orthodox caliphs, as long as the non-Muslims paid their taxes and adhered to the dhimmi laws, administrators were enjoined to leave non-Muslims "in their religion and their land".[141]

Under Abbasid rule, Muslim Iranians (who by then were in the majority) in many instances showed severe disregard for and mistreated local Zoroastrians. For example, in the 9th century, a deeply venerated cypress tree in Khorasan (which Parthian-era legend supposed had been planted by Zoroaster himself) was felled for the construction of a palace in Baghdad, 2,000 miles (3,200 km) away. In the 10th century, on the day that a Tower of Silence had been completed at much trouble and expense, a Muslim official contrived to get up onto it, and to call the adhan (the Muslim call to prayer) from its walls. This was turned into a pretext to annex the building.[142]

Ultimately, Muslim scholars like Al-Biruni found few records left of the belief of for instance the Khawarizmians because figures like Qutayba ibn Muslim "extinguished and ruined in every possible way all those who knew how to write and read the Khawarizmi writing, who knew the history of the country and who studied their sciences." As a result, "these things are involved in so much obscurity that it is impossible to obtain an accurate knowledge of the history of the country since the time of Islam..."[143]

Conversion

Though subject to a new leadership and harassment, the Zoroastrians were able to continue their former ways, although there was a slow but steady social and economic pressure to convert,[144][145] with the nobility and city-dwellers being the first to do so, while Islam was accepted more slowly among the peasantry and landed gentry.[146] "Power and worldly-advantage" now lay with followers of Islam, and although the "official policy was one of aloof contempt, there were individual Muslims eager to proselytize and ready to use all sorts of means to do so."[145]

In time, a tradition evolved by which Islam was made to appear as a partly Iranian religion. One example of this was a legend that Husayn, son of the fourth caliph Ali and grandson of Islam's prophet Muhammad, had married a captive Sassanid princess named Shahrbanu. This "wholly fictitious figure"[147] was said to have borne Husayn a son, the historical fourth Shi'a imam, who insisted that the caliphate rightly belonged to him and his descendants, and that the Umayyads had wrongfully wrested it from him. The alleged descent from the Sassanid house counterbalanced the Arab nationalism of the Umayyads, and the Iranian national association with a Zoroastrian past was disarmed. Thus, according to scholar Mary Boyce, "it was no longer the Zoroastrians alone who stood for patriotism and loyalty to the past."[147] The "damning indictment" that becoming Muslim was un-Iranian only remained an idiom in Zoroastrian texts.[147]

With Iranian support, the Abbasids overthrew the Umayyads in 750, and in the subsequent caliphate government—that nominally lasted until 1258—Muslim Iranians received marked favor in the new government, both in Iran and at the capital in Baghdad. This mitigated the antagonism between Arabs and Iranians but sharpened the distinction between Muslims and non-Muslims. The Abbasids zealously persecuted heretics, and although this was directed mainly at Muslim sectarians, it also created a harsher climate for non-Muslims.[148]

Survival

Despite economic and social incentives to convert, Zoroastrianism remained strong in some regions, particularly in those furthest away from the Caliphate capital at Baghdad. In Bukhara (present-day Uzbekistan), resistance to Islam required the 9th-century Arab commander Qutaiba to convert his province four times. The first three times the citizens reverted to their old religion. Finally, the governor made their religion "difficult for them in every way", turned the local fire temple into a mosque, and encouraged the local population to attend Friday prayers by paying each attendee two dirhams.[145] The cities where Arab governors resided were particularly vulnerable to such pressures, and in these cases the Zoroastrians were left with no choice but to either conform or migrate to regions that had a more amicable administration.[145]

The 9th century came to define the great number of Zoroastrian texts that were composed or re-written during the 8th to 10th centuries (excluding copying and lesser amendments, which continued for some time thereafter). All of these works are in the Middle Persian dialect of that period (free of Arabic words) and written in the difficult Pahlavi script (hence the adoption of the term "Pahlavi" as the name of the variant of the language, and of the genre, of those Zoroastrian books). If read aloud, these books would still have been intelligible to the laity. Many of these texts are responses to the tribulations of the time, and all of them include exhortations to stand fast in their religious beliefs.[citation needed]

In Khorasan in northeastern Iran, a 10th-century Iranian nobleman brought together four Zoroastrian priests to transcribe a Sassanid-era Middle Persian work titled Book of the Lord (Khwaday Namag) from Pahlavi script into Arabic script. This transcription, which remained in Middle Persian prose (an Arabic version, by al-Muqaffa, also exists), was completed in 957 and subsequently became the basis for Firdausi's Book of Kings. It became enormously popular among both Zoroastrians and Muslims, and also served to propagate the Sassanid justification for overthrowing the Arsacids.[citation needed]

Among migrations were those to cities in (or on the margins of) the great salt deserts, in particular to Yazd and Kerman, which remain centers of Iranian Zoroastrianism to this day. Yazd became the seat of the Iranian high priests during Mongol Ilkhanate rule, when the "best hope for survival [for a non-Muslim] was to be inconspicuous."[149] Crucial to the present-day survival of Zoroastrianism was a migration from the northeastern Iranian town of "Sanjan in south-western Khorasan",[150] to Gujarat, in western India. The descendants of that group are today known as the Parsis—"as the Gujaratis, from long tradition, called anyone from Iran"[150]—who today represent the larger of the two groups of Zoroastrians in India.[151]

The struggle between Zoroastrianism and Islam declined in the 10th and 11th centuries. Local Iranian dynasties, "all vigorously Muslim,"[150] had emerged as largely independent vassals of the Caliphs. In the 16th century, in one of the early letters between Iranian Zoroastrians and their co-religionists in India, the priests of Yazd lamented that "no period [in human history], not even that of Alexander, had been more grievous or troublesome for the faithful than 'this millennium of the demon of Wrath'."[152]

Modern

Zoroastrianism has survived into the modern period, particularly in India, where the Parsis are thought to have been present since about the 9th century.[153]

Today Zoroastrianism can be divided in two main schools of thought: reformists and traditionalists. Traditionalists are mostly Parsis and accept, beside the Gathas and Avesta, also the Middle Persian literature and like the reformists mostly developed in their modern form from 19th century developments. They generally do not allow conversion to the faith and, as such, for someone to be a Zoroastrian they must be born of Zoroastrian parents. Some traditionalists recognize the children of mixed marriages as Zoroastrians, though usually only if the father is a born Zoroastrian.[154] Not all Zoroastrians identify with either school and notable examples are getting traction including Neo-Zoroastrians/Revivalists, which are usually reinterpretations of Zoroastrianism appealing towards Western concerns,[155] and centering the idea of Zoroastrianism as a living religion and advocate the revival and maintenance of old rituals and prayers while supporting ethical and social progressive reforms. Both of these latter schools tend to center the Gathas without outright rejecting other texts except the Vendidad.[citation needed]

From the 19th century onward, the Parsis gained a reputation for their education and widespread influence in all aspects of society. They played an instrumental role in the economic development of the region over many decades; several of the best-known business conglomerates of India are run by Parsi-Zoroastrians, including the Tata,[156] Godrej, Wadia families, and others.[157]

For a variety of social and political factors the Zoroastrians of the Indian subcontinent, namely the Parsis and Iranis, have not engaged in conversion since at least the 18th century. Zoroastrian high priests have historically opined there is no reason to not allow conversion which is also supported by the Revayats and other scripture though later priests have condemned these judgements.[158][26] Within Iran, many of the beleaguered Zoroastrians have been also historically opposed or not practically concerned with the matter of conversion. Currently though, The Council of Tehran Mobeds (the highest ecclesiastical authority within Iran) endorses conversion but conversion from Islam to Zoroastrianism is illegal under the laws of the Islamic Republic of Iran.[154][26]

Though the Armenians share a rich history affiliated with Zoroastrianism (that eventually declined with the advent of Christianity), reports indicate that there were Zoroastrians in Armenia until the 1920s.[159]

At the request of the government of Tajikistan, UNESCO declared 2003 a year to celebrate the "3000th anniversary of Zoroastrian culture", with special events throughout the world. In 2011, the Tehran Mobeds Anjuman announced that for the first time in the history of modern Iran and of the modern Zoroastrian communities worldwide, women had been ordained in Iran and North America as mobedyars, meaning women assistant mobeds (Zoroastrian clergy).[160][161][162] The women hold official certificates and can perform the lower-rung religious functions and can initiate people into the religion.[163][164]

The current Zoroastrian population is said be around 100,000 to 200,000 and reportedly declining.[165] However, further studies are needed to confirm this, as numbers have also been rising in some areas, such as Iran.[166][167][168]

Demographics

Zoroastrian communities internationally tend to comprise mostly two main groups of people: Indian Parsis and Iranian Zoroastrians. According to a study in 2012 by the Federation of Zoroastrian Associations of North America, the number of Zoroastrians worldwide was estimated to be between 111,691 and 121,962. The number is imprecise because of diverging counts in Iran.[164]

Иран и Центральная Азия

Численность зороастрийцев в Иране сильно различается; последняя перепись (1974 г.) перед революцией 1979 г. выявила 21 400 зороастрийцев. [ 169 ] Около 10 000 приверженцев остаются в регионах Центральной Азии, которые когда-то считались традиционным оплотом зороастризма, т. е. в Бактрии (см. также Балх ), которая находится в Северном Афганистане; Согдиана ; Маргиана ; и другие области, близкие к родине Зороастра . В Иране эмиграция, внебрачные браки и низкий уровень рождаемости также приводят к сокращению зороастрийского населения. Зороастрийские группы в Иране заявляют, что их число составляет около 60 000 человек. [ 170 ] По данным иранской переписи населения 2011 года, число зороастрийцев в Иране составило 25 271 человек. [ 171 ]

Сообщества существуют в Тегеране , а также в Йезде , Кермане и Керманшахе , где многие до сих пор говорят на иранском языке, отличном от обычного персидского . Свой язык они называют дари , не путать с дари, на котором говорят в Афганистане . Их язык также называется Гаври или Бехдини , что буквально означает «Хорошая Религия». Иногда их язык называют в честь городов, в которых на нем говорят, например, Язди или Кермани . Иранских зороастрийцев исторически называли габрами . [ нужна ссылка ]

Численность курдов-зороастрийцев, а также новообращенных неэтнического происхождения оценивается по-разному. [ 172 ] Зороастрийский представитель регионального правительства Курдистана в Ираке сообщил, что около 100 000 человек в Иракском Курдистане недавно обратились в зороастризм, при этом некоторые лидеры общин предполагают, что еще больше зороастрийцев в регионе тайно исповедуют свою веру. [ 173 ] [ 174 ] [ 175 ] Однако это не было подтверждено независимыми источниками. [ 176 ]

Всплеск числа курдских мусульман, обращающихся в зороастризм, во многом объясняется разочарованием в исламе после того, как они пережили насилие и угнетение, совершаемые ИГИЛ в этом районе. [ 177 ]

Южная Азия

| Год | Поп. | ±% годовых |

|---|---|---|

| 1872 | 69,476 | — |

| 1881 | 85,397 | +2.32% |

| 1891 | 89,904 | +0.52% |

| 1901 | 94,190 | +0.47% |

| 1911 | 100,096 | +0.61% |

| 1921 | 101,778 | +0.17% |

| 1931 | 109,752 | +0.76% |

| 1941 | 114,890 | +0.46% |

| 1971 | 91,266 | −0.76% |

| 1981 | 71,630 | −2.39% |

| 2001 | 69,601 | −0.14% |

| 2011 | 57,264 | −1.93% |

| 2019 | 69,000 | +2.36% |

| Источники: [ 178 ] [ 179 ] [ 180 ] [ 181 ] [ 182 ] [ 183 ] [ 184 ] [ 185 ] [ 186 ] [ 187 ] [ 188 ] [ 189 ] | ||

Индия считается домом для большого количества зороастрийцев – потомков мигрантов из Ирана, сегодня известных как парсы . По данным переписи населения Индии 2001 года, население парсов насчитывало 69 601 человек, что составляет около 0,006% от общей численности населения Индии, с концентрацией в городе Мумбаи и его окрестностях . К 2008 году соотношение рождаемости и смертности составило 1:5; От 200 рождений в год до 1000 смертей. [ 190 ] Перепись 2011 года в Индии зафиксировала 57 264 парса-зороастрийца. [ 188 ]

По оценкам, в 2012 году зороастрийское население Пакистана составляло 1675 человек. [ 164 ] в основном живут в Синде (особенно в Карачи ), за которым следует Хайбер-Пахтунхва . [ 191 ] [ 192 ] Национальная база данных и регистрационный орган (NADRA) Пакистана сообщила, что на выборах в Пакистане в 2013 году в Пакистане проголосовало 3650 избирателей-парсов, а в 2018 году — 4235. [ 193 ] Согласно переписи населения Пакистана 2023 года , по всей стране проживало 2348 парсов, из них 1656 (70,5%) проживали в округе Карачи . [ 194 ] [ 195 ]

Западный мир

Считается, что в Северной Америке проживают 18 000–25 000 зороастрийцев как южноазиатского, так и иранского происхождения. Еще 3500 живут в Австралии (в основном в Сиднее ). По состоянию на 2012 год население зороастрийцев в США составляло 15 000 человек, что делало его третьим по величине зороастрийским населением в мире после Индии и Ирана. [ 196 ] Согласно переписи населения Канады 2021 года , зороастрийское население Канады составляло 7285 человек, из которых 3630 были парсами ( южноазиатского происхождения ) и еще 2390 выходцами из Западной Азии . [ 197 ] Стюарт, Хинце и Уильямс пишут, что в Швеции 3000 курдов обратились в зороастризм. [ 198 ] По данным переписи населения Великобритании 2021 года проживало 4105 зороастрийцев , в Англии и Уэльсе , из них 4043 — в Англии. Большинство (51%) из них (2050) находились в Лондоне , особенно в районах Барнет , Харроу и Вестминстер . Остальные 49% английских зороастрийцев были относительно равномерно разбросаны по стране, при этом вторая и третья по величине концентрация приходится на Бирмингем (72) и Манчестер (47). [ 199 ] В 2020 году «Историческая Англия» опубликовала «Обзор зороастрийских зданий в Англии» с целью предоставить информацию о зданиях, которые зороастрийцы используют в Англии, чтобы HE мог работать с сообществами над улучшением и защитой этих зданий сейчас и в будущем. В ходе предварительного обследования были выявлены четыре здания в Англии. [ 200 ]

Отношение к другим религиям и культурам

Индо-иранское происхождение

Религия зороастризм в разной степени наиболее близка к исторической ведической религии . [ нужны разъяснения ] Некоторые историки полагают, что зороастризм, наряду с аналогичными философскими революциями в Южной Азии, представлял собой взаимосвязанную цепочку реформаций, направленную против общей индоарийской нити. Многие черты зороастризма можно проследить до культуры и верований доисторического индоиранского периода, то есть до времени, предшествовавшего миграциям, которые привели к тому, что индоарии и иранцы стали отдельными народами. Следовательно, зороастризм имеет общие элементы с исторической ведической религией , которая также берет свое начало в ту эпоху. Некоторые примеры включают родственные слова авестийского слова Ахура («Ахура Мазда») и ведического санскритского слова Асура («демон», «злой полубог»); а также даэва («демон») и дэва («бог»), и оба они происходят от общей протоиндоиранской религии . [ нужна ссылка ]

Зороастризм сам по себе унаследовал идеи других систем верований и, как и другие «практикуемые» религии, допускает некоторую степень синкретизма . [ 201 ] с зороастризмом в Согдиане , Кушанской империи , Армении, Китае и других местах, включающим местные и зарубежные обычаи и божеств. [ 202 ] зороастрийское влияние на венгерскую , славянскую , осетинскую , тюркскую и монгольскую Также было отмечено мифологии, каждая из которых несет в себе обширный дуализм света и тьмы и возможные теонимы бога солнца, связанные с Хваре-хшата . [ 203 ] [ 204 ] [ 205 ]

Авраамические религии

Зороастризм иногда называют первой монотеистической религией в истории. [ 21 ] предшествовали израильтянам и оставили прочный и глубокий отпечаток на иудаизме Второго Храма , а через него и на более поздних монотеистических религиях, таких как раннее христианство и ислам. [ 25 ] [ 206 ] Между зороастризмом, иудаизмом и христианством существуют явные общие черты и сходства, такие как: монотеизм, дуализм (т.е. устойчивое представление о Дьяволе, но с позитивной оценкой материального творения), символика божественного, рая(ов) и ада. (с), ангелы и демоны, эсхатология и Страшный суд, мессианская фигура и идея спасителя, святой дух, забота о ритуальной чистоте, идеализация мудрости и праведности и другие доктрины, символы, практики и религиозные особенности. [ 207 ]

По словам Мэри Бойс , «Зороастр был, таким образом, первым, кто учил доктринам индивидуального суда, рая и ада, будущего воскресения тела, общего последнего суда и вечной жизни для воссоединившихся души и тела. Эти доктрины должны были стали привычными для большей части человечества символами веры благодаря заимствованиям из иудаизма, христианства и ислама, однако именно в самом зороастризме они имеют наибольшую логическую последовательность, поскольку Зороастр настаивал как на благости материального творения, так и, следовательно, физического тела. и о непоколебимой беспристрастности божественной справедливости». [ 208 ]

Взаимодействие между иудаизмом и зороастризмом привело к передаче религиозных идей между двумя религиями, и в результате считается, что евреи во время правления Ахеменидов находились под влиянием зороастрийской ангелологии, демонологии, эсхатологии, а также зороастрийских идей о компенсирующей справедливости в жизни. и после смерти. [ 209 ] Также предполагается, что еврейская высокая монотеистическая концепция Бога развилась во время и после периода вавилонского плена, когда евреи имели длительное воздействие сложных зороастрийских верований. [ 210 ]

В дополнение к этому, зороастрийские дуалистические концепции оказывали влияние на ближневосточные религии, такие как иудео-христианские верования, начиная с периода Ахеменидов и до первых веков нашей эры. Дуалистические идеи еврейской эсхатологии, такие как вера в спасителя, последнюю битву между добром и злом, триумф добра и воскресение мертвых, испытали влияние зороастрийских верований. Эти идеи позже перешли в христианство из зороастрийских текстов Ветхого Завета. [ 211 ]

Согласно некоторым источникам, таким как Еврейская энциклопедия (1906 г.), [ 212 ] существует много общего между зороастризмом и иудаизмом. Это побудило некоторых предположить, что ключевые зороастрийские концепции повлияли на иудаизм. Однако другие ученые не согласны с этим, считая, что общее социальное влияние зороастризма было гораздо более ограниченным и что в еврейских или христианских текстах невозможно найти никакой связи. [ 213 ]

Сторонники связи ссылаются на сходство между ними: такие как дуализм (добро и зло, божественные близнецы Ахура Мазда «Бог» и Ангра-Майнью «Сатана»), образ божества, эсхатология , воскресение и Страшный суд , мессианизм , откровение Зороастра. на горе с Моисеем на горе Синай , три сына Ферейдуна с тремя сыновьями Ноя , рай и ад , ангелология и демонология, космология шести дней или периодов творения, свободная воля и другие. Другие ученые преуменьшают или отвергают такое влияние. [ 214 ] [ 215 ] [ 212 ] [ 216 ] [ 217 ] [ 213 ] отмечая, что «зороастризм имеет уникальную теистическую доктрину, которая сочетает в себе дуализм, политеизм и пантеизм», а не является монотеистической религией. [ 213 ] Другие говорят, что «существует мало конкретных доказательств точного происхождения и развития» зороастризма. [ 218 ] и что «зороастризм не идет ни в какое сравнение с еврейской верой в суверенитет Бога над всем творением». [ 219 ]

Другие, такие как Лестер Л. Граббе , заявили, что «существует общее мнение, что персидская религия и традиция оказывали влияние на иудаизм на протяжении веков» и «вопрос в том, где было это влияние и какое из событий в иудаизме можно приписать». иранской стороны в отличие от влияния греческой или других культур». [ 215 ] Существуют различия, но также и сходства между зороастрийскими и еврейскими законами относительно брака и деторождения. [ 220 ] При этом Мэри Бойс говорит, что, помимо авраамических религий, ее влияние распространялось и на северный буддизм . [ 221 ]

ислам

считают зороастрийцев « людьми Книги ». Мусульмане [ 222 ]

манихейство

Зороастризм часто сравнивают с манихейством . Номинально являясь иранской религией, манихейство было в значительной степени вдохновлено зороастризмом. [ нужна ссылка ] из-за иранского происхождения Мани, а также из-за прежних ближневосточных гностических верований. [ 214 ] [ 221 ] [ 215 ]

Манихейство приняло многих язатов в свой пантеон. [ нужна ссылка ] Герардо Ньоли в «Энциклопедии религии » [ 223 ] говорит, что «мы можем утверждать, что манихейство имеет свои корни в иранской религиозной традиции и что его отношение к маздеизму или зороастризму более или менее похоже на отношение христианства к иудаизму». [ 224 ]

Эти две религии имеют существенные различия. [ 225 ]

Современный Иран

Многие аспекты зороастризма присутствуют в культуре и мифологии народов Большого Ирана , не в последнюю очередь потому, что зороастризм на протяжении тысячи лет оказывал доминирующее влияние на народы культурного континента. Даже после возникновения ислама и утраты прямого влияния зороастризм оставался частью культурного наследия ираноязычного мира , отчасти как фестивали и обычаи, но также и потому, что Фирдоуси включил в себя ряд фигур и историй из Авесты. в своем эпосе «Шахнаме» , который имеет решающее значение для иранской идентичности. Одним из ярких примеров является включение Язата Сраоши в число ангелов, почитаемых в шиитском исламе в Иране. [ 226 ]

См. также

Ссылки

Цитаты

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Бойд, Джеймс В.; Кросби, Дональд А. (1979). «Зороастризм дуалистический или монотеистический?». Журнал Американской академии религии . 47 (4): 557–88. дои : 10.1093/jaarel/XLVII.4.557 . ISSN 0002-7189 . JSTOR 1462275 .

Короче говоря, наша интерпретация состоит в том, что зороастризм сочетает в себе космогонический дуализм и эсхатологический монотеизм уникальным образом среди основных религий мира. Эта комбинация приводит к религиозному мировоззрению, которое нельзя отнести ни к прямому дуализму, ни к прямому монотеизму, а это означает, что вопрос в заголовке этой статьи представляет собой ложную дихотомию. Мы считаем, что эта дихотомия возникает из-за неспособности достаточно серьезно отнестись к центральной роли, которую играет время в зороастрийской теологии. Зороастризм провозглашает движение во времени от дуализма к монотеизму, т. е. дуализм, который делается ложным динамикой времени, и монотеизм, который делается истинным той же самой динамикой времени. Таким образом, смысл эсхатона в зороастризме заключается в триумфе монотеизма, когда добрый Бог Ахура Мазда наконец добился своего пути к полному и окончательному господству. Но в то же время в дуализме есть жизненно важная истина, пренебрежение которой может привести только к искажению основных учений религии.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Скьярво 2005 , с. 14–15: В число спутников Ахура Мазды входят шесть «Живоносных Бессмертных» и великие боги, такие как Митра, бог Солнца, и другие [...]. К силам зла относятся, в частности, Ангра Манью, Злой Дух, плохие, старые боги ( даэвас ) и Гнев ( аешма ), который, вероятно, воплощает само темное ночное небо. Таким образом, зороастризм — это дуалистическая и политеистическая религия, но с одним верховным богом, который является отцом упорядоченного космоса».

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Скьярво 2005 , стр. 15 со сноской 1.

- ^ Hintze 2014 : «Таким образом, религия, похоже, включает в себя одновременно монотеистические, политеистические и дуалистические черты».

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Слышали о зороастризме? У этой древней религии до сих пор есть пылкие последователи» . Нэшнл Географик . 6 июля 2024 г. Проверено 6 июля 2024 г.

- ^ «Зороастризм» . ИСТОРИЯ . 5 июня 2023 г. Проверено 6 июля 2024 г.

- ^ Круг древних иранских исследований | ИРАНСКАЯ КОСМОГОНИЯ И ДУАЛИЗМ | Автор: Герардо Ньоли.

- ^ «Авеста | Определение, содержание и факты | Британика» . www.britanica.com . Проверено 6 июля 2024 г.

- ^ Роми, Кристин (6 июля 2024 г.). «Слышали о зороастризме? У древней религии до сих пор есть ярые последователи» . Культура. Нэшнл Географик . Проверено 6 июля 2024 г.

- ^ «Спента-Майнью | Ахура Мазда, Высшее Существо, зороастризм | Британника» . www.britanica.com . Проверено 6 июля 2024 г.

- ^ «Ангра-Майнью | Определение и факты | Британника» . www.britanica.com . Проверено 6 июля 2024 г.

- ^ Моральные и этические учения древней зороастрийской религии Чикагского университета, стр. 58-59.

- ^ Масани, сэр Растом. Зороастризм: религия хорошей жизни . Нью-Йорк: Макмиллан, 1968.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Шмитт, Рюдигер (20 июля 2002 г.). «Зороастр и. Имя» . Энциклопедия Ираника . Архивировано из оригинала 16 января 2017 года . Проверено 1 августа 2019 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж Бойс 1983 .

- ^ Рассел, Джеймс Р. (15 декабря 1989 г.). «Бехдин» . Энциклопедия Ираника . Том. IV. Архивировано из оригинала 5 октября 2023 года . Проверено 1 августа 2019 г.

- ^ Каранджиа, Рамияр П. (14 августа 2016 г.). «Понимание наших религиозных титулов» . Парси Таймс . Архивировано из оригинала 21 марта 2023 года . Проверено 30 января 2021 г.

- ^ Браун, Т. (1643) "Религия Медичи"

- ^ «Маздаизм» . Оксфордский справочник . Архивировано из оригинала 28 февраля 2021 года . Проверено 1 августа 2019 г.

- ^ Нагасава, Юджин (10 декабря 2019 г.), «Панпсихизм против пантеизма, политеизма и космопсихизма», The Routledge Handbook of Panpsychism , Routledge, стр. 259–268, doi : 10.4324/9781315717708-22 , ISBN 978-1-315-71770-8

{{citation}}:|access-date=требует|url=( помощь ) - ^ Перейти обратно: а б Сайем, Мэриленд Абу (2011). «Краткий исторический обзор монотеистической концепции в религиозной вере» . Международный журнал истории и исследований . 1 (1): 33–44 – через Researchgate.

- ^ Ферреро, Марио (2021). «От политеизма к монотеизму: Зороастр и некоторые экономические теории» . Хомо Оэкономик . 38 (1–4): 77–108. дои : 10.1007/s41412-021-00113-4 .

- ^ Фольц 2013 , с. xiv.

- ^ Брайан Артур Браун (2016). Четыре Завета: Дао Дэ Цзин, Аналекты, Дхаммапада, Бхагавад Гита: Священные Писания даосизма, конфуцианства, буддизма и индуизма . Издательство Rowman & Littlefield. стр. 347–349. ISBN 978-1-4422-6578-3 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Ферреро, Марио (2021). «От политеизма к монотеизму: Зороастр и некоторые экономические теории» . Хомо Оэкономик . 38 (1–4): 77–108. дои : 10.1007/s41412-021-00113-4 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Хиннеллс, Джон; Уильямс, Алан (2007). Парсы в Индии и диаспоре . Рутледж . п. 165. ИСБН 978-1-134-06752-7 .

- ^ ХИНЦЕ, АЛМУТ (2014). «Монотеизм по зороастрийскому пути» . Журнал Королевского азиатского общества . 24 (2): 225–49. ISSN 1356-1863 . JSTOR 43307294 . Архивировано из оригинала 22 апреля 2021 года . Проверено 5 апреля 2021 г.

- ^ Мехр, Фарханг (2003). Зороастрийская традиция: введение в древнюю мудрость Заратуштры . Издательство Мазда. п. 44. ИСБН 978-1-56859-110-0 . Архивировано из оригинала 31 марта 2024 года . Проверено 7 апреля 2021 г.

- ^ Франсуа Ленорман и Э. Шевалье. Учебное пособие по истории Востока для студентов: мидяне и персы, финикийцы и арабы , с. 38

- ^ Констанс Э. Пламптре (2011). Общий очерк истории пантеизма . Издательство Кембриджского университета. п. 81. ИСБН 9781108028011 . Проверено 14 июня 2017 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с «АХУРА» . Энциклопедия Ираника . Архивировано из оригинала 2 сентября 2023 года . Проверено 13 июля 2019 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Бойс, Мэри (1983), «Ахура Мазда» , Энциклопедия Ираника , том. 1, Нью-Йорк: Routledge & Kegan Paul, стр. 684–687, заархивировано из оригинала 17 мая 2020 г. , получено 13 июля 2019 г.

- ^ «Ахура Мазда» . Архивировано из оригинала 16 июля 2024 года . Проверено 16 июля 2024 г.

- ^ «(PDF) Зороастризм и Библия: монотеизм по совпадению? | Эрхард Герстенбергер - Academia.edu» . Архивировано из оригинала 17 марта 2024 года . Проверено 17 марта 2024 г.

- ^ Фонд, Энциклопедия Ираника. «Митра и — Иранская энциклопедия» . iranicaonline.org . Проверено 24 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Бюхнер 1934 , с. 1161.

- ^ Бойс 2001 , с. XXI.

- ^ Гейгер 1885 , с. XLIX.

- ^ Бойс 2001 , с. 157 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Рафаэлли, Энрико Г. «Амеша-спутники и их помощники: зороастрийские хам-кары» . Архивировано из оригинала 17 марта 2024 года . Проверено 17 марта 2024 г.

- ^ «ГАТАС» . Энциклопедия Ираника . Архивировано из оригинала 30 июня 2019 года . Проверено 13 июля 2019 г.

- ^ «ДЭН» . Энциклопедия Ираника . Архивировано из оригинала 10 августа 2019 года . Проверено 13 июля 2019 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д «Зороастрийские РИТУАЛЫ» . Энциклопедия Ираника . Архивировано из оригинала 30 июня 2019 года . Проверено 13 июля 2019 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и «АṦА (Аша «Истина»)» . Энциклопедия Ираника . Архивировано из оригинала 26 мая 2020 года . Проверено 14 июня 2017 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с «ГЕТЕГ И МЕНОГ» . Энциклопедия Ираника . Архивировано из оригинала 24 июня 2023 года . Проверено 13 июля 2019 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Дружь» . Энциклопедия Ираника . Архивировано из оригинала 5 октября 2023 года . Проверено 14 июня 2017 г.