Анархизм

| Часть серии на |

| Анархизм |

|---|

|

Анархизм - это политическая философия и движение , которое противоречит всем формам власти и стремится отменить институты, которые, как утверждают, поддерживают ненужное принуждение и иерархию , как правило, включая государство и капитализм . Анархизм выступает за замену государства обществами без гражданства и добровольными свободными ассоциациями . Как исторически левое движение, это чтение анархизма помещается в самый дальний левый от политического спектра , обычно описываемый как либертарианское крыло социалистического движения ( либертарианский социализм ).

Хотя следы анархистских идей встречаются на протяжении всей истории, современный анархизм возник из просветления . Во второй половине 19 -го и первых десятилетий 20 -го века анархистское движение процветало в большинстве частей мира и играло значительную роль в борьбе работников за освобождение . Различные анархистские школы мышления сформировались в этот период. Анархисты приняли участие в нескольких революциях , особенно в Парижской коммуне , гражданской войне России и гражданской войне в Испании , конец которого ознаменовала конец классической эры анархизма . В последние десятилетия 20-го и в 21-м веке анархистское движение снова возродилось, растут в популярности и влиянии в антикапиталистических , антивоенных и антиглобализационных движениях.

Anarchists employ diverse approaches, which may be generally divided into revolutionary and evolutionary strategies; there is significant overlap between the two. Evolutionary methods try to simulate what an anarchist society might be like, but revolutionary tactics, which have historically taken a violent turn, aim to overthrow authority and the state. Many facets of human civilization have been influenced by anarchist theory, critique, and praxis.

Etymology, terminology, and definition

The etymological origin of anarchism is from the Ancient Greek anarkhia (ἀναρχία), meaning "without a ruler", composed of the prefix an- ("without") and the word arkhos ("leader" or "ruler"). The suffix -ism denotes the ideological current that favours anarchy.[2] Anarchism appears in English from 1642 as anarchisme and anarchy from 1539; early English usages emphasised a sense of disorder.[3] Various factions within the French Revolution labelled their opponents as anarchists, although few such accused shared many views with later anarchists. Many revolutionaries of the 19th century such as William Godwin (1756–1836) and Wilhelm Weitling (1808–1871) would contribute to the anarchist doctrines of the next generation but did not use anarchist or anarchism in describing themselves or their beliefs.[4]

The first political philosopher to call himself an anarchist (French: anarchiste) was Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (1809–1865), marking the formal birth of anarchism in the mid-19th century. Since the 1890s and beginning in France,[5] libertarianism has often been used as a synonym for anarchism;[6] its use as a synonym is still common outside the United States.[7] Some usages of libertarianism refer to individualistic free-market philosophy only, and free-market anarchism in particular is termed libertarian anarchism.[8]

While the term libertarian has been largely synonymous with anarchism,[9] its meaning has more recently been diluted by wider adoption from ideologically disparate groups,[10] including both the New Left and libertarian Marxists, who do not associate themselves with authoritarian socialists or a vanguard party, and extreme cultural liberals, who are primarily concerned with civil liberties.[10] Additionally, some anarchists use libertarian socialist[11] to avoid anarchism's negative connotations and emphasise its connections with socialism.[10] Anarchism is broadly used to describe the anti-authoritarian wing of the socialist movement.[12][nb 1] Anarchism is contrasted to socialist forms which are state-oriented or from above.[16] Scholars of anarchism generally highlight anarchism's socialist credentials[17] and criticise attempts at creating dichotomies between the two.[18] Some scholars describe anarchism as having many influences from liberalism,[10] and being both liberal and socialist but more so.[19] Many scholars reject anarcho-capitalism as a misunderstanding of anarchist principles.[20][nb 2]

While opposition to the state is central to anarchist thought, defining anarchism is not an easy task for scholars, as there is a lot of discussion among scholars and anarchists on the matter, and various currents perceive anarchism slightly differently.[22][nb 3] Major definitional elements include the will for a non-coercive society, the rejection of the state apparatus, the belief that human nature allows humans to exist in or progress toward such a non-coercive society, and a suggestion on how to act to pursue the ideal of anarchy.[25]

History

Pre-modern era

The most notable precursors to anarchism in the ancient world were in China and Greece. In China, philosophical anarchism (the discussion on the legitimacy of the state) was delineated by Taoist philosophers Zhuang Zhou and Laozi.[27] Alongside Stoicism, Taoism has been said to have had "significant anticipations" of anarchism.[28]

Anarchic attitudes were also articulated by tragedians and philosophers in Greece. Aeschylus and Sophocles used the myth of Antigone to illustrate the conflict between laws imposed by the state and personal autonomy. Socrates questioned Athenian authorities constantly and insisted on the right of individual freedom of conscience. Cynics dismissed human law (nomos) and associated authorities while trying to live according to nature (physis). Stoics were supportive of a society based on unofficial and friendly relations among its citizens without the presence of a state.[29]

In medieval Europe, there was no anarchistic activity except some ascetic religious movements. These, and other Muslim movements, later gave birth to religious anarchism. In the Sasanian Empire, Mazdak called for an egalitarian society and the abolition of monarchy, only to be soon executed by Emperor Kavad I.[30] In Basra, religious sects preached against the state.[31] In Europe, various religious sects developed anti-state and libertarian tendencies.[32]

Renewed interest in antiquity during the Renaissance and in private judgment during the Reformation restored elements of anti-authoritarian secularism in Europe, particularly in France.[33] Enlightenment challenges to intellectual authority (secular and religious) and the revolutions of the 1790s and 1848 all spurred the ideological development of what became the era of classical anarchism.[34]

Modern era

During the French Revolution, partisan groups such as the Enragés and the sans-culottes saw a turning point in the fermentation of anti-state and federalist sentiments.[35] The first anarchist currents developed throughout the 18th century as William Godwin espoused philosophical anarchism in England, morally delegitimising the state, Max Stirner's thinking paved the way to individualism and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon's theory of mutualism found fertile soil in France.[36] By the late 1870s, various anarchist schools of thought had become well-defined and a wave of then-unprecedented globalisation occurred from 1880 to 1914.[37] This era of classical anarchism lasted until the end of the Spanish Civil War and is considered the golden age of anarchism.[36]

Drawing from mutualism, Mikhail Bakunin founded collectivist anarchism and entered the International Workingmen's Association, a class worker union later known as the First International that formed in 1864 to unite diverse revolutionary currents. The International became a significant political force, with Karl Marx being a leading figure and a member of its General Council. Bakunin's faction (the Jura Federation) and Proudhon's followers (the mutualists) opposed state socialism, advocating political abstentionism and small property holdings.[38] After bitter disputes, the Bakuninists were expelled from the International by the Marxists at the 1872 Hague Congress.[39] Anarchists were treated similarly in the Second International, being ultimately expelled in 1896.[40] Bakunin predicted that if revolutionaries gained power by Marx's terms, they would end up the new tyrants of workers. In response to their expulsion from the First International, anarchists formed the St. Imier International. Under the influence of Peter Kropotkin, a Russian philosopher and scientist, anarcho-communism overlapped with collectivism.[41] Anarcho-communists, who drew inspiration from the 1871 Paris Commune, advocated for free federation and for the distribution of goods according to one's needs.[42]

By the turn of the 20th century, anarchism had spread all over the world.[43] It was a notable feature of the international syndicalist movement.[44] In China, small groups of students imported the humanistic pro-science version of anarcho-communism.[45] Tokyo was a hotspot for rebellious youth from East Asian countries, who moved to the Japanese capital to study.[46] In Latin America, Argentina was a stronghold for anarcho-syndicalism, where it became the most prominent left-wing ideology.[47] During this time, a minority of anarchists adopted tactics of revolutionary political violence, known as propaganda of the deed.[48] The dismemberment of the French socialist movement into many groups and the execution and exile of many Communards to penal colonies following the suppression of the Paris Commune favoured individualist political expression and acts.[49] Even though many anarchists distanced themselves from these terrorist acts, infamy came upon the movement and attempts were made to prevent anarchists immigrating to the US, including the Immigration Act of 1903, also called the Anarchist Exclusion Act.[50] Illegalism was another strategy which some anarchists adopted during this period.[51]

Despite concerns, anarchists enthusiastically participated in the Russian Revolution in opposition to the White movement, especially in the Makhnovshchina; however, they met harsh suppression after the Bolshevik government had stabilised, including during the Kronstadt rebellion.[52] Several anarchists from Petrograd and Moscow fled to Ukraine, before the Bolsheviks crushed the anarchist movement there too.[52] With the anarchists being repressed in Russia, two new antithetical currents emerged, namely platformism and synthesis anarchism. The former sought to create a coherent group that would push for revolution while the latter were against anything that would resemble a political party. Seeing the victories of the Bolsheviks in the October Revolution and the resulting Russian Civil War, many workers and activists turned to communist parties, which grew at the expense of anarchism and other socialist movements. In France and the United States, members of major syndicalist movements such as the General Confederation of Labour and the Industrial Workers of the World left their organisations and joined the Communist International.[53]

In the Spanish Civil War of 1936–39, anarchists and syndicalists (CNT and FAI) once again allied themselves with various currents of leftists. A long tradition of Spanish anarchism led to anarchists playing a pivotal role in the war, and particularly in the Spanish Revolution of 1936. In response to the army rebellion, an anarchist-inspired movement of peasants and workers, supported by armed militias, took control of Barcelona and of large areas of rural Spain, where they collectivised the land.[54] The Soviet Union provided some limited assistance at the beginning of the war, but the result was a bitter fight between communists and other leftists in a series of events known as the May Days, as Joseph Stalin asserted Soviet control of the Republican government, ending in another defeat of anarchists at the hands of the communists.[55]

Post-WWII

By the end of World War II, the anarchist movement had been severely weakened.[56] The 1960s witnessed a revival of anarchism, likely caused by a perceived failure of Marxism–Leninism and tensions built by the Cold War.[57] During this time, anarchism found a presence in other movements critical towards both capitalism and the state such as the anti-nuclear, environmental, and peace movements, the counterculture of the 1960s, and the New Left.[58] It also saw a transition from its previous revolutionary nature to provocative anti-capitalist reformism.[59] Anarchism became associated with punk subculture as exemplified by bands such as Crass and the Sex Pistols.[60] The established feminist tendencies of anarcha-feminism returned with vigour during the second wave of feminism.[61] Black anarchism began to take form at this time and influenced anarchism's move from a Eurocentric demographic.[62] This coincided with its failure to gain traction in Northern Europe and its unprecedented height in Latin America.[63]

Around the turn of the 21st century, anarchism grew in popularity and influence within anti-capitalist, anti-war and anti-globalisation movements.[64] Anarchists became known for their involvement in protests against the World Trade Organization (WTO), the Group of Eight and the World Economic Forum. During the protests, ad hoc leaderless anonymous cadres known as black blocs engaged in rioting, property destruction and violent confrontations with the police. Other organisational tactics pioneered at this time include affinity groups, security culture and the use of decentralised technologies such as the Internet. A significant event of this period was the confrontations at the 1999 Seattle WTO conference.[64] Anarchist ideas have been influential in the development of the Zapatistas in Mexico and the Democratic Federation of Northern Syria, more commonly known as Rojava, a de facto autonomous region in northern Syria.[65]

While having revolutionary aspirations, many contemporary forms of anarchism are not confrontational. Instead, they are trying to build an alternative way of social organization (following the theories of dual power), based on mutual interdependence and voluntary cooperation. Scholar Carissa Honeywell takes the example of Food Not Bombs group of collectives, to highlight some features of how contemporary anarchist groups work: direct action, working together and in solidarity with those left behind. While doing so, Food Not Bombs provides consciousness raising about the rising rates of world hunger and suggest policies to tackle hunger, ranging from de-funding the arms industry to addressing Monsanto seed-saving policies and patents, helping farmers, and resisting the commodification of food and housing.[66] Honeywell also emphasizes that contemporary anarchists are interested in the flourishing not only of humans, but non-humans and the environment as well.[67] Honeywell argues that their analysis of capitalism and governments results in anarchists rejecting representative democracy and the state as a whole.[68]

Schools of thought

Anarchist schools of thought have been generally grouped into two main historical traditions, social anarchism and individualist anarchism, owing to their different origins, values and evolution.[69] The individualist current emphasises negative liberty in opposing restraints upon the free individual, while the social current emphasises positive liberty in aiming to achieve the free potential of society through equality and social ownership.[70] In a chronological sense, anarchism can be segmented by the classical currents of the late 19th century and the post-classical currents (anarcha-feminism, green anarchism, and post-anarchism) developed thereafter.[71]

Beyond the specific factions of anarchist movements which constitute political anarchism lies philosophical anarchism which holds that the state lacks moral legitimacy, without necessarily accepting the imperative of revolution to eliminate it.[72] A component especially of individualist anarchism,[73] philosophical anarchism may tolerate the existence of a minimal state but claims that citizens have no moral obligation to obey government when it conflicts with individual autonomy.[74] Anarchism pays significant attention to moral arguments since ethics have a central role in anarchist philosophy.[75] Anarchism's emphasis on anti-capitalism, egalitarianism, and for the extension of community and individuality sets it apart from anarcho-capitalism and other types of economic libertarianism.[20]

Anarchism is usually placed on the far-left of the political spectrum.[76] Much of its economics and legal philosophy reflect anti-authoritarian, anti-statist, libertarian, and radical interpretations of left-wing and socialist politics[13] such as collectivism, communism, individualism, mutualism, and syndicalism, among other libertarian socialist economic theories.[77] As anarchism does not offer a fixed body of doctrine from a single particular worldview,[78] many anarchist types and traditions exist and varieties of anarchy diverge widely.[79] One reaction against sectarianism within the anarchist milieu was anarchism without adjectives, a call for toleration and unity among anarchists first adopted by Fernando Tarrida del Mármol in 1889 in response to the bitter debates of anarchist theory at the time.[80] Belief in political nihilism has been espoused by anarchists.[81] Despite separation, the various anarchist schools of thought are not seen as distinct entities but rather as tendencies that intermingle and are connected through a set of shared principles such as autonomy, mutual aid, anti-authoritarianism and decentralisation.[82]

Classical

Inceptive currents among classical anarchist currents were mutualism and individualism. They were followed by the major currents of social anarchism (collectivist, communist and syndicalist). They differ on organisational and economic aspects of their ideal society.[84]

Mutualism is an 18th-century economic theory that was developed into anarchist theory by Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. Its aims include "abolishing the state",[85] reciprocity, free association, voluntary contract, federation and monetary reform of both credit and currency that would be regulated by a bank of the people.[86] Mutualism has been retrospectively characterised as ideologically situated between individualist and collectivist forms of anarchism.[87] In What Is Property? (1840), Proudhon first characterised his goal as a "third form of society, the synthesis of communism and property."[88] Collectivist anarchism is a revolutionary socialist form of anarchism[89] commonly associated with Mikhail Bakunin.[90] Collectivist anarchists advocate collective ownership of the means of production which is theorised to be achieved through violent revolution[91] and that workers be paid according to time worked, rather than goods being distributed according to need as in communism. Collectivist anarchism arose alongside Marxism but rejected the dictatorship of the proletariat despite the stated Marxist goal of a collectivist stateless society.[92]

Anarcho-communism is a theory of anarchism that advocates a communist society with common ownership of the means of production,[93] held by a federal network of voluntary associations,[94] with production and consumption based on the guiding principle "From each according to his ability, to each according to his need."[95] Anarcho-communism developed from radical socialist currents after the French Revolution[96] but was first formulated as such in the Italian section of the First International.[97] It was later expanded upon in the theoretical work of Peter Kropotkin,[98] whose specific style would go onto become the dominating view of anarchists by the late 19th century.[99] Anarcho-syndicalism is a branch of anarchism that views labour syndicates as a potential force for revolutionary social change, replacing capitalism and the state with a new society democratically self-managed by workers. The basic principles of anarcho-syndicalism are direct action, workers' solidarity and workers' self-management.[100]

Individualist anarchism is a set of several traditions of thought within the anarchist movement that emphasise the individual and their will over any kinds of external determinants.[101] Early influences on individualist forms of anarchism include William Godwin, Max Stirner, and Henry David Thoreau. Through many countries, individualist anarchism attracted a small yet diverse following of Bohemian artists and intellectuals[102] as well as young anarchist outlaws in what became known as illegalism and individual reclamation.[103]

Post-classical and contemporary

Anarchist principles undergird contemporary radical social movements of the left. Interest in the anarchist movement developed alongside momentum in the anti-globalisation movement,[104] whose leading activist networks were anarchist in orientation.[105] As the movement shaped 21st century radicalism, wider embrace of anarchist principles signaled a revival of interest.[105] Anarchism has continued to generate many philosophies and movements, at times eclectic, drawing upon various sources and combining disparate concepts to create new philosophical approaches.[106] The anti-capitalist tradition of classical anarchism has remained prominent within contemporary currents.[107]

Contemporary news coverage which emphasizes black bloc demonstrations has reinforced anarchism's historical association with chaos and violence. Its publicity has also led more scholars in fields such as anthropology and history to engage with the anarchist movement, although contemporary anarchism favours actions over academic theory.[108] Various anarchist groups, tendencies, and schools of thought exist today, making it difficult to describe the contemporary anarchist movement.[109] While theorists and activists have established "relatively stable constellations of anarchist principles", there is no consensus on which principles are core and commentators describe multiple anarchisms, rather than a singular anarchism, in which common principles are shared between schools of anarchism while each group prioritizes those principles differently. Gender equality can be a common principle, although it ranks as a higher priority to anarcha-feminists than anarcho-communists.[110]

Anarchists are generally committed against coercive authority in all forms, namely "all centralized and hierarchical forms of government (e.g., monarchy, representative democracy, state socialism, etc.), economic class systems (e.g., capitalism, Bolshevism, feudalism, slavery, etc.), autocratic religions (e.g., fundamentalist Islam, Roman Catholicism, etc.), patriarchy, heterosexism, white supremacy, and imperialism."[111] Anarchist schools disagree on the methods by which these forms should be opposed.[112] The principle of equal liberty is closer to anarchist political ethics in that it transcends both the liberal and socialist traditions. This entails that liberty and equality cannot be implemented within the state, resulting in the questioning of all forms of domination and hierarchy.[113]

Tactics

Anarchists' tactics take various forms but in general serve two major goals, namely, to first oppose the Establishment and secondly to promote anarchist ethics and reflect an anarchist vision of society, illustrating the unity of means and ends.[114] A broad categorisation can be made between aims to destroy oppressive states and institutions by revolutionary means on one hand and aims to change society through evolutionary means on the other.[115] Evolutionary tactics embrace nonviolence and take a gradual approach to anarchist aims, although there is significant overlap between the two.[116]

Anarchist tactics have shifted during the course of the last century. Anarchists during the early 20th century focused more on strikes and militancy while contemporary anarchists use a broader array of approaches.[117]

Classical era

During the classical era, anarchists had a militant tendency. Not only did they confront state armed forces, as in Spain and Ukraine, but some of them also employed terrorism as propaganda of the deed. Assassination attempts were carried out against heads of state, some of which were successful. Anarchists also took part in revolutions.[118] Many anarchists, especially the Galleanists, believed that these attempts would be the impetus for a revolution against capitalism and the state.[119] Many of these attacks were done by individual assailants and the majority took place in the late 1870s, the early 1880s and the 1890s, with some still occurring in the early 1900s.[120] Their decrease in prevalence was the result of further judicial power and of targeting and cataloging by state institutions.[121]

Anarchist perspectives towards violence have always been controversial.[122] Anarcho-pacifists advocate for non-violence means to achieve their stateless, nonviolent ends.[123] Other anarchist groups advocate direct action, a tactic which can include acts of sabotage or terrorism. This attitude was quite prominent a century ago when seeing the state as a tyrant and some anarchists believing that they had every right to oppose its oppression by any means possible.[124] Emma Goldman and Errico Malatesta, who were proponents of limited use of violence, stated that violence is merely a reaction to state violence as a necessary evil.[125]

Anarchists took an active role in strike actions, although they tended to be antipathetic to formal syndicalism, seeing it as reformist. They saw it as a part of the movement which sought to overthrow the state and capitalism.[126] Anarchists also reinforced their propaganda within the arts, some of whom practiced naturism and nudism. Those anarchists also built communities which were based on friendship and were involved in the news media.[127]

Revolutionary

In the current era, Italian anarchist Alfredo Bonanno, a proponent of insurrectionary anarchism, has reinstated the debate on violence by rejecting the nonviolence tactic adopted since the late 19th century by Kropotkin and other prominent anarchists afterwards. Both Bonanno and the French group The Invisible Committee advocate for small, informal affiliation groups, where each member is responsible for their own actions but works together to bring down oppression utilizing sabotage and other violent means against state, capitalism, and other enemies. Members of The Invisible Committee were arrested in 2008 on various charges, terrorism included.[128]

Overall, contemporary anarchists are much less violent and militant than their ideological ancestors. They mostly engage in confronting the police during demonstrations and riots, especially in countries such as Canada, Greece, and Mexico. Militant black bloc protest groups are known for clashing with the police;[129] however, anarchists not only clash with state operators, they also engage in the struggle against fascists and racists, taking anti-fascist action and mobilizing to prevent hate rallies from happening.[130]

Evolutionary

Anarchists commonly employ direct action. This can take the form of disrupting and protesting against unjust hierarchy, or the form of self-managing their lives through the creation of counter-institutions such as communes and non-hierarchical collectives.[115] Decision-making is often handled in an anti-authoritarian way, with everyone having equal say in each decision, an approach known as horizontalism.[131] Contemporary-era anarchists have been engaging with various grassroots movements that are more or less based on horizontalism, although not explicitly anarchist, respecting personal autonomy and participating in mass activism such as strikes and demonstrations. In contrast with the "big-A Anarchism" of the classical era, the newly coined term "small-a anarchism" signals their tendency not to base their thoughts and actions on classical-era anarchism or to refer to classical anarchists such as Peter Kropotkin and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon to justify their opinions. Those anarchists would rather base their thought and praxis on their own experience, which they will later theorize.[132]

The concept of prefigurative politics is enacted by many contemporary anarchist groups, striving to embody the principles, organization and tactics of the changed social structure they hope to bring about. As part of this the decision-making process of small anarchist affinity groups plays a significant tactical role.[133] Anarchists have employed various methods in order to build a rough consensus among members of their group without the need of a leader or a leading group. One way is for an individual from the group to play the role of facilitator to help achieve a consensus without taking part in the discussion themselves or promoting a specific point. Minorities usually accept rough consensus, except when they feel the proposal contradicts anarchist ethics, goals and values. Anarchists usually form small groups (5–20 individuals) to enhance autonomy and friendships among their members. These kinds of groups more often than not interconnect with each other, forming larger networks. Anarchists still support and participate in strikes, especially wildcat strikes as these are leaderless strikes not organised centrally by a syndicate.[134]

Как и в прошлом, используются газеты и журналы, и анархисты вышли в интернет, чтобы распространить свое сообщение. Анархисты были проще создавать веб -сайты из -за дистрибуции и других трудностей, размещения электронных библиотек и других порталов. [135] Anarchists were also involved in developing various software that are available for free. The way these hacktivists work to develop and distribute resembles the anarchist ideals, especially when it comes to preserving users' privacy from state surveillance.[ 136 ]

Анархисты организуют себя, чтобы приседать и восстановить общественные места . Во время важных событий, таких как протесты и когда пространства занимаются, их часто называют временными автономными зонами (TAZ), пространствами, где искусство , поэзия и сюрреализм смешиваются, чтобы показать анархистский идеал. [ 137 ] Как видно из анархистов, приседание - это способ восстановить городское пространство с капиталистического рынка, удовлетворение прагматических потребностей, а также является образцовым прямым действием. [ 138 ] Приобретение пространства позволяет анархистам экспериментировать со своими идеями и строить социальные связи. [ 139 ] Установите эту тактику, имея в виду, что не все анархисты имеют одинаковое отношение к ним, наряду с различными формами протеста в очень символических событиях, составляют карнавальную атмосферу, которая является частью современной анархистской жарости. [ 140 ]

Ключевые проблемы

Поскольку анархизм - это философия, которая воплощает множество разнообразных взглядов, тенденций и школ мышления, разногласия по вопросам ценностей, идеологии и тактики . Его разнообразие привело к широкому использованию идентичных терминов между различными анархистскими традициями, что создало ряд определения в анархистской теории . Совместимость капитализма , [ 141 ] Национализм и религия с анархизмом широко оспариваются, и анархизм обладает сложными отношениями с такими идеологиями, как коммунизм, коллективизм , марксизм и профсоюзный . Анархисты могут быть мотивированы гуманизмом , божественной властью , просвещенным личным интересом , веганством или любым количеством альтернативных этических доктрин. Такие явления, как цивилизация , технологии (например, в рамках анархо-лифтивизма) и демократический процесс , могут подвергаться резкой критике в рамках некоторых анархистских тенденций и одновременно хвалится в других. [ 142 ]

Государство

Возражение против государства и его институтов - это не анархизм. [ 143 ] Анархисты считают государство как инструмент господства и считают, что оно является незаконным независимо от его политических тенденций. принимает основные решения Вместо того, чтобы люди могли контролировать аспекты своей жизни, небольшая элита . В конечном итоге власть опирается исключительно на власть, независимо от того, является ли эта власть открытой или прозрачной , поскольку она все еще имеет возможность принуждать людей. Еще один анархистский аргумент против государств заключается в том, что люди, составляющие правительство, даже самое альтруистическое среди чиновников, неизбежно стремятся получить больше власти, что приведет к коррупции. Анархисты считают идею о том, что государство является коллективной волей народа, чтобы быть недостижимой художественной литературой из -за того, что правящий класс отличается от остальной части общества. [ 144 ]

Конкретное анархистское отношение к государству различается. Роберт Пол Вольф полагал, что напряженность между властью и автономией будет означать, что государство никогда не может быть законным. Бакунин считал, что государство означает «принуждение, доминирование посредством принуждения, замаскированное, если это возможно, но не рецертиниально и явное, если необходимо». А. Джон Симмонс и Лесли Грин , которые склонялись к философскому анархизму, полагали, что государство может быть законным, если оно регулируется консенсусом, хотя они считали это крайне маловероятным. [ 145 ] Убеждения о том, как отменить государство, также различаются. [ 146 ]

Пол, сексуальность и бесплатная любовь

Поскольку пол и сексуальность несут в себе динамику иерархии, многие анархисты обращаются, анализируют и выступают против подавления своей автономии, налагаемой гендерными ролями. [ 147 ]

Сексуальность часто обсуждалась классическими анархистами, а те немногие, которые чувствовали, что анархистское общество приведет к естественным развитию сексуальности. [ 148 ] Сексуальное насилие было проблемой для анархистов, таких как Бенджамин Такер , который выступал против законов о возрасте согласия , полагая, что они принесут пользу хищным мужчинам. [ 149 ] Исторический поток, который возник и процветал в 1890 и 1920 годах в рамках анархизма, был свободной любовью . В современном анархизме этот ток сохраняется как тенденция поддерживать полиаморию , анархию отношений и квир анархизм . [ 150 ] Свободные защитники любви были против брака , который они считали способом, чтобы мужчины навязывали власть над женщинами , в основном потому, что закон о браке значительно предпочитал власть мужчин. Понятие свободной любви было намного шире и включало критику установленного порядка, который ограничивал сексуальную свободу и удовольствие женщин. [ 151 ] Эти бесплатные любовные движения способствовали созданию коммунальных домов, где большие группы путешественников, анархистов и других активистов спали в постели вместе. [ 152 ] Свободная любовь имела корни как в Европе, так и в Соединенных Штатах; Тем не менее, некоторые анархисты боролись с ревностью, возникшей от свободной любви. [ 153 ] Анархистские феминистки были сторонниками свободной любви, против брака и за выбор (используя современный термин) и имели аналогичную повестку дня. Анархистские и ненархистские феминистки отличались от избирательного права , но поддерживали друг друга. [ 154 ]

Во второй половине 20 -го века анархизм смешался со второй волной феминизма , радикализация некоторых течений феминистского движения и оказав также влияние. К последним десятилетиям 20 -го века анархисты и феминистки выступали за права и автономию женщин, геев, Queers и других маргинальных групп, а некоторые феминистские мыслители предлагают слияние двух токов. [ 155 ] С третьей волной феминизма сексуальная идентичность и обязательная гетеросексуальность стали предметом исследования для анархистов, что дает постструктуралистскую критику сексуальной нормальности . [ 156 ] Некоторые анархисты дистанцировались от этой линии мышления, предполагая, что он склонялся к индивидуализму, который отбрасывал дело социального освобождения. [ 157 ]

Образование

| Анархистское образование | Государственное образование | |

|---|---|---|

| Концепция | Образование как самообладание | Образование в качестве услуги |

| Управление | Сообщество | Государственный пробег |

| Методы | Практическое обучение | Профессиональная подготовка |

| Цели | Быть критическим членом общества | Быть продуктивным членом общества |

Интерес анархистов к образованию возрождается на первое появление классического анархизма. Анархисты считают правильное образование, которое устанавливает основы будущей автономии человека и общества, как акт взаимной помощи . [ 159 ] Анархистские писатели, такие как Уильям Годвин ( политическая справедливость ) и Макс Стирнер (« ложный принцип нашего образования »), напали на государственное образование, так и частное образование , как еще одно средство, с помощью которого правящий класс повторяет свои привилегии. [ 160 ]

В 1901 году каталонский анархист и свободный мыслитель Франсиско Феррер основал Escuela Moderna в Барселоне в качестве противодействия установленной системе образования, которая была в значительной степени продиктована католической церковью. [ 161 ] Подход Феррера был светским, отвергая как государственное, так и церковное участие в образовательном процессе, в то же время давая ученикам большое количество автономии в планировании их работы и посещаемости. Феррер стремился обучить рабочий класс и явно стремился развивать классовое сознание среди студентов. Школа закрылась после постоянного преследования со стороны штата, а Феррер был позже арестован. Тем не менее, его идеи сформировали вдохновение для серии современных школ по всему миру. [ 162 ] Христианский анархист Лео Толстой эссе , который опубликовал образование и культуру , также создал аналогичную школу с его основополагающим принципом, заключающейся в том, что «для того, чтобы образование было эффективным, оно должно быть свободным». [ 163 ] В аналогичном токене, когда Нил основал то, что стало школой Саммерхилл в 1921 году, также объявив, что он свободен от принуждения. [ 164 ]

Анархистское образование основано во многом на идее, что право ребенка на свободу развиваться и без манипуляций должно быть уважаемо, и что рациональность приведет детей к морально хорошим выводам; Тем не менее, среди анархистских фигур было мало консенсуса относительно того, что составляет манипуляции . Феррер полагал, что моральная идеологическая обработка была необходима, и явно научил учеников, что равенство, свобода и социальная справедливость не были возможны под капитализмом, наряду с другими критиками правительства и национализма. [ 165 ]

Конец 20 -го века и современные анархистские писатели ( Пол Гудман , Герберт Рид и Колин Уорд ) усилили и расширили анархистскую критику государственного образования , в значительной степени сосредоточившись на необходимости системы, которая фокусируется на творчестве детей, а не на их способности достичь карьеры или участвовать в потребительстве как часть потребительского общества. [ 166 ] Современные анархисты, такие как Уорд, утверждают, что государственное образование служит для увековечивания социально -экономического неравенства . [ 167 ]

В то время как немногие анархистские учебные заведения выжили в современных, основных принципах анархистских школ, среди них уважение к автономии ребенка и полагаясь на рассуждения, а не на идеологическую обработку в качестве метода обучения, распространились среди основных учебных заведений. Джудит Суйсса называет три школы как явные школы анархистов, а именно бесплатный племян Испания. [ 168 ]

Искусство

Связь между анархизмом и искусством была довольно глубокой в классическую эру анархизма, особенно среди художественных течений, которые развивались в ту эпоху, такие как футуристы, сюрреалисты и другие. [ 170 ] В литературе анархизм был в основном ассоциирован с новой апокалиптикой и неоронутическим движением. [ 171 ] В музыке анархизм был связан с музыкальными сценами, такими как панк . [ 172 ] Анархисты, такие как Лео Толстой и Герберт Рид, заявили, что граница между художником и небортистом, которая отделяет искусство от ежедневного акта, является конструкцией, вызванной отчуждением, вызванным капитализмом, и не позволяет людям жить радостной жизнью. [ 173 ]

Другие анархисты выступали за или использовали искусство в качестве средства для достижения анархистских целей. [ 174 ] В своей книге « Разбивая заклинание: история анархистских кинематографистов, видеозаписей партизан и цифровых ниндзя », Крис Робе утверждает, что «анархистские практики все чаще структурировали видео-активизм на основе движения». [ 175 ] В течение 20 -го века многие выдающиеся анархисты ( Питер Кропоткин , Эмма Голдман , Густав Ландауэр и Камилло Бернери ) и публикации, такие как Анархия, писали о вопросах, относящихся к искусству. [ 176 ]

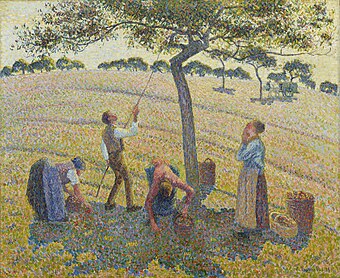

Три перекрывающихся свойства сделали искусство полезным для анархистов. Он может изобразить критику существующего общества и иерархий, служить префигуративным инструментом для отражения анархистского идеального общества и даже превращения в средства прямых действий, например, в протестах. Поскольку это привлекает как эмоции, так и разум, искусство может понравиться всему человеку и иметь мощный эффект. [ 177 ] движение 19-го века Неимпрессионистское имело экологическую эстетику и привело пример анархистского восприятия дороги к социализму. [ 178 ] В Les Chataigniers Anarchist Painter Camille Camille Pissarro смешивание эстетической и социальной гармонии предвещает идеальное анархистское аграрное сообщество. [ 169 ]

Критика

Наиболее распространенной критикой анархизма является утверждение о том, что люди не могут самоуправляться , и поэтому для выживания человека необходимо государство. Философ Бертран Рассел поддержал эту критику, заявив, что «[P] и война, тарифы , правила санитарных условий и продажа вредных лекарств , сохранение справедливой системы распределения: это, среди прочего, являются функциями, которые вряд ли могут быть Выступал в сообществе, в котором не было центрального правительства ». [ 179 ] Другая распространенная критика анархизма заключается в том, что он подходит миру изоляции , в котором только достаточно маленькие сущности могут быть самоуправляющими; Ответ будет заключаться в том, что крупные анархистские мыслители выступали за анархистский федерализм. [ 180 ]

Другая критика анархизма - это вера в то, что она по своей сути нестабильна: что анархистское общество неизбежно вырастет обратно в государство. Томас Гоббс и другие теоретики раннего общественного контракта утверждали, что государство появляется в ответ на естественную анархию, чтобы защитить интересы народа и поддерживать порядок. Философ Роберт Нозик утверждал, что « государство ночного наблюдения », или минархия, появится из анархии в процессе невидимой руки , в которой люди будут осуществлять свою свободу и покупать защиту от защитных агентств, превращаясь в минимальное состояние. Анархисты отвергают эту критику, утверждая, что люди в состоянии природы будут не только в состоянии войны. В частности, анархо-пермитивисты утверждают, что люди были лучше в состоянии природы в мелких племенах, живущих близко к земле , в то время как анархисты в целом утверждают, что негативы государственной организации, такие как иерархии, монополии и неравенство, перевешивают преимущества. [ 181 ]

Лектор философии Эндрю Г. Фиала составил список общих аргументов против анархизма, который включает в себя критические замечания, такая как то, что анархизм врожденно связан с насилием и разрушением не только в прагматическом мире, например, в протестах, но и в мире этики. Во -вторых, анархизм оценивается как невозможный или утопический, поскольку государство не может быть побеждено практически. Эта линия аргументов чаще всего требует политических действий в системе, чтобы реформировать ее. Третий аргумент состоит в том, что анархизм является самообладающим как правящая теория, которая не имеет теории правления. Анархизм также требует коллективных действий, одновременно одобряя автономию человека, поэтому нельзя предпринять никаких коллективных действий. Наконец, Фиала упоминает критику в отношении философского анархизма неэффективного (все разговоры и мысли), а в то же время капитализм и буржуазный класс остаются сильными. [ 182 ]

Философский анархизм встретил критику членов академии после освобождения про-анархистских книг, таких как А. Джона Симмонса моральные принципы и политические обязательства . [ 183 ] Профессор права Уильям А. Эдмундсон написал эссе, чтобы спорить с тремя крупными философскими анархистскими принципами, которые он находит ошибочным. Эдмундсон говорит, что, хотя человек не обязан государству обязанностью послушать, это не означает, что анархизм является неизбежным выводом, а государство все еще морально законное. [ 184 ] В проблеме политической власти Майкл Хумер защищает философский анархизм, [ 185 ] утверждая, что «политическая власть - это моральная иллюзия». [ 186 ]

Одна из самых ранних критических замечаний заключается в том, что анархизм бросает вызов и не понимает биологическую склонность к власти. [ 187 ] Джозеф Раз утверждает, что принятие власти подразумевает убеждение, что следование их инструкциям позволит получить больший успех. [ 188 ] Раз считает, что этот аргумент верен в соответствии с успешным и ошибочным инструкцией обоих властей. [ 189 ] Анархисты отвергают эту критику, потому что оспаривание или непослушание власти не влечет за собой исчезновение ее преимуществ, признавая такую власть, как врачи или адвокаты как надежные, а также не включает в себя полную отказ от независимого суждения. [ 190 ] Анархистское восприятие человеческой природы, отказ от государства и приверженность социальной революции подвергалось критике со стороны ученых как наивные, чрезмерно упрощенные и нереалистичные, соответственно. [ 191 ] Классический анархизм подвергся критике за то, что он слишком сильно полагается на веру в то, что отмена государства приведет к процветанию сотрудничества в человеческом человеке. [ 148 ]

Фридрих Энгельс , который считается одним из главных основателей марксизма, критиковал антиавторитаризм анархизма как контрреволюционный, потому что, по его мнению, революция сама по себе является авторитарной. [ 192 ] Академик Джон Молинье пишет в своей книге анархизм: марксистская критика , что «анархизм не может победить», полагая, что ему не хватает способности должным образом реализовать свои идеи. [ 193 ] Марксистская критика анархизма заключается в том, что он имеет утопический характер, потому что у всех людей должны быть анархистские взгляды и ценности. Согласно марксистскому взгляду, что социальная идея будет следовать непосредственно от этого человеческого идеала и из свободной воли каждого человека, сформированной своей сущности. Марксисты утверждают, что это противоречие было ответственным за их неспособность действовать. В анархистском видении конфликт между свободой и равенством был разрешен посредством сосуществования и переплетения. [ 194 ]

Смотрите также

- Схема анархизма

- Список анархистских движений по региону

- Список анархистских политических идеологий

- Список книг об анархизме

- Список фильмов, касающихся анархизма

Анархистские сообщества

- Список общества без гражданства

- Список преднамеренных сообществ

- Список самоуправленных социальных центров

Ссылки

Пояснительные заметки

- ^ В анархизме: от теории к практике (1970), [ 13 ] Анархистский историк Даниэль Герин описал это как синоним либертарианского социализма и писал, что анархизм «действительно является синонимом социализма. Анархист - это, прежде всего, социалист, цель которого состоит в Социалистической мысли, того потока, чьи основные компоненты заботятся о свободе и спешке, чтобы отменить государство ». [ 14 ] В своих многочисленных работах по анархизму историк Ноам Хомский описывает анархизм наряду с либертарианским марксизмом , как либертарианское крыло социализма . [ 15 ]

- ^ Герберт Л. Осгуд утверждал, что анархизм является «крайней антитезой» авторитарного коммунизма и государственного социализма . [ 16 ] Петр Маршалл утверждает, что «[я] общий анархизм ближе к социализму, чем либерализм ... Анархизм оказывается в значительной степени в социалистическом лагере, но он также обладает возмущными в либерализме. Его нельзя свести к социализму и лучше всего рассматривать как как Отдельная и отличительная доктрина ". [ 10 ] Согласно Джереми Дженнингсу , «[я] не может сделать вывод, что эти идеи», относящиеся к анархо-капитализму », описываются как анархисты только на основе недопонимания того, что такое анархизм». Дженнингс добавляет, что «анархизм не вызывает непрерывную свободу человека (как кажется,« анархо-капиталисты »), но, как мы уже видели, для расширения индивидуальности и общины». [ 21 ] Николас Уолтер писал, что «анархизм происходит из либерализма и социализма как исторически, так и идеологически. Либералы, но больше, и социалисты, но больше, ". [ 19 ] Майкл Ньюман включает в себя анархизм как одну из многих социалистических традиций , особенно более выравниваемые социалистическими традициями после Прайдхона и Михаила Бакунина . [ 17 ] Брайан Моррис утверждает, что «концептуально и исторически вводит в заблуждение», чтобы «создать дихотомию между социализмом и анархизмом». [ 18 ]

- ^ Одно общее определение, принятое анархистами, заключается в том, что анархизм является группой политической философии, противоположной власти и иерархической организации , включая капитализм , национализм , государство и все связанные институты , в поведении всех человеческих отношений в пользу общества, основанного на децентрализации , свобода и добровольная ассоциация . Ученые подчеркивают, что это определение имеет те же недостатки, что и определение, основанное на антиавторитаризме ( задний вывод), антистатизм (анархизм гораздо больше, чем это), [ 23 ] и этимология (отрицание правителей). [ 24 ]

Цитаты

- ^ Carlson 1972 , стр. 22-23.

- ^ Бейтс 2017 , с. 128; Long 2013 , p. 217

- ^ Merriam-Webster 2019 , «Анархизм»; Оксфордский английский словарь 2005 , «Анархизм»; Сильван 2007 , с. 260

- ^ Joll 1964 , стр. 27–37.

- ^ Nettlau 1996 , p. 162.

- ^ Гурин 1970 , «Основные идеи анархизма».

- ^ Ward 2004 , p. 62; Goodway 2006 , p. 4; 2002 Написание , с. 183; Фернандес 2009 , с. 9

- ^ Моррис 2002 , с. 61.

- ^ Маршалл 1992 , с. 641; Cohn 2009 , p. 6

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и Marshall 1992 , p. 641.

- ^ Маршалл 1992 , с. 641; Cohn 2009 , p. 6; Levy & Adams 2018 , с. 104

- ^ Леви и Адамс 2018 , с. 104

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Герин 1970 , с. 12

- ^ Arvidsson 2017 .

- ^ Otero 1994 , p. 617.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Осгуд 1889 , с. 1

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Newman 2005 , p. 15

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Morris 2015 , p. 64

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Walter 2002 , p. 44

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Marshall 1992 , с. 564–565; Дженнингс 1993 , с. 143; Gay & Gay 1999 , p. 15; Моррис 2008 , с. 13; Джонсон 2008 , с. 169; Franks 2013 , с. 393–394.

- ^ Дженнингс 1999 , с. 147

- ^ Long 2013 , с. 217

- ^ Маклафлин 2007 , с. 166; Jun 2009 , с. 507; Franks 2013 , с. 386–388.

- ^ McLaughlin 2007 , с. 25–29; Long 2013 , с. 217.

- ^ McLaughlin 2007 , с. 25–26.

- ^ Маршалл 1993 , с. 70

- ^ Coutinho 2016 ; Marshall 1993 , p. 54

- ^ Сильван 2007 , с. 257

- ^ Маршалл 1993 , с. 4, 66–73.

- ^ Маршалл 1993 , с. 86

- ^ Крона 2000 , с. 3, 21-25.

- ^ Nettlau 1996 , p. 8

- ^ Маршалл 1993 , с. 108

- ^ Леви и Адамс 2018 , с. 307

- ^ Маршалл 1993 , с. 4

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Маршалл 1993 , с. 4–5.

- ^ Levy 2011 , с. 10–15.

- ^ Додсон 2002 , с. 312; Thomas 1985 , p. 187; Chaliand & Blin 2007 , p. 116

- ^ Грэм 2019 , с. 334–336; Marshall 1993 , p. 24

- ^ Леви 2011 , с. 12

- ^ Маршалл 1993 , с. 5

- ^ Грэм 2005 , с. Полем

- ^ Moya 2015 , p. 327.

- ^ Леви 2011 , с. 16

- ^ Маршалл 1993 , с. 519–521.

- ^ Dirlik 1991 , p. 133; Ramnath 2019 , стр. 681–682.

- ^ Леви 2011 , с. 23; Laursen 2019 , с. 157; Маршалл 1993 , с. 504–508.

- ^ Маршалл 1993 , с. 633–636.

- ^ Андерсон 2004 .

- ^ Маршалл 1993 , с. 633–636; Lutz & Ulmschneider 2019 , с. 46

- ^ Bantman 2019 , с. 374.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Avrich 2006 , p. 204

- ^ Кочевник 1966 , с. 88

- ^ Боллотен 1984 , с.

- ^ Маршалл 1993 , с. XI, 466.

- ^ Маршалл 1993 , с. Xi.

- ^ Маршалл 1993 , с. 539.

- ^ Маршалл 1993 , с. XI, 539.

- ^ Levy 2011 , с. 5.

- ^ Маршалл 1993 , с. 493–494.

- ^ Маршалл 1993 , с. 556–557.

- ^ Уильямс 2015 , с. 680.

- ^ Хармон 2011 , с. 70

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Руперт 2006 , с. 66

- ^ Рамнатх 2019 , с. 691.

- ^ Honeywell 2021 , с. 34–44.

- ^ Honeywell 2021 , с. 1–2.

- ^ Honeywell 2021 , с. 1–3.

- ^ McLean & McMillan 2003 , «Анархизм»; Ostergaard 2003 , p. 14, «Анархизм».

- ^ Harrison & Boyd 2003 , p. 251.

- ^ Леви и Адамс 2018 , с. 9

- ^ Egoumenides 2014 , p. 2

- ^ Ostergaard 2003 , p. 12; Габарди 1986 , с. 300-302.

- ^ Klosko 2005 , p. 4

- ^ Franks 2019 , с. 549.

- ^ Брукс 1994 , с. XI; Кан 2000 ; Мойнихан 2007 .

- ^ Маршалл 1993 , с. 14–17.

- ^ Сильван 2007 , с. 262

- ^ Аврих 1996 , с. 6

- ^ Walter 2002 , p. 52

- ^ Маршалл 1993 , с. 1–6; Angelbeck & Grier 2012 , с. 551.

- ^ Уилбур 2019 , с. 216–218.

- ^ Леви и Адамс 2018 , с. 2

- ^ Райт, Эдмунд, изд. (2006). Стол Энциклопедия мировой истории . Нью -Йорк: издательство Оксфордского университета . С. 20–21. ISBN 978-0-7394-7809-7 .

- ^ Уилбур 2019 , с. 213–218.

- ^ Аврих 1996 , с. 6; Миллер 1991 , с. 11

- ^ Pierson 2013 , p. 187.

- ^ Моррис 1993 , с. 76

- ^ Шеннон 2019 , с. 101.

- ^ Avrich 1996 , с. 3–4.

- ^ Heywood 2017 , с. 146–147; Бакунин 1990 .

- ^ Мейн 1999 , с. 131.

- ^ Маршалл 1993 , с. 327.

- ^ Маршалл 1993 , с. 327; Turcato 2019 , с. 237–238.

- ^ Грэм 2005 .

- ^ Pernicone 2009 , стр. 111-113.

- ^ Turcato 2019 , стр. 239–244.

- ^ Леви 2011 , с. 6

- ^ Van der Walt 2019 , p. 249

- ^ Ryley 2019 , с. 225

- ^ Маршалл 1993 , с. 440.

- ^ Имри 1994 ; Parry 1987 , p. 15

- ^ Even 2011 , с. 1

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Even 2011 , с. 2

- ^ Уильямс 2007 , с. 303.

- ^ Уильямс 2018 , с. 4

- ^ Уильямс 2010 , с. 110; Even 2011 , с. 1; Angelbeck & Grier 2012 , с. 549.

- ^ Franks 2013 , с. 385–386.

- ^ Franks 2013 , p. 386.

- ^ Июнь 2009 г. , стр. 507–508.

- ^ Jun 2009 , с. 507

- ^ Egoumenides 2014 , p. 91

- ^ Williams 2019 , с. 107–108.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Williams 2018 , с. 4–5.

- ^ Кинна 2019 , с.

- ^ Уильямс 2019 , с. 112.

- ^ Williams 2019 , с. 112–113.

- ^ Норрис 2020 , с. 7–8.

- ^ Леви 2011 , с. 13; Nesser 2012 , с. 62

- ^ Хармон 2011 , с. 55

- ^ Картер 1978 , с. 320.

- ^ Fiala 2017 , раздел 3.1.

- ^ Kinna 2019 , стр. 116-117.

- ^ Картер 1978 , с. 320–325.

- ^ Уильямс 2019 , с. 113.

- ^ Уильямс 2019 , с. 114

- ^ Kinna 2019 , стр. 134-135.

- ^ Уильямс 2019 , с. 115.

- ^ Уильямс 2019 , с. 117

- ^ Williams 2019 , с. 109–117.

- ^ Kinna 2019 , стр. 145-149.

- ^ Williams 2019 , с. 109, 119.

- ^ Williams 2019 , с. 119–121.

- ^ Williams 2019 , с. 118–119.

- ^ Williams 2019 , с. 120–121.

- ^ Кинна 2019 , с. 139; Mattern 2019 , p. 596; Williams 2018 , с. 5–6.

- ^ Кинна 2012 , с. 250; Williams 2019 , p. 119

- ^ Уильямс 2019 , с. 122

- ^ Morland 2004 , с. 37–38.

- ^ Маршалл 1993 , с. 565; Honderich 1995 , p. 31; Плавал 2000 , с. 50; Goodway 2006 , p. 4; Newman 2010 , с. 53

- ^ De George 2005 , стр. 31–32.

- ^ Картер 1971 , с. 14; Jun 2019 , с. 29–30.

- ^ Июнь 2019 , стр. 32–38.

- ^ Wendt 2020 , с. 2; Эшвуд 2018 , с. 727.

- ^ Эшвуд 2018 , с. 735.

- ^ Николас 2019 , с. 603.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Люси 2020 , с. 162.

- ^ Люси 2020 , с. 178.

- ^ Николас 2019 , с. 611; Jeppeesen & Nazar 2012 , стр. 175-176.

- ^ Jeppesen & Nazar 2012 , с. 175–176.

- ^ Jeppesen & Nazar 2012 , с.

- ^ Jeppesen & Nazar 2012 , с. 175–177.

- ^ Kinna 2019 , стр. 166-167.

- ^ Николас 2019 , с. 609–611.

- ^ Николас 2019 , с. 610–611.

- ^ Николас 2019 , с. 616–617.

- ^ Кинна 2019 , с.

- ^ Kinna 2019 , стр. 83-85.

- ^ Suissa 2019 , стр. 514, 521; Kinna 2019 , с. 83-86; Marshall 1993 , p. 222

- ^ Только 2019 , с. 511-512.

- ^ Только 2019 , с. 511-514.

- ^ Только 2019 , с. 517-518.

- ^ Только 2019 , с. 518-519.

- ^ Аврих 1980 , стр. 3-33; Утверждение 2019 , с. 519-522.

- ^ Kinna 2019 , стр. 89-96.

- ^ Ward 1973 , pp. 39–48.

- ^ Только 2019 , с. 523-526.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Antliff 1998 , p. 99

- ^ Материал 2019 , с. 592.

- ^ Гиффорд 2019 , с. 577.

- ^ Маршалл 1993 , с. 493–494; Dunn 2012 ; Even, Kinna & Rouselle 2013 .

- ^ Mattern 2019 , с. 592–593.

- ^ Материал 2019 , с. 593.

- ^ Я украду 2017 , с. 44

- ^ Miller et al. 2019 , с. 1

- ^ Mattern 2019 , с. 593–596.

- ^ Antliff 1998 , p. 78

- ^ Crimerman & Perry 1966 , p. 494.

- ^ Ward 2004 , p. 78

- ^ Фиала, Эндрю (2021), «Анархизм» , в Залте, Эдвард Н. (ред.), Стэнфордская энциклопедия философии (Зима 2021 года изд.), Исследовательская лаборатория метафизики, Стэнфордский университет , извлечен 17 июня 2023 года.

- ^ Fiala 2017 , «4. Возражения и ответы».

- ^ Клоско 1999 , с. 536.

- ^ Клоско 1999 , с. 536; Kristjánsson 2000 , p. 896.

- ^ Кинжал 2018 , с. 35

- ^ Роджерс 2020 .

- ^ Фергюсон 1886 .

- ^ Ганс 1992 , с. 37

- ^ Ганс 1992 , с. 38

- ^ Gans 1992 , с. 34, 38.

- ^ Брим 2020 , с. 206

- ^ Такер 1978 .

- ^ Доддс 2011 .

- ^ Baár et al. 2016 , с. 488.

Общие и цитируемые источники

Первичные источники

- Бакунин, Михаил (1990) [1873]. Шац, Маршалл (ред.). Статизм и анархия . Кембридж текст в истории политической мысли. Перевод Шаца, Маршалл. Кембридж, Англия: издательство Кембриджского университета . doi : 10.1017/cbo9781139168083 . ISBN 978-0-5213-6182-8 Полем LCCN 89077393 . OCLC 20826465 .

Вторичные источники

- Ангелбек, Билл; Грир, Колин (2012). «Анархизм и археология анархических обществ: сопротивление централизации в побережье Салиш -районе на северо -западном побережье Тихого океана» . Текущая антропология . 53 (5): 547–587. doi : 10.1086/667621 . ISSN 0011-3204 . S2CID 142786065 . Архивировано из оригинала 21 июля 2018 года . Получено 24 июня 2021 года .

- Antliff, Mark (1998). «Кубизм, футуризм, анархизм:« эстетизм »группы" Action d'Art ", 1906–1920». Оксфордский художественный журнал . 21 (2): 101–120. doi : 10.1093/oxartj/21.2.99 . JSTOR 1360616 .

- Андерсон, Бенедикт (2004). «В мировой тени Бисмарка и Нобелевской» . Новый левый обзор . 2 (28): 85–129. Архивировано из оригинала 19 декабря 2015 года . Получено 7 января 2016 года .

- Аврих, Пол (1995). Анархистские голоса: устная история анархизма в Америке . Принстон: издательство Принстонского университета. ISBN 978-0-6910-3412-6 Полем OCLC 68772773 .

- Arvidsson, Stefan (2017). Стиль и мифология социализма: социалистический идеализм, 1871–1914 (1 -е изд.). Лондон: Routledge . ISBN 978-0-3673-4880-9 .

- Эшвуд, Лока (2018). «Сельский консерватизм или анархизм? Сельская социология . 83 (4): 717–748. doi : 10.1111/ruso.12226 . S2CID 158802675 .

- Аврих, Пол (1996). Анархистские голоса: устная история анархизма в Америке . ПРИЗНАЯ УНИВЕРСИТЕТА ПРИСЕТА . ISBN 978-0-6910-4494-1 .

- —— (2006). Русские анархисты . Стерлинг: Ак Пресс . ISBN 978-1-9048-5948-2 .

- —— (1980). Современное школьное движение: анархизм и образование в Соединенных Штатах . ПРИЗНАЯ УНИВЕРСИТЕТА ПРИСЕТА . С. 3–33. ISBN 978-1-4008-5318-2 Полем OCLC 489692159 .

- Бар, Моника; Фалина, Мария; Яновски, Макия; Kopeček, Michal; Trencsényi, Balázs Trencesioni (2016). История современной политической мысли в Восточной Центральной Европе: ведение переговоров о современности в «длинном девятнадцатом веке» . Том. Оксфорд: издательство Оксфордского университета . ISBN 978-0-1910-5695-6 .

- Бантман, Констанс (2019). «Эра пропаганды поступок» . В Леви, Карл ; Адамс, Мэтью С. (ред.). Пальмовая справочник анархизма . Springer Publishing . С. 371–388. ISBN 978-3-3197-5620-2 .

- Бейтс, Дэвид (2017). «Анархизм» . В Wetherly, Пол (ред.). Политические идеологии . Издательство Оксфордского университета . ISBN 978-0-1987-2785-9 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 18 февраля 2021 года . Получено 28 февраля 2019 года .

- Bolloten, Burnett (1984). Гражданская война в Испании: революция и контрреволюция . Университет Северной Каролины Пресс . ISBN 978-0-8078-1906-7 .

- Бринн, Gearóid (2020). «Нежно разбивая государство: радикальный реализм и реалистический анархизм». Европейский журнал политической теории . 19 (2): 206–227. doi : 10.1177/14748855119865975 . S2CID 202278143 .

- Брукс, Фрэнк Х. (1994). Индивидуалистические анархисты: антология свободы (1881–1908) . ПРИБОРЫ Издатели. ISBN 978-1-5600-0132-4 .

- Карлсон, Эндрю Р. (1972). Анархизм в Германии; Тол. 1: раннее движение . Metuchen, Нью -Джерси: Пресса ScareCrow. ISBN 978-0-8108-0484-5 .

- Картер, апрель (1971). Политическая теория анархизма . Routledge . ISBN 978-0-4155-5593-7 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 15 января 2021 года . Получено 7 марта 2019 года .

- Картер, апрель (1978). «Анархизм и насилие». Номос 19 Американское общество политической и юридической философии: 320–340. JSTOR 24219053 .

- Чалянин, Джерард; Блин, Арно, ред. (2007). История терроризма: от античности до Аль-Кваиды . Беркли; Лос -Анджелес; Лондон: издательство Калифорнийского университета . ISBN 978-0-5202-4709-3 Полем OCLC 634891265 .

- Cohn, Jesse (2009). "Анархизм". В Несс, Иммануэль (ред.). Международная энциклопедия революции и протеста . Оксфорд: Джон Уайли и сыновья . С. 1–11. doi : 10.1002/9781405198073.wbierp0039 . ISBN 978-1-4051-9807-3 .

- Крона, Патриция (2000). «Мусульманские анархисты девятого века» (PDF) . Прошлое и настоящее (167): 3–28. doi : 10.1093/прошлое/167.1.3 . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 28 августа 2020 года . Получено 3 января 2022 года .

- Кинжал, Тристан Дж. (2018). Играть справедливо: политические обязательства и проблемы наказания . Оксфорд: издательство Оксфордского университета . ISBN 978-0-1993-8883-7 .

- Дирлик, Ариф (1991). Анархизм в китайской революции . Беркли: Университет Калифорнийской прессы . ISBN 978-0-5200-7297-8 .

- Доддс, Джонатан (октябрь 2011 г.). «Анархизм: марксистская критика» . Социалистический обзор . Архивировано из оригинала 18 февраля 2021 года . Получено 31 июля 2020 года .

- Додсон, Эдвард (2002). Открытие первых принципов . Тол. 2. Автор. ISBN 978-0-5952-4912-1 .

- Данн, Кевин (август 2012 г.). «Анархо-панк и сопротивление в повседневной жизни». Панк и пост-панк . 1 (2). Интеллект: 201–218. doi : 10.1386/punk.1.2.201_1 .

- Egoumenides, Magda (2014). Философский анархизм и политические обязательства . Нью -Йорк: Bloomsbury Publishing . ISBN 978-1-4411-2445-6 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 18 февраля 2021 года . Получено 21 февраля 2022 года .

- Эсенвейн, Джордж (1989). Анархистская идеология и рабочее движение в Испании, 1868–1898 . Беркли: Университет Калифорнийской прессы. ISBN 978-0-5200-6398-3 .

- Even, Süreyyya (2011). «Как новый анархизм изменил мир (оппозиции) после Сиэтла и родил пост-анархизм». В Русселе, Дуэйн ; Эврен, Сурейя (ред.). Пост-анархизм: читатель . Плутовая пресса . С. 1–19. ISBN 978-0-7453-3086-0 .

- Эврен, Сурейя ; Кинна, Рут ; Русель, Дуэйн (2013). Взрыв канона . Санта -Барбара, Калифорния: Пунктум Книги . ISBN 978-0-6158-3862-5 .

- Фергюсон, Фрэнсис Л. (август 1886 г.). «Ошибки анархизма». Североамериканский обзор . 143 (357). Университет Северной Айовы : 204–206. ISSN 0029-2397 . JSTOR 25101094 .

- Фернандес, Фрэнк (2009) [2001]. Кубинский анархизм: история движения . Sharp Press.

- Фрэнкс, Бенджамин (август 2013 г.). "Анархизм". В Фридене Майкл; Стейс, Марк (ред.). Оксфордский справочник политических идеологий . Издательство Оксфордского университета . С. 385–404. doi : 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199585977.013.0001 .

- —— (2019). «Анархизм и этика». В Леви, Карл ; Адамс, Мэтью С. (ред.). Пальмовая справочник анархизма . Springer Publishing . С. 549–570. ISBN 978-3-3197-5620-2 .

- Габарди, Уэйн (1986). «Анархизм. Дэвид Миллер. (Лондон: JM Dent and Sons, 1984. С. 216 [Обзор книги])». Американское политологическое обзор . 80 (1): 300–302. doi : 10.2307/1957102 . JSTOR 446800 . S2CID 151950709 .

- Ганс, Хаим (1992). Философский анархизм и политическое непослушание (переиздание изд.). Кембридж: издательство Кембриджского университета . ISBN 978-0-5214-1450-0 .

- Гей, Кэтлин; Гей, Мартин (1999). Энциклопедия политической анархии . ABC-Clio . ISBN 978-0-8743-6982-3 .

- Гиффорд, Джеймс (2019). «Литература и анархизм». В Леви, Карл ; Адамс, Мэтью С. (ред.). Пальмовая справочник анархизма . Springer Publishing . ISBN 978-3-3197-5620-2 .

- Гудвей, Дэвид (2006). Анархистские семена под снегом . Ливерпульская пресса. ISBN 978-1-8463-1025-6 .

- Грэм, Роберт (2005). Анархизм: документальная история либертарианских идей: от анархии до анархизма . Монреал: Книги Черной Розы . ISBN 978-1-5516-4250-5 .

- —— (2019). «Анархизм и первый международный» . В Леви, Карл ; Адамс, Мэтью С. (ред.). Пальмовая справочник анархизма . Springer Publishing . С. 325–342. ISBN 978-3-3197-5620-2 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 26 июля 2020 года . Получено 17 мая 2020 года .

- Герин, Даниэль (1970). Анархизм: от теории до практики . Ежемесячная обзорная пресса. ISBN 978-0-8534-5128-0 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 14 июля 2020 года . Получено 16 февраля 2013 года .

- Харрисон, Кевин; Бойд, Тони (2003). Понимание политических идей и движений . Манчестерское университетское издательство . ISBN 978-0-7190-6151-6 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 8 марта 2021 года . Получено 7 марта 2019 года .

- Хармон, Кристофер С. (2011). «Как заканчиваются террористические группы: исследования двадцатого века». Соединения . 10 (2): 51–104. JSTOR 26310649 .

- Хейвуд, Эндрю (2017). Политические идеологии: введение (6 -е изд.). Макмиллан международное высшее образование. ISBN 978-1-1376-0604-4 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 18 февраля 2021 года . Получено 13 марта 2019 года .

- Хондерих, Тед (1995). Оксфордский компаньон к философии . Издательство Оксфордского университета . ISBN 978-0-1986-6132-0 .

- Honeywell, C. (2021). Анархизм . Ключевые понятия в политической теории. Уайли. ISBN 978-1-5095-2390-0 Полем Получено 13 августа 2022 года .

- Имри, Даг (1994). «Нелегалисты» . Анархия: журнал о желании вооружен . Архивировано с оригинала 8 сентября 2015 года . Получено 9 декабря 2010 года .

- Дженнингс, Джереми (1993). "Анархизм". В Eatwell, Роджер ; Райт, Энтони (ред.). Современные политические идеологии . Лондон: Пинтер. С. 127–146. ISBN 978-0-8618-7096-7 .

- Дженнингс, Джереми (1999). "Анархизм". В Eatwell, Роджер ; Райт, Энтони (ред.). Современные политические идеологии (перепечатано, 2 -е изд.). Лондон: A & C Black. ISBN 978-0-8264-5173-6 .

- Jeppesen, Sandra; Назар, Холли (2012). «Полы и сексуальность в анархистских движениях». В Кинне, Рут (ред.). Блумсбери -компаньон для анархизма . Bloomsbury Publishing . ISBN 978-1-4411-4270-2 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 15 января 2021 года . Получено 26 января 2020 года .

- Джонсон, Чарльз (2008). «Свобода, равенство, солидарность к диалектическому анархизму». В долгом, Roderick T.; Мачан, Тибор Р. (ред.). Анархизм/минархизм: правительственная часть свободной страны? Полем Ashgate Publishing . С. 155–188. ISBN 978-0-7546-6066-8 .

- Джолл, Джеймс (1964). Анархисты . Гарвардский университет издательство . ISBN 978-0-6740-3642-0 .

- Джун, Натан (сентябрь 2009 г.). «Анархистская философия и борьба рабочего класса: краткая история и комментарии» . Workingusa . 12 (3): 505–519. doi : 10.1111/j.1743-4580.2009.00251.x . ISSN 1089-7011 .

- Jun, Nathan (2019). "Государство". В Леви, Карл ; Адамс, Мэтью С. (ред.). Пальмовая справочник анархизма . Springer Publishing . С. 27–47. ISBN 978-3-3197-5620-2 .

- Кан, Джозеф (2000). «Анархизм, вероисповедание, которое не останется мертвым; распространение мирового капитализма возрождает долгосрочное движение». New York Times . № 5 августа.

- Кинна, Рут (2012). Блумсбери -компаньон для анархизма . Bloomsbury Academic . ISBN 978-1-6289-2430-5 .

- Кинна, Рут (2019). Правительство никого: теория и практика анархизма . Пингвин Рэндом Хаус . ISBN 978-0-2413-9655-1 .

- Клоско, Джордж (1999). «Больше, чем обязательство - Уильям А. Эдмундсон: три анархические ошибки: эссе о политической власти». Обзор политики . 61 (3): 536–538. doi : 10.1017/s0034670500028989 . ISSN 1748-6858 . S2CID 144417469 .

- Клоско, Джордж (2005). Политические обязательства . Издательство Оксфордского университета . ISBN 978-0-1995-5104-0 Полем Архивировано с оригинала 24 ноября 2020 года . Получено 7 марта 2019 года .

- Кримерман, Леонард I.; Перри, Льюис, ред. (1966). Образцы анархии: коллекция сочинений по анархистской традиции . Гарден -Сити, Нью -Йорк: якоря книги.

- Кристьянссон, Кристьян (2000). «Три анархические ошибки: эссе о политической власти Уильяма А. Эдмундсона». Разум . 109 (436): 896–900. JSTOR 2660038 .

- Лаурсен, Оле Бирк (2019). «Антиимпериализм» . В Леви, Карл ; Адамс, Мэтью С. (ред.). Пальмовая справочник анархизма . Springer Publishing . С. 149–168. ISBN 978-3-3197-5620-2 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 26 июля 2020 года . Получено 17 мая 2020 года .

- Леви, Карл (8 мая 2011 г.). «Социальные истории анархизма». Журнал для изучения радикализма . 4 (2): 1–44. doi : 10.1353/jsr.2010.0003 . ISSN 1930-1197 . S2CID 144317650 .

- Леви, Карл ; Адамс, Мэтью С., ред. (2018). Пальмовая справочник анархизма . Palgrave Macmillan . ISBN 978-3-3197-5619-6 .

- Лонг, Родерик Т. (2013). Год, Джеральд Ф.; Д'Агостино, Фред (ред.). Спутник Routledge для социальной и политической философии . Routledge . ISBN 978-0-4158-7456-4 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 9 августа 2020 года . Получено 28 февраля 2019 года .

- Люси, Николас (2020). «Анархизм и сексуальность» . Мудрец Справочник по глобальной сексуальности . Sage Publishing . С. 160–183. ISBN 978-1-5297-2194-2 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 15 января 2021 года . Получено 21 февраля 2022 года .

- Лутц, Джеймс М.; Ulmschneider, Georgia Wralstad (2019). «Гражданские свободы, национальная безопасность и суды США во времена терроризма». Перспективы терроризма . 13 (6): 43–57. JSTOR 26853740 .

- Маршалл, Питер (1992). Требование невозможного: история анархизма . Лондон: HarperCollins . ISBN 978-0-0021-7855-6 .

- —— (1993). Требование невозможного: история анархизма . Окленд, Калифорния: PM Press. ISBN 978-1-6048-6064-1 .

- Маттерн, Марк (2019). «Анархизм и искусство». В Леви, Карл ; Адамс, Мэтью С. (ред.). Пальмовая справочник анархизма . Springer Publishing . С. 589–602. ISBN 978-3-3197-5620-2 .

- Мейн, Алан Джеймс (1999). От политики прошлого до политики будущее: интегрированный анализ нынешних и возникающих парадигм . Greenwood Publishing Group . ISBN 978-0-2759-6151-0 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 18 апреля 2021 года . Получено 20 сентября 2010 года .

- Маклафлин, Пол (2007). Анархизм и власть: философское введение в классический анархизм . Aldershot: Ashgate . ISBN 978-0-7546-6196-2 .

- Morland, Dave (2004). «Антикапитализм и постструктуралистический анархизм». В Пуркисе, Джонатан; Боуэн, Джеймс (ред.). Изменение анархизма: анархистская теория и практика в глобальной эпохе . Манчестерское университетское издательство . С. 23–38. ISBN 978-0-7190-6694-8 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 18 февраля 2021 года . Получено 24 января 2020 года .

- Мельцер, Альберт (2000). Анархизм: аргументы за и против . А.К. Пресс . ISBN 978-1-8731-7657-3 .

- Моррис, Брайан (1993). Бакунин: философия свободы . Черная розовая книга . ISBN 978-1-8954-3166-7 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 25 февраля 2021 года . Получено 8 марта 2019 года .

- —— (2015). Антропология, экология и анархизм: читатель Брайана Морриса . Маршалл, Питер (иллюстрированный изд.). Окленд: PM Press . ISBN 978-1-6048-6093-1 .

- Моррис, Кристофер В. (2002). Эссе о современном государстве . Издательство Кембриджского университета . ISBN 978-0-5215-2407-0 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 15 января 2021 года . Получено 15 сентября 2018 года .

- Мойнихан, Колин (16 апреля 2007 г.). «Книжная ярмарка объединяет анархистов. В любом случае, в духе» . New York Times . Архивировано из оригинала 14 сентября 2021 года.

- Мойя, Хосе С. (2015). «Перенос, культура и критикуют циркуляцию анархистских идей и практик» . В Лафоркаде Джеффрой де (ред.). В неповиновении границ: анархизм в латиноамериканской истории . Кирвин Р. Шаффер. Университетская пресса Флориды . ISBN 978-0-8130-5138-3 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 9 августа 2020 года . Получено 6 марта 2019 года .

- Nesser, Petter (2012). «Примечание исследования: терроризм с одним актером: охват, характеристики и объяснения». Перспективы терроризма . 6 (6): 61–73. JSTOR 26296894 .

- Nettlau, Max (1996). Короткая история анархизма . Freedom Press. ISBN 978-0-9003-8489-9 .

- Ньюман, Майкл (2005). Социализм: очень короткое введение . Оксфорд: издательство Оксфордского университета . ISBN 978-0-1928-0431-0 .

- Ньюман, Саул (2010). Политика почтанархизма . Эдинбургский университет издательство . ISBN 978-0-7486-3495-8 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 3 января 2020 года . Получено 29 октября 2015 года .

- Николас, Люси (2019). «Пол и сексуальность». В Леви, Карл ; Адамс, Мэтью С. (ред.). Пальмовая справочник анархизма . Springer Publishing . ISBN 978-3-3197-5620-2 .

- Норрис, Джесси Дж. (2020). «Уникальный терроризм: дезагрегация недооцененной концепции». Перспективы терроризма . 14 (3). ISSN 2334-3745 . JSTOR 26918296S .

- Nomad, Max (1966). «Анархистская традиция». В Drachkovitch, Milorad M. (ed.). Революционные интернационалы 1864–1943 гг . Издательство Стэнфордского университета . п. 88. ISBN 978-0-8047-0293-5 .

- Осгуд, Герберт Л. (март 1889 г.). «Научный анархизм». Политология ежеквартально . 4 (1). Академия политологии: 1–36. doi : 10.2307/2139424 . JSTOR 2139424 .

- Отеро, Карлос Перегрин (1994). Ноам Хомский: Критические оценки . Тол. 2–3. Лондон: Routledge . ISBN 978-0-4150-1005-4 .

- Парри, Ричард (1987). Банда Бонтон . Rebel Press. ISBN 978-0-9460-6104-4 .

- Pernicone, Nunzio (2009). Итальянский анархизм, 1864–1892 . ПРИЗНАЯ УНИВЕРСИТЕТА ПРИСЕТА . ISBN 978-0-6916-3268-1 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 19 августа 2020 года . Получено 8 марта 2019 года .

- Пирсон, Кристофер (2013). Just Property: Просвещение, революция и история . Издательство Оксфордского университета . ISBN 978-0-1996-7329-2 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 16 марта 2021 года . Получено 8 марта 2019 года .

- Рамнатх, Майя (2019). «Незападные анархизмы и постколониализм» . В Леви, Карл ; Адамс, Мэтью С. (ред.). Пальмовая справочник анархизма . Springer Publishing . ISBN 978-3-3197-5620-2 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 26 июля 2020 года . Получено 17 мая 2020 года .

- Робе, Крис (2017). Разрушение заклинания: история анархистских кинематографистов, видеозаписей партизан и цифровых ниндзя . PM Press . ISBN 978-1-6296-3233-9 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 21 февраля 2022 года . Получено 21 февраля 2022 года - через ResearchGate.

- Роджерс, Тристан Дж. (2020). Авторитет добродетели: институты и характер в хорошем обществе . Лондон: Routledge . ISBN 978-1-0002-2264-7 .

- Руперт, Марк (2006). Globalization and International Political Economy . Ланхэм: издатели Rowman & Littlefield . ISBN 978-0-7425-2943-4 .

- Райли, Питер (2019). "Индивидуализм". В Леви, Карл ; Адамс, Мэтью С. (ред.). Пальмовая справочник анархизма . Springer Publishing . С. 225–236. ISBN 978-3-3197-5620-2 .

- Shannon, Deric (2019). «Антикапитализм и либертарианская политическая экономия». В Леви, Карл ; Адамс, Мэтью С. (ред.). Пальмовая справочник анархизма . Springer Publishing . С. 91–106. ISBN 978-3-3197-5620-2 .

- Skirda, Александр (2002). Столкнувшись с врагом: история анархистской организации от Прайдхона до мая 1968 года . А.К. Пресс . ISBN 978-1-9025-9319-7 .

- Сильван, Ричард (2007). "Анархизм". В Гудине Роберт Э .; Петтит, Филипп ; Погге, Томас (ред.). Компаньон современной политической философии . Блэквелл компаньоны к философии. Тол. 5 (2 -е изд.). Blackwell Publishing . ISBN 978-1-4051-3653-2 .

- Суйсса, Джудит (2019). «Анархистское образование» . В Леви, Карл ; Адамс, Мэтью С. (ред.). Пальмовая справочник анархизма . Springer Publishing . ISBN 978-3-3197-5620-2 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 26 июля 2020 года . Получено 17 мая 2020 года .

- Томас, Пол (1985). Карл Маркс и анархисты . Лондон: Routledge & Kegan Paul. ISBN 978-0-7102-0685-5 .

- Такер, Роберт С., изд. (1978). Читатель Marx-Engels (2-е изд.). Нью -Йорк: WW Norton & Company . ISBN 0-3930-5684-8 Полем OCLC 3415145 .

- Turcato, Davide (2019). «Анархистский коммунизм». В Леви, Карл ; Адамс, Мэтью С. (ред.). Пальмовая справочник анархизма . Springer Publishing . ISBN 978-3-3197-5620-2 .

- Ван дер Уолт, ЛЮДИН (2019). "Синдикализм". В Леви, Карл ; Адамс, Мэтью С. (ред.). Пальмовая справочник анархизма . Springer Publishing . С. 249–264. ISBN 978-3-3197-5620-2 .

- Уорд, Колин (1973). «Роль государства». Образование без школ : 39–48.

- —— (2004). Анархизм: очень короткое введение . Оксфорд: издательство Оксфордского университета . ISBN 978-0-1928-0477-8 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 4 марта 2021 года . Получено 12 марта 2019 года .

- Уолтер, Николас (2002). Об анархизме . Лондон: Freedom Press. ISBN 978-0-9003-8490-5 .

- Вендт, Фабиан (2020). «Против философского анархизма». Закон и философия . 39 (5): 527–544. doi : 10.1007/s10982-020-09377-4 . S2CID 213742949 .

- Уилбур, Шон (2019). «Мутвуализм». В Леви, Карл ; Адамс, Мэтью С. (ред.). Пальмовая справочник анархизма . Springer Publishing . ISBN 978-3-3197-5620-2 .

- Уильямс, Дана М. (2015). «Радикализация черной пантеры и развитие черного анархизма». Журнал чернокожих исследований . 46 (7). Тысяча дубов: мудрец издательство : 678–703. doi : 10.1177/0021934715593053 . JSTOR 24572914 . S2CID 145663405 .

- —— (2018). «Современные анархистские и анархистские движения». Социология компас . 12 (6). Wiley : E12582. doi : 10.1111/soc4.12582 . ISSN 1751-9020 .