Ансельм Кентерберийский

Ансельм | |

|---|---|

| Архиепископ Кентерберийский Доктор Церкви | |

Ансельм изображен на его печати | |

| Церковь | Католическая церковь |

| Архиепископия | Кентербери |

| Видеть | Кентербери |

| Назначен | 1093 |

| Срок закончился | 21 апреля 1109 г. |

| Предшественник | Ланфранк |

| Преемник | Ральф д'Эскюр |

| Другие сообщения | Настоятель Бека |

| Заказы | |

| Посвящение | 4 декабря 1093 г. |

| Личные данные | |

| Рожденный | Ансельмо Аостский в. 1033 |

| Умер | 21 апреля 1109 г. Кентербери , Англия |

| Похороненный | Кентерберийский собор |

| Родители | Гундульф Эрменберге |

| Занятие | Монах, настоятель, настоятель, архиепископ |

| Святость | |

| Праздник | 21 апреля |

| Почитается в | Католическая церковь Англиканское сообщество [1] лютеранство [2] |

| Титул как Святой | Епископ, Исповедник , Учитель Церкви ( Доктор Великолепный ) |

| канонизирован | 4 октября 1494 г. Рим , Папская область Папой Александром VI |

| Атрибуты | Его митра , паллий и посох Его книги Корабль, олицетворяющий духовную независимость Церкви. |

Philosophy career | |

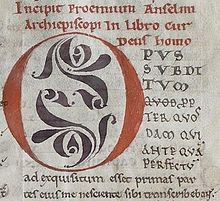

| Notable work | Proslogion Cur Deus Homo |

| Era | Medieval philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Scholasticism Neoplatonism[3] Augustinianism |

Main interests | Metaphysics, theology |

Notable ideas | |

Ансельм Кентерберийский OSB ( / ˈ æ n s ɛ l m / ; 1033/4–1109), также называемый Ансельмом Аостским (французский: Ансельм д'Аосте , итальянский: Ансельмо д'Аоста ) в честь места его рождения и Ансельмом Беком ( Французский: Anselme du Bec ) по монастырю , был итальянцем. [7] Бенедиктинский монах , аббат , философ и богослов католической церкви , занимавший пост архиепископа Кентерберийского с 1093 по 1109 год. После смерти был канонизирован в лики святых ; его праздник - 21 апреля. в 1720 году провозгласил Церкви Папа Учителем его Климент XI .

Будучи архиепископом Кентерберийским, он защищал интересы церкви в Англии во время споров об инвеститурах . За сопротивление английским королям Вильгельму II и Генриху I он был дважды сослан: один раз с 1097 по 1100 год, а затем с 1105 по 1107 год. Находясь в изгнании, он помогал греко-католическим епископам южной Италии принять римские обряды в Совет Бари . Он добивался главенства Кентербери над архиепископом Йоркским и епископами Уэльскими , но, хотя после своей смерти он, казалось, добился успеха, Папа Пасхал II позже отменил папские решения по этому вопросу и восстановил прежний статус Йорка.

Начиная с Бека , Ансельм сочинял диалоги и трактаты с рациональным и философским подходом, что иногда заставляло его считать основателем схоластики . Несмотря на отсутствие признания в этой области в свое время, Ансельм сейчас известен как создатель онтологического аргумента в пользу существования Бога и теории искупления удовлетворения .

Биография

[ редактировать ]

Семья

[ редактировать ]Ансельм родился в или ее окрестностях Аосте в Верхней Бургундии где-то между апрелем 1033 и апрелем 1034 года. [9] Сейчас эта территория является частью Итальянской Республики , но Аоста была частью посткаролингского Бургундского королевства до смерти бездетного Рудольфа III в 1032 году. [10] Затем император Конрад II и Одо II, граф Блуа, вступили в войну из-за престолонаследия. Гумберт Белорукий , граф Мориенн , настолько отличился, что ему было пожаловано новое графство , выделенное из светских владений епископа Аосты . Сыну Гумберта Отто впоследствии было разрешено унаследовать обширный марш Суз через его жену Аделаиду. [11] отдавая предпочтение семьям ее дяди, которые поддержали усилия по созданию независимого Королевства Италии под руководством Вильгельма V, герцога Аквитании . Объединенные земли Отто и Аделаиды [12] затем контролировал важнейшие проходы в Западных Альпах и образовал графство Савойя которого , династия позже управляла королевствами Сардинии и Италии . [13][14]

Records during this period are scanty, but both sides of Anselm's immediate family appear to have been dispossessed by these decisions[15] in favour of their extended relations.[16] His father Gundulph[17] or Gundulf[18] or Gondulphe[19] was a Lombard noble,[20] probably one of Adelaide's Arduinici uncles or cousins;[21] his mother Ermenberge[19] was almost certainly the granddaughter of Conrad the Peaceful, related both to the Anselmid bishops of Aosta and to the heirs of Henry II who had been passed over in favour of Conrad.[21] The marriage was thus probably arranged for political reasons but proved ineffective in opposing Conrad after his successful annexation of Burgundy on 1 August 1034.[22] (Bishop Burchard subsequently revolted against imperial control but was defeated and was ultimately translated to the diocese of Lyon.) Ermenberge appears to have been the wealthier partner in the marriage. Gundulph moved to his wife's town,[10] where she held a palace, most likely near the cathedral, along with a villa in the valley.[23] Anselm's father is sometimes described as having a harsh and violent temper[17] but contemporary accounts merely portray him as having been overgenerous or careless with his wealth;[24] Meanwhile, Anselm's mother Ermenberge, patient and devoutly religious,[17] made up for her husband's faults by her prudent management of the family estates.[24] In later life, there are records of three relations who visited Bec: Folceraldus, Haimo, and Rainaldus. The first repeatedly attempted to exploit Anselm's renown, but was rebuffed since he already had his ties to another monastery, whereas Anselm's attempts to persuade the other two to join the Bec community were unsuccessful.[25]

Early life

[edit]

At the age of fifteen, Anselm felt the call to enter a monastery but, failing to obtain his father's consent, he was refused by the abbot.[26] The illness he then suffered has been considered by some a psychosomatic effect of his disappointment,[17] but upon his recovery he gave up his studies and for a time lived a carefree life.[17]

Following the death of his mother, probably at the birth of his sister Richera,[27] Anselm's father repented his own earlier lifestyle but professed his new faith with a severity that the boy found likewise unbearable.[28] When Gundulph entered a monastery,[29] Anselm, at age 23,[30] left home with a single attendant,[17] crossed the Alps, and wandered through Burgundy and France for three years.[26][a] His countryman Lanfranc of Pavia was then prior of the Benedictine abbey of Bec in Normandy. Attracted by Lanfranc's reputation, Anselm reached Normandy in 1059.[17] After spending some time in Avranches, he returned the next year. His father having died, he consulted with Lanfranc as to whether to return to his estates and employ their income in providing alms for the poor or to renounce them, becoming a hermit or a monk at Bec or Cluny.[31] Given what he saw as his own conflict of interest, Lanfranc sent Anselm to Maurilius, the archbishop of Rouen, who convinced him to enter Bec as a novice at the age of 27.[26] Probably in his first year, he wrote his first work on philosophy, a treatment of Latin paradoxes called the Grammarian.[32] Over the next decade, the Rule of Saint Benedict reshaped his thought.[33]

Abbot of Bec

[edit]Early years

[edit]

Three years later, in 1063, Duke William II summoned Lanfranc to serve as the abbot of his new abbey of St Stephen at Caen[17] and the monks of Bec, despite the initial hesitation of some on account of his youth,[26] elected Anselm prior.[34] A notable opponent was a young monk named Osborne. Anselm overcame his hostility first by praising, indulging, and privileging him in all things despite his hostility and then, when his affection and trust were gained, gradually withdrawing all preference until he upheld the strictest obedience.[35] Along similar lines, he remonstrated with a neighbouring abbot who complained that his charges were incorrigible despite being beaten "night and day".[36] After fifteen years, in 1078, Anselm was unanimously elected as Bec's abbot following the death of its founder,[37] the warrior-monk Herluin.[17] He was blessed as abbot by Gilbert d'Arques, Bishop of Évreux, on 22 February 1079.[38]

Under Anselm's direction, Bec became the foremost seat of learning in Europe,[17] attracting students from France, Italy, and elsewhere.[39] During this time, he wrote the Monologion and Proslogion.[17] He then composed a series of dialogues on the nature of truth, free will,[17] and the fall of Satan.[32] When the nominalist Roscelin attempted to appeal to the authority of Lanfranc and Anselm at his trial for the heresy of tritheism at Soissons in 1092,[40] Anselm composed the first draft of De Fide Trinitatis as a rebuttal and as a defence of Trinitarianism and universals.[41] The fame of the monastery grew not only from his intellectual achievements, however, but also from his good example[31] and his loving, kindly method of discipline,[17] particularly with the younger monks.[26] There was also admiration for his spirited defence of the abbey's independence from lay and archiepiscopal control, especially in the face of Robert de Beaumont, Earl of Leicester and the new Archbishop of Rouen, William Bona Anima.[42]

In England

[edit]

Following the Norman Conquest of England in 1066, devoted lords had given the abbey extensive lands across the Channel.[17] Anselm occasionally visited to oversee the monastery's property, to wait upon his sovereign William I of England (formerly Duke William II of Normandy),[43] and to visit Lanfranc, who had been installed as archbishop of Canterbury in 1070.[44] He was respected by William I[45] and the good impression he made while in Canterbury made him the favourite of its cathedral chapter as a future successor to Lanfranc.[17] Instead, upon the archbishop's death in 1089, King William II—William Rufus or William the Red—refused the appointment of any successor and appropriated the see's lands and revenues for himself.[17] Fearing the difficulties that would attend being named to the position in opposition to the king, Anselm avoided journeying to England during this time.[17] The gravely ill Hugh, Earl of Chester, finally lured him over with three pressing messages in 1092,[46] seeking advice on how best to handle the establishment of a new monastery at St Werburgh's.[26] Hugh was recovered by the time of Anselm's arrival,[26] but he was occupied four[17] or five months by his assistance.[26] He then travelled to his former pupil Gilbert Crispin, abbot of Westminster, and waited, apparently delayed by the need to assemble the donors of Bec's new lands in order to obtain royal approval of the grants.[47]

| Part of a series on |

| Catholic philosophy |

|---|

|

At Christmas, William II pledged by the Holy Face of Lucca that neither Anselm nor any other would sit at Canterbury while he lived[48] but in March he fell seriously ill at Alveston. Believing his sinful behavior was responsible,[49] he summoned Anselm to hear his confession and administer last rites.[47] He published a proclamation releasing his captives, discharging his debts, and promising to henceforth govern according to the law.[26] On 6 March 1093, he further nominated Anselm to fill the vacancy at Canterbury; the clerics gathered at court acclaiming him, forcing the crozier into his hands, and bodily carrying him to a nearby church amid a Te Deum.[50] Anselm tried to refuse on the grounds of age and ill-health for months[44] and the monks of Bec refused to give him permission to leave them.[51] Negotiations were handled by the recently restored Bishop William of Durham and Robert, count of Meulan.[52] On 24 August, Anselm gave King William the conditions under which he would accept the position, which amounted to the agenda of the Gregorian Reform: the king would have to return the Catholic Church lands which had been seized, accept his spiritual counsel, and forswear Antipope Clement III in favour of Urban II.[53] William Rufus was exceedingly reluctant to accept these conditions: he consented only to the first[54] and, a few days afterwards, reneged on that, suspending preparations for Anselm's investiture.[citation needed] Public pressure forced William to return to Anselm and in the end they settled on a partial return of Canterbury's lands as his own concession.[55] Anselm received dispensation from his duties in Normandy,[17] did homage to William, and—on 25 September 1093—was enthroned at Canterbury Cathedral.[56] The same day, William II finally returned the lands of the see.[54]

From the mid-8th century, it had become the custom that metropolitan bishops could not be consecrated without a woollen pallium given or sent by the pope himself.[57] Anselm insisted that he journey to Rome for this purpose but William would not permit it. Amid the Investiture Controversy, Pope Gregory VII and Emperor Henry IV had deposed each other twice; bishops loyal to Henry finally elected Guibert, archbishop of Ravenna, as a second pope. In France, Philip I had recognized Gregory and his successors Victor III and Urban II, but Guibert (as "Clement III") held Rome after 1084.[58] William had not chosen a side and maintained his right to prevent the acknowledgement of either pope by an English subject prior to his choice.[59] In the end, a ceremony was held to consecrate Anselm as archbishop on 4 December, without the pallium.[54]

Archbishop of Canterbury

[edit]As archbishop, Anselm maintained his monastic ideals, including stewardship, prudence, and proper instruction, prayer and contemplation.[60] Anselm advocated for reform and interests of Canterbury.[61] As such, he repeatedly pressed the English monarchy for support of the reform agenda.[62] His principled opposition to royal prerogatives over the Catholic Church, meanwhile, twice led to his exile from England.[63]

The traditional view of historians has been to see Anselm as aligned with the papacy against lay authority and Anselm's term in office as the English theatre of the Investiture Controversy begun by Pope Gregory VII and the emperor Henry IV.[63] By the end of his life, he had proven successful, having freed Canterbury from submission to the English king,[64] received papal recognition of the submission of wayward York[65] and the Welsh bishops, and gained strong authority over the Irish bishops.[66] He died before the Canterbury–York dispute was definitively settled, however, and Pope Honorius II finally found in favour of York instead.[67]

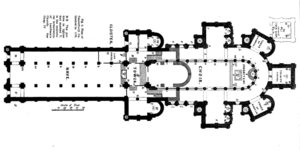

Although the work was largely handled by Christ Church's priors Ernulf (1096–1107) and Conrad (1108–1126), Anselm's episcopate also saw the expansion of Canterbury Cathedral from Lanfranc's initial plans.[69] The eastern end was demolished and an expanded choir placed over a large and well-decorated crypt, doubling the cathedral's length.[70] The new choir formed a church unto itself with its own transepts and a semicircular ambulatory opening into three chapels.[71]

Conflicts with William Rufus

[edit]Anselm's vision was of a Catholic Church with its own internal authority, which clashed with William II's desire for royal control over both church and State.[62] One of Anselm's first conflicts with William came in the month he was consecrated. William II was preparing to wrest Normandy from his elder brother, Robert II, and needed funds.[72] Anselm was among those expected to pay him. He offered £500 but William refused, encouraged by his courtiers to insist on £1000 as a kind of annates for Anselm's elevation to archbishop. Anselm not only refused, he further pressed the king to fill England's other vacant positions, permit bishops to meet freely in councils, and to allow Anselm to resume enforcement of canon law, particularly against incestuous marriages,[26] until he was ordered to silence.[73] When a group of bishops subsequently suggested that William might now settle for the original sum, Anselm replied that he had already given the money to the poor and "that he disdained to purchase his master's favour as he would a horse or ass".[40] The king being told this, he replied Anselm's blessing for his invasion would not be needed as "I hated him before, I hate him now, and shall hate him still more hereafter".[73] Withdrawing to Canterbury, Anselm began work on the Cur Deus Homo.[40]

Upon William's return, Anselm insisted that he travel to the court of Urban II to secure the pallium that legitimized his office.[40] On 25 February 1095, the Lords Spiritual and Temporal of England met in a council at Rockingham to discuss the issue. The next day, William ordered the bishops not to treat Anselm as their primate or as Canterbury's archbishop, as he openly adhered to Urban. The bishops sided with the king, the Bishop of Durham presenting his case[75] and even advising William to depose and exile Anselm.[76] The nobles siding with Anselm, the conference ended in deadlock and the matter was postponed. Immediately following this, William secretly sent William Warelwast and Gerard to Italy,[61] prevailing on Urban to send a legate bearing Canterbury's pallium.[77] Walter, bishop of Albano, was chosen and negotiated in secret with William's representative, the Bishop of Durham.[78] The king agreed to publicly support Urban's cause in exchange for acknowledgement of his rights to accept no legates without invitation and to block clerics from receiving or obeying papal letters without his approval. William's greatest desire was for Anselm to be removed from office. Walter said that "there was good reason to expect a successful issue in accordance with the king's wishes" but, upon William's open acknowledgement of Urban as pope, Walter refused to depose the archbishop.[79] William then tried to sell the pallium to others, failed,[80] tried to extract a payment from Anselm for the pallium, but was again refused. William then tried to personally bestow the pallium to Anselm, an act connoting the church's subservience to the throne, and was again refused.[81] In the end, the pallium was laid on the altar at Canterbury, whence Anselm took it on 10 June 1095.[81]

The First Crusade was declared at the Council of Clermont in November.[b] Despite his service for the king which earned him rough treatment from Anselm's biographer Eadmer,[83][84] upon the grave illness of the Bishop of Durham in December, Anselm journeyed to console and bless him on his deathbed.[85] Over the next two years, William opposed several of Anselm's efforts at reform—including his right to convene a council[45]—but no overt dispute is known. However, in 1094, the Welsh had begun to recover their lands from the Marcher Lords and William's 1095 invasion had accomplished little; two larger forays were made in 1097 against Cadwgan in Powys and Gruffudd in Gwynedd. These were also unsuccessful and William was compelled to erect a series of border fortresses.[86] He charged Anselm with having given him insufficient knights for the campaign and tried to fine him.[87] In the face of William's refusal to fulfill his promise of church reform, Anselm resolved to proceed to Rome—where an army of French crusaders had finally installed Urban—in order to seek the counsel of the pope.[62] William again denied him permission. The negotiations ended with Anselm being "given the choice of exile or total submission": if he left, William declared he would seize Canterbury and never again receive Anselm as archbishop; if he were to stay, William would impose his fine and force him to swear never again to appeal to the papacy.[88]

First exile

[edit]

Anselm chose to depart in October 1097.[62] Although Anselm retained his nominal title, William immediately seized the revenues of his bishopric and retained them til death.[89] From Lyon, Anselm wrote to Urban, requesting that he be permitted to resign his office. Urban refused but commissioned him to prepare a defence of the Western doctrine of the procession of the Holy Spirit against representatives from the Greek Church.[90] Anselm arrived in Rome by April[90] and, according to his biographer Eadmer, lived beside the pope during the Siege of Capua in May.[91] Count Roger's Saracen troops supposedly offered him food and other gifts but the count actively resisted the clerics' attempts to convert them to Catholicism.[91]

At the Council of Bari in October, Anselm delivered his defence of the Filioque and the use of unleavened bread in the Eucharist before 185 bishops.[92] Although this is sometimes portrayed as a failed ecumenical dialogue, it is more likely that the "Greeks" present were the local bishops of Southern Italy,[93] some of whom had been ruled by Constantinople as recently as 1071.[92] The formal acts of the council have been lost and Eadmer's account of Anselm's speech principally consists of descriptions of the bishops' vestments, but Anselm later collected his arguments on the topic as De Processione Spiritus Sancti.[93] Under pressure from their Norman lords, the Italian Greeks seem to have accepted papal supremacy and Anselm's theology.[93] The council also condemned William II. Eadmer credited Anselm with restraining the pope from excommunicating him,[90] although others attribute Urban's politic nature.[94]

Anselm was present in a seat of honour at the Easter Council at St Peter's in Rome the next year.[95] There, amid an outcry to address Anselm's situation, Urban renewed bans on lay investiture and on clerics doing homage.[96] Anselm departed the next day, first for Schiavi—where he completed his work Cur Deus Homo—and then for Lyon.[94][97]

Conflicts with Henry I

[edit]

William Rufus was killed hunting in the New Forest on 2 August 1100. His brother Henry was present and moved quickly to secure the throne before the return of his elder brother Robert, Duke of Normandy, from the First Crusade. Henry invited Anselm to return, pledging in his letter to submit himself to the archbishop's counsel.[98] The cleric's support of Robert would have caused great trouble but Anselm returned before establishing any other terms than those offered by Henry.[99] Once in England, Anselm was ordered by Henry to do homage for his Canterbury estates[100] and to receive his investiture by ring and crozier anew.[101] Despite having done so under William, the bishop now refused to violate canon law. Henry for his part refused to relinquish a right possessed by his predecessors and even sent an embassy to Pope Paschal II to present his case.[94] Paschal reaffirmed Urban's bans to that mission and the one that followed it.[94]

Meanwhile, Anselm publicly supported Henry against the claims and threatened invasion of his brother Robert Curthose. Anselm wooed wavering barons to the king's cause, emphasizing the religious nature of their oaths and duty of loyalty;[102] he supported the deposition of Ranulf Flambard, the disloyal new bishop of Durham;[103] and he threatened Robert with excommunication.[104] The lack of popular support greeting his invasion near Portsmouth compelled Robert to accept the Treaty of Alton instead, renouncing his claims for an annual payment of 3000 marks.

Anselm held a council at Lambeth Palace which found that Henry's beloved Matilda had not technically become a nun and was thus eligible to wed and become queen.[105] On Michaelmas in 1102, Anselm was finally able to convene a general church council at London, establishing the Gregorian Reform within England. The council prohibited marriage, concubinage, and drunkenness to all those in holy orders,[106] condemned sodomy[107] and simony,[104] and regulated clerical dress.[104] Anselm also obtained a resolution against the British slave trade.[108] Henry supported Anselm's reforms and his authority over the English Church but continued to assert his own authority over Anselm. Upon their return, the three bishops he had dispatched on his second delegation to the pope claimed—in defiance of Paschal's sealed letter to Anselm, his public acts, and the testimony of the two monks who had accompanied them—that the pontiff had been receptive to Henry's counsel and secretly approved of Anselm's submission to the crown.[109] In 1103, then, Anselm consented to journey himself to Rome, along with the king's envoy William Warelwast.[110] Anselm supposedly travelled in order to argue the king's case for a dispensation[111] but, in response to this third mission, Paschal fully excommunicated the bishops who had accepted investment from Henry, though sparing the king himself.[94]

Second exile

[edit]After this ruling, Anselm received a letter forbidding his return and withdrew to Lyon to await Paschal's response.[94] On 26 March 1105, Paschal again excommunicated prelates who had accepted investment from Henry and the advisors responsible, this time including Robert de Beaumont, Henry's chief advisor.[112] He further finally threatened Henry with the same;[113] in April, Anselm sent messages to the king directly[114] and through his sister Adela expressing his own willingness to excommunicate Henry.[94] This was probably a negotiation tactic[115] but it came at a critical period in Henry's reign[94] and it worked: a meeting was arranged and a compromise concluded at L'Aigle on 22 July 1105. Henry would forsake lay investiture if Anselm obtained Paschal's permission for clerics to do homage for their lands;[116][117] Henry's bishops'[94] and counsellors' excommunications were to be lifted provided they advise him to obey the papacy (Anselm performed this act on his own authority and later had to answer for it to Paschal);[116] the revenues of Canterbury would be returned to the archbishop; and priests would no longer be permitted to marry.[117] Anselm insisted on the agreement's ratification by the pope before he would consent to return to England, but wrote to Paschal in favour of the deal, arguing that Henry's forsaking of lay investiture was a greater victory than the matter of homage.[118] On 23 March 1106, Paschal wrote Anselm accepting the terms established at L'Aigle, although both clerics saw this as a temporary compromise and intended to continue pressing for reforms,[119] including the ending of homage to lay authorities.[120]

Even after this, Anselm refused to return to England.[121] Henry travelled to Bec and met with him on 15 August 1106. Henry was forced to make further concessions. He restored to Canterbury all the churches that had been seized by William or during Anselm's exile, promising that nothing more would be taken from them and even providing Anselm with a security payment.[citation needed] Henry had initially taxed married clergy and, when their situation had been outlawed, had made up the lost revenue by controversially extending the tax over all Churchmen.[122] He now agreed that any prelate who had paid this would be exempt from taxation for three years.[citation needed] These compromises on Henry's part strengthened the rights of the church against the king. Anselm returned to England before the new year.[94]

Final years

[edit]

In 1107, the Concordat of London formalized the agreements between the king and archbishop,[64] Henry formally renounced the right of English kings to invest the bishops of the church.[94] The remaining two years of Anselm's life were spent in the duties of his archbishopric.[94] He succeeded in getting Paschal to send the pallium for the archbishop of York to Canterbury so that future archbishops-elect would have to profess obedience before receiving it.[65] The incumbent archbishop Thomas II had received his own pallium directly and insisted on York's independence. From his deathbed, Anselm anathematized all who failed to recognize Canterbury's primacy over all the English Church. This ultimately forced Henry to order Thomas to confess his obedience to Anselm's successor.[66] On his deathbed, he announced himself content, except that he had a treatise in mind on the origin of the soul and did not know, once he was gone, if another was likely to compose it.[125]

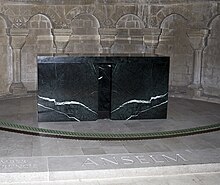

He died on Holy Wednesday, 21 April 1109.[111] His remains were translated to Canterbury Cathedral[126] and laid at the head of Lanfranc at his initial resting place to the south of the Altar of the Holy Trinity (now St Thomas's Chapel).[129] During the church's reconstruction after the disastrous fire of the 1170s, his remains were relocated,[129] although it is now uncertain where.

On 23 December 1752, Archbishop Herring was contacted by Count Perron, the Sardinian ambassador, on behalf of King Charles Emmanuel, who requested permission to translate Anselm's relics to Italy.[130] (Charles had been duke of Aosta during his minority.) Herring ordered his dean to look into the matter, saying that while "the parting with the rotten Remains of a Rebel to his King, a Slave to the Popedom, and an Enemy to the married Clergy (all this Anselm was)" would be no great matter, he likewise "should make no Conscience of palming on the Simpletons any other old Bishop with the Name of Anselm".[132] The ambassador insisted on witnessing the excavation, however,[134] and resistance on the part of the prebendaries seems to have quieted the matter.[127] They considered the state of the cathedral's crypts would have offended the sensibilities of a Catholic and that it was probable that Anselm had been removed to near the altar of SS Peter and Paul, whose side chapel to the right (i.e., south) of the high altar took Anselm's name following his canonization. At that time, his relics would presumably have been placed in a shrine and its contents "disposed of" during the Reformation.[129] The ambassador's own investigation was of the opinion that Anselm's body had been confused with Archbishop Theobald's and likely remained entombed near the altar of the Virgin Mary,[136] but in the uncertainty nothing further seems to have been done then or when inquiries were renewed in 1841.[138]

Writings

[edit]

Anselm has been called "the most luminous and penetrating intellect between St Augustine and St Thomas Aquinas"[111] and "the father of scholasticism",[41] Scotus Erigena having employed more mysticism in his arguments.[94] Anselm's works are considered philosophical as well as theological since they endeavour to render Christian tenets of faith, traditionally taken as a revealed truth, as a rational system.[139] Anselm also studiously analyzed the language used in his subjects, carefully distinguishing the meaning of the terms employed from the verbal forms, which he found at times wholly inadequate.[140] His worldview was broadly Neoplatonic, as it was reconciled with Christianity in the works of St Augustine and Pseudo-Dionysius,[3][c] with his understanding of Aristotelian logic gathered from the works of Boethius.[142][143][41] He or the thinkers in northern France who shortly followed him—including Abelard, William of Conches, and Gilbert of Poitiers—inaugurated "one of the most brilliant periods of Western philosophy", innovating logic, semantics, ethics, metaphysics, and other areas of philosophical theology.[144]

Anselm held that faith necessarily precedes reason, but that reason can expand upon faith:[145] "And I do not seek to understand that I may believe but believe that I might understand. For this too I believe since, unless I first believe, I shall not understand".[d][146] This is possibly drawn from Tractate XXIX of St Augustine's Ten Homilies on the First Epistle of John: regarding John 7:14–18, Augustine counseled "Do not seek to understand in order to believe but believe that thou may understand".[147] Anselm rephrased the idea repeatedly[e] and Thomas Williams(SEP 2007) considered that his aptest motto was the original title of the Proslogion, "faith seeking understanding", which intended "an active love of God seeking a deeper knowledge of God".[148] Once the faith is held fast, however, he argued an attempt must be made to demonstrate its truth by means of reason: "To me, it seems to be negligence if, after confirmation in the faith, we do not study to understand that which we believe".[f][146] Merely rational proofs are always, however, to be tested by scripture[149][150] and he employs Biblical passages and "what we believe" (quod credimus) at times to raise problems or to present erroneous understandings, whose inconsistencies are then resolved by reason.[151]

Stylistically, Anselm's treatises take two basic forms, dialogues and sustained meditations.[151] In both, he strove to state the rational grounds for central aspects of Christian doctrines as a pedagogical exercise for his initial audience of fellow monks and correspondents.[151] The subjects of Anselm's works were sometimes dictated by contemporary events, such as his speech at the Council of Bari or the need to refute his association with the thinking of Roscelin, but he intended for his books to form a unity, with his letters and latter works advising the reader to consult his other books for the arguments supporting various points in his reasoning.[152] It seems to have been a recurring problem that early drafts of his works were copied and circulated without his permission.[151]

While at Bec, Anselm composed:[32]

- De Grammatico

- Monologion

- Proslogion

- De Veritate

- De Libertate Arbitrii

- De Casu Diaboli

- De Fide Trinitatis, also known as De Incarnatione Verbi[41]

While archbishop of Canterbury, he composed:[32]

- Cur Deus Homo

- De Conceptu Virginali

- De Processione Spiritus Sancti

- De Sacrificio Azymi et Fermentati

- De Sacramentis Ecclesiae

- De Concordia

Monologion

[edit]The Monologion (Latin: Monologium, "Monologue"), originally entitled A Monologue on the Reason for Faith (Monoloquium de Ratione Fidei)[153][g] and sometimes also known as An Example of Meditation on the Reason for Faith (Exemplum Meditandi de Ratione Fidei),[155][h] was written in 1075 and 1076.[32] It follows St Augustine to such an extent that Gibson argues neither Boethius nor Anselm state anything which was not already dealt with in greater detail by Augustine's De Trinitate;[157] Anselm even acknowledges his debt to that work in the Monologion's prologue.[158] However, he takes pains to present his reasons for belief in God without appeal to scriptural or patristic authority,[159] using new and bold arguments.[160] He attributes this style—and the book's existence—to the requests of his fellow monks that "nothing whatsoever in these matters should be made convincing by the authority of Scripture, but whatsoever... the necessity of reason would concisely prove".[161]

In the first chapter, Anselm begins with a statement that anyone should be able to convince themselves of the existence of God through reason alone "if he is even moderately intelligent".[162] He argues that many different things are known as "good", in many varying kinds and degrees. These must be understood as being judged relative to a single attribute of goodness.[163] He then argues that goodness is itself very good and, further, is good through itself. As such, it must be the highest good and, further, "that which is supremely good is also supremely great. There is, therefore, some one thing that is supremely good and supremely great—in other words, supreme among all existing things."[164] Chapter 2 follows a similar argument, while Chapter 3 argues that the "best and greatest and supreme among all existing things" must be responsible for the existence of all other things.[164] Chapter 4 argues that there must be the highest level of dignity among existing things and that the highest level must have a single member. "Therefore, there is a certain nature or substance or essence who through himself is good and great and through himself is what he is; through whom exists whatever truly is good or great or anything at all; and who is the supreme good, the supreme great thing, the supreme being or subsistent, that is, supreme among all existing things."[164] The remaining chapters of the book are devoted to consideration of the attributes necessary to such a being.[164] The Euthyphro dilemma, although not addressed by that name, is dealt with as a false dichotomy.[165] God is taken to neither conform to nor invent the moral order but to embody it:[165] in each case of his attributes, "God having that attribute is precisely that attribute itself".[166]

A letter survives of Anselm responding to Lanfranc's criticism of the work. The elder cleric took exception to its lack of appeals to scripture and authority.[158] The preface of the Proslogion records his own dissatisfaction with the Monologion's arguments, since they are rooted in a posteriori evidence and inductive reasoning.[160]

Proslogion

[edit]The Proslogion (Latin: Proslogium, "Discourse"), originally entitled Faith Seeking Understanding (Fides Quaerens Intellectum) and then An Address on God's Existence (Alloquium de Dei Existentia),[153][167][i] was written over the next two years (1077–1078).[32] It is written in the form of an extended direct address to God.[151] It grew out of his dissatisfaction with the Monologion's interlinking and contingent arguments.[151] His "single argument that needed nothing but itself alone for proof, that would by itself be enough to show that God really exists"[168] is commonly[j] taken to be merely the second chapter of the work. In it, Anselm reasoned that even atheists can imagine the greatest being, having such attributes that nothing greater could exist (id quo nihil maius cogitari possit).[111] However, if such a being's attributes did not include existence, a still greater being could be imagined: one with all of the attributes of the first and existence. Therefore, the truly greatest possible being must necessarily exist. Further, this necessarily-existing greatest being must be God, who therefore necessarily exists.[160] This reasoning was known to the Scholastics as "Anselm's argument" (ratio Anselmi) but it became known as the ontological argument for the existence of God following Kant's treatment of it.[168][k]

Более вероятно, что Ансельм намеревался включить в свой «единственный аргумент» и большую часть остальной работы: [151] wherein he establishes the attributes of God and their compatibility with one another. Continuing to construct a being greater than which nothing else can be conceived, Anselm proposes such a being must be "just, truthful, happy, and whatever it is better to be than not to be".[171] Chapter 6 specifically enumerates the additional qualities of awareness, omnipotence, mercifulness, impassibility (inability to suffer),[170] and immateriality;[172] Chapter 11, self-existent,[172] wisdom, goodness, happiness, and permanence; and Chapter 18, unity.[170] Anselm addresses the question-begging nature of "greatness" in this formula partially by appeal to intuition and partially by independent consideration of the attributes being examined.[172] The incompatibility of, e.g., omnipotence, justness, and mercifulness are addressed in the abstract by reason, although Anselm concedes that specific acts of God are a matter of revelation beyond the scope of reasoning.[173] At one point during the 15th chapter, he reaches the conclusion that God is "not only that than which nothing greater can be thought but something greater than can be thought".[151] In any case, God's unity is such that all of his attributes are to be understood as facets of a single nature: "all of them are one and each of them is entirely what [God is] and what the other[s] are".[174] Затем это используется для аргументации триединой природы Бога, Иисуса и «единой любви, общей для [Бога] и [его] Сына, то есть Святого Духа, исходящего от обоих». [175] Последние три главы представляют собой отступление от того, что может повлечь за собой Божья благость. [151] Выдержки из работы позже были собраны под названием «Размышления» или «Руководство святого Остина» . [26]

Отвечать

[ редактировать ]Аргументация, представленная в Прослогионе, редко казалась удовлетворительной. [160] [л] и ему сразу же противостоял Гаунило , монах из аббатства Мармутье в Туре . [179] Его книга «Для дураков» ( Liber pro Insipiente ). [м] утверждает, что мы не можем произвольно перейти от идеи к реальности [160] ( вывод делается не из возможности к бытию ). [41] Самое известное из возражений Гаунило — это пародия на аргумент Ансельма, касающийся острова, большего которого невозможно помыслить. [168] Поскольку мы можем представить себе такой остров, он существует в нашем понимании и поэтому должен существовать в реальности. Однако это абсурдно, так как его берег может быть произвольно увеличен и в любом случае меняется в зависимости от прилива.

Ответ Ансельма ( Responsio ) или извинение ( Liber Apologeticus ) [160] не обращается непосредственно к этому аргументу, который привел Климу , [182] Гжесик, [41] и другие, чтобы составить для него ответы, и возглавил Вольтерсторфа. [183] и другие пришли к выводу, что атака Гаунило является окончательной. [168] Ансельм, однако, считал, что Гаунило неправильно понял его аргумент. [168] [179] В каждом из четырех аргументов Гаунило он считает описание Ансельма «того, больше чего нельзя мыслить», эквивалентным «тому, что больше всего, что можно мыслить». [179] Ансельм возражал, что все, что на самом деле не существует, обязательно исключено из его рассуждений, и все, что могло бы существовать или, вероятно, не существовать, также остается в стороне. В Прослогионе уже говорилось, что «можно считать, что все остальное, кроме [Бога], не существует». [184] единственной величайшей Аргумент Прослогиона касается и может касаться только сущности из всех существующих вещей. Эта сущность должна существовать и быть Богом. [168]

Диалоги

[ редактировать ]

Ансельма Все диалоги представляют собой урок между одаренным и любознательным учеником и знающим учителем. За исключением Cur Deus Homo , ученик не идентифицирован, но учителем всегда узнаваем сам Ансельм. [151]

Ансельма De Grammatico («О грамматике»), дата неизвестна, [н] занимается устранением различных парадоксов, возникающих из грамматики латинских существительных и прилагательных. [155] исследуя задействованные силлогизмы , чтобы убедиться, что термины в посылках совпадают по значению, а не просто по выражению. [186] трактовка явно обязана трактовке Боэция Аристотеля Эта . [142]

Между 1080 и 1086 годами, еще находясь в Беке, Ансельм сочинил диалоги De Veritate («Об истине»), De Libertate Arbitrii («О свободе выбора») и De Casu Diaboli («О падении дьявола»). [32] De Veritate заботится не только об истинности утверждений, но и о правильности воли, действия и сущности. [187] Правильность в таких вопросах понимается как выполнение того, что вещь должна или для чего была предназначена. [187] Ансельм использует аристотелевскую логику, чтобы подтвердить существование абсолютной истины, отдельные виды которой образуют все остальные истины. Эту абсолютную истину он отождествляет с Богом, который, следовательно, образует фундаментальный принцип как существования вещей, так и правильности мысли. [160] Как следствие, он утверждает, что «все, что есть, правильно». [189] De Libertate Arbitrii развивает рассуждения Ансельма о правильности в отношении свободы воли . Он считает это не способностью грешить , а способностью творить добро ради самого себя (а не из-за принуждения или корысти). [187] Таким образом, Бог и добрые ангелы обладают свободной волей, несмотря на то, что они неспособны грешить; Точно так же непринудительный аспект свободной воли позволил человеку и восставшим ангелам грешить, несмотря на то, что это не является необходимым элементом самой свободы воли. [190] В De Casu Diaboli Ансельм далее рассматривает случай падших ангелов, который служит для обсуждения случая рациональных агентов в целом. [191] Учитель утверждает, что существуют две формы добра — справедливость ( justicia ) и польза ( commodum ) — и две формы зла: несправедливость и вред ( incommodum ). Все разумные существа стремятся к выгоде и избегают вреда самостоятельно, но независимый выбор позволяет им выйти за рамки, наложенные справедливостью. [191] Некоторые ангелы предпочли свое счастье справедливости и были наказаны Богом за свою несправедливость меньшим счастьем. Ангелы, отстаивавшие справедливость, были вознаграждены таким счастьем, что теперь они неспособны грешить, и им не осталось счастья, которое они могли бы искать вопреки границам справедливости. [190] Между тем, люди сохраняют теоретическую способность желать справедливо, но из-за грехопадения они не способны делать это на практике, кроме как по божественной благодати. [192]

Почему Бог — мужчина?

[ редактировать ]Cur Deus Homo («Почему Бог был человеком») была написана с 1095 по 1098 год, когда Ансельм уже был архиепископом Кентерберийским. [32] в ответ на просьбы обсудить Воплощение . [193] Оно принимает форму диалога между Ансельмом и Бозо, одним из его учеников. [194] Его ядром является чисто рациональный аргумент в пользу необходимости христианской тайны искупления , вера в то, что распятие Иисуса было необходимо для искупления грехов человечества. Ансельм утверждает, что из-за Падения и падшей природы человечества с тех пор человечество оскорбило Бога. Божественная справедливость требует возмещения грехов, но люди неспособны обеспечить ее, поскольку все действия людей уже направлены на содействие славе Божией. [195] Более того, бесконечная справедливость Бога требует бесконечного возмещения за оскорбление Его бесконечного достоинства. [192] Чудовищность преступления побудила Ансельма отвергнуть личные акты искупления, даже Питера Дамиана , бичевание как неадекватные. [196] и в конечном итоге тщетно. [197] Вместо этого полное возмещение могло быть произведено только Богом, и Его бесконечная милость склоняет Его предоставить. Однако искупление человечества могло быть совершено только через фигуру Иисуса , как безгрешного существа, одновременно полностью божественного и полностью человеческого. [193] Взяв на себя ответственность отдать свою жизнь ради нас, его распятие приобретает бесконечную ценность, более чем просто искупление человечества и предоставление ему возможности наслаждаться справедливой волей в соответствии с его предназначенной природой. [192] Эта интерпретация примечательна тем, что допускает полную совместимость божественного правосудия и милосердия. [163] и оказал огромное влияние на церковное учение, [160] [198] во многом вытеснив более раннюю теорию, разработанную Оригеном и Григорием Нисским. [111] в первую очередь это было сосредоточено на сатаны власти над падшим человеком . [160] Cur Deus Homo часто называют величайшим произведением Ансельма. [111] но законнический и аморальный характер этого аргумента, наряду с его пренебрежением к реально искупаемым людям, подвергался критике как по сравнению с трактовкой Абеляра, так и [160] и для его последующего развития в протестантском богословии. [199]

Другие работы

[ редактировать ]Ансельма De Fide Trinitatis et de Incarnatione Verbi Contra Blasphemias Ruzelini («О вере в Троицу и о воплощении слова против богохульств Росцелина») [41] также известный как Epistolae de Incarnatione Verbi («Письма о воплощении Слова»), [32] был написан в двух черновиках в 1092 и 1094 годах. [41] Он защищал Ланфранка и Ансельма от ассоциации с якобы тритеистической ересью, которую поддерживал Росселин Компьеньский , а также выступал в пользу тринитаризма и универсалий .

De Conceptu Virginali et de Originali Peccato («О непорочном зачатии и первородном грехе») было написано в 1099 году. [32] Он утверждал, что написал это из-за желания расширить один из аспектов Cur Deus Homo для своего ученика и друга Босо и принял форму половины разговора Ансельма с ним. [151] Хотя Ансельм отрицал веру в Марии непорочное зачатие , [200] его мышление заложило два принципа, которые легли в основу развития этой догмы. Во-первых, было правильно, что Мария была настолько чиста, что, кроме Бога, нельзя было вообразить более чистое существо. Вторым было его лечение первородного греха. Раньше богословы считали, что секс передается из поколения в поколение благодаря греховной природе секса . Как и в своих более ранних работах, Ансельм вместо этого утверждал, что грех Адама был перенесен на его потомки через изменение человеческой природы, произошедшее во время Падения. Родители не смогли воспитать в своих детях справедливую природу, которой у них самих никогда не было. [201] Впоследствии в случае Мэри это будет решено с помощью догмы, касающейся обстоятельств ее собственного рождения.

Об исхождении Святого Духа на греков [167] написано в 1102 году, [32] представляет собой резюме подхода Ансельма к этому вопросу на Совете Бари . [93] Сначала он обсудил Троицу, заявив, что люди не могут познать Бога от Него Самого, а только по аналогии. Аналогией, которую он использовал, было самосознание человека. Своеобразная двойная природа сознания, памяти и разума представляет отношение Отца к Сыну. Взаимная любовь этих двоих (памяти и разума), исходя из их отношения друг к другу, символизирует Святого Духа. [160]

«О гармонии предузнания и предопределения и благодати Божией со свободным выбором» было написано с 1107 по 1108 год. [32] Как и « De Conceptu Virginali» , он принимает форму одного рассказчика в диалоге, предлагающего вероятные возражения с другой стороны. [151] Его трактовка свободы воли основана на более ранних работах Ансельма, но более подробно описывает способы, которыми не существует фактической несовместимости или парадокса, созданного божественными атрибутами. [152] В пятой главе Ансельм повторяет свое рассмотрение вечности из «Монологиона» . «Хотя там нет ничего, кроме настоящего, это не временное настоящее, как наше, а скорее вечное, внутри которого содержатся все времена. Если определенным образом настоящее время содержит каждое место и все вещи, которые находятся в любом месте, точно так же каждое время заключено в вечном настоящем, и все, что есть, в любом времени». [203] Это всеобъемлющее настоящее, все одновременно увиденное Богом, что позволяет как Его «предвидение», так и подлинный свободный выбор со стороны человечества. [204]

Сохранились фрагменты работы, которую Ансельм оставил незавершенной после своей смерти, которая представляла собой диалог об определенных парах противоположностей, включая способность/неспособность, возможность/невозможность и необходимость/свобода. [205] Поэтому его иногда цитируют под названиями « Власть и бессилие», «Возможность и невозможность», «Необходимость и свобода» . [41] Другой работой, вероятно, оставленной Ансельмом незавершенной и впоследствии переработанной и расширенной, была De Humanis Moribus per Similitudines («О морали человечества, рассказанная через сходства») или De Similitudinibus («О сходствах»). [206] Сборник его изречений ( Dicta Anselmi ) составил, вероятно, монах Александр. [207] Он также составил молитвы различным святым. [20]

Ансельм написал около 500 сохранившихся писем ( Epistolae ) священнослужителям, монахам, родственникам и другим людям. [208] самые ранние из них были написаны норманнским монахам, которые последовали за Ланфранком в Англию в 1070 году. [20] Саузерн утверждает, что все письма Ансельма, «даже самые сокровенные», представляют собой изложения его религиозных убеждений, сознательно составленные так, чтобы их могли прочитать многие другие. [209] Его длинные письма Вальтраму , епископу Наумберга ( в Германии ( Epistolae ad Walerannum ) De Sacrificio Azymi et Fermentati («О пресных и квасных жертвах») и De Sacramentis Ecclesiae «О церковных таинствах») были написаны между 1106 и 1107 годами. иногда переплетаются как отдельные книги. [32] Хотя он редко просил других молиться за него, два его письма к отшельникам делают это, что является «свидетельством его веры в их духовное мастерство». [210] Его рекомендательные письма — одно Хью, отшельнику недалеко от Кана , и два общине монахинь-мирянок — подтверждают, что их жизнь является убежищем от трудностей политического мира, с которыми Ансельму приходилось бороться. [210]

Многие письма Ансельма содержат страстные выражения привязанности и нежности, часто адресованные «возлюбленному возлюбленному» ( dilecto dilectori ). Хотя существует широкое согласие в том, что Ансельм лично был привержен монашескому идеалу безбрачия , некоторые учёные, такие как Макгуайр, [211] и Босуэлл [212] охарактеризовали эти произведения как выражение гомосексуальных наклонностей. [213] Общая точка зрения, высказанная Олсеном [214] и Саузерн считает, что эти выражения представляют собой «полностью духовную» привязанность, «питаемую бестелесным идеалом». [215]

Наследие

[ редактировать ]

Две биографии Ансельма были написаны вскоре после его смерти его капелланом и секретарем Эдмером ( Vita et Conversatione Anselmi Cantuariensis ) и монахом Александром ( Ex Dictis Beati Anselmi ). [31] Эдмер также подробно описал борьбу Ансельма с английскими монархами в своей истории ( Historia Novorum ). Другой был составлен примерно пятьдесят лет спустя Джоном Солсберийским по указанию Томаса Бекета . [208] Историки Уильям Малмсберийский , Ордерик Виталис и Мэтью Пэрис оставили полные отчеты о его борьбе против второго и третьего нормандских королей. [208]

Среди учеников Ансельма были Эдмер , Александр, Гилберт Криспин , Гонорий Августодуненсис и Ансельм Лаонский . Его работы копировались и распространялись при его жизни и оказали влияние на схоластиков , в том числе на Бонавентуру , Фому Аквинского , Дунса Скота и Уильяма Оккама . [143] Его мысли направляли многие последующие дискуссии об исхождении Святого Духа и искуплении . Его работа также предвосхищает многие из более поздних споров о свободе воли и предопределении . [59] В начале 1930-х годов произошли обширные дебаты — в первую очередь среди французских ученых — о «природе и возможностях» христианской философии , которые во многом опирались на работы Ансельма. [143]

Современные ученые по-прежнему резко разделены по поводу характера епископского руководства Ансельма. Некоторые, в том числе Фрелих [216] и Шмитт , [217] Приведите аргументы в пользу попыток Ансельма сохранить свою репутацию набожного ученого и священнослужителя, сводя к минимуму мирские конфликты, в которые он оказался вынужден. [217] Вон [218] а другие утверждают, что «тщательно взращиваемый образ простой святости и глубокого мышления» был использован искусным и неискренним политическим деятелем как инструмент. [217] в то время как традиционный взгляд на благочестивого и упорного церковного лидера, зафиксированный Эдмером, — человека, который искренне «вынашивал глубоко укоренившийся ужас перед мирским прогрессом», — поддерживается южными [219] среди других. [210] [217]

Почитание

[ редактировать ]

Ансельма В агиографии записано, что, когда он был ребенком, ему было чудесное видение на Бога вершине Бекка -ди-Нона недалеко от его дома, когда Бог спросил его имя, его дом и его поиски, прежде чем поделиться с ним хлебом. Затем Ансельм заснул, проснулся, вернулся в Аосту, а затем вернулся по своим следам, прежде чем вернуться, чтобы поговорить со своей матерью. [220]

Ансельма Канонизация была запрошена у Папы Александра III Томасом Бекетом на Турском совете в 1163 году . [208] Возможно, он был официально канонизирован до убийства Беккета в 1170 году: никаких записей об этом не сохранилось, но впоследствии он был причислен к лику святых в Кентербери и других местах. [ нужна ссылка ] Однако обычно считается, что его культ был формально санкционирован папой Александром VI лишь в 1494 году. [94] [221] или 1497 [136] по просьбе архиепископа Мортона . [136] Его праздник отмечается в день его смерти, 21 апреля, католической церковью , большей частью англиканской общины . [31] и некоторые формы лютеранства высокой церкви . [ нужна ссылка ] Местоположение его мощей неизвестно . Его самый распространенный атрибут — корабль, олицетворяющий духовную независимость церкви. [ нужна ссылка ]

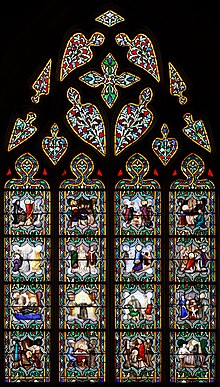

Ансельм был провозглашен Учителем Церкви Папой Климентом XI в 1720 году; [26] он известен как доктор магнификус («Великолепный доктор»). [41] или доктор Мариан (« Марианский врач»). [222] часовня Кентерберийского собора Ему посвящена к югу от главного алтаря; он включает в себя современное витражное изображение святого в окружении его наставника Ланфранка и его управляющего Болдуина , а также королей Вильгельма II и Генриха I. [223] [224] Папский Атеней Святого Ансельма , названный в его честь, был основан в Риме Папой Львом XIII в 1887 году. Прилегающий к нему Сант-Ансельмо алл'Авентино , резиденция аббата-примата Федерации черных монахов (всех монахов под Правление святого Бенедикта, за исключением цистерцианцев и траппистов ), было посвящено ему в 1900 году. Через 800 лет после его смерти, 21 апреля 1909 года, Папа Пий X издал энциклику « Communium Rerum », восхваляющую Ансельма, его церковную карьеру и его сочинения. В Соединенных Штатах аббатство Святого Ансельма и связанный с ним колледж расположены в Нью-Гэмпшире ; в 2009 году они провели празднование 900-летия со дня смерти Ансельма. В 2015 году архиепископ Кентерберийский создал Джастин Уэлби Общину Святого Ансельма , англиканский религиозный орден , который находится в Ламбетском дворце и занимается « молитвой и служением бедным». [225]

Ансельма поминают в англиканской и епископальной церкви 21 апреля . [226] [227]

Издания произведений Ансельма

[ редактировать ]- Герберон, Габриэль (1675), Opuscula Anselmi ex Beccensi Abbate Cantuariensis Archiepiscopi Opera, nec non Eadmeri Monachi Cantuariensis Historia Novorum, et Alia Sancti второстепенные произведения Эдмера, монаха Кентерберийского ] (на латыни), Париж: Луи Биллен и Пюи Жан ( 2-е Другие дю изд. серии его Patrologia Latina в 1853 и 1854 гг.)

- Убагс, Жерар Казимир [Gerardus Casimirus] (1854), О познании Бога, или Монолог и пролог с приложениями, святого Ансельма, архиепископа Кентерберийского и Учителя Церкви [ О познании Бога, или Монолог и пролог с приложениями , святой Ансельм, архиепископ Кентерберийский и Учитель Церкви ] (на латыни и французском языке), Лувен: Vanlinthout & Cie

- Рэджи, Филиберт (1883), Мариале или Книга Precum Metricarum Пресвятой Девы Марии Daily Said (на латыни), Лондон: Burns & Oates

- Дин, Сидней Нортон (1903), Святой Ансельм: Прослогиум, Монологий, Приложение от имени дурака Гаунилона и Cur Deus Homo с введением, библиографией и перепечатками мнений ведущих философов и писателей об онтологическом аргументе , Чикаго: Open Court Publishing Co. (переиздано и расширено как «Св. Ансельм: Основные сочинения» в 1962 г.)

- Уэбб, Клемент Чарльз Джулиан (1903), Посвящения святого Ансельма, архиепископа Кентерберийского , Лондон: Метуэн и компания (перевод Прослогиона , «Размышлений» , а также некоторых молитв и писем)

- Шмитт, Франц Салезиус [Франциско Салезиус] (1936), « Новая незаконченная работа святого Ансельма Кентерберийского », Вклад в историю философии и теологии средневековья [ Вклады в историю философии и теологии средневековья ], Том XXXIII, №. 3 (на латыни и немецком языке), Мюнстер: Ашендорф, стр. 22–43.

- Генри, Десмонд Пол (1964), Грамматика ( Святого Ансельма на латыни и английском языке), Саут-Бенд: University of Notre Dame Press

- Чарльзворт, Максвелл Джон (1965), Святого Ансельма Прослогион (на латыни и английском языке), Саут-Бенд: University of Notre Dame Press

- Шмитт, Франц Салес [Франциско Салезиус] (1968), С. Ансельми Cantuariensis Archiepiscopi Opera Omnia [ Полное собрание сочинений святого Ансельма, архиепископа Кентерберийского ] (на латыни), Штутгарт: Фридрих Фроманн Верлаг

- Саутерн, Ричард В .; и др. (1969), Мемориалы святого Ансельма (на латыни и английском языке), Оксфорд: Oxford University Press

- Уорд, Бенедикта (1973), Молитвы и размышления святого Ансельма , Нью-Йорк: Penguin Books

- Хопкинс, Джаспер; и др. (1976), Ансельм Кентерберийский , Эдвин Меллен (переиздание более ранних отдельных переводов; переиздано Артуром Дж. Бэннингом Пресс как Полные философские и теологические трактаты Ансельма Кентерберийского в 2000 году) (переводы Хопкинса доступны здесь [1] ).

- Фрелих, Уолтер (1990–1994), Письма святого Ансельма Кентерберийского (на латыни и английском языке), Каламазу: цистерцианские публикации

- Дэвис, Брайан; и др. (1998), Ансельм Кентерберийский: Основные произведения , Оксфорд: Oxford University Press

- Уильямс, Томас (2007), Ансельм: Основные сочинения , Индианаполис: Hackett Publishing (перепечатка более ранних отдельных переводов)

См. также

[ редактировать ]- Вера ищет понимания

- Другие Ансельмы и святые Ансельмы

- Святой Ансельм , различные места, названные в честь Ансельма.

- Почему Бог — мужчина?

- Аббатство Клюни , григорианская реформа и церковное безбрачие

- Споры об инвестициях

- Кентерберийско-йоркский спор

- Святой Ансельм Кентерберийский, покровитель архива

- Рабство на Британских островах

- Схоластика

- Существование Бога

Примечания

[ редактировать ]- ↑ Запись о родителях Ансельма в записях Крайст-Черч в Кентербери оставляет возможность более позднего примирения. [18]

- ↑ Ансельм публично не осудил крестовый поход, но ответил итальянцу, чей брат тогда находился в Малой Азии, что вместо этого ему было бы лучше в монастыре. Саузерн резюмировал свою позицию следующим образом: «Для него важным выбором был просто между небесным Иерусалимом , истинным видением Мира, обозначаемым именем Иерусалим, которое можно было найти в монашеской жизни, и резней земного мира. Иерусалим в этом мире, который под каким бы названием ни был ничем иным, как видением разрушения». [82]

- ^ Непосредственные знания о произведениях Платона были еще весьма ограничены. , сделанный Кальцидием, Неполный латинский перевод Платона « Тимей» был доступен и стал основным продуктом философии XII века, но «похоже, не заинтересовал Ансельма». [141]

- ^ Латынь : Ибо я не стремлюсь понять, чтобы верить, но верю, что могу понять . Ибо я тоже верю в это, потому что, если я не поверю, я не пойму.

- ^ идти к вере через понимание» Другие примеры включают: «Христианин должен идти к пониманию через веру, а не и «Правильный порядок требует, чтобы мы поверили в глубины христианской веры, прежде чем осмелиться обсуждать ее разумно » [94]

- ^ Латынь : Мне кажется небрежностью, если, укрепившись в вере, мы не стремимся понять то, во что верим.

- ↑ Ансельм в письме Хью, архиепископу Лиона , просил переименовать произведения. [154] но не объяснил, почему он решил использовать греческие формы. Логан предполагает, что это могло произойти из-за случайного знакомства Ансельма со стоическими терминами, используемыми святым Августином и Марсианом Капеллой . [153]

- ^ Хотя латинское meditandus обычно переводится как « медитация », Ансельм использовал этот термин не в его современном смысле «саморефлексия» или «рассмотрение», а вместо этого как философский термин искусства , который описывал более активный процесс молчания. стремление к неизведанному». [156]

- ^ См. примечание выше о переименовании произведений Ансельма.

- ^ Согласно Томасу Уильямсу. [168]

- ^ Различные ученые оспаривают использование термина «онтологический» в отношении аргумента Ансельма. Список до его времени предоставлен МакЭвоем . [169]

- ^ Вариации аргумента были разработаны и защищены Дунсом Скотом , Декартом , Лейбницем , Гёделем , Плантингой и Малькольмом . Помимо Гаунило, среди других заметных противников его рассуждений можно назвать Фому Аквинского и Иммануила Канта , причем наиболее тщательный анализ был проведен Оппенгеймером и Залтой . [176] [177] [178]

- ↑ Название является отсылкой к обращению Ансельма к Псалмам : «Глупец сказал в своем сердце: «Бога нет»». [180] [181] Гаунило предполагает, что, если бы аргументы Ансельма были единственным подтверждением существования Бога, глупец был бы прав, отвергая его рассуждения. [168]

- ^ Южный [185] и Томас Уильямс [32] датируют его 1059–1060 гг., а Маренбон помещает его «вероятно... вскоре после» 1087 г. [141]

Цитаты

[ редактировать ]- ^ Церковный пенсионный фонд (2010) , с. [ нужна страница ] .

- ^ «Выдающиеся лютеранские святые» . Resurrectionpeople.org . Архивировано из оригинала 16 мая 2019 года . Проверено 16 июля 2019 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Чарльзуорт (2003) , стр. 23–24.

- ^ Смит (2014) , с. 66.

- ^ Дэвис и Лефтоу (2004) , с. 120.

- ^ Браун (2014) , с. 146.

- ^ «Святой Ансельм Кентерберийский» . Britannica.com . Проверено 24 ноября 2018 г.

- ^ Правило (1883) , с. 2–3 .

- ^ Правило (1883) , с. 1–2 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Южный (1990) , с. 7.

- ^ Превит-Ортон (1912) , с. 155.

- ^ Кирш (1911) .

- ^ Смит (1989) , с. [ нужна страница ] .

- ^ Виллари (1911) , стр. 254–257.

- ^ Правило (1883) , с. 1–4 .

- ^ Южный (1990) , с. 8.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж г час я дж к л м н тот п д р с ЭБ (1878) , с. 91.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Робсон (1996) .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Риволин (2009) .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Кросс и Ливингстон (2005) , с. 73 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Правило (1883) , с. 1 .

- ^ Правило (1883) , с. 2 .

- ^ Правило (1883) , с. 4–7 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Правило (1883) , с. 7–8 .

- ^ Южный (1990) , с. 9.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж г час я дж к л Батлер (1864) .

- ^ Уилмот-Бакстон (1915) , Гл. 3.

- ^ Рамблер (1853) , с. 365–366.

- ^ Рамблер (1853) , с. 366.

- ^ Чарльзворт (2003) , с. 9.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д Сэдлер (2006) , §1.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж г час я дж к л м н СЭП (2007) , §1.

- ^ Южный (1990) , с. 32.

- ^ Чарльзворт (2003) , с. 10.

- ^ Рамблер (1853) , стр. 366–367.

- ^ Рамблер (1853) , с. 367–368.

- ^ Рамблер (1853) , с. 368.

- ^ Вон (1975) , с. 282.

- ^ Чарльзворт (2003) , с. 15.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д Рамблер (1853) , с. 483 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж г час я дж Гжесик (2000) .

- ^ Вон (1975) , с. 281.

- ^ Рамблер (1853) , с. 369.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Чарльзуорт (2003) , с. 16.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Кросс и Ливингстон (2005) , с. 74.

- ^ Рамблер (1853) , с. 370.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Южный (1990) , с. 189 .

- ^ Рамблер (1853) , с. 371.

- ^ Барлоу (1983) , стр. 298–299.

- ^ Южный (1990) , с. 189–190 .

- ^ Южный (1990) , с. 191–192 .

- ^ Барлоу (1983) , с. 306.

- ^ Вон (1974) , с. 246.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Вон (1975) , с. 286.

- ^ Вон (1974) , с. 248.

- ^ Чарльзворт (2003) , с. 17.

- ^ Бонифаций (747) , Письмо Катберту.

- ^ Хейс (1911) , с. 683.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Кент (1907) .

- ^ Вон (1988) , с. 218.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Вон (1978) , с. 357.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д Вон (1975) , с. 293.

- ^ Jump up to: а б ЭБ (1878) , стр. 91–92.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Вон (1980) , с. 82.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Вон (1980) , с. 83.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Вон (1975) , с. 298.

- ^ Дагган (1965) , стр. 98–99.

- ^ Уиллис (1845) , с. 38 .

- ^ Уиллис (1845) , стр. 17–18 .

- ^ Кук (1949) , с. 49.

- ^ Уиллис (1845) , стр. 45–47 .

- ^ Вон (1975) , с. 287.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Рамблер (1853) , с. 482 .

- ^ Уилмот-Бакстон (1915) , с. 136.

- ^ Пауэлл и др. (1968) , с. 52.

- ^ Вон (1987) , стр. 182–185.

- ^ Вон (1975) , с. 289.

- ^ Кантор (1958) , с. 92.

- ^ Барлоу (1983) , стр. 342–344.

- ^ Дэвис (1874) , с. 73 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Рамблер (1853) , с. 485 .

- ^ Южный (1990) , с. 169.

- ^ Кантор (1958) , с. 97.

- ^ Вон (1987) , с. 188.

- ^ Вон (1987) , с. 194.

- ^ Поттер (2009) , с. 47 .

- ^ Вон (1975) , с. 291.

- ^ Вон (1975) , с. 292.

- ^ Вон (1978) , с. 360.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Южный (1990) , с. 279 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Южный (1963) .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Кидд (1927) , стр. 252–3 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д Фортескью (1907) , с. 203 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж г час я дж к л м н тот ЭБ (1878) , с. 92.

- ^ Южный (1990) , с. 280.

- ^ Южный (1990) , с. 281.

- ^ Шарп (2009) .

- ^ Вон (1980) , с. 63.

- ^ Южный (1990) , с. 291 .

- ^ Холлистер (1983) , с. 120.

- ^ Вон (1980) , с. 67.

- ^ Холлистер (2003) , стр. 137–138.

- ^ Холлистер (2003) , стр. 135–136.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Вон (1975) , с. 295.

- ^ Холлистер (2003) , стр. 128–129.

- ^ Партнер (1973) , стр. 467–475, 468.

- ^ Босуэлл (1980) , с. 215.

- ^ Кроули (1910) .

- ^ Рамблер (1853) , с. 489–91 .

- ^ Вон (1980) , с. 71.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж Кросс и Ливингстон (2005) , с. 74 .

- ^ Вон (1980) , с. 74.

- ^ Чарльзворт (2003) , стр. 19–20.

- ^ Рамблер (1853) , с. 496–97 .

- ^ Вон (1980) , с. 75.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Вон (1978) , с. 367.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Вон (1980) , с. 76.

- ^ Вон (1980) , с. 77.

- ^ Рамблер (1853) , с. 497–98 .

- ^ Вон (1975) , стр. 296–297.

- ^ Вон (1980) , с. 80.

- ^ Вон (1975) , с. 297.

- ^ Кросс, Майкл, «Алтарь в часовне Святого Ансельма» , Кентерберийское историко-археологическое общество , получено 30 июня 2015 г.

- ^ «Алтарь часовни Святого Ансельма» , Waymarking , Сиэтл: Groundspeak, 28 апреля 2012 г. , получено 30 июня 2015 г.

- ^ Рамблер (1853) , с. 498 .

- ^ Уиллис (1845) , с. 46 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Оллард и др. (1931) , заяв. Д, с. 21 .

- ^ HMC (1901) , с. 227–228 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Письмо СС от 9 января 1753 г. (вероятно, Сэмюэля Шакфорда, но, возможно, Сэмюэля Стедмана) [127] Томасу Херрингу . [128]

- ^ Оллард и др. (1931) , заяв. Д, с. 20 .

- ^ HMC (1901) , с. 226 .

- ↑ Письмо Томаса Херринга от Джону Линчу 23 декабря 1752 года . [131]

- ^ HMC (1901) , с. 227 .

- ↑ Письмо Томаса Херринга Джону Линчу от 6 января 1753 года . [133]

- ^ HMC (1901) , с. 229–230 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Письмо П. Брэдли от 31 марта 1753 г. графу Перрону . [135]

- ^ HMC (1901) , с. 230–231 .

- ↑ Письмо лорда Болтона от 16 августа 1841 года, возможно, У. Р. Лайаллу. [137]

- ^ Дэвис и Лефтоу (2004) , с. 2 .

- ^ Сэдлер (2006) , Введение.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Маренбон (2005) , с. 170

- ^ Jump up to: а б Логан (2009) , с. 14 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Сэдлер (2006) , §2.

- ^ Маренбон (2005) , с. 169–170 .

- ^ Холлистер (1982) , с. 302.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Чисхолм (1911) , с. 82.

- ^ Шафф (2005) .

- ^ Сентябрь (2007) .

- ^ Ансельм Кентерберийский , Cur Deus Homo , Vol. Я, §2.

- ^ Ансельм Кентерберийский , О вере Троицы , §2.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж г час я дж к л м Сэдлер (2006) , §3.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Дэвис и Лефтоу (2004) , с. 201 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Логан (2009) , с. 85 .

- ↑ Ансельм Кентерберийский , Письма , № 109.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Ласкомб (1997) , с. 44 .

- ^ Логан (2009) , с. 86 .

- ^ Гибсон (1981) , с. 214.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Логан (2009) , с. 21 .

- ^ Логан (2009) , с. 21–22 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж г час я дж к ЭБ (1878) , с. 93.

- ^ Ансельм Кентерберийский , Монологион , с. 7, перевод Сэдлера . [151]

- ^ Сентябрь (2007) , §2.1.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Сэдлер (2006) , лок. ??.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д СЭП (2007) , §2.2.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Роджерс (2008) , с. 8.

- ^ Сэдлер (2006) , §6.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Форшалл (1840) , с. 74 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж г час СЭП (2007) , §2.3.

- ^ McEvoy (1994) .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж Сэдлер (2006) , §4.

- ^ Ансельм Кентерберийский , Прослогион , с. 104, перевод Сэдлера . [170]

- ^ Jump up to: а б с СЭП (2007) , §3.1.

- ^ Сентябрь (2007) , §3.2.

- ^ Ансельм Кентерберийский , Прослогион , с. 115, перевод Сэдлера . [170]

- ^ Ансельм Кентерберийский , Прослогион , с. 117, перевод Сэдлера . [170]

- ^ Оппенгеймер и Залта (1991) .

- ^ Оппенгеймер и Залта (2007) .

- ^ Оппенгеймер и Залта (2011) .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Сэдлер (2006) , §5.

- ^ Псалом 14:1.

- ^ Псалом 53:1.

- ^ Климат (2000) .

- ^ Вольтерсторфф (1993) .

- ^ Ансельм Кентерберийский , Прослогион , с. 103, перевод Сэдлера . [170]

- ^ Южный (1990) , с. 65.

- ^ Сэдлер (2006) , §8.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с СЭП (2007) , §4.1.

- ^ Сэдлер (2006) , §9.

- ^ Ансельм Кентерберийский , De Veritate , с. 185, перевод Сэдлера . [188]

- ^ Jump up to: а б СЭП (2007) , §4.2.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Сэдлер (2006) , §11.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с СЭП (2007) , §4.3.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Сэдлер (2006) , §7.

- ^ Сэдлер (2006) , §3 и 7.

- ^ Чисхолм (1911) , с. 83.

- ^ Фултон (2002) , с. 176 .

- ^ Фултон (2002) , с. 178 .

- ^ Фоли (1909) .

- ^ Фоли (1909) , стр. 256–7.

- ^ Генерал (2006) , с. 51.

- ^ Генерал (2006) , с. 52.

- ^ Сэдлер (2006) , §12.

- ^ Ансельм Кентерберийский , De Concordia , с. 254, перевод Сэдлера . [202]

- ^ Голландия (2012) , с. 43 .

- ^ Сэдлер (2006) , §13.

- ^ Динкова-Браун (2015) , с. 85 .

- ^ Сэдлер (2006) , §14.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д Рамблер (1853) , с. 361.

- ^ Южный (1990) , с. 396.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Хьюз-Эдвардс (2012) , с. 19 .

- ^ МакГуайр (1985) .

- ^ Босуэлл (1980) , стр. 218–219.

- ^ Доу (2000) , с. 18.

- ^ Олсен (1988) .

- ^ Южный (1990) , с. 157.

- ^ Фрелих (1990) , стр. 37–52.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д Гейл (2010) .

- ^ Вон (1987) .

- ^ Саузерн (1990) , стр. 459–481.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Правило (1883) , с. 12–14 .

- ^ Южный (1990) , с. XXIX.

- ^ Джексон (1909) .

- ^ «Кентерберийский витраж, современное издание» , клерк Оксфорда , 27 апреля 2011 г. , получено 29 июня 2015 г.

- ^ Тистлтон, Алан, «Окно Святого Ансельма» , Кентерберийское историко-археологическое общество , получено 30 июня 2015 г.

- ^ Лодж, Кэри (18 сентября 2015 г.). «Архиепископ Уэлби основывает монашескую общину в Ламбетском дворце» . Христианин сегодня . Проверено 5 апреля 2016 г.

- ^ «Календарь» . Англиканская церковь . Проверено 27 марта 2021 г.

- ^ Протестантская епископальная церковь (2019) , с. [ нужна страница ] .

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- «Обзоры: Св. Григорий и Св. Ансельм: Святой Ансельм Кентерберийский. Картина монашеской жизни и борьба духовной власти с светской властью в одиннадцатом веке . Автор MC де Ремюза. Дидье, Париж, 1853 г.», The Rambler, Католический журнал и обзор, Vol. XII, № 71 и 72 , Лондон: Леви, Робсон и Франклин для Бернса и Ламберта, 1853, стр. 360–374, 480–499

- «Святой Ансельм» , Стэнфордская энциклопедия философии , Стэнфордский университет, 2000 г. [пересмотрено в 2007 г.]

- Ансельм Кентерберийский, De Concordia (на латыни), ( издание Шмитта )

- Барлоу, Фрэнк (1983), Уильям Руфус , Беркли : Калифорнийский университет Press, ISBN 0-520-04936-5

- Бэйнс, Т.С., изд. (1878), , Британская энциклопедия , том. 2 (9-е изд.), Нью-Йорк: Сыновья Чарльза Скрибнера, стр. 91–93.

- Бонифаций (747 г.), Письмо Катберту, архиепископу Кентерберийскому , перевод Талбота

- Босуэлл, Джон (1980), Христианство, социальная толерантность и гомосексуализм: геи в Западной Европе от начала христианской эры до четырнадцатого века , University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-06711-4

- Батлер, Албан (1864 г.), «Святой Ансельм, архиепископ Кентерберийский» , «Жития отцов, мучеников и других главных святых», Vol. VI , D. & J. Sadlier & Co.

- Кантор, Норман Ф. (1958), Церковь, королевская власть и мирское вложение в Англию 1089–1135 , Принстон : Princeton University Press, OCLC 2179163

- Чарльзворт, Максвелл Дж. (2003) [Первоначально опубликовано в 1965 году], «Введение», Святого Ансельма Прослогион с ответом Гаунило от имени дурака и ответом автора Гаунило , Саут-Бенд: University of Notre Dame Press

- Чисхолм, Хью , изд. (1911). . Британская энциклопедия . Том. 2 (11-е изд.). Издательство Кембриджского университета. стр. 81–83.

- Церковный пенсионный фонд (2010 г.). Святые мужчины и святые женщины (PDF) . Нью-Йорк: Церковное издательство. ISBN 978-0-89869-637-0 .

- Кук, GH (1949), Портрет Кентерберийского собора , Лондон: Дом Феникса

- Кроули, Джон Дж. (1910), Жития святых , Джон Дж. Кроули и компания.

- Крозе-Муше, Жозеф, Святой Ансельм (Аостский), архиепископ Кентерберийский: История его жизни и времен .

- Кросс, Фрэнк Лесли; Ливингстон, Элизабет А., ред. (2005), «Святой Ансельм» , Оксфордский словарь христианской церкви (3-е изд.), Оксфорд: Oxford University Press, стр. 73–75, ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3

- Дэвис, Брайан; Лефтоу, Брайан, ред. (2004), Кембриджский спутник Ансельма , Кембридж : Издательство Кембриджского университета, ISBN 0-521-00205-2

- Дэвис, Джеймс (1874), История Англии от смерти «Эдварда Исповедника» до смерти Джона, (1066–1216) н.э. , Лондон: Джордж Филип и сын

- Динкова-Бруун, Грети (2015), «Nummus Falsus: Восприятие фальшивых денег в одиннадцатом и начале двенадцатого века» , Деньги и церковь в средневековой Европе, 1000–1200: практика, мораль и мысль , Фарнхэм: Ashgate Publishing , стр. 77–92, ISBN. 9781472420992

- Доу, Майкл (2000), В поисках истины в любви: Церковь и гомосексуализм , Дартон, Лонгман и Тодд, с. 18, ISBN 978-0-232-52399-7

- Дагган, Чарльз (1965), «От завоевания до смерти Джона», Английская церковь и папство в средние века , [Перепечатано в 1999 году издательством Sutton Publishing], стр. 63–116, ISBN. 0-7509-1947-7

- Фэйрвезер, Юджин Р. (1959). « «Iustitia Dei» как «Соотношение» Воплощения» . Spicilegium Beccense: Международный конгресс, посвященный 9-летию прибытия Ансельма в Бек . Полет. I. Ле Бек-Эллуэн / Париж : Аббатство Нотр-Дам-дю-Бек / Философский книжный магазин Ж. Врена . стр. 327–335. ASIN B00DULQV7C .

- Фэйрвезер, Юджин (1960). «Истина, справедливость и моральная ответственность в мысли святого Ансельма» . Человек и его судьба по мнению мыслителей Средневековья: Материалы первого международного конгресса средневековой философии . Лувен / Париж : Éditions Nauwelaerts/Beatrice-Nauwelaerts. АСИН B0727L3NVQ .

- Фэйрвезер, Юджин Р. (1961), «Воплощение и искупление: ансельмийский ответ на Христа Виктора Олена » (PDF) , Canadian Journal of Theology , VII (3): 167–175

- Фоли, Джордж Кадваладер (1909), Теория искупления Ансельма , Лондон: Longmans, Green, & Co.

- Форшалл, Джозия, изд. (1840), Каталог рукописей Британского музея, новая серия, том. Я, Пт. II: Рукописи Берни , Лондон: Британский музей.

- Фортескью, Адриан ХТК (1907), Православная Восточная церковь , Католическое общество истины, ISBN 9780971598614

- Фрелих, Вальтер (1990), «Введение», Письма святого Ансельма Кентерберийского, Том. Я , Каламазу: цистерцианские публикации

- Фултон, Рэйчел (2002), От суда к страсти: преданность Христу и Деве Марии, 800–1200 , Нью-Йорк: издательство Колумбийского университета, ISBN 0-231-12550-Х