Индийские религии

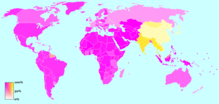

Indian religions as a percentage of world population

Индийские религии , иногда также называемые религиями Дхармы или индийскими религиями , — это религии , зародившиеся на Индийском субконтиненте . Эти религии, в число которых входят буддизм , индуизм , джайнизм и сикхизм , [ сеть 1 ] [ примечание 1 ] также относят к восточным религиям . Хотя индийские религии связаны историей Индии , они составляют широкий спектр религиозных общин и не ограничиваются Индийским субконтинентом. [ сеть 1 ]

| Religion | Population |

|---|---|

| Hindus |

1.25 billion |

| Buddhists |

520 million |

| Sikhs |

30 million |

| Jains |

6 million |

| Others | 4 million |

| Total | 1.81 billion |

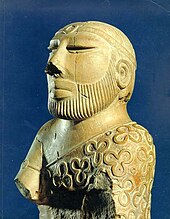

Доказательства существования доисторической религии на Индийском субконтиненте основаны на разрозненных наскальных рисунках мезолита . Хараппцы . , цивилизации долины Инда существовавшие с 3300 по 1300 год до н. э. (период зрелости 2600–1900 до н. э.), имели раннюю урбанизированную культуру, предшествовавшую ведической религии [ 5 ] [ нужен лучший источник ]

The documented history of Indian religions begins with the historical Vedic religion, the religious practices of the early Indo-Aryan peoples, which were collected and later redacted into the Vedas, as well as the Agamas of Dravidian origin. The period of the composition, redaction, and commentary of these texts is known as the Vedic period, which lasted from roughly 1750 to 500 BCE.[6] The philosophical portions of the Vedas were summarized in Upanishads, which are commonly referred to as Vedānta, variously interpreted to mean either the "last chapters, parts of the Veda" or "the object, the highest purpose of the Veda".[7] The early Upanishads all predate the Common Era, five[note 2] of the eleven principal Upanishads were composed in all likelihood before 6th century BCE,[8][9] and contain the earliest mentions of Yoga and Moksha.[10]

The śramaṇa period between 800 and 200 BCE marks a "turning point between the Vedic Hinduism and Puranic Hinduism".[11] The Shramana movement, an ancient Indian religious movement parallel to but separate from Vedic tradition, often defied many of the Vedic and Upanishadic concepts of soul (Atman) and the ultimate reality (Brahman). In 6th century BCE, the Shramnic movement matured into Jainism[12] and Buddhism[13] and was responsible for the schism of Indian religions into two main philosophical branches of astika, which venerates Veda (e.g., six orthodox schools of Hinduism) and nastika (e.g., Buddhism, Jainism, Charvaka, etc.). However, both branches shared the related concepts of Yoga, saṃsāra (the cycle of birth and death) and moksha (liberation from that cycle).[note 3][note 4][note 5]

The Puranic Period (200 BCE – 500 CE) and Early Medieval period (500–1100 CE) gave rise to new configurations of Hinduism, especially bhakti and Shaivism, Shaktism, Vaishnavism, Smarta, and smaller groups like the conservative Shrauta.

The early Islamic period (1100–1500 CE) also gave rise to new movements. Sikhism was founded in the 15th century on the teachings of Guru Nanak and the nine successive Sikh Gurus in Northern India.[web 2] The vast majority of its adherents originate in the Punjab region. During the period of British rule in India, a reinterpretation and synthesis of Hinduism arose, which aided the Indian independence movement.

History

| History of South Asia |

|---|

|

Periodisation

Scottish historian James Mill, in his seminal work The History of British India (1817), distinguished three phases in the history of India, namely the Hindu, Muslim, and British periods. This periodisation has been criticised, for the misconceptions it has given rise to. Another periodisation is the division into "ancient, classical, medieval, and modern periods", although this periodization has also received criticism.[16]

Romila Thapar notes that the division of Hindu-Muslim-British periods of Indian history gives too much weight to "ruling dynasties and foreign invasions",[17] neglecting the social-economic history which often showed a strong continuity.[17] The division in Ancient-Medieval-Modern overlooks the fact that the Muslim-conquests took place between the eight and the fourteenth century, while the south was never completely conquered.[17] According to Thapar, a periodisation could also be based on "significant social and economic changes", which are not strictly related to a change of ruling powers.[18][note 6]

Smart and Michaels seem to follow Mill's periodisation, while Flood and Muesse follow the "ancient, classical, mediaeval and modern periods" periodisation. An elaborate periodisation may be as follows:[19]

- Indian pre-history including Indus Valley civilisation (until c. 1750 BCE)

- Iron Age including Vedic period (c. 1750–600 BCE)

- "Second Urbanisation" (c. 600–200 BCE)

- Classical period (c. 200 BCE-1200 CE)[note 7]

- Pre-Classical period (c. 200 BCE-320 CE)

- "Golden Age" (Gupta Empire) (c. 320–650 CE)

- Late-Classical period (c. 650–1200 CE)

- Medieval period (c. 1200–1500 CE)

- Early Modern (c. 1500–1850)

- Modern period (British Raj and independence) (from c. 1850)

Prevedic religions (before c. 1750 BCE)

Prehistory

The earliest religion followed by the peoples of the Indian subcontinent, including those of the Indus Valley and Ganges Valley, was likely local animism that did not have missionaries.[24]

Evidence attesting to prehistoric religion in the Indian subcontinent derives from scattered Mesolithic rock paintings such as at Bhimbetka, depicting dances and rituals. Neolithic agriculturalists inhabiting the Indus River Valley buried their dead in a manner suggestive of spiritual practices that incorporated notions of an afterlife and belief in magic.[25] Other South Asian Stone Age sites, such as the Bhimbetka rock shelters in central Madhya Pradesh and the Kupgal petroglyphs of eastern Karnataka, contain rock art portraying religious rites and evidence of possible ritualised music.[web 3]

Indus Valley civilisation

The religion and belief system of the Indus Valley people has received considerable attention, especially from the view of identifying precursors to deities and religious practices of Indian religions that later developed in the area. However, due to the sparsity of evidence, which is open to varying interpretations, and the fact that the Indus script remains undeciphered, the conclusions are partly speculative and largely based on a retrospective view from a much later Hindu perspective.[26] An early and influential work in the area that set the trend for Hindu interpretations of archaeological evidence from the Harrapan sites[27] was that of John Marshall, who in 1931 identified the following as prominent features of the Indus religion: a Great Male God and a Mother Goddess; deification or veneration of animals and plants; symbolic representation of the phallus (linga) and vulva (yoni); and, use of baths and water in religious practice. Marshall's interpretations have been much debated, and sometimes disputed over the following decades.[28][29]

One Indus valley seal shows a seated, possibly ithyphallic and tricephalic, figure with a horned headdress, surrounded by animals. Marshall identified the figure as an early form of the Hindu god Shiva (or Rudra), who is associated with asceticism, yoga, and linga; regarded as a lord of animals; and often depicted as having three eyes. The seal has hence come to be known as the Pashupati Seal, after Pashupati (lord of all animals), an epithet of Shiva.[28][30] While Marshall's work has earned some support, many critics and even supporters have raised several objections. Doris Srinivasan has argued that the figure does not have three faces, or yogic posture, and that in Vedic literature Rudra was not a protector of wild animals.[31][32] Herbert Sullivan and Alf Hiltebeitel also rejected Marshall's conclusions, with the former claiming that the figure was female, while the latter associated the figure with Mahisha, the Buffalo God and the surrounding animals with vahanas (vehicles) of deities for the four cardinal directions.[33][34] Writing in 2002, Gregory L. Possehl concluded that while it would be appropriate to recognise the figure as a deity, its association with the water buffalo, and its posture as one of ritual discipline, regarding it as a proto-Shiva would be going too far.[30] Despite the criticisms of Marshall's association of the seal with a proto-Shiva icon, it has been interpreted as the Tirthankara Rishabha by Jains and Vilas Sangave[35] or an early Buddha by Buddhists.[27] Historians like Heinrich Zimmer, Thomas McEvilley are of the opinion that there exists some link between first Jain Tirthankara Rishabha and Indus Valley civilisation.[36][37]

Marshall hypothesized the existence of a cult of Mother Goddess worship based upon excavation of several female figurines, and thought that this was a precursor of the Hindu sect of Shaktism. However the function of the female figurines in the life of Indus Valley people remains unclear, and Possehl does not regard the evidence for Marshall's hypothesis to be "terribly robust".[38] Some of the baetyls interpreted by Marshall to be sacred phallic representations are now thought to have been used as pestles or game counters instead, while the ring stones that were thought to symbolise yoni were determined to be architectural features used to stand pillars, although the possibility of their religious symbolism cannot be eliminated.[39]

Many Indus Valley seals show animals, with some depicting them being carried in processions, while others show chimeric creations.[40] One seal from Mohen-jodaro shows a half-human, half-buffalo monster attacking a tiger, which may be a reference to the Sumerian myth of such a monster created by goddess Aruru to fight Gilgamesh.[41] Some seals show a man wearing a hat with two horns and a plant sitting on a throne with animals surrounding him.[42] Some scholars theorize that this was a predecessor to Shiva wearing a hat worn by some Sumerian divine beings and kings.[42]

In contrast to contemporary Egyptian and Mesopotamian civilisations, the Indus Valley lacks any monumental palaces, even though excavated cities indicate that the society possessed the requisite engineering knowledge.[43][44] This may suggest that religious ceremonies, if any, may have been largely confined to individual homes, small temples, or the open air. Several sites have been proposed by Marshall and later scholars as possibly devoted to religious purpose, but at present only the Great Bath at Mohenjo-daro is widely thought to have been so used, as a place for ritual purification.[38][45] The funerary practices of the Harappan civilisation is marked by its diversity with evidence of supine burial; fractional burial in which the body is reduced to skeletal remains by exposure to the elements before final interment; and even cremation.[46][47]

Vedic period (1750–800 BCE)

The documented history of Indian religions begins with the historical Vedic religion, the religious practices of the early Indo-Aryans, which were collected and later redacted into the Samhitas (usually known as the Vedas), four canonical collections of hymns or mantras composed in archaic Sanskrit. These texts are the central shruti (revealed) texts of Hinduism. The period of the composition, redaction, and commentary of these texts is known as the Vedic period, which lasted from roughly 1750 to 500 BCE.[6]

The Vedic Period is most significant for the composition of the four Vedas, Brahmanas and the older Upanishads (both presented as discussions on the rituals, mantras and concepts found in the four Vedas), which today are some of the most important canonical texts of Hinduism, and are the codification of much of what developed into the core beliefs of Hinduism.[48]

Some modern Hindu scholars use the "Vedic religion" synonymously with "Hinduism."[49] According to Sundararajan, Hinduism is also known as the Vedic religion.[50] Other authors state that the Vedas contain "the fundamental truths about Hindu Dharma"[note 8] which is called "the modern version of the ancient Vedic Dharma"[52] The Arya Samaj is recognize the Vedic religion as true Hinduism.[53] Nevertheless, according to Jamison and Witzel,

... to call this period Vedic Hinduism is a contradiction in terms since Vedic religion is very different from what we generally call Hindu religion – at least as much as Old Hebrew religion is from medieval and modern Christian religion. However, Vedic religion is treatable as a predecessor of Hinduism."[48][note 9]

Early Vedic period – early Vedic compositions (c. 1750–1200 BCE)

The rishis, the composers of the hymns of the Rigveda, were considered inspired poets and seers.[note 10]

The mode of worship was the performance of Yajna, sacrifices which involved sacrifice and sublimation of the havana sámagri (herbal preparations)[55] in the fire, accompanied by the singing of Samans and 'mumbling' of Yajus, the sacrificial mantras. The sublime meaning of the word yajna is derived from the Sanskrit verb yaj, which has a three-fold meaning of worship of deities (devapujana), unity (saògatikaraña), and charity (dána).[56] An essential element was the sacrificial fire – the divine Agni – into which oblations were poured, as everything offered into the fire was believed to reach God.[citation needed]

Central concepts in the Vedas are Satya and Rta. Satya is derived from Sat, the present participle of the verbal root as, "to be, to exist, to live".[57] Sat means "that which really exists [...] the really existent truth; the Good",[57] and Sat-ya means "is-ness".[58] Rta, "that which is properly joined; order, rule; truth", is the principle of natural order which regulates and coordinates the operation of the universe and everything within it.[59] "Satya (truth as being) and rita (truth as law) are the primary principles of Reality and its manifestation is the background of the canons of dharma, or a life of righteousness."[60] "Satya is the principle of integration rooted in the Absolute, rita is its application and function as the rule and order operating in the universe."[61] Conformity with Ṛta would enable progress whereas its violation would lead to punishment. Panikkar remarks:

Ṛta is the ultimate foundation of everything; it is "the supreme", although this is not to be understood in a static sense. [...] It is the expression of the primordial dynamism that is inherent in everything...."[62]

The term rta is inherited from the Proto-Indo-Iranian religion, the religion of the Indo-Iranian peoples prior to the earliest Vedic (Indo-Aryan) and Zoroastrian (Iranian) scriptures. "Asha" is the Avestan language term (corresponding to Vedic language ṛta) for a concept of cardinal importance[63] to Zoroastrian theology and doctrine. The term "dharma" was already used in Brahmanical thought, where it was conceived as an aspect of Rta.[64]

Major philosophers of this era were Rishis Narayana, Kanva, Rishaba, Vamadeva, and Angiras.[65]

Middle Vedic period (c. 1200–850 BCE)

During the Middle Vedic period, the mantras of the Yajurveda and the older Brahmana texts were composed.[66] The Brahmans became powerful intermediairies.[67]

Historical roots of Jainism in India is traced back to 9th-century BC with the rise of Parshvanatha and his non-violent philosophy.[68][69]

Late Vedic period (from 850 BCE)

The Vedic religion evolved into Hinduism and Vedanta, a religious path considering itself the 'essence' of the Vedas, interpreting the Vedic pantheon as a unitary view of the universe with 'God' (Brahman) seen as immanent and transcendent in the forms of Ishvara and Brahman. This post-Vedic systems of thought, along with the Upanishads and later texts like the epics (the Ramayana and the Mahabharata), is a major component of modern Hinduism. The ritualistic traditions of Vedic religion are preserved in the conservative Śrauta tradition.[citation needed]

Sanskritization

Since Vedic times, "people from many strata of society throughout the subcontinent tended to adapt their religious and social life to Brahmanic norms", a process sometimes called Sanskritization.[70] It is reflected in the tendency to identify local deities with the gods of the Sanskrit texts.[70]

Shramanic period (c. 800–200 BCE)

During the time of the shramanic reform movements "many elements of the Vedic religion were lost".[11] According to Michaels, "it is justified to see a turning point between the Vedic religion and Hindu religions".[11]

Late Vedic period – Brahmanas and Upanishads – Vedanta (850–500 BCE)

The late Vedic period (9th to 6th centuries BCE) marks the beginning of the Upanisadic or Vedantic period.[web 4][note 11][71][note 12] This period heralded the beginning of much of what became classical Hinduism, with the composition of the Upanishads,[73] later the Sanskrit epics, still later followed by the Puranas.

Upanishads form the speculative-philosophical basis of classical Hinduism and are known as Vedanta (conclusion of the Vedas).[74] The older Upanishads launched attacks of increasing intensity on the ritual. Anyone who worships a divinity other than the Self is called a domestic animal of the gods in the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad. The Mundaka launches the most scathing attack on the ritual by comparing those who value sacrifice with an unsafe boat that is endlessly overtaken by old age and death.[75]

Scholars believe that Parsva, the 23rd Jain tirthankara lived during this period in the 9th century BCE.[76]

Rise of Shramanic tradition (7th to 5th centuries BCE)

Jainism and Buddhism belong to the śramaṇa traditions. These religions rose into prominence in 700–500 BCE [12][13][77] in the Magadha kingdom., reflecting "the cosmology and anthropology of a much older, pre-Aryan upper class of northeastern India",[78] and were responsible for the related concepts of saṃsāra (the cycle of birth and death) and moksha (liberation from that cycle).[79][note 13]

The shramana movements challenged the orthodoxy of the rituals.[80] The shramanas were wandering ascetics distinct from Vedism.[81][82][note 14][83][note 15][84][note 16] Mahavira, proponent of Jainism, and Buddha (c. 563-483), founder of Buddhism were the most prominent icons of this movement.

Shramana gave rise to the concept of the cycle of birth and death, the concept of samsara, and the concept of liberation.[79][note 17][85][note 18][87][note 19][note 20] The influence of Upanishads on Buddhism has been a subject of debate among scholars. While Radhakrishnan, Oldenberg and Neumann were convinced of Upanishadic influence on the Buddhist canon, Eliot and Thomas highlighted the points where Buddhism was opposed to Upanishads.[90] Buddhism may have been influenced by some Upanishadic ideas, it however discarded their orthodox tendencies.[91] In Buddhist texts Buddha is presented as rejecting avenues of salvation as "pernicious views".[92]

Jainism

Jainism was established by a lineage of 24 enlightened beings culminating with Parshvanatha (9th century BCE) and Mahavira (6th century BCE).[93][note 21]

The 24th Tirthankara of Jainism, Mahavira, stressed five vows, including ahimsa (non-violence), satya (truthfulness), asteya (non-stealing), and aparigraha (non-attachment). Jain orthodoxy believes the teachings of the Tirthankaras predates all known time and scholars believe Parshva, accorded status as the 23rd Tirthankara, was a historical figure. The Vedas are believed to have documented a few Tirthankaras and an ascetic order similar to the shramana movement.[94][note 22]

Buddhism

Buddhism was historically founded by Siddhartha Gautama, a Kshatriya prince-turned-ascetic,[95] and was spread beyond India through missionaries.[96] It later experienced a decline in India, but survived in Nepal[97] and Sri Lanka, and remains more widespread in Southeast and East Asia.[98]

Gautama Buddha, who was called an "awakened one" (Buddha), was born into the Shakya clan living at Kapilavastu and Lumbini in what is now southern Nepal. The Buddha was born at Lumbini, as emperor Ashoka's Lumbini pillar records, just before the kingdom of Magadha (which traditionally is said to have lasted from c. 546–324 BCE) rose to power. The Shakyas claimed Angirasa and Gautama Maharishi lineage,[99] via descent from the royal lineage of Ayodhya.

Buddhism emphasises enlightenment (nibbana, nirvana) and liberation from the rounds of rebirth. This objective is pursued through two schools, Theravada, the Way of the Elders (practiced in Sri Lanka, Burma, Thailand, SE Asia, etc.) [100] and Mahayana, the Greater Way (practiced in Tibet, China, Japan, etc.).[101] There may be some differences in the practice between the two schools in reaching the objective.[citation needed]

Spread of Jainism and Buddhism (500–200 BCE)

Both Jainism and Buddhism spread throughout India during the period of the Magadha empire.[citation needed]

Buddhism flourished during the reign of Ashoka of the Maurya Empire, who patronised Buddhist teachings and unified the Indian subcontinent in the 3rd century BCE. He sent missionaries abroad, allowing Buddhism to spread across Asia.[102]

Jainism began its golden period during the reign of Emperor Kharavela of Kalinga in the 2nd century BCE due to his significant patronage of the religion. His reign is considered a period of growth and influence for the religion, although Jainism had flourished for centuries before and continued to develop in prominence after his time.[103]

Dravidian culture

The early Dravidian religion constituted of non-Vedic form of Hinduism in that they were either historically or are at present Āgamic. The Agamas are non-vedic in origin[104] and have been dated either as post-vedic texts.[105] or as pre-vedic oral compositions.[106] The Agamas are a collection of Tamil and later Sanskrit scriptures chiefly constituting the methods of temple construction and creation of murti, worship means of deities, philosophical doctrines, meditative practices, attainment of sixfold desires and four kinds of yoga.[107] The worship of tutelary deity, sacred flora and fauna in Hinduism is also recognized as a survival of the pre-Vedic Dravidian religion.[108]

Ancient Tamil grammatical works Tolkappiyam, the ten anthologies Pattuppāṭṭu, the eight anthologies Eṭṭuttokai also sheds light on early religion of ancient Dravidians. Seyon was glorified as the red god seated on the blue peacock, who is ever young and resplendent, as the favored god of the Tamils.[109] Sivan was also seen as the supreme God.[109] Early iconography of Seyyon[110] and Sivan[111][112][113][114][115] and their association with native flora and fauna goes back to Indus Valley Civilization.[111][113][116][117][118][112][119] The Sangam landscape was classified into five categories, thinais, based on the mood, the season and the land. Tolkappiyam, mentions that each of these thinai had an associated deity such Seyyon in Kurinji-the hills, Thirumaal in Mullai-the forests, and Kotravai in Marutham-the plains, and Wanji-ko in the Neithal-the coasts and the seas. Other gods mentioned were Mayyon and Vaali who were all assimilated into Hinduism over time. Dravidian linguistic influence[120] on early Vedic religion is evident, many of these features are already present in the oldest known Indo-Aryan language, the language of the Rigveda (c. 1500 BCE),[120] which also includes over a dozen words borrowed from Dravidian.[121] [122] This represents an early religious and cultural fusion[123][note 23] or synthesis[125] between ancient Dravidians and Indo-Aryans, which became more evident over time with sacred iconography, traditions, philosophy, flora, and fauna that went on to influence Hinduism, Buddhism, Charvaka, Sramana, and Jainism.[126][124][127][128]

Throughout Tamilakam, a king was considered to be divine by nature and possessed religious significance.[129] The king was 'the representative of God on earth' and lived in a "koyil", which means the "residence of a god". The Modern Tamil word for temple is koil. Titual worship was also given to kings.[130][131] Modern words for god like "kō" ("king"), "iṟai" ("emperor"), and "āṇḍavar" ("conqueror") now primarily refer to gods. These elements were incorporated later into Hinduism like the legendary marriage of Shiva to Queen Mīnātchi who ruled Madurai or Wanji-ko, a god who later merged into Indra.[132] Tolkappiyar refers to the Three Crowned Kings as the "Three Glorified by Heaven".[133] In the Dravidian-speaking South, the concept of divine kingship led to the assumption of major roles by state and temple.[134]

The cult of the mother goddess is treated as an indication of a society which venerated femininity. This mother goddess was conceived as a virgin, one who has given birth to all and one, typically associated with Shaktism.[135] The temples of the Sangam days, mainly of Madurai, seem to have had priestesses to the deity, which also appear predominantly a goddess.[136] In the Sangam literature, there is an elaborate description of the rites performed by the Kurava priestess in the shrine Palamutircholai.[137] Among the early Dravidians the practice of erecting memorial stones Natukal or Hero Stone had appeared, and it continued for quite a long time after the Sangam age, down to about 16th century.[138] It was customary for people who sought victory in war to worship these hero stones to bless them with victory.[139]

Epic and Early Puranic Period (200 BCE – 500 CE)

Flood and Muesse take the period between 200 BCE and 500 BCE as a separate period,[140][141] in which the epics and the first puranas were being written.[141] Michaels takes a greater timespan, namely the period between 200 BCE and 1100 CE,[11] which saw the rise of so-called "Classical Hinduism",[11] with its "golden age"[142] during the Gupta Empire.[142]

According to Alf Hiltebeitel, a period of consolidation in the development of Hinduism took place between the time of the late Vedic Upanishad (c. 500 BCE) and the period of the rise of the Guptas (c. 320–467 CE), which he calls the "Hindus synthesis", "Brahmanic synthesis", or "orthodox synthesis".[143] It develops in interaction with other religions and peoples:

The emerging self-definitions of Hinduism were forged in the context of continuous interaction with heterodox religions (Buddhists, Jains, Ajivikas) throughout this whole period, and with foreign people (Yavanas, or Greeks; Sakas, or Scythians; Pahlavas, or Parthians; and Kusanas, or Kushans) from the third phase on [between the Mauryan empire and the rise of the Guptas].[144]

The end of the Vedantic period around the 2nd century CE spawned a number of branches that furthered Vedantic philosophy, and which ended up being seminaries in their own right. Prominent among these developers were Yoga, Dvaita, Advaita, and the medieval Bhakti movement.[citation needed]

Smriti

The smriti texts of the period between 200 BCE–100 CE proclaim the authority of the Vedas, and "nonrejection of the Vedas comes to be one of the most important touchstones for defining Hinduism over and against the heterodoxies, which rejected the Vedas."[145] Of the six Hindu darsanas, the Mimamsa and the Vedanta "are rooted primarily in the Vedic sruti tradition and are sometimes called smarta schools in the sense that they develop smarta orthodox current of thoughts that are based, like smriti, directly on sruti."[146] According to Hiltebeitel, "the consolidation of Hinduism takes place under the sign of bhakti."[147] It is the Bhagavadgita that seals this achievement. The result is a universal achievement that may be called smarta. It views Shiva and Vishnu as "complementary in their functions but ontologically identical".[147]

Vedanta – Brahma sutras (200 BCE)

In earlier writings, Sanskrit 'Vedānta' simply referred to the Upanishads, the most speculative and philosophical of the Vedic texts. However, in the medieval period of Hinduism, the word Vedānta came to mean the school of philosophy that interpreted the Upanishads. Traditional Vedānta considers shabda pramāṇa (scriptural evidence) as the most authentic means of knowledge, while pratyakṣa (perception) and anumāna (logical inference) are considered to be subordinate (but valid).[148][149]

The systematisation of Vedantic ideas into one coherent treatise was undertaken by Badarāyana in the Brahma Sutras which was composed around 200 BCE.[150] The cryptic aphorisms of the Brahma Sutras are open to a variety of interpretations. This resulted in the formation of numerous Vedanta schools, each interpreting the texts in its own way and producing its own sub-commentaries.[citation needed]

Indian philosophy

After 200 CE several schools of thought were formally codified in Indian philosophy, including Samkhya, Yoga, Nyaya, Vaisheshika, Mimāṃsā and Advaita Vedanta.[151] Hinduism, otherwise a highly polytheistic, pantheistic or monotheistic religion, also tolerated atheistic schools. The thoroughly materialistic and anti-religious philosophical Cārvāka school that originated around the 6th century BCE is the most explicitly atheistic school of Indian philosophy. Cārvāka is classified as a nāstika ("heterodox") system; it is not included among the six schools of Hinduism generally regarded as orthodox. It is noteworthy as evidence of a materialistic movement within Hinduism.[152] Our understanding of Cārvāka philosophy is fragmentary, based largely on criticism of the ideas by other schools, and it is no longer a living tradition.[153] Other Indian philosophies generally regarded as atheistic include Samkhya and Mimāṃsā.[citation needed]

Hindu literature

Two of Hinduism's most revered epics, the Mahabharata and Ramayana were compositions of this period. Devotion to particular deities was reflected from the composition of texts composed to their worship. For example, the Ganapati Purana was written for devotion to Ganapati (or Ganesha). Popular deities of this era were Shiva, Vishnu, Durga, Surya, Skanda, and Ganesha (including the forms/incarnations of these deities).[citation needed]

In the latter Vedantic period, several texts were also composed as summaries/attachments to the Upanishads. These texts collectively called as Puranas allowed for a divine and mythical interpretation of the world, not unlike the ancient Hellenic or Roman religions. Legends and epics with a multitude of gods and goddesses with human-like characteristics were composed.[citation needed]

Jainism and Buddhism

The Gupta period marked a watershed of Indian culture: the Guptas performed Vedic sacrifices to legitimize their rule, but they also patronized Buddhism, which continued to provide an alternative to Brahmanical orthodoxy. Buddhism continued to have a significant presence in some regions of India until the 12th century.[citation needed]

There were several Buddhistic kings who worshiped Vishnu, such as the Gupta Empire, Pala Empire, Chalukyas, Somavanshi, and Satavahana.[154] Buddhism survived followed by Hindus.[155]

Tantra

Tantrism originated in the early centuries CE and developed into a fully articulated tradition by the end of the Gupta period. According to Michaels this was the "Golden Age of Hinduism"[156] (c. 320–650 CE[156]), which flourished during the Gupta Empire[142] (320 to 550 CE) until the fall of the Harsha Empire[142] (606 to 647 CE). During this period, power was centralised, along with a growth of far distance trade, standardizarion of legal procedures, and general spread of literacy.[142] Mahayana Buddhism flourished, but the orthodox Brahmana culture began to be rejuvenated by the patronage of the Gupta Dynasty.[157] The position of the Brahmans was reinforced,[142] and the first Hindu temples emerged during the late Gupta age.[142]

Medieval and Late Puranic Period (500–1500 CE)

Late-Classical Period (c. 650–1100 CE)

- See also Late-Classical Age and Hinduism Middle Ages[broken anchor]

After the end of the Gupta Empire and the collapse of the Harsha Empire, power became decentralised in India. Several larger kingdoms emerged, with "countless vasal states".[158][note 24] The kingdoms were ruled via a feudal system. Smaller kingdoms were dependent on the protection of the larger kingdoms. "The great king was remote, was exalted and deified",[158] as reflected in the Tantric Mandala, which could also depict the king as the centre of the mandala.[159]

The disintegration of central power also lead to regionalisation of religiosity, and religious rivalry.[160][note 25] Local cults and languages were enhanced, and the influence of "Brahmanic ritualistic Hinduism"[160] was diminished.[160] Rural and devotional movements arose, along with Shaivism, Vaisnavism, Bhakti, and Tantra,[160] though "sectarian groupings were only at the beginning of their development".[160] Religious movements had to compete for recognition by the local lords.[160] Buddhism lost its position, and began to disappear in India.[160]

Vedanta

In the same period Vedanta changed, incorporating Buddhist thought and its emphasis on consciousness and the working of the mind.[162] Buddhism, which was supported by the ancient Indian urban civilisation lost influence to the traditional religions, which were rooted in the countryside.[163] In Bengal, Buddhism was even prosecuted. But at the same time, Buddhism was incorporated into Hinduism, when Gaudapada used Buddhist philosophy to reinterpret the Upanishads.[162] This also marked a shift from Atman and Brahman as a "living substance"[164] to "maya-vada"[note 26], where Atman and Brahman are seen as "pure knowledge-consciousness".[165] According to Scheepers, it is this "maya-vada" view which has come to dominate Indian thought.[163]

Buddhism

Between 400 and 1000 CE Hinduism expanded as the decline of Buddhism in India continued.[166] Buddhism subsequently became effectively extinct in India but survived in Nepal and Sri Lanka.[citation needed]

Bhakti

The Bhakti movement began with the emphasis on the worship of God, regardless of one's status – whether priestly or laypeople, men or women, higher social status or lower social status. The movements were mainly centered on the forms of Vishnu (Rama and Krishna) and Shiva. There were however popular devotees of this era of Durga.[citation needed] The best-known proponents of this movement were the Alvars and the Nayanars from southern India. The most popular Shaiva teacher of the south was Basava, while of the north it was Gorakhnath.[citation needed] Female saints include figures like Akkamadevi, Lalleshvari and Molla.[citation needed]

The Alvars (Tamil: ஆழ்வார்கள், āḻvārkaḷ [aːɻʋaːr], those immersed in god) were the Tamil poet-saints of south India, who lived between the 6th and 9th centuries CE and espoused "emotional devotion" or bhakti to Vishnu-Krishna in their songs of longing, ecstasy and service.[167] The most popular Vaishnava teacher of the south was Ramanuja, while of the north it was Ramananda.[citation needed]

Several important icons were women. For example, within the Mahanubhava sect, the women outnumbered the men,[168] and administration was many times composed mainly of women.[169] Mirabai is the most popular female saint in India.[citation needed]

Sri Vallabha Acharya (1479–1531) is a very important figure from this era. He founded the Shuddha Advaita (Pure Non-dualism) school of Vedanta thought.

According to The Centre for Cultural Resources and Training,

Vaishanava bhakti literature was an all-India phenomenon, which started in the 6th–7th century A.D. in the Tamil-speaking region of South India, with twelve Alvar (one immersed in God) saint-poets, who wrote devotional songs. The religion of Alvar poets, which included a woman poet, Andal, was devotion to God through love (bhakti), and in the ecstasy of such devotions they sang hundreds of songs which embodied both depth of feeling and felicity of expressions.[web 8]

Early Islamic rule (c. 1100–1500 CE)

In the 12th and 13th centuries, Turks and Afghans invaded parts of northern India and established the Delhi Sultanate in the former Rajput holdings.[170] The subsequent Slave dynasty of Delhi managed to conquer large areas of northern India, approximately equal in extent to the ancient Gupta Empire, while the Khalji dynasty conquered most of central India but were ultimately unsuccessful in conquering and uniting the subcontinent. The Sultanate ushered in a period of Indian cultural renaissance. The resulting "Indo-Muslim" fusion of cultures left lasting syncretic monuments in architecture, music, literature, religion, and clothing.[citation needed]

Bhakti movement

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2013) |

During the 14th to 17th centuries, a great Bhakti movement swept through central and northern India, initiated by a loosely associated group of teachers or Sants. Ramananda, Ravidas, Srimanta Sankardeva, Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, Vallabha Acharya, Sur, Meera, Kabir, Tulsidas, Namdev, Dnyaneshwar, Tukaram, and other mystics spearheaded the Bhakti movement in the North while Annamacharya, Bhadrachala Ramadas, Tyagaraja, and others propagated Bhakti in the South. They taught that people could cast aside the heavy burdens of ritual and caste, and the subtle complexities of philosophy, and simply express their overwhelming love for God. This period was also characterized by a spate of devotional literature in vernacular prose and poetry in the ethnic languages of the various Indian states or provinces.

Lingayatism

Lingayatism is a distinct Shaivite tradition in India, established in the 12th century by the philosopher and social reformer Basavanna.[citation needed] The adherents of this tradition are known as Lingayats. The term is derived from Lingavantha in Kannada, meaning "one who wears Ishtalinga on their body" (Ishtalinga is the representation of the God). In Lingayat theology, Ishtalinga is an oval-shaped emblem symbolising Parasiva, the absolute reality. Contemporary Lingayatism follows a progressive reform–based theology propounded, which has great influence in South India, especially in the state of Karnataka.[171]

Unifying Hinduism

According to Nicholson, already between the 12th and 16th century,

... certain thinkers began to treat as a single whole the diverse philosophival teachings of the Upanishads, epics, Puranas, and the schools known retrospectively as the "six systems" (saddarsana) of mainstream Hindu philosophy.[172]

The tendency of "a blurring of philosophical distinctions" has also been noted by Mikel Burley.[173] Lorenzen locates the origins of a distinct Hindu identity in the interaction between Muslims and Hindus,[174] and a process of "mutual self-definition with a contrasting Muslim other",[175] which started well before 1800.[176] Both the Indian and the European thinkers who developed the term "Hinduism" in the 19th century were influenced by these philosophers.[172]

Sikhism (15th century)

Sikhism originated in 15th-century Punjab, Delhi Sultanate (present-day India and Pakistan) with the teachings of Nanak and nine successive gurus. The principal belief in Sikhism is faith in Vāhigurū— represented by the sacred symbol of ēk ōaṅkār [meaning one god]. Sikhism's traditions and teachings are distinctly associated with the history, society and culture of the Punjab. Adherents of Sikhism are known as Sikhs (students or disciples) and number over 27 million across the world.[citation needed]

Modern period (1500–present)

Early modern period

According to Gavin Flood, the modern period in India begins with the first contacts with western nations around 1500.[140][141] The period of Mughal rule in India[177] saw the rise of new forms of religiosity.[178]

Modern India (after 1800)

Hinduism

In the 19th century, under influence of the colonial forces, a synthetic vision of Hinduism was formulated by Raja Ram Mohan Roy, Swami Vivekananda, Sri Aurobindo, Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan and Mahatma Gandhi.[181] These thinkers have tended to take an inclusive view of India's religious history, emphasising the similarities between the various Indian religions.[181]

The modern era has given rise to dozens of Hindu saints with international influence.[182] For example, Brahma Baba established the Brahma Kumaris, one of the largest new Hindu religious movements which teaches the discipline of Raja Yoga to millions.[citation needed] Representing traditional Gaudiya Vaishnavism, Prabhupada founded the Hare Krishna movement, another organisation with a global reach. In late 18th-century India, Swaminarayan founded the Swaminarayan Sampraday. Anandamurti, founder of the Ananda Marga, has also influenced many worldwide. Through the international influence of all of these new Hindu denominations, many Hindu practices such as yoga, meditation, mantra, divination, and vegetarianism have been adopted by new converts.[citation needed]

Jainism

Jainism continues to be an influential religion and Jain communities live in Indian states Gujarat, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu. Jains authored several classical books in different Indian languages for a considerable period of time.[citation needed]

Buddhism

The Dalit Buddhist movement also referred to as Navayana[183] is a 19th- and 20th-century Buddhist revival movement in India. It received its most substantial impetus from B. R. Ambedkar's call for the conversion of Dalits to Buddhism in 1956 and the opportunity to escape the caste-based society that considered them to be the lowest in the hierarchy.[184]

Similarities and differences

According to Tilak, the religions of India can be interpreted "differentially" or "integrally",[185] that is by either highlighting the differences or the similarities.[185] According to Sherma and Sarma, western Indologists have tended to emphasise the differences, while Indian Indologists have tended to emphasise the similarities.[185]

Similarities

Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism share certain key concepts, which are interpreted differently by different groups and individuals.[185] Until the 19th century, adherents of those various religions did not tend to label themselves as in opposition to each other, but "perceived themselves as belonging to the same extended cultural family."[186]

Dharma

The spectrum of these religions are called Dharmic religions because of their overlap over the core concept of Dharma. It has various meanings depending on the context. For example it could mean duty, righteousness, spiritual teachings, conduct, etc.

Soteriology

Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism share the concept of moksha, liberation from the cycle of rebirth.[187] They differ however on the exact nature of this liberation.[187]

Ritual

Common traits can also be observed in ritual. The head-anointing ritual of abhiseka is of importance in three of these distinct traditions, excluding Sikhism (in Buddhism it is found within Vajrayana).[188] Other noteworthy rituals are the cremation of the dead, the wearing of vermilion on the head by married women, and various marital rituals.[188] In literature, many classical narratives and purana have Hindu, Buddhist or Jain versions.[web 9] All four traditions have notions of karma, dharma, samsara, moksha and various forms of Yoga.[188]

Mythology

Rama is a heroic figure in all of these religions. In Hinduism he is the God-incarnate in the form of a princely king; in Buddhism, he is a Bodhisattva-incarnate; in Jainism, he is the perfect human being. Among the Buddhist Ramayanas are: Vessantarajataka,[189] Reamker, Ramakien, Phra Lak Phra Lam, Hikayat Seri Rama, etc. There also exists the Khamti Ramayana among the Khamti tribe of Asom wherein Rama is an Avatar of a Bodhisattva who incarnates to punish the demon king Ravana (B.Datta 1993). The Tai Ramayana is another book retelling the divine story in Asom.[ нужна ссылка ]

Различия

Критики отмечают, что существуют огромные различия между различными индийскими религиями и даже внутри них. [ 190 ] [ 191 ] Все основные религии состоят из бесчисленных сект и подсект. [ 192 ]

Мифология

Индийская мифология также отражает конкуренцию между различными индийскими религиями. Популярная история рассказывает, как Ваджрапани убивает Махешвару , проявление Шивы, изображаемого как злое существо. [ 193 ] [ 194 ] Эта история встречается в нескольких писаниях, в первую очередь в « Сарвататхагатататтвасамграхе» и «Ваджрапани-абхисека-махатантре» . [ 195 ] [ примечание 27 ] По словам Калупаханы, эта история «перекликается» с историей обращения Амбатты. [ 194 ] Это следует понимать в контексте конкуренции между буддийскими институтами и шиваизмом . [ 199 ]

астики и настики Классификация

Астика и настика — это термины с разными определениями, которые иногда используются для классификации индийских религий. Традиционное определение, которому придерживается Ади Шанкара , классифицирует религии и людей как астику и настику в зависимости от того, признают ли они авторитет основных индуистских текстов, Вед, как высших богооткровенных писаний, или нет. Согласно этому определению, Ньяя , Вайшешика , Санкхья , Йога , Пурва Мимамса и Веданта классифицируются как школы астики , а Чарвака классифицируется как школа настики . Таким образом, буддизм и джайнизм также классифицируются как религии настика , поскольку они не признают авторитет Вед. [ нужна ссылка ]

Другой набор определений, заметно отличающийся от использования индуистской философии, свободно характеризует астику как « теиста », а настику как « атеиста ». Согласно этим определениям, санкхью можно считать философией настики , хотя она традиционно причисляется к ведическим школам астики . С этой точки зрения буддизм и джайнизм остаются настика . религиями [ нужна ссылка ]

Буддисты и джайны не согласились с тем, что они настика, и дали новое определение фразам «астика» и «настика», по своему усмотрению. Джайны присваивают термин настика тому, кто не знает смысла религиозных текстов. [ 200 ] или те, кто отрицает существование души, были хорошо известны джайнам. [ 201 ]

Использование термина «Дхармические религии»

Фроули и Малхотра используют термин «дхармические традиции», чтобы подчеркнуть сходство между различными индийскими религиями. [ 202 ] [ 203 ] [ примечание 28 ] По словам Фроули, «все религии в Индии назывались Дхармой». [ 202 ] и может быть

... помещены под более широкий круг «дхармических традиций», которые мы можем рассматривать как индуизм или духовные традиции Индии в самом широком смысле. [ 202 ]

По мнению Пола Хакера, в описании Хальбфасса, термин «дхарма»

... приобрело принципиально новое значение и функцию в современной индийской мысли, начиная с Банкима Чандры Чаттерджи в девятнадцатом веке. Этот процесс, в котором дхарма была представлена как эквивалент западного понятия «религия», но также и как ответ на него, отражает фундаментальное изменение в индуистском чувстве идентичности и в отношении к другим религиозным и культурным традициям. Иностранные инструменты «религии» и «нации» стали инструментами самоопределения, и укоренилось новое и шаткое чувство «единства индуизма», а также национальной и религиозной идентичности. [ 205 ]

Акцент на сходстве и целостном единстве дхармических религий подвергался критике за игнорирование огромных различий между различными индийскими религиями и традициями и даже внутри них. [ 190 ] [ 191 ] По словам Ричарда Э. Кинга, это типично для «инклюзивистского присвоения других традиций». [ 181 ] Нео -Веданты :

Инклюзивное присвоение других традиций, столь характерное для идеологии неоведанты, проявляется на трех основных уровнях. Во-первых, это очевидно из предположения, что философия (Адвайта) Веданты Шанкары (ок. восьмого века н.э.) составляет центральную философию индуизма. Во-вторых, в индийском контексте философия неоведанты включает в себя буддийскую философию с точки зрения своей собственной ведантической идеологии. Будда становится членом традиции Веданты, просто пытаясь реформировать ее изнутри. Наконец, на глобальном уровне нео-Веданта колонизирует религиозные традиции мира, утверждая центральную роль недуалистической позиции как philosophia perennis, лежащей в основе всех культурных различий. [ 181 ]

«Совет дхармических вер» (Великобритания) рассматривает зороастризм , хотя и не зародившийся на Индийском субконтиненте, но также как дхармическую религию. [ 206 ]

Статус неиндуистов в Республике Индия

Включение буддистов , джайнов и сикхов в индуизм является частью индийской правовой системы. Закон о индуистском браке 1955 года «[определяет] индуистами всех буддистов, джайнов, сикхов и всех, кто не является христианином , мусульманином , парсом ( зороастрийцем ) или евреем ». [ 207 ] А в Конституции Индии говорится, что «упоминание индуистов должно быть истолковано как включающее упоминание лиц, исповедующих сикхскую, джайнскую или буддийскую религию». [ 207 ]

В качестве судебного напоминания Верховный суд Индии отметил, что сикхизм и джайнизм являются подсектами или особыми религиями внутри более крупного индуистского сообщества. [ сеть 10 ] [ примечание 29 ] и что джайнизм — это деноминация внутри индуизма. [ сеть 10 ] [ примечание 30 ] Хотя правительство Индии считало джайнов в Индии основной религиозной общиной с момента первой переписи населения, проведенной в 1873 году, после обретения независимости в 1947 году сикхи и джайны не рассматривались как национальные меньшинства. [ сеть 10 ] [ примечание 31 ] В 2005 году Верховный суд Индии отказался выдать постановление Мандамуса о предоставлении джайнам статуса религиозного меньшинства на всей территории Индии. Однако Суд оставил на усмотрение соответствующих штатов принятие решения о статусе джайнской религии как меньшинства. [ 208 ] [ сеть 10 ] [ примечание 32 ]

Однако в течение последних нескольких десятилетий некоторые отдельные штаты расходились во мнениях относительно того, являются ли джайны, буддисты и сикхи религиозными меньшинствами, либо вынося решения, либо принимая законы. Одним из примеров является решение, вынесенное Верховным судом в 2006 году по делу штата Уттар-Прадеш, в котором джайнизм был признан неоспоримо отличным от индуизма, но упомянуто, что «вопрос о том, являются ли джайны частью Индуистская религия открыта для дискуссий. [ 209 ] Однако Верховный суд также отметил различные судебные дела, в которых джайнизм был признан отдельной религией . [ 210 ]

Другим примером является законопроект о свободе религии Гуджарата , который представляет собой поправку к законодательству, которое стремилось определить джайнов и буддистов как конфессии в индуизме. [ сеть 11 ] В конечном итоге 31 июля 2007 года, посчитав, что он не соответствует концепции свободы религии, воплощенной в статье 25 (1) Конституции, губернатор Навал Кишоре Шарма вернул законопроект о свободе религии Гуджарата (поправка) 2006 года, сославшись на массовые протесты. джайны [ сеть 12 ] а также внесудебное замечание Верховного суда о том, что джайнизм является «особой религией, созданной Верховным судом на основе квинтэссенции индуистской религии». [ сеть 13 ]

См. также

- Авраамические религии — аналогичный термин, используемый для обозначения иудаизма, христианства и ислама.

- Даосские религии — аналогичные термины, используемые для обозначения религий Восточной Азии, таких как даосизм, синтоизм и муизм.

- Ахимса

- Буддизм в Индии

- Христианство в Индии

- Демография Индии

- Индуизм в Индии

- Индология

- Иранские религии

- Джайнизм в Индии

- Калаша (религия)

- Протоиндоевропейская мифология

- Протоиндоиранская религия

- Санамахизм

- Сикхизм в Индии

- Племенные религии в Индии

- Вегетарианство

- Зороастризм в Индии

Примечания

- ^ Адамс: «Индийские религии, включая ранний буддизм, индуизм, джайнизм и сикхизм, а иногда также буддизм Тхеравады и индуистские и буддийские религии Южной и Юго-Восточной Азии».

- ^ Добуддийские Упанишады: Брихадараньяка, Чандогья, Каушитаки, Айтарейя и Тайттирия Упанишады. [ 8 ]

- ^ Общие концепции включают перерождение, самсару, карму, медитацию, отречение и мокшу. [ 14 ]

- ^ Традиции отречения Упанишад, буддизма и джайна образуют параллельные традиции, которые имеют некоторые общие концепции и интересы. В то время как Куру - Панчала на центральной равнине Ганга сформировал центр ранней традиции Упанишад, Косала - Магадха на центральной равнине Ганга сформировал центр других шраманических традиций. [ 15 ]

- ^ Сходства буддизма и индуизма

- ^ См. также Танвир Анджум, Временные границы: критический обзор основных схем периодизации в истории Индии .

- ^ Различные периоды обозначаются как «классический индуизм»:

- Смарт называет период между 1000 г. до н.э. и 100 г. н.э. «доклассическим». Это период формирования Упанишад и брахманизма. [ примечание 1 ] Джайнизм и буддизм. Для Смарта «классический период» длится от 100 до 1000 г. н. э. и совпадает с расцветом «классического индуизма», а также с расцветом и упадком махаянского буддизма в Индии. [ 21 ]

- Для Майклса период между 500 г. до н. э. и 200 г. до н. э. является временем «аскетического реформизма». [ 22 ] тогда как период между 200 г. до н.э. и 1100 г. н.э. является временем «классического индуизма», поскольку произошел «поворотный момент между ведической религией и индуистскими религиями». [ 11 ]

- Мюссе различает более длительный период перемен, а именно между 800 и 200 годами до нашей эры, который он называет «классическим периодом». По мнению Мюссе, в это время получили развитие некоторые фундаментальные концепции индуизма, а именно карма, реинкарнация и «личное просветление и трансформация», которых не существовало в ведической религии. [ 23 ]

- ^ Ашим Кумар Бхаттачарья заявляет, что Веды содержат фундаментальные истины об индуистской Дхарме. [ 51 ]

- ↑ Ричард Э. Кинг отмечает: «Следовательно, проецирование понятия «индуизма», как его обычно понимают, на доколониальную историю, остается анахронизмом». [ 54 ]

- ^ В постведические времена, понимаемые как «слушатели» вечно существующей Веды, Шраута означает «то, что слышно».

- ^ «Упанишады были составлены уже в девятом и восьмом веках до нашей эры и продолжали составляться даже в первые века нашей эры. Брахманы и араньяки несколько старше, начиная с одиннадцатого и даже двенадцатого века до нашей эры». [ сеть 4 ]

- ^ Дойссен: «Эти трактаты - не работа одного гения, а общий философский продукт целой эпохи, которая простирается [от] примерно 1000 или 800 г. до н.э. до примерно 500 г. до н.э., но которая в своих ответвлениях простирается далеко за пределы этот последний предел времени». [ 72 ]

- ^ Гэвин Флуд и Патрик Оливель : «Вторая половина первого тысячелетия до нашей эры была периодом, который создал многие идеологические и институциональные элементы, которые характеризуют более поздние индийские религии. Традиция отречения играла центральную роль в этот формирующий период индийской религиозной истории. ... Некоторые из фундаментальных ценностей и убеждений, которые мы обычно связываем с индийскими религиями в целом и индуизмом в частности, были частично созданы традицией отречения. К ним относятся два столпа индийской теологии: сансара – вера в то, что жизнь в этом. мир наполнен страданиями и подвержен повторяющимся смертям и рождениям (перерождениям) – цели человеческого существования...». [ 79 ]

- ^ Кромвель Круафорд: «Наряду с брахманизмом существовала неарийская шраманическая (самодостаточная) культура, корни которой уходят в доисторические времена». [ 82 ]

- ^ Масих: «Нет никаких доказательств того, что джайнизм и буддизм когда-либо придерживались ведических жертвоприношений, ведических божеств или каст. Они являются параллельными или местными религиями Индии и внесли большой вклад в [sic] рост даже классического индуизма Индии. настоящее время». [ 83 ]

- ^ Падманабх С. Джайни: «Сами джайны не помнят того времени, когда они попали в ведические традиции. Более того, любая теория, которая пытается связать две традиции, не может оценить довольно своеобразный и очень неведический характер джайнской космологии, души теория, кармическое учение и атеизм». [ 84 ]

- ^ Наводнение: «Вторая половина первого тысячелетия до нашей эры была периодом, который создал многие идеологические и институциональные элементы, которые характеризуют более поздние индийские религии. Традиция отречения играла центральную роль в этот формирующий период индийской религиозной истории.... Некоторые Фундаментальные ценности и убеждения, которые мы обычно связываем с индийскими религиями в целом и индуизмом в частности, были частично созданы традицией отречения. К ним относятся два столпа индийской теологии: сансара – вера в то, что жизнь в этом мире является одним из основных принципов. страдания и подверженные повторным смертям и рождениям (перерождениям) – цель человеческого существования...». [ 79 ]

- ^ Наводнение: «Происхождение и доктрина кармы и самсары неясны. Эти концепции, безусловно, циркулировали среди шраманов, а джайнизм и буддизм разработали конкретные и сложные идеи о процессе переселения людей. Вполне возможно, что карма и реинкарнация вошли в мейнстрим. брахманическая мысль шрамана или традиции отречения». [ 86 ]

- ^ Падманабх С. Джайни: «Нежелание и манера Яджнавалкьи излагать учение о карме на собрании Джанаки (сопротивление, не проявлявшееся ни в одном другом случае), возможно, можно объяснить предположением, что это было похоже на переселение души , небрахманического происхождения. Учитывая тот факт, что это учение изображено почти на каждой странице писаний шрамана, весьма вероятно, что оно произошло от них». [ 88 ]

- ^ Джеффри Бродд и Грегори Соболевски: «Джайнизм разделяет многие основные доктрины индуизма и буддизма». [ 89 ]

- ^ Олдмидоу: «Со временем возникли очевидные недопонимания относительно происхождения джайнизма и отношений с родственными ему религиями индуизмом и буддизмом. Между джайнизмом и ведическим индуизмом продолжаются споры о том, какое откровение предшествовало другому. Что известно исторически? Суть в том, что наряду с ведическим индуизмом существовала традиция, известная как Шрамана Дхарма . По сути, традиция шрамана включала в себя джайнскую и буддийскую традиции, которые не соглашались с вечностью Вед, необходимостью ритуальных жертвоприношений и верховенством Вед. Брамины». [ 93 ] Страница 141

- ^ Фишер: «Чрезвычайная древность джайнизма как неведической коренной индийской религии хорошо документирована. Древние индуистские и буддийские писания относятся к джайнизму как к существующей традиции, которая началась задолго до Махавиры». [ 94 ] Страница 115

- ^ Локард: «Встречи, возникшие в результате арийской миграции, объединили несколько совершенно разных народов и культур, изменив конфигурацию индийского общества. На протяжении многих столетий произошло слияние арийцев и дравидов - сложный процесс, который историки назвали индоарийским синтезом». [ 123 ] Локкард: «Исторически индуизм можно рассматривать как синтез арийских верований с хараппскими и другими дравидийскими традициями, развивавшимися на протяжении многих столетий». [ 124 ]

- ^ На востоке Империя Пала [ 158 ] (770–1125 гг. Н. Э. [ 158 ] ), на западе и севере Гурджара-Пратихара [ 158 ] (7–10 века [ 158 ] ), на юго-западе династия Раштракута [ 158 ] (752–973 [ 158 ] ), в Декхане династии Чалукья [ 158 ] (7–8 вв. [ 158 ] ), а на юге династия Паллавов [ 158 ] (7–9 вв. [ 158 ] ) и династия Чола [ 158 ] (9 век [ 158 ] ).

- ^ Это напоминает развитие китайского чань во время восстания Ань Лу-шаня и периода пяти династий и десяти королевств (907–960/979) , во время которых власть стала децентрализованной и возникли новые школы чань. [ 161 ]

- ^ Термин «майя-вада» в основном используется не-адвайтинами. Видеть [ сеть 5 ] [ сеть 6 ] [ сеть 7 ]

- ^ История начинается с превращения Бодхисаттвы Самантабхадры в Ваджрапани Вайрочаной, космическим Буддой, получившим ваджру и имя «Ваджрапани». [ 196 ] Затем Вайрочана просит Ваджрапани создать его несокрушимую семью, чтобы создать мандалу . Ваджрапани отказывается, потому что Махешвара (Шива) «вводит существ в заблуждение своими лживыми религиозными доктринами и участвует во всех видах агрессивного преступного поведения». [ 197 ] Махешвару и его свиту тянут на гору Сумеру , и все, кроме Махешвары, подчиняются. Ваджрапани и Махешвара вступают в магическую битву, в которой побеждает Ваджрапани. Свита Махешвары становится частью мандалы Вайрочаны, за исключением Махешвары, который убит, а его жизнь перенесена в другое царство, где он становится буддой по имени Бхасмешвара-ниргхоша, «Беззвучный Повелитель Пепла». [ 198 ]

- ^ Иногда этот термин используют и другие авторы. Дэвид Вестерлунд: «... может предоставить некоторые возможности для сотрудничества с сикхами, джайнами и буддистами, которые, как и индуисты, считаются приверженцами «дхармических» религий». [ 204 ]

- ^ В различных кодифицированных обычных законах, таких как Закон о индуистском браке, Закон о наследовании индуистов, Закон об усыновлении и содержании индуистов и других законах периода до и после конституции, определение «индуизма» включало все секты и подсекты индуистских религий, включая сикхов и Джайны [ сеть 10 ]

- ↑ Верховный суд отметил в решении по делу Бал Патил против Союза Индии: «Таким образом, «индуизм» можно назвать общей религией и общей верой Индии, тогда как «джайнизм» — это особая религия, сформированная на основе квинтэссенция индуистской религии. Джайнизм уделяет больше внимания ненасилию («Ахимса») и состраданию («Каруна»). Их единственное отличие от индуистов состоит в том, что джайны не верят ни в какого творца, подобного Богу, а поклоняются только совершенному человеческому существу. которого они называли Тиратханкаром». [ сеть 10 ]

- ^ Так называемые сообщества меньшинств, такие как сикхи и джайны, не рассматривались как национальные меньшинства во время разработки Конституции. [ сеть 10 ]

- ↑ Во внесудебном замечании, не являющемся частью решения, суд отметил: «Таким образом, «индуизм» можно назвать общей религией и общей верой Индии, тогда как «джайнизм» - это особая религия, сформированная на основе квинтэссенции индуизма. религия джайнизм уделяет больше внимания ненасилию («ахимса») и состраданию («каруна»). Их единственное отличие от индуистов состоит в том, что джайны не верят ни в какого творца, подобного Богу, а поклоняются только совершенному человеческому существу, которого они называют. Тиратханкар». [ сеть 10 ]

Ссылки

- ^ «Центральное статистическое управление» . Nepszamlalas.hu. Архивировано из оригинала 7 января 2019 года . Проверено 2 октября 2013 г.

- ^ «Христианство 2015: религиозное разнообразие и личный контакт» (PDF) . gordonconwell.edu . Январь 2015 г. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 25 мая 2017 г. . Проверено 29 мая 2015 г.

- ^ «Точка зрения: почему сикхи прославляют доброту - BBC News» . Новости Би-би-си . 15 июля 2021 года. Архивировано из оригинала 28 июня 2023 года . Проверено 17 июля 2021 г.

- ^ «Страны с самым большим джайнским населением - WorldAtlas» . 11 июня 2020 года. Архивировано из оригинала 4 июля 2023 года . Проверено 17 июля 2021 г.

- ^ Вир Сангви. «Грубое путешествие: Вниз по мудрецам» . Индостан Таймс . Архивировано из оригинала 24 марта 2019 года . Проверено 2 июля 2021 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Майклс 2004 , с. 33.

- ^ Макс Мюллер, Упанишады , Часть 1, Oxford University Press, страница LXXXVI, сноска 1.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Оливель 2014 , стр. 12–14.

- ^ Кинг 1995 , с. 52.

- ^ Оливель 1998 , с. xxiii

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж Майклс 2004 , с. 38.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Джайн 2008 , с. 210.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Сваргезе 2008 , с. 259-60.

- ^ Olivelle 1998 , стр. xx – xxiv.

- ^ Самуэль 2010 .

- ^ Тапар 1978 , с. 19-20.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Тапар 1978 , с. 19.

- ^ Тапар 1978 , с. 20.

- ^ Майклс 2004 .

- ^ Смарт 2003 , с. 52, 83–86.

- ^ Смарт 2003 , с. 52.

- ^ Майклс 2004 , с. 36.

- ^ Моисей 2003 , с. 14.

- ^ Харари, Юваль Ной (2015). Sapiens: Краткая история человечества . Перевод Харари, Юваль Ной ; Перселл, Джон; Вацман, Хаим . Лондон: Penguin Random House UK. стр. 235–236. ISBN 978-0-09-959008-8 . OCLC 910498369 .

- ^ Хехс 2002 , с. 39.

- ^ Райт 2009 , стр. 281–282.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Ратнагар 2004 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Маршалл, 1931 , стр. 48–78.

- ^ Поссель 2002 , стр. 141–156.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Поссель 2002 , стр. 141–144.

- ^ Шринивасан 1975 .

- ^ Шринивасан 1997 , стр. 180–181.

- ^ Салливан 1964 .

- ^ Хилтебейтель 2011 , стр. 399–432.

- ^ Вилас Сангаве (2001). Грани джайнологии: избранные исследовательские статьи о джайнском обществе, религии и культуре . Мумбаи: Популярный Пракашан. ISBN 978-81-7154-839-2 .

- ^ Циммер 1969 , стр. 60, 208–209.

- ^ Томас МакЭвилли (2002) Форма древней мысли: сравнительные исследования греческой и индийской философии . Allworth Communications, Inc. 816 страниц; ISBN 1-58115-203-5

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Поссель 2002 , стр. 141–145.

- ^ Макинтош 2008 , стр. 286–287.

- ^ Уиллард Гердон Окстоби, изд. (2002). Мировые религии: восточные традиции (2-е изд.). Дон Миллс, Онтарио: Издательство Оксфордского университета . стр. 18–19. ISBN 0-19-541521-3 . OCLC 46661540 .

- ^ Маршалл 1931 , с. 67.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Уиллард Гердон Окстоби, изд. (2002). Мировые религии: восточные традиции (2-е изд.). Дон Миллс, Онтарио: Издательство Оксфордского университета . п. 18. ISBN 0-19-541521-3 . OCLC 46661540 .

- ^ Поссель 2002 , с. 18.

- ^ Тапар 2004 , с. 85.

- ^ Макинтош 2008 , стр. 275–277, 292.

- ^ Поссель 2002 , стр. 152, 157–176.

- ^ Макинтош 2008 , стр. 293–299.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Стефани В. Джеймисон и Майкл Витцель в книге Арвинда Шармы, редактора журнала «Исследование индуизма» . Университет Южной Каролины Press, 2003, стр. 65.

- ^ История Древней Индии (портреты нации), 1/e Камлеша Капура

- ^ P. 382 Индуистская духовность: Веды через Веданту, Том 1 под редакцией К. Р. Сундарараджана, Битики Мукерджи

- ^ Ашим Кумар Бхаттачарья. Индуистская Дхарма: Введение в Священные Писания и теологию . п. 6.

- ^ стр. 46 Я горжусь тем, что я индуист Дж. Агарвал.

- ^ стр. 41 Индуизм: Алфавитный путеводитель Рошен Далал

- ^ Кинг 1999 , с. 176.

- ^ Пармар, Маниш Сингх (10 апреля 2018 г.). Древняя Индия: взгляд на славное древнее прошлое Индии . БукРикс. ISBN 978-3-7438-6452-8 . Архивировано из оригинала 29 октября 2023 года . Проверено 17 декабря 2022 г.

- ^ Нигал, С.Г. Аксиологический подход к Ведам. Северный книжный центр, 1986. С. 81. ISBN 81-85119-18-Х .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Циммер 1989 , с. 166.

- ^ Циммер 1989 , с. 167.

- ^ Холдреге 2004 , стр. 215.

- ^ Кришнананда 1994 , с. 17.

- ^ Кришнананда 1994 , с. 24.

- ^ Паниккар 2001 , стр. 350–351.

- ^ Дюшен-Гиймен 1963 , с. 46.

- ^ День 1982 г. , стр. 42–45.

- ^ P. 285 Индийская социология через Гурье, словарь С. Девадаса Пиллая.

- ^ Майклс 2004 , с. 34.

- ^ Майклс 2004 , с. 35.

- ^ Дандас 2002 , с. 30.

- ^ Циммер 1953 , с. 182-183.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Британская энциклопедия, Другие источники: процесс «санскритизации» » . Архивировано из оригинала 26 апреля 2015 года . Проверено 23 июня 2022 г.

- ^ Деуссен 1966 , с. [ нужна страница ] .

- ^ Деуссен 1966 , с. 51 .

- ^ Нойснер, Джейкоб (2009). Мировые религии в Америке: Введение . Вестминстер Джон Нокс Пресс. п. 183. ИСБН 978-0-664-23320-4 .

- ^ Мелтон, Дж. Гордон; Бауманн, Мартин (2010), Религии мира, Второе издание: Всеобъемлющая энциклопедия верований и практик , ABC-CLIO, стр. 1324, ISBN 978-1-59884-204-3

- ^ Махадеван, TMP (1956), Сарвепалли Радхакришнан (редактор), История восточной и западной философии , George Allen & Unwin Ltd, стр. 57

- ^ фон Глазенапп 1999 , с. 16.

- ^ Мэллинсон 2007 , стр. 17–18, 32–33.

- ^ Циммер 1989 , с. 217.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Флад и Оливель 2003 , с. 273–274.

- ^ Наводнение 1996 , с. 82 .

- ^ Калхатги, Т.Г. 1988 В: Исследование джайнизма, Академия Пракрита Бхарти, Джайпур.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б С. Кромвель Кроуфорд, обзор Л. М. Джоши, Брахманизм, буддизм и индуизм , Философия Востока и Запада (1972)

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Ю. Масих (2000) В: Сравнительное исследование религий, Motilal Banarsidass Publ: Дели, ISBN 81-208-0815-0 Страница 18

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Падманабх С. Джайни, (1979), Путь джайнов к очищению, Мотилал Банарсидасс, Дели, стр. 169

- ^ Наводнение 1996 , с. [ нужна страница ] .

- ^ Наводнение 1996 , с. 86.

- ^ Джайни 2001 , с. [ нужна страница ] .

- ^ Джайни 2001 , с. 51.

- ^ Стр. 93 Мировые религии Джеффри Бродда, Грегори Соболевски.

- ^ Пратт, Джеймс Биссетт (1996), Буддийское паломничество и буддийское паломничество , Азиатские образовательные службы, стр. 90, ISBN 978-81-206-1196-2 , заархивировано из оригинала 23 декабря 2023 года , получено 7 ноября 2015 года.

- ^ Упадхьяя, Каши Натх (1998), Ранний буддизм и Бхагавадгита , Мотилал Банарсидасс, стр. 103–104, ISBN 978-81-208-0880-5

- ^ Хадзиме Накамура, История ранней философии Веданты: Часть первая. Перепечатка издательства Motilal Banarsidass Publ., 1990, стр. 139.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Гарри Олдмидоу (2007) Свет с Востока: Восточная мудрость для современного Запада, World Wisdom , Inc. ISBN 1-933316-22-5

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Мэри Пэт Фишер (1997) В: Живые религии: Энциклопедия мировых верований IBTauris: Лондон ISBN 1-86064-148-2

- ^ «Жизнь Гаутамы Будды и происхождение буддизма» . Британская энциклопедия . 1 июля 1997 года. Архивировано из оригинала 1 февраля 2024 года . Проверено 1 февраля 2024 г.

- ^ Лирман Л. (ред.), Линда (2005). Буддийские миссионеры в эпоху глобализации . Гавайский университет Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2810-3 . JSTOR j.ctvvn4jw . Архивировано из оригинала 1 февраля 2024 года . Проверено 1 февраля 2024 г.

- ^ Джайн, Панкадж (1 сентября 2011 г.). «Буддизм: зарождение, распространение и упадок» . ХаффПост . Архивировано из оригинала 1 февраля 2024 года . Проверено 1 февраля 2024 г.

- ^ «Буддизм» . Британская энциклопедия . 28 сентября 1998 г. Архивировано из оригинала 1 февраля 2024 г. Проверено 1 февраля 2024 г.

- ^ Жизнь Будды как легенда и история , Эдвард Джозеф Томас

- ^ Киоун, Дэмиен; Ходж, Стивен; Джонс, Чарльз; Тинти, Паола (2003). «Тхеравада». Словарь буддизма (1-е изд.). Оксфорд: Оксфордский университет. Нажимать. ISBN 978-0-19-860560-7 .

- ^ Киоун, Дэмиен; Ходж, Стивен; Джонс, Чарльз; Тинти, Паола (2003). «Махаяна». Словарь буддизма (1-е изд.). Оксфорд: Оксфордский университет. Нажимать. ISBN 978-0-19-860560-7 .

- ^ Хехс 2002 , с. 106.

- ^ «Харавела – Великий император-филантроп» (PDF) . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 10 марта 2024 года . Проверено 10 марта 2024 г.

- ^ Мудумби Нарасимхачари, изд. (1976). Агамапраманья Ямуначарьи . Выпуск 160 восточной серии Гэквада. Восточный институт Университета Махараджи Саяджирао в Бароде.

- ^ Трипат, С.М. (2001). Психорелигиозные исследования человека, разума и природы . Издательство «Глобал Вижн». ISBN 978-81-87746-04-1 . Архивировано из оригинала 7 октября 2023 года . Проверено 15 ноября 2015 г. [ нужна страница ]

- ^ Нагалингам, Патмараджа (2009). Глава " Религия Агам Теоретические публикации. Архивировано из оригинала 19 октября. Получено 27 июля.

- ^ Граймс, Джон А. (1996). Краткий словарь индийской философии: санскритские термины, определенные на английском языке . СУНИ Пресс. ISBN 978-0-7914-3068-2 . LCCN 96012383 . [ нужна страница ]

- ^ Современный обзор: Том 28 . Прабаси Пресс. 1920. [ нужна полная цитата ]

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Канчан Синха, Картикея в индийском искусстве и литературе, Дели: Сандип Пракашан (1979).

- ^ Махадеван, Ираватам (6 мая 2006 г.). «Заметка о знаке Муруку индийского письма в свете открытия каменного топора Майиладутурай» . Harappa.com . Архивировано из оригинала 4 сентября 2006 года.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Ранбир Вохра (2000). Создание Индии: исторический обзор . Я Шарп. п. 15.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Григорий Максимович Бонгард-Левин (1985). Древняя индийская цивилизация . Арнольд-Хайнеманн. п. 45.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Стивен Розен; Грэм М. Швейг (2006). Основополагающий индуизм . Издательская группа Гринвуд. п. 45.

- ^ Сингх 1989 .

- ^ Кенойер, Джонатан Марк. Древние города цивилизации долины Инда . Карачи: Издательство Оксфордского университета, 1998.

- ^ Бэшам 1967 , стр. 11–14.

- ^ Фредерик Дж. Симунс (1998). Растения жизни, растения смерти . п. 363.

- ^ Наводнение 1996 , с. 29, Рисунок 1: Рисунок печати.

- ^ Джон Кей. Индия: История . Гроув Пресс. п. 14. [ нужна полная цитата ]

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Дж. П. Мэллори и Д. К. Адамс, Энциклопедия индоевропейской культуры (1997), стр. 308.

- ^ К. Звелебил, Дравидийская лингвистика: введение , (Пондичерри: Институт лингвистики и культуры Пондичерри, 1990), стр. 81.

- ^ Кришнамурти 2003 , с. 6.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Локкард 2007 , стр. 50.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Локкард 2007 , стр. 52.

- ^ Хилтебейтель 2007 , с. 12.

- ^ Тивари 2002 , с. в.

- ^ Комната 1951 , с. 218-219.

- ^ Ларсон 1995 , с. 81.

- ^ Харман, Уильям П. (1992). Священный брак индуистской богини Мотилал Банарсидасс. п. 6.

- ^ Ананд, Мулк Радж (1980). Великолепие Тамилнада . Публикации Марга. Архивировано из оригинала 21 июля 2022 года . Проверено 21 июля 2022 г.

- ^ Чопра, Пран Натх (1979). История Южной Индии . С. Чанд.

- ^ Бейт, Бернард (2009). Тамильское ораторское искусство и дравидийская эстетика: демократическая практика на юге Индии . Издательство Колумбийского университета.

- ^ А. Кирутинан (2000). Тамильская культура: религия, культура и литература . Бхаратия Кала Пракашан. п. 17.

- ^ Эмбри, Эйнсли Томас (1988). Энциклопедия истории Азии: Том 1 . Скрибнер. ISBN 978-0-684-18898-0 .

- ^ Тиручандран, Селви (1997). Идеология, каста, класс и пол . Викас Паб. Дом.

- ^ Маникам, Валлиаппа Субраманиам (1968). Взгляд на тамилологию . Академия тамильских ученых Тамил Наду. п. 75.

- ^ Лал, Мохан (2006). Энциклопедия индийской литературы, том 5 (Сасай То Зоргот) . Сахитья Академия. п. 4396. ИСБН 81-260-1221-8 .

- ^ Шаши, СС (1996). Энциклопедия Indica: Индия, Пакистан, Бангладеш: Том 100 . Публикации Анмола.

- ^ Субраманиум, Н. (1980). Государство Шангам: управление и общественная жизнь тамилов Шангама . Публикации Эннеса.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Наводнение 1996 года .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Мюссе 2011 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г Майклс 2004 , с. 40.

- ^ Хилтебейтель 2002 , с. 12.

- ^ Хилтебейтель 2002 , с. 13.

- ^ Хилтебейтель 2002 , с. 14.

- ^ Хилтебейтель 2002 , с. 18.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Хилтебейтель 2002 , с. 20.

- ^ Пулигандла 1997 .

- ^ Раджу 1992 .

- ^ Радхакришнан, С. (1996), Индийская философия, Том II , Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-563820-4

- ^ Радхакришнан и Мур 1967 , стр. XVIII–XXI.

- ^ Радхакришнан и Мур 1967 , стр. 227–249.

- ^ Чаттерджи и Датта 1984 , с. 55.

- ^ Дурга Прасад, стр. 116, История Андхрас до 1565 года нашей эры.

- ^ National Geographic , январь 2008 г., VOL. 213, НЕТ. 1 «Поток между конфессиями был таким, что на протяжении сотен лет почти все буддийские храмы, включая храмы в Аджанте , строились под правлением и покровительством индуистских королей». [ нужна полная цитата ]

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Майклс 2004 , с. 40-41.

- ^ Накамура 2004 , с. 687.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я дж к л м н Майклс 2004 , с. 41.

- ^ Уайт 2000 , стр. 25–28.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г Майклс 2004 , с. 42.

- ^ Макрей 2003 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Шиперс 2000 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Шиперс 2000 , с. 127-129.

- ^ Шиперс 2000 , с. 123.

- ^ Шиперс 2000 , стр. 123–124.

- ^ «Расцвет буддизма и джайнизма» . Религия и этика — Индуизм: другие религиозные влияния . Би-би-си. 26 июля 2004 г. Архивировано из оригинала 5 августа 2011 г. Проверено 21 апреля 2007 г.

- ^ Андреа Ниппард. «Альвары» (PDF) . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 3 декабря 2013 года . Проверено 20 апреля 2013 г.

- ^ Рамасвами, стр. 204 «Хождение обнаженным» .

- ^ Рамасвами, стр. 210 «Хождение обнаженным» .

- ↑ Путешествия Баттуты: Дели, столица мусульманской Индии. Архивировано 23 апреля 2008 г. в Wayback Machine.

- ^ М. Р. Сакхаре, История и философия религии лингаят, Прасаранга, Университет Карнатаки, Дхарвад

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Николсон 2010 , с. 2.

- ^ Берли 2007 , с. 34.

- ^ Лоренцен 2006 , с. 24-33.

- ^ Лоренцен 2006 , с. 27.

- ^ Лоренцен 2006 , с. 26-27.

- ^ Майклс 2004 , с. 43.

- ^ Майклс 2004 , с. 43-44.

- ^ «Фестиваль Махамагам» . Проверено 14 февраля 2014 г.

- ^ Мадан Прасад Безбаруа; Кришна Гопал; Пхал С. Гирота (2003), Ярмарки и фестивали Индии , Издательство Gyan, стр. 326, ISBN 978-81-212-0809-3 , получено 14 февраля 2014 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Кинг 1999 года .

- ^ Майклс 2004 , с. [ нужна страница ] .

- ^ Омведт, Гейл. Буддизм в Индии: вызов брахманизму и кастам. 3-е изд. Лондон/Нью-Дели/Таузенд-Оукс: Sage, 2003. страницы: 2, 3–7, 8, 14–15, 19, 240, 266, 271.

- ^ Томас Пэнтэм; Враджендра Радж Мехта; Враджендра Радж Мехта (2006), Политические идеи в современной Индии: тематические исследования , Sage Publications, ISBN 0-7619-3420-0 , заархивировано из оригинала 18 сентября 2023 года , получено 26 октября 2020 года.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Шерма и Сарма 2008 , с. 239.

- ^ Липнер 1998 , стр. 12.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Октябрь 1983 г. , с. 210.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Другие, Музаффар Х. Сайед и (20 февраля 2022 г.). История индийской нации: Древняя Индия . Публикации КК. п. 358. Архивировано из оригинала 23 сентября 2023 года . Проверено 1 декабря 2023 г.

- ^ Поллок, стр. 661 Литературные культуры в истории:

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Ларсон 2012 , стр. 313–314.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Йелле 2012 , стр. 338–339.

- ^ Родрикес и Хардинг 2008 , с. 14.

- ^ Дэвидсон 2004 , стр. 148–153.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Бизнес 1994 , с. 220.

- ^ Дэвидсон 2004 , с. 148.

- ^ Дэвидсон 2004 , стр. 148–150.

- ^ Дэвидсон 2004 , с. 150.