Преследование христиан

В этой статье есть несколько проблем. Пожалуйста, помогите улучшить его или обсудите эти проблемы на странице обсуждения . ( Узнайте, как и когда удалять эти шаблонные сообщения )

|

| Часть серии о |

| Дискриминация |

|---|

|

Гонения на христиан прослеживаются исторически с первого века христианской эры до наших дней . Христианские миссионеры и новообращенные в христианство подвергались преследованиям, иногда вплоть до мученической смерти за свою веру , с момента появления христианства.

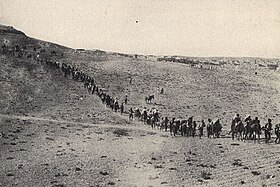

Ранние христиане подвергались преследованиям со стороны как евреев , из чьей религии возникло христианство , так и римлян, которые контролировали многие ранние центры христианства в Римской империи . С момента возникновения христианских государств в поздней античности христиане также подвергались преследованиям со стороны других христиан из-за различий в доктринах , которые были объявлены еретическими . В начале четвертого века официальные гонения в империи были прекращены Сердикским эдиктом в 311 году, а практика христианства была легализована Миланским эдиктом в 312 году. К 380 году христиане начали преследовать друг друга. Расколы расколы между и поздней античности средневековья , в том числе Римом и Константинополем и многочисленные христологические споры , вместе с позднейшей протестантской Реформацией спровоцировали серьезные конфликты между христианскими конфессиями . Во время этих конфликтов представители различных конфессий часто преследовали друг друга и участвовали в межконфессиональном насилии . В 20 веке, Христианское население подвергалось преследованиям, иногда вплоть до геноцида , со стороны различных государств, включая Османскую империю и ее государство-преемник , которые совершили Хамидийскую резню , геноцид армян , геноцид ассирийцев , геноцид греков и Диярбекир. геноцид и атеистические государства, такие как страны бывшего Восточного блока .

Гонения на христиан продолжаются и в XXI веке . Христианство является крупнейшей мировой религией , и его приверженцы живут по всему миру. Примерно 10% христиан мира являются членами групп меньшинств, которые живут в государствах с нехристианским большинством. [4] Современные преследования христиан включают официальные государственные преследования, которые чаще всего происходят в странах, расположенных в Африке и Азии, потому что там есть государственные религии или потому, что их правительства и общества практикуют религиозный фаворитизм. Подобный фаворитизм часто сопровождается религиозной дискриминацией и религиозными преследованиями .

Согласно отчету Комиссии США по международной религиозной свободе за 2020 год, христиане в Бирме , Китае , Эритрее , Индии , Иране , Нигерии , Северной Корее , Пакистане , России , Саудовской Аравии , Сирии и Вьетнаме подвергаются преследованиям; назвал эти страны «странами, вызывающими особую озабоченность» Государственный департамент США из-за участия или терпимости их правительств к «серьезным нарушениям свободы вероисповедания». [5] : 2 В том же докладе рекомендуется, чтобы Афганистан , Алжир , Азербайджан , Бахрейн , Центральноафриканская Республика, Куба , Египет , Индонезия , Ирак , Казахстан , Малайзия , Судан и Турция вошли в «специальный список» Госдепартамента США стран, в которых правительство разрешает или участвует в «серьезных нарушениях свободы вероисповедания ». [5] : 2

Большая часть преследований христиан в последнее время совершается негосударственными субъектами , которых Государственный департамент США называет «организациями, вызывающими особую озабоченность», включая исламистские группировки «Боко Харам» в Нигерии , движение хуситов в Йемене , Исламское Государство Ирак и Левант – провинция Хорасан в Пакистане , «Аш-Шабааб» в Сомали , Талибан в Афганистане , « Исламское государство» , а также Объединенная армия штата Ва и участники Качинского конфликта в Мьянме . [5] : 2

Античность

Новый Завет

Раннее христианство зародилось как секта среди евреев Второго Храма . Межобщинные раздоры начались практически сразу. [6] Согласно сообщению Нового Завета , Савл из Тарса до своего обращения в христианство преследовал первых иудео-христиан . Согласно Деяниям апостолов , через год после римского распятия Иисуса Стефан был побит камнями за преступления иудейского закона . [7] И Саул (также известный как Пол ) согласился, наблюдая и становясь свидетелем смерти Стивена. [6] Позже Павел начинает перечисление своих собственных страданий после обращения во 2 Коринфянам 11: «Пять раз получал я от иудеев по сорок ударов плетью минус один. Трижды меня били розгами, один раз побивали камнями...» [8]

Ранний иудео-христианин

В 41 году нашей эры Ирод Агриппа , уже владевший территорией Ирода Антипы и Филиппа (его бывших соратников по Иродовой Тетрархии ), получил титул царя иудейского и в каком-то смысле реформировал Иудейское царство Ирода . Великий ( годы правления 37–4 до н. э. ). Сообщается, что Ирод Агриппа стремился завоевать расположение своих еврейских подданных и продолжал преследование, в результате которого Иаков Великий погиб , святой Петр чудом спасся, а остальные апостолы обратились в бегство. [6] После смерти Агриппы в 44 г. началась римская прокуратура (до 41 г. они были префектами в провинции Иудея), и эти лидеры поддерживали нейтральный мир, пока прокуратор Порций Фест не умер в 62 г. и первосвященник Анан бен Анан не воспользовался вакуумом власти, чтобы напасть на Церковь и казнить Иакова Справедливого , тогдашнего лидера иерусалимских христиан .

В Новом Завете говорится, что Павел сам несколько раз был заключен в тюрьму римскими властями, побит камнями фарисеями и однажды оставлен умирать, а в конечном итоге был доставлен в Рим в качестве пленника. Петра и других первых христиан также сажали в тюрьму, избивали и преследовали. Первое еврейское восстание , спровоцированное убийством римлянами 3000 евреев, привело к разрушению Иерусалима в 70 году нашей эры , концу иудаизма Второго Храма (и последующему медленному подъему раввинистического иудаизма ). [6]

Клаудия Сетцер утверждает, что «евреи не считали христиан четко отделенными от своей общины, по крайней мере, до середины второго века», но большинство ученых относят «разлучение путей» гораздо раньше, при этом богословское разделение произошло немедленно. [9] Иудаизм Второго Храма допускал несколько способов быть евреем. После падения Храма один путь привел к раввинистическому иудаизму, а другой — к христианству; но христианство «было сформировано вокруг убеждения, что еврей, Иисус из Назарета, был не только Мессией, обещанным евреям, но и сыном Божьим, предлагающим доступ к Богу и Божье благословение нееврею, а, возможно, в конечном итоге и больше». чем евреям». [10] : 189 Хотя мессианская эсхатология имела глубокие корни в иудаизме, а идея страдающего слуги, известного как Мессия Ефрем, была аспектом со времен Исайи (7 век до н.э.), в первом веке эта идея рассматривалась как узурпированная христиане. Затем оно было подавлено и не возвращалось в раввинское учение до сочинений Песикта Рабати в седьмом веке. [11]

Традиционный взгляд на разделение иудаизма и христианства предполагает массовое бегство евреев-христиан в Пеллу (незадолго до падения Храма в 70 году нашей эры) в результате еврейских преследований и ненависти. [12] Стивен Д. Кац говорит, что «не может быть никаких сомнений в том, что ситуация после 70-х годов стала свидетелем изменения в отношениях евреев и христиан». [13] Иудаизм стремился восстановиться после катастрофы, что включало в себя определение правильного ответа на еврейское христианство. Точная форма этого неизвестна, но традиционно предполагается, что оно принимало четыре формы: распространение официальных антихристианских заявлений, введение официального запрета христианам на посещение синагоги, запрет на чтение христианских писаний и распространение проклятие христианских еретиков: Биркат ха-Миним . [13]

Римская империя

Неронианское преследование

Первый задокументированный случай преследования христиан в Римской империи под надзором императора начинается с Нерона (54–68). В « Анналах » Тацит утверждает, что Нерон обвинил христиан в Великом пожаре в Риме , и хотя эта точка зрения обычно считается достоверной и достоверной, некоторые современные ученые ставят под сомнение эту точку зрения, главным образом потому, что нет дальнейших ссылок на обвинения Нерона в «Великом пожаре Рима». Христиане за огнём до конца 4 века. [14] [15] Светоний упоминает о наказаниях, которым подвергались христиане, определяемые как люди, следующие новому и пагубному суеверию, но не уточняет причин наказания; он просто перечисляет этот факт вместе с другими злоупотреблениями, зафиксированными Нероном. [15] : 269 Широко распространено мнение, что число зверя в Книге Откровения , составляющее 666, происходит от гематрии имени Нерона Цезаря, что указывает на то, что Нерон считался исключительно злой фигурой. [16] Несколько христианских источников сообщают, что апостол Павел и святой Петр умерли во время неронианских преследований. [17] [18] [19] [20]

От Нерона до Деция

В первые два столетия христианство было относительно небольшой сектой, которая не вызывала серьезного беспокойства императора. По оценкам Родни Старка , в 100 году было менее 10 000 христиан. менее 2% от общей численности населения империи. [21] По мнению Гая Лори , Церковь в первые века своего существования не боролась за свое существование. [22] Однако Бернард Грин говорит, что, хотя ранние гонения на христиан, как правило, были спорадическими, локальными и проводились под руководством региональных губернаторов, а не императоров, христиане «всегда подвергались притеснениям и подвергались риску открытых преследований». [23] Политика Траяна по отношению к христианам ничем не отличалась от обращения с другими сектами, то есть их наказывали только в том случае, если они отказывались поклоняться императору и богам, но их нельзя было разыскивать. [24]

Джеймс Л. Папандреа говорит, что существует десять императоров, которые, как принято считать, спонсировали санкционированные государством преследования христиан: [25] хотя первое преследование, спонсируемое правительством всей империи, началось только в 249 году при Деции. [26] Одним из первых сообщений о массовых убийствах является преследование в Лионе, в ходе которого христиан якобы подвергали массовой резне, бросая их на съедение диким зверям по указу римских чиновников за то, что они якобы отказались отречься от своей веры, согласно Иринею . [27] [28] В III веке императора Севера Александра в доме было много христиан, но его преемник Максимин Фракс , ненавидя этот дом, приказал казнить глав церквей. [29] [30] По словам Евсевия, это преследование отправило Ипполита Римского и Папу Понтиана в изгнание, но другие данные свидетельствуют о том, что преследования были локальными в тех провинциях, где они происходили, а не происходили под руководством Императора. [31]

According to two different Christian traditions, Simon bar Kokhba, the leader of the second Jewish revolt against Rome (132–136 AD), who was proclaimed Messiah, persecuted the Christians: Justin Martyr claims that Christians were punished if they did not deny and blaspheme Jesus Christ, while Eusebius asserts that Bar Kokhba harassed them because they refused to join his revolt against the Romans.[32]

Voluntary martyrdom

Some early Christians sought out and welcomed martyrdom.[33][34] According to Droge and Tabor, "in 185 the proconsul of Asia, Arrius Antoninus, was approached by a group of Christians demanding to be executed. The proconsul obliged some of them and then sent the rest away, saying that if they wanted to kill themselves there was plenty of rope available or cliffs they could jump off."[35] Such enthusiasm for death is found in the letters of Saint Ignatius of Antioch who was arrested and condemned as a criminal before writing his letters while on the way to execution. Ignatius casts his own martyrdom as a voluntary eucharistic sacrifice to be embraced.[36]: 55

"Many martyr acts present martyrdom as a sharp choice that cut to the core of Christian identity – life or death, salvation or damnation, Christ or apostacy..."[36]: 145 Subsequently, the martyr literature has drawn distinctions between those who were enthusiastically pro-voluntary-martyrdom (the Montanists and Donatists), those who occupied a neutral, moderate position (the orthodox), and those who were anti-martyrdom (the Gnostics).[36]: 145

The category of voluntary martyr began to emerge only in the third century in the context of efforts to justify flight from persecution.[37] The condemnation of voluntary martyrdom is used to justify Clement fleeing the Severan persecution in Alexandria in 202 AD, and the Martyrdom of Polycarp justifies Polycarp's flight on the same grounds. "Voluntary martyrdom is parsed as passionate foolishness" whereas "flight from persecution is patience" and the result a true martyrdom.[36]: 155

Daniel Boyarin rejects use of the term "voluntary martyrdom", saying, "if martyrdom is not voluntary, it is not martyrdom".[38] G. E. M. de Ste. Croix adds a category of "quasi-voluntary martyrdom": "martyrs who were not directly responsible for their own arrest but who, after being arrested, behaved with" a stubborn refusal to obey or comply with authority.[36]: 153 Candida Moss asserts that De Ste. Croix's judgment of what values are worth dying for is modern, and does not represent classical values. According to her there was no such concept as "quasi-volunteer martyrdom" in ancient times.[36]: 153

Decian persecution

In the reign of the emperor Decius (r. 249–251), a decree was issued requiring that all residents of the empire should perform sacrifices, to be enforced by the issuing of each person with a libellus certifying that they had performed the necessary ritual.[39] It is not known what motivated Decius's decree, or whether it was intended to target Christians, though it is possible the emperor was seeking divine favors in the forthcoming wars with the Carpi and the Goths.[39] Christians that refused to publicly offer sacrifices or burn incense to Roman gods were accused of impiety and punished by arrest, imprisonment, torture or execution.[26] According to Eusebius, bishops Alexander of Jerusalem, Babylas of Antioch, and Fabian of Rome were all imprisoned and killed.[39] The patriarch Dionysius of Alexandria escaped captivity, while the bishop Cyprian of Carthage fled his episcopal see to the countryside.[39] The Christian church, despite no indication in the surviving texts that the edict targeted any specific group, never forgot the reign of Decius whom they labelled as that "fierce tyrant".[26] After Decius died, Trebonianus Gallus (r. 251–253) succeeded him and continued the Decian persecution for the duration of his reign.[39]

Valerianic persecution

The accession of Trebonianus Gallus's successor Valerian (r. 253–260) ended the Decian persecution.[39] In 257 however, Valerian began to enforce public religion. Cyprian of Carthage was exiled and executed the following year, while Pope Sixtus II was also put to death.[39] Dionysius of Alexandria was tried, urged to recognize "the natural gods" in the hope his congregation would imitate him, and exiled when he refused.[39]

Valerian was defeated by the Persians at the Battle of Edessa and himself taken prisoner in 260. According to Eusebius, Valerian's son, co-augustus, and successor Gallienus (r. 253–268) allowed Christian communities to use again their cemeteries and made restitution of their confiscated buildings.[39] Eusebius wrote that Gallienus allowed the Christians "freedom of action".[39]

Late antiquity

Roman Empire

The Great Persecution

The Great Persecution, or Diocletianic Persecution, was begun by the senior augustus and Roman emperor Diocletian (r. 284–305) on 23 February 303.[39] In the eastern Roman empire, the official persecution lasted intermittently until 313, while in the western Roman empire the persecution went unenforced from 306.[39] According to Lactantius's De mortibus persecutorum ("on the deaths of the persecutors"), Diocletian's junior emperor, the caesar Galerius (r. 293–311) pressured the augustus to begin persecuting Christians.[39] Eusebius of Caesarea's Church History reports that imperial edicts were promulgated to destroy churches and confiscate scriptures, and to remove Christian occupants of government positions, while Christian priests were to be imprisoned and required to perform sacrifice in ancient Roman religion.[39] In the account of Eusebius, an unnamed Christian man (named by later hagiographers as Euethius of Nicomedia and venerated on 27 February) tore down a public notice of an imperial edict while the emperors Diocletian and Galerius were in Nicomedia (İzmit), one of Diocletian's capitals; according to Lactantius, he was tortured and burned alive.[40] According to Lactantius, the church at Nicomedia (İzmit) was destroyed, while the Optatan Appendix has an account from the praetorian prefecture of Africa involving the confiscation of written materials which led to the Donatist schism.[39] According to Eusebius's Martyrs of Palestine and Lactantius's De mortibus persecutorum, a fourth edict in 304 demanded that everyone perform sacrifices, though in the western empire this was not enforced.[39]

An "unusually philosophical" dialogue is recorded in the trial proceedings of Phileas of Thmuis, bishop of Thmuis in Egypt's Nile Delta, which survive on Greek papyri from the 4th century among the Bodmer Papyri and the Chester Beatty Papyri of the Bodmer and Chester Beatty libraries and in manuscripts in Latin, Ethiopic, and Coptic languages from later centuries, a body of hagiography known as the Acts of Phileas.[39] Phileas was condemned at his fifth trial at Alexandria under Clodius Culcianus, the praefectus Aegypti on 4 February 305 (the 10th day of Mecheir).

In the western empire, the Diocletianic Persecution ceased with the usurpation by two emperors' sons in 306: that of Constantine, who was acclaimed augustus by the army after his father Constantius I (r. 293–306) died, and that of Maxentius (r. 306–312) who was elevated to augustus by the Roman Senate after the grudging retirement of his father Maximian (r. 285–305) and his co-augustus Diocletian in May 305.[39] Of Maxentius, who controlled Italy with his now un-retired father, and Constantine, who controlled Britain, Gaul, and Iberia, neither was inclined to continue the persecution.[39] In the eastern empire however, Galerius, now augustus, continued Diocletian's policy.[39] Eusebius's Church History and Martyrs of Palestine both give accounts of martyrdom and persecution of Christians, including Eusebius's own mentor Pamphilus of Caesarea, with whom he was imprisoned during the persecution.[39]

When Galerius died in May 311, he is reported by Lactantius and Eusebius to have composed a deathbed edict – the Edict of Serdica – allowing the assembly of Christians in conventicles and explaining the motives for the prior persecution.[39] Eusebius wrote that Easter was celebrated openly.[39] By autumn however, Galerius's nephew, former caesar, and co-augustus Maximinus Daia (r. 310–313) was enforcing Diocletian's persecution in his territories in Anatolia and the Diocese of the East in response to petitions from numerous cities and provinces, including Antioch, Tyre, Lycia, and Pisidia.[39] Maximinus was also encouraged to act by an oracular pronouncement made by a statue of Zeus Philios set up in Antioch by Theotecnus of Antioch, who also organized an anti-Christian petition to be sent from the Antiochenes to Maximinus, requesting that the Christians there be expelled.[39] Among the Christians known to have died in this phase of the persecution are the presbyter Lucian of Antioch, the bishop Methodius of Olympus in Lycia, and Peter, the patriarch of Alexandria. Defeated in a civil war by the augustus Licinius (r. 308–324), Maximinus died in 313, ending the systematic persecution of Christianity as a whole in the Roman Empire.[39] Only one martyr is known by name from the reign of Licinius, who issued the Edict of Milan jointly with his ally, co-augustus, and brother-in-law Constantine, which had the effect of resuming the toleration of before the persecution and returning confiscated property to Christian owners.[39]

The New Catholic Encyclopedia states that "Ancient, medieval and early modern hagiographers were inclined to exaggerate the number of martyrs. Since the title of martyr is the highest title to which a Christian can aspire, this tendency is natural".[41] Attempts at estimating the numbers involved are inevitably based on inadequate sources.[42]

Constantinian period

The Christian church marked the conversion of Constantine the Great as the final fulfillment of its heavenly victory over the "false gods".[43]: xxxii The Roman state had always seen itself as divinely directed, now it saw the first great age of persecution, in which the Devil was considered to have used open violence to dissuade the growth of Christianity, at an end.[44] The orthodox catholic Christians close to the Roman state represented imperial persecution as an historical phenomenon, rather than a contemporary one.[44] According to MacMullan, the Christian histories are colored by this "triumphalism".[45]: 4

Peter Leithart says that, "[Constantine] did not punish pagans for being pagans, or Jews for being Jews, and did not adopt a policy of forced conversion".[46]: 61 Pagans remained in important positions at his court.[46]: 302 He outlawed the gladiatorial shows, destroyed some temples and plundered more, and used forceful rhetoric against non-Christians, but he never engaged in a purge.[46]: 302 Maxentius' supporters were not slaughtered when Constantine took the capital; Licinius' family and court were not killed.[46]: 304 However, followers of doctrines which were seen as heretical or causing schism were persecuted during the reign of Constantine, the first Christian Roman emperor, and they would be persecuted again later in the 4th century.[47] The consequence of Christian doctrinal disputes was generally mutual excommunication, but once Roman government became involved in ecclesiastical politics, rival factions could find themselves subject to "repression, expulsion, imprisonment or exile" carried out by the Roman army.[48]: 317

In 312, the Christian sect called Donatists appealed to Constantine to solve a dispute. He convened a synod of bishops to hear the case, but the synod sided against them. The Donatists refused to accept the ruling, so a second gathering of 200 at Arles, in 314, was called, but they also ruled against them. The Donatists again refused to accept the ruling, and proceeded to act accordingly by establishing their own bishop, building their own churches, and refusing cooperation.[48]: 317 [47]: xv This was a defiance of imperial authority, and it produced the same response Rome had taken in the past against such refusals. For a Roman emperor, "religion could be tolerated only as long as it contributed to the stability of the state".[49]: 87 Constantine used the army in an effort to compel Donatist' obedience, burning churches and martyring some from 317 – 321.[47]: ix, xv Constantine failed in reaching his goal and ultimately conceded defeat. The schism remained and Donatism continued.[48]: 318 After Constantine, his youngest son Flavius Julius Constans, initiated the Macarian campaign against the Donatists from 346 – 348 which only succeeded in renewing sectarian strife and creating more martyrs. Donatism continued.[47]: xvii

The fourth century was dominated by its many conflicts defining orthodoxy versus heterodoxy and heresy. In the Eastern Roman empire, known as Byzantium, the Arian controversy began with its debate of Trinitarian formulas which lasted 56 years.[50]: 141 As it moved into the West, the center of the controversy was the "champion of orthodoxy", Athanasius. In 355 Constantius, who supported Arianism, ordered the suppression and exile of Athanasius, expelled the orthodox Pope Liberius from Rome, and exiled bishops who refused to assent to Athanasius's exile.[51] In 355, Dionysius, bishop of Mediolanum (Milan) was expelled from his episcopal see and replaced by the Arian Christian Auxentius of Milan.[52] When Constantius returned to Rome in 357, he consented to allow the return of Liberius to the papacy; the Arian Pope Felix II, who had replaced him, was then driven out along with his followers.[51]

The last emperor of the Constantinian dynasty, Constantine's half-brother's son Julian (r. 361–363) opposed Christianity and sought to restore traditional religion, though he did not arrange a general or official persecution.[39]

Valentinianic–Theodosian period

According to the Collectio Avellana, on the death of Pope Liberius in 366, Damasus, assisted by hired gangs of "charioteers" and men "from the arena", broke into the Basilica Julia to violently prevent the election of Pope Ursicinus.[51] The battle lasted three days, "with great slaughter of the faithful" and a week later Damasus seized the Lateran Basilica, had himself ordained as Pope Damasus I, and compelled the praefectus urbi Viventius and the praefectus annonae to exile Ursicinus.[51] Damasus then had seven Christian priests arrested and awaiting banishment, but they escaped and "gravediggers" and minor clergy joined another mob of hippodrome and amphitheatre men assembled by the pope to attack the Liberian Basilica, where Ursacinus's loyalists had taken refuge.[51] According to Ammianus Marcellinus, on 26 October, the pope's mob killed 137 people in the church in just one day, and many more died subsequently.[51] The Roman public frequently enjoined the emperor Valentinian the Great to remove Damasus from the throne of Saint Peter, calling him a murderer for having waged a "filthy war" against the Christians.[51]

In the 4th century, the Terving king Athanaric in c. 375 ordered the Gothic persecution of Christians.[53] Athanaric was perturbed by the spread of Gothic Christianity among his followers, and feared for the displacement of Gothic paganism.

It was not until the later 4th century reigns of the augusti Gratian (r. 367–383), Valentinian II (r. 375–392), and Theodosius I (r. 379–395) that Christianity would become the official religion of the empire with the joint promulgation of the Edict of Thessalonica, establishing Nicene Christianity as the state religion and as the state church of the Roman Empire on 27 February 380. After this began state persecution of non-Nicene Christians, including Arian and Nontrinitarian devotees.[54]: 267

When Augustine became coadjutor Bishop of Hippo in 395, both Donatist and Catholic parties had, for decades, existed side-by-side, with a double line of bishops for the same cities, all competing for the loyalty of the people.[47]: xv [a]: 334 Augustine was distressed by the ongoing schism, but he held the view that belief cannot be compelled, so he appealed to the Donatists using popular propaganda, debate, personal appeal, General Councils, appeals to the emperor and political pressure, but all attempts failed.[56]: 242, 254 The Donatists fomented protests and street violence, accosted travelers, attacked random Catholics without warning, often doing serious and unprovoked bodily harm such as beating people with clubs, cutting off their hands and feet, and gouging out eyes while also inviting their own martyrdom.[57]: 120–121 By 408, Augustine supported the state's use of force against them.[55]: 107–116 Historian Frederick Russell says that Augustine did not believe this would "make the Donatists more virtuous" but he did believe it would make them "less vicious".[58]: 128

Augustine wrote that there had, in the past, been ten Christian persecutions, beginning with the Neronian persecution, and alleging persecutions by the emperors Domitian, Trajan, "Antoninus" (Marcus Aurelius), "Severus" (Septimius Severus), and Maximinus (Thrax), as well as Decian and Valerianic persecutions, and then another by Aurelian as well as by Diocletian and Maximian.[44] These ten persecutions Augustine compared with the 10 Plagues of Egypt in the Book of Exodus.[note 1][59] Augustine did not see these early persecutions in the same light as that of fourth century heretics. In Augustine's view, when the purpose of persecution is to "lovingly correct and instruct", then it becomes discipline and is just.[60]: 2 Augustine wrote that "coercion cannot transmit the truth to the heretic, but it can prepare them to hear and receive the truth".[55]: 107–116 He said the church would discipline its people out of a loving desire to heal them, and that, "once compelled to come in, heretics would gradually give their voluntary assent to the truth of Christian orthodoxy."[58]: 115 He opposed the severity of Rome and the execution of heretics.[61]: 768

It is his teaching on coercion that has literature on Augustine frequently referring to him as le prince et patriarche de persecuteurs (the prince and patriarch of persecutors).[57]: 116 [55]: 107 Russell says Augustine's theory of coercion "was not crafted from dogma, but in response to a unique historical situation" and is therefore context dependent, while others see it as inconsistent with his other teachings.[58]: 125 His authority on the question of coercion was undisputed for over a millennium in Western Christianity, and according to Brown "it provided the theological foundation for the justification of medieval persecution."[55]: 107–116

Heraclian period

Callinicus I, initially a priest and skeuophylax in the Church of the Theotokos of Blachernae, became patriarch of Constantinople in 693 or 694.[62]: 58–59 Having refused to consent to the demolition of a chapel in the Great Palace, the Theotokos ton Metropolitou, and having possibly been involved in the deposition and exile of Justinian II (r. 685–695, 705–711), an allegation denied by the Synaxarion of Constantinople, he was himself exiled to Rome on the return of Justinian to power in 705.[62]: 58–59 The emperor had Callinicus immured.[62]: 58–59 He is said to have survived forty days when the wall was opened to check his condition, though he died four days later.[62]: 58–59

Sassanian Empire

Violent persecutions of Christians began in earnest in the long reign of Shapur II (r. 309–379).[63] A persecution of Christians at Kirkuk is recorded in Shapur's first decade, though most persecution happened after 341.[63] At war with the Roman emperor Constantius II (r. 337–361), Shapur imposed a tax to cover the war expenditure, and Shemon Bar Sabbae, the Bishop of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, refused to collect it.[63] Often citing collaboration with the Romans, the Persians began persecuting and executing Christians.[63] Passio narratives describe the fate of some Christians venerated as martyrs; they are of varying historical reliability, some being contemporary records by eyewitnesses, others were reliant on popular tradition at some remove from the events.[63] An appendix to the Syriac Martyrology of 411 lists the Christian martyrs of Persia, but other accounts of martyrs' trials contain important historical details on the workings of the Sassanian Empire's historical geography and judicial and administrative practices.[63] Some were translated into Sogdian and discovered at Turpan.[63]

Under Yazdegerd I (r. 399–420) there were occasional persecutions, including an instance of persecution in reprisal for the burning of a Zoroastrian fire temple by a Christian priest, and further persecutions occurred in the reign of Bahram V (r. 420–438).[63] Under Yazdegerd II (r. 438–457) an instance of persecution in 446 is recorded in the Syriac martyrology Acts of Ādur-hormizd and of Anāhīd.[63] Some individual martyrdoms are recorded from the reign of Khosrow I (r. 531–579), but there were likely no mass persecutions.[63] While according to a peace treaty of 562 between Khosrow and his Roman counterpart Justinian I (r. 527–565), Persia's Christians were granted the freedom of religion; proselytism was, however, a capital crime.[63] By this time the Church of the East and its head, the Catholicose of the East, were integrated into the administration of the empire and mass persecution was rare.[63]

The Sassanian policy shifted from tolerance of other religions under Shapur I to intolerance under Bahram I and apparently a return to the policy of Shapur until the reign of Shapur II. The persecution at that time was initiated by Constantine's conversion to Christianity which followed that of Armenian king Tiridates in about 301. The Christians were thus viewed with suspicions of secretly being partisans of the Roman Empire. This did not change until the fifth century when the Church of the East broke off from the Church of the West.[64] Zoroastrian elites continued viewing the Christians with enmity and distrust throughout the fifth century with threat of persecution remaining significant, especially during war against the Romans.[65]

Zoroastrian high priest Kartir, refers in his inscription dated about 280 on the Ka'ba-ye Zartosht monument in the Naqsh-e Rostam necropolis near Zangiabad, Fars, to persecution (zatan – "to beat, kill") of Christians ("Nazareans n'zl'y and Christians klstyd'n"). Kartir took Christianity as a serious opponent. The use of the double expression may be indicative of the Greek-speaking Christians deported by Shapur I from Antioch and other cities during his war against the Romans.[66] Constantine's efforts to protect the Persian Christians made them a target of accusations of disloyalty to Sasanians. With the resumption of Roman-Sasanian conflict under Constantius II, the Christian position became untenable. Zoroastrian priests targeted clergy and ascetics of local Christians to eliminate the leaders of the church. A Syriac manuscript in Edessa in 411 documents dozens executed in various parts of western Sasanian Empire.[65]

In 341, Shapur II ordered the persecution of all Christians.[67][68] In response to their subversive attitude and support of Romans, Shapur II doubled the tax on Christians. Shemon Bar Sabbae informed him that he could not pay the taxes demanded from him and his community. He was martyred and a forty-year-long period of persecution of Christians began. The Council of Seleucia-Ctesiphon gave up choosing bishops since it would result in death. The local mobads – Zoroastrian clerics – with the help of satraps organized slaughters of Christians in Adiabene, Beth Garmae, Khuzistan and many other provinces.[69]

Yazdegerd I showed tolerance towards Jews and Christians for much of his rule. He allowed Christians to practice their religion freely, demolished monasteries and churches were rebuilt and missionaries were allowed to operate freely. He reversed his policies during the later part of his reign however, suppressing missionary activities.[70] Bahram V continued and intensified their persecution, resulting in many of them fleeing to the eastern Roman empire. Bahram demanded their return, beginning the Roman–Sasanian War of 421–422. The war ended with an agreement of freedom of religion for Christians in Iran with that of Mazdaism in Rome. Meanwhile, Christians suffered destruction of churches, renounced the faith, had their private property confiscated and many were expelled.[71]

Yazdegerd II had ordered all his subjects to embrace Mazdeism in an attempt to unite his empire ideologically. The Caucasus rebelled to defend Christianity which had become integrated in their local culture, with Armenian aristocrats turning to the Romans for help. The rebels were however defeated in a battle on the Avarayr Plain. Yeghishe in his The History of Vardan and the Armenian War, pays a tribute to the battles waged to defend Christianity.[72] Another revolt was waged from 481 to 483 which was suppressed. However, the Armenians succeeded in gaining freedom of religion among other improvements.[73]

Accounts of executions for apostasy of Zoroastrians who converted to Christianity during Sasanian rule proliferated from the fifth to early seventh century, and continued to be produced even after collapse of Sasanians. The punishment of apostates increased under Yazdegerd I and continued under successive kings. It was normative for apostates who were brought to the notice of authorities to be executed, although the prosecution of apostasy depended on political circumstances and Zoroastrian jurisprudence. Per Richard E. Payne, the executions were meant to create a mutually recognised boundary between interactions of the people of the two religions and preventing one religion challenging another's viability. Although the violence on Christians was selective and especially carried out on elites, it served to keep Christian communities in a subordinate and yet viable position in relation to Zoroastrianism. Christians were allowed to build religious buildings and serve in the government as long as they did not expand their institutions and population at the expense of Zoroastrianism.[74]

Khosrow I was generally regarded as tolerant of Christians and interested in the philosophical and theological disputes during his reign. Sebeos claimed he had converted to Christianity on his deathbed. John of Ephesus describes an Armenian revolt where he claims that Khusrow had attempted to impose Zoroastrianism in Armenia. The account, however, is very similar to the one of Armenian revolt of 451. In addition, Sebeos does not mention any religious persecution in his account of the revolt of 571.[75] A story about Hormizd IV's tolerance is preserved by the historian al-Tabari. Upon being asked why he tolerated Christians, he replied, "Just as our royal throne cannot stand upon its front legs without its two back ones, our kingdom cannot stand or endure firmly if we cause the Christians and adherents of other faiths, who differ in belief from ourselves, to become hostile to us."[76]

During the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628

Several months after the Persian conquest in AD 614, a riot occurred in Jerusalem, and the Jewish governor of Jerusalem Nehemiah was killed by a band of young Christians along with his "council of the righteous" while he was making plans for the building of the Third Temple. At this time the Christians had allied themselves with the Eastern Roman Empire. Shortly afterward, the events escalated into a full-scale Christian rebellion, resulting in a battle against the Jews and Christians who were living in Jerusalem. In the battle's aftermath, many Jews were killed and the survivors fled to Caesarea, which was still being held by the Persian army.

The Judeo-Persian reaction was ruthless – Persian Sasanian general Xorheam assembled Judeo-Persian troops and went and encamped around Jerusalem and besieged it for 19 days.[77] Eventually, digging beneath the foundations of the Jerusalem, they destroyed the wall and on the 19th day of the siege, the Judeo-Persian forces took Jerusalem.[77]

According to the account of the Armenian ecclesiastic and historian Sebeos, the siege resulted in a total Christian death toll of 17,000, the earliest and thus most commonly accepted figure.[78]: 207 Per Strategius, 4,518 prisoners alone were massacred near Mamilla reservoir.[79] A cave containing hundreds of skeletons near the Jaffa Gate, 200 metres east of the large Roman-era pool in Mamilla, correlates with the massacre of Christians at hands of the Persians mentioned in the writings of Strategius. While reinforcing the evidence of massacre of Christians, the archaeological evidence seem less conclusive on the destruction of Christian churches and monasteries in Jerusalem.[79][80][failed verification]

According to the later account of Strategius, whose perspective appears to be that of a Byzantine Greek and shows an antipathy towards the Jews,[81] thousands of Christians were massacred during the conquest of the city. Estimates based on varying copies of Strategos's manuscripts range from 4,518 to 66,509 killed.[79] Strategos wrote that the Jews offered to help them escape death if they "become Jews and deny Christ", and the Christian captives refused. In anger the Jews allegedly purchased Christians to kill them.[82] In 1989, a mass burial grave at Mamilla cave was discovered in by Israeli archeologist Ronny Reich, near the site where Strategius recorded the massacre took place. The human remains were in poor condition containing a minimum of 526 individuals.[83]

From the many excavations carried out in the Galilee, it is clear that all churches had been destroyed during the period between the Persian invasion and the Arab conquest in 637. The church at Shave Ziyyon was destroyed and burnt in 614. Similar fate befell churches at Evron, Nahariya, 'Arabe and monastery of Shelomi. The monastery at Kursi was damaged in the invasion.[84]

Pre-Islamic Arabia

In AD 516, tribal unrest broke out in Yemen and several tribal elites fought for power. One of those elites was Joseph Dhu Nuwas or "Yousef Asa'ar", a Jewish king of the Himyarite Kingdom who is mentioned in ancient south Arabian inscriptions. Syriac and Byzantine Greek sources claim that he fought his war because Christians in Yemen refused to renounce Christianity. In 2009, a documentary that aired on the BBC defended the claim that the villagers had been offered the choice between conversion to Judaism or death and 20,000 Christians were then massacred by stating that "The production team spoke to many historians over a period of 18 months, among them Nigel Groom, who was our consultant, and Professor Abdul Rahman Al-Ansary, a former professor of archaeology at the King Saud University in Riyadh."[85] Inscriptions documented by Yousef himself show the great pride that he expressed after killing more than 22,000 Christians in Zafar and Najran.[86] Historian Glen Bowersock described this massacre as a "savage pogrom that the Jewish king of the Arabs launched against the Christians in the city of Najran. The king himself reported in excruciating detail to his Arab and Persian allies about the massacres that he had inflicted on all Christians who refused to convert to Judaism."[87]

Early Middle Ages

Rashidun Caliphate

Since they are considered "People of the Book" in the Islamic religion, Christians under Muslim rule were subjected to the status of dhimmi (along with Jews, Samaritans, Gnostics, Mandeans, and Zoroastrians), which was inferior to the status of Muslims.[88][89] Christians and other religious minorities thus faced religious discrimination and persecution in that they were banned from proselytising (for Christians, it was forbidden to evangelize or spread Christianity) in the lands invaded by the Arab Muslims on pain of death, they were banned from bearing arms, undertaking certain professions, and were obligated to dress differently in order to distinguish themselves from Arabs.[88] Under the Islamic law (sharīʿa), Non-Muslims were obligated to pay the jizya and kharaj taxes,[88][89] together with periodic heavy ransom levied upon Christian communities by Muslim rulers in order to fund military campaigns, all of which contributed a significant proportion of income to the Islamic states while conversely reducing many Christians to poverty, and these financial and social hardships forced many Christians to convert to Islam.[88] Christians unable to pay these taxes were forced to surrender their children to the Muslim rulers as payment who would sell them as slaves to Muslim households where they were forced to convert to Islam.[88]

According to the tradition of the Syriac Orthodox Church, the Muslim conquest of the Levant was a relief for Christians oppressed by the Western Roman Empire.[89] Michael the Syrian, patriarch of Antioch, wrote later that the Christian God had "raised from the south the children of Ishmael to deliver us by them from the hands of the Romans".[89] Various Christian communities in the regions of Palestine, Syria, Lebanon, and Armenia resented either the governance of the Western Roman Empire or that of the Byzantine Empire, and therefore preferred to live under more favourable economic and political conditions as dhimmi under the Muslim rulers.[89] However, modern historians also recognize that the Christian populations living in the lands invaded by the Arab Muslim armies between the 7th and 10th centuries AD suffered religious persecution, religious violence, and martyrdom multiple times at the hands of Arab Muslim officials and rulers;[89][90][91][92] many were executed under the Islamic death penalty for defending their Christian faith through dramatic acts of resistance such as refusing to convert to Islam, repudiation of the Islamic religion and subsequent reconversion to Christianity, and blasphemy towards Muslim beliefs.[90][91][92]

When Amr ibn al-As conquered Tripoli in 643, he forced the Jewish and Christian Berbers to give their wives and children as slaves to the Arab army as part of their jizya.[93][94][95]

Around the year 666 C.E Uqba ibn Nafi “conquered the southern Tunisian cities... slaughtering all the Christians living there."[96] Muslim sources report him waging countless raids, often ending with the complete ransacking and mass enslavement of cities.[97]

Archaeological evidence from North Africa in the region of Cyrenaica points to the destruction of churches along the route the Islamic conquerors followed in the late seventh century, and the remarkable artistic treasures buried along the routes leading to the North of Spain by fleeing Visigoths and Hispano-Romans during the early eighth century consist largely of religious and dynastic paraphernalia that the Christian inhabitants obviously wanted to protect from Muslim looting and desecration.[98]

Umayyad Caliphate

According to the Ḥanafī school of Islamic law (sharīʿa), the testimony of a Non-Muslim (such as a Christian or a Jew) was not considered valid against the testimony of a Muslim in legal or civil matters. Historically, in Islamic culture and traditional Islamic law, Muslim women have been forbidden from marrying Christian or Jewish men, whereas Muslim men have been permitted to marry Christian or Jewish women[99][100] (see: Interfaith marriage in Islam). Christians under Islamic rule had the right to convert to Islam or any other religion, while conversely a murtad, or an apostate from Islam, faced severe penalties or even hadd, which could include the Islamic death penalty.[90][91][92]

In general, Christians subject to Islamic rule were allowed to practice their religion with some notable limitations stemming from the apocryphal Pact of Umar. This treaty, supposedly enacted in 717 AD, forbade Christians from publicly displaying the cross on church buildings, from summoning congregants to prayer with a bell, from re-building or repairing churches and monasteries after they had been destroyed or damaged, and imposed other restrictions relating to occupations, clothing, and weapons.[101] The Umayyad Caliphate persecuted many Berber Christians in the 7th and 8th centuries AD, who slowly converted to Islam.[102]

In Umayyad al-Andalus (the Iberian Peninsula), the Mālikī school of Islamic law was the most prevalent.[91] The martyrdoms of forty-eight Christian martyrs that took place in the Emirate of Córdoba between 850 and 859 AD[103] are recorded in the hagiographical treatise written by the Iberian Christian and Latinist scholar Eulogius of Córdoba.[90][91][92] The Martyrs of Córdoba were executed under the rule of Abd al-Rahman II and Muhammad I, and Eulogius' hagiography describes in detail the executions of the martyrs for capital violations of Islamic law, including apostasy and blasphemy.[90][91][92]

After the Arab conquests a number of Christian Arab tribes suffered enslavement and forced conversion.[104]

In the early eighth century under the Umayyads, 63 out of a group of 70 Christian pilgrims from Iconium were captured, tortured, and executed under the orders of the Arab Governor of Ceaserea for refusing to convert to Islam (seven were forcibly converted to Islam under torture). Soon afterwards, sixty more Christian pilgrims from Amorium were crucified in Jerusalem.[105]

Almoravid Caliphate

The Almohads wreaked enormous destruction on the Christian population of Iberia. Tens of thousands of the native Christians in Iberia (Hispania) were deported from their ancestral lands to Africa by the Almoravids and Almohads.They suspected that the Christians could pose as a fifth column that could potentially help their coreligionists in the north of Iberia. Many Christians died en route to north Africa during these expulsions.[106][107] Christians under the Almoravids suffered persecutions and mass expulsions to Africa. In 1099 the Almoravids sacked the great church of the city of Granada. In 1101 Christians fled from the city of Valencia to the Catholic kingdoms. In 1106 the Almoravids deported Christians from Malaga to Africa. In 1126, after a failed Christian rebellion in Granada, the Almoravids expelled the city's entire Christian population to Africa. And in 1138, Ibn Tashufin forcibly took many thousands of Christians with him to Africa.[108]

The oppressed Mozarabs sent emissaries to the king of Aragon, Alphonso 1st le Batailleur (1104–1134), asking him to come to their rescue and deliver them from the Almoravids. Following the raid the king of Aragon launched in Andalusia in 1125–26 in responding to the pleas of Grenada's Mozarabs, the latter were deported en masse to Morocco in the fall of 1126.[109] Another wave of expulsions to Africa took place 11 years later and as a result very very few Christians were left in Andalusia. Whatever was left of the Christian Catholic population in Granada was exterminated in the aftermath of a revolt against the Almohads in 1164. The Caliph Abu Yaqub Yusuf boasted that he had left no church or synagogue standing in al-Andalus.[107]

Muslim clerics in Al Andalus viewed Christians and Jews as unclean and dirty and feared that too much contact with them would contaminate Muslims. In Seville the faqih Ibn Abdun issued these regulations segregating people of the two faiths:[110]

A Muslim must not massage a Jew or a Christian nor throw away his refuse nor clean his latrines. The Jew and the Christian are better fitted for such trades, since they are the trades of those who are vile. A Muslim should not attend to the animal of a Jew or of a Christian, nor serve him as a muleteer [neither Catholics nor Jews could ride horses; only Muslims could], nor hold his stirrup. If any Muslim is known to do this, he should be denounced.… No … [unconverted] Jew or Christian must be allowed to dress in the costume of people of position, of a jurist, or of a worthy man [this provision echoes the Pact of Umar]. They must on the contrary be abhorred and shunned and should not be greeted with the formula, “Peace be with you,” for the devil has gained mastery over them and has made them forget the name of God. They are the devil's party, “and indeed the devil's party are the losers” (Qur’an 57:22). They must have a distinguishing sign by which they are recognized to their shame [emphasis added].

Byzantine Empire

George Limnaiotes, a monk on Mount Olympus known only from the Synaxarion of Constantinople and other synaxaria, was supposed to have been 95 years old when he was tortured for his iconodulism.[62]: 43 In the reign of Leo III the Isaurian (r. 717–741), he was mutilated by rhinotomy and his head burnt.[62]: 43

Germanus I of Constantinople, a son of the patrikios Justinian, a courtier of the emperor Heraclius (r. 610–641), having been castrated and enrolled in the cathedral clergy of Hagia Sophia when his father was executed in 669, was later bishop of Cyzicus and then patriarch of Constantinople from 715.[62]: 45–46 In 730, in the reign of Leo III (r. 717–741), Germanus was deposed and banished, dying in exile at Plantanion (Akçaabat).[62]: 45–46 Leo III also exiled the monk John the Psichaites, an iconodule, to Cherson, where he remained until after the emperor's death.[62]: 57

According only to the Synaxarion of Constantinople, the clerics Hypatios and Andrew from the Thracesian thema were, during the persecution of Leo III, brought to the capital, jailed and tortured.[62]: 49 The Synaxarion claims that they had the embers of burnt icons applied to their heads, subjected to other torments, and then dragged though the Byzantine streets to their public execution in the area of the city's VIIth Hill, the so-called Medieval Greek: ξηρόλοφος, romanized: Χērólophos, lit. 'dry hill' near the Forum of Arcadius.[62]: 49

Andrew of Crete was beaten and imprisoned in Constantinople after having debated with the iconoclast emperor Constantine V (r. 741–775), possibly in 767 or 768, and then abused by the Byzantines as he was dragged through the city, dying of blood loss when a fisherman cut off his foot in the Forum of the Ox.[62]: 19 The church of Saint Andrew in Krisei was named after him, though his existence is doubted by scholars.[62]: 19

Having defeated and killed the emperor Nikephoros I (r. 802–811) at the Battle of Pliska in 811, the First Bulgarian Empire's khan, Krum, also put to death a number of Roman soldiers who refused to renounce Christianity, though these martyrdoms, known only from the Synaxarion of Constantinople, may be entierely legendary.[62]: 66–67 In 813 the Bulgarians invaded the thema of Thrace, led by Krum, and the city of Adrianople (Edirne) was captured.[62]: 66 Krum's successor Dukum died shortly after Krum himself, being succeeded by Ditzevg, who killed Manuel the archbishop of Adrianople in January 815.[62]: 66 According to the Synaxarion of Constantinople and the Menologion of Basil II, Ditzevg's own successor Omurtag killed some 380 Christians later that month.[62]: 66 The victims included the archbishop of Develtos, George, and the bishop of Thracian Nicaea, Leo, as well as two strategoi called John and Leo. Collectively these are known as the Martyrs of Adrianople.[62]: 66

The Byzantine monk Makarios, of the Pelekete monastery in Bithynia, having already refused an enviable position at court offered by the iconoclast emperor Leo IV the Khazar (r. 775–780) in return for the repudiation of his iconodulism, was expelled from the monastery by Leo V the Armenian (r. 813–820), who also imprisoned and exiled him.[62]: 65

The patriarch Nikephoros I of Constantinople dissented from the iconoclast Council of Constantinople of 815 and was exiled by Leo V as a result.[62]: 74–75 He died in exile in 828.[62]: 74–75

In spring 816, the Constantinopolitan monk Athanasios of Paulopetrion was tortured and exiled for his iconophilism by the emperor Leo V.[62]: 28 In 815, during the reign of Leo V, having been appointed hegoumenos of the Kathara Monastery in Bithynia by the emperor Nikephoros I, John of Kathara was exiled and imprisoned first in Pentadactylon, a stronghold in Phrygia, and then in the fortress of Kriotauros in the Bucellarian thema.[62]: 55–56 In the reign of Michael II he was recalled, but exiled again under Theophilos, being banished to Aphousia (Avşa) where he died, probably in 835.[62]: 55–56

Eustratios of Agauros, a monk and hegumenos of the Agauros Monastery at the foot of Mount Trichalikos, near Prusa's Mount Olympus in Bithynia, was forced into exile by the persecutions of Leo V and Theophilos (r. 829–842).[62]: 37–38 Leo V and Theophilos also persecuted and exiled Hilarion of Dalmatos, the son of Peter the Cappadocian, who had been made hegumenos of the Dalmatos Monastery by the patriarch Nikephoros I.[62]: 48–49 Hilarion was allowed to return to his post only in the regency of Theodora.[62]: 48–49 The same emperors also persecuted Michael Synkellos, an Arab monk of the Mar Saba monastery in Palestine who, as the syncellus of the patriarch of Jerusalem, had travelled to Constantinople on behalf of the patriarch Thomas I.[62]: 70–71 On the Triumph of Orthodoxy, Michael declined the ecumenical patriarchate and became instead the hegumenos of the Chora Monastery.[62]: 70–71

According to Theophanes Continuatus, the Armenian monk and iconographer of Khazar origin Lazarus Zographos refused to cease painting icons in the second official iconoclast period.[62]: 61–62 Theophilos had him tortured and his hands burned with heated irons, though he was released at the intercession of the empress Theodora and hidden at the Monastery of John the Baptist tou Phoberou, where he was able to paint an image of the patron saint.[62]: 61–62 After the death of Theophilos, and the Triumph of Orthodoxy, Lazarus re-painted the representation of Christ on the Chalke Gate of the Great Palace of Constantinople.[62]: 61–62

Symeon Stylites of Lesbos was persecuted for his iconodulism in the second period of official iconoclasm. He was imprisoned and exiled, returning to Lesbos only after the vernation of icons was restored in 842.[62]: 32–33 The bishop George of Mytilene, who may have been Symeon's brother, was exiled from Constantinople in 815 on account of his iconophilia. He spent the last six years of his life in exile on an island, probably one of the Princes' Islands, dying in 820 or 821.[62]: 42–43 George's relics were taken to Mytilene to be venerated after the restoration of iconodulism to orthodoxy under the patriarch Methodios I, during which the hagiography of George was written.[62]: 42–43

The bishop Euthymius of Sardis was the victim of several iconoclast Christian persecutions. Euthymius had previously been exiled to Pantelleria by the emperor Nikephoros I (r. 802–811), recalled in 806, led the iconodule resistance against Leo V (r. 813–820), and exiled again to Thasos in 814.[62]: 38 After his recall to Constantinople in the reign of Michael II (r. 820–829), he was again imprisoned and exiled to Saint Andrew's Island, off Cape Akritas (Tuzla, Istanbul).[62]: 38 According to the hagiography of by the patriarch Methodios I of Constantinople, who claimed to have shared Euthymius's exile and been present at his death, Theoktistos and two other imperial officials personally whipped Euthymius to death on account of his iconodulism; Theoktistos was active in the persecution of iconodules under the iconoclast emperors, but later championed the iconodule cause.[62]: 38, 68–69 [111]: 218 Theoktistos was later venerated as a saint in the Eastern Orthodox Church, listed in the Synaxarion of Constantinople.[111]: 217–218 The last of the iconoclast emperors, Theophilos (r. 829–842), was posthumously rehabilitated by the iconodule Orthodox Church on the intervention of his wife Theodora, who claimed he had had a deathbed conversion to iconodulism in the presence of Theoktistos and had given 60 Byzantine pounds of gold to each of his victims in his will.[111]: 219 The rehabilitation of the iconoclast emperor was a precondition of his widow for convoking the Council of Constantinople in March 843, at which the veneration of icons was restored to orthodoxy and which became celebrated as the Triumph of Orthodoxy.[111]: 219

Evaristos, a relative of Theoktistos Bryennios and a monk of the Monastery of Stoudios, was exiled to the Thracian Chersonese (Gallipoli peninsula) for his support of his hegumenos Nicholas and his patron the patriarch Ignatios of Constantinople when the latter was deposed by Photios I in 858.[62]: 41, 72–73 Both Nicholas and Evaristos went into exile.[62]: 41, 72–73 Only after many years was Evaristos allowed to return to Constantinople to found a monastery of his own.[62]: 41, 72–73 The hegumenos Nicholas, who had accompanied Evaristos to the Chersonese, was restored to his post at the Stoudios Monastery.[62]: 72–73 A partisan of Ignatios of Constantinople and a refugee from the Muslim conquest of Sicily, the monk Joseph the Hymnographer was banished to Cherson from Constantinople on the elevation of Ignatios's rival Photios in 858. Only after the end of Photios's patriarchate was Joseph allowed to return to the capital and become the cathedral skeuophylax of Hagia Sophia.[62]: 57–58

Euthymius, a monk, senator, and synkellos favored by Leo VI (r. 870–912), was first made a hegumenos and then in 907 patriarch of Constantinople by the emperor. When Leo VI died and Nicholas Mystikos was recalled to the patriarchal throne, Euthymius was exiled.[62]: 38–40

Abbasid Caliphate

The Abbasid Caliphate was less tolerant of Christianity than had been the Umayyad caliphs.[89] Nonetheless, Christian officials continued to be employed in the government, and the Christians of the Church of the East were often tasked with the translation of Ancient Greek philosophy and Greek mathematics.[89] The writings of al-Jahiz attacked Christians for being too prosperous, and indicates they were able to ignore even those restrictions placed on them by the state.[89] In the late 9th century, the patriarch of Jerusalem, Theodosius, wrote to his colleague the patriarch of Constantinople Ignatios that "they are just and do us no wrong nor show us any violence".[89]

Elias of Heliopolis, having moved to Damascus from Heliopolis (Ba'albek), was accused of apostasy from Christianity after attending a party held by a Muslim Arab, and was forced to flee Damascus for his hometown, returning eight years later, where he was recognized and imprisoned by the "eparch", probably the jurist al-Layth ibn Sa'd.[62]: 34 After refusing to convert to Islam under torture, he was brought before the Damascene emir and relative of the caliph al-Mahdi (r. 775–785), Muhammad ibn-Ibrahim, who promised good treatment if Elias would convert.[62]: 34 On his repeated refusal, Elias was tortured and beheaded and his body burnt, cut up, and thrown into the river Chrysorrhoes (the Barada) in 779 AD.[62]: 34

According to the Synaxarion of Constantinople, the hegumenos Michael of Zobe and thirty-six of his monks at the Monastery of Zobe near Sebasteia (Sivas) were killed by a raid on the community.[62]: 70 The perpetrator was the "emir of the Hagarenes", "Alim", probably Ali ibn-Sulayman, an Abbasid governor who raided Roman territory in 785 AD.[62]: 70 Bacchus the Younger was beheaded in Jerusalem in 786–787 AD. Bacchus was Palestinian, whose family, having been Christian, had been converted to Islam by their father.[62]: 29–30 Bacchus however, remained crypto-Christian and undertook a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, upon which he was baptized and entered the monastery of Mar Saba.[62]: 29–30 Reunion with his family prompted their reconversion to Christianity and Bacchus's trial and execution for apostasy under the governing emir Harthama ibn A'yan.[62]: 29–30

After the 838 Sack of Amorium, the hometown of the emperor Theophilos (r. 829–842) and his Amorian dynasty, the caliph al-Mu'tasim (r. 833–842) took more than forty Roman prisoners.[62]: 41–42 These were taken to the capital, Samarra, where after seven years of theological debates and repeated refusals to convert to Islam, they were put to death in March 845 under the caliph al-Wathiq (r. 842–847).[62]: 41–42 Within a generation they were venerated as the 42 Martyrs of Amorium. According to their hagiographer Euodius, probably writing within a generation of the events, the defeat at Amorium was to be blamed on Theophilos and his iconoclasm.[62]: 41–42 According to some later hagiographies, including one by one of several Middle Byzantine writers known as Michael the Synkellos, among the forty-two were Kallistos, the doux of the Koloneian thema, and the heroic martyr Theodore Karteros.[62]: 41–42

During the 10th-century phase of the Arab–Byzantine wars, the victories of the Romans over the Arabs resulted in mob attacks on Christians, who were believed to sympathize with the Roman state.[89] According to Bar Hebraeus, the catholicus of the Church of the East, Abraham III (r. 906–937), wrote to the grand vizier that "we Nestorians are the friends of the Arabs and pray for their victories".[89] The attitude of the Nestorians "who have no other king but the Arabs", he contrasted with the Greek Orthodox Church, whose emperors he said "had never cease to make war against the Arabs.[89] Between 923 and 924, several Orthodox churches were destroyed in mob violence in Ramla, Ascalon, Caesarea Maritima, and Damascus.[89] In each instance, according to the Arab Melkite Christian chronicler Eutychius of Alexandria, the caliph al-Muqtadir (r. 908–932) contributed to the rebuilding of ecclesiastical property.[89]

During the late 700s in the Abbasid Empire, Muslims destroyed two churches and a monastery near Bethlehem and slaughtered its monks. In 796, Muslims burned another twenty monks to death. In the years 809 and 813 AD, multiple monasteries, convents, and churches were attacked in and around Jerusalem; both male and female Christians were gang raped and massacred. In 929, on Palm Sunday, another wave of atrocities broke out; churches were destroyed and Christians slaughtered. al-Maqrizi records that in the year 936, “the Muslims in Jerusalem made a rising and burnt down the Church of the Resurrection [the Holy Sepulchre] which they plundered, and destroyed all they could of it".[112]

According to the Synaxarion of Constantinople, Dounale-Stephen, having journeyed to Jerusalem, continued his pilgrimage to Egypt, where he was arrested by the local emir and, refusing to relinquish his beliefs, died in jail c. 950.[62]: 33–34 </ref>

When Abd Allah ibn Tahir went to besiege Kaisum, the fortress of Nasr: "There had been great oppression in the whole country because the inhabitants [christian dhimmis] were forced to bring provisions to the camp; and in every place it was a time of famine and a dearth of all sorts of things." In order to rotect themselves from their attackers cannons, Nasr ibn Shabath and his Arab troops used a stratagem that had already been tried at the siege of Balis (using Christian women and children as human shields): they forced Christian women and their children to mount the walls so that they were exposed as targets for the Persians. Nasr used the same tactics at the second siege of Kaisum.[113]

High Middle Ages (1000–1200)

Fatimid Caliphate

The caliph al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah (r. 996–1021) engaged in a persecution of Christians.[114] Al-Hakim was "half-insane", and had perpetrated the only general persecution of Christians by Muslims until the Crusades.[115] Al-Hakim's mother was a Christian, and he had been raised mainly by Christians, and even through the persecution al-Hakim employed Christian ministers in his government.[116] Between 1004 and 1014, the caliph produced legislation to confiscate ecclesiastical property and burn crosses; later, he ordered that small mosques be built atop church roofs, and later still decreed that churches were to be burned.[116] The caliph's Jewish and Muslim subjects were subjected to similarly arbitrary treatment.[116] As part of al-Hakim's persecution, thirty thousand churches were reportedly destroyed, and in 1009 the caliph ordered the demolition of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, on the pretext that the annual Holy Fire miracle on Easter was a fake.[116] The persecution of al-Hakim and the demolition of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre prompted Pope Sergius IV to issue a call for soldiers to expel the Muslims from the Holy Land, while European Christians engaged in a retaliatory persecution of Jews, whom they conjectured were in some way responsible for al-Hakim's actions.[117] In the second half of the eleventh century, pilgrims brought home news of how the rise of the Turks and their conflict with the Egyptians increased the persecution of Christian pilgrims.[117]

In 1013, at the intervention of the emperor Basil II (r. 960–1025), Christians were given permission to leave Fatimid territory.[116] In 1016 however, the caliph was proclaimed divine, alienating his Muslim subjects by banning the hajj and the fast of ramadan, and causing him to again favor the Christians.[116] In 1017, al-Hakim issued an order of toleration regarding Christians and Jews, while the following year confiscated ecclesiastical property was returned to the Church, including the construction materials seized by the authorities from demolished buildings.[116]

In 1027, the emperor Constantine VIII (r. 962–1028) concluded a treaty with Salih ibn Mirdas, the emir of Aleppo, allowing the emperor to repair the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and permitting the Christians forced to convert to Islam under al-Hakim to return to Christianity.[116] Though the treaty was re-confirmed in 1036, actual building on the shrine began only in the later 1040s, under the emperor Constantine IX Monomachos (r. 1042–1055).[116] According to al-Maqdisi, the Christians seemed largely in control of the Holy Land, and the emperor himself was rumored, according to Nasir Khusraw, to have been among the many Christian pilgrims that came to the Holy Sepulchre.[116]

Seljuk Empire

Sultan Alp Arslan pledged: “I shall consume with the sword all those people who venerate the cross, and all the lands of the Christians shall be enslaved.”[118] Alp Arslan ordered the Turks:[119]

Henceforth all of you be like lion cubs and eagle young, racing through the countryside day and night, slaying the Christians and not sparing any mercy on the Roman nation

It was said that “the emirs spread like locusts, over the face of the land,”[120] invading every corner of Anatolia, sacking some of ancient Christianity's most important cities, including Ephesus, home of Saint John the Evangelist; Nicaea, where Christendom's creed was formulated in 325; and Antioch, the original see of Saint Peter, and enslaved many.[121][122][123] According to French historian J. Laurent, hundreds of thousands of the native Anatolian Christians were reported to have been massacred or enslaved during the invasions of Anatolia by the Seljuk Turks.[124][125]

Destruction and desecration of Churches became very widespread during the Turkic invasions of Anatolia which caused enormous damage to the ecclesiastical foundations throughout Asia minor:[126]

Even before the battle of Manzikert, Turkish raids resulted in the pillaging of the famous churches of St. Basil at caesareia and of the Archangel Michael at Chonae. In the decade following 1071 the destruction of churches and the flight of the clergy became widespread. churches were often pillaged and destroyed. The churches of St. Phocas in Sinope and Nicholas at Myra, both important centers of pilgrimage, were destroyed. The monasteries of Mt. Latrus, Strobilus, and elanoudium on the western coast were sacked and the monks driven out during the early invasions, so that the monastic foundations in this area were completely abandoned until the Byzantine reconquest and the extensive support of successive Byzantine emperors once more reconstituted them. Greeks were forced to surround the church of St. John at Ephesus with walls to protect it from the Turks. The disruption of active religious life in the Cappadocian cave-monastic communies is also indicated for the twelfth century.

News of the great tribulation and persecutions of the eastern Christians reached European Christians in the west in the few years after the battle of Manzikert. A Frankish eyewitness says: "Far and wide they [Muslim Turks] ravaged cities and castles together with their settlements. Churches were razed down to the ground. Of the clergyman and monks whom they captured, some were slaughtered while others were with unspeakable wickedness given up, priests and all, to their dire dominion and nuns—alas for the sorrow of it!—were subjected to their lusts."[127] In a letter to count Robert of Flanders, Byzantine emperor Alexios I Komnenos writes:[128]

The holy places are desecrated and destroyed in countless ways. Noble matrons and their daughters, robbed of everything, are violated one after another, like animals. Some [of their attackers] shamelessly place virgins in front of their own mothers and force them to sing wicked and obscene songs until they have finished having their ways with them... men of every age and description, boys, youths, old men, nobles, peasants and what is worse still and yet more distressing, clerics and monks and woe of unprecedented woes, even bishops are defiled with the sin of sodomy and it is now trumpeted abroad that one bishop has succumbed to this abominable sin.

In a poem, Malik Danishmend boasts: "I am Al Ghazi Danishmend, the destroyer of churches and towers". Destruction and pillaging of churches figure prominently in his poem. Another part of the poem talks about the simultaneous conversion of 5,000 people to Islam and the murder of 5,000 others.[129]

Michael the Syrian wrote: “As the Turks were ruling the lands of Syria and Palestine, they inflicted injuries on Christians who went to pray in Jerusalem, beat them, pillaged them, and levied the poll tax [jizya]. Every time they saw a caravan of Christians, particularly of those from Rome and the lands of Italy, they made every effort to cause their death in diverse ways".[130] Such was the fate German pilgrimage to Jerusalem in 1064. According to one of the surviving pilgrims:[131]

Accompanying this journey was a noble abbess of graceful body and of a religious outlook. Setting aside the cares of the sisters committed to her and against the advice of the wise, she undertook this great and dangerous pilgrimage. The pagans captured her, and the sight of all, these shameless men raped her until she breathed her last, to the dishonor of all Christians. Christ's enemies performed such abuses and others like them on the christians.

Crusades

After the Seljuks invaded Anatolia and the levant, every Anatolian village they controlled along the route to Jerusalem began exacting tolls on Christian pilgrims. In principle the Seljuks allowed Christian pilgrims access to Jerusalem, but they often imposed huge ransoms and condoned local attacks against Christians. many pilgrims were seized and sold into slavery while others were tortured (seemingly for entertainment). Soon only very large, well-armed and wealthy groups would dare attempt a pilgrimage, and even so, many died and many more turned back.The pilgrims that survived these extremely dangerous journeys, “returned to the West weary and impoverished, with a dreadful tale to tell.”[132][133]

In 1064 7,000 pilgrims lead by Bishop Gunther of Bamberg were ambushed by Muslims near Caesarea, and two-thirds of the pilgrims were slaughtered.[134]

In the Middle Ages, the crusades were promoted as defensive response of Christianity against persecution of Eastern Christianity in the Levant.[117] Western Catholic contemporaries believed the First Crusade was a movement against Muslim attacks on Eastern Christians and Christian sites in the Holy Land.[117] In the mid-11th century, relations between the Byzantine Empire and the Fatimid Caliphate and between Christians and Muslims were peaceful, and there had not been persecution of Christians since the death of al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah.[114] As a result of the migration of Turkic peoples into the Levant and the Seljuk Empire's wars with the Fatimid Caliphate in the later 11th century, reports of Christian pilgrims increasingly mentioned persecution of Christians there.[117] Similarly, accounts sent to the West of the Byzantines' medieval wars with various Muslim states alleged persecutions of Christians and atrocities against holy places.[135] Western soldiers were encouraged to take up soldiering against the empire's Muslim enemies; a recruiting bureau was even established in London.[117] After the 1071 Battle of Manzikert, the sense of Byzantine distress increased and Pope Gregory VII suggested that he himself would ride to the rescue at the head of an army, claiming Christians were being "slaughtered like cattle".[135] In the 1090s, the emperor Alexios I Komnenos (r. 1081–1118) issued appeals for help against the Seljuks to western Europe.[135] In 1091 his ambassadors told the king of Croatia Muslims were destroying sacred sites, while his letter to Robert I, Count of Flanders, deliberately described emotively the rape and maltreatment of Christians and the sacrilege of the Jerusalem shrines.[135]

Pope Urban II, who convoked the First Crusade at the 1095 Council of Clermont, spoke of the defense of his co-religionists in the Levant and the protection of the Christian holy places, while ordinary crusaders are also known to have been motivated by the notion of persecution of Christians by Muslims.[117] According to Fulcher of Chartres, the pope described his holy wars as being contra barbaros, 'against the barbarians', while the pope's own letters indicate that the Muslims were barbarians fanatically persecuting Christians.[136] The same idea, expressed in similar language, was evident in the writings of the bishop Gerald of Cahors, the abbot Guibert of Nogent, the priest Peter Tudebode, and the monk Robert of Reims.[136] Outside the clergy, the Gesta Francorum's author likewise described the Crusaders' opponents as persecuting barbarians, language not used for non-Muslim non-Christians.[136] These authors, together with Albert of Aix and Baldric of Dol, all referred to the Arabs, Saracens, and Turks as barbarae nationes, 'barbarian races'.[136] Peter the Venerable, William of Tyre, and The Song of Roland all took the view that Muslims were barbarians, and in calling for the Third Crusade, Pope Gregory VIII expounded on the Muslim threat from Saladin, accusing the Muslims of being "barbarians thirsting for the blood of Christians".[136] In numerous instances Pope Innocent III called on the Catholics to defend the Holy Land in a holy war against the impugnes barbariem paganorum, 'attacks of the pagan barbarians'.[136] Crusaders believed that by fighting off the Muslims, the persecution of Christians would abate, in accordance to their god's will, and this ideology – much promoted by the Crusader-era propagandists – was shared at every level of literate medieval western European society.[136]