Метамфетамин

Метамфетамин [ примечание 1 ] (полученный из N -метиламфетамина ) является мощным центральной нервной системы (ЦНС) стимулятором , который в основном используется в качестве рекреационного наркотика и реже в качестве лечения второй линии при синдроме дефицита внимания с гиперактивностью и ожирении . [ 23 ] Метамфетамин был открыт в 1893 году и существует в виде двух энантиомеров : лево-метамфетамина и декстро-метамфетамина. [ примечание 2 ] Метамфетамин правильно относится к конкретному химическому веществу, рацемическому свободному основанию , которое представляет собой равную смесь левометамфетамина и декстрометамфетамина в их чистых аминных формах, но гидрохлоридная широко используется соль, обычно называемая кристаллическим метамфетамином. Метамфетамин редко назначают из-за опасений, связанных с его потенциалом рекреационного использования в качестве афродизиака и эйфорианта , среди прочего, а также из-за наличия более безопасных лекарств-заменителей с сопоставимой эффективностью лечения, таких как Аддералл и Виванс . [ 23 ] Декстрометамфетамин является более сильным стимулятором ЦНС, чем левометамфетамин.

Как рацемический метамфетамин, так и декстрометамфетамин подвергаются незаконному обороту и продаже из-за их потенциального использования в рекреационных целях. Самая высокая распространенность незаконного употребления метамфетамина наблюдается в некоторых частях Азии и Океании, а также в Соединенных Штатах, где рацемический метамфетамин и декстрометамфетамин классифицируются как Списка II контролируемые вещества . Левометамфетамин доступен в виде безрецептурного препарата для использования в качестве ингаляционного противозастойного средства для носа в Соединенных Штатах. [ примечание 3 ] На международном уровне производство, распространение, продажа и хранение метамфетамина ограничены или запрещены во многих странах из-за его включения в список II Конвенции Организации Объединенных Наций о психотропных веществах . Хотя декстрометамфетамин является более сильнодействующим наркотиком, рацемический метамфетамин незаконно производится чаще из-за относительной простоты синтеза и нормативных ограничений доступности химических прекурсоров .

В низких и умеренных дозах метамфетамин может повышать настроение , повышать бдительность, концентрацию и энергию у утомленных людей, снижать аппетит и способствовать снижению веса. В очень высоких дозах он может вызвать психоз , разрушение скелетных мышц , судороги и кровоизлияние в мозг . Хроническое употребление высоких доз может спровоцировать непредсказуемые и быстрые перепады настроения , стимулирующий психоз (например, паранойю , галлюцинации , бред и бред ) и агрессивное поведение . В рекреационном плане способность метамфетамина увеличивать энергию , как сообщается, поднимает настроение и увеличивает сексуальное желание до такой степени, что потребители могут непрерывно заниматься сексуальной деятельностью в течение нескольких дней, одновременно принимая наркотик. [ 27 ] Известно, что метамфетамин обладает высокой склонностью к привыканию (т.е. высокая вероятность того, что длительное употребление или употребление высоких доз приведет к компульсивному употреблению наркотиков) и высокой склонностью к зависимости (т.е. высокая вероятность абстиненции возникновения симптомов после прекращения употребления метамфетамина). Отказ от метамфетамина после интенсивного употребления может привести к постострому синдрому отмены , который может сохраняться в течение нескольких месяцев после типичного периода отмены. Метамфетамин в высоких дозах нейротоксичен для среднего мозга дофаминергических нейронов человека и, в меньшей степени, для серотонинергических нейронов. [ 28 ] [ 29 ] Нейротоксичность метамфетамина вызывает неблагоприятные изменения в структуре и функциях мозга, такие как уменьшение объема серого вещества в нескольких областях мозга, а также неблагоприятные изменения маркеров метаболической целостности. [ 29 ]

Метамфетамин принадлежит к замещенных фенэтиламинов и замещенных амфетаминов химическим классам . Он связан с другими диметилфенетиламинами как позиционный изомер этих соединений, которые имеют общую химическую формулу. С 10 Ч 15 Н .

Использование

Медицинский

В Соединенных Штатах гидрохлорид метамфетамина, продаваемый под торговой маркой Desoxyn , одобрен FDA для лечения СДВГ и ожирения как у взрослых, так и у детей; [ 3 ] [ 30 ] однако FDA также указывает, что ограниченную терапевтическую полезность метамфетамина следует сопоставлять с присущими ему рисками, связанными с его использованием. [ 3 ] Чтобы избежать токсичности и риска побочных эффектов, рекомендации FDA рекомендуют начальную дозу метамфетамина 5–10 мг/день при СДВГ взрослым и детям старше шести лет и могут увеличиваться с еженедельными интервалами на 5 мг, вплоть до 25 мг/день до достижения оптимального клинического ответа; обычная эффективная доза составляет около 20–25 мг/день. [ 7 ] [ 3 ] Метамфетамин иногда назначают по назначению при нарколепсии и идиопатической гиперсомнии . [ 31 ] [ 32 ] В Соединенных Штатах левовращающая форма метамфетамина доступна в некоторых безрецептурных противозастойных средствах для носа . [ примечание 3 ]

Поскольку метамфетамин связан с высоким потенциалом злоупотребления, этот препарат регулируется Законом о контролируемых веществах и внесен в список II в Соединенных Штатах. [ 3 ] Гидрохлорид метамфетамина, отпускаемый в Соединенных Штатах, должен включать в себя предупреждение в рамке о его возможности злоупотребления в рекреационных целях и ответственности за зависимость . [ 3 ]

Дезоксин и Дезоксин Градумет являются фармацевтическими формами препарата. Последний больше не производится и представляет собой форму препарата пролонгированного действия , сглаживающую кривую эффекта препарата при одновременном его продлении. [ 33 ]

Рекреационный

Метамфетамин часто используется в рекреационных целях из-за его действия как мощного эйфорианта и стимулятора, а также как афродизиака . [ 34 ]

Согласно документальному фильму National Geographic TV о метамфетамине, целая субкультура, известная как вечеринки и игры , основана на сексуальной активности и употреблении метамфетамина. [ 34 ] Участники этой субкультуры, которая почти полностью состоит из мужчин-гомосексуалистов, употребляющих метамфетамин, обычно встречаются через сайты знакомств в Интернете и занимаются сексом. [ 34 ] Из-за его сильного стимулирующего и афродизиака, а также тормозящего воздействия на эякуляцию , при многократном использовании эти сексуальные контакты иногда происходят непрерывно в течение нескольких дней подряд. [ 34 ] Крах после употребления метамфетамина таким образом очень часто бывает тяжелым, с выраженной гиперсомнией (чрезмерной дневной сонливостью). [ 34 ] Субкультура вечеринок и игр распространена в крупных городах США, таких как Сан-Франциско и Нью-Йорк. [ 34 ] [ 35 ]

Противопоказания

Метамфетамин противопоказан лицам, имеющим в анамнезе расстройства, связанные с употреблением психоактивных веществ , заболеваниями сердца , тяжелым возбуждением или тревогой, а также лицам, страдающим в настоящее время атеросклерозом , глаукомой , гипертиреозом или тяжелой гипертонией . [ 3 ] FDA заявляет, что людям, которые в прошлом испытывали реакции гиперчувствительности на другие стимуляторы или в настоящее время принимают ингибиторы моноаминоксидазы, не следует принимать метамфетамин. [ 3 ] FDA также советует людям с биполярным расстройством , депрессией , повышенным кровяным давлением , проблемами с печенью или почками, манией , психозом , феноменом Рейно , судорогами , щитовидной железы проблемами , тиками или синдромом Туретта контролировать свои симптомы во время приема метамфетамина. [ 3 ] Из-за возможности задержки роста FDA рекомендует контролировать рост и вес растущих детей и подростков во время лечения. [ 3 ]

Побочные эффекты

Физический

Метамфетамин – симпатомеметический препарат, вызывающий сужение сосудов и тахикардию. Последствия также могут включать потерю аппетита , гиперактивность, расширение зрачков , покраснение кожи , чрезмерное потоотделение , повышенную подвижность , сухость во рту и скрежетание зубами (что приводит к « метамфетамину »), головную боль, нерегулярное сердцебиение (обычно в виде учащенного или замедленного сердцебиения ). , учащенное дыхание , высокое кровяное давление , низкое кровяное давление , высокая температура тела , диарея, запор, помутнение зрения , головокружение , подергивание , онемение , тремор , сухость кожи, прыщи и бледность . [ 3 ] [ 37 ] У тех, кто длительное время употребляет метамфетамин, могут появиться язвы на коже; [ 38 ] [ 39 ] они могут быть вызваны расчесыванием из-за зуда или убеждением, что насекомые ползают под кожей; [ 38 ] ущерб усугубляется плохим питанием и гигиеной. [ 39 ] Сообщалось о многочисленных случаях смерти, связанных с передозировкой метамфетамина. [ 40 ] [ 41 ] Кроме того, «[p] патологоанатомические исследования тканей человека связали использование препарата с заболеваниями, связанными со старением, такими как коронарный атеросклероз и фиброз легких», [ 42 ] что может быть вызвано «значительным увеличением образования церамидов , провоспалительных молекул, которые могут способствовать старению и гибели клеток». [ 42 ]

Мет рот

Потребители метамфетамина и наркоманы могут аномально быстро потерять зубы, независимо от пути введения, из-за состояния, неофициально известного как « рот метамфетамина» . [ 43 ] Состояние, как правило, наиболее тяжелое у потребителей, которые вводят наркотик, а не глотают, курят или вдыхают его. [ 43 ] По данным Американской стоматологической ассоциации , рот метамфетамина «вероятно вызван сочетанием вызванных наркотиками психологических и физиологических изменений, приводящих к ксеростомии (сухости во рту), длительным периодам плохой гигиены полости рта , частому потреблению высококалорийных газированных напитков и бруксизму». (скрежетание и сжимание зубов)». [ 43 ] [ 44 ] Поскольку сухость во рту также является частым побочным эффектом других стимуляторов, которые, как известно, не способствуют серьезному разрушению зубов, многие исследователи предполагают, что кариес, связанный с употреблением метамфетамина, в большей степени обусловлен другим выбором потребителей. Они предполагают, что побочный эффект был преувеличен и стилизован для создания стереотипа о нынешних пользователях как сдерживающего фактора для новых. [ 30 ]

Инфекция, передающаяся половым путем

Было обнаружено, что употребление метамфетамина связано с более высокой частотой незащищенных половых контактов как у ВИЧ-положительных , так и у неизвестных случайных партнеров, причем эта связь более выражена у ВИЧ-положительных участников. [ 45 ] Эти данные свидетельствуют о том, что употребление метамфетамина и участие в незащищенном анальном сексе являются сопутствующими рискованными видами поведения, которые потенциально повышают риск передачи ВИЧ среди геев и бисексуальных мужчин. [ 45 ] Употребление метамфетамина позволяет потребителям обоих полов вести длительную сексуальную активность, что может вызвать язвы и ссадины на половых органах, а также приапизм у мужчин. [ 3 ] [ 46 ] Метамфетамин также может вызывать язвы и ссадины во рту из-за бруксизма , увеличивая риск заражения инфекциями, передающимися половым путем. [ 3 ] [ 46 ]

Помимо передачи ВИЧ половым путем, он также может передаваться между пользователями, пользующимися общей иглой . [ 47 ] Уровень совместного использования игл среди потребителей метамфетамина аналогичен уровню использования других инъекционных наркотиков. [ 47 ]

Психологический

Психологические эффекты метамфетамина могут включать эйфорию , дисфорию , изменения либидо , бдительности , опасений и концентрации , снижение чувства усталости, бессонницу или бодрствование , уверенность в себе , общительность, раздражительность, беспокойство, грандиозность , повторяющееся и навязчивое поведение. [ 3 ] [ 37 ] [ 48 ] Характерной особенностью метамфетамина и родственных ему стимуляторов является « пундирование », постоянная, бесцельная, повторяющаяся деятельность. [ 49 ] Употребление метамфетамина также тесно связано с тревогой , депрессией , амфетаминовым психозом , самоубийством и агрессивным поведением. [ 50 ] [ 51 ]

Нейротоксичные и нейроиммунологические

Метамфетамин непосредственно нейротоксичен для дофаминергических нейронов как у лабораторных животных, так и у людей. [ 28 ] [ 29 ] Эксайтотоксичность , окислительный стресс , метаболический компромисс, дисфункция ИБП, нитрование белка, стресс эндоплазматического ретикулума , экспрессия р53 и другие процессы способствовали этой нейротоксичности. [ 55 ] [ 56 ] [ 57 ] В соответствии с дофаминергической нейротоксичностью употребление метамфетамина связано с более высоким риском болезни Паркинсона . [ 58 ] Помимо дофаминергической нейротоксичности, обзор данных на людях показал, что употребление высоких доз метамфетамина также может быть нейротоксичным для серотонинергических нейронов. [ 29 ] Было продемонстрировано, что высокая температура тела коррелирует с усилением нейротоксического действия метамфетамина. [ 59 ] Отказ от метамфетамина у зависимых лиц может привести к послеострой абстиненции , которая сохраняется на несколько месяцев после типичного периода абстиненции. [ 57 ]

Исследования магнитно-резонансной томографии на людях, употребляющих метамфетамин, также обнаружили доказательства нейродегенерации или неблагоприятных нейропластических изменений в структуре и функциях мозга. [ 29 ] В частности, метамфетамин, по-видимому, вызывает гиперинтенсивность и гипертрофию , белого вещества заметное сокращение гиппокампа и уменьшение серого вещества в поясной извилине , лимбической коре и паралимбической коре у рекреационных потребителей метамфетамина. [ 29 ] Более того, данные свидетельствуют о том, что у рекреационных потребителей происходят неблагоприятные изменения в уровне биомаркеров метаболической целостности и синтеза, такие как снижение уровней N -ацетиласпартата и креатина и повышенные уровни холина и миоинозитола . [ 29 ]

Было показано, что метамфетамин активирует TAAR1 в астроцитах человека и генерирует цАМФ . в результате [ 58 ] Активация локализованного в астроцитах TAAR1, по-видимому, действует как механизм, с помощью которого метамфетамин снижает уровни мембраносвязанного EAAT2 (SLC1A2) и его функционирование в этих клетках. [ 58 ]

Метамфетамин связывается и активирует оба и подтипа сигма-рецепторов, σ2 σ1 , с микромолярным сродством. [ 54 ] [ 60 ] Активация сигма-рецептора может способствовать нейротоксичности, вызванной метамфетамином, облегчая гипертермию , увеличивая синтез и высвобождение дофамина, влияя на активацию микроглии и модулируя апоптотические сигнальные каскады и образование активных форм кислорода. [ 54 ] [ 60 ]

Захватывающий

| Словарь наркомании и зависимости [ 61 ] [ 62 ] [ 63 ] |

|---|

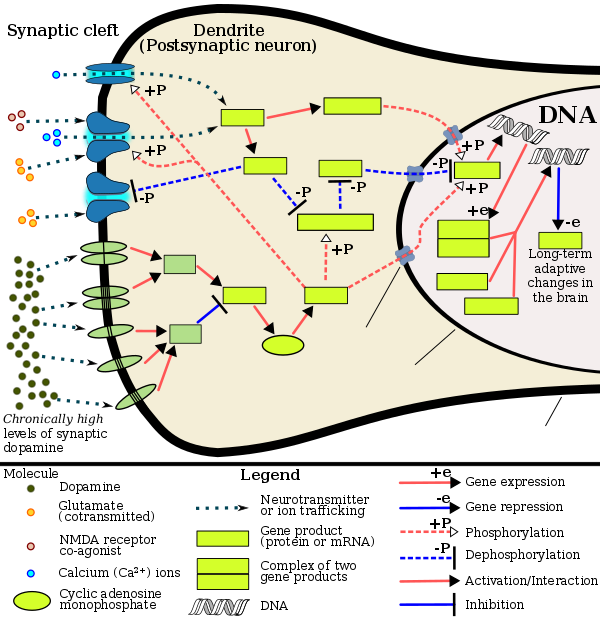

Современные модели зависимости от хронического употребления наркотиков включают изменения в экспрессии генов в определенных частях мозга, особенно в прилежащем ядре . [ 71 ] [ 72 ] Наиболее важные факторы транскрипции [ примечание 4 ] Эти изменения вызывают ΔFosB , цАМФ белок, связывающий элемент ответа ( CREB ), и ядерный фактор каппа B ( NFκB ). [ 72 ] ΔFosB играет решающую роль в развитии наркозависимости, поскольку его сверхэкспрессия в D1-типа средних шипиковых нейронах прилежащего ядра необходима и достаточна. [ примечание 5 ] для большинства поведенческих и нервных адаптаций, возникающих в результате зависимости. [ 62 ] [ 72 ] [ 74 ] Как только ΔFosB достаточно сверхэкспрессируется, это вызывает состояние зависимости, которое становится все более тяжелым по мере дальнейшего увеличения экспрессии ΔFosB. [ 62 ] [ 74 ] Это связано, среди прочего, с зависимостью от алкоголя , каннабиноидов , кокаина , метилфенидата , никотина , опиоидов , фенциклидина , пропофола и замещенных амфетаминов . [ 72 ] [ 74 ] [ 75 ] [ 76 ] [ 77 ]

ΔJunD , фактор транскрипции, и G9a , фермент гистон-метилтрансферазы , оба напрямую противодействуют индукции ΔFosB в прилежащем ядре (т.е. они противостоят увеличению его экспрессии). [ 62 ] [ 72 ] [ 78 ] Достаточно сверхэкспрессия ΔJunD в прилежащем ядре с помощью вирусных векторов может полностью блокировать многие нервные и поведенческие изменения, наблюдаемые при хроническом употреблении наркотиков (т.е. изменения, опосредованные ΔFosB). [ 72 ] ΔFosB также играет важную роль в регулировании поведенческих реакций на естественные вознаграждения , такие как вкусная еда, секс и физические упражнения. [ 72 ] [ 75 ] [ 79 ] Поскольку и естественные вознаграждения, и наркотики, вызывающие привыкание, вызывают экспрессию ΔFosB (т. е. заставляют мозг производить его в большем количестве), хроническое приобретение этих вознаграждений может привести к аналогичному патологическому состоянию зависимости. [ 72 ] [ 75 ] ΔFosB является наиболее значимым фактором, участвующим как в амфетаминовой зависимости, так и в сексуальной зависимости, вызванной амфетамином , которая представляет собой компульсивное сексуальное поведение, возникающее в результате чрезмерной сексуальной активности и употребления амфетамина. [ примечание 6 ] [ 75 ] [ 80 ] Эти сексуальные пристрастия (т.е. компульсивное сексуальное поведение, вызванное наркотиками) связаны с синдромом нарушения регуляции дофамина , который возникает у некоторых пациентов, принимающих дофаминергические препараты , такие как амфетамин или метамфетамин. [ 75 ] [ 79 ] [ 80 ]

Эпигенетические факторы

Зависимость от метамфетамина является стойкой для многих людей: у 61% людей, прошедших лечение от зависимости, в течение одного года возникает рецидив. [ 81 ] Около половины людей с зависимостью от метамфетамина продолжают употреблять его в течение десяти лет, тогда как другая половина сокращает употребление, начиная примерно через один-четыре года после первоначального употребления. [ 82 ]

Частое сохранение зависимости предполагает, что долговременные изменения в экспрессии генов могут происходить в определенных областях мозга и могут вносить важный вклад в фенотип зависимости. В 2014 году была обнаружена решающая роль эпигенетических механизмов в обеспечении долгосрочных изменений экспрессии генов в мозге. [ 83 ]

Обзор 2015 года [ 84 ] обобщили ряд исследований, посвященных хроническому употреблению метамфетамина на грызунах. Эпигенетические изменения наблюдались в путях вознаграждения мозга , включая такие области, как вентральная покрышка , прилежащее ядро и дорсальное полосатое тело , гиппокамп и префронтальная кора . Хроническое употребление метамфетамина вызывало геноспецифическое ацетилирование, деацетилирование и метилирование гистонов . Также наблюдалось ген-специфическое метилирование ДНК в определенных областях мозга. Различные эпигенетические изменения вызывали подавление или усиление определенных генов, важных для зависимости. Например, хроническое употребление метамфетамина вызывало метилирование лизина в положении 4 гистона 3, расположенного на промоторах генов c-fos и рецептора 2 хемокинов CC (ccr2) , активируя эти гены в прилежащем ядре (NAc). [ 84 ] Известно, что c-fos важен при зависимости . [ 85 ] Ген ccr2 также важен при зависимости, поскольку мутационная инактивация этого гена ухудшает зависимость. [ 84 ]

У крыс, зависимых от метамфетамина, эпигенетическая регуляция посредством снижения ацетилирования гистонов в нейронах полосатого мозга вызывала снижение транскрипции рецепторов глутамата . [ 86 ] Глутаматные рецепторы играют важную роль в регулировании усиливающего эффекта наркотиков, вызывающих привыкание. [ 87 ]

Введение метамфетамина грызунам вызывает повреждение ДНК в их мозге, особенно в области прилежащего ядра . [ 88 ] [ 89 ] Во время репарации таких повреждений ДНК могут возникать стойкие изменения хроматина, например, метилирование ДНК или ацетилирование или метилирование гистонов в местах репарации. [ 90 ] Эти изменения могут представлять собой эпигенетические рубцы в хроматине , которые способствуют стойким эпигенетическим изменениям, обнаруживаемым при зависимости от метамфетамина.

Лечение и ведение

Систематический обзор и сетевой метаанализ 50 исследований, проведенных в 2018 году с участием 12 различных психосоциальных вмешательств при амфетаминовой, метамфетаминовой или кокаиновой зависимости, показали, что комбинированная терапия, сочетающая как управление непредвиденными обстоятельствами , так и подход к укреплению сообщества, имела самую высокую эффективность (т. е. уровень воздержания) и приемлемость ( т. т.е. самый низкий процент отсева). [ 91 ] Другие методы лечения, рассмотренные в анализе, включали монотерапию с подходом управления непредвиденными обстоятельствами или подходом укрепления сообщества, когнитивно-поведенческую терапию , 12-шаговые программы , необусловленную терапию, основанную на вознаграждении, психодинамическую терапию и другие комбинированные методы лечения, включающие их. [ 91 ]

По состоянию на декабрь 2019 г. [update] не существует . Однако эффективной фармакотерапии метамфетаминовой зависимости [ 92 ] [ 93 ] [ 94 ] Систематический обзор и метаанализ 2019 года оценили эффективность 17 различных фармакотерапевтических методов, использованных в рандомизированных контролируемых исследованиях (РКИ) при лечении зависимости от амфетамина и метамфетамина; [ 93 ] было обнаружено лишь слабые доказательства того, что метилфенидат может снизить уровень самостоятельного приема амфетамина или метамфетамина. [ 93 ] Имелись доказательства низкой и умеренной эффективности отсутствия пользы для большинства других препаратов, использованных в РКИ, включая антидепрессанты (бупропион, миртазапин , сертралин ), нейролептики ( арипипразол ), противосудорожные средства ( топирамат , баклофен , габапентин ), налтрексон , варениклин. , цитиколин , ондансетрон , промета , рилузол , атомоксетин , декстроамфетамин и модафинил . [ 93 ] [ нужна проверка ]

Зависимость и абстиненция

толерантность развивается при регулярном употреблении метамфетамина, а при рекреационном употреблении эта толерантность развивается быстро. Ожидается, что [ 95 ] [ 96 ] У зависимых потребителей симптомы абстиненции положительно коррелируют с уровнем толерантности к препарату. [ 97 ] Депрессия от отмены метамфетамина длится дольше и более тяжелая, чем депрессия от отмены кокаина . [ 98 ]

Согласно текущему Кокрейновскому обзору наркотической зависимости и абстиненции у рекреационных потребителей метамфетамина, «когда хронические заядлые потребители внезапно прекращают употребление [метамфетамина], многие сообщают о ограниченном по времени синдроме отмены, который возникает в течение 24 часов после приема последней дозы». [ 97 ] Симптомы абстиненции у хронических потребителей высоких доз наблюдаются часто, встречаются в 87,6% случаев и сохраняются в течение трех-четырех недель, при этом в течение первой недели возникает выраженная фаза «кризиса». [ 97 ] Симптомы отмены метамфетамина могут включать тревогу, тягу к наркотикам , дисфорическое настроение , усталость , повышенный аппетит , повышенную или пониженную подвижность , отсутствие мотивации , бессонницу или сонливость , а также яркие или осознанные сновидения . [ 97 ]

матери, Метамфетамин, присутствующий в кровотоке может проникнуть через плаценту к плоду и попасть в грудное молоко . [ 98 ] У младенцев, рожденных от матерей, злоупотребляющих метамфетамином, может наблюдаться неонатальный абстинентный синдром с симптомами нарушения сна, плохого питания, тремора и гипертонии . [ 98 ] Этот синдром отмены относительно легкий и требует медицинского вмешательства примерно в 4% случаев. [ 98 ]

| Форма нейропластичности или поведенческая пластичность |

Тип подкрепления | Источники | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Опиаты | Психостимуляторы | Пища с высоким содержанием жира или сахара | Половой акт | Физические упражнения (аэробный) |

Относящийся к окружающей среде обогащение | ||

| Экспрессия ΔFosB в прилежащее ядро D1-типа MSN |

↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | [ 75 ] |

| Поведенческая пластичность | |||||||

| Увеличение потребления | Да | Да | Да | [ 75 ] | |||

| Психостимуляторы перекрестная сенсибилизация |

Да | Непригодный | Да | Да | Ослабленный | Ослабленный | [ 75 ] |

| Психостимуляторы самоуправление |

↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | [ 75 ] | |

| Психостимуляторы обусловленное предпочтение места |

↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | [ 75 ] |

| Восстановление поведения, связанного с употреблением наркотиков | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | [ 75 ] | ||

| Нейрохимическая пластичность | |||||||

| CREB Tooltip Фосфорилирование в прилежащем ядре |

↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | [ 75 ] | |

| Сенсибилизированная дофаминовая реакция в прилежащем ядре |

Нет | Да | Нет | Да | [ 75 ] | ||

| Измененная в полосатом теле передача сигналов дофамина | ↓ DRD2 , ↑ DRD3 | ↑ DRD1 , ↓ DRD2 , ↑ DRD3 | ↑ DRD1 , ↓ DRD2 , ↑ DRD3 | ↑ DRD2 | ↑ DRD2 | [ 75 ] | |

| Измененная передача сигналов опиоидов в полосатом теле | Никаких изменений или ↑ мю-опиоидные рецепторы |

↑ мю-опиоидные рецепторы ↑ κ-опиоидные рецепторы |

↑ мю-опиоидные рецепторы | ↑ мю-опиоидные рецепторы | Без изменений | Без изменений | [ 75 ] |

| Изменения в полосатых опиоидных пептидах | ↑ dynorphin Без изменений: энкефалин |

↑ dynorphin | ↓ enkephalin | ↑ dynorphin | ↑ dynorphin | [ 75 ] | |

| Мезокортиколимбическая синаптическая пластичность | |||||||

| Количество дендритов в прилежащем ядре | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | [ 75 ] | |||

| Плотность дендритных шипов в ядро прилежащее |

↓ | ↑ | ↑ | [ 75 ] | |||

Неонатальный

В отличие от других наркотиков, у младенцев, подвергшихся внутриутробному воздействию метамфетамина, не наблюдается немедленных признаков абстиненции. Вместо этого когнитивные и поведенческие проблемы начинают проявляться, когда дети достигают школьного возраста. [ 99 ]

Проспективное когортное исследование с участием 330 детей показало, что в возрасте 3 лет у детей, подвергшихся воздействию метамфетамина, наблюдалась повышенная эмоциональная реактивность, а также больше признаков тревоги и депрессии; а в возрасте 5 лет у детей наблюдались более высокие показатели экстернализации и расстройств дефицита внимания/гиперактивности . [ 100 ]

Передозировка

Передозировка метамфетамина может привести к широкому спектру симптомов. [ 5 ] [ 3 ] У молодых здоровых людей сердечно-сосудистые эффекты обычно не наблюдаются. Гипертензия и тахикардия не проявляются, пока не будут измерены. Умеренная передозировка метамфетамина может вызвать такие симптомы, как: нарушение сердечного ритма , спутанность сознания, затрудненное и/или болезненное мочеиспускание , высокое или низкое кровяное давление, высокая температура тела , сверхактивные и/или сверхчувствительные рефлексы , мышечные боли , сильное возбуждение. , учащенное дыхание , тремор , задержка мочеиспускания и неспособность мочиться . [ 5 ] [ 37 ] Чрезвычайно большая передозировка может вызвать такие симптомы, как адренергический шторм , метамфетаминовый психоз , существенное снижение или отсутствие диуреза , кардиогенный шок , кровоизлияние в мозг , сосудистый коллапс , гиперпирексия (т. е. опасно высокая температура тела), легочная гипертензия , почечная недостаточность , быстрый распад мышц , серотониновый синдром и форма стереотипии («подстройка»). [ источники 1 ] Передозировка метамфетамина, вероятно, также приведет к легкому повреждению головного мозга из-за дофаминергической и серотонинергической нейротоксичности. [ 104 ] [ 29 ] Смерти от отравления метамфетамином обычно предшествуют судороги и кома . [ 3 ]

Психоз

Употребление метамфетамина может привести к стимулирующему психозу, который может проявляться различными симптомами (например, паранойей , галлюцинациями , бредом и бредом ). [ 5 ] [ 105 ] В обзоре Кокрановского сотрудничества по лечению психоза, вызванного употреблением амфетамина, декстроамфетамина и метамфетамина, говорится, что около 5–15% потребителей не могут полностью выздороветь. [ 105 ] [ 106 ] В том же обзоре утверждается, что на основании по крайней мере одного исследования антипсихотические препараты эффективно устраняют симптомы острого амфетаминового психоза. [ 105 ] амфетаминовый психоз . Иногда в качестве побочного эффекта, возникшего во время лечения, может также развиться [ 107 ]

Смерть от передозировки

Передозировка метамфетамина – это разнообразный термин. Это часто относится к преувеличению необычных эффектов с такими признаками, как раздражительность, возбуждение, галлюцинации и паранойя. Это также может относиться к умышленному членовредительству или летальному исходу. CDC сообщил, что число смертей в США, связанных с психостимуляторами, потенциально злоупотребляющими, составит 23 837 в 2020 году и 32 537 в 2021 году. [ 108 ] Этот код категории (МКБ-10 Т43.6) включает в первую очередь метамфетамин, а также другие стимуляторы, такие как амфетамин и метилфенидат. Механизм смерти в этих случаях не указан в этой статистике, и его трудно определить. [ 109 ] В отличие от фентанила, который вызывает угнетение дыхания, метамфетамин не является респираторным депрессантом. Некоторые случаи смерти происходят в результате внутричерепного кровоизлияния. [ 110 ] некоторые случаи смерти имеют сердечно-сосудистую природу, включая внезапный отек легких. [ 111 ] и фибрилляция желудочков. [ 112 ]

Неотложная помощь

Острая интоксикация метамфетамином в основном лечится путем лечения симптомов, а лечение может первоначально включать введение активированного угля и седативных препаратов . [ 5 ] Недостаточно данных о гемодиализе или перитонеальном диализе в случаях интоксикации метамфетамином, чтобы определить их полезность. [ 3 ] Форсированный кислотный диурез (например, с помощью витамина С ) увеличивает выведение метамфетамина, но не рекомендуется, так как может увеличить риск усугубления ацидоза или вызвать судороги или рабдомиолиз. [ 5 ] Гипертония представляет риск внутричерепного кровоизлияния (т.е. кровоизлияния в мозг), и в тяжелых случаях ее обычно лечат внутривенным введением фентоламина или нитропруссида . [ 5 ] Артериальное давление часто падает постепенно после достаточной седации бензодиазепинами и создания успокаивающей обстановки. [ 5 ]

Нейролептики, такие как галоперидол, эффективны при лечении возбуждения и психоза, вызванных передозировкой метамфетамина. [ 113 ] [ 114 ] Бета-блокаторы с липофильными свойствами и способностью проникать в ЦНС, такие как метопролол и лабеталол, могут быть полезны для лечения ЦНС и сердечно-сосудистой токсичности. [ 115 ] [ не удалось пройти проверку ] Смешанный альфа- и бета-блокатор лабеталол особенно полезен для лечения сопутствующей тахикардии и гипертонии, вызванных метамфетамином. [ 113 ] Феномен «беспрепятственной альфа-стимуляции» не был зарегистрирован при использовании бета-блокаторов для лечения токсичности метамфетамина. [ 113 ]

Взаимодействия

Метамфетамин метаболизируется ферментом печени CYP2D6 , поэтому ингибиторы CYP2D6 продлевают период полувыведения метамфетамина. [ 116 ] Метамфетамин также взаимодействует с ингибиторами моноаминоксидазы (ИМАО), поскольку и ИМАО, и метамфетамин повышают уровень катехоламинов в плазме; поэтому одновременное использование обоих опасно. [ 3 ] Метамфетамин может уменьшать действие седативных и депрессантов усиливать действие антидепрессантов и других стимуляторов . , а также [ 3 ] Метамфетамин может противодействовать действию антигипертензивных и антипсихотических средств из-за его воздействия на сердечно-сосудистую систему и когнитивные функции соответственно. [ 3 ] Уровень pH содержимого желудочно-кишечного тракта и мочи влияет на всасывание и выведение метамфетамина. [ 3 ] В частности, кислые вещества уменьшают всасывание метамфетамина и увеличивают его выведение с мочой, тогда как щелочные вещества действуют наоборот. [ 3 ] Известно , что из-за влияния pH на всасывание ингибиторы протонной помпы , снижающие кислотность желудочного сока , взаимодействуют с метамфетамином. [ 3 ]

Фармакология

Фармакодинамика

Метамфетамин был идентифицирован как мощный полный агонист рецептора 1, связанного с следами аминов (TAAR1), рецептора, связанного с G-белком (GPCR), который регулирует катехоламиновые системы мозга. [ 117 ] [ 118 ] Активация TAAR1 увеличивает выработку циклического аденозинмонофосфата (цАМФ) и либо полностью ингибирует, либо меняет направление транспорта переносчика дофамина (DAT), переносчика норадреналина (NET) и переносчика серотонина (SERT). [ 117 ] [ 119 ] Когда метамфетамин связывается с TAAR1, он запускает фосфорилирование транспортера посредством передачи сигналов протеинкиназы A (PKA) и протеинкиназы C (PKC), что в конечном итоге приводит к интернализации или обратной функции переносчиков моноаминов . [ 117 ] [ 120 ] Известно также, что метамфетамин увеличивает внутриклеточный кальций, эффект, который связан с фосфорилированием DAT через Ca2+/кальмодулин-зависимый сигнальный путь протеинкиназы (CAMK), что, в свою очередь, вызывает отток дофамина. [ 121 ] [ 122 ] [ 123 ] Было показано, что TAAR1 снижает частоту возбуждения нейронов за счет прямой активации связанных с G-белком внутренних выпрямляющих калиевых каналов . [ 124 ] [ 125 ] [ 126 ] Активация TAAR1 метамфетамином в астроцитах , по-видимому, отрицательно модулирует мембранную экспрессию и функцию EAAT2 , типа переносчика глутамата . [ 58 ]

Помимо воздействия на переносчики моноаминов плазматической мембраны, метамфетамин ингибирует функцию синаптических везикул путем ингибирования VMAT2 , что предотвращает захват моноаминов в везикулы и способствует их высвобождению. [ 127 ] Это приводит к оттоку моноаминов из синаптических везикул в цитозоль (внутриклеточную жидкость) пресинаптического нейрона и их последующему высвобождению в синаптическую щель фосфорилированными переносчиками. [ 128 ] Другими переносчиками , которые, как известно, ингибирует метамфетамин, являются SLC22A3 и SLC22A5 . [ 127 ] SLC22A3 представляет собой вненейрональный переносчик моноаминов, присутствующий в астроцитах, а SLC22A5 представляет собой высокоаффинный переносчик карнитина . [ 118 ] [ 129 ]

Метамфетамин также является агонистом альфа -2-адренергических рецепторов и сигма-рецепторов с большим сродством к σ1 , чем , к σ2 и ингибирует моноаминоксидазу А (МАО-А) и моноаминоксидазу В (МАО-В). [ 54 ] [ 118 ] [ 60 ] Активация сигма-рецептора метамфетамином может способствовать его стимулирующему действию на центральную нервную систему и способствовать нейротоксичности в головном мозге. [ 54 ] [ 60 ] Декстрометамфетамин является более сильным психостимулятором , но левометамфетамин имеет более сильные периферические эффекты, более длительный период полураспада и более длительные эффекты, воспринимаемые наркоманами. [ 130 ] [ 131 ] [ 132 ] В высоких дозах оба энантиомера метамфетамина могут вызывать схожие стереотипии и метамфетаминовый психоз . [ 131 ] но левометамфетамин имеет более короткие психодинамические эффекты. [ 132 ]

Фармакокинетика

Биодоступность ) метамфетамина составляет 67% при пероральном приеме , 79% при интраназальном введении , от 67 до 90% при курение вдыхании ( и 100% при внутривенном введении . [ 4 ] [ 5 ] [ 6 ] После перорального приема метамфетамин хорошо всасывается в кровоток, при этом пиковые концентрации метамфетамина в плазме достигаются примерно через 3,13–6,3 часа после приема. [ 133 ] Метамфетамин также хорошо всасывается при вдыхании и интраназальном введении. [ 5 ] Из-за высокой липофильности метамфетамина благодаря его метильной группе он может легко проходить через гематоэнцефалический барьер быстрее, чем другие стимуляторы, где он более устойчив к расщеплению моноаминоксидазой . [ 5 ] [ 133 ] [ 134 ] Пик метаболита амфетамина приходится на 10–24 часа. [ 5 ] Метамфетамин выводится почками, при этом на скорость выведения с мочой сильно влияет pH мочи. [ 3 ] [ 133 ] При пероральном приеме 30–54% дозы выводится с мочой в виде метамфетамина и 10–23% в виде амфетамина. [ 133 ] После внутривенного введения около 45% выводится в виде метамфетамина и 7% в виде амфетамина. [ 133 ] Период полувыведения метамфетамина варьируется в пределах 5–30 он составляет в среднем от 9 до 12 часов. часов, но в большинстве исследований [ 5 ] [ 4 ] Период полувыведения метамфетамина не зависит от пути введения , но подвержен значительной индивидуальной вариабельности . [ 4 ]

CYP2D6 , дофамин-β-гидроксилаза , флавинсодержащая монооксигеназа 3 , бутират-КоА-лигаза и глицин-N-ацилтрансфераза являются ферментами, которые, как известно, метаболизируют метамфетамин или его метаболиты у людей. [ источники 2 ] Первичными метаболитами являются амфетамин и 4-гидроксиметамфетамин ; [ 133 ] другие второстепенные метаболиты включают: 4-гидроксиамфетамин , 4-гидроксинорэфедрин , 4-гидроксифенилацетон , бензойную кислоту , гиппуровую кислоту , норэфедрин и фенилацетон , метаболиты амфетамина. [ 10 ] [ 133 ] [ 135 ] Среди этих метаболитов активными симпатомиметиками являются амфетамин, 4-гидроксиамфетамин , [ 141 ] 4‑гидроксинорэфедрин , [ 142 ] 4-гидроксиметамфетамин , [ 133 ] и норэфедрин. [ 143 ] Метамфетамин является ингибитором CYP2D6. [ 116 ]

Основные пути метаболизма включают ароматическое парагидроксилирование, алифатическое альфа- и бета-гидроксилирование, N-окисление, N-дезалкилирование и дезаминирование. [ 10 ] [ 133 ] [ 144 ] Известные метаболические пути включают:

Метаболические пути метамфетамина у человека [ источники 2 ]

|

Обнаружение в биологических жидкостях

Метамфетамин и амфетамин часто измеряются в моче или крови в рамках тестов на наркотики при занятиях спортом, трудоустройстве, диагностике отравлений и судебно-медицинской экспертизе. [ 147 ] [ 148 ] [ 149 ] [ 150 ] Хиральные методы могут использоваться, чтобы помочь определить источник препарата и определить, было ли оно получено незаконно или легально по рецепту или пролекарству. [ 151 ] Хиральное разделение необходимо для оценки возможного вклада левометамфетамина , который является активным ингредиентом некоторых безрецептурных назальных противозастойных средств. [ примечание 3 ] к положительному результату теста. [ 151 ] [ 152 ] [ 153 ] Диетические добавки цинка могут маскировать присутствие метамфетамина и других наркотиков в моче. [ 154 ]

Химия

Метамфетамин представляет собой хиральное соединение с двумя энантиомерами: декстрометамфетамином и левометамфетамином . При комнатной температуре свободное основание метамфетамина представляет собой прозрачную бесцветную жидкость с запахом, характерным для герани . листьев [ 13 ] Он растворим в диэтиловом эфире и этаноле , а также смешивается с хлороформом . [ 13 ]

Напротив, гидрохлоридная соль метамфетамина не имеет запаха и имеет горький вкус. [ 13 ] Он имеет температуру плавления от 170 до 175 ° C (от 338 до 347 ° F) и при комнатной температуре представляет собой белые кристаллы или белый кристаллический порошок. [ 13 ] Гидрохлоридная соль также свободно растворима в этаноле и воде. [ 13 ] Кристаллическая структура любого энантиомера является моноклинной с P2 1 пространственной группой ; при 90 К (-183,2 ° C; -297,7 ° F) он имеет параметры решетки a = 7,10 Å , b = 7,29 Å, c = 10,81 Å и β = 97,29 °. [ 155 ]

Деградация

Исследование уничтожения метамфетамина с помощью отбеливателя, проведенное в 2011 году, показало, что эффективность коррелирует со временем воздействия и концентрацией. [ 156 ] Годичное исследование (также проведенное в 2011 году) показало, что метамфетамин в почвах является стойким загрязнителем. [ 157 ] В исследовании биореакторов сточных вод , проведенном в 2013 году , было обнаружено, что метамфетамин в значительной степени разлагается в течение 30 дней под воздействием света. [ 158 ]

Синтез

Рацемический метамфетамин можно получить, исходя из фенилацетона, с помощью Лейкарта . [ 159 ] или методы восстановительного аминирования . [ 160 ] В реакции Лейкарта один эквивалент фенилацетона взаимодействует с двумя эквивалентами N -метилформамида с образованием формиламида метамфетамина , а также диоксида углерода и метиламина в качестве побочных продуктов. [ 160 ] В этой реакции иминия в качестве промежуточного продукта образуется катион , который восстанавливается вторым эквивалентом N -метилформамида . [ 160 ] Промежуточный формиламид затем гидролизуют в кислых водных условиях с получением метамфетамина в качестве конечного продукта. [ 160 ] Альтернативно, фенилацетон можно подвергнуть реакции с метиламином в восстанавливающих условиях с получением метамфетамина. [ 160 ]

История, общество и культура

Амфетамин, открытый раньше метамфетамина, был впервые синтезирован в 1887 году в Германии румынским химиком Лазаром Эделеану, который назвал его фенилизопропиламином . [ 163 ] [ 164 ] синтезировал метамфетамин из эфедрина Вскоре после этого в 1893 году японский химик Нагаи Нагайоши . [ 165 ] синтезировал гидрохлорид метамфетамина Три десятилетия спустя, в 1919 году, фармаколог Акира Огата путем восстановления эфедрина с использованием красного фосфора и йода . [166]

From 1938, methamphetamine was marketed on a large scale in Germany as a nonprescription drug under the brand name Pervitin, produced by the Berlin-based Temmler pharmaceutical company.[167][168] It was used by all branches of the combined armed forces of the Third Reich, for its stimulant effects and to induce extended wakefulness.[169][170] Pervitin became colloquially known among the German troops as "Stuka-Tablets" (Stuka-Tabletten) and "Herman-Göring-Pills" (Hermann-Göring-Pillen), as a snide allusion to Göring's widely-known addiction to drugs. However, the side effects, particularly the withdrawal symptoms, were so serious that the army sharply cut back its usage in 1940.[171] By 1941, usage was restricted to a doctor's prescription, and the military tightly controlled its distribution. Soldiers would only receive a couple of tablets at a time, and were discouraged from using them in combat. Historian Łukasz Kamieński says,

A soldier going to battle on Pervitin usually found himself unable to perform effectively for the next day or two. Suffering from a drug hangover and looking more like a zombie than a great warrior, he had to recover from the side effects.

Some soldiers turned violent, committing war crimes against civilians; others attacked their own officers.[171] At the end of the war, it was used as part of a new drug: D-IX.

Obetrol, patented by Obetrol Pharmaceuticals in the 1950s and indicated for treatment of obesity, was one of the first brands of pharmaceutical methamphetamine products.[172] Because of the psychological and stimulant effects of methamphetamine, Obetrol became a popular diet pill in America in the 1950s and 1960s.[172] Eventually, as the addictive properties of the drug became known, governments began to strictly regulate the production and distribution of methamphetamine.[164] For example, during the early 1970s in the United States, methamphetamine became a schedule II controlled substance under the Controlled Substances Act.[173] Currently, methamphetamine is sold under the trade name Desoxyn, trademarked by the Danish pharmaceutical company Lundbeck.[174] As of January 2013, the Desoxyn trademark had been sold to Italian pharmaceutical company Recordati.[175]

Trafficking

The Golden Triangle (Southeast Asia), specifically Shan State, Myanmar, is the world's leading producer of methamphetamine as production has shifted to Yaba and crystalline methamphetamine, including for export to the United States and across East and Southeast Asia and the Pacific.[176]

Concerning the accelerating synthetic drug production in the region, the Cantonese Chinese syndicate Sam Gor, also known as The Company, is understood to be the main international crime syndicate responsible for this shift.[177] It is made up of members of five different triads. Sam Gor is primarily involved in drug trafficking, earning at least $8 billion per year.[178] Sam Gor is alleged to control 40% of the Asia-Pacific methamphetamine market, while also trafficking heroin and ketamine. The organization is active in a variety of countries, including Myanmar, Thailand, New Zealand, Australia, Japan, China, and Taiwan. Sam Gor previously produced meth in Southern China and is now believed to manufacture mainly in the Golden Triangle, specifically Shan State, Myanmar, responsible for much of the massive surge of crystal meth in circa 2019.[179] The group is understood to be headed by Tse Chi Lop, a gangster born in Guangzhou, China who also holds a Canadian passport.

Liu Zhaohua was another individual involved in the production and trafficking of methamphetamine until his arrest in 2005.[180] It was estimated over 18 tonnes of methamphetamine were produced under his watch.[180]

Legal status

The production, distribution, sale, and possession of methamphetamine is restricted or illegal in many jurisdictions.[181][182] Methamphetamine has been placed in schedule II of the United Nations Convention on Psychotropic Substances treaty.[182]

Research

It has been suggested, based on animal research, that calcitriol, the active metabolite of vitamin D, can provide significant protection against the DA- and 5-HT-depleting effects of neurotoxic doses of methamphetamine.[183]

See also

- 18-MC

- Breaking Bad, a TV drama series centered on illicit methamphetamine synthesis

- Drug checking

- Faces of Meth, a drug prevention project

- Harm reduction

- Methamphetamine and Native Americans

- Methamphetamine in Australia

- Methamphetamine in Bangladesh

- Methamphetamine in the Philippines

- Methamphetamine in the United States

- Montana Meth Project, a Montana-based organization aiming to reduce meth use among teenagers

- Recreational drug use

- Rolling meth lab, a transportable laboratory that is used to illegally produce methamphetamine

- Ya ba, Southeast Asian tablets containing a mixture of methamphetamine and caffeine

Footnotes

- ^ (Text color) Transcription factors

- ^ Synonyms and alternate spellings include: N-methylamphetamine, desoxyephedrine, Syndrox, Methedrine, and Desoxyn.[14][15][16] Common slang terms for methamphetamine include: meth, speed, crank and shabu (also sabu and shabu-shabu) in Indonesia and the Philippines,[17][18][19][20] and for the hydrochloride crystal, crystal meth, glass, shards, and ice,[21] and, in New Zealand, P.[22]

- ^ Enantiomers are molecules that are mirror images of one another; they are structurally identical, but of the opposite orientation.

Levomethamphetamine and dextromethamphetamine are also known as L-methamphetamine, (R)-methamphetamine, or levmetamfetamine (International Nonproprietary Name [INN]) and D-methamphetamine, (S)-methamphetamine, or metamfetamine (INN), respectively.[14][24] - ^ Jump up to: a b c The active ingredient in some OTC inhalers in the United States is listed as levmetamfetamine, the INN and USAN of levomethamphetamine.[25][26]

- ^ Transcription factors are proteins that increase or decrease the expression of specific genes.[73]

- ^ In simpler terms, this necessary and sufficient relationship means that ΔFosB overexpression in the nucleus accumbens and addiction-related behavioral and neural adaptations always occur together and never occur alone.

- ^ The associated research only involved amphetamine, not methamphetamine; however, this statement is included here due to the similarity between the pharmacodynamics and aphrodisiac effects of amphetamine and methamphetamine.

Reference notes

References

- ^ "methamphetamine". Methamphetamine. Lexico. Archived from the original on 14 June 2021. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ Anvisa (24 July 2023). "RDC Nº 804 – Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 804 – Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 25 July 2023). Archived from the original on 27 August 2023. Retrieved 27 August 2023.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y "Desoxyn- methamphetamine hydrochloride tablet". DailyMed. 8 September 2022. Retrieved 20 June 2024.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l Cruickshank CC, Dyer KR (July 2009). "A review of the clinical pharmacology of methamphetamine". Addiction. 104 (7): 1085–99. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02564.x. PMID 19426289. S2CID 37079117.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Schep LJ, Slaughter RJ, Beasley DM (August 2010). "The clinical toxicology of metamfetamine". Clinical Toxicology. 48 (7): 675–694. doi:10.3109/15563650.2010.516752. ISSN 1556-3650. PMID 20849327. S2CID 42588722.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Courtney KE, Ray LA (October 2014). "Methamphetamine: an update on epidemiology, pharmacology, clinical phenomenology, and treatment literature". Drug Alcohol Depend. 143: 11–21. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.08.003. PMC 4164186. PMID 25176528.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Rau T, Ziemniak J, Poulsen D (2015). "The neuroprotective potential of low-dose methamphetamine in preclinical models of stroke and traumatic brain injury". Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 64: 231–6. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2015.02.013. ISSN 0278-5846. PMID 25724762.

In humans, the oral bioavailability of methamphetamine is approximately 70% but increases to 100% following intravenous (IV) delivery (Ares-Santos et al., 2013).

- ^ "Methamphetamine: Toxicity". PubChem Compound. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Archived from the original on 4 January 2015. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sellers EM, Tyndale RF (2000). "Mimicking gene defects to treat drug dependence". Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 909 (1): 233–246. Bibcode:2000NYASA.909..233S. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06685.x. PMID 10911933. S2CID 27787938.

Methamphetamine, a central nervous system stimulant drug, is p-hydroxylated by CYP2D6 to less active p-OH-methamphetamine.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Adderall XR Prescribing Information" (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. Shire US Inc. December 2013. pp. 12–13. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Krueger SK, Williams DE (June 2005). "Mammalian flavin-containing monooxygenases: structure/function, genetic polymorphisms and role in drug metabolism". Pharmacol. Ther. 106 (3): 357–387. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.01.001. PMC 1828602. PMID 15922018.

Table 5: N-containing drugs and xenobiotics oxygenated by FMO Archived 16 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine - ^ Jump up to: a b Cashman JR, Xiong YN, Xu L, Janowsky A (March 1999). "N-oxygenation of amphetamine and methamphetamine by the human flavin-containing monooxygenase (form 3): role in bioactivation and detoxication". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 288 (3): 1251–1260. PMID 10027866.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g "Methamphetamine: Chemical and Physical Properties". PubChem Compound. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Archived from the original on 4 January 2015. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Methamphetamine". Drug profiles. European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA). 8 January 2015. Archived from the original on 15 April 2016. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

The term metamfetamine (the International Non-Proprietary Name: INN) strictly relates to the specific enantiomer (S)-N,α-dimethylbenzeneethanamine.

- ^ "Methamphetamine: Identification". DrugBank. University of Alberta. 8 February 2013. Archived from the original on 28 December 2015. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- ^ "Methedrine (methamphetamine hydrochloride): Uses, Symptoms, Signs and Addiction Treatment". Addictionlibrary.org. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- ^ "Polisi Tangkap Bandar Shabu-shabu". Detik News (in Indonesian). Retrieved 29 July 2023.

- ^ "P1-M shabu seized from 3 drug pushers". Manila Bulletin. Retrieved 29 July 2023.

- ^ "Jadi pengedar sabu seorang IRT di Pidoli Dolok ditangkap Polisi – ANTARA News Sumatera Utara". ANTARA News Agency. Retrieved 29 July 2023.

- ^ Marantal RD. "E-bike driver nabbed in drug bust, shabu worth almost P1 million seized". Philstar.com. Retrieved 29 July 2023.

- ^ "Meth Slang Names". MethhelpOnline. Archived from the original on 7 December 2013. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- ^ "Methamphetamine and the law". Archived from the original on 28 January 2015. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Moszczynska A, Callan SP (September 2017). "Molecular, Behavioral, and Physiological Consequences of Methamphetamine Neurotoxicity: Implications for Treatment". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 362 (3): 474–488. doi:10.1124/jpet.116.238501. PMC 11047030. PMID 28630283.

METH is a schedule II drug, which can only be prescribed for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), extreme obesity, or narcolepsy (as Desoxyn; Recordati Rare Diseases LLC, Lebanon, NJ), with amphetamine being prescribed more often for these conditions due to amphetamine having lower reinforcing potential than METH (Lile et al., 2013).

- ^ "Levomethamphetamine". Pubchem Compound. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- ^ "Code of Federal Regulations Title 21: Subchapter D – Drugs for human use, Part 341 – cold, cough, allergy, bronchodilator, and antiasthmatic drug products for over-the-counter human use". United States Food and Drug Administration. April 2015. Archived from the original on 25 December 2019. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

Topical nasal decongestants --(i) For products containing levmetamfetamine identified in 341.20(b)(1) when used in an inhalant dosage form. The product delivers in every 800 milliliters of air 0.04 to 0.150 milligrams of levmetamfetamine.

- ^ "Levomethamphetamine: Identification". Pubchem Compound. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- ^ "Meth's aphrodisiac effect adds to drug's allure". NBC News. Associated Press. 3 December 2004. Archived from the original on 12 August 2013. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Yu S, Zhu L, Shen Q, Bai X, Di X (2015). "Recent advances in methamphetamine neurotoxicity mechanisms and its molecular pathophysiology". Behav Neurol. 2015: 1–11. doi:10.1155/2015/103969. PMC 4377385. PMID 25861156.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Krasnova IN, Cadet JL (May 2009). "Methamphetamine toxicity and messengers of death". Brain Res. Rev. 60 (2): 379–407. doi:10.1016/j.brainresrev.2009.03.002. PMC 2731235. PMID 19328213.

Neuroimaging studies have revealed that METH can indeed cause neurodegenerative changes in the brains of human addicts (Aron and Paulus, 2007; Chang et al., 2007). These abnormalities include persistent decreases in the levels of dopamine transporters (DAT) in the orbitofrontal cortex, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, and the caudate-putamen (McCann et al., 1998, 2008; Sekine et al., 2003; Volkow et al., 2001a, 2001c). The density of serotonin transporters (5-HTT) is also decreased in the midbrain, caudate, putamen, hypothalamus, thalamus, the orbitofrontal, temporal, and cingulate cortices of METH-dependent individuals (Sekine et al., 2006) ...

Neuropsychological studies have detected deficits in attention, working memory, and decision-making in chronic METH addicts ...

There is compelling evidence that the negative neuropsychiatric consequences of METH abuse are due, at least in part, to drug-induced neuropathological changes in the brains of these METH-exposed individuals ...

Structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies in METH addicts have revealed substantial morphological changes in their brains. These include loss of gray matter in the cingulate, limbic and paralimbic cortices, significant shrinkage of hippocampi, and hypertrophy of white matter (Thompson et al., 2004). In addition, the brains of METH abusers show evidence of hyperintensities in white matter (Bae et al., 2006; Ernst et al., 2000), decreases in the neuronal marker, N-acetylaspartate (Ernst et al., 2000; Sung et al., 2007), reductions in a marker of metabolic integrity, creatine (Sekine et al., 2002) and increases in a marker of glial activation, myoinositol (Chang et al., 2002; Ernst et al., 2000; Sung et al., 2007; Yen et al., 1994). Elevated choline levels, which are indicative of increased cellular membrane synthesis and turnover are also evident in the frontal gray matter of METH abusers (Ernst et al., 2000; Salo et al., 2007; Taylor et al., 2007). - ^ Jump up to: a b Hart CL, Marvin CB, Silver R, Smith EE (February 2012). "Is cognitive functioning impaired in methamphetamine users? A critical review". Neuropsychopharmacology. 37 (3): 586–608. doi:10.1038/npp.2011.276. PMC 3260986. PMID 22089317.

- ^ Mitler MM, Hajdukovic R, Erman MK (1993). "Treatment of narcolepsy with methamphetamine". Sleep. 16 (4): 306–317. PMC 2267865. PMID 8341891.

- ^ Morgenthaler TI, Kapur VK, Brown T, Swick TJ, Alessi C, Aurora RN, et al. (2007). "Practice parameters for the treatment of narcolepsy and other hypersomnias of central origin". Sleep. 30 (12): 1705–11. doi:10.1093/sleep/30.12.1705. PMC 2276123. PMID 18246980.

- ^ "Desoxyn Gradumet Side Effects". Drugs.com. 19 March 2022. Archived from the original on 18 October 2022. Retrieved 18 October 2022.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f San Francisco Meth Zombies (TV documentary). National Geographic Channel. August 2013. ASIN B00EHAOBAO. Archived from the original on 8 July 2016. Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- ^ Nelson LS, Lewin NA, Howland MA, Hoffman RS, Goldfrank LR, Flomenbaum NE (2011). Goldfrank's toxicologic emergencies (9th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 1080. ISBN 978-0-07-160593-9.

- ^ Nutt DJ, King LA, Phillips LD (November 2010). "Drug harms in the UK: a multicriteria decision analysis". Lancet. 376 (9752): 1558–65. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.690.1283. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61462-6. PMID 21036393. S2CID 5667719.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Westfall DP, Westfall TC (2010). "Miscellaneous Sympathomimetic Agonists". In Brunton LL, Chabner BA, Knollmann BC (eds.). Goodman & Gilman's Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (12th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-162442-8. Archived from the original on 10 November 2013. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "What are the long-term effects of methamphetamine misuse?". National Institute on Drug Abuse. National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. October 2019. Archived from the original on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Elkins C (27 February 2020). "Meth Sores". DrugRehab.com. Advanced Recovery Systems. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ "Meth Overdose Symptoms, Effects & Treatment | BlueCrest". Bluecrest Recovery Center. 17 June 2019. Archived from the original on 16 January 2021. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- ^ National Institute on Drug Abuse (29 January 2021). "Overdose Death Rates". National Institute on Drug Abuse. Archived from the original on 25 January 2018. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Accelerated cellular aging caused by methamphetamine use limited in lab". ScienceDaily. 11 February 2015. Retrieved 29 July 2024.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Hussain F, Frare RW, Py Berrios KL (2012). "Drug abuse identification and pain management in dental patients: a case study and literature review". Gen. Dent. 60 (4): 334–345. PMID 22782046.

- ^ "Methamphetamine Use (Meth Mouth)". American Dental Association. Archived from the original on 1 June 2008. Retrieved 15 December 2006.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Halkitis PN, Pandey Mukherjee P, Palamar JJ (2008). "Longitudinal Modeling of Methamphetamine Use and Sexual Risk Behaviors in Gay and Bisexual Men". AIDS and Behavior. 13 (4): 783–791. doi:10.1007/s10461-008-9432-y. PMC 4669892. PMID 18661225.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Moore P (June 2005). "We Are Not OK". VillageVoice. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 15 January 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Methamphetamine Use and Health | UNSW: The University of New South Wales – Faculty of Medicine" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 August 2008. Retrieved 15 January 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b O'Connor PG (February 2012). "Amphetamines". Merck Manual for Health Care Professionals. Merck. Archived from the original on 6 May 2012. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- ^ Rusinyak DE (2011). "Neurologic manifestations of chronic methamphetamine abuse". Neurologic Clinics. 29 (3): 641–655. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2011.05.004. PMC 3148451. PMID 21803215.

- ^ Darke S, Kaye S, McKetin R, Duflou J (May 2008). "Major physical and psychological harms of methamphetamine use". Drug Alcohol Rev. 27 (3): 253–262. doi:10.1080/09595230801923702. PMID 18368606.

- ^ Raskin S (26 December 2021). "Missouri sword slay suspect smiles for mug shot after allegedly killing beau". New York Post. Archived from the original on 26 December 2021. Retrieved 26 December 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Beardsley PM, Hauser KF (2014). "Glial Modulators as Potential Treatments of Psychostimulant Abuse". Emerging Targets & Therapeutics in the Treatment of Psychostimulant Abuse. Advances in Pharmacology. Vol. 69. Academic Press. pp. 1–69. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-420118-7.00001-9. ISBN 978-0-12-420118-7. PMC 4103010. PMID 24484974.

Glia (including astrocytes, microglia, and oligodendrocytes), which constitute the majority of cells in the brain, have many of the same receptors as neurons, secrete neurotransmitters and neurotrophic and neuroinflammatory factors, control clearance of neurotransmitters from synaptic clefts, and are intimately involved in synaptic plasticity. Despite their prevalence and spectrum of functions, appreciation of their potential general importance has been elusive since their identification in the mid-1800s, and only relatively recently have they been gaining their due respect. This development of appreciation has been nurtured by the growing awareness that drugs of abuse, including the psychostimulants, affect glial activity, and glial activity, in turn, has been found to modulate the effects of the psychostimulants

- ^ Loftis JM, Janowsky A (2014). "Neuroimmune basis of methamphetamine toxicity". Neuroimmune Signaling in Drug Actions and Addictions. International Review of Neurobiology. Vol. 118. Academic Press. pp. 165–197. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-801284-0.00007-5. ISBN 978-0-12-801284-0. PMC 4418472. PMID 25175865.

Collectively, these pathological processes contribute to neurotoxicity (e.g., increased BBB permeability, inflammation, neuronal degeneration, cell death) and neuropsychiatric impairments (e.g., cognitive deficits, mood disorders)

"Figure 7.1: Neuroimmune mechanisms of methamphetamine-induced CNS toxicity Archived 16 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine" - ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Kaushal N, Matsumoto RR (March 2011). "Role of sigma receptors in methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity". Curr Neuropharmacol. 9 (1): 54–57. doi:10.2174/157015911795016930. PMC 3137201. PMID 21886562.

σ Receptors seem to play an important role in many of the effects of METH. They are present in the organs that mediate the actions of METH (e.g. brain, heart, lungs) [5]. In the brain, METH acts primarily on the dopaminergic system to cause acute locomotor stimulant, subchronic sensitized, and neurotoxic effects. σ Receptors are present on dopaminergic neurons and their activation stimulates dopamine synthesis and release [11–13]. σ-2 Receptors modulate DAT and the release of dopamine via protein kinase C (PKC) and Ca2+-calmodulin systems [14].

σ-1 Receptor antisense and antagonists have been shown to block the acute locomotor stimulant effects of METH [4]. Repeated administration or self administration of METH has been shown to upregulate σ-1 receptor protein and mRNA in various brain regions including the substantia nigra, frontal cortex, cerebellum, midbrain, and hippocampus [15, 16]. Additionally, σ receptor antagonists ... prevent the development of behavioral sensitization to METH [17, 18]. ...

σ Receptor agonists have been shown to facilitate dopamine release, through both σ-1 and σ-2 receptors [11–14]. - ^ Yu S, Zhu L, Shen Q, Bai X, Di X (2015). "Recent advances in methamphetamine neurotoxicity mechanisms and its molecular pathophysiology". Behavioural Neurology. 2015: 103969. doi:10.1155/2015/103969. PMC 4377385. PMID 25861156.

- ^ Carvalho M, Carmo H, Costa VM, Capela JP, Pontes H, Remião F, et al. (August 2012). "Toxicity of amphetamines: an update". Arch. Toxicol. 86 (8): 1167–1231. Bibcode:2012ArTox..86.1167C. doi:10.1007/s00204-012-0815-5. PMID 22392347. S2CID 2873101.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Cruickshank CC, Dyer KR (July 2009). "A review of the clinical pharmacology of methamphetamine". Addiction. 104 (7): 1085–1099. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02564.x. PMID 19426289. S2CID 37079117.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d • Cisneros IE, Ghorpade A (October 2014). "Methamphetamine and HIV-1-induced neurotoxicity: role of trace amine associated receptor 1 cAMP signaling in astrocytes". Neuropharmacology. 85: 499–507. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.06.011. PMC 4315503. PMID 24950453.

TAAR1 overexpression significantly decreased EAAT-2 levels and glutamate clearance ... METH treatment activated TAAR1 leading to intracellular cAMP in human astrocytes and modulated glutamate clearance abilities. Furthermore, molecular alterations in astrocyte TAAR1 levels correspond to changes in astrocyte EAAT-2 levels and function.

• Jing L, Li JX (August 2015). "Trace amine-associated receptor 1: A promising target for the treatment of psychostimulant addiction". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 761: 345–352. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.06.019. PMC 4532615. PMID 26092759.TAAR1 is largely located in the intracellular compartments both in neurons (Miller, 2011), in glial cells (Cisneros and Ghorpade, 2014) and in peripheral tissues (Grandy, 2007)

- ^ Yuan J, Hatzidimitriou G, Suthar P, Mueller M, McCann U, Ricaurte G (March 2006). "Relationship between temperature, dopaminergic neurotoxicity, and plasma drug concentrations in methamphetamine-treated squirrel monkeys". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 316 (3): 1210–1218. doi:10.1124/jpet.105.096503. PMID 16293712. S2CID 11909155.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Rodvelt KR, Miller DK (September 2010). "Could sigma receptor ligands be a treatment for methamphetamine addiction?". Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 3 (3): 156–162. doi:10.2174/1874473711003030156. PMID 21054260.

- ^ Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 15: Reinforcement and Addictive Disorders". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 364–375. ISBN 9780071481274.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Nestler EJ (December 2013). "Cellular basis of memory for addiction". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 15 (4): 431–443. PMC 3898681. PMID 24459410.

Despite the importance of numerous psychosocial factors, at its core, drug addiction involves a biological process: the ability of repeated exposure to a drug of abuse to induce changes in a vulnerable brain that drive the compulsive seeking and taking of drugs, and loss of control over drug use, that define a state of addiction. ... A large body of literature has demonstrated that such ΔFosB induction in D1-type [nucleus accumbens] neurons increases an animal's sensitivity to drug as well as natural rewards and promotes drug self-administration, presumably through a process of positive reinforcement ... Another ΔFosB target is cFos: as ΔFosB accumulates with repeated drug exposure it represses c-Fos and contributes to the molecular switch whereby ΔFosB is selectively induced in the chronic drug-treated state.41. ... Moreover, there is increasing evidence that, despite a range of genetic risks for addiction across the population, exposure to sufficiently high doses of a drug for long periods of time can transform someone who has relatively lower genetic loading into an addict.

- ^ Volkow ND, Koob GF, McLellan AT (January 2016). "Neurobiologic Advances from the Brain Disease Model of Addiction". New England Journal of Medicine. 374 (4): 363–371. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1511480. PMC 6135257. PMID 26816013.

Substance-use disorder: A diagnostic term in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) referring to recurrent use of alcohol or other drugs that causes clinically and functionally significant impairment, such as health problems, disability, and failure to meet major responsibilities at work, school, or home. Depending on the level of severity, this disorder is classified as mild, moderate, or severe.

Addiction: A term used to indicate the most severe, chronic stage of substance-use disorder, in which there is a substantial loss of self-control, as indicated by compulsive drug taking despite the desire to stop taking the drug. In the DSM-5, the term addiction is synonymous with the classification of severe substance-use disorder. - ^ Jump up to: a b c Renthal W, Nestler EJ (September 2009). "Chromatin regulation in drug addiction and depression". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 11 (3): 257–268. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2009.11.3/wrenthal. PMC 2834246. PMID 19877494.

[Psychostimulants] increase cAMP levels in striatum, which activates protein kinase A (PKA) and leads to phosphorylation of its targets. This includes the cAMP response element binding protein (CREB), the phosphorylation of which induces its association with the histone acetyltransferase, CREB binding protein (CBP) to acetylate histones and facilitate gene activation. This is known to occur on many genes including fosB and c-fos in response to psychostimulant exposure. ΔFosB is also upregulated by chronic psychostimulant treatments, and is known to activate certain genes (eg, cdk5) and repress others (eg, c-fos) where it recruits HDAC1 as a corepressor. ... Chronic exposure to psychostimulants increases glutamatergic [signaling] from the prefrontal cortex to the NAc. Glutamatergic signaling elevates Ca2+ levels in NAc postsynaptic elements where it activates CaMK (calcium/calmodulin protein kinases) signaling, which, in addition to phosphorylating CREB, also phosphorylates HDAC5.

Figure 2: Psychostimulant-induced signaling events - ^ Broussard JI (January 2012). "Co-transmission of dopamine and glutamate". The Journal of General Physiology. 139 (1): 93–96. doi:10.1085/jgp.201110659. PMC 3250102. PMID 22200950.

Coincident and convergent input often induces plasticity on a postsynaptic neuron. The NAc integrates processed information about the environment from basolateral amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex (PFC), as well as projections from midbrain dopamine neurons. Previous studies have demonstrated how dopamine modulates this integrative process. For example, high frequency stimulation potentiates hippocampal inputs to the NAc while simultaneously depressing PFC synapses (Goto and Grace, 2005). The converse was also shown to be true; stimulation at PFC potentiates PFC–NAc synapses but depresses hippocampal–NAc synapses. In light of the new functional evidence of midbrain dopamine/glutamate co-transmission (references above), new experiments of NAc function will have to test whether midbrain glutamatergic inputs bias or filter either limbic or cortical inputs to guide goal-directed behavior.

- ^ Kanehisa Laboratories (10 October 2014). "Amphetamine – Homo sapiens (human)". KEGG Pathway. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

Most addictive drugs increase extracellular concentrations of dopamine (DA) in nucleus accumbens (NAc) and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), projection areas of mesocorticolimbic DA neurons and key components of the "brain reward circuit". Amphetamine achieves this elevation in extracellular levels of DA by promoting efflux from synaptic terminals. ... Chronic exposure to amphetamine induces a unique transcription factor delta FosB, which plays an essential role in long-term adaptive changes in the brain.

- ^ Cadet JL, Brannock C, Jayanthi S, Krasnova IN (2015). "Transcriptional and epigenetic substrates of methamphetamine addiction and withdrawal: evidence from a long-access self-administration model in the rat". Molecular Neurobiology. 51 (2): 696–717 (Figure 1). doi:10.1007/s12035-014-8776-8. PMC 4359351. PMID 24939695.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Robison AJ, Nestler EJ (November 2011). "Transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms of addiction". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 12 (11): 623–637. doi:10.1038/nrn3111. PMC 3272277. PMID 21989194.

ΔFosB serves as one of the master control proteins governing this structural plasticity. ... ΔFosB also represses G9a expression, leading to reduced repressive histone methylation at the cdk5 gene. The net result is gene activation and increased CDK5 expression. ... In contrast, ΔFosB binds to the c-fos gene and recruits several co-repressors, including HDAC1 (histone deacetylase 1) and SIRT 1 (sirtuin 1). ... The net result is c-fos gene repression.

Figure 4: Epigenetic basis of drug regulation of gene expression - ^ Jump up to: a b c Nestler EJ (December 2012). "Transcriptional mechanisms of drug addiction". Clinical Psychopharmacology and Neuroscience. 10 (3): 136–143. doi:10.9758/cpn.2012.10.3.136. PMC 3569166. PMID 23430970.

The 35-37 kD ΔFosB isoforms accumulate with chronic drug exposure due to their extraordinarily long half-lives. ... As a result of its stability, the ΔFosB protein persists in neurons for at least several weeks after cessation of drug exposure. ... ΔFosB overexpression in nucleus accumbens induces NFκB ... In contrast, the ability of ΔFosB to repress the c-Fos gene occurs in concert with the recruitment of a histone deacetylase and presumably several other repressive proteins such as a repressive histone methyltransferase

- ^ Nestler EJ (October 2008). "Transcriptional mechanisms of addiction: Role of ΔFosB". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 363 (1507): 3245–3255. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0067. PMC 2607320. PMID 18640924.

Recent evidence has shown that ΔFosB also represses the c-fos gene that helps create the molecular switch—from the induction of several short-lived Fos family proteins after acute drug exposure to the predominant accumulation of ΔFosB after chronic drug exposure

- ^ Hyman SE, Malenka RC, Nestler EJ (July 2006). "Neural mechanisms of addiction: the role of reward-related learning and memory" (PDF). Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 29: 565–598. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.113009. PMID 16776597. S2CID 15139406. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 September 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Robison AJ, Nestler EJ (November 2011). "Transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms of addiction". Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 12 (11): 623–637. doi:10.1038/nrn3111. PMC 3272277. PMID 21989194.

ΔFosB has been linked directly to several addiction-related behaviors ... Importantly, genetic or viral overexpression of ΔJunD, a dominant-negative mutant of JunD which antagonizes ΔFosB- and other AP-1-mediated transcriptional activity, in the NAc or OFC blocks these key effects of drug exposure14,22–24. This indicates that ΔFosB is both necessary and sufficient for many of the changes wrought in the brain by chronic drug exposure. ΔFosB is also induced in D1-type NAc MSNs by chronic consumption of several natural rewards, including sucrose, high-fat food, sex, wheel running, where it promotes that consumption14,26–30. This implicates ΔFosB in the regulation of natural rewards under normal conditions and perhaps during pathological addictive-like states.

- ^ Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 4: Signal Transduction in the Brain". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York, USA: McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-07-148127-4.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Ruffle JK (November 2014). "Molecular neurobiology of addiction: what's all the (Δ)FosB about?". Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse. 40 (6): 428–437. doi:10.3109/00952990.2014.933840. PMID 25083822. S2CID 19157711.

ΔFosB is an essential transcription factor implicated in the molecular and behavioral pathways of addiction following repeated drug exposure.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Olsen CM (December 2011). "Natural rewards, neuroplasticity, and non-drug addictions". Neuropharmacology. 61 (7): 1109–1122. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.03.010. PMC 3139704. PMID 21459101.

Similar to environmental enrichment, studies have found that exercise reduces self-administration and relapse to drugs of abuse (Cosgrove et al., 2002; Zlebnik et al., 2010). There is also some evidence that these preclinical findings translate to human populations, as exercise reduces withdrawal symptoms and relapse in abstinent smokers (Daniel et al., 2006; Prochaska et al., 2008), and one drug recovery program has seen success in participants that train for and compete in a marathon as part of the program (Butler, 2005). ... In humans, the role of dopamine signaling in incentive-sensitization processes has recently been highlighted by the observation of a dopamine dysregulation syndrome in some patients taking dopaminergic drugs. This syndrome is characterized by a medication-induced increase in (or compulsive) engagement in non-drug rewards such as gambling, shopping, or sex (Evans et al., 2006; Aiken, 2007; Lader, 2008).

- ^ Kanehisa Laboratories (29 October 2014). "Alcoholism – Homo sapiens (human)". KEGG Pathway. Archived from the original on 13 October 2014. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ^ Kim Y, Teylan MA, Baron M, Sands A, Nairn AC, Greengard P (February 2009). "Methylphenidate-induced dendritic spine formation and DeltaFosB expression in nucleus accumbens". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 (8): 2915–2920. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.2915K. doi:10.1073/pnas.0813179106. PMC 2650365. PMID 19202072.

- ^ Nestler EJ (January 2014). "Epigenetic mechanisms of drug addiction". Neuropharmacology. 76 (Pt B): 259–268. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.04.004. PMC 3766384. PMID 23643695.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Blum K, Werner T, Carnes S, Carnes P, Bowirrat A, Giordano J, et al. (March 2012). "Sex, drugs, and rock 'n' roll: hypothesizing common mesolimbic activation as a function of reward gene polymorphisms". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 44 (1): 38–55. doi:10.1080/02791072.2012.662112. PMC 4040958. PMID 22641964.