Атлантическая работорговля

| Часть серии о |

| Принудительный труд и рабство |

|---|

|

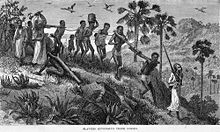

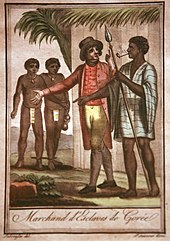

Атлантическая работорговля или трансатлантическая работорговля включала транспортировку работорговцами порабощенных африканцев в Америку . Европейские невольничьи корабли регулярно использовали треугольный торговый путь и его Средний проход . Европейцы наладили прибрежную работорговлю в 15 веке, а торговля с Америкой началась в 16 веке и продолжалась до 19 века. [ 1 ] Подавляющее большинство тех, кто был перевезен в ходе трансатлантической работорговли, были выходцами из Центральной Африки и Западной Африки и были проданы западноафриканскими работорговцами европейским работорговцам. [ 2 ] [ 3 ] в то время как другие были захвачены непосредственно работорговцами во время прибрежных рейдов. [ 4 ] [ 5 ] Европейские работорговцы собирали и заключали рабов в форты на африканском побережье, а затем привозили их в Америку. [ 6 ] [ 7 ] Некоторые португальцы и европейцы участвовали в набегах рабов. Как поясняют Национальные музеи Ливерпуля : «Европейские торговцы захватили некоторых африканцев во время набегов вдоль побережья, но купили большую часть из них у местных африканских или афроевропейских торговцев». [ 8 ] Многие европейские работорговцы обычно не участвовали в набегах рабов , поскольку ожидаемая продолжительность жизни европейцев в странах Африки к югу от Сахары в период работорговли составляла менее одного года из-за малярии , которая была эндемической на африканском континенте. [ 9 ] В статье PBS поясняется: «Малярия, дизентерия, желтая лихорадка и другие болезни довели немногих европейцев, живущих и торгующих вдоль побережья Западной Африки, до хронического состояния плохого здоровья и заслужили прозвище Африки «могила белого человека». В таких условиях европейские купцы редко имели возможность принимать решения». [ 10 ] Самое раннее известное использование этой фразы началось в 1830-х годах, а самые ранние письменные свидетельства были найдены в опубликованной в 1836 году книге Ф. Х. Ранкина. [ 11 ] Португальские прибрежные рейдеры обнаружили, что набеги на рабов обходятся слишком дорого и часто неэффективно, и предпочли установить коммерческие отношения. [ 12 ]

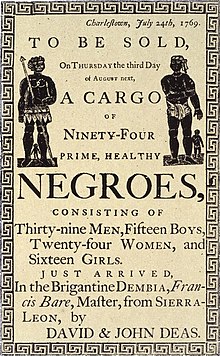

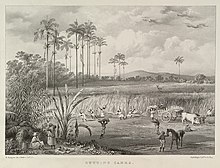

Колониальные экономики Южной Атлантики и Карибского бассейна особенно зависели от рабского труда при производстве сахарного тростника и других товаров. [ 13 ] [ 14 ] Это рассматривалось как решающее значение для тех западноевропейских государств, которые соперничали друг с другом за создание зарубежных империй . [ 15 ] [ 16 ] Португальцы в 16 веке первыми перевезли рабов через Атлантику. В 1526 году они совершили первое трансатлантическое путешествие рабов в Бразилию , а вскоре за ними последовали и другие европейцы. [ 17 ] Судовладельцы считали рабов грузом, который нужно перевезти в Америку как можно быстрее и дешевле. [ 15 ] их будут продавать для работы на плантациях кофе, табака, какао, сахара и хлопка , на золотых и серебряных рудниках, рисовых полях, в строительной промышленности, на заготовке леса для кораблей, в качестве квалифицированной рабочей силы и в качестве домашней прислуги. [ 18 ] Первые порабощенные африканцы, отправленные в английские колонии, были классифицированы как наемные слуги с правовым статусом, аналогичным статусу наемных рабочих, прибывших из Великобритании и Ирландии. Однако к середине 17 века рабство закрепилось как расовая каста: африканские рабы и их будущие потомки по закону были собственностью их владельцев, поскольку дети, рожденные от матерей-рабынь, также были рабами ( partus sequitur ventrem ). В качестве собственности люди считались товаром или единицей труда и продавались на рынках вместе с другими товарами и услугами. [ 19 ]

Основными странами работорговли в Атлантике, в порядке объема торговли, были Португалия , Великобритания , Испания , Франция , Нидерланды , США и Дания . Некоторые из них основали аванпосты на африканском побережье, где покупали рабов у местных африканских лидеров. [ 20 ] Этими рабами управляла компания , основанная на побережье или вблизи него для ускорения доставки рабов в Новый Свет. Рабы были заключены в тюрьму на фабрике в ожидании отправки. По текущим оценкам, за 400 лет через Атлантику было переправлено от 12 до 12,8 миллионов африканцев. [ 21 ] [ 22 ] Число, купленное торговцами, было значительно выше, поскольку во время путешествия был высокий уровень смертности: от 1,2 до 2,4 миллиона человек умерли во время путешествия, а еще миллионы - в лагерях для приправ на Карибах после прибытия в Новый Свет. Миллионы людей также погибли в результате набегов рабов, войн и при транспортировке на побережье для продажи европейским работорговцам. [ 23 ] [ 24 ] [ 25 ] [ 26 ] Ближе к началу 19 века различные правительства запретили торговлю, хотя незаконная контрабанда все еще имела место. Обычно считалось, что трансатлантическая работорговля закончилась в 1867 году, но позже были обнаружены доказательства плаваний до 1873 года. [ 27 ] В начале 21 века несколько правительств извинились за трансатлантическую работорговлю.

Фон

Атлантическое путешествие

Атлантическая работорговля получила развитие после установления торговых контактов между « Старым Светом » ( Афро-Евразией ) и « Новым Светом » (Америкой). На протяжении веков приливные течения делали путешествия по океану особенно трудными и рискованными для кораблей, которые тогда были доступны. Таким образом, между народами, живущими на этих континентах, было очень мало морских контактов, если они вообще были. [ 28 ] Однако в 15 веке новые европейские разработки в области морских технологий, такие как изобретение каравеллы , привели к тому, что корабли были лучше оснащены для борьбы с приливными течениями и смогли начать пересекать Атлантический океан; португальцы основали Школу мореплавателей (хотя существует много споров о том, существовала ли она и если существовала, то что именно). Между 1600 и 1800 годами Западную Африку посетило около 300 000 моряков, занимавшихся работорговлей. [ 29 ] При этом они вступили в контакт с обществами, живущими вдоль побережья Западной Африки и в Америке, с которыми они никогда раньше не сталкивались. [ 30 ] Историк Пьер Шоню назвал последствия европейского мореплавания «разлучением», поскольку оно знаменует собой конец изоляции для некоторых обществ и увеличение межобщественных контактов для большинства других. [ 31 ] [ 32 ]

Историк Джон Торнтон отметил: «Ряд технических и географических факторов в совокупности сделали европейцев наиболее вероятными людьми для исследования Атлантики и развития ее торговли». [ 33 ] Он определил это как стремление найти новые и прибыльные коммерческие возможности за пределами Европы. Кроме того, существовало желание создать торговую сеть, альтернативную той, которая контролировалась мусульманской Османской империей Ближнего Востока, что рассматривалось как коммерческая, политическая и религиозная угроза европейскому христианскому миру. В частности, европейские торговцы хотели торговать золотом, которое можно было найти в Западной Африке, и найти морской путь в «Индию» (Индию), где они могли бы торговать предметами роскоши, такими как специи, без необходимости приобретать эти предметы. от ближневосточных исламских торговцев. [ 34 ]

Во время первой волны европейской колонизации , хотя многие первоначальные военно-морские исследования Атлантики проводились под руководством иберийских конкистадоров , в них были задействованы представители многих европейских национальностей, в том числе моряки из Испании , Португалии , Франции , Англии , итальянских государств и Нидерландов . Это разнообразие побудило Торнтона охарактеризовать первоначальное «исследование Атлантики» как «поистине международное мероприятие, даже несмотря на то, что многие драматические открытия были сделаны при поддержке иберийских монархов». Это руководство позже породило миф о том, что «иберийцы были единственными лидерами исследований». [ 36 ]

Европейская заморская экспансия привела к контакту между Старым и Новым Светом, в результате чего образовалась Колумбийская биржа , названная в честь итальянского исследователя Христофора Колумба . [ 37 ] Это положило начало мировой торговле серебром с 16 по 18 века и привело к прямому участию Европы в торговле китайским фарфором . Он включал в себя передачу товаров, уникальных для одного полушария, в другое. Европейцы завезли в Новый Свет крупный рогатый скот, лошадей и овец, а из Нового Света европейцы получили табак, картофель, помидоры и кукурузу. Другими предметами и товарами, которые стали важными в мировой торговле, были табак, сахарный тростник и хлопок из Америки, а также золото и серебро, привезенные с американского континента не только в Европу, но и в другие места Старого Света. [ 38 ] [ 39 ] [ 40 ] [ 41 ]

Европейское рабство в Португалии и Испании

К 15 веку рабство существовало на Пиренейском полуострове (Португалия и Испания) в Западной Европе на протяжении всей зарегистрированной истории. Римская империя установила свою систему рабства еще в древние времена. Историк Бенджамин Исаак предполагает, что проторасизм существовал в древние времена среди греко-римских народов . Расовые предрассудки были основаны на дегуманизации иностранных народов, завоеванных ими в ходе войны. [ 42 ] [ 43 ] [ 44 ] После падения Западной Римской империи различные системы рабства продолжались в последующих исламских и христианских королевствах полуострова до начала современной эпохи работорговли в Атлантике. [ 45 ] [ нужна страница ] [ 46 ] В 1441–1444 португальские торговцы впервые захватили африканцев на атлантическом побережье Африки (на территории нынешней Мавритании ), увезли их пленников в рабство в Европу, и основали форт для работорговли в заливе Арген . [ 47 ]

В средние века религия, а не раса, была определяющим фактором в определении того, кто считался законной целью рабства. Хотя христиане не порабощали христиан, а мусульмане не порабощали мусульман, оба допускали порабощение людей, которых они считали еретиками или недостаточно правильными в своей религии, что позволяло христианам-католикам порабощать православных христиан, а мусульманам-суннитам порабощать мусульман-шиитов; [ 48 ] аналогичным образом и христиане, и мусульмане одобряли порабощение язычников , которые стали предпочтительной и сравнительно прибыльной целью работорговли в средние века: [ 48 ] Испания и Португалия получали рабов-некатоликов из Восточной Европы через балканскую работорговлю и работорговлю на Черном море . [ 49 ]

В 15 веке, когда работорговля на Балканах перешла под контроль Османской империи. [ 50 ] а черноморская работорговля была вытеснена крымской работорговлей и закрыта от Европы, Испания и Португалия заменили этот источник рабов импортом рабов сначала с завоеванных Канарских островов , а затем из материковой Африки, первоначально от арабских работорговцев через Транс -Сахарская работорговля из Ливии , а затем напрямую с западного побережья Африки через португальские аванпосты, которая переросла в атлантическую работорговлю. [ 51 ] и значительно расширился после основания колоний в Америке в 1492 году. [ 52 ]

В 15 веке Испания приняла расово-дискриминационный закон под названием limpieza de sangre , что переводится как «чистота крови» или «чистота крови», проторасовый закон. Это не позволило людям еврейского и мусульманского происхождения поселиться в Новом Свете. Limpieza de sangre не гарантировала прав евреям и мусульманам, принявшим католицизм . Евреев и мусульман, принявших католицизм, называли соответственно conversos и moriscos . Некоторые евреи и мусульмане обратились в христианство, надеясь, что оно предоставит им права в соответствии с испанскими законами. После «открытия» новых земель за Атлантикой Испания не хотела, чтобы евреи и мусульмане иммигрировали в Америку, потому что испанская корона беспокоилась, что мусульмане и нехристиане могут познакомить коренных американцев с исламом и другими религиями. [ 53 ] Закон также привел к порабощению евреев и мусульман, запретил евреям въезд в страну и поступление на военную службу, в университеты и на другие государственные службы. [ 54 ] [ 55 ] [ 56 ] [ 57 ] [ 58 ] Хотя евреи-конверсос и мусульмане подвергались религиозной и расовой дискриминации, некоторые из них также участвовали в работорговле африканцев. В Лиссабоне в XVI и XVII веках мусульмане, финансируемые еврейскими конверсос, торговали африканцами через пустыню Сахара и порабощали африканцев до и во время атлантической работорговли в Европе и Африке. [ 59 ] В Новой Испании испанцы применили limpieza de sangre к африканцам и коренным американцам и создали расовую кастовую систему, считая их нечистыми, поскольку они не были христианами. [ 60 ] [ 61 ] [ 62 ]

Европейцы порабощали мусульман и людей, исповедующих другие религии, чтобы оправдать их христианизацию. В 1452 году папа Николай V издал папскую буллу Dum Diversas , которая давала королю Португалии право порабощать нехристиан в вечное рабство. Этот пункт включал мусульман в Западной Африке и узаконил работорговлю в рамках католической церкви. В 1454 году папа Николай издал Romanus Pontifex . «Написанный как логическое продолжение Dum Diversas, Romanus Pontifex позволил европейским католическим народам расширить свое господство над «открытыми» землями. Владение нехристианскими землями было бы оправдано наряду с порабощением местных, нехристианских «язычников» в Африка и «Новый Свет». [ 63 ] [ 64 ] [ 65 ] Dum Diversas и Romanus Pontifex, возможно, оказали влияние на создание доктрин, поддерживающих строительство империи. [ 66 ]

В 1493 году « Доктрина первооткрывателей», изданная папой Александром VI , была использована Испанией в качестве оправдания для захвата земель у нехристиан к западу от Азорских островов . В Доктрине Открытия говорилось, что нехристианские земли должны быть захвачены и управляться христианскими народами, а коренные народы (африканцы и коренные американцы ), живущие на их землях, должны обратиться в христианство. [ 67 ] [ 68 ] В 1493 году папа Александр VI издал папскую буллу под названием Inter Caetera , которая давала Испании и Португалии право требовать и колонизировать все нехристианские земли в Америке , а также порабощать коренных американцев и африканцев. [ 69 ] Inter Caetera также урегулировала спор между Португалией и Испанией по поводу этих земель. Декларация включала разделение севера и юга на 100 лиг к западу от островов Зеленого Мыса и давала испанской короне исключительные права путешествовать и торговать к западу от этой линии. [ 70 ] [ 71 ]

В Португалии и Испании люди были порабощены из-за своей религиозной принадлежности, раса не была развитым фактором порабощения людей; тем не менее, к 15 веку европейцы использовали как расу, так и религию в качестве оправдания для порабощения африканцев к югу от Сахары . Увеличение числа порабощенных африканцев из Сенегала произошло на Пиренейском полуострове в 15 веке. По мере того как число сенегальских рабов росло, европейцы разработали новую терминологию, связывающую рабство с цветом кожи. В испанском городе Севилья проживало самое большое африканское население . « Алькакувасский договор 1479 года предоставил торговцам право снабжать испанцев африканцами». [ 73 ]

Кроме того, в 15 веке -доминиканец монах Анний Витербо использовал в своих трудах «Проклятие Хама » из библейской истории порабощения, чтобы объяснить различия между европейцами и африканцами. Анний, который часто писал о «превосходстве христиан над сарацинами », утверждал, что из-за проклятия, наложенного на чернокожих людей , они неизбежно останутся навсегда порабощенными арабами и другими мусульманами . Он писал, что тот факт, что так много африканцев было порабощено даже мусульманами-еретиками, считается доказательством их неполноценности. Посредством этих и других сочинений европейские писатели установили невиданную доселе связь между проклятым народом, Африкой и рабством, что заложило идеологическую основу для оправдания трансатлантической работорговли. [ 74 ] [ 75 ] Термин «раса» использовался англичанами начиная с 16 века и относился к семье, происхождению и породе. Идея расы продолжала развиваться на протяжении веков и использовалась как оправдание продолжения работорговли и расовой дискриминации. [ 76 ] [ 77 ] [ 78 ] [ 79 ]

Африканское рабство

Рабство было распространено во многих частях Африки. [ 80 ] за много столетий до начала работорговли в Атлантике. В статье PBS объясняются различия между африканским рабством и европейским рабством в Америке . «Важно различать европейское рабство и африканское рабство. В большинстве случаев системы рабства в Африке больше напоминали кабальное рабство, поскольку рабы сохраняли некоторые права, а дети, рожденные у рабов, обычно рождались свободными. Рабов можно было освободить от рабства. и присоединиться к семейному клану. Напротив, европейские рабы были движимым имуществом или собственностью, лишенной своих прав. Цикл рабства был вечным; дети рабов по умолчанию также были рабами». [ 10 ]

Миллионы порабощенных людей из некоторых частей Африки были экспортированы в государства Африки, Европы и Азии до европейской колонизации Америки . [ 81 ] [ 82 ] Транссахарская работорговля через Сахару действовала с древности и продолжала действовать вплоть до 20 века; В 652 году халифат Рашидун в Египте ввел ежегодную дань в размере 400 рабов из христианского королевства Мукурия согласно договору Бакт , который должен был действовать на протяжении веков. [ 83 ] Оно поставляло африканцев в рабство в Рашидунский халифат (632–661), Омейядский халифат (661–750), Аббасидский халифат (750–1258) и мамлюкский султанат .

Работорговля в Атлантике была не единственной работорговлей из Африки; как писала Эликия Мбоколо в Le Monde Diplomatique :

Африканский континент лишился человеческих ресурсов всеми возможными путями. Через Сахару, через Красное море, из портов Индийского океана и через Атлантику. Не менее десяти веков рабства на благо мусульманских стран (с девятого по девятнадцатый век)... Четыре миллиона порабощенных людей вывезено через Красное море , еще четыре миллиона [ 84 ] через суахили порты в Индийском океане , возможно, целых девять миллионов по транссахарскому караванному маршруту и от одиннадцати до двадцати миллионов (в зависимости от автора) через Атлантический океан. [ 85 ]

Рабов в кандалах гнали к побережью Судана, Эфиопии и Сомали, помещали на дау и переправляли через Индийский океан в Персидский залив или Аден. Других переправляли через Красное море в Аравию и Аден, выбрасывая за борт больных рабов, или гнали через пустыню Сахару по транссахарскому маршруту работорговли к Нилу, многие из них умирали от холода или опухших ног вдоль реки. способ. [ 86 ]

Однако оценки неточны, что может повлиять на сравнение между различными видами работорговли. По двум приблизительным оценкам ученых, количество африканских рабов, удерживаемых на протяжении двенадцати столетий в мусульманском мире, составляет 11,5 миллионов. [ 87 ] [ нужна страница ] и 14 миллионов, [ 88 ] [ 89 ] в то время как другие оценки указывают на от 12 до 15 миллионов африканских рабов до 20 века. [ 90 ]

По словам Джона К. Торнтона, европейцы обычно покупали порабощенных людей, попавших в плен в ходе эндемичных войн между африканскими государствами. [ 3 ] Некоторые африканцы сделали бизнес на захвате военнопленных или представителей соседних этнических групп и их продаже. [ 91 ] Напоминание об этой практике задокументировано в Дебатах о работорговле в Англии в начале XIX века: «Все старые писатели... сходятся во мнении, что войны ведутся не только с единственной целью заготавливать рабов, но и что они подстрекаемый европейцами с этой целью». [ 92 ] Людей, живущих вокруг реки Нигер, будут переправлять с этих рынков на побережье и продавать в европейских торговых портах в обмен на мушкеты и промышленные товары, такие как ткань или алкоголь. [ 93 ] Европейский спрос на рабов обеспечил новый и более крупный рынок для уже существующей торговли. [ 94 ] В то время как те, кого держали в рабстве в их собственном регионе Африки, могли надеяться на побег, у тех, кого отправили, было мало шансов вернуться на родину. [ 95 ]

Европейская колонизация и рабство в Западной и Центральной Африке

Работорговля африканцами в Атлантическом океане началась в 1441 году двумя португальскими исследователями, Нуну Тристаном и Антониу Гонсалвишем. Тристан и Гонсалвиш отплыли в Мавританию в Западной Африке , похитили двенадцать африканцев, вернулись в Португалию и преподнесли пленных африканцев в качестве подарков принцу Генриху Мореплавателю . К 1460 году ежегодно от семисот до восьмисот африканцев вывозили и ввозили в Португалию. В Португалии взятых африканцев использовали в качестве домашней прислуги. С 1460 по 1500 год переселение африканцев усилилось, поскольку Португалия и Испания построили форты вдоль побережья Западной Африки. К 1500 году Португалия и Испания вывезли около 50 000 тысяч жителей Западной Африки. Африканцы работали домашней прислугой, ремесленниками и фермерами. Других африканцев забрали на работу на сахарные плантации на Азорских островах, Мадейре, [ 98 ] Канарские острова и острова Зеленого Мыса . Европейцы участвовали в порабощении Африки из-за своей потребности в труде, прибыли и религиозных мотивов. [ 99 ] [ 100 ]

Открыв новые земли в ходе морских исследований, европейские колонизаторы вскоре начали мигрировать и селиться на землях за пределами своего родного континента. У берегов Африки европейские мигранты под руководством Королевства вторглись Кастилия и колонизировали Канарские острова в 15 веке, где они превратили большую часть земель для производства вина и сахара. Наряду с этим они также захватили коренных жителей Канарских островов, гуанчей , для использования в качестве рабов как на островах, так и по всему христианскому Средиземноморью. [ 101 ]

За успехом Португалии и Испании в работорговле последовали и другие европейские страны. В 1530 году английский купец из Плимута Уильям Хокинс посетил побережье Гвинеи и уехал с несколькими рабами. В 1564 году сын Хокинса Джон Хокинс отплыл к побережью Гвинеи, и его путешествие было поддержано королевой Елизаветой I. Позже Джон обратился к пиратству и похитил 300 африканцев с испанского невольничьего корабля после неудачных попыток захватить африканцев в Гвинее, поскольку большинство его людей погибли после боев с местными африканцами. [ 100 ]

Как заметил историк Джон Торнтон, «действительная мотивация европейской экспансии и навигационных прорывов заключалась не более чем в использовании возможности немедленной прибыли, полученной за счет набегов и захвата или покупки торговых товаров». [ 105 ] Используя Канарские острова в качестве военно-морской базы, европейцы, в то время в основном португальские торговцы, начали перемещать свою деятельность вдоль западного побережья Африки, совершая набеги, в ходе которых захватывали рабов для последующей продажи в Средиземноморье. [ 106 ] Хотя поначалу это предприятие было успешным, «вскоре африканские военно-морские силы были предупреждены о новых опасностях, и португальские [совершающие набеги] корабли начали встречать сильное и эффективное сопротивление», причем экипажи некоторых из них были убиты африканцами. моряки, чьи лодки были лучше оснащены для пересечения западно-центральноафриканских побережий и речных систем. [ 107 ]

К 1494 году португальский король заключил соглашения с правителями нескольких западноафриканских государств, которые разрешали торговлю между их соответствующими народами, что позволило португальцам «подключиться» к «хорошо развитой торговой экономике Африки… не участвуя в военных действиях». ". [ 108 ] «Мирная торговля стала правилом на всем африканском побережье», хотя были и редкие исключения, когда акты агрессии приводили к насилию. Например, португальские торговцы пытались завоевать острова Биссагос в 1535 году. [ 109 ] В 1571 году Португалия при поддержке Королевства Конго взяла под свой контроль юго-западный регион Анголы , чтобы защитить свои экономические интересы в этом районе. Хотя Конго позже присоединился к коалиции в 1591 году, чтобы вытеснить португальцев, Португалия закрепилась на континенте, который она продолжала оккупировать до 20 века. [ 110 ] Несмотря на эти случайные случаи насилия между африканскими и европейскими силами, многие африканские государства следили за тем, чтобы любая торговля велась на их собственных условиях, например, вводя таможенные пошлины на иностранные суда. В 1525 году конголезский король Афонсу I захватил французское судно и его команду за незаконную торговлю на своем побережье. Кроме того, Афонсу пожаловался королю Португалии, что португальские работорговцы продолжают похищать его народ, что приводит к депопуляции в его королевстве. [ 111 ] [ 109 ] Королева Нзинга (Нзинга Мбанде) боролась против распространения португальской работорговли на земли народа Мбунду в Центральной Африке в 1620-х годах. Португальцы вторглись на земли Мбунду, чтобы расширить свою миссию по торговле рабами и созданию поселений. армию под названием « киломбо» Нзинга предоставила убежище беглым рабам в своей стране и организовала против португальцев . Нзинга заключил союзы с другими соперничающими африканскими странами и возглавил армию против португальских работорговцев в тридцатилетней войне. [ 112 ] [ 113 ] [ 114 ]

Историки широко обсуждают характер отношений между этими африканскими королевствами и европейскими торговцами. Гайанский историк Уолтер Родни (1972) утверждал, что это были неравные отношения, когда африканцев вынуждали вести «колониальную» торговлю с более экономически развитыми европейцами, обменивая сырье и человеческие ресурсы (т.е. рабов) на промышленные товары. Он утверждал, что именно это торгово-экономическое соглашение, заключенное в 16 веке, привело к тому, что Африка в его время была слаборазвитой. [ 115 ] Эти идеи были поддержаны другими историками, в том числе Ральфом Остином (1987). [ 116 ] Эта идея неравных отношений была оспорена Джоном Торнтоном (1998), который утверждал, что «работорговля в Атлантике была далеко не так важна для африканской экономики, как считали эти ученые» и что «африканское производство [в этот период] было более чем способный выдержать конкуренцию со стороны доиндустриальной Европы». [ 117 ] Однако Энн Бейли, комментируя предположение Торнтона о том, что африканцы и европейцы были равными партнерами в атлантической работорговле, писала:

[T]o рассматривать африканцев как партнеров подразумевает равные условия и равное влияние на глобальные и межконтинентальные торговые процессы. Африканцы имели большое влияние на самом континенте, но они не имели прямого влияния на движущие силы торговли в капитальных фирмах, судоходных и страховых компаниях Европы и Америки или плантационных системах в Америке. Никакого влияния на строительство промышленных центров Запада они не имели. [ 118 ]

Африканские движения сопротивления против работорговли в Атлантике

Иногда торговля между европейцами и африканскими лидерами не была равноправной. Например, европейцы оказали влияние на африканцев, чтобы они предоставили больше рабов, сформировав военные союзы с воюющими африканскими обществами, чтобы спровоцировать новые боевые действия, которые предоставили бы африканским правителям больше военных пленников для торговли в качестве рабов на европейские потребительские товары. Кроме того, европейцы сместили расположение пунктов высадки для торговли вдоль африканского побережья, чтобы следить за военными конфликтами в Западной и Центральной Африке. В районах Африки, где рабство не было распространено, европейские работорговцы работали и вели переговоры с африканскими правителями об условиях торговли, а африканские правители отказывались удовлетворять европейские требования. Африканцы и европейцы получали прибыль от работорговли; однако африканское население, социальные, политические и военные изменения в африканских обществах сильно пострадали. Например, Mossi Kingdoms сопротивлялись работорговле в Атлантике и отказывались участвовать в продаже африканцев. Однако с течением времени все больше европейских работорговцев проникали в Западную Африку и имели большее влияние в африканских странах, и в 1800-х годах мосси стали участвовать в работорговле. [ 119 ] [ 120 ]

Хотя были африканские страны, которые участвовали и получали прибыль от работорговли в Атлантике, многие африканские страны сопротивлялись, такие как Джола и Баланта . [ 121 ] Некоторые африканские страны организовались в движения военного сопротивления и боролись с африканскими налетчиками рабов и европейскими работорговцами, проникавшими в их деревни. Например, народы Акан , Эци, Фету, Эгуафо, Агона и Асебу организовались в коалицию Фанте и боролись с африканскими и европейскими налетчиками рабов и защищали себя от захвата и порабощения. [ 122 ] Вождь Томба родился в 1700 году, а его приемный отец был генералом из народа, говорящего на ялонке, и боролся против работорговли. Томба стал правителем народа бага на территории современной Гвинеи-Бисау в Западной Африке и заключил союзы с близлежащими африканскими деревнями против африканских и европейских работорговцев. Его усилия не увенчались успехом: Томба был захвачен африканскими торговцами и продан в рабство. [ 123 ]

Король Дагомеи Агаджа с 1718 по 1740 год выступал против работорговли в Атлантике, отказывался продавать африканцев и нападал на европейские форты, построенные вдоль невольничьего побережья в Западной Африке. Донна Беатрис Кимпа Вита из Конго и лидер Сенегала Абд аль-Кадир выступали за сопротивление принудительному вывозу африканцев. [ 124 ] В 1770-х годах лидер Абдул Кадер Хан выступал против работорговли в Атлантике через Фута Торо , современный Сенегал . Абдул Кадер Хан и нация Фута Торо сопротивлялись французским работорговцам и колонизаторам, которые хотели поработить африканцев и мусульман из Фута Торо. [ 125 ] Другие формы сопротивления африканской работорговле в Атлантике заключались в миграции в различные районы Западной Африки, такие как болота и озерные регионы, чтобы избежать набегов рабов. В Западной Африке работорговцы Эфик участвовали в работорговле как форме защиты от порабощения. [ 126 ] Африканские движения сопротивления осуществлялись на каждом этапе работорговли: марши сопротивления к станциям содержания рабов, сопротивление на невольничьем побережье и сопротивление на невольничьих кораблях. [ 127 ]

Например, на борту невольничьего корабля «Клэр» порабощенные африканцы восстали, изгнали команду с судна, взяли под свой контроль корабль, освободились и высадились возле замка Кейп-Кост на территории современной Ганы в 1729 году. На других невольничьих кораблях затонули порабощенные африканцы. корабли, убили экипаж и подожгли корабли взрывчаткой. Работорговцы и белые члены экипажа готовили и предотвращали возможные восстания, загружая женщин, мужчин и детей отдельно на невольничьи корабли, поскольку порабощенные дети использовали куски дерева, инструменты и любые предметы, которые они находили, и передавали их мужчинам, чтобы освободиться и сражаться с экипаж. Согласно историческим исследованиям, основанным на записях капитанов невольничьих кораблей, в период с 1698 по 1807 год на борту невольничьих кораблей произошло 353 акта восстания. Большинство восстаний африканцев было подавлено. Рабы игбо на кораблях покончили жизнь самоубийством, прыгнув за борт в знак сопротивления порабощению. Чтобы предотвратить дальнейшие самоубийства, белые члены экипажа расставляли сети вокруг невольничьих кораблей, чтобы ловить порабощенных людей, прыгнувших за борт. Белые капитаны и члены экипажа инвестировали в огнестрельное оружие, поворотные пушки и приказал экипажам кораблей следить за рабами, чтобы предотвратить или подготовиться к возможным восстаниям рабов. [ 129 ] Джон Ньютон был капитаном невольничьих кораблей и записывал в своем личном дневнике, как африканцы взбунтовались на кораблях, а некоторым удалось захватить команду. [ 130 ] [ 131 ] Например, в 1730 году невольничий корабль « Маленький Джордж» отбыл от побережья Гвинеи по пути в Род-Айленд с грузом, состоящим из девяноста шести порабощенных африканцев. Несколько рабов вырвались из железных цепей и убили троих сторожей на палубе, а капитана и остальную команду заключили в тюрьму. Капитан и команда заключили сделку с африканцами и пообещали им свободу. Африканцы взяли под свой контроль корабль и поплыли обратно к берегу Африки. Капитан и его команда пытались снова поработить африканцев, но безуспешно. [ 132 ]

16, 17 и 18 века

Работорговлю в Атлантике обычно делят на две эпохи, известные как первая и вторая атлантические системы. Чуть более 3% порабощенных людей, вывезенных из Африки, были проданы в период с 1525 по 1600 год, а в 17 веке - 16%. [ нужна ссылка ]

Первой атлантической системой была торговля порабощенными африканцами, прежде всего, с американскими колониями Португальской и Испанской империй. До 1520-х годов работорговцы вывозили африканцев в Севилью или на Канарские острова , а затем вывозили некоторых из них из Испании в ее колонии в Эспаньоле и Пуэрто-Рико, поставляя от 1 до 40 рабов на корабль. Они дополняли порабощенных коренных американцев. В 1518 году испанский король дал разрешение кораблям идти напрямую из Африки в карибские колонии, и за рейс они стали брать по 200-300 кораблей. [ 133 ] [ нужен лучший источник ]

Во времена первой Атлантической системы большинство этих работорговцев были португальцами, что давало им почти монополию. Решающим стал Тордесильясский договор 1494 года , который не позволял испанским кораблям заходить в африканские порты. Испании пришлось полагаться на португальские корабли и моряков, чтобы переправлять рабов через Атлантику. С 1525 года рабов переправляли напрямую из португальской колонии Сан-Томе через Атлантику на Эспаньолу . [ 134 ]

Могильник в Кампече , Мексика, предполагает, что порабощенные африканцы были доставлены туда вскоре после того, как Эрнан Кортес завершил покорение Мексики ацтеков и майя в 1519 году. Кладбище использовалось примерно с 1550 года до конца 17 века. [ 135 ]

В 1562 году Джон Хокинс захватил африканцев на территории нынешней Сьерра-Леоне и вывез 300 человек на продажу в Карибское море. В 1564 году он повторил этот процесс, на этот раз используя собственный корабль королевы Елизаветы « Хесус из Любека» , и последовали многочисленные английские путешествия. [ 136 ]

Около 1560 года португальцы начали регулярную работорговлю в Бразилию. С 1580 по 1640 год Португалия была временно объединена с Испанией в Пиренейский союз . Большинство португальских подрядчиков, получивших asiento между 1580 и 1640 годами, были conversos . [ 137 ] [ нужна страница ] Для португальских купцов, многие из которых были « новыми христианами » или их потомками, союз корон открыл коммерческие возможности в работорговле с Испанской Америкой. [ 138 ] [ 139 ] [ нужна страница ]

До середины 17 века Мексика была крупнейшим рынком рабов в Испанской Америке. [ 140 ] В то время как португальцы непосредственно участвовали в торговле порабощенными народами с Бразилией, Испанская империя полагалась на систему Asiento de Negros , предоставляя (католическим) генуэзским торговым банкирам лицензию на торговлю порабощенными людьми из Африки в их колонии в Испанской Америке . Картахена, Веракрус, Буэнос-Айрес и Эспаньола приняли большинство рабов, прибывших, в основном из Анголы. [ 141 ] Это разделение работорговли между Испанией и Португалией расстроило британцев и голландцев, которые инвестировали в Британскую Вест-Индию и голландскую Бразилию, производящие сахар. После распада Пиренейского союза Испания запретила Португалии напрямую участвовать в работорговле в качестве перевозчика. Согласно Мюнстерскому договору, работорговля была открыта для традиционных врагов Испании, в результате чего большая часть торговли была уступлена голландцам, французам и англичанам. В течение 150 лет испанские трансатлантические перевозки осуществлялись на незначительном уровне. За многие годы ни одно испанское рабское путешествие не отправилось из Африки. В отличие от всех своих имперских конкурентов, испанцы почти никогда не доставляли рабов на чужие территории. Напротив, британцы, а до них голландцы, продавали рабов повсюду в Америке. [ 142 ]

Вторая атлантическая система заключалась в торговле порабощенными африканцами преимущественно английскими, французскими и голландскими торговцами и инвесторами. [ 143 ] Основными пунктами назначения на этом этапе были карибские острова Кюрасао , Ямайка и Мартиника , поскольку европейские страны создавали экономически зависимые от рабов колонии в Новом Свете. [ 144 ] [ нужна страница ] [ 145 ] В 1672 году Королевская африканская компания была основана . В 1674 году Новая Вест-Индская компания стала более активно заниматься работорговлей. [ 146 ] С 1677 года компания Compagnie du Sénegal использовала Горе для размещения рабов . Испанцы предлагали получить рабов из Кабо-Верде , расположенного ближе к линии разграничения между Испанской и Португальской империями, но это противоречило уставу WIC». [ 147 ] Королевская африканская компания обычно отказывалась доставлять рабов в испанские колонии, хотя и продавала их всем желающим со своих фабрик в Кингстоне, Ямайка , и Бриджтауне, Барбадос . [ 148 ] В 1682 году Испания разрешила губернаторам Гаваны, Порто-Белло, Панамы и Картахены, Колумбия, закупать рабов с Ямайки. [ 149 ]

К 1690-м годам англичане вывозили большую часть рабов из Западной Африки. [ 150 ] К 18 веку португальская Ангола снова стала одним из основных источников работорговли в Атлантике. [ 151 ] После окончания Войны за испанское наследство , в рамках положений Утрехтского договора (1713 г.) , Asiento был передан Компании Южных морей . [ 152 ] Несмотря на « пузырь в Южных морях» , британцы сохраняли эту позицию в XVIII веке, став крупнейшими грузоотправителями рабов через Атлантику. [ 153 ] [ 154 ] Подсчитано, что более половины всей работорговли приходилось на 18 век, причем португальцы, британцы и французы были основными носителями девяти из десяти рабов, похищенных в Африке. [ 155 ] В то время работорговля считалась решающим фактором для морской экономики Европы, как заметил один английский работорговец: «Какая это славная и выгодная торговля… Это стержень, на котором движется вся торговля на этом земном шаре». [ 156 ] [ 157 ]

Между тем, это стало бизнесом для частных предприятий , что уменьшило международные осложнения. [ 140 ] Напротив, после 1790 года капитаны обычно проверяли цены на рабов по крайней мере на двух крупных рынках — Кингстоне, Гаване и Чарльстоне, Южная Каролина (где цены к тому времени были одинаковыми), прежде чем решить, где продать. [ 158 ] В течение последних шестнадцати лет трансатлантической работорговли Испания была единственной трансатлантической империей работорговли. [ 159 ]

После принятия Закона о британской работорговле 1807 года и запрета США на африканскую работорговлю в том же году она снизилась, но в последующий период все еще приходилось 28,5% от общего объема работорговли в Атлантике. [ 160 ] [ нужна страница ] Между 1810 и 1860 годами было перевезено более 3,5 миллионов рабов, из них 850 000 - в 1820-е годы. [ 161 ]

Треугольная торговля

Первой стороной треугольника был экспорт товаров из Европы в Африку. Ряд африканских королей и купцов принимали участие в торговле порабощенными людьми с 1440 по 1833 год. За каждого пленника африканские правители получали разнообразные товары из Европы. В их число входили оружие, боеприпасы, алкоголь, индийский текстиль, окрашенный в цвет индиго , и другие товары фабричного производства. [ 162 ] Вторая часть треугольника экспортировала порабощенных африканцев через Атлантический океан в Америку и на Карибские острова. Третьей и последней частью треугольника был возврат товаров в Европу из Америки. Товары представляли собой продукцию рабских плантаций и включали хлопок, сахар, табак, патоку и ром. [ 163 ] Сэр Джон Хокинс , считающийся пионером английской работорговли, был первым, кто запустил трехстороннюю торговлю, получая прибыль на каждой остановке. [ 164 ]

Труд и рабство

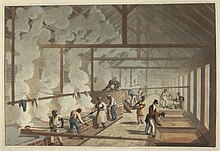

Работорговля в Атлантике была результатом, среди прочего, нехватки рабочей силы , которая, в свою очередь, была вызвана желанием европейских колонистов эксплуатировать земли и ресурсы Нового Света для получения капитальных прибылей. Коренные народы сначала использовались европейцами в качестве рабского труда, пока большое их количество не умерло от переутомления и болезней Старого Света . [ 165 ] Кроме того, в середине 16 века испанские Новые законы запретили рабство коренных народов. Возникла нехватка рабочей силы. Альтернативные источники рабочей силы, такие как подневольное рабство , не смогли обеспечить достаточную рабочую силу. Многие культуры невозможно было продать с целью получения прибыли или даже вырастить в Европе. Экспорт урожая и товаров из Нового Света в Европу часто оказывался более выгодным, чем производство их на материковой части Европы. Огромное количество рабочей силы было необходимо для создания и поддержания плантаций, которые требовали интенсивного труда для выращивания, сбора и переработки ценных тропических культур. Западная Африка (часть которой стала известна как « Невольничий берег »), Ангола и близлежащие королевства, а затем и Центральная Африка , стали источником порабощенных людей для удовлетворения спроса на рабочую силу. [ 166 ]

Основная причина постоянной нехватки рабочей силы заключалась в том, что при наличии большого количества дешевой земли и многих землевладельцев, ищущих рабочую силу, свободные европейские иммигранты смогли относительно быстро сами стать землевладельцами, тем самым увеличивая потребность в рабочей силе. [ 167 ] Нехватку рабочей силы в основном восполняли англичане, французы и португальцы с помощью африканского рабского труда.

Томас Джефферсон отчасти объяснял использование рабского труда климатом и, как следствие, праздным досугом, обеспечиваемым рабским трудом: «Ибо в теплом климате ни один человек не будет работать на себя, если он может выполнить для него другой труд. что из владельцев рабов действительно очень небольшая часть когда-либо работала». [ 168 ] В статье 2015 года экономист Елена Эспозито утверждала, что порабощение африканцев в колониальной Америке было связано с тем фактом, что американский юг был достаточно теплым и влажным для распространения малярии; болезнь оказала изнурительное воздействие на европейских поселенцев. И наоборот, многие порабощенные африканцы были вывезены из регионов Африки, где были распространены особенно сильные штаммы болезни, поэтому африканцы уже выработали естественную устойчивость к малярии. Это, как утверждал Эспозито, привело к более высокому уровню выживаемости от малярии на юге Америки среди порабощенных африканцев, чем среди европейских рабочих, что сделало их более прибыльным источником рабочей силы и поощряло их использование. [ 169 ]

Историк Дэвид Элтис утверждает, что африканцы были порабощены из-за культурных верований в Европе, которые запрещали порабощение представителей культуры, даже если существовал источник рабочей силы, которую можно было поработить (например, осужденные, военнопленные и бродяги). Элтис утверждает, что в Европе существовали традиционные убеждения против порабощения христиан (немногие европейцы не были христианами в то время), и те рабы, которые существовали в Европе, как правило, были нехристианами и их непосредственными потомками (поскольку обращение раба в христианство не гарантировало эмансипацию). и, таким образом, к XV веку европейцев в целом стали считать инсайдерами. Элтис утверждает, что, хотя все рабовладельческие общества разделяли своих и чужих, европейцы пошли дальше, распространив статус инсайдера на весь европейский континент, что сделало немыслимым порабощение европейца, поскольку для этого потребовалось бы порабощение инсайдера. И наоборот, африканцы рассматривались как чужаки и, таким образом, имели право на порабощение. Хотя европейцы, возможно, относились к некоторым видам труда, таким как труд заключенных, с условиями, аналогичными условиям рабов, эти рабочие не считались движимым имуществом, а их потомство не могло унаследовать их подчиненный статус, что не делало их рабами в глазах Европейцы. Таким образом, статус рабства движимого имущества распространялся только на неевропейцев, например африканцев. [ 170 ]

Для британцев рабы были не более чем животными, и с ними можно было обращаться как с товаром, поэтому такие ситуации, как резня в Цзун, происходили без какой-либо справедливости для жертв. [ 171 ]

Участие Африки в работорговле

Африканские партнеры, в том числе правители, торговцы и военные аристократы, играли непосредственную роль в работорговле. Они продавали рабов, приобретенных в результате войн или похищений, европейцам или их агентам. [ 84 ] Проданные в рабство обычно были представителями другой этнической группы, чем те, кто их захватил, будь то враги или просто соседи. [ 119 ] Эти пленные рабы считались «другими», а не частью народа этноса или «племени»; Африканские короли были заинтересованы только в защите своей собственной этнической группы, но иногда преступников продавали, чтобы избавиться от них. Большинство других рабов были получены в результате похищений людей или в результате набегов, совершавшихся под дулом пистолета через совместные предприятия с европейцами. [ 84 ] [ 172 ] Королевство Дагомея поставляло военнопленных европейским работорговцам. [ 173 ]

По словам Пернилле Ипсен, автора книги «Дочери торговли: атлантические работорговцы и межрасовые браки на Золотом Берегу», африканцы с Золотого Берега (современная Гана) также участвовали в работорговле посредством смешанных браков, или кассаре (взято из итальянского, испанского или португальский), что означает «построить дом». Оно происходит от португальского слова «casar» , что означает «жениться». Кассаре сформировал политические и экономические связи между европейскими и африканскими работорговцами. Кассаре был доевропейской контактной практикой, использовавшейся для интеграции «других» из другого африканского племени. На заре работорговли в Атлантике влиятельные элитные западноафриканские семьи обычно выдавали своих женщин замуж за европейских торговцев, вступивших в союз, тем самым укрепляя свой синдикат. Браки даже заключались по африканским обычаям, против чего европейцы не возражали, видя, насколько важны связи. [ 174 ]

Осведомленность Африки об условиях работорговли

Трудно реконструировать и обобщить то, как африканцы, проживающие в Африке, понимали работорговлю в Атлантике, хотя в некоторых обществах есть свидетельства того, что африканская элита и работорговцы знали об условиях рабов, которых переправляли в Америку. [ 175 ] [ 176 ] По мнению Робина Лоу, королевская элита королевства Дагомея должна была иметь «осведомленное понимание» судеб африканцев, которых они продали в рабство. [ 175 ] Дагомея отправила дипломатов в Бразилию и Португалию, которые вернулись с информацией о своих поездках. [ 175 ] Кроме того, несколько представителей королевской элиты Дагомеи испытали на себе рабство в Америке, прежде чем вернуться на родину. [ 175 ] Единственной очевидной моральной проблемой, с которой королевство столкнулось в связи с рабством, было порабощение собратьев-дагомейцев, преступление, караемое смертью, а не сам институт рабства. [ 175 ]

На Золотом Берегу африканские правители-работорговцы обычно поощряли своих детей узнавать о европейцах, отправляя их плавать на европейских кораблях, жить в европейских фортах или путешествовать в Европу или Америку для получения образования. [ 177 ] Дипломаты также посетили европейские столицы. Элиты даже спасли своих собратьев, которых обманом заманили в рабство в Америке, отправив требования голландскому и британскому правительствам, которые выполнили их из-за опасений сокращения торговли и физического вреда заложникам. [ 177 ] Примером может служить случай Уильяма Ансы Сессараку , который был спасен из рабства на Барбадосе после того, как его узнал приезжий работорговец той же этнической группы фанте, а позже сам стал работорговцем. [ 178 ]

Фенда Лоуренс была работорговцем из Гамбии , которая жила и торговала в Джорджии и Южной Каролине как свободный человек. [ 179 ]

Африканцы, которые не знали об истинной цели работорговли в Атлантике, обычно предполагали, что европейцы были каннибалами, которые планировали приготовить и съесть своих пленников. [ 180 ] Этот слух был частым источником серьезных страданий для порабощенных африканцев. [ 180 ]

Европейское участие в работорговле

Европейцы обеспечивали рынок рабов, редко выезжая за пределы побережья или проникая во внутренние районы Африки из-за страха перед болезнями и местного сопротивления. [ 181 ] Обычно они проживали в крепостях на побережье, где ждали, пока африканцы предоставят им захваченных рабов из внутренних районов в обмен на товары. Случаи, когда европейские купцы похищали свободных африканцев в рабство, часто приводили к жестоким возмездиям со стороны африканцев, которые могли на мгновение остановить торговлю и даже захватить или убить европейцев. [ 182 ] Европейцы, желавшие безопасной и бесперебойной торговли, стремились предотвратить случаи похищения людей, а британцы приняли «Акты парламента о регулировании работорговли» в 1750 году, которые объявили вне закона похищение свободных африканцев путем «мошенничества, силы или насилия». [ 182 ] По словам источника из цифровой библиотеки Лоукантри в Чарльстонском колледже , «когда португальцы, а позже и их европейские конкуренты, обнаружили, что сами по себе мирные коммерческие отношения не привели к появлению достаточного количества порабощенных африканцев, чтобы удовлетворить растущие потребности трансатлантической работорговли, они заключили военные союзы с некоторыми африканскими группами против своих врагов. Это способствовало более масштабным войнам с целью привлечения пленников для торговли». [ 183 ]

В 1778 году Томас Китчин подсчитал, что европейцы ежегодно привозят в Карибский бассейн около 52 000 рабов, при этом французы привозят больше всего африканцев во Французскую Вест-Индию (13 000 из ежегодной оценки). [ 184 ] Пик работорговли в Атлантике пришелся на последние два десятилетия XVIII века. [ 185 ] во время и после гражданской войны в Конго . [ 186 ] Войны между крошечными государствами вдоль реки Нигер, населенными игбо , и сопровождающий их бандитизм также резко возросли в этот период. [ 91 ] Другой причиной избыточного предложения порабощенных людей были крупные войны, которые вели расширяющиеся государства, такие как Королевство Дагомея . [ 187 ] Империя Ойо и Империя Ашанти . [ 188 ]

Рабство в Африке и Новом Свете в сравнении

Forms of slavery varied both in Africa and in the New World. In general, slavery in Africa was not heritable—that is, the children of slaves were free—while in the Americas, children of slave mothers were considered born into slavery. This was connected to another distinction: slavery in West Africa was not reserved for racial or religious minorities, as it was in European colonies, although the case was otherwise in places such as Somalia, where Bantus were taken as slaves for the ethnic Somalis.[189][190]

The treatment of slaves in Africa was more variable than in the Americas. At one extreme, the kings of Dahomey routinely slaughtered slaves in hundreds or thousands in sacrificial rituals, and slaves as human sacrifices were also known in Cameroon.[191][192] On the other hand, slaves in other places were often treated as part of the family, "adopted children", with significant rights including the right to marry without their masters' permission.[193] Scottish explorer Mungo Park wrote:

The slaves in Africa, I suppose, are nearly in the proportion of three to one to the freemen. They claim no reward for their services except food and clothing, and are treated with kindness or severity, according to the good or bad disposition of their masters ... The slaves which are thus brought from the interior may be divided into two distinct classes—first, such as were slaves from their birth, having been born of enslaved mothers; secondly, such as were born free, but who afterwards, by whatever means, became slaves. Those of the first description are by far the most numerous ...[194]

In the Americas, slaves were denied the right to marry freely and masters did not generally accept them as equal members of the family. New World slaves were considered the property of their owners, and slaves convicted of revolt or murder were executed.[195]

Slave market regions and participation

Europeans would buy and ship slaves to the Western Hemisphere from markets across West Africa. The number of enslaved people sold to the New World varied throughout the slave trade. As for the distribution of slaves from regions of activity, certain areas produced far more enslaved people than others. Between 1650 and 1900, 10.2 million enslaved Africans arrived in the Americas from the following regions in the following proportions:[196][page needed]

- Senegambia (Senegal and the Gambia): 4.8%

- Upper Guinea (Guinea-Bissau, Guinea and Sierra Leone): 4.1%

- Windward Coast (Liberia and Ivory Coast): 1.8%

- Gold Coast (Ghana and east of Ivory Coast): 10.4%

- Bight of Benin (Togo, Benin and Nigeria west of the Niger Delta): 20.2%

- Bight of Biafra (Nigeria east of the Niger Delta, Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea and Gabon): 14.6%

- West Central Africa (Republic of the Congo, Democratic Republic of the Congo and Angola): 39.4%

- Southeastern Africa (Mozambique and Madagascar): 4.7%

Although the slave trade was largely global, there was considerable intracontinental slave trade in which 8 million people were enslaved within the African continent.[197] Of those who did move out of Africa, 8 million were forced out of Eastern Africa to be sent to Asia.[197]

African kingdoms of the era

There were over 173 city-states and kingdoms in the African regions affected by the slave trade between 1502 and 1853, when Brazil became the last Atlantic import nation to outlaw the slave trade. Of those 173, no fewer than 68 could be deemed nation-states with political and military infrastructures that enabled them to dominate their neighbours. Nearly every present-day nation had a pre-colonial predecessor, sometimes an African empire with which European traders had to barter.

Ethnic groups

The different ethnic groups brought to the Americas closely correspond to the regions of heaviest activity in the slave trade. Over 45 distinct ethnic groups were taken to the Americas during the trade. Of the 45, the ten most prominent, according to slave documentation of the era and modern genealogical studies are listed below.[198][199][200]

- The BaKongo of the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Republic of the Congo and Angola

- The Mandé of Upper Guinea

- The Gbe speakers of Togo, Ghana, and Benin (Fon, Ewe, Adja, Mina)

- The Akan of Ghana and Ivory Coast

- The Wolof of Senegal and the Gambia

- The Igbo of southeastern Nigeria

- The Ambundu of Angola

- The Yoruba of southwestern Nigeria and Benin

- The Tikar and Bamileke of Cameroon

- The Makua of Mozambique

Human toll

| Part of a series on |

| Genocide |

|---|

|

| Issues |

| Related topics |

| Category |

The transatlantic slave trade resulted in a vast and as yet unknown loss of life for African captives both in and outside the Americas. Estimates have ranged from as low as 2 million[201] to as high 60 million.[202] "More than a million people are thought to have died" during their transport to the New World according to a BBC report.[203] More died soon after their arrival. The number of lives lost in the procurement of slaves remains a mystery but may equal or exceed the number who survived to be enslaved.[24]

The trade led to the destruction of individuals and cultures. Historian Ana Lucia Araujo has noted that the process of enslavement did not end with arrival on Western Hemisphere shores; the different paths taken by the individuals and groups who were victims of the Atlantic slave trade were influenced by different factors—including the disembarking region, the ability to be sold on the market, the kind of work performed, gender, age, religion, and language.[204][205]

Patrick Manning estimates that about 12 million slaves entered the Atlantic trade between the 16th and 19th centuries, but about 1.5 million died on board ship. About 10.5 million slaves arrived in the Americas. Besides the slaves who died on the Middle Passage, more Africans likely died during the slave raids and wars in Africa and forced marches to ports. Manning estimates that 4 million died inside Africa after capture, and many more died young. Manning's estimate covers the 12 million who were originally destined for the Atlantic, as well as the 6 million destined for Arabian slave markets and the 8 million destined for African markets.[23] Of the slaves shipped to the Americas, the largest share went to Brazil and the Caribbean.[206]

Canadian scholar Adam Jones characterized the deaths of millions of Africans during the Atlantic slave trade as genocide. He called it "one of the worst holocausts in human history", and claims arguments to the contrary such as "it was in slave owners' interest to keep slaves alive, not exterminate them" to be "mostly sophistry" stating: "the killing and destruction were intentional, whatever the incentives to preserve survivors of the Atlantic passage for labour exploitation. To revisit the issue of intent already touched on: If an institution is deliberately maintained and expanded by discernible agents, though all are aware of the hecatombs of casualties it is inflicting on a definable human group, then why should this not qualify as genocide?"[207]

Saidiya Hartman has argued that the deaths of enslaved people was incidental to the acquisition of profit and to the rise of capitalism: "Death wasn't a goal of its own but just a by-product of commerce, which has the lasting effect of making negligible all the millions of lives lost. Incidental death occurs when life has no normative value, when no humans are involved, when the population is, in effect, seen as already dead."[208] Hartman highlights how the Atlantic slave trade created millions of corpses but, unlike the concentration camp or the gulag, extermination was not the final objective; it was a corollary to the making of commodities.

Destinations and flags of carriers

Most of the Atlantic slave trade was carried out by seven nations and most of the slaves were carried to their own colonies in the new world. But there was also significant other trading which is shown in the table below.[209] The records are not complete, and some data is uncertain. The last rows show that there were also smaller numbers of slaves carried to Europe and to other parts of Africa, and at least 1.8 million did not survive the journey and were buried at sea with little ceremony.

| Destination | Portuguese | British | French | Spanish | Dutch | American | Danish | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Portuguese Brazil | 4,821,127 | 3,804 | 9,402 | 1,033 | 27,702 | 1,174 | 130 | 4,864,372 |

| British Caribbean | 7,919 | 2,208,296 | 22,920 | 5,795 | 6,996 | 64,836 | 1,489 | 2,318,251 |

| French Caribbean | 2,562 | 90,984 | 1,003,905 | 725 | 12,736 | 6,242 | 3,062 | 1,120,216 |

| Spanish Americas | 195,482 | 103,009 | 92,944 | 808,851 | 24,197 | 54,901 | 13,527 | 1,061,524 |

| Dutch Americas | 500 | 32,446 | 5,189 | 0 | 392,022 | 9,574 | 4,998 | 444,729 |

| North America | 382 | 264,910 | 8,877 | 1,851 | 1,212 | 110,532 | 983 | 388,747 |

| Danish West Indies | 0 | 25,594 | 7,782 | 277 | 5,161 | 2,799 | 67,385 | 108,998 |

| Europe | 2,636 | 3,438 | 664 | 0 | 2,004 | 119 | 0 | 8,861 |

| Africa | 69,206 | 841 | 13,282 | 66,391 | 3,210 | 2,476 | 162 | 155,568 |

| did not arrive | 748,452 | 526,121 | 216,439 | 176,601 | 79,096 | 52,673 | 19,304 | 1,818,686 |

| Total | 5,848,266 | 3,259,443 | 1,381,404 | 1,061,524 | 554,336 | 305,326 | 111,040 | 12,521,339 |

The timeline chart when the different nations transported most of their slaves.

The regions of Africa from which these slaves were taken is given in the following table, from the same source.

| Region | Embarked | Disembarked | did not arrive | % did not arrive |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angola Coast, Loango Coast, and Saint Helena | 5,694,570 | 4,955,430 | 739,140 | 12.98% |

| Bight of Benin | 1,999,060 | 1,724,834 | 274,226 | 13.72% |

| Bight of Biafra | 1,594,564 | 1,317,776 | 276,788 | 17.36% |

| Gold Coast | 1,209,322 | 1,030,917 | 178,405 | 14.75% |

| Senegambia and off-shore Atlantic | 755,515 | 611,017 | 144,498 | 19.13% |

| Southeast Africa and Indian Ocean islands | 542,668 | 436,529 | 106,139 | 19.56% |

| Sierra Leone | 388,771 | 338,783 | 49,988 | 12.87% |

| Windward Coast | 336,869 | 287,366 | 49,503 | 14.70% |

| Total | 12,521,339 | 10,702,652 | 1,818,687 | 14.52% |

African conflicts

According to Kimani Nehusi, the presence of European slavers affected the way in which the legal code in African societies responded to offenders. Crimes traditionally punishable by some other form of punishment became punishable by enslavement and sale to slave traders.[210][119] According to David Stannard's American Holocaust, 50% of African deaths occurred in Africa as a result of wars between native kingdoms, which produced the majority of slaves.[24] This includes not only those who died in battles but also those who died as a result of forced marches from inland areas to slave ports on the various coasts.[211] The practice of enslaving enemy combatants and their villages was widespread throughout Western and West Central Africa, although wars were rarely started to procure slaves. The slave trade was largely a by-product of tribal and state warfare as a way of removing potential dissidents after victory or financing future wars.[212][page needed] In addition, European nations instigated war between African nations and increased the number of war captives by making alliances with warring nations and shifted trade locations in coastal areas to follow patterns of African military conflicts to acquire more slaves.[119] Some African groups proved particularly adept and brutal at the practice of enslaving, such as Bono State, Oyo, Benin, Igala, Kaabu, Ashanti, Dahomey, the Aro Confederacy and the Imbangala war bands.[213][214][page needed]

In letters written by the Manikongo, Nzinga Mbemba Afonso, to the King João III of Portugal, he writes that Portuguese merchandise flowing in is what is fueling the trade in Africans. He requests the King of Portugal to stop sending merchandise but should only send missionaries. In one of his letters he writes:

Each day the traders are kidnapping our people—children of this country, sons of our nobles and vassals, even people of our own family. This corruption and depravity are so widespread that our land is entirely depopulated. We need in this kingdom only priests and schoolteachers, and no merchandise, unless it is wine and flour for Mass. It is our wish that this Kingdom not be a place for the trade or transport of slaves ... Many of our subjects eagerly lust after Portuguese merchandise that your subjects have brought into our domains. To satisfy this inordinate appetite, they seize many of our black free subjects ... They sell them. After having taken these prisoners [to the coast] secretly or at night ... As soon as the captives are in the hands of white men they are branded with a red-hot iron.[215]

Before the arrival of the Portuguese, slavery had already existed in the Kingdom of Kongo. Afonso I of Kongo believed that the slave trade should be subject to Kongo law. When he suspected the Portuguese of receiving illegally enslaved persons to sell, he wrote to King João III in 1526 imploring him to put a stop to the practice.[216]

The kings of Dahomey sold war captives into transatlantic slavery; they would otherwise have been killed in a ceremony known as the Annual Customs. As one of West Africa's principal slave states, Dahomey became extremely unpopular with neighbouring peoples.[217][218][219] Like the Bambara Empire to the east, the Khasso kingdoms depended heavily on the slave trade for their economy. A family's status was indicated by the number of slaves it owned, leading to wars for the sole purpose of taking more captives. This trade led the Khasso into increasing contact with the European settlements of Africa's west coast, particularly the French.[220] Benin grew increasingly rich during the 16th and 17th centuries on the slave trade with Europe; slaves from enemy states of the interior were sold and carried to the Americas in Dutch and Portuguese ships. The Bight of Benin's shore soon came to be known as the "Slave Coast".[221]

King Gezo of Dahomey said in the 1840s:

The slave trade is the ruling principle of my people. It is the source and the glory of their wealth ... the mother lulls the child to sleep with notes of triumph over an enemy reduced to slavery ...[222][223]

In 1807, the UK Parliament passed the Bill that abolished the trading of slaves. The King of Bonny (now in Nigeria) was horrified at the conclusion of the practice:

We think this trade must go on. That is the verdict of our oracle and the priests. They say that your country, however great, can never stop a trade ordained by God himself.[223]

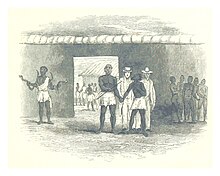

Port factories

After being marched to the coast for sale, enslaved people were held in large forts called factories. The amount of time in factories varied, but Milton Meltzer states in Slavery: A World History that around 4.5% of deaths attributed to the transatlantic slave trade occurred during this phase.[224] In other words, over 820,000 people are believed to have died in African ports such as Benguela, Elmina, and Bonny, reducing the number of those shipped to 17.5 million.[224][page needed]

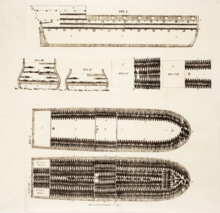

Atlantic shipment

After being captured and held in the factories, slaves entered the infamous Middle Passage. Meltzer's research puts this phase of the slave trade's overall mortality at 12.5%.[224] Their deaths were the result of brutal treatment and poor care from the time of their capture and throughout their voyage.[225] Around 2.2 million Africans died during these voyages, where they were packed into tight, unsanitary spaces on ships for months at a time.[226] Measures were taken to stem the onboard mortality rate, such as enforced "dancing" (as exercise) above deck and the practice of force-feeding enslaved persons who tried to starve themselves.[211] The conditions on board also resulted in the spread of fatal diseases. Other fatalities were suicides, slaves who escaped by jumping overboard.[211] The slave traders would try to fit anywhere from 350 to 600 slaves on one ship. Before the African slave trade was completely banned by participating nations in 1853, 15.3 million enslaved people had arrived in the Americas.

Raymond L. Cohn, an economics professor whose research has focused on economic history and international migration,[227] has researched the mortality rates among Africans during the voyages of the Atlantic slave trade. He found that mortality rates decreased over the history of the slave trade, primarily because the length of time necessary for the voyage was declining. "In the eighteenth century many slave voyages took at least 2½ months. In the nineteenth century, 2 months appears to have been the maximum length of the voyage, and many voyages were far shorter. Fewer slaves died in the Middle Passage over time mainly because the passage was shorter."[228]

Despite the vast profits of slavery, the ordinary sailors on slave ships were badly paid and subject to harsh discipline. Mortality of around 20%, a number similar and sometimes greater than those of the slaves,[229] was expected in a ship's crew during the course of a voyage; this was due to disease, flogging, overwork, or slave uprisings.[230] Disease (malaria or yellow fever) was the most common cause of death among sailors. A high crew mortality rate on the return voyage was in the captain's interests as it reduced the number of sailors who had to be paid on reaching the home port.[231]

The slave trade was hated by many sailors, and those who joined the crews of slave ships often did so through coercion or because they could find no other employment.[232]

Seasoning camps

Meltzer also states that 33% of Africans would have died in the first year at the seasoning camps found throughout the Caribbean.[224] Jamaica held one of the most notorious of these camps. Dysentery was the leading cause of death.[233] Captives who could not be sold were inevitably destroyed.[205] Around 5 million Africans died in these camps, reducing the number of survivors to about 10 million.[224] The purpose of seasoning camps were to obliterate the Africans' identities and culture and prepare them for enslavement. In seasoning camps, enslaved Africans learned a new language and adopted new customs. This process of seasoning slaves took about two or three years.[234]

Conditions of slavery on plantations before and after abolition of the transatlantic slave trade

Caribbean

Over the colony's hundred-year course, about a million slaves succumbed to the conditions of slavery in Haiti.[235] A slave imported into Haiti was expected to die, on average, within 3 years of arrival, and slaves born on the island had a life expectancy of only 15 years.[236]

In the Caribbean, Dutch Guiana, and Brazil, the death rate of enslaved people was high, and the birth rates were low, slaveholders imported more Africans to sustain the slave population. The rate of natural decline in the slave population ran as high as 5 percent a year. While the death rate of enslaved populations in the United States was the same on Jamaican plantations. In the Danish West Indies, and for most of the Caribbean, mortality rate was high because of the taxing labor of sugar cultivation. Sugar was a major cash crop and as the Caribbean plantations exported sugar to Europe and North America, they needed an enslaved work force to make its production economically viable, so slaves were imported from Africa. Enslaved Africans lived in inhumane conditions and the mortality rate of enslaved children under the age of five was forty percent. Many enslaved persons died from smallpox and intestinal worms contracted from contaminated food and water.[237]

The Atlantic slave trade exportation of slaves to Cuba was illegal by 1820; however, Cuba continued to import enslaved Africans from Africa until slavery was abolished in 1886. After the abolition of the slave trade to the United States and British colonies in 1807, Florida imported enslaved Africans from Cuba, many landing in Amelia Island. A clandestine slave ferry operated between Havana, Cuba and Pensacola, Florida. Florida remained under Spanish control until 1821 which made it difficult for the United States to cease the smuggling of enslaved Africans from Cuba. In 1821, Florida was ceded to the United States and the smuggling of enslaved Africans continued, and from 1821 to 1841 Cuba became a main supplier of enslaved Africans for the United States. Between 1859 and 1862, slave traders made 40 illegal voyages between Cuba and the United States.[238][239]

The costs of the shipment of human cargo from Africa and operating costs of the slave trade from Africa into Cuba rose in the mid-19th century. Historian Laird Bergad writes of the Cuban slave trade and slave prices: "...slave prices on the African coast seem to have remained remarkably stable from the 1840s through the mid-1860s, although shipping and operating costs for slave traders seem to have risen considerably. In addition, increased bribes to Spanish colonial officials effectively raised operating costs for slavers. These factors did not restrict the number of Africans embarking for Cuba, nor can they be used alone to explain Cuban slave price rises in the late 1850s and early 1860s. Three interacting factors produced the overwhelming demand for slaves responsible for pushing prices to the high levels[...] The first was the uncertainty surrounding the future of the slave trade itself. The long and persistent British campaign to force an end to the Cuban trade had traditionally been circumvented by collusion between Spanish colonial officials and Cuban slave traders. An additional obstacle to British efforts was the unwillingness of the United States to permit the search of U.S.-flag vessels suspected of involvement in the slave trade". By the mid-1860s, prices of Africans in their elderly years decreased while prices of younger Africans increased because they were considered to be of prime working age. According to research, in 1860 in Matanzas, about 39.6 percent of slaves sold were young prime aged Africans of either sex; in 1870 the percentage was 74.3 percent. In addition, as the cost of sugar increased so did the price of slaves.[240]

South America

The life expectancy for Brazil's slave plantation's for African descended slaves was around 23 years.[241][page needed] The trans-Atlantic slave trade into Brazil was outlawed in 1831. To replace the demand for slaves, slaveholders in Brazil turned to slave reproduction. Enslaved women were forced to give birth to eight or more enslaved children. Some slaveholders promised enslaved women their freedom if they gave birth to eight children. In 1873 in the village of Santa Ana, province of Ceará an enslaved woman named Macária was promised her freedom after she gave birth to eight children. An enslaved woman Delfina killed her baby because she did not want her enslaver Manoel Bento da Costa to own her baby and enslave her child. Brazil practiced partus sequitur ventrem to increase the slave population through enslaved female reproduction, because in the 19th century, Brazil needed a large enslaved labor force to work on the sugar plantations in Bahia and the agricultural and mining industries of Minas Gerais, São Paulo, and Rio de Janeiro. After the abolition of the Atlantic slave trade to Brazil, the inter-provincial trade increased which slaveholders forced and depended on enslaved women to give birth to as many children as possible to supply the demand for slaves. Abolitionists in Brazil wanted to abolish slavery by removing partus sequitur ventrem because it was used to perpetuate slavery. For example, historian Martha Santos writes of the slave trade, female reproduction, and abolition in Brazil: "A proposal centered on the 'emancipation of the womb', authored by the influential jurist and politician Agostinho Marques Perdigão Malheiro, was officially endorsed by Pedro II as the most practical means to end slavery in a controlled and peaceful manner. This conservative proposal, a modified version of which became the 'free womb' law passed by Parliament in 1871, did provide for the freedom of children subsequently born of enslaved women, while it forced those children to serve their mothers' masters until age twenty-one, and deferred complete emancipation to a later date".[242]

United States

The birth rate was more than 80 percent higher in the United States because of a natural growth in the slave population and slave breeding farms.[243][244][245] Birth rates were low for the first generation of slaves imported from Africa, but, in the US, may have increased in the 19th century to some 55 per thousand, approaching the biological maximum for human populations.[246][247]

After the prohibition of the trans-atlantic slave trade in 1807, slaveholders in the Deep South of the United States needed more slaves to work in the cotton and sugar fields. To fill the demand for more slaves, slave breeding was practiced in Richmond, Virginia. Richmond sold thousands of enslaved people to slaveholders in the Deep South to work the cotton, rice, and sugar plantations. Virginia was known as a "breeder state." A slaveholder in Virginia bragged his slaves produced 6,000 enslaved children for sale. About 300,000 to 350,000 enslaved people were sold from Richmond's slave breeding farms.[248] Slave breeding farms and forced reproduction on enslaved young girls and women caused reproductive health issues. Enslaved women found ways to resist forced reproduction by causing miscarriages and abortions by taking plants and medicines.[249][250] Slaveholders tried to control enslaved women's reproduction by encouraging them to have relationships with enslaved men. "Some slaveholders took matters into their own hands, however, and paired enslaved men and women together with the intent that they would procreate."[251][252] Enslaved teenage girls gave birth at the ages of fifteen or sixteen years old. Enslaved women gave birth in their early twenties. To meet the demands of slaveholders' needs to birth more slaves, enslaved girls and women had seven or nine children. Enslaved girls and women were forced to give birth to as many slaves as possible. The mortality rate of enslaved mothers and children was high because of poor nutrition, sanitation, lack of medical care, and overwork.[253][254] In the United States a slave's life expectancy was 21 to 22 years, and a black child through the age of 1 to 14 had twice the risk of dying of a white child of the same age.[255]

Slave breeding replaced the demand for enslaved laborers after the decline of the Atlantic slave trade to the United States which caused an increase in the domestic slave trade. The sailing of slaves in the domestic slave trade is known as "sold down the river," indicating slaves being sold from Louisville, Kentucky which was a slave trading city and supplier of slaves. Louisville, Kentucky, Virginia, and other states in the Upper South supplied slaves to the Deep South carried on boats going down the Mississippi River to Southern slave markets.[256][257][258][259][260] New Orleans, Louisiana became a major slave market in the United States domestic slave trade after the prohibition of the Atlantic slave trade in 1807. Between 1819 and 1860, 71,000 enslaved people were transported to New Orlean's slave market on slave ships that departed from ports in the United States along the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico to New Orleans to supply the demand for slaves in the Deep South.[261][262]