Римская империя

Римская империя | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 27 г. до н.э. - 395 г. н.э. (унифицированный) [ А ] 395 г. - 476/480 ( Западный ) 395–1453 гг ( Восточный ) | |||||||||||

Имперская Аквила

| |||||||||||

империя в 117 Римская г. | |||||||||||

Римская территориальная эволюция от роста городского государства Рима до падения западной Римской империи | |||||||||||

| Капитал |

| ||||||||||

| Общие языки | |||||||||||

| Религия |

| ||||||||||

| Демоним (ы) | Римский | ||||||||||

| Правительство | Самодержавие | ||||||||||

| ( Список ) | |||||||||||

| Историческая эра | Классическая эра до позднего средневековья ( Временная шкала ) | ||||||||||

| Область | |||||||||||

| 25 до н.э. [ 16 ] | 2 750 000 км 2 (1 060 000 кв. МИ) | ||||||||||

| Объявление 117 [ 16 ] [ 17 ] | 5 000 000 км 2 (1 900 000 кв. МИ) | ||||||||||

| 390 г. н.э. [ 16 ] | 3400 000 км 2 (1 300 000 кв. МИ) | ||||||||||

| Население | |||||||||||

• 25 до н.э. [ 18 ] | 56,800,000 | ||||||||||

| Валюта | Как ; [ E ] aureus , твердый , номинальный | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Римская империя управляла Средиземноморью и большей частью Европы, Западной Азии и Северной Африки. Римляне н.э. завоевали большую часть этого во время Республики , и им управляли императоры после до предположения Октавиана о эффективном единственном правлении в 27 г. Западная империя рухнула в 476 году нашей эры, но Восточная империя длилась до падения Константинополя в 1453 году.

К 100 до н.э. Рим расширил свое правление до большинства средиземноморских и за его пределами. Тем не менее, он был серьезно дестабилизирован гражданскими войнами и политическими конфликтами , которые завершились победой Октавиана над Марком Энтони и Клеопатрой в битве при Актиуме в 31 году до нашей эры и последующим завоеванием Птолемейского королевства в Египте. В 27 г. до н.э. римский Сенат предоставил Октавианскую военную силу ( Империум ) и новое звание Августа , отметив его вступление в качестве первого римского императора . Огромные римские территории были организованы в сенаторские провинции, управляемые проконсулами, которые были назначены Лотом ежегодно, и имперские провинции, которые принадлежали императору, но управлялись легатами . [ 19 ]

Первые два столетия империи увидели период беспрецедентной стабильности и процветания, известного как Pax Romana ( Lit. « Римский мир » ). Рим достиг своей величайшей территориальной степени при Траджане ( р. 98–117 г. н.э. ), но период растущих неприятностей и снижения начался при Коммодусе ( р. 180–192 ). В 3-м веке империя претерпела 50-летний кризис , который угрожал его существованию из-за гражданской войны, чумы и варварских вторжений . Империи галликов и пальмиролов оторвались от государства, и серия недолговечных императоров возглавляла империю, которая впоследствии была воссоединена под аурелианом ( р. 270–275 ). Гражданские войны закончились победой Диоклетиана ( р . 284–305 ), который установил два разных имперских суда на Востоке Греции и Латинского запада . Константин Великий ( р. 306–337 ), первый христианский император , переместил имперское место из Рима в Византию в 330 и переименовал его в Константинополь . Период миграции , включающий вторжения германских народов и гуннов Аттилы , крупные привел к снижению Западная Римская империя . С падением Равенны до германских герилианцев и показания Ромула Августа в 476 году Одоацером , Западная империя наконец рухнула. Восточная Римская империя выжила еще на тысячелетие с Константинополем в качестве единственной столицы до падения города в 1453 году. [ f ]

Из -за масштабов и выносливости империи ее институты и культура оказали длительное влияние на развитие языка , религии , искусства , архитектуры , литературы , философии , права и форм правительства на его территориях. Латинский превратился в романтические языки , в то время как средневековый грек стал языком Востока. христианства Принятие империи привело христианского к формированию средневекового христианского . Романское и греческое искусство оказали глубокое влияние на итальянский ренессанс . Архитектурная традиция Рима послужила основой для романской , эпохи Возрождения и неоклассической архитектуры , влияющей на исламскую архитектуру . Повторное открытие классической науки и техники (которая основывалась на основе исламской науки ) в средневековой Европе способствовало научному возрождению и научной революции . Многие современные правовые системы, такие как Наполеоновский кодекс , спускаются от римского права. Республиканские институты Рима повлияли на итальянские городские государственные республики средневекового периода, раннее Соединенные Штаты и современные демократические республики .

История

Переход от Республики к империи

Рим начал расширяться вскоре после основания Римской Республики в 6 веке до нашей эры, хотя и не за пределами итальянского полуострова до 3 -го века до нашей эры. Таким образом, это была «империя» (великая сила) задолго до того, как у нее появился император. [ 21 ] Республика была не национальным государством в современном смысле, а сетью самоутвержденных городов (с различной степенью независимости от Сената ) и провинций, управляемых военными командирами. Он регулировался ежегодно избранными магистратами ( римские консулы, прежде всего) в сочетании с Сенатом. [ 22 ] 1 -й век до н.э. был временем политических и военных потрясений, что в конечном итоге привело к правлению императоров. [ 23 ] [ 24 ] [ 25 ] Военная власть консулов опиралась в римскую юридическую концепцию Империума , что означает «командование» (обычно в военном смысле). [ 26 ] Иногда успешным консулам или генералам получали почетный титул Imperator (Commander); Это происхождение слова Императора , так как этот заголовок всегда был присваивается ранним императорам. [ 27 ] [ G ]

Рим перенесли длинную серию внутренних конфликтов, заговоров и гражданских войн в конце второго века до нашей эры (см. Кризис Римской Республики ), в то же время значительно расширяя свою власть за пределы Италии. В 44 году до нашей эры Юлиус Цезарь был кратко вечным диктатором, прежде чем был убит фракцией, которая выступала против его концентрации власти. Эта фракция была извлечена из Рима и побеждена в битве при Филиппи в 42 году до нашей эры Марком Антони и приемным сыном Цезаря Октавиан . Энтони и Октавиан разделили римский мир между ними, но это не длилось долго. Силы Октавиана победили силы Марка Антония и Клеопатры в битве при Актиуме в 31 году до нашей эры. В 27 г. до н.э. Сенат дал ему титул Августа («Почитаемый») и сделал его Принцепс («Прежде всего») с проконкулярным империумом , тем самым начав принциат , первую эпоху римской имперской истории. Хотя Республика стояла под именем, Август имел весь значимый авторитет. [ 29 ] Во время его 40-летнего правила появился новый конституционный приказ, чтобы после его смерти Тиберий сменил его как нового фактического монарха. [ 30 ]

Поскольку римские провинции были созданы по всему Средиземноморью, Италия сохранила особый статус, который сделал его Доминой Провинс («Правитель провинций»),),), [ 31 ] [ 32 ] [ 33 ] и - особенно в отношении первых веков имперской стабильности - Ретрикс Мунди («Губернатор мира») [ 34 ] [ 35 ] и родитель мира («родитель всех земель»). [ 36 ] [ 37 ]

Pax Romana

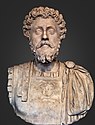

200 лет, которые начались с правления Августа, традиционно рассматриваются как Pax Romana («Римский мир»). Сплоченность Империи была продвинута от определенной степени социальной стабильности и экономического процветания, которую Рим никогда раньше не испытывал. Восприятия в провинциях были нечастыми и подавляли «беспощадно и быстро». [ 38 ] Успех Августа в установлении принципов династической преемственности был ограничен его переживанием ряда талантливых потенциальных наследников. Династия Хулио-Клаудина длилась еще четырех императора - Тиберий , Калигула , Клавдий и Нерон -до того, как она уступила в 69 году нашей эры в год разорванного раздора от четырех императоров , из которого Веспасиан стал победителем. Веспасиан стал основателем короткой династии Флавийской династии , за которой последовал династия Нерв -Антонина , которая привела к « пять хороших императоров »: Нерда , Траджан , Адриан , Антонинус Пий и Маркус Аурелиус . [ 39 ]

Переход от классической к поздней античности

По мнению современного греческого историка Кассиуса Дио , вступление Коммодуса в 180 году ознаменовало спуск «от золотого королевства до одного из ржавчины и железа», [ 40 ] Комментарий, который привел некоторых историков, особенно Эдварда Гиббона , принять правление Коммодуса в качестве начала упадка империи . [ 41 ] [ 42 ]

году во время правления Каракаллы В 212 было предоставлено римское гражданство всем свободным жителям империи. Династия Северана была бурной; Царствование императора регулярно заканчивалось его убийством или казнью, и после его краха империя была охвачена кризисом третьего века , периодом вторжений , гражданских раздоров , экономического расстройства и чумы . [ 43 ] В определении исторических эпох этот кризис иногда отмечает переход от классической к поздней древности . Аурелиан ( р. 270–275 ) стабилизировал империю в военном отношении, а Диоклетиан реорганизовал и восстановил большую часть ее в 285 году. [ 44 ] Царствование Диоклетиана принесло самые согласованные усилия империи против воспринимаемой угрозы христианства , « великого преследования ». [ 45 ]

Диоклетиан разделил империю на четыре региона, каждый из которых управлял отдельным тетрархом . [ 46 ] тетрархия Убедитесь, что он исправил беспорядок, из которого из-за Рим, он отрекся от своего со-императора, но вскоре после этого рухнула . Порядок был в конечном итоге восстановлен Константином Великим , который стал первым императором, который обратился в христианство , и который основал Константинополь как новую столицу Восточной империи. В течение десятилетий константинских и валентинских династий империя была разделена вдоль оси Восточного Запада, с двойными электростанциями в Константинополе и Риме. Джулиан , который под влиянием своего советника Мардониуса попытался восстановить классическую римскую и эллинистическую религию , лишь кратко прервал преемственность христианских императоров. Феодосия I , последний император, который правят как Востоком, так и Западом, умер в 395 году после того, как сделал христианство государственной религией . [ 47 ]

Упасть на западе и выживание на востоке

Западная Римская империя начала распаться в начале 5 -го века. Римляне боролись с всеми захватчиками, наиболее известной Аттилой , [ 48 ] Но Империя ассимилировала так много германских народов сомнительной верности в Риме, что империя начала расчленять. [ 49 ] Большинство хронологий помещают конец западной Римской империи в 476 году, когда Ромулус Августил был отречься от германского военачальника вынужден . [ 50 ] [ 51 ] [ 52 ]

Odoacer завершил западную империю, объявив император Zeno и стал номинальным подчиненным Зено. В действительности Италия управляла только Odoacer. [ 50 ] [ 51 ] [ 53 ] Восточная Римская империя, называемая Византийской империей более поздними историками, продолжалась до правления Константина Си Палайологос , последнего римского императора. Он умер в битве в 1453 году против Мехмеда II и его османских сил во время осады Константинополя . Мехмед II принял титул Цезаря в попытке претендовать на связь с бывшей империей. [ 54 ] [ 55 ] Его требование вскоре было признано патриархатом Константинополя , но не большинством европейских монархов.

География и демография

Римская империя была одной из крупнейших в истории, с смежными территориями по всей Европе, Северной Африке и на Ближнем Востоке. [ 56 ] Латинская фраза Imperium sine fine («Империя без конца» [ 57 ] ) выразил идеологию, что ни время, ни пространство не ограничивали империю. В , безграничной империи Вирджила Aeneid , говорят римляне Юпитером . [ 58 ] Это утверждение универсального владычества было возобновлено, когда империя попала под христианское правление в 4 -м веке. [ H ] В дополнение к аннексии больших регионов, римляне напрямую изменили свою географию, например, отрубив целые леса . [ 60 ]

Римская экспансия была в основном достигнута под Республикой , хотя части Северной Европы были завоеваны в 1 -м веке, когда римский контроль в Европе, Африке и Азии был укреплен. В соответствии с Августом «глобальная карта известного мира» была впервые продемонстрирована в Риме в Риме, что совпадает с созданием самой комплексной географии , которая выживает от древности, географии Страбона политической . [ 61 ] Когда Август умер, рассказ о его достижениях ( res gestae ) заметно показал географическое каталогизацию империи. [ 62 ] География наряду с тщательными письменными записями была центральной проблемой римской имперской администрации . [ 63 ]

Империя достигла своего крупнейшего пространства при Траджане ( р. 98–117 ), [ 64 ] охватывая 5 миллионов км 2 . [ 16 ] [ 17 ] Традиционная оценка населения 55–60 миллионов жителей [ 65 ] составлял между одной шестой до четверти от общей численности населения мира [ 66 ] и сделал его самым густонаселенным объединенным политическим сущностью на Западе до середины 19-го века. [ 67 ] Недавние демографические исследования утверждают, что население пика от 70 миллионов до более чем 100 миллионов . [ 68 ] Каждый из трех крупнейших городов в Империи - Риме, Александрии и Антиохии - почти вдвое больше, чем в любом европейском городе в начале 17 -го века. [ 69 ]

историк Кристофер Келли Как описал :

Затем империя простиралась от стены Адриана в пропитанной моросящей северной Англии до запеченных солнечных берегов Евфрата в Сирии; От великой речной системы Рейна - Дунай , которая проникала через плодородные плоские земли Европы от низких стран до Черного моря , до богатых равнин побережья Северной Африки и роскошной раны долины Нила в Египте. Империя полностью окружила Средиземноморье ... называемой ее завоевателями как кобыла нострам - «Море». [ 65 ]

Преемник Траджана Адриан принял политику поддержания, а не расширения империи. Границы ( штрафы ) были отмечены, а границы ( ограничения ) патрулированы. [ 64 ] Наиболее сильно укрепленные границы были самыми нестабильными. [ 24 ] Стена Адриана , которая отделяла римский мир от того, что воспринималось как постоянная варварская угроза, является основным сохранившимся памятником этих усилий. [ 71 ]

Языки

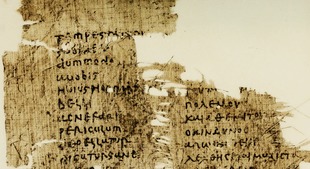

Латинские и греческие были основными языками империи, [ я ] Но империя была намеренно многоязычной. [ 76 ] Эндрю Уоллес-Хадрилл говорит: «Основное желание римского правительства было понять». [ 77 ] В начале империи знание греческого было полезно, чтобы пройти, поскольку образованная благородство, и знание латыни было полезным для карьеры в армии, правительстве или законе. [ 78 ] Двуязычные надписи указывают на повседневную интерпетрацию двух языков. [ 79 ]

Взаимное лингвистическое и культурное влияние латинского и греческого языка является сложной темой. [ 80 ] Латинские слова, включенные в грек, были очень распространены в ранней имперской эпохе, особенно по вопросам военных, административных, а также торговли и торговли. [ 81 ] Греческая грамматика, литература, поэзия и философия в форме латинского языка и культуры. [ 82 ] [ 83 ]

В Империи никогда не было юридического требования для латинской, но это представляло определенный статус. [ 85 ] Высокие стандарты латинского, латинитас , начались с появления латинской литературы. [ 86 ] Из -за гибкой языковой политики Империи появилась естественная конкуренция языка, которая стимулировала латиниты , чтобы защитить латынь от более сильного культурного влияния греческого языка. [ 87 ] Со временем использование латинского использования использовалось для проекта власти и более высокого социального класса. [ 88 ] [ 89 ] Большинство императоров были двуязычными, но предпочитали латынь в общественной сфере по политическим причинам, «правило», которое впервые началось во время Пунических войн . [ 90 ] Различные императоры вплоть до тех пор, пока Джастиниан не попытался бы потребовать использования латыни в различных разделах администрации, но нет никаких доказательств того, что во время ранней империи существовал лингвистический империализм. [ 91 ]

все жители свободного рода были повсеместно , После того, как в 212 году многим римским гражданам не хватало бы знаний о латыни. [ 92 ] Широкое использование Койнового грека было то, что позволило распространению христианства и отражает ее роль лингва франки Средиземного моря во время империи. [ 93 ] После реформ Диоклетиана в 3 -м веке нашей эры произошли снижение знаний о греческом языке на Западе. [ 94 ] Поздравляем позже латинский фрагмент в зарождающиеся романтические языки в 7 -м веке нашей эры после распада Запада империи. [ 95 ]

Доминирование латинской и греческой среди грамотной элиты скрывает непрерывность других разговорных языков в империи. [ 96 ] Латинский, называемый в его устной форме как вульгарной латинской , постепенно заменял кельтские и курсивные языки . [ 97 ] [ 98 ] Ссылки на переводчики указывают на постоянное использование местных языков, особенно в Египте с коптским , и в военных условиях вдоль Рейна и Дунака. Римские юристы также демонстрируют обеспокоенность у местных языков, таких как Пуник , Галльский и арамейский, в обеспечении правильного понимания законов и клятв. [ 99 ] В Африке либико-бербер и пуник использовались в надписях во втором веке. [ 96 ] В Сирии солдаты Палмирена на надписи, исключение из использовали свой диалект арамейских правила, что латынь был языком военных. [ 100 ] Последняя ссылка на галльского был между 560 и 575. [ 101 ] [ 102 ] Выступающие языки галло-романсии тогда будут сформированы галльским. [ 103 ] Прото-баска или аквитанский развился с латинскими ссудными словами в современный баск . [ 104 ] Фрацианский язык , как и несколько нынешних языков в Анатолии, подтверждаются над надписями имперской эпохи. [ 93 ] [ 96 ]

Общество

Империя была удивительно многокультурной, с «удивительной связной способностью» создавать общую идентичность, охватывая различные народы. [ 106 ] Общественные памятники и коммунальные пространства открыты для всех - такие как форумы , амфитеатр , ипподромы и ванны - способствовали ощущению «римности». [ 107 ]

Римское общество имело несколько, перекрывающихся социальных иерархий . [ 108 ] Гражданская война, предшествующая Августу, вызвала потрясения, [ 109 ] но не повлиял на немедленное перераспределение богатства и социальной власти. С точки зрения нижних классов, пик был просто добавлен к социальной пирамиде. [ 110 ] Личные отношения - покровительство , дружба ( амисиа ), семья , брак - связаны с влиянием политики. [ 111 ] Однако к моменту Нерона не было необычно найти бывшего раба, который был богаче, чем гражданин свободного рода, или на конном, который осуществлял большую власть, чем сенатор. [ 112 ]

Размытие более жесткой иерархии Республики привело к увеличению социальной мобильности , [ 113 ] Как вверх, так и вниз, в большей степени, чем все другие хорошо документированные древние общества. [ 114 ] Женщины, свободные люди и рабы имели возможность получить влияние и оказывать влияние таким образом, ранее менее доступными для них. [ 115 ] Общественная жизнь, особенно для тех, чьи личные ресурсы были ограничены, была еще более способна распространению добровольных ассоциаций и конфликтов ( коллегии и содатитов ): профессиональные и торговые гильдии, группы ветеранов, религиозные соды, питьевые и столовые, клубы, клубы для питья и столовых, [ 116 ] Выполняя труппы, [ 117 ] и захоронения . [ 118 ]

Юридический статус

По словам юриста Гайуса , основным различием в римском « законе лиц » было то, что все люди были либо свободными ( либери ), либо рабы ( Серви ). [ 119 ] Правовой статус свободных лиц был дополнительно определен их гражданством. Большинство граждан имели ограниченные права (такие как латиноамериканцы IUS , «Латинское право»), но имели право на юридическую защиту и привилегии, которые не пользуются негражданами. Свободные люди не считали граждан, но жили в римском мире, были Перегрини , не романы. [ 120 ] В 212 году конституция Антониниана распространила гражданство всем свободным жителям империи. Этот юридический эгалитаризм требовал далеко идущего пересмотра существующих законов, которые различают граждан и неграждан. [ 121 ]

Женщины в римском праве

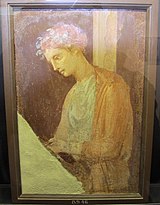

Справа: бронзовая статуэтка (1 -й век н.э.) чтения молодой женщины, основанная на эллинистическом оригинале

Свободные римские женщины считались гражданами, но не голосовали, не занимали политические должности или служили в армии. Статус гражданина Матери определил статус ее детей, о чем свидетельствует фраза ex duobus civibus romanis natos («Дети, рожденные от двух римских граждан»). [ J ] Римская женщина сохранила свою собственную фамилию ( номен ) на всю жизнь. Дети чаще всего брали имя отца, за некоторыми исключениями. [ 124 ] Женщины могут владеть имуществом, вводить контракты и заниматься бизнесом. [ 125 ] Надписи по всему Империи Честь женщин в качестве благотворителей в финансировании общественных работ, что может иметь значительные успехи. [ 126 ]

Архаичный Мануса брак , в котором женщина подвергалась власти мужа, был в значительной степени оставлен имперской эрой, а замужняя женщина сохранила право собственности на любую собственность, которую она принесла в брак. Технически она оставалась под юридической властью своего отца, хотя она переехала в дом своего мужа, но когда ее отец умер, она стала юридически освобождена. [ 127 ] Эта договоренность была фактором в степени независимости, которые пользовались римскими женщинами по сравнению со многими другими культурами до современного периода: [ 128 ] Хотя она должна была ответить отцу в юридических вопросах, она была свободна от его прямого контроля в повседневной жизни, [ 129 ] И ее муж не имел юридической власти над ней. [ 130 ] Хотя это была точка гордости быть «женщиной с одной человек» ( Univira ), которая вышла замуж только один раз, было мало стигмы, прикрепленного к разводу , а также скорейшего повторного брака после овдова или развода. [ 131 ] Девочки имели равные права наследства с мальчиками, если их отец умер, не оставляя завещания. [ 132 ] Право матери на владение и распоряжение имуществом, включая установление условий ее воли, дало ей огромное влияние на своих сыновей во взрослую жизнь. [ 133 ]

В рамках программы Августа по восстановлению традиционной морали и социального порядка моральное законодательство пыталось регулировать поведение как средство продвижения « семейных ценностей ». Прелюбодеяние было криминализовано, [ 134 ] и в широком смысле определяется как незаконный половой акт ( Stuprum ) между гражданином -мужчиной и замужней женщиной, или между замужней женщиной и любым мужчиной, кроме ее мужа. То есть на месте был двойной стандарт : замужняя женщина могла заниматься сексом только со своим мужем, но женатый мужчина не совершил прелюбодеяния, если бы занимался сексом с проституткой или человеком маргинального статуса. [ 135 ] Детому было воодушевлено: женщина, которая родила троих детей, получила символические награды и большую юридическую свободу (IUS Trium Liberorum ). [ 136 ]

Рабы и закон

Во время Августа, целых 35% людей в римской Италии были рабами, [ 137 ] Сделав Рим одним из пяти исторических «рабских обществ», в котором рабы составляли по крайней мере пятую часть населения и сыграли важную роль в экономике. [ k ] [ 137 ] Рабство было сложным институтом, которое поддерживало традиционные римские социальные структуры, а также способствовали экономической полезности. [ 138 ] В городских условиях рабы могут быть профессионалами, такими как учителя, врачи, повара и бухгалтеры; Большинство рабов предоставили обученный или неквалифицированный труд. Сельское хозяйство и промышленность, такие как фрезерование и добыча полезных ископаемых, полагались на эксплуатацию рабов. За пределами Италии рабы были в среднем примерно от 10 до 20% населения, редко в римском Египте , но более сконцентрированы в некоторых греческих районах. Расширение римской собственности на пахотные земли и отрасли отрасли повлияло на ранее существовавшие практики рабства в провинциях. [ 139 ] Хотя рабство часто рассматривалось как ослабление в 3 -м и 4 -м веках, оно оставалось неотъемлемой частью римского общества до постепенного прекращения в 6 -м и 7 -м веках с распадом сложной имперской экономики. [ 140 ]

Законы, относящиеся к рабству, были «чрезвычайно сложными». [ 141 ] Рабы считались имуществом и не имели юридической личности . Они могут быть подвергнуты формам телесного наказания, которые обычно не осуществляются на граждан, сексуальную эксплуатацию , пытки и сводное исполнение . Раб не мог быть изнасилован; Насильник раба должен был быть привлечен к ответственности владельцем за ущерб имуществом в соответствии с законом Аквилиана . [ 142 ] Рабы не имели права на форму законного брака под названием Conubium , но их союзы иногда были признаны. [ 143 ] Технически, раб не мог владеть имуществом, [ 144 ] Но рабом, который ведет бизнес, может получить доступ к отдельному фонду ( Peculium ), который он мог бы использовать, в зависимости от степени доверия и сотрудничества между владельцем и рабом. [ 145 ] В домашнем хозяйстве или на рабочем месте может существовать иерархия рабов, причем один рабыня выступает в роли мастера других. [ 146 ] Талантливые рабы могут накапливать достаточно большой печи , чтобы оправдать свою свободу или быть сделанным для оказанных услуг. Маньем стало достаточно частым, чтобы в 2 до н.э. закон ( Lex Fufia Caninia ) ограничивал количество рабов, которые владельцу было разрешено освободиться по его воле. [ 147 ]

После рабских войн в Республике законодательство в соответствии с Августом и его преемниками проявляет вождение в борьбе с контролем угрозы восстаний путем ограничения размера рабочих групп и для охоты на беглых рабов. [ 148 ] Со временем рабы повысили правовой защиты, в том числе право подавать жалобы на своих хозяев. Счет продажи может содержать пункт, в котором говорится о том, что раб не мог быть использован для проституции, поскольку проститутки в древнем Риме часто были рабами. [ 149 ] Растущая торговля евнухами в конце 1 -го века вызвала законодательство, которое запрещало кастрацию раба против его воли «для похоти или выгоды». [ 150 ]

Римское рабство не было основано на расе . [ 151 ] Как правило, рабы в Италии были коренными итальянцами, [ 152 ] С меньшинством иностранцев (включая как рабов, так и свободных), оцениваемое в 5% от общего числа капитала на пике, где их число было наибольшим. Иностранные рабы имели более высокую смертность и более низкие показатели рождаемости, чем коренные жители, и иногда даже подвергались массовому изгнанию. [ 153 ] Средний записанный возраст в смерти для рабов города Рима составлял семнадцать с половиной лет (17,2 для мужчин; 17,9 для женщин). [ 154 ]

В период республиканского экспансионизма, когда рабство стало распространенным, военные пленники были основным источником рабов. Диапазон этнических групп среди рабов в некоторой степени отражал, что Римские армии победили в войне, и завоевание Греции принесло ряд высококвалифицированных и образованных рабов. Рабы также продавались на рынках и иногда продаются пиратами . Рядом с младенцем и самоуверенностью среди бедных были другие источники. [ 155 ] Верна , напротив, были «доморощенными» рабами, родившимися от женщин -рабы в домашнем хозяйстве, поместье или ферме. Хотя у них не было особого юридического статуса, владелец, который плохо обращался или не заботился о его Vernae, столкнулся с социальным неодобрением, поскольку они считались частью семейного домохозяйства, а в некоторых случаях могут быть детьми свободных мужчин в семье. [ 156 ]

Свободные

Рим отличался от греческих городов-государств, позволяя освобожденным рабам стать гражданами; Любые будущие дети свободного, родились свободными, с полными правами гражданства. После манеры раб, который принадлежал к римскому гражданину, пользовалась активной политической свободой ( либератов ), включая право голоса. [ 157 ] Его бывший хозяин стал его покровителем ( покровительством ): эти двое продолжали иметь обычные и юридические обязательства друг перед другом. [ 158 ] [ 159 ] Фридман не имел права занимать государственную должность или высшее государственное священство, но мог сыграть священную роль . Он не мог жениться на женщине из сенаторской семьи и не достичь законного сенатского ранга сам, но во время ранней империи, освободители занимали ключевые должности в государственной бюрократии, настолько, что Адриан ограничивал их участие в законе. [ 159 ] Рост успешных свободных - через политическое влияние или богатство - является характерной для раннего имперского общества. Процветание высокопоставленной группы свободных людей подтверждается надписями по всей Империи .

Перепись ранга

Латинское слово Ordo (множественное число ) переводится по -разному и неточно на английский как «класс, порядок, ранга». Одной из целей римской переписи было определить ордо , к которому принадлежал человек. [ 160 ] Два из самых высоких порядков в Риме были сенаторскими и конными. За пределами Рима, города или колонии возглавляли выпуклы , также известные как Curiales . [ 161 ]

«Сенатор» сам не был избранным офисом в Древнем Риме; Человек получил поступление в Сенат после того, как он был избран и отбыл по крайней мере один срок в качестве исполнительного магистрата . Сенатор также должен был удовлетворить минимальное требование имущества в 1 миллион Sesterii . [ 162 ] Не все мужчины, которые имели право на сенатор Ordo, решили занять место в Сенате, которое потребовало юридического места жительства в Риме. Императоры часто заполняли вакансии в органе 600 членов по предварительной записи. [ 163 ] Сын сенатора принадлежал с сенатором Ордо , но ему пришлось претендовать на свои достоинства для поступления в Сенат. Сенатор может быть удален за нарушение моральных стандартов. [ 164 ]

Во времена Нерона сенаторы все еще были в основном из Италии , с некоторыми с полуострова иберийского полуострова и Южной Франции; Мужчины из грекоязычных провинций Востока стали добавлять под Vespasian. [ 165 ] Первый сенатор из самой восточной провинции, Каппадоция , был принят под руководством Маркуса Аурелия. [ L ] Династия Северана (193–235) итальянцы составляли менее половины Сената. [ 167 ] В течение 3 -го века место жительства в Риме стало непрактичным, и надписи свидетельствуют о сенаторах, которые были активны в политике и позабоченности на своей родине ( Патрия ). [ 164 ]

Сенаторы были традиционным управляющим классом, который вырос через Cursus Honorum , политическую карьеру, но наездники часто обладали большим богатством и политической властью. Членство в конном порядке было основано на имуществе; В первые дни Рима рахи или рыцари были отличаются их способностью служить в качестве установленных воинов, но кавалерийская служба была отдельной функцией в Империи. [ м ] Оценка переписи 400 000 Sesterces и три поколения свободных родов квалифицировало человека в качестве конного спорта. [ 169 ] Перепись 28 г. до н.э. обнаружила большое количество мужчин, которые квалифицировались, и в 14 году нашей эры тысяча конных консервов была зарегистрирована только в Кадисе и Падуи . [ n ] [ 171 ] Энгоры поднялись через военную карьеру ( TRES Militiae ), чтобы стать высокопоставленными префектами и прокурорами в имперской администрации. [ 172 ]

Рост провинциальных мужчин к сенаторским и конным ордерам является аспектом социальной мобильности в ранней империи. Римская аристократия была основана на соревнованиях, и, в отличие от более поздней европейской дворянства , римская семья не могла сохранить свою позицию только через наследственную преемственность или иметь титул на земли. [ 173 ] Прием в более высокие постановления принесли различие и привилегии, а также обязанности. В древности город зависел от своих ведущих граждан для финансирования общественных работ, мероприятий и услуг ( Munera ). Поддержание своего звания требовало массовых личных расходов. [ 174 ] Декурионы были настолько жизненно важны для функционирования городов, что в более поздней империи, когда ряды городских советов были истощены, тем, кто поднялся в Сенат, было рекомендовано вернуться в свои родные города, пытаясь поддерживать гражданскую жизнь. [ 175 ]

В более поздней империи Dignitas («стоимость, уважение»), которые присутствовали на сенаторском или конном звании, были усовершенствованы в дальнейшем с такими названиями, как Vir Illustris («Прославленный человек»). [ 176 ] Клариссимус . (греческий Lamprotatos ) использовался для обозначения Dignitas некоторых сенаторов и их ближайших семей, включая женщин [ 177 ] «Оценки» статуса конного спорта размножались. [ 178 ]

Неравное правосудие

Поскольку республиканский принцип равенства граждан в соответствии с законом исчез, символические и социальные привилегии высших классов привели к неформальному разделению римского общества на тех, кто приобрел большие почести ( честные ) и смиренных людей ( Humiliores ). В целом, честные члены были членами трех более высоких «заказов», а также некоторых военных офицеров. [ 179 ] Предполагается, что предоставление универсального гражданства в 212 году увеличило конкурентное желание среди высших классов подтвердить свое превосходство, особенно в системе правосудия. [ 180 ] Приговор зависел от решения председательствующего должностного лица относительно относительной «стоимости» ( Dignitas ) ответчика: честность может заплатить штраф за преступление, за которое обезжирил, может получить бревень . [ 181 ]

Исполнение, которое было нечастого юридического штрафа за свободных мужчин под республикой, [ 182 ] Может быть быстрым и относительно безболезненным для честных , в то время как униолионы могут пострадать от мучительной смерти, ранее предназначенной для рабов, таких как распятие и осуждение зверей . [ 183 ] В ранней империи те, кто обратился к христианству, могут потерять свое положение в качестве честных , особенно если они отказались выполнять религиозные обязанности и, таким образом, стали подвергаться наказаниям, которые создали условия мученичества . [ 184 ]

Правительство и военные

Три основных элемента имперского государства были центральное правительство, военные и правительство провинции. [ 185 ] Военные установили контроль над территорией через войну, но после того, как город или народ был доставлен в соответствии с договором, миссия обратилась к полицейской деятельности: защита римских граждан, сельскохозяйственных площадок и религиозных мест. [ 186 ] Римлянам не хватало достаточной рабочей силы или ресурсов, чтобы править только через силу. Сотрудничество с местными элитами было необходимо для поддержания порядка, сбора информации и извлечения доходов. Римляне часто эксплуатировали внутренние политические подразделения. [ 187 ]

Сообщества с продемонстрированной лояльностью к Риму сохраняли свои собственные законы, могли собирать свои собственные налоги на местном уровне, а в исключительных случаях были освобождены от римского налогообложения. Правовые привилегии и относительная независимость стимулировали соответствие. [ 188 ] Таким образом, римское правительство было ограничено , но эффективным в использовании имеющихся ресурсов. [ 189 ]

Центральное правительство

Имперский культ древнего Рима определил императоров и некоторых членов их семей с божественно санкционированной властью ( Auctoritas ). Обряд апофеоза (также называемый Consecratio ) означал обожествление умершего императора. [ 190 ] Доминирование императора было основано на консолидации полномочий из нескольких республиканских офисов. [ 191 ] Император сделал себя центральной религиозной властью как Pontifex Maximus и централизовал право объявлять войну, ратифицировать договоры и вести переговоры с иностранными лидерами. [ 192 ] Хотя эти функции были четко определены во время принципата , полномочия Императора со временем стали менее конституционными и более монархическими, кульминацией которых является доминирование . [ 193 ]

Император был окончательным авторитетом в принятии политики и принятия решений, но в раннем принципе он должен был быть доступен и будет иметь дело лично с официальными бизнесом и петициями. Бюрократия сформировалась вокруг него только постепенно. [ 194 ] Императоры Хулио-Клаудиан полагались на неформальный состав советников, в которые входили не только сенаторов и консерв, но и доверяли рабов и свободных. [ 195 ] После Нерона влияние последнего рассматривалось с подозрением, и Совет Императора ( Консалиум ) стал обязательством официального назначения для большей прозрачности . [ 196 ] Хотя Сенат взял на себя инициативу в политических дискуссиях до конца династии Антонина , наездники играли все более важную роль в кончилии . [ 197 ] Женщины семьи Императора часто вмешались непосредственно в его решения. [ 198 ]

Доступ к Императору может быть получен на ежедневном приеме ( Salutatio ), развитии традиционного дань, которое клиент, оплаченный своему покровителю; Общественные банкеты, размещенные во дворце; и религиозные церемонии. Простые люди, которым не хватало этого доступа, могут проявить их одобрение или неудовольствие в качестве группы в играх . [ 199 ] К 4 -м веку христианские императоры стали отдаленными подставками, которые издали общие решения, больше не отвечая на отдельные петиции. [ 200 ] Хотя Сенат мог бы не лишить убийства и открытого восстания, чтобы нарушить волю императора, он сохранил свою символическую политическую центральность. [ 201 ] Сенат узаконил правление императора, а император нанимал сенаторов в качестве легатов ( Легати ): генералы, дипломаты и администраторы. [ 202 ]

Практическим источником власти и власти императора были военные. Легионеры клятвой были оплачены имперской казначейством и поклялись ежегодной верности императору. [ 203 ] Большинство императоров выбрали преемника, обычно близкого члена семьи или принятого наследника. Новый император должен был обратиться за быстрым признанием своего статуса и полномочий для стабилизации политического ландшафта. Ни один император не мог бы надеяться выжить без верности преторийской гвардии и легионов. Чтобы обеспечить свою верность, несколько императоров заплатили Donativum , денежную награду. Теоретически, Сенат имел право выбирать нового императора, но это помнило о том, чтобы армия или преторийцы. [ 204 ]

Военный

После Пунических войн римская армия включала профессиональных солдат, которые добровольно вызвались в течение 20 лет активной службы и пять в качестве резервов. Переход к профессиональным военным начался в конце республики и был одним из многих глубоких смен от республиканизма, под которым армия граждан призывников защищала родину от определенной угрозы. Римляне расширили свою военную машину, «организовав сообщества, которые они завоевали в Италии в систему, которая создала огромные резервуары рабочей силы для своей армии». [ 205 ] В Imperial Times, военная служба была карьерой на полный рабочий день. [ 206 ] Распространение военных гарнизонов по всей Империи оказала серьезное влияние в процессе романизации . [ 207 ]

Основной миссией военных ранней империи было сохранение Pax Romana . [ 208 ] Три основных подразделения военных были:

- Гарнизон в Риме, в состав которого входят преторийская гвардия , когорты Урбанаэ и Бенитов , которые работали как полиция и пожарные;

- провинциальная армия, состоящая из римских легионов и вспомогательных организаций, предоставленных провинциями ( Auxilia );

- флот Военно -морской .

Благодаря его военным реформам, которые включали консолидацию или расформирование подразделений сомнительной лояльности, Август регулировал легион. Легион был организован в десять когортов , каждая из которых состояла из шести веков , с столетием еще из десяти команд ( Контуберния ); Точный размер имперского легиона, который, вероятно, определялся логистикой , оценивался в диапазоне от 4800 до 5280. [ 209 ] После того, как германские племена уничтожили три легиона в битве при Тевтобургском лесу в 9 году нашей эры, число легионов было увеличено с 25 до 30 лет. [ 210 ] У армии было около 300 000 солдат в 1 -м веке, а младше 400 000 во 2 -м, «значительно меньше», чем коллективные вооруженные силы завоеванных территорий. Не более 2% взрослых мужчин, живущих в империи, служили в имперской армии. [ 211 ] Август также создал преторийскую гвардию : девять когортов, якобы для поддержания общественного мира, который был гарнизирован в Италии. Лучше платят, чем легионеры, преторианцы отбывали всего шестнадцать лет. [ 212 ]

Вспомогательные были завербованы из числа негражденных. Организованные в небольших единицах с примерно когортной силой, им платили меньше, чем легионеры, и после 25 лет службы были вознаграждены римским гражданством , также распространялись на их сыновья. Согласно Тациту [ 213 ] Было примерно столько вспомогательных услуг, сколько было легионеров - таким образом, около 125 000 человек, что подразумевает приблизительно 250 вспомогательных полков. [ 214 ] Римская кавалерия самой ранней империи была в основном из кельтских, латиноамериканских или германских районов. Несколько аспектов обучения и оборудования, полученных из кельтов. [ 215 ]

Римский флот не только помогал в поставках и транспортировке легионов, но и в защите границ вдоль рек Рейн и Дунай . Другая обязанность - защищать морскую торговлю от пиратов. Он патрулировал Средиземноморье, части северного атлантического побережья и Черное море . Тем не менее, армия считалась старшей и более престижной филиалом. [ 216 ]

Правительство провинции

Прилагаемая территория стала римской провинцией в трех шагах: создание реестра городов, перепись и обследование земли. [ 217 ] Дальнейшее государственное ведение включало роды и смерти, сделки с недвижимостью, налоги и юридические разбирательства. [ 218 ] В 1 -м и 2 -м веках центральное правительство ежегодно отправляло около 160 чиновников, чтобы управлять за пределами Италии. [ 22 ] Среди этих чиновников были римские губернаторы : магистраты, избранные в Риме , которые во имя римского народа управляли сенаторскими провинциями ; или губернаторы, обычно из конного звания, которые держали свой Империум от имени Императора в имперских провинциях , в частности, Римский Египет . [ 219 ] Губернатор должен был сделать себя доступным для людей, которыми он управлял, но он мог делегировать различные обязанности. [ 220 ] Его сотрудники, однако, были минимальными: его официальные служители ( Appreatores ), включая Licsors , Heralds, посланников, писцов и телохранителей; легаты , как гражданские, так и военные, обычно из конного звания; и друзья, которые сопровождали его неофициально. [ 220 ]

Другие чиновники были назначены руководителями государственных финансов. [ 22 ] Отделение финансовой ответственности от правосудия и администрации было реформой имперской эпохи, чтобы избежать губернаторов провинций и налоговых фермеров, эксплуатирующих местное население за личную выгоду. [ 221 ] Конные прокураторы , власть которой изначально была «внеработной и внеконституционной», управляли как государственным имуществом, так и личным имуществом Императора ( Res Privata ). [ 220 ] Поскольку чиновникам римского правительства было мало, провинция, которая нуждалась в помощи с юридическим спором или уголовным делом, может искать каких -либо римских, которые, по мнению, имеют какой -то официальный потенциал. [ 222 ]

Закон

Римские суды обладали первоначальной юрисдикцией по делам о делах римских граждан по всей Империи, но было слишком мало судебных чиновников, чтобы навязывать римское право равномерно в провинции. В большинстве частей Восточной империи уже были устоявшиеся кодексы законодательства и юридические процедуры. [ 109 ] Как правило, римская политика была уважать региона MOS («региональная традиция» или «закон земли») и рассматривать местные законы как источник юридического прецедента и социальной стабильности. [ 109 ] [ 223 ] Считалось, что совместимость римского и местного законодательства отражает основной гендиум IUS , «Закон наций» или международное право, которое считается обычным и обычным. [ 224 ] Если провинциальный закон в противоречии с римским законодательством или обычаем, римские суды услышали апелляции , а император владел окончательным органом, принимающим решения. [ 109 ] [ 223 ] [ O ]

На Западе закон был введен на высокую локализованную или племенную основу, и права частной собственности, возможно, были новизны римской эпохи, особенно среди кельтов . Римское закон способствовал приобретению богатства про-римской элитой. [ 109 ] Расширение универсального гражданства на всех свободных жителей Империи в 212 году потребовало единого применения римского права, заменив коды местного права, которые применялись к негражданам. Усилия Диоклетиана по стабилизации Империи после кризиса третьего века включали два основных сборника закона за четыре года: Кодекс Грегориан и Кодекс Хермогенан , чтобы направлять администраторов провинции в установлении последовательных юридических стандартов. [ 225 ]

Распространенность римского права по всей Западной Европе сильно повлияла на западную правовую традицию, отраженную путем дальнейшего использования латинской правовой терминологии в современном праве.

Налогообложение

Налогообложение под империей составило около 5% его валового продукта . [ 226 ] Типичная налоговая ставка для отдельных лиц варьировалась от 2 до 5%. [ 227 ] Налоговый кодекс был «сбивающим с толку» в его сложной системе прямых и косвенных налогов , некоторые из которых выплачивались наличными, а некоторые - в натуральной форме . Налоги могут быть специфичными для провинции или видов недвижимости, таких как рыболовство ; Они могут быть временными. [ 228 ] Сбор налогов был оправдан необходимостью поддерживать военные, [ 229 ] И налогоплательщики иногда получали возмещение, если армия захватила избыток добычи. [ 230 ] Налоги в натуральной форме были приняты из менее монетизированных районов, особенно тех, кто мог поставлять зерно или товары армейским лагерям. [ 231 ]

Основным источником прямых налоговых поступлений были лица, которые платили налог на опрос и налог на свою землю, истолковывавшись как налог на его продукцию или производительные мощности. [ 227 ] Налоговые обязательства определялись переписью: каждый глава домохозяйства предоставил численность своего домашнего хозяйства, а также бухгалтерский учет его имущества. [ 232 ] Основным источником доходов от непрямого налога были портория , таможня и платы за торговлю, в том числе среди провинций. [ 227 ] Towards the end of his reign, Augustus instituted a 4% tax on the sale of slaves,[233] which Nero shifted from the purchaser to the dealers, who responded by raising their prices.[234] An owner who manumitted a slave paid a "freedom tax", calculated at 5% of value.[p] An inheritance tax of 5% was assessed when Roman citizens above a certain net worth left property to anyone outside their immediate family. Revenues from the estate tax and from an auction tax went towards the veterans' pension fund (aerarium militare).[227]

Low taxes helped the Roman aristocracy increase their wealth, which equalled or exceeded the revenues of the central government. An emperor sometimes replenished his treasury by confiscating the estates of the "super-rich", but in the later period, the resistance of the wealthy to paying taxes was one of the factors contributing to the collapse of the Empire.[66]

Economy

The Empire is best thought of as a network of regional economies, based on a form of "political capitalism" in which the state regulated commerce to assure its own revenues.[235] Economic growth, though not comparable to modern economies, was greater than that of most other societies prior to industrialization.[236] Territorial conquests permitted a large-scale reorganization of land use that resulted in agricultural surplus and specialization, particularly in north Africa.[237] Some cities were known for particular industries. The scale of urban building indicates a significant construction industry.[237] Papyri preserve complex accounting methods that suggest elements of economic rationalism,[237] and the Empire was highly monetized.[238] Although the means of communication and transport were limited in antiquity, transportation in the 1st and 2nd centuries expanded greatly, and trade routes connected regional economies.[239] The supply contracts for the army drew on local suppliers near the base (castrum), throughout the province, and across provincial borders.[240] Economic historians vary in their calculations of the gross domestic product during the Principate.[241] In the sample years of 14, 100, and 150 AD, estimates of per capita GDP range from 166 to 380 HS. The GDP per capita of Italy is estimated as 40[242] to 66%[243] higher than in the rest of the Empire, due to tax transfers from the provinces and the concentration of elite income.

Economic dynamism resulted in social mobility. Although aristocratic values permeated traditional elite society, wealth requirements for rank indicate a strong tendency towards plutocracy. Prestige could be obtained through investing one's wealth in grand estates or townhouses, luxury items, public entertainments, funerary monuments, and religious dedications. Guilds (collegia) and corporations (corpora) provided support for individuals to succeed through networking.[179] "There can be little doubt that the lower classes of ... provincial towns of the Roman Empire enjoyed a high standard of living not equaled again in Western Europe until the 19th century".[244] Households in the top 1.5% of income distribution captured about 20% of income. The "vast majority" produced more than half of the total income, but lived near subsistence.[245]

Currency and banking

The early Empire was monetized to a near-universal extent, using money as a way to express prices and debts.[247] The sestertius (English "sesterces", symbolized as HS) was the basic unit of reckoning value into the 4th century,[248] though the silver denarius, worth four sesterces, was also used beginning in the Severan dynasty.[249] The smallest coin commonly circulated was the bronze as, one-tenth denarius.[250] Bullion and ingots seem not to have counted as pecunia ("money") and were used only on the frontiers. Romans in the first and second centuries counted coins, rather than weighing them—an indication that the coin was valued on its face. This tendency towards fiat money led to the debasement of Roman coinage in the later Empire.[251] The standardization of money throughout the Empire promoted trade and market integration.[247] The high amount of metal coinage in circulation increased the money supply for trading or saving.[252] Rome had no central bank, and regulation of the banking system was minimal. Banks of classical antiquity typically kept less in reserves than the full total of customers' deposits. A typical bank had fairly limited capital, and often only one principal. Seneca assumes that anyone involved in Roman commerce needs access to credit.[251] A professional deposit banker received and held deposits for a fixed or indefinite term, and lent money to third parties. The senatorial elite were involved heavily in private lending, both as creditors and borrowers.[253] The holder of a debt could use it as a means of payment by transferring it to another party, without cash changing hands. Although it has sometimes been thought that ancient Rome lacked documentary transactions, the system of banks throughout the Empire permitted the exchange of large sums without physically transferring coins, in part because of the risks of moving large amounts of cash. Only one serious credit shortage is known to have occurred in the early Empire, in 33 AD;[254] generally, available capital exceeded the amount needed by borrowers.[251] The central government itself did not borrow money, and without public debt had to fund deficits from cash reserves.[255]

Emperors of the Antonine and Severan dynasties debased the currency, particularly the denarius, under the pressures of meeting military payrolls.[248] Sudden inflation under Commodus damaged the credit market.[251] In the mid-200s, the supply of specie contracted sharply.[248] Conditions during the Crisis of the Third Century—such as reductions in long-distance trade, disruption of mining operations, and the physical transfer of gold coinage outside the empire by invading enemies—greatly diminished the money supply and the banking sector.[248][251] Although Roman coinage had long been fiat money or fiduciary currency, general economic anxieties came to a head under Aurelian, and bankers lost confidence in coins. Despite Diocletian's introduction of the gold solidus and monetary reforms, the credit market of the Empire never recovered its former robustness.[251]

Mining and metallurgy

The main mining regions of the Empire were the Iberian Peninsula (silver, copper, lead, iron and gold);[4] Gaul (gold, silver, iron);[4] Britain (mainly iron, lead, tin),[256] the Danubian provinces (gold, iron);[257] Macedonia and Thrace (gold, silver); and Asia Minor (gold, silver, iron, tin). Intensive large-scale mining—of alluvial deposits, and by means of open-cast mining and underground mining—took place from the reign of Augustus up to the early 3rd century, when the instability of the Empire disrupted production.[citation needed]

Hydraulic mining allowed base and precious metals to be extracted on a proto-industrial scale.[258] The total annual iron output is estimated at 82,500 tonnes.[259] Copper and lead production levels were unmatched until the Industrial Revolution.[260][261][262][263] At its peak around the mid-2nd century, the Roman silver stock is estimated at 10,000 t, five to ten times larger than the combined silver mass of medieval Europe and the Caliphate around 800 AD.[262][264] As an indication of the scale of Roman metal production, lead pollution in the Greenland ice sheet quadrupled over prehistoric levels during the Imperial era and dropped thereafter.[265]

Transportation and communication

The Empire completely encircled the Mediterranean, which they called "our sea" (Mare Nostrum).[266] Roman sailing vessels navigated the Mediterranean as well as major rivers.[69] Transport by water was preferred where possible, as moving commodities by land was more difficult.[267] Vehicles, wheels, and ships indicate the existence of a great number of skilled woodworkers.[268]

Land transport utilized the advanced system of Roman roads, called "viae". These roads were primarily built for military purposes,[269] but also served commercial ends. The in-kind taxes paid by communities included the provision of personnel, animals, or vehicles for the cursus publicus, the state mail and transport service established by Augustus.[231] Relay stations were located along the roads every seven to twelve Roman miles, and tended to grow into villages or trading posts.[270] A mansio (plural mansiones) was a privately run service station franchised by the imperial bureaucracy for the cursus publicus. The distance between mansiones was determined by how far a wagon could travel in a day.[270] Carts were usually pulled by mules, travelling about 4 mph.[271]

Trade and commodities

Roman provinces traded among themselves, but trade extended outside the frontiers to regions as far away as China and India.[272] Chinese trade was mostly conducted overland through middle men along the Silk Road; Indian trade also occurred by sea from Egyptian ports. The main commodity was grain.[273] Also traded were olive oil, foodstuffs, garum (fish sauce), slaves, ore and manufactured metal objects, fibres and textiles, timber, pottery, glassware, marble, papyrus, spices and materia medica, ivory, pearls, and gemstones.[274] Though most provinces could produce wine, regional varietals were desirable and wine was a central trade good.[275]

Labour and occupations

Inscriptions record 268 different occupations in Rome and 85 in Pompeii.[211] Professional associations or trade guilds (collegia) are attested for a wide range of occupations, some quite specialized.[179]

Work performed by slaves falls into five general categories: domestic, with epitaphs recording at least 55 different household jobs; imperial or public service; urban crafts and services; agriculture; and mining. Convicts provided much of the labour in the mines or quarries, where conditions were notoriously brutal.[276] In practice, there was little division of labour between slave and free,[109] and most workers were illiterate and without special skills.[277] The greatest number of common labourers were employed in agriculture: in Italian industrial farming (latifundia), these may have been mostly slaves, but elsewhere slave farm labour was probably less important.[109]

Textile and clothing production was a major source of employment. Both textiles and finished garments were traded and products were often named for peoples or towns, like a fashion "label".[278] Better ready-to-wear was exported by local businessmen (negotiatores or mercatores).[279] Finished garments might be retailed by their sales agents, by vestiarii (clothing dealers), or peddled by itinerant merchants.[279] The fullers (fullones) and dye workers (coloratores) had their own guilds.[280] Centonarii were guild workers who specialized in textile production and the recycling of old clothes into pieced goods.[q]

Architecture and engineering

The chief Roman contributions to architecture were the arch, vault and dome. Some Roman structures still stand today, due in part to sophisticated methods of making cements and concrete.[283] Roman temples developed Etruscan and Greek forms, with some distinctive elements. Roman roads are considered the most advanced built until the early 19th century.[citation needed]

Roman bridges were among the first large and lasting bridges, built from stone (and in most cases concrete) with the arch as the basic structure. The largest Roman bridge was Trajan's bridge over the lower Danube, constructed by Apollodorus of Damascus, which remained for over a millennium the longest bridge to have been built.[284] The Romans built many dams and reservoirs for water collection, such as the Subiaco Dams, two of which fed the Anio Novus, one of the largest aqueducts of Rome.[285]

The Romans constructed numerous aqueducts. De aquaeductu, a treatise by Frontinus, who served as water commissioner, reflects the administrative importance placed on the water supply. Masonry channels carried water along a precise gradient, using gravity alone. It was then collected in tanks and fed through pipes to public fountains, baths, toilets, or industrial sites.[286] The main aqueducts in Rome were the Aqua Claudia and the Aqua Marcia.[287] The complex system built to supply Constantinople had its most distant supply drawn from over 120 km away along a route of more than 336 km.[288] Roman aqueducts were built to remarkably fine tolerance, and to a technological standard not equalled until modern times.[289] The Romans also used aqueducts in their extensive mining operations across the empire.[290]

Insulated glazing (or "double glazing") was used in the construction of public baths. Elite housing in cooler climates might have hypocausts, a form of central heating. The Romans were the first culture to assemble all essential components of the much later steam engine: the crank and connecting rod system, Hero's aeolipile (generating steam power), the cylinder and piston (in metal force pumps), non-return valves (in water pumps), and gearing (in water mills and clocks).[291]

Daily life

City and country

The city was viewed as fostering civilization by being "properly designed, ordered, and adorned".[292] Augustus undertook a vast building programme in Rome, supported public displays of art that expressed imperial ideology, and reorganized the city into neighbourhoods (vici) administered at the local level with police and firefighting services.[293] A focus of Augustan monumental architecture was the Campus Martius, an open area outside the city centre: the Altar of Augustan Peace (Ara Pacis Augustae) was located there, as was an obelisk imported from Egypt that formed the pointer (gnomon) of a horologium. With its public gardens, the Campus was among the most attractive places in Rome to visit.[293]

City planning and urban lifestyles was influenced by the Greeks early on,[294] and in the Eastern Empire, Roman rule shaped the development of cities that already had a strong Hellenistic character. Cities such as Athens, Aphrodisias, Ephesus and Gerasa tailored city planning and architecture to imperial ideals, while expressing their individual identity and regional preeminence.[295] In areas inhabited by Celtic-speaking peoples, Rome encouraged the development of urban centres with stone temples, forums, monumental fountains, and amphitheatres, often on or near the sites of preexisting walled settlements known as oppida.[296][297][r] Urbanization in Roman Africa expanded on Greek and Punic coastal cities.[270]

The network of cities (coloniae, municipia, civitates or in Greek terms poleis) was a primary cohesive force during the Pax Romana.[200] Romans of the 1st and 2nd centuries were encouraged to "inculcate the habits of peacetime".[299] As the classicist Clifford Ando noted:

Most of the cultural appurtenances popularly associated with imperial culture—public cult and its games and civic banquets, competitions for artists, speakers, and athletes, as well as the funding of the great majority of public buildings and public display of art—were financed by private individuals, whose expenditures in this regard helped to justify their economic power and legal and provincial privileges.[300]

In the city of Rome, most people lived in multistory apartment buildings (insulae) that were often squalid firetraps. Public facilities—such as baths (thermae), toilets with running water (latrinae), basins or elaborate fountains (nymphea) delivering fresh water,[297] and large-scale entertainments such as chariot races and gladiator combat—were aimed primarily at the common people.[301]

The public baths served hygienic, social and cultural functions.[302] Bathing was the focus of daily socializing.[303] Roman baths were distinguished by a series of rooms that offered communal bathing in three temperatures, with amenities that might include an exercise room, sauna, exfoliation spa, ball court, or outdoor swimming pool. Baths had hypocaust heating: the floors were suspended over hot-air channels.[304] Public baths were part of urban culture throughout the provinces, but in the late 4th century, individual tubs began to replace communal bathing. Christians were advised to go to the baths only for hygiene.[305]

Rich families from Rome usually had two or more houses: a townhouse (domus) and at least one luxury home (villa) outside the city. The domus was a privately owned single-family house, and might be furnished with a private bath (balneum),[304] but it was not a place to retreat from public life.[306] Although some neighbourhoods show a higher concentration of such houses, they were not segregated enclaves. The domus was meant to be visible and accessible. The atrium served as a reception hall in which the paterfamilias (head of household) met with clients every morning.[293] It was a centre of family religious rites, containing a shrine and images of family ancestors.[307] The houses were located on busy public roads, and ground-level spaces were often rented out as shops (tabernae).[308] In addition to a kitchen garden—windowboxes might substitute in the insulae—townhouses typically enclosed a peristyle garden.[309]

The villa by contrast was an escape from the city, and in literature represents a lifestyle that balances intellectual and artistic interests (otium) with an appreciation of nature and agriculture.[310] Ideally a villa commanded a view or vista, carefully framed by the architectural design.[311]

Augustus' programme of urban renewal, and the growth of Rome's population to as many as one million, was accompanied by nostalgia for rural life. Poetry idealized the lives of farmers and shepherds. Interior decorating often featured painted gardens, fountains, landscapes, vegetative ornament,[311] and animals, rendered accurately enough to be identified by species.[312] On a more practical level, the central government took an active interest in supporting agriculture.[313] Producing food was the priority of land use.[314] Larger farms (latifundia) achieved an economy of scale that sustained urban life.[313] Small farmers benefited from the development of local markets in towns and trade centres. Agricultural techniques such as crop rotation and selective breeding were disseminated throughout the Empire, and new crops were introduced from one province to another.[315]

Maintaining an affordable food supply to the city of Rome had become a major political issue in the late Republic, when the state began to provide a grain dole (Cura Annonae) to citizens who registered for it[313] (about 200,000–250,000 adult males in Rome).[316] The dole cost at least 15% of state revenues,[313] but improved living conditions among the lower classes,[317] and subsidized the rich by allowing workers to spend more of their earnings on the wine and olive oil produced on estates.[313] The grain dole also had symbolic value: it affirmed the emperor's position as universal benefactor, and the right of citizens to share in "the fruits of conquest".[313] The annona, public facilities, and spectacular entertainments mitigated the otherwise dreary living conditions of lower-class Romans, and kept social unrest in check. The satirist Juvenal, however, saw "bread and circuses" (panem et circenses) as emblematic of the loss of republican political liberty:[318]

The public has long since cast off its cares: the people that once bestowed commands, consulships, legions and all else, now meddles no more and longs eagerly for just two things: bread and circuses.[319]

Health and disease

Epidemics were common in the ancient world, and occasional pandemics in the Empire killed millions. The Roman population was unhealthy. About 20 percent—a large percentage by ancient standards—lived in cities, Rome being the largest. The cities were a "demographic sink": the death rate exceeded the birth rate and constant immigration was necessary to maintain the population. Average lifespan is estimated at the mid-twenties, and perhaps more than half of children died before reaching adulthood. Dense urban populations and poor sanitation contributed to disease. Land and sea connections facilitated and sped the transfer of infectious diseases across the empire's territories. The rich were not immune; only two of emperor Marcus Aurelius's fourteen children are known to have reached adulthood.[320]

The importance of a good diet to health was recognized by medical writers such as Galen (2nd century). Views on nutrition were influenced by beliefs like humoral theory.[321] A good indicator of nutrition and disease burden is average height: the average Roman was shorter in stature than the population of pre-Roman Italian societies and medieval Europe.[322]

Food and dining

Most apartments in Rome lacked kitchens, though a charcoal brazier could be used for rudimentary cookery.[323] Prepared food was sold at pubs and bars, inns, and food stalls (tabernae, cauponae, popinae, thermopolia).[324] Carryout and restaurants were for the lower classes; fine dining appeared only at dinner parties in wealthy homes with a chef (archimagirus) and kitchen staff,[325] or banquets hosted by social clubs (collegia).[326]

Most Romans consumed at least 70% of their daily calories in the form of cereals and legumes.[327] Puls (pottage) was considered the food of the Romans,[328] and could be elaborated to produce dishes similar to polenta or risotto.[329] Urban populations and the military preferred bread.[327] By the reign of Aurelian, the state had begun to distribute the annona as a daily ration of bread baked in state factories, and added olive oil, wine, and pork to the dole.[330]

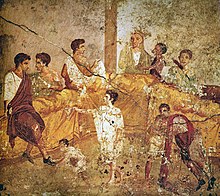

Roman literature focuses on the dining habits of the upper classes,[331] for whom the evening meal (cena) had important social functions.[332] Guests were entertained in a finely decorated dining room (triclinium) furnished with couches. By the late Republic, women dined, reclined, and drank wine along with men.[333] The poet Martial describes a dinner, beginning with the gustatio ("tasting" or "appetizer") salad. The main course was kid, beans, greens, a chicken, and leftover ham, followed by a dessert of fruit and wine.[334] Roman "foodies" indulged in wild game, fowl such as peacock and flamingo, large fish (mullet was especially prized), and shellfish. Luxury ingredients were imported from the far reaches of empire.[335] A book-length collection of Roman recipes is attributed to Apicius, a name for several figures in antiquity that became synonymous with "gourmet".[336]

Refined cuisine could be moralized as a sign of either civilized progress or decadent decline.[337] Most often, because of the importance of landowning in Roman culture, produce—cereals, legumes, vegetables, and fruit—were considered more civilized foods than meat. The Mediterranean staples of bread, wine, and oil were sacralized by Roman Christianity, while Germanic meat consumption became a mark of paganism.[338] Some philosophers and Christians resisted the demands of the body and the pleasures of food, and adopted fasting as an ideal.[339] Food became simpler in general as urban life in the West diminished and trade routes were disrupted;[340] the Church formally discouraged gluttony,[341] and hunting and pastoralism were seen as simple and virtuous.[340]

Spectacles

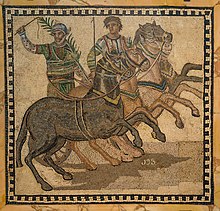

When Juvenal complained that the Roman people had exchanged their political liberty for "bread and circuses", he was referring to the state-provided grain dole and the circenses, events held in the entertainment venue called a circus. The largest such venue in Rome was the Circus Maximus, the setting of horse races, chariot races, the equestrian Troy Game, staged beast hunts (venationes), athletic contests, gladiator combat, and historical re-enactments. From earliest times, several religious festivals had featured games (ludi), primarily horse and chariot races (ludi circenses).[342] The races retained religious significance in connection with agriculture, initiation, and the cycle of birth and death.[s]

Under Augustus, public entertainments were presented on 77 days of the year; by the reign of Marcus Aurelius, this had expanded to 135.[344] Circus games were preceded by an elaborate parade (pompa circensis) that ended at the venue.[345] Competitive events were held also in smaller venues such as the amphitheatre, which became the characteristic Roman spectacle venue, and stadium. Greek-style athletics included footraces, boxing, wrestling, and the pancratium.[346] Aquatic displays, such as the mock sea battle (naumachia) and a form of "water ballet", were presented in engineered pools.[347] State-supported theatrical events (ludi scaenici) took place on temple steps or in grand stone theatres, or in the smaller enclosed theatre called an odeon.[348]

Circuses were the largest structure regularly built in the Roman world.[349] The Flavian Amphitheatre, better known as the Colosseum, became the regular arena for blood sports in Rome.[350] Many Roman amphitheatres, circuses and theatres built in cities outside Italy are visible as ruins today.[350] The local ruling elite were responsible for sponsoring spectacles and arena events, which both enhanced their status and drained their resources.[183] The physical arrangement of the amphitheatre represented the order of Roman society: the emperor in his opulent box; senators and equestrians in reserved advantageous seats; women seated at a remove from the action; slaves given the worst places, and everybody else in-between.[351] The crowd could call for an outcome by booing or cheering, but the emperor had the final say. Spectacles could quickly become sites of social and political protest, and emperors sometimes had to deploy force to put down crowd unrest, most notoriously at the Nika riots in 532.[352]

The chariot teams were known by the colours they wore. Fan loyalty was fierce and at times erupted into sports riots.[354] Racing was perilous, but charioteers were among the most celebrated and well-compensated athletes.[355] Circuses were designed to ensure that no team had an unfair advantage and to minimize collisions (naufragia),[356] which were nonetheless frequent and satisfying to the crowd.[357] The races retained a magical aura through their early association with chthonic rituals: circus images were considered protective or lucky, curse tablets have been found buried at the site of racetracks, and charioteers were often suspected of sorcery.[358] Chariot racing continued into the Byzantine period under imperial sponsorship, but the decline of cities in the 6th and 7th centuries led to its eventual demise.[349]

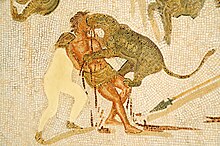

The Romans thought gladiator contests had originated with funeral games and sacrifices. Some of the earliest styles of gladiator fighting had ethnic designations such as "Thracian" or "Gallic".[359] The staged combats were considered munera, "services, offerings, benefactions", initially distinct from the festival games (ludi).[360] To mark the opening of the Colosseum, Titus presented 100 days of arena events, with 3,000 gladiators competing on a single day.[361] Roman fascination with gladiators is indicated by how widely they are depicted on mosaics, wall paintings, lamps, and in graffiti.[362] Gladiators were trained combatants who might be slaves, convicts, or free volunteers.[363] Death was not a necessary or even desirable outcome in matches between these highly skilled fighters, whose training was costly and time-consuming.[364] By contrast, noxii were convicts sentenced to the arena with little or no training, often unarmed, and with no expectation of survival; physical suffering and humiliation were considered appropriate retributive justice.[183] These executions were sometimes staged or ritualized as re-enactments of myths, and amphitheatres were equipped with elaborate stage machinery to create special effects.[183][365]

Modern scholars have found the pleasure Romans took in the "theatre of life and death"[366] difficult to understand.[367] Pliny the Younger rationalized gladiator spectacles as good for the people, "to inspire them to face honourable wounds and despise death, by exhibiting love of glory and desire for victory".[368] Some Romans such as Seneca were critical of the brutal spectacles, but found virtue in the courage and dignity of the defeated fighter[369]—an attitude that finds its fullest expression with the Christians martyred in the arena. Tertullian considered deaths in the arena to be nothing more than a dressed-up form of human sacrifice.[370] Even martyr literature, however, offers "detailed, indeed luxuriant, descriptions of bodily suffering",[371] and became a popular genre at times indistinguishable from fiction.[372]

Recreation

The singular ludus, "play, game, sport, training", had a wide range of meanings such as "word play", "theatrical performance", "board game", "primary school", and even "gladiator training school" (as in Ludus Magnus).[373] Activities for children and young people in the Empire included hoop rolling and knucklebones (astragali or "jacks"). Girls had dolls made of wood, terracotta, and especially bone and ivory.[374] Ball games include trigon and harpastum.[375] People of all ages played board games, including latrunculi ("Raiders") and XII scripta ("Twelve Marks").[376] A game referred to as alea (dice) or tabula (the board) may have been similar to backgammon.[377] Dicing as a form of gambling was disapproved of, but was a popular pastime during the festival of the Saturnalia.[378]

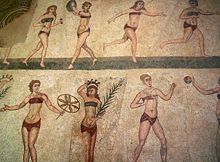

After adolescence, most physical training for males was of a military nature. The Campus Martius originally was an exercise field where young men learned horsemanship and warfare. Hunting was also considered an appropriate pastime. According to Plutarch, conservative Romans disapproved of Greek-style athletics that promoted a fine body for its own sake, and condemned Nero's efforts to encourage Greek-style athletic games.[379] Some women trained as gymnasts and dancers, and a rare few as female gladiators. The "Bikini Girls" mosaic shows young women engaging in routines comparable to rhythmic gymnastics.[t][381] Women were encouraged to maintain health through activities such as playing ball, swimming, walking, or reading aloud (as a breathing exercise).[382]

Clothing

In a status-conscious society like that of the Romans, clothing and personal adornment indicated the etiquette of interacting with the wearer.[383] Wearing the correct clothing reflected a society in good order.[384] There is little direct evidence of how Romans dressed in daily life, since portraiture may show the subject in clothing with symbolic value, and surviving textiles are rare.[385][386]

The toga was the distinctive national garment of the male citizen, but it was heavy and impractical, worn mainly for conducting political or court business and religious rites.[387][385] It was a "vast expanse" of semi-circular white wool that could not be put on and draped correctly without assistance.[387] The drapery became more intricate and structured over time.[388] The toga praetexta, with a purple or purplish-red stripe representing inviolability, was worn by children who had not come of age, curule magistrates, and state priests. Only the emperor could wear an all-purple toga (toga picta).[389]

Ordinary clothing was dark or colourful. The basic garment for all Romans, regardless of gender or wealth, was the simple sleeved tunic, with length differing by wearer.[390] The tunics of poor people and labouring slaves were made from coarse wool in natural, dull shades; finer tunics were made of lightweight wool or linen. A man of the senatorial or equestrian order wore a tunic with two purple stripes (clavi) woven vertically: the wider the stripe, the higher the wearer's status.[390] Other garments could be layered over the tunic. Common male attire also included cloaks and in some regions trousers.[391] In the 2nd century, emperors and elite men are often portrayed wearing the pallium, an originally Greek mantle; women are also portrayed in the pallium. Tertullian considered the pallium an appropriate garment both for Christians, in contrast to the toga, and for educated people.[384][385][392]