Тысяча и одна ночь

| |

| Язык | арабский |

|---|---|

| Genre | Frame story, folklore |

| Set in | Middle Ages |

| Text | One Thousand and One Nights at Wikisource |

| Part of a series on |

| Arabic culture |

|---|

|

Тысяча и одна ночь ( арабский : тысяча ночей и ночи , Альф Лейла Ва-Лейла ) [ 1 ] ( Персидский : هزار یک t و ش Это часто известно на английском языке как « Аравийские ночи» , из первого английского издания ( ок. 1706–1721 ), которое стало титулом как развлечения арабских ночей . [ 2 ]

Работа была собрана на протяжении многих веков различными авторами, переводчиками и учеными по всей Западной Азии , Центральной Азии , Южной Азии и Северной Африке . Некоторые сказки прослеживают свои корни до древней и средневековой арабской , санскритской , персидской и месопотамской литературы. [ 3 ] Большинство рассказов, однако, изначально были народными историями из эпох Abbasid и Mamluk , в то время как другие, особенно история о кадре, взяты из персидской работы Pahlavi Hezār Afsān ( Persian : هزار افسان , Lit. Тысяча рассказов ) , в котором в Поворот может быть переводом старых индийских текстов . [4]

Common to all the editions of the Nights is the framing device of the story of the ruler Shahryar being narrated the tales by his wife Scheherazade, with one tale told over each night of storytelling. The stories proceed from this original tale; some are framed within other tales, while some are self-contained. Some editions contain only a few hundred nights of storytelling, while others include 1001 or more. The bulk of the text is in prose, although verse is occasionally used for songs and riddles and to express heightened emotion. Most of the poems are single couplets or quatrains, although some are longer.

Some of the stories commonly associated with the Arabian Nights—particularly "Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp" and "Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves"—were not part of the collection in the original Arabic versions, but were instead added to the collection by French translator Antoine Galland after he heard them from Syrian writer Hanna Diyab during the latter's visit to Paris.[5][6][7] Other stories, such as "The Seven Voyages of Sinbad the Sailor", had an independent existence before being added to the collection.

Synopsis

[edit]

The main frame story concerns Shahryār, whom the narrator calls a "Sasanian king" ruling in "India and China".[8] Shahryār is shocked to learn that his brother's wife is unfaithful. Discovering that his own wife's infidelity has been even more flagrant, he has her killed. In his bitterness and grief, he decides that all women are the same. Shahryār begins to marry a succession of virgins only to execute each one the next morning, before she has a chance to dishonor him.

Eventually the Vizier (Wazir), whose duty it is to provide them, cannot find any more virgins. Scheherazade, the vizier's daughter, offers herself as the next bride and her father reluctantly agrees. On the night of their marriage, Scheherazade begins to tell the king a tale, but does not end it. The king, curious about how the story ends, is thus forced to postpone her execution in order to hear the conclusion. The next night, as soon as she finishes the tale, she begins another one, and the king, eager to hear the conclusion of that tale as well, postpones her execution once again. This goes on for one thousand and one nights, hence the name.

The tales vary widely: they include historical tales, love stories, tragedies, comedies, poems, burlesques, and various forms of erotica. Numerous stories depict jinn, ghouls, ape people, sorcerers, magicians, and legendary places, which are often intermingled with real people and geography, not always rationally. Common protagonists include the historical Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid, his Grand Vizier, Jafar al-Barmaki, and the famous poet Abu Nuwas, despite the fact that these figures lived some 200 years after the fall of the Sassanid Empire, in which the frame tale of Scheherazade is set. Sometimes a character in Scheherazade's tale will begin telling other characters a story of their own, and that story may have another one told within it, resulting in a richly layered narrative texture.

Versions differ, at least in detail, as to final endings (in some Scheherazade asks for a pardon, in some the king sees their children and decides not to execute his wife, in some other things happen that make the king distracted) but they all end with the king giving his wife a pardon and sparing her life.

The narrator's standards for what constitutes a cliffhanger seem broader than in modern literature. While in many cases a story is cut off with the hero in danger of losing their life or another kind of deep trouble, in some parts of the full text Scheherazade stops her narration in the middle of an exposition of abstract philosophical principles or complex points of Islamic philosophy, and in one case during a detailed description of human anatomy according to Galen—and in all of these cases she turns out to be justified in her belief that the king's curiosity about the sequel would buy her another day of life.

A number of stories within the One Thousand and One Nights also feature science fiction elements. One example is "The Adventures of Bulukiya", where the protagonist Bulukiya's quest for the herb of immortality leads him to explore the seas, journey to the Garden of Eden and to Jahannam, and travel across the cosmos to different worlds much larger than his own world, anticipating elements of galactic science fiction;[9] along the way, he encounters societies of jinns,[10] mermaids, talking serpents, talking trees, and other forms of life.[9] In another Arabian Nights tale, the protagonist Abdullah the Fisherman gains the ability to breathe underwater and discovers an underwater submarine society that is portrayed as an inverted reflection of society on land, in that the underwater society follows a form of primitive communism where concepts like money and clothing do not exist. Other Arabian Nights tales deal with lost ancient technologies, advanced ancient civilizations that went astray, and catastrophes which overwhelmed them.[11] "The City of Brass" features a group of travellers on an archaeological expedition[12] across the Sahara to find an ancient lost city and attempt to recover a brass vessel that Solomon once used to trap a jinn,[13] and, along the way, encounter a mummified queen, petrified inhabitants,[14] life-like humanoid robots and automata, seductive marionettes dancing without strings,[15] and a brass horseman robot who directs the party towards the ancient city. "The Ebony Horse" features a robot[16] in the form of a flying mechanical horse controlled using keys that could fly into outer space and towards the Sun,[17] while the "Third Qalandar's Tale" also features a robot in the form of an uncanny boatman.[16] "The City of Brass" and "The Ebony Horse" can be considered early examples of proto-science fiction.[18]

History, versions and translations

[edit]The history of the Nights is extremely complex and modern scholars have made many attempts to untangle the story of how the collection as it currently exists came about. Robert Irwin summarises their findings:

In the 1880s and 1890s a lot of work was done on the Nights by Zotenberg and others, in the course of which a consensus view of the history of the text emerged. Most scholars agreed that the Nights was a composite work and that the earliest tales in it came from India and Persia. At some time, probably in the early eighth century, these tales were translated into Arabic under the title Alf Layla, or 'The Thousand Nights'. This collection then formed the basis of The Thousand and One Nights. The original core of stories was quite small. Then, in Iraq in the ninth or tenth century, this original core had Arab stories added to it—among them some tales about the Caliph Harun al-Rashid. Also, perhaps from the tenth century onwards, previously independent sagas and story cycles were added to the compilation [...] Then, from the 13th century onwards, a further layer of stories was added in Syria and Egypt, many of these showing a preoccupation with sex, magic or low life. In the early modern period yet more stories were added to the Egyptian collections so as to swell the bulk of the text sufficiently to bring its length up to the full 1,001 nights of storytelling promised by the book's title.[19]

Possible Indian influence

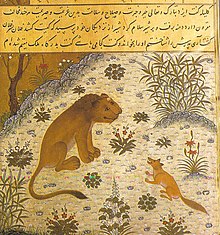

[edit]Devices found in Sanskrit literature such as frame stories and animal fables are seen by some scholars as lying at the root of the conception of the Nights.[20] The motif of the wise young woman who delays and finally removes an impending danger by telling stories has been traced back to Indian sources.[21] Indian folklore is represented in the Nights by certain animal stories, which reflect influence from ancient Sanskrit fables. The influence of the Panchatantra and Baital Pachisi is particularly notable.[22]

It is possible that the influence of the Panchatantra is via a Sanskrit adaptation called the Tantropakhyana. Only fragments of the original Sanskrit form of the Tantropakhyana survive, but translations or adaptations exist in Tamil,[23] Lao,[24] Thai,[25] and Old Javanese.[26] The frame story follows the broad outline of a concubine telling stories in order to maintain the interest and favour of a king—although the basis of the collection of stories is from the Panchatantra—with its original Indian setting.[27]

The Panchatantra and various tales from Jatakas were first translated into Persian by Borzūya in 570 CE;[28] they were later translated into Arabic by Ibn al-Muqaffa in 750 CE.[29] The Arabic version was translated into several languages, including Syriac, Greek, Hebrew and Spanish.[30]

Persian prototype: Hezār Afsān

[edit]

The earliest mentions of the Nights refer to it as an Arabic translation from a Persian book, Hezār Afsān (also known as Afsaneh or Afsana), meaning 'The Thousand Stories'. In the tenth century, Ibn al-Nadim compiled a catalogue of books (the "Fihrist") in Baghdad. He noted that the Sassanid kings of Iran enjoyed "evening tales and fables".[31] Al-Nadim then writes about the Persian Hezār Afsān, explaining the frame story it employs: a bloodthirsty king kills off a succession of wives after their wedding night. Eventually one has the intelligence to save herself by telling him a story every evening, leaving each tale unfinished until the next night so that the king will delay her execution.[32]

However, according to al-Nadim, the book contains only 200 stories. He also writes disparagingly of the collection's literary quality, observing that "it is truly a coarse book, without warmth in the telling".[33] In the same century Al-Masudi also refers to the Hezār Afsān, saying the Arabic translation is called Alf Khurafa ('A Thousand Entertaining Tales'), but is generally known as Alf Layla ('A Thousand Nights'). He mentions the characters Shirāzd (Scheherazade) and Dināzād.[34]

No physical evidence of the Hezār Afsān has survived,[20] so its exact relationship with the existing later Arabic versions remains a mystery.[35] Apart from the Scheherazade frame story, several other tales have Persian origins, although it is unclear how they entered the collection.[36] These stories include the cycle of "King Jali'ad and his Wazir Shimas" and "The Ten Wazirs or the History of King Azadbakht and his Son" (derived from the seventh-century Persian Bakhtiyārnāma).[37]

In the 1950s, the Iraqi scholar Safa Khulusi suggested (on internal rather than historical evidence) that the Persian writer Ibn al-Muqaffa' was responsible for the first Arabic translation of the frame story and some of the Persian stories later incorporated into the Nights. This would place genesis of the collection in the eighth century.[38][39]

Evolving Arabic versions

[edit]

In the mid-20th century, the scholar Nabia Abbott found a document with a few lines of an Arabic work with the title The Book of the Tale of a Thousand Nights, dating from the ninth century. This is the earliest known surviving fragment of the Nights.[35] The first reference to the Arabic version under its full title The One Thousand and One Nights appears in Cairo in the 12th century.[41] Professor Dwight Reynolds describes the subsequent transformations of the Arabic version:

Some of the earlier Persian tales may have survived within the Arabic tradition altered such that Arabic Muslim names and new locations were substituted for pre-Islamic Persian ones, but it is also clear that whole cycles of Arabic tales were eventually added to the collection and apparently replaced most of the Persian materials. One such cycle of Arabic tales centres around a small group of historical figures from ninth-century Baghdad, including the caliph Harun al-Rashid (died 809), his vizier Jafar al-Barmaki (d. 803) and the licentious poet Abu Nuwas (d. c. 813). Another cluster is a body of stories from late medieval Cairo in which are mentioned persons and places that date to as late as the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.[42]

Two main Arabic manuscript traditions of the Nights are known: the Syrian and the Egyptian. The Syrian tradition is primarily represented by the earliest extensive manuscript of the Nights, a fourteenth- or fifteenth-century Syrian manuscript now known as the Galland Manuscript. It and surviving copies of it are much shorter and include fewer tales than the Egyptian tradition. It is represented in print by the so-called Calcutta I (1814–1818) and most notably by the 'Leiden edition' (1984).[43][44] The Leiden Edition, prepared by Muhsin Mahdi, is the only critical edition of 1001 Nights to date,[45] believed to be most stylistically faithful representation of medieval Arabic versions currently available.[43][44]

Texts of the Egyptian tradition emerge later and contain many more tales of much more varied content; a much larger number of originally independent tales have been incorporated into the collection over the centuries, most of them after the Galland manuscript was written,[46] and were being included as late as in the 18th and 19th centuries.

All extant substantial versions of both recensions share a small common core of tales:[47]

- The Merchant and the Genie

- The Fisherman and the Genie

- The Porter and the Three Ladies

- The Three Apples

- Nur al-Din Ali and Shams al-Din (and Badr al-Din Hasan)

- Nur al-Din Ali and Anis al-Jalis

- Ali Ibn Bakkar and Shams al-Nahar

The texts of the Syrian recension do not contain much beside that core. It is debated which of the Arabic recensions is more "authentic" and closer to the original: the Egyptian ones have been modified more extensively and more recently, and scholars such as Muhsin Mahdi have suspected that this was caused in part by European demand for a "complete version"; but it appears that this type of modification has been common throughout the history of the collection, and independent tales have always been added to it.[46][48]

Printed Arabic editions

[edit]The first printed Arabic-language edition of the One Thousand and One Nights was published in 1775. It contained an Egyptian version of The Nights known as "ZER" (Zotenberg's Egyptian Recension) and 200 tales. No copy of this edition survives, but it was the basis for an 1835 edition by Bulaq, published by the Egyptian government.

The Nights were next printed in Arabic in two volumes in Calcutta by the British East India Company in 1814–1818. Each volume contained one hundred tales.

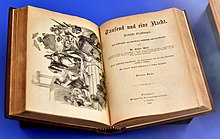

Soon after, the Prussian scholar Christian Maximilian Habicht collaborated with the Tunisian Mordecai ibn al-Najjar to create an edition containing 1001 nights both in the original Arabic and in German translation, initially in a series of eight volumes published in Breslau in 1825–1838. A further four volumes followed in 1842–1843. In addition to the Galland manuscript, Habicht and al-Najjar used what they believed to be a Tunisian manuscript, which was later revealed as a forgery by al-Najjar.[45]

Both the ZER printing and Habicht and al-Najjar's edition influenced the next printing, a four-volume edition also from Calcutta (known as the Macnaghten or Calcutta II edition).[49] This claimed to be based on an older Egyptian manuscript (which has never been found).

A major recent edition, which reverts to the Syrian recension, is a critical edition based on the fourteenth- or fifteenth-century Syrian manuscript in the Bibliothèque Nationale originally used by Galland.[50] This edition, known as the Leiden text, was compiled in Arabic by Muhsin Mahdi (1984–1994).[51] Mahdi argued that this version is the earliest extant one (a view that is largely accepted today) and that it reflects most closely a "definitive" coherent text ancestral to all others that he believed to have existed during the Mamluk period (a view that remains contentious).[46][52][53] Still, even scholars who deny this version the exclusive status of "the only real Arabian Nights" recognize it as being the best source on the original style and linguistic form of the medieval work.[43][44]

In 1997, a further Arabic edition appeared, containing tales from the Arabian Nights transcribed from a seventeenth-century manuscript in the Egyptian dialect of Arabic.[54]

Modern translations

[edit]

The first European version (1704–1717) was translated into French by Antoine Galland[55] from an Arabic text of the Syrian recension and other sources. This 12-volume work,[55] Les Mille et une nuits, contes arabes traduits en français ('The Thousand and one nights, Arab stories translated into French'), included stories that were not in the original Arabic manuscript. "Aladdin's Lamp", and "Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves" (as well as several other lesser-known tales) appeared first in Galland's translation and cannot be found in any of the original manuscripts. He wrote that he heard them from the Christian Maronite storyteller Hanna Diab during Diab's visit to Paris. Galland's version of the Nights was immensely popular throughout Europe, and later versions were issued by Galland's publisher using Galland's name without his consent.

As scholars were looking for the presumed "complete" and "original" form of the Nights, they naturally turned to the more voluminous texts of the Egyptian recension, which soon came to be viewed as the "standard version". The first translations of this kind, such as that of Edward Lane (1840, 1859), were bowdlerized. Unabridged and unexpurgated translations were made, first by John Payne, under the title The Book of the Thousand Nights and One Night (1882, nine volumes), and then by Sir Richard Francis Burton, entitled The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night (1885, ten volumes) – the latter was, according to some assessments, partially based on the former, leading to charges of plagiarism.[56][57]

In view of the sexual imagery in the source texts (which Burton emphasized even further, especially by adding extensive footnotes and appendices on Oriental sexual mores[57]) and the strict Victorian laws on obscene material, both of these translations were printed as private editions for subscribers only, rather than published in the usual manner. Burton's original 10 volumes were followed by a further six (seven in the Baghdad Edition and perhaps others) entitled The Supplemental Nights to the Thousand Nights and a Night, which were printed between 1886 and 1888.[55] It has, however, been criticized for its "archaic language and extravagant idiom" and "obsessive focus on sexuality" (and has even been called an "eccentric ego-trip" and a "highly personal reworking of the text").[57]

Later versions of the Nights include that of the French doctor J. C. Mardrus, issued from 1898 to 1904. It was translated into English by Powys Mathers, and issued in 1923. Like Payne's and Burton's texts, it is based on the Egyptian recension and retains the erotic material, indeed expanding on it, but it has been criticized for inaccuracy.[56]

Muhsin Mahdi's 1984 Leiden edition, based on the Galland Manuscript, was rendered into English by Husain Haddawy (1990).[58] This translation has been praised as "very readable" and "strongly recommended for anyone who wishes to taste the authentic flavour of those tales".[59] An additional second volume of Arabian nights translated by Haddawy, composed of popular tales not present in the Leiden edition, was published in 1995.[60] Both volumes were the basis for a single-volume reprint of selected tales of Haddawy's translations.[61]

A new English translation was published by Penguin Classics in three volumes in 2008.[62][63] It is translated by Malcolm C. Lyons and Ursula Lyons with introduction and annotations by Robert Irwin. This is the first complete translation of the Macnaghten or Calcutta II edition (Egyptian recension) since Burton's. It contains, in addition to the standard text of 1001 Nights, the so-called "orphan stories" of Aladdin and Ali Baba as well as an alternative ending to The seventh journey of Sindbad from Antoine Galland's original French. As the translator himself notes in his preface to the three volumes, "[N]o attempt has been made to superimpose on the translation changes that would be needed to 'rectify' ... accretions, ... repetitions, non sequiturs and confusions that mark the present text," and the work is a "representation of what is primarily oral literature, appealing to the ear rather than the eye".[64] The Lyons translation includes all the poetry (in plain prose paraphrase) but does not attempt to reproduce in English the internal rhyming of some prose sections of the original Arabic. Moreover, it streamlines somewhat and has cuts. In this sense it is not, as claimed, a complete translation. This translation was generally well-received upon release.[65]

A new English language translation was published in December 2021, the first solely by a female author, Yasmine Seale, which removes earlier sexist and racist references. The new translation includes all the tales from Hanna Diyab and additionally includes stories previously omitted featuring female protagonists, such as tales about Parizade, Pari Banu, and the horror story Sidi Numan.[66]

Timeline

[edit]

Scholars have assembled a timeline concerning the publication history of The Nights:[67][59][68]

- One of the oldest Arabic manuscript fragments from Syria (a few handwritten pages) dating to the early ninth century. Discovered by scholar Nabia Abbott in 1948, it bears the title Kitab Hadith Alf Layla ("The Book of the Tale of the Thousand Nights") and the first few lines of the book in which Dinazad asks Shirazad (Scheherazade) to tell her stories.[42]

- 10th century: mention of Hezār Afsān in Ibn al-Nadim's "Fihrist" (Catalogue of books) in Baghdad. He attributes a pre-Islamic Sassanid Persian origin to the collection and refers to the frame story of Scheherazade telling stories over a thousand nights to save her life.[33]

- 10th century: reference to The Thousand Nights, an Arabic translation of the Persian Hezār Afsān ("Thousand Stories"), in Muruj Al-Dhahab (The Meadows of Gold) by Al-Mas'udi.[34]

- 12th century: a document from Cairo refers to a Jewish bookseller lending a copy of The Thousand and One Nights (this is the first appearance of the final form of the title).[41]

- 14th century: existing Syrian manuscript in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris (contains about 300 tales).[50]

- 1704: Antoine Galland's French translation is the first European version of Nights. Later volumes were introduced using Galland's name, though the stories were written by unknown persons at the behest of the publisher, who wanted to capitalize on the popularity of the collection.

- c. 1706 – c. 1721: an anonymously translated 12-volume English version appears in Europe, dubbed the "Grub Street" version. This is entitled Arabian Nights' Entertainments—the first known use of the common English title of the work.[69]

- 1768: first Polish translation, 12 volumes. Based, as with many European versions, on the French translation.

- 1775: Egyptian version of Nights called "ZER" (Hermann Zotenberg's Egyptian Recension) with 200 tales (no extant edition).

- 1804–1806, 1825: Austrian polyglot and orientalist Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall (1774–1856) translates a subsequently lost manuscript into French between 1804 and 1806. His French translation, which was partially abridged and included Galland's "orphan stories", has been lost, but its translation into German, published in 1825, survives.[70]

- 1814: Calcutta I, the earliest existing Arabic printed version, is published by the British East India Company. A second volume was released in 1818. Both had 100 tales each.

- 1811: Jonathan Scott (1754–1829), an Englishman who learned Arabic and Persian in India, produces an English translation, mostly based on Galland's French version, supplemented by other sources. Robert Irwin calls it the "first literary translation into English", in contrast to earlier translations from French by "Grub Street hacks".[71]

- Early 19th century: Modern Persian translations of the text are made, variously under the title Alf leile va leile, Hezār-o yek šhab (هزار و یک شب), or, in distorted Arabic, Alf al-leil. Muhammad Baqir Khurasani Buzanjirdi (b.1770) finalized his translation in 1814, patronized by Henry Russell, 2nd Baronet (1783–1852), British Resident in Hyderabad. Three decades later, Abdul Latif Tasuji completed his translation.[72] It was later illustrated by Sani ol Molk (1814–1866) for Mohammad Shah Qajar.[73]

- 1825–1838: the Breslau/Habicht edition is published in Arabic in 8 volumes. Christian Maximilian Habicht (born in Breslau, Prussia, 1775) collaborated with the Tunisian Mordecai ibn al-Najjar to create this edition containing 1001 nights. In addition to the Galland manuscript, they used what they believed to be a Tunisian manuscript, which was later revealed as a forgery by al-Najjar.[45] Using versions of Nights, tales from Al-Najjar, and other stories of unknown origin, Habicht published his version in Arabic and German.

- 1842–1843: Four additional volumes by Habicht.

- 1835: Bulaq version: these two volumes, printed by the Egyptian government, are the oldest printed and published version of Nights in Arabic by a non-European. It is primarily a reprinting of the ZER text.

- 1839–1842: Calcutta II (4 volumes) is published. It claims to be based on an older Egyptian manuscript (this has never been found). This version contains many elements and stories from the Habicht edition.

- 1838: Torrens version in English.

- 1838–1840: Edward William Lane publishes an English translation. Notable for Lane's exclusion of content he found immoral and for his anthropological notes on Arab customs.

- 1882–1884: John Payne publishes an English version translated entirely from Calcutta II, adding some tales from Calcutta I and Breslau.

- 1885–1888: Sir Richard Francis Burton publishes an English translation from several sources (largely the same as Payne[56]). His version accentuated the sexuality of the stories vis-à-vis Lane's bowdlerized translation.

- 1889–1904: J. C. Mardrus publishes a French version using Bulaq and Calcutta II editions.

- 1973: First Polish translation based on the original language edition, but compressed 12 volumes to 9, by Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy.

- 1984: Muhsin Mahdi publishes an Arabic edition based on the oldest surviving Arabic manuscript (based on the oldest surviving Syrian manuscript currently held in the Bibliothèque Nationale).

- 1986–1987: French translation by Arabist René R. Khawam.

- 1990: Husain Haddawy publishes an English translation of Mahdi.

- 1991: French translation by Arabists Jamel-Eddine Bencheikh and André Miquel for the Bibliothèque de la Pléiade.

- 2008: New Penguin Classics translation (in three volumes) by Malcolm C. Lyons and Ursula Lyons of the Calcutta II edition

Literary themes and techniques

[edit]

The One Thousand and One Nights and various tales within it make use of many innovative literary techniques, which the storytellers of the tales rely on for increased drama, suspense, or other emotions.[74] Some of these date back to earlier Persian, Indian and Arabic literature, while others were original to the One Thousand and One Nights.

Frame story

[edit]The One Thousand and One Nights employs an early example of the frame story, or framing device: the character Scheherazade narrates a set of tales (most often fairy tales) to the Sultan Shahriyar over many nights. Many of Scheherazade's tales are themselves frame stories, such as the Tale of Sinbad the Seaman and Sinbad the Landsman, which is a collection of adventures related by Sinbad the Seaman to Sinbad the Landsman.

In folkloristics, the frame story is classified as ATU 875B*, "Storytelling Saves a Wife from Death".[75]

Embedded narrative

[edit]Another technique featured in the One Thousand and One Nights is an early example of the "story within a story", or embedded narrative technique: this can be traced back to earlier Persian and Indian storytelling traditions, most notably the Panchatantra of ancient Sanskrit literature. The Nights, however, improved on the Panchatantra in several ways, particularly in the way a story is introduced. In the Panchatantra, stories are introduced as didactic analogies, with the frame story referring to these stories with variants of the phrase "If you're not careful, that which happened to the louse and the flea will happen to you." In the Nights, this didactic framework is the least common way of introducing the story: instead, a story is most commonly introduced through subtle means, particularly as an answer to questions raised in a previous tale.[76]

The general story is narrated by an unknown narrator, and in this narration the stories are told by Scheherazade. In most of Scheherazade's narrations there are also stories narrated, and even in some of these, there are some other stories.[77] This is particularly the case for the "Sinbad the Sailor" story narrated by Scheherazade in the One Thousand and One Nights. Within the "Sinbad the Sailor" story itself, the protagonist Sinbad the Sailor narrates the stories of his seven voyages to Sinbad the Porter. The device is also used to great effect in stories such as "The Three Apples" and "The Seven Viziers". In yet another tale Scheherazade narrates, "The Fisherman and the Jinni", the "Tale of the Wazir and the Sage Duban" is narrated within it, and within that there are three more tales narrated.

Dramatic visualization

[edit]Dramatic visualization is "the representing of an object or character with an abundance of descriptive detail, or the mimetic rendering of gestures and dialogue in such a way as to make a given scene 'visual' or imaginatively present to an audience". This technique is used in several tales of the One Thousand and One Nights,[78] such as the tale of "The Three Apples" (see Crime fiction elements below).

Fate and destiny

[edit]A common theme in many Arabian Nights tales is fate and destiny. Italian filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini observed:[79]

[E]very tale in The Thousand and One Nights begins with an 'appearance of destiny' which manifests itself through an anomaly, and one anomaly always generates another. So a chain of anomalies is set up. And the more logical, tightly knit, essential this chain is, the more beautiful the tale. By 'beautiful' I mean vital, absorbing and exhilarating. The chain of anomalies always tends to lead back to normality. The end of every tale in The One Thousand and One Nights consists of a 'disappearance' of destiny, which sinks back to the somnolence of daily life ... The protagonist of the stories is in fact destiny itself.

Though invisible, fate may be considered a leading character in the One Thousand and One Nights.[80] The plot devices often used to present this theme are coincidence,[81] reverse causation, and the self-fulfilling prophecy (see Foreshadowing section below).

Foreshadowing

[edit]

Early examples of the foreshadowing technique of repetitive designation, now known as "Chekhov's gun", occur in the One Thousand and One Nights, which contains "repeated references to some character or object which appears insignificant when first mentioned but which reappears later to intrude suddenly in the narrative."[82] A notable example is in the tale of "The Three Apples" (see Crime fiction elements below).

Another early foreshadowing technique is formal patterning, "the organization of the events, actions and gestures which constitute a narrative and give shape to a story; when done well, formal patterning allows the audience the pleasure of discerning and anticipating the structure of the plot as it unfolds." This technique is also found in One Thousand and One Nights.[78]

The self-fulfilling prophecy

[edit]Several tales in the One Thousand and One Nights use the self-fulfilling prophecy, as a special form of literary prolepsis, to foreshadow what is going to happen. This literary device dates back to the story of Krishna in ancient Sanskrit literature, and Oedipus or the death of Heracles in the plays of Sophocles. A variation of this device is the self-fulfilling dream, which can be found in Arabic literature (or the dreams of Joseph and his conflicts with his brothers, in the Hebrew Bible).

A notable example is "The Ruined Man who Became Rich Again through a Dream", in which a man is told in his dream to leave his native city of Baghdad and travel to Cairo, where he will discover the whereabouts of some hidden treasure. The man travels there and experiences misfortune, ending up in jail, where he tells his dream to a police officer. The officer mocks the idea of foreboding dreams and tells the protagonist that he himself had a dream about a house with a courtyard and fountain in Baghdad where treasure is buried under the fountain. The man recognizes the place as his own house and, after he is released from jail, he returns home and digs up the treasure. In other words, the foreboding dream not only predicted the future, but the dream was the cause of its prediction coming true. A variant of this story later appears in English folklore as the "Pedlar of Swaffham" and Paulo Coelho's The Alchemist; Jorge Luis Borges' collection of short stories A Universal History of Infamy featured his translation of this particular story into Spanish, as "The Story of the Two Dreamers".[83]

"The Tale of Attaf" depicts another variation of the self-fulfilling prophecy, whereby Harun al-Rashid consults his library (the House of Wisdom), reads a random book, "falls to laughing and weeping and dismisses the faithful vizier Ja'far ibn Yahya from sight. Ja'afar, disturbed and upset, flees Baghdad and plunges into a series of adventures in Damascus, involving Attaf and the woman whom Attaf eventually marries". After returning to Baghdad, Ja'afar reads the same book that caused Harun to laugh and weep, and discovers that it describes his own adventures with Attaf. In other words, it was Harun's reading of the book that provoked the adventures described in the book to take place. This is an early example of reverse causation.[84]

Near the end of the tale, Attaf is given a death sentence for a crime he did not commit but Harun, knowing the truth from what he has read in the book, prevents this and has Attaf released from prison. In the 12th century, this tale was translated into Latin by Petrus Alphonsi and included in his Disciplina Clericalis,[85] alongside the "Sindibad" story cycle.[86] In the 14th century, a version of "The Tale of Attaf" also appears in the Gesta Romanorum and Giovanni Boccaccio's The Decameron.[85]

Repetition

[edit]

Leitwortstil is "the purposeful repetition of words" in a given literary piece that "usually expresses a motif or theme important to the given story." This device occurs in the One Thousand and One Nights, which binds several tales in a story cycle. The storytellers of the tales relied on this technique "to shape the constituent members of their story cycles into a coherent whole".[74]

Another technique used in the One Thousand and One Nights is thematic patterning, which is:

[T]he distribution of recurrent thematic concepts and moralistic motifs among the various incidents and frames of a story. In a skillfully crafted tale, thematic patterning may be arranged so as to emphasize the unifying argument or salient idea which disparate events and disparate frames have in common.[78]

Several different variants of the "Cinderella" story, which has its origins in the ancient Greek story of Rhodopis, appear in the One Thousand and One Nights, including "The Second Shaykh's Story", "The Eldest Lady's Tale" and "Abdallah ibn Fadil and His Brothers", all dealing with the theme of a younger sibling harassed by two jealous elders. In some of these, the siblings are female, while in others they are male. One of the tales, "Judar and His Brethren", departs from the happy endings of previous variants and reworks the plot to give it a tragic ending instead, with the younger brother being poisoned by his elder brothers.[87]

Sexual humour

[edit]The Nights contain many examples of sexual humour. Some of this borders on satire, as in the tale called "Ali with the Large Member" which pokes fun at obsession with penis size.[88][89]

Unreliable narrator

[edit]The literary device of the unreliable narrator was used in several fictional medieval Arabic tales of the One Thousand and One Nights. In one tale, "The Seven Viziers" (also known as "Craft and Malice of Women or The Tale of the King, His Son, His Concubine and the Seven Wazirs"), a courtesan accuses a king's son of having assaulted her, when in reality she had failed to seduce him (inspired by the Qur'anic/Biblical story of Yusuf/Joseph). Seven viziers attempt to save his life by narrating seven stories to prove the unreliability of women, and the courtesan responds by narrating a story to prove the unreliability of viziers.[90] The unreliable narrator device is also used to generate suspense in "The Three Apples" and humor in "The Hunchback's Tale" (see Crime fiction elements below).

Genre elements

[edit]

Crime fiction

[edit]

An example of the murder mystery[91] and suspense thriller genres in the collection, with multiple plot twists[92] and detective fiction elements[93] was "The Three Apples", also known as Hikayat al-sabiyya 'l-maqtula ('The Tale of the Murdered Young Woman').[94]

In this tale, Harun al-Rashid comes to possess a chest, which, when opened, contains the body of a young woman. Harun gives his vizier, Ja'far, three days to find the culprit or be executed. At the end of three days, when Ja'far is about to be executed for his failure, two men come forward, both claiming to be the murderer. As they tell their story it transpires that, although the younger of them, the woman's husband, was responsible for her death, some of the blame attaches to a slave, who had taken one of the apples mentioned in the title and caused the woman's murder.

Harun then gives Ja'far three more days to find the guilty slave. When he yet again fails to find the culprit, and bids his family goodbye before his execution, he discovers by chance his daughter has the apple, which she obtained from Ja'far's own slave, Rayhan. Thus the mystery is solved.

Another Nights tale with crime fiction elements was "The Hunchback's Tale" story cycle which, unlike "The Three Apples", was more of a suspenseful comedy and courtroom drama rather than a murder mystery or detective fiction. The story is set in a fictional China and begins with a hunchback, the emperor's favourite comedian, being invited to dinner by a tailor couple. The hunchback accidentally chokes on his food from laughing too hard and the couple, fearful that the emperor will be furious, take his body to a Jewish doctor's clinic and leave him there. This leads to the next tale in the cycle, the "Tale of the Jewish Doctor", where the doctor accidentally trips over the hunchback's body, falls down the stairs with him, and finds him dead, leading him to believe that the fall had killed him. The doctor then dumps his body down a chimney, and this leads to yet another tale in the cycle, which continues with twelve tales in total, leading to all the people involved in this incident finding themselves in a courtroom, all making different claims over how the hunchback had died.[95] Crime fiction elements are also present near the end of "The Tale of Attaf" (see Foreshadowing above).

Horror fiction

[edit]Haunting is used as a plot device in gothic fiction and horror fiction, as well as modern paranormal fiction. Legends about haunted houses have long appeared in literature. In particular, the Arabian Nights tale of "Ali the Cairene and the Haunted House in Baghdad" revolves around a house haunted by jinn.[96] The Nights is almost certainly the earliest surviving literature that mentions ghouls, and many of the stories in that collection involve or reference ghouls. A prime example is the story The History of Gherib and His Brother Agib (from Nights vol. 6), in which Gherib, an outcast prince, fights off a family of ravenous Ghouls and then enslaves them and converts them to Islam.[97]

Horror fiction elements are also found in "The City of Brass" tale, which revolves around a ghost town.[98]

The horrific nature of Scheherazade's situation is magnified in Stephen King's Misery, in which the protagonist is forced to write a novel to keep his captor from torturing and killing him. The influence of the Nights on modern horror fiction is certainly discernible in the work of H. P. Lovecraft. As a child, he was fascinated by the adventures recounted in the book, and he attributes some of his creations to his love of the 1001 Nights.[99]

Fantasy and science fiction

[edit]

Several stories within the One Thousand and One Nights feature early science fiction elements. One example is "The Adventures of Bulukiya", in which the protagonist Bulukiya's quest for the herb of immortality leads him to explore the seas, journey to Paradise and to Hell, and travel across the cosmos to different worlds much larger than his own world, anticipating elements of galactic science fiction;[100] along the way, he encounters societies of jinn,[101] mermaids, talking serpents, talking trees, and other forms of life.[100] In "Abu al-Husn and His Slave-Girl Tawaddud", the heroine Tawaddud gives an impromptu lecture on the mansions of the Moon, and the benevolent and sinister aspects of the planets.[102]

In another 1001 Nights tale, "Abdullah the Fisherman and Abdullah the Merman", the protagonist Abdullah the Fisherman gains the ability to breathe underwater and discovers an underwater society that is portrayed as an inverted reflection of society on land, in that the underwater society follows a form of primitive communism where concepts like money and clothing do not exist. Other Arabian Nights tales also depict Amazon societies dominated by women, lost ancient technologies, advanced ancient civilizations that went astray, and catastrophes which overwhelmed them.[103]

"The City of Brass" features a group of travellers on an archaeological expedition[104] across the Sahara to find an ancient lost city and attempt to recover a brass vessel that Solomon once used to trap a jinni,[105] and, along the way, encounter a mummified queen, petrified inhabitants,[106] lifelike humanoid robots and automata, seductive marionettes dancing without strings,[107] and a brass horseman robot who directs the party towards the ancient city,[16] which has now become a ghost town.[98] The "Third Qalandar's Tale" also features a robot in the form of an uncanny boatman.[16]

Poetry

[edit]There is an abundance of Arabic poetry in One Thousand and One Nights. It is often deployed by stories' narrators to provide detailed descriptions, usually of the beauty of characters. Characters also occasionally quote or speak in verse in certain settings. The uses include but are not limited to:

- Giving advice, warning, and solutions.

- Praising God, royalties and those in power.

- Pleading for mercy and forgiveness.

- Lamenting wrong decisions or bad luck.

- Providing riddles, laying questions, challenges.

- Criticizing elements of life, wondering.

- Expressing feelings to others or one's self: happiness, sadness, anxiety, surprise, anger.

In a typical example, expressing feelings of happiness to oneself from Night 203, Prince Qamar Al-Zaman, standing outside the castle, wants to inform Queen Bodour of his arrival.[108] He wraps his ring in a paper and hands it to the servant who delivers it to the Queen. When she opens it and sees the ring, joy conquers her, and out of happiness she chants this poem:

وَلَقدْ نَدِمْتُ عَلى تَفَرُّقِ شَمْلِنا |

Wa-laqad nadimtu 'alá tafarruqi shamlinā |

Translations:

And I have regretted the separation of our companionship |

Long, long have I bewailed the sev'rance of our loves, |

| —Literal translation | —Burton's verse translation |

In world culture

[edit]The influence of the versions of The Nights on world literature is immense. Writers as diverse as Henry Fielding to Naguib Mahfouz have alluded to the collection by name in their own works. Other writers who have been influenced by the Nights include John Barth, Jorge Luis Borges, Salman Rushdie, Orhan Pamuk, Goethe, Walter Scott, Thackeray, Wilkie Collins, Elizabeth Gaskell, Nodier, Flaubert, Marcel Schwob, Stendhal, Dumas, Hugo, Gérard de Nerval, Gobineau, Pushkin, Tolstoy, Hofmannsthal, Conan Doyle, W. B. Yeats, H. G. Wells, Cavafy, Calvino, Georges Perec, H. P. Lovecraft, Marcel Proust, A. S. Byatt and Angela Carter.[109]

Различные персонажи из этого эпоса сами стали культурными иконами в западной культуре, такие как Аладдин , Синбад и Али Баба . Часть его популярности, возможно, возникла из -за улучшенных стандартов исторических и географических знаний. Чудесные существа и события, типичные для сказки, кажутся менее невероятными, если они становятся дальше «давно» или дальше «далеко»; Этот процесс завершается в фэнтезийном мире, имеющем небольшую связь, если таковые имеются, с фактическими временами и местами. Несколько элементов из арабской мифологии в настоящее время распространены в современной фантазии , такие как джинсы , багамуты , магические ковры , магические лампы и т. Д. Когда Л. Франк Баум предложил написать современную сказку, которая изгнала стереотипные элементы, он включил Джинн, а также карлики и фея как стереотипы, чтобы пойти. [ 110 ]

В 1982 году Международный астрономический союз (МАУ) начал называть особенности на после Сатурна луне персонажей и мест в Бертона переводе [ 111 ] Потому что «его поверхность настолько странна и загадочна, что ей дали арабские ночи как банк имен, связывающий фантастический пейзаж с литературной фантазией». [ 112 ]

В арабской культуре

[ редактировать ]Есть мало доказательств того, что ночи были особенно цены в арабском мире. Он редко упоминается в списках популярной литературы, и существуют несколько рукописей коллекции до 18-го века. [ 113 ] Художественная литература имела низкий культурный статус среди средневековых арабов по сравнению с поэзией, и рассказы были отклонены как Хурафа (невероятные фантазии, подходящие только для развлекательных женщин и детей). По словам Роберта Ирвина, «даже сегодня, за исключением некоторых писателей и ученых, ночи рассматриваются с презрением в арабском мире. Его истории регулярно осуждаются как вульгарные, невероятные, детские и, прежде всего, плохо написаны». [ 114 ]

Тем не менее, ночи оказались вдохновением для некоторых современных египетских писателей, таких как Tawfiq al-Hakim (автор Symbolist Play Shahrazad , 1934), Таха Хуссейн ( Dreams Scheherazade , 1943) [ 115 ] и Нагуиб Махфуз ( арабские ночи и дни , 1979). Идрис Шах находит численное эквивалент арабского названия, Альф Лейла ва Лейла , в арабской фразе «Сумма аль-циша» , что означает «мать историй». Далее он заявляет, что многие из историй «закодированы суфийские преподавательские истории , описания психологических процессов или зашифрованные знания того или иного вида». [ 116 ]

На более популярном уровне, кино и телевизионные адаптации, основанные на таких историях, как Синбад и Аладдин, наслаждались долгосрочной популярностью в арабских странах.

Ранняя европейская литература

[ редактировать ]Хотя первый известный перевод на европейский язык появился в 1704 году, возможно, что ночи начали оказывать свое влияние на западную культуру гораздо раньше. Христианские писатели в средневековой Испании перевели много работ с арабского языка, в основном философии и математики, а также арабской фантастики, о чем свидетельствуют Хуана Мануэля коллекция рассказов Эль -Конде Луканор и Рамон Ллулл « Книга зверей» . [ 117 ]

Знание работы, прямое или косвенное, по -видимому, распространяется за пределы Испании. Темы и мотивы с параллелями по ночам встречаются в Чосера » «Кентерберийских рассказах (в сказке Сквайра, которую путешествует по летающей медной лошади) и Боккаччо Декамерона герой . Эхо в Джованни Серкамби и романе Орландо предполагает Ариосто Фуриозо , что история Шахрияр и Шахзамана также была известна. [ 118 ] Похоже, что доказательства также показывают, что истории распространились на Балканы , и перевод ночей в Румынский существовал в 17 веке, основанный на греческой версии коллекции. [ 119 ]

Западная литература (18 -й век и далее)

[ редактировать ]Галландские переводы (1700 -е годы)

[ редактировать ]

Современная слава ночей проистекает из первого известного европейского перевода Антуина Галланда , который появился в 1704 году. По словам Роберта Ирвина , Галланд »сыграл настолько большую роль в открытии рассказов, в популяризации их в Европе и в формировании того, что придет Чтобы рассматриваться как каноническая коллекция, которая при некотором риске гиперболы и парадокса его называли настоящим автором ночей » . [ 120 ]

Непосредственный успех версии Галланда с французской публикой, возможно, произошел потому, что она совпала с Vogue For Contes de Fées («сказочные истории»). Эта мода началась с публикации «Мадам Д'Алноя » гиполита в 1690 году. Книга Д'Алноя имеет удивительно схожую структуру на ночи , а рассказы рассказчика рассказчика. Успех ночей распространился по всей Европе, и к концу столетия были переводы Галланда на английский, немецкий, итальянский, голландский, датский, русский, фламандский и идиш. [ 121 ]

Версия Галланда спровоцировала всплеск псевдоооооооооооо. В то же время некоторые французские писатели начали пародировать стиль и придумывать надуманные истории в поверхностно-восточных условиях. Эти насмешливые пастики включают в себя Энтони Гамильтона ( Les Quatre Facarins 1730), Crebillon Les Sopha (1742) и Idiscrets 's Les Bijoux (1748). Они часто содержали завуалированные намеки на современное французское общество. Самым известным примером является Voltaire Zadig (1748 ) (1748), нападение на религиозное фанатизм против смутного доисламского ближневосточного фона. [ 122 ] Английские версии «восточной сказки» обычно содержали тяжелый морализирующий элемент, [ 123 ] За заметным исключением (1786) Уильяма Бекфорда фантастического Vathek , который оказал решительное влияние на развитие готического романа . польского дворянина Яна Потоки Роман Сарагосса Рукопись (Betun 1797) обязан глубоким долгом перед ночами с его восточным ароматом и лабиринтной серией встроенных сказок. [ 124 ]

Работа была включена в цену книг по богословии, истории и картографии, который был отправлен шотландским продавцом книг Эндрю Миллара (тогда ученик) министру Пресвитерианского . Это иллюстрирует широкую популярность и доступность названия в 1720 -х годах. [ 125 ]

19 век - 20 век

[ редактировать ]Ночи продолжали оставаться любимой книгой многих британских авторов романтических и викторианских эпох. Согласно Ас -Байтту , «в британской романтической поэзии арабские ночи стояли за чудесное против мирского, образное против прозаичного и редактивно рационального». [ 126 ] В своих автобиографических работах и Коулридж , и де Куинси называют кошмарами, которые книга вызвала их в молодости. Вордсворт и Теннисон также написали о своем детском чтении рассказов в их стихи. [ 127 ] Чарльз Диккенс был еще одним энтузиастом, и атмосфера ночей проникает в открытие своего последнего романа «Тайна Эдвина Друд» (1870). [ 128 ]

Несколько писателей попытались добавить тысячу и второй рассказ, [ 129 ] Включая Теофил Готье ( второй Nuit , 1842). [ 115 ] и Джозеф Рот ( история 1002 ночи , 1939). [ 129 ] Эдгар Аллан По написал « тысяча и второй рассказ о Шехеразаде » (1845), рассказ, изображающий восьмой и последний рейс Синдбада Сморяка вместе с различными загадками Синдбад и его команда встречи; Затем аномалии описываются как сноски к истории. Хотя король не уверен - за исключением случаев, когда слоны, несущие мир на задней части черепахи, - что эти загадки реальны, это реальные современные события, которые происходили в разных местах во время или ранее, жизни По. История заканчивается тем, что король в таком отвращении к сказке Шехеразаде только что сплетен, что он казнен на следующий день.

Другая важная литературная фигура, ирландский поэт В.Б. Йейтс также был очарован арабскими ночами, когда он написал в своей прозе-книге « Видение » «Автобиографическое стихотворение» под названием «Дар Харуна Аль-Рашида» , [ 130 ] В связи с его совместными экспериментами со своей женой Джорджи Хайд-Ли , с автоматическим письмом . Автоматическое письмо - это техника, используемая многими оккультистами для различения сообщений из подсознательного разума или других духовных существ, когда рука перемещает карандаш или ручку, написав только на простом листе бумаги и когда глаза человека закрыть. Кроме того, одаренная и талантливая жена играет в стихотворении Йейтса как «дар», который только предположительно предположительно халиф христианскому и византийскому философу Куста ибн Лука , который действует в стихотворении как олицетворение WB Yeats. В июле 1934 года его спросил Луи Ламберт, во время тура в Соединенных Штатах, что шесть книг удовлетворили его больше всего. Список, который он дал, разместил арабские ночи, второстепенные только для произведений Уильяма Шекспира. [ 131 ]

Современные авторы под влиянием ночей включают Джеймса Джойса , Марселя Пруста , Хорхе Луиса Борхеса , Джона Барта и Теда Чианга .

Фильм, радио и телевидение

[ редактировать ]Истории из тысячи и одной ночи были популярными предметами для фильмов, начиная с Жоржа Мелемаса « Ле Палас де Милле и Уне » (1905).

Критик Роберт Ирвин выделяет две версии вора Багдада ( версия 1924 года , режиссер Рауль Уолш; Версия 1940 года, созданная Александром Кордой) и Пир Паоло Пасолини Ир Фиоре Дель Милле Э. Шедевры мирового кино ". [ 132 ] Майкл Джеймс Ланделл называет Ил Фиоре «самой верной адаптацией в своей акценте на сексуальности 1001 ночи в самой старой форме». [ 133 ]

Алиф Лайла ( перевод тысяча ночей ; 1933) был фантастическим фильмом на хинди , основанном на тысяче тысячи и одной ночи от ранней эпохи индийского кино , режиссер Балвант Бхатт и Шанти Дейв . К. Амарнатхал , Алиф Лайла (1953), еще один индийский фэнтезийный фильм на хинди, основанный на фольклорном зале Аладдина . [ 134 ] Нирена Лахири , Аравийские ночи адаптация фильмов о приключениях, выпущенная в 1946 году. [ 135 ] ряд индийских фильмов, основанных на ночах и воре Багдада На протяжении многих лет был снят , в том числе Багдад Ка -Чор (1946), Багдад Тирудан (1960) и Багдад Гаджа Донга (1968). [ 134 ] Телесериал, Thief of Baghdad , также был сделан в Индии, которая вышла в эфир на Zee TV в период с 2000 по 2001 год.

UPA , американская анимационная студия, выпустила анимационную художественную версию 1001 Arabian Nights (1959) с участием персонажа мультфильма мистера Магу . [ 136 ]

Анимационный фильм 1949 года «Поющая принцесса» , еще один фильм, снятый в Италии, вдохновлен арабскими ночами. Анимационный художественный фильм « Тысяча и один арабский ночи » (1969), созданный в Японии и режиссер Осаму Тезука и Эйхии Ямамото, показал психоделические образы и звуки, а также эротический материал, предназначенный для взрослых. [ 137 ]

Алиф Лайла ( The Arabian Nights ), индийский сериал 1993–1997 годов, основанный на рассказах о тысяче тысячи и одной ночи, созданных Sagar Entertainment Ltd , транслировался на DD National , когда Шехеразаде рассказывала свои истории Шахриару и содержит оба хорошо известные и менее известные истории из тысячи и одной ночи . Еще один индийский телесериал, Алиф Лайла , основанный на различных историях из коллекции, транслируемых на Dangal TV в 2020 году. [ 138 ]

Альф Лейла ва Лейла , египетские телевизионные адаптации историй были транслировались между 1980 -х и началом 1990 -х годов, в каждом сериале с участием знаменитых египетских исполнителей, таких как Хусейн Фахми , Рагра , Лайла Эльви , Юсуф Шаабан (актер) , нелли (Египтанская Антир) , Шерихан и Иехия Эль-Фахарани . Каждая серия премьера проводилась каждый ежегодный месяц Рамадана в период с 1980 -х по 1990 -е годы. [ 139 ]

Одним из самых известных фильмов «Аравийские ночи» является Уолта Диснея анимационный фильм 1992 года «Аладдин» , который основан на одном и том же имени.

Arabian Nights (2000), двухэтапный телевизионный мини-сериал, принятый для BBC и ABC Studios, с участием Мили Авитал , Дугрей Скотт и Джона Легузамо и режиссера Стива Баррона , основан на переводе сэра Ричарда Фрэнсиса Бертона .

Создали Шабнам Резаи и Али Джета, а в Vancouver Big Bad Boo Studios продюсировали 1001 Nights (2011), анимационный телесериал для детей, который был запущен на телепустую и транслирует в 80 странах мира, включая Discovery Kids Asia. [ 140 ]

Arabian Nights (2015, на португальском языке: как Mil E Uma Noites ), фильм с тремя частями, снятый Мигелем Гомес , основан на тысяче и одной ночи . [ 141 ]

Альф Лейла ва Лейла , популярная египетская радиоприемник, транслировалась на египетских радиостанциях в течение 26 лет. Режиссер знаменитый радиорежиссер Мохамед Махмуд Шабаан, также известный под его прозвищем Баба Шаран , в сериале участвовал в составе уважаемых египетских актеров, среди которых Зузу Набил в роли Шехеризаде и Абдельрахима Эль Заракани в роли Шахраира. [ 142 ]

Aladdin (2019)-это музыкальный фэнтезийный фильм, снятый Гай Ричи из сценария, который он написал с Джоном Августом . Совместно, созданный Уолтом Диснеем Pictures и Rideback , это римейк в прямом эфире анимационного художественного фильма Disney 1992 года того же названия .

Музыка

[ редактировать ]Ночи : вдохновили много музыкальных произведений, в том числе

Классический

- Франсуа-Адриен Боилдеу : Халиф Багдад (1800)

- Карл Мария фон Вебер : Абу Хасан (1811)

- Луиджи Черубини : Али Баба (1833)

- Роберт Шуман : Scheherazade (1848)

- Питер Корнелиус : парикмахер Багдад (1858)

- Эрнест Рейер : Статуя (1861)

- CFE Horneman : Aladdin (увертюра), (1864)

- Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov : Scheherazade Op. 35 (1888) [ 143 ]

- Иоганн Штраус II : Индиго и сорок грабителей (1871)

- Иоганн Штраус II : тысяча и одна ночь (1871)

- Тиграран Чухаджян : Земир (1891)

- Морис Равель : Шехеразаде (1898)

- Ferrucio busoni : концертный план в C Major (1904)

- Анри Рабо : Mârouf, Savetier du Cairo (1914)

- Карл Нильсен : Aladdin Suite (1918–1919)

- College Musicum : Suite после тысячи и одну ночь (1969)

- Фикрет Амиров : Аравийские ночи (Балет, 1979)

- Эзекиэль Виньяо : Ночь ночи (1990)

- Карл Дэвис : Аладдин (Балет, 1999)

Поп, рок и металл

- Умм Култум : «Альф Лейла ва Лейла» (1969)

- Ренессанс : Scheherazade и другие истории (1975)

- Сладкий : «Аль-Баба, человек Аравии» (1981)

- Icehouse : « Нет обещаний » (из меры альбома для меры ) (1986)

- Камелот : «Ночи Аравии» (из альбома «Четвертое наследие ») (1999)

- Сара Брайтман : «Гарем» и «Арабские ночи» (из альбома Harem ) (2003)

- CH! PZ : " 1001 Arabian Nights (Song) " (из альбома World of Ch! Pz ) (2006)

- Nightwish : «Сахара» (2007)

- Рок на !! : «Синбад моряк» (2008)

- Абни Парк : "Scheherazade" (2013)

Музыкальный театр

- «Тысяча и одну ночь» (от Twisted: Untold Story of the Royal Vizier ) (2013)

- Призрачный квартет (2014)

Игры

[ редактировать ]Популярные современные игры с темой арабских ночей включают серию «Принц Персии» , «Crash Bandicoot: Warped » , «Sonic» и «Секретные кольца» , «Аладдин Диснея» , «Приключения книжного червя» и « Сказки на пинбол» «Арабские ночи ». Кроме того, популярная игра Magic: The Gathering выпустила набор расширения под названием Arabian Nights .

У Demoman in Team Fortress 2 набор под названием «Тысяча и один демокс», в том числе три оружия и один косметический предмет. [ 144 ]

Иллюстраторы

[ редактировать ]Многие искусства проиллюстрировали арабские ночи , в том числе: Пьер-Климент Марильер для Le Cabinet des Fées (1785–1789), Гюстав Доре , Леон Карре (Гранвиль, 1878-Альгер, 1942), Роджер Блахон, Франсуаз Будиньон, Андре Дахан, любимый Соро, Альберт Робида , Альцид Теофил Робади и Марселино Труонг; Vittorio Zecchin (Murano, 1878 - Murano, 1947) и Emanuele Luzzati ; Немецкий Морган; Мохаммед Расим (Алжир, 1896-Алгиерс, 1975), Сани Ол-Молк (1849–1856), Антон Пик и Эмре Охон, Вирджиния Фрэнсис Стерретт (1928).

Знаменитые иллюстраторы для британских изданий включают: Артур Бойд Хоутон , Джон Тенниэль , Джон Эверетт Милле и Джордж Джон Пинвелл для иллюстрированных развлечений арабских ночей Далзиэля, опубликованные в 1865 году; Уолтер Крэйн для книжки по картинке Аладдина (1876); Фрэнк Брангвин для выпуска 1896 года перевода Лейна ; Альберт Летчфорд для издания 1897 года перевода Бертона; Эдмунд Дюлак для историй из арабских ночей (1907), принцесса Бадуры (1913) и Синдбада «Моряк и другие рассказы из арабских ночей» (1914). Другие художники включают Джон Д. Баттен (сказки из арабских ночей, 1893), Кей Нильсен , Эрик Фрейзер , Эррол Ле Каин , Максфилд Парриш , В. Хит Робинсон и Артур Тик (1954). [ 145 ]

Комиксы

[ редактировать ]- Классика иллюстрирована № 8 (1947) [ 146 ] - Сокращенная версия тысячи и одну ночь в форме комиксов.

- Карл Баркс , создатель Скруджа МакДука , написал две существенные приключенческие истории, основанные на ночи .

- «Пустынные тени», Meet Mreams (Heavy Metal, 2000), Альфонсо Азпири .

- «Рамадан», Sandman #50 (DC Vertigo, июнь 1993 г.), Нил Гайман (история) и П. Крейг Рассел (искусство).

- Одна тысяча и одну ночь от Чон Джин Сок (история) и Хан Сейги (искусство) - Манхва переписывание ночей для женских корейских подростков.

- 1001 ночи Шехеризаде . Париж: Альбин Мишель, 2001, Эрик Мальтиат.

Галерея

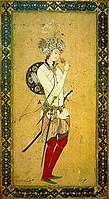

[ редактировать ]-

Султан

-

Тысяча и одна ноча книга.

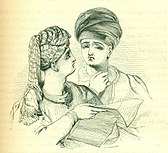

-

Харун Ар-Рашид , ведущий персонаж 1001 ночи

-

Пятое путешествие Синдбада

-

Уильям Харви , пятое путешествие по море Эс-Синдбад , 1838–40, на дереве

-

Уильям Харви , История Город Ласс , 1838–40, на дереве

-

Уильям Харви , история двух принцев Эль-Амджад и Эль-Ас-Ас , 1838–40, навес

-

Уильям Харви , история Абд Аллаха из земли и Абд Аллаха моря

-

Уильям Харви , История рыбака , 1838–40, на дереве

-

Фридрих Гросс , Ante 1830, Woodcut

-

Фридрих Гросс , Ante 1830, Woodcut

-

Фридрих Гросс , Ante 1830, Woodcut

-

Фридрих Гросс , Ante 1830, Woodcut

-

Фридрих Гросс , Ante 1830, Woodcut

-

Фридрих Гросс , Ante 1830, Woodcut

-

Фридрих Гросс , Ante 1830, Woodcut

-

Фридрих Гросс , Ante 1830, Woodcut

-

Фрэнк Брангвин , история Абон-Хасана «Ваг» («Он оказался на королевском диване»), 1895–96, акварель и темпера на Миллборде

-

Фрэнк Брангвин , история торговца («SheereZade рассказывает истории»), 1895–96, акварель и темпера на Миллборде

-

Фрэнк Брангвин , история Ансал-Ваджуду, Роуз-Блум («Дочь висела сидела у окна решетки»), 1895–96, акварель и темпера на Миллборде

-

Фрэнк Брангвин , История Гулнара («Торговец обнаружил ее лицо»), 1895–96, акварель и темпера на мельнице

-

Фрэнк Брангвин , история о базиме Бедера («После чего она стала уходом кукурузы»), 1895–96, акварель и темпера на мельнице

-

Фрэнк Брангвин , история об Абдалле («Абдалла моря сидела в воде, недалеко от берега»), 1895–96, акварель и темпера на мельнице

-

Фрэнк Брангвин , история о Маромед Али («Он сидел с собой свою лодку на плаву»), 1895–96, акварель и темпера на мельнице

-

Фрэнк Брэнгвин , история о городе Латун («Они перестали не подниматься по этой лестнице»), 1895–96, акварель и темпера на мельнице

Смотрите также

[ редактировать ]- Арабская литература

- Призрачные истории

- Хамзанама

- Список тысячи и одну ночь персонажей

- Список историй из книги тысячи тысяч и одной ночи (перевод Р.Ф. Бертона )

- Список работ под влиянием тысячи и одной ночи

- Персидская литература

- Шахнамех

- Панчатантра - древняя индийская коллекция взаимосвязанных животных басни в санскритских стихах и прозе, расположенная в рамках истории

- Сто одну ночь (книга) - аналогичная средневековая коллекция, используя ту же историю кадров, что и тысяча и один ночи

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ Марзолф, Ульрих (2007). «Аравийские ночи». В Кейт Флот; Гудрун Крамер; Денис Матринге; Джон Навас; Эверетт Роусон (ред.). Энциклопедия Ислама (3 -е изд.). doi : 10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_com_0021 .

Аравийские ночи, работа, известная на арабском языке как Альф Лейла Ва-Лейла

- ^ См. Иллюстрацию титульного листа Grub ST Edition в Yamanaka и Nishio (стр. 225)

- ^ Бен Пестелл; Pietra Palazzolo; Леон Бернетт, ред. (2016). Перевод мифа . Routledge. п. 87. ISBN 978-1-134-86256-6 .

- ^ Марзолф (2007), «Арабские ночи», Энциклопедия Ислама , вып. Я, Лейден: Брилл.

- ^ Джон Пейн, Аладдин и Зачарованная лампа и другие истории (Лондон 1901) рассказывают подробности встречи Галланда с «Ханной» в 1709 году и об открытии в библиотеке, Париже двух арабских рукописи, содержащих Аладдин и еще два добавленных сказки. Текст "Алаэддина и Зачарованной лампы"

- ^ Horta, Paulo Lemos (2017-01-16). Чудесные воры . Гарвардский университет издательство. ISBN 978-0-674-97377-0 .

- ^ Дойл, Лора (2020-11-02). Интеримпеальность: сочетание империй, гендерного труда и литературного искусства Альянса . Герцогский издательство Университета Герцога. ISBN 978-1-4780-1261-0 .

- ^ Аравийские ночи , переведенные Малкольмом С. Лайонсом и Урсулой Лайонс (Penguin Classics, 2008), Vol. 1, с. 1

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Ирвин, Роберт (2003). Аравийские ночи: компаньон Таурис Парк в мягкой обложке П. 209. ISBN 1-86064-983-1 .

- ^ Ирвин, Роберт (2003). Аравийские ночи: компаньон Таурис Парк в мягкой обложке П. 204. ISBN 1-86064-983-1 .

- ^ Ирвин, Роберт (2003). Аравийские ночи: компаньон Таурис Парк в мягкой обложке Стр. 211–2 ISBN 1-86064-983-1 .

- ^ Hamori, Andras (1971). «Аллегория из арабских ночей: городс -город». Бюллетень школы восточных и африканских исследований . 34 (1). Издательство Кембриджского университета : 9–19 [9]. doi : 10.1017/s0041977x00141540 . S2CID 161610007 .

- ^ Пино, Дэвид (1992). Техника рассказывания историй в арабских ночах . Brill Publishers . С. 148–9 и 217–9. ISBN 90-04-09530-6 .

- ^ Ирвин, Роберт (2003). Аравийские ночи: компаньон Таурис Парк в мягкой обложке П. 213. ISBN 1-86064-983-1 .

- ^ Hamori, Andras (1971). «Аллегория из арабских ночей: городс -город». Бюллетень школы восточных и африканских исследований . 34 (1). Издательство Кембриджского университета : 9–19 [12–3]. doi : 10.1017/s0041977x00141540 . S2CID 161610007 .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в дюймовый Пино, Дэвид (1992). Техника рассказывания историй в арабских ночах . Brill Publishers . С. 10–11. ISBN 90-04-09530-6 .

- ^ Джеральдин МакКуареан, Розамунд Фаулер (1999). Тысяча и одна арабская ночи . Издательство Оксфордского университета . С. 247–51. ISBN 0-19-275013-5 .

- ^ Академическая литература Архивирована 2017-06-30 на машине Wayback , ислам и научной фантастике

- ^ Ирвин 2004 , с. 48

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Рейнольдс с. 271

- ^ Hamori, A. (2012). "Sijhād" в P. Bearman; Тур Бьянквиз; Се Босворт; Э. Ван Донзел; WP Heinrichs (ред.). Энциклопедия Ислама (2 -е изд.). Брилль Doi : 10.1163/ 1573-3912_islam_sim_6

- ^ «Викрам и вампир, или, рассказы о индуистской дьяволах, Ричард Фрэнсис Бертон - электронная книга проекта Гутенберг» . www.gutenberg.org . п. xiii.

- ^ Артола. Рукописи Pancatantra из Южной Индии в бюллетене библиотеки Адьяр . 1957. С. 45 и далее.

- ^ К. Раксамани. Нандакапракарана, приписываемая Васубхаге, сравнительному исследованию . Тезис Университета Торонто. 1978. С. 221ff.

- ^ E. Lorgeou. Артисты Нанга Тантрара Париж. 1924.

- ^ C. Hooykaas. Bibliotheca javaneca no. 2. Бандонг. 1931.

- ^ AK Warder. Индийская литература кавя: искусство рассказывания историй, том VI . Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. 1992. С. 61–62, 76–82.

- ^ Iis.ac.uk Dr Fahmida Suleman, «Калила ва Димна», архивировав 2013-11-03 на машине Wayback , в средневековой исламской цивилизации, энциклопедии , вып. II, с. 432–33, изд. Josef W. Meri, New York-London: Routledge, 2006

- ^ Басни Калилы и Димна , переведенные с арабского языка Салехом Сааде Джалладом, 2002. Мелисенде, Лондон, ISBN 1-901764-14-1

- ^ Калила и Димна; или басни Бидпаи; Быть рассказом об их литературной истории, с. XIV

- ^ Pinault p. 1

- ^ Pinault p. 4

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Ирвин 2004 , с. 49–50.

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Ирвин 2004 , с. 49

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Ирвин 2004 , с. 51

- ^ Eva Sallis Scheherazade через видиционное стекло: метаморфоза тысячи и одной ночи (Routledge, 1999), с. 2 и примечание 6

- ^ Ирвин 2004 , с. 76

- ^ Сафа Хулуси, Исследования в сравнительной литературе и западных литературных школах, глава: Qisas Alf Laylah WA Laylah ( тысяча и одну ночь ), с. 15–85. Al-Rabita Press, Baghdad, 1957.

- ^ Сафа Хулуси, Влияние Ибн аль-Мукаффа в арабские ночи. Исламский обзор , декабрь 1960 г., с. 29–31

- ^ Тысяча и одну ночь; Или развлечения арабской ночи - Дэвид Клэйпул Джонстон - Google Books . Books.google.com.pk. Получено на 2013-09-23.

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Ирвин 2004 , с. 50

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Рейнольдс с. 270

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в Бомонт, Даниэль. Литературный стиль и повествовательная техника в арабских ночах. п. 1. В арабских ночах энциклопедия , том 1

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в Ирвин 2004 , с. 55

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в Марзолф, Ульрих (2017). "Аравийские ночи" Во флоте Чеман; Гудрур Кррур Крэмер; Денис Марингин; Джон Голый; Эверетт Роусон (ред.). Ислам . Брилль doi : 10.1163/ 1573-3912_e3_com_

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в Саллис, Ева . 1999. Шехеразаде сквозь выглядящее стекло: метаморфоза тысячи и одной ночи. С. 18–43

- ^ Пейн, Джон (1901). Книга тысячи ночей и одна ночь . Тол. IX. Лондон п. 289 Получено 19 марта 2018 года .

{{cite book}}: CS1 Maint: местоположение отсутствует издатель ( ссылка ) - ^ Пино, Дэвид. Техника рассказывания историй в арабских ночах. С. 1–12. Также в энциклопедии арабской литературы, т. 1

- ^ Алиф Лайла или, Книга тысячи ночей и одна ночь, широко известная как «Арабские ночи» развлечения », теперь впервые опубликовано на первоначальном арабском языке, из египетской рукописи, привезенной в Индию покойным Майор Тернер Макан , изд. WH Macnaghten, vol. 4 (Калькутта: Такер, 1839–42).

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный «Тысяча и одну ночь» . Национальная библиотека Франции . Получено 29 сентября 2020 года .

- ^ Тысяча и одна ночи (Альф Лейла ва-лейла), из самых ранних известных источников , изд. Мухсин Махди, 3 тома (Лейден: Брилл, 1984–1994), ISBN 90-04-07428-7 .

- ^ Мадлен Доби, 2009. Перевод в зоне контакта: Антуан Галландс Милле и Уни -нюиты: Арабские. п. 37. В Макдиси, Сари и Фелисити Нуссбаум (ред.): «Аравийские ночи в историческом контексте: между Востоком и Западом»

- ^ Ирвин 2004 , стр. 1-9.

- ^ Alf Laylaah: Bi-Al-ʹm Leaveyah al-Mice Al-Mice Al-Mice: Ly New-G- Gold , ed. Хишмам aa abd al-aaz-azīzed azļ ́dil ʻabdil ʻabd al-demils (Cay-Caiy: доктор ISBN 977-19-2252-1 .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в Goeje, Майкл Ян де (1911). . В Чисхолме, Хью (ред.). Encyclopædia Britannica . Тол. 28 (11 -е изд.). Издательство Кембриджского университета. п. 883.

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в Саллис, Ева. 1999. Шехеразаде сквозь выглядящее стекло: метаморфоза тысячи и одной ночи. С. 4 Passim

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в Марзолф, Ульрих и Ричард Ван Леувен. 2004. Энциклопедия Аравийских ночей , том 1. С. 506–08

- ^ Аравийские ночи , транс. Хусейн Хаддави (Нью -Йорк: Нортон, 1990).

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Ирвин 2004 .

- ^ Аравийские ночи II: Синдбад и другие популярные истории , пер. Хусейн Хаддави (Нью -Йорк: Нортон, 1995).

- ^ Аравийские ночи: перевод Хусейна Хаддави, основанный на тексту, отредактированном Мухсином Махди, Контексты, Критика , изд. Даниэль Хеллер-Розен (Нью-Йорк: Нортон, 2010).

- ^ Бьюкен, Джеймс (2008-12-27). «1 001 полета фантазии» . Хранитель . ISSN 0261-3077 . Получено 2023-06-28 .

- ^ "Truyen Audio Full" . 2023-06-28 .

- ^ ПЕР АМЕРИКАНСКИЙ ЦЕНТР . Pen.org. Получено на 2013-09-23.

- ^ «Аравийские ночи: сказки 1001 ночи» . Всеядное . Архивировано из оригинала 13 сентября 2012 года . Получено 12 июля 2024 года .

- ^ Потоп, Элисон (15 декабря 2021 г.). «Новые арабские ночи перевод, чтобы лишить расизм и сексизм в более ранних версиях» . www.theguardian.com . Получено 15 декабря 2021 года .

- ^ Дуайт Рейнольдс. «Тысяча и одну ночь: история текста и его прием». Кембриджская история арабской литературы: арабская литература в постклассический период . Кембридж UP, 2006.

- ^ «Восточная сказка в Англии в восемнадцатом веке», Марта Пайк Конант, доктор философии. Издательство Columbia University Press (1908)

- ^ Mack, Robert L., ed. (2009) [1995]. Арабские ночи развлечения . Оксфорд: издательство Оксфордского университета. С. XVI, XXV. ISBN 978-0-19-283479-9 Полем Получено 2 июля 2018 года .

- ^ Ирвин 2010 , с. 474.

- ^ Ирвин 2010 , с. 497.

- ^ Ганджави, Махди. Скрытая история тысячи и одну ночь на персидском языке. Презентация в Университете Британской Колумбии. Декабрь 2021 года

- ^ Ульрих Марзолф, Арабские ночи в транснациональной перспективе , 2007, 978-0-8143–3287-0 . , с 230 .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Хит, Петр (май 1994). «Рассматриваемая работа (и): методы рассказывания историй в арабских ночах Дэвида Пина». Международный журнал исследований на Ближнем Востоке . 26 (2). Издательство Кембриджского университета : 358–60 [359–60]. doi : 10.1017/s0020743800060633 . S2CID 162223060 .

- ^ Утер, Ханс-Джорг (2004). Типы международных народных сказков: рассказы о животных, сказки о магии, религиозные сказки и реалистичные рассказы, с введением. FF Communications . Academia Scientiarum Fennica. п. 499.

- ^ Ульрих Марзолф, Ричард Ван Леувен, Хасан Вассуф (2004). Энциклопедия арабских ночей . ABC-Clio. С. 3–4. ISBN 1-57607-204-5 .

- ^ Бертон, Ричард (сентябрь 2003 г.). Книга тысячи ночей и ночь, том 1 . Проект Гутенберг . Архивировано из оригинала 2012-01-18 . Получено 2008-10-17 .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в Хит, Петр (май 1994). «Рассматриваемая работа (и): методы рассказывания историй в арабских ночах Дэвида Пина». Международный журнал исследований на Ближнем Востоке . 26 (2). Издательство Кембриджского университета : 358–60 [360]. doi : 10.1017/s0020743800060633 . S2CID 162223060 .

- ^ Ирвин 2004 , с. 200

- ^ Ирвин 2004 , с. 198.

- ^ Ирвин 2004 , стр. 199-200.

- ^ Хит, Петр (май 1994). «Рассматриваемая работа (и): методы рассказывания историй в арабских ночах Дэвида Пина». Международный журнал исследований на Ближнем Востоке . 26 (2). Издательство Кембриджского университета : 358–60 [359]. doi : 10.1017/s0020743800060633 . S2CID 162223060 .

- ^ Ирвин 2004 , стр. 193-194.

- ^ Ирвин 2004 , стр. 199.

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Ульрих Марзолф, Ричард Ван Леувен, Хасан Вассуф (2004). Энциклопедия арабских ночей . ABC-Clio . п. 109. ISBN 1-57607-204-5 .

- ^ Ирвин 2004 , с. 93.

- ^ Ульрих Марзолф, Ричард Ван Леувен, Хасан Вассуф (2004). Энциклопедия арабских ночей . ABC-Clio . п. 4. ISBN 1-57607-204-5 .

- ^ Ульрих Марзолф, Ричард Ван Леувен, Хасан Вассуф (2004). Энциклопедия арабских ночей . ABC-Clio. С. 97–98. ISBN 1-57607-204-5 .

- ^ «Али с большим членом» находится только в рукописи Уортли Монтегю (1764), которая находится в библиотеке Бодлея и не встречается в Бертоне или в каких -либо других стандартных переводах. (Ссылка: Энциклопедия арабских ночей ).

- ^ Пино, Дэвид (1992). Техника рассказывания историй в арабских ночах . Brill Publishers . п. 59. ISBN 90-04-09530-6 .

- ^ Марзолф, Ульрих (2006). Читатель Arabian Nights . Уэйн Государственный университет издательство . С. 240–42. ISBN 0-8143-3259-5 .

- ^ Пино, Дэвид (1992). Техника рассказывания историй в арабских ночах . Брилль с. 93, 95, 97. ISBN 90-04-09530-6 .

- ^ Пино, Дэвид (1992). Техника рассказывания историй в арабских ночах . Brill Publishers . стр. 91, 93. ISBN 90-04-09530-6 .

- ^ Марзолф, Ульрих (2006). Читатель Arabian Nights . Уэйн Государственный университет издательство . п. 240. ISBN 0-8143-3259-5 .

- ^ Ульрих Марзолф, Ричард Ван Леувен, Хасан Вассуф (2004). Энциклопедия арабских ночей . ABC-Clio . С. 2–4. ISBN 1-57607-204-5 .

- ^ Юрико Яманака, Тецуо Нишио (2006). Аравийские ночи и ориентализм: перспективы с востока и запада . Ib tauris . п. 83. ISBN 1-85043-768-8 .

- ^ Аль-Хакавати. « История Гериба и его брата Агиба » . Тысяча ночей и одна ночь . Архивировано из оригинала 21 декабря 2008 года . Получено 2 октября 2008 года .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Hamori, Andras (1971). «Аллегория из арабских ночей: городс -город». Бюллетень школы восточных и африканских исследований . 34 (1). Издательство Кембриджского университета : 9–19 [10]. doi : 10.1017/s0041977x00141540 . S2CID 161610007 . Герой сказки - исторический человек, Муса бин Нусайр .