ислам

| ислам | |

|---|---|

| ٱلْإِسْلَامислам Аль-Ислам | |

| |

| Классификация | авраамический |

| Писание | Коран |

| Теология | Монотеистический |

| Область | Middle East, North Africa, East Africa, Central Asia, South Asia, Southeast Asia, Southeastern Europe[1] |

| Language | Quranic Arabic |

| Territory | Muslim world |

| Founder | Muhammad[2] |

| Origin | 610 CE Jabal al-Nour, Mecca, Hejaz, Arabian Peninsula |

| Separated from | Arabian polytheism |

| Separations | Bábism[3] Baháʼí Faith[4] Druze Faith[5] |

| Number of followers | c. 1.9 billion[6] |

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

Islam ( / ˈ ɪ z l ɑː m , ˈ ɪ z l æ m / IZ -la(h)m ; [7] Арабский : Ислам , латинизированный : аль-Ислам , IPA: [alʔɪsˈlaːm] , букв. « подчинение [воле Бога ] » ) — авраамическая монотеистическая религия, основанная на Коране и учении Мухаммеда , основателя религии. Приверженцами ислама называются мусульмане , которые, по оценкам, насчитывают около 1,9 миллиарда человек во всем мире в мире и являются вторым по величине религиозным населением после христиан . [8]

Muslims believe that Islam is the complete and universal version of a primordial faith that was revealed many times through earlier prophets and messengers, including Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses, and Jesus. Muslims consider the Quran to be the verbatim word of God and the unaltered, final revelation. Alongside the Quran, Muslims also believe in previous revelations, such as the Tawrat (the Torah), the Zabur (Psalms), and the Injil (Gospel). They believe that Muhammad is the main and final Islamic prophet, through whom the religion was completed. The teachings and normative examples of Muhammad, called the sunnah, documented in accounts called the hadith, provide a constitutional model for Muslims. Islam emphasizes that God is one and incomparable. It states that there will be a "Final Judgment" wherein the righteous will be rewarded in paradise (jannah) and the unrighteous will be punished in hell (jahannam). The Five Pillars—considered obligatory acts of worship—comprise the Islamic oath and creed (шахада ); ежедневные молитвы ( салах ); милостыня ( закят ); пост ( саум ) в месяц Рамадан ; и паломничество ( хадж ) в Мекку . Исламское право, шариат , затрагивает практически все аспекты жизни: от банковского дела, финансов и социального обеспечения до ролей мужчин и женщин и окружающей среды . Двумя главными религиозными праздниками являются Курбан-байрам и Курбан-байрам . Три самых святых места в исламе — это Масджид аль-Харам в Мекке, Мечеть Пророка в Медине и Мечеть Аль-Акса в Иерусалиме .

The religion of Islam originated in Mecca in 610 CE. Muslims believe this is when Muhammad received his first revelation. By the time of his death, most of the Arabian Peninsula had converted to Islam. Muslim rule expanded outside Arabia under the Rashidun Caliphate and the subsequent Umayyad Caliphate ruled from the Iberian Peninsula to the Indus Valley. In the Islamic Golden Age, specifically during the reign of the Abbasid Caliphate, much of the Muslim world experienced a scientific, economic and cultural flourishing. The expansion of the Muslim world involved various states and caliphates as well as extensive trade and religious conversion as a result of Islamic missionary activities (dawah), as well as through conquests.

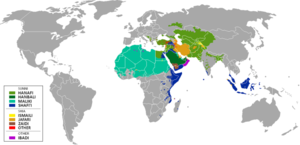

The two main Islamic branches are Sunni Islam (85–90%) and Shia Islam (10–15%). While the Shia–Sunni divide initially arose from disagreements over the succession to Muhammad, they grew to cover a broader dimension, both theologically and juridically. Muslims make up a majority of the population in 49 countries. Approximately 12% of the world's Muslims live in Indonesia, the most populous Muslim-majority country; 31% live in South Asia; 20% live in the Middle East–North Africa; and 15% live in sub-Saharan Africa. Muslim communities are also present in the Americas, China, and Europe. Largely due to having a high proportion of young people, and a high fertility rate, Muslims are the world's fastest-growing major religious group.

Etymology

In Arabic, Islam (Arabic: إسلام, lit. 'submission [to God]')[9][10][11] is the verbal noun of Form IV originating from the verb سلم (salama), from the triliteral root س-ل-م (S-L-M), which forms a large class of words mostly relating to concepts of submission, safeness, and peace.[12] In a religious context, it refers to the total surrender to the will of God.[13] A Muslim (مُسْلِم), the word for a follower of Islam,[14] is the active participle of the same verb form, and means "submitter (to God)" or "one who surrenders (to God)". In the Hadith of Gabriel, Islam is presented as one part of a triad that also includes imān (faith), and ihsān (excellence).[15][16]

Islam itself was historically called Mohammedanism in the English-speaking world. This term has fallen out of use and is sometimes said to be offensive, as it suggests that a human being, rather than God, is central to Muslims' religion.[17]

Articles of faith

The Islamic creed (aqidah) requires belief in six articles: God, angels, revelation, prophets, the Day of Resurrection, and the divine predestination.[18]

God

The central concept of Islam is tawḥīd (Arabic: توحيد), the oneness of God. It is usually thought of as a precise monotheism, but is also panentheistic in Islamic mystical teachings.[19][20] God is seen as incomparable and without partners such as in the Christian Trinity, and associating partners to God or attributing God's attributes to others is seen as idolatory, called shirk. God is seen as transcendent of creation and so is beyond comprehension. Thus, Muslims are not iconodules and do not attribute forms to God. God is instead described and referred to by several names or attributes, the most common being Ar-Rahmān (الرحمان) meaning "The Entirely Merciful," and Ar-Rahīm (الرحيم) meaning "The Especially Merciful" which are invoked at the beginning of most chapters of the Quran.[21][22]

Islam teaches that the creation of everything in the universe was brought into being by God's command as expressed by the wording, "Be, and it is,"[i][9] and that the purpose of existence is to worship God.[23] He is viewed as a personal god[9] and there are no intermediaries, such as clergy, to contact God. Consciousness and awareness of God is referred to as Taqwa. Allāh is a term with no plural or gender being ascribed to it and is also used by Muslims and Arabic-speaking Christians and Jews in reference to God, whereas ʾilāh (إله) is a term used for a deity or a god in general.[24]

Angels

Angels (Arabic: ملك, malak) are beings described in the Quran[25] and hadith.[26] They are described as created to worship God and also to serve in other specific duties such as communicating revelations from God, recording every person's actions, and taking a person's soul at the time of death. They are described as being created variously from 'light' (nūr)[27][28][29] or 'fire' (nār).[30][31][32][33] Islamic angels are often represented in anthropomorphic forms combined with supernatural images, such as wings, being of great size or wearing heavenly articles.[34][35][36][37] Common characteristics for angels include a lack of bodily needs and desires, such as eating and drinking.[38] Some of them, such as Gabriel (Jibrīl) and Michael (Mika'il), are mentioned by name in the Quran. Angels play a significant role in literature about the Mi'raj, where Muhammad encounters several angels during his journey through the heavens.[26] Further angels have often been featured in Islamic eschatology, theology and philosophy.[39]

Scriptures

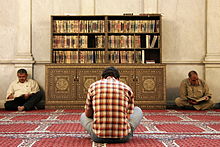

The pre-eminent holy text of Islam is the Quran. Muslims believe that the verses of the Quran were revealed to Muhammad by God, through the archangel Gabriel, on multiple occasions between 610 CE[40][41] and 632, the year Muhammad died.[42] While Muhammad was alive, these revelations were written down by his companions, although the primary method of transmission was orally through memorization.[43] The Quran is divided into 114 chapters (sūrah) which contain a combined 6,236 verses (āyāt). The chronologically earlier chapters, revealed at Mecca, are concerned primarily with spiritual topics, while the later Medinan chapters discuss more social and legal issues relevant to the Muslim community.[9][44] Muslim jurists consult the hadith ('accounts'), or the written record of Muhammad's life, to both supplement the Quran and assist with its interpretation. The science of Quranic commentary and exegesis is known as tafsir.[45][46] In addition to its religious significance, the Quran is widely regarded as the finest work in Arabic literature,[47][48] and has influenced art and the Arabic language.[49]

Islam also holds that God has sent revelations, called wahy, to different prophets numerous times throughout history. However, Islam teaches that parts of the previously revealed scriptures, such as the Tawrat (Torah) and the Injil (Gospel), have become distorted—either in interpretation, in text, or both,[50][51][52][53] while the Quran (lit. 'Recitation') is viewed as the final, verbatim and unaltered word of God.[44][54][55][56]

Prophets

Prophets (Arabic: أنبياء, anbiyāʾ) are believed to have been chosen by God to preach a divine message. Some of these prophets additionally deliver a new book and are called "messengers" (رسول, rasūl).[58] Muslims believe prophets are human and not divine. All of the prophets are said to have preached the same basic message of Islam – submission to the will of God – to various nations in the past, and this is said to account for many similarities among religions. The Quran recounts the names of numerous figures considered prophets in Islam, including Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses and Jesus, among others.[9][59] The stories associated with the prophets beyond the Quranic accounts are collected and explored in the Qisas al-Anbiya (Stories of the Prophets).

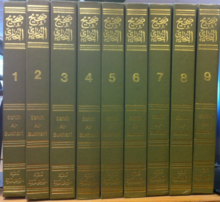

Muslims believe that God sent Muhammad as the final prophet ("Seal of the prophets") to convey the completed message of Islam.[60][61] In Islam, the "normative" example of Muhammad's life is called the sunnah (literally "trodden path"). Muslims are encouraged to emulate Muhammad's moral behaviors in their daily lives, and the sunnah is seen as crucial to guiding interpretation of the Quran.[62][63][64][65] This example is preserved in traditions known as hadith, which are accounts of his words, actions, and personal characteristics. Hadith Qudsi is a sub-category of hadith, regarded as God's verbatim words quoted by Muhammad that are not part of the Quran. A hadith involves two elements: a chain of narrators, called sanad[broken anchor], and the actual wording, called matn. There are various methodologies to classify the authenticity of hadiths, with the commonly used grading grading scale being "authentic" or "correct" (صحيح, ṣaḥīḥ); "good" (حسن, ḥasan); or "weak" (ضعيف, ḍaʻīf), among others. The Kutub al-Sittah are a collection of six books, regarded as the most authentic reports in Sunni Islam. Among them is Sahih al-Bukhari, often considered by Sunnis to be one of the most authentic sources after the Quran.[66] Another well-known source of hadiths is known as The Four Books, which Shias consider as the most authentic hadith reference.[67][68]

Resurrection and judgment

Belief in the "Day of Resurrection" or Yawm al-Qiyāmah (Arabic: يوم القيامة) is also crucial for Muslims. It is believed that the time of Qiyāmah is preordained by God, but unknown to man. The Quran and the hadith, as well as the commentaries of scholars, describe the trials and tribulations preceding and during the Qiyāmah. The Quran emphasizes bodily resurrection, a break from the pre-Islamic Arabian understanding of death.[69][70][71]

On Yawm al-Qiyāmah, Muslims believe all humankind will be judged by their good and bad deeds and consigned to Jannah (paradise) or Jahannam (hell).[72] The Quran in Surat al-Zalzalah describes this as: "So whoever does an atom's weight of good will see it. And whoever does an atom's weight of evil will see it." The Quran lists several sins that can condemn a person to hell. However, the Quran makes it clear that God will forgive the sins of those who repent if he wishes. Good deeds, like charity, prayer, and compassion towards animals[73] will be rewarded with entry to heaven. Muslims view heaven as a place of joy and blessings, with Quranic references describing its features. Mystical traditions in Islam place these heavenly delights in the context of an ecstatic awareness of God.[74][75][76] Yawm al-Qiyāmah is also identified in the Quran as Yawm ad-Dīn (يوم الدين "Day of Religion");[ii] as-Sāʿah (الساعة "the Last Hour");[iii] and al-Qāriʿah (القارعة "The Clatterer").[iv]

Divine predestination

The concept of divine predestination in Islam (Arabic: القضاء والقدر, al-qadāʾ wa l-qadar) means that every matter, good or bad, is believed to have been decreed by God. Al-qadar, meaning "power", derives from a root that means "to measure" or "calculating".[77][78][79][80] Muslims often express this belief in divine destiny with the phrase "In-sha-Allah" (Arabic: إن شاء الله) meaning "if God wills" when speaking on future events.[81]

Acts of worship

There are five acts of worship that are considered duties – the Shahada (declaration of faith), the five daily prayers, Zakat (alms-giving), fasting during Ramadan and the Hajj pilgrimage – collectively known as "The Pillars of Islam" (Arkān al-Islām).[82] In addition, Muslims also perform other optional supererogatory acts that are encouraged but not considered to be duties.[83]

Declaration of faith

The shahadah[84] is an oath declaring belief in Islam. The expanded statement is "ʾašhadu ʾal-lā ʾilāha ʾillā-llāhu wa ʾašhadu ʾanna muħammadan rasūlu-llāh" (أشهد أن لا إله إلا الله وأشهد أن محمداً رسول الله), or, "I testify that there is no deity except God and I testify that Muhammad is the messenger of God."[85] Islam is sometimes argued to have a very simple creed with the shahada being the premise for the rest of the religion. Non-Muslims wishing to convert to Islam are required to recite the shahada in front of witnesses.[86][87]

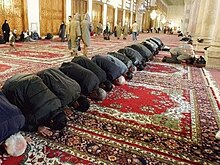

Prayer

Prayer in Islam, called as-salah or aṣ-ṣalāt (Arabic: الصلاة), is seen as a personal communication with God and consists of repeating units called rakat that include bowing and prostrating to God. There are five timed prayers each day that are considered duties. The prayers are recited in the Arabic language and performed in the direction of the Kaaba. The act also requires a state of ritual purity achieved by means of either a routine wudu ritual wash or, in certain circumstances, a ghusl full body ritual wash.[88][89][90][91]

A mosque is a place of worship for Muslims, who often refer to it by its Arabic name masjid. Although the primary purpose of the mosque is to serve as a place of prayer, it is also an important social center for the Muslim community. For example, the Masjid an-Nabawi ("Prophetic Mosque") in Medina, Saudi Arabia, used to also serve as a shelter for the poor.[92] Minarets are towers used to call the adhan, a vocal call to signal the prayer time.[93][94]

Almsgiving

Zakat (Arabic: زكاة, zakāh), also spelled Zakāt or Zakah, is a type of almsgiving characterized by the giving of a fixed portion (2.5% annually)[95] of accumulated wealth by those who can afford it to help the poor or needy, such as for freeing captives, those in debt, or for (stranded) travellers, and for those employed to collect zakat. It acts as a form of welfare in Muslim societies.[96] It is considered a religious obligation that the well-off owe the needy because their wealth is seen as a trust from God's bounty,[97] and is seen as a purification of one's excess wealth.[98] The total annual value contributed due to zakat is 15 times greater than global humanitarian aid donations, using conservative estimates.[99] Sadaqah, as opposed to Zakat, is a much-encouraged optional charity.[100][101] A waqf is a perpetual charitable trust, which finances hospitals and schools in Muslim societies.[102]

Fasting

In Islam, fasting (Arabic: صوم, ṣawm) precludes food and drink, as well as other forms of consumption, such as smoking, and is performed from dawn to sunset. During the month of Ramadan, it is considered a duty for Muslims to fast.[103] The fast is to encourage a feeling of nearness to God by restraining oneself for God's sake from what is otherwise permissible and to think of the needy. In addition, there are other days, such as the Day of Arafah, when fasting is optional.[104]

Pilgrimage

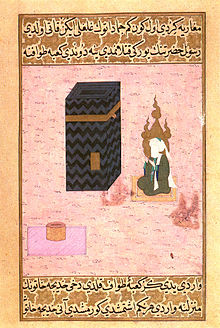

The Islamic pilgrimage, called the "ḥajj" (Arabic: حج), is to be done at least once a lifetime by every Muslim with the means to do so during the Islamic month of Dhu al-Hijjah. Rituals of the Hajj mostly imitate the story of the family of Abraham. In Mecca, pilgrims walk seven times around the Kaaba, which Muslims believe Abraham built as a place of worship, and they walk seven times between Mount Safa and Marwa, recounting the steps of Abraham's wife, Hagar, who was looking for water for her baby Ishmael in the desert before Mecca developed into a settlement.[105][106][107] The pilgrimage also involves spending a day praying and worshipping in the plain of Mount Arafat as well as symbolically stoning the Devil.[108] All Muslim men wear only two simple white unstitched pieces of cloth called ihram, intended to bring continuity through generations and uniformity among pilgrims despite class or origin.[109][110] Another form of pilgrimage, Umrah, is optional and can be undertaken at any time of the year. Other sites of Islamic pilgrimage are Medina, where Muhammad died, as well as Jerusalem, a city of many Islamic prophets and the site of Al-Aqsa, which was the direction of prayer before Mecca.[111][112]

Other acts of worship

Muslims recite and memorize the whole or parts of the Quran as acts of virtue. Tajwid refers to the set of rules for the proper elocution of the Quran.[113] Many Muslims recite the whole Quran during the month of Ramadan.[114] One who has memorized the whole Quran is called a hafiz ("memorizer"), and hadiths mention that these individuals will be able to intercede for others on Judgment Day.[115]

Supplication to God, called in Arabic duʿāʾ (Arabic: دعاء IPA: [dʊˈʕæːʔ]) has its own etiquette such as raising hands as if begging.[116]

Remembrance of God (ذكر, Dhikr') refers to phrases repeated referencing God. Commonly, this includes Tahmid, declaring praise be due to God (الحمد لله, al-Ḥamdu lillāh) during prayer or when feeling thankful, Tasbih, declaring glory to God during prayer or when in awe of something and saying 'in the name of God' (بسملة, basmalah) before starting an act such as eating.[117]

History

Muhammad and the beginning of Islam (570–632)

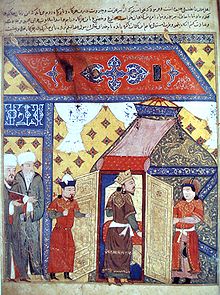

According to Islamic tradition, Muhammad was born in Mecca in 570 CE and was orphaned early in life. Growing up as a trader, he became known as the "trusted one" (Arabic: الامين) and was sought after as an impartial arbitrator. He later married his employer, the businesswoman Khadija.[118] In the year 610 CE, troubled by the moral decline and idolatry prevalent in Mecca and seeking seclusion and spiritual contemplation, Muhammad retreated to the Cave of Hira in the mountain Jabal al-Nour, near Mecca. It was during his time in the cave that he is said to have received the first revelation of the Quran from the angel Gabriel.[119] The event of Muhammad's retreat to the cave and subsequent revelation is known as the "Night of Power" (Laylat al-Qadr) and is considered a significant event in Islamic history. During the next 22 years of his life, from age 40 onwards, Muhammad continued to receive revelations from God, becoming the last or seal of the prophets sent to mankind.[50][51][120]

During this time, while in Mecca, Muhammad preached first in secret and then in public, imploring his listeners to abandon polytheism and worship one God. Many early converts to Islam were women, the poor, foreigners, and slaves like the first muezzin Bilal ibn Rabah al-Habashi.[122] The Meccan elite felt Muhammad was destabilizing their social order by preaching about one God and giving questionable ideas to the poor and slaves because they profited from the pilgrimages to the idols of the Kaaba.[123][124]

After 12 years of the persecution of Muslims by the Meccans, Muhammad and his companions performed the Hijra ("emigration") in 622 to the city of Yathrib (current-day Medina). There, with the Medinan converts (the Ansar) and the Meccan migrants (the Muhajirun), Muhammad in Medina established his political and religious authority. The Constitution of Medina was signed by all the tribes of Medina. This established religious freedoms and freedom to use their own laws among the Muslim and non-Muslim communities as well as an agreement to defend Medina from external threats.[125] Meccan forces and their allies lost against the Muslims at the Battle of Badr in 624 and then fought an inconclusive battle in the Battle of Uhud[126] before unsuccessfully besieging Medina in the Battle of the Trench (March–April 627). In 628, the Treaty of Hudaybiyyah was signed between Mecca and the Muslims, but it was broken by Mecca two years later. As more tribes converted to Islam, Meccan trade routes were cut off by the Muslims.[127][128] By 629 Muhammad was victorious in the nearly bloodless conquest of Mecca, and by the time of his death in 632 (at age 62) he had united the tribes of Arabia into a single religious polity.[129][40]

Early Islamic period (632–750)

Muhammad died in 632 and the first successors, called Caliphs – Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman ibn al-Affan, Ali ibn Abi Talib and sometimes Hasan ibn Ali[130] – are known in Sunni Islam as al-khulafā' ar-rāshidūn ("Rightly Guided Caliphs").[131] Some tribes left Islam and rebelled under leaders who declared themselves new prophets but were crushed by Abu Bakr in the Ridda wars.[132][133][134][135][136] Local populations of Jews and indigenous Christians, persecuted as religious minorities and heretics and taxed heavily, often helped Muslims take over their lands,[137] resulting in rapid expansion of the caliphate into the Persian and Byzantine empires.[138][139][140][141] Uthman was elected in 644 and his assassination by rebels led to Ali being elected the next Caliph. In the First Civil War, Muhammad's widow, Aisha, raised an army against Ali, attempting to avenge the death of Uthman, but was defeated at the Battle of the Camel. Ali attempted to remove the governor of Syria, Mu'awiya, who was seen as corrupt. Mu'awiya then declared war on Ali and was defeated in the Battle of Siffin. Ali's decision to arbitrate angered the Kharijites, an extremist sect, who felt that by not fighting a sinner, Ali became a sinner as well. The Kharijites rebelled and were defeated in the Battle of Nahrawan but a Kharijite assassin later killed Ali. Ali's son, Hasan ibn Ali, was elected Caliph and signed a peace treaty to avoid further fighting, abdicating to Mu'awiya in return for Mu'awiya not appointing a successor.[142] Mu'awiya began the Umayyad dynasty with the appointment of his son Yazid I as successor, sparking the Second Civil War. During the Battle of Karbala, Husayn ibn Ali was killed by Yazid's forces; the event has been annually commemorated by Shias ever since. Sunnis, led by Ibn al-Zubayr and opposed to a dynastic caliphate, were defeated in the siege of Mecca. These disputes over leadership would give rise to the Sunni-Shia schism,[143] with the Shia believing leadership belongs to Muhammad's family through Ali, called the ahl al-bayt.[144]Abu Bakr's leadership oversaw the beginning of the compilation of the Quran. The Caliph Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz set up the committee, The Seven Fuqaha of Medina,[145][146] and Malik ibn Anas wrote one of the earliest books on Islamic jurisprudence, the Muwatta, as a consensus of the opinion of those jurists.[147][148][149] The Kharijites believed there was no compromised middle ground between good and evil, and any Muslim who committed a grave sin would become an unbeliever. The term "kharijites" would also be used to refer to later groups such as ISIS.[150] The Murji'ah taught that people's righteousness could be judged by God alone. Therefore, wrongdoers might be considered misguided, but not denounced as unbelievers.[151] This attitude came to prevail into mainstream Islamic beliefs.[152]

The Umayyad dynasty conquered the Maghreb, the Iberian Peninsula, Narbonnese Gaul and Sindh.[153] The Umayyads struggled with a lack of legitimacy and relied on a heavily patronized military.[154] Since the jizya tax was a tax paid by non-Muslims which exempted them from military service, the Umayyads denied recognizing the conversion of non-Arabs, as it reduced revenue.[152] While the Rashidun Caliphate emphasized austerity, with Umar even requiring an inventory of each official's possessions,[155] Umayyad luxury bred dissatisfaction among the pious.[152] The Kharijites led the Berber Revolt, leading to the first Muslim states independent of the Caliphate. In the Abbasid Revolution, non-Arab converts (mawali), Arab clans pushed aside by the Umayyad clan, and some Shi'a rallied and overthrew the Umayyads, inaugurating the more cosmopolitan Abbasid dynasty in 750.[156][157]

Classical era (750–1258)

Al-Shafi'i codified a method to determine the reliability of hadith.[158] During the early Abbasid era, scholars such as Muhammad al-Bukhari and Muslim ibn al-Hajjaj compiled the major Sunni hadith collections while scholars like Al-Kulayni and Ibn Babawayh compiled major Shia hadith collections. The four Sunni Madh'habs, the Hanafi, Hanbali, Maliki, and Shafi'i, were established around the teachings of Abū Ḥanīfa, Ahmad ibn Hanbal, Malik ibn Anas and al-Shafi'i. In contrast, the teachings of Ja'far al-Sadiq formed the Ja'fari jurisprudence. In the 9th century, Al-Tabari completed the first commentary of the Quran, the Tafsir al-Tabari, which became one of the most cited commentaries in Sunni Islam. Some Muslims began questioning the piety of indulgence in worldly life and emphasized poverty, humility, and avoidance of sin based on renunciation of bodily desires. Ascetics such as Hasan al-Basri inspired a movement that would evolve into tasawwuf or Sufism.[159][160]

At this time, theological problems, notably on free will, were prominently tackled, with Hasan al Basri holding that although God knows people's actions, good and evil come from abuse of free will and the devil.[161][a] Greek rationalist philosophy influenced a speculative school of thought known as Muʿtazila, who famously advocated the notion of free-will originated by Wasil ibn Ata.[163] Caliph Mamun al Rashid made it an official creed and unsuccessfully attempted to force this position on the majority.[164] Caliph Al-Mu'tasim carried out inquisitions, with the traditionalist Ahmad ibn Hanbal notably refusing to conform to the Muʿtazila idea that the Quran was created rather than being eternal, which resulted in him being tortured and kept in an unlit prison cell for nearly thirty months.[165] However, other schools of speculative theology – Māturīdism founded by Abu Mansur al-Maturidi and Ash'ari founded by Al-Ash'ari – were more successful in being widely adopted. Philosophers such as Al-Farabi, Avicenna and Averroes sought to harmonize Aristotle's ideas with the teachings of Islam, similar to later scholasticism within Christianity in Europe and Maimonides' work within Judaism, while others like Al-Ghazali argued against such syncretism and ultimately prevailed.[166][167]

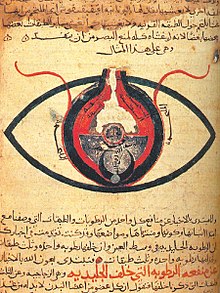

This era is sometimes called the "Islamic Golden Age".[168][169][170][171][139] Islamic scientific achievements spanned a wide range of subject areas including medicine, mathematics, astronomy, and agriculture as well as physics, economics, engineering and optics.[172][173][174][175] Avicenna was a pioneer in experimental medicine,[176][177] and his The Canon of Medicine was used as a standard medicinal text in the Islamic world and Europe for centuries. Rhazes was the first to identify the diseases smallpox and measles.[178] Public hospitals of the time issued the first medical diplomas to license doctors.[179][180] Ibn al-Haytham is regarded as the father of the modern scientific method and often referred to as the "world's first true scientist", in particular regarding his work in optics.[181][182][183] In engineering, the Banū Mūsā brothers' automatic flute player is considered to have been the first programmable machine.[184] In mathematics, the concept of the algorithm is named after Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi, who is considered a founder of algebra, which is named after his book al-jabr, while others developed the concept of a function.[185] The government paid scientists the equivalent salary of professional athletes today.[186] Guinness World Records recognizes the University of Al Karaouine, founded in 859, as the world's oldest degree-granting university.[187] Many non-Muslims, such as Christians, Jews and Sabians,[188] contributed to the Islamic civilization in various fields,[189][190] and the institution known as the House of Wisdom employed Christian and Persian scholars to both translate works into Arabic and to develop new knowledge.[191][188][192]

Soldiers broke away from the Abbasid empire and established their own dynasties, such as the Tulunids in 868 in Egypt[193] and the Ghaznavid dynasty in 977 in Central Asia.[194] In this fragmentation came the Shi'a Century, roughly between 945 and 1055, which saw the rise of the millennialist Isma'ili Shi'a missionary movement. One Isma'ili group, the Fatimid dynasty, took control of North Africa in the 10th century[195] and another Isma'ili group, the Qarmatians, sacked Mecca and stole the Black Stone, a rock placed within the Kaaba, in their unsuccessful rebellion.[196] Yet another Isma'ili group, the Buyid dynasty, conquered Baghdad and turned the Abbasids into a figurehead monarchy. The Sunni Seljuk dynasty campaigned to reassert Sunni Islam by promulgating the scholarly opinions of the time, notably with the construction of educational institutions known as Nezamiyeh, which are associated with Al-Ghazali and Saadi Shirazi.[197]

The expansion of the Muslim world continued with religious missions converting Volga Bulgaria to Islam. The Delhi Sultanate reached deep into the Indian Subcontinent and many converted to Islam,[198] in particular low-caste Hindus whose descendants make up the vast majority of Indian Muslims.[199] Trade brought many Muslims to China, where they virtually dominated the import and export industry of the Song dynasty.[200] Muslims were recruited as a governing minority class in the Yuan dynasty.[201]

Pre-Modern era (1258–18th century)

Through Muslim trade networks and the activity of Sufi orders,[202] Islam spread into new areas[203] and Muslims assimilated into new cultures.

Under the Ottoman Empire, Islam spread to Southeast Europe.[204] Conversion to Islam often involved a degree of syncretism,[205] as illustrated by Muhammad's appearance in Hindu folklore.[206] Muslim Turks incorporated elements of Turkish Shamanism beliefs to Islam.[b][208] Muslims in Ming Dynasty China who were descended from earlier immigrants were assimilated, sometimes through laws mandating assimilation,[209] by adopting Chinese names and culture while Nanjing became an important center of Islamic study.[210][211]

Cultural shifts were evident with the decrease in Arab influence after the Mongol destruction of the Abbasid Caliphate.[212] The Muslim Mongol Khanates in Iran and Central Asia benefited from increased cross-cultural access to East Asia under Mongol rule and thus flourished and developed more distinctively from Arab influence, such as the Timurid Renaissance under the Timurid dynasty.[213] Nasir al-Din al-Tusi (1201–1274) proposed the mathematical model that was later argued to be adopted by Copernicus unrevised in his heliocentric model,[214] and Jamshīd al-Kāshī's estimate of pi would not be surpassed for 180 years.[215]

After the introduction of gunpowder weapons, large and centralized Muslim states consolidated around gunpowder empires, these had been previously splintered amongst various territories. The caliphate was claimed by the Ottoman dynasty of the Ottoman Empire and its claims were strengthened in 1517 as Selim I became the ruler of Mecca and Medina.[216] The Shia Safavid dynasty rose to power in 1501 and later conquered all of Iran.[217] In South Asia, Babur founded the Mughal Empire.[218]

The religion of the centralized states of the gunpowder empires influenced the religious practice of their constituent populations. A symbiosis between Ottoman rulers and Sufism strongly influenced Islamic reign by the Ottomans from the beginning. The Mevlevi Order and Bektashi Order had a close relation to the sultans,[219] as Sufi-mystical as well as heterodox and syncretic approaches to Islam flourished.[220] The often forceful Safavid conversion of Iran to the Twelver Shia Islam of the Safavid Empire ensured the final dominance of the Twelver sect within Shia Islam. Persian migrants to South Asia, as influential bureaucrats and landholders, helped spread Shia Islam, forming some of the largest Shia populations outside Iran.[221] Nader Shah, who overthrew the Safavids, attempted to improve relations with Sunnis by propagating the integration of Twelverism into Sunni Islam as a fifth madhhab, called Ja'farism,[222] which failed to gain recognition from the Ottomans.[223]

Modern era (18th–20th centuries)

Earlier in the 14th century, Ibn Taymiyya promoted a puritanical form of Islam,[224] rejecting philosophical approaches in favor of simpler theology,[224] and called to open the gates of itjihad rather than blind imitation of scholars.[225] He called for a jihad against those he deemed heretics,[226] but his writings only played a marginal role during his lifetime.[227] During the 18th century in Arabia, Muhammad ibn 'Abd al-Wahhab, influenced by the works of Ibn Taymiyya and Ibn al-Qayyim, founded a movement called Wahhabi to return to what he saw as unadultered Islam.[228][229] He condemned many local Islamic customs, such as visiting the grave of Muhammad or saints, as later innovations and sinful[229][230] and destroyed sacred rocks and trees, Sufi shrines, the tombs of Muhammad and his companions and the tomb of Husayn at Karbala, a major Shia pilgrimage site.[230][231][232] He formed an alliance with the Saud family, which, by the 1920s, completed their conquest of the area that would become Saudi Arabia.[230][233] Ma Wanfu and Ma Debao promoted salafist movements in the 19th century such as Sailaifengye in China after returning from Mecca but were eventually persecuted and forced into hiding by Sufi groups.[234] Other groups sought to reform Sufism rather than reject it, with the Senusiyya and Muhammad Ahmad both waging war and establishing states in Libya and Sudan respectively.[235] In India, Shah Waliullah Dehlawi attempted a more conciliatory style against Sufism and influenced the Deobandi movement.[236] In response to the Deobandi movement, the Barelwi movement was founded as a mass movement, defending popular Sufism and reforming its practices.[237][238]

The Muslim world was generally in political decline starting the 1800s, especially compared to non-Muslim European powers. Earlier, in the 15th century, the Reconquista succeeded in ending the Muslim presence in Iberia. By the 19th century, the British East India Company had formally annexed the Mughal dynasty in India.[239] As a response to Western Imperialism, many intellectuals sought to reform Islam.[240] Islamic modernism, initially labelled by Western scholars as Salafiyya, embraced modern values and institutions such as democracy while being scripture oriented. Notable forerunners in the movement include Muhammad 'Abduh and Jamal al-Din al-Afghani.[241] Abul A'la Maududi helped influence modern political Islam.[242][243] Similar to contemporary codification, sharia was for the first time partially codified into law in 1869 in the Ottoman Empire's Mecelle code.[244]

The Ottoman Empire dissolved after World War I, the Ottoman Caliphate was abolished in 1924[245] and the subsequent Sharifian Caliphate fell quickly,[246][247][248] thus leaving Islam without a Caliph.[248] Pan-Islamists attempted to unify Muslims and competed with growing nationalist forces, such as pan-Arabism.[249][250] The Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), consisting of Muslim-majority countries, was established in 1969 after the burning of the Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem.[251]

Contact with industrialized nations brought Muslim populations to new areas through economic migration. Many Muslims migrated as indentured servants (mostly from India and Indonesia) to the Caribbean, forming the largest Muslim populations by percentage in the Americas.[252] Migration from Syria and Lebanon contributed to the Muslim population in Latin America.[253] The resulting urbanization and increase in trade in sub-Saharan Africa brought Muslims to settle in new areas and spread their faith,[254] likely doubling its Muslim population between 1869 and 1914.[255]

Contemporary era (20th century–present)

Forerunners of Islamic modernism influenced Islamist political movements such as the Muslim Brotherhood and related parties in the Arab world,[256][257] which performed well in elections following the Arab Spring,[258] Jamaat-e-Islami in South Asia and the AK Party, which has democratically been in power in Turkey for decades. In Iran, revolution replaced a secular monarchy with an Islamic state. Others such as Sayyid Rashid Rida broke away from Islamic modernists[259] and pushed against embracing what he saw as Western influence.[260] The group Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant would even attempt to recreate the modern gold dinar as their monetary system. While some of those who broke away were quietist, others believed in violence against those opposing them, even against other Muslims.[261]

In opposition to Islamic political movements, in 20th century Turkey, the military carried out coups to oust Islamist governments, and headscarves were legally restricted, as also happened in Tunisia.[262][263] In other places, religious authority was co-opted and is now often seen as puppets of the state. For example, in Saudi Arabia, the state monopolized religious scholarship[264] and, in Egypt, the state nationalized Al-Azhar University, previously an independent voice checking state power.[265] Salafism was funded in the Middle East for its quietism.[266] Saudi Arabia campaigned against revolutionary Islamist movements in the Middle East, in opposition to Iran.[267]

Muslim minorities of various ethnicities have been persecuted as a religious group.[268] This has been undertaken by communist forces like the Khmer Rouge, who viewed them as their primary enemy to be exterminated since their religious practice made them stand out from the rest of the population,[269] the Chinese Communist Party in Xinjiang[270] and by nationalist forces such as during the Bosnian genocide.[271] Myanmar military's Tatmadaw targeting of Rohingya Muslims has been labeled as a crime against humanity by the UN and Amnesty International,[272][273] while the OHCHR Fact-Finding Mission identified genocide, ethnic cleansing, and other crimes against humanity.[274]

The advancement of global communication has facilitated the widespread dissemination of religious knowledge. The adoption of the hijab has grown more common[275] and some Muslim intellectuals are increasingly striving to separate scriptural Islamic beliefs from cultural traditions.[276] Among other groups, this access to information has led to the rise of popular "televangelist" preachers, such as Amr Khaled, who compete with the traditional ulema in their reach and have decentralized religious authority.[277][278] More "individualized" interpretations of Islam[279] notably involve Liberal Muslims who attempt to align religious traditions with contemporary secular governance,[280][281] an approach that has been criticized by some regarding its compatibility.[282][283] Moreover, secularism is perceived as a foreign ideology imposed by invaders and perpetuated by post-colonial ruling elites,[284] and is frequently understood to be equivalent to anti-religion.[285]

Demographics

As of 2020, about 24% of the global population, or about 1.9 billion people, are Muslims.[6][8][287][288][289][290] In 1900, this estimate was 12.3%,[291] in 1990 it was 19.9%[254] and projections suggest the proportion will be 29.7% by 2050.[292] The Pew Research Center estimates that 87–90% of Muslims are Sunni and 10–13% are Shia.[293] Approximately 49 countries are Muslim-majority,[294][295][296][297][298][299] with 62% of the world's Muslims living in Asia, and 683 million adherents in Indonesia,[300] Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh alone.[301][302][303] Arab Muslims form the largest ethnic group among Muslims in the world,[304] followed by Bengalis[305][306] and Punjabis.[307] Most estimates indicate China has approximately 20 to 30 million Muslims (1.5% to 2% of the population).[308][309] Islam in Europe is the second-largest religion after Christianity in many countries, with growth rates due primarily to immigration and higher birth rates of Muslims in 2005,[310] accounting for 4.9% of all of Europe's population in 2016.[311]

Religious conversion has no net impact on the Muslim population growth as "the number of people who become Muslims through conversion seems to be roughly equal to the number of Muslims who leave the faith."[312] Although, Islam is expected to experience a modest gain of 3 million through religious conversion between 2010 and 2050, mostly from Sub Saharan Africa (2.9 million).[313][314]

According to a report by CNN, "Islam has drawn converts from all walks of life, most notably African-Americans".[315] In Britain, around 6,000 people convert to Islam per year and, according to an article in the British Muslims Monthly Survey, the majority of new Muslim converts in Britain were women.[316] According to The Huffington Post, "observers estimate that as many as 20,000 Americans convert to Islam annually", most of them being women and African-Americans.[317][318]

By both percentage and total numbers, Islam is the world's fastest growing major religious group, and is projected to be the world's largest by the end of the 21st century, surpassing that of Christianity.[319][292] It is estimated that, by 2050, the number of Muslims will nearly equal the number of Christians around the world, "due to the young age and high fertility rate of Muslims relative to other religious groups."[292]

Main branches or denominations

Sunni

Sunni Islam, or Sunnism, is the name for the largest denomination in Islam.[320][321][322] The term is a contraction of the phrase "ahl as-sunna wa'l-jamaat", which means "people of the sunna (the traditions of Muhammad) and the community".[323] Sunni Islam is sometimes referred to as "orthodox Islam",[324][325][326] though some scholars view this as inappropriate, and many non-Sunnis may find this offensive.[327] Sunnis, or sometimes Sunnites, believe that the first four caliphs were the rightful successors to Muhammad and primarily reference six major hadith works for legal matters, while following one of the four traditional schools of jurisprudence: Hanafi, Hanbali, Maliki or Shafi'i.[328][329]

Traditionalist theology is a Sunni school of thought, prominently advocated by Ahmad ibn Hanbal (780–855 CE), that is characterized by its adherence to a textualist understanding of the Quran and the sunnah, the belief that the Quran is uncreated and eternal, and opposition to speculative theology, called kalam, in religious and ethical matters.[330] Mu'tazilism is a Sunni school of thought inspired by Ancient Greek Philosophy. Maturidism, founded by Abu Mansur al-Maturidi (853–944 CE), asserts that scripture is not needed for basic ethics and that good and evil can be understood by reason alone,[331] but people rely on revelation, for matters beyond human's comprehension. Ash'arism, founded by Al-Ashʿarī (c. 874–936), holds that ethics can derive just from divine revelation but accepts reason regarding exegetical matters and combines Muʿtazila approaches with traditionalist ideas.[332]

Salafism is a revival movement advocating the return to the practices of the earliest generations of Muslims. In the 18th century, Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab led a Salafi movement, referred by outsiders as Wahhabism, in modern-day Saudi Arabia.[333] A similar movement called Ahl al-Hadith also de-emphasized the centuries' old Sunni legal tradition, preferring to directly follow the Quran and Hadith. The Nurcu Sunni movement was by Said Nursi (1877–1960);[334] it incorporates elements of Sufism and science.[334][335]

Shia

Shia Islam, or Shi'ism, is the second-largest Muslim denomination.[336][337][293] Shias, or Shiites, maintain that Muhammad's successor as leader, must be from certain descendants of Muhammad's family known as the Ahl al-Bayt and those leaders, referred to as Imams, have additional spiritual authority.[338][339] Shias are guided by the Ja'fari school of jurisprudence.[340]

According to both Sunni and Shia Muslims, a significant event took place at Ghadir Khumm during Muhammad's return from his final pilgrimage to Mecca, where he stopped thousands of Muslims in the midday heat.[341] Muhammad appointed his cousin Ali as the executor of his last will and testament, as well as his Wali (authority).[342][343] Shias recognize that Muhammad designated Ali as his successor (khalīfa) and Imam (spiritual and political leader) after him, but was prevented from succeeding Muhammad as the leader of the Muslims because of some other companions who selected Abū Bakr as caliph.[344] Sunnis, instead believe that Muhammad did not appoint a successor before his death and consider Abū Bakr to be the first rightful caliph after Muhammad.[345] Shias state the community deliberately ignored Ali's nomination,[346] citing Umar's appointment by Abu Bakr,[347] other historical evidence,[348] and the Qur'an's stance that majority does not imply legitimacy.[349]

Some of the first Shia Imams are revered by all Shia and Sunnis Muslims, such as Ali and Husayn.[350] Twelvers, the largest Shia branch and most influential, believe in Twelve Imams, the last of whom went into occultation to return one day. They recognize that the prophecy of the Twelve Imams has been foretold in the Hadith of the Twelve Successors which is recorded by both Sunni and Shia sources.[351] Zaidism rejects special powers of Imams and are sometimes considered a 'fifth school' of Sunni Islam rather than a Shia denomination.[352][353] They differed with other Shias over the status of the fifth imam and are sometimes known as "Fivers".[354] The Isma'ilis split with the Twelvers over who was the seventh Imam and have further fragmented into more groups over the status of successive Imams, with the largest group being the Nizaris.[355]

For Shias, the Imam Ali Shrine in Najaf, the Imam Husayn Shrine in Karbala, and the Fatima Masumeh Shrine in Qom are also among the Islamic Holy sites.[356]

Muhakkima

Ibadi Islam or Ibadism is practised by 1.45 million Muslims around the world (~0.08% of all Muslims), most of them in Oman.[357] Ibadism is often associated with and viewed as a moderate variation of the kharijites, though Ibadis themselves object to this classification. The kharijites were groups that rebelled against Caliph Ali for his acceptance of arbitration with someone they viewed as a sinner. Unlike most kharijite groups, Ibadism does not regard sinful Muslims as unbelievers. Ibadi hadiths, such as the Jami Sahih collection, use chains of narrators from early Islamic history they consider trustworthy, but most Ibadi hadiths are also found in standard Sunni collections and contemporary Ibadis often approve of the standard Sunni collections.[358]

Other denominations

- The Ahmadiyya Movement was founded in British India in 1889 by Mirza Ghulam Ahmad of Qadian, who claimed to be the promised Messiah ("Second Coming of Christ"), the Mahdi awaited by the Muslims as well as a "subordinate" prophet to the Islamic prophet Muhammad.[359][360] There are a wide variety of distinct beliefs and teachings of Ahmadis compared to those of most other Muslims,[359][361][362][360] which include the interpretation of the Quranic title Khatam an-Nabiyyin[363] and interpretation of the Messiah's Second Coming.[361][364] These perceived deviations from normative Islamic thought have resulted in rejection by most Muslims as heretics[365] and persecution of Ahmadis in various countries,[361] particularly Pakistan,[361][366] where they have been officially declared as non-Muslims by the Government of Pakistan.[367] The followers of the Ahmadiyya Movement in Islam are divided into two groups: the first being the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, currently the dominant group, and the Lahore Ahmadiyya Movement for the Propagation of Islam.[361]

- Alevism is a syncretic and heterodox local Islamic tradition, whose adherents follow the mystical (bāṭenī) teachings of Ali and Haji Bektash Veli.[368] Alevism is a blend of traditional 14th century Turkish beliefs,[369] with possible syncretist origins in Shamanism and Animism, alongside Shia and Sufi beliefs. It has been estimated that there are 10 million to over 20 million (~0.5–1% of all Muslims) Alevis worldwide.[370]

- Quranism is a religious movement of Islam based on the belief that Islamic law and guidance should only be based on the Quran and not the sunnah or Hadith,[371] with Quranists notably differing in their approach to the five pillars of Islam.[372] The movement developed from the 19th century onwards, with thinkers like Syed Ahmad Khan, Abdullah Chakralawi and Ghulam Ahmed Perwez in India questioning the hadith tradition.[373] In Egypt, Muhammad Tawfiq Sidqi penned the article Islam is the Quran alone in the magazine Al-Manār, arguing for the sole authority of the Quran.[374] A prominent late 20th century Quranist was Rashad Khalifa, an Egyptian-American biochemist who claimed to have discovered a numerological code in the Quran, and founded the Quranist organization United Submitters International.[375]

Non-denominational Muslims

Non-denominational Muslims is an umbrella term that has been used for and by Muslims who do not belong to or do not self-identify with a specific Islamic denomination.[376][377] Recent surveys report that large proportions of Muslims in some parts of the world self-identify as "just Muslim", although there is little published analysis available regarding the motivations underlying this response.[378][379][380] The Pew Research Center reports that respondents self-identifying as "just Muslim" make up a majority of Muslims in seven countries (and a plurality in three others), with the highest proportion in Kazakhstan at 74%. At least one in five Muslims in at least 22 countries self-identifies in this way.[381]

Mysticism

Sufism (Arabic: تصوف, tasawwuf), is a mystical-ascetic approach to Islam that seeks to find a direct personal experience of God. Classical Sufi scholars defined tasawwuf as "a science whose objective is the reparation of the heart and turning it away from all else but God", through "intuitive and emotional faculties" that one must be trained to use.[382][383][384][385] It is not a sect of Islam, and its adherents belong to the various Muslim denominations. Isma'ilism, whose teachings are rooted in Gnosticism and Neoplatonism[386] as well as by the Illuminationist and Isfahan schools of Islamic philosophy, has developed mystical interpretations of Islam.[387] Hasan al-Basri, the early Sufi ascetic often portrayed as one of the earliest Sufis,[388] emphasized fear of failing God's expectations of obedience. In contrast, later prominent Sufis, such as Mansur Al-Hallaj and Jalaluddin Rumi, emphasized religiosity based on love towards God. Such devotion would also have an impact on the arts, with Rumi still one of the bestselling poets in America.[389][390]

Sufis see tasawwuf as an inseparable part of Islam.[391] Traditional Sufis, such as Bayazid Bastami, Jalaluddin Rumi, Haji Bektash Veli, Junaid Baghdadi, and Al-Ghazali, argued for Sufism as being based upon the tenets of Islam and the teachings of the prophet.[392][391] Historian Nile Green argued that Islam in the Medieval period was more or less Sufism.[393] Followers of the Sunni revivalist movement known as Salafism have viewed popular devotional practices, such as the veneration of Sufi saints, as innovations from the original religion. Salafists have sometimes physically attacked Sufis, leading to a deterioration in Sufi–Salafi relations.[394]

Sufi congregations form orders (tariqa) centered around a teacher (wali) who traces a spiritual chain back to Muhammad.[395] Sufis played an important role in the formation of Muslim societies through their missionary and educational activities.[159] The Sufism-influenced Ahle Sunnat movement or Barelvi movement claims over 200 million followers in South Asia.[396][397][398] Sufism is prominent in Central Asia,[399][400] as well as in African countries like Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco, Senegal, Chad and Niger.[381][401]

Law and jurisprudence

Sharia is the religious law forming part of the Islamic tradition.[328][402] It is derived from the religious precepts of Islam, particularly the Quran and the Hadith. In Arabic, the term sharīʿah refers to God's divine law and is contrasted with fiqh, which refers to its scholarly interpretations.[403][404] The manner of its application in modern times has been a subject of dispute between Muslim traditionalists and reformists.[328]

Traditional theory of Islamic jurisprudence recognizes four sources of sharia: the Quran, sunnah (Hadith and Sira), qiyas (analogical reasoning), and ijma (juridical consensus).[405] Different legal schools developed methodologies for deriving sharia rulings from scriptural sources using a process known as ijtihad.[403] Traditional jurisprudence distinguishes two principal branches of law,ʿibādāt (rituals) and muʿāmalāt (social relations), which together comprise a wide range of topics.[403] Its rulings assign actions to one of five categories called ahkam: mandatory (fard), recommended (mustahabb), permitted (mubah), abhorred (makruh), and prohibited (haram).[403][404] Forgiveness is much celebrated in Islam[406] and, in criminal law, while imposing a penalty on an offender in proportion to their offense is considered permissible, forgiving the offender is better. To go one step further by offering a favor to the offender is regarded as the peak of excellence.[407] Some areas of sharia overlap with the Western notion of law while others correspond more broadly to living life in accordance with God's will.[404]

Historically, sharia was interpreted by independent jurists (muftis). Their legal opinions (fatwa) were taken into account by ruler-appointed judges who presided over qāḍī's courts, and by maẓālim courts, which were controlled by the ruler's council and administered criminal law.[403][404] In the modern era, sharia-based criminal laws were widely replaced by statutes inspired by European models.[404] The Ottoman Empire's 19th century Tanzimat reforms led to the Mecelle civil code and represented the first attempt to codify sharia.[244] While the constitutions of most Muslim-majority states contain references to sharia, its classical rules were largely retained only in personal status (family) laws.[404] Legislative bodies which codified these laws sought to modernize them without abandoning their foundations in traditional jurisprudence.[404][408] The Islamic revival of the late 20th century brought along calls by Islamist movements for complete implementation of sharia.[404][408] The role of sharia has become a contested topic around the world. There are ongoing debates as to whether sharia is compatible with secular forms of government, human rights, freedom of thought, and women's rights.[409][410]

Schools of jurisprudence

A school of jurisprudence is referred to as a madhhab (Arabic: مذهب). The four major Sunni schools are the Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi'i and Hanbali schools while the three major Shia schools are the Ja'fari, Zaidi and Isma'ili schools. Each differs in their methodology, called Usul al-fiqh ("principles of jurisprudence"). The conformity in following of decisions by a religious expert or school is called taqlid. The term ghair muqallid refers to those who do not use taqlid and, by extension, do not have a madhab.[411] The practice of an individual interpreting law with independent reasoning is called ijtihad.[412]

Society

Religious personages

Islam has no clergy in the sacerdotal sense, such as priests who mediate between God and people. Imam (إمام) is the religious title used to refer to an Islamic leadership position, often in the context of conducting an Islamic worship service.[413] Religious interpretation is presided over by the 'ulama (Arabic: علماء), a term used describe the body of Muslim scholars who have received training in Islamic studies. A scholar of the hadith is called a muhaddith, a scholar of jurisprudence is called a faqih (فقيه), a jurist who is qualified to issue legal opinions or fatwas is called a mufti, and a qadi is an Islamic judge. Honorific titles given to scholars include sheikh, mullah and mawlawi. Some Muslims also venerate saints associated with miracles (كرامات, karāmāt).[414]

Governance

In Islamic economic jurisprudence, hoarding of wealth is reviled and thus monopolistic behavior is frowned upon.[415] Attempts to comply with sharia has led to the development of Islamic banking. Islam prohibits riba, usually translated as usury, which refers to any unfair gain in trade and is most commonly used to mean interest.[416] Instead, Islamic banks go into partnership with the borrower, and both share from the profits and any losses from the venture. Another feature is the avoidance of uncertainty, which is seen as gambling[417] and Islamic banks traditionally avoid derivative instruments such as futures or options which has historically protected them from market downturns.[418] The Rashidun and Umayyad Caliphate used to be involved in distribution of charity from the treasury, known as Bayt al-mal, before it became a largely individual pursuit around the year 720. The first Caliph, Abu Bakr, distributed zakat as one of the first examples of a guaranteed minimum income, with each citizen getting 10 to 20 dirhams annually.[419] During the reign of the second Caliph Umar, child support was introduced and the old and disabled were entitled to stipends,[420][421] while the Umayyad Caliph Umar II assigned a servant for each blind person and for every two chronically ill persons.[422]

Jihad means "to strive or struggle [in the way of God]" and, in its broadest sense, is "exerting one's utmost power, efforts, endeavors, or ability in contending with an object of disapprobation".[423] Shias in particular emphasize the "greater jihad" of striving to attain spiritual self-perfection[424][425][426] while the "lesser jihad" is defined as warfare.[427][428] When used without a qualifier, jihad is often understood in its military form.[423][424] Jihad is the only form of warfare permissible in Islamic law and may be declared against illegal works, terrorists, criminal groups, rebels, apostates, and leaders or states who oppress Muslims.[427][428] Most Muslims today interpret Jihad as only a defensive form of warfare.[429] Jihad only becomes an individual duty for those vested with authority. For the rest of the populace, this happens only in the case of a general mobilization.[428] For most Twelver Shias, offensive jihad can only be declared by a divinely appointed leader of the Muslim community, and as such, is suspended since Muhammad al-Mahdi's occultation in 868 CE.[430][431]

Daily and family life

Many daily practices fall in the category of adab, or etiquette. Specific prohibited foods include pork products, blood and carrion. Health is viewed as a trust from God and intoxicants, such as alcoholic drinks, are prohibited.[432] All meat must come from a herbivorous animal slaughtered in the name of God by a Muslim, Jew, or Christian, except for game that one has hunted or fished for oneself.[433][434][435] Beards are often encouraged among men as something natural[436] and body modifications, such as permanent tattoos, are usually forbidden as violating the creation.[c][438] Silk and gold are prohibited for men in Islam to maintain a state of sobriety.[439] Haya, often translated as "shame" or "modesty", is sometimes described as the innate character of Islam[440] and informs much of Muslim daily life. For example, clothing in Islam emphasizes a standard of modesty, which has included the hijab for women. Similarly, personal hygiene is encouraged with certain requirements.[441]

In Islamic marriage, the groom is required to pay a bridal gift (mahr).[442][443][444]Most families in the Islamic world are monogamous.[445][446] Muslim men are allowed to practice polygyny and can have up to four wives simultaneously. Islamic teachings strongly advise that if a man cannot ensure equal financial and emotional support for each of his wives, it is recommended that he marry just one woman. One reason cited for polygyny is that it allows a man to give financial protection to multiple women, who might otherwise not have any support (e.g. widows). However, the first wife can set a condition in the marriage contract that the husband cannot marry another woman during their marriage.[447][448] There are also cultural variations in weddings.[449] Polyandry, a practice wherein a woman takes on two or more husbands, is prohibited in Islam.[450]

After the birth of a child, the adhan is pronounced in the right ear.[451] On the seventh day, the aqiqah ceremony is performed, in which an animal is sacrificed and its meat is distributed among the poor.[452] The child's head is shaved, and an amount of money equaling the weight of its hair is donated to the poor.[452] Male circumcision, called khitan,[453] is often practised in the Muslim world.[454][455] Respecting and obeying one's parents, and taking care of them especially in their old age is a religious obligation.[456]

A dying Muslim is encouraged to pronounce the Shahada as their last words.[457] Paying respects to the dead and attending funerals in the community are considered among the virtuous acts. In Islamic burial rituals, burial is encouraged as soon as possible, usually within 24 hours. The body is washed, except for martyrs, by members of the same gender and enshrouded in a garment that must not be elaborate called kafan.[458] A "funeral prayer" called Salat al-Janazah is performed. Wailing, or loud, mournful outcrying, is discouraged. Coffins are often not preferred and graves are often unmarked, even for kings.[459]

Arts and culture

The term "Islamic culture" can be used to mean aspects of culture that pertain to the religion, such as festivals and dress code. It is also controversially used to denote the cultural aspects of traditionally Muslim people.[460] Finally, "Islamic civilization" may also refer to the aspects of the synthesized culture of the early Caliphates, including that of non-Muslims,[461] sometimes referred to as "Islamicate".[462]

Islamic art encompasses the visual arts including fields as varied as architecture, calligraphy, painting, and ceramics, among others.[463][464] While the making of images of animate beings has often been frowned upon in connection with laws against idolatry, this rule has been interpreted in different ways by different scholars and in different historical periods. This stricture has been used to explain the prevalence of calligraphy, tessellation, and pattern as key aspects of Islamic artistic culture.[465] Additionally, the depiction of Muhammad is a contentious issue among Muslims.[466] In Islamic architecture, varying cultures show influence such as North African and Spanish Islamic architecture such as the Great Mosque of Kairouan containing marble and porphyry columns from Roman and Byzantine buildings,[467] while mosques in Indonesia often have multi-tiered roofs from local Javanese styles.[468]

The Islamic calendar is a lunar calendar that begins with the Hijra of 622 CE, a date that was reportedly chosen by Caliph Umar as it was an important turning point in Muhammad's fortunes.[469] Islamic holy days fall on fixed dates of the lunar calendar, meaning they occur in different seasons in different years in the Gregorian calendar. The most important Islamic festivals are Eid al-Fitr (Arabic: عيد الفطر) on the 1st of Shawwal, marking the end of the fasting month Ramadan, and Eid al-Adha (عيد الأضحى) on the 10th of Dhu al-Hijjah, coinciding with the end of the Hajj (pilgrimage).[470][82]

Cultural Muslims are religiously non-practicing individuals who still identify with Islam due to family backgrounds, personal experiences, or the social and cultural environment in which they grew up.[471][472]

- 14th century Great Mosque of Xi'an in China

- 16th century Menara Kudus Mosque in Indonesia showing Indian influence

Influences on other religions

Some movements, such as the Druze,[473][474][475] Berghouata and Ha-Mim, either emerged from Islam or came to share certain beliefs with Islam, and whether each is a separate religion or a sect of Islam is sometimes controversial.[476] The Druze faith further split from Isma'ilism as it developed its own unique doctrines, and finally separated from both Ismāʿīlīsm and Islam altogether; these include the belief that the Imam Al-Ḥākim bi-Amr Allāh was God incarnate.[477][478] Yazdânism is seen as a blend of local Kurdish beliefs and Islamic Sufi doctrine introduced to Kurdistan by Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir in the 12th century.[479] Bábism stems from Twelver Shia passed through Siyyid 'Ali Muhammad i-Shirazi al-Bab while one of his followers Mirza Husayn 'Ali Nuri Baha'u'llah founded the Baháʼí Faith.[480] Sikhism, founded by Guru Nanak in late 15th century Punjab, primarily incorporates aspects of Hinduism, with some Islamic influences.[481]

Criticism

Criticism of Islam has existed since its formative stages. Early criticism came from Jewish authors, such as Ibn Kammuna, and Christian authors, many of whom viewed Islam as a Christian heresy or a form of idolatry, often explaining it in apocalyptic terms.[483]

Christian writers criticized Islam's sensual descriptions of paradise. Ali ibn Sahl Rabban al-Tabari defended the Quranic description of paradise by asserting that the Bible also implies such ideas, such as drinking wine in the Gospel of Matthew. Catholic theologian Augustine of Hippo's doctrines led to the broad repudiation of bodily pleasure in both life and the afterlife. [484]

Defamatory images of Muhammad, derived from early 7th century depictions of the Byzantine Church,[485] appear in the 14th-century epic poem Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri.[486] Here, Muhammad is depicted in the eighth circle of hell, along with Ali. Dante does not blame Islam as a whole but accuses Muhammad of schism, by establishing another religion after Christianity.[486]

Other criticisms center on the treatment of individuals within modern Muslim-majority countries, including issues related to human rights, particularly in relation to the application of Islamic law.[487] Furthermore, in the wake of the recent multiculturalism trend, Islam's influence on the ability of Muslim immigrants in the West to assimilate has been criticized.[488]

See also

- Glossary of Islam

- Index of Islam-related articles

- Islamic mythology

- Islamic studies

- Major religious groups

- Outline of Islam

References

Footnotes

- ^ "Hasan al Basri is often considered one of the first who rejected an angelic origin for the devil, arguing that his fall was the result of his own free-will, not God's determination. Hasan al Basri also argued that angels are incapable of sin or errors and nobler than humans and even prophets. Both early Shias and Sunnis opposed his view.[162]

- ^ "In recent years, the idea of syncretism has been challenged. Given the lack of authority to define or enforce an Orthodox doctrine about Islam, some scholars argue there had no prescribed beliefs, only prescribed practise, in Islam before the 16th century.[207]

- ^ Some Muslims in dynastic era China resisted footbinding of girls for the same reason.[437]

Quran and hadith

Citations

- ^ Center, Pew Research (30 April 2013). "The World's Muslims: Religion, Politics and Society". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. Archived from the original on 25 October 2023. Retrieved 20 March 2024.

- ^ Welch, Alford T.; Moussalli, Ahmad S.; Newby, Gordon D. (2009). "Muḥammad". In John L. Esposito (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 11 February 2017.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Bausani, A. (1999). "Bāb". Encyclopedia of Islam. Leiden, The Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV.

- ^ Van der Vyer, J.D. (1996). Religious human rights in global perspective: religious perspectives. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 449. ISBN 90-411-0176-4.

- ^ Yazbeck Haddad, Yvonne (2014). The Oxford Handbook of American Islam. Oxford University Press. p. 142. ISBN 9780199862634.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Religious Composition by Country, 2010-2050". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 21 December 2022. Archived from the original on 28 January 2023. Retrieved 9 March 2024.

- ^ "English pronunciation of Islam". Cambridge Dictionary. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures Project - Research and data from Pew Research Center". 21 December 2022. Archived from the original on 5 February 2023. Retrieved 27 November 2023.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Schimmel, Annemarie. "Islam". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 4 May 2015. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ^ "Definition of Islam | Dictionary.com". www.dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 9 May 2022. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ Haywood, John (2002). Historical Atlas of the Medieval World (AD 600 - 1492) (1st ed.). Spain: Barnes & Noble, Inc. p. 3.13. ISBN 0-7607-1975-6.

- ^ "Siin Archived 7 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine." Lane's Lexicon 4. – via StudyQuran.

- ^ Lewis, Barnard; Churchill, Buntzie Ellis (2009). Islam: The Religion and The People. Wharton School Publishing. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-13-223085-8.

- ^ "Muslim." Lexico. UK: Oxford University Press. 2020.

- ^ Esposito (2000), pp. 76–77.

- ^ Mahmutćehajić, Rusmir (2006). The mosque: the heart of submission. Fordham University Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-8232-2584-2.

- ^ Gibb, Sir Hamilton (1969). Mohammedanism: an historical survey. Oxford University Press. p. 1. ISBN 9780195002454.

Modern Muslims dislike the terms Mohammedan and Mohammedanism, which seem to them to carry the implication of worship of Mohammed, as Christian and Christianity imply the worship of Christ.

- ^ Beversluis, Joel, ed. (2011). Sourcebook of the World's Religions: An Interfaith Guide to Religion and Spirituality. New World Library. pp. 68–9. ISBN 9781577313328. Archived from the original on 28 December 2023. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- ^ "Tawhid". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 7 November 2021. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ^ Gimaret, D. "Tawḥīd". In Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.) (2012). doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_7454

- ^ Ali, Kecia; Leaman, Oliver (2008). Islam : the key concepts. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-39638-7. OCLC 123136939.

- ^ Campo (2009), p. 34, "Allah".

- ^ Leeming, David. 2005. The Oxford Companion to World Mythology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-195-15669-0. p. 209.

- ^ "God". Islam: Empire of Faith. PBS. Archived from the original on 27 March 2014. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- ^ Burge (2015), p. 23.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Burge (2015), p. 79.

- ^ "Nūr Archived 23 April 2022 at the Wayback Machine." The Concise Oxford Dictionary of World Religions. – via Encyclopedia.com.

- ^ Hartner, W.; Tj Boer. "Nūr". In Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.) (2012). doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0874

- ^ Elias, Jamal J. "Light". In McAuliffe (2003). doi:10.1163/1875-3922_q3_EQSIM_00261

- ^ Campo, Juan E. "Nar". In Martin (2004).. – via Encyclopedia.com.

- ^ Fahd, T. "Nār". In Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.) (2012). doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0846

- ^ Toelle, Heidi. "Fire". In McAuliffe (2002). doi:10.1163/1875-3922_q3_EQSIM_00156

- ^ McAuliffe (2003), p. 45

- ^ Burge (2015), pp. 97–99.

- ^ Esposito (2002b), pp. 26–28

- ^ Webb, Gisela. "Angel". In McAuliffe (n.d.).

- ^ MacDonald, D. B.; Madelung, W. "Malāʾika". In Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.) (2012).doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0642

- ^ Çakmak (2017), p. 140.

- ^ Burge (2015), p. 22.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Buhl, F.; Welch, A.T. "Muhammad". In Encyclopaedia of Islam Online (n.d.).

- ^ Watt, William Montgomery (2003). Islam and the Integration of Society. Psychology Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-415-17587-6. Archived from the original on 28 December 2023. Retrieved 15 June 2021.

- ^ Esposito (2004), pp. 17–18, 21.

- ^ Al Faruqi, Lois Ibsen (1987). "The Cantillation of the Qur'an". Asian Music (Autumn – Winter 1987): 3–4.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ringgren, Helmer. "Qurʾān". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 5 May 2015. Retrieved 17 September 2021. "The word Quran was invented and first used in the Quran itself. There are two different theories about this term and its formation."

- ^ "Tafsīr". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 19 October 2021. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ^ Esposito (2004), pp. 79–81.

- ^ Jones, Alan (1994). The Koran. London: Charles E. Tuttle Company. p. 1. ISBN 1842126091.

Its outstanding literary merit should also be noted: it is by far, the finest work of Arabic prose in existence.

- ^ Arberry, Arthur (1956). The Koran Interpreted. London: Allen & Unwin. p. 191. ISBN 0684825074.

It may be affirmed that within the literature of the Arabs, wide and fecund as it is both in poetry and in elevated prose, there is nothing to compare with it.

- ^ Kadi, Wadad, and Mustansir Mir. "Literature and the Quran." In Encyclopaedia of the Qur'an 3. pp. 213, 216.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Esposito (2002b), pp. 4–5

- ^ Jump up to: a b Peters (2003), p. 9

- ^ Buhl, F.; Welch, A.T. "Muhammad". In Encyclopaedia of Islam Online (n.d.).

- ^ Hava Lazarus-Yafeh. "Tahrif". In Encyclopaedia of Islam Online (n.d.).

- ^ Teece (2003), pp. 12–13

- ^ Turner (2006), p. 42

- ^ Bennett (2010), p. 101.

- ^ "BnF. Département des Manuscrits. Supplément turc 190". Bibliothèque nationale de France. Archived from the original on 9 September 2023. Retrieved 7 September 2023.

- ^ Esposito (2003), p. 225

- ^ Reeves, J. C. (2004). Bible and Qurʼān: Essays in scriptural intertextuality. Leiden: Brill. p. 177. ISBN 90-04-12726-7. Archived from the original on 19 April 2023. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- ^ Esposito, John L. 2009. "Islam." In The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World, edited by J. L. Esposito. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-530513-5. (See also: quick reference Archived 10 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine.) "Profession of Faith...affirms Islam's absolute monotheism and acceptance of Muḥammad as the messenger of Allah, the last and final prophet."

- ^ Peters, F. E. 2009. "Allāh." In The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World, edited by J. L. Esposito. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-530513-5. (See also: quick reference Archived 26 September 2020 at the Wayback Machine.) "[T]he Muslims' understanding of Allāh is based...on the Qurʿān's public witness. Allāh is Unique, the Creator, Sovereign, and Judge of mankind. It is Allāh who directs the universe through his direct action on nature and who has guided human history through his prophets, Abraham, with whom he made his covenant, Moses/Moosa, Jesus/Eesa, and Muḥammad, through all of whom he founded his chosen communities, the 'Peoples of the Book.'"

- ^ Martin (2004), p. 666

- ^ J. Robson. "Hadith". In Encyclopaedia of Islam Online (n.d.).

- ^ D.W. Brown. "Sunna". In Encyclopaedia of Islam Online (n.d.).

- ^ Goldman, Elizabeth (1995). Believers: Spiritual Leaders of the World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-19-508240-1.

- ^ al-Rahman, Aisha Abd, ed. 1990. Muqaddimah Ibn al-Ṣalāḥ. Cairo: Dar al-Ma'arif, 1990. pp. 160–69

- ^ Awliya'i, Mustafa. "The Four Books Archived 12 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine." In Outlines of the Development of the Science of Hadith 1, translated by A. Q. Qara'i. – via Al-Islam.org. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- ^ Rizvi, Sayyid Sa'eed Akhtar. "The Hadith §The Four Books (Al-Kutubu'l-Arb'ah) Archived 12 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine." Ch 4 in The Qur'an and Hadith. Tanzania: Bilal Muslim Mission. – via Al-Islam.org. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- ^ Glassé (2003), pp. 382–383, "Resurrection"

- ^ Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.) (2012), "Avicenna". doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_DUM_0467: "Ibn Sīnā, Abū ʿAlī al-Ḥusayn b. ʿAbd Allāh b. Sīnā is known in the West as 'Avicenna'."

- ^ Gardet, L. "Qiyama". In Encyclopaedia of Islam Online (n.d.).

- ^ Esposito, John L. (ed.). "Eschatology". The Oxford Dictionary of Islam. Archived from the original on 13 September 2010. Retrieved 18 April 2017 – via Oxford Islamic Studies Online.

- ^ Esposito (2011), p. 130.

- ^ Smith (2006), p. 89; Encyclopedia of Islam and Muslim World, p. 565

- ^ Afsaruddin, Asma. "Garden". In McAuliffe (n.d.).

- ^ "Paradise". Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ^ "Andras Rajki's A. E. D. (Arabic Etymological Dictionary)". 2002. Archived from the original on 8 December 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- ^ Cohen-Mor (2001), p. 4: "The idea of predestination is reinforced by the frequent mention of events 'being written' or 'being in a book' before they happen": Say: "Nothing will happen to us except what Allah has decreed for us..."

- ^ Karamustafa, Ahmet T. "Fate". In McAuliffe (n.d.).: The verb qadara literally means "to measure, to determine". Here it is used to mean that "God measures and orders his creation".