Mahatma Gandhi

Gandhi | |

|---|---|

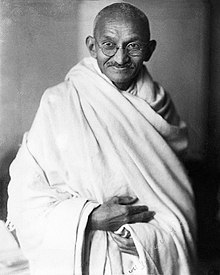

Gandhi in 1931 | |

| Born | Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi 2 October 1869 |

| Died | 30 January 1948 (aged 78) |

| Cause of death | Assassination (gunshot wounds) |

| Monuments | |

| Other names | Bāpū (father), Rāṣṭrapitā (the Father of the Nation) |

| Citizenship |

|

| Alma mater | Inns of Court School of Law |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1893–1948 |

| Era | British Raj |

| Known for |

|

| Political party | Indian National Congress (1920–1934) |

| Spouse | |

| Children | |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives | Family of Mahatma Gandhi |

| President of the Indian National Congress | |

| In office December 1924 – April 1925 | |

| Preceded by | Abul Kalam Azad |

| Succeeded by | Sarojini Naidu |

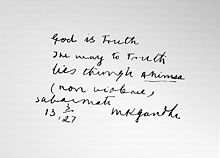

| Signature | |

| |

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (ISO: Mōhanadāsa Karamacaṁda Gāṁdhī;[c] 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948) was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist, and political ethicist who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful campaign for India's independence from British rule. He inspired movements for civil rights and freedom across the world. The honorific Mahātmā (from Sanskrit 'great-souled, venerable'), first applied to him in South Africa in 1914, is now used throughout the world.[2]

Born and raised in a Hindu family in coastal Gujarat, Gandhi trained in the law at the Inner Temple in London and was called to the bar in June 1891, at the age of 22. After two uncertain years in India, where he was unable to start a successful law practice, Gandhi moved to South Africa in 1893 to represent an Indian merchant in a lawsuit. He went on to live in South Africa for 21 years. There, Gandhi raised a family and first employed nonviolent resistance in a campaign for civil rights. In 1915, aged 45, he returned to India and soon set about organising peasants, farmers, and urban labourers to protest against discrimination and excessive land-tax.

Assuming leadership of the Indian National Congress in 1921, Gandhi led nationwide campaigns for easing poverty, expanding women's rights, building religious and ethnic amity, ending untouchability, and, above all, achieving swaraj or self-rule. Gandhi adopted the short dhoti woven with hand-spun yarn as a mark of identification with India's rural poor. He began to live in a self-sufficient residential community, to eat simple food, and undertake long fasts as a means of both introspection and political protest. Bringing anti-colonial nationalism to the common Indians, Gandhi led them in challenging the British-imposed salt tax with the 400 km (250 mi) Dandi Salt March in 1930 and in calling for the British to quit India in 1942. He was imprisoned many times and for many years in both South Africa and India.

Gandhi's vision of an independent India based on religious pluralism was challenged in the early 1940s by a Muslim nationalism which demanded a separate homeland for Muslims within British India. In August 1947, Britain granted independence, but the British Indian Empire was partitioned into two dominions, a Hindu-majority India and a Muslim-majority Pakistan. As many displaced Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs made their way to their new lands, religious violence broke out, especially in the Punjab and Bengal. Abstaining from the official celebration of independence, Gandhi visited the affected areas, attempting to alleviate distress. In the months following, he undertook several hunger strikes to stop the religious violence. The last of these was begun in Delhi on 12 January 1948, when Gandhi was 78. The belief that Gandhi had been too resolute in his defence of both Pakistan and Indian Muslims spread among some Hindus in India. Among these was Nathuram Godse, a militant Hindu nationalist from Pune, western India, who assassinated Gandhi by firing three bullets into his chest at an interfaith prayer meeting in Delhi on 30 January 1948.

Gandhi's birthday, 2 October, is commemorated in India as Gandhi Jayanti, a national holiday, and worldwide as the International Day of Nonviolence. Gandhi is considered to be the Father of the Nation in post-colonial India. During India's nationalist movement and in several decades immediately after, he was also commonly called Bapu (Gujarati endearment for "father", roughly "papa",[3] "daddy"[4]).

Early life and background

Parents

Gandhi's father, Karamchand Uttamchand Gandhi (1822–1885), served as the dewan (chief minister) of Porbandar state.[5][6] His family originated from the then village of Kutiana in what was then Junagadh State.[7] Although Karamchand only had been a clerk in the state administration and had an elementary education, he proved a capable chief minister.[7]

During his tenure, Karamchand married four times. His first two wives died young, after each had given birth to a daughter, and his third marriage was childless. In 1857, Karamchand sought his third wife's permission to remarry; that year, he married Putlibai (1844–1891), who also came from Junagadh,[7] and was from a Pranami Vaishnava family.[8][9][10] Karamchand and Putlibai had four children: a son, Laxmidas (c. 1860–1914); a daughter, Raliatbehn (1862–1960); a second son, Karsandas (c. 1866–1913).[11][12] and a third son, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi[13] who was born on 2 October 1869 in Porbandar (also known as Sudamapuri), a coastal town on the Kathiawar Peninsula and then part of the small princely state of Porbandar in the Kathiawar Agency of the British Raj.[14]

In 1874, Gandhi's father, Karamchand, left Porbandar for the smaller state of Rajkot, where he became a counsellor to its ruler, the Thakur Sahib; though Rajkot was a less prestigious state than Porbandar, the British regional political agency was located there, which gave the state's diwan a measure of security.[15] In 1876, Karamchand became diwan of Rajkot and was succeeded as diwan of Porbandar by his brother Tulsidas. Karamchand's family then rejoined him in Rajkot.[15] They moved to their family home Kaba Gandhi No Delo in 1881.[16]

Childhood

As a child, Gandhi was described by his sister Raliat as "restless as mercury, either playing or roaming about. One of his favourite pastimes was twisting dogs' ears."[17] The Indian classics, especially the stories of Shravana and king Harishchandra, had a great impact on Gandhi in his childhood. In his autobiography, Gandhi states that they left an indelible impression on his mind. Gandhi writes: "It haunted me and I must have acted Harishchandra to myself times without number." Gandhi's early self-identification with truth and love as supreme values is traceable to these epic characters.[18][19]

The family's religious background was eclectic. Mohandas was born into a Gujarati Hindu Modh Bania family.[20][21] Gandhi's father, Karamchand, was Hindu and his mother Putlibai was from a Pranami Vaishnava Hindu family.[22][23] Gandhi's father was of Modh Baniya caste in the varna of Vaishya.[24] His mother came from the medieval Krishna bhakti-based Pranami tradition, whose religious texts include the Bhagavad Gita, the Bhagavata Purana, and a collection of 14 texts with teachings that the tradition believes to include the essence of the Vedas, the Quran and the Bible.[23][25] Gandhi was deeply influenced by his mother, an extremely pious lady who "would not think of taking her meals without her daily prayers... she would take the hardest vows and keep them without flinching. To keep two or three consecutive fasts was nothing to her."[26]

At the age of nine, Gandhi entered the local school in Rajkot, near his home. There, he studied the rudiments of arithmetic, history, the Gujarati language and geography.[15] At the age of 11, Gandhi joined the High School in Rajkot, Alfred High School.[28] He was an average student, won some prizes, but was a shy and tongue-tied student, with no interest in games; Gandhi's only companions were books and school lessons.[29]

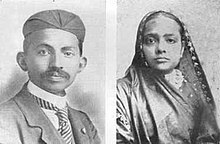

Marriage

In May 1883, the 13-year-old Mohandas Gandhi was married to 14-year-old Kasturbai Gokuldas Kapadia (her first name was usually shortened to "Kasturba", and affectionately to "Ba") in an arranged marriage, according to the custom of the region at that time.[30] In the process, he lost a year at school but was later allowed to make up by accelerating his studies.[31] Gandhi's wedding was a joint event, where his brother and cousin were also married. Recalling the day of their marriage, Gandhi once said, "As we didn't know much about marriage, for us it meant only wearing new clothes, eating sweets and playing with relatives." As was the prevailing tradition, the adolescent bride was to spend much time at her parents' house, and away from her husband.[32]

Writing many years later, Mohandas described with regret the lustful feelings he felt for his young bride by saying, "Even at school I used to think of her, and the thought of nightfall and our subsequent meeting was ever haunting me." Gandhi later recalled feeling jealous and possessive of her, such as when Kasturba would visit a temple with her girlfriends and being sexually lustful in his feelings for her.[33]

In late 1885, Gandhi's father, Karamchand, died.[34] Later, Gandhi, then 16 years old, and his wife of age 17, had their first child, who survived only a few days. The two deaths anguished Gandhi.[34] The Gandhi couple had four more children, all sons: Harilal, born in 1888; Manilal, born in 1892; Ramdas, born in 1897; and Devdas, born in 1900.[30]

In November 1887, the 18-year-old Gandhi graduated from high school in Ahmedabad.[35] In January 1888, he enrolled at Samaldas College in Bhavnagar State, then the sole degree-granting institution of higher education in the region. However, Gandhi dropped out, and returned to his family in Porbandar.[36]

Three years in London

Student of law

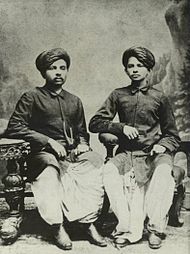

Gandhi had dropped out of the cheapest college he could afford in Bombay.[37] Mavji Dave Joshiji, a Brahmin priest and family friend, advised Gandhi and his family that he should consider law studies in London.[36][38] In July 1888, Gandhi's wife Kasturba gave birth to their first surviving child, Harilal.[39] Gandhi's mother was not comfortable about Gandhi leaving his wife and family and going so far from home. Gandhi's uncle Tulsidas also tried to dissuade his nephew, but Gandhi wanted to go. To persuade his wife and mother, Gandhi made a vow in front of his mother that he would abstain from meat, alcohol, and women. Gandhi's brother, Laxmidas, who was already a lawyer, cheered Gandhi's London studies plan and offered to support him. Putlibai gave Gandhi her permission and blessing.[36][40]

On 10 August 1888, Gandhi, aged 18, left Porbandar for Mumbai, then known as Bombay. Upon arrival, he stayed with the local Modh Bania community whose elders warned Gandhi that England would tempt him to compromise his religion, and eat and drink in Western ways. Despite Gandhi informing them of his promise to his mother and her blessings, Gandhi was excommunicated from his caste. Gandhi ignored this, and on 4 September, he sailed from Bombay to London, with his brother seeing him off.[37][39] Gandhi attended University College, London, where he took classes in English literature with Henry Morley in 1888–1889.[41]

Gandhi also enrolled at the Inns of Court School of Law in Inner Temple with the intention of becoming a barrister.[38] His childhood shyness and self-withdrawal had continued through his teens. Gandhi retained these traits when he arrived in London, but joined a public speaking practice group and overcame his shyness sufficiently to practise law.[42]

Gandhi demonstrated a keen interest in the welfare of London's impoverished dockland communities. In 1889, a bitter trade dispute broke out in London, with dockers striking for better pay and conditions, and seamen, shipbuilders, factory girls and other joining the strike in solidarity. The strikers were successful, in part due to the mediation of Cardinal Manning, leading Gandhi and an Indian friend to make a point of visiting the cardinal and thanking him for his work.[43]

Vegetarianism and committee work

Gandhi's time in London was influenced by the vow he had made to his mother. Gandhi tried to adopt "English" customs, including taking dancing lessons. However, he did not appreciate the bland vegetarian food offered by his landlady and was frequently hungry until finding one of London's few vegetarian restaurants. Influenced by Henry Salt's writing, Gandhi joined the London Vegetarian Society and was elected to its executive committee under the aegis of its president and benefactor Arnold Hills.[44] An achievement while on the committee was the establishment of a Bayswater chapter.[45] Some of the vegetarians Gandhi met were members of the Theosophical Society, which had been founded in 1875 to further universal brotherhood, and which was devoted to the study of Buddhist and Hindu literature. They encouraged Gandhi to join them in reading the Bhagavad Gita both in translation as well as in the original.[44]

Gandhi had a friendly and productive relationship with Hills, but the two men took a different view on the continued LVS membership of fellow committee member Thomas Allinson. Their disagreement is the first known example of Gandhi challenging authority, despite his shyness and temperamental disinclination towards confrontation.

Allinson had been promoting newly available birth control methods, but Hills disapproved of these, believing they undermined public morality. He believed vegetarianism to be a moral movement and that Allinson should therefore no longer remain a member of the LVS. Gandhi shared Hills' views on the dangers of birth control, but defended Allinson's right to differ.[46] It would have been hard for Gandhi to challenge Hills; Hills was 12 years his senior and unlike Gandhi, highly eloquent. Hills bankrolled the LVS and was a captain of industry with his Thames Ironworks company employing more than 6,000 people in the East End of London. Hills was also a highly accomplished sportsman who later founded the football club West Ham United. In his 1927 An Autobiography, Vol. I, Gandhi wrote:

The question deeply interested me...I had a high regard for Mr. Hills and his generosity. But I thought it was quite improper to exclude a man from a vegetarian society simply because he refused to regard puritan morals as one of the objects of the society[46]

A motion to remove Allinson was raised, and was debated and voted on by the committee. Gandhi's shyness was an obstacle to his defence of Allinson at the committee meeting. Gandhi wrote his views down on paper, but shyness prevented Gandhi from reading out his arguments, so Hills, the President, asked another committee member to read them out for him. Although some other members of the committee agreed with Gandhi, the vote was lost and Allinson was excluded. There were no hard feelings, with Hills proposing the toast at the LVS farewell dinner in honour of Gandhi's return to India.[47]

Called to the bar

Gandhi, at age 22, was called to the bar in June 1891 and then left London for India, where he learned that his mother had died while he was in London and that his family had kept the news from Gandhi.[44] His attempts at establishing a law practice in Bombay failed because Gandhi was psychologically unable to cross-examine witnesses. He returned to Rajkot to make a modest living drafting petitions for litigants, but Gandhi was forced to stop after running afoul of British officer Sam Sunny.[44][45]

In 1893, a Muslim merchant in Kathiawar named Dada Abdullah contacted Gandhi. Abdullah owned a large successful shipping business in South Africa. His distant cousin in Johannesburg needed a lawyer, and they preferred someone with Kathiawari heritage. Gandhi inquired about his pay for the work. They offered a total salary of £105 (~$4,143 in 2023 money) plus travel expenses. He accepted it, knowing that it would be at least a one-year commitment in the Colony of Natal, South Africa, also a part of the British Empire.[45][48]

Civil rights activist in South Africa (1893–1914)

In April 1893, Gandhi, aged 23, set sail for South Africa to be the lawyer for Abdullah's cousin.[48][49] Gandhi spent 21 years in South Africa, where he developed his political views, ethics, and politics.[50][51]

Immediately upon arriving in South Africa, Gandhi faced discrimination due to his skin colour and heritage.[52] Gandhi was not allowed to sit with European passengers in the stagecoach and was told to sit on the floor near the driver, then beaten when he refused; elsewhere, Gandhi was kicked into a gutter for daring to walk near a house, in another instance thrown off a train at Pietermaritzburg after refusing to leave the first-class.[37][53] Gandhi sat in the train station, shivering all night and pondering if he should return to India or protest for his rights.[53] Gandhi chose to protest and was allowed to board the train the next day.[54] In another incident, the magistrate of a Durban court ordered Gandhi to remove his turban, which he refused to do.[37] Indians were not allowed to walk on public footpaths in South Africa. Gandhi was kicked by a police officer out of the footpath onto the street without warning.[37]

When Gandhi arrived in South Africa, according to Arthur Herman, he thought of himself as "a Briton first, and an Indian second."[55] However, the prejudice against Gandhi and his fellow Indians from British people that Gandhi experienced and observed deeply bothered him. Gandhi found it humiliating, struggling to understand how some people can feel honour or superiority or pleasure in such inhumane practices.[53] Gandhi began to question his people's standing in the British Empire.[56]

The Abdullah case that had brought him to South Africa concluded in May 1894, and the Indian community organised a farewell party for Gandhi as he prepared to return to India.[57] However, a new Natal government discriminatory proposal led to Gandhi extending his original period of stay in South Africa. Gandhi planned to assist Indians in opposing a bill to deny them the right to vote, a right then proposed to be an exclusive European right. He asked Joseph Chamberlain, the British Colonial Secretary, to reconsider his position on this bill.[50] Though unable to halt the bill's passage, Gandhi's campaign was successful in drawing attention to the grievances of Indians in South Africa. He helped found the Natal Indian Congress in 1894,[45][54] and through this organisation, Gandhi moulded the Indian community of South Africa into a unified political force. In January 1897, when Gandhi landed in Durban, a mob of white settlers attacked him,[58] and Gandhi escaped only through the efforts of the wife of the police superintendent.[citation needed] However, Gandhi refused to press charges against any member of the mob.[45]

During the Boer War, Gandhi volunteered in 1900 to form a group of stretcher-bearers as the Natal Indian Ambulance Corps. According to Arthur Herman, Gandhi wanted to disprove the British colonial stereotype that Hindus were not fit for "manly" activities involving danger and exertion, unlike the Muslim "martial races."[59] Gandhi raised 1,100 Indian volunteers, to support British combat troops against the Boers. They were trained and medically certified to serve on the front lines. They were auxiliaries at the Battle of Colenso to a White volunteer ambulance corps. At the Battle of Spion Kop, Gandhi and his bearers moved to the front line and had to carry wounded soldiers for miles to a field hospital since the terrain was too rough for the ambulances. Gandhi and 37 other Indians received the Queen's South Africa Medal.[60][61]

In 1906, the Transvaal government promulgated a new Act compelling registration of the colony's Indian and Chinese populations. At a mass protest meeting held in Johannesburg on 11 September that year, Gandhi adopted his still evolving methodology of Satyagraha (devotion to the truth), or nonviolent protest, for the first time.[62] According to Anthony Parel, Gandhi was also influenced by the Tamil moral text Tirukkuṛaḷ after Leo Tolstoy mentioned it in their correspondence that began with "A Letter to a Hindu."[63][64] Gandhi urged Indians to defy the new law and to suffer the punishments for doing so. His ideas of protests, persuasion skills, and public relations had emerged. Gandhi took these back to India in 1915.[65][66]

Europeans, Indians and Africans

Gandhi focused his attention on Indians and Africans while he was in South Africa. Initially, Gandhi was not interested in politics, but this changed after he was discriminated against and bullied, such as by being thrown out of a train coach due to his skin colour by a white train official. After several such incidents with Whites in South Africa, Gandhi's thinking and focus changed, and he felt he must resist this and fight for rights. Gandhi entered politics by forming the Natal Indian Congress.[67] According to Ashwin Desai and Goolam Vahed, Gandhi's views on racism are contentious in some cases. He suffered persecution from the beginning in South Africa. Like with other coloured people, white officials denied Gandhi his rights, and the press and those in the streets bullied and called Gandhi a "parasite", "semi-barbarous", "canker", "squalid coolie", "yellow man", and other epithets. People would even spit on him as an expression of racial hate.[68]

While in South Africa, Gandhi focused on the racial persecution of Indians before he started to focus on racism against Africans. In some cases, state Desai and Vahed, Gandhi's behaviour was one of being a willing part of racial stereotyping and African exploitation.[68] During a speech in September 1896, Gandhi complained that the whites in the British colony of South Africa were "degrading the Indian to the level of a raw Kaffir."[69] Scholars cite it as an example of evidence that Gandhi at that time thought of Indians and black South Africans differently.[68] As another example given by Herman, Gandhi, at the age of 24, prepared a legal brief for the Natal Assembly in 1895, seeking voting rights for Indians. Gandhi cited race history and European Orientalists' opinions that "Anglo-Saxons and Indians are sprung from the same Aryan stock or rather the Indo-European peoples" and argued that Indians should not be grouped with the Africans.[57]

Years later, Gandhi and his colleagues served and helped Africans as nurses and by opposing racism. The Nobel Peace Prize winner Nelson Mandela is among admirers of Gandhi's efforts to fight against racism in Africa.[70] The general image of Gandhi, state Desai and Vahed, has been reinvented since his assassination as though Gandhi was always a saint, when in reality, his life was more complex, contained inconvenient truths, and was one that changed over time.[68] Scholars have also pointed the evidence to a rich history of co-operation and efforts by Gandhi and Indian people with nonwhite South Africans against persecution of Africans and the Apartheid.[71]

In 1906, when the Bambatha Rebellion broke out in the colony of Natal, the then 36-year-old Gandhi, despite sympathising with the Zulu rebels, encouraged Indian South Africans to form a volunteer stretcher-bearer unit.[72] Writing in the Indian Opinion, Gandhi argued that military service would be beneficial to the Indian community and claimed it would give them "health and happiness."[73] Gandhi eventually led a volunteer mixed unit of Indian and African stretcher-bearers to treat wounded combatants during the suppression of the rebellion.[72]

The medical unit commanded by Gandhi operated for less than two months before being disbanded.[72] After the suppression of the rebellion, the colonial establishment showed no interest in extending to the Indian community the civil rights granted to white South Africans. This led Gandhi to becoming disillusioned with the Empire and aroused a spiritual awakening with him; historian Arthur L. Herman wrote that Gandhi's African experience was a part of his great disillusionment with the West, transforming Gandhi into an "uncompromising non-cooperator."[73]

By 1910, Gandhi's newspaper, Indian Opinion, was covering reports on discrimination against Africans by the colonial regime. Gandhi remarked that the Africans are "alone are the original inhabitants of the land. … The whites, on the other hand, have occupied the land forcibly and appropriated it to themselves."[74]

In 1910, Gandhi established, with the help of his friend Hermann Kallenbach, an idealistic community they named Tolstoy Farm near Johannesburg.[75][76] There, Gandhi nurtured his policy of peaceful resistance.[77]

In the years after black South Africans gained the right to vote in South Africa (1994), Gandhi was proclaimed a national hero with numerous monuments.[78]

Struggle for Indian independence (1915–1947)

At the request of Gopal Krishna Gokhale, conveyed to Gandhi by C. F. Andrews, Gandhi returned to India in 1915. He brought an international reputation as a leading Indian nationalist, theorist and community organiser.

Gandhi joined the Indian National Congress and was introduced to Indian issues, politics and the Indian people primarily by Gokhale. Gokhale was a key leader of the Congress Party best known for his restraint and moderation, and his insistence on working inside the system. Gandhi took Gokhale's liberal approach based on British Whiggish traditions and transformed it to make it look Indian.[79]

Gandhi took leadership of the Congress in 1920 and began escalating demands until on 26 January 1930 the Indian National Congress declared the independence of India. The British did not recognise the declaration, but negotiations ensued, with the Congress taking a role in provincial government in the late 1930s. Gandhi and the Congress withdrew their support of the Raj when the Viceroy declared war on Germany in September 1939 without consultation. Tensions escalated until Gandhi demanded immediate independence in 1942, and the British responded by imprisoning him and tens of thousands of Congress leaders. Meanwhile, the Muslim League did co-operate with Britain and moved, against Gandhi's strong opposition, to demands for a totally separate Muslim state of Pakistan. In August 1947, the British partitioned the land with India and Pakistan each achieving independence on terms that Gandhi disapproved.[80]

Role in World War I

In April 1918, during the latter part of World War I, the Viceroy invited Gandhi to a War Conference in Delhi.[81] Gandhi agreed to support the war effort.[37][82] In contrast to the Zulu War of 1906 and the outbreak of World War I in 1914, when he recruited volunteers for the Ambulance Corps, this time Gandhi attempted to recruit combatants. In a June 1918 leaflet entitled "Appeal for Enlistment", Gandhi wrote: "To bring about such a state of things we should have the ability to defend ourselves, that is, the ability to bear arms and to use them... If we want to learn the use of arms with the greatest possible despatch, it is our duty to enlist ourselves in the army."[83] However, Gandhi stipulated in a letter to the Viceroy's private secretary that he "personally will not kill or injure anybody, friend or foe."[84]

Gandhi's support for the war campaign brought into question his consistency on nonviolence. Gandhi's private secretary noted that "The question of the consistency between his creed of 'Ahimsa' (nonviolence) and his recruiting campaign was raised not only then but has been discussed ever since."[82] According to political and educational scientist Christian Bartolf, Gandhi's support for the war stemmed from his belief that true ahimsa could not exist simultaneously with cowardice. Therefore, Gandhi felt that Indians needed to be willing and capable of using arms before they voluntarily chose non-violence.[85]

In July 1918, Gandhi admitted that he could not persuade even one individual to enlist for the world war. "So far I have not a single recruit to my credit apart," Gandhi wrote. He added: "They object because they fear to die."[86]

Champaran agitations

Gandhi's first major achievement came in 1917 with the Champaran agitation in Bihar. The Champaran agitation pitted the local peasantry against largely Anglo-Indian plantation owners who were backed by the local administration. The peasants were forced to grow indigo (Indigofera sp.), a cash crop for Indigo dye whose demand had been declining over two decades and were forced to sell their crops to the planters at a fixed price. Unhappy with this, the peasantry appealed to Gandhi at his ashram in Ahmedabad. Pursuing a strategy of nonviolent protest, Gandhi took the administration by surprise and won concessions from the authorities.[87]

Kheda agitations

In 1918, Kheda was hit by floods and famine and the peasantry was demanding relief from taxes. Gandhi moved his headquarters to Nadiad,[88] organising scores of supporters and fresh volunteers from the region, the most notable being Vallabhbhai Patel.[89] Using non-co-operation as a technique, Gandhi initiated a signature campaign where peasants pledged non-payment of revenue even under the threat of confiscation of land. A social boycott of mamlatdars and talatdars (revenue officials within the district) accompanied the agitation. Gandhi worked hard to win public support for the agitation across the country. For five months, the administration refused, but by the end of May 1918, the government gave way on important provisions and relaxed the conditions of payment of revenue tax until the famine ended. In Kheda, Vallabhbhai Patel represented the farmers in negotiations with the British, who suspended revenue collection and released all the prisoners.[90]

Khilafat movement

In 1919, following World War I, Gandhi (aged 49) sought political co-operation from Muslims in his fight against British imperialism by supporting the Ottoman Empire that had been defeated in the World War. Before this initiative of Gandhi, communal disputes and religious riots between Hindus and Muslims were common in British India, such as the riots of 1917–18. Gandhi had already vocally supported the British crown in the first world war.[91] This decision of Gandhi was in part motivated by the British promise to reciprocate the help with swaraj (self-government) to Indians after the end of World War I.[92] The British government had offered, instead of self-government, minor reforms instead, disappointing Gandhi.[93] He announced his satyagraha (civil disobedience) intentions. The British colonial officials made their counter move by passing the Rowlatt Act, to block Gandhi's movement. The Act allowed the British government to treat civil disobedience participants as criminals and gave it the legal basis to arrest anyone for "preventive indefinite detention, incarceration without judicial review or any need for a trial."[94]

Gandhi felt that Hindu-Muslim co-operation was necessary for political progress against the British. He leveraged the Khilafat movement, wherein Sunni Muslims in India, their leaders such as the sultans of princely states in India and Ali brothers championed the Turkish Caliph as a solidarity symbol of Sunni Islamic community (ummah). They saw the Caliph as their means to support Islam and the Islamic law after the defeat of Ottoman Empire in World War I.[95][96][97] Gandhi's support to the Khilafat movement led to mixed results. It initially led to a strong Muslim support for Gandhi. However, the Hindu leaders including Rabindranath Tagore questioned Gandhi's leadership because they were largely against recognising or supporting the Sunni Islamic Caliph in Turkey.[d]

The increasing Muslim support for Gandhi, after he championed the Caliph's cause, temporarily stopped the Hindu-Muslim communal violence. It offered evidence of inter-communal harmony in joint Rowlatt satyagraha demonstration rallies, raising Gandhi's stature as the political leader to the British.[101][102] His support for the Khilafat movement also helped Gandhi sideline Muhammad Ali Jinnah, who had announced his opposition to the satyagraha non-co-operation movement approach of Gandhi. Jinnah began creating his independent support, and later went on to lead the demand for West and East Pakistan. Though they agreed in general terms on Indian independence, they disagreed on the means of achieving this. Jinnah was mainly interested in dealing with the British via constitutional negotiation, rather than attempting to agitate the masses.[103][104][105]

In 1922, the Khilafat movement gradually collapsed following the end of the non-cooperation movement with the arrest of Gandhi.[106] A number of Muslim leaders and delegates abandoned Gandhi and Congress.[107] Hindu-Muslim communal conflicts reignited, and deadly religious riots re-appeared in numerous cities, with 91 in United Provinces of Agra and Oudh alone.[108][109]

Non-co-operation

With his book Hind Swaraj (1909) Gandhi, aged 40, declared that British rule was established in India with the co-operation of Indians and had survived only because of this co-operation. If Indians refused to co-operate, British rule would collapse and swaraj (Indian independence) would come.[6][110]

In February 1919, Gandhi cautioned the Viceroy of India with a cable communication that if the British were to pass the Rowlatt Act, he would appeal to Indians to start civil disobedience.[111] The British government ignored him and passed the law, stating it would not yield to threats. The satyagraha civil disobedience followed, with people assembling to protest the Rowlatt Act. On 30 March 1919, British law officers opened fire on an assembly of unarmed people, peacefully gathered, participating in satyagraha in Delhi.[111]

People rioted in retaliation. On 6 April 1919, a Hindu festival day, Gandhi asked a crowd to remember not to injure or kill British people, but to express their frustration with peace, to boycott British goods and burn any British clothing they owned. He emphasised the use of non-violence to the British and towards each other, even if the other side used violence. Communities across India announced plans to gather in greater numbers to protest. Government warned him not to enter Delhi, but Gandhi defied the order and was arrested on 9 April.[111]

On 13 April 1919, people including women with children gathered in an Amritsar park, and British Indian Army officer Reginald Dyer surrounded them and ordered troops under his command to fire on them. The resulting Jallianwala Bagh massacre (or Amritsar massacre) of hundreds of Sikh and Hindu civilians enraged the subcontinent but was supported by some Britons and parts of the British media as a necessary response. Gandhi in Ahmedabad, on the day after the massacre in Amritsar, did not criticise the British and instead criticised his fellow countrymen for not exclusively using 'love' to deal with the 'hate' of the British government.[111] Gandhi demanded that the Indian people stop all violence, stop all property destruction, and went on fast-to-death to pressure Indians to stop their rioting.[112]

The massacre and Gandhi's non-violent response to it moved many, but also made some Sikhs and Hindus upset that Dyer was getting away with murder. Investigation committees were formed by the British, which Gandhi asked Indians to boycott.[111] The unfolding events, the massacre and the British response, led Gandhi to the belief that Indians will never get a fair equal treatment under British rulers, and he shifted his attention to swaraj and political independence for India.[113] In 1921, Gandhi was the leader of the Indian National Congress.[97] He reorganised the Congress. With Congress now behind Gandhi, and Muslim support triggered by his backing the Khilafat movement to restore the Caliph in Turkey,[97] Gandhi had the political support and the attention of the British Raj.[100][94][96]

Gandhi expanded his nonviolent non-co-operation platform to include the swadeshi policy – the boycott of foreign-made goods, especially British goods. Linked to this was his advocacy that khadi (homespun cloth) be worn by all Indians instead of British-made textiles. Gandhi exhorted Indian men and women, rich or poor, to spend time each day spinning khadi in support of the independence movement.[114] In addition to boycotting British products, Gandhi urged the people to boycott British institutions and law courts, to resign from government employment, and to forsake British titles and honours. Gandhi thus began his journey aimed at crippling the British India government economically, politically and administratively.[115]

The appeal of "Non-cooperation" grew, its social popularity drew participation from all strata of Indian society. Gandhi was arrested on 10 March 1922, tried for sedition, and sentenced to six years' imprisonment. He began his sentence on 18 March 1922. With Gandhi isolated in prison, the Indian National Congress split into two factions, one led by Chitta Ranjan Das and Motilal Nehru favouring party participation in the legislatures, and the other led by Chakravarti Rajagopalachari and Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, opposing this move.[116] Furthermore, co-operation among Hindus and Muslims ended as Khilafat movement collapsed with the rise of Atatürk in Turkey. Muslim leaders left the Congress and began forming Muslim organisations. The political base behind Gandhi had broken into factions. He was released in February 1924 for an appendicitis operation, having served only two years.[117][118]

Salt Satyagraha (Salt March/Civil Disobedience Movement)

After his early release from prison for political crimes in 1924, Gandhi continued to pursue swaraj over the second half of the 1920s. He pushed through a resolution at the Calcutta Congress in December 1928 calling on the British government to grant India dominion status or face a new campaign of non-cooperation with complete independence for the country as its goal.[119] After Gandhi's support for World War I with Indian combat troops, and the failure of Khilafat movement in preserving the rule of Caliph in Turkey, followed by a collapse in Muslim support for his leadership, some such as Subhas Chandra Bose and Bhagat Singh questioned his values and non-violent approach.[96][120] While many Hindu leaders championed a demand for immediate independence, Gandhi revised his own call to a one-year wait, instead of two.[119]

The British did not respond favourably to Gandhi's proposal. British political leaders such as Lord Birkenhead and Winston Churchill announced opposition to "the appeasers of Gandhi" in their discussions with European diplomats who sympathised with Indian demands.[121] On 31 December 1929, an Indian flag was unfurled in Lahore. Gandhi led Congress in a celebration on 26 January 1930 of India's Independence Day in Lahore. This day was commemorated by almost every other Indian organisation. Gandhi then launched a new Satyagraha against the British salt tax in March 1930. He sent an ultimatum in the form of a letter personally addressed to Lord Irwin, the viceroy of India, on 2 March. Gandhi condemned British rule in the letter, describing it as "a curse" that "has impoverished the dumb millions by a system of progressive exploitation and by a ruinously expensive military and civil administration... It has reduced us politically to serfdom." Gandhi also mentioned in the letter that the viceroy received a salary "over five thousand times India's average income." In the letter, Gandhi also stressed his continued adherence to non-violent forms of protest.[122]

This was highlighted by the Salt March to Dandi from 12 March to 6 April, where, together with 78 volunteers, Gandhi marched 388 kilometres (241 mi) from Ahmedabad to Dandi, Gujarat to make salt himself, with the declared intention of breaking the salt laws. The march took 25 days to cover 240 miles with Gandhi speaking to often huge crowds along the way. Thousands of Indians joined him in Dandi.

According to Sarma, Gandhi recruited women to participate in the salt tax campaigns and the boycott of foreign products, which gave many women a new self-confidence and dignity in the mainstream of Indian public life.[123] However, other scholars such as Marilyn French state that Gandhi barred women from joining his civil disobedience movement because Gandhi feared he would be accused of using women as a political shield.[124] When women insisted on joining the movement and participating in public demonstrations, Gandhi asked the volunteers to get permissions of their guardians and only those women who can arrange child-care should join him.[125] Regardless of Gandhi's apprehensions and views, Indian women joined the Salt March by the thousands to defy the British salt taxes and monopoly on salt mining. On 5 May, Gandhi was interned under a regulation dating from 1827 in anticipation of a protest that he had planned. The protest at Dharasana salt works on 21 May went ahead without Gandhi. A horrified American journalist, Webb Miller, described the British response thus:

In complete silence the Gandhi men drew up and halted a hundred yards from the stockade. A picked column advanced from the crowd, waded the ditches and approached the barbed wire stockade... at a word of command, scores of native policemen rushed upon the advancing marchers and rained blows on their heads with their steel-shot lathis [long bamboo sticks]. Not one of the marchers even raised an arm to fend off blows. They went down like ninepins. From where I stood I heard the sickening whack of the clubs on unprotected skulls... Those struck down fell sprawling, unconscious or writhing with fractured skulls or broken shoulders.[126]

This went on for hours until some 300 or more protesters had been beaten, many seriously injured and two killed. At no time did they offer any resistance. After Gandhi's arrest, the women marched and picketed shops on their own, accepting violence and verbal abuse from British authorities for the cause in the manner Gandhi inspired.[124]

This campaign was one of Gandhi's most successful at upsetting British hold on India; Britain responded by imprisoning over 60,000 people.[127] However, Congress estimates put the figure at 90,000. Among them was one of Gandhi's lieutenants, Jawaharlal Nehru.

Gandhi as folk hero

Indian Congress in the 1920s appealed to Andhra Pradesh peasants by creating Telugu language plays that combined Indian mythology and legends, linked them to Gandhi's ideas, and portrayed Gandhi as a messiah, a reincarnation of ancient and medieval Indian nationalist leaders and saints. The plays built support among peasants steeped in traditional Hindu culture, according to Murali, and this effort made Gandhi a folk hero in Telugu speaking villages, a sacred messiah-like figure.[128]

According to Dennis Dalton, it was Gandhi's ideas that were responsible for his wide following. Gandhi criticised Western civilisation as one driven by "brute force and immorality", contrasting it with his categorisation of Indian civilisation as one driven by "soul force and morality."[129] Gandhi captured the imagination of the people of his heritage with his ideas about winning "hate with love." These ideas are evidenced in his pamphlets from the 1890s, in South Africa, where too Gandhi was popular among the Indian indentured workers. After he returned to India, people flocked to Gandhi because he reflected their values.[129]

Gandhi also campaigned hard going from one rural corner of the Indian subcontinent to another. He used terminology and phrases such as Rama-rajya from Ramayana, Prahlada as a paradigmatic icon, and such cultural symbols as another facet of swaraj and satyagraha.[130] During Gandhi's lifetime, these ideas sounded strange outside India, but they readily and deeply resonated with the culture and historic values of his people.[129][131]

Negotiations

The government, represented by Lord Irwin, decided to negotiate with Gandhi. The Gandhi–Irwin Pact was signed in March 1931. The British Government agreed to free all political prisoners, in return for the suspension of the civil disobedience movement. According to the pact, Gandhi was invited to attend the Round Table Conference in London for discussions and as the sole representative of the Indian National Congress. The conference was a disappointment to Gandhi and the nationalists. Gandhi expected to discuss India's independence, while the British side focused on the Indian princes and Indian minorities rather than on a transfer of power. Lord Irwin's successor, Lord Willingdon, took a hard line against India as an independent nation, began a new campaign of controlling and subduing the nationalist movement. Gandhi was again arrested, and the government tried and failed to negate his influence by completely isolating him from his followers.[132]

In Britain, Winston Churchill, a prominent Conservative politician who was then out of office but later became its prime minister, became a vigorous and articulate critic of Gandhi and opponent of his long-term plans. Churchill often ridiculed Gandhi, saying in a widely reported 1931 speech:

It is alarming and also nauseating to see Mr Gandhi, a seditious Middle Temple lawyer, now posing as a fakir of a type well known in the East, striding half-naked up the steps of the Vice-regal palace....to parley on equal terms with the representative of the King-Emperor.[133]

Churchill's bitterness against Gandhi grew in the 1930s. He called Gandhi as the one who was "seditious in aim" whose evil genius and multiform menace was attacking the British empire. Churchill called him a dictator, a "Hindu Mussolini", fomenting a race war, trying to replace the Raj with Brahmin cronies, playing on the ignorance of Indian masses, all for selfish gain.[134] Churchill attempted to isolate Gandhi, and his criticism of Gandhi was widely covered by European and American press. It gained Churchill sympathetic support, but it also increased support for Gandhi among Europeans. The developments heightened Churchill's anxiety that the "British themselves would give up out of pacifism and misplaced conscience."[134]

Round Table Conferences

During the discussions between Gandhi and the British government over 1931–32 at the Round Table Conferences, Gandhi, now aged about 62, sought constitutional reforms as a preparation to the end of colonial British rule, and begin the self-rule by Indians.[135] The British side sought reforms that would keep the Indian subcontinent as a colony. The British negotiators proposed constitutional reforms on a British Dominion model that established separate electorates based on religious and social divisions. The British questioned the Congress party and Gandhi's authority to speak for all of India.[136] They invited Indian religious leaders, such as Muslims and Sikhs, to press their demands along religious lines, as well as B. R. Ambedkar as the representative leader of the untouchables.[135] Gandhi vehemently opposed a constitution that enshrined rights or representations based on communal divisions, because he feared that it would not bring people together but divide them, perpetuate their status, and divert the attention from India's struggle to end the colonial rule.[137][138]

The Second Round Table conference was the only time Gandhi left India between 1914 and his death in 1948. Gandhi declined the government's offer of accommodation in an expensive West End hotel, preferring to stay in the East End, to live among working-class people, as he did in India.[139] Gandhi based himself in a small cell-bedroom at Kingsley Hall for the three-month duration of his stay and was enthusiastically received by East Enders.[140] During this time, Gandhi renewed his links with the British vegetarian movement.

After Gandhi returned from the Second Round Table conference, he started a new satyagraha. Gandhi was arrested and imprisoned at the Yerwada Jail, Pune. While he was in prison, the British government enacted a new law that granted untouchables a separate electorate. It came to be known as the Communal Award.[141] In protest, Gandhi started a fast-unto-death, while he was held in prison.[142] The resulting public outcry forced the government, in consultations with Ambedkar, to replace the Communal Award with a compromise Poona Pact.[143][144]

Congress politics

In 1934, Gandhi resigned from Congress party membership. He did not disagree with the party's position, but felt that if he resigned, Gandhi's popularity with Indians would cease to stifle the party's membership, which actually varied, including communists, socialists, trade unionists, students, religious conservatives, and those with pro-business convictions, and that these various voices would get a chance to make themselves heard. Gandhi also wanted to avoid being a target for Raj propaganda by leading a party that had temporarily accepted political accommodation with the Raj.[145]

In 1936, Gandhi returned to active politics again with the Nehru presidency and the Lucknow session of the Congress. Although Gandhi wanted a total focus on the task of winning independence and not speculation about India's future, he did not restrain the Congress from adopting socialism as its goal. Gandhi had a clash with Subhas Chandra Bose, who had been elected president in 1938, and who had previously expressed a lack of faith in nonviolence as a means of protest.[146] Despite Gandhi's opposition, Bose won a second term as Congress President, against Gandhi's nominee, Bhogaraju Pattabhi Sitaramayya. Gandhi declared that Sitaramayya's defeat was his defeat.[147] Bose later left the Congress when the All-India leaders resigned en masse in protest of his abandonment of the principles introduced by Gandhi.[148][149]

World War II and Quit India movement

Gandhi opposed providing any help to the British war effort and he campaigned against any Indian participation in World War II.[150] The British government responded with the arrests of Gandhi and many other Congress leaders and killed over 1,000 Indians who participated in this movement.[151] A number of violent attacks were also carried out by the nationalists against the British government.[152] While Gandhi's campaign did not enjoy the support of a number of Indian leaders, and over 2.5 million Indians volunteered and joined the British military to fight on various fronts of the Allied Forces, the movement played a role in weakening the control over the South Asian region by the British regime and it ultimately paved the way for Indian independence.[150][152]

Gandhi's opposition to the Indian participation in World War II was motivated by his belief that India could not be party to a war ostensibly being fought for democratic freedom while that freedom was denied to India itself.[153] Gandhi also condemned Nazism and Fascism, a view which won endorsement of other Indian leaders. As the war progressed, Gandhi intensified his demand for independence, calling for the British to Quit India in a 1942 speech in Mumbai.[154] This was Gandhi's and the Congress Party's most definitive revolt aimed at securing the British exit from India.[155] The British government responded quickly to the Quit India speech, and within hours after Gandhi's speech arrested Gandhi and all the members of the Congress Working Committee.[156] His countrymen retaliated the arrests by damaging or burning down hundreds of government owned railway stations, police stations, and cutting down telegraph wires.[157]

In 1942, Gandhi now nearing age 73, urged his people to completely stop co-operating with the imperial government. In this effort, Gandhi urged that they neither kill nor injure British people but be willing to suffer and die if violence is initiated by the British officials.[154] He clarified that the movement would not be stopped because of any individual acts of violence, saying that the "ordered anarchy" of "the present system of administration" was "worse than real anarchy."[158][159] Gandhi urged Indians to karo ya maro ("do or die") in the cause of their rights and freedoms.[154][160]

Gandhi's arrest lasted two years, as he was held in the Aga Khan Palace in Pune. During this period, Gandhi's longtime secretary Mahadev Desai died of a heart attack, his wife Kasturba died after 18 months' imprisonment on 22 February 1944, and Gandhi suffered a severe malaria attack.[157] While in jail, he agreed to an interview with Stuart Gelder, a British journalist. Gelder then composed and released an interview summary, cabled it to the mainstream press, that announced sudden concessions Gandhi was willing to make, comments that shocked his countrymen, the Congress workers and even Gandhi. The latter two claimed that it distorted what Gandhi actually said on a range of topics and falsely repudiated the Quit India movement.[157]

Gandhi was released before the end of the war on 6 May 1944 because of his failing health and necessary surgery; the Raj did not want him to die in prison and enrage the nation. Gandhi came out of detention to an altered political scene – the Muslim League for example, which a few years earlier had appeared marginal, "now occupied the centre of the political stage"[161] and the topic of Jinnah's campaign for Pakistan was a major talking point. Gandhi and Jinnah had extensive correspondence and the two men met several times over a period of two weeks in September 1944 at Jinnah's house in Bombay, where Gandhi insisted on a united religiously plural and independent India which included Muslims and non-Muslims of the Indian subcontinent coexisting. Jinnah rejected this proposal and insisted instead for partitioning the subcontinent on religious lines to create a separate Muslim homeland (later Pakistan).[162] These discussions continued through 1947.[163]

While the leaders of Congress languished in jail, the other parties supported the war and gained organisational strength. Underground publications flailed at the ruthless suppression of Congress, but it had little control over events.[164] At the end of the war, the British gave clear indications that power would be transferred to Indian hands. At this point, Gandhi called off the struggle, and around 100,000 political prisoners were released, including the Congress's leadership.[165]

Partition and independence

Gandhi opposed the partition of the Indian subcontinent along religious lines.[162][166][167] The Indian National Congress and Gandhi called for the British to Quit India. However, the All-India Muslim League demanded "Divide and Quit India."[168][169] Gandhi suggested an agreement which required the Congress and the Muslim League to co-operate and attain independence under a provisional government, thereafter, the question of partition could be resolved by a plebiscite in the districts with a Muslim majority.[170]

Jinnah rejected Gandhi's proposal and called for Direct Action Day, on 16 August 1946, to press Muslims to publicly gather in cities and support his proposal for the partition of the Indian subcontinent into a Muslim state and non-Muslim state. Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, the Muslim League Chief Minister of Bengal – now Bangladesh and West Bengal, gave Calcutta's police special holiday to celebrate the Direct Action Day.[171] The Direct Action Day triggered a mass murder of Calcutta Hindus and the torching of their property, and holidaying police were missing to contain or stop the conflict.[172] The British government did not order its army to move in to contain the violence.[171] The violence on Direct Action Day led to retaliatory violence against Muslims across India. Thousands of Hindus and Muslims were murdered, and tens of thousands were injured in the cycle of violence in the days that followed.[173] Gandhi visited the most riot-prone areas to appeal a stop to the massacres.[172]

Archibald Wavell, the Viceroy and Governor-General of British India for three years through February 1947, had worked with Gandhi and Jinnah to find a common ground, before and after accepting Indian independence in principle. Wavell condemned Gandhi's character and motives as well as his ideas. Wavell accused Gandhi of harbouring the single-minded idea to "overthrow British rule and influence and to establish a Hindu raj", and called Gandhi a "malignant, malevolent, exceedingly shrewd" politician.[174] Wavell feared a civil war on the Indian subcontinent, and doubted Gandhi would be able to stop it.[174]

The British reluctantly agreed to grant independence to the people of the Indian subcontinent, but accepted Jinnah's proposal of partitioning the land into Pakistan and India. Gandhi was involved in the final negotiations, but Stanley Wolpert states the "plan to carve up British India was never approved of or accepted by Gandhi".[175]

The partition was controversial and violently disputed. More than half a million were killed in religious riots as 10 million to 12 million non-Muslims (Hindus and Sikhs mostly) migrated from Pakistan into India, and Muslims migrated from India into Pakistan, across the newly created borders of India, West Pakistan and East Pakistan.[176]

Gandhi spent the day of independence not celebrating the end of the British rule, but appealing for peace among his countrymen by fasting and spinning in Calcutta on 15 August 1947. The partition had gripped the Indian subcontinent with religious violence and the streets were filled with corpses.[177] Gandhi's fasting and protests are credited for stopping the religious riots and communal violence.[174][178][179][180][181][182][183][184][185]

Death

At 5:17 p.m. on 30 January 1948, Gandhi was with his grandnieces in the garden of Birla House (now Gandhi Smriti), on his way to address a prayer meeting, when Nathuram Godse, a Hindu nationalist, fired three bullets into Gandhi's chest from a pistol at close range.[186][187] According to some accounts, Gandhi died instantly.[188][189] In other accounts, such as one prepared by an eyewitness journalist, Gandhi was carried into the Birla House, into a bedroom. There, he died about 30 minutes later as one of Gandhi's family members read verses from Hindu scriptures.[190][191][192][193][178]

Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru addressed his countrymen over the All-India Radio saying:[194]

Friends and comrades, the light has gone out of our lives, and there is darkness everywhere, and I do not quite know what to tell you or how to say it. Our beloved leader, Bapu as we called him, the father of the nation, is no more. Perhaps I am wrong to say that; nevertheless, we will not see him again, as we have seen him for these many years, we will not run to him for advice or seek solace from him, and that is a terrible blow, not only for me, but for millions and millions in this country.[195]

Godse, a Hindu nationalist,[196][187][197] with links to the Hindu Mahasabha and the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh,[198][199][200][201][178] made no attempt to escape; several other conspirators were soon arrested as well. The accused were Nathuram Vinayak Godse, Narayan Apte, Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, Shankar Kistayya, Dattatraya Parchure, Vishnu Karkare, Madanlal Pahwa, and Gopal Godse.[178][201][202][203][204][205]

The trial began on 27 May 1948 and ran for eight months before Justice Atma Charan passed his final order on 10 February 1949. The prosecution called 149 witnesses, the defence none.[206] The court found all of the defendants except one guilty as charged. Eight men were convicted for the murder conspiracy, and others were convicted for violation of the Explosive Substances Act. Savarkar was acquitted and set free. Nathuram Godse and Narayan Apte were sentenced to death by hanging[207] while the remaining six (including Godse's brother, Gopal) were sentenced to life imprisonment.[208]

Funeral and memorials

Gandhi's death was mourned nationwide.[191][192][193][178] Over a million people joined the five-mile-long funeral procession that took over five hours to reach Raj Ghat from Birla house, where Gandhi was assassinated, and another million watched the procession pass by.[209] His body was transported on a weapons carrier, whose chassis was dismantled overnight to allow a high-floor to be installed so that people could catch a glimpse of Gandhi's body. The engine of the vehicle was not used; instead, four drag-ropes held by 50 people each pulled the vehicle.[210] All Indian-owned establishments in London remained closed in mourning as thousands of people from all faiths and denominations and Indians from all over Britain converged at India House in London.[211]

Gandhi was cremated in accordance with Hindu tradition. His ashes were poured into urns which were sent across India for memorial services.[213] Most of the ashes were immersed at the Sangam at Allahabad on 12 February 1948, but some were secretly taken away. In 1997, Tushar Gandhi immersed the contents of one urn, found in a bank vault and reclaimed through the courts, at the Sangam at Allahabad.[214][215] Some of Gandhi's ashes were scattered at the source of the Nile River near Jinja, Uganda, and a memorial plaque marks the event. On 30 January 2008, the contents of another urn were immersed at Girgaum Chowpatty. Another urn is at the palace of the Aga Khan in Pune (where Gandhi was held as a political prisoner from 1942 to 1944[216][217]) and another in the Self-Realization Fellowship Lake Shrine in Los Angeles.[214][218][219]

The Birla House site where Gandhi was assassinated is now a memorial called Gandhi Smriti. The place near Yamuna River where he was cremated is the Rāj Ghāt memorial in New Delhi.[220] A black marble platform, it bears the epigraph "Hē Rāma" (Devanagari: हे ! राम or, Hey Raam). These are said to be Gandhi's last words after he was shot.[221]

Principles, practices, and beliefs

Gandhi's spirituality was greatly based on his embracement of the five great vows of Jainism and Hindu Yoga philosophy, viz. Satya (truth), ahimsa (nonviolence), brahmacharya (celibacy), asteya (non-stealing), and aparigraha (non-attachment).[222] He stated that "Unless you impose on yourselves the five vows you may not embark on the experiment at all."[222] Gandhi's statements, letters and life have attracted much political and scholarly analysis of his principles, practices and beliefs, including what influenced him. Some writers present Gandhi as a paragon of ethical living and pacifism, while others present him as a more complex, contradictory and evolving character influenced by his culture and circumstances.[223][224]

Truth and Satyagraha

Gandhi dedicated his life to discovering and pursuing truth, or Satya, and called his movement satyagraha, which means "appeal to, insistence on, or reliance on the Truth."[225] The first formulation of the satyagraha as a political movement and principle occurred in 1920, which Gandhi tabled as "Resolution on Non-cooperation" in September that year before a session of the Indian Congress. It was the satyagraha formulation and step, states Dennis Dalton, that deeply resonated with beliefs and culture of his people, embedded him into the popular consciousness, transforming him quickly into Mahatma.[226]

Gandhi based Satyagraha on the Vedantic ideal of self-realisation, ahimsa (nonviolence), vegetarianism, and universal love. William Borman states that the key to his satyagraha is rooted in the Hindu Upanishadic texts.[227] According to Indira Carr, Gandhi's ideas on ahimsa and satyagraha were founded on the philosophical foundations of Advaita Vedanta.[228] I. Bruce Watson states that some of these ideas are found not only in traditions within Hinduism, but also in Jainism or Buddhism, particularly those about non-violence, vegetarianism and universal love, but Gandhi's synthesis was to politicise these ideas.[229] His concept of satya as a civil movement, states Glyn Richards, are best understood in the context of the Hindu terminology of Dharma and Ṛta.[230]

Gandhi stated that the most important battle to fight was overcoming his own demons, fears, and insecurities. Gandhi summarised his beliefs first when he said, "God is Truth." Gandhi would later change this statement to "Truth is God." Thus, satya (truth) in Gandhi's philosophy is "God".[231] Gandhi, states Richards, described the term "God" not as a separate power, but as the Being (Brahman, Atman) of the Advaita Vedanta tradition, a nondual universal that pervades in all things, in each person and all life.[230] According to Nicholas Gier, this to Gandhi meant the unity of God and humans, that all beings have the same one soul and therefore equality, that atman exists and is same as everything in the universe, ahimsa (non-violence) is the very nature of this atman.[232]

The essence of Satyagraha is "soul force" as a political means, refusing to use brute force against the oppressor, seeking to eliminate antagonisms between the oppressor and the oppressed, aiming to transform or "purify" the oppressor. It is not inaction but determined passive resistance and non-co-operation where, states Arthur Herman, "love conquers hate".[235] A euphemism sometimes used for Satyagraha is that it is a "silent force" or a "soul force" (a term also used by Martin Luther King Jr. during his "I Have a Dream" speech). It arms the individual with moral power rather than physical power. Satyagraha is also termed a "universal force", as it essentially "makes no distinction between kinsmen and strangers, young and old, man and woman, friend and foe."[e]

Gandhi wrote: "There must be no impatience, no barbarity, no insolence, no undue pressure. If we want to cultivate a true spirit of democracy, we cannot afford to be intolerant. Intolerance betrays want of faith in one's cause."[239] Civil disobedience and non-co-operation as practised under Satyagraha are based on the "law of suffering",[240] a doctrine that the endurance of suffering is a means to an end. This end usually implies a moral upliftment or progress of an individual or society. Therefore, non-co-operation in Satyagraha is in fact a means to secure the co-operation of the opponent consistently with truth and justice.[241]

While Gandhi's idea of satyagraha as a political means attracted a widespread following among Indians, the support was not universal. For example, Muslim leaders such as Jinnah opposed the satyagraha idea, accused Gandhi to be reviving Hinduism through political activism, and began effort to counter Gandhi with Muslim nationalism and a demand for Muslim homeland.[242][243][244] The untouchability leader Ambedkar, in June 1945, after his decision to convert to Buddhism and the first Law and Justice minister of modern India, dismissed Gandhi's ideas as loved by "blind Hindu devotees", primitive, influenced by spurious brew of Tolstoy and Ruskin, and "there is always some simpleton to preach them".[245][246][247] Winston Churchill caricatured Gandhi as a "cunning huckster" seeking selfish gain, an "aspiring dictator", and an "atavistic spokesman of a pagan Hinduism." Churchill stated that the civil disobedience movement spectacle of Gandhi only increased "the danger to which white people there [British India] are exposed."[248]

Nonviolence

Although Gandhi was not the originator of the principle of nonviolence, he was the first to apply it in the political field on a large scale.[249][250] The concept of nonviolence (ahimsa) has a long history in Indian religious thought, and is considered the highest dharma (ethical value/virtue), a precept to be observed towards all living beings (sarvbhuta), at all times (sarvada), in all respects (sarvatha), in action, words and thought.[251] Gandhi explains his philosophy and ideas about ahimsa as a political means in his autobiography The Story of My Experiments with Truth.[252][253][254][255]

Although Gandhi considered non-violence to be "infinitely superior to violence", he preferred violence to cowardice.[256][257] Gandhi added that he "would rather have India resort to arms in order to defend her honor than that she should in a cowardly manner become or remain a helpless witness to her own dishonor."[257]

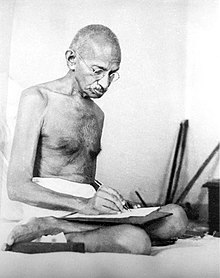

Literary works

Gandhi was a prolific writer. His signature style was simple, precise, clear and as devoid of artificialities.[258] One of Gandhi's earliest publications, Hind Swaraj, published in Gujarati in 1909, became "the intellectual blueprint" for India's independence movement. The book was translated into English the next year, with a copyright legend that read "No Rights Reserved".[259] For decades, Gandhi edited several newspapers including Harijan in Gujarati, in Hindi and in the English language; Indian Opinion while in South Africa and, Young India, in English, and Navajivan, a Gujarati monthly, on his return to India. Later, Navajivan was also published in Hindi. Gandhi also wrote letters almost every day to individuals and newspapers.[260]

Gandhi also wrote several books, including his autobiography, The Story of My Experiments with Truth (Gujarātī "સત્યના પ્રયોગો અથવા આત્મકથા"), of which Gandhi bought the entire first edition to make sure it was reprinted.[261] His other autobiographies included: Satyagraha in South Africa about his struggle there, Hind Swaraj or Indian Home Rule, a political pamphlet, and a paraphrase in Gujarati of John Ruskin's Unto This Last which was an early critique of political economy.[262] This last essay can be considered his programme on economics. Gandhi also wrote extensively on vegetarianism, diet and health, religion, social reforms, etc. Gandhi usually wrote in Gujarati, though he also revised the Hindi and English translations of his books.[263] In 1934, Gandhi wrote Songs from Prison while prisoned in Yerawada jail in Maharashtra.[264]

Gandhi's complete works were published by the Indian government under the name The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi in the 1960s. The writings comprise about 50,000 pages published in about 100 volumes. In 2000, a revised edition of the complete works sparked a controversy, as it contained a large number of errors and omissions.[265] The Indian government later withdrew the revised edition.[266]

Legacy

Gandhi is noted as the greatest figure of the successful Indian independence movement against the British rule. He is also hailed as the greatest figure of modern India.[f] American historian Stanley Wolpert described Gandhi as "India's greatest revolutionary nationalist leader" and the greatest Indian since the Buddha.[273] In 1999, Gandhi was named "Asian of the century" by Asiaweek.[274] In a 2000 BBC poll, he was voted as the greatest man of the millennium.[275][276]

The word Mahatma, while often mistaken for Gandhi's given name in the West, is taken from the Sanskrit words maha (meaning Great) and atma (meaning Soul).[277][278] He was publicly bestowed with the honorific title "Mahatma" in July 1914 at farewell meeting in Town Hall, Durban.[279][280] Rabindranath Tagore is said to have accorded the title to Gandhi by 1915.[281][g] In his autobiography, Gandhi nevertheless explains that he never valued the title, and was often pained by it.[284][285][286]

Innumerable streets, roads, and localities in India are named after Gandhi. These include M.G.Road (the main street of a number of Indian cities including Mumbai, Bangalore, Kolkata, Lucknow, Kanpur, Gangtok and Indore), Gandhi Market (near Sion, Mumbai) and Gandhinagar (the capital of the state of Gujarat, Gandhi's birthplace).[288]

As of 2008, over 150 countries have released stamps on Gandhi.[289] In October 2019, about 87 countries including Turkey, the United States, Russia, Iran, Uzbekistan, and Palestine released commemorative Gandhi stamps on the 150th anniversary of his birth.[290][291][292][293]

In 2014, Brisbane's Indian community commissioned a statue of Gandhi, created by Ram V. Sutar and Anil Sutar in the Roma Street Parkland,[294][295] It was unveiled by Narendra Modi, then Prime Minister of India.

Florian asteroid 120461 Gandhi was named in his honour in September 2020.[296] In October 2022, a statue of Gandhi was installed in Astana on the embankment of the rowing canal, opposite the cult monument to the defenders of Kazakhstan.[297]

On 15 December 2022, the United Nations headquarters in New York unveiled the statue of Gandhi. UN Secretary-General António Guterres called Gandhi an "uncompromising advocate for peaceful co-existence."[298]

Followers and international influence

Gandhi influenced important leaders and political movements.[255] Leaders of the civil rights movement in the United States, including Martin Luther King Jr., James Lawson, and James Bevel, drew from the writings of Gandhi in the development of their own theories about nonviolence.[299][300][301] King said, "Christ gave us the goals and Mahatma Gandhi the tactics."[302] King sometimes referred to Gandhi as "the little brown saint."[303] Anti-apartheid activist and former President of South Africa, Nelson Mandela, was inspired by Gandhi.[304] Others include Steve Biko, Václav Havel,[305] and Aung San Suu Kyi.[306]

|

|

|

In his early years, the former President of South Africa Nelson Mandela was a follower of the nonviolent resistance philosophy of Gandhi.[304] Bhana and Vahed commented on these events as "Gandhi inspired succeeding generations of South African activists seeking to end White rule. This legacy connects him to Nelson Mandela...in a sense, Mandela completed what Gandhi started."[307]

Gandhi's life and teachings inspired many who specifically referred to Gandhi as their mentor or who dedicated their lives to spreading his ideas. In Europe, Romain Rolland was the first to discuss Gandhi in his 1924 book Mahatma Gandhi, and Brazilian anarchist and feminist Maria Lacerda de Moura wrote about Gandhi in her work on pacifism. In 1931, physicist Albert Einstein exchanged letters with Gandhi and called him "a role model for the generations to come" in a letter writing about him.[308] Einstein said of Gandhi:

Mahatma Gandhi's life achievement stands unique in political history. He has invented a completely new and humane means for the liberation war of an oppressed country, and practised it with greatest energy and devotion. The moral influence he had on the consciously thinking human being of the entire civilised world will probably be much more lasting than it seems in our time with its overestimation of brutal violent forces. Because lasting will only be the work of such statesmen who wake up and strengthen the moral power of their people through their example and educational works. We may all be happy and grateful that destiny gifted us with such an enlightened contemporary, a role model for the generations to come. Generations to come will scarce believe that such a one as this walked the earth in flesh and blood.

Farah Omar, a political activist from Somaliland, visited India in 1930, where he met Gandhi and was influenced by Gandhi's non-violent philosophy, which he adopted in his campaign in British Somaliland.[309]

Lanza del Vasto went to India in 1936 intending to live with Gandhi; he later returned to Europe to spread Gandhi's philosophy and founded the Community of the Ark in 1948 (modelled after Gandhi's ashrams). Madeleine Slade (known as "Mirabehn") was the daughter of a British admiral who spent much of her adult life in India as a devotee of Gandhi.[310][311]

In addition, the British musician John Lennon referred to Gandhi when discussing his views on nonviolence.[312] In 2007, former US Vice-President and environmentalist Al Gore drew upon Gandhi's idea of satyagraha in a speech on climate change.[313] 44th President of the United States Barack Obama said in September 2009 that his biggest inspiration came from Gandhi. His reply was in response to the question: "Who was the one person, dead or live, that you would choose to dine with?" Obama added, "He's somebody I find a lot of inspiration in. He inspired Dr. King with his message of nonviolence. He ended up doing so much and changed the world just by the power of his ethics."[314]

Time magazine named The 14th Dalai Lama, Lech Wałęsa, Martin Luther King Jr., Cesar Chavez, Aung San Suu Kyi, Benigno Aquino Jr., Desmond Tutu, and Nelson Mandela as Children of Gandhi and his spiritual heirs to nonviolence.[315] The Mahatma Gandhi District in Houston, Texas, United States, an ethnic Indian enclave, is officially named after Gandhi.[316]

Gandhi's ideas had a significant influence on 20th-century philosophy. It began with his engagement with Romain Rolland and Martin Buber. Jean-Luc Nancy said that the French philosopher Maurice Blanchot engaged critically with Gandhi from the point of view of "European spirituality."[317] Since then philosophers including Hannah Arendt, Etienne Balibar and Slavoj Žižek found that Gandhi was a necessary reference to discuss morality in politics. American political scientist Gene Sharp wrote an analytical text, Gandhi as a political strategist, on the significance of Gandhi's ideas, for creating nonviolent social change. Recently, in the light of climate change, Gandhi's views on technology are gaining importance in the fields of environmental philosophy and philosophy of technology.[317]

Global days that celebrate Gandhi

In 2007, the United Nations General Assembly declared Gandhi's birthday, 2 October, as "the International Day of Nonviolence."[318] First proposed by UNESCO in 1948, as the School Day of Nonviolence and Peace (DENIP in Spanish),[319] 30 January is observed as the School Day of Nonviolence and Peace in schools of many countries.[320] In countries with a Southern Hemisphere school calendar, it is observed on 30 March.[320]

Awards

Time magazine named Gandhi the Man of the Year in 1930.[276] In the same magazine's 1999 list of The Most Important People of the Century, Gandhi was second only to Albert Einstein, who had called Gandhi "the greatest man of our age."[321] The University of Nagpur awarded him an LL.D. in 1937.[322] The Government of India awarded the annual Gandhi Peace Prize to distinguished social workers, world leaders and citizens. Nelson Mandela, the leader of South Africa's struggle to eradicate racial discrimination and segregation, was a prominent non-Indian recipient. In 2003, Gandhi was posthumously awarded with the World Peace Prize.[323] Two years later, he was posthumously awarded with the Order of the Companions of O. R. Tambo.[324] In 2011, Gandhi topped the TIME's list of top 25 political icons of all time.[325]