Мария, мать Иисуса

Мэри | |

|---|---|

| |

| Рожденный | в. 20 г. до н.э. [ б ] |

| Умер | После ц. 33 год нашей эры |

| Супруг | Джозеф |

| Дети | Иисус |

| Родители) | Иоаким и Анна (по некоторым апокрифическим сочинениям) |

Мэри [ с ] , жившей в первом веке была еврейкой из Назарета , [ 6 ] жена Иосифа и мать Иисуса . Она является важной фигурой христианства , почитаемой под различными титулами, такими как дева или королева , многие из которых упоминаются в Литании Лорето . Восточная церкви верят , и Восточная Православная , Католическая , Англиканская и Лютеранская что Мария, как мать Иисуса, является Матерью Божией . Церковь Востока исторически считала ее Христотокос - термин, который до сих пор используется в литургии Ассирийской Церкви Востока . [ 7 ] Другие протестантские взгляды на Марию различаются: некоторые считают, что она имеет меньший статус.

Она занимает самое высокое положение в исламе среди всех женщин и неоднократно упоминается в Коране , в том числе в главе, названной в ее честь . [ 8 ] [ 9 ] [ 10 ] Ее также почитают в вере бахаи и вере друзов . [ 11 ]

Синоптические Евангелия называют Марию матерью Иисуса. Евангелия от Матфея и Луки описывают Марию как девственницу. [ д ] которая была избрана Богом, чтобы зачать Иисуса через Святого Духа . Родив Иисуса в Вифлееме , она воспитала его в городе Назарете в Галилее , была в Иерусалиме при его распятии и с апостолами после его вознесения . Хотя ее дальнейшая жизнь не упоминается в Библии , римско-католическая , восточно-православная и некоторые протестантские традиции полагают, что ее тело было поднято на небеса в конце ее земной жизни, что известно в западном христианстве как Успение Богородицы , а в Восточное христианство как Успение Божией Матери .

Марию почитали со времен раннего христианства . [ 15 ] [ 16 ] и часто считается самым святым и величайшим святым . Существует определенное разнообразие в мариологии и религиозных практиках основных христианских традиций. Католическая церковь придерживается отличительных догматов Марии , а именно ее непорочного зачатия и телесного вознесения на небеса. [ 17 ] Многие протестанты придерживаются менее возвышенных взглядов на роль Марии, часто основанных на предполагаемом отсутствии библейской поддержки многих традиционных христианских догм, касающихся ее. [ 18 ]

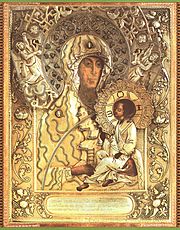

Многочисленные формы богослужения Марии включают в себя различные молитвы и гимны , празднование нескольких Богородичных праздников в литургии , почитание образов и реликвий , строительство посвященных ей церквей и паломничество к Марианским святыням . о многих явлениях Марии и чудесах, приписываемых ее заступничеству Верующие на протяжении веков сообщали . Она была традиционным предметом в искусстве , особенно в византийском искусстве , средневековом искусстве и искусстве эпохи Возрождения .

Имена и титулы

| Часть серии статей о |

| Мать Иисуса |

| Хронология |

|---|

|

|

| Марианские перспективы |

|

|

| Католическая мариология |

|

|

| Марианские догматы |

|

|

| Мария в культуре |

Имя Марии в оригинальных рукописях Нового Завета было основано на ее оригинальном арамейском имени מרים , транслитерированном как Марьям или Мариам . [ 19 ] Английское имя Мэри происходит от греческого Мариа , сокращенной формы имени Мариам . И Мария , и Мариам появляются в Новом Завете.

В христианстве

В христианстве Марию обычно называют Девой Марией, в соответствии с верой в то, что Святой Дух зачав своего первенца Иисуса оплодотворил ее, тем самым чудесным образом , без половой связи со своим обручником Иосифом, «до тех пор, пока ее сын [Иисус] родился». [ 20 ] Слово «пока» послужило поводом для серьезного анализа того, родили ли Иосиф и Мария братьев и сестер после рождения Иисуса или нет. [ и ] Среди ее многих других имен и титулов - Пресвятая Дева Мария (часто сокращается до «BVM» после латинского Беата Мария Дева ), [ 22 ] Святая Мария (иногда), Богородица (в первую очередь в западном христианстве ), Богородица (в первую очередь в восточном христианстве ), Богоматерь (средневековый итальянский язык : Мадонна ) и Царица Небесная ( Regina caeli ; см. также здесь ). [ 23 ] [ 24 ] Титул « царица небес » ранее использовался как эпитет для ряда богинь, таких как Исида или Иштар .

Используемые титулы различаются у англиканцев , лютеран и других протестантов , а также у мормонов , католиков , православных и других христиан .

Три основных титула Марии, используемые православными, - это Богородица ( Θεοτόκος или «Богоносица»), Эйпарфенос ( ἀειπαρθένος ), что означает «приснодева», что подтверждено на Втором Константинопольском соборе в 553 году, и Панагия ( Παναγία ), означающая « всесвятая». [ 25 ] Католики используют самые разные титулы для Марии, и эти титулы, в свою очередь, породили множество художественных изображений.

Титул Богородицы , что означает «Богоносица», был признан на Эфесском соборе в 431 году. [ 26 ] [ 27 ] Прямыми эквивалентами титула на латыни являются Deipara и Dei Genitrix , хотя эта фраза чаще всего переводится на латынь как Mater Dei («Мать Божья»), с аналогичными образцами для других языков, используемых в Латинской церкви . Однако эта же фраза на греческом языке ( Μήτηρ Θεοῦ ), в сокращенной форме ΜΡ ΘΥ , является указанием, обычно прилагаемым к ее изображению в византийских иконах . Собор заявил, что Отцы Церкви «не стеснялись говорить о Святой Деве как о Богородице». [ 28 ] [ 29 ] [ 30 ]

Некоторые марианские титулы имеют прямую библейскую основу. Например, титул «Царица-мать» был дан Марии, поскольку она была матерью Иисуса, которого иногда называют «Царем царей» из-за его предков от царя Давида . [ 31 ] [ 32 ] [ 33 ] [ 34 ] [ 35 ] Это также основано на еврейской традиции «Царицы-Матери», Гебиры или «Великой Госпожи». [ 36 ] [ 37 ] Другие титулы возникли в результате сообщений о чудесах , особых призывах или случаях обращения к Марии. [ ж ]

В исламе

В исламе Мария известна как Марьям ( араб . مريم , латинизировано : Марьям ), мать Исы ( عيسى بن مريم ). Ее часто называют почетным титулом «Сайидатуна» , что означает «Богоматерь»; этот титул аналогичен титулу «Сайидуна» («Наш Господь»), используемому для пророков. [ 42 ] Родственный термин нежности - «Сиддика» . [ 43 ] что означает «та, кто подтверждает истину» и «та, кто искренне верит полностью». Другой титул Марии — «Канита» , что означает как постоянное подчинение Богу, так и поглощенность молитвой и призывом в исламе. [ 44 ] Ее также называют «Тахира» , что означает «тот, кто был очищен» и представляет ее статус одного из двух людей в творении (и единственной женщины), к которой сатана никогда не прикасается. [ 45 ] В Коране она описывается одновременно как «дочь Имрана» и «сестра Аарона». [ 46 ]

Жизнь в древних источниках

Новый Завет

Канонические Евангелия и Деяния апостолов являются основными источниками исторических сведений о Марии. [ 47 ] [ 48 ] Это почти современные источники, поскольку синоптические Евангелия и Деяния апостолов обычно считаются датируемыми примерно 66–90 годами нашей эры, а Евангелие от Иоанна датируется 90–110 годами нашей эры. Они предоставляют ограниченную информацию о Марии, поскольку в первую очередь сосредоточены на учении Иисуса и его апостолов . [ 47 ] Историческая достоверность Евангелий и историческая достоверность Деяний апостолов являются предметом споров, поскольку в ранних христианских писаниях было обычной практикой смешивать исторические факты с легендарными историями. [ 47 ]

Самое раннее повествование о Марии в Новом Завете содержится в послании к Галатам , написанном до появления Евангелий . Она названа «женщиной» и не названа по имени: «Но когда пришла полнота времени, Бог послал Сына Своего, рожденного от женщины, рожденного под законом» (Галатам 4:4). [ 48 ]

Мария несколько раз упоминается в канонических Евангелиях и Деяниях апостолов:

- В Евангелии от Луки Мария упоминается чаще всего, называя ее по имени двенадцать раз, и все это в повествовании о детстве (Лк. 1:27–2:34). [ 49 ]

- В Евангелии от Матфея ее имя упоминается пять раз, из них четыре (1:16, 18, 20:2:12). [ 50 ] в повествовании о младенчестве и только один раз (Мф. 13:55) [ 51 ] вне повествования о детстве.

- В Евангелии от Марка она упоминается один раз (Марка 6:3). [ 52 ] и упоминает мать Иисуса, не называя ее имени в Марка 3:31–32. [ 53 ]

- В Евангелии от Иоанна мать Иисуса упоминается дважды, но никогда не упоминается ее имя. Впервые ее можно увидеть на свадьбе в Кане (Иоанна 2:1–12). [ 54 ] Во втором упоминании она стоит возле креста Иисуса вместе с Марией Магдалиной , Марией Клеоповой (или Клеофой) и собственной сестрой (возможно, той же, что и Мария Клеопская; формулировка семантически неоднозначна), вместе с « учеником, которого Иисус любил » (Иоанна 19:25–26). [ 55 ] Иоанна 2:1–12 [ 54 ] — единственный текст в канонических Евангелиях, в котором взрослый Иисус беседует с Марией. Он обращается к ней не как «Мать», а как «Женщина». На греческом койне (языке, на котором было написано Евангелие от Иоанна) называть мать «Женщиной» не было неуважением и даже могло быть нежным. [ 56 ] Соответственно, некоторые версии Библии переводят это слово как «Дорогая женщина». [ 57 ]

- В Деяниях апостолов Мария и братья Иисуса упоминаются в компании одиннадцати апостолов, собравшихся в горнице после Вознесения Иисуса (Деяния 1:14). [ 58 ]

В Книге Откровения , также являющейся частью Нового Завета , « жена, облеченная в солнце » (Откровение 12:1, 12:5–6) [ 59 ] иногда идентифицируется как Мэри.

Генеалогия

Новый Завет мало рассказывает о ранней истории Марии. Евангелие от Матфея дает генеалогию Иисуса по отцовской линии, идентифицируя Марию только как жену Иосифа. Иоанна 19:25 [ 60 ] утверждает, что у Мэри была сестра; семантически неясно, является ли эта сестра той же самой, что и Мария Клопская , или она осталась безымянной. Иероним идентифицирует Марию Клопскую как сестру Марии, матери Иисуса. [ 61 ] По словам историка начала 2-го века Гегесиппа , Мария Клопская, вероятно, была невесткой Марии, понимая, что Клопа (Клеопа) был братом Иосифа. [ 62 ]

По словам автора Луки, Мария была родственницей Елисаветы , жены священника Захарии из священнического отдела Авии , которая сама была частью рода Аарона и, следовательно, колена Левия . [ 63 ] Некоторые из тех, кто считает, что родство с Елисаветой было по материнской линии, полагают, что Мария, как и Иосиф, была из царской линии Давида и, следовательно, из колена Иуды , и что родословная Иисуса, представленная в Луки 3, происходит от Нафана , на самом деле это родословная Марии, тогда как родословная Соломона, данная в Евангелии от Матфея 1, является родословной Иосифа. [ 64 ] [ 65 ] [ 66 ] (Жена Аарона Елисева была из колена Иуды, поэтому все их потомки происходят как от Левия, так и от Иуды.) [ 67 ]

Благовещение

Мэри жила в «собственном доме» [ 68 ] в Назарете в Галилее , возможно, с родителями, и во время обручения — первого этапа еврейского брака . Еврейские девочки считались выданными на брак в возрасте двенадцати лет и шести месяцев, хотя фактический возраст невесты варьировался в зависимости от обстоятельств. Браку предшествовало обручение, после которого невеста по закону принадлежала жениху, хотя и жила с ним лишь примерно через год, когда состоялось бракосочетание. [ 69 ]

Ангел . Гавриил объявил ей, что она станет матерью обещанного Мессии , зачав его от Святого Духа, и, сначала выразив недоверие этому объявлению, она ответила: «Я — служанка Господня. Да будет так» сделано со мной по слову Твоему». [ 70 ] [ г ] Джозеф планировал тихо развестись с ней, но ему сказали, что она была зачата Святым Духом во сне «Ангелом Господним»; ангел велел ему, не колеблясь, взять ее себе в жены, что Иосиф и сделал, тем самым формально завершив свадебные обряды. [ 71 ] [ 72 ]

Поскольку ангел Гавриил сообщил Марии, что Елисавета, прежде бывшая бесплодной, чудесным образом забеременела, [ 73 ] Мария поспешила навестить Елисавету, которая жила со своим мужем Захарией в «горной стране... [в] городе Иудейском». Мария прибыла в дом и поприветствовала Елизавету, которая назвала Марию «матерью моего Господа», и Мария произнесла хвалебные слова, которые позже стали известны как Магнификат по ее первому слову в латинской версии. [ 74 ] Примерно через три месяца Мэри вернулась в свой дом. [ 75 ]

Рождение Иисуса

Согласно Евангелию от Луки , указ римского императора Августа требовал, чтобы Иосиф вернулся в свой родной город Вифлеем, чтобы зарегистрироваться для участия в римской переписи населения . [ ч ] Пока он был там с Марией, она родила Иисуса; но так как в гостинице для них не было места, она использовала ясли вместо колыбели. [ 77 ] : стр. 14 [ 78 ] Не сказано, сколько лет было Марии во время Рождества. [ 79 ] но были предприняты попытки сделать вывод об этом, исходя из возраста типичной еврейской матери того времени. Мэри Джоан Уинн Лейт представляет точку зрения, согласно которой еврейские девушки обычно выходят замуж вскоре после наступления половой зрелости. [ 80 ] в то время как, по словам Амрама Троппера, еврейские женщины в Палестине и Западной диаспоре обычно выходили замуж позже, чем в Вавилонии. [ 81 ] Некоторые ученые придерживаются мнения, что среди них это обычно происходило в середине и конце подросткового возраста. [ 82 ] или поздний подростковый возраст и начало двадцатых годов. [ 79 ] [ 81 ] Через восемь дней мальчик был обрезан по еврейскому закону и назван « Иисус » ( ישוע , Йешуа ), что означает « Яхве есть спасение». [ 83 ]

После того, как Мария пробыла в « очистительной крови своей » еще 33 дня, всего 40 дней, она принесла свое всесожжение и жертву за грех в Храм в Иерусалиме (Луки 2:22), [ 84 ] чтобы священник мог искупить ее. [ 85 ] Они также представили Иисуса: «Как написано в законе Господнем: всякий мужчина, разверзающий утробу, наречется святыней пред Господом» (Луки 2:23; Исход 13:2; 23:12–15; 22: 29; 34:19–20; Числа 3:13; [ 86 ] После пророчеств Симеона и пророчицы Анны в Луки 2:25–38, [ 87 ] семья «вернулась в Галилею, в свой город Назарет». [ 88 ]

Согласно Евангелию от Матфея , волхвы, пришедшие из восточных регионов, прибыли в Вифлеем, где жил Иисус и его семья, и поклонились ему. Затем во сне Иосифа предупредили, что царь Ирод хочет убить младенца, и семья ночью бежала в Египет и оставалась там некоторое время. После смерти Ирода в 4 г. до н. э. они вернулись в Назарет в Галилее, а не в Вифлеем, поскольку сын Ирода Архелай . правителем Иудеи был [ 89 ]

Мария участвует в единственном событии из юношеской жизни Иисуса, описанном в Новом Завете. В 12-летнем возрасте Иисус, разлучившись со своими родителями на обратном пути с празднования Пасхи в Иерусалиме, был найден в Храме среди религиозных учителей. [ 90 ] : стр.210 [ 91 ]

Служение Иисуса

Мария присутствовала, когда по ее предложению Иисус сотворил свое первое чудо во время свадьбы в Кане , превратив воду в вино. [ 92 ] Впоследствии происходят события, когда Мария присутствует вместе с Иаковом , Иосифом , Симоном и Иудой , называемыми братьями Иисуса , и безымянными сестрами. [ 93 ] По мнению Епифания , Оригена и Евсевия , эти «братья» и «сестры» должны были быть сыновьями Иосифа от предыдущего брака. Эта точка зрения до сих пор является официальной позицией Восточных Православных церквей. Если следовать Иерониму , то на самом деле это будут двоюродные братья Иисуса, дети сестры Марии. Это остается официальной позицией римско-католической церкви. Для Гельвидия это были бы родные братья и сестры Иисуса, рожденные от Марии и Иосифа после первенца Иисуса. Это была наиболее распространенная протестантская позиция. [ 94 ] [ 95 ] [ 96 ]

Агиографию Марии и Святого Семейства можно противопоставить другим материалам Евангелий. Эти ссылки включают в себя инцидент, который можно интерпретировать как отказ Иисуса от своей семьи в Новом Завете: «И пришли его мать и его братья и, стоя снаружи, послали с сообщением, прося о нем [...] и глядя на тех, кто сев вокруг него, Иисус сказал: «Это моя мать и мои братья, кто исполняет волю Божию, тот мне брат, и сестра, и мать». [ 97 ] [ 98 ]

Мария также изображена присутствующей в группе женщин при распятии, стоящей возле ученика, которого любил Иисус вместе с Марией Клопской и Марией Магдалиной . [ 55 ] к какому списку Матфея 27:56 [ 99 ] добавляет «мать сыновей Зеведея», предположительно Саломея, упомянутая в Марка 15:40. [ 100 ]

После Вознесения Иисуса

В Деяниях 1:12–26: [ 101 ] особенно в стихе 14, Мария — единственная, кроме одиннадцати апостолов, упомянутая по имени, которая жила в горнице , когда они вернулись с горы Елеонской . Ее присутствие с апостолами во время Пятидесятницы не является явным, хотя христианская традиция считает это фактом. [ нужна ссылка ]

С этого времени она исчезает из библейских повествований, хотя католики считают, что она снова изображается как небесная женщина в Книге Откровения . [ 102 ]

Ее смерть не записана в Священных Писаниях, но православная традиция, которую терпят и католики, предписывает ее первую смерть естественной смертью, известной как Успение Марии . [ 103 ] а затем, вскоре после этого, само ее тело также было принято (взято телесно) на Небеса . Вера в телесное вознесение Марии является догмой Католической церкви , как в Латинской , так и в Восточной Католической Церкви , а также в Восточную Православную Церковь . [ 104 ] [ 105 ] Восточная Православная Церковь , а также части Англиканского Сообщества и Продолжающегося Англиканского движения . [ 106 ]

Более поздние произведения

| Часть серии о |

| христианство |

|---|

|

Согласно апокрифическому Евангелию от Иакова , Мария была дочерью Иоакима и Анны . До зачатия Мэри Анна была бесплодна и находилась в далеком преклонном возрасте. Мария была отдана на службу посвященной девой в Иерусалимский Храм, когда ей было три года. [ 107 ] И это несмотря на очевидную невозможность его предпосылки о том, что девушку можно было содержать в Иерусалимском храме вместе с некоторыми спутницами. [ 108 ]

В некоторых недоказанных апокрифах, таких как апокрифическое Евангелие от Иакова 8:2, утверждается, что на момент обручения с Иосифом Марии было 12–14 лет. [ 109 ] В апокрифических источниках ее возраст во время беременности варьировался до 17 лет. [ 110 ] [ 111 ] В значительной части апокрифические тексты исторически недостоверны. [ 112 ] Согласно древнему еврейскому обычаю, Марию технически могли обручить примерно в 12 лет. [ 113 ] но некоторые ученые придерживаются мнения, что в Иудее это обычно происходило позже. [ 79 ]

Ипполит Фивский говорит, что Мария прожила 11 лет после смерти своего сына Иисуса, умершего в 41 году нашей эры. [ 114 ]

Самым ранним из сохранившихся биографических сочинений о Марии является «Житие Богородицы» , приписываемое святому Максиму Исповеднику VII века , в котором она изображается как ключевой элемент ранней христианской церкви после смерти Иисуса. [ 115 ] [ 116 ] [ 117 ]

Религиозные перспективы

Мэри | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Заслуженный в | Христианство, ислам, вера друзов [ 118 ] |

| канонизирован | Предварительное собрание |

| Главный храм | Санта-Мария-Маджоре (см. святыни Марии ) |

| Праздник | Увидеть Марианские праздники |

| Атрибуты | Голубая мантия, корона из 12 звезд, беременная женщина, розы, женщина с ребенком, женщина, топчущая змею, полумесяц, женщина, одетая в солнце, сердце, пронзенное мечом, четки |

| Покровительство | См. Покровительство Пресвятой Богородицы. |

христианин

Христианские взгляды Мариан включают в себя большое разнообразие. В то время как некоторые христиане, такие как католики и православные, имеют устоявшиеся марианские традиции, протестанты в целом мало внимания уделяют мариологическим темам. Католики, восточно-православные, восточно-православные, англиканцы и лютеране почитают Деву Марию. Это почитание особенно принимает форму молитвы о заступничестве перед Ее Сыном Иисусом Христом. Кроме того, это включает в себя сочинение стихов и песен в честь Марии, рисование икон или вырезание ее статуй, а также присвоение Марии титулов , отражающих ее положение среди святых. [ 24 ] [ 25 ] [ 119 ] [ 120 ]

Католик

В католической церкви Марии присвоен титул «Блаженная» ( beata , μακάρια ) в знак признания ее вознесения на Небеса и ее способности ходатайствовать за тех, кто ей молится. Существует разница между использованием термина «блаженный» по отношению к Марии и его использованием по отношению к блаженному человеку. Титул Марии «Блаженная» указывает на ее возвышенное состояние как величайшей среди святых; С другой стороны, для человека, объявленного беатифицированным, «благословенный» просто указывает на то, что его можно почитать, несмотря на то, что он не канонизирован . Католическое учение ясно дает понять, что Мария не считается божественной и на молитвы к ней отвечает не она, а Бог через ее заступничество. [ 121 ] Четыре католических догмы относительно Марии: ее статус Богородицы , или Матери Божией; ее вечная девственность; Непорочное Зачатие; и ее телесное Успение на Небесах. [ 122 ] [ 123 ] [ 124 ]

Пресвятая Дева Мария , мать Иисуса, играет более центральную роль в римско-католических учениях и верованиях, чем в любой другой крупной христианской группе. У католиков не только больше богословских доктрин и учений, касающихся Марии, но у них больше праздников, молитв, религиозных и почитательных практик, чем у любой другой группы. [ 119 ] В Катехизисе Католической Церкви говорится: «Преданность Церкви Пресвятой Деве является неотъемлемой частью христианского богослужения». [ 125 ]

На протяжении веков католики совершали акты посвящения и вверения Марии на личном, общественном и региональном уровнях. Эти действия могут быть направлены к самой Деве, Непорочному Сердцу Марии и Непорочному Зачатию . В католическом учении посвящение Марии не уменьшает и не заменяет любовь к Богу, а усиливает ее, поскольку любое посвящение в конечном итоге совершается Богу. [ 126 ] [ 127 ]

После роста преданности Марии в 16 веке католические святые написали такие книги, как «Слава Марии» и «Истинная преданность Марии» , в которых подчеркивалось почитание Марии и учили, что «путь к Иисусу лежит через Марию». [ 128 ] Поклонение Марии иногда связано с христоцентрическим поклонением (например, Союз сердец Иисуса и Марии ). [ 129 ]

Основные богослужения Марии включают: Семь скорбей Марии , Розарий и лопатку , Чудесную медаль и Возмещение ущерба Марии . [ 130 ] [ 131 ] Май и октябрь традиционно являются «марианскими месяцами» для католиков; ежедневные четки поощряются в октябре, а в мае во многих регионах проходят богослужения Мариан. [ 132 ] [ 133 ] [ 134 ] Папы издали ряд Марианских энциклик и апостольских писем, чтобы поощрить преданность и почитание Девы Марии.

Католики придают большое значение роли Марии как защитницы и заступницы, а в Катехизисе Мария упоминается как «удостоенная титула «Богородица», к защите которой верующие прибегают во всех своих опасностях и нуждах». [ 125 ] [ 135 ] [ 136 ] [ 137 ] [ 138 ] Ключевые молитвы Марии включают: «Радуйся, Мария » , «Альма Искупительница» , «Под твоей защитой» , «Радуйся, Звезда Морская» , «Царица Небесная» , «Радуйся, Царица Небесная» и « Магнификат» . [ 139 ]

Участие Марии в процессах спасения и искупления также подчеркивается в католической традиции, но это не доктрины. [ 140 ] [ 141 ] [ 142 ] [ 143 ] Энциклика Папы Иоанна Павла II 1987 года Redemptoris Mater началась с предложения: «Матери Искупителя принадлежит определенное место в плане спасения». [ 144 ]

В 20 веке и Папы Иоанн Павел II, и Бенедикт XVI подчеркивали марианскую направленность католической церкви. Кардинал Йозеф Ратцингер (впоследствии Папа Бенедикт XVI) предложил переориентировать всю церковь на программу Папы Иоанна Павла II, чтобы обеспечить аутентичный подход к христологии через возврат к «всей истине о Марии». [ 145 ] письмо:

«Необходимо вернуться к Марии, если мы хотим вернуться к той «правде об Иисусе Христе», «правде о Церкви» и «правде о человеке . » [ 145 ]

В доктринах Марии, приписываемых ей в первую очередь католической церковью, существует значительное разнообразие. Ключевые марианские доктрины, которых придерживается прежде всего католицизм, можно кратко изложить следующим образом:

- Непорочное зачатие : Мария была зачата без первородного греха .

- Богородица : Мария, как мать Иисуса, есть Богородица (Богоносица), или Богородица.

- Непорочное рождение Иисуса : Мария зачала Иисуса действием Святого Духа , оставаясь девственницей.

- Вечная девственность : Мария оставалась девственницей всю свою жизнь, даже после рождения Иисуса.

- Успение : отмечает «засыпание» Марии или естественную смерть незадолго до ее Успения. Успение является частью принятого восточно-католического богословия, но не частью римско-католической доктрины. [ 146 ]

- Предположение : Мария была взята на небеса телесно либо во время, либо до ее смерти.

Принятие этих марианских доктрин католиками и другими христианами можно резюмировать следующим образом: [ 18 ] [ 147 ] [ 148 ]

| Доктрина | Церковное действие | Принято |

|---|---|---|

| Непорочное рождение Иисуса | Первый Никейский собор , 325 г. | Католики, православные, восточные православные, ассирийцы, англиканцы, баптисты, основные протестанты. |

| Богородица | Первый Эфесский собор , 431 г. | Католики, восточные православные, восточные православные, англиканцы, лютеране, некоторые методисты, некоторые евангелисты. [ 149 ] |

| Вечная девственность | Второй Вселенский Константинопольский Собор , 553 г. Статьи Смалькальда , 1537 г. | Католики, православные, восточные православные, ассирийцы, некоторые англиканцы, некоторые лютеране (Мартин Лютер) |

| Непорочное зачатие | невыразимого Бога Энциклика Папа Пий IX , 1854 г. | Католики, некоторые англиканцы, некоторые лютеране (ранний Мартин Лютер) |

| Успение Богородицы | Самая щедрая энциклика Бога Папа Пий XII , 1950 год. | Католики, восточные и восточные православные (только после ее естественной смерти), некоторые англиканцы, некоторые лютеране. |

Титул «Богородицы» ( Богородицы ) для Марии был подтвержден Первым Эфесским собором , состоявшимся в церкви Марии в 431 году. Собор постановил, что Мария — Богородица, потому что ее сын Иисус — одно лицо, которое одновременно является Бог и человек, божественное и человеческое. [ 28 ] Эта доктрина широко принята христианами в целом, и термин «Богородица» уже использовался в самой древней известной молитве Марии, Sub tuum praesidium , датируемой примерно 250 годом нашей эры. [ 150 ]

Непорочное зачатие Иисуса было почти повсеместно распространенной верой среди христиан со 2-го по 19-й век. [ 151 ] Он включен в два наиболее широко используемых христианских символа веры , в которых говорится, что Иисус «воплотился от Святого Духа и Девы Марии» ( Никейский символ веры в его ныне знакомой форме). [ 152 ] и Апостольский Символ веры . Евангелие от Матфея описывает Марию как деву, исполнившую пророчество Исайи 7:14: [ 153 ] Авторы Евангелий от Матфея и Луки считают зачатие Иисуса не результатом полового акта и утверждают, что Мария до рождения Иисуса «не имела никаких отношений с человеком». [ 154 ] Это намекает на веру в то, что Мария зачала Иисуса через действие Бога Святого Духа, а не через общение с Иосифом или кем-либо еще. [ 155 ]

Доктрины Успения или Успения Марии относятся к ее смерти и телесному вознесению на небо. Римско-католическая церковь догматически определила доктрину Успения, что было сделано в 1950 году Папой Пием XII в Munificentissimus Deus . Однако догматически не определено, умерла ли Мария или нет, хотя ссылка на смерть Марии содержится в Munificentissimus Deus . В Восточной Православной Церкви верят в Успение Девы Марии и отмечают ее Успение , где, по их мнению, она умерла.

Католики верят в непорочное зачатие Марии , провозглашенное ex cathedra папой Пием IX в 1854 году, а именно в то, что она была исполнена благодати с самого момента своего зачатия в утробе матери и сохранена от пятна первородного греха . В Латинской церкви есть литургический праздник с таким названием , который отмечается 8 декабря. [ 156 ] Православные христиане отвергают догмат о непорочном зачатии главным образом потому, что их понимание первородного греха (греческого термина, соответствующего латинскому «первородному греху») отличается от интерпретации Августина и католической церкви. [ 157 ]

Вечная девственность Марии утверждает настоящую и вечную девственность Марии даже в акте рождения Сына Божия, ставшего Человеком. термин «Привечная Дева» (греч. ἀειπάρθενος В этом случае применяется ), означающий, что Мария оставалась девственницей до конца своей жизни, что сделало Иисуса своим биологическим и единственным сыном, чье зачатие и рождение считаются чудесными. [ 122 ] [ 155 ] [ 158 ] Православные церкви придерживаются позиции, сформулированной в Протоевангелии Иакова , что братья и сестры Иисуса были детьми Иосифа от брака, предшествующего браку с Марией, в результате которого он овдовел. Римско-католическое учение следует за латинским отцом Иеронимом , считая их двоюродными братьями Иисуса.

Восточно-православный

Восточное православие включает в себя большое количество традиций, касающихся Приснодевы Марии, Богородицы . [ 159 ] Православные верят, что она была и оставалась девственницей до и после рождения Христа. [ 25 ] ( Богородичные гимны гимны Богородице ) являются неотъемлемой частью богослужения в Восточной Церкви , и их расположение в литургической последовательности фактически ставит Богородицу на самое видное место после Христа. [ 160 ] В православной традиции порядок святых начинается с: Богородицы , Ангелов, Пророков, Апостолов, Отцов и Мучеников, отдавая приоритет Деве Марии над ангелами. Ее также провозглашают «Леди Ангелов». [ 160 ]

Взгляды отцов церкви по-прежнему играют важную роль в формировании православной марианской точки зрения. Однако православные взгляды на Марию носят по большей части славословный , а не академический характер: они выражаются в гимнах, хвалебных словах, литургической поэзии, иконопочитании. Один из самых любимых православных акафистов ( постоянных гимнов ) посвящен Марии, и его часто называют просто Акафистом . [ 161 ] Пять из двенадцати Великих праздников в православии посвящены Марии. [ 25 ] Неделя Православия напрямую связывает личность Девы Марии как Богородицы с иконопочитанием. [ 162 ] связан ряд православных праздников С чудотворными иконами Божией Матери . [ 160 ]

Православные считают Марию «превосходящей всех созданных существ», хотя и не божественной. [ 163 ] Таким образом, обозначение Святой Марии как Святой Марии неуместно. [ 164 ] Православные не почитают Марию как зачатую непорочной. Григорий Назианзин , архиепископ Константинопольский в IV веке нашей эры, говоря о Рождестве Иисуса Христа, утверждает, что «Зачатый Девой, которая прежде телом и душой очистилась Святым Духом, Он вышел как Бог с тем, что Он предполагал, что Одна Личность в двух Природах, Плоти и Духе, из которых последняя определяет первую». [ 165 ] Православные празднуют Успение Пресвятой Богородицы , а не Успение. [ 25 ]

«Протоевангелие Иакова» , внеканоническая книга, было источником многих православных представлений о Марии. Представленный рассказ о жизни Марии включает ее посвящение в девственницу в храме в трехлетнем возрасте. Первосвященник Захария благословил Марию и сообщил ей , что Бог возвеличил ее имя среди многих поколений. Захария поместил Марию на третью ступень жертвенника, чем Бог даровал ей благодать. Находясь в храме, Мария чудесным образом питалась ангелом, пока ей не исполнилось 12 лет. В этот момент ангел сказал Захарии обручить Марию с вдовцом в Израиле, который будет указан. Эта история легла в основу многих гимнов праздника Сретения Богородицы , а иконы праздника изображают эту историю. [ 166 ] Православные верят, что Мария сыграла важную роль в росте христианства во время жизни Иисуса и после его Распятия, а православный богослов Сергей Булгаков писал: «Дева Мария — невидимый, но реальный центр Апостольской Церкви».

Богословы православной традиции внесли выдающийся вклад в развитие Марианской мысли и преданности. Иоанн Дамаскин ( ок. 650 – ок. 750 ) был одним из крупнейших православных богословов. Среди других сочинений Марии он провозгласил сущностную природу небесного Успения Марии и ее медитативную роль.

Необходимо было, чтобы тело той, которая сохранила свое девство в неприкосновенности при рождении, сохранялось нетленным и после смерти. Необходимо было, чтобы она, носившая в своем чреве Творца, когда он был младенцем, обитала среди небесных скиний. [ 167 ]

От нее мы собрали виноград жизни; от нее мы взрастили семя бессмертия. Ради нас она стала Посредницей всех благ; в ней Бог стал человеком, а человек стал Богом. [ 168 ]

Совсем недавно Сергей Булгаков выразил православное отношение к Марии следующим образом: [ 163 ]

Мария — не просто инструмент, но непосредственное положительное условие Воплощения, его человеческий аспект. Христос не мог воплотиться посредством какого-то механического процесса, нарушающего человеческую природу. Надо было самой природе сказать за себя устами чистейшего человека: «Се, Раба Господня, да будет она мне по слову Твоему».

протестант

Протестанты в целом отвергают почитание Святых и обращение к ним. [ 18 ] : 1174 Они разделяют веру в то, что Мария — мать Иисуса и «благословена среди жен» (Луки 1:42). [ 169 ] но они обычно не согласны с тем, что Марию следует почитать. Она считается выдающимся примером жизни, посвященной Богу. [ 170 ] Таким образом, они склонны не принимать определенные церковные доктрины, такие как сохранение ее от греха. [ 171 ] Богослов Карл Барт писал, что «ересь католической церкви — это ее мариология ». [ 172 ]

Некоторые ранние протестанты почитали Марию. Мартин Лютер писал, что: «Мария полна благодати, провозглашена совершенно безгрешной. Божья благодать наполняет ее всем добром и делает ее лишенной всякого зла». [ 173 ] Однако с 1532 года Лютер прекратил праздновать праздник Успения Богородицы , а также прекратил поддержку Непорочного Зачатия . [ 174 ] Жан Кальвин заметил: «Нельзя отрицать, что Бог, избрав и предназначив Марию стать Матерью Своего Сына, оказал ей высшую честь». [ я ] Однако Кальвин решительно отверг идею о том, что Мария может ходатайствовать между Христом и человеком. [ 177 ]

Хотя Кальвин и Хульдрих Цвингли почитали Марию как Мать Христа в 16 веке, они делали это меньше, чем Мартин Лютер. [ 178 ] Таким образом, идея уважения и высокой чести Марии не была отвергнута первыми протестантами; однако они пришли критиковать католиков за почитание Марии. После Тридентского собора в 16 веке, когда почитание Марии стало ассоциироваться с католиками, протестантский интерес к Марии уменьшился. В эпоху Просвещения всякий остаточный интерес к Марии в протестантских церквях почти исчез, хотя англиканцы и лютеране продолжали чтить ее. [ 18 ]

В 20 веке некоторые протестанты выступили против католического догмата Успения Марии . [ нужна ссылка ] Тон Второго Ватиканского Собора начал устранять экуменические разногласия, и протестанты начали проявлять интерес к марианским темам. [ нужна ссылка ] В 1997 и 1998 годах состоялись экуменические диалоги между католиками и протестантами, но на сегодняшний день большинство протестантов не согласны с почитанием Марии, а некоторые рассматривают его как вызов авторитету Священного Писания . [ 18 ] [ нужен лучший источник ]

англиканский

Различные церкви, образующие Англиканское Сообщество и Продолжающееся англиканское движение, имеют разные взгляды на Марианские доктрины и почитательные практики, учитывая, что внутри Сообщества не существует единой церкви с универсальной властью и что материнская церковь ( Англиканская церковь ) понимает себя как как «католические», так и « реформатские ». [ 179 ] Таким образом, в отличие от протестантских церквей в целом, англиканская община включает в себя сегменты, которые до сих пор сохраняют некоторое почитание Марии. [ 120 ]

Особое положение Марии в Божьей цели спасения как «Богоносицы» по-разному признается некоторыми англиканскими христианами. [ 180 ] Все церкви-члены Англиканской общины подтверждают в исторических символах веры, что Иисус родился от Девы Марии, и отмечают праздники Сретения Христа в храме . называется Этот праздник в старинных молитвенниках Очищением Пресвятой Богородицы 2 февраля. Благовещение Беды Господа Пресвятой Богородице 25 марта было со времен до Нового года 18 века в Англии. Благовещение названо «Благовещением Богородицы» в Книге общей молитвы 1662 года . Англиканцы также празднуют Посещение Пресвятой Богородицы 31 мая, хотя в некоторых провинциях сохраняется традиционная дата 2 июля. Праздник Пресвятой Богородицы отмечается в традиционный день Успения Пресвятой Богородицы, 15 августа. Рождество Пресвятой Богородицы празднуется 8 сентября. [ 120 ]

Зачатие Пресвятой Девы Марии записано в Книге общей молитвы 1662 года 8 декабря. В некоторых англо-католических приходах этот праздник называют Непорочным зачатием. Опять же, в Успение Марии верят большинство англо-католиков, но считают это благочестивым умеренные англиканцы мнением. Протестантски настроенные англиканцы отвергают празднование этих праздников. [ 120 ]

Молитвы и почитательные практики сильно различаются. Например, начиная с 19-го века, после Оксфордского движения , англо-католики часто молятся Розарию , Ангелусу , Regina caeli и другим литаниям и гимнам Марии, напоминающим католические обычаи. [ 181 ] И наоборот, англиканцы низкой церкви редко призывают Пресвятую Деву, за исключением некоторых гимнов, таких как вторая строфа « Вы, наблюдатели» и «Вы, святые» . [ 180 ] [ 182 ]

Англиканское общество Марии было основано в 1931 году и имеет отделения во многих странах. Цель общества — способствовать развитию преданности Марии среди англикан. [ 120 ] [ 183 ] Англиканцы высокой церкви поддерживают доктрины, которые ближе к римско-католическим, и сохраняют почитание Марии, например, англиканские паломничества к Богоматери Лурдской , которые происходят с 1963 года, и паломничества к Богоматери Уолсингемской , которые имели место в течение сотен годы. [ 184 ]

Исторически сложилось так, что между католиками и англиканами существовало достаточно точек соприкосновения по вопросам Марии, поэтому в 2005 году совместное заявление под названием «Мария: благодать и надежда во Христе» в ходе экуменических встреч англиканцев и римско-католических богословов было принято . Этот документ, неофициально известный как «Сиэтлское заявление», формально не одобрен ни Католической церковью, ни Англиканским сообществом, но рассматривается его авторами как начало совместного понимания Марии. [ 120 ] [ 185 ]

лютеранин

Несмотря на резкую полемику Мартина Лютера со своими римско-католическими противниками по вопросам, касающимся Марии и святых, богословы, похоже, согласны с тем, что Лютер придерживался марианских постановлений вселенских соборов и догм церкви. Он твердо придерживался веры в то, что Мария была вечной девой и Богородицей. [ 186 ] [ 187 ] Особое внимание уделяется утверждению, что Лютер примерно за 300 лет до догматизации непорочного зачатия папой Пием IX в 1854 г. был твердым приверженцем этой точки зрения. [ нужна ссылка ] . Другие утверждают, что Лютер в последующие годы изменил свою позицию по вопросу о Непорочном зачатии, которая в то время не имела определения в церкви, сохраняя, однако, безгрешность Марии на протяжении всей ее жизни . [ 188 ] [ 189 ] Для Лютера в начале жизни Успение Богородицы было понятным фактом, хотя позже он заявил, что в Библии ничего об этом не сказано, и перестал праздновать этот праздник. Важным для него была вера в то, что Мария и святые продолжают жить после смерти. [ 190 ] [ 191 ] [ 192 ] «На протяжении всей своей карьеры священника-профессора-реформатора Лютер проповедовал, учил и спорил о почитании Марии с многословием, которое варьировалось от детского благочестия до изощренной полемики. Его взгляды тесно связаны с его христоцентрическим богословием и его последствиями для литургии. и благочестие». [ 193 ]

Лютер, почитая Марию, стал критиковать «папистов» за стирание границы между высоким восхищением благодатью Божией, где бы она ни проявлялась в человеке, и религиозным служением, оказываемым другому творению. римско-католическую практику празднования дней святых и обращения с ходатайственными просьбами, адресованными особенно Марии и другим усопшим святым Он считал идолопоклонством . [ 194 ] [ 195 ] Его последние мысли о преданности и почитании Марии сохранились в проповеди, произнесенной в Виттенберге всего за месяц до его смерти:

Поэтому, когда мы проповедуем веру, что не должны поклоняться ничему, кроме Бога, Отца Господа нашего Иисуса Христа, как мы говорим в Символе веры: «Верую в Бога Отца Всемогущего и в Иисуса Христа», то мы остаемся в храм в Иерусалиме. Еще раз: «Это Мой возлюбленный Сын; послушай его. «Вы найдете его в яслях». Он один это делает. Но разум говорит обратное: Что, мы? Должны ли мы поклоняться только Христу? Действительно, не должны ли и мы чтить святую Матерь Христову? Это женщина, которая поразила змея в голову. Услышь нас, Мария, ибо Сын Твой так чтит Тебя, что ни в чем не может отказать Тебе. Здесь Бернар зашел слишком далеко в своих «Проповедях на Евангелие: Missus est Angelus» . [ 196 ] Бог повелел нам почитать родителей; поэтому я призову Марию. Она ходатайствует за Меня перед Сыном, и Сын перед Отцом, который услышит Сына. Итак, у вас есть образ разгневанного Бога и Христа как судьи; Мария показывает Христу свою грудь, а Христос показывает гневному Отцу свои раны. Вот что готовит эта прекрасная невеста, мудрость разума: Мария — мать Христова, непременно Христос услышит ее; Христос — строгий судья, поэтому я призову святого Георгия и святого Христофора. Нет, мы по повелению Божию были крещены во имя Отца, Сына и Святого Духа, как иудеи были обрезаны. [ 197 ] [ 198 ]

Некоторые лютеранские церкви, такие как англо-лютеранская католическая церковь, продолжают почитать Марию и святых так же, как и католики, и считают все марианские догмы частью своей веры. [ 199 ]

методист

Никаких дополнительных учений о Деве Марии, кроме упомянутых в Священном Писании и вселенском Символе веры, у методистов нет. Таким образом, методисты обычно принимают доктрину непорочного зачатия, но отвергают доктрину непорочного зачатия. [ 200 ] Джон Уэсли , главный основатель методистского движения в англиканской церкви, считал, что Мария «оставалась чистой и незапятнанной девой », поддерживая тем самым доктрину вечной девственности Марии. [ 201 ] [ 202 ] Современный методизм утверждает, что Мария была девственницей до, во время и сразу после рождения Христа. [ 203 ] [ 204 ] Кроме того, некоторые методисты также считают учение об Успении Марии благочестивым мнением. [ 205 ]

Нетринитарный

Нетринитаристы , такие как унитарии , христадельфиане , Свидетели Иеговы и Святые последних дней. [ 206 ] также признают Марию биологической матерью Иисуса Христа, но большинство отвергают любое непорочное зачатие и не признают марианские титулы, такие как «Богородица». подтверждает Точка зрения движения Святых последних дней непорочное зачатие Иисуса. [ 207 ] и божественность Христа, но только как существо, отдельное от Бога-Отца . Книга Мормона упоминает Марию в пророчествах по имени и описывает ее как «самую красивую и прекрасную среди всех других дев». [ 208 ] и как «драгоценный и избранный сосуд». [ 209 ] [ 210 ]

В нетринитарных группах, которые также являются христианскими смертниками , Мария не рассматривается как посредник между человечеством и Иисусом, которого смертники считали бы «спящим», ожидающим воскресения. [ 211 ]

еврейский

Вопрос о происхождении Иисуса в Талмуде также влияет на взгляды евреев на Марию. Однако в Талмуде Мария не упоминается по имени, и это скорее внимательно, чем просто полемика. [ 212 ] [ 213 ] Рассказ о Пантере также встречается в Толедотском Йешу , литературное происхождение которого невозможно проследить с какой-либо уверенностью, а учитывая, что он вряд ли датируется ранее IV века, слишком поздно включать в него подлинные воспоминания об Иисусе. [ 214 ] «Блэквеллский спутник Иисуса» утверждает, что Толедот Йешу не имеет исторических фактов и, возможно, был создан как инструмент для предотвращения обращения в христианство. [ 215 ] Рассказы из « Толедот Йешу» действительно создали у обычных еврейских читателей негативное представление о Марии. [ 216 ] Распространение Толедот Йешу было широко распространено среди еврейских общин Европы и Ближнего Востока с 9 века. [ 217 ] Название «Пантера» может быть искажением термина « парфенос » («девственница»), и Рэймонд Э. Браун считает историю Пантеры причудливым объяснением рождения Иисуса, которое включает в себя очень мало исторических свидетельств. [ 218 ] Роберт Ван Вурст утверждает, что, поскольку Толедот Йешу представляет собой средневековый документ с отсутствием фиксированной формы и ориентацией на широкую аудиторию, «крайне маловероятно» наличие достоверной исторической информации. [ 219 ] Стопки экземпляров Талмуда были сожжены по постановлению суда после диспута 1240 года за то, что они якобы содержали материалы, порочащие характер Марии. [ 216 ]

исламский

Дева Мария занимает исключительно высокое место в исламе считает ее , и Коран величайшей женщиной в истории человечества. Исламское писание перечисляет Божественное Обещание, данное Марии, следующим образом: «О Мария! Воистину, Аллах избрал тебя, очистил тебя и выбрал тебя среди всех женщин мира» ( 3:42 ).

Мусульмане часто называют Марию почетным титулом Саедетина («Богоматерь»). Она упоминается в Коране как дочь Имрана. [ 220 ]

Более того, Мария — единственная женщина, имя которой упоминается в Коране, и она упоминается в Священном Писании в общей сложности 50 раз. [ Дж ] Mary holds a singularly distinguished and honored position among women in the Quran. A sura (chapter) in the Quran is titled "Maryam" (Mary), the only sura in the Quran named after a woman, in which the story of Mary (Maryam) and Jesus (Isa) is recounted according to the view of Jesus in Islam.[10]

Birth

In a narration of hadith from Imam Ja'far al-Sadiq, he mentions that Allah revealed to Imran, "I will grant you a boy, blessed, one who will cure the blind and the leper and one who will raise the dead by My permission. And I will send him as an apostle to the Children of Israel." Then Imran related the story to his wife, Hannah, the mother of Mary. When she became pregnant, she conceived it was a boy, but when she gave birth to a girl, she stated "Oh my Lord! Verily I have delivered a female, and the male is not like the female, for a girl will not be a prophet," to which Allah replies in the Quran, "Allah knows better what has been delivered" (3:36). When Allah bestowed Jesus to Mary, he fulfilled his promise to Imran.[221]

Motherhood

Mary was declared (uniquely along with Jesus) to be a "Sign of God" to humanity;[222] as one who "guarded her chastity";[44] an "obedient one";[44] and dedicated by her mother to Allah whilst still in the womb;[45] uniquely (amongst women) "Accepted into service by God";[223] cared for by (one of the prophets as per Islam) Zakariya (Zacharias);[223] that in her childhood she resided in the Temple and uniquely had access to Al-Mihrab (understood to be the Holy of Holies), and was provided with heavenly "provisions" by God.[223][220]

Mary is also called a "Chosen One";[224] a "Purified One";[224] a "Truthful one";[225] her child conceived through "a Word from God";[226] and "chosen you above the women of the worlds(the material and heavenly worlds)".[224]

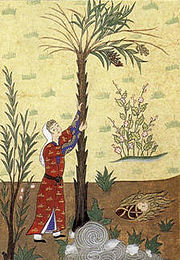

The Quran relates detailed narrative accounts of Maryam (Mary) in two places, 3:35-47 and 19:16-34. These state beliefs in both the Immaculate Conception of Mary and the virgin birth of Jesus.[227][228][229] The account given in Surah Maryam 19 is nearly identical with that in the Gospel according to Luke, and both of these (Luke, Sura 19) begin with an account of the visitation of an angel upon Zakariya (Zecharias) and "Good News of the birth of Yahya (John)", followed by the account of the annunciation. It mentions how Mary was informed by an angel that she would become the mother of Jesus through the actions of God alone.[230]

In the Islamic tradition, Mary and Jesus were the only children who could not be touched by Satan at the moment of their birth, for God imposed a veil between them and Satan.[231][232] According to the author Shabbir Akhtar, the Islamic perspective on Mary's Immaculate Conception is compatible with the Catholic doctrine of the same topic.

"O People of the Book! Do not go to extremes regarding your faith; say nothing about Allah except the truth. The Messiah, Jesus, son of Mary, was no more than a messenger of Allah and the fulfilment of His Word through Mary and a spirit ˹created by a command˺ from Him. So believe in Allah and His messengers and do not say, "Trinity." Stop!—for your own good. Allah is only One God. Glory be to Him! He is far above having a son! To Him belongs whatever is in the heavens and whatever is on the earth. And Allah is sufficient as a Trustee of Affairs.

The Quran says that Jesus was the result of a virgin birth. The most detailed account of the annunciation and birth of Jesus is provided in Suras 3 and 19 of the Quran, where it is written that God sent an angel to announce that she could shortly expect to bear a son, despite being a virgin.[235]

Druze Faith

The Druze faith holds the Virgin Mary, known as Sayyida Maryam, in high regard.[118] Although the Druze religion is distinct from mainstream Islam and Christianity, it incorporates elements from both and honors many of their figures, including the Virgin Mary.[118] The Druze revere Mary as a holy and pure figure, embodying virtue and piety.[236][118] She is respected not only for her role as the mother of Messiah Jesus but also for her spiritual purity and dedication to God.[236][118] In regions where Druze and Christians coexist, such as parts of Lebanon, Syria and Israel, the veneration of Mary often reflects a blend of traditions.[237] Shared pilgrimage sites and mutual respect for places like the Church of Saidet et Tallé in Deir el Qamar, the Our Lady of Lebanon shrine in Harrisa, the Our Lady of Saidnaya Monastery in Saidnaya, and the Stella Maris Monastery in Haifa exemplify this.[237]

Historical records and writings by authors like Pierre-Marie Martin and Glenn Bowman show that Druze leaders and community members have historically shown deep reverence for Marian sites.[11] They often sought her intercession before battles or during times of need, demonstrating a cultural and spiritual integration of Marian veneration into their religious practices.[11]

Bahá'í Faith

The Bahá'í Faith venerates Mary as the mother of Jesus. The Kitáb-i-Íqán, the primary theological work of the Bahá'í religion, describes Mary as "that most beauteous countenance," and "that veiled and immortal Countenance." The Bahá'í writings claim Jesus Christ was "conceived of the Holy Ghost"[238] and assert that in the Bahá'í Faith "the reality of the mystery of the Immaculacy of the Virgin Mary is confessed."[239]

Biblical scholars

The statement found in Matthew 1:25 that Joseph did not have sexual relations with Mary before she gave birth to Jesus has been debated among scholars, with some saying that she did not remain a virgin and some saying that she was a perpetual virgin.[240] Other scholars contend that the Greek word heos ("until") denotes a state up to a point, but does not mean that the state ended after that point, and that Matthew 1:25 does not confirm or deny the virginity of Mary after the birth of Jesus.[241][242][243] According to Biblical scholar Bart Ehrman, the Hebrew word almah, meaning young woman of childbearing age, was translated into Greek as parthenos, which often, though not always, refers to a young woman who has never had sex. In Isaiah 7:14, it is commonly believed by Christians to be the prophecy of the Virgin Mary referred to in Matthew 1:23.[244] While Matthew and Luke give differing versions of the virgin birth, John quotes the uninitiated Philip and the disbelieving Jews gathered at Galilee referring to Joseph as Jesus' father.[245][246][247][248]

Other biblical verses have also been debated; for example, the reference made by Paul the Apostle that Jesus was made "of the seed of David according to the flesh" (Romans 1:3)[249] meaning that he was a descendant of David through Joseph.[250]

Pre-Christian Rome

From the early stages of Christianity, belief in the virginity of Mary and the virgin conception of Jesus, as stated in the gospels, holy and supernatural, was used by detractors, both political and religious, as a topic for discussions, debates, and writings, specifically aimed to challenge the divinity of Jesus and thus Christians and Christianity alike.[251] In the 2nd century, as part of his anti-Christian polemic The True Word, the pagan philosopher Celsus contended that Jesus was actually the illegitimate son of a Roman soldier named Panthera.[252] The church father Origen dismissed this assertion as a complete fabrication in his apologetic treatise Against Celsus.[253] How far Celsus sourced his view from Jewish sources remains a subject of discussion.[254]

Christian devotions

History

2nd century

Justin Martyr was among the first to draw a parallel between Eve and Mary. This derives from his comparison of Adam and Jesus. In his Dialogue with Trypho, written sometime between 155 and 167,[255] he explains:

He became man by the Virgin, in order that the disobedience which proceeded from the serpent might receive its destruction in the same manner in which it derived its origin. For Eve, who was a virgin and undefiled, having conceived the word of the serpent, brought forth disobedience and death. But the Virgin Mary received faith and joy, when the angel Gabriel announced the good tidings to her that the Spirit of the Lord would come upon her, and the power of the Highest would overshadow her: wherefore also the Holy Thing begotten of her is the Son of God; and she replied, 'Be it unto me according to thy word." And by her has He been born, to whom we have proved so many scriptures refer, and by whom God destroys both the serpent and those angels and men who are like him; but works deliverance from death to those who repent of their wickedness and believe upon Him.[256]

It is possible that the teaching of Mary as the New Eve was part of the apostolic tradition rather than merely Justin Martyr's own creation.[257] Irenaeus, bishop of Lyon, also takes this up, in Against Heresies, written about the year 182:[258]

In accordance with this design, Mary the Virgin is found obedient, saying, "Behold the handmaid of the Lord; be it unto me according to your word." Luke 1:38 But Eve was disobedient; for she did not obey when as yet she was a virgin. ... having become disobedient, was made the cause of death, both to herself and to the entire human race; so also did Mary, having a man betrothed [to her], and being nevertheless a virgin, by yielding obedience, become the cause of salvation, both to herself and the whole human race. And on this account does the law term a woman betrothed to a man, the wife of him who had betrothed her, although she was as yet a virgin; thus indicating the back-reference from Mary to Eve,...For the Lord, having been born "the First-begotten of the dead," Revelation 1:5 and receiving into His bosom the ancient fathers, has regenerated them into the life of God, He having been made Himself the beginning of those that live, as Adam became the beginning of those who die. 1 Corinthians 15:20–22 Wherefore also Luke, commencing the genealogy with the Lord, carried it back to Adam, indicating that it was He who regenerated them into the Gospel of life, and not they Him. And thus also it was that the knot of Eve's disobedience was loosed by the obedience of Mary. For what the virgin Eve had bound fast through unbelief, this did the virgin Mary set free through faith.[259]

During the second century, the Gospel of James was also written. According to Stephen J. Shoemaker, "its interest in Mary as a figure in her own right and its reverence for her sacred purity mark the beginnings of Marian piety within early Christianity".[260]

3rd to 5th centuries

During the Age of Martyrs and at the latest in the fourth century, the majority of the most essential ideas of Marian devotion already appeared in some form – in the writings of the Church Fathers, apocrypha and visual arts. The lack of sources makes it unclear whether the devotion to Mary played a role in liturgical use during the first centuries of Christianity.[261] In the 4th century, Marian devotion in a liturgical context becomes evident.[262]

The earliest known Marian prayer (the Sub tuum praesidium, or Beneath Thy Protection) is from the 3rd century (perhaps 270), and its text was rediscovered in 1917 on a papyrus in Egypt.[263][264] According to some sources, Theonas of Alexandria consecrated one of the first holy places dedicated to Mary during the late 3rd century. An even earlier place has been found in Nazareth, dated to the previous century by some scholars.[265] Following the Edict of Milan in 313, by the 5th century artistic images of Mary began to appear in public and larger churches were being dedicated to Mary, such as the Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome.[266][267][268] At the Council of Ephesus in 431, Mary was officially declared the Theotokos, meaning "God-bearer"[269] or "Mother of God". The term had possibly been used for centuries[270] or at least since the early 300s, when it seems to have already been in established use.[271]

The Council of Ephesus was long thought to have been held at a church in Ephesus which had been dedicated to Mary about a hundred years before.[272][273][274] Though, recent archeological surveys indicate that St. Mary's Church in Ephesus did not exist at the time of the Council or, at least, the building was not dedicated to Mary before 500.[275] The Church of the Seat of Mary in Judea was built shortly after the introduction of Marian liturgy at the council of Ephesus, in 456, by a widow named Ikelia.[276]

According to the 4th-century heresiologist Epiphanius of Salamis, the Virgin Mary was worshipped as a mother goddess in the Christian sect of Collyridianism, which was found throughout Arabia sometime during the 300s AD. Collyridianism had women performing priestly acts, and made bread offerings to the Virgin Mary. The group was condemned as heretical by the Roman Catholic Church and was preached against by Epiphanius of Salamis, who wrote about the group in his writings titled Panarion.[277]

Byzantium

During the era of the Byzantine Empire, Mary was venerated as the virginal Mother of God and as an intercessor.[278]

Ephesus is a cultic centre of Mary, the site of the first church dedicated to her and the rumoured place of her death. Ephesus was previously a centre for worship of Artemis, a virgin goddess; the Temple of Artemis there is regarded as one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. The cult of Mary was furthered by Queen Theodora in the 6th century.[279][280] According to William E. Phipps, in the book Survivals of Roman Religion,[281] "Gordon Laing argues convincingly that the worship of Artemis as both virgin and mother at the grand Ephesian temple contributed to the veneration of Mary."[282]

Middle Ages

The Middle Ages saw many legends about Mary, her parents, and even her grandparents.[283] Mary's popularity increased dramatically from the 12th century,[284] linked to the Roman Catholic Church’s designation of Mary as Mediatrix.[285][286]

Post-Reformation

Over the centuries, devotion and veneration to Mary has varied greatly among Christian traditions. For instance, while Protestants show scant attention to Marian prayers or devotions, of all the saints whom the Orthodox venerate, the most honored is Mary, who is considered "more honorable than the Cherubim and more glorious than the Seraphim".[25]

Orthodox theologian Sergei Bulgakov wrote: "Love and veneration of the Blessed Virgin Mary is the soul of Orthodox piety. A faith in Christ which does not include his mother is another faith, another Christianity from that of the Orthodox church."[163]

Although the Catholics and the Orthodox may honor and venerate Mary, they do not view her as divine, nor do they worship her. Roman Catholics view Mary as subordinate to Christ, but uniquely so, in that she is seen as above all other creatures.[287] Similarly, Theologian Sergei Bulgakov wrote that the Orthodox view Mary as "superior to all created beings" and "ceaselessly pray for her intercession". However, she is not considered a "substitute for the One Mediator" who is Christ.[163] "Let Mary be in honor, but let worship be given to the Lord", he wrote.[288] Similarly, Catholics do not worship Mary as a divine being, but rather "hyper-venerate" her. In Roman Catholic theology, the term hyperdulia is reserved for Marian veneration, latria for the worship of God, and dulia for the veneration of other saints and angels.[289] The definition of the three level hierarchy of latria, hyperdulia and dulia goes back to the Second Council of Nicaea in 787.[290]

Devotions to artistic depictions of Mary vary among Christian traditions. There is a long tradition of Catholic Marian art and no image permeates Catholic art as does the image of Madonna and Child.[291] The icon of the Virgin Theotokos with Christ is, without doubt, the most venerated icon in the Orthodox Church.[292] Both Roman Catholic and Orthodox Christians venerate images and icons of Mary, given that the Second Council of Nicaea in 787 permitted their veneration with the understanding that those who venerate the image are venerating the reality of the person it represents,[293] and the 842 Synod of Constantinople confirming the same.[294] According to Orthodox piety and traditional practice, however, believers ought to pray before and venerate only flat, two-dimensional icons, and not three-dimensional statues.[295]

The Anglican position towards Mary is in general more conciliatory than that of Protestants at large and in a book he wrote about praying with the icons of Mary, Rowan Williams, former archbishop of Canterbury, said: "It is not only that we cannot understand Mary without seeing her as pointing to Christ; we cannot understand Christ without seeing his attention to Mary."[120][296]

On 4 September 1781, 11 families of pobladores arrived from the Gulf of California and established a city in the name of King Carlos III. The small town was named El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora de los Ángeles de la Porciúncula (after our Lady of the Angels), a city that today is known simply as Los Angeles. In an attempt to revive the custom of religious processions within the Archdiocese of Los Angeles, in September 2011 the Queen of Angels Foundation, and founder Mark Anchor Albert, inaugurated an annual Grand Marian Procession in the heart of Downtown Los Angeles' historic core. This yearly procession, held on the last Saturday of August and intended to coincide with the anniversary of the founding of the City of Los Angeles, begins at the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels and concludes at the parish of La Iglesia de Nuestra Señora Reina de los Angeles which is part of the Los Angeles Plaza Historic District, better known as "La Placita".[citation needed]

Feasts

The earliest feasts that relate to Mary grew out of the cycle of feasts that celebrated the Nativity of Jesus. Given that according to the Gospel of Luke (Luke 2:22–40),[297] 40 days after the birth of Jesus, along with the Presentation of Jesus at the Temple, Mary was purified according to Jewish customs. The Feast of the Purification began to be celebrated by the 5th century, and became the "Feast of Simeon" in Byzantium.[298]

In the 7th and 8th centuries, four more Marian feasts were established in Eastern Christianity. In the West, a feast dedicated to Mary, just before Christmas was celebrated in the Churches of Milan and Ravenna in Italy in the 7th century. The four Roman Marian feasts of Purification, Annunciation, Assumption and Nativity of Mary were gradually and sporadically introduced into England by the 11th century.[298]

Over time, the number and nature of feasts (and the associated Titles of Mary) and the venerative practices that accompany them have varied a great deal among diverse Christian traditions. Overall, there are significantly more titles, feasts and venerative Marian practices among Roman Catholics than any other Christians traditions.[119] Some such feasts relate to specific events, such as the Feast of Our Lady of Victory, based on the 1571 victory of the Papal States in the Battle of Lepanto.[299][300]

Differences in feasts may also originate from doctrinal issues—the Feast of the Assumption is such an example. Given that there is no agreement among all Christians on the circumstances of the death, Dormition or Assumption of Mary, the feast of assumption is celebrated among some denominations and not others.[24][301] While the Catholic Church celebrates the Feast of the Assumption on 15 August, some Eastern Catholics celebrate it as Dormition of the Theotokos, and may do so on 28 August, if they follow the Julian calendar. The Eastern Orthodox also celebrate it as the Dormition of the Theotokos, one of their 12 Great Feasts. Protestants do not celebrate this, or any other Marian feasts.[24]

Relics

The veneration of marian relics used to be common practice before the Reformation. It was later largely surpassed by the veneration of marian images.

Bodily relics

As Mary's body is believed by most Christians to have been taken up into the glory of heaven, her bodily relics have been limited to hair, nails and breast milk.

According to John Calvin's 1543 Treatise on Relics, her hair was exposed for veneration in several churches, including in Rome, Saint-Flour, Cluny and Nevers.[302]

In this book, Calvin criticized the veneration of the Holy Milk due to the lack of biblical references to it and the doubts about the veracity of such relics:

With regard to the milk, there is not perhaps a town, a convent, or nunnery, where it is not shown in large or small quantities. Indeed, had the Virgin been a wet-nurse her whole life, or a dairy, she could not have produced more than is shown as hers in various parts. How they obtained all this milk they do not say, and it is superfluous here to remark that there is no foundation in the Gospels for these foolish and blasphemous extravagances.

Although the veneration of Marian bodily relics is no longer a common practice today, there are some remaining traces of it, such as the Chapel of the Milk Grotto in Bethlehem, named after Mary's milk.

Clothes

Clothes which are believed to have belonged to Mary include the Cincture of the Theotokos kept in the Vatopedi monastery and her Holy Girdle kept in Mount Athos.

Other relics are said to have been collected during later marian apparitions, such as her robe, veil, and part of her belt which were kept in Blachernae church in Constantinople after she appeared there during the 10th century. These relics, now lost, are celebrated by the Eastern Orthodox and Byzantine Catholic Churches as the Intercession of the Theotokos.

Few other objects are said to have been touched or given by Mary during apparitions, notably a 1531 image printed on a tilma, known as Our Lady of Guadalupe, belonging to Juan Diego.

Places

Places where Mary is believed to have lived include the Basilica della Santa Casa in Loreto, Marche, and the House of the Virgin Mary in Ephesus.

Eastern Christians believe that she died and was put in the Tomb of the Virgin Mary near Jerusalem before the Assumption.

The belief that Mary's house was in Ephesus is recent, as it was claimed in the 19th century based on the visions of Anne Catherine Emmerich, an Augustinian nun in Germany.[303][304] It has since been named as the House of the Virgin Mary by Roman Catholic pilgrims who consider it the place where Mary lived until her assumption.[305][306][307][308] The Gospel of John states that Mary went to live with the Disciple whom Jesus loved,[309] traditionally identified as John the Evangelist[310] and John the Apostle. Irenaeus and Eusebius of Caesarea wrote in their histories that John later went to Ephesus, which may provide the basis for the early belief that Mary also lived in Ephesus with John.[311][312]

The apparition of Our Lady of the Pillar in the first century was believed to be a bilocation, as it occurred in Spain while Mary was living in Ephesus or Jerusalem. The pillar on which she was standing during the apparition is believed to be kept in the Cathedral-Basilica of Our Lady of the Pillar in Zaragoza and is therefore venerated as a relics, as it was in physical contact with Mary.

In arts

Iconography

In paintings, Mary is traditionally portrayed in blue. This tradition can trace its origin to the Byzantine Empire, from c. 500 AD, where blue was "the colour of an empress". A more practical explanation for the use of this colour is that in Medieval and Renaissance Europe, the blue pigment was derived from the rock lapis lazuli, a stone of greater value than gold, which was imported from Afghanistan. Beyond a painter's retainer, patrons were expected to purchase any gold or lapis lazuli to be used in the painting. Hence, it was an expression of devotion and glorification to swathe the Virgin in gowns of blue. Transformations in visual depictions of Mary from the 13th to 15th centuries mirror her "social" standing within the Church and in society.[313]

Traditional representations of Mary include the crucifixion scene, called Stabat Mater.[314][315] While not recorded in the Gospel accounts, Mary cradling the dead body of her son is a common motif in art, called a "pietà" or "pity".

In the Egyptian, Eritrean, and Ethiopian tradition, Mary has been portrayed in story and paint for centuries.[316] Beginning in the 1600s, however, highland Ethiopians began portraying Mary performing a variety of miracles for the faithful, including paintings of her giving water to a thirsty dog, healing monks with her breast milk, and saving a man eaten by a crocodile.[317] Over 1,000 such stories about her exist in this tradition, and about one hundred of those have hundreds of paintings each, in various manuscripts, adding up to thousands of paintings.[318]

-

Our Lady of Vladimir, a Byzantine representation of the Theotokos

-

Theotokos Panachranta, from the 11th century Gertrude Psalter

-

Chinese Madonna, St. Francis' Church, Macao

-

Adoration of the Magi, Rubens, 1634

-

Virgin and Child, French (15th century)

-

Mary and Jesus, outside the Jongno Catholic Church in Seoul, South Korea.

-

Statue of Mary and Jesus at Gwanghwamun, pictured at the time of Pope Francis' visit to South Korea, 2014.

-

Mary outside St. Nikolai Catholic Church in Ystad 2021

-

A kneeling Virgin Mary pictured in the former coat of arms of Maaria

Cinematic portrayals

Mary has been portrayed in various films and on television, including:

- The Miracle (1912) color silent film of the 1911 play The Miracle, a statue of Mary, played by Maria Carmi, comes to life

- Das Mirakel (1912) silent film; a German version of the 1911 play The Miracle

- The Song of Bernadette (1943 film), played by Linda Darnell.

- The Living Christ Series (1951 non-theatrical, non-television film twelve-part series), played by Eileen Rowe.

- The Miracle of Our Lady of Fatima (1952 film), played by Virginia Gibson.

- Ben-Hur (1959 film), played by José Greci.[319]

- The Miracle (1959 film; a loose remake of the 1912 film Das Mirakel)

- King of Kings (1961 film), played by Siobhán McKenna.[320]

- The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965 film), played by Dorothy McGuire.[321]

- Jesus of Nazareth (1977 two-part television miniseries), played by Olivia Hussey.[322]

- The Last Temptation of Christ (1988 film), played by Verna Bloom.[323]

- Mary, Mother of Jesus (1999 television film), played by Pernilla August.[324]

- Saint Mary (2002 film), played by Shabnam Gholikhani.[325]

- The Passion of the Christ (2004 film), played by Maia Morgenstern.[326]

- Imperium: Saint Peter (2005 television film), played by Lina Sastri.

- Color of the Cross (2006 film), played by Debbi Morgan.[327]

- The Nativity Story (2006 film), played by Keisha Castle-Hughes.[328]

- The Passion (2008 television miniseries), played by Paloma Baeza.[329][330]

- The Nativity (2010 four-part miniseries), played by Tatiana Maslany.

- Mary of Nazareth (2012 film), played by Alissa Jung.

- Son of God (2014 film), played by Roma Downey.[331]

- The Chosen (2017 TV series), played by Vanessa Benavente.

- Mary Magdalene (2018 film), played by Irit Sheleg.[332]

- Jesus: His Life (2019 TV series), played by Houda Echouafni.[333]

- Fatima (2020 film), played by Joana Ribeiro.

Music

- Claudio Monteverdi: Vespro della Beata Vergine (1610)

- Johann Sebastian Bach: Magnificat (1723, rev. 1733)

- Franz Schubert: Ave Maria (1835)

- Charles Gounod: Ave Maria (1859)

- John Tavener: Mother and Child, setting a poem by Brian Keeble for choir, organ and temple gong (2002)

See also

Notes

- ^ if we got the early Christian traditions on Mary's birthday on September 8th and Jesus's birthday on December 25th we would get that Mary would be 17 when giving birth to Jesus

- ^ Per the Jewish customs surrounding marriage at the time, and the apocryphal Gospel of James, Mary was approximately 16-17[a] years old when giving birth to Jesus.[1] Her year of birth is therefore contingent on that of Jesus, and though some posit slightly different dates (such as Meier's dating of c. 7 or 6 BC)[2] general consensus places Jesus' birth in c. 4 BC,[3] thus placing Mary's birth in c. 20 BC.

- ^ Hebrew: מִרְיָם, romanized: Mīryām; Classical Syriac: ܡܪܝܡ, romanized: Maryam; Arabic: مريم, romanized: Maryam; Ancient Greek: Μαρία, romanized: María; Latin: Maria; Coptic: Ⲙⲁⲣⲓⲁ, romanized: Maria

- ^ παρθένος; Matthew 1:23[12] uses the Greek parthénos, "virgin", whereas only the Hebrew of Isaiah 7:14,[13] from which the New Testament ostensibly quotes, as Almah – "young maiden". See article on parthénos in Bauercc/(Arndt)/Gingrich/Danker, A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature.[14]

- ^ See Sabine R. Huebner's succinct analysis of the issue: "Jesus is described as the 'first-born son' of Mary in Mt 1:25 and Lk 2:7. From this wording alone we can conclude that there were later-born sons […] The family […] had at least five sons and an unknown number of daughters."[21]

- ^ To give a few examples, Our Lady of Good Counsel, Our Lady of Navigators, and Our Lady Undoer of Knots fit this description.[38][39][40][41]

- ^ This event is described by some Christians as the Annunciation.

- ^ The historicity of this census' relationship to the birth of Jesus continues to be one of scholarly disagreement; see, for example, p. 71 in Edwards, James R. (2015).[76]

- ^ Alternately: "It cannot even be denied that God conferred the highest honour on Mary, by choosing and appointing her to be the mother of his Son."[175][176]

- ^ See the following verses: 5:114, 5:116, 7:158, 9:31, 17:57, 17:104, 18:102, 19:16, 19:17, 19:18, 19:20, 19:22, 19:24, 19:27, 19:28, 19:29, 19:34, 21:26, 21:91, 21:101, 23:50, 25:17, 33:7, 39:45, 43:57, 43:61, 57:27, 61:6, 61:14, 66:12.

References

- ^ "CHURCH FATHERS: Protoevangelium of James". www.newadvent.org. Retrieved 27 August 2024.

And she was sixteen years old when these mysteries happened.

- ^ Meier, John P. (1991). A Marginal Jew: The Roots of the Problem and the Person. Yale University Press. p. 407. ISBN 978-0-300-14018-7.

- ^ Sanders, E. P. (1993). The Historical Figure of Jesus. Allen Lane Penguin Press. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-0-14-192822-7. Archived from the original on 18 April 2017. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- ^ "Catholic Enncyclopedia: Tomb of the Blessed Virgin Mary". New Advent. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ "Tomb of Mary: Location and Significance: University of Dayton, Ohio". udayton.edu. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ Raymond Edward Brown; Joseph A. Fitzmyer; Karl Paul Donfried (1978). Mary in the New Testament. NJ: Paulist Press. p. 140. ISBN 978-0809121687. Archived from the original on 17 August 2021. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

...consonant with Mary's Jewish background

- ^ "Liturgy of the Assyrian Church of the East".

- ^ Quran 3:42; cited in Stowasser, Barbara Freyer, "Mary", in: Encyclopaedia of the Qurʾān, General Editor: Jane Dammen McAuliffe, Georgetown University, Washington DC.

- ^ J.D. McAuliffe, Chosen of all women

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jestice, Phyllis G. Holy people of the world: a cross-cultural encyclopedia, Volume 3. 2004 ISBN 1-57607-355-6 p. 558 Sayyidana Maryam Archived 27 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Bowman, Glenn (2012). Sharing the Sacra: The Politics and Pragmatics of Intercommunal Relations Around Holy Places. Berghahn Books. p. 17. ISBN 9780857454867.

- ^ Matthew 1:23

- ^ Isaiah 7:14

- ^ Bauercc/(Arndt)/Gingrich/Danker, A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature, 2nd ed., University of Chicago Press, 1979, p. 627.

- ^ Mark Miravalle, Raymond L. Burke; (2008). Mariology: A Guide for Priests, Deacons, Seminarians, and Consecrated Persons ISBN 978-1-57918-355-4 p. 178

- ^ Mary for evangelicals by Tim S. Perry, William J. Abraham 2006 ISBN 0-8308-2569-X p. 142

- ^ "Mary, the mother of Jesus." The New Dictionary of Cultural Literacy, Houghton Mifflin. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2002. Credo Reference. Web. 28 September 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Encyclopedia of Protestantism, Volume 3 2003 by Hans Joachim Hillerbrand ISBN 0-415-92472-3 p. 1174 Archived 5 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Mary", A Dictionary of First Names by Patrick Hanks, Kate Hardcastle and Flavia Hodges (2006). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198610602.

- ^ Matthew 1:25

- ^ Sabine R. Huebner, Papyri and the Social World of the New Testament (Cambridge University Press, 2019), p. 73. ISBN 1108470254

- ^ Fulbert of Chatres, O Beata Virgo Maria, archived from the original on 4 March 2021, retrieved 27 March 2020

- ^ Encyclopedia of Catholicism by Frank K. Flinn, J. Gordon Melton, 2007, ISBN 0-8160-5455-X, pp. 443–444

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Hillerbrand, Hans Joachim. Encyclopedia of Protestantism, Volume 3, 2003. ISBN 0-415-92472-3, p. 1174