Евангелизм

| Часть серии о |

| протестантизм |

|---|

|

|

|

| Часть серии о |

| христианство |

|---|

|

Евангелизм ( / ˌ iː v æ n ˈ dʒ ɛ l ɪ k əl ɪ z əm , ˌ ɛ v æ n -, - ə n -/ ), также называемый евангелическим христианством или евангелическим протестантизмом , представляет собой всемирное межконфессиональное движение внутри протестантского христианства , которое подчеркивает центральную роль распространения «благих новостей» христианства, « рождения свыше », в ходе которого человек переживает личное обращение, авторитетно руководствуясь Библией , Божьим откровением человечеству. [ 1 ] [ 2 ] [ 3 ] [ 4 ] [ 5 ] Слово евангелический происходит от греческого слова, означающего « хорошие новости » ( евангелион ). [ 6 ]

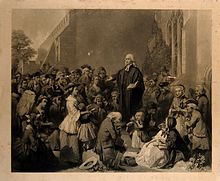

Богословская в природа евангелизма была впервые исследована во время протестантской Реформации Европе 16 века . Мартина Лютера , В «Девяносто пяти тезисах» изданных в 1517 году, подчеркивалось, что Священные Писания и проповедь Евангелия имеют высшую власть над церковной практикой . Истоки современного евангелизма обычно относят к 1738 году, при этом различные богословские течения способствовали его основанию, включая пиетизм и радикальный пиетизм , пуританство , квакерство и моравианство (в частности, его епископ Николаус Зинцендорф и его община в Хернхуте ). [ 7 ] [ 8 ] [ 9 ] В первую очередь, Джон Уэсли и другие ранние методисты стояли у истоков этого нового движения во время Первого Великого Пробуждения . Сегодня евангелисты встречаются во многих протестантских ветвях, а также в различных конфессиях по всему миру, не отнесенные к какой-либо конкретной ветви. [ 10 ] Среди лидеров и крупных деятелей евангелического протестантского движения были Николаус Зинцендорф , Джордж Фокс , Джон Уэсли , Джордж Уайтфилд , Джонатан Эдвардс , Билли Грэм , Билл Брайт , Гарольд Окенга , Гудина Тумса , Джон Стотт , Франсиско Оласабаль , Уильям Дж. Сеймур и Мартин Ллойд-Джонс . [ 7 ] [ 9 ] [ 11 ] [ 12 ] [ 13 ]

Движение уже давно присутствует в англосфере, а затем распространилось дальше в 19, 20 и начале 21 веков. Движение получило значительный импульс в 18 и 19 веках с Великим Пробуждением в евангелических Соединённых Штатах и Великобритании .

По состоянию на 2016 год [update] По оценкам, в мире насчитывается 619 миллионов евангелистов, а это означает, что каждый четвертый христианин может быть отнесен к евангелистам. [ 14 ] В Соединенных Штатах самая большая доля евангелистов в мире. [ 15 ] Американские евангелисты составляют четверть населения страны и ее самую крупную религиозную группу . [ 16 ] [ 17 ] В качестве трансконфессиональной коалиции евангелистов можно встретить почти в каждой протестантской деноминации и традиции, особенно в реформатских ( континентальных реформатских , англиканских , пресвитерианских , конгрегационалистских ), Плимутских братьях , баптистских , методистских ( уэслианско-арминианских ), лютеранских , моравских , свободных церквях. , Меннониты , Квакеры , Пятидесятнические / харизматические и внеконфессиональные церкви. [ 18 ] [ 19 ] [ 20 ] [ 21 ] [ 12 ]

Терминология

[ редактировать ]Слово «евангелический» имеет этимологические корни в греческом слове, означающем « евангелие » или «хорошие новости»: εὐαγγέλιον euangelion , от eu «добрый», ангел — , основа среди прочего, от angelos «вестник, ангел» и среднего рода. суффикс -ион . [ 22 ] К английскому Средневековью этот термин семантически расширился и включил не только послание, но и Новый Завет , который содержал это послание, а также, более конкретно, Евангелия , в которых изображена жизнь, смерть и воскресение Иисуса . [ 23 ] Первое опубликованное использование слова «евангелистский» на английском языке было в 1531 году, когда Уильям Тиндейл написал: «Он призывает их постоянно следовать евангельской истине». Год спустя Томас Мор написал самое раннее зарегистрированное употребление термина в отношении богословского различия, когда он говорил о «Тиндейле [и] его брате-евангелисте Барнсе». [ 24 ]

During the Reformation, Protestant theologians embraced the term as referring to "gospel truth." Martin Luther referred to the evangelische Kirche ("evangelical church") to distinguish Protestants from Catholics in the Catholic Church.[25][26] Into the 21st century, evangelical has continued in use as a synonym for Mainline Protestant in continental Europe. This usage is reflected in the names of Protestant denominations, such as the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America.[23] The German term evangelisch more accurately corresponds to the broad English term Protestant[27] and should not be confused with the narrower German term evangelikal, or the term pietistisch (a term etymologically related to the Pietist and Radical Pietist movements), which are used to described Evangelicalism in the sense used in this article. Mainline Protestant denominations with a Lutheran or semi-Lutheran background, like the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Canada, and the Evangelical Lutheran Church of England, who are not evangelical in the evangelikal sense but Protestant in the evangelisch sense, have translated the German term evangelisch (or Protestant) into the English term Evangelical, although the two German words have different meanings.[27] In other parts of the world, especially in the English-speaking world, evangelical (German: evangelikal or pietistisch) is commonly applied to describe the interdenominational Born-Again believing movement.[28][29][30][31][32]

Christian historian David W. Bebbington writes that, "Although 'evangelical,' with a lower-case initial, is occasionally used to mean 'of the gospel,' the term 'Evangelical' with a capital letter, is applied to any aspect of the movement beginning in the 1730s."[33] According to the Oxford English Dictionary, evangelicalism was first used in 1831.[34] In 1812, the term evangelicalism appeared in The History of Lynn by William Richards.[35] In the summer of 1811 the term evangelicalists was used in The Sin and Danger of Schism by Rev. Dr. Andrew Burnaby, Archdeacon of Leicester.[36]

The term may also be used outside any religious context to characterize a generic missionary, reforming, or redeeming impulse or purpose. For example, The Times Literary Supplement refers to "the rise and fall of evangelical fervor within the Socialist movement."[37] This usage refers to evangelism, rather than evangelicalism as discussed here; though sharing an etymology and conceptual basis, the words have diverged significantly in meaning.

Beliefs

[edit]

One influential definition of evangelicalism has been proposed by historian David Bebbington.[38] Bebbington notes four distinctive aspects of evangelical faith: conversionism, biblicism, crucicentrism, and activism, noting, "Together they form a quadrilateral of priorities that is the basis of Evangelicalism."[39]

Conversionism, or belief in the necessity of being "born again," has been a constant theme of evangelicalism since its beginnings.[3] To evangelicals, the central message of the gospel is justification by faith in Christ and repentance, or turning away, from sin. Conversion differentiates the Christian from the non-Christian, and the change in life it leads to is marked by both a rejection of sin and a corresponding personal holiness of life. A conversion experience can be emotional, including grief and sorrow for sin followed by great relief at receiving forgiveness. The stress on conversion differentiates evangelicalism from other forms of Protestantism by the associated belief that an assurance will accompany conversion.[40] Among evangelicals, individuals have testified to both sudden and gradual conversions.[41][42]

Biblicism is reverence for the Bible and high regard for biblical authority. All evangelicals believe in biblical inspiration, though they disagree over how this inspiration should be defined. Many evangelicals believe in biblical inerrancy, while other evangelicals believe in biblical infallibility.[43]

Crucicentrism is the centrality that evangelicals give to the Atonement, the saving death and the resurrection of Jesus, that offers forgiveness of sins and new life. This is understood most commonly in terms of a substitutionary atonement, in which Christ died as a substitute for sinful humanity by taking on himself the guilt and punishment for sin.[44]

Activism describes the tendency toward active expression and sharing of the gospel in diverse ways that include preaching and social action. This aspect of evangelicalism continues to be seen today in the proliferation of evangelical voluntary religious groups and parachurch organizations.[45]

Church government and organizations

[edit]

The word church has several meanings among evangelicals. It can refer to the universal church (the body of Christ) including all Christians everywhere.[46] It can also refer to the church (congregation), which is the visible representation of the invisible church. It is responsible for teaching and administering the sacraments or ordinances (baptism and the Lord's Supper, but some evangelicals also count footwashing as an ordinance as well).[47]

Many evangelical traditions adhere to the doctrine of the believers' Church, which teaches that one becomes a member of the Church by the new birth and profession of faith.[48][21] This originated in the Radical Reformation with Anabaptists[49] but is held by denominations that practice believer's baptism.[50] Evangelicals in the Anglican, Methodist and Reformed traditions practice infant baptism as one's initiation into the community of faith and the New Testament counterpart to circumcision, while also stressing the necessity of personal conversion later in life for salvation.[51][52][53]

Some evangelical denominations operate according to episcopal polity or presbyterian polity. However, the most common form of church government within Evangelicalism is congregational polity. This is especially common among nondenominational evangelical churches.[54] Many churches are members of a national and international denomination for a cooperative relationship in common organizations, for the mission and social areas, such as humanitarian aid, schools, theological institutes and hospitals.[55][56][57][58] Common ministries within evangelical congregations are pastor, elder, deacon, evangelist and worship leader.[59] The ministry of bishop with a function of supervision over churches on a regional or national scale is present in all the Evangelical Christian denominations, even if the titles president of the council or general overseer are mainly used for this function.[60][61] The term bishop is explicitly used in certain denominations.[62] Some evangelical denominations are members of the World Evangelical Alliance and its 129 national alliances.[63]

Some evangelical denominations officially authorize the ordination of women in churches.[64] The female ministry is justified by the fact that Mary Magdalene was chosen by Jesus to announce his resurrection to the apostles.[65] The first Baptist woman who was consecrated pastor is the American Clarissa Danforth in the denomination Free Will Baptist in 1815.[66] In 1882, in the American Baptist Churches USA.[67] In the Assemblies of God of the United States, since 1927.[68] In 1965, in the National Baptist Convention, USA.[69] In 1969, in the Progressive National Baptist Convention.[70] In 1975, in The Foursquare Church.[71]

Worship service

[edit]

For evangelicals, there are three interrelated meanings to the term worship. It can refer to living a "God-pleasing and God-focused way of life," specific actions of praise to God, and a public worship service.[72] Diversity characterizes evangelical worship practices. Liturgical, contemporary, charismatic and seeker-sensitive worship styles can all be found among evangelical churches. Overall, evangelicals tend to be more flexible and experimental with worship practices than mainline Protestant churches.[73] It is usually run by a Christian pastor. A service is often divided into several parts, including congregational singing, a sermon, intercessory prayer, and other ministry.[74][75][76][77] During worship there is usually a nursery for babies.[78] Children and young people receive an adapted education, Sunday school, in a separate room.[79]

Places of worship are usually called "churches."[80][81][82] In some megachurches, the building is called "campus."[83][84] The architecture of places of worship is mainly characterized by its sobriety.[85][86] The Latin cross is one of the only spiritual symbols that can usually be seen on the building of an evangelical church and that identifies the place's belonging.[87][88]

Some services take place in theaters, schools or multipurpose rooms, rented for Sunday only.[89][90][91] Because of their understanding of the second of the Ten Commandments, some evangelicals do not have religious material representations such as statues, icons, or paintings in their places of worship.[92][93] There is usually a baptistery on what is variously known as the chancel (also called sanctuary) or stage, though they may be alternatively found in a separate room, for the baptisms by immersion.[94][95]

In some countries of the world which apply sharia or communism, government authorizations for worship are complex for Evangelical Christians.[96][97][98] Because of persecution of Christians, Evangelical house churches are the only option for many Christians to live their faith in community.[99] For example, there is the Evangelical house churches in China movement.[100] The meetings thus take place in private houses, in secret and in illegality.[101]

The main Christian feasts celebrated by the Evangelicals are Christmas, Pentecost (by a majority of Evangelical denominations) and Easter for all believers.[102][103][104]

Education

[edit]

Evangelical churches have been involved in the establishment of elementary and secondary schools.[105] It also enabled the development of several bible colleges, colleges and universities in the United States during the 19th century.[106][107] Other evangelical universities have been established in various countries of the world.[108]

The Council for Christian Colleges and Universities was founded in 1976.[109][110] In 2023, the CCCU had 185 members in 21 countries.[111]

The Association of Christian Schools International was founded in 1978 by 3 American associations of evangelical Christian schools.[112] Various international schools have joined the network.[113] In 2023, it had 23,000 schools in 100 countries.[114]

The International Council for Evangelical Theological Education was founded in 1980 by the Theological Commission of the World Evangelical Alliance.[115] In 2023, it had 850 member schools in 113 countries.[116]

Sexuality

[edit]

In matters of sexuality, there is a wide variety of thought among evangelicals and evangelical churches, but they tend to be conservative and prescriptive in general.[117] Many evangelical churches promote the virginity pledge (abstinence pledge) among young evangelical Christians, who are invited to commit themselves, during a public ceremony, to sexual abstinence until Christian marriage.[118] This pledge is often symbolized by a purity ring.[119]

In some evangelical churches, young adults and unmarried couples are encouraged to marry early in order to live a sexuality according to the will of God.[120][121]

A 2009 American study of the National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy reported that 80 percent of young, unmarried evangelicals have had sex and that 42 percent were in a relationship with sex, when surveyed.[122]

The majority of evangelical Christian churches are against abortion and support adoption agencies and social support agencies for young mothers.[123]

Masturbation is seen as forbidden by some evangelical pastors because of the sexual thoughts that may accompany it.[124][125] However, evangelical pastors have pointed out that the practice has been erroneously associated with Onan by scholars, that it is not a sin if it is not practiced with fantasies or compulsively, and that it was useful in a married couple, if his or her partner did not have the same frequency of sexual needs.[126][127]

Some evangelical churches speak only of sexual abstinence and do not speak of sexuality in marriage.[128][129][130] Other evangelical churches in the United States and Switzerland speak of satisfying sexuality as a gift from God and a component of a Christian marriage harmonious, in messages during worship services or conferences.[131][132][133] Many evangelical books and websites are specialized on the subject.[134][135] The book The Act of Marriage: The Beauty of Sexual Love published in 1976 by Baptist pastor Tim LaHaye and his wife Beverly LaHaye was a pioneer in the field.[136]

The perceptions of homosexuality in the Evangelical Churches are varied. They range from liberal to fundamentalist or moderate conservative and neutral.[137][138] A 2011 Pew Research Center study found that 84 percent of evangelical leaders surveyed believed homosexuality should be discouraged.[139] It is in the fundamentalist conservative positions that there are antigay activists on TV or radio who claim that homosexuality is the cause of many social problems, such as terrorism.[140][141][142] Some churches have a conservative moderate position.[143] Although they do not approve homosexual practices, they claim to show sympathy and respect for homosexuals.[144] Some evangelical denominations have adopted neutral positions, leaving the choice to local churches to decide for same-sex marriage.[145][146] There are some international evangelical denominations that are gay-friendly.[147][148]

Christian marriage is presented by some churches as a protection against sexual misconduct and a compulsory step to obtain a position of responsibility in the church.[149] This concept, however, has been challenged by numerous sex scandals involving married evangelical leaders.[150][151] Finally, evangelical theologians recalled that celibacy should be more valued in the Church today, since the gift of celibacy was taught and lived by Jesus Christ and Paul of Tarsus.[152][153]

Other views

[edit]For a majority of evangelical Christians, a belief in biblical inerrancy ensures that the miracles described in the Bible are still relevant and may be present in the life of the believer.[154][155] Healings, academic or professional successes, the birth of a child after several attempts, the end of an addiction, etc., would be tangible examples of God's intervention with the faith and prayer, by the Holy Spirit.[156] In the 1980s, the neo-charismatic movement re-emphasized miracles and faith healing.[157] In certain churches, a special place is thus reserved for faith healings with laying on of hands during worship services or for evangelization campaigns.[158][159] Faith healing or divine healing is considered to be an inheritance of Jesus acquired by his death and resurrection.[160] This view is typically ascribed to Pentecostal denominations, and not others that are cessationist (believing that miraculous gifts have ceased.)

In terms of denominational beliefs regarding science and the origin of the earth and human life, some evangelicals support young Earth creationism.[161] For example, Answers in Genesis, founded in Australia in 1986, is an evangelical organization that seeks to defend the thesis.[162] In 2007, they founded the Creation Museum in Petersburg, in Kentucky[163] and in 2016 the Ark Encounter in Williamstown.[164] Since the end of the 20th century, literalist creationism has been abandoned by some evangelicals in favor of intelligent design.[165] For example, the think tank Discovery Institute, established in 1991 in Seattle, defends this thesis.[166] Other evangelicals who accept the scientific consensus on evolution and the age of Earth believe in theistic evolution or evolutionary creation—the notion that God used the process of evolution to create life; a Christian organization that espouses this view is the BioLogos Foundation.[167]

Diversity

[edit]

The Reformed, Baptist, Methodist, Pentecostal, Churches of Christ, Plymouth Brethren, charismatic Protestant, and nondenominational Protestant traditions have all had strong influence within contemporary evangelicalism.[168][8] Some Anabaptist denominations (such as the Brethren Church)[169] are evangelical, and some Lutherans self-identify as evangelicals. There are also evangelical Anglicans and Quakers.[170][7][171]

In the early 20th century, evangelical influence declined within mainline Protestantism and Christian fundamentalism developed as a distinct religious movement. Between 1950 and 2000 a mainstream evangelical consensus developed that sought to be more inclusive and more culturally relevant than fundamentalism while maintaining theologically conservative Protestant teaching. According to Brian Stanley, professor of world Christianity, this new postwar consensus is termed neoevangelicalism, the new evangelicalism, or simply evangelicalism in the United States, while in Great Britain and in other English-speaking countries, it is commonly termed conservative evangelicalism. Over the years, less conservative evangelicals have challenged this mainstream consensus to varying degrees. Such movements have been classified by a variety of labels, such as progressive, open, postconservative, and postevangelical.[172]

Evangelical leaders like Tony Perkins of the Family Research Council have called attention to the problem of equating the term Christian right with theological conservatism and Evangelicalism. Although evangelicals constitute the core constituency of the Christian right within the United States, not all evangelicals fit that political description (and not all of the Christian right are evangelicals).[173] The problem of describing the Christian right which in most cases is conflated with theological conservatism in secular media, is further complicated by the fact that the label religious conservative or conservative Christian applies to other religious groups who are theologically, socially, and culturally conservative but do not have overtly political organizations associated with some of these Christian denominations, which are usually uninvolved, uninterested, apathetic, or indifferent towards politics.[173][174] Tim Keller, an Evangelical theologian and Presbyterian Church in America pastor, shows that Conservative Christianity (theology) predates the Christian right (politics), and that being a theological conservative did not necessitate being a political conservative, that some political progressive views around economics, helping the poor, the redistribution of wealth, and racial diversity are compatible with theologically conservative Christianity.[175][176] Rod Dreher, a senior editor for The American Conservative, a secular conservative magazine, also argues the same differences, even claiming that a "traditional Christian" a theological conservative, can simultaneously be left on economics (economic progressive) and even a socialist at that while maintaining traditional Christian beliefs.[177][5]

Outside of self-consciously evangelical denominations, there is a broader "evangelical streak" in mainline Protestantism.[48] Mainline Protestant churches predominantly have a liberal theology while evangelical churches predominantly have a fundamentalist or moderate conservative theology.[178][179][180][181]

Some commentators have complained that Evangelicalism as a movement is too broad and its definition too vague to be of any practical value. Theologian Donald Dayton has called for a "moratorium" on use of the term.[182] Historian D. G. Hart has also argued that "evangelicalism needs to be relinquished as a religious identity because it does not exist".[183]

Christian fundamentalism

[edit]Christian fundamentalism has been called a subset[184] or "subspecies"[185] of Evangelicalism. Fundamentalism[186] regards biblical inerrancy, the virgin birth of Jesus, penal substitutionary atonement, the literal resurrection of Christ, and the Second Coming of Christ as fundamental Christian doctrines.[187] Fundamentalism arose among evangelicals in the 1920s—primarily as an American phenomenon, but with counterparts in Britain and British Empire[185]—to combat modernist or liberal theology in mainline Protestant churches. Failing to reform the mainline churches, fundamentalists separated from them and established their own churches, refusing to participate in ecumenical organizations (such as the National Council of Churches, founded in 1950), and making separatism (rigid separation from nonfundamentalist churches and their culture) a true test of faith. Most fundamentalists are Baptists and dispensationalist [188] or Pentecostals and Charismatics.[189]

Great emphasis is placed on the literal interpretation of the Bible as the primary method of Bible study as well as the biblical inerrancy and the infallibility of their interpretation.[190]

Mainstream varieties

[edit]

Mainstream evangelicalism is historically divided between two main orientations: confessionalism and revivalism. These two streams have been critical of each other. Confessional evangelicals have been suspicious of unguarded religious experience, while revivalist evangelicals have been critical of overly intellectual teaching that (they suspect) stifles vibrant spirituality.[191] In an effort to broaden their appeal, many contemporary evangelical congregations intentionally avoid identifying with any single form of evangelicalism. These "generic evangelicals" are usually theologically and socially conservative, but their churches often present themselves as nondenominational (or, if a denominational member, strongly deemphasize its ties to such, such as a church name which excludes the denominational name) within the broader evangelical movement.[192]

In the words of Albert Mohler, president of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, confessional evangelicalism refers to "that movement of Christian believers who seek a constant convictional continuity with the theological formulas of the Protestant Reformation". While approving of the evangelical distinctions proposed by Bebbington, confessional evangelicals believe that authentic evangelicalism requires more concrete definition in order to protect the movement from theological liberalism and from heresy. According to confessional evangelicals, subscription to the ecumenical creeds and to the Reformation-era confessions of faith (such as the confessions of the Reformed churches) provides such protection.[193] Confessional evangelicals are represented by conservative Presbyterian churches (emphasizing the Westminster Confession), certain Baptist churches that emphasize historic Baptist confessions such as the Second London Confession, evangelical Anglicans who emphasize the Thirty-Nine Articles (such as in the Anglican Diocese of Sydney, Australia[194]), Methodist churches that adhere to the Articles of Religion, and some confessional Lutherans with pietistic convictions.[195][170]

The emphasis on historic Protestant orthodoxy among confessional evangelicals stands in direct contrast to an anticreedal outlook that has exerted its own influence on evangelicalism, particularly among churches strongly affected by revivalism and by pietism. Revivalist evangelicals are represented by some quarters of Methodism, the Wesleyan Holiness churches, the Pentecostal and charismatic churches, some Anabaptist churches, and some Baptists and Presbyterians.[170] Revivalist evangelicals tend to place greater emphasis on religious experience than their confessional counterparts.[191]

Moderate evangelicals

[edit]Moderate evangelical Christianity emerged in the 1940s in the United States in response to the Fundamentalist movement of the 1910s.[196] In the late 1940s, evangelical theologians from Fuller Theological Seminary founded in Pasadena, California, in 1947, championed the Christian importance of social activism.[197][198] In this movement called neo-evangelicalism, new organizations, social agencies, media and Bible colleges were established in the 1950s.[199][200]

Progressive evangelicals

[edit]Evangelicals dissatisfied with the movement's fundamentalism mainstream have been variously described as progressive evangelicals, postconservative evangelicals, open evangelicals and postevangelicals. Progressive evangelicals, also known as the evangelical left, share theological or social views with other progressive Christians while also identifying with evangelicalism. Progressive evangelicals commonly advocate for women's equality, pacifism and social justice.[201]

As described by Baptist theologian Roger E. Olson, postconservative evangelicalism is a theological school of thought that adheres to the four marks of evangelicalism, while being less rigid and more inclusive of other Christians.[202] According to Olson, postconservatives believe that doctrinal truth is secondary to spiritual experience shaped by Scripture. Postconservative evangelicals seek greater dialogue with other Christian traditions and support the development of a multicultural evangelical theology that incorporates the voices of women, racial minorities, and Christians in the developing world. Some postconservative evangelicals also support open theism and the possibility of near universal salvation.

The term "open evangelical" refers to a particular Christian school of thought or churchmanship, primarily in Great Britain (especially in the Church of England).[203] Open evangelicals describe their position as combining a traditional evangelical emphasis on the nature of scriptural authority, the teaching of the ecumenical creeds and other traditional doctrinal teachings, with an approach towards culture and other theological points-of-view which tends to be more inclusive than that taken by other evangelicals. Some open evangelicals aim to take a middle position between conservative and charismatic evangelicals, while others would combine conservative theological emphases with more liberal social positions.

British author Dave Tomlinson coined the phrase postevangelical to describe a movement comprising various trends of dissatisfaction among evangelicals. Others use the term with comparable intent, often to distinguish evangelicals in the emerging church movement from postevangelicals and antievangelicals. Tomlinson argues that "linguistically, the distinction [between evangelical and postevangelical] resembles the one that sociologists make between the modern and postmodern eras".[204]

History

[edit]Background

[edit]Evangelicalism emerged in the 18th century,[205] first in Britain and its North American colonies. Nevertheless, there were earlier developments within the larger Protestant world that preceded and influenced the later evangelical revivals. According to religion scholar Randall Balmer, Evangelicalism resulted "from the confluence of Pietism, Presbyterianism, and the vestiges of Puritanism. Evangelicalism picked up the peculiar characteristics from each strain – warmhearted spirituality from the Pietists (for instance), doctrinal precisionism from the Presbyterians, and individualistic introspection from the Puritans".[206] Historian Mark Noll adds to this list High Church Anglicanism, which contributed to Evangelicalism a legacy of "rigorous spirituality and innovative organization."[207] Historian Rick Kennedy has identified New England Puritan clergyman Cotton Mather as the "first American Evangelical".[208]

During the 17th century, Pietism emerged in Europe as a movement for the revival of piety and devotion within the Lutheran church. As a protest against "cold orthodoxy" or against an overly formal and rational Christianity, Pietists advocated for an experiential religion that stressed high moral standards both for clergy and for lay people. The movement included both Christians who remained in the liturgical, state churches as well as separatist groups who rejected the use of baptismal fonts, altars, pulpits, and confessionals. As Radical Pietism spread, the movement's ideals and aspirations influenced and were absorbed by evangelicals.[209]

When George Fox, who is considered the founder of Quakerism,[210] was eleven, he wrote that God spoke to him about "keeping pure and being faithful to God and man."[11] After being troubled when his friends asked him to drink alcohol with them at the age of nineteen, Fox spent the night in prayer and soon afterwards he left his home in a four year search for spiritual satisfaction.[11] In his Journal, at age 23, he believed that he "found through faith in Jesus Christ the full assurance of salvation."[11] Fox began to spread his message and his emphasis on "the necessity of an inward transformation of heart", as well as the possibility of Christian perfection, drew opposition from English clergy and laity.[11] In the mid-1600s, many people became attracted to Fox's preaching and his followers became known as the Religious Society of Friends.[11] By 1660, the Quakers grew to 35,000, and while the two movements are distinct and have important differences like the doctrine of the Inward Light, they are considered by some to be among the first in the evangelical Christian movement.[7][11]

The Presbyterian heritage not only gave Evangelicalism a commitment to Protestant orthodoxy but also contributed a revival tradition that stretched back to the 1620s in Scotland and Northern Ireland.[211] Central to this tradition was the communion season, which normally occurred in the summer months. For Presbyterians, celebrations of Holy Communion were infrequent but popular events preceded by several Sundays of preparatory preaching and accompanied with preaching, singing, and prayers.[212]

Puritanism combined Calvinism with a doctrine that conversion was a prerequisite for church membership and with an emphasis on the study of Scripture by lay people. It took root in the colonies of New England, where the Congregational church became an established religion. There the Half-Way Covenant of 1662 allowed parents who had not testified to a conversion experience to have their children baptized, while reserving Holy Communion for converted church members alone.[213] By the 18th century Puritanism was in decline and many ministers expressed alarm at the loss of religious piety. This concern over declining religious commitment led many[quantify] people to support evangelical revival.[214]

High-Church Anglicanism also exerted influence on early Evangelicalism. High Churchmen were distinguished by their desire to adhere to primitive Christianity. This desire included imitating the faith and ascetic practices of early Christians as well as regularly partaking of Holy Communion. High Churchmen were also enthusiastic organizers of voluntary religious societies. Two of the most prominent were the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (founded in London in 1698), which distributed Bibles and other literature and built schools, and the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts, which was founded in England in 1701 to facilitate missionary work in British colonies (especially among colonists in North America). Samuel and Susanna Wesley, the parents of John and Charles Wesley (born 1703 and 1707 respectively), were both devoted advocates of High-Church ideas.[215][216]

18th century

[edit]

In the 1730s, Evangelicalism emerged as a distinct phenomenon out of religious revivals that began in Britain and New England. While religious revivals had occurred within Protestant churches in the past, the evangelical revivals that marked the 18th century were more intense and radical.[217] Evangelical revivalism imbued ordinary men and women with a confidence and enthusiasm for sharing the gospel and converting others outside of the control of established churches, a key discontinuity with the Protestantism of the previous era.[218]

It was developments in the doctrine of assurance that differentiated Evangelicalism from what went before. Bebbington says, "The dynamism of the Evangelical movement was possible only because its adherents were assured in their faith."[219] He goes on:

Whereas the Puritans had held that assurance is rare, late and the fruit of struggle in the experience of believers, the Evangelicals believed it to be general, normally given at conversion and the result of simple acceptance of the gift of God. The consequence of the altered form of the doctrine was a metamorphosis in the nature of popular Protestantism. There was a change in patterns of piety, affecting devotional and practical life in all its departments. The shift, in fact, was responsible for creating in Evangelicalism a new movement and not merely a variation on themes heard since the Reformation.[220]

The first local revival occurred in Northampton, Massachusetts, under the leadership of Congregationalist minister Jonathan Edwards. In the fall of 1734, Edwards preached a sermon series on "Justification By Faith Alone", and the community's response was extraordinary. Signs of religious commitment among the laity increased, especially among the town's young people. The revival ultimately spread to 25 communities in western Massachusetts and central Connecticut until it began to wane by the spring of 1735.[221] Edwards was heavily influenced by Pietism, so much so that one historian has stressed his "American Pietism".[222] One practice clearly copied from European Pietists was the use of small groups divided by age and gender, which met in private homes to conserve and promote the fruits of revival.[223]

At the same time, students at Yale University (at that time Yale College) in New Haven, Connecticut, were also experiencing revival. Among them was Aaron Burr Sr., who would become a prominent Presbyterian minister and future president of Princeton University. In New Jersey, Gilbert Tennent, another Presbyterian minister, was preaching the evangelical message and urging the Presbyterian Church to stress the necessity of converted ministers.[224]

The spring of 1735 also marked important events in England and Wales. Howell Harris, a Welsh schoolteacher, had a conversion experience on May 25 during a communion service. He described receiving assurance of God's grace after a period of fasting, self-examination, and despair over his sins.[225] Sometime later, Daniel Rowland, the Anglican curate of Llangeitho, Wales, experienced conversion as well. Both men began preaching the evangelical message to large audiences, becoming leaders of the Welsh Methodist revival.[226] At about the same time that Harris experienced conversion in Wales, George Whitefield was converted at Oxford University after his own prolonged spiritual crisis. Whitefield later remarked, "About this time God was pleased to enlighten my soul and bring me into the knowledge of His free grace, and the necessity of being justified in His sight by faith only."[227]

Whitefield's fellow Holy Club member and spiritual mentor, Charles Wesley, reported an evangelical conversion in 1738.[226] In the same week, Charles' brother and future founder of Methodism, John Wesley was also converted after a long period of inward struggle. During this spiritual crisis, John Wesley was directly influenced by Pietism. Two years before his conversion, Wesley had traveled to the newly established colony of Georgia as a missionary for the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. He shared his voyage with a group of Moravian Brethren led by August Gottlieb Spangenberg. The Moravians' faith and piety deeply impressed Wesley, especially their belief that it was a normal part of Christian life to have an assurance of one's salvation.[228] Wesley recounted the following exchange with Spangenberg on February 7, 1736:

[Spangenberg] said, "My brother, I must first ask you one or two questions. Have you the witness within yourself? Does the Spirit of God bear witness with your spirit that you are a child of God?" I was surprised, and knew not what to answer. He observed it, and asked, "Do you know Jesus Christ?" I paused, and said, "I know he is the Savior of the world." "True," he replied, "but do you know he has saved you?" I answered, "I hope he has died to save me." He only added, "Do you know yourself?" I said, "I do." But I fear they were vain words.[229]

Wesley finally received the assurance he had been searching for at a meeting of a religious society in London. While listening to a reading from Martin Luther's preface to the Epistle to the Romans, Wesley felt spiritually transformed:

About a quarter before nine, while [the speaker] was describing the change which God works in the heart through faith in Christ, I felt my heart strangely warmed. I felt I did trust in Christ, Christ alone for salvation, and an assurance was given me that he had taken away my sins, even mine, and saved me from the law of sin and death.[230]

Pietism continued to influence Wesley, who had translated 33 Pietist hymns from German to English. Numerous German Pietist hymns became part of the English Evangelical repertoire.[231] By 1737, Whitefield had become a national celebrity in England where his preaching drew large crowds, especially in London where the Fetter Lane Society had become a center of evangelical activity.[232] Whitfield joined forces with Edwards to "fan the flame of revival" in the Thirteen Colonies in 1739–40. Soon the First Great Awakening stirred Protestants throughout America.[226]

Evangelical preachers emphasized personal salvation and piety more than ritual and tradition. Pamphlets and printed sermons crisscrossed the Atlantic, encouraging the revivalists.[233] The Awakening resulted from powerful preaching that gave listeners a sense of deep personal revelation of their need of salvation by Jesus Christ. Pulling away from ritual and ceremony, the Great Awakening made Christianity intensely personal to the average person by fostering a deep sense of spiritual conviction and redemption, and by encouraging introspection and a commitment to a new standard of personal morality. It reached people who were already church members. It changed their rituals, their piety and their self-awareness. To the evangelical imperatives of Reformation Protestantism, 18th century American Christians added emphases on divine outpourings of the Holy Spirit and conversions that implanted within new believers an intense love for God. Revivals encapsulated those hallmarks and forwarded the newly created Evangelicalism into the early republic.[234]

By the 1790s, the Evangelical party in the Church of England remained a small minority but were not without influence. John Newton and Joseph Milner were influential evangelical clerics. Evangelical clergy networked together through societies such as the Eclectic Society in London and the Elland Society in Yorkshire.[235] The Old Dissenter denominations (the Baptists, Congregationalists and Quakers) were falling under evangelical influence, with the Baptists most affected and Quakers the least. Evangelical ministers dissatisfied with both Anglicanism and Methodism often chose to work within these churches.[236] In the 1790s, all of these evangelical groups, including the Anglicans, were Calvinist in orientation.[237]

Methodism (the "New Dissent") was the most visible expression of evangelicalism by the end of the 18th century. The Wesleyan Methodists boasted around 70,000 members throughout the British Isles, in addition to the Calvinistic Methodists in Wales and the Countess of Huntingdon's Connexion, which was organized under George Whitefield's influence. The Wesleyan Methodists, however, were still nominally affiliated with the Church of England and would not completely separate until 1795, four years after Wesley's death. The Wesleyan Methodist Church's Arminianism distinguished it from the other evangelical groups.[238]

At the same time, evangelicals were an important faction within the Presbyterian Church of Scotland. Influential ministers included John Erskine, Henry Wellwood Moncrieff and Stevenson Macgill. The church's General Assembly, however, was controlled by the Moderate Party, and evangelicals were involved in the First and Second Secessions from the national church during the 18th century.[239]

19th century

[edit]The start of the 19th century saw an increase in missionary work and many of the major missionary societies were founded around this time (see Timeline of Christian missions). Both the Evangelical and high church movements sponsored missionaries.

The Second Great Awakening (which actually began in 1790) was primarily an American revivalist movement and resulted in substantial growth of the Methodist and Baptist churches. Charles Grandison Finney was an important preacher of this period.

In Britain in addition to stressing the traditional Wesleyan combination of "Bible, cross, conversion, and activism", the revivalist movement sought a universal appeal, hoping to include rich and poor, urban and rural, and men and women. Special efforts were made to attract children and to generate literature to spread the revivalist message.[240]

"Christian conscience" was used by the British Evangelical movement to promote social activism. Evangelicals believed activism in government and the social sphere was an essential method in reaching the goal of eliminating sin in a world drenched in wickedness.[241] The Evangelicals in the Clapham Sect included figures such as William Wilberforce who successfully campaigned for the abolition of slavery.

In the late 19th century, the revivalist Wesleyan-Holiness movement based on John Wesley's doctrine of "entire sanctification" came to the forefront, and while many adherents remained within mainline Methodism, others established new denominations, such as the Free Methodist Church and Wesleyan Methodist Church.[242] In urban Britain the Holiness message was less exclusive and censorious.[243]

Keswickianism taught the doctrine of the second blessing in non-Methodist circles and came to influence evangelicals of the Calvinistic (Reformed) tradition, leading to the establishment of denominations such as the Christian and Missionary Alliance.[244][245]

John Nelson Darby of the Plymouth Brethren was a 19th-century Irish Anglican minister who devised modern dispensationalism, an innovative Protestant theological interpretation of the Bible that was incorporated in the development of modern Evangelicalism. Cyrus Scofield further promoted the influence of dispensationalism through the explanatory notes to his Scofield Reference Bible. According to scholar Mark S. Sweetnam, who takes a cultural studies perspective, dispensationalism can be defined in terms of its Evangelicalism, its insistence on the literal interpretation of Scripture, its recognition of stages in God's dealings with humanity, its expectation of the imminent return of Christ to rapture His saints, and its focus on both apocalypticism and premillennialism.[246]

During the 19th century, the megachurches, churches with more than 2,000 people, began to develop.[247] The first evangelical megachurch, the Metropolitan Tabernacle with a 6000-seat auditorium, was inaugurated in 1861 in London by Charles Spurgeon.[248] Dwight L. Moody founded the Illinois Street Church in Chicago.[249][250]

An advanced theological perspective came from the Princeton theologians from the 1850s to the 1920s, such as Charles Hodge, Archibald Alexander and B.B. Warfield.[251]

20th century

[edit]After 1910 the Fundamentalist movement dominated Evangelicalism in the early part of the 20th century; the Fundamentalists rejected liberal theology and emphasized the inerrancy of the Scriptures.

Following the 1904–1905 Welsh revival, the Azusa Street Revival in 1906 began the spread of Pentecostalism in North America.

The 20th century also marked by the emergence of the televangelism. Aimee Semple McPherson, who founded the megachurch Angelus Temple in Los Angeles, used radio in the 1920s to reach a wider audience.[252]

After the Scopes trial in 1925, Christian Century wrote of "Vanishing Fundamentalism".[253] In 1929 Princeton University, once the bastion of conservative theology, added several modernists to its faculty, resulting in the departure of J. Gresham Machen and a split in the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America.

Evangelicalism began to reassert itself in the second half of the 1930s. One factor was the advent of the radio as a means of mass communication. When [Charles E. Fuller] began his "Old Fashioned Revival Hour" on October 3, 1937, he sought to avoid the contentious issues that had caused fundamentalists to be characterized as narrow.[254]

One hundred forty-seven representatives from thirty-four denominations met from April 7 through 9, 1942, in St. Louis, Missouri, for a "National Conference for United Action among Evangelicals." The next year six hundred representatives in Chicago established the National Association of Evangelicals (NAE) with Harold Ockenga as its first president. The NAE was partly a reaction to the founding of the American Council of Christian Churches (ACCC) under the leadership of the fundamentalist Carl McIntire. The ACCC in turn had been founded to counter the influence of the Federal Council of Churches (later merged into the National Council of Churches), which fundamentalists saw as increasingly embracing modernism in its ecumenism.[255] Those who established the NAE had come to view the name fundamentalist as "an embarrassment instead of a badge of honor."[256]

Evangelical revivalist radio preachers organized themselves in the National Religious Broadcasters in 1944 in order to regulate their activity.[257]

With the founding of the NAE, American Protestantism was divided into three large groups—the fundamentalists, the modernists, and the new evangelicals, who sought to position themselves between the other two. In 1947 Harold Ockenga coined the term neo-evangelicalism to identify a movement distinct from fundamentalism. The neo-evangelicals had three broad characteristics that distinguished them from the conservative fundamentalism of the ACCC:

Each of these characteristics took concrete shape by the mid-1950s. In 1947 Carl F. H. Henry's book The Uneasy Conscience of Fundamentalism called on evangelicals to engage in addressing social concerns:

[I]t remains true that the evangelical, in the very proportion that the culture in which he lives is not actually Christian, must unite with non-evangelicals for social betterment if it is to be achieved at all, simply because the evangelical forces do not predominate. To say that evangelicalism should not voice its convictions in a non-evangelical environment is simply to rob evangelicalism of its missionary vision.[260]

In the same year Fuller Theological Seminary was established with Ockenga as its president and Henry as the head of its theology department.

The strongest impetus, however, was the development of the work of Billy Graham. In 1951, with producer Dick Ross, he founded the film production company World Wide Pictures.[261] Graham had begun his career with the support of McIntire and fellow conservatives Bob Jones Sr. and John R. Rice. However, in broadening the reach of his London crusade of 1954, he accepted the support of denominations that those men disapproved of. When he went even further in his 1957 New York crusade, conservatives strongly condemned him and withdrew their support.[262][263] According to William Martin:

The New York crusade did not cause the division between the old Fundamentalists and the New Evangelicals; that had been signaled by the nearly simultaneous founding of the NAE and McIntire's American Council of Christian Churches 15 years earlier. But it did provide an event around which the two groups were forced to define themselves.[264]

A fourth development—the founding of Christianity Today (CT) with Henry as its first editor—was strategic in giving neo-evangelicals a platform to promote their views and in positioning them between the fundamentalists and modernists. In a letter to Harold Lindsell, Graham said that CT would:

plant the evangelical flag in the middle of the road, taking a conservative theological position but a definite liberal approach to social problems. It would combine the best in liberalism and the best in fundamentalism without compromising theologically.[265]

The postwar period also saw growth of the ecumenical movement and the founding of the World Council of Churches, which the Evangelical community generally regarded with suspicion.[266]

In the United Kingdom, John Stott (1921–2011) and Martyn Lloyd-Jones (1899–1981) emerged as key leaders in Evangelical Christianity.

The charismatic movement began in the 1960s and resulted in the introduction of Pentecostal theology and practice into many mainline denominations. New charismatic groups such as the Association of Vineyard Churches and Newfrontiers trace their roots to this period (see also British New Church Movement).

The closing years of the 20th century saw controversial postmodern influences entering some parts of Evangelicalism, particularly with the emerging church movement. Also controversial is the relationship between spiritualism and contemporary military metaphors and practices animating many branches of Christianity but especially relevant in the sphere of Evangelicalism. Spiritual warfare is the latest iteration in a long-standing partnership between religious organization and militarization, two spheres that are rarely considered together, although aggressive forms of prayer have long been used to further the aims of expanding Evangelical influence. Major moments of increased political militarization have occurred concurrently with the growth of prominence of militaristic imagery in evangelical communities. This paradigmatic language, paired with an increasing reliance on sociological and academic research to bolster militarized sensibility, serves to illustrate the violent ethos that effectively underscores militarized forms of evangelical prayer.[267]

21st century

[edit]In Nigeria, evangelical megachurches, such as Redeemed Christian Church of God and Living Faith Church Worldwide, have built autonomous cities with houses, supermarkets, banks, universities, and power plants.[268]

Evangelical Christian film production societies were founded, such as Pure Flix in 2005 and Kendrick Brothers in 2013.[269][270]

The growth of evangelical churches continues with the construction of new places of worship or enlargements in various regions of the world.[271][272][273]

Global statistics

[edit]

According to a 2011 Pew Forum study on global Christianity, 285,480,000 or 13.1 percent of all Christians are Evangelicals.[274]: 17 These figures do not include the Pentecostalism and Charismatic movements. The study states that the category "Evangelicals" should not be considered as a separate category of "Pentecostal and Charismatic" categories, since some believers consider themselves in both movements where their church is affiliated with an Evangelical association.[274]: 18

In 2015, the World Evangelical Alliance is "a network of churches in 129 nations that have each formed an Evangelical alliance and over 100 international organizations joining together to give a world-wide identity, voice, and platform to more than 600 million Evangelical Christians".[275][276] The Alliance was formed in 1951 by Evangelicals from 21 countries. It has worked to support its members to work together globally.

According to Sébastien Fath of CNRS, in 2016, there are 619 million Evangelicals in the world, one in four Christians.[14] In 2017, about 630 million, an increase of 11 million, including Pentecostals.[277]

Operation World estimates the number of Evangelicals at 545.9 million, which makes for 7.9 percent of the world's population.[278] From 1960 to 2000, the global growth of the number of reported Evangelicals grew three times the world's population rate, and twice that of Islam.[279] According to Operation World, the Evangelical population's current annual growth rate is 2.6 percent, still more than twice the world's population growth rate.[278]

Africa

[edit]In the 21st century, there are Evangelical churches active in many African countries. They have grown especially since independence came in the 1960s,[280] the strongest movements are based on Pentecostal beliefs. There is a wide range of theology and organizations, including some international movements.

Nigeria

[edit]

In Nigeria the Evangelical Church Winning All (formerly "Evangelical Church of West Africa") is the largest church organization with five thousand congregations and over ten million members. It sponsors three seminaries and eight Bible colleges, and 1600 missionaries who serve in Nigeria and other countries with the Evangelical Missionary Society (EMS). There have been serious confrontations since 1999 between Muslims and Christians standing in opposition to the expansion of Sharia law in northern Nigeria. The confrontation has radicalized and politicized the Christians. Violence has been escalating.[281][clarification needed]

Ethiopia and Eritrea

[edit]In Ethiopia, Eritrea, and the Ethiopian and Eritrean diaspora, P'ent'ay (from Ge'ez: ጴንጤ), also known as Ethiopian–Eritrean Evangelicalism, or Wenigēlawī (from Ge'ez: ወንጌላዊ – which directly translates to "Evangelical") are terms used for Evangelical Christians and other Eastern/Oriental-oriented Protestant Christians within Ethiopia and Eritrea, and the Ethiopian and Eritrean diaspora abroad.[282][283][284] Prominent movements among them have been Pentecostalism (Ethiopian Full Gospel Believers' Church), the Baptist tradition (Ethiopian Kale Heywet Church), Lutheranism (Ethiopian Evangelical Church Mekane Yesus and Evangelical Lutheran Church of Eritrea), and the Mennonite-Anabaptist tradition (Meserete Kristos Church).[285]

Kenya

[edit]In Kenya, mainstream Evangelical denominations have taken the lead[dubious – discuss] in promoting political activism and backers, with the smaller Evangelical sects of less importance. Daniel arap Moi was president 1978 to 2002 and claimed to be an Evangelical; he proved intolerant of dissent or pluralism or decentralization of power.[286]

South Africa

[edit]

The Berlin Missionary Society (BMS) was one of four German Protestant mission societies active in South Africa before 1914. It emerged from the German tradition of Pietism after 1815 and sent its first missionaries to South Africa in 1834. There were few positive reports in the early years, but it was especially active 1859–1914. It was especially strong in the Boer republics. The World War cut off contact with Germany, but the missions continued at a reduced pace. After 1945 the missionaries had to deal with decolonization across Africa and especially with the apartheid government. At all times the BMS emphasized spiritual inwardness, and values such as morality, hard work and self-discipline. It proved unable to speak and act decisively against injustice and racial discrimination and was disbanded in 1972.[287]

Malawi

[edit]Since 1974, young professionals have been the active proselytizers of Evangelicalism in the cities of Malawi.[288]

Mozambique

[edit]In Mozambique, Evangelical Protestant Christianity emerged around 1900 from black migrants whose converted previously in South Africa. They were assisted by European missionaries, but, as industrial workers, they paid for their own churches and proselytizing. They prepared southern Mozambique for the spread of Evangelical Protestantism. During its time as a colonial power in Mozambique, the Catholic Portuguese government tried to counter the spread of Evangelical Protestantism.[289]

East African Revival

[edit]The East African Revival was a renewal movement within Evangelical churches in East Africa during the late 1920s and 1930s[290] that began at a Church Missionary Society mission station in the Belgian territory of Ruanda-Urundi in 1929, and spread to: Uganda, Tanzania and Kenya during the 1930s and 1940s contributing to the significant growth of the church in East Africa through the 1970s and had a visible influence on Western missionaries who were observer-participants of the movement.[291][page needed]

Latin America

[edit]

In modern Latin America, the term "Evangelical" is often simply a synonym for "Protestant".[292][293][294]

Brazil

[edit]

Protestantism in Brazil largely originated with German immigrants and British and American missionaries in the 19th century, following up on efforts that began in the 1820s.[295]

In the late nineteenth century, while the vast majority of Brazilians were nominal Catholics, the nation was underserved by priests, and for large numbers their religion was only nominal.[citation needed] The Catholic Church in Brazil was de-established in 1890, and responded by increasing the number of dioceses and the efficiency of its clergy. Many Protestants came from a large German immigrant community, but they were seldom engaged in proselytism and grew mostly by natural increase.

Methodists were active along with Presbyterians and Baptists. The Scottish missionary Robert Reid Kalley, with support from the Free Church of Scotland, moved to Brazil in 1855, founding the first Evangelical church among the Portuguese-speaking population there in 1856. It was organized according to the Congregational policy as the Igreja Evangélica Fluminense; it became the mother church of Congregationalism in Brazil.[296] The Seventh-day Adventists arrived in 1894, and the YMCA was organized in 1896. The missionaries promoted schools colleges and seminaries, including a liberal arts college in São Paulo, later known as Mackenzie, and an agricultural school in Lavras. The Presbyterian schools in particular later became the nucleus of the governmental system. In 1887 Protestants in Rio de Janeiro formed a hospital. The missionaries largely reached a working-class audience, as the Brazilian upper-class was wedded either to Catholicism or to secularism. By 1914, Protestant churches founded by American missionaries had 47,000 communicants, served by 282 missionaries. In general, these missionaries were more successful than they had been in Mexico, Argentina or elsewhere in Latin America.[297]

There were 700,000 Protestants by 1930, and increasingly they were in charge of their own affairs. In 1930, the Methodist Church of Brazil became independent of the missionary societies and elected its own bishop. Protestants were largely from a working-class, but their religious networks help speed their upward social mobility.[298][299][unreliable source?]

Protestants accounted for fewer than 5 percent of the population until the 1960s but grew exponentially by proselytizing and by 2000 made up over 15 percent of Brazilians affiliated with a church. Pentecostals and charismatic groups account for the vast majority of this expansion.

Pentecostal missionaries arrived early in the 20th century. Pentecostal conversions surged during the 1950s and 1960s, when native Brazilians began founding autonomous churches. The most influential included Brasil Para o Cristo (Brazil for Christ), founded in 1955 by Manoel de Mello. With an emphasis on personal salvation, on God's healing power, and on strict moral codes these groups have developed broad appeal, particularly among the booming urban migrant communities. In Brazil, since the mid-1990s, groups committed to uniting black identity, antiracism, and Evangelical theology have rapidly proliferated.[300] Pentecostalism arrived in Brazil with Swedish and American missionaries in 1911. it grew rapidly but endured numerous schisms and splits. In some areas the Evangelical Assemblies of God churches have taken a leadership role in politics since the 1960s. They claimed major credit for the election of Fernando Collor de Mello as president of Brazil in 1990.[301]

According to the 2000 census, 15.4 percent of the Brazilian population was Protestant. Recent research conducted by the Datafolha institute shows that 25 percent of Brazilians are Protestants, of which 19 percent are followers of Pentecostal denominations. The 2010 census found out that 22.2 percent were Protestant at that date. Protestant denominations saw a rapid growth in their number of followers since the last decades of the 20th century.[302] They are politically and socially conservative, and emphasize that God's favor translates into business success.[303] The rich and the poor remained traditional Catholics, while most Evangelical Protestants were in the new lower-middle class – known as the "C class" (in a A–E classification system).[304]

Chesnut argues that Pentecostalism has become "one of the principal organizations of the poor", for these churches provide the sort of social network that teach members the skills they need to thrive in a rapidly developing meritocratic society.[305]

One large Evangelical church that originated from Brazil is the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God (IURD), a neo‐Pentecostal denomination begun in 1977. It now has a presence in many countries, and claims millions of members worldwide.[306]

Guatemala

[edit]Protestants remained a small portion of the population until the late-twentieth century, when various Protestant groups experienced a demographic boom that coincided with the increasing violence of the Guatemalan Civil War. Two former Guatemalan heads of state, General Efraín Ríos Montt and Jorge Serrano Elías have been practicing Evangelical Protestants, as is Guatemala's former President, Jimmy Morales.[307][308] General Montt, an Evangelical from the Pentecostal tradition, came to power through a coup. He escalated the war against leftist guerrilla insurgents as a holy war against atheistic "forces of evil".[309]

Asia

[edit]

China

[edit]Evangelical Christianity came to China through Protestant missionaries in the 19th century. Starting in 1907, with the Manchurian Revival, evangelicalism grew through native preachers with homegrown traditions.[310]

Counting the number of Christians in China presents numerous difficulties.[311] French researcher Sebastian Fath has estimated that there are 66 million evangelicals in mainland China as of 2020.[312] Showing the issues in counting, a 2023 survey showed only a total of 18 million Protestant adults.[311]

South Korea

[edit]Protestant missionary activity in Asia was most successful in Korea. American Presbyterians and Methodists arrived in the 1880s and were well received. Between 1910 and 1945, when Korea was a Japanese colony, Christianity became in part an expression of nationalism in opposition to Japan's efforts to enforce the Japanese language and the Shinto religion.[313] In 1914, out of 16 million people, there were 86,000 Protestants and 79,000 Catholics; by 1934, the numbers were 168,000 and 147,000. Presbyterian missionaries were especially successful.[314] Since the Korean War (1950–53), many Korean Christians have migrated to the U.S., while those who remained behind have risen sharply in social and economic status. Most Korean Protestant churches in the 21st century emphasize their Evangelical heritage. Korean Evangelicalism is characterized by theological conservatism[clarification needed] coupled with an emotional revivalist[clarification needed] style. Most churches sponsor revival meetings once or twice a year. Missionary work is a high priority, with 13,000 men and women serving in missions across the world, putting Korea in second place just behind the US.[315]

Sukman argues that since 1945, Protestantism has been widely seen by Koreans as the religion of the middle class, youth, intellectuals, urbanites, and modernists.[316][317] It has been a powerful force[dubious – discuss] supporting South Korea's pursuit of modernity and emulation[dubious – discuss] of the United States, and opposition to the old Japanese colonialism and to the authoritarianism of North Korea.[318][unreliable source?]

South Korea has been referred as an "evangelical superpower" for being the home to some of the largest and most dynamic Christian churches in the world; South Korea is also second to the U.S. in the number of missionaries sent abroad.[319][320][321]

According to 2015 South Korean census, 9.7 million or 19.7 percent of the population described themselves as Protestants, many of whom belong to Presbyterian churches shaped by Evangelicalism.[322]

Philippines

[edit]According to the 2010 census, 2.68 percent of Filipinos are Evangelicals. The Philippine Council of Evangelical Churches (PCEC), an organization of more than seventy Evangelical and Mainline Protestant churches, and more than 210 para-church organizations in the Philippines, counts more than 11 million members as of 2011.[323]

Europe

[edit]

France

[edit]In 2019, it was reported that Evangelicalism in France was growing, and a new Evangelical church was built every 10 days and now counts 700,000 followers across France.[324]

Great Britain

[edit]John Wesley (1703–1791) was an Anglican cleric and theologian who, with his brother Charles Wesley (1707–1788) and fellow cleric George Whitefield (1714–1770), founded Methodism. After 1791 the movement became independent of the Anglican Church as the "Methodist Connection". It became a force in its own right, especially among the working class.[325]

The Clapham Sect was a group of Church of England evangelicals and social reformers based in Clapham, London; they were active 1780s–1840s). John Newton (1725–1807) was the founder. They are described by the historian Stephen Tomkins as "a network of friends and families in England, with William Wilberforce as its center of gravity, who were powerfully bound together by their shared moral and spiritual values, by their religious mission and social activism, by their love for each other, and by marriage".[326]

Evangelicalism was a major force in the Anglican Church from about 1800 to the 1860s. By 1848 when an evangelical John Bird Sumner became Archbishop of Canterbury, between a quarter and a third of all Anglican clergy were linked to the movement, which by then had diversified greatly in its goals and they were no longer considered an organized faction.[327][328][329]

In the 21st century there are an estimated 2 million Evangelicals in the UK.[330] According to research performed by the Evangelical Alliance in 2013, 87 percent of UK evangelicals attend Sunday morning church services every week and 63 percent attend weekly or fortnightly small groups.[331] An earlier survey conducted in 2012 found that 92 percent of evangelicals agree it is a Christian's duty to help those in poverty and 45 percent attend a church which has a fund or scheme that helps people in immediate need, and 42 percent go to a church that supports or runs a foodbank. 63 percent believe in tithing, and so give around 10 percent of their income to their church, Christian organizations and various charities[332] 83 percent of UK evangelicals believe that the Bible has supreme authority in guiding their beliefs, views and behavior and 52 percent read or listen to the Bible daily.[333] The Evangelical Alliance, formed in 1846, was the first ecumenical evangelical body in the world and works to unite evangelicals, helping them listen to, and be heard by, the government, media and society.

Switzerland

[edit]Since the 1970s, the number of Evangelicals and Evangelical congregations has grown strongly in Switzerland. Population censuses suggest that these congregations saw the number of their members triple from 1970 to 2000, qualified as a "spectacular development" by specialists.[334] Sociologists Jörg Stolz and Olivier Favre show that the growth is due to charismatic and Pentecostal groups, while classical evangelical groups are stable and fundamentalist groups are in decline.[335] A quantitative national census on religious congregations reveals the important diversity of evangelicalism in Switzerland.[336]

Anglo America

[edit]United States

[edit]

By the late 19th to early 20th century, most American Protestants were Evangelicals. A bitter divide had arisen between the more liberal-modernist mainline denominations and the fundamentalist denominations, the latter typically consisting of Evangelicals. Key issues included the truth of the Bible—literal or figurative, and teaching of evolution in the schools.[337]

During and after World War II, Evangelicals became increasingly organized. There was a great expansion of Evangelical activity within the United States, "a revival of revivalism". Youth for Christ was formed; it later became the base for Billy Graham's revivals. The National Association of Evangelicals formed in 1942 as a counterpoise to the mainline Federal Council of Churches. In 1942–43, the Old-Fashioned Revival Hour had a record-setting national radio audience.[338][page needed] With this organization, though, fundamentalist groups separated from Evangelicals.

According to a Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life study, Evangelicals can be broadly divided into three camps: traditionalist, centrist, and modernist.[339] A 2004 Pew survey identified that while 70.4 percent of Americans call themselves "Christian", Evangelicals only make up 26.3 percent of the population, while Catholics make up 22 percent and mainline Protestants make up 16 percent.[340] Among the Christian population in 2020, mainline Protestants began to outnumber Evangelicals.[341][342][343]

Evangelicals have been socially active throughout US history, a tradition dating back to the abolitionist movement of the Antebellum period and the prohibition movement.[344] As a group, evangelicals are most often associated with the Christian right. However, a large number of black self-labeled Evangelicals, and a small proportion of liberal white self-labeled Evangelicals, gravitate towards the Christian left.[345][346]

Recurrent themes within American Evangelical discourse include abortion,[347] evolution denial,[348] secularism,[349] and the notion of the United States as a Christian nation.[350][351][352]

Evangelical humanitarian aid

[edit]

In the 1940s, in the United States, neo-evangelicalism developed the importance of social justice and Christian humanitarian aid actions in Evangelical churches.[353][354] The majority of evangelical Christian humanitarian organizations were founded in the second half of the 20th century.[355] Among those with the most partner countries, there was the foundation of World Vision International (1950), Samaritan's Purse (1970), Mercy Ships (1978), Prison Fellowship International (1979), International Justice Mission (1997).[356]

See also

[edit]- Biblical literalism

- Child evangelism movement

- Christianese

- Christian eschatology

- Christian fundamentalism

- Christian nationalism

- Christian right

- Christian Zionism

- Christianity and politics

- Conservative Evangelicalism in Britain

- Evangelical Council of Venezuela

- Evangelical Fellowship of Canada

- Exvangelical

- Jesus and John Wayne

- List of the largest evangelical churches

- List of the largest evangelical church auditoriums

- List of evangelical Christians

- List of evangelical seminaries and theological colleges

- National Association of Evangelicals

- Red-Letter Christian

- The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind

- World Evangelical Alliance

- Worship service (evangelicalism)

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "Evangelicals and Evangelicalism". University of Southern California. Retrieved May 11, 2022.

At its most basic level, evangelical Christianity is characterized by a belief in the literal truth of the Bible, a "personal relationship with Jesus Christ", the importance of encouraging others to be "born again" in Jesus and a lively worship culture. This characterization is true regardless the size of the church, what the people sitting in the pews look like or how they express their beliefs.

- ^ Sweet, Leonard I. (1997). The Evangelical Tradition in America. Mercer University Press. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-86554-554-0.

...evangelical Christianity, which united by a common authority (the Bible), shared experience (new birth/conversion), and commitment to the same sense of duty (obedience to Christ through evangelism and benevolence).

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kidd, Thomas S. (September 24, 2019). Who Is an Evangelical?. Yale University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-300-24141-9.

What does it mean to be evangelical? The simple answer is that evangelical Christianity is the religion of the born again.

- ^ Stanley 2013, p. 11. "As a transnational and transdenominational movement, evangelicalism had from the outset encompassed considerable and often problematic diversity, but this diversity had been held in check by the commonalities evangelicals on either side of the North Atlantic shared – most notably a clear consensus about the essential content of the gospel and a shared sense of the priority of awakening those who inhabited a broadly Christian environment to the urgent necessity of a conscious individual decision to turn to Christ in repentance and faith. Evangelicalism had maintained an ambiguous relationship with the structures of Christendom, whether those structures took the institutional form of a legal union between church and state, as in most of the United Kingdom, or the more elusive character that obtained in the United States, where the sharp constitutional independence of the church from state political rulership masked an underlying set of shared assumptions about the Christian (and indeed Protestant) identity of the nation. Evangelicals had differed over whether the moral imperative of national recognition of godly religion should also imply the national recognition of a particular church, but all had been agreed that being born or baptized within the boundaries of Christendom did not in itself make one a Christian."

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Evangelical Manifesto – Os Guinness". Retrieved January 20, 2023.

- ^ "Evangelical church | Definition, History, Beliefs, Key Figures, & Facts | Britannica". britannica.com. Retrieved April 26, 2022.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Christian Scholar's Review, Volume 27. Hope College. 1997. p. 205.