Контркультура 1960-х годов

Контркультура 1960-х годов была культурным явлением и политическим движением, направленным против истеблишмента , которое развилось в западном мире в середине 20-го века. [3] Это началось в начале 1960-х годов, [4] и продолжалось до начала 1970-х годов. [5] Это часто является синонимом культурного либерализма и различных социальных изменений десятилетия. Последствия движения [5] продолжаются и по сей день. Совокупное движение набрало силу, поскольку движение за гражданские права в Соединенных Штатах добилось значительного прогресса, например, Закона об избирательных правах 1965 года , а с усилением войны во Вьетнаме в том же году оно стало революционным . для некоторых [6] [7] [8] По мере развития движения широко распространенная социальная напряженность также развивалась в отношении других вопросов и имела тенденцию распространяться по поколениям в отношении уважения к личности , человеческой сексуальности , прав женщин , традиционных способов власти , прав цветных людей , прекращения расовой сегрегации, экспериментирования. психоактивными веществами и различными интерпретациями американской мечты . Многие ключевые движения, связанные с этими проблемами, зародились или развивались в рамках контркультуры 1960-х годов. [9]

По мере развития эпохи возникали новые культурные формы и динамичная субкультура , которая прославляла экспериментирование, индивидуальность, [10] современные воплощения богемы , а также рост хиппи и других альтернативных образов жизни . Этот охват экспериментов особенно заметен в работах таких популярных музыкальных коллективов, как «Битлз» , Джими Хендрикс , Джим Моррисон , Дженис Джоплин и Боб Дилан , а также Нового Голливуда , французской «Новой волны » и японской «Новой волны» кинематографистов , чьи работы стала гораздо менее ограниченной цензурой. Внутри и во многих дисциплинах многие другие творческие художники, писатели и мыслители помогли определить движение контркультуры. Повседневная мода переживала упадок костюма и особенно ношения шляп; другие изменения включали нормализацию стираемости длинных волос у женщин (как и у многих мужчин того времени), [11] популяризация традиционных африканских, индийских и ближневосточных стилей одежды (в том числе ношение натуральных волос для лиц африканского происхождения), изобретение и популяризация мини -юбки , приподнимающей подол выше колен, а также развитие выдающейся молодежи -возглавляемые модные субкультуры . Стили, основанные на джинсах , как для мужчин, так и для женщин, стали важным модным движением, которое продолжается и по сей день.

Несколько факторов отличали контркультуру 1960-х годов от антиавторитарных движений предыдущих эпох. войны Бэби-бум после Второй мировой [12] [13] породило беспрецедентное количество потенциально недовольной молодежи как потенциальных участников переосмысления направления развития Соединенных Штатов и других демократических обществ . [14] Послевоенное изобилие позволило большей части поколения контркультуры выйти за рамки обеспечения материальных жизненных потребностей, которые занимали их родителей эпохи Депрессии . [15] Эта эпоха также была примечательна тем, что значительная часть множества моделей поведения и «причин» внутри более крупного движения была быстро ассимилирована в основном обществе, особенно в США, даже несмотря на то, что участники контркультуры составляли явное меньшинство внутри населения своих стран. [16] [17]

Историческая справка

[ редактировать ]Послевоенная геополитика

[ редактировать ]

Холодная война между коммунистическими и капиталистическими государствами включала шпионаж и подготовку к войне между могущественными странами. [18] [19] наряду с политическим и военным вмешательством могущественных государств во внутренние дела менее могущественных стран. Плохие результаты некоторых из этих мероприятий создали основу для разочарования и недоверия к послевоенным правительствам. [20] Примеры включают резкую реакцию Советского Союза (СССР) на народные антикоммунистические восстания, такие как Венгерская революция 1956 года и в Чехословакии 1968 года Пражская весна ; и неудачное вторжение США в заливе Свиней на Кубу в 1961 году.

В США президента Дуайта Д. Эйзенхауэра первый обман [21] Вопрос о характере инцидента с U-2 в 1960 году привел к тому, что правительство было уличено в откровенной лжи на самом высоком уровне, и способствовал росту недоверия к власти среди многих, кто достиг совершеннолетия в тот период. [22] [23] [24] Договор о частичном запрещении ядерных испытаний разделил истеблишмент США по политическим и военным линиям. [25] [26] [27] Внутриполитические разногласия относительно договорных обязательств в Юго-Восточной Азии ( СЕАТО ), особенно во Вьетнаме , и дебаты о том, как следует противостоять другим коммунистическим восстаниям , также создали раскол инакомыслия внутри истеблишмента. [28] [29] [30] В Великобритании дело Профьюмо также связано с тем, что лидеры истеблишмента были уличены в обмане, что привело к разочарованию и послужило катализатором либерального активизма. [31]

Кубинский ракетный кризис , поставивший мир на грань ядерной войны в октябре 1962 года, был во многом спровоцирован двуличными речами и действиями со стороны Советского Союза. [32] [33] Убийство президента США Джона Ф. Кеннеди в ноябре 1963 года и сопутствующие теории, касающиеся этого события, привели к дальнейшему снижению доверия к правительству, в том числе среди молодежи. [34] [35] [36]

Социальные проблемы и призывы к действию

[ редактировать ]

Многие социальные проблемы способствовали росту более крупного контркультурного движения. Одним из них было ненасильственное движение в Соединенных Штатах, стремившееся устранить незаконные конституционные гражданские права , особенно в отношении общей расовой сегрегации , давнего лишения избирательных прав чернокожих людей на Юге правительством штата , в котором доминируют белые, и продолжающейся расовой дискриминации в сфере рабочих мест, жилья и доступа к общественные места как на Севере, так и на Юге.

В колледжах и университетах студенческие активисты боролись за право осуществлять свои основные конституционные права, особенно свободу слова и свободу собраний . [37] Многие активисты контркультуры узнали о тяжелом положении бедных, а общественные организаторы боролись за финансирование программ борьбы с бедностью , особенно на Юге и в городских районах Соединенных Штатов. [38] [39]

Экологизм вырос из лучшего понимания продолжающегося ущерба, причиненного индустриализацией, вызванным этим загрязнением и ошибочным использованием химических веществ, таких как пестициды, в благонамеренных усилиях по улучшению качества жизни быстро растущего населения. [40] Такие авторы, как Рэйчел Карсон, сыграли ключевую роль в развитии нового осознания среди населения мира хрупкости нашей планеты , несмотря на сопротивление со стороны представителей истеблишмента во многих странах. [41]

Необходимость решения проблем прав меньшинств женщин, геев, инвалидов и многих других игнорируемых слоев населения вышла на первый план, когда все большее число преимущественно молодых людей вырвалось на свободу из ограничений ортодоксальности 1950-х годов и изо всех сил пыталось создать более инклюзивный и толерантный социальный ландшафт. [42] [43]

Доступность новых и более эффективных форм контроля над рождаемостью стала ключевой основой сексуальной революции . Понятие «развлекательного секса» без угрозы нежелательной беременности радикально изменило социальную динамику и предоставило как женщинам, так и мужчинам гораздо большую свободу в выборе сексуального образа жизни за пределами традиционного брака. [44] Благодаря такому изменению отношения к 1990-м годам доля детей, рожденных вне брака, выросла с 5% до 25% для белых и с 25% до 66% для афроамериканцев. [45]

Новые СМИ

[ редактировать ]

Телевидение

[ редактировать ]Для тех, кто родился после Второй мировой войны , появление телевидения как источника развлечений и информации, а также связанное с ним массовое распространение потребительства, вызванное послевоенным изобилием и поощряемое телевизионной рекламой, были ключевыми компонентами, вызывающими разочарование у некоторых молодых людей. людей и в формировании нового социального поведения, даже несмотря на то, что рекламные агентства активно ухаживали за «модным» молодежным рынком. [46] [47] В США почти в реальном времени телевизионные новости в эпоху движения за гражданские права 1963 года освещали Бирмингемскую кампанию , «Кровавое воскресенье» во время маршей Сельмы в Монтгомери 1965 года , а также графические новостные кадры из Вьетнама принесли ужасающие, трогательные картины кровавой реальности. вооруженного конфликта впервые в гостиных. [48]

New cinema

[edit]The breakdown of enforcement of the US Hays Code[49] concerning censorship in motion picture production, the use of new forms of artistic expression in European and Asian cinema, and the advent of modern production values heralded a new era of art-house, pornographic, and mainstream film production, distribution, and exhibition. The end of censorship resulted in a complete reformation of the western film industry. With new-found artistic freedom, a generation of exceptionally talented New Wave film makers working across all genres brought realistic depictions of previously prohibited subject matter to neighborhood theater screens for the first time, even as Hollywood film studios were still considered a part of the establishment by some elements of the counterculture. Successful 1960s new films of the New Hollywood were Bonnie and Clyde, The Graduate, The Wild Bunch, and Dennis Hopper's Easy Rider.

Other examples of hippie modernist cinema includes experimental short films made by figures like Jordan Belson and Bruce Conner, the concert film Gimme Shelter, Medium Cool, Zabriskie Point and Punishment Park.[50][51][52]

New radio

[edit]

By the later 1960s, previously under-regarded FM radio replaced AM radio as the focal point for the ongoing explosion of rock and roll music, and became the nexus of youth-oriented news and advertising for the counterculture generation.[53][54]

Changing lifestyles

[edit]Communes, collectives, and intentional communities regained popularity during this era.[55] Early communities such as the Hog Farm, Quarry Hill, and Drop City in the US were established as straightforward agrarian attempts to return to the land and live free of interference from outside influences. As the era progressed, many people established and populated new communities in response to not only disillusionment with standard community forms, but also dissatisfaction with certain elements of the counterculture itself. Some of these self-sustaining communities have been credited with the birth and propagation of the international Green Movement.

The emergence of an interest in expanded spiritual consciousness, yoga, occult practices and increased human potential helped to shift views on organized religion during the era. In 1957, 69% of US residents polled by Gallup said religion was increasing in influence. By the late 1960s, polls indicated less than 20% still held that belief.[56]

The "Generation Gap", or the inevitable perceived divide in worldview between the old and young, was perhaps never greater than during the counterculture era.[57] A large measure of the generational chasm of the 1960s and early 1970s was born of rapidly evolving fashion and hairstyle trends that were readily adopted by the young, but often misunderstood and ridiculed by the old. These included the wearing of very long hair by men,[58] the wearing of natural or "Afro" hairstyles by Black people, the donning of revealing clothing by women in public, and the mainstreaming of the psychedelic clothing and regalia of the short-lived hippie culture. Ultimately, practical and comfortable casual apparel, namely updated forms of T-shirts (often tie-dyed, or emblazoned with political or advertising statements), and Levi Strauss-branded blue denim jeans[59] became the enduring uniform of the generation, as daily wearing of suits along with traditional Western dress codes declined in use. The fashion dominance of the counterculture effectively ended with the rise of the Disco and Punk Rock eras in the later 1970s, even as the global popularity of T-shirts, denim jeans, and casual clothing in general have continued to grow.

Emergent middle-class drug culture

[edit]In the western world, the ongoing criminal legal status of the recreational drug industry was instrumental in the formation of an anti-establishment social dynamic by some of those coming of age during the counterculture era. The explosion of marijuana use during the era, in large part by students on fast-expanding college campuses,[60] created an attendant need for increasing numbers of people to conduct their personal affairs in secret in the procurement and use of banned substances. The classification of marijuana as a narcotic, and the attachment of severe criminal penalties for its use, drove the act of smoking marijuana, and experimentation with substances in general, deep underground. Many began to live largely clandestine lives because of their choice to use such drugs and substances, fearing retribution from their governments.[61][62]

Law enforcement

[edit]

The confrontations between college students (and other activists) and law enforcement officials became one of the hallmarks of the era. Many younger people began to show deep distrust of police, and terms such as "fuzz" and "pig" as derogatory epithets for police reappeared, and became key words within the counterculture lexicon. The distrust of police was based not only on fear of police brutality during political protests, but also on generalized police corruption—especially police manufacture of false evidence, and outright entrapment, in drug cases. In the US, the social tension between elements of the counterculture and law enforcement reached the breaking point in many notable cases, including: the Columbia University protests of 1968 in New York City,[63][64][65] the 1968 Democratic National Convention protests in Chicago,[66][67][68] the arrest and imprisonment of John Sinclair in Ann Arbor, Michigan,[69] and the Kent State shootings at Kent State University in Kent, Ohio, where National Guardsman acted as surrogates for police.[70] Police malfeasance was also an ongoing issue in the UK during the era.[71]

Vietnam War

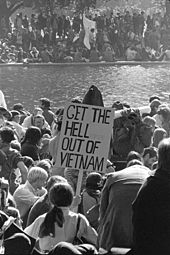

[edit]The Vietnam War, and the protracted national divide between supporters and opponents of the war, were arguably the most important factors contributing to the rise of the larger counterculture movement.

The widely accepted assertion that anti-war opinion was held only among the young is a myth,[72][73] but enormous war protests consisting of thousands of mostly younger people in every major US city, and elsewhere across the Western world, effectively united millions against the war, and against the war policy that prevailed under five US congresses and during two presidential administrations.

Regions

[edit]Western Europe

[edit]The counterculture movement took hold in Western Europe, with London, Amsterdam, Paris, Rome and Milan, Copenhagen and West Berlin rivaling San Francisco and New York as counterculture centers.

The UK Underground was a movement linked to the growing subculture in the US and associated with the hippie phenomenon, generating its own magazines and newspapers, fashion, music groups, and clubs. Underground figure Barry Miles said, "The underground was a catch-all sobriquet for a community of like-minded anti-establishment, anti-war, pro-rock'n'roll individuals, most of whom had a common interest in recreational drugs. They saw peace, exploring a widened area of consciousness, love and sexual experimentation as more worthy of their attention than entering the rat race. The straight, consumerist lifestyle was not to their liking, but they did not object to others living it. But at that time the middle classes still felt they had the right to impose their values on everyone else, which resulted in conflict."[74]

In the Netherlands, Provo was a counterculture movement that focused on "provocative direct action ('pranks' and 'happenings') to arouse society from political and social indifference".[75][76]

In France, the General Strike centered in Paris in May 1968 united French students, and nearly toppled the government.[77]

Kommune 1 or K1 was a commune in West Berlin known for its bizarre staged events that fluctuated between satire and provocation. These events served as inspiration for the "Sponti" movement and other leftist groups. In the late summer of 1968, the commune moved into a deserted factory on Stephanstraße to reorient. This second phase of Kommune 1 was characterized by sex, music and drugs. Soon, the commune was receiving visitors from all over the world, including Jimi Hendrix.[78][79]

Eastern Europe

[edit]Mánička is a Czech term used for young people with long hair, usually males, in Czechoslovakia through the 1960s and 1970s. Long hair for males during this time was considered an expression of political and social attitudes in communist Czechoslovakia. From the mid-1960s, the long-haired and "untidy" persons (so called máničky or vlasatci (in English: Mops) were banned from entering pubs, cinema halls, theatres and using public transportation in several Czech cities and towns.[80] In 1964, the public transportation regulations in Most and Litvínov excluded long-haired máničky as displeasure-evoking persons. Two years later, the municipal council in Poděbrady banned máničky from entering cultural institutions in the town.[80] In August 1966, Rudé právo informed that máničky in Prague were banned from visiting restaurants of the I. and II. price category.[80]

In 1966, during a big campaign coordinated by the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, around 4,000 young males were forced to cut their hair, often in the cells with the assistance of the state police.[81] On August 19, 1966, during a "safety intervention" organized by the state police, 140 long-haired people were arrested. As a response, the "community of long-haired" organized a protest in Prague. More than 100 people cheered slogans such as "Give us back our hair!" or "Away with hairdressers!". The state police arrested the organizers and several participants of the meeting. Some of them were given prison sentences.[80] According to the newspaper Mladá fronta Dnes, the Czechoslovak Ministry of Interior in 1966 even compiled a detailed map of the frequency of occurrence of long-haired males in Czechoslovakia.[82] In August 1969, during the first anniversary of the Soviet occupation of Czechoslovakia, the long-haired youth were one of the most active voices in the state protesting against the occupation.[80] Youth protesters have been labeled as "vagabonds" and "slackers" by the official normalized press.[80]

Australia

[edit]

Oz magazine was first published as a satirical humour magazine between 1963 and 1969 in Sydney, and, in its second and better known incarnation, became a "psychedelic hippy" magazine from 1967 to 1973 in London. Strongly identified as part of the underground press, it was the subject of two celebrated obscenity trials, one in Australia in 1964 and the other in the United Kingdom in 1971.[83][84]

The Digger was published monthly between 1972 and 1975 and served as a national outlet for many movements within Australia's counterculture with notable contributors—including second-wave feminists Anne Summers and Helen Garner; Californian cartoonist Ron Cobb's observations during a year-long stay in the country; Aboriginal activist Cheryl Buchanan (who was active in the 1972 setup of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy;[85] and later partner of poet and activist Lionel Fogarty[86]) and radical scientist Alan Roberts (1925–2017[87]) on global warming—and ongoing coverage of cultural trailblazers such as the Australian Performing Group (aka Pram Factory), and emerging Australian filmmakers. The Digger was produced by an evolving collective, many of whom had previously produced counterculture newspapers Revolution and High Times, and all three of these magazines were co-founded by publisher/editor Phillip Frazer, who launched Australia's legendary pop music paper Go-Set in 1966, when he was himself a teenager.

Latin America

[edit]

In Mexico, rock music was tied into the youth revolt of the 1960s. Mexico City, as well as northern cities such as Monterrey, Nuevo Laredo, Ciudad Juárez, and Tijuana, were exposed to US music. Many Mexican rock stars became involved in the counterculture. The three-day Festival Rock y Ruedas de Avándaro, held in 1971, was organized in the valley of Avándaro near the city of Toluca, a town neighboring Mexico City, and became known as "The Mexican Woodstock". Nudity, drug use, and the presence of the US flag scandalized conservative Mexican society to such an extent that the government clamped down on rock and roll performances for the rest of the decade. The festival, marketed as proof of Mexico's modernization, was never expected to attract the masses it did, and the government had to evacuate stranded attendees en masse at the end. This occurred during the era of President Luis Echeverría, an extremely repressive era in Mexican history. Anything that could be connected to the counterculture or student protests was prohibited from being broadcast on public airwaves, with the government fearing a repeat of the student protests of 1968. Few bands survived the prohibition, though the ones that did, like Three Souls in My Mind (now El Tri), remained popular due in part to their adoption of Spanish for their lyrics, but mostly as a result of a dedicated underground following. While Mexican rock groups were eventually able to perform publicly by the mid-1980s, the ban prohibiting tours of Mexico by foreign acts lasted until 1989.[88]

The Cordobazo was a civil uprising in the city of Córdoba, Argentina, in the end of May 1969, during the military dictatorship of General Juan Carlos Onganía, which occurred a few days after the Rosariazo, and a year after the French May '68. Contrary to previous protests, the Cordobazo did not correspond to previous struggles, headed by Marxist workers' leaders, but associated students and workers in the same struggle against the military government.[89]

Social and political movements

[edit]Ethnic and Racial movements

[edit]

The Civil Rights Movement, a key element of the larger counterculture movement, involved the use of applied nonviolence to assure that equal rights guaranteed under the US Constitution would apply to all citizens. Many states illegally denied many of these rights to African-Americans, and this was partially successfully addressed in the early and mid-1960s in several major nonviolent movements.[90][91]

The Chicano Movement of the 1960s, also called the Chicano civil rights movement, was a civil rights movement extending the Mexican-American civil rights movement of the 1960s with the stated goal of achieving Mexican American empowerment.

The American Indian Movement (or AIM) is a Native American grassroots movement that was founded in July 1968 in Minneapolis, Minnesota.[92] A.I.M. was initially formed in urban areas to address systemic issues of poverty and police brutality against Native Americans.[93] A.I.M. soon widened its focus from urban issues to include many Indigenous Tribal issues that Native American groups have faced due to settler colonialism of the Americas, such as treaty rights, high rates of unemployment, education, cultural continuity, and preservation of Indigenous cultures.[93][94]

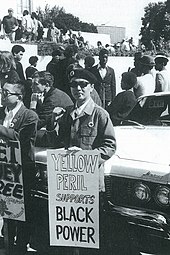

The Asian American movement was a sociopolitical movement in which the widespread grassroots effort of Asian Americans affected racial, social and political change in the US, reaching its peak in the late 1960s to mid-1970s. During this period Asian Americans promoted antiwar and anti-imperialist activism, directly opposing what was viewed as an unjust Vietnam war.The American Asian Movement differs from previous Asian-American activism due to its emphasis on Pan-Asianism and its solidarity with US and international Third World movements.

"Its founding principle of coalition politics emphasizes solidarity among Asians of all ethnicities, multiracial solidarity among Asian Americans as well as with African, Latino, and Native Americans in the United States, and transnational solidarity with peoples around the globe impacted by U.S. militarism."[95]

and intellectual movement involving poets, writers, musicians and artists who are Puerto Rican or of Puerto-Rican descent, who live in or near New York City, and either call themselves or are known as Nuyoricans.[96] It originated in the late 1960s and early 1970s in neighborhoods such as Loisaida, East Harlem, Williamsburg, and the South Bronx as a means to validate Puerto Rican experience in the United States, particularly for poor and working-class people who suffered from marginalization, ostracism, and discrimination.

Young Cuban exiles in the United States would develop interests in Cuban identity, and politics.[97] This younger generation had experienced the United States during the rising anti-war movement, civil rights movement, and feminist movement of the 1960s, causing them to be influenced by radicals that encouraged political introspection, and social justice. Figures like Fidel Castro and Che Guevara were also heavily praised among American student radicals at the time. These factors helped push some young Cubans into advocating for different degrees of rapprochement with Cuba.[citation needed] Those most likely to become more radical were Cubans who were more culturally isolated from being outside the Cuban enclave of Miami.[98]

Free Speech

[edit]Much of the 1960s counterculture originated on college campuses. The 1964 Free Speech Movement at the University of California, Berkeley, which had its roots in the Civil Rights Movement of the southern United States, was one early example. At Berkeley a group of students began to identify themselves as having interests as a class that were at odds with the interests and practices of the university and its corporate sponsors. Other rebellious young people, who were not students, also contributed to the Free Speech Movement.[99]

New Left

[edit]The New Left is a term used in different countries to describe left-wing movements that occurred in the 1960s and 1970s in the Western world. They differed from earlier leftist movements that had been more oriented towards labour activism, and instead adopted social activism. The American "New Left" is associated with college campus mass protests and radical leftist movements. The British "New Left" was an intellectually driven movement that attempted to correct the perceived errors of "Old Left" parties in the post–World War II period. The movements began to wind down in the 1970s, when activists either committed themselves to party projects, developed social justice organizations, moved into identity politics or alternative lifestyles, or became politically inactive.[100][101][102]

The emergence of the New Left in the 1950s and 1960s led to a revival of interest in libertarian socialism.[105] The New Left's critique of the Old Left's authoritarianism was associated with a strong interest in personal liberty, autonomy (see the thinking of Cornelius Castoriadis) and led to a rediscovery of older socialist traditions, such as left communism, council communism, and the Industrial Workers of the World. The New Left also led to a revival of anarchism. Journals like Radical America and Black Mask in America, Solidarity, Big Flame and Democracy & Nature, succeeded by The International Journal of Inclusive Democracy,[106] in the UK, introduced a range of left libertarian ideas to a new generation. Social ecology, autonomism and, more recently, participatory economics (parecon), and Inclusive Democracy emerged from this.

A surge of popular interest in anarchism occurred in western nations during the 1960s and 1970s.[107] Anarchism was influential in the counterculture of the 1960s[108][109][110] and anarchists actively participated in the late 1960s students and workers revolts.[111] During the IX Congress of the Italian Anarchist Federation in Carrara in 1965, a group decided to split off from this organization and created the Gruppi di Iniziativa Anarchica. In the 1970s, it was mostly composed of "veteran individualist anarchists with a pacifism orientation, naturism, etc, ...".[112] In 1968, in Carrara, Italy the International of Anarchist Federations was founded during an international anarchist conference held there in 1968 by the three existing European federations of France, the Italian and the Iberian Anarchist Federation as well as the Bulgarian federation in French exile.[113][114] During the events of May 68 the anarchist groups active in France were Fédération Anarchiste, Mouvement communiste libertaire, Union fédérale des anarchistes, Alliance ouvrière anarchiste, Union des groupes anarchistes communistes, Noir et Rouge, Confédération nationale du travail, Union anarcho-syndicaliste, Organisation révolutionnaire anarchiste, Cahiers socialistes libertaires, À contre-courant, La Révolution prolétarienne, and the publications close to Émile Armand.

The New Left in the United States also included anarchist, countercultural and hippie-related radical groups such as the Yippies who were led by Abbie Hoffman, The Diggers[115] and Up Against the Wall Motherfuckers. By late 1966, the Diggers opened free stores which simply gave away their stock, provided free food, distributed free drugs, gave away money, organized free music concerts, and performed works of political art.[116] The Diggers took their name from the original English Diggers led by Gerrard Winstanley[117] and sought to create a mini-society free of money and capitalism.[118] On the other hand, the Yippies employed theatrical gestures, such as advancing a pig ("Pigasus the Immortal") as a candidate for president in 1968, to mock the social status quo.[119] They have been described as a highly theatrical, anti-authoritarian and anarchist[120] youth movement of "symbolic politics".[121] Since they were well known for street theater and politically themed pranks, many of the "old school" political left either ignored or denounced them. According to ABC News, "The group was known for street theater pranks and was once referred to as the 'Groucho Marxists'."[122]

Anti-war

[edit]

In Trafalgar Square, London in 1958,[123] in an act of civil disobedience, 60,000–100,000 protesters made up of students and pacifists converged in what was to become the "ban the Bomb" demonstrations.[124]

Opposition to the Vietnam War began in 1964 on United States college campuses. Student activism became a dominant theme among the baby boomers, growing to include many other demographic groups. Exemptions and deferments for the middle and upper classes resulted in the induction of a disproportionate number of poor, working-class, and minority registrants. Countercultural books such as MacBird by Barbara Garson and much of the counterculture music encouraged a spirit of non-conformism and anti-establishmentarianism. By 1968, the year after a large march to the United Nations in New York City and a large protest at the Pentagon were undertaken, a majority of people in the country opposed the war.[125]

Anti-nuclear

[edit]

The application of nuclear technology, both as a source of energy and as an instrument of war, has been controversial.[126][127][128][129][130]

Scientists and diplomats have debated the nuclear weapons policy since before the atomic bombing of Hiroshima in 1945.[131] The public became concerned about nuclear weapons testing from about 1954, following extensive nuclear testing in the Pacific. In 1961 and 1962, at the height of the Cold War, about 50,000 women brought together by Women Strike for Peace marched in 60 cities in the United States to demonstrate against nuclear weapons.[132][133] In 1963, many countries ratified the Partial Test Ban Treaty which prohibited atmospheric nuclear testing.[134]

Some local opposition to nuclear power emerged in the early 1960s,[135] and in the late 1960s some members of the scientific community began to express their concerns.[136] In the early 1970s, there were large protests about a proposed nuclear power plant in Wyhl, Germany. The project was cancelled in 1975 and anti-nuclear success at Wyhl inspired opposition to nuclear power in other parts of Europe and North America.[137] Nuclear power became an issue of major public protest in the 1970s.[138]

Feminism

[edit]The role of women as full-time homemakers in industrial society was challenged in 1963, when US feminist Betty Friedan published The Feminine Mystique, giving momentum to the women's movement and influencing what many called Second-wave feminism. Other activists, such as Gloria Steinem and Angela Davis, either organized, influenced, or educated many of a younger generation of women to endorse and expand feminist thought. Feminism gained further currency within the protest movements of the late 1960s, as women in movements such as Students for a Democratic Society rebelled against the "support" role they believed they had been consigned to within the male-dominated New Left, as well as against perceived manifestations and statements of sexism within some radical groups. The 1970 pamphlet Women and Their Bodies, soon expanded into the 1971 book Our Bodies, Ourselves, was particularly influential in bringing about the new feminist consciousness.[139]

Free school movement

[edit]Environmentalism

[edit]

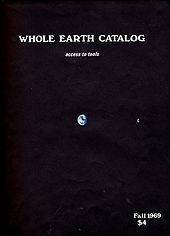

The 1960s counterculture embraced a back-to-the-land ethic, and communes of the era often relocated to the country from cities. Influential books of the 1960s included Rachel Carson's Silent Spring and Paul Ehrlich's The Population Bomb. Counterculture environmentalists were quick to grasp the implications of Ehrlich's writings on overpopulation, the Hubbert "peak oil" prediction, and more general concerns over pollution, litter, the environmental effects of the Vietnam War, automobile-dependent lifestyles, and nuclear energy. More broadly they saw that the dilemmas of energy and resource allocation would have implications for geo-politics, lifestyle, environment, and other dimensions of modern life. The "back to nature" theme was already prevalent in the counterculture by the time of the 1969 Woodstock festival, while the first Earth Day in 1970 was significant in bringing environmental concerns to the forefront of youth culture. At the start of the 1970s, counterculture-oriented publications like the Whole Earth Catalog and The Mother Earth News were popular, out of which emerged a back to the land movement. The 1960s and early 1970s counterculture were early adopters of practices such as recycling and organic farming long before they became mainstream. The counterculture interest in ecology progressed well into the 1970s: particularly influential were New Left eco-anarchist Murray Bookchin, Jerry Mander's criticism of the effects of television on society, Ernest Callenbach's novel Ecotopia, Edward Abbey's fiction and non-fiction writings, and E.F. Schumacher's economics book Small Is Beautiful.

Also in these years environmentalist global organizations arose, as Greenpeace and World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF).

Producerist

[edit]The National Farmers Organization (NFO) is a producerist movement founded in 1955. It became notorious for being associated with property violence and threats committed without official approval of the organization, from a 1964 incident when two members were crushed under the rear wheels of a cattle truck, for orchestrating the withholding of commodities, and for opposition to co-ops unwilling to withhold. During withholding protests, farmers would purposely destroy food or wastefully slaughter their animals in an attempt to raise prices and gain media exposure. The NFO failed to persuade the US government to establish a quota system as is currently practiced today in the milk, cheese, eggs and poultry supply management programs in Canada.

Gay liberation

[edit]The Stonewall riots were a series of spontaneous, violent demonstrations against a police raid that took place in the early morning hours of June 28, 1969, at the Stonewall Inn, a gay bar in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of New York City. This is frequently cited as the first instance in US history when people in the gay community fought back against a government-sponsored system that persecuted them, and became the defining event that marked the start of the gay rights movement in the United States and around the world.

Culture

[edit]Mod subculture

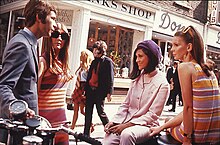

[edit]Mod is a subculture that began in London and spread throughout Great Britain and elsewhere, eventually influencing fashions and trends in other countries,[140] and continues today on a smaller scale. Focused on music and fashion, the subculture has its roots in a small group of stylish London-based young men in the late 1950s who were termed modernists because they listened to modern jazz.[141]Elements of the mod subculture include fashion (often tailor-made suits); music (including soul, rhythm and blues, ska, jazz, and later splintering off into rock and freakbeat after the peak Mod era); and motor scooters (usually Lambretta or Vespa). The original mod scene was associated with amphetamine-fuelled all-night dancing at clubs.[142]

During the early to mid-1960s, as mod grew and spread throughout the UK, certain elements of the mod scene became engaged in well-publicised clashes with members of rival subculture, rockers. The mods and rockers conflict led sociologist Stanley Cohen to use the term "moral panic" in his study about the two youth subcultures,[143] which examined media coverage of the mod and rocker riots in the 1960s.[144]

By 1965, conflicts between mods and rockers began to subside and mods increasingly gravitated towards pop art and psychedelia. London became synonymous with fashion, music, and pop culture in these years, a period often referred to as "Swinging London". During this time, mod fashions spread to other countries and became popular in the United States and elsewhere—with mod now viewed less as an isolated subculture, but emblematic of the larger youth culture of the era.

Hippies

[edit]After the January 14, 1967, Human Be-In in San Francisco organized by artist Michael Bowen, the media's attention on culture was fully activated.[145] In 1967, Scott McKenzie's rendition of the song "San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair)" brought as many as 100,000 young people from all over the world to celebrate San Francisco's "Summer of Love". While the song had originally been written by John Phillips of The Mamas & the Papas to promote the June 1967 Monterey Pop Festival, it became an instant hit worldwide (#4 in the United States, No. 1 in Europe) and quickly transcended its original purpose.

San Francisco's flower children, also called "hippies" by local newspaper columnist Herb Caen, adopted new styles of dress, experimented with psychedelic drugs, lived communally and developed a vibrant music scene. When people returned home from "The Summer of Love" these styles and behaviors spread quickly from San Francisco and Berkeley to many US and Canadian cities and European capitals. Some hippies formed communes to live as far outside of the established system as possible. This aspect of the counterculture rejected active political engagement with the mainstream and, following the dictate of Timothy Leary to "Turn on, tune in, drop out", hoped to change society by dropping out of it. Looking back on his own life (as a Harvard professor) prior to 1960, Leary interpreted it to have been that of "an anonymous institutional employee who drove to work each morning in a long line of commuter cars and drove home each night and drank martinis ... like several million middle-class, liberal, intellectual robots."

As members of the hippie movement grew older and moderated their lives and their views, and especially after US involvement in the Vietnam War ended in the mid-1970s, the counterculture was largely absorbed by the mainstream, leaving a lasting impact on philosophy, morality, music, art, alternative health and diet, lifestyle and fashion.

In addition to a new style of clothing, philosophy, art, music and various views on anti-war, and anti-establishment, some hippies decided to turn away from modern society and re-settle on ranches, or communes. The very first of communes in the United States was on a seven-acre tract of land in southeastern Colorado, named Drop City. According to Timothy Miller,[146]

"Drop City brought together most of the themes that had been developing in other recent communities-anarchy, pacifism, sexual freedom, rural isolation, interest in drugs, art-and wrapped them flamboyantly into a commune not quite like any that had gone before"

Many of the inhabitants practiced acts like reusing trash and recycled materials to build geodesic domes for shelter and other various purposes, using various drugs like marijuana and LSD, and creating various pieces of Drop Art. After the initial success of Drop City, visitors would take the idea of communes and spread them. Another commune called "The Ranch" was very similar to the culture of Drop City, as well as new concepts like giving children of the commune extensive freedoms known as "children's rights".[147] There were many hippie communes in New Mexico, including New Buffalo[148] and Tawapa.[149]

Marijuana, LSD, and other recreational drugs

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Psychedelia |

|---|

| Part of a series on |

| Cannabis |

|---|

|

During the 1960s, this second group of casual lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) users evolved and expanded into a subculture that extolled the mystical and religious symbolism often engendered by the drug's powerful effects, and advocated its use as a method of raising consciousness. The personalities associated with the subculture, gurus such as Timothy Leary and psychedelic rock musicians such as the Grateful Dead, Pink Floyd, Jimi Hendrix, the Byrds, Janis Joplin, the Doors, and the Beatles, soon attracted a great deal of publicity, generating further interest in LSD.

The popularization of LSD outside of the medical world was hastened when individuals such as Ken Kesey participated in drug trials and liked what they saw. Tom Wolfe wrote a widely read account of these early days of LSD's entrance into the non-academic world in his book The Electric Kool Aid Acid Test, which documented the cross-country, acid-fueled voyage of Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters on the psychedelic bus Furthur and the Pranksters' later "Acid Test" LSD parties. In 1965, Sandoz laboratories stopped its still legal shipments of LSD to the United States for research and psychiatric use, after a request from the US government concerned about its use. By April 1966, LSD use had become so widespread that Time magazine warned about its dangers.[150] In December 1966, the exploitation film Hallucination Generation was released.[citation needed] This was followed by The Trip in 1967 and Psych-Out in 1968.

Psychedelic research and experimentation

[edit]As most research on psychedelics began in the 1940s and 1950s, heavy experimentation made its effect in the 1960s during this era of change and movement. Researchers were gaining acknowledgment and popularity with their promotion of psychedelia. This really anchored the change that counterculture instigators and followers began. Most research was conducted at top collegiate institutes, such as Harvard University.

Timothy Leary and his Harvard research team had hopes for potential changes in society. Their research began with psilocybin mushrooms and was called the Harvard Psilocybin Project. In one study known as the Concord Prison Experiment, Leary investigated the potential for psilocybin to reduce recidivism in criminals being released from prison. After the research sessions, Leary did a follow-up. He found that "75% of the turned on prisoners who were released had stayed out of jail."[151] He believed he had solved the nation's crime problem. But with many officials skeptical, this breakthrough was not promoted.

Because of the personal experiences with these drugs, Leary and his many outstanding colleagues, including Aldous Huxley (The Doors of Perception) and Alan Watts (The Joyous Cosmology), believed that these were the mechanisms that could bring peace to not only the nation but the world. As their research continued the media followed them and published their work and documented their behavior, the trend of this counterculture drug experimentation began.[152]

Leary made attempts to bring more organized awareness to people interested in the study of psychedelics. He confronted the Senate committee in Washington and recommended for colleges to authorize the conduction of laboratory courses in psychedelics. He noted that these courses would "end the indiscriminate use of LSD and would be the most popular and productive courses ever offered".[153] Although these men were seeking an ultimate enlightenment, reality eventually proved that the potential they thought was there could not be reached, at least in this time. The change they sought for the world had not been permitted by the political systems of all the nations these men pursued their research in. Ram Dass states, "Tim and I actually had a chart on the wall about how soon everyone would be enlightened ... We found out that real change is harder. We downplayed the fact that the psychedelic experience isn't for everyone."[151]

Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters

[edit]Ken Kesey and his Merry Pranksters helped shape the developing character of the 1960s counterculture when they embarked on a cross-country voyage during the summer of 1964 in a psychedelic school bus named Furthur.[154] Beginning in 1959, Kesey had volunteered as a research subject for medical trials financed by the CIA's MK ULTRA project. These trials tested the effects of LSD, psilocybin, mescaline, and other psychedelic drugs. After the medical trials, Kesey continued experimenting on his own, and involved many close friends; collectively they became known as the "Merry Pranksters". The Pranksters visited Harvard LSD proponent Timothy Leary at his Millbrook, New York, retreat, and experimentation with LSD and other psychedelic drugs, primarily as a means for internal reflection and personal growth, became a constant during the Prankster trip.

The Pranksters created a direct link between the 1950s Beat Generation and the 1960s psychedelic scene; the bus was driven by Beat icon Neal Cassady, Beat poet Allen Ginsberg was on board for a time, and they dropped in on Cassady's friend, Beat author Jack Kerouac—though Kerouac declined to participate in the Prankster scene. After the Pranksters returned to California, they popularized the use of LSD at so-called "Acid Tests", which initially were held at Kesey's home in La Honda, California, and then at many other West Coast venues. The cross country trip and Prankster experiments were documented in Tom Wolfe's The Electric Kool Aid Acid Test, a masterpiece of New Journalism.[155]

Other psychedelics

[edit]Experimentation with LSD, DMT, peyote, psilocybin mushrooms, MDA, marijuana, and other psychedelic drugs became a major component of 1960s counterculture, influencing philosophy, art, music and styles of dress. Jim DeRogatis wrote that peyote, a small cactus containing the psychedelic alkaloid mescaline, was widely available in Austin, Texas, a countercultural hub in the early 1960s.[156]

Sexual revolution

[edit]The sexual revolution (also known as a time of "sexual liberation") was a social movement that challenged traditional codes of behavior related to sexuality and interpersonal relationships throughout the Western world from the 1960s to the 1980s. Contraception and the pill, public nudity, the normalization of premarital sex, homosexuality and alternative forms of sexuality, and the legalization of abortion all followed.[157][158]

Alternative media

[edit]Underground newspapers sprang up in most cities and college towns, serving to define and communicate the range of phenomena that defined the counterculture: radical political opposition to "The Establishment", colorful experimental (and often explicitly drug-influenced) approaches to art, music and cinema, and uninhibited indulgence in sex and drugs as a symbol of freedom. The papers also often included comic strips, from which the underground comix were an outgrowth.

Alternative disc sports (Frisbee)

[edit]

As numbers of young people became alienated from social norms, they resisted and looked for alternatives. The forms of escape and resistance manifest in many ways including social activism, alternative lifestyles, dress, music and alternative recreational activities, including that of throwing a Frisbee. From hippies tossing the Frisbee at festivals and concerts came today's popular disc sports.[159][160] Disc sports such as disc freestyle, double disc court, disc guts, Ultimate and disc golf became this sport's first events.[161][162]

Avant-garde art and anti-art

[edit]The Situationist International was a restricted group of international revolutionaries founded in 1957, and which had its peak in its influence on the unprecedented general wildcat strikes of May 1968 in France. With their ideas rooted in Marxism and the 20th-century European artistic avant-gardes, they advocated experiences of life being alternative to those admitted by the capitalist order, for the fulfillment of human primitive desires and the pursuing of a superior passional quality. For this purpose they suggested and experimented with the construction of situations, namely the setting up of environments favorable for the fulfillment of such desires. Using methods drawn from the arts, they developed a series of experimental fields of study for the construction of such situations, like unitary urbanism and psychogeography. They fought against the main obstacle on the fulfillment of such superior passional living, identified by them in advanced capitalism. Their theoretical work peaked on the highly influential book The Society of the Spectacle by Guy Debord. Debord argued in 1967 that spectacular features like mass media and advertising have a central role in an advanced capitalist society, which is to show a fake reality to mask the real capitalist degradation of human life. Raoul Vaneigem wrote The Revolution of Everyday Life which takes the field of "everyday life" as the ground upon which communication and participation can occur, or, as is more commonly the case, be perverted and abstracted into pseudo-forms.

Fluxus (a name taken from a Latin word meaning "to flow") is an international network of artists, composers and designers noted for blending different artistic media and disciplines in the 1960s. They have been active in Neo-Dada noise music, visual art, literature, urban planning, architecture, and design. Fluxus is often described as intermedia, a term coined by Fluxus artist Dick Higgins in a famous 1966 essay. Fluxus encouraged a "do-it-yourself" aesthetic, and valued simplicity over complexity. Like Dada before it, Fluxus included a strong current of anti-commercialism and an anti-art sensibility, disparaging the conventional market-driven art world in favor of an artist-centered creative practice. As Fluxus artist Robert Filliou wrote, however, Fluxus differed from Dada in its richer set of aspirations, and the positive social and communitarian aspirations of Fluxus far outweighed the anti-art tendency that also marked the group.

In the 1960s, the Dada-influenced art group Black Mask declared that revolutionary art should be "an integral part of life, as in primitive society, and not an appendage to wealth."[163] Black Mask disrupted cultural events in New York by giving made up flyers of art events to the homeless with the lure of free drinks.[164] After, the Motherfuckers grew out of a combination of Black Mask and another group called Angry Arts. Up Against the Wall Motherfuckers (often referred to as simply "the Motherfuckers", or UAW/MF) was an anarchist affinity group based in New York City.

Music

[edit]The 60s were a leap in human consciousness. Mahatma Gandhi, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Che Guevara, Mother Teresa, they led a revolution of conscience. The Beatles, The Doors, Jimi Hendrix created revolution and evolution themes. The music was like Dalí, with many colors and revolutionary ways. The youth of today must go there to find themselves.

Bob Dylan's early career as a protest singer had been inspired by his hero Woody Guthrie,[166]: 25 and his iconic lyrics and protest anthems helped propel the Folk Revival of the 1960s, which was arguably the first major sub-movement of the Counterculture. Although Dylan was first popular for his protest music, the song Mr. Tambourine Man saw a stylistic shift in Dylan's work, from topical to abstract and imaginative, included some of the first uses of surrealistic imagery in popular music and has been viewed as a call to drugs such as LSD.

The Beach Boys' 1966 album Pet Sounds served as a major source of inspiration for other contemporary acts, most notably directly inspiring the Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. The single "Good Vibrations" soared to number one globally, completely changing the perception of what a record could be.[167] It was during this period that the highly anticipated album Smile was to be released. However, the project collapsed and The Beach Boys released a stripped down and reimagined version called Smiley Smile, which failed to make a big commercial impact but was also highly influential, most notably on The Who's Pete Townshend.

The Beatles went on to become the most prominent commercial exponents of the "psychedelic revolution" (e.g., Revolver, Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band and Magical Mystery Tour) in the late 1960s.[168]

Detroit's MC5 also came out of the underground rock music scene of the late 1960s. They introduced a more aggressive evolution of garage rock which was often fused with sociopolitical and countercultural lyrics of the era, such as in the song "Motor City Is Burning" (a John Lee Hooker cover adapting the story of the Detroit Race Riot of 1943 to the Detroit riot of 1967). MC5 had ties to radical leftist organizations such as "Up Against the Wall Motherfuckers" and John Sinclair's White Panther Party.[166]: 117

Another hotbed of the 1960s counterculture was Austin, Texas, with two of the era's legendary music venues-the Vulcan Gas Company and the Armadillo World Headquarters-and musical talent like Janis Joplin, the 13th Floor Elevators, Shiva's Headband, the Conqueroo, and, later, Stevie Ray Vaughan. Austin was also home to a large New Left activist movement, one of the earliest underground papers, The Rag, and cutting edge graphic artists like Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers creator Gilbert Shelton, underground comix pioneer Jack Jackson (Jaxon), and surrealist armadillo artist Jim Franklin.[169]

The 1960s was also an era of rock festivals, which played an important role in spreading the counterculture across the US.[170] The Monterey Pop Festival, which launched Hendrix's career in the US, was one of the first of these festivals.[171] The 1969 Woodstock Festival in New York state became a symbol of the movement,[172] although the 1970 Isle of Wight Festival drew a larger crowd.[166]: 58 Some believe the era came to an abrupt end with the infamous Altamont Free Concert held by the Rolling Stones, in which heavy-handed security from the Hells Angels resulted in the stabbing of an audience member, apparently in self-defense, as the show descended into chaos.[173]

The 1960s saw the protest song gain a sense of political self-importance, with Phil Ochs's "I Ain't Marching Anymore" and Country Joe and the Fish's "I-Feel-Like-I'm-Fixin'-to-Die-Rag" among the many anti-war anthems that were important to the era.[166]

Free jazz is an approach to jazz music that was first developed in the 1950s and 1960s. Although the music produced by free jazz composers varied widely, the common feature was a dissatisfaction with the limitations of bebop, hard bop, and modal jazz, which had developed in the 1940s and 1950s. Each in their own way, free jazz musicians attempted to alter, extend, or break down the conventions of jazz, often by discarding hitherto invariable features of jazz, such as fixed chord changes or tempos. While usually considered experimental and avant-garde, free jazz has also oppositely been conceived as an attempt to return jazz to its "primitive", often religious roots, and emphasis on collective improv. Free jazz is strongly associated with the 1950s innovations of Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor and the later works of saxophonist John Coltrane. Other important pioneers included Charles Mingus, Eric Dolphy, Albert Ayler, Archie Shepp, Joe Maneri and Sun Ra. Although today "free jazz" is the generally used term, many other terms were used to describe the loosely defined movement, including "avant-garde", "energy music" and "The New Thing". During its early and mid-60s heyday, much free jazz was released by established labels such as Prestige, Blue Note and Impulse, as well as independents such as ESP Disk and BYG Actuel. Free improv or free music is improvised music without any rules beyond the logic or inclination of the musician(s) involved. The term can refer to both a technique (employed by any musician in any genre) and as a recognizable genre in its own right. Free improvisation as a genre of music, developed in the US and Europe in the mid- to late 1960s, largely as an outgrowth of free jazz and modern classical musics. None of its primary exponents can be said to be famous within the mainstream; however, in experimental circles, a number of free musicians are well known, including saxophonists Evan Parker, Anthony Braxton, Peter Brötzmann and John Zorn, drummer Christian Lillinger, trombonist George E. Lewis, guitarists Derek Bailey, Henry Kaiser and Fred Frith and the improvising groups The Art Ensemble of Chicago and AMM.

AllMusic Guide states that "until around 1967, the worlds of jazz and rock were nearly completely separate".[174] The term, "jazz-rock" (or "jazz/rock") is often used as a synonym for the term "jazz fusion". However, some make a distinction between the two terms. The Free Spirits have sometimes been cited as the earliest jazz-rock band.[175] During the late 1960s, at the same time that jazz musicians were experimenting with rock rhythms and electric instruments, rock groups such as Cream and the Grateful Dead were "beginning to incorporate elements of jazz into their music" by "experimenting with extended free-form improvisation". Other "groups such as Blood, Sweat & Tears directly borrowed harmonic, melodic, rhythmic and instrumentational elements from the jazz tradition".[176] The rock groups that drew on jazz ideas (like Soft Machine, Colosseum, Caravan, Nucleus, Chicago, Spirit and Frank Zappa) turned the blend of the two styles with electric instruments.[177] Since rock often emphasized directness and simplicity over virtuosity, jazz-rock generally grew out of the most artistically ambitious rock subgenres of the late 1960s and early 70s: psychedelia, progressive rock, and the singer-songwriter movement.[178] Miles Davis' Bitches Brew sessions, recorded in August 1969 and released the following year, mostly abandoned jazz's usual swing beat in favor of a rock-style backbeat anchored by electric bass grooves. The recording "mixed free jazz blowing by a large ensemble with electronic keyboards and guitar, plus a dense mix of percussion."[179] Davis also drew on the rock influence by playing his trumpet through electronic effects and pedals. While the album gave Davis a gold record, the use of electric instruments and rock beats created a great deal of consternation among some more conservative jazz critics.

Film

[edit]The counterculture was not only affected by cinema, but was also instrumental in the provision of era-relevant content and talent for the film industry. Bonnie and Clyde struck a chord with the youth as "the alienation of the young in the 1960s was comparable to the director's image of the 1930s."[180] Films of this time also focused on the changes happening in the world. A sign of this was the visibility that the hippie subculture gained in various mainstream and underground media. Hippie exploitation films are 1960s exploitation films about the hippie counterculture[181] with stereotypical situations associated with the movement such as marijuana and LSD use, sex and wild psychedelic parties. Examples include The Love-ins, Psych-Out, The Trip, and Wild in the Streets. The musical play Hair shocked stage audiences with full-frontal nudity. Dennis Hopper's "Road Trip" adventure Easy Rider (1969) became accepted as one of the landmark films of the era.[182] Medium Cool portrayed the 1968 Democratic Convention alongside the 1968 Chicago police riots.[183]

Inaugurated by the 1969 release of Andy Warhol's Blue Movie, the phenomenon of adult erotic films being publicly discussed by celebrities (like Johnny Carson and Bob Hope),[184] and taken seriously by critics (like Roger Ebert),[185][186] a development referred to, by Ralph Blumenthal of The New York Times, as "porno chic", and later known as the Golden Age of Porn, began, for the first time, in modern American culture.[184][187][188] According to award-winning author Toni Bentley, Radley Metzger's 1976 film The Opening of Misty Beethoven, based on the play Pygmalion by George Bernard Shaw (and its derivative, My Fair Lady), is considered the "crown jewel" of this 'Golden Age'.[189][190]

In France the New Wave was a blanket term coined by critics for a group of French filmmakers of the late 1950s and 1960s, influenced by Italian Neorealism and classical Hollywood cinema. Although never a formally organized movement, the New Wave filmmakers were linked by their self-conscious rejection of classical cinematic form and their spirit of youthful iconoclasm and is an example of European art cinema. Many also engaged in their work with the social and political upheavals of the era, making their radical experiments with editing, visual style and narrative part of a general break with the conservative paradigm. The Left Bank, or Rive Gauche, group is a contingent of filmmakers associated with the French New Wave, first identified as such by Richard Roud.[191] The corresponding "right bank" group comprises the more famous and financially successful New Wave directors associated with Cahiers du cinéma (Claude Chabrol, François Truffaut, and Jean-Luc Godard).[191] Left Bank directors include Chris Marker, Alain Resnais, and Agnès Varda.[191] Roud described a distinctive "fondness for a kind of Bohemian life and an impatience with the conformity of the Right Bank, a high degree of involvement in literature and the plastic arts, and a consequent interest in experimental filmmaking", as well as an identification with the political left.[191] Other film "new waves" from around the world associated with the 1960s are New German Cinema, Czechoslovak New Wave, Brazilian Cinema Novo and Japanese New Wave. During the 1960s, the term "art film" began to be much more widely used in the United States than in Europe. In the US, the term is often defined very broadly, to include foreign-language (non-English) "auteur" films, independent films, experimental films, documentaries and short films. In the 1960s "art film" became a euphemism in the US for racy Italian and French B-movies. By the 1970s, the term was used to describe sexually explicit European films with artistic structure such as the Swedish film I Am Curious (Yellow). The 1960s was an important period in art film; the release of a number of groundbreaking films giving rise to the European art cinema which had countercultural traits in filmmakers such as Michelangelo Antonioni, Federico Fellini, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Luis Buñuel and Bernardo Bertolucci.

Technology

[edit]| External videos | |

|---|---|

Cultural historians—such as Theodore Roszak in his 1986 essay "From Satori to Silicon Valley" and John Markoff in his book What the Dormouse Said,[192] have pointed out that many of the early pioneers of personal computing emerged from within the West Coast counterculture. Many early computing and networking pioneers, after discovering LSD and roaming the campuses of UC Berkeley, Stanford, and MIT in the late 1960s and early 1970s, would emerge from this caste of social "misfits" to shape the modern world of technology, especially in Silicon Valley.

Religion, spirituality and the occult

[edit]Many hippies rejected mainstream organized religion in favor of a more personal spiritual experience, often drawing on indigenous and folk beliefs. If they adhered to mainstream faiths, hippies were likely to embrace Buddhism, Daoism, Hinduism, Sufism, Unitarian Universalism and the restorationist Christianity of the Jesus Movement. Some hippies embraced neo-paganism, especially Wicca. Wicca is a witchcraft religion which became more prominent beginning in 1951, with the repeal of the Witchcraft Act 1735, after which Gerald Gardner and then others such as Charles Cardell and Cecil Williamson began publicising their own versions of the Craft. Gardner and others never used the term "Wicca" as a religious identifier, simply referring to the "witch cult", "witchcraft", and the "Old Religion". However, Gardner did refer to witches as "the Wica".[193] During the 1960s, the name of the religion normalised to "Wicca".[194][195] Gardner's tradition, later termed Gardnerianism, soon became the dominant form in England and spread to other parts of the British Isles. Following Gardner's death in 1964, the Craft continued to grow unabated despite sensationalism and negative portrayals in British tabloids, with new traditions being propagated by figures like Robert Cochrane, Sybil Leek and most importantly Alex Sanders, whose Alexandrian Wicca, which was predominantly based upon Gardnerian Wicca, albeit with an emphasis placed on ceremonial magic, spread quickly and gained much media attention.

In his 1991 book, Hippies and American Values, Timothy Miller described the hippie ethos as essentially a "religious movement" whose goal was to transcend the limitations of mainstream religious institutions. "Like many dissenting religions, the hippies were enormously hostile to the religious institutions of the dominant culture, and they tried to find new and adequate ways to do the tasks the dominant religions failed to perform."[196] In his seminal, contemporaneous work, The Hippie Trip, author Lewis Yablonsky notes that those who were most respected in hippie settings were the spiritual leaders, the so-called "high priests" who emerged during that era.[197]

One such hippie "high priest" was San Francisco State College instructor Stephen Gaskin. Beginning in 1966, Gaskin's "Monday Night Class" eventually outgrew the lecture hall, and attracted 1,500 hippie followers in an open discussion of spiritual values, drawing from Christian, Buddhist, and Hindu teachings. In 1970, Gaskin founded a Tennessee community called The Farm, and he still lists his religion as "Hippie".[198][199][200]

Timothy Leary was an American psychologist and writer, known for his advocacy of psychedelic drugs. On September 19, 1966, Leary founded the League for Spiritual Discovery, a religion declaring LSD as its holy sacrament, in part as an unsuccessful attempt to maintain legal status for the use of LSD and other psychedelics for the religion's adherents based on a "freedom of religion" argument. The Psychedelic Experience was the inspiration for John Lennon's song "Tomorrow Never Knows" in The Beatles' album Revolver.[201] He published a pamphlet in 1967 called Start Your Own Religion to encourage just that (see below under "writings") and was invited to attend the January 14, 1967 Human Be-In a gathering of 30,000 hippies in San Francisco's Golden Gate Park In speaking to the group, he coined the famous phrase "Turn on, tune in, drop out".[202]

The Principia Discordia is the founding text of Discordianism written by Greg Hill (Malaclypse the Younger) and Kerry Wendell Thornley (Lord Omar Khayyam Ravenhurst). It was originally published under the title "Principia Discordia or How The West Was Lost" in a limited edition of five copies in 1965. The title, literally meaning "Discordant Principles", is in keeping with the tendency of Latin to prefer hypotactic grammatical arrangements. In English, one would expect the title to be "Principles of Discord".[203]

Criticism and legacy

[edit]The lasting impact (including unintended consequences), creative output, and general legacy of the counterculture era continue to be actively discussed, debated, despised and celebrated.

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Even the notions of when the counterculture subsumed the Beat Generation, when it gave way to the successor generation, and what happened in between are open for debate. According to notable UK Underground and counterculture author Barry Miles,[204]

It seemed to me that the Seventies was when most of the things that people attribute to the sixties really happened: this was the age of extremes, people took more drugs, had longer hair, weirder clothes, had more sex, protested more violently and encountered more opposition from the establishment. It was the era of sex and drugs and rock'n'roll, as Ian Dury said. The countercultural explosion of the 1960s really only involved a few thousand people in the UK and perhaps ten times that in the USA—largely because of opposition to the Vietnam war, whereas in the Seventies the ideas had spread out across the world.

A Columbia University teaching unit on the counterculture era notes: "Although historians disagree over the influence of the counterculture on American politics and society, most describe the counterculture in similar terms. Virtually all authors—for example, on the right, Robert Bork in Slouching Toward Gomorrah: Modern Liberalism and American Decline (New York: Regan Books,1996) and, on the left, Todd Gitlin in The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage (New York: Bantam Books, 1987)—characterize the counterculture as self-indulgent, childish, irrational, narcissistic, and even dangerous. Even so, many liberal and leftist historians find constructive elements in it, while those on the right tend not to."[205]

Actor John Wayne equated aspects of 1960s social programs with the rise of the welfare state, "I know all about that. In the late Twenties, when I was a sophomore at USC, I was a socialist myself—but not when I left. The average college kid idealistically wishes everybody could have ice cream and cake for every meal. But as he gets older and gives more thought to his and his fellow man's responsibilities, he finds that it can't work out that way—that some people just won't carry their load ... I believe in welfare—a welfare work program. I don't think a fella should be able to sit on his backside and receive welfare. I'd like to know why well-educated idiots keep apologizing for lazy and complaining people who think the world owes them a living. I'd like to know why they make excuses for cowards who spit in the faces of the police and then run behind the judicial sob sisters. I can't understand these people who carry placards to save the life of some criminal, yet have no thought for the innocent victim."[206]

Former liberal Democrat Ronald Reagan, who later became a conservative Governor of California and 40th President of the US, remarked about one group of protesters carrying signs, "The last bunch of pickets were carrying signs that said 'Make love, not war.' The only trouble was they didn't look capable of doing either."[207][208]

The "generation gap" between the affluent young and their often poverty-scarred parents was a critical component of 1960s culture. In an interview with journalist Gloria Steinem during the 1968 US presidential campaign, soon-to-be First Lady Pat Nixon exposed the generational chasm in worldview between Steinem, 20 years her junior, and herself after Steinem probed Mrs. Nixon as to her youth, role models, and lifestyle. A hardscrabble child of the Great Depression, Pat Nixon told Steinem, "I never had time to think about things like that, who I wanted to be, or who I admired, or to have ideas. I never had time to dream about being anyone else. I had to work. I haven't just sat back and thought of myself or my ideas or what I wanted to do ... I've kept working. I don't have time to worry about who I admire or who I identify with. I never had it easy. I'm not at all like you ... all those people who had it easy."[209]

In economic terms, it has been contended that the counterculture really only amounted to creating new marketing segments for the "hip" crowd.[210]

Even before the counterculture movement reached its peak of influence, the concept of the adoption of socially-responsible policies by establishment corporations was discussed by economist and Nobel laureate Milton Friedman (1962): "Few trends could so thoroughly undermine the very foundation of our free society as the acceptance by corporate officials of a social responsibility other than to make as much money for their stockholders as possible. This is a fundamentally subversive doctrine. If businessmen do have a social responsibility other than making maximum profits for stockholders, how are they to know what it is? Can self-selected private individuals decide what the social interest is?"[211]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

In 2003, author and former Free Speech activist Greil Marcus was quoted, "What happened four decades ago is history. It's not just a blip in the history of trends. Whoever shows up at a march against war in Iraq, it always takes place with a memory of the efficacy and joy and gratification of similar protests that took place in years before ... It doesn't matter that there is no counterculture, because counterculture of the past gives people a sense that their own difference matters."[212]

When asked about the prospects of the counterculture movement moving forward in the digital age, former Grateful Dead lyricist and self-styled "cyberlibertarian" John Perry Barlow said, "I started out as a teenage beatnik and then became a hippie and then became a cyberpunk. And now I'm still a member of the counterculture, but I don't know what to call that. And I'd been inclined to think that that was a good thing, because once the counterculture in America gets a name then the media can coopt it, and the advertising industry can turn it into a marketing foil. But you know, right now I'm not sure that it is a good thing, because we don't have any flag to rally around. Without a name there may be no coherent movement."[213]

During the era, conservative students objected to the counterculture and found ways to celebrate their conservative ideals by reading books like J. Edgar Hoover's A Study of Communism, joining student organizations like the College Republicans, and organizing Greek events which reinforced gender norms.[214]

Free speech advocate and social anthropologist Jentri Anders observed that a number of freedoms were endorsed within a countercultural community in which she lived and studied: "freedom to explore one's potential, freedom to create one's Self, freedom of personal expression, freedom from scheduling, freedom from rigidly defined roles and hierarchical statuses". Additionally, Anders believed some in the counterculture wished to modify children's education so that it did not discourage, but rather encouraged, "aesthetic sense, love of nature, passion for music, desire for reflection, or strongly marked independence."[215][216]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

In 2007, Merry Prankster Carolyn "Mountain Girl" Garcia commented, "I see remnants of that movement everywhere. It's sort of like the nuts in Ben and Jerry's ice cream—it's so thoroughly mixed in, we sort of expect it. The nice thing is that eccentricity is no longer so foreign. We've embraced diversity in a lot of ways in this country. I do think it's done us a tremendous service."[217]

The 1990 Oscar-nominated documentary film Berkeley in the Sixties[218][219] highlighted what Owen Gleiberman from Entertainment Weekly noted:

The film doesn't shrink from saying that many of the '60s social-protest movements went too far. It demonstrates that by the end of the decade, protest had become a narcotic in itself.[220]

An art exhibition (that originated at the Walker Art Center in 2015[221] before expanding it to California) called Hippie Modernism: The Struggle for Uptopia reframes a more radically meditative story of the counterculture that contrasts to the popular perception for said era.[222]

In popular culture

[edit]Такие фильмы, как «Возвращение Секаука 7» и «Большой холод». [223] tackled life of the idealistic Boomers from the countercultural 1960s to their older selfs in the 80s alongside the TV series thirtysomething.[224] этого поколения Ностальгия по указанному десятилетию также подверглась критике. [225] [226]

Панос Косматос , режиссер фильма 2010 года «За черной радугой» , признает, что ему не нравится духовные идеалы бэби-бумеров , и эту проблему он рассматривает в «За черной радугой» . По его мнению, поиск бумерами альтернативных систем верований заставил их погрузиться в темную сторону оккультизма , что, в свою очередь, испортило их поиски духовного просветления. [227] использование психоделических препаратов в целях расширения сознания. Также исследуется [228] хотя взгляд Косматоса на него «мрачный и тревожный», «бренд психоделии, который находится в прямой противоположности « Дитя цветов » и «Путешествие в мир с волшебными грибами », - написал рецензент. [229] Джордан Хоффман из UGO Networks отметил оба элемента, заявив в своем обзоре, что в фильме некоторые «никчемные ученые нового века позволили своим экспериментам с наркотиками, изменяющими сознание, мутировать молодую женщину». [230] – в данном случае Елена. Косматос объясняет, почему миссия доктора Арбории по созданию превосходного человека в конечном итоге провалилась: