Реинкарнация

Реинкарнация , также известная как перерождение или переселение , — это философская или религиозная концепция, согласно которой нефизическая сущность живого существа начинает новую жизнь в другой физической форме или теле после биологической смерти . [ 1 ] [ 2 ] В большинстве верований, связанных с реинкарнацией, душа человека бессмертна и не рассеивается после гибели физического тела. После смерти душа просто переселяется в новорожденного ребенка или животное, чтобы продолжить свое бессмертие . Термин «переселение» означает переход души из одного тела в другое после смерти.

Реинкарнация ( пунарджанма ) является центральным принципом индийских религий, таких как индуизм , буддизм , джайнизм и сикхизм . [ 3 ] [ 4 ] [ 5 ] [ 6 ] В различных формах оно встречается как эзотерическая вера во многих течениях иудаизма , некоторых языческих религиях, включая Викку , и в некоторых верованиях коренных народов Америки. [ 7 ] и австралийские аборигены (хотя большинство из них верят в загробную жизнь или духовный мир ). [ 8 ] Веру в возрождение или миграцию души ( метемпсихоз ) выражали некоторые древнегреческие исторические деятели, такие как Пифагор , Сократ и Платон . [9]

Although the majority of denominations within Abrahamic religions do not believe that individuals reincarnate, particular groups within these religions do refer to reincarnation; these groups include the mainstream historical and contemporary followers of Cathars, Alawites, Hassidics, the Druze,[10] Kabbalistics, and the Rosicrucians.[11] The historical relations between these sects and the beliefs about reincarnation that were characteristic of Neoplatonism, Orphism, Hermeticism, Manichaenism, and Gnosticism of the Roman era as well as the Indian religions have been the subject of recent scholarly research.[12] In recent decades, many Europeans and North Americans have developed an interest in reincarnation,[13] and many contemporary works mention it.

Conceptual definitions

[edit]The word reincarnation derives from a Latin term that literally means 'entering the flesh again'. Reincarnation refers to the belief that an aspect of every human being (or all living beings in some cultures) continues to exist after death. This aspect may be the soul, mind, consciousness, or something transcendent which is reborn in an interconnected cycle of existence; the transmigration belief varies by culture, and is envisioned to be in the form of a newly born human being, animal, plant, spirit, or as a being in some other non-human realm of existence.[14][15][16]

An alternative term is transmigration, implying migration from one life (body) to another.[17] The term has been used by modern philosophers such as Kurt Gödel[18] and has entered the English language.

The Greek equivalent to reincarnation, metempsychosis (μετεμψύχωσις), derives from meta ('change') and empsykhoun ('to put a soul into'),[19] a term attributed to Pythagoras.[20] Another Greek term sometimes used synonymously is palingenesis, 'being born again'.[21]

Rebirth is a key concept found in major Indian religions, and discussed using various terms. Reincarnation, or Punarjanman (Sanskrit: पुनर्जन्मन्, 'rebirth, transmigration'),[22][23] is discussed in the ancient Sanskrit texts of Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism, with many alternate terms such as punarāvṛtti (पुनरावृत्ति), punarājāti (पुनराजाति), punarjīvātu (पुनर्जीवातु), punarbhava (पुनर्भव), āgati-gati (आगति-गति, common in Buddhist Pali text), nibbattin (निब्बत्तिन्), upapatti (उपपत्ति), and uppajjana (उप्पज्जन).[22][24]

These religions believe that this reincarnation is cyclic and an endless Saṃsāra, unless one gains spiritual insights that ends this cycle leading to liberation.[3][25] The reincarnation concept is considered in Indian religions as a step that starts each "cycle of aimless drifting, wandering or mundane existence",[3] but one that is an opportunity to seek spiritual liberation through ethical living and a variety of meditative, yogic (marga), or other spiritual practices.[26] They consider the release from the cycle of reincarnations as the ultimate spiritual goal, and call the liberation by terms such as moksha, nirvana, mukti and kaivalya.[27][28][29] However, the Buddhist, Hindu and Jain traditions have differed, since ancient times, in their assumptions and in their details on what reincarnates, how reincarnation occurs and what leads to liberation.[30][31]

Gilgul, Gilgul neshamot, or Gilgulei Ha Neshamot (Hebrew: גלגול הנשמות) is the concept of reincarnation in Kabbalistic Judaism, found in much Yiddish literature among Ashkenazi Jews. Gilgul means 'cycle' and neshamot is 'souls'. Kabbalistic reincarnation says that humans reincarnate only to humans unless YHWH/Ein Sof/God chooses.

History

[edit]Origins

[edit]The origins of the notion of reincarnation are obscure.[32] Discussion of the subject appears in the philosophical traditions of Ancient India. The Greek Pre-Socratics discussed reincarnation, and the Celtic druids are also reported to have taught a doctrine of reincarnation.[33]

Early Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism

[edit]The concepts of the cycle of birth and death, saṁsāra, and liberation partly derive from ascetic traditions that arose in India around the middle of the first millennium BCE.[34] The first textual references to the idea of reincarnation appear in the Rigveda, Yajurveda and Upanishads of the late Vedic period (c. 1100 – c. 500 BCE), predating the Buddha and Mahavira.[35][36] Though no direct evidence of this has been found, the tribes of the Ganges valley or the Dravidian traditions of South India have been proposed as another early source of reincarnation beliefs.[37]

The idea of reincarnation, saṁsāra, did exist in the early Vedic religions.[38][39][40] The early Vedas do mention the doctrine of karma and rebirth.[25][41][42] It is in the early Upanishads, which are pre-Buddha and pre-Mahavira, where these ideas are developed and described in a general way.[43][44][45] Detailed descriptions first appear around the mid-1st millennium BCE in diverse traditions, including Buddhism, Jainism and various schools of Hindu philosophy, each of which gave unique expression to the general principle.[25]

Sangam literature[46] connotes the ancient Tamil literature and is the earliest known literature of South India. The Tamil tradition and legends link it to three literary gatherings around Madurai. According to Kamil Zvelebil, a Tamil literature and history scholar, the most acceptable range for the Sangam literature is 100 BCE to 250 CE, based on the linguistic, prosodic and quasi-historic allusions within the texts and the colophons.[47] There are several mentions of rebirth and moksha in the Purananuru.[48] The text explains Hindu rituals surrounding death such as making riceballs called pinda and cremation. The text states that good souls get a place in Indraloka where Indra welcomes them.[49]

The texts of ancient Jainism that have survived into the modern era are post-Mahavira, likely from the last centuries of the first millennium BCE, and extensively mention rebirth and karma doctrines.[50][51] The Jaina philosophy assumes that the soul (jiva in Jainism; atman in Hinduism) exists and is eternal, passing through cycles of transmigration and rebirth.[52] After death, reincarnation into a new body is asserted to be instantaneous in early Jaina texts.[51] Depending upon the accumulated karma, rebirth occurs into a higher or lower bodily form, either in heaven or hell or earthly realm.[53][54] No bodily form is permanent: everyone dies and reincarnates further. Liberation (kevalya) from reincarnation is possible, however, through removing and ending karmic accumulations to one's soul.[55] From the early stages of Jainism on, a human being was considered the highest mortal being, with the potential to achieve liberation, particularly through asceticism.[56][57][58]

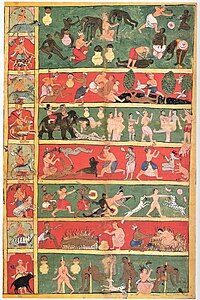

The early Buddhist texts discuss rebirth as part of the doctrine of saṃsāra. This asserts that the nature of existence is a "suffering-laden cycle of life, death, and rebirth, without beginning or end".[59][60] Also referred to as the wheel of existence (Bhavacakra), it is often mentioned in Buddhist texts with the term punarbhava (rebirth, re-becoming). Liberation from this cycle of existence, Nirvana, is the foundation and the most important purpose of Buddhism.[59][61][62] Buddhist texts also assert that an enlightened person knows his previous births, a knowledge achieved through high levels of meditative concentration.[63] Tibetan Buddhism discusses death, bardo (an intermediate state), and rebirth in texts such as the Tibetan Book of the Dead. While Nirvana is taught as the ultimate goal in the Theravadin Buddhism, and is essential to Mahayana Buddhism, the vast majority of contemporary lay Buddhists focus on accumulating good karma and acquiring merit to achieve a better reincarnation in the next life.[64][65]

In early Buddhist traditions, saṃsāra cosmology consisted of five realms through which the wheel of existence cycled.[59] This included hells (niraya), hungry ghosts (pretas), animals (tiryaka), humans (manushya), and gods (devas, heavenly).[59][60][66] In latter Buddhist traditions, this list grew to a list of six realms of rebirth, adding demigods (asuras).[59][67]

Rationale

[edit]The earliest layers of Vedic text incorporate the concept of life, followed by an afterlife in heaven and hell based on cumulative virtues (merit) or vices (demerit).[68] However, the ancient Vedic rishis challenged this idea of afterlife as simplistic, because people do not live equally moral or immoral lives. Between generally virtuous lives, some are more virtuous; while evil too has degrees, and the texts assert that it would be unfair for people, with varying degrees of virtue or vices, to end up in heaven or hell, in "either or" and disproportionate manner irrespective of how virtuous or vicious their lives were.[69][70][71] They introduced the idea of an afterlife in heaven or hell in proportion to one's merit.[72][73][74]

Comparison

[edit]Early texts of Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism share the concepts and terminology related to reincarnation.[75] They also emphasize similar virtuous practices and karma as necessary for liberation and what influences future rebirths.[35][76] For example, all three discuss various virtues—sometimes grouped as Yamas and Niyamas—such as non-violence, truthfulness, non-stealing, non-possessiveness, compassion for all living beings, charity and many others.[77][78]

Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism disagree in their assumptions and theories about rebirth. Hinduism relies on its foundational assumption that 'soul, Self exists' (atman or attā), in contrast to Buddhist assumption that there is 'no soul, no Self' (anatta or anatman).[79][80][81][82][83][84][85][86][87][88] Hindu traditions consider soul to be the unchanging eternal essence of a living being, and what journeys across reincarnations until it attains self-knowledge.[89][90][91] Buddhism, in contrast, asserts a rebirth theory without a Self, and considers realization of non-Self or Emptiness as Nirvana (nibbana). Thus Buddhism and Hinduism have a very different view on whether a self or soul exists, which impacts the details of their respective rebirth theories.[92][93][94]

The reincarnation doctrine in Jainism differs from those in Buddhism, even though both are non-theistic Sramana traditions.[95][96] Jainism, in contrast to Buddhism, accepts the foundational assumption that soul exists (Jiva) and asserts this soul is involved in the rebirth mechanism.[97] Further, Jainism considers asceticism as an important means to spiritual liberation that ends all reincarnation, while Buddhism does not.[95][98][99]

Classical antiquity

[edit]

Early Greek discussion of the concept dates to the sixth century BCE. An early Greek thinker known to have considered rebirth is Pherecydes of Syros (fl. 540 BCE).[100] His younger contemporary Pythagoras (c. 570–c. 495 BCE[101]), its first famous exponent, instituted societies for its diffusion. Some authorities believe that Pythagoras was Pherecydes' pupil, others that Pythagoras took up the idea of reincarnation from the doctrine of Orphism, a Thracian religion, or brought the teaching from India.

Plato (428/427–348/347 BCE) presented accounts of reincarnation in his works, particularly the Myth of Er, where Plato makes Socrates tell how Er, the son of Armenius, miraculously returned to life on the twelfth day after death and recounted the secrets of the other world. There are myths and theories to the same effect in other dialogues, in the Chariot allegory of the Phaedrus,[102] in the Meno,[103] Timaeus and Laws. The soul, once separated from the body, spends an indeterminate amount of time in the intelligible realm (see The Allegory of the Cave in The Republic) and then assumes another body. In the Timaeus, Plato believes that the soul moves from body to body without any distinct reward-or-punishment phase between lives, because the reincarnation is itself a punishment or reward for how a person has lived.[104]

In Phaedo, Plato has his teacher Socrates, prior to his death, state: "I am confident that there truly is such a thing as living again, and that the living spring from the dead." However, Xenophon does not mention Socrates as believing in reincarnation, and Plato may have systematized Socrates' thought with concepts he took directly from Pythagoreanism or Orphism. Recent scholars have come to see that Plato has multiple reasons for the belief in reincarnation.[105] One argument concerns the theory of reincarnation's usefulness for explaining why non-human animals exist: they are former humans, being punished for their vices; Plato gives this argument at the end of the Timaeus.[106]

Mystery cults

[edit]The Orphic religion, which taught reincarnation, about the sixth century BCE, produced a copious literature.[107][108][109] Orpheus, its legendary founder, is said to have taught that the immortal soul aspires to freedom while the body holds it prisoner. The wheel of birth revolves, the soul alternates between freedom and captivity round the wide circle of necessity. Orpheus proclaimed the need of the grace of the gods, Dionysus in particular, and of self-purification until the soul has completed the spiral ascent of destiny to live forever.

An association between Pythagorean philosophy and reincarnation was routinely accepted throughout antiquity, as Pythagoras also taught about reincarnation. However, unlike the Orphics, who considered metempsychosis a cycle of grief that could be escaped by attaining liberation from it, Pythagoras seems to postulate an eternal, neutral reincarnation where subsequent lives would not be conditioned by any action done in the previous.[110]

Later authors

[edit]In later Greek literature the doctrine is mentioned in a fragment of Menander[111] and satirized by Lucian.[112] In Roman literature it is found as early as Ennius,[113] who, in a lost passage of his Annals, told how he had seen Homer in a dream, who had assured him that the same soul which had animated both the poets had once belonged to a peacock. Persius in his satires (vi. 9) laughs at this; it is referred to also by Lucretius[114] and Horace.[115]

Virgil works the idea into his account of the Underworld in the sixth book of the Aeneid.[116] It persists down to the late classic thinkers, Plotinus and the other Neoplatonists. In the Hermetica, a Graeco-Egyptian series of writings on cosmology and spirituality attributed to Hermes Trismegistus/Thoth, the doctrine of reincarnation is central.

Celtic paganism

[edit]In the first century BCE Alexander Cornelius Polyhistor wrote:

The Pythagorean doctrine prevails among the Gauls' teaching that the souls of men are immortal, and that after a fixed number of years they will enter into another body.

Julius Caesar recorded that the druids of Gaul, Britain and Ireland had metempsychosis as one of their core doctrines:[117]

The principal point of their doctrine is that the soul does not die and that after death it passes from one body into another... the main object of all education is, in their opinion, to imbue their scholars with a firm belief in the indestructibility of the human soul, which, according to their belief, merely passes at death from one tenement to another; for by such doctrine alone, they say, which robs death of all its terrors, can the highest form of human courage be developed.

Diodorus also recorded the Gaul belief that human souls were immortal, and that after a prescribed number of years they would commence upon a new life in another body. He added that Gauls had the custom of casting letters to their deceased upon the funeral pyres, through which the dead would be able to read them.[118] Valerius Maximus also recounted they had the custom of lending sums of money to each other which would be repayable in the next world.[119] This was mentioned by Pomponius Mela, who also recorded Gauls buried or burnt with them things they would need in a next life, to the point some would jump into the funeral piles of their relatives in order to cohabit in the new life with them.[120]

Hippolytus of Rome believed the Gauls had been taught the doctrine of reincarnation by a slave of Pythagoras named Zalmoxis. Conversely, Clement of Alexandria believed Pythagoras himself had learned it from the Celts and not the opposite, claiming he had been taught by Galatian Gauls, Hindu priests and Zoroastrians.[121][122] However, author T. D. Kendrick rejected a real connection between Pythagoras and the Celtic idea reincarnation, noting their beliefs to have substantial differences, and any contact to be historically unlikely.[120] Nonetheless, he proposed the possibility of an ancient common source, also related to the Orphic religion and Thracian systems of belief.[123]

Germanic paganism

[edit]Surviving texts indicate that there was a belief in rebirth in Germanic paganism. Examples include figures from eddic poetry and sagas, potentially by way of a process of naming and/or through the family line. Scholars have discussed the implications of these attestations and proposed theories regarding belief in reincarnation among the Germanic peoples prior to Christianization and potentially to some extent in folk belief thereafter.

Judaism

[edit]The belief in reincarnation developed among Jewish mystics in the medieval world, among whom differing explanations were given of the afterlife, although with a universal belief in an immortal soul.[124] It was explicitly rejected by Saadiah Gaon.[125] Today, reincarnation is an esoteric belief within many streams of modern Judaism. Kabbalah teaches a belief in gilgul, transmigration of souls, and hence the belief in reincarnation is universal in Hasidic Judaism, which regards the Kabbalah as sacred and authoritative, and is also sometimes held as an esoteric belief within other strains of Orthodox Judaism. In Judaism, the Zohar, first published in the 13th century, discusses reincarnation at length, especially in the Torah portion "Balak." The most comprehensive kabbalistic work on reincarnation, Shaar HaGilgulim,[126][127] was written by Chaim Vital, based on the teachings of his mentor, the 16th-century kabbalist Isaac Luria, who was said to know the past lives of each person through his semi-prophetic abilities. The 18th-century Lithuanian master scholar and kabbalist, Elijah of Vilna, known as the Vilna Gaon, authored a commentary on the biblical Book of Jonah as an allegory of reincarnation.

The practice of conversion to Judaism is sometimes understood within Orthodox Judaism in terms of reincarnation. According to this school of thought in Judaism, when non-Jews are drawn to Judaism, it is because they had been Jews in a former life. Such souls may "wander among nations" through multiple lives, until they find their way back to Judaism, including through finding themselves born in a gentile family with a "lost" Jewish ancestor.[128]

There is an extensive literature of Jewish folk and traditional stories that refer to reincarnation.[129]

Christianity

[edit]Reincarnationism or biblical reincarnation is the belief that certain people are or can be reincarnations of biblical figures, such as Jesus Christ and the Virgin Mary.[130] Some Christians believe that certain New Testament figures are reincarnations of Old Testament figures. For example, John the Baptist is believed by some to be a reincarnation of the prophet Elijah, and a few take this further by suggesting Jesus was the reincarnation of Elijah's disciple Elisha.[130][131] Other Christians believe the Second Coming of Jesus would be fulfilled by reincarnation. Sun Myung Moon, the founder of the Unification Church, considered himself to be the fulfillment of Jesus' return.

The Catholic Church does not believe in reincarnation, which it regards as being incompatible with death.[132] Nonetheless, the leaders of certain sects in the church have taught that they are reincarnations of Mary - for example, Marie-Paule Giguère of the Army of Mary[133][134] and Maria Franciszka of the former Mariavites.[135] The Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith excommunicated the Army of Mary for teaching heresy, including reincarnationism.[136]

Gnosticism

[edit]Several Gnostic sects professed reincarnation. The Sethians and followers of Valentinus believed in it.[137] The followers of Bardaisan of Mesopotamia, a sect of the second century deemed heretical by the Catholic Church, drew upon Chaldean astrology, to which Bardaisan's son Harmonius, educated in Athens, added Greek ideas including a sort of metempsychosis. Another such teacher was Basilides (132–? CE/AD), known to us through the criticisms of Irenaeus and the work of Clement of Alexandria (see also Neoplatonism and Gnosticism and Buddhism and Gnosticism).

In the third Christian century Manichaeism spread both east and west from Babylonia, then within the Sassanid Empire, where its founder Mani lived about 216–276. Manichaean monasteries existed in Rome in 312 AD. Noting Mani's early travels to the Kushan Empire and other Buddhist influences in Manichaeism, Richard Foltz[138] attributes Mani's teaching of reincarnation to Buddhist influence. However the inter-relation of Manicheanism, Orphism, Gnosticism and neo-Platonism is far from clear.

Taoism

[edit]Taoist documents from as early as the Han Dynasty claimed that Lao Tzu appeared on earth as different persons in different times beginning in the legendary era of Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors. The (ca. third century BC) Chuang Tzu states: "Birth is not a beginning; death is not an end. There is existence without limitation; there is continuity without a starting-point. Existence without limitation is Space. Continuity without a starting point is Time. There is birth, there is death, there is issuing forth, there is entering in."[139][better source needed]

European Middle Ages

[edit]Around the 11–12th century in Europe, several reincarnationist movements were persecuted as heresies, through the establishment of the Inquisition in the Latin west. These included the Cathar, Paterene or Albigensian church of western Europe, the Paulician movement, which arose in Armenia,[140] and the Bogomils in Bulgaria.[141]

Christian sects such as the Bogomils and the Cathars, who professed reincarnation and other gnostic beliefs, were referred to as "Manichaean", and are today sometimes described by scholars as "Neo-Manichaean".[142] As there is no known Manichaean mythology or terminology in the writings of these groups there has been some dispute among historians as to whether these groups truly were descendants of Manichaeism.[143]

Renaissance and Early Modern period

[edit]While reincarnation has been a matter of faith in some communities from an early date it has also frequently been argued for on principle, as Plato does when he argues that the number of souls must be finite because souls are indestructible,[144] Benjamin Franklin held a similar view.[145] Sometimes such convictions, as in Socrates' case, arise from a more general personal faith, at other times from anecdotal evidence such as Plato makes Socrates offer in the Myth of Er.

During the Renaissance translations of Plato, the Hermetica and other works fostered new European interest in reincarnation. Marsilio Ficino[146] argued that Plato's references to reincarnation were intended allegorically, Shakespeare alluded to the doctrine of reincarnation[147] but Giordano Bruno was burned at the stake by authorities after being found guilty of heresy by the Roman Inquisition for his teachings.[148] But the Greek philosophical works remained available and, particularly in north Europe, were discussed by groups such as the Cambridge Platonists. Emanuel Swedenborg believed that we leave the physical world once, but then go through several lives in the spiritual world—a kind of hybrid of Christian tradition and the popular view of reincarnation.[149]

19th to 20th centuries

[edit]By the 19th century the philosophers Schopenhauer[150] and Nietzsche[151] could access the Indian scriptures for discussion of the doctrine of reincarnation, which recommended itself to the American Transcendentalists Henry David Thoreau, Walt Whitman and Ralph Waldo Emerson and was adapted by Francis Bowen into Christian Metempsychosis.[152]

By the early 20th century, interest in reincarnation had been introduced into the nascent discipline of psychology, largely due to the influence of William James, who raised aspects of the philosophy of mind, comparative religion, the psychology of religious experience and the nature of empiricism.[153] James was influential in the founding of the American Society for Psychical Research (ASPR) in New York City in 1885, three years after the British Society for Psychical Research (SPR) was inaugurated in London,[154] leading to systematic, critical investigation of paranormal phenomena. Famous World War II American General George Patton was a strong believer in reincarnation, believing, among other things, he was a reincarnation of the Carthaginian General Hannibal.

At this time popular awareness of the idea of reincarnation was boosted by the Theosophical Society's dissemination of systematised and universalised Indian concepts and also by the influence of magical societies like The Golden Dawn. Notable personalities like Annie Besant, W. B. Yeats and Dion Fortune made the subject almost as familiar an element of the popular culture of the west as of the east. By 1924 the subject could be satirised in popular children's books.[155] Humorist Don Marquis created a fictional cat named Mehitabel who claimed to be a reincarnation of Queen Cleopatra.[156]

Théodore Flournoy was among the first to study a claim of past-life recall in the course of his investigation of the medium Hélène Smith, published in 1900, in which he defined the possibility of cryptomnesia in such accounts.[157] Carl Gustav Jung, like Flournoy based in Switzerland, also emulated him in his thesis based on a study of cryptomnesia in psychism. Later Jung would emphasise the importance of the persistence of memory and ego in psychological study of reincarnation: "This concept of rebirth necessarily implies the continuity of personality... (that) one is able, at least potentially, to remember that one has lived through previous existences, and that these existences were one's own...."[152] Hypnosis, used in psychoanalysis for retrieving forgotten memories, was eventually tried as a means of studying the phenomenon of past life recall.

More recently, many people in the West have developed an interest in and acceptance of reincarnation.[13] Many new religious movements include reincarnation among their beliefs, e.g. modern Neopagans, Spiritism, Astara,[158] Dianetics, and Scientology. Many esoteric philosophies also include reincarnation, e.g. Theosophy, Anthroposophy, Kabbalah, and Gnostic and Esoteric Christianity such as the works of Martinus Thomsen.

Demographic survey data from 1999 to 2002 shows a significant minority of people from Europe (22%) and America (20%) believe in the existence of life before birth and after death, leading to a physical rebirth.[13][159] The belief in reincarnation is particularly high in the Baltic countries, with Lithuania having the highest figure for the whole of Europe, 44%, while the lowest figure is in East Germany, 12%.[13] A quarter of U.S. Christians, including 10% of all born again Christians, embrace the idea.[160]

Academic psychiatrist Ian Stevenson reported that belief in reincarnation is held (with variations in details) by adherents of almost all major religions except Christianity and Islam. In addition, between 20 and 30 percent of persons in western countries who may be nominal Christians also believe in reincarnation.[161] One 1999 study by Walter and Waterhouse reviewed the previous data on the level of reincarnation belief and performed a set of thirty in-depth interviews in Britain among people who did not belong to a religion advocating reincarnation.[162] The authors reported that surveys have found about one fifth to one quarter of Europeans have some level of belief in reincarnation, with similar results found in the USA. In the interviewed group, the belief in the existence of this phenomenon appeared independent of their age, or the type of religion that these people belonged to, with most being Christians. The beliefs of this group also did not appear to contain any more than usual of "new age" ideas (broadly defined) and the authors interpreted their ideas on reincarnation as "one way of tackling issues of suffering", but noted that this seemed to have little effect on their private lives.

Waterhouse also published a detailed discussion of beliefs expressed in the interviews.[163] She noted that although most people "hold their belief in reincarnation quite lightly" and were unclear on the details of their ideas, personal experiences such as past-life memories and near-death experiences had influenced most believers, although only a few had direct experience of these phenomena. Waterhouse analyzed the influences of second-hand accounts of reincarnation, writing that most of the people in the survey had heard other people's accounts of past-lives from regression hypnosis and dreams and found these fascinating, feeling that there "must be something in it" if other people were having such experiences.

Other influential contemporary figures that have written on reincarnation include Alice Ann Bailey, one of the first writers to use the terms New Age and age of Aquarius, Torkom Saraydarian, an Armenian-American musician and religious author, Dolores Cannon, Atul Gawande, Michael Newton, Bruce Greyson, Raymond Moody and Unity Church founder Charles Fillmore.[164] Neale Donald Walsch, an American author of the series Conversations with God clcaims that he has reincarnated more than 600 times.[165] The Indian spiritual teacher Meher Baba who had significant following in the West taught that reincarnation followed from human desire and ceased once a person was freed from desire.[166]

Religions and philosophies

[edit]Buddhism

[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

According to various Buddhist scriptures, Gautama Buddha believed in the existence of an afterlife in another world and in reincarnation,

Since there actually is another world (any world other than the present human one, i.e. different rebirth realms), one who holds the view 'there is no other world' has wrong view...

— Buddha, Majjhima Nikaya i.402, Apannaka Sutta, translated by Peter Harvey[167]

The Buddha also asserted that karma influences rebirth, and that the cycles of repeated births and deaths are endless.[167][168] Before the birth of Buddha, ancient Indian scholars had developed competing theories of afterlife, including the materialistic school such as Charvaka,[169] which posited that death is the end, there is no afterlife, no soul, no rebirth, no karma, and they described death to be a state where a living being is completely annihilated, dissolved.[170] Buddha rejected this theory, adopted the alternative existing theories on rebirth, criticizing the materialistic schools that denied rebirth and karma, states Damien Keown.[171] Such beliefs are inappropriate and dangerous, stated Buddha, because such annihilationism views encourage moral irresponsibility and material hedonism;[172] he tied moral responsibility to rebirth.[167][171]

The Buddha introduced the concept that there is no permanent self (soul), and this central concept in Buddhism is called anattā.[173][174][175] Major contemporary Buddhist traditions such as Theravada, Mahayana and Vajrayana traditions accept the teachings of Buddha. These teachings assert there is rebirth, there is no permanent self and no irreducible ātman (soul) moving from life to another and tying these lives together, there is impermanence, that all compounded things such as living beings are aggregates dissolve at death, but every being reincarnates.[176][177][178] The rebirth cycles continue endlessly, states Buddhism, and it is a source of duhkha (suffering, pain), but this reincarnation and duhkha cycle can be stopped through nirvana. The anattā doctrine of Buddhism is a contrast to Hinduism, the latter asserting that "soul exists, it is involved in rebirth, and it is through this soul that everything is connected".[179][180][181]

Different traditions within Buddhism have offered different theories on what reincarnates and how reincarnation happens. One theory suggests that it occurs through consciousness (Sanskrit: vijñāna; Pali: samvattanika-viññana)[182][183] or stream of consciousness (Sanskrit: citta-santāna, vijñāna-srotām, or vijñāna-santāna; Pali: viññana-sotam)[184] upon death, which reincarnates into a new aggregation. This process, states this theory, is similar to the flame of a dying candle lighting up another.[185][186] The consciousness in the newly born being is neither identical to nor entirely different from that in the deceased but the two form a causal continuum or stream in this Buddhist theory. Transmigration is influenced by a being's past karma (Pali: kamma).[187][188] The root cause of rebirth, states Buddhism, is the abiding of consciousness in ignorance (Sanskrit: avidya; Pali: avijja) about the nature of reality, and when this ignorance is uprooted, rebirth ceases.[189]

Buddhist traditions also vary in their mechanistic details on rebirth. Most Theravada Buddhists assert that rebirth is immediate while the Tibetan and most Chinese and Japanese schools hold to the notion of a bardo (intermediate state) that can last up to 49 days.[190][191] The bardo rebirth concept of Tibetan Buddhism, originally developed in India but spread to Tibet and other Buddhist countries, and involves 42 peaceful deities, and 58 wrathful deities.[192] These ideas led to maps on karma and what form of rebirth one takes after death, discussed in texts such as The Tibetan Book of the Dead.[193][194] The major Buddhist traditions accept that the reincarnation of a being depends on the past karma and merit (demerit) accumulated, and that there are six realms of existence in which the rebirth may occur after each death.[195][15][64]

Within Japanese Zen, reincarnation is accepted by some, but rejected by others. A distinction can be drawn between 'folk Zen', as in the Zen practiced by devotional lay people, and 'philosophical Zen'. Folk Zen generally accepts the various supernatural elements of Buddhism such as rebirth. Philosophical Zen, however, places more emphasis on the present moment.[196][197]

Some schools conclude that karma continues to exist and adhere to the person until it works out its consequences. For the Sautrantika school, each act "perfumes" the individual or "plants a seed" that later germinates. Tibetan Buddhism stresses the state of mind at the time of death. To die with a peaceful mind will stimulate a virtuous seed and a fortunate rebirth; a disturbed mind will stimulate a non-virtuous seed and an unfortunate rebirth.[198]

Christianity

[edit]In a survey by the Pew Forum in 2009, 22% of American Christians expressed a belief in reincarnation,[199] and in a 1981 survey 31% of regular churchgoing European Catholics expressed a belief in reincarnation.[200]

Some Christian theologians interpret certain Biblical passages as referring to reincarnation. These passages include the questioning of Jesus as to whether he is Elijah, John the Baptist, Jeremiah, or another prophet (Matthew 16:13–15 and John 1:21–22) and, less clearly (while Elijah was said not to have died, but to have been taken up to heaven), John the Baptist being asked if he is not Elijah (John 1:25).[201][202][203] Geddes MacGregor, an Episcopalian priest and professor of philosophy, has made a case for the compatibility of Christian doctrine and reincarnation.[204] The Catholic Church and theologians such as Norman Geisler argue that reincarnation is unorthodox and reject the reincarnationist interpretation of texts about John the Baptist and biblical texts used to defend this belief.[205][206]

Early

[edit]There is evidence[207][208] that Origen, a Church father in early Christian times, taught reincarnation in his lifetime but that when his works were translated into Latin these references were concealed. One of the epistles written by St. Jerome, "To Avitus" (Letter 124; Ad Avitum. Epistula CXXIV),[209] which asserts that Origen's On the First Principles (Latin: De Principiis; Greek: Περὶ Ἀρχῶν)[210] was mistranscribed:

About ten years ago that saintly man Pammachius sent me a copy of a certain person's [ Rufinus's[209] ] rendering, or rather misrendering, of Origen's First Principles; with a request that in a Latin version I should give the true sense of the Greek and should set down the writer's words for good or for evil without bias in either direction. When I did as he wished and sent him the book, he was shocked to read it and locked it up in his desk lest being circulated it might wound the souls of many.[208]

Under the impression that Origen was a heretic like Arius, St. Jerome criticizes ideas described in On the First Principles. Further in "To Avitus" (Letter 124), St. Jerome writes about "convincing proof" that Origen teaches reincarnation in the original version of the book:

The following passage is a convincing proof that he holds the transmigration of the souls and annihilation of bodies. 'If it can be shown that an incorporeal and reasonable being has life in itself independently of the body and that it is worse off in the body than out of it; then beyond a doubt bodies are only of secondary importance and arise from time to time to meet the varying conditions of reasonable creatures. Those who require bodies are clothed with them, and contrariwise, when fallen souls have lifted themselves up to better things, their bodies are once more annihilated. They are thus ever vanishing and ever reappearing.'[208]

The original text of On First Principles has almost completely disappeared. It remains extant as De Principiis in fragments faithfully translated into Latin by St. Jerome and in "the not very reliable Latin translation of Rufinus."[210]

However, Origen's supposed belief in reincarnation is controversial. Christian scholar Dan R. Schlesinger has written an extensive monograph in which he argues that Origen never taught reincarnation.[211]

Reincarnation was taught by several gnostics such as Marcion of Sinope.[212] Belief in reincarnation was rejected by several church fathers, including Augustine of Hippo in The City of God.[213][214][206]

Druze

[edit]| Part of a series on

Druze |

|---|

Reincarnation is a paramount tenet in the Druze faith.[215] There is an eternal duality of the body and the soul and it is impossible for the soul to exist without the body. Therefore, reincarnations occur instantly at one's death. While in the Hindu and Buddhist belief system a soul can be transmitted to any living creature, in the Druze belief system this is not possible and a human soul will only transfer to a human body. Furthermore, souls cannot be divided into different or separate parts and the number of souls existing is finite.[216]

Few Druzes are able to recall their past but, if they are able to they are called a Nateq. Typically souls who have died violent deaths in their previous incarnation will be able to recall memories. Since death is seen as a quick transient state, mourning is discouraged.[216] Unlike other Abrahamic faiths, heaven and hell are spiritual. Heaven is the ultimate happiness received when soul escapes the cycle of rebirths and reunites with the Creator, while hell is conceptualized as the bitterness of being unable to reunite with the Creator and escape from the cycle of rebirth.[217]

Hinduism

[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Hinduism |

|---|

|

The body dies, assert the Hindu traditions, but not the soul, which they assume to be the eternal reality, indestructible and bliss.[218] Everything and all existence is believed to be connected and cyclical in many Hinduism-sects, all living beings composed of two things, the soul and the body or matter.[219] Ātman does not change and cannot change by its innate nature in the Hindu belief.[220] Current Karma impacts the future circumstances in this life, as well as the future forms and realms of lives.[221] Good intent and actions lead to good future, bad intent and actions lead to bad future, impacting how one reincarnates, in the Hindu view of existence.[222]

There is no permanent heaven or hell in most Hinduism-sects.[223] In the afterlife, based on one's karma, the soul is reborn as another being in heaven, hell, or a living being on earth (human, animal).[223] Gods, too, die once their past karmic merit runs out, as do those in hell, and they return getting another chance on earth. This reincarnation continues, endlessly in cycles, until one embarks on a spiritual pursuit, realizes self-knowledge, and thereby gains mokṣa, the final release out of the reincarnation cycles.[224] This release is believed to be a state of utter bliss, which Hindu traditions believe is either related or identical to Brahman, the unchanging reality that existed before the creation of universe, continues to exist, and shall exist after the universe ends.[225][226][227]

The Upanishads, part of the scriptures of the Hindu traditions, primarily focus on the liberation from reincarnation.[228][229] The Bhagavad Gita discusses various paths to liberation.[218] The Upanishads, states Harold Coward, offer a "very optimistic view regarding the perfectibility of human nature", and the goal of human effort in these texts is a continuous journey to self-perfection and self-knowledge so as to end Saṃsāra—the endless cycle of rebirth and redeath.[230] The aim of spiritual quest in the Upanishadic traditions is find the true self within and to know one's soul, a state that they assert leads to blissful state of freedom, moksha.[231]

The Bhagavad Gita states:

Just as in the body childhood, adulthood and old age happen to an embodied being. So also he (the embodied being) acquires another body. The wise one is not deluded about this. (2:13)[232]

As, after casting away worn out garments, a man later takes new ones. So after casting away worn out bodies, the embodied Self encounters other new ones. (2:22)[233]

When an embodied being transcends, these three qualities which are the source of the body, Released from birth, death, old age and pain, he attains immortality. (14:20)[234]

There are internal differences within Hindu traditions on reincarnation and the state of moksha. For example, the dualistic devotional traditions such as Madhvacharya's Dvaita Vedanta tradition of Hinduism champion a theistic premise, assert that human soul and Brahman are different, loving devotion to Brahman (god Vishnu in Madhvacharya's theology) is the means to release from Samsara, it is the grace of God which leads to moksha, and spiritual liberation is achievable only in after-life (videhamukti).[235] The non-dualistic traditions such as Adi Shankara's Advaita Vedanta tradition of Hinduism champion a monistic premise, asserting that the individual human soul and Brahman are identical, only ignorance, impulsiveness and inertia leads to suffering through Saṃsāra, in reality there are no dualities, meditation and self-knowledge is the path to liberation, the realization that one's soul is identical to Brahman is moksha, and spiritual liberation is achievable in this life (jivanmukti).[86][236]

Twentieth-century Indian philosopher Sri Aurobindo said that rebirth was the mechanism of evolution – plants are reborn as animals, which are reborn as humans, gaining intelligence each time.[237] He said that this progression was irreversible, and that a human cannot be reborn as an animal.[238]

Islam

[edit]Most Islamic schools of thought reject any idea of reincarnation of living beings.[239][240][241] It teaches a linear concept of life, wherein a human being has only one life and upon death he or she is judged by God, then rewarded in heaven or punished in hell.[239][242] Islam teaches final resurrection and Judgement Day,[240] but there is no prospect for the reincarnation of a human being into a different body or being.[239] During the early history of Islam, some of the Caliphs persecuted all reincarnation-believing people, such as Manichaeism, to the point of extinction in Mesopotamia and Persia (modern day Iraq and Iran).[240] However, some Muslim minority sects such as those found among Sufis, and some Muslims in South Asia and Indonesia have retained their pre-Islamic Hindu and Buddhist beliefs in reincarnation.[240] For instance, historically, South Asian Isma'ilis performed chantas yearly, one of which is for seeking forgiveness of sins committed in past lives.[243]

Ghulat sects

[edit]The idea of reincarnation is accepted by a few heterodox sects, particularly of the Ghulat.[244] Alawites hold that they were originally stars or divine lights that were cast out of heaven through disobedience and must undergo repeated reincarnation (or metempsychosis) before returning to heaven.[245] They can be reincarnated as Christians or others through sin and as animals if they become infidels.[246]

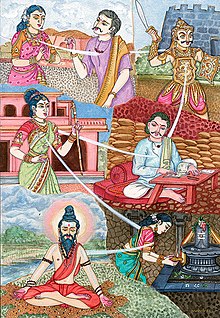

Jainism

[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Jainism |

|---|

|

In Jainism, the reincarnation doctrine, along with its theories of Saṃsāra and Karma, are central to its theological foundations, as evidenced by the extensive literature on it in the major sects of Jainism, and their pioneering ideas on these topics from the earliest times of the Jaina tradition.[247][51] Reincarnation in contemporary Jainism traditions is the belief that the worldly life is characterized by continuous rebirths and suffering in various realms of existence.[52][51][248]

Karma forms a central and fundamental part of Jain faith, being intricately connected to other of its philosophical concepts like transmigration, reincarnation, liberation, non-violence (ahiṃsā) and non-attachment, among others. Actions are seen to have consequences: some immediate, some delayed, even into future incarnations. So the doctrine of karma is not considered simply in relation to one life-time, but also in relation to both future incarnations and past lives.[249] Uttarādhyayana Sūtra 3.3–4 states: "The jīva or the soul is sometimes born in the world of gods, sometimes in hell. Sometimes it acquires the body of a demon; all this happens on account of its karma. This jīva sometimes takes birth as a worm, as an insect or as an ant."[250] The text further states (32.7): "Karma is the root of birth and death. The souls bound by karma go round and round in the cycle of existence."[250]

Actions and emotions in the current lifetime affect future incarnations depending on the nature of the particular karma. For example, a good and virtuous life indicates a latent desire to experience good and virtuous themes of life. Therefore, such a person attracts karma that ensures that their future births will allow them to experience and manifest their virtues and good feelings unhindered.[251] In this case, they may take birth in heaven or in a prosperous and virtuous human family. On the other hand, a person who has indulged in immoral deeds, or with a cruel disposition, indicates a latent desire to experience cruel themes of life.[252] As a natural consequence, they will attract karma which will ensure that they are reincarnated in hell, or in lower life forms, to enable their soul to experience the cruel themes of life.[252]

There is no retribution, judgment or reward involved but a natural consequences of the choices in life made either knowingly or unknowingly. Hence, whatever suffering or pleasure that a soul may be experiencing in its present life is on account of choices that it has made in the past.[253] As a result of this doctrine, Jainism attributes supreme importance to pure thinking and moral behavior.[254]

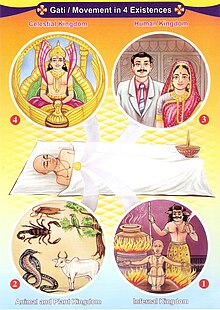

The Jain texts postulate four gatis, that is states-of-existence or birth-categories, within which the soul transmigrates. The four gatis are: deva (demigods), manuṣya (humans), nāraki (hell beings), and tiryañca (animals, plants, and microorganisms).[255] The four gatis have four corresponding realms or habitation levels in the vertically tiered Jain universe: deva occupy the higher levels where the heavens are situated; manuṣya and tiryañca occupy the middle levels; and nāraki occupy the lower levels where seven hells are situated.[255]

Single-sensed souls, however, called nigoda,[256] and element-bodied souls pervade all tiers of this universe. Nigodas are souls at the bottom end of the existential hierarchy. They are so tiny and undifferentiated, that they lack even individual bodies, living in colonies. According to Jain texts, this infinity of nigodas can also be found in plant tissues, root vegetables and animal bodies.[257] Depending on its karma, a soul transmigrates and reincarnates within the scope of this cosmology of destinies. The four main destinies are further divided into sub-categories and still smaller sub-sub-categories. In all, Jain texts speak of a cycle of 8.4 million birth destinies in which souls find themselves again and again as they cycle within samsara.[258]

In Jainism, God has no role to play in an individual's destiny; one's personal destiny is not seen as a consequence of any system of reward or punishment, but rather as a result of its own personal karma. A text from a volume of the ancient Jain canon, Bhagvati sūtra 8.9.9, links specific states of existence to specific karmas. Violent deeds, killing of creatures having five sense organs, eating fish, and so on, lead to rebirth in hell. Deception, fraud and falsehood lead to rebirth in the animal and vegetable world. Kindness, compassion and humble character result in human birth; while austerities and the making and keeping of vows lead to rebirth in heaven.[259]

Each soul is thus responsible for its own predicament, as well as its own salvation. Accumulated karma represent a sum total of all unfulfilled desires, attachments and aspirations of a soul.[260][261] It enables the soul to experience the various themes of the lives that it desires to experience.[260] Hence a soul may transmigrate from one life form to another for countless of years, taking with it the karma that it has earned, until it finds conditions that bring about the required fruits. In certain philosophies, heavens and hells are often viewed as places for eternal salvation or eternal damnation for good and bad deeds. But according to Jainism, such places, including the earth are simply the places which allow the soul to experience its unfulfilled karma.[262]

Judaism

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Kabbalah |

|---|

|

The doctrine of reincarnation has had a complex evolution within Judaism. Initially alien to Jewish tradition, it began to emerge in the 8th century, possibly influenced by Muslim mystics, gaining acceptance among Karaites and Jewish dissenters.[263][264] It was first mentioned in Jewish literature by Saadia Gaon, who criticized it.[265][263] However, it remained a minority belief, facing little resistance until the spread of Kabbalah in the 12th century. The "Book of Clarity" (Sefer ha-Bahir) of this period introduced concepts such as the transmigration of souls, strengthening the foundation of Kabbalah with mystical symbolism.[266] Kabbalah also teaches that "The soul of Moses is reincarnated in every generation."[267] This teaching found more significant ground in Kabbalistic circles in Provence and Spain.[264]

Despite not being widely accepted in Orthodox Judaism, the doctrine of reincarnation attracted some modern Jews involved in mysticism.[263] Hasidic Judaism and followers of Kabbalah remained firm in their belief in the transmigration of souls. Other branches of Judaism, such as Reform and Conservative, do not teach it.[268]

The 16th century mystical renaissance in communal Safed replaced scholastic Rationalism as mainstream traditional Jewish theology, both in scholarly circles and in the popular imagination. References to gilgul in former Kabbalah became systematized as part of the metaphysical purpose of creation. Isaac Luria (the Ari) brought the issue to the centre of his new mystical articulation, for the first time, and advocated identification of the reincarnations of historic Jewish figures that were compiled by Haim Vital in his Shaar HaGilgulim.[269] Gilgul is contrasted with the other processes in Kabbalah of Ibbur ('pregnancy'), the attachment of a second soul to an individual for (or by) good means, and Dybuk ('possession'), the attachment of a spirit, demon, etc. to an individual for (or by) "bad" means.

In Lurianic Kabbalah, reincarnation is not retributive or fatalistic, but an expression of Divine compassion, the microcosm of the doctrine of cosmic rectification of creation. Gilgul is a heavenly agreement with the individual soul, conditional upon circumstances. Luria's radical system focused on rectification of the Divine soul, played out through Creation. The true essence of anything is the divine spark within that gives it existence. Even a stone or leaf possesses such a soul that "came into this world to receive a rectification". A human soul may occasionally be exiled into lower inanimate, vegetative or animal creations. The most basic component of the soul, the nefesh, must leave at the cessation of blood production. There are four other soul components and different nations of the world possess different forms of souls with different purposes. Each Jewish soul is reincarnated in order to fulfill each of the 613 Mosaic commandments that elevate a particular spark of holiness associated with each commandment. Once all the Sparks are redeemed to their spiritual source, the Messianic Era begins. Non-Jewish observance of the 7 Laws of Noah assists the Jewish people, though Biblical adversaries of Israel reincarnate to oppose.

Among the many rabbis who accepted reincarnation are Kabbalists like Nahmanides (the Ramban) and Rabbenu Bahya ben Asher, Levi ibn Habib (the Ralbah), Shelomoh Alkabez, Moses Cordovero, Moses Chaim Luzzatto; early Hasidic masters such as the Baal Shem Tov, Schneur Zalman of Liadi and Nachman of Breslov, as well as virtually all later Hasidic masters; contemporary Hasidic teachers such as DovBer Pinson, Moshe Weinberger and Joel Landau; and key Mitnagdic leaders, such as the Vilna Gaon and Chaim Volozhin and their school, as well as Rabbi Shalom Sharabi (known at the RaShaSH), the Ben Ish Chai of Baghdad, and the Baba Sali.[270] Rabbis who have rejected the idea include Saadia Gaon, David Kimhi, Hasdai Crescas, Joseph Albo, Abraham ibn Daud, Leon de Modena, Solomon ben Aderet, Maimonides and Asher ben Jehiel. Among the Geonim, Hai Gaon argued in favour of gilgulim.

Inuit

[edit]In the Western Hemisphere, belief in reincarnation is most prevalent in the now heavily Christian Polar North (now mainly parts of Greenland and Nunavut).[271] The concept of reincarnation is enshrined in the Inuit languages,[272] and in many Inuit cultures it is traditional to name a newborn child after a recently deceased person under the belief that the child is the namesake reincarnated.[271]

Ho-Chunk

[edit]Reincarnation is an intrinsic part of some Northeastern Native American traditions.[271] The following is a story of human-to-human reincarnation as told by Thunder Cloud, a Winnebago (Ho-Chunk) shaman. Here Thunder Cloud talks about his two previous lives and how he died and came back again to this his third lifetime. He describes his time between lives, when he was "blessed" by Earth Maker and all the abiding spirits and given special powers, including the ability to heal the sick.

Thunder Cloud's account of his two reincarnations:

I (my ghost) was taken to the place where the sun sets (the west). ... While at that place, I thought I would come back to earth again, and the old man with whom I was staying said to me, "My son, did you not speak about wanting to go to the earth again?" I had, as a matter of fact, only thought of it, yet he knew what I wanted. Then he said to me, "You can go, but you must ask the chief first." Then I went and told the chief of the village of my desire, and he said to me, "You may go and obtain your revenge upon the people who killed your relatives and you." Then I was brought down to earth. ... There I lived until I died of old age. ... As I was lying [in my grave], someone said to me, "Come, let us go away." So then we went toward the setting of the sun. There we came to a village where we met all the dead. ... From that place I came to this earth again for the third time, and here I am.

— Radin (1923)[273]

Sikhism

[edit]Founded in the 15th century, Sikhism's founder Guru Nanak had a choice between the cyclical reincarnation concept of ancient Indian religions and the linear concept of Islam, he chose the cyclical concept of time.[274][275] Sikhism teaches reincarnation theory similar to those in Hinduism, but with some differences from its traditional doctrines.[276] Sikh rebirth theories about the nature of existence are similar to ideas that developed during the devotional Bhakti movement particularly within some Vaishnava traditions, which define liberation as a state of union with God attained through the grace of God.[277][278][279]

The doctrines of Sikhism teach that the soul exists, and is passed from one body to another in endless cycles of Saṃsāra, until liberation from the death and rebirth cycle. Each birth begins with karma (karam), and these actions leave a karmic signature (karni) on one's soul which influences future rebirths, but it is God whose grace that liberates from the death and rebirth cycle.[276] The way out of the reincarnation cycle, asserts Sikhism, is to live an ethical life, devote oneself to God and constantly remember God's name.[276] The precepts of Sikhism encourage the bhakti of One Lord for mukti (liberation from the death and rebirth cycle).[276][280]

Yoruba

[edit]The Yoruba religion teaches that Olodumare, the Supreme Being and divine Creator who rules over His Creation, created eniyan, or humanity, to achieve balance between heaven and earth and bring about Ipo Rere, or the Good Condition.[281] To cause achievement of the Good Condition, humanity reincarnates.[282] Once achieved, Ipo Rere provides the ultimate state of supreme existence with Olodumare, a goal which elevates reincarnation to a key position in the Yoruba religion.[283]

Atunwaye[284] (also called atunwa[281]) is the Yoruba term for reincarnation. Predestination is a foundational component of atunwaye. Just prior to incarnation, a person first chooses their Ayanmo (destiny) before also choosing their Akunyelan (lot) in the presence of Olodumare and Orunmila with Olodumare's approval.[285] By atunwaye, a person may incarnate only in a human being and may choose to reincarnate in either sex, regardless of choice in the prior incarnation.[283]

Ipadawaye

[edit]The most common, widespread Yoruba reincarnation belief is ipadawaye, meaning "the ancestor's rebirth".[284] According to this belief, the reincarnating person will reincarnate along their familial lineage.[282][283][286][287] When a person dies, they go to orun (heaven) and will live with the ancestors in either orunrere (good heaven) or orunapaadi (bad heaven). Reincarnation is believed to be a gift bestowed on ancestors who lived well and experienced a "good" death. Only ancestors living in orunrere may return as grandchildren, reincarnating out of their love for the family or the world. Children may be given names to indicate which ancestor is believed to have returned, such as Babatide ("father has come"), Babatunde ("father has come again"), and Yetunde ("mother has come again").[284][286]

A "bad" death (which includes deaths of children, cruel, or childless people and deaths by punishments from the gods, accidents, suicides, and gruesome murders) is generally believed to prevent the deceased from joining the ancestors and reincarnating again,[288] though some practitioners also believe a person experiencing a "bad" death will be reborn much later into conditions of poverty.[281]

Abiku

[edit]Another Yoruba reincarnation belief is abiku, meaning "born to die"[281][284][289] According to Yoruba custom, an abiku is a reincarnating child who repeatedly experiences death and rebirth with the same mother in a vicious cycle. Because childlessness is considered a curse in Yoruba culture,[289] parents with an abiku child will always attempt to help the abiku child by preventing their death. However, abiku are believed to possess a power to ensure their eventual death, so rendering assistance is often a frustrating endeavor causing significant pain to the parents. This pain is believed to bring happiness to the abiku.[289]

Abiku are believed to be a "species of spirit" thought to live apart from people in, for example, secluded parts of villages, jungles, and footpaths. Modern belief in abiku has significantly waned among urban populations, with the decline attributed to improved hygiene and medical care reducing infant mortality rates.[289]

Akudaaya

[edit]Akudaaya, meaning "born to die and reappear"[284] (also called akuda[290]), is a Yoruba reincarnation belief of "a person that is dead[] but has not gone to heaven".[291] Akudaaya is based on the belief that, if a recently-deceased person's destiny in that life remained unfulfilled, the deceased cannot join the ancestors and therefore must roam the world.[290] Following death, an akudaaya returns to their previous existence by reappearing in the same physical form. However, the new existence will be lived in a different physical location from the first, and the akudaaya will not be recognized by a still-living relative, should they happen to meet. The akudaaya lives their new existence working to fulfill their destiny from the previous life.

The concept of akudaaya is the subject of Akudaaya (The Wraith), a 2023 Nigerian drama film in the Yoruba language.[292] The film is said to center on a deceased son who "has begun living life as a spirit in another state and has fallen in love".[293]

New religious and spiritual movements

[edit]| Part of a series on the |

| Paranormal |

|---|

Spiritism

[edit]

Spiritism, a spiritualist philosophy codified in the 19th century by the French educator Allan Kardec, teaches reincarnation or rebirth into human life after death. According to this doctrine, free will and cause and effect are the corollaries of reincarnation, and reincarnation provides a mechanism for a person's spiritual evolution in successive lives.[294]

Theosophy

[edit]The Theosophical Society draws much of its inspiration from India.[295] In the Theosophical world-view reincarnation is the vast rhythmic process by which the soul, the part of a person which belongs to the formless non-material and timeless worlds, unfolds its spiritual powers in the world and comes to know itself.[296] It descends from sublime, free, spiritual realms and gathers experience through its effort to express itself in the world. Afterwards there is a withdrawal from the physical plane to successively higher levels of reality, in death, a purification and assimilation of the past life. Having cast off all instruments of personal experience it stands again in its spiritual and formless nature, ready to begin its next rhythmic manifestation, every lifetime bringing it closer to complete self-knowledge and self-expression.[296] However, it may attract old mental, emotional, and energetic karma patterns to form the new personality.[297]

Anthroposophy

[edit]Anthroposophy describes reincarnation from the point of view of Western philosophy and culture. The ego is believed to transmute transient soul experiences into universals that form the basis for an individuality that can endure after death. These universals include ideas, which are intersubjective and thus transcend the purely personal (spiritual consciousness), intentionally formed human character (spiritual life), and becoming a fully conscious human being (spiritual humanity). Rudolf Steiner described both the general principles he believed to be operative in reincarnation, such as that one's will activity in one life forms the basis for the thinking of the next,[298] and a number of successive lives of various individualities.[299]

Similarly, other famous people's life stories are not primarily the result of genes, upbringing or biographical vicissitudes. Steiner relates that a large estate in north-eastern France was held during the early Middle Ages by a martial feudal lord. During a military campaign, this estate was captured by a rival. The previous owner had no means of retaliating, and was forced to see his property lost to an enemy. He was filled with a smoldering resentment towards the propertied classes, not only for the remainder of his life in the Middle Ages, but also in a much later incarnation—as Karl Marx. His rival was reborn as Friedrich Engels.[300]

— Olav Hammer, Coda. On Belief and Evidence

Modern astrology

[edit]Inspired by Helena Blavatsky's major works, including Isis Unveiled and The Secret Doctrine, astrologers in the early twentieth-century integrated the concepts of karma and reincarnation into the practice of Western astrology. Notable astrologers who advanced this development included Alan Leo, Charles E. O. Carter, Marc Edmund Jones, and Dane Rudhyar. A new synthesis of East and West resulted as Hindu and Buddhist concepts of reincarnation were fused with Western astrology's deep roots in Hermeticism and Neoplatonism. In the case of Rudhyar, this synthesis was enhanced with the addition of Jungian depth psychology.[301] This dynamic integration of astrology, reincarnation and depth psychology has continued into the modern era with the work of astrologers Steven Forrest and Jeffrey Wolf Green. Their respective schools of Evolutionary Astrology are based on "an acceptance of the fact that human beings incarnate in a succession of lifetimes".[302]

Scientology

[edit]Past reincarnation, usually termed past lives, is a key part of the principles and practices of the Church of Scientology. Scientologists believe that the human individual is actually a thetan, an immortal spiritual entity, that has fallen into a degraded state as a result of past-life experiences. Scientology auditing is intended to free the person of these past-life traumas and recover past-life memory, leading to a higher state of spiritual awareness.

This idea is echoed in their highest fraternal religious order, Sea Org, whose motto is "Revenimus" ('We Come Back'), and whose members sign a "billion-year contract" as a sign of commitment to that ideal. L. Ron Hubbard, the founder of Scientology, does not use the word "reincarnation" to describe its beliefs, noting that: "The common definition of reincarnation has been altered from its original meaning. The word has come to mean 'to be born again in different life forms' whereas its actual definition is 'to be born again into the flesh of another body.' Scientology ascribes to this latter, original definition of reincarnation."[303]

The first writings in Scientology regarding past lives date from around 1951 and slightly earlier. In 1960, Hubbard published a book on past lives entitled Have You Lived Before This Life. In 1968 he wrote Mission Into Time, a report on a five-week sailing expedition to Sardinia, Sicily and Carthage to see if specific evidence could be found to substantiate L. Ron Hubbard's recall of incidents in his own past, centuries ago.

Wicca

[edit]Wicca is a neo-pagan religion focused on nature, guided by the philosophy of Wiccan Rede that advocates the tenets "Harm None, Do As Ye Will". Wiccans believe in a form of karmic return where one's deeds are returned, either in the current life or in another life, threefold or multiple times in order to teach one lessons (the Threefold Law). Reincarnation is therefore an accepted part of the Wiccan faith.[304][full citation needed] Wiccans also believe that death and afterlife are important experiences for the soul to transform and prepare for future lifetimes.[citation needed]

Reincarnation and science

[edit]

Хотя научного подтверждения физической реальности реинкарнации не было, там, где эта тема обсуждалась, возникают вопросы о том, могут ли такие убеждения быть оправданы в дискурсе науки и религии и если да, то каким образом. Некоторые поборники академической парапсихологии утверждают, что у них есть научные доказательства, хотя их недоброжелатели обвиняют их в той или иной форме псевдонауки . [305][306] Скептик Карл Саган спросил Далай-ламу, что бы он сделал, если бы фундаментальный принцип его религии (реинкарнация) был окончательно опровергнут наукой. Далай-лама ответил: «Если наука сможет опровергнуть реинкарнацию, тибетский буддизм откажется от реинкарнации... но опровергнуть реинкарнацию будет очень сложно». [ 307 ] Саган считал утверждения о воспоминаниях о прошлых жизнях достойными исследования, хотя считал реинкарнацию маловероятным объяснением этих событий. [ 308 ]

Утверждения прошлых жизней

[ редактировать ]На протяжении 40 лет психиатр Ян Стивенсон из Университета Вирджинии записывал тематические исследования маленьких детей, которые утверждали, что помнят прошлые жизни. Он опубликовал двенадцать книг, в том числе «Двадцать случаев, указывающих на реинкарнацию» , «Реинкарнация и биология: вклад в этиологию родимых пятен и врожденных дефектов» (монография, состоящая из двух частей), «Европейские случаи типа реинкарнации » и «Там, где реинкарнация и биология пересекаются» . В своих случаях он сообщал заявления ребенка и показания членов семьи и других лиц, часто вместе с тем, что, по его мнению, было связано с умершим человеком, которое в некотором смысле, казалось, соответствовало воспоминаниям ребенка. Стивенсон также расследовал случаи, когда, по его мнению, родимые пятна и врожденные дефекты соответствовали ранам и шрамам на умершем. Иногда в его документацию входили медицинские записи, например, вскрытия . фотографии [ 309 ] Поскольку любое заявление о воспоминаниях о прошлых жизнях может быть обвинено в ложных воспоминаниях и в легкости, с которой такие утверждения могут быть подделаны , Стивенсон ожидал, что последуют противоречия и скептицизм в отношении его убеждений. Он сказал, что искал опровергающие доказательства и альтернативные объяснения сообщений, но, как сообщила газета Washington Post , он обычно приходил к выводу, что никаких нормальных объяснений недостаточно. [ 310 ]

Среди других академических исследователей, которые предприняли аналогичные действия, — Джим Б. Такер , Антония Миллс , [ 311 ] Сатвант Пасрича , Годвин Самараратне и Эрлендур Харальдссон , но публикации Стивенсона остаются наиболее известными. [ 312 ] Работа Стивенсона в этом отношении была настолько впечатляющей для Карла Сагана , что он сослался на исследования Стивенсона в своей книге «Мир, населенный демонами» как на пример тщательно собранных эмпирических данных, и хотя он отверг реинкарнацию как скупое объяснение этих историй, он писал, что феномен предполагаемых воспоминаний о прошлых жизнях требует дальнейшего исследования. [ 313 ] [ 314 ] Сэм Харрис процитировал работы Стивенсона в своей книге «Конец веры» как часть массива данных, которые, кажется, подтверждают реальность психических явлений. [ 315 ] [ 316 ]

Утверждения Стивенсона подвергались критике и разоблачению , например, со стороны философа Пола Эдвардса , который утверждал, что рассказы Яна Стивенсона о реинкарнации были чисто анекдотическими и тщательно отобранными . [ 317 ] Эдвардс объяснил эти истории избирательным мышлением , предположениями и ложными воспоминаниями , которые возникли в результате систем убеждений семьи или исследователя и, таким образом, не соответствовали стандарту достаточно выборочных эмпирических данных . [ 318 ] Философ Кит Августин критиковал, что тот факт, что «подавляющее большинство случаев Стивенсона происходят из стран, где сильна религиозная вера в реинкарнацию, и редко где-либо еще, по-видимому, указывает на то, что культурная обусловленность (а не реинкарнация) порождает утверждения о спонтанном прошлом. - жизненные воспоминания». [ 319 ] Далее Ян Уилсон писал, что большое количество случаев Стивенсона состояло из бедных детей, помнящих богатую жизнь или принадлежащих к высшей касте . В этих обществах утверждения о реинкарнации использовались как схемы для получения денег от более богатых семей предполагаемых прошлых воплощений. [ 320 ] Роберт Бейкер утверждал, что все переживания прошлых жизней, исследованные Стивенсоном и другими парапсихологами, понятны с точки зрения известных психологических факторов, включая смесь криптомнезии и конфабуляции . [ 321 ] Эдвардс также возразил, что реинкарнация вызывает предположения, несовместимые с современной наукой. [ 322 ] Поскольку подавляющее большинство людей не помнят предыдущие жизни и не существует известного эмпирически документированного механизма, позволяющего личности пережить смерть и отправиться в другое тело, утверждение о существовании реинкарнации подчиняется принципу, согласно которому « экстраординарные утверждения требуют экстраординарных доказательств ».

Стивенсон также заявил, что было несколько случаев, свидетельствующих о ксеноглоссии , в том числе два, когда субъект под гипнозом якобы разговаривал с людьми, говорящими на иностранном языке, вместо того, чтобы просто произносить иностранные слова. Сара Томасон , лингвист (и скептически настроенный исследователь) из Мичиганского университета, повторно проанализировала эти случаи и пришла к выводу, что «лингвистические доказательства слишком слабы, чтобы поддержать утверждения о ксеноглоссии». [ 323 ]

Регрессия в прошлую жизнь

[ редактировать ]Некоторые сторонники реинкарнации (Стивенсон не входит в их число) придают большое значение предполагаемым воспоминаниям прошлых жизней, извлеченным под гипнозом во время регрессий в прошлые жизни . Популяризированный психиатром Брайаном Вайсом , который утверждает, что с 1980 года ему удалось добиться регрессии более чем у 4000 пациентов. [ 324 ] [ 325 ] эту технику часто называют своего рода псевдонаучной практикой . [ 326 ] Документально подтверждено, что такие предполагаемые воспоминания содержат исторические неточности, происходящие из современной популярной культуры, распространенных представлений об истории или книг, в которых обсуждаются исторические события. Эксперименты с субъектами, подвергшимися регрессии в прошлые жизни, показывают, что вера в реинкарнацию и внушения гипнотизера являются двумя наиболее важными факторами, касающимися содержания сообщаемых воспоминаний. [ 327 ] [ 326 ] [ 328 ] Использование гипноза и наводящих вопросов может привести к тому, что у субъекта с большой вероятностью останутся искаженные или ложные воспоминания . [ 329 ] Вместо воспоминаний о предыдущем существовании источником воспоминаний, скорее всего, является криптомнезия и конфабуляции , которые сочетают в себе опыт, знания, воображение и внушение или руководство гипнотизера. Однажды созданные, эти воспоминания неотличимы от воспоминаний, основанных на событиях, произошедших в течение жизни субъекта. [ 327 ] [ 330 ]

Регрессию в прошлые жизни критиковали за ее неэтичность на том основании, что у нее отсутствуют какие-либо доказательства, подтверждающие ее утверждения, и что она увеличивает восприимчивость к ложным воспоминаниям. Луис Кордон утверждает, что это может быть проблематичным, поскольку порождает заблуждения под видом терапии . Воспоминания воспринимаются столь же яркими, как и воспоминания, основанные на событиях, пережитых в жизни, и их невозможно отличить от истинных воспоминаний о реальных событиях, и, соответственно, любой ущерб может быть трудно исправить. [ 330 ] [ 331 ]

Организации, аккредитованные APA, выступили против использования регрессий в прошлые жизни в качестве терапевтического метода, назвав это неэтичным. Кроме того, гипнотическая методология, лежащая в основе регрессии в прошлые жизни, подверглась критике как ставящая участника в уязвимое положение, подверженное имплантации ложных воспоминаний. [ 331 ] Поскольку имплантация ложных воспоминаний может быть вредной, Габриэль Андраде утверждает, что регрессия в прошлые жизни нарушает принцип « не навреди» ( ненавреди ), часть клятвы Гиппократа . [ 331 ]

См. также

[ редактировать ]Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ Макклелланд, Норман К. (2010). Энциклопедия реинкарнации и кармы . МакФарланд. стр. 24–29, 171. ISBN. 978-0-7864-5675-8 . Архивировано из оригинала 26 ноября 2016 года . Проверено 25 сентября 2016 г.

- ^ Юргенсмейер, Марк; Крыша, Уэйд Кларк (2011). Энциклопедия мировой религии . Публикации SAGE. стр. 271–272. ISBN 978-1-4522-6656-5 . Архивировано из оригинала 31 марта 2019 года . Проверено 25 сентября 2016 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Юргенсмейер и Руф 2011 , стр. 271–272.

- ^ Лаумакис, Стивен Дж. (2008). Введение в буддийскую философию . Издательство Кембриджского университета. стр. 90–99. ISBN 978-1-139-46966-1 . Архивировано из оригинала 21 января 2017 года . Проверено 25 сентября 2016 г.

- ^ Рита М. Гросс (1993). Буддизм после патриархата: феминистская история, анализ и реконструкция буддизма . Издательство Государственного университета Нью-Йорка. п. 148 . ISBN 978-1-4384-0513-1 .

- ↑ Флуд, Гэвин Д. (1996), Введение в индуизм , издательство Кембриджского университета.