индуизм

| Часть серии о |

| индуизм |

|---|

|

Индуизм ( / ˈ h ɪ n d u ˌ ɪ z əm / ) [ 1 ] [ 2 ] — индийская религия или дхарма , религиозный и универсальный порядок , которому следуют его последователи. [ примечание 1 ] [ примечание 2 ] Слово индус является экзонимом . [ примечание 3 ] и хотя индуизм называют старейшей религией в мире, [ примечание 4 ] ее также называют санатана дхарма ( санскрит : सनातन धर्म , букв. «вечная дхарма»), современное использование, основанное на убеждении, что ее происхождение лежит за пределами человеческой истории , как показано в индуистских текстах . [ примечание 5 ] Другой эндоним индуизма — Вайдика дхарма . [ сеть 1 ]

Индуизм предполагает разнообразные системы мышления, отмеченные рядом общих концепций, которые обсуждают теологию , мифологию и другие темы в текстовых источниках. [ 3 ] Индуистские тексты делятся на шрути («услышанные») и смрити («вспомнившиеся»). Основными индуистскими писаниями являются Веды , Упанишады , Пураны , Махабхарата (включая Бхагавад-гиту ), Рамаяна и Агамы . [ 4 ] [ 5 ] Выдающиеся темы в индуистских верованиях включают карму (действие, намерение и последствия). [ 4 ] [ 6 ] и четыре Пурушартхи , истинные цели или задачи человеческой жизни, а именно: дхарма (этика/обязанности), артха (процветание/работа), кама (желания/страсти) и мокша (освобождение/свобода от страстей и цикла смерти и смерти). возрождение ). [ 7 ] [ 8 ] Индуистские религиозные практики включают преданность ( бхакти ), поклонение ( пуджа ), жертвенные обряды ( ягья ), медитацию ( дхьяна ) и йогу . [ 9 ] Основными индуистскими конфессиями являются вайшнавизм , шиваизм , шактизм и традиция смарта . Шестью астики школами индуистской философии , признающими авторитет Вед, являются: санкхья , йога , ньяя , вайшешика , мимамса и веданта . [ 10 ] [ 11 ]

В то время как традиционная Итихаса-Пурана и производная от нее эпико-пураническая хронология представляют индуизм как традицию, существующую на протяжении тысячелетий, ученые рассматривают индуизм как сплав [ примечание 6 ] или синтез [ примечание 7 ] брахманической ортопраксии [ примечание 8 ] с различными индийскими культурами, [ примечание 9 ] имеющие разные корни [ примечание 10 ] и нет конкретного основателя. [ 12 ] Этот индуистский синтез возник после ведического периода, между ок. 500 [ 13 ] –200 [ 14 ] до н.э. и ок. 300 г. н. э. , [ 13 ] в период второй урбанизации и раннеклассического периода индуизма, когда были составлены эпос и первые Пураны. [ 13 ] [ 14 ] Его расцвет пришелся на средневековый период , с упадком буддизма в Индии . [ 15 ] С 19-го века современный индуизм , находящийся под влиянием западной культуры, также имеет большую привлекательность для Запада, особенно в популяризации йоги и различных сект, таких как Трансцендентальная Медитация и движение Харе Кришна .

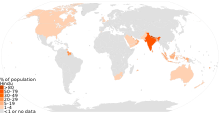

Индуизм — третья по величине религия в мире, насчитывающая около 1,20 миллиарда последователей, или около 15% мирового населения, известного как индуисты . [ 16 ] [ сеть 2 ] [ сеть 3 ] Это наиболее широко исповедуемая вера в Индии . [ 17 ] Непал , Маврикий и Бали , Индонезия . [ 18 ] Значительное число индуистских общин имеется в других странах Южной Азии , Юго-Восточной Азии , в странах Карибского бассейна , на Ближнем Востоке , в Северной Америке , Европе , Океании , Африке и других регионах . [ 19 ] [ 20 ]

Этимология

Слово индуизм является экзонимом . [ 21 ] [ 22 ] и происходит от санскрита [ 23 ] корень Синдху , [ 24 ] [ 25 ] Считается, что это название реки Инд в северо-западной части Индийского субконтинента . [ 26 ] [ 24 ] [ примечание 11 ]

Изменение протоиранского звука *s > h произошло между 850 и 600 годами до нашей эры. [ 28 ] По словам Гэвина Флада , «настоящий термин «индус» впервые встречается как персидский географический термин для обозначения людей, живших за рекой Инд (санскрит: синдху )», [ 24 ] VI века до н.э. более конкретно, в надписи Дария I (550–486 гг. До н.э.) [ 29 ] Термин «индуист» в этих древних записях является географическим термином и не относится к религии. [ 24 ] Слово «индуист» встречается как гептахинду в Авесте , что эквивалентно ригведическому сапта синдху , тогда как хндстн (произносится как «Хиндустан» ) встречается в сасанидской надписи III века нашей эры, оба из которых относятся к частям северо-запада Южной Азии. [ 30 ] В арабских текстах аль-Хинд называл землю за Индом. [ 31 ] и поэтому все люди на этой земле были индуистами. [ 32 ] Этот арабский термин сам по себе был взят из доисламского персидского термина « хинду» . К 13 веку Индостан стал популярным альтернативным названием Индии , что означает «земля индуистов». [ 33 ]

Среди самых ранних известных записей об «индуизме», имеющих религиозный оттенок, может быть китайский текст VII века н.э. « западных регионов» Сюаньцзана Записи , [ 29 ] и персидский текст XIV века «Футуху-салатин» Абд аль-Малика Исами . [ примечание 3 ] XVI–XVIII веков В некоторых бенгальских текстах Гаудия-вайшнавов упоминаются индуистская и индуистская дхарма, чтобы отличить их от мусульман, но без положительного определения этих терминов. [ 34 ] В 18 веке европейские купцы и колонисты стали называть последователей индийских религий индуистами. [ 35 ] [ 36 ] [ примечание 12 ] Использование английского термина «индуизм» для описания совокупности практик и верований возникло сравнительно недавно. Термин «индуизм» впервые был использован Раджей Рам Моханом Роем в 1816–1817 годах. [ 26 ] К 1840-м годам термин «индуизм» использовался теми индийцами, которые выступали против британского колониализма и хотели отличить себя от мусульман и христиан. [ 24 ] [ 40 ] [ 41 ] [ 42 ] До того, как британцы начали классифицировать сообщества строго по религии, индийцы, как правило, не определяли себя исключительно через свои религиозные убеждения; вместо этого идентичности были в основном сегментированы на основе местности, языка, варны , джати , рода занятий и секты. [ 43 ] [ примечание 13 ]

Определения

«Индуизм» — это обобщающий термин, [ 45 ] [ 46 ] имея в виду широкий спектр иногда противоположных, а часто и конкурирующих традиций. [ 10 ] [ 11 ] [ 47 ] [ 48 ] Термин «индуизм» был придуман в западной этнографии в 18 веке. [ 36 ] [ примечание 14 ] и относится к слиянию, [ примечание 6 ] или синтез, [ примечание 7 ] [ 49 ] различных индийских культур и традиций, [ 50 ] [ примечание 9 ] с разными корнями [ 51 ] [ примечание 10 ] и нет основателя. [ 12 ] Этот индуистский синтез возник после ведического периода, между ок. 500 [ 13 ] –200 [ 14 ] до н.э. и ок. 300 г. н. э. , [ 13 ] в период Второй урбанизации и раннеклассический период индуизма, когда были составлены эпос и первые Пураны. [ 13 ] [ 14 ] Его расцвет пришелся на средневековый период , с упадком буддизма в Индии . [ 15 ] Разнообразие верований и широкий спектр традиций индуизма затрудняют определение религии в соответствии с традиционными западными концепциями. [ 52 ]

Индуизм включает в себя разнообразие идей о духовности и традициях; Индуисты могут быть политеистами , пантеистами , панентеистами , пандеистами , генотеистами , монотеистами , монистами , агностиками , атеистами или гуманистами . [ 53 ] [ 54 ] По словам Махатмы Ганди , «человек может не верить в Бога и при этом называть себя индуистом». [ 55 ] По словам Венди Донигер , «идеи обо всех основных вопросах веры и образа жизни – вегетарианстве, ненасилии, вере в перерождение и даже кастах – являются предметом дискуссий, а не догм ». [ 43 ]

Из-за широкого спектра традиций и идей, охватываемых термином «индуизм», прийти к исчерпывающему определению сложно. [ 24 ] Религия «бросает вызов нашему желанию дать ей определение и классифицировать ее». [ 56 ] Индуизм по-разному определяли как религию, религиозную традицию, набор религиозных убеждений и «образ жизни». [ 57 ] [ примечание 1 ] С западной лексической точки зрения индуизм, как и другие религии, уместно называть религией. термин «дхарма» , который является более широким, чем западный термин «религия». В Индии предпочитают [ 58 ]

Изучение Индии, ее культуры и религии, а также определение «индуизма» были сформированы интересами колониализма и западными представлениями о религии. [ 59 ] [ 60 ] С 1990-х годов это влияние и его последствия были темой дискуссий среди ученых-индуистов. [ 59 ] [ примечание 15 ] а также были подхвачены критиками западного взгляда на Индию. [ 61 ] [ примечание 16 ]

Типология

Индуизм, как его обычно называют, можно разделить на ряд основных течений. Из исторического разделения на шесть даршанов (философий) в настоящее время наиболее заметными являются две школы, Веданта и Йога . [ 62 ] Шестью школами астики индуистской философии, признающими авторитет Вед, являются: санкхья , йога , ньяя , вайшешика , мимамса и веданта . [ 10 ] [ 11 ]

Четыре основных современных течения индуизма, классифицированные по основным божествам или божествам, - это вайшнавизм (Вишну), шиваизм (Шива), шактизм (Деви) и смартизм (пять божеств рассматриваются как равные). [ 63 ] [ 64 ] [ 65 ] [ 66 ] Индуизм также принимает многочисленные божественные существа, при этом многие индуисты считают божества аспектами или проявлениями единой безличной абсолютной или высшей реальности или Верховного Бога , в то время как некоторые индуисты утверждают, что конкретное божество представляет верховного, а различные божества являются низшими проявлениями этого верховного Бога. . [ 67 ] Другие примечательные характеристики включают веру в существование атмана (я), реинкарнацию своего атмана и кармы, а также веру в дхарму (обязанности, права, законы, поведение, добродетели и правильный образ жизни), хотя существуют вариации. некоторые не следуют этим убеждениям.

Джун МакДэниел (2007) классифицирует индуизм на шесть основных видов и множество второстепенных видов, чтобы понять выражение эмоций среди индуистов. [ 47 ] Основными видами, по мнению Макдэниела, являются народный индуизм , основанный на местных традициях и культах местных божеств и являющийся древнейшей бесписьменной системой; Ведический индуизм, основанный на самых ранних слоях Вед, относящихся ко 2-му тысячелетию до нашей эры; Ведантический индуизм, основанный на философии Упанишад , включая Адвайта Веданту , делающий упор на знание и мудрость; Йогический индуизм, следующий тексту Йога-сутр Патанджали, подчеркивающий интроспективное осознание; Дхармический индуизм или «повседневная мораль», которая, по утверждению Макдэниела, стереотипно представлена в некоторых книгах как «единственная форма индуистской религии с верой в карму, коров и касту»; и бхакти , или религиозный индуизм, где сильные эмоции тщательно включены в стремление к духовному. [ 47 ]

Майклс различает три индуистские религии и четыре формы индуистской религиозности. [ 48 ] Три индуистские религии — это «брахманско-санскритский индуизм», «народные религии и племенные религии» и «основанные религии». [ 68 ] Четыре формы индуистской религиозности — это классическая «карма-марга». [ 69 ] путь познания , [ 70 ] путь преданности , [ 70 ] и «героизм», коренящийся в милитаристских традициях . К этим милитаристским традициям относятся рамаизм (поклонение герою эпической литературы Раме , считая его воплощением Вишну) [ 71 ] и части политического индуизма . [ 69 ] «Героизм» также называют вирья-марга . [ 70 ] По словам Майклса, каждый девятый индуист по рождению принадлежит к одной или обеим типологиям брахманско-санскритского индуизма и народной религии, независимо от того, практикуют они или нет. Он классифицирует большинство индуистов как принадлежащих по выбору к одной из «основанных религий», таких как вайшнавизм и шиваизм, которые ориентированы на мокшу и часто преуменьшают значение священнической власти Брахмана (брамина), но включают в себя ритуальную грамматику брахманско-санскритского индуизма. [ 72 ] Он включает в число «основанных религий» буддизм , джайнизм , сикхизм, которые теперь являются отдельными религиями, синкретические движения, такие как Брахмо Самадж и Теософское общество , а также различные « гуру -измы» и новые религиозные движения, такие как Махариши Махеш Йоги , БАПС и ИСККОН . [ 73 ]

Инден утверждает, что попытки классифицировать индуизм по типологии начались еще во времена Империи, когда обращавшиеся в свою веру миссионеры и колониальные чиновники стремились понять и изобразить индуизм с точки зрения своих интересов. [ 74 ] Индуизм был истолкован как исходящий не из разума духа, а из фантазии и творческого воображения, не концептуального, а символического, не этического, а эмоционального, не рационального или духовного, а когнитивного мистицизма. По мнению Индена, этот стереотип соответствовал имперским императивам той эпохи, обеспечивая моральное оправдание колониального проекта. [ 74 ] От племенного анимизма до буддизма – все считалось частью индуизма. Ранние отчеты устанавливают традиции и научные предпосылки для типологии индуизма, а также основные предположения и ошибочные предпосылки, которые легли в основу индологии . Индуизм, по мнению Индена, не был тем, чем его стереотипно представляли имперские религиозные деятели, и неуместно приравнивать индуизм к просто монистическому пантеизму и философскому идеализму Адвайта Веданты. [ 74 ]

Некоторые ученые предполагают, что индуизм можно рассматривать как категорию с «размытыми краями», а не как четко определенную и жесткую сущность. Некоторые формы религиозного выражения занимают центральное место в индуизме, а другие, хотя и не столь центральные, все же остаются в рамках этой категории. Основываясь на этой идее, Габриэлла Эйхингер Ферро-Луцци разработала «подход теории прототипов» к определению индуизма. [ 75 ]

Санатана Дхарма

Для его приверженцев индуизм — традиционный образ жизни. [ 79 ] Многие практикующие называют «ортодоксальную» форму индуизма Санатана Дхармой , «вечным законом» или «вечным путем». [ 80 ] [ 81 ] Индуисты считают, что индуизму тысячи лет. Пураническая хронология , изложенная в Махабхарате , Рамаяне и Пуранах , представляет собой хронологию событий, связанных с индуизмом, которые начались задолго до [ ласковые слова ] 3000 г. до н.э. Слово дхарма используется здесь для обозначения религии, сходной с современными индоарийскими языками , а не с ее первоначальным санскритским значением. Все аспекты индуистской жизни, а именно приобретение богатства ( артха ), исполнение желаний ( кама ) и достижение освобождения ( мокша ), рассматриваются здесь как часть «дхармы», заключающей в себе «правильный образ жизни» и вечную гармонию. принципы их реализации. [ 82 ] [ 83 ] Использование термина Санатана Дхарма для обозначения индуизма — это современное употребление, основанное на убеждении, что истоки индуизма лежат за пределами человеческой истории, как показано в индуистских текстах . [ 84 ] [ 85 ] [ 86 ] [ 87 ] [ нужны разъяснения ]

Санатана Дхарма относится к «вневременному, вечному набору истин», и именно так индуисты видят истоки своей религии. Его рассматривают как вечные истины и традиции, берущие свое начало за пределами человеческой истории, — истины, божественно открытые ( Шрути ) в Ведах , самом древнем из мировых писаний. [ 88 ] [ 89 ] Для многих индуистов индуизм — это традиция, восходящая как минимум к древней ведической эпохе. Западный термин «религия» в той степени, в которой он означает «догму и институт, восходящий к одному основателю», не соответствует их традиции, утверждает Хэтчер. [ 88 ] [ 90 ] [ примечание 17 ]

Санатана Дхарма исторически относилась к «вечным» обязанностям, религиозно предписанным в индуизме, таким обязанностям, как честность, воздержание от причинения вреда живым существам ( ахимса ), чистота, доброжелательность, милосердие, терпение, терпимость, сдержанность, щедрость и аскетизм. Эти обязанности применялись независимо от класса, касты или секты индуиста, и они контрастировали со свадхармой , «собственным долгом» человека в соответствии с его классом или кастой ( варна ) и этапом жизни ( пурушартха ). [ сеть 5 ] В последние годы этот термин использовался индуистскими лидерами, реформаторами и националистами для обозначения индуизма. Санатана дхарма стала синонимом «вечной» истины и учения индуизма, которые выходят за рамки истории и являются «неизменными, неделимыми и в конечном итоге несектантскими». [ сеть 5 ]

Ведическая религия

Некоторые называют индуизм Вайдика-дхармой . [ 92 ] Слово «Вайдика» на санскрите означает «происходящий из Веды или соответствующий ей» или «относящийся к Веде». [ сеть 6 ] Традиционные ученые использовали термины Вайдика и Аваидика, те, кто принимает Веды как источник авторитетного знания, и те, кто не принимают, чтобы отличить различные индийские школы от джайнизма, буддизма и чарваки. По словам Клауса Клостермайера, термин Вайдика дхарма является самым ранним самоназванием индуизма. [ 93 ] [ 94 ] По словам Арвинда Шармы «индусы называли свою религию термином вайдика дхарма или его вариантом». , исторические данные свидетельствуют о том, что в IV веке нашей эры [ 95 ] По словам Брайана К. Смита, «[по крайней мере спорно] относительно того, не может ли термин Вайдика Дхарма , с соответствующими уступками исторической, культурной и идеологической специфике, быть сопоставим и переведен как «индуизм». или «Индуистская религия». [ 96 ]

Как бы то ни было, многие индуистские религиозные источники рассматривают людей или группы, которых они считают неведическими (и которые отвергают ведическую варнашраму - ортодоксальность «касты и жизненного этапа»), как еретиков (пашанда / пакханда). Например, «Бхагавата-пурана» считает буддистов, джайнов, а также некоторые шайвов группы , такие как пашупаты и капалины , пашандами (еретиками). [ 97 ]

По словам Алексиса Сандерсона , ранние санскритские тексты различают традиции вайдиков, вайшнавов, шайвов, шактов, саур, буддистов и джайнов. Однако индийский консенсус конца I тысячелетия н. э. «действительно пришел к концептуализации сложной сущности, соответствующей индуизму, в отличие от буддизма и джайнизма, исключив из своей среды только определенные формы антиномичной шакта-шайвы». [ сеть 7 ] Некоторые представители Мимамса школы индуистской философии считали Агамы, такие как Панчаратрика, недействительными, поскольку они не соответствуют Ведам. Некоторые кашмирские ученые отвергли эзотерические тантрические традиции как часть Вайдика-дхармы. [ сеть 7 ] [ сеть 8 ] Аскетическая традиция Атимарга-шиваизма, датируемая примерно 500 годом нашей эры, бросила вызов системе вайдиков и настаивала на том, что их агамы и практики не только действительны, но и превосходят агамы и практики вайдиков. [ сеть 9 ] Однако, добавляет Сандерсон, эта шиваитская аскетическая традиция считала себя искренне верными ведической традиции и «единогласно считала, что шрути и смрити брахманизма универсальны и уникальны в своей сфере, [...] и что как таковые они [Веды] являются единственным средством познания человеком достоверного знания [...]». [ сеть 9 ]

Термин Вайдика-дхарма означает свод правил, «основанный на Ведах», но неясно, что на самом деле означает «основанный на Ведах», - утверждает Юлиус Липнер. [ 90 ] Вайдика-дхарма или «ведический образ жизни», утверждает Липнер, не означает, что «индуизм обязательно религиозен» или что индуисты имеют общепринятое «традиционное или институциональное значение» для этого термина. [ 90 ] Для многих это культурный термин. У многих индуистов нет копии Вед, и они никогда не видели и не читали лично части Вед, как христианин, который может иметь отношение к Библии, или мусульманин, возможно, к Корану. Тем не менее, утверждает Липнер, «это не означает, что ориентация всей их [индусов] жизни не может быть прослежена до Вед или что она каким-то образом не вытекает из них». [ 90 ]

Хотя многие религиозные индуисты безоговорочно признают авторитет Вед, это признание часто является «не более чем заявлением о том, что кто-то считает себя [или себя] индуистом». [ 98 ] [ примечание 18 ] и «большинство индийцев сегодня на словах верят Ведам и не обращают внимания на содержание текста». [ 99 ] Некоторые индуисты бросают вызов авторитету Вед, тем самым неявно признавая их важность для истории индуизма, утверждает Липнер. [ 90 ]

Юридическое определение

Бал Гангадхар Тилак дал следующее определение в «Гите Рахасья» (1915): «Принятие Вед с почтением; признание того факта, что средства или пути спасения разнообразны; и осознание истины о том, что число богов, которым следует поклоняться, невелико. большой". [ 100 ] [ 101 ] Его процитировал Верховный суд Индии в 1966 году. [ 100 ] [ 101 ] и снова в 1995 году «как «адекватное и удовлетворительное определение» [ 102 ] и до сих пор является юридическим определением индуиста. [ 103 ]

Разнообразие и единство

Разнообразие

Индуистские верования обширны и разнообразны, поэтому индуизм часто называют семьей религий, а не одной религией. [ сеть 10 ] Внутри каждой религии этой семьи религий существуют разные теологии, практики и священные тексты. [ сеть 11 ] [ 104 ] [ 105 ] [ 106 ] [ сеть 12 ] В индуизме нет «единой системы верований, закодированной в декларации веры или вероучениях ». [ 24 ] но это скорее общий термин, охватывающий множество религиозных явлений Индии. [ 107 ] [ 108 ] По мнению Верховного суда Индии ,

В отличие от других религий мира, индуистская религия не претендует ни на одного Пророка, не поклоняется какому-либо Богу, не верит ни в одну философскую концепцию, не следует ни одному акту религиозных обрядов или представлений; на самом деле, оно не соответствует традиционным чертам религии или вероисповедания. Это образ жизни и ничего более». [ 109 ]

Частично проблема с единым определением термина «Индуизм» заключается в том, что у индуизма нет основателя. [ 110 ] Это синтез различных традиций, [ 111 ] «Брахманическая ортопраксия, традиции отречения и народные или местные традиции». [ 112 ]

Теизм также трудно использовать в качестве объединяющей доктрины индуизма, поскольку, хотя некоторые индуистские философии постулируют теистическую онтологию творения, другие индуисты являются или были атеистами . [ 113 ]

Чувство единства

Несмотря на различия, существует и чувство единства. [ 114 ] Большинство индуистских традиций почитают свод религиозной или священной литературы — Веды. [ 115 ] хотя есть исключения. [ 116 ] Эти тексты являются напоминанием о древнем культурном наследии и предметом гордости индуистов. [ 117 ] [ 118 ] хотя Луи Рену заявил, что «даже в самых ортодоксальных областях почитание Вед стало простым поднятием шляпы». [ 117 ] [ 119 ]

Хальбфасс утверждает, что, хотя шиваизм и вайшнавизм можно рассматривать как «самостоятельные религиозные созвездия», [ 114 ] между «теоретиками и представителями литературы» существует определенная степень взаимодействия и ссылок. [ 114 ] каждой традиции, что указывает на наличие «более широкого чувства идентичности, чувства согласованности в общем контексте и включения в общие рамки и горизонт». [ 114 ]

Классический индуизм

Брахманы сыграли важную роль в развитии постведического индуистского синтеза, распространении ведической культуры среди местных сообществ и интеграции местной религиозности в трансрегиональную брахманическую культуру. [ 120 ] В период после Гуптов Веданта развивалась на юге Индии, где ортодоксальная брахманская культура и индуистская культура. сохранились [ 121 ] опираясь на древние ведические традиции, «принимая во внимание многочисленные требования индуизма». [ 122 ]

Средневековые события

Понятие общего знаменателя для нескольких религий и традиций Индии получило дальнейшее развитие с XII века нашей эры. [ 123 ] Лоренцен прослеживает возникновение «семейного сходства» и то, что он называет «началами средневекового и современного индуизма», обретающими форму в ок. 300–600 гг. Н. Э., с развитием ранних Пуран и продолжением ранней ведической религии. [ 124 ] Лоренцен утверждает, что установление индуистской самоидентичности произошло «в процессе взаимного самоопределения с контрастирующим мусульманским Другим». [ 125 ] По Лоренцену, это «присутствие Другого» [ 125 ] Необходимо признать «свободное семейное сходство» между различными традициями и школами. [ 126 ]

По словам индолога Алексиса Сандерсона , до того, как ислам пришел в Индию, «санскритские источники различали традиции вайдика, вайшнавов, шиваитов, шактов, саур, буддистов и джайнов, но у них не было названия, обозначающего первые пять из них как единое целое. за и против буддизма и джайнизма». Отсутствие официального названия, утверждает Сандерсон, не означает, что соответствующей концепции индуизма не существовало. К концу I тысячелетия нашей эры возникла концепция веры и традиции, отличная от буддизма и джайнизма. [ сеть 7 ] Эта сложная традиция приняла в своей идентичности почти все, что в настоящее время является индуизмом, за исключением некоторых антиномических тантрических движений. [ сеть 7 ] Некоторые консервативные мыслители того времени задавались вопросом, согласуются ли определенные тексты или практики Шайвов, Вайшнавов и Шактов с Ведами или они полностью недействительны. Тогда умеренные, а позже и большинство исследователей ортопракса согласились, что, хотя существуют некоторые различия, основа их верований, ритуальная грамматика, духовные предпосылки и сотериологии были одинаковыми. «Это чувство большего единства, - утверждает Сандерсон, - стало называться индуизмом». [ сеть 7 ]

По мнению Николсона, уже между XII и XVI веками «некоторые мыслители стали рассматривать как единое целое разнообразные философские учения Упанишад, эпосов, Пуран и школ, известных ретроспективно как «шесть систем» ( саддаршана ) господствующего течения. Индуистская философия». [ 127 ] Тенденцию «смывания философских различий» отмечал и Микель Берли . [ 128 ] Хакер назвал это «инклюзивизмом». [ 115 ] и Майклс говорит о «привычке к идентификации». [ 3 ] Лоренцен находит истоки особой индуистской идентичности во взаимодействии между мусульманами и индуистами. [ 129 ] и процесс «взаимного самоопределения с контрастирующим мусульманским другим», [ 130 ] [ 29 ] который начался задолго до 1800 года. [ 131 ] Майклс отмечает:

В качестве противодействия исламскому превосходству и как часть продолжающегося процесса регионализации в индуистских религиях возникли две религиозные инновации: формирование сект и историзация, которая предшествовала более позднему национализму ... [С]аинты, а иногда и воинственные лидеры сект, такие как как поэты маратхи Тукарам (1609–1649) и Рамдас (1608–1681) сформулировали идеи, в которых они прославляли индуизм и прошлое. Брахманы также создавали все больше исторических текстов, особенно восхвалений и хроник священных мест (махатмий), или развили рефлексивную страсть к сбору и составлению обширных коллекций цитат на различные темы. [ 132 ]

Колониальные виды

Понятие и сообщения об «индуизме» как «единой мировой религиозной традиции». [ 133 ] был также популяризирован миссионерами-прозелитами 19-го века и европейскими индологами, роли, которые иногда выполнял один и тот же человек, который полагался на тексты, сохраненные браминами (священниками) для получения информации об индийских религиях, и анимистические наблюдения, которые, по мнению миссионеров-востоковедов, были индуизмом. [ 133 ] [ 74 ] [ 134 ] Эти отчеты повлияли на представления об индуизме. Такие ученые, как Пеннингтон, утверждают, что колониальные полемические сообщения привели к созданию сфабрикованных стереотипов, согласно которым индуизм был просто мистическим язычеством, посвященным служению дьяволам. [ примечание 19 ] в то время как другие ученые заявляют, что колониальные постройки повлияли на веру в то, что Веды , Бхагавад-гита , Манусмрити и подобные тексты были сутью индуистской религиозности, а также на современную ассоциацию «индуистской доктрины» со школами Веданты (в частности, Адвайта Веданта) как парадигматический пример мистической природы индуизма». [ 136 ] [ примечание 20 ] Пеннингтон, соглашаясь с тем, что изучение индуизма как мировой религии началось в колониальную эпоху, не согласен с тем, что индуизм является изобретением колониальной европейской эпохи. [ 137 ] Он утверждает, что общая теология, общая ритуальная грамматика и образ жизни тех, кто называет себя индуистами, восходят к древним временам. [ 137 ] [ примечание 21 ]

Индуистский модернизм и неоведанта

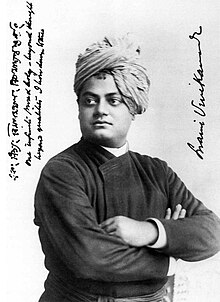

Вся религия содержится в Веданте, то есть в трех стадиях философии Веданты: Двайте, Вишиштадвайте и Адвайте; одно приходит за другим. Это три стадии духовного роста человека. Каждый из них необходим. В этом суть религии: Веданта, примененная к различным этническим обычаям и верованиям Индии, представляет собой индуизм.

— Свами Вивекананда [ сеть 13 ]

Этот инклюзивизм [ 146 ] получила дальнейшее развитие в 19 и 20 веках благодаря индуистским реформаторским движениям и неоведанте. [ 147 ] и стало характерным для современного индуизма. [ 115 ]

Начиная с XIX века, индийские модернисты вновь заявили, что индуизм является главным достоянием индийской цивилизации. [ 60 ] тем временем «очищая» индуизм от его тантрических элементов [ 148 ] и возвышение ведических элементов. Западные стереотипы были перевернуты, подчеркнуты универсальные аспекты и представлены современные подходы к социальным проблемам. [ 60 ] Этот подход имел большую привлекательность не только в Индии, но и на Западе. [ 60 ] Крупнейшие представители «индуистского модернизма» [ 149 ] Рам Мохан Рой , Свами Вивекананда , Сарвепалли Радхакришнан и Махатма Ганди . [ 150 ]

Раджа Раммохан Рой известен как отец индуистского Возрождения . [ 151 ] Он оказал большое влияние на Свами Вивекананду, который, по словам Флада, был «фигурой огромной важности в развитии современного индуистского самопонимания и в формулировании западного взгляда на индуизм». [ 152 ] Центральное место в его философии занимает идея о том, что божественное существует во всех существах, что все люди могут достичь единения с этой «врожденной божественностью». [ 149 ] и что рассмотрение этого божественного как сущности других будет способствовать развитию любви и социальной гармонии. [ 149 ] По мнению Вивекананды, в индуизме существует существенное единство, лежащее в основе разнообразия его многочисленных форм. [ 149 ] По словам Флуда, видение индуизма Вивекананды «в настоящее время общепринято большинством англоговорящих индуистов среднего класса». [ 153 ] Сарвепалли Радхакришнан стремился примирить западный рационализм с индуизмом, «представляя индуизм как по существу рационалистический и гуманистический религиозный опыт». [ 154 ]

Этот «глобальный индуизм» [ 155 ] имеет всемирную привлекательность, выходя за пределы национальных границ [ 155 ] и, по словам Флада, «став мировой религией наряду с христианством, исламом и буддизмом». [ 155 ] как для общин индуистской диаспоры, так и для жителей Запада, которых привлекают незападные культуры и религии. [ 155 ] Он подчеркивает универсальные духовные ценности, такие как социальная справедливость, мир и «духовное преобразование человечества». [ 155 ] Частично оно развилось благодаря «реинкультурации», [ 156 ] или эффект пиццы , [ 156 ] в котором элементы индуистской культуры были экспортированы на Запад, завоевав там популярность и, как следствие, также приобрели большую популярность в Индии. [ 156 ] Эта глобализация индуистской культуры принесла «на Запад учения, которые стали важной культурной силой в западных обществах и, в свою очередь, стали важной культурной силой в Индии, месте их происхождения». [ 157 ]

Современная Индия и мир

Движение Хиндутва с древних времен активно выступало за единство индуизма, игнорируя различия и рассматривая Индию как индуистскую страну. [ 158 ] И есть предположения о политическом доминировании индуистского национализма в Индии , также известного как «нео-индутва» . [ 159 ] [ 160 ] также наблюдается рост преобладания хиндутвы В Непале , как и в Индии . [ 161 ] Масштабы индуизма также растут в других частях мира из-за культурных влияний, таких как йога и движение Харе Кришна , со стороны многих миссионерских организаций, особенно ИСККОН , а также из-за миграции индийских индуистов в другие страны. мира. [ 162 ] [ 163 ] Индуизм быстро растет во многих западных странах и в некоторых африканских странах . [ примечание 22 ]

Основные традиции

Номиналы

Индуизм не имеет центрального доктринального авторитета, и многие практикующие индуисты не заявляют о своей принадлежности к какой-либо конкретной конфессии или традиции. [ 166 ] Однако в научных исследованиях используются четыре основные конфессии: шиваизм , шактизм , смартизм и вайшнавизм . [ 63 ] [ 64 ] [ 65 ] [ 66 ] Эти конфессии различаются прежде всего центральным божеством, которому поклоняются, традициями и сотериологическим мировоззрением. [ 167 ] Конфессии индуизма, утверждает Липнер, не похожи на те, которые встречаются в основных религиях мира, потому что индуистские конфессии размыты, и люди исповедуют более одной, и он предлагает термин «индуистский полицентризм». [ 168 ]

Нет данных переписи населения о демографической истории или тенденциях традиций в индуизме. [ 169 ] Оценки различаются в зависимости от относительного числа приверженцев различных традиций индуизма. По оценке Джонсона и Грима за 2010 год, традиция вайшнавизма является самой крупной группой, насчитывающей около 641 миллиона или 67,6% индуистов, за ней следуют шиваизм с 252 миллионами или 26,6%, шактизм с 30 миллионами или 3,2% и другие традиции, включая нео- Индуизм и реформистский индуизм с 25 миллионами или 2,6%. [ 170 ] [ 171 ] Напротив, по мнению Джонса и Райана, шиваизм является крупнейшей традицией индуизма. [ 172 ] [ примечание 23 ]

Вайшнавизм — это религиозная традиция поклонения Вишну. [ примечание 24 ] и его аватары, особенно Кришна и Рама. [ 174 ] Приверженцы этой секты, как правило, не аскетические, монашеские, ориентированные на общественные мероприятия и практики преданности, вдохновленные «интимно любящим, радостным, игривым» Кришной и другими аватарами Вишну. [ 167 ] Эти практики иногда включают коллективные танцы, пение киртанов и бхаджанов со звуком и музыкой, которые, как полагают некоторые, обладают медитативной и духовной силой. [ 175 ] Храмовое богослужение и фестивали в вайшнавизме обычно тщательно продуманы. [ 176 ] Бхагавад-гита и Рамаяна, а также Пураны, ориентированные на Вишну, составляют ее теистическую основу. [ 177 ]

Шиваизм – это традиция, которая фокусируется на Шиве. Шайвов больше привлекает аскетический индивидуализм, и у него есть несколько подшкол. [ 167 ] Их практики включают преданность в стиле бхакти, однако их убеждения склоняются к недвойственным монистическим школам индуизма, таким как Адвайта и Раджа-йога. [ 178 ] [ 175 ] Некоторые Шайвы поклоняются в храмах, в то время как другие делают упор на йоге, стремясь быть едиными с Шивой внутри. [ 179 ] Аватары встречаются редко, и некоторые Шайвы визуализируют бога наполовину мужчиной, наполовину женщиной, как слияние мужского и женского начал ( Ардханаришвара ). Шиваизм связан с шактизмом, в котором Шакти рассматривается как супруга Шивы. [ 178 ] Общественные праздники включают фестивали и участие вайшнавов в паломничествах, таких как Кумбха Мела . [ 180 ] Шиваизм чаще практиковался на севере Гималаев от Кашмира до Непала и на юге Индии. [ 181 ]

Шактизм фокусируется на поклонении богине Шакти или Деви как космической матери. [ 167 ] и это особенно распространено в северо-восточных и восточных штатах Индии, таких как Ассам и Бенгалия . Деви изображается в более мягких формах, как Парвати , супруга Шивы; или как свирепые богини-воины, такие как Кали и Дурга . Последователи шактизма признают Шакти силой, лежащей в основе мужского начала. Шактизм также связан с практиками Тантры . [ 182 ] Общественные праздники включают фестивали, некоторые из которых включают шествия и погружение идолов в море или другие водоемы. [ 183 ]

Смартизм сосредотачивает свое поклонение одновременно на всех основных индуистских божествах : Шиве, Вишну, Шакти, Ганеше, Сурье и Сканде . [ 184 ] Традиция смарта развивалась в (ранний) классический период индуизма примерно в начале нашей эры, когда индуизм возник в результате взаимодействия брахманизма и местных традиций. [ 185 ] [ 186 ] Традиция Смарта соответствует Адвайта Веданте и считает Ади Шанкару своим основателем или реформатором, который рассматривал поклонение Богу с атрибутами ( Сагуна Брахман ) как путешествие к окончательной реализации Бога без атрибутов (Ниргуна Брахман, Атман, Самость). -знание). [ 187 ] [ 188 ] Термин «смартизм» происходит от текстов индуизма смрити, что означает тех, кто помнит традиции в текстах. [ 178 ] [ 189 ] Эта индуистская секта практикует философскую джняна-йогу, изучение Священных Писаний, размышления, медитативный путь, стремящийся к пониманию единства своего «Я» с Богом. [ 178 ] [ 190 ]

Этническая принадлежность

Индуизм традиционно является много- или полиэтнической религией. На Индийском субконтиненте широко распространен среди многих индоарийских , дравидийских и других южноазиатских этносов . [ 191 ] например, народ мейтей ( тибето-бирманская этническая группа в северо-восточном индийском штате Манипур ). [ 192 ]

Кроме того, в древности и в средние века индуизм был государственной религией во многих индианизированных королевствах Азии, Великой Индии — от Афганистана ( Кабул ) на Западе и включая почти всю Юго-Восточную Азию на Востоке ( Камбоджа , Вьетнам , Индонезия). , частично Филиппины ) – и только к 15 веку почти повсеместно был вытеснен буддизмом и исламом, [ 193 ] [ 194 ] за исключением нескольких все еще индуистских второстепенных австронезийских этнических групп, таких как балийцы. [ 18 ] и тенгерцы [ 195 ] в Индонезии и чамы во Вьетнаме. [ 196 ] Кроме того, небольшая община афганских пуштунов , мигрировавших в Индию после раздела, остается приверженной индуизму. [ 197 ]

Индоарийский народ калаш в Пакистане традиционно исповедует местную религию, которую некоторые авторы характеризуют как форму древнего индуизма . [ 198 ] [ 199 ]

В Гане появилось много новых этнических ганских индуистов , которые обратились в индуизм благодаря работам Свами Ганананды Сарасвати и индуистского монастыря Африки. [ 200 ] С начала 20 века силами Бабы Премананды Бхарати (1858–1914), Свами Вивекананды , А.Ч. Бхактиведанты Свами Прабхупады и других миссионеров индуизм получил определенное распространение среди западных народов. [ 201 ]

Священные Писания

Древние писания индуизма написаны на санскрите. Эти тексты делятся на две части: Шрути и Смрити . Шрути - это апаурушейа , «не созданный из человека», но открытый риши ( провидцам) и считается обладающим высшим авторитетом, в то время как смрити созданы человеком и имеют второстепенный авторитет. [ 202 ] Это два высших источника дхармы , два других — это Шишта Ачара/Садачара (поведение благородных людей) и, наконец, Атма тушти («то, что доставляет удовольствие самому себе»). [ примечание 26 ]

Индуистские писания составлялись, запоминались и передавались устно из поколения в поколение за многие столетия до того, как они были записаны. [ 203 ] [ 204 ] На протяжении многих столетий мудрецы уточняли учения и расширяли Шрути и Смрити, а также разрабатывали Шастры с эпистемологическими и метафизическими теориями шести классических школ индуизма. [ нужна ссылка ]

Шрути (букв. то, что слышно) [ 205 ] в первую очередь относится к Ведам , которые составляют самую раннюю запись индуистских писаний и считаются вечными истинами, открытыми древним мудрецам ( риши ). [ 206 ] Существует четыре Веды – Ригведа , Самаведа , Яджурведа и Атхарваведа . Каждая Веда подразделяется на четыре основных типа текстов: Самхиты (мантры и благословения), Араньяки (тексты о ритуалах, церемониях, жертвоприношениях и символических жертвоприношениях), Брахманы (комментарии к ритуалам, церемониям и жертвоприношениям) и Упанишады. (текст, посвященный медитации, философии и духовному знанию). [ 207 ] [ 208 ] [ 209 ] Первые две части Вед впоследствии были названы Кармакандой (ритуальная часть), а последние две образуют Джнянаканду (часть знаний, в которой обсуждаются духовные прозрения и философские учения). [ 210 ] [ 211 ] [ 212 ] [ 213 ]

Упанишады являются основой индуистской философской мысли и оказали глубокое влияние на различные традиции. [ 214 ] [ 215 ] [ 142 ] Из шрути (корпуса Вед) только Упанишады пользуются большим влиянием среди индуистов и считаются выдающимися писаниями индуизма, и их центральные идеи продолжают влиять на его мысли и традиции. [ 214 ] [ 140 ] Сарвепалли Радхакришнан утверждает, что Упанишады играли доминирующую роль с момента своего появления. [ 216 ] В индуизме существует 108 Муктика -упанишад, из которых от 10 до 13 по-разному считаются учеными основными Упанишадами . [ 213 ] [ 217 ]

Наиболее известными из смрити («вспомнившихся») являются индуистские эпос и Пураны . Эпосы состоят из Махабхараты и Рамаяны . Бхагавад -гита является неотъемлемой частью Махабхараты и одним из самых популярных священных текстов индуизма. [ 218 ] Иногда его называют Гитопанишад , а затем помещают в категорию Шрути («услышанное»), поскольку по содержанию он является Упанишадой. [ 219 ] Пураны , которые начали составляться с ок. 300 г. н.э. и далее, [ 220 ] содержат обширную мифологию и играют центральную роль в распространении общих тем индуизма посредством ярких повествований. Йога -сутры — это классический текст традиции индуистской йоги, получивший новую популярность в 20 веке. [ 221 ]

С тех пор, как индийские модернисты XIX века вновь заявили об «арийском происхождении» индуизма, «очистив» индуизм от его тантрических элементов. [ 148 ] и возвышение ведических элементов. Индуистские модернисты, такие как Вивекананда, рассматривают Веды как законы духовного мира, которые все еще существовали бы, даже если бы они не были открыты мудрецам. [ 222 ] [ 223 ]

Тантра — это религиозные писания, в которых особое внимание уделяется женской энергии божества, которая в своей персонифицированной форме имеет как нежную, так и жестокую форму. В тантрической традиции Радхе , Парвати , Дурге и Кали поклоняются как символически, так и в их персонифицированных формах. [ 224 ] Агамы в Тантре относятся к авторитетным писаниям или учениям Шивы к Шакти. [ 225 ] в то время как Нигамы относятся к Ведам и учению Шакти Шиве. [ 225 ] В агамических школах индуизма ведическая литература и агамы имеют одинаковый авторитет. [ 226 ] [ 227 ]

Убеждения

Выдающиеся темы в индуистских верованиях включают (но не ограничиваются ими) Дхарму (этику/обязанности), сансару (продолжающийся цикл запутанности страстями и, как следствие, рождение, жизнь, смерть и возрождение), Карму (действие, намерение и последствия). ), мокша (освобождение от привязанностей и сансары) и различные йоги (пути или практики). [ 6 ] Однако не все эти темы встречаются в различных системах индуистских верований. Вера в мокшу или сансару отсутствует в некоторых индуистских верованиях, а также отсутствовала среди ранних форм индуизма, для которого характерна вера в загробную жизнь , причем следы этого до сих пор можно найти в различных индуистских верованиях, таких как Шраддха . Культ предков когда-то был неотъемлемой частью индуистских верований и сегодня до сих пор является важным элементом в различных народных индуистских течениях. [ 228 ] [ 229 ] [ 230 ] [ 231 ] [ 232 ] [ 233 ] [ 234 ]

Пурушартхи

Пурушартхи относятся к целям человеческой жизни. Классическая индуистская мысль принимает четыре правильные цели или задачи человеческой жизни, известные как Пурушартхи – Дхарма , Артха , Кама и Мокша . [ 7 ] [ 235 ]

Дхарма (моральные обязанности, праведность, этика)

В индуизме Дхарма считается главной целью человека. [ 236 ] Концепция дхармы включает в себя поведение, которое считается соответствующим рита , порядку, который делает жизнь и вселенную возможными. [ 237 ] и включает в себя обязанности, права, законы, поведение, добродетели и «правильный образ жизни». [ 238 ] Индуистская дхарма включает в себя религиозные обязанности, моральные права и обязанности каждого человека, а также поведение, обеспечивающее социальный порядок, правильное и добродетельное поведение. [ 238 ] Дхарма – это то, что все существующие существа должны принять и уважать, чтобы поддерживать гармонию и порядок в мире. Это стремление и реализация своей природы и истинного призвания, таким образом играя свою роль в космическом концерте. [ 239 ] Брихадараньяка -упанишада утверждает это так:

Нет ничего выше Дхармы. Слабый побеждает сильного с помощью Дхармы, как над царем. Воистину, Дхарма — это Истина ( Сатья ); Поэтому, когда человек говорит Истину, они говорят: «Он говорит Дхарму»; и если он говорит Дхарму, они говорят: «Он говорит Истину!» Ибо оба суть одно.

В Махабхарате Кришна определяет дхарму как поддержание дел как в этом, так и в потустороннем мире. (Мбх 12.110.11). Слово Санатана означает вечный , многолетний или навсегда ; таким образом, Санатана Дхарма означает, что это дхарма, не имеющая ни начала, ни конца. [ 242 ]

Артха (средства или ресурсы, необходимые для полноценной жизни)

Артха — это добродетельное стремление к средствам, ресурсам, активам или средствам к существованию с целью выполнения обязательств, экономического процветания и полноценной жизни. Оно включает в себя политическую жизнь, дипломатию и материальное благополучие. Концепция артхи включает в себя все «средства жизни», виды деятельности и ресурсы, позволяющие человеку находиться в желаемом состоянии, богатство, карьеру и финансовую безопасность. [ 243 ] Правильное стремление к артхе считается важной целью человеческой жизни в индуизме. [ 244 ] [ 245 ]

Центральная предпосылка индуистской философии заключается в том, что каждый человек должен жить радостной, приятной и полноценной жизнью, в которой потребности каждого человека признаются и удовлетворяются. Потребности человека могут быть удовлетворены только при наличии достаточных средств. Таким образом, артху лучше всего можно описать как поиск средств, необходимых для радостной, приятной и полноценной жизни. [ 246 ]

Кама (сенсорное, эмоциональное и эстетическое удовольствие)

Кама (санскрит, пали : काम) означает желание, желание, страсть, тоска и чувственное удовольствие , эстетическое наслаждение жизнью, привязанность и любовь, с сексуальным подтекстом или без него. [ 247 ] [ 248 ]

В современной индийской литературе кама часто используется для обозначения сексуального желания, но в древнеиндийской литературе кама имеет обширное значение и включает в себя любые виды наслаждения и удовольствия, например, удовольствие, получаемое от искусства. Древнеиндийский эпос « Махабхарата» описывает каму как любой приятный и желательный опыт, возникающий в результате взаимодействия одного или нескольких из пяти чувств со всем, что связано с этим чувством, когда он находится в гармонии с другими целями человеческой жизни (дхарма, артха и мокша). . [ 249 ]

В индуизме кама считается важной и здоровой целью человеческой жизни, если следовать ей без ущерба для дхармы, артхи и мокши. [ 250 ]

Мокша (освобождение, свобода от страданий)

Мокша ( санскрит : मोक्ष , латинизировано : мокша ) или мукти (санскрит: मुक्ति ) — конечная и самая важная цель в индуизме. Мокша — это концепция, связанная с освобождением от печали, страданий, а для многих теистических школ индуизма — с освобождением от сансары (цикла рождения-перерождения). Выход из этого эсхатологического цикла в загробной жизни в теистических школах индуизма называется мокшей. [ 239 ] [ 251 ] [ 252 ]

Из-за веры в индуизме, что Атман вечен, и концепции Пуруши (космического Я или космического сознания), [ 253 ] смерть можно рассматривать как незначительную по сравнению с вечным Атманом или Пурушей. [ 254 ]

Разные взгляды на природу мокши

Значение мокши различается в разных индуистских школах мысли.

Адвайта Веданта утверждает, что после достижения мокши человек осознает свою сущность, или «я», как чистое сознание или сознание-свидетеля, и идентифицирует его как тождественное Брахману . [ 255 ] [ 256 ]

Последователи школ Двайты (дуалистических) верят, что в загробном состоянии мокши отдельные сущности отличны от Брахмана, но бесконечно близки, и после достижения мокши они рассчитывают провести вечность на локе (раю). [ нужна ссылка ]

В более общем смысле, в теистических школах индуизма мокша обычно рассматривается как освобождение от сансары, тогда как в других школах, таких как монистическая школа, мокша происходит в течение жизни человека и является психологической концепцией. [ 257 ] [ 255 ] [ 258 ] [ 259 ] [ 256 ]

По мнению Дойча, мокша — это трансцендентальное сознание совершенного состояния бытия, самореализации, свободы и «осознания всей вселенной как Самости». [ 257 ] [ 255 ] [ 259 ] Мокша, если рассматривать ее как психологическую концепцию, предполагает Клаус Клостермайер , [ 256 ] подразумевает освобождение от до сих пор скованных способностей, устранение препятствий на пути к неограниченной жизни, позволяя человеку более истинно быть личностью в самом полном смысле этого слова. Эта концепция предполагает неиспользованный человеческий потенциал творчества, сострадания и понимания, который ранее был заблокирован и игнорирован. [ 256 ]

Из-за различных взглядов на природу мокши школа Веданты разделяет ее на два взгляда – Дживанмукти (освобождение в этой жизни) и Видехамукти (освобождение после смерти). [ 256 ] [ 260 ] [ 261 ]

Карма и сансара

Карма буквально переводится как действие , работа или поступок . [ 262 ] а также относится к ведической теории «морального закона причины и следствия». [ 263 ] [ 264 ] Теория представляет собой комбинацию (1) причинности, которая может быть этической или неэтической; (2) этизация, то есть хорошие или плохие действия имеют последствия; и (3) возрождение. [ 265 ] Теория кармы интерпретируется как объяснение нынешних обстоятельств человека со ссылкой на его или ее действия в прошлом. Эти действия и их последствия могут быть в текущей жизни человека или, согласно некоторым школам индуизма, в прошлых жизнях. [ 265 ] [ 266 ] Этот цикл рождения, жизни, смерти и возрождения называется сансарой . Считается, что освобождение от сансары посредством мокши обеспечивает длительное счастье и мир . [ 267 ] [ 268 ] Индуистские писания учат, что будущее является одновременно функцией текущих человеческих усилий, основанных на свободной воле, и прошлых человеческих действий, которые определяют обстоятельства. [ 269 ] The idea of reincarnation, or saṃsāra, is not mentioned in the early layers of historical Hindu texts such as the Rigveda.[270][271] The later layers of the Rigveda do mention ideas that suggest an approach towards the idea of rebirth, according to Ranade.[272][273] According to Sayers, these earliest layers of Hindu literature show ancestor worship and rites such as sraddha (offering food to the ancestors). The later Vedic texts such as the Aranyakas and the Upanisads show a different soteriology based on reincarnation, they show little concern with ancestor rites, and they begin to philosophically interpret the earlier rituals.[274][275][276] The idea of reincarnation and karma have roots in the Upanishads of the late Vedic period, predating the Buddha and the Mahavira.[277][278]

Concept of God

Hinduism is a diverse system of thought with a wide variety of beliefs[53][279][web 15] its concept of God is complex and depends upon each individual and the tradition and philosophy followed. It is sometimes referred to as henotheistic (i.e., involving devotion to a single god while accepting the existence of others), but any such term is an overgeneralisation.[280][281]

Who really knows?

Who will here proclaim it?

Whence was it produced? Whence is this creation?

The gods came afterwards, with the creation of this universe.

Who then knows whence it has arisen?

The Nasadiya Sukta (Creation Hymn) of the Rig Veda is one of the earliest texts[285] which "demonstrates a sense of metaphysical speculation" about what created the universe, the concept of god(s) and The One, and whether even The One knows how the universe came into being.[286][287] The Rig Veda praises various deities, none superior nor inferior, in a henotheistic manner.[288] The hymns repeatedly refer to One Truth and One Ultimate Reality. The "One Truth" of Vedic literature, in modern era scholarship, has been interpreted as monotheism, monism, as well as a deified Hidden Principles behind the great happenings and processes of nature.[289]

Hindus believe that all living creatures have a Self. This true "Self" of every person, is called the ātman. The Self is believed to be eternal.[290] According to the monistic/pantheistic (non-dualist) theologies of Hinduism (such as Advaita Vedanta school), this Atman is indistinct from Brahman, the supreme spirit or the Ultimate Reality.[291] The goal of life, according to the Advaita school, is to realise that one's Self is identical to supreme Self, that the supreme Self is present in everything and everyone, all life is interconnected and there is oneness in all life.[292][293][294] Dualistic schools (Dvaita and Bhakti) understand Brahman as a Supreme Being separate from individual Selfs.[295] They worship the Supreme Being variously as Vishnu, Brahma, Shiva, or Shakti, depending upon the sect. God is called Ishvara, Bhagavan, Parameshwara, Deva or Devi, and these terms have different meanings in different schools of Hinduism.[296][297][298]

Hindu texts accept a polytheistic framework, but this is generally conceptualised as the divine essence or luminosity that gives vitality and animation to the inanimate natural substances.[299] There is a divine in everything, human beings, animals, trees and rivers. It is observable in offerings to rivers, trees, tools of one's work, animals and birds, rising sun, friends and guests, teachers and parents.[299][300][301] It is the divine in these that makes each sacred and worthy of reverence, rather than them being sacred in and of themselves. This perception of divinity manifested in all things, as Buttimer and Wallin view it, makes the Vedic foundations of Hinduism quite distinct from animism, in which all things are themselves divine.[299] The animistic premise sees multiplicity, and therefore an equality of ability to compete for power when it comes to man and man, man and animal, man and nature, etc. The Vedic view does not perceive this competition, equality of man to nature, or multiplicity so much as an overwhelming and interconnecting single divinity that unifies everyone and everything.[299][302][303]

The Hindu scriptures name celestial entities called Devas (or Devi in feminine form), which may be translated into English as gods or heavenly beings.[note 27] The devas are an integral part of Hindu culture and are depicted in art, architecture and through icons, and stories about them are related in the scriptures, particularly in Indian epic poetry and the Puranas. They are, however, often distinguished from Ishvara, a personal god, with many Hindus worshipping Ishvara in one of its particular manifestations as their iṣṭa devatā, or chosen ideal.[304][305] The choice is a matter of individual preference,[306] and of regional and family traditions.[306][note 28] The multitude of Devas is considered manifestations of Brahman.[308]

The word avatar does not appear in the Vedic literature; [309] It appears in verb forms in post-Vedic literature, and as a noun particularly in the Puranic literature after the 6th century CE.[310] Theologically, the reincarnation idea is most often associated with the avatars of Hindu god Vishnu, though the idea has been applied to other deities.[311] Varying lists of avatars of Vishnu appear in Hindu scriptures, including the ten Dashavatara of the Garuda Purana and the twenty-two avatars in the Bhagavata Purana, though the latter adds that the incarnations of Vishnu are innumerable.[312] The avatars of Vishnu are important in Vaishnavism theology. In the goddess-based Shaktism tradition, avatars of the Devi are found and all goddesses are considered to be different aspects of the same metaphysical Brahman[313] and Shakti (energy).[314][315] While avatars of other deities such as Ganesha and Shiva are also mentioned in medieval Hindu texts, this is minor and occasional.[316]

Both theistic and atheistic ideas, for epistemological and metaphysical reasons, are profuse in different schools of Hinduism. The early Nyaya school of Hinduism, for example, was non-theist/atheist,[317] but later Nyaya school scholars argued that God exists and offered proofs using its theory of logic.[318][319] Other schools disagreed with Nyaya scholars. Samkhya,[320] Mimamsa[321] and Carvaka schools of Hinduism, were non-theist/atheist, arguing that "God was an unnecessary metaphysical assumption".[web 16][322][323] Its Vaisheshika school started as another non-theistic tradition relying on naturalism and that all matter is eternal, but it later introduced the concept of a non-creator God.[324][325][326] The Yoga school of Hinduism accepted the concept of a "personal god" and left it to the Hindu to define his or her god.[327] Advaita Vedanta taught a monistic, abstract Self and Oneness in everything, with no room for gods or deity, a perspective that Mohanty calls, "spiritual, not religious".[328] Bhakti sub-schools of Vedanta taught a creator God that is distinct from each human being.[295]

God in Hinduism is often represented having both the feminine and masculine aspects. The notion of the feminine in deity is much more pronounced and is evident in the pairings of Shiva with Parvati (Ardhanarishvara), Vishnu accompanied by Lakshmi, Radha with Krishna and Sita with Rama.[329]

According to Graham Schweig, Hinduism has the strongest presence of the divine feminine in world religion from ancient times to the present.[330] The goddess is viewed as the heart of the most esoteric Saiva traditions.[331]

Authority

Authority and eternal truths play an important role in Hinduism.[332] Religious traditions and truths are believed to be contained in its sacred texts, which are accessed and taught by sages, gurus, saints or avatars.[332] But there is also a strong tradition of the questioning of authority, internal debate and challenging of religious texts in Hinduism. The Hindus believe that this deepens the understanding of the eternal truths and further develops the tradition. Authority "was mediated through [...] an intellectual culture that tended to develop ideas collaboratively, and according to the shared logic of natural reason."[332] Narratives in the Upanishads present characters questioning persons of authority.[332] The Kena Upanishad repeatedly asks kena, 'by what' power something is the case.[332] The Katha Upanishad and Bhagavad Gita present narratives where the student criticises the teacher's inferior answers.[332] In the Shiva Purana, Shiva questions Vishnu and Brahma.[332] Doubt plays a repeated role in the Mahabharata.[332] Jayadeva's Gita Govinda presents criticism via Radha.[332]

Practices

Rituals

Most Hindus observe religious rituals at home.[334] The rituals vary greatly among regions, villages, and individuals. They are not mandatory in Hinduism. The nature and place of rituals is an individual's choice. Some devout Hindus perform daily rituals such as worshiping at dawn after bathing (usually at a family shrine, and typically includes lighting a lamp and offering foodstuffs before the images of deities), recitation from religious scripts, singing bhajans (devotional hymns), yoga, meditation, chanting mantras and others.[335]

Vedic rituals of fire-oblation (yajna) and chanting of Vedic hymns are observed on special occasions, such as a Hindu wedding.[336] Other major life-stage events, such as rituals after death, include the yajña and chanting of Vedic mantras.[web 17]

The words of the mantras are "themselves sacred,"[337] and "do not constitute linguistic utterances."[338] Instead, as Klostermaier notes, in their application in Vedic rituals they become magical sounds, "means to an end."[note 29] In the Brahmanical perspective, the sounds have their own meaning, mantras are considered "primordial rhythms of creation", preceding the forms to which they refer.[338] By reciting them the cosmos is regenerated, "by enlivening and nourishing the forms of creation at their base. As long as the purity of the sounds is preserved, the recitation of the mantras will be efficacious, irrespective of whether their discursive meaning is understood by human beings."[338][321]

Sādhanā

Sādhanā is derived from the root "sādh-", meaning "to accomplish", and denotes a means for the realisation of spiritual goals. Although different denominations of Hinduism have their own particular notions of sādhana, they share the feature of liberation from bondage. They differ on what causes bondage, how one can become free of that bondage, and who or what can lead one on that path.[339][340]

Life-cycle rites of passage

Major life stage milestones are celebrated as sanskara (saṃskāra, rites of passage) in Hinduism.[341][342] The rites of passage are not mandatory, and vary in details by gender, community and regionally.[343] Gautama Dharmasutras composed in about the middle of 1st millennium BCE lists 48 sanskaras,[344] while Gryhasutra and other texts composed centuries later list between 12 and 16 sanskaras.[341][345] The list of sanskaras in Hinduism include both external rituals such as those marking a baby's birth and a baby's name giving ceremony, as well as inner rites of resolutions and ethics such as compassion towards all living beings and positive attitude.[344]

The major traditional rites of passage in Hinduism include[343] Garbhadhana (pregnancy), Pumsavana (rite before the fetus begins moving and kicking in womb), Simantonnayana (parting of pregnant woman's hair, baby shower), Jatakarman (rite celebrating the new born baby), Namakarana (naming the child), Nishkramana (baby's first outing from home into the world), Annaprashana (baby's first feeding of solid food), Chudakarana (baby's first haircut, tonsure), Karnavedha (ear piercing), Vidyarambha (baby's start with knowledge), Upanayana (entry into a school rite),[346][347] Keshanta and Ritusuddhi (first shave for boys, menarche for girls), Samavartana (graduation ceremony), Vivaha (wedding), Vratas (fasting, spiritual studies) and Antyeshti (cremation for an adult, burial for a child).[348] In contemporary times, there is regional variation among Hindus as to which of these sanskaras are observed; in some cases, additional regional rites of passage such as Śrāddha (ritual of feeding people after cremation) are practised.[343][349]

Bhakti (worship)

Bhakti refers to devotion, participation in and the love of a personal god or a representational god by a devotee.[web 18][350] Bhakti-marga is considered in Hinduism to be one of many possible paths of spirituality and alternative means to moksha.[351] The other paths, left to the choice of a Hindu, are Jnana-marga (path of knowledge), Karma-marga (path of works), Rāja-marga (path of contemplation and meditation).[352][353]

Bhakti is practised in a number of ways, ranging from reciting mantras, japas (incantations), to individual private prayers in one's home shrine,[354] or in a temple before a murti or sacred image of a deity.[355][356] Hindu temples and domestic altars, are important elements of worship in contemporary theistic Hinduism.[357] While many visit a temple on special occasions, most offer daily prayers at a domestic altar, typically a dedicated part of the home that includes sacred images of deities or gurus.[357]

One form of daily worship is aarti, or "supplication", a ritual in which a flame is offered and "accompanied by a song of praise".[358] Notable aartis include Om Jai Jagdish Hare, a Hindi prayer to Vishnu, and Sukhakarta Dukhaharta, a Marathi prayer to Ganesha.[359][360] Aarti can be used to make offerings to entities ranging from deities to "human exemplar[s]".[358] For instance, Aarti is offered to Hanuman, a devotee of God, in many temples, including Balaji temples, where the primary deity is an incarnation of Vishnu.[361] In Swaminarayan temples and home shrines, aarti is offered to Swaminarayan, considered by followers to be Supreme God.[362]

Other personal and community practices include puja as well as aarti,[363] kirtan, or bhajan, where devotional verses and hymns are read or poems are sung by a group of devotees.[web 19][364] While the choice of the deity is at the discretion of the Hindu, the most observed traditions of Hindu devotion include Vaishnavism, Shaivism, and Shaktism.[365] A Hindu may worship multiple deities, all as henotheistic manifestations of the same ultimate reality, cosmic spirit and absolute spiritual concept called Brahman.[366][367][308] Bhakti-marga, states Pechelis, is more than ritual devotionalism, it includes practices and spiritual activities aimed at refining one's state of mind, knowing god, participating in god, and internalising god.[368][369] While bhakti practices are popular and easily observable aspect of Hinduism, not all Hindus practice bhakti, or believe in god-with-attributes (saguna Brahman).[370][371] Concurrent Hindu practices include a belief in god-without-attributes (nirguna Brahman), and god within oneself.[372][373]

Festivals

Hindu festivals (Sanskrit: Utsava; literally: "to lift higher") are ceremonies that weave individual and social life to dharma.[374][375] Hinduism has many festivals throughout the year, where the dates are set by the lunisolar Hindu calendar, many coinciding with either the full moon (Holi) or the new moon (Diwali), often with seasonal changes.[376] Some festivals are found only regionally and they celebrate local traditions, while a few such as Holi and Diwali are pan-Hindu.[376][377] The festivals typically celebrate events from Hinduism, connoting spiritual themes and celebrating aspects of human relationships such as the sister-brother bond over the Raksha Bandhan (or Bhai Dooj) festival.[375][378] The same festival sometimes marks different stories depending on the Hindu denomination, and the celebrations incorporate regional themes, traditional agriculture, local arts, family get togethers, Puja rituals and feasts.[374][379]

Some major regional or pan-Hindu festivals include:

- Ashadhi Ekadashi

- Bonalu

- Chhath

- Dashain

- Diwali or Tihar or Deepawali

- Durga Puja

- Dussehra

- Ganesh Chaturthi

- Gowri Habba

- Gudi Padwa

- Holi

- Karva Chauth

- Kartika Purnima

- Krishna Janmashtami

- Maha Shivaratri

- Makar Sankranti

- Navaratri

- Onam

- Pongal

- Radhashtami

- Raksha Bandhan

- Rama Navami

- Ratha Yatra

- Sharad Purnima

- Shigmo

- Thaipusam

- Ugadi

- Vasant Panchami

- Vishu

Pilgrimage

Many adherents undertake pilgrimages, which have historically been an important part of Hinduism and remain so today.[380] Pilgrimage sites are called Tirtha, Kshetra, Gopitha or Mahalaya.[381][382] The process or journey associated with Tirtha is called Tirtha-yatra.[383] According to the Hindu text Skanda Purana, Tirtha are of three kinds: Jangam Tirtha is to a place movable of a sadhu, a rishi, a guru; Sthawar Tirtha is to a place immovable, like Benaras, Haridwar, Mount Kailash, holy rivers; while Manas Tirtha is to a place of mind of truth, charity, patience, compassion, soft speech, Self.[384][385] Tīrtha-yatra is, states Knut A. Jacobsen, anything that has a salvific value to a Hindu, and includes pilgrimage sites such as mountains or forests or seashore or rivers or ponds, as well as virtues, actions, studies or state of mind.[386][387]

Pilgrimage sites of Hinduism are mentioned in the epic Mahabharata and the Puranas.[388][389] Most Puranas include large sections on Tirtha Mahatmya along with tourist guides,[390] which describe sacred sites and places to visit.[391][392][393] In these texts, Varanasi (Benares, Kashi), Rameswaram, Kanchipuram, Dwarka, Puri, Haridwar, Sri Rangam, Vrindavan, Ayodhya, Tirupati, Mayapur, Nathdwara, twelve Jyotirlinga and Shakti Pitha have been mentioned as particularly holy sites, along with geographies where major rivers meet (sangam) or join the sea.[394][389] Kumbh Mela is another major pilgrimage on the eve of the solar festival Makar Sankranti. This pilgrimage rotates at a gap of three years among four sites: Prayagraj at the confluence of the Ganges and Yamuna rivers, Haridwar near source of the Ganges, Ujjain on the Shipra river and Nashik on the bank of the Godavari river.[395] This is one of world's largest mass pilgrimage, with an estimated 40 to 100 million people attending the event.[395][396][web 20] At this event, they say a prayer to the sun and bathe in the river,[395] a tradition attributed to Adi Shankara.[397]

Some pilgrimages are part of a Vrata (vow), which a Hindu may make for a number of reasons.[398][399] It may mark a special occasion, such as the birth of a baby, or as part of a rite of passage such as a baby's first haircut, or after healing from a sickness.[400][401] It may also be the result of prayers answered.[400] An alternative reason for Tirtha, for some Hindus, is to respect wishes or in memory of a beloved person after his or her death.[400] This may include dispersing their cremation ashes in a Tirtha region in a stream, river or sea to honour the wishes of the dead. The journey to a Tirtha, assert some Hindu texts, helps one overcome the sorrow of the loss.[400][note 30]

Other reasons for a Tirtha in Hinduism is to rejuvenate or gain spiritual merit by travelling to famed temples or bathe in rivers such as the Ganges.[404][405][406] Tirtha has been one of the recommended means of addressing remorse and to perform penance, for unintentional errors and intentional sins, in the Hindu tradition.[407][408] The proper procedure for a pilgrimage is widely discussed in Hindu texts.[409] The most accepted view is that the greatest austerity comes from travelling on foot, or part of the journey is on foot, and that the use of a conveyance is only acceptable if the pilgrimage is otherwise impossible.[410]

Culture

The term "Hindu culture" refers to mean aspects of culture that pertain to the religion, such as festivals and dress codes followed by the Hindus which is mainly can be inspired from the culture of India and Southeast Asia.

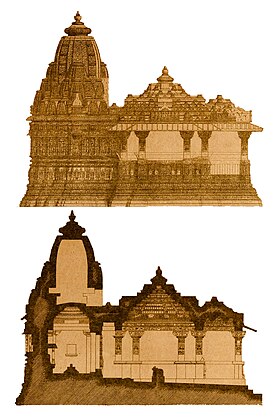

Architecture

Hindu architecture is the traditional system of Indian architecture for structures such as temples, monasteries, statues, homes, market places, gardens and town planning as described in Hindu texts.[411][412] The architectural guidelines survive in Sanskrit manuscripts and in some cases also in other regional languages. These texts include the Vastu shastras, Shilpa Shastras, the Brihat Samhita, architectural portions of the Puranas and the Agamas, and regional texts such as the Manasara among others.[413][414]

By far the most important, characteristic and numerous surviving examples of Hindu architecture are Hindu temples, with an architectural tradition that has left surviving examples in stone, brick, and rock-cut architecture dating back to the Gupta Empire. These architectures had influence of Ancient Persian and Hellenistic architecture.[415] Far fewer secular Hindu architecture have survived into the modern era, such as palaces, homes and cities. Ruins and archaeological studies provide a view of early secular architecture in India.[416]

Studies on Indian palaces and civic architectural history have largely focussed on the Mughal and Indo-Islamic architecture particularly of the northern and western India given their relative abundance. In other regions of India, particularly the South, Hindu architecture continued to thrive through the 16th-century, such as those exemplified by the temples, ruined cities and secular spaces of the Vijayanagara Empire and the Nayakas.[417][418] The secular architecture was never opposed to the religious in India, and it is the sacred architecture such as those found in the Hindu temples which were inspired by and adaptations of the secular ones. Further, states Harle, it is in the reliefs on temple walls, pillars, toranas and madapams where miniature version of the secular architecture can be found.[419]Art

Hindu art encompasses the artistic traditions and styles culturally connected to Hinduism and have a long history of religious association with Hindu scriptures, rituals and worship.

Calendar

The Hindu calendar, Panchanga (Sanskrit: पञ्चाङ्ग) or Panjika is one of various lunisolar calendars that are traditionally used in the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia, with further regional variations for social and Hindu religious purposes. They adopt a similar underlying concept for timekeeping based on sidereal year for solar cycle and adjustment of lunar cycles in every three years, but differ in their relative emphasis to moon cycle or the sun cycle and the names of months and when they consider the New Year to start.[420] Of the various regional calendars, the most studied and known Hindu calendars are the Shalivahana Shaka (Based on the King Shalivahana, also the Indian national calendar) found in the Deccan region of Southern India and the Vikram Samvat (Bikrami) found in Nepal and the North and Central regions of India – both of which emphasise the lunar cycle. Their new year starts in spring. In regions such as Tamil Nadu and Kerala, the solar cycle is emphasised and this is called the Tamil calendar (though Tamil calendar uses month names like in Hindu Calendar) and Malayalam calendar and these have origins in the second half of the 1st millennium CE.[420][421] A Hindu calendar is sometimes referred to as Panchangam (पञ्चाङ्गम्), which is also known as Panjika in Eastern India.[422]

The ancient Hindu calendar conceptual design is also found in the Hebrew calendar, the Chinese calendar, and the Babylonian calendar, but different from the Gregorian calendar.[423] Unlike the Gregorian calendar which adds additional days to the month to adjust for the mismatch between twelve lunar cycles (354 lunar days)[424] and nearly 365 solar days, the Hindu calendar maintains the integrity of the lunar month, but inserts an extra full month, once every 32–33 months, to ensure that the festivals and crop-related rituals fall in the appropriate season.[423][421]

The Hindu calendars have been in use in the Indian subcontinent since Vedic times, and remain in use by the Hindus all over the world, particularly to set Hindu festival dates. Early Buddhist communities of India adopted the ancient Vedic calendar, later Vikrami calendar and then local Buddhist calendars. Buddhist festivals continue to be scheduled according to a lunar system.[425] The Buddhist calendar and the traditional lunisolar calendars of Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Sri Lanka and Thailand are also based on an older version of the Hindu calendar. Similarly, the ancient Jain traditions have followed the same lunisolar system as the Hindu calendar for festivals, texts and inscriptions. However, the Buddhist and Jain timekeeping systems have attempted to use the Buddha and the Mahavira's lifetimes as their reference points.[426][427][428]

The Hindu calendar is also important to the practice of Hindu astrology and zodiac system. It is also employed for observing the auspicious days of deities and occasions of fasting, such as Ekadashi.[429]

Person and society

Varnas

Hindu society has been categorised into four classes, called varṇas. They are the Brahmins: Vedic teachers and priests; the Kshatriyas: warriors and kings; the Vaishyas: farmers and merchants; and the Shudras: servants and labourers.[430] The Bhagavad Gītā links the varṇa to an individual's duty (svadharma), inborn nature (svabhāva), and natural tendencies (guṇa).[431] The Manusmriti categorises the different castes.[web 21] Some mobility and flexibility within the varṇas challenge allegations of social discrimination in the caste system, as has been pointed out by several sociologists,[432][433] although some other scholars disagree.[434] Scholars debate whether the so-called caste system is part of Hinduism sanctioned by the scriptures or social custom.[435][web 22][note 31] And various contemporary scholars have argued that the caste system was constructed by the British colonial regime.[436]

A renunciant man of knowledge is usually called Varṇatita or "beyond all varṇas" in Vedantic works. The bhiksu is advised to not bother about the caste of the family from which he begs his food. Scholars like Adi Sankara affirm that not only is Brahman beyond all varṇas, the man who is identified with Him also transcends the distinctions and limitations of caste.[437]

Yoga

In whatever way a Hindu defines the goal of life, there are several methods (yogas) that sages have taught for reaching that goal. Yoga is a Hindu discipline which trains the body, mind, and consciousness for health, tranquility, and spiritual insight.[438] Texts dedicated to yoga include the Yoga Sutras, the Hatha Yoga Pradipika, the Bhagavad Gita and, as their philosophical and historical basis, the Upanishads. Yoga is means, and the four major marga (paths) of Hinduism are: Bhakti Yoga (the path of love and devotion), Karma Yoga (the path of right action), Rāja Yoga (the path of meditation), and Jñāna Yoga (the path of wisdom)[439] An individual may prefer one or some yogas over others, according to his or her inclination and understanding. Practice of one yoga does not exclude others. The modern practice of yoga as exercise (traditionally Hatha yoga) has a contested relationship with Hinduism.[440]

Symbolism

Hinduism has a developed system of symbolism and iconography to represent the sacred in art, architecture, literature and worship. These symbols gain their meaning from the scriptures or cultural traditions. The syllable Om (which represents the Brahman and Atman) has grown to represent Hinduism itself, while other markings such as the Swastika (from the Sanskrit: स्वस्तिक, romanized: svastika) a sign that represents auspiciousness,[441] and Tilaka (literally, seed) on forehead – considered to be the location of spiritual third eye,[442] marks ceremonious welcome, blessing or one's participation in a ritual or rite of passage.[443] Elaborate Tilaka with lines may also identify a devotee of a particular denomination. Flowers, birds, animals, instruments, symmetric mandala drawings, objects, lingam, idols are all part of symbolic iconography in Hinduism.[444][445] [446]

Ahiṃsā and food customs

Hindus advocate the practice of ahiṃsā (nonviolence) and respect for all life because divinity is believed to permeate all beings, including plants and non-human animals.[447] The term ahiṃsā appears in the Upanishads,[448] the epic Mahabharata[449] and ahiṃsā is the first of the five Yamas (vows of self-restraint) in Patanjali's Yoga Sutras.[450]