Германское язычество

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

Германское язычество или германская религия относится к традиционной, культурно значимой религии германских народов . С хронологическим диапазоном не менее тысячи лет на территории, охватывающей Скандинавию, Британские острова, современную Германию, Нидерланды, а иногда и другие части Европы, верования и практики германского язычества различались. Ученые обычно предполагают некоторую степень преемственности между верованиями римской эпохи и верованиями норвежского язычества , а также между германской религией и реконструированной индоевропейской религией после обращения и фольклором , хотя точная степень и детали этой преемственности являются предметом споров. . Германская религия находилась под влиянием соседних культур, в том числе кельтов, римлян, а позже и христианской религии. Существует очень мало источников, написанных самими язычниками; вместо этого большинство из них были написаны посторонними людьми и, таким образом, могут представлять проблемы для реконструкции подлинных германских верований и обычаев.

Some basic aspects of Germanic belief can be reconstructed, including the existence of one or more origin myths, the existence of a myth of the end of the world, a general belief in the inhabited world being a "middle-earth", as well as some aspects of belief in fate and the afterlife. The Germanic peoples believed in a multitude of gods, and in other supernatural beings such as jötnar (often glossed as giants), dwarfs, elves, and dragons. Roman-era sources, using Roman names, mention several important male gods, as well as several goddesses such as Nerthus and the matronae. Early medieval sources identify a pantheon consisting of the gods *Wodanaz (Odin), *Thunraz (Thor), *Tiwaz (Tyr), and *Frijjō (Frigg),[a] а также множество других богов, многие из которых засвидетельствованы только из скандинавских источников (см. Протогерманский фольклор ).

Textual and archaeological sources allow the reconstruction of aspects of Germanic ritual and practice. These include well-attested burial practices, which likely had religious significance, such as rich grave goods and the burial in ships or wagons. Wooden carved figures that may represent gods have been discovered in bogs throughout northern Europe, and rich sacrificial deposits, including objects, animals, and human remains, have been discovered in springs, bogs, and under the foundations of new structures. Evidence for sacred places includes not only natural locations such as sacred groves but also early evidence for the construction of structures such as temples and the worship of standing poles in some places. Other known Germanic religious practices include divination and magic, and there is some evidence for festivals and the existence of priests.

Subject and terminology

[edit]Definition

[edit]Germanic religion is principally defined as the religious traditions of speakers of Germanic languages (the Germanic peoples).[2] The term "religion" in this context is itself controversial, Bernhard Maier noting that it "implies a specifically modern point of view, which reflects the modern conceptual isolation of 'religion' from other aspects of culture".[3] Never a unified or codified set of beliefs or practices, Germanic religion showed strong regional variations and Rudolf Simek writes that it is better to refer to "Germanic religions".[4] In many contact areas (e.g. Rhineland and eastern and northern Scandinavia), Germanic paganism was similar to neighboring religions such as those of the Slavs, Celts, or Finnic peoples.[5] The use of the qualifier "Germanic" (e.g. "Germanic religion" and its variants) remains common in German-language scholarship, but is less commonly used in English and other scholarly languages, where scholars usually specify which branch of paganism is meant (e.g. Norse paganism or Anglo-Saxon paganism).[6] The term "Germanic religion" is sometimes applied to practices dating to as early as the Stone Age or Bronze Age, but its use is more generally restricted to the time period after the Germanic languages had become distinct from other Indo-European languages (early Iron Age). Germanic paganism covers a period of around one thousand years in terms of written sources, from the first reports in Roman sources to the final conversion to Christianity.[7]

Continuity

[edit]

Because of the amount of time and space covered by the term "Germanic religion", controversy exists as to the degree of continuity of beliefs and practices between the earliest attestations in Tacitus and the later attestations of Norse paganism from the high Middle Ages. Many scholars argue for continuity, seeing evidence of commonalities between the Roman, early medieval, and Norse attestations, while many other scholars are skeptical.[9] The majority of Germanic gods attested by name during the Roman period cannot be related to a later Norse god; many names attested in the Nordic sources are similarly without any known non-Nordic equivalents.[10][11] The much higher number of sources on Scandinavian religion has led to a methodologically problematic tendency to use Scandinavian material to complete and interpret the much more sparsely attested information on continental Germanic religion.[12]

Most scholars accept some form of continuity between Indo-European and Germanic religion,[13] but the degree of continuity is a subject of controversy.[14] Jens Peter Schjødt writes that while many scholars view comparisons of Germanic religion with other attested Indo-European religions positively, "just as many, or perhaps even more, have been sceptical".[15] While supportive of Indo-European comparison, Schjødt notes that the "dangers" of comparison are taking disparate elements out of context and arguing that myths and mythical structures found around the world must be Indo-European just because they appear in multiple Indo-European cultures.[16] Bernhard Maier argues that similarities with other Indo-European religions do not necessarily result from a common origin, but can also be the result of convergence.[17]

Continuity also concerns the question of whether popular, post-conversion beliefs and practices (folklore) found among Germanic speakers up to the modern day reflect a continuity with earlier Germanic religion. Earlier scholars, beginning with Jacob Grimm, believed that modern folklore was of ancient origin and had changed little over the centuries, which allowed the use of folklore and fairy tales as sources of Germanic religion.[18][19] These ideas later came under the influence of völkisch ideology, which stressed the organic unity of a Germanic "national spirit" (Volksgeist), as expressed in Otto Höfler's "Germanic continuity theory".[20][21] As a result, the use of folklore as a source went out of fashion after World War II, especially in Germany,[22] but has experienced a revival since the 1990s in Nordic scholarship.[23] Today, scholars are cautious in their use of folkloric material, keeping in mind that most was collected long after the conversion and the advent of writing.[24] Areas where continuity can be noted include agrarian rites and magical ideas,[23] as well as the root elements of some folktales.[25]

Sources

[edit]

Sources on Germanic religion can be divided between primary sources and secondary sources. Primary sources include texts, structures, place names, personal names, and objects that were created by devotees of the religion; secondary sources are normally texts that were written by outsiders.[27]

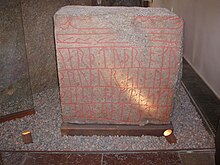

Primary sources

[edit]Examples of primary sources include some Latin alphabet and Runic inscriptions, as well as poetic texts such as the Merseburg Charms and heroic texts that may date from pagan times, but were written down by Christians.[28] The poems of the Edda, while pagan in origin, continued to circulate orally in a Christian context before being written down, which makes an application to pre-Christian times difficult.[12] In contrast, pre-Christian images such as on bracteates, gold foil figures, and rune and picture stones are direct attestations of Germanic religion. The interpretation of these images is not always immediately obvious.[29] Archaeological evidence is also extensive, including evidence from burials and sacrificial sites.[30] Ancient votive altars from the Rhineland often contain inscriptions naming gods with Germanic or partially Germanic names.[31]

Secondary sources

[edit]

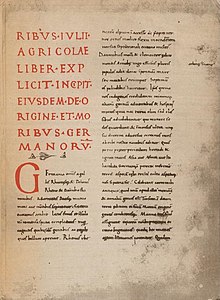

Most textual sources on Germanic religion were written by outsiders.[12] The chief textual source for Germanic religion in the Roman period is Tacitus's Germania.[33][b] There are problems with Tacitus's work, however, as it is unclear how much he really knew about the Germanic peoples he described and because he employed numerous topoi dating back to Herodotus that were used when describing a barbarian people.[35] Tacitus' reliability as a source can be characterized by his rhetorical tendencies, since one of the purposes of Germania was to present his Roman compatriots with an example of the virtues he believed they lacked.[36] Julius Caesar, Procopius, and other ancient authors also offer some information on Germanic religion.[37][c]

Textual sources for post-Roman continental Germanic religion are written by Christian authors: Some of the gods of the Lombards are described in the 7th-century Origo gentis Langobardorum ("Origin of the Lombard People"), while a small amount of information on the religion of the pagan Franks can be found in Gregory of Tours's late 6th-century Historia Francorum ("History of the Franks").[39] An important source for the pre-Christian religion of the Anglo-Saxons is Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People (c. 731).[40] Other sources include historians such as Jordanes (6th century CE) and Paul the Deacon (8th century), as well as saint lives and Christian legislation against various practices.[37]

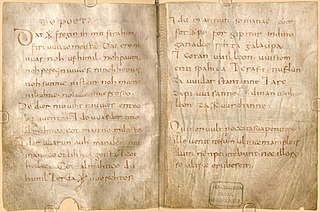

Textual sources for Scandinavian religion are much more extensive. They include the aforementioned poems of the Poetic Edda, Eddic poetry found in other sources, the Prose Edda, which is usually attributed to the Icelander Snorri Sturluson (13th century CE), Skaldic poetry, poetic kennings with mythological content, Snorri's Heimskringla, the Gesta Danorum of Saxo Grammaticus (12th-13th century CE), Icelandic historical writing and sagas, as well as outsider sources such as the report on the Rus' made by the Arab traveler Ahmad ibn Fadlan (10th century), the Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum by bishop Adam of Bremen (11th century CE), and various saints' lives.[41][42]

Outside influences and syncretism

[edit]

Germanic religion has been influenced by the beliefs of other cultures. Celtic and Germanic peoples were in close contact in the first millennium BCE, and evidence for Celtic influence on Germanic religion is found in religious vocabulary. This includes, for instance, the name of the deity *Þun(a)raz (Thor), which is identical to Celtic *Toranos (Taranis), the Germanic name of the runes (Celtic *rūna 'secret, magic'), and the Germanic name for the sacred groves, *nemeđaz (Celtic nemeton).[44] Evidence for further close religious contacts is found in the Roman-era Rhineland goddesses known as matronae, which display both Celtic and Germanic names.[45] During the Viking Age, there is evidence for continued Irish mythological and Insular Celtic influence on Norse religion.[46]

During the Roman period, Germanic gods were equated with Roman gods and worshipped with Roman names in contact zones, a process known as Interpretatio Romana; later, Germanic names were also applied to Roman gods (Interpretatio Germanica).This was done to better understand one another's religions as well as to syncretize elements of each religion.[47][48] This resulted in various aspects of Roman worship and iconography being adopted among the Germanic peoples, including those living at some distance from the Roman frontier.[49]

In later centuries, Germanic religion was also influenced by Christianity. There is evidence for the appropriation of Christian symbolism on gold bracteates and possibly in the understanding of the roles of particular gods.[50] The Christianization of the Germanic peoples was a long process during which there are many textual and archaeological examples of the co-existence and sometimes mixture of pagan and Christian worship and ideas.[51] Christian sources frequently equate Germanic gods with demons and forms of the devil (Interpretatio Christiana).[52]

Cosmology

[edit]Creation myth

[edit]

It is likely that multiple creation myths existed among Germanic peoples.[54] Creation myths are not attested for the continental Germanic peoples or Anglo-Saxons;[55] Tacitus includes the story of Germanic tribes' descent from the gods Tuisto (or Tuisco), who is born from the earth,[56] and Mannus (Germania chapter 2), resulting in a division into three or five Germanic subgroups.[55][57] Tuisto appears to mean "twin" or "double-being", suggesting that he was a hermaphroditic being capable of impregnating himself.[58][59][60] These gods are only attested in Germania.[61] It is not possible to decide based on Tacitus's report whether the myth was meant to describe an origin of the gods or of humans.[59] Tacitus also includes a second myth: the Semnones believed that they originated in a sacred grove of fetters where a particular god dwelled (Germania chapter 39, for more on this see "Sacred trees, groves, and poles" below).[62]

The only Nordic comprehensive origin myth is provided by the Prose Edda book Gylfaginning. According to Gylfaginning, the first being was the giant Ymir, who was followed by the cow Auðumbla, eventually leading to the birth of Odin and his two brothers. The brothers kill Ymir and make the world out of his body, before finally making the first man and woman out of trees (Ask and Embla).[63] Some scholars suspect that Gylfaginning had been compiled from various contradictory sources, with some details from those sources having been left out.[64] Besides Gylfaginning, the most important sources on Nordic creation myths are the Eddic poems Vǫluspá, Vafþrúðnismál, and Grímnismál.[54] The 9th-century Old High German Wessobrunn Prayer begins with a series of negative pairs to describe the time before creation that show similarity to a number of Nordic descriptions of the time before the world, suggesting an orally transmitted formula.[53][60]

There may be a continuity between Tacitus's account of Tuisto and Mannus and the Gylfaginning account of the creation of the world.[65] The name Tuisto, if it means 'twin' or 'double-being', could connect him to the name of the primordial being Ymir, whose name probably has a similar meaning. On the other hand, the form "Tuisco" may suggest a connection to Tyr.[66] Similarly, both myths have a genealogy consisting of a grandfather, a father, and then three sons.[67] Ymir's name is etymologically connected to the Sanskrit Yama and Iranian Yima, while the creation of the world from Ymir's body is paralleled by the creation of the world from the primordial being Purusha in Indic mythology, suggesting not only a Proto-Germanic origin for Ymir but an even older Indo-European origin (see Indo-European cosmogony).[58]

Myth of the end of the world

[edit]

There is evidence of a myth of the end of the world in Germanic mythology, which can be reconstructed in very general terms from the surviving sources.[69] The best known is the myth of Ragnarök, attested from Old Norse sources, which involves a war between the gods and the beings of chaos, leading to the destruction of almost all gods, giants, and living things in a cataclysm of fire. It is followed by a rebirth of the world.[70] The notion of the world's destruction by fire in the Southern Germanic area seems confirmed by the existence of the word Muspilli (probably "world conflagration") to refer to the end of the world in Old High German; however, it is possible that this aspect derives from Christian influence.[71] Scholarship on Ragnarök tends to either argue that it is a myth with composite, partially non-Scandinavian origins, that it has Indo-European parallels and thus origins, or that it derives from Christian influence.[72]

Physical cosmos

[edit]

Information on Germanic cosmology is only provided in Nordic sources,[74] but there is evidence for considerable continuity of beliefs despite variation over time and space.[75] Scholarship is marked by disagreement about whether Snorri Sturlason's Edda is a reliable source for pre-Christian Norse cosmology, as Snorri has undoubtedly imposed an ordered, Christian worldview on his material.[76]

Midgard ("dwelling place in the middle") is used to refer to the inhabited world or a barrier surrounding the inhabited world in Norse mythology.[77] The term is first attested as midjungards in Gothic with Wulfila's translation of the bible (c. 370 CE), and has cognates in Saxon, Old English, and Old High German. It is thus probably an old Germanic designation. In the Prose Edda, Midgard also seems to be the part of the world inhabited by the gods.[77] The dwelling place of the gods themselves is known as Asgard, while the giants dwell in lands sometimes referred to as Jötunheimar, outside of Midgard.[78] The ash tree Yggdrasill is at the center of the world,[79] and propped up the heavens in the same way as the Saxon pillar Irminsul was said to.[78] The world of the dead (Hel) seems to have been underground, and it is possible that the realm of the gods was originally subterranean as well.[80][78] The Norse imagined the inhabited world to be surrounded by a sort of dragon or serpent, Jörmungandr; although only explicitly attested in Scandinavian sources, allusions to a world-surrounding monster from southern Germany and England suggest that this concept may have been common Germanic.[81]

Fate

[edit]Some Christian authors of the Middle Ages, such as Bede (c. 700) and Thietmar of Merseburg (c. 1000), attribute a strong belief in fate and chance to the followers of Germanic religion. Similarly, Old English, Old High German, and Old Saxon associate a word for fate, wyrd, as referring to an inescapable, impersonal fate or death.[82] While scholarship of the early 20th century believed that this meant that Germanic religion was essentially fatalistic, scholars since 1969 have noted that this concept appears to have been heavily influenced by the Christianized Greco-Roman notion of fortuna fatalis ("fatal fortune") rather than reflecting Germanic belief.[83][84] Nevertheless, Norse myth attests the belief that even the gods were subject to fate.[85][86] While it is thus clear that older scholarship exaggerated the importance of fate in Germanic religion, it still had its own concept of fate. Most Norse texts dealing with fate are heroic, which probably influences their portrayal of fate.[87]

In Norse myth, fate was created by supernatural female beings called Norns, who appear either individually or as a collective and who give people their fate at birth and are somehow involved in their deaths.[88] Other female beings, the disir and valkyries, were also associated with fate.[89]

Afterlife

[edit]

Early Germanic beliefs about the afterlife are not well known; however, the sources indicate a variety of beliefs, including belief in an underworld, continued life in the grave, a world of the dead in the sky, and reincarnation.[92] Beliefs varied by time and place and may have contradictory in the same time and place.[93] The two most important afterlives in the attested corpus were located at Hel and Valhalla, while additional destinations for the dead are also mentioned.[92] A number of sources refer to Hel as the general abode of the dead.[94]

The Old Norse proper noun Hel and its cognates in other Germanic languages are used for the Christian hell, but they originally refer to a Germanic underworld and/or afterlife location that predates Christianization.[95] Its relation to the West Germanic verb helan ("to hide") suggests that it may have originally referred to the grave itself.[96][97] It could also suggest the idea that the realm of the dead is hidden from human view.[98] It was not conceived of as a place of punishment until the high Middle Ages, when it takes on some characteristics of the Christian hell. It is described as cold, dark, and in the north.[99] Valhalla ("hall of the slain"), on the other hand, is a hall in Asgard where the illustrious dead dwell with Odin, feasting and fighting.[100]

Old Norse material often include the notion that the dead lived in their graves, and that they can sometimes come back as revenants.[101] Several inscriptions in the Elder Futhark found on stones marking graves seem intended to prevent this.[95] The concept of the Wild Hunt of the dead, first attested in the 11th century, is found throughout the Germanic-speaking regions.[102][103]

Religiously significant numbers

[edit]In Germanic mythology, the numbers three, nine, and twelve play an important role.[104] The symbolic importance of the number three is attested widely among many cultures,[105] and the number twelve is also attested as significant in other cultures, meaning that foreign influence is possible. The number three often occurs as a symbol of completeness, which is probably how the frequent use in Germanic religion of triads of gods or giants should be understood.[104] Groups of three gods are mentioned in a number of sources, including Adam of Bremen, the Nordendorf Fibula, the Old Saxon Baptismal Formula, Gylfaginning, and Þorsteins þáttr uxafóts.[106] The number nine can be understood as three threes.[107] Its importance is attested in both mythology and worship.[108]

Supernatural and divine beings

[edit]Gods

[edit]

The Germanic gods were a category of supernatural beings who interacted with humans, as well as with other supernatural beings such as giants (jötnar), elves, and dwarfs.[109] The distinction between gods and other supernaturally powerful beings might not always be clear.[110] Unlike the Christian god, the Germanic gods were born, can die, and are unable to change the fate of the world.[111] The gods had mostly human features, with human forms, male or female gender, and familial relationships, and lived in a society organized like human society; however, their sight, hearing, and strength were superhuman, and they possessed a superhuman ability to influence the world.[112] Within the religion, they functioned as helpers of humans,[113] granting heil ("good luck, good fortune") for correct religious observance. The adjectival form heilag (English holy) is attested in all Germanic languages, including Gothic on the Ring of Pietroassa.[114]

Based on Old Norse evidence, Germanic paganism probably had a variety of words to refer to gods.[115] Words descended from Proto-Germanic *ansuz, the origin of the Old Norse family of gods known as the Aesir (singular Áss), are attested as a name for divine beings from around the Germanic world.[116] The earliest attestations are the name of a war goddess Vih-ansa ("battle goddess") that appears on a Roman inscription from Tongeren, with a second early attestion on a Runic belt-buckle found at Vimose, Denmark from around 200 CE.[117] The historian Jordanes mentions the Latinized form anses in the Getica, while the Old English rune poem attests the Old English form ōs, and personal names also exist using the word from the area where Old High German was spoken.[116][118] The Indo-European word for god, *deiuos, is only found in Old Norse, where it occurs as týr; it mostly appears in the plural (tívar) or in compound bynames.[119]

In Norse mythology, the Aesir are one of two families of gods, the other being the Vanir: the most important gods of Norse mythology belong to the Aesir and the term can also be used for the gods in general.[117] The Vanir appear to have been mostly fertility gods.[120] There is no evidence for the existence of a separate Vanir family of gods outside of Icelandic mythological texts,[121] namely the Eddic poem Vǫluspá and Snorri Sturluson's Prose Edda and Ynglinga Saga. These sources detail a mythical Æsir–Vanir War, which, however, is portrayed quite differently in the different accounts.[122]

Giants (Jötnar)

[edit]

Giants (Jötnar) play a significant role in Germanic myth as preserved in Iceland, being just as important as the gods in myths of the cosmology and the creation and the end of the world.[124] They appear to have been various types of powerful, non-divine supernatural beings who lived in a kind of wilderness and were mostly hostile to humans and gods.[125] They have human form and live in families, but can sometimes take on animal form.[126] In addition to Old Norse: jötnar, the beings are also commonly referred to as þursar, both terms having cognates in West Germanic;[127][128] jötunn is probably derived from the verb "to eat", either referring to their strength,[127] or possibly to cannibalism as a characteristic trait of giants.[128] Giants often have a special association with some phenomena of nature, such as frost, mountains, water, and fire.[129][130] Scholars are divided as to whether there were any religious offerings or rituals offered to giants in Germanic religion.[131] Scholars such as Gro Steisland and Nanna Løkka have suggested that the division of the gods from giants is not actually very clear.[132]

Elves, dwarfs and other beings

[edit]Germanic religion also contained various other mythological beings, such as the monstrous wolf Fenrir, as well as beings such as elves, dwarfs, and other non-divine supernatural beings.[133]

Elves are beings of Germanic lower mythology that are mostly male and appear as a collective.[135] Snorri Sturluson divides the elves into two groups, the dark elves and the light elves; however, this division is not attested elsewhere.[136] People's understanding of elves varied by time and place: in some instances they were godlike beings, in others dead ancestors, nature spirits, or demons.[137] In Norse pagan belief, elves seem to have been worshipped to some extent.[138] The concept of elves begins to differ between Scandinavia and the West Germanic peoples in the Middle Ages, possibly under Celtic influence.[139] In Anglo-Saxon England, elves seem to have been potentially dangerous, powerful supernatural beings associated with woods, fields, hills, and bodies of water.[140]

Like elves, dwarfs are beings of Germanic lower mythology. They are mostly male and imagined as a collective;[141] however, individual named dwarfs also play an important role in Norse mythology.[142] In Norse and German texts, dwarfs live in mountains and are known as great smiths and craftsmen. They may have originally been nature spirits or demons of death.[138][143] Snorri Sturluson equates the dwarfs to a subgroup of the elves,[138] and many high medieval German epics and some Old Norse myths give dwarfs names with the word alp or álf- ("elf") in them, suggesting some confusion between the two.[144][145] However, there is no evidence that the dwarfs were worshipped.[138] In Anglo-Saxon England, dwarfs were potentially dangerous supernatural beings associated with madness, fever, and dementia, and have no known association with mountains.[146]

Dragons occur in Germanic mythology, with Norse examples including Níðhöggr and the world-serpent Jörmungandr. In the (late) sources for Scandinavian religion, dragons play an important role in the mythic cosmology.[147] It is difficult to tell how much existing sources have been influenced by Greco-Roman and Christian ideas about dragons.[148] Based on the native word (Old High German: lintwurm, related to Old Norse: linnr, "snake"), the early description in Beowulf, and early pictorial depictions, they were probably imagined as snake-like and of large size, able to spit poison or fire, and dwelled under the earth.[149] Scholarly consensus is that Germanic dragons were originally more snake- or worm-like and could not fly, but that the idea of flying dragons entered from Greco-Roman culture.[150] The medieval Germanic languages did not distinguish linguistically or conceptually between snakes and dragons in their mythology.[151]

Pantheon

[edit]Due to the scarcity of sources and the origin of the Germanic gods over a broad period of time and in different locations, it is not possible to reconstruct a full pantheon of Germanic deities that is valid for Germanic religion everywhere; this is only possible for the last stage of Germanic religion, Norse paganism.[17] People in different times and places would have worshiped different individual gods and groups of gods.[152] Placename evidence containing divine names gives some indication of which gods were important in particular regions,[153] however, such names are not well attested or researched outside Scandinavia.[154]

The following section first includes some information on the gods attested during the Roman period, then the four main Germanic gods *Tiwaz (Tyr), Thunraz (Thor), *Wodanaz (Odin), and Frijjō (Frigg), who are securely attested since the early Middle Ages but were probably worshiped during Roman times,[155] and finally some information on other gods, many of whom are only attested in Norse paganism.[156]

Roman-era

[edit]Germanic gods with Roman names

[edit]

The Roman authors Julius Caesar and Tacitus both use Roman names to describe foreign gods, but whereas Caesar claims the Germani worshiped no individual gods but only natural phenomena such as the sun, moon, and fire, Tacitus mentions a number of deities, saying that the most worshiped god is Mercury, followed by Hercules, and Mars;[158] he also mentions Isis, Odysseus, and Laertes.[61] Scholars generally interpret Mercury as meaning Odin, Hercules as meaning Thor, and Mars as meaning Tyr.[159] As these names are only attested much later, however, there is some doubt about these identifications and it has been suggested that the gods Tacitus names were not worshiped by all Germanic peoples or that he has transferred information about the Gauls to the Germans.[160][161]

The Germani themselves also worshiped gods with Roman names at votive altars constructed according to Roman tradition; while isolated instances of Germanic bynames (such as "Mars Thingsus") indicate that a Germanic god was meant, often it is not possible to know if the Roman god or a Germanic equivalent is meant.[162] Most surviving dedications are to Mercury.[163] Female deities, on the other hand, were not given Roman names.[164] Additionally, the Germanic speakers also translated Roman gods' names into their own languages (interpretatio Germanica) most prominently in the Germanic days of the week. Usually the translation of the days of the week is dated to the 3rd or 4th century CE; however, they are not attested until the early Middle Ages.[165] This late attestation causes some scholars to question the usefulness of the days of the week for reconstructing early Germanic religion.[159][166]

Alcis

[edit]

Tacitus mentions a divine pair of twins called the Alcis worshipped by the Naharvali, whom he compares to the Roman twin horsemen Castor and Pollux.[168] These twins can be associated with the Indo-European myth of the divine twin horsemen (Dioscuri) attested in various Indo-European cultures.[169] Among later Germanic peoples, twin founding figures such as Hengist and Horsa allude to the motif of the divine twins; Hengist and Horsa's names both mean "horse", strengthening the connection.[170][171] In Scandinavia, images of divine twins are attested from 15th century BCE until the 8th century CE, after which they disappear, apparently as a result of religious change. Norse texts contain no identifiable divine twins, though scholars have looked for parallels among gods and heroes.[172]

Nerthus

[edit]In Germania, Tacitus mentions that the Lombards and Suebi venerated a goddess, Nerthus, and describes the rites of the goddess in some detail. At their center is a ceremonial wagon procession. Nerthus's cart is found on an unspecified island in the "ocean", where it is kept in a sacred grove and draped in white cloth. Only a priest may touch it. When the priest detects Nerthus's presence by the cart, the cart is drawn by heifers. Nerthus's cart is met with celebration and peacetime everywhere it goes, and during her procession no one goes to war and all iron objects are locked away. In time, after the goddess has had her fill of human company, the priest returns the cart to her "temple" and slaves ritually wash the goddess, her cart, and the cloth in a "secluded lake". According to Tacitus, the slaves are then immediately drowned in the lake.[173]

The majority of modern scholars identify Nerthus as a direct etymological precursor to the Old Norse deity Njörðr, attested over a thousand years later. However, Njörðr is attested as male, leading to many proposals regarding this apparent change, such as incest motifs described among the Vanir, a group of gods to which Njörðr belongs, in Old Norse sources.[173]

Matronae

[edit]

Collectives of three goddess known as matronae appear on numerous votive altars from the Roman province of Germania inferior, especially from Cologne,[174] dating to the third and fourth centuries CE.[175] The altars depict three women in non-Roman dress.[176] About half of serving matronae altars can be identified as Germanic because of their bynames; other have Latin or Celtic bynames.[175] The bynames are often connected to a place or ethnic group, but a number are associated with water,[177] and many of them seem to indicate a giving and protecting nature.[178] Despite their frequency in the archaeological record, the matronae receive no mention in any written source.[175]

The matronae may be connected to female deities attested in collectives from later times, such as the Norns, the disir and valkyries; Rudolf Simek suggests that a connection to the disir is most likely.[179] The disir may be etymologically connected to minor Hindu deities known as dhisanās, who likewise appear in a group; this would give them an Indo-European origin.[180] Since Jacob Grimm, scholars have sought to connect the disir with the idisi found in the Old High German First Merseburg Charm and with a conjecturally corrected place name from Tacitus; however, these connections are contested.[181] The disir share some functions with the Norns and valkyries,[182] and the Nordic sources suggest a close association between the three groups of Norse minor female deities.[180] Further connections of the matronae have been proposed: the Anglo-Saxon pagan festival of modranicht ("night of the mothers") mentioned by Bede has been associated with the matronae.[183] Likewise, the poorly attested Anglo-Saxon goddesses Eostre and Rheda may be connected with the matronae.[184]

Other female deities

[edit]

Besides Nerthus, Tacitus elsewhere mentions other important female deities worshiped by the Germanic peoples, such as Tamfana by the Marsi (Annals, 1:50) and the "mother of the gods" (mater deum) by the Aestii (Germania, chapter 45).[186]

In addition to the collective matronae, votive altars from Roman Germania attest a number of individual goddesses.[187] A goddess Nehelenia is attested on numerous votive altars from the 3rd century CE on the Rhine islands of Walcheren and Noord-Beveland, as well as at Cologne.[188] Dedicatory inscriptions to Nehelenia make up 15% of all extant dedications to gods from the Roman province Germania inferior and 50% of dedications to female deities.[189] She appears to have been associated with trade and commerce, and was possibly a chthonic deity: she is usually depicted with baskets of fruit, a dog, or the prow of a ship or an oar.[190] Her attributes are shared with the Hellenistic-Egyptian goddess Isis, suggesting a connection to the Isis of the Suebi mentioned by Tacitus.[191] Despite her obvious importance, she is not attested in later periods.[190]

Another goddess, Hludana, is also attested from five votive inscriptions along the Rhine; her name is cognate with Old Norse Hlóðyn, one of the names of Jörð (earth), the mother of Thor. It has thus been suggested she may have been a chthonic deity, possibly also connected to later attested figures such as Hel, Huld and Frau Holle.[192][190]

Post-Roman era

[edit]*Tiwaz/Tyr

[edit]

The god *Tiwaz (Tyr) may be attested as early as 450-350 BCE on the Negau helmet.[8] Etymologically, his name is related to the Vedic Dyaus and Greek Zeus, indicating an origin in the reconstructed Indo-European sky deity *Dyēus.[194] He is thus the only attested Germanic god who was already important in Indo-European times.[195] When the days of the week were translated into Germanic, Tyr was associated with the Roman god Mars, so that dies Martis (day of Mars) became "Tuesday" ("day of *Tiwaz/Tyr").[196] A votive inscription to "Mars Thingsus" (Mars of the thing) suggests he also had a connection to the legal sphere.[197]

Scholars generally believe that Tyr became less and less important in the Scandinavian branch of Germanic paganism over time and had largely ceased to be worshiped by the Viking Age.[198][199] He plays a major role in only one myth, the binding of the monstrous wolf Fenrir, during which Tyr loses his hand.[200]

*Thunraz/Thor

[edit]Thor was the most widely known and perhaps the most widely worshiped god in Viking Age Scandinavia.[201] When the days of the week were translated into Germanic, he was associated with Jupiter, so that dies Jovis ("Day of Jupiter") becomes "Thursday" ["day of Thunraz/Thor"]). This contradicts the earlier interpretatio Romana, where Thor is generally thought to be Hercules.[202] Textual sources such as Adam of Bremen as well as the association with Jupiter in the interpretatio Germanica suggest he may have been the head of the pantheon, at least in some times and places.[203] Alternatively, Thor's hammer may have been equated with Jupiter's lightning bolt.[204] Outside of Scandinavia, he appears on the Nordendorf fibulae (6th or 7th century CE) and in the Old Saxon Baptismal Vow (9th century CE).[205] The Oak of Jupiter, destroyed by Saint Boniface among the Chatti in 723 CE, is also usually presumed to have been dedicated to Thor.[201]

Viking age runestones as well as the Nordendorf fibulae appear to call upon Thor to bless objects.[206] The most important archaeological evidence for the worship of Thor in Viking Age Scandinavia is found in the form of Thor's hammer pendants.[207] Myths about Thor are only attested from Scandinavia, and it is unclear how representative the Nordic corpus is for the entire Germanic region.[208] As Thor's name means "thunder", scholars since Jacob Grimm have interpreted him to be a sky and weather god. In Norse mythology, he shares features with other Indo-European thunder gods, including his slaying of monsters; these features likely derive from a common Indo-European source.[209] In the extant mythology of Thor, however, he has very little association with thunder.[210]

*Wodanaz/Odin

[edit]

Odin (*Wodanaz) plays the main role in a number of myths as well as well-attested Norse rituals; he appears to have been venerated by many Germanic peoples in the early Middle Ages, though his exact characteristics probably varied in different times and places.[213] In the Germanic days of the week, Odin is equated with Mercury (dies Mercurii [day of Mercury] which became "Wednesday" ["day of *Wodanaz/Odin"]), an association that accords with the usual scholarly interpretation of the interpretatio Romana[204] and is also found in early medieval authors.[214] It may have been inspired by both gods' connections to arcane knowledge and the dead.[215]

The age of the cult of Odin is disputed.[216] The earliest clear reference to Odin by name is found on a C-bracteate discovered in Denmark in 2020. Dated to as early as the 400s, the bracteate features a Proto-Norse Elder Futhark inscription reading "He is Odin’s man".[217] Archaeological evidence for Odin is found in the form of his later bynames on Runic inscriptions found in Danish bogs from 4th or 5th century AD; other possible archaeological attestations may date to the 3rd century CE.[218] Images of Odin dating to the late migration period are known from Frisia, but appear to have come there from Scandinavia.[219]

In Norse myths, Odin plays one of the most important roles of all the gods.[220] He is also attested in myths outside of the Norse area. In the mid-7th century CE, the Franco-Burgundian chronicler Fredegar narrates that "Wodan" gave the Lombards their name; this story also appears in the roughly contemporary Origo gentis Langobardorum and later in the Historia Langobardorum of Paul the Deacon (790 CE).[221] In Germany, Odin is attested as part of a divine triad on the Nordendorf fibulae and the second Merseburg charm, in which he heals Balder's horse. In England, he appears as a healing magician in the Nine Herbs Charm[222] and in Anglo-Saxon genealogies.[223] It is disputed whether he was worshiped among the Goths.[224][225]

*Frijjō/Frigg

[edit]The only major Norse goddess also found in the pre-Viking period is Frigg, Odin's wife.[226] When the Germanic days of the week were translated, Frigg was equated with Venus, so that dies Veneris ("day of Venus") became "Friday" ("day of Frijjō/Frigg").[202] This translation suggests a connection to fertility and sexuality, and her name is etymologically derived from an Indo-European root meaning "love".[227] In the stories of how the Lombards got their name, Frea (Frigg) plays an important role in tricking her husband Vodan (Odin) into giving the Lombards victory.[221] She is also mentioned in the Merseburg Charms, where she displays magical abilities.[228][229] The only Norse myth in which Frigg plays a major role is the death of Baldr,[230] and there is only little evidence for a cult of Frigg in Scandinavia.[231]

Other gods

[edit]

The god Baldr is attested from Scandinavia, England, and Germany; except for the Old High German Second Merseburg Charm (9th century CE), all literary references to the god are from Scandinavia and nothing is known of his worship.[233]

The god Freyr was the most important fertility god of the Viking Age.[234] He is sometimes known as Yngvi-Freyr, which would associate him with the god or hero *Ingwaz, the presumed progenitor of the Inguaeones found in Tacitus's Germania,[235] whose name is attested in the Old English rune poem (8th or 9th century CE) as Ing.[236] A minor god named Forseti is attested in a few Old Norse sources; he is generally associated with the Frisian god Fosite who was worshiped on Helgoland,[237] but this connection is uncertain.[238] The Old Saxon Baptismal Formula and some Old English genealogies mention a god Saxnot, who appears to be the founder of the Saxons; some scholars identify him as a form of Tyr, while others propose that he may be a form of Freyr.[239]

The most important goddess in the recorded Old Norse pantheon was Freyr's sister, Freyja,[240] who features in more myths and appears to have been worshiped more than Frigg, Odin's wife.[241] She was associated with sexuality and fertility, as well as war, death, and magic.[242] It is unclear how old the worship of Freyja is, and there is no indisputable evidence for her or any of the vanir gods in the southern Germanic area.[241] There is considerable debate about whether Frigg and Freyja were originally the same goddess or aspects of the same goddess.[243]

Besides Freyja, many gods and goddesses are only known from Scandinavia, including Ægir, Höðr, Hönir, Heimdall, Idunn, Loki, Njörðr, Sif, and Ullr.[156] There are a number of minor or regional gods mentioned in various medieval Norse sources: in some cases, it is unclear whether or not they are post-conversion literary creations.[244] Many regional or highly local gods and spirits are probably not mentioned in the sources at all.[245] It is also likely that many Roman-era and continental Germanic gods do not appear in Norse mythology.[246]

Places and objects of worship

[edit]Divine images

[edit]

Julius Caesar and Tacitus claimed that the Germani did not venerate their gods in human form; however, this is a topos of ancient ethnography when describing supposedly primitive people.[248][249] Archaeologists have found Germanic statues that appear to depict gods, and Tacitus appears to contradict himself when discussing the cult of Nerthus (Germania chapter 40); the Eddic poem Hávamál also mentions wooden statues of gods, while Gregory of Tours (Historia Francorum II: 29) mentions wooden statues and ones made of stone and metal.[250] Archaeologists have not found any divine statues dating from after the end of the migration period; it is likely that they were destroyed during Christianization, as is repeatedly depicted in the Norse sagas.[251]

Roughly carved wooden male and female figures that may depict gods are frequent finds in bogs;[252] these figures generally follow the natural form of a branch. It is unclear whether the figures themselves were sacrifices or if they were the beings to whom the sacrifice was given.[249] Most date from the first several centuries CE.[253] For the pre-Roman Iron Age, board-like statues that were set up in dangerous places encountered in everyday life are also attested.[254] Most statues were made out of oak wood.[255] Small animal figurines of cattle and horses are also found in bogs; some may have been worn as amulets while others seem to have been placed by hearths before they were sacrificed.[256]

Holy sites from the migration period frequently contain gold bracteates and gold foil figures that depict obviously divine figures.[257][258] The bracteates are originally based on motifs found on Roman gold medallions and coins of the era of Constantine the Great, but have become highly stylized.[259] A few them have runic inscriptions that may be names of Odin.[260] Others, such as Trollhätten-A, may display scenes known from later mythological texts.[261]

The stone altars of the matronae and Nehalennia show women in Germanic dress, but otherwise follow Roman models, while images of Mercury, Hercules, or Mars do not show any difference from Roman models.[262] Many bronze and silver statues of Roman gods have been found throughout Germania, some made by the Germani themselves, suggesting an appropriation of these figures by the Germani.[263] Heiko Steuer suggests that these statues likely were reinterpreted as local, Germanic gods and used on home altars: a find from Odense dating c. 100-300 CE includes statues of Mercury, Mars, Jupiter, and Apollo.[264] Imported Roman swords, found from Scandinavia to the Black Sea, frequently depicted the Roman god Mars Ultor ("Mars the Avenger").[265]

Sacred places

[edit]

Caesar and Tacitus claimed that the ancient Germans had no temples and only worshipped in sacred groves.[252] However, while groves, trees, bogs, springs, and lakes undoubtedly were seen as holy places by the Germani, there is archaeological evidence for temples.[267] Archaeology also indicates that neolithic structures and Bronze Age tumuli were used as places of worship.[268] Steuer argues that finds of sacrificial places enclosed with a palisade in England indicate that similarly enclosed areas in northern Germany and Jutland may have been holy sites.[266] Large fire pits near settlements, found in many sites including those from the Bronze Age, the pre-Roman Iron Age, and the migration period, probably served as ritual, political, and social locations.[269] Large halls in settlements probably also fulfilled ceremonial religious functions.[270]

Tacitus mentions a temple of the goddess Tamfana in Annales 1.51, and also uses the word templum in reference to Nerthus in Germania, though this could simply mean a consecrated place rather than a building.[271] Later Christian sources refer to temples (fana) used by the Franks, Lombards, continental Saxons, and Anglo-Saxons, while the post-conversion Lex Frisionum (Frisian Law) continued to include punishments for those who broke into or desecrated temples.[272] A temple dedicated to Hercules from the territory of the Batavi at Empel in the Netherlands shows a typical Romano-Celtic building style.[270] Other Roman-style temples dedicated to the matronae are known from the Lower Rhine region.[273]

An early Scandinavian temple has been identified at Uppåkra, modern Sweden.[275] The building, a very large hall with two entrances, was rebuilt on exactly the same site 7 times from 200 to 950 CE.[276] Architecturally, the temple resembles later Scandinavian stave churches in construction.[277] The building was surrounded by animal bones and a few human bones.[278] A similar building has been found at Møllebækvej on Zealand dating from the 3rd century CE,[279] while the later stages of a ritual house at Tissø in Zealand (850-950 CE) likewise resemble a stave church.[280]

The most important description of a Scandinavian temple is of the Temple of Uppsala by Adam of Bremen (11th century): he describes the temple as containing the idols of Borr, Thor, Odin, and Frey (Fricco). Glosses mention the existence of a large tree and well nearby where sacrifices were made.[281] Some aspects of Adam's description appear to be inaccurate, possibly influenced by Norse mythology.[282][283] Archaeology has shown that Uppsala became an important cult center around 500 CE, with a main royal hall dating from 600 to 800 CE and having large doors with iron spirals flat against the wood.[284][285] Four large grave mounds were constructed southwest of the main hall, and there were ritual roads with rows of large wooden posts and lines of fireplaces. The arrangements indicate that there were different processions and rituals both inside and around Gamla Uppsala. The only material remains from the rituals once performed there are of animals; the age of the animals indicates that they were deposited in March, which agrees with the written sources on the Dísablót.[286]

Sacred trees, groves, and poles

[edit]

Sacred trees occur as important symbols in many pre-modern cultures, particularly those of Indo-European origin.[287] Modern scholars, on the basis of Greco-Roman religious understanding, usually distinguish between sacred groves and trees, where a god is worshiped, and the worship of trees as divine (tree cult); it is unclear whether this distinction is valid for Germanic religion.[288] Tacitus describes the ancient Germani as worshiping in sacred groves, including the grove of fetters of the Semnones and the grove where the Alcis were worshipped by the Nahanarvali.[289] Tacitus mentions the following functions for Germanic sacred groves: the display of captured enemy standards and weapons, the keeping of the animal-shaped standards of the Batavii (Tac. hist. 4.22), and human sacrifice.[290] Reconstructed Germanic words for sacred groves include *nimið-, *alh-, and *haruh-, which may have originally described different functions of the groves.[291]

Physical trees or poles could represent either a world tree, (Yggdrasil in Norse mythology),[292] or a world pillar.[293] Modern scholars describe such a sacred tree as an axis mundi ("hub of the world"), a center that runs along and connects multiple levels of the universe while also representing the world itself.[294] In Roman Germania, columns depicting the god Jupiter as a rider are commonly found; they probably have a Celtic background and some connection to the notion of the world tree or column.[295][296][297] One example of a sacred tree during the Middle Ages is the Oak of Jupiter purportedly felled by Saint Boniface in 724 CE in Hesse.[298] Adam of Bremen mentions a sacred tree at the Temple of Uppsala, but the existence of this tree is controversial among scholars. It is also mentioned in Hervarar saga, and it may have been the central focus at the site and represented the world tree Yggdrasil.[299] Further support for the existence of votive trees is provided by a birch root surrounded by animal skulls that was excavated at Frösö.[299] Pagan Anglo-Saxon settlements often contained large standing poles, which were condemned as focuses of pagan worship by 6th-century English bishop Aldhelm.[300] The Irminsul (Old Saxon great pillar) among the continental Saxons may have also been part of such a pole cult.[301]

Personnel and devotees

[edit]Animal symbolism and warrior bands

[edit]

Post-conversion Norse texts mention dedicated groups of warriors, some of whom, the berserkir (berserkers) and ulfheðnar, were associated with bears and wolves respectively. In Ynglinga saga, Snorri Sturluson associates these warriors with Odin.[303] Many scholars argue that warrior bands, with their initiation rites and forms of organization, can be traced to the time of Tacitus, who discusses several warrior bands and societies among the Germani. These scholars further argue that these bands can be traced further back to Proto-Indo-European precursors to some extent. Other scholars, such as Hans Kuhn, dispute continuity between Norse and earlier warrior bands.[304] Inhumation and cremation graves containing bear claws, teeth, and hides are found throughout the Germanic-speaking area, being especially common on the Elbe from 100 BCE to 100 CE and in Scandinavia from the 2nd to 5th centuries CE; these may be connected to the warrior societies.[305]

Archaeologists have found metal objects, especially on weapons and brooches,[306] decorated with animal art and dating from the 4th to the 12th centuries CE in Scandinavia.[307] Animals depicted include snakes, birds of prey, wolves, and boars.[306] Some scholars have discussed these images as related to shamanism, while others view animal art as similar to Skaldic kennings, capable of expressing both Christian and pagan meanings.[308]

Ritual specialists

[edit]

Scholars are divided as to the nature and function of Germanic ritual specialists: many religious studies scholars believe that there was originally no class of priests and cultic functions were mostly carried out by kings and chieftains; many philologists, however, argue on the basis of reconstructed words for "priest" that a specialized class of priests existed.[310] Caesar says the Germani had no druids, while Tacitus mentions several priests.[311] Roman sources do not otherwise mention Germanic cultic functionaries.[202] Later descriptions of similar rituals to those mentioned in Tacitus do not mention any ritual specialists; however, it is reasonable to assume that they continued to exist.[312] While ritual specialists in Viking Age Scandinavia may have had defining insignia such as staffs and oath rings, it is unclear if they formed a hierarchy and they seem to have fulfilled non-cultic roles in society as well.[313]

Caesar and Tacitus both mention women engaged in casting lots and prophecy and there are some other indications of female ritual specialists.[314] Tacitus and the Roman writer Cassius Dio (163-c. 229 CE) both mention several seeresses by name, while an ostracon from Egypt attests one living in the second century CE.[315] A female ritual specialist named Gambara appears in Paul the Deacon (8th century).[316] A gap in the historical record occurs until the North Germanic record began over a millennium later, when the Old Norse sagas frequently mention female ritual specialists among the North Germanic peoples, both in the form of priestesses and diviners.[317] Both Tacitus and Eiríks saga rauða mention the seeress prophesying from a raised platform, while Eiríks saga rauða also mentions the use of a wand.[318][319]

Practices

[edit]Burial practices

[edit]

Некоторое представление о германской религии могут дать погребальные обычаи, [321] which varied widely in time and space but nonetheless show a few consistent practices.[322] The Germanic peoples generally practiced cremation until the first century BCE, when limited inhumation burials begin to appear.[323] The ashes were usually placed in an urn, but the use of pits, mounds, and cases when the ashes were left on the pyre after cremation are also known.[324] В Скандинавии эпохи викингов около половины населения могло не получить могилы, а их прах был развеян, а тела непогребены. [325] Погребальный инвентарь, который можно было сломать и положить в могилу или сжечь на костре вместе с телом, включал в себя одежду, украшения, еду, напитки, посуду и утварь. [326] [327] Начиная с начала I века н. э., в меньшинстве могил также было оружие. [328] На континенте к концу миграционного периода ингумационное захоронение становится наиболее распространенной формой захоронения у южногерманских народов. [329] в то время как кремация остается более распространенной в Скандинавии. [330] В период переселения народов и период Меровингов могилу часто открывали заново и удаляли эти могильные дары. [331] либо как ограбление могилы, либо как часть санкционированного вывоза. [332] К периоду Меровингов большинство мужских захоронений содержало оружие. [320]

Часто урны покрывали камнями, а затем окружали кругами из камней. [324] Урны умерших часто помещались в погребальный дом , который, возможно, служил культовым сооружением. [333] Кладбища могли располагаться вокруг старых курганов бронзового века или повторно использовать их, а затем располагаться рядом с римскими руинами и дорогами, возможно, чтобы облегчить переход мертвых в загробную жизнь. [334] [335] [336] В некоторых могилах были захоронения лошадей и собак; [337] лошади, возможно, предназначались для перевозки в загробную жизнь. [91] Захоронения с собаками встречаются на обширной территории в период миграции; возможно, что они предназначались либо для защиты умершего в загробной жизни, либо для предотвращения возвращения умершего в качестве ревенанта . [337]

После I г. н.э. на всей германской территории начинают появляться погребения в больших курганах с деревянными или каменными могильными камерами, которые содержали дорогой инвентарь и были отделены от обычных кладбищ. [338] [339] К III веку элитные захоронения засвидетельствованы от Норвегии до Словакии, большое количество которых обнаружено в Ютландии. [340] В этих могилах обычно есть посуда и столовая посуда: она могла предназначаться для использования умершим в загробной жизни или использоваться во время погребальной трапезы. [341] В 400-х годах н. э. у континентальных германских народов появляется практика возведения элитных Reihengräber ( «рядных могил» ): эти могилы располагались рядами и содержали большое количество золота, драгоценностей, украшений и других предметов роскоши. В отличие от кладбищ кремации, на кладбищах Райхенграбера похоронено всего несколько сотен человек. [342] Элитные камерные могилы становятся особенно распространенными в Скандинавии в IX-X веках, в которых тело умершего иногда хоронили сидя с предметами в руках или на коленях. [343]

Камни в форме корабля известны из Скандинавии, где они иногда окружены могилами, а иногда содержат одну или несколько кремаций. [345] [346] Самое раннее захоронение корабля обнаружено в Ютландии периода поздней Римской империи. Еще одно более раннее захоронение находится за пределами Скандинавии, недалеко от Ремена на реке Везер в северной Германии, датируется 4 или 5 веком нашей эры. [347] Захоронения кораблей засвидетельствованы в Англии примерно с 600 г. н. э., а также по всей Скандинавии и в регионах, куда путешествовали скандинавы, начиная примерно в то же время и на протяжении столетий после этого. [348] [349] В некоторых случаях покойного, очевидно, кремировали на корабле, прежде чем над ним набрасывали курган, как это описывает Ахмад ибн Фадлан для русов . [350] Ученые спорят о значении этих захоронений: корабль мог быть средством передвижения в следующую жизнь или представлять собой пиршественный зал. Части кораблей часто оставались открытыми в течение длительного периода времени. [351]

Гадание

[ редактировать ]В германском язычестве засвидетельствованы различные практики предсказания будущего, некоторые из которых, вероятно, практиковались только в определенное время или в определенном месте. [352] Основными источниками германского гадания являются Тацит, христианские раннесредневековые тексты миссионерского периода (такие как каянники и франкские капитуляры ), а также различные тексты, описывающие скандинавские практики; однако ценность всех этих источников для подлинных германских практик обсуждается. [353]

Жеребьевка и жребий для определения будущего хорошо засвидетельствованы у германских народов в средневековых и древних текстах; лингвистический анализ подтверждает, что это была старая практика. [355] По состоянию на 2002 год на археологических памятниках римской эпохи и периода миграции было обнаружено около 160 лотов из различных материалов. [356] Наиболее подробное описание германских жребий содержится у Тацита «Германия», глава 10. Согласно Тациту, германцы бросали жребий, сделанный из древесины плодоносящих деревьев и отмеченный знаками, на белый лист, после чего три жребия разыгрывались. нарисованный главой семьи или священником. [355] Хотя знаки, упомянутые Тацитом, интерпретировались как руны , большинство ученых полагают, что это были простые символы. [357] Исландские источники XIII века также свидетельствуют о жеребьевке с вырезанными знаками; однако ведутся споры о том, представляют ли эти поздние источники форму испытаний , пришедшую с христианством, или продолжение германской практики. [358]

Другая важная форма гадания связана с животными. Интерпретация действий птиц является распространенной практикой во всем мире и хорошо засвидетельствована у германцев и норвежцев. [359] [360] Еще более уникально то, что Тацит говорит, что германцы использовали ржание лошадей, чтобы предсказывать будущее. [361] Хотя более поздних или подтверждающих свидетельств о гадании Тацита на лошадях нет, важность лошадей в германской религии хорошо подтверждена. [362] Обе формы гадания могут быть связаны с изображением птиц и лошадей на золотых брактеатах. [361]

Также засвидетельствовано несколько других методов гадания. Тацит упоминает дуэли как способ узнать будущее; хотя скандинавские источники свидетельствуют о многих дуэлях, ни один из них, очевидно, не используется для гадания. [363] Римские и христианские источники иногда утверждали, что германские народы использовали кровь или внутренности человеческих жертвоприношений, чтобы предсказать будущее. Это может быть связано с древними топосами, а не с реальностью. [364] хотя кровь играла важную роль в языческом ритуале. Скандинавские источники включают дополнительные формы гадания, такие как форма некромантии, известная как útiseta , а также ритуалы seiðr . [365]

Праздники и фестивали

[ редактировать ]Факты свидетельствуют о том, что у германских народов в определенное время года регулярно проводились жертвоприношения и праздники. [366] Часто эти праздники включали в себя жертвоприношения во время общей трапезы, ритуальные питья, а также шествия и гадания. [367] Почти вся информация о германских религиозных праздниках касается Западной Скандинавии, [368] но Тацит упоминает, что жертвоприношение богине Тамфане имело место осенью, а Беда упоминает фестиваль под названием Модранихт , который произошел в начале февраля. [366] и Йонас из Боббио «Жизни святого Колумбана» (640-е гг.) упоминает праздник Водана (Одина), проводимый свебами, на котором было распито пиво. [368] На основе нескольких информаторов и, возможно, текстовых источников, Адам Бременский описывает шведский жертвенный фестиваль, проводимый каждые девять лет в храме Упсалы, а Титмар Мерзебургский упоминает аналогичный фестиваль, проходящий каждый январь в Лейре в Зеландии . [369] Шведский праздник, известный как Дистинг, проходил в феврале, в то же время, что и древнеанглийский модранихт ; единственный другой широко засвидетельствованный фестиваль - это Йоль перед Рождеством. Снорри Стурлусон упоминает три дополнительных праздника в «Саге об Инглингах» : праздник в начале зимы, посвященный хорошему урожаю, один в середине зимы, посвященный плодородию, и один в начале лета, посвященный победе. Летний фестиваль нигде не засвидетельствован, но Рудольф Симек утверждает, что зимний фестиваль, вероятно, проводился в честь предков, а другой весенний фестиваль был посвящен плодородию. [366]

Магия

[ редактировать ]

Магия – это элемент религии, целью которого является воздействие на мир с помощью потустороннего путем использования определенных ритуалов, средств или слов. [373] [374] Источниками по дохристианской магии у германских народов являются либо текстовые описания, либо археологические находки предметов. [375] В германских языках нет общего слова, которое можно было бы перевести как «магия». [376] и нет никаких указаний на то, что германские народы различали «белую» и «черную магию». [377] В скандинавских текстах бог Один особенно связан с магией, эта связь также встречается, например, в древневерхненемецком Втором Мерзебургском заклинании . [378] Хотя руны часто ассоциируются с магией, большинство ученых больше не верят, что руны сами по себе считались магическими. [379]

Надписи эпохи миграции на брактеатах и более поздних рунических камнях содержат ряд ранних магических слов и формул, наиболее засвидетельствованная из которых, alu , встречается на нескольких объектах от 200 до 700 гг. н.э. [380] Христианские источники после обращения из континентальной Европы упоминают формы магии, включая амулеты, амулеты, «колдовство», гадание и особенно погодную магию. [381] Древнескандинавская мифология и литература после обращения также свидетельствуют о различных формах магии, включая гадание, магию, влияющую на природу (погоду или что-то еще), заклинания, делающие воинов неуязвимыми для оружия, заклинания, усиливающие оружие, и заклинания, причиняющие вред и причиняющие страдания другим. [382]

Термин «очарование» используется для обозначения магической поэзии, которая может быть благословением или проклятием; большинство засвидетельствованных чар являются благословениями и ищут защиты, защиты от магии или болезней и исцеления; Единственная форма проклятий, засвидетельствованная за пределами литературы, — это призывы к смерти. [383] В древнескандинавском языке определенный размер аллитеративного стиха использовался ( галдралаг ), и некоторые дохристианские заклинания сохранились, начертанные на металле или кости. [384] В остальном, за пределами литературы, в древнеисландском языке засвидетельствовано мало чар. [385] Более поздние исландские заклинания после обращения иногда упоминают Одина или Тора, но они могут отражать христианские представления о магии. [386] Многочисленные заклинания засвидетельствованы на древневерхненемецком языке, но только Мерзебургские заклинания существуют в нехристианизированной форме. [387] Аналогичная ситуация существует и в древнеанглийском языке, где засвидетельствовано более 100 заклинаний, в том числе заклинание «Девять трав» , в котором упоминается Водан (Один). [388]

Ритуальное шествие

[ редактировать ]

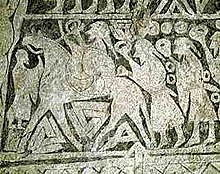

Ритуальные процессии идола бога на каком-либо транспортном средстве, обычно в повозке, засвидетельствованы во многих религиях Европы и Азии. [391] Различные археологические находки указывают на существование подобных ритуалов в Скандинавии еще в эпоху бронзы . [392] Корабли также могли использоваться для шествий, как, например, корабль, найденный на болотах Обердорла в Тюрингии времен миграции. Процессии обычно интерпретируются как обряды плодородия . [393] Изображение какого-то процесса эпохи викингов, включающего мужчин, женщин и повозки, дают фрагменты гобелена Осеберга . [394]

Самый ранний письменный источник ритуального шествия в германской религии находится в «Германии » Тацита , глава 40, где он описывает поклонение Нертусу. [395] По словам Тацита, идола Нерта несколько дней возят по земле на телеге, запряженной коровами, прежде чем его привозят к озеру и очищают рабы, которых затем топят в озере. [396] Описание Тацита напоминает археологические находки богато украшенных повозок в воде и в захоронениях южной Скандинавии, примерно современных Тациту. [397] [398] Подобный ритуал засвидетельствован у готов, которые заставляли христиан участвовать во время готских гонений на христиан (369-372 гг. н.э.), а также у франков у Григория Турского , хотя последний устанавливает свой ритуал в догерманской Галлии для восточная богиня. [399] Сообщается также, что франкских королей Меровингов возили на собрания на повозке, запряженной волами, что напоминает описание Тацита. [400] [401] Подробное описание ритуальной процессии бога Фрейра можно найти во « Флатейярбоке» (1394 г.); в нем описывается, как Фрейра ездят в повозке, чтобы обеспечить хороший урожай. [402] Этот и несколько других скандинавских источников о таких процессиях после обращения в христианство могут происходить из устной традиции поклонения Фрейру. [403]

Жертвы

[ редактировать ]

Археология предоставляет свидетельства жертвоприношений различных типов. Залежи ценных предметов, в том числе золота и серебра, захороненных в земле, часто датируются периодом 1-100 гг. н.э. Хотя эти предметы могли быть захоронены с намерением их снова вывезти позже, также возможно, что они предназначались для жертвоприношений богам или для использования в загробной жизни. [405] Металлические предметы, отложенные в источниках, засвидетельствованы в Бад-Пирмонте и Духцове , а также такие предметы, отложенные в болотах. [406] Есть также примеры волос, одежды и текстиля ок. 500 г. до н.э.-200 г. н.э. найдены в водно-болотных угодьях Скандинавии. [407] Григорий Турский, описывая франкское святилище близ Кельна, изображает верующих, оставляющих деревянные резные изображения частей человеческого тела всякий раз, когда они чувствуют боль. [312]

Жертвоприношения животных засвидетельствованы костями в различных святых местах, связанных с пшеворской культурой , а также в Дании, при этом в жертву приносились крупный рогатый скот, лошади, свиньи, овцы или козы; есть также свидетельства человеческих жертвоприношений. [408] В Скандинавии кости животных часто находят в болотах и озерах, где находят более высокую долю костей лошадей и костей молодых животных, чем в поселениях. [409] Подробное описание скандинавского жертвоприношения животных в Ладе дано Снорри Стурлусоном в «Hákonar saga góða» , хотя его точность сомнительна. [410] Свидетельства принесения в жертву предметов, людей и животных также встречаются в поселениях по всей Германии, возможно, в ознаменование начала строительства здания. [411] Собаки, закопанные под порогами домов, вероятно, служили защитниками. [412]

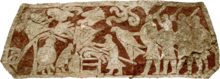

Человеческие жертвоприношения периодически упоминаются римскими авторами, обычно для того, чтобы подчеркнуть элементы, которые они считали шокирующими или ненормальными. [413] Отдельные находки в болотах человеческих тел всех возрастов и обоих полов имеют признаки насильственной смерти и могли быть человеческими жертвами или жертвами смертной казни. [414] [415] Только в Дании имеется более 100 болотных тел, датируемых периодом с 800 г. до н.э. по 200 г. н.э. Части человеческого тела, такие как черепа, были отложены в тот же период, примерно в 1100 году нашей эры. [416] Регулярно происходящие человеческие жертвоприношения среди норвежцев упоминаются такими авторами, как Титмар Мерзебургский и Адам Бременский, а также Гутасага . [417] Изображение на картинном камне Стора Хаммарс I обычно интерпретируется как изображение человеческого жертвоприношения. [418]

Жертвы оружия поверженных врагов были обнаружены в болотах Ютландии, а также в реках по всей Германии: [420] такие жертвоприношения, вероятно, происходили и в других частях Германии на суше. Тацит сообщает о подобном жертвоприношении и уничтожении оружия, совершенных в лесу после победы Арминия над римлянами в битве в Тевтобургском лесу . [252] Крупные залежи оружия засвидетельствованы с 350 г. до н.э. по 400 г. н.э., а более мелкие залежи продолжали оставаться до 600 г. н.э. [421] Отложения разного размера были обычным явлением и часто включали в себя не только оружие, но и предметы, даже сожженные и уничтоженные военные корабли. [422] [423] Похоже, они являются частью ритуала, проводимого над побежденным врагом, чтобы передать оружие богам. [422] Археологических свидетельств того, что случилось с воинами, носившими это оружие, нет, но римские источники описывают, что их тоже принесли в жертву. [424] [425] Возможным исключением является болото Алькен-Энге в Ютландии: там находятся раздавленные и расчлененные тела около 200 мужчин в возрасте от 13 до 45 лет, которые, судя по всему, погибли на поле боя. [426] Ни в каких более поздних скандинавских источниках ритуалы, связанные с уничтожением оружия, не упоминаются, подразумевая, что эти обряды вымерли и были давно забыты. [427]

Вариации германского язычества

[ редактировать ]- Англосаксонское язычество

- Континентальная германская мифология

- Франкская мифология

- Готическое язычество

- Древнескандинавская религия

См. также

[ редактировать ]- Древняя кельтская религия

- Древнегреческая религия

- Древняя иранская религия

- Германская мифология

- Хеттская мифология и религия

- Историческая ведическая религия

- Религия в Древнем Риме

- Скифская религия

- Славянское язычество

Примечания

[ редактировать ]- ^ Примечание: божественные имена, отмеченные звездочкой, не засвидетельствованы в исторических записях, но в противном случае реконструируются с помощью сравнительного метода в лингвистике .

- ↑ Подробное описание германской религии Тацитом было написано около 100 г. н.э. Его этнографические описания в Германии по-прежнему оспариваются современными учеными. Согласно Тациту, германские народы приносили в жертву своим богам как людей, так и других животных. [34] Он также сообщает, что самая большая группа, свевы , также приносили в жертву римских военнопленных богине, которую он отождествлял с Исидой . [34]

- ↑ » Юлия Цезаря Одним из старейших письменных источников по германской религии являются «Комментарии Белло Галлико , где он сравнивает очень сложные кельтские обычаи с тем, что, по его мнению, было очень «примитивными» германскими традициями. Цезарь писал: Немецкий образ жизни совсем другой. У них нет друидов, которые управляли бы делами, связанными с божественным, и они не испытывают особого энтузиазма к жертвоприношениям. Они считают богами только те явления, которые они могут воспринимать и чья сила им явно помогает: Солнце, Огонь и Луна; других они не знают даже понаслышке. Вся их жизнь посвящена охоте и военным занятиям» (Цезарь, Галльская война 6.21.1–6.21.3). [38]

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ Симек 1993 , с. 278.

- ^ Hultgård 2010a , с. 863.

- ^ Майер 2018 , с. 99.

- ^ Симек 2004 , с. 74.

- ^ Hultgård 2010a , стр. 865–866.

- ^ Зернак 2018 , стр. 527–528.

- ^ Hultgård 2010a , стр. 866–867.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Шёдт 2020b , стр. 250.

- ^ Шёдт 2020b , стр. 265.

- ^ Пол 2004 , с. 83.

- ^ Майер 2010b , с. 591.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Хултгард 2010a , с. 872.

- ^ Шёдт 2020a , стр. 246.

- ^ Тимпе и Скардигли, 2010 , с. 385.

- ^ Шёдт 2020a , стр. 241.

- ^ Schjødt 2020a , стр. 243–244.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Майер 2010а , с. 573.

- ^ Зернак 2018 , с. 533.

- ^ Gunnell 2020a , стр. 197–198.

- ^ Демандт и Гетц 2010 , с. 468-470.

- ^ Зернак 2018 , с. 537.

- ^ Gunnell 2020a , стр. 201–202.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Брат, Хайцманн и Патцольд, 2021 , с. 27.

- ^ Gunnell 2020a , стр. 198–199.

- ^ Gunnell 2020a , стр. 199–201.

- ^ Линдоу 2020d , с. 1095.

- ^ Hultgård 2010a , стр. 871–872.

- ^ Schjødt 2020b , стр. 255–256.

- ^ Hultgård 2010a , стр. 872–873.

- ^ Шёдт 2020b , стр. 256.

- ^ Налог 2021 , с. 647.

- ^ Шьёдт 2020b , стр. 257.

- ^ Симек 1993 , с. х.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Тацит 2009 , с. 42.

- ^ Schjødt 2020b , стр. 257–258.

- ^ Беар 1964 , с. 72–73.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Эбенбауэр 1984 , с. 512.

- ^ Цезарь 2017 , с. 187.

- ^ Данн 2013 , стр. 11–12.

- ^ Симек 1993 , с. 33.

- ^ Эбенбауэр 1984 , стр. 514–515.

- ^ Линдоу 2020c , стр. 67–101.

- ^ Эгелер 2020 , с. 291.

- ^ Кох 2020 .

- ^ Эгелер 2020 , стр. 299–300.

- ^ Эгелер 2020 , стр. 302–309.

- ^ Майер 2010d , стр. 921–922.

- ^ Симек 2020a , с. 274.

- ^ Симек 2020a , стр. 286–287.

- ^ Ан, Падберг и Хултгард 2010 , стр. 438–440.

- ^ Ан, Падберг и Хултгард 2010 , стр. 240–246.

- ^ Майер 2010d , с. 925-926.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Hultgård 2010c , с. 485, 488-489.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Нордвиг 2020а , стр. 989.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Hultgård 2010c , стр. 484–485.

- ^ Нордвиг 2020a , стр. 993.

- ^ Уолтерс 2001 , с. 467-468.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Шёдт 2020a , стр. 239.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Уолтерс 2001 , с. 471.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Симек 2004 , с. 91.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Кульманн 2022 , с. 328.

- ^ Hultgård 2010c , стр. 484–485, 505.

- ^ Hultgård 2010c , с. 485.

- ^ Hultgård 2010c , стр. 485–486.

- ^ Schjødt 2020b , стр. 266–267.

- ^ Шёдт 2020b , стр. 267.

- ^ Нордвиг 2020a , стр. 995.

- ^ Хултгард 2020 , стр. 1022-1023.

- ^ Schjødt 2010 , стр. 987–988.

- ^ Schjødt 2010 , стр. 983–984.

- ^ Шьёдт 2010 , стр. 985.

- ^ Хултгард 2020 , стр. 1025.

- ^ Нордвиг 2020b , стр. 1012-1013.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Симек 1993 , с. 53.

- ^ Нордвиг 2020b , стр. 1001.

- ^ Нордвиг 2020b , стр. 1014.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Симек 1993 , с. 214.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Симек 1993 , с. 54.

- ^ Андрен 2014 , стр. 37.

- ^ Нордвиг 2020b , стр. 1004-1005.

- ^ Симек и Райхштейн 2010 , стр. 290–291.

- ^ Симек 2010a , с. 16-17.

- ^ Линдоу 2020a , стр. 948–949.

- ^ Симек 1993 , с. 374.

- ^ Симек 2010a , с. 17-18.

- ^ Линдоу 2020a , стр. 936–937.

- ^ Линдоу 2020a , с. 949-950.

- ^ Линдоу 2020a , стр. 930–931.

- ^ Линдоу 2020a , с. 750.

- ^ Линдоу и Андрен 2020 , стр. 907–908.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Линдоу и Андрен 2020 , стр. 915.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Hultgård 2010d , с. 944.

- ^ Линдоу и Андрен 2020 , стр. 925.

- ^ Hultgård 2010d , с. 949.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Линдоу и Андрен 2020 , стр. 898.

- ^ Симек 1993 , с. 138.

- ^ Линдоу 2001 , с. 172.

- ^ Линдоу и Андрен 2020 , стр. 899.

- ^ Симек 1993 , с. 137.

- ^ Симек 1993 , с. 347.

- ^ Цена 2020 , с. 861-862.

- ^ Даксельмюллер 2010a , с. 1180.

- ^ Симек 1993 , с. 372.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Шуппер 2010 , с. 1620.

- ^ Симек 1993 , с. 232.

- ^ Бек 1998 , с. 481.

- ^ Шойнер 2010 , стр. 1620–1621.