ЛСД

Диэтиламид лизергиновой кислоты , широко известный как ЛСД (от немецкого Lysergsäure-diэтиламид ), а также известный в просторечии как кислота или люси , является мощным психоделическим препаратом . [12] Эффекты обычно включают усиление мыслей, эмоций и сенсорного восприятия. [13] В достаточно высоких дозировках ЛСД проявляется прежде всего психическими, зрительными и слуховыми галлюцинациями . [14] [15] Типичны расширение зрачков, повышение артериального давления и повышение температуры тела. [16]

Эффект обычно начинается в течение получаса и может длиться до 20 часов (хотя в среднем опыт длится 8–12 часов). [16] [17] ЛСД также способен вызывать мистические переживания и растворение эго . [15] [18] Его используют главным образом в качестве рекреационного наркотика или по духовным причинам . [16] [19] ЛСД является одновременно прототипом психоделика и одним из «классических» психоделиков, имея величайшее научное и культурное значение. [12] ЛСД синтезируется в виде твердого соединения, обычно в форме порошка или кристаллического материала. Этот твердый ЛСД затем растворяют в жидком растворителе, таком как этанол или дистиллированная вода, для получения раствора. Жидкость служит носителем ЛСД, позволяя точно дозировать и наносить его на небольшие кусочки промокательной бумаги, называемые таблетками. ЛСД обычно либо глотают, либо держат под языком. [13] In pure form, LSD is clear or white in color, has no smell, and is crystalline.[13] It breaks down with exposure to ultraviolet light.[16]

LSD is pharmacologically considered to be non-addictive with a low potential for abuse. Adverse psychological reactions are possible, such as anxiety, paranoia, and delusions.[7] In rare cases, LSD can induce "flashbacks", known as hallucinogen persisting perception disorder, in which a person experiences apparent lasting or persistent visual hallucinations or perceptual distortions, such as visual snow and palinopsia.[20][21]

LSD is structurally related to substituted tryptamines, a class of compounds that includes psilocybin, the active compound found in psychedelic mushrooms. Thus, LSD shares some mechanisms of action and psychedelic effects with psilocybin and other tryptamines.[22][23][24]

The effects of LSD are thought to stem primarily from it being an agonist at the 5-HT2A serotonin receptor. While exactly how LSD exerts its effects by agonism at this receptor is not fully understood, corresponding increased glutamatergic neurotransmission and reduced default mode network activity are thought to be key mechanisms of action.[7][12][25][26][27] LSD also binds to dopamine D1 and D2 receptors, which is thought to contribute to reports of LSD being more stimulating than compounds such as psilocybin.[28][29]

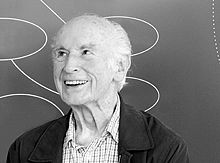

Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann first synthesized LSD in 1938 from lysergic acid, a chemical derived from the hydrolysis of ergotamine, an alkaloid found in ergot, a fungus that infects grain.[16][20] LSD was the 25th of various lysergamides Hofmann synthesized from lysergic acid while trying to develop a new analeptic, hence the alternate name LSD-25. Hofmann discovered its effects in humans in 1943, after unintentionally ingesting an unknown amount, possibly absorbing it through his skin.[30][31][32] LSD was subject to exceptional interest within the field of psychiatry in the 1950s and early 1960s, with Sandoz distributing LSD to researchers under the trademark name Delysid in an attempt to find a marketable use for it.[31]

LSD-assisted psychotherapy was used in the 1950s and early 1960s by psychiatrists such as Humphry Osmond, who pioneered the application of LSD to the treatment of alcoholism, with promising results.[31][33][34][35] Osmond coined the term "psychedelic" (lit. mind manifesting) as a term for LSD and related hallucinogens, superseding the previously held "psychotomimetic" model in which LSD was believed to mimic schizophrenia. In contrast to schizophrenia, LSD can induce transcendent experiences, or mental states that transcend the experience of everyday consciousness, with lasting psychological benefit.[12][31] During this time, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) began using LSD in the research project Project MKUltra, which used psychoactive substances to aid interrogation. The CIA administered LSD to unwitting test subjects in order to observe how they would react, the most well-known example of this being Operation Midnight Climax.[31] LSD was one of several psychoactive substances evaluated by the U.S. Army Chemical Corps as possible non-lethal incapacitants in the Edgewood Arsenal human experiments.[31]

In the 1960s, LSD and other psychedelics were adopted by, and became synonymous with, the counterculture movement due to their perceived ability to expand consciousness. This resulted in LSD being viewed as a cultural threat to American values and the Vietnam war effort, and it was designated as a Schedule I (illegal for medical as well as recreational use) substance in 1968.[36] It was listed as a Schedule 1 controlled substance by the United Nations in 1971 and currently has no approved medical uses.[16] As of 2017[update], about 10% of people in the United States have used LSD at some point in their lives, while 0.7% have used it in the last year.[37] It was most popular in the 1960s to 1980s.[16] The use of LSD among US adults increased 56.4% from 2015 to 2018.[38]

Uses

[edit]Recreational

[edit]LSD is commonly used as a recreational drug.[39]

Spiritual

[edit]LSD can catalyze intense spiritual experiences and is thus considered an entheogen. Some users have reported out of body experiences. In 1966, Timothy Leary established the League for Spiritual Discovery with LSD as its sacrament.[40][41] Stanislav Grof has written that religious and mystical experiences observed during LSD sessions appear to be phenomenologically indistinguishable from similar descriptions in the sacred scriptures of the great religions of the world and the texts of ancient civilizations.[42]

Medical

[edit]LSD currently has no approved uses in medicine.[43][44] A meta analysis concluded that a single dose was shown to be effective at reducing alcohol consumption in people suffering from alcoholism.[35] LSD has also been studied in depression, anxiety,[45][46] and drug dependence, with positive preliminary results.[47][48]

Effects

[edit]LSD is exceptionally potent, with as little as 20 μg capable of producing a noticeable effect.[16]

Physical

[edit]

LSD can induce physical effects such as pupil dilation, decreased appetite, increased sweating, and wakefulness. The physical reactions to LSD vary greatly and some may be a result of its psychological effects. Commonly observed symptoms include increased body temperature, blood sugar, and heart rate, as well as goose bumps, jaw clenching, dry mouth, and hyperreflexia. In cases of adverse reactions, users may experience numbness, weakness, nausea, and tremors.[16]

Psychological

[edit]The primary immediate psychological effects of LSD are visual hallucinations and illusions, often referred to as "trips". These effects typically begin within 20–30 minutes of oral ingestion, peak three to four hours after ingestion, and can last up to 20 hours, particularly with higher doses. An "afterglow" effect, characterized by an improved mood or perceived mental state, may persist for days or weeks following ingestion.[51] Positive experiences, or "good trips", are described as intensely pleasurable and can include feelings of joy, euphoria, an increased appreciation for life, decreased anxiety, a sense of spiritual enlightenment, and a feeling of interconnectedness with the universe.[52][53]

Conversely, negative experiences, known as "bad trips," can induce feelings of fear, anxiety, panic, paranoia, and even suicidal ideation.[54] While the occurrence of a bad trip is unpredictable, factors such as mood, surroundings, sleep, hydration, and social setting, collectively referred to as "set and setting", can influence the risk and are considered important in minimizing the likelihood of a negative experience.[55][56]

Sensory

[edit]LSD induces an animated sensory experience affecting senses, emotions, memories, time, and awareness, lasting from 6 to 20 hours, with the duration dependent on dosage and individual tolerance. Effects typically commence within 30 to 90 minutes post-ingestion, ranging from subtle perceptual changes to profound cognitive shifts. Alterations in auditory and visual perception are common.[57][58]

Users may experience enhanced visual phenomena, such as vibrant colors, objects appearing to morph, ripple or move, and geometric patterns on various surfaces. Changes in the perception of food's texture and taste are also noted, sometimes leading to aversion towards certain foods.[57][59]

There are reports of inanimate objects appearing animated, with static objects seeming to move in additional spatial dimensions.[60] The auditory effects of LSD may include echo-like distortions of sounds. Basic visual effects often resemble phosphenes and can be influenced by concentration, thoughts, emotions, or music.[61] Auditory effects may include echo-like distortions and an intensified experience of music. Higher doses can lead to more intense sensory perception alterations, including synesthesia, perception of additional dimensions, and temporary dissociation.

Adverse effects

[edit]

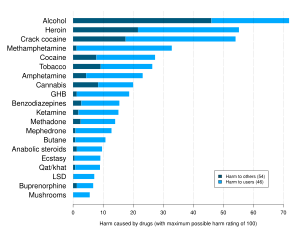

LSD, a classical psychedelic, is deemed physiologically safe at standard dosages (50–200 μg) and its primary risks lie in psychological effects rather than physiological harm.[25][64] A 2010 study by David Nutt ranked LSD as significantly less harmful than alcohol, placing it near the bottom of a list assessing the harm of 20 drugs.[65]

Psychological effects

[edit]Mental disorders

[edit]LSD can induce panic attacks or extreme anxiety, colloquially termed a "bad trip". Despite lower rates of depression and substance abuse found in psychedelic drug users compared to controls, LSD presents heightened risks for individuals with severe mental illnesses like schizophrenia.[66][67] These hallucinogens can catalyze psychiatric disorders in predisposed individuals, although they do not tend to induce illness in emotionally healthy people.[25]

Suggestibility

[edit]While research from the 1960s indicated increased suggestibility under the influence of LSD among both mentally ill and healthy individuals, recent documents suggest that the CIA and Department of Defense have discontinued research into LSD as a means of mind control.[68][69][70][non-primary source needed]

Flashbacks

[edit]Flashbacks are psychological episodes where individuals re-experience some of LSD's subjective effects after the drug has worn off, persisting for days or months post-hallucinogen use.[71][72] These experiences are associated with hallucinogen persisting perception disorder (HPPD), where flashbacks occur intermittently or chronically, causing distress or functional impairment.[21]

The etiology of flashbacks is varied. Some cases are attributed to somatic symptom disorder, where individuals fixate on normal somatic experiences previously unnoticed prior to drug consumption.[73] Other instances are linked to associative reactions to contextual cues, similar to responses observed in individuals with past trauma or emotional experiences.[74] The risk factors for flashbacks remain unclear, but pre-existing psychopathologies may be significant contributors.[75]

Estimating the prevalence of HPPD is challenging. It is considered rare, with occurrences ranging from 1 in 20 users experiencing the transient and less severe type 1 HPPD, to 1 in 50,000 for the more concerning type 2 HPPD.[21] Contrary to internet rumors, LSD is not stored long-term in the spinal cord or other body parts. Pharmacological evidence indicates LSD has a half-life of 175 minutes and is metabolized into water-soluble compounds like 2-oxo-3-hydroxy-LSD, eliminated through urine without evidence of long-term storage.[7] Clinical evidence also suggests that chronic use of SSRIs can potentiate LSD-induced flashbacks, even months after stopping LSD use.[76]: 145

Drug-interactions

[edit]Several psychedelics, including LSD, are metabolized by CYP2D6. Concurrent use of SSRIs, potent inhibitors of CYP2D6, with LSD may heighten the risk of serotonin syndrome.[76]: 145 Chronic usage of SSRIs, TCAs, and MAOIs is believed to diminish the subjective effects of psychedelics, likely due to SSRI-induced 5-HT2A receptor downregulation and MAOI-induced 5-HT2A receptor desensitization.[7][76]: 145 Interactions between psychedelics and antipsychotics or anticonvulsants are not well-documented; however, co-use with mood stabilizers like lithium may induce seizures and dissociative effects, particularly in individuals with bipolar disorder.[76]: 146 [77][78] Lithium notably intensifies LSD reactions, potentially leading to acute comatose states when combined.[7]

Fatal dose

[edit]Lethal oral dose of LSD in humans is estimated at 100 mg, based on LD50 and lethal blood concentrations observed in rodent studies.[64]

Tolerance

[edit]LSD shows significant tachyphylaxis, with tolerance developing 24 hours after administration. The progression of tolerance at intervals shorter than 24 hours remains largely unknown.[79] Tolerance typically resets to baseline after 3–4 days of abstinence.[80][81] Cross-tolerance occurs between LSD, mescaline, psilocybin,[82][83] and to some degree DMT.[a] Tolerance to LSD also builds up with consistent use,[86] and is believed to result from serotonin 5-HT2A receptor downregulation.[80] Researchers believe that tolerance returns to baseline after two weeks of not using psychedelics.[87]

Addiction and dependence liability

[edit]The NIH states that LSD is addictive,[20] while most other sources state it is not.[64][88] A 2009 textbook states that it "rarely produce[s] compulsive use."[5] A 2006 review states it is readily abused, but does not result in addiction.[88] There are no recorded successful attempts to train animals to self-administer LSD in laboratory settings.[25] A study reports that although tolerance to LSD builds up rapidly, a withdrawal syndrome does not appear, suggesting that a potential syndrome does not necessarily relate to the possibility of acquiring rapid tolerance to a substance.[89] A report examining substance use disorder for DSM-IV noted that almost no hallucinogens produced dependence, unlike psychoactive drugs of other classes such as stimulants and depressants.[90][91]

Cancer and pregnancy

[edit]The mutagenic potential of LSD is unclear. Overall, the evidence seems to point to limited or no effect at commonly used doses.[92] Studies showed no evidence of teratogenic or mutagenic effects.[7]

Overdose

[edit]There have been no documented fatal human overdoses from LSD,[7][93] although there has been no "comprehensive review since the 1950s" and "almost no legal clinical research since the 1970s".[7] Eight individuals who had accidentally consumed an exceedingly high amount of LSD, mistaking it for cocaine, and had gastric levels of 1000–7000 μg LSD tartrate per 100 mL and blood plasma levels up to 26 μg/ml, had suffered from comatose states, vomiting, respiratory problems, hyperthermia, and light gastrointestinal bleeding; however, all of them survived without residual effects upon hospital intervention.[7][94]

Individuals experiencing a bad trip after LSD intoxication may be presented with severe anxiety, tachycardia, often accompanied by phases of psychotic agitation and varying degrees of delusions.[64] Cases of death on a bad trip have been reported due to prone maximal restraint (PMR) and positional asphyxia when the individuals were held restraint by law enforcement personnel.[64]

Massive doses are largely managed by symptomatic treatments, and agitation can be addressed with benzodiazepines.[95][96] Reassurance in a calm, safe environment is beneficial.[97] Antipsychotic agents such as neuroleptics and haloperidol are not recommended as they may have adverse psychotomimetic effects.[95] Gastrointestinal decontamination with activated charcoal is of little use due to the rapid absorption of LSD, unless done within 30–60 minutes of ingesting exceedingly huge amounts.[95] Administration of anticoagulants, vasodilators, and sympatholytics may be useful for treating ergotism.[95]

Designer drug overdose

[edit]Many novel psychoactive substances of 25-NB (NBOMe) series, such as 25I-NBOMe and 25B-NBOMe, are regularly sold as LSD in blotter papers.[98][99] NBOMe compounds are often associated with life-threatening toxicity and death.[98][100] Fatalities involved in NBOMe intoxication suggest that a significant number of individuals ingested the substance which they believed was LSD,[101] and researchers report that "users familiar with LSD may have a false sense of security when ingesting NBOMe inadvertently".[93] Researchers state that the alleged physiological toxicity of LSD is likely due to psychoactive substances other than LSD.[64] NBOMe compounds are reported to have a bitter taste,[93] and are not active orally,[b] and are usually taken sublingually.[103] When NBOMes are administered sublingually, numbness of the tongue and mouth followed by a metallic chemical taste was observed, and researchers describe this physical side effect as one of the main discriminants between NBOMe compounds and LSD.[104][105][106] Despite high potency, recreational doses of LSD have only produced low incidents of acute toxicity, but NBOMe compounds have extremely different safety profiles.[93][100] Ehrlich's reagent can be used to test for the presence of LSD.[107]

Pharmacology

[edit]Pharmacodynamics

[edit]

| Receptor | Ki (nM) |

|---|---|

| 5-HT1A | 1.1 |

| 5-HT2A | 2.9 |

| 5-HT2B | 4.9 |

| 5-HT2C | 23 |

| 5-HT5A | 9 |

| 5-HT6 | 2.3 |

Most serotonergic psychedelics are not significantly dopaminergic, and LSD is therefore atypical in this regard. The agonism of the D2 receptor by LSD may contribute to its psychoactive effects in humans.[29]

LSD binds to most serotonin receptor subtypes except for the 5-HT3 and 5-HT4 receptors. However, most of these receptors are affected at too low affinity to be sufficiently activated by the brain concentration of approximately 10–20 nM.[25] In humans, recreational doses of LSD can affect 5-HT1A (Ki = 1.1 nM), 5-HT2A (Ki = 2.9 nM), 5-HT2B (Ki = 4.9 nM), 5-HT2C (Ki = 23 nM), 5-HT5A (Ki = 9 nM [in cloned rat tissues]), and 5-HT6 receptors (Ki = 2.3 nM).[108] Although not present in humans, 5-HT5B receptors found in rodents also have a high affinity for LSD.[109] The psychedelic effects of LSD are attributed to cross-activation of 5-HT2A receptor heteromers.[110] Many but not all 5-HT2A agonists are psychedelics and 5-HT2A antagonists block the psychedelic activity of LSD. LSD exhibits functional selectivity at the 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptors in that it activates the signal transduction enzyme phospholipase A2 instead of activating the enzyme phospholipase C as the endogenous ligand serotonin does.[111]

Exactly how LSD produces its effects is unknown, but it is thought that it works by increasing glutamate release in the cerebral cortex[25] and therefore excitation in this area, specifically in layer V.[112] LSD, like many other drugs of recreational use, has been shown to activate DARPP-32-related pathways.[113] The drug enhances dopamine D2 receptor protomer recognition and signaling of D2–5-HT2A receptor complexes,[28] which may contribute to its psychotropic effects.[28] LSD has been shown to have low affinity for H1 receptors, displaying antihistamine effects.[114][115]

LSD is a biased agonist that induces a conformation in serotonin receptors that preferentially recruits β-arrestin over activating G proteins.[116] LSD also has an exceptionally long residence time when bound to serotonin receptors lasting hours, consistent with the long lasting effects of LSD despite its relatively rapid clearance.[116] A crystal structure of 5-HT2B bound to LSD reveals an extracellular loop that forms a lid over the diethylamide end of the binding cavity which explains the slow rate of LSD unbinding from serotonin receptors.[117] The related lysergamide lysergic acid amide (LSA) that lacks the diethylamide moiety is far less hallucinogenic in comparison.[117]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]

The acute effects of LSD normally last between 6 and 10 hours depending on dosage, tolerance, and age.[118][119] Aghajanian and Bing (1964) found LSD had an elimination half-life of only 175 minutes (about 3 hours).[108] However, using more accurate techniques, Papac and Foltz (1990) reported that 1 μg/kg oral LSD given to a single male volunteer had an apparent plasma half-life of 5.1 hours, with a peak plasma concentration of 5 ng/mL at 3 hours post-dose.[120]

The pharmacokinetics of LSD were not properly determined until 2015, which is not surprising for a drug with the kind of low-μg potency that LSD possesses.[6][9] In a sample of 16 healthy subjects, a single mid-range 200 μg oral dose of LSD was found to produce mean maximal concentrations of 4.5 ng/mL at a median of 1.5 hours (range 0.5–4 hours) post-administration.[6][9] Concentrations of LSD decreased following first-order kinetics with a half-life of 3.6±0.9 hours and a terminal half-life of 8.9±5.9 hours.[6][9]

The effects of the dose of LSD given lasted for up to 12 hours and were closely correlated with the concentrations of LSD present in circulation over time, with no acute tolerance observed.[6][9] Only 1% of the drug was eliminated in urine unchanged, whereas 13% was eliminated as the major metabolite 2-oxo-3-hydroxy-LSD (O-H-LSD) within 24 hours.[6][9] O-H-LSD is formed by cytochrome P450 enzymes, although the specific enzymes involved are unknown, and it does not appear to be known whether O-H-LSD is pharmacologically active or not.[6][9] The oral bioavailability of LSD was crudely estimated as approximately 71% using previous data on intravenous administration of LSD.[6][9] The sample was equally divided between male and female subjects and there were no significant sex differences observed in the pharmacokinetics of LSD.[6][9]

Mechanisms of action

[edit]Neuroimaging studies using resting state fMRI recently suggested that LSD changes the cortical functional architecture.[121] These modifications spatially overlap with the distribution of serotoninergic receptors. In particular, increased connectivity and activity were observed in regions with high expression of 5-HT2A receptor, while a decrease in activity and connectivity was observed in cortical areas that are dense with 5-HT1A receptor.[122] Experimental data suggest that subcortical structures, particularly the thalamus, play a synergistic role with the cerebral cortex in mediating the psychedelic experience. LSD, through its binding to cortical 5-HT2A receptor, may enhance excitatory neurotransmission along frontostriatal projections and, consequently, reduce thalamic filtering of sensory stimuli towards the cortex.[123] This phenomenon appears to selectively involve ventral, intralaminar, and pulvinar nuclei.[123]

Chemistry

[edit]

LSD is a chiral compound with two stereocenters at the carbon atoms C-5 and C-8, so that theoretically four different optical isomers of LSD could exist. LSD, also called (+)-d-LSD,[124] has the absolute configuration (5R,8R). 5S stereoisomers of lysergamides do not exist in nature and are not formed during the synthesis from d-lysergic acid. Retrosynthetically, the C-5 stereocenter could be analysed as having the same configuration of the alpha carbon of the naturally occurring amino acid L-tryptophan, the precursor to all biosynthetic ergoline compounds.

However, LSD and iso-LSD, the two C-8 isomers, rapidly interconvert in the presence of bases, as the alpha proton is acidic and can be deprotonated and reprotonated. Non-psychoactive iso-LSD which has formed during the synthesis can be separated by chromatography and can be isomerized to LSD.

Pure salts of LSD are triboluminescent, emitting small flashes of white light when shaken in the dark.[118] LSD is strongly fluorescent and will glow bluish-white under UV light.

Synthesis

[edit]LSD is an ergoline derivative. It is commonly synthesized by reacting diethylamine with an activated form of lysergic acid. Activating reagents include phosphoryl chloride[125] and peptide coupling reagents.[115] Lysergic acid is made by alkaline hydrolysis of lysergamides like ergotamine, a substance usually derived from the ergot fungus on agar plate; or, theoretically possible, but impractical and uncommon, from ergine (lysergic acid amide, LSA) extracted from morning glory seeds.[126] Lysergic acid can also be produced synthetically, although these processes are not used in clandestine manufacture due to their low yields and high complexity.[127][128]

Research

[edit]The precursor for LSD, lysergic acid, has been produced by GMO baker's yeast.[129]

Dosage

[edit]

A single dose of LSD may be between 40 and 500 micrograms—an amount roughly equal to one-tenth the mass of a grain of sand. Threshold effects can be felt with as little as 25 micrograms of LSD.[130][131] The practice of using sub-threshold doses is called microdosing.[132] Dosages of LSD are measured in micrograms (μg), or millionths of a gram.

In the mid-1960s, the most important black market LSD manufacturer (Owsley Stanley) distributed LSD at a standard concentration of 270 μg,[133] while street samples of the 1970s contained 30 to 300 μg. By the 1980s, the amount had reduced to between 100 and 125 μg, dropping more in the 1990s to the 20–80 μg range,[134] and even more in the 2000s (decade).[133][135]

Reactivity and degradation

[edit]"LSD," writes the chemist Alexander Shulgin, "is an unusually fragile molecule ... As a salt, in water, cold, and free from air and light exposure, it is stable indefinitely."[118]

LSD has two labile protons at the tertiary stereogenic C5 and C8 positions, rendering these centers prone to epimerisation. The C8 proton is more labile due to the electron-withdrawing carboxamide attachment, but removal of the chiral proton at the C5 position (which was once also an alpha proton of the parent molecule tryptophan) is assisted by the inductively withdrawing nitrogen and pi electron delocalisation with the indole ring.[citation needed]

LSD also has enamine-type reactivity because of the electron-donating effects of the indole ring. Because of this, chlorine destroys LSD molecules on contact; even though chlorinated tap water contains only a slight amount of chlorine, the small quantity of compound typical to an LSD solution will likely be eliminated when dissolved in tap water.[118] The double bond between the 8-position and the aromatic ring, being conjugated with the indole ring, is susceptible to nucleophilic attacks by water or alcohol, especially in the presence of UV or other kinds of light. LSD often converts to "lumi-LSD," which is inactive in human beings.[118]

A controlled study was undertaken to determine the stability of LSD in pooled urine samples.[136]The concentrations of LSD in urine samples were followed over time at various temperatures, in different types of storage containers, at various exposures to different wavelengths of light, and at varying pH values. These studies demonstrated no significant loss in LSD concentration at 25 °C for up to four weeks. After four weeks of incubation, a 30% loss in LSD concentration at 37 °C and up to a 40% at 45 °C were observed. Urine fortified with LSD and stored in amber glass or nontransparent polyethylene containers showed no change in concentration under any light conditions. Stability of LSD in transparent containers under light was dependent on the distance between the light source and the samples, the wavelength of light, exposure time, and the intensity of light. After prolonged exposure to heat in alkaline pH conditions, 10 to 15% of the parent LSD epimerized to iso-LSD. Under acidic conditions, less than 5% of the LSD was converted to iso-LSD. It was also demonstrated that trace amounts of metal ions in buffer or urine could catalyze the decomposition of LSD and that this process can be avoided by the addition of EDTA.

Detection

[edit]

LSD can be detected in concentrations larger than approximately 10% in a sample using Ehrlich's reagent and Hofmann's reagent. However, detecting LSD in human tissues is more challenging due to its active dosage being significantly lower (in micrograms) compared to most other drugs (in milligrams).[137]

LSD may be quantified in urine for drug abuse testing programs, in plasma or serum to confirm poisoning in hospitalized victims, or in whole blood for forensic investigations. The parent drug and its major metabolite are unstable in biofluids when exposed to light, heat, or alkaline conditions, necessitating protection from light, low-temperature storage, and quick analysis to minimize losses.[138] Maximum plasma concentrations are typically observed 1.4 to 1.5 hours after oral administration of 100 μg and 200 μg, respectively, with a plasma half-life of approximately 2.6 hours (ranging from 2.2 to 3.4 hours among test subjects).[139]

Due to its potency in microgram quantities, LSD is often not included in standard pre-employment urine or hair analyses.[137][140] However, advanced liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry methods can detect LSD in biological samples even after a single use.[140]

History

[edit]... affected by a remarkable restlessness, combined with a slight dizziness. At home I lay down and sank into a not unpleasant intoxicated-like condition, characterized by an extremely stimulated imagination. In a dreamlike state, with eyes closed (I found the daylight to be unpleasantly glaring), I perceived an uninterrupted stream of fantastic pictures, extraordinary shapes with intense, kaleidoscopic play of colors. After some two hours this condition faded away.

—Albert Hofmann, on his first experience with LSD[141]: 15

LSD was first synthesized on November 16, 1938[142] by Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann at the Sandoz Laboratories in Basel, Switzerland as part of a large research program searching for medically useful ergot alkaloid derivatives. The abbreviation "LSD" is from the German "Lysergsäurediethylamid".[143]

LSD's psychedelic properties were discovered 5 years later when Hofmann himself accidentally ingested an unknown quantity of the chemical.[144] The first intentional ingestion of LSD occurred on April 19, 1943,[141] when Hofmann ingested 250 μg of LSD. He said this would be a threshold dose based on the dosages of other ergot alkaloids. Hofmann found the effects to be much stronger than he anticipated.[145] Sandoz Laboratories introduced LSD as a psychiatric drug in 1947 and marketed LSD as a psychiatric panacea, hailing it "as a cure for everything from schizophrenia to criminal behavior, 'sexual perversions', and alcoholism."[146] Sandoz would send the drug for free to researchers investigating its effects.[30]

Beginning in the 1950s, the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) began a research program code named Project MKUltra. The CIA introduced LSD to the United States, purchasing the entire world's supply for $240,000 and propagating the LSD through CIA front organizations to American hospitals, clinics, prisons and research centers.[147] Experiments included administering LSD to CIA employees, military personnel, doctors, other government agents, prostitutes, mentally ill patients, and members of the general public in order to study their reactions, usually without the subjects' knowledge. The project was revealed in the US congressional Rockefeller Commission report in 1975.

In 1963, the Sandoz patents on LSD expired[134] and the Czech company Spofa began to produce the substance.[30] Sandoz stopped the production and distribution in 1965.[30]

Several figures, including Aldous Huxley, Timothy Leary, and Al Hubbard, had begun to advocate the consumption of LSD. LSD became central to the counterculture of the 1960s.[148] In the early 1960s the use of LSD and other hallucinogens was advocated by new proponents of consciousness expansion such as Leary, Huxley, Alan Watts and Arthur Koestler,[149][150] and according to L. R. Veysey they profoundly influenced the thinking of the new generation of youth.[151]

On October 24, 1968, possession of LSD was made illegal in the United States.[152] The last FDA approved study of LSD in patients ended in 1980, while a study in healthy volunteers was made in the late 1980s. Legally approved and regulated psychiatric use of LSD continued in Switzerland until 1993.[153]

In November 2020, Oregon became the first US state to decriminalize possession of small amounts of LSD after voters approved Ballot Measure 110.[154]

Society and culture

[edit]Counterculture

[edit]By the mid-1960s, the youth countercultures in California, particularly in San Francisco, had widely adopted the use of hallucinogenic drugs, including LSD. The first major underground LSD factory was established by Owsley Stanley.[155] Around this time, the Merry Pranksters, associated with novelist Ken Kesey, organized the Acid Tests, events in San Francisco involving LSD consumption, accompanied by light shows and improvised music.[156][157] Their activities, including cross-country trips in a psychedelically decorated bus and interactions with major figures of the beat movement, were later documented in Tom Wolfe's The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test (1968).[158]

In San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury neighborhood, the Psychedelic Shop was opened in January 1966 by brothers Ron and Jay Thelin to promote safe use of LSD. This shop played a significant role in popularizing LSD in the area and establishing Haight-Ashbury as the epicenter of the hippie counterculture. The Thelins also organized the Love Pageant Rally in Golden Gate Park in October 1966, protesting against California's ban on LSD.[159][160]

A similar movement developed in London, led by British academic Michael Hollingshead, who first tried LSD in America in 1961. After experiencing LSD and interacting with notable figures such as Aldous Huxley, Timothy Leary, and Richard Alpert, Hollingshead played a key role in the famous LSD research at Millbrook before moving to New York City for his own experiments. In 1965, he returned to the UK and founded the World Psychedelic Center in Chelsea, London.[161]

Music and Art

[edit]

The influence of LSD in the realms of music and art became pronounced in the 1960s, especially through the Acid Tests and related events involving bands like the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, and Big Brother and the Holding Company. San Francisco-based artists such as Rick Griffin, Victor Moscoso, and Wes Wilson contributed to this movement through their psychedelic poster and album art. The Grateful Dead, in particular, became central to the culture of "Deadheads," with their music heavily influenced by LSD.[162]

In the United Kingdom, Michael Hollingshead, reputed for introducing LSD to various artists and musicians like Storm Thorgerson, Donovan, Keith Richards, and members of the Beatles, played a significant role in the drug's proliferation in the British art and music scene. Despite LSD's illegal status from 1966, it was widely used by groups including the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, and the Moody Blues. Their experiences influenced works such as the Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band and Cream's Disraeli Gears, featuring psychedelic-themed music and artwork.[163]

Psychedelic music of the 1960s often sought to replicate the LSD experience, incorporating exotic instrumentation, electric guitars with effects pedals, and elaborate studio techniques. Artists and bands utilized instruments like sitars and tablas, and employed studio effects such as backwards tapes, panning, and phasing.[164][165] Songs such as John Prine's "Illegal Smile" and the Beatles' "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds" have been associated with LSD, although the latter's authors denied such claims.[166][page needed][167]

Contemporary artists influenced by LSD include Keith Haring in the visual arts,[168] various electronic dance music creators,[169] and the jam band Phish.[170] The 2018 Leo Butler play All You Need is LSD is inspired by the author's interest in the history of LSD.[171]

Legal status

[edit]The United Nations Convention on Psychotropic Substances of 1971 mandates that signing parties, including the United States, Australia, New Zealand, and most of Europe, prohibit LSD. Enforcement of these laws varies by country. The convention allows medical and scientific research with LSD.[172]

Australia

[edit]In Australia, LSD is classified as a Schedule 9 prohibited substance under the Poisons Standard (February 2017), indicating it may be abused or misused and its manufacture, possession, sale, or use should be prohibited except for approved research purposes.[173] In Western Australia, the Misuse of Drugs Act 1981 provides guidelines for possession and trafficking of substances like LSD.[174]

Canada

[edit]In Canada, LSD is listed under Schedule III of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act. Unauthorized possession and trafficking of the substance can lead to significant legal penalties.[54]

United Kingdom

[edit]In the United Kingdom, LSD is a Class A drug under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971, making unauthorized possession and trafficking punishable by severe penalties. The Runciman Report and Transform Drug Policy Foundation have made recommendations and proposals regarding the legal regulation of LSD and other psychedelics.[175][176]

United States

[edit]In the United States, LSD is classified as a Schedule I controlled substance under the Controlled Substances Act of 1970, making its manufacture, possession, and distribution illegal without a DEA license. The law considers LSD to have a high potential for abuse, no legitimate medical use, and to be unsafe even under medical supervision. The US Supreme Court case Neal v. United States (1995) clarified the sentencing guidelines related to LSD possession.[177]

Oregon decriminalized personal possession of small amounts of drugs, including LSD, in February 2021, and California has seen legislative efforts to decriminalize psychedelics.[178]

Mexico

[edit]Mexico decriminalized the possession of small amounts of drugs, including LSD, for personal use in 2009. The law specifies possession limits and establishes that possession is not a crime within designated quantities.[179]

Czech Republic

[edit]In the Czech Republic, possession of "amount larger than small" of LSD is criminalized, while possession of smaller amounts is a misdemeanor. The definition of "amount larger than small" is determined by judicial practice and specific regulations.[180][181]

Economics

[edit]Production

[edit]

An active dose of LSD is very minute, allowing a large number of doses to be synthesized from a comparatively small amount of raw material. Twenty five kilograms of precursor ergotamine tartrate can produce 5–6 kg of pure crystalline LSD; this corresponds to around 50–60 million doses at 100 μg. Because the masses involved are so small, concealing and transporting illicit LSD is much easier than smuggling cocaine, cannabis, or other illegal drugs.[182]

Manufacturing LSD requires laboratory equipment and experience in the field of organic chemistry. It takes two to three days to produce 30 to 100 grams of pure compound. It is believed that LSD is not usually produced in large quantities, but rather in a series of small batches. This technique minimizes the loss of precursor chemicals in case a step does not work as expected.[182]

Forms

[edit]

LSD is produced in crystalline form and is then mixed with excipients or redissolved for production in ingestible forms. Liquid solution is either distributed in small vials or, more commonly, sprayed onto or soaked into a distribution medium. Historically, LSD solutions were first sold on sugar cubes, but practical considerations forced a change to tablet form. Appearing in 1968 as an orange tablet measuring about 6 mm across, "Orange Sunshine" acid was the first largely available form of LSD after its possession was made illegal. Tim Scully, a prominent chemist, made some of these tablets, but said that most "Sunshine" in the USA came by way of Ronald Stark, who imported approximately thirty-five million doses from Europe.[183]

Over a period of time, tablet dimensions, weight, shape and concentration of LSD evolved from large (4.5–8.1 mm diameter), heavyweight (≥150 mg), round, high concentration (90–350 μg/tab) dosage units to small (2.0–3.5 mm diameter) lightweight (as low as 4.7 mg/tab), variously shaped, lower concentration (12–85 μg/tab, average range 30–40 μg/tab) dosage units. LSD tablet shapes have included cylinders, cones, stars, spacecraft, and heart shapes. The smallest tablets became known as "Microdots."[184]

After tablets came "computer acid" or "blotter paper LSD," typically made by dipping a preprinted sheet of blotting paper into an LSD/water/alcohol solution.[183][184] More than 200 types of LSD tablets have been encountered since 1969 and more than 350 blotter paper designs have been observed since 1975.[184] About the same time as blotter paper LSD came "Windowpane" (AKA "Clearlight"), which contained LSD inside a thin gelatin square a quarter of an inch (6 mm) across.[183] LSD has been sold under a wide variety of often short-lived and regionally restricted street names including Acid, Trips, Uncle Sid, Blotter, Lucy, Alice and doses, as well as names that reflect the designs on the sheets of blotter paper.[52][185] Authorities have encountered the drug in other forms—including powder or crystal, and capsule.[186]

Modern distribution

[edit]LSD manufacturers and traffickers in the United States can be categorized into two groups: A few large-scale producers, and an equally limited number of small, clandestine chemists, consisting of independent producers who, operating on a comparatively limited scale, can be found throughout the country.[187][188]

As a group, independent producers are of less concern to the Drug Enforcement Administration than the large-scale groups because their product reaches only local markets.[146]

Many LSD dealers and chemists describe a religious or humanitarian purpose that motivates their illicit activity. Nicholas Schou's book Orange Sunshine: The Brotherhood of Eternal Love and Its Quest to Spread Peace, Love, and Acid to the World describes one such group, the Brotherhood of Eternal Love. The group was a major American LSD trafficking group in the late 1960s and early 1970s.[189]

In the second half of the 20th century, dealers and chemists loosely associated with the Grateful Dead like Owsley Stanley, Nicholas Sand, Karen Horning, Sarah Maltzer, "Dealer McDope," and Leonard Pickard played an essential role in distributing LSD.[162]

Mimics

[edit]

Since 2005, law enforcement in the United States and elsewhere has seized several chemicals and combinations of chemicals in blotter paper which were sold as LSD mimics, including DOB,[190][191] a mixture of DOC and DOI,[192] 25I-NBOMe,[193] and a mixture of DOC and DOB.[194] Many mimics are toxic in comparatively small doses, or have extremely different safety profiles. Many street users of LSD are often under the impression that blotter paper which is actively hallucinogenic can only be LSD because that is the only chemical with low enough doses to fit on a small square of blotter paper. While it is true that LSD requires lower doses than most other hallucinogens, blotter paper is capable of absorbing a much larger amount of material. The DEA performed a chromatographic analysis of blotter paper containing 2C-C which showed that the paper contained a much greater concentration of the active chemical than typical LSD doses, although the exact quantity was not determined.[195] Blotter LSD mimics can have relatively small dose squares; a sample of blotter paper containing DOC seized by Concord, California police had dose markings approximately 6 mm apart.[196] Several deaths have been attributed to 25I-NBOMe.[197][198][199][200]

Research

[edit]In the United States the earliest research began in the 1950s. Albert Kurland and his colleagues published research on LSD's therapeutic potential to treat schizophrenia. In Canada, Humphry Osmond and Abram Hoffer completed LSD studies as early as 1952.[201] By the 1960s, controversies surrounding "hippie" counterculture began to deplete institutional support for continued studies.

Currently, a number of organizations—including the Beckley Foundation, MAPS, Heffter Research Institute and the Albert Hofmann Foundation—exist to fund, encourage and coordinate research into the medicinal and spiritual uses of LSD and related psychedelics.[202] New clinical LSD experiments in humans started in 2009 for the first time in 35 years.[203] As it is illegal in many areas of the world, potential medical uses are difficult to study.[43]

In 2001 the United States Drug Enforcement Administration stated that LSD "produces no aphrodisiac effects, does not increase creativity, has no lasting positive effect in treating alcoholics or criminals, does not produce a "model psychosis", and does not generate immediate personality change."[146] More recently, experimental uses of LSD have included the treatment of alcoholism,[204] pain and cluster headache relief,[7][205][206] and prospective studies on depression.[207]

A 2020 meta-review indicated possible positive effects of LSD in reducing psychiatric symptoms, mainly in cases of alcoholism.[208] There is evidence that psychedelics induce molecular and cellular adaptations related to neuroplasticity and that these could potentially underlie therapeutic benefits.[209][210]

Psychedelic therapy

[edit]In the 1950s and 1960s, LSD was used in psychiatry to enhance psychotherapy, known as psychedelic therapy. Some psychiatrists, such as Ronald A. Sandison, who pioneered its use at Powick Hospital in England, believed LSD was especially useful at helping patients to "unblock" repressed subconscious material through other psychotherapeutic methods,[211] and also for treating alcoholism.[212][213] One study concluded, "The root of the therapeutic value of the LSD experience is its potential for producing self-acceptance and self-surrender,"[34] presumably by forcing the user to face issues and problems in that individual's psyche.

Two recent reviews concluded that conclusions drawn from most of these early trials are unreliable due to serious methodological flaws. These include the absence of adequate control groups, lack of followup, and vague criteria for therapeutic outcome. In many cases studies failed to convincingly demonstrate whether the drug or the therapeutic interaction was responsible for any beneficial effects.[214][215]

In recent years, organizations like the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies have renewed clinical research of LSD.[203]

It has been proposed that LSD be studied for use in the therapeutic setting, particularly in anxiety.[45][46][216][217] In 2024, the FDA designated a form of LSD as a breakthrough therapy to treat generalized anxiety disorder.[218]

Other uses

[edit]In the 1950s and 1960s, some psychiatrists (e.g. Oscar Janiger) explored the potential effect of LSD on creativity. Experimental studies attempted to measure the effect of LSD on creative activity and aesthetic appreciation.[53][219][220][221] In 1966 Dr. James Fadiman conducted a study with the central question "How can psychedelics be used to facilitate problem solving?" This study attempted to solve 44 different problems and had 40 satisfactory solutions when the FDA banned all research into psychedelics. LSD was a key component of this study.[222][223]

Since 2008 there has been ongoing research into using LSD to alleviate anxiety for terminally ill cancer patients coping with their impending deaths.[45][203][224]

A 2012 meta-analysis found evidence that a single dose of LSD in conjunction with various alcoholism treatment programs was associated with a decrease in alcohol abuse, lasting for several months, but no effect was seen at one year. Adverse events included seizure, moderate confusion and agitation, nausea, vomiting, and acting in a bizarre fashion.[35]

LSD has been used as a treatment for cluster headaches with positive results in some small studies.[7]

Recently, researchers discovered that LSD is a potent psychoplastogen, a compound capable of promoting rapid and sustained neural plasticity that may have wide-ranging therapeutic benefit.[225] LSD has been shown to increase markers of neuroplasticity in human brain organoids and improve memory performance in human subjects.[226]

LSD may have analgesic properties related to pain in terminally ill patients and phantom pain and may be useful for treating inflammatory diseases including rheumatoid arthritis.[227]

Notable individuals

[edit]Some notable individuals have commented publicly on their experiences with LSD.[228][229] Some of these comments date from the era when it was legally available in the US and Europe for non-medical uses, and others pertain to psychiatric treatment in the 1950s and 1960s. Still others describe experiences with illegal LSD, obtained for philosophic, artistic, therapeutic, spiritual, or recreational purposes.

- W. H. Auden, the poet, said, "I myself have taken mescaline once and L.S.D. once. Aside from a slight schizophrenic dissociation of the I from the Not-I, including my body, nothing happened at all."[230] He also said, "LSD was a complete frost. … What it does seem to destroy is the power of communication. I have listened to tapes done by highly articulate people under LSD, for example, and they talk absolute drivel. They may have seen something interesting, but they certainly lose either the power or the wish to communicate."[231] He also said, "Nothing much happened but I did get the distinct impression that some birds were trying to communicate with me."[232]

- Daniel Ellsberg, an American peace activist, says he has had several hundred experiences with psychedelics.[233]

- Richard Feynman, a notable physicist at California Institute of Technology, tried LSD during his professorship at Caltech. Feynman largely sidestepped the issue when dictating his anecdotes; he mentions it in passing in the "O Americano, Outra Vez" section.[234][235]

- Jerry Garcia stated in a July 3, 1989 interview for Relix Magazine, in response to the question "Have your feelings about LSD changed over the years?," "They haven't changed much. My feelings about LSD are mixed. It's something that I both fear and that I love at the same time. I never take any psychedelic, have a psychedelic experience, without having that feeling of, "I don't know what's going to happen." In that sense, it's still fundamentally an enigma and a mystery."[236]

- Bill Gates implied in an interview with Playboy that he tried LSD during his youth.[237]

- Aldous Huxley, author of Brave New World, became a user of psychedelics after moving to Hollywood. He was at the forefront of the counterculture's use of psychedelic drugs, which led to his 1954 work The Doors of Perception. Dying from cancer, he asked his wife on 22 November 1963 to inject him with 100 μg of LSD. He died later that day.[238]

- Steve Jobs, co-founder and former CEO of Apple Inc., said, "Taking LSD was a profound experience, one of the most important things in my life."[239]

- Ernst Jünger, German writer and philosopher, throughout his life had experimented with drugs such as ether, cocaine, and hashish; and later in life he used mescaline and LSD. These experiments were recorded comprehensively in Annäherungen (1970, Approaches). The novel Besuch auf Godenholm (1952, Visit to Godenholm) is clearly influenced by his early experiments with mescaline and LSD. He met with LSD inventor Albert Hofmann and they took LSD together several times. Hofmann's memoir LSD, My Problem Child describes some of these meetings.[240]

- In a 2004 interview, Paul McCartney said that The Beatles' songs "Day Tripper" and "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds" were inspired by LSD trips.[166]: 182 Nonetheless, John Lennon consistently stated over the course of many years that the fact that the initials of "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds" spelled out L-S-D was a coincidence (he stated that the title came from a picture drawn by his son Julian) and that the band members did not notice until after the song had been released, and Paul McCartney corroborated that story.[241] John Lennon, George Harrison, and Ringo Starr also used the drug, although McCartney cautioned that "it's easy to overestimate the influence of drugs on the Beatles' music."[242]

- Michel Foucault had an LSD experience with Simeon Wade in Death Valley and later wrote "it was the greatest experience of his life, and that it profoundly changed his life and his work."[243][244] According to Wade, as soon as he came back to Paris, Foucault scrapped the second History of Sexuality's manuscript, and totally rethought the whole project.[245]

- Кэри Маллис Сообщается, что считает, что ЛСД помог ему в разработке технологии амплификации ДНК , за что он получил Нобелевскую премию по химии в 1993 году. [246]

- Карло Ровелли , итальянский физик-теоретик и писатель, считает, что употребление ЛСД пробудило в нем интерес к теоретической физике. [247]

- Оливер Сакс , невролог, известный автором бестселлеров о расстройствах и необычных переживаниях своих пациентов, рассказывает о своем собственном опыте употребления ЛСД и других химических веществ, изменяющих восприятие, в своей книге « Галлюцинации» . [248]

- Мэтт Стоун и Трей Паркер , создатели сериала « Южный парк », утверждали, что появились на 72-й церемонии вручения премии «Оскар» , на которой они были номинированы на премию «Лучшая оригинальная песня», под воздействием ЛСД. [249]

См. также

[ редактировать ]- 1П-ЛСД

- 1cP-ЛСД

- Claviceps purpurea (спорынья)

- ЛСД искусство

- ЛСЗ

- Психопластоген

Примечания

[ редактировать ]- ^ Хотя перекрестная толерантность к ДМТ отмечена как незначительная, [84] некоторые сообщения предполагают, что люди, толерантные к ЛСД, показали неослабленную реакцию на ДМТ. [85]

- ^ Эффективность соединениями - бензилфенэтиламинов N при буккальной, сублингвальной или назальной абсорбции в 50–100 раз выше (по массе), чем при пероральном введении, по сравнению с исходными 2C-x . [102] Исследования предполагают, что низкая метаболическая стабильность N -бензилфенэтиламинов при пероральном приеме, вероятно, является причиной низкой биодоступности при пероральном введении, хотя метаболический профиль этих соединений остается непредсказуемым; поэтому исследования утверждают, что смертельные случаи, связанные с этими веществами, могут частично объясняться различиями в метаболизме между людьми. [102]

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ «Определение понятия «амид» » . Словарь английского языка Коллинза . Архивировано из оригинала 2 апреля 2015 года . Проверено 31 января 2015 г.

- ^ «Запись в словаре американского наследия: амид» . Ahdictionary.com. Архивировано из оригинала 2 апреля 2015 года . Проверено 31 января 2015 г.

- ^ «амид – определение амида на английском языке из Оксфордского словаря » . Oxforddictionaries.com. Архивировано из оригинала 2 апреля 2015 года . Проверено 31 января 2015 г.

- ^ Халперн Дж. Х., Сузуки Дж., Уэртас П. Е., Пасси Т. (7 июня 2014 г.). «Злоупотребление галлюциногенами и зависимость». В Прайс Л.Х., Столерман И.П. (ред.). Энциклопедия психофармакологии. Живой справочник Springer . Гейдельберг, Германия: Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg. стр. 1–5. дои : 10.1007/978-3-642-27772-6_43-2 . ISBN 978-3-642-27772-6 .

Злоупотребление галлюциногенами и зависимость являются известными осложнениями, возникающими в результате... ЛСД и псилоцибина. У потребителей не возникают симптомы абстиненции, но в остальном применяются общие критерии злоупотребления психоактивными веществами и зависимости. Зависимость оценивается примерно у 2% недавно принявших наркотики.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Маленка Р.К., Нестлер Э.Дж., Хайман С.Е. (2009). «Глава 15: Подкрепление и аддиктивные расстройства». В Сидоре А., Брауне Р.Ю. (ред.). Молекулярная нейрофармакология: фонд клинической неврологии (2-е изд.). Нью-Йорк: McGraw-Hill Medical. п. 375. ИСБН 9780071481274 . Архивировано из оригинала 28 августа 2023 года . Проверено 12 июня 2023 г.

Некоторые другие классы наркотиков относятся к категории наркотиков, вызывающих злоупотребление, но редко вызывают компульсивное употребление. К ним относятся психоделические агенты, такие как диэтиламид лизергиновой кислоты (ЛСД).

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я дж к л м Долдер ПК, Шмид Й, Хашке М, Рентч КМ, Лихти МЭ (июнь 2015 г.). «Фармакокинетика и взаимосвязь концентрация-эффект перорального ЛСД у людей» . Международный журнал нейропсихофармакологии . 19 (1): pyv072. дои : 10.1093/ijnp/pyv072 . ПМЦ 4772267 . ПМИД 26108222 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я дж к л Пасси Т., Халперн Дж.Х., Стихтенот Д.О., Эмрих Х.М., Хинтцен А. (2008). «Фармакология диэтиламида лизергиновой кислоты: обзор» . Нейронауки и терапия ЦНС . 14 (4): 295–314. дои : 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2008.00059.x . ПМК 6494066 . ПМИД 19040555 .

- ^ Нейнштейн Л.С. (2008). Охрана здоровья подростков: Практическое руководство . Липпинкотт Уильямс и Уилкинс. п. 931. ИСБН 9780781792561 . Архивировано из оригинала 26 декабря 2018 года . Проверено 27 января 2017 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я дж Муке ХА (июль 2016 г.). «От психиатрии к силе цветов и обратно: удивительная история диэтиламида лизергиновой кислоты». Технологии анализа и разработки лекарств . 14 (5): 276–281. дои : 10.1089/adt.2016.747 . ПМИД 27392130 .

- ^ Кранцлер Х.Р., Сирауло Д.А. (2 апреля 2007 г.). Клиническое руководство по психофармакологии наркологии . Американский психиатрический паб. п. 216. ИСБН 9781585626632 . Архивировано из оригинала 26 декабря 2018 года . Проверено 27 января 2017 г.

- ^ «Лизергид» . pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov . Архивировано из оригинала 12 апреля 2023 года . Проверено 12 апреля 2023 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Николс Д.Э. (апрель 2016 г.). Баркер Э.Л. (ред.). «Психоделики» . Фармакологические обзоры . 68 (2): 264–355. дои : 10.1124/пр.115.011478 . ISSN 0031-6997 . ПМЦ 4813425 . ПМИД 26841800 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с «Что такое галлюциногены?» . Национальный институт злоупотребления наркотиками . Январь 2016. Архивировано из оригинала 17 апреля 2016 года . Проверено 24 апреля 2016 г.

- ^ Лептургос П., Фортье-Дэви М., Кархарт-Харрис Р., Корлетт П.Р., Дюпюи Д., Хальберштадт А.Л. и др. (декабрь 2020 г.). «Галлюцинации под воздействием психоделиков и в спектре шизофрении: междисциплинарное и многомасштабное сравнение» . Бюллетень шизофрении . 46 (6): 1396–1408. дои : 10.1093/schbul/sbaa117 . ПМК 7707069 . ПМИД 32944778 .

Таламокортикальные связи были обнаружены измененными в психоделических состояниях. В частности, было обнаружено, что ЛСД избирательно увеличивает эффективную связь таламуса с определенными областями DMN, в то время как другие связи ослабляются. Кроме того, усиление связей таламуса с правой веретенообразной извилиной и передней островковой частью коррелировало со зрительными и слуховыми галлюцинациями (АГ) соответственно.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Хольце Ф., Визели П., Лей Л., Мюллер Ф., Дольдер П., Стокер М. и др. (февраль 2021 г.). «Острые дозозависимые эффекты диэтиламида лизергиновой кислоты в двойном слепом плацебо-контролируемом исследовании на здоровых добровольцах» . Нейропсихофармакология . 46 (3): 537–544. дои : 10.1038/s41386-020-00883-6 . ПМК 8027607 . ПМИД 33059356 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я «Профиль ЛСД (химия, эффекты, другие названия, синтез, способ применения, фармакология, медицинское применение, контрольный статус)» . ЕЦМНДА . Архивировано из оригинала 28 апреля 2021 года . Проверено 14 июля 2018 г.

- ^ Слоат С (27 января 2017 г.). «Вот почему вам не избежать многочасового кислотного трипа» . Инверсия . Архивировано из оригинала 11 июня 2021 года . Проверено 3 февраля 2020 г.

- ^ Лихти М.Э., Долдер ПК, Шмид Й. (май 2017 г.). «Изменения сознания и переживания мистического типа после острого ЛСД у людей» . Психофармакология . 234 (9–10): 1499–1510. дои : 10.1007/s00213-016-4453-0 . ПМК 5420386 . ПМИД 27714429 .

- ^ Гершон Л. (19 июля 2016 г.). «Как ЛСД перешел от исследования к религии» . JSTOR Daily . Архивировано из оригинала 28 января 2021 года . Проверено 14 июля 2018 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с «Таблица наиболее часто злоупотребляемых наркотиков» . Национальный институт по борьбе со злоупотреблением наркотиками . 2 июля 2018 г. Архивировано из оригинала 1 марта 2020 г. Проверено 14 июля 2018 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Халперн Дж. Х., Лернер А. Г., Пасси Т. (2018). Обзор стойкого расстройства восприятия галлюциногенов (HPPD) и предварительное исследование субъектов, заявляющих о симптомах HPPD . Актуальные темы поведенческой нейронауки. Том. 36. С. 333–360. дои : 10.1007/7854_2016_457 . ISBN 978-3-662-55878-2 . ПМИД 27822679 .

- ^ Вонг С., Ю А.Ю., Фабиано Н., Финкельштейн О., Пасрича А., Джонс БДМ и др. (август 2023 г.). «Помимо псилоцибина: обзор терапевтического потенциала других серотонинергических психоделиков при психических расстройствах и расстройствах, связанных с употреблением психоактивных веществ». Журнал психоактивных препаратов : 1–17. дои : 10.1080/02791072.2023.2251133 . ПМИД 37615379 . S2CID 261098164 .

- ^ Уокер С.Р., Пулелла Г.А., Пигготт М.Дж., Дагган П.Дж. (июль 2023 г.). «Введение в химию и фармакологию психоделических препаратов» . Австралийский химический журнал . 76 (5): 236–257. дои : 10.1071/CH23050 .

- ^ Малларони П., Мейсон Н.Л., Винкенбош ФРД, Рамаекерс Дж.Г. (апрель 2022 г.). «Схемы использования новых психоделиков: экспериментальные отпечатки пальцев замещенных фенэтиламинов, триптаминов и лизергамидов» . Психофармакология . 239 (6): 1783–1796. дои : 10.1007/s00213-022-06142-4 . ПМК 9166850 . ПМИД 35487983 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж Николс Д.Е. (февраль 2004 г.). «Галлюциногены». Фармакология и терапия . 101 (2): 131–181. doi : 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2003.11.002 . ISSN 1879-016X . ПМИД 14761703 .

- ^ Гирн М., Роузман Л., Бернхардт Б., Смоллвуд Дж., Кархарт-Харрис Р., Спренг Р.Н. (3 мая 2020 г.). «Серотонинергические психоделические препараты ЛСД и псилоцибин уменьшают иерархическую дифференциацию унимодальной и трансмодальной коры» . биоRxiv . дои : 10.1101/2020.05.01.072314 . S2CID 233346402 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Кархарт-Харрис Р.Л., Мутукумарасвами С., Роузман Л., Кэлен М., Дрог В., Мерфи К. и др. (11 апреля 2016 г.). «Нейронные корреляты опыта ЛСД, выявленные с помощью мультимодальной нейровизуализации» . Труды Национальной академии наук Соединенных Штатов Америки . 113 (17): 4853–4858. Бибкод : 2016PNAS..113.4853C . дои : 10.1073/pnas.1518377113 . ПМЦ 4855588 . ПМИД 27071089 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Боррото-Эскуэла Д.О., Ромеро-Фернандес В., Нарваес М., Офлихан Дж., Агнати Л.Ф., Фуксе К. (январь 2014 г.). «Галлюциногенные агонисты 5-HT2AR LSD и DOI усиливают распознавание протомера дофамина D2R и передачу сигналов гетерорецепторных комплексов D2-5-HT2A». Связь с биохимическими и биофизическими исследованиями . 443 (1): 278–84. дои : 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.11.104 . ПМИД 24309097 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Марона-Левика Д., Тистед Р.А., Николс Д.Е. (июль 2005 г.). «Отличные временные фазы в поведенческой фармакологии ЛСД: эффекты, опосредованные рецептором дофамина D2, у крыс и последствия психоза». Психофармакология . 180 (3): 427–35. дои : 10.1007/s00213-005-2183-9 . ПМИД 15723230 . S2CID 23565306 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Хофманн А (2009). ЛСД, мой трудный ребенок: размышления о священных наркотиках, мистике и науке (4-е изд.). Санта-Крус, Калифорния: Многопрофильная ассоциация психоделических исследований. ISBN 978-0-9798622-2-9 . OCLC 610059315 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж Ли М.А., Шлейн Б. (1992). Кислотные сны: полная социальная история ЛСД: ЦРУ, шестидесятые и далее . Нью-Йорк: Гроув Вайденфельд. ISBN 0-8021-3062-3 . ОСЛК 25281992 .

- ^ Эттингер Р.Х. (2017). Психофармакология . Психология Пресс. п. 226. ИСБН 978-1-351-97870-5 . Архивировано из оригинала 27 сентября 2021 года . Проверено 27 сентября 2021 г.

- ^ «Психиатрические исследования галлюциногенов» . www.druglibrary.org . Архивировано из оригинала 26 июля 2021 года . Проверено 26 июля 2021 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Чвелос Н., Блюетт Д.Б., Смит К.М., Хоффер А. (сентябрь 1959 г.). «Использование диэтиламида d-лизергиновой кислоты при лечении алкоголизма». Ежеквартальный журнал исследований алкоголя . 20 (3): 577–590. дои : 10.15288/qjsa.1959.20.577 . ПМИД 13810249 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Кребс Т.С., Йохансен ПО (июль 2012 г.). «Диэтиламид лизергиновой кислоты (ЛСД) при алкоголизме: метаанализ рандомизированных контролируемых исследований». Журнал психофармакологии . 26 (7): 994–1002. дои : 10.1177/0269881112439253 . ПМИД 22406913 . S2CID 10677273 .

- ^ Подкомитет по общественному здравоохранению и благосостоянию Комитета Палаты представителей Конгресса США по межштатной и внешней торговле (1968). Усиление контроля над галлюциногенами и другими опасными наркотиками . Типография правительства США. Архивировано из оригинала 13 июля 2020 года . Проверено 3 августа 2021 г.

- ^ Национальный институт по борьбе со злоупотреблением наркотиками. «Галлюциногены» . Архивировано из оригинала 3 июня 2020 года . Проверено 14 июля 2018 г.

- ^ Йоки Р.А., Видурек Р.А., Кинг К.А. (июль 2020 г.). «Тенденции в употреблении ЛСД среди взрослых в США: 2015–2018 гг.». Наркотическая и алкогольная зависимость . 212 : 108071. doi : 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108071 . ПМИД 32450479 . S2CID 218893155 .

- ^ «Факты о наркотиках: галлюциногены – ЛСД, пейот, псилоцибин и PCP» . Национальный институт по борьбе со злоупотреблением наркотиками. Декабрь 2014. Архивировано из оригинала 16 февраля 2015 года . Проверено 17 февраля 2015 г.

- ^ Фэйи Д., Миллер Дж.С. (ред.). Алкоголь и наркотики в Северной Америке: Историческая энциклопедия . п. 375. ИСБН 978-1-59884-478-8 .

- ↑ San Francisco Chronicle , 20 сентября 1966 г., страница первая.

- ^ Гроф С. , Гроф Дж.Х. (1979). Царства человеческого бессознательного (наблюдения в ходе исследований ЛСД) . Лондон: Souvenir Press (E & A) Ltd., стр. 13–14. ISBN 978-0-285-64882-1 . Архивировано из оригинала 18 октября 2007 года . Проверено 18 ноября 2007 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Натт DJ, Кинг Лос-Анджелес, Николс Д.Э. (август 2013 г.). «Влияние законов о наркотиках Списка I на нейробиологические исследования и инновации в лечении». Обзоры природы. Нейронаука . 14 (8): 577–585. дои : 10.1038/nrn3530 . ПМИД 23756634 . S2CID 1956833 .

- ^ Кэмпбелл Д. (23 июля 2016 г.). «Ученые изучают возможную пользу ЛСД и экстази для здоровья | Наука» . Хранитель . Архивировано из оригинала 23 июля 2016 года . Проверено 23 июля 2016 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Люстберг Д. (14 октября 2022 г.). «Кислота от беспокойства: быстрый и длительный анксиолитический эффект ЛСД» . Обзор психоделической науки . Архивировано из оригинала 1 декабря 2022 года . Проверено 1 декабря 2022 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Хольце Ф., Гассер П., Мюллер Ф., Долдер ПК, Лихти М.Э. (сентябрь 2022 г.). «Терапия с применением диэтиламида лизергиновой кислоты у пациентов с тревогой, имеющими или не угрожающими жизни заболеваниями: рандомизированное двойное слепое плацебо-контролируемое исследование фазы II» . Биологическая психиатрия . 93 (3): 215–223. doi : 10.1016/j.biopsych.2022.08.025 . ПМИД 36266118 . S2CID 252095586 .

- ^ Дос Сантос Р.Г., Осорио Флорида, Криппа Х.А., Риба Дж., Зуарди А.В., Халлак Дж.Е. (июнь 2016 г.). «Антидепрессивное, анксиолитическое и антиаддиктивное действие аяуаски, псилоцибина и диэтиламида лизергиновой кислоты (ЛСД): систематический обзор клинических исследований, опубликованных за последние 25 лет» . Терапевтические достижения в психофармакологии . 6 (3): 193–213. дои : 10.1177/2045125316638008 . ПМК 4910400 . ПМИД 27354908 .

- ^ «История ЛСД-терапии» . Druglibrary.org . Архивировано из оригинала 7 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 7 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ «Галлюциногены – ЛСД, пейот, псилоцибин и PCP» . Информационные факты о НИДА . Национальный институт по борьбе со злоупотреблением наркотиками (NIDA). Июнь 2009 г. Архивировано из оригинала 21 ноября 2009 г.

- ^ Шифф П.Л. (октябрь 2006 г.). «Спорынья и ее алкалоиды» . Американский журнал фармацевтического образования . 70 (5): 98. дои : 10.5688/aj700598 . ПМК 1637017 . ПМИД 17149427 .

- ^ Маич Т., Шмидт Т.Т., Галлинат Дж. (март 2015 г.). «Пиковые переживания и феномен послесвечения: когда и как терапевтические эффекты галлюциногенов зависят от психоделических переживаний?». Журнал психофармакологии . 29 (3): 241–253. дои : 10.1177/0269881114568040 . ПМИД 25670401 . S2CID 16483172 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Хониг Д. «Часто задаваемые вопросы» . Эровид . Архивировано из оригинала 12 февраля 2016 года.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б МакГлотлин В., Коэн С., МакГлотлин М.С. (ноябрь 1967 г.). «Длительное воздействие ЛСД на нормальных людей» (PDF) . Архив общей психиатрии . 17 (5): 521–532. doi : 10.1001/archpsyc.1967.01730290009002 . ПМИД 6054248 . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 30 апреля 2011 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Правительство Канады (1996 г.). «Закон о контролируемых наркотиках и веществах» . Законы о справедливости . Министерство юстиции Канады. Архивировано из оригинала 15 декабря 2013 года . Проверено 15 декабря 2013 г.

- ^ Рогге Т. (21 мая 2014 г.), Употребление психоактивных веществ - ЛСД , MedlinePlus, Национальная медицинская библиотека США, заархивировано из оригинала 28 июля 2016 г. , получено 14 июля 2016 г.

- ^ CESAR (29 октября 2013 г.), LSD , Центр исследований злоупотребления психоактивными веществами, Университет Мэриленда, заархивировано из оригинала 15 июля 2016 г. , получено 14 июля 2016 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Линтон Х.Р., Лэнгс Р.Дж. (май 1962 г.). «Субъективные реакции на диэтиламид лизергиновой кислоты (ЛСД-25)». Архив общей психиатрии . 6 (5): 352–368. doi : 10.1001/archpsyc.1962.01710230020003 .

- ^ Кац М.М., Васков И.Е., Олссон Дж. (февраль 1968 г.). «Характеристика психологического состояния, вызванного ЛСД». Журнал аномальной психологии . 73 (1): 1–14. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.409.4030 . дои : 10.1037/h0020114 . ПМИД 5639999 .

- ^ Паркер Л.А. (июнь 1996 г.). «ЛСД вызывает предпочтение места и избегание вкуса, но не вызывает отвращения к вкусу у крыс». Поведенческая нейронаука . 110 (3): 503–508. дои : 10.1037/0735-7044.110.3.503 . ПМИД 8888996 .

- ^ Остер Г (1966). «Муаровые узоры и зрительные галлюцинации» (PDF) . Психоделический обзор . 7 : 33–40. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 19 апреля 2017 г.

- ^ Кэлен М., Роузман Л., Кахан Дж., Сантос-Рибейро А., Орбан С., Лоренц Р. и др. (июль 2016 г.). «ЛСД модулирует образы, вызванные музыкой, посредством изменений в парагиппокампальных связях». Европейская нейропсихофармакология . 26 (7): 1099–1109. дои : 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2016.03.018 . ПМИД 27084302 . S2CID 24037275 .

- ^ Натт DJ, King LA, Phillips LD (ноябрь 2010 г.). «Вред от наркотиков в Великобритании: многокритериальный анализ решений». Ланцет . 376 (9752): 1558–1565. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.690.1283 . дои : 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61462-6 . ПМИД 21036393 . S2CID 5667719 .

- ^ Натт Д., Кинг Л.А., Солсбери В., Блейкмор К. (март 2007 г.). «Разработка рациональной шкалы оценки вреда наркотиков, потенциально злоупотребляемых». Ланцет . 369 (9566): 1047–53. дои : 10.1016/s0140-6736(07)60464-4 . ПМИД 17382831 . S2CID 5903121 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж Николс Д.Э., Гроб К.С. (март 2018 г.). «Является ли ЛСД токсичным?». Международная судебно-медицинская экспертиза . 284 : 141–145. doi : 10.1016/j.forsciint.2018.01.006 . ПМИД 29408722 .

- ^ Натт DJ, King LA, Phillips LD (ноябрь 2010 г.). «Вред от наркотиков в Великобритании: многокритериальный анализ решений». Ланцет . 376 (9752): 1558–65. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.690.1283 . дои : 10.1016/s0140-6736(10)61462-6 . ПМИД 21036393 . S2CID 5667719 .

- ^ Кребс Т.С., Йохансен ПО (19 августа 2013 г.). Лу Л (ред.). «Психоделики и психическое здоровье: популяционное исследование» . ПЛОС ОДИН . 8 (8): e63972. Бибкод : 2013PLoSO...863972K . дои : 10.1371/journal.pone.0063972 . ПМЦ 3747247 . ПМИД 23976938 .

- ^ Мюррей Р.М., Папарелли А., Моррисон П.Д., Маркони А., Ди Форти М (октябрь 2013 г.), «Что мы можем узнать о шизофрении, изучая человеческую модель психоза, вызванного лекарствами?», Американский журнал медицинской генетики, часть B , специальный выпуск : Выявление истоков психических заболеваний: Фестиваль в честь Мин Т. Цуана, 162 (7): 661–670, doi : 10.1002/ajmg.b.32177 , PMID 24132898 , S2CID 205326399

- ^ Рокфеллер IV JD (8 декабря 1994 г.). «Опасны ли военные исследования для здоровья ветеранов? Уроки за полвека, часть F. ГАЛЛЮЦИНОГЕНЫ» . Западная Вирджиния: 103-й Конгресс, 2-я сессия-S. Прт. 103-97; Отчет штаба подготовлен для комитета по делам ветеранов. Архивировано из оригинала 13 августа 2006 года . Проверено 13 декабря 2018 г.

- ^ Миддфелл Р. (март 1967 г.). «Влияние ЛСД на внушаемость раскачивания тела у группы больничных пациентов» (PDF) . Британский журнал психиатрии . 113 (496): 277–280. дои : 10.1192/bjp.113.496.277 . ПМИД 6029626 . S2CID 19439549 . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 30 апреля 2011 г.

- ^ Сьоберг Б.М., Холлистер Л.Е. (ноябрь 1965 г.). «Влияние психотомиметических препаратов на первичную внушаемость». Психофармакология . 8 (4): 251–262. дои : 10.1007/BF00407857 . ПМИД 5885648 . S2CID 15249061 .

- ^ Халперн Дж. Х., Папа Х. Г. (март 2003 г.). «Стойкое галлюциногенное расстройство восприятия: что мы знаем спустя 50 лет?». Наркотическая и алкогольная зависимость . 69 (2): 109–19. дои : 10.1016/S0376-8716(02)00306-X . ПМИД 12609692 .

- ^ Мюллер Ф., Краус Э., Хольце Ф., Беккер А., Лей Л., Шмид Ю. и др. (январь 2022 г.). «Флэшбэк-феномены после приема ЛСД и псилоцибина в контролируемых исследованиях со здоровыми участниками» . Психофармакология . 239 (6): 1933–1943. дои : 10.1007/s00213-022-06066-z . ПМЦ 9166883 . ПМИД 35076721 . S2CID 246276633 .

- ^ Йохансен ПО, Кребс Т.С. (март 2015 г.). «Психоделики, не связанные с проблемами психического здоровья или суицидальным поведением: исследование населения». Журнал психофармакологии . 29 (3): 270–279. дои : 10.1177/0269881114568039 . ПМИД 25744618 . S2CID 2025731 .

- ^ Холланд Д., Пасси Т. (2011). Феномен флэшбека как последствие приема галлюциногенов . Сознание – Познание – Опыт (на немецком языке). Том 2. Отчет ВВБ. ISBN 978-3-86135-207-5 . Архивировано из оригинала 9 июня 2023 года . Проверено 9 июня 2023 г.

- ^ Авраам Х.Д., Даффи Ф.Х. (октябрь 1996 г.). «Стабильная количественная разница ЭЭГ при расстройстве зрения после ЛСД с помощью анализа разделенных половин: доказательства растормаживания». Психиатрические исследования . 67 (3): 173–87. дои : 10.1016/0925-4927(96)02833-8 . ПМИД 8912957 . S2CID 7587687 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Натт DJ, Castle D (7 марта 2023 г.). «Лекарственное взаимодействие с психотропными средствами». Психоделики как психиатрические лекарства . Издательство Оксфордского университета . ISBN 9780192678522 . Архивировано из оригинала 21 мая 2023 года . Проверено 21 мая 2023 г.

- ^ Симонссон О., Голдберг С.Б., Чемберс Р., Осика В., Лонг Д.М., Хендрикс П.С. (1 октября 2022 г.). «Распространенность и ассоциации классических припадков, связанных с психоделическими веществами, в популяционной выборке» . Наркотическая и алкогольная зависимость . 239 . 109586. doi : 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2022.109586 . ПМЦ 9627432 . ПМИД 35981469 .

- ^ Фишер Д., Унгерлейдер Дж. (1967). «Большие эпилептические припадки после приема ЛСД» . Западный медицинский журнал . 106 (3): 201–211. ПМЦ 1502729 . ПМИД 4962683 .

- ^ Бухборн Т., Грекш Г., Дитрих Д., Холлт В. (2016). «Глава 79 - Толерантность к диэтиламиду лизергиновой кислоты: обзор, корреляции и клинические последствия». Невропатология наркозависимости и злоупотребления психоактивными веществами . Том. 2. Академическая пресса . стр. 848–849. дои : 10.1016/B978-0-12-800212-4.00079-0 . ISBN 978-0-12-800212-4 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Дольдер Д.С., Грюнблатт Э., Мюллер Ф., Боргвардт С.Дж., Лихти М.Э. (28 июня 2017 г.). «Однократная доза ЛСД не изменяет экспрессию гена рецептора серотонина 2А (HTR2A) или генов реакции раннего роста (EGR1-3) у здоровых субъектов» . Границы в неврологии . 8 : 423. дои : 10.3389/fphar.2017.00423 . ПМЦ 5487530 . ПМИД 28701958 .

- ^ Койман Н.И., Виллегерс Т., Ройзер А., Мюллерс В.М., Крамерс С., Виссерс ККП и др. (4 января 2023 г.). «Являются ли психоделики ответом на хроническую боль: обзор современной литературы» . Болевая практика . 23 (4): 455. doi : 10.1111/papr.13203 . hdl : 2066/291903 . ISSN 1533-2500 . ПМИД 36597700 . S2CID 255470638 .

- ^ Вольбах А.Б., Исбелл Х., Майнер Э.Дж. (март 1962 г.). «Перекрестная толерантность между мескалином и ЛСД-25, сравнение реакций на мескалин и ЛСД» . Психофармакология . 3 : 1–14. дои : 10.1007/BF00413101 . ПМИД 14007904 . S2CID 23803624 . Архивировано из оригинала 19 апреля 2014 года . Проверено 1 декабря 2007 г.

- ^ Исбелл Х., Вольбах А.Б., Виклер А., Майнер Э.Дж. (1961). «Перекрестная толерантность между ЛСД и псилоцибином» . Психофармакология . 2 (3): 147–159. дои : 10.1007/BF00407974 . ПМИД 13717955 . S2CID 7746880 . Архивировано из оригинала 15 марта 2016 года . Проверено 1 декабря 2007 г.

- ^ Розенберг Д., Исбелл Х., Майнер Э., Логан С. (7 августа 1963 г.). «Действие N,N-диметилтриптамина на людей, толерантных к диэтиламиду лизергиновой кислоты». Психофармакология . 5 (3): 223–224. дои : 10.1007/BF00413244 . ПМИД 14138757 . S2CID 32950588 .

- ^ Страссман Р.Дж., Куаллс Ч.Р., Берг Л.М. (1 мая 1996 г.). «Дифференциальная толерантность к биологическим и субъективным эффектам четырех близко расположенных доз N,N-диметилтриптамина у людей» . Биологическая психиатрия . 39 (9): 784–785. дои : 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00200-6 . ПМИД 8731519 . S2CID 3220559 . Архивировано из оригинала 4 мая 2023 года . Проверено 4 мая 2023 г.

- ^ Джонас С., Даунер Дж.Д. (октябрь 1964 г.). «Грубые изменения в поведении обезьян после введения ЛСД-25 и развитие толерантности к ЛСД-25». Психофармакология . 6 (4): 303–386. дои : 10.1007/BF00413161 . ПМИД 4953438 . S2CID 11768927 .