Итальянская кухня

| Часть серии о |

| Культура Италии |

|---|

|

| Люди |

| Традиции |

Итальянская кухня – это средиземноморская кухня. [1] Состоит из ингредиентов , рецептов и методов приготовления, разработанных в Италии со времен Римской империи и позже распространившихся по всему миру вместе с волнами итальянской диаспоры . [2] [3] [4] Значительные изменения произошли с колонизацией Америки и появлением картофеля , помидоров , перца , кукурузы и сахарной свеклы — последняя в больших количествах появилась в 18 веке. [5] [6] Это одно из самых известных и уважаемых гастрономических заведений мира. [7]

Итальянская кухня включает в себя глубоко укоренившиеся традиции, общие для всей страны, а также все региональные гастрономии , отличающиеся друг от друга, особенно между севером , центром и югом Италии, которые находятся в постоянном обмене. [8] [9] [10] Многие блюда, которые когда-то были региональными, в различных вариациях распространились по всей стране. [11] [12] Итальянская кухня предлагает изобилие вкусов и является одной из самых популярных и копируемых во всем мире. [13] Кухня оказала влияние на несколько других кухонь мира, в основном на кухню Соединенных Штатов в форме итало-американской кухни . [14]

One of the main characteristics of Italian cuisine is its simplicity, with many dishes made up of few ingredients, and therefore Italian cooks often rely on the quality of the ingredients, rather than the complexity of preparation.[15][16] Italian cuisine is at the origin of a turnover of more than €200 billion worldwide.[17] The most popular dishes and recipes, over the centuries, have often been created by ordinary people more so than by chefs, which is why many Italian recipes are suitable for home and daily cooking, respecting regional specificities, privileging only raw materials and ingredients from the region of origin of the dish and preserving its seasonality.[18][19][20]

The Mediterranean diet forms the basis of Italian cuisine, rich in pasta, fish, fruits, and vegetables.[21] Cheese, cold cuts, and wine are central to Italian cuisine, and along with pizza and coffee (especially espresso) form part of Italian gastronomic culture.[22] Desserts have a long tradition of merging local flavours such as citrus fruits, pistachio, and almonds with sweet cheeses such as mascarpone and ricotta or exotic tastes as cocoa, vanilla, and cinnamon. Gelato,[23] tiramisu,[24] and cassata are among the most famous examples of Italian desserts, cakes, and patisserie. Italian cuisine relies heavily on traditional products; the country has a large number of traditional specialities protected under EU law.[25] Italy is the world's largest producer of wine, as well as the country with the widest variety of indigenous grapevine varieties in the world.[26][27]

History

[edit]

Italian cuisine has developed over the centuries. Although the country known as Italy did not unite until the 19th century, the cuisine can claim traceable roots as far back as the 4th century BC. Food and culture were very important at that time evident from the cookbook (Apicius) which dates to the first century BC.[28] Through the centuries, neighbouring regions, conquerors, high-profile chefs, political upheaval, and the discovery of the New World have influenced its development. Italian cuisine started to form after the fall of the Roman Empire, when different cities began to separate and form their own traditions. Many different types of bread and pasta were made, and there was a variation in cooking techniques and preparation.

|

| Italian cuisine |

|---|

Trade and the location on the Silk Road with its routes to Asia also influenced the local development of special dishes. Due to the climatic conditions and the different proximity to the sea, different basic foods and spices were available from region to region. Regional cuisine is represented by some of the major cities in Italy. For example, Milan (in the north of Italy) is known for risottos, Trieste (in the northeast of Italy) is known for multicultural food, Bologna (in the centre of Italy) is known for its tortellini, and Naples (in the south of Italy) is famous for its pizzas.[29] Additionally, spaghetti is believed to have spread across Africa to Sicily and then on to Naples.[30][31]

Antiquity

[edit]The first known Italian food writer was a Greek Sicilian named Archestratus from Syracuse in the 4th century BC. He wrote a poem that spoke of using "top quality and seasonal" ingredients. He said that flavours should not be masked by spices, herbs or other seasonings. He placed importance on simple preparation of fish.[32]

Simplicity was abandoned and replaced by a culture of gastronomy as the Roman Empire developed. By the time De re coquinaria was published in the 1st century AD, it contained 470 recipes calling for heavy use of spices and herbs. The Romans employed Greek bakers to produce breads and imported cheeses from Sicily, as the Sicilians had a reputation as the best cheesemakers. The Romans reared goats for butchering, and grew artichokes and leeks.[32]

Some foods considered traditional were imported to Italy from foreign countries during the Roman era. This includes the jujube (Italian: giuggiole), which is celebrated as a regional cuisine in Arquà Petrarca.[33] The Romans also imported cherries, apricots, and peaches.[33]

Middle Ages

[edit]

Arabs invaded Sicily in the 9th century, introducing spinach, almonds, and rice.[34] They also brought with them foods from foreign lands that are celebrated as traditional Italian foods: citrus fruit, artichokes, chickpeas, pistachios, sugarcane, aubergines, and durum wheat, which is used to make pasta.[33] During the 12th century, a Norman king surveyed Sicily and saw people making long strings made from flour and water called atriya, which eventually became trii, a term still used for spaghetti in southern Italy.[35] Normans also introduced the casserole, salt cod (Italian: baccalà), and stockfish, all of which remain popular.[36]

Food preservation was either chemical or physical, as refrigeration did not exist. Meats and fish were smoked, dried, or kept on ice. Brine and salt were used to pickle items such as herring, and to cure pork. Root vegetables were preserved in brine after they had been parboiled. Other means of preservation included oil, vinegar, or immersing meat in congealed, rendered fat. For preserving fruits, liquor, honey, and sugar were used.[37]

The oldest Italian book on cuisine is the 13th century Liber de coquina (English: Cookbook) written in Naples. Dishes include "Roman-style" cabbage (ad usum romanorum), ad usum campanie which were "small leaves" prepared in the "Campanian manner", a bean dish from the Marca di Trevisio, a torta, compositum londardicum, dishes similar to dishes the modern day. Two other books from the 14th century include recipes for Roman pastello, Lasagna pie, and call for the use of salt from Sardinia or Chioggia.[38]

In the 15th century, Maestro Martino was chef to the Patriarch of Aquileia at the Vatican. His Libro de arte coquinaria (English: Culinary art book) describes a more refined and elegant cuisine. His book contains a recipe for Maccaroni Siciliani, made by wrapping dough around a thin iron rod to dry in the sun. The macaroni was cooked in capon stock flavoured with saffron, displaying Persian influences. Martino noted the avoidance of excessive spices in favour of fresh herbs.[36] The Roman recipes include coppiette (air-dried salami) and cabbage dishes. His Florentine dishes include eggs with Bolognese torta, Sienese torta and Genoese recipes such as piperata (sweets), macaroni, squash, mushrooms, and spinach pie with onions.[39]

Martino's text was included in a 1475 book by Bartolomeo Platina printed in Venice entitled De honesta voluptate et valetudine (English: On Honest Pleasure and Good Health). Platina puts Martino's "Libro" in a regional context, writing about perch from Lake Maggiore, sardines from Lake Garda, grayling from Adda, hens from Padua, olives from Bologna and Piceno, turbot from Ravenna, rudd from Lake Trasimeno, carrots from Viterbo, bass from the Tiber, roviglioni and shad from Lake Albano, snails from Rieti, figs from Tuscolo, grapes from Narni, oil from Cassino, oranges from Naples and eels from Campania. Grains from Lombardy and Campania are mentioned as is honey from Sicily and Taranto. Wine from the Ligurian coast, Greco from Tuscany and San Severino, and Trebbiano from Tuscany and Piceno are also mentioned in the book.[40]

Early modern era

[edit]The courts of Florence, Rome, Venice, and Ferrara were central to the cuisine. Cristoforo di Messisbugo, steward to Ippolito d'Este, published Banchetti Composizioni di Vivande (English: Banquets Compositions of Food) in 1549. Messisbugo gives recipes for pies and tarts (containing 124 recipes with various fillings). The work emphasizes the use of Eastern spices and sugar.[41]

In 1570, Bartolomeo Scappi, personal chef to Pope Pius V, wrote his Opera (English: Work) in five volumes, giving a comprehensive view of Italian cooking of that period. It contains over 1,000 recipes, with information on banquets including displays and menus as well as illustrations of kitchen and table utensils. This book differs from most books written for the royal courts in its preference for domestic animals and courtyard birds rather than game.

Recipes include lesser cuts of meats such as tongue, head, and shoulder. The third volume has recipes for fish in Lent. These fish recipes are simple, including poaching, broiling, grilling, and frying after marination.

Particular attention is given to seasons and places where fish should be caught. The final volume includes pies, tarts, fritters, and a recipe for a sweet Neapolitan pizza (not the current savoury version, as tomatoes had not yet been introduced to Italy). However, such items from the New World as corn (maize) and turkey are included.[42] Eventually, through the Columbian exchange, Italian cuisine would also adopt not just tomatoes as a key flavour, but also beans, pumpkins, courgette, and peppers, all of which came from the Americas during the last few hundred years.[33]

In the first decade of the 17th century, Giacomo Castelvetro wrote Breve Racconto di Tutte le Radici di Tutte l'Herbe et di Tutti i Frutti (English: A Brief Account of All Roots, Herbs, and Fruit), translated into English by Gillian Riley. Originally from Modena, Castelvetro moved to England because he was a Protestant. The book lists Italian vegetables and fruits along with their preparation. He featured vegetables as a central part of the meal, not just as accompaniments.[42] Castelvetro favoured simmering vegetables in salted water and serving them warm or cold with olive oil, salt, fresh ground pepper, lemon juice, verjus, or orange juice. He also suggested roasting vegetables wrapped in damp paper over charcoal or embers with a drizzle of olive oil. Castelvetro's book is separated into seasons with hop shoots in the spring and truffles in the winter, detailing the use of pigs in the search for truffles.[42]

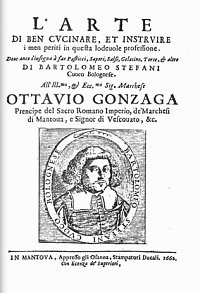

In 1662, Bartolomeo Stefani, chef to the Duchy of Mantua, published L'Arte di Ben Cucinare (English: The Art of Well Cooking). He was the first to offer a section on vitto ordinario (English: ordinary food). The book described a banquet given by Duke Charles for Queen Christina of Sweden, with details of the food and table settings for each guest, including a knife, fork, spoon, glass, a plate (instead of the bowls more often used), and a napkin.[43]

Other books from this time, such as Galatheo (English: Etiquette) by Giovanni della Casa, tell how scalci (English: waiters) should manage themselves while serving their guests. Waiters should not scratch their heads or other parts of themselves, or spit, sniff, cough or sneeze while serving diners. The book also told diners not to use their fingers while eating and not to wipe sweat with their napkin.[43]

Modern era

[edit]

At the beginning of the 18th century, Italian culinary books began to emphasize the regionalism of Italian cuisine rather than French cuisine. Books written then were no longer addressed to professional chefs but to bourgeois housewives.[44] Periodicals in booklet form such as La cuoca cremonese (English: The Cook of Cremona) in 1794 give a sequence of ingredients according to season along with chapters on meat, fish, and vegetables. As the century progressed these books increased in size, popularity, and frequency.[45]

In the 18th century, medical texts warned peasants against eating refined foods as it was believed that these were poor for their digestion and their bodies required heavy meals. It was believed that peasants ate poorly because they preferred eating poorly. However, many peasants had to eat rotten food and mouldy bread because that was all they could afford.[46]

In 1779, Antonio Nebbia from Macerata in the Marche region, wrote Il Cuoco Maceratese (English: The Cook of Macerata). Nebbia addressed the importance of local vegetables and pasta, rice, and gnocchi. For stock, he preferred vegetables and chicken over other meats.

In 1773, the Neapolitan Vincenzo Corrado's Il Cuoco Galante (English: The Courteous Cook) gave particular emphasis to vitto pitagorico (English: vegetarian food). "Pythagorean food consists of fresh herbs, roots, flowers, fruits, seeds and all that is produced in the earth for our nourishment. It is so-called because Pythagoras, as is well known, only used such produce. There is no doubt that this kind of food appears to be more natural to man, and the use of meat is noxious." This book was the first to give the tomato a central role with 13 recipes.

Zuppa al pomodoro (lit. 'tomato soup') in Corrado's book is a dish similar to today's Tuscan pappa al pomodoro. Corrado's 1798 edition introduced a "Treatise on the Potato" after the French Antoine-Augustin Parmentier's successful promotion of the tuber.[48] In 1790, Francesco Leonardi in his book L'Apicio moderno (English: Modern Apicius) sketches a history of the Italian cuisine from the Roman Age and gives the first recipe of a tomato-based sauce.[49]

In the 19th century, Giovanni Vialardi, chef to King Victor Emmanuel II, wrote Trattato di cucina, Pasticceria moderna, Credenza e relativa Confettureria (English: A Treatise of Modern Cookery and Patisserie) with recipes "suitable for a modest household". Many of his recipes are for regional dishes from Turin, including 12 for potatoes such as Genoese Cappon Magro. In 1829, Il Nuovo Cuoco Milanese Economico (English: The New Economic Milanese Chef) by Giovanni Felice Luraschi featured Milanese dishes such as kidney with anchovies and lemon and gnocchi alla romana. Gian Battista and Giovanni Ratto's La Cucina Genovese (English: Genoese cuisine) in 1871 addressed the cuisine of Liguria. This book contained the first recipe for pesto. La Cucina Teorico-Pratica (English: The Theoretical-Practical Cuisine) written by Ippolito Cavalcanti described the first recipe for pasta with tomatoes.[50]

La scienza in cucina e l'arte di mangiare bene (English: The Science of Cooking and the Art of Eating Well), by Pellegrino Artusi, first published in 1891, is widely regarded as the canon of classic modern Italian cuisine, and it is still in print. Its recipes predominantly originate from Romagna and Tuscany, where he lived. Around 1880, two decades after the Unification of Italy, was the beginning of Italian diaspora, and with it started the spread of Italian cuisine in the world.[51]

Contemporary era

[edit]

Italy has a large number of traditional specialities protected under EU law.[25] From the 1950s onwards, a great variety of typical products of Italian cuisine have been recognised as PDO, PGI, TSG and GI by the Council of the European Union, to which they are added the indicazione geografica tipica (IGT), the regional prodotto agroalimentare tradizionale (PAT) and the municipal denominazione comunale d'origine (De.C.O.).[52][53] In the oenological field, there are specific legal protections: the denominazione di origine controllata (DOC) and the denominazione di origine controllata e garantita (DOCG).[54] protected designation of origin (PDO) and protected geographical indications (PGI) have also been established in olive growing.[55] Some of these are new introductions: the kiwifruit was introduced from New Zealand to Italy in the 1970s, and three decades later, the province of Latina was designated the "Land of the Kiwi" and given protected status as a regional delicacy.[33]

Italian cuisine is one of the most popular and copied cultures worldwide.[13] The lack or total unavailability of some of its most characteristic ingredients outside of Italy, leads to the complete de-naturalization of Italian ingredients, and above all else leads to falsifications (or food fraud).[58] This phenomenon, widespread in all continents, is better known as Italian Sounding, consisting in the use of Italian words as well as images, colour combinations (the Italian tricolour), geographical references, and brands evocative of Italy to promote and market agri-food products which in reality have nothing to do with Italian cuisine.[57] Italian Sounding invests in almost every sector of Italian food, from the most famous Italian cheeses to cured meats, a variety of pasta, regional bread, extra virgin olive oils, and wines.[58] Counterfeit products violate registered trademarks or other distinctive signs protected by law such as the designations of origin (DOC, PDO, DOCG, PGI, TSG, IGT). Therefore, the counterfeiting is legally punishable.[59] However, Italian Sounding cannot be classified as illegal from a strictly legal standpoint, but they still represent "a huge damage to the Italian economy and to the potential resources of Made in Italy".[60] Two out of three Italian agri-food products sold worldwide are not made in Italy.[61] The Italian Sounding phenomenon is estimated to generate €55 billion worldwide annually.[62]

Following the spread of fast food, also in Italy, imported from Anglo-Saxon countries and in particular from the United States in 1986, in Bra, Piedmont, the Slow Food cultural and gastronomic movement was founded, then converted into an institution with the aim of protecting culinary specificities and to safeguard various regional products of Italian cuisine under the control of the Slow Food Presidia.[63] Slow Food also focuses on food quality, rather than quantity.[64] It speaks out against overproduction and food waste,[65] and sees globalization as a process in which small and local farmers and food producers should be simultaneously protected from and included in the global food system.[66][67]

The Italian chef Gualtiero Marchesi (1930–2017) is unanimously considered the founder of the new Italian cuisine[68] and, in the opinion of many, the most famous Italian chef in the world.[69] He contributed mostly to the development of Italian cuisine, placing the Italian culinary culture among the most important around the world, with the creation, thanks to the use of Italian ingredients, dishes and culinary traditions, of the Italian version of the French nouvelle cuisine.[70] Italian nouvelle cuisine is characterized by lighter, more delicate dishes and an increased emphasis on presentation, and it designed for the most expensive restaurants.[71] It is defined as a "cuisine of the head rather than the throat" and it is characterized by the separation of flavours, without ever upsetting the ancient Italian culinary tradition despite the use, in its recipes, of some culinary traditions of other countries.[71][72] He is known for using modern technology and classic cuisine.

Basic foods

[edit]

Italian cuisine has a great variety of different ingredients which are commonly used, ranging from fruits and vegetables to grains to cheeses, meats, and fish. In northern Italy, fish (such as cod, or baccalà), potatoes, rice, corn (maize), sausages, pork, and different types of cheese are the most common ingredients. Pasta dishes with tomato are common throughout Italy.[73][74] Italians use ingredients that are fresh and subtly seasoned and spiced.[75]

In northern Italy there are many types of stuffed pasta, although polenta and risotto are equally popular if not more so.[76] Ligurian ingredients include several types of fish and seafood dishes. Basil (found in pesto), nuts, and olive oil are very common. In Emilia-Romagna, common ingredients include prosciutto (Italian ham), cotechino, different sorts of salami, truffles, grana, Parmesan (Italian: Parmigiano Reggiano), tomatoes (Bolognese sauce or ragù) and balsamic vinegar (Italian: aceto balsamico).

Traditional central Italian cuisine uses ingredients such as tomatoes, all types of meat, fish, and pecorino.[78] In Tuscany, pasta (especially pappardelle) is traditionally served with meat sauce (including game meat).[79] In southern Italy, tomatoes (fresh or cooked into tomato sauce), peppers, olives and olive oil, garlic, artichokes, oranges, ricotta cheese, aubergines, courgette, certain types of fish (anchovies, sardines, and tuna), and capers are important components to the local cuisine.[80]

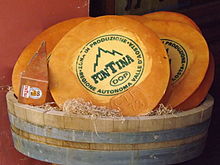

Many cheeses and dairy products are made in Italy.[81] There are more than 600 distinct types throughout the country,[82][83] of which 490 are protected and marked as PDO (protected designation of origin), PGI (protected geographical indication) and PAT (prodotto agroalimentare tradizionale).[84]

Olive oil is the most commonly used vegetable fat in Italian cooking and as the basis for sauces, replaced only in some recipes and in some geographical areas by butter or lard.[85] Italy is the largest consumer of olive oil, at 30% of the world total.[86] It also has the largest range of olive cultivars in existence and is the second largest producer and exporter in the world, producing more than 464,000 tons.[87][88] Bread has always been, as it has for other Mediterranean countries, a fundamental food in Italian cuisine.[89] There are numerous regional types of bread.[89]

Italian cuisine has a great variety of sausages and cured meats, many of which are protected and marked as PDO and PGI,[90] and make up 34% of the total of sausages and cured meats consumed in Europe,[91] while others are marked as PAT.[92] Salumi are Italian meat products typical of an antipasto, predominantly made from pork and cured. They are also include bresaola, which is made from beef, and some cooked products, such as mortadella and prosciutto.

Meat, especially beef, pork and poultry, is very present in Italian cuisine, in a very wide range of preparations and recipes.[93] It is also important as an ingredient in the preparation of sauces for pasta. In addition to the varieties mentioned, albeit less commonly, sheep, goat, horse, rabbit and, even less commonly, game meat are also consumed in Italy.[93]

Since Italy is largely surrounded by the sea, therefore having a great coastal development and being rich in lakes, fish (both marine and freshwater), as well as crustaceans, molluscs, and other seafood, enjoy a prominent place in Italian cuisine, as in general in the Mediterranean cuisine.[94] Fish is the second course in meals and is also an ingredient in the preparation of seasonings for types of pasta.[95] It is also widely used in appetisers.[96]

Italian cuisine is also well known (and well regarded) for its use of a diverse variety of pasta. Pasta include noodles in various lengths, widths, and shapes.[97] Most pastas may be distinguished by the shapes for which they are named—penne, maccheroni, spaghetti, linguine, fusilli, lasagne. Many more varieties are filled with other ingredients, such as ravioli and tortellini.[97]

The word pasta is also used to refer to dishes in which pasta products are a primary ingredient.[98] It is usually served with sauce. There are hundreds of different shapes of pasta with at least locally recognised names. Examples include spaghetti ('thin rods'), rigatoni ('tubes' or 'cylinders'), fusilli ('swirls'), and lasagne ('sheets'). Dumplings, such as gnocchi (made with potatoes or pumpkin) and noodles such as spätzle, are sometimes considered pasta.[99]

Pasta is divided into two broad categories: dry pasta (100% durum wheat flour mixed with water) and fresh pasta (also with soft wheat flour and almost always mixed with eggs).[100] Pasta is generally cooked by boiling. Under Italian law, dry pasta (pasta secca) can only be made from durum wheat flour or durum wheat semolina, and is more commonly used in southern Italy compared to their northern counterparts, who traditionally prefer the fresh egg variety.[101]

Durum flour and durum semolina have a yellow tinge in colour.[102] Italian dried pasta is traditionally cooked al dente (lit. 'to the tooth').[103] There are many types of wheat flour with varying gluten and protein levels depending on the variety of grain used.[104]

Particular varieties of pasta may also use other grains and milling methods to make the flour, as specified by law. Some pasta varieties, such as pizzoccheri, are made from buckwheat flour.[105] Fresh pasta may include eggs (Italian: pasta all'uovo, lit. 'egg pasta').[106]

Both dry and fresh pasta are used to prepare the dish, in three different ways:[107][108][109]

- pastasciutta: pasta is cooked and then served with a sauce or other condiment;

- minestrone: pasta is cooked and served in meat or vegetable broth (minestra), even together with chopped vegetables (minestrone);

- pasta al forno: the pasta is first cooked and seasoned, and then passed back to the oven.

Pizza, consisting of a usually round, flat base of leavened wheat-based dough topped with tomatoes, cheese, and often various other ingredients (such as anchovies, mushrooms, onions, olives, meats, and more), which is then baked at a high temperature, traditionally in a wood-fired oven,[110] is the best known and most consumed Italian food in the world.[111]

In 2009, upon Italy's request, Neapolitan pizza was registered with the European Union as a traditional speciality guaranteed dish,[112][113] and in 2017 the art of its making was included on UNESCO's list of intangible cultural heritage.[114] Up to 20% of the flour in the traditional pizza crust can be strong Manitoba flour, which was introduced to Italy from Canada as part of the Marshall Plan after World War II.[33] In Italy it is consumed as a single dish (pizza al piatto) or as a snack, even on the go (pizza al taglio).[115] In the various regions, dishes similar to pizza are the various types of focaccia, such as piadina, crescia, or sfincione.[116]

Regional cuisines

[edit]Each area has its own specialties, primarily at a regional level, but also at the provincial level. The differences can come from a bordering country (such as France, Austria, or Slovenia), whether a region is close to the sea or the mountains, and economics.[117] Italian cuisine is also seasonal with priority placed on the use of fresh produce.[118][119]

Abruzzo and Molise

[edit]

Pasta, meat, and vegetables are central to the cuisine of Abruzzo and Molise. Chili peppers (Italian: peperoncini) are typical of Abruzzo, where they are called diavoletti ('little devils') for their spicy heat. Due to the long history of shepherding in Abruzzo and Molise, lamb dishes are common. Lamb meat is often paired with pasta.[120] Mushrooms (usually wild mushrooms), rosemary, and garlic are also extensively used in Abruzzese cuisine.

Best-known is the extra virgin olive oil produced in the local farms on the hills of the region, marked by the quality level DOP and considered one of the best in the country.[121] Renowned wines such as Montepulciano DOCG and Trebbiano d'Abruzzo DOC are considered amongst the world's finest wines.[122] In 2012, a bottle of Trebbiano d'Abruzzo Colline Teramane ranked No. 1 in the top 50 Italian wine award.[123] Centerbe is a strong (72% alcohol), spicy herbal liqueur drunk by the locals. Another liqueur is genziana, a soft distillate of gentian roots.

The best-known dish from Abruzzo is arrosticini, little pieces of castrated lamb on a wooden stick and cooked on coals. The chitarra (lit. 'guitar') is a fine stringed tool that pasta dough is pressed through for cutting. In the province of Teramo, famous local dishes include the virtù soup (made with legumes, vegetables, and pork meat), the timballo (pasta sheets filled with meat, vegetables, or rice), and the mazzarelle (lamb intestines filled with garlic, marjoram, lettuce, and various spices). The popularity of saffron, grown in the province of L'Aquila, has waned in recent years.[120]

Also seafood is part important of cuisine of Abruzzo with fish products are brodetti,[124] scapece alla vastese,[125] baccalà all'abruzzese,[126] Mussels with saffron, classic cooked mussels prepared with parsley, onion, bay leaf, white wine, and olive oil, and seasoned with Saffron of l'Aquila sauce,[127] and coregone di Campotosto,[128][129] typical lake fish.

The most famous dish of Molise is cavatelli, a long shaped, handmade macaroni-type pasta made of flour, semolina, and water, often served with meat sauce, broccoli, or mushrooms. Pizzelle waffles are a common dessert, especially around Christmas.

Apulia

[edit]

Apulia is a massive food producer; major production includes wheat, tomatoes, courgette, broccoli, bell peppers, potatoes, spinach, aubergines, cauliflower, fennel, endive, chickpeas, lentils, beans, and cheese (such as the traditional caciocavallo and the famous burrata). Apulia is also the largest producer of olive oil in Italy. The sea offers abundant fish and seafood that are extensively used in the regional cuisine, especially oysters, and mussels.

Goat and lamb are occasionally used.[130] The region is known for pasta made from durum wheat and traditional pasta dishes featuring orecchiette-style pasta, often served with tomato sauce, potatoes, mussels, or broccoli rabe. Pasta with cherry tomatoes and arugula is also popular.[131]

Regional desserts include zeppole, doughnuts usually topped with powdered sugar and filled with custard, jelly, cannoli-style pastry cream, or a butter-and-honey mixture. For Christmas, Apulians make a very traditional rose-shaped pastry called cartellate. These are fried or baked and dipped in vin cotto, which is either a wine or fig juice reduction.

Most famous street foods are focaccia barese (focaccia with fresh cherry tomatoes), panzerotto (a variant of the pizza that can be baked or fried) and rustico (puff pastry with tomato, bechamel and mozzarella cheese, popular especially in Lecce and Salento)

Basilicata

[edit]

The cuisine of Basilicata is mostly based on inexpensive ingredients and deeply anchored in rural traditions.

Pork is an integral part of the regional cuisine, often made into sausages or roasted on a spit. Famous dry sausages from the region are lucanica and soppressata. Wild boar, mutton, and lamb are also popular. Pasta sauces are generally based on meats or vegetables. Horseradish is often used as a spice and condiment, known in the region as "poor man's truffle".[132] The region produces cheeses such as pecorino di Filiano, canestrato di Moliterno, pallone di Gravina, and padraccio and olive oils such as the Vulture.[133] The peperone crusco (lit. 'crusco pepper') is a staple of the local cuisine, defined as the "red gold of Basilicata".[134] It is consumed as a snack or as a main ingredient for several regional recipes.[135]

Among the traditional dishes are pasta con i peperoni cruschi, pasta served with dried crunchy pepper and bread crumbs;[136] lagane e ceci, also known as piatto del brigante (lit. 'brigand's dish'), pasta prepared with chickpeas and peeled tomatoes;[137] tumact me tulez, tagliatelle-dish of Arbëreshe culture; rafanata, a type of omelet with horseradish; ciaudedda, a vegetable stew with artichokes, potatoes, broad beans, and pancetta;[138] and the baccalà alla lucana, one of the few recipes made with fish. Desserts include taralli dolci, made with sugar glaze and scented with anise and calzoncelli, fried pastries filled with a cream of chestnuts and chocolate.

The most famous wine of the region is the Aglianico del Vulture; others include Matera, Terre dell'Alta Val d'Agri, and Grottino di Roccanova.[139]

Basilicata is also known for its mineral waters which are sold widely in Italy. The springs are mostly located in the volcanic basin of the Vulture area.[140]

Calabria

[edit]

In Calabria, a history of French rule under the House of Anjou and Napoleon, along with Spanish influences, affected the language and culinary skills as seen in the naming of foods such as cake, gatò, from the French gateau. Seafood includes swordfish, shrimp, lobster, sea urchin, and squid. Macaroni-type pasta is widely used in regional dishes, often served with goat, beef, or pork sauce and salty ricotta.[141]

Main courses include frittuli (prepared by boiling pork rind, meat, and trimmings in pork fat), different varieties of spicy sausages (such as 'nduja and capicola), goat, and land snails. Melon and watermelon are traditionally served in a chilled fruit salad or wrapped in prosciutto.[142] Calabrian wines include Greco di Bianco, Bivongi, Cirò, Dominici, Lamezia, Melissa, Pollino, Sant'Anna di Isola Capo Rizzuto, San Vito di Luzzi, Savuto, Scavigna, and Verbicaro.

Calabrese pizza has a Neapolitan-based structure with fresh tomato sauce and a cheese base, but is unique because of its spicy flavour. Some of the ingredients included in a Calabrese pizza are thinly sliced hot soppressata, hot capicola, hot peppers, and fresh mozzarella.

Campania

[edit]

Campania extensively produces tomatoes, peppers, spring onions, potatoes, artichokes, fennel, lemons, and oranges which all take on the flavour of volcanic soil. The Gulf of Naples offers fish and seafood. Campania is one of the largest producers and consumers of pasta in Italy, especially spaghetti. In the regional cuisine, pasta is prepared in various styles that can feature tomato sauce, cheese, clams, and shellfish.[143]

Spaghetti alla puttanesca is a popular dish made with olives, tomatoes, anchovies, capers, chili peppers, and garlic. The region is well known for its mozzarella production (especially from the milk of water buffalo) that is used in a variety of dishes, including parmigiana (shallow fried aubergine slices layered with cheese and tomato sauce, then baked). Desserts include struffoli (deep fried balls of dough), ricotta-based pastiera, sfogliatelle, torta caprese and rum baba.[143]

Originating in Neapolitan cuisine, pizza has become popular worldwide.[144] Pizza is an oven-baked, flat, disc-shaped bread typically topped with a tomato sauce, cheese (usually mozzarella), and various toppings depending on the culture. Since the original pizza, several other types of pizzas have evolved.

Since Naples was the capital of the Kingdom of Two Sicilies, its cuisine took much from the culinary traditions of all the Campania region, reaching a balance between dishes based on rural ingredients (pasta, vegetables, cheese) and seafood dishes (fish, crustaceans, mollusks). A vast variety of recipes is influenced by the local aristocratic cuisine, such as timballo and sartù di riso, pasta or rice dishes with very elaborate preparation, while the dishes coming from the popular traditions contain inexpensive but nutritionally healthy ingredients, such as pasta with beans and other pasta dishes with vegetables.

Famous regional wines are Aglianico (Taurasi), Fiano, Falanghina, Lacryma Christi, Coda di Volpe dei Campi Flegrei and Greco di Tufo.

Emilia-Romagna

[edit]

Emilia-Romagna is especially known for its egg and filled pasta made with soft wheat flour. The Romagna subregion is renowned for pasta dishes such as cappelletti, garganelli, strozzapreti, sfoglia lorda, and tortelli alla lastra as well as cheeses such as squacquerone, piadina snacks are also a specialty of the subregion.

Bologna and Modena are notable for pasta dishes such as tortellini, tortelloni, lasagne, gramigna, and tagliatelle, which are found also in many other parts of the region in different declinations, while Ferrara is known for cappellacci di zucca, pumpkin-filled dumplings, and Piacenza for pisarei e faśö, wheat gnocchi with beans and lard. The celebrated balsamic vinegar is made only in the Emilian cities of Modena and Reggio Emilia, following legally binding traditional procedures.[145]

In the Emilia subregion, except Piacenza which is heavily influenced by the cuisines of Lombardy, rice is eaten to a lesser extent than the rest of northern Italy. Polenta, a maize-based side dish, is common in both Emilia and Romagna.

Parmesan (Italian: Parmigiano Reggiano) cheese is produced in Reggio Emilia (and it was invented in Bibbiano, a little town near Reggio Emilia; this city is also known for erbazzone, a type of egg and vegetables quiche). Grana Padano cheese is produced in Piacenza.

Although the Adriatic coast is a major fishing area (well known for its eels and clams harvested in the Comacchio lagoon), the region is more famous for its meat products, especially pork-based, that include cold cuts such as Parma's prosciutto, culatello, and salame Felino; Piacenza's pancetta, coppa, and salami; Bologna's mortadella and salame rosa; zampone, cotechino, and cappello del prete; and Ferrara's salama da sugo. Piacenza is also known for some dishes prepared with horse and donkey meat. Regional desserts include zuppa inglese (custard-based dessert made with sponge cake and Alchermes liqueur), panpepato (Christmas cake made with pepper, chocolate, spices, and almonds), tenerina (butter and chocolate cake) and torta degli addobbi (rice and milk cake).

Friuli-Venezia Giulia

[edit]

The cuisine of Friuli-Venezia Giulia can vary depending on the territory, as certain areas are home to German and Slovene minorities whose local cuisine conserves greater Austro-Hungarian influences and often differs from mainstream Friulian cuisine. Udine and Pordenone, in the western part of the region, are known for their traditional prosciutto di San Daniele, Montasio cheese, cjarsons stuffed pasta and frico cheese dish. Other typical dishes are pitina (meatballs made of smoked meats), game, and various types of gnocchi and polenta.

Typical dishes in the eastern provinces of Gorizia and Trieste include brovada (fermented turnips), Jota (soup of beans, sauerkraut, potatoes, pancetta and onions), local variations of goulash, apple strudel, pinza and presnitz. Pork can be spicy and is often prepared over an open hearth called a fogolar. Collio Goriziano, Friuli Isonzo, Colli Orientali del Friuli, and Ramandolo are well-known denominazione di origine controllata regional wines.

Seafood from the Adriatic is also used in this area, mainly prepared according to Istrian and Venetian recipes. While the tuna fishing has declined, the pilchards from the Gulf of Trieste off Barcola (in the local dialect: sardoni barcolani) are a special and sought-after delicacy.[146][147][148]

Liguria

[edit]

Liguria is known for herbs and vegetables (as well as seafood) in its cuisine. Savory pies are popular, mixing greens and artichokes along with cheeses, milk curds, and eggs. Onions and olive oil are used. Due to a lack of land suitable for wheat, the Ligurians use chickpeas in farinata and polenta-like panissa. The former is served plain or topped with onions, artichokes, sausage, cheese or young anchovies.[149] Farinata is typically cooked in a wood-fired oven, similar to southern pizzas. Furthermore, fresh fish features heavily in Ligurian cuisine. Baccalà, or salted cod, features prominently as a source of protein in coastal regions. It is traditionally prepared in a soup.

Hilly districts use chestnuts as a source of carbohydrates. Ligurian pastas include corzetti, typically stamped with traditional designs, from the Polcevera Valley; pansoti, a triangular shaped ravioli filled with vegetables; piccagge, pasta ribbons made with a small amount of egg and served with artichoke sauce or pesto sauce; trenette, made from whole wheat flour cut into long strips and served with pesto; boiled beans and potatoes; and trofie, a Ligurian gnocchi made from wheat flour and boiled potatoes, made into a spiral shape and often tossed in pesto.[149] Many Ligurians emigrated to Argentina in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, influencing the cuisine of the country (which was otherwise dominated by meat and dairy products that the narrow Ligurian hinterland would not have allowed). Pesto, sauce made from basil and other herbs, is uniquely Ligurian, and features prominently among Ligurian pastas.

Lazio

[edit]

It features fresh, seasonal and simply-prepared ingredients from Roman Campagna.[150] These include peas, globe artichokes and fava beans, shellfish, milk-fed lamb and goat, and cheeses such as pecorino romano and ricotta.[151] Olive oil is used mostly to dress raw vegetables, while strutto (pork lard) and fat from prosciutto are preferred for frying.[150] The most popular sweets in Rome are small individual pastries called pasticcini, gelato and handmade chocolates and candies.[152] Special dishes are often reserved for different days of the week; for example, gnocchi is eaten on Thursdays, baccalà (salted cod) on Fridays, and trippa (lit. 'tripe') on Saturdays.

Pasta dishes based on the use of guanciale (unsmoked bacon prepared with pig's jowl or cheeks) are often found in Lazio, such as carbonara pasta and amatriciana pasta. Another pasta dish of the region is arrabbiata, with spicy tomato sauce. The regional cuisine widely use offal, resulting in dishes such as the entrail-based rigatoni with pajata sauce and coda alla vaccinara.[153] Abbacchio is a meat dish based on lamb from the Roman cuisine.

Iconic of Lazio is cheese made from ewes' milk (pecorino romano), porchetta (savory, fatty, and moist boneless pork roast) and Frascati white wine. The influence of the ancient Jewish community can be noticed in the Roman cuisine's traditional carciofi alla giudia.[153]

Lombardy

[edit]

Due to the different historical events of its provinces and the variety of its territory, Lombard cuisine has a very varied culinary tradition. First courses in Lombard cuisine range from risotto, to soups and stuffed pasta, in broth or not. Main courses offer a variegated choice of meat or fish dishes of the tradition of the many lakes and rivers of Lombardy.[154]

In general, the cuisine of the various provinces of Lombardy can be united by the prevalence of rice and stuffed pasta over dry pasta, butter instead of olive oil for cooking, prolonged cooking, the widespread use of pork, milk and derivatives, egg-based preparations, and the consumption of polenta that is common to all of northern Italy.[155]

Rice dishes are very popular in this region, often found in soups as well as risotto. The best-known version is risotto alla milanese, flavoured with saffron. Due to its characteristic yellow colour, it is often called risotto giallo. The dish is sometimes served with ossobuco (cross-cut veal shanks braised with vegetables, white wine and broth).[156]

Other regional specialties include cotoletta alla milanese (a fried breaded cutlet of veal similar to Wiener schnitzel, but cooked "bone-in"), cassoeula (a typically winter dish prepared with cabbage and pork), mostarda (rich condiment made with candied fruit and a mustard flavoured syrup), Valtellina's bresaola (air-dried salted beef), pizzoccheri (a flat ribbon pasta made with 80% buckwheat flour and 20% wheat flour cooked along with greens, cubed potatoes, and layered with pieces of Valtellina Casera cheese), Pavese agnolotti (a type of ravioli with Pavese stew filling), casoncelli (a type of stuffed pasta, usually garnished with melted butter and sage, typical of Bergamo) and tortelli di zucca (a type of ravioli with pumpkin filling, usually garnished with melted butter and sage or tomato).[157]

Common in the whole Insubria area are bruscitti, originating from Alto Milanese, which consist in a braised meat dish cut very thin and cooked in wine and fennel seeds, historically obtained by stripping leftover meat. Regional cheeses include Grana Padano, Gorgonzola, crescenza, robiola, and Taleggio (the plains of central and southern Lombardy allow intensive cattle farming). Polenta is common across the region. Regional desserts include the famous panettone (soft sweet bread with raisins and candied citron and orange chunks).

Marche

[edit]

On the coast of Marche, fish and seafood are produced. Inland, wild and domestic pigs are used for sausages and prosciutti. These prosciutti are not thinly sliced, but cut into bite-sized chunks. Suckling pig, chicken, and fish are often stuffed with rosemary or fennel fronds and garlic before being roasted or placed on the spit.[158]

Ascoli, Marche's southernmost province, is well known for olive all'ascolana (stoned olives stuffed with several minced meats, egg, and Parmesan, then fried).[159] Another well-known Marche product are the maccheroncini di Campofilone, from little town of Campofilone, a type of hand-made pasta made only of hard grain flour and eggs, cut so thin that melts in one's mouth.

Piedmont

[edit]

Between the Alps and the Po Valley, featuring a large number of different ecosystems, the Piedmont region offers a refined and varied cuisine. As a point of union between traditional Italian and French cuisine, Piedmont is the Italian region with the largest number of cheeses with protected geographical status and wines under DOC. It is also the region where both the Slow Food association and the most prestigious school of Italian cooking, the University of Gastronomic Sciences, were founded.[160]

Piedmont is a region where gathering nuts, mushrooms, and cardoons, as well as hunting and fishing, are commonplace. Truffles, garlic, seasonal vegetables, cheese, and rice feature in the cuisine. Wines from the Nebbiolo grape such as Barolo and Barbaresco are produced as well as wines from the Barbera grape, fine sparkling wines, and the sweet, lightly sparkling, Moscato d'Asti. The region is also famous for its Vermouth and Ratafia production.[160]

Castelmagno is a prized cheese of the region. Piedmont is also famous for the quality of its Carrù beef (particularly bue grasso, lit. 'fat ox'), hence the tradition of eating raw meat seasoned with garlic oil, lemon, and salt; carpaccio; brasato al vino, wine stew made from marinated beef; and boiled beef served with various sauces.[160]

The food most typical of the Piedmont tradition are agnolotti (pasta folded over with roast beef and vegetable stuffing), paniscia (a typical dish of Novara, a type of risotto with Arborio rice or Maratelli rice, the typical kind of Saluggia beans, onion, Barbera wine, lard, salami, season vegetables, salt and pepper), taglierini (thinner version of tagliatelle), bagna càuda (sauce of garlic, anchovies, olive oil, and butter), and bicerin (hot drink made of coffee, chocolate, and whole milk). Piedmont is one of the Italian capitals of pastry and chocolate in particular, with products such as Nutella, gianduiotto, and marron glacé that are famous worldwide.[160]

Sardinia

[edit]

Suckling pig and wild boar are roasted on the spit or boiled in stews of beans and vegetables, thickened with bread. Herbs such as mint and myrtle are widely used in the regional cuisine. Sardinia also has many special types of bread, made dry, which keeps longer than high-moisture breads.[161] Malloreddus is a typical pasta of the region.

Also baked are carasau bread, civraxu bread, coccoi a pitzus, a highly decorative bread, and pistocu bread, made with flour and water only, originally meant for herders, but often served at home with tomatoes, basil, oregano, garlic, and a strong cheese. Rock lobster, scampi, squid, tuna, and sardines are the predominant seafoods.[161]

Casu marzu is a sheep's cheese produced in Sardinia, but is of questionable legality due to hygiene concerns.[162]

Sicily

[edit]

Sicily shows traces of all the cultures which established themselves on the island over the last two millennia. Although its cuisine undoubtedly has a predominantly Italian base, Sicilian food also has Spanish, Greek and Arab influences.

The ancient Romans introduced lavish dishes based on goose. The Byzantines favoured sweet and sour flavours and the Arabs brought sugar, citrus, rice, spinach, and saffron. The Normans and Hohenstaufens had a fondness for meat dishes. The Spanish introduced items from the New World including chocolate, maize, turkey, and tomatoes.[163]

Much of the island's cuisine encourages the use of fresh vegetables such as aubergine, peppers, and tomatoes, as well as fish such as tuna, seabream, sea bass, swordfish and cuttlefish. In Trapani, in the extreme western corner of the island, North African influences are clear in the use of various couscous based dishes, usually combined with fish.[164] Mint is used extensively in cooking unlike the rest of Italy.

Traditional specialties from Sicily include arancini (a form of deep-fried rice croquettes), pasta alla Norma, caponata, pani câ meusa, and a host of desserts and sweets such as cannoli, granita, and cassata.[165]

Typical of Sicily is Marsala, a red, fortified wine similar to Port and largely exported.[166][167]

Trentino-Alto Adige

[edit]

The cuisine of South Tyrol—the northern half of the Trentino-Alto Adige region—combines culinary influences from Italy and the Mediterranean with a strong alpine regional and Austrian influence.[168] Before the Council of Trent in the middle of the 16th century, the region was known for the simplicity of its peasant cuisine. When the prelates of the Catholic Church established there, they brought the art of fine cooking with them. Later, also influences from Venice and the Austrian Habsburg Empire came in.[169]

The most renowned local product is traditional speck juniper-flavoured prosciutto which, as speck Alto Adige, is regulated by the European Union under the PGI status. Goulash, knödel, apple strudel, kaiserschmarrn, krapfen, rösti, spätzle, and rye bread are regular dishes, along with potatoes, dumpling, homemade sauerkraut, and lard.[169] Since the 20th century the cuisine has come under the influence of other Italian regions, so that various pizza and pasta dishes have become staples.[170] This fusion has led to the creation of dishes such as pasta with speck cream sauce and baked apple rings.[170] The territory of Bolzano is also reputed for its Müller-Thurgau white wines.

The cuisine of the Trentino subregion leans more towards Veneto. It is influenced by its geographical position which ranges from isolated Alpine valleys to the southern prealpine lakes. The cuisine is characterized by its peasant dishes and especially the wide presence of soups. Trentino produces various types of sausages, polenta, yogurt, cheese, gnocchi, buckwheat, potato cake, funnel cake and freshwater fish. Typical dishes from Trentino include zuppa d'orzo (barley soup), canederli (bread dumplings), strangolapreti (spinach gnocchi), smacafam (savory Carnival pie), panada (bread soup), brö brusà (toasted soup), tortel di patate (potato pancakes) and risotto with Teroldego. Trentino's protected products include its Non Valley apples.

Tuscany

[edit]

Simplicity is central to the Tuscan cuisine. Legumes, bread, cheese, vegetables, mushrooms, and fresh fruit are used. A good example of typical Tuscan food is ribollita, a notable soup whose name literally means 'reboiled'. Like most Tuscan cuisine, the soup has peasant origins. Ribollita was originally made by reheating (i.e. reboiling) the leftover minestrone or vegetable soup from the previous day. There are many variations, but the main ingredients always include leftover bread, cannellini beans, and inexpensive vegetables such as carrot, cabbage, beans, silverbeet, cavolo nero (Tuscan kale), onion, and olive oil.

A regional Tuscan pasta known as pici resembles thick, grainy-surfaced spaghetti, and is often rolled by hand. White truffles from San Miniato appear in October and November. High-quality beef, used for the traditional Florentine steak, come from the Chianina cattle breed of the Chiana Valley and the Maremmana from Maremma.

Pork is also produced.[171] The region is well-known also for its rich game, especially wild boar, hare, fallow deer, roe deer, and pheasant that often are used to prepare pappardelle dishes. Maiale Ubriaco, or "Drunken Pork", is another regional preparation in which pork is braised in Chianti wine and often paired with Tuscan kale.[172] Lardo is a salume of cured fatback, served as thin slices or as a paste; a famous variety is lardo di colonnata.

Regional desserts include cantucci (oblong-shaped almond biscuits), castagnaccio (a chestnut flour cake), pan di ramerino (a sweet bread containing raisins and rosemary), panforte (prepared with honey, fruits, and nuts), ricciarelli (biscuits made using an almond base with sugar, honey, and egg white), necci (galettes made with chestnut flour) and cavallucci (pastry made with almonds, candied fruits, coriander, flour, and honey).

Well-known regional wines include Brunello di Montalcino, Carmignano, Chianti, Morellino di Scansano, Parrina, Sassicaia, and Vernaccia di San Gimignano.

Umbria

[edit]

Many Umbrian dishes are prepared by boiling or roasting with local olive oil and herbs. Vegetable dishes are popular in the spring and summer,[173] while fall and winter sees meat from hunting and black truffles from Norcia. Meat dishes include the traditional wild boar sausages, pheasants, geese, pigeons, frogs, and snails.

Castelluccio is known for its lentils. Spoleto and Monteleone are known for spelt. Freshwater fish include lasca, trout, freshwater perch, grayling, eel, barbel, whitefish, and tench.[174] Orvieto and Sagrantino di Montefalco are important regional wines.

Valle d'Aosta

[edit]

In the Aosta Valley, bread-thickened soups are customary as well as cheese fondue, chestnuts, potatoes, rice. Polenta is a staple along with rye bread, smoked bacon, motsetta (cured chamois meat), and game from the mountains and forests. Butter and cream are important in stewed, roasted, and braised dishes.[175]

Typical regional products include Fontina cheese, Vallée d'Aoste Lard d'Arnad, red wines and Génépi Artemisia-based liqueur.[119]

Veneto

[edit]

Venice and many surrounding parts of Veneto are known for risotto, a dish whose ingredients can highly vary upon different areas. Fish and seafood are added in regions closer to the coast while pumpkin, asparagus, radicchio, and frog legs appear farther away from the Adriatic Sea.

Made from finely ground maize meal, polenta is a traditional, rural food typical of Veneto and most of northern Italy. It may be included in stirred dishes and baked dishes. Polenta can be served with various cheese, stockfish, or meat dishes. Some polenta dishes include porcini, rapini, or other vegetables or meats, such as small songbirds in the case of the Venetian and Lombard dish polenta e osei, or sausages. In some areas of Veneto it can be also made of a particular variety of cornmeal, named biancoperla, so that the colour of polenta is white and not yellow (the so-called polenta bianca).

Beans, peas, and other legumes are seen in these areas with pasta e fagioli (lit. 'beans and pasta') and risi e bisi (lit. 'rice and peas'). Venice features heavy dishes using exotic spices and sauces. Ingredients such as stockfish or simple marinated anchovies are found here as well.

Less fish and more meat is eaten away from the coast. Other typical products are sausages such as sopressa, garlic salami, Piave cheese, and Asiago cheese. High quality vegetables are prized, such as red radicchio from Treviso and white asparagus from Bassano del Grappa. Perhaps the most popular dish of Venice is fegato alla veneziana, thinly-sliced veal liver sautéed with onions.

Squid and cuttlefish are common ingredients, as is squid ink, called nero di seppia.[176][177] Regional desserts include tiramisu (made of biscuits dipped in coffee, layered with a whipped mixture of egg yolks and mascarpone, and flavoured with liquor and cocoa[178]), baicoli (biscuits made with butter and vanilla), and nougat.

The most celebrated Venetian wines include Bardolino, Prosecco, Soave, Amarone, and Valpolicella DOC wines.

Meal structure

[edit]

Italian meal structure is typical of the European Mediterranean region and differs from North, Central, and Eastern European meal structure, though it still often consists of breakfast (Italian: colazione), lunch (Italian: pranzo), and supper (Italian: cena).[179] However, much less emphasis is placed on breakfast, and breakfast itself is often skipped or involves lighter meal portions than are seen in non-Mediterranean Western countries.[180] Late-morning and mid-afternoon snacks, called merenda, are also often included in this meal structure.[181]

Traditional meals in Italy typically contained four or five courses.[182] Especially on weekends, meals are often seen as a time to spend with family and friends rather than simply for sustenance; thus, meals tend to be longer than in other cultures. During holidays such as Christmas and New Year's Eve, feasts can last for hours.[183]

Today, full-course meals are mainly reserved for special events such as weddings, while everyday meals include only a first or second course (sometimes both), a side dish, and coffee.[184][185] The primo (first course) is usually a filling dish, such as risotto or pasta, with sauces made from meat, vegetables, or seafood.[186] Whole pieces of meat such as sausages, meatballs, and poultry are eaten in the secondo (second course).[187] Italian cuisine has some single-course meals (Italian: piatto unico) combining starches and proteins.[188]

| Meal stage | Description |

|---|---|

| Aperitivo | Apéritif usually enjoyed as an appetiser before a large meal, may be: Campari, Martini, Cinzano, Prosecco, Aperol, Spritz, Vermouth, Negroni.[182] |

| Antipasto | lit. 'before (the) meal', hot or cold, usually consists of cheese, prosciutto, sliced sausage, marinated vegetables or fish, bruschetta and bread appetisers.[182] |

| Primo | "First course", usually consists of a hot dish such as pasta, risotto, gnocchi, or soup with a sauce, vegetarian, meat or fish sugo or ragù as a sauce.[182] |

| Secondo | "Second course", the main dish, usually fish or meat with potatoes. Traditionally, veal, pork, and chicken are most commonly used, at least in the north, though beef has become more popular since World War II, and wild game is also found, particularly in Tuscany. Fish is also very popular, especially in the south.[182] |

| Contorno | "Side dish", may be a salad or cooked vegetables. A traditional menu features salad along with the main course.[182] |

| Formaggio e frutta | "Cheese and fruits", the first dessert. Local cheeses may be part of the antipasto or contorno as well.[182] |

| Dolce | "Sweet", such as cakes (such as tiramisu), cookies or ice cream.[182] |

| Caffè | Coffee.[182] |

| Digestivo | "Digestives", liquors and liqueurs (grappa, amaro, limoncello, sambuca, nocino, sometimes referred to as ammazzacaffè, 'coffee killer').[182] |

Food establishments

[edit]

Each type of establishment has a defined role and traditionally sticks to it.[189]

| Establishment | Description |

|---|---|

| Agriturismo | Working farms that offer accommodations and meals. Sometimes meals are served to guests only. According to Italian law, they can only serve locally-made products (except drinks). Marked by a green and gold sign with a knife and fork.[190] |

| Bar/caffè | Locations which serve coffee, soft drinks, juice and alcohol. Hours are generally from 6 am to 10 pm. Foods may include croissants and other sweet breads (often called "brioche" in northern Italy), panini, tramezzini (sandwiches) and spuntini (snacks such as olives, potato crisps and small pieces of frittata).[190] |

| Caffetteria | Locations where coffee and similar drinks are consumed, and desserts can also be eaten.[191] |

| Birreria | A bar that offers beer; found in central and northern regions of Italy.[190] |

| Bruschetteria | Specialises in bruschetta, though other dishes may also be offered. |

| Enoteca | Place where wines are sold or offered for tasting, displayed to the public on the basis of criteria that facilitate their choice.[192] |

| Fiaschetteria | Locations which serve wine in fiaschi and bottles, though other dishes may also be offered.[193] |

| Formaggeria | A shop serving cheese.[194] |

| Frasca | Friulian wine producers that open for the evening and may offer food along with their wines.[190] |

| Gelateria | A shop where the customer can get gelato to go, or sit down and eat it in a cup or a cone. Bigger ice desserts, coffee, or liquors may also be ordered. |

| Locanda | Locations where it is possible to consume food and where one can be accommodated.[195] |

| Osteria | Focused on simple food of the region, often having no written menu. Many are open only at night, but some are open for lunch.[196] The name has become fashionable for upscale restaurants with a rustic regional style. |

| Panificio or panetteria | A shop serving flour-based food baked in an oven such as bread, cookies, cakes, pastries, and pies.[197] |

| Paninoteca or panineria | Sandwich shop open during the day.[196] |

| Pasticceria | A shop serving a variety of pastries, confectioneries, biscuits and cakes.[198] |

| Pastificio | A shop serving artisanal pasta.[199] |

| Piadineria | Specialises in piadina, though other dishes may also be offered.[200] |

| Pizzeria | Specialises in pizza, often with wood-fired ovens.[201] |

| Polenteria | Serving polenta; uncommon, and found only in northern regions.[201] |

| Ristorante | Often offers upscale cuisine and printed menus.[201] |

| Rosticceria | Fast food restaurant, offering local dishes such as cotoletta alla milanese, roasted meat (usually pork or chicken), supplì and arancini even as take-away. |

| Sagra | Popular festival, which takes place in a town or in a district to celebrate an event, or an agro-food product, where it is possible to consume food.[202] |

| Salumeria | A shop serving salumi and cheese.[203] |

| Spaghetteria | Originating in Naples, offering pasta dishes and other main courses.[204] |

| Tavola calda | lit. 'hot table', offers pre-made regional dishes. Most open at 11 am and close late.[205] |

| Trattoria | A dining establishment, often family-run, with inexpensive prices and an informal atmosphere.[205] |

- Food establishments

- A pizzeria in Naples, Italy, c. 1910

Drinks

[edit]Coffee

[edit]

Italian style coffee (Italian: caffè), also known as espresso, is made from a blend of coffee beans. Espresso beans are roasted medium to medium dark in the north, and darker as one moves south.

A common misconception is that espresso has more caffeine than other coffee; in fact, the opposite is true. The longer roasting period extracts more caffeine. The modern espresso machine, invented in 1937 by Achille Gaggia, uses a pump and pressure system with water heated to 90 to 95 °C (194 to 203 °F) and forced at high pressure through a few grams of finely ground coffee in 25–30 seconds, resulting in about 25 millilitres (0.85 fl oz, two tablespoons) of liquid.[206]

Home coffee makers are simpler but work under the same principle. La napoletana is a four-part stove-top unit with grounds loosely placed inside a filter; the kettle portion is filled with water and once boiling, the unit is inverted to drip through the grounds. The moka per il caffè is a three-part stove-top unit that is placed on the stovetop with loosely packed grounds in a strainer; the water rises from steam pressure and is forced through the grounds into the top portion. In both cases, the water passes through the grounds just once.[207]

Espresso is usually served in a demitasse cup. Caffè macchiato is topped with a bit of steamed milk or foam; ristretto is made with less water, and is stronger; cappuccino is mixed or topped with steamed, mostly frothy, milk. It is generally considered a morning beverage, and usually is not taken after a meal; caffè latte is equal parts espresso and steamed milk, similar to café au lait, and is typically served in a large cup. Latte macchiato (spotted milk) is a glass of warm milk with a bit of coffee and caffè corretto is "corrected" with a few drops of an alcoholic beverage such as grappa or brandy.

The bicerin is also an Italian coffee, from Turin. It is a mixture of cappuccino and traditional hot chocolate, as it consists of a mix of coffee and drinking chocolate, and with a small addition of milk. It is quite thick and often whipped cream/foam with chocolate powder and sugar is added on top.

Alcoholic beverages

[edit]Wine

[edit]

Italy is the world's largest producer of wine, as well as the country with the widest variety of indigenous grapevine varieties in the world.[26][27] Only about a quarter of this wine is put into bottles for individual sale. Two-thirds is bulk wine used for blending in France and Germany. The wine distilled into spirits in Italy exceeds the production of wine in the entirety of the New World.[208] There are twenty separate wine regions.[209] The Italian wine industry is among the most varied in the world due to hundreds of indigenous grape varieties grown throughout Italy. Some of the most iconic red wines include Barolo, Barbaresco, Brunello di Montalcino and Amarone.[210]

The Italian government passed the denominazione di origine controllata (DOC) law in 1963 to regulate place of origin, quality, production method, and type of grape. The designation indicazione geografica tipica (IGT) is a less restrictive designation to help a wine maker graduate to the DOC level. In 1980, the government created the denominazione di origine controllata e garantita (DOCG), reserved for only the best wines.[211]

In Italy wine is commonly consumed (alongside water) in meals, which are rarely served without it, though it is extremely uncommon for meals to be served with any other drink, alcoholic, or otherwise.

Beer

[edit]Italy is considered to be part of the wine belt of Europe. Nevertheless, beer, particularly mass-produced pale lagers, are common in the country. It is traditionally considered to be an ideal accompaniment to pizza; since the 1970s, beer has spread from pizzerias and has become much more popular for drinking in other situations.[212] Among many popular brands, the most notable Italian breweries are Peroni and Moretti.

Other

[edit]

There are also several other popular alcoholic drinks in Italy. Limoncello, a traditional lemon liqueur from Campania (Sorrento, Amalfi and the Gulf of Naples) is the second most popular liqueur in Italy after Campari.[213] Made from lemon, it is usually consumed in very small proportions, served chilled in small glasses or cups.[213]

Amaro siciliano are common Sicilian digestifs, made with herbs, which are usually drunk after heavy meals. Mirto, an herbal distillate made from the berries (red mirto) and leaves (white mirto) of the myrtle bush, is popular in Sardinia and other regions. Another well-known digestif is Amaro Lucano from Basilicata.[214]

Grappa is the typical alcoholic drink of northern Italy, generally associated with the culture of the Alps and of the Po Valley. The most famous grappas are distilled in Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Veneto, Piedmont, and Trentino. The three most notable and recognisable Italian aperitifs are Martini, Vermouth, and Campari. A sparkling drink which is becoming internationally popular as a less expensive substitute for French champagne is Prosecco, from the Veneto region.[215][216]

Desserts

[edit]From the Italian perspective, cookies and candy belong to the same category of sweets.[217] Traditional candies include candied fruits, torrone, and nut brittles, all of which are still popular in the modern era. In medieval times, northern Italy became so famous for the quality of its stiff fruit pastes (similar to marmalade or conserves, except stiff enough to mold into shapes) that "Paste of Genoa" became a generic name for high-quality fruit conserves.[218] Italy is famous for artisanal gelato (the Italian ice cream) and has become widespread with the ice cream cone, covering 55% of the Italian market.[219]

Silver-coated almond dragées, which are called "confetti" in Italian, are thrown at weddings (white coating) and baptisms (blue or pink coating, according to the sex of the newborn baby), or graduations (red coating), often wrapped in a small tulle bag as a gift to the guests.[220] The idea of including a romantic note with candy may have begun with Italian dragées, no later than the early 19th century, and is carried on with the multilingual love notes included in boxes of Italy's most famous chocolate, Baci by Perugina in Milan.[221] The most significant chocolate style is a combination of hazelnuts and milk chocolate, which is featured in gianduja pastes such as Nutella, which is made by Ferrero SpA in Alba, Piedmont, as well as Perugnia's Baci and many other chocolate confections.[217]

- Panettone is a traditional Christmas cake.

- Gelato is Italian ice cream.

- Panna cotta with garnish

- Tiramisu with cocoa powder garnish

- Cannoli with pistachio, candied fruit, and chocolate chips

- Cassata marzipan cake

- Sfogliatelle with custard filling

Holiday cuisine

[edit]

Every region has its own holiday recipes. During la Festa di San Giuseppe ("St. Joseph's Day") on 19 March, Sicilians give thanks to St. Joseph for preventing a famine during the Middle Ages.[222][223] The fava bean saved the population from starvation, and is a traditional part of St. Joseph's Day altars and traditions.[224] Other customs celebrating this festival include wearing red clothing and eating zeppole.[225]

On Easter Sunday, lamb (called abbacchio in Central Italy) is served throughout Italy.[226] The common cake for Easter Day is the colomba pasquale (literally, "Easter dove"), which is often simply known as "Italian Easter Cake" abroad.[227] It represents a dove,[228] and is topped with almonds and pearl sugar.

On Christmas Eve a symbolic fast is observed with the cena di magro, a meatless meal, following traditional Catholic fasting practice. It is an elaborate and rich family dinner, based on fish and seafood.[229] Typical cakes of the Christmas season are panettone and pandoro.[230]

International

[edit]Africa

[edit]Former Italian colonies

[edit]

Due to several Italian colonies established in Africa, mainly in Ethiopia, Eritrea, Libya, and Somalia (except the northern part, which was under British rule), there is a considerable Italian influence on the cuisines of these nations.[231]

South Africa

[edit]All major cities and towns in South Africa have substantial populations of Italian South Africans. Italian foods, such as ham and cheeses, are imported and some also made locally, and every city has a popular Italian restaurant or two, as well as pizzerias.[232] The production of good quality olive oil is on the rise in South Africa, especially in the drier south-western parts where there is a more Mediterranean-type of rainfall pattern.[233] Some oils have even won top international awards.[234]

Asia

[edit]

In Japan, Italian dishes such as pizza and spaghetti became popular in the 1990s. Itameshi, or Japanese-Italian fusion cuisine, developed over the last few decades, with dishes such as Naporitan and Ankake spaghetti.

Europe

[edit]Croatia

[edit]The Croatian cuisine of Istria, Fiume and Dalmatia was influenced by Italian cuisine, given the historical presence of local ethnic Italians (Istrian Italians and Dalmatian Italians), influence that has eased after the Istrian–Dalmatian exodus.[235][236] For example, the influence of Italian cuisine on Croatian dishes can be seen in the pršut (similar to Italian prosciutto) and on the preparation of homemade pasta.[237] Traditional dishes of Italian origin also include gnocchi (njoki), risotto (rižot), focaccia (pogača), polenta (palenta), and brudet.[238]

France

[edit]

Во Франции кухня Корсики имеет много общего с итальянской кухней, поскольку с раннего средневековья до 1768 года остров был владением Пизы , а затем владениями Генуи . [239] На кухню графства Ницца также повлияла итальянская кухня из-за ее близости к Италии и того факта, что графство Ницца принадлежало Королевству Пьемонт-Сардиния до 1860 года, когда оно было аннексировано Францией. [240]

Мальта

[ редактировать ]Мальтийская кухня , учитывая близость Мальты к Италии, демонстрирует сильное итальянское влияние, а также влияние испанской , французской , провансальской и других средиземноморских кухонь , с некоторым более поздним британским кулинарным влиянием. [241]

Монако

[ редактировать ]Кухня Монако подверглась значительному влиянию итальянской кухни (особенно лигурийской кухни ), учитывая близость Монако к Италии, а также провансальской и французской кухонь. [242]

Сан-Марино

[ редактировать ]

Саммаринская кухня очень похожа на итальянскую кухню, особенно на кухню соседних регионов Эмилия-Романья и Марке . [244] [245] Сан-Марино Основными сельскохозяйственными продуктами являются сыр, вино и домашний скот, а производство сыра является основным видом экономической деятельности в Сан-Марино. [246] [247]

Словения

[ редактировать ]Учитывая близость Словении к Италии, словенская кухня находилась под влиянием итальянской кухни. [248] Словенские блюда итальянского происхождения — это ньоки (похожие на итальянские ньокки ), ризота (словенский вариант ризотто ) и зилкрофи (похожий на итальянские равиоли ). [249] Итальянская кухня особенно повлияла на кухню словенской Истрии , учитывая историческое присутствие местных этнических итальянцев ( истрийских итальянцев ), влияние, которое ослабло после истрийско-далматинского исхода. [236] [250]

Швейцария

[ редактировать ]

Кухня кантона Тичино находится под сильным влиянием итальянской кухни и, прежде всего, ломбардской кухни из-за многовекового господства Миланского герцогства , а также экономических и языковых связей с Ломбардией . [251] Италоязычная часть Швейцарии по существу совпадает с Тичино, но также и с южными долинами Граубюндена .

Популярными блюдами являются полента и ризотто , часто сопровождаемые луганиге и луганигеттой , разновидностью итальянских ремесленных колбас, или другими региональными колбасными изделиями, такими как салями , коппа и прошутто . В частности, ризотто – еще одно распространенное блюдо Тичино. [252] Его готовят с грибами, шафраном или сыром.

Пиццоккери родом из Вальтеллины , долины в северной итальянской области Ломбардия . Они также популярны в Валь Поскьяво , боковой долине Вальтеллина, принадлежащей швейцарскому кантону Граубюнден . Брусчитти — итальянское блюдо из одного блюда ломбардской кухни (Италия), пьемонтской кухни (Италия) и кухни Нижнего Тичино . [253] (Швейцария), на основе мелко нарезанной, говядины . длительно приготовленной [254] Завершается это блюдо добавлением поленты, [255] Миланское ризотто или пюре . [253] [256]

Северная и Центральная Америка

[ редактировать ]

Соединенные Штаты

[ редактировать ]Большая часть итало-американской кухни основана на итальянской кухне, американизированной с учетом ингредиентов и условий, встречающихся в Соединенных Штатах. Американцы итальянского происхождения часто идентифицируют продукты питания со своим региональным наследием . Основные продукты Южной Италии включают сухую пасту , томатный соус и оливковое масло , тогда как основные продукты Северной Италии включают такие продукты, как ризотто , белый соус и полента . [257]

Пицца прибыла в Соединенные Штаты в начале 20 века вместе с волнами итальянских иммигрантов, которые поселились в основном в крупных городах Северо-Востока. возросли Его популярность и региональное распространение после того, как солдаты, дислоцированные в Италии, вернулись со Второй мировой войны . [258]

Мексика

[ редактировать ]По всей стране миланская торта является обычным продуктом, который продают в тележках и киосках с едой. [259] Это бутерброд из местного хлеба, в который входит обжаренная в панировке котлета из свинины или говядины. [259]

Южная Америка

[ редактировать ]Аргентина

[ редактировать ]Из-за большой иммиграции итальянцев в Аргентину , итальянская еда и напитки широко представлены в аргентинской кухне . [260] Примером может быть milanesas (название происходит от оригинального слова cotoletta alla milanese из Милана , Италия). [261] Есть еще несколько итальянско-аргентинских блюд, например, соррентино и аргентинские ньокки. [262]

Бразилия

[ редактировать ]

Итальянская кухня популярна в Бразилии из-за большой иммиграции туда в конце 1800-х - начале 1900-х годов. [263] Благодаря огромному итальянскому сообществу, Сан-Паулу является местом, где эта кухня ценится больше всего. [263] В городе также разработали свой особый сорт пиццы , отличающийся как от неаполитанских , так и от американских сортов, и он широко популярен на ужинах по выходным. [264]

Уругвай

[ редактировать ]

Заметная итальянская иммиграция в Уругвай сильно повлияла на уругвайскую кухню : огромное количество блюд итальянской кухни заимствовано из блюд из всех регионов Италии. [265] [266] Помимо широкого использования макаронных изделий, включая талларины (итальянские тальятелле ), равиолези (итальянские равиоли ), капелетис (итальянские каппеллетти ) и тортелины (итальянские тортеллини ), они являются частью уругвайской кухни baña cauda (итальянские Bagna càuda ), болоньеса (итальянское рагу ), казуэла де мондонго (итальянский рубец по-милански ), песто и торте фрита (итальянские жареные ньокко ). [265] [266]

Венесуэла