Slavery

| Part of a series on |

| Forced labour and slavery |

|---|

|

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour.[1] Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavement is the placement of a person into slavery, and the person is called a slave or an enslaved person (see § Terminology).

Many historical cases of enslavement occurred as a result of breaking the law, becoming indebted, suffering a military defeat, or exploitation for cheaper labor; other forms of slavery were instituted along demographic lines such as race or sex. Slaves may be kept in bondage for life, or for a fixed period of time after which they would be granted freedom.[2] Although slavery is usually involuntary and involves coercion, there are also cases where people voluntarily enter into slavery to pay a debt or earn money due to poverty. In the course of human history, slavery was a typical feature of civilization,[3] and was legal in most societies, but it is now outlawed in most countries of the world, except as a punishment for a crime.[4][5]

In chattel slavery, the slave is legally rendered the personal property (chattel) of the slave owner. In economics, the term de facto slavery describes the conditions of unfree labour and forced labour that most slaves endure.[6]

Mauritania was the last country in the world to officially ban slavery, in 1981,[7] with legal prosecution of slaveholders established in 2007.[8] However, in 2019, approximately 40 million people, of whom 26% were children, were still enslaved throughout the world despite slavery being illegal. In the modern world, more than 50% of slaves provide forced labour, usually in the factories and sweatshops of the private sector of a country's economy.[9] In industrialised countries, human trafficking is a modern variety of slavery; in non-industrialised countries, debt bondage is a common form of enslavement,[6] such as captive domestic servants, people in forced marriages, and child soldiers.[10]

Etymology

The word slave was borrowed into Middle English through the Old French esclave which ultimately derives from Byzantine Greek σκλάβος (sklábos) or εσκλαβήνος (ésklabḗnos).

According to the widespread view, which has been known since the 18th century, the Byzantine Σκλάβινοι (Sklábinoi), Έσκλαβηνοί (Ésklabēnoí), borrowed from a Slavic tribe self-name *Slověne, turned into σκλάβος, εσκλαβήνος (Late Latin sclāvus) in the meaning 'prisoner of war slave', 'slave' in the 8th/9th century, because they often became captured and enslaved.[11][12][13][14] However this version has been disputed since the 19th century.[15][16]

An alternative contemporary hypothesis states that Medieval Latin sclāvus via *scylāvus derives from Byzantine σκυλάω (skūláō, skyláō) or σκυλεύω (skūleúō, skyleúō) with the meaning "to strip the enemy (killed in a battle)" or "to make booty / extract spoils of war".[17][18][19][20] This version has been criticized as well.[21]

Terminology

There is a dispute among historians about whether terms such as "unfree labourer" or "enslaved person", rather than "slave", should be used when describing the victims of slavery. According to those proposing a change in terminology, slave perpetuates the crime of slavery in language by reducing its victims to a nonhuman noun instead of "carry[ing] them forward as people, not the property that they were" (see also People-first language). Other historians prefer slave because the term is familiar and shorter, or because it accurately reflects the inhumanity of slavery, with person implying a degree of autonomy that slavery does not allow.[22]

Chattel slavery

As a social institution, chattel slavery classes slaves as chattels (personal property) owned by the enslaver; like livestock, they can be bought and sold at will.[23] Chattel slavery was historically the normal form of slavery and was practiced in places such as the Roman Empire and classical Greece, where it was considered a keystone of society.[24][25][26] Other places where it was extensively practiced include Medieval Egypt,[27] Subsaharan Africa,[28] Brazil, the United States and parts of the Caribbean such as Cuba and Haiti.[29][30] The Iroquois enslaved others in ways that “looked very like chattel slavery."[31]

Beginning in the 18th century, a series of abolitionist movements saw slavery as a violation of the slaves' rights as people ("all men are created equal"), and sought to abolish it. Abolitionism encountered extreme resistance but was eventually successful. Several of the states of the United States began abolishing slavery during the American Revolutionary War. The French Revolution tried to abolish slavery in 1794, but a permanent abolition did not occur until 1848. In the much of the British Empire, slavery was subject to abolition in 1833, throughout the United States it was abolished in 1865 and in Cuba in 1886. The last country in the Americas to abolish slavery was Brazil, in 1888.[32]

Chattel slavery survived longest in the Muslim Middle East. After the Trans-Atlantic slave trade had been suppressed, the ancient Trans-Saharan slave trade, the Indian Ocean slave trade and the Red Sea slave trade continued to traffic slaves from the African continent to the Middle East. During the 20th century, the issue of chattel slavery was addressed and investigated globally by international bodies created by the League of Nations and the United Nations, such as the Temporary Slavery Commission in 1924–1926, the Committee of Experts on Slavery in 1932, and the Advisory Committee of Experts on Slavery in 1934–1939.[33] By the time of the UN Ad Hoc Committee on Slavery in 1950–1951, legal chattel slavery still existed only in the Arabian Peninsula: in Oman, in Qatar, in Saudi Arabia, in the Trucial States and in Yemen.[33] Legal chattel slavery was finally abolished in the Arabian Peninsula in the 1960s: Saudi Arabia and Yemen in 1962, in Dubai in 1963, and Oman as the last in 1970.[33]

The last country to abolish slavery, Mauritania, did so in 1981. The 1981 ban on slavery was not effectively enforced in practice, as there were no legal mechanisms to prosecute those who used slaves. This only came in 2007.

Bonded labour

Indenture, also known as bonded labour or debt bondage, is a form of unfree labour in which a person works to pay off a debt by pledging himself or herself as collateral. The services required to repay the debt, and their duration, may be undefined. Debt bondage can be passed on from generation to generation, with children required to pay off their progenitors' debt.[34] It is the most widespread form of slavery today.[35] Debt bondage is most prevalent in South Asia.[34] Money marriage refers to a marriage where a girl, usually, is married off to a man to settle debts owed by her parents.[36] The Chukri system is a debt bondage system found in parts of Bengal where a female can be coerced into prostitution in order to pay off debts.[37]

Dependents

The word slavery has also been used to refer to a legal state of dependency to somebody else.[38][39] For example, in Persia, the situations and lives of such slaves could be better than those of common citizens.[40]

Forced labour

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is sometimes used to describe an individual who is forced to work against their own will, under threat of violence or other punishment. This may also include institutions not commonly classified as slavery, such as serfdom, conscription and penal labour. As slavery has been legally outlawed in all countries, forced labour in the present day (frequently referred to as "modern slavery") revolves around illegal control.

Human trafficking primarily involves women and children forced into prostitution and is the fastest growing form of forced labour, with Thailand, Cambodia, India, Brazil and Mexico having been identified as leading hotspots of commercial sexual exploitation of children.[41][42]

Child soldiers and child labour

In 2007, Human Rights Watch estimated that 200,000 to 300,000 children served as soldiers in then-current conflicts.[43] More girls under 16 work as domestic workers than any other category of child labour, often sent to cities by parents living in rural poverty as with the Haitian restaveks.[44]

Forced marriage

Forced marriages or early marriages are often considered types of slavery. Forced marriage continues to be practiced in parts of the world including some parts of Asia and Africa and in immigrant communities in the West.[45][46][47][48] Marriage by abduction occurs in many places in the world today, with a 2003 study finding a national average of 69% of marriages in Ethiopia being through abduction.[49]

Other uses of the term

The word slavery is often used as a pejorative to describe any activity in which one is coerced into performing. Some argue that military drafts and other forms of coerced government labour constitute "state-operated slavery."[50][51] Some libertarians and anarcho-capitalists view government taxation as a form of slavery.[52]

"Slavery" has been used by some anti-psychiatry proponents to define involuntary psychiatric patients, claiming there are no unbiased physical tests for mental illness and yet the psychiatric patient must follow the orders of the psychiatrist. They assert that instead of chains to control the slave, the psychiatrist uses drugs to control the mind.[53] Drapetomania was a pseudoscientific psychiatric diagnosis for a slave who desired freedom; "symptoms" included laziness and the tendency to flee captivity.[54][55]

Some proponents of animal rights have applied the term slavery to the condition of some or all human-owned animals, arguing that their status is comparable to that of human slaves.[56]

The labour market, as institutionalized under contemporary capitalist systems, has been criticized by mainstream socialists and by anarcho-syndicalists, who utilise the term wage slavery as a pejorative or dysphemism for wage labour.[57][58][59] Socialists draw parallels between the trade of labour as a commodity and slavery. Cicero is also known to have suggested such parallels.[60]

Characteristics

Economics

Economists have modeled the circumstances under which slavery (and variants such as serfdom) appear and disappear. One observation is that slavery becomes more desirable for landowners where land is abundant, but labour is scarce, such that rent is depressed and paid workers can demand high wages. If the opposite holds true, then it is more costly for landowners to guard the slaves than to employ paid workers who can demand only low wages because of the degree of competition.[61] Thus, first slavery and then serfdom gradually decreased in Europe as the population grew. They were reintroduced in the Americas and in Russia as large areas of land with few inhabitants became available.[62]

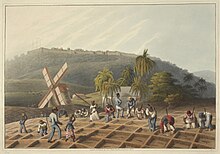

Slavery is more common when the tasks are relatively simple and thus easy to supervise, such as large-scale monocrops such as sugarcane and cotton, in which output depended on economies of scale. This enables systems of labour, such as the gang system in the United States, to become prominent on large plantations where field hands toiled with factory-like precision. Then, each work gang was based on an internal division of labour that assigned every member of the gang to a task and made each worker's performance dependent on the actions of the others. The slaves chopped out the weeds that surrounded the cotton plants as well as excess sprouts. Plow gangs followed behind, stirring the soil near the plants and tossing it back around the plants. Thus, the gang system worked like an assembly line.[63]

Since the 18th century, critics have argued that slavery hinders technological advancement because the focus is on increasing the number of slaves doing simple tasks rather than upgrading their efficiency. For example, it is sometimes argued that, because of this narrow focus, technology in Greece – and later in Rome – was not applied to ease physical labour or improve manufacturing.[64][65]

Scottish economist Adam Smith stated that free labour was economically better than slave labour, and that it was nearly impossible to end slavery in a free, democratic, or republican form of government since many of its legislators or political figures were slave owners and would not punish themselves. He further stated that slaves would be better able to gain their freedom under centralized government, or a central authority like a king or church.[66][67] Similar arguments appeared later in the works of Auguste Comte, especially given Smith's belief in the separation of powers, or what Comte called the "separation of the spiritual and the temporal" during the Middle Ages and the end of slavery, and Smith's criticism of masters, past and present. As Smith stated in the Lectures on Jurisprudence, "The great power of the clergy thus concurring with that of the king set the slaves at liberty. But it was absolutely necessary both that the authority of the king and of the clergy should be great. Where ever any one of these was wanting, slavery still continues..."[68]

Even after slavery became a criminal offense, slave owners could get high returns. According to researcher Siddharth Kara, the profits generated worldwide by all forms of slavery in 2007 were $91.2 billion. That was second only to drug trafficking, in terms of global criminal enterprises. At the time the weighted average global sales price of a slave was estimated to be approximately $340, with a high of $1,895 for the average trafficked sex slave, and a low of $40 to $50 for debt bondage slaves in part of Asia and Africa. The weighted average annual profits generated by a slave in 2007 was $3,175, with a low of an average $950 for bonded labour and $29,210 for a trafficked sex slave. Approximately 40% of slave profits each year were generated by trafficked sex slaves, representing slightly more than 4% of the world's 29 million slaves.[69]

Identification

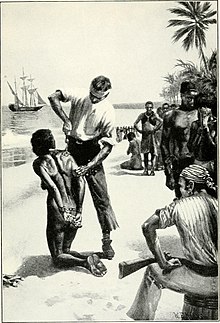

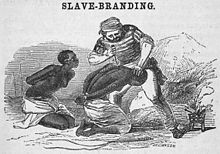

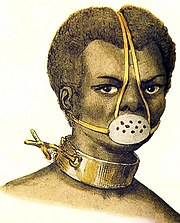

A widespread practice was branding, either to explicitly mark slaves as property or as punishment.

Legal aspects

Private versus state-owned slaves

Slaves have been owned privately by individuals but have also been under state ownership. For example, the kisaeng were women from low castes in pre modern Korea, who were owned by the state under government officials known as hojang and were required to provide entertainment to the aristocracy. In the 2020s, in North Korea, Kippumjo ("Pleasure Brigades") are made up of women selected from the general population to serve as entertainers and as concubines to the rulers of North Korea.[70][71] "Tribute labor" is compulsory labor for the state and has been used in various iterations such as corvée, mit'a and repartimiento. The internment camps of totalitarian regimes such as the Nazis and the Soviet Union placed increasing importance on the labor provided in those camps, leading to a growing tendency among historians to designate such systems as slavery.[72]

A combination of these include the encomienda where the Spanish Crown granted private individuals the right to the free labour of a specified number of natives in a given area.[73] In the "Red Rubber System" of both the Congo Free State and French ruled Ubangi-Shari,[74] labour was demanded as taxation; private companies were conceded areas within which they were allowed to use any measures to increase rubber production.[75] Convict leasing was common in the Southern United States where the state would lease prisoners for their free labour to companies.

Legal rights

Depending upon the era and the country, slaves sometimes had a limited set of legal rights. For example, in the Province of New York, people who deliberately killed slaves were punishable under a 1686 statute.[76] And, as already mentioned, certain legal rights attached to the nobi in Korea, to slaves in various African societies, and to black female slaves in the French colony of Louisiana. Giving slaves legal rights has sometimes been a matter of morality, but also sometimes a matter of self-interest. For example, in ancient Athens, protecting slaves from mistreatment simultaneously protected people who might be mistaken for slaves, and giving slaves limited property rights incentivized slaves to work harder to get more property.[77] In the southern United States prior to the extirpation of slavery in 1865, a proslavery legal treatise reported that slaves accused of crimes typically had a legal right to counsel, freedom from double jeopardy, a right to trial by jury in graver cases, and the right to grand jury indictment, but they lacked many other rights such as white adults' ability to control their own lives.[78]

History

Slavery predates written records and has existed in many cultures.[3] Slavery is rare among hunter-gatherer populations because it requires economic surpluses and a substantial population density. Thus, although it has existed among unusually resource-rich hunter gatherers, such as the American Indian peoples of the salmon-rich rivers of the Pacific Northwest coast, slavery became widespread only with the invention of agriculture during the Neolithic Revolution about 11,000 years ago.[79] Slavery was practiced in almost every ancient civilization.[3] Such institutions included debt bondage, punishment for crime, the enslavement of prisoners of war, child abandonment, and the enslavement of slaves' offspring.[80]

Africa

Slavery was widespread in Africa, which pursued both internal and external slave trade.[81] In the Senegambia region, between 1300 and 1900, close to one-third of the population was enslaved. In early Islamic states of the western Sahel, including Ghana, Mali, Segou, and Songhai, about a third of the population were enslaved.[82]

In European courtly society, and European aristocracy, black African slaves and their children became visible in the late 1300s and 1400s. Starting with Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, black Africans were included in the retinue. In 1402 an Ethiopian embassy reached Venice. In the 1470s black Africans were painted as court attendants in wall paintings that were displayed in Mantua and Ferrara. In the 1490s black Africans were included on the emblem of the Duke of Milan.[83]

During the trans-Saharan slave trade, slaves from West Africa were transported across the Sahara desert to North Africa to be sold to Mediterranean and Middle eastern civilizations. During the Red Sea slave trade, slaves were transported from Africa across the Red Sea to the Arabian Peninsula. The Indian Ocean slave trade, sometimes known as the east African slave trade, was multi-directional. Africans were sent as slaves to the Arabian Peninsula, to Indian Ocean islands (including Madagascar), to the Indian subcontinent, and later to the Americas. These traders captured Bantu peoples (Zanj) from the interior in present-day Kenya, Mozambique and Tanzania and brought them to the coast.[85][86] There, the slaves gradually assimilated in rural areas, particularly on Unguja and Pemba islands.[87]

Some historians assert that as many as 17 million people were sold into slavery on the coast of the Indian Ocean, the Middle East, and North Africa, and approximately 5 million African slaves were bought by Muslim slave traders and taken from Africa across the Red Sea, Indian Ocean, and Sahara Desert between 1500 and 1900.[88] The captives were sold throughout the Middle East. This trade accelerated as superior ships led to more trade and greater demand for labour on plantations in the region. Eventually, tens of thousands of captives were being taken every year.[87][89][90] The Indian Ocean slave trade was multi-directional and changed over time. To meet the demand for menial labour, Bantu slaves bought by east African slave traders from southeastern Africa were sold in cumulatively large numbers over the centuries to customers in Egypt, Arabia, the Persian Gulf, India, European colonies in the Far East, the Indian Ocean islands, Ethiopia and Somalia.[91]

According to the Encyclopedia of African History, "It is estimated that by the 1890s the largest slave population of the world, about 2 million people, was concentrated in the territories of the Sokoto Caliphate. The use of slave labour was extensive, especially in agriculture."[92][93] The Anti-Slavery Society estimated there were 2 million slaves in Ethiopia in the early 1930s out of an estimated population of 8 to 16 million.[94]

Slave labour in East Africa was drawn from the Zanj, Bantu peoples that lived along the East African coast.[86][95] The Zanj were for centuries shipped as slaves by Arab traders to all the countries bordering the Indian Ocean during the Indian Ocean slave trade. The Umayyad and Abbasid caliphs recruited many Zanj slaves as soldiers and, as early as 696, there were slave revolts of the Zanj against their Arab enslavers during their slavery in the Umayyad Caliphate in Iraq. The Zanj Rebellion, a series of uprisings that took place between 869 and 883 near Basra (also known as Basara), against the slavery in the Abbasid Caliphate situated in present-day Iraq, is believed to have involved enslaved Zanj that had originally been captured from the African Great Lakes region and areas further south in East Africa.[96] It grew to involve over 500,000 slaves and free men who were imported from across the Muslim empire and claimed over "tens of thousands of lives in lower Iraq".[97]

The Zanj who were taken as slaves to the Middle East were often used in strenuous agricultural work.[98] As the plantation economy boomed and the Arabs became richer, agriculture and other manual labour work was thought to be demeaning. The resulting labour shortage led to an increased slave market.

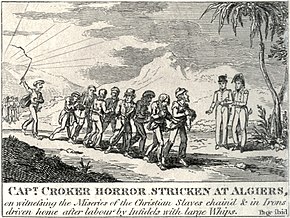

In Algiers, the capital of Algeria, captured Christians and Europeans were forced into slavery. In about 1650, there were as many as 35,000 Christian slaves in Algiers.[99] By one estimate, raids by Barbary slave traders on coastal villages and ships extending from Italy to Iceland, enslaved an estimated 1 to 1.25 million Europeans between the 16th and 19th centuries.[100][101][102] However, this estimate is the result of an extrapolation which assumes that the number of European slaves captured by Barbary pirates was constant for a 250-year period:

There are no records of how many men, women and children were enslaved, but it is possible to calculate roughly the number of fresh captives that would have been needed to keep populations steady and replace those slaves who died, escaped, were ransomed, or converted to Islam. On this basis it is thought that around 8,500 new slaves were needed annually to replenish numbers – about 850,000 captives over the century from 1580 to 1680. By extension, for the 250 years between 1530 and 1780, the figure could easily have been as high as 1,250,000.[103]

Davis' numbers have been refuted by other historians, such as David Earle, who cautions that true picture of Europeans slaves is clouded by the fact the corsairs also seized non-Christian whites from eastern Europe.[103] In addition, the number of slaves traded was hyperactive,[clarification needed] with exaggerated estimates relying on peak years to calculate averages for entire centuries, or millennia. Hence, there were wide fluctuations year-to-year, particularly in the 18th and 19th centuries, given slave imports, and also given the fact that, prior to the 1840s, there are no consistent records. Middle East expert, John Wright, cautions that modern estimates are based on back-calculations from human observation.[104] Such observations, across the late 16th and early 17th century observers, account for around 35,000 European Christian slaves held throughout this period on the Barbary Coast, across Tripoli, Tunis, but mostly in Algiers. The majority were sailors (particularly those who were English), taken with their ships, but others were fishermen and coastal villagers. However, most of these captives were people from lands close to Africa, particularly Spain and Italy.[105] This eventually led to the bombardment of Algiers by an Anglo-Dutch fleet in 1816.[106][107]

Under Omani Arabs, Zanzibar became East Africa's main slave port, with as many as 50,000 African slaves passing through every year during the 19th century.[108][109] Some historians estimate that between 11 and 18 million African slaves crossed the Red Sea, Indian Ocean, and Sahara Desert from 650 to 1900 AD.[3][failed verification][110] Eduard Rüppell described the losses of Sudanese slaves being transported on foot to Egypt: "after the Daftardar bey's 1822 campaign in the southern Nuba mountains, nearly 40,000 slaves were captured. However, through bad treatment, disease and desert travel barely 5,000 made it to Egypt."[111] W.A. Veenhoven wrote: "The German doctor, Gustav Nachtigal, an eye-witness, believed that for every slave who arrived at a market three or four died on the way ... Keltie (The Partition of Africa, London, 1920) believes that for every slave the Arabs brought to the coast at least six died on the way or during the slavers' raid. Livingstone puts the figure as high as ten to one."[112]

Systems of servitude and slavery were common in parts of Africa, as they were in much of the ancient world. In many African societies where slavery was prevalent, the slaves were not treated as chattel slaves and were given certain rights in a system similar to indentured servitude elsewhere in the world. The forms of slavery in Africa were closely related to kinship structures. In many African communities, where land could not be owned, enslavement of individuals was used as a means to increase the influence a person had and expand connections.[113] This made slaves a permanent part of a master's lineage and the children of slaves could become closely connected with the larger family ties.[114] Children of slaves born into families could be integrated into the master's kinship group and rise to prominent positions within society, even to the level of chief in some instances. However, stigma often remained attached and there could be strict separations between slave members of a kinship group and those related to the master.[113] Slavery was practiced in many different forms: debt slavery, enslavement of war captives, military slavery, and criminal slavery were all practiced in various parts of Africa.[115] Slavery for domestic and court purposes was widespread throughout Africa.

When the Atlantic slave trade began, many of the local slave systems began supplying captives for chattel slave markets outside Africa. Although the Atlantic slave trade was not the only slave trade from Africa, it was the largest in volume and intensity. As Elikia M'bokolo wrote in Le Monde diplomatique:

The African continent was bled of its human resources via all possible routes. Across the Sahara, through the Red Sea, from the Indian Ocean ports and across the Atlantic. At least ten centuries of slavery for the benefit of the Muslim countries (from the ninth to the nineteenth).... Four million enslaved people exported via the Red Sea, another four million through the Swahili ports of the Indian Ocean, perhaps as many as nine million along the trans-Saharan caravan route, and eleven to twenty million (depending on the author) across the Atlantic Ocean.[116]

The trans-Atlantic slave trade peaked in the late 18th century, when the largest number of slaves were captured on raiding expeditions into the interior of West Africa.

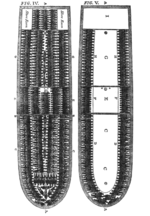

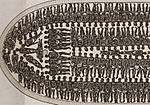

These expeditions were typically carried out by African kingdoms, such as the Oyo Empire (Yoruba), the Ashanti Empire,[117] the kingdom of Dahomey,[118] and the Aro Confederacy.[119] It is estimated that about 15 percent of slaves died during the voyage, with mortality rates considerably higher in Africa itself in the process of capturing and transporting indigenous peoples to the ships.[120][121]

Americas

Slavery in Mexico can be traced back to the Aztecs.[122] Other Amerindians, such as the Inca of the Andes, the Tupinambá of Brazil, the Creek of Georgia, and the Comanche of Texas, also practiced slavery.[3]

Slavery in Canada was practiced by First Nations and by European settlers.[123] Slave-owning people of what became Canada were, for example, the fishing societies, such as the Yurok, that lived along the Pacific coast from Alaska to California,[124] on what is sometimes described as the Pacific or Northern Northwest Coast. Some of the indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast, such as the Haida and Tlingit, were traditionally known as fierce warriors and slave-traders, raiding as far as California. Slavery was hereditary, the slaves being prisoners of war and their descendants were slaves.[125] Some nations in British Columbia continued to segregate and ostracize the descendants of slaves as late as the 1970s.[126]

Slavery in America remains a contentious issue and played a major role in the history and evolution of some countries, triggering a revolution, a civil war, and numerous rebellions.

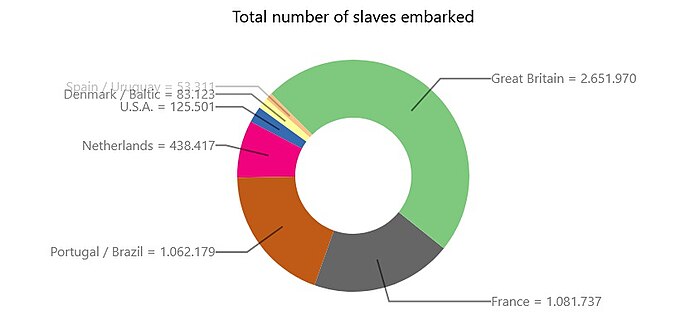

The countries that controlled most of the transatlantic slave market in terms of number of slaves shipped were the UK, Portugal and France.

In order to establish itself as an American empire, Spain had to fight against the relatively powerful civilizations of the New World. The Spanish conquest of the indigenous peoples in the Americas included using the Natives as forced labour. The Spanish colonies were the first Europeans to use African slaves in the New World on islands such as Cuba and Hispaniola.[127] It was argued by some contemporary writers to be intrinsically immoral.[128][129][130] Bartolomé de las Casas, a 16th-century Dominican friar and Spanish historian, participated in campaigns in Cuba (at Bayamo and Camagüey) and was present at the massacre of Hatuey; his observation of that massacre led him to fight for a social movement away from the use of natives as slaves. Also, the alarming decline in the native population had spurred the first royal laws protecting the native population. The first African slaves arrived in Hispaniola in 1501.[131] This era saw a growth in race-based slavery.[132] England played a prominent role in the Atlantic slave trade. The "slave triangle" was pioneered by Francis Drake and his associates, though English slave-trading would not take off until the mid-17th century.

Many whites who arrived in North America during the 17th and 18th centuries came under contract as indentured servants.[133] The transformation from indentured servitude to slavery was a gradual process in Virginia. The earliest legal documentation of such a shift was in 1640 where a black man, John Punch, was sentenced to lifetime slavery, forcing him to serve his master, Hugh Gwyn, for the remainder of his life, for attempting to run away. This case was significant because it established the disparity between his sentence as a black man and that of the two white indentured servants who escaped with him (one described as Dutch and one as a Scotchman). It is the first documented case of a black man sentenced to lifetime servitude and is considered one of the first legal cases to make a racial distinction between black and white indentured servants.[134][135]

After 1640, planters started to ignore the expiration of indentured contracts and keep their servants as slaves for life. This was demonstrated by the 1655 case Johnson v. Parker, where the court ruled that a black man, Anthony Johnson of Virginia, was granted ownership of another black man, John Casor, as the result of a civil case.[136] This was the first instance of a judicial determination in the Thirteen Colonies holding that a person who had committed no crime could be held in servitude for life.[137][138]

Spanish colonial America

In 1519, Hernán Cortés brought the first modern slave to the area.[139] In the mid-16th century, the Spanish New Laws, prohibited slavery of the indigenous people, including the Aztecs. A labour shortage resulted. This led to the African slaves being imported, as they were not susceptible to smallpox. In exchange, many Africans were afforded the opportunity to buy their freedom, while eventually others were granted their freedom by their masters.[139] In Jamaica, the Spanish enslaved many of the Taino; some escaped, but most died from European diseases and overwork. The Spaniards also introduced the first African slaves.[140]

Spain practically did not trade in slaves until 1810 after the rebellions and independence of its American territories or viceroyalties. After the Napoleonic invasions, Spain had lost its industry and its American territories, except in Cuba and Puerto Rico, where the African slave trade to Cuba began on a massive scale from 1810 onwards. It was started by French planters exiled from the French lost colony Saint Domingue (Haiti) who settled in the eastern part of Cuba.

In 1789, the Spanish Crown led an effort to reform slavery, as the demand for slave labour in Cuba was growing. The Crown issued a decree, Código Negro Español (Spanish Black Code), that specified food and clothing provisions, put limits on the number of work hours, limited punishments, required religious instruction, and protected marriages, forbidding the sale of young children away from their mothers. The British made other changes to the institution of slavery in Cuba. However, planters often flouted the laws and protested against them, considering them a threat to their authority and an intrusion into their personal lives.[141]

English and Dutch Caribbean

In the early 17th century, the majority of the labour in Barbados was provided by European indentured servants, mainly English, Irish and Scottish, with African and native American slaves providing little of the workforce. The introduction of sugar cane in 1640 completely transformed society and the economy. Barbados eventually had one of the world's largest sugar industries.[142] The workable sugar plantation required a large investment and a great deal of heavy labour. At first, Dutch traders supplied the equipment, financing, and African slaves, in addition to transporting most of the sugar to Europe. In 1644, the population of Barbados was estimated at 30,000, of which about 800 were of African descent, with the remainder mainly of English descent. By 1700, there were 15,000 free whites and 50,000 enslaved Africans. In Jamaica, although the African slave population in the 1670s and 1680s never exceeded 10,000, by 1800 it had increased to over 300,000. The increased implementation of slave codes or black codes, which created differential treatment between Africans and the white workers and ruling planter class. In response to these codes, several slave rebellions were attempted or planned during this time, but none succeeded.

The planters of the Dutch colony of Suriname relied heavily on African slaves to cultivate, harvest and process the commodity crops of coffee, cocoa, sugar cane and cotton plantations.[143] The Netherlands abolished slavery in Suriname in 1863.

Many slaves escaped the plantations. With the help of the native South Americans living in the adjoining rain forests, these runaway slaves established a new and unique culture in the interior that was highly successful in its own right. They were known collectively in English as Maroons, in French as Nèg'Marrons (literally meaning "brown negroes", that is "pale-skinned negroes"), and in Dutch as Marrons. The Maroons gradually developed several independent tribes through a process of ethnogenesis, as they were made up of slaves from different African ethnicities. These tribes include the Saramaka, Paramaka, Ndyuka or Aukan, Kwinti, Aluku or Boni, and Matawai. The Maroons often raided plantations to recruit new members from the slaves and capture women, as well as to acquire weapons, food and supplies. They sometimes killed planters and their families in the raids.[144] The colonists also mounted armed campaigns against the Maroons, who generally escaped through the rain forest, which they knew much better than did the colonists. To end hostilities, in the 18th century the European colonial authorities signed several peace treaties with different tribes. They granted the Maroons sovereign status and trade rights in their inland territories, giving them autonomy.

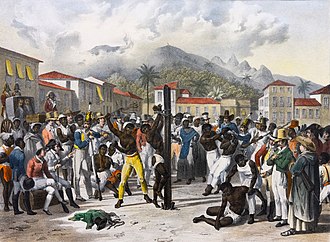

Brazil

Slavery in Brazil began long before the first Portuguese settlement was established in 1532, as members of one tribe would enslave captured members of another.[145]

Later, Portuguese colonists were heavily dependent on indigenous labour during the initial phases of settlement to maintain the subsistence economy, and natives were often captured by expeditions called bandeiras. The importation of African slaves began midway through the 16th century, but the enslavement of indigenous peoples continued well into the 17th and 18th centuries.

During the Atlantic slave trade era, Brazil imported more African slaves than any other country. Nearly 5 million slaves were brought from Africa to Brazil during the period from 1501 to 1866.[146] Until the early 1850s, most African slaves who arrived on Brazilian shores were forced to embark at West Central African ports, especially in Luanda (in present-day Angola). Today, with the exception of Nigeria, the country with the largest population of people of African descent is Brazil.[147]

Slave labour was the driving force behind the growth of the sugar economy in Brazil, and sugar was the primary export of the colony from 1600 to 1650. Gold and diamond deposits were discovered in Brazil in 1690, which sparked an increase in the importation of African slaves to power this newly profitable market. Transportation systems were developed for the mining infrastructure, and population boomed from immigrants seeking to take part in gold and diamond mining. Demand for African slaves did not wane after the decline of the mining industry in the second half of the 18th century. Cattle ranching and foodstuff production proliferated after the population growth, both of which relied heavily on slave labour. 1.7 million slaves were imported to Brazil from Africa from 1700 to 1800, and the rise of coffee in the 1830s further enticed expansion of the slave trade.

Brazil was the last country in the Western world to abolish slavery. Forty percent of the total number of slaves brought to the Americas were sent to Brazil. For reference, the United States received 10 percent. Despite being abolished, there are still people working in slavery-like conditions in Brazil in the 21st century.

Haiti

Slavery in Haiti started with the arrival of Christopher Columbus on the island in 1492. The practice was devastating to the native population.[148] Following the indigenous Taíno's near decimation from forced labour, disease and war, the Spanish, under advisement of the Catholic priest Bartolomé de las Casas, and with the blessing of the Catholic church, who also wished to protect the indigenous people, began engaging in earnest in the use of African slaves.[clarification needed] During the French colonial period beginning in 1625, the economy of Haiti (then known as Saint-Domingue) was based on slavery, and the practice there was regarded as the most brutal in the world.

Following the Treaty of Ryswick of 1697, Hispaniola was divided between France and Spain. France received the western third and subsequently named it Saint-Domingue. To develop it into sugarcane plantations, the French imported thousands of slaves from Africa. Sugar was a lucrative commodity crop throughout the 18th century. By 1789, approximately 40,000 white colonists lived in Saint-Domingue. The whites were vastly outnumbered by the tens of thousands of African slaves they had imported to work on their plantations, which were primarily devoted to the production of sugarcane. In the north of the island, slaves were able to retain many ties to African cultures, religion and language; these ties were continually being renewed by newly imported Africans. Blacks outnumbered whites by about ten to one.

The French-enacted Code Noir ("Black Code"), prepared by Jean-Baptiste Colbert and ratified by Louis XIV, had established rules on slave treatment and permissible freedoms. Saint-Domingue has been described as one of the most brutally efficient slave colonies; one-third of newly imported Africans died within a few years.[149] Many slaves died from diseases such as smallpox and typhoid fever.[150] They had birth rates around 3 percent, and there is evidence that some women aborted fetuses, or committed infanticide, rather than allow their children to live within the bonds of slavery.[151][152]

As in its Louisiana colony, the French colonial government allowed some rights to free people of color: the mixed-race descendants of white male colonists and black female slaves (and later, mixed-race women). Over time, many were released from slavery. They established a separate social class. White French Creole fathers frequently sent their mixed-race sons to France for their education. Some men of color were admitted into the military. More of the free people of color lived in the south of the island, near Port-au-Prince, and many intermarried within their community. They frequently worked as artisans and tradesmen, and began to own some property. Some became slave holders. The free people of color petitioned the colonial government to expand their rights.

Slaves that made it to Haiti from the trans-Atlantic journey and slaves born in Haiti were first documented in Haiti's archives and transferred to France's Ministry of Defense and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. As of 2015[update], these records are in The National Archives of France. According to the 1788 Census, Haiti's population consisted of nearly 40,000 whites, 30,000 free coloureds and 450,000 slaves.[153]

The Haitian Revolution of 1804, the only successful slave revolt in human history, precipitated the end of slavery in all French colonies, which came in 1848.

United States

Slavery in the United States was the legal institution of human chattel enslavement, primarily of Africans and African Americans, that existed in the United States of America in the 18th and 19th centuries, after it gained independence from the British and before the end of the American Civil War. Slavery had been practiced in British America from early colonial days and was legal in all Thirteen Colonies, at the time of the Declaration of Independence in 1776. By the time of the American Revolution, the status of slave had been institutionalized as a racial caste associated with African ancestry.[154] The United States became polarized over the issue of slavery, represented by the slave and free states divided by the Mason–Dixon line, which separated free Pennsylvania from slave Maryland and Delaware.

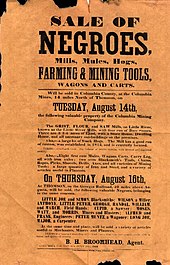

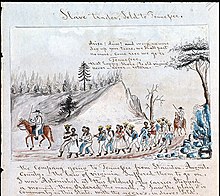

Congress, during the Jefferson administration, prohibited the importation of slaves, effective 1808, although smuggling (illegal importing) was not unusual.[155] Domestic slave trading, however, continued at a rapid pace, driven by labour demands from the development of cotton plantations in the Deep South. Those states attempted to extend slavery into the new western territories to keep their share of political power in the nation. Such laws proposed to Congress to continue the spread of slavery into newly ratified states include the Kansas-Nebraska Act.

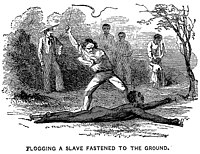

The treatment of slaves in the United States varied widely depending on conditions, times, and places. The power relationships of slavery corrupted many whites who had authority over slaves, with children showing their own cruelty. Masters and overseers resorted to physical punishments to impose their wills. Slaves were punished by whipping, shackling, hanging, beating, burning, mutilation, branding and imprisonment. Punishment was most often meted out in response to disobedience or perceived infractions, but sometimes abuse was carried out to re-assert the dominance of the master or overseer of the slave.[156] Treatment was usually harsher on large plantations, which were often managed by overseers and owned by absentee slaveholders.

William Wells Brown, who escaped to freedom, reported that on one plantation, slave men were required to pick 80 pounds (36 kg) of cotton per day, while women were required to pick 70 pounds (32 kg) per day; if any slave failed in their quota, they were subject to whip lashes for each pound they were short. The whipping post stood next to the cotton scales.[157] A New York man who attended a slave auction in the mid-19th century reported that at least three-quarters of the male slaves he saw at sale had scars on their backs from whipping.[158] By contrast, small slave-owning families had closer relationships between the owners and slaves; this sometimes resulted in a more humane environment but was not a given.[156]

More than one million slaves were sold from the Upper South, which had a surplus of labour, and taken to the Deep South in a forced migration, splitting up many families. New communities of African American culture were developed in the Deep South, and the total slave population in the South eventually reached 4 million before liberation.[159][160] In the 19th century, proponents of slavery often defended the institution as a "necessary evil". White people of that time feared that emancipation of black slaves would have more harmful social and economic consequences than the continuation of slavery. The French writer and traveler Alexis de Tocqueville, in Democracy in America (1835), expressed opposition to slavery while observing its effects on American society. He felt that a multiracial society without slavery was untenable, as he believed that prejudice against black people increased as they were granted more rights. Others, like James Henry Hammond argued that slavery was a "positive good" stating: "Such a class you must have, or you would not have that other class which leads progress, civilization, and refinement."

The Southern state governments wanted to keep a balance between the number of slave and free states to maintain a political balance of power in Congress. The new territories acquired from Britain, France, and Mexico were the subject of major political compromises. By 1850, the newly rich cotton-growing South was threatening to secede from the Union, and tensions continued to rise. Many white Southern Christians, including church ministers, attempted to justify their support for slavery as modified by Christian paternalism.[161] The largest denominations, the Baptist, Methodist, and Presbyterian churches, split over the slavery issue into regional organizations of the North and South.

When Abraham Lincoln won the 1860 election on a platform of halting the expansion of slavery, according to the 1860 U.S. census, roughly 400,000 individuals, representing 8% of all U.S. families, owned nearly 4,000,000 slaves.[162] One-third of Southern families owned slaves.[163] The South was heavily invested in slavery. As such, upon Lincoln's election, seven states broke away to form the Confederate States of America. The first six states to secede held the greatest number of slaves in the South. Shortly after, over the issue of slavery, the United States erupted into an all-out Civil War, with slavery legally ceasing as an institution following the war in December 1865.

In 1865, the United States ratified the 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution, which banned slavery and involuntary servitude "except as punishment for a crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted," providing a legal basis for forced labor to continue in the country. This led to the system of convict leasing, which affected primarily African Americans. The Prison Policy Initiative, an American criminal justice think tank, cites the 2020 US prison population as 2.3 million, and nearly all able-bodied inmates work in some fashion. In Texas, Georgia, Alabama and Arkansas, prisoners are not paid at all for their work. In other states, prisoners are paid between $0.12 and $1.15 per hour. Federal Prison Industries paid inmates an average of $0.90 per hour in 2017. Inmates who refuse to work may be indefinitely remanded into solitary confinement or have family visitation revoked. From 2010 to 2015 and again in 2016 and in 2018, some prisoners in the US refused to work, protesting for better pay, better conditions, and for the end of forced labor. Strike leaders were punished with indefinite solitary confinement. Forced prison labor occurs in both government-run prisons and private prisons. CoreCivic and GEO Group constitute half the market share of private prisons, and they made a combined revenue of $3.5 billion in 2015. The value of all labor by inmates in the United States is estimated to be in the billions. In California, 2,500 incarcerated workers fought wildfires for only $1 per hour through the CDCR's Conservation Camp Program, which saves the state as much as $100 million a year.[164]

Asia-Pacific

East Asia

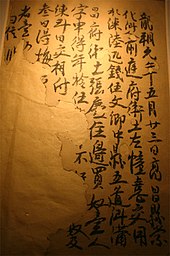

Slavery existed in ancient China as early as the Shang dynasty.[165] Slavery was employed largely by governments as a means of maintaining a public labour force.[166][167] Until the Han dynasty, slaves were sometimes discriminated against but their legal status was guaranteed. As can be seen from the some historical records as “Duansheng, Marquis of Shouxiang, had his territory confiscated because he killed a female slave”(Han dynasty records in DongGuan), “Wang Mang's son Wang Huo murdered a slave, Wang Mang severely criticized him and forced him to commit suicide”(Book of Han: Biography of Wang Mang), Murder against slaves was as taboo as murder against free people, and perpetrators were always severely punished. Han dynasty can be said to be very distinctive compared to other countries of the same period(In most cases, lords were free to kill their slaves) in terms of slaves human rights.

After the Southern and Northern Dynasties, Due to years of poor harvests, the influx of foreign tribes, and the resulting wars, The number of slaves exploded. They became a class and were called "jianmin (Chinese: 贱民)", The word literally means "inferior person". As stated in The commentary of Tang Code: “Slaves and inferior people are legally equivalent to livestock products”, They always had a low social status, and even if they were deliberately murdered, the perpetrators received only a year in prison, and were punished even when they reported the crimes of their lords.[168] However, in the Later period of the dynasty, perhaps because the increase in the number of slaves slowed down again, the penalties for crimes against them became harsh again. For example, the famous contemporary female poet Yu Xuanji, she was publicly executed for murdering her own slave.

Many Han Chinese were enslaved in the process of the Mongol invasion of China proper.[169] According to Japanese historians Sugiyama Masaaki (杉山正明) and Funada Yoshiyuki (舩田善之), Mongolian slaves were owned by Han Chinese during the Yuan dynasty.[170][171] Slavery has taken various forms throughout China's history. It was reportedly abolished as a legally recognized institution, including in a 1909 law[172][173] fully enacted in 1910,[174] although the practice continued until at least 1949.[169] Tang Chinese soldiers and pirates enslaved Koreans, Turks, Persians, Indonesians, and people from Inner Mongolia, central Asia, and northern India.[175][176] The greatest source of slaves came from southern tribes, including Thais and aboriginals from the southern provinces of Fujian, Guangdong, Guangxi, and Guizhou. Malays, Khmers, Indians, and "black skinned" peoples (who were either Austronesian Negritos of Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands, or Africans, or both) were also purchased as slaves in the Tang dynasty.[177]

In the 17th century Qing dynasty, there was a hereditarily servile people called Booi Aha (Manchu: booi niyalma; Chinese transliteration: 包衣阿哈), which is a Manchu word literally translated as "household person" and sometimes rendered as "nucai." The Manchu was establishing close personal and paternalist relationship between masters and their slaves, as Nurhachi said, "The Master should love the slaves and eat the same food as him".[178] However, booi aha "did not correspond exactly to the Chinese category of "bond-servant slave" (Chinese:奴僕); instead, it was a relationship of personal dependency on a master which in theory guaranteed close personal relationships and equal treatment, even though many western scholars would directly translate "booi" as "bond-servant" (some of the "booi" even had their own servant).[169] Chinese Muslim (Tungans) Sufis who were charged with practicing xiejiao (heterodox religion), were punished by exile to Xinjiang and being sold as a slave to other Muslims, such as the Sufi begs.[179] Han Chinese who committed crimes such as those dealing with opium became slaves to the begs, this practice was administered by Qing law.[180] Most Chinese in Altishahr were exile slaves to Turkestani Begs.[181] While free Chinese merchants generally did not engage in relationships with East Turkestani women, some of the Chinese slaves belonging to begs, along with Green Standard soldiers, Bannermen, and Manchus, engaged in affairs with the East Turkestani women that were serious in nature.[182]

Slavery in Korea existed since before the Three Kingdoms of Korea period, in the first century BCE.[183] Slavery has been described as "very important in medieval Korea, probably more important than in any other East Asian country, but by the 16th century, population growth was making [it] unnecessary".[184] Slavery went into decline around the 10th century but came back in the late Goryeo period when Korea also experienced multiple slave rebellions.[183] In the Joseon period of Korea, members of the slave class were known as nobi. The nobi were socially indistinct from freemen (i.e., the middle and common classes) other than the ruling yangban class, and some possessed property rights, and legal and civil rights. Hence, some scholars argue that it is inappropriate to call them "slaves",[185] while some scholars describe them as serfs.[186][187] The nobi population could fluctuate up to about one-third of the total, but on average the nobi made up about 10% of the total population.[183] In 1801, the majority of government nobi were emancipated,[188] and by 1858, the nobi population stood at about 1.5 percent of the Korean population.[189] During the Joseon period, the nobi population could fluctuate up to about one-third of the population, but on average the nobi made up about 10% of the total population.[183] The nobi system declined beginning in the 18th century.[190] Since the outset of the Joseon dynasty and especially beginning in the 17th century, there was harsh criticism among prominent thinkers in Korea about the nobi system. Even within the Joseon government, there were indications of a shift in attitude toward the nobi.[191] King Yeongjo implemented a policy of gradual emancipation in 1775,[184] and he and his successor King Jeongjo made many proposals and developments that lessened the burden on nobi, which led to the emancipation of the vast majority of government nobi in 1801.[191] In addition, population growth,[184] numerous escaped slaves,[183] growing commercialization of agriculture, and the rise of the independent small farmer class contributed to the decline in the number of nobi to about 1.5% of the total population by 1858.[189] The hereditary nobi system was officially abolished around 1886–87,[183][189] and the rest of the nobi system was abolished with the Gabo Reform of 1894.[183][192] However, slavery did not completely disappear in Korea until 1930, during Imperial Japanese rule. During the Imperial Japanese occupation of Korea around World War II, some Koreans were used in forced labour by the Imperial Japanese, in conditions which have been compared to slavery.[183][193] These included women forced into sexual slavery by the Imperial Japanese Army before and during World War II, known as "comfort women".[183][193]

After the Portuguese first made contact with Japan in 1543, slave trade developed in which Portuguese purchased Japanese as slaves in Japan and sold them to various locations overseas, including Portugal, throughout the 16th and 17th centuries.[194][195] Many documents mention the slave trade along with protests against the enslavement of Japanese. Japanese slaves are believed to be the first of their nation to end up in Europe, and the Portuguese purchased numbers of Japanese slave girls to bring to Portugal for sexual purposes, as noted by the Church[196] in 1555. Japanese slave women were even sold as concubines to Asian lascar and African crew members, along with their European counterparts serving on Portuguese ships trading in Japan, mentioned by Luis Cerqueira, a Portuguese Jesuit, in a 1598 document.[197] Japanese slaves were brought by the Portuguese to Macau, where they were enslaved to Portuguese or became slaves to other slaves.[198][199] Some Korean slaves were bought by the Portuguese and brought back to Portugal from Japan, where they had been among the tens of thousands of Korean prisoners of war transported to Japan during the Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–98).[200][201] Historians pointed out that at the same time Hideyoshi expressed his indignation and outrage at the Portuguese trade in Japanese slaves, he was engaging in a mass slave trade of Korean prisoners of war in Japan.[202][203] Fillippo Sassetti saw some Chinese and Japanese slaves in Lisbon among the large slave community in 1578, although most of the slaves were black.[204][205][206][207][208]

The Portuguese also valued Oriental slaves more than the black Africans and the Moors for their rarity. Chinese slaves were more expensive than Moors and blacks and showed off the high status of the owner.[209] The Portuguese attributed qualities like intelligence and industriousness to Chinese, Japanese and Indian slaves.[210][206] King Sebastian of Portugal feared rampant slavery was having a negative effect on Catholic proselytization, so he commanded that it be banned in 1571.[211] Hideyoshi was so disgusted that his own Japanese people were being sold en masse into slavery on Kyushu, that he wrote a letter to Jesuit Vice-Provincial Gaspar Coelho on July 24, 1587, to demand the Portuguese, Siamese (Thai), and Cambodians stop purchasing and enslaving Japanese and return Japanese slaves who ended up as far as India.[212][213][214] Hideyoshi blamed the Portuguese and Jesuits for this slave trade and banned Christian proselytizing as a result.[215][self-published source][216] In 1595, a law was passed by Portugal banning the selling and buying of Chinese and Japanese slaves.[217]

South Asia

Slavery in India was widespread by the 6th century BC, and perhaps even as far back as the Vedic period.[218] Slavery intensified during the Muslim domination of northern India after the 11th-century.[219] Slavery existed in Portuguese India after the 16th century. The Dutch, too, largely dealt in Abyssian slaves, known in India as Habshis or Sheedes.[220] Arakan/Bengal, Malabar, and Coromandel remained the largest sources of forced labour until the 1660s.

Between 1626 and 1662, the Dutch exported on an average 150–400 slaves annually from the Arakan-Bengal coast. During the first 30 years of Batavia's existence, Indian and Arakanese slaves provided the main labour force of the Dutch East India Company, Asian headquarters. An increase in Coromandel slaves occurred during a famine following the revolt of the Nayaka Indian rulers of South India (Tanjavur, Senji, and Madurai) against Bijapur overlordship (1645) and the subsequent devastation of the Tanjavur countryside by the Bijapur army. Reportedly, more than 150,000 people were taken by the invading Deccani Muslim armies to Bijapur and Golconda. In 1646, 2,118 slaves were exported to Batavia, the overwhelming majority from southern Coromandel. Some slaves were also acquired further south at Tondi, Adirampatnam, and Kayalpatnam. Another increase in slaving took place between 1659 and 1661 from Tanjavur as a result of a series of successive Bijapuri raids. At Nagapatnam, Pulicat, and elsewhere, the company purchased 8,000–10,000 slaves, the bulk of whom were sent to Ceylon, while a small portion were exported to Batavia and Malacca. Finally, following a long drought in Madurai and southern Coromandel, in 1673, which intensified the prolonged Madurai-Maratha struggle over Tanjavur and punitive fiscal practices, thousands of people from Tanjavur, mostly children, were sold into slavery and exported by Asian traders from Nagapattinam to Aceh, Johor, and other slave markets.

In September 1687, 665 slaves were exported by the English from Fort St. George, Madras. And, in 1694–96, when warfare once more ravaged South India, a total of 3,859 slaves were imported from Coromandel by private individuals into Ceylon.[221][222][223][224] The volume of the total Dutch Indian Ocean slave trade has been estimated to be about 15–30% of the Atlantic slave trade, slightly smaller than the trans-Saharan slave trade, and one-and-a-half to three times the size of the Swahili and Red Sea coast and the Dutch West India Company slave trades.[225]

According to Sir Henry Bartle Frere (who sat on the Viceroy's Council), there were an estimated 8 or 9 million slaves in India in 1841. About 15% of the population of Malabar were slaves. Slavery was legally abolished in the possessions of the East India Company by the Indian Slavery Act, 1843.[3]

South East Asia

The hill tribe people in Indochina were "hunted incessantly and carried off as slaves by the Siamese (Thai), the Anamites (Vietnamese), and the Cambodians".[226] A Siamese military campaign in Laos in 1876 was described by a British observer as having been "transformed into slave-hunting raids on a large scale".[226] The census, taken in 1879, showed that 6% of the population in the Malay sultanate of Perak were slaves.[227] Enslaved people made up about two-thirds of the population in part of North Borneo in the 1880s.[227]

Oceania

Slaves (he mōkai) had a recognised social role in traditional Māori society in New Zealand.[228]

Blackbirding occurred on islands in the Pacific Ocean and Australia, especially in the 19th century.

Europe

Ancient Greece and Rome

Records of slavery in Ancient Greece begin with Mycenaean Greece. Classical Athens had the largest slave population, with as many as 80,000 in the 6th and 5th centuries BC.[229] As the Roman Republic expanded outward, entire populations were enslaved, across Europe and the Mediterranean. Slaves were used for labour, as well as for amusement (e.g., gladiators and sex slaves). This oppression by an elite minority eventually led to slave revolts (see Roman Servile Wars); the Third Servile War was led by Spartacus.

By the late Republican era, slavery had become an economic pillar of Roman wealth, as well as Roman society.[230] It is estimated that 25% or more of the population of Ancient Rome was enslaved, although the actual percentage is debated by scholars and varied from region to region.[231][232] Slaves represented 15–25% of Italy's population,[233] mostly war captives,[233] especially from Gaul[234] and Epirus. Estimates of the number of slaves in the Roman Empire suggest that the majority were scattered throughout the provinces outside of Italy.[233] Generally, slaves in Italy were indigenous Italians.[235] Foreigners (including both slaves and freedmen) born outside of Italy were estimated to have peaked at 5% of the total in the capital, where their number was largest. Those from outside of Europe were predominantly of Greek descent. Jewish slaves never fully assimilated into Roman society, remaining an identifiable minority. These slaves (especially the foreigners) had higher death rates and lower birth rates than natives and were sometimes subjected to mass expulsions.[236] The average recorded age at death for the slaves in Rome was seventeen and a half years (17.2 for males; 17.9 for females).[237]

Medieval and early modern Europe

Slavery in early medieval Europe was so common that the Catholic Church repeatedly prohibited it, or at least the export of Christian slaves to non-Christian lands, as for example at the Council of Koblenz (922), the Council of London (1102) (which aimed mainly at the sale of English slaves to Ireland)[238] and the Council of Armagh (1171). Serfdom, on the contrary, was widely accepted. In 1452, Pope Nicholas V issued the papal bull Dum Diversas, granting the kings of Spain and Portugal the right to reduce any "Saracens (Muslims), pagans and any other unbelievers" to perpetual slavery, legitimizing the slave trade as a result of war.[239] The approval of slavery under these conditions was reaffirmed and extended in his Romanus Pontifex bull of 1455. Large-scale trading in slaves was mainly confined to the South and East of early medieval Europe: the Byzantine Empire and the Muslim world were the destinations, while pagan Central and Eastern Europe (along with the Caucasus and Tartary) were important sources. Viking, Arab, Greek, and Radhanite Jewish merchants were all involved in the slave trade during the Early Middle Ages.[240][241][242] The trade in European slaves reached a peak in the 10th century following the Zanj Rebellion, which dampened the use of African slaves in the Arab world.[243][244]

In Britain, slavery continued to be practiced following the fall of Rome, while sections of Æthelstan's and Hywel the Good's laws dealt with slaves in medieval England and medieval Wales respectively.[245][246] The trade particularly picked up after the Viking invasions, with major markets at Chester[247] and Bristol[248] supplied by Danish, Mercian, and Welsh raiding of one another's borderlands. At the time of the Domesday Book, nearly 10% of the English population were slaves.[249] William the Conqueror introduced a law preventing the sale of slaves overseas.[250] According to historian John Gillingham, by 1200 slavery in the British Isles was non-existent.[251] Slavery had never been authorized by statute within England and Wales, and in 1772, in the case Somerset v Stewart, Lord Mansfield declared that it was also unsupported within England by the common law. The slave trade was abolished by the Slave Trade Act 1807, although slavery remained legal in possessions outside Europe until the passage of the Slavery Abolition Act 1833 and the Indian Slavery Act, 1843.[252] However, when England began to have colonies in the Americas, and particularly from the 1640s, African slaves began to make their appearance in England and remained a presence until the eighteenth century. In Scotland, slaves continued to be sold as chattels until late in the eighteenth century (on the second May 1722, an advertisement appeared in the Edinburgh Evening Courant, announcing that a stolen slave had been found, who would be sold to pay expenses, unless claimed within two weeks).[253] For nearly two hundred years in the history of coal mining in Scotland, miners were bonded to their "maisters" by a 1606 Act "Anent Coalyers and Salters". The Colliers and Salters (Scotland) Act 1775 stated that "many colliers and salters are in a state of slavery and bondage" and announced emancipation; those starting work after July 1, 1775, would not become slaves, while those already in a state of slavery could, after 7 or 10 years depending on their age, apply for a decree of the Sheriff's Court granting their freedom. Few could afford this, until a further law in 1799 established their freedom and made this slavery and bondage illegal.[253][254]

The Byzantine-Ottoman wars and the Ottoman wars in Europe brought large numbers of slaves into the Islamic world.[255] To staff its bureaucracy, the Ottoman Empire established a janissary system which seized hundreds of thousands of Christian boys through the devşirme system. They were well cared for but were legally slaves owned by the government and were not allowed to marry. They were never bought or sold. The empire gave them significant administrative and military roles. The system began about 1365; there were 135,000 janissaries in 1826, when the system ended.[256] After the Battle of Lepanto, 12,000 Christian galley slaves were recaptured and freed from the Ottoman fleet.[257] Eastern Europe suffered a series of Tatar invasions, the goal of which was to loot and capture slaves for selling them to Ottomans as jasyr.[258] Seventy-five Crimean Tatar raids were recorded into Poland–Lithuania between 1474 and 1569.[259]

Medieval Spain and Portugal were the scene of almost constant Muslim invasion of the predominantly Christian area. Periodic raiding expeditions were sent from Al-Andalus to ravage the Iberian Christian kingdoms, bringing back booty and slaves. In a raid against Lisbon in 1189, for example, the Almohad caliph Yaqub al-Mansur took 3,000 female and child captives, while his governor of Córdoba, in a subsequent attack upon Silves, Portugal, in 1191, took 3,000 Christian slaves.[260] From the 11th to the 19th century, North African Barbary Pirates engaged in raids on European coastal towns to capture Christian slaves to sell at slave markets in places such as Algeria and Morocco.[261]

The maritime town of Lagos was the first slave market created in Portugal (one of the earliest colonizers of the Americas) for the sale of imported African slaves – the Mercado de Escravos, opened in 1444.[262][263] In 1441, the first slaves were brought to Portugal from northern Mauritania.[263] By 1552, black African slaves made up 10% of the population of Lisbon.[264][265] In the second half of the 16th century, the Crown gave up the monopoly on slave trade, and the focus of European trade in African slaves shifted from import to Europe to slave transports directly to tropical colonies in the Americas – especially Brazil.[263] In the 15th century one-third of the slaves were resold to the African market in exchange of gold.[266]

Until the late 18th century, the Crimean Khanate (a Muslim Tatar state) maintained a massive slave trade with the Ottoman Empire and the Middle East.[258] The slaves were captured in southern Russia, Poland-Lithuania, Moldavia, Wallachia, and Circassia by Tatar horsemen[267] and sold in the Crimean port of Kaffa.[268] About 2 million mostly Christian slaves were exported over the 16th and 17th centuries[269] until the Crimean Khanate was destroyed by the Russian Empire in 1783.[270]

In Kievan Rus and Muscovy, slaves were usually classified as kholops. According to David P. Forsythe, "In 1649 up to three-quarters of Muscovy's peasants, or 13 to 14 million people, were serfs whose material lives were barely distinguishable from slaves. Perhaps another 1.5 million were formally enslaved, with Russian slaves serving Russian masters."[272] Slavery remained a major institution in Russia until 1723, when Peter the Great converted the household slaves into house serfs. Russian agricultural slaves were formally converted into serfs earlier in 1679.[273] Slavery in Poland was forbidden in the 15th century; in Lithuania, slavery was formally abolished in 1588; they were replaced by the second serfdom.

In Scandinavia, thralldom was abolished in the mid-14th century.[274]

World War II

During the Second World War, Nazi Germany effectively enslaved about 12 million people, both those considered undesirable and citizens of conquered countries, with the avowed intention of treating these Untermenschen (sub-humans) as a permanent slave-class of inferior beings who could be worked until they died, and who possessed neither the rights nor the legal status of members of the Aryan race.[275]

Besides Jews, the harshest deportation and forced labour policies were applied to the populations of Poland,[276] Belarus, Ukraine, and Russia. By the end of the war, half of Belarus' population had been killed or deported.[277][278]

Communist states

Between 1930 and 1960, the Soviet Union created a system of, according to Anne Applebaum and the "perspective of the Kremlin", slave labor camps called the Gulag (Russian: ГУЛаг, romanized: GULag).[279]

Prisoners in these camps were worked to death by a combination of extreme production quotas, physical and psychological brutality, hunger, lack of medical care, and the harsh environment. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, who survived eight years of Gulag incarceration, provided firsthand testimony about the camps with the publication of The Gulag Archipelago, after which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature.[280][281] Fatality rate was as high as 80% during the first months in many camps. Hundreds of thousands of people, possibly millions, died as a direct result of forced labour under the Soviets.[282]

Golfo Alexopoulos suggests comparing labor in the Gulag with "other forms of slave labor" and notes its "violence of human exploitation" in Illness and Inhumanity in Stalin's Gulag:[283]

Stalin's Gulag was, in many ways, less a concentration camp than a forced labor camp and less a prison system than a system of slavery. The image of the slave appears often in Gulag memoir literature. As Varlam Shalamov wrote: "Hungry and exhausted, we leaned into a horse collar, raising blood blisters on our chests and pulling a stone-filled cart up the slanted mine floor. The collar was the same device used long ago by the ancient Egyptians." Thoughtful and rigorous historical comparisons of Soviet forced labor and other forms of slave labor would be worthy of scholarly attention, in my view. For as in the case of global slavery, the Gulag found legitimacy in an elaborate narrative of difference that involved the presumption of dangerousness and guilt. This ideology of difference and the violence of human exploitation have left lasting legacies in contemporary Russia.

Historian Anne Applebaum writes in the introduction of her book that the word GULAG has come to represent "the system of Soviet slave labor itself, in all its forms and varieties":[284]

The word "GULAG" is an acronym for Glavnoe Upravlenie Lagerei, or Main Camp Administration, the institution which ran the Soviet camps. But over time, the word has also come to signify the system of Soviet slave labor itself, in all its forms and varieties: labor camps, punishment camps, criminal and political camps, women's camps, children's camps, transit camps. Even more broadly, "Gulag" has come to mean the Soviet repressive system itself, the set of procedures that Alexander Solzhenitsyn once called "our meat grinder": the arrests, the interrogations, the transport in unheated cattle cars, the forced labor, the destruction of families, the years spent in exile, the early and unnecessary deaths.

Applebaum's introduction has been criticized by Gulag researcher Wilson Bell,[285] stating that her book "is, aside from the introduction, a well-done overview of the Gulag, but it did not offer an interpretative framework much beyond Solzhenitsyn's paradigms".[286]

Middle East

In the earliest known records, slavery is treated as an established institution. The Code of Hammurabi (c. 1760 BC), for example, prescribed death for anyone who helped a slave escape or who sheltered a fugitive.[287] The Bible mentions slavery as an established institution.[3] Slavery existed in Pharaonic Egypt, but studying it is complicated by terminology used by the Egyptians to refer to different classes of servitude over the course of history. Interpretation of the textual evidence of classes of slaves in ancient Egypt has been difficult to differentiate by word usage alone.[288][289] The three apparent types of enslavement in Ancient Egypt: chattel slavery, bonded labour, and forced labour.[290][291][292]

Historically, slaves in the Arab World came from many different regions, including Sub-Saharan Africa (mainly Zanj),[293] the Caucasus (mainly Circassians),[294] Central Asia (mainly Tartars), and Central and Eastern Europe (mainly Slavs Saqaliba).[295] These slaves were trafficked to the Arab world from Africa via the Trans-Saharan slave trade, the Baqt treaty, the Red Sea slave trade and the Indian Ocean slave trade; from Asia via the Bukhara slave trade; and from Europe via the Prague slave trade, the Venetian slave trade and the Barbary slave trade, respectively.

Between 1517 and 1917, most of the Middle East consisted of the Ottoman Empire. In the Ottoman capital of Constantinople, about one-fifth of the population consisted of slaves.[79] The city was a major centre of the slave trade in the 15th and later centuries.

Eastern European slaves were provided to the Ottoman Empire via the Crimean slave trade by Tatar raids on Slavic villages[296] but also by conquest and the suppression of rebellions, in the aftermath of which entire populations were sometimes enslaved and sold across the Empire, reducing the risk of future rebellion. The Ottomans also purchased slaves from traders who brought slaves into the Empire from Europe and Africa. It has been estimated that some 200,000 slaves – mainly Circassians – were imported into the Ottoman Empire between 1800 and 1909.[227] In 1908, women slaves were still sold in the Ottoman Empire.[297] German orientalist, Gustaf Dalman, reported seeing slaves in Muslim houses in Aleppo, belonging to Ottoman Syria, in 1899, and that boys could be bought as slaves in Damascus and Cairo in as late as 1909.[298]

A major center of slave trade to the Middle east was central Asia, where the Bukhara slave trade had supplied slaves to the Middle East for thousands of years from antiquity until the 1870s. A slave market for captured Russian and Persian slaves was the Khivan slave trade centred in the Central Asian khanate of Khiva.[299] In the early 1840s, the population of the Uzbek states of Bukhara and Khiva included about 900,000 slaves.[227]