Конфуцианство

| Часть серии о |

| Конфуцианство |

|---|

|

| Конфуцианство | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||

| Chinese | 儒家 | ||

| Literal meaning | Ru school of thought | ||

| |||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||

| Chinese | 儒教 | ||

| Literal meaning | Ru religious doctrine | ||

| |||

| Second alternative Chinese name | |||

| Traditional Chinese | 儒學 | ||

| Simplified Chinese | 儒学 | ||

| Literal meaning | Ru studies | ||

| |||

| Vietnamese name | |||

| Vietnamese alphabet | Nho giáo | ||

| Chữ Hán | 儒教 | ||

| Korean name | |||

| Hangul | 유교 | ||

| Hanja | 儒敎 | ||

| |||

| Japanese name | |||

| Kanji | 儒教 | ||

| Hiragana | じゅきょう | ||

| Katakana | ジュキョウ | ||

| |||

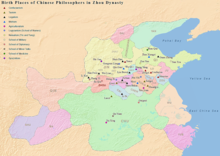

Конфуцианство , также известное как руизм или ру классицизм , [ 1 ] — это система мышления и поведения, зародившаяся в древнем Китае и описываемая по-разному как традиция, философия ( гуманистическая или рационалистическая ), религия , теория правления или образ жизни. [ 2 ] Конфуцианство развилось на основе учения китайского философа Конфуция (551–479 до н.э.) в период, который позже был назван эпохой ста школ мысли . Конфуций считал себя передатчиком культурных ценностей, унаследованных от династий Ся (ок. 2070–1600 до н.э.), Шан (ок. 1600–1046 до н.э.) и Западной Чжоу (ок. 1046–771 до н.э.). [ 3 ] Конфуцианство было подавлено во времена легалистской и самодержавной династии Цинь (221–206 гг. до н.э.), но выжило. Во времена династии Хань (206 г. до н.э. – 220 г. н.э.) конфуцианские подходы вытеснили «протодаосскую» Хуан-Лао в качестве официальной идеологии, в то время как императоры смешивали и то, и другое с реалистическими методами легизма. [ 4 ]

Confucianism regards principles contained in the Five Classics the key tenets that should be followed to promote the harmony of the family and the society as a whole. A Confucian revival began during the Tang dynasty (618–907 CE). In the late Tang, Confucianism further developed in response to the increasing influence of Buddhism and Taoism and was reformulated as Neo-Confucianism. This reinvigorated form was adopted as the basis of the imperial exams and the core philosophy of the scholar-official class in the Song dynasty (960–1297). The abolition of the examination system in 1905 marked the end of official Confucianism. The intellectuals of the New Culture Movement of the early twentieth century blamed Confucianism for China's weaknesses. They searched for new doctrines to replace Confucian teachings; some of these new ideologies include the "Three Principles of the People" with the establishment of the Republic of China, and then Maoism under the People's Republic of China. In the late twentieth century, the Confucian work ethic has been credited with the rise of the East Asian economy.[4]

With particular emphasis on the importance of the family and social harmony, rather than on an otherworldly source of spiritual values,[5] the core of Confucianism is humanistic.[6] According to American philosopher Herbert Fingarette's conceptualisation of Confucianism as a philosophical system which regards "the secular as sacred",[7] Confucianism transcends the dichotomy between religion and humanism, considering the ordinary activities of human life—and especially human relationships—as a manifestation of the sacred,[8] because they are the expression of humanity's moral nature (性; xìng), which has a transcendent anchorage in tian (天; tiān; 'heaven').[9] While the Confucian concept of tian shares some similarities with the concept of a deity, it is primarily an impersonal absolute principle like the tao or the Brahman. Most scholars[10] and practitioners do not think of tian as a god, and the deities that many Confucians worship do not originate from orthodox Confucianism.[11] Confucianism focuses on the practical order that is given by a this-worldly awareness of tian.[12]

The worldly concern of Confucianism rests upon the belief that human beings are fundamentally good, and teachable, improvable, and perfectible through personal and communal endeavor, especially self-cultivation and self-creation. Confucian thought focuses on the cultivation of virtue in a morally organised world.[13] Some of the basic Confucian ethical concepts and practices include ren, yi, li, and zhi. Ren is the essence of the human being which manifests as compassion. It is the virtue-form of Heaven.[14] Yi is the upholding of righteousness and the moral disposition to do good. Li is a system of ritual norms and propriety that determines how a person should properly act in everyday life in harmony with the law of Heaven. Zhi (智; zhì) is the ability to see what is right and fair, or the converse, in the behaviors exhibited by others. Confucianism holds one in contempt, either passively or actively, for failure to uphold the cardinal moral values of ren and yi.

Traditionally, cultures and countries in the Chinese cultural sphere are strongly influenced by Confucianism, including China, Taiwan, Korea, Japan, and Vietnam, as well as various territories settled predominantly by Han Chinese people, such as Singapore and Myanmar's Kokang. Today, it has been credited for shaping East Asian societies and overseas Chinese communities, and to some extent, other parts of Asia.[15][16] Most Confucianist movements have had significant differences from the original Zhou-era teachings,[17] and are typically much more complex because of their reliance on "elaborate doctrine"[18] and other factors such as traditions with long histories. In the past few decades, there have been talks of a "Confucian Revival" in the academic and the scholarly community,[19][20] and there has been a grassroots proliferation of various types of Confucian churches.[21] In late 2015, many Confucian personalities formally established a national Confucian Church (孔圣会; 孔聖會; Kǒngshènghuì) in China to unify the many Confucian congregations and civil society organisations.

Terminology

Strictly speaking, there is no term in Chinese which directly corresponds to "Confucianism". The closest catch-all term for things related to Confucianism is the word ru (儒; rú). Its literal meanings in modern Chinese include 'scholar', 'learned', or 'refined man'. In Old Chinese the word had a distinct set of meanings, including 'to tame', 'to mould', 'to educate', and 'to refine'.[23]: 190–197 Several different terms, some of which with modern origin, are used in different situations to express different facets of Confucianism, including:

- 儒家; Rújiā – "the ru school of thought";

- 儒教; Rújiào – "ru religious doctrine";

- 儒学; 儒學; Rúxué – "ru studies";

- 孔教; Kǒngjiào – "Confucius's religious doctrine";

- 孔家店; Kǒngjiādiàn – "Confucius's family's business", a pejorative phrase used during the New Culture Movement and the Cultural Revolution.

Three of them use ru. These names do not use the name "Confucius" at all, but instead focus on the ideal of the Confucian man. The use of the term "Confucianism" has been avoided by some modern scholars, who favor "Ruism" and "Ruists" instead. Robert Eno argues that the term has been "burdened ... with the ambiguities and irrelevant traditional associations". Ruism, as he states, is more faithful to the original Chinese name for the school.[23]: 7

The term "Traditionalist" has been suggested by David Schaberg to emphasize the connection to the past, its standards, and inherited forms, in which Confucius himself placed so much importance.[24] This translation of the word ru is followed by e.g. Yuri Pines.[25]

According to Zhou Youguang, ru originally referred to shamanic methods of holding rites and existed before Confucius's times, but with Confucius it came to mean devotion to propagating such teachings to bring civilisation to the people. Confucianism was initiated by the disciples of Confucius, developed by Mencius (c. 372–289 BCE) and inherited by later generations, undergoing constant transformations and restructuring since its establishment, but preserving the principles of humaneness and righteousness at its core.[26]

In the Western world, the character for water is often used as a symbol for Confucianism, which is not the case in modern China.[citation needed] However, the five phases were used as important symbols representing leadership in Han dynasty thought, including Confucianist works.[27]

Five Classics and the Confucian vision

Traditionally, Confucius was thought to be the author or editor of the Five Classics which were the basic texts of Confucianism, all edited into their received versions around 500 years later by Imperial Librarian Liu Xin.[28]: 51 The scholar Yao Xinzhong allows that there are good reasons to believe that Confucian classics took shape in the hands of Confucius, but that "nothing can be taken for granted in the matter of the early versions of the classics". Yao suggests that most modern scholars hold the "pragmatic" view that Confucius and his followers did not intend to create a system of classics, but nonetheless "contributed to their formation".[29]

The scholar Tu Weiming explains these classics as embodying "five visions" which underlie the development of Confucianism:

- I Ching (Classic of Change or Book of Changes), generally held to be the earliest of the classics, shows a metaphysical vision which combines divinatory art with numerological technique and ethical insight; philosophy of change sees cosmos as interaction between the two energies yin and yang; universe always shows organismic unity and dynamism.

- Classic of Poetry or Book of Songs is the earliest anthology of Chinese poems and songs, with the earliest strata antedating the Zhou conquest. It shows the poetic vision in the belief that poetry and music convey common human feelings and mutual responsiveness.

- Book of Documents or Book of History is a compilation of speeches of major figures and records of events in ancient times, embodying the political vision and addressing the kingly way in terms of the ethical foundation for humane government. The documents show the sagacity, filial piety, and work ethic of mythical sage-emperors Yao, Shun, and Yu, who established a political culture which was based on responsibility and trust. Their virtue formed a covenant of social harmony which did not depend on punishment or coercion.

- Book of Rites describes the social forms, administration, and ceremonial rites of the Zhou Dynasty. This social vision defined society not as an adversarial system based on contractual relations but as a network of kinship groups bound by cultural identity and ritual practice, socially responsible for one another and the transmission of proper antique forms. The four functional occupations are cooperative (farmer, scholar, artisan, merchant).

- Spring and Autumn Annals chronicles the period to which it gives its name, Spring and Autumn period (771–481 BCE), from the perspective of Confucius's home state of Lu. These events emphasise the significance of collective memory for communal self-identification, for reanimating the old is the best way to attain the new.[30]

Doctrines

Theory and theology

Confucianism revolves around the pursuit of the unity of the individual self and tian ("heaven"). To put it another way, it focuses on the relationship between humanity and heaven.[32][33] The principle or way of Heaven (tian li or tian tao) is the order of the world and the source of divine authority.[33] Tian li or tian tao is monistic, meaning that it is singular and indivisible. Individuals may realise their humanity and become one with Heaven through the contemplation of such order.[33] This transformation of the self may be extended to the family and society to create a harmonious community.[33] Joël Thoraval studied Confucianism as a diffused civil religion in contemporary China, finding that it expresses itself in the widespread worship of five cosmological entities: Heaven and Earth (地; dì), the sovereign or the government (君; jūn), ancestors (親; qīn), and masters (師; shī).[34]

According to the scholar Stephan Feuchtwang, in Chinese cosmology, which is not merely Confucian but shared by many Chinese religions, "the universe creates itself out of a primary chaos of material energy" (hundun and qi), and is organized through the polarity of yin and yang that characterises any thing and life. Creation is therefore a continuous ordering; it is not creation ex nihilo. "Yin and yang are the invisible and visible, the receptive and the active, the unshaped and the shaped; they characterise the yearly cycle (winter and summer), the landscape (shady and bright), the sexes (female and male), and even sociopolitical history (disorder and order). Confucianism is concerned with finding "middle ways" between yin and yang at every new configuration of the world."[35]

Confucianism conciliates both the inner and outer polarities of spiritual cultivation—that is to say self-cultivation and world redemption—synthesised in the ideal of "sageliness within and kingliness without".[33] Ren, translated as "humaneness" or the essence proper of a human being, is the character of compassionate mind; it is the virtue endowed by Heaven and at the same time the means by which man may achieve oneness with Heaven comprehending his own origin in Heaven and therefore divine essence. In the Datong Shu, it is defined as "to form one body with all things" and "when the self and others are not separated ... compassion is aroused".[14]

"Lord Heaven" and "Jade Emperor" were terms for a Confucianist supreme deity who was an anthropromorphized tian,[36] and some conceptions of it thought of the two names as synonymous.

Tian and the gods

Tian, a key concept in Chinese thought, refers to the God of Heaven, the northern culmen of the skies and its spinning stars,[40] earthly nature and its laws which come from Heaven, to 'Heaven and Earth' (that is, "all things"), and to the awe-inspiring forces beyond human control.[44] There are so many uses in Chinese thought that it is impossible to give a single English translation.[45]

Confucius used the term in a mystical way.[46] He wrote in the Analects (7.23) that tian gave him life, and that tian watched and judged (6.28; 9.12). In 9.5 Confucius says that a person may know the movements of tian, and this provides with the sense of having a special place in the universe. In 17.19 Confucius says that tian spoke to him, though not in words. The scholar Ronnie Littlejohn warns that tian was not to be interpreted as a personal God comparable to that of the Abrahamic faiths, in the sense of an otherworldly or transcendent creator.[47] Rather it is similar to what Taoists meant by Dao: "the way things are" or "the regularities of the world",[44] which Stephan Feuchtwang equates with the ancient Greek concept of physis, "nature" as the generation and regenerations of things and of the moral order.[48] Tian may also be compared to the Brahman of Hindu and Vedic traditions.[32] The scholar Promise Hsu, in the wake of Robert B. Louden, explained 17:19 ("What does Tian ever say? Yet there are four seasons going round and there are the hundred things coming into being. What does Tian say?") as implying that even though Tian is not a "speaking person", it constantly "does" through the rhythms of nature, and communicates "how human beings ought to live and act", at least to those who have learnt to carefully listen to it.[46]

Duanmu Ci, a disciple of Confucius, said that Tian had set the master on the path to become a wise man (9.6). In 7.23 Confucius says that he has no doubt left that Tian gave him life, and from it he had developed right virtue (de). In 8.19, he says that the lives of the sages are interwoven with Tian.[45]

Regarding personal gods (shen, energies who emanate from and reproduce Tian) enliving nature, in the Analects Confucius says that it is appropriate (yi) for people to worship (敬; jìng) them,[49] although only through proper rites (li), implying respect of positions and discretion.[49] Confucius himself was a ritual and sacrificial master.[50]

Answering to a disciple who asked whether it is better to sacrifice to the god of the stove or to the god of the family (a popular saying), in 3.13 Confucius says that in order to appropriately pray to gods, one should first know and respect Heaven. In 3.12, he explains that religious rituals produce meaningful experiences,[51] and one has to offer sacrifices in person, acting in presence, otherwise "it is the same as not having sacrificed at all". Rites and sacrifices to the gods have an ethical importance: they generate good life, because taking part in them leads to the overcoming of the self.[52] Analects 10.11 tells that Confucius always took a small part of his food and placed it on the sacrificial bowls as an offering to his ancestors.[50]

Some Confucian movements worship Confucius,[53] although not as a supreme being or anything else approaching the power of tian or the tao, and/or gods from Chinese folk religion. These movements are not a part of mainstream Confucianism, although the boundary between Chinese folk religion and Confucianism can be blurred.[citation needed]

Other movements, such as Mohism which was later absorbed by Taoism, developed a more theistic idea of Heaven.[54] Feuchtwang explains that the difference between Confucianism and Taoism primarily lies in the fact that the former focuses on the realisation of the starry order of Heaven in human society, while the latter on the contemplation of the Dao which spontaneously arises in nature.[48] However, Confucianism does venerate many aspects of nature[16] and also respects various tao,[55] as well as what Confucius saw as the main tao, the "[Way] of Heaven."[13]

The Way of Heaven involves "lifelong and sincere devotion to traditional cultural forms" and wu wei, "a state of spontaneous harmony between individual inclinations and the sacred Way".[13]

Kelly James Clark argued that Confucius himself saw Tian as an anthropomorphic god that Clark hypothetically refers to as "Heavenly Supreme Emperor", although most other scholars on Confucianism disagree with this view.[56]

Social morality and ethics

As explained by Stephan Feuchtwang, the order coming from Heaven preserves the world, and has to be followed by humanity finding a "middle way" between yin and yang forces in each new configuration of reality. Social harmony or morality is identified as patriarchy, which is expressed in the worship of ancestors and deified progenitors in the male line, at ancestral shrines.[48]

Confucian ethical codes are described as humanistic.[6] They may be practiced by all the members of a society. Confucian ethics is characterised by the promotion of virtues, encompassed by the Five Constants, elaborated by Confucian scholars out of the inherited tradition during the Han dynasty.[57] The Five Constants are:[57]

- Ren (benevolence, humaneness)

- Yi (righteousness, justice)

- Li (propriety, rites)

- Zhi (智; zhì: wisdom, knowledge)

- Xin (sincerity, faithfulness)

These are accompanied by the classical four virtues (四字; sìzì), one of which (Yi) is also included among the Five Constants:

- Yi (see above)

- Loyalty (忠; zhōng)

- Filial piety (孝; xiào)

- Continence (节; 節; jié)

There are many other traditionally Confucian values, such as 'honesty' (诚; chéng), 'bravery' (勇; yǒng), 'incorruptibility' (廉; lián), 'kindness', 'forgiveness' (恕; shù), a 'sense of right and wrong' (耻; chǐ), 'gentleness' (温; wēn), 'kindheartenedness' (良; liáng), 'respect' (恭; gōng), 'frugality' (俭; jiǎn), and 让; ràng; 'modesty').

Ren

Ren (仁 ) is the Confucian virtue denoting the good feeling a virtuous human experiences when being altruistic. Internally ren can mean "to look up" meaning "to aspire to higher Heavenly principles or ideals", It is exemplified by a normal adult's protective feelings for children. It is considered the essence of the human being, endowed by Heaven, and at the same time the means by which someone may act according to the principle of Heaven and become one with it.[14]

Yan Hui, Confucius's most outstanding student, once asked his master to describe the rules of ren and Confucius replied, "one should see nothing improper, hear nothing improper, say nothing improper, do nothing improper."[58] Confucius also defined ren in the following way: "wishing to be established himself, seeks also to establish others; wishing to be enlarged himself, he seeks also to enlarge others."[59]

Another meaning of ren is "not to do to others as you would not wish done to yourself."[60] Confucius also said, "ren is not far off; he who seeks it has already found it." Ren is close to man and never leaves him.

Rite and centring

Li (礼; 禮) is a word which finds its most extensive use in Confucian and post-Confucian Chinese philosophy. Li is variously translated as 'rite' or 'reason', 'ratio' in the pure sense of Vedic ṛta ('right', 'order') when referring to the cosmic law, but when referring to its realisation in the context of human social behaviour it has also been translated as 'customs', 'measures' and 'rules', among other terms. Li also means religious rites which establish relations between humanity and the gods.

According to Stephan Feuchtwang, rites are conceived as "what makes the invisible visible", making possible for humans to cultivate the underlying order of nature. Correctly performed rituals move society in alignment with earthly and heavenly (astral) forces, establishing the harmony of the three realms—Heaven, Earth and humanity. This practice is defined as "centering" (央; yāng or 中; zhōng). Among all things of creation, humans themselves are "central" because they have the ability to cultivate and centre natural forces.[61]

Li embodies the entire web of interaction between humanity, human objects, and nature. Confucius includes in his discussions of li such diverse topics as learning, tea drinking, titles, mourning, and governance. Xunzi cites "songs and laughter, weeping and lamentation ... rice and millet, fish and meat ... the wearing of ceremonial caps, embroidered robes, and patterned silks, or of fasting clothes and mourning clothes ... spacious rooms and secluded halls, soft mats, couches and benches" as vital parts of the fabric of li.

Confucius envisioned proper government being guided by the principles of li. Some Confucians proposed that all human beings may pursue perfection by learning and practising li. Overall, Confucians believe that governments should place more emphasis on li and rely much less on penal punishment when they govern.

Loyalty

Loyalty (忠; zhōng) is particularly relevant for the social class to which most of Confucius's students belonged, because the most important way for an ambitious young scholar to become a prominent official was to enter a ruler's civil service.

Confucius himself did not propose that "might makes right", but rather that a superior should be obeyed because of his moral rectitude. In addition, loyalty does not mean subservience to authority. This is because reciprocity is demanded from the superior as well. As Confucius stated "a prince should employ his minister according to the rules of propriety; ministers should serve their prince with faithfulness (loyalty)."[62]

Similarly, Mencius also said that "when the prince regards his ministers as his hands and feet, his ministers regard their prince as their belly and heart; when he regards them as his dogs and horses, they regard him as another man; when he regards them as the ground or as grass, they regard him as a robber and an enemy."[63] Moreover, Mencius indicated that if the ruler is incompetent, he should be replaced. If the ruler is evil, then the people have the right to overthrow him.[64] A good Confucian is also expected to remonstrate with his superiors when necessary.[65] At the same time, a proper Confucian ruler should also accept his ministers' advice, as this will help him govern the realm better.

In later ages, however, emphasis was often placed more on the obligations of the ruled to the ruler, and less on the ruler's obligations to the ruled. Like filial piety, loyalty was often subverted by the autocratic regimes in China. Nonetheless, throughout the ages, many Confucians continued to fight against unrighteous superiors and rulers. Many of these Confucians suffered and sometimes died because of their conviction and action.[66] During the Ming-Qing era, prominent Confucians such as Wang Yangming promoted individuality and independent thinking as a counterweight to subservience to authority.[67] The famous thinker Huang Zongxi also strongly criticised the autocratic nature of the imperial system and wanted to keep imperial power in check.[68]

Many Confucians also realised that loyalty and filial piety have the potential of coming into conflict with one another. This may be true especially in times of social chaos, such as during the period of the Ming-Qing transition.[69]

Filial piety

In Confucian philosophy, "filial piety" (孝; xiào) is a virtue of respect for one's parents and ancestors, and of the hierarchies within society: father–son, elder–junior and male–female.[48] The Confucian classic Xiaojing ("Book of Piety"), thought to be written during the Qin or Han dynasties, has historically been the authoritative source on the Confucian tenet of xiao. The book, a conversation between Confucius and his disciple Zeng Shen, is about how to set up a good society using the principle of xiao.[70]

In more general terms, filial piety means to be good to one's parents; to take care of one's parents; to engage in good conduct not just towards parents but also outside the home so as to bring a good name to one's parents and ancestors; to perform the duties of one's job well so as to obtain the material means to support parents as well as carry out sacrifices to the ancestors; not be rebellious; show love, respect and support; the wife in filial piety must obey her husband absolutely and take care of the whole family wholeheartedly. display courtesy; ensure male heirs, uphold fraternity among brothers; wisely advise one's parents, including dissuading them from moral unrighteousness, for blindly following the parents' wishes is not considered to be xiao; display sorrow for their sickness and death; and carry out sacrifices after their death.

Filial piety is considered a key virtue in Chinese culture, and it is the main concern of a large number of stories. One of the most famous collections of such stories is "The Twenty-four Filial Exemplars". These stories depict how children exercised their filial piety in the past. While China has always had a diversity of religious beliefs, filial piety has been common to almost all of them; historian Hugh D.R. Baker calls respect for the family the only element common to almost all Chinese believers.[71]

Relationships

Social harmony results in part from every individual knowing his or her place in the natural order, and playing his or her part well. Reciprocity or responsibility (renqing) extends beyond filial piety and involves the entire network of social relations, even the respect for rulers.[48] This is shown in the story where Duke Jing of Qi asks Confucius about government, by which he meant proper administration so as to bring social harmony:

齊景公問政於孔子。孔子對曰:君君,臣臣,父父,子子。

The duke Jing, of Qi, asked Confucius about government. Confucius replied, "There is government, when the prince is prince, and the minister is minister; when the father is father, and the son is son."— Analects 12.11 (Legge translation).

Particular duties arise from one's particular situation in relation to others. The individual stands simultaneously in several different relationships with different people: as a junior in relation to parents and elders, and as a senior in relation to younger siblings, students, and others. While juniors are considered in Confucianism to owe their seniors reverence, seniors also have duties of benevolence and concern toward juniors. The same is true with the husband and wife relationship where the husband needs to show benevolence towards his wife and the wife needs to respect the husband in return. This theme of mutuality still exists in East Asian cultures even to this day.

The Five Bonds are: ruler to ruled, father to son, husband to wife, elder brother to younger brother, friend to friend. Specific duties were prescribed to each of the participants in these sets of relationships. Such duties are also extended to the dead, where the living stand as sons to their deceased family. The only relationship where respect for elders is not stressed was the friend to friend relationship, where mutual equal respect is emphasised instead. All these duties take the practical form of prescribed rituals, for instance wedding and death rituals.[48]

Junzi

The junzi ('lord's son') is a Chinese philosophical term often translated as "gentleman" or "superior person"[72] and employed by Confucius in the Analects to describe the ideal man.

In Confucianism, the sage or wise is the ideal personality; however, it is very hard to become one of them. Confucius created the model of junzi, gentleman, which may be achieved by any individual. Later, Zhu Xi defined junzi as second only to the sage. There are many characteristics of the junzi: he may live in poverty, he does more and speaks less, he is loyal, obedient and knowledgeable. The junzi disciplines himself. Ren is fundamental to become a junzi.[73]

As the potential leader of a nation, a son of the ruler is raised to have a superior ethical and moral position while gaining inner peace through his virtue. To Confucius, the junzi sustained the functions of government and social stratification through his ethical values. Despite its literal meaning, any righteous man willing to improve himself may become a junzi.

In contrast to the junzi, the xiaoren (小人; xiăorén, "small or petty person") does not grasp the value of virtues and seeks only immediate gains. The petty person is egotistic and does not consider the consequences of his action in the overall scheme of things. Should the ruler be surrounded by xiaoren as opposed to junzi, his governance and his people will suffer due to their small-mindness. Examples of such xiaoren individuals may range from those who continually indulge in sensual and emotional pleasures all day to the politician who is interested merely in power and fame; neither sincerely aims for the long-term benefit of others.

The junzi enforces his rule over his subjects by acting virtuously himself. It is thought that his pure virtue would lead others to follow his example. The ultimate goal is that the government behaves much like a family, the junzi being a beacon of filial piety.

Rectification of names

Confucius believed that social disorder often stemmed from failure to perceive, understand, and deal with reality. Fundamentally, then, social disorder may stem from the failure to call things by their proper names, and his solution to this was the "rectification of names" (正名; zhèngmíng). He gave an explanation of this concept to one of his disciples:

Zi-lu said, "The vassal of Wei has been waiting for you, in order with you to administer the government. What will you consider the first thing to be done?"

The Master replied, "What is necessary to rectify names."

"So! indeed!" said Zi-lu. "You are wide off the mark! Why must there be such rectification?"

The Master said, "How uncultivated you are, Yu! The superior man [Junzi] cannot care about the everything, just as he cannot go to check all himself!

If names be not correct, language is not in accordance with the truth of things.

If language be not in accordance with the truth of things, affairs cannot be carried on to success.

When affairs cannot be carried on to success, proprieties and music do not flourish.

When proprieties and music do not flourish, punishments will not be properly awarded.

When punishments are not properly awarded, the people do not know how to move hand or foot.

Therefore a superior man considers it necessary that the names he uses may be spoken appropriately, and also that what he speaks may be carried out appropriately. What the superior man requires is just that in his words there may be nothing incorrect."

(Analects XIII, 3, tr. Legge)

Xunzi chapter (22) "On the Rectification of Names" claims the ancient sage-kings chose names (名; míng) that directly corresponded with actualities (實; shí), but later generations confused terminology, coined new nomenclature, and thus could no longer distinguish right from wrong. Since social harmony is of utmost importance, without the proper rectification of names, society would essentially crumble and "undertakings [would] not [be] completed."[74]

History

Metaphysical antecedents

According to He Guanghu, Confucianism may be identified as a continuation of the Shang-Zhou (c. 1600–256 BCE) official religion, or the Chinese aboriginal religion which has lasted uninterrupted for three thousand years.[76] Both the dynasties worshipped a supreme "godhead", called Shangdi ('Highest Deity') or Di by the Shang and Tian ('Heaven') by the Zhou. Shangdi was conceived as the first ancestor of the Shang royal house,[77] an alternate name for him being the "Supreme Progenitor" (上甲; Shàngjiǎ).[78] Shang theology viewed the multiplicity of gods of nature and ancestors as parts of Di. Di manifests as the Wufang Shangdi with the winds (風; fēng) as its cosmic will.[79] With the Zhou dynasty, which overthrew the Shang, the name for the supreme godhead became tian.[77] While the Shang identified Shangdi as their ancestor-god to assert their claim to power by divine right, the Zhou transformed this claim into a legitimacy based on moral power, the Mandate of Heaven. In Zhou theology, Tian had no singular earthly progeny, but bestowed divine favour on virtuous rulers. Zhou kings declared that their victory over the Shang was because they were virtuous and loved their people, while the Shang were tyrants and thus were deprived of power by Tian.[3]

John C. Didier and David Pankenier relate the shapes of both the ancient Chinese characters for Di and Tian to the patterns of stars in the northern skies, either drawn, in Didier's theory by connecting the constellations bracketing the north celestial pole as a square,[80] or in Pankenier's theory by connecting some of the stars which form the constellations of the Big Dipper and broader Ursa Major, and Ursa Minor (Little Dipper).[81] Cultures in other parts of the world have also conceived these stars or constellations as symbols of the origin of things, the supreme godhead, divinity and royal power.[82] The supreme godhead was also identified with the dragon, symbol of unlimited power (qi),[77] of the protean primordial power which embodies both yin and yang in unity, associated to the constellation Draco which winds around the north ecliptic pole,[75] and slithers between the Little and Big Dipper.

Zhou traditions wane

By the 6th century BCE, the power of Tian and the symbols that represented it on earth (architecture of cities, temples, altars and ritual vessels, and the Zhou system of rites) became "diffuse" and claimed by different potentates in the Zhou states to legitimise economic, political, and military ambitions. Communication with the divine no longer was an exclusive privilege of the Zhou royal house, but might be bought by anyone able to afford the elaborate ceremonies and the old and new rites required to access the authority of Tian.[83]

Besides the waning Zhou ritual system, what may be defined as 'wild' (野; yě) traditions, or traditions outside of the official system, developed as attempts to access the will of Tian. As central political authority crumbled in the wake of the collapse of the Western Zhou, the population lost faith in the official tradition, which was no longer perceived as an effective way to communicate with Heaven. The traditions of the 'Nine Fields' (九野) and of the Yijing flourished.[84] Chinese thinkers, faced with this challenge to legitimacy, diverged in a "Hundred Schools of Thought", each positing its own philosophical lens for understanding the processes of the world.

Confucius (551–479 BCE) appeared in this period of political reconfiguration and spiritual questioning. He was educated in Shang–Zhou traditions, which he contributed to transmit and reformulate giving centrality to self-cultivation and agency of humans,[3] and the educational power of the self-established individual in assisting others to establish themselves (the 愛人; àirén; 'principle of loving others').[85] As the Zhou reign collapsed, traditional values were abandoned resulting in a period of perceived moral decline. Confucius saw an opportunity to reinforce values of compassion and tradition into society, with the intended goal of reconstructing what he believed to be a lost perfect moral order of high antiquity. Disillusioned with the culture, opposing scholars, and religious authorities of the time, he began to advance an ethical interpretation of traditional Zhou religion.[13] In his view, the power of Tian is pervasive, and responds positively to the sincere heart driven by humaneness and rightness, decency and altruism. Confucius conceived these qualities as the foundation needed to restore socio-political harmony. Like many contemporaries, Confucius saw ritual practices as efficacious ways to access Tian, but he thought that the crucial knot was the reverent inner state that participants enter prior to engaging in the ritual acts.[86] Confucius is said to have amended and recodified the classical books inherited from the Xia-Shang-Zhou dynasties, and to have composed the Spring and Autumn Annals.[26]

Confucianism rises

Philosophers in the Warring States period, both focused on state-endorsed ritual and non-aligned to state ritual built upon Confucius's legacy, compiled in the Analects, and formulated the classical metaphysics that became the lash of Confucianism. In accordance with Confucius, they identified mental tranquility as the state of Tian, or 'the One' (一; Yī), which in each individual is the Heaven-bestowed divine power to rule one's own life and the world. They also extended the theory, proposing the oneness of production and reabsorption into the cosmic source, and the possibility to understand and therefore reattain it through correct state of mind. This line of thought would have influenced all Chinese individual and collective-political mystical theories and practices thereafter.[87]

In the Han dynasty, Confucians beginning with Dong Zhongshu synthesised Warring States Confucianism with ideas of yin and yang, and wuxing, as well as folk superstition and the prior schools that led up to the School of Naturalists.[88]

In the 460s, Confucianism competed with Chinese Buddhism and "traditional Confucianism" was "a broad cosmology that was as much about personal ethics as about spiritual beliefs" and had roots that went back to Confucianist philosophers from over a thousand years before.[89]

Organisation and liturgy

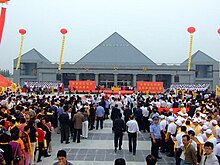

Since the 2000s, there has been a growing identification of the Chinese intellectual class with Confucianism.[90] In 2003, the Confucian intellectual Kang Xiaoguang published a manifesto in which he made four suggestions: Confucian education should enter official education at any level, from elementary to high school; the state should establish Confucianism as the state religion by law; Confucian religion should enter the daily life of ordinary people through standardisation and development of doctrines, rituals, organisations, churches and activity sites; the Confucian religion should be spread through non-governmental organisations.[90] Another modern proponent of the institutionalisation of Confucianism in a state church is Jiang Qing.[91]

In 2005, the Center for the Study of Confucian Religion was established,[90] and guoxue started to be implemented in public schools on all levels. Being well received by the population, even Confucian preachers have appeared on television since 2006.[90] The most enthusiastic New Confucians proclaim the uniqueness and superiority of Confucian Chinese culture, and have generated some popular sentiment against Western cultural influences in China.[90]

The idea of a "Confucian church" as the state religion of China has roots in the thought of Kang Youwei, an exponent of the early New Confucian search for a regeneration of the social relevance of Confucianism, at a time when it was de-institutionalised with the collapse of the Qing dynasty and the Chinese empire.[92] Kang modeled his ideal "Confucian Church" after European national Christian churches, as a hierarchic and centralised institution, closely bound to the state, with local church branches, devoted to the worship and the spread of the teachings of Confucius.[92]

In contemporary China, the Confucian revival has developed into various interwoven directions: the proliferation of Confucian schools or academies,[91] the resurgence of Confucian rites,[91] and the birth of new forms of Confucian activity on the popular level, such as the Confucian communities (社區儒學; shèqū rúxué). Some scholars also consider the reconstruction of lineage churches and their ancestral temples, as well as cults and temples of natural and national gods within broader Chinese traditional religion, as part of the renewal of Confucianism.[93]

Other forms of revival are salvationist folk religious movements[94] groups with a specifically Confucian focus, or Confucian churches, for example the Yīdān xuétáng (一耽學堂) of Beijing,[95] the Mèngmǔtáng (孟母堂) of Shanghai,[96] Confucian Shenism (also known as the "phoenix churches"),[97] the Confucian Fellowship (儒教道壇; Rújiào Dàotán) in northern Fujian which has spread rapidly over the years after its foundation,[97] and ancestral temples of the Kong kin (the lineage of the descendants of Confucius himself) operating as Confucian-teaching churches.[96]

Also, the Hong Kong Confucian Academy, one of the direct heirs of Kang Youwei's Confucian Church, has expanded its activities to the mainland, with the construction of statues of Confucius, Confucian hospitals, restoration of temples and other activities.[98] In 2009, Zhou Beichen founded another institution which inherits the idea of Kang Youwei's Confucian Church, the Holy Hall of Confucius (孔聖堂; Kǒngshèngtáng) in Shenzhen, affiliated with the Federation of Confucian Culture of Qufu City.[99][100] It was the first of a nationwide movement of congregations and civil organisations that was unified in 2015 in the Holy Confucian Church. The first spiritual leader of the church is the scholar Jiang Qing, the founder and manager of the Yangming Confucian Abode (陽明精舍; Yángmíng jīngshě), a Confucian academy in Guiyang, Guizhou.

Chinese folk religious temples and kinship ancestral shrines may, on peculiar occasions, choose Confucian liturgy (called 儒; rú or 正統 (zhèngtǒng; 'orthopraxy') led by Confucian ritual masters (禮生; lǐshēng) to worship the gods, instead of Taoist or popular ritual.[101] "Confucian businessmen" (儒商人; rúshāngrén, also "refined businessman") is a recently "rediscovered" concept defining people of the economic-entrepreneurial elite who recognise their social responsibility and therefore apply Confucian culture to their business.[102]

Confucianists historically tried to proselytize to others,[103] although this is rarely done in modern times. Given Confucianism's place of importance in historical Chinese governments, the argument has been made that Imperial China's wars were Confucianism's wars, but the connection between Confucianism and war is not so direct or simple.[104] Modern Confucianism is the descendant of movements that greatly changed how they practiced the teachings of Confucius and his disciples from previous orthodox teachings.[17]

Governance

子曰:為政以德,譬如北辰,居其所而眾星共之。

The Master said, "He who exercises government by means of his virtue may be compared to the north polar star, which keeps its place and all the stars turn towards it."— Analects 2.1 (Legge translation).

A key Confucian concept is that in order to govern others one must first govern oneself according to the universal order. When actual, the king's personal virtue (de) spreads beneficent influence throughout the kingdom. This idea is developed further in the Great Learning and is tightly linked with the Taoist concept of wu wei: the less the king does, the more gets done. By being the "calm center" around which the kingdom turns, the king allows everything to function smoothly and avoids having to tamper with the individual parts of the whole.

This idea may be traced back to the ancient shamanic beliefs of the king being the axle between the sky, human beings, and the Earth.[citation needed] The emperors of China were considered agents of Heaven, endowed with the Mandate of Heaven,[105] one of the most vital concepts in imperial-era political theory. Some Confucianists believed they held the power to define the hierarchy of divinities, by bestowing titles upon mountains, rivers and dead people, acknowledging them as powerful and therefore establishing their cults.[106]

Confucianism, despite supporting the importance of obeying national authority, places this obedience under absolute moral principles that curbed the willful exercise of power, rather than being unconditional. Submission to authority was only taken within the context of the moral obligations that rulers had toward their subjects, in particular ren. Confucians—including the most pro-authoritarian scholars such as Xunzi—have always recognised the right of revolution against tyranny.[107]

Meritocracy

子曰:有教無類。

The Master said: "In teaching, there should be no distinction of classes."— Analects 15.39 (Legge translation).

Although Confucius claimed that he never invented anything but was only transmitting ancient knowledge (Analects 7.1), he did produce a number of new ideas. Many European and American admirers such as Voltaire and Herrlee G. Creel point to the revolutionary idea of replacing nobility of blood with nobility of virtue.[108] Junzi ('lord's son'), which originally signified the younger, non-inheriting, offspring of a noble, became, in Confucius's work, an epithet having much the same meaning and evolution as the English "gentleman".

A virtuous commoner who cultivates his qualities may be a "gentleman", while a shameless son of the king is only a "petty person". That Confucius admitted students of different classes as disciples is a clear demonstration that he fought against the feudal structures that defined pre-imperial Chinese society.[109][page needed]

Another new idea, that of meritocracy, led to the introduction of the imperial examination system in China. This system allowed anyone who passed an examination to become a government officer, a position which would bring wealth and honour to the whole family. The Chinese imperial examination system started in the Sui dynasty. Over the following centuries the system grew until finally almost anyone who wished to become an official had to prove his worth by passing a set of written government examinations.[110]

Confucian political meritocracy is not merely a historical phenomenon. The practice of meritocracy still exists across China and East Asia today, and a wide range of contemporary intellectuals—from Daniel Bell to Tongdong Bai, Joseph Chan, and Jiang Qing—defend political meritocracy as a viable alternative to liberal democracy.[111]

In Just Hierarchy, Daniel Bell and Wang Pei argue that hierarchies are inevitable.[112] Faced with ever-increasing complexity at scale, modern societies must build hierarchies to coordinate collective action and tackle long-term problems such as climate change. In this context, people need not—and should not—want to flatten hierarchies as much as possible. They ought to ask what makes political hierarchies just and use these criteria to decide the institutions that deserve preservation, those that require reform, and those that need radical transformation. They call this approach "progressive conservatism", a term that reflects the ambiguous place of the Confucian tradition within the Left-Right dichotomy.[112]: 8–21

Bell and Wang propose two justifications for political hierarchies that do not depend on a "one person, one vote" system. First is raw efficiency, which may require centralized rule in the hands of the competent few. Second, and most important, is serving the interests of the people (and the common good more broadly).[112]: 66–93 In Against Political Equality, Tongdong Bai complements this account by using a proto-Rawlsian "political difference principle". Just as Rawls claims that economic inequality is justified so long as it benefits those at the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder, so Bai argues that political inequality is justified so long as it benefits those materially worse off.[113]: 102–106

Bell, Wang, and Bai all criticize liberal democracy to argue that government by the people may not be government for the people in any meaningful sense of the term. They argue that voters tend to act in irrational, tribal, short-termist ways; they are vulnerable to populism and struggle to account for the interests of future generations. In other words, at a minimum, democracy needs Confucian meritocratic checks.[113]: 32–47

В «Китайской модели » Белл утверждает, что конфуцианская политическая меритократия обеспечивает – и предоставила – план развития Китая. [114] For Bell, the ideal according to which China should reform itself (and has reformed itself) follows a simple structure: Aspiring rulers first pass hyper-selective examinations, then have to rule well at the local level to be promoted to positions as the provincial level, then have to excel at the provincial level to access positions at the national level, and so on.[114]: 151–179 Эта система соответствует тому, что гарвардский историк Джеймс Хэнкинс называет «политикой добродетели» или идеей о том, что институты должны быть созданы для выбора наиболее компетентных и добродетельных правителей, а не институтов, озабоченных в первую очередь ограничением власти правителей. [ 115 ]

Хотя все современные защитники конфуцианской политической меритократии принимают эту широкую концепцию, они расходятся во мнениях друг с другом по трем основным вопросам: институциональный дизайн, средства продвижения меритократов и совместимость конфуцианской политической меритократии с либерализмом.

Институциональный дизайн

Белл и Ван выступают за систему, в которой чиновники на местном уровне избираются демократическим путем, а чиновники более высокого уровня продвигаются по службе коллегами. [ 112 ] : 66–93 По словам Белла, он защищает «демократию внизу, экспериментирование посередине и меритократию наверху». [ 114 ] : 151–179 Белл и Ван утверждают, что эта комбинация сохраняет основные преимущества демократии — вовлечение людей в общественные дела на местном уровне, укрепление легитимности системы, принуждение к некоторой степени прямой подотчетности и т. д. — сохраняя при этом более широкий меритократический характер власти. режим.

Цзян Цин, напротив, представляет себе трехпалатное правительство с одной палатой, избираемой народом ( 庶民院 ; «Палата простолюдинов»), и другой палатой, состоящей из конфуцианских меритократов, избранных путем экзаменов и постепенного продвижения по службе ( 通儒院 ; «Палата простолюдинов»). конфуцианской традиции») и одно тело, состоящее из потомков самого Конфуция ( 國體院 ; «Дом национальной сущности»). [ 116 ] Цель Цзяна – создать легитимность, которая выйдет за рамки того, что он считает атомистическим, индивидуалистическим и утилитарным этосом современных демократий, и обосновать власть в чем-то священном и традиционном. Хотя модель Цзяна ближе к идеальной теории, чем предложения Белла, она представляет собой более традиционалистскую альтернативу.

Тонгдон Бай представляет промежуточное решение, предлагая двухуровневую двухпалатную систему. [ 113 ] : 52–110 На местном уровне, как и Белл, Бай выступает за демократию участия Дьюи. На национальном уровне Бай предлагает две палаты: одну из меритократов (выбираемых путем экзаменов, путем экзаменов и продвижения по службе из числа лидеров в определенных профессиональных областях и т. д.) и одну из представителей, избранных народом. Хотя нижняя палата сама по себе не обладает законодательной властью, она действует как народный механизм подотчетности, защищая народ и оказывая давление на верхнюю палату. В более общем плане Бай утверждает, что его модель сочетает в себе лучшее из меритократии и демократии. Следуя описанию Дьюи о демократии как образе жизни, он указывает на особенности участия в своей местной модели: граждане по-прежнему могут вести демократический образ жизни, участвовать в политических делах и получать образование как «демократические люди». Аналогичным образом, нижняя палата позволяет гражданам быть представленными, иметь голос в общественных делах (хотя и слабый) и обеспечивать подотчетность. Между тем, меритократический дом сохраняет компетентность, государственную мудрость и конфуцианские добродетели.

Система продвижения

Защитники конфуцианской политической меритократии обычно отстаивают систему, в которой правители выбираются на основе интеллекта, социальных навыков и добродетели. Белл предлагает модель, в которой честолюбивые меритократы сдают сверхвыборочные экзамены и доказывают свою эффективность на местных уровнях власти, прежде чем достичь более высоких уровней власти, где они обладают более централизованной властью. [ 114 ] : 151–179 По его словам, на экзаменах отбираются интеллект и другие добродетели — например, способность аргументировать три разные точки зрения по спорному вопросу может указывать на определенную степень открытости. [ 114 ] : 63–110 Подход Тонгдон Бая включает в себя различные способы отбора членов меритократической палаты: от экзаменов до результатов в различных областях — бизнесе, науке, управлении и так далее. В каждом случае конфуцианские меритократы опираются на обширную историю меритократического управления в Китае, чтобы обрисовать плюсы и минусы конкурирующих методов отбора. [ 113 ] : 67–97

Для тех, кто, как Белл, защищает модель, согласно которой деятельность на местном уровне власти определяет будущее продвижение по службе, важным вопросом является то, как система оценивает, кто «работает лучше всего». Другими словами, хотя экзамены могут гарантировать, что начинающие чиновники являются компетентными и образованными, как впоследствии можно гарантировать, что продвижение по службе получат только те, кто хорошо управляет? Литература выступает против тех, кто предпочитает оценку коллег оценке со стороны начальства, при этом некоторые мыслители включают в себя квазидемократические механизмы отбора. Белл и Ван выступают за систему, в которой чиновники на местном уровне избираются демократическим путем, а чиновники более высокого уровня продвигаются по службе коллегами. [ 112 ] : 84–106 Поскольку они считают, что продвижение по службе должно зависеть только от оценок коллег, Белл и Ванг выступают против прозрачности, т.е. общественность не должна знать, как отбираются чиновники, поскольку обычные люди не в состоянии судить чиновников за пределами местного уровня. [ 112 ] : 76–78 Другие, такие как Цзян Цин, защищают модель, в которой начальство решает, кого продвигать по службе; этот метод соответствует более традиционалистским направлениям конфуцианской политической мысли, которые уделяют больше внимания строгой иерархии и эпистемическому патернализму, то есть идее о том, что старшие и более опытные люди знают больше. [ 116 ] : 27–44

Совместимость с либерализмом и демократией и критика политической меритократии

Другой ключевой вопрос заключается в том, совместима ли конфуцианская политическая мысль с либерализмом. Тонгдонг Бай, например, утверждает, что, хотя конфуцианская политическая мысль отходит от модели «один человек — один голос», она может сохранить многие существенные характеристики либерализма, такие как свобода слова и права личности. [ 113 ] : 97–110 Фактически, и Дэниел Белл, и Тонгдонг Бай считают, что конфуцианская политическая меритократия может решать проблемы, которые либерализм хочет решить, но не может сам по себе. Например, на культурном уровне конфуцианство, его институты и ритуалы служат защитой от атомизации и индивидуализма. На политическом уровне недемократическая сторона политической меритократии – по мнению Белла и Бая – более эффективна в решении долгосрочных вопросов, таких как изменение климата, отчасти потому, что меритократам не нужно беспокоиться о прихотях общественного мнения. [ 114 ] : 14–63

Джозеф Чан защищает совместимость конфуцианства как с либерализмом, так и с демократией. В своей книге «Конфуцианский перфекционизм » он утверждает, что конфуцианцы могут принять как демократию, так и либерализм на инструментальных основаниях; то есть, хотя либеральная демократия, возможно, не ценна сама по себе, ее институты остаются ценными – особенно в сочетании с широко конфуцианской культурой – для служения конфуцианским целям и привития конфуцианских добродетелей. [ 117 ]

Другие конфуцианцы критиковали конфуцианских меритократов, таких как Белл, за их неприятие демократии. По их мнению, конфуцианство не должно основываться на предположении, что достойное, добродетельное политическое руководство по своей сути несовместимо с народным суверенитетом, политическим равенством и правом на политическое участие. [ 118 ] Эти мыслители обвиняют меритократов в переоценке недостатков демократии, ошибочном принятии временных недостатков за постоянные и присущие ей особенности и недооценке проблем, которые создает на практике построение истинной политической меритократии, в том числе тех, с которыми сталкиваются современные Китай и Сингапур. [ 119 ] Франц Манг утверждает, что, будучи отделенной от демократии, меритократия имеет тенденцию перерастать в репрессивный режим под руководством якобы «достойных», но на самом деле «авторитарных» правителей; Манг обвиняет китайскую модель Белла в саморазрушении, о чем, как утверждает Манг, свидетельствуют авторитарные способы взаимодействия КПК с несогласными. [ 120 ] Хэ Баоган и Марк Уоррен добавляют, что «меритократию» следует понимать как концепцию, описывающую характер режима, а не его тип, который определяется распределением политической власти. компетентность. [ 121 ]

Рой Ценг, опираясь на новых конфуцианцев двадцатого века, утверждает, что конфуцианство и либеральная демократия могут вступить в диалектический процесс, в котором либеральные права и избирательные права переосмысливаются в решительно современный, но, тем не менее, конфуцианский образ жизни. [ 122 ] Этот синтез, сочетающий конфуцианские ритуалы и институты с более широкой либерально-демократической структурой, отличается как от либерализма западного типа, который, по мнению Цзэна, страдает от чрезмерного индивидуализма и отсутствия морального видения, так и от традиционного конфуцианства, которое, по мнению Цзэна, исторически страдала от жесткой иерархии и склеротических элит. Выступая против защитников политической меритократии, Ценг утверждает, что слияние конфуцианских и демократических институтов может сохранить лучшее из обоих миров, создав более общинную демократию, которая опирается на богатые этические традиции, борется со злоупотреблениями властью и сочетает в себе подотчетность народа с ясным вниманием. к культивированию добродетели в элитах.

Влияние

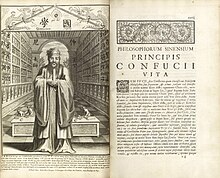

В Европе 17 века

Труды Конфуция были переведены на европейские языки через миссионеров -иезуитов, дислоцированных в Китае . [ примечание 3 ] Маттео Риччи был одним из первых, кто сообщил о мыслях Конфуция, а отец Просперо Инторчетта написал о жизни и творчестве Конфуция на латыни в 1687 году. [ 123 ]

Переводы конфуцианских текстов оказали влияние на европейских мыслителей того периода. [ 124 ] особенно среди деистов и других философских групп эпохи Просвещения , которые были заинтересованы в интеграции системы морали Конфуция в западную цивилизацию . [ 123 ] [ 125 ]

Конфуцианство оказало влияние на немецкого философа Готфрида Вильгельма Лейбница , которого привлекла эта философия из-за ее сходства с его собственной. Предполагается, что некоторые элементы философии Лейбница, такие как «простая субстанция» и « предустановленная гармония », были заимствованы из его взаимодействия с конфуцианством. [ 124 ]

Французский философ Вольтер , интеллектуальный соперник Лейбница, также находился под влиянием Конфуция, рассматривая концепцию конфуцианского рационализма как альтернативу христианской догме. [ 126 ] Он восхвалял конфуцианскую этику и политику, изображая социально-политическую иерархию Китая как модель для Европы: [ 126 ]

Конфуция не интересует ложь; он не претендовал на роль пророка; он не претендовал на вдохновение; он не учил никакой новой религии; он не использовал заблуждений; не льстил императору, при котором жил ...

Об исламской мысли

в Китае развивалась целая литература, известная как Хань Китаб С конца 17 века среди мусульман-хуэй , которая наполняла исламскую мысль конфуцианством. В частности, работы Лю Чжи, такие как Тяньфан Дяньли ( 天方典禮 ; Tiānfāng Diώnlǐ ), стремились гармонизировать ислам не только с конфуцианством, но и с даосизмом , и считаются одним из главных достижений китайской исламской культуры. [ 127 ]

В наше время

Важные военные и политические деятели современной китайской истории продолжали находиться под влиянием конфуцианства, например, мусульманский военачальник Ма Фусян . [ 128 ] Движение «Новая жизнь» в начале 20 века также находилось под влиянием конфуцианства.

Среди политологов и экономистов существует теория, согласно которой конфуцианство играет большую скрытую роль в якобы неконфуцианских культурах современного Востока. Азии, в форме строгой трудовой этики, которой она наделила эти культуры. Эти ученые считали, что, если бы не влияние конфуцианства на эти культуры, многие жители региона Восточной Азии не смогли бы модернизироваться и индустриализироваться так быстро, как Сингапур , Малайзия , Гонконг , Тайвань , Япония , Южная Корея и даже Китай сделал это.

Например, влияние Вьетнамской войны на Вьетнам было разрушительным, но за последние несколько десятилетий Вьетнам начал заново развиваться очень быстрыми темпами. Большинство ученых приписывают истоки этой идеи книге футуролога Германа Кана « Мировое экономическое развитие: 1979 год и далее» . [ 129 ]

Другие исследования, например, « Почему Восточная Азия обогнала Латинскую Америку: аграрная реформа, индустриализация и развитие» Кристобаля Кея , объясняют экономический рост в Азии другими факторами, например характером аграрных реформ, «государственным искусством» ( государственным потенциалом ) и взаимодействие сельского хозяйства и промышленности. [ 130 ]

Исторические и нынешние конфуцианцы были и часто являются защитниками окружающей среды. [ 16 ] из уважения к Тянь и другим аспектам природы, а также к «Принципу», который исходит из их единства и, в более общем смысле, гармонии в целом, что является «основой искреннего разума». [ 131 ]

О китайских боевых искусствах

После того как конфуцианство стало официальной «государственной религией» в Китае, его влияние проникло во все сферы жизни и все направления мысли китайского общества для будущих поколений. Это не исключало культуру боевых искусств. Хотя в свое время Конфуций отверг практику боевых искусств (за исключением стрельбы из лука), он служил под началом правителей, которые широко использовали военную силу для достижения своих целей. В последующие столетия конфуцианство сильно повлияло на многих образованных мастеров боевых искусств, оказавших большое влияние, таких как Сунь Лутан , [ нужна ссылка ] особенно с 19-го века, когда боевые искусства голыми руками в Китае стали более распространенными и начали с большей готовностью поглощать философские влияния конфуцианства, буддизма и даосизма .

Критика

| Новое культурное движение |

|---|

|

|

Конфуций и конфуцианство с самого начала подвергались критике или критике, включая Лао-цзы философию и критику Мо -цзы, а законники, такие как Хан Фэй, высмеивали идею о том, что добродетель приведет людей к порядку. В наше время волны оппозиции и поношения показали, что конфуцианству вместо того, чтобы приписать себе славу китайской цивилизации, теперь пришлось взять на себя вину за ее неудачи. описывало Восстание тайпинов мудрецов конфуцианства, а также богов в даосизме и буддизме как дьяволов.

Противоречие с модернистскими ценностями

В « Движении за новую культуру» Лу Синь критиковал конфуцианство за то, что оно привело китайцев в состояние, которого они достигли во времена поздней династии Цин : его критика выражена метафорически в произведении « Дневник сумасшедшего », в котором традиционное китайское конфуцианское общество изображается как феодальный, лицемерный, социально-каннибалистический, деспотический, поощряющий «рабский менталитет», благоприятствующий деспотизму, отсутствие критического мышления, слепое повиновение и поклонение власти, подпитывающие форму «конфуцианского авторитаризма», которая сохраняется и по сей день. [ 132 ] Левые во время Культурной революции называли Конфуция представителем класса рабовладельцев. [ 133 ]

В Южной Корее уже давно существует критика. Некоторые южнокорейцы считают, что конфуцианство не способствовало модернизации Южной Кореи. Например, южнокорейский писатель Ким Кён Ир в 1998 году написал книгу под названием «Конфуций должен умереть, чтобы нация жила» ( 공자가 죽어야 나라가 산다 , гонджага джуг-эоя нарага санда ). Ким сказал, что сыновняя почтительность является односторонней и слепой, и если она будет продолжаться, социальные проблемы будут продолжаться, поскольку правительство продолжает навязывать семьям конфуцианские сыновние обязательства. [ 134 ]

Женщины в конфуцианской мысли

Конфуцианство «во многом определяло основной дискурс о гендере в Китае, начиная с династии Хань ». [ 135 ] Гендерные роли, предписанные в « Трех послушаниях» и «Четырех добродетелях», стали краеугольным камнем семьи и, следовательно, стабильности общества. «Три послушания и четыре добродетели» — один из моральных стандартов феодального этикета, связывающих женщин. [ 136 ] Начиная с периода Хань, конфуцианцы начали учить, что добродетельная женщина должна следовать за мужчинами в своей семье: за отцом до замужества, за мужем после замужества и за сыновьями в вдовстве. В более поздних династиях больше внимания уделялось целомудрию. из династии Сун Конфуцианец Чэн И заявил: «Умереть от голода — небольшое дело, но потерять целомудрие — великое дело». [ 137 ] Именно во времена династии Сун ценность целомудрия была настолько суровой, что конфуцианские ученые объявили повторный брак вдов уголовным преступлением. [ 136 ] Вдов почитали и увековечивали память в периоды Мин и Цин . Принцип целомудренного вдовства стал официальным институтом во времена династии Мин. Соответственно, этот « культ целомудрия » обрекал многих вдов на бедность и одиночество, накладывая социальное клеймо на повторный брак. [ 135 ] Хотя последствия для вдов иногда выходили за рамки бедности и одиночества, поскольку для некоторых сохранение целомудрия приводило к самоубийству. Идеал целомудренной вдовы стал чрезвычайно высокой честью и уважением, особенно для женщины, решившей покончить с собой после смерти мужа. Многие случаи таких действий были записаны в «Биографиях добродетельных женщин», «сборнике историй о женщинах, которые отличились тем, что покончили жизнь самоубийством после смерти своего мужа, чтобы сохранить свое целомудрие и чистоту». Хотя можно оспорить, можно ли считать все эти случаи самопожертвованием ради целомудрия, поскольку принуждение женщин к самоубийству после смерти мужа стало обычной практикой. Это было результатом почести, которую получало целомудренное вдовство, приносящее как семье мужа, так и его клану или деревне. [ 136 ]

В течение многих лет многие современные ученые считали конфуцианство сексистской, патриархальной идеологией, которая исторически наносила ущерб китайским женщинам. [ 136 ] [ 138 ] : 15–16 Некоторые китайские и западные писатели также утверждали, что рост неоконфуцианства во время династии Сун привел к снижению статуса женщин. [ 137 ] : 10–12 Некоторые критики также обвинили выдающегося ученого-неоконфуцианца Сун Чжу Си в том, что он верил в неполноценность женщин и в то, что мужчин и женщин необходимо держать строго отдельно. [ 139 ] в то время как Сыма Гуан также считал, что женщины должны оставаться дома и не заниматься делами мужчин во внешнем мире. [ 137 ] : 24–25 [ 140 ] Наконец, ученые обсудили отношение к женщинам в конфуцианских текстах, таких как «Аналитики» . В широко обсуждаемом отрывке женщины группируются вместе с «маленькими людьми» ( 小人 ), что означает людей с низким статусом или низкой моралью) и описываются как люди, с которыми трудно воспитывать или иметь дело. [ 141 ] Многие традиционные комментаторы и современные ученые спорят о точном значении этого отрывка, а также о том, говорил ли Конфуций обо всех женщинах или только об определенных группах женщин. [ 142 ] [ 143 ]

Однако дальнейший анализ показывает, что место женщины в конфуцианском обществе может быть более сложным. [ 135 ] Во времена династии Хань влиятельный конфуцианский текст «Уроки для женщин (45–114 гг. н. э.) написала Бань Чжао », чтобы научить своих дочерей быть настоящими конфуцианскими женами и матерями, то есть быть молчаливыми, трудолюбивыми и уступчивыми. . Она подчеркивает взаимодополняемость и равную важность мужской и женской ролей согласно теории инь-ян, но явно признает доминирование мужчины. Тем не менее, она считает образование и литературную силу важными для женщин. В более поздних династиях ряд женщин воспользовались конфуцианским признанием образования, чтобы стать независимыми в мыслях. [ 135 ]

Джозеф А. Адлер отмечает, что «неоконфуцианские сочинения не обязательно отражают ни преобладающие социальные практики, ни собственные взгляды и практики ученых в отношении реальных женщин». [ 135 ] Мэтью Соммерс также указал, что правительство династии Цин начало осознавать утопическую природу насаждения «культа целомудрия» и начало разрешать такие практики, как повторный брак вдов. [ 144 ] Более того, в некоторых конфуцианских текстах, таких как Дун Чжуншу , « Роскошная роса весенних и осенних летописей» есть отрывки, предполагающие более равные отношения между мужем и женой. [ 145 ] Совсем недавно некоторые ученые также начали обсуждать жизнеспособность построения «конфуцианского феминизма». [ 138 ] : 4, 149–160

Католические споры по поводу китайских обрядов

С тех пор, как европейцы впервые столкнулись с конфуцианством, вопрос о том, как следует классифицировать конфуцианство, стал предметом дискуссий. В XVI и XVII веках первые европейцы, прибывшие в Китай, христианские иезуиты , считали конфуцианство этической системой, а не религией, совместимой с христианством. [ 146 ] Иезуиты, в том числе Маттео Риччи , рассматривали китайские ритуалы как «гражданские ритуалы», которые могли сосуществовать рядом с духовными ритуалами католицизма. [ 146 ]

К началу 18 века это первоначальное изображение было отвергнуто доминиканцами и францисканцами , что вызвало спор между католиками в Восточной Азии , известный как «Спор об обрядах». [ 147 ] Доминиканцы и францисканцы утверждали, что китайское поклонение предкам было формой идолопоклонства, противоречащей принципам христианства. Эту точку зрения поддержал Папа Бенедикт XIV , который приказал запретить китайские ритуалы. [ 147 ] хотя этот запрет был пересмотрен и отменен в 1939 году Папой Пием XII при условии, что такие традиции гармонируют с истинным и подлинным духом литургии. [ 148 ]

Некоторые критики считают конфуцианство определенно пантеистическим и нетеистическим , поскольку оно не основано на вере в сверхъестественное или в личного бога, существующего отдельно от временного плана. [ 8 ] [ 149 ] Взгляды Конфуция на тянь и на божественное провидение, управляющее миром, можно найти выше (на этой странице), а также, например, в Аналектах 6:26, 7:22 и 9:12. О духовности Конфуций сказал Чи Лу, одному из своих учеников: «Ты еще не способен служить людям, как ты можешь служить духам?» [ 150 ] Такие атрибуты, как поклонение предкам , ритуалы и жертвоприношения , пропагандировались Конфуцием как необходимые для социальной гармонии; эти атрибуты можно отнести к традиционной китайской народной религии .

Ученые признают, что классификация в конечном итоге зависит от того, как человек определяет религию. Используя более строгие определения религии, конфуцианство было описано как моральная наука или философия. [ 151 ] [ 152 ] Но если использовать более широкое определение, такое как Фредериком Стренгом как «средство окончательной трансформации», характеристика религии [ 153 ] Конфуцианство можно охарактеризовать как «социально-политическую доктрину, имеющую религиозные качества». [ 149 ] Согласно последнему определению, конфуцианство является религиозным, хотя и нетеистическим, в том смысле, что оно «выполняет некоторые из основных психосоциальных функций полноценных религий». [ 149 ]

См. также

- Китайская культура

- Китайская народная религия

- Конфуцианское искусство

- Конфуцианская церковь

- Конфуцианский взгляд на брак

- Конфуцианство в Индонезии

- Конфуцианство в США

- Институт Конфуция

- кровное родство

- Эдо неоконфуцианство

- Семья как модель государства

- Корейское конфуцианство

- Корейский шаманизм

- Неоконфуцианство

- Радикальная ортодоксальность

- Религиозное конфуцианство

- Религиозный гуманизм

- Синология

- даосизм

- Храм Конфуция

- Религия вьетнамского народа

- Вьетнамская философия

- Список конфуцианских государств и династий

Примечания

- ^ Независимо от того, расположены ли они на изменчивом прецессионном северном полюсе мира или на фиксированном северном полюсе эклиптики , вращающиеся созвездия рисуют символ卍 вокруг центра.

- ↑ Фраза « 魚水君臣 » («Рыба (и) водный повелитель (и) подданный») относится к термину « 君臣魚水 » из «Хроник Трех Королевств» , где Лю Бэй относится к получению услуг Чжугэ Ляна, как если бы «рыба набираю воду».

- ↑ Первым был Микеле Руджери , который вернулся из Китая в Италию в 1588 году и продолжал переводить на латынь китайскую классику, проживая в Салерно.

Цитаты

- ^ Нилан, Майкл (1 октября 2008 г.). Пять «конфуцианских» классиков . Издательство Йельского университета. п. 23. ISBN 978-0-300-13033-1 . Проверено 12 марта 2022 г.

- ^ Яо 2000 , стр. 38–47.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Фунг (2008) , с. 163.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Лин, Джастин Ифу (2012). Демистификация китайской экономики . Издательство Кембриджского университета. п. 107. ИСБН 978-0-521-19180-7 .

- ^ Фингаретт (1972) , стр. 1–2.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Юргенсмейер, Марк (2005). Юргенсмайер, Марк (ред.). Религия в глобальном гражданском обществе . Издательство Оксфордского университета. п. 70. дои : 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195188356.001.0001 . ISBN 978-0-19-518835-6 .

... гуманистические философии, такие как конфуцианство, которые не разделяют веру в божественный закон и не превозносят верность высшему закону как проявление божественной воли

. - ^ Фингаретт (1972) .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Адлер (2014) , с. 12.

- ^ Литтлджон (2010) , стр. 34–36.

- ^ «Конфуцианство» . Британская энциклопедия . Проверено 30 апреля 2023 г.

- ^ «Конфуцианство» . Национальное географическое общество . 20 мая 2022 г. Проверено 30 апреля 2023 г.

- ^ Адлер (2014) , стр. 10, 12.

- Цитата, с. 10: «Конфуцианство в своей основе нетеистично . Хотя тянь имеет некоторые характеристики, которые перекрывают категорию божества, оно в первую очередь является безличным абсолютом, подобно дао и Брахману . «Божество» ( theos , deus ), с другой стороны, означает нечто личное. (он или она, а не оно)».

- Цитата, с. 12: «Конфуцианство деконструирует дихотомию священного и светского; оно утверждает, что священность следует искать в обычной деятельности человеческой жизни, а не за ней или за ее пределами, и особенно в человеческих отношениях. Человеческие отношения священны в конфуцианстве, потому что они являются выражением нашей моральной природы ( 性 ; xìng ), которая имеет трансцендентную опору на Небесах ( 天 ; tiān ), Герберт Фингаретт отразил эту важную особенность конфуцианства в названии своей книги 1972 года «Конфуций: Светское как священное» . отношения между священным и мирским, и использовать это в качестве критерия религии — значит поставить вопрос о том, может ли конфуцианство считаться религиозной традицией».

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Айвенго, Филип Дж .; Ван Норден, Брайан В. (2005). Чтения по классической китайской философии (2-е изд.). Индианаполис: Издательская компания Hackett . п. 2. ISBN 0-87220-781-1 . OCLC 60826646 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Тай (2010) , с. 102.

- ^ Каплан, Роберт Д. (6 февраля 2015 г.). «В основе подъема Азии лежат конфуцианские ценности» . Уолл Стрит Джорнал .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Такер, Мэри Эвелин (1998). «Конфуцианство и экология: потенциал и пределы» . Форум по религии и экологии в Йельском университете . Йельский университет . Проверено 29 апреля 2023 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Харари, Юваль Ной (2015). Sapiens: Краткая история человечества . Перевод Харари, Юваль Ной ; Перселл, Джон; Вацман, Хаим . Лондон: Penguin Random House UK. п. 391. ИСБН 978-0-09-959008-8 . OCLC 910498369 .

- ^ Фридман, Рассел (сентябрь 2002 г.). Конфуций: Золотое правило (1-е изд.). Нью-Йорк: Книги Артура А. Левина . п. 38. ISBN 978-0-439-13957-1 .

- ^ Бенджамин Элман, Джон Дункан и Герман Оомс изд. Переосмысление конфуцианства: прошлое и настоящее в Китае, Японии, Корее и Вьетнаме (Лос-Анджелес: Серия монографий Азиатско-Тихоокеанского региона Калифорнийского университета в Лос-Анджелесе, 2002).

- ^ Ю Инши, Сяньдай Руксуэ Лунь (River Edge: Global Publishing, 1996).

- ^ Billioud & Thoraval (2015) , проход .

- ^ Яо (2000) , с. 19.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Ино, Роберт (1990). Конфуцианское сотворение небес: философия и защита ритуального мастерства (1-е изд.). Издательство Государственного университета Нью-Йорка. ISBN 978-0-7914-0191-0 .

- ^ Шаберг, Дэвид (1997). «Протест в истории Восточной Чжоу». Ранний Китай . 22 . Издательство Кембриджского университета: 130–179 на 138 . дои : 10.1017/S0362502800003266 . JSTOR 23354245 . S2CID 163038164 .

- ^ Сосны, Юрий (2005–2006). «Предрассудки и их источники: история Цинь в «Шиджи» ». Ориенс Экстремус . 45 . Харрасовиц Верлаг: 10–34 в 30 лет . JSTOR 24047638 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Чжоу (2012) , с. 1.