Caffeine

Caffeine is a central nervous system (CNS) stimulant of the methylxanthine class.[9] It is mainly used as a eugeroic (wakefulness promoter) or as a mild cognitive enhancer to increase alertness and attentional performance.[10][11] Caffeine acts by blocking binding of adenosine to the adenosine A1 receptor, which enhances release of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine.[12] Caffeine has a three-dimensional structure similar to that of adenosine, which allows it to bind and block its receptors.[13] Caffeine also increases cyclic AMP levels through nonselective inhibition of phosphodiesterase.[14]

Caffeine is a bitter, white crystalline purine, a methylxanthine alkaloid, and is chemically related to the adenine and guanine bases of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA). It is found in the seeds, fruits, nuts, or leaves of a number of plants native to Africa, East Asia and South America[15] and helps to protect them against herbivores and from competition by preventing the germination of nearby seeds,[16] as well as encouraging consumption by select animals such as honey bees.[17] The best-known source of caffeine is the coffee bean, the seed of the Coffea plant. People may drink beverages containing caffeine to relieve or prevent drowsiness and to improve cognitive performance. To make these drinks, caffeine is extracted by steeping the plant product in water, a process called infusion. Caffeine-containing drinks, such as coffee, tea, and cola, are consumed globally in high volumes. In 2020, almost 10 million tonnes of coffee beans were consumed globally.[18] Caffeine is the world's most widely consumed psychoactive drug.[19][20] Unlike most other psychoactive substances, caffeine remains largely unregulated and legal in nearly all parts of the world. Caffeine is also an outlier as its use is seen as socially acceptable in most cultures and even encouraged in others.

Caffeine has both positive and negative health effects. It can treat and prevent the premature infant breathing disorders bronchopulmonary dysplasia of prematurity and apnea of prematurity. Caffeine citrate is on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines.[21] It may confer a modest protective effect against some diseases,[22] including Parkinson's disease.[23] Some people experience sleep disruption or anxiety if they consume caffeine,[24] but others show little disturbance. Evidence of a risk during pregnancy is equivocal; some authorities recommend that pregnant women limit caffeine to the equivalent of two cups of coffee per day or less.[25][26] Caffeine can produce a mild form of drug dependence – associated with withdrawal symptoms such as sleepiness, headache, and irritability – when an individual stops using caffeine after repeated daily intake.[27][28][2] Tolerance to the autonomic effects of increased blood pressure and heart rate, and increased urine output, develops with chronic use (i.e., these symptoms become less pronounced or do not occur following consistent use).[29]

Caffeine is classified by the US Food and Drug Administration as generally recognized as safe. Toxic doses, over 10 grams per day for an adult, are much higher than the typical dose of under 500 milligrams per day.[30] The European Food Safety Authority reported that up to 400 mg of caffeine per day (around 5.7 mg/kg of body mass per day) does not raise safety concerns for non-pregnant adults, while intakes up to 200 mg per day for pregnant and lactating women do not raise safety concerns for the fetus or the breast-fed infants.[31] A cup of coffee contains 80–175 mg of caffeine, depending on what "bean" (seed) is used, how it is roasted, and how it is prepared (e.g., drip, percolation, or espresso).[32] Thus it requires roughly 50–100 ordinary cups of coffee to reach the toxic dose. However, pure powdered caffeine, which is available as a dietary supplement, can be lethal in tablespoon-sized amounts.

Uses

[edit]Medical

[edit]Caffeine is used for both prevention[33] and treatment[34] of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in premature infants. It may improve weight gain during therapy[35] and reduce the incidence of cerebral palsy as well as reduce language and cognitive delay.[36][37] On the other hand, subtle long-term side effects are possible.[38]

Caffeine is used as a primary treatment for apnea of prematurity,[39] but not prevention.[40][41] It is also used for orthostatic hypotension treatment.[42][41][43]

Some people use caffeine-containing beverages such as coffee or tea to try to treat their asthma.[44] Evidence to support this practice is poor.[44] It appears that caffeine in low doses improves airway function in people with asthma, increasing forced expiratory volume (FEV1) by 5% to 18% for up to four hours.[45]

The addition of caffeine (100–130 mg) to commonly prescribed pain relievers such as paracetamol or ibuprofen modestly improves the proportion of people who achieve pain relief.[46]

Consumption of caffeine after abdominal surgery shortens the time to recovery of normal bowel function and shortens length of hospital stay.[47]

Caffeine was formerly used as a second-line treatment for ADHD. It is considered less effective than methylphenidate or amphetamine but more so than placebo for children with ADHD.[48][49] Children, adolescents, and adults with ADHD are more likely to consume caffeine, perhaps as a form of self-medication.[49][50]

Enhancing performance

[edit]Cognitive performance

[edit]Caffeine is a central nervous system stimulant that may reduce fatigue and drowsiness.[9] At normal doses, caffeine has variable effects on learning and memory, but it generally improves reaction time, wakefulness, concentration, and motor coordination.[51][52] The amount of caffeine needed to produce these effects varies from person to person, depending on body size and degree of tolerance.[51] The desired effects arise approximately one hour after consumption, and the desired effects of a moderate dose usually subside after about three or four hours.[4]

Caffeine can delay or prevent sleep and improves task performance during sleep deprivation.[53] Shift workers who use caffeine make fewer mistakes that could result from drowsiness.[54]

Caffeine in a dose dependent manner increases alertness in both fatigued and normal individuals.[55]

A systematic review and meta-analysis from 2014 found that concurrent caffeine and L-theanine use has synergistic psychoactive effects that promote alertness, attention, and task switching;[56] these effects are most pronounced during the first hour post-dose.[56]

Physical performance

[edit]Caffeine is a proven ergogenic aid in humans.[57] Caffeine improves athletic performance in aerobic (especially endurance sports) and anaerobic conditions.[57] Moderate doses of caffeine (around 5 mg/kg[57]) can improve sprint performance,[58] cycling and running time trial performance,[57] endurance (i.e., it delays the onset of muscle fatigue and central fatigue),[57][59][60] and cycling power output.[57] Caffeine increases basal metabolic rate in adults.[61][62][63] Caffeine ingestion prior to aerobic exercise increases fat oxidation, particularly in persons with low physical fitness.[64]

Caffeine improves muscular strength and power,[65] and may enhance muscular endurance.[66] Caffeine also enhances performance on anaerobic tests.[67] Caffeine consumption before constant load exercise is associated with reduced perceived exertion. While this effect is not present during exercise-to-exhaustion exercise, performance is significantly enhanced. This is congruent with caffeine reducing perceived exertion, because exercise-to-exhaustion should end at the same point of fatigue.[68] Caffeine also improves power output and reduces time to completion in aerobic time trials,[69] an effect positively (but not exclusively) associated with longer duration exercise.[70]

Specific populations

[edit]Adults

[edit]For the general population of healthy adults, Health Canada advises a daily intake of no more than 400 mg.[71] This limit was found to be safe by a 2017 systematic review on caffeine toxicology.[72]

Children

[edit]In healthy children, moderate caffeine intake under 400 mg produces effects that are "modest and typically innocuous".[73][74] As early as six months old, infants can metabolize caffeine at the same rate as that of adults.[75] Higher doses of caffeine (>400 mg) can cause physiological, psychological and behavioral harm, particularly for children with psychiatric or cardiac conditions.[73] There is no evidence that coffee stunts a child's growth.[76] The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that caffeine consumption, particularly in the case of energy and sports drinks, is not appropriate for children and adolescents and should be avoided.[77] This recommendation is based on a clinical report released by American Academy of Pediatrics in 2011 with a review of 45 publications from 1994 to 2011 and includes inputs from various stakeholders (Pediatricians, Committee on nutrition, Canadian Pediatric Society, Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, Food and Drug Administration, Sports Medicine & Fitness committee, National Federations of High School Associations).[77] For children age 12 and under, Health Canada recommends a maximum daily caffeine intake of no more than 2.5 milligrams per kilogram of body weight. Based on average body weights of children, this translates to the following age-based intake limits:[71]

| Age range | Maximum recommended daily caffeine intake |

|---|---|

| 4–6 | 45 mg (slightly more than in 355 ml (12 fl. oz) of a typical caffeinated soft drink) |

| 7–9 | 62.5 mg |

| 10–12 | 85 mg (about 1⁄2 cup of coffee) |

Adolescents

[edit]Health Canada has not developed advice for adolescents because of insufficient data. However, they suggest that daily caffeine intake for this age group be no more than 2.5 mg/kg body weight. This is because the maximum adult caffeine dose may not be appropriate for light-weight adolescents or for younger adolescents who are still growing. The daily dose of 2.5 mg/kg body weight would not cause adverse health effects in the majority of adolescent caffeine consumers. This is a conservative suggestion since older and heavier-weight adolescents may be able to consume adult doses of caffeine without experiencing adverse effects.[71]

Pregnancy and breastfeeding

[edit]The metabolism of caffeine is reduced in pregnancy, especially in the third trimester, and the half-life of caffeine during pregnancy can be increased up to 15 hours (as compared to 2.5 to 4.5 hours in non-pregnant adults).[78] Evidence regarding the effects of caffeine on pregnancy and for breastfeeding are inconclusive.[25] There is limited primary and secondary advice for, or against, caffeine use during pregnancy and its effects on the fetus or newborn.[25]

The UK Food Standards Agency has recommended that pregnant women should limit their caffeine intake, out of prudence, to less than 200 mg of caffeine a day – the equivalent of two cups of instant coffee, or one and a half to two cups of fresh coffee.[79] The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) concluded in 2010 that caffeine consumption is safe up to 200 mg per day in pregnant women.[26] For women who breastfeed, are pregnant, or may become pregnant, Health Canada recommends a maximum daily caffeine intake of no more than 300 mg, or a little over two 8 oz (237 mL) cups of coffee.[71] A 2017 systematic review on caffeine toxicology found evidence supporting that caffeine consumption up to 300 mg/day for pregnant women is generally not associated with adverse reproductive or developmental effect.[72]

There are conflicting reports in the scientific literature about caffeine use during pregnancy.[80] A 2011 review found that caffeine during pregnancy does not appear to increase the risk of congenital malformations, miscarriage or growth retardation even when consumed in moderate to high amounts.[81] Other reviews, however, concluded that there is some evidence that higher caffeine intake by pregnant women may be associated with a higher risk of giving birth to a low birth weight baby,[82] and may be associated with a higher risk of pregnancy loss.[83] A systematic review, analyzing the results of observational studies, suggests that women who consume large amounts of caffeine (greater than 300 mg/day) prior to becoming pregnant may have a higher risk of experiencing pregnancy loss.[84]

Adverse effects

[edit]Physiological

[edit]Caffeine in coffee and other caffeinated drinks can affect gastrointestinal motility and gastric acid secretion.[85][86][87] In postmenopausal women, high caffeine consumption can accelerate bone loss.[88][89]

Acute ingestion of caffeine in large doses (at least 250–300 mg, equivalent to the amount found in 2–3 cups of coffee or 5–8 cups of tea) results in a short-term stimulation of urine output in individuals who have been deprived of caffeine for a period of days or weeks.[90] This increase is due to both a diuresis (increase in water excretion) and a natriuresis (increase in saline excretion); it is mediated via proximal tubular adenosine receptor blockade.[91] The acute increase in urinary output may increase the risk of dehydration. However, chronic users of caffeine develop a tolerance to this effect and experience no increase in urinary output.[92][93][94]

Psychological

[edit]Minor undesired symptoms from caffeine ingestion not sufficiently severe to warrant a psychiatric diagnosis are common and include mild anxiety, jitteriness, insomnia, increased sleep latency, and reduced coordination.[51][95] Caffeine can have negative effects on anxiety disorders.[96] According to a 2011 literature review, caffeine use may induce anxiety and panic disorders in people with Parkinson's disease.[97] At high doses, typically greater than 300 mg, caffeine can both cause and worsen anxiety.[98] For some people, discontinuing caffeine use can significantly reduce anxiety.[99]

In moderate doses, caffeine has been associated with reduced symptoms of depression and lower suicide risk.[100] Two reviews indicate that increased consumption of coffee and caffeine may reduce the risk of depression.[101][102]

Some textbooks state that caffeine is a mild euphoriant,[103][104][105] while others state that it is not a euphoriant.[106][107]

Caffeine-induced anxiety disorder is a subclass of the DSM-5 diagnosis of substance/medication-induced anxiety disorder.[108]

Reinforcement disorders

[edit]Addiction

[edit]Whether caffeine can result in an addictive disorder depends on how addiction is defined. Compulsive caffeine consumption under any circumstances has not been observed, and caffeine is therefore not generally considered addictive.[109] However, some diagnostic models, such as the ICDM-9 and ICD-10, include a classification of caffeine addiction under a broader diagnostic model.[110] Some state that certain users can become addicted and therefore unable to decrease use even though they know there are negative health effects.[3][111]

Caffeine does not appear to be a reinforcing stimulus, and some degree of aversion may actually occur, with people preferring placebo over caffeine in a study on drug abuse liability published in an NIDA research monograph.[112] Some state that research does not provide support for an underlying biochemical mechanism for caffeine addiction.[27][113][114][115] Other research states it can affect the reward system.[116]

"Caffeine addiction" was added to the ICDM-9 and ICD-10. However, its addition was contested with claims that this diagnostic model of caffeine addiction is not supported by evidence.[27][117][118] The American Psychiatric Association's DSM-5 does not include the diagnosis of a caffeine addiction but proposes criteria for the disorder for more study.[108][119]

Dependence and withdrawal

[edit]Withdrawal can cause mild to clinically significant distress or impairment in daily functioning. The frequency at which this occurs is self-reported at 11%, but in lab tests only half of the people who report withdrawal actually experience it, casting doubt on many claims of dependence.[120] and most cases of caffeine withdrawal were 13% in the moderate sense. Moderately physical dependence and withdrawal symptoms may occur upon abstinence, with greater than 100 mg caffeine per day, although these symptoms last no longer than a day.[27] Some symptoms associated with psychological dependence may also occur during withdrawal.[2] The diagnostic criteria for caffeine withdrawal require a previous prolonged daily use of caffeine.[121] Following 24 hours of a marked reduction in consumption, a minimum of 3 of these signs or symptoms is required to meet withdrawal criteria: difficulty concentrating, depressed mood/irritability, flu-like symptoms, headache, and fatigue.[121] Additionally, the signs and symptoms must disrupt important areas of functioning and are not associated with effects of another condition.[121]

The ICD-11 includes caffeine dependence as a distinct diagnostic category, which closely mirrors the DSM-5's proposed set of criteria for "caffeine-use disorder".[119][122] Caffeine use disorder refers to dependence on caffeine characterized by failure to control caffeine consumption despite negative physiological consequences.[119][122] The APA, which published the DSM-5, acknowledged that there was sufficient evidence in order to create a diagnostic model of caffeine dependence for the DSM-5, but they noted that the clinical significance of the disorder is unclear.[123] Due to this inconclusive evidence on clinical significance, the DSM-5 classifies caffeine-use disorder as a "condition for further study".[119]

Tolerance to the effects of caffeine occurs for caffeine-induced elevations in blood pressure and the subjective feelings of nervousness. Sensitization, the process whereby effects become more prominent with use, may occur for positive effects such as feelings of alertness and wellbeing.[120] Tolerance varies for daily, regular caffeine users and high caffeine users. High doses of caffeine (750 to 1200 mg/day spread throughout the day) have been shown to produce complete tolerance to some, but not all of the effects of caffeine. Doses as low as 100 mg/day, such as a 6 oz (170 g) cup of coffee or two to three 12 oz (340 g) servings of caffeinated soft-drink, may continue to cause sleep disruption, among other intolerances. Non-regular caffeine users have the least caffeine tolerance for sleep disruption.[124] Some coffee drinkers develop tolerance to its undesired sleep-disrupting effects, but others apparently do not.[125]

Risk of other diseases

[edit]A neuroprotective effect of caffeine against Alzheimer's disease and dementia is possible but the evidence is inconclusive.[126][127]

Regular consumption of caffeine may protect people from liver cirrhosis.[128] It was also found to slow the progression of liver disease in people who already have the condition, reduce the risk of liver fibrosis, and offer a protective effect against liver cancer among moderate coffee drinkers. A study conducted in 2017 found that the effects of caffeine from coffee consumption on the liver were observed regardless of how the drink was prepared.[129]

Caffeine may lessen the severity of acute mountain sickness if taken a few hours prior to attaining a high altitude.[130] One meta analysis has found that caffeine consumption is associated with a reduced risk of type 2 diabetes.[131] Regular caffeine consumption may reduce the risk of developing Parkinson's disease and may slow the progression of Parkinson's disease.[132][133][23]

Caffeine increases intraocular pressure in those with glaucoma but does not appear to affect normal individuals.[134]

The DSM-5 also includes other caffeine-induced disorders consisting of caffeine-induced anxiety disorder, caffeine-induced sleep disorder and unspecified caffeine-related disorders. The first two disorders are classified under "Anxiety Disorder" and "Sleep-Wake Disorder" because they share similar characteristics. Other disorders that present with significant distress and impairment of daily functioning that warrant clinical attention but do not meet the criteria to be diagnosed under any specific disorders are listed under "Unspecified Caffeine-Related Disorders".[135]

Energy crash

[edit]Caffeine is reputed to cause a fall in energy several hours after drinking, but this is not well researched.[136][137][138][139]

Overdose

[edit]This section needs expansion with: practical management of overdose, see PMID 30893206. You can help by adding to it. (November 2019) |

Consumption of 1–1.5 grams (1,000–1,500 mg) per day is associated with a condition known as caffeinism.[141] Caffeinism usually combines caffeine dependency with a wide range of unpleasant symptoms including nervousness, irritability, restlessness, insomnia, headaches, and palpitations after caffeine use.[142]

Caffeine overdose can result in a state of central nervous system overstimulation known as caffeine intoxication, a clinically significant temporary condition that develops during, or shortly after, the consumption of caffeine.[143] This syndrome typically occurs only after ingestion of large amounts of caffeine, well over the amounts found in typical caffeinated beverages and caffeine tablets (e.g., more than 400–500 mg at a time). According to the DSM-5, caffeine intoxication may be diagnosed if five (or more) of the following symptoms develop after recent consumption of caffeine: restlessness, nervousness, excitement, insomnia, flushed face, diuresis, gastrointestinal disturbance, muscle twitching, rambling flow of thought and speech, tachycardia or cardiac arrhythmia, periods of inexhaustibility, and psychomotor agitation.[144]

According to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11), cases of very high caffeine intake (e.g. > 5 g) may result in caffeine intoxication with symptoms including mania, depression, lapses in judgment, disorientation, disinhibition, delusions, hallucinations or psychosis, and rhabdomyolysis.[143]

Energy drinks

[edit]High caffeine consumption in energy drinks (at least one liter or 320 mg of caffeine) was associated with short-term cardiovascular side effects including hypertension, prolonged QT interval, and heart palpitations. These cardiovascular side effects were not seen with smaller amounts of caffeine consumption in energy drinks (less than 200 mg).[78]

Severe intoxication

[edit]As of 2007[update] there is no known antidote or reversal agent for caffeine intoxication. Treatment of mild caffeine intoxication is directed toward symptom relief; severe intoxication may require peritoneal dialysis, hemodialysis, or hemofiltration.[140][145][146] Intralipid infusion therapy is indicated in cases of imminent risk of cardiac arrest in order to scavenge the free serum caffeine.[146]

Lethal dose

[edit]Death from caffeine ingestion appears to be rare, and most commonly caused by an intentional overdose of medications.[147] In 2016, 3702 caffeine-related exposures were reported to Poison Control Centers in the United States, of which 846 required treatment at a medical facility, and 16 had a major outcome; and several caffeine-related deaths are reported in case studies.[147] The LD50 of caffeine in rats is 192 milligrams per kilogram, the fatal dose in humans is estimated to be 150–200 milligrams per kilogram (2.2 lb) of body mass (75–100 cups of coffee for a 70 kg (150 lb) adult).[148][149] There are cases where doses as low as 57 milligrams per kilogram have been fatal.[150] A number of fatalities have been caused by overdoses of readily available powdered caffeine supplements, for which the estimated lethal amount is less than a tablespoon.[151] The lethal dose is lower in individuals whose ability to metabolize caffeine is impaired due to genetics or chronic liver disease.[152] A death was reported in 2013 of a man with liver cirrhosis who overdosed on caffeinated mints.[153][154]

Interactions

[edit]Caffeine is a substrate for CYP1A2, and interacts with many substances through this and other mechanisms.[155]

Alcohol

[edit]According to DSST, alcohol causes a decrease in performance on their standardized tests, and caffeine causes a significant improvement.[156] When alcohol and caffeine are consumed jointly, the effects of the caffeine are changed, but the alcohol effects remain the same.[157] For example, consuming additional caffeine does not reduce the effect of alcohol.[157] However, the jitteriness and alertness given by caffeine is decreased when additional alcohol is consumed.[157] Alcohol consumption alone reduces both inhibitory and activational aspects of behavioral control. Caffeine antagonizes the effect of alcohol on the activational aspect of behavioral control, but has no effect on the inhibitory behavioral control.[158] The Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommend avoidance of concomitant consumption of alcohol and caffeine, as taking them together may lead to increased alcohol consumption, with a higher risk of alcohol-associated injury.

Tobacco

[edit]Smoking tobacco increases caffeine clearance by 56%.[159] Cigarette smoking induces the cytochrome P450 1A2 enzyme that breaks down caffeine, which may lead to increased caffeine tolerance and coffee consumption for regular smokers.[160]

Birth control

[edit]Birth control pills can extend the half-life of caffeine, requiring greater attention to caffeine consumption.[161]

Medications

[edit]Caffeine sometimes increases the effectiveness of some medications, such as those for headaches.[162] Caffeine was determined to increase the potency of some over-the-counter analgesic medications by 40%.[163]

The pharmacological effects of adenosine may be blunted in individuals taking large quantities of methylxanthines like caffeine.[164] Some other examples of methylxanthines include the medications theophylline and aminophylline, which are prescribed to relieve symptoms of asthma or COPD.[165]

Pharmacology

[edit]Pharmacodynamics

[edit]

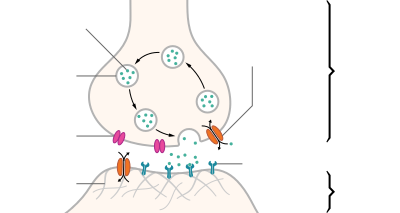

In the absence of caffeine and when a person is awake and alert, little adenosine is present in CNS neurons. With a continued wakeful state, over time adenosine accumulates in the neuronal synapse, in turn binding to and activating adenosine receptors found on certain CNS neurons; when activated, these receptors produce a cellular response that ultimately increases drowsiness. When caffeine is consumed, it antagonizes adenosine receptors; in other words, caffeine prevents adenosine from activating the receptor by blocking the location on the receptor where adenosine binds to it. As a result, caffeine temporarily prevents or relieves drowsiness, and thus maintains or restores alertness.[5]

Receptor and ion channel targets

[edit]Caffeine is an antagonist of adenosine A2A receptors, and knockout mouse studies have specifically implicated antagonism of the A2A receptor as responsible for the wakefulness-promoting effects of caffeine.[166] Antagonism of A2A receptors in the ventrolateral preoptic area (VLPO) reduces inhibitory GABA neurotransmission to the tuberomammillary nucleus, a histaminergic projection nucleus that activation-dependently promotes arousal.[167] This disinhibition of the tuberomammillary nucleus is the downstream mechanism by which caffeine produces wakefulness-promoting effects.[167] Caffeine is an antagonist of all four adenosine receptor subtypes (A1, A2A, A2B, and A3), although with varying potencies.[5][166] The affinity (KD) values of caffeine for the human adenosine receptors are 12 μM at A1, 2.4 μM at A2A, 13 μM at A2B, and 80 μM at A3.[166]

Antagonism of adenosine receptors by caffeine also stimulates the medullary vagal, vasomotor, and respiratory centers, which increases respiratory rate, reduces heart rate, and constricts blood vessels.[5] Adenosine receptor antagonism also promotes neurotransmitter release (e.g., monoamines and acetylcholine), which endows caffeine with its stimulant effects;[5][168] adenosine acts as an inhibitory neurotransmitter that suppresses activity in the central nervous system. Heart palpitations are caused by blockade of the A1 receptor.[5]

Because caffeine is both water- and lipid-soluble, it readily crosses the blood–brain barrier that separates the bloodstream from the interior of the brain. Once in the brain, the principal mode of action is as a nonselective antagonist of adenosine receptors (in other words, an agent that reduces the effects of adenosine). The caffeine molecule is structurally similar to adenosine, and is capable of binding to adenosine receptors on the surface of cells without activating them, thereby acting as a competitive antagonist.[169]

In addition to its activity at adenosine receptors, caffeine is an inositol trisphosphate receptor 1 antagonist and a voltage-independent activator of the ryanodine receptors (RYR1, RYR2, and RYR3).[170] It is also a competitive antagonist of the ionotropic glycine receptor.[171]

Effects on striatal dopamine

[edit]While caffeine does not directly bind to any dopamine receptors, it influences the binding activity of dopamine at its receptors in the striatum by binding to adenosine receptors that have formed GPCR heteromers with dopamine receptors, specifically the A1–D1 receptor heterodimer (this is a receptor complex with one adenosine A1 receptor and one dopamine D1 receptor) and the A2A–D2 receptor heterotetramer (this is a receptor complex with two adenosine A2A receptors and two dopamine D2 receptors).[172][173][174][175] The A2A–D2 receptor heterotetramer has been identified as a primary pharmacological target of caffeine, primarily because it mediates some of its psychostimulant effects and its pharmacodynamic interactions with dopaminergic psychostimulants.[173][174][175]

Caffeine also causes the release of dopamine in the dorsal striatum and nucleus accumbens core (a substructure within the ventral striatum), but not the nucleus accumbens shell, by antagonizing A1 receptors in the axon terminal of dopamine neurons and A1–A2A heterodimers (a receptor complex composed of one adenosine A1 receptor and one adenosine A2A receptor) in the axon terminal of glutamate neurons.[172][167] During chronic caffeine use, caffeine-induced dopamine release within the nucleus accumbens core is markedly reduced due to drug tolerance.[172][167]

Enzyme targets

[edit]Caffeine, like other xanthines, also acts as a phosphodiesterase inhibitor.[176] As a competitive nonselective phosphodiesterase inhibitor,[177] caffeine raises intracellular cyclic AMP, activates protein kinase A, inhibits TNF-alpha[178][179] and leukotriene[180] synthesis, and reduces inflammation and innate immunity.[180] Caffeine also affects the cholinergic system where it is a moderate inhibitor of the enzyme acetylcholinesterase.[181][182]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]

Caffeine from coffee or other beverages is absorbed by the small intestine within 45 minutes of ingestion and distributed throughout all bodily tissues.[184] Peak blood concentration is reached within 1–2 hours.[185] It is eliminated by first-order kinetics.[186] Caffeine can also be absorbed rectally, evidenced by suppositories of ergotamine tartrate and caffeine (for the relief of migraine)[187] and of chlorobutanol and caffeine (for the treatment of hyperemesis).[188] However, rectal absorption is less efficient than oral: the maximum concentration (Cmax) and total amount absorbed (AUC) are both about 30% (i.e., 1/3.5) of the oral amounts.[189]

Caffeine's biological half-life – the time required for the body to eliminate one-half of a dose – varies widely among individuals according to factors such as pregnancy, other drugs, liver enzyme function level (needed for caffeine metabolism) and age. In healthy adults, caffeine's half-life is between 3 and 7 hours.[5] The half-life is decreased by 30-50% in adult male smokers, approximately doubled in women taking oral contraceptives, and prolonged in the last trimester of pregnancy.[125] In newborns the half-life can be 80 hours or more, dropping rapidly with age, possibly to less than the adult value by age 6 months.[125] The antidepressant fluvoxamine (Luvox) reduces the clearance of caffeine by more than 90%, and increases its elimination half-life more than tenfold, from 4.9 hours to 56 hours.[190]

Caffeine is metabolized in the liver by the cytochrome P450 oxidase enzyme system (particularly by the CYP1A2 isozyme) into three dimethylxanthines,[191] each of which has its own effects on the body:

- Paraxanthine (84%): Increases lipolysis, leading to elevated glycerol and free fatty acid levels in blood plasma.

- Theobromine (12%): Dilates blood vessels and increases urine volume. Theobromine is also the principal alkaloid in the cocoa bean (chocolate).

- Theophylline (4%): Relaxes smooth muscles of the bronchi, and is used to treat asthma. The therapeutic dose of theophylline, however, is many times greater than the levels attained from caffeine metabolism.[45]

1,3,7-Trimethyluric acid is a minor caffeine metabolite.[5] 7-Methylxanthine is also a metabolite of caffeine.[192][193] Each of the above metabolites is further metabolized and then excreted in the urine. Caffeine can accumulate in individuals with severe liver disease, increasing its half-life.[194]

A 2011 review found that increased caffeine intake was associated with a variation in two genes that increase the rate of caffeine catabolism. Subjects who had this mutation on both chromosomes consumed 40 mg more caffeine per day than others.[195] This is presumably due to the need for a higher intake to achieve a comparable desired effect, not that the gene led to a disposition for greater incentive of habituation.

Chemistry

[edit]Pure anhydrous caffeine is a bitter-tasting, white, odorless powder with a melting point of 235–238 °C.[7][8] Caffeine is moderately soluble in water at room temperature (2 g/100 mL), but quickly soluble in boiling water (66 g/100 mL).[196] It is also moderately soluble in ethanol (1.5 g/100 mL).[196] It is weakly basic (pKa of conjugate acid = ~0.6) requiring strong acid to protonate it.[197] Caffeine does not contain any stereogenic centers[198] and hence is classified as an achiral molecule.[199]

The xanthine core of caffeine contains two fused rings, a pyrimidinedione and imidazole. The pyrimidinedione in turn contains two amide functional groups that exist predominantly in a zwitterionic resonance the location from which the nitrogen atoms are double bonded to their adjacent amide carbons atoms. Hence all six of the atoms within the pyrimidinedione ring system are sp2 hybridized and planar. The imidazole ring also has a resonance. Therefore, the fused 5,6 ring core of caffeine contains a total of ten pi electrons and hence according to Hückel's rule is aromatic.[200]

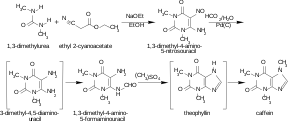

Synthesis

[edit]

The biosynthesis of caffeine is an example of convergent evolution among different species.[205][206][207]

Caffeine may be synthesized in the lab starting with dimethylurea and malonic acid.[clarification needed][203][204][208] Production of synthesized caffeine largely takes place in pharmaceutical plants in China. Synthetic and natural caffeine are chemically identical and nearly indistinguishable. The primary distinction is that synthetic caffeine is manufactured from urea and chloroacetic acid, while natural caffeine is extracted from plant sources, a process known as decaffeination.[209]

Despite the different production methods, the final product and its effects on the body are similar. Research on synthetic caffeine supports that it has the same stimulating effects on the body as natural caffeine.[210] And although many claim that natural caffeine is absorbed slower and therefore leads to a gentler caffeine crash, there is little scientific evidence supporting the notion.[209]

Decaffeination

[edit]

Extraction of caffeine from coffee, to produce caffeine and decaffeinated coffee, can be performed using a number of solvents. Following are main methods:

- Water extraction: Coffee beans are soaked in water. The water, which contains many other compounds in addition to caffeine and contributes to the flavor of coffee, is then passed through activated charcoal, which removes the caffeine. The water can then be put back with the beans and evaporated dry, leaving decaffeinated coffee with its original flavor. Coffee manufacturers recover the caffeine and resell it for use in soft drinks and over-the-counter caffeine tablets.[211]

- Supercritical carbon dioxide extraction: Supercritical carbon dioxide is an excellent nonpolar solvent for caffeine, and is safer than the organic solvents that are otherwise used. The extraction process is simple: CO2 is forced through the green coffee beans at temperatures above 31.1 °C and pressures above 73 atm. Under these conditions, CO2 is in a "supercritical" state: It has gaslike properties that allow it to penetrate deep into the beans but also liquid-like properties that dissolve 97–99% of the caffeine. The caffeine-laden CO2 is then sprayed with high-pressure water to remove the caffeine. The caffeine can then be isolated by charcoal adsorption (as above) or by distillation, recrystallization, or reverse osmosis.[211]

- Extraction by organic solvents: Certain organic solvents such as ethyl acetate present much less health and environmental hazard than chlorinated and aromatic organic solvents used formerly. Another method is to use triglyceride oils obtained from spent coffee grounds.[211]

"Decaffeinated" coffees do in fact contain caffeine in many cases – some commercially available decaffeinated coffee products contain considerable levels. One study found that decaffeinated coffee contained 10 mg of caffeine per cup, compared to approximately 85 mg of caffeine per cup for regular coffee.[212]

Detection in body fluids

[edit]Caffeine can be quantified in blood, plasma, or serum to monitor therapy in neonates, confirm a diagnosis of poisoning, or facilitate a medicolegal death investigation. Plasma caffeine levels are usually in the range of 2–10 mg/L in coffee drinkers, 12–36 mg/L in neonates receiving treatment for apnea, and 40–400 mg/L in victims of acute overdosage. Urinary caffeine concentration is frequently measured in competitive sports programs, for which a level in excess of 15 mg/L is usually considered to represent abuse.[213]

Analogs

[edit]Some analog substances have been created which mimic caffeine's properties with either function or structure or both. Of the latter group are the xanthines DMPX[214] and 8-chlorotheophylline, which is an ingredient in dramamine. Members of a class of nitrogen substituted xanthines are often proposed as potential alternatives to caffeine.[215][unreliable source?] Many other xanthine analogues constituting the adenosine receptor antagonist class have also been elucidated.[216]

Some other caffeine analogs:

Precipitation of tannins

[edit]Caffeine, as do other alkaloids such as cinchonine, quinine or strychnine, precipitates polyphenols and tannins. This property can be used in a quantitation method.[clarification needed][217]

Natural occurrence

[edit]

Around thirty plant species are known to contain caffeine.[218] Common sources are the "beans" (seeds) of the two cultivated coffee plants, Coffea arabica and Coffea canephora (the quantity varies, but 1.3% is a typical value); and of the cocoa plant, Theobroma cacao; the leaves of the tea plant; and kola nuts. Other sources include the leaves of yaupon holly, South American holly yerba mate, and Amazonian holly guayusa; and seeds from Amazonian maple guarana berries. Temperate climates around the world have produced unrelated caffeine-containing plants.

Caffeine in plants acts as a natural pesticide: it can paralyze and kill predator insects feeding on the plant.[219] High caffeine levels are found in coffee seedlings when they are developing foliage and lack mechanical protection.[220] In addition, high caffeine levels are found in the surrounding soil of coffee seedlings, which inhibits seed germination of nearby coffee seedlings, thus giving seedlings with the highest caffeine levels fewer competitors for existing resources for survival.[221] Caffeine is stored in tea leaves in two places. Firstly, in the cell vacuoles where it is complexed with polyphenols. This caffeine probably is released into the mouth parts of insects, to discourage herbivory. Secondly, around the vascular bundles, where it probably inhibits pathogenic fungi from entering and colonizing the vascular bundles.[222] Caffeine in nectar may improve the reproductive success of the pollen producing plants by enhancing the reward memory of pollinators such as honey bees.[17]

The differing perceptions in the effects of ingesting beverages made from various plants containing caffeine could be explained by the fact that these beverages also contain varying mixtures of other methylxanthine alkaloids, including the cardiac stimulants theophylline and theobromine, and polyphenols that can form insoluble complexes with caffeine.[223]

Products

[edit]| Product | Serving size | Caffeine per serving (mg) | Caffeine (mg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caffeine tablet (regular-strength) | 1 tablet | 100 | — |

| Caffeine tablet (extra-strength) | 1 tablet | 200 | — |

| Excedrin tablet | 1 tablet | 65 | — |

| Percolated coffee | 207 mL (7.0 US fl oz) | 80–135 | 386–652 |

| Drip coffee | 207 mL (7.0 US fl oz) | 115–175 | 555–845 |

| Coffee, decaffeinated | 207 mL (7.0 US fl oz) | 5–15 | 24–72 |

| Coffee, espresso | 44–60 mL (1.5–2.0 US fl oz) | 100 | 1,691–2,254 |

| Tea – black, green, and other types, – steeped for 3 min. | 177 mL (6.0 US fl oz) | 22–74[227][228] | 124–418 |

| Guayakí yerba mate (loose leaf) | 6 g (0.21 oz) | 85[229] | approx. 358 |

| Coca-Cola | 355 mL (12.0 US fl oz) | 34 | 96 |

| Mountain Dew | 355 mL (12.0 US fl oz) | 54 | 154 |

| Pepsi Zero Sugar | 355 mL (12.0 US fl oz) | 69 | 194 |

| Guaraná Antarctica | 350 mL (12 US fl oz) | 30 | 100 |

| Jolt Cola | 695 mL (23.5 US fl oz) | 280 | 403 |

| Red Bull | 250 mL (8.5 US fl oz) | 80 | 320 |

| Coffee-flavored milk drink | 300–600 mL (10–20 US fl oz) | 33–197[230] | 66–354[230] |

| Cocoa, dry powder, unsweetened [unspecified strain] | 100 g | 230[231] | — |

| Cocoa solids, defatted, Criollo strain | 100 g | 1130[232] | — |

| Cocoa solids, defatted, Forastero strain | 100 g | 130[232] | — |

| Cocoa solids, defatted, Nacional strain | 100 g | 240[232] | — |

| Cocoa solids, defatted, Trinitario strain | 100 g | 630[232] | — |

| Chocolate, dark, 70-85% cacao solids | 100 g | 80[233] | — |

| Chocolate, dark, 60-69% cacao solids | 100 g | 86[234] | — |

| Chocolate, dark, 45- 59% cacao solids | 100 g | 43[235] | — |

| Candies, milk chocolate | 100 g | 20[236] | — |

| Hershey's Special Dark (45% cacao content) | 1 bar (43 g or 1.5 oz) | 31 | — |

| Hershey's Milk Chocolate (11% cacao content) | 1 bar (43 g or 1.5 oz) | 10 | — |

Products containing caffeine include coffee, tea, soft drinks ("colas"), energy drinks, other beverages, chocolate,[237] caffeine tablets, other oral products, and inhalation products. According to a 2020 study in the United States, coffee is the major source of caffeine intake in middle-aged adults, while soft drinks and tea are the major sources in adolescents.[78] Energy drinks are more commonly consumed as a source of caffeine in adolescents as compared to adults.[78]

Beverages

[edit]Coffee

[edit]The world's primary source of caffeine is the coffee "bean" (the seed of the coffee plant), from which coffee is brewed. Caffeine content in coffee varies widely depending on the type of coffee bean and the method of preparation used;[238] even beans within a given bush can show variations in concentration. In general, one serving of coffee ranges from 80 to 100 milligrams, for a single shot (30 milliliters) of arabica-variety espresso, to approximately 100–125 milligrams for a cup (120 milliliters) of drip coffee.[239][240] Arabica coffee typically contains half the caffeine of the robusta variety.[238] In general, dark-roast coffee has slightly less caffeine than lighter roasts because the roasting process reduces caffeine content of the bean by a small amount.[239][240]

Tea

[edit]Tea contains more caffeine than coffee by dry weight. A typical serving, however, contains much less, since less of the product is used as compared to an equivalent serving of coffee. Also contributing to caffeine content are growing conditions, processing techniques, and other variables. Thus, teas contain varying amounts of caffeine.[241]

Tea contains small amounts of theobromine and slightly higher levels of theophylline than coffee. Preparation and many other factors have a significant impact on tea, and color is a poor indicator of caffeine content. Teas like the pale Japanese green tea, gyokuro, for example, contain far more caffeine than much darker teas like lapsang souchong, which has minimal content.[241]

Soft drinks and energy drinks

[edit]Caffeine is also a common ingredient of soft drinks, such as cola, originally prepared from kola nuts. Soft drinks typically contain 0 to 55 milligrams of caffeine per 12 ounce (350 mL) serving.[242] By contrast, energy drinks, such as Red Bull, can start at 80 milligrams of caffeine per serving. The caffeine in these drinks either originates from the ingredients used or is an additive derived from the product of decaffeination or from chemical synthesis. Guarana, a prime ingredient of energy drinks, contains large amounts of caffeine with small amounts of theobromine and theophylline in a naturally occurring slow-release excipient.[243]

Other beverages

[edit]- Mate is a drink popular in many parts of South America. Its preparation consists of filling a gourd with the leaves of the South American holly yerba mate, pouring hot but not boiling water over the leaves, and drinking with a straw, the bombilla, which acts as a filter so as to draw only the liquid and not the yerba leaves.[244]

- Guaraná is a soft drink originating in Brazil made from the seeds of the Guaraná fruit.

- The leaves of Ilex guayusa, the Ecuadorian holly tree, are placed in boiling water to make a guayusa tea.[245]

- The leaves of Ilex vomitoria, the yaupon holly tree, are placed in boiling water to make a yaupon tea.

- Commercially prepared coffee-flavoured milk beverages are popular in Australia.[246] Examples include Oak's Ice Coffee and Farmers Union Iced Coffee. The amount of caffeine in these beverages can vary widely. Caffeine concentrations can differ significantly from the manufacturer's claims.[230]

Cacao solids

[edit]Cocoa solids (derived from cocoa bean) contain 230 mg caffeine per 100 g.[231]

The caffeine content varies between cocoa bean strains. Caffeine content mg/g (sorted by lowest caffeine content):[232]

- Forastero (defatted): 1.3 mg/g

- Nacional (defatted): 2.4 mg/g

- Trinitario (defatted): 6.3/g

- Criollo (defatted): 11.3 mg/g

Chocolate

[edit]Caffeine per 100 g:

- Dark chocolate, 70-85% cacao solids: 80 mg[233]

- Dark chocolate, 60-69% cacao solids: 86 mg[234]

- Dark chocolate, 45- 59% cacao solids: 43 mg[235]

- Milk chocolate: 20 mg[236]

The stimulant effect of chocolate may be due to a combination of theobromine and theophylline, as well as caffeine.[247]

Tablets

[edit]

Tablets offer several advantages over coffee, tea, and other caffeinated beverages, including convenience, known dosage, and avoidance of concomitant intake of sugar, acids, and fluids. A use of caffeine in this form is said to improve mental alertness.[248] These tablets are commonly used by students studying for their exams and by people who work or drive for long hours.[249]

Other oral products

[edit]One U.S. company is marketing oral dissolvable caffeine strips.[250] Another intake route is SpazzStick, a caffeinated lip balm.[251] Alert Energy Caffeine Gum was introduced in the United States in 2013, but was voluntarily withdrawn after an announcement of an investigation by the FDA of the health effects of added caffeine in foods.[252]

Inhalants

[edit]Similar to an e-cigarette, a caffeine inhaler may be used to deliver caffeine or a stimulant like guarana by vaping.[253] In 2012, the FDA sent a warning letter to one of the companies marketing an inhaler, expressing concerns for the lack of safety information available about inhaled caffeine.[254][255]

Combinations with other drugs

[edit]- Some beverages combine alcohol with caffeine to create a caffeinated alcoholic drink. The stimulant effects of caffeine may mask the depressant effects of alcohol, potentially reducing the user's awareness of their level of intoxication. Such beverages have been the subject of bans due to safety concerns. In particular, the United States Food and Drug Administration has classified caffeine added to malt liquor beverages as an "unsafe food additive".[256]

- Ya ba contains a combination of methamphetamine and caffeine.

- Painkillers such as propyphenazone/paracetamol/caffeine combine caffeine with an analgesic.

History

[edit]Discovery and spread of use

[edit]

According to Chinese legend, the Chinese emperor Shennong, reputed to have reigned in about 3000 BCE, inadvertently discovered tea when he noted that when certain leaves fell into boiling water, a fragrant and restorative drink resulted.[257] Shennong is also mentioned in Lu Yu's Cha Jing, a famous early work on the subject of tea.[258]

The earliest credible evidence of either coffee drinking or knowledge of the coffee plant appears in the middle of the fifteenth century, in the Sufi monasteries of the Yemen in southern Arabia.[259] From Mocha, coffee spread to Egypt and North Africa, and by the 16th century, it had reached the rest of the Middle East, Persia and Turkey. From the Middle East, coffee drinking spread to Italy, then to the rest of Europe, and coffee plants were transported by the Dutch to the East Indies and to the Americas.[260]

Kola nut use appears to have ancient origins. It is chewed in many West African cultures, in both private and social settings, to restore vitality and ease hunger pangs.[261]

The earliest evidence of cocoa bean use comes from residue found in an ancient Mayan pot dated to 600 BCE. Also, chocolate was consumed in a bitter and spicy drink called xocolatl, often seasoned with vanilla, chile pepper, and achiote. Xocolatl was believed to fight fatigue, a belief probably attributable to the theobromine and caffeine content. Chocolate was an important luxury good throughout pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, and cocoa beans were often used as currency.[262]

Xocolatl was introduced to Europe by the Spaniards, and became a popular beverage by 1700. The Spaniards also introduced the cacao tree into the West Indies[263] and the Philippines.[264]

The leaves and stems of the yaupon holly (Ilex vomitoria) were used by Native Americans to brew a tea called asi or the "black drink".[265] Archaeologists have found evidence of this use far into antiquity,[266] possibly dating to Late Archaic times.[265]

Chemical identification, isolation, and synthesis

[edit]

In 1819, the German chemist Friedlieb Ferdinand Runge isolated relatively pure[vague] caffeine for the first time; he called it "Kaffebase" (i.e., a base that exists in coffee).[267] According to Runge, he did this at the behest of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.[a][269] In 1821, caffeine was isolated both by the French chemist Pierre Jean Robiquet and by another pair of French chemists, Pierre-Joseph Pelletier and Joseph Bienaimé Caventou, according to Swedish chemist Jöns Jacob Berzelius in his yearly journal. Furthermore, Berzelius stated that the French chemists had made their discoveries independently of any knowledge of Runge's or each other's work.[270] However, Berzelius later acknowledged Runge's priority in the extraction of caffeine, stating:[271] "However, at this point, it should not remain unmentioned that Runge (in his Phytochemical Discoveries, 1820, pages 146–147) specified the same method and described caffeine under the name Caffeebase a year earlier than Robiquet, to whom the discovery of this substance is usually attributed, having made the first oral announcement about it at a meeting of the Pharmacy Society in Paris."

Pelletier's article on caffeine was the first to use the term in print (in the French form Caféine from the French word for coffee: café).[272] It corroborates Berzelius's account:

Caffeine, noun (feminine). Crystallizable substance discovered in coffee in 1821 by Mr. Robiquet. During the same period – while they were searching for quinine in coffee because coffee is considered by several doctors to be a medicine that reduces fevers and because coffee belongs to the same family as the cinchona [quinine] tree – on their part, Messrs. Pelletier and Caventou obtained caffeine; but because their research had a different goal and because their research had not been finished, they left priority on this subject to Mr. Robiquet. We do not know why Mr. Robiquet has not published the analysis of coffee which he read to the Pharmacy Society. Its publication would have allowed us to make caffeine better known and give us accurate ideas of coffee's composition ...

Robiquet was one of the first to isolate and describe the properties of pure caffeine,[273] whereas Pelletier was the first to perform an elemental analysis.[274]

In 1827, M. Oudry isolated "théine" from tea,[275] but in 1838 it was proved by Mulder[276] and by Carl Jobst[277] that theine was actually the same as caffeine.

In 1895, German chemist Hermann Emil Fischer (1852–1919) first synthesized caffeine from its chemical components (i.e. a "total synthesis"), and two years later, he also derived the structural formula of the compound.[278] This was part of the work for which Fischer was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1902.[279]

Historic regulations

[edit]Because it was recognized that coffee contained some compound that acted as a stimulant, first coffee and later also caffeine has sometimes been subject to regulation. For example, in the 16th century Islamists in Mecca and in the Ottoman Empire made coffee illegal for some classes.[280][281][282] Charles II of England tried to ban it in 1676,[283][284] Frederick II of Prussia banned it in 1777,[285][286] and coffee was banned in Sweden at various times between 1756 and 1823.

In 1911, caffeine became the focus of one of the earliest documented health scares, when the US government seized 40 barrels and 20 kegs of Coca-Cola syrup in Chattanooga, Tennessee, alleging the caffeine in its drink was "injurious to health".[287] Although the Supreme Court later ruled in favor of Coca-Cola in United States v. Forty Barrels and Twenty Kegs of Coca-Cola, two bills were introduced to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1912 to amend the Pure Food and Drug Act, adding caffeine to the list of "habit-forming" and "deleterious" substances, which must be listed on a product's label.[288]

Society and culture

[edit]Regulations

[edit]The examples and perspective in this section deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (October 2020) |

United States

[edit]The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) considers safe beverages containing less than 0.02% caffeine;[289] but caffeine powder, which is sold as a dietary supplement, is unregulated.[290] It is a regulatory requirement that the label of most prepackaged foods must declare a list of ingredients, including food additives such as caffeine, in descending order of proportion. However, there is no regulatory provision for mandatory quantitative labeling of caffeine, (e.g., milligrams caffeine per stated serving size). There are a number of food ingredients that naturally contain caffeine. These ingredients must appear in food ingredient lists. However, as is the case for "food additive caffeine", there is no requirement to identify the quantitative amount of caffeine in composite foods containing ingredients that are natural sources of caffeine. While coffee or chocolate are broadly recognized as caffeine sources, some ingredients (e.g., guarana, yerba maté) are likely less recognized as caffeine sources. For these natural sources of caffeine, there is no regulatory provision requiring that a food label identify the presence of caffeine nor state the amount of caffeine present in the food.[291] The FDA guidance was updated in 2018.[292]

Consumption

[edit]Global consumption of caffeine has been estimated at 120,000 tonnes per year, making it the world's most popular psychoactive substance.[19] The consumption of caffeine has remained stable between 1997 and 2015.[293] Coffee, tea and soft drinks are the most common caffeine sources, with energy drinks contributing little to the total caffeine intake across all age groups.[293]

Religions

[edit]The Seventh-day Adventist Church asked for its members to "abstain from caffeinated drinks", but has removed this from baptismal vows (while still recommending abstention as policy).[294] Some from these religions believe that one is not supposed to consume a non-medical, psychoactive substance, or believe that one is not supposed to consume a substance that is addictive. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has said the following with regard to caffeinated beverages: "... the Church revelation spelling out health practices (Doctrine and Covenants 89) does not mention the use of caffeine. The Church's health guidelines prohibit alcoholic drinks, smoking or chewing of tobacco, and 'hot drinks' – taught by Church leaders to refer specifically to tea and coffee."[295]

Gaudiya Vaishnavas generally also abstain from caffeine, because they believe it clouds the mind and overstimulates the senses.[296] To be initiated under a guru, one must have had no caffeine, alcohol, nicotine or other drugs, for at least a year.[297]

Caffeinated beverages are widely consumed by Muslims. In the 16th century, some Muslim authorities made unsuccessful attempts to ban them as forbidden "intoxicating beverages" under Islamic dietary laws.[298][299]

Other organisms

[edit]

The bacteria Pseudomonas putida CBB5 can live on pure caffeine and can cleave caffeine into carbon dioxide and ammonia.[300]

Caffeine is toxic to birds[301] and to dogs and cats,[302] and has a pronounced adverse effect on mollusks, various insects, and spiders.[303] This is at least partly due to a poor ability to metabolize the compound, causing higher levels for a given dose per unit weight.[183] Caffeine has also been found to enhance the reward memory of honey bees.[17]

Research

[edit]Caffeine has been used to double chromosomes in haploid wheat.[304]

See also

[edit]- Theobromine

- Theophylline

- Methylliberine

- Adderall

- Amphetamine

- Cocaine

- Nootropic

- Wakefulness-promoting agent

- Health effects of coffee

- Health effects of tea

- List of chemical compounds in coffee

References

[edit]- Notes

- ^ In 1819, Runge was invited to show Goethe how belladonna caused dilation of the pupil, which Runge did, using a cat as an experimental subject. Goethe was so impressed with the demonstration that:

("After Goethe had expressed to me his greatest satisfaction regarding the account of the man [whom I'd] rescued [from serving in Napoleon's army] by apparent "black star" [i.e., amaurosis, blindness] as well as the other, he handed me a carton of coffee beans, which a Greek had sent him as a delicacy. 'You can also use these in your investigations,' said Goethe. He was right; for soon thereafter I discovered therein caffeine, which became so famous on account of its high nitrogen content.").[268]Nachdem Goethe mir seine größte Zufriedenheit sowol über die Erzählung des durch scheinbaren schwarzen Staar Geretteten, wie auch über das andere ausgesprochen, übergab er mir noch eine Schachtel mit Kaffeebohnen, die ein Grieche ihm als etwas Vorzügliches gesandt. "Auch diese können Sie zu Ihren Untersuchungen brauchen," sagte Goethe. Er hatte recht; denn bald darauf entdeckte ich darin das, wegen seines großen Stickstoffgehaltes so berühmt gewordene Coffein.

- Citations

- ^ "Caffeine". ChemSpider. Archived from the original on 14 May 2019. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Juliano LM, Griffiths RR (October 2004). "A critical review of caffeine withdrawal: empirical validation of symptoms and signs, incidence, severity, and associated features". Psychopharmacology. 176 (1): 1–29. doi:10.1007/s00213-004-2000-x. PMID 15448977. S2CID 5572188.

Results: Of 49 symptom categories identified, the following 10 fulfilled validity criteria: headache, fatigue, decreased energy/ activeness, decreased alertness, drowsiness, decreased contentedness, depressed mood, difficulty concentrating, irritability, and foggy/not clearheaded. In addition, flu-like symptoms, nausea/vomiting, and muscle pain/stiffness were judged likely to represent valid symptom categories. In experimental studies, the incidence of headache was 50% and the incidence of clinically significant distress or functional impairment was 13%. Typically, onset of symptoms occurred 12–24 h after abstinence, with peak intensity at 20–51 h, and for a duration of 2–9 days.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Meredith SE, Juliano LM, Hughes JR, Griffiths RR (September 2013). "Caffeine Use Disorder: A Comprehensive Review and Research Agenda". Journal of Caffeine Research. 3 (3): 114–130. doi:10.1089/jcr.2013.0016. PMC 3777290. PMID 24761279.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Poleszak E, Szopa A, Wyska E, Kukuła-Koch W, Serefko A, Wośko S, et al. (February 2016). "Caffeine augments the antidepressant-like activity of mianserin and agomelatine in forced swim and tail suspension tests in mice". Pharmacological Reports. 68 (1): 56–61. doi:10.1016/j.pharep.2015.06.138. ISSN 1734-1140. PMID 26721352. S2CID 19471083.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Caffeine". DrugBank. University of Alberta. 16 September 2013. Archived from the original on 4 May 2015. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ^ Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Military Nutrition Research (2001). "2, Pharmacology of Caffeine". Pharmacology of Caffeine. National Academies Press (US). Archived from the original on 28 September 2021. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Caffeine". Pubchem Compound. NCBI. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

Boiling Point

178 °C (sublimes)

Melting Point

238 DEG C (ANHYD) - ^ Jump up to: a b "Caffeine". ChemSpider. Royal Society of Chemistry. Archived from the original on 14 May 2019. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

Experimental Melting Point:

234–236 °C Alfa Aesar

237 °C Oxford University Chemical Safety Data

238 °C LKT Labs [C0221]

237 °C Jean-Claude Bradley Open Melting Point Dataset 14937

238 °C Jean-Claude Bradley Open Melting Point Dataset 17008, 17229, 22105, 27892, 27893, 27894, 27895

235.25 °C Jean-Claude Bradley Open Melting Point Dataset 27892, 27893, 27894, 27895

236 °C Jean-Claude Bradley Open Melting Point Dataset 27892, 27893, 27894, 27895

235 °C Jean-Claude Bradley Open Melting Point Dataset 6603

234–236 °C Alfa Aesar A10431, 39214

Experimental Boiling Point:

178 °C (Sublimes) Alfa Aesar

178 °C (Sublimes) Alfa Aesar 39214 - ^ Jump up to: a b Nehlig A, Daval JL, Debry G (1992). "Caffeine and the central nervous system: mechanisms of action, biochemical, metabolic and psychostimulant effects". Brain Research. Brain Research Reviews. 17 (2): 139–170. doi:10.1016/0165-0173(92)90012-B. PMID 1356551. S2CID 14277779.

- ^ Camfield DA, Stough C, Farrimond J, Scholey AB (August 2014). "Acute effects of tea constituents L-theanine, caffeine, and epigallocatechin gallate on cognitive function and mood: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Nutrition Reviews. 72 (8): 507–522. doi:10.1111/nure.12120. PMID 24946991.

- ^ Wood S, Sage JR, Shuman T, Anagnostaras SG (January 2014). "Psychostimulants and cognition: a continuum of behavioral and cognitive activation". Pharmacological Reviews. 66 (1): 193–221. doi:10.1124/pr.112.007054. PMC 3880463. PMID 24344115.

- ^ Ribeiro JA, Sebastião AM (2010). "Caffeine and adenosine". Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 20 (Suppl 1): S3-15. doi:10.3233/JAD-2010-1379. PMID 20164566.

- ^ Hillis DM, Sadava D, Hill RW, Price MV (2015). Principles of Life (2 ed.). Macmillan Learning. pp. 102–103. ISBN 978-1-4641-8652-3.

- ^ Faudone G, Arifi S, Merk D (June 2021). "The Medicinal Chemistry of Caffeine". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 64 (11): 7156–7178. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00261. PMID 34019396. S2CID 235094871.

- ^ Caballero B, Finglas P, Toldra F (2015). Encyclopedia of Food and Health. Elsevier Science. p. 561. ISBN 978-0-12-384953-3. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- ^ Myers RL (2007). The 100 Most Important Chemical Compounds: A Reference Guide. Greenwood Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-313-33758-1. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Wright GA, Baker DD, Palmer MJ, Stabler D, Mustard JA, Power EF, et al. (March 2013). "Caffeine in floral nectar enhances a pollinator's memory of reward". Science. 339 (6124): 1202–4. Bibcode:2013Sci...339.1202W. doi:10.1126/science.1228806. PMC 4521368. PMID 23471406.

- ^ "Global coffee consumption, 2020/21". Statista. Archived from the original on 3 March 2021. Retrieved 10 March 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Burchfield G (1997). Meredith H (ed.). "What's your poison: caffeine". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 26 July 2009. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ^ Ferré S (June 2013). "Caffeine and Substance Use Disorders". Journal of Caffeine Research. 3 (2): 57–58. doi:10.1089/jcr.2013.0015. PMC 3680974. PMID 24761274.

- ^ WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (PDF) (18th ed.). World Health Organization. October 2013 [April 2013]. p. 34 [p. 38 of pdf]. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 April 2014. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ^ Cano-Marquina A, Tarín JJ, Cano A (May 2013). "The impact of coffee on health". Maturitas. 75 (1): 7–21. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2013.02.002. PMID 23465359.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Qi H, Li S (April 2014). "Dose-response meta-analysis on coffee, tea and caffeine consumption with risk of Parkinson's disease". Geriatrics & Gerontology International. 14 (2): 430–9. doi:10.1111/ggi.12123. PMID 23879665. S2CID 42527557.

- ^ O'Callaghan F, Muurlink O, Reid N (7 December 2018). "Effects of caffeine on sleep quality and daytime functioning". Risk Management and Healthcare Policy. 11: 263–271. doi:10.2147/RMHP.S156404. PMC 6292246. PMID 30573997.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Jahanfar S, Jaafar SH, et al. (Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group) (June 2015). "Effects of restricted caffeine intake by mother on fetal, neonatal and pregnancy outcomes". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015 (6): CD006965. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006965.pub4. PMC 10682844. PMID 26058966.

- ^ Jump up to: a b American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (August 2010). "ACOG CommitteeOpinion No. 462: Moderate caffeine consumption during pregnancy". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 116 (2 Pt 1): 467–8. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181eeb2a1. PMID 20664420.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 15: Reinforcement and Addictive Disorders". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 375. ISBN 978-0-07-148127-4.

Long-term caffeine use can lead to mild physical dependence. A withdrawal syndrome characterized by drowsiness, irritability, and headache typically lasts no longer than a day. True compulsive use of caffeine has not been documented.

- ^ American Psychiatric Association (2013). "Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders" (PDF). American Psychiatric Publishing. pp. 1–2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

Substance use disorder in DSM-5 combines the DSM-IV categories of substance abuse and substance dependence into a single disorder measured on a continuum from mild to severe. ... Additionally, the diagnosis of dependence caused much confusion. Most people link dependence with "addiction" when in fact dependence can be a normal body response to a substance. ... DSM-5 will not include caffeine use disorder, although research shows that as little as two to three cups of coffee can trigger a withdrawal effect marked by tiredness or sleepiness. There is sufficient evidence to support this as a condition, however it is not yet clear to what extent it is a clinically significant disorder.

- ^ Robertson D, Wade D, Workman R, Woosley RL, Oates JA (April 1981). "Tolerance to the humoral and hemodynamic effects of caffeine in man". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 67 (4): 1111–7. doi:10.1172/JCI110124. PMC 370671. PMID 7009653.

- ^ Heckman MA, Weil J, Gonzalez de Mejia E (April 2010). "Caffeine (1, 3, 7-trimethylxanthine) in foods: a comprehensive review on consumption, functionality, safety, and regulatory matters". Journal of Food Science. 75 (3): R77–R87. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3841.2010.01561.x. PMID 20492310.

- ^ EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (2015). "Scientific Opinion on the safety of caffeine". EFSA Journal. 13 (5): 4102. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2015.4102.

- ^ Awwad S, Issa R, Alnsour L, Albals D, Al-Momani I (December 2021). "Quantification of Caffeine and Chlorogenic Acid in Green and Roasted Coffee Samples Using HPLC-DAD and Evaluation of the Effect of Degree of Roasting on Their Levels". Molecules. 26 (24): 7502. doi:10.3390/molecules26247502. PMC 8705492. PMID 34946584.

- ^ Kugelman A, Durand M (December 2011). "A comprehensive approach to the prevention of bronchopulmonary dysplasia". Pediatric Pulmonology. 46 (12): 1153–65. doi:10.1002/ppul.21508. PMID 21815280. S2CID 28339831.

- ^ Schmidt B (2005). "Methylxanthine therapy for apnea of prematurity: evaluation of treatment benefits and risks at age 5 years in the international Caffeine for Apnea of Prematurity (CAP) trial". Biology of the Neonate. 88 (3): 208–13. doi:10.1159/000087584 (inactive 22 June 2024). PMID 16210843. S2CID 30123372.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of June 2024 (link) - ^ Schmidt B, Roberts RS, Davis P, Doyle LW, Barrington KJ, Ohlsson A, et al. (May 2006). "Caffeine therapy for apnea of prematurity". The New England Journal of Medicine. 354 (20): 2112–21. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa054065. PMID 16707748. S2CID 22587234. Archived from the original on 22 April 2020. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ^ Schmidt B, Roberts RS, Davis P, Doyle LW, Barrington KJ, Ohlsson A, et al. (November 2007). "Long-term effects of caffeine therapy for apnea of prematurity". The New England Journal of Medicine. 357 (19): 1893–902. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa073679. PMID 17989382. S2CID 22983543.

- ^ Schmidt B, Anderson PJ, Doyle LW, Dewey D, Grunau RE, Asztalos EV, et al. (January 2012). "Survival without disability to age 5 years after neonatal caffeine therapy for apnea of prematurity". JAMA. 307 (3): 275–82. doi:10.1001/jama.2011.2024. PMID 22253394.

- ^ Funk GD (November 2009). "Losing sleep over the caffeination of prematurity". The Journal of Physiology. 587 (Pt 22): 5299–300. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2009.182303. PMC 2793860. PMID 19915211.

- ^ Mathew OP (May 2011). "Apnea of prematurity: pathogenesis and management strategies". Journal of Perinatology. 31 (5): 302–10. doi:10.1038/jp.2010.126. PMID 21127467.

- ^ Henderson-Smart DJ, De Paoli AG (December 2010). "Prophylactic methylxanthine for prevention of apnoea in preterm infants". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010 (12): CD000432. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000432.pub2. PMC 7032541. PMID 21154344.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Caffeine: Summary of Clinical Use". IUPHAR Guide to Pharmacology. The International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. Archived from the original on 14 February 2015. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- ^ Gibbons CH, Schmidt P, Biaggioni I, Frazier-Mills C, Freeman R, Isaacson S, et al. (August 2017). "The recommendations of a consensus panel for the screening, diagnosis, and treatment of neurogenic orthostatic hypotension and associated supine hypertension". J. Neurol. 264 (8): 1567–1582. doi:10.1007/s00415-016-8375-x. PMC 5533816. PMID 28050656.

- ^ Gupta V, Lipsitz LA (October 2007). "Orthostatic hypotension in the elderly: diagnosis and treatment". The American Journal of Medicine. 120 (10): 841–7. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.02.023. PMID 17904451.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Alfaro TM, Monteiro RA, Cunha RA, Cordeiro CR (March 2018). "Chronic coffee consumption and respiratory disease: A systematic review". The Clinical Respiratory Journal. 12 (3): 1283–1294. doi:10.1111/crj.12662. PMID 28671769. S2CID 4334842.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Welsh EJ, Bara A, Barley E, Cates CJ (January 2010). Welsh EJ (ed.). "Caffeine for asthma". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010 (1): CD001112. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001112.pub2. PMC 7053252. PMID 20091514.

- ^ Derry CJ, Derry S, Moore RA (December 2014). "Caffeine as an analgesic adjuvant for acute pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (12): CD009281. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd009281.pub3. PMC 6485702. PMID 25502052.

- ^ Yang TW, Wang CC, Sung WW, Ting WC, Lin CC, Tsai MC (March 2022). "The effect of coffee/caffeine on postoperative ileus following elective colorectal surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". International Journal of Colorectal Disease. 37 (3): 623–630. doi:10.1007/s00384-021-04086-3. PMC 8885519. PMID 34993568. S2CID 245773922.

- ^ Grimes LM, Kennedy AE, Labaton RS, Hine JF, Warzak WJ (2015). "Caffeine as an Independent Variable in Behavioral Research: Trends from the Literature Specific to ADHD". Journal of Caffeine Research. 5 (3): 95–104. doi:10.1089/jcr.2014.0032.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Downs J, Giust J, Dunn DW (September 2017). "Considerations for ADHD in the child with epilepsy and the child with migraine". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 17 (9): 861–869. doi:10.1080/14737175.2017.1360136. PMID 28749241. S2CID 29659192.

- ^ Temple JL (January 2019). "Review: Trends, Safety, and Recommendations for Caffeine Use in Children and Adolescents". Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 58 (1): 36–45. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2018.06.030. PMID 30577937. S2CID 58539710.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Bolton S, Null G (1981). "Caffeine: Psychological Effects, Use and Abuse" (PDF). Orthomolecular Psychiatry. 10 (3): 202–211. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 October 2008.

- ^ Nehlig A (2010). "Is caffeine a cognitive enhancer?" (PDF). Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 20 (Suppl 1): S85–94. doi:10.3233/JAD-2010-091315. PMID 20182035. S2CID 17392483. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 January 2021.

Caffeine does not usually affect performance in learning and memory tasks, although caffeine may occasionally have facilitatory or inhibitory effects on memory and learning. Caffeine facilitates learning in tasks in which information is presented passively; in tasks in which material is learned intentionally, caffeine has no effect. Caffeine facilitates performance in tasks involving working memory to a limited extent, but hinders performance in tasks that heavily depend on this, and caffeine appears to improve memory performance under suboptimal alertness. Most studies, however, found improvements in reaction time. The ingestion of caffeine does not seem to affect long-term memory. ... Its indirect action on arousal, mood and concentration contributes in large part to its cognitive enhancing properties.

- ^ Snel J, Lorist MM (2011). "Effects of caffeine on sleep and cognition". Human Sleep and Cognition Part II - Clinical and Applied Research. Progress in Brain Research. Vol. 190. pp. 105–17. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-53817-8.00006-2. ISBN 978-0-444-53817-8. PMID 21531247.

- ^ Ker K, Edwards PJ, Felix LM, Blackhall K, Roberts I (May 2010). Ker K (ed.). "Caffeine for the prevention of injuries and errors in shift workers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010 (5): CD008508. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008508. PMC 4160007. PMID 20464765.

- ^ McLellan TM, Caldwell JA, Lieberman HR (December 2016). "A review of caffeine's effects on cognitive, physical and occupational performance". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 71: 294–312. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.09.001. PMID 27612937.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Camfield DA, Stough C, Farrimond J, Scholey AB (August 2014). "Acute effects of tea constituents L-theanine, caffeine, and epigallocatechin gallate on cognitive function and mood: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Nutrition Reviews. 72 (8): 507–22. doi:10.1111/nure.12120. PMID 24946991. S2CID 42039737.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Pesta DH, Angadi SS, Burtscher M, Roberts CK (December 2013). "The effects of caffeine, nicotine, ethanol, and tetrahydrocannabinol on exercise performance". Nutrition & Metabolism. 10 (1): 71. doi:10.1186/1743-7075-10-71. PMC 3878772. PMID 24330705. Quote:

Вызванное кофеином увеличение производительности наблюдалось как в аэробных, так и в анаэробных видах спорта (обзоры см. в [26,30,31])...

- ^ Епископ Д. (декабрь 2010 г.). «Пищевые добавки и командные виды спорта». Спортивная медицина . 40 (12): 995–1017. дои : 10.2165/11536870-000000000-00000 . ПМИД 21058748 . S2CID 1884713 .

- ^ Конгер С.А., Уоррен Г.Л., Харди М.А., Миллард-Стаффорд М.Л. (февраль 2011 г.). «Приносит ли кофеин, добавленный к углеводам, дополнительную эргогенную пользу для выносливости?» (PDF) . Международный журнал спортивного питания и метаболизма при физических нагрузках . 21 (1): 71–84. дои : 10.1123/ijsnem.21.1.71 . ПМИД 21411838 . S2CID 7109086 . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 14 ноября 2020 года.

- ^ Лиддл Д.Г., Коннор DJ (июнь 2013 г.). «Пищевые добавки и эргогенный СПИД». Первичный уход . 40 (2): 487–505. дои : 10.1016/j.pop.2013.02.009 . ПМИД 23668655 .