Нью Эйдж

| Нью Эйдж Верования Список тем Нью Эйдж |

|---|

|

| Концепции |

| Духовные практики |

| Доктрины |

Нью-эйдж — это ряд духовных или религиозных практик и верований, которые быстро распространились в западном обществе в начале 1970-х годов. Его крайне эклектичная и бессистемная структура затрудняет точное определение. Хотя многие ученые считают это религиозным движением, его приверженцы обычно рассматривают его как духовное или объединяющее разум, тело и дух, и сами редко используют термин Нью Эйдж . Ученые часто называют это движением Нью Эйдж , хотя другие оспаривают этот термин и полагают, что его лучше рассматривать как среду или дух времени .

Как форма западного эзотеризма , Нью Эйдж в значительной степени опирался на эзотерические традиции, такие как оккультизм восемнадцатого и девятнадцатого веков, включая работы Эмануэля Сведенборга и Франца Месмера , а также спиритуализм , новую мысль и теософию . Более того, оно возникло под влиянием таких влияний середины двадцатого века, как религии НЛО 1950-х годов, контркультура 1960-х годов и Движение за человеческий потенциал . Его точное происхождение остается спорным, но оно стало крупным движением в 1970-х годах, когда оно было сосредоточено в основном в Соединенном Королевстве. Он широко распространился в 1980-х и 1990-х годах, особенно в Соединенных Штатах. К началу 21 века термин « Новый век» все чаще отвергался в этой среде, при этом некоторые ученые утверждали, что феномену «Нового века» пришел конец.

Несмотря на свой эклектичный характер, Нью Эйдж имеет несколько основных течений. Теологически Нью Эйдж обычно принимает целостную форму божественности, которая пронизывает вселенную, включая самих людей, что приводит к сильному акценту на духовном авторитете личности. Это сопровождается общей верой в множество полубожественных нечеловеческих существ, таких как ангелы , с которыми люди могут общаться, в частности, через посредника -человека. Обычно рассматривая историю как разделенную на духовные эпохи, распространенная вера Нью Эйдж находится в забытой эпохе великого технического прогресса и духовной мудрости, скатывающейся в периоды возрастающего насилия и духовного вырождения, которые теперь будут исправлены появлением Эры Водолея. , от которого среда получила свое название. Также уделяется большое внимание исцелению, особенно с использованием форм альтернативной медицины , и упору на объединение науки с духовностью.

Преданность сторонников Нью Эйдж значительно различалась: от тех, кто перенял ряд идей и практик Нью Эйдж, до тех, кто полностью принял и посвятил им свою жизнь. Новый век вызвал критику со стороны христиан, а также современных языческих и коренных общин . Начиная с 1990-х годов, Нью Эйдж стал предметом исследований академических ученых- религиоведов .

Определения

[ редактировать ]Одна из немногих вещей, в которых согласны все ученые относительно Нью Эйдж, — это то, что ему трудно дать определение. Часто данное определение фактически отражает опыт ученого, дающего это определение. Таким образом, сторонники Нью-Эйджера рассматривают Нью-Эйдж как революционный период истории, продиктованный звездами; христианские апологеты часто определяли нью-эйдж как культ; историк идей понимает это как проявление многолетней традиции; философ рассматривает Нью Эйдж как монистическое или целостное мировоззрение; социолог характеризует Нью Эйдж как новое религиозное движение (НРМ); в то время как психолог описывает это как форму нарциссизма.

- Религиовед Дарен Кемп, 2004 г. [1]

Феномен Нью Эйдж оказался трудным для определения. [2] с большим количеством научных разногласий относительно его масштаба. [3] Ученые Стивен Дж. Сатклифф и Ингвильд Салид Гилхус даже предположили, что она остается «одной из самых спорных категорий в изучении религии». [4]

Религиовед Пол Хилас охарактеризовал Нью Эйдж как «эклектичную смесь верований, практик и образов жизни», которую можно идентифицировать как уникальное явление благодаря использованию «одного и того же (или очень похожего) лингва франка в что делать с состоянием человека (и планеты) и как его можно изменить ». [5] Точно так же историк религии Олав Хаммер назвал это «общим знаменателем для множества весьма расходящихся современных популярных практик и верований», которые возникли с конца 1970-х годов и «в значительной степени объединены историческими связями, общим дискурсом и семейным духом». ". [6] По словам Хаммера, этот Нью Эйдж представлял собой «подвижную и нечеткую культовую среду». [7] Социолог религии Майкл Йорк описал Нью Эйдж как «объединяющий термин, включающий в себя большое разнообразие групп и идентичностей», которых объединяет «ожидание крупных и универсальных изменений, основанных в первую очередь на индивидуальном и коллективном развитии человеческого потенциала». ." [8]

Религиовед Воутер Ханеграаф придерживался другого подхода, утверждая, что «Новый век» - это « ярлык, прикрепленный без разбора ко всему, что кажется ему подходящим», и что в результате он «означает очень разные вещи для разных людей». [9] Таким образом, он выступал против идеи, что Нью Эйдж можно считать «единой идеологией или Weltanschauung ». [10] хотя он считал, что это можно считать «более или менее единым «движением». [11] Другие ученые предположили, что Нью Эйдж слишком разнообразен, чтобы быть единым движением . [12] Религиовед Джордж Д. Криссайдс назвал это «контркультурным духом времени ». [13] в то время как социолог религии Стивен Брюс предположил, что Нью Эйдж был средой ; [14] Хилас и религиовед Линда Вудхед назвали это «целостной средой». [15]

В феномене Нью-Эйдж не существует центральной власти, которая могла бы определять, что считать Нью-Эйджем, а что нет. [16] Многие из тех групп и отдельных лиц, которых аналитически можно отнести к категории «Новый век», отвергают термин « Новый век» по отношению к себе. [17] Некоторые даже выражают активную враждебность к этому термину. [18] Вместо того, чтобы называть себя представителями движения «Новый век» , те, кто вовлечен в эту среду, обычно называют себя духовными «искателями». [19] а некоторые идентифицируют себя как члены другой религиозной группы, такой как христианство, иудаизм или буддизм. [20] В 2003 году Сатклифф заметил, что использование термина « Новый век» было «необязательным, эпизодическим и в целом сокращалось», добавив, что среди очень немногих людей, которые его использовали, они обычно делали это с оговорками, например, заключая его в кавычки. [21] Другие ученые, такие как Сара Маккиан, утверждали, что само разнообразие Нью Эйдж делает этот термин слишком проблематичным для использования учеными. [22] Маккиан предложил в качестве альтернативного термина «повседневную духовность». [23]

Признавая, что « Новый век» был проблематичным термином, религиовед Джеймс Р. Льюис заявил, что он остается полезной этической категорией для использования учеными, потому что «не существует сопоставимого термина, который охватывал бы все аспекты движения». [24] Точно так же Криссайдс утверждал, что тот факт, что «Новый век» является «теоретической концепцией», «не подрывает ее полезность или возможность трудоустройства»; он проводил сравнения с « индуизмом », похожим «западным этическим словарем», который использовали исследователи религии, несмотря на его проблемы. [25]

Религия, духовность и эзотерика

[ редактировать ]Обсуждая Нью Эйдж, ученые по-разному называли «духовность Нью Эйдж» и «религию Нью Эйдж». [1] Те, кто вовлечен в Нью Эйдж, редко считают его «религией» - негативно связывая этот термин исключительно с организованной религией - и вместо этого описывают свои практики как «духовность». [26] Однако ученые-религиоведы неоднократно называли среду Нью Эйдж «религией». [27] Йорк описал Нью Эйдж как новое религиозное движение (НРМ). [28] И наоборот, и Хилас, и Сатклифф отвергли эту категоризацию; [29] Хилас считал, что, хотя элементы Нью-Эйдж представляют собой НРД, это не применимо ко всем группам Нью-Эйдж. [30] Точно так же Криссайдс заявил, что Нью Эйдж не может рассматриваться как «религия» сама по себе. [31]

Движение Нью Эйдж — это культовая среда, осознавшая себя в конце 1970-х годов как более или менее единое «движение». Все проявления этого движения характеризуются популярной критикой западной культуры, выраженной в терминах секуляризованного эзотеризма.

- Ученый эзотерики Воутер Ханеграаф, 1996. [11]

Нью Эйдж также является формой западного эзотеризма . [32] Ханеграаф рассматривал Нью-Эйдж как форму «критики популярной культуры», поскольку он представлял собой реакцию на доминирующие западные ценности иудео-христианской религии и рационализма. [33] добавляя, что «религия Нью Эйдж формулирует такую критику не случайно, а опирается» на идеи более ранних западных эзотерических групп. [10]

Различные исследователи религии также идентифицировали Нью Эйдж как часть культовой среды. [34] Эта концепция, разработанная социологом Колином Кэмпбеллом, относится к социальной сети маргинальных идей. Благодаря общей маргинализации внутри данного общества эти разрозненные идеи взаимодействуют и создают новый синтез. [35]

Хаммер определил, что большая часть Нью Эйдж соответствует концепции « народных религий », поскольку она стремится решать экзистенциальные вопросы, касающиеся таких тем, как смерть и болезни, «бессистемным образом, часто посредством процесса бриколажа из уже имеющихся повествований и ритуалов». ". [6] Йорк также эвристически делит Нью-Эйдж на три широких направления. Первый, социальный лагерь , представляет группы, которые в первую очередь стремятся вызвать социальные изменения, тогда как второй, оккультный лагерь , вместо этого сосредотачивается на контакте с духовными сущностями и ченнелинге. Третья группа Йорка, духовный лагерь , представляет собой золотую середину между этими двумя лагерями и фокусируется в основном на индивидуальном развитии . [36]

Терминология

[ редактировать ]Термин «новый век» , наряду со связанными с ним терминами, такими как «новая эра» и «новый мир» , появился задолго до появления движения «Новый век» и широко использовался для утверждения о том, что лучший образ жизни . для человечества зарождается [37] Это обычно происходит, например, в политическом контексте; Большая печать Соединенных Штатов , созданная в 1782 году, провозглашает «новый порядок эпох», а в 1980-х годах СССР генеральный секретарь Михаил Горбачев провозгласил, что «все человечество вступает в новую эпоху». [37] [ нужна цитата для проверки ] [38] Этот термин также появился в западных эзотерических школах мысли и начал широко использоваться с середины девятнадцатого века. [39] В 1864 году американский сведенборгианец Уоррен Фелт Эванс опубликовал «Новый век и его послание» , а в 1907 году Альфред Орейдж и Холбрук Джексон начали редактировать еженедельный журнал христианского либерализма и социализма под названием «Новый век» . [40] Концепция грядущей «новой эпохи», которая откроется возвращением на Землю Иисуса Христа, была темой поэзии Уэлсли Тюдора Поула (1884–1968) и Джоанны Брандт (1876–1964). [41] а затем также появился в работах американской теософки британского происхождения Элис Бейли (1880–1949), фигурирующей в таких названиях, как «Ученичество в новом веке» (1944) и «Образование в новом веке» (1954). [41]

Между 1930-ми и 1960-ми годами небольшое количество групп и отдельных лиц были озабочены концепцией грядущего «Нового века» и использовали этот термин соответствующим образом. [42] Таким образом, этот термин стал повторяющимся мотивом в среде эзотерической духовности. [43] Поэтому Сатклифф выразил мнение, что, хотя термин « Новый век » изначально был «апокалиптической эмблемой», лишь позже он стал «тегом или кодовым словом для «духовной» идиомы». [44]

История

[ редактировать ]Предшественники

[ редактировать ]По мнению ученого Невилла Друри , Нью Эйдж имеет «осязаемую историю». [45] хотя Ханеграаф выразил мнение, что большинство сторонников движения «Новый век» «на удивление невежественны в отношении реальных исторических корней своих убеждений». [46] Точно так же Хаммер считал, что «исходная амнезия» была «строительным блоком мировоззрения Нью Эйдж», поскольку представители Нью Эйдж обычно перенимают идеи, не осознавая, откуда эти идеи возникли. [47]

Как форма западного эзотеризма, [48] У Нью Эйдж есть предшественники, уходящие корнями в южную Европу поздней античности . [49] После эпохи Просвещения в Европе 18-го века в ответ на развитие научной рациональности возникли новые эзотерические идеи. Ученые называют это новое эзотерическое течение оккультизмом , и этот оккультизм был ключевым фактором в развитии мировоззрения, из которого возник Нью Эйдж. [50]

Одним из первых людей, оказавших влияние на Нью Эйдж, был шведский христианский мистик 18-го века Эмануэль Сведенборг , который исповедовал способность общаться с ангелами, демонами и духами. Попытка Сведенборга объединить науку и религию и, в частности, его предсказание наступающей эры были названы прообразом Нового времени. [51] конца 18-го и начала 19-го века Другим ранним влиянием был немецкий врач и гипнотизер Франц Месмер , который писал о существовании силы, известной как « животный магнетизм », проходящей через человеческое тело. [52] Утверждение спиритуализма , оккультной религии, находящейся под влиянием как сведенборгианизма, так и месмеризма, в США в 1840-х годах также было идентифицировано как предшественник Нового века, в частности, из-за его отказа от устоявшегося христианства, представляя себя как научный подход к религии. и его акцент на передаче духовных сущностей. [53]

Большинство верований, характеризующих Нью-Эйдж, уже существовали к концу XIX века, даже в такой степени, что можно законно задаться вопросом, приносит ли Нью-Эйдж вообще что-то новое.

— Историк религии Воутер Ханеграаф , 1996 г. [54]

Еще одним важным влиянием на Нью-Эйдж было Теософское общество , оккультная группа, соучредителем которой была россиянка Елена Блаватская в конце 19 века. В своих книгах «Разоблаченная Изида» (1877 г.) и «Тайная доктрина» (1888 г.) Блаватская писала, что ее Общество передает суть всех мировых религий, и, таким образом, оно подчеркивает акцент на сравнительном религиоведении . [55] Частичным мостом между теософскими идеями и идеями Нью-Эйдж был американский эзотерик Эдгар Кейси , основавший Ассоциацию исследований и просвещения . [56] Еще одним неполным мостом был датский мистик Мартинус , популярный в Скандинавии. [57]

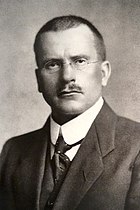

Другим влиянием стала «Новая мысль» в конце девятнадцатого века , которая развилась в Новой Англии как христианско-ориентированное движение исцеления, а затем распространилось по Соединенным Штатам. [58] Еще одно влияние оказал психолог Карл Юнг . [59] Друри также определил, что большое влияние на Нью Эйдж оказал индийский Свами Вивекананда , приверженец философии Веданты , который впервые принес индуизм на Запад в конце 19 века. [60]

Ханеграаф считал, что прямых предшественников Нью Эйдж можно найти в религиях НЛО 1950-х годов, которые он назвал «движением прото-Нью Эйдж». [61] Многие из этих новых религиозных движений имели сильные апокалиптические убеждения относительно наступления новой эпохи, которая, как они обычно утверждали, наступит в результате контакта с инопланетянами. [62] Примерами таких групп были Общество Этериуса , основанное в Великобритании в 1955 году, и Вестники Нового Века, созданные в Новой Зеландии в 1956 году. [63]

1960-е годы

[ редактировать ]С исторической точки зрения феномен Нью Эйдж больше всего связан с контркультурой 1960-х годов . [64] По словам автора Эндрю Гранта Джексона, Джорджем Харрисоном принятие индуистской философии и индийских инструментов в своих песнях с «Битлз» в середине 1960-х годов вместе с широко разрекламированным исследованием группы « Трансцендентальная медитация » «по-настоящему дало толчок» развитию человеческого потенциала. Движение, впоследствии ставшее Нью Эйдж. [65] Хотя это и не распространено в контркультуре, в ней было обнаружено использование терминов «Новый век» и «Эра Водолея» , используемых по отношению к грядущей эпохе. [66] например, появившись в рекламе фестиваля Вудсток 1969 года, [67] и в текстах « Водолея », вступительной песни мюзикла 1967 года « Hair: The American Tribal Love-Rock Musical» . [68] Это десятилетие также стало свидетелем появления множества новых религиозных движений и недавно созданных религий в Соединенных Штатах, создавших духовную среду, из которой черпался Нью Эйдж; в их число входили Дзен-центр Сан-Франциско , Трансцендентальная Медитация, Сока Гаккай , Движение Внутреннего Мира, Церковь Всех Миров и Церковь Сатаны . [69] Хотя интерес к азиатским религиозным идеям в США существовал, по крайней мере, с восемнадцатого века, [70] многие из этих новых разработок были вариантами индуизма, буддизма и суфизма , которые были импортированы на Запад из Азии после решения правительства США отменить Закон об исключении азиатов в 1965 году. [71] В 1962 году Институт Эсален , был основан в Биг-Суре , Калифорния . [72] Эсален и подобные центры личностного роста установили связи с гуманистической психологией , и из этого возникло движение за человеческий потенциал , которое сильно повлияло на Нью Эйдж. [73]

В Британии ряд небольших религиозных групп, которые стали называться «светлым» движением, начали провозглашать существование грядущего нового века, находясь под сильным влиянием теософских идей Блаватской и Бейли. [74] Самой известной из этих групп был Фонд Финдхорна , который в 1962 году основал экодеревню Финдхорн в шотландском районе Финдхорн , Морей . [75] Хотя его основатели принадлежали к старшему поколению, в 1960-е годы Финдхорн привлекал все большее число контркультурных бэби-бумеров, настолько, что его население выросло в шесть раз до ок. 120 жителей к 1972 году. [76] В октябре 1965 года соучредитель Фонда Финдхорна Питер Кэдди , бывший член оккультного Ордена розенкрейцеров Братства Кротона , присутствовал на встрече различных деятелей эзотерической среды Великобритании; рекламируемый как «Значение группы в Новом веке», он проводился в Аттингем-парке в течение выходных. [77]

Все эти группы создали фон, на котором возникло движение Нью Эйдж. Джеймс Р. Льюис и Дж. Гордон Мелтон , феномен Нью Эйдж представляет собой «синтез множества различных ранее существовавших движений и направлений мысли». Как отмечают [78] Тем не менее, Йорк утверждал, что, хотя «Новый век» имел много общего как с более ранними формами западного эзотеризма, так и с азиатской религией, он оставался «отличающимся от своих предшественников в своем собственном самосознании как новый образ мышления». [79]

Возникновение и развитие: c. 1970–2000 гг.

[ редактировать ]

В конце 1950-х годов в культовой среде появились первые движения веры в наступающую новую эпоху. Возникло множество небольших движений, вращающихся вокруг откровенных посланий существ из космоса и представляющих синтез посттеософских и других эзотерических доктрин. Эти движения могли бы так и остаться маргинальными, если бы не взрыв контркультуры в 1960-х и начале 1970-х годов. Различные исторические нити... начали сходиться: доктринальные элементы девятнадцатого века, такие как теософия и посттеософский эзотеризм, а также гармоничное или позитивное мышление, теперь эклектично сочетались с... религиозной психологией: трансперсональной психологией, юнгианством и различными восточными учениями. . Для одних и тех же людей стало вполне возможным обращаться к «И Цзин», практиковать юнгианскую астрологию, читать работы Абрахама Маслоу о пиковых переживаниях и т. д. Причиной быстрого включения таких разрозненных источников была аналогичная цель исследования индивидуализированного и в значительной степени не- Христианская религиозность.

— Исследователь эзотерики Олав Хаммер, 2001 г. [80]

К началу 1970-х годов использование термина « Новый век» стало все более распространенным в культовой среде. [80] Это произошло потому, что, по мнению Сатклиффа, «эмблема» «Нового века» была передана от «пионеров субкультуры» в таких группах, как Финдхорн, к более широкому кругу «контркультурных бэби-бумеров» между ок. 1967 и 1974 годы. Он отметил, что когда это произошло, значение термина « Новый век» изменилось; хотя когда-то оно относилось конкретно к грядущей эпохе, теперь оно стало использоваться в более широком смысле для обозначения различных духовных действий и практик. [81] Во второй половине 1970-х годов «Новый век» расширился и стал охватывать широкий спектр альтернативных духовных и религиозных верований и практик, не все из которых явно придерживались веры в Эру Водолея, но, тем не менее, были широко признаны как во многом схожие. их поиск «альтернатив» основному обществу. [82] При этом «Новый век» стал знаменем, под которым объединилась более широкая «культовая среда» американского общества. [48]

К началу 1970-х годов контркультура 1960-х годов быстро пришла в упадок, во многом из-за краха общинного движения . [83] но именно многие бывшие представители контркультуры и субкультуры хиппи впоследствии стали ранними приверженцами движения Нью-Эйдж. [78] Точные истоки движения Нью Эйдж остаются предметом споров; Мелтон утверждал, что он появился в начале 1970-х годов. [84] тогда как Ханеграаф вместо этого отнес его возникновение к концу 1970-х годов, добавив, что свое полное развитие он вступил в 1980-е годы. [85] Эта ранняя форма движения базировалась в основном в Британии и демонстрировала сильное влияние теософии и антропософии . [82] Ханеграаф назвал это раннее ядро движения New Age sensu stricto , или «Нью-Эйдж в строгом смысле слова». [86]

Ханеграаф называет более широкое развитие « Новым веком в широком смысле слова» , или «Новым веком в более широком смысле». [86] Открылись магазины, которые стали известны как «магазины Нью-Эйдж», в которых продавались соответствующие книги, журналы, ювелирные изделия и кристаллы, и их типичными признаками были игра музыки Нью-Эйдж и запах благовоний. [87] Вероятно, это повлияло на несколько тысяч небольших метафизических книжных и сувенирных магазинов, которые все чаще называли себя «книжными магазинами Нью-Эйдж». [88] в то время как издания в стиле Нью Эйдж стали все более доступными в обычных книжных магазинах, а затем на таких сайтах, как Amazon.com . [89]

Не все, кто стал ассоциироваться с феноменом Нью Эйдж, открыто приняли термин Нью Эйдж , хотя он был популяризирован в таких книгах, как работа Дэвида Спенглера 1977 года «Откровение: рождение нового века» и книга Марка Сатина 1979 года «Политика Нью Эйдж». : Исцеление себя и общества . [90] Книга Мэрилин Фергюсон « 1982 года Заговор Водолея» также считается знаковой работой в развитии Нового времени, продвигающей идею о наступлении новой эры. [91] Другие термины, которые использовались в этой среде как синонимы Нью Эйдж , включали «Зеленый», «Целостный», «Альтернативный» и «Духовный». [92]

основал ЭСТ , В 1971 году Вернер Х. Эрхард курс трансформационного обучения, который стал частью раннего движения. [93] Мелтон предположил, что 1970-е годы стали свидетелями роста отношений между движением Нью Эйдж и более старым движением Новой Мысли, о чем свидетельствует широкое использование Хелен Шукман » «Курса чудес (1975), музыки Нью Эйдж и исцеления кристаллами в Церкви Новой мысли. [94] Некоторые деятели движения «Новая мысль» были настроены скептически, ставя под сомнение совместимость взглядов «Нового века» и «Новой мысли». [95] За эти десятилетия Финдхорн стал местом паломничества многих сторонников движения «Новый век» и значительно расширился по мере того, как люди присоединялись к сообществу: там проводились семинары и конференции, объединявшие мыслителей движения «Новый век» со всего мира. [96]

Произошло несколько ключевых событий, которые повысили осведомленность общественности о субкультуре Нью Эйдж: публикация Линды Гудман бестселлеров по астрологии «Солнечные знаки» (1968) и «Знаки любви» (1978); выпуск Ширли Маклейн книги «На краю» (1983), позже адаптированной в одноименный телевизионный мини-сериал (1987); « Гармонической Конвергенции » и планетарное выравнивание 16 и 17 августа 1987 года. [97] organized by José Argüelles in Sedona, Arizona. The Convergence attracted more people to the movement than any other single event.[98] Heelas suggested that the movement was influenced by the "enterprise culture" encouraged by the U.S. and U.K. governments during the 1980s onward, with its emphasis on initiative and self-reliance resonating with any New Age ideas.[99]

Channelers Jane Roberts (Seth Material), Helen Schucman (A Course in Miracles), J. Z. Knight (Ramtha), Neale Donald Walsch (Conversations with God) contributed to the movement's growth.[100][101] The first significant exponent of the New Age movement in the U.S. has been cited as Ram Dass.[102] Core works in the propagating of New Age ideas included Jane Roberts's Seth series, published from 1972 onward,[89] Helen Schucman's 1975 publication A Course in Miracles,[103] and James Redfield's 1993 work The Celestine Prophecy.[104] A number of these books became best sellers, such as the Seth book series which quickly sold over a million copies.[89] Supplementing these books were videos, audiotapes, compact discs and websites.[105] The development of the internet in particular further popularized New Age ideas and made them more widely accessible.[106]

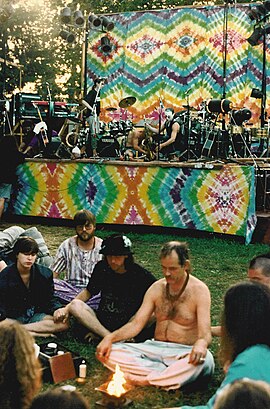

New Age ideas influenced the development of rave culture in the late 1980s and 1990s.[107] In Britain during the 1980s, the term New Age Travellers came into use,[108] although York characterised this term as "a misnomer created by the media".[109] These New Age Travellers had little to do with the New Age as the term was used more widely,[110] with scholar of religion Daren Kemp observing that "New Age spirituality is not an essential part of New Age Traveller culture, although there are similarities between the two worldviews".[111] The term New Age came to be used increasingly widely by the popular media in the 1990s.[108]

Decline or transformation: 1990–present

[edit]By the late 1980s, some publishers dropped the term New Age as a marketing device.[112] In 1994, the scholar of religion Gordon J. Melton presented a conference paper in which he argued that, given that he knew of nobody describing their practices as "New Age" anymore, the New Age had died.[113] In 2001, Hammer observed that the term New Age had increasingly been rejected as either pejorative or meaningless by individuals within the Western cultic milieu.[114] He also noted that within this milieu it was not being replaced by any alternative and that as such a sense of collective identity was being lost.[114]

Other scholars disagreed with Melton's idea; in 2004 Daren Kemp stated that "New Age is still very much alive".[115] Hammer himself stated that "the New Age movement may be on the wane, but the wider New Age religiosity... shows no sign of disappearing".[116] MacKian suggested that the New Age "movement" had been replaced by a wider "New Age sentiment" which had come to pervade "the socio-cultural landscape" of Western countries.[117] Its diffusion into the mainstream may have been influenced by the adoption of New Age concepts by high-profile figures: U.S. First Lady Nancy Reagan consulted an astrologer, British Princess Diana visited spirit mediums, and Norwegian Princess Märtha Louise established a school devoted to communicating with angels.[118] New Age shops continued to operate, although many have been remarketed as "Mind, Body, Spirit".[119]

In 2015, the scholar of religion Hugh Urban argued that New Age spirituality is growing in the United States and can be expected to become more visible: "According to many recent surveys of religious affiliation, the 'spiritual but not religious' category is one of the fastest-growing trends in American culture, so the New Age attitude of spiritual individualism and eclecticism may well be an increasingly visible one in the decades to come".[120]

Australian scholar Paul J. Farrelly, in his 2017 doctoral dissertation at Australian National University, argued that, while the term New Age may become less popular in the West, it is actually booming in Taiwan, where it is regarded as something comparatively new and is being exported from Taiwan to the Mainland China, where it is more or less tolerated by the authorities.[121]

Beliefs and practices

[edit]Eclecticism and self-spirituality

[edit]The New Age places strong emphasis on the idea that the individual and their own experiences are the primary source of authority on spiritual matters.[122] It exhibits what Heelas termed "unmediated individualism",[123] and reflects a world-view that is "radically democratic".[124] It places an emphasis on the freedom and autonomy of the individual.[125] This emphasis has led to ethical disagreements; some New Agers believe helping others is beneficial, although another view is that doing so encourages dependency and conflicts with a reliance on the self.[126] Nevertheless, within the New Age, there are differences in the role accorded to voices of authority outside of the self.[127] Hammer stated that "a belief in the existence of a core or true Self" is a "recurring theme" in New Age texts.[128] The concept of "personal growth" is also greatly emphasised among New Agers,[129] while Heelas noted that "for participants spirituality is life-itself".[130]

New Age religiosity is typified by its eclecticism.[131] Generally believing that there is no one true way to pursue spirituality,[132] New Agers develop their own worldview "by combining bits and pieces to form their own individual mix",[133] seeking what Drury called "a spirituality without borders or confining dogmas".[134] The anthropologist David J. Hess noted that in his experience, a common attitude among New Agers was that "any alternative spiritual path is good because it is spiritual and alternative".[135] This approach that has generated a common jibe that New Age represents "supermarket spirituality".[136] York suggested that this eclecticism stemmed from the New Age's origins within late modern capitalism, with New Agers subscribing to a belief in a free market of spiritual ideas as a parallel to a free market in economics.[137]

As part of its eclecticism, the New Age draws ideas from many different cultural and spiritual traditions from across the world, often legitimising this approach by reference to "a very vague claim" about underlying global unity.[138] Certain societies are more usually chosen over others;[139] examples include the ancient Celts, ancient Egyptians, the Essenes, Atlanteans, and ancient extraterrestrials.[140] As noted by Hammer: "to put it bluntly, no significant spokespersons within the New Age community claim to represent ancient Albanian wisdom, simply because beliefs regarding ancient Albanians are not part of our cultural stereotypes".[141] According to Hess, these ancient or foreign societies represent an exotic "Other" for New Agers, who are predominantly white Westerners.[142]

Theology, cosmogony, and cosmology

[edit]A belief in divinity is integral to New Age ideas, although understandings of this divinity vary.[143] New Age theology exhibits an inclusive and universalistic approach that accepts all personal perspectives on the divine as equally valid.[144] This intentional vagueness as to the nature of divinity also reflects the New Age idea that divinity cannot be comprehended by the human mind or language.[145] New Age literature nevertheless displays recurring traits in its depiction of the divine: the first is the idea that it is holistic, thus frequently being described with such terms as an "Ocean of Oneness", "Infinite Spirit", "Primal Stream", "One Essence", and "Universal Principle".[145] A second trait is the characterisation of divinity as "Mind", "Consciousness", and "Intelligence",[146] while a third is the description of divinity as a form of "energy".[147] A fourth trait is the characterisation of divinity as a "life force", the essence of which is creativity, while a fifth is the concept that divinity consists of love.[148]

Most New Age groups believe in an Ultimate Source from which all things originate, which is usually conflated with the divine.[149] Various creation myths have been articulated in New Age publications outlining how this Ultimate Source created the universe and everything in it.[150] In contrast, some New Agers emphasize the idea of a universal inter-relatedness that is not always emanating from a single source.[151] The New Age worldview emphasises holism and the idea that everything in existence is intricately connected as part of a single whole,[152] in doing so rejecting both the dualism of the Christian division of matter and spirit and the reductionism of Cartesian science.[153] A number of New Agers have linked this holistic interpretation of the universe to the Gaia hypothesis of James Lovelock.[154] The idea of holistic divinity results in a common New Age belief that humans themselves are divine in essence, a concept described using such terms as "droplet of divinity", "inner Godhead", and "divine self".[155] Influenced by Theosophical and Anthroposophical ideas regarding 'subtle bodies',[156] a common New Age idea holds to the existence of a Higher Self that is a part of the human but connects with the divine essence of the universe, and which can advise the human mind through intuition.[157]

Cosmogonical creation stories are common in New Age sources,[158] with these accounts reflecting the movement's holistic framework by describing an original, primal oneness from which all things in the universe emanated.[159] An additional common theme is that human souls—once living in a spiritual world—then descended into a world of matter.[160] The New Age movement typically views the material universe as a meaningful illusion, which humans should try to use constructively rather than focus on escaping into other spiritual realms.[161] This physical world is hence seen as "a domain for learning and growth" after which the human soul might pass on to higher levels of existence.[162] There is thus a widespread belief that reality is engaged in an ongoing process of evolution; rather than Darwinian evolution, this is typically seen as either a teleological evolution which assumes a process headed to a specific goal or an open-ended, creative evolution.[163]

Spirit and channeling

[edit]In the flood of channeled material which has been published or delivered to "live" audiences in the last two decades, there is much indeed that is trivial, contradictory, and confusing. The authors of much of this material make claims that, while not necessarily untrue or fraudulent, are difficult or impossible for the reader to verify. A number of other channeled documents address issues more immediately relevant to the human condition. The best of these writings are not only coherent and plausible, but eloquently persuasive and sometimes disarmingly moving.

— Academic Suzanne Riordan, 1992.[164]

A conduit, in esoterism, and spiritual discourse, is a specific object, person, location, or process (such as engaging in a séance or entering a trance, or using psychedelic medicines) which allows a person to connect or communicate with a spiritual realm, metaphysical energy, or spiritual entity, or vice versa. The use of such a conduit may be entirely metaphoric or symbolic, or it may be earnestly believed to be functional.

MacKian argued that a central, but often overlooked, element of the phenomenon was an emphasis on "spirit", and in particular participants' desire for a relationship with spirit.[165] Many practitioners in her UK-focused study described themselves as "workers for spirit", expressing the desire to help people learn about spirit.[166] They understood various material signs as marking the presence of spirit, for instance, the unexpected appearance of a feather.[167] New Agers often call upon this spirit to assist them in everyday situations, for instance, to ease the traffic flow on their way to work.[168]

New Age literature often refers to benevolent non-human spirit-beings who are interested in humanity's spiritual development; these are variously referred to as angels, guardian angels, personal guides, masters, teachers, and contacts.[169] New Age angelology is nevertheless unsystematic, reflecting the idiosyncrasies of individual authors.[170] The figure of Jesus Christ is often mentioned within New Age literature as a mediating principle between divinity and humanity, as well as an exemplar of a spiritually advanced human being.[171]

Although not present in every New Age group,[172] a core belief within the milieu is in channeling.[173] This is the idea that humans beings, sometimes (although not always) in a state of trance, can act "as a channel of information from sources other than their normal selves".[174] These sources are varyingly described as being God, gods and goddesses, ascended masters, spirit guides, extraterrestrials, angels, devas, historical figures, the collective unconscious, elementals, or nature spirits.[174] Hanegraaff described channeling as a form of "articulated revelation",[175] and identified four forms: trance channeling, automatisms, clairaudient channeling, and open channeling.[176]

A notable channeler in the early 1900s was Rose Edith Kelly, wife of the English occultist and ceremonial magician Aleister Crowley (1875–1947). She allegedly channeled the voice of a non-physical entity named Aiwass during their honeymoon in Cairo, Egypt (1904).[177][178][179] Others purport to channel spirits from "future dimensions", ascended masters,[180] or, in the case of the trance mediums of the Brahma Kumaris, God.[181] Another channeler in the early 1900s was Edgar Cayce, who said that he was able to channel his higher self while in a trance-like state.

In the later half of the 20th century, Western mediumship developed in two different ways. One type involves clairaudience, in which the medium is said to hear spirits and relay what they hear to their clients. The other is a form of channeling in which the channeler seemingly goes into a trance, and purports to leave their body allowing a spirit entity to borrow it and then speak through them.[182] When in a trance the medium appears to enter into a cataleptic state,[183] although modern channelers may not.[citation needed] Some channelers open the eyes when channeling, and remain able to walk and behave normally. The rhythm and the intonation of the voice may also change completely.[183]

Examples of New Age channeling include Jane Roberts' belief that she was contacted by an entity called Seth, and Helen Schucman's belief that she had channeled Jesus Christ.[184] The academic Suzanne Riordan examined a variety of these New Age channeled messages, noting that they typically "echoed each other in tone and content", offering an analysis of the human condition and giving instructions or advice for how humanity can discover its true destiny.[185] For many New Agers, these channeled messages rival the scriptures of the main world religions as sources of spiritual authority,[186] although often New Agers describe historical religious revelations as forms of "channeling" as well, thus attempting to legitimate and authenticate their own contemporary practices.[187] Although the concept of channeling from discarnate spirit entities has links to Spiritualism and psychical research, the New Age does not feature Spiritualism's emphasis on proving the existence of life after death, nor psychical research's focus of testing mediums for consistency.[188]

Other New Age channels include:[189][better source needed]

- J. Z. Knight (b. 1946), who channels the spirit "Ramtha", a 30-thousand-year-old man from Lemuria

- Esther Hicks (b. 1948), who channels a purported collective consciousness she calls "Abraham".

Astrological cycles and the Age of Aquarius

[edit]New Age thought typically envisions the world as developing through cosmological cycles that can be identified astrologically.[190] It adopts this concept from Theosophy, although often presents it in a looser and more eclectic way than is found in Theosophical teaching.[191] New Age literature often proposes that humanity once lived in an age of spiritual wisdom.[192] In the writings of New Agers like Edgar Cayce, the ancient period of spiritual wisdom is associated with concepts of supremely-advanced societies living on lost continents such as Atlantis, Lemuria, and Mu, as well as the idea that ancient societies like those of Ancient Egypt were far more technologically advanced than modern scholarship accepts.[193] New Age literature often posits that the ancient period of spiritual wisdom gave way to an age of spiritual decline, sometimes termed the Age of Pisces.[192] Although characterised as being a negative period for humanity, New Age literature views the Age of Pisces as an important learning experience for the species.[194] Hanegraaff stated that New Age perceptions of history were "extremely sketchy" in their use of description,[194] reflecting little interest in historiography and conflating history with myth.[195] He also noted that they were highly ethnocentric in placing Western civilization at the centre of historical development.[191]

A common belief among the New Age is that humanity has entered, or is coming to enter, a new period known as the Age of Aquarius,[196] which Melton has characterised as a "New Age of love, joy, peace, abundance, and harmony[...] the Golden Age heretofore only dreamed about."[197] In accepting this belief in a coming new age, the milieu has been described as "highly positive, celebratory, [and] utopian",[198] and has also been cited as an apocalyptic movement.[199] Opinions about the nature of the coming Age of Aquarius differ among New Agers.[200] There are for instance differences in belief about its commencement; New Age author David Spangler wrote that it began in 1967,[201] others placed its beginning with the Harmonic Convergence of 1987,[202] author José Argüelles predicted its start in 2012,[203] and some believe that it will not begin until several centuries into the third millennium.[204]

There are also differences in how this new age is envisioned.[205] Those adhering to what Hanegraaff termed the "moderate" perspective believed that it would be marked by an improvement to current society, which affected both New Age concerns—through the convergence of science and mysticism and the global embrace of alternative medicine—to more general concerns, including an end to violence, crime and war, a healthier environment, and international co-operation.[206] Other New Agers adopt a fully utopian vision, believing that the world will be wholly transformed into an "Age of Light", with humans evolving into totally spiritual beings and experiencing unlimited love, bliss, and happiness.[207] Rather than conceiving of the Age of Aquarius as an indefinite period, many believe that it would last for around two thousand years before being replaced by a further age.[208]

There are various beliefs within the milieu as to how this new age will come about, but most emphasise the idea that it will be established through human agency; others assert that it will be established with the aid of non-human forces such as spirits or extraterrestrials.[209] Ferguson, for instance, said that there was a vanguard of humans known as the "Aquarian conspiracy" who were helping to bring the Age of Aquarius forth through their actions.[210] Participants in the New Age typically express the view that their own spiritual actions are helping to bring about the Age of Aquarius,[211] with writers like Ferguson and Argüelles presenting themselves as prophets ushering forth this future era.[212]

Healing and alternative medicine

[edit]Another recurring element of New Age is an emphasis on healing and alternative medicine.[213] The general New Age ethos is that health is the natural state for the human being and that illness is a disruption of that natural balance.[214] Hence, New Age therapies seek to heal "illness" as a general concept that includes physical, mental, and spiritual aspects; in doing so it critiques mainstream Western medicine for simply attempting to cure disease, and thus has an affinity with most forms of traditional medicine.[215] Its focus of self-spirituality has led to the emphasis of self-healing,[216] although also present are ideas on healing both others and the Earth itself.[217]

The healing elements of the movement are difficult to classify given that a variety of terms are used, with some New Age authors using different terms to refer to the same trends, while others use the same term to refer to different things.[218] However, Hanegraaff developed a set of categories into which the forms of New Age healing could be roughly categorised. The first of these was the Human Potential Movement, which argues that contemporary Western society suppresses much human potential, and accordingly professes to offer a path through which individuals can access those parts of themselves that they have alienated and suppressed, thus enabling them to reach their full potential and live a meaningful life.[219] Hanegraaff described transpersonal psychology as the "theoretical wing" of this Human Potential Movement; in contrast to other schools of psychological thought, transpersonal psychology takes religious and mystical experiences seriously by exploring the uses of altered states of consciousness.[220] Closely connected to this is the shamanic consciousness current, which argues that the shaman was a specialist in altered states of consciousness and seeks to adopt and imitate traditional shamanic techniques as a form of personal healing and growth.[221]

Hanegraaff identified the second main healing current in the New Age movement as being holistic health. This emerged in the 1970s out of the free clinic movement of the 1960s, and has various connections with the Human Potential Movement.[222] It emphasises the idea that the human individual is a holistic, interdependent relationship between mind, body, and spirit, and that healing is a process in which an individual becomes whole by integrating with the powers of the universe.[223] A very wide array of methods are utilised within the holistic health movement, with some of the most common including acupuncture, reiki, biofeedback, chiropractic, yoga, applied kinesiology, homeopathy, aromatherapy, iridology, massage and other forms of bodywork, meditation and visualisation, nutritional therapy, psychic healing, herbal medicine, healing using crystals, metals, music, chromotherapy, and reincarnation therapy.[224] Although the use of crystal healing has become a visual trope within the New Age,[225] this practice was not common in esotericism prior to their adoption in the New Age milieu.[226] The mainstreaming of the Holistic Health movement in the UK is discussed by Maria Tighe. The inter-relation of holistic health with the New Age movement is illustrated in Jenny Butler's ethnographic description of "Angel therapy" in Ireland.[227]

New Age science

[edit]The New Age is essentially about the search for spiritual and philosophical perspectives that will help transform humanity and the world. New Agers are willing to absorb wisdom teachings wherever they can find them, whether from an Indian guru, a renegade Christian priest, an itinerant Buddhist monk, an experiential psychotherapist or a Native American shaman. They are eager to explore their own inner potential with a view to becoming part of a broader process of social transformation. Their journey is towards totality of being.[228]

According to Drury, the New Age attempts to create "a worldview that includes both science and spirituality",[45] while Hess noted how New Agers have "a penchant for bringing together the technical and the spiritual, the scientific and the religious".[229] Although New Agers typically reject rationalism, the scientific method, and the academic establishment, they employ terminology and concepts borrowed from science and particularly from new physics.[230] Moreover, a number of influences on New Age, such as David Bohm and Ilya Prigogine, had backgrounds as professional scientists.[231] Hanegraaff identified "New Age science" as a form of Naturphilosophie.[232]

In this, the milieu is interested in developing unified world views to discover the nature of the divine and establish a scientific basis for religious belief.[231] Figures in the New Age movement—most notably Fritjof Capra in his The Tao of Physics (1975) and Gary Zukav in The Dancing Wu Li Masters (1979)—have drawn parallels between theories in the New Physics and traditional forms of mysticism, thus arguing that ancient religious ideas are now being proven by contemporary science.[233] Many New Agers have adopted James Lovelock's Gaia hypothesis that the Earth acts akin to a single living organism, going further to propound that the Earth has a consciousness and intelligence.[234]

Despite New Agers' appeals to science, most of the academic and scientific establishments dismiss "New Age science" as pseudo-science, or at best existing in part on the fringes of genuine scientific research.[235] This is an attitude also shared by many active in the field of parapsychology.[236] In turn, New Agers often accuse the scientific establishment of pursuing a dogmatic and outmoded approach to scientific enquiry,[237] believing that their own understandings of the universe will replace those of the academic establishment in a paradigm shift.[230]

Ethics and afterlife

[edit]There is no ethical cohesion within the New Age phenomenon,[238] although Hanegraaff argued that the central ethical tenet of the New Age is to cultivate one's own divine potential.[239] Given that the movement's holistic interpretation of the universe prohibits a belief in a dualistic good and evil,[240] negative events that happen are interpreted not as the result of evil but as lessons designed to teach an individual and enable them to advance spiritually.[241] It rejects the Christian emphasis on sin and guilt, believing that these generate fear and thus negativity, which then hinder spiritual evolution.[242] It also typically criticises the blaming and judging of others for their actions, believing that if an individual adopts these negative attitudes it harms their own spiritual evolution.[243] Instead, the movement emphasizes positive thinking, although beliefs regarding the power behind such thoughts vary within New Age literature.[244] Common New Age examples of how to generate such positive thinking include the repeated recitation of mantras and statements carrying positive messages,[245] and the visualisation of a white light.[246]

According to Hanegraaff, the question of death and afterlife is not a "pressing problem requiring an answer" in the New Age.[247] A belief in reincarnation is very common, where it is often viewed as being part of an individual's progressive spiritual evolution toward realisation of their own divinity.[248] In New Age literature, the reality of reincarnation is usually treated as self-evident, with no explanation as to why practitioners embrace this afterlife belief over others,[249] although New Agers endorse it in the belief that it ensures cosmic justice.[250] Many New Agers believe in karma, treating it as a law of cause and effect that assures cosmic balance, although in some cases they stress that it is not a system that enforces punishment for past actions.[251] Much New Age literature on reincarnation says that part of the human soul, that which carries the personality, perishes with the death of the body, while the Higher Self—that which connects with divinity—survives in order to be reborn into another body.[252] It is believed that the Higher Self chooses the body and circumstances into which it will be born, in order to use it as a vessel through which to learn new lessons and thus advance its own spiritual evolution.[253] New Age writers like Shakti Gawain and Louise Hay therefore express the view that humans are responsible for the events that happen to them during their life, an idea that many New Agers regard as empowering.[254] At times, past life regression are employed within the New Age in order to reveal a Higher Soul's previous incarnations, usually with an explicit healing purpose.[255] Some practitioners espouse the idea of a "soul group" or "soul family", a group of connected souls who reincarnate together as family of friendship units.[256] Rather than reincarnation, another afterlife belief found among New Agers holds that an individual's soul returns to a "universal energy" on bodily death.[256]

Demographics

[edit]By the early twenty-first century... [the New Age phenomenon] has an almost entirely white, middle-class demography largely made up of professional, managerial, arts, and entrepreneurial occupations.

— Religious studies scholar Steven J. Sutcliffe.[257]

In the mid-1990s, the New Age was found primarily in the United States and Canada, Western Europe, and Australia and New Zealand.[258] The fact that most individuals engaging in New Age activity do not describe themselves as "New Agers" renders it difficult to determine the total number of practitioners.[24] Heelas highlighted the range of attempts to establish the number of New Age participants in the U.S. during this period, noting that estimates ranged from 20,000 to 6 million; he believed that the higher ranges of these estimates were greatly inflated by, for instance, an erroneous assumption that all Americans who believed in reincarnation were part of the New Age.[259] He nevertheless suggested that over 10 million people in the U.S. had had some contact with New Age practices or ideas.[260] Between 2000 and 2002, Heelas and Woodhead conducted research into the New Age in the English town of Kendal, Cumbria; they found 600 people actively attended New Age activities on a weekly basis, representing 1.6% of the town's population.[261] From this, they extrapolated that around 900,000 Britons regularly took part in New Age activities.[262] In 2006, Heelas stated that New Age practices had grown to such an extent that they were "increasingly rivaling the sway of Christianity in Western settings".[263]

Sociological investigation indicates that certain sectors of society are more likely to engage in New Age practices than others.[264] In the United States, the first people to embrace the New Age belonged to the baby boomer generation, those born between 1946 and 1964.[265]

Sutcliffe noted that although most influential New Age figureheads were male,[266] approximately two-thirds of its participants were female.[267] Heelas and Woodhead's Kendal Project found that of those regularly attending New Age activities in the town, 80% were female, while 78% of those running such activities were female.[268] They attributed this female dominance to "deeply entrenched cultural values and divisions of labour" in Western society, according to which women were accorded greater responsibility for the well-being of others, thus making New Age practices more attractive to them.[269] They suggested that men were less attracted to New Age activities because they were hampered by a "masculinist ideal of autonomy and self-sufficiency" which discouraged them from seeking the assistance of others for their inner development.[270]

The majority of New Agers are from the middle and upper-middle classes of Western society.[271] Heelas and Woodhead found that of the active Kendal New Agers, 57% had a university or college degree.[272] Their Kendal Project also determined that 73% of active New Agers were aged over 45, and 55% were aged between 40 and 59; it also determined that many got involved while middle-aged.[273] Comparatively few were either young or elderly.[274] Heelas and Woodhead suggested that the dominance of middle-aged people, particularly women, was because at this stage of life they had greater time to devote to their own inner development, with their time previously having been dominated by raising children.[275] They also suggested that middle-aged people were experiencing more age-related ailments than the young, and thus more keen to pursue New Age activities to improve their health.[276]

Heelas added that within the baby boomers, the movement had nevertheless attracted a diverse clientele.[277] He typified the typical New Ager as someone who was well-educated yet disenchanted with mainstream society, thus arguing that the movement catered to those who believe that modernity is in crisis.[278] He suggested that the movement appealed to many former practitioners of the 1960s counter-culture because while they came to feel that they were unable to change society, they were nonetheless interested in changing the self.[279] He believed that many individuals had been "culturally primed for what the New Age has to offer",[280] with the New Age attracting "expressive" people who were already comfortable with the ideals and outlooks of the movement's self-spirituality focus.[281] It could be particularly appealing because the New Age suited the needs of the individual, whereas traditional religious options that are available primarily catered for the needs of a community.[282] He believed that although the adoption of New Age beliefs and practices by some fitted the model of religious conversion,[283] others who adopted some of its practices could not easily be considered to have converted to the religion.[284] Sutcliffe described the "typical" participant in the New Age milieu as being "a religious individualist, mixing and matching cultural resources in an animated spiritual quest".[19]

The degree to which individuals are involved in the New Age varies.[285] Heelas argued that those involved could be divided into three broad groups; the first comprised those who were completely dedicated to it and its ideals, often working in professions that furthered those goals. The second consisted of "serious part-timers" who worked in unrelated fields but who nevertheless spent much of their free time involved in movement activities. The third was that of "casual part-timers" who occasionally involved themselves in New Age activities but for whom the movement was not a central aspect of their life.[286] MacKian instead suggested that involvement could be seen as being layered like an onion; at the core are "consultative" practitioners who devote their life to New Age practices, around that are "serious" practitioners who still invest considerable effort into New Age activities, and on the periphery are "non-practitioner consumers", individuals affected by the general dissemination of New Age ideas but who do not devote themselves more fully to them.[287] Many New Age practices have filtered into wider Western society, with a 2000 poll, for instance, revealing that 39% of the UK population had tried alternative therapies.[288]

In 1995, Kyle stated that on the whole, New Agers in the United States preferred the values of the Democratic Party over those of the Republican Party. He added that most New Agers "soundly rejected" the agenda of former Republican President Ronald Reagan.[289]

Social communities

[edit]MacKian suggested that this phenomenon was "an inherently social mode of spirituality", one which cultivated a sense of belonging among its participants and encouraged relations both with other humans and with non-human, otherworldly spirit entities.[290] MacKian suggested that these communities "may look very different" from those of traditional religious groups.[291]

Online connections were one of the ways that interested individuals met new contacts and established networks.[292]

Commercial aspects

[edit]

Some New Agers advocate living in a simple and sustainable manner to reduce humanity's impact on the natural resources of Earth; and they shun consumerism.[293][294] The New Age movement has been centered around rebuilding a sense of community to counter social disintegration; this has been attempted through the formation of intentional communities, where individuals come together to live and work in a communal lifestyle.[295] New Age centres have been set up in various parts of the world, representing an institutionalised form of the movement.[296] Notable examples include the Naropa Institute in Boulder, Colorado, Holly Hock Farm near to Vancouver, the Wrekin Trust in West Malvern, Worcestershire, and the Skyros Centre in Skyros.[297] Criticising mainstream Western education as counterproductive to the ethos of the movement, many New Age groups have established their own schools for the education of children, although in other cases such groups have sought to introduce New Age spiritual techniques into pre-existing establishments.[298]

Bruce argued that in seeking to "denying the validity of externally imposed controls and privileging the divine within", the New Age sought to dismantle pre-existing social order, but that it failed to present anything adequate in its place.[299] Heelas, however, cautioned that Bruce had arrived at this conclusion based on "flimsy evidence",[300] and Aldred argued that only a minority of New Agers participate in community-focused activities; instead, she argued, the majority of New Agers participate mainly through the purchase of books and products targeted at the New Age market, positioning New Age as a primarily consumerist and commercial movement.[301]

Fairs and festivals

[edit]New Age spirituality has led to a wide array of literature on the subject and an active niche market, with books, music, crafts, and services in alternative medicine available at New Age stores, fairs, and festivals.[citation needed] New Age fairs—sometimes known as "Mind, Body, Spirit fairs", "psychic fairs", or "alternative health fairs"—are spaces in which a variety of goods and services are displayed by different vendors, including forms of alternative medicine and esoteric practices such as palmistry or tarot card reading.[302] An example is the Mind Body Spirit Festival, held annually in the United Kingdom,[303] at which—the religious studies scholar Christopher Partridge noted—one could encounter "a wide range of beliefs and practices from crystal healing to ... Kirlian photography to psychic art, from angels to past-life therapy, from Theosophy to UFO religion, and from New Age music to the vegetarianism of Suma Chign Hai."[304] Similar festivals are held across Europe and in Australia and the United States.[305]

Approaches to financial prosperity and business

[edit]A number of New Age proponents have emphasised the use of spiritual techniques as a tool for attaining financial prosperity, thus moving the movement away from its counter-cultural origins.[306] Commenting on this "New Age capitalism", Hess observed that it was largely small-scale and entrepreneurial, focused around small companies run by members of the petty bourgeoisie, rather than being dominated by large scale multinational corporations.[307] The links between New Age and commercial products have resulted in the accusation that New Age itself is little more than a manifestation of consumerism.[308] This idea is generally rejected by New Age participants, who often reject any link between their practices and consumerist activities.[309]

Embracing this attitude, various books have been published espousing such an ethos, established New Age centres have held spiritual retreats and classes aimed specifically at business people, and New Age groups have developed specialised training for businesses.[310] During the 1980s, many U.S. corporations—among them IBM, AT&T, and General Motors—embraced New Age seminars, hoping that they could increase productivity and efficiency among their workforce,[311] although in several cases this resulted in employees bringing legal action against their employers, saying that such seminars had infringed on their religious beliefs or damaged their psychological health.[312] However, the use of spiritual techniques as a method for attaining profit has been an issue of major dispute within the wider New Age movement,[313] with New Agers such as Spangler and Matthew Fox criticising what they see as trends within the community that are narcissistic and lack a social conscience.[314] In particular, the movement's commercial elements have caused problems given that they often conflict with its general economically egalitarian ethos; as York highlighted, "a tension exists in New Age between socialistic egalitarianism and capitalistic private enterprise".[315]

Given that it encourages individuals to choose spiritual practices on the grounds of personal preference and thus encourages them to behave as a consumer, the New Age has been considered to be well suited to modern society.[316]

Music

[edit]The term "new-age music" is applied, sometimes negatively, to forms of ambient music, a genre that developed in the 1960s and was popularised in the 1970s, particularly with the work of Brian Eno.[317] The genre's relaxing nature resulted in it becoming popular within New Age circles,[317] with some forms of the genre having a specifically New Age orientation.[318] Studies have determined that new-age music can be an effective component of stress management.[319]

The style began in the late 1960s and early 1970s with the works of free-form jazz groups recording on the ECM label; such as Oregon, the Paul Winter Consort, and other pre-ambient bands; as well as ambient music performer Brian Eno, classical avant-garde musician Daniel Kobialka,[320][321] and the psychoacoustic environments recordings of Irv Teibel.[322] In the early 1970s, it was mostly instrumental with both acoustic and electronic styles. New-age music evolved to include a wide range of styles from electronic space music using synthesizers and acoustic instrumentals using Native American flutes and drums, singing bowls, Australian didgeridoos and world music sounds to spiritual chanting from other cultures.[320][321]

Politics

[edit]While many commentators have focused on the spiritual and cultural aspects of the New Age movement, it also has a political component. The New Age political movement became visible in the 1970s, peaked in the 1980s, and continued into the 1990s.[323] The sociologist of religion Steven Bruce noted that the New Age provides ideas on how to deal with "our socio-psychological problems".[324] Scholar of religion James R. Lewis observed that, despite the common caricature of New Agers as narcissistic, "significant numbers" of them were "trying to make the planet a better place on which to live,"[325] and scholar J. Gordon Melton's New Age Encyclopedia (1990) included an entry called "New Age politics".[326] Some New Agers have entered the political system in an attempt to advocate for the societal transformation that the New Age promotes.[327]

Ideas

[edit]Although New Age activists have been motivated by New Age concepts like holism, interconnectedness, monism, and environmentalism, their political ideas are diverse,[327] ranging from far-right and conservative through to liberal, socialist, and libertarian.[137] Accordingly, Kyle stated that "New Age politics is difficult to describe and categorize. The standard political labels—left or right, liberal or conservative—miss the mark."[327] MacKian suggested that the New Age operated as a form of "world-realigning infrapolitics" that undermines the disenchantment of modern Western society.[328]

The extent to which New Age spokespeople mix religion and politics varies.[329] New Agers are often critical of the established political order, regarding it as "fragmented, unjust, hierarchical, patriarchal, and obsolete".[327] The New Ager Mark Satin for instance spoke of "New Age politics" as a politically radical "third force" that was "neither left nor right". He believed that in contrast to the conventional political focus on the "institutional and economic symptoms" of society's problems, his "New Age politics" would focus on "psychocultural roots" of these issues.[330] Ferguson regarded New Age politics as "a kind of Radical Centre", one that was "not neutral, not middle-of-the-road, but a view of the whole road."[331] Fritjof Capra argued that Western societies have become sclerotic because of their adherence to an outdated and mechanistic view of reality, which he calls the Newtonian/Cartesian paradigm.[332] In Capra's view, the West needs to develop an organic and ecological "systems view" of reality in order to successfully address its social and political issues.[332] Corinne McLaughlin argued that politics need not connote endless power struggles, that a new "spiritual politics" could attempt to synthesize opposing views on issues into higher levels of understanding.[333]

Many New Agers advocate globalisation and localisation, but reject nationalism and the role of the nation-state.[334] Some New Age spokespeople have called for greater decentralisation and global unity, but are vague about how this might be achieved; others call for a global, centralised government.[335] Satin for example argued for a move away from the nation-state and towards self-governing regions that, through improved global communication networks, would help engender world unity.[336] Benjamin Creme conversely argued that "the Christ", a great Avatar, Maitreya, the World Teacher, expected by all the major religions as their "Awaited One", would return to the world and establish a strong, centralised global government in the form of the United Nations; this would be politically re-organised along a spiritual hierarchy.[337] Kyle observed that New Agers often speak favourably of democracy and citizens' involvement in policy making but are critical of representative democracy and majority rule, thus displaying elitist ideas to their thinking.[289]

Groups

[edit]

Scholars have noted several New Age political groups. Self-Determination: A Personal/Political Network, lauded by Ferguson[338] and Satin,[339] was described at length by sociology of religion scholar Steven Tipton.[340] Founded in 1975 by California state legislator John Vasconcellos and others, it encouraged Californians to engage in personal growth work and political activities at the same time, especially at the grassroots level.[341] Hanegraaff noted another California-based group, the Institute of Noetic Sciences, headed by the author Willis Harman. It advocated a change in consciousness—in "basic underlying assumptions"—in order to come to grips with global crises.[342] Kyle said that the New York City-based Planetary Citizens organization, headed by United Nations consultant and Earth at Omega author Donald Keys, sought to implement New Age political ideas.[343]

Scholar J. Gordon Melton and colleagues focused on the New World Alliance, a Washington, DC-based organization founded in 1979 by Mark Satin and others. According to Melton et al., the Alliance tried to combine left- and right-wing ideas as well as personal growth work and political activities. Group decision-making was facilitated by short periods of silence.[344] Sponsors of the Alliance's national political newsletter included Willis Harman and John Vasconcellos.[345] Scholar James R. Lewis counted "Green politics" as one of the New Age's more visible activities.[325] One academic book says that the U.S. Green Party movement began as an initiative of a handful of activists including Charlene Spretnak, co-author of a "'new age' interpretation" of the German Green movement (Capra and Spretnak's Green Politics), and Mark Satin, author of New Age Politics.[346] Another academic publication says Spretnak and Satin largely co-drafted the U.S. Greens' founding document, the "Ten Key Values" statement.[347]

In the 21st century

[edit]

While the term New Age may have fallen out of favor,[114][349] scholar George Chryssides notes that the New Age by whatever name is "still alive and active" in the 21st century.[13] In the realm of politics, New Ager Mark Satin's book Radical Middle (2004) reached out to mainstream liberals.[350][351] York (2005) identified "key New Age spokespeople" including William Bloom, Satish Kumar, and Starhawk who were emphasizing a link between spirituality and environmental consciousness.[352] Former Esalen Institute staffer Stephen Dinan's Sacred America, Sacred World (2016) prompted a long interview of Dinan in Psychology Today, which called the book a "manifesto for our country's evolution that is both political and deeply spiritual".[353]

In 2013 longtime New Age author Marianne Williamson launched a campaign for a seat in the United States House of Representatives, telling The New York Times that her type of spirituality was what American politics needed.[354] "America has swerved from its ethical center", she said.[354] Running as an independent in west Los Angeles, she finished fourth in her district's open primary election with 13% of the vote.[355] In early 2019, Williamson announced her candidacy for the Democratic Party nomination for president of the United States in the 2020 United States presidential election.[356][357] A 5,300-word article about her presidential campaign in The Washington Post said she had "plans to fix America with love. Tough love".[357] In January 2020 she withdrew her bid for the nomination.[358]

Reception

[edit]Popular media

[edit]Mainstream periodicals tended to be less than sympathetic; sociologist Paul Ray and psychologist Sherry Anderson discussed in their 2000 book The Cultural Creatives, what they called the media's "zest for attacking" New Age ideas, and offered the example of a 1996 Lance Morrow essay in Time magazine.[349] Nearly a decade earlier, Time had run a long cover story critical of New Age culture; the cover featured a headshot of a famous actress beside the headline, "Om.... THE NEW AGE starring Shirley MacLaine, faith healers, channelers, space travelers, and crystals galore".[359] The story itself, by former Saturday Evening Post editor Otto Friedrich, was sub-titled, "A Strange Mix of Spirituality and Superstition Is Sweeping Across the Country".[360] In 1988, the magazine The New Republic ran a four-page critique of New Age culture and politics by a journalist Richard Blow entitled simply, "Moronic Convergence".[361]

Some New Agers and New Age sympathizers responded to such criticisms. For example, sympathizers Ray and Anderson said that much of it was an attempt to "stereotype" the movement for idealistic and spiritual change, and to cut back on its popularity.[349] New Age theoretician David Spangler tried to distance himself from what he called the "New Age glamour" of crystals, talk-show channelers, and other easily commercialized phenomena, and sought to underscore his commitment to the New Age as a vision of genuine social transformation.[362]

Academia

[edit]

Initially, academic interest in the New Age was minimal.[363] The earliest academic studies of the New Age phenomenon were performed by specialists in the study of new religious movements such as Robert Ellwood.[364] This research was often scanty because many scholars regarded the New Age as an insignificant cultural fad.[365] Having been influenced by the U.S. anti-cult movement, much of it was also largely negative and critical of New Age groups.[366] The "first truly scholarly study" of the phenomenon was an edited volume put together by James R. Lewis and J. Gordon Melton in 1992.[363] From that point on, the number of published academic studies steadily increased.[363]

In 1994, Christoph Bochinger published his study of the New Age in Germany, "New Age" und moderne Religion.[363] This was followed by Michael York's sociological study in 1995 and Richard Kyle's U.S.-focused work in 1995.[367] In 1996, Paul Heelas published a sociological study of the movement in Britain, being the first to discuss its relationship with business.[368] That same year, Wouter Hanegraaff published New Age Religion and Western Culture, a historical analysis of New Age texts;[369] Hammer later described it as having "a well-deserved reputation as the standard reference work on the New Age".[370] Most of these early studies were based on a textual analysis of New Age publications, rather than on an ethnographic analysis of its practitioners.[371]

Sutcliffe and Gilhus argued that 'New Age studies' could be seen as having experienced two waves; in the first, scholars focused on "macro-level analyses of the content and boundaries" of the "movement", while the second wave featured "more variegated and contextualized studies of particular beliefs and practices".[372] Sutcliffe and Gilhus have also expressed concern that, as of 2013, 'New Age studies' has yet to formulate a set of research questions scholars can pursue.[372] The New Age has proved a challenge for scholars of religion operating under more formative models of what "religion" is.[373] By 2006, Heelas noted that the New Age was so vast and diverse that no scholar of the subject could hope to keep up with all of it.[374]

Christian perspectives

[edit]Mainstream Christianity has typically rejected the ideas of the New Age;[375] Christian critiques often emphasise that the New Age places the human individual before God.[376] Most published criticism of the New Age has been produced by Christians, particularly those on the religion's fundamentalist wing.[377] In the United States, the New Age became a major concern of evangelical Christian groups in the 1980s, an attitude that influenced British evangelical groups.[378] During that decade, evangelical writers such as Constance Cumbey, Dave Hunt, Gary North, and Douglas Groothuis published books criticising the New Age; a number propagated conspiracy theories regarding its origin and purpose.[379] The most successful such publication was Frank E. Peretti's 1986 novel This Present Darkness, which sold over a million copies; it depicted the New Age as being in league with feminism and secular education as part of a conspiracy to overthrow Christianity.[380] Modern Christian critics of the New Age include Doreen Virtue, a former New Age writer from California who converted to fundamentalist Christianity in 2017.[381]