Латинская церковь

Латинская церковь | |

|---|---|

| Английский | |

Archbasilica of Saint John Latean в Риме , Италия | |

| Тип | Конкретная церковь ( независимая ) |

| Классификация | Католик |

| Ориентация | Западное христианство |

| Писание | Библия |

| Theology | Catholic theology |

| Polity | Episcopal[1] |

| Governance | Holy See |

| Pope | Francis |

| Full communion | Catholic Church |

| Region | Mainly in Western Europe, Central Europe, the Americas, the Philippines, pockets of Africa, Madagascar, Oceania, with several episcopal conferences around the world |

| Language | Ecclesiastical Latin |

| Liturgy | Latin liturgical rites |

| Headquarters | Archbasilica of Saint John Lateran, Rome, Italy |

| Territory | Worldwide |

| Origin | 1st century Rome, Roman Empire |

| Separations |

|

| Members | 1.2 billion (2015)[2] |

| Other name(s) |

|

| Official website | Holy See |

| Part of a series on |

| Particular churches sui iuris of the Catholic Church |

|---|

| Particular churches are grouped by liturgical rite |

| Alexandrian Rite |

| Armenian Rite |

| Byzantine Rite |

| East Syriac Rite |

| Latin liturgical rites |

| West Syriac Rite |

|

Eastern Catholic Churches Eastern Catholic liturgy |

| Part of a series on the |

| Catholic Church |

|---|

|

| Overview |

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

Латинская церковь ( латинская : Экклесия Латина ) является крупнейшей автономной ( суй -иурисом ) конкретной церковью в католической церкви , члены которых составляют подавляющее большинство 1,3 миллиарда католиков. Латинская церковь - одна из 24 церквей, которые в полном общении с Папой ; Остальные 23 в совокупности называются Восточными католическими церквями и составляют около 18 миллионов членов. [ 3 ]

Латинская церковь прямо возглавляется Папой в своей роли епископа Рима , чье собор в качестве епископа расположена в архисалице Святого Иоанна Латерэн в Риме , Италия . Латинская церковь развивалась внутри и сильно повлияла на западную культуру ; Таким образом, он также известен как Западная Церковь ( латынь : Ecclesia occidentalis ). Он также известен как римская церковь ( латинская : Екклезия Романа ), [ 4 ] [ 5 ] Латинская католическая церковь , [ 6 ] [ 7 ] и в некоторых контекстах как римско -католическая церковь (хотя это имя также может относиться к католической церкви в целом). [ 8 ] [ А ] One of the pope's traditional titles in some eras and contexts has been the Patriarch of the West.[9]

The Latin Church was in full communion with what is referred to as the Eastern Orthodox Church until the East-West schism of Rome and Constantinople in 1054. From that time, but also before it, it became common to refer to Western Christians as Latins in contrast to Byzantines or Greeks.

The Latin Church employs the Latin liturgical rites, which since the mid-20th century are very often translated into the vernacular. The predominant liturgical rite is the Roman Rite, elements of which have been practiced since the fourth century.[10] There exist and have existed since ancient times additional Latin liturgical rites and uses, including the currently used Mozarabic Rite in restricted use in Spain, the Ambrosian Rite in parts of Italy, and the Anglican Use in the personal ordinariates.

In the early modern period and subsequently, the Latin Church carried out evangelizing missions to the Americas, and from the late modern period to Sub-Saharan Africa and East Asia. The Protestant Reformation in the 16th century resulted in Protestantism breaking away, resulting in the fragmentation of Western Christianity, including not only Protestant offshoots of the Latin Church, but also smaller groups of 19th-century break-away Independent Catholic denominations.

Terminology

[edit]Name

[edit]The historical part of the Catholic Church in the West is called the Latin Church to distinguish itself from the Eastern Catholic Churches which are also under the pope's primacy. In historical context, before the East–West Schism in 1054 the Latin Church is sometimes referred to as the Western Church. Writers belonging to various Protestant denominations sometime use the term Western Church as an implicit claim to legitimacy.[clarification needed]

The term Latin Catholic refers to followers of the Latin liturgical rites, of which the Roman Rite is predominant. The Latin liturgical rites are contrasted with the liturgical rites of the Eastern Catholic Churches.

"Church" and "rite"

[edit]The 1990 Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches defines the use within that code of the words "church" and "rite".[11][12] In accordance with these definitions of usage within the code that governs the Eastern Catholic Churches, the Latin Church is one such group of Christian faithful united by a hierarchy and recognized by the supreme authority of the Catholic Church as a sui iuris particular Church. The "Latin Rite" is the whole of the patrimony of that distinct particular church, by which it manifests its own manner of living the faith, including its own liturgy, its theology, its spiritual practices and traditions and its canon law. A Catholic, as an individual person, is necessarily a member of a particular church. A person also inherits, or "is of",[13][14][15][16][17] a particular patrimony or rite. Since the rite has liturgical, theological, spiritual and disciplinary elements, a person is also to worship, to be catechized, to pray and to be governed according to a particular rite.

Particular churches that inherit and perpetuate a particular patrimony are identified by the metonymy "church" or "rite". Accordingly, "Rite" has been defined as "a division of the Christian Church using a distinctive liturgy",[18] or simply as "a Christian Church".[19] In this sense, "Rite" and "Church" are treated as synonymous, as in the glossary prepared by the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops and revised in 1999, which states that each "Eastern-rite (Oriental) Church ... is considered equal to the Latin rite within the Church".[20] The Second Vatican Council likewise stated that "it is the mind of the Catholic Church that each individual Church or Rite should retain its traditions whole and entire and likewise that it should adapt its way of life to the different needs of time and place"[21] and spoke of patriarchs and of "major archbishops, who rule the whole of some individual Church or Rite".[22] It thus used the word "Rite" as "a technical designation of what may now be called a particular Church".[23] "Church or rite" is also used as a single heading in the United States Library of Congress classification of works.[24]

History

[edit]Historically, the governing entity of the Latin Church (i.e. the Holy See) has been viewed as one of the five patriarchates of the Pentarchy of early Christianity, along with the patriarchates of Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem. Due to geographic and cultural considerations, the latter patriarchates developed into churches with distinct Eastern Christian traditions. This scheme, tacitly at least accepted by Rome, is constructed from the viewpoint of Greek Christianity and does not take into consideration other churches of great antiquity which developed in the East outside the frontiers of the Roman Empire. The majority of Eastern Christian Churches broke full communion with the Bishop of Rome and the Latin Church, following various theological and jurisdictional disputes in the centuries following the Council of Chalcedon in AD 451. These included notably the Nestorian Schism (431–544) (Church of the East), Chalcedonian Schism (451) (Oriental Orthodoxy), and the East-West Schism (1054) (Eastern Orthodoxy).[25] The Protestant Reformation of the 16th century saw a schism which was not analogous since it was not based upon the same historical factors and involved far more profound theological dissent from the teaching of the totality of previously existing historical Christian churches. Until 2005, the pope claimed the title "patriarch of the West"; Benedict XVI set aside this title.

Following the Islamic conquests, the Crusades were launched by the West from 1095 to 1291 in order to defend Christians and their properties in the Holy Land against persecution. In the long term the Crusaders did not succeed in re-establishing political and military control of Palestine, which like former Christian North Africa and the rest of the Middle East remained under Islamic control. The names of many former Christian dioceses of this vast area are still used by the Catholic Church as the names of Catholic titular sees, irrespective of the question of liturgical families.

Membership

[edit]In the Catholic Church, in addition to the Latin Church—directly headed by the pope as Latin patriarch and notable within Western Christianity for its sacred tradition and seven sacraments— there are 23 Eastern Catholic Churches, self-governing particular churches sui iuris with their own hierarchies. Most of these churches trace their origins to the other four patriarchates of the ancient pentarchy, but either never historically broke full communion or returned to it with the Papacy at some time. These differ from each other in liturgical rite (ceremonies, vestments, chants, language), devotional traditions, theology, canon law, and clergy, but all maintain the same faith, and all see full communion with the pope as bishop of Rome as essential to being Catholic as well as part of the one true church as defined by the Four Marks of the Church in Catholic ecclesiology.

The approximately 18 million Eastern Catholics represent a minority of Christians in communion with the pope,[3] compared to well over 1 billion Latin Catholics. Additionally, there are roughly 250 million Eastern Orthodox and 86 million Oriental Orthodox around the world that are not in union with Rome. Unlike the Latin Church, the pope does not exercise a direct patriarchal role over the Eastern Catholic churches and their faithful, instead encouraging their internal hierarchies, which while separate from that of the Latin Church and function analogously to it, and follow the traditions shared with the corresponding Eastern Christian churches in Eastern and Oriental Orthodoxy.[25]

Organisation

[edit]Liturgical patrimony

[edit]Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI) described the Latin liturgical rites on 24 October 1998:[26]

Several forms of the Latin rite have always existed, and were only slowly withdrawn, as a result of the coming together of the different parts of Europe. Before the Council there existed, side by side with the Roman rite, the Ambrosian rite, the Mozarabic rite of Toledo, the rite of Braga, the Carthusian rite, the Carmelite rite, and best known of all, the Dominican rite, and perhaps still other rites of which I am not aware.

Today, the most common Latin liturgical rites are the Roman Rite—either the post-Vatican II Mass promulgated by Pope Paul VI in 1969 and revised by Pope John Paul II in 2002 (the "Ordinary Form"), or the 1962 form of the Tridentine Mass (the "Extraordinary Form"); the Ambrosian Rite; the Mozarabic Rite; and variations of the Roman Rite (such as the Anglican Use). The 23 Eastern Catholic Churches employ five different families of liturgical rites. The Latin liturgical rites are used only in a single sui iuris particular church.

Of other liturgical families, the main survivors are what is now referred to officially as the Hispano-Mozarabic Rite, still in restricted use in Spain; the Ambrosian Rite, centred geographically on the Archdiocese of Milan, in Italy, and much closer in form, though not specific content, to the Roman Rite; and the Carthusian Rite, practised within the strict Carthusian monastic Order, which also employs in general terms forms similar to the Roman Rite, but with a number of significant divergences which have adapted it to the distinctive way of life of the Carthusians.

There once existed what is referred to as the Gallican Rite, used in Gaulish or Frankish territories. This was a conglomeration of varying forms, not unlike the present Hispano-Mozarabic Rite in its general structures, but never strictly codified and which from at least the seventh century was gradually infiltrated, and then eventually for the most part replaced, by liturgical texts and forms which had their origin in the diocese of Rome. Other former "Rites" in past times practised in certain religious orders and important cities were in truth usually partial variants upon the Roman Rite and have almost entirely disappeared from current use, despite limited nostalgic efforts at revival of some of them and a certain indulgence by the Roman authorities.

Disciplinary patrimony

[edit] |

| Part of a series on the |

| Canon law of the Catholic Church |

|---|

|

|

Canon law for the Latin Church is codified in the Code of Canon Law, of which there have been two codifications, the first promulgated by Pope Benedict XV in 1917 and the second by Pope John Paul II in 1983.[27]

In the Latin Church, the norm for administration of confirmation is that, except when in danger of death, the person to be confirmed should "have the use of reason, be suitably instructed, properly disposed, and able to renew the baptismal promises",[28] and "the administration of the Most Holy Eucharist to children requires that they have sufficient knowledge and careful preparation so that they understand the mystery of Christ according to their capacity and are able to receive the body of Christ with faith and devotion."[29] In the Eastern Churches these sacraments are usually administered immediately after baptism, even for an infant.[30]

Celibacy, as a consequence of the duty to observe perfect continence, is obligatory for priests in the Latin Church.[31] An exception is made for married clergy from other churches, who join the Catholic Church; they may continue as married priests.[32] In the Latin Church, a married man may not be admitted even to the diaconate unless he is legitimately destined to remain a deacon and not become a priest.[33] Marriage after ordination is not possible, and attempting it can result in canonical penalties.[34] The Eastern Catholic Churches, unlike the Latin Church, have a married clergy.

At the present time, Bishops in the Latin Church are generally appointed by the pope after hearing the advice of the various dicasteries of the Roman Curia, specifically the Congregation for Bishops, the Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples (for countries in its care), the Section for Relations with States of the Secretariat of State (for appointments that require the consent or prior notification of civil governments), and the Congregation for the Oriental Churches (in the areas in its charge, even for the appointment of Latin bishops). The Congregations generally work from a "terna" or list of three names advanced to them by the local church, most often through the Apostolic Nuncio or the Cathedral Chapter in those places where the Chapter retains the right to nominate bishops.[citation needed]

Theology and philosophy

[edit]Augustinianism

[edit]

Augustine of Hippo was a Roman African, philosopher and bishop in the Catholic Church. He helped shape Latin Christianity, and is viewed as one of the most important Church Fathers in the Latin Church for his writings in the Patristic Period. Among his works are The City of God, De doctrina Christiana, and Confessions.

In his youth he was drawn to Manichaeism and later to neoplatonism. After his baptism and conversion in 386, Augustine developed his own approach to philosophy and theology, accommodating a variety of methods and perspectives.[35] Believing that the grace of Christ was indispensable to human freedom, he helped formulate the doctrine of original sin and made seminal contributions to the development of just war theory. His thoughts profoundly influenced the medieval worldview. The segment of the church that adhered to the concept of the Trinity as defined by the Council of Nicaea and the Council of Constantinople[36] closely identified with Augustine's On the Trinity

When the Western Roman Empire began to disintegrate, Augustine imagined the church as a spiritual City of God, distinct from the material Earthly City.[37] in his book On the city of God against the pagans, often called The City of God, Augustine declared its message to be spiritual rather than political. Christianity, he argued, should be concerned with the mystical, heavenly city, the New Jerusalem, rather than with earthly politics.

The City of God presents human history as a conflict between what Augustine calls the Earthly City (often colloquially referred to as the City of Man, but never by Augustine) and the City of God, a conflict that is destined to end in victory for the latter. The City of God is marked by people who forego earthly pleasure to dedicate themselves to the eternal truths of God, now revealed fully in the Christian faith. The Earthly City, on the other hand, consists of people who have immersed themselves in the cares and pleasures of the present, passing world.

For Augustine, the Logos "took on flesh" in Christ, in whom the logos was present as in no other man.[38][39][40] He strongly influenced Early Medieval Christian Philosophy.[41]

Like other Church Fathers such as Athenagoras,[42] Tertullian,[43] Clement of Alexandria and Basil of Caesarea,[44] Augustine "vigorously condemned the practice of induced abortion", and although he disapproved of an abortion during any stage of pregnancy, he made a distinction between early abortions and later ones.[45] He acknowledged the distinction between "formed" and "unformed" fetuses mentioned in the Septuagint translation of Exodus 21:22–23, which is considered as wrong translation of the word "harm" from the original Hebrew text as "form" in the Greek Septuagint and based in Aristotelian distinction "between the fetus before and after its supposed 'vivification'", and did not classify as murder the abortion of an "unformed" fetus since he thought that it could not be said with certainty that the fetus had already received a soul.[45][46]

Augustine also used the term "Catholic" to distinguish the "true" church from heretical groups:

In the Catholic Church, there are many other things which most justly keep me in her bosom. The consent of peoples and nations keeps me in the Church; so does her authority, inaugurated by miracles, nourished by hope, enlarged by love, established by age. The succession of priests keeps me, beginning from the very seat of the Apostle Peter, to whom the Lord, after His resurrection, gave it in charge to feed His sheep (Jn 21:15–19), down to the present episcopate.

And so, lastly, does the very name of Catholic, which, not without reason, amid so many heresies, the Church has thus retained; so that, though all heretics wish to be called Catholics, yet when a stranger asks where the Catholic Church meets, no heretic will venture to point to his own chapel or house.

Such then in number and importance are the precious ties belonging to the Christian name which keep a believer in the Catholic Church, as it is right they should. ...With you, there is none of these things to attract or keep me. ...No one shall move me from the faith which binds my mind with ties so many and so strong to the Christian religion. ...For my part, I should not believe the gospel except as moved by the authority of the Catholic Church.

- — St. Augustine (354–430): Against the Epistle of Manichaeus called Fundamental, chapter 4: Proofs of the Catholic Faith.[47]

In both his philosophical and theological reasoning, Augustine was greatly influenced by Stoicism, Platonism and Neoplatonism, particularly by the work of Plotinus, author of the Enneads, probably through the mediation of Porphyry and Victorinus (as Pierre Hadot has argued). Although he later abandoned Neoplatonism, some ideas are still visible in his early writings.[48] His early and influential writing on the human will, a central topic in ethics, would become a focus for later philosophers such as Schopenhauer, Kierkegaard, and Nietzsche. He was also influenced by the works of Virgil (known for his teaching on language), and Cicero (known for his teaching on argument).[49]

In the East, his teachings are more disputed, and were notably attacked by John Romanides.[50] But other theologians and figures of the Eastern Orthodox Church have shown significant approbation of his writings, chiefly Georges Florovsky.[51] The most controversial doctrine associated with him, the filioque,[52] was rejected by the Orthodox Church[53] as heretical.[citation needed] Other disputed teachings include his views on original sin, the doctrine of grace, and predestination.[52] Nevertheless, though considered to be mistaken on some points, he is still considered a saint, and has even had influence on some Eastern Church Fathers, most notably the Greek theologian Gregory Palamas.[54] In the Orthodox Church his feast day is celebrated on 15 June.[52][55] Historian Diarmaid MacCulloch has written: "[Augustine's] impact on Western Christian thought can hardly be overstated; only his beloved example Paul of Tarsus has been more influential, and Westerners have generally seen Paul through Augustine's eyes."[56]

In his autobiographical book Milestones, Pope Benedict XVI claims Augustine as one of the deepest influences in his thought.

Scholasticism

[edit]

Scholasticism is a method of critical thought which dominated teaching by the academics ("scholastics", or "schoolmen") of medieval universities in Europe from about 1100 to 1700, The 13th and early 14th centuries are generally seen as the high period of scholasticism. The early 13th century witnessed the culmination of the recovery of Greek philosophy. Schools of translation grew up in Italy and Sicily, and eventually in the rest of Europe. Powerful Norman kings gathered men of knowledge from Italy and other areas into their courts as a sign of their prestige.[57] William of Moerbeke's translations and editions of Greek philosophical texts in the middle half of the thirteenth century helped form a clearer picture of Greek philosophy, particularly of Aristotle, than was given by the Arabic versions on which they had previously relied. Edward Grant writes: "Not only was the structure of the Arabic language radically different from that of Latin, but some Arabic versions had been derived from earlier Syriac translations and were thus twice removed from the original Greek text. Word-for-word translations of such Arabic texts could produce tortured readings. By contrast, the structural closeness of Latin to Greek permitted literal, but intelligible, word-for-word translations."[58]

Universities developed in the large cities of Europe during this period, and rival clerical orders within the church began to battle for political and intellectual control over these centers of educational life. The two main orders founded in this period were the Franciscans and the Dominicans. The Franciscans were founded by Francis of Assisi in 1209. Their leader in the middle of the century was Bonaventure, a traditionalist who defended the theology of Augustine and the philosophy of Plato, incorporating only a little of Aristotle in with the more neoplatonist elements. Following Anselm, Bonaventure supposed that reason can only discover truth when philosophy is illuminated by religious faith.[59] Other important Franciscan scholastics were Duns Scotus, Peter Auriol and William of Ockham.[60][61]

Thomism

[edit]

Saint Thomas Aquinas,[62][63] an Italian Dominican friar, philosopher and priest, was immensely influential in the tradition of scholasticism, within which he is also known as the Doctor Angelicus and the Doctor Communis.[64]

Aquinas emphasized that "Synderesis is said to be the law of our mind, because it is a habit containing the precepts of the natural law, which are the first principles of human actions."[65][66]

According to Aquinas "…all acts of virtue are prescribed by the natural law, since each one's reason naturally dictates to him to act virtuously. But if we speak of virtuous acts, considered in themselves, i.e., in their proper species, not all virtuous acts are prescribed by the natural law for many things are done virtuously to which nature does not incline at first; but that, through the inquiry of reason, have been found by men to be conducive to well living." Therefore, we must determine if we are speaking of virtuous acts as under the aspect of virtuous or as an act in its species.[67]

Thomas defined the four cardinal virtues as prudence, temperance, justice, and fortitude. The cardinal virtues are natural and revealed in nature, and they are binding on everyone. There are, however, three theological virtues: faith, hope, and charity. Thomas also describes the virtues as imperfect (incomplete) and perfect (complete) virtues. A perfect virtue is any virtue with charity, which completes a cardinal virtue. A non-Christian can display courage, but it would be courage with temperance. A Christian would display courage with charity. These are somewhat supernatural and are distinct from other virtues in their object, namely, God:

Now the object of the theological virtues is God Himself, Who is the last end of all, as surpassing the knowledge of our reason. On the other hand, the object of the intellectual and moral virtues is something comprehensible to human reason. Wherefore the theological virtues are specifically distinct from the moral and intellectual virtues.[68]

Thomas Aquinas wrote: "[Greed] is a sin against God, just as all mortal sins, in as much as man condemns things eternal for the sake of temporal things."[69]

Aquinas also contributed to economic thought as an aspect of ethics and justice. He dealt with the concept of a just price, normally its market price or a regulated price sufficient to cover seller costs of production. He argued it was immoral for sellers to raise their prices simply because buyers were in pressing need for a product.[70][71]

Aquinas later expanded his argument to oppose any unfair earnings made in trade, basing the argument on the Golden Rule. The Christian should "do unto others as you would have them do unto you", meaning he should trade value for value. Aquinas believed that it was specifically immoral to raise prices because a particular buyer had an urgent need for what was being sold and could be persuaded to pay a higher price because of local conditions:

- If someone would be greatly helped by something belonging to someone else, and the seller not similarly harmed by losing it, the seller must not sell for a higher price: because the usefulness that goes to the buyer comes not from the seller, but from the buyer's needy condition: no one ought to sell something that doesn't belong to him.[72]

- — Summa Theologiae, 2-2, q. 77, art. 1

Aquinas would therefore condemn practices such as raising the price of building supplies in the wake of a natural disaster. Increased demand caused by the destruction of existing buildings does not add to a seller's costs, so to take advantage of buyers' increased willingness to pay constituted a species of fraud in Aquinas's view.[73]

Five Ways

[edit]

In his Summa Theologica and Summa contra Gentiles, Aquinas laid out five arguments for the existence of God, known as the quinque viae ("five ways").[74][75] He also enumerated five divine qualities, all framed as negatives.[76]

Impact

[edit]Aquinas shifted Scholasticism away from neoplatonism and towards Aristotle. The ensuing school of thought, through its influence on Latin Christianity and the ethics of the Catholic school, is one of the most influential philosophies of all time, also significant due to the number of people living by its teachings.

In theology, his Summa Theologica is one of the most influential documents in medieval theology and continued into the 20th century to be the central point of reference for the philosophy and theology of Latin Christianity. In the 1914 encyclical Doctoris Angelici,[77] Pope Pius X cautioned that the teachings of the Catholic Church cannot be understood without the basic philosophical underpinnings of Aquinas' major theses:

The capital theses in the philosophy of St. Thomas are not to be placed in the category of opinions capable of being debated one way or another, but are to be considered as the foundations upon which the whole science of natural and divine things is based; if such principles are once removed or in any way impaired, it must necessarily follow that students of the sacred sciences will ultimately fail to perceive so much as the meaning of the words in which the dogmas of divine revelation are proposed by the magistracy of the Church.[78]

The Second Vatican Council described Aquinas' system as the "Perennial Philosophy".[79]

Actus purus

[edit]Actus purus is the absolute perfection of God. According to Scholasticism, created beings have potentiality—that is not actuality, imperfections as well as perfection. Only God is simultaneously all that He can be, infinitely real and infinitely perfect: 'I am who I am' (Exodus 3:14). His attributes or His operations are really identical with His essence, and His essence necessitates His existence.

Lack of essence-energies distinction

[edit]Later, the Eastern Orthodox ascetic and archbishop of Thessaloniki, (Saint) Gregory Palamas argued in defense of hesychast spirituality, the uncreated character of the light of the Transfiguration, and the distinction between God's essence and energies. His teaching unfolded over the course of three major controversies, (1) with the Italo-Greek Barlaam between 1336 and 1341, (2) with the monk Gregory Akindynos between 1341 and 1347, and (3) with the philosopher Gregoras, from 1348 to 1355. His theological contributions are sometimes referred to as Palamism, and his followers as Palamites.

Historically Latin Christianity has tended to reject Palamism, especially the essence-energies distinction, some times characterizing it as a heretical introduction of an unacceptable division in the Trinity and suggestive of polytheism.[80][81] Further, the associated practice of hesychasm used to achieve theosis was characterized as "magic".[82][83] More recently, some Roman Catholic thinkers have taken a positive view of Palamas's teachings, including the essence-energies distinction, arguing that it does not represent an insurmountable theological division between Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy,[84] and his feast day as a saint is celebrated by some Byzantine Catholic churches in communion with Rome.[85][86]

The rejection of Palamism by the West and by those in the East who favoured union with the West (the "Latinophrones"), actually contributed to its acceptance in the East, according to Martin Jugie, who adds: "Very soon Latinism and Antipalamism, in the minds of many, would come to be seen as one and the same thing".[87]

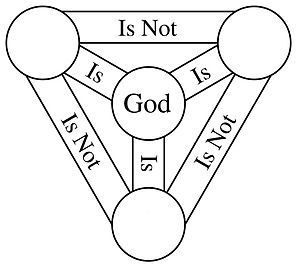

Filioque

[edit]Filioque is a Latin term added to the original Nicene Creed, and which has been the subject of great controversy between Eastern and Western Christianity. It is not in the original text of the Creed, attributed to the First Council of Constantinople (381), the second ecumenical council, which says that the Holy Spirit proceeds "from the Father", without additions of any kind, such as "and the Son" or "alone".[88]

The phrase Filioque first appears as an anti-Arian[89][90] interpolation in the Creed at the Third Council of Toledo (589), at which Visigothic Spain renounced Arianism, accepting Catholic Christianity. The addition was confirmed by subsequent local councils in Toledo and soon spread throughout the West, not only in Spain but also in the kingdom of the Franks, who had adopted the Catholic faith in 496,[91] and in England, where the Council of Hatfield imposed it in 680 as a response to Monothelitism.[92] However, it was not adopted in Rome.

In the late 6th century, some Latin churches added the words "and from the Son" (Filioque) to the description of the procession of the Holy Spirit, in what many Eastern Orthodox Christians have at a later stage argued is a violation of Canon VII of the Council of Ephesus, since the words were not included in the text by either the First Council of Nicaea or that of Constantinople.[93] This was incorporated into the liturgical practice of Rome in 1014,[94] but was rejected by Eastern Christianity.

Whether that term Filioque is included, as well as how it is translated and understood, can have important implications for how one understands the doctrine of the Trinity, which is central to the majority of Christian churches. For some, the term implies a serious underestimation of God the Father's role in the Trinity; for others, denial of what it expresses implies a serious underestimation of the role of God the Son in the Trinity.

The Filioque phrase has been included in the Creed throughout all the Latin liturgical rites except where Greek is used in the liturgy,[95][96] although it was never adopted by Eastern Catholic Churches.[97]

Purgatory

[edit]

Another doctrine of Latin Christianity is purgatory, about which Latin Christianity holds that "all who die in God's grace and friendship but still imperfectly purified" undergo the process of purification which the Catholic Church calls purgatory, "so as to achieve the holiness necessary to enter the joy of heaven". It has formulated this doctrine by reference to biblical verses that speak of purifying fire (1 Corinthians 3:15 and 1 Peter 1:7) and to the mention by Jesus of forgiveness in the age to come (Matthew 12:32). It bases its teaching also on the practice of praying for the dead in use within the church ever since the church began and which is mentioned even earlier in 2 Macc 12:46.[98][99]

The idea of purgatory has roots that date back into antiquity. A sort of proto-purgatory called the "celestial Hades" appears in the writings of Plato and Heraclides Ponticus and in many other pagan writers. This concept is distinguished from the Hades of the underworld described in the works of Homer and Hesiod. In contrast, the celestial Hades was understood as an intermediary place where souls spent an undetermined time after death before either moving on to a higher level of existence or being reincarnated back on earth. Its exact location varied from author to author. Heraclides of Pontus thought it was in the Milky Way; the Academicians, the Stoics, Cicero, Virgil, Plutarch, the Hermetical writings situated it between the Moon and the Earth or around the Moon; while Numenius and the Latin Neoplatonists thought it was located between the sphere of the fixed stars and the Earth.[100]

Perhaps under the influence of Hellenistic thought, the intermediate state entered Jewish religious thought in the last centuries before Christ. In Maccabees, we find the practice of prayer for the dead with a view to their after life purification,[101] a practice accepted by some Christians. The same practice appears in other traditions, such as the medieval Chinese Buddhist practice of making offerings on behalf of the dead, who are said to suffer numerous trials.[102] Among other reasons, Western Catholic teaching of purgatory is based on the pre-Christian (Judaic) practice of prayers for the dead.[103]

Specific examples of belief in a purification after death and of the communion of the living with the dead through prayer are found in many of the Church Fathers.[104] Irenaeus (c. 130–202) mentioned an abode where the souls of the dead remained until the universal judgment, a process that has been described as one which "contains the concept of ... purgatory".[105] Both Clement of Alexandria (c. 150–215) and his pupil Origen of Alexandria (c. 185–254) developed a view of purification after death;[106] this view drew upon the notion that fire is a divine instrument from the Old Testament, and understood this in the context of New Testament teachings such as baptism by fire, from the Gospels, and a purificatory trial after death, from St. Paul.[107] Origen, in arguing against soul sleep, stated that the souls of the elect immediately entered paradise unless not yet purified, in which case they passed into a state of punishment, a penal fire, which is to be conceived as a place of purification.[108] For both Clement and Origen, the fire was neither a material thing nor a metaphor, but a "spiritual fire".[109] The early Latin author Tertullian (c. 160–225) also articulated a view of purification after death.[110] In Tertullian's understanding of the afterlife, the souls of martyrs entered directly into eternal blessedness,[111] whereas the rest entered a generic realm of the dead. There the wicked suffered a foretaste of their eternal punishments,[111] whilst the good experienced various stages and places of bliss wherein "the idea of a kind of purgatory … is quite plainly found," an idea that is representative of a view widely dispersed in antiquity.[112] Later examples, wherein further elaborations are articulated, include St. Cyprian (d. 258),[113] St. John Chrysostom (c. 347–407),[114] and St. Augustine (354–430),[115] among others.

Pope Gregory the Great's Dialogues, written in the late 6th century, evidence a development in the understanding of the afterlife distinctive of the direction that Latin Christendom would take:

As for certain lesser faults, we must believe that, before the Final Judgment, there is a purifying fire. He who is truth says that whoever utters blasphemy against the Holy Spirit will be pardoned neither in this age nor in the age to come. From this sentence we understand that certain offenses can be forgiven in this age, but certain others in the age to come.[116]

Speculations and imaginings about purgatory

[edit]

Some Catholic saints and theologians have had sometimes conflicting ideas about purgatory beyond those adopted by the Catholic Church, reflecting or contributing to the popular image, which includes the notions of purification by actual fire, in a determined place and for a precise length of time. Paul J. Griffiths notes: "Recent Catholic thought on purgatory typically preserves the essentials of the basic doctrine while also offering second-hand speculative interpretations of these elements."[117] Thus Joseph Ratzinger wrote: "Purgatory is not, as Tertullian thought, some kind of supra-worldly concentration camp where man is forced to undergo punishment in a more or less arbitrary fashion. Rather it is the inwardly necessary process of transformation in which a person becomes capable of Christ, capable of God, and thus capable of unity with the whole communion of saints."[118]

In Theological Studies, John E. Thiel argued that "purgatory virtually disappeared from Catholic belief and practice since Vatican II" because it has been based on "a competitive spirituality, gravitating around the religious vocation of ascetics from the late Middle Ages". "The birth of purgatory negotiated the eschatological anxiety of the laity. [...] In a manner similar to the ascetic's lifelong lengthening of the temporal field of competition with the martyr, belief in purgatory lengthened the layperson's temporal field of competition with the ascetic."[119]

The speculations and popular imaginings that, especially in late medieval times, were common in the Western or Latin Church have not necessarily found acceptance in the Eastern Catholic Churches, of which there are 23 in full communion with the pope. Some have explicitly rejected the notions of punishment by fire in a particular place that are prominent in the popular picture of purgatory. The representatives of the Eastern Orthodox Church at the Council of Florence argued against these notions, while declaring that they do hold that there is a cleansing after death of the souls of the saved and that these are assisted by the prayers of the living: "If souls depart from this life in faith and charity but marked with some defilements, whether unrepented minor ones or major ones repented of but without having yet borne the fruits of repentance, we believe that within reason they are purified of those faults, but not by some purifying fire and particular punishments in some place."[120] The definition of purgatory adopted by that council excluded the two notions with which the Orthodox disagreed and mentioned only the two points that, they said, were part of their faith also. Accordingly, the agreement, known as the Union of Brest, that formalized the admission of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church into the full communion of the Roman Catholic Church stated: "We shall not debate about purgatory, but we entrust ourselves to the teaching of the Holy Church".[121]

Mary Magdalene of Bethany

[edit]

In the medieval Western tradition, Mary of Bethany the sister of Lazarus was identified as Mary Magdalene perhaps in large part because of a homily given by Pope Gregory the Great in which he taught about several women in the New Testament as though they were the same person. This led to a conflation of Mary of Bethany with Mary Magdalene as well as with another woman (besides Mary of Bethany who anointed Jesus), the woman caught in adultery. Eastern Christianity never adopted this identification. In his article in the 1910 Catholic Encyclopedia, Hugh Pope stated, "The Greek Fathers, as a whole, distinguish the three persons: the 'sinner' of Luke 7:36–50; the sister of Martha and Lazarus, Luke 10:38–42 and John 11; and Mary Magdalen.[122]

Французский ученый Виктор Саксер датируется идентификацией Мэри Магдалины как проститутки, и как Мария Бетани, к проповеди Папе Грегори Великого 21 сентября, 591 г. н.э., где он, казалось, объединил действия трех женщин, упомянутых в Новом Завете. а также идентифицировала неназванную женщину как Мэри Магдалину. В другой проповеди Грегори специально идентифицировал Мэри Магдалину как сестру Марты, упомянутой в Луки 10. [ 123 ] Но, согласно мнению, выраженной недавно богословиком Джейн Шаберг, Грегори только поступил на легенду, которая уже существовала перед ним. [ 124 ]

Идентификация Латинского христианства Марии Магдалины и Марии Бетани была отражена в расположении общего римского календаря, пока это не было изменено в 1969 году, [ 125 ] Отраслевая тот факт, что к тому времени общая интерпретация в католической церкви заключалась в том, что Мария Бетании, Мария Магдалина и грешная женщина, которая помазала ноги Иисуса, были тремя разными женщинами. [ 126 ]

Первоначальный грех

[ редактировать ]Катехизис католической церкви говорит:

Его грехом Адам , как первый человек, потерял первоначальную святость и справедливость, которую он получил от Бога не только за себя, но и для всех людей.

Адам и Ева передали своим потомкам человеческую природу, раненую их собственным первым грехом и, следовательно, лишены первоначальной святости и справедливости; Это лишение называется «Первоначальный грех».

В результате первоначального греха человеческая природа ослаблена в его силах, подверженной невежеству, страданиям и господству смерти и склонна к греху (эта склонность называется «вступление в голову»). [ 127 ]

Концепция первоначального греха была сначала упомянута во 2 -м веке Сент -Иренаем , епископом Лиона в его противоречии с определенными дуалистическими гностиками . [ 128 ] Другие отцы церкви, такие как Августин, также сформировали и разработали доктрину, [ 129 ] [ 130 ] Видя это как основанное на Новом Завете, обучение Павла Апостола ( Римлянам 5: 12–21 и 1 Коринфянам 15: 21–22 ) и в Ветхом Заветном стихе Псалма 51: 5 . [ 131 ] [ 132 ] [ 133 ] [ 134 ] [ 135 ] Тертуллиан , киприан , Амброуз и Амброзиастер считали, что человечество разделяет грех Адама, передаваемую человеческим поколением. Августина первоначального года . после Создание 412 греха Полем До 412 года Августин сказал, что свободная воля была ослаблена, но не разрушена первоначальным грехом. [ 130 ] Но после 412 это изменилось до потери свободной воли, кроме греха. [ 136 ] Современный Августинский кальвинизм считает это позже. Движение Янсениста , которое католическая церковь объявила еретической, также утверждало, что первоначальный грех разрушил свободу воли . [ 137 ] Вместо этого западная католическая церковь заявляет: «Крещение, передавая жизнь благодати Христа , стирает первоначальный грех и возвращает человека обратно к Богу, но последствия для природы, ослабленные и склонные к злу, настойчиво в человеке и призывают его к духовной битве . " [ 138 ] «Освобожденная и уменьшенная от падения Адама, свободная воля еще не разрушена в гонке». [ 139 ]

Святой Ансельм говорит: «Грех Адама был одним вещью, но грех детей при их рождении совсем другой, первая была причиной, последний - это эффект». [ 140 ] У ребенка первоначальный грех отличается от вины Адама, это одно из его последствий. Эффекты греха Адама в соответствии с католической энциклопедией:

- Смерть и страдания: «Один человек передал всю человеческую расу не только смерть тела, которая является наказанием греха, но даже сам грех, который является смертью души».

- Согласованность или склонность к греху. Крещение стирает первоначальный грех, но склонность к греху остается.

- Отсутствие освященной благодати у новорожденного ребенка также является эффектом первого греха, потому что Адам получил святость и справедливость от Бога, потерял его не только за себя, но и для нас. Крещение дает первоначальную освящающую благодать, потерянную из -за греха Адама, что устраняет первоначальный грех и любой личный грех. [ 141 ]

Восточные католики и восточное христианство, в целом, не имеют такого же богословия осени и первоначального греха, как латинские католики. [ 142 ] Но с Ватикана II в католическом мышлении наблюдалось развитие. Некоторые предупреждают против того, чтобы принимать Genesis 3 слишком буквально. Они принимают во внимание, что «Бог имел в виду Церковь перед основанием мира» (как в Ефесянам 1: 4). [ 143 ] как и в 2 Тимофею 1: 9: «... его собственная цель и благодать, которые были даны нам во Христе Иисусе до начала мира». [ 144 ] И Папа Бенедикт XVI в своей книге в начале ... называл термин «оригинальный грех» как «вводящий в заблуждение и беспрепятственный». [ 145 ] Бенедикт не требует буквальной интерпретации Бытия, или происхождения или зла, но пишет: «Как это было возможно, как это произошло? Это остается неясным. ... Зло остается таинственным. Он был представлен в великих образах, Как и глава 3 Бытия, с видением двух деревьев, змея, грешного человека ». [ 146 ] [ 147 ]

Непорочное зачатие

[ редактировать ]

Непорочное зачатие - это концепция Пресвятой свободной Девы Марии, от первоначального греха благодаря достоинствам ее Сына Иисуса . Хотя вера широко удерживалась с момента поздней античности , доктрина была догматически определена в католической церкви только в 1854 году, когда Папа Пий IX объявил, что это бывшие соборы , т. Е. Используя папскую непогрешимость, в его папском бычьем неэффективном . [ 148 ]

Признается, что доктрина, определенная Pius IX, не была явно отмечена до 12 -го века. Также согласовано, что «прямые или категориальные и строгие доказательства догмы не могут быть выдвинуты из Писания ». [ 149 ] Но утверждается, что доктрина неявно содержится в обучении отцов. Их выражения на тему безгрешности Марии, как указывается, настолько достаточно и настолько абсолютно, что их нужно взять, чтобы включить как первоначальный грех, так и фактический. Таким образом, в первые пять веков такие эпитеты, как «во всех отношениях святыми», «во всех вещах», «супер-незаконные» и «единственные святые» применяются к ней; Ее сравнивают с Евой до осени, как происхождение искупленного народа; Она «Земля до того, как она была проклята». Известные слова святого Августина (ум. 430) можно цитировать: «Что касается матери Божьей,-говорит он,-я не допущу ни один вопрос о грехе». Это правда, что он здесь говорит непосредственно о реальном или личном грехе. Но его аргумент в том, что все люди грешники; что они так через оригинальную порочность; что эта первоначальная порочность может быть преодолена Божьей милостью, и он добавляет, что он не знает, но что у Марии, возможно, было достаточно благодать, чтобы преодолеть грех «любого рода» ( Вся часть ). [ 150 ]

Бернард Клерво в 12 веке поднял вопрос о безупречном зачатии. Праздник концепции Пресвятой Девы уже начал отмечаться в некоторых церквях Запада. Сент -Бернард обвиняет каноны столичной церкви Лиона в проведении такого фестиваля без разрешения Святого Престола. При этом он принимает случай, чтобы полностью отказаться от взгляда, что концепция Марии была безгрешной, назвав это «новистью». Некоторые сомневаются, однако, использовал ли он термин «концепция» в том же смысле, в котором он используется в определении Папы Пия IX . Казалось бы, Бернард говорил о зачатии в активном смысле сотрудничества матери, потому что в своем аргументе он говорит: «Как может отсутствие греха, где есть согласование ( либидо )?» и более сильные выражения следуют, которые можно интерпретировать, чтобы указать, что он говорил о матери, а не о ребенке. Тем не менее, Бернард также осуждает тех, кто поддерживает праздник за попытку «добавить к славе Марии», что доказывает, что он действительно говорил о Марии. [ 150 ]

Богословские основы безупречного зачатия были предметом дебатов в средние века с оппозицией, предоставленными такими цифрами, как Святой Томас Аквинский , доминиканский. Тем не менее, поддерживающие аргументы францисканцев Уильяма из Уэйра и Пелбартуса Ладислаус из Темесвара , [ 151 ] и общая вера среди католиков сделала доктрину более приемлемой, так что Совет Базеля поддержал ее в 15 -м веке, но Совет Трента обошел этот вопрос. Папа Sixtus IV , францисканец, попытался успокоить ситуацию, запретив любую сторону критиковать другую, и поместил праздник безупречного зачатия в римском календаре в 1477 году, но папа Пий V , доминиканский концепции Марии. Клемент XI сделал праздник универсальным в 1708 году, но все еще не назвал его праздником безупречного зачатия. [ 152 ] Популярная и богословская поддержка концепции продолжала расти, и к 18 -м веку она была широко изображена в искусстве. [ 153 ] [ 154 ] [ 155 ] [ 156 ]

Duns Scotus

[ редактировать ]

Благословенный как Святой Бонавентура, утверждал, что Джон Данс Скот (ум. 1308), минор, с рациональной точки Грех, чтобы сказать, что она сначала заключила срок его контракта, а затем была доставлена. [ 150 ] Предлагая решение богословской проблемы примирения доктрины с проблемой универсального искупления во Христе, он утверждал, что безупречное зачатие Марии не удалило ее из искупления со стороны Христа; Скорее это был результат более совершенного искупления, предоставленного ей из -за ее особой роли в истории спасения. [ 157 ]

Аргументы Scotus, в сочетании с лучшим знакомым с языком ранних отцов, постепенно преобладали в школах Западной Церкви. В 1387 году Парижский университет решительно осудил противоположную точку зрения. [ 150 ]

Однако аргументы Скота оставались противоречивыми, особенно среди доминиканцев, которые были достаточно готовы отпраздновать Sanctificatio Марию (становятся свободными от греха), но после аргументов доминиканского Томаса Аквинского продолжали настаивать на том, чтобы ее освящение не могло произойти до после нее. концепция. [ 149 ]

Скот отметил, что безупречное зачатие Марии усиливает искупительную работу Иисуса. [ 158 ]

Аргумент Скота появляется в Декларации Папы Пия IX 1854 года о догме о безупречном зачатии «В первый момент ее зачатия Мария была сохранена свободна от пятна первоначального греха с учетом достоинств Иисуса Христа». [ 159 ] Позиция Скота была провозглашена как «правильное выражение веры апостолов». [ 159 ]

Догматически определяется

[ редактировать ]Полная определенная догма непорочного зачатия гласит:

Мы объявляем, произносим и определяем, что доктрина, которая утверждает, что самая благословенная Дева Мария, в первую очередь ее концепции, единственной благодати и привилегией, предоставленными Всемогущим Богом, с учетом достоинств Иисуса Христа, Спасителя Человеческая раса, была сохранена свободна от всех пятен первоначального греха, является доктриной, раскрытой Богом и, следовательно, будет верить твердо и постоянно всеми верующими. [ 160 ] Заявитель и определить доктрину, которая удерживает, благословенная девственница Мария в первом момент его концепции была единственная всемошняя благодать Божьи и привилегию, ввиду человеческой расы, от всей первоначальной ошибки распада бессознательного, от Бога, Бога, Бога, Бога, Бога, Бога, Бога, от Бога, Бога раскрыта и, следовательно, Богом все верующие твердо постоянно верили. Таким образом, если они иначе и нами.

Папа Пий IX явно подтвердил, что Мария была выкуплена более возвышенным. Он заявил, что Мария, вместо того, чтобы быть очищенной после греха, была полностью помешана сократить первоначальный грех ввиду предвидящих достоинств Иисуса Христа, Спасителя человеческой расы. В Луки 1:47 Мария заявляет: «Мой дух радовался Богу, мой Спаситель». Это называется предварительным восстановлением Марии Христом. После второго совета апельсина против полупелагианства католическая церковь учила, что даже человек никогда не согрешил в Эдемском саду и был безгрешным, он все равно потребовал бы, чтобы Божья благодать оставалась безгрешной. [ 161 ] [ 162 ]

Определение касается только первоначального греха, и оно не делает заявления о убеждении Церкви, что благословенная девственница была безгрешной в смысле свободы от реального или личного греха. [ 150 ] Доктрина учит, что из ее зачатия Мария, всегда свободная от первоначального греха, получила освящающую благодать , которая обычно приходит с крещением после рождения.

Восточные католики и восточное христианство, в целом, считают, что Мария была безгрешной , но у них нет такого же богословия осени и первоначального греха, как латинские католики. [ 142 ]

Предположение о Марии

[ редактировать ]

Предположение о Марии в небеса (часто сокращается до предположения ) - это телесное занятие Девы Марии на небеса в конце ее земной жизни.

1 ноября 1950 года в Апостольской конституции Munifcentissimus deus папа Пий XII объявил о предположении Марии как догмы:

Властью нашего Господа Иисуса Христа, благословенных апостолов Петра и Павла, и нашей собственной властью, мы произносим, объявляем и определяем это как божественно раскрытая догма: что Непорочная Мать Бога, вечно Дева Мария, Завершив курс своей земной жизни, было предполагаемое тело и душу в небесную славу. [ 163 ]

В догматическом заявлении Пия XII фраза «завершила ход своей земной жизни», оставляет открытой вопрос о том, умерла ли Дева Мария до своего предположения или нет. Говорят, что предположение Марии было божественным даром для нее как «матери Божьей». Людвиг Отт считает, что, когда Мэри завершила свою жизнь в качестве яркого примера для человеческой расы, перспектива дара предположения предлагается всей человеческой расе. [ 164 ]

Людвиг Отт пишет в своей книге «Основы католической догмы» , что «факт ее смерти почти общепризнан отцами и богословами, и явно подтверждается в литургии церкви», к которой он добавляет ряд полезных цитат. Он приходит к выводу: «Ибо Мария смерть, в результате ее свободы от первоначального греха и личного греха, не была следствием наказания греха. Однако кажется уместным, что тело Марии, которое было по природе смертным, должно быть, в Соответствие с ее божественным сыном , в зависимости от общего закона смерти ». [ 165 ]

Смысл ее телесной смерти не была непогрешимо. Многие католики считают, что она вообще не умерла, но была предполагалась прямо на небеса. Догматическое определение в рамках апостольской конституции Munifcentissimus deus , которое, согласно римско -католической догме, непогрешимо провозглашает доктрину того, что предположение оставляет открытым вопрос о том, подвергла ли Мария смерть. Это не догматически определяет точку, так или иначе, как показано словами «завершив ход своей земной жизни». [ 166 ]

До догматического определения в Deiparae virginis mariae pipe pius xii искали мнение католических епископов. Большое количество из них указывало на книгу Бытия ( 3:15 ) в качестве Священной поддержки догмы. [ 167 ] В Munificentissimus deus как в Бытии 3:15 и «завершить победу над грехом и смерть (пункт 39) Пий XII сослался на «борьбу против адского врага» , Мария, которую предполагают на небеса, как в 1 Коринфянам 15:54 : «Тогда приступит к выступлению, написанное, написанное, смерть поглощена победой». [ 167 ] [ 168 ]

Предположение против общежития

[ редактировать ]Западный праздник этого предположения отмечается 15 августа, а восточные православные и католики общежитие матери отмечают греческие Божьей 14-дневный быстрый период. Восточные христиане считают, что Мария умерла естественной смертью, что ее душа была принята Христом после смерти, и что ее тело было воскрешено на третий день после ее смерти и что она была вовлечена в небеса в ожидании общего воскресения . Ее гробница была найдена пустой на третий день.

Православная традиция ясна и непоколебима в отношении центральной точки [общежития]: Святая Дева перенесла, как и ее сын, физическая смерть, но ее тело - как его - впоследствии воскрес из мертвых, и она была взята в небеса, в ее теле, а также в ее душе. Она вышла за рамки смерти и суждения, и живет полностью в будущем. Воскресение тела ... в ее случае ожидалось и уже является опытным фактом. Это не означает, однако, что она диссоциирована от остальной части человечества и помещена в совершенно другую категорию: поскольку мы все надеемся поделиться однажды в той же славе воскресения тела, которое она наслаждается даже сейчас. [ 169 ]

Многие католики также считают, что Мэри впервые умерла до того, как ее предположили, но они верят, что она чудесным образом воскресила, прежде чем быть принято. Другие считают, что она была принята телесным на небеса, не умирая. [ 170 ] [ 171 ] Любое понимание может быть законно проведено католиками, а восточные католики наблюдают за праздником как общежитие.

Многие богословы отмечают в качестве сравнения, что в католической церкви это предположение определяется догматически, в то время как в восточной православной традиции общежитие менее догматически, чем литургически и мистически определено. Такие различия возникают от более широкой схемы в двух традициях, в которых католические учения часто догматически и авторитетно определены - отчасти из -за более централизованной структуры католической церкви - в то время как в восточной православии многие доктрины менее авторитетны. [ 172 ]

Древние дни

[ редактировать ]

Древние дни - это имя Бога , которое появляется в книге Даниила .

В ранней венецианской школьной коронации девственницы Джованни д'Алеманья и Антонио Виварини ( ок. 1443 ), Бог Отец показывается в представлении, последовательно используемом другими художниками, а именно в качестве патриарха, с доброкачественным, но мощным лицом и с длинными белыми волосами и бородой, изображением, в основном полученным и оправданным описанием древних дней в Ветхом Завете , ближайшего подхода к физическому описанию Бога в Ветхом Завете: [ 173 ]

... Древние дни сидели, чья одежда была белой, как снег, а волосы его головы, как чистая шерсть: его трон был похож на огненное пламя, а его колеса как горящий огонь. ( Даниил 7: 9)

Сент -Томас Аквинский вспоминает, что некоторые выдвигают возражение о том, что древние дни соответствуют человеку Отца, не обязательно соглашая с этим заявлением. [ 174 ]

К двенадцатому веку изображения фигуры Божьей Отца, по сути, основанным на древних днях в книге Даниила , начали появляться во французских рукописях и в окнах церкви из витража в Англии. В 14 -м веке иллюстрированная Библия Неаполя имела изображение Бога отца в горящем кустах . К 15 веку в Книге часов Рохана была изображения Бога отца в человеческой форме или антропоморфных образах, и ко времени художественных представлений о возрождении Бога, отец свободно использовался в западной церкви. [ 175 ]

Художественные изображения Бога Отец были бесспорными в католическом искусстве после этого, но менее распространенные изображения Троицы были осуждены. В 1745 году Папа Бенедикт XIV явно поддержал трон изображения милосердия все еще необходимо , ссылаясь на «древние дни», но в 1786 году папу Пий VI выпустить папского быка , осуждающий решение итальянского церковного совета об устранении всех изображений Троицы из церквей. [ 176 ]

Описание остается редким и часто спорным в восточном православном искусстве. восточной православной церкви В гимнах и иконах древние дни наиболее правильно отождествляются с Богом Сыном или Иисусом, а не с Богом, Отцом. Большинство отцов восточной церкви, которые комментируют проход в Даниил (7: 9–10, 13–14), интерпретировали пожилую фигуру как пророческое откровение Сына перед его физическим воплощением. [ 177 ] Таким образом, восточное христианское искусство иногда изображает Иисуса Христа как старика, древний дни, чтобы символически показать, что он существовал от всей вечности, а иногда как молодой человек или мудрый ребенок, чтобы изобразить его, как он был воплощен. Эта иконография появилась в 6 -м веке, в основном в Восточной империи с пожилыми изображениями, хотя обычно не должным образом или специально идентифицируется как «древние дни». [ 178 ] Первые образы древних дней, названные так, названные над надписью, были разработаны иконографы в разных рукописках, самые ранние из которых датируются 11 -м веком. Изображения в этих рукописях включали надпись «Иисус Христос, древние дни», подтверждая, что это был способ идентифицировать Христа как предварительного эфира с Богом Отцом. [ 179 ] Действительно, позже она была объявлена русской православной церковью в Великом Синоде Москвы в 1667 году, что древние дни были сыном, а не отцом. [ 180 ]

Социальные и культурные проблемы

[ редактировать ]Дело о сексуальном насилии

[ редактировать ]С 1990 -х годов вопрос о сексуальном насилии над несовершеннолетними со стороны западного католического духовенства и других членов церкви стала предметом гражданского судебного разбирательства, уголовного преследования, освещения в средствах массовой информации и общественных дебатов в странах мира . Западная католическая церковь подверглась критике за его обращение с жалобами на злоупотребления, когда стало известно, что некоторые епископы защитили обвиняемых священников, передавая их на другие пастырские задания, где некоторые продолжали совершать сексуальные преступления.

В ответ на скандал были созданы официальные процедуры, чтобы помочь предотвратить злоупотребление, поощрять отчет о любом происходящем злоупотреблении и быстро обрабатывать такие отчеты, хотя группы, представляющие жертв, оспаривали их эффективность. [ 181 ] В 2014 году Папа Франциск внедрил Папскую комиссию по защите несовершеннолетних за защиту несовершеннолетних от злоупотреблений. [ 182 ]

Смотрите также

[ редактировать ]- Ранняя африканская церковь

- Контрреформация

- Латинская церковь на Ближнем Востоке

- Латинские литургические обряды

- Джеймс Великий#Испания

- Пол Апостол#Путешествие из Рима в Испанию

- Святой Петр#Связь с Римом

- Общий римский календарь

- Восточный -Западный раскол

Примечания

[ редактировать ]- ^ Термин римско-католическая церковь также используется для обозначения католической церкви в целом, особенно в некатолическом контексте, а также иногда используется в отношении Латинской церкви по отношению к восточной католической церкви. "Знаете ли вы различия между римскими, византийскими католическими церквями?" Полем Компас . 2011-11-30. Архивировано из оригинала 2023-04-16 . Получено 2021-04-08 .

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ Маршалл, Томас Уильям (1844). Примечания епископальной политики Святой католической церкви . Лондон: Леви, Россен и Франклин.

- ^ Макализ, Мэри (2019). Права и обязательства детей в каноническом законодательстве: контракт на крещение . Brill Publishers . ISBN 978-90-04-41117-3 .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Андерсон, Джон (7 марта 2019 г.). «Прекрасное свидетельство восточных католических церквей» . Католический геральд . Архивировано с оригинала 29 сентября 2019 года . Получено 29 сентября 2019 года .

- ^ Тернер, Пол (2007). Когда другие христиане становятся католиками . Литургическая пресса. п. 141. ISBN 978-0-8146-6216-8 Полем

Когда другие христиане становятся католиками: человек становится восточным католиком, а не римско -католиком

- ^ Fortescue, Adrian (1910). "Латинская церковь" " . Католическая энциклопедия .

Без сомнения, дальнейшей расширением римской церкви может использоваться как эквивалентная латинской церкви для патриархата

- ^ Фарис, Джон Д. (2002). «Латинская церковь суи -иурис » . Юрист . 62 : 280.

- ^ Ашни, Ал; Сантош Р. (декабрь 2019). «Католическая церковь, рыбаки и переговоры о развитии: исследование проекта порта Вичинджам» . Обзор разработки и перемен . 24 (2): 187–204. doi : 10.1177/09722666119883165 . ISSN 0972-2661 . S2CID 213671195 .

- ^ Тернер, Пол (2007). Когда другие христиане становятся католиками . Литургическая пресса. п. 141. ISBN 978-0-8146-6216-8 Полем

Когда другие христиане становятся католиками: человек становится восточным католиком, а не римско -католиком

- ^ Манчини, Марко (2017-08-11). «Патриарх Запада? Нет, спасибо, сказал Бенедикт XVI» [Патриарх Запада? Нет, спасибо, сказал Бенедикт XVI]. ACI Stampa (на итальянском языке). Ватикан . Получено 2023-11-28 .

- ^ Fortescue, Adrian (1914). Уорд, Бернард; Терстон, Герберт (ред.). Месса: изучение римской литургии . Вестминстерская библиотека (новое изд.). Лондон: Longmans, Green and Co. p. 167

- ^ "Cceo, Canon 27" . W2.vatican.Va . Получено 1 апреля 2019 года .

- ^ Cceo, Canon 28 §1

- ^ «Кодекс канонического права, каноны 383 §2» . Священное Престол . Получено 1 апреля 2019 года .

- ^ 450 §1

- ^ 476

- ^ 479 §2

- ^ 1021

- ^ Rite , Merriam Webster Dictionary, 3 октября 2023 г.

- ^ Rite , Collins English Dictionary

- ^ «Глоссарий церковных терминов» . USCCB.org . Архивировано из оригинала 6 июля 2013 года . Получено 1 апреля 2019 года .

- ^ Папа 6 (1964-11-21). «Указ на восточный обряд восточных церквей » . Рим.

- ^ Восточные церкви 10

- ^ Бассетт, Уильям У. (1967). Определение обряда, исторического и юридического исследования . Analecta Gregoriana. Тол. 157. Рим: издательство Грегорианского университета. п. 73. ISBN 978-88-7652129-4 .

- ^ «Классификация Библиотеки Конгресса - KBS Таблица 2» (PDF) . loc.gov . Получено 1 апреля 2019 года .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный

Fortescue, Adrian (1910). « Латинская церковь ». В Гербермане, Чарльз (ред.). Католическая энциклопедия . Нью -Йорк: Роберт Эпплтон Компания.

Fortescue, Adrian (1910). « Латинская церковь ». В Гербермане, Чарльз (ред.). Католическая энциклопедия . Нью -Йорк: Роберт Эпплтон Компания.

- ^ Rowland, Tracey (2008). Вера Ратцингера: богословие Папы Бенедикт XVI . Издательство Оксфордского университета. ISBN 9780191623394 Полем Получено 24 ноября 2017 года .

- ^ «Коды канонического права - архив» . Священное Престол . Получено 1 апреля 2019 года .

- ^ "Кодекс Canon Law, Canon 889 §2" . Священное Престол . Получено 1 апреля 2019 года .

- ^ "Кодекс канонического права, Canon 913 §1" . Священное Престол . Получено 1 апреля 2019 года .

- ^ «Кодекс канонов восточных церквей, каноны 695 §1 и 710» . W2.vatican.Va . Получено 1 апреля 2019 года .

- ^ "Кодекс канонического права, Canon 277 §1" . Священное Престол . Получено 1 апреля 2019 года .

- ^ « Группы Англии , 6 §§1-2» . W2.vatican.Va . Получено 1 апреля 2019 года .

- ^ "Кодекс Canon Law, Canon 1042" . Священное Престол . Получено 1 апреля 2019 года .

- ^ "Кодекс Canon Law, Canon 1087" . Священное Престол . Получено 1 апреля 2019 года .

- ^ Тесель, Юджин (1970). Августин богослов . Лондон С. 347–349 . ISBN 978-0-223-97728-0 .

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) 2002: ISBN 1-57910-918-7 . - ^ Уилкен, Роберт Л. (2003). Дух раннего христианского мышления . Нью -Хейвен: издательство Йельского университета . п. 291. ISBN 978-0-300-10598-8 .

- ^ Дюрант, Уилл (1992). Цезарь и Христос: история римской цивилизации и христианства от их начала до 325 г. н.э. Нью -Йорк: Книги MJF. ISBN 978-1-56731-014-6 .

- ^ Августин, признания, книга 7.9.13–14

- ^ De Emermortitation Animae of Augustine: текст, перевод и комментарий, святой Августин (епископ бегемота), CW Wolfskeel, Введение

- ^ 1 Иоанна 1:14

- ^ Приобрести преимущества Isked I, статья Down Runia

- ^ Афинцы, Афинагор. «Призыв к христиан» . Новое Адвент.

- ^ Флинн, Фрэнк К. и Мелтон, Дж. Гордон (2007) Энциклопедия католицизма . Факты по файлам энциклопедии мировых религий. 978-0-8160–5455-8 ) , с. 4

- ^ Кристин, Лукер (1985) Аборт и политика материнства . Калифорнийский университет. ISBN 978-0-5209-0792-8 ), с. 12

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Бауэршмидт, Джон С. (1999). "Аборт" . В Фицджеральде, Аллан Д. (ред.). Августин на протяжении веков: энциклопедия . Wm B Eerdmans. п. 1. ISBN 978-0-8028-3843-8 .

- ^ Уважение к нерожденной человеческой жизни: постоянное учение церкви . Американская конференция католических епископов

- ^ «ГЛАВА 5. - Среди названия Послания Манихуса» . Христианская классика Эфирная библиотека . Получено 21 ноября 2008 года .

- ^ Рассел , Книга II, Глава IV

- ^ Мендельсон, Майкл (2000-03-24). "Святой Августин" . Стэнфордская энциклопедия философии . Получено 21 декабря 2012 года .

- ^ «Некоторые основные должности этого сайта» . www.romanity.org . Получено 2015-09-30 .

- ^ «Пределы церкви» . www.fatheralexander.org . Получено 2015-09-30 .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в Papademetriou, Джордж С. "Святой Августин в греческой православной традиции" . goarch.org архивировал 5 ноября 2010 года на машине Wayback

- ^ Siecienski, Энтони Эдвард (2010). Филиоке: История доктринального спора . Издательство Оксфордского университета. С. 53–67. ISBN 978-0195372045 .

- ^ Каппес, Кристиан (2015-09-30). «Использование Грегори Паламас де-тринитат для первоначального греха и его применения к паламитико-аугустинианству Theotokos & Scholarius (Стокгольм 28.vi.15)» (документ). Стокгольмский университет издательство.

- ^ Архимандрит . «Обзор книги: место благословенного Августина в православной церкви » . Православная традиция . II (3 и 4): 40–43. Архивировано из оригинала 10 июля 2007 года . Получено 28 июня 2007 года .

- ^ Диармиид МакКаллох (2010). История христианства: первые три тысячи лет . Книги пингвинов. п. 319. ISBN 978-0-14-102189-8 .

- ^ Линдберг, Дэвид С. (1978). Наука в средние века . Чикаго: Университет Чикагской Прессы. С. 70–72. ISBN 978-0-226-48232-3 .

- ^ Грант, Эдвард и почетный Эдвард Грант. Основы современной науки в средние века: их религиозные, институциональные и интеллектуальные контексты. Издательство Кембриджского университета, 1996, 23–28

- ^ Хаммонд, Джей; Хеллманн, Уэйн; Гофф, Джаред, ред. (2014). Компаньон в бонавентуре . Брилл -спутники христианской традиции. Тол. 48. Брилл. п. 122. doi : 10.1163/9789004260733 . ISBN 978-90-04-26072-6 .

- ^ Эванс, Джиллиан Розмари (2002). Пятьдесят ключевых средневековых мыслителей . Руководство с ключевыми направляющими. Routledge. С. 93, 147–149, 164–169. ISBN 9780415236638 .

- ^ Грация, Хорхе Дже; Никто, Тимоти Б., ред. (2005). Компаньон философии в средние века . Джон Уайли и сыновья. С. 353–369, 494–503, 696–712. ISBN 978-0-631-21673-5 .

- ^ Воган, Роджер Беде (1871). Жизнь и труды Святого Томаса Аквин . Тол. 1. Лондон.

{{cite book}}: CS1 Maint: местоположение отсутствует издатель ( ссылка ) - ^ Conway, Placid (1911). Святой Томас Аквинский . Святые. Тол. 1. Лондон: Лонгманс, Грин и Ко.

- ^ См. Pius XI, Studiorum Ducem 11 (29 июня 1923 г.), AAS, XV («Non Modo Angelicum, Sed Etiam Communem Seu Universalem Ecclesiae Doctorem»). Титул Доктор Коммунис датируется четырнадцатым веком; Название Доктор Ангельс датируется пятнадцатым веком, см. Вальц, Ксения Томистика , III, с. 164 н. 4. Толомео да Лучка пишет в Истории Экклесиастца» человек является высшим среди современных учителей философии и богослови « (1317): « Этот Назовите его доктором Communis из -за выдающейся ясности его учения ». Historia Eccles. xxiii, c. 9

- ^ Лэнгстон, Дуглас (5 февраля 2015 г.). «Средневековые теории совести» . В Залте, Эдвард Н. (ред.). Стэнфордская энциклопедия философии (осень 2015 года изд.). Исследовательская лаборатория метафизики, Стэнфордский университет.

- ^ Summa Theologica, первая часть второй части, вопрос 94 Ответ OBJ. 2

- ^ Summa Вопрос 94, A.3

- ^ « Summa , Q62A2» . Ccel.org . Получено 2012-02-02 .

- ^ Summa Theologica , вторая часть второй части, вопрос 118, статья 1. Получено 26 октября 2018 года.

- ^ Томас Аквинский. Summa Theologica. «Обман, который совершается в покупке и продаже». Перевод отцов английской доминиканской провинции [1] Получено 19 июня 2012 г.

- ^ Барри Гордон (1987). «Аквинский, Сент -Томас (1225–1274)», т. 1, с. 100

- ^ Если, однако, многому поможет предмет другого, чем он получил, но тем, кто продал, не был проклят, заряжая его, это не должно его превзойти. Поскольку полезность другого начисления связана не с продажи, а из -за условий покупки, никто не должен продавать другого, который не является его собственным. Полем Полем

- ^ Аквинский, Summa Theologica , 2ª-2ae q. 77 Pr. « Теперь мы рассматриваем грехи, которые касаются добровольных изменений. Во -первых, мошенничество, которое начинается с покупок и продаж ... »

- ^ «Summa Theologica: существование Бога (первая часть, Q. 2) » . Новое Адвент .

- ^ Сумма богословия I, Q.2, Пять способов философов доказали существование Бога

- ^ Рак, стр. 74–112.

- ^ «Доктор Анжеличи» . Архивировано из оригинала 31 августа 2009 года . Получено 4 ноября 2009 года . Доступ 25 октября 2012 г.

- ^ Папа Пий 10 , ангельский доктор , 29 июня 1914 года.

- ^ Второй Ватиканский совет , Опел (28 октября 1965 г.) 15.

- ^ Джон Мейендорф (редактор), Грегори Паламас - Триады , с. xi. Paulist Press, 1983, ISBN 978-0809124473 , хотя это отношение никогда не было повсеместно распространено в католической церкви и было еще более широко критиковано в католической богословии за прошлый век (см. Раздел 3 этой статьи). Получено 12 сентября 2014 года.

- ^ «Без сомнения, лидеры партии, удерживаемые в стороне от этих вульгарных практик более невежественных монахов, но, с другой стороны Восприятие Божественности. Барлаам, от GICEPHORUS GREGORAS и Acthyndinus. Отцы церкви «и его писания были провозглашены« непогрешимым руководством христианской веры ». Саймон Вайлхе (1909). «Греческая церковь» . Католическая энциклопедия, Нью -Йорк: компания Роберта Эпплтона.

- ^ Fortescue, Adrian (1910), Hesychasm , Vol. VII, Нью-Йорк: компания Robert Appleton , извлеченная 2008-02-03

- ^ «Без сомнения, лидеры партии, удерживаемые в стороне от этих вульгарных практик более невежественных монахов, но, с другой стороны Восприятие Божественности. Барлаам, от GICEPHORUS GREGORAS и Acthyndinus. Отцы церкви «и его писания были провозглашены« непогрешимым руководством христианской веры ». Саймон Вейлхе, «Греческая церковь» в католической энциклопедии (Нью -Йорк: Роберт Эпплтон Компания, 1909)

- ^ Майкл Дж. Кристенсен, Джеффри А. Виттунг (редакторы), причастники божественной природы (Associated University Preses 2007 ISBN 0-8386-411-3 ), стр. 243-244

- ^ Поиск священной тишины (melkite.org)

- ^ Второе воскресенье великого быстрого Грегори Паламас (SSPP.CA)

- ^ «Мартин Юги, паломная спор» . 13 июня 2009 г. Получено 2010-12-27 .

- ^ Реформатская церковь в Америке. Комиссия по богословию (2002). «Никейский вероисповедание и процессия духа» . В Кук, Джеймс I. (ред.). Церковь говорит: документы Комиссии по богословии, Реформатская церковь в Америке, 1959–1984 . Историческая серия реформатской церкви в Америке. Тол. 40. Гранд -Рапидс, MI: Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-80280980-3 .

- ^ Дейл Т. Ирвин, Скотт Санквист, История Мирового Христианского движения (2001) , том 1, с. 340

- ^ Дикс, форма литургии (2005), с, 487

- ^ Преобразование CLOVIS

- ^ Пеплент, «Филиоке» у Джона Энтони МакГакин, Энциклопедия восточного православного христианства (Wiley, John & Sons 2011 978-1-4051-8539-4 ) , Vol. 1, с. 251

- ^ Для другого взгляда, см. EG Excursus об словах веры

- ^ «Греческие и латинские традиции на Святого Духа» . Ewtn.com .

- ^ Папский совет по продвижению христианского единства: греческие и латинские традиции относительно процессии Святого Духа и того же документа на другом сайте

- Римский миссал , Синодический комитет божественного поклонения 2005, i, p. 347

- ^ Статья 1 Договора о Бресте

- ^ Катехизис католической церкви, «окончательная очистка или чистилище»

- ^ "Пий IV Совет Трента-25" . www.ewtn.com .

- ^ Адриан Михай, «Аид Небесный.

- ^ ср . 2 Maccabees 12: 42–44

- ^ Чистилище в Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Катехизис католической церкви , 1032

- ^ Джеральд О'Коллинс и Эдвард Г. Фаррудж, Краткий словарь богословия (Эдинбург: T & T Clark, 2000) с. 27

- ^ Christian Dogmatics vol. 2 (Филадельфия: Fortress Press, 1984) с. 503; ср. Irenaeus, против ереси 5.31.2, в анте-отцах . Александр Робертс и Джеймс Дональдсон (Гранд -Рапидс: Eerdmans, 1979) 1: 560 ср. 5.36.2 / 1: 567; ср. Джордж Кросс, «Дифференциация римских и греческих католических взглядов на будущую жизнь», в библейском мире (1912) с. 107

- ^ Джеральд О'Коллинс и Эдвард Г. Фаррудж, Краткий словарь богословия (Эдинбург: T & T Clark, 2000) с. 27; ср. Адольф Харнак, История догмы, вып. 2, транс. Нил Бьюкенен (Лондон, Williams & Norgate, 1995) с. 337; Клемент Александрии, Стромата 6:14

- ^ Жак Ле Гофф, Рождение Чистилища (Университет Чикагской Прессы, 1984) с. 53; ср. Левит 10: 1–2 , Второзаконие 32:22 , 1Corinthians 3: 10–15

- ^ Адольф Харнак , История догмы, том. 2, транс. Нил Бьюкенен (Лондон: Williams & Norgate, 1905) с. 377. Читать онлайн .

- ^ Жак Ле Гофф, Рождение Чистилища (Университет Чикагской Прессы, 1984) с. 55–57; ср. Клемент Александрийской, Стромата 7: 6 и 5:14